Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2010-11 (1. samling)

L 168 Bilag 7

Offentligt

Country Report The Netherlandsby Tineke Strik, Maaike Luiten and Ricky van Oers

The INTEC project:Integration and Naturalisation tests: the new way toEuropean CitizenshipThis report is part of a comparative study in nine Member Stateson the national policies concerning integration and naturalisationtests and their effects on integration.

Financed by the European Integration Fund

November 2010Centre for Migration LawRadboud University NijmegenNetherlands

THENETHERLANDS

IntroductionChapter 1: Overview of the policy developmentsChapter 2: Integration test abroad2.1 Description of the test2.2 Purpose of the test2.3 Effects of the test2.4 Strengthening the requirements: what effects are to be foreseen?Chapter 3: Integration test in the country3.1 Description of the test3.2 Purpose of the test within the framework of theWet Inburgering3.3 Evaluation and policy changes3.4 Effects: statistics3.5 Effects of the test on the residence rightsChapter 4: Integration test in the naturalisation procedure4.1 Description of the test4.2 Purpose of the test4.3 Effects of the test: statistics4.4 Effects of the naturalisation test: other researchChapter 5: Analysis of the interviews regarding the test in the country5.1 Introduction5.2 Motives of the migrants to take the integration test5.3 Obligatory status of the test5.4 The content of the course5.5 The level of the course5.6 General impression of the test5.7 Effects on integration5.8 Groups finding it difficult to meet the integration obligation5.9 Exemptions and dispensations5.10 Other purposes of the integration requirement5.11 Costs and finesChapter 6: ConclusionsBibliography

59

14182838

4149545562

64687284

8687899295969899100102102105113

3

THENETHERLANDS

IntroductionIn the Netherlands, a certain level of integration is required from immigrantsat three stages: at their application for admission to the Netherlands, at theirapplication for a permanent or independent residence permit and finally attheir application for Dutch citizenship.1The required language level in theadmission procedure is A1 minus (from 1 January 2011 it will be A1); in theother two procedures the required level is A2. Furthermore, immigrants areobliged to pass the integration examination at level A2 within 3.5 years aftertheir arrival. If they fail, a fine can be imposed or their social security can becut.These requirements have all been introduced in the last decade, in orderto promote integration of immigrants. This report tries to give an overviewof the social effects of these requirements. Do the requirements effectivelypromote integration? Do they have other intended or unintended effects?Hence this analysis aims to contribute to the question whether the goals ofthe introduction of the test have been accomplished. To this end, the cominginto force of the relevant acts will be described, including the political de-bates on the bills and the political response to the evaluations of the acts. Fur-thermore the content of the tests, comments from (international) experts andjurisprudence on the integration requirements and literature have been in-vestigated. The study on the effects has been based not only on special eval-uations and figures, but also on empirical research. This field research con-sisted of 56 interviews we conducted from March until mid-May 2010 in theNetherlands and in Turkey with several relevant actors. A description of thevarious respondents is given below.

Selection of the respondents and responseThe field research consisted of 56 interviews. In the Netherlands we inter-viewed 28 immigrants, five language teachers, five NGOs representing theinterests of certain groups of immigrants and five civil servants from differ-ent municipalities. In Turkey we interviewed three language teachers and tenparticipants on a Dutch language course. From the immigrants in the Nether-lands, we interviewed 25 at the test centre (11 in Amsterdam, 8 in Eindhoven1Since 1 April 2007 the tests for permanent residence and naturalisation have been simi-lar. Hence, once someone has passed the integration examination, he/she can apply foreither permanent residence or naturalisation. Those exempted from passing the integra-tion examination within the framework of the Integration Act will however need topass the examination when applying for naturalisation.

5

THENETHERLANDSand 6 in Nijmegen). Most of them had just taken the test; some of them werewaiting in between different parts of the test.2The interviews took on aver-age 15 minutes. A large group of migrants had difficulty giving detailed an-swers in the Dutch language. As one interviewer was of Turkish origin, Tur-kish respondents gave much more detailed answers to our questions. Thiswas also the case for three respondents we found through the individualnetwork of this Turkish colleague. These three interviews took on average 30minutes. Chapter five offers background information on these interviewedrespondents.The interviewed civil servants of the municipalities were all responsiblefor supporting the immigrants who have to comply with their legal integra-tion obligations and monitoring the achievements of the institutes of lan-guage and integration education. We interviewed civil servants in the twolargest cities (Amsterdam �750,000 and Rotterdam � 600,000 inhabitants),two smaller cities (Eindhoven � 212,000 and Nijmegen � 160,000 inhabitants)and one small university town (Wageningen � 35,000 inhabitants). These in-terviews took on average 90 minutes.The NGOs we interviewed are to be distinguished between organisationswhich represent immigrants from a certain country and organisations whichpromote the interests of immigrants with specific backgrounds or problems.In the first category we interviewed the chair of the Moroccan organisation(EmCeMo), the director of the Chinese organisation (IOC) and a policy advi-sor of a Turkish organisation (IOT).3In the second category we interviewed amember of the board of an organisation for victims of domestic violence inmigrant families (Kesban), a policy officer from the headquarters of theDutch Refugee Council (VVN) and a coordinator of a regional refugee orga-nisation (Vluchtelingen Werk Rivierenland), which supports the integrationof migrants with an asylum related background. All five organisations wereinvolved in supporting migrants with legal or social problems and acted astheir advocates before national or local decision makers. These interviewstook 60 to 90 minutes.

2

3

Efforts to find respondents at counters of municipalities or legal advisors, failed becausethere were not many people in a waiting room (they have consultations by appoint-ment), and most of them dealt with other questions or topics. Also efforts to arrangeappointments with clients of the civil servant in Nijmegen failed: a written request foran interview only led to one response from a newly arrived Somali man who couldbarely speak Dutch.The number of people in the Netherlands originating from Turkey is (in 2010) about384,000 and from Morocco (in 2010) about 349,000, source: CBS (Dutch Central Bureauof Statistics). The Chinese people in the Netherlands originate from different countries,such as: the Peoples Republic of China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia, Surinam, Viet-nam and Singapore. The total size of this group is estimated at 80,000.

6

All language teachers we interviewed were employed at the RegionalEducation Centre (ROC), a national institute for vocational training, whichalso offers language courses. Three of them were based in Amsterdam, twoin Nijmegen. These interviews took on average 60 minutes.From the 56 interviews, we conducted 13 interviews in Turkey: 3 lan-guage teachers and 10 participants on a language course. The three languageteachers had lived in the Netherlands for a long time and had founded theirown language course in Turkey (in Bursa one year previously, in Ankara 3.5years previously, in Karaman 3 years previously). These interviews took 60to 90 minutes. Via these teachers, we got in contact with ten migrants who(had) participated in their courses, in preparation for the integration testabroad. Seven respondents had already passed the examination applied forfamily reunification or family formation, three were still preparing for it. Asthe interviewer was Turkish, these respondents gave detailed information ontheir background, their motivation for passing the test and their opinion onthis requirement, and the problems they perceived, also in relation to theother requirements for family reunification. The interviews with immigrantstook 30 to 45 minutes.

Working methodAfter giving a description of the content and the application of the test (in-cluding target group, exemption, costs etc), we assessed the purpose of therequirement and the arguments and positions taken during the political de-bate in the decision making process. We also investigated to what extent theact had been amended after the entry into force, in reaction to evaluation re-sults, jurisprudence or other reasons. In assessing the effects of the tests, weinvestigated whether the purpose(s) of the acts had been achieved by thetests and if there were side effects which had affected the integration or otherpurposes of the requirement.

Already conducted empirical researchAs the number of respondents was relatively low, we tested our research re-sults against the results of accomplished empirical research on the integra-tion and naturalisation tests. These were the official evaluation of the CivicIntegration Act Abroad (hereafterWet Inburgering,WIB) of 2009 (paragraph2.3) and the official evaluation of the Civic Integration Act (WetInburgering,WI) in 2010 (paragraph 3.3 and chapter 5). With regard to the integration testabroad we also involved the results of interviews conducted in 2009/2010 bythe Turkish organisation IOT with people who faced problems with(re)uniting with their partner residing in Turkey (paragraph 2.3). These in-7

THENETHERLANDSterviews offered some insight into the causes of these problems. With regardto the naturalisation test we involved the results of the research by Van Oers,conducted in 2006 (see paragraph 4.3 and chapter 6).We finally thank Anita Böcker, Ayse Ekmek§i, Carolus Grütters andMarjolein Hopman for conducting and analysing the interviews and Hannievan de Put for the lay out of the report.

Overview reportThis report starts in chapter one with an overview of the developments of theintegration requirements, in order to show the interaction between the de-bate and introduction of the various tests. Chapter two describes the contentof the integration test abroad and the way the introduction was motivatedand discussed. The final paragraph in this chapter deals with the outcome ofthe Intec interviews and the evaluation of the act. Chapter three deals withthe content and the establishment of the integration requirement for perma-nent and independent residence. Chapter four deals with the development ofthe integration requirement for citizenship and the development of the num-bers and background of applicants for naturalisation. As the integration testfor permanent residence and naturalisation have the same content, the inter-views regarding the integration test in the Netherlands have not distin-guished between the two application procedures. The outcome of the inter-views in the Netherlands and background information on the interviewedimmigrants are described in chapter five. The conclusions of the research onthe effects of integration tests are described in chapter six.As the Dutch integration policy is developing rapidly, the reader hasto be aware that developments after November 2010 have not been taken intoaccount.

8

Chapter 1: Overview of the relevant policy developments4In the Netherlands, the discussions regarding a more demanding integrationtest for naturalisation started in the early 1990s. Since 1985 the immigrant hashad to fulfil the requirement of being ‘sufficiently integrated’ to become aDutch citizen. A ‘reasonable knowledge’ of the Dutch language and a certainlevel of integration into Dutch society served as indications for this criterion.5A civil servant from the municipality of registration of the immigrant as-sessed the fulfilment of this requirement on the basis of a short conversationwith the immigrant on ‘everyday issues’.6Proof of written skills was expli-citly excluded. Proof of having social contacts with Dutch citizens also servedas an indication of being integrated. The instructions for the civil servants re-jected a uniform application and prescribed that with regard to elderly, loweducated, illiterate and handicapped immigrants insufficient knowledge ofthe Dutch language should not be a reason for rejection of the naturalisationapplication. According to the instructions, the requirements for women couldalso be less severe.7The instructions were based on the basic principle thatnaturalisation fits into the process of increasing participation in Dutch socie-ty. This process however did not need to be accomplished at the moment ofnaturalisation.This principle was part of the view laid down in the integration policy atthat time, the so-called ‘Minorities’ policy’, that a strong legal position wouldfurther immigrant integration. Naturalisation was seen as a means of achiev-ing integration, as a step towards complete integration.8In 1995, the Chris-tian Democrats (CDA) in parliament started to oppose this notion. Theyfound that the demands on future Dutch citizens should be increased, andtherefore proposed to add the requirement of written language skills andknowledge of Dutch society. Instead of a means for integration, this partysaw naturalisation as the ‘legal and emotional completion of the integration’,thereby deviating from the position the government had so far held.9Thisidea was opposed by other political parties in parliament (the Liberal Demo-

4

56789

Parts of this overview have been taken from R. van Oers,‚Citizenship Tests in the Nether-lands, Germany and the UK‛,in Van Oers, Ersbøll and Kostakopoulou,‚A Re-definition ofBelonging?‛,2010, Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 51-105.Article 8 (1) sub dRijkswet op het Nederlandschap1985.Until 1990 each applicant had an interview with a public prosecutor and a police officer(Groenendijk, 2010).Handleiding Rijkswet op het Nederlandschap,A1, pp. 10-21.Rijkswet op het Nederlandschap1985, A1– Article 8, p. 19.HandelingenTK, 16 February 1995, no. 49, p. 3150.

