Udvalget for Fødevarer, Landbrug og Fiskeri 2011-12

FLF Alm.del Bilag 10

Offentligt

COUNCIL OFTHE EUROPEAN UNION

Brussels, 12 September 2011 (13.09)(OR. fr)

6751/11EXT 1 ADD 1

PECHE 52

ADDENDUM No 1 TO THE PARTIAL DECLASSIFICATIONof:6751/11 RESTREINT UEdated:18 February 2011newpublicclassification:Subject:Specific Agreement No 26: Ex-post evaluation of the current Protocol to theFisheries Partnership Agreement between the European Union and the Kingdomof Morocco, Impact study for a possible future Protocol to the Agreement

Delegations will find attached the above document partially declassified (second part1).

_______________

1

See also EXT 1 INIT + ADD 2-5.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1DG B III

tim/RGR/cz

1

EN

ANNEX

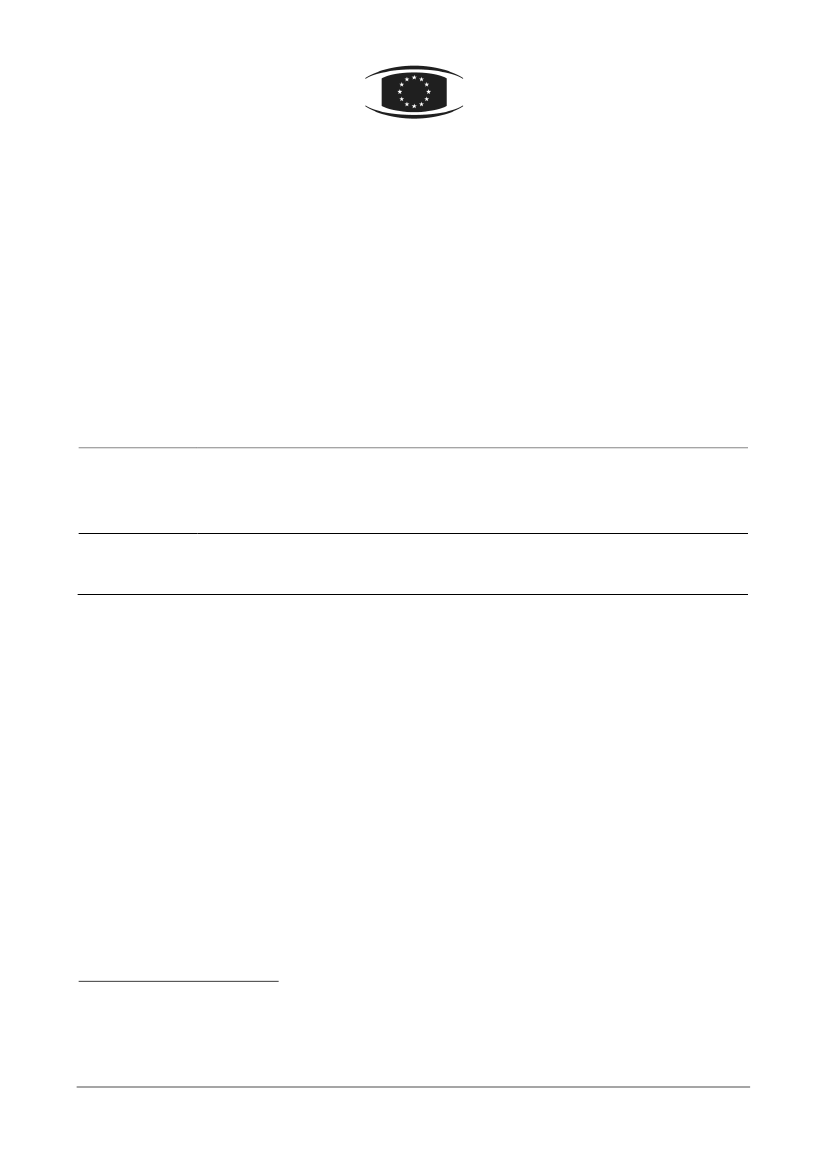

Table 4: Principal budgetary aspects. Source: annual Finance Acts(EUR million)I- Total ResourcesRevenue general budgetTuna trap feesFishing licence feesOther feesSea fisheries contributionsFishing finesSundry incomeSub-total fisheriesRevenue Government department budgetRevenue special Treasury accountsII- Total ExpenditureOperating general budgetOperating Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (staff)Operating Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (expenditure)Investment general budgetInvestment Ministry of Agriculture and FisheriesSurplus of expenditure over revenue200718 96515 975200821 08317 2710.12.52.539.90.20.745.81473 66522 18110 97072.293.74 653275.11 098200926 28821 4050.22.22.040.20.20.745.41894 69427 44613 42379.298.65 675497.61 158201023 70719 3950.11.90.736.50.20.740.22074 10424 86612 29061.7131.07 359666.61 159

43.81422 84820 3329 77366.8102.93 477267.81 367

→The fisheries sector and the budgetThe general budget revenue from the fisheries sector amounts to approximately EUR 45 million per year.Consequently, it represents only a very small part of the revenue of the country (0.2% to 0.3%). The financialcompensation paid under the Fisheries Agreement of EUR 36.1 million per year equally is of littlesignificance in the public finance equilibrium (0.2% of budget revenue). The contribution of the EU under theFisheries Agreement comes under the "Sea Fisheries contribution" where it is added to the compensationreceived under the Fisheries Agreement with Russia, which can therefore be calculated by subtraction asvarying between EUR 5 million and 10 million per year. Overall, the compensation paid by the EU for theAgreement in progress represents about 80% of the public revenue from the fisheries sector.As regards expenditure, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries receives approximately 1.5% of operatingexpenditure from the general budget and is among the smallest Ministries in this respect, far behind theMinistries of Education, Defence, the Interior, Health or Justice. On the other hand, the Ministry of Agricultureand Fisheries receives far larger investment appropriations (approximately 9% of the total investmentexpenditure), with a clear upwards tendency. In 2010, the Ministry has received one of the largest investmentappropriations, less than the Ministry of Education, but more than the Ministries of Public Works andTransport, Defence or the Interior. Nevertheless, the bulk of the budget resources allocated to this Ministryare for agriculture. The Sea Fisheries Department in fact receives only the equivalent of EUR 30 million ininvestment budget, i.e. 4% to 5% of the total appropriation assigned to the Ministry.2.4Foreign investment and the business climate

Morocco claims to be a country which is resolutely open to foreign enterprise. With positive law which doesnot discriminate in any way between nationals and foreigners, the country is open to foreign capital, whichhas come to account for a significant share of investment. The reforms adopted at regular intervals aim toimprove the business climate in favour of all operators.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

2

EN

With a supply of skilled labour close to Europe (Morocco is only 14 km from Spain), Morocco aims to positionitself as a platform for production and export of European know-how. Its advanced status with the EU in thecontext of the neighbourhood policy, its free trade agreement with the USA and its membership of the ArabLeague have already earned it a large number of establishments of foreign enterprises: historically Frenchand Spanish, more recently Chinese and Japanese. This foreign investment is undertaken under theliberalisations and privatisations in the field of ICT, energy, water and electricity distribution, infrastructures,etc.This progressive opening up, which affects almost all sectors, is accompanied by the gradual establishmentof a climate which is more favourable especially to foreign investment. With the adoption of reforms of theInvestment Charter in 2005, the State restructured the tax system in 2007 and is engaged in improving theguarantees given to investors. The State has also created installation sites adapted to the needs ofinvestors, such as free zones, business parks for outsourced services (offshoring) and integrated industrialplatforms.

