Europaudvalget 2011-12

EUU Alm.del Bilag 517

Offentligt

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anDmIGRaTIon conTRol

amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaignto end grave abuses of human rights.Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universalDeclaration of human rights and other international human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

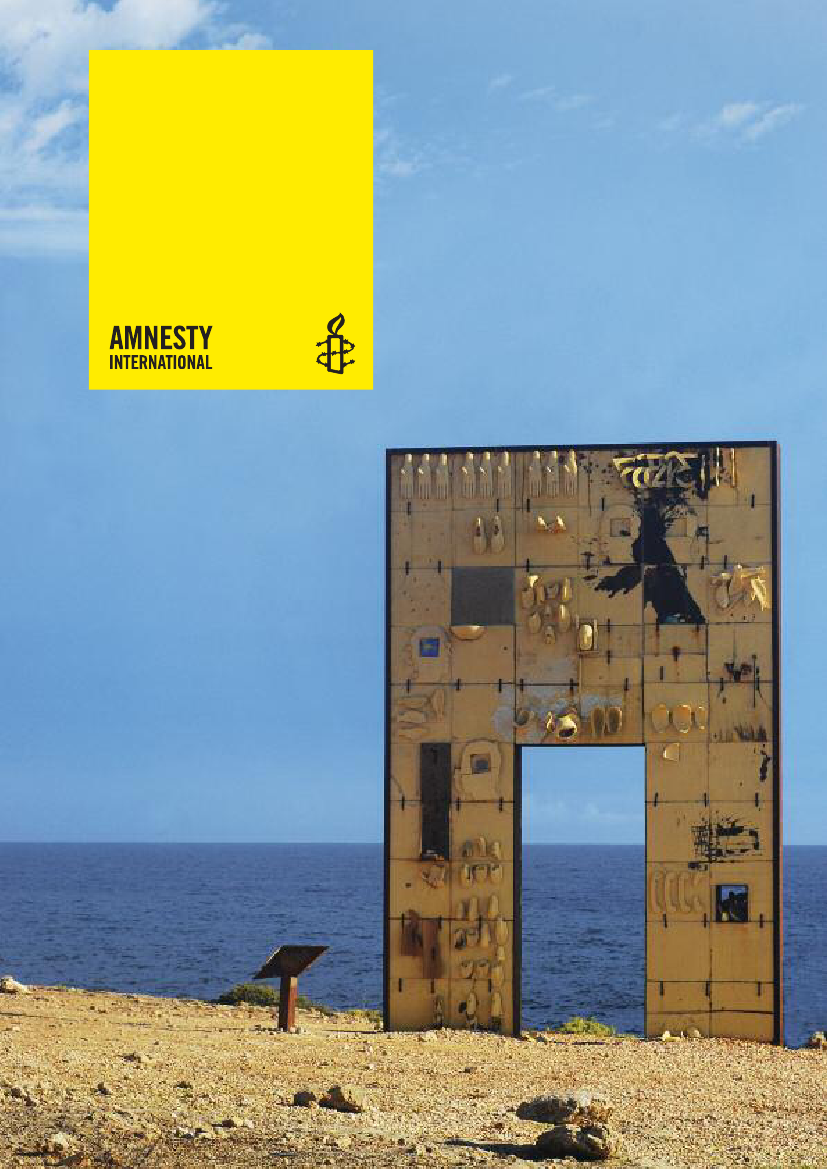

First published in 2012 byamnesty International ltdpeter Benenson house1 Easton Streetlondon Wc1X 0DWunited Kingdom� amnesty International 2012Index: Eur 01/013/2012 EnglishOriginal language: Englishprinted by amnesty International,International Secretariat, united Kingdomall rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.The copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. For copying inany other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.To request permission, or for any other inquiries, pleasecontact [email protected]Cover photo:“la porta d’Europa”, or “la porta di lampedusa”, Italy.a monument honouring more than 10,000 refugees andmigrants who died on the mediterranean Sea in theirattempt to reach the island, October 2011.� Xander Stockmans – Tussen Vrijheid en Geluk

amnesty.org

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

1

COntEntS

GlOSSAry1. IntrOduCtIOn2. MIGrAtIOn COntrOl AGrEEMEntSbEtwEEn ItAly And lIbyA3. rESCuE At SEA4. HuMAn rIGHtS OblIGAtIOnSbEyOnd bOrdErS5. COnCluSIOn6. rECOMMEndAtIOnSEndnOtES

2351216171820

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

2S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

GlOSSAry

Arefugeeis a person who has fled from their owncountry because their human rights have been abused.This means that their fundamental freedoms have beentaken away, they have been discriminated against orthey have suffered violence because of who they are,their beliefs or their opinions, and their governmentcannot or will not protect them.Asylum proceduresare designed to determine whether someone meets thelegal definition of a refugee or not. When a countryrecognizes someone as a refugee, it gives theminternational protectionas a substitute for theprotection of their country of origin.Anasylum-seekeris someone who has left theircountry seeking protection but has yet to be recognizedas a refugee. During the time that an asylum claim isbeing examined, asylum-seekers cannot be forced toreturn to their country of origin.Amigrantis someone who leaves their country to livein another country for work, study, or family reasons.A migrant who is authorized to stay in a country, forexample by having a valid visa or residency permit, is aregular migrant.Anirregular migrantis someone who isnot authorized to stay by the authorities of the country.

Refoulementis the forcible return of an individualto a country where they would be at risk of serioushuman rights violations. It is prohibited by internationallaw to return refugees and asylum-seekers to thecountry they fled – this is known as the principle ofnon-refoulement.The principle also applies to otherpeople who risk serious human rights violations suchas torture and the death penalty, but do not meetthe legal definition of a refugee.Collective deportation or collective expulsionis the deportation of a group of people (migrants,asylum-seekers and/or refugees) without lookingat each case individually and considering theindividual circumstances of each person separately.It is prohibited under international law.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

3

1. IntrOduCtIOn

Every year, thousands of people embark on periloussea voyages on unseaworthy vessels, without a propercrew or any safety equipment, in an attempt to reachEurope from north and west Africa. Some are fleeingconflict; others are trying to escape grinding poverty.they are all looking for a better future. Many nevermake it to Europe: they die at sea from dehydration;they drown; or they are intercepted by patrol boatsand returned to the country from which they departed.While some of the women, men and childrenattempting this dangerous journey to Europe areleaving their own country, for many others the countryof departure is not their own, but somewhere throughwhich they were transiting in an attempt to reachEurope. If returned there, they will usually beconsidered “illegal” migrants, and face a real risk ofarbitrary and prolonged detention, ill-treatment andother human rights violations.1Even when notdetained, irregular migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers can be subjected to abuses at the hands ofpolice and employers who exploit the vulnerabilityinherent in their irregular status.

wHAt IS ExtErnAlIzAtIOn?Over the last decade, European countries haveincreasingly sought to prevent people from reachingEurope by boat from Africa, and have “externalized”elements of their border and immigration control.Externalization refers to a range of border controlmeasures including measures implemented outsideof the territory of the state – either in the territory ofanother state or on the high seas. It also includesmeasures that shift responsibility for preventingirregular migration into Europe from Europeancountries to countries of departure or transit.European externalization measures are usually basedon bilateral agreements between individual countriesin Europe and Africa. Many European countries havesuch agreements, but the majority do not publicize thedetails. For example, Italy has co-operation agreementsin the field of “migration and security” with Egypt,Gambia, Ghana, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal andTunisia,2while Spain has co-operation agreementson migration with Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea,Guinea-Bissau, Mali and Mauritania.3

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

4S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

At another level, the European Union (EU) engagesdirectly with countries in North and West Africa onmigration control, using political dialogue and a varietyof mechanisms and financial instruments. For examplein 2010, the European Commission agreed a co-operation agenda on migration with Libya, which wassuspended when conflict erupted in 2011. Since theend of the conflict, however, dialogue between the EUand Libya on migration issues has resumed.The European Agency for the Management ofOperational Co-operation at the External Bordersof the Member States of the EU (known as FRONTEX)also operates outside European territory. FRONTEXundertakes sea patrols beyond European waters inthe Mediterranean Sea, and off West African coasts,including in the territorial waters of Senegal andMauritania, where patrols are carried out in co-operation with the authorities of those countries.

