Europaudvalget 2011-12

EUU Alm.del Bilag 33

Offentligt

October 2011

Sixteenth Bi-annual Report:Developments in European UnionProcedures and PracticesRelevant to Parliamentary Scrutiny

Prepared by the COSAC Secretariat and presented to:XLVI Conference of Parliamentary Committeesfor Union Affairs of Parliamentsof the European Union2 - 4 October 2011Warsaw

Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairsof Parliaments of the European UnionCOSAC SECRETARIATWIE 05 U 041, 30-50 rue Wiertz, B-1047 Brussels, BelgiumE-mail:[email protected]| Fax: +32 2 284 4925

2

Table of ContentsBACKGROUND........................................................................................................................ 4ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................... 5CHAPTER 1: MULTIANNUAL FINANCIAL FRAMEWORK FOR EUROPE 2020STRATEGY............................................................................................................................. 111.1 Involvement of Parliaments in establishing the position of their Governments ................ 111.1.1 Scope of parliamentary scrutiny, procedures ............................................................ 121.1.2 Future involvement of national Parliaments ............................................................. 141.2 Proposal to shorten the duration of the MFF from seven to five years ............................. 151.3 Proposal to reduce the GNI-based contributions of Member States to the EU budget ...... 161.4 New system of EU own resources................................................................................... 181.4.1 EU own resources .................................................................................................... 181.4.2 Financial Transaction Tax ........................................................................................ 201.5 Support for the Europe 2020 Project Bond initiative ....................................................... 211.6 Implementation of the goals of the Europe 2020 Strategy through the MFF 2014-2020... 221.7 Structure of EU budgetary expenditure in the MFF 2014-2020 ....................................... 231.7.1 Transfer of funds from Sub-heading 1b to Sub-heading 1a ....................................... 241.8 Unspent EU funds........................................................................................................... 24CHAPTER 2: TWO YEARS AFTER THE ENTRY INTO FORCE OF THE TREATY OFLISBON - PARLIAMENTARY EXPERIENCE ...................................................................... 262.1 Reasoned opinions .......................................................................................................... 262.1.1 Reasoned opinions adopted since the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon .......... 262.1.2 Publication of reasoned opinions on IPEX................................................................ 312.1.3 Replies from the European Commission on reasoned opinions ................................. 322.1.4 Quality of the Commission’s replies to reasoned opinions........................................ 332.1.5 Dealing with the Commission's replies in national Parliaments................................. 332.1.6 Reflection of reasoned opinions in EU draft legislative acts ..................................... 342.1.7 Continued dialogue with the Commission after receiving its replies ......................... 352.1.8 Sufficiency of the eight-week period for the evaluation of EU draft legislative acts.. 352.1.9 Lack of a legal basis and lack of (or insufficient) subsidiarity justification ............... 372.1.10 Impact assessments of EU draft legislative acts ...................................................... 412.1.11 Internal subsidiarity control mechanisms of national Parliaments ........................... 462.1.12 Treatment of reasoned opinions and contributions by the European Parliament ...... 492.1.13 Reasoned opinions and contributions in documents of the European Parliament..... 512.2 Informal political dialogue.............................................................................................. 522.2.1 Number of contributions sent to the Commission ..................................................... 522.2.2 The Commission's replies to contributions ............................................................... 532.2.3 Quality of the Commission’s replies to the contributions.......................................... 542.2.4 Dealing with the Commission's replies in national Parliaments................................. 542.2.5 Further informal political dialogue after receiving Commission's replies .................. 552.3 Parliamentary scrutiny and delegated acts under Article 290 of the TFEU ...................... 552.3.1 Opinions on proposals that provide for delegated acts .............................................. 552.3.2 Possible cooperation with the EU institutions for monitoring delegated acts............. 60

3

BACKGROUNDThis is the Sixteenth Bi-annual Report from the COSAC Secretariat.COSAC Bi-annual ReportsThe XXX COSAC decided that the COSAC Secretariat should producefactual Bi-annual Reports, to be published ahead of each ordinary meetingof the Conference. The purpose of the Reports is to give an overview of thedevelopments in procedures and practices in the European Union that arerelevant to parliamentary scrutiny.All the Bi-annual Reports are available on the COSAC website at:http://www.cosac.eu/en/documents/biannual/

The two chapters of this Bi-annual Report are based on information provided by the nationalParliaments of the European Union Member States and the European Parliament. The deadlinefor submitting replies to the questionnaire for the 16th Bi-annual Report was 26 August 2011.Both chapters of this Report begin with relevant parts of the outline adopted by the meeting ofthe Chairpersons of COSAC, held on 11 July 2011 in Warsaw.As a general rule, the Report does not specify all Parliaments or Chambers whose case isrelevant for each point. Instead, illustrative examples introduced in the text as "e.g." are used.The COSAC Secretariat is grateful to the contributing Parliaments/Chambers for theircooperation.

Note on NumbersOf the 27 Member States of the European Union, 14 have a unicameralParliament and 13 have a bicameral Parliament. Due to this combination ofunicameral and bicameral systems, there are 40 national parliamentary Chambersin the 27 Member States of the European Union.Although they have bicameral systems, the national Parliaments of Austria,Belgium, Ireland and Spain each submitted a single set of replies to thequestionnaire circulated by the COSAC Secretariat.The COSAC Secretariat received replies from all 40 national Parliaments/Chambers of 27 Member States and the European Parliament. These replies andtheir annexes are published in a separate Annex to this Bi-annual Report which isavailableontheCOSACwebsiteat:http://www.cosac.eu/en/documents/biannual/.

4

ABSTRACTCHAPTER 1: MULTIANNUAL FINANCIAL FRAMEWORK FOR EUROPE 2020STRATEGYAbouthalfof the national Parliaments/Chambers havenot yet discussedthe differentaspects ofthe Multiannual Financial Framework for 2014-2020(hereinafter referred to as "the MFF").However, a majority of the Parliaments/Chambers expect the MFF to be on the agenda of theirrespective Committees on EU Affairsduring the autumn session of 2011.So far, the MFF hasbeen mainly discussed in theCommittees on EU Affairs,sometimes injoint meetings withother competent committees,to which Government representatives have been invited. SomeParliaments/Chambers have organisedpublic hearingsandmeetings with Members of theEuropean CommissionandMembers of the European Parliament.The issue of the MFF hasalso been dealt with in a number of parliamentaryreports.Most Parliaments/Chambers areagainstthe proposal to shorten the duration of the MFF. It isargued that the presentseven-year period guarantees long-term consistency and stability,while a five-year period would jeopardize the sustainability of the EU planning process withpotential disadvantages outweighing possible benefits. Proponents of the five-year period,including the European Parliament, advocate that it wouldmatch the tenureof the EuropeanParliament and of the European Commission (hereinafter referred to as "the Commission"), thusincreasingdemocratic responsibility, accountability and legitimacy.The proposal to reduce GNI-based contributions of Member States to the EU budget has notbeen thoroughly considered by the majority of Parliaments/Chambers, although theprevailingviewis in favour ofpreserving the present levelof GNI-based contributions.As far as the question of thenew system of EU own resourcesis concerned,a quarterofParliaments/Chambers areagainstintroducing new taxes, some of them underlining that the taxpolicy is an area of sovereign competence of the Member States. The Financial Transaction Tax(hereinafter referred to as "the FTT") is viewed by some Parliaments/Chambers as atool ofgenerating significant fiscal revenues.Other Parliaments/Chambers oppose the measurefearing that the introduction of the FTT might drive investors towards countries with more liberaltax regimes.Amajorityof the Parliaments/Chambers that have discussedthe Europe 2020 Project Bondinitiative believe it isa good idea.This is, however, not without reservations. Several of themwarn that the initiative of attracting private sector financing for the promotion of individualinfrastructure projects mustnot lead to the need for the EU to provide additional fundsbeyond what was originally allocated to the project.There is aconsensusamong Parliaments/Chambers which have already discussed the issue thatthe MFF should allow forthe full implementation of the goals of the Europe 2020 Strategy.A majority of Parliaments/Chambers do, however, argue that the focus on the goals of theEurope 2020 Strategy in the MFF should be balanced with other EU priorities and theindividualsituation of Member States.

5

Concerning the Commission's proposed structure of the EU budgetary expenditure in the MFF,themajorityof Parliaments/Chambers, which have discussed the subject, donot think it issufficiently specificas it combines several different policy areas under one general heading.Furthermore,the lack of a special heading for cohesionis acommon concernof themajorityof Parliaments/Chambers.Balanceis again thekey focusfor Parliaments/Chambers which have discussed the issue oftransferring funds from Sub-heading 1b (Cohesion for growth and employment) to Sub-heading1a (Competitiveness). Although themajorityof Parliaments/Chambers that have replied donotsupport the suggestion,several point out that it is a matter of striking the right balance betweenthe two areas, thus combiningefficiency and solidarity.With regard to the question ofunspent EU funds being used as EU own resources,themajority of Parliaments/Chambers have yet to discuss the issue. However,more than halfof theremaining Parliaments/Chambersdo not supportthe suggestion that unspent EU funds shouldbe used in future accounting periods as EU own resources instead of following the currentpractice where the unspent funds are returned to the Member States.CHAPTER 2: TWO YEARS AFTER THE ENTRY INTO FORCE OF THE TREATY OFLISBON - PARLIAMENTARY EXPERIENCESince the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon amajorityof national Parliaments/Chambers,i.e.29,haveadopted at least one reasoned opinion.Out of40national Parliaments/Chamberselevenhavenot adoptedany reasoned opinion yet.Thelargest number of reasoned opinions,i.e.eight,has been adopted by thePolishSenat.The most frequently contested draft legislative actswith regard to their compliance with theprinciple of subsidiarity are the proposal for a Council Directive on a Common ConsolidatedCorporate Tax Base (CCCTB) (COM(2011)121)and the proposal for a Directive of theEuropean Parliament and of the Council on the conditions of entry and residence of third-countrynationals for the purposes of seasonal employment (COM(2010)379). NinenationalParliaments/Chambers issuedreasoned opinionson these draft legislative acts.Most national Parliaments/Chambers indicate that the Commissionreplies to all reasonedopinions.As to the Commission’s self-imposedthree-month time-limitfor replying to reasoned opinions,national Parliaments/Chambers indicate that usually the time-limit isnot respected.Fromamong 19 Parliaments/Chambers that have adopted reasoned opinion at least three months beforethe deadline for the replies to the questionnaire for this report1, amajority(i.e.13)note that thethree-month deadline wasnot metin at least one case. In some cases, nationalParliaments/Chambers have had towaitfor the Commission's replyfor four to six months.FourParliaments/Chambers aresatisfiedwith the quality of the Commission's replies, withoutany reservations. Some Parliaments/Chambers note that the quality of replies hasnot (yet) been

