Udvalget for Fødevarer, Landbrug og Fiskeri 2011-12

FLF Alm.del Bilag 343

Offentligt

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

This report has been prepared with the financial support of the European Commission.The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of theEuropean Commission or of its services.The content of this report may not be reproduced, or even part thereof, without explicit reference to the source.POSEIDON, MRAG, COFREPECHE & NFDS, 2012. - Ex-post evaluation of the current Protocol to theFisheries Partnership Agreement between the European Union and Republic of Kiribati, and ex-anteevaluation including an analysis of the impact of the future Protocol on sustainability, Framework contractMARE/2011/01 - Lot 3, specific contract n�01. Final report: final version, May 2012. Bruxelles, 138 p.COFREPECHE: 32 rue de Paradis, 75010 Paris, France.[email protected]Version: Final Report,final versionReport ref: KIR95R01E1Number of pages: 138 (all included)Date issued: 21 May 2012

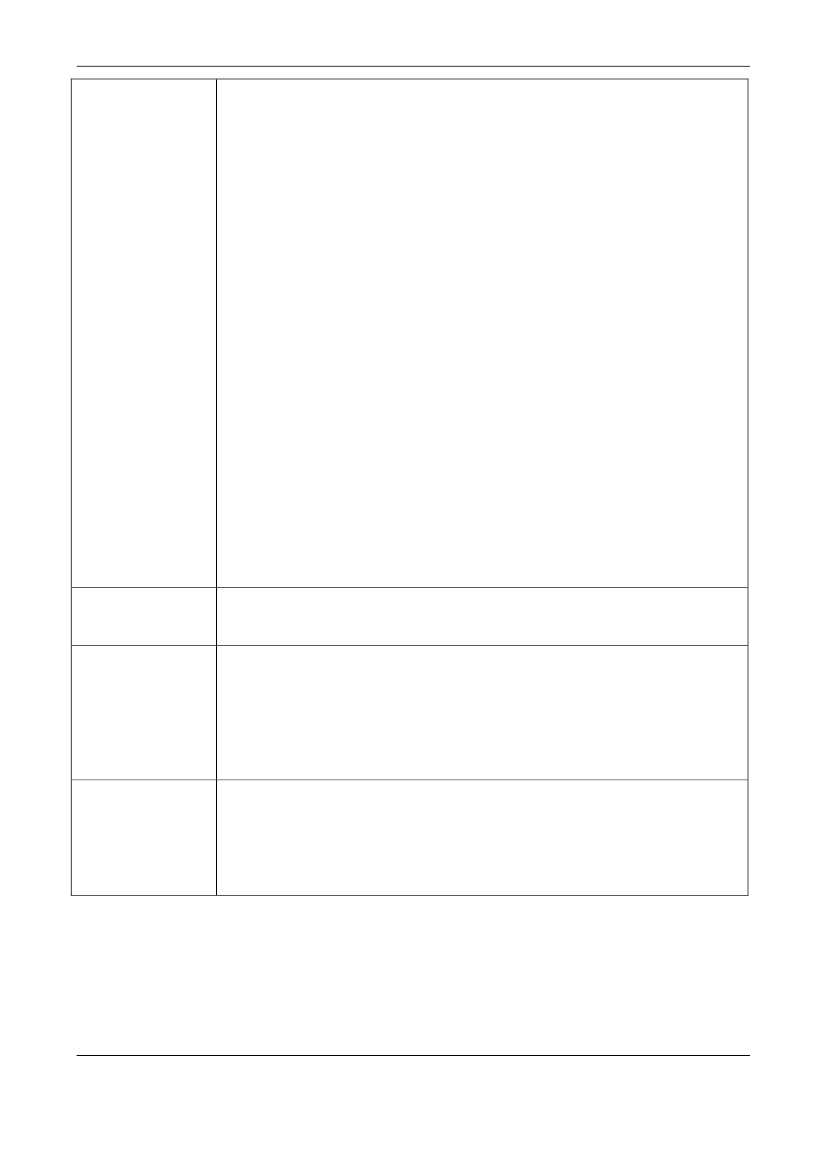

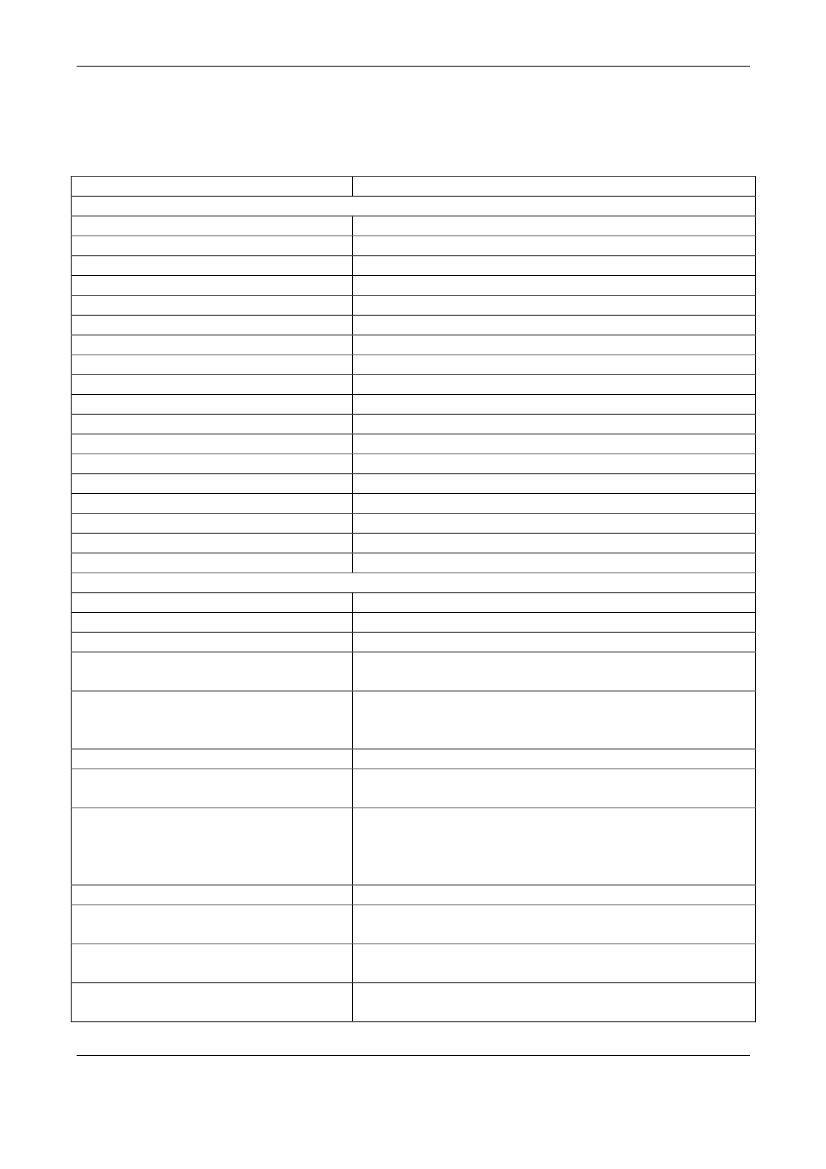

ActionAuthors

SURNAMEMACFADYEN

First nameGraeme

OrganisationPositionPOSEIDONDirector /Team leader - Fisheries economistPOSEIDONDirector /Fisheries economistMRAGManaging Director /Senior fisheries expertPOSEIDONDirectorCOFREPECHEProject officersCOFREPECHEProjects DirectorCOFREPECHEDeputy Managing Director

CategoryI

BANKS

Richard

I

Peer review(draft final report)Proof readingEditionApprovalValidation

MEES

Chris

I

HUNTINGTONPICAULTLE FOLDEFAUXSILVA

TimDavidGwendalVincentJean-Pierre

IIIII

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage iEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

Acronyms and abbreviationsACPADBAFADAERALCAUS$B/CBETCCMCCSCFPCICIFCMMCNMCPPLAfrican, Caribbean and PacificAsian Development BankAnchored FADAnnual Economic ReportAutomatic Location CommunicatorAustralian DollarBenefit/costBigeye TunaCommission Cooperating MemberCatch Certificate SchemeCommon Fisheries PolicyConservation InternationalCarriage Insurance and FreightinsINTERCOITIUUJCKDPkglbLDCMCSMDGSMFEDMFMRDmmmnMoUMPAMSYMTCMTUMYNEAOFPOPAGACORTHONGELPACPPAEPIPAPNAPNAOPNGPROCFISHRERFInchesInternational Code of SignalsInformation TechnologyIllegal, Unregulated or UnreportedJoint CommitteeKiribati Development PlanKilogrammesPoundsLesser Developing CountryMonitoring, Control and SurveillanceMillennium Development GoalsMinistry of Finance and EconomicDevelopmentMinistry of Fisheries and MarineResources DevelopmentmillimetersmillionMemorandum of UnderstandingMarine Protected AreaMaximum Sustainable YieldMinimum Terms and ConditionsMobilisation Transmission UnitManagement YearNew England AquariumOceanic Fisheries ProgrammeOrganización de Productores Asociadosde Grandes Atuneros CongeladoresOrganisation de Producteurs de ThonCongeléPacific ACPsParty Allowable EffortPhoenix Islands Protected AreaParties to the Nauru AgreementParties to the Nauru Agreement OfficePapua New GuineaPacific Regional Coastal FisheriesDevelopment ProgrammeRevenue Equalisation Reserve Fund

Conservation and Management MeasuresCommission Non Cooperating MemberCentral Pacific Producers LimitedCommittee of Representatives ofCRGAGovernments and AdministrationsCRISP Coral Reef Initiative for the PacificDCFData Collection FrameworkDCRData Collection RegulationDEVFI The Development of Tuna Fisheries in theSHPacific ACP Countries ProjectDFADDGMAREDWFNEAFMEBITECEDFEEZENSOEPEPAEPODrifting FADDirectorate General for Maritime Affairsand FisheriesDistant Water Fishing NationsEcosystem Approach to FisheriesManagementEarnings Before Interest and TaxEuropean CommissionEuropean Development FundExclusive Economic ZoneEl Niño Southern OscillationEuropean ParliamentEconomic Partnership AgreementEastern Pacific Ocean

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage iiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

EUFFADFAMEFAOFFAFFCFMISFMSYFOBFPAFSMFSMAFTEGATTGDPGSPHSHSPIAIATTCIEOIEPAIMF

European UnionFishing mortalityFish Aggregation DeviceFisheries, Aquaculture and MarineEcosystemsFood and Agriculture OrganisationForum Fisheries AgencyForum Fisheries CommissionFisheries Monitoring Information SystemFishing mortality rate that would giveMaximum Sustainable YieldFree OnBoardFisheries Partnership AgreementFederated States of MicronesiaFSM ArrangementFull Time EquivalentGeneral Agreement on Tariffs and TradeGross Domestic ProductGeneralised System Of PreferencesHigh SeasHigh Seas PocketsImplementing AgreementInter-American Tropical Tuna CommissionInsituto Español oceanograficoInterim Economic Partnership AgreementInternational Monetary Fund

Regional Fisheries ManagementOrganisationRMIRepublic of the Marshall IslandsScientific Support for the ManagementSCICOFISH of Coastal and Oceanic Fisheries in thePacific Islands RegionSEAPODY Spatial Ecosystem and PopulationsMDynamics ModelSIDSSmall island developing statesRFMOSJKSMACFishSOESPCTAETCCTUFMAWUNICEFUNFSAUS$USLMTVDSVDSCVMSWCPWCPFCWCPOWTOYFTSkipjack TunaSustainable Management of Aquacultureand Coastal Fisheries in the PacificRegion for Food Security and Small-scale LivelihoodsState Owned EnterpriseSecretariat of the Pacific CommunityTotal Allowable EffortTechnical and Science CommitteeTuna Fisheries Database ManagementSystemUnited Nations International Children'sEmergency FundUnited Nations Fish Stocks AgreementUnited States DollarUnited States Multi-Lateral TreatyVessel Day SchemeVessel Day Scheme CommitteeVessel Monitoring SystemWestern Central PacificWestern Central Pacific CommissionWestern Central Pacific OceanWorld Trade OrganisationYellowfin Tuna

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage iiiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

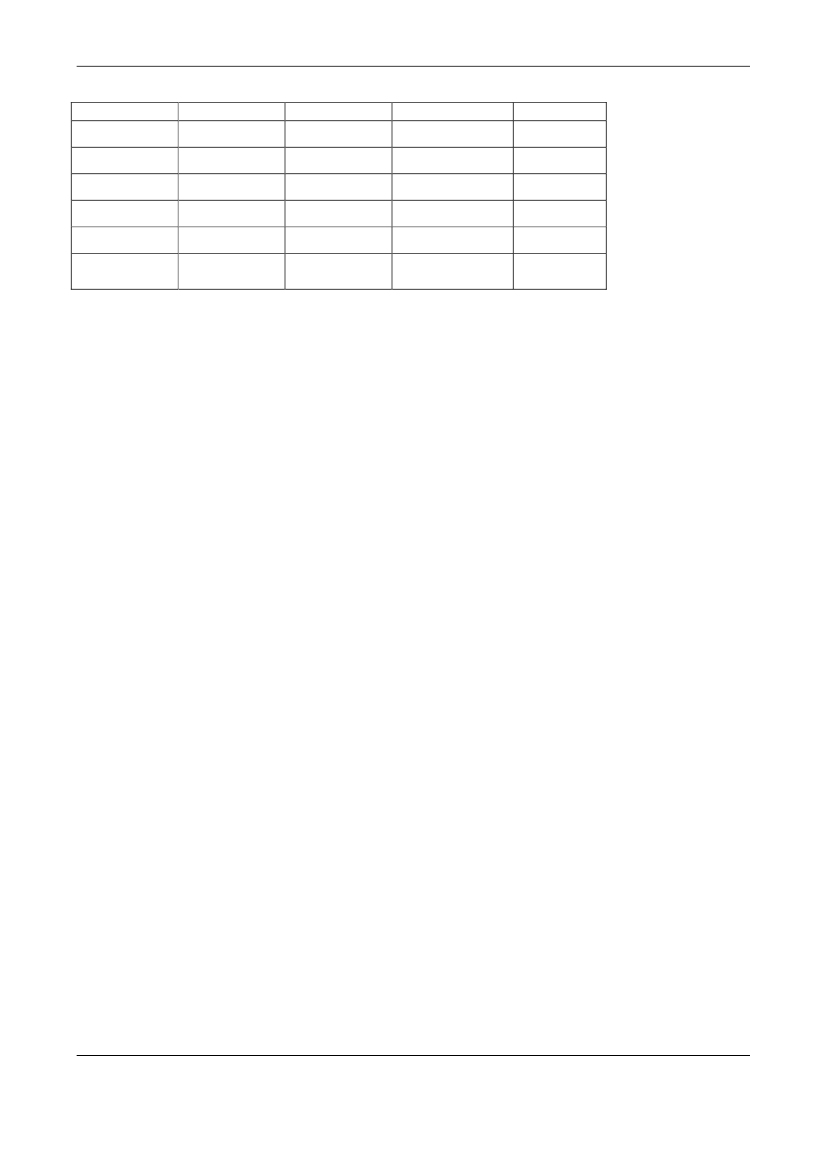

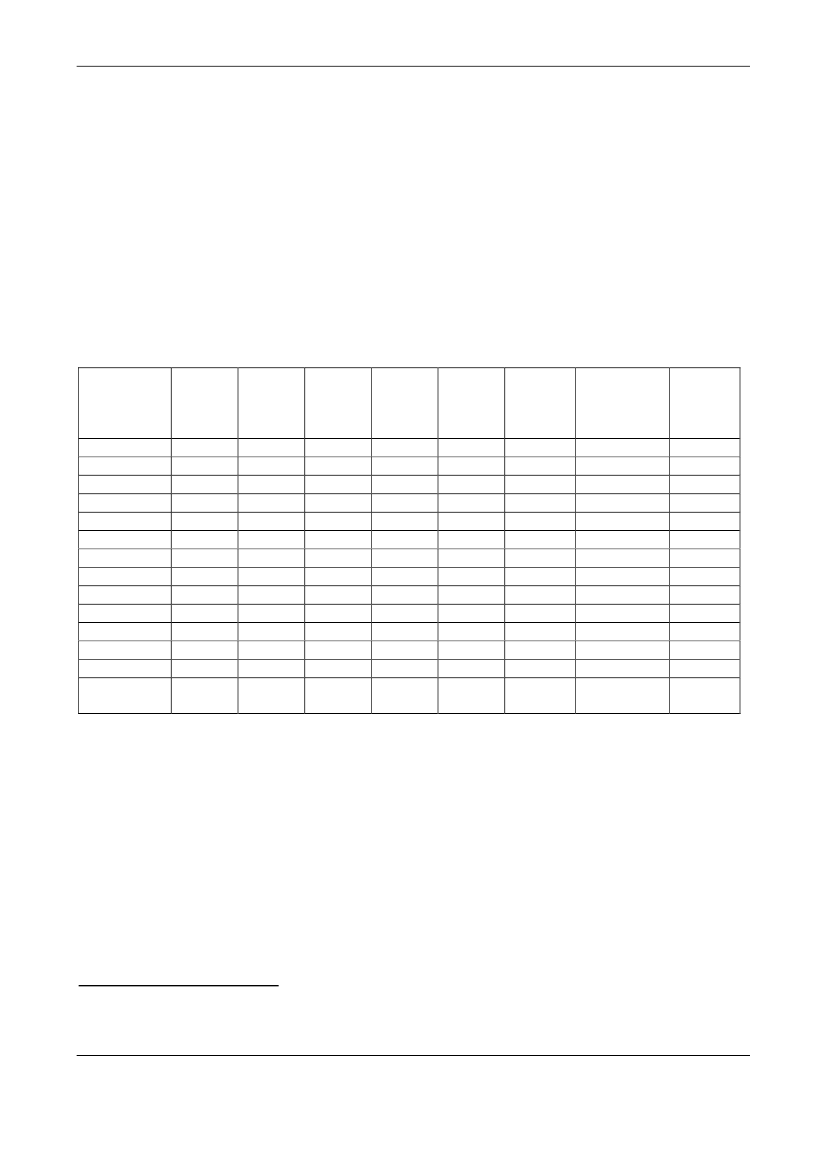

Currency Exchange Rates used in this report (www.oanda.com)€1 =2007200820092010US$1.351.581.411.22AUS$1.591.641.741.44

20111.451.35

20121.341.25

Rates are mid-year rates, except for 2012 which is rate at time of writing (Feb/March 2012)

AcknowledgementsThe consultants are grateful to all stakeholders who shared their time, thoughts, information and data with theconsulting team which completed this specific contract.