9

THENETHERLANDScratic D66, Green Left and the Social Democratic PvdA).10Also the ChristianDemocratic Minister of Justice was not in favour of adding the requirementof written language skills. He expressed the wish for Dutch nationality toremain open to ‘weaker’ groups living in the Netherlands.In 1998, the introduction of the Newcomers Integration Act (WetInbur-gering Nieuwkomers,hereafter WIN) emphasised the immigrant’s own re-sponsibility to integrate. The new act obliged newcomers to attend a civic in-tegration programme (inburgeringsprogramma), which included a test at thebeginning and the end in order to measure the progress the participant hadmade. Although the tests were intended simply as a measurement of thelevel of Dutch language knowledge that had been attained, the first step insubjecting immigrants to formalised integration tests had been taken. In thatsame period, the political debate regarding the requirements for naturalisa-tion started to concentrate on the language and integration requirements.The CDA (Christian Democrats) were now supported by the VVD (Conserv-ative Liberal) and the small Christian parties in their desire to demand writ-ten language skills for immigrants who wanted to become Dutch nationals.Together, they argued in favour of a higher proficiency in the Dutch lan-guage than the level targeted under the WIN. Although this level was only agoal of the WIN and not a requirement (unlike the language requirement fornaturalisation), the level of language proficiency of the WIN apparently ex-erted upward pressure on the level of language proficiency for naturalisa-tion. This time the Christian Democrats won, and the newly introduced natu-ralisation test required sufficient knowledge of Dutch society and being ableto speak, understand, read and write Dutch at level A2 of the Council of Eu-rope’s Framework of Reference.11The conviction that naturalisation wouldstrengthen the integration and should therefore be stimulated, was now re-placed by the idea that naturalisation was the reward for completed integra-tion. The Conservative Liberal Minister for Integration and Alien AffairsVerdonk carried out this idea, repeatedly referring to citizenship as the ‘firstprize’.12She nevertheless rejected in 2003 a new request by the Christian De-mocrats to raise the language level required for citizenship, with the argu-ment that this requirement should not serve as a selection criterion for citi-zenship.Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the rise of Pim Fortuyn’s right wingparty (LPF) and his subsequent murder shortly before the 2002 elections, acentre-right government came into power. This government decided to re-form the 1998 act, the results of which they referred to as disappointing101112HandelingenTK, 21 February 1995, no. 50, p. 3200.Staatsblad,21 December 2000, no. 618. The act entered into force on 1 April 2003.TK 29200 VI, no. 7, p. 3 (November 2003) andHandelingenTK 10 December 2003, p.2486; TK 27083, no. 63, p. 15 (June 2004) andHandelingenTK 2 September 2004, p. 6075and 6096.

10

(Groenendijk, 2010). A parliamentary commission was established to evalu-ate the results of the integration policies.13In its 2004 report, this commissionconcluded that the integration of many aliens had been successful, but that itremained questionable to what extent this was due to pursued integrationpolicy. The commission also concluded that only a small percentage of theparticipants in the integration courses had attained level A2, the level in-tended by the WIN. The commission however did not regard this failure asproof of the immigrants’ unwillingness to integrate, but pointed to failurefactors such as the slow development of courses and the existence of longwaiting lists.14These balanced conclusions however led to the demand inparliament and government for a radical change in the integration regime bystrengthening the responsibility and obligations of the migrant regardinghis/her integration. The government announced that in future immigrantswould be required to first pass a basic examination in the country of origin asa condition for family reunification. Furthermore, all immigrants who de-sired to stay in the Netherlands on a permanent basis would have to attendintegration courses, for which they would have to pay themselves. Not pass-ing the integration examination at the end of the course would entail finan-cial sanctions and would keep the residence right of the migrant on a tempo-rary basis.At the same time, the government installed a commission, the Franssencommission, which was requested to define the concept of integration and toassess the most appropriate level of integration requirements.15In September2005, a proposal for a new WI, which was meant to replace the WI of 1998,was introduced in parliament.16According to the centre-right government, amore obliging and result-oriented integration policy was required in order tocombat the supposedly failed integration of ‘large groups’ of immigrants.17Inthe explanatory memorandum to the bill, the government stated that in order‘for immigrants to catch up and to allow them to successfully participate inthe social markets’, they would need to have knowledge of the Dutch lan-guage and to know and accept Dutch norms and values.18The new WI em-phasised the responsibility of the migrant to meet these criteria. Hence,courses would no longer be organised and financed by the government ormunicipalities, but left to the market and the immigrants. The WI came into

131415

161718

‘Building Bridges’, report of the temporary research commission integration policy, TK2003-2004, 28 689, nos. 8-9.TK 2003-2004, 28 689, no. 9, p. 522.Advice regarding the level of the new integration examination by the Franssen Commission,TheHague, June 2004. For the advice, see http://www.degeschiedenisvaninburgering.nl/docs/advies-franssen.TK 2005-2006, 30308, nos. 1-2.TK 2005-2006, 30308, no. 3, p. 13.TK 2005-2006, 30308, no. 3, p. 14.

11

THENETHERLANDSforce on 1 January 2007, introducing the integration examination as a condi-tion for permanent or independent residence.19Since the level of the integra-tion examination was equal to the level of the naturalisation test, it was de-cided that the integration examination would replace the naturalisation test.Hence, since 1 April 2007, the Netherlands has required newcomers to meetthe same standards as future citizens. This development again led to a call byChristian Democrats, the Christian Union and the Conservative Liberals toraise the language level of the naturalisation test, in order to emphasise thedifference between a permanent residence permit and citizenship.Until now,this political desire has not been fulfilled.The Civic Integration Abroad Act (WetInburgering Buitenland,hereafterWIB) entered into force on 15 March 2006.20The act sets an additional condi-tion for obtaining a regular temporary residence permit, namely that peoplemust first have a basic knowledge of the Dutch language (listening andspeaking skills) and Dutch society.21The WIB was meant to force migrants tostart their integration in their country of origin in order to improve their po-sition in the Netherlands. Furthermore the government intended to makemigrants more aware of their responsibilities and to select the motivatedones among them for admission.This outline of the developments regarding integration requirements inthe last 15 years shows that the principal idea that a strong legal position of amigrant promotes his/her integration has been replaced by the convictionthat this position serves as a reward for having reached a certain integrationlevel. This swing in thinking illustrates the shift from an equally shared re-sponsibility by the authorities and the migrant to the sole responsibility ofthe migrant regarding his/her integration.The integration requirement was first introduced as a condition for citi-zenship, and second as an obligation for admitted migrants. The introductionof a test for migrants (although it did not include an obligation to pass) led toan increase in the required level for naturalisation. The evaluation of the in-tegration courses and tests (and the political conclusion that the integrationpolicy had failed) became the reason for the introduction of integration re-quirements for admission as well as for independent and permanent resi-dence rights. Although in 2003 the government warned that language testsshould not serve as a selection of new Dutch citizens, nowadays a generalpolitical acceptance has emerged that integration tests function as selectioncriteria for admission and for permanent and independent residence rights.

192021

WI of 30 November 2006,Staatsblad625.Staatsblad.2006, no. 94.Article 16 (1) sub hVreemdelingenwetjo. Article 3.71aVreemdelingenwet.

12

Development of the government’s interpretation of integration22In 1979 the Dutch government introduced the first integration policy (the so-called ethnic minority policy), which aimed at granting equal rights to ethnicminorities and improving their position on the labour market and in the fieldof education, housing and public health. Already in this period, the ScientificCouncil for Government Policy (WRR) called for attention to the importanceof language courses for labour migrants and their family members.23Becausethe government did not feel responsible for offering language courses, exceptfor refugees, language education was depending from the work of volun-teers. Only after a second advice from the WRR to invest in language educa-tion in order to strengthen the socio-economic position of migrants (especial-ly the first generation Turkish and Moroccan migrants lagged behind in thatsense) and to promote their integration, the government started to offer edu-cation for adult migrants in the beginning of the nineties. For two reasons itdid not oblige migrants to attend a language course: the limited educationcapacity would be insufficient and the notion was dominant that migrantsdid not need to be obliged, as they were motivated to learn the Dutch lan-guage.In 1994, the government reformulated its integration policy, aiming atthe development of migrants towards active and responsible citizens. Thepurpose of the Integration Act, theWet Inburgering Nieuwkomers (WIN),wasthat migrants would achieve a certain level of capability to live independent-ly, in a social, educational and/or professional sense. Attendance of thecourse offered in the framework of the WIN would result in a first but essen-tial step towards integration.For the preparation Civic Integration Act, which would replace the WIN,the Franssen commission advised (on request of the government BalkenendeII) in 2004 on the content of the new integration examination.24In its advice,the commission defined active participation in society as the goal of integra-tion. According to the commission, everyone should be able to acquire a fullsocial position as free and autonomous citizens. Dutch language skills andknowledge of social relations, norms and values are mentioned as require-ments for achieving this goal. Furthermore, integration and ‘the proper func-

22

2324

For this subparagraph we made use of the article of Odé and De Vries, De Geschiedenisvan inburgering in Nederland, in Odé et al.,Jaarboek Minderheden 2010, Inburgering inNederland,The Hague: Sdu, 2010, pp. 15-32.Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid (1979),Etnische Minderheden. Deelrap-port A. Advies aan de regering.The Hague: WRR.Advice regarding the level of the new integration examination by the Franssen Commission,TheHague, June 2004. For the advice, see http://www.degeschiedenisvaninburgering.nl/docs/advies-franssen.

13

THENETHERLANDStioning of a migrant’ implies knowing and living up to unwritten rules,codes and agreements. This aspect of integration requires the immigrant toassimilate into Dutch society by prescribing the way he/she is supposed tobehave. Finally the commission mentioned that integrated citizens are re-quired to be active in societal life in one way or another. The commissionmentioned voluntary activities at a community centre, in a sports club or as amember of the school board as examples. The commission advised to streng-then the own responsibility for migrants, but under the condition that thegovernment offers adequate tools to take this responsibility.In its integration acts, the governments’ definition on integration seemsto be only partly inspired by the Franssen Commission. The three successiveBalkenende governments (2002-2007) increasingly put emphasis on the indi-vidual responsibility of the migrant and on shared values, amongst othersequal rights for men and women and the separation of religion and state.Hence, the aim of socio-economic participation of the nineties has been re-placed since 2002 by the purpose of cultural adaption of migrants to Dutchsociety. The responsibility for the integration itself was no longer equallyshared between the state and migrants, but merely shifted to the migrants.The integration tests which are assessed in the Intec research, are based onthese principles of integration policy.

14

Chapter 2: Integration test abroad2.1Description of the test

2.1.1 The integration examination abroadThe Civic Integration Abroad Act (WetInburgering Buitenland,hereafter WIB)entered into force on 15 March 2006.25The act sets an additional condition forobtaining a regular temporary residence permit, namely that people mustfirst have a basic knowledge of the Dutch language and Dutch society.26Thisbasic knowledge will be tested in the Basic Civic Integration Examination inthe country of residence of the applicant. The proof of having passed this ex-amination must be handed over at the application for admission.27The level of the knowledge that is tested in the examination has been laiddown in theVreemdelingenbesluit.28Listening and speaking skills in the Dutchlanguage and knowledge of Dutch society will be tested in the integrationexamination abroad. The examination consists of two parts: knowledge ofthe Dutch language and knowledge of Dutch society. The knowledge of bothparts is tested by an oral examination conducted over the telephone fromDutch consulates and embassies abroad, using voice recognition software,which is based in the US. This computer programme also decides whetherthe candidate has passed the examination.29If there is no Dutch consulate orembassy in the country of residence, the examination will be held at thenearest Dutch representation in a neighbouring country.Knowledge of the Dutch languageThe required basic level is A1 minus of the Common European Frameworkfor Modern Languages. This level, which is one step lower than A1, meansthat the examination candidate understands announcements and instruc-tions, simple questions and answers which are related to his/her immediatepersonal life, can give elementary information on his/her identity and per-sonal life and can express himself/herself to a very limited degree (with theassistance of isolated words and standard formulas). The language require-ments are limited to listening and speaking skills. The language test consistsof repeating sentences (the sentences presented become increasingly more2526272829Staatsblad.2006, no. 94.Article 16 (1) sub hVreemdelingenwetjuncto Article 3.71aVreemdelingenbesluit.Article 3.102 (1)Vreemdelingenbesluit.Article 3.98aVreemdelingenbesluit.Article 3.98cVreemdelingenbesluit.