The policy of externalization of border control activitieshas been controversial. Critics have accused the EUand some of its member states of entering intoagreements or engaging in initiatives that place therights of migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers atrisk. A lack of transparency around the variousagreements and activities has fuelled criticism.This report examines some of the human rightsconsequences for migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers that have occurred in the context of Italy’smigration agreements with Libya. It also raises concernsabout serious failures in relation to rescue-at-seaoperations, which require further investigation. Thereport is produced as part of wider work by AmnestyInternational to examine the human rights impacts ofEuropean externalization policies and practices.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

5

2. MIGrAtIOn COntrOl AGrEEMEntSbEtwEEn ItAly And lIbyA

tHE rIGHtS Of MIGrAntS AndrEfuGEES In lIbyALibya has a long history of inward migration fromother parts of Africa. Those entering Libya include:“regular” migrants who come to work in the countryin a range of sectors; “irregular” migrants who cometo Libya seeking work and – sometimes – trying toreach Europe; and refugees fleeing conflict andpersecution. The vast majority of those who leaveLibya seeking to reach Europe by boat are not Libyans,but from countries such as Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somaliaand Sudan, as well as Iraq and Palestine. In the past,Libya tolerated such inward migration, but thosewithout regular status have always been at risk ofhuman rights violations. As Libya has no asylumsystem, people in need of international protection,such as refugees and asylum-seekers, are usuallyviewed as irregular migrants.Research by Amnesty International and other humanrights groups has exposed widespread abuses againstrefugees, asylum-seekers and irregular migrants inLibya during Colonel al-Gaddafi’s rule, as well asduring and following the conflict that deposed him.4Documented violations and abuses include indefinitedetention in extremely poor conditions, beatings andother ill-treatment, in some cases amounting to torture.Refugees and asylum-seekers also face a real risk ofrefoulement(being returned to a country where theyare at risk of persecution or serious human rightsabuses). Libya is not a party to the 1951 UNConvention relating to the Status of Refugees and its

Refugees and migrants in the yard at Misratah DetentionCentre, Libya, November 2008.

“the problem is my black skin; thethuwwar [revolutionaries] think I amwith Colonel al-Gaddafi. Mu’ammar[al-Gaddafi] repressed my people,and those opposing him because ofhis brutality are now doing the same.”Detainee held in misratah’s Zarouq cultural centre, libya, may 2011

� Gabriele del Grande

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

6S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

1967 Protocol. The operations of the UN HighCommissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have alwaysbeen limited by the authorities in Libya in the past.The situation deteriorated further in June 2010 whenthe then Libyan authorities suspended the UNHCR’soperations in the country. By May 2012 UNHCR,although present in Libya, had not been able tosecure an official agreement to operate with thenew Libyan authorities.Since the fall of the al-Gaddafi government, thehuman rights situation for asylum-seekers, refugeesand irregular migrants in the country has deteriorated.There has been a breakdown of law and order,weapons have proliferated across the country, andracism and xenophobia are on the rise. Thewidespread belief that al-Gaddafi forces used “Africanmercenaries” in an effort to crush the opposition hasmade Sub-Saharan Africans – regardless of theirmigration status – targets of violent attacks, detentionand torture. During and in the immediate aftermathof the conflict, armed militias arrested and detainedthousands of alleged al-Gaddafi supporters andsoldiers, including hundreds of suspected foreignmercenaries, most of whom were in fact migrantworkers. Amnesty International researchers found thatthe worst treatment was reserved for nationals fromSub-Saharan Africa and black Libyans. Many werebeaten or otherwise abused in detention, and severalreported being tortured.While many Sub-Saharan Africans were detainedduring the conflict and in its immediate aftermathbecause of the belief that they were mercenariesfighting for al-Gaddafi, hundreds are now beingarrested by armed militias on so-called “migration

related offences”. Almost daily, Libyan media reportfresh arrests of irregular migrants entering the countrythrough its porous borders. One official claimed in April2012 that “more than 1,000 persons are coming heredaily”.5Those arrested have not been charged with anycrimes and they cannot challenge the legality of theirdetention. The justice system in Libya remainsparalyzed. There is widespread tolerance of thearmed militias’ abuse of non-nationals.

