Udenrigsudvalget 2010-11 (1. samling)

URU Alm.del Bilag 114

Offentligt

statE vIolEncE DurIngantI-govErnMEnt protEsts

tunisia inrevolt

amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaignto end grave abuses of human rights.our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universaldeclaration of Human rights and other international human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

First published in 2011 byamnesty international ltdpeter Benenson House1 easton streetlondon Wc1X 0dWunited Kingdom� amnesty international 2011index: mde 30/011/2011 englishoriginal language: englishprinted by amnesty international,international secretariat, united Kingdomall rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.the copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. For copying inany other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission mustbe obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.to request permission, or for any other inquiries, pleasecontact [email protected]Cover photo:mass protest in the capital, tunis, on 14 January2011, the day president Zine el abidine Ben ali fled thecountry. � private

amnesty.org

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURINGANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

conTenTs

1 inTroducTionAbOUT ThIS REPORT

15

2 The proTesTs and Tunisia’s obligaTionsLEGAL AND hUMAN RIGhTS fRAMEwORk

711

3 Killings and injuries of proTesTersThALAREGUEbkASSERINETUNIShAMMAMETbIzERTE

15151720232627

4 TorTure and oTher ill-TreaTmenT5 conclusions and recommendaTionsRECOMMENDATIONS

293537

endnoTes

39

BizerteBIZERTE

TunisJENDOUBABEJAZAGHOUANLE KEFSILIANASOUSSEKAIROUANThalaKASSERINEKasserineReguebSIDI BOUZIDSFAXMAHDIAMONASTIRNABEULHammamet

ALGERIA

GAFSA

MEDITERRANEANSEAGABES

TOZEUR

MEDENINEKEBILI

TATAOUINE

LIBYA� Amnesty International

Map of Tunisia showinggovernorates (regions) andselected towns.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

1

1/inTroducTion

‘Why did they kill our children?’Hassan Jamali, father of 19-year-old Marwan Jamali, killed by gunfire on 8 January in Thala during anti-governmentprotests

14 January 2011 was a truly momentous day for Tunisia, one whose repercussions areresonating across the Middle East and North Africa, and beyond. On that day Tunisians heardthe news for which they had taken to the streets and braved police gunfire and brutality: after23 years in power President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali had been toppled. With the last vestigesof his support collapsing, he slipped away, along with his rapacious family, in search of a safehaven beyond the reach of Tunisian justice, eventually landing in Saudi Arabia. A Presidentwho, only weeks before, had seemed so unassailable, had been brought down by spirallingdemonstrations fuelled by frustration and anger at his corrupt, complacent and repressive rule.The mass protests that drove Zine El Abidine Ben Ali from power were sparked, quite literallyand tragically, by the act of one young man just a month before. On 17 December 2010 inSidi Bouzid, a small town in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, aged just 24, publicly sethimself alight in despair and protest at the misery of his situation. Unable to find work, he hadsought to make a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a handcart, but was preventedfrom doing so by a local official, who also allegedly struck and insulted him. He went tocomplain about the incident to the Governor of Sidi Bouzid but, according to some sources,the Governor refused to meet him. It was one assault on his dignity too far, so he set himselfon fire and set in train a cycle of events that are still unfolding.Mohamed Bouazizi’s act of self-immolation, as a result of which he died on 4 January, strucka nerve within the local community. It unleashed their frustration over the harsh conditions oftheir lives – the lack of jobs, amenities and other basic services – and their fury over theirrelentless marginalization into poverty by a government that just did not care. While theprotests initially surfaced in central Tunisia and focused on socio-economic demands, theyquickly spread to other parts of the country and metamorphosed into demands for freedomand the expression of wider grievances against the authorities, popularly seen as corrupt andresponsible for poverty and unemployment. On top of this, the government’s heavy-handedresponse to contain and quell the protests further ignited anger and led directly to a rising tideof calls for President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to go.Toppling President Ben Ali, however, was achieved at a heavy price. Scores of people werekilled, mostly by security force gunfire, and many others were injured, by live ammunition,

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

2Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

rubber bullets, tear gas or beatings. The current caretaker government says that 78 peopledied during the protests, with a further 100 injured.1Tunisian human rights NGOs say the realdeath toll was greater and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights(OHCHR) has put it at 147 in addition to 72 people who died in prison in incidents linked tothe unrest.2Most of the killings and human rights violations during the protests are believed tohave been committed by the Public Order Brigade (Brigade de l’Ordre Publique, BOP).The first day that any protesters are known to have been killed by security forces using liveammunition was 24 December.3The highest toll of casualties occurred between 8-10 Januaryin the interior of the country, and on 12-13 January in the capital, Tunis, and its suburbs andin coastal areas. Other people were killed in unclear circumstances in the days following ZineEl Abidine Ben Ali’s flight on 14 January, some apparently by members of the security forcesstill loyal to their ousted leader.An Amnesty International fact-finding team in Tunisia from 14 to 23 January 2011 foundevidence of excessive use of force by security forces across the country, including lethal forceagainst protesters and others posing no threat to their or others’ lives. It found evidence too ofsystematic abuse by the security forces of demonstrators.While the Tunisian authorities, like any government, had a responsibility to ensure publicsafety and maintain law and order, including through the use of force when necessary andjustified, it is clear that they went far beyond what is permissible under relevant internationallaw and standards. They used excessive force, including lethal fire, in circumstances wherethis was unjustifiable and represented a violation of human rights law and standards.Force may only be used by state security forces in very limited and particular conditions, inresponse to activities that genuinely threaten lives and public safety. Even then, such forcemust be governed by the principles of necessity and proportionality as set out in internationallaw and standards. Amnesty International found that security forces in Tunisia policingprotests neither respected international standards as set out in the UN Basic Principles on theUse of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and the UN Code of Conduct for LawEnforcement Officials, nor complied with safeguards provided for in Tunisian legislation on theuse of force and firearms.Security forces used tear gas, rubber bullets and live ammunition to disperse crowds duringdemonstrations. They beat protesters they apprehended with batons and kicked them,including in circumstances suggesting that the protesters could not possibly have posed aserious threat to the security forces.The security forces used force disproportionately and resorted to firearms when it was notstrictly necessary. Even in situations where protesters were behaving violently, for instancethrowing rocks and more rarely petrol bombs, the security forces did not use firearms lawfully.They showed a flagrant disregard for human life and did not exercise restraint or seek tominimize injury. Many protesters died as a result of a single shot to the head or chest,suggesting that shots were fired by trained professionals with the intention to kill.In most cases documented by Amnesty International, security forces fired live ammunition atprotesters who did not pose a threat to the lives of the security forces or others. In other cases,security forces shot fleeing protesters and even bystanders.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

The absence of evidence that members of security forces were killed or seriously injuredduring confrontations with protesters reinforces findings that security forces used excessiveforce and firearms when it was not necessary to preserve life.Amnesty International is also concerned by reports that security officials at times obstructedthe arrival of ambulances or prevented private individuals from helping those injured bycontinuing to fire shots rather than ensuring that medical assistance was rendered to injuredpeople as quickly as possible.In waves of arrests during the unrest, about 1,200 individuals had been detained by 22January, according to a senior official at the Interior Ministry whom Amnesty International metthat day. While most were released without charge, as of mid-January, 382 had been referredto the courts on charges of violent conduct, according to officials. Amnesty International isconcerned by evidence that those detained have systematically faced beatings and other ill-treatment at the hands of the security forces.The caretaker government, established in the days following Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’sdeparture, announced that three commissions would be set up. One of them – the Fact-Finding Commission on Abuses Committed in the Last Period – was specifically set up toinvestigate human rights violations that took place in the context of the anti-governmentdemonstrations, including violations of the right to life and physical integrity.4The Commissionis headed by Taoufik Bouderbala, former head of the Tunisian League for Human Rights, aleading human rights NGO. At the time of writing at the end of January 2011, the authoritieshave not made public the Commission’s exact mandate, terms of reference, remit or

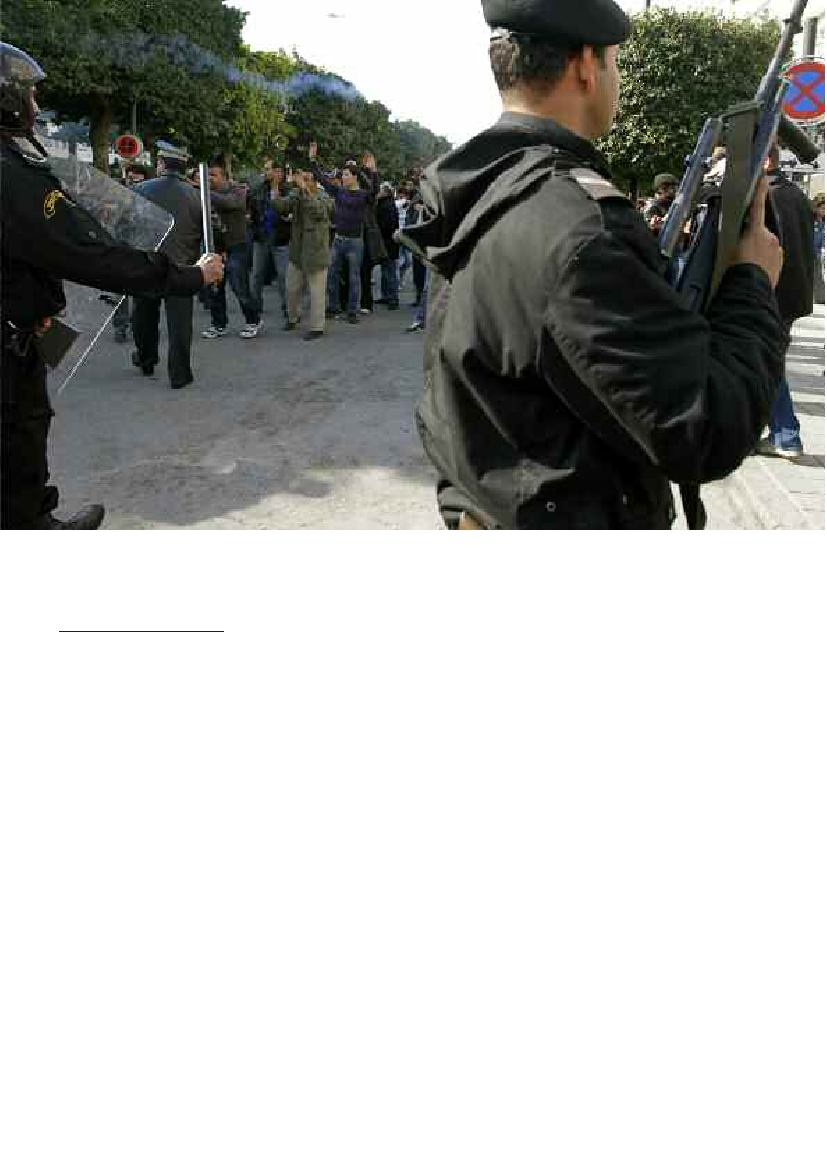

Tunisian demonstrators andlawyers chant slogans in front ofthe Interior Ministry in HabibBourgiba Avenue in Tunis a dayafter President Zine El AbidineBen Ali’s last address to thenation on 13 January 2011.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

