Udvalget for Videnskab og Teknologi 2010-11 (1. samling)

UVT Alm.del

Offentligt

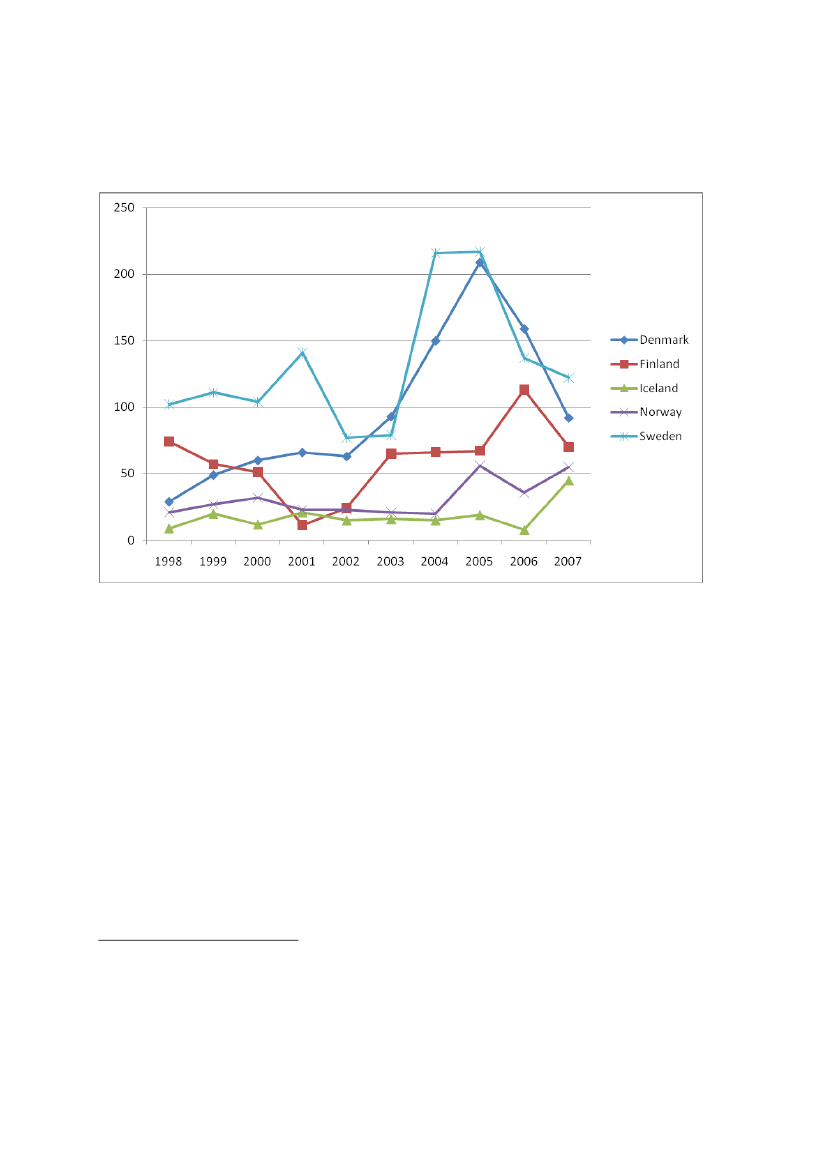

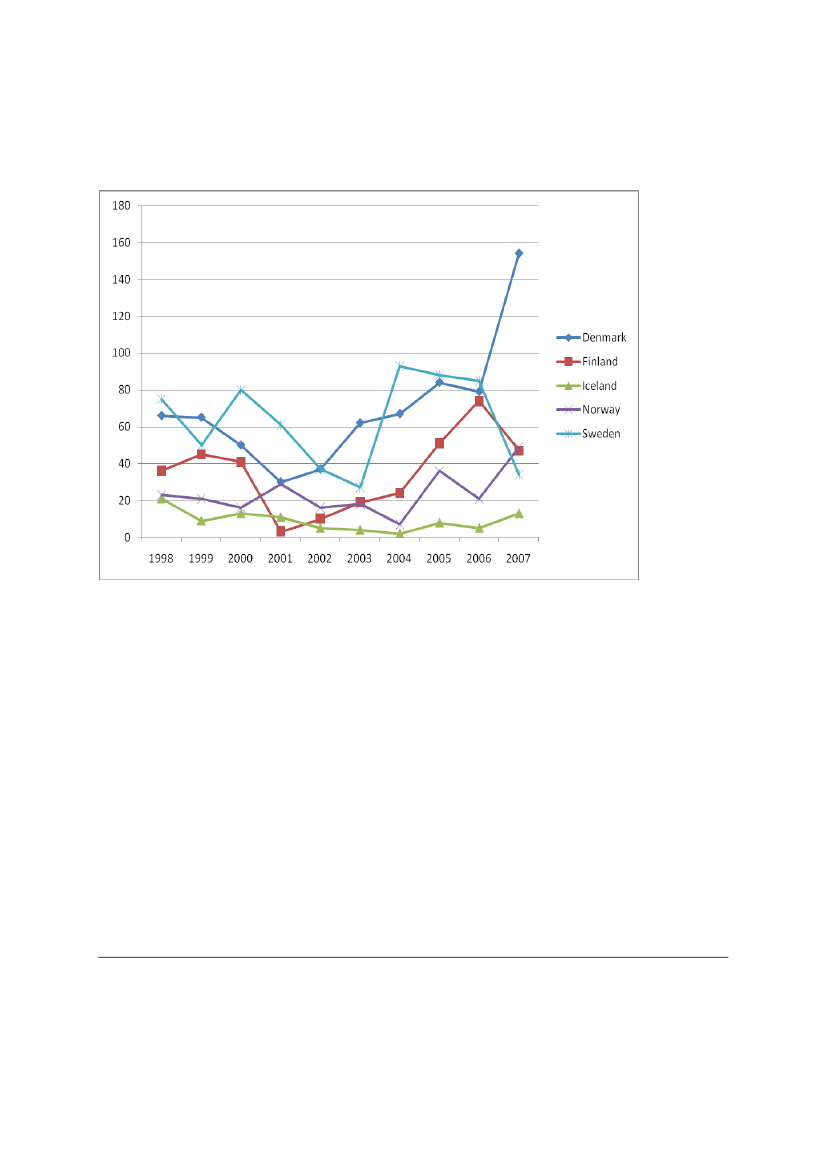

3.3.1. RESOURCES AND FUNDINGThe resource/funding topic group encompasses seven issues. . For Denmark, Finland and Iceland we can see arising trend for funding/resource issues from 2002 onwards but which then declined in 2005/2006. For Icelandand Norway the trend is rather stable until 2004/2005 and reaches its highest level in 2007.21

Figure 13.1 Economic issues by country and year (N=3768)

V36 Total national level of financial resources for research (e.g. Percent of GNP)V37 The distribution of financial resources for research on public and private researchV38 The distribution of financial resources for research on scientific fieldsV39 The distribution of financial resources for research on different types of researchV40 The prioritization of financial resources for research between different types of research institutions (macro-level)V41 Ways of financing total national research activity (macro-level)V42 Ways of financing different types of research institutions/specific themes (macro-level)V43 Different models for financing research (including different funds)