15

THENETHERLANDSdifficult), answering short questions on basic information, responding towords by saying a word with an opposite meaning, and retelling a short sto-ry. The topics dealt with are randomly selected from an item bank of 50items, in order to present a different set of items to each candidate.Knowledge of Dutch societyThe required knowledge of Dutch society consists of ‘elementary practicalknowledge’ on the Netherlands, (including geography, history, legislationand political science), housing, education, the labour market, the system ofhealth care and civic integration. Furthermore the required knowledge cov-ers the rights and duties of migrants and citizens in the Netherlands and theaccepted norms in everyday life and in society.30The knowledge is tested ona level not higher than A1 minus. This part of the examination includes 30questions which correspond to images selected from the film ‚Coming to theNetherlands‛. The questions vary between yes/no questions, open questionsand closed questions with two options.Costs and preparationApplicants are charged €350 each time they take the examination.Passing the examination is a condition for granting an authorisation for tem-porary stay, which is for certain nationalities a necessary document for enter-ing the Netherlands. This authorisation is known as‘Machtiging VoorlopigVerblijf(hereafter MVV).31The migrant must apply for a MVV within oneyear after having passed the examination.32After this period, the result ofthe examination becomes invalid and he/she must take a new test in order tobe admitted.The Dutch government does not provide either courses or learning ma-terial. It has however compiled a practice pack which can be purchased at€ 70.40 and which consists of the film ‚Coming to the Netherlands‛ and apicture booklet about Dutch society, an exhaustive list of questions that mayarise during the knowledge of society test, and a set of mock language tests.

2.1.2 Who has to take the examination?This entry condition applies to those persons aged between 18 and 65 who:1. apply for admission to the Netherlands with a view to settling perma-nently,2. and need to have a MVV,3330313233Article 3.98 (6).Vreemdelingenbesluit.Article 16 (1) a juncto h and Article 16aVreemdelingenwet.Article 3.71a (1)Vreemdelingenbesluit.Article 17 (1)Vreemdelingenwetmentions the exemptions for the requirement of a MVV.

16

3.

and are obliged as newcomers, under the terms of the WI to participatein a civic integration programme after arrival in the Netherlands.34

In practice this obligation primarily concerns applicants for family formationor family reunification with a citizen of the Netherlands or with a migrantoriginating from a non-EU country.35Furthermore the WIB applies to reli-gious leaders coming to the Netherlands in order to enter the labour mar-ket.36ExemptionsAs persons with a certain nationality are not required to apply for a MVV,they are exempted from taking the test. These are citizens from the MemberStates of the EU and EEA, Surinam, Australia, Canada, US, Switzerland, NewZealand, Iceland, Japan and North Korea.37Furthermore migrants coming tothe Netherlands for a temporary reason, such as study, au pair work, ex-change or medical treatment, are exempt, as well as persons with a workingpermit, self-employed and highly educated migrants. Also migrants whowere granted a status on the basis of the Long-term Residence Directive(2003/109/EC) in another Member State and who fulfilled an integration con-dition for this purpose, are exempted.38Finally, family members of a migrantwith an asylum-related residence permit do not need to take the test, unlessthe marriage was concluded after the sponsor was granted a residence per-mit (family formation).39Exemptions for medical reasonsMigrants who belong to the category to which the act applies are exempt ifthey have demonstrated (to the satisfaction of the Minister of Integration)that they are permanently unable to take the examination due to a mental orphysical disability.40The legislator refers to the situation where the applicantis blind or deaf, or has difficulty hearing, seeing or speaking and is not inpossession of audio-visual aids.41Proof of this disability consists of a declara-tion from a doctor or expert appointed by the head of the embassy or consu-late. This medical assessment takes place at the expense of the applicant.423435Detailed information on this act is to be found in paragraph 3.Family reunification means that the marriage was concluded before the applicant wasadmitted to the Netherlands; in other cases (including marriages to Dutch nationals) thedefinition family formation is used.Article 3.71 (3)Vreemdelingenbesluit.Article 17(1) a and bVreemdelingenwet.Article 3.71a (2b)Vreemdelingenbesluit.Artikel 3.71a (2a)Vreemdelingenbesluit.Article 3.71a (2c).Article B1/4.7.2Vreemdelingencirculaire.Article 3.10Voorschrift Vreemdelingen.

36373839404142

17

THENETHERLANDSBeing functionally illiterate does not constitute a ground for exemption.During the legislative process, the Minister of Alien Affairs and Integrationpointed out that the test is taken orally, which should therefore be possiblefor illiterates to pass.43The administrative law section of the Council of State(AfdelingBestuursrechtspraak Raad van State),the highest court in this regard,did not consider this assumption unreasonable, and therefore confirmed thatbeing illiterate was no reason for exemption.44

2.1.3 Consequences of failing the testIf the immigrant fails, he/she will not be granted a MVV, and will thus not beadmitted to the Netherlands. There is no legal remedy with regard to theoutcome of the examination.45The applicant is allowed to do the test as many times as necessary, aslong as he/she pays € 350 for each examination.

2.2

Purpose of the test46

2.2.1 When was it first proposed, by whom and with what arguments?In the Coalition Agreement of the second right-wing Balkenende govern-ment in 2003, the following principles were included: ‘Any newcomer whocomes voluntarily to our country and to whom the WIN applies, first have tolearn the Dutch language in their home country as a condition for admission.Once arrived in the Netherlands, he or she has to gain more in-depth know-ledge of the Dutch society.’47One year later this agreement led to the propos-al for the WIB.48This was only a few months after the entry into force of thedecree that raised the minimum age for spouses to 21 and the income re-quirement to 120 per cent of the minimum wage in the case of family forma-tion.4943444546TK, 2004-2005, 29700, no. 6, pp. 40-41.ABRS, 200806121/1, 9 February 2009, JV 2009/151.Article 3.98dVreemdelingenbesluit.For this paragraph, I gratefully made use of the article by S. Bonjour: ‚Between Integra-tion Provision and Selection Mechanism. Party Politics, Judicial Constraints, and theMaking of French and Dutch Policies of Civic Integration Abroad‛, European Journal ofMigration and Law, 2010, no. 3.TK 2002-2003, 28637 no. 19, p. 14. The coalition of this ‘Balkenende II’ government con-sisted of Christian Democrats (CDA), Conservative Liberals (VVD) and Social Liberals(D66).TK 2003-2004, 29700, nos. 1-2, 21 July 2004.Koninklijk Besluitof 29 September 2004,Staatsblad.2004, no. 496.

47

4849

18

According to the explanatory memorandum, the WIB concerns mainlymigrants who come to the Netherlands for family reunification or familyformation reasons. The government selected this target group because familymigration (in 2002 responsible for one-third of total migration to the Nether-lands) would cause the largest integration problems. It stated that ‘the largescale immigration of the last ten years has seriously disrupted the integrationof migrants at group level. We must break out of the process of (family) mi-gration which time and again causes integration to fall behind’. In particular,the integration process was thought to have been ‘held back by the fact that alarge number of second generation migrants opts for a marital partner fromthe country of origin’. According to the government, ‘an important part ofthese [family migrants] has characteristics that are adverse to a good integra-tion into Dutch society. Most prominent among these – also in scale – is thegroup of marriage migrants from Turkey and Morocco’.50Almost half of thefamily migrants would belong to these communities and would find them-selves in a bad socio-economic position. The government described familymigration as a ‘self-repeating phenomenon of serial migration’, whichseemed to be a ‘self-repeating phenomenon of continuous growth of ethnicminority groups in a socio-economic deprived position’.51As it appeared thaton the basis of the integration programmes offered in the Netherlands, 25 to30 per cent of the newcomers did not reach the required level, the govern-ment found it necessary to start the integration before admission.52This wasin line with two motions adopted by the parliament in 2002, calling formeasures which led to a start of the integration in the country of origin.53The government mentioned four purposes of the introduction of the in-tegration test abroad. First, the test would enable family migrants to ‘get by’better on their arrival. Second, it would allow them to make a more deliber-ate and better informed choice on moving to the Netherlands. Third, itwould make the migrant and his or her partner residing in the Netherlandsmore aware of their responsibility for the integration of the newcomer intoDutch society. The government felt that the ‘supply-oriented approach’ wasno longer appropriate: emphasising the own responsibility of the migrantwould fit into the new approach to integration that it had in mind. In thisview, supporting the migrant in his/her preparation for the test abroadwould send the wrong signal. Furthermore, offering no support would allowthe migrant more freedom of choice on how to prepare for the examination.54As a fourth and final purpose of the WIB, the government expected theintegration requirement would work as a ‘selection mechanism’: only those5051525354TK 29700 no. 3, p. 4. Bonjour (2010), p. 306.TK 29700 no. 3, pp. 2-5.TK 29700 no. 3, pp. 15-16.TK 29700, no. 3, pp. 1-2 andStaatsblad2006, no. 94, p. 5.TK 29700, no. 3, pp. 15-16.

19

THENETHERLANDSwith the ‘motivation and perseverance’ necessary to integrate successfully inthe Netherlands would be admitted.55At the same time, the ones who wouldnot be able to make themselves familiar with the Dutch language wouldcause serious integration problems in Dutch society and therefore not be al-lowed to settle in the Netherlands.56The government stated that reduction inimmigration was ‘not a primary goal’, but welcomed the ‘side-effect’ that theWIB was expected to result in a decrease in family migration flows by an es-timated 25 per cent.57The government explained that it would prefer delayor even cancellation of family migration to the situation in which integrationimmediately after arrival in the Netherlands would lag behind.58According to the government, the integration requirement was in linewith ‘recent European developments in the field of migration of third coun-try nationals’, referring to the Family Reunification Directive and the Long-term Residents Directive. As a matter of fact, the Dutch government itselfwas a strong promoter of the insertion of an optional clause regarding inte-gration requirements in those directives.59Even more interesting to note, isthat the government referred to the ‘Tampere conclusions’, in which theEuropean leaders of governments in 1999 announced the strengthening ofthe residence rights of migrants in order to improve their integration.60

2.2.2 Debate in parliamentIn the Dutch parliament, all political parties shared the government’s viewthat family migration, in particular marriage migration from Turkey and Mo-rocco, had very problematic consequences for the migrants themselves, fortheir partners and children, and for society at large.61All political parties ex-cept the Green Left (Greens) agreed with the proposal to require a certainlevel of knowledge of the Dutch language and society before being admittedto the Netherlands. The motions to which the government referred were filedby members of the ‘Balkenende II’ coalition: VVD (Conservative Liberals)

5556575859

6061

TK 29700 no. 3: p. 6 and 11.TK 29700, no. 3, pp. 4-6.TK 29700 no. 3 p. 6 and pp. 14-15, and no. 6, p. 43. Bonjour (2010), p. 306.TK 29700 no. 3, p. 14.TK/EK 23490, nos. 8e and 254, pp. 16-17. At that time the government only had the ideato introduce the admission condition that the applicant for family reunification wouldpre-finance the integration course in which he/she had to participate after admission;TK/EK 2002-2003, 23490, nos. 8 and 244, pp. 22-23.TK 29700, no. 3, p. 2. See no. 18 and 21 of the Tampere conclusions of the EuropeanCouncil, 15 and 16 October 1999, Conclusions of the Presidency, SN 200/1/99.Bonjour (2010), p. 308.