� FETHI BELAID/AFP/Getty Images

� Private

Protesters chant slogans whileriot police stand by during ademonstration in downtown Tunis,17 January 2011.

methodology. It remains unclear whether the Commission will have the power to compelwitnesses, including members of the security forces, to testify. It also remains unknownwhether the Commission will have access to all necessary documentation and archives, andbe tasked with the identification of perpetrators of human rights abuses. Families of thosekilled have a right to know the truth about the circumstances of the deaths of their loved ones,including information on the individual perpetrators, the official organs responsible, and thechain of command.Amnesty International calls on the Tunisian authorities to ensure that the investigation into theunrest is independent, transparent, thorough and impartial – and that the Commission’s finalreport is promptly made public. Those identified as responsible for human rights abuses mustbe brought to justice in fair trials. Families of those unlawfully killed, as well as other victims ofexcessive use of force or torture and other ill-treatment at the hands of security forces, mustbe provided with adequate reparation including, but not limited to, financial compensation.In order to truly break with the legacy of human rights violations and impunity for such crimes,the Tunisian authorities must also introduce comprehensive institutional and legal reforms toguarantee that such abuses will not be repeated.5Only then will Tunisians, particularly families ofthose killed during the unrest, start to trust public institutions and to heal after decades of abuse.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

5

abouT This reporTThe findings in this report are largely based on Amnesty International’s visit to Tunisia between14 and 23 January 2011 to inquire into human rights violations committed in the context ofthe unrest that began on 17 December. During the visit, Amnesty International delegates wentto several cities affected by the unrest, including Bizerte, Hammamet, Kasserine, Regueb,Thala and Tunis. Amnesty International interviewed families of individuals killed in the unrest,people injured during protests, other witnesses, former detainees, lawyers, human rightsdefenders and trade unionists. Delegates visited hospitals in Kasserine, Regueb, Thala andTunis and interviewed medical professionals and patients receiving treatment for injuriessustained during the unrest. An Amnesty International delegate also met representatives of theInterior Ministry and briefly spoke to the head of the Commission established to investigatehuman rights violations committed during the unrest.Amnesty International is grateful to all those individuals who met its delegates, in particular thefamilies of those killed who shared their stories and grief with the organization. AmnestyInternational also appreciates the time and assistance provided by Tunisian human rightslawyers and NGOs, including the International Association for the Assistance of PoliticalPrisoners (Association internationale de soutien aux prisonniers politiques, AISPP), theAssociation against Torture in Tunisia (Association de lutte contre la torture en Tunisie, ALTT),and the Tunisian League for Human Rights (Ligue Tunisienne pour la défense des droits del’homme, LTDH). Amnesty International is particularly grateful to the human rights NGOLiberty and Equity, which was instrumental in securing the organization’s access to families ofthose killed.This report does not provide a comprehensive review of human rights violations that took placeduring the weeks preceding the fall of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, nor does it address the socio-economic grievances that sparked the protests. The unrest in prisons in Tunisia that led to 72deaths is also beyond the scope of this report.The aim of the report is to highlight the pattern of human rights violations committed bysecurity forces when policing demonstrations and detaining protesters and others during theunrest leading to the departure of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, and in the days immediately after,through documenting emblematic cases in cities across Tunisia, namely Bizerte, Hammamet,Kasserine, Regueb, Thala and Tunis.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

� Amnesty International

Smoke seen rising from Tunisduring the unrest in January 2011.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

7

2/TheproTesTs andTunisia’s obligaTions

‘We want both: the freedom to work and thefreedom to speak. Instead, I got beaten.’Walid Malahi, who suffered a broken leg and was beaten by riot police during a protest in Kasserine on 10 January

The anti-government protests that erupted following the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizion 17 December 2010 did not come out of the blue. Dissatisfaction and anger at theauthorities, seen as corrupt and responsible for the widespread poverty, had been visible beforeon the streets, most notably in January 2008 in Gafsa region. Then, the results of a recruitmentcompetition by the Gafsa Phosphate Company, the region’s major employer, triggered a wave ofprotests because the results were widely seen as fraudulent by candidates and some membersof the General Union of Tunisian Workers (Union générale tunisienne du travail, UGTT). Theprotests, which started in Redeyef, soon spread to other cities and continued sporadically for sixmonths. They drew in a wide range of people disaffected by economic and other social issues.As was the usual pattern, the protests were ruthlessly suppressed, leading to two deaths andmany injuries. Hundreds of protesters and people suspected of organizing or supporting thedemonstrations were arrested and at least 200 were prosecuted. Some were sentenced toprison terms of up to 10 years, before being pardoned by the President in November 2009.6The messages and lessons of the Gafsa protests went unheeded by the Tunisian authorities.Despite promises that the government would enhance economic development, the regioncontinued to suffer from high levels of unemployment. Many of those pardoned by thePresident were not reinstated to their jobs but instead faced persistent harassment by police.The spread of the protests across Tunisia from late 2010 reflected regional disparities in thelevels of poverty, unemployment and frustration. Economic development and governmentefforts to eradicate poverty had improved living standards for some Tunisians,7but theprogress has not been evenly spread. The northern and coastal regions as well as Tunisia’stourist destinations have benefited, but the south and rural areas have become furthermarginalized. Indeed, the centre, west and south have been left far behind in terms of accessto basic infrastructure and social services, resulting in higher rates of illiteracy andunemployment. They also lack or have inadequate access to safe drinking water, sewerageand sanitation services, electricity, household equipment and adequate housing.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

8Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

The resentment felt in such areas contributed to and partly explains the wave of solidarityaction that was prompted by Mohamed Bouazizi’s act of despair and protest, and by theoutpouring of rage in Sidi Bouzid.At first the security forces did not respond to demonstrations by using lethal force. The turningpoint came on 24 December, when security forces fired live ammunition at protesters inManzel Bouzayane, a small town in the province of Sidi Bouzid, killing 18-year-oldMohamedAmmariand 44-year-oldChaouki Belhoussine El Hadri.Protests spread like wildfire to Tunis;cities in the country’s interior, including Kasserine, Thala and Regueb; and coastal areas fromthe north to the south-east, including Bizerte, Hammamet, Nabeul and Sfax.After several days of silence, the first official response came on 28 December, when PresidentZine El Abidine Ben Ali visited the dying Mohamed Bouazizi in hospital and made a statementpromising to address some of the protesters’ socio-economic demands. However, he alsowarned that the law would be firmly enforced against the “extremists and agitators”.8� Amnesty International� Amnesty International

Left:Tear gas canisters collectedin Thala during the unrest inJanuary 2011.Right:CS gas cartridge at thecorner of Carthage Avenue andOum Kalthoum Street, Tunis,15 January 2011.

The law he was possibly referring to – Law No.69-4 of 24 January 1969 regulating publicmeetings, processions, parades, demonstrations and gatherings – stipulates that theauthorities must be informed before such an event takes place, which they can then forbid ifthey deem it likely to disturb the peace. In practice, this meant that anti-government protestswere not tolerated under the presidency of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. In the rare instances whenprotesters defied the repressive legislation, such as in Gafsa in 2008, they were met withexcessive use of force, arbitrary arrests and detention, and unfair trials.Despite such precedents, protesters ignored the President’s ominous warning. Indeed, theprotests picked up momentum, particularly after the death of Mohamed Bouazizi on 4 January2011, and after his funeral the following day. Angry crowds burned several governmentbuildings, including police stations and the headquarters of the ruling political party, theConstitutional Democratic Rally (Rassemblement constitutionnel démocratique, RCD). Theauthorities responded with a wave of arrests, including of bloggers, and by reinforcing securityaround areas most affected by protests.As the wave of solidarity with the people of Sidi Bouzid spread to other regions, lawyers inTunis sought to organize a nationwide protest on 31 December. Ahead of the planned sit-in,lawyer and human rights defenderAbderraouf Ayadiwas abducted by members of thesecurity forces outside his home on 28 December. He told Amnesty International that theydragged him away, beating him as he resisted, and forced him into an unmarked car. His

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

9

� Amnesty International

Burned police station at Ariana,north of Tunis, January 2011.

22-year-old son, who tried to defend him, was also beaten and lost consciousness. Hisyoungest son, aged 18, was sprayed with tear gas when he too tried to help. Abderraouf Ayadiwas driven for about 45 minutes and then taken into a building. There, someone senior to hisabductors threatened him with death and made other threats against his family. The next dayhe was driven home. On the day of the sit-in, security officials prevented him from joining theprotest at the court building and threatened him with death. The security forces assaultedother lawyers in several regions following the attempted nationwide sit-in on 31 December. Inresponse, thousands of lawyers went on strike on 6 January 2011.Information about the unfolding demonstrations and ongoing repression was absent from thenational media, most of which is strictly controlled by the government. Several independentjournalists were barred from going to Sidi Bouzid to report on the unrest.Ammar Amroussia,a political activist and correspondent for the banned newspaperal-Badil,was arrested on 29December for covering the protest in Sidi Bouzid and for calling on people to demonstrate. Hewas released without charge on 18 January 2011.The Tunisian authorities also tried to prevent the spread of protests by enforcing a mediablackout, blocking websites and closing the email accounts of internet activists.None of this prevented the protests, which continued to swell and spread. The bloodiestconfrontations between security forces and protesters in the interior of the country took placebetween 8 and 10 January in the provinces of Kasserine and Sidi Bouzid, where at least 25people were shot dead by security forces – 14 in Kasserine, six in Thala and five in Regueb.9