21

48

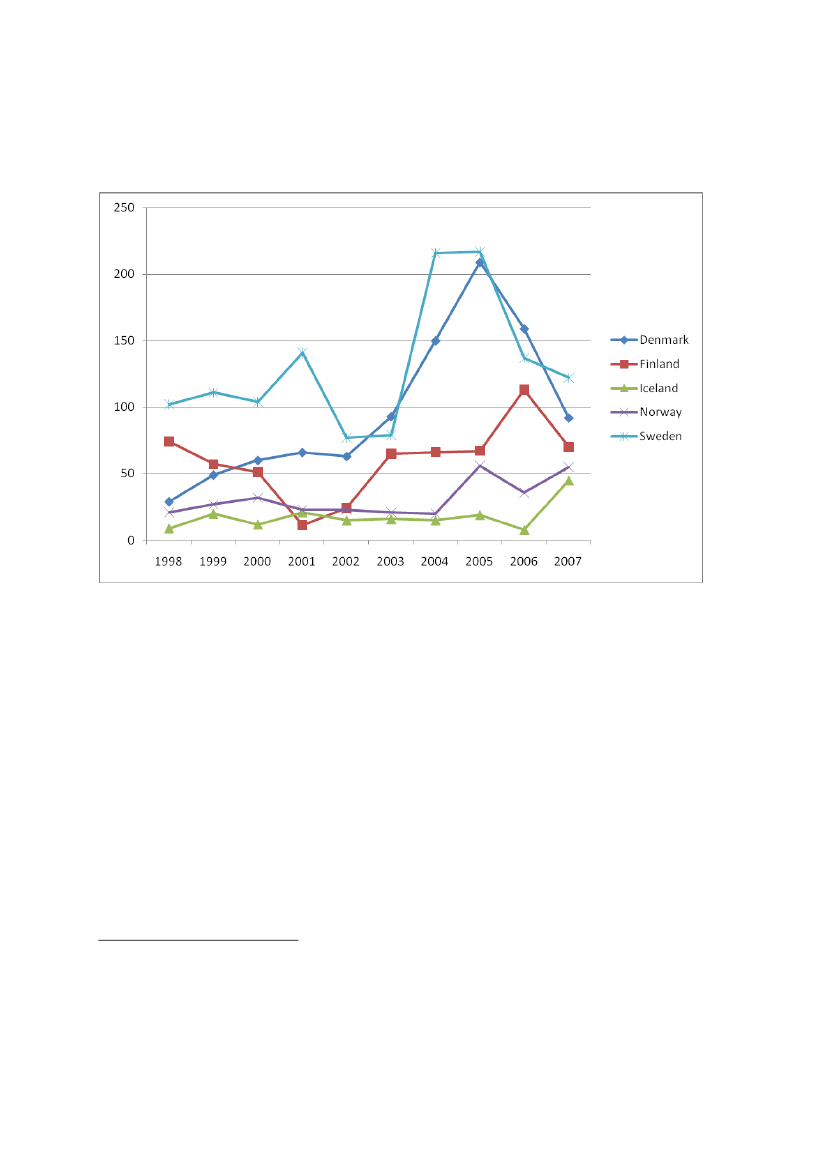

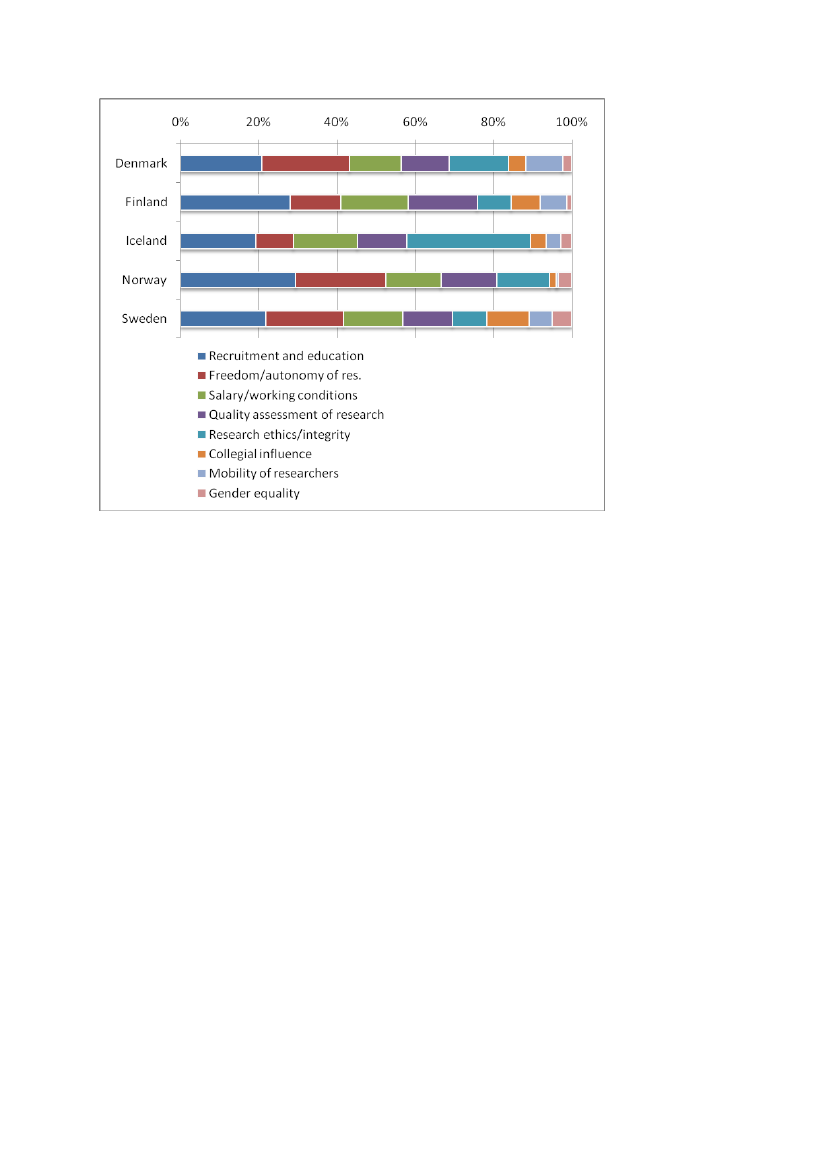

Figure 13.2 Economic issues by country and sub-themes (N=3768)In Figure 13.2 the relative prevalence of the different financial/resource issues is indicated for each of theNordic countries, enabling comparisons between countries for the whole 10 year period.DenmarkIn Denmark economic issues became an increasingly important topic on the public agenda until 2006 whenconcerns about economy declined somewhat in Denmark. The concern is primarily about the total level ofnational funding. Many actors were involved in this debate which put the Minister of Science, Helge Sander,under pressure to find more money for Danish universities. A regular debate has taken place about the politicalgoal, stated and repeated by the Minister of Science every year since 2003, to reach the so-called Barcelonatarget of 1% of GDP to be invested in public funding. Much of the debate in Denmark focused on how far orhow close Denmark was to this 1%. The Minister of Finance participated in that debate, as did severaljournalists, university leaders and individual researchers. In this the debate Denmark was frequently comparedto Sweden and Finland.FinlandPrinciples of funding have been the subject of debate over time in Finland, especially in 1998 and 2007. Thedistribution of resources by the Academy of Finland has provoked critical comments that question the role ofthe Academy, and proposals to change the status of the Academy. Accusations were made that the Academyand its committees have favoured certain circles and groups of researchers when allocating funds. The debatehas been broad and covered topics such as the overall shortage of money in the universities and the one-sidedfunding policy of the Academy after it had started promoting the Centres of Excellence. Concerns were voicedthat its funding principles would lead to unnecessary polarization between researchers by labelling someresearchers as “top” researchers and others as “mediocre”.

49

A somewhat frequent subject in the public debate has been R&D expenditure as a share of GDP. Even thoughthe high levels of R&D investments in Finland are usually taken as an example of success, there were criticalvoices in the public debate starting already in 1999. State funding had been cut in all sectors and savings weremade in the early 1990s which created a deficit in funding as some writers claimed. In addition it was argued inthe debate that the state’s investments in R&D have not substantially increased. Furthermore, criticism hasbeen directed at the fragmentation of research funding. In 2002 and 2003 it became clear that there wasdissatisfaction with investments in R&D, especially with the relation between public and private investments inR&D. One reason for the accelerated public debate was the difficulties experienced by technology companieswho had to fire employees as global competition caused a shift of jobs to low cost countries. The newgovernment programme was criticized and commented by the editorials in Kauppalehti (2003-03-14 and 2003-04-30), stating that Prime Minister Lipponen’s second government has left the R&D investments on theshoulders of private companies.IcelandFinancial issues were important in the Icelandic debate. The structure of the financial system was frequentlydiscussed, and increasingly so during the period. Iceland at this time was among the top five OECD nations interms of overall R&D expenditure, and at the very top as concerns public funding of R&D. A prominent issue inthis discussion was how to distribute public funds. Historically, Icelandic public organisations have beenallocated a block amount to finance R&D activities, leaving to the organisations themselves to decide on theuse of these funds. By increasing the competitive research funds, applicants were increasingly required tocompete for financial support. Some claimed that this would harm basic research, while others saw this as anappropriate way to allocate public funds. Articles about lack of funding for either research and development orfor innovation were also common. According to some, lack of funding of R&D in emerging fields could delay thepossibility to exploit the opportunities of these fields.NorwayResource issues in general and overall levels of research funding in particular were at the core of the debate inNorway throughout the period. Sixty percent of all articles touched upon at least one resource issue, and one-third of all articles addressed resource level issues.In 1999 Norway set the target to raise the overall level of R&D resources as proportion of GDP to “the averageof the OECD countries”, which at the time meant increasing the level from 1.7 to 2.3 percent of GDP. In 2005,the target was aligned with the EU Barcelona target and raised to 3 percent. While these formal targets madethe overall level of research funding a core issue of research policy throughout the period, the debate on theinsufficient funding and poor conditions for research in Norway predated them by far. The public debate maybe seen to have exerted a pressure on the policy-making process, and contributed to its adoption. The issue ofinsufficient funding was initially most strongly voiced by medical researchers. The inferior position ofNorwegian research and research funding compared to its Scandinavian neighbours is a rhetorical figure thatpervades the debate on the resource issue throughout the period. The adoption of the targets has created abasis for depicting Norwegian research as deficient, and of Norwegian research policy as complacent, whereother countries have taken up the challenge. The arguments about the low level of funding in Norway havebeen voiced particularly vocally by academic professionals and address, often implicitly but sometime alsoexplicitly, university or basic research in particular. The coordinated campaign of universities for more fundingon the basis of arguments drawn from the GDP indicators and targets culminated in a common statement bythe six university rectors in July 2007. This statement is part of the general reactions among universities to theweak appropriation in the 2007 budget, including a cut in the core funding part of universities budgets, justifiedby the minister as a temporary pause in the promised growth of university funding. By using the term22“hvileskjær” to justify and emphasize the temporary nature of the cuts, he inadvertently provided his(university) critics with a term incorporating strong rhetorical impact to characterize what they saw as the22

Untranslatable term from speed skating, denoting a brief rest or pause in the even rhythm of the skater’s glide.

50

overallfailure of his (funding) policy. The term became stuck as a rallying call for this criticism, and contributedno doubt to the overall impression of his failure, leading to his resignation in the autumn of 2007. The generalpolitical consensus on both the 1999 and the 2005 GDP targets gave them a status as practically above criticaldebate, and just a few gave voice to skepticism and criticism. The most notable exception was one of theeditors ofDagens Næringslivwho wrote several, sometimes harshly critical, leaders and editorial comments(nine in our material) on what he saw as an unrealistic and superfluous target.SwedenEconomic issues were very high on the agenda in the Swedish debate already in the beginning of the period.They became particularly intensively debated in 2004 and 2005, and dropped somewhat surprisingly in 2006and 2007. One possible explanation for this was the change of government; another might be a “wait and see”attitude towards the outcomes of the Brändström Resource Inquiry.One major controversy in Sweden on funding levels took place in 2004 when a number of prominent actorsjoined forces and criticised the government. The SUHF, the Swedish Research Council, Vinnova, the RoyalAcademy of Sciences and the Royal Academy of Engineering Sciences signed an article which spelled out howdirect state funding had decreased over a number of years. The driving force in this debate was the vice-chancellor at Uppsala University, Bo Sundqvist. When the article was not responded to, he followed up with anew article inSvenska Dagbladet(2004-06-23), claiming that “Swedish Research is under Threat”. Precedingthis campaign, the government had described Swedish funding of R&D as being at “historically high levels”.Minister of education, Thomas Östros, declared that “No other OECD country allocates as much money toresearch”. The funding issues were also commented by other actors in an article inUppsala Nya Tidning(2004-11-30) written by institutional leaders from SLU (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences).Interestingly, the under-funding has also triggered comments from the opposition parties. “We are notresponsible” (SvD 2003-07-05) was the heading of an article written by representatives from the Moderaterna.Also a Kristdemokraterna politician (SvD 2002-09-01) said that the rationalization processes in education andresearch were a threat to quality. The DN editor wrote that the government parties once again deceivedresearch, and consequently lacked interest in their own future (DN 2004-09-12).In 2006, the new government promised massive investment in research. However, the budget presented in2007 did not impress university professors. The funding increases “were hopelessly insufficient and do not turnthe negative trend” claimed Vinnova, IVA and Volvo and others in SvD (2007-10-17). While public investmentsin research are decreasing, industry makes the most out of them. The authors urged that public research fundsbe raised to at least 1 percent of GDP.During the election campaign, the Alliance parties had promised an increase of research money to 1 percent ofGDP, and they were often reminded of that fact, for instance by academics union leader, Anna Ekström: “Fulfillthe one percent target” in UNT (2007-09-19). However, one journalist wrote an article about “the curse of theone percent target”. Research is swept in a cross-political benevolence; everybody assures its importance butnobody is prepared to pay for it (Expressen 2007-04-12).Over the years there has been growing discussion about the balance between direct state funding andcompetitive funding allocated, for instance, by research councils. Some strong professors, especially at UppsalaUniversity, such as Sverker Gustavsson (DN 2000-01-11), Li Bennich-Björkman (UNT 2003-03-30) and ToreFrängsmyr (SvD 2001-01-03; 2006-06-09) have argued for more direct money to higher education institutions.Professor Håkan Eriksson claimed that increasing dependence on external funding leads to universities losingtheir souls (SvD 2002-10-21). One of rather few defenders of external funding has been Sverker Sörlin:“Researchers have to motivate their funds” he wrote in DN 2005-05-24.The peer review processes have been criticized above all by individual researchers. One main issue has beenthe time-consuming aspects of external funding. Other aspects have included the ethical sides of peer review.51

One of the most frequent debaters on this issue has been Professor Bo Rothstein at Gothenburg University. Ona couple of occasions he has attacked, what he considers, a flawed and corrupt system. “Swedish Research isrun by Social democrat commissars” he wrote for instance in DN (2006-06-05). In the article, several fundingbodies and agencies were pointed to as being run by people with close connections to the social democraticparty. Furthermore, he argued in another DN debate article that the government politicised the entire Swedishresearch system (DN 2005-05-08).Increasingly, there have been arguments for more performance-based funding system in Sweden. Actually, thatwas one of the promises the right wing and liberal parties made before the last election in 2006. More moneyshould be allocated directly to higher education institutions, but based on the results of ex-post quality reviews(DN 2005-04-06). The new research policy should be based upon quality, freedom for institutions, strong basicresearch and innovation. In fact, it was the former government which launched the so-called Resource Inquiry,whose task was to reform the Swedish research funding system. They presented their results in late 2007. Inbrief, they proposed a new cyclic ex-post evaluation system for both education and research. Clearly, theBritish RAE has been the model inspiring the inquiry. The recommendations made by the committee on theresearch funding system are still discussed, not least the bibliometric methods to be used. The consequenceswill be fundamental for the system.