20

and CDA (Christian Democrats).62But the left opposition parties SP (SocialistParty) and PvdA (Social Democrats) also agreed with the possible migrationreducing effect of the act as a purpose. The last party went a step furtherwith the proposal to require a certain education level from the spouseabroad.63As a matter of fact, the WIB can be regarded as a continuation ofthe policy of the government which included the Social Democrats(‘PaarsII’),to link migration to integration and to consider family migration as acause for large societal problems. All approving parties accepted that somemigrants might never be able to meet the requirement. They agreed with thedecision of the government to withhold its support from migrants while theywere preparing for the test. The Social Democrats found it legitimate to askmigrants to prepare for their integration, but nevertheless requested ade-quate and accessible learning material. The parliament did not adopt thismotion.64The Greens, who voted against the act, however, thought a lan-guage could be much more effectively learned in the country in which it wascommonly spoken and considered it unacceptable that ‘the reduction of thefreedom of choice due to family pressure’ be ‘replaced by a reduction of thefreedom of partner choice by the government’.65Despite the political support for the principle of the bill, there was criti-cism on the execution of the requirement. The debate concentrated on twoquestions: on the admissibility of a mandatory language test without provid-ing sufficient facilities for immigrants to learn Dutch in their country and onthe validity of the language test, as it was based on software developed in theUnited States for a completely different purpose.66The Minister for Alien Af-fairs and Integration had disregarded the conclusion by linguists (who hadbeen asked for advice by the Minister herself) that civic integration could notbe properly tested abroad. The majority of parliament however was satisfiedwith the promise by the Minister to verify the outcome of the computer testduring the first period.During the parliamentary debate on the bill, the government announcedthat it would evaluate the effectiveness and effects of the act on the integra-62Motie-Blokc.s. (VVD), 10 December 2002, TK 28600 VI no. 60 andMotie-Sterkc.s.(CDA), 17 December 2002, TK 27083, no. 25. At that time, Balkenende I was in power, inwhich both parties also participated.TK 2004-2005,Handelingennr. 60, 16 March 2005, pp. 3885-3888.TK 29700, no. 25. TK 2004-2005,Handelingenno. 60, p. 3886, Bonjour (2010), p. 309.TK 2004-2005,Handelingenno. 60, p. 3895 andHandelingenno. 62, p. 4028, Bonjour(2010), p. 309.J. v.d. Winden,Wet inburgering in het buitenland,Den Haag: Sdu 2006; T. Spijkerboer,Ze-ker weten: Inburgering en de fundamenten van het Nederlandse politieke bestel,Den Haag: Sdu2007. About the linguistic arguments: Willemine Willems, De politiek aan de knoppenvan de machine: spraaktechnologie in het inburgeringsbeleid, in H. Dijstelbloem and A.Meijer (eds),De migratiemachine: de rol van technologie in het migratiebeleid,Amsterdam:Van Gennep 2009, pp. 123-156.

63646566

21

THENETHERLANDStion and participation in the Netherlands and the legal effect in practice. Inparticular attention would be paid to the situations in which exemption wasrequired, for instance by Article 8 ECHR.67The act however does not providefor an exemption ground based on Article 8 ECHR. Furthermore, the Minis-ter promised to monitor the application of the act each half year.68

2.2.3 Comments of experts during the legislative processThe advisory committee involved in alien affairs (AdviescommissieVreemde-lingenzaken),appointed by the government, concluded that not all legal ques-tions could be answered immediately, as there was no precedent in Europe.69The committee thought that the requirement was in compliance with theFamily Reunification Directive, but advised not to apply the requirement ifArticle 8 ECHR obliged it to do so. Furthermore, the committee pointed to apossible violation of the principle of equality, as certain nationalities wereexempt.70According to the committee, an exception on grounds of nationali-ty should have a proper justification. Finally, the advisory committeestressed that the government should ensure that all knowledge necessary forpassing the test was easily accessible abroad.71The general advisory body on legislation of the Council of State (RaadvanState)went less far, but advised the government to take responsibility for thedevelopment of appropriate teaching materials. Furthermore the Councilstressed the importance of exemption from the requirement relating to Ar-ticle 8 ECHR.72Groenendijk rejected the one-sided responsibility of the migrant andwarned not to be too optimistic about the reliability of the computer results.7367 TK 29700, no. 3. pp. 10-11.68 TK 2004-2005,Handelingenno. 62.69Advies inzake het concept voorstel van een wet inburgering in het buitenland, Adviescommissievoor Vreemdelingenzaken,27 November 2003, www.acvz.com.70AdviesACVZ van 27 november 2003, p. 5.71Inburgeringseisen als voorwaarde voor verblijf in Nederland, Advies van de ACVZ over het ver-eiste om te beschikken over kennis op basisniveau van de Nederlandse taal en maatschappij alsvoorwaarde voor toelating tot Nederland en over het inburgeringsvereiste voor een verblijfsver-gunning voor onbepaalde tijd‛,ACVZ 2003/07, februari 2004, p. 3, www.acvz.com.72Advies Raad van State en Nader Rapport bij het wetsvoorstel Wet inburgering in het buiten-land,TK 2003-2004, 29700, no. 4, p. 5.73 C.A. Groenendijk, Het inburgeringsexamen in het buitenland: vier onjuistheden en tienvragen,Journaal Vreemdelingenrecht2006, p. 450-455 en Dupliek: Het inburgeringsexa-men in het buitenland, validiteit niet aangetoond en onrechtmatigheid verdonkere-maand,Journaal Vreemdelingenrecht2006, p. 511-513; C.A. Groenendijk, Integratie en uit-sluiting in het Nederlandse vreemdelingenrecht, in: P. Boeles en G. G. Lodder,Integratieen uitsluiting,Den Haag: Sdu 2005, p. 9-32; C.A. Groenendijk, Inburgeren in het buiten-→

22

These arguments and questions were raised in the political debate, but themajority of the parliament was quickly convinced by the Minister, who didnot bring up new arguments. One year after the coming into force of the act,the court judged that the government was allowed to make the migrant fullyresponsible for the preparation for the examination. According to the judge,the legislator had taken these possible obstacles into account.74

2.2.4 The WIB in force: international comments and national jurisprudenceTwo years after the WIB had entered into force, Human Rights Watch urgedfor the abolition of the civic integration examination abroad. The organisa-tion deemed the act discriminatory, as it only applied to family membersfrom ‘non-western’ countries. As the difference in treatment bore no relationto the aim of the measure (better integration in the country of destination),and the government had failed to justify the difference, Human Rights Watchconsidered the distinction as (direct) discrimination on the basis of ethnicorigin and nationality and therefore incompatible with Article 14 ECHR andArticle 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.75Fur-thermore, Human Rights Watch argued that the Dutch legislation amountedto indirect racial discrimination (and therefore to violation of the UN conven-tion on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination) because it dis-proportionately affected residents of Turkish and Moroccan origin in theNetherlands who wanted to live with their spouse and children. From theparliamentary debate it appeared that the government was especially target-ing these two groups. The Social Democratic Minister of Housing Communi-ties and Integration replied that the measure was in compliance with Euro-pean and international treaties. She mentioned three justifications for the dif-ferent treatment. First, the requirement was linked with the existing differ-ence between countries whose citizens did not need to apply for a MVV andother countries. Second, citizens who were exempted because of their natio-nality were in a cultural, economic and social situation from which it couldbe expected that they would have a good understanding of the Dutch socialrelations, norms and values. Third, the interest in requiring an integrationlevel from them was lower than the Dutch interest in maintaining good for-eign and economic relations with these countries. These interests could be atstake if the government decided to introduce a MVV and an obligation to in-land: de Gezinsherenigingsrichtlijn biedt meer bescherming dan artikel 8 EVRM,Mi-grantenrecht3- 07, pp. 111-113.Rechtbank Den Haag, nevenzittingsplaats Middelburg, 16 augustus 2007, LJN: BB3524,JV2007/492.The Netherlands: Discrimination in the name of Integration. Migrants’ Rights under the WIB,May 2008, www.hrw.org, p. 4 and pp. 24-29.

7475

23

THENETHERLANDStegrate before admission for citizens who were currently exempt from thisrequirement on the basis of their nationality. The Minister added that theDutch policy served as an example within the European Union.76A fewmonths before this reply by the government, a court had judged that the WIBwas not discriminatory, because the protection of the economic relations withthese countries justified the ground for exemption.77In March 2010, thecommittee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), in its con-cluding observations on the application of the UN convention in the Nether-lands, endorsed the point of view of Human Rights Watch. The CERD foundthat the exemption led to discrimination on the basis of nationality, particu-larly between ‘western’ and ‘non-western’ state nationals, and recommendedthat the Netherlands review its legislation.78Two critical comments emerged from the Council of Europe. In 2008, theEuropean Commission against Racism and Intolerance expressed its con-cerns about the reduction in applications and the fees for the examination. Itrecommended monitoring the impact of the test abroad and reviewing thesystem of exemptions, in order to comply with the prohibition of discrimina-tion on grounds of nationality.79In spring 2009, the Commissioner for Hu-man Rights of the Council of Europe Hammarberg presented his findings onthe Dutch policy regarding human rights. In his view, the Family Reunifica-tion Directive did not allow Member States to impose passing an examina-tion as a condition for family reunification. He requested that the govern-ment review entry conditions for family migration to ensure that tests, feesand age requirements did not amount to a disproportionate obstacle.80In itsreply, the Dutch government agreed with this recommendation and referredto the coming results on the evaluation of the WIB.81

2.2.5 Political reaction on figures and the evaluation: new measuresFrom the report on the monitoring of the first year after the entry into forceof the WIB, it became clear that approximately 90 per cent of the candidates

7677787980

81

TK 29700, no. 56; TK 2007-2008,Aanhangsel van de Handelingenno. 2687; EK 2007-2008,Aanhangsel van de Handelingen,no. 13. See also TK 29700 no. 3 p. 19.Rechtbank Den Haag, nevenzittingsplaats Rotterdam,23 April 2008, AWB 07/35128, JV2008/282.CERD/C/CLD/17-18 of 16.European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, ‚Third periodical report on theNetherlands‛, Strasbourg, February 12, 2008, points 50, 57 and 58.Report by the Commissioner for Human Rights Thomas Hammarberg, on his visit tothe Netherlands, 21-25 September 2008, 11 March 2009, paragraph 4.2, no. 83 and rec-ommendation no. 15.TK 31700V, no. 95, 27 April 2009.

24

passed the test.82This information formed the reason for the Minister to con-sider the introduction of two strengthening measures: raising the limit topass in order to decrease the number of successful candidates, and increasingthe minimum test level from A1 minus to A1, which would make the exami-nation more difficult. These conclusions and measures made clear that thegovernment intended to obtain a lower pass rate. Both measures werestrongly supported by the majority of the parliament. The limit to pass hasbeen raised since 15 March 2008, but the Minister felt that raising the test lev-el to A1 would only be justified if the government facilitated the preparationof the test. To this end the Minister would assess the possibility of coopera-tion with the Goethe Institute, which supports candidates worldwide withtheir preparation for the test on the German language.83In October 2009, the government responded to the evaluation on the in-tegration requirement abroad and the increase in the age limit and incomerequirement for family formation (see paragraph 2.3).84The governmentmentioned the drop in the number of applications without judging this con-sequence of the measures positively or negatively. It expressed its concernabout the fact that a quarter of the partners still had a poor education andthat the lasting impact of the integration test appeared to be limited. Accord-ing to the government, the latter was due to the low level of the examination.It therefore announced that it would raise the examination level to A1 andinclude a written examination. In spite of its former position that a better fa-cilitation of the candidates first had to be realised before the level could beraised, the government now only announced it would develop ‘specific ma-terial’. It also did not pay attention to its argument, put forward until now,that illiterate migrants should be able to fulfil the integration criterion be-cause there was no written examination involved. As researchers already hadconcluded (on a request of the government) that requiring writing and read-ing skills without offering personal education, would probably lead to theexclusion of large groups of family members, the decision to introduce areading test can be seen as an acceptance that certain groups of family mem-bers are excluded because of the integration requirements.85In the same reaction to the evaluation, the government informed the par-liament of its intention to introduce the requirement of a certain educationlevel for both the applicant in the Netherlands and his/her spouse abroad. Ifthe spouse lacked sufficient education, he/she would be obliged to reach thiseducation level after admission into the Netherlands. The government ac-knowledged the non-compliance of these proposals (and a number of otherwishes that would restrict the right to family reunification) with the Family82838485SeeMonitor Inburgeringsexamen Buitenland,April 2007, INDIAC.TK 2007-2008, 29700, nos. 47 en 48 andHandelingenTK 2007-2008, no. 51, p. 3725.Kabinetsaanpak huwelijks- en gezinsmigratie,TK 2009-2010, 32175 no. 1, 2 October 2009.See paragraph 2.3 for the advice on strengthening the requirements.