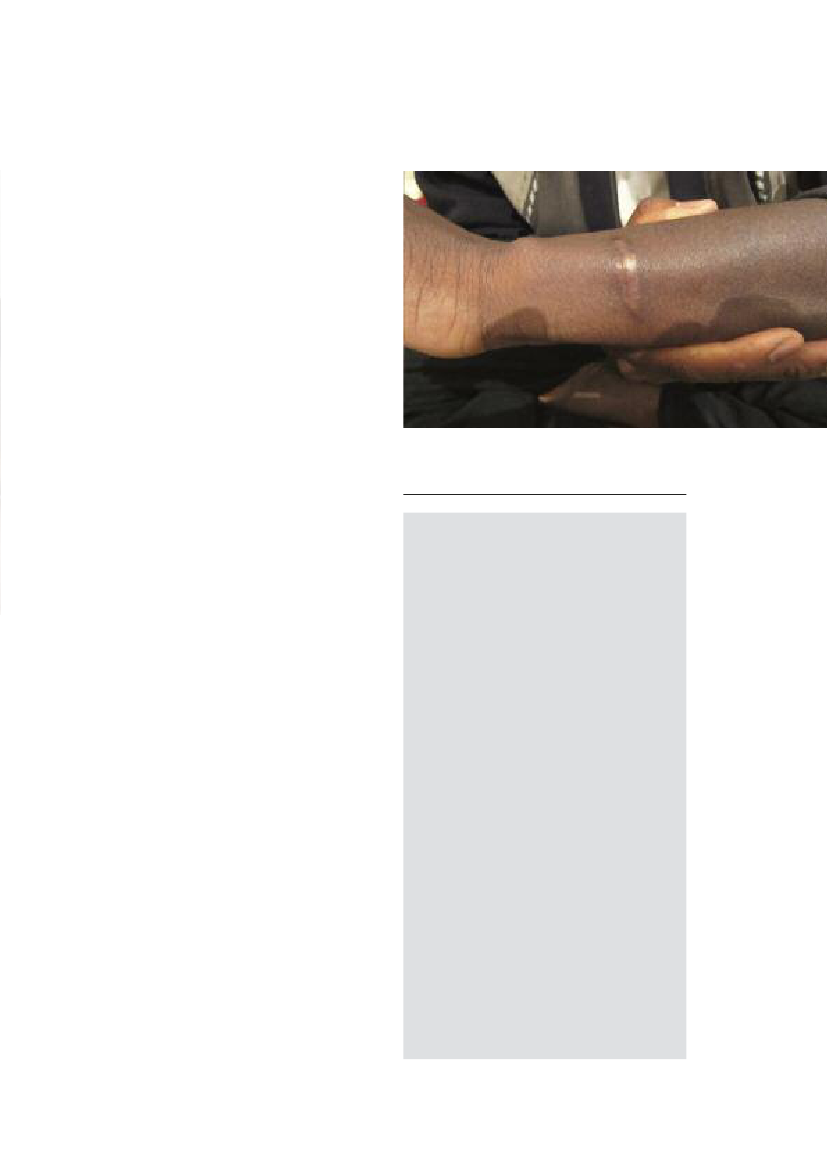

Al-MAdInA Al-KAdIMA In trIpOlIArmed fighters who opposed the government ofColonel al-Gaddafi raided the al-Madina al-Kadimaneighbourhood of tripoli on 26 August 2011. they searchedhouses, looking for weapons and money, and then seizeddozens of black libyans and Sub-Saharan African nationalsfrom Chad, Mali, niger and Sudan. twenty-six of thosetaken from their homes that day told Amnesty Internationalthat their hands were tied with metal wire and that theywere blindfolded. they said they were beaten during theraid, and again at a football club near al-Madina al-Kadimato which they were taken. there, they were forced to lieface down on the ground and were beaten with rifle butts,sticks and electric wires. when Amnesty Internationalinterviewed them some nine days after the beatings, theystill had marks consistent with their testimonies. Adetainee recounted that his cousin was shot three timeswhile tied. One of the detainees told Amnesty International:“I was at home with my wife and children. I heard bangingon the doors, and then people forced the door and entered.They were screaming “murtazaqa[mercenaries]”.Theyalready condemned me because of the colour of my skin.In front of the house, they started beating me… Theycontinued to beat us at thefootball club…”

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

7

� Gabriele del Grande

AGrEEMEntS bEtwEEn ItAlyAnd lIbyADespite substantial public evidence that migrants,refugees and asylum-seekers were being subjected toserious abuses in Libya between 2006 and 2010, Italyconcluded a number of agreements with the Libyanauthorities. They included direct references to migrationcontrol and provided financial and technical assistancefor migration control activities. Italy also agreed thatpeople attempting the sea crossing to Europe could bereturned to Libya but no processes were established toprevent human rights abuses occuring in this context.6

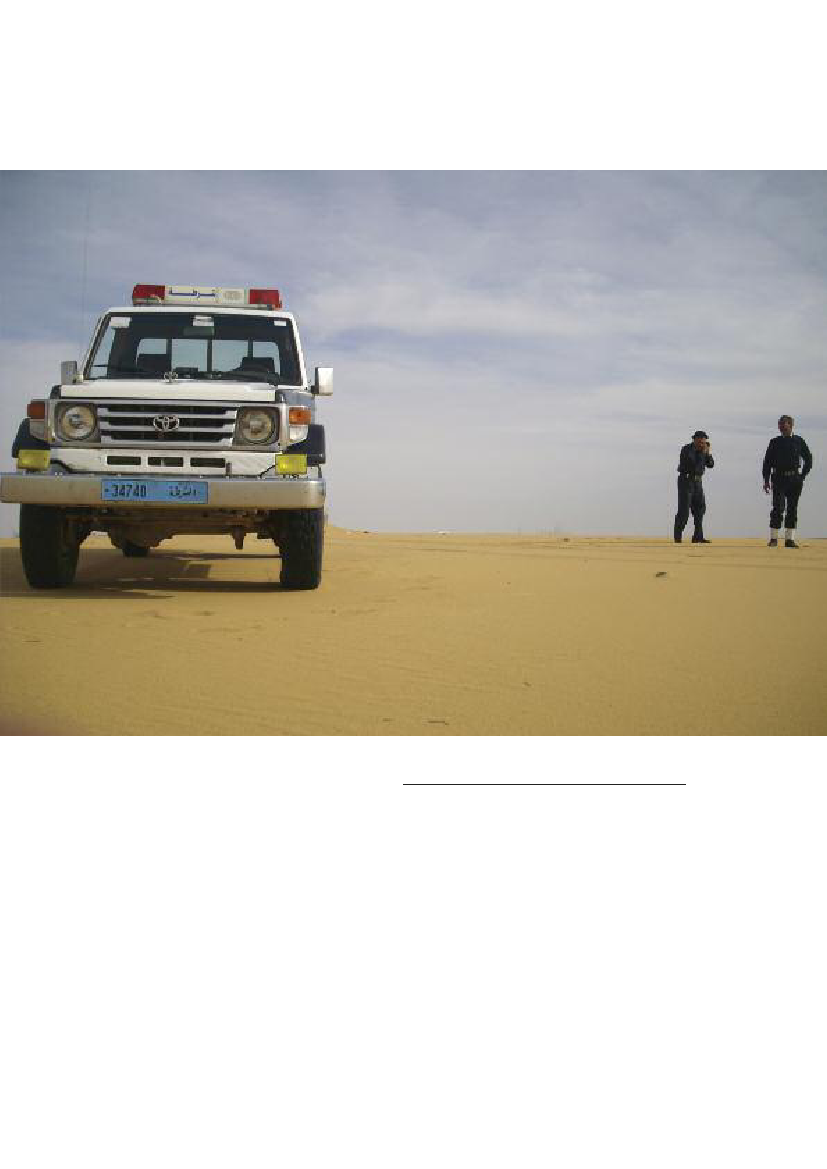

Sebha patrol in the desert in Libya, 2008.

In 2008, Libya and Italy signed the Treaty ofFriendship, Partnership and Co-operation. The Treaty,which included a US$5bn package for constructionprojects, student grants and pensions for Libyansoldiers who served with Italian forces during theSecond World War, also included provisions on“control of migration”. In April 2012, the Chairmanof the Libyan National Transitional Council confirmedLibya’s commitment to the Treaty.

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

8S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

� Gabriele del Grande

Several technical agreements, concluded beforethe 2011 conflict, established the specifics of Italy-Libya co-operation in combating “illegal migration”.None of these agreements has ever been made publicthrough official channels, and any details have comethrough unofficial sources or have been exposed incourt actions.7A “Protocol”, signed in December 2007, and an“Additional Technical-Operational Protocol”, signedin February 2009, provided for joint patrolling ofinternational and territorial waters – Libyan and Italian– by mixed Libyan and Italian crews, and for joint“control, search and rescue” operations. In the“Additional Technical-Operational Protocol”, the twocountries also agreed that each country would “carryout the repatriation of illegal migrants from its territory”;no safeguards were included in this agreement tospecifically protect human rights; nor were there anyprovisions to identify and screen individuals potentiallyin need of international protection. A third “Technical-Operational Protocol to combat illegal migration throughthe sea” was signed on 7 December 2010 in Rome.

Zliten detention centre, Libya, November 2008.