1

26 August 2011

6

debated.However, several national Parliaments/Chambers arecriticalof the quality of thereplies believing them to betoo short and too general.The practices of dealing with the Commission's replies in national Parliaments/Chambers vary.Out of 40 national Parliaments/Chambers,17responded with their experience and practices. Forinstance, infourParliaments/Chambers information on the replies is provided only to theCommittees on EU Affairsand/or other relevantspecialised committees.The group ofrecipients of the Commission's replies is sometimes wider, including staff of political groups.Several Parliaments/Chambers state that theypublishthe replies on theirwebsites,print them asofficial documents, include them inweekly reportson documents received from theCommission or make them available in theirlibraries.The issue of howreasoned opinionsare reflected in the content of EU draft legislative acts isdifficult to examine at this stage because of thelimited available material.Nevertheless,twonational Parliaments/Chambers findpotential reflectionof their reasoned opinions in one draftlegislative act, i.e. in the proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Councilon Deposit Guarantee Schemes COM(2010) 368.None of the 40national Parliaments/Chambers state that they havecontinued dialoguewith theCommission after receiving the Commission's replies to their reasoned opinions.Parliaments/Chambersare dividedon the issue of thesufficiency of the eight-week periodforthe assessment of the compliance of EU draft legislative acts with the principle of subsidiarityaccording to Protocol 2 on the application of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality ofthe Treaty of Lisbon (hereinafter referred to as "Protocol 2").TenParliaments/Chambersaresatisfiedwith the time-frame of Protocol 2,14although generally satisfied, have variousreservations, tenfind itinsufficient or problematicand the remaining five provide generalcomments without taking a formal position. The 24 Parliaments/Chambers which voicereservations and general dissatisfaction with the eight-week period as (potentially) too shortpoint out theneed to verify other aspectsof draft legislative acts, such as their compliance withthe principle of proportionality, adequacy of the legal basis and substantive provisions as well asthe time needed to comply with internal procedural requirements, such as the need to hearopinions of specialised committees or to have reasoned opinions voted in the plenary.Almost halfof the national Parliaments/Chambers (i.e.16 out of 33)which have sent in theirreplies, indicate that they havefound the lack of a legal basisand/orlack of (or insufficient)subsidiarity justificationto be aninfringementof the principle of subsidiarity and have as aconsequence adoptedreasoned opinions.A significant numberof national Parliaments/Chambers (i.e.17)comment on the consequencesof thelack of or insufficient justificationof draft legislative acts with regard to the principle ofsubsidiarity. They point out that it is theobligation of the initiatorof an EU draft legislative act,in most cases,the Commissionto produce proper justification of the acts in compliance with therequirements of Article 5 of Protocol 2, in particular a detailed statement, including anassessment of a financial impact and implications for national rules. On numerous occasionsParliaments/Chambers havecriticised the justification as insufficient, lacking in substance, orabsent all together.As to theCommission's impact assessments,Parliaments/Chambers generally consider themuseful and necessaryfor the parliamentary scrutiny of EU draft legislative acts. However,12

7

Parliaments/Chambers voicecriticismwith regard to thequalityof the impact assessments, attimes finding themschematic and lacking in substance,whilefourParliaments/Chambersvoiceconcernswith theirindependent nature,advocating,inter alia,the independence of theCommission's Impact Assessment Board.Furthermore,more than a halfof Parliaments/Chambers (i.e. 15 out of 24) that have expressedtheir views on the subject are of the opinion that thefull text of impact assessments should betranslated into all official languages of the EU.A further nine Parliaments/Chambers seelimited or no added value in this exercise.Out of 39national Parliaments/Chambers which have replied to the question on the amendmentsto their internal subsidiarity control mechanisms,20 consider them satisfactory.An equalnumber of Parliaments/Chambers report that such amendments have been introduced due to thenew role of national Parliaments in the EU enshrined in the Treaty of Lisbon. This Bi-annualReport details several examples of such amendments.Following the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, theEuropean Parliament amended itsRules of Procedurein order to implement the new mechanism under Protocol 2 andset up aninternal procedure for dealing with reasoned opinions and contributionsfrom nationalParliaments. According to the European Parliament'sdefinitions"reasoned opinions" aresubmissions of national Parliaments on the non-compliance of a draft legislative act with theprinciple of subsidiarity that are communicated to the European Parliament within the eight weekdeadline referred to in Article 6 of Protocol 2, while "contributions" are any other submissionswhich do not fulfil the criteria for a reasoned opinion.Upon receipt, allreasoned opinionsare referred to the committee(s) responsible for the draftlegislative act and forwarded to the Committee on Legal Affairs (JURI), which examines themand has themtranslated into all official languages of the EU.Reasoned opinions aredistributed to all Members of the competent committees,areincluded in the filefor thecommittee meeting andpublished on the committee website pageunder the heading "meetingdocuments". Furthermore,the text of draft legislative resolutions must make reference to anyreasoned opinions receivedin relation to their subject matter. In its reply to the questionnairefor the 16th Bi-annual Report the European Parliament also gives a detailed account of theprocedureto be followed in case the requisite "yellowcard" and "orange card"thresholds arereached.Upon receipt,contributions- which may also be submissions which positively assess a givenlegislative proposal's compliance with the principle of subsidiarity - arereferred to thecommittee(s) of the European Parliament that is responsiblefor the file. Transmission to therelevant committees is done by the Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments.Committee secretariats are then responsible for the transmission of contributionsto therespective committee Chairs and/or rapporteurswho may request translation.Furthermore, the European Parliament's Directorate for Relations with National Parliamentscirculates to all committee secretariats, political groups and any other interested EuropeanParliament services amonthly summary tableand an explanatory noteoutlining the reasonedopinions and contributionsof national Parliaments received during the preceding month. TheConference of Committee Chairs receives these documents for information.

8

It is noteworthy that the European Parliament is theonly EU institution to translate all reasonedopinions(and potentially contributions)in all EU official languages,thus allowing its Membersto fully take into account the views expressed by national Parliaments. The European Parliamentunderlines that itslegislative reports systematically make reference to reasoned opinionsreceivedin the context of Protocol 2 and gives four recent examples.Theinformal political dialogue(also known as "the Barroso initiative") was launched in 2006with the aim of encouraging national Parliaments to express their opinions on the Commission'sinitiatives not only in relation to the principles of subsidiarity but also in a more general way. Thistool has been in use ever since and its use is on the increase since the entry into force of the Treatyof Lisbon, as the Annual Report 2010 from the Commission on relations between the EuropeanCommission and national Parliaments confirms. Theactivityof Parliaments/Chambers within theframework of the informal political dialogue, however,greatly differs,with the number ofcontributions ranging from 0 to 220.NineParliaments/Chambers havenot yet usedthisopportunity.The number of the Commission's replies to the contributions of national Parliaments/Chambersdoes not coincide with the number of submitted contributions. Thehighest number of replieshas been given to the CzechSenát,i.e. 32 replies to its 52 contributions.Concerning thequalityof the replies of the Commission,the majorityof Parliaments/Chambersconsider themsatisfactory. A groupof Parliaments/Chambers finds themtoo generalor reportthat sometimes they aresent too late.In most cases, the Commission's replies to the contributions submitted within the framework ofthe informal political dialogue aredealt with in the same manner as the responses toreasoned opinionsunder Protocol 2. In addition to being distributed to the Members of theCommittees on EU Affairs they are sometimes sent to competent specialised committees andpublished on the websites of respective Parliaments/Chambers as well.Out of the large majority of Parliaments/Chambers that have replied to the questionnaire manyhave not (yet) discussed the issue or have not (yet) adopted an officialpositionon delegatedacts.Core elements of concernfor numerous Parliaments/Chambers are the potentialexcessiveuseof delegated acts, possiblescrutiny problems,the difficulty todefine and assess non-essential elements,and the possibleweakening of national Parliamentsas a result of theimproper application of Article 290 of the TFEU. A few Parliaments/Chambers highlight themonitoring role of theEU legislator,referring to the Common Understanding between theCommission, the European Parliament and the Council. Four Parliaments/Chambers refer to theirresolutionsin which they have voiced their concerns.In a few Parliaments/Chambers specificconcerns related to the actual subjectof delegatedacts have not yet been raised. Numerous Parliaments/Chambers voice their concerns, often inresolutions, reasoned opinions or other documents, and include examples, e.g. on the Citizens'Initiative regulation. Several Parliaments/Chambers insist that delegation of power to theCommission should be "kept to a strict minimum".On the issue of the adequatedescription of essential featuresof delegated acts only a handfulof Parliaments/Chambers have not yet identified problems. Others address a range ofissues thatare of concern,such as the lack of sufficient evidence toproof the needto resort to delegated

9

acts, thevaguenature of the objectives, theimprecisedescription of the content, the presence ofessential elementsin delegated acts, theinsufficiently explicitdefinition of the scope and theindeterminate periodof delegation of power to the Commission compounded by the narrowtime frame for EU legislators to react.Views on whether and how to cooperate with EU institutions range fromprudencetosupportfor the idea. Some Parliaments/Chambers donotconsider itas a first optionor state that the EUlegislators and finally the Court of Justice of the European Union (hereinafter referred to as "theCourt of Justice") have a specific role to secure uniform application of the criteria. OtherParliaments/Chambers urgecloser cooperation between governments and nationalParliamentsor see,inter alia,reasoned opinionsand thepolitical dialogueas useful tools.Several Parliaments/Chambers say that they aregenerally open to (informal) cooperationand/or find it(very) useful,most of them without going into detail.Cooperation with theEuropean Parliamentin particular is advocated byfourParliaments/Chambers, while theEuropean Parliament itself willassess the Common Understandingwith the Commission andthe Council one year after it became operational and possibly initiate a revision of it.