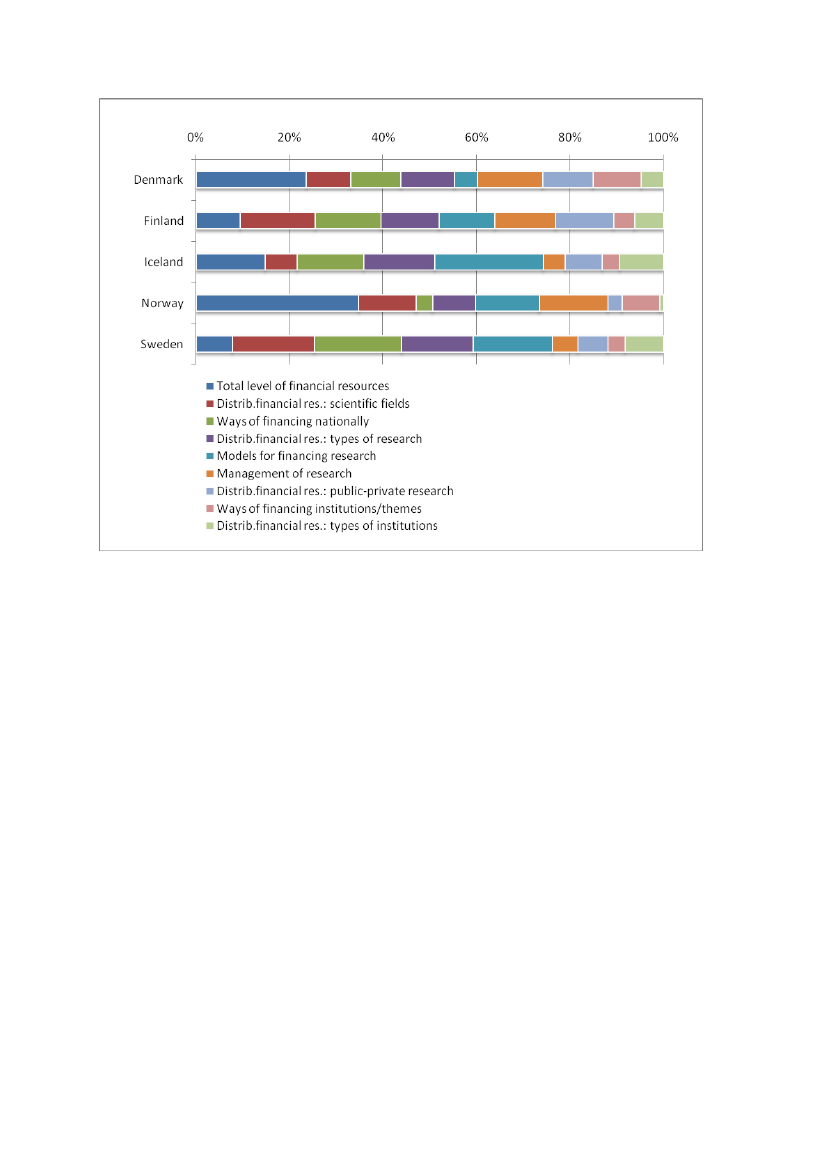

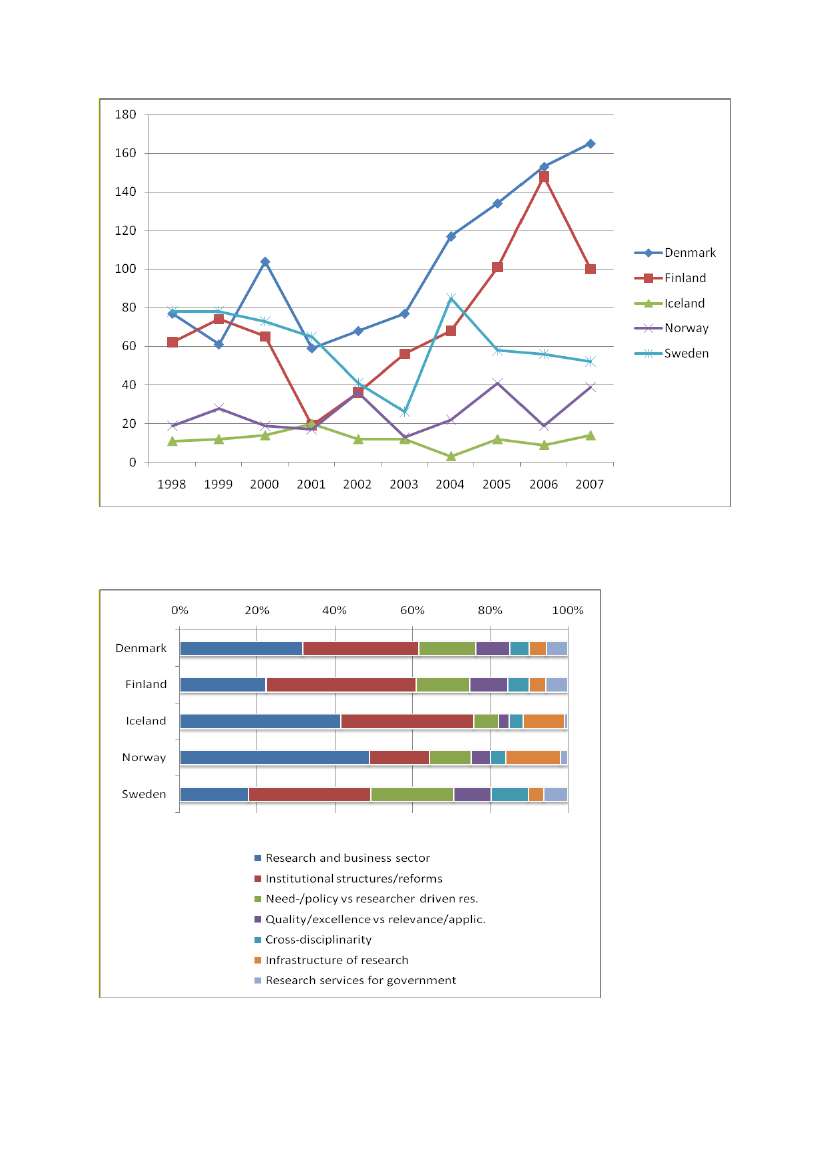

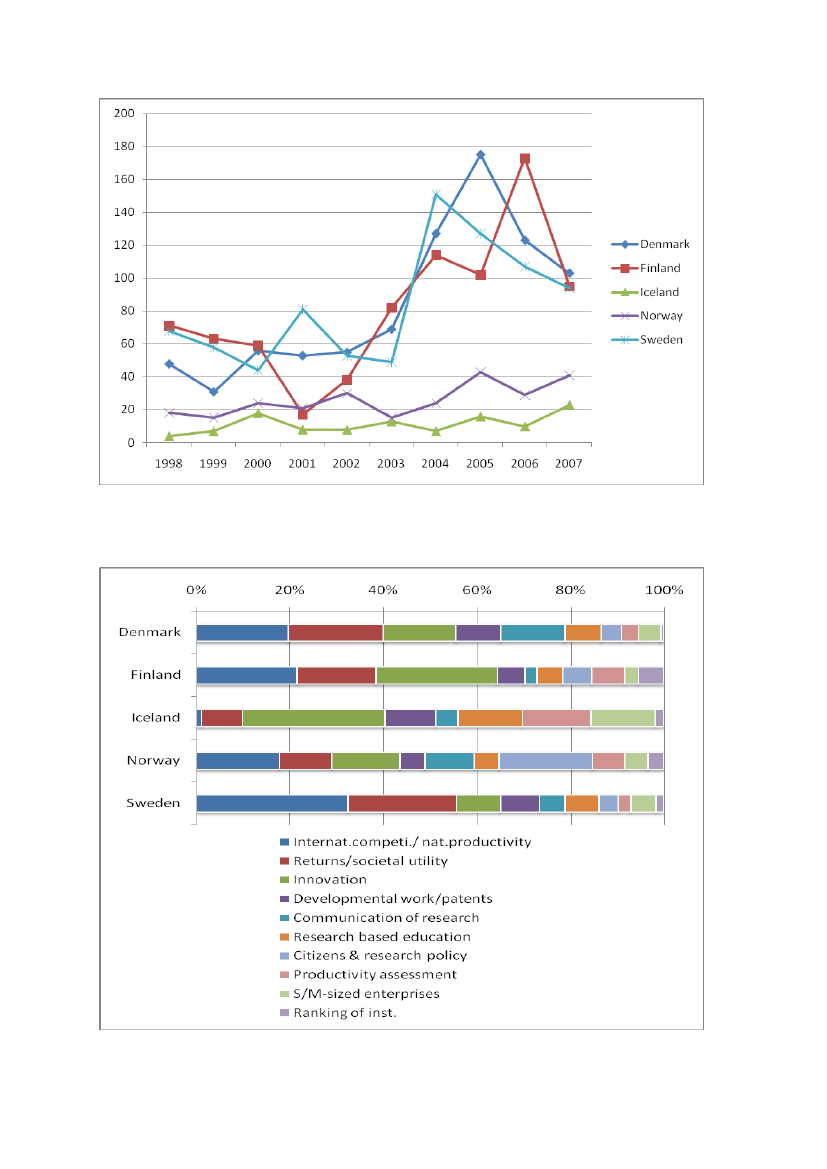

3.3.2. ORGANISATION,INSTITUTIONS AND REFORMThe organisational topic consists of eight issues ranging from institutional structures/system reforms to23quality/excellence versus relevance/application of research. .For Denmark and Finland we observe a rising trend for organisational issues from 2001 until 2006. On the otherhand, organisational issues show a quite unstable and fluctuating trend in Norway and Sweden while forIceland there are small variations on the prevalence of these issues during the ten year period.

The full list of organisational issues:V44 Institutional structures/systems reforms related to researchV45 Management of research, including management tools at the level of institutesV46 Research based services for governmental authorities.V47 Cross-disciplinary researchV48 Research and the business sectorV49 Need-/policy driven versus researcher driven researchV50 Quality/excellence versus relevance/application of researchV51 Infrastructure of scientific research

23

52

Figure 14.1 Organisational issues by country and year (N=3768):

Figure 14.2: Organisational issue by country and sub-topic (N=2348)

53

DenmarkOrganisational issues figure very frequently on the public agenda in the Danish debate. The political initiativesthat set the agenda started in 2001, focusing in particular on governmental research institutes. In 2003 it wasthe new University Act, in 2004 the change in the law for governmental research institutes, following whichsome institutes were incorporated into universities, and in 2006 the political announcement of mergersbetween universities and governmental research institutes.Organisationalissues were in focus in the media inDenmark with more than 60 articles in the public debate every year since 1998. In the beginning of the periodthe Danish research institutes awaited the conclusions from the committee organised in 1999 and later theissue reached a peak with more than 160 articles in 2007. The majority of these were triggered by politicalstatements, either from commissions or directly by Government/the Minister of Science.The main rationale for reorganisation was efficiency, and to enhance contact between all parts of publicresearch. Quality of research is also referred to in these communications, but not as main argument in any ofthem. Almost all the above-mentioned initiatives met with resistance from researchers, often expressing fearsthat the freedom of researchers would suffer. Reactions to these structural reforms came primarily fromresearchers working in these institutions.Cooperation between the public research sector and the private business sector attracted quite a number ofopinions, not the least from Danish Industry and others representing private business, such as the organisationfor trade and service (Handel og Service).Policy-driven research was on the agenda as well, similar to that which took place in Finland, but not to thesame extent as in Sweden. Services for government were an issue connected to the discussions aboutstructural reforms of the governmental research institutes.FinlandOrganisational issues have played an increasing role in the Finnish debate following pressure to centralize thehigher education system and especially the universities. The debate increased substantially after the PrimeMinister’s Office commenced a project “Finland in a Global Economy” and produced a report in 2004 whichproposed to increase the share of competitive funding of the universities as well as their financial autonomy.The report called for more specialization in order to form larger networks between research groups. In 2005the government made a decision in principle on the structural development of the research system, andassigned the task of clarifying the effects on the research system to the Academy of Finland and Tekes (theFinnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation).The debate in Finland on the need of structural reforms is apparent, and to some extent overlaps the issues ofglobalisation. The expansion of the university system has become a core issue in the debate as the role ofuniversities is being reconsidered. The whole research system was debated in 2006 when the discussion on theresources and goals of research heated up. This was connected to the increasing debate on the innovationsystem and the role of research and universities associated with this. Some have pointed to the tensionsbetween research and innovation policy goals since the production of innovations, and commercialisation ofresearch results have been increasingly emphasized.In addition to the need to carry out research in relevant fields, there has been a debate on which disciplinesshould be fostered in order to gain competitive advantages in global markets. One solution has been themerger of three universities that are said to represent the potential needed in the future. The so-called“innovation university” (now known as Aalto University) is a merger of Helsinki Business School, HelsinkiUniversity of Arts and Design, and Helsinki University of Technology. It was set up quite quickly and there was astrong push from the industry and business sector to support this new university. The government made aresolution to establish the university in 2007 but the idea was first introduced by the rector of HelsinkiUniversity of Arts and Design in 2005. The idea was received with mixed feelings in the public debate and54

