Udvalget for Videnskab og Teknologi 2010-11 (1. samling)

UVT Alm.del

Offentligt

Public Debate on Research Policyin the Nordic CountriesA Comparative Analysis of Actors and Issues(1998 – 2007)Egil Kallerud, Thorvald Finnbjørnsson, Lars Geschwind,Marja Häyrinen-Alestalo, Inge Ramberg, Karen Siune &Terhi TuominenRapport 11/2011

Public Debate on Research Policyin the Nordic CountriesA Comparative Analysis of Actors and Issues(1998 – 2007)Egil Kallerud, Thorvald Finnbjørnsson, Lars Geschwind,Marja Häyrinen-Alestalo, Inge Ramberg, Karen Siune &Terhi TuominenRapport 11/2011

Rapport nr.Utgitt avAdresse

Rapport 11/2011Nordisk institutt for studier av innovasjon, forskning og utdanningPB 5183, Majorstuen NO-0302. Besøksadresse: Wergelandsveien 7.

OppdragsgiverAdresse

NordForskStensberggata 25, N-0170 Oslo

TrykkISBNISSN

Link Grafisk978-82-7218-742-11892-2597

www.nifu.no

PREFACEIn 2007 NordForsk initiated and supported a comparative, exploratory study of public debate on researchpolicy issues in the Nordic countries during 2004–2007. The focus of interest was narrowed down to includepublic debate on research policy aspects of globalisation. The results of the study were published in NordForskMagazine 1/2007. Based on the experiences gained from the preparatory study, NordForsk decided in 2008 tofund a full-scale comparative study of research policy debate in the Nordic countries during the period 1998–2007. This report presents the results of the comparative study. The study was performed by a consortium offive national teams coordinated by NIFU STEP, Norway (led by senior researcher Egil Kallerud). The other teamswere teams were of the Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy, the University of Aarhus,Denmark (led by Director Karen Siune), SISTER, Sweden (led by senior researcher Lars Geschwind), Rannis,Iceland (led by head of department Thorvald Finnbjørnsson), and University of Helsinki, Finland of (led byProfessor of Science and Technology Studies Marja Häyrinen-Alestalo). NordForsk appointed a reference groupfor the study with these members: Professor Anker Brink Lund, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark;director Carl Jacobsson, Swedish Research Council, Sweden; secretary general Esko-Olavi Seppala, Science andTechnology Policy Council, Finland; special adviser Gro Helgesen, The Research Council of Norway, Norway.The content of the report is the full responsibility of the authors and NIFU.

Oslo, January 2011

Sveinung SkuleDirector, NIFU

CONTENTSPreface .................................................................................................................................................................... 3Executive summary ................................................................................................................................................. 71.Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 131.1.1.2.1.3.2.The Nordic countries – vanguards of the knowledge economy? ........................................................ 13Public debate – a neglected domain in research policy analyses ........................................................ 15The study – objectives, methodology, participants ............................................................................. 16

Background - main policy events and issues ................................................................................................. 192.1.2.2.2.3.2.4.2.5.Denmark .............................................................................................................................................. 19Finland ................................................................................................................................................. 20Iceland ................................................................................................................................................. 23Norway ................................................................................................................................................ 25Sweden ................................................................................................................................................ 27

3.

The public debate – who, what, when? ........................................................................................................ 293.1.3.2.3.2.1.3.2.2.3.2.3.3.2.4.3.2.5.3.2.6.3.3.3.3.1.3.3.2.3.3.3.3.3.4.3.3.5.3.4.3.5.3.6.Changing trends in research policy debate 1998 - 2007 ..................................................................... 29Which voices were dominant? ............................................................................................................ 30Editorial and public contributions ................................................................................................... 31Main actors – the authors ............................................................................................................... 32Did the relative participation of main actor groups change during the period?............................. 34Setting the agenda – who, what, how? ........................................................................................... 39Who disagrees with whom? ............................................................................................................ 43Values at stake ................................................................................................................................ 44What topics and issues were debated? ............................................................................................... 47Resources and funding .................................................................................................................... 48Organisation, institutions and reform ............................................................................................. 52Human resources ............................................................................................................................ 56Output issues................................................................................................................................... 60Which topics and issues were most frequently discussed? ............................................................ 64Which disciplines were discussed? ...................................................................................................... 65What challenges were picked up? ....................................................................................................... 68International dimensions of research overshadowed by the national ................................................ 70

4.5.

Discussion and conclusions ........................................................................................................................... 73Appendices .................................................................................................................................................... 77

Appendix 1: Cross Tables and figures.................................................................................................................... 77Appendix 2: Code Key for the Content Analysis .................................................................................................... 81

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYPublic debate on research policy issues is arguably a neglected domain in studies of research and researchpolicy. This comparative study on this kind of debate is thus a study which may lay claim to some novelty in itschoice of topic. It may be seen as an exploration of this aspect of the development of the “knowledge society”and “knowledge economy”. These concepts not only suggest that knowledgein generalis becoming moreimportant, they also emphasize more particularly the increasing importance of formal, advanced, research-based knowledge as immediate sources of economic growth, as a dimension that occupies a larger share of theactivities of society as such, and of (an increasing share of) its individual members. The increasing societal andeconomic role of advanced, research-based knowledge may also be expected to be mirrored in both in theincreasing political importance or priority of knowledge policies and may lead to more public debate and mediacoverage of knowledge-related issues, developments and controversies.A key part of policy discourse on the knowledge society and economy is the development and active use of arange of indicators and rankings to measure and monitor how individual countries and regions make progressin this process of structural change. From these rankings a map has emerged of “leading” and “lagging” nationsand regions. While such rankings often vary as a function of differences between methodologies andaggregation of indicators, they invariably put some or all of the Nordic countries in top positions. This applies inparticular to the indicators used by the EU in order to monitor Europe’s progress towards the knowledge-basedeconomy. Within these EU rankings the Nordic member countries in general, and Finland and Sweden inparticular, are seen to pave the way which the EU as a whole should follow and, specifically, to provideevidence that the target to increase R&D investment to 3 percent of GDP is possible and viable. There is, assuch, a “look to the Nordic countries” element in much global and European debate on policies for the“knowledge economy” in general and for R&D (research and development) in particular. Consequently a studyof the public debate on research policy issues in the Nordic countries may be an exploration of how and towhat extent the allegedly increasing importance of research is reflected in public awareness and incharacteristics of public debate on research policy issues. Some of the Nordic countries have strong traditionsof extensive civic participation and public engagement in public debates. One could expect that the widening ofdebates on research policy in these countries may involve broader constituencies than immediate stakeholdersin research, industry and policymaking.As advanced welfare states, the Nordic countries are also committed to values of equality and social security,key references in policy debates about knowledge societies and economies in terms of providing evidence thatthe “European social model” which combines knowledge-based growth and “social cohesion” is possible andviable. Is there evidence of public awareness that fundamental values may be at stake in the “knowledgesociety/economy” developments and issues? To what extent and how does awareness about values inparticular surface in the public debate on research policy issues?This study attempts to address such issues through a combined quantitative and qualitative study of articles onresearch policy published in 3–5 newspapers in each of the Nordic countries during the 10-year period 1998 to2007. This was a period during which a large number of initiatives were launched and debated in all the Nordiccountries as indicated by an overview provided in the report of key policy developments and eventsThe main findings of the study are as follows.Increase in public debate.We see an overall pattern where public debate on research policy increased duringthe ten year period covered. While the extent of research policy debate remained relatively stable during thefirst half of the period, there was an overall increase in all countries except Iceland during the period 2002–2006. The increase was, however, uneven between years and between countries, and seems to correlate withparticular policy initiatives and events.7