10

CHAPTER 1: MULTIANNUALEUROPE 2020 STRATEGY

FINANCIAL

FRAMEWORK

FOR

With the publication of the Commission’s proposal on the MFF on 29 June 2011, a debate hasstarted.One of the aims of the 16th Bi-annual Report is to assess the present and future role of nationalParliaments as regards cooperation with and scrutiny of their governments throughout theprocess of developing the new MFF in view of the targets outlined in the Europe 2020 Strategy.Contrary to common hopes and expectations the European economic and financial crisis has notbeen fully overcome. Growing economic disparities between Member States and a lack ofappropriate measures to remedy this situation lead to controversial views, such as the need tobuild a multiple-speed Europe. Attempts to save the euro area by rationalising the EU budgetaryspending at the expense of the cohesion policy provoke unnecessary divisions within theEuropean Union. In principle, the successive EU budgets have been adjusted to their respectivegoals. Therefore, the new financial framework should make it possible to finance all theobjectives set in the Europe 2020 Strategy, including the consolidation of the EU’s internalmarket.Given the serious challenges currently facing the EU, it would be advisable to define the role andpowers of national Parliaments and the European Parliament in co-creating and scrutinising keyEU policies in the post-Lisbon era. This would require a concerted action by all decision-makers,both at the national and the EU level. European solidarity, which is one of the corner stones oftoday’s European Union, requires the achievement, without delay, of a broad consensus on thefull involvement of national Parliaments and the European Parliament in the EU governanceprocess, especially in order to prevent further global crises.

1.1 Involvement of Parliaments in establishing the position of their GovernmentsOut of 41 Parliaments/Chambers that have replied on the issue,182have so far beenactivelyinvolvedin establishing their Governments’ position on the MFF, while some otherParliaments/Chambers are planning to get involved.Two Parliaments/Chambers neither have been involved nor plan to do so in the future3.The Committees on Finances of the BelgianChambre des représentantsandSénatdiscussed theMFF in two joint hearings on 27 and 29 April 2011. However, as the hearings were initiated bythe Parliament, the Government was not actively involved. On the other hand, the FederalAdvisory Committee on European Affairs of the BelgianChambre des représentantsandSénathas regularly discussed the MFF with the Belgian Prime Minister.2

I.e. the AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,the CzechSenát,the EstonianRiigikogu,the FinnishEduskunta,theGermanBundestagandBundesrat,the DutchTweede Kamer,the GreekVouli ton Ellinon,the ItalianCamera deiDeputati,the LatvianSaeima,the PolishSejmandSenat,the PortugueseAssembleia da República,the RomanianCamera Deputaţilor,the SpanishCortes Generalesand the UKHouse of Lords3I.e. the MalteseKamra tad-Deputatiand the SlovenianDržavni svet

11

1.1.1 Scope of parliamentary scrutiny, proceduresParliaments/Chambers have been mainly involved in the work on the MFF through theirrespective Committees on EU Affairswhich sometimes closely cooperate withotherspecialised committees in organisingdebates, joint committee meetings, at times with theparticipation of Government representatives.The EU Affairs Committee of the EstonianRiigikoguconsidered the future MFF as early on as 9April and 26 November 2010 in meetings attended by the Minister of Finance. Also, the GermanBundestagdiscussed different aspects of the MFF with the federal Government. The GermanBundesratadopted detailed opinions on the Commission Communication "Reforming thebudget, changing Europe"4on 14 March 2008 and on the Communication "The EU BudgetReview"5on 17 December 2010. The Federal Government was required to take these opinionsinto account inestablishing its negotiating position.The Committee on European Affairs and the Committee on Budget of the ItalianCamera deiDeputatistarted a jointscrutinyof the Commission proposal on the MFF on 27 July 2011. On28 July 2011, the Minister of Foreign Affairs reported on the MFF to a joint meeting of theCommittees on Budget, the Committees on EU Policies and the Committees on Foreign Affairsof the ItalianCamera dei DeputatiandSenato della Repubblica.The ItalianCamera dei Deputatiexpressed some general views on the revision of the EU budgetin its resolution, approved on 13 July 2010, in which it urged the Government to,inter alia,ensure that during the negotiations on the MFF the relationship between the EU policy prioritiesand theirspending is clearly and transparently defined,and reaffirm theprinciple ofsolidarityand parity among Member States, as well as securing an amount of resourcesconsiderably higher than the one envisaged in the MFF for 2007-2013, while maintaining thefunding for cohesion policies at the level envisaged in the current MFF.The Committee on European Affairs of the LatvianSaeimagives a mandate to the Governmenton all Latvia’s official positions on EU matters. In this case, the first position of the committeewas adopted on 28 July 2011. Moreover, theSaeimain its extraordinary plenary sitting of 14July 2011 adopted statements on "the Equitable Common Agricultural Policy of the EU after2013" and on "the EU Budget Financing for Reducing Social and Economic Disparities after2013".The Committee on European Affairs and the Committee on National Economy of the PolishSenatwere briefed by representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry ofNational Economy on 27 July 2011 on the subject of "the Real and Potential Sources of Financefor the Europe 2020 Strategy Goals in the Context of Proposals for the MFF 2014-2020". TheCommittee on EU Affairs of the PolishSenatcooperates with competent ministers within theframework of the MFF. The Committee on European Affairs, the Committee on Local Self-Government and the Regional Committee of the PolishSejmheld a joint meeting during whichthey approved the Government's information on the future of the cohesion policy and the newMFF in connection with the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament,45

http://ec.europa.eu/budget/reform2008/library/issue_paper/consultation_paper_en.pdfhttp://ec.europa.eu/commission_2010-2014/president/pdf/eu_budget_review_en.pdf

12

the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions andthe European Investment Bank Conclusions of the fifth report on economic, social and territorialcohesion: the future of cohesion policy6. On 16 February 2011 the Committee on EuropeanAffairs of the DutchTweede Kamerheld a publicvideoconference with the Dutch Members ofthe European Parliamentfrominter aliathe Special Committee on policy challenges andbudgetary resources for a sustainable European Union after 2013 (SURE)7, during which,interalia,the possibility of new EU taxes and the Dutch position on 1 billion euro extra rebate werediscussed.Similarly, on July 7 2011, the Committee on European Affairs of the GreekVouli ton Ellinonheld a meeting on this topic. The alternate minister for Foreign Affairs, competent for EuropeanAffairs gave an account of the Government's first reactions to the Commission’s proposals, itspositions and envisaged steps. The Committee on European Affairs also held a joint meetingwith the Committee for Trade and Production, which focused on the MFF of the commonagricultural policy.On 23 May 2011, the Austrian Parliament held apublic hearingwith Governmentrepresentatives, experts and stakeholders on the future of the common agricultural policy, theresults of which were debated during the plenary session of both theNationalratandBundesratin June 2011. Moreover, the European Affairs Committees of theNationalratandBundesratintend to discuss the Commission’s proposal on the MFF in September 2011, and may decide onthe Austrian position which will be binding on the Government.A few Parliaments/Chambers organizedmeetingson the future MFFwith Members of theCommission.On 3 March 2011 the Committee on EU Affairs of the PolishSejmheld a meetingwith the Commissioner for Financial Programming and Budget Mr Janusz LEWANDOWSKI onthe Commission Communication on the EU Budget Review8. In addition, on 1 April 2011, theEU Affairs Committee, the Committee on Economy and the Committee on EnvironmentProtection, Natural Resources and Forestry of the PolishSejmheld a joint meeting with theCommissioner for Climate Action Ms Connie HEDEGAARD. In June 2011, the Committees onEuropean Affairs of the RomanianCamera DeputaţilorandSenatulin a joint meeting with theCommissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development Mr Dacian CIOLOŞ discussed the futureMFF. Also, the ItalianCamera dei Deputatidecided to hold a meeting with Commissioner MrJanusz LEWANDOWSKI.The DanishFolketing,for its part, reports that there is ageneral agreement among politicalpartiesin Denmark concerning the MFF. Although theFolketinghas not been directly involvedin establishing the position of the Government, the latter will have to obtain a mandate from theEuropean Affairs Committee of theFolketingbefore signing up to the MFF in the Council.In total, eight Parliaments/Chambers haveproduced reports dealing with the MFFor will doso in future. On 5 April 2011, the EU Select Committee of the UKHouse of Lordspublished thereport "EU Financial Framework from 2014"9. On 6 June 2011, the FrenchSénatadopted aninformative report by Mr Fran§ois MARC10. Reports on the MFF were also produced as a resultof the joint hearings on 27 and 29 April 2011 in the BelgianChambre des représentantsand67

http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/cohesion5/pdf/conclu_5cr_part1_en.pdfhttp://www.europarl.europa.eu/activities/committees/homeCom.do?language=EN&body=SURE8http://ec.europa.eu/commission_2010-2014/president/pdf/eu_budget_review_en.pdf9http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201011/ldselect/ldeucom/125/125.pdf10http://www.senat.fr/rap/r10-738/r10-738.html

13

Sénat.Another report concerning the meeting held by the Federal Committee on EU Affairs ofthe BelgianChambre des représentantsandSénatwith the Belgian Prime Minister on 26 June2011 dedicated to the results of the Euro- zone summit will be published shortly.The European Parliament with a view to establishing the political priorities for the next MFFcreateda Special Committeeon policy challenges and budgetary resources for a sustainableEuropean Union after 2013 (SURE) which ended its work on 8 June 2011 following the adoptionin the plenary of the resolution on "Investing in the future: a new Multiannual FinancialFramework (MFF) for a competitive, sustainable and inclusive Europe" (rapporteur Mr SalvadorGARRIGA POLLEDO)11.The SpanishCortes Generalesadopted their report on 14 June 2011 after a number of hearingswith the participation of Government ministers and high ranking officials of the EU institutions.The LithuanianSeimasis also drafting a report on the MFF, and an associated review of EUhorizontal policies. The report will be submitted for consideration to theSeimasin the autumnsession of 2011.The reports of the LithuanianSeimasand the SpanishCortes Generalesare prepared byworkinggroupsthat were established by their respective Committees on European Affairs. The workinggroup of the LithuanianSeimasis composed of the Members of the Committee on EuropeanAffairs, the Committee on Rural Affairs and the Committee on Budget and Finance, assisted bythe staff of the Office of theSeimasand invited experts.1.1.2 Future involvement of national ParliamentsAlthoughalmost a quarter ofParliaments/Chambers havenot yet discussed the MFFyet,some of them due to the summer recess, they plan to do so in the future12.Due to the parliamentary recess no official consultation has to date taken place between theHungarianOrszággyűlésand the Government. However, it will oversee the Government’sposition via the scrutiny procedure. The MFF will also be on the agenda of the so-calledConsultation Meeting, during which ahead of the European Council meetings, the Prime Ministerwill present the position of the Government to be represented at the European Council. With theaim of raising public awareness and intensifying parliamentary debates, the HungarianOrszággyűlésis considering organising an"open day" dedicated exclusively to the MFFduring the autumn session.The ItalianSenato della Repubblicahas not been actively involved in establishing theGovernment’s position so far, but it intends to debate the MFF in the framework of its oversightof Government action and as a part of its political dialogue with the Commission.The RomanianSenatulforesees regular meetings with representatives of the Government as ofSeptember 2011. Also the Joint Committee on EU Affairs of the IrishHouses of the Oireachtas

