Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2010-11 (1. samling)

L 168 Bilag 7

Offentligt

Country Report Germanyby Marina Seveker & Anne Walter

The INTEC project:Integration and Naturalisation tests: the new way toEuropean CitizenshipThis report is part of a comparative study in nine Member Stateson the national policies concerning integration and naturalisationtests and their effects on integration.Financed by the European Integration Fund

November 2010Centre for Migration LawRadboud University Nijmegen

GERMANY

List of Abbreviations

ALTEArt.AufenthG

AufenthVAuslGBAMFBMFSFJ

BMIBRat-Drs.BTag-Drs.CEFRcf.DaFDaZDIMRDTZe.g.e.V.ibid.EC/EUECHR

Ed.(s.)EEAEIFEMN

Association of Language Testers in EuropeArticle(s)Act on the Residence, Economic Activity and Integration of Fo-reigners in the Federal Territory (Residence Act),Gesetz über denAufenthalt, die Erwerbstätigkeit und die Integration von Ausländernim Bundesgebiet (Aufenthaltsgesetz)(German)Ordinance Governing Residence,Aufenthaltsverordnung(Ger-man)Aliens Act,Ausländergesetz(German)Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, Bundesamt für Mi-gration und Flüchtlinge (German)Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women andYouth, Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen undJugend (German)Federal Ministry of the Interior,Bundesministerium des Innern(German)Printed papers of the GermanBundesrat(Federal chamber),Drucksachen des Deutschen Bundesrates(German)Printed papers of the GermanBundestag(Parliament),Drucksa-chen des Deutschen Bundestages(German)Common European Framework of Reference: Learning, Teach-ing, AssessmentCompare withDeutsch als FremdspracheDeutsch als ZweitspracheGerman Institute for Human Rights, Deutsches Institut fürMenschenrechte (German)German Test for Immigrants,Deutsch-Test für ZuwandererFor exampleincorporated society,eingetragener Verein(German)Ibidem = ‘in the same source’European Community/European UnionEuropean Convention for the Protection of Human Rights andFundamental Freedoms,Europäische Menschenrechtskonvention(German)Editor(s)European Economic AreaEuropean Integration FundEuropean Migration Network

GERMANY

et al.ff.GGGmbHi.e.IafIMISIMKInfAuslRJZKJKShlit.Mio.NIPNJWNo.NVwZOVGp.Par.RLUmsG

SGBStAGSYPTGDTLUEUSDVHSVwVZAR

and othersfollowing pagesBasic Constitutional Law,Grundgesetz(German)Pivate limited company,Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung(German)that isAssociation of Dual Nationality Families and Partnerships,Ver-band binationaler Familien und Partnerschaften e.V.(German)Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies,Insti-tut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien(German)Conference of the German Federal Ministers of the Interior In-nenministerkonferenz (German)Fact Sheet for Alien Legislation,Informationsblatt für Ausländer-recht(German)Legal Journal,JuristenzeitungCritical Justice,Kritische JustizKenyan ShillingLiteraMillionNational Integration Plan,Nationaler Integrationsplan(German)New Legal Weekly, Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (German)NumberNew Journal of Administrative Law,Neue Zeitschrift für Verwal-tungsrechtHigher Administrative Court,Oberverwaltungsgericht(German)PageParagraphAct to Implement Residence and Asylum-Related EU Directives(Directives Implementation Act), Gesetz zur Umsetzung aufen-thalts- und asylrechtlicher Richtlinien der Europäischen Union(Richtlinienumsetzungsgesetz) (German)Code of Social Law,Sozialgesetzbuch(German)Nationality Act,Staatsangehörigkeitsgesetz(German)Syrian poundTurkish Community in Germany,Türkische Gemeinde Deut-schland(German)Turkish liraTeaching units,Unterrichtseinheiten(German)US–dollarAdult Education Center,Volkshochschule(German)Administrative Ordinance,Verwaltungsvorschrift(German)Journal for Alien Legislation and Policy,Zeitschrift fürAusländerrecht- und Ausländerpolitik(German)

GERMANY

1

IntroductionObjectives, Sources and Research MethodsThis report reviews the reasons for and effects of the German language test,the test of basic knowledge of the legal and social system and the way of lifein the Federal territory. The tests have become a recent condition for admis-sion to Germany within the context of the subsequent immigration of aspouse, a settlement permit, or naturalisation. The aims of the study are toidentify the legislation and the practices of these so-called integration and na-turalisation tests and to analyse their effects.Sources and MethodsThe legal basis and legal reasons for the introduction of the various testswill be described on the basis of the law in force at the time and the respec-tive legislative materials. They will be compared, in part, with the former le-gal situation. A limited literature review should provide an overall picture ofthe backgrounds and legal issues surrounding the tests. The current imple-mentation practices have been considered in official documents and statisticsby the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), the Federal Gov-ernment Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration and the Fed-eral Statistical Office of Germany, among others. Semi-structured interviewsfollow from these sources and provide an empirical basis for analysing theeffects of the tests. Interviews will be conducted with immigrants who sat thetests, immigrants who are preparing for the tests and immigrants who arenot sure if they want to do the test or who decided not to do the test, as wellas with teachers of integration courses, advisory services for immigrants andmunicipal officials.

Selection of Respondents and ResponseForty-nine persons were interviewed between 9 March and 20 May 2010. Thelength of interviews varied from ten minutes, for interviews with immi-grants, to 130 minutes for interviews with migrant advisory services andmunicipal officials. The interviews took place in ten towns in eight federalstates (Bundesländer): Berlin (in the districts of Mitte, Kreuzberg, Neuköllnand Spandau), Cologne (North Rhine-Westphalia), Frankfurt am Main (Hes-sen), Hamburg, Munich (Bavaria), Osnabrueck (Lower Saxony), Potsdam(Brandenburg), Stuttgart (Baden-Wurttemberg), Wesel (North Rhine-Westphalia) and Weyhe (Lower Saxony). The main focus was on interviewswith immigrants. Twenty-seven immigrants were interviewed: 12 womenand 15 men.

GERMANY

Immigrants were mainly contacted through Adult Education Centres(VHS) and/ or test centres, supported by staff members. Persons with a mi-gration background aged 22 to 50 as well as three immigrants aged 18 andyounger, who took part in integration courses for youth, were interviewed aspart of the study. Respondents with a migration background came from thefollowing 18 countries of origin: Egypt, Argentina, Bosnia, Brazil, China, In-dia, Indonesia, Iraq, Kenya, Lebanon, Nicaragua, Romania, Russia, Serbia, SriLanka, Syria, Thailand and Turkey. The length of their respective stays inGermany was at least one month and at most 20 years. The respondents weremostly course participants and test candidates. Most course participantswere unemployed at the time of the study. The test candidates were (self-)employed and/or qualified in professions such as architect, orchestral con-ductor, postgraduate student at the Law Faculty, waiter, cook, taxi driverand shop assistant. At least four respondents had obtained a settlement per-mit. Twelve out of the 27 respondents had passed the integration test at thetime of the study. Eight respondents had passed the integration test as a con-dition for admission. Ten respondents had passed the integration test for na-turalisation at level B1. One woman had passed the ‘Deutschfür Beruf’test atlevel B2; the language ability of two respondents was tested as part of the vi-sa procedure by officials abroad. Two immigrants had been awarded an aca-demic degree in Germany and fulfilled the requirements for naturalisationwithout taking part in integration tests.Two staff members from the Goethe Institute and three teachers of inte-gration and basic language courses who had acquired long-term experiencewith various test formats took part in the interviews. The interviews wereconducted with two Heads of Language Department at the VHS, seven offi-cials from Foreigners’ Authorities or Naturalisation Authorities and an offi-cial from the Office of Multicultural Affairs. Overall, the authorities ex-pressed either very little interest in participation and critical attitudes.Espe-ciallynoteworthy in this regard isthe particularparticipation of the local au-thorities(Kreisverwaltungsreferat)in Munich.In addition, interviews were conducted with two adult migrant advisersfrom the Workers’ Welfare Association (AWO), a team member from an In-ternet portal (http://www.info4alien.de), a staff member of the Association ofDual Nationality Families and Partnerships (Iaf e.V.) and three representa-tives of the following migration organisations: Turkish Community in Ger-many (TGD), Association Against International Sexual and Racist Exploita-tion (Agisra e.V.) and BAN YING e.V.The AWO was founded more than 90 years ago. It has 145,000 employeesand is divided nationwide into 29 district associations andLandassociations,480 regional associations and 3,800 local associations (http://www.awo.de).The AWO has made efforts to integrate migrants and advised them for over40 years. It also provides advice on long-term care, pensions and legal mat-ters.

GERMANY

Info4alien.de is a commercial-free Internet portal for the Aliens Act andthe Naturalisation Act that is also free of charge. Current and former officialsas well as concerned users offer information (laws and links), professional fo-rums and regular chats for interested people and officials from foreigners’authorities, voluntarily and without public subsidies. The public Board hasnearly 14,000 members, while 1,800 members are registered on the internalBoard.The Association of Dual Nationality Families and Partnerships wasfounded in 1972 as a ‘Community of Interests for Women Married to Fo-reigners’ (Iaf e.V.). It supports dual nationality partnerships and families asan intercultural family association and lobbies for their legal and social equaltreatment (http://www.verband-binationaler.de/). Iaf e.V. has a nationwidestructure. It offers advisory services in 25 towns. Around 10 full-time staffmembers guarantee the framework of its activity and continuity. On average,it receives 16,000 inquiries from throughout Germany per year. The centraloffice alone receives 800 inquiries via e-mail.TGD was founded in 1995 in Hamburg. It is currently an umbrella orga-nisation of 270 associations in Germany (http://www.tgd.de). The aim of theactivity of the TGD is to achieve equal rights for all minorities. In particular,it represents interests of the Turkish community in Germany.Agisra e.V. was founded in 1993. It is an autonomous, feminist advisoryservice organised by migrants for migrants, black women, Jews and refugeewomen who face problems because of the situation in their country of origin,migration or life situations in Germany (http://www.agisra.org/). Agisra e.V.is a member organisation of theParitätische(Welfare Organisation) and theGerman Nationwide Activist Coordination Group Against Trafficking inWomen and Violence against Women in the Process of Migration.BAN YING e.V. provides informational events concerning the social andlegal systems with translation into the mother tongues of immigrants. It alsoorganises integration courses and German language courses for Thai womenin cooperation with the VHS of Berlin Mitte and supports monthly meetingsof a Thai integration group (http://www.ban-ying.de/). It also offers advisoryservices for women with a migration background, predominantly Asianwomen who have marriage problems or are concerned about human traffick-ing.

