Udenrigsudvalget 2010-11 (1. samling)

URU Alm.del

Offentligt

8thApril 2008

For The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark

Focus-paper - FinalAchievements in the Iraqi-Danish Partnership forReconstructionBased on a Desk Review of Documents and Workshop Discussions

104.Irak.2-21

By Kimiko Hibri Pedersen, COWI A/S and FinnSkadkær Pedersen.

Focus-paper

i

Table of ContentAbbreviationsExecutive Summary123Background and IntroductionObjectives of the PartnershipWorking in Fragile States12691111121414

3.1 Definitions3.2 Development Assistance to Fragile States3.3 Civilian-Military Co-planning3.4 Guiding principles for Provincial Reconstruction Team

45

Methodological issuesThe Context in which the Partnership took place

151717

5.1 Some milestones in the political developments in Iraq 2003-2007

5.2 International and Danish assistance in relation to political developments195.3 Developments and security in Basra Province5.4 Security situation in Basra Governorate1920

6

Agriculture and Irrigation

232325262627

6.1 Project Status6.2 Effectiveness6.3 Efficiency6.4 Relevance6.5 Lessons learned

Iraqi-Danish Partnership

Focus-paper

ii

7

Infrastructure

2828293031

7.1 Blood Gas Analysers7.2 Jetting and Suction Trucks7.3 The Buoy Vessel7.4 Transport Corridor study

8

Human Rights, Judicial Reforms and Democratisation

3535383838

8.1 Improving the Rule of Law8.2 Human Rights and democracy8.3 Democracy and local governance8.4 Local Governance Fund

9

Danish Advisory Assistance and Steering Unit

444447

9.1 Danish Advisers9.2 Steering Unit

10 Lessons learned and questions to be considered10.149

49

Overall findings and recommendations of the review

10.2 Findings and questions in relation to the Principles for Good InternationalEngagement in Fragile States & Situations51

Annex 1 – Terms of Reference

55

Annex 2 – Provincial Reconstruction Teams’ Guiding Principles57Annex 3 – Overview of Danish Reconstruction and HumanitarianActivities in Iraq 2003-200859Annex 4 – List of Participants in Workshop, 4th-6thFeb. 2008, inAmman61

Iraqi-Danish Partnership

Focus-paper

1

AbbreviationsAMGASWGCPACSODACDANCON, DANBAT, DANBNDIISDIHRDKKEUFSGGCPIHRIEDIDALICUSLCCLGFMDGMENAMFAMoAMoTNGOOECDPDFPRTRUDSMEToRUSDAid Management GuidelinesAgriculture Sector Working GroupCoalition Provisional AdministrationCivil Society OrganisationDevelopment Assistance Committee (OECD)Danish Military Contingency in BasraDanish Institute for International StudiesDanish Institute for Human RightsDanish Kroner (Danish Currency)European UnionFragile States Group (DAC-OECD)General Company of Ports in IraqHuman RightsImprovised Explosive DeviseInternational Development Association (under World Bank)Low Income Countries Under StressLocal Council CommitteeLocal Governance FundMillennium Development GoalsOffice in MFA responsible for relations with Middle East and NorthAfricaMinistry of Foreign Affairs, DenmarkMinistry of AgricultureMinistry of TransportNon Governmental OrganisationOrganisation for Economic Cooperation and DevelopmentProvincial Development FundProvincial Reconstruction TeamReconstruction Unit, DenmarkSmall and Medium-sized EnterprisesTerms of ReferenceUnited States Dollar

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

2

Executive SummaryThe focus of this paper is on the achievements of thereconstructionefforts in the Basra province ofIraq for which the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs was directly responsible and covers the periodfrom April 20031.The objective of the reconstruction efforts was as quoted from the appropriation document of June2005 to“…contribute to the development of a stable and democratic Iraq, enable to secureeconomic and social development for the population in the country, and in addition promote humanrights and good governance.”2The security situation in Basra was difficult in the whole period and very difficult in some periods,and from the end of 2003 it was decided that all advisers travelling outside the guarded camp hadto be protected by an armoured protection team. While there were “ups-and-downs” in the securitysituation for advisers and staff working on Danish supported reconstruction programmes, thesituation became generally very difficult from the start of 2006, where e.g. the cartoon crisis lead tosuspension of most activities for months and the steering unit and advisers were moved three timesduring the period from start of 2006 until April 2007 when the steering unit was moved to Kuwait.Seven Danish soldiers lost their lives in Iraq in the period covered by this report.The difficult situation not only made planning, dialogue with local stakeholders, implementationand monitoring of reconstruction projects and programmes a major challenge but also contributedto a lack of systematic documentation of achievements. The steering unit was relocated a numberof times due to the security situation, sometimes leading to the evacuation of civilian staff at shortnotice and often without the possibility of retrieving documents and computers.It is important to note that the main source of information for this paper has been availabledocumentation and that this for above mentioned circumstances has been limited in some areas.This has meant that it has been a challenge to make a full and fair review of the achievements. Thereview, besides the existing documentation, relies on a site inspection report of most reconstructionprojects. The site inspection took place from mid – October to November 2007. In addition morenarrative reporting was obtained from stakeholders participating in a work-shop in Amman the 4th-6thFebruary 2008.There were four main areas of reconstruction efforts; 1) Agriculture, 2) Infrastructure, 3) HumanRights and Judicial Reforms, and 4) Advisory Assistance. The paper attempts to determine theresults and review these in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, and relevance as well as discussesissues of sustainability and impact. Based on this is presented some tentative “lessons learned”.

1

It does not cover humanitarian assistance, multilateral assistance or assistance under “the regions of origin initiative” orthose projects implemented by the Danish Military, Police, Human Rights Centre or ICRT.2Parliamentary Appropriation no. 158. Copenhagen 1st June 2005

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

3

Despite the difficult context in which the reconstruction efforts were implemented there have beenremarkable results:The support to agriculture including irrigation (financial contribution in total 30,5 mill DKK) isassessed to be effective, especially the rehabilitation of irrigation schemes, but also the smallerprojects and the advisory services to agriculture. Also concerning efficiency and not least relevancethe agricultural support is assessed to have been well planned and executed. The activities appearto be sustainable, but this is difficult to assess from present knowledge, but the impact is potentiallygreat for an estimated population of 200.000 who are dependent of the activities.The infrastructure projects are very positively assessed overall. Especially the support to therehabilitation of the Buoy vessel “Nisr”(26,5 mill DKK) and the “Transport Corridor Study” (6,86 millDKK) were very well executed projects and score high on effectiveness, efficiency and relevanceand have a very high potential for a major impact of the economic development of the province andover time for the whole of Iraq. Also the provision of Jetting and Suction Trucks (6,23 mill DKK) waseffective and relevant as it met immediate needs by improving the sanitation in Basra. Theachievement of the delivery of 11 Blood Gas Analysers to hospitals probably also met immediateneeds, but as only one of these were part of the site inspections, it is difficult to determine howeffective this project has been and whether it is sustainable.The Human Rights, Judicial Reforms and Democratisation programme contains a number of projectsfor which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has not been directly responsible for implementation, e.g.police training, rehabilitation of torture victims and support to civil society and human rightstraining. The specific Danish support to judicial improvement is difficult to assess as this has mainlybeen supported together with US and UK support. The refurbishment of the court house in Basrawas jointly done with the US but the provision of furniture was a specific Danish project (0,85 millDKK) and this has been done effectively, efficiently and was relevant. Local Governance Fundsupported 18 projects identified by local councils to meet public service needs, e.g. in education,roads, health and water. The projects have been effective and relevant in relation to expressedneeds of the local councils. To what extent they have contributed to improved governance anddemocracy is less well documented, but it is likely that the LGF-projects have been assisting inbuilding capacity of local councils in prioritising, planning and monitoring the implementation oflocal public service projects.The advisory assistance has been provided in a very difficult security situation and with often verylimited possibilities for movement. It is therefore not surprising that achievements are less welldocumented and appear to have been mixed, but there are valuable experiences, which the MFAhave learned from in the provision of technical advisory assistance to the central government levelin Baghdad from 2007.The overall findings and recommendations are:It is the overall assessment that the Iraqi-Danish partnership has from April 2003 to December 2007produced some noteworthy achievements. These are documented in relation to economic andsocial development, such as improvements to infrastructure, especially in transport, agriculture andirrigation and small-scale rehabilitation of public utilities. The achievements concerning “softer” –but equally important – issues such as democracy, human rights and good governance are less welldocumented.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