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage ivEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

EXECUTIVESUMMARYINTRODUCTIONi.This report provides an ex-post evaluation of the current Protocol to the Fisheries Partnership Agreement(FPA) between the European Union and the Republic of Kiribati. It also provides an ex-ante evaluationand analysis of impacts of a potential future Protocol on sustainability. The evaluation covers the periodSeptember 2006 to March 2012. The FPA provides fishing opportunities for EU purse seine and longlinevessels to fish in the waters of Kiribati.

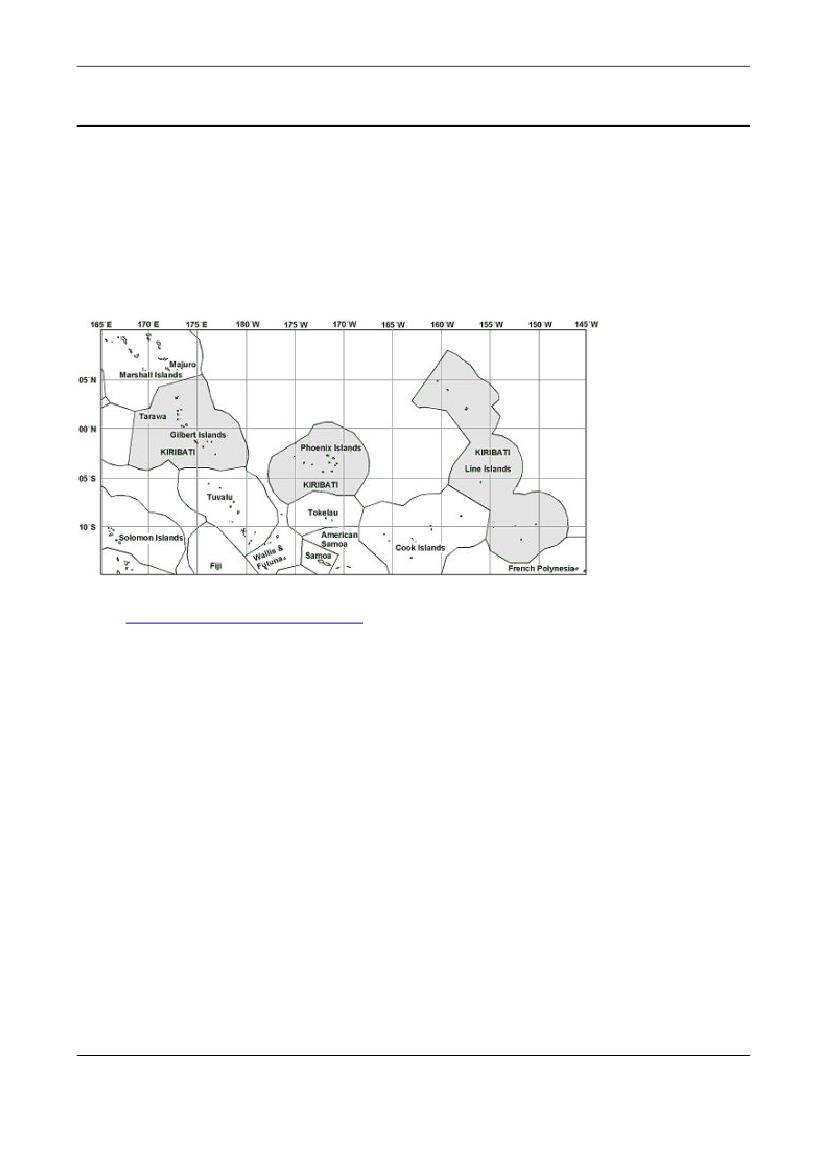

COUNTRY BACKGROUNDii.Kiribati is a remote Pacific nation made up of 33 widely dispersed islands (21 inhabited) divided intogroups (Gilbert Group, Phoenix Group and the Line Group) that straddle the equator. While the total landarea is only 726 km2, the related exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is the largest EEZ of the Pacific islandscountries at 3.55 mn km2. Kiribati’s population was 103,280 in 2011 and is almost entirely concentrated inthe Gilbert Islands. At the current population growth rate of 1.25 %, the population is expected to double inthe next 20 years. Kiribati is a sovereign democratic republic within the Commonwealth.The Kiribati economy faces significant constraints common to other island atoll states. Gross DomesticProduct (GDP) stands at€109mn (2010), expanding by an estimated 2-3 % per annum. GDP per capita isone of the lowest of the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) nations at€1,047and Kiribati is classifiedas a least developed African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) State. Challenges to economic developmentinclude size, remoteness and geographical fragmentation, infertile soils, limited exploitable resources andan expanding population. A major distinctive feature of national resources is the Revenue EqualisationReserve Fund (RERF) with a value of around€410mn (in 2011). Initially established from royalties fromphosphate mining, the RERF is used to fund fiscal deficits. The Kiribati Development Plan (KDP) 2008–2011 builds upon the previous National Development Strategy 2004–2007 with actions to address fiscalmanagement, population growth, and improved access to international labour markets. While progress inimplementation has been slow, the strategic focus remains: (i) improving the economic environment in theouter islands, particularly Kiritimati (Christmas Island); (ii) strengthening access to health services; and (iii)addressing climate change.Kiribati relies heavily on licence fees from distant water fishing nations (worth an annual average of€24.4mn in the period 2009 - 2011) that provide 23-30 % of government revenue and remittances from Kiribaticitizens employed abroad, mainly as seafarers. Fishing is also an important subsistence activity, with over80 % of households involved in fishing. Fish consumption per capita per year is high by global and Pacificstandards (between 72 kg and 207 kg for the entire country). The fishing sector contributes around 10 %of GDP. Kiribati has bilateral fisheries arrangements with the European Union, Japan, Taiwan, and theRepublic of Korea, as well as private company agreements with vessels from Ecuador and El Salvador.Kiribati also receives revenue from a multilateral treaty signed with the United States.EU relations with the Pacific ACP countries, based on the Lome Conventions and the Cotonou Agreementhave been aimed at supporting stabilisation following decolonisation, while at the same time supportingeconomic and social progress. At the regional level the 10th European Development Fund (EDF) (2008-2013) includes as a priority the sustainable management of natural resources and the environment, withsupport to programmes under the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) and Secretariat of the PacificCommunity (SPC). While Kiribati benefits from regional initiatives, fisheries remain outside the 10th EDFCountry Strategy Paper and National Indicative Programme for Kiribati. Fisheries-specific support isinstead provided through the sectoral policy support component of the FPA. The Kiribati fisheries sectoralso benefits from regional initiatives by other donors (notably Australia, New Zealand and the US) andnational support under the Australian-Kiribati Partnership for development.In September 2004, the EU and 14 Pacific ACP countries, including Kiribati, opened negotiations on anEconomic Partnership Agreement (EPA), which should eventually replace the preferential access schemeConsortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage vEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

iii.

iv.

v.

vi.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

contained in the Cotonou Agreement that expired at the end of 2007. EPA negotiations are still inprogress. Whilst there is presently no trade in fishery products between Kiribati and the EU, the countryhas future aspirations in trading fresh tuna loins.

TUNA FISHERIES INKIRIBATI AND THE REGIONvii.The Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) is the main fishing ground for tunas, accounting foraround 60 % of world catches. Total WCPO tuna catch for 2010 was estimated at 2.28 mn tonnes, with thepurse seine fishery accounting for 80 %, pole-and-line fishing 6.5 %, and longline fishing about 6 %. EUpurse seine vessels account for 2 % of catches in the WCP.Purse seine fishing expanded rapidly during the 1980s, mainly through the operations of Japanese and USfleets. More recently the composition of the fleet became more diverse, with an expansion to include otherAsian fishing nations, New Zealand and EU vessels. Vessels predominantly target skipjack tuna (81 % ofthe total catch) along with yellowfin (17 %) and bigeye (2 %) and overall dependency on free school fishinghas increased over the years. Access to fishing by distant water purse seine vessels takes the form ofregional or bilateral fisheries partnership arrangements or agreements, including: bilateralintergovernmental agreements; EU FPAs; commercial agreements between associations or companies;individual agreements between countries which are Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA); and the USTuna Treaty.The longline fishery catches mainly yellowfin and bigeye tunas, but also albacore, billfish, swordfish andother species including pelagic and reef sharks. The total number of vessels involved in the tropicalWCPO fisheries has generally been around 3,000. European longliners operate primarily south of 20�S,outside the tropical area and the EU longline vessels have never fished in Kiribati waters. Together EUlongliners account for less than 1 % of total WCPO longline catches.The status of the three main tuna stocks exploited in the WCP equatorial area is monitored by theScientific Committee installed under the Western Central Pacific Commission (WCPFC) (the tuna RegionalFisheries Management Organisation (RFMO) for the WCPO). Currently skipjack is being exploited atmoderate levels and overfishing is not occurring, yellowfin is currently fully exploited and there is a 50 %chance that overfishing is occurring, and recent assessments show that overfishing of bigeye tuna iscurrently occurring with present catch levels unlikely to be sustainable.The key governance and fishery management organisations for tuna and related species in the WCPO,and the tuna purse seine fisheries in particular include: The WCPFC; The Parties to the Nauru Agreement(PNA); Regional organisations that provide management services to the WCPFC and the PNA, inparticular the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) based in Solomon Islands, and the SPC based in NewCaledonia; and the PNA national governments. A number of WCPFC Commission Management Measures(CMMs) have been formulated in the annual sessions of the Commission. The PNA has also introduced aVessel Day Scheme (VDS) for the Management of the Western Purse Seine Fishery, with Party AllowableEffort (PAE) days allocated to PNA countries, and agreed that a minimum fee of US$5,000 /€3,450perfishing day shall be applied to foreign fishing vessels from 2012 onwards.Within Kiribati itself, the Kiribati Development Plan focus for fisheries includes maximizing the sustainableeconomic benefits from the tuna resource; conserving coastal resources in the face of rising demand forfood and cash incomes; and managing the transition from government research to commercial productionand export. Overriding governance priorities are identified as: maintaining close collaboration with the PNAand FFA and to obtain maximum sustainable EEZ access fees; promoting public-private partnerships withreputable foreign investors in catching and onshore domestic processing of tuna; conducting participatoryeducation programmes with fishers and communities engaged with vulnerable species/stocks; andensuring legal sanctions are observed to enforce the conservation regime and prosecute when necessary.Responsible for this is the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development with a staff of 115.Kiribati has established the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) which is one of the largest MarineProtected Areas (MPAs) in the Pacific at 408,250 km�.Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage viEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

viii.

ix.

x.

xi.

xii.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

EVALUATIONxiii.The Protocol provides for 4 purse seine fishing authorisations (1 for France and 3 for Spain), and 12longline fishing authorisations, evenly split between Portugal and Spain. Apart from two longline fishingauthorisations taken during the first year of the FPA there has been 0 % utilisation of the longline fishingauthorisation possibilities, and no longline catches made during the FPA. On the other hand utilisation ofthe 4 purse seine fishing authorisations has been 100 % for each of year of the FPA, and utilisation ofcatch possibilities in excess of 100 % each year of the FPA. In 2011 catch utilisation is expected to exceed200 % of the reference tonnage of 6,400 tonnes for the first time.Payments made to Kiribati during the FPA have averaged€1.2mn per year, with 2/3 paid by the EU and1/3 by vessel owners. The average payment over 2007 to 2011 was€3,350/ US$4,675 a day i.e. close tothe current PNA benchmark price of US$5,000/day.The covenants and obligations of the FPA and Protocol are generally being complied with by all parties.However some areas of concern include: the failure of the Joint Committee (JC) meetings to take placeuntil 2011; the slow payments in recent years for the financial support for the sectoral policy; the failure byKiribati to supply inspection certificates and observer reports to shipowners; and the lack of any realimpetus towards joint enterprises or local landings for processing.The economic analysis of the Protocol shows that ex-vessel fish prices are lower than internationalstandards, probably due to smaller fish sizes caught in the FAD fishery, but that fish prices have risen byaround 50 % over the period of the evaluation. Given the increasing trend in catches made in Kiribati overthe evaluation period, the landed value of fish caught under the Protocol also shows a rising trend and in2010 exceeded€14million.A total of€6.4mn of value-added is accrued each year when considering the benefits to both theEuropean Union and Kiribati. 75 % of this accrues to the EU and 25 % to Kiribati. EU value-added is mostprominent in the catching and upstream sectors, and less marked in downstream processing. In Kiribativalue-added is almost entirely focused in the upstream/input sub-sector, principally in the form ofpayments made to the Government for access and sectoral support, but also from vessel support servicesi.e. transshipment. Some small value-added is made through the employment of Kiribati crew andobservers.In terms of costs and benefits, for the EU as a whole the Protocol generated an average annualbenefit/cost (B/C) ratio of 4.0, demonstrating that the Protocol provides good value for money with every€1invested by the EU and fleet owners generating€4.0of benefit in terms of value-added. The cost ofaccess for vessel owners (€35/tonne) represents 4.1-4.4 % of the average weighted sales prices receivedfor catches made under the Protocol. Annual average catch values made under the Protocol are€9.5mn,and vessel profits as a proportion of sales revenues range between 11 % and 23 % for the two vesselclasses (84m and 100+m). The benefits to Kiribati were€1.2mn per year on average from the EU, plussmaller benefits in the form of value-added made from port calls by EU vessels and from local crew andobservers onboard EU vessels.The contribution of catch made under the Protocol to the EU processing sector was small at around 2 % ofloined imports to the EU in 2010, while fish caught under the Protocol and imported to the EU in cannedform represented around 1 % of EU imports of canned tuna in 2010.The employment generated by the Protocol is estimated at 98 Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) jobs. Thisemployment generation represents 116 tonnes of fish caught under the Protocol for every job, and€23,810of payments by the EU and vessel owners for every one job. Employment creation is dividedroughly equally between the EU and Kiribati. The social clause elements of the Protocol in terms of wagelevels, seamen having contracts, etc., are being fully complied with.

xiv.

xv.

xvi.

xvii.

xviii.

xix.

xx.

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage viiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

xxi.

xxii.

xxiii.

xxiv.

xxv.

xxvi.

With respect to effectiveness, the EU fleet plays only a small role in terms of overall fleet activity in bothKiribati and WCP. Its ability to impact on responsible fishing is therefore limited. However some concernsare noted in relation to responsible fishing in terms of high percentages of catches being comprised ofbigeye tuna (which is assessed as being over-exploited), vessel discards, vessels exceeding high seasdays limits, bycatch of pelagic sharks, and weaknesses in MCS capacity in Kiribati. The Protocol has beeneffective in supporting the EU catching sub-sector in particular, but not in creating any joint enterprises orany significant developments of the Kiribati fish catching or processing sub-sectors, due largely to theeconomics of doing so. As noted above, the Protocol has also been effective in creating someemployment in both the EU and Kiribati.With respect to efficiency, the Protocol has been efficient for the EU in providing access at an affordablerate for EU vessels owners, and in generating a good benefit/cost ratio of 4.0. But the cost per EU job hasbeen€23,810.For Kiribati, payments made by the EU under the Protocol have represented 4-7 % ofnational fishing licence revenue and 1-2 % of total annual government revenues.The Protocol has significantly contributed to the viability and sustainability of the EU purse seine catchingsub-sector operating in the Pacific and its related employment, but has made no contribution to thesustainability of the longline sector, and only small contributions to the sustainability of the EU upstreamand processing sub-sectors. The Protocol does not appear to threaten the sustainability of the Kiribatifishing sector. The Protocol has not however been successful in resulting in any sustainable joint catchingsub-sector operations, or in making any contributions to sustainable Kiribati processing sector operations,although has contributed to sustainable upstream/vessel support activities.The EU is a Commission Contracting Member to the WCPFC, and the Protocol is consistent with both theCFP and WCPFC policies management measures, as well as with the Food and AgricultureOrganisation’s (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, and with the International LabourOrganisation’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. There are no inconsistencies inthe Protocol text or its implementation, and EU trade policy. The Protocol is also consistent with nationalKiribati policy and national legislation. Perhaps the key issue of concern in relation to consistencyhowever, is the fact that the Protocol is a tonnage-based Protocol, with payments for access made pertonne. National Kiribati policy, in line with evolving regional initiatives, is now strongly in favour ofnegotiating and providing access based on vessel days.All of the above comments mean that the Protocol is relevant to the needs of the EU, and in particular toits purse seine fleet (although not to the longline fleet). The generation of access fees means the Protocolis also relevant to the needs of Kiribati. The Protocol does not however satisfy the needs/desires of Kiribatias expressed to the consultants to have a Protocol which is structured around paying for access based onvessel days, although this desire has not been formally expressed to the EU. This is explained by the factthat the VDS was not in place when the Protocol was negotiated, but has evolved in recent years. Inaddition, while the Protocol has an objective for the creation of joint enterprises and support for localprocessing activity, which satisfies the needs of Kiribati, implementation of the Protocol has not managedto bring about any such activity or to satisfy these needs and aspirations.Looking forward to a potential future Protocol, potential new management measures being considered inthe region to improve the management regime (e.g. a one month extension of the Fish AggregationDevice (FAD) closure, an increase in minimum mesh sizes, closure of the Phoenix Island Protected Areato fishing, high seas closures around the Kiribati EEZ) would have a negative impact on the activities andprofitability of EU purse seine vessels. Other changes which could have an impact if mandated by theWCPFC include potential changes in crewing requirements to 10 % and then 20 % being from PNAcountries – this would require changes to the text of the Protocol to ensure coherence, as the textcurrently states a minimum of 6 crew on the fleet of purse seiners, which represents around 5 % of currentvessel crew numbers (this figure is exceeded by the EU fleet, with around 9 % of total crew alreadysourced from Kiribati).Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage viiiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

xxvii.

