Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2010-11 (1. samling)

UUI Alm.del Bilag 49

Offentligt

TRANSFERS OFASYLUM-SEEKERSTO GREECE

THE DUBLIN IITRAP

Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters, members andactivists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abusesof human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in theUniversal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religionand are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

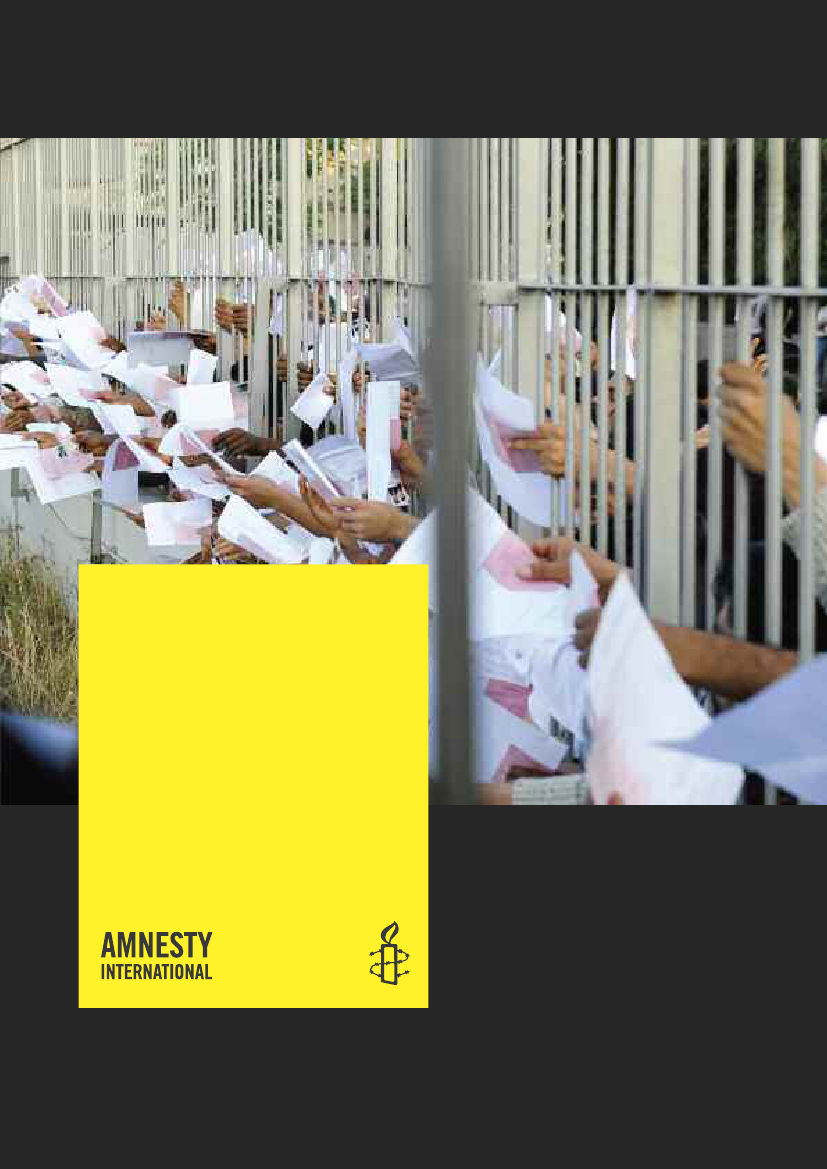

Amnesty International PublicationsFirst published in 2010 byAmnesty International PublicationsInternational SecretariatPeter Benenson House1 Easton StreetLondon WC1X 0DWUnited Kingdomwww.amnesty.org� Amnesty International Publications 2010Index: EUR 25/001/2010Original language: EnglishPrinted by Amnesty International,International Secretariat, United KingdomAll rights reserved. This publication is copyright, butmay be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.The copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. For copying inany other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.Cover photo:Asylum-seekers waiting to submit their asylumapplications at the entrance of the Police Asylum Departmentof the Aliens Directorate, Headquarters of Hellenic Police, inPetrou Ralli, Athens, June 2009.� Nikolas Kominis – Studio Kominis

CONTENTSGlossary .......................................................................................................................41. Introduction .............................................................................................................52. Research methodology...............................................................................................83. Background information.............................................................................................93.1. The Dublin II system ...........................................................................................93.2. Recent reports and actions on Greece ...................................................................94. Dublin II returns to Greece: Detention, Refugee status determination, and risk ofrefoulement................................................................................................................114.1 Detention at Athens airport .................................................................................114.2. Difficulties in lodging asylum applications...........................................................154.3. Lack of an impartial and specialized decision-making authority .............................184.4. Lack of thorough interviews and examinations of claims........................................194.5. Lack of interpretation services............................................................................214.6. Administrative barriers to accessing the asylum system due to homelessness ..........234.7. Limited access to legal assistance ......................................................................254.8. The right to an effective appeal ..........................................................................275. Expulsions and the principle ofnon-refoulement.......................................................306. Economic and social rights of asylum-seekers transferred to Greece .............................356.1. Access to Accommodation .................................................................................366.2. Access to health care ........................................................................................397. Conclusion .............................................................................................................428. Recommendations ..................................................................................................43

4

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

GLOSSARYConvention against TortureCPTECHRConvention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman orDegrading Treatment or PunishmentEuropean Committee for the Prevention of Torture andInhuman or Degrading Treatment or PunishmentEuropean Convention for the Protection of HumanRights and Fundamental Freedoms (EuropeanConvention on Human Rights)European Court of JusticeEuropean Council on Refugees and ExilesEuropean Court of Human RightsEuropean UnionGreek Council of RefugeesInternational Covenant on Civil and Political RightsInternational Covenant on Economic, Social andCultural RightsMedical Rehabilitation Centre for Torture VictimsMédecins sans frontièresNon-Governmental OrganizationPresidential Decree1951 Convention relating to the Status of RefugeesRefugee status determinationUnited Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNRefugee Agency)

ECJECREECtHREUGCRICCPRICESCRMRCTVMSFNGOPDRefugee ConventionRSDUNHCR

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

5

1. INTRODUCTIONAmnesty International is concerned that state parties to the European Union (EU) DublinRegulation continue or have resumed the return of asylum-seekers under this Regulation1toGreece despite continuing serious concerns with regard to the treatment of asylum-seekers,refugees and migrants in Greece. The Dublin Regulation is an EU law for determining whichmember state is responsible for deciding an asylum application lodged within the EU,2andusually requires that asylum-seekers be returned to the first country they entered uponarriving in the EU. Individuals transferred under the Dublin II system3face a myriad of risksto their human rights in Greece, including most seriously a risk ofrefoulementthroughfailures in the asylum system at both procedural and substantive levels. As this report willhighlight, these failings are: difficulties in accessing the asylum system and registering aclaim; unfair examinations of asylum claims; a lack of procedural safeguards as required byinternational law to ensure the correct identification of those in need of internationalprotection, and to prevent violation of the principle ofnon-refoulement.4These proceduralfailings include the abolition of a substantive appeal, and a lack of legal counselling,interpretation and information about the asylum procedure. On top of these systemic failings,expulsions to Turkey, including of asylum-seekers, are creating further risks of indirect orchainrefoulement.5In addition, the vast majority of asylum-seekers transferred under theDublin Regulation are automatically detained in inadequate conditions at the airport upontheir arrival in Greece. Elsewhere in the country reception conditions fall far short of requisitestandards, and economic and social rights are not met. In view of these findings, AmnestyInternational must repeat its call to state parties to the Dublin Regulation to immediatelysuspend all transfers to Greece under the Regulation until such time as reforms areimplemented ensuring that requisite levels of human rights protection are met for refugeesand asylum-seekers in Greece.During 2007/8, in response to growing concern about the dire asylum conditions in Greeceexpressed by, among others, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the Commissioner for HumanRights of the Council of Europe and various non-governmental organizations (NGOs), anumber of European countries took steps to suspend or reduce Dublin II transfers to Greece.Given the evidence of serious continuing problems outlined in this report it is therefore ofsignificant concern that, since the first half of 2009, some state parties to the DublinRegulation, including Finland, the Netherlands, Belgium and Norway, which were previouslycircumspect in or had suspended applying the Regulation, have resumed returns of asylum-seekers to Greece.6European countries commonly argue that if breaches of human rightstake place in Greece then individuals can seek redress there since Greece is a party to therelevant human rights conventions and treaties. However, Amnesty International and otherorganizations have repeatedly raised concerns about the obstacles faced by individuals inaccessing their rights or effective remedies in practice.Since March 2008, Amnesty International has called upon EU member states to make use ofthe sovereignty clause under Article 3.2 of the Dublin Regulation.7This allows a state toexamine an asylum claim, even if such examination is not its responsibility under the criteriaof the Regulation, including to avoid transferring asylum-seekers to the state which is