4

It is worth noting that in relation to the difficult and changing security situation in Basra and giventhe fact that strict security measures have been imposed on advisers, it has in most instances beenpossible to use good practices for development assistance e.g. stakeholder involvement, promotionof transparent decision making and tendering processes and promotion of cooperation betweenvarious levels of authorities. These are in themselves very noteworthy achievements. But there aresome instances where the use of general good practices and guidelines for reconstruction anddevelopment activities could have been improved.There was in Iraq – as is often the case in fragile situations and in reconstruction efforts - a demandand a need for demonstrating quick results, not least to the local population in the BasraGovernorate, to prove that there was more to win from peace and reconstruction than fromcounter insurgency but also to the public in donor countries as fragile situations often generateconsiderable media-interest. This would suggest that;In reconstruction efforts in fragile situations attention to and use of good practices ofdevelopment programmes and projects – concerning identification, planning,implementation, monitoring and follow up, employment of development staff, to ensurelocal ownership, harmonisation and coordination - should be prioritised and that it isimportant to secure that experienced and professional development experts are involvedat decision-making levels.Planning horizons - as defined by the Parliamentary appropriations - have been too short –20 to 42 months at best but in reality less (e.g. due to a decision early 2007 to re-focusDanish assistance)- from the time of identifying a problem through local stakeholderdialogue to addressing it through design and implementation and to completion of theintervention and closure of Danish assistance. This has not been conducive to fosteringgood development planning and implementation practices.In fragile situations it is necessary to make resources and conditions available soexperienced professional staff can be attracted and support this with simple efficientadministrative procedures and the creation of a human resource base for fragile situations.It appears that most projects concerning infrastructure have been managed professionally anddocumentation available is of sufficient quality to analyse achievements. When there is a lack ofoverall programme and project documents and more systematic reporting – such as is the caseespecially with some of the governance projects and the adviser assistance – this makes it difficultto review the achievements and therefore to distil lessons, which could be utilised in similar fragilesituations.When new experiences are being made it is particularly important that these bedocumented and that the lessons learned are extracted, documented, and communicated.This enables a learning process to take place. Creative use of IT could facilitate that normalguidelines for project management and reporting also in difficult circumstances could beadhered to, despite the eventual loss of laptop computers etc. in the field.At the workshop in Amman the 4-6thFebruary 2008 (see list of participants in annex 4) there wasgratefulness among the Iraqi participants for the Danish support. Especially that the support hadmaterialised as promised, while there was an expressed sense that assistance from some otherdonors had not been according to the promises made. In addition there was generally satisfactionwith the quality of Danish assistance also compared to assistance from other donors. Moreimportantly there was from all participants a general agreement for the need now to move away

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

5

from a project approach and increase process facilitation and capacity building. Iraqi participantsexpressed that Iraq does not lack financial resources but needs expertise in how to use theresources fruitfully by transforming policies into concrete implementation of programmes andensure their sustainability. There was consequently in general terms support to the shift of focus inthe Iraqi-Danish partnership jointly decided in 2007 to concentrate on capacity building of centralIraqi ministries in Baghdad, but there was some dissatisfaction expressed by the local level that thefocus was only on the central level and several requested support also to the de-central level notleast in Basra as a continuation of the past Danish support.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

6

1 Background and IntroductionSince April 2003, shortly after the invasion of Iraq and the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime,Denmark has provided support to reconstruction efforts in Iraq, focusing mainly on the Basra-province.The support has been implemented in accordance with Parliamentary Appropriations 111 (2003),158 (2005) and 106 (2007) through a number of projects and programmes covering a broad field ofsubjects and issues, such as agriculture and irrigation, infrastructure, (e.g. development of harboursand the transport sector), human rights and democracy, humanitarian projects and capacitybuilding.It should be recognised that the Danish assistance was provided within a very difficult and shiftingIraqi context of deteriorating security situation and political turmoil. The location of the SteeringUnit office and its staff in Basra was shifted a number of times and this, obviously, did not onlyaffect the possibility of long term planning but also the possibility of documenting results. Oftenareas of implementation became ‘no go’ areas for reasons of security and sometimes computersand files were lost or left behind. Hence the assistance provided had to be flexible and adaptableand with a rather short planning and implementation horizon. The context is described briefly inchapter 5.The Danish military contingency (DANCON later renamed DANBN) was withdrawn from the Basra-province in July 2007 and the Danish support for reconstruction will according to Appropriation 106in the future mainly be in the form of support to capacity-building at central government level andconsequently no longer focus specifically on the Basra area. As a consequence of this decision, andin agreement with the Government of Iraq, a civilian technical advisory office was established inBaghdad in March 2007.The Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs has - based on this change of focus - decided to initiate aprocess to document the outcome of the past Iraqi-Danish partnership, which focussed onsupporting reconstruction in and around Basra and during this process identify possible lessonslearned from the Iraqi-Danish Partnership for Reconstruction. The process has included variousactivities, including an important site inspection carried out from 15thOctober to mid-November2007 to assess the activities and structures created with financial support from Denmark. Theinspection is documented in a separate site inspection report3.A second important activity was a two day workshop for key stakeholders, Danish and Iraqi, whichtook place in Amman on 4th-6thFebruary 2008 (list of participants presented in annex 4). Thepresent focus-paper has been developed based on a draft discussed at the workshop. The mainconclusions from the workshop are included in this final focus paper.3

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Danida:”Basrah, Iraq: Site Inspection of Selected Bilateral projects.” COWI A/S.December 2007

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

7

Since April 2003 various forms of Danish assistance have been provided to Iraq and funded frombudget-lines according to the form or “modality” of assistance: humanitarian, multilateral, theregions of origin initiative, advisers, and reconstruction.For the purpose of this paper it has been decided to concentrate on two aspects:A. The reconstruction efforts and especially the economic reconstructionB. The efforts for which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has been directly responsible andhence the paper does not include Danish support channelled through multilateralorganisations nor those activities which have been executed by other institutions andorganisations such as the Danish Police, DANBN, the Danish Human Rights Centre, andNGOs.Consequently neither the Civilian-Military Co-planning nor the new focus on supporting the IraqCompact and the establishment of a civilian advisory office in Bagdad will be part of this paper. TheCivilian-Military Co-planning in Iraq will be subject to a separate study covering also Afghanistanwhich is being carried out by Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS).The workshop in Amman 4-6thFebruary 2008 discussed four issues and this paper will be organisedaccording to these issues;1.2.3.4.Agricultural supportEconomic Development (infrastructure)Human Rights, Justice Sector Reforms and DemocratisationDanish Adviser Assistance and the Steering Unit in Basra

The paper does not pretend to establish an exhaustive overview of all reconstruction efforts4, butbased on the available documentation and the discussions at the work-shop, the paper provides anoverview of some of the main achievements. Partly due to difficult circumstances of the planningand implementation of the assistance, the written documentation available is not complete, whichis why the effort to collect the documented experience was supplemented by a workshop, wherefurther documentation was provided through first hand narratives from the involved stakeholders.The information supplied by the participants during the workshop has been included in this paper.During the period of implementation of reconstruction projects in Basra – 2003 to 2ndhalf of 2007 -development assistance to - what has been termed -fragile states(or fragile situations) has beenthe object of increasing attention among development actors. A brief overview of current thinkingconcerning development assistance to fragile states is presented in chapter 2 of this paper. This mayprovide a framework for raising some pertinent questions and drawing some preliminaryconclusions in relation to the Danish support to reconstruction in Iraq. The lessons learned may beused in other Danish support to reconstruction in fragile states and may – where relevant – feedinto the international discussions on the same.

4

An overview of Danish support to reconstruction and humanitarian activities in Iraq from 2003-2008 and itsfinancial allocations is presented in annex 1 to “Danmarks Engagement i Irak” Maj 2007, Udenrigsministerietand copied as annex 3 to this report.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

8

It should be stressed that the content of this paper is the responsibility of the consultants only andthe opinions expressed therein do not necessarily reflect those of any other institution ororganisation except when explicitly stated.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

9

2

Objectives of the Partnership

The overall objective for the Danish support to reconstruction in Iraq was from the outset (2003)formulated as;“… promote stability and reconciliation and support the democratisation and reconstruction of astate built on law and order.”5The support to reconstruction was planned as complementary to the Danish military engagement inIraq. The humanitarian and reconstruction assistance in Iraq was one of the first examples of Danishcivilian and military engagements being planned simultaneously, and while not jointly it was tosome extent mutually dependent, and with the intention of creating synergy between the two. Themilitary engagement by providing security for the implementation of the reconstruction efforts –and the reconstruction efforts by providing short term concrete results on the ground, and therebyaffecting the local population’s perception of and cooperation with also the Danish militarypresence. But it should be stressed that the reconstruction efforts were planned to benefit thewhole province and not specifically the geographic area, which the Danish military contingency wasresponsible for. Originally the area of operation was the four southern governorates. When theDanish civilian head of the four governorates handed over to UK in September 2003 the focusshifted to the Basra governorate.The initial reconstruction assistance was planned to cover the period from approval by DanishParliament of the appropriation in April 2003 to the end of 2004, i.e. some 20 months.The second appropriation for reconstruction assistance was approved in June 2005 and covered theperiod till end 2008, i.e. 42 months. However in reality the planning and implementation period ofassistance to Basra was reduced with the approval of a third appropriation.The objective is in this appropriation the objective is more comprehensively formulated as;“…contribute to the development of a stable and democratic Iraq, enable to secure economic andsocial development for the population in the country, and in addition promote human rights andgood governance.”6This formulated objective was maintained in the third appropriation, also requesting the phase-outof project assistance to Basra and the shift of focus to capacity building in Baghdad, which wasapproved in April 2007. The planning horizon for this appropriation is end 2008, i.e. 20 months.Initially in 2003 four sectors were identified as possible areas for Danish support: Education andHealth, Infrastructure, Democratisation, and Renovation of the Oil-Industry. But it was also statedthat this would be based on further identification efforts and assessments. In addition, it was