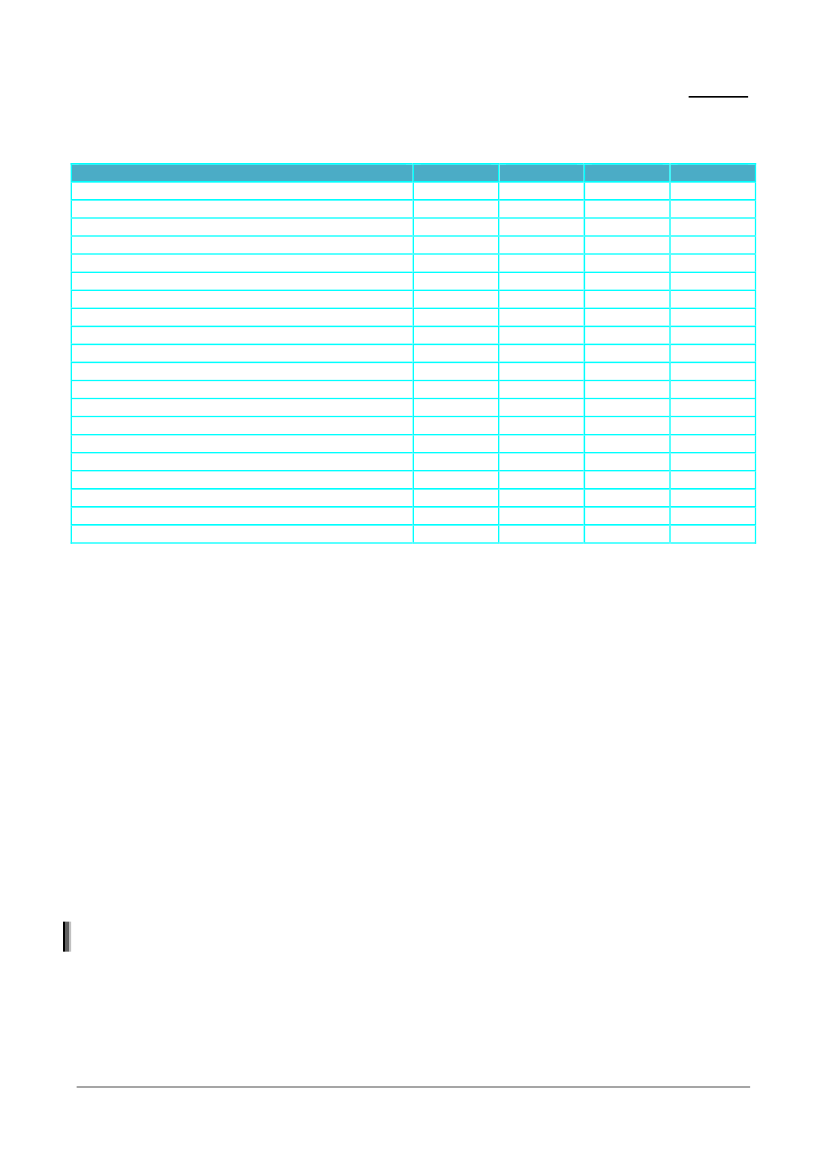

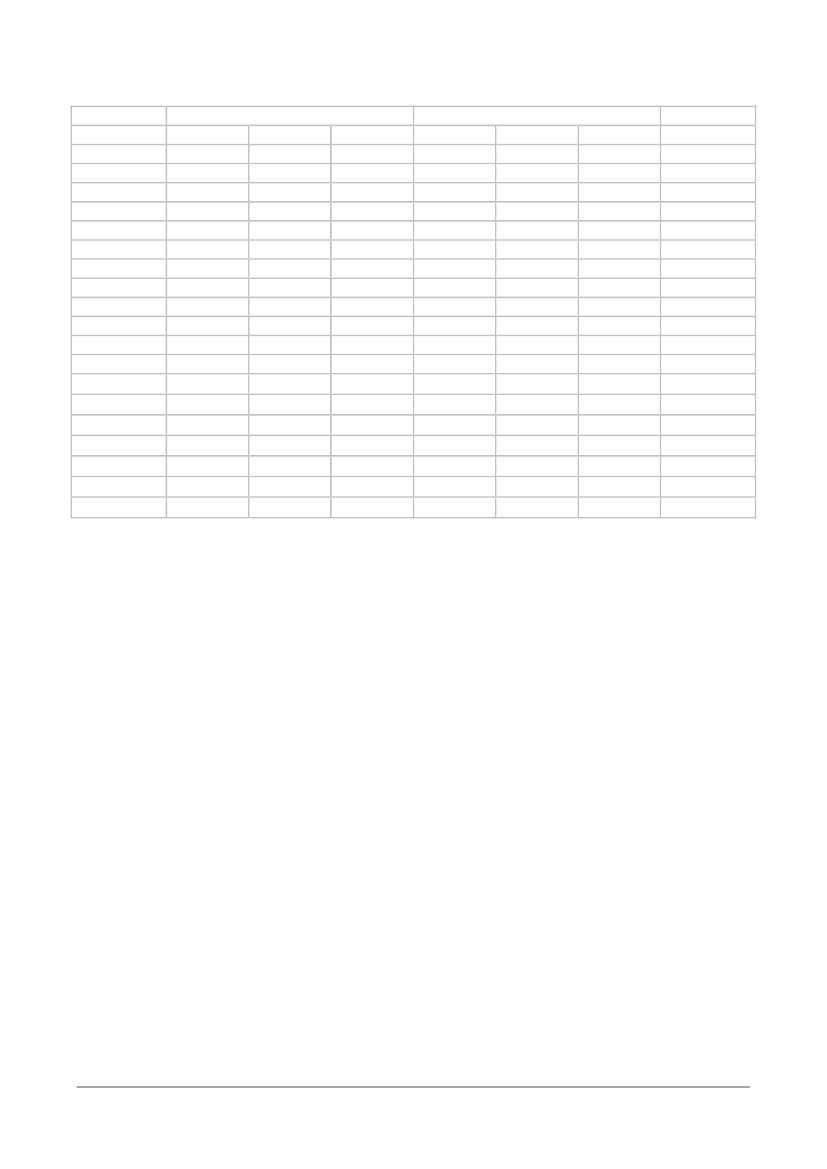

Table 5: Data relating to direct foreign investment in Morocco. Source: CNUCED, World Investment Report 2010(USD million)IncomingOutgoing1995-20051 109352006DFI flows2 4504452 8036212 4874851 1314702008720082009

As % of fixed capital formationIncomingOutgoing10.40.3DFI stockIncomingOutgoing5 1262698 842402As % of GDPIncomingOutgoing13.90.751.31.845.52462.538 6131 33739 3881 69940 7192 16911.92.691.84.51.6

As shown in the table above, foreign investment is nevertheless down in 2008 and 2009, as a consequenceof the financial crisis affecting the developed countries. Nevertheless, the start of the upturn has promptedthe announcement of new major projects concerning a diversified portfolio of sectors: metallurgy with aBritish group, power stations with a group from the Emirates, motor vehicles with a French group,telecommunications, banking and tourism. European enterprises account for two thirds of DFI flows,compared to a quarter for the Persian Gulf States.This said, the business climate in Morocco could still be improved further. According to the reportDoingBusiness 2010,sponsored by the World Bank, Morocco is classified only in 128th place in the world out of183 classified countries, down two places compared to its 2009 classification. In the World Bank’s analysis,Morocco is penalised compared to other third countries by indicators relating to employment of workers(176th place), property registration (123rd), investment protection (165th), respect of contract law (108th)and tax systems (125th). The favourable indicators for Morocco are those relating to the registration of newcompanies (76th), access to international trade (72nd) and obtaining credit (87th). Another factor which isunfavourable to the business climate is Morocco’s classification in the corruption index measured by the

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

3

EN

NGOTransparency Internationalis tending to deteriorate, with the country falling from 72nd place in theworld in 2007 to 80th place in 2008.

2.5

Employment

According to the statistics of the High Commission for Planning, just over 10 million people aged 15 yearsand over are employed in Morocco. About 41% of jobs are in the primary sectors of agriculture, forestry orfishing, 20% in general administration and social services for the community, 13% in trade and 9% inindustry. Jobs in the primary sector are logically mainly in the rural areas (75% of total jobs), with a verysmall minority in urban areas (5%). Moreover, this sector essentially employs people without qualifications(79% of the workers in the rural areas have no diploma).

Table 6: Situation of employment by sectors of economic activity. Source: High Commission for Planning(in thousands)Agriculture, forestry andfishingIndustryBuildings and public worksTradeTransportAdministrationSocial servicesOther servicesTOTAL20074 233.61 277.1844.71 257402.21 025.71 005.610.110 05620084 157.11 304.2906.81 273.6448.31 018.91 049.520.410178.8Trend 2007/2008-1.82.17.41.311.5-0.74.4102.61.2

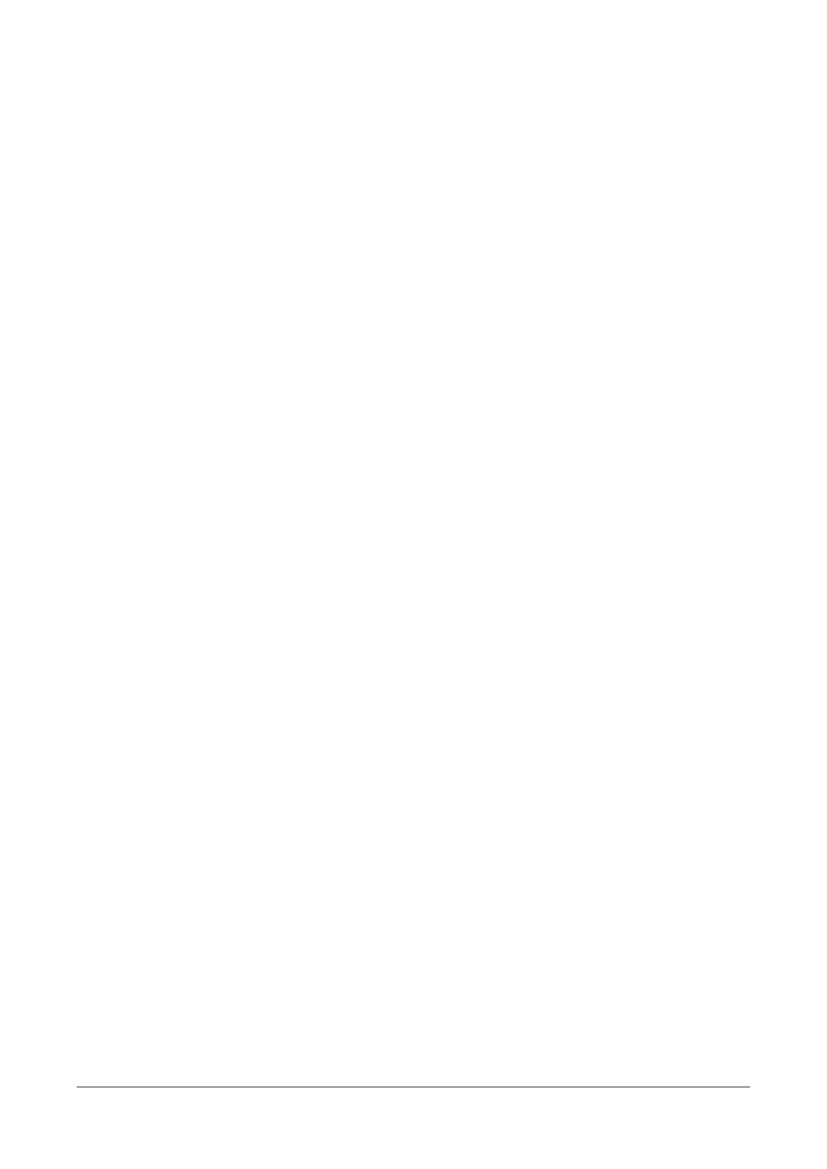

In 2009, the unemployment rate of the population was estimated at 9.6% (i.e. just over 1 million people), witha greater prevalence in urban areas (13.8%) as opposed to rural areas (4%). As shown in the graph below,the unemployment rate is tending to fall in Morocco. Unemployment mainly affects the population aged 15 to24 years (18%), followed by the 25-34 year age group (12.7%).Trend in the unemployment rate (in %)16141210864201999200020012002200320042005200620072008