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

10Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

In an effort to quell the unrest, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali addressed the nation on 10 January,acknowledging casualties among demonstrators and making further promises to improvesocio-economic conditions. However, he also described protesters as “terrorists” who werebeing manipulated by outside forces hostile to Tunisian interests.10In reaction, protestscontinued across the country, government buildings were attacked and clashes eruptedbetween protesters and security forces, leading to further casualties.11The use of lethal force then spread to the north of the country, including Tunis and itssuburbs, Bizerte and surrounding regions, Nabeul and surrounding areas where protesterswere shot by security forces on 12 and 13 January.In a final attempt to maintain control, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali replaced the Minister of Interioron 12 January and the following day again addressed the nation. He expressed regret over thedeaths and promised an independent investigation into abuses and far-reaching socio-economic reforms. He also announced that he would not stand for election in 2014 andvowed to uphold freedom of expression.12This was too little too late. The following day a vast demonstration in Tunis in front of theInterior Ministry demanded his departure. It was eventually dispersed with tear gas, but hourslater news came that Zine El Abidine Ben Ali had fled the country.In the following days, pillaging, looting and killings continued, including in the suburbs ofTunis. Many people interviewed by Amnesty international, among them residents of affectedareas as well as human rights activists and lawyers, blamed forces affiliated with the toppledPresident for the unrest, in particular for drive-by shootings. The army then moved into severalcities to attempt to establish law and order, and protect public institutions. Media broadcastsissued warnings that gatherings of more than three people would not be tolerated, and thatanyone breaking the curfew would put themselves at risk of being shot. The officialsanctioning of a “shoot on sight” policy appeared to grant the security forces permission tocarry out extrajudicial executions.13A state of emergency and a nationwide curfew were announced on 14 January. They remainedin force at the time of writing, although the period of curfew had been progressively reduced.Protests have continued across the country since the departure of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.This has resulted in the resignation of Mohammed Ghannouchi less than 24 hours after heassumed the presidency on 14 January, the resignation of government ministers from theRCD, and the reshuffling of ministers.Security forces have continued to use water canon and tear gas to disperse demonstrators. On28 and 29 January 2011, for example, police beat and kicked protesters when trying to breakup a week-long sit-in in Kasbah Square by the parliament building, and assaulted a Frenchphotographer documenting such attacks.The caretaker government and interim President Fouad Mebazaa – the former speaker ofparliament – need to demonstrate that they have truly broken with the repressive past by reiningin the security forces and instructing them clearly that they may only use lethal force whenstrictly necessary to protect lives. The caretaker authorities must allow Tunisians to express theiropinions and participate in peaceful protests without fear of death or injury or arbitrary arrest.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

11

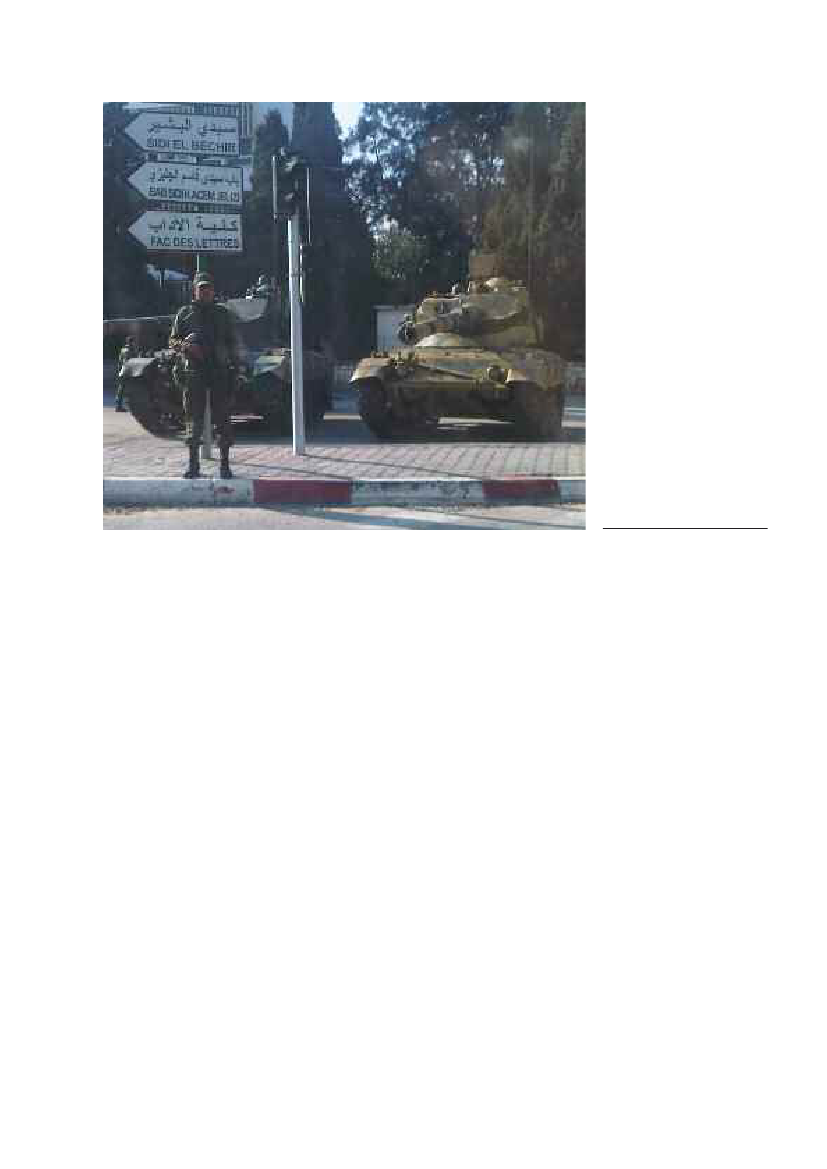

� Amnesty International

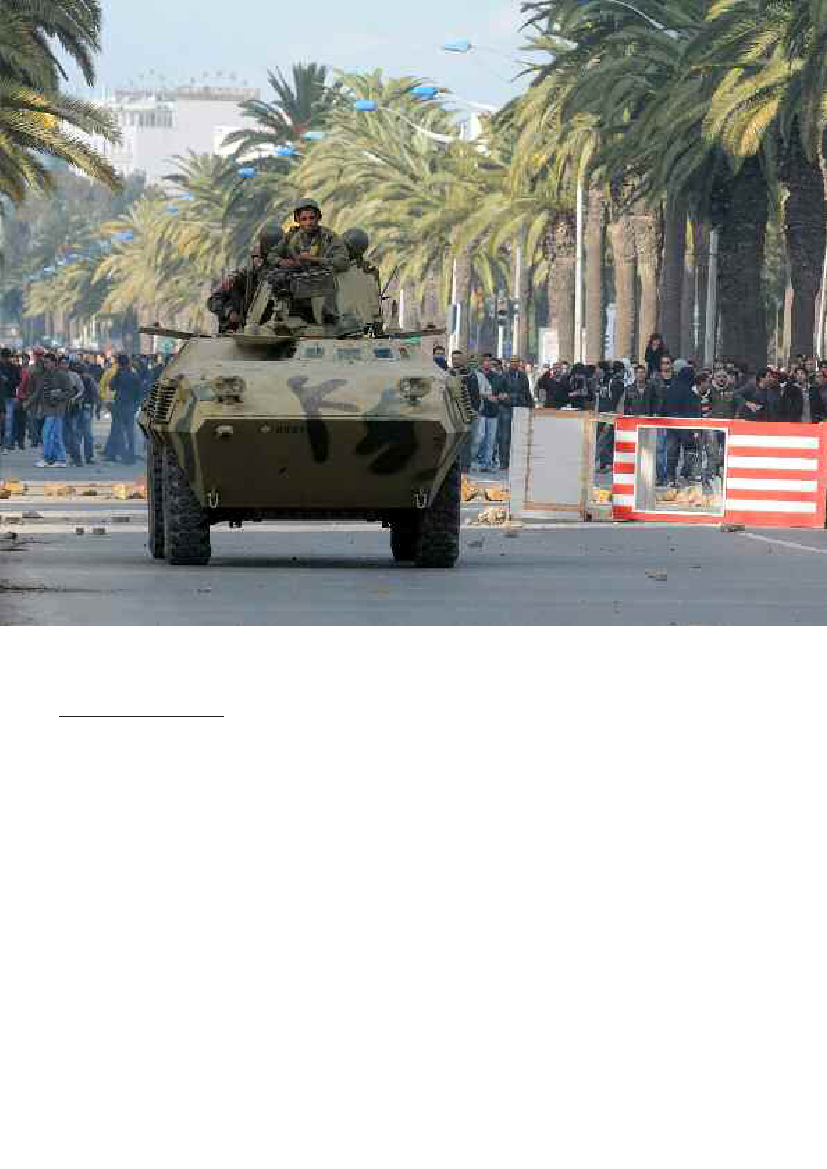

Army patrolling the streets ofTunis, January 2011.

legal and human righTs frameWorKStates have a duty to uphold the right to freedom of assembly. According to the InternationalCovenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Tunisia is a state party, anyrestrictions on the right to freedom of assembly must be in accordance with the law andstrictly necessary to preserve national security or public safety, public order, public health ormorals or protect the rights and freedoms of others.14Any such restrictions must beproportionate to a legitimate purpose and without recourse to discrimination, including ongrounds of political opinion. Even when a restriction on the right to protest is justifiable underinternational law, the policing of demonstrations (whether or not they have been prohibited)must be carried out in accordance with international standards, which prohibit the use of forceby law enforcement officials unless strictly necessary and to the extent required for theperformance of their duty, and permit the use of firearms only when strictly unavoidable inorder to protect life.In policing protests and responding to the unrest that shook Tunisia between late Decemberand mid-January, Tunisian security forces used excessive force, in contravention ofinternational standards, most notably the Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearmsby Law Enforcement Officials, the Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, andTunisia’s Law 69-4 of January 1969. The relevant provisions are as follows:

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

12Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

The Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement OfficialsPrinciple 3:The development and deployment of non-lethal incapacitating weapons shouldbe carefully evaluated in order to minimize the risk of endangering uninvolved persons, andthe use of such weapons should be carefully controlled.Principle 5:Whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, law enforcementofficials shall:(a) Exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence andthe legitimate objective to be achieved;(b) Minimize damage and injury, and respect and preserve human life;(c) Ensure that assistance and medical aid are rendered to any injured or affected persons atthe earliest possible moment;(d) Ensure that relatives or close friends of the injured or affected person are notified at theearliest possible moment.Principle 9:Law enforcement officials shall not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury, to preventthe perpetration of a particularly serious crime involving grave threat to life, to arrest a personpresenting such a danger and resisting their authority, or to prevent his or her escape, andonly when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives. In any event,intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order toprotect life.Principle 10:In the circumstances provided for under principle 9, law enforcement officialsshall identify themselves as such and give a clear warning of their intent to use firearms, withsufficient time for the warning to be observed, unless to do so would unduly place the lawenforcement officials at risk or would create a risk of death or serious harm to other persons,or would be clearly inappropriate or pointless in the circumstances of the incident.The Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement OfficialsArticle 3:Law enforcement officials may use force only when strictly necessary and to theextent required for the performance of their duty.(c) The use of firearms is considered an extreme measure. Every effort should be made toexclude the use of firearms, especially against children. In general, firearms should not beused except when a suspected offender offers armed resistance or otherwise jeopardizes thelives of others and less extreme measures are not sufficient to restrain or apprehend thesuspected offender. In every instance in which a firearm is discharged, a report should bemade promptly to the competent authorities.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