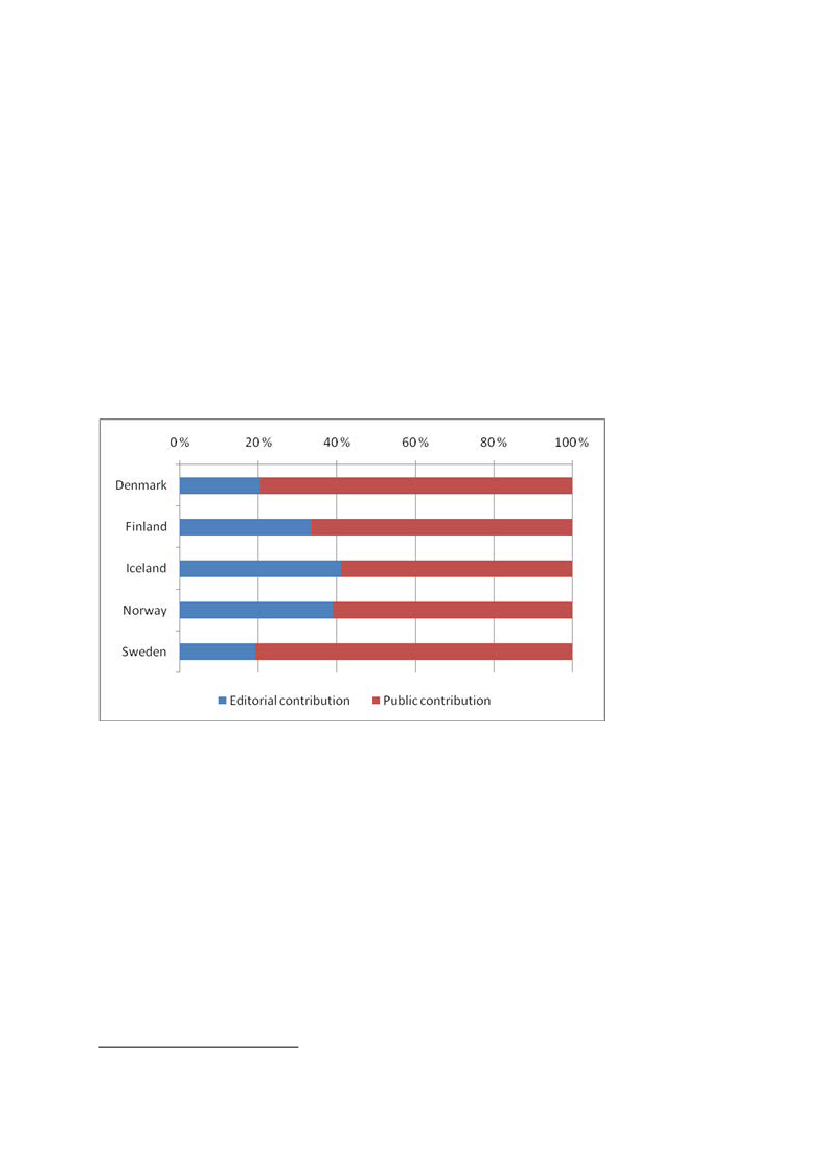

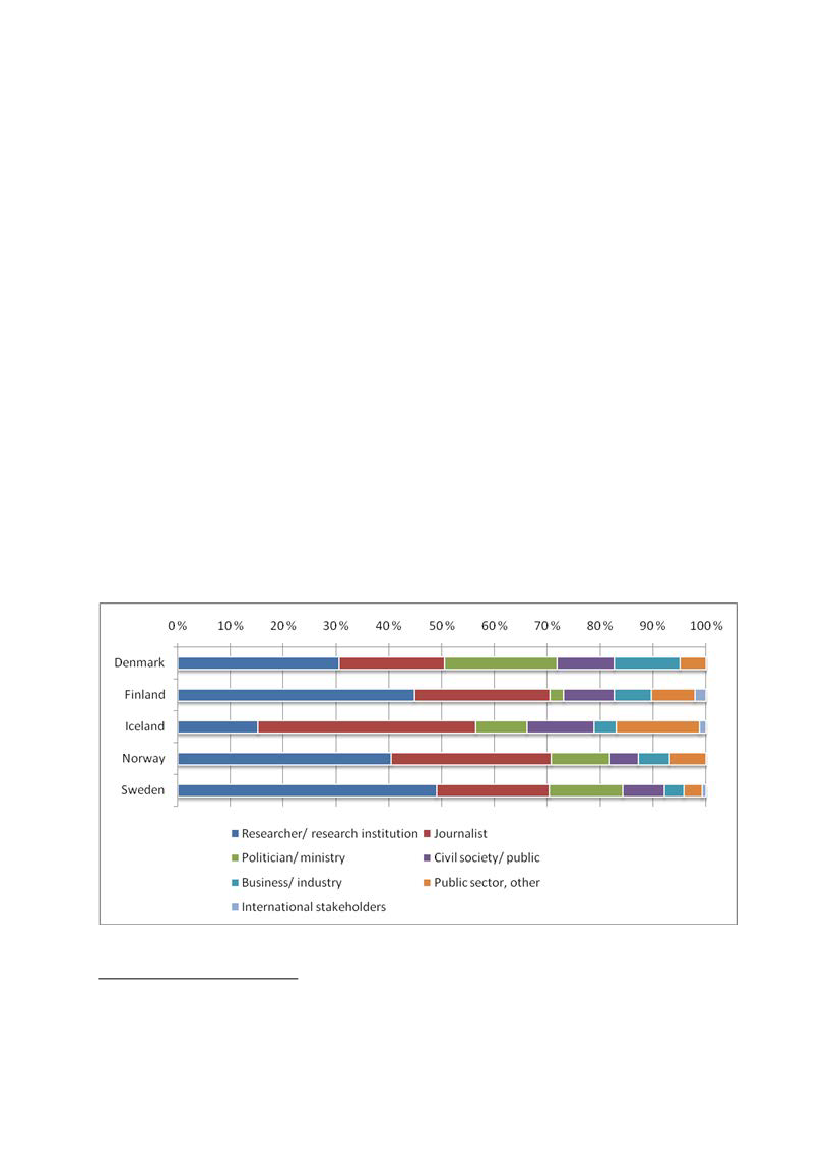

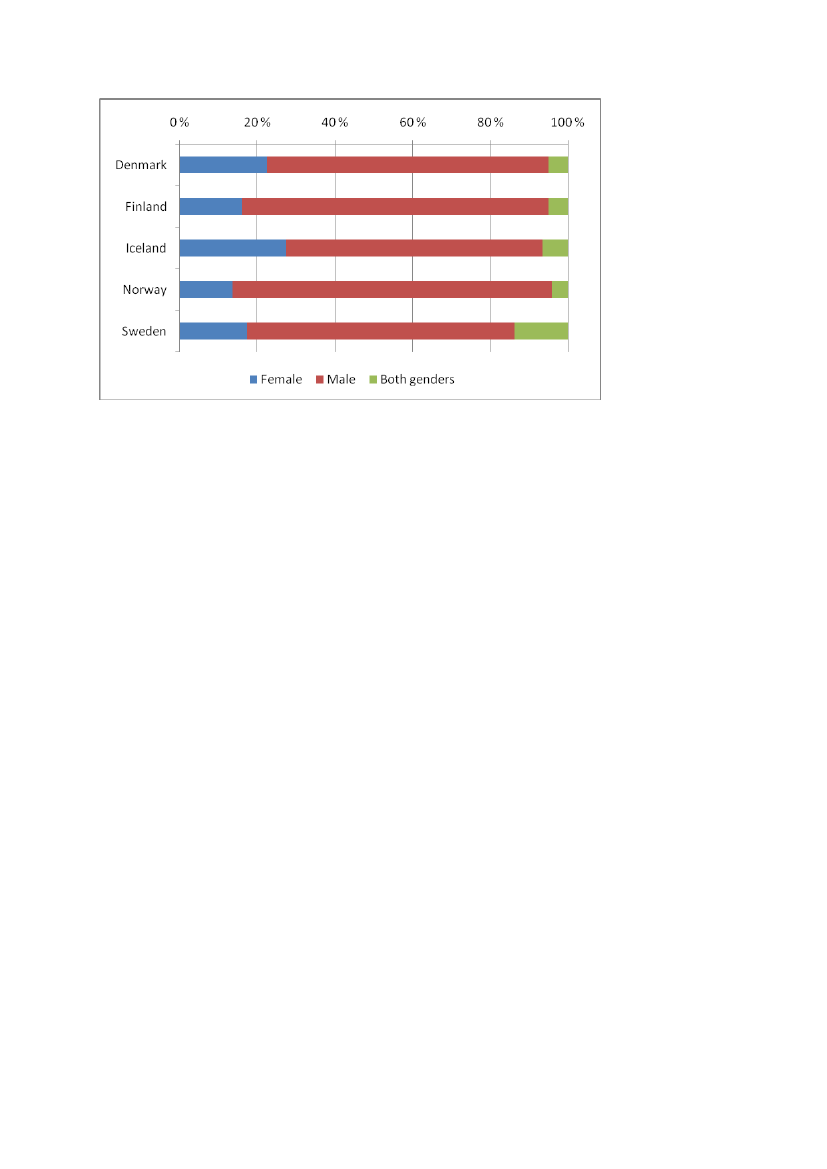

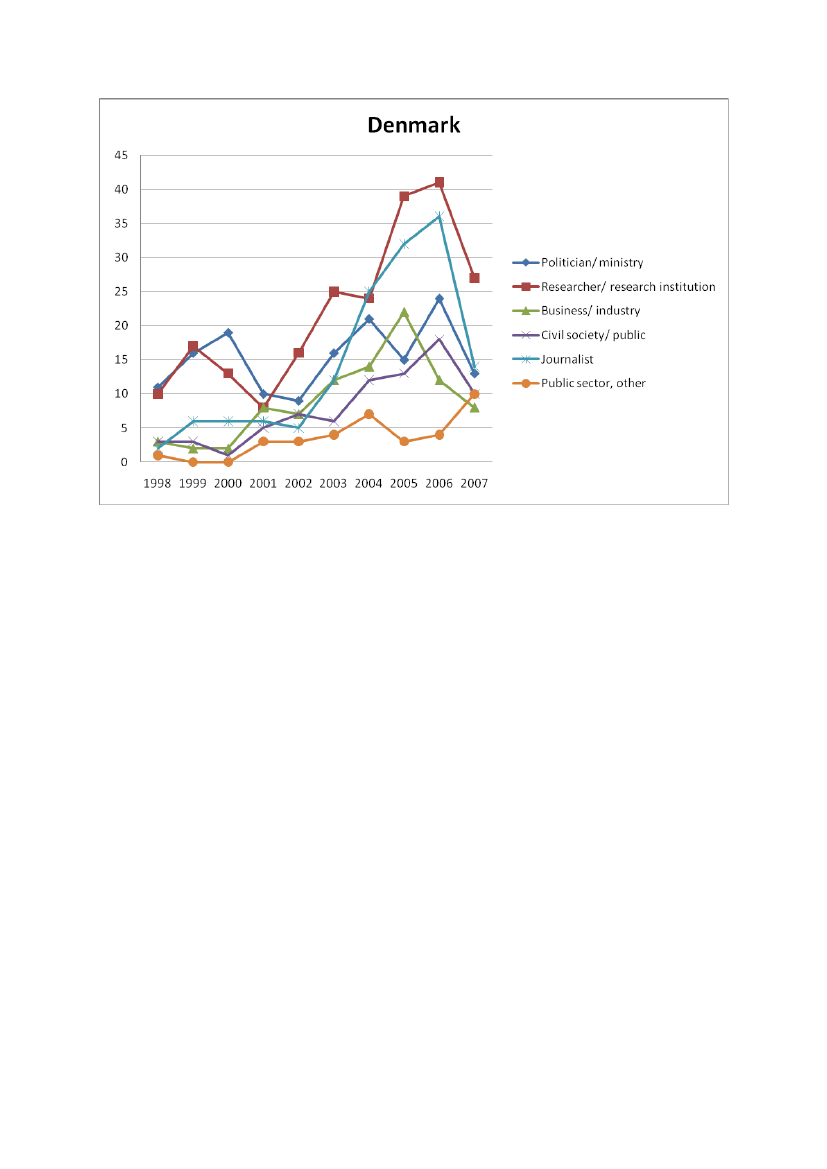

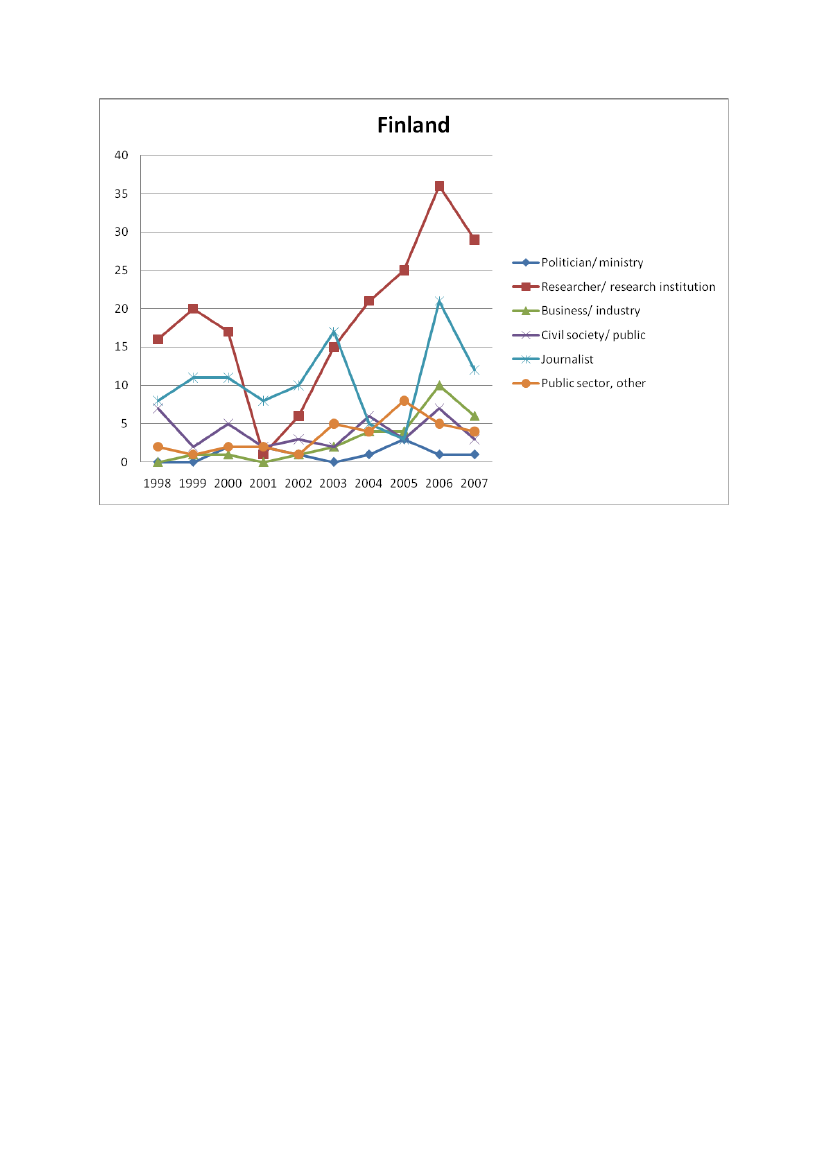

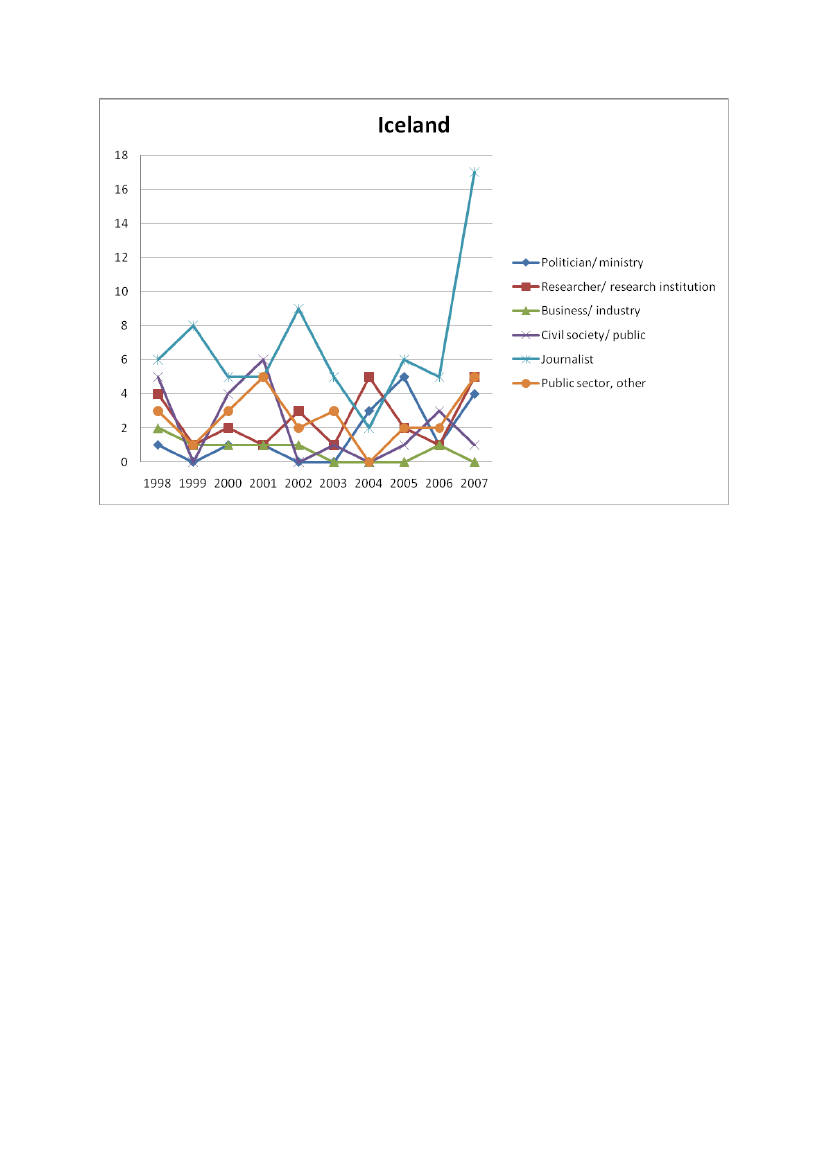

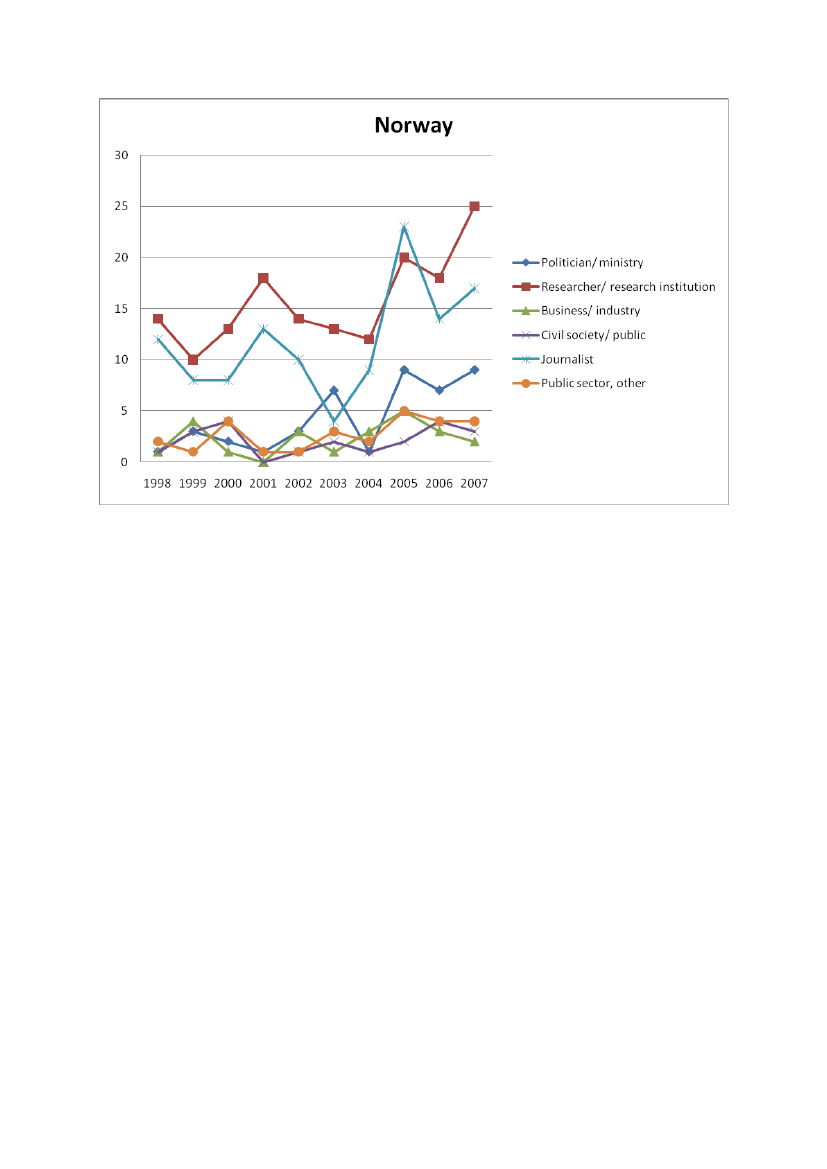

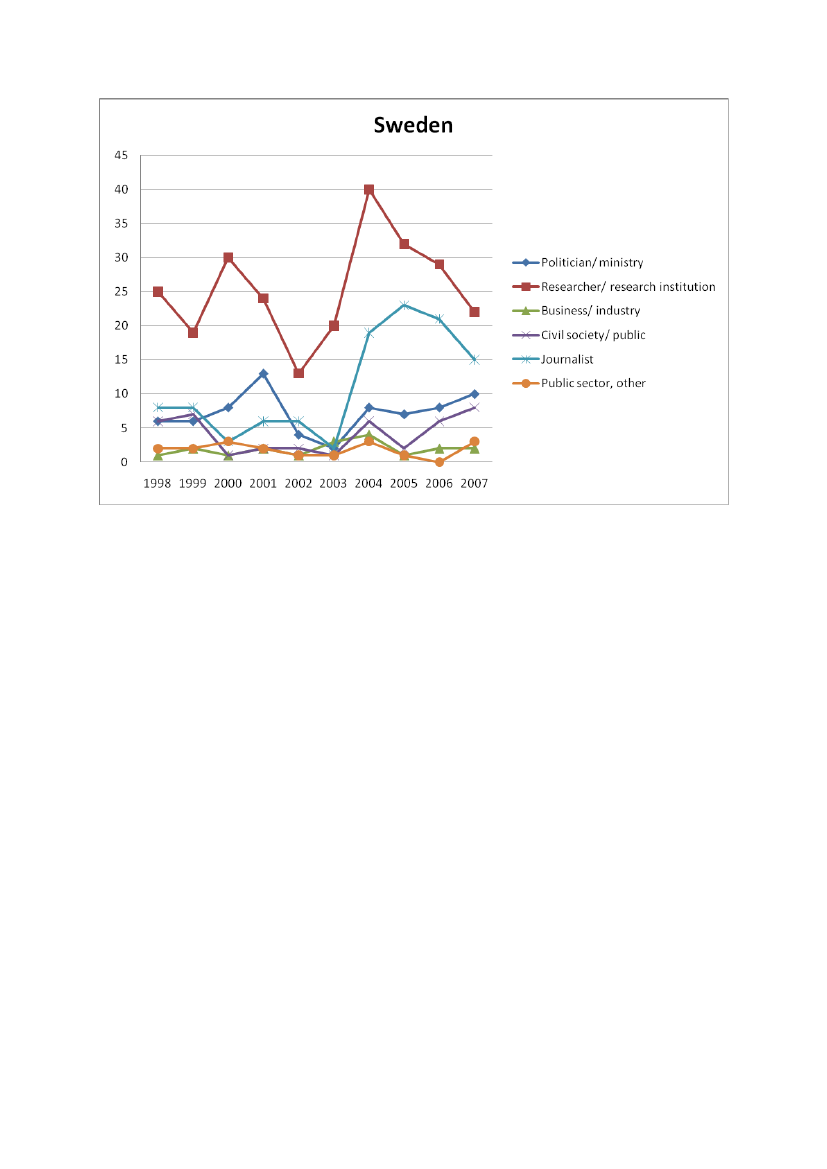

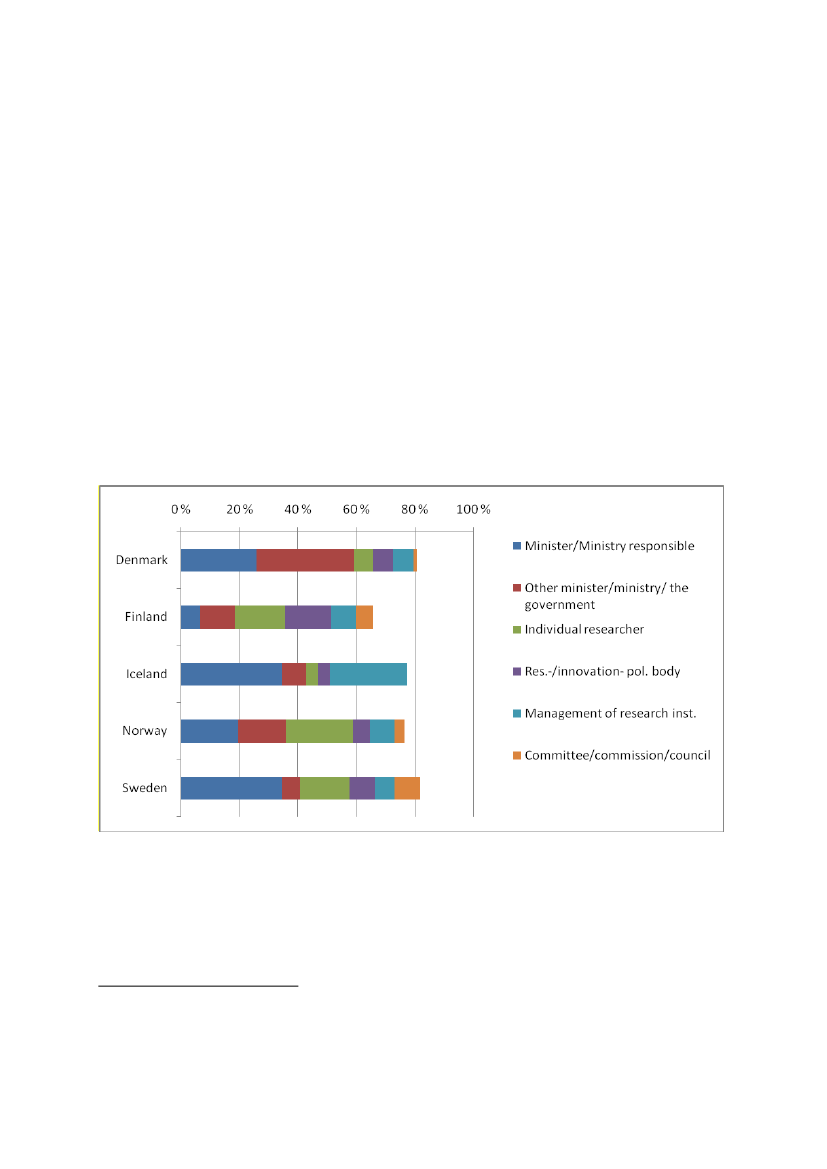

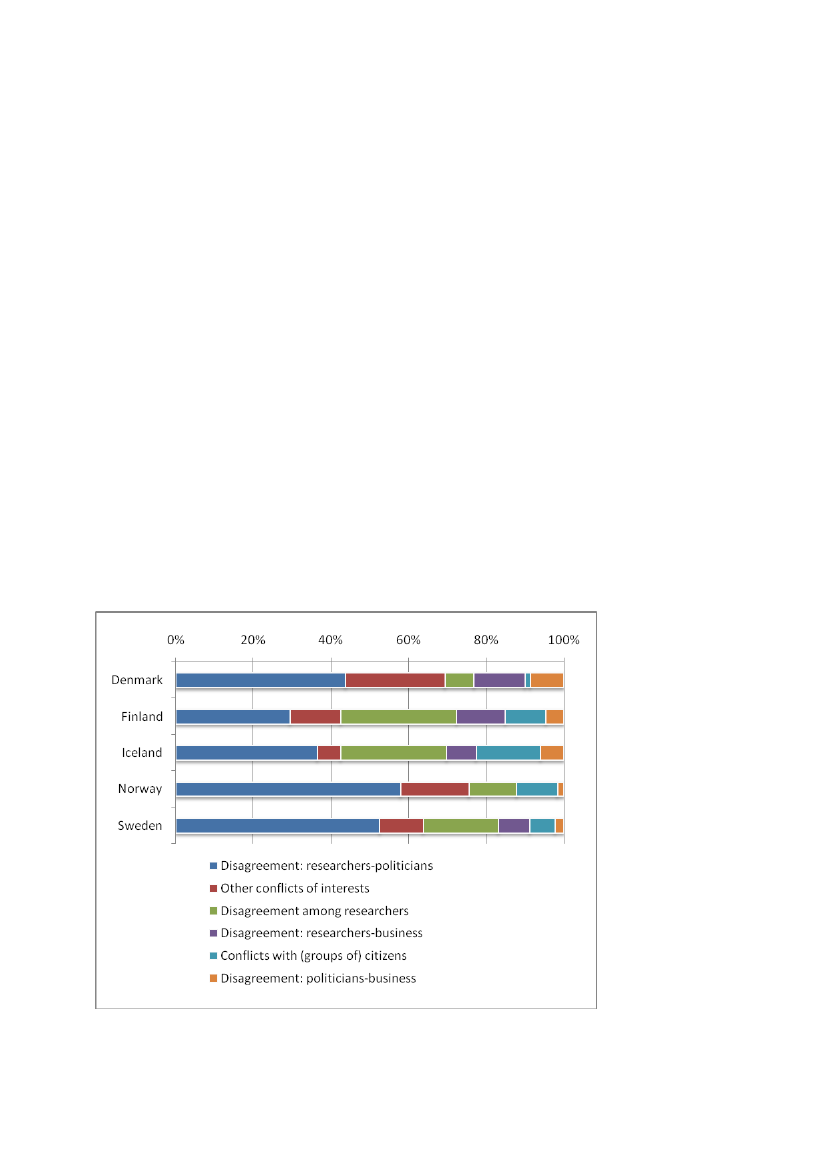

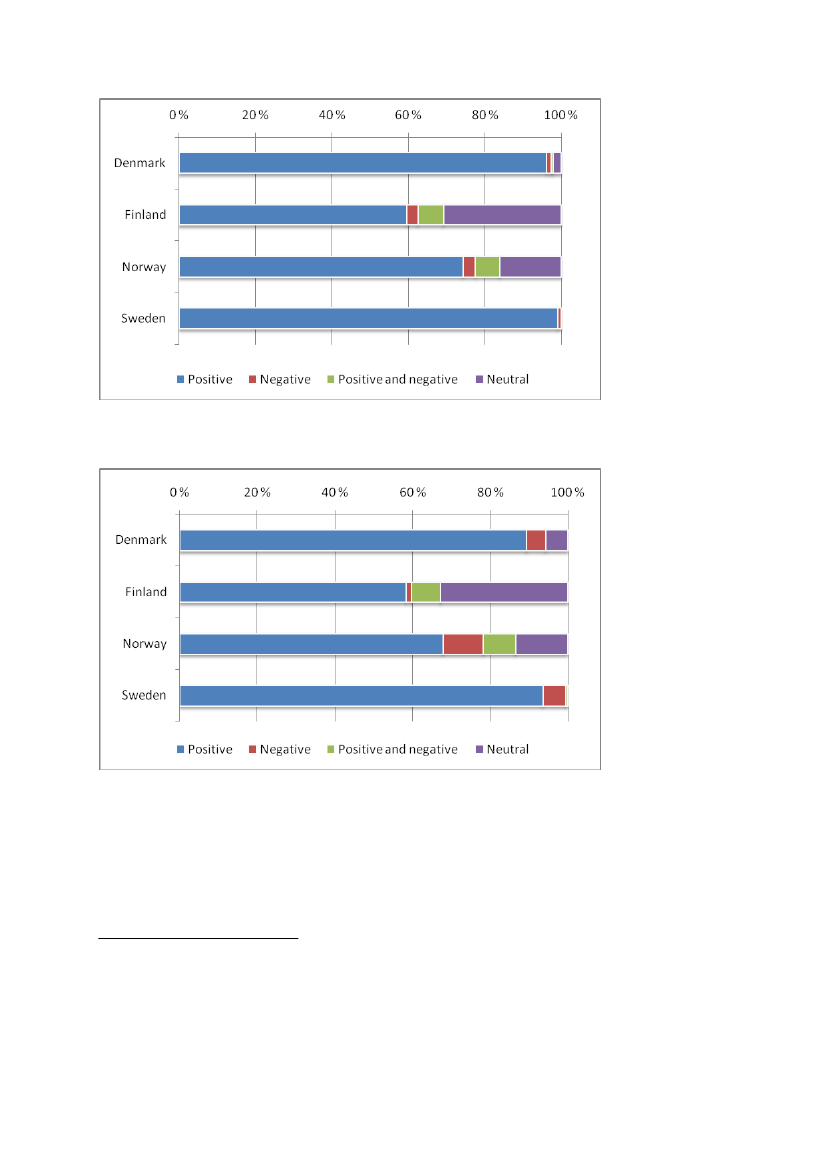

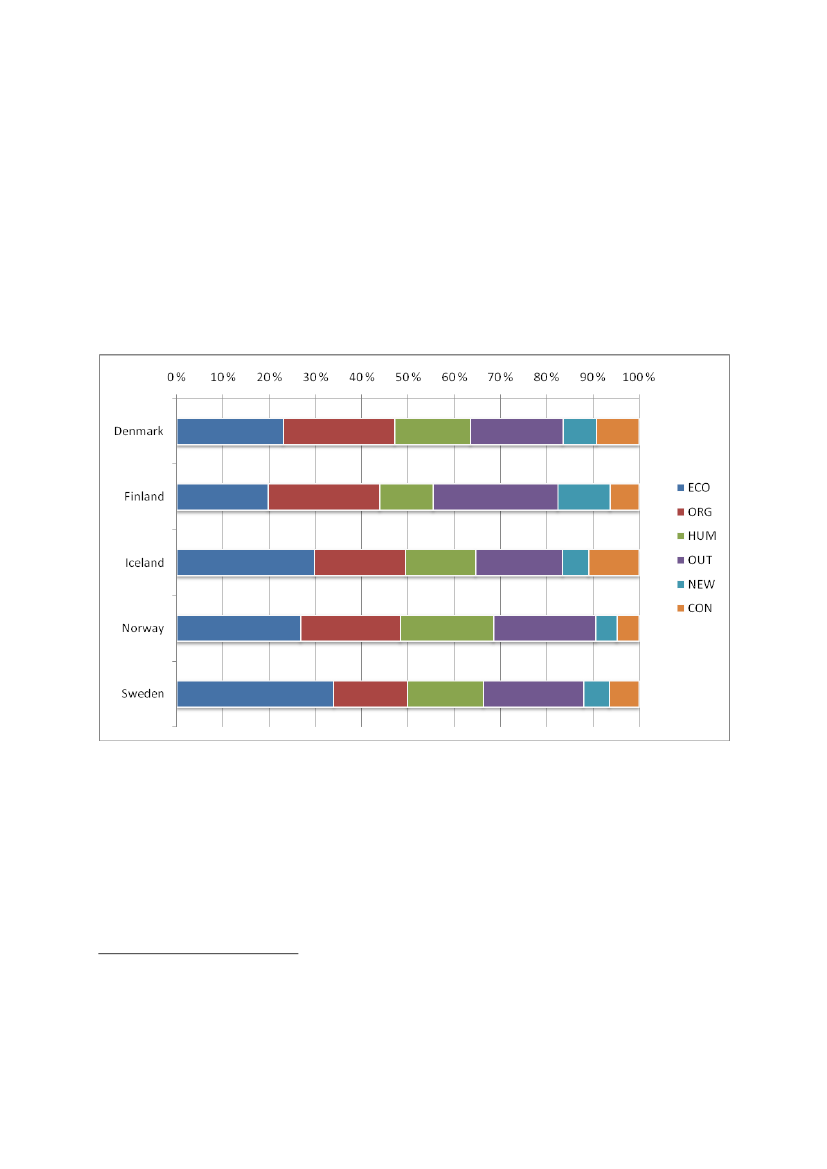

Researchers are the dominant actor group.Researchers and research institutions combined are the dominantgroup of authors in all countries except Iceland, where the dominant group is journalists. The dominant role ofresearchers is particularly salient in Sweden. In these countries (excluding Iceland) journalists are the secondlargest actor group. However, the relative weight of both these two and the other groups varies considerablybetween the countries. The presence of civil society is relatively marginal in all countries and does not providesupport for the assumption of a general shift in the participation in research policy debates from immediatestakeholders to wider social groups. Thus we find no firm indication that groups beyond immediatestakeholders feel affected by, and engage actively in research policy issues.Politicians’ and business roles vary strongly.In Denmark, politicians and representatives of the ministries aremore active than in any other country while their relative presence in Finland is very low. This reflects thedifferent characteristics of the political process in the two countries. There is also a large variation in theparticipation in the debate of actors from business/industry, which in Denmark plays a more prominent rolethan their counterparts in other Nordic countries. Women were more active in Iceland and Denmark than inthe other countries. Sweden and Denmark display a higher degree of policy initiation (through laws, bills,executive orders or appropriations of financial resources) compared to other Nordic countries. The amount ofresearcher- and journalist-initiated debate is lowest in Iceland and Finland.Politicians are often referred to in the debate.While the politician/ministry group has a relatively minor role asauthor, the minister/ministry of research and other ministries taken together are by far the largest referredactor groups (persons referred to in an article) in all countries except Finland. Within this group, otherministers or ministries are more frequently referred to than the research minister/ministry in the debates inDenmark and Finland. In Iceland leaders of research institutions are referred to much more frequently than inthe other countries. In Sweden, state initiated committees/inquiries are relatively frequently referred to,compared to the other Nordic countries.Researchers and politicians disagree.Disagreements among researchers and politicians were by far the mostcommon in all the Nordic countries. Disagreements among researchers occurred most frequently in Finlandand Iceland, while this was rarely the case in Denmark.Limited explicit value awareness.In around half the articles some explicit reference to one of four values(knowledge, economy, welfare, sustainability) could be detected. The knowledge society and economic growthdimensions were by far those which were most often frequently referred to. Economic growth is moredominant than the knowledge economy dimension, particularly in Norway and Sweden, and references tothese two dimensions are nearly equally frequent in Finland and Iceland. Denmark differs from the othercountries in this respect with considerable more references to the knowledge society than to economic growth.Different topics prevail in the various countries.The topics of the articles were coded into forty subjects, eachassigned to one of six main topic groups: Financial management/resource issues, organisational management,human resources, output-related issues, challenges and conflicts. While economic/resource topics,organisational topics and output-related issues are the dominant topic groups in all countries, the relativeprevalence of topics groups differs between the countries. In debates in Denmark, issues of organisation andmanagement were most common, output-related issues were the most frequently debated in Finland, whiledebates in Iceland, Norway and Sweden were predominantly on financial and resource issues. Our analysis ofthe topics is to a large extent qualitative, highlighting a number of national specificities.Much debate about health science in some countries.Unsurprisingly, issues about technical science andtechnology were common in all countries, particularly in Finland and Denmark, but in Norway, Iceland andSweden discussions on health science were more common, and in Sweden and Norway issues pertaining to thehumanities were also common, and much more so than in any other country.