25

THENETHERLANDSReunification Directive. It therefore announced it would make an effort toadapt the directive in this regard.In February 2010, the Advisory Committee on Alien Affairs published itsadvice regarding these new proposals. The committee referred to the con-clusion in the evaluation that it was too early to draw conclusions on thequestion whether the integration test abroad served the purpose of improv-ing the integration in the Netherlands. The committee therefore thought thatthe proposals to strengthen the integration requirements abroad were lackingfoundation. According to the committee, restrictive measures should not leadto a permanent obstacle for certain groups to (re)unite with their family inthe Netherlands. The committee pointed out that the official evaluation didnot give clarity on this aspect related to Article 8 ECHR, especially regardingthe cumulation of conditions for admission. Furthermore, the committee ex-pressed its opinion that problems, which concentrated on a certain group,should be dealt with by more targeted measures rather than general ones. Itemphasised the need for proportionate and effective measures and urged formore research on the effects of the current requirements before new require-ments were introduced.86In its reaction to this advice, the government referred to the strong sup-port in parliament for the new proposals, and emphasised that the advice ofthe committee would take nothing away from the political decisions in thisregard. The government pointed to the fact that the raising of the level of thetest abroad to A1 and its extension to a test in literacy and reading, were al-ready under preparation for execution.87This letter made clear that the gov-ernment had decided not to introduce a test in writing, but only in reading.A few months later the Advisory Department of the Council of State offeredits advice on the proposal to strengthen the integration requirements abroad.The Council expressed its doubts that illiterates and people who had beeneducated in another alphabet (Chinese or Arabic) would be able to learn toread and write in Dutch on the basis of a DVD or the Internet. The Counciltherefore advised the government to substantiate this presumption. Becauseof its doubts whether all immigrants would be able to fulfil the new require-ments, the Council warned that certain groups would be excluded fromfamily migration. In this regard the Council of State pointed to the risk thatthe Dutch policy would not be in compliance with the purpose of the FamilyReunification Directive, thereby referring to the interpretation by the Euro-pean Commission of Article 7 (2) of the Family Reunification Directive andthe explanation of this directive by the Court of Justice in the case ‘Cha-kroun’.88The Council therefore advised the government to substantiate thatno group would be excluded, or otherwise to change the draft legislation. Fi-868788Briefadvies huwelijks- en gezinsmigratie,ACVZ, 19 February 2010, www.acvz.org.TK 2009-2010, 32 175, no. 9, 20 April 2010.COM (2008) 610, October 2008 and C-578/08, 4 March 2010.

26

nally, the Council pointed to the risk that the application of the (streng-thened) integration requirement abroad to Turkish nationals was not incompliance with Article 13 of Decision 1/80, hereby referring to the decisionof the Court of Justice of September 2009 in the case Sahin.89In its reaction,the government emphasised the own responsibility of the immigrant to meetthe integration requirement and referred to the development of special edu-cational material for illiterates. With regard to the Turkish nationals, it rep-lied that jurisprudence on the scope of the standstill clause of the AssociationTreaty was still developing. Hence, it was, according to the government, tooearly to draw conclusions on this jurisprudence.90In September 2010 thegovernment informed the parliament that the level would be raised to A1 on1 January 2011, and that the tests in literacy and reading would be intro-duced on 1 April 2011.91In reply to questions from the Senate, the government stated that the sta-tistics and the evaluation of the Wib show that the Act has not led to the ex-clusion of large groups. It compared however the numbers of visa granted in2006 and 2008 (both 15.000), not mentioning that the Wib has been intro-duced in March 2006. In 2005 the number of granted visa was 21.900. Regard-ing the application of the Act on Turkish nationals, the government informedthe Parliament that no other EU Member State had drawn further conclu-sions out of the Jurisprudence of the Court of Justice.92It probably was notyet informed on the decision of the Danish government to exclude Turkishcitizens from the integration test for admission, in order to comply with therelevant jurisprudence of the Court of Justice (see the Danish report, chapter1). In its letter to the Senate, the government explained that the limitation totesting reading skills (instead of reading and writing) had two reasons:avoidance of the need to adapt the examination infrastructure and of theneed to introduce an education infrastructure. According to the government,also illiterates and migrants with another alphabet should be able to learnreading Dutch with the support of a specially developed learning package.93

89909192

93

EUCJ Case C-242/06 (Sahin), 17 September 2007 and C-92/07, European Commissionagainst the Netherlands, 29 April 2010.Adviesno. Wo8.10.0119/IV, 15 July 2010,Staatscourant2010, no. 13998.TK 2010-2011, 32 175, no. 12, 9 September 2010.Staatsblad2010 nr. 679.The Senate had referred to the decision of April 2010 in the case Commission againstthe Netherlands, C-92/07, in which the Court judged that the high fees for admission ofTurkish nationals were not in compliance with the stand still clauses of Regulation 1/80.EK 2010-2011, 31791 G, 26 November 2010.