GERMANY

Chapter 1. Integration Tests in Germany1.1Which Integration Tests are used in Germany?

Three different integration tests were introduced in Germany in the period2005-2010: a German language test before entry, tests after entering the Fed-eral territory at the end of an integration course – consisting of a Germanlanguage test and an orientation course test (referred to here as an integra-tion course test) – and a naturalisation test. There have been various chrono-logical developments regarding the legal basis: the integration courses afterentry (into the country) were first introduced in accordance with the Immi-gration Act 2004; the language tests for admission to Germany (abroad) wereintroduced as statutory requirements in 2007. Furthermore, the possession of‘basic knowledge of the legal and social system and the way of life in theFederal territory’ was imposed as a further condition for naturalisation. SinceSeptember 2008, this knowledge has been demonstrated in the nationallystandardised naturalisation test.With the introduction of this legal integration policy, the ImmigrationAct (ZuwG) marked a legal turning point compared to the previous legal sit-uation: In the Aliens Act 1990, the fact of immigration itself was ignored.Formal access to the job market and issues of legal equal treatment – socialrights, residence or citizenship rights – formed the cornerstone of the debate(cf. 7.Lagebericht 2007).Moreover, language ability at a basic or at an ‘ade-quate’ or intermediate level of proficiency was particularly relevant as a con-dition to a permanent residence permit as well as – since the reform of theNaturalisation Act in 2000 – for (entitlement) naturalisation (Anspruch-seinbürgerung).An overview of the relevant language assessment criteria inthe Aliens Act 1990 (in force until 2004) is given in table 1.1Since 2005, integration in Germany has meant, above all, language inte-gration. The new ZuwG contains integration courses as the central and onlyintegration instrument. These courses comprise, above all, a basic languagecourse and an advanced language course. In addition, the so-called orienta-tion course is supposed to impart a basic knowledge of the legal system, cul-ture and history (Hentges 2010). Both the language course and the orienta-tion course (also nationally standardised since the end of 2007) have to cul-minate each in a final examination and together they constitute the integra-tion test. The integration course programme is intended to facilitate newlyarrived immigrants’ first steps in integration. Immigrants for family reunifi-cation, for employment or refugees or residents whose stay in Germany isnot temporary are the target group. Immigrants who stay temporarily in

GERMANY

Germany should be exempt from the integration course.1The aim is theCEFR (Common European Framework of Reference: Learning, Teaching, As-sessment) level B1 – the previous intermediate level of proficiency. Immi-grants who reach level B1 should be able to produce a simple connected texton topics that are familiar or of personal interest and to understand the mainpoints of standard input about work, school, leisure, etc. The integrationcourse is aimed not only at newly arrived immigrants, but also permanentresidents in Germany to promote so-called sustainable integration (cf. e.g.Coalition Agreement, 2009). For both groups, newly arrived immigrants andimmigrants with long-term residence, CEFR level B1 is a condition for apermanent residence permit and naturalisation.For the first time, the German language testbeforeentry was introducedin accordance with the Directives Implementation Act (RLUmsG) in 2007.The background was adaptation to Community Law in the area of migration,developed in parallel. Now, spouses of a third-country national or a Germanmust prove a basic oral and written command of language at CEFR level A1before entering Germany.The integration requirements for naturalisation were also changed. Since2007, level B1 has been a national standardised requirement. Moreover, proofof ‘knowledge of the legal and social system and the way of life in the Feder-al territory’ was introduced in Germany. This regulation is based on theorientation course, which has been required for the settlement permit since2005. To prove this societal knowledge, immigrants must pass a naturalisa-tion test, in force since September 2008. An overview of the legal situation inthe Immigration Act (ZuwG) 2004 is given in table 1.2.

1

For example, students, au pairs, trainees, seasonal workers, etc. This also excludes mi-grants who have been granted a temporary status on the basis of a decision by theCouncil within the meaning of Directive 2001/55/EC (Temporary protection). The resi-dence permit can be limited in this case by the possibility of renewal for six months at atime. They have access to the (self-employed) labour market and have to live in a placeassigned to them. The residence permit will not be withdrawn if the country fled be-comes safe or if the person requests social security assistance (Section 24 Residence Act).The general rules apply to the possibility of changing to a permanent status.