It is likely that a future Protocol would generate considerable levels of value-added to both the EU and toKiribati, but few changes in employment or the balance of value-added creation between the EU andKiribati. It would be in the interest of both the EU and Kiribati to have a new Protocol. For the EU fleet a ‘noProtocol’ would cause fishing rights as a proportion of sales revenues to rise considerably, while forKiribati a failure to sign a new Protocol would eliminate the ear-marked funds for special sectoral supportprovided by the EU under the Protocol, and could result in under-utilisation of Kiribati’s PAE days underthe VDS.

RECOMMENDATIONSxxviii.The recommendations made in this report are necessarily brief, given that it is not the job of theconsultants to present a strategy to the EU for negotiation, but rather to provide the EU negotiators withthe economic data to prepare for the negotiations. Thus the principal recommendation made is to base thenegotiations on the economic and social data provided in this report, and to ensure that there is indeedsignature of a new Protocol.The ongoing CFP reform also means that there is as yet, not clear direction or guidance on changing thebalance of access payments per tonne between the EU and fleet owners, and the current balance shouldtherefore be retained.From a purely technical perspective, this evaluation recommends that the longline fishing opportunities beremoved from the Protocol, given the fact that there have been zero catches made by the longline fleetunder the Protocol. However a final decision on this issue would also need to reflect the political wishesand agreement by EU Member States.Given the high level of juvenile bigeye tuna catches taken in the FAD fishery by the EU fleet, theevaluation also recommends that direct measures should be included in the Protocol (and Annex) tomitigate against this problem. Such measures should be agreed jointly by all parties, but could include theuse of, and reporting on, FAD management plans.The levels of payments in a future Protocol, and the basis on which they are paid (e.g. tonnage or vesseldays), will be the subject of negotiation, but should be informed by recent catch levels, rates of utilisation,and fish prices.A recommendation is made for greater emphasis and recognition by all parties of the importance of theJoint Committee meetings. These meetings represent a vital monitoring mechanism for implementation ofthe FPA – a mechanism which has historically not been especially effective. The Joint Committeemeetings must be yearly as required in the text of the FPA, and should be used both to review sectoralpolicy implementation, and to ensure ongoing compliance with the covenants and obligations laid out inthe FPA and Protocol (and necessary action if such compliance is found to be lacking). Current areas ofweakness in compliance with other covenants and obligations required in the FPA and Protocol shouldalso be addressed as a matter of urgency.The evaluation recommends that focus be given to the issue of strengthening MCS capacity in Kiribati. Forexample, FPA sectoral funds, and other EU development support, could be used to enhance observercapacities so as to ensure mutual recognition by WCPFC and Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission(IATTC) of each other’s observers. The evaluation also recommends greater recognition by EUdevelopment projects of the important nature of the Kiribati FPA, and therefore for the use of funds tosupport Kiribati. The view of this evaluation is that there should be a special effort to better align sectoralpolicy support provided by the FPA with other EU development aid in a mutually enforcing manner, whilebeing careful to avoid duplication. This could be supported by the appointment of a fisheries attaché to theEU Delegation in Fiji, and the EU is believed to be in process of recruiting someone to such a position.Finally, the evaluation notes the importance of the EU continuing to engage actively with the WCPFC inefforts to ensure responsible fisheries in the WCPO. As part of this process, given some of theweaknesses identified in the evolving VDS system, the evaluation recommends that the EU supports theestablishing of target and limit reference points for tuna stocks, so as to ensure the integrity of the schemeby linking stock status to the management system.Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage ixEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

xxix.xxx.

xxxi.

xxxii.xxxiii.

xxxiv.

xxxv.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

RÉSUMÉINTRODUCTIONi.Ce rapport fournit une évaluation ex-post du protocole de l’Accord de Partenariat dans le secteur de laPêche (APP) entre l’Union européenne (UE) et la République de Kiribati (ci-après citée ‘Kiribati’). Ilprocure également une évaluation ex-ante et une analyse d’impacts en termes de durabilité d’un possiblefutur protocole. L’évaluation couvre la période de septembre 2006 à mars 2012. L’APP garantit desopportunités de pêche pour les senneurs et les palangriers de l’UE dans les eaux de Kiribati.

CONTEXTE DU PAYSii.Kiribati est une nation éloignée du Pacifique, constituée de 33 îles fortement dispersées (dont 21habitées) divisées en groupes d’îles (îles Gilbert, îles Phénix et îles de la Ligne) et chevauchantl’équateur. Alors que la superficie des terres émergées est de seulement 726 km2, la Zone ÉconomiqueExclusive (ZEE) associée est la plus vaste ZEE des pays insulaires du Pacifique avec 3,55 millions dekm2. La population de Kiribati était de 103 280 habitants en 2011 et est presque exclusivement concentréedans les Îles Gilbert. Au taux de croissance démographique actuel de 1,25 %, il est prévu que lapopulation double dans les 20 prochaines années. Kiribati est une république démocratique souveraineparmi le Commonwealth.L’économie de Kiribati fait face à des contraintes non négligeables communes à d’autres états atoll. LeProduit Intérieur Brut (PIB) est de 109 millions d’euros (2010), avec une croissance estimée de 2- 3 % paran. Le PIB par habitant par an est parmi les plus bas des Parties à l’Accord de Nauru, PAN (en anglais,PNA) à 1 047€et Kiribati est classé dans les états ACP (Afrique, Caraïbes, Pacifique) les moinsdéveloppés. Les contraintes limitant son développement économique incluent la taille de l’archipel,l’isolement et la fragmentation géographique, l’infertilité des sols, les ressources exploitables limitées etune population croissante. Un aspect majeur et distinct des ressources nationales est le fonds de réserved’égalisation de revenu (en anglais, RERF) ayant une valeur d’environ 410 millions d’euros (en 2011).Etabli initialement à partir des redevances issues des mines de phosphate, le fonds de réserve RERF estutilisé pour compenser les déficits fiscaux. Le Plan de Développement de Kiribati 2008-2011 se base surla précédente Stratégie de Développement National 2004-2007 avec des actions ciblant la gestion fiscale,la croissance de la population et un accès amélioré aux marchés du travail internationaux. Alors que lamise enœuvrea été lente, la stratégie reste focalisée sur : (i) améliorer le contexte économique dans lesîles périphériques, particulièrement Kiritimati (île Christmas) ; (ii) renforcer l’accès aux services de santé ;et (iii) gérer les effets de changement climatique.Kiribati est fortement dépendante des droits de licences de pêches lointaines d’autres nations (valeurmoyenne de 24,4 millions d’euros dans la période 2009 - 2011) qui procurent 23 – 30 % des recettes del’état ainsi que des envois de fonds des citoyens de Kiribati employés à l’étranger, principalement en tantque marins. La pêche est aussi une activité de subsistance importante, avec plus de 80 % des foyersimpliqués dans le secteur. La consommation annuelle de poisson par habitant est élevée selon lesstandards mondiaux et les standards du Pacifique (variant entre 72 kg et 207 kg dans l’ensemble dupays). Le secteur de la pêche contribue à 10 % du PIB. Kiribati a signé des accords de pêche bilatérauxavec l’Union Européenne, le Japon, Taiwan, et la République de Corée ainsi que des accords privés avecdes navires venant d’Équateur et du Salvador. Kiribati re§oit aussi des revenus du traité multilatéral signéavec les États-Unis.Les relations de l’UE avec les états ACP du Pacifique, basées sur les Conventions de Lomé et lesAccords de Cotonou visent à renforcer la stabilité suite à la décolonisation, tout en favorisant le progrèséconomique et social. Au niveau régional le 10ème Fonds Européen de Développement, FED (2008 -2013) inclut en tant que priorité la gestion durable des ressources naturelles et de l’environnement, avecl’appui de programmes sous l’égide de l’Agence des Pêches du Forum des îles du Pacifique(communément nommé par son acronyme anglais FFA) et le Secrétariat Général de la Communautés duConsortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

iii.

iv.

v.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

vi.

Pacifique (SCP). Alors que Kiribati bénéficie d’initiatives régionales, les pêcheries restent exclues duDocument de stratégie et du Programme Indicatif National du 10ème FED. L’appui spécifique auxpêcheries se fait plutôt à travers de la composante de l’APP d’appui de mise enœuvred’une politiquesectorielle. Le secteur de la pêche de Kiribati bénéficie aussi d’initiatives régionales par d’autresdonateurs (notamment l’Australie, la Nouvelle Zélande et les États-Unis) ainsi qu’un soutien national sousle Partenariat pour le développement entre l’Australie et Kiribati.En septembre 2004, l’Union européenne et 14 pays ACP du Pacifique, dont Kiribati, ont ouvert desnégociations sur un Accord de Partenariat Économique, APE, qui devrait à terme remplacer le régimed’accès préférentiel, ayant expiré à la fin de 2007 et contenu dans l’Accord de Cotonou. Les négociationssur l’APE sont toujours en cours. Alors qu’il n’y a pas actuellement de transactions de produits de la pêcheentre Kiribati et l’UE, le pays a des aspirations futures portant sur le commerce de longes de thon frais.

LA PECHE AUX THONS AKIRIBATI ET DANS LA REGIONvii.L’Océan Pacifique occidental et central, OPOC est la zone de pêche principale pour le thon, représentantautour de 60 % des prises mondiales. La prise totale de thon au sein de l’OPOC pour 2010 a été estiméeà 2,28 millions de tonnes, dont 80 % sont représentés par la pêcherie des thoniers senneurs, 6,5 % parles canneurs et environ 6 % par les palangriers. Les navires senneurs européens représentent 2 % desprises dans le Pacifique occidental et central, POC.La pêche à la senne a connu un essor rapide dans les années 1980, principalement par le biais desopérations de flottes japonaises et américaines. Plus récemment la composition de la flotte s’estdiversifiée, avec une augmentation, pour inclure d’autres nations de pêche asiatiques, la Nouvelle-Zélande et les navires européens. Les navires ciblent préférentiellement le listao (81 % de la capturetotale) en parallèle avec l’albacore (17 %) et le thon obèse (2 %) ; la dépendance globale de la pêche surbanc libre a augmenté au fil des années. L’accès à la pêcherie par des navires de pêche lointaine à lasenne prend la forme d’arrangements ou d’accords de partenariat de pêche régionaux ou bilatéraux,incluant : des accords bilatéraux intergouvernementaux, des APP avec l’UE, des accords commerciauxentre associations ou sociétés, des accords individuels entre pays Parties à l’Accord de Nauru (PAN) et letraité américain portant sur le thon (USTuna Treaty).La pêcherie palangrière capture principalement de l’albacore et du thon obèse, mais aussi du germon, despoissons à rostre (e.g. espadons) ainsi que d’autres espèces dont des requins pélagiques et de récifs. Lenombre total de navires impliqués dans les pêcheries tropicales de l’OPOC a généralement été de3 000.Les palangriers européens opèrent principalement au sud de 20�S, en dehors de la zone tropicale et lesnavires palangriers de l’UE n’ont jamais pêché dans les eaux de Kiribati. Ensemble les palangrierseuropéens représentent moins de 1 % des captures totales à la palangre dans l’OPOC.L’état des trois principaux stocks exploités dans la zone équatoriale du POC est surveillé par le ComitéScientifique installé sous la Commission des Pêches du Pacifique occidental et central, CPPOC (enanglais, WCPFC), organisation de gestion régionale des pêches thonières, ORGP, pour l’OPOC. Le listaoest actuellement exploité à des niveaux modérés sans cas de surpêche. L’albacore est actuellementexploité pleinement avec une probabilité de 50 % que de la surpêche ait lieu. Des évaluations récentesmontrent que la surpêche de thon obèse est avérée avec des niveaux de capture ayant peu de chanced’être durables.Les organisations clés de gestion et de gouvernance pour le thon et les espèces associées au sein del’OPOC, et pour les pêcheries à la senne en particulier, comprennent : la CPPOC, les PAN, en particulierla FFA basée aux Îles Salomon, le SCP basé en Nouvelle Calédonie et les gouvernements nationaux desPAN. Un certain nombre de Mesures de Gestion de la Commission (CommissionManagement Measures,CMMs) ont été formulées durant les sessions annuelles de la Commission. Les PAN ont aussi présentéun régime de contrôle par jours de mer par navire,Vessel Day Scheme(VDS) pour la gestion des pêchesà la senne du Pacifique ouest, avec des jours d’effort autorisés par partie (PartyAllowable Effort,PAE)alloués aux pays PAN, et se sont mises d’accord pour qu’un tarif minimum de 5 000 US$/ 3 450€par jourde pêche soit appliqué aux navires étrangers à partir de 2012.Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

viii.

ix.

x.

xi.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

xii.

À Kiribati même, les éléments centraux du Plan de Développement de Kiribati portant sur la pêcheincluent la maximisation des bénéfices économiques durables issus des ressources thonières, laconservation des ressources côtières face à la demande croissante en revenus alimentaires et enespèces, et la gestion de la transition d’une recherche gouvernementale à une production commerciale età l’exportation. Les objectifs majeurs de gouvernance sont identifiés comme étant : maintenir unecollaboration étroite avec les PAN et la FFA, obtenir des droits durables d’accès à la Zone d’ExclusivitéÉconomique (ZEE) à leur niveau maximum, promouvoir des partenariats public-privé pour les captures etla transformation domestique à terre du thon avec des investisseurs étrangers réputés, animer desprogrammes éducationnels participatifs avec des pêcheurs et des communautés engagées dans despêches sur des espèces/stocks vulnérables, et s’assurer que des sanctions légales soient appliquéespour mettre enœuvreles mécanismes de conservation, en engageant des poursuites lorsque nécessaire.Cette responsabilité incombe au Ministère des Pêches et du Développement des Ressources Marinesemployant 115 personnes. Kiribati a établi l’Aire Protégée des Îles Phénix (PhoenixIslands ProtectedArea,PIPA), qui est l’une des Aires Marines Protégées (AMPs) les plus vastes du Pacifique mesurant408 250 km2.

EVALUATIONxiii.Le protocole dispense de 4 autorisations de pêches à la senne (1 pour la France et 3 pour l’Espagne), et12 autorisations de pêche à la palangre partagées équitablement entre le Portugal et l’Espagne. À partdeux autorisations de pêche à la palangre prises durant la première année du protocole, il y a eu 0 %d’utilisation des possibilités de pêche à la palangre, et aucune capture à la palangre n’a été effectuéedurant le protocole. D’autre part, chaque année du protocole, l’utilisation des 4 autorisations de pêche à lasenne a été de 100 %, et l’utilisation des possibilités de captures en excès de 100 % chaque année duprotocole. En 2011, l’utilisation des captures est prévue de dépasser les 200 % du tonnage de référencede 6 400 tonnes pour la première fois.Les paiements effectués auprès de Kiribati durant le protocole ont été en moyenne de 1,2 millions d’eurospar an, dont les 2/3 payés par l’Union européenne (UE) et 1/3 par les armateurs des navires. Le paiementmoyen entre 2007 et 2011 était de 3 350€/4 675 US$ par jour, proche du seuil actuel de prix des PAN de5 000 US$ par jour.Les engagements et obligations de l’accord et de son protocole ont généralement été respectés par toutesles parties. Cependant, certains domaines de préoccupation comprennent l’échec de la tenue desréunions de Commission mixte jusqu’en 2011 ; la lenteur des paiements au cours des dernières annéesde l’appui financier à la politique sectorielle ; l’échec de la transmission par Kiribati de certificatsd’inspection et de rapports d’observateurs aux armateurs ; ainsi que l’ absence d’un élan réel vers dessociétés mixtes ou vers des sites de débarquement locaux pour la transformation.L’analyse économique du protocole montre que les prix de poissons en sortie navire sont plus bas que lesstandards internationaux, probablement en raison des tailles plus faibles de poissons capturés au seindes pêcheries sur DCPs (Dispositifs de Concentration de Poissons), mais les prix ont augmenté d’environ50 % durant la période de l’évaluation. Étant donné la tendance à la hausse des captures réalisées àKiribati durant la période de l’évaluation, la valeur au débarquement des poissons capturés dans le cadrede l’APP présente une tendance à la hausse et a dépassé 14 millions d’euros en 2010.Une valeur ajoutée totale de 6,4 millions d’euros est accumulée chaque année lorsque l’on prend encompte les bénéfices pour l’Union européenne et pour Kiribati. La valeur ajoutée est plus marquée pourl’UE en amont dans les secteurs de la capture, et moins marquée en aval de la transformation. À Kiribatila valeur ajoutée est presque entièrement concentrée dans le sous-secteur en amont, principalement sousforme de paiements au gouvernement de Kiribati pour l’accès et l’appui sous-sectoriel, mais dans lesservices d’appui aux navires, notamment le transbordement. Une petite plus-value est réalisée au traversde l’emploi d’équipages et d’observateurs de Kiribati.Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xiiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

xiv.

xv.

xvi.