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

6

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

responsible until that state guarantees access to a fair asylum procedure and adequatereception conditions in compliance with international human rights law and standards as wellas EU law.8In April 2008, UNHCR advised EU member states to refrain from returning asylum-seekers toGreece under the Dublin Regulation until further notice. This advice was based on concernsregarding the access to and quality of the Greek asylum procedure, the fact that thereception conditions continued to fall short of international and European standards, and theundue hardships faced by asylum-seekers, including “Dublin returnees”, in having theirclaims heard and adequately adjudicated. UNHCR’s view was that a combination of thesefactors may give rise to the risk ofrefoulement.In December 2009 the UN Refugee Agencyissued an updated report in which it stated that it “continues to advise Governments torefrain from returning asylum-seekers to Greece under the Dublin Regulation or otherwise”.9Amnesty International’s research findings indicate that the situation for asylum-seekers whoare returned to Greece has not improved since it called upon the EU member states not totransfer asylum-seekers to Greece. Concerns relate to both the Presidential Decree (PD) No.90/2008 of July 2008 (which transposed the EU Asylums Procedure Directive) and theamending PD No. 81/2009 of July 2009. Indeed, the situation has worsened with theadoption of PD 81/2009, which abolished the second stage of asylum procedures, leavingasylum-seekers with no recourse to an effective appeal. An asylum-seeker whose applicationhas been rejected may only apply to the Council of State for annulment of that decision.According to UNHCR, the adoption of this new legislation has introduced changes to theasylum procedure “which have further diminished the prospects of asylum-seekers, includingDublin II transferees, having their claims determined in a fair procedure in Greece”.10Moreover, the detention conditions in which people returned to Greece are held at Athensairport, particularly vulnerable individuals such as children, as well as the small number ofreception facilities for asylum-seekers, raise serious concern.This report assesses transfers of asylum-seekers to Greece under the Dublin Regulationagainst the legislation and practices of the authorities in recent years. Although Greece hasformally transposed relevant EU asylum legislation, Amnesty International’s research hasfound that this legislation as well Greece’s obligations under wider international law are notbeing complied with in practice.Greece, as a state party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (RefugeeConvention) and its Protocol as well as other relevant instruments, including the InternationalCovenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture and OtherCruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and the European Convention for theProtection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR), must ensure that it doesnot breach the principle ofnon-refoulement.11Amnesty International reiterates that, in orderto meet this obligation, and as required by international standards, Greece must giveindividuals within its jurisdiction12and seeking international protection access to an asylumdetermination system with full procedural safeguards.In 2007, out of 20,684 asylum applications examined at first instance, only eight applicants(0.04 per cent) were granted asylum; out of 6,448 applications examined on appeal, refugee

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

7

status was granted in 132 cases (2.05 per cent).13In 2008 out of 29,573 applications,refugee status was granted in 14 cases (0.05 per cent) in the first instance, and 344applications for asylum were granted out of 3,342 applications examined in the secondinstance (10.29 per cent).14According to the statistics provided to UNHCR by the Ministry ofInterior, in the first seven months of 2009 approximately 20,000 asylum applications(19,640 at the first instance, 810 at the second instance) were examined, of which 20asylum claims were granted. Over the same period, 24 asylum-seekers were grantedhumanitarian status (including those whose status was renewed), while 61 receivedsubsidiary protection (under PD 90/2008). Amnesty International considers that theserecognition rates are disturbingly low.Amnesty International believes that in view of current huge divergences in the quality of EUmember states’ asylum systems coupled with the absence of an automatic suspensive right ofappeal against Dublin II transfers where the safety of a receiving state is questioned, thecurrent Dublin system places individuals at risk ofrefoulement.In this regard, amendmentsto the Dublin Regulation proposed by the European Commission in December 2008 toprovide effective remedies against transfers and to introduce a temporary suspensionmechanism are to be welcomed.15However, pending revision of the Dublin system, there isan urgent need to ensure that arrangements for returning asylum-seekers under the DublinRegulation comply with the obligations of EU member states under international law,particularly where these obligations apply to vulnerable groups, the maintenance of familyunity and the protection of asylum-seekers fromrefoulementor other human rights violations.At the end of 2009 the newly elected Greek government publicly acknowledged a number ofproblems in the current asylum system in Greece and announced that changes were neededto the asylum determination procedure. Among the plans announced were the removal ofdecision-making powers on asylum applications from the police and the establishment of aCentral Asylum Service as the authority determining asylum applications at first instance.16In addition, it was announced that until more substantial changes came into effect theexisting legal framework (PD 81/2009) should immediately be improved so that asylum-seekers can receive better and faster assistance. A Committee of Experts, comprising ofrepresentatives of the UNHCR and national NGOs, was established to prepare proposals onthe issues concerned. Draft new legislation on asylum determination procedures isanticipated in March.While Amnesty International welcomes the acknowledgement of current failings and proposednew measures, any such measures will need to comprehensively address all of the issueshighlighted in this report. Furthermore the real test will be in the implementation of any newmeasures. Amnesty International remains concerned that even if new and improvedlegislation is introduced, the practice may remain inadequate and will require carefulmonitoring before Greece is considered to have a fair asylum procedure.

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

8

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGYBetween September 2008 and October 2009, Amnesty International representatives carriedout fact-finding visits and conducted interviews in Athens, Patras, Lavrio, Thessaloniki, Crete,Igoumenitsa, Konitsa and the Evros area. They spoke to: refugees, asylum-seekers andirregular migrants as well as government authorities, intergovernmental agencies, NGOs andlawyers working with asylum-seekers; and representatives of embassies of EU member states.Amnesty International was given access to the detention facilities in Athens airport whereDublin II returnees are often detained upon their return to Greece. Amnesty International alsovisited detention facilities in Evros, Igoumenitsa and Patras, where asylum-seekers as well asirregular migrants are detained; shelters for child asylum-seekers in Crete and Konitsa; andresidential centres for asylum-seekers in Lavrio and Thessaloniki. In the course of thesevisits, although the organization focussed particularly on the plight of Dublin II returnees, italso collected information about the asylum system in Greece as a whole. AmnestyInternational continued to collect information until February 2010.Amnesty International wishes to thank all the individuals and organizations that assisted inthe research and provided information, particularly the asylum-seekers who agreed to beinterviewed.Amnesty International interviewed 51 asylum-seekers – 44 men and seven women – who hadbeen transferred to Greece from other states (Germany, Iceland, UK, the Netherlands,Sweden, Belgium, Austria, Denmark, Switzerland and Cyprus). Their countries of originincluded Afghanistan, Armenia, Iran, Iraq, Somalia and Sudan. Three of the male asylum-seekers said they were minors, in spite of their asylum application cards recording them asadults. Four of the asylum-seekers had been transferred with children aged between fivemonths and 17 years. The first transfer documented took place in 2002, the last in January2010. Care has been taken to avoid the inclusion of information that could reveal the identityof the asylum-seekers interviewed in order to respect confidentiality, and to ensure that anyinformation provided does not prejudice their ongoing asylum proceedings.