The implementation of the agreements betweenLibya and Italy was suspended in practice during thefirst months of the conflict in Libya, although theagreements themselves were not set aside. Whilethe armed conflict was still raging in Libya, Italy signeda memorandum of understanding with the LibyanNational Transitional Council in which the two partiesconfirmed their commitment to co-operate in the areaof irregular migration including through “the repatriationof immigrants in an irregular situation.”8In spite ofrepresentations by Amnesty International and others onthe current level of human rights abuses, on 3 April2012 Italy signed another agreement with Libya to“curtail the flow of migrants”.9The agreement has notbeen made public. A press release announced theagreement, but did not include any details on themeasures that have been agreed, or anything tosuggest that the present dire human rights predicamentconfronting migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers inLibya will be addressed.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

9

hUman RIGhTS vIolaTIonSThe co-operation between Italy and Libya gives riseto a number of serious human rights concerns fallingbroadly into two categories: violations committedby Libyan authorities that Italy has ignored or tacitlycondoned; and violations committed by Italy outsideits territory.When Italy entered agreements with Libya, thegovernment knew or ought to have known that irregularmigrants, refugees and asylum-seekers – the verypeople who attempt to reach Europe by boat fromLibya – were subjected to arbitrary and prolongeddetention, beatings and other human rights abusesin Libya. The third “Technical-Operational Protocol tocombat illegal migration through the sea” was signedin December 2010, despite the fact that Libya hadsuspended the already extremely limited operationsof UNHCR six month earlier, which had left refugeesand asylum-seekers in an even more vulnerableposition than before.The April 2012 agreement between Italy and thenew Libyan authorities was also established, despitepublicly available information exposing ongoing andwidespread human rights abuses against migrants,asylum-seekers and refugees, and despite the factthere are still no provisions in place in Libya forrefugee status determination.When states take any immigration and border controlmeasures they must do so in a manner that complieswith their human rights obligations. However, someof the measures implemented within the context ofexternalization agreements between Italy and Libyaviolate international law. Moreover, the Italianauthorities have reached agreements with Libya,turning a blind eye to the fact that migrants, refugeesand asylum-seekers risk serious human rights abusesin Libya. The agreements between Italy and Libya donot include any effective human rights safeguards.The inclusion of a human rights clause in the 2008Italy-Libya Treaty of Friendship, Partnership andCo-operation appears entirely tokenistic as nomeasures were ever taken to implement it.Italy has, at best, ignored the dire plight of migrants,refugees and asylum-seekers. At worst, it has shownitself willing to condone human rights abuses in orderto meet national political self-interest.

� Amnesty International

Migrant shows Amnesty International a scar caused byabuse, Libya, January 2012.

SafEGUaRDInG hUman RIGhTSwIThIn mIGRaTIon conTRolaGREEmEnTSThe existence of bilateral or multilateral agreementsbetween states does not relieve states of their humanrights obligations. all agreements must be consistentwith human rights.migration control agreements should include specificmeasures that ensure that the rights of migrants,refugees and asylum-seekers are safeguarded. The exactnature of these protections will vary to some extent,depending on the context and the nature of theagreement. however, all agreements should include:guarantees of access to effective procedures for peopleto make claims for asylum; the prohibition of any form ofsummary or collective expulsions; and a clearcommitment to uphold the principle ofnon-refoulement.agreements should guarantee people’s access toadequate information and to mechanisms for effectiveremedies. They should also include specific commitmentsto minimize the use of detention and prevent separationof families. The provision of technical and financialassistance should be made consistent with human rights.States should not enter into agreements unless there areeffective mechanisms to ensure that the human rightssafeguards will be implemented.

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

10S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

REfUGEES TRappED In lIbyaPrior to June 2010, in the absence of asylumprocedures in Libya, UNHCR was responsible forregistering asylum-seekers and processing their claimsfor international protection. As of January 2011, therewere about 8,000 recognized refugees awaitingresettlement and 3,200 asylum-seekers whose claimsUNHCR was yet to process, in Libya. When UNHCR’soperations were shut down in June 2010, these peoplewere left with no support in the country, while newarrivals could not even register their need for protection.Although UNHCR is still present in Libya, it has not beenable to secure an agreement with the new Libyanauthorities to operate – in sharp contrast to the swiftlyconcluded agreement between Libya and Italy on“migration control”.The options for refugees and asylum-seekers arrivingin Libya from countries where they faced conflict andpersecution, such as Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia andSudan, are limited. None of Libya’s neighbouring stateshas effective refugee protection systems in place.10Italyhas made agreements which accept that people in needof international protection remain effectively trapped.They are left in a country where they are not recognizedas refugees, and where they are at risk of human rightsabuses, including forced return to a country where theywould face further threats to their lives.

human rights and refugee law, including the obligationto provide asylum-seekers with an opportunity to applyfor international protection. However, from mid-2009the Italian coastguard and customs police beganintercepting vessels on the high seas and returningtheir occupants directly back to Libya. In some cases,people intercepted were taken on board Italian vesselsand returned directly by Italian officials to Libya; inothers, people picked up by Italian ships weretransferred to Libyan patrol boats.

puSH-bACK tO lIbyAAmnesty International interviewed r., a 25-year-oldwoman from Eritrea, at the Choucha refugee camp intunisia in June 2011. She had attempted to leave libya forEurope in June 2009. with the assistance of smugglers intripoli, she boarded a boat carrying 82 people, mainlyEritrean nationals, bound for Italy. After four days driftingat sea, their boat was approached by an Italian ship whichtook them on board. r. thought she was being taken toItaly. However, a libyan boat pulled alongside and libyansoldiers boarded the Italian vessel. All of the 82 peoplewere then forced to board the libyan vessel. r. says thatthe men were handcuffed and that she witnessed the menbeing beaten. On arrival in libya, r. was detained and heldfor approximately 12 months. when conflict erupted inlibya in 2011, r. was forced to flee again, and ended upin Choucha refugee camp in tunisia.The number of people intercepted at sea and returnedto Libya by the Italian authorities is not known, asneither country has disclosed this information. The onlyofficial data available is for the period between 5 Mayand 7 September 2009: according to the ItalianAmbassador to Libya more than 1,000 individuals werereturned to Libya in that four-month period.11Furtherpush-backs are reported to have taken place afterSeptember 2009, but the number of individualsaffected is not known.12The fact that boats leaving Libya include asylum-seekers and refugees as well as migrants was wellknown to the Italian authorities before they

opERaTIonS aT SEa: InTERcEpTIon anD‘pUSh-backS’One of the most disquieting elements of Europe’smigration control system is the practice of interceptionof boats and push-backs at sea. Under agreementssigned between Italy and Libya surveillance operationshave been carried out in the Mediterranean Sea withthe aim of intercepting boats attempting to reachEurope and pushing or diverting them back to Libya.Prior to concluding agreements on migration controlwith Libya, Italy had brought people intercepted at seato Italian territory for an assessment of their protectionneeds. This was in keeping with its obligations under

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

11

commenced push-backs. UNHCR estimates that in2008, before push-backs began, 75 per cent of theforeign nationals arriving in Italy on boats – the vastmajority of whom came from Libya – were asylum-seekers, and 50 per cent of those seeking asylum weregranted some form of international protection.13Someof the people who had been pushed back by Italy toLibya spoke to UNHCR. It confirmed that among thoseinterviewed there were individuals immediately in needof international protection. It also confirmed that someof those interviewed reported being subjected toviolence during their transfer to Libyan territory and onarrival at detention centres.14

International and European human rights and refugeelaw prohibits Italy from removing anyone to a countryor territory where they face a real risk of serious humanrights abuses, or where they may face a real risk ofrefoulement.Human rights law also precludescollective expulsions without an examination of eachperson’s individual situation. In 2012 the GrandChamber of the European Court of Human Rightsfound that push-backs, which involved the mass returnof people to Libya without any assessment of theirindividual personal circumstances, amounted tocollective expulsions, and thus violated the humanrights of the people subjected to this measure.