GERMANY

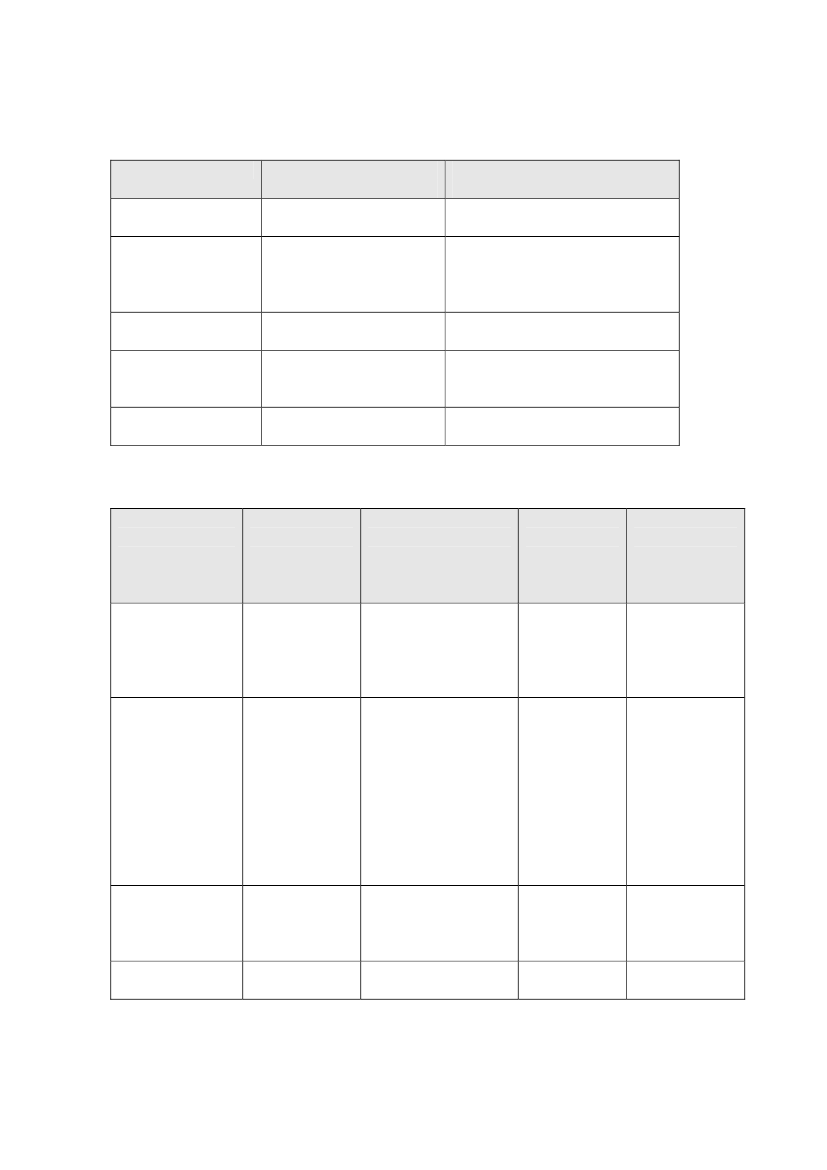

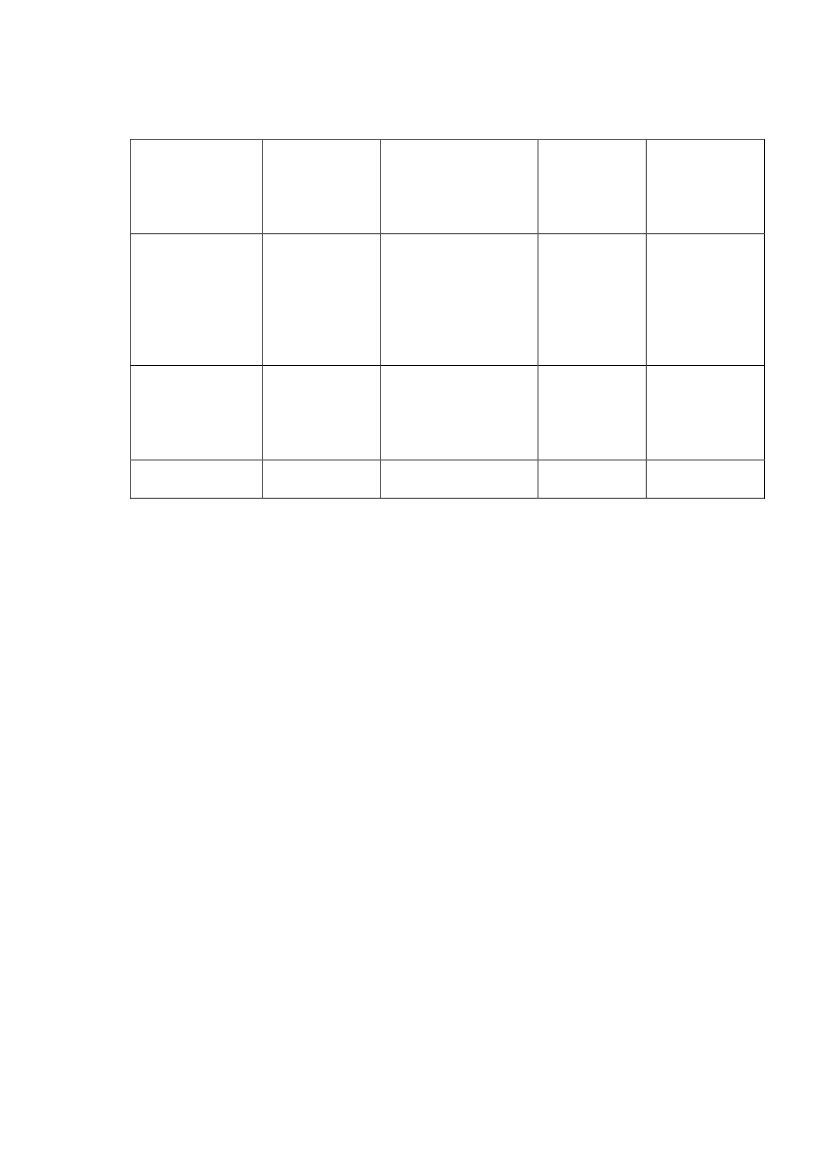

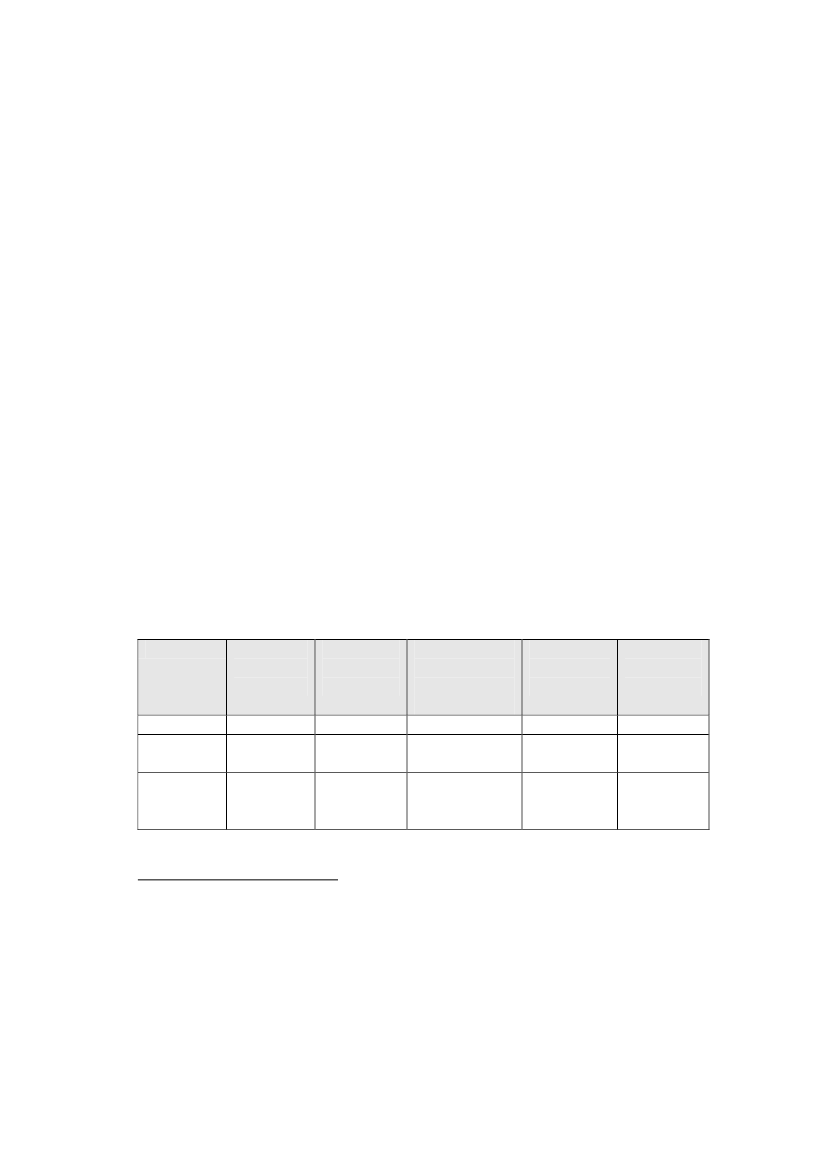

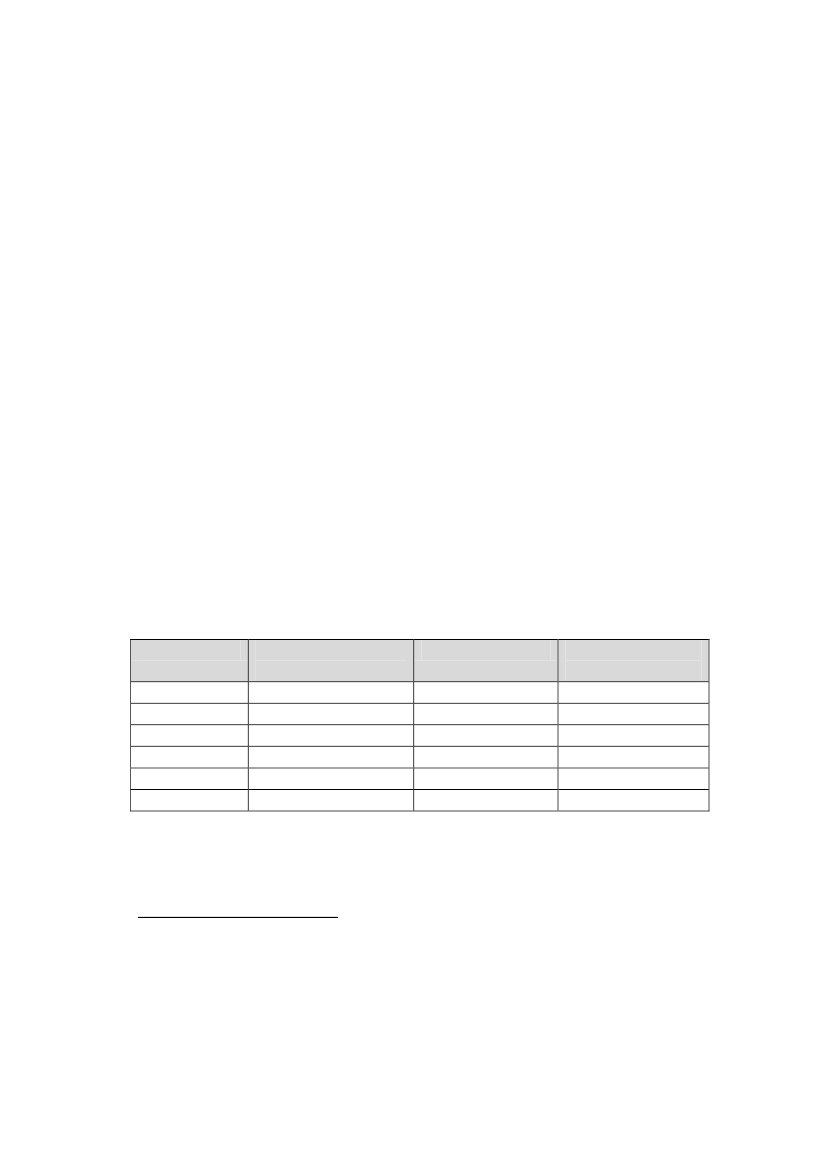

Table 1.1: Language assessment criteria for third-country nationals in the formerAliens Act of 1990Levels of proficiencyBefore entryAfter three yearsPermanent residence per-mitfor the foreign spouse of aGermanPermanent residence per-mit for foreignersPermanent residence per-mit(Aufenthaltsberechtigung)Basic oral language ability(einfach)Intermediate language ability(ausreichend)Subsequent immigration of child-ren aged 16-18

After five yearsAfter eight years

After eight years/Nationality Act

Permanent residence permit forsubsequent immigrated childrenon reaching the age of 16Naturalisation(since the Reform of 2000)

Table 1.2: Levels of proficiency for third-country nationals since the Immigration Actof 2004Level/layed down in…ActA1(‘basic’ oral andwritten lan-guage ability,‘Breakthrough’)RLUmsG (2007)spouse of athird-countrynational or of aGermanB1(‘intermediate’ oraland written languageability, ‘Threshold’)B2(‘Independ-ent’)C1(‘proficient’use, ‘EffectiveOperationalProficiency’)ZuwG (2004)subsequent im-migration ofchildren aged16-18

Before entrylanguage test/Residence Act

After entry and in-tegration course(= language andorientation course)Language test andorientation coursetest/Residence Act

After three years/Residence Act/Nationality ActAfter five years/Residence Act

ZuwG (2004)Settlement per-mit of spousesof a German

Settlement permit andresidence permitZuwG (2004)employees, spouses ofa third-country na-tional or a German,refugeesRLUmsG (2007)mobile long-term resi-dentsRLUmsG (2007)Naturalisation ofspouses of a GermanZuwG (2004)Settlement permit

GERMANY

Level/layed down in <Act

A1(‘basic’ oral andwritten lan-guage ability,‘Breakthrough’)

B1(‘intermediate’ oraland written languageability, ‘Threshold’)

B2(‘Indepen-dent’)

C1(‘proficient’ use,‘Effective Op-erational Profi-ciency’)

After six years/Nationality Act

RLUmsG(2007)Naturalisationin cases ofspecial inte-grationachievementsRLUmsG (2007)Naturalisationif an integration coursehas been successfullycompletedRLUmsG (2007)Naturalisation

After seven years/Nationality Act

After eight years/Nationality Act

1.2

Development of the Debate on Integration Tests

The chronology of legal developments shows that the introduction of variousintegration tests was not the original idea. The reform process in the area ofmigration policy was gradual, but the debate on it had already started at theend of the 1990s. A changed legal and political understanding of immigrationis supported by this reform process, after summing up the lack of consistentimmigration and integration policy in the final report of the ‘SüssmuthCommission’, named after its head. As a comparison, the commission par-ticularly referred to Dutch and Swedish experiences in the area of integrationprogrammes for newly arrived immigrants available at that time. Their pro-posals for the introduction of promotional material for newly arrived immi-grants (besidesSpätaussiedler)based on these ‘models’ were voted at cross-party level (Michalowski, 2007) and were utilised in the draft law. The re-quirement of the Immigration Act 2004 was to initiate a historical paradigmshift in issues of immigration in modern law. The perspective of Germanimmigration law has been moved from the entry and immigration to resi-dence and integration. In general, the introduction of the first national inte-gration concept was positively emphasised. Furthermore, section 43 of theResidence Act (former version) reads as follows: ‘Foreigners living lawfullyin the Federal territory on a permanent basis are provided with support inintegrating into the economic, cultural and social life of the Federal Republicof Germany and are expected to undertake commensurate integration effortsin return’.