triggered off deliberations about the need for a Finnish “top-university”. Those in favour of the merger saw itas a step towards top research and international prestige, but the opponents claimed that it would diminishthe autonomy of the universities and diminish the quality of research.IcelandA growing discussion of organisational matters related to the research and innovation system can be noted.The former Research Council and the new Science and Technology Policy Council discussed the role of researchorganisations, taking into account OECD work in that area. The role of research organisations and ofuniversities in research and development were discussed. During this period a considerable number of mergersbetween research organisations took place, as did various kinds of mergers between public organisations,universities and even R&D-performing firms.NorwayThe period saw extensive reforms and reorganisation within the research system. One was the so-called“quality reform” of higher education institutions which was an issue on the policy agenda throughout most ofthe period – first with its preparation with the Mjøs and Ryssdal commissions, its formal implementation from2003, and its taking full effect during the following years. This process triggered much debate, but its focus wasalmost exclusively on governance issues and on the educational parts of the higher education institutionsactivities, not on research. Hence, only a part of this emerges in our material on research policy, even ifarguably it did implicitly affect research. During the latter part of the period the emphasis shifted towardsresearch, which is captured in our material. This debate combines several separate issues, including such issuesas the position of free research, in particular the shrinking resource base for free, researcher-initiated academicresearch, but also the issue of the need for a formal legal protection of academic freedom (see HumanResources below), and the so-called “tellekantsystemet” (see the Output section below).The other major issue of reform/reorganisation was the evaluation and subsequent reorganisation of theResearch Council of Norway. The debate triggered by this process overlapped with issues concerning thereform of higher education institutions in the debate about the relationship between the council and theuniversities, something which has been a recurrent organisational topic in Norwegian debate throughout theperiod. While the tensions between these institutions have surfaced in the policy process and public debateson research policy for decades, it resurfaced at the beginning of our period through a relatively harsh responseby the rector of University of Oslo to criticism of the quality and effectiveness of university research (“For mye“mosjonsforskning” i Norge” (Aftenposten 16.4.98 – 4079) voiced by the director of the Research Council.According to the RCN director, universities do too little to stimulate the quality of research. According to hisuniversity opponents, however, the universities are, under-funded, and the council itself is too bureaucraticand does not, through its numerous steering schemes respect to sufficient extent the autonomy of basicresearch. It is again academic medical researchers who voiced strong criticism of the RCN, and claim at onepoint that they see a “cultural clash” (“kulturkollisjon”,Aftenposten31.8.99 – 4361) between the universitiesand the council.A strong ”elitist” trend gained hegemony within both policy and public debate during this period, as seen bythe implementation of a large number of “elite” schemes, including centres of excellence, centres for research-based innovation, and a scheme for generous support of the very best young researchers. We find in the recordof the debate several statements that supported and justified these schemes, many by the responsible ministerand Research Council officials. We find very few voices which opposed this new, saliently “elitist” thrust – oftenexplicitly justified in that very term – of Norwegian research policies that gained momentum during the early2000s.The data for Norway show a strong presence of articles that in some way or another touch upon issuespertaining to public/private research relationships. While this should not be taken to indicate that such issues

55

were primary in debates to the extent that the distribution in Figure 14.2 suggests, it does indicate apervasive awareness of these issues, also in debates that were primarily about other issues. This may providean indirect indication that issues related to private research, commercialisation and innovation had a strongerpresence in the debate than a picture based only upon main topics might indicate.SwedenIncreasingly, the structure of the Swedish research landscape has become an issue in public debate, following along period of expansion of the system. There are, however, articles in the media debate that claim thatresources are spread too thinly, and too many poor and mediocre research environments were funded (DN2004-12-22). One important article, showing a shift in focus, was written by minister of education, LeifPagrotsky, in DN (2004-04-12): “Government stops new universities”. Expansion of the sector and promotion ofinstitutions had come to an end. This was obviously bad news for those university colleges who had anambition to reach full university status, for instance Malmö högskola and Södertörns högskola.University chancellor Anders Flodström’s proposal to reduce the number of universities to five also resulted insome discussion in the press. Three vice-chancellors in the south east of Sweden declared that they were “sickand tired of sweeping arguments of research money spread too thinly”. Their own argument was to create astrategic alliance between the three institutions. An elite institution, they argued, was feasible and interesting,but there was also a need for other universities. There are, however, not many articles defending furtherexpansion of the sector. Hence, there has been an elitist turn in the sector without much controversy. Thisdoes not necessarily indicate that there is consensus on this in the sector, but it is not easy to oppose therhetoric on higher quality, world class, excellence (who would defend less than excellent research?)There are a number of articles which actually deal with fundamental issues in the sector. One theme is the roledivision between higher education institutions and other knowledge producers, for example, the essence ofacademic research. Other themes include academic freedom and integrity. Universities must stand up for theiracademic integrity. Short term, opportunistic behaviour is a serious threat to academic values (SydsvenskaDagbladet2004-03-12). In an article in UNT in 2003 (06-10), a number of leaders of higher educationinstitutions vented their frustration. High quality of both research and education was considered difficult tomaintain. Less money per student, weaker teaching research links, too much external funding and nonautonomous universities were serious threats to quality.Many of the issues included in this theme in Sweden are related to different modes of research. This could berelated to different actors in the system. Firstly, all the calls for more basic research – a core universityfunction, are expressed by a number of actors. However, researchers at higher education institutions arerepresented in most of these. Professors (mostly) could either act individually or from another platform, suchas SUHF (The Association of Swedish Higher Education), the Royal Academy of Sciences, or the SwedishResearch Council.On the other side, we find the “innovation lobby” (Benner 2008). The frontrunners are The Royal Academy ofEngineering Sciences (IVA), often in strong alliance with the Swedish Innovation Agency (Vinnova). Other actorsinclude the unions and the employer organisations, such as Civilingenjörsförbundet and Svenskt Näringsliv(Confederation of Swedish Enterprise).

24

3.3.3. HUMAN RESOURCESThe human resources topic comprises seven issues. The issues include items such as recruitment and education25of researchers as well as research ethics/integrity and gender equality.

24

The coding does not distinguish between primary and secondary topics, only if a topic is present or not. There areindications of a somewhat lower threshold in the Norwegian coding the presence or not of this variable in the articles.25The full list of topics in the human resources category is:

56

For Denmark, Finland and Iceland we can see a rising trend for human resource issues from 2001 until 2006.Then this topic suddenly drops in Finland while continuing with reinforced strength in Denmark. On the otherhand, human resources issues exhibit a quite unstable and fluctuating trend in Norway and Sweden while forIceland there are small variations on the prevalence of these issues during the ten year period.

Figure 15.1 Human Resources by country and year (N=2322)

V52 Recruitment and education of researchersV53 Salary and working conditions of researchers (e.g. degree of permanent tenure)V54 Mobility of researchersV55 Academic freedom/autonomy of researchV56 Collegial influence for researchersV57 Research ethics/research integrityV58 Gender equality

57

Figure 15.2: Human Resources by country and sub-topic (N=2322)

DenmarkHuman resources issues, and especially recruitment and education of researchers were already high on theDanish policy agenda at the end of the 1990s, and were in particular top items on the agenda in 2004, 2005 and2006. The issue is of great interest to many actors, and was a key issue in the Globalisation Council formed bythe government in 2005. Human resources, especially education and training of new scientists, were thereforecentral issues in the April 2006 report from the Council. This remained high on the agenda in 2007 since theagreed increase in additional resources for human resources and more researcher-training was distributed thatyear. The debate increasingly turned into one on academic freedom and autonomy of research, which explainsthe very high level of hits on this topic group (see Figure 15.2).FinlandEven though human resource issues are not the most dominant theme in the debate, this has evoked criticalviews and strong opinions whenever it arises. Some of these issues are connected to structural reforms such asthe reformation of the financial and administrative status of universities in 2007. Much of the debatecontinued after the study period, although some of it began earlier. There have been references to theappointment principles of professors (HS 1999-05-29) as well as to the workload of professors when fundinghas become more competitive. Basically, this has meant that professors have had to use an excessive amountof their time in finding funding and undertaking administrative tasks, rather than carrying out research orsupervising students.One specific issue that raised critical voices was the new payroll system in the universities (HS 2006-12-08). Thenew system was to be more performance-based and linked to personal evaluation. The system was largelyopposed by the researchers because it was said to curtail freedom and create more bureaucracy in theuniversities (HS 2005-04-05).

58

Other HR issues have been connected to the overall conditions of employment. The wage level of universityemployees has lagged behind and there has been an increasing use of short-term or temporary contracts (TS2007-09-02). The European Union Year declared 2005 as the Year of the Researcher. The Academy of Finlandpromoted the academic career of researchers by organizing campaigns to get more young people interested inresearch. However, this was met with critical views as researchers complained about the poor employmentconditions and salaries (HS 2005-09-03 and HS 2006-12-07).IcelandEthical issues were more frequently discussed in the debate of research and development in Iceland than in theother Nordic countries. A large number of ethical questions were raised during the debate of the Healthdatabase of deCode Genetics. This topic has remained high on the public research policy agenda even thoughthe content has shifted to other concerns. The other issue prominent in the Icelandic case was the debatearound salaries and working condition of researchers. During this period an increase in doctoral education andenrolment occurred. Icelanders have traditionally gone abroad to study at foreign universities, especially forMasters and PhD degrees, but in recent years the supply in Iceland for these kinds of studies has increaseddramatically.Norway