27

THENETHERLANDS2.3Effects of the test

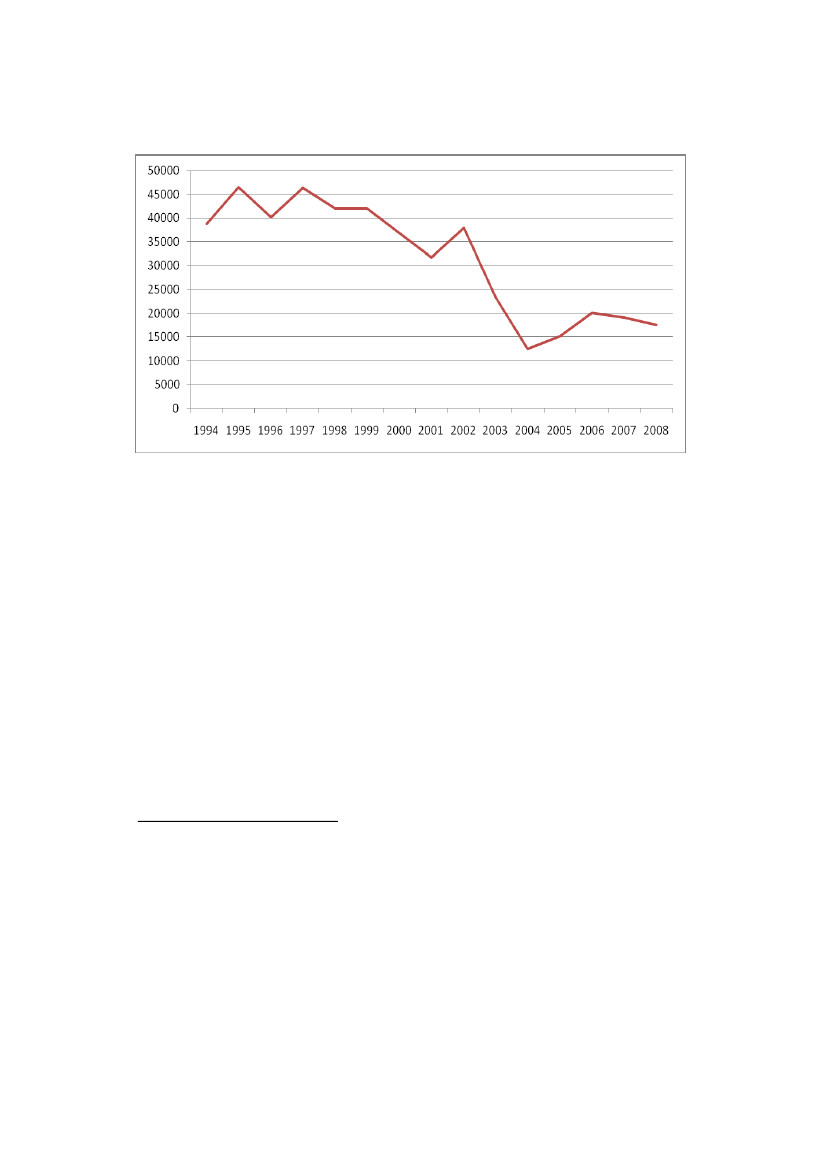

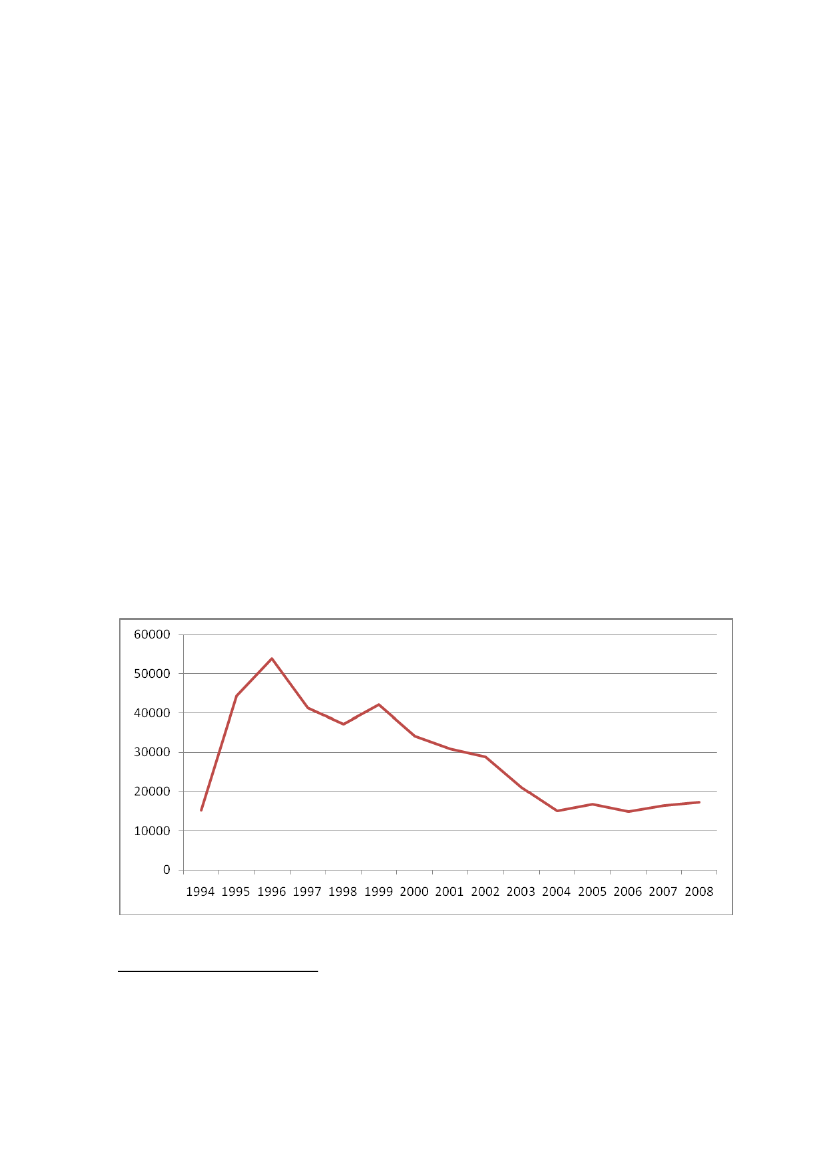

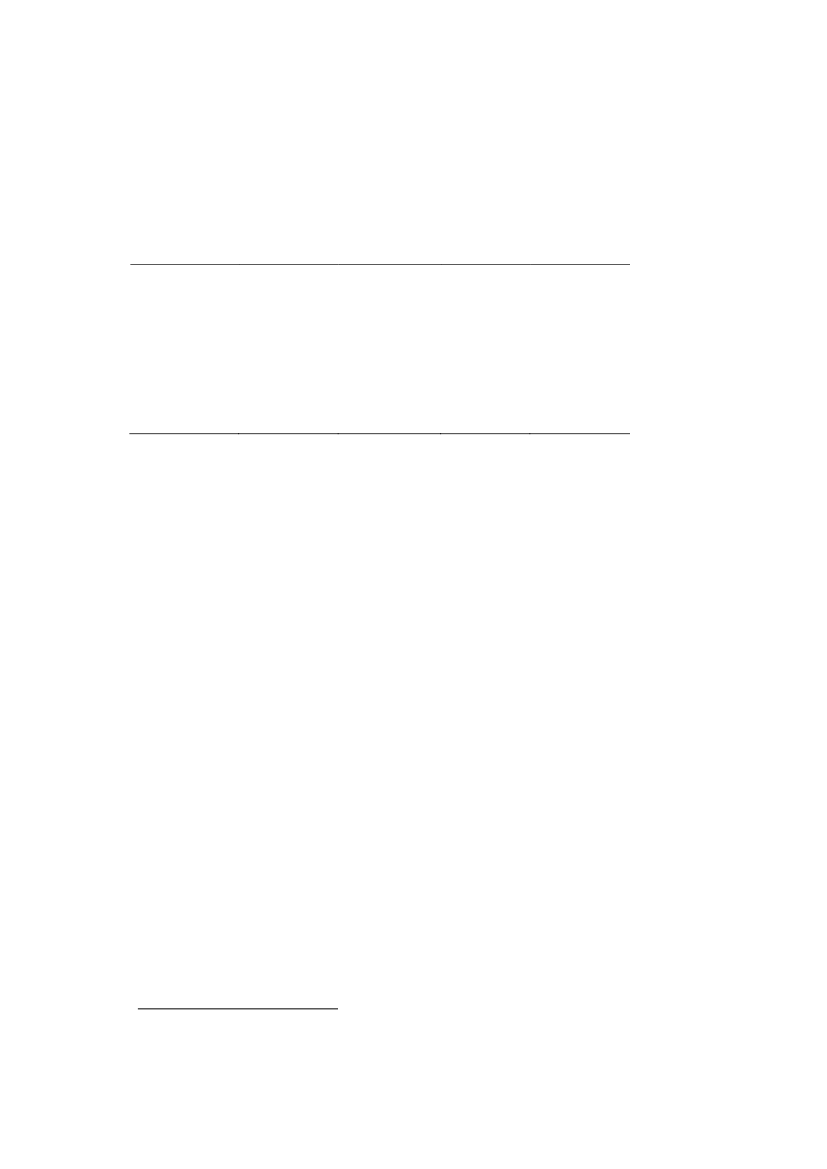

2.3.1 StatisticsIn May 2008, the Minister of Housing, Communities and Integration (afterthe change of government in 2007 the integration portfolio had been trans-ferred from the Ministry of Justice to the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Plan-ning and Environment) wrote that 89 per cent of the candidates passed theexamination the first time. Nearly 75 per cent of the candidates had an aver-age or high education. At the same time the attached monitoring reportshowed that the number of MVV applications for family reunification andfamily formation had dropped from 21,947 in 2005 to 12,105 in 2007.94Al-though the higher income requirement and the raising of the age limit formarriage immigrants (these measure were introduced in 2004 and thereforeespecially affected the numbers of 2005) have also influenced the number ofapplications, several studies have indicated that the WIB is the main cause ofthis drastic decline.95The number of MVV applications for family migrationrose to 15,025.96Figures on the first half of 2010 indicate a rise in the numberof applications to 18,000 in 2010. The largest part of this rise is explained bythe inreasing number of Somalian applications. Most of them are not re-quired to do a test.97Therefore the slight ‘recovery’ of the numbers cannotonly be seen as an indication for a better preparation for the integration ex-amination.According to the monitor report for 2008 and the first quarter of 2009, thepass rate remained unchanged compared to 2007, as well as the number ofdistributed teaching materials. The number of requests for exemptions formedical reasons increased slightly in 2008 compared to 2007, but the numberof granted requests remained unchanged. The number of requests for an ex-emption is still relatively low.98The reports are silent on the grounds for ex-emption for other reasons, such as Article 8 ECHR. This is remarkable, as the

9495

9697

98

TK 2007-2008, 29 700, no. 55 and Monitor Inburgeringsexamen Buitenland, april 2008,IND, pp. 30-31.Monitor Inburgeringsexamen Buitenland,april 2008, IND, p. 6; IND-rapport,Jaarresultaten2006, Den Haag, maart 2007, p. 3;Jaarrapport Integratie2007, Sociaal Cultureel Planbu-reau, J. Dagevos en M. Gijsberts, 16 april 2007, p. 316;Korte termijn evaluatie Wet inburge-ring buitenland, eindrapportage,WODC, Ministerie van Justitie, Januari 2008.Monitor Inburgeringsexamen Buitenland,augustus 2009, INDIAC, en TK 2009-2010, 32005,no. 3, 19 November 2009.Monitor Inburgeringsexamen Buitenland, eerste helft 2010,Significant, 21 October 2010, 25-26. The figures on the family members who are obliged to take the integration tests, areonly available from 2009.In 2007, 19 out of 41 requests for exemption were granted (out of 12,000 applications fora MVV), in 2008 this was 18 out of 59 requests (out of 15,025 applications for a MVV).

28

Minister had promised to monitor this aspect in reaction to the concerns ofthe advisory bodies.In November 2009, the government sent the first evaluation of the act tothe parliament, together with a study on the possibility of raising the exami-nation level to A1.99The researchers who conducted the evaluation con-nected the decline in the number of applications for a MVV for family reuni-fication reasons with the introduction of the integration test. They concludedthat the number of MVV applications dropped most dramatically for immi-grants originating from Turkey, Morocco, Brazil and Indonesia. Remarkably,the drop in the number of applications for family reunification seemed to re-cover less than the drop in the number of applications for family formation,although the introduction of the test targeted this latter form of family migra-tion. According to the researchers, there is no indication that migrants useopportunities to avoid the integration requirement, such as the applicationfor a residence permit on grounds other than family migration.100In anotherresearch authorised by the government, no evidence appeared of a massiveuse by Dutch nationals of the union rules regarding free movement (the socalled-Belgian route) in order to avoid the Dutch family reunification rules.There was an increase in the number of Dutch citizens requesting familyreunification during their stay in another Member State, but they were gen-erally found to have resided there for a long time.101In April 2010 the government presented some figures on the effects of thetest abroad in 2009 to the parliament.102These figures show that the pass ratefor candidates doing the examination for the first time is quite stable (anoverall percentage of 89 per cent) but that the pass rate reduces for migrantswho have to do the examination twice or more (72 per cent). This could indi-cate the existence of a group which does not manage to pass, no matter howmany times the examination is taken. In the same letter the governmentwrote that in 2009 six out of 38 requests for exemption from the test weregranted, which is only one-third of the number in former years.

99

TK 32005, no. 1.De Wet Inburgering Buitenland, een onderzoek naar de werking, de resultatenen de eerste effecten,Regioplan publicatie no. 1754, april 2009. Zie ook A. Odé, De WetInburgering buitenland: zelfselectie belangrijker dan selectie,Migrantenrecht2009, no. 7,pp. 288-292.100 G.G. Lodder, ‚Legal aspects of the WIB‛, part two of the research, p. 34.101 ‚Gemeenschapsrechten Gezinsmigratie, het gebruik van het gemeenschapsrecht door gezinsmi-granten uit derde landen‛, Regioplan Beleidsonderzoek in samenwerking met het Instituut voorImmigratierecht en INDIAC, in opdracht van het WODC,November 2009, www.wodc.nl.102 TK 2009-2010, 32 175, no. 9, 20 April 2010.