xvii.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

En termes de coûts et bénéfices pour l’UE dans son ensemble le protocole a généré un ratio moyenbénéfices/coûts (B/C) de 1:4,6, démontrant que le protocole fournit un bon rapport qualité/prix ; chaqueeuro investi par l’UE et les armateurs générant 4,60€de bénéfice en termes de valeur ajoutée. Le coûtd’accès pour les armateurs (35€/tonne)représente 4,1 - 4,4 % du prix moyen des ventes à la pesée pourles captures réalisées sous le protocole. Les valeurs moyennes annuelles des captures réalisées dans lecadre du protocole sont proches de 9,5 millions d’euros, et les profits pour les navires en tant queproportion du revenu des ventes sont compris entre 11 % et 23 % pour les deux classes de navires (73 met 100+ m). Pour Kiribati, les bénéfices en provenance de l’UE étaient de 1,2 millions d’euros par an enmoyenne, s’y ajoutant des bénéfices plus faibles générés par la plus-value issue des escales portuairesdes navires de l’UE ainsi des équipages locaux et des observateurs à bord des navires de l’UE.xix.La contribution des captures réalisées dans le cadre du protocole au secteur de transformation de l’UE aété faible à environ 2 % d’imports de longes par l’UE en 2010, alors que le poisson capturé dans le cadredu protocole et importé par l’UE sous forme de conserves a représenté autour de 1 % des imports deconserves de thons par l’UE en 2010.xx.L’emploi généré par le protocole est estimé à 98 emplois en équivalent temps plein. Cette générationd’emploi représente 116 tonnes de poisson capturés sous le protocole pour chaque emploi et 23 810€enpaiements par l’UE pour chaque emploi. La création d’emploi est divisée approximativement en part égaleentre l’UE et Kiribati. Les clauses sociales du protocole en matière de niveaux de rémunération, de lanécessité pour les marins d’être sous contrat, etc., ont été complètement respectées.xxi.En ce qui concerne l’efficacité, la flotte de l’UE ne joue qu’un petit rôle sur le plan de l’activité de la flottetotale présente à Kiribati et dans le POC. Sa capacité à influencer une pêche responsable est donclimitée. Cependant, des préoccupations sont à noter en relation avec la pêche responsable. Elles portentsur le pourcentage élevé de captures composées de thon obèse (qui est estimé en surexploitation), lesrejets des navires, le navires dépassant le nombre de jours autorisé en haute mer, les capturesaccessoires de requins pélagiques, et les faiblesses en capacité de suivi, contrôle et surveillance (SCS)de Kiribati. Le protocole a été efficace dans son appui au sous-secteur UE des captures en particulier,mais ne l’a pas été dans la création de sociétés mixtes ou dans le développement significatif des sous-secteurs de capture ou de transformation de Kiribati, largement pour des raisons de coûts. Ainsi qu’il a étémentionné précédemment, le protocole a aussi été efficace dans la création de l’emploi tant pour l’UE quepour Kiribati.xxii.S’agissant de l’efficience, le protocole a été utile pour l’UE en fournissant un accès à un coût raisonnablepour les armateurs des navires de l’UE, et en générant un bon ratio bénéfice/coût de 4,6. Cependant lecoût par emploi de l’UE a été de 23 810€.Pour Kiribati, les paiements effectués par l’UE dans le cadre duprotocole ont représenté 4-7 % du revenu national des licences de pêche et 1-2 % du revenugouvernemental annuel total.xxiii.Le protocole a contribué de manière significative à la viabilité et à la durabilité du sous-secteur descaptures à la senne de l’UE opérant dans le Pacifique et de ses emplois liés, mais il n’a aucunementcontribué à la durabilité du secteur palangrier ; et a contribué faiblement à la durabilité des sous-secteursen amont et de transformation de l’UE. Le protocole ne semble pas menacer la durabilité du secteur de lapêche de Kiribati. Le protocole n’a cependant pas eu de succès dans le développement d’opérations decaptures par des sociétés mixtes, ni en contribuant durablement aux opérations du sous-secteur de latransformation de Kiribati, bien qu’il ait contribué aux activités durables en amont/de soutien aux navires.xxiv.L’UE est une partie contractante de la CPPOC, et le protocole est en cohérence avec à la fois les mesuresde gestion politiques de la Politique Commune des Pêches (PCP) et de la CPPOC, ainsi qu’avec le Codede Conduite pour des Pêcheries Responsables de la FAO (Foodand Agriculture Organisation),et avec laDéclaration de l’Organisation Internationale du Travail sur les Principes Fondamentaux et les Droits auTravail. Il n’y a pas d’incohérences entre le texte du protocole ou sa mise enœuvreet les politiquescommerciales de l’UE. Le protocole est aussi cohérent avec les politiques nationales et les législationsnationales de Kiribati. L’élément-clé de préoccupation au sujet de la cohérence pourrait cependant êtreque le protocole est basé sur le tonnage, avec des paiements par accès par tonne. La politique nationaleConsortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xiiiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

xviii.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

xxv.

xxvi.

xxvii.

de Kiribati, en accord avec des initiatives régionales en évolution, est maintenant fortement en faveurd’une négociation et de fournir des accès basés sur des jours de mer par navire.Tous les commentaires précédents signifient que le protocole est pertinent vis-à-vis des besoins de l’UE,et en particulier de ceux de sa flotte de pêche à la senne (bien que ne l’étant pas pour ceux de la flottepalangrière). La génération des droits d’accès signifie que le protocole est aussi pertinent aux besoins deKiribati. Le protocole ne satisfait cependant pas les besoins/souhaits de Kiribati d’avoir un protocolestructuré autour de paiements par accès basés sur des jours de mer, bien que ce souhait n’ait pasformellement été exprimé à l’UE. Ceci s’explique par le fait que le VDS n’était pas en place lorsque leprotocole était négocié mais qu’il a évolué dans les récentes années. De plus, alors que le protocole a unobjectif de création de sociétés mixtes et de soutien à l’activité locale de transformation, satisfaisant lesbesoins de Kiribati, la mise enœuvredu protocole n’a pas réussi à créer de telles activités ou à satisfaireces besoins et aspirations.En se projetant vers un éventuel futur protocole, de nouvelles mesures de gestion potentielles étantconsidérées dans la région pour améliorer le mode de gestion (ex : une extension d’un mois de la clôturedes Dispositifs de Concentration de Poissons (DCPs), une augmentation des tailles minimales demaillage, la fermeture à la pêche de l’Aire Protégée de l’Île Phénix, les fermetures de zones de haute merautour de la ZEE de Kiribati) auraient un impact négatif sur les activités et la profitabilité des naviressenneurs de l’UE. D’autres changements qui pourraient avoir un impact si mandatés par la CPPOCcomprennent des changements potentiels dans les exigences d’équipages à 10 % puis 20 % d’originesdes pays PAN – ceci nécessiterait des changements de texte du protocole afin d’assurer sa cohérence,puisque le texte actuellement cite un minimum de 6 hommes d’équipage dans la flotte de senneurs, ce quireprésente environ 5 % du nombre total de marins à bord (ce chiffre est dépassé par la flotte de l’UE avecenviron 9 % de l’équipage total déjà originaire de Kiribati).Il est probable que le futur protocole génère des niveaux conséquents de valeur ajoutée à la fois pour l’UEet Kiribati, mais peu de changements sur l’emploi ou la répartition de la création de valeur ajoutée entrel’UE et Kiribati. Il serait ainsi dans l’intérêt de l’UE et de Kiribati d’avoir un nouvel protocole. Pour l’UE, un« non protocole » signifierait une hausse importante des droits de pêche dans le revenus des ventes,pendant que pour Kiribati l’absence de signature d’un nouveau protocole éliminerait les fonds réservés àl’appui sectoriel spécial fourni par l’UE sous le protocole et pourrait résulter par une sous-utilisation desjours de PAE sous le VDS.

RECOMMANDATIONSxxviii.Les recommandations soumises dans ce rapport sont nécessairement brèves, puisque il n’est pas du rôledes consultants de présenter une stratégie à l’UE pour la négociation, mais plutôt de fournir à l’UE lesdonnées économiques pour préparer les négociations. C’est pourquoi la recommandation principale estde baser les négociations sur les données économiques et sociales fournies dans ce rapport afin des’assurer qu’il y ait ainsi signature d’un nouveau protocole.La réforme en cours de la PCP signifie aussi qu’il n’y a pas encore de direction ou d’orientation sur unchangement de ratio de droits d’accès à la tonne entre l’UE et les armateurs, et que le ratio actuel doitdonc être maintenu.D'un point de vue purement technique, cette évaluation recommande que les possibilités de pêche à lapalangre soient retirées du protocole, compte tenu du fait qu'il n'y ait eu aucune capture effectuées par laflottille palangrière au titre du protocole. Toutefois, une décision finale sur cette question devra égalementtenir compte des souhaits politiques et de l'aval des Etats membres de l'UE.Compte tenu du niveau élevé de juvéniles de thon obèse capturés dans la pêche sous DCPs par la flottede l'UE, l'évaluation recommande également que des mesures directes soient incluses dans le protocole(et son annexe) afin d'atténuer ce problème. Ces mesures devraient être adoptées conjointement partoutes les parties, mais pourrait inclure l'utilisation de, et des rapports sur des, plans de gestion des DCPs.Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xivEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

xxix.xxx.

xxxi.

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

xxxii.xxxiii.

xxxiv.

xxxv.

Les niveaux de paiements dans un futur protocole, et la base sur laquelle ils sont payés (ex. tonnage oujours de pêche des navires), seront sujets à négociation, mais devront être renseignés des niveaux decaptures récents, des taux d’utilisation et des prix du poisson.Une recommandation est exprimée pour une plus grande mise en évidence et reconnaissance par toutesles parties de l’importance des réunions de la commission mixte. Ces réunions représentent unmécanisme de suivi vital pour la mise enœuvrede l’APP – un mécanisme qui n’a pas été historiquementtrès efficace. Les réunions de la commission mixte doivent être annuels, tel que requis dans le texte del’APP, et devraient être utilisés pour revoir à la fois la mise enœuvredes politiques sectorielles et pours’assurer du respect des engagements et des obligations détaillées dans l’APP et le protocole (et lesactions nécessaires à un tel respect sont insuffisants). Les zones de faiblesse actuelles dans le respectdes autres engagements et obligations requises dans l’APP et le protocole devraient aussi être traitées enurgence.L’évaluation recommande que l’accent soit mis sur le renforcement de la capacité de suivi, contrôle etsurveillance (SCS) à Kiribati. Par exemple, les fonds sectoriels de l’APP, et autres appuis audéveloppement de l’UE, pourraient être utilisés pour augmenter les capacités d’observation afin d’assurerune reconnaissance mutuelle des observateurs de la CPPOC et de la Commission Inter-américaine duthon tropical (CIAT ; en anglais IATTC). L’évaluation recommande aussi une plus grande reconnaissancepar les projets de développement de l’UE de l’importance de l’APP avec Kiribati, et donc pour l’utilisationdes fonds d’appuis à Kiribati. Le point de vue de cette évaluation est qu’il devrait y avoir un effortparticulier pour mieux aligner l’appui à la politique sectorielle fournie dans le cadre de l’APP avec d’autresprojets de développement de l’UE de manière à se renforcer mutuellement tout en prenant garde à éviterdes duplications. Ceci pourrait être appuyé par la nomination d'un attaché à la pêche à la délégation del'UE aux îles Fidji, l'UE serait sous le processus de recruter pour pourvoir un tel poste.Enfin, l’évaluation note l’engagement actif de l’UE à collaborer avec la CPPOC dans le but de garantir despêches responsables au sein de l’OPOC. En tant que partie intégrante de ce processus, étant donnécertaines des faiblesses grandissantes identifiées du système VDS en évolution, l’évaluation recommandeque l’UE soutienne l’établissement de points de références cibles et de références limites pour les stocksde thons afin d’assurer l’intégrité du programme VDS en liant l’état des stocks au système de gestion.

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xvEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

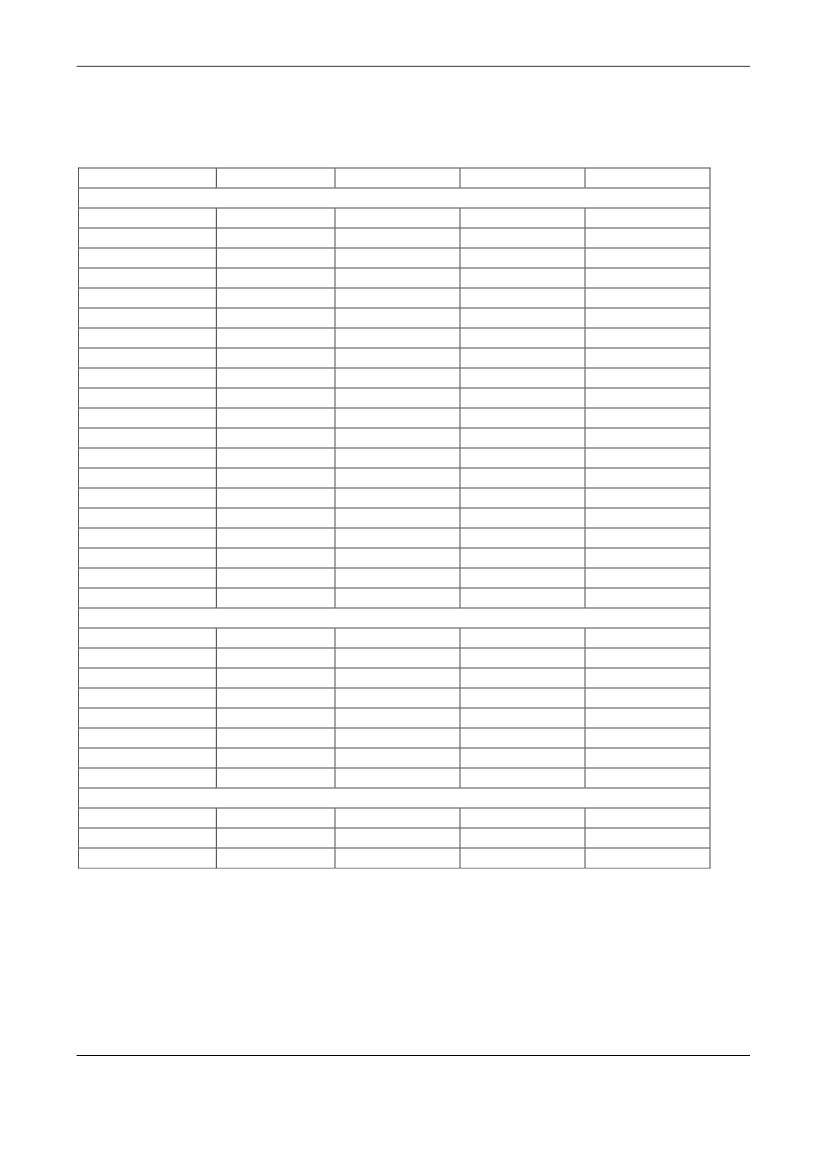

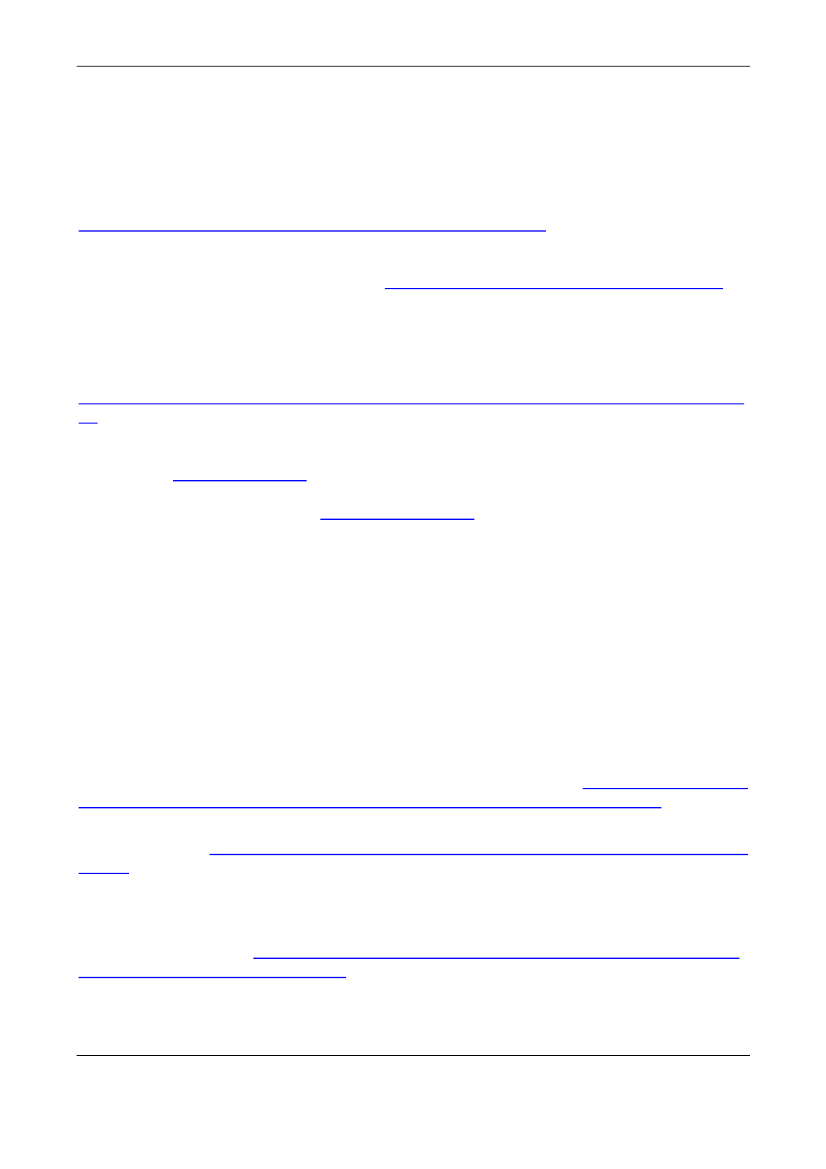

TABLE OFCONTENTS12INTRODUCTION - PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS EVALUATION................................................. 1GENERAL BACKGROUND AND SITUATION IN THE PARTNER COUNTRY ................................... 22.1COUNTRY BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................... 22.1.1 Geography.................................................................................................................................... 22.1.2 Population .................................................................................................................................... 32.2POLITICAL,ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL ISSUES............................................................................................ 32.2.1 Political and institutional aspects.................................................................................................. 32.2.2 General economic situation and outlook....................................................................................... 42.2.3 National budgetary and social objectives ..................................................................................... 52.2.4 Contribution of fisheries to national economy............................................................................... 52.2.5 Balance of trade ........................................................................................................................... 62.2.6 Employment ................................................................................................................................. 72.2.7 Food security................................................................................................................................ 72.3EUANDKIRIBATI RELATIONSHIPS IN THE REGIONAL CONTEXT.................................................................. 72.3.1 EU cooperation strategy ............................................................................................................... 72.3.2 10th EDF commitments................................................................................................................ 82.3.3 9thEDF commitments..................................................................................................................102.3.4 Millennium Development Goal Initiative.......................................................................................102.3.5 Trade relationships between Kiribati and the EU.........................................................................102.4OTHER DONOR RELATIONS..................................................................................................................113TUNA FISHERIES IN KIRIBATI AND THE REGION ..........................................................................133.1REGIONAL OVERVIEW.........................................................................................................................133.2THE PURSE SEINE FISHERY..................................................................................................................143.2.1 Fleet evolution .............................................................................................................................143.2.2 Purse seine catch by species ......................................................................................................153.2.3 Purse seine effort ........................................................................................................................173.2.4 FAD and free school set dependencies.......................................................................................183.3THELONGLINE FISHERY......................................................................................................................183.3.1 The fleet ......................................................................................................................................183.3.2 Longline catch by species ...........................................................................................................193.4STATUS OFFISH STOCKS IN THE REGION..............................................................................................203.5ECOSYSTEM ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH TUNA FISHERIES........................................................................223.6MANAGEMENT AGREEMENTS IN THEWCPAND THEIR IMPLICATIONS.......................................................243.6.1 The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) ............................................243.6.2 Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) and related management arrangements........................283.6.3 The Palau Arrangement and Vessel Day Scheme (VDS)............................................................333.6.4 Niue Treaty..................................................................................................................................383.6.5 Regional Organizations (FFA and SPC)......................................................................................393.7THEEASTERNPACIFICFISHERY: STATUS ANDMANAGEMENT ISSUES.....................................................413.7.1 Status and management issues ..................................................................................................413.7.2 Issues of special concern to vessels fishing under the Kiribati FPA ............................................423.8FLEETS FISHING IN THEKIRIBATIEEZ ..................................................................................................433.8.1 EU purse seine fleet ....................................................................................................................433.8.2 EU longline fleet ..........................................................................................................................46Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xviEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