GERMANY

These resulted in two fundamental developments during the subsequentyears: On the one hand, a shift in terms of content took place. Knowledge ofthe German language was regarded as a key to successful integration and isthe main focus of integration policy now (7.Lagebericht 2007).Language abil-ity is also a central issue in the discourse on social integration (cf. Zwengel &Hentges, 2010). In accordance with the Coalition Agreement 2009, ‘commandof the German language is a basic prerequisite for education and training, forintegration into a profession, for civic participation and for social advance-ment’. It also justifies most statutory measures. On the other hand, imple-mentation took place between the two poles of the principle known as ‘pro-moting and demanding’.2The statutory possibility of obliging an immigrant to attend an integra-tion course was an important instrument from the beginning. It was justifiedby the meaning of integration assistance as well as by the argument thatwomen who are isolated at home can be accessed and brought into Germansociety using this tool (Administrative Ordinance). Since 2007, the aspect of‘demanding’ has definitely become more important. Section 43 of the Resi-dence Act, mentioned above, says: ‘Foreigners *<+ are expected to undertakecommensurate integration efforts in return’. The tool of legal obligation wasexpanded gradually: the obligation to attend the course was coupled withthe obligation to take the final test. The statutory aim of successful atten-dance on the course was extended to successful completion of the course.Failure to pass the final test is tied to possible sanctions. In addition, thebinding language test before entry was introduced for spouses, based on ar-guments in favour of integration assistance and the prevention of forcedmarriages. Since the end of 2007, the orientation course has culminated in thepassing of the nationally standardised test. A naturalisation test with an ap-propriate (non-binding) course was introduced nationwide in 2008. The cur-rent idea of an integration agreement according to the French model shouldalso help ‘to increase commitment levels in individual integration assistance’and create an integration agreement instrument ‘that will apply to both newimmigrants as well as those that have lived in the country for some time’ (cf.Coalition Agreement 2009, in further detail see in 2.1.3 at the end).

1.3

The Relationship between the Different Tests

The developments3over the various tests mutually influence each other.

2

3

See the Coalition Agreement 2002: ‘Wewant to promote and also demandthe integration ofimmigrants by means of better national integration assistance *authors’ emphasis]. Wewant to see the decade of integration.’The respective arguments will be discussed in subsection 2.1.2, 2.2.2 and 2.3.2.

GERMANY

-

-

-

-

-

Higher level of proficiency and societal knowledge for permanent residence.Thesettlement permit has been combined with higher language requirementssince 2005: ‘Adequate (oral and written) knowledge of the German lan-guage as well as basic knowledge of the legal and social system and theway of life in the Federal territory or if an integration course has beensuccessfully completed’. The requirements are different from the perma-nent residence permit in the Aliens Act 1990 in that (only) basic oral lan-guage ability had to be demonstrated, not the societal knowledge. In thisrespect, the orientation course is a novelty of the integration policy(Hentges 2010).Higher level of proficiency and societal knowledge for naturalisation.As a con-sequence, the level of knowledge required for the settlement permit hasalso influenced the level required for naturalisation: the proof of the lan-guage ability at the level B1 has been a nationally standardised conditionsince 2007. As a result, the level of language proficiency for permanentresidence and naturalisation were brought more into line insofar as thosewho passed the language test at the end of the integration course havefulfilled the language requirement for naturalisation.Interaction between the orientation course test and the naturalisation test.Theorientation courses were introduced in 2005 and, since 2007, have beensupplemented by passing the nationally standardised test. By contrast,the naturalisation course (test), introduced in 2008, should be based onthe subjects from the orientation course within the integration courses. Inthe mean time, the high content overlap raises the question of a long-term merger of the tests.Higher and previous language requirements for spouses.The statutory inte-gration concepts are different for family immigrants. Since 2004, the lawhas provided for the obligation to attend a German language course inGermany in the event of the lack of any basic command of the language.With the introduction of the pre-entry tests in 2007, the underlying as-sumption of the targeted promotion of initial language integration afterarrival through integration courses did not ssem sufficient for spouses.Compared to other immigrants, proof of language ability or initial lan-guage integration has already been required of them abroad. The concep-tual contradiction with the obligation to attend an integration course hasbeen fixed, while the level of spouses’ proficiency was raised: the degreeof obligation to attend an integration course after arrival is derived fromthe criterion of adequate (intermediate) language ability – the (previous)level for naturalisation.No further exception for illiteracy in the naturalisation procedure.‘To be ableto communicate on topics which are familiar or of personal interest with-out any significant problems’ (to some extent, without including writtenlanguage ability), is no longer sufficient for naturalisation in cases theyapply under Article 10 StAG (‘entitlement naturalisation’,Anspruchsein-

GERMANY

-

-

bürgerung).While this question had been treated differently before, illit-eracy has also been a statutory obstacle to entitlement naturalisationsince 2007, after the requirement of written language ability came to beconsidered in conjunction with admission to Germany and the integra-tion course.4Reduction in the privileged position of marriage to a German in the ResidenceAct (AufenthG) and the Nationality Act (StAG).Marriage to a German is nolonger sufficient for the assumption of integration into the host country.Persons wishing to join a spouse in Germany have been obliged to meetthe integration requirement through the language test before entry since2007. Privileged early naturalisation of spouses and civil partners ofGerman nationals has so far also built on the particularly favourable in-tegration situation brought about by conjugal community with a Germanpartner. Proof of language ability at level B1 is a new condition now.Effect of the Residence Act (AufenthG) on naturalisation: less stringent andstricter requirements.The incentive system for the so-called last integra-tion step towards naturalisation is new: The term for the ‘entitlementnaturalisation’(Anspruchseinbürgerung)may be reduced from eight toseven years based on successful attendance of an integration course.Moreover, the possibility exists of reducing the required length of timespent in Germany to six years by submitting special integration achieve-ments, such as language ability above CEFR level B1.

In general, there is a high level of course offerings and course diversity, butalso a higher degree of (test) obligation. However, this allows not only forstricter obligation enforcement and measurability of the obligations, it alsoopens up new control options (Michalowski 2007). While there has been onlyone nationally standardised language test at the end of the integration coursesince the Immigration Act 2004 came into force, four possible ‘integrationtests’ currently lead to naturalisation. In this respect, immigrants can reachnaturalisation level towards the end of the integration course.

4

The possibility to apply Art. 8 StAG – discretionary naturalisation (Ermessenseinbür-gerung)– represents rather an exception in practice.

GERMANY

Chapter 22.1Integration Test as a Condition for Admission

The language requirements as a condition for ‘integration in advance’ andadmission to Germany concern spouses of a German or a foreigner5living inGermany who intend to live together in the Federal territory. The followingsection will debate and discuss the procedure in which the required languageability of spouses may be tested or should be valid as achieved. Higher inte-gration requirements also exist for the subsequent migration of children whoare between the ages of 16 and 18 and whose parent(s) are already been liv-ing in Germany (Section 32, par. 2, Residence Act). Generally, a positive inte-gration forecast is decisive for the settlement permit. It depends on whetherthe child possesses the language ability at CEFR level C1 or if it appears, onthe basis of the child's education and way of life to date, that the child will beable to integrate into the German way of life.6This consideration has alreadybeen expressed in the Aliens Act 1990. However, only a sufficient commandof language was required. Moreover, a principal consideration in the policyregarding foreigners and a decisive factor in the language test for admissionin cases involving ethnic Germans (Aussiedler) was that they were not immi-grants and were able to integrate more easily into the way of life in Germanyas repatriates because of their German ethnicity. The use of a German dialecthas served as an indication of their German ethnicity. A basic command oflanguage has been required of spouses and descendents of ethnic Germanapplicants in order to improve their integration capacity before entry sincethe Immigration Act came into force on 1 January 2005 (cf. Seveker 2008: 198-226). Jewish immigrants7as well as their spouses and descendents who areaged 15 and over also have to prove their language ability at level A1 in theadmission procedure before entry.

56

7

See, for the reasons for the requirement of means of subsistence with regard to targetgroups, footnote 17.The certificate, issued by a reliable and appropriate organisation after passing the lan-guage acquisition test, which may not be dated more than one year previously, servesas proof of language ability (BRat-Drs. 669/09, p. 260). It is assumed that children aremore easily able to integrate if they have grown up in a Member State of the EU or EEA(cf. § 41 paragraph 1, sentence 1, Ordinance Governing Residence) or if they come froma German-speaking parental home or have attended a German-speaking school abroadfor a substantial period.Pursuant to the Immigration Act, the test before entry was extended to that populationgroup. Jewish immigrants may obtain the settlement permit with a specific residenceimmediately after arrival in Germany.