EURopEan coURT of hUman RIGhTS:Hirsi Jamaa and OtHers v. italyIn the landmark judgement in february 2012, the Grandchamber of the European court of human Rights found thata push-back operation conducted by Italy in may 2009violated the European convention on human Rights. onthat occasion, Italian military ships forcibly returned 11Somalis and 13 Eritreans to libya as part of a group ofapproximately 200 people who had left that country aboardthree vessels, attempting to reach Italy. The forcible returnstook place despite the fact that Italy knew or ought to haveknown that the individuals concerned would face a real riskof ill-treatment in libya. In returning them there, Italy wouldalso expose them to the risk of onwardrefoulementtoEritrea and Somalia, where, in turn, they would face a realrisk of persecution or other forms of serious harm.The Grand chamber noted the fact that, although Italyhad intercepted the boats on the high seas, once onboard Italian ships they were under Italian jurisdiction.The court held that, since the applicants were underItalian jurisdiction, Italy had an obligation to safeguardtheir human rights. Italy failed to do this. on the contrary,the Italian authorities did not inform them that they were

being returned to libya, much less provide them with themeans to challenge this decision. In its defence, Italyargued that its agreements with libya providedlegitimacy for returns to libya and effectively relievedItaly of its human rights obligations under the Europeanconvention on human Rights. Italy also attempted toevade the jurisdiction of the court by describing theevents as rescue operations on the high seas.The Grand chamber rejected each objection and foundthat by its actions Italy had violated the applicants’ rightnot to be returned to face a real risk of ill-treatment andtheir right not to be subjected to collective expulsions.The Italian authorities reacted to the judgement bystating that the court’s decision would, as a matter ofcourse, be implemented, rather than being a topic ofdebate. further, Italy stated that any new co-operationinitiative with the new libyan authorities would beinformed by an “absolute respect for human rights andthe need to safeguard the life of people at sea”.nevertheless, soon afterwards, Italy and libya concludeda new agreement regarding migration control (asmentioned on page 9). To date, the contents remainsecret, thus shielded from public scrutiny.

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

12S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

3. rESCuE At SEA

Migrants’ boat journeys to Europe are often facilitatedby smugglers or traffickers. The vessels used arefrequently overcrowded and unseaworthy. Normally,there is no professional crew, nor any safetyequipment. Situations of migrant boats in distress atsea are common. According to UNHCR, at least 1,500people are known to have lost their lives attempting tocross the Mediterranean Sea in 2011.15The international law of the sea sets out the principlesfor aiding boats and people in distress in the sea. A keyprinciple is that countries must assist those in distress atsea, without regard to their nationality, their status or thecircumstances in which they are found; private vesselsalso have an obligation to help any boat in distress.However, the policies and practices of several Europeancountries have resulted in delays in rescuing boats indistress; in some cases the delays appear to be anattempt to avoid taking responsibility for migrants andrefugees. Malta and Italy have both refused, on severaloccasions, to allow people rescued in internationalwaters by private boats to disembark on their territory,leaving the private vessels (often fishing boats) carryingdistressed and traumatised passengers until there is apolitical agreement on where they can go.16

Malta received the distress call, it failed to mount asearch and rescue operation, claiming that Italy’s searchand rescue assets were geographically closer. By thetime an Italian vessel arrived, most of those on the boatwere dead; only 47 people survived. The Italianauthorities claimed that Malta had failed to meet itsinternational obligations, a claim Malta has refuted.17One of the most shocking instances of failure to rescuepeople at sea occurred only days before, when 63people lost their lives in the Mediterranean Sea. At theend of March 2011, while NATO forces were patrollingthe area, a small boat carrying 72 people from Sudan,Nigeria, Ghana, Eritrea and Ethiopia, including twobabies, was left drifting in the Mediterranean Sea forover two weeks.The boat had departed from Libya and the passengerswere trying to escape the ongoing conflict and reachEurope. However, they quickly ran out of fuel and oftheir meagre supply of water and food. People on theboat made desperate calls using a satellite phonealerting an Eritrean priest in Rome to their predicament.He in turn contacted both the Italian Coast Guard andNATO headquarters in Naples. According to survivors, amilitary helicopter lowered some water and biscuits witha rope but never returned. Fishing boats and militaryvessels also reportedly approached or saw the strandedboat, but nobody rescued them. After a week, peoplestarted dying; the dead bodies were lowered into thesea. By then, those still alive on the boat had becomedelirious. In despair, some people jumped overboard.Eventually, the boat drifted back to Libya. Only nine ofthe 72 people survived this horrific journey.18

dIStrESS CAllS GO unAnSwErEdSeveral cases have come to light, through the testimonyof survivors. For example, on 6 April 2011, more than200 people drowned when a boat carrying mostlySomalis and Eritreans from Libya capsized. The incidentoccurred in Malta’s search and rescue area. Although

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

13

� UNHCR/F. Noy

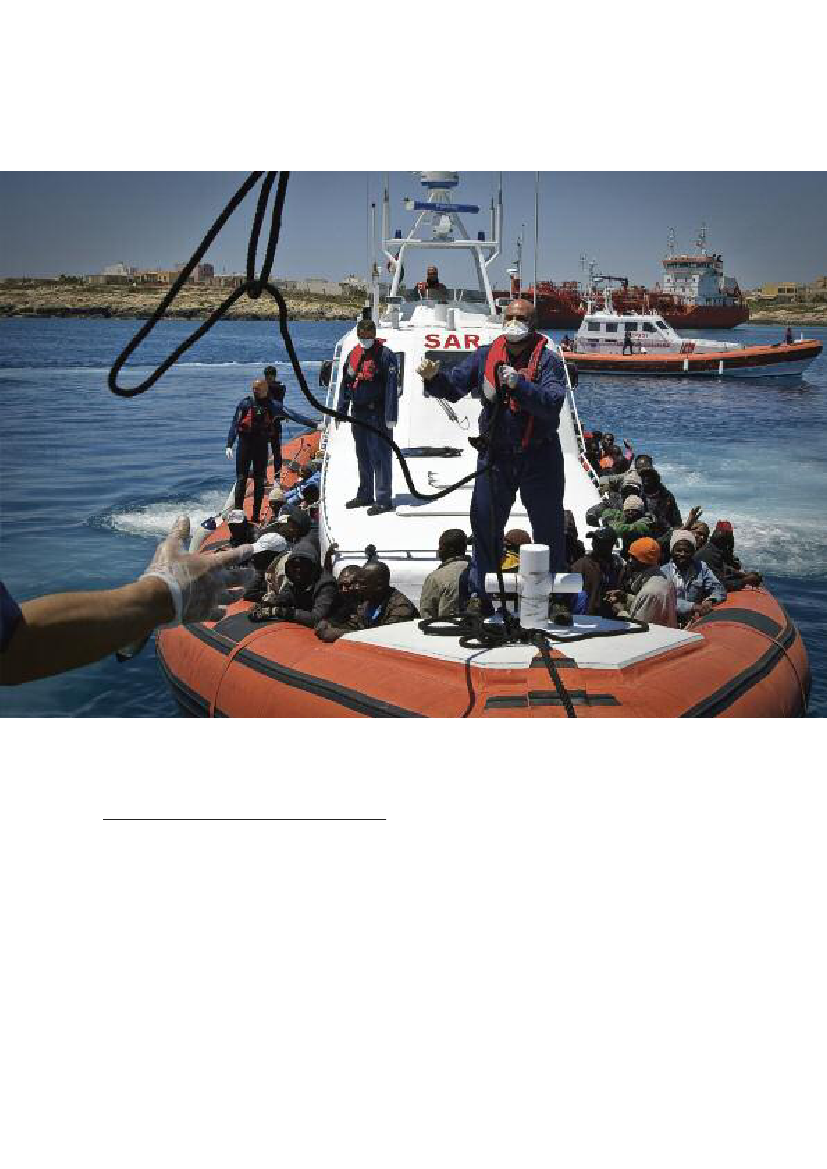

An Italian coastguard vessel prepares to dock in Lampedusa’sport, Italy, May 2011. It was carrying 142 people who hadsailed from Tripoli, Libya, including 30 women and threechildren. They were rescued before their boat sank at sea.