13

Tunisia’s Law 69-4 of January 1969Article 18:Before dispersing protesters, law enforcement officials are required to issue twoclear audible or visible warnings.Article 19:Prior to the use of firearms, law enforcement officials are required to repeat theirsecond warning twice.Articles 20 and 21:Law enforcement officials may use firearms when it is strictly necessaryand proportionate to the achievement of a legitimate objective as stipulated by the Law. In theframework of policing demonstrations, law enforcement officials are permitted to use firearmsshould protesters not heed warnings to disperse, but only after other non-lethal means suchas water cannons and tear gas are exhausted. Shots must first be fired in the air, then over theprotesters’ heads and finally in the direction of their legs.The cases highlighted below and other evidence show that on many occasions the Tunisiansecurity forces breached these laws and standards and used excessive force, in some casesleading to deaths. They also violated the right to life as enshrined in Article 6 of the ICCPR.The UN Human Rights Committee, in its General Comment No. 6, noted that the right to life isnon-derogable even in cases of “public emergencies”. The Committee added: “States partiesshould take measures not only to prevent and punish deprivation of life by criminal acts, butalso prevent arbitrary killings by their own security forces.” The prohibition of torture and othercruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment is also non-derogable.Under international law, governments also have an obligation to provide victims of humanrights abuses with an effective remedy.15This obligation includes three elements:truth–establishing the facts about violations of human rights;justice– investigating past violationsand, if enough admissible evidence is gathered, prosecuting the suspected perpetrators; andreparation– providing full and effective reparation to the victims and their families, in its fiveforms: restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition.16The Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victimsof Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations ofInternational Humanitarian Law17Principle 7:Remedies for gross violations of international human rights law and seriousviolations of international humanitarian law include the victim’s right to the following asprovided for under international law: (a) Equal and effective access to justice; (b) Adequate,effective and prompt reparation for harm suffered; and (c) Access to relevant informationconcerning violations and reparation mechanisms.Such laws and standards must guide the interim government – and future governments – inTunisia as they steer the country towards a future in which the human rights of all people inTunisia, whether it be their civil and political rights, or their social and economic rights, arerespected.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

� AFP/Getty Images

Funeral in Thala on 9 January2011 of people killed in theunrest.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

15

3/Killingsand injuriesof proTesTers

‘Such atrocities cannot go unpunished.’Abdelkarim Hajji, 45-year-old father of four and teacher at the secondary school of Regueb, who was injured by alive bullet fired during the funeral of a young man killed by security forces during protests in Regueb

As the protests spread and intensified across Tunisia, the security forces increasingly resortedto violent means to disperse crowds and intimidate protesters. This chapter looks at the unrestin various places in chronological order of fatalities, namely Thala, Regueb, Kasserine, Tunis,Hammamet and Bizerte.

ThalaThe small city of Thala is in the province of Kasserine, central Tunisia, one of the leastdeveloped and poorest regions in the country. When Amnesty International visited the town on19 January, residents complained about economic marginalization and the lack of jobopportunities, even for university graduates.Residents said that demonstrations began in their city in late December by unemployed youth,initially in solidarity with the protesters of Sidi Bouzid but also to raise their socio-economicdemands. Political undertones were evident from the start, with protesters chanting“Employment is a right, oh gang of thieves” in clear reference to government corruption.From 3 January, protests grew in size as students returned to school after the winter break. Theyalso became more politicized, with slogans such as “Free [Sidi] Bouzid, Ben Ali out”. Participantssaid that while in general protests were peaceful during the day, violent confrontations broke outbetween young male protesters and security forces during evening protests.According to individuals interviewed in Thala, protests turned violent around 5-6 January,particularly after the intervention of riot police, allegedly the BOP brought in from outsideThala. These police started to use tear gas, rubber bullets and, from 8 January, liveammunition against protesters. Several buildings associated with repression, such as thepremises of the ruling RCD and police stations, were burned by protesters.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

16Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

At least six people were killed by live ammunition in Thala in the context of the unrest: five on8 January and one on 12 January. More were injured, but the exact numbers are difficult toascertain as some of those seriously injured were transferred to hospitals outside of Thala.According to a doctor in Thala hospital, 51 people were also injured between 3 and 7 January,both protesters and security forces – most sustaining minor wounds. He said that 16protesters were admitted to the hospital on 8 January and in the early hours of 9 January withgun-related injuries, five of them fatal. Two more were brought in on 12 January, includingWajdi Saihiwho died of his wounds.Nineteen-year-old studentMarwan Jamaliwas shot dead at about 8pm on 8 January near themain street in Thala, Habib Bourguiba Avenue. According to his father, Marwan joinedthe protests because he had experienced injustice. His friend Bilal Saihi, who witnessed theshooting of Marwan, told Amnesty International that Marwan had not been engaged in anyviolent behaviour when two bullets were fired at him: one hit him in the chest, the other in theback. Bilal Saihi said that members of the BOP, positioned in the street and on the roofs ofnearby buildings, had attempted to disperse protesters by throwing tear gas grenades at them,but then started firing live ammunition without warning – verbal or otherwise.Makram Hassnaoui, aged 29, also witnessed the killing of Marwan Jamali and was himselfinjured that evening. He told Amnesty International that protesters only resorted to throwingrocks at the security forces after tear gas was used against them. He said that youths hadgathered there to “demand their rights”. Makram was hit by two bullets, one grazing his rightleg and the other going through his thigh. He said that a security officer in riot gear shot himfrom a distance of around 5 metres without issuing any warning.Ghassan Chaniti,a 19-year-old seasonal worker, was also killed on 8 January. His father toldAmnesty International: “My son worked and got paid about 150 dinars a month [70 euros] tohelp out the whole family. He went to participate in the protest… Our income is not enough tofeed the family.” Ghassan was shot in the back at about 9.25pm in the centre of town as hewas fleeing the area, according to youths who were with him. A doctor who examined his bodyin Kasserine Hospital confirmed that he had been shot from behind.Another young man killed on the evening of 8 January was 17-year-oldYassine Rtibi,whodespite his age was providing for his family, including six siblings, by doing odd jobs. Hisfather, Hammadi Rtibi, told Amnesty International that Yassine joined the “protests from thebeginning of the movement because of poverty and our desperate situation”. According to thefamily, four bullets hit him, including one to the chest that killed him.All three families expressed to Amnesty International their desire for justice and for theperpetrators – both those who fired the bullets and those who gave the order – to be punished.They said they would file official complaints with the judicial authorities asking forinvestigations to be opened.The three families also complained about the behaviour of the security forces during thefunerals, held the next day on 9 January. The funerals, attended by hundreds of people,turned into protests with participants shouting “God is Great. God loves martyrs”, in referenceto the young men killed. When the funeral procession attempted to leave the main mosque inthe centre of town heading towards the cemetery, security forces fired tear gas at it to dispersethe crowd.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

17

� Amnesty International

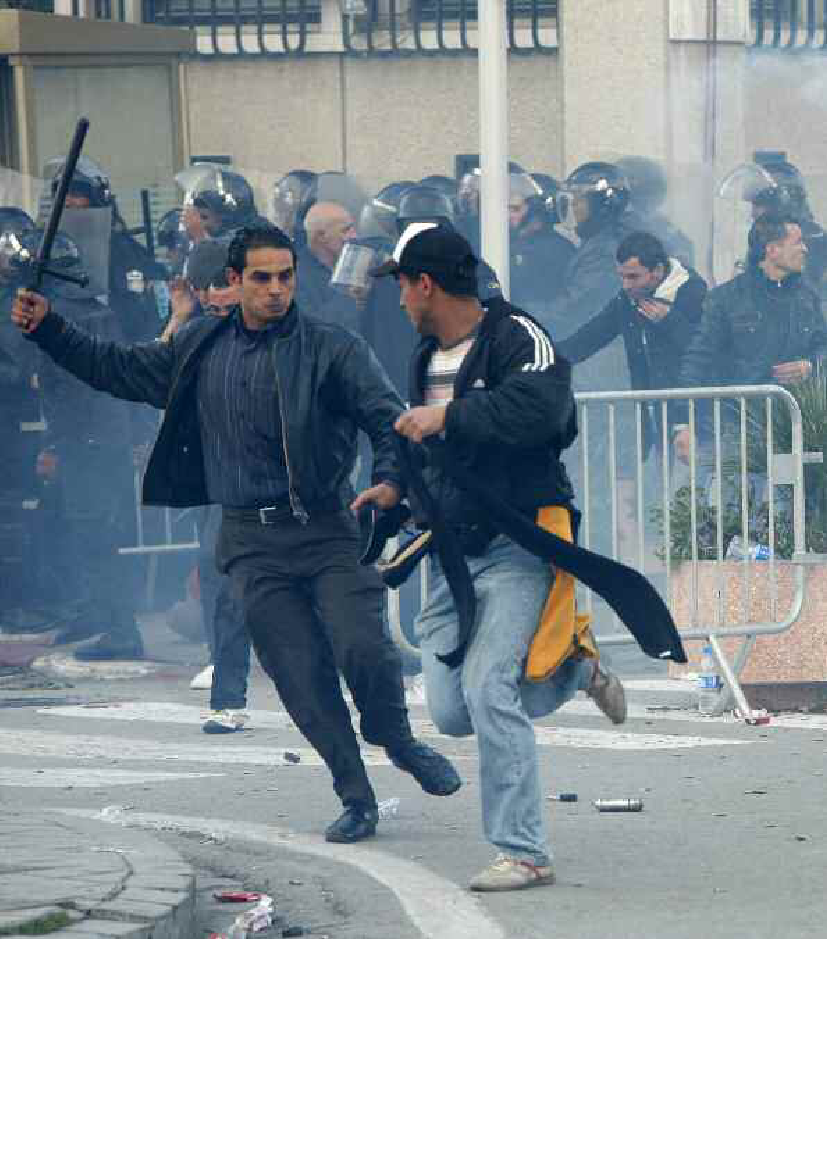

Security forces across the countryused tear gas, rubber bullets andlive ammunition againstprotesters. In Regueb,picturedleft,five people were killed bygunfire.