GERMANY

2.1.1 Description of the TestTarget GroupsThe subsequent migration of the spouse of a German or a foreigner wasmade dependent on demonstration of language ability before entry after theintroduction of the Directives Implementation Act (RLUmsG) on 28 August20078. Spouses have to prove, as part of the visa procedure, that they are ableto communicate in German at least at a basic level (Section 30, par. 1, sen-tence 1 no. 2 and Section 28, par. 1, sentence 4 Residence Act).Exemptions- By NationalityExemptions are made from the language criterion for spouses of a sponsorfrom the USA, Australia, Israel, Japan, Canada, the Republic of Korea andNew Zealand, as well as Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and Honduras (new:Brazil and El Salvador) in the interests of close economic relations. Spousesof the nationals who may enter Germany without a visa pursuant to Section41AufenthVand may obtain the residence permit in the Federal territory arealso excluded from having to demonstrate language ability.- For certain groups/on humanitarian groundsSpouses of a third-country national or a German must pass the German lan-guage test before entry. Some exceptions are made in relation to spouses of athird-country national: firstly, the subsequent migration of spouses who aremarried to a highly skilled person, a researcher or a self-employee as well asa (mobile) permanent resident is possible without taking a test before entry(‘because of migration policy-related interest from the Federal Republic’).Secondly, exceptions are made to the language criterion in cases involvingmarriage to a resident on humanitarian grounds: Spouses of a foreigner whois recognised as being entitled to asylum or a refugee according to the Refu-gee Convention 1951 (including after naturalisation) do not have to take theGerman language test. Pregnancy is not an exception on humanitariangrounds.- Illness or handicap/No exception for illiteratesFurthermore, the exceptions to the language criterion are considered forspouses of a third-country national or a German, who are unable to provideevidence of a basic command of language on account of a physical, mental or

8

The EU Directives on the Right of Residence and Asylum,Bundesgesetzblatt 2007 I,p.1970.

GERMANY

psychological illness or handicap9. Illiteracy10is not accepted as an illness orhandicap (Higher Administrative Court of Berlin-Brandenburg, ruling of 14November 2008). Pregnancy is not regarded as an illness either.- Temporary stay/Minimal need for integrationSpouses whose need for integration is discernibly minimal (Section 4, par. 2,Ordinance on Integration Courses) and spouses whose stay in the Federalterritory is temporary (Section 44, Ordinance on Integration Courses) are alsoexempt from the language test abroad. Therefore, the spouses’ need for inte-gration is discernibly minimal if they are in possession of an academic degreeor a comparable qualification11or if they are employed as managing execu-tives, professional sportsmen, journalists, scientists, researchers or teachers.Moreover, business people who have been transferred by the Head Office ofan enterprise to a branch in Germany for a maximum of three years (Section31, BeschV) and their spouses (Section 4, par. 2, no. 2, Ordinance on Integra-tion Courses) are also covered by this exception. The Foreigners’ Authorityhas to give consideration to the integration and employment forecast in astatement on the visa granting procedure (no. 30.1.4.2.3.1 Administrative Or-dinance - Residence Act).In practice the requirement is targeted at poorly-educated spouses fromcertain non-Western third-party countries, i.e. Turkey, Kosovo, Russia orThailand respectively spouses of a foreigner in Germany.Type of test‘Reliable and appropriate certificates of language acquisition are accepted asproof of language ability in the visa procedure: certificates of successful at-tendance of one of the following standardised language tests should be rec-ognised: ‘StartDeutsch 1’test set by the Goethe Institute or telc GmbH;9In individual cases, proof of language ability is not required of spouses, e.g., if theywere 65 years of age on 31 December 2009 (BRat-Drs. 669/09, p. 561). According to theGoethe Institute, German Diplomatic Missions abroad have some latitude in dealingwith the age limit (WS 30039 interview of 29 April 2010).Initial literacy in the mother tongue is the competence of educational institutions in therespective country of origin, which is why the Goethe Institute has only limited meansfor offering language courses for functional and primary illiterates. However, prelimi-nary courses in the German language have recently been offered in Thailand and Ghana(WS 30039 interview of 29 April 2010).In conjunction with the Foreigners’ Authorities, the German Diplomatic Mission shouldcontrol whether such an exception is made and whether the foreigners can start work-ing in the Federal territory in line with their qualifications within a reasonable period(no. 30.1.4.2.2 General Administrative Ordinance - Residence Act). Nevertheless, a de-tailed inspection of the qualification in the country of origin can often be debatable if apositive employment situation and integration cannot be predicted for the foreigner(BTag-Drs. 16/10732, p. 14).

10

11

GERMANY

‘GrundstufeDeutsch 1’test for the Austrian Language Diploma (ÖSD); or‘TestDaF’ organised by the TestDaF Institute e.V. (ibid. p. 257). The GoetheInstitute, telc GmbH and the TestDaF Institute are German members of theAssociation of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE). Language tests at ahigher level administered by other members of the ALTE should be also rec-ognised in the visa procedure. If an appropriate language certificate cannotbe obtained in the country of origin, the Diplomatic Mission has to ascertainin an appropriate way whether the applicant possesses a basic command ofthe German language at CEFR level A1 (BRat-Drs. 669/09, p. 247). This canoccur in a free ‘interview’ based on the ‘StartDeutsch 1’test. In this regard,the ‘StartDeutsch 1’test is of indicative value for family reunification. There-fore, this test format will be considered below in more detail.The ‘StartDeutsch 1’test can be taken in Germany as well as abroad atthe Goethe Institute or telc GmbH (at VHS in Germany and at the telc officein Istanbul). The Goethe Institute is closely involved in providing proof oflanguage ability abroad. Its current responsibility consists of creating an in-frastructure and offering examinations to cover the new need, which origi-nated from this amended legislation. Currently, 149 Goethe Institutes and tenliaison offices exist in 91 countries, as well as test centres in at least 104 coun-tries. The introduction of the test as a condition for admission implied a re-orientation of language services or an expansion of language courses for theGoethe Institute in new regions and provinces,12as well as a new targetgroup that is no longer represented by an academic clientele and is consulta-tion-intensive (WS 3003913interview of 29 April 2010).In this regard, teachers and 80 multipliers were trained, new coursemodels and information and consultation services were offered, e.g., thewebsite of the Goethe Institute in 18 languages, phone hotlines dealing withthe subsequent migration of spouses in German, English and French in Ger-many and in the respective national languages in Turkey and Thailand(ibid.). Two EU projects are financed by the European Integration Fund (EIF)and the BAMF, and the EIF and the Goethe Institute that are dedicated to a‘pre-integration language test’, set by the Goethe Institute and aimed at ex-panding consultation and information services (1), improvement of languagecourses (2) and language learning materials (3), safety measures and expan-sion of the network (ibid.). The experience of the Goethe Institute shows thatthe duration of language acquisition varies between 80 and 200 teachingunits (UE) depending on individual learning conditions (WS 30039 interviewof 29 April 2010). The Goethe Institute offers language courses at CEFR levelA1, which usually consist of 160 UE with a duration of 45 minutes per UE12The institute’s networks and the licensee’s networks were extended. The test centres inTurkey were also extended from three to eight (soon to be nine); in addition, eight testcentres were established in Morocco (WS 30039 interview of 29 April 2010).This is an automated filename of the WS 300-M Digital Recorder Olympus.

13

GERMANY

and last for about two or more months, depending on the frequency of theteaching units. In order to fulfil language requirements for the subsequentmigration of spouses, it is not important how – independently or as part ofthe course – the spouse has achieved basic oral and written language abilityin German.14The ‘StartDeutsch 1’test requires payment of a fee. It is offered by theGoethe Institute and telc GmbH jointly. It consists of a written individual ex-amination and an oral examination in a group. Two testers evaluate the testachievements. The tasks of the language test are action-oriented and involveall four language skills. The written examination lasts 65 minutes and con-tains listening, reading and writing. The oral examination lasts approxi-mately 15 minutes and is taken in a group: each candidate has to introducehimself, provide information and ask for information, as well as make a re-quest and respond to it. The maximum number of test candidates in thegroup oral examination is four. Every task in the oral examination is compli-cated and involves several cognitive operations: test candidates have tocommunicate basic information about their name, age, country, address, ac-tive working languages, profession and hobby. They also have to be able tospell their names and to deal fluently with numbers. Every task should be in-troduced with a sample. Furthermore, the appropriate situational use of lin-guistic means is decisive. This means the candidate’s knowledge of certaineveryday situations in Germany in which they know how to react linguisti-cally. That means that candidates must be familiar with text types such assigns, posters, catalogues, e-mails, postcards, and similar forms. They mustalso possess specific information about the country, culture and everydaylife. To pass the test, the candidates must score 60 points.15ProofsThe statutory condition of being able to communicate in German at a basiclevel corresponds in practice to the definition of CEFR level A1 (BRat-Drs.669/09, p. 246, BTag-Drs. 16/5065, p. 311). Proof of language ability is basi-cally led in the visa procedure. Nevertheless, proof of the language acquisi-tion is not required if it is evident from a personal conversation that thespouse possesses German language ability at least at level A1 (BRat-Drs.669/09, p. 248). Level A1 is the lowest level of proficiency. It includes all four14The ‘place of language acquisition’ is of particular importance for ethnic German appli-cants. Since 1996, they have had to demonstrate German language knowledge that hasbeen acquired in a family and is sufficient for basic communication in German in an in-terview (Anhörung) organised in the country of origin (Seveker 2008: 199).It is to be emphasised here that the test of language acquisition for dependants of ethnicGermans (Aussiedler) is also based on the directives of the ‘StartDeutsch 1’test. If theyhave non-German spouses aged 60 and over or descendants aged 14-16, knowledge ofthe German language at a reduced level of 52 points is accepted as adequate (Seveker2008: 211).