29

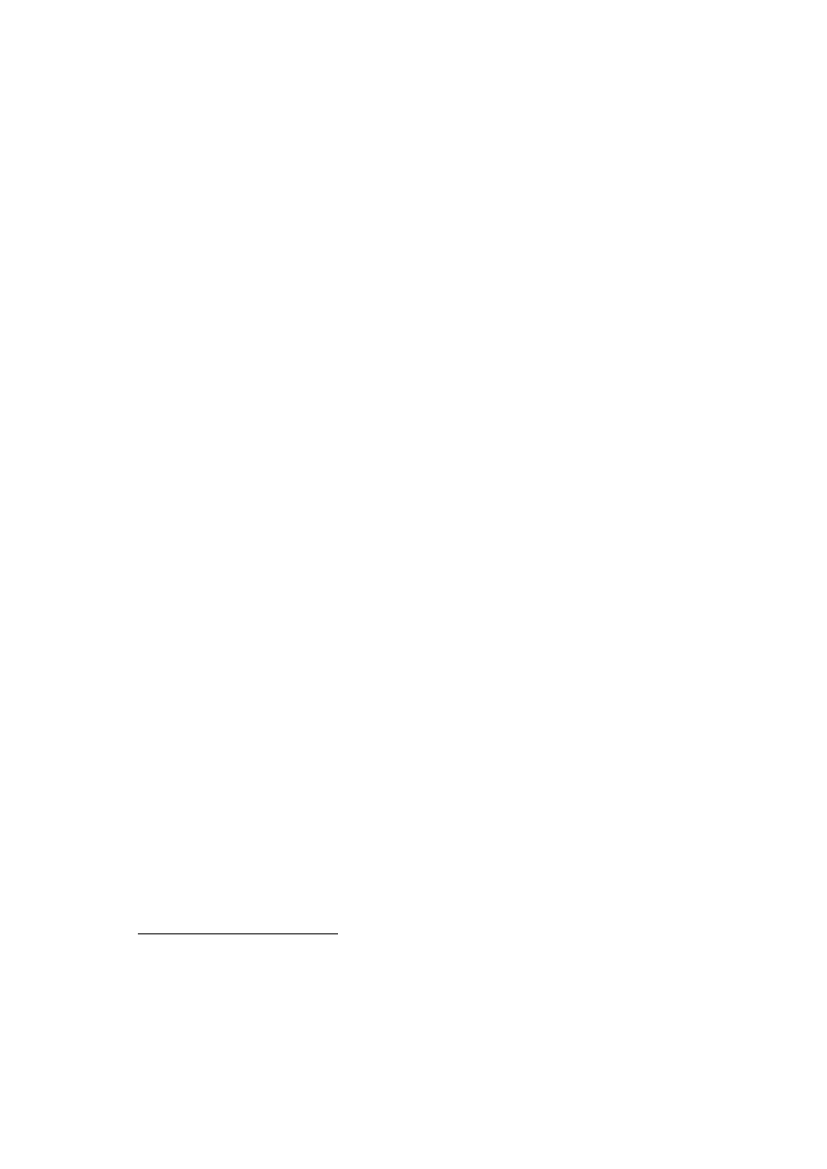

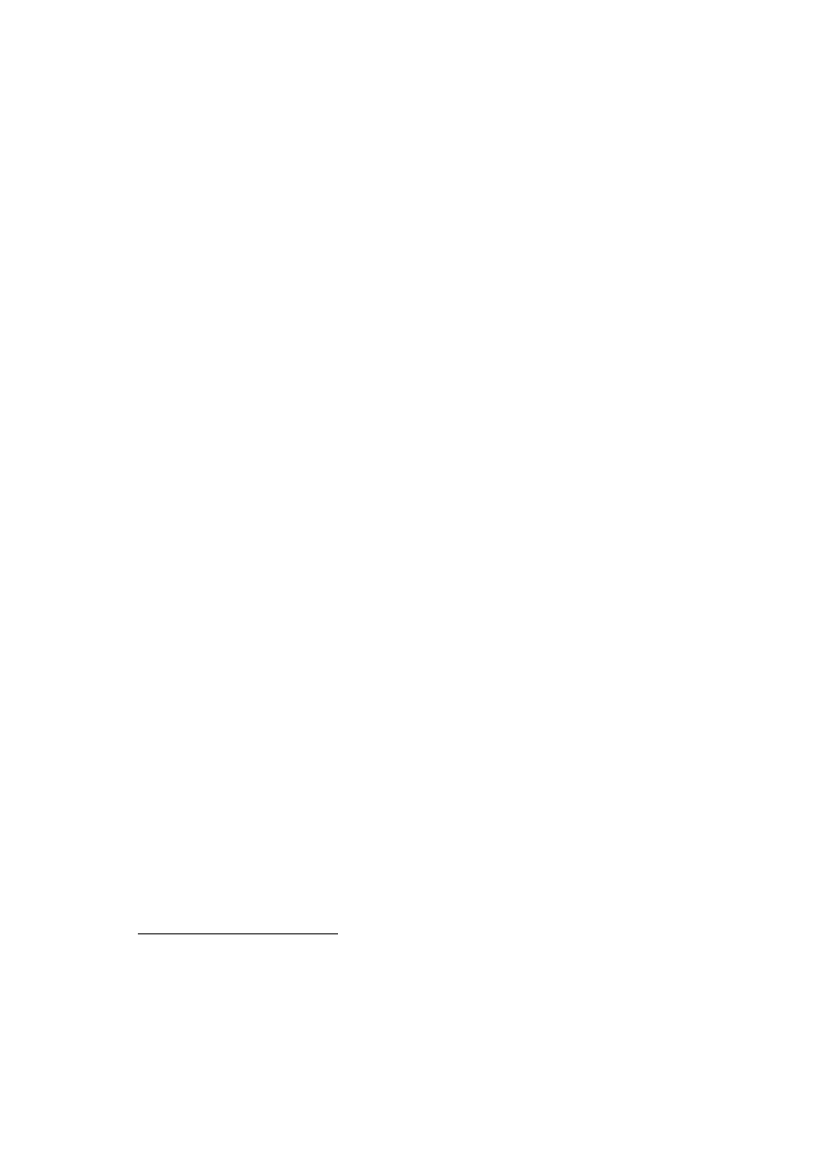

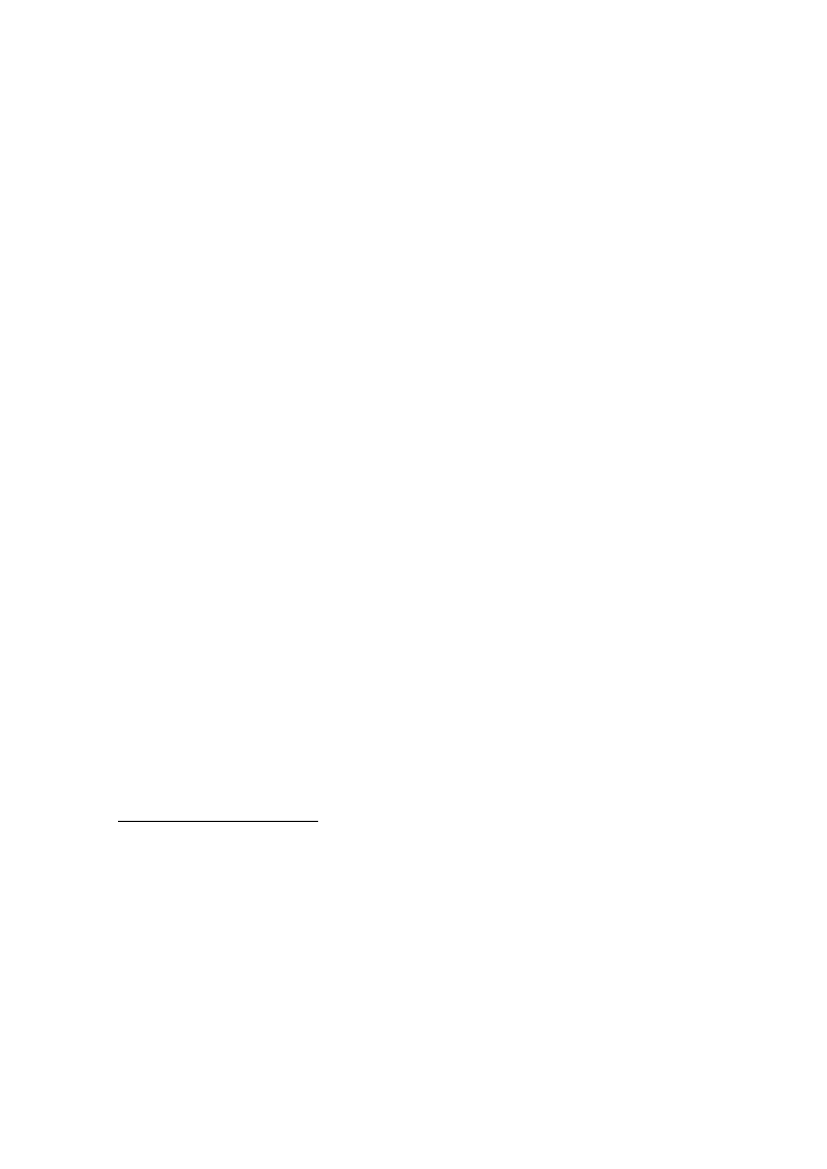

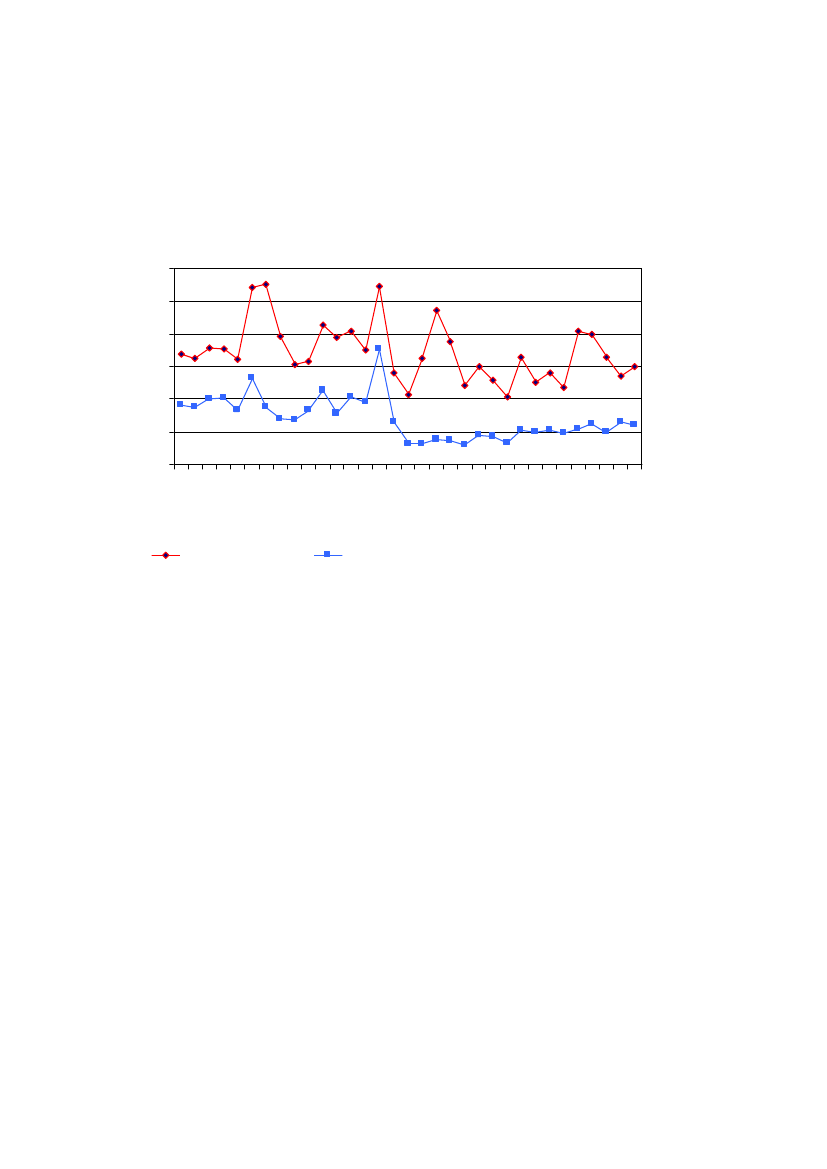

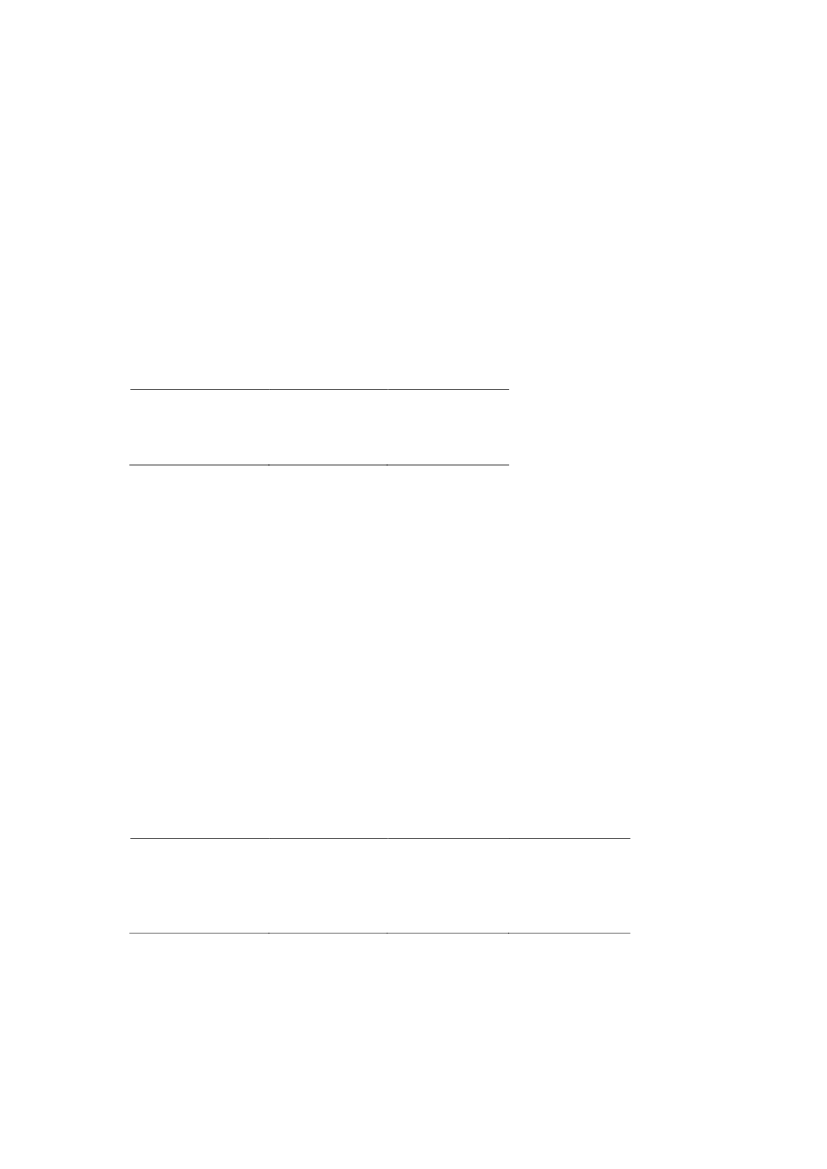

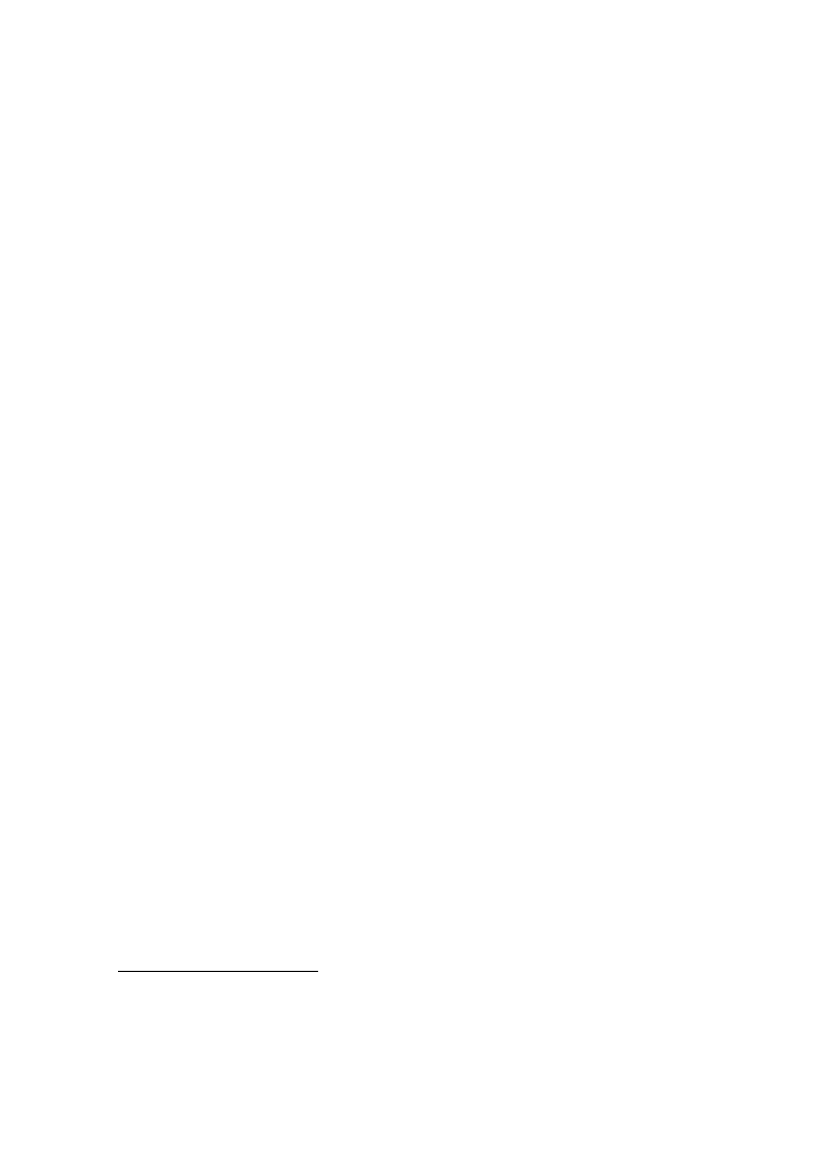

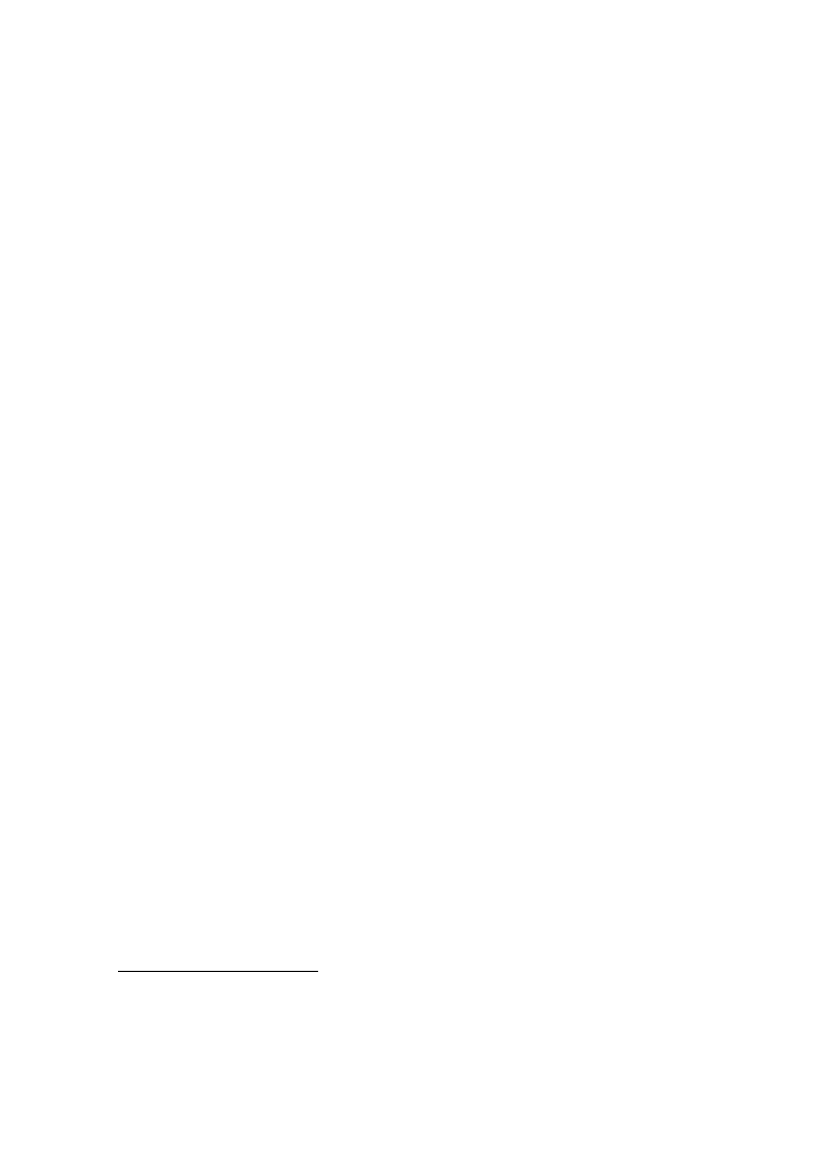

THENETHERLANDSFigure 1. Number of Visa applications for family reunification (or family formation)to the Netherlands, 2005-2008 (source Indiac 2008).

6.0005.0004.0003.0002.0001.00005566jan-05jan-06jan-07jul-0jul-0v-07nor-0t-0r-0t-007mei-56

ap

ok

ap

all applications

applications from ACAI countries

2.3.2 Did the test achieve its goals?In this paragraph, the results of the evaluation conducted by Regioplan (un-der the authority of the government) and the interviews conducted withinthe framework of Intec are investigated. After an introductory paragraph onthe methods of Regioplan, the results will be categorised in line with thepurposes of the legislator with regard to the WIB.MethodsThe methods applied in the Intec research are described in the introductorychapter of this report. In this subparagraph a short description is given onthe methods of the two other researches to which this report refers and onthe way they are incorporated into this research.Regioplan, an independent policy research firm that conducted the eval-uation under the authority of the government, assessed the compatibility ofthe act with international and European law, the functioning of the tests andits effects on the language level and the integration of the immigrants. Forthe last two parts, Regioplan assessed 34 replies on questionnaires from staffmembers of the embassies or consulates where the test is taken, and six in-terviews with staff members on the telephone. Furthermore, Regioplan paidfour working visits to embassies and received replies on a questionnaire30

ok

from 444 candidates. This questionnaire mainly dealt with the preparationfor the examination. The main assessment of the effectiveness of the test con-sisted of a comparison of the language level between immigrants who hadjust arrived in the Netherlands after having taken the test abroad, and thosewho had not taken the integration test abroad. The results of the research onthe effects and the conclusions from them are reflected in the following sub-paragraph, and compared with the results of the Intec interviews.Another research question concerned the possibility and effectiveness ofraising the level of the test to A1 and the extension to writing and readingskills.103The government wanted to know which preconditions were neces-sary to avoid the exclusion of large groups of family members by this streng-thening of the requirements. The second principal question in this regardwas whether level A1 would contribute more to the integration of immi-grants than level A minus. This second question was assessed in a workshopwith experts in the field of integration and with an academic feedback group.In 2009, the Turkish organisation IOT conducted in-depth interviewswith 25 Turkish citizens in the Netherlands who were forced to live sepa-rated from their partners in Turkey.104The respondents were selected be-cause of their difficulties complying with the admission conditions. As theserespondents are not representative of all immigrants, their information is on-ly involved in defining the role of the integration test abroad in their difficul-ties meeting the conditions for family reunification or formation.Research resultsIn order to assess whether the purposes of the WIB have been achieved, thefindings of Intec interviews will be categorised in line with the four purpos-es: getting by after arrival, a more deliberate and better informed choice, em-phasising the own responsibility of the