11

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN12I.e. the CypriotVouli ton Antiprosopon,the DutchEerste Kamer,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the Luxembourg,Chambre des Députés,the UKHouse of Commons,the SlovakNárodná rada,the DutchEerste Kamer,the FrenchAssemblée nationale,the LuxembourgChambre des Députés

14

intends to fully engage in consideration of the MFF and will consult with the Government andother stakeholders in the autumn 2011.Debates on the MFF are also foreseen in the CzechPoslanecká sněmovna(on 8 September2011), the LithuanianSeimas(during the autumn session of 2011), in the Committee on Financeof the SwedishRiksdag(in September), the Committee on EU Affairs and the plenary of theSlovenianDržavni zbor(in September 2011), in the BulgarianNarodno sabranie(end ofSeptember), the GermanBundesrat.The Committee on EU Affairs of the GreekVouli tonEllinonwill hold another joint meeting with other committees of joint competence at the end ofSeptember, during which competent ministers will report on developments and progress ofdiscussions.Also, the Committee on European Affairs of the SlovakNárodná radawill continuously dealwith the legislative acts issued within the context of preparation of the MFF after year 2013. Bythe end of the year, the Committee on European Affairs of the FrenchAssemblée nationaleshould present its position in a draft resolution, which will then examined by the Committee onBudget.On 20 September 2011, the Committee on Finances and Budget of the LuxembourgChambredes Députésintends to discuss the Commission’s proposal on the MFF, while on 27 September2011, the Committee on European Affairs of the DutchTweede Kamerwill have a debate withthe Government on how the latter will inform theTweede Kamerabout the course of thenegotiations on the MFF.1.2 Proposal to shorten the duration of the MFF from seven to five yearsAs regards the debate on shortening the duration of the MFF from seven to five years,13Parliaments/Chambers13do not support it,underlining thatstability and long-term planningare necessary preconditionsfor success.The BulgarianNarodno sabranieconsiders that such an idea should becarefully approached,warning that thecoincidence between the general and local elections period(every four years)and the proposed five-year MFF period wouldjeopardise the sustainability of the EUplanning processin the long run. Furthermore, theNarodno sabraniebelieves that a seven-yearMFF rather than a five-year one can facilitate the accomplishment of the goals of the seven-yearEurope 2020 Strategy, and ensures thelong-term consistency and predictability.This view isalso shared by the PolishSejm.The EstonianRiigikoguunderscores that the seven-year period ensures the necessaryfinancialand political stabilityfor planning and investing the funds. The GermanBundesratfinds thatthe seven-year timeframe hasproved effectivefor the Structural Funds programmes and forother programmes funded from the EU budget. The GreekVouli ton Ellinonbelieves that theseven year periodensures flexibilityin the mobilisation of resources.

13

I.e. the AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,the BulgarianNarodno sabranie, theCzechPoslanecká sněmovna,the EstonianRiigikogu,the GermanBundesrat,the GreekVouli ton Ellinon,theLatvian Saeima,the PolishSejmandSenat,the RomanianCamera DeputaţilorandSenatul,the SlovakNárodná rada.

15

Furthermore, the GermanBundesratwarns that introducing shorter periods for the MFF wouldunnecessarily increase the effort required to reach agreements and for administration, and wouldrender planning more uncertain. Thesedisadvantages outweigh the possible benefitsof thesynchronising of the MFF with the terms in office of the Commission and the EuropeanParliament.The PolishSenatwarns that shortening the duration of the MFFcould provokeserious problems with the implementation of key EU policies,including the cohesion policy.The RomanianCamera Deputaţilordeems the seven year period asappropriateto the interestsof Romania.The FinnishEduskuntahas reservations about the proposal, noting that five years is too short forlong-term policy cohesion, it wouldprefer a ten-year framework with a mid-term review(the"five + five model").There aretwoParliaments/Chamberssupportingthe proposal. The European Parliament, in theresolution14of the Special Committee on policy challenges and budgetary resources for asustainable European Union after 2013 (SURE)15voted on 8 June 2011, is of the opinion that theduration of the MFF should match the tenure of the European Parliament and theCommission(i.e. five years) in order to ensure democratic accountability, legitimacy andresponsibility. Also the UKHouse of Lordswelcomes and supports the proposal because itwould match the European Parliament and Commission terms in office, making the Europeanelections more meaningful. TheHouse of Lordsalso believes that the less the flexibility withinthe MFF, the shorter it should be "as it would be unwise to lock in austerity for seven or tenyears, and would also be likely to prove unacceptable to the European Parliament".There are Parliaments/Chambers that have nottaken a final position yet16, although some ofthem have had intensive debates17on the issue, sometimes in the presence of Members of theEuropean Parliament, as it was the case of the PortugueseAssembleia da República.TheCommittee on European Affairs of the GermanBundestagdebated this issue at a hearing withlegal experts in May 2011. The CzechSenátnotices that there are strong arguments for bothoptions, the seven-year period ensures medium-term security for all participants in terms ofavailable resources and stable conditions for the drawing of finances, while on the other hand,there is an added value in aligning the length of the MFF with the tenure of the Commission andthe European Parliament. The HungarianOrszággyűlésbelieves that this question should bediscussed in a larger inter-institutional context and supports the European Parliament’s idea oforganizing an inter-parliamentary conference with the participation of national Parliaments. TheSlovenianDržavni zborintends to debate the issue in September 2011.As a general comment, the ItalianSenato della Repubblicabelieves that the MFF should be moreflexible and more swiftly adaptable to the changing economic circumstances in the EU.1.3 Proposal to reduce the GNI-based contributions of Member States to the EU budget

14

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN15http://www.europarl.europa.eu/activities/committees/presCom.do?language=EN&body=SURE16I.e. the CzechSenát,the FrenchSénat,the GermanBundestag,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the ItalianSenatodella Repubblica,the IrishHouses of the Oireachtas,the LithuanianSeimas,the MalteseKamra tad-Deputati,thePortugueseAssembleia da República,the SlovenianDržavni zborandDržavni svet,the UKHouse of Commons.17The SpanishCortes Generales

16

A significant number of 19 Parliaments/Chambers have not debated or reached the final positionon the issue yet18.FiveParliaments/Chambers that have replied to the question on the proposal to reduce the GNI-based contributions of the Member States to the EU budget areagainstthe proposal. Thus, theBulgarianNarodno sabraniewarns that any reduction of the GNI-based contribution to the EUbudget wouldlead to a higher risk of a "two-speed Europe",and keeping GNI as one of themain sources of the own resources system would serve as a guarantee that the actual economicdevelopment of each Member State is being taken into account. TheNarodno sabraniebelievesthat "in order to guarantee that the European Union achieves a high level of convergencebetween the new and old Member States, the long-term trend should be aimed at the reduction ofthe Disposable Personal Income (DPI) gap between them".The CzechPoslanecká sněmovnaprefers the GNI-based contributionsof Member Statesrather than adding other types of sources. It is also in favour of maintaining the actual extent ofthe budget. The DanishFolketingsupports the position of its Government which is againstreducing GNI-based contributions, but is willing to look at specific proposals from theCommission on own resources. The PolishSenatnotices that the new MFF is to be the first oneunder the Treaty of Lisbon, offering the EU new opportunities while also imposing newobligations on it. TheSenatunderlines that the EU budget should bepreserved at least at thepresent level of 1.13% of the GNI-based contributionsof the Members States, to make a realimpact on the Member States’ national policies and their economic situation.The IrishHouses of the Oireachtasbelieve that the 1.05% GNI proposal made by theCommission isbroadly acceptable.The ItalianSenato della Repubblicainforms thatno opinionhas been developed on thisproposal, but stresses thatthe Italian Government has welcomed a gradual and carefullyconsidered reduction of the contribution based on the GNP.It underlines that Italy has beena net contributor to the EU budget for several years, without ever receiving any of thecompensation measures envisaged by the MFF for certain States.In the GreekVouli ton Ellinonthere is a broad agreement that that the old system which isprimarily based on state contributions should bemodernised and enriched with additionaltools and resources.Although the LithuanianSeimashas not expressed its opinion yet, thepreliminary positionoftheSeimaswould be tosupport the increaseof Member States contributions to the EU budget.The additional funds should be allocated for the implementation of the strategic European goals.Also the LatvianSaeimais infavour of increasingthe proportion of the GNI-basedcontributions.The CzechSenátbelieves that the GNI-based component of the EU’s own resources should playa major role in the future financing of the EU, andreplace the current resource based on

18

I.e. the BelgianChambre des représentantsandSénat,the CypriotVouli ton Antiprosopon,the EstonianRiigikogu,the FrenchAssemblée nationaleand theSénat,the GermanBundestagandBundesrat,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the ItalianCamera dei Deputatiand theSenato della Repubblica,the LithuanianSeimas,theLuxembourgChambre des Députés,the MalteseKamra tad-Deputati,the PortugueseAssembleia da República,theSlovenianDržavni zborandDržavni svet,the SwedishRiksdagand the UKHouse of Commons