In other protests in the city, security forces not only used live ammunition when it was notstrictly necessary to save lives, but also beat protesters, including minors. For instance, on 4January, security forces prevented students from the local college in Thala from protestingoutside their school. According to a teacher present at the time, security forces closed thegates of the school and beat the 15-year-old children over a period of around two hours. Theyalso fired tear gas at the students. An ambulance driver, who was trying to reach the school toprovide medical assistance to the children, told Amnesty International that security forcesstopped him from passing through the school gates, a further violation of the rights of thesechildren.Several residents of Thala also said that security forces fired tear gas into residential areas,including into their homes, during protests. International standards make clear thatincapacitating weapons such as tear gas must only be used in ways that minimize the risk tobystanders. One victim, Fatoum Rtibi, a 55-year-old woman who lives near the centre of Thala,told Amnesty International that during the unrest three tear gas canisters came into her house.Her neighbours had similar experiences.

reguebAnti-government protests in Regueb, a small town in the province of Sidi Bouzid, started inlate December. Residents told Amnesty International that the first protests were peaceful andthat local law enforcement officials, including police and plain-clothed security agents, merelyobserved the protests without intervening. The situation changed with the arrival of riot police,

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

18Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

allegedly the BOP, on about 25 December, who used tear gas to disperse protesters – mostlystudents and unemployed youths. In response, protesters threw rocks at them and clashesbroke out with security forces. On 31 December, young protesters also allegedly burned thefacade of a bank and a local court.Tensions escalated on the afternoon of 7 January when security forces and young protestersclashed in the centre of town, near the police station, the headquarters of the National Guardand the building of the Mou'tamadiya (delegation), the representative of the governorate at thelocal level. A tear gas canister was thrown into the main mosque near the confrontationsapparently to disperse those attending Friday prayer before they had the opportunity to jointhe protests outside. When Amnesty International visited the mosque on 21 January, the imamshowed delegates the window broken by the canister and said that the suffocating effects ofthe tear gas caused a near stampede as people tried to flee.Lethal force was first used against protesters in Regueb on 9 January. A large crowd of men,women and children had gathered in front of the Mou'tamadiya building demanding thedeparture of the BOP and threatening a general strike. Protesters were chanting: “Nostudying, no teaching until the police leave”. According to testimonies gathered by AmnestyInternational, the demonstration was sparked by an incident earlier that morning when amember of the BOP insulted and hit a 40-year-old man delivering milk to the town.Participants in the protests that day told Amnesty International that while a trade unionmember was trying to negotiate with the security forces, tear gas was thrown into the crowd.Most of the older men and women fled, but a number of youths remained and engaged in aviolent confrontation with the riot police, who were deployed in the main streets and on top ofbuildings. The confrontation lasted from about 11am to 2pm. Eyewitnesses said that the riotpolice started firing rubber bullets and then immediately afterwards live ammunition, in bothcases without warning.A total of five people were shot dead that day: Manal Boualagi and Raouf Kadous at around1pm; Mohamed Omran Jabali during the procession bringing Raouf Kadous’ body from thehospital; and Mouez Omar Khalifi and Nizar Ibrahim Slimi at around 4pm duringconfrontations with security forces.According to a doctor working in the emergency room on 9 January, 16 injured protesterswere brought to the hospital, including five people shot by live ammunition and two hit byrubber bullets. The doctor noted that throughout the period of unrest, only one member of thesecurity forces was admitted to the hospital for treatment – for cuts caused by glass thrown inhis face by protesters. The doctor said that the injuries to the protesters who were shot led himto believe that the bullets had been fired by professionals, possibly snipers, including from thetop of buildings as the exit wounds were lower than the entry points.One of the victims, 26-year-oldManal Boualagi,was not involved in the protests. Accordingto the doctor, she was killed by a single bullet to the chest fired from above. AmnestyInternational visited the home of Chadia, Manal’s mother, in the neighbourhood of Istiqlal.Chadia said that her daughter had visited her in the early afternoon on 9 January. Shortlyafter Manal left to tend to her children, six-year-old Chadia and three-year-old Eyad, hermother heard shots outside. She could not leave as members of the security forces werestationed outside her house, shots were being fired and tear gas was filling the street. Afemale relative who was walking with Manal when she was shot told Amnesty International:

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

19

Amnesty International also interviewed thefamilies of two other people killed during theprotests –Mouez Omar Khalifi,a 25-year-oldman who worked at a petrol station; and 22-year-oldNizar Ibrahim Slimi,who didseasonal work when available. Despite theirlimited incomes, both were the main providersfor their families.The two men were killed in the centre of town.According to an eyewitness, Nizar was shot inthe chest by a sniper positioned on top of atelephone tower. Mouez also died as a result ofa single shot to the chest, according to thedoctor on emergency duty that night. Bothfamilies want justice, including for those whoordered the shooting to be held to account,and to receive adequate financialcompensation for their loss.Mohamed Omran Jabali,married with onechild, died after being hit by a bullet in hiswaist during the procession of Raouf Kadous’funeral. According to eyewitnesses, AymanAkriti, Lotfi Akrami and Abdelkarim Hajji, who participated in Raouf Kadous’ funeralprocession, the gathering was peaceful. They said that despite this, members of the BOPstarted firing tear gas at them, and soon after started shooting at them without warning.Mohamed Jabali, who was walking near the front of the procession, was killed and severalothers were injured. Abdelkarim Hajji, a teacher and father of four, was hit by a live bullet inhis right thigh when he was trying to leave the march. Similarly, Lotfi Akrami was hit in theshoulder from behind when he was fleeing.

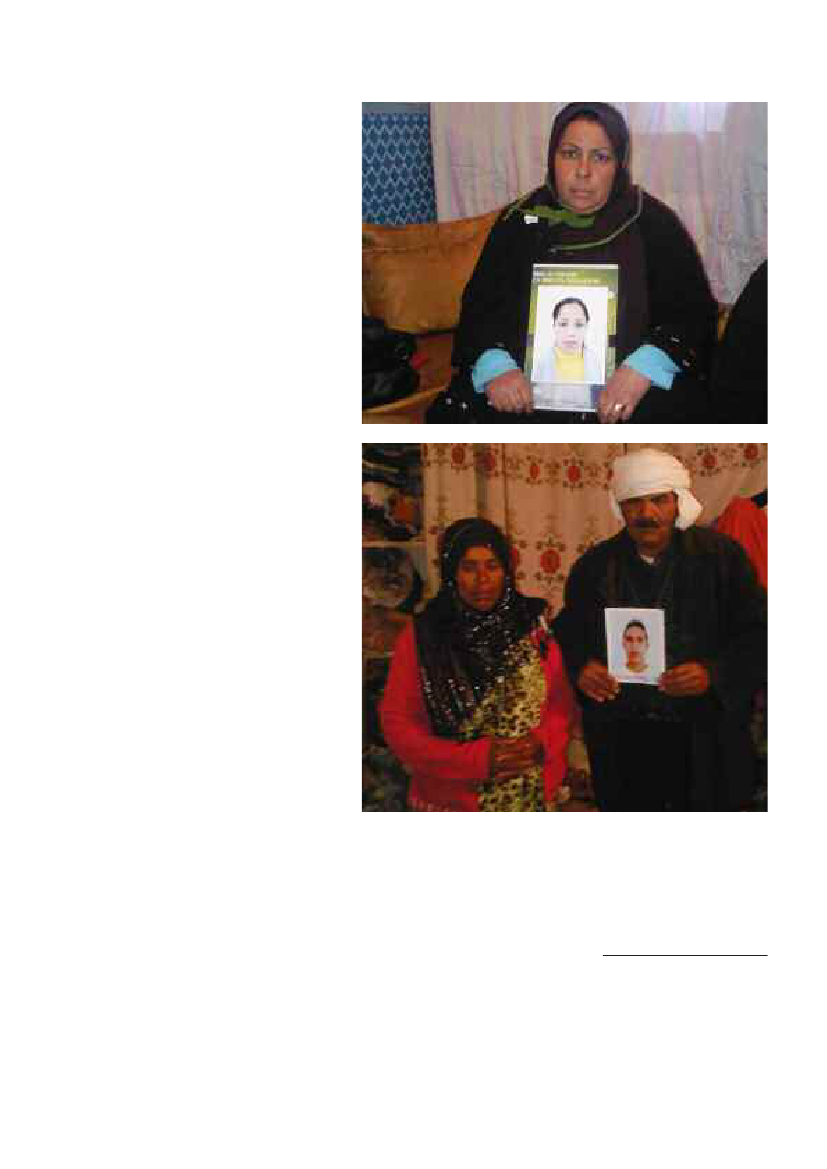

Top:The mother of ManalBoualagi, holding a picture of herdaughter who was shot dead on9 January in Regueb.Below:Family of Nizar IbrahimSlimi, who was shot dead on9 January in Regueb.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

� Amnesty International

� Amnesty International

“We were just walking and talking, in a rush toreach Manal’s house where her children were.Suddenly, she screamed and fell to theground.” Manal was rushed to the hospital inRegueb, where a doctor ordered her transfer tothe better-equipped hospital in Sfax. She diedon the way. Her mother told AmnestyInternational: “There are now two little kids leftbehind, deprived of their mother’s affection.We were both living below zero [in sub-standard conditions]. All I want is for the twolittle ones to live a better life, with somedignity.” Manal’s husband and father of herchildren is unemployed. Chadia told AmnestyInternational that she wants to see theperpetrators of her daughter’s killing brought tojustice.

20Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

� Amnesty International

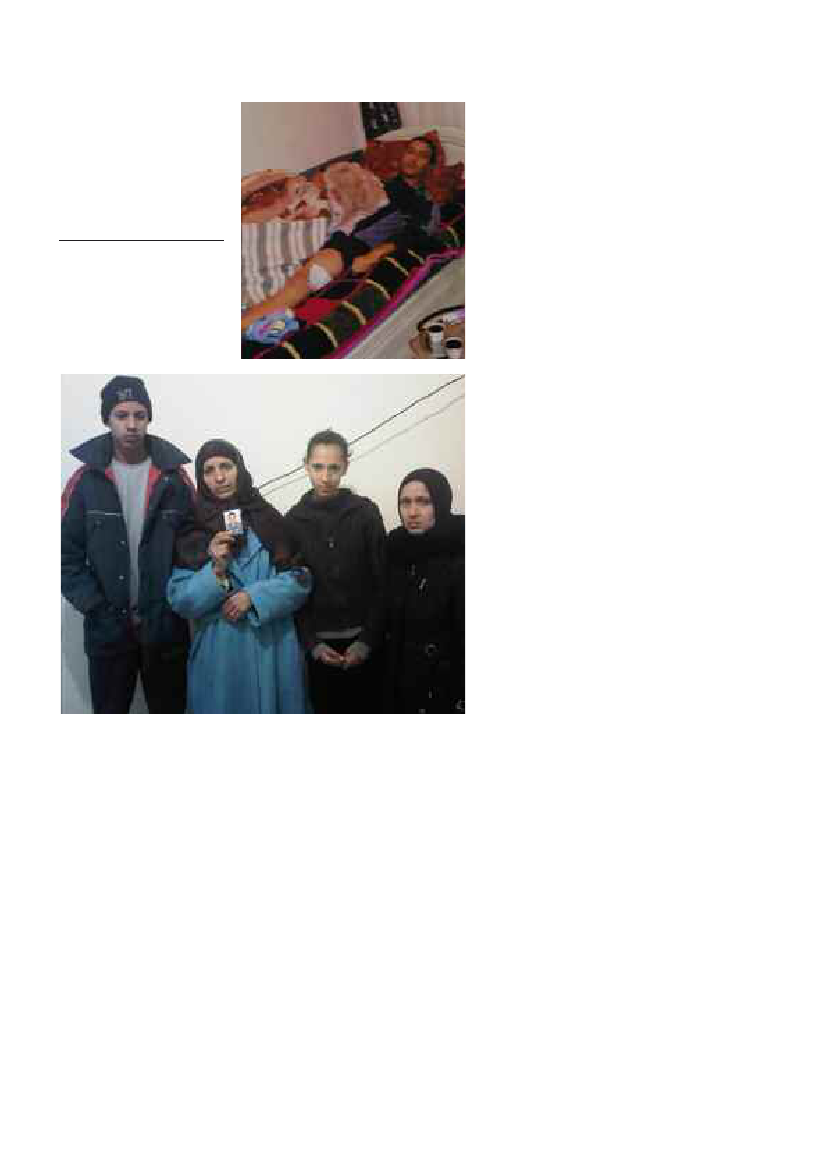

Right:Chadi Adibi, recovering athis home after he was shot in theleg during protests in Regueb on9 January.Below:Family of Ramzi HabibHoussein who was shot on 8January and died of his wounds.