56

Parliamentary Appropriation no. 111. Copenhagen 9 April 2003.(Our translation from Danish)Parliamentary Appropriation no. 158. Copenhagen 1st June 2005

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

10

considered likely that it might be necessary to establish a steering unit and recruit a number ofadvisers.Subsequently, in the second appropriation in 2005, it was specified that the majority of activitiesshould continue to be implemented in the southern part of Iraq and with civilian-military co-planning to be continued.The areas to be covered were – after a process of establishing matches between local (by CPA)defined priorities combined with Danish know-how and capacities - defined as follows;1.2.3.4.Human Rights and justice-sector reforms, including police training.DemocratisationInfrastructureAgriculture

In addition, it was specified that the monitoring unit in Basra would be continued.The three appropriations cover both reconstruction and other forms of assistance to Iraq, e.g.humanitarian assistance. Reconstruction assistance alone amounted to 372 mill. DKK of whichapproximately 260 mill. DKK was spent mainly in Basra between 2003 and 2007.The main risks, which were explicitly mentioned in the appropriations, were the security situationand the relatively weak political and administrative structures in Iraq. The non-presence oftraditional development partners, inter alia the UN and the World Bank, is also mentioned.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

11

3 Working in Fragile States7Recent years have witnessed considerable progress in the international efforts within thedevelopment community to increase aid effectiveness in general. This has taken place in variousfora but the developments have to a large extent been driven by the Development AssistanceCommittee - DAC (under OECD).This has culminated in theParis Declaration on Aid Effectiveness8from March 2005. Within theframework of this Declaration developed and developing countries resolved to ensure moreefficient development assistance with increasing impact on poverty and decreasing transactioncosts - for recipients as well as for donors – by ensuring national ownership, alignment andharmonisation.The objective is to:Ensureownershipby recipient government and population of poverty reduction strategies definedthrough an inclusive and participatory process.Aligndonor assistance with partners' strategies and to the extent possible use partners' procedures.Harmonizedonor assistance by sharing information, developing common donor arrangements andusing the same and simplified procedures.Manage for results,which emphasises the importance of focusing on outputs.Following the Paris Declaration there have been increased efforts to ensure more efficientassistance also to fragile states. The rationale is a concern that donors prefer to support countrieswhere it is easier to get results – the so-called good performers – and shy away from more difficultsituations. Donors who were engaged in providing development assistance to difficult situationssuch as in Iraq were especially active in this work on fragile states. The importance of this work isunderlined by numbers: Some sources put the number of people living in these countries at 870million people or 14% of the World's population9and it is increasingly clear that in order for theinternational community to live up to its commitments concerning the Millennium DevelopmentGoals (the MDGs) it is necessary to increase development efforts to fragile states. Of the 84countries eligible for soft loans (IDA) from the World Bank, 32 are characterised as fragile states – orLow Income Countries under Stress (LICUS).

3.1 DefinitionsThe term "fragile states" is being used by the international community to characterise states thatseriously lack the capacity and/or willingness to perform a series of functions regarded as essentialto the security and well-being of their citizens. There is, however, no precise definition - and theterm "fragile" is often used interchangeably alongside other adjectives such as poorly performing,difficult partnership, weak, under stress, failing, failed, collapsed - with some variation in meaning.7

This chapter is a condensed version of parts of: ”Development Assistance in Fragile States”. By Julian Brettand Finn Skadkær Pedersen, written for the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. May 2007.8http://www1.worldbank.org/harmonization/Paris/FINALPARISDECLARATION.pdf9“Why we need to work more effectively in fragile states”,DfID, January 2005, p7.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

12

To a varying degree, fragile states are countries affected by conflict.Among countries falling within these categories there is understandably some unease about beingclassified as such because of the perceived negative connotations. This perception is importantbecause the principal objective of current international efforts is greater engagement and the use ofterminology should not detract from this objective. In the on-going discussions on the issue, it hasbeen suggested that a more neutral term, such as "fragile situations", could be better.10

3.2 Development Assistance to Fragile StatesFighting poverty is the overriding goal of the development community. It should, however, be notedthat in addition to this goal there are many additional and arguably equally important politicalconcerns when it comes to working in fragile states e.g. humanitarian needs, security, counter-terrorism, human rights, and migration and trafficking.DAC's Fragile States Group (FSG) has developed a series of principles for more effectiveinternational engagement in fragile states.11ThePrinciples for Good International Engagement inFragile States and Situationsaim to complement the Paris Declaration and take their starting pointin the recognition that a durable exit from poverty and insecurity has to be driven by localleadership and people and that, while it will not put an end to state fragility, international assistancebased upon shared principles of engagement can help promote positive impacts and minimiseunintentional harm. ThePrinciplescan also apply in stronger performing countries during periods oftemporary fragility.ThePrinciplesare currently the best and most widely recognised set of guidelines for aidinterventions in fragile states and they are the result of an extensive piloting exercise by DACmembers in ten countries.12Box 1: Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States & SituationsThe Basics:1.Take context as the starting point:Understand specific context anddevelop a shared view of the strategic response required. It is especiallyimportant to recognise different constraints ofcapacity, political willandlegitimacyand also difference between countries intransitionsituations,recoveringfrom crisis, countriesdeterioratingin governance, and countriesin prolonged crisis.2.Do no harm:avoiding activities which create societal divisions and worsencorruption and abuse. Responses should be based upon sound conflict andgovernance analysis and must be carefully judged so as not to exacerbatepoverty, conflict and insecurity.

1011

SeeSummary record of the 6th meeting of the Fragile States Group (FSG),DAC, 15th June 2006.The "Principlesfor Good International Engagement in Fragile States and Situations"were endorsed by the Ministers andHeads of Agencies of the OECD DAC in April 2007. This is available athttp://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/61/45/38368714.pdf12DRC - Belgium, Guinea-Bissau - Portugal, Haiti - Canada, Nepal - UK, Somalia - World Bank & UK, Solomon Islands -Australia & New Zealand, Sudan - Norway, Yemen - UN and UK, Zimbabwe - EC. Phase 2 of the piloting ended in October2006 following which the findings were synthesised and fed into the final set of principles agreed in April 2007.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

13

The Role of State-Building & Peace-Building:3.Focus on state-building as the central objective,strengthening therelationship between the state and society through enhancing the state'slegitimacy and accountabilityand thecapabilityof state structures toperform core functions. Civil society has a key role in both of these areasand may play a key role in service delivery.4.Prioritise prevention,sharing and responding to risk analysis, support civilsociety involved in conflict prevention, addressing the root causes of statefragility and strengthening indigenous capacities, especially those ofwomen, and the peace-building role of regional organisations.5.Recognise the links between political, security and developmentobjectives,while there might be tensions and trade-offs betweenobjectives, especially in the short run such as a focus on peace-keeping andpeace- building as a prerequisite for progress against the MDGs. Aim forpolicy coherence and joined up strategies while preserving the neutralityand impartiality of humanitarian aid.6.Promote non-discrimination as a basis for inclusive and stable societies.Consistently promote gender equity, social inclusion and human rights.Measures to promote voice and participation of women, youth and otherexcluded groups should be included in state-building and service deliverystrategies from the outset.The Practicalities:7.Align with local prioritiesin different ways in different contexts. Alignassistance with government strategies where there is political will to fosterdevelopment but a lack of capacity. Where donor-government consensus isnot possible, seek wider consultations with national stakeholders andpartial or shadow alignment which helps build the basis for governmentownership and alignment in the future. Avoid activities that underminenational institution building, such as parallel systems, without thought totransition mechanisms and long term capacity development.8.Agree on practical co-ordination mechanismsbetween internationalactors, including upstream analysis; joint assessments; shared strategies;co-ordination of political engagement; joint offices, multi-donor trust fundsand common reporting frameworks. Work jointly with national reformers,including civil society.9.Act fast…. but stay engagedlong enough to give success a chance.Flexibility to take advantages of opportunities that occur and respond tochanges. Capacity development in core institutions will take at least tenyears. Ensure aid predictability by developing systems of mutualconsultation and co-ordination, especially prior to changes to aidprogramming.10.Avoid pockets of exclusion,addressing "aid orphans" where there are nosignificant barriers to engagement but where aid volumes are low. Ensureco-ordination on field presence and mechanisms to finance promisingdevelopments in such countries.It is also worth highlighting that accompanying the adoption of thePrincipleswas a policycommitment from Ministers and Heads of Agency on a range of actions to support their

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

14

operationalisation. These actions include: mainstreaming thePrincipleswith efforts to implementtheParis Declaration;improvingWhole-of-Government Approaches(i.e. joining up economic,development, diplomatic and security actors); taking steps to improve agency organisationalcapacity and responsiveness (including field presence, skills, incentives, and policy cohesion);improving the targeting, co-ordination and transparency of resource allocations to fragile states;and setting realistic, transparent, and monitorable goals and objectives.13