Figure 3: Trend in the unemployment rate in Morocco. Source: High Commission for Planning

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

4

EN

→The fisheriessector and employmentAccording to the Ministry responsible for fisheries, approximately 170 000 people are directlyemployed in the fisheries sector, of whom 110 080 in the production sector (on-boardemployment), 61 650 in the processing industries and 165 in aquaculture. Direct employment inthe sector therefore accounts for approximately 1.6% of employment in Morocco and on-boardemployment 2.6% of jobs in the primary sector. The Ministry’s estimates indicate that in addition tothis direct employment, fisheries also generate 490 000 jobs in related sectors, giving a total of660 000 jobs, bringing the contribution of the sector to total employment to 6.5%.According to the information supplied by the Ministry, employment in the fisheries sector isparticularly important in the southern regions where it accounts for about 30% of jobs.

3

REGIONAL DATA

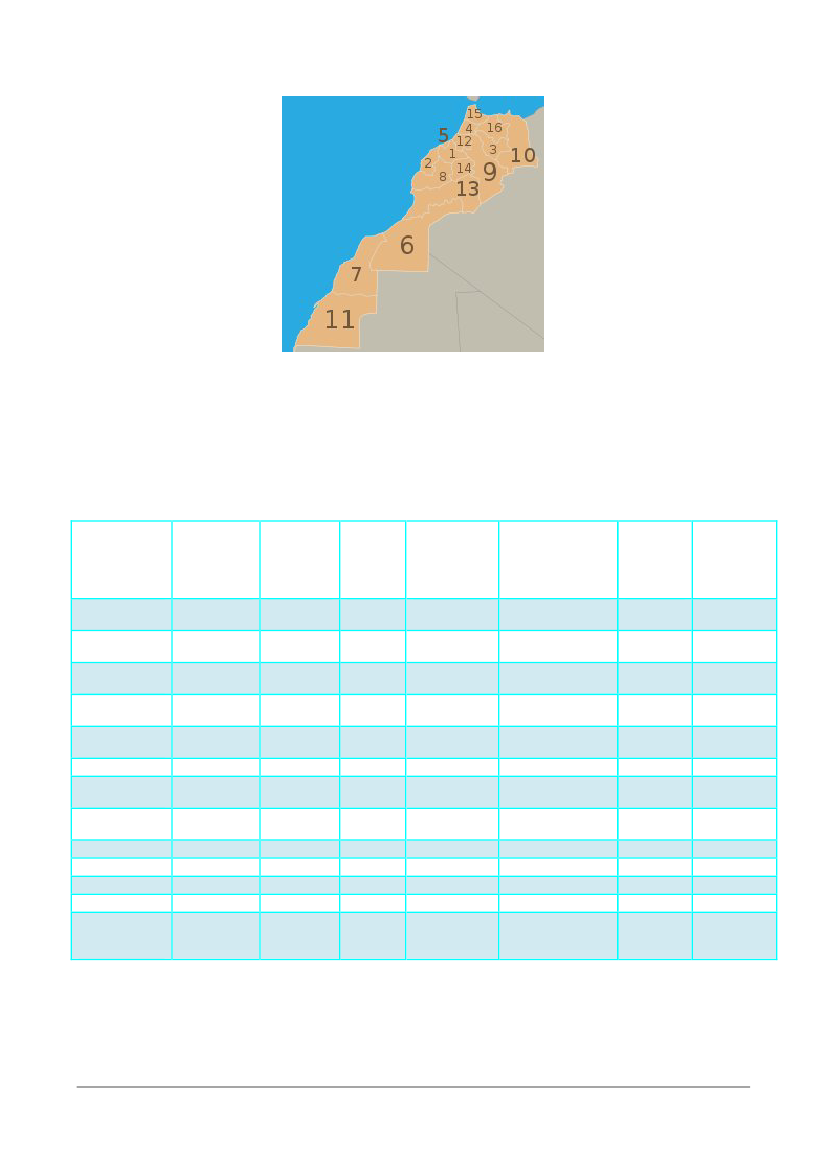

Morocco has sixteen regions, each headed by a Wali, and a regional council, which represents the"living strength" of the region. These regions have the status of local authorities. According to thecountry’s Constitution, "the local authorities shall elect the assemblies responsible for thedemocratic management of their affairs under the conditions determined by law. The governorsshall implement the decisions taken by the provincial, prefectoral and regional assemblies underthe conditions determined by law."The various regions in the list below correspond to the numbers shown on the map on the nextpage:1. Chaouia-Ouardigha;2. Doukhala-Abd;3. Fès-Boulemane;4. Gharb-Chrarda-Beni Hssen;5. Grand Casablanca;6. Guelmim-Es Smara (includes part of the Western Sahara, the province of Es Smara);7. Laâyoune-Boujdour-Sakia el Hamra (includes part of the Western Sahara);8. Marrakech-Tensift-Al Haouz;9. Meknès-Tafilalet;10. Oriental;11. Oued Ed-Dahab-Lagouira (located in the Western Sahara);12. Rabat-Salé-Zemmour-Zaër;13. Sous-Massa-Drâa;14. Tadla-Azilal;15. Tangier-Tétouan;16. Taza-Al Hoceima-Taounate.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

