Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2010-11 (1. samling)

UPN Alm.del Bilag 81

Offentligt

DIIS polIcy brIefGrowing Jasmines:What Should the EUdo in Tunisia Now?January 2011the eU misread the situation in tunisia. However, the fact that the eU approach did not work as expected should not lead now to a hasty overhaul of the existing policy frame-work. But the eU will have to be clearer, smarter and stricter about how its policy instruments are implemented.The ‘Jasmine Revolution’ has caught Europe off-guard.European Union institutions, member states and influentialsouthern European governments supported the Tunisian re-gime up until the very day, on 14 January 2011, when Pre-sident Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was forced to flee the coun-try. On the website of the Italian foreign ministry, for one,Tunisia is still praised for its “political and social stability.”So rosy was the assessment of the Tunis regime that, accor-ding to EU Commissioner Stefan Füle who is in charge ofthe Union’s flagshipEuropean Neighbourhood Policy,ENP,(including Tunisia as its partner country): “Tunisia is an im-portant and reliable partner for the EU, with which it hasforged strong relations based on shared values and mutualrespect and understanding.” Accordingly, in May 2010 theEU was prepared to grant Tunisia ‘advanced status’, whichwould have ensured a more intense political dialogue andincluded the prospect of a deep free trade agreement.The popular uprising that ousted Ben Ali has shatteredthis optimism. With events still unfolding in Tunisia, theEU policy-mix in the Mediterranean region is now beingseriously questioned. Why has Brussels’ existing policyframe-work underperformed? How should the EU relateto popular Islamist forces in Tunisia and the region? Whatshould the Union and its Member States now do, both inthe immediate future and in the medium term? Ahead ofan EU Foreign Affairs Council on January 31st, which willalso discuss Tunisia, this policy brief seeks to address someof these questions.Recommendations- the ongoing european neighbourhood Policy Review process and the forth-coming commission communication on the subject should now include an explicit reference to the tunisian events and elicit a frank reflection on eU prio-rities and how eU values are reflected in its policies.- the eU should freeze talks on ‘advan-ced status’ and hold out that prospect should the new tunisian authorities consolidate their power peacefully and elections be held freely. - the eU must stand ready to activate the suspension clause enshrined in the association agreement with tunisia, in the event that documented cases of re-pression and human rights abuses by the new tunisian authorities should arise. - eU member states must refrain from launching parallel bilateral initiatives at this stage. in the immediate future they should provide political and diplomatic support to a common eU consensus and channel this through the role of HR ashton. - islamist parties must be allowed to join the political process and stand in elec-tions and Western governments should engage these parties.

�

DIIS polIcy brIefWHat Went WRong: a cRitical aPPRaisal of eU Policies When it comes to furthering democratic reforms in theMediterranean and the Middle East, the EU has severalinstruments and policies at its disposal. However, despitethe Union’s self-image as a normative power, its democracypromotion policies in the region over the last two decadeshave been marked by ambivalence and hesitancy. The nowformer Barcelona Process (EMP) launched in 1995 was tohelp bring “stability, peace and prosperity to the region”through political and economic liberalization. Long be-fore September 11 and the Bush Administration’s push fordemocratization in the Middle East, the EU had linkedsecurity and political reform, realizing that if stability wereto be secured in the long run, the authoritarian Arab stateswould need to engage in reform.In principle the Barcelona Process did indeed allow the EUto use its economic muscle to push for reforms. The EUwas – and still is – the main donor and trading partner formost Mediterranean countries. A clause in the AssociationAgreements opened up the possibility of suspending Euro-pean trade and aid if a particular Arab government grosslyviolated human rights. However, despite obvious cases ofabuse in Algeria and Egypt in particular, the EU has neverused this conditionality measure. In the end the EU putmore emphasis on the economic than on the political sideof the partnership, and proved unwilling to rock existingauthoritarian regime structures.The EU’s Neighbourhood Policy was launched in 2004in part to correct some of these flaws. The EU seemedto acknowledge that it had dragged its feet on reform inNorth Africa for too long and changed track from a ne-gative to a positive conditionality approach. The EU nowoffered economic and political benefits and, potentially,a stake in the internal market in return for democraticreforms. Through so-called Action Plans the EU and indi-vidual Mediterranean governments were, ideally, to agreeon specific targets for reform. Progress and willingness toreform were, in turn, to be rewarded with further coop-eration and aid.Seven years on the ENP has fared no better than the Bar-celona Process. The Arab governments remain unwilling toundertake any real change that could lessen their grip onpower. They have tacitly engaged in political reform ini-tiatives and cooperation programmes with the EU, libera-lizing with one hand, while repressing with the other. TheEU has, to a large extent, turned a blind eye to this tacticof engagement. The ENP framework ultimately embracesthe regimes’ gradualist argument about the need for undertaking reforms at their own pace, and the Action Planshave accordingly ended up as rather vague and uncom-mitted documents that have easily sustained the Arabgovernments’ fa§ade of liberalization.The launch of the Mediterranean Union in 2008 onlyexacerbated this tendency. With its emphasis on meretechno-economical cooperation, the EU sent the wrongsignal to the incumbent Arab leaders. The JordanianSecretary General of the Mediterranean Union has nowdeclared his resignation on the grounds that the Mediter-ranean Union has been unable to address the real politicalproblems of the region.