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

9

3. BACKGROUND INFORMATION3.1. THE DUBLIN II SYSTEM…at the level of implementation, it has become evident that asylum applications areassessed differently in similar situations.Dutch State Secretary for Justice Nebahat Albayrak17

Since 1999 the European Union has been working to create a Common European AsylumSystem (CEAS) with common asylum procedures and uniform status for refugees throughoutthe EU. The first phase of the system was completed in 2005 with the adoption of a set offour main legal instruments: the Dublin Regulation, the Reception Conditions Directive,18theQualification Directive19and the Asylum Procedures Directive.20These directives provideminimum standards for the treatment of asylum claims in the EU but in practice have not yetbeen fully implemented by all member states.21The second phase is now underway,including recast proposals to amend the above instruments, with the stated intention ofcompleting the CEAS by 2012.The Dublin Regulation is premised on the assumption that there are equivalent standards ofprotection in all EU member states. However, practices and refugee recognition rates differwidely between the member states resulting in what amounts to a lottery for asylum-seekersarriving in the EU. This fundamentally calls into question the fairness of the Dublin IIsystem.

3.2. RECENT REPORTS AND ACTIONS ON GREECEOver recent years many organizations have reported on the deplorable treatment of asylum-seekers in Greece. In its 2005 report,Out of the Spotlight: The rights of foreigners andminorities are still a grey area,22Amnesty International highlighted the failure of the Greekgovernment to comply with human rights law and standards regarding access to asylumprocedures, the detention of migrants and their protection from discrimination and ill-treatment. Since 2008, a succession of further reports have been provided by, among others,UNHCR,23the Council of Europe,24Pro Asyl,25and Human Rights Watch.26Key concernsidentified included: a lack of procedural safeguards and access to the asylum procedure;arbitrary detention often in inadequate detention conditions; a lack of proper receptionconditions; and the low recognition rate of refugees and those in need of other forms ofprotection. Further impediments to those seeking asylum, such as the effective removal of asubstantive appeal right, have arisen from the adoption of PD 81/2009. The Pro Asyl, HumanRights Watch and UNHCR reports also refer to cases in which Greek coastguards have forcedasylum-seekers back to Turkey or conducted unlawful expulsions at the border.On 31 March 2008 the European Commission initiated an infringement procedure againstGreece before the European Court of Justice (ECJ). According to the Commission, Greecefailed to adopt the laws, regulations and administrative measures necessary “to ensure, inevery case, examination of the merits on applications for asylum of third-country national who… are transferred to Greece”,27as provided for in the Dublin Regulation.28On 22 October

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

10

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

2008 this procedure was withdrawn as a result of legislative changes introduced by Greece intransposing the EU Asylum Procedures Directive.29However, due to ongoing concerns aboutimplementation in practice and the new July 2009 legislation on the asylum procedure, inNovember 2009, the Dutch Refugee Council, Pro Asyl, the British Refugee and MigrantJustice and the Finnish Refugee Advice Centre filed a complaint with the EuropeanCommission against Greece, concerning the country’s failure to comply with EU law.30Amnesty International Greece, among other bodies, including the National Commission forHuman Rights31and the Greek Council for Refugees, also submitted a complaint to theEuropean Commission in November 2009. The complaint argued that PD 81/2009,amending PD 90/2008, is incompatible with Article 39 of the Asylum Procedures Directive.Although PD 81/2009 permits asylum-seekers rejected at first instance to submit anapplication for annulment before the Council of State, it does not qualify as an effectiveremedy since the Council of State can only examine the legality of the administrative rulingrejecting an asylum application at first instance, and not the substantive merits of a claim.On 3 November 2009, the European Commission sent Greece a letter of formal notice, whichconstitutes the first stage of an infringement procedure, on the issue of access to the asylumprocedure, respect of fundamental rights, including the principle ofnon-refoulement,whenconducting border controls and treatment of asylum-seeking unaccompanied minors.32It is worth noting that, with the aim of improving the situation of asylum-seekers in Greece,bilateral agreements have been concluded between the Greek and Dutch authorities.33However, Amnesty International considers that these agreements alone do not justify thereturn of asylum-seekers to Greece while the legislation and practice in the asylum proceduredo not comply with international and regional law and standards. Moreover, even if the Greekgovernment were to engage in a genuine and full reform of the asylum system, itsimplementation will not be achieved in the short term and will need to be carefullymonitored.

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

11

4. DUBLIN II RETURNS TO GREECE:DETENTION, REFUGEE STATUSDETERMINATION, AND RISK OFREFOULEMENTAt present, the refugee status determination (RSD) system in Greece lacks the necessaryprocedural safeguards required by international law to ensure the correct identification ofthose in need of international protection, and to prevent violation of the principle ofnon-refoulement(see further below under Expulsions and the principle ofnon-refoulement).However, despite these failings, Dublin II transfers continue to take place. In the first 10months of 2009 there were 7,857 applications for transfers from EU member states toGreece, which agreed to take 2,770 people. A total of 995 transfers actually took place.34Amnesty International’s research has shown that, after their return to Greece, individuals(consistent with the general treatment of asylum-seekers in Greece) face a range of humanrights violations, rendering the inclusion of this country in the Dublin II system of transfersunacceptable at the present time. The following sections of the report will assess: thechallenges asylum-seekers face upon return to Greece including detention; difficulties ingaining access to the asylum procedure, and to lawyers and interpreters; the lack of anindependent and specialized decision-making authority; and the lack of thoroughexaminations of asylum claims, including the right to an effective appeal. The researchfindings confirm that Greece is currently in breach of its international obligations, whichrequire that asylum-seekers be given access to a fair and satisfactory asylum system, with fullprocedural safeguards.35

4.1 DETENTION AT ATHENS AIRPORT

REFUGEE CONVENTIONArticle 31Refugees unlawfully in the country of refuge1. The Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugeeswho, coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened in the sense of Article 1, enteror are present in their territory without authorization, provided they present themselves without delay to theauthorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

12

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

ASYLUM PROCEDURES DIRECTIVEArticle 18Detention1. Member States shall not hold a person in detention for the sole reason that he/she is an applicant forasylum.2. Where an applicant for asylum is held in detention, Member States shall ensure that there is a possibility ofspeedy judicial review.

EU CHARTER OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTSArticle 6Right to liberty and securityEveryone has the right to liberty and security of person.

EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTSArticle 51. Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person.No one shall be deprived of his liberty save in the following cases and in accordance with a procedureprescribed by law:(f) the lawful arrest or detention of a person to prevent his effecting an unauthorized entry into the country orof a person against whom action is being taken with a view to deportation or extradition.4. Everyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings by whichthe lawfulness of his detention shall be decided speedily by a court and his release ordered if the detention isnot lawful.In order to go to the toilet at nights I had to step over dozens of persons, men and women,sleeping on the floor of the cell and corridor.Detained woman from Afghanistan

Under international law, the detention of asylum-seekers and migrants should only ever beused as a last resort, when it can be justified in each individual case that it is a necessaryand proportionate measure that complies with international law.36Alternative non-custodialmeasures should be the preferred solution and should always be considered before resortingto detention.37Article 13(1) of PD 90/2008, currently in force, stipulates that: “a national of a third countryor a stateless person who is applying for refugee status cannot be detained for the sole reasonof his illegal entry and stay in the country.” However, Article 13(2) states that police have aright to “confine” asylum-seekers in certain locations for as long as necessary in order toascertain the method of entry, identity and country of origin of asylum-seekers who haveentered the country irregularly and en masse; or on grounds of public interest or public order;or when this is considered necessary for the speedy and effective completion of the aboveprocedure. The time limit of the “confinement” cannot exceed 60 days.