5

EN

Figure 4: Outline map of the administrative regions of Morocco

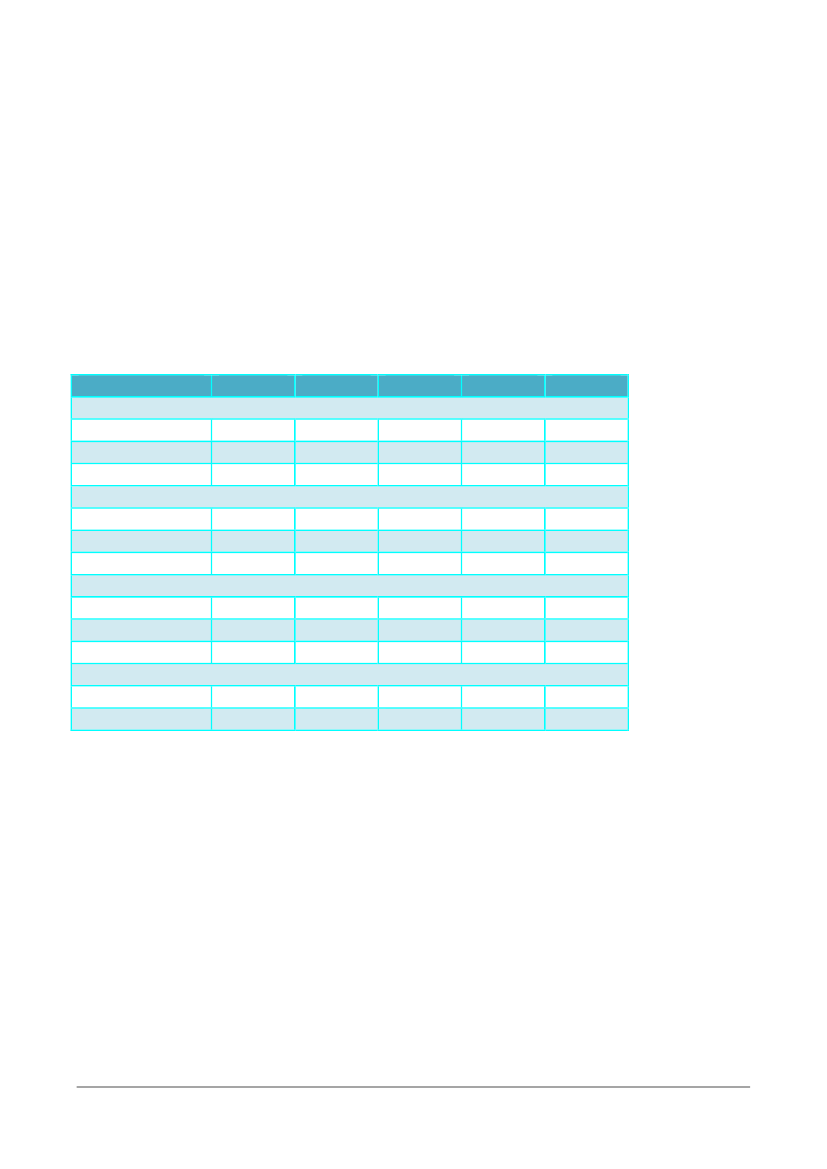

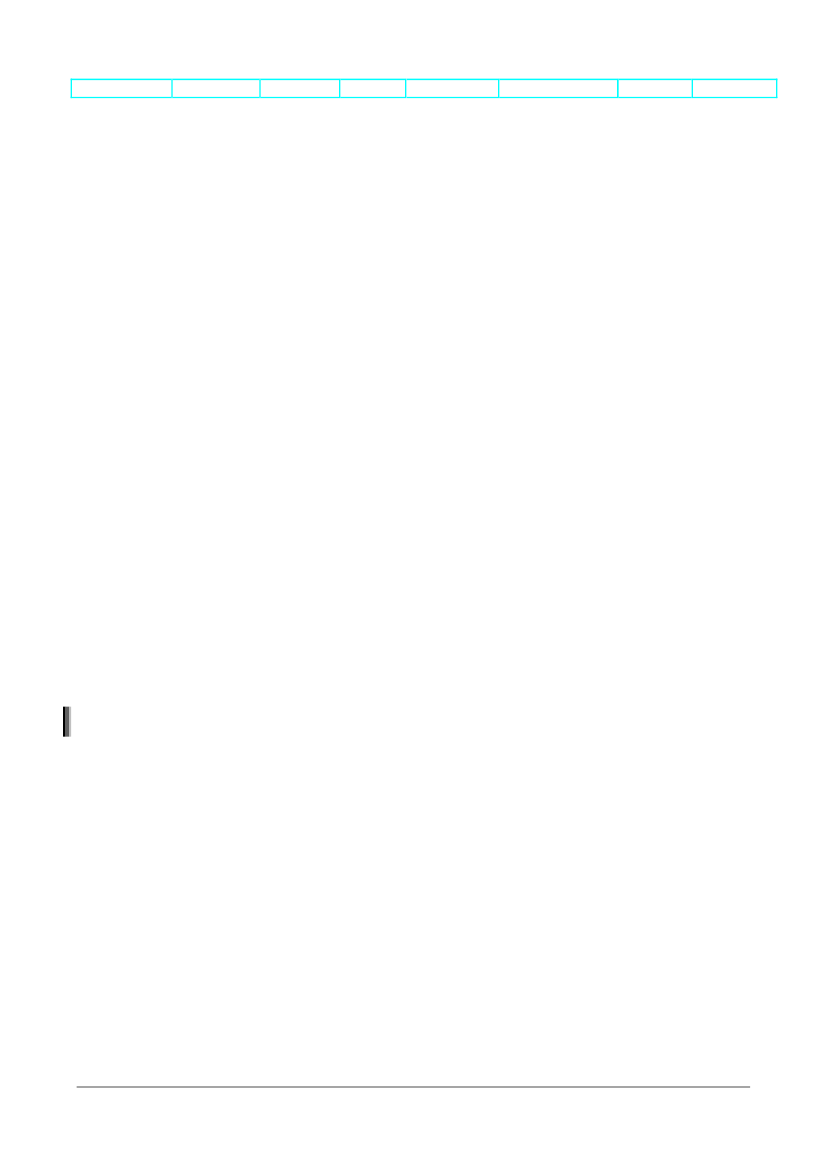

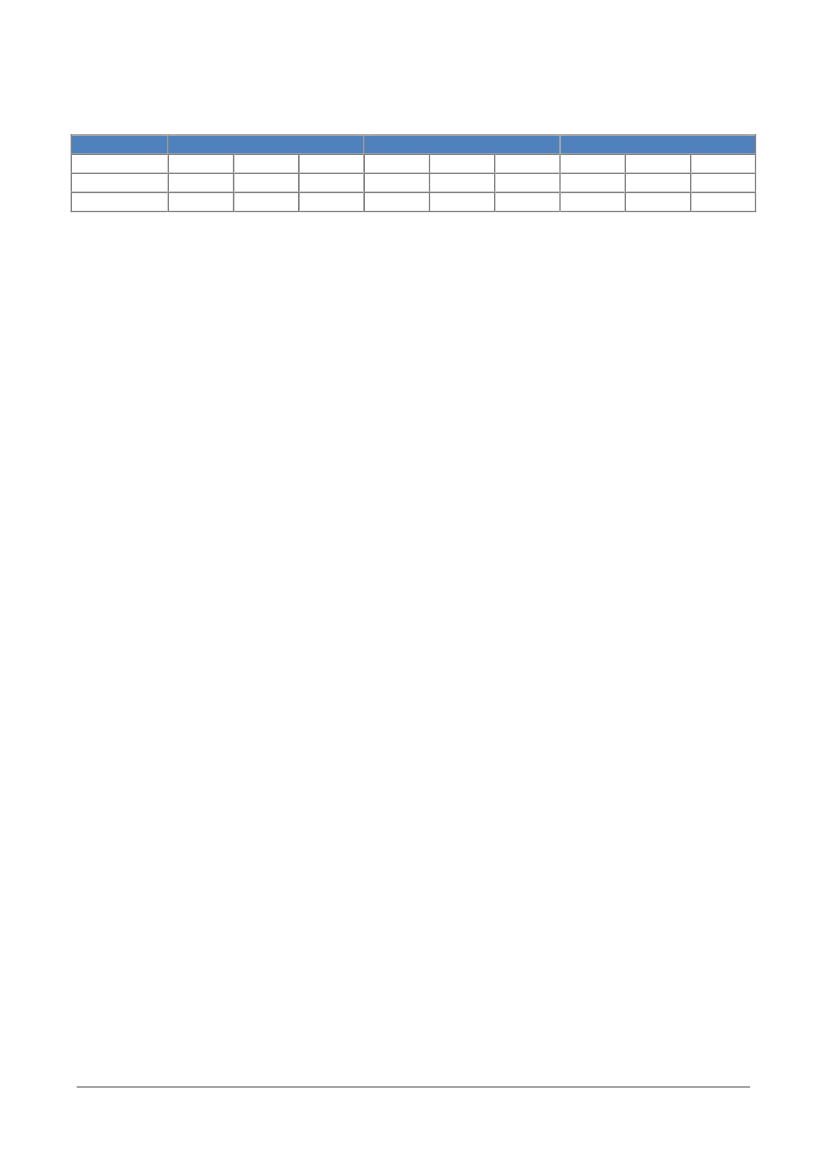

The principal regional economic indicators are shown in the table below. They were drawn up bythe High Commission for Planning for the years 2004 and 2007 with regard to the GDP data andfor 2009 regarding the employment indicators. The data on the regional distribution of thepopulation date back to the last census of 2004.Table 7: Selection of regional indicators. Source: High Commission for PlanningRegionsPopulationRegionalGDP (2007)Growth2004-2007Share offisheries inregional GDP(2007)10.4%4.5%0.3%0.0%0.1%0.4%0.3%0.0%0.6%0.0%0.0%0.0%0.7%Contribution offisheries to nationalsectoral GDP(2007)36.4%35.4%1.1%0.0%1.2%2.0%7.4%0.2%3.5%0.0%0.0%0.0%2.2%Labourforcepartic-ipationrate (2009)45.9%51.5%58.6%56.5%54.5%44.3%47.0%45.0%58.1%51.2%45.9%48.4%52.3%Unemploy-ment rate(2009)

Southernregions*Sous-Massa-DrâaGharb-Chrarda-Beni HssenChaouia-OuardighaMarrakech-Tensift-Al HaouzOrientalGrandCasablancaRabat-Salé-Zemmour-ZaërDoukhala-AbdTadla-AzilalMeknès-TafilaletFès-BoulemaneTaza-AlHoceima-Taounate

2.7%10.4%6.2%5.5%10.4%6.4%12.1%7.9%6.6%4.9%7.2%5.3%6.0%

3.5%8.0%3.9%5.0%8.9%5.1%21.3%13.6%6.4%2.6%5.2%4.5%3.0%

9.2%6.0%1.5%5.1%13.4%5.7%3.1%10.4%7.0%0.0%6.5%8.5%4.3%

13.7%7.2%11.3%6.1%4.9%18.2%11.6%12.5%7.4%5.0%8.4%7.0%8.1%

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

6

EN

Tangier-Tétouan

8.3%

8.8%

12.7%

1.2%

10.7%

42.8%

8.9%

* The Moroccan statistics cover the regions of Oued Ed-Dahab-Lagouira, Laâyoune-Boujdour-Sakia el Hamra and Guelmim-Es Smara in a southernregion aggregate for reasons of representativeness mentioned.