confirmed that the Italian and Maltese nationalMaritime Rescue Co-ordination Centres, FRONTEX andNATO had all been alerted to the plight of the boat indistress. The report of the investigation stated:“[A] catalogue of failures became apparent: the Libyanauthorities failed to maintain responsibility for theirSearch and Rescue zone, the Italian and MalteseMaritime Rescue Co-ordination Centres failed to launchany search and rescue operation, and NATO failed toreact to the distress calls, even though there weremilitary vessels under its control in the boat’s vicinitywhen the distress call was sent… Perhaps of mostconcern in this case is the alleged failure of thehelicopter and the naval vessel to go to the aid of theboat in distress, regardless of whether these wereunder national command or the command of NATO.”

These deaths took place at the time when prevention ofcivilian casualties had been advanced as the primaryjustification for military intervention in Libya and thearea of the South Mediterranean Sea where people losttheir lives was at its busiest, precisely because of themilitary deployment.Following public exposure of the tragedy, theParliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe(PACE) appointed one of its members to investigate thecase. The investigation, published on 29 March 2012,

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

14S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

The investigation also raised concern about measuresbeing taken by European coastal states that negativelyaffect the willingness of fishing and commercial vesselsto fulfil their rescue-at-sea obligations. These includedelays by the state to agree where the rescued peopleshould be disembarked. This in turn can lead toserious financial losses for the vessels concerned, aswell as the risk of being prosecuted for offences relatedto assisting “clandestine immigration”. In a Resolutionfollowing the investigation, adopted on 24 April 2012,PACE recommended action to address these amongseveral other issues.

The 27 Somalis were then taken back to Libya, wherethey lacked any prospect of international protection,and where they were at risk of torture and other humanrights abuses. All 27 were immediately detained inLibya for periods ranging from a few days to a fewweeks. In detention, according to reports, all maleswere lined up against a wall and beaten with batons,and some were given electric shocks duringinterrogation.The 28 Somalis taken to Malta were all released fromdetention within two months and granted internationalprotection. The Maltese authorities continue to denyany wrongdoing. In September 2010 they told AmnestyInternational that, in the context of the 17 July andother similar incidents, Malta does not consider that theobligation ofnon-refoulementapplies on the high seas.Malta stated that it believes that it has no obligationtowards asylum-seekers outside its territorial jurisdictionbeyond ensuring the physical safety of individuals indistress at sea.19This position appears contrary to arecent ruling of the European Court of Human Rights(SeeHirsi Jamaa and other v. Italy,page 11).

rESCuE dOES nOt AlwAySMEAn SAfEtyIn some cases, those in need of rescue foundthemselves victims of push-back operations thatviolated their human rights.On 17 July 2010, a group of 55 Somalis travellingin a dinghy from Libya to Europe found themselvesin distress and were intercepted and rescued, some73km south-east of Malta. Twenty-eight were taken toMalta by an Armed Forces of Malta (AFM) P-52 patrolvessel, while 27 were returned to Libya by a Libyanpatrol boat. The Maltese authorities said that the 27 –18 men and nine women – returned to Libya voluntarily,but some of the Somalis interviewed by AmnestyInternational gave a different account. They said thatthe first vessel to approach them was the Maltese boat:it picked up five women considered particularlyvulnerable, but left everyone else in the dinghy afterhanding out life-jackets, water and biscuits. Shortlyafter, another ship approached. The Somalis wereaddressed in English and Italian. Thinking that theywould be taken to Italy, 27 of them boarded the vessel.When one of them overheard Arabic, he attempted tojump overboard screaming “they are Libyans”. Thosestill in the dinghy refused to board the ship once theyrealized it was Libyan. Some panicked, jumping into thewater or threatening to commit suicide. The Maltesevessel, which was reportedly standing nearby, thenpicked up the remaining Somalis on the dinghy andtook them to Malta.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

15

� UNHCR/F. Noy

These people were among almost 500 people rescued froma skiff in the Mediterranean Sea and taken by six Italianboats to Lampedusa, Italy, May 2011.

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

16S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

4. HuMAn rIGHtS OblIGAtIOnSbEyOnd bOrdErS

Human rights and refugee law requires all states torespect and protect the rights of people within theirjurisdiction: this includes people within the state’sterritorial waters, and also includes a range of differentcontexts where individuals may be deemed to be withina certain state’s jurisdiction.Externalization of border control measures has givenrise to a number of jurisdictional questions, bothbecause states act on the high seas and becauseexternalization involves the officials of one state actingin the territorial waters of another state, or onboardvessels flying the flag of another state.20When state authorities take people intercepted orrescued at sea on board a vessel flying their flag, thosepeople are within that state’s jurisdiction. Even in caseswhere interception or rescue operations on the highseas do not involve taking people on board a statevessel, the state will, in most cases, exercise effectivecontrol and authority over those intercepted or rescuedand must uphold international legal obligations withrespect to human rights and rescue at sea. This meanstaking immediate action to address urgent needs formedical assistance, food and water, ensuring thatpeople are taken to a safe destination where theirrights, including the right ofnon-refoulement,will berespected. People intercepted or rescued at sea mustalso have access to individualized procedures. Theyshould be allowed to explain their circumstances andthose who wish to apply for international protectionshould have access to fair and effective asylumdetermination procedures.

Where people are returned to their country ofdeparture or origin, the process must be done in safetyand dignity. Wherever state responsibility is engagedunder international human rights and refugee law andthe law of the sea, the state cannot relieve itself of thatresponsibility by referring to the involvement of oragreements with other states.States must also ensure that they do not enter intoagreements – bilaterally or multilaterally – that wouldresult in human rights abuses. This means statesshould assess all agreements to ensure that they arenot based on, or likely to cause or contribute to, humanrights violations. In the context of externalization, thisraises serious questions about the legitimacy ofEuropean involvement – whether at a state-to-statelevel or through FRONTEX – in operations to interceptboats in the territorial waters of another state, whenthose intercepted would be at a real risk of humanrights abuses.A state cannot deploy its official resources, agents orequipment to implement actions that would constituteor lead to human rights violations, including within theterritorial jurisdiction of another state.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

17

5. COnCluSIOn

Agreements between Italy and Libya include measuresthat result in serious human rights violations. Agreementsbetween other countries in Europe and North and WestAfrica, and agreements and operations involving the EUand FRONTEX, also need to be examined in terms oftheir human rights impacts. However, with so littletransparency surrounding migration control agreementsand practices, scrutiny to date has been limited.The desire of some European countries to prevent“irregular migration” is undermining safe and timelyrescues at sea. Desperate men, women and childrenhave been left at sea for days while countries argueabout where they should be taken. Those who survivethe terrifying ordeal may be returned to a countrywhere they risk further human rights abuses andwhere their legitimate need for international protectionis ignored. Delayed rescues have reportedly cost thelives of hundreds of people, and the full extent of theproblem has not been documented.States must be held accountable for the human rightsabuses committed in the context of externalization. A lackof transparency surrounding many European countries’border management practices and agreements with thirdcountries means that the violations continue unchecked.In the permissive environment created by this lack ofscrutiny, migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers aredenied any protection of their rights.