8

Basic research a key concern.For all countries except Finland, debates were about basic research in the caseswhere references to types of research could be detected. In Finland the main reference was to “research anddevelopment”. This was also common in Norway and Iceland. Only Danish debates referred to any significantextent to “strategic research”.Extremely strong national bias in research policy debates in all countries.A main finding of our study is that inall the Nordic countries the research policy debate had analmost exclusivelynational focus. References to theNordic countries or other regions were rare. References to non-Nordic EU countries were more frequent inFinnish debate articles than in articles in other Nordic countries. This picture is also sustained by our findingthat relatively few articles made any reference to issues of international research cooperation. As a large partof the debate in several countries was concerned with inadequate resource levels, references to the Barcelonatarget were frequently made as part of the argument. In this way the EU dimension did figure in the nationalpublic debate as pressure on national governments to increase (public) funding of research. To a certain extentpublic debate may be seen to have acted as an “ally” to the European Union wanting to exert pressure onnational policymakers to increase research funding.***SammendragInnen feltet studier av forskning og forskningspolitikk er det gjort få undersøkelser av den rolle som offentligdebatt om forskningspolitiske spørsmål spiller. Herværende komparative studie av slik debatt kan altså til enviss grad gjøre krav på å være nyskapende i valg av tema. Den kan leses som en utforskning av denne spesiellesiden ved utviklingen av “kunnskapssamfunnet” og “kunnskapsøkonomien”. Disse begrepene indikerer ikkebare at kunnskap generelt er i ferd med å bli viktigere, de understreker også at formell, avansert ogforskningsbasert kunnskap blir viktigere som umiddelbare kilder til økonomisk vekst, og utgjør en stadig størredel av samfunnets og den enkeltes aktiviteter. En vil derfor også kunne forvente at den økende samfunns-messige og økonomiske betydning som avansert, forskningsbasert kunnskap får også kommer til uttrykk ved atkunnskapspolitiske spørsmål får høyere politisk prioritet, og at det fører til mer offentlig debatt og mer dekningi mediene om kunnskapsrelaterte saker, utviklingstrekk og kontroverser.En sentral del av den politiske diskusjon om kunnskapssamfunn og kunnskapspolitikk er utvikling og aktiv brukav en lang rekke indikatorer og rangeringer for å måle og overvåke hvordan enkeltland og -regioner plassererseg i slike strukturelle endringsprosesser. Fra disse rangeringene har det vokst fram et bilde av enkelte nasjonerog regioner som ledende, mens andre sakker akterut. Slike rangeringer gir, som en følge av ulike metoder ogulike måter å aggregere indikatorer på, ofte ulikt resultat, men de plasserer nesten uten unntak nordiske land itopposisjoner. Dette gjelder spesielt for indikatorer som brukes av EU for å overvåke utviklingen av Europaskunnskapsbaserte økonomi. På disse blir de nordiske land generelt, og Finland og Sverige spesielt, ansett somland som viser vei for EU som helhet, og de framstår som bevis for at det er mulig og riktig å øke de nasjonaleinvesteringene i forskning og utvikling (FoU) til tre prosent av brutto nasjonalprodukt (BNP). Det er med andreord et element av “look to the Nordic countries” i mye global and europeisk forskningspolitisk debatt om“kunnskapsøkonomien” generelt og om FoU spesielt. Derfor kan en studie av offentlig debatt omforskningspolitiske spørsmål i de nordiske landene si noe om hvordan og i hvilken grad forskningens påståttøkende betydning kommer til uttrykk i offentlig oppmerksomhet for forskning og i kjennetegn ved denoffentlige debatten om forskningspolitiske spørsmål. Noen av de nordiske landene har også sterke tradisjonerfor bred folkelig deltakelse i offentlig debatt, og en kan forvente at en utvidelse av interessen for og debattenom forskningsspørsmål også fører til at bredere grupper deltar i debatten enn bare de grupper innen forskning,industri og forvaltning/politikk som er direkte berørt.I egenskap av å være framskredne velferdsstater er også de nordiske landene forpliktet på verdier som likhetog sosial sikkerhet, og det blir ofte vist til at disse landene har lykkes med å virkeliggjøre den ”europeiske9