The results of the production accounts show that five regions out of 16 were responsible for nearly 60.6% ofthe national wealth creation in 2007. Grand Casablanca is in first place with 21.3%, followed by Rabat-Salé-Zemmour-Zaer (13.6%), Marrakech-Tensift-Al Haouz (8.9%), Tangier-Tétouan (8.8%) and Souss-Massa-Daraâ (8%). They are followed by four regions which contribute 21.7% to GDP. These are Doukkala-Abda(6.4%), Mèknes-Tafilalt (5.2%), Oriental (5.1%) and Chaouia-Ouardigha (5%). The contribution of each of theother regions varies between 2.6% (Tadla-Azilal) and 4.5% (Fès-Boulemane).The regions which posted a two-digit GDP growth rate – or nearly – between 2004 and 2007 are the regionsof Marrakech-Tensift-Al Haouz (+13.4%), Tangier-Tétouan (+12.7%), Rabat-Salé-Zemmour-Zaër (+10.4%)and the south (+9.2%).The economic activities are of variable importance according to the regions. In Grand Casablanca forexample, the dominant activities are the extractive and processing industries (28%), trade (11,5%), financialactivities and insurance (16%) and property-renting and services (15.8%). The other production contributes ashare of less than 6% to the total added value of the region. This region has a different configuration fromthe others, where at best two activities account for the bulk of added value. For example, agriculture remainssignificant in the regions of Tangier-Tétouan, Gharb-Chrarda-Béni Hsan, Tadla-Azilal and Meknès-Tafilalt,where it contributes between 22.4% and 30.1% to the formation of added value.The contribution of the fisheries sector to regional GDP is greatest in the southern regions (10.4%), beforethe region of Souss Massa Drâa (Agadir) with 4.5% and the region of Tangier Tétouan (1.2%). It is pointedout that over 70% of national GDP of the fisheries sector is generated in the southern regions (36.4% ofnational fisheries GDP) and in the region of Souss Massa Drâ (35.4%). Only the region of Tangier Tétouanmakes a significant contribution to the fisheries sector GDP (10.7%) in addition to the two regions mentionedabove.The unemployment rate is highest in the Oriental region (18.2%), followed by the southern regions (13.7%).The unemployment rate is also high in the large economic centres of Grand Casablanca and Rabat-Salé(approximately 12% compared to a national average of 9.6%). The labour force participation rate, whichindicates the proportion of people who are participating or are seeking to participate in the production ofgoods and services in a given population, is the lowest in the regions of Tangier and Tétouan (42.8%) andthe south (45.9%).44.1RELATIONS WITH THE EUROPEAN UNIONPolitical aspects

As early as 1963, Morocco requested the opening of negotiations to conclude a commercial agreement in1969. This cooperation then developed to end in a new Agreement in 1976 containing both trade provisionsand a financial contribution in the form of donations to the socio-economic development of the Kingdom.This agreement was flanked by four financial protocols signed during the period 1976 to 1996, supplementedby loans from the European Investment Bank. During the period following the financial protocols, the MEDA Iprogramme (1996-99), which represents a tripling of the aid to Morocco compared to the financial protocols,allowed support to be given to the economic transition and socio-economic equilibrium in Morocco. TheMEDA II programme, with some projects still in progress, allowed a considerable increase in the amount offinance allocated to Morocco.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

7

EN

At regional level, the Barcelona Conference of November 1995, which brought together the European Unionand the 12 Mediterranean partner countries, led to the Barcelona Declaration, a programme of dialogue,trade and cooperation to guarantee peace, stability and prosperity in the region. This unprecedented politicalcommitment covers the "Political and Security", "Economic and Financial" and "Social, cultural and human"facets. This partnership is established at bilateral level by an association agreement between eachMediterranean partner and the European Union. Morocco, which plays a strategic role in the Euro-Mediterranean partnership, signed this Association Agreement in February 1996 and it entered into force inMarch 2000. The main objectives of this agreement are:to strengthen political dialogue,to establish the conditions necessary for the progressive liberalisation of trade in goods, services andcapital, including that in fisheries products,to develop balanced economic and social relations between the parties,to support the South-South integration initiatives,to promote cooperation in the economic, social, cultural and financial fields.In 2003, the EU launched the neighbourhood policy, which supplements, specifies and deepens the Euro-Mediterranean partnership. This initiative takes the concrete form of the joint adoption of an action planwhich sets out a programme of economic and political reforms with short and medium-term priorities. Thefisheries sector does not appear explicitly in this action plan. A new action plan is currently being drawn upfor the period 2010-2015, with the possibility of including fisheries and maritime policy in the priority sectorsfor cooperation.In October 2008, advanced status , the first in the southern Mediterranean region, was granted to Morocco,marking a new phase in special relations. The advanced status will take the form of strengthening thepolitical dialogue, economic and social cooperation, in the parliamentary, security and justice fields and invarious sectors, notably agriculture, transport, energy and the environment, as well as the progressiveintegration of Morocco in the common internal market and convergence of laws and regulations. Morocco willalso be able to apply to participate in the work of certain Community agencies.2

4.2

Financial aspects

Since January 2007, the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) has been financingthe cooperation between the EU and Morocco with a budget earmarked under the National IndicativeProgramme for the period 2007-2010 of EUR 654 million (≈EUR 163 million per year over four years), whichmakes Morocco the leading beneficiary from European funds in the region. The distribution of this budgetaccording to the major components of the cooperation is as follows:Social componentGovernance componentInstitutional support componentEconomic componentEnvironment componentTotal programme 2007-2010296 M€28 M€40 M€240 M€50 M€654 M€45%4%6%37%8%100%

For the period 2011-2013, the NIP in the process of adoption provides for a budget of nearly EUR 580 million(≈EUR 193 million per year forthree years). The details of the commitments per component are not yet inthe public domain.By way of comparison, the annual EU financial contribution under the current Fisheries Agreement amountsto EUR 36.1 million per year (4 to 5 times less than the annualised amounts provided for the NIPs), butfocuses on a sector which appears only implicitly in the strategic priorities of the NIP 2007-2010. There istherefore no problema prioriof consistency between the various components of the EU policy in relation toMorocco.

2

Commonly defined by commentators as "more than association, less than accession".

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

8

EN

4.3

Relations with other donors

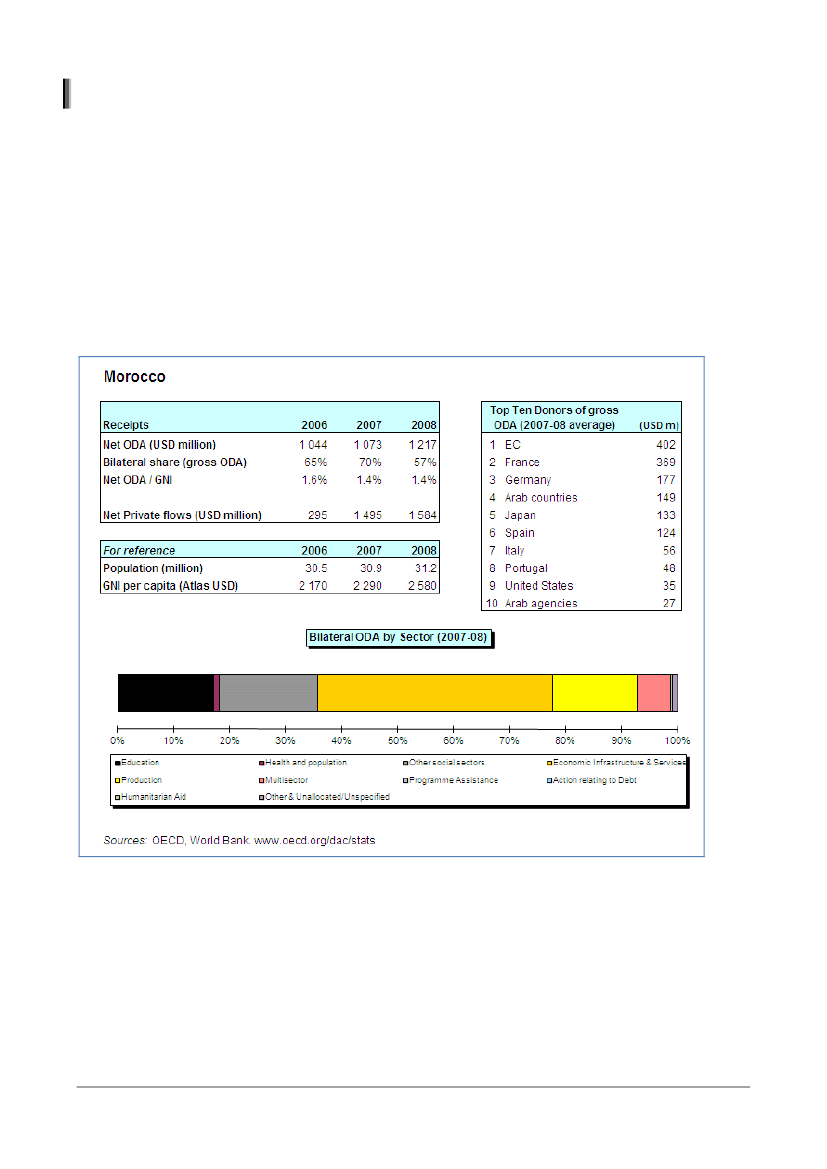

The figure below provides a summary of the main financial support received by Morocco according to thedata published by the OECD Development Assistance Committee. The statistics confirm the pole position ofthe European Union among the donors, with in addition substantial bilateral interventions by certain MemberStates, including France, Germany and Spain. The development assistance received by Morocco is in theregion of EUR 1 billion per year, i.e. 1.4% of GDP. The EU is at the origin of a third of this developmentassistance.For France, the sectoral priorities concern modernisation of the public sector, development of the privatesector, vocational training, social development and basic infrastructures. For Germany, the sectoral prioritiesfor intervention are sustainable development of the economy, including vocational training, protection of theenvironment and natural resources including renewable energies and water and sanitation. Finally, for Spain,the aid is concentrated in the sectors of health, basic social infrastructures, training, urban regeneration,agriculture and tourism. The themes of the Spanish cooperation include actions in favour of the fisheriessector (fishing village as basic infrastructure).