3.8.3 Non-EU distant water fishing activity in the Kiribati EEZ..............................................................463.8.4 Domestic sector...........................................................................................................................503.9FISHERIES GOVERNANCE INKIRIBATI....................................................................................................513.9.1 Policy and institutional framework ...............................................................................................513.9.2 Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development (MFMRD) Budget.............................553.9.3 National Fisheries Laws ..............................................................................................................563.9.4 Specific national marine protected area measures......................................................................573.9.5 Monitoring, control and surveillance ............................................................................................583.9.6 Catch certification........................................................................................................................604EX-POST EVALUATION SPECIFIC TO THE PROTOCOL OF THE FISHERIES PARTNERSHIPAGREEMENT ......................................................................................................................................614.1INTRODUCTION TO THEFISHERIESPARTNERSHIPAGREEMENT...............................................................614.2UTILISATION.......................................................................................................................................624.2.1 Fishing authorisations and uptake of the possibilities negotiated ................................................624.2.2 Catches and utilisation of the possibilities negotiated..................................................................634.3COSTS OF THEPROTOCOL..................................................................................................................634.4COMPLIANCE WITH THE COVENANTS AND OBLIGATIONS SPECIFIED IN THEFPA.........................................664.5ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OFPROTOCOL....................................................................................................674.5.1 Findings and discussion of the economic and financial impacts of the Protocol..........................674.6EMPLOYMENT ANALYSIS OF THEPROTOCOL..........................................................................................754.7EFFECTIVENESS– THE EXTENT TO WHICH THE SPECIFICFPAOBJECTIVES WERE ACHIEVED.....................774.8EFFICIENCY– THE EXTENT TO WHICH THE DESIRED EFFECTS WERE ACHIEVED AT A REASONABLE COST.....794.9SUSTAINABILITY– THE EXTENT TO WHICH POSITIVE/NEGATIVE EFFECTS ARE LIKELY TO LAST AFTER THEFPAHAS TERMINATED.................................................................................................................................804.10 CONSISTENCY– THE EXTENT TO WHICH POSITIVE/NEGATIVE SPILL-OVER ONTO OTHER ECONOMIC,SOCIALOR ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AREAS ARE BEING MAXIMISED/MINIMISED............................................................824.11 RELEVANCE– THE EXTENT TO WHICH THEFPA’S OBJECTIVES WERE PERTINENT TO THE NEEDS,PROBLEMSAND ISSUES FACED BY STAKEHOLDERS..........................................................................................................8355.15.25.36ANALYSIS OF IMPACTS AND EX-ANTE EVALUATION OF A FUTURE PROTOCOL OF THEFISHERIES PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT........................................................................................85STAKEHOLDERS TO A FUTURE PROTOCOL AND THEIR VIEWS...................................................................85SECTORAL POLICY DEVELOPMENT........................................................................................................86EX-ANTE EVALUATION CRITERIA...........................................................................................................89CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS....................................................................................92

6.1CONCLUSIONS...................................................................................................................................926.2RECOMMENDATIONS...........................................................................................................................94APPENDICESAPPENDIXA: REFERENCES......................................................................................................................................................................96APPENDIXB: PERSONS CONSULTED........................................................................................................................................................102APPENDIXC: COMPLIANCE WITH KEY COVENANTS AND OBLIGATIONS IN THEAGREEMENT, PROTOCOL ANDANNEX......................................104APPENDIXD: COSTS ANDEARNINGS MODELS FOR84M AND100+MEUPURSE SEINE VESSELS UTILISING FISHING POSSIBILITIES PROVIDED BYTHEPROTOCOL............................................................................................................................................................................113APPENDIXE: METHODOLOGY USED IN THIS EVALUATION..........................................................................................................................114APPENDIXF: PURSE SEINE CATCHES IN THEWCPOBY NATIONALITY, 2006TO2010 (TONNES) .................................................................116APPENDIXG: LONGLINE CATCHES IN THEWCPOBY NATIONALITY, 2006TO2010 (TONNES)......................................................................117APPENDIXH: PURSE SEINE AND LONGLINE CATCHES INKIRIBATIEEZBY NATIONALITY, 2007TO2010 (TONNES) ........................................118

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xviiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