3.3 Civilian-Military Co-planningAs one of a few countries in the world Denmark has developed principles for the cooperationbetween military and civilian actors in situations where both are present. This exercise was basedon the increased engagement of the Danish military in international crises from the 1990s e.g.West-Balkans, Ethiopia/Eritrea, Afghanistan, and Iraq. This pointed to the need for an intensifiedcoordination of civilian and military interventions. In March 2004, such an initiative was launched bythe Ministers of Defence and Foreign Affairs.The principles guiding this initiative include the following14:To normalise and stabilise the situation for the local population in a conflict area as there isa direct connection between improved socio-economic conditions and securityTo ensure the best use of Danish resources within an internationally co-ordinatedframework.To the greatest extent possible, ensure a concentrated Danish humanitarian input in theDanish military's area of responsibility.As a general rule, private Danish and international humanitarian organisations shouldundertake [non-military] stabilisation interventions financed by Denmark. However, insituations where the security situation prevents these organisations from operating, militaryforces may be required to provide minor support in the local area.It has been stressed that the intention of the initiative is not to create an armed emergency-brigadeout of the Danish military forces. The importance of the initiative lies in ensuring that Danishparticipation is coordinated in such a way that it has maximum impact and that assistance reachespeople in need. NGOs have been involved in discussing the co-operation principles, and they werefirst and foremost implemented in Iraq and are now in use in Afghanistan.

3.4 Guiding principles for Provincial Reconstruction TeamThePrinciples for Good International Engagement in Fragile States & Situationsand thecivilian-military co-planning presented above could be the frame for discussing the Iraq-Danishpartnership.In addition the PRT Guiding Principles which came out of a recent workshop in London (in late 2007)could more practically be included as a background to these discussions. They are included in annex2.

1314

Policy Commitment to Improve Development Effectiveness in Fragile States,DCD/DAC(2007)29, April 2007.http://www.um.dk/da/menu/Udviklingspolitik/BistandIPraksis/Civil-militær+samtænkning/(our translation)

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

15

4 Methodological issuesThis focus-paper is based mainly on available reports and documentation. Unfortunately, thecurrent systematic collection of relevant material has not been finalised yet and some of thefindings and conclusions included in this paper might therefore be based on incompleteinformation. The written information has been supplemented by narrative reports and discussionsat the workshop in Amman 4-6thFebruary 2008.It has been attempted in the review of the Danish supported activities in Iraq first of all briefly todescribe the concrete outputs produced. When dealing with project activities, which have producedconcrete material outputs e.g. buildings or sluices, the recent site inspection report15has been themain source, while it has been more difficult to find documentation for results of projects with aless tangible output.After a brief presentation of the concrete outputs, each of the relevant projects is subjected to acritical review based on the available project documentation. Such reviews are based on standard“Danida policies”16, good practices of development management as presented in the AidManagement Guidelines (AMG)17and especially the internationally accepted DAC criteria forevaluations18.The first step has consequently been an attempt to identify if the results are in line with formulatedproject objectives, if possible to review the quality of the identification and preparation processes,and the implementation and follow-up processes.The review is structured according to the following logic;1. Description of results – mainly based on the Site Inspection Report2. Brief review of effectiveness, including reviewing to what extent the project has met theintended project objectives and – to the extent possible – review how it contributed to thereconstruction process3. Brief review of relevance, including if the support was in line with Iraqi (originally CPA) plansand priorities, quality of needs assessment and risks analysis, and extent of consultationsand involvement of relevant stakeholders4. Brief review of efficiency in relation to cost-efficiency and time, and – if possible – inrelation to alternatives5. Brief discussion of issues of sustainability and impact6. Based on the five points above, some preliminary lessons learned are presented15

COWI A/S : “Basrah, Iraq: Site Inspection Report of selected Bilateral projects”. December 2007The overall policy is presented in ”Partnership 2000” MFA-Danida, October 2000, and has been updatedwith annual, more short-term policy papers.17http://amg.um.dk/en18http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/15/21/39119068.pdf16

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

16

It should be stressed that most of the written documentation and verbal information providedduring the work-shop is provided by actors, who have been involved in implementing theprojects. The security situation in Basra has throughout the relevant period been such that siteinspections and review missions to implementing entities have not been possible withoutmilitary protection. Although a relatively small proportion of the documentation andinformation can thus be considered to be of an independent nature, the Site Inspection Report,as well as this paper, is the products of independent consultants.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

17

5 The Context in which the Partnership took placeWhile a full and comprehensive description of the political and security situation in which thepartnership was implemented is not possible inside the limits of this paper, a few importantmilestones in the development of the political situation during the implementation period in Iraqand especially in Basra are briefly presented below.

5.1 Some milestones in the political developments in Iraq 2003-2007From April 2003 to 28thJune 2004 Iraq was administered by the Coalition Provisional Authority(CPA) representing the occupation forces and led by an American Administrator. On the Iraqi side agoverning council and a government with a number of ministries were established.The CPA - or rather the freshly appointed chief of CPA – took two very wide-ranging decisionsi.e. 1) the order banning the Baath party and excluding its members from all important publicemployment and 2) the decision to abolish the security apparatus, including the army and police.The De-Baathification of Iraqi society meant “the removal of “senior party members” from“positions of authority and responsibility in Iraqi society” and those of lower party rank from the topthree layers of management, in one swoop deprived Iraq of its managerial class, regardless of thosemanagers’ character or past conduct19.The disbandment of the army put up to 350,000 men in the street without pay, the promise of apension or, for senior officers, the prospect of recruitment into the new security organisations. Themajority of the rank and file in the army had been Shiites so the decision led to mass protests inmost cities in Iraq, including in Basra. The International Crisis group states; “In the absence ofcomprehensive research, anecdotal evidence collected over the past two-and-a-half years suggeststhat many former soldiers and officers joined (and perhaps even gave rise to) the incipientinsurgency during the hot summer months of 2003 or, in even greater numbers, resorted to crimeas a way of making ends meet”20.It in addition led to looting of many ministries and public institutions and banks were closed andpayments became very difficult for months.During the summer of 2003 a steering unit for the Danish assistance was established in Basraheaded by a Danish diplomat. It was soon after decided to transfer him to Bagdad to facilitateliaison with the UN-system and with CPA centrally. The diplomat later in the autumn 2003 becamehead of the Danish Liaison office in Bagdad. When a new head of the steering unit was employed itwas initially not possible to accommodate him in Basra and he therefore was attached as

19

International Crisis Group Report. “The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil Conflict. Crisis Group -Middle East.” Report N�52, 27 February 2006 p. 920ibid

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

18

development administrator to the office in Bagdad. When sovereignty was handed over to the Iraqisin 2004 this Liaison Office became the Danish Embassy.The security situation for international staff in Iraq changed dramatically during the second half of2003 after the car-bombings of the UN Headquarter in Bagdad on the 19th of August and in October2003 with the attack on the hotel in the International zone, which housed most of the internationalstaff based in Bagdad, including a number of Danish citizens.The general deterioration of the security situation also meant a reduction in the number ofinternational aid workers, e.g. the UN decided to pull all international staff out of Iraq after thebombing of their headquarters. Likewise, most international NGOs discontinued their work in Iraq.During November 2003 an agreement was released by CPA in Bagdad spelling out Iraq's path tosovereignty and in March, 2004 an interim Constitution; The Law of Administration for the State ofIraq for the Transitional Period, was approved by the Iraqi governing council.From June 2004 up to the first national elections in January 2005 an Interim Coalition governmentwas created composed of representatives from the three main groups in Iraq; Sunnis, Shiites andKurds. Each of these groups form a majority in their respective areas of Iraq and the Shiitecommunity - while also being the largest of the three – is dominant in the Southern part of Iraq andthus also in the Basra province.On 30thof January 2005 a majority of Iraqi voters voted in an election prepared by the transitionalgovernment, which established a 275-member Transitional National Assembly.The Assembly served as Iraq's national legislature. It appointed a Presidency Council, consisting of aPresident and two Vice Presidents. The Presidency Council in turn appointed a Prime Minister and,on his recommendation, cabinet ministers. The second and more important role of the Assemblywas to oversee the drafting of a new constitution. This constitution was presented to the Iraqipeople for their approval in a national referendum in October 2005. Under the new constitution,Iraq would elect a new permanent government.The current government took office in May 2006. This followed the general elections in December2005. A broad coalition government with participation of Shiites, Sunni and Kurds under theleadership of Nouri Al-Maliki, who is the leader of the Dawa Shiite party, was formed. The results ofthe political processes have however been mixed. Work on some important laws have progressede.g. an investment-law and a law concerning the formation of new regions. Also work on importantlaws concerning the oil sector and on elections to the provincial councils are reported to beprogressing. On the other hand the political process has, since the formation of the coalitiongovernment, been hampered by increasing religious and ethnic tensions and polarisations, alongwith an increase in sectarian violence not least after the bombing of the Golden Mosque in Samarrain February 2006. However during the 2ndhalf of 2007 there has been a significant improvement inthe security situation, with the number casualties being at the same level as of January 2005. Thisstill has to translate into an improved trust and cooperation between the political opponents.As is well known, the security situation in Iraq has been and still is difficult. Some features of thespecific situation in Basra Governorate will be attempted presented below.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