Figure 5: Summary of the development assistance received by Morocco. Source: OECD

Among the other multilateral donors, mention is made of the contributions of the World Bank, which focus onthe reduction of poverty in rural areas, the development of basic social services and the promotion of goodgovernance. The World Bank also supports sectoral reforms in the field of public administration, the businessenvironment and agricultural policy. The annual financing from the Islamic Development Bank (IDB),amounting to just over EUR 1 million, is intended for social development, the development of human

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

9

EN

resources and agriculture. The African Development Bank commenced operations in Morocco in1970.As regards bilateral aid from third countries, mention is made of the United States, with activitycentred on education, fostering enterprise and environmental management. Support under theMillennium Challenge Account has just been approved by both parties. It provides for fundingamounting to USD 698 million (≈EUR 550 million) over 5 years, of which USD 116 million (≈ EUR89 million) targeting on support for artisanal fishing (creation of landing sites and fish wholesalemarkets). The United States and Morocco also have special relations. The two partners concludeda free trade agreement in 2004, which entered into force on 1January 2006.Japan finances cooperation activities in the sectors of the drinking water distribution, roadconstruction and in the fisheries sector. Cooperation in this field is longstanding. It started in the1980s with the training of ships’ officers on fishing vessels, then turned to support for artisanalfishing, the conservation of fisheries resources and South-South cooperation. For the period 2010-2015, Japan based a project in Agadir with a view to supporting the small pelagic species resourcemanagement capacities. The financial commitment under this project is not known.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

10

EN

PART 2: ANALYSIS OF THE FISHERIES SECTOR

11.1

OCEANOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MOROCCAN EEZExclusive Economic Zone

Morocco has two coastlines: one bordering the Mediterranean and the other the Atlantic.The Mediterranean coastline bordering the south of the western part of the Alboran Sea andextending over a distance of about 500 km from east to west, from Saïdia at the border with Algeriato Cape Spartel, at the southern entry to the Straight of Gibraltar. In the Mediterranean, the area ofthe Moroccan continental shelf (up to the 200 m isobath) is approximately 5 600 km2.The Atlantic coastline is nearly 3 000 km long, from Cape Spartel in the north to the border withMauritania in the south, of which 1 100 km along the Western Sahara (from Cape Juby to CapeBlanc). The area of the continental shelf off this Atlantic coast is approximately 117 000 km2, ofwhich 54% bordering the Western Sahara.Table 8: Distribution of the areas of Moroccan continental shelf to the 200 m isobath (according to Belvèze and Bravo deLaguna, 1980)Portion of coastlineCape Spartel - El JadidaEl Jadida - Cape GhirCape Ghir – Cape DrâaCape Drâa – Cape JubyCape Juby – Cape BlancTOTALContinental shelf (km2)14 95014 05010 12015 18062 650116 950Continental shelf (%)131281354100

Off its Atlantic coastline (from Cape Spartel to Cape Blanc), Morocco also has an EEZ estimated atover one million km2. Legally, the Moroccan territorial waters and exclusive fishing zone wereextended to 12 nautical miles in 1973 and an exclusive economic zone of 200 miles wasestablished off the Moroccan (Atlantic) coastline in 1981. According to the information obtained,the border with the Mauritanian EEZ to the south has been defined, but disagreements exist on thedelimitation with Spain for the Canaries in the Atlantic and certain islands in the Mediterranean.1.2Hydrological conditions of the Moroccan Atlantic coastline

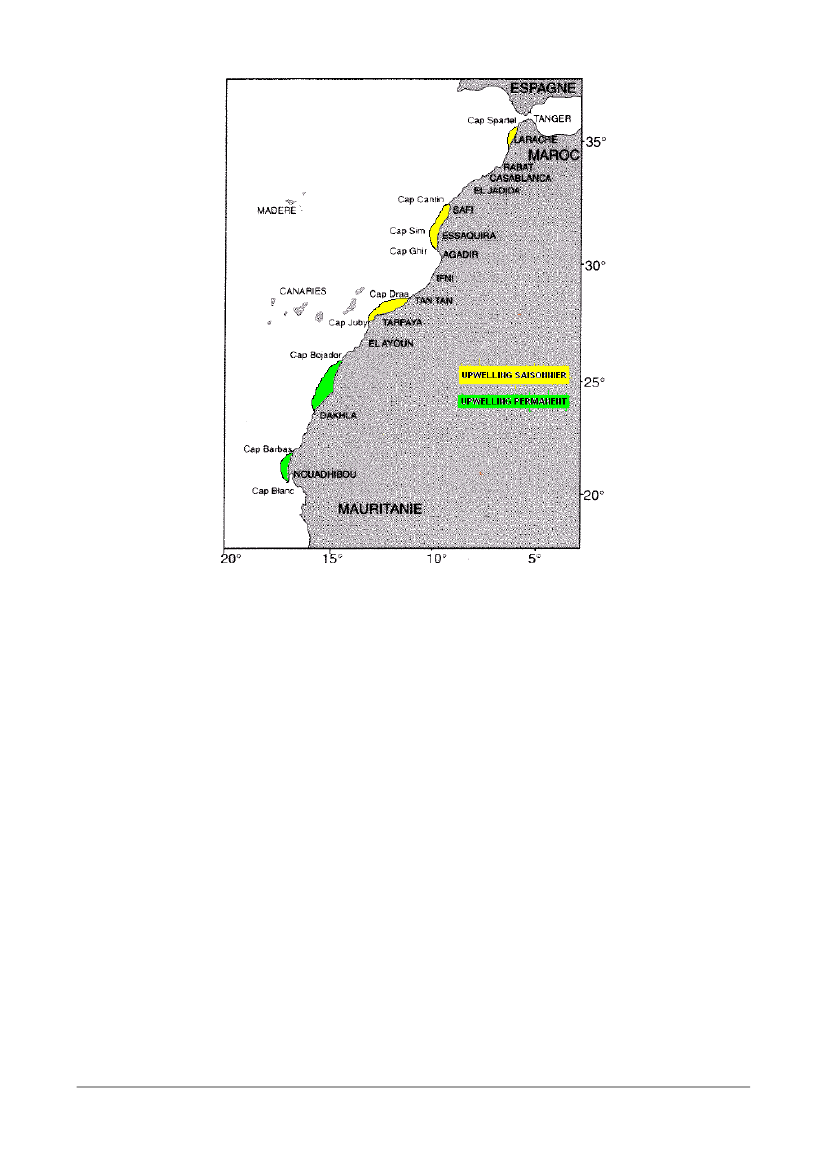

Along the Moroccan Atlantic coastline, from Cape Spartel (35� N) to Cape Blanc (21� N), theaverage circulation of the surface waters is dominated by the Canary current in the direction north-east/south-west. The combination of this general displacement of the waters and the north-easttrade winds, which are the dominant winds, causes upwellings, bringing cold waters rich in nutritivesalts to the surface, in several places along the ocean coastline. These upwellings, which originatefrom sub-superficial layers of the continental shelf, are the main hydrological characteristic of theMoroccan coastal areas. Their origins differ from zone to zone and are at depths of between 70and 200 m depending on the extent of the continental shelf in the zone considered.This hydrodynamic phenomenon of upwelling, which also occurs along the coasts of Mauritaniaand Senegambia, is at the origin of the ecosystem of the upwelling of the Canary current.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

11

EN

This is one of the four major upwelling ecosystems of the planet, which are all characterised bygreat abundance of fisheries resources, especially in the form of coastal small pelagic species.Under the effect of the seasonal displacement of the Azores anticyclone, the Saharan depressionand the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), the north-east trade winds appear off Gibraltar inthe summer and further south in the winter. This seasonal shift in the trade winds is reflected in theposition and intensity of the upwellings, which move from the north in summer to the south inwinter.To the north of Cape Bojador, the upwelling is seasonal and occurs between the months of Marchand August; from Cape Bojador to Cape Blanc, it is almost permanent and is particularly active inthe spring. To the south of Cape Blanc, the upwelling is again seasonal. It occurs from October toJune along the coasts of Mauritania; and from December to May alongside those of Senegal andGambia.