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

13

Article 13(3) provides asylum-seekers with a right to challenge the decision ordering theirdetention by submitting objections or an appeal against it to the competent administrativecourt. Moreover, Article 13(4) states that women asylum-seekers should be detained separatelyfrom men, that the authorities should refrain from detaining children and pregnant womenseeking asylum, and that adequate medical care should be provided to detained asylum-seekers. Article 13(4) also requires that the relevant authorities should inform the detainedasylum-seekers of the reasons for and expected duration of their detention. However, AmnestyInternational is concerned that these standards are not being observed in practice.In 2009, the European Court of Human Rights found Greece to be in breach of Article 3ECHR twice in relation to detention, in the cases of an asylum-seeker and an Afghan irregularmigrant respectively inS.D. v. GreeceandTabesh v. Greece.38In the case ofS.D. v. Greecethe Court held unanimously that there had been violations of Article 3 and Article 5 (1) and(4) (right to liberty and security). The Court ruled that S.D., while an asylum-seeker, hadexperienced detention conditions that amounted to degrading treatment, that his detentionwas unlawful and that he had been unable to have the lawfulness of his detention reviewedby the Greek courts. The European Court found similar violations in the case ofTabesh v.Greece.As this report will show further, lodging a complaint at national or international levelis problematic for Dublin II returnees, as access to legal aid is denied to most of them ormade difficult.39Amnesty International is concerned that the vast majority of Dublin II returnees interviewedby the organization were automatically detained, normally for a period of a few days, onarrival at the Athens airport.40If they are detained they are always held in the main detentionfacility, guarded by police. The facility is divided into two sectors. The first consists of threerooms, each of which is approximately 7m2. The second includes three rooms, eachapproximately 50m2. The same facilities are used for the detention of irregular migrants orother asylum-seekers who have been detained after attempting to leave Greece, allegedly withfalse documents. Amnesty International visited the Athens airport detention facility inOctober 2009. At that time the detained asylum-seekers included a number of children, heldtogether with their families, and a woman who was clearly in an advanced stage of pregnancy.None of the asylum-seekers interviewed by Amnesty International said that they had beeninformed of the reasons for their detention, nor of their right to challenge the decision todetain them.

A., an Afghan national, was transferred to Greece from Sweden in late 2008. He holds an Afghan birthcertificate, which Amnesty International has seen, according to which he was 16 at the time of his return toGreece. He reported that his father had been abducted by Taliban fighters, and subsequently tortured andkilled. He told Amnesty International representatives that, immediately upon his arrival in Greece, he wasdetained at the airport without being informed of the reasons for his detention. He said his detention lastedfour days, following which he was given a pink card that is the legal documentation proving that the holderhas applied for asylum in Greece,41without having undergone an asylum interview.42The pink card records adifferent date of birth, appearing to show that he was an adult at the time of his first entry into Greece, whenhe was allegedly 14 years old.In 2009 UNHCR also reported on Dublin II cases of minors returned from Finland who wereregistered with duplicate data, both as children and as adults.43

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

14

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

In its April 2008 position paper on “Dublin returnees” to Greece, UNHCR noted that: “[d]ueto the lack of sufficient asylum personnel to ensure the immediate identification, registrationand processing of asylum applicants, ‘Dublin returnees’, including vulnerable individuals, areautomatically detained, before their status is clarified and a decision taken to either interviewthe applicant or refer him/her to the Central Asylum Department”.44On the basis ofinterviews with asylum-seekers carried out by Amnesty International in 2009, the situationdoes not appear to have changed since then, and the routine detention of Dublin II returneescontinues to be reported.Many asylum-seekers interviewed told Amnesty International they were verbally abused while indetention, including two asylum-seekers who claimed that they had been ill-treated by policeofficers while held at the Athens airport detention facility. Interviewed asylum-seekers reportedthat one police officer in particular had violently pushed and verbally abused the detainees.

M., an Iraqi national who claims that he belongs to the Christian minority, was transferred to Greece in mid-2008, after he had applied for asylum in another EU country. He was detained at the airport immediately uponarrival, and told Amnesty International: “While I was speaking on the card phone with a friend, a police officertold me to stop talking, punched me and broke my tooth. He grabbed me violently by the hair and pushed meback into my cell.” Allegedly he complained to another officer about the incident but no action was taken bythe authorities to investigate the incident.Another Afghan asylum-seeker told Amnesty International that he had been verbally abused,stripped and punched by police officers while in detention at the airport in late 2009.Incidents of ill-treatment by the police, including of detained asylum-seekers and migrants,have been documented in the past by Amnesty International,45as well as by otherorganizations.46Most recently, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discriminationexpressed its concern about “reported cases of ill-treatment of asylum-seekers and illegalimmigrants, including unaccompanied children”.47During the October 2009 visit of Amnesty International representatives to the detentionfacility at Athens airport, the Greek police informed them that no medical examination isroutinely carried out on asylum-seekers when they are detained but that medical care isprovided, whenever necessary, either by a medical doctor or nurse at the airport, or in ahospital. It is to be noted that a medical unit providing health care for detained asylum-seekers at the airport operated from October 2009 for a trial period of three months.According to information available to Amnesty International, this service is currently nolonger provided. Prior to that, no such services existed, and medical care was provided onlyexternally, in hospitals to which asylum-seekers could be transferred. If Dublin II returneeshave severe health problems, the Greek police are usually informed of this by the authoritiesof the EU countries from which returnees have come. It appears that in some cases, asylum-seekers suffering from severe illnesses have been less likely to be detained.In individual interviews with asylum-seekers who were not currently in detention, AmnestyInternational was told that during their detention at the airport they were not allowed by thepolice to have access to their medication, which was in their luggage.48During the visit to the airport detention facility, Amnesty International observed that detainedasylum-seekers or irregular migrants were held in conditions of severe overcrowding and that

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

15

the material conditions of detention were inadequate. Although there were 46 beds availablefor detained people, the total number held in the facility, according to the police, wasbetween 80 and 90 individuals.49The floors of the three larger rooms were covered withmattresses, which looked unhygienic and dirty, for those who did not have a bed. Theproblem of overcrowding at the airport detention facility was also reported in articles in thepress, which noted that, on some occasions, the number of detained persons in the facilityreached 240.50According to a statement made to the press by a police officer at the airport,“Every time a representative of AI or the UNHCR visits the area, the reality is being ‘hidden’with the immediate transfer of detainees to other detention areas.”51Poor conditions of detention in general are recognized by the police authorities. In particular,the Panhellenic Federation of Police Officers stated that they are very concerned about thedetention, transfer and deportation conditions of “illegal migrants”, the insufficient humanresources and infrastructure, as well as the inadequate hygiene and security in the workplaceand especially in detention facilities in police stations and the areas where migrants arebeing accommodated.52In conclusion, Amnesty International is concerned that most Dublin II returnees interviewedby the organization had been detained upon their arrival in Greece, and is also concernedabout the detention conditions, especially the overcrowding, lack of hygiene, detention ofunaccompanied minors and pregnant women, and incidence of alleged ill-treatment.