sosiale modellen” ved å kombinere kunnskapsbasert økonomisk vekst og sosial solidaritet/sammenhengskraft(social cohesion). Gir debatten belegg for at det finnes en sensitivitet i befolkningen for at slike fundamentaleverdier står på spill i og med utviklingen av “kunnskapssamfunnet/-økonomien”? I hvilken grad og på hvilkenmåte kommer evt. en slik verdibevissthet til uttrykk i den offentlige debatten om forskningspolitiske temaer?Denne studien søker å reise slike spørsmål i form av en kombinert kvantitativ og kvalitativ studie av publiserteartikler om forskningspolitikk i 3-5 aviser i hvert av de nordiske landene i løpet av tiårsperioden fra 1998 til2007. Vår oversikt over de viktigste forskningspolitiske utviklingstrekk og begivenheter i denne perioden viserat dette var i samtlige nordiske land en periode da et stort antall forskningspolitiske initiativ ble tatt ogdebattert.Hovedfunnene i studien er disse:Økt offentlig debatt.Vårt material viser at den offentlige debatt om forskningspolitiske spørsmål økte I løpetav perioden. Mens omfanget av debatt var ganske stabilt i første halvdel av perioden, var det en generelløkning io alle landene unntatt Island i perioden mellom 2002 og 2006. Økningen var imidlertid ujevnt fordeltmellom år og mellom land, og synes å korrelere godt med spesielle politiske initiativ og begivenheter.Forskere den mest aktive gruppen.Gruppen forskere og forskningsinstitusjoner er i alle land dominerende somforfattere av de artikler vårt materiale omfatter. Unntaket er Island, der journalistgruppen dominerer.Forskernes dominerende rolle er særlig tydelig i Sverige. Journalister er den nest mest aktive gruppen. Detrelative tyngdeforhold mellom så vel disse to gruppene som mellom de øvrige forfattergrupper variererimidlertid betydelig landene imellom. Vi finner kun marginal deltakelse fra det sivile samfunn, noe som ikkestøtter antakelsen om at debatten utvides til å omfatte bredere grupper enn de som er direkte berørt.Politikeres og industrirepresentanters rolle varierer mye.I Danmark spiller politikere og representanter fordepartementene en mer aktiv rolle enn i noen av de andre landene. denne gruppen har svært lav deltakelse iFinland. Dette gjenspeiler særtrekk ved de politiske prosessene i de to landene. Det er også stor variasjonenlandene imellom i hvor stor grad representanter for næringsliv deltar i debatten. Denne gruppen spiller IDanmark en mer framtredende rolle enn i de øvrige land. Kvinner var mer aktive i Island og Danmark enn iøvrige land. Debatter ble i størst grad utløst av politiske initiativ (lovforslag, politisk beslutning, bevilgning) iDanmark og Sverige. Debatt initiert av forskere eller journalister forekom sjeldnere i Island og Finland enn Iøvrige land.Ofte referanse til politikere.Selv om politikere og departementsrepresentanter kan spille en beskjeden rollesom forfattere av artikler, er ministre/departementer den gruppe det hyppigst blir referert til i artiklene. Detgjelder alle land unntatt Finland. Innenfor denne gruppen blir det i Danmark og Finland hyppigere vist til andredepartementer/ministre enn forskningsministeren/-departementet. I Island er det oftere referanser til ledereav forskningsinstitusjoner enn i andre land, mens det i Sverige er mer hyppige referanser til komiteer oglignende enn i øvrige land.Forskere og politikere er uenige.I alle de nordiske landene var det klart mest uenighet mellom forskere ogpolitikere. Uenighet mellom forskere forekom hyppigst i Finland og Island, mens dette forkom sjelden iDanmark.Begrenset med eksplisitt referanse til verdier.I om lag halvparten av artiklene var det mulig å finne eksplisittereferanser til minst en av fire verdier: kunnskapssamfunnet, økonomisk vekst, velferd og bærekraftig utvikling.Klart flest referanser var til de to førstnevnte verdiene, kunnskap og vekst. Særlig i Norge og Sverige var dethyppigere referanse til vekst enn til kunnskap, mens de forekom omtrent like hyppig i Finland og Island.Danmark skiller seg ut ved et betraktelig høyere antall referanser til kunnskap enn til vekst.