Chadi Abidi,a 20-year-old man who was shotin his leg on 9 January during protests inRegueb, told Amnesty International: “I, like allthe others, participated in the demonstrationsagainst repressive rulers. I wanted to expressmy opinion. We are marginalized compared tothe coastal areas. We want life opportunitieslike others.”

KasserineKasserine, the capital of the central Tunisianprovince of the same name, had one of theheaviest death tolls during the unrest in theweeks preceding Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’sdeparture. It is also one of the poorest regionsin Tunisia, with one of the highestunemployment rates.Anti-government protests began in Kasserinefrom late December and at first passed offpeacefully. After riot police arrived in earlyJanuary, tear gas and rubber bullets were usedto disperse protesters. The size of protestsgrew, and on 7 January violence by thesecurity forces and protesters escalated,reportedly sparked by news that a young manfrom the Salam neighbourhood in Kasserinehad tried to commit suicide by setting himselfon fire. According to Kasserine Hospital staff,his desperate act and subsequent deathsparked angry protests, particularly in theNour neighbourhood of Kasserine, wherethe premises of the RCD were burned and thewindows of two banks were broken.According to the chief of forensic medicine in Kasserine, the first casualties of lethal shooting bysecurity forces arrived at the hospital on 9 January. Hospital records show thatMohamed AminMbarki(see below) andSaber Rtibiwere killed by live ammunition that day. A further 10 peopledied as a result of shooting on 10 January. Amnesty International believes that the total death tollwas higher as a number of seriously injured people were transferred to hospitals outside ofKasserine.Amnesty International visited the family home ofRamzi Habib Houssein,a 28-year-old man whowas shot on 8 January and whose name was not included in hospital records in Kasserine. Hewas the sole breadwinner in his household, which included his aunt who raised him, and hisyounger siblings. According to an eyewitness, Ramzi was with some 20 other youths in the Nourneighbourhood close to the municipality building. The witness said that members of the BOP fired

amnesty international february 2011

� Amnesty International

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

21

tear gas at them, and that some of the youths reacted by throwing petrol bombs and rocks at thesecurity forces. Shots were fired and most of the protesters dispersed. However, according to thewitness, members of the BOP apprehended Ramzi and started beating him with batons on hisback and neck as he was prone on his front on the ground. Family members who saw Ramzi’sbody confirmed that his shoulders were covered in wounds, corroborating the testimony that hewas beaten before being shot. The eyewitness continued: “One of the BOP shot Ramzi at closerange. I could see it from across the street”. Ramzi was transferred to the Sousse Hospital, wherehe died.Even though confrontations between protesters and security forces had been violent, the useof firearms against an apprehended protester, who clearly no longer presented a threat to thesecurity forces, was not legitimate and constitutes a violation to the right of life. Ramzi’s familytold Amnesty International that they are asking that the authorities conduct a full investigationinto his killing, bring the perpetrators to justice and provide Ramzi’s family with adequatecompensation.Several men were shot dead at the funeral ofanother victim,Mohamed Amin Mbarki,whodied after being hit in the face by liveammunition, according to the forensic doctorwho examined his body on 9 January. On10 January, when his funeral procession washeading to the cemetery, violence erupted nearthe police station in the Zouhour neighbourhood.Amnesty International delegates met the familyofIssa Griri,a 27-year-old man who was theonly breadwinner for his family, which includesseven siblings. He was shot during MohamedAmin Mbarki’s funeral at about 12.30pm. Asconfirmed by the forensic doctor who examinedhim, he was shot in the back of the head.According to eyewitnesses, he was trying tohelp another victim of the shooting at thefuneral,Ahmed Jabbari,when he was fatallywounded. They said that the bullet was firedfrom the roof of a house near the police station.Walid Saadaoui,aged 28, was also fatallywounded in the early afternoon of 10 Januaryin the Zouhour neighbourhood during thefuneral procession for Mohamed Amin Mbarki.He was standing with a group of other youths,including his brother Anouar Sadat, protestingagainst government corruption, whenmembers of the riot police started throwingtear gas. When the crowd did not disperse andsome youths retaliated with rock-throwing,security forces fired live ammunition. A bullethit Walid in the waist. His family took him toAbove:Family hold a picture ofIssa Griri, who was shot dead on9 January at a funeral of anothervictim of the unrest.Left:Body ofWalid Saadaoui,

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

� Private

who died in Kasserine Hospitalon 10 January after being shotduring a funeral earlier thatday for another victim of theunrest.

amnesty international february 2011

� Amnesty International

22Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

Kasserine Hospital, but he died shortly after. His relatives are not only demanding justice andreparation for the killing, but also want the Tunisian authorities to address the issue thatmotivated Walid to protest, namely unemployment.Amnesty International interviewed the family of 21-year-oldMohamed Nasri,who was also killedon the afternoon of 10 January. According to his relatives, while Mohamed Amin Mbarki’sfuneral was happening, Mohamed Nasri was going home to the Zouhour neighbourhood fromwork when he was shot in the stomach. According to eyewitnesses, his friendMohamedKhadraouirushed to help him, but was shot in the forehead. The forensic doctor at KasserineHospital, who examined both bodies, confirmed that they arrived at the hospital at around thesame time in the afternoon of 10 January. Mohamed Nasri’s family said that they received a callfrom the Minister of Health offering his condolences, but that they will not be satisfied until thegovernment officially recognizes the killings in Kasserine, offers families financial compensation,provides job opportunities and guarantees social justice by ending nepotism and corruption.Another man killed during the afternoon of 10 January was 61-year-oldAhmed Jabbari,whowas hit in the chest by a bullet. According to his family, he was not participating in theprotests, but was on his way to the mosque across the street to pray. Before leaving, he hadwarned his sister not to leave the house due to disturbances. His family is asking for justiceand reparation for his death, and for better job opportunities and the eradication of corruptionfor all Tunisians.Other bystanders paid a heavy price for being outside during protests and confrontationsbetween protesters and security forces. Khames Karmazi, his wife and their seven-month-olddaughter Yakin were on their way home after visiting their in-laws in the Nour neighbourhood.When they were near the municipality building, the scene of protests and confrontationsbetween security forces and youths, the family was exposed to tear gas. That night, Yakin hadtrouble sleeping and cried a lot, so the next morning her family rushed her to the emergencyunit at Kasserine Hospital. She died at about 2pm that afternoon. A medical certificate signedby the hospital’s chief paediatrician confirmed that Yakin died as a result of “exposure to verytoxic tear gas”. Her father told Amnesty International: “She was my only child. We have beentrying to have children for five years... I want to know why this happened. Who is responsible?”Scores of protesters were injured in the unrestby bullets or during beatings by securityforces.Rayed Saihi,a 23-year-old studentwhom Amnesty International interviewed inKasserine Hospital, said that three of hisfingers were broken when security forces beathim during a funeral procession in the Nourneighbourhood on 10 January. He said thatsecurity forces used tear gas to disperse themassive turnout for the procession, and thenbeat anyone who did not disperse.� AmnestyInternational

Three of Rayed Saihi’s fingerswere broken when security forcesbeat him on 10 January.

Walid Malahi,who shared Rayed Saihi’s hospital room, told Amnesty International that his legwas broken during a protest in the Zouhour neighbourhood on 10 January. He said that aftersecurity forces threw tear gas to disperse the crowd, he tried to flee but was hit from behind bya vehicle used by riot police. He said that members of the BOP beat him with batons all over hisbody, including his injured leg. He lost consciousness and only woke up in Kasserine Hospital.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

23

He told Amnesty International: “I participated in the protests because of our difficult livingconditions, particularly unemployment. We were hoping for democracy in our country.”

TunisAfter the bloody weekend of 8-10 January in the interior of the country, protests involving theburning of public buildings, looting and confrontations between security forces and protestersspread to the capital. Tens of people were killed and more were injured.The director of Charles Nicolle Hospital in Tunis told Amnesty International on 17 January thatsince the onset of the protests in the capital and its suburbs, the hospital had received 28bodies of protesters who died from gunshot wounds, and over 100 people injured during theunrest, including 30 hit by live ammunition. He said the hospital had the only forensicmedicine department in Tunis. Outside the hospital morgue, where coffins were lined up, a listwas posted with 17 names of people who died on 15 and 16 January, according to the doctoron duty. Amnesty International believes that the total number of fatalities during the protests inTunis was more than 28 as some families interviewed said they did not take the bodies of theirkilled relatives to Charles Nicolle Hospital.To the best of Amnesty International’s knowledge, the majority of deaths in greater Tunis tookplace between 12 and 16 January in working class neighbourhoods such as Tadhamoun,Sijoumi and Mallassine. Residents of these neighbourhoods described their difficult livingconditions and their daily struggle to survive in the face of unemployment, poor housing,poverty, lack of education opportunities and the rising cost of living.In the Tadhamoun neighbourhood, one of thelargest and poorest suburbs of Tunis, AmnestyInternational spoke to four families who had lostloved ones during the unrest. Eyewitnesses saidthat protests in the area escalated on 12January, and further violence broke out thenext day, particularly after Zine El Abidine BenAli’s last address to the nation. Thousands ofpeople took to the streets calling for the end ofhis rule, chanting slogans such as “Bread andwater, and no Ben Ali”. Security forces,including riot police, fired tear gas and liveammunition at the protesters, some of whomwere throwing rocks at security forces.Twenty-four-year-oldMalek Habbachi,who hadrecently become engaged to be married, waskilled by a single bullet to his neck on theevening of 12 January. He joined the protestswith his older brother Youssri to call for betterlife opportunities. Their father said: “My sonsdid their duty. All Tunisian people refuse toaccept their living conditions. Malek wasfighting against corruption”.