4.2. DIFFICULTIES IN LODGING ASYLUM APPLICATIONS

ASYLUM PROCEDURES DIRECTIVEArticle 6 (5)Member States shall ensure that authorities likely to be addressed by someone who wishes to make anapplication for asylum are able to advise that person how and where he/she may make such an applicationand/or may require these authorities to forward the application to the competent authority.When I got to Greece they just kicked me out of the airport without explaining anything to me.S., asylum-seeker from Afghanistan

Article 4 of PD 90/2008, on procedures for recognition of refugee status, stipulates that“every foreign national or stateless person has the right to submit an asylum application”.Registered asylum-seekers should be informed about the procedure, their rights andobligations, the deadlines and the result of their application in a language that theyunderstand (Article 8).Amnesty International is concerned that, in practice, provisions in Greek law which protectthe right to apply for asylum are not fully implemented and that some individuals returned toGreece under the Dublin Regulation have been unable to gain access to an asylumdetermination procedure.

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

16

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

Prior to July 2009, Dublin II returnees, who had not previously applied for asylum in Greece,generally applied for asylum at Athens airport, where asylum interviews were also conducted(see below under Lack of impartial and specialized decision making authority).53Under PD81/2009, however, asylum-seekers have experienced additional problems in gaining accessto an asylum determination procedure.When asylum-seekers submit their asylum application to the authorities they receive adocument known as a pink card, which needs to be renewed every six months.Under the new system, Dublin II returnees are required, within three days of their releasefrom Athens airport, to go to the Central Police Asylum Department of the Aliens Directorate,Headquarters of Hellenic Police, in Petrou Ralli, Athens (hereafter Attica PoliceHeadquarters), to present their asylum applications.54Under the law this is the only authorityin the Attica area that can receive asylum applications. At present, around 20 claims areregistered in one day, although up to 2,000 persons may be queuing to apply for asylum,while there is no standard system for prioritizing those who want to enter the building andsubmit their asylum applications.55Some asylum-seekers interviewed by Amnesty International reported that they were notclearly informed, in a language they understood, about the three-day deadline. Many whowent to the Asylum Department of the Attica Police Headquarters had to wait in line forseveral hours, sometimes overnight, in order to gain access to the Police Headquarters.Similar problems were experienced by registered Dublin II returned asylum-seekers, who haveto report their address to the Asylum Department.

N. is an Iraqi asylum-seeker. Allegedly his father was working for a US company as a translator and was killedby Iraqis because of his post. N. was also allegedly working for a US company when he was kidnapped for oneweek and his family was asked to pay US$20,000 in order for him to be set free.He first arrived in Greece in 2007 with one of his brothers and his sister and travelled to Belgium, where one ofhis brothers had obtained asylum. He was returned to Greece with his brother and sister under Dublin II. Theyallegedly all received pink cards without being given the opportunity to explain their reasons for seekingasylum.Since they were homeless and living on the streets in Athens, N. went to the Iraqi embassy and asked for hissister to be sent back to Iraq. He explained to Amnesty International representatives that he continued living inGreece and was not able to renew his pink card after the six- month expiry period. So he remained in thecountry without any documentation.N. left Greece for a second time in 2008 and reached another EU country; he was returned to Greece for asecond time under Dublin II in 2009. He said that, in the airport, he was asked to give his reasons for seekingasylum in a short paragraph. He was not given any written notice by the airport police.When Amnesty International representatives contacted the airport police to request that a notice be issued sothat this asylum-seeker could go to Attica Police Headquarters, the police explained that his name was notincluded in their papers. As a result he was not allowed to enter the building. With the assistance of the RedCross, he was finally given permission to enter after weeks of trying. The police told him that, in order toreceive an asylum application card, he would have to bring a rental contract within two weeks. Since he had

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

17

no money, no job and was homeless, he could not register his asylum claim. As of November 2009, hecontinued to hold no legal documents.On several occasions while conducting research for this report, Amnesty International delegatesobserved very long lines of asylum-seekers in front of the Attica Police Headquarters. Concernsabout access to the Petrou Ralli building for asylum-seekers have been raised by a number ofother organizations, including Human Rights Watch56and Pro Asyl.57These problems, including long waiting times and difficulties in gaining access to the AtticaPolice Headquarters building, are discussed further below.58They present a significantadministrative barrier to accessing the asylum system, and in some cases have posedsignificant dangers to the physical integrity of asylum-seekers who have to queue for manyhours outside Petrou Ralli.

In October 2008 a Pakistani asylum-seeker was killed and 15 other people were injured while they werequeuing to submit their asylum application at the Police Headquarters in Petrou Ralli. The incidents arereported to have happened during a stampede which followed police attempts to forcibly prevent an outbreakof disorder among a group of approximately 3,000 asylum-seekers who had assembled in front of the building.The Police Headquarters Asylum Department had reportedly been refusing to accept new asylum applicationsfor the previous two months.59In January 2009 a Bangladeshi asylum-seeker was killed in similar circumstances, when police reportedlyused force to control the crowd, after a long line of asylum-seekers had formed at the Police Headquarters.In view of the practical difficulties for all asylum-seekers in lodging applications at theAsylum Department in Athens, Amnesty International is concerned that the new requirementfor Dublin returnees to submit – within a short deadline – their asylum applications there mayresult in significant additional obstacles to their access to the asylum system.In addition, Amnesty International is concerned that some Dublin II returnees may not beallowed to have their asylum application substantively determined. According to UNHCR, ifthe Dublin II returned asylum-seeker had already applied for asylum in Greece and hisapplication had been rejected and the period to appeal had lapsed during his absence, he orshe will be served his deportation order at the airport and he will not have access to theasylum procedure.60

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

18

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

4.3. LACK OF AN IMPARTIAL AND SPECIALIZED DECISION-MAKING AUTHORITY

ASYLUM PROCEDURES DIRECTIVEArticle 8(2)Member States shall ensure that decisions by the determining authority on applications for asylum are takenafter an appropriate examination. To that end, Member States shall ensure that:(a) applications are examined and decisions are taken individually, objectively and impartially;(b) precise and up-to-date information is obtained from various sources, such as the United Nations HighCommissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as to the general situation prevailing in the countries of origin ofapplicants for asylum and, where necessary, in countries through which they have transited, and that suchinformation is made available to the personnel responsible for examining applications and taking decisions;(c) the personnel examining applications and taking decisions have the knowledge with respect to relevantstandards applicable in the field of asylum and refugee law.Amnesty International has concerns about the lack of independent and specialized decision-making personnel to conduct refugee status determinations, including for returnees to Greeceunder the Dublin Regulation.Under Greek law, the police are responsible for all aspects of the asylum determinationprocedure, including receiving applications, interviewing asylum-seekers and taking decisionson granting asylum at first instance.61Under the system in place until July 2009, Dublin IIreturnees who had not applied for asylum in Greece were supposed to be interviewed bypolice officers at the airport, while a first instance decision on their asylum application wastaken at the Police Headquarters in Petrou Ralli. The police were also represented on appealpanels taking second instance decisions on asylum claims.Under the new PD, the police continue to be tasked with receiving and deciding on asylumapplications. These decisions are normally taken by police officers at the Department Directorlevel at the Asylum Department of the Aliens Department of the Attica Police Headquarters.The police decisions are meant to take into consideration the advice provided by AdvisoryRefugee Committees which should include representatives of the police, the localmunicipality and UNHCR. As of the end of February 2010, however, UNHCR has refused toparticipate on such panels, citing concerns that the new procedures “do not sufficientlyguarantee the efficiency and fairness of the refugee status determination procedure in Greeceas required by international and European legislation”.62Moreover, under PD 81/2009 thesecond instance appeal stage has been abolished, thus depriving asylum-seekers of theirright to an effective remedy (see below under The right to an effective appeal).The Greek National Commission for Human Rights, a national, advisory, human rights body, hasnoted that “the police cannot be tasked with the prevention of illegal migration as well asasylum procedures”, and has repeatedly requested that asylum determination procedures beassigned to bodies other than the police.63Partly similar concerns were raised by UNHCR,which reported that, in 2008, 65 officers were available to decide asylum claims at the CentralPolice Asylum Department in Petrou Ralli. Of these, only 11 were qualified Asylum Officers.64