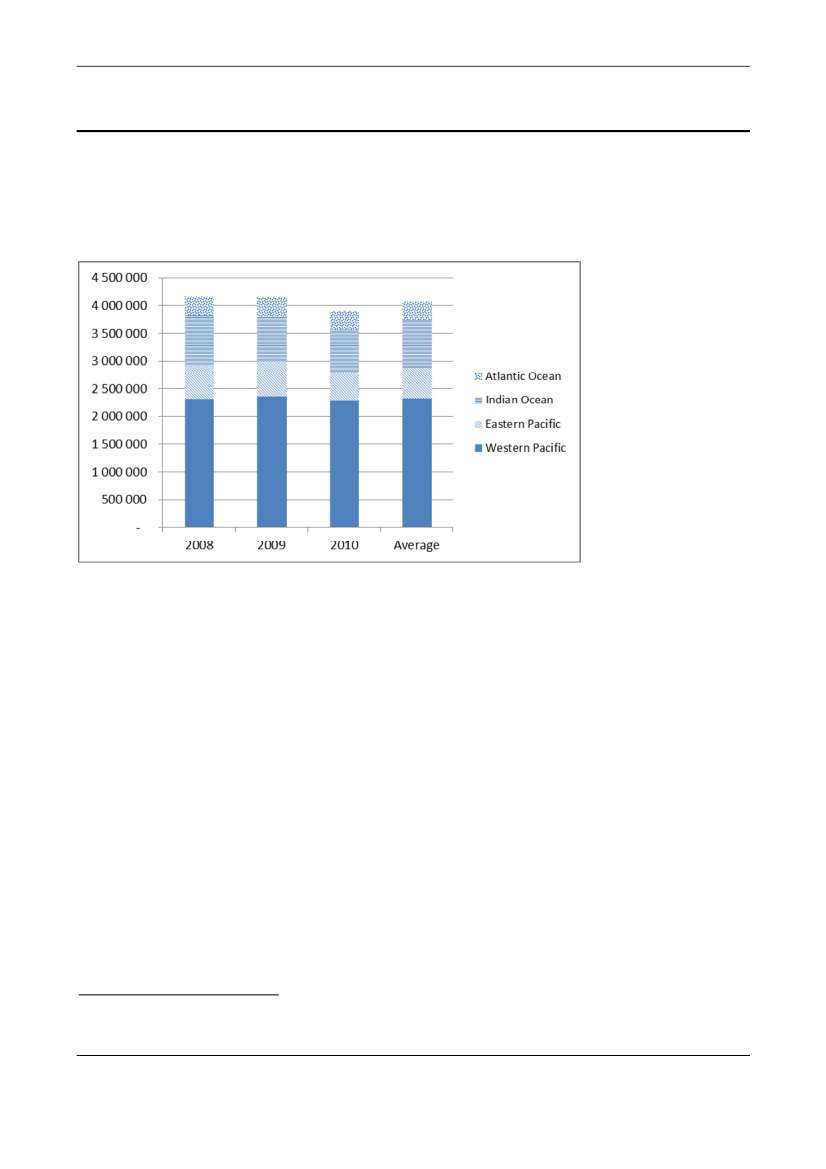

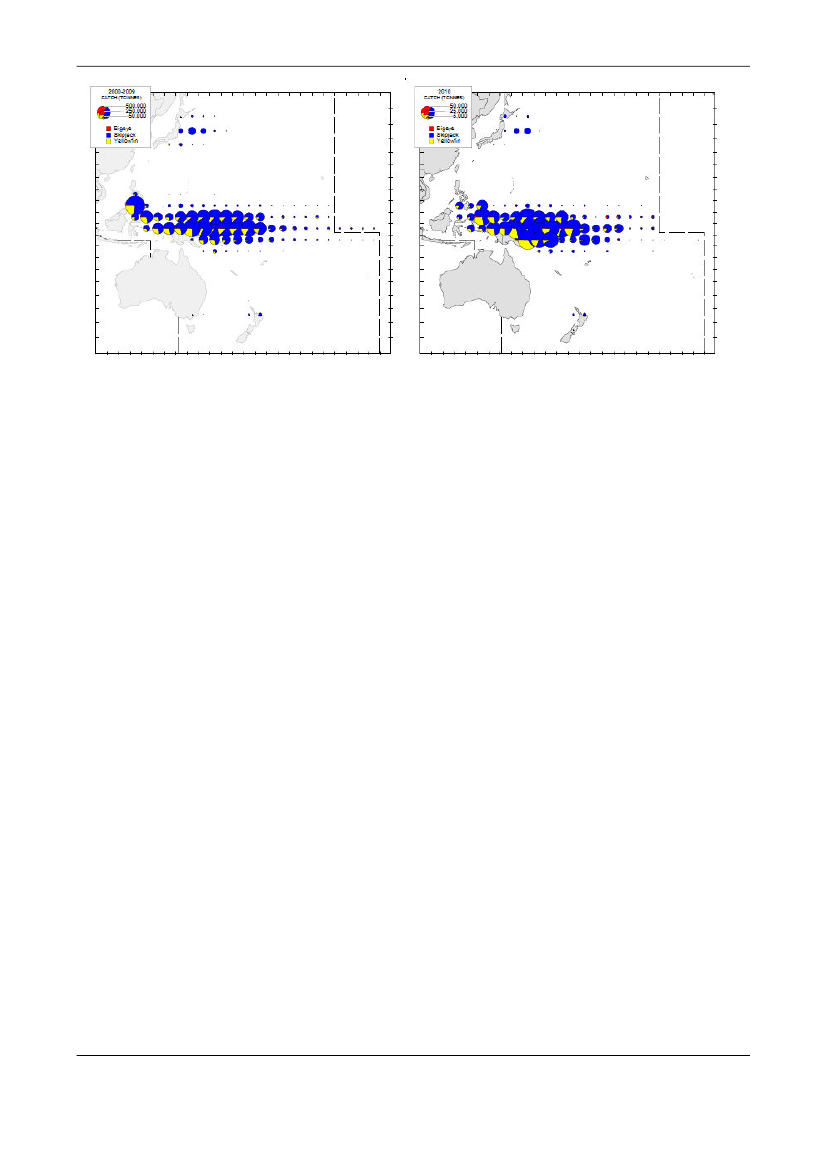

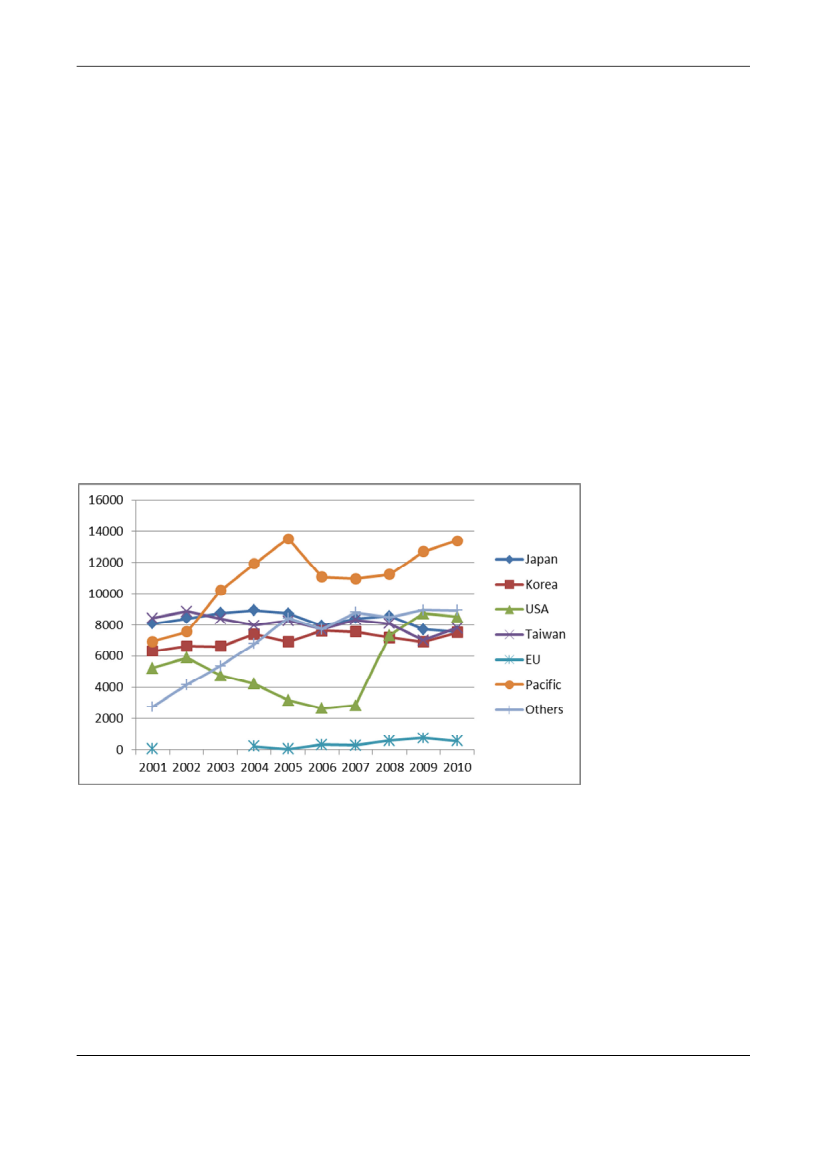

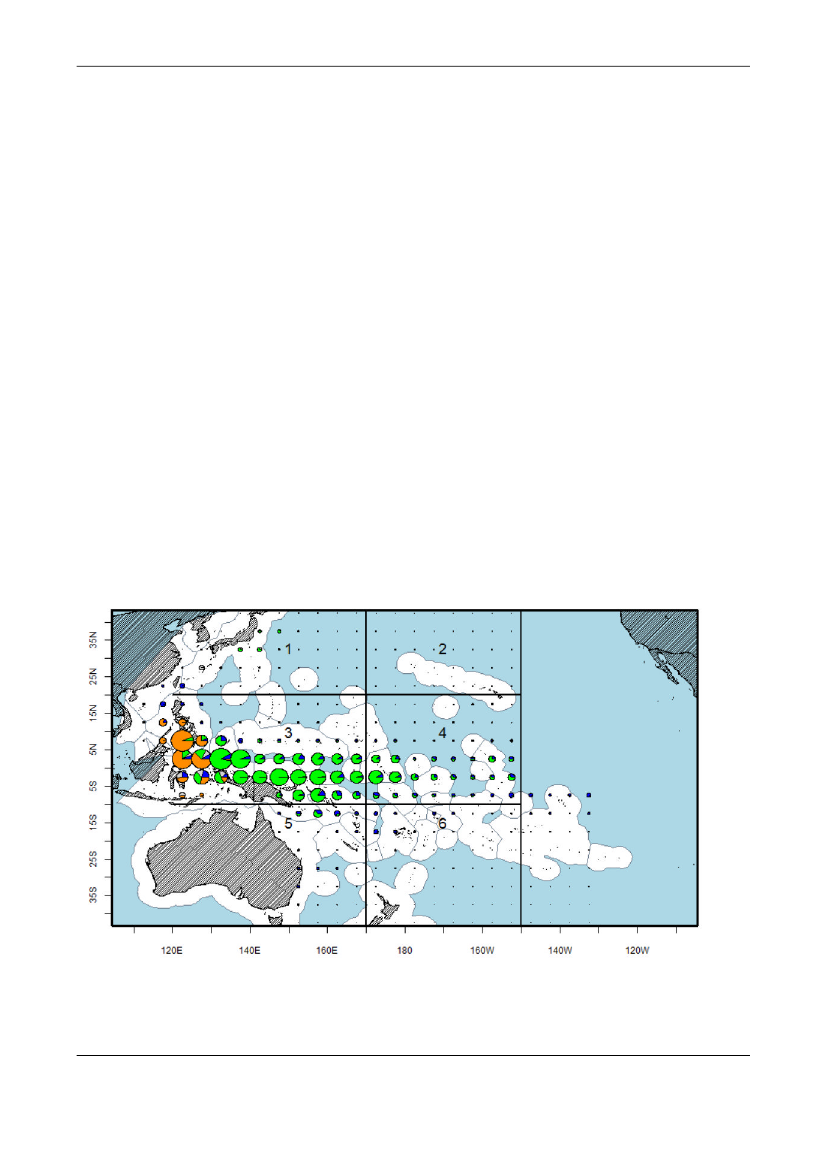

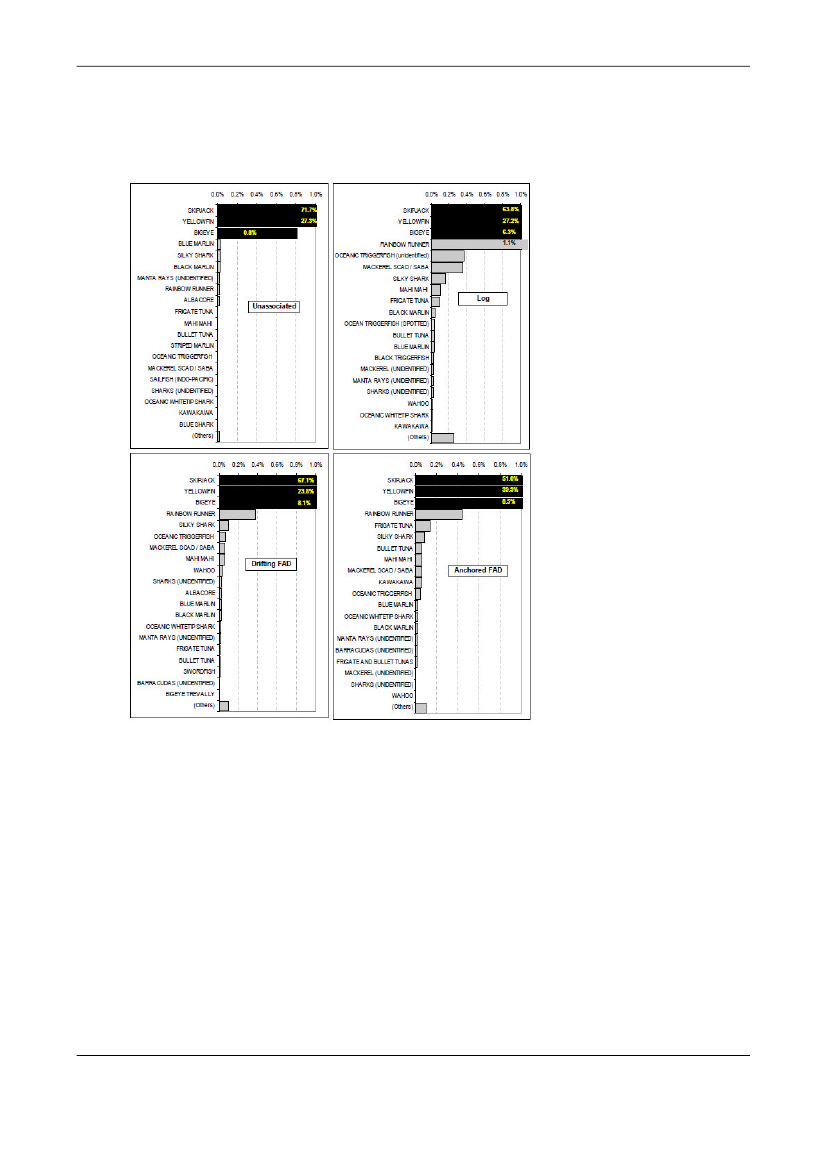

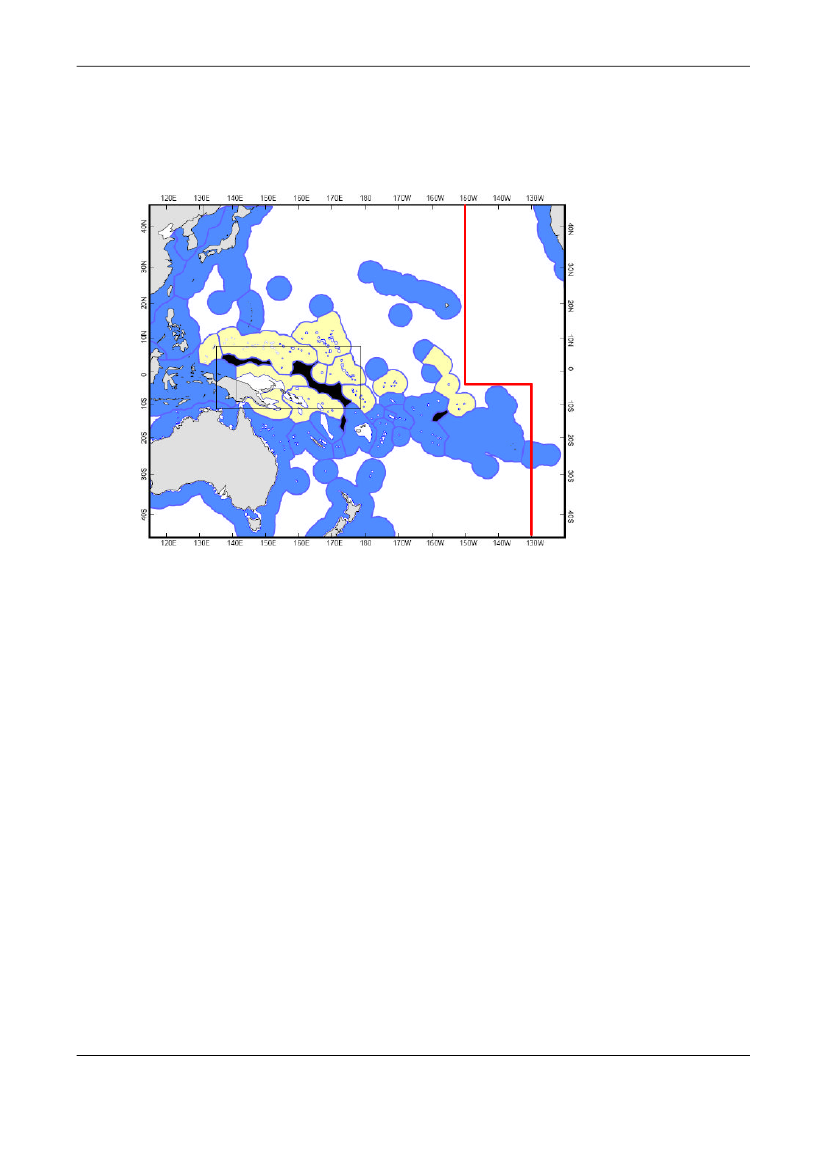

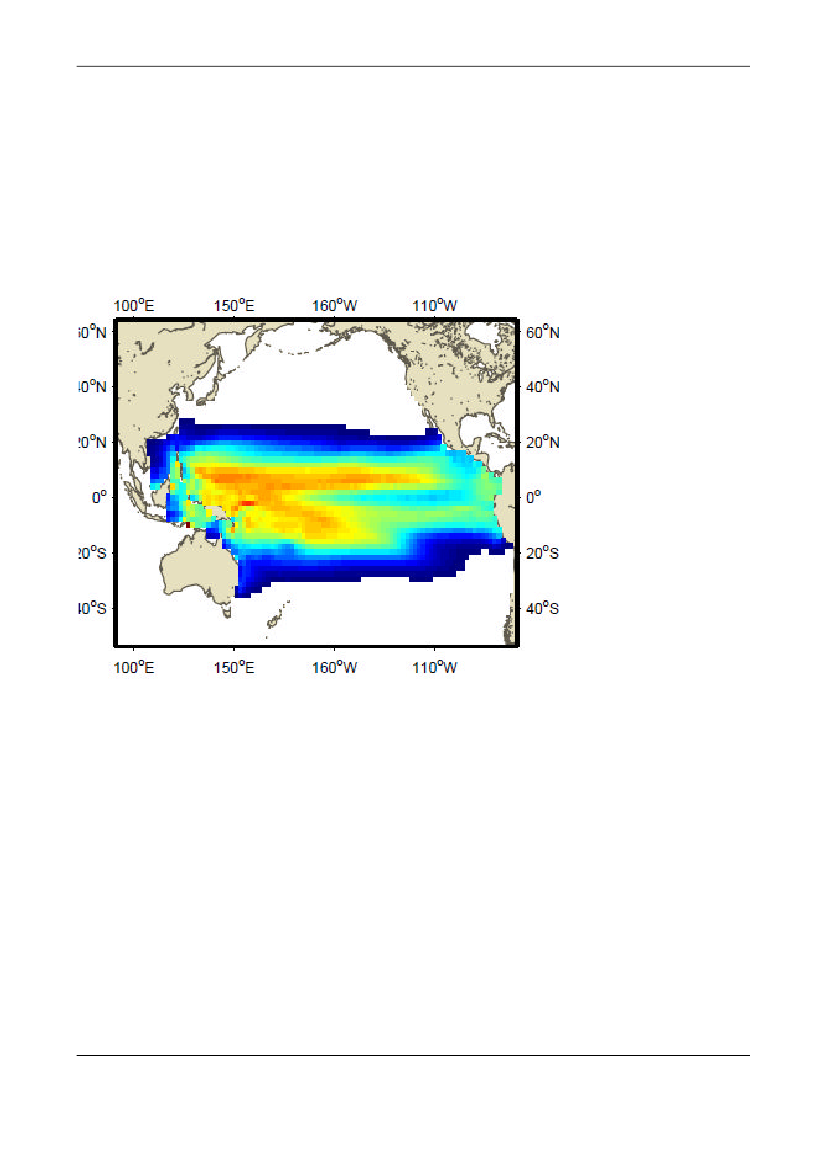

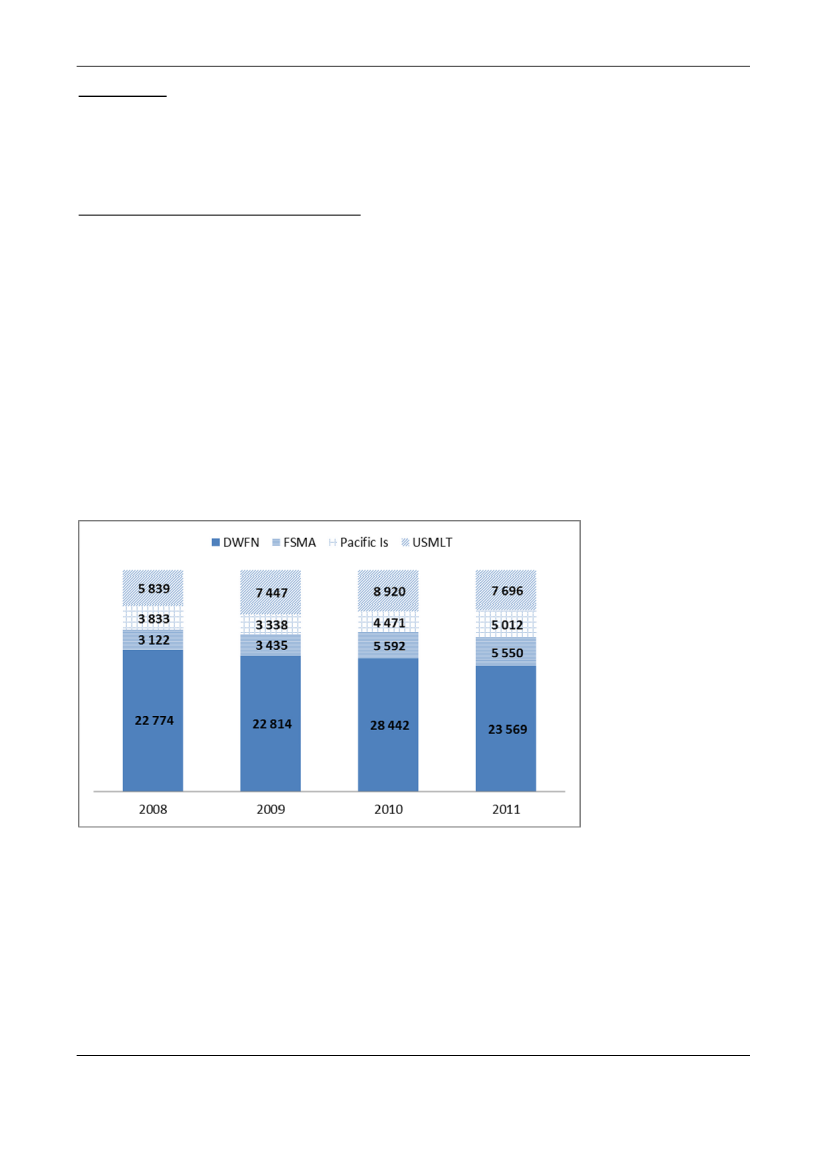

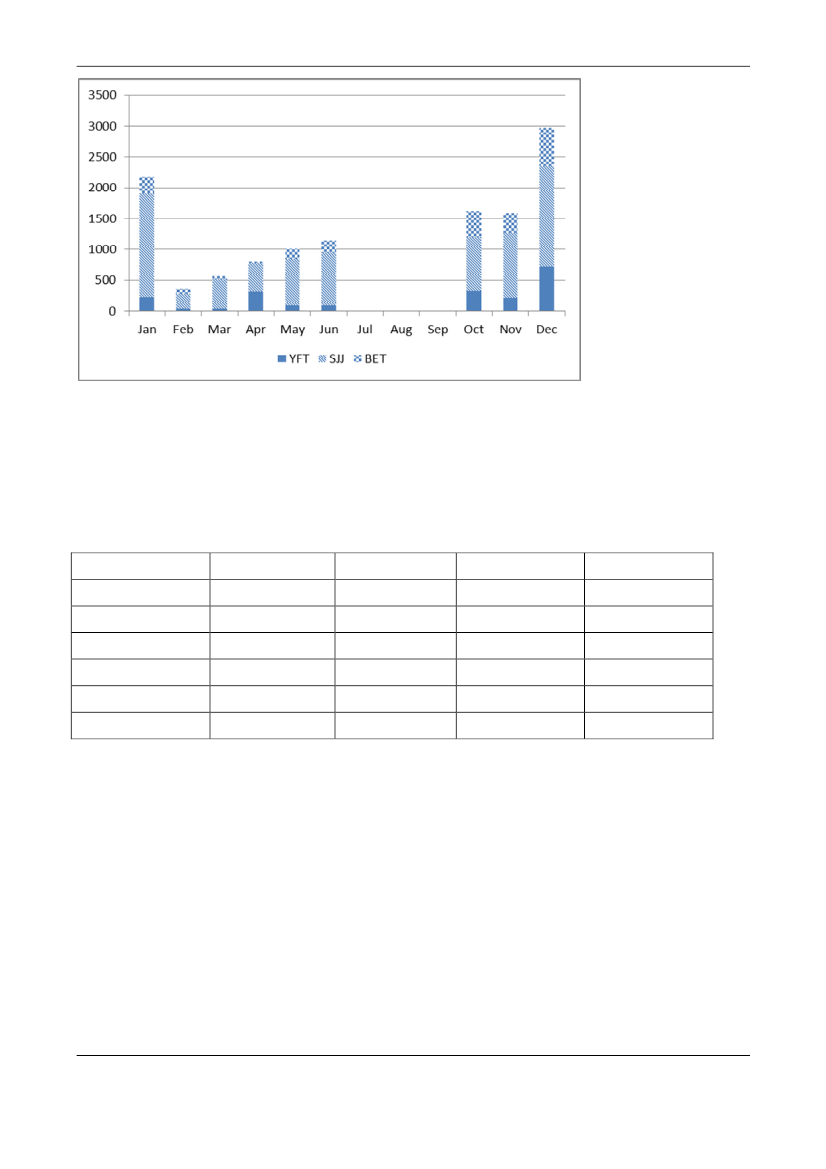

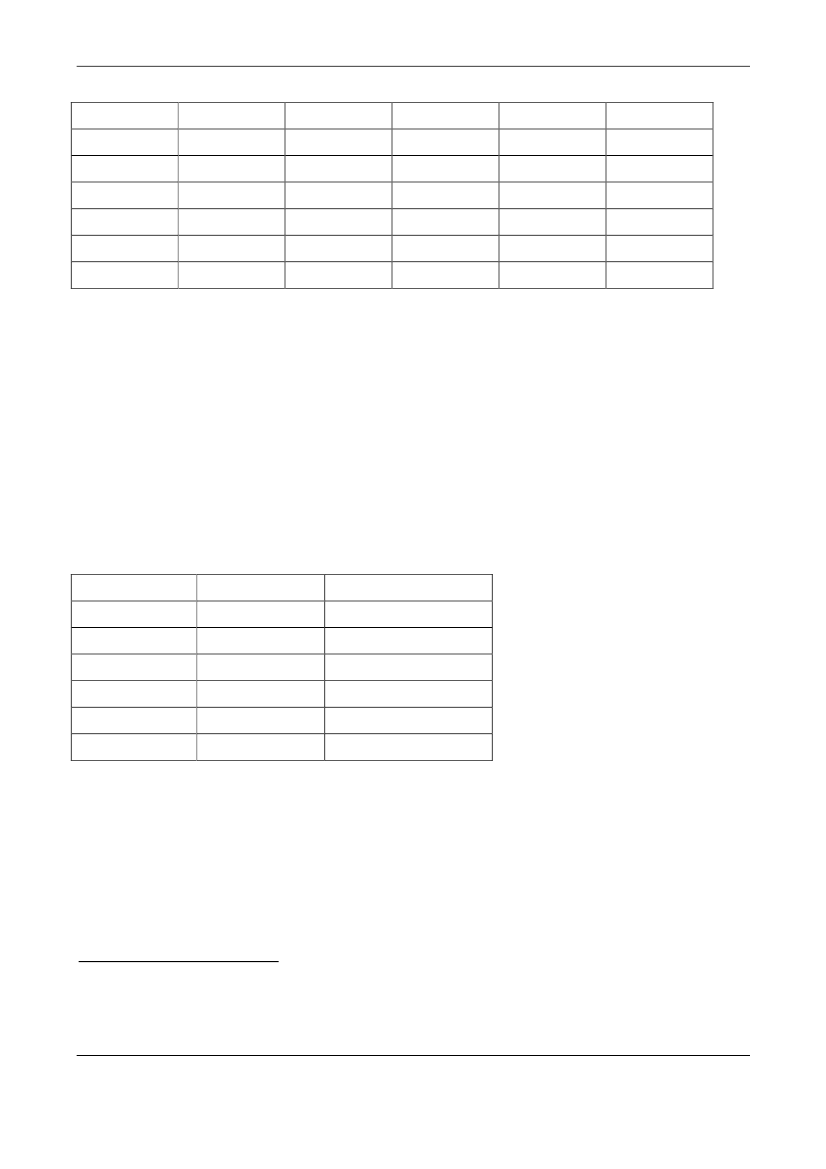

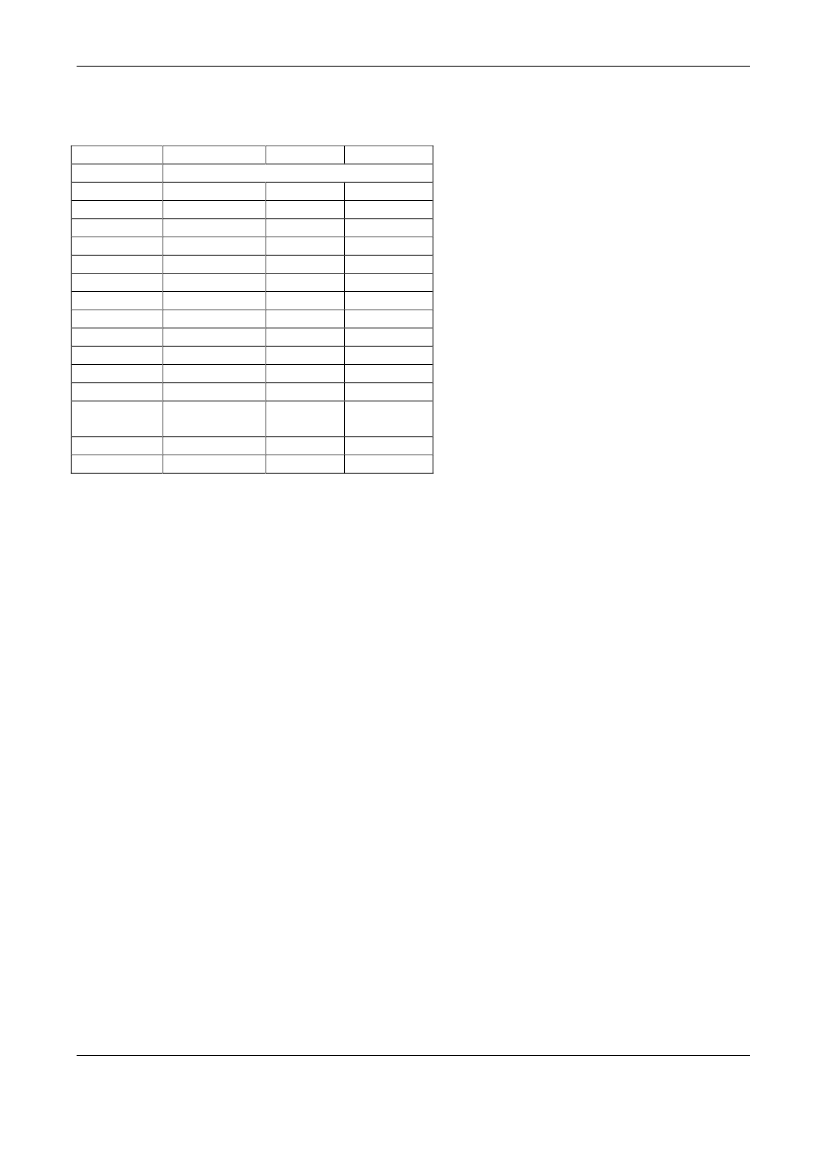

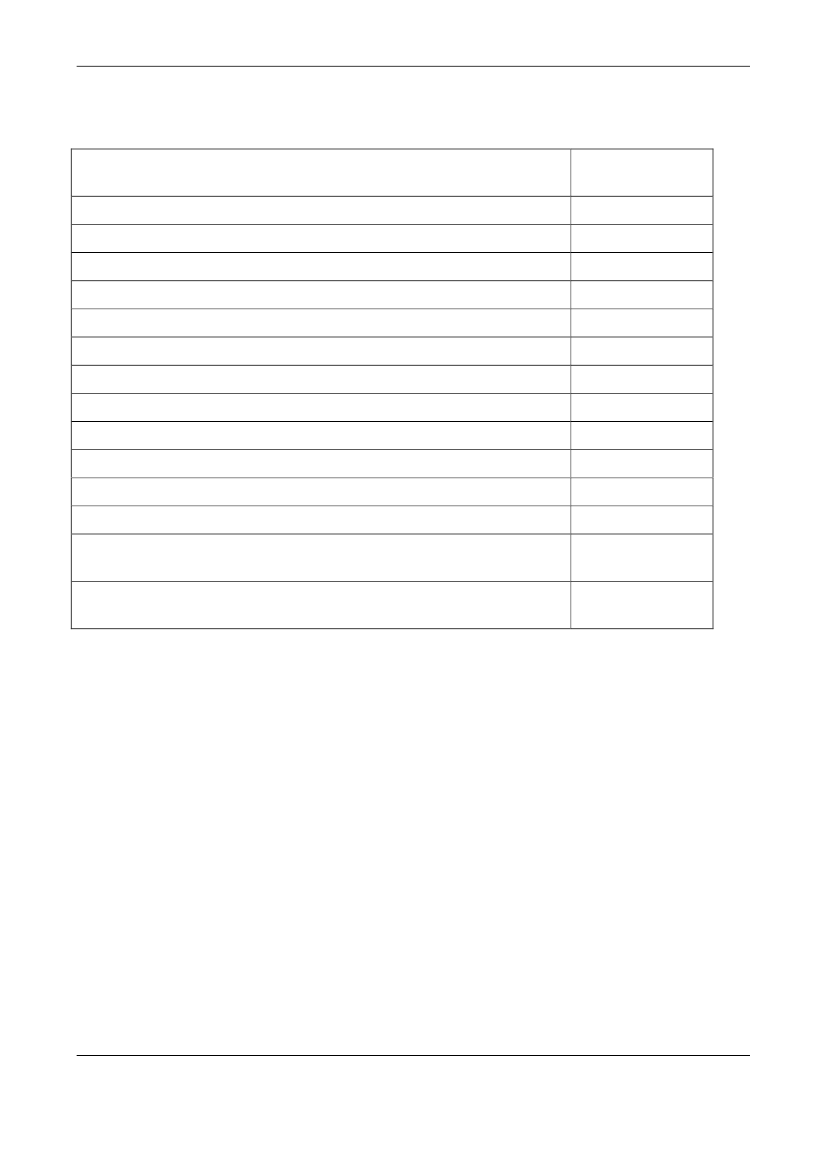

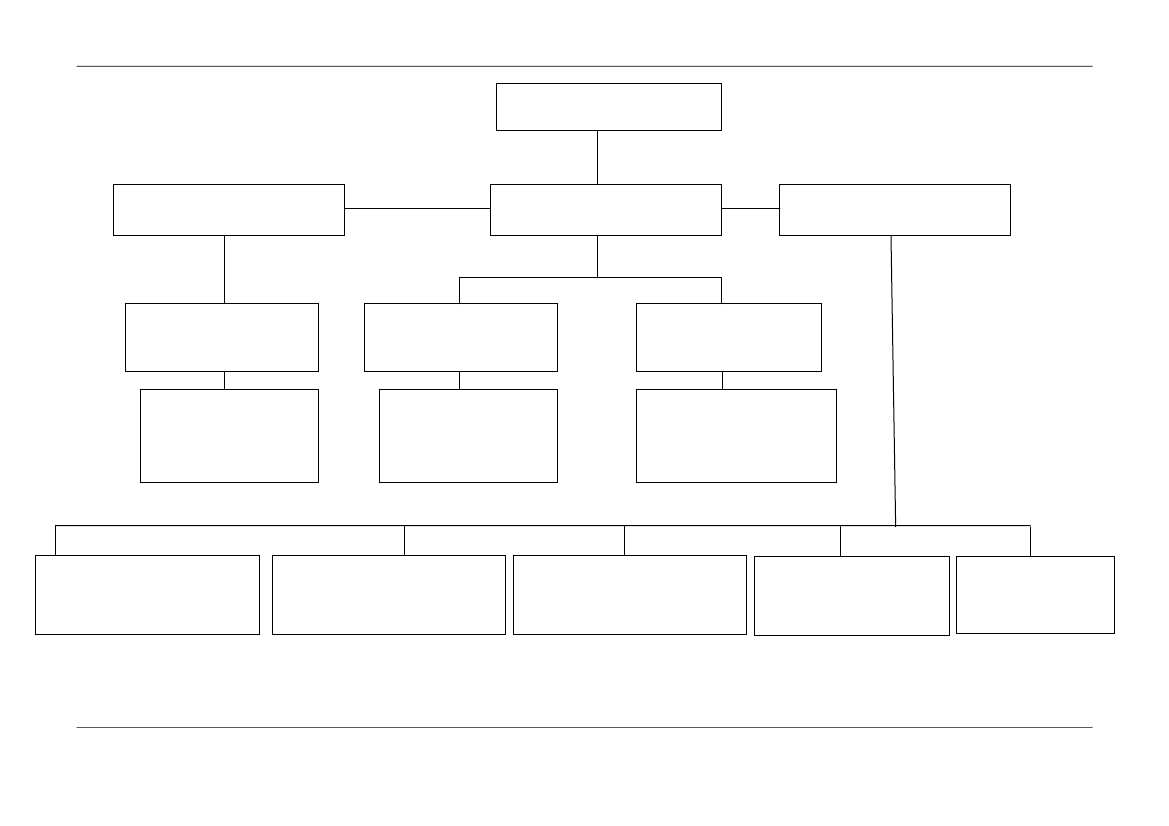

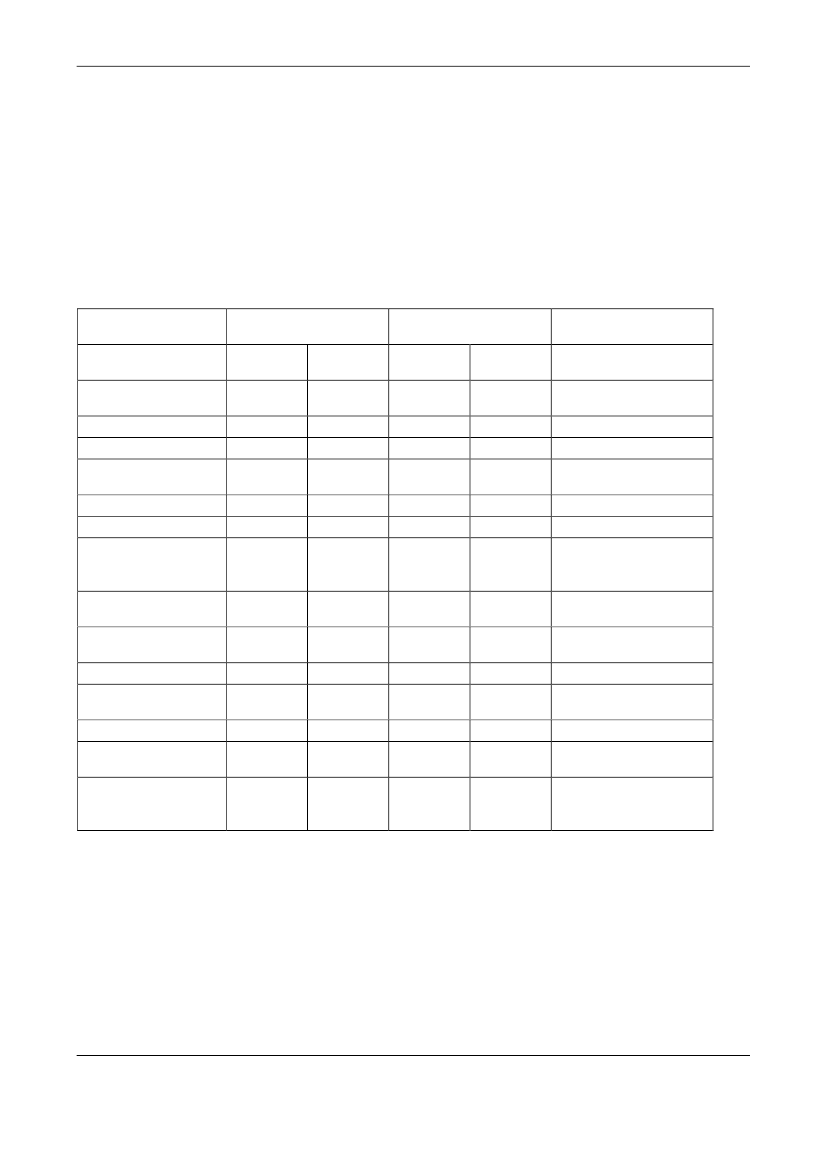

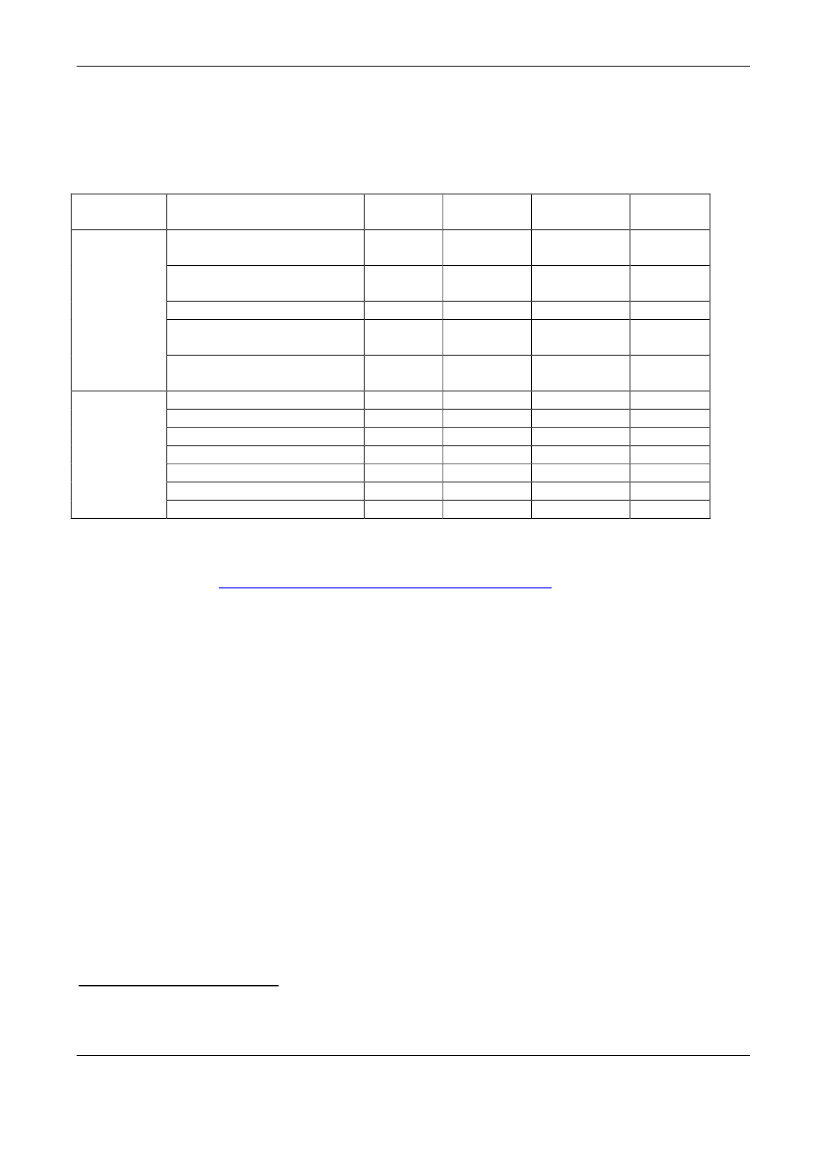

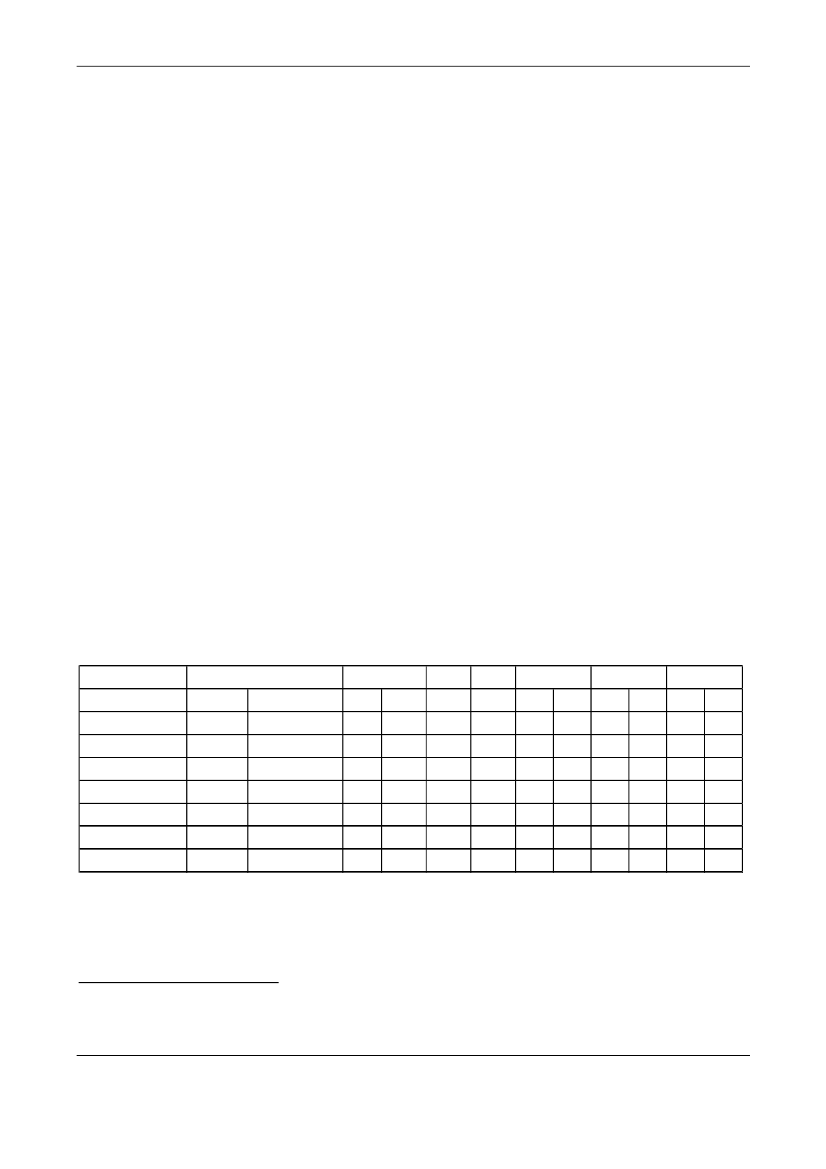

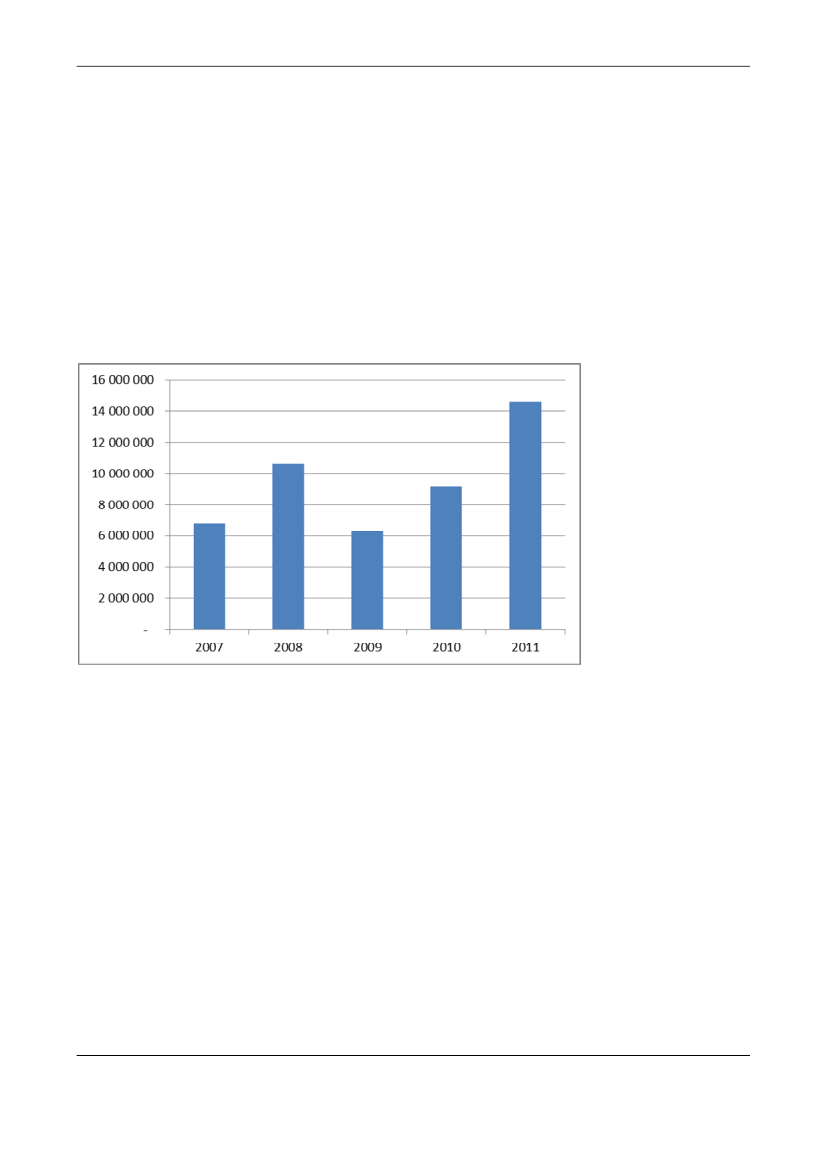

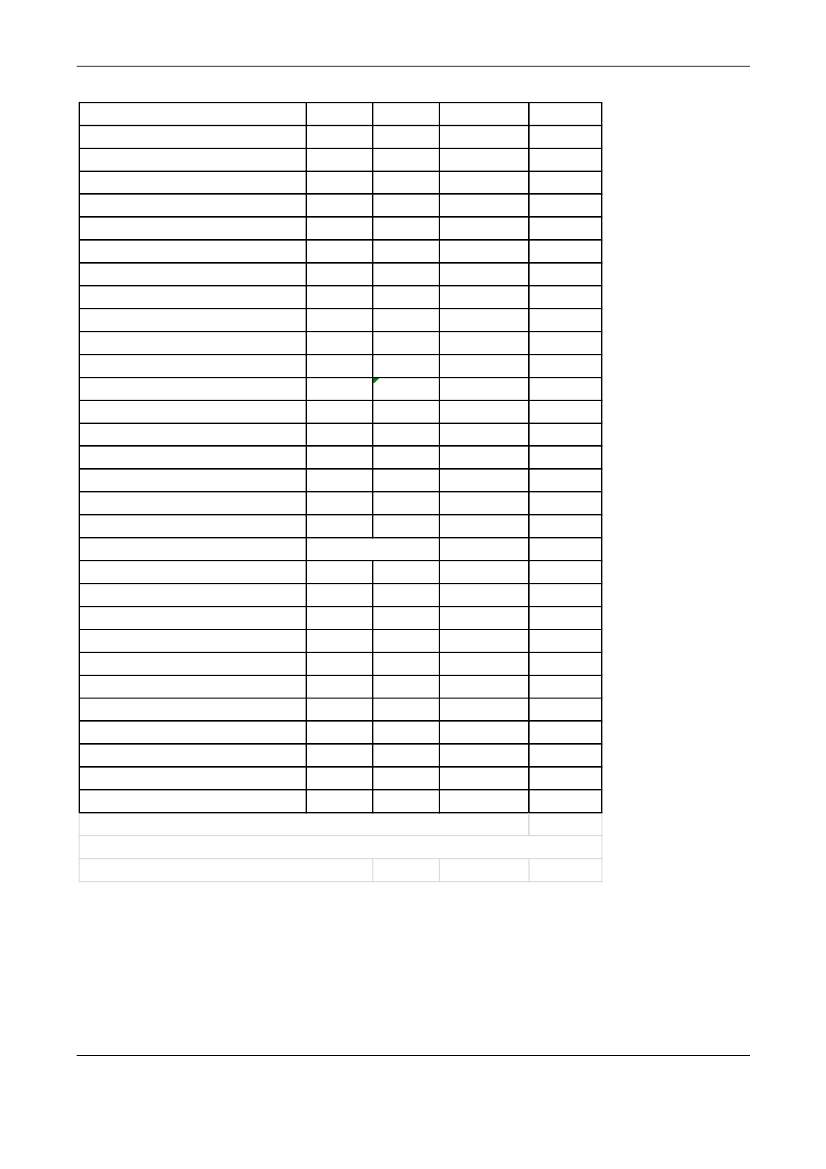

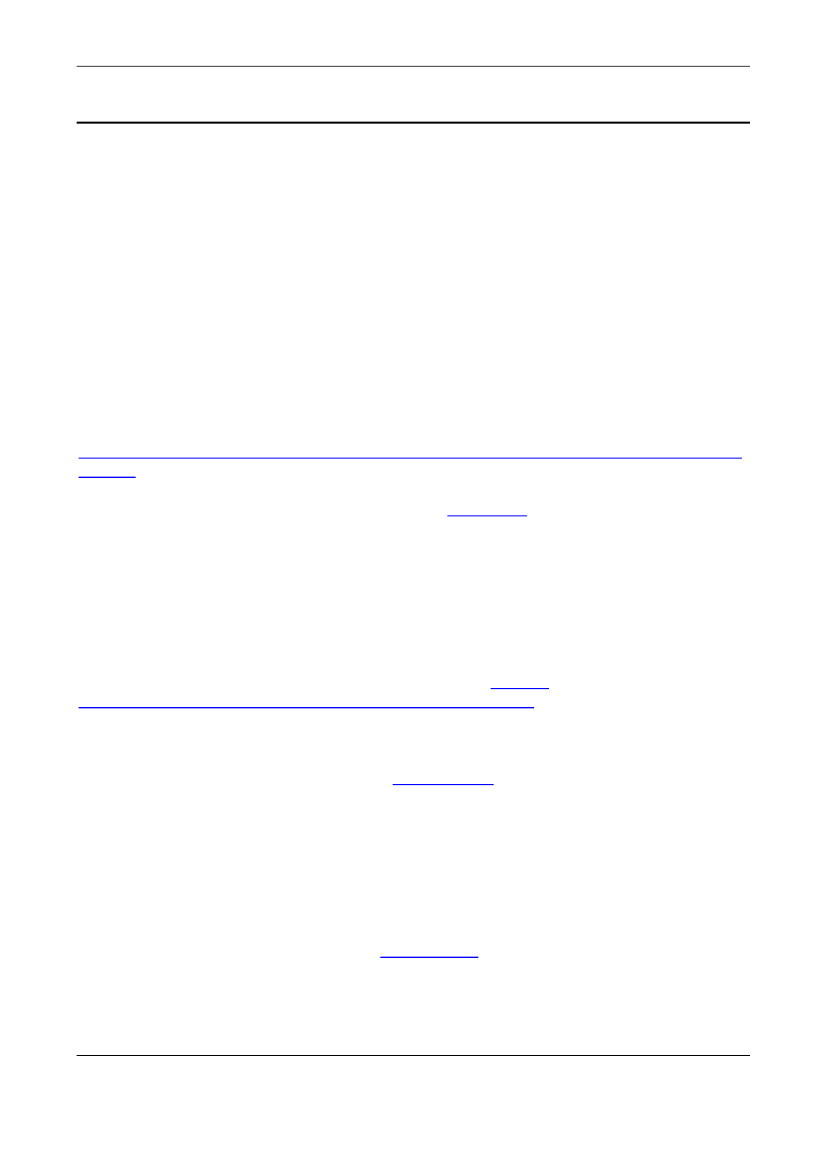

Figures, Tables and BoxesFiguresFIGURE1: KIRIBATIEXCLUSIVEECONOMICZONE.........................................................................................................................................2FIGURE2: WORLD TUNA CATCH, 2008-2010 (TONNES)..............................................................................................................................13FIGURE3: DISTRIBUTION OF CATCHES OF TUNAS IN THEWCPAREA BY GEAR OVER THE2000-2009PERIOD,AND2010................................14FIGURE4: TRENDS IN ANNUAL EFFORT(DAYS AT SEA)FOR THE TOP FOUR PURSE SEINE FLEETS, FSMA/DOMESTIC AND OTHERS OPERATING INTHE TROPICALWCP, 2001–2010 ...................................................................................................................................................17FIGURE5: DISTRIBUTION OF CUMULATIVEWCPFCYELLOWFIN TUNA CATCH FROM2000-2009BY5DEGREE SQUARES OF LATITUDE ANDLONGITUDE AND FISHING GEAR;.......................................................................................................................................................21FIGURE6: PERCENTAGE COMPOSITION OF THE20MAIN SPECIES CAUGHT BY UNASSOCIATED,LOG-DRIFTINGFADAND ANCHOREDFADPURSE-SEINE SETS(BY WEIGHT)IN THEWCP–CADETERMINED FROM RECENT OBSERVER DATA(2001–2006). .............................................23FIGURE7: WCPFC HIGHSEA POCKETS....................................................................................................................................................27FIGURE8: MEAN DISTRIBUTION OF SKIPJACK LARVAE, 1STQUARTER FOR THE DECADE1990-1999................................................................28FIGURE9: DWFN / FSMAANDDOMESTICPURSE SEINE EFFORT BYPNALICENSED PURSE SEINE FLEET.....................................................35FIGURE10: MONTHLY CATCHES BYEUPURSE SEINE VESSELS FOR2010BY SPECIES(TONNES) ..................................................................44FIGURE11: FISHERIESDIVISION ORGANISATION CHART..............................................................................................................................54FIGURE12: AVERAGE MONTHLY IMPORT PRICES PAID BYBANGKOK CANNERIES FOR PURSE SEINE CAUGHT FISH(EURO/TONNE, 2006TOJULY2011)............................................................................................................................................................................................68FIGURE13: ANNUAL VALUE OF CATCHES MADE INKIRIBATIEEZBYEUVESSELS UNDER THEPROTOCOL(EUROS)........................................69