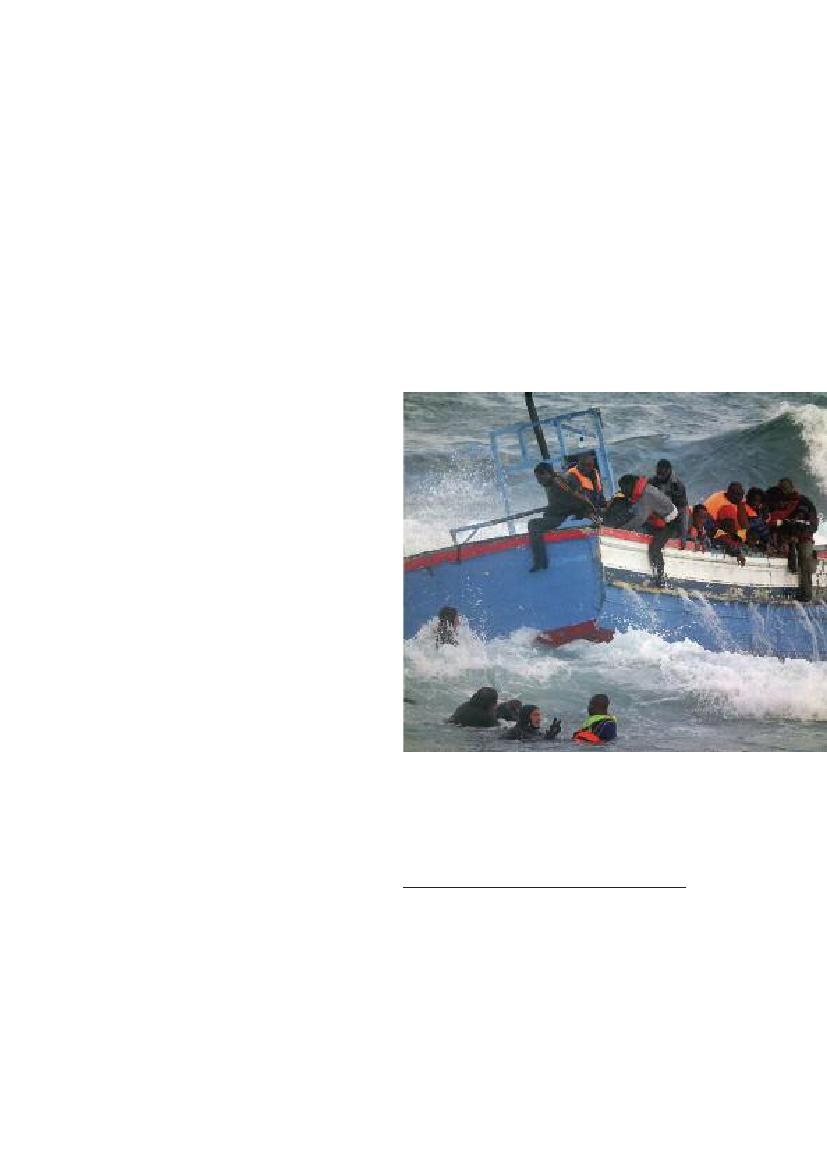

Italian Coast Guard scuba divers, seen bottom left,rescue migrants in Pantelleria, Italy, 13 April 2011.Officials say two women drowned while attemptingto reach Italy from North Africa after their boat with250 people aboard went off course and ran agroundjust off an Italian island.

� AP Photo/Italian Coast Guard, Francesco Malavolta

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

18S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

6. rEcOmmEndAtIOnS

Amnesty International urges all states to protect therights of migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers,according to international standards, This report hasfocused on Italy.

EURopEan coUnTRIES anD ThE EU ShoUlD:n

ThE ITalIan GovERnmEnT ShoUlD:n

ensure that their migration control policies andpractices do not cause, contribute to, or benefit fromhuman rights violations;ensure their migration control agreements fullyrespect international and European human rights andrefugee law, as well as the law of the sea; includeadequate safeguards to protect human rights withappropriate implementation mechanisms; and bemade public;ensure their interception operations look to thesafety of people in distress in interception and rescueoperations and include measures that provide accessto individualized assessment procedures, including theopportunity to claim asylum;ensure their search-and-rescue bodies increasetheir capacity and co-operation in the MediterraneanSea; publicly report on measures to reduce deaths atsea; and that Search and Rescue obligations are readand implemented in a manner that is consistent withthe requirements of refugee and human rights law.

n

set aside its existing migration controlagreements with Libya;not enter into any further agreements with Libyauntil the latter is able to demonstrate that it respectsand protects the human rights of refugees, asylumseekers and migrants and has in place a satisfactorysystem for assessing and recognizing claims forinternational protection;ensure that all migration control agreementsnegotiated with Libya or any other countries aremade public.

n

n

n

n

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

19

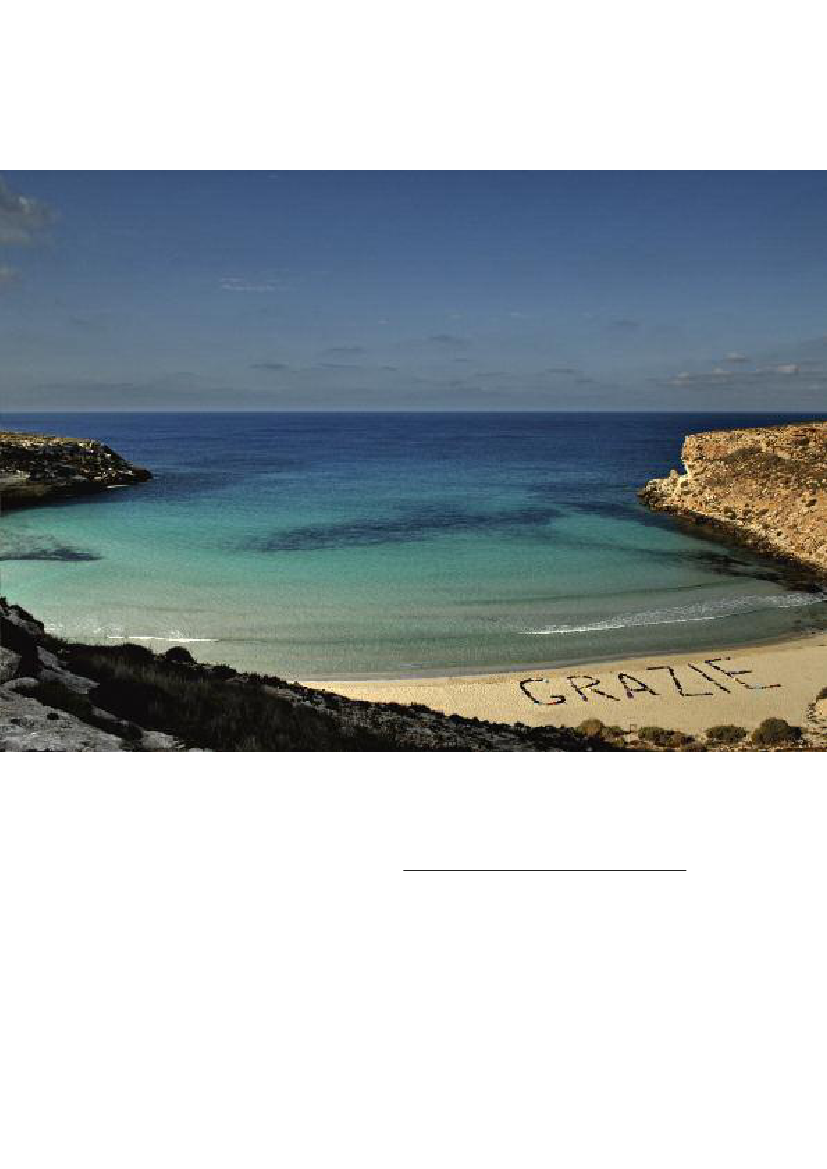

� Fulvio Bugani

Amnesty International members formed the word “Grazie”with their bodies on a beach in Lampedusa, Italy, to saythank you to the inhabitants of the island for their solidaritywith thousands of refugees and migrants from Tunisia,Libya and Africa. July 2011.