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

19

In addition, the Greek Ombudsman in October 2009 referred to a number of flaws in theasylum application procedures carried out by the police. In particular, the Ombudsmanreferred to a practice that has been reported by a number of NGOs and asylum-seekers overthe past two years. According to them, decisions rejecting asylum applications were written inGreek, and handed by the police to the asylum applicants simultaneously with their pinkcards, with the result that they were not able to understand either the decision on theirapplication, or the relevant deadline for lodging an appeal.65The non-participation of UNHCR in the Advisory Refugee Committees renders concern aboutthe fairness and effectiveness of the asylum procedure even greater, since the specializationof its staff and their impartiality will now be absent from any part of the process, havingpreviously at least been part of the second-tier appeal panels.Amnesty International considers that the examination of asylum applications by policeofficers who lack proper training, qualifications or expertise, not only jeopardizes the fairnessand efficiency of the asylum determination procedure, but also contravenes Article 8(2)(c) ofthe Asylum Procedures Directive, according to which, “… Member States shall ensure that:the personnel examining applications and taking decisions have the knowledge with respectto relevant standards applicable in the field of asylum and refugee law”.

4.4. LACK OF THOROUGH INTERVIEWS AND EXAMINATIONS OF CLAIMS

ASYLUM PROCEDURES DIRECTIVEArticle 12Personal interviewBefore a decision is taken by the determining authority, the applicant for asylum shall be given the opportunityof a personal interview on his/her application for asylum with a person competent under national law toconduct such an interview. A personal interview shall take place under conditions which ensure appropriateconfidentiality.I was asked to write in a few lines the reasons for my asylum application. I wrote in mylanguage “I want a lawyer, I want a translator, I want asylum”.M., asylum-seeker from Afghanistan returned from Belgium

One or more full and thorough asylum interviews are an important component of a fair asylumdetermination procedure. Interviewers should create a climate of confidence, enablingasylum-seekers to bring their stories to light and put forward in full their reasons for claimingasylum.66International standards require a shared duty between the determining authorityand the asylum-seeker of ascertaining and evaluating relevant facts. If the determiningauthority fails to take proper steps to ascertain relevant facts, it may be unable to properlyidentify whether the person is a refugee and therefore risks breaching its obligations, mostnotably the principle ofnon-refoulement.

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

20

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

Under the asylum system in force until July 2009, Greek law stipulated that decisions onasylum should normally be based on a personal interview with the applicant.67Article 10 ofPresidential Decree 90/2008 stated that the interview was aimed, amongst other things, atconfirming what is alleged in the asylum application, including an explanation by theapplicant of the reasons for leaving his or her country of origin and for requesting protection.In addition, Article 10(1) provided that asylum-seekers had to be given sufficient time toprepare for the interview.Under PD 81/2009, Article 3 no longer states explicitly that asylum-seekers should be givenadequate time to prepare for the interview.Previous and current Greek law are clear on the need to carry out asylum interviews to make anassessment of and take decisions on asylum applications. However, Amnesty International isconcerned that, in the vast majority of cases examined during this research, in practice asyluminterviews were either not conducted at all or were conducted in a perfunctory manner.Until July 2009, asylum interviews with Dublin II returnees, who had not previously appliedfor asylum in Greece,68were conducted at Athens airport, often after a detention period of afew days. Reportedly, they usually consisted only of basic questions about the applicant’sname, date of birth and nationality. Asylum-seekers have told Amnesty International that thepolice at the airport who interviewed them did not inform them explicitly that they werehaving an “asylum interview”, or that they were required to provide relevant information andevidence in support of their claim for international protection. Many of the asylum-seekersinterviewed by Amnesty International stated that, at the airport, they were asked neitherabout the reasons for having fled their countries nor about their fears of returning.69Some ofthe asylum-seekers interviewed by Amnesty International stated that they were notinterviewed at all but were just provided with a pink card. Under the system at the time,receiving a pink card meant that an interview had been conducted, even if it had not. Thisreported practice could have serious implications for the fair determination of the asylumclaims since important information regarding the validity of their claims was not registeredand seen by the competent decision-making bodies.

O. was returned to Greece from Germany under the Dublin II system in mid-2008. He is a Sudanese national,and had not applied for asylum in Greece before. He claims he is of Darfuri origin and that he had beendetained by the secret services of the Sudanese authorities in 1997 and tortured, in an unofficial detentionfacility. He was subsequently released from detention and left the country. He told Amnesty International that,upon arrival at Athens airport, he was not interviewed for the purpose of asylum determination and was onlygiven a pink card. Signs of torture were subsequently recorded and documented by a medical doctor from theMedical Rehabilitation Centre for Victims of Torture, a Greek NGO.70K. and her brother A., Iranian nationals, were returned to Greece from the UK at the end of 2008. They had notapplied for asylum in Greece before. In interviews with Amnesty International, A. alleged that he had beenimprisoned in Iran because of his political activities as a local leader of a Kurdish minority group. K. statedthat she had been beaten by Iranian police, apparently in connection with the political activities of her brother.She claimed that her knee had been injured as a result of the beatings and that this caused ongoingdifficulties for her in walking. Both A. and K. told Amnesty International that, after their return to Greece underthe Dublin Regulation, police at the airport did not carry out an asylum interview with them and that they wereimmediately given a pink card.

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

21

Amnesty International’s findings are consistent with information from other NGOs working onrefugee and asylum issues in Greece.71Alexia Vassiliou, a member of the legal assistanceunit of the Greek Council of Refugees (GCR),72in her article on Dublin II transfers to Greece,noted that: “the ‘interview’ usually lasts five minutes and, in most cases, the only questionasked – in English – is why the applicant came to Greece”.73According to Greek HelsinkiMonitor, asylum interviews in Petrou Ralli are “brief and superficial and do not provide asound base for examining the particular asylum cases”.74Amnesty International remains concerned that the failure to provide proper and thoroughinterviews for those who were returned to Greece before July 2009 hampered their access toan effective asylum determination procedure and impaired their chances of receivinginternational protection.Since July 2009, asylum interviews with Dublin II returnees applying for asylum in Greece forthe first time have usually been carried out at the Asylum Department of the Attica PoliceHeadquarters. (As noted above, Dublin II returnees now have to report to the PoliceHeadquarters in Athens within three days of their release from the airport.)Although there are some designated asylum personnel to carry out asylum interviews at thePolice Headquarters, Amnesty International remains concerned that, given the concernsabout the lack of training, expertise and sufficiency of specialized personnel, asylum-seekersare not being provided with full and thorough interviews which would assist in theidentification of people who require international protection.