15

GERMANY

basic language skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing). Proof of so-cietal knowledge16before entering Germany is not required. It is differentfrom granting a settlement permit, or the naturalisation procedure.Costs of the (preparation for the) testAccording to the Goethe Institute, the amount of the test fee is adapted to thelocal conditions, to cover the costs of management and administration of thetest (WS 30039 interview of 29 April 2010). Moreover, no allowances aremade. Internal test candidates pay reduced fees; internal test candidates arepeople who have taken part in a language course at the Goethe Institute. Insome countries, internal test candidates have only to pay the course fee andare exempt from the test fee (to some extent in Turkey). A reduced fee is re-quired in few countries to retake the test: The test fee in Kenya amounts to5,000 KSh (approximately €50) for internal test candidates (3,500 KSh for re-takes) and 6,500 KSh for external test candidates (5,000 KSh for retakes); thefee for the test preparatory course at level A1 amounts to 2,000 KSh (ap-proximately €18, situation on 6 July 2010). No language courses are offered inIraq, the test fee here is 200 USD (approximately €135). The test fee in Syriaamount to 3,500 SYP (approximately €58) for internal candidates and 4,500SYP for external candidates. The test fee in Bangkok (Thailand) is 2,500 THB.The course fee in Turkey is normally 990 TL (approximately €490) and thetest fee (e.g. in Istanbul) 140 TL (approximately €68, external) and 120 TL(approximately €60, internal). Payment by instalment is possible at theGoethe Institute of Ankara.Spouses have to acquire the required language skills at their own ex-pense. The test fee at the Goethe Institute in Germany does not differ consid-erably from the fee abroad. Internal test candidates at the Goethe Institute inGermany should pay €60 for the test (external €80). A higher test fee of €150is due at telc GmbH (situation on 6 July 2010). A standard fee of €60 may benormally charged for issuing visas (Section 46AufenthV).The costs for an immigrant from Turkey, for example, in order to fulfilthe integration requirement for admission amount to €610 (€490 course fee,€60 test fee and €60 visa fee).The visa may not be granted if a spouse has not passed the language testbefore entry. Therefore, it is not possible to enter the Federal territory. Thetest can be repeated unlimited times. This does not imply legal consequencesfor the affected parties. However, it does imply high financial costs and along period of separation. The language certificate issued by the Goethe In-stitute does not expire. Nevertheless, the Goethe Institute emphasises that16The TGD offers orientation courses for spouses who live mostly in the eastern areas ofTurkey and throughout Turkey and wish to join a spouse in Germany. The aim of thesecourses is to improve the integration of Turkish families in Germany (WS 30029 inter-view of 25 April 2010).

GERMANY

employers and institutions usually require a language certificate that shouldhave been issued within the past two years. If the language certificate was is-sued more than a year ago, the content reliability of the certified languageability can be demonstrated in the visa procedure (BRat-Drs. 669/09, p. 248).The reason given for this is the quick loss of acquired language ability. Thispractice calls into question the reliability of the language requirements beforeentry with a view to the subsequent migration of spouses.

2.1.2 Purpose of the TestThe language test was introduced with reference to non-compulsory restric-tions of the Family Reunification Directive, pursuant to the Act on the Im-plementation of the Directives of the EU on the Right of Residence and Asy-lum that came into force on 28 August 2007. Although there is no direct rela-tionship, the Directive constituted the ‘folio of new rules’ (Kreienbrink &Rühl 2007).The debate showed the clear influence of the politics of other countries:in the legal policy debate about the restrictions on the reunification ofspouses, reference was made to the integration requirements of the neigh-bouring country and it was pointed out that Denmark and the Netherlandshad had ‘positive experiences’ with raising the age limit for spouses. Thelanguage test was also extended to spouses of Germans. However, an explicitdistinction between Germans, or a special legal justification of Germans asopposed to third-country nationals, is lacking in terms of restrictions. The re-strictions initially apply to both. Although the restrictions on the family re-unification of spouses are phrased neutrally in the wording of the law andapply to reunification with German nationals as well as foreign nationals,they are meant to avoid the situation where Turks, in particular, who holdtraditional values and who are living here, bring very young wives uninflu-enced by Western values from their country of origin to Germany. This objec-tive is the direct result of the Explanatory Memorandum as far as it argues infavour of application of the language requirement for third-country nation-als. According to this, the language requirements are geared towards certainnaturalised immigrants on the assumption of a certain ‘family concept of theaffected groups’: They are justified by promoting or demanding integration(through language), protection from forced marriages and violations of hu-man rights as well as the protection of the social welfare state (BT-Drs.16/5065 of 23 April 2007, pp. 307-314).17This objective is the result of the17The position of German law regarding Germans with a migration background becomeseven clearer in the justification of economic discrimination, which was introduced withrespect to family reunification with Germans. Concerning the requirements guarantee-ing subsistence, a decisive factor is whether it is possible to build family unity in the→

GERMANY

regulation system after the deduction of numerous exceptions concerninghighly skilled persons, researchers or self-employed persons and, in the caseof permanent residence status, of the sponsor, or in the interests of close eco-nomic relations with certain countries (see 2.1.1).Protection from forced marriages through the introduction of the lan-guage test before entry was crucial in public debates and the media. This led,above all, to the death of the young Kurd, Hatun Sürücü, in the spring of2005, a victim of a so-called ‘honour killing’ after the separation of a forcedmarriage.18In public discussions in Germany, forced marriage is often de-fined a human rights question (Ratia & Walter 2009). The participants in thepublic debates on forced marriages are intellectuals (such as philosophers),politicians, and women’s rights advocates with a Turkish background. Biele-feldt and Folmar-Otto, both philosophers at the DIMR (German Institute forHuman Rights) and leaders of intellectual debates on the multicultural soci-ety, and the Berlin NGO Papatya for migrant women, stress that forced mar-riage is a breach of human rights.One can consider the introduction of forced marriage as a specific offencein 2005 as the first legal outcome of this debate.19Since then, the debates havemostly focused on how to prevent forced marriages in the area of migrationlaw, especially through the two new additional entry requirements – theminimum age as well as a basic knowledge of the language prior to entry –for spouses of third-country nationals and Germans. By this time, the formerred-green Government had been followed in 2005 by the new coalition part-ners CDU/CSU and SPD. Afterthepresentation ofthe official draft of theRLUmsG by the Government on 28 March 2007, numerousexperts, officials oftheBundesländer,NGOs, migrant organisations as well as representatives of thechurches, gave their statements in a session of the Bundestag in May 2007.20On the

181920

country of origin of a spouse. The law makes a distinction between German nationals:in future, family reunification cannot only be denied to third-country nationals but alsoto Germans if the sponsor cannot guarantee a sufficient income (cf. Section 28, par. 1,sentences 2-4 Residence Act). The former privilege for spouses of a German ceases toapply. Pursuant to the Explanatory Memorandum, ‘special circumstances’ exist for per-sons of whom matrimonial cohabitation abroad can reasonably be expected. This espe-cially concerns holders of dual citizenship with regard to the country whose nationalitythey possess in addition to German nationality, or Germans who have lived andworked for a fairly long time in the spouse’s country of origin and who speak the lan-guage of this country (BRat-Drs. 224/07, p. 293 f.).TheTerre des femmesGerman organisation has already drawn particular attention to theproblem through various campaigns since 2002.Political parties, such as the SPD and the CDU/CSU, have also argued for banningforced marriages in their election programme’s for the Bundestag elections of 2005.See the materials: http://fluechtlingsinfo-berlin.de/fr/gesetzgebung/2_AendG.html#mozTocId858737. The hearing of the Committee on Internal Affairs in March 2006 was simi-→

GERMANY

one hand, therewas strong disagreement concerning the constitutional con-formity of the provisions, criticised for example by the German Institute forHuman Rights,Verband binationaler Familien und Partnerschaften(iaf),Deutscher Juristinnenbund(djb), Jesuit Refugee Service, Amnesty Interna-tional, TGD or German Bar Association (DAV). On the other hand, alterna-tive measures with more of a trend towards victim protection have been de-bated. The green party (Bündnis90/DieGrünen)and human rights organisa-tions proposed a further enhancement or establishment of protective provi-sions, especially the right to return after six months in cases of forced mar-riage where the right of residence has expired in the foreign country (Sect. 51AufenthG).21Other critics argue that the phenomenon of forced marriageneeds more research before the introduction of legal measures. In the view ofthe Ministry of the Interior these alternatives are an invitation to abuse andthe preventive concept of the official draft is more favourable.22In spite ofnumerous statements in the legal procedure, the language requirement en-tered into force in 2007.Finally, in the Explanatory Memorandum much emphasis was alsoplaced on protection from forced marriages in terms of human rights. Ac-cording to the Explanatory Memorandum, in-law families use the lack of theGerman language ability deliberately or indirectly to prevent the victim(usually female) from having an independent social life. The legislator arguesthat the obligation to attend the integration course after entering Germanyshould not apply equally because of the time delay before the beginning ofthe course and the process of language learning, while the victim would besubjected to the will of the family-in-law. Besides, German language learningwould be possible in the country of origin and guarantees (result-oriented)successful language acquisition. The regulation would have a more preven-tive effect than the attendance obligation after arrival in Germany. Educatedmen and women would be more unattractive, according to the family con-cept of affected circles, and would be difficult to ‘control’, which is allegedlysignificant for those applying force. A basic command of the language wouldalso be imparted by this education (BRat-Drs. 224/07, pp. 298f.). In general,the Courts also accept these arguments.23The Goethe Institute collects the data on language tests within the con-text of subsequent migration of spouses. The ‘test centres’ are the Goethe In-stitutes and the German Diplomatic Missions. An evaluation report on the

212223

lar, concerning the Ministry draft (Referentenentwurf), which came from the formerred-green Government in 2005.See 6. Lagebericht (2005), p. 300. There is however a longer time for long-term residents,Art. 9 par. 2 Directive 2003/109/EG (long-term residents).SeeEvaluationsbericht 2006 BMI(p. 114).Higher Administrative Court Berlin-Brandenburg, judgment of 28 April 2009, FederalAdministrative Court, judgment of 30 March 2010 (Reference no. 1 C 8.09).