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

20S.O.S. EurOpEhUman RIGhTS anD mIGRaTIon conTRol

EndnOtES

1Amnesty International has documented detention andabuses in the past in Mauritania and both past and presentin Libya. See:Mauritania: “Nobody wants to have anythingto do with us”: Arrests and collective expulsions of migrantsdenied entry into Europe(Index: AFR 38/001/2008);Libyaof Tomorrow. What hope for human rights?(Index: MDE19/007/2010);Libya: Militias threaten hopes for new Libya(Index: MDE 19/002/2012).2See news release (in Italian) on the website of the ItalianMinistry of the Interior, online at http://bit.ly/JK4YKn, lastvisited on 21 May 2012.3See bilateral agreements on the Spanish governmentwebsite, online at: http://bit.ly/JgXJXG, last visited on21 May 2012.4See for example Amnesty International reports:Libya ofTomorrow, What hope for human rights?(Index: MDE19/007/2010), June 2010;Libya: Militias threaten hopes fornew Libya,(Index: MDE 19/002/2012), 16 February 2012.5Libya struggles with illegal migrants, arms trafficking,28 April 2012, online at: http://www.alarabiya.net/articles/2012/04/28/210863.html, last visited on 17 May 2012.6See text of the Treaty (in Italian) online athttp://bit.ly/MUUPwn, last visited 29 May 2012.7See for example:Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy(application no. 27765/09), the judgement of the GrandChamber of the European Court of Human Rights isavailable at http://www.echr.coe.int/ECHR/EN/hudoc8Report by Thomas Hammarberg, Commissioner forHuman Rights of the Council of Europe, following hisvisit to Italy from 26 to 27 May 2011, para. 51, online at:http://bit.ly/LaQsYM last visited on 21 May 2012.9See the press release of the Italian Ministry of theInterior (in Italian) online at http://bit.ly/LtV55S, lastvisited on 21 May 2012. See also press report in English“Italy, Libya sign anti-migrant pact”, http://bit.ly/HlbgKO,last visited on 21 May 2012.10While UNHCR has operations in Algeria, Chad, Egypt,Niger, Tunisia and Sudan, at the moment none of thesecountries can offer long term protection to refugees orothers in need of international protection.11The Italian Ambassador to Libya provided thisinformation during an inquiry of a parliamentarycommittee on 13 October 2009 – cited on this sitehttp://www.asgi.it/home_asgi.php?n=760&l=it.

12See, for example, Amnesty International publicstatementItaly: Over 100 reportedly “pushed back”at sea(Index: EUR 30/017/2011), 30 August 2011,andSeeking safety, finding fear: Refugees, asylum-seekersand migrants in Libya andMalta,(Index: REG 01/004/2010), 14 December 2010.13UNHCR press briefing, 10 December 2010.14See Submission by the Office of the United Nations HighCommissioner for Refugees in the Case ofHirsi and Othersv. Italy(Application no. 27765/09), 29 March 2011, onlineat http://bit.ly/KDNS0F, last visited on 17 May 2012.15“More than 1,500 drown or go missing trying to cross theMediterranean in 2011”, online at http://www.unhcr.org/4f2803949.html, last visited on 17 May 2012.16See Amnesty International’sState of the World’s HumanRights 2010.See also “Italy allows ship with rescuedmigrants to dock”,Guardian,19 April 2009; “UN rebuke asgovernments squabble over immigrants found clinging totuna nets”,Guardian,29 May 2007.17UNHCR reported this case http://www.unhcr.org/4d9c8bf56.html. Issues related to Italy and Malta werereported in the Italian and Maltese press: for example,LaRepubblicahttp://www.repubblica.it/cronaca/2011/04/06/news/lampedusa_naufraga_barcone_strage_immigrati-14584220/?ref=HREA-1; andTimes of Malta–http://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20110407/local/maroni-implies-blame-on-malta-for-migrants-tragedy.358699.18Amnesty International interviewed two of the survivors ofthis incident. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council ofEurope’s reportLives lost in the Mediterranean Sea: who isresponsible?,published 29 March 2012, is available onlineat http://assembly.coe.int/CommitteeDocs/2012/20120329_mig_RPT.EN.pdf. The incident has been widely reported inthe media.19Amnesty International,Seeking safety, finding fear:Refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in Libya and Malta,(Index: REG 01/004/2010), 14 December 2010.20The full judgement of the Grand Chamber of theEuropean Court of Human Rights onHirsi Jamaa and Othersv. Italyis a helpful tool in clarifying some of these questions.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 01/013/2012

WhEThER In a hIGh-PRoFIlE conFlIcToR a FoRGoTTEn coRnER oF ThEGloBE,amnESTY InTErnaTIOnalcamPaIGnS FoR JUSTIcE, FREEDomanD DIGnITY FoR all anD SEEKS ToGalVanIZE PUBlIc SUPPoRT To BUIlDa BETTER WoRlDWhaT can YOu DO?Activists around the world have shown that it is possible to resistthe dangerous forces that are undermining human rights. Be partof this movement. Combat those who peddle fear and hate.Join Amnesty International and become part of a worldwidemovement campaigning for an end to human rights violations.Help us make a difference.Make a donation to support Amnesty International’s work.

Together we can make our voices heard.I am interested in receiving further information on becoming a member of amnestyInternationalnameaddresscountryemail

I wish to make a donation to amnesty International (donations will be taken in UK£, US$ or €)amount

number

I WanTTO hElp

expiry datesignaturePlease return this form to the amnesty International office in your country.For amnesty International offices worldwide: www.amnesty.org/en/worldwide-sitesIf there is not an amnesty International office in your country, please return this form to:amnesty International,International Secretariat, Peter Benenson house,1 Easton Street, london Wc1X 0DW, United Kingdom

amnesty.org

please debit my

Visa

mastercard

S.O.S. EurOpE

human rIGhTS anD mIGraTIOn cOnTrOlIn an attempt to prevent “irregular migration” from africa to Europe,

some European countries implement border control measures

outside their own territory, at sea and on land. States have reached

agreements to intercept boats at sea and return people to countries

in West and north africa, in circumstances that expose people to

serious human rights violations. as there is an almost complete lack

of transparency surrounding many European countries’ border

management practices and agreements with north and West african

states, these violations go unchecked.

This short report examines some aspects of the human rights impacts

of European migration control policies, looking in particular at the

agreements between Italy and libya and their consequences. It calls for

all border control polices to be consistent with human rights

obligations, and for transparency from all governments on agreements

on migration control.

The report is published as part of amnesty International’s campaign

“When you don’t exist”, which aims to protect the rights of migrants,

refugees and asylum-seekers across Europe.

amnesty.orgIndex: EUR 01/013/2012June 2012