10

Ulike tema i fokus i landene.Artiklene i materialet ble kodet på så mye som førti temaer, som igjen bletilordnet en av seks hovedtemaer: finansiering/ressurser, organisering/ledelse, menneskelige ressurser,resultater/effekter, utfordringer og konflikter. Finansiering/ressurser, organisering/ledelse og resultater/effekter var de dominerende hovedtemaene i alle landene, men den relative fordelingen mellom dem variertemye fra land til land. I Danmark var debatt om organisering/ledelse mest vanlig, mens det i Finland var mestdebatt om resultater/effekter. I Island, Sverige og Norge dreide debatten seg i størst grad om finansiering/ressurser. Vår analyse av temaer er i stor grad kvalitativ og avdekker flere nasjonale særtrekk.Mye debatt om helseforskning i noen land.Ikke overraskende dreide debatten seg i alle land i stor grad omspørsmål knyttet til naturvitenskap og teknologi, og særlig i Finland og Danmark. I Norge, Island og Sverige vardiskusjon om helseforskning mer vanlig, og i Sverige og Norge var også spørsmål knyttet til humanistiskforskning vanlig, og dette forekom her i vesentlig større grad enn i de øvrige landene.Stor interesse for grunnforskning.Når det I debatten forekom referanse til forskningsarter, var disse i alle landunntatt Finland i hovedsak til grunnforskning. I Finland var hovedreferansen til ”forskning og utvikling”, ogdenne forekom også i betydelig grad i Norge og Island. Bare i dansk debatt forekom i nevneverdig gradreferanser til ”strategisk forskning”.Meget sterk nasjonal slagside.Et hovedfunn i vår undersøkelse er at den forskningspolitiske debatten i alle denordiske landenenesten utelukkendehadde et nasjonalt fokus. Referanser til de nordiske land eller andreregioner forekom sjelden. Referanser til EU-land utenfor Norden forekom oftere i finsk debatt enn ellers. Dettehovedbildet støttes også av at bare et fåtall artikler hadde referanser til internasjonalt forskningssamarbeid.Siden en stor del av debatten dreide seg om at forskningen har utilstrekkelige ressurser, ble henvisninger tilEUs Barcelona-mål (tre prosent av BNP til FoU) ofte brukt som argument. På den måten ble EU-dimensjonen endel av den nasjonale debatten for å øve press på nasjonale regjeringer for å øke forskningsbevilgningene. Påden måten kan den offentlige debatt sies å ha fungert som en ”alliert” til EU som ønsker å legge press pånasjonale politikere for å øke de nasjonale forskningsbevilgningene.

11

12

1. INTRODUCTION1.1. THENORDIC COUNTRIES–VANGUARDS OF THE KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY?Contemporary society is allegedly being transformed into a “knowledge society”, and a large variety ofindicators provide evidence that its economy is becoming increasingly “knowledge-based”. These concepts notonly suggest that knowledgein generalis becoming more important, they also emphasize more particularly theincreasing importance of formal, advanced, research-based knowledge as immediate sources of economicgrowth as a dimension that occupies a larger share of the activities of society as such and of (an increasingshare of) its individual members. The notion of “the knowledge economy” has become particularly pervasive,emphasizing the increasing role of advanced, research-based scientific and technological knowledge for firms’innovative capacity and competitiveness. The increasing societal and economic role of advanced, research-based knowledge may also be expected to be mirrored in both the increasing political importance ofknowledge policies, and in a stronger presence in public debate and media of knowledge-related issues,developments and controversies.Today, in countries and regions all over the world these knowledge policies are framed in terms that borrowextensively from a narrative about the knowledge-based economy which pervades policy discourse,emphasizing in particular the increasing role of science and technology in the new global economic order. Thisnarrative has been articulated and strongly promoted by such cross-national players as the OECD and theEuropean Union (EU). The idea of the knowledge-based economy has also been taken up by most membercountries of these organisations. This concept is at the core of the overall agenda of the EU, the Lisbonstrategy, which states that the EU aims to develop the most dynamic, knowledge-based economy of the world.EU emphasizes that this “transition towards a knowledge-based economy involves a fundamental structural1change … all the challenges facing Europe need to be reconsidered in the light of this new paradigm”.An important part of the development of the policy framework built on the concept of the knowledge economyis the development and active use of a range of indicators and rankings to measure and monitor how individualcountries and regions make progress in this process of structural change. From these rankings a map of“leading” and “lagging” nations and regions has emerged. While such rankings often vary as a function ofdifferences between methodologies and aggregation of indicators, they invariably place some or all Nordiccountries in top positions. This applies in particular for the indicators used by the EU itself in order to monitor2Europe’s progress towards the knowledge-based economy. Within these EU rankings the Nordic membercountries in general, and Finland and Sweden in particular, are seen to pave the way that the EU as a wholeshould follow and, specifically, to provide evidence that the target to increase R&D investments to 3 percent ofGDP is possible and viable. The World Bank’s “Knowledge Economy Index” (KEI) provides an even moreconsistent picture ofallNordic countries as top performers in the world on aggregate knowledge economyindicators. In the 2008 KEI rankings, Denmark occupies first position, followed by Sweden and Finland, whilethth3Norway and Iceland closely follow at 5 and 13 places respectively.There is, then, a “look to the Nordic countries” element in much global and European debate on policies for the“knowledge economy” in general and for R&D (research and development) in particular. An additional aspectof this picture is also the idea that others could and should “learn from” these countries, that they should bestudied as sources of “best practices” which other countries should adopt and adapt.

European Commission (2003)Third European Report on Science and Technology Indicators 2003. Towards a Knowledge-Based Economy,Brussels, p. 1.2European Commission (2008)A more research-intensive and integrated European Research Area. Science, Technology andCompetitiveness Key Figures Report 2008/20093Seewww.worldbank.com/kam

1

13

This study does not necessarily subscribe to the ideas embedded in these indicators, rankings and assumptionsabout the transferability of selected “best practices” between countries. They often come with assumptions4that deserve close scrutiny. It is questionable that single indicators, taken in isolation or as composites, cancapture the complex interplay of complementary resources and framework conditions that sustain creativityand innovation, neither do they easily capture specificities and comparative advantages that may often behidden in combinations of “weak” and “strong” performance on single and composite indicators.These reservations and caveats notwithstanding, such indicators do suggest that the Nordic countries maynevertheless be doing “something right” as concerns the role of knowledge, research and innovation in modernsocieties. Thus, what takes place in the Nordic countries may lay claim to a broader interest in terms ofidentifying and analyzing aspects of the emergent knowledge economy and society.However, the broader interest of the Nordic countries reaches beyond the European agenda for developing anadvanced “knowledge-based economy”; they are also, as advanced welfare states, key references in debatesabout that other part of the Lisbon agenda which pertains to the “social cohesion” pillar, that Europeanprogress towards the knowledge-based economy must build on and retain the fundamental values of the“European social model”. The experiences of the Nordic countries in integrating and balancing the twinobjectives of competitiveness and social cohesion may thus be sites of exploration of a “balanced”, Europeanvenue to the future knowledge society. It cannot be assumeda priorithat this delineates a viable venue, northat the balance of these twin sets of objectives can be combined easily and without costs. The knowledgeeconomy discourse and indicators tend to exclude from view tensions and compromises between theseobjectives. Finland, for example, is often heralded as a “super model” of the knowledge-based economy, but itsperformance on welfare is less stellar. Despite several periods of rapid economic growth during the last 15–20years, several welfare indicators remain at levels comparable to the time of the severe economic recession of1992.While all five Nordic countries may be seen to adhere to the so-called Nordic model of democracy and of thewelfare state, the narratives provided in this study are as much about different, even divergent, trajectories ofdevelopment and strategic political choices, which reflect fundamental differences in socio-economicstructures, national systems of innovation and science and technology policy priorities.This is, according to some, the effect of a shift in orientation that has been clearer in Finland than any of the5other Nordic countries from welfare to competition state. Some speak of a specific form of Nordic capitalism6that is a mixture of the competition and the welfare state. Many aspects of “knowledge economy” policieshave a clear “elitist” character – by emphasizing excellence, the priority of the “very best”, critical mass andconcentration of resources. Therefore they go against ingrained egalitarian sensitivities and are met withresistance by Nordic audiences. Another question is to what extent, and in what way, efforts to implementmore market-oriented academic policies, by developing more entrepreneurial universities and increasingsensitivity in the academic community to the commercial potential of academic research, are reflected in publicdebate. The European dimension plays a key role in these developments. The EU takes a particular interest,within the “Open Method of Coordination” in the firmness that member states exhibit in their development ofeffective national policies that comply with the Lisbon agenda and the Barcelona target. Have, then, Nordicpublics acted as an “ally” of the European Commission by exerting pressure on national policy-makers toincrease public research funding and create conducive conditions for private research investments?4

See e.g., Godin, B (2006): The knowledge-based economy: conceptual framework or buzzword?The Journal of TechnologyTransfer31.5Jessop, B. (2002):The Future of the Capitalist State.Polity Press, Cambridge; Pelkonen, A. (2008):The Finnish CompetitionState and Entrepreneurial Policies in the Helsinki Region.University of Helsinki. Department of Sociology. Research ReportsNo. 254.6Ollila, J. (2009): Pohjoismainen malli on kapitalismin tulevaisuus.Helsingin Sanomat24.3.2009 (The Nordic Model is thefuture of capitalism).

14

It cannot, however, be assumeda priorithat this interest and those potential lessons must necessarily besought in what is common to these countries. When seen from a distance the Nordic countries are oftenlumped together, focusing on what makes them similar – strong welfare state policies, strong trade unions andwell-developed mechanisms for collaboration between social partners as well as combination of flexible workmarkets and high social security, social equality and “compressed” wage structures. In addition, these countrieshave well-developed educational systems, including generous support schemes for higher education and PhD-education alongside high levels of public expenditure on R&D. These similarities and affinities are important,and provide extensive opportunities for coordination and collaboration, also within the domains of researchand innovation (as epitomized by NordForsk and NICE).Looked at from a closer standpoint, important differences emerge, many of which relate directly to “knowledgeeconomy” issues. One key difference concerns the extensive differences in the history and structure of theireconomies, as seen by that extremely high level of private investments in R&D in Sweden and Finland on theone hand, compared to the moderate to low level of private R&D investments in Norway on the other. As alarge number of comparative studies attest, there are important differences between these countries whichhave their origins in different histories, social structures, political cultures and geo-political alliances. Thesedifferences must also be accommodated in the picture of the “Nordic progress” towards the knowledgeeconomy/society, indicating that policies need to beappropriate,that their effectiveness remains context-dependent, and that even when the Nordic countries are concerned there may be several, and diverging, pathsto the future.

1.2. PUBLIC DEBATE–A NEGLECTED DOMAIN IN RESEARCH POLICY ANALYSESThis study is not a mapping and analysis of national and regionalpoliciesfor knowledge and research in theNordic area. A number of sources and studies exist which provide detailed, often explicitly comparative, maps7of the region’s national and regional policies for research and innovation. What is often left out of theseaccounts of policy developments is, however, thepublic debateabout these issues and developments. Thereare many reasons why this may be a major flaw of these accounts as well as of policies themselves that do nottake into account sufficiently the role that public debate may and can play in these developments.There is, for one, an ambition in contemporary policies, as embedded in the very concept of the knowledgeeconomy/society, that the effective development, management and deployment of knowledge and research isbecoming more central, integral and essential to theoveralldevelopment of modern societies. Consequently,the policies for these areas have to shed their traditional character as only affecting and involving a relativelynarrow range of stakeholders and experts. Knowledge and research are too important to be left to the expertsalone: issues of public interest are at stake, and need to be justified and shaped in compliance with publiclyvoiced interests.An increasingly attentive and knowledgeable public may thus be expected to become a critical “passage point”for any policy within this field, to which policymakers within these areas have to become increasingly attentiveand responsive. Policy development and public debate may interact in several ways. Public debate may triggerresponses to policy initiatives that need to be taken into account in the way they are articulated andimplemented. Public debate may generate new issues or concerns to which adequate policy responses mayhave to be developed. Public debate may be an essential “allied” in the development and promotion of“knowledge economy/society” policies, and may be a sounding-board for the viability of policy options.Nordic experiments and experiences on lay participation in debates about issues pertaining to issues of science,technology and innovation have achieved word-wide awareness, seen as good practice models that othercountries may emulate and learn from in terms of enhancing the democratic character and public legitimacy of7

See for example, the parts of the European projects Erawatch (http://cordis.europa.eu/erawatch/) and PRO-INNO Europe(http://www.proinno-europe.eu/) that cover the Nordic countries.