Figure 13.2. illustrates that research recruitment and education issues played a larger part in human resourcematters in Norway than in the other countries. This topic, as so many others, is closely linked to the debatesabout resources for university research in particular. This debate was to a large extent about insufficientrecruitment of researchers, in particular within science and engineering, and about the (in)effectiveness ofresearch education. Throughout the period ambitious quantitative targets were set for new PhDs and newresearch education positions. Any failure to reach those targets in annual budget appropriations providedoccasion for public criticism of the allegedly inadequate funding policies.While there are few examples where the autonomy of research (academic freedom, “free research”) is themain topic, the importance of this issue is more strongly indicated by being referred to pervasively, withoutbeing the only/main topic. About one-fifth of all articles have some reference to this type of issue. It is, forexample, a key part of the debate on the funding of basic research and on the relationship between universitiesand the research council.SwedenHR issues were discussed throughout the period in Sweden. General discontent with working conditions foracademic staff was expressed by researchers themselves as well as by the influential Union for UniversityTeachers (SULF). At the system level, one journalist raised the question in DN: “Long education, high debts, lowsalaries, tough working conditions – is it really a priority to put more souls on the academic ghost ship” (2004-08-17).During the first year of this study, 1998, a bill on doctoral training was launched, with the main aim ofimproving working conditions for students. The state also wanted to make doctoral training less time-consuming and more effective. The bill was intensely debated in Swedish media. The strongest protests camefrom scholars in the social science and humanities, claiming that this reform would more or less be the demiseof many research environments. “Government policy creates a crisis at Humanities Faculties”, a number ofdoctoral students at Uppsala University wrote (UNT 1998-04-05). The Liberal party (Folkpartiet) defended theold order, with a more flexible admission policy while the new Minister of Education, Thomas Östros, referredto the old system as cynical and exploitative.At this time, Carl Tham was minister of education. In 1999 he launched the so-called promotion reform whichwas another controversial issue with a strong impact on the Swedish academic staff structure. Anotherprovocative issue was a 2004 committee report on doctoral training. This declared that in future, disciplines59

would no longer be the primary base for knowledge production, which was a provocative statement forprofessors in the well-established disciplines. The recommendation to make doctoral training three yearsinstead of years was regarded by some, for instance professor Bo Rothstein, as a serious threat to Sweden’sinternational reputation and quality of doctoral theses (DN 2004-05-15).Increasingly, as the output of doctors reached a historically high level, concern with the situation for earlycareer academics has become pervasive. Too many researchers go abroad, in particular to the USA, wherecareer prospects are regarded as more favourable. The Swedish/European system is characterized byapprenticeship, disciplinary conflict, nepotism and inertia. The lack of mobility endangers the Swedish system.One radical solution suggested was to create posts at higher education institutions for non-Swedes only (DN2005-12-10).In 2000, 125 researchers signed an article which focused on the poor working conditions for young researchersin Sweden. The career system needed a thorough restructuring, they argued: a whole generation ofresearchers is moving to other countries, due to insecure working conditions, poor salaries and lack of fundingopportunities (see also DN Debate 2004-09-12). Head of editorial at DN called the current research HR policy a“proletarization of researchers” (DN 2006-03-19).An article on human resources, but also on the research landscape, by a professor at Karolinska Institute statedthat “It is meaningless to appoint new professors in Karlstad, Örebro and Växjö, and to make senior lecturersprofessors”. The promoted professors cause inflation in the career system, so there should be fewer professorsthan today (DN 1998-07-17). A state committee report proposed a new academic career system, ”Karriär förkvalitet” (SOU 2007:98), inspired by the US tenure track system. This has not, however, caused much debate sofar.

3.3.4. OUTPUT ISSUESThe output topic consists of eleven issues ranging from quality assessments to patents. .Denmark and Finland exhibit a rising trend for output issues from 2001 until 2004/2005. Output issues show anunstable and fluctuating trend in Denmark, Iceland and Sweden in particular during the ten year period. Inaddition these issues were far less frequently taken up in the debate in Norway and Iceland than in the othercountries.26

26

The full list of topics in the output category:V59 Quality assessment of research (including methods and indicators)V60 Assessment of productivity of researchers (including methods and indicators)V61 Ranking of research institutions (including criteria)V62 Research based educationV63 Communication of research resultsV64 Developmental work, patentsV65 InnovationV66 Research and small-/medium-sized enterprisesV67 Research and international competitiveness/productivity at a national economic levelV68 Returns from research/societal utilityV69 Citizens and research

60

Figure 16.1: Output-related issues by country and year (N=2553)

Figure 16.2 Output-related issues by country and sub-topic (N=2553)61

DenmarkOutput-related issues were increasingly taken up in research policy debate in Denmark from 1998 to 2005. Thechange in government in 2001 increased the focus on this aspect, partly triggered by a new action plan in 2003from Helge Sander, who became Minister of Science, Innovation and Technology in 2001. The publication ofthis action plan, promoting closer cooperation between universities and the private sector, is the mainexplanation of the frequency of the societal utility category in Danish debate at this time.Innovation during the ten-year period is not a theme that is as salient in the public debate as it was in Icelandand Finland. This, despite the fact that Denmark may be seen to perform strongly on innovation policy, andgiven the many initiatives that have been taken that relate to innovation (see Pro-Inno Europe Trend Chart).Innovation has increasingly become a central element on the agenda for research policy.FinlandOutput-related issues were the dominant theme in the Finnish debate during the period, and increase at a timewhen the debate peaked in 2006. This is connected to the debate about the structure of the university systemand the new role of universities. The debate at that time revolved around innovation due to the absorption ofscience and technology policies into innovation policy. There is an increase in innovation-related debate in2003 which continues steadily and peaks in 2006, when three-fifths of all articles address this issue. Some ofthe articles use innovation only as a rhetorical tool, but nevertheless there is a strong connection betweenresearch, innovation and national competitiveness.Whenever the innovation system is addressed, universities and research are considered to be vital elements.However, criticism is addressed at the education and research system for favouring quantity over quality. Thisis especially related to mathematics and technical sciences where resources for teaching and basic research areallegedly weak (KL 2006-01-20). International competitiveness became topical during 2003–2006, and there is astrong tendency to see innovation as a key factor in promoting global competitiveness and supporting thenational economy. Concerning the returns from research or societal utility, the debate seems to have beensomewhat topical during 1998–2000, but declined thereafter, re-emerging in 2003 since when it is addressedjust occasionally.Another issue closely related to innovation and competitiveness is the incapacity of universities and companiesto develop products and commercialise them. There are frequent proposals to establish a national programmefor promoting business know-how and studies within business and marketing (HS 2000-04-14, KL 2002-02-20and KL 2003-01-15). The fact that output-related issues dominate the debate can be seen as the need forstrengthening the national economy, especially since the ICT-sector has proved to be unable to create thecompetitive advantage is was assumed to have.IcelandWhile Icelandic research policy has been strongly focused on input issues, the debate in recent years hasshifted towards output, with a considerable increase in concern for innovation and the need for support of newknowledge-based firms. The need to broaden the industrial base has been focused and innovation is seen asessential for that development. The discussion about small and medium-sized firms has increased. Lack offinancing of start-up firms has been criticized. Knowledge-based firms have started a forum within theboundaries of the Confederation of Icelandic industries, the members of which have taken an active part in thedebate. Debate on research-based education has increased in recent years with expanded opportunities forstudying for Masters and PhD degrees in Iceland itself. It is noticeable that the international competitivenessand productivity of firms has not been more extensively taken up in the debate, given the extensive coverageof the World Economic Forum in the period.

62

NorwayOne relatively extensively debated output-related issue was how the component in the new budgeting systemfor higher education institutions for calculating a minor part of institutional funds on the basis of registeredscientific publications would affect researchers’ behaviour. Although the scheme triggered much controversy,parts of which also surfaced in the general media, little opposition can be discerned in the debate against theprinciple that a scheme of performance-based funding crediting scientific publication activity is justified. Thecontroversy focused on aspects of thedesignof the scheme, in particular pertaining to aspects that would,allegedly, have distorting effects on publication practices: Norwegian will lose out as scholarly language;participation in public debate and dissemination activities are not credited; quality will deteriorate as aconsequence of splitting up results into as many separate publications as possible and seeking “easy”27publication outlets. Judged by well-documented changes in the publication behaviour of universityresearchers, they seem to support the system top a higher extent than the extensive public controversy aboutits introduction may indicate.As seen in Figure 14.2, the issue of university rankings is a relatively minor issue in Norwegian debate. When itdid emerge, it was often linked to the issue of enabling colleges to become universities, and the debate about“elite universities”.The design and implementation of the Skattefunn scheme for tax deduction for R&D expenses wascontroversial and the scheme found its final form after several years of discussion and re-design. Its majorjustification was the novel scheme required to respond to the challenge of the low level of private R&D fundingin Norway. This paved the way for the scheme despite strong reluctance and resistance (which didnotsurfacein the debate) within Government and, initially, in the RCN itself. Part of the controversy surfaced in the publicdebates where some, in particular as stated in editorial comments inDagens Næringsliv,saw the scheme as anunproductive subsidy to private companiesFigure 14.2 indicates that issues pertaining to the role of citizens in research policy have been more salient inNorwegian debate than in other Nordic countries. Citizen’s issues may, indeed, be seen to be a strongdimension in Norwegian research policy. Norway has a highly well-developed system for addressing issues ofresearch ethics: the Technology Board which was established in 1998 on the Danish model for supporting laytechnology assessment, and the many public controversies during the early part of the period over genetechnology research, may be expected to have spilled over into research policy debates in the more restrictedsense of the term, as applied within this project. Some resonance can also be found at the beginning of ourperiod of a debate which peaked earlier on the collusion of research and politics and the integrity of researchtriggered by some cases of dubious commissioned research. It seems, however, that Figure 14.2 may overstatethe role of citizen related issues in Norwegian debate, perhaps due to differences in coding. While there aresome articles with this as their main topic, including articles that pertain to the Technology Board controversyin 1998, public dissemination of research (see also “tellekantsystemet” above), and – in particular – theinfamous Sudbø fraud case that exploded in early 2006 and made Norwegian research an unwelcome newsitem all over the world for a few weeks. With a restrictive application of the “citizens and research” criteria,this topic does not seem to have been salient during the period. We saw also in Figure 3 (section 4.2.2) thatfew “outsiders” beyond the immediate stakeholders groups took active parts in the debate.It is also noteworthy that Norwegian debate has a much higher number of references to citizens than in anyother country.SwedenIssues related to international competition have been very common during the period. Many articles draw apicture in which Sweden’s position is threatened, or might be threatened unless action is taken. Thus, other27

Ulf Sandström,Forskningspolitikk1/2009

63

countries are mainly referred to as competitors and benchmarks. The ranking issues are not yet raised inSweden; however they might be in the near future, in addition to publication issues. The calls for Nobel prizesto Sweden could be seen in that perspective.The teaching research links are sometimes discussed, not only in relation to doctoral training. Some articles onresearch policy refer to the need of close relations to education, almost routine-like with references to theHumboldtian ideas. One exception was the director at the Swedish Research Council, who suggested separateunits for education and research at higher education institutions. Departments should be abolished andinstitutions should try other ways to organize their activities, he argued (DN 2003-07-27).On the whole, there has been an important and clear shift from expansion and quantity to consolidation,concentration of resources and emphasis on excellence. Another important shift is the increasing focus oninnovation. The use of that concept has indeed developed over time and, significantly, the latest governmentresearch bill was called the researchand innovationbill.