Figure 6: Location and seasonality of the coastal upwellings in North-West Africa (according to Roy 1992 and Maus1997, in Ould Taleb Sidi, 2005)

Five principal areas of upwelling have been identified along the Atlantic coast of Morocco and theWestern Sahara. These are, from north to south:the Larache region;from Cape Cantin to Cape Ghir;from Cape Drâa to Cape Juby;from Cape Bojador to Dakhla; andfrom Cape Barbas to Cape Blanc.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

12

EN

Figure 7: Location of the main areas of upwelling along the Moroccan Atlantic coast (according to Orbi et al., 1992;Makaoui et al., 2001)

On the continental shelf, the enrichment in nutritive salts of the surface waters (euphotic layer) isresponsible for high levels of biological production in the coastal area. In each area, primaryproduction varies with the seasonal fluctuations in the intensity of the upwelling. Moreover, it islargely conditioned by the width of the continental shelf. A wide continental shelf in fact increasesthe residence time of the resurgent waters near the coast and in this way favours the retention anddevelopment of the plankton populations in the coastal area. It is to the south of Cape Juby, in theareas where of the resurgence of deep waters rich in nutritive salts are almost permanent, that theprimary phytoplanktonic production is the highest.Phytoplanktonic production is the first link in the trophic chain extending to the top predators viazooplankton (secondary production), invertebrates and fish. In this meshed and complex network,the coastal small pelagic species (sardine, sardinella, anchovy, horse mackerel, mackerel) occupyintermediate layers and constitute abundant stocks, the fluctuations in which depend to a largeextent on the spatio-temporal variability of the hydrodynamic upwelling phenomenon.The extremely favourable oceanographic conditions, especially along the coastal areas of theregions to the south of Cape Juby, explain the very strong fisheries potential of the Moroccan zoneand especially the abundance of small pelagic species.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

13

EN

2

THE MOROCCAN FISHERIES SECTOR

This section of the report presents information relating to the fisheries sector operating in thenational EEZ, including marketing and processing.

2.1

National fishing fleet

2.1.1 Structural dataThe national fishing fleet can be divided into three separate categories: deep-sea vessels, coastalvessels and artisanal vessels. There is no precise legal definition of these categories in fisherieslaw. However, the National Fisheries Office (ONP), which is responsible for the modernisation ofthe fleet, considers artisanal vessels to be less than 5 GRT and coastal fishing vessels to bebetween 5 and 150 GRT. The vessels with a higher tonnage are the deep-sea vessels.This situation does not appear to have posed any problem so far, while the three categories ofvessels show very clear-cut characteristics. However, the appearance of coastal fishing vesselsengaging in on-board freezing (37 out of nearly 2000 vessels of this category) is starting to makethe demarcation from deep-sea vessels difficult to establish.The situation of the fleet registered in 2008 by home port is summarised in the table below. In total,the Moroccan fleet is composed of more than 18 300 fishing vessels, 84% of which are artisanalvessels, 14% coastal vessels and 2% deep-sea vessels. 82% of the fleet is based in ports on theAtlantic coast. The capacity expressed in gross registered tonnage is nearly 300 000 GRT, ofwhich nearly 50% is concentrated in the deep-sea segment, 40% in the coastal segment and 10%in the artisanal segment. The total engine power of the deep-sea fleet and the coastal fleet is notfar short of 1.2 million KW, of which 40% in the deep-sea segment and 60% in the coastalsegment. The engine power of the Moroccan fleet is equivalent to the power of the Italian fishingfleet, which is the largest fleet of the EU Member States and exceeds the combined power of theSpanish or French fishing fleet. The tonnage capacity cannot be compared on account of thedifferent units taken into account (GRT in one case, GT in the other).

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

14

EN

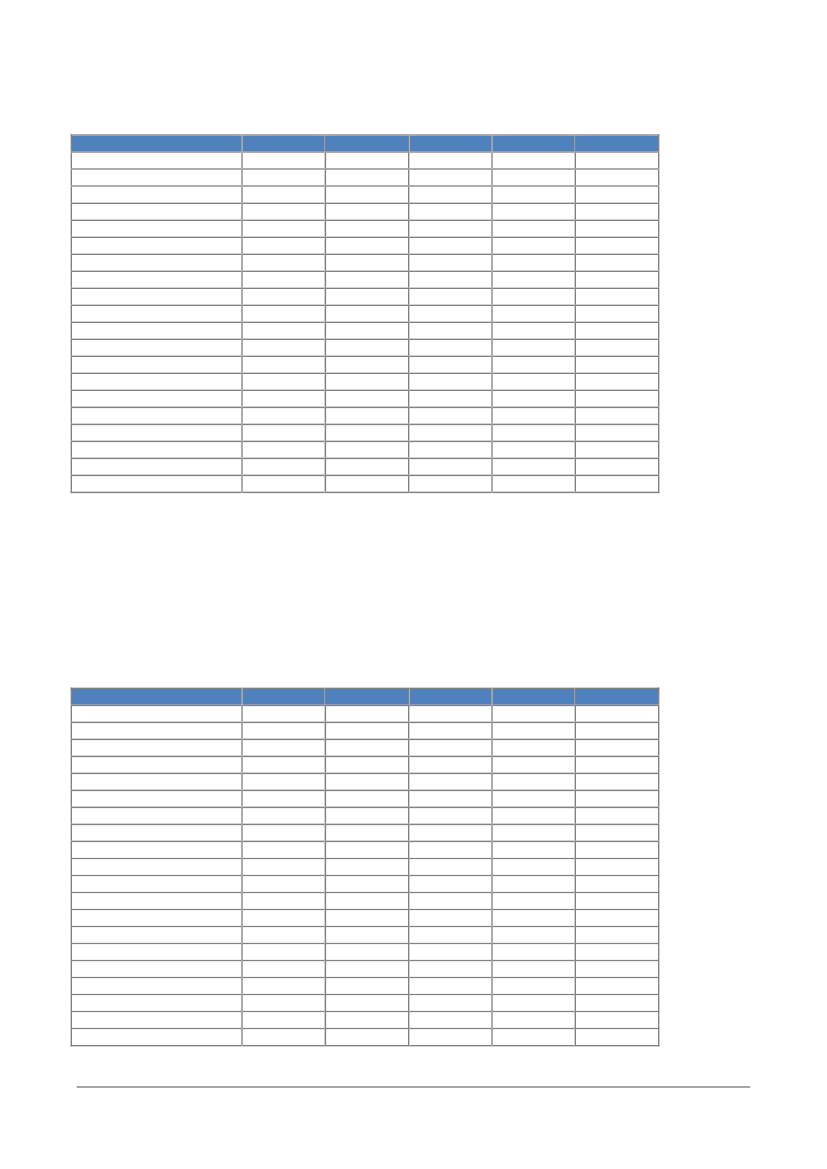

Table 9: Situation of the registered Moroccan fishing fleet in 2008 by port. Source: DPMDeep-sea fleetNumberMediterraneanTangierAsilahLaracheKenitraRabatMohammediaCasablancaEl JadidiaEssaouiraSafiAgadirSidi IfniTan TanLaayouneBoujdourDakhlaAtlanticTOTAL144514515 014146 043146 04316 002458 343458 343211 9952 5621 22496 940117 6006 345570 516707 14612671441031493 03215414 5862 8211 250271 55883651 8409 6507321 35572 47191 4416 780327 32727 956GRTKWNumber567353331289357223283863513422412151Coastal fleetGRT20 66014 5636235 5764 7271212 90612 3063 4614 24813 55422 4171 6246 0273 473KW136 63087 0384 44438 30129 94739118 87469 20122 22224 92187 776121 5478 94331 27619 291Artisanal fleetNumber2 7523761042053382052702531 6486241 0981 4574961834431 8293 08912 61815 370

At regional level, the deep-sea fleet is clearly concentrated around Agadir (60% of the capacity ofthis segment), with Casablanca, Tan Tan and Tangier as other important centres. The southernregion (maritime districts of Laayoune, Boujdour and Dakhla) has only a few registered industrialvessels. In 2008, no deep-sea vessels were registered in the Mediterranean.The coastal fishing fleet is concentrated between Tangier and Agadir, with 18% of the capacity atTangier, 12% in Casablanca, and 35% between Safi and Agadir. Only 4% of the vessels of thecoastal fleet are registered in the ports of the southern region, but there would in fact appear to bemore in operation in these ports (about 300 in Laayoune and 100 in Dakhla). As in Europe, the portof operations may be different from the port of registry.The artisanal fleet has a high proportion of its number registered in the ports of the southern region(42% of the Atlantic artisanal fleet), with Dakhla as the main port of registry (24% of the nationalAtlantic fleet). The other two major hubs are El Jedida (13%) and Agadir (12%).There is a difference between the registered fleet and the fleet deemed to be active, i.e. that of thevessels which have obtained a fishing licence. In 2007, 329 deep-sea vessels were considered tobe operational, as opposed to 449 registered (73%), 1 816 coastal vessels out of 2 544 (71%) and14 225 artisanal vessels out of 15 428 registered (92%). The data for 2008 are not available. Themain explanation for the difference is the unavailability of fishing opportunities in the managedfisheries (octopus in particular), revealing overcapacity in certain segments of the fleet.The development of the deep-sea fleet and the coastal fleet is shown in the table below. Thecapacity of the deep-sea segment has remained unchanged overall, which is attributable to thefreeze decided from 2002 in response to the collapse of certain stocks. The capacity of the coastalsegment has increased by about 15%, evidencing new investments in the pelagic fish sector(seiners in particular). There is no comparable indicator for artisanal fishing. The vessel registrationoperations were still in progress in 2004.