19

5.2 International and Danish assistance in relation to political developmentsShortly after the invasion of Iraq an international donor conference led to the creation of a commoninternational frame for reconstruction of Iraq called the International Reconstruction Fund Facilityfor Iraq (IRFFI).This facility consisted of a UN administered fund and a fund administered by theWorld Bank. The original needs assessment was conducted by international experts and formed thebasis for the first national development plan in October 2004 covering 2005 to 2007.21A newnational development plan also building on provincial and district development plans is presentlybeing formulated.As more and more responsibility was transferred to the Iraqi authorities, a gradual change in theway Danish assistance was implemented and especially in the way the advisers were workingobviously had to follow. While the advisers were initially part of the CPA-structures and as suchdirectly implementing, although to the extent possible in consultation with rudimentary councilstructures and with the help of existing “bureaucracies”, this changed when power was transferredto the Iraqi government. While initially there might in practice have been little difference, the morerepresentative the structures became especially after the elections in January 2005 and the morethe provincial council took over responsibilities, the more the Iraqi authorities became the mainpartners and decision-makers for activities, while advisers increasingly concentrated on advisingthem. However, the security precautions meant that a very close working relationship betweenadvisers and their counterparts was often difficult.Towards the end of 2005, the coalition in Iraq decided to set up Provincial Reconstruction Teams(PRT) in all Iraqi governorates in close coordination and cooperation with the coalition’s militarypresence. In Basra three Danish advisers were assigned to this structure which would help defineand implement a Provincial development strategy.Although the Danish support to the International Compact with Iraq is not covered in this paper, itshould be noted that The Iraqi Government, the UN and the international donors on the 27thof July2007 launched a comprehensive five year plan or “vision” for establishing a “United, Federal,Democratic country”22. The donor support is now provided inside the framework of the Compact.

5.3 Developments and security in Basra ProvinceThe so-called “Southern Sector” was under British military protection and the British military wasfrom May 2003 assisted by a Danish military contingency. The Southern Sector, was – under the CPAin Bagdad – governed from Basra city. Basra is the second largest city in Iraq and the Governorate iseconomically very important due to its rich oil reserves and its important harbours at the PersianGulf.A senior Danish civil servant, Ambassador Wøhlers Olsen, was from May 2003 attached to the CPA,Basra, in charge of the Southern Sector and was in September substituted by a British national.The first MFA identification mission took place in May and early June. In May 2003, a MFA-missionfocussed on support to infrastructure and health visited Basra and surrounding areas and thismission identified the important markers for the support to large infrastructure projects (study of21

Seewww.irffi.organdhttp://www.iraqcompact.org/en/default.asp(visited 28.02.2008)

http://www.irffi.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/IRFFI/0,,contentMDK:20241588~menuPK:497701~pagePK:64168627~piPK:64167475~theSitePK:491458,00.html(visited 06.01.2008)22

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

20

transport corridor, harbour improvement etc.) and also concluded that the regional hospitals hadno reconstruction needs. The early June mission was based on an invitation from the Americanadministration to assist in a mission to assess the judicial sector in Iraq. The Danish part of themission concentrated its efforts on assessing the Human Rights (HR) situation and the possibilitiesfor supporting the re-establishment of law and order in the Basra-area. The mission formulated thebasis for what became the Danish governance programme (police-training, support to NGOs, courtimprovements, etc.).The initial decision to establish a steering unit in Basra in mid 2003 was not implemented fully untillate 2003 in order to assist in the implementation of the Danish reconstruction support and ensurecoordination with the much larger US and UK programmes in the Basra province. From the end of2003, a Danish steering unit was created including 3-4 advisers, who at the time were also workingin the CPA-Basra structure.