17

VAT, which were overly complicated.Also the LatvianSaeimasupports the Commission’sproposal to revoke the value-added-tax-based contributions.The DutchTweede Kamersupports its Government and believes that the contributions from theMember States to the European Union need to be made more fair and transparent. Preference isgiven to using afixed percentage of the GNIas resource to finance the EU budget. Using theGNI as the basis for contributions is simple and transparent and also ensures a fair distribution ofcontributions across the Member States, namely based on the size of the Member States’economies19.As a general remark, the SpanishCortes Generalesbelieve that the structure of the contributionto the EU Budget should be established on the principles of equity in revenues and transparency.It favours a system of resources based both on GNI, as well as on the EU traditional resources.According to the PolishSejm,it is necessary to provide for financial support to the new policiesintroduced by the Treaty of Lisbon. TheSejmtakes the position that the effective achievement ofthe Europe 2020 goals will be impossible without proper funding guaranteed in the EU budget.The RomanianSenatulwould like the EU Budget to contribute to the reduction of expenses atthe national level.In its resolution on "Investing in the future: a new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for acompetitive, sustainable and inclusive Europe"20the European Parliament is convinced that theintroduction ofone or several genuine own resources replacing the GNI-based systemisindispensable "if the Union is ever to get the budget it needs to significantly contribute tofinancial stability and economic recovery".1.4 New system of EU own resources1.4.1 EU own resourcesAs for the proposal to introduce a new system of EU own resources i.e. a modernised VATsystem and taxes on, for example, carbon dioxide emissions, air transport, corporate profits,financial transactions or sale of energy carriers, 14 Parliaments/Chambers have not considered orreached a final stance on the issue21or do not have an opinion22.1223Parliaments/Chambers areagainstthe measure. The BulgarianNarodno sabraniebelievesthat new EU taxes would additionally burden the economies and citizens of the Member States.The CzechSenátbelieves that the tax policy is an area of sovereign competence of MemberStates, in which the EU should not interfere, while the CzechPoslanecká sněmovnadoes notsupport setting up new EU own resources and is in favour of traditional EU own resources andGNI-based contributions.1920

https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/behandelddossier/32500-XIII/kst-32502-7.html(in Dutch)http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN21I.e. the BelgianChambre des représentantsandSénat,the CypriotVouli ton Antiprosopon,the FrenchAssembléenationaleand theSénat,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the ItalianCamera dei Deputatiand theSenato dellaRepubblica,the LuxembourgChambre des Députés,the MalteseKamra tad-Deputati,the SlovenianDržavni zborandDržavni svet,the SwedishRiksdagand the UKHouse of Commons22I.e. the DanishFolketing23E.g. the BulgarianNarodno Sabranie,the CzechPoslanecká sněmovnaand theSenát,the LatvianSaeima

18

The FinnishEduskuntahasreservations,as the various proposals for new own resources do notappear to be very realistic and that own resources imply a lesser degree of political insight by theMember States' political bodies, thereby reducing the democratic legitimacy of the EU budget.The GermanBundestagis unlikely to support a European tax, as the governing coalition partieshave stipulated so in their coalition agreement. The GermanBundesrattakes the stance that thetraditional own resources (in particular customs duties) should continue to accrue to the EU, andrejects the alternative of a tax-based revenue source for own resources. The DutchTweedeKameris not convinced that the introduction of a European tax is desirable. This applies to theproposal to introduce a financial transaction tax (hereinafter referred to as "the FTT"), as well asto the proposed transfer of a part of the nationally collected VAT to the EU budget.The PolishSejm,too, isagainstintroducing any new taxes, which may cause excessive financialburden to the economies of the poorer EU Members. The PolishSenatbelieves that some of theproposed options are unacceptable and underlines that a possible "eurotax" should respect theprinciple of equitable burden-sharing proportional to Member States’ levels of wealth. Inparticular itshould not be based on CO2emissionssince such a solution would hit mostseverely the citizens of the "new" Member States where "power sectors are often coal-reliant".Finally, the UKHouse of Lordsin its report "EU Financial Framework from 2014"24agreed withthe UK Government that the new own resources are an "unfortunate distraction".The LithuanianSeimasgives a detailed account of its position underlining that EU MemberStates themselves should be free to choose the most appropriate measures to reduce greenhousegas emissions. It also stresses that excise tariff review is not necessary for pursuingenvironmental targets, as the introduction of the environmental element would result in the lossof simplicity of the excise system and encumber the administration of the excise duties. It alsowarns that the review would result in the increase of minimum excise tariffs on all energyproducts, with the exception of petrol and energy; thus having a negative impact on thecompetitiveness of many sectors of economy, especially transport and agriculture.There arefourParliaments/Chambersfavouringa new system of EU own resources, or some ofits elements. The Austrian Parliament strongly supports the introduction of the FTT. Although afinal position has not yet been adopted in the RomanianSenatul,favourable opinions concerningthe introduction of new taxes were expressed. Similarly, the European Parliament has beenadvocating a reform of the current system of the EU own resources in recent years25. In theresolution on "Investing in the future: a new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for acompetitive, sustainable and inclusive Europe", the European Parliament26takes note of thepotential new own resources proposed by the Commission in its Communication on the BudgetReview27(e.g. taxation of the financial sector, auctioning under the greenhouse gas EmissionsTrading System, EU charge related to air transport, VAT, energy tax, corporate income tax) andawaits the conclusions of the impact analysis of these options.

2425

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201011/ldselect/ldeucom/125/125.pdfhttp://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2004_2009/documents/ta/p6_ta-prov(2007)0098_/p6_ta-prov(2007)0098_en.pdf26http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN27http://ec.europa.eu/commission_2010-2014/president/pdf/eu_budget_review_en.pdf

19

The SlovakNárodná radaagrees on the necessity for a new system of EU own resources andbelieves that the efforts should concentrate on the abolition of the own resource based on theVAT. TheNárodná radaopposes, however, the introduction of a new EU VAT own resource asit infringes the national sovereignty in the area of tax policy.The GreekVouli ton Ellinonviews positively the elimination of the traditional own resourcessystem.There is a number of Parliaments/Chambers that areopento discussing new forms of EU ownresources. The EstonianRiigikoguholds the opinion that the new own resources must fulfil thecriteria of stability and sufficiency. The SlovenianDržavni zborremains open for discussion onnew own resources underlining, however, that neither the proposed FTT nor the VAT have beenclarified. Also the RomanianCamera Deputaţilorremains open to consider the introduction ofnew own resources (FTT, European VAT).Although the HungarianOrszággyűléshas not taken a position yet, it believes that division ofcompetences between the EU institutions and the Member States and the present legal baseprovided by the Treaties should be respected when introducing a new system of own resources.Similarly, the Committee on EU Affairs of the FrenchAssemblée nationalehas not taken aposition yet. It is of note, though, that the Committee held several meetings with Mr AlainLAMASSOURE, the Chairman of the Budget Committee of the European Parliament (BUDG)28.Four Parliaments/Chambers underline the need tosimplifythe current system of own resourcesand make itmore transparent.The BulgarianNarodno sabranieconsiders it too complex atpresent, while the EstonianRiigikoguwants it to be more transparent, a view which is shared bythe European Parliament29. The SlovakNárodná radabelieves that the current system of ownresources isexcessively complex, opaque, lacks fairnessand is finallyincomprehensible tothe European citizens.TheNárodná radabelieves that the process of simplification could startfrom 2014 in the form of the abolition of the own resource based on the VAT.Concerning the modernisation of the VAT system the EstonianRiigikoguisin favour of theelimination of the current VAT-based own fundsand correction mechanisms; this view isshared by the SlovakNárodná rada,while the UKHouse of Lordsis concerned that losing theVAT-based resource should not compromise the UK abatement. The GreekVouli ton Ellinonisin favour of reformed VAT.1.4.2 Financial Transaction TaxThere aresixParliaments/Chamberssupporting the introduction of the FTT.The AustrianParliament strongly supports the introduction of the FTT and believes that, if implemented at theEU level or within the Euro area, the FTT wouldgenerate significant fiscal revenueswithoutnegative side effects on the real economy and would complement the necessary re-regulation offinancial markets. Moreover, it would put an end to unjust privileges of financial actors withregard to taxation and also strengthen citizens’ trust into EU institutions.

2829

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/activities/committees/homeCom.do?body=BUDGThe report on "Investing in the future: a new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for a competitive,sustainable and inclusive Europe" point 167http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN

20

On 14 June 2011, the FrenchAssemblée nationaleadopted a resolution on introducing the FTTin Europe30favouring the introduction of the FTTin the European Union, or failing that, inthe Euro zone or by a group of Member States. Nevertheless, this resolution does not tackle thequestion of using the FTT as an own resource of the EU.The RomanianCamera Deputaţilorwarns that the issues related to the FTT will have to becarefully assessed"in order to avoid excessive burdens on the financial sector liable to generatedistortion or delocalisation effects that might postpone a sustainable economic recovery". TheCamera Deputaţilorthinks the FTT "should be enforced homogeneously" in the EU or evenmore broadly at G-20 level. The RomanianSenatul,for its part, thinks that the FTT should beintroduced throughout the EU. The European Parliament takes the view that the FTT "couldconstitute a substantial contribution, by the financial sector, to the economic and social cost ofthe crisis, and could also contribute partially to the financing of the EU budget, as well as tolowering Member States' GNI contributions". It adds that "the Union should also act as anexample in relation to the movement of funds towards fiscal havens". The GreekVouli tonEllinon,in turn, believes that the introduction of the FTT may ensure the autonomy of the EUbudget.There arefourParliaments/Chambersopposingthe idea of introducing the FTT. Thus, theBulgarianNarodno sabraniewarns that introducing a new FTT in the EU without an agreementon introducing such a tax on the global level would endanger the competitiveness of the financialinstitutions within the EU. Also, the majority of the Members of the DutchTweede Kamerisopposed to a FTT as EU own resource31feeling that any tax on transactions can best beimplemented worldwide, because, otherwise, this tax would be too easy to evade. Also the ItalianSenato della Repubblicadoubts whether an own resource based on the taxation of financialtransactions will be effective or will merely drive investors towards countries with a more liberaltax regime. The SlovakNárodná radapoints out the scepticism expressed in connection with theproposed FTT.1.5 Support for the Europe 2020 Project Bond initiativeParliaments/Chambers have been asked whether they support the Commission’s proposal on theEurope 2020 Project Bond initiative, the aim of which is to promote individual infrastructureprojects by attracting additional private sector financing.11of the Parliaments/Chambers report that their respective Committees on EU Affairs havenotyet discussedthe Project Bond initiative of the Europe 2020 Strategy (e.g. the FrenchSénat,theSlovenianDržavni zborand the LithuanianSeimas).Out of the16Parliaments/Chambers which haveexamined the Europe 2020 Project Bondinitiative, 1232generally supportthe idea. As expressed by the BulgarianNarodno sabranie,"the project bonds might prove to bea useful toolof realization of multi-regional EU projectswithin strategies, such as the Danube Strategy, the Black Sea Strategy etc." The CzechSenáthas303132

http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/ta/ta0680.asphttps://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/dossier/21501-20/kst-21501-20-546.html