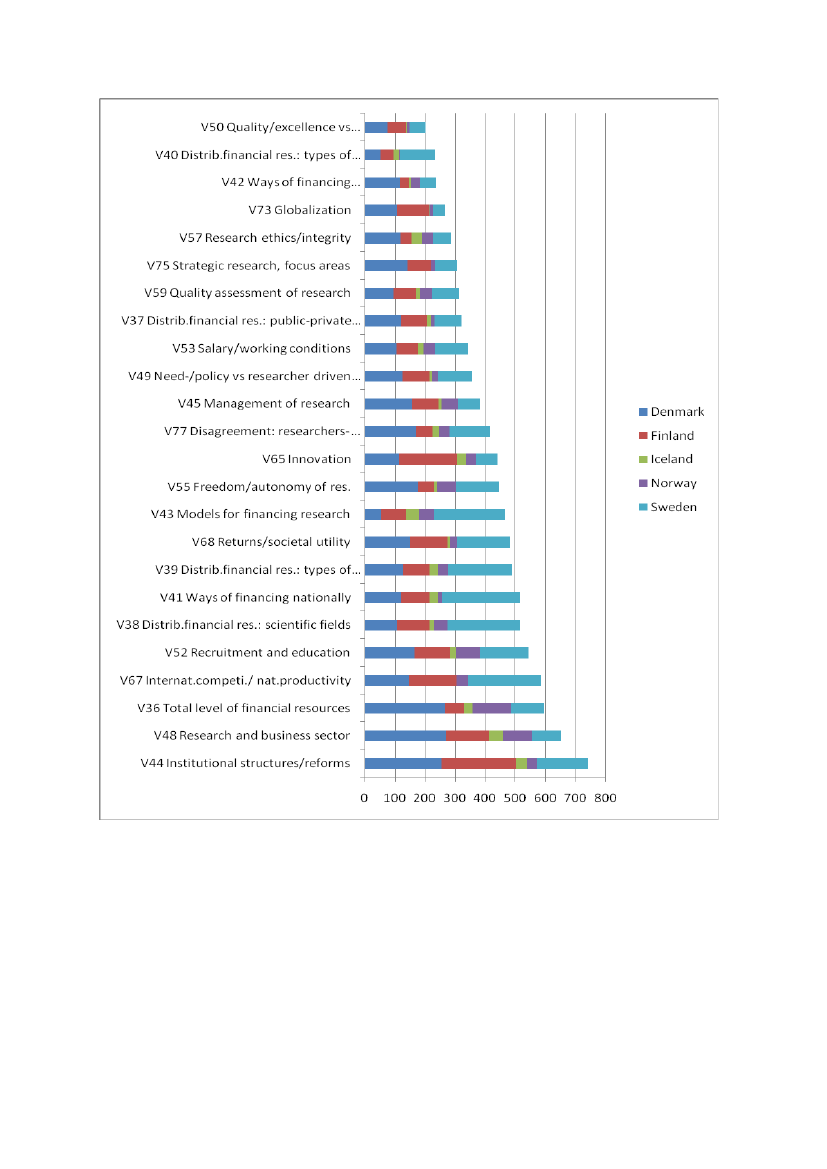

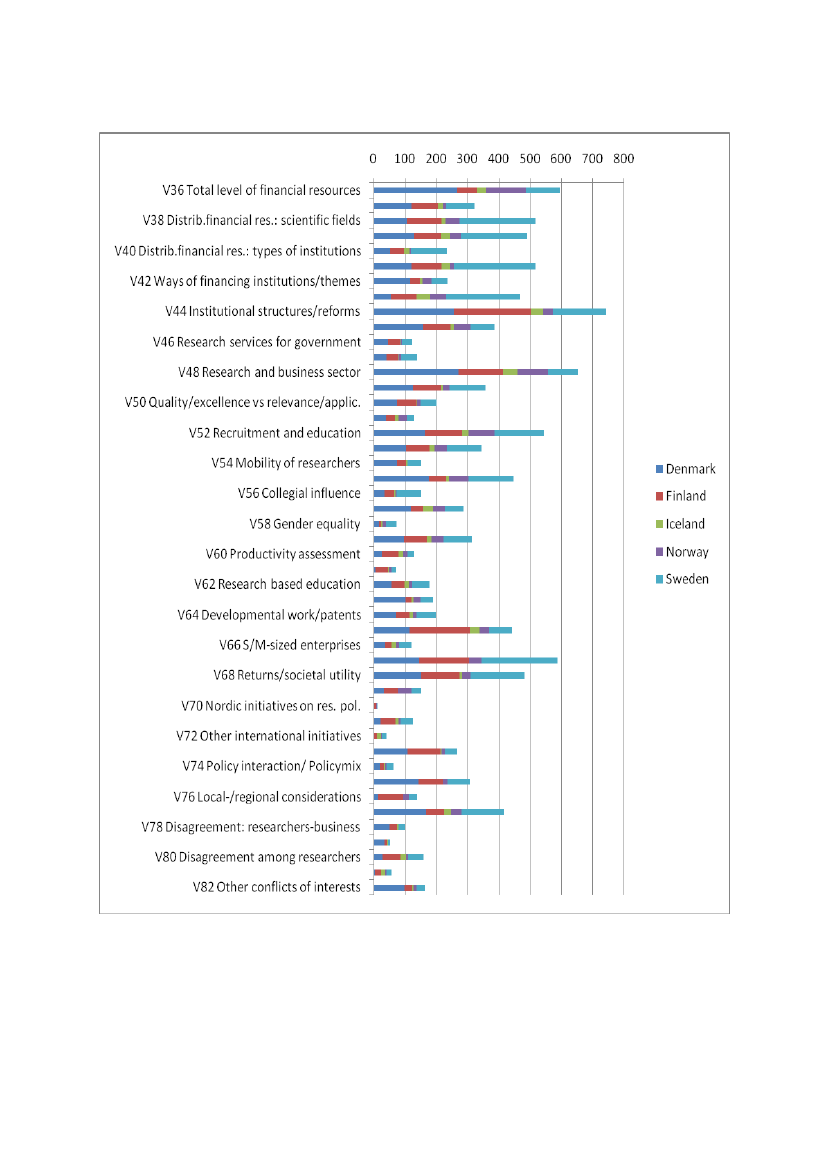

3.3.5. WHICH TOPICS AND ISSUES WERE MOST FREQUENTLY DISCUSSED?Figure 17 below provides an overview of the specific issues that were the most frequently taken up by thearticles in our material. The figure indicates that out of the total 47 issues covered by our analysis, the 24 in thefigure were the most frequently discussed, with the most frequent at the bottom of the figure. Each country isrepresented by the number of articles on that topic in that country.

64

Figure 17 Specific sub-topics on top of the Nordic public agenda (N=12880)The order of frequency in the overall material is different from that of each country taken separately. Forexample, in Denmark the issue “research and business sector” (V48) is relatively more prevalent than the“institutional structures/ reform” issue (V44). The opposite is the case for Finland. While the “models forfinancing research” issue (V43), is among the most frequently occurring issue in the Swedish material; it is onlyat position number ten in the total for the all Nordic countries during the period.

3.4. WHICH DISCIPLINES WERE DISCUSSED?In this sub-chapter we map the content of debate articles in terms of which scientific fields and what forms ofresearch (basic/applied research, e.g.) that are discussed in them. These aspects of article content are only65

indirectly related to the specific topics and issues. The measure “scientific field referred to” is coded accordingto the dominant field in the article. If no specific field or dominant is mentioned, the article is coded ‘researchin general’.The coding encompasses six categories. The category ‘agricultural, veterinary and fishery science, forestryincluded’ was virtually unused in the categorization of the debate article. The term ‘research in general’ on theother hand was frequently applied in all countries except for Norway as indicated in Figure 18. For all countriesconsidered together, technical science/new technology is the dominant category, followed by health science.At national level, the health science field was the most dominant category in Iceland and Norway, while playinga more subdued role in Denmark and Finland where technical science/new technology prevailed. Thehumanities had a comparatively more prominent role in Danish, Norwegian and Swedish debate articles than in28the Finnish and Icelandic material .

0%DenmarkFinlandIcelandNorwaySwedenTotal

20 %

40 %

60 %

80 %

100 %Technical science/newtechnologyHealth scienceHumanitiesNatural scienceSocial science

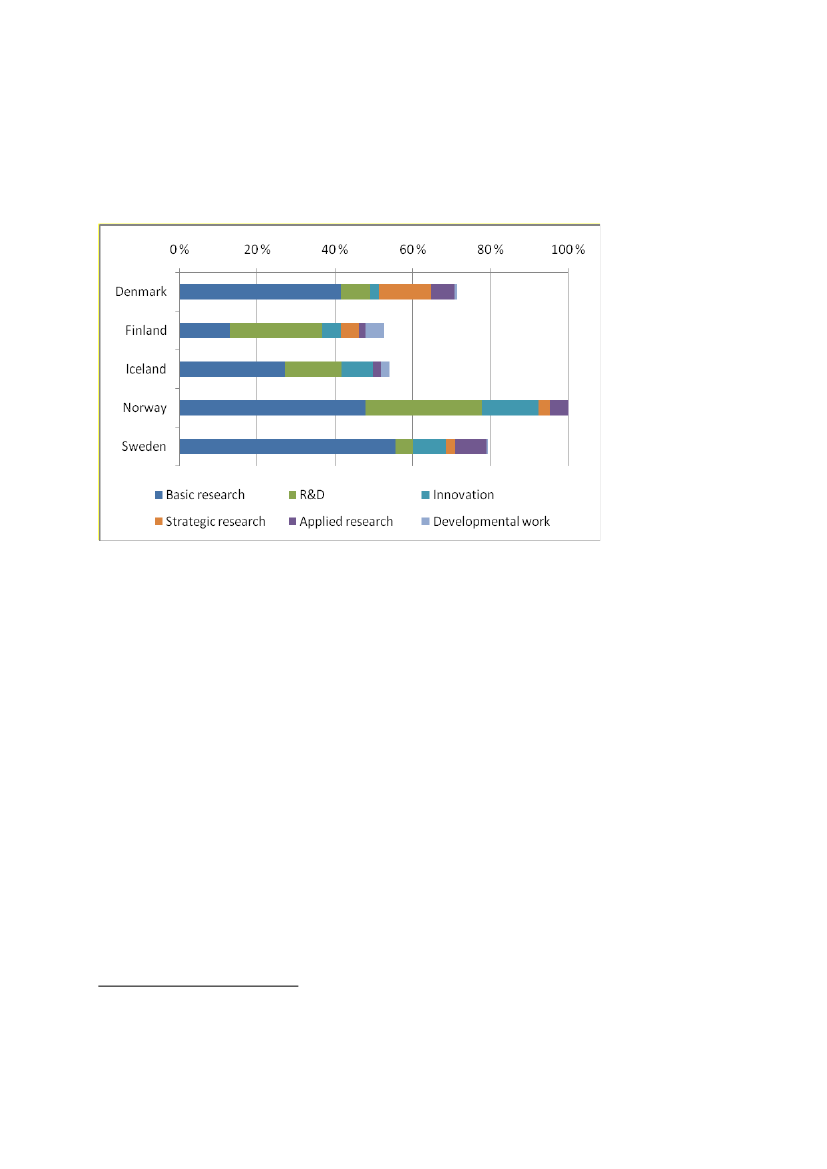

Figure 18 Scientific field referred to – the five most prevalent categories, excluding ‘research in general(references to a plurality of fields)’. Percentage (N=1703)The forms of research referred to in articles were also coded for differences along the research/application29dimension, see Figure 19 below. We observe that the categories “basic research” and “research anddevelopment” are the forms of research that are most frequently addressed in the articles. These patterns maybe seen to confirm that the large part of research policy debates had a university (research) bias, and also thatthe notion that “R&D” should be seen as a whole, often as a share of GDP, played a salient role in thesedebates. To what extent this is a direct impact of the European Barcelona target is more uncertain; in somecases – such as Norway – the “R&D share of GDP” issue predated the Barcelona target. But these results canprobably be taken as an indication of any influence by the EU agenda on national policy debates.Only 40 percent of the total set of articles that were coded in the five countries was classified as about specific fields ofresearch, i.e. the majority were coded under ‘research in general’. For Norway only 20 percent of the articles were coded as‘research in general’. This difference may partly be the result of different interpretation of the categories used in thecoding.29If several forms of research are addressed, but no form has a dominant role in the content of the article, up to threeforms of research may be coded. Different applications in the coding of categories for ‘form of research’ may to a largeextent also account for the deviating results for Norway. See footnote 18.28

66

Figure 19 provides a picture of the distribution of articles in terms of the forms of research addressed. We seethat basic research is the dominant reference in all countries except Finland where the more applied ‘Researchand development’ is much more prevalent. We also note that ‘strategic research’ is more prominent in the30Danish and Finnish debates than in the other countries.

Figure 19 Forms of research, the category ‘Research in general’ is excluded. Percentage (N=1703)DenmarkThis figure shows that more than two-thirds of the debates in Denmark refer to science policy in general,indicating that it is the situation for science in general which is featured on the agenda, more so than forspecific scientific fields.FinlandTechnical science and new technology play a prominent part in the Finnish debate. Figure 19 shows that inFinland R&D is the dominant form of research referred to. Even though basic research seems to be somewhatneglected, the debaters have been concerned about its role compared to R&D investments. This has beenespecially mentioned in the debates on external funding and research as a service activity. Researchers areafraid that they will not be able to use funding for basic research or teaching because the external fundersexpect to benefit from the research in a certain way and will steer the research strategically (HS 2003-01-30).IcelandSimilarly to the other Nordic countries except Finland, basic research is referred to in half the cases which canbe assigned to a specific area of research and development. This may be seen to reflect the vigorous debate onuniversity research. When scientific field is taken into consideration, Health and Medicine is quite prominent.Research and development in general is also rather prominent.