15

policy processes, debates and decisions that are regarded as dominated by experts and directly affectedstakeholders. Denmark in particular has a well-established, worldwide reputation as a country in which the laypublic and civic groups take active part in debates on science, technology and innovation (for example, in so-called “consensus conferences”) and other countries may point to similar experiences of broad and active8public/civic participation in policy debates and process about such issues. In this particular respect the Nordiccountries may also be appropriate sites for articulating and testing hypotheses about if, how and/or to whatextent public debates about research policy issues in these countries mayactuallybe described as becomingmore extensive and intensive. Is it empirically true that “general citizens” do take a more active part in thesedebates in these countries, or are they, even in these allegedly “public participation oriented” countries, asstrongly as previously dominated by the “usual suspects” – stakeholders that are immediately affected,lobbyists, the familiar, narrow range of experts?Assuming that Nordic countries are, relatively speaking, at an advanced stage in the development of knowledgeeconomies and societies, a better understanding of public debate on research policy issues in the Nordiccountries during the last 10 years may provide insight into the changing roles and characteristics which publicdebate plays in the development and implementation of policies for research within a knowledge economyframework. Our analyses may,inter alia,provide a basis for answering questions about the public support andacceptability of values that sustain knowledge economy policies, and about public sensitivity to values that areat stake in their development. There may be potential tensions and contradictions between different valuesassociated with research and its uses within a societal and political context characterized in particular bygrowing awareness of the importance of knowledge as source of economic competitiveness and in “knowledgesociety” more pervasively. This may interact and compete with values that are entrenched in politics and publicsensitivities in the Nordic countries – with welfare and equality as well as sustainability and environmentalprotection. Do such value sensitivities, or even tensions, surface in the debates on research and, if so, how? Arethey explicitly or implicitly present in the debate? Does the relative emphasis on these values differ from oneNordic country to the other?

1.3. THE STUDY–OBJECTIVES,METHODOLOGY,PARTICIPANTSOur analysis is based on a mapping of public debates on research policy issues that appeared in a selection ofnational newspapers during the 10 year period from 1998 to 2007. This was a period during which, as ouroverview of policy developments indicates (see Chap. 3), a large number of initiatives were launched anddebated in all the Nordic countries. Most of the papers selected were available on-line. The aim of the projectis to cover debates onin principleall main issues of research policy, and to ensure a common thematic focusfor all research partners, an initialindicativelist of topics to be covered was set up. The point of departure fordeveloping a common coding key was on the following preliminary list of topics that was agreed upon by theteam on the basis of discussions to reach consensus on a common core of “research policy” topics:---------8

Resource issues; the level of public and private expenditure (including the Barcelona target)Resource distribution, i.a. between institutions, between objectives (priorities/priority-setting),resource concentration/distributionInstitutional structures and systems reforms (higher education institutions, public researchorganisations)Academic freedom/autonomy of research institutionsResearch ethics (gene technology, research integrity …)Conflicts of interests (habilitet, jäv, ...)Peer review, evaluationNeeds-/policy- vs. researcher-driven researchQuality/excellence vs. relevance/application;

Häyrinen-Alestalo, M & E Kallerud (eds):Mediating Public Concern in Biotechnology. A map of sites, actors and issues inDenmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden,NIFU Report 2/2004, NIFU: Oslo; Hagendijk, R. and Irwin, A. (2006) PublicDeliberation and Governance: Engaging with Science and Technology in Contemporary Europe,Minerva44: 167-84.

16

---

Commercialisation; collaboration research/industry;Research organisation and management9Globalisation (based on results from an explorative pre-study)

The code key defines a large number of specific content elements to be used for coding each unit of analysis(article, statement) and specifies further details within the topics listed above. These include identificationvariables, variables describing the actors (the authors of the articles), and characteristics of the research fieldas well as the specific policy themes and issues. To ensure comparability across countries, common selectioncriteria for the unit of analysis and a code key (coding scheme) were developed. The coding key included aguide on how to apply the coding criteria. Also, a common data registration procedure was developed enablingthe quantitative data to be simply merged into a common data set. The code key was first developed and testcoded by the Danish team in cooperation with other Nordic team members. The first version was written inDanish and later translated into English prior to the coding process. The complete code key is included inAppendix 2.The unit of analysis in our study is defined asa single debate articlein the selected newspapers. Altogether,close to 2300 articles have been coded. The unit of analysis is a unique debate articles that may be classifiedunder one of the following categories:••••••Column comment (DK/NO: Kronik(k), SV: Krönika, FI: Kolumni: IS: Umræðugrein)Comment/analysis (editorial discussion article) (DK/NO/SV: Kommentar/analys(e), FI: Kommentti; ISFréttaskýring)Editorial/leader (DK/NO: Leder, SV:Ledare; FI: Pääkirjoitus; IS: Leiðari)Opinions (DK: Debatindlæg, NO: Debattinnlegg, SV: Debatt), FI: Mielipide/debatti; IS: Kjallaragrein)Letter to the editor (DK/NO: Læserbrev/leserbrev, SV: Insändere, FI: Yleisönosasto; IS: bréf til blaðsins)Interview focusing on research policy (NO/SV: Intervju, FI: Haastattelu)

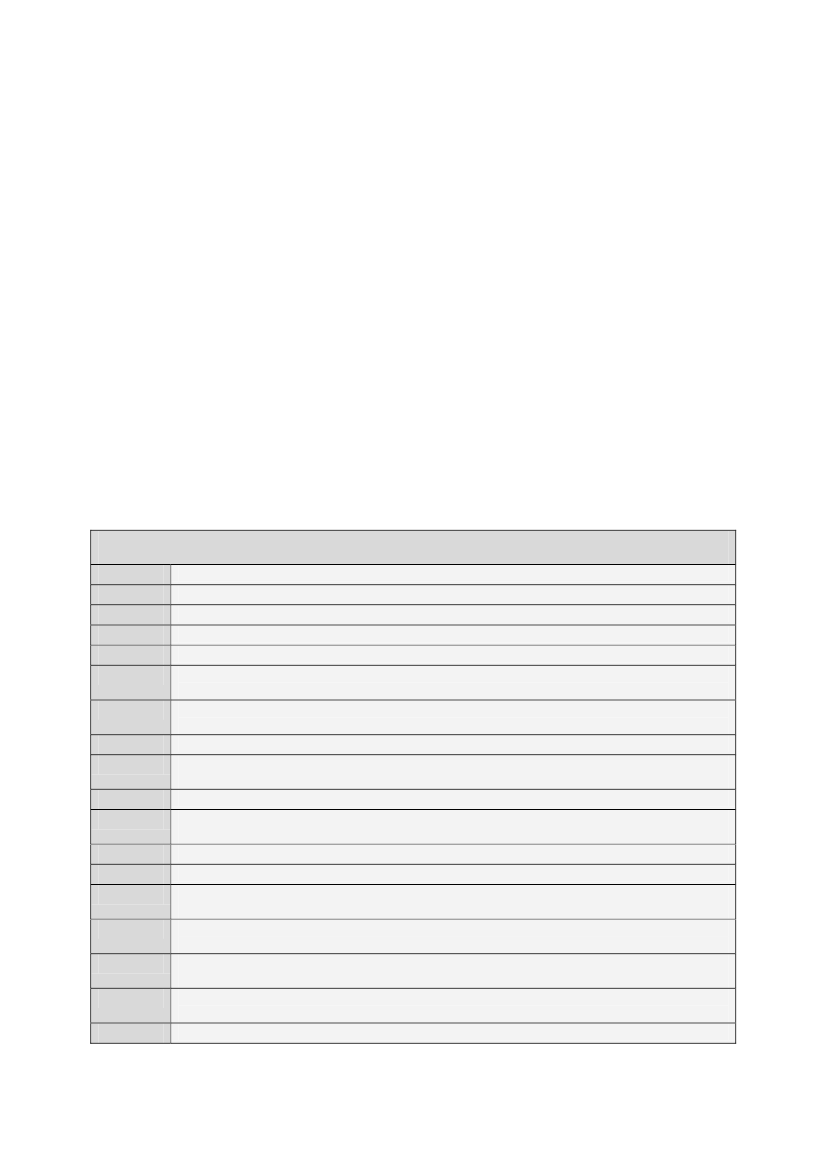

News reports about research are not included in our material.We selected national daily papers that are known to take up public debate on research policy. Three to fivenewspapers were selected in each country:CountryDenmarkIcelandFinlandNorwaySwedenNewspaperBørsen, Berlinske Tidende, Information,Jyllandsposten and PolitikkenMorgunblaðið, Fréttablaðið and 24 stundirHelsingin Sanomat ,Kauppalehti and Turun SanomatAftenposten, Dagbladet, Dagens Næringsliv andKlassekampenDagens Industri, Dagens Nyheter, Svenska Dagbladet,Sydsvenska Dagbladet, Upsala Nya Tidning

The units of analysis from the majority of these papers were available in these on-line databases:•DenmarkInfomedia is an online database containing full text articles and was used forBerlingske Tidende,

9

Kallerud, E., Häyrinen-Alestalo, M., Sandström, U., Siune, K. & Finnbjörnsson, T. (2007): Public debate on globalisation andresearch in the Nordic countries.NordForsk Magasin1: 11–13.

17

Information, JyllandspostenandPolitiken.Børsens own online database, also including full textarticles, was accessed because it wasn’t included in the Infomedia data base.•IcelandMorgunblaðiðhas a comprehensive database of searchable articles for all the years covered.Fréttablaðiðhas a database dating from 2003; articles from previous years were searched by pdf onthe paper’s web site.24 stundirwas also searched by pdf. In addition the web site www.timarit.is wasused to complement the material.FinlandFinland does not have article databases as in other Nordic countries, and the team had to rely ononline archives that were accessible through the internet. The three newspapers selected have onlinearchives that cover the wanted period 1998-2007.NorwayThe Retriever Atekst-database was accessed in order to search for the relevant debate articles. Atekstcontains full text versions of the relevant articles in the four selected Norwegian newspapers for thisanalysis. The database includes newspaper and specialized press articles and is updated on a dailybasis.SwedenThe database Artikelsøk was used in the search for articles. Most articles were found as full textversion whereas some articles were tracked through the individual newspapers.

•

•

•

An initial set of common search strings were agreed upon, most of which were based on the ‘research policy’term (“forskningspolitikk”), including truncated versions of the terms. Linguistic differences made it necessaryfor each partner to add unique terms from their own language in order to get as homogenous sets of data aspossible.These were the research teams involved in the project:•DenmarkDirector of the Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy, dr.scient.pol. Karen Siune,research assistant cand.scient.pol. Erik Ravn and project assistant stud.scient.pol. Rasmus JensenFinlandProfessor of Science and Technology Studies Marja Häyrinen-Alestalo and M.Soc.Sc. Terhi TuominenHelsinki Institute of Science and Technology Studies, University of HelsinkiIcelandHead of section Thorvald Finnbjörnsson at the Research Centre of Iceland-Rannis and research studentSveinbjörn Ásgeirsson University of IcelandNorwaySenior researcher Egil Kallerud, and researcher Inge Ramberg, both NIFU STEP. Kallerud was alsooverall project coordinator.SwedenSenior researcher Lars Geschwind and research assistants Karla Anya-Carlsson and Karin Larsson,SISTER.

•

•

•

•

18

2. BACKGROUND-MAIN POLICY EVENTS AND ISSUESAs a background to our subsequent analysis of public debate, we provide a short overview of main trends andevents in research policy in each country during the time that our analysis covers.

2.1. DENMARKThe period 1998 to 2007 is interesting in Danish research policy, spanning a period that commences five yearsafter the establishment of a Danish Ministry for Research and Technology, by which science policy may be seento become a policy area in itself, attracting growing public debate as such. A change in government took placein 2001 when the social-democrat government under Prime minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen ceded to a centre–right coalition government consisting of Liberals and Conservatives lead by Prime Minister Anders FoghRasmussen from the Liberals.Under the social-democrat government from 1993 to 2001, a large number of ministers were responsible forresearch: four different ministers were actually in office within the period 1997–2001. The rapid turnover ofministers responsible for research indicates that none of them had much the time to leave their fingerprint onthe area. That was not the situation for the centre–right coalition Government.Frank Jensen (1995–97) was responsible for reorganizing the Danish research political advisory system aimingto coordinate the numerous advisory bodies, including the research funding organisations. Jytte Hilden (1997–1998) will be remembered especially for her FREJA initiative where the focus was on female researchers. JanTrøjborg, Minister (1998–1999) assumed responsibility not only for public research activities but also foruniversities. He took the initiative to establish contracts between the ministry and the universities. Birthe Weiss(1999–2001) will be remembered for the establishment of The Research Committee, even though the report ofcommittee was not published until after the change of government in 2001.During the end of the 1990s there were a number of initiatives from the responsible research ministers underthe social-democrat government. The rationale of many of the initiatives was to reorganize public research andstimulate collaboration and interplay between public research and private business. In 1998 the governmentpresented a research package under the title “Forskning som vækstlokomotiv”, under which appropriationswere allocated during the 1998–2001 period to a number of business-oriented initiatives aiming to strengthenapplications of research, innovation and technology within the private sector. In the 1999 research package thegovernment focused on innovative universities and special funds were allocated to public research institutions,providing incentives to support innovation and commercialization, including patenting. The interplay betweenpublic and private research returned to the agenda in 2000 when fresh resources were allocated to establishcontacts between different types of research centres for the 2000–2003 period.Helge Sander from the Liberals became the research minister of the new centre-right government following thegeneral elections in 2001. His title was new: Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation. In 2005 PrimeMinister Anders Fogh Rasmussen called an election, which was won by the government coalition. Helge Sanderremained in office as Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation and has established himself as the primefigure in Danish research policy debate since 2001. This period was characterized by a large number of politicalinitiatives targeting the management of universities.