4.5. LACK OF INTERPRETATION SERVICES

ASYLUM PROCEDURES DIRECTIVEArticle 10Guarantees for applicants for asylum1. With respect to the procedures provided for in Chapter III, Member States shall ensure that all applicants forasylum enjoy the following guarantees:(a) they shall be informed in a language which they may reasonably be supposed to understand of theprocedure to be followed and of their rights and obligations during the procedure and the possibleconsequences of not complying with their obligations and not cooperating with the authorities.(b) they shall receive the services of an interpreter for submitting their case to the competent authoritieswhenever necessary … these services shall be paid for out of public funds.At the airport there was no interview and no interpreter, they only shouted to me in Greek toget out of the airport.H., asylum-seeker from Somalia returned from the UK

According to Greek legal provisions on the asylum procedure, the personal interview shouldtake place with the assistance of an interpreter.75

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

22

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

Reports have been received about the apparent lack of sufficient interpretation servicesavailable during the stages of registration and examination of asylum claims for all asylum-seekers, at both the airport and Attica Police Headquarters.A leaflet issued by the Ministry of Interior, which explains the basic asylum procedure inGreece, exists in five languages in order to inform asylum-seekers of their rights. However,although Amnesty International representatives have seen this leaflet in other detention areasacross Greece, it is not distributed in the detention facilities at the airport and was not givento any Dublin II returnees interviewed by Amnesty International upon their arrival in Greece.(The leaflet referred to the asylum system before July 2009.)All but one of the asylum-seekers interviewed by Amnesty International stated that there wereno interpreters or translators at the airport, including nine of whom were interviewed afterJuly 2009.

N., an Afghan asylum-seeker, was returned to Greece from Austria in October 2009. At Athens airport he wasdetained and then, upon release, given a notice in Greek requiring him to report to Petrou Ralli within threedays. N. claimed that he does not speak Greek or English, and the airport police did not explain to him in anylanguage that he understands what was contained in the notice. The police officer gave him the paper andsaid, in Greek: “Go away.” As a result, N. did not go to Petrou Ralli to apply for his asylum application cardbefore the required deadline.A lack of interpreters has resulted in many asylum interviews being conducted in English,even though neither the police officer nor the asylum-seeker had a satisfactory command ofthe language. There were also instances in which the interpreter was left alone with theapplicant76and the interview was actually conducted by the interpreter. Human Rights Watchreported that: “It also appears that, because of the lack of interpreters, some asylum-seekersare being asked to provide interpretation services, without receiving any payment.”77TheEuropean Commissioner for Human Rights has reported a “severe shortage of interpreters” inthe Greek asylum determination system.78Although police officers assured Amnesty International representatives on 25 September2008 that interpreters are provided for interviews, it was not possible to verify this given thatAmnesty International was only allowed to attend one asylum interview at the airport. Thiswas in the case of A., a female Afghan asylum-seeker, transferred with her four children fromDenmark. In that case, in April 2009, Amnesty International provided a male interpreterduring the asylum interview, since there was no interpreter at the airport to assist the police.Asylum-seekers told Amnesty International that the questions were usually asked in Englishor Greek, even if the interviewee could barely or not at all understand the language. UNHCRhas also concluded that: “due to a lack of interpretation and legal services, asylum-seekersare often interviewed in a language they do not understand and without being counselled ontheir rights during the asylum process”.79Under the new PD 81/2009 system the asylum interviews of most asylum-seekers take placeat the Attica Police Headquarters. The PD does not refer explicitly to Dublin II returnees, butin practice this is the office where they are interviewed.

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

23

An Afghan asylum-seeker transferred from Belgium under the Dublin Regulation in October 2009 told AmnestyInternational representatives that, when he arrived at the airport, he received a notice to present himself atthe Attica Police Headquarters on a given Saturday morning. There were so many people waiting when hearrived there that the police told him to come back the following Wednesday. After waiting for three hours, hisfingerprints were taken and he was given a pink card. There was a translator present, who simply wrote hisname on the card. He was given a notice (in Farsi) to report at the office in February 2010 for an asyluminterview. Of all the people interviewed by Amnesty International, this was the only case of someone beinggiven a notice in a language they could understand.80Amnesty International’s findings on the lack of sufficient and appropriate interpreters havebeen echoed by other organizations. The Greek Ombudsman reported in October 2009 on the“insufficient interpretation services” during the asylum application procedure.81Based on itsobservations of asylum interviews, UNHCR reported in December 2009 that interpreters wereoften unable to provide quality translations.82Amnesty International is concerned that there is still a severe lack of sufficient andappropriate interpretation services available in the Greek asylum system. This raises concernsabout whether Dublin returnees receive information, in a language they understand, abouttheir right to seek asylum, the reasons for and length of their detention, and the asylumapplication procedure. Moreover, it raises serious concerns that asylum applicants are unableto explain fully and thoroughly the reasons why they are applying for asylum in Greece. Thiscreates risks that incorrect decisions are made and refugees are not identified, in breach ofGreece’s obligations.

4.6. ADMINISTRATIVE BARRIERS TO ACCESSING THE ASYLUM SYSTEM DUE TOHOMELESSNESS“Is this why Greece asked me to come back? In order to let me [live] on the streets with nothing?This is the second time I have been returned to Greece under Dublin II and I’m homeless again. Iknow how things are here and I don’t want to stay. They don’t give me a pink card because I don’thave a rental contract.”N., Iraqi asylum-seeker, transferred under the Dublin Regulation

Until July 2009, the majority of asylum-seekers returned to Greece under Dublin II weregiven a pink card by the airport police. This card did not state their address; instead, asylum-seekers had to go to the Asylum Department of the Attica Police Headquarters to report theiraddress. However, a significant number of the asylum-seekers interviewed by AmnestyInternational reported that the airport police did not inform them of this obligation.It is very common for asylum-seekers transferred under the Dublin Regulation to be homeless.Greek legislation makes it difficult to find employment, and due to the small number ofavailable places in reception centres, many asylum-seekers are destitute. The legislation allowsa pink card holder (registered asylum-seeker) to be issued a work permit. However, there aremany bureaucratic obstacles to this, including the procedure for obtaining a tax identificationnumber which requires the asylum-seeker to provide proof of a permanent address.

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

24

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

According to Greek law, a person applying for asylum can make a declaration to the police,when they submit their asylum application, that they are homeless (PD 220/2007 Article 6).Indeed, this declaration of homelessness is a necessary step, without which the Ministry ofInterior (and since October 2009, the Ministry of Citizens’ Protection) will not notify theMinistry of Health to seek accommodation for the asylum-seeker.83In practice the police donot always inform asylum-seekers of their right, if homeless, to be enrolled in the relevant listof the Ministry of Health so as to be provided with accommodation and do not automaticallyaccept such declarations.Without an address registered on the asylum application card, the pink card will not berenewed after six months and the applicant will not be in possession of a document whichlegally entitles him or her to stay in the country. This results in a risk of the asylum-seekerbeing arrested, detained and even deported. Six of the Dublin II returnees interviewed byAmnesty International had experienced problems renewing their pink cards. Some had triedto renew their card in Patras in 2008 but the police would not renew their card since theywere homeless and living in a camp, and could not provide a permanent address.84Although, in law, homelessness should not be a barrier to renewal of the card, in practice thepolice generally refuse to register individuals as “homeless”. In the few cases where theyhave registered homeless asylum-seekers, they usually have only done so after theintervention of a third party, such as an NGO.85

M., an asylum-seeker from Iran, who was transferred from Belgium at the end of 2008, was not allowed toregister on his card the address of the hotel where he was staying because he was not renting an apartment.The fact that he was staying at a hotel was considered insufficient. The police finally permitted him to registerhis address as the name of the hotel after Amnesty International intervened.The homelessness of Dublin II returnees has wider implications. According to UNHCR,Dublin II returnees who could not provide an address upon arrival in Greece and who werenotified by the Greek authorities on the status of their asylum application through the“Notification of Persons of Unknown Residence Procedure”, were particularlydisadvantaged.86The absence of an effective notification mechanism resulted in returneesnot being able to follow up the outcome of their asylum applications, and risked missing thedeadline to lodge their appeal according to the requirements of the former system (PD90/2008).Under the new system (PD 81/2009), Dublin II returnees are asked not only to report theiraddress but also to provide a rental contract or official notice from the person who rents theflat where they are living. They receive their pink cards from the Asylum Department atPetrou Ralli, but the asylum application cards will not be supplied unless they can producethis evidence of their address. This condition constitutes yet another barrier to access to theasylum procedure.