tHe islamist cHallenge One key reason behind European (and American) cautionabout reforms in North Africa and the Middle East hasbeen the rise of Islamism. Islamism has been perceivedpotentially as leading to terrorism both in the Arab coun-tries and in the West. Throughout North Africa moderateIslamist parties, groups and movements are very popularforces. Both Arab regimes and Western actors perceivethem as a threat – the former to Western values and thelatter to regime survival.North African regimes have at the same time instrumen-talized Islam in a quest for legitimacy, attempting tocounter violent Islamism. Arab regimes tend to controlreligious education, mosque construction, the appoint-ment and remuneration of imams and the content oftheir sermons. Moralization of behaviour in the name ofa conservative version of Islam is on the regimes’ politi-cal agenda. Islamism as a political tool for shaping futurepolitics has been repressed, whereas Islam as a tool forchannelling and relieving the populations’ despair has beenpromoted.Under this general agenda the actual managementof Islamist opposition on the part of North Africanregimes has oscillated between selective repression andcontrolled integration of Islamist participation in thepolitical system. In Tunisia the Ben Ali regime neverattempted to co-opt Islamists by controlling their entryinto the politicalsystem. The successful Tunisian IslamistpartyAl Nahda(‘Renaissance’) has been banned and re-pressed since elections in 1989, when the party gained14% of the vote.In the past days the western media have been quick tozoom in on Tunisian Islamists and Al Nahda in parti-cular, speculating what role they will, or should, play inthe Tunisian transition. The Al Nahda leadership has beenin exile for many years and lacks an operational partymachine. Unlike in Egypt, Algeria, Morocco and Libya,the Tunisian opposition is not coming from Islamists butfrom secular intellectuals, lawyers and trade unionists. Ifgeneral elections are going to be held in the near future– two-to-six months are the options more frequently beingmentioned – there might be parties that present them-selves as Islamist. While it is desirable not to rush towards

�

popular consultation during the present turmoil, theconfused circumstances that persist on the ground makeit hard to judge whether there is potential for Islamistparties. However, the participation of Islamists in theelections will be a crucial test of the democratic cre-dentials of the uprising and of the new Tunisian autho-rities.Just as importantly, the inclusion of Islamist parties willrepresent a test for EU and the US policy. The Tunisianevents should make EU and US policy-makers reconsidertheir axiomatic linkage between marginalization of Islam-ists in return for stability. Open societies, political and civilliberties, and the rule of law are the foundation of Westernpolities and, accordingly, of Western policies in the region.From this follows that the credibility of these policies isinextricably bound to accepting the full inclusion of mo-derate Islamist parties in any discussion about the future oftheir respective countries.Inspired by the Tunisian revolt, the Muslim Brotherhoodin Egypt has called on the government to end the state ofemergency, dissolve the new Parliament and conduct freeand fair elections and for the entire government to be dis-missed. At a time when the popular protests are spreadingto the streets of Cairo and beyond, the region is likely topose yet another test to the West with the 2011 EgyptianPresidential elections – if not before.

work. These standards are applicable to any new govern-ment sitting in Tunis.At the same time the EU will have to be clearer, smarterand stricter about how its policy instruments are imple-mented. Any talk of penalties or even sanctions is asso-ciated throughout the region with the complex historicallegacies that tie North African states to the past of Euro-pean exploitation and colonization. However, negativeconditionalities are nevertheless important means to sendsignals to governments that are moving away from theircommitments. Just as importantly, the political and eco-nomic interests of some EU member states have hamperedstricter implementation of the EU policies.In these hectic days pundits are forcing analogies betweenthe Central European velvet revolutions of the late 1980sor the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the Tuni-sian situation. These analogies are misguided in a numberof historical and geopolitical respects, but above all in thefact that the EU had treated the Ben Ali regime as a poster-child of its policy in the region. If nothing else, this blun-der should lead the EU to temporarily freeze any talk of‘advanced status’ for Tunisia. The op-portunities enshrined in that statusThe dramaticshould however be dangled in frontevents in Tunisiaof the new Tunisian authorities, if andshould elicitwhen their grip on power is consolidat-a profounded in a peaceful and orderly manner andreflection withineurope about howlegitimized by free and fair elections.This also leads to our central re-commendation. The dramatic eventsin Tunisia, whose contagion is nowspreading to other North Africancountries such as Egypt, Algeria andMauritania, should elicit a profound reflection withinEurope about how the EU portrays itself as an actor, andhow it is perceived by its counter-parts. This is not about repeatingthe inward-looking exercise that hasThe reflectioncharacterized the EU institutionalshould primarily bedebate over the past half-decade. Theabout the prioritiesreflection should primarily be aboutand values thatthe priorities and values that the EUthe eU aims toaims to promote, and about howpromotethese should be promoted. The on-going review process of the EuropeanNeighbourhood Policy is the most immediate occasion tobegin such reflection. The review, which will culminatewith a new Commission document inthe spring of 2011, should explicitlyThe ongoingacknowledge the Tunisian events andreview of the eNpdetail which aspects of the existingshould explicitlyEU toolkit should be emphasized andacknowledge theif necessary strengthened, to supportTunisian eventspost-Ben Ali Tunisia.the eU portraysitself as an actor,and how it isperceived by itscounterparts