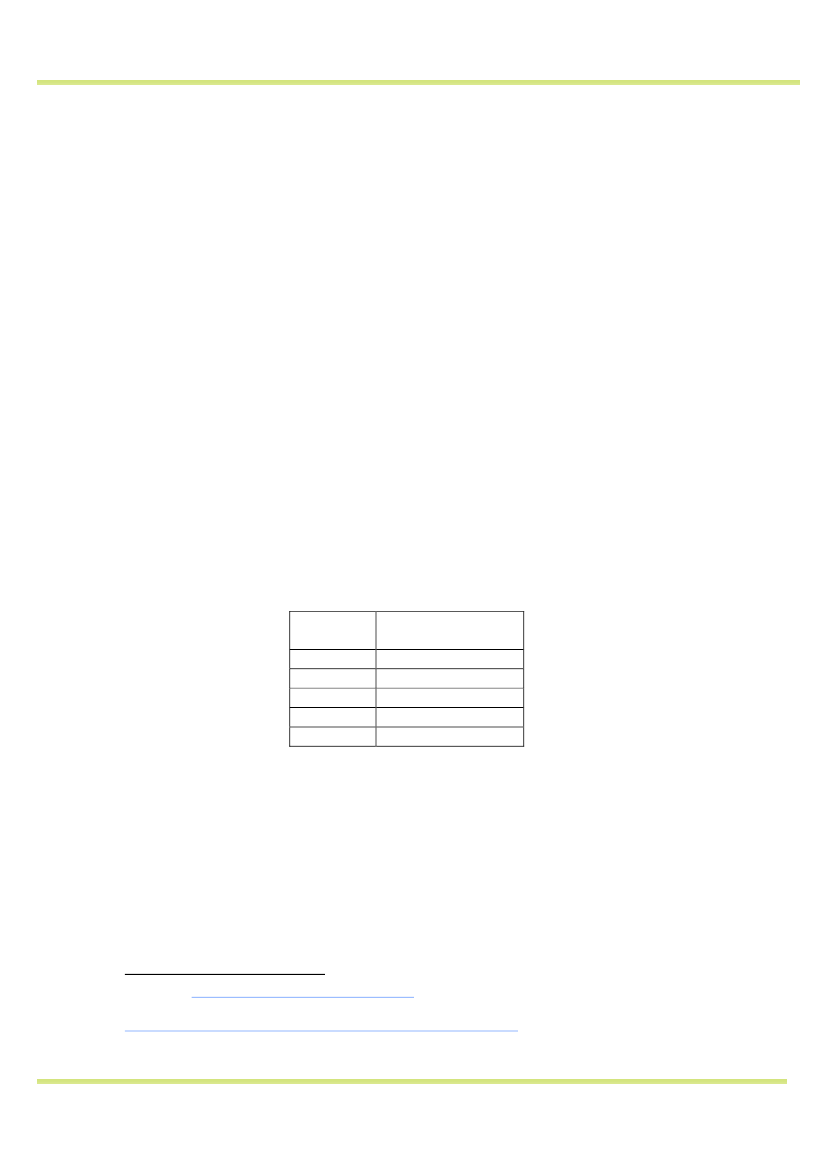

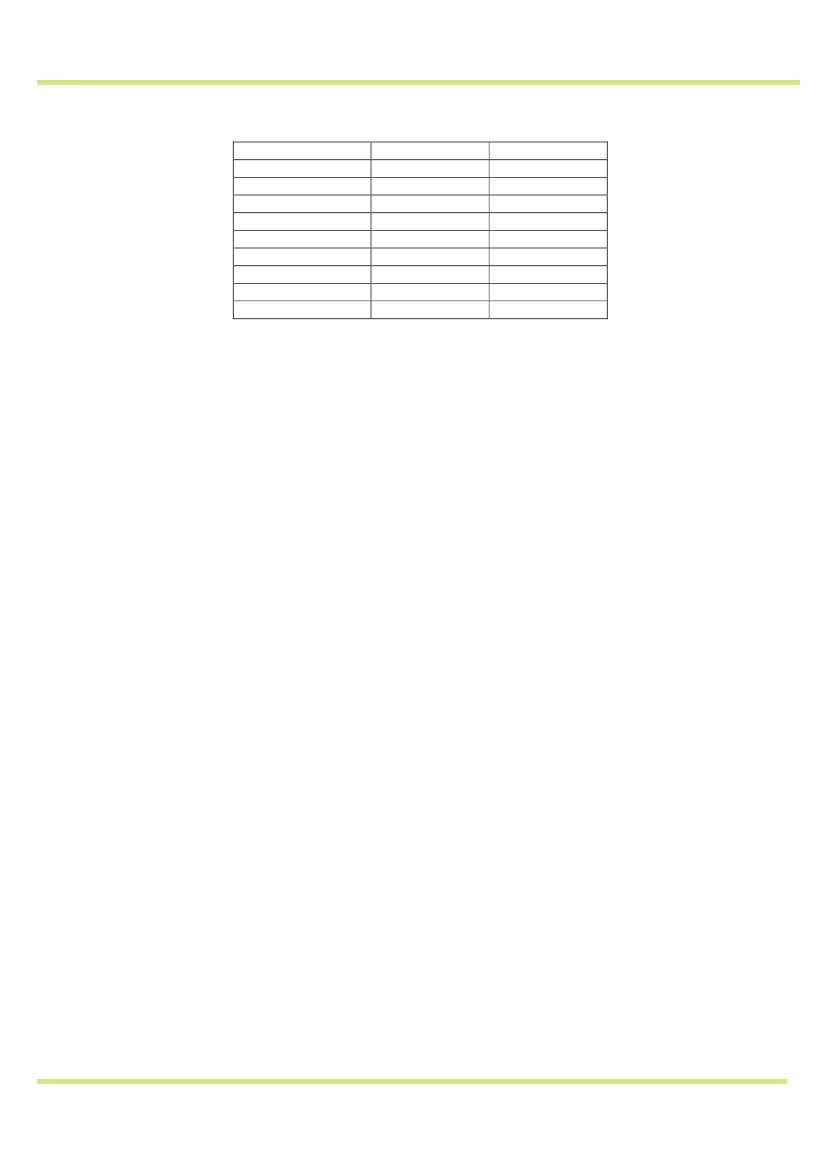

5.4 Security situation in Basra GovernorateWhile the security situation was initially much less serious in and around Basra, the Danish advisersalong with other international civilian staff nonetheless moved into better and more securepremises in the Basra Palace during the second half of 2003. As there were an increasing number ofincidents of road-side bombs and other attacks on occupation forces and civilian international staffin late 2003 and early 2004, it was decided to provide armed protection to the advisers whentravelling outside of the Palace.An indication of the change in the security situation may be the casualties which the coalition forcessuffered in the Province. In the period the numbers were as follows:23Year20032004200520062007Number ofcasualties3016183343

The Danish contingency had seven fatal casualties; one in 2003, none in 2004, one in 2005, four in2006, and one in 2007.The Danish Defence Intelligence has provided a number of evaluations of the threat in Iraq atvarious times to inform the parliamentary committees, when the members of the committee andthe Parliaments discussed the Danish support to Iraq24.Based on this information the development in the security situation can be described as follows:

2324

Based onhttp://icasualties.org/oif/Province.aspxvisited 27.01.08Available on the parliaments website www. Folketinget.dk andhttp://forsvaret.dk/FE/Presserum/Situations-+og+trusselsvurderinger”are “Situations ogTrusselsvurderinger” dated 10. Nov. 2004, 10. January 2005, May 2005, 9. January 2006, 7. Februar 2006, and10. May 2006 samt “Efterretningsmæssig trusselsvurdering” fra December 2005 og December 2006.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

21

From second half of 2003 to mid 2004 there were relatively few attacks, while there appears tohave been a considerable increase up to the 28thof August 2004 (when Muqtada al-Sadra agreed toa cease-fire).At the general elections in January 2005 also Provincial councils were elected and so were somedistrict councils while others were appointed through a so-called caucus process, which was anarrangement, introduced by the CPA. The local councils had consequently from then on a muchmore representative and legitimate character than prior to 2005, although many of them, includingin Basra, were hampered by a lack of willingness to cooperate and compromise among the majorpolitical forces (and their respective militia) alsointernallyin the Shiite community. And in additionthere was a lack of cooperation between the central and the provincial governments. But initiallythe security situation improved. With an increase in the use of Improvised Explosive Devices (IED’s)in Basra in mid 2005 the security situation again deteriorated.The cartoon-crisis led in February 2006 to a temporary cessation of most Danish activities. The BasraProvincial Council boycotted all cooperation with Danish and British (UK troops being accused ofhaving used torture) supported reconstruction efforts. The boycott was lifted again in May 2006.Based on other information25September 2006 saw the start of “Operation Sinbad”. This operationwas a joint operation between Coalition Forces and Iraqi security Forces and was an attempt tocrack down on local militias and hand security over to newly vetted and stronger Iraqi securityforces while kick-starting economic reconstruction. The initiation of the operation was followed by arise in attacks against Coalition bases in Basra, among them Basra Palace.In September 2006, following the death of Danish soldier from the Danish advisers’ protection teamand - probably more importantly – following an incident where the British troops destroyed a policestation to free two British soldiers, the security situation became so difficult that it was deemednecessary to move the Danish advisers from Basra Palace in the centre of Basra to Sheiba Log Base,outside Basra city, where the Danish battalion was based. When the Danish battalion in January2007 moved from Sheiba Log Base to Basra Air Station the Danish advisors were again moved.By March–April 2007, renewed political tensions once more threatened to destabilize the city, andrelentless attacks against British forces meant that they had difficulties in patrolling the city26. Andin April 2007 due, to security considerations, the Danish advisors were moved to Kuwait.The difficult security situation meant that through most of 2006 and until second half of 2007 themovement of advisors outside the camp was restricted by the availability of the armoured vehiclesand accompanying security staff, and although it was possible to receive Iraqi cooperation partnersin the camp, security arrangements made this at least cumbersome and sometimes difficult. Withincreasing threats against Iraqis who cooperated with the foreign forces, the possibilities forcooperation were further crippled. The camps were also often attacked, at periods several times aday with mortars and sometimes rockets, making working conditions very difficult and sometimesleading to the evacuation of civilian staff at short notice and often without the possibility ofretrieving documents and computers.25

International Crisis Group Report: “Where is Iraq heading? Lessons from Basra” Middle East Report N�67. 25June 2007. The report is critical of the situation in which Basra was left by the withdrawal of the CoalitionForces.26ibid