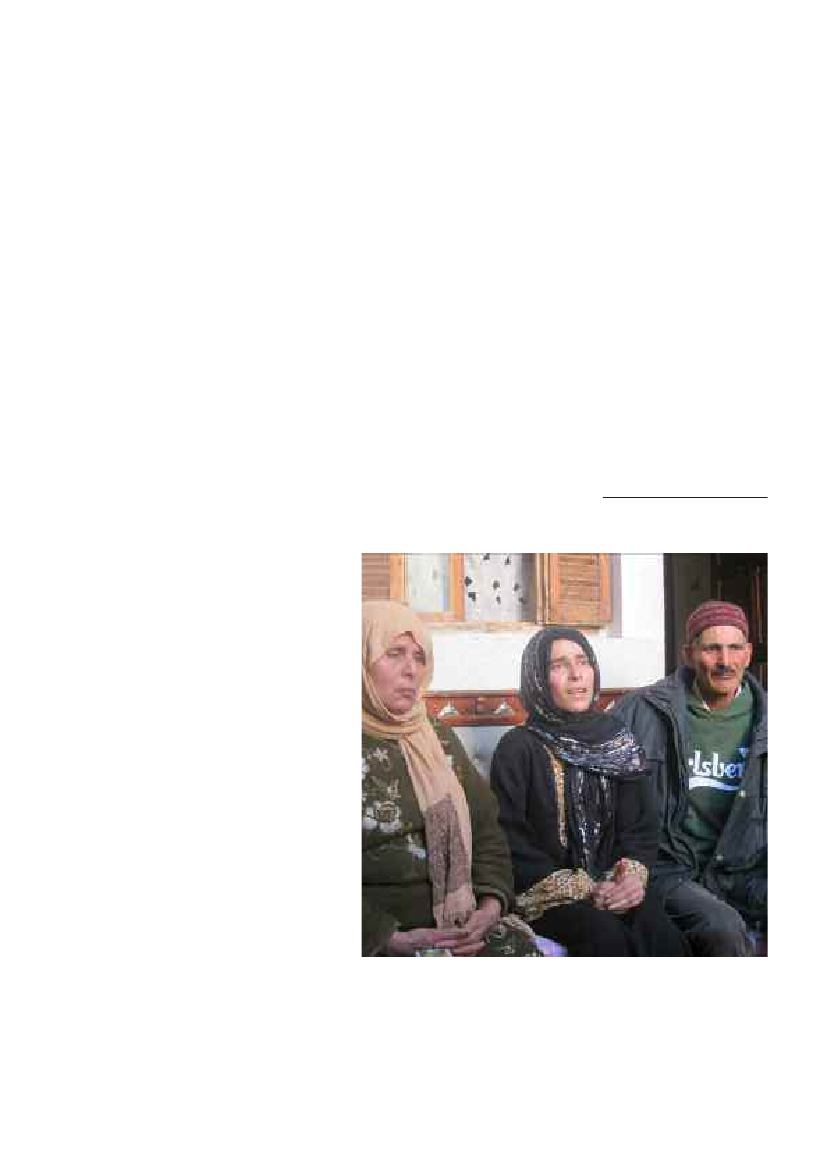

Family of Malek Habbachi,January 2011.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

� Amnesty International

24Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

According to eyewitnesses, Malek was shot by a sniper wearing riot gear while he wasprotesting on Bi'a Street, close to the municipality building, along with other young peoplefrom the neighbourhood. The witnesses said that three other men from the Tadhamounneighbourhood were killed that evening, and others injured. When Malek was shot, his brotherYoussri tried to carry him home, but he was attacked by riot police who hit him with batons onhis head, back and legs. When Amnesty International delegates met Youssri on 17 January,he was still bedridden and could not speak, barely communicating in nods. The Habbachifamily expressed their determination to obtain justice. Malek’s sister, who is studying law, said:“We want justice. They took away his life prematurely. Some people are living in palaces, whileothers are struggling to survive. Enough fear!”

Family of Majdi Monstri, abystander shot dead on 13 Januaryin Tunis.

Amnesty International also interviewed the family ofMajdi Monstri,who was shot while hewas on Taib Mhiri Avenue in the Tadhamoun neighbourhood at about 7.30pm on 13 January.Eyewitnesses told Amnesty International that he had not been participating in protests, butwas merely going home, a few metres from where he was shot. An eyewitness said that amember of the National Guard, recognized by people in the neighbourhood, shouted at Majdiordering him to stop. Majdi complied, raising his hands to show that he was not armed. Hewas nonetheless shot in the chest. His father told Amnesty International: “I am asking forjustice. I want the person who fired the bullet, as well as the person who gave the order, andanyone else who participated in the crime to be held accountable.”Amnesty International met another family whose son was shot in the chest on 13 January in theJomhuriya area of the Tadhamoun neighbourhood. A sister of 36-year-oldHisham MoumnitoldAmnesty International that he had called the family at about 2.30pm to say that he was about tocome home, but he never arrived. His family then had the grim task of collecting his body fromCharles Nicolle Hospital morgue. They are asking for a transparent investigation into thecircumstances of his death and for those responsible to be brought to justice.Amnesty International also spoke to Mansour al-'Iari whose 21-year-old sonThabet Iyariwasshot dead on the afternoon of 13 January in the Jomhuriya area of the Tadhamounneighbourhood. At the time, riot police were trying to disperse protesters by using tear gas andlive ammunition. According to eyewitnesses, Thabet was shot by a sniper positioned on top of

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

� Amnesty International

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

25

the local police station. His father told Amnesty International: “Nothing will bring back my son.Nonetheless, there must be an investigation into who killed him and who gave the order tokill him.”Police also used lethal force during protests in the neighbourhood of Sijoumi, another workingclass suburb of Tunis. On the evening of 13 January, at least two young men, 24-year-oldWalid Hafid Gamai,and 22-year-oldMahdi Laouni,were killed by gunfire. Walid Hafid’smother, a widow, told Amnesty International that she is not sure how she will cope without heroldest son, who had been taking care of the family. Eyewitnesses told Amnesty Internationalthat Walid Hafid, who was not participating in protests, was shot by a sniper positioned some100 metres away on the roof of a building across the road. They said that the sniper was aknown member of the security forces serving in the local Sidi Houssein police station. Severalwitnesses confirmed that Walid Hafid was shot from behind in his back – strongly suggestingthat he was not posing a danger to the lives of security forces. Other witnesses said that MahdiLaouni, who was unemployed, was also shot from behind, and that the bullet hit his kidney.Relatives who washed his body in preparation for the burial told Amnesty International that hisbody was covered with bruises on his arms and side, suggesting that he was beaten beforebeing shot.On 14 January, 32-year-old French-German dual national photographerLucas MebroukDolega,who was working for the Paris-based European Pressphoto Agency (EPA), wascovering protests outside the Interior Ministry in central Tunis. At around 2pm he was hit in theface by a tear gas canister fired at point-blank range by a police officer, according to reports.He was rushed to hospital and operated on, but died on 17 January. Horacio Villalobos, EPA’sParis bureau chief, said: “If a police officer shoots a tear gas canister, such as in this case,less than five metres away, aiming for the head, it’s with the goal of injuring someone, if notkilling him.”18It is not clear whether an investigation into the death has been initiated.As happened in Thala and Kasserine, funeral processions in Tunis for people killed during theunrest turned into anti-government protests and were violently dispersed by security forces.Walid Sabai,who sustained a minor injury on 14 January during Mahdi Laouni’s funeral, toldAmnesty International that security forces fired tear gas at the mourners and hit several ofthem with batons. He told Amnesty International that he heard several shots being fired, butdid not know if anyone was killed.Amnesty International documented the cases of several people injured by live ammunitionwho were not involved in the protests.Regueb Hamchi,for instance, told AmnestyInternational that he was standing on the porch of his house with his wife on 14 January,when they were hit by a bullet fired by members of the BOP who were chasing youths. Thebullet grazed his right thigh before hitting his wife’s thigh, causing her serious injury. She wasstill in hospital when Amnesty International interviewed Regueb on 17 January. Regueb saidthat members of the BOP gave no warning before shooting, even though they were entering aresidential area.After the departure of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, further violence and shootings took place inTunis and its outskirts, the circumstances of which remain unclear. Residents of affectedareas, including Khadra and Mallassine neighbourhoods, said that the violence waspropagated by elements within security forces loyal to the toppled President in order to instilfear and a sense of insecurity. This could not be confirmed.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

26Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

In Mallassine, a 23-year-old law student,Marwa Amina,was killed apparently by a stray bulleton 15 January at about 8.30pm. She was at home when the bullet flew through her window onthe second floor, hitting her in the right eye. According to a doctor in Charles Nicolle Hospital,her skull fractured on impact and she died instantaneously.A few hours later, at about 1.25am on 16January, 32-year-oldElyas Krirwas shot in theback of the head by an unidentified man. Atthe time of his death, he was patrolling theKhadra neighbourhood along with around 50other men to stop vandalism and pillaging,which had become rampant around that time.According to eyewitnesses, a black car drovepast the group, then a man got out and firedseveral shots without warning. Elyas wascarried to the clinic across the road, but hedied on the way. Residents of Khadraneighbourhood who had gathered at his houseto give their condolences told Amnesty International that the black car was following two othervehicles, which were later seen in front of the offices of the security services of Khadraneighbourhood, adding to their suspicion that the perpetrators were linked to the security forces.The same night another young man,Kamel Razak,was shot in his shoulder with liveammunition in the Khadra neighbourhood. His mother told Amnesty International that shewent outside to look for her son having heard shots, and was herself injured in the right wristby a live bullet. She showed Amnesty International her bandaged hand, lamenting that shereceived 16 stitches at the hospital.Full, impartial and independent investigations must be conducted to elucidate thecircumstances of all of the shootings by unidentified assailants.� AmnestyInternational

The body of Elyas Krir, who wasshot in the back of the head on16 January in Khadraneighbourhood in Tunis whiletrying to protect residents fromlooting.

hammameTThe coastal town of Hammamet, a tourist centre, was not left untouched by the protests andwitnessed one fatal shooting.Local union leader and member of the Tunisian League for Human Rights, Kamel Masaoud,told Amnesty International that a large march took place in Hammamet on 12 January. Hesaid that it started peacefully, with protesters calling for economic and political changes. Whenthe march reached the police station near Hadi Chaker Street, however, security forces startedusing tear gas. The trade unionists lost control of the march as chaos ensued, and someyoung people started throwing rocks at the security forces. In response, security forces usedlive ammunition without warning, killingZoheir Souissi,deputy manager of a prestigious hotelin Hammamet.According to his brother Anouar, also a member of the Tunisian League for Human Rights,Zoheir came upon the demonstration on his way home from work, and was still wearing hiswork uniform. They marched peacefully together, but lost sight of each other after tear gasspread over the crowd. The family rushed Zoheir, who was hit in the neck, to the poorly