I.e. the BulgarianNarodno sabranie,the CzechSenát,the FinnishEduskunta,the GermanBundesrat,the GreekVouli ton Ellinon,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the ItalianCamera dei Deputati,the PolishSenat,the RomanianCamera DeputaţilorandSenatul,the UKHouse of Lordsand the European Parliament

21

requested the Commission to further elaborate the concept of project bonds and the FinnishEduskuntacalls for "the proposals to be coordinated with the various financing instrumentsresulting from the economic crisis". The European Parliament alsowelcomesthe Europe 2020Project Bond Initiative, "as a risk-sharing mechanism with the European Investment Bank (EIB),providing capped support from the EU budget that should leverage the EU funds and attractadditional interest of private investors for participating in priority EU projects in line withEurope 2020 objectives". Furthermore, the European Parliament calls on the Commission "topresent a fully fledged proposalon EU project bonds, building on the existing experience withjoint EU-EIB instruments, and to include clear and transparent criteria for project eligibility andselection" and reminds "that projects of EU interest which generate little revenue will continue torequire financing through grants"33.Themain concernfor a number of Parliaments/Chambers is, however, that theprivate sectormust bear a fair share of the riskregarding the Project Bond initiative (e.g. the PolishSenatand the GreekVouli ton Ellinon).As underlined by the UKHouse of Lords"it should not beallowed to lead to the EU having to provide additional funds beyond its intended contribution".The European Parliament, on its part, is concerned that "the limited size of the EU budget mighteventually impose limitations to providing additional leverage for new initiatives"34.Out of the Parliaments/Chambers which have replied to this questionfour are not convincedthat private financing instruments should be applied to finance EU projects (i.e. the AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,the DutchTweede Kamerand the SlovakNárodná rada).1.6 Implementation of the goals of the Europe 2020 Strategy through the MFF 2014-2020All of the Parliaments/Chambers which have discussed the question generallysupportthe notionthat the MFF should provide for the implementation of the goals of the Europe 2020 Strategy35.However, the GermanBundesratexplains that "a policy of EU expenditure cannot andshouldnot constitute the main instrumentfor macro-economic management and for implementationof the Europe 2020 strategy" and that the coordination of the Member States' economic policiesand the completion of the legal framework at EU level is ofgreater importancethan theimplementation of the Europe 2020 Strategy. This point is made even more explicit in the replyof the GreekVouli ton Ellinonwhich writes that because of the reduction in public expenditures,as a result of the financial crisis, it has become almost impossible for "countries like Greece" tosufficiently finance growth and to enhance its participation in the single market.SixParliaments/Chambersexplicitly supportthe inclusion of financing initiatives aimed atstrengthening the Single Market36. The European Parliament, for instance, is convinced that33

See paragraph 27 of the European Parliament resolution on Investing in the future: a new Multiannual FinancialFramework (MFF) for a competitive, sustainable and inclusive Europe,http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN34Ibid.35

I.e. the AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,the BulgarianNarodno sabranie,the CzechSenát,the DanishFolketing,the EstonianRiigikogu,the FinnishEduskunta,the GermanBundesrat,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,theItalianCamera dei Deputati,the LatvianSaeima,the LithuanianSeimas,the PolishSejmandSenat,the PortugueseAssembleia da República,the RomanianCamera DeputaţilorandSenatul,the SlovakNárodná rada,the SlovenianDržavni zbor,the SpanishCortes Generales,the UKHouse of Lordsand the European Parliament

22

"the re-launch of the single market is an essential element of the Europe 2020 Strategy whichincreases the synergy between its various flagship initiatives"37.Furthermore amajorityof the Parliaments/Chambers argue that even though the Europe 2020Strategy should be one of the main objectives of the MFF it should be balanced with the need tofundother prioritiesof the EU. For example, several Parliaments/Chambers mention the needto allocate financial resources to projects focusing on the development of infrastructure withinthe sectors of transport, energy and information and communication technologies (e.g. theBulgarianNarodno sabranie,the HungarianOrszággyűlésand the CzechSenát)but also ondevelopment aid, environmental protection, biodiversity and the area of freedom, security andjustice. The latter areas are highlighted as EU priorities by the UKHouse of Lordsso as torespond clearly to the principal challenges facing the EU today. Finally, more traditional policiessuch as the cohesion policy and the common agricultural policy are also mentioned as areaswhich should be sufficiently funded (e.g. the RomanianCamera Deputaţilorand the SpanishCortes Generales).As the PolishSejmargues, the way to implement the Europe 2020 Strategy is"to use verified and solid mechanisms of the cohesion policy, the common agricultural policyand other EU budget instruments". Furthermore the European Parliament specifies that "theEurope 2020 Strategy should bethe main policy referencefor the next MFF", maintaining, atthe same time, that "Europe 2020 isnot an all-inclusive strategycovering all Union policyfields" and stressing that "other Treaty-based policies pursuing different objectives need to beduly reflected in the next MFF"38.About halfof the Parliaments/Chambers having replied to this question, report that theirrespective Committees on EU Affairs havenot yet discussedthe MFF (e.g. the CypriotVouliton Antiprosoponand the CzechPoslanecká sněmovna).Some indicate that the proposal isexpected to be discussed during the autumn of 2011 (e.g. the SlovenianDržavni svetand theFrenchSénat).The IrishHouses of the Oireachtassuggest that the questions considering theMFF "might bemore suited to the COSAC in the first half of 2012"as it would allow theCommittees on EU Affairs of national Parliaments "to consult as appropriate and to produce aconsidered view" on the matter.1.7 Structure of EU budgetary expenditure in the MFF 2014-2020More than a halfof the Parliaments/Chambers which have replied to this question report thattheir respective Committees on EU Affairshave not yet discussedthe structure of the EUbudgetary expenditure in the context of the MFF 2014-2020.Out of those Parliaments/Chambers which have examined the structure of EU budgetaryexpenditure in the MFFonlythe BulgarianNarodno sabranieconsiders that the structureproposed by the Commission issuitableas "it gives more visibility to the Europe 2020 and at thesame time is easy to be understood by the stakeholders".

36

I.e. the DanishFolketing,the EstonianRiigikogu,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the LithuanianSeimas,the PolishSenatand the European Parliament37Ibid, paragraph 4138See paragraph 38 of the European Parliament resolution on Investing in the future: a new Multiannual FinancialFramework (MFF) for a competitive, sustainable and inclusive Europe,http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN

23

12Parliaments/Chambersdo not believethat the proposed structure issufficiently specific.Asexplained by the CzechSenát"the change in the structure of the EU expenditure headings asoutlined in the EU Budget Review isnot appropriateas it means further aggregation of variousexpenditures under a single general and often unrelated heading". This view is supported by theEstonianRiigikoguwhich states that "it is very important how and under what conditions thefunds are distributed within the headings and under what conditions they can be used".Furthermore, thelack of a heading dedicated solely to the cohesion policyis a recurrentconcern for a number of Parliaments/Chambers (e.g. the FinnishEduskunta,the RomanianCamera Deputaţilor,the RomanianSenatuland the SlovakNárodná rada).The European Parliament, for its part, reiterates its position thatmore flexibility within andacross headingsis an absolute necessity for the functioning capacities of the Union not only toface the new challenges but also to facilitate the decision-making process within the institutions.It also presents aspecific tablein which it proposes a new MFF structure39that groups underone single heading all internal policies under the title "Europe 2020".1.7.1 Transfer of funds from Sub-heading 1b to Sub-heading 1aA majorityof the Parliaments/Chambers that have replied to this questiondo not supportthesuggestion of transferring funds from the Sub-heading 1b (Cohesion for growth andemployment) to the Sub-heading 1a (Competitiveness)40. However, it is a question of achievingthe right balance between efficiency and solidarity when considering the transfer of funds fromcohesion to competitiveness, as the RomanianCamera Deputaţiloremphasises. The FinishEduskuntanotes that "a more coherent approach to cohesion policies should make additionalfunds available for competitiveness projects".A fewParliaments/Chambers find that the transferring of funds from the Sub-heading 1b to theSub-heading 1awould benefitthe economic, social and territorial cohesion of all Member States(e.g. the DanishFolketingand the SwedishRiksdag).In the present situation where the economycould use an "additional boost", the SlovenianDržavni zboris of the opinion that an increase ofresources in the area of competitiveness is "more than welcome".Of those Parliaments/Chambers that have answered the question,11 have yet to discusstheissue in their respective Committees on EU Affairs (e.g. the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the UKHouse of Commonsand the CypriotVouli ton Antiprosopon).A number of these intend todiscuss the question during the autumn of 2011 (e.g. the FrenchSénat,the IrishHouses of theOireachtasand the PolishSejm).1.8 Unspent EU funds

39

See paragraphs 128-142 of the European Parliament resolution on Investing in the future: a new MultiannualFinancial Framework (MFF) for a competitive, sustainable and inclusive Europe",http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2011-0266+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN40

I.e. the BulgarianNarodno sabranie,the CzechPoslanecká sněmovna,the FinnishEduskunta,the GermanBundesrat,the ItalianCamera dei Deputati,the ItalianSenato della Repubblica,the LatvianSaeima,the LithuanianSeimas,the PolishSenat,the PortugueseAssembleia da República,the RomanianCamera DeputaţilorandSenatuland the SlovakNárodná rada

24

Taking into account the scarcity of EU budgetary funds and the need for their efficient use, theParliaments/Chambers were asked whether they would be in favour of adopting a principle thatunspent EU funds should not be returned to the Member States, as is the case now, but insteadused in future accounting periods as EU own resources.Themajorityof the Parliaments/Chambers having answered the questionhave not yetdiscussedthe issue in their respective Committees on EU Affairs. However, several of themexpect the issue to be debated during the autumn of 2011 (e.g. the SlovenianDržavni zborandthe PolishSejm).Among those Parliaments/Chambers that have discussed this issue,six do not supportthesuggestion (e.g. the DanishFolketingand the ItalianSenato della Repubblica).Three mainexplanationsfor the lack of support are found in the following replies:Instead of carrying unspent funds over to the next fiscal period as EU own resources theeffective useof EU budgetary resources should be improved (i.e. the CzechSenátand theBulgarianNarodno sabranie).Thelimited budgetary fundsin the Member States should take precedence (i.e. theAustrianNationalratandBundesrat).Democratic legitimacy- "both the Union's outlays and its fundraising need to be subjectto advance political approval by the Member States" (i.e. the FinnishEduskunta).Of the Parliaments/Chambers which have discussed the question of unspent EU funds,three arein favourof transferring the funds to future accounting periods (the CzechPoslaneckásněmovna,the LithuanianSeimasand the European Parliament). The PolishSenat,in turn,believes that the suggestion isworth consideringand the PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicathinks the proposal should be subject of a thorough discussion.