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

15

EN

Table 10: Trend in the fishing capacity of the deep-sea and coastal segments between 2004 and 2008. Source: DPM2004NumberDeep-sea fleetCoastal fleet4472 495GRT144 669102 311KW455 518618 547Number4512 5622008GRT146 043117 600KW458 343707 146Variation 2004/2008Number1%3%GRT1%15%KW1%14%

2.1.2

Typology of the fleets

The deep-sea fishing fleet consists of nearly 75% cephalopod vessels and 20% shrimp vessels.These vessels are trawlers, with an average tonnage higher for the cephalopod vessels (nearly350 GRT on average) than for the shrimpers (210 GRT on average). These vessels deep-freezetheir catches on board and make trips lasting several weeks (from 45 days to 2.5 months). Someof these vessels fish in foreign EEZs (Mauritania, Guinea) under private agreements, especiallyduring periods of biological recovery. The deep-sea segment also includes some vesselsspecialising in large and small pelagic species (twelve vessels) and mixed vessels. There is strongforeign participation in deep-sea fishing. Spanish operators estimate at about 64 the number ofdeep-sea vessels working under a joint venture regime (≈15% of the deep-seafleet). There arealso Chinese joint ventures, the number of which was unobtainable, but which is relatively high.The coastal fishing vessels are decked vessels measuring between 15 and 25 m, most of whichconserve their catches on ice on board or in refrigerated seawater (RSW). In recent years, a fewcoastal freezer vessels have made their appearance (37). In 2007, 1 816 vessels were active inthis category, of which 535 (29%) were longliners specialised in sea-bottom fish, 525 trawlerstargeting species of all types, including cephalopods and crustaceans, 444 seiners (24%)specialised in fishing small pelagic species and 314 multipurpose vessels. The fishing trips of thisfleet last between 1 and 3 days at most, but longer for the few freezer vessels. The capital investedin this coastal fleet is essentially of Moroccan origin.The artisanal fishing vessels are open-deck wooden boats measuring between 5 and 6 m,powered by outboard motors, which conserve the fish on ice on board. The gear used is varied, butessentially passive (lines, pots, nets, octopus pots). Fishing trips are one-day. The capital investedin the artisanal fishing sector is of national origin.2.1.3National fisheries production

National fisheries production came to slightly over 900 000 tonnes in 2008. It is dominated by thecontributions from artisanal and coastal fishing (86% of landings), ahead of the landings fromdeep-sea fishing (12%). The Ministry statistics also include the production from on-shore fishing,with the gathering of seaweed and bluefin tuna fishing using traps as the main productive sectors.The production of coastal and artisanal fishing has tended to stagnate and even to dwindle overthe period 2004-2008, whereas the landings from industrial fishing have increased significantly, inparallel with the cephalopod fishing opportunities which had hit a record low in 2004 (the octopuscrisis which led to the landings of this species plummeting from over 100 000 tonnes in 2000 to10 000 tonnes in 2004, triggering profound restructuring of the sector).

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

16

EN

Table 11: Trend in landings of the Moroccan fleet in weight (tonnes). Source: DPM2004Coastal and artisanal fishingPelagic fish speciesCephalopodsDemersal fish speciesCrustaceansShellfishDeep-sea fishingCephalopodsDemersal fish speciesCrustaceansPelagic fish speciesShore activitiesSeaweedAquacultureCoralTuna trapsTOTAL862 390748 05816 34891 9855 40559475 48013 71712 0454 02045 69815 45413 12697561 347953 3242005865 378742 35428 91685 9575 3572 794113 21542 30218 0764 15848 67916 18012 8121 46631 899994 7732006702 322579 04128 46687 4615 0462 30890 37535 50619 3783 65731 83417 16514 87029122 002809 8622007680 255572 15226 79673 3926 7191 19788 45724 02921 6854 01438 72915 39412 37344112 579784 1062008779 386657 47836 12079 6395 501648112 31240 78217 1204 10450 30611 2129 03721421 959902 910

In terms of value at first sale, national production is just under EUR 710 million, but with artisanal and coastalfishing accounting for 53% of the total value (compared to 86% in weight) and deep-sea fishing contributing43%. The on-shore activities contribute 4% to the value of national fishery product production. The mostsignificant trend is the increase in the value of the landings of coastal and artisanal fishing (+ 36% between2004 and 2008 with practically constant tonnages), which is attributable to the adding value more effectivelyto the small pelagic species and cephalopods.

Table 12: Trend in value at first sale of the landings of the Moroccan fleet (EUR million). Source: DPM; original data inMAD2004Coastal and artisanal fishingPelagic fish speciesCephalopodsDemersal fish speciesCrustaceansShellfishDeep-sea fishingCephalopodsDemersal fish speciesCrustaceansPelagic fish speciesShore activitiesSeaweedAquacultureCoralTuna trapsTOTAL114.869.76.534.83.818.88.23.30.76.6409.7275.6217.712.239.86.024.38.75.50.49.7608.7246.5187.114.041.73.621.49.40.80.111.0589.1224.4145.025.547.46.531.011.01.00.118.8567.1304.0237.317.543.65.628.97.80.70.220.2710.0276.1113.546.797.018.92005308.9114.182.994.816.62006321.2122.080.2101.616.92007311.7116.879.296.019.42008377.2130.8127.699.918.7

6751/11 EXT 1 ADD 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

17

EN

In terms of species group, it is small pelagic species (sardine, anchovy, mackerel, horse mackerel) whichdominate Moroccan production in weight in 2008, accounting for approximately 80% of the landings of thenational vessels. Demersal species and cephalopods contribute 10% each in weight. As regards thecontribution of the various groups of species to the value of national production, cephalopods make thelargest contribution to turnover with 54% of the value. Small pelagic species contribute 20%, ahead of thecontribution of demersal species (17%)

90%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%Small pelagic speciesCephalopodsCrustaceansDemersal fish speciesWeightValue

Figure 8: Contribution in 2008 of the various groups of species to the landings of the national fleet in weight and value.Source: DPM data

At regional level, the landings from deep-sea fishing are concentrated in Agadir (72% of the value in 2008)and Tan Tan (18%), with few or no landings in the ports of the southern regions or the Mediterranean.As regards coastal and artisanal fishing, the table below shows that whereas the landings fell by over 30% inweight in the Mediterranean but increased by 6% in value, the increase in the landings on the Atlantic coastwas 14% in weight and 19% in value over the period 2006-2008. As regards the southern region (fromTarfaya in the north to Labouirda in the south), the landings in the ports or landing areas for artisanal fishing(fish landing sites or fishing villages) have risen by 16% in weight and 25% in value, i.e. more quickly than inthe ports of the northern and central region of the Atlantic coast (11% in weight and 12% in value). In 2008,the southern region accounted for 59% of the landings of the coastal and artisanal fleets on the Atlanticcoast and 51% in value.Table 13: Trend in landings by large regional blocks in weight and value Source: DPM data2006TonnesMediterraneanAtlanticof which southern ports*Other Atlantic ports* : from Tarfaya to Labouirda48 814653 508380 813272 695M€27.6293.6143.41502007Tonnes40 191640 065318 867321 198M€27.1284.5113.81712008Tonnes33 757745 627442 050303 577M€29.2348.0179.1169ChangeTonnes-31%14%16%11%M€6%19%25%12%

As regards the southern ports, most of the landings are concentrated in the sites where there are ports ableto handle the vessels of the national coastal fishing fleet (Laayoune 86% of the landings in weight, Dakhla8%) specialised in small pelagic species (seiners, trawlers). In value, the major contributions of artisanalfishing at certain sites give a different breakdown, with 43% of the turnover of the national coastal and

6751/11 EXT 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

18

EN

artisanal fleet in the southern region landed at Laayoune, 11% at Dakhla, but 13% at the artisanal site ofNtirifit and 11% in that of Lassarga (near Dakhla). Laayoune is the principal national port for landings fromnational artisanal and coastal fishing.

2.2

Foreign fishing fleet[DELETED]

2.3

Summary: fishing fleets in the Moroccan EEZ[DELETED]

2.4

Aquaculture

Aquaculture is still in its infancy in Morocco. As shown in the table below, production has neverreally taken off and remains very marginal (less than 1 000 tonnes) compared to the fisheriesproduction (close to one million tonnes).Fish farming (bass, sea bream) is of interest in the Mediterranean area. The attempts made herehave been similar to the production techniques in Greece or Turkey (sea cages), but have failedessentially on account of insufficient mastery of the technologies (hatcheries, prophylactictreatments). Farming of bivalve molluscs (oysters and mussels) requires simpler extensive farmingtechnology and national production is starting to develop. Morocco has some prime sites forbreeding shellfish, including Dakhla Bay and the Knefiss lagoon in the south of the country. It waspossible to visit some installations which are growing spat imported from Europe for resale on thelocal market, which is more remunerative than the European market. The quality of the waters ofDakhla Bay means that it takes about a third of the time to grow an oyster to its commercial sizethan it does in Europe.Table 20: Trend in aquaculture production in Morocco in tonnes. Source: DPMSea bream

Bass

Eel

Oyster

Meagre

Mussels

Other

TOTAL

2004

3503703016005015975

2005

3328452724320001467

2006

03602401500291

2007

0790362000441

2008

0290181040214

Aquaculture has hitherto never been considered a public policy priority. The possible sites havebeen poorly identified in view of the other coastal activities and there are no national technologicalresearch and development capacities or any real support structure within the Ministry. Thissituation is likely to change in the near future. The new Halieutis strategy has in fact adopted theprincople of support for the development of this sector with production by 2020 of 200 000 tonnesof various specifed including shellfish, flatfish and meagre. An agency specialised in thedevelopment of the sector will shortly be established with the initial tasks of identifying the sitesand techniques, defining the regulatory framework and the incentive measures to propose toinvestors. Morocco will also acquire research and development expertise through the INRH.

2.5

Land-based industries

6751/11 EXT 1ANNEX

tim/RGR/czDG B III

19

EN