TablesTABLE1: KIRIBATIGROSSDOMESTICPRODUCT BYECONOMICACTIVITY ATCONSTANT2006 PRICES, 2007–09 (€MNS).................................6TABLE2: BALANCE OF EXTERNAL TRADE(€,MN)..........................................................................................................................................6TABLE3: BREAKDOWN OF PURSE SEINE DISTANT WATER VESSELS(EEZAND HIGH SEAS)FISHING IN THEWESTERNPACIFIC, 31 JUNE2010AND AT THREE PRIOR TIMES IN THE FISHERY.....................................................................................................................................15TABLE4: PURSE SEINE CATCH(TONNES)BY TROPICAL TUNA SPECIES INWCPO, 2010................................................................................16TABLE5: PNACATCH BY SET TYPE(AVERAGE2005-2009) ........................................................................................................................18TABLE6: LONGLINE CATCHES IN THEWCPO,TONNES, 2010. ....................................................................................................................20TABLE7: WCPFCMEASURES RELEVANT TO THE FISHERIES UNDER ASSESSMENT........................................................................................25TABLE8: PNA VDSALLOCATIONS,UPTAKE BY MANAGEMENT YEAR(2008-2011)AND TRANSFERS...............................................................36TABLE9: IMPLEMENTATION OFPAE ALLOCATIONS BYPNAMEMBERS ATFEBRUARY2011 ..........................................................................37TABLE10: STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF THEVDS .............................................................................................................................37TABLE11: EUZONAL PURSE SEINE CATCHES IN THEWCPO (EEZANDHS) 2007-2010 .............................................................................43TABLE12: EUPURSE SEINE SPECIES CATCH IN THEWCPO (EEZANDHS) 2006-2011. .............................................................................44TABLE13: EUPURSE SEINE FISHING DAYS BY ZONE(2007-2010) ..............................................................................................................45TABLE14: CATCH STATISTICS FOREUFLEET INKIRIBATI PROVIDED BY DIFFERENT MANAGEMENT ORGANISATIONS(2007-2010) ...................45TABLE15: EUCATCH BYKIRIBATI ZONE(2007-2010)................................................................................................................................46TABLE16: CATCHES OF TUNA(TONNES)BYDWFNANDFSMAPURSE SEINE AND LONGLINE VESSELS IN THEKIRIBATIEEZ .........................47TABLE17: SUMMARY OF FOREIGN VESSELS LICENSED TO FISH INKIRIBATI WATERS, 2011 ...........................................................................48TABLE18: ESTIMATES OF ANNUAL AVERAGE LICENCE REVENUES ACCRUED TOKIRIBATI IN THE PERIOD2009-2011.......................................49TABLE19: USE OFKIRIBATIPAEDAYS, 2007TO2010..............................................................................................................................50TABLE20: MFMRD EXPENDITUREFRAMEWORK, 2011AND2012 (AUS$AND€).......................................................................................55TABLE21: MARINEPROTECTEDAREAS INKIRIBATI....................................................................................................................................57TABLE22: UTILISATION OF FISHING AUTHORISATIONS PROVIDED FOR IN THEPROTOCOL..............................................................................62TABLE23: UTILISATION OF CATCH POSSIBILITIES PROVIDED FOR IN THEPROTOCOL.....................................................................................63TABLE24: PAYMENTS MADE TOKIRIBATI BY THEEUAND FLEET OWNERS....................................................................................................65TABLE25: PAYMENTS MADE TOKIRIBATI PER TONNE OF FISH AND PER DAY, 2007-2010..............................................................................66TABLE26: CARRIAGEINSURANCE ANDFREIGHT(CIF)PRICES PAID FOR FISH CAUGHT BYEUPURSE SEINERS FISHING UNDER THEPROTOCOL.....................................................................................................................................................................................................67TABLE27: AVERAGE YEARLY IMPORT PRICES PAID BYBANGKOK CANNERIES FOR PURSE SEINE CAUGHT FISH(EURO/TONNE).........................68TABLE28: AVERAGE YEARLY EX-VESSEL PRICES(€/TONNE) .......................................................................................................................68TABLE29: AVERAGE ANNUAL VALUE ADDED ACCRUING TO THEEUAND TOKIRIBATI FROM THEPROTOCOL...................................................70TABLE30: BALANCE OF VALUE-ADDED BETWEEN SUB-SECTORS,AND BETWEEN THEEUANDKIRIBATI..........................................................72TABLE31: AVERAGE ANNUAL COSTS AND BENEFITS(€)OF THEPROTOCOL(2007TO2011) ........................................................................73Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xviiiEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

TABLE32: EUIMPORTS OF CANNED AND LOINED TUNA AND ESTIMATED CONTRIBUTIONS OF CATCH MADE UNDER THEPROTOCOL TOEUIMPORTS........................................................................................................................................................................................74TABLE33: EMPLOYMENT GENERATED BY THEPROTOCOL...........................................................................................................................76TABLE34: EX-ANTE EVALUATION OF THE RENEWAL OF THEEU/KIRIBATIPROTOCOL....................................................................................89

BOXESBOX1: SUMMARY OF FISHERIES PROGRAMMES COVERED UNDER THE10THEDF............................................................................................9BOX2: FISHERIESPERFORMANCEINCENTIVEFUND(AUSAID, 2010-2011) ................................................................................................12BOX3: CONTENTS OF THENAURUAGREEMENT.........................................................................................................................................29BOX4: THEHARMONISEDMINIMUMTERMS ANDCONDITIONS FORFOREIGNFISHINGVESSELACCESS.........................................................32

Consortium: COFREPECHE (leader) – MRAG – NFDS – POSEIDONPage xixEx-post evaluation of the current protocol to the FPA between the EU and Kiribati, and ex-ante evaluation with analysis of impacts of a futureprotocolFinal Report – final version

DG MARE 2011/01/Lot 3 - SC1

KIR95R01E1

1