19

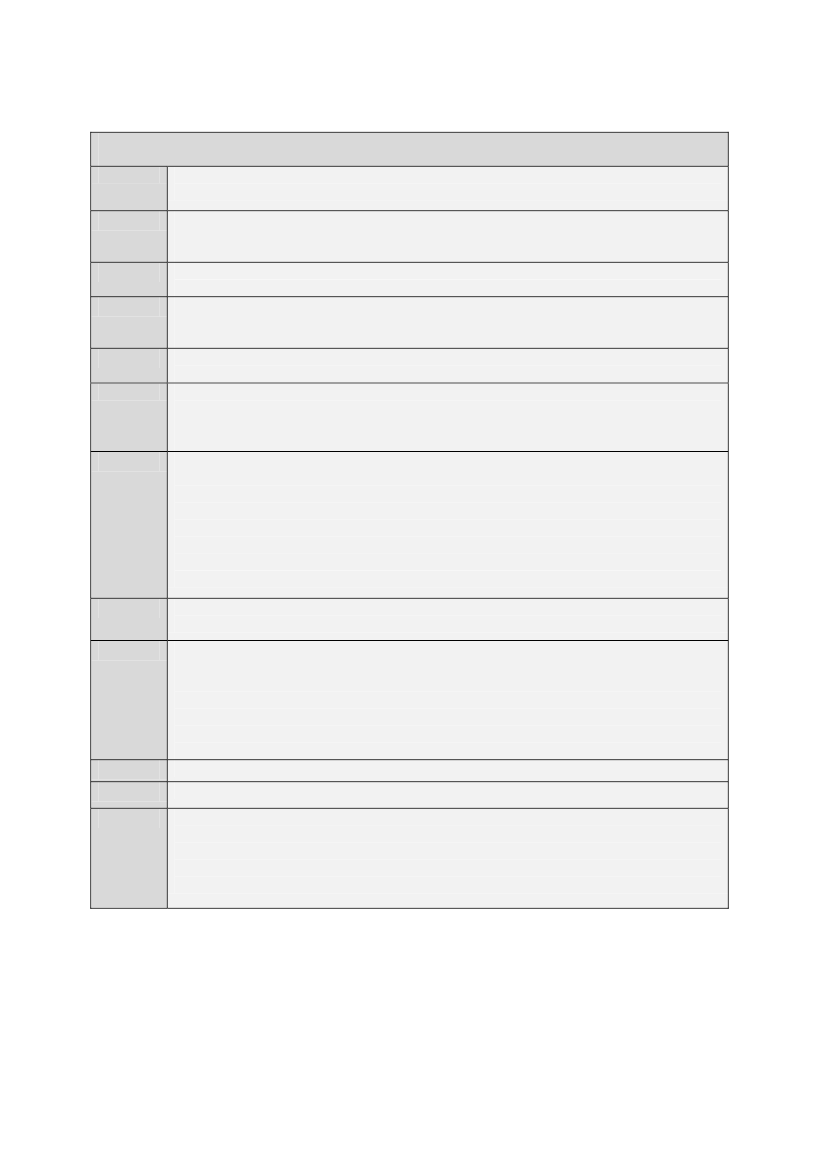

Initiatives in Danish research policy since 19981998-2000Research package “Forskning som vækstlokomotiv” allocated means to business-orientedinitiatives focusing on economic growth through strengthening interplay between publicresearch and private business.Research commission established (2000) with focus on Danish research landscape.Innovation politics transferred from Ministry of Business and Economy and integrated in toMinistry of Science, Technology and Innovation.Report with recommendations from Research commission; special focus on governmentalresearch institutes, attached to different ministries.Law for universities changing management structure and changes into hiring of directors at alllevels in contrast to former election of leaders.Reform of research council structure, resulting in two councils:Free research council and strategic research council.Initiatives regarding research communication, dissemination becoming the third leg atuniversities in addition to the traditional two: research and research based education.Plan for action: ’fra tanke til faktura’. Universities told to be more open and more adaptable tocooperation with private enterprises; economic orientation was presented as dominant in thisrelationship.Reform of law for governmental research institutions, bringing some of these into universities.Establishment of special funding for high technology (Højteknologifonden)Globalisation Council established with representatives from a broad spectrum of Danish society(and with participation of 5 ministries) discussing funding of public research and allocations toresearchers education (Ph.D. schools) in the light of increasing globalisation.Government Strategies attached to report from The Globalisation Council, presented in thereport: “Fremgang, Fornyelse og Tryghed”, April 2006Processes of Fusions among universities announced publicly March 2006Fusions among universities announced March 2006 to take place from January 2007.Result: reduction in number of universities (from 12 to 8) and integration of research institutesfrom ministries to universities, all but a few national centres became integrated in universities.Reforms of models for financing universities (indicator-based model)Among indicators are degree of external funding, cooperation with private enterprises andpublication activities.Evaluations of research council structure and of university law, special issue “freedom” or lack offreedom among university researchers.

2001

2003200320032003200420052005200620072008-092009

2.2. FINLANDCommencing in the early 1990s Finland experienced a radical shift in government orientation from state-regulation towards a market-driven science, technology and innovation policy (STI). This process began earlierin Finland than in the other Nordic countries and was related to the ideological change from a welfare state toan internationally oriented competition state. The new orientation reflected an economic risk taking aiming athigh positions in the global market. Government funds for research were increased by privatising state-ownedcompanies and by using this money strategically. As a result the expenditure of R&D increased to more than 3percent of GDP in 1999. In 2007, R&D was at 3.5 percent of GDP.In 1998 the Finnish government comprised the Social Democrats, the Rightist Party, the Green League, the LeftAlliance and the Swedish People’s Party of Finland. This “rainbow government” was led by Prime MinisterLipponen (Social Democrats) who had commenced his first term of office after the electoral victory of SocialDemocrats in 1995. The same year Finland became a member of the EU. Lipponen’s first government (1995–20

1999) was followed upon his re-election by Lipponen II (1999–2003). During these years the Minister ofEducation came from the Rightist Party and from Social Democrats. Even though deep recession and highunemployment rates were the most demanding tasks at hand, these two governments strongly promotedtechnology and industrial policy.Due to an early start towards the knowledge economy, most of the reforms during the study period areattempts at continuing the building of the knowledge economy in which the opening up of the market andcompetition, productivity, and new technologies are the basic elements. The Finnish policy-makers have had astrong trust in the ability of the competition state to act as a homogenizer of various policies. The governmenthas also introduced ideas of policy integration to solve new cross-cutting global problems (energy, climatechange). Within this framework universities have to be rejuvenated to fulfil the needs of a modern competitionstate and its aims of globalisation.After the elections in 2003 the government was formed by the Centre party, the Social Democrats and SwedishPeople’s Party of Finland. Matti Vanhanen (Centre Party) started his first term as prime minister (2003–2007).The Left Alliance, which had been left in opposition, directed criticism to the undermining of the welfare state,and which has been topical in the elections ever since. During Vanhanen I, the Minister of Education came fromthe Social Democrats. Vanhanen continued in office after the 2007 elections when the Centre Party and theNational Coalition Party formed the government leaving the Social Democrats in the opposition. The Ministerof Education came from the Rightist Party. The Lisbon strategy together with the issues of globalisation hasbecome important aspect of policy.In Finland the competition state has been strong in its economic orientation but much weaker in the promotionof the social dimension. There has been permanent tension between the economic and the social issues as well10as between the public and the private sectors. In order to solve the problem the governments have referredto the innovation system and introduced a broad concept of innovation. To serve government interests botheconomic and social innovations should be flexible. Flexibility is also mentioned as a means by which to meetthe increasingly complicated elements of socio-economic progress. The current government has prepared anew strategy of innovation that also speaks of innovation policy from the viewpoint of productivity andcompetition. Similar tendencies can be seen in the efforts to reorganize academic and sectoral researchinstitutions, the responsibilities of the key ministries, and the interaction between the knowledge producers,policy-makers and industry. As in the EU, the Finnish knowledge economy has been expanded to includeservices as the most growing sector of production. According to the studies on local and global aspects of thistransformation (Pelkonen 2008) global problems also set demands for the development of national andregional needs.The study period includes some policy events that are either directly addressed in the debate or appear in thebackground when certain themes are debated. Below is a short description on main policy events during 1998–2007.1998 – 2001Years between 1998 and 2001 cover a period of strengthening and centralizing the regional activities but also adownturn in the economy in 2001 which affected especially the ICT-sector. The Centre of Expertise Programmethat had been established in 1994 was broadened in 1999 and it has been the main instrument to supportregional innovation infrastructures striving for knowledge-based growth (Pelkonen 2008, 74–75). During thistime the idea of a metropolitan area and urban regions with competitive locations for business gainedmomentum. The Regional Centre Programme was established in 2001 in attempt to establish regional network10

Häyrinen-Alestalo, Marja, Pelkonen, Antti, Teräväinen, Tuula & Villanen, Sampo (2005): Changing Governance forInnovation Policy Integration in Finland. In Remoe, Svend-Otto (ed.):Governance of Innovation Systems: Volume 2: CaseStudies in Innovation Policy.Paris: OECD. pp. 111–138.

21

centres alongside the metropolitan area to secure balanced economic growth. As part of investing inknowledge Finland has been active in establishing programmes for the enhancement of knowledge. Most ofthese initiatives were launched during the study period (The Second National Information Society Strategy in1998 and the National Information Society Programme in 2003). The Centre of Expertise Programme wasestablished earlier in 1994 but broadened in 1999 and 2003.2002–2004After the poor economic outlook in 2001 globalisation issues became topical and changes were called for bothin the private and public sectors. The role of services (particularly knowledge-intensive services) wasemphasized as was collaboration between universities and companies. Universities in particular were supposedto assume a broader and more active role in the knowledge society (Science and Technology Council 2003, 18).At the same time speculations on the fragmentation of the university system intensified when a one-mancommittee published a review of the structure of university and polytechnic research (OPM 2004, 16) statingthat the university system cannot be expanded anymore but more attention should be paid to the quality,content and impact of the system. Furthermore, the role of universities was addressed in a globalisationproject initiated by Prime Minister Vanhanen who was concerned about the transition in global economy. Oneof the key actors within technology policy, Tekes (The Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation),has strengthened its role in other policy fields through technology programmes. There has been a change in thecontents of the technology programmes, as business knowhow and service innovations are strongly promoted.During the last decade Tekes has stepped outside its traditional role as a technology developer since it has11taken extensive initiatives in new fields such as health and social services.During the last few years the government has introduced a number of reforms and initiatives concerningeducation, technology and innovation policies, the reform of the university system, structural development ofhigher education, national innovation strategy and renewal of the sector research, to name just a few.Particularly, internationalisation and strengthening of the research and innovation funding has featured on theagenda. In 2005 the government decision on the structural development of the research system took place atthe same time as the new university Act came into effect. The tendency has been to exploit the results ofresearch and technological development more effectively. Additional pressure has been placed on theuniversities since the government Productivity Programme threatened to decrease personnel substantially.According to the guidelines of Science and Technology Policy Council (2006) the establishment of new StrategicCentres in Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) commenced. The centres are intended to enhanceresearch cooperation between research units and business enterprises. The strategic centres have connectionswith the renewed Centre of Expertise Programme (2007) that emphasizes cluster competence and regionalaspects. The latest change in is the renaming of the Science and Technology Policy Council. The new Researchand Innovation Council began operating at the beginning of 2009.

11

Tekes Annual Reviews 2005 and 2006.