A six-member Iraqi family, returned to Greece from the Netherlands in late 2009, was not given accommodationby the state. In order to be provided with pink cards, the family was asked by the Asylum Department not only toprovide the police with its address but also to submit a rental contract. The family, who had no financialresources, was provided with accommodation through other Iraqi asylum-seekers who paid their rent, and theywere finally issued with pink cards. Due to the hardship of the situation in which they found themselves, the

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

25

family decided to go back to Iraq voluntarily after less than a month in Greece. The reasons why the family hadsought asylum were that the father had allegedly been threatened and injured because he had served as awitness in a criminal case in Iraq, while his two sons had been shot and injured when their house was brokeninto. The father was also suffering from psychological and physical problems that were diagnosed by doctors inthe Netherlands.Amnesty International is concerned that asylum-seekers returned to Greece under Dublin II –who have neither the means to rent accommodation nor family members or friends who canhost them and provide relevant documentation, or who are not given any of the limitedaccommodation places provided by the state (see below under Reception Conditions) – willface significant obstacles in accessing the asylum application procedure, and will be at riskof not obtaining legal documentation. This can result in a risk of arrest, ill-treatment,detention or expulsion, includingrefoulement(see below under Expulsions and the principleofnon-refoulement).

4.7. LIMITED ACCESS TO LEGAL ASSISTANCE

ASYLUM PROCEDURES DIRECTIVEArticle 15Right to legal assistance and representationMember States shall allow applicants for asylum the opportunity, at their own cost, to consult in an effectivemanner a legal adviser or other counsellor, admitted or permitted as such under national law, on mattersrelating to their asylum applications.In the event of a negative decision by a determining authority, Member States shall ensure that free legalassistance and/or representation be granted on request.Asylum-seekers in Greece do not enjoy sufficient free legal aid. The number of lawyersproviding free legal assistance is very small in comparison to the huge number of asylum-seekers. NGOs, teams and lawyers acting on a voluntary basis do provide free legalassistance. They usually focus on the most serious and urgent cases.Mariana Tzeferakou, lawyer

Amnesty International believes that as part of a fair asylum procedure, asylum-seekers mustbe provided with access to free legal assistance, to UNHCR and to appropriate NGOs, andmust be made aware of these rights. The Greek asylum procedure falls short of thesestandards and cannot be considered fair or effective at the present time.According to Greek law, registered asylum-seekers have the right to be advised at their ownexpense by a legal or other counsellor.87In reality, asylum-seekers rarely have the financialresources to pay for legal counsel.

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

26

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

The asylum-seekers interviewed by Amnesty International reported that, while at the airport,they did not receive any legal advice. Apart from the Afghan woman with four childrentransferred from Denmark described above, who had access to an Amnesty Internationalrepresentative, none of them was made aware of their rights and duties while in detention atthe airport facilities or during their asylum interview or had access to effective legal counsel,UNHCR or appropriate NGOs.88As a general rule, lawyers representing asylum-seekers should have access to their records.According to GCR, it is difficult for lawyers to gain access to the files of asylum-seekersbecause asylum-seekers need to give specific authorization, and the authorities (police orother state authorities) have to authenticate their signatures. Such authentication is notalways possible for people whose pink cards have expired or who have received a deportationorder. Consequently, if an asylum-seeker fails or is not able to authorize his or her lawyer dueto their status, then the lawyer will be unable to obtain the asylum-seeker’s files in order toeffectively represent them. The Greek Ombudsman has also raised concern about thisadministrative obstacle.89Even when the lawyer has the necessary authorization, access tothe file is not immediately granted. There are cases in which lawyers, who requested copiesof the files, had still not received them a year later.90As outlined above, the absence of a legal aid system during the first stage of the asylumprocedure severely limits the ability of most asylum-seekers to access legal advice orrepresentation.91The only way to receive free legal assistance is through the non-governmental or charity sector, but the number of lawyers in Greece who can provide theirservices to registered asylum-seekers free of charge is extremely limited. Those, who do so,include lawyers working for NGOs such as the GCR, the Ecumenical Programme for Refugeesor the Team of Lawyers for the Rights of Refugees and Migrants. The Red Cross also ran aprogramme of legal advice for refugees in Patras following the campsite evictions of July2009 (see below under Access to accommodation).Greek legislation provides for the granting of legal aid only with regard to an application toannul a negative decision to the Council of State.92Article 11(2) of PD 90/2008 states: “Theasylum applicant who files an annulment application against the negative decision isprovided with free legal aid in accordance with Law 3226/2004 (Legal aid for low incomepersons).” However, the provision of legal aid for applications for annulment is not immediatebut must be granted by the Council of State judge in charge of the case. Moreover, one of themain problems with the free legal aid system is that lawyers are reluctant to add their namesto the legal aid lists of local Bar Associations since the proceedings are lengthy and paymentoften takes over a year.93While there are private lawyers who could take on asylum applications, their fees are usuallytoo high for asylum-seekers’ budgets.94Most NGOs which offer legal counselling to asylum-seekers suffer from a lack of resources and/or are reliant on project funding of limitedduration. According to Lazaros Petromelidis, Director of GCR: “Therecannot be nationalstrategies and policies with occasional funding given by the EU. When this funding stops thestructures stop working as well.”Many organizations working on refugee issues are currently struggling to find adequate funding.According to Giannatos Dimitrios, director of Mosaic, an NGO offering psychological support to

Amnesty International March 2010

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE

27

asylum-seekers: “Now, as the years go by, no new structures are being created. Support forrefugees’ legalization is getting harder. We have entered a descending phase. In the comingyears we think that the situation will become even more tense.”On 17 December 2008 the Board of the Union of Trainees and New Lawyers of the AthensBar Association expressed its deep dissatisfaction about the fact that hundreds of lawyersfaced obstacles in submitting asylum applications at the Petrou Ralli building, with theaverage waiting time to submit asylum applications on behalf of their clients exceeding sixhours.95On 17 June 2009 the Athens Bar Association commented on the organization ofasylum determination procedures in Greece as “tragic”.96

4.8. THE RIGHT TO AN EFFECTIVE APPEAL

EU CHARTER OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTSArticle 47Right to an effective remedy and to a fair trialEveryone whose rights and freedoms guaranteed by the law of the Union are violated has the right to aneffective remedy before a tribunal in compliance with the conditions laid down in this Article.Everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartialtribunal previously established by law.Everyone shall have the possibility of being advised, defended and represented.Legal aid shall be made available to those who lack sufficient resources in so far as such aid is necessary toensure effective access to justice.97

EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTSArticle 13Right to an effective remedyEveryone whose rights and freedoms as set forth in this Convention are violated shall have an effective remedybefore a national authority notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in anofficial capacity.98

ASYLUM PROCEDURES DIRECTIVEArticle 39Member States shall ensure that applicants for asylum have the right to an effective remedy before a court ortribunal.Until July 2009 there was a right of appeal against a first instance refusal of an asylum claimbefore a six-member Appeals Board. This was made up of a legal adviser, acting as Presidentof the Board, two representatives from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (diplomatic officer andlegal adviser to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs), a senior police officer, a representative of theAthens Bar Association, and a representative of UNHCR in Greece. Although the Appeals

Index: EUR 25/001/2010

Amnesty International March 2010

28

THE DUBLIN II TRAPTRANSFERS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS TO GREECE