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

22

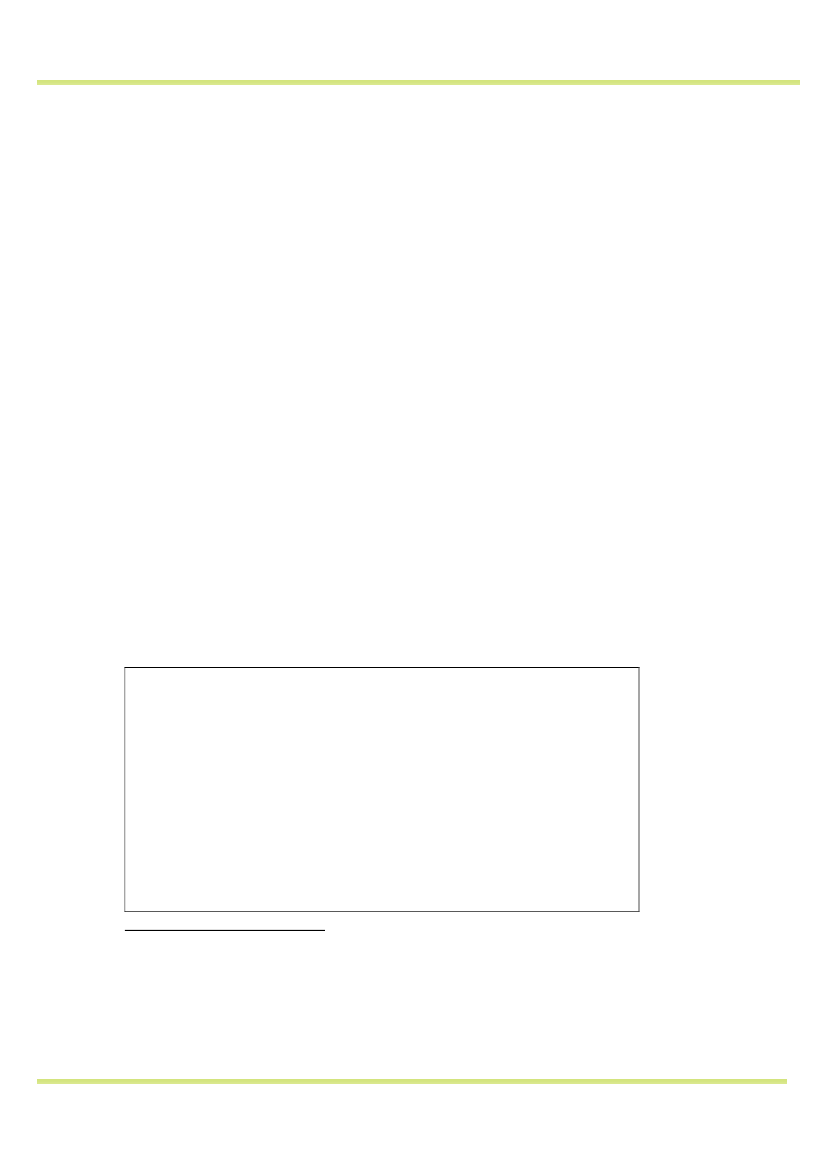

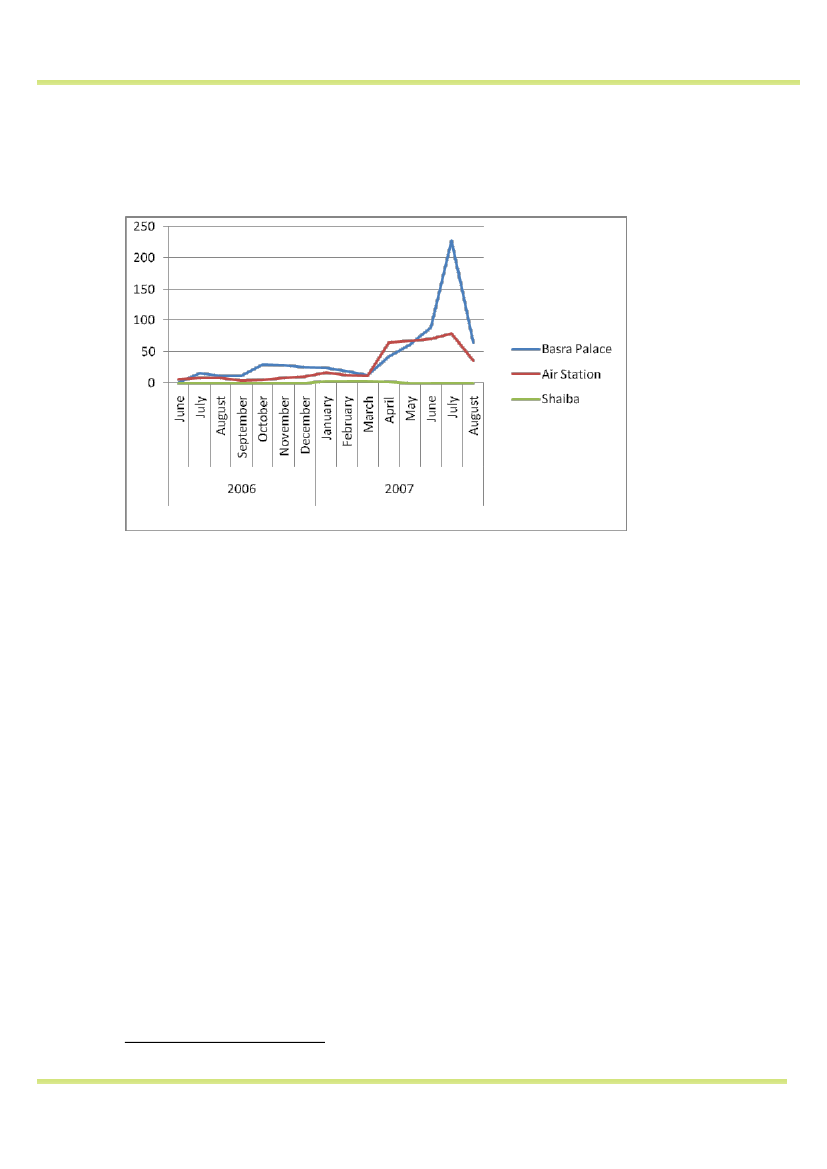

The following figure provides an indication of counts of explosion incidents caused by attacks on themain camps of the coalition forces in Basra during 2006 and 200727;

This difficult working environment should be taken into consideration when reviewing theachievements of the Iraqi-Danish partnership.Limitations in the documentation of some of the Danish supported development activities shouldconsequently be seen against this background: With a rapidly deteriorating security situation andnumerous unforeseen interruptions in the work flow, it is understandable that relevant projectdocuments may have been lost and reports not produced. The information provided by participantsin the work-shop in Amman in early February 2008 to some extent has compensated for this.

27

Unofficial count by the British Defense Forces (information provided through Danish advisors)

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

23

6 Agriculture and IrrigationDenmark has since 2003 supported the agricultural sector in the Basra Province and has furtherprioritised its support to the sector as of 2005. This section covers the period up to February 2007,when it was decided to focus Danish support capacity building at the central level in Baghdad. Thelast irrigation projects in Basra are almost complete and will be handed over to the IraqiGovernment in March 2008.As stated in the Draft Inception report (January 2006), the long term objective of Danish support tothe agricultural sector is:' to improve the livelihood of the people living in the Southern region by creating rural employmentopportunities and raising income'.More specifically, the objectives of the support provided to agriculture until early 2007 revolvedaround three components, namely:The provision of technical support to the Ministry of Agriculture and other ministries involved inthe development of sustainable production and employment generation within the fields offood, agriculture and irrigation in the southern region (though a Senior AgriculturalDevelopment Advisor)The identification and implementation of other smaller projects within the agricultural sectorthat would lead to improvements in the sector's performanceThe rehabilitation of essential infrastructure, with focus on labour intensive activities andtechnologies within the local communities (namely irrigation schemes in the Basra Governorate)It is worth noting that the focus of agriculture sector development support from 2005 was onirrigation rehabilitation as stated in the Inception Report and less so on capacity developmentthrough process facilitation, coordination and policy issues.The following section attempts to address the five key issues highlighted in Chapter 4, namelyproject status, effectiveness, efficiency, and relevance. Findings are based on a literature review ofdocuments made available by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, primarily the draft inceptionreport of the Senior Agricultural Development Advisor of January 2006, a summary report28highlighting activities and achievements within Danish support to agricultural sector developmentfrom 2003-2007, selected monthly progress reports from the years 2004, 2005 and 2006 as well asthe COWI Site Inspection Report of December 2007. Additional information was acquired from theworkshop held in Amman in February 2008.

6.1 Project StatusSenior Agricultural Development Advisor:28

“Danish support to the Agricultural Sector Development in Iraq 2003to 2007 (2008)” 10 June 2007 seniorAgricultural Advisor.

th

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

24

Danish Advisory Assistance and the Steering Unit will be addressed in more details in Chapter 8.However, a brief project status will be presented below, since such assistance constituted one (outof three) component of agricultural support.The Senior Agricultural Development Advisor was originally posted to Basra CPA by“Landbrugsrådet”29. The Advisor was later assigned, based on an EU tendering process, with theresponsibility to coordinate overall activities under all three components and to liaise/cooperatewith other donors. The Advisor has been providing technical assistance and process facilitation atprovincial and central levels. A core aspect of the support entailed process facilitation regardingstrategy and planning at the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA). As mentioned in the workshop,institutional capacity building was undertaken. An Agricultural Sector Working Group (ASWG)headed by the Basra Council/Governorate representative was formed. The ASWG held its firstmeeting in December 2005 and thereafter periodically, when possible, to discuss issues relating toagricultural sector development and the planning of the Basra provincial development strategy. Atthe meeting, the need for a baseline survey was mentioned to be a priority for gaining a betteroverview of the situation in the Basra province and improving planning. To date, and as noted in theworkshop, it seems that the strategy is still in the process of finalisation.Technical assistance provided to MoA also extended to the Ministry of Water Resources and itsIrrigation Directorates as well as the Ministry of Trade in relation to the food ration scheme. Someof the main achievements that overall advisory services contributed to include according to thereports produced by the Adviser:the restoration of the Marshlands at a rate of around 60% in Basra, Maysan and Dhi Qarprovinces.the rehabilitation and restoration of the date palm sectorimprovements in tomato productionthe design and implementation of a seasonal credit scheme jointly with MoA and theAgricultural bank across Iraqrestoration of irrigation and drainage infrastructure including l cleaning of canals (aselaborated below)With respect to donor coordination, meetings with donors were held. However, according to thediscussions in the workshop, not many donors operated within the agricultural sector as a start,though interest for agriculture grew over time. As such, donor coordination took place to the extentthat donors were present in the sector. The sector work group meetings were also held but mainlycomprised Iraqi stakeholders (e.g. ministries and farmer groups). The frequency of meetings wasoften constrained by the security situation.Overall, and according to the reviewed documentation, Iraqi and Danish parties seemed to besatisfied with the input of the Danish Senior Agricultural Development Advisor in relation to theadvisory services provided.Smaller projects:The small projects part of the programme was intended to support overall process facilitation andcapacity building. The inception report re-defined activities under this component to include someactivities that initially fell under the first component.

29

The Danish Interest Organisation for Agriculture

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

25

Process facilitation within this component primarily revolved around private sector and businessdevelopment, training and study tour, integrated pest management and solar energy. Mainactivities included:the organisation of tomato farmers into cooperatives (5 registered in 2005)training courses to MoA and related staff on IT, project planning and administrationtwo study tours to Denmark in 2004 and 2007 for MoA personnelone study tour to Kuwait in 2007 for tomato producing cooperatives to explore a potentiallift of the current ban on import of Iraqi products to Kuwait.studies and training for the promotion of the provincial development fund (PDF) forfinancing SMEs in the agribusiness and food industry sectorsa solar energy powered water pump as demonstration activity for drip irrigation (2004).Rehabilitation of irrigation schemes:Technical assistance was also separately provided to the irrigation component. An irrigationspecialist was employed for six months (August 2005-February 2006) to assist in identifying,planning and implementing support to the irrigation and drainage infrastructure system.Subsequently, a senior construction engineer was assigned for six months (March 2006-August2007) to supervise the design, tender process and construction of the irrigation and drainageinfrastructure, which is still ongoing.The rehabilitation of irrigation infrastructure today includes a total of seven projects that werecovered by the COWI Site Inspection Report (December 2007, information collected from 15. Oct. tomid Nov. 2007) namely:1. Talha Medina Sluices (20)2. Al Medina Sluices (5)3. Ez El Deen Saleem Sluices (5)4. Al Querna Sluices (5)5. Al Dayr Sluices (9)6. Al Nashwa Foot Bridges (6)7. Talha Medina Drainage canalTwo of the projects were at the date of the site inspections completed, four were due to becompleted in December 2007 and one was under tender. The report shows that the two completedprojects had good quality, were fully functional and are in full use. However, some of the completedprojects faced constraints (lack of qualified staff) or needed safety adjustments (which after the siteinspection is being followed-up). The report states that delays in construction primarily resultedfrom delays in payments to contractors. This was also confirmed at the workshop, where delayedpayment was also repeatedly mentioned. The delayed payments were due to various circumstancessuch as the inefficient banking system in Iraq but also due to the fact that payments should only bemade, when the necessary inspections of finalisation and quality had been done. It should be notedthat the site identification process and data collection were lengthy, which might also havecontributed to time delays, particularly given the security situation.