30

Caution must be exercised in drawing conclusions on this point since this dimension is sensitive to national particularitiesin the wording of the terms. The criteria to code this variable were however based on the principle that the central words ofthe substantial categories (or their synonyms) were explicitly present in the text. All terms where defined in the guide tothe code key and referred to the international standard for research and development statistical purposes, i.e., the OECDFrascati Manual.

67

NorwayThe relative distribution of scientific fields reflects the salient role that university researchers in general andmedical researchers in particular have played in Norwegian debates. Medical researchers were highly activeduring the late 1990s when resource issues rose to the top of the research agenda, and the poverty ofNorwegian medical research was focused, and documented. The active role of medical researchers lingeredthrough active role of some highly prominent and visible players, such as the 1999–2001 rector of theUniversity of Oslo (Kåre Norum), and professor Per Brandtzæg, who wrote several long debate articlesthroughout the period under analysis (and continues to do so to this day). While phrasing his arguments interms of “research”, using the low Norwegian “R&D share of GDP” as evidence, he generally refers to universityresearch, and often to experience from his own (fields of) research. We also note a relatively high frequency ofarticles that address the humanities.SwedenAs for scientific fields, the majority of the articles in Sweden concern Humanities and Medicine. One obvious, orat least relatively unsurprising, reason is that both fields demand more money, although not always asstraightforwardly phrased as: “More money for Humanities Research!” (UNT 2005-05-15). However, the fieldsdiffer somewhat in the way they argue. As far as medicine is concerned, there seems to be no requirement toargue for the societal needs for research in this field. The starting point is rather that Swedish Medicineresearch is losing ground in an international perspective. International competition is the argument for moreresources. A bibliometric report from the Swedish Research Council showed that Sweden was losing ground toother countries such as the US, which spent far more money on medicine and health science research. Theinternationalisation issues have been discussed in the Humanities as well. Swedish Humanities scholars shouldbe more internationally recognized and active in networks, one journalist wrote (DN 2005-04-12). In fact, thegreat Humanities debate in 2005 started with professor Sverker Sörlin’s critical reflections on Swedishuniversities’ positions in the ranking tables. However, the debate soon became narrower, more national andeven disciplinary. The lack of international contacts and national publishing in Swedish Humanities research hasbeen discussed by a number of writers, although most of them represent only a few disciplines such asliterature and history of ideas.

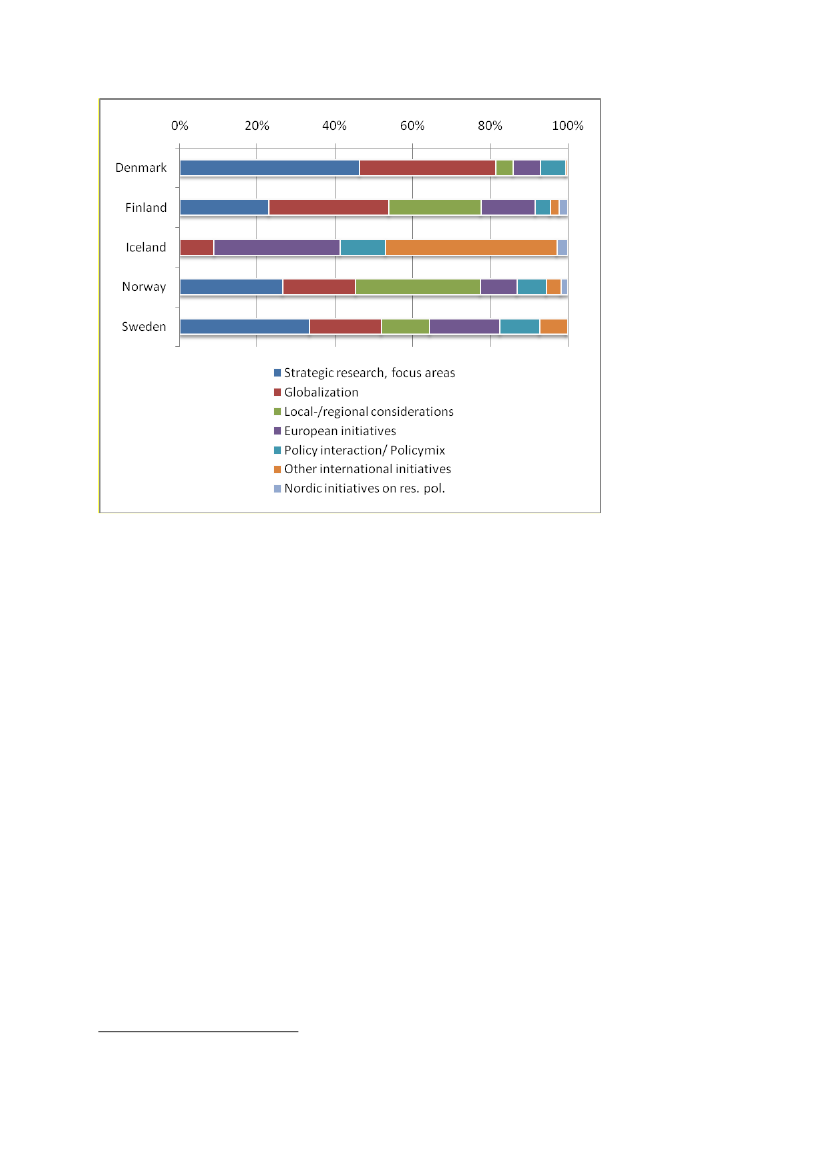

3.5. WHAT CHALLENGES WERE PICKED UP?The forms of research classification are also linked to the topic ‘New Challenges’ which we defined as acollection of strategic issues of research policy. The ‘new challenges’ topic consists of seven issues ranging from31local/ regional initiatives to globalisation, see Figure 20.

31

A full list of issues under the “new challenges” category:V70 Nordic initiatives on research policy (e.g. NORIA)V71 European initiatives on research policyV72 Other international initiatives on research policy (e.g. from OECD, GLOREA)V73 GlobalisationV74 Policy interaction/Policy-mixV75 Strategic research focus areasV76 Local-/regional considerations

68

Figure 20: New Challenges by country and sub-topic (N=954)Figure 20 indicates that the two categories Strategic research focus areas (selected by research councils/government) as well as references to the globalisation challenge prevailed in the debate articles in all countriesexcept Iceland. In Iceland, funding of R&D through research programmes has not been common. The largestpart of competitive funding has been for general research funds rather than programmes. R&D programmeshave increased in importance after the establishment of the Science and Technology Policy Council, but theirbudgets remain rather small.DenmarkAs shown in Figure 18 strategic research is on the agenda in Denmark more than in any other Nordic country,and this discussion includes references to initiatives presented by research funding councils especially createdfor strategic research.FinlandGlobalisation issues turn up clearly in 2004 when the first globalisation report was published. The backgroundfor the report was Prime Minister Vanhanen’s initiative to find out the possible consequences of the upturn inthe economies of China and other low-cost countries. In the Preface, the globalisation report states that thestarting point for the report is the same as Wim Kok’s committee, and a clear reference is made to theEuropean Union and its targets (VN 2004, 5). As globalisation is the major challenge in the Finnish debate,education and research play a crucial part in this.Globalisation is linked with the efforts to move from science and technology policy to innovation policy in allareas of society. This also emerges in the debate since innovation issues become topical at the same timewhen globalisation is debated. The occurrence of the so-called China phenomenon can be seen in all the32

32

Note that “strategic research” is one form of research, see figure 19, as well as a challenge “strategic research focusareas”, see figure 20.

69

papers, and to some extent the debate reflects the ideas presented by the Science and Technology Council andthe second globalisation report in 2006 when a decision was made to establish Strategic Centres of Excellence.Another aspect of the globalisation debate is the tension between global and local issues. The regionaldimension of the education and research system has been extensive but as globalisation has paved the way fora need to reshape the innovation system, universities and higher education are challenged. Behind this is theidea that Finland cannot afford to sustain the university system as such and more specialization is needed. Atthe same time, however, there is a push towards bigger units and networks, preferably with some internationalcooperation.IcelandThe Icelandic system of research and development is very small and it is difficult to reach a critical mass ofresearch in most fields of science, even though research in earth sciences and medical and health science isconsiderable in Iceland relative to the size of the country. Thus, foreign cooperation is essential, and the debatereflects the necessity for Iceland to take part in international cooperation, including the European Frameworkprogrammes, Nordic cooperation and international cooperation based on individual research organisations.NorwayAs in virtually every developed country research policy has in Norway, has been increasingly framed in terms ofenhancing the competitiveness of the national economy. This reflects, apparently, the framing of EU science,technology and innovation policy in its Lisbon agenda in general, and the Barcelona target in particular. Hence,the linking of competitiveness as core policy objective and issues of national/regional R&D finding may be seento reflect the influence of EU STI policy. This is also the case for Norway, despite its not being a EU-member,inter aliathrough the adoption of the Barcelona target in the 2005 White Paper on research policy. It seems,however, that the specific EU phrasing of the competitiveness/R&D funding nexus did not shape the Norwegiandebate to the same extent as in other Nordic countries. While globalisation is salient within the set of articlesthat discusses one or more topic within the “new challenges” category, that set consists of only one tenth of allNorwegian articles. Local/regional aspects, on the other hand, are highly salient in the Norwegian debate, moreso than in any other country. These include both supportive and critical articles.SwedenAs far as Sweden is concerned, globalisation is primarily mentioned at the beginning of newspaper articles, as apoint of departure for the ensuing argument. For instance: “In a globalised world, Sweden has to remaincompetitive in research and innovation”. There was a globalisation committee founded in 2006, including manyprominent representatives from the sector, and chaired by the minister of education and research, LarsLeijonborg. The committee has produced many reports, many of which are related to R&D issues.

3.6. INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS OF RESEARCH OVERSHADOWED BY THE NATIONALThe articles were also coded to capture references to geographic areas and to international cooperation.“Geographic area” covers both the country and regional levels in order to see whether or not the researchpolicy debate in the Nordic countries looks to other countries or regions for lessons and/or models.