WHicH Way aHead? Along with all other Western actors, the EU misread thesituation in Tunisia. However, the fact that the EUapproach did not work as expected should not lead now toa hasty overhaul of the existing policy framework.When confronted with daunting arrays of challenges suchas those now arising from North Africa, conventional wis-dom among independent observers would have it that theEU has tough choices to make. Brussels should either ‘pull’the partner governments more decisively by relaxing its re-strictive visa regime and opening up its market, especiallyin sensitive areas. Alternatively, the argument goes, the EUshould ‘push’ more vehemently for democratic reforms byimposing its rules.We believe that a more effective EU po-The eU’s policylicy, however deeply desirable, shouldtoolbox is compre-not be based on such stark choices.hensive and detailedThe EU’s policy toolbox is comprehen-enough to ensure asive and detailed enough to ensure astrong support forstrong support for the reform process.the reform processThe guiding principles of governancereform such as accountability, the ability of a govern-ment to implement policies and the quality of the publicservices, are all enshrined in the existing policy frame-

�

DIIS polIcy brIef

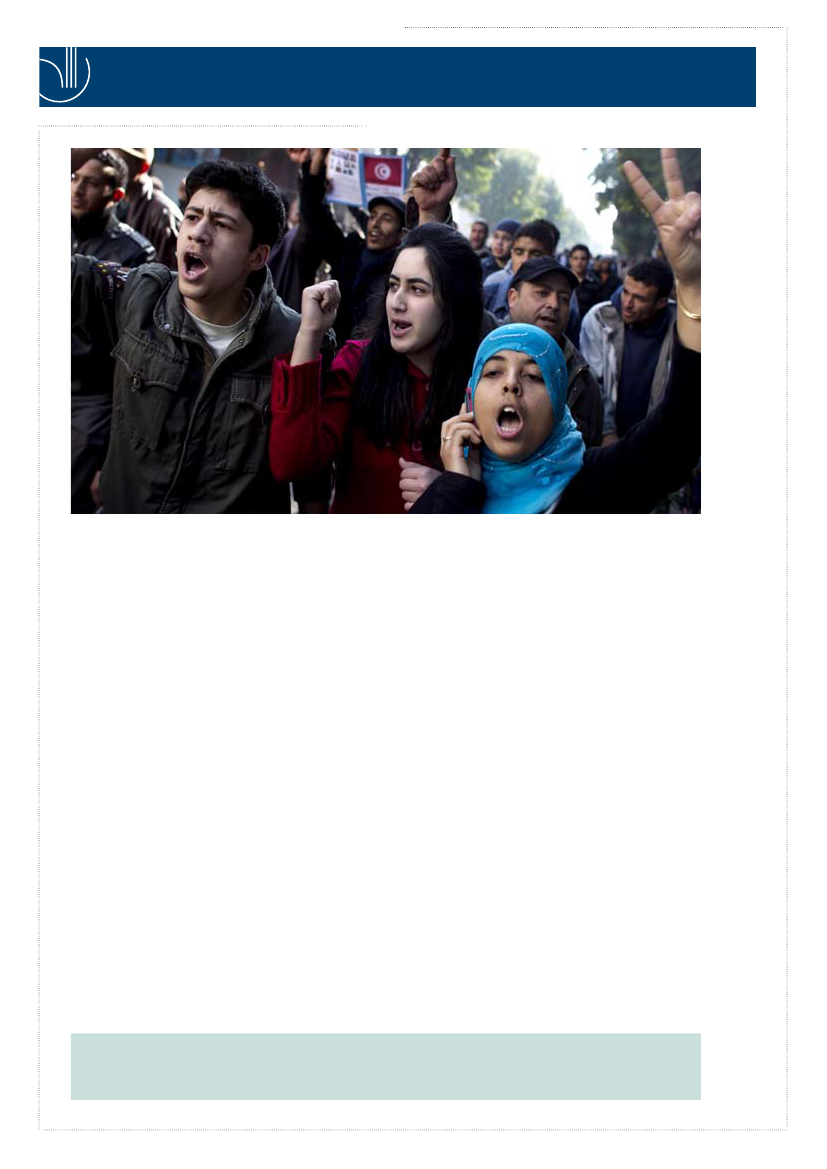

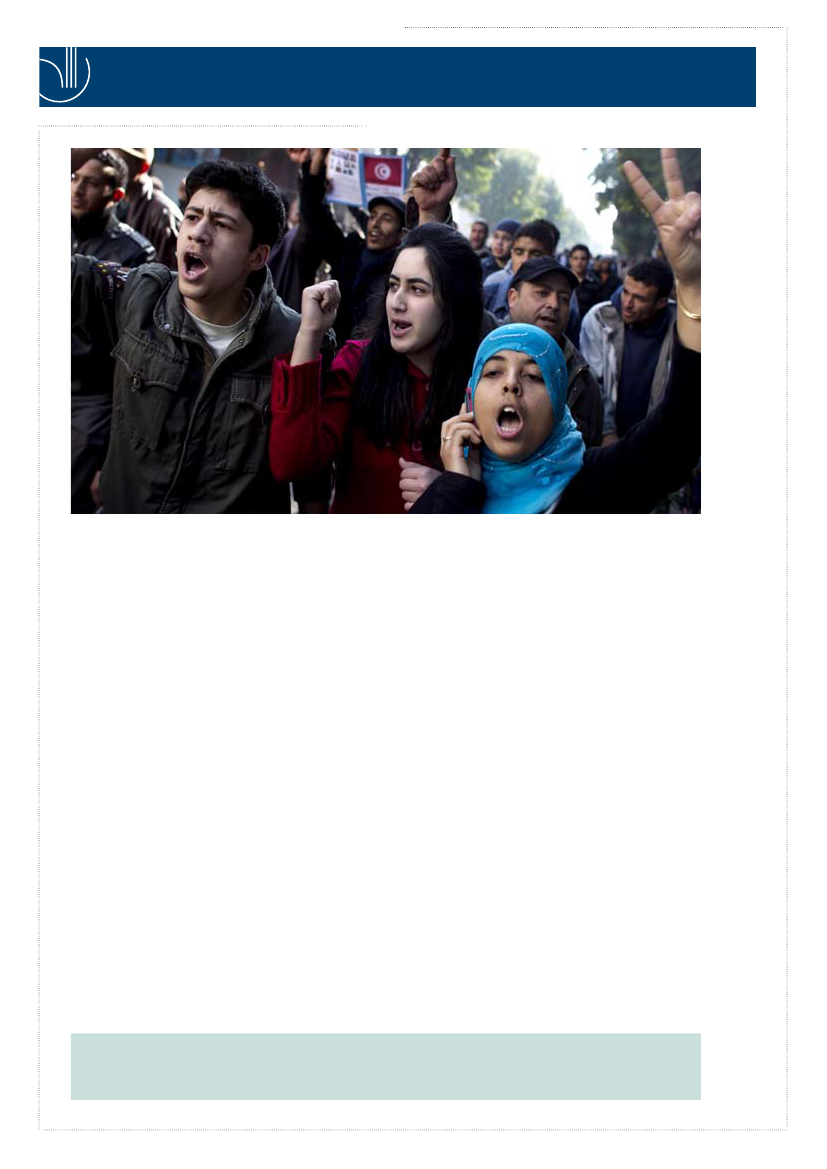

Demonstrations in Tunis, 17 January 2011 (� Niels Hougaard/POLFOTO)

Moreover, EU policy-making, espe-cially its foreign policy, is never aTunisia may wellpurely technocratic exercise. Evenend up becomingnegligible technical measures are in-the first test casefor post-lisbon eUherently political, as they are tied towhat the European integration projectforeign policy.is supposed to stand for. The govern-ments of all EU Member States shouldcontribute to this goal by supporting politically anddiplomatically the measures that the European Commis-sion will propose, and refraining from launching paral-lel initiatives. Following the Foreign Affairs Council ofJanuary 31st, they should channel this support and dele-gate action to High Representative Catherine Ashton.Also, in this respect, Tunisia may well end up becomingthe first test case for post-Lisbon EU foreign policy.

diis ¶ danisH institUte foR inteRnational stUdiesStrandgade 56, DK-��0� Copenhagen, Denmark ¶ tel: +�5 �� 69 87 87 ¶ Fax: +�5 �� 69 87 00 ¶ e-mail: [email protected] ¶ www.diis.dk