25

CHAPTER 2: TWO YEARS AFTER THE ENTRY INTO FORCE OF THETREATY OF LISBON - PARLIAMENTARY EXPERIENCEIn December 2011 it will be two years since the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon. The aimof the chapter 2 of this report is to evaluate best parliamentary practices and experience of theimplementation of the Treaty of Lisbon (including Protocol 2 on the application of the principlesof subsidiarity and proportionality).Since the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon national Parliaments have been involved inensuring the compliance with the principle of subsidiarity according to Protocol 2 and haveadopted their internal subsidiarity check mechanisms.National Parliaments send the Commission reasoned opinions on EU draft legislative acts statingwhy they consider that the draft in question does not comply with the principle of subsidiarity.Reasoned opinions are also notified to the European Parliament and the Council. NationalParliaments receive responses from the Commission to their reasoned opinions. This chapterevaluates the national Parliaments' opinions on the replies sent to them by the Commission anddescribes how reasoned opinions are dealt with in the European Parliament.According to Article 5 of Protocol 2 draft legislative acts shall contain the justification that theUnion objective can be better achieved at the EU level. This chapter assesses to what extent non-fulfilment of this formal criterion hinders national Parliaments’ examination of the EU draftlegislative act’s compliance with the principle of subsidiarity.Cooperation between national Parliaments and the EU institutions also takes other formsincluding informal political dialogue between the Commission and national Parliaments. Theexperience of national Parliaments in this field is also evaluated in this chapter of the report.Article 290 of the TFEU states that legislative acts may delegate to the Commission the power toadopt non-legislative acts of general application to supplement or amend certain non-essentialelements of the legislative act. According to the Treaty of Lisbon the essential elements of anarea shall be reserved for the EU draft legislative acts and accordingly shall not be the subject ofa delegation of power. However, in the opinion of many national Parliaments essential elementsare introduced to the delegated acts of the Commission which are outside the scope of control ofnational Parliaments. The chapter evaluates Parliaments' current practices and views in thatrespect.2.1 Reasoned opinions2.1.1 Reasoned opinions adopted since the entry into force of the Treaty of LisbonSince the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon amajorityof national Parliaments/Chambers,i.e.29,haveadopted at least one reasoned opinion.Out of40national Parliaments/Chambers,11havenot adopteda reasoned opinion yet41.41

I.e. the BelgianChambre des ReprésentantsandSénat,the CypriotVouli ton Antiprosopon,the EstonianRiigikogu,the FinnishEduskunta,the GreekVouli ton Ellinon,the HungarianOrszággyűlés,the LatvianSaeima,thePortugueseAssembleia da República,the SlovenianDržavni zborandDržavni svet