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

27

equipped local hospital, after a private clinicknown as the “violettes clinic” allegedlyrefused to treat him. He was then transferredto the Maamouri Hospital, but it was too lateto save his life.His wife, the mother of their 17-year-old sonand 11-year-old daughter, told AmnestyInternational that while nothing will bringZoheir back, she would like to see justice runits course against those who fired the shotsand those who gave the orders to fire onprotesters. The family intends to file an officialcomplaint with the General Prosecution.After the 12 January demonstration, protestsspread to surrounding areas, includingNabeul, where two people were shot dead bysecurity forces.

biZerTeAt least three people were killed during protests in the northern town of Bizerte, according toinformation available to Amnesty International.The family ofIskander Rahali,who was shot in the back of the head on 13 January at about8pm, met Amnesty International on 23 January. According to his brother Omar, who was withhim at the time of the shooting, the two had joined a group of young people protesting againstunemployment and corruption. When the protesters reached the police station in Hachedneighbourhood they decided to break in, allegedly under the impression that the post wasabandoned. Omar said: “When the door opened, the electricity came on. We started to fleebut we were shot at, even though no warning was uttered... Iskander received a bullet in theback of the head. He was trying to flee.” Two others were injured. A death certificate seen byAmnesty International confirmed that Iskander was shot in the back of the head. The familylodged a complaint with the General Prosecution.

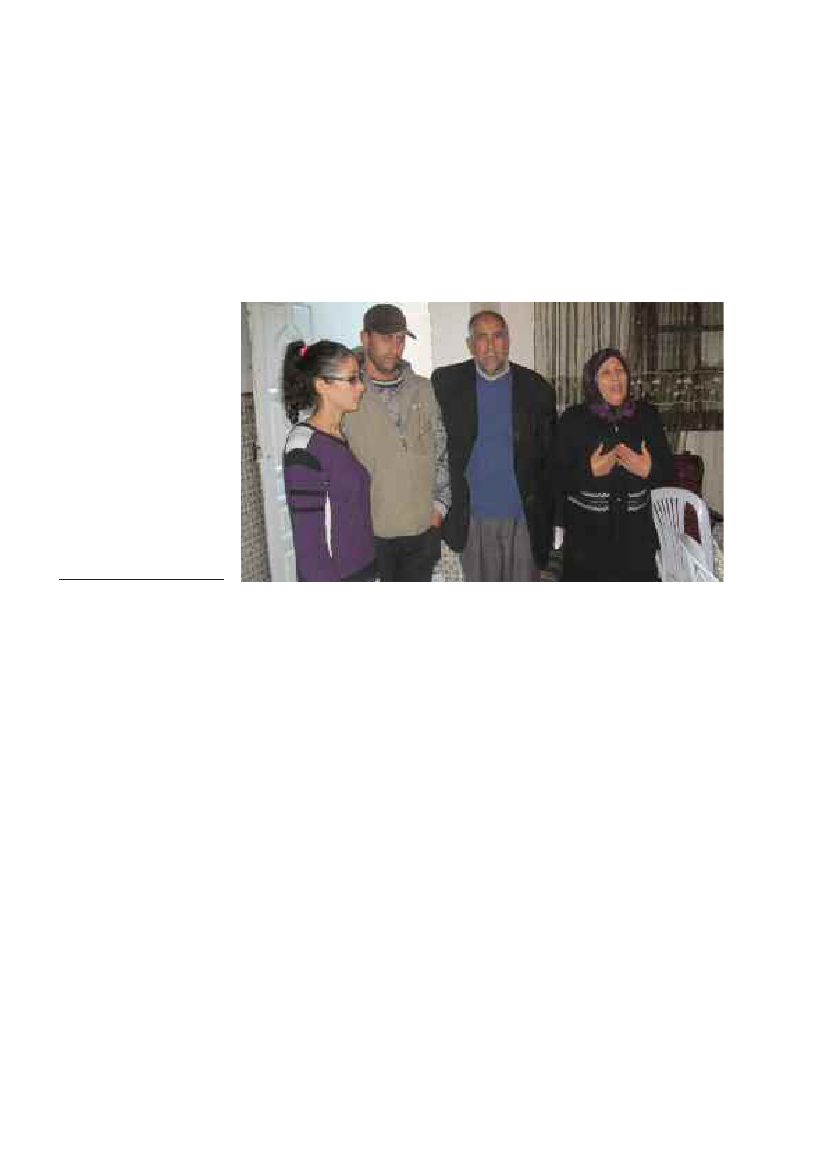

The wife of Zoheir Souissi,showing Amnesty Internationaldelegates a picture of herhusband; he was shot dead duringa protest.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

� Amnesty International

� EPA/Lucas Dolega

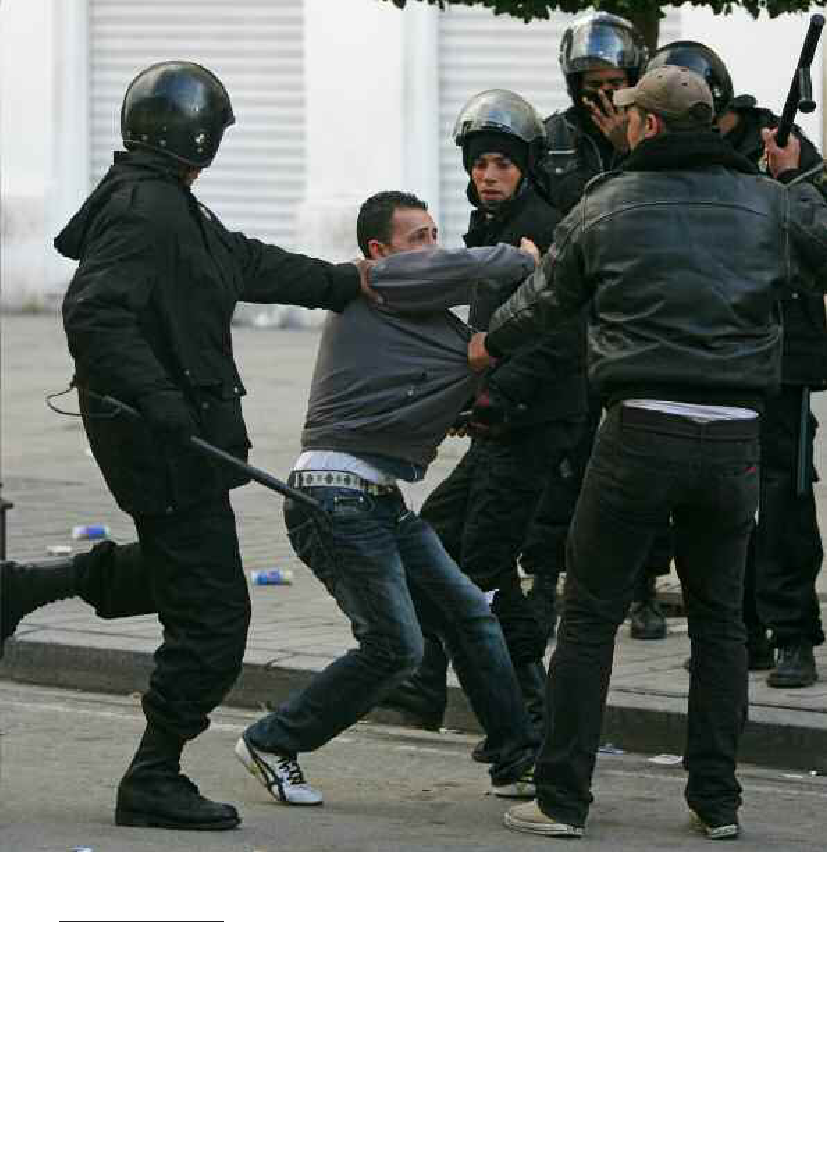

A demonstrator being beaten bypolice during a protest in Tunison 14 January 2011.

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

29

4/TorTureand oTherill-TreaTmenT

‘Riot police beat me with batons and kickedme in the street.’Abdelhafid Arbaoui

Thousands of people were arrested by security forces during the unrest, according torepresentatives of the Ministry of Interior. Those making the arrests included riot police andsecurity agents in plain clothes. Some people were arrested during protests on suspicion ofparticipating in violent acts or for no apparent reason. Some were arrested at their homeswithout the presentation of arrest warrants. Some, including bloggers, union leaders andpolitical figures, appear to have been arrested because of their perceived role in the anti-government movement, rather than because of their direct participation in the protests.There were persistent reports that those arrested were tortured or otherwise ill-treated. Mostfrequently, detainees were beaten with batons or kicked by members of the security forcesduring arrest or in detention. Some were also forced to remain in contorted or uncomfortablepositions for long periods. Such treatment appeared to be aimed at deterring protesters fromtaking part in further action, or to punish them for participating in anti-government protests. Insome instances, torture or other ill-treatment were used to extract information about perceivedorganizers or forces behind the protests.Amnesty International documented cases in most cities visited by its fact-finding delegation.Some of those interviewed said they had been so badly beaten that they had sufferedfractured limbs, had open wounds or had lost consciousness. Amnesty Internationalconcluded that torture and other ill-treatment appeared to be widespread and systematicacross the country.Saifallah Slimitold Amnesty International that he was arrested on Bi'a Street in Regueb alongwith a friend on 9 January during a protest. Members of the security forces hit them both withbatons on the head, arms and stomach. The beatings lasted about 10 minutes before theywere forced into a car and taken to a local police station. Saifallah Slimi said that there wereabout 70 or 80 young people detained at the police station at the time, all of whom had beenbeaten by security forces. He was released at about 8pm without charge, but threatened with

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

� EPA/Lucas Dolega

amnesty international february 2011

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

Tunisia in revolTSTATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS

31

A photograph dated 14 January2011 and taken by the EuropeanPressphoto Agency (EPA)photographer Lucas Dolega showspolice officers clashing withdemonstrators during a protest inTunis. The image was transmittedby a colleague the following day,15 January, after Lucas Dolegawas hit by a tear gas grenade andrushed to a hospital in Tunis withsevere head injuries. LucasDolega, who had been working forthe EPA’s office in Paris, France,since April 2006, died of hisinjuries on 17 January 2011 atthe age of 32.

Index: MDE 30/011/2011

amnesty international february 2011

32Tunisia in revolT

STATE VIOLENCE DURING ANTI-GOVERNMENT PROTESTS