immigrant and selection on motiva-tion and perseverance. Under each theme the findings of the interviews willbe compared with the findings of the evaluation by Regioplan. Afterwards,some additional findings and conclusions are investigated.2.3.2.1 Getting by after arrivalIntecOne teacher in Turkey pointed to the advantage of the larger vocabulary ofDutch words migrants benefit from after their arrival in the Netherlands.Most of the migrants in Turkey are aware that their level of the Dutch lan-103 This part of the research has mainly been conducted by Triarii Bv,Randvoorwaarden ni-veau A1 Inburgeringsexamen Buitenland, Deel I Hoofdrapport, Deel II Feitenonderzoek en sce-nario’s.These rapports form part of the official evaluation, for which Regioplan is re-sponsible.104Gescheiden gezinnen,by Ömer Hünkar Ilik, under the authority of IOT, April 2010.

31

THENETHERLANDSguage is just a first basis and insufficient for participating in the labour mar-ket. They however expect that their preparation will enable them to act moreindependently in the Netherlands (see a doctor, go shopping). It is notewor-thy that this expectation does not correspond with the experience of the threerespondents who had already entered the Netherlands after having passedthe test. The level appears to be too low and the knowledge too soon forgot-ten to enable them to act independently in the Netherlands. One of thesethree respondents thought it had helped him in learning the Dutch languageafter arrival. Also four out of five teachers in the Netherlands hardly noticedany difference between migrants who did the test abroad and others. Oneexplanatory factor could be the time that passes between the test and thestart of a course in the Netherlands. Some respondents in Turkey said theyhad terminated their study or employment, because they were awaiting theadmission procedure and were concentrating on the test. A long waiting pe-riod in these circumstances (which was mostly the case) could diminish theirintegration chances in the Netherlands. According to the respondent fromthe Dutch Refugee Council (VluchtelingenWerkNederland),migrants in theNetherlands find it hard to concentrate on their integration as long as theirfamily is still abroad. These experiences imply that the integration process ofboth partners can be slowed down by long application procedures.Most of the respondents argued that learning the language in the Nether-lands would be much quicker and more effective. According to one teacher,knowledge of Dutch society is appreciated and is regarded as the most usefuleducation. It helps migrants to prepare for their stay in the Netherlands.Two teachers pointed to the importance of the contact old participants keepwith each other in the Netherlands, which prevents them from isolation. Thisadvantage is of course only applicable to immigrants who are able to attend acourse.RegioplanIt is noteworthy that in the Regioplan evaluation the young and highly edu-cated in particular complained that they hardly learned the Dutch languagein their preparation. This could be related to their relatively high expecta-tions.105With regard to the language level, Regioplan found no large differ-ences between migrants who took the examination abroad and migrants whodid not do so. They only noticed slightly better listening skills in migrantswho took the examination at their time of arrival in the Netherlands, in com-parison with migrants who did not take an examination abroad. The re-searchers based this conclusion on a comparison between these two groupsof their level of listening during the intake soon after admission to the Neth-

105De Wet Inburgering Buitenland, een onderzoek naar de werking, de resultaten en de eerste effec-ten,Regioplan, April 2009, pp. 26-27.

32