70

0%

20 %

40 %

60 %

80 %

100 %Denmark

Denmark

SwedenNorway

FinlandFinlandIcelandIcelandEU, non-Nordic EU-countriesOECDNordic (two or more)

Norway

Sweden

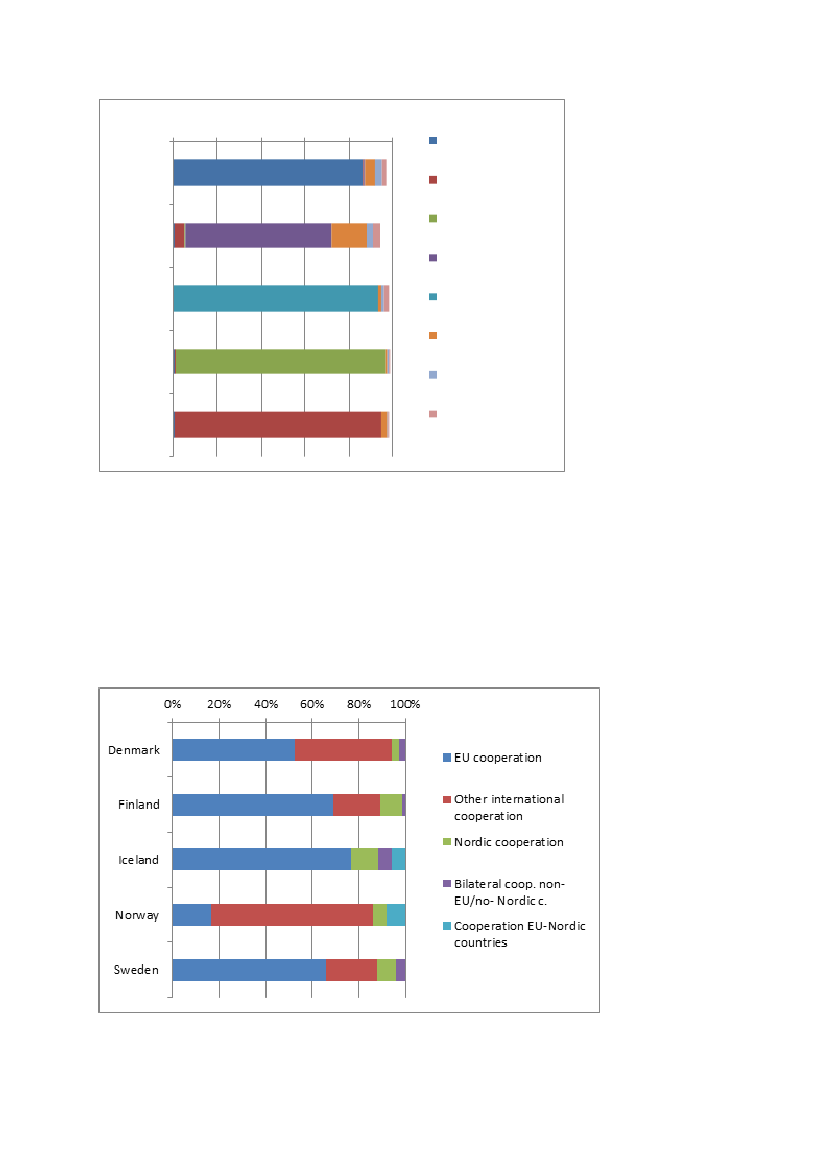

Figure 21.1 Geographic area referred to. Percentage (N=2267)Figure 21.1 indicates that in all the Nordic countries the research policy debate had an almost exclusivelynational focus. References to the Nordic countries or other regions were seldom. References to non-Nordic EUcountries were more frequent in Finnish debate articles than in articles in other Nordic countries.Figure 21.2 maps the types of international collaboration which was the topic of a relatively low number ofarticles that did refer to international research cooperation. This variable was coded accordingly to the mostdominant feature of international cooperation the articles. For all countries except Norway, EU cooperation isthe most prevalent form of international collaboration discussed.

Figure 21.2 Reference to international research cooperation. Percentage (N=275)

71

DenmarkAs in the other Nordic countries the Danish debate is almost exclusively national. This is partly due to the factthat the scientific environment has undergone large transformations. Many of these transformations havebeen made without making comparisons to the other countries which Denmark is ordinarily compared to.References to other countries have therefore been kept to a minimum. When reference to internationalresearch has been on the agenda – as seen in Figure 17.2 – this has been caused by the Lisbon agreement in2000 and the Barcelona target from 2002. The Danish “Globalisation Council” from 2005 also brought upreferences to the EU cooperation. In other words the EU has functioned as a frame of reference when wedepart from pure national orientation. The OECD closely follows because of the many recommendations andreferences also included in the “Globalisation Councils” report in 2005.FinlandWhile the research policy debate is very national in focus and scope in all the countries, articles in Finland referto the European Union more frequently (see Fig. 21.1.) This includes debates on guidelines of Europeanresearch policy, and the establishment of the European Technology Institute (KL 2006-03-31 and KL 2006-04-07). It also seems that the Finnish debaters tend to compare the targets of the Finnish policy with those of theEU. Therefore any achievement at the European level is automatically regarded as an example of success.As concerns Nordic aspects of the debate, a short exchange of views took place inHelsingin Sanomatin 2007when a proposal was made that the Nordic countries should build a network of technology centres outsideEurope (HS 2007-06-11). It was argued that especially in the fields of science, technology and culture, all fivecountries could share a common potential. Nordic cooperation seems, it was noted, to diminish in the wake ofEuropean integration, and these countries should invest more in utilization of technology. Some rather daringdebaters urged the Nordic countries to maintain dialogical connections and creative thinking but to close downthe Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers (HS 2007-06-12). To replace the Councils a think tankinstitute was suggested to be established.IcelandIceland has had access to the EU framework programmes since the coming into force of the EuropeanEconomic Area (EEA) in 1994. Unsurprisingly, discussions have emerged about the opportunities for Iceland inthis cooperation. The Nordic financial system has also been extensively utilized by Icelandic researchers for thebenefit of their work. One might have expected to see a larger proportion of articles dedicated to bilateralcooperation with non-Nordic and non-EU countries where cooperation on an institutional basis has been quitefrequent in Iceland.NorwayAs seen in Figure 17.1, the debate in Norway has an almost exclusive focus on national issues. References toother countries are most often in the form of comparisons particularly with other Nordic countries,substantiating claims that Norway is lagging behind on virtually every indicator of “sound” R&D policy. Nordicand European research policy are rarely the topic of the debate, with some exceptions. One of theseexceptions was an article by the director of the RCN in 2005 supporting the Lisbon strategy (Aftp. 18-09-2006).It is noteworthy that the only references in our material to specific Nordic policies (NordForsk, NORIA) arefound in just one article – by Nordic ministers on the establishment of NordForsk and of the NORIA conceptionfrom July 2004.SwedenAlso the Swedish debate’s main concern is the national level. References to other countries are seldom, andmost often, as in the Norwegian comparisons, almost exclusively with the aim to show how Sweden is laggingbehind and losing out in the global competition. There are a few references to EU issues and even fewer toother Nordic countries.

72

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONSIn this study we raised questions about what a more detailed mapping of research public debate during thisrecent ten-year period could say about the main trends of research policy developments in the Nordiccountries. These countries – or at least most of them, are “frontier” countries in the progress towards the“knowledge-based economy” and “knowledge society”, if international rankings and benchmarks are to bebelieved. Does this mean that research issues become more intensely and widely debated by the general publicand in the media in these countries? Do groups beyond the inner circle of “usual suspects” – immediatestakeholders and directly affected parties in research and industry – make a stronger impact on the publicdebate? Are issues and forces that are often seen to drive developments such as competition and innovation,internationalisation and globalisation debated to an increasing extent?At the same time, allegedly, there is a unique “Nordic approach” to these developments in which retaining thequalities of the welfare state, while pursuing the goals of competitiveness and innovation, are seen to beessential. Is this seen to raise conflicts that find expression in public concern, and how and to what extent doespublic debate play a critical and/or promotional role in relation to policy development and implementation? Ispublic debate primarily “reactive” or does it anticipate and push issues that are still not taken up on the policyagenda?Our data do not provide simple and conclusive answers to these questions. In our analyses we have found anumber of similarities and parallel developments, but also variation and divergences.We asked if our material would support the assumption that research issues, in relative terms, are on the movefrom the periphery to the centre of both the general political process and public debates in general newsmedia. We did indeed find some support for this. We saw (Figure 1) that while the extent of research policydebate remained relatively stable during the first half of the period, there was an overall increase in allcountries except Iceland during the period 2002–2006. The increase was, however, uneven, and for allcountries the number of articles fluctuated widely from one year to the next. These variations could to someextent be seen to reflect peculiarities of policy developments in each country supporting the interpretationthat the increasing importance of knowledge in the economy and society also makes an impact on the volumeof public debate on research.A key question is, however, whether a more pervasive societal influence of knowledge in public perceptionsalso has an impact on the structure of public debate, in terms of which social groups take an active part inthese debates. It follows from the assumption that knowledge is perceived to become increasingly importantthat broader sections of the public would also see themselves as affected to an increasing extent by researchpolicy issues and decisions. Or, contrary to these predictions, does research policy remain a confined,suigeneristype of policy, in which the role of the “usual suspects” – immediate stakeholders in academia, industryand research institutions, as well as actors directly responsible for policy development and implementation inresearch ministries and agencies – remain as dominant as they have been?We did not find much support to for the assumption that extensive change is taking place in the structure ofpublic debate. The role of researchers and representatives of research institutions combined as the dominantgroup of authors of interventions in the debate was clear in all countries except Iceland where controversyover a genetic database has triggered a broad public debate. The dominant role in the debate of researchers isparticularly strong in Sweden. The presence of civil society remains marginal in all countries, the least so inIceland, which does not provide much support for the idea that a general shift is taking place in terms ofparticipation in research policy debate from immediate stakeholders to wider social groups. The perception ofthe Nordic countries as countries where civil society and the lay public play particularly active roles in publicdebates and policy process concerning science and technology is thus not confirmed by our data. This appearsat least to be the case for issues of research policy as defined in our project. There is, independently of this73

project, strong evidence that these groupsdogenerally take active part in debates where research, technologyand innovation issues are strongly linked to applications and/or broader policy issues, such as ethics (e.g., gene33technology), environmental and health policy (e.g., risk regulation).We did find a notable difference in particular between Denmark and Finland concerning the relative roles ofpoliticians and representatives of ministries. While this group was particularly active in Denmark, it took amuch less prominent role in Finnish debates. The role of business was also relatively minor in all countries, butwas more active in Denmark than in the other countries.We also found (Figure 5) that public debate on research policy issues are to a large extentpolicy-drivenin mostcountries. The policy-making process and actors largely determine and frame the agenda of the debate, whichresponds to and follows initiatives and statements by policymakers. If this is a feature of the debates in allcountries, it is much more salient in Denmark and Sweden than in Norway and Finland. This pattern is also validfor the “referred actors” variable (Figure 7). While other ministers than the minister responsible for researchwere often referred to in Denmark, the Finnish minister for research and education was hardly referred to atall. Researchers were the most dominant “referred actor” group in Norway, as it was, if to a lesser extent, inFinland and Sweden.Overall, we find that disagreements between researchers and politicians are by far the most common in all theNordic countries. However, we find a higher level of disagreement among researchers in Finland and Icelandand more disagreements between politicians and researchers in Denmark, Norway and Sweden.We could see little evidence that potential conflicts between values at stake surfaced in the debate. Therewere few explicit references to sustainability/environment and to welfare: references to economic growth andknowledge society were more frequent. This was particularly the case for Finland, and – for the knowledgesociety – for Denmark. There were very few negative references to the role of research as sustaining thesevalues. A few more negative references to research as instrument for economic growth did appear in theNorwegian debate.There was a similar overall research policy agenda in all the countries. Main issues in all of these were resourceissues, in particular unmet resource needs in research and the level of overall national research investments;the reorganisation of research institutions, in particular higher education institution; the freedom of research,including both the availability of funds for “free” research and academic freedom. A less homogenous pictureemerges when we move from the “core” of research policy to the interface of research with society, in terms ofthe role of research for innovation and enhancing the competitiveness of the national economy. These issueswere more strongly voiced and advanced in the research policies in Finland and Denmark, and consequentlywere more salient in the debates on research in these countries. “Innovation” is the output issue that was themost extensively debated in Finland where technology policy has been more dominant than science policy bothin the official policy documents and in the public debate. Recently innovation policy has taken the lead andbecome linked to all policy sectors making innovation an important aspect of both economic and academicperformance. The role of innovation policy has become particularly evident through globalisation reports,restructuring of the university system and innovation strategies that have been formulated at the end of the2000s.Even though public debates respond to, and are triggered by policy initiatives and agendas, this does not meanthat all important initiatives and issues within the policy are also reflected in the debate. One may argue that in33

See e.g., Gutteling et al. (2003), Media coverage 1973–1996:Ttrends and dynamics, in M. Bauer & G. Gaskell:Biotechnology. The Making of a Controversy,pp. 95–128, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. For a somewhat differentpicture for Finland: Karoliina Snell (2009),Social Responsibility in Developing New Biotechnology: Interpretations onResponsibility in the Governance of Finnish Biotechnology,University of Helsinki.

74