26

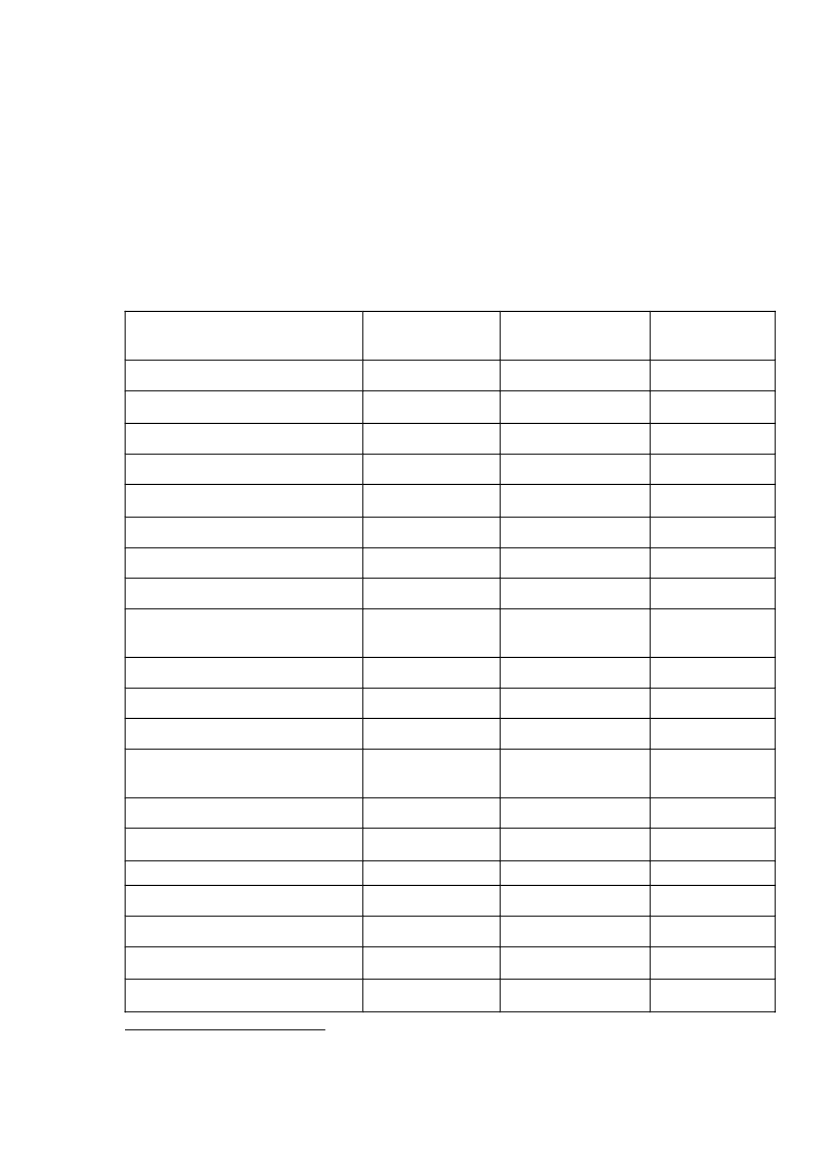

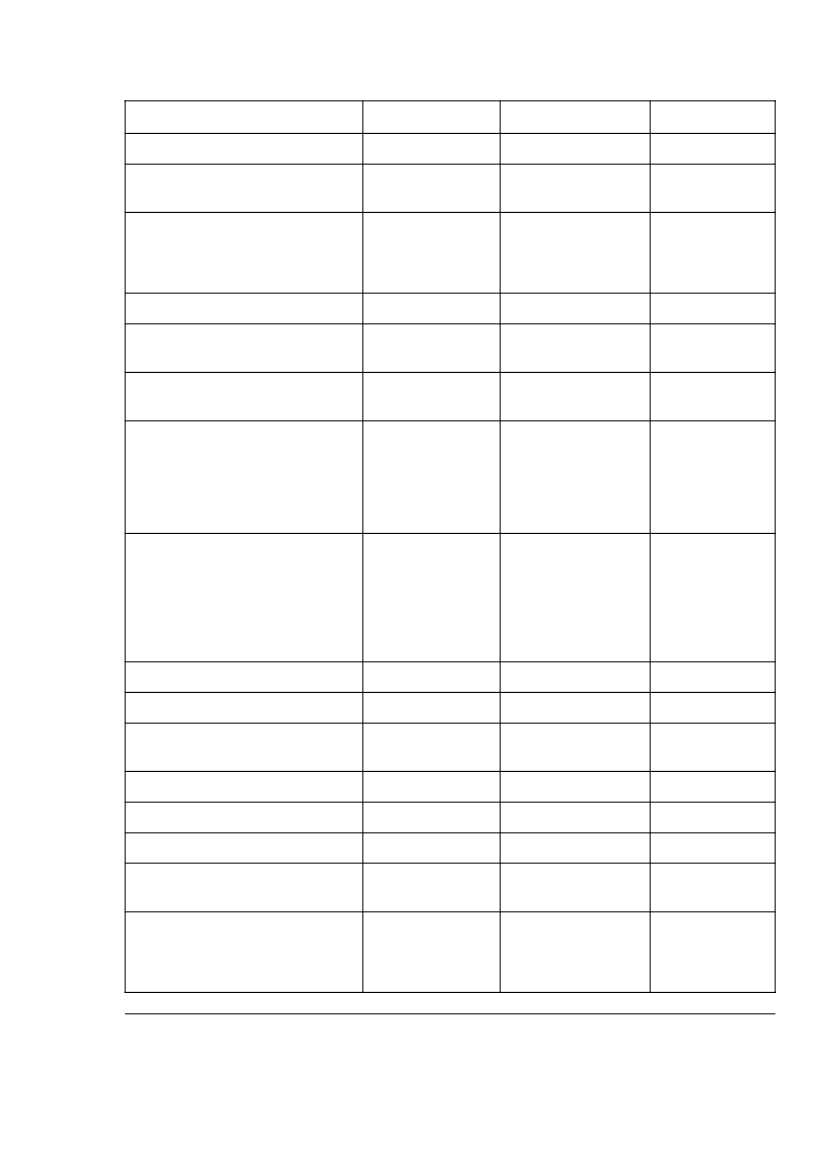

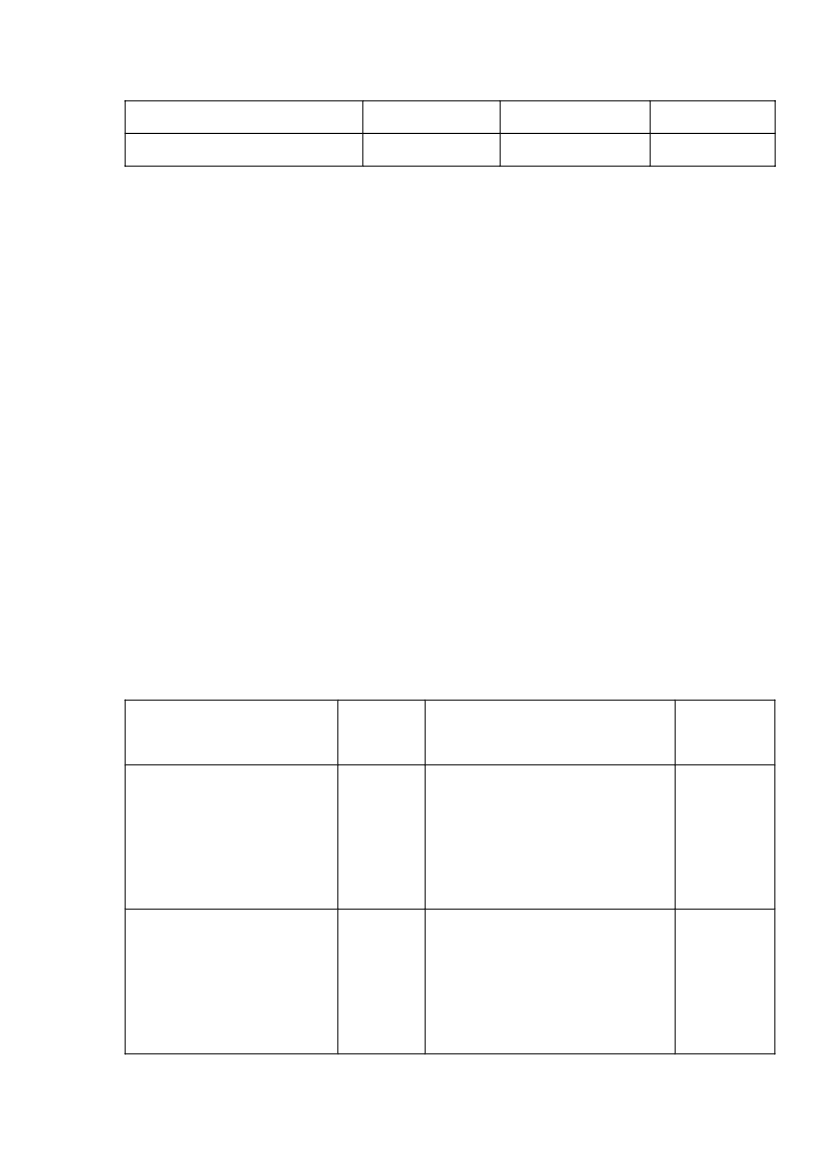

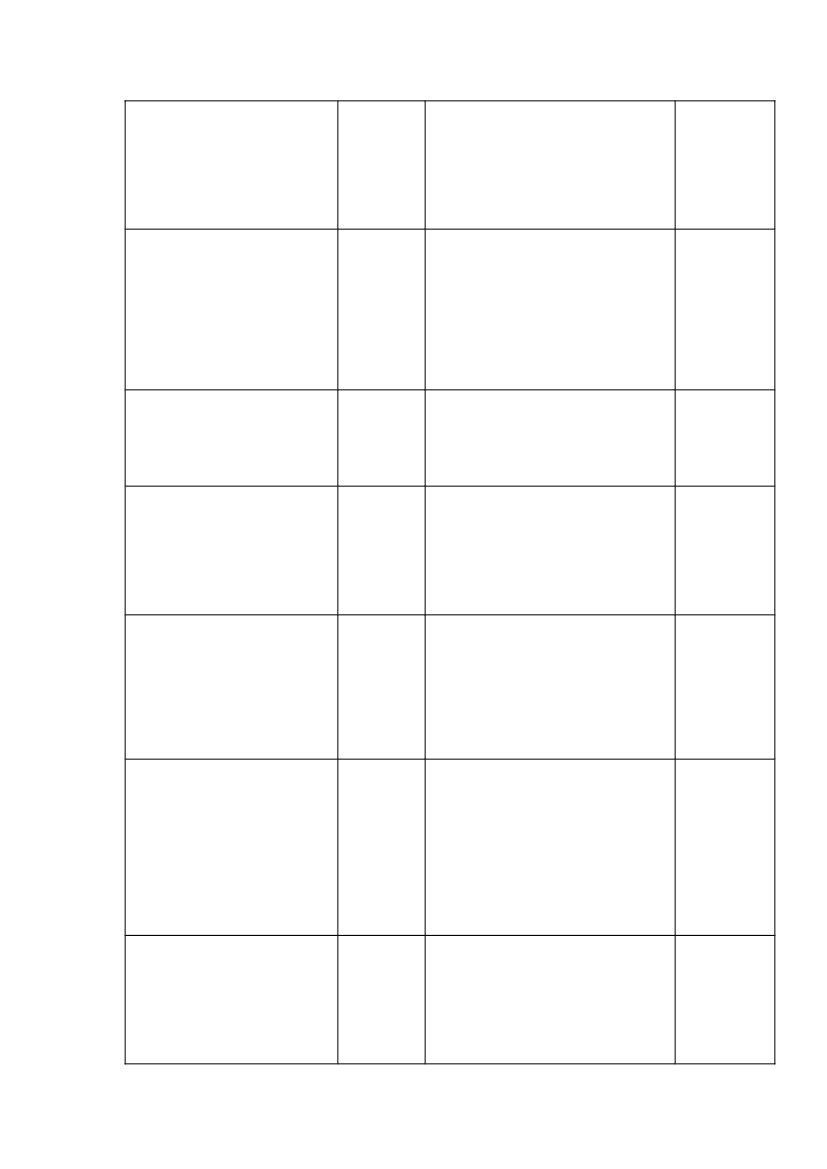

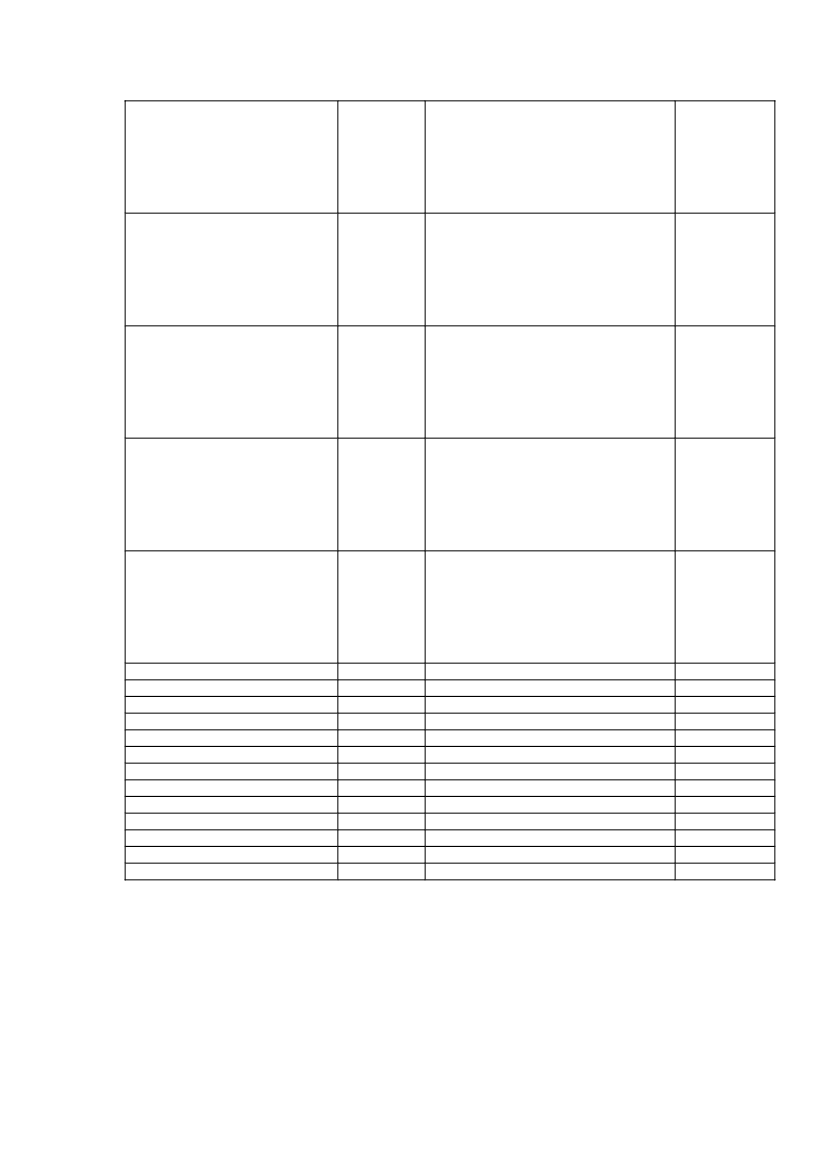

Thelargest numberof reasoned opinions, i.e.eight,has been adopted by the PolishSenat.ThePolishSejmhas adoptedsevenreasoned opinions, the SwedishRiksdagand the LuxembourgChambre des Députés- five, the ItalianSenato della Repubblica- four, the DanishFolketing,theFrenchSénat,the LithuanianSeimas,the DutchTweede Kamer,the DutchEerste Kamerand theRomanianSenatul- three each. The remaining18national Parliaments/Chambers have adoptedone or two reasoned opinions. For more information, please see Table 1 below.Table 1: Reasoned opinions (by Parliament/Chamber)Parliament/ChamberNumber of reasonedopinions(in replies)1200201130013120011434Draft legislative acts(in replies)COM (2010) 379COM (2010) 82 *COM (2010) 379--COM(2011) 121COM(2011) 169-COM(2010) 379COM(2010) 379COM(2010) 368COM(2010) 486 *COM(2010) 799--COM(2011) 169 �COM(2010) 76◄COM(2010) 486COM(2010) 471◄COM(2010) 368●COM(2010) 368●PE-CONS 2/10♥--COM(2011)121COM(2011) 215COM(2011) 216COM(2010) 176COM(2011) 126 �Number ofreasoned opinions(on IPEX)421200201130003110011344

AustrianNationalratAustrianBundesratBelgianChambre des représentantsBelgianSénatBulgarianNarodno sabranieCypriotVouli ton AntiprosoponCzechPoslanecká sněmovnaCzechSenátDanishFolketingEstonianRiigikoguFinnishEduskuntaFrenchAssemblée nationaleFrenchSénatGermanBundestagGermanBundesratGreekVouli ton EllinonHungarianOrszággyűlésIrishHouses of the OireachtasItalianCamera dei DeputatiItalianSenato della Repubblica4243

The data as of 8-9 September 2011The ItalianCamera dei Deputatiadopted one reasoned opinion on COM(2011) 215 and COM (2011) 216

27

LatvianSaeimaLithuanianSeimasLuxembourgChambre des Députés

035