GERMANY

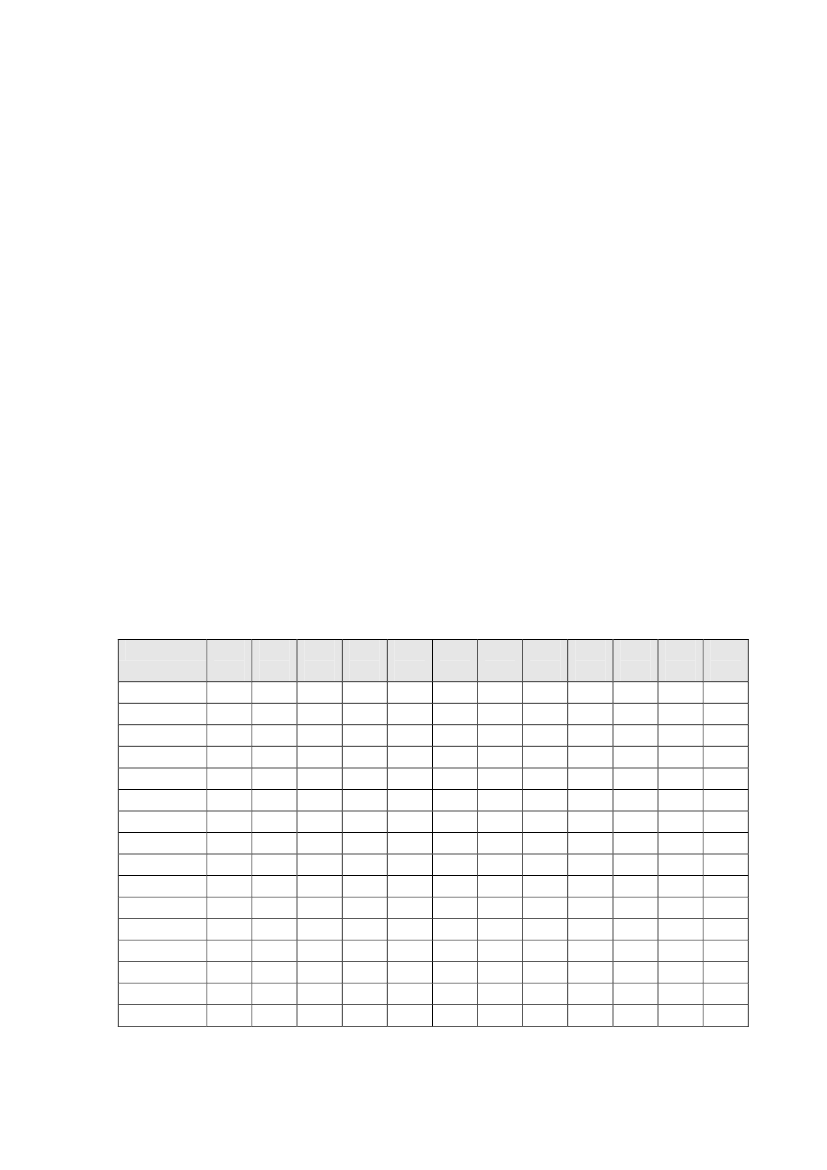

practices for demonstrating language ability has been prepared by the Fed-eral Foreign Office, the Federal Ministry of Internal Affairs and the FederalGovernment Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration (BTag-Drs. 17/3019 of 24 September 2010).Effects of the TestStatisticsA downward trend in visas granted for spouses becomes obvious after theintroduction of the proof of the language ability as a condition for admissionin 2007 (cf.8. Lagebericht 2010:469). The comparison of the visas issued beforethe amended legislation with visas issued after the legal amendment resultedin a decrease of 25% for the reference period, in general (BTag-Drs. 16/13978,p. 1), and of about 35 to 42% (BTag-Drs. 16/10215) in four main countries oforigin (Turkey, Kosovo, Russia and Thailand), and of about 38% only in Tur-key (BTag-Drs. 16/13678, p. 1).The quarterly comparison of visa statistics in 2009 shows an irregulardevelopment. An increase in visas issued of about 2.91% is evident from7,825 visas issued in the first quarter to 8,053 visas granted in the secondquarter and an increase of approximately 12.1% to 9,027 visas issued in thethird quarter (BTag-Drs. 16/13978, p. 2; BTag-Drs. 17/194, p. 2). In the fourthquarter of 2009, the number of visas issued amounted to 8,289. Therefore, itwas lower than in the previous quarter (BTag-Drs. 17/1112, p. 2).Table 2.1: Family Reunification of Spouses 2007-2009 (main countries of origin)I/2007TurkeyKosovoRussian Fed.ThailandMoroccoIndiaChinaBosnia Herz.SerbiaTunisiaMacedoniaKazakstanUkraineVietnamIranWeltweit25839177314994122771942722182201811841571741579449II/200723148687755303583275332572052321702001531691549267III/200720687136644333263111902263052011831601461511228603IV/2007673313468191161288201158160931161051531041125147I/20081405413453266268380167150184138133431791191106458II/200817786314773293294462322362551551441052291131087771III/200820038505403833544192602192181511531182621381468445IV/200817007945473543383932632062142091471142541401578093I/20091798732419340262469278169173194144832001341117825II/20091714615494353322450269177173156155892281311438053III/20091771809609294436466281198210191181972561561549027IV/20091622693635338393380258203158161129932441461338289

Source: Evaluation Bundesregierung 2010, BTag-Drs. 17/3090, p. 32

GERMANY

In 2008, 30,767 visas as part of the subsequent migration of spouses weregranted and 33,194 similar visas in 2009 (ibid.). This means a general increaseof about 7.89% over the whole year 2009. Generally, a downward trend in vi-sas has become obvious between 2002 and 2006. In 2002, 64,021 visas weregranted and 39,585 in 2006 or before the relevant law amendment. Its causecan be found in the accession of ten new Member States (BTag-Drs. 16/13978,p. 3). A sample comparison with the figures for spouses who entered Ger-many at municipal level – e.g. in Munich – also shows a clear decrease be-tween 2006 and 2008 of on average about 41% (from 4,725 to 2,795); note inparticular 34% in cases of the subsequent migration of the spouse of a Ger-man and 45% for family reunification with a foreigner. From the municipalofficials’ point of view, this decrease is related to the introduction of the lan-guage tests before entry as well as to the accession of Romania and Bulgaria.Without the observed avoidance cases, the decrease would have been evenmore significant (WS 30038 interview of 28 April 2010). Entering Germany ona Visitor’s Visa to learn German in the country and subsequently applyinghere for family reunification is only an example of bypassing the tests abroad(ibid.).Since the amendment in August 2007, the number of tests at the GoetheInstitute abroad has risen rapidly within a very short time. According to theGoethe Institute, the number of the test candidates has decreased from 60,111in 2008 to approximately 45,242 in 2009 (situation on 9 April 2010). TheGoethe Institute explained this by the fact that some of those affected becamestuck because of the introduction of new language requirements (WS 30039interview of 29 April 2010). The success rate24was to 59% (54% external and73% internal test candidates25) in 2008 and to 64% (61% external and 74% in-ternal test candidates) in 2009 (data from the Goethe Institute, situation on 9April 2010). In this respect, a clear increase in the number of the external testcandidates who passed the test is noticeable. On the one hand, this is pre-sumably related to the attendance of future spouses at language courses inGermany, who had given a different purpose for their stay in Germany, inthe visa procedure, than language acquisition or family reunification. Theteachers interviewed in this study emphasised an increase in interest in the24Interestingly, the data on the success rate in 2008 provided by the Goethe Institute(situation on 9 April 2010) did not coincide with those in the printed papers from theBundestagfor the same period (situation on 13 March 2009). The comparison of the suc-cess rates in 2008 with those in 2009 given in the printed papers from theBundestagshows a decrease from 66% (BTag-Drs. 16/3978, p. 13) to 64% (61% externally (in thiscase a stagnation) and 78-74% internally). This reduces the validity of success rates andcan (presumably) be explained by technical problems concerning the data collection,which currently mean that the data on the retakes have not yet been collected by theGoethe Institute.Internal test candidates are people who have taken part in a language course at theGoethe Institute.

25

GERMANY

language course at level A1 in Germany (WS 30044 interview of 30 April2010, WS 30056 interview of 20 May 2010). Language courses for self-supporting participants at levels A1.1 and A1.2 were offered on request inStuttgart. To some extent, Serbian citizens have taken part in these courses inorder to return subsequently to Belgrade to take the test there. Moreover, itshould be pointed out that external possibilities for learning German inde-pendently are also available on the Internet or by attending a languagecourse given by private providers in the country of origin, for whom the testbefore entry makes the market attractive because of interest from spouses in-tending to live together in Germany as a couple.On the other hand, the increase in the number of the external test candi-dates who had passed the language test before entry is also dependent on‘test tourism’, as migrant advisory services referred to this trend (WS 30023interview of 16 March 2010). According to the Goethe Institute, the fact thatthe test candidates made their first attempt, for example in Albania, and theirsecond attempt in Macedonia, makes it difficult to collect data on retakes.‘There are rumours concerning the tests that it is easier to pass the test in onestate than in another. We usually prove this if it becomes known. We inspectthe institutes and carry out audits. So, there may be a difference with regardto external conditions, but the test itself corresponds closely to uniform stan-dards’ (WS 30039 interview of 29 April 2010). With this ‘test tourism’ inmind‚ a special regulation was introduced by the Goethe Institutes in Alba-nia, Kosovo and Macedonia, specifying that these countries’ nationals shouldbe tested in the country of origin (ibid.).Looking at the statistics for success rates, the situation is different, it ismore of a rising trend from 59% in 2008 (54% externally and 80% internally)to 65% in 2009 (61% externally and 81% internally) in 15 main countries oforigin (ibid.). This is an indication of a clear increase, looking at the successrate in Turkey, from 60% in 2008 (92% internally and 57% externally) to 68%in 2009 (92% internally and 64% externally) (data from the Goethe Institute,situation on 9 April 2010). This is (presumably) related to the improved di-dactic aspects of language learning at the Goethe Institute26abroad and theactivities of the TGD in Turkey. On the one hand, a detailed comparison ofthe success rates in the main countries of origin shows that the internal can-didates usually perform better in the test before entry than in the external

26

The Goethe Institute has developed not only a book in German and Turkish(MeinSprach- und Deutschlandbegleiter,Ethem Yilmaz,Verlag für Deutsch-Türkische Kommunika-tion,Bochum 2009), also including to some extent data on the respective advisory cen-tres for immigrants, but also a photo box or linguistic game relating to everyday life inGermany for special use in DaF and DaZ courses, covering Shopping, Health, Mobility,Lessons and Living in Germany including tips for beginners’ lessons (WS 30039 inter-view of 29 April 2010). The 7-minute film by Hülya Çağlar(Guten Morgen Almanya,Iz-mir 2007) also offers an insight into the language courses abroad.