22

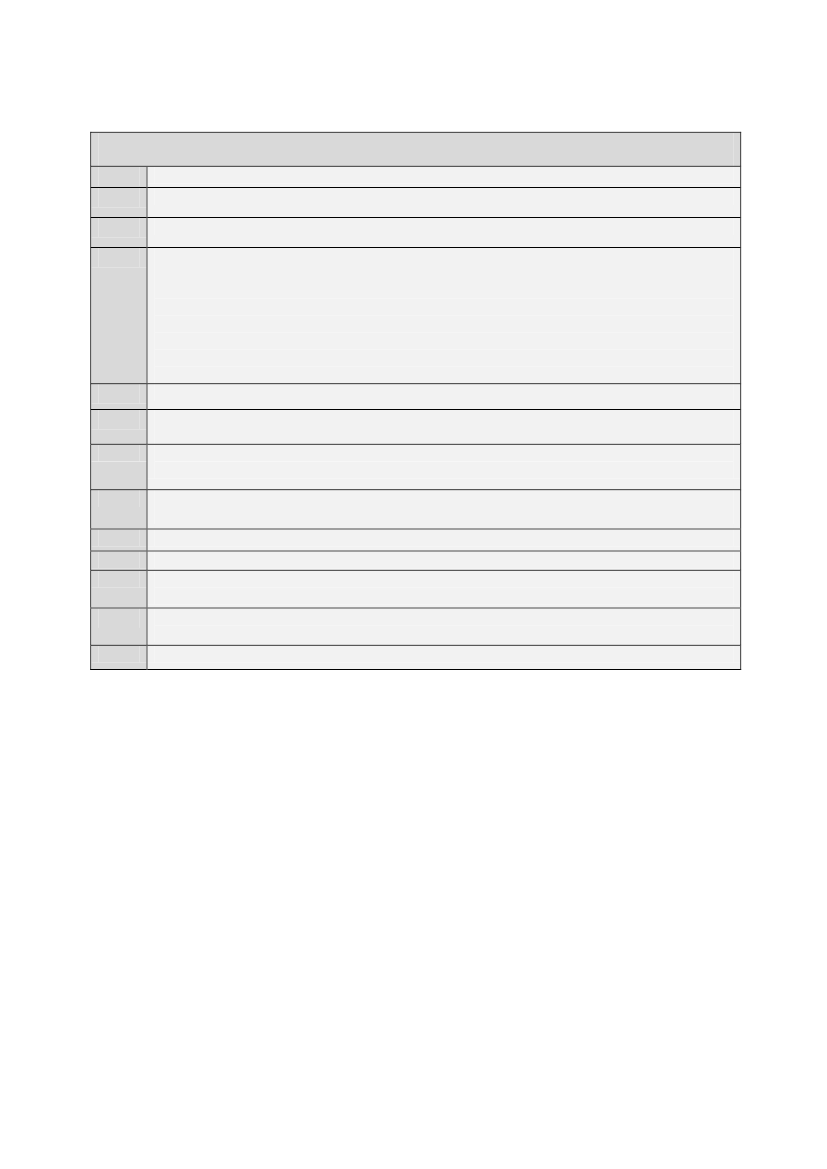

Main events in Finnish science and technology policy 1998–2007199819992000200120022003Amendment of the University law (Barcelona model introduced). The second nationalinformation society strategy is publishedCentre of Expertise Programme is broadened. In the period 1997–1999 the government grantsthe National Agency for Technology (Tekes) a significant amount of money, focus beingespecially on ICT.The Academy of Finland starts a Centres of Excellence Programme in Science (2000–2005) afterthe first Centres of Excellence had been introduced 1995–1999End of rapid growth period and a steep downturn in the economy. The Regional CentreProgramme starts in attempt to establish regional network centres in areas of nationalimportanceAnother Centres of Excellence Programme in Science by the Academy of Finland starts (2002–2007)General elections: Vanhanen I GovernmentNational Information Society Programme is published.Report “Knowledge, Innovation and Internationalisation“ is published by the Science andTechnology Policy CouncilGlobalisation Report “Strengthening competence and openness – Finland in the GlobalEconomy” by the Prime Minister’s Office addresses the role of universities in the globaleconomy. Speculations on the fragmentation of the university system intensify when a one-mancommittee publishes a review stating that the university system cannot be expanded anymorebut more attention should be paid to the quality, content and impact of the system.The report “Internationalisation of Finnish Science and Technology” is published by the Scienceand Technology Policy Council.International Evaluation of the Academy of FinlandGovernment makes a decision in principle on the structural development of the public researchsystem and the University law is changed in order to shorten study timesInnovation policy is highlighted and national strategy “Science, Technology, Innovation” ispublished by the Science and Technology policy Council. The Council also publishes a report onthe establishment of Strategic Centres of Excellence in STI. The Centres are intended to enhanceresearch cooperation between research units and business enterprises and have connectionswith the renewed Centre of Expertise Programme (2007) that emphasizes cluster competence.Academy of Finland and Tekes start a joint funding programme “FiDiPro – Finland DistinguishedProfessor Programme”General elections: Vanhanen II GovernmentNational Innovation Strategy is publishedNew university Act comes into effect enabling private funding for universities and stipulatingoutside representatives in universities’ boards. The new law alters the status of universities,making them legal entities. The number of universities is reduced from 20 to 16, including theestablishment of Aalto University through a merger of three universities. Furthermore, Scienceand Technology policy Council is renamed as Research and Innovation Council

2004

20052006

200720082009

2.3. ICELANDThe Period 1998 to 2007 can be characterized as a period of change. Already before the end of the last centurythe former minister of Education, Science and Culture, Björn Bjarnason, laid the foundation for change thatwould take place by law in 2003, and entered into force in 2004.

23

Simultaneously a revision of the structure of higher education institution and public research institutions tookplace, resulting in a considerable number of mergers. In 2000 the national and city hospitals were merged intothe University hospital, to be followed by mergers of sectoral research institutions and institutions in highereducation and research.The governance system of science, technology and innovation changed drastically in 2003 as a result of threelaws endorsed in 2003. The laws were directed towards public support to scientific research, Science andTechnology Policy Council and on public support for technological development and innovation in industry. Thelaw on public support to scientific research stipulated a new role and organisation of the Icelandic Centre forResearch (Rannis). When these laws entered into force, the former Research Council was terminated and theformer office of the Council became a service organisation to the new system.The Science and Technology Policy Council (SPTC) is headed by the Prime Minister of Iceland. Three otherministers have a permanent seat on the Council: The Minister of Education and Science, the Minister ofIndustry and Commerce and the Minister of Finance. At the discretion of the prime minister, two otherministers with research in their portfolio may join the Council. Currently these are the Minister of Fisheries andthe Minister of Agriculture. Fourteen other members are appointed to the Council upon nominations by theMinisters with a research portfolio (6 nominations), parties to the Employers Association and Employees Union(4 nominations) and by the coordinating committee of higher education institutions (4 nominations).The Science and Technology Policy Council have met on regular basis twice a year. The composition of theCouncil is to be considered well suited to meet the needs of STI society. Now politicians are actively taking partin STI policy-making. The Council publishes any resolutions after each of its meetings, issuing the main policiesand emphasis.The Council operates in three-year periods. Before each period the council publishes a policy document for theensuing four years. The policies that have been published are for the periods 2003–6, 2006–9, and 2009–12.In 2006 the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture embarked on a Foresight exercise to gain opinion of thescience and technology community on future priorities. About 200 people took part in this exercise.Traditionally, the financial support system for research and development together with innovation has beenmanaged by research funds with a rather general and broad agenda. Through the period three Excellenceprogrammes have been established.The governance system of research, development and innovation in Iceland Evaluations has been submitted toevaluations, as have the research funds and excellence systems.

24

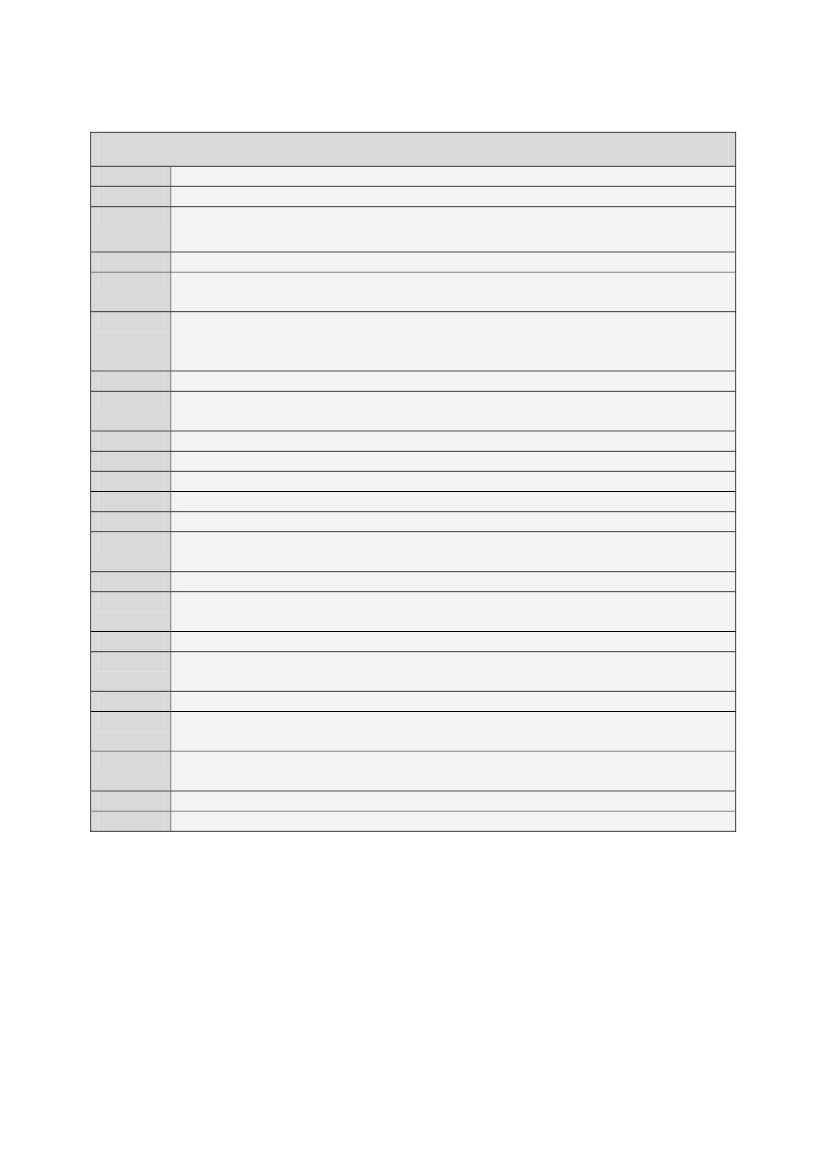

Events in the Icelandic science and technology policy 1998–20071999200020002003Rannis operates a new excellence programme on Information technology and Environment.Merger of the University Hospital system from a national and a city hospital into one hospital system.Icelandic delegation visits Finland in order to study the Finish STI governance system.Three bills for support of Science and technology and for innovation were passed by the Althingi inFebruary 2003.-Law (2/2003) on the Science and Technology Policy Council - under the Office of the PrimeMinister-Law (3/2003) on Public Support to Scientific Research - under the Ministry of Education,Science and Culture-Law (4/2003) on Public Support to Technology Development and Innovation in the Economy -under the Ministry of Industry and CommerceEstablishment of the Science and Technology Policy Council (STPC).The Research fund is established as a merger of former Technology fund and Science fund. A new fundis established, the Technology Development fund. Both funds are managed by Rannis.An Excellence programme on Genetics and Nanotechnology was accepted by the Science andTechnological Policy Council.The Science and Technology Policy Council publish a policy for the year 2006 to 2009 a Policydocument were emphasis of the council are stated.OECD publishes a review of Icelandic innovation policy.The STPC starts a general Foresight exercise to determine the emphasis of the STI system.Evaluation of the performance of the STPC is published. The Council has reached most of the goals setin former policy documents.A new Excellence programme on Centres of Excellence and Clusters was under construction andwould be in operation from 2009The STPC put together a draft for Science and Technology policy for the period 2009–2012.

200320042004200520052006200720082008

2.4. NORWAYBetween 1998 and 2007 Norway had a minority centre–right government led by Prime Minister Kjell MagneBondevik (Christian Democrats). The Minister for research was Jon Lilletun (Christian Democrats) whopublished a White Paper on research policy in spring 1999. After a 1½ year hiatus, when the Labour Party-based “Stoltenberg I”-government held office, a new minority centre–right government, “Bondevik II” was inpower between 2001 and 2005. The Minister for research of the 2001–2005 government was Kristin Clemet(Conservative Party) who published the 2005 White Paper on research policy. After the general elections in2005, a new centre–left majority coalition government headed by Jens Stoltenberg - hence “Stoltenberg II” -took office. Øystein Djupedal (Left Socialist Party) was its first research minister. He was replaced by his partyfellow, Tora Aasland, in late 2007.The beginning of the period covered by our study is also the last phase of a period spanning the larger part ofthe 1990s when there was moderate growth in public expenditure for research. This affected in particular theResearch Council of Norway, established in 1993 through a fusion of the five former research councils.Contracting appropriations exacerbated governance and organisational conflicts paralysed the council duringits first years, ending in early 1995 when both the Chair of the Board and the managing director were forced toresign. Controversies over the Council persisted through the first years of the period we analyse, leading up tothe evaluation of the Council in 2000–2001 and its major reorganisation in 2003.25

The reinvigorated council put a strong imprint on the White paper that was published in 1999. This documentlaid down the overall framework for research policy for most of the period covered by this study and wassupported by all political parties inthe Storting.The White Paper had the goal of raising overall nationalresources spent on R&D to be the highest priority of research policy: national R&D expenditure should rise tothe “average level of the OECD countries”, i.e. up from 1.7 percent to 2.2 percent of GDP. The target wasreiterated and strengthened in the 2005 White Paper, in which the OECD target was replaced by the literaladaption of the Barcelona target.As part of the policy for increasing public funding of research, a new Fund for Research and Innovation wasestablished in 1999 as a mechanism to sustain stable growth in public funds for research through annualincreases in the fund capital.Both the 1999 and the 2005 White Papers expressed particularly strong concern over the low overall level ofprivate R&D investmentin Norway. This issue had been a top priority item on the research policy agenda sincewell before the start of the period of analysis, and remained a high priority issue throughout 1998–2007.Several committees were set up to review the issue and propose measures to increase private R&Dexpenditure during the latter part of the 1990s, including the so-called “Aakvåk-utvalget” (1995) and the“Hervig-utvalget” (2000). Based on proposal from the latter, the tax deduction scheme SkatteFUNN wasintroduced in 2002, as the first and only indirect R&D support scheme in Norwegian R&D policy. The schemewas controversial and underwent some redesign during its first couple of years in operation. A proposal in the2005 White Paper to establish a new scheme to stimulate private donations for research was also endorsed bythe Storting.The 1998–2007 period was also one of extensive reorganisation of higher education institutions. A processalready long underway gained speed and momentum with the reports from two commissions (the “Mjøs” and“Ryssdal” commissions), leading up to extensive reforms of higher education institutions under the heading ofthe “Quality Reform”, by which higher education institutions acquired more institutional and financialautonomy, including freedom to establish new governance structures, (partial) separation of core funding ofresearch and teaching – a new component of performance-based funding of research (“tellekantsystemet”) –was introduced, and after a separate commission report a stipulation to protect academic freedom was–incorporated into the Higher Education Act.The 1990s and early 2000s was also a period when the framework of “systems of innovation” was adopted andhesitantly implemented, making a strong imprint on the overall framing of research policy in both the 1999 and2005 White Papers. The “IT Fornebu” case, the idea of a Norwegian ICT “Silicon Valley” on the location of theformer Oslo airport, turned into a highly controversial case, straddling conventional party positions, which wasdebated in terms of enhancing Norwegian entrepreneurship and competitiveness within the emergent,increasingly globalised “new economy”.Issues of ethics, democracy and public understanding of science had emerged during the 1990s as an integralpart the research policy agenda, triggered by controversial science and technology-related policy issues (GMOs,biopatent directive). An already strong research ethics system was strengthened, and the NorwegianTechnology Board was established in 1998 as an institutional stronghold for lay technology assessment, andwhen concerns over declining interest and support of science and technology became pervasive. For a timeresearch ethics became a particularly salient public issue with the infamous “Sudbø research fraud case” in2006.

26