6.2 Effectiveness6.2.1 Meeting intended objectivesBased on the available documentation and workshop, the support to agriculture seemed to havegreatly achieved its objectives, taking the difficult working environment into account. Advisoryservices have been provided to MoA in support of national policies and priorities as well as capacity

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

26

building activities. Donor coordination has also been initiated. A relatively large number of smallerprojects were implemented in support to process facilitation and capacity building. Finally, but notleast, irrigation infrastructure was repaired or is being made operational. Due to limiteddocumentation, the extent, to which employment generation was induced and the extent focus hasbeen on labour intensive technologies within the local communities, have not been examined.

6.2.2 Contribution to the reconstruction processAs mentioned in chapter 2 above, the objective of reconstruction assistance is to “contribute to thedevelopment of a stable and democratic Iraq, enable to secure economic and social developmentfor the population”. The support provided to the agricultural sector can be said to have contributedto this reconstruction, particularly in relation to initiating steps towards economic development.

6.3

Efficiency

Open tendering was undertaken for the rehabilitation of irrigation projects, where in principle thelowest bid wins, though the evaluation committee is not bound to accept the cheapest bid, takingother criteria into account. This does not in itself ensure a balance between cost efficiency andachievements of outputs on time, but provides a sound basis for achieving efficiency. Currently,most projects are ongoing as delays have been experienced. As mentioned above, delays have beencaused by delayed payment, though mostly by the security situation, thereby reducing timeefficiency.Although no basic baseline or impact data have been collected to capture future socio-economicimpact of the irrigation projects, the reviewed documentation notes that the projects are expectedto benefit 200,000 persons once completed. Should this assessment hold, it is important that futuremaintenance is carried out to ensure that the achieved benefits are sustained. Follow-up monitoringusing satellite imaging of the areas before and after the irrigation projects were initiated andplanned should contribute to further documenting the impact of the projects.

6.4 Relevance6.4.1 Responsive to Local Population NeedsThe Senior Advisor on different occasions initiated visits to community representatives and localauthorities to discuss potential project activities, when possible. Given limited mobility and difficultworking conditions, needs were primarily identified based on guidelines from key stakeholders. Forinstance, the identification of priority irrigation rehabilitation areas was guided by the expressedwishes of local authorities and of community groups, while their participation in the wholeidentification exercise was not necessarily ensured. This was mainly due to the limited capacity oflocal authorities and the prevailing lack of security. It should be mentioned that a communitycommittee was formed in November 2005 for the irrigation component in one of the sites, incollaboration with the civil military cooperation (CIMIC) input. Documentation shows that thecommittee often met at the start up phase but does not clearly note who the members were.In relation to gender considerations, and as confirmed in the workshop, little attention was given tothis issue. However, the workshop underscored the future relevance of accounting for genderissues.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

27

6.4.2 Stakeholder ConsultationStakeholder meetings were planned to the extent possible, particularly for the irrigationcomponent, but not always held due to the security situation and limited mobility. Generally,stakeholders included central and local governments but also donors and communityrepresentatives such as farmer groups and traditional leaders.

6.4.3 Alignment with national plansAccording to the Inception Report, project objectives of agricultural support, including processfacilitation for the transition from planned to market economy, are in line with the vision andstrategy of the National Development Strategy 2005-2007. The latter highlights the role of theagricultural sector in the envisioned future market oriented economy as part of its four pillars:strengthening the foundation of economic growthrevitalising the private sectorimproving the quality of lifestrengthening good governance and securityThe focus on irrigation and drainage falls in line with the Basra provincial agricultural sectorstrategy, which prioritised irrigation as it is deemed to have large impacts on enhancing productivityand livelihoods in rural areas.Finally, the workshop confirmed that the vision of the Government of Iraq is still to continuesupporting market-led, private sector development including agribusiness development, agriculturalfinancing, further restoration of irrigation and drainage infrastructure and revitalisation of theMarshland as well as fishery development.

6.5 Lessons learnedLessons learned were discussed in the workshop of February 2008. The following is a summary ofkey lessons learned as seen by the authors with the input from the workshop participants:Continuity on the advisor post(s) is seen as an asset, though focus should always be on Iraqiownership to foster self sustaining processes. Accordingly, exit strategies should be wellplanned at the start-up phase.Quick impact projects should be technologically context-specific and 'do no harm' to longerterm strategies. At the same time, support to processes and longer term strategies shouldnot be overlooked at the expense of implementing shorter term projectsConsultations between central level – the MoA – and the local activities appear to havebeen useful as it tackled differences in approach and understanding at an early stageDocumentation on how implementation involved various stakeholders and groups and theextent to which communities and various grouping in communities ( e.g. women and youth)were involved in planning and implementation would have been useful in order to assessthe applicability of an inclusive approach even in difficult working environmentsWritten documentation on how the security issues have affected implementation - andwhat measures were taken to deal with them - would have been usefulTo enable the documentation of impact, it would have been beneficial if a simple socio-economic baseline study of affected communities had been undertaken, particularly for thelarger irrigation projects. However the intended follow-up by satellite surveys will enable amonitoring of some of the impactsTo maintain the value created by the projects, it is important to ensure that local capacityand structures exist to carry out future maintenance tasks.

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

28

7 Infrastructure7.1 Blood Gas AnalysersThe project basically consisted of the purchase and delivery of 11 Blood Gas Analysers. Only the onedelivered to Basra town to the Basra Teaching Hospital is part of the Site Inspection Report and onlythis has been reviewed in this report.From the Site Inspection Report it appears that the Blood Gas Analyser in Basra only functioned forone week after delivery in October 2004 due to damages caused by interruptions in power supplies.This information is, however, probably incorrect. Based on the Service Report from the Supplier;Radiometer, and the Warranty Service and Maintenance Service Visit reports signed by officialsfrom the hospital, the Blood Gas Analyser was installed and put to use on the 9thOctober 2004. InSeptember 2005 - about a year after it had been installed – a fuse in the analyser blew because offluctuations in the electric current. The fuse was changed on 16thNovember 2005 and the analyserput to use again. According to the reports, Radiometer made three service visits to the hospitalduring the twelve months. Based on the available documentation, it is not possible to establishwhen the analyser stopped functioning as documented in the Site Inspection Report. Nor is it clearwhy the Site Inspection Team was misinformed about the performance of the Analyser. WarrantyService and Maintenance Service Visit reports also exist for the remaining ten blood gas analyzers.MFA is currently considering a separate verification of the blood gas analysers supplied.The request for the blood gas analysers had come from the Ministry of Health. A procurement agentwas involved in selecting the best supplier, which was selected mainly because the instrumentswere of a type which had previously been used in Iraq. The Ministry probably also provided someassurance of its ability to maintain them.The firm delivering the analysers carried out agreed training of users and carried out three agreedservicing schedules of the equipment.Theeffectivenessof this project cannot be fairly assessed based on the one example from Basra.While a service agreement with the provider for 12 months after delivery was included in thecontract, the assessment of availability of spare parts and ability of maintenance in the long runmay have been based on a too optimistic outlook regarding development in the security situation,but was an optimism which at the time was shared by most donors. Given the knowledge of thehighly irregular electricity supply, some sort of safety equipment may have been considereddelivered to protect the equipment from the strains of the power interruptions.The project appears to have been relevant, which it arguably still is. The project was entered intobased on a request from relevant officials in Iraq, and it has contributed to maintain the relativehigh standard of the health services in Iraq. The equipment is believed to have alleviated a

Iraqi-Danish Partnership 2003-2007

Focus-paper

29

significant and acute problem faced by the hospitals, and the ministry had even requested that anadditional delivery of 11 analysers should be made. This latter delivery did not materialise.Efficiency concerning cost and quality was mainly addressed through the use of an independentprocurement agent.Based on the one example above, it is probably not relevant to look at sustainability. Similarly, theimpact can not be assessed fairly.Tentative lessons learned:A more thorough analysis of risk scenarios and their effect on spare part availability andmaintenance ability might have been useful including aspects concerning the specificphysical context – e.g. power interruptions - in which the instrument was usedFurther follow-up after the service visits could have made chances of sustainability better

7.2

Jetting and Suction Trucks