GERMANY

test. On the other hand, there is no indication of a constant increase in thesuccess rates for internal candidates. This can be illustrated by the successrates in Macedonia, which were 99% in 2008 and 85% in 2009 (internally).Moreover, an analysis of available statistics shows that available figures cancurrently provide only limited reliable data for evaluating the effects of thetest for entry27from outside Germany.SelectionFrom the migrant advisory services’ point of view, the test before entry con-stitutes a form of selection because it is regarded as an obstacle only for a cer-tain population group with regard to origin, level of education and languagelearning experiences: ‘Only men and women who can read and write maymarry de facto’ (WS 30027 interview of 14 April 2010). From the teachers’point of view, the test format is an obstacle for a certain population group aswell (WS 30038 interview of 28 April 2010 and WS 30044 interview of 30April 2010). To some extent, the distinction is blurred between CEFR levelsA1 and A2, which can be recognised through the use of text types and is anadditional difficulty for test candidates, e.g., it causes problems when dealingwith a written task. The tasks of the test are related to living situations inGermany, which are unfamiliar to the test candidates abroad. It makes thelanguage standards more difficult because not only language ability, but alsocertain cultural patterns must be demonstrated by the test (WS 30025 inter-view of 9 April 2010 and WS 30048 interview of 5 May 2010 with a Thaiwoman, 26 eyars old), it is ‘a sort of colonial education’ (WS 30027 interviewof 14 April 2010) if, for example, a Thai woman has to explain snow or activi-ties within associations in Germany during the test, with which she is notfamiliar (ibid.).Which part of the test is the most difficult?From the immigrants’ point of view, listening is the most difficult disciplinein the test abroad. The spoken language in the recordings for the test and thespeech of officials in the Diplomatic Mission is regarded as rapid. To someextent, migrants explain the high number of retakes by the fact that the test27Furthermore, looking at the statistics for the success rates in the tests before entry, dataare also available for the success rates of the ‘StartDeutsch 1’test candidates collected in2009 in Finland, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Japan, Canada, New Zealand, Norway,Portugal, Scotland, Sweden and Uruguay (situation on 9 April 2010). There are no dif-ferentiated data on the test candidates to explain the participation of this populationgroup in the test before entry. It mainly concerns a small number of test candidates. Thelanguage ability of Union citizens does not have to be demonstrated in family reunifica-tion. This means that changes caused by the rulings in the Metock case do not seem tohave reached every country. Besides, it is interesting to note here that success rates havebeen optimum in the countries mentioned above as well as in Singapore, Sudan andUruguay.

GERMANY

candidates do not pass the listening part of the test or they sit the test with-out being prepared for it. The Goethe Institute also confirms that somespouses intending to migrate to Germany register for the test to learn moreabout it without being prepared (WS 30039 interview of 29 April 2010). ‘Na-ive perceptions’ by the immigrants with regard to language learning thatpersist after admission to Germany, when course participants assume thatthe language can be learned automatically without making any attemptwhile the learner is regularly present on the course, can be also recognised inthe language courses abroad (WS 30056 interview of 20 May 2010). Further-more, it is remarkable that teachers abroad as well as teachers of integrationcourses in Germany have to motivate the participants, not only regarding thepurpose of the law concerning the subsequent migration of spouses but also,to some extent, regarding language learning in the obligatory integrationcourses (ibid, WS 30039 interview of 29 April 2010).FraudThe Goethe Institute had to address its efforts not only to language teaching,but also to safety measures in some countries. ‘A virtual industry was builtup – with brand-name ball pens, headscarves and walkie-talkies, as well aspassport forgeries. Teachers and course participants have been threatened’(ibid.). There have been cases of avoidance as well as attempts at fraud. Toimprove identity controls, registration for the test takes place in person andon a different day from the test itself. It is seen as a burden by those affectedbecause of distances to the examination location and the financial expense(WS 30027 interview of 14 April 2010). For an unknown reason, the oral ex-amination also takes place, in some cases, for instance in Egypt, three dayslater than the written examination (WS 30025 interview of 20 May 2010). Inaddition, an applicant’s fingerprints can be checked during the visa proce-dure in some countries – West Africa, Nigeria or Guinea – to identify the per-son in the light of apparently false statements about a previous stay in Ger-many.Furthermore, the uncertain source of documents, such as in Nigeria, con-stitutes serious problems in the visa procedure, let alone in demonstratinglanguage ability. ‘The issue of documents and certificates is not based ondocuments that are registered there, but hearsay. The result of this is differ-ent spelling variations and doubts concerning authenticity. However, thedocument can also be authentic, but with the wrong content. Real life is notstraightforward and people get stuck at the edges and corners’ (WS 30025 in-terview of 9 April 2010). The visa procedure is repeatedly criticised in that itlacks transparency and constitutes, in addition, a tripwire.Test abroad: are the goals achieved?The purpose of the test is to promote integration and to provide protectionfrom forced marriages. Not only teachers of integration courses, but also mi-

GERMANY

grant advisory services and migrants regard the courses as positive but seethe costs and efforts involved in the test as a burden for those affected. Onthe one hand, those affected as well as the municipal officials in Germanyview the possibility of learning German through courses abroad as positivebecause a basic command of the language may help the persons involved tomake purchases by themselves, to ask questions independently and makesthe newly arrived immigrants more self-confident (WS 30045 interview of 30April 2010 with a migrant woman from Turkey, 22 years old, a woman fromKenia (24 Jahre alt) and a migrant woman from China (23 years old) and WS30054 interview of 17 May 2010). A migrant woman from Turkey inter-viewed in Stuttgart was graded at a level higher than A1 at the VHS on ac-count of her present language ability in German. In her opinion, this was in-dicative of the quality of the courses in Turkey. On the other hand, migrantsand migrant advisory services have repeatedly closed the discrepancy be-tween what is demanded and the knowledge that those involved actuallypossess after the test abroad. ‘I do not think it is good because people do notspeak German after passing the test’ (WS 30055 interview of 20 May 2010with a migrant from Egypt, 30 years old). Some of the immigrants inter-viewed failed the test several times. Several of the migrants interviewed tookpart not only in the German language courses at the Goethe Institute but alsoin private German classes, e.g., in Egypt and Kenya. None of the interviewedmigrants emphasised that the language requirements for the subsequent mi-gration of spouses were easy to fulfil.The fulfilment of language requirements is associated with strenuous ef-fort, psychological burdens, partner stress and family stress: ‘Many peopleare at breaking point over it, which means that I give these couples adviceabout family reunification and then transfer them to my colleague in the de-partment of separation and divorce’ (WS 30025 interview of 9 April 2010).From the migrant advisory services’ point of view, this regulation reinforcesthe imbalance of power between women and men and makes a wife emo-tionally and financially dependent on her husband. It was quite incompre-hensible to all the interviewees how the language test could prevent forcedmarriages. Migrants, their spouses and migrant advisory services have re-peatedly felt that the language test does not prevent forced marriages, butdoes select or prevent entry from outside Germany: ‘A mixed marriage wasonce forbidden, today, it can be prevented or broken’ (WS 30048 interview of5 May 2010). ‘We often had dramatic cases; a girl in Afghanistan had to go toKabul, through enemy territory, not only to take the course, but also to applyfor a visa. Then she was smuggled across the border. *<+ We will not get agrasp of the problem of forced marriages through measures provided pro-vided for in the migration law’ (WS 30039 interview of 28 April 2010). Ac-cording to the evaluation of the government however, teachers abroad hadnoticed in some cases that women deliberately failed the examination in or-der to avoid a forced marriage in Germany (BTag-Drs. 17/3090, p. 5).

GERMANY

The fact that spouses willing to migrate to Germany for family reunifica-tion can be repeatedly controlled by the visa procedure based on their lan-guage ability is perceived by those affected individuals as trickery and arbi-trary measures on the part of the authorities. The Diplomatic Mission provesthe authenticity and the correct content of documents suitable for an applica-tion, including proof of language ability on the basis of the lists of partici-pants issued by the test centres and asks them for a statement if there are anydoubts. If there are considerable doubts about the correctness of the languagecertificate in the visa procedure, the language ability of the applicant can beproved in a basic conversation in German (BTag-Drs. 17/1112). Those af-fected were asked, at the Embassy in Thailand, for example, what colourtheir blouse was and they had to write down their name and address despitehaving passed the language test (WS 30027 interview of 14 April 2010). Therewere also complaints about spouses who had migrated to Berlin and weretested by the Foreigner’s Authority a second time (WS 30023 interview of 16March 2010). These administrative procedures and costs on the part of theauthorities, as well as the efforts made and expenses incurred by those af-fected would appear to be disproportionate to a low success rate, taking intoaccount the statements of the teachers in Germany.Most of the teachers of integration courses interviewed as part of thisstudy considered that the output of the language test before entry is low andthe costs for those involved are high. Generally, the teachers in Germany donot regard the results of the language test at level A1 as significant because ofdifferences in the language ability at the first level of proficiency: ‘[the resultof the language assessment test in Germany] is very low, although the par-ticipants had passed the language test abroad. As a rule, they decline a littlebit’ (WS 30044 from 30 April 2010). ‘The tests at levels A1 and A2 contributenothing. Since the introduction of the ‘Deutschtestfür Zuwanderer’(DTZ),other tests are dispensable’ (WS 30047 interview of 5 May 2010). ‘Many par-ticipants are only present, they do not say a lot, they can do nothing, andthey say proudly that they passed the test at level A1. They have a certaindegree of trust in the test; they also do not want to be graded in spite of theirobvious lack of language ability’ (WS 30056 interview of 20 May 2010). Amore or less clear line of reasoning is also adopted by migrant advisory ser-vices in Germany interviewed for this study. They do not question that mi-grants must learn the German language; however, they have spoken outagainst the fact that this is bound to the tests in the visa procedure. From themigrant advisory services’ point of view, attendance of the language courseat the Goethe Institute constitutes the best preparation for the test in terms ofquality. The fact that more language courses have been offered and teachershave been trained does not change the regulation governing the languagetest before entry and considered absurd by the migrant advisory services(WS 30025 interview of 9 April 2010). From the migrant advisory services’point of view, it is incomprehensible that those affected have to learn by rote

GERMANY