Forsvarsudvalget 2010-11 (1. samling), Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2010-11 (1. samling)

FOU Alm.del Bilag 34, UPN Alm.del Bilag 29

Offentligt

DEFENCE ANDSECURITY213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1Original: English

NATO Parliamentary Assembly

SUB-COMMITTEE ONTRANSATLANTIC DEFENCE ANDSECURITY CO-OPERATION

SECURITY AT THE TOP OF THE WORLD:IS THERE A NATO ROLE IN THE HIGH NORTH?

REPORT

RAGNHEIDURARNADOTTIR (ICELAND)RAPPORTEUR

International Secretariat

14 November 2010

Assembly documents are available on its website, http://www.nato-pa.int

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

i

TABLE OF CONTENTSI.II.INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1NEW OPPORTUNITIES FROM A CHANGING CLIMATE ..................................................... 2A.SHIPPING LANES........................................................................................................ 2B.ACCESS TO POSSIBLE ENERGY RESERVES .......................................................... 3C.FISHING....................................................................................................................... 4D.TOURISM ..................................................................................................................... 4NATIONAL ARCTIC POLICIES IN AN EVOLVING GEOPOLITICAL SITUATION ................ 4A.RUSSIA ........................................................................................................................ 5B.CANADA....................................................................................................................... 7C.THE UNITED STATES ................................................................................................. 8D.NORWAY ..................................................................................................................... 8E.DENMARK.................................................................................................................... 9F.ICELAND .................................................................................................................... 10G.OTHER NATIONS/ACTORS....................................................................................... 11TERRITORIAL DISPUTES AND LEGAL/INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS........................ 12A.ARCTIC OCEAN DISPUTES ...................................................................................... 12B.UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA ................................ 12C.THE ARCTIC COUNCIL ............................................................................................. 13MANAGING CHANGE IN THE ARCTIC: IS THERE A ROLE FOR NATO? ......................... 14A.A ROLE FOR NATO PROPER? ................................................................................. 15B.CO-OPERATION WITH RUSSIA? .............................................................................. 16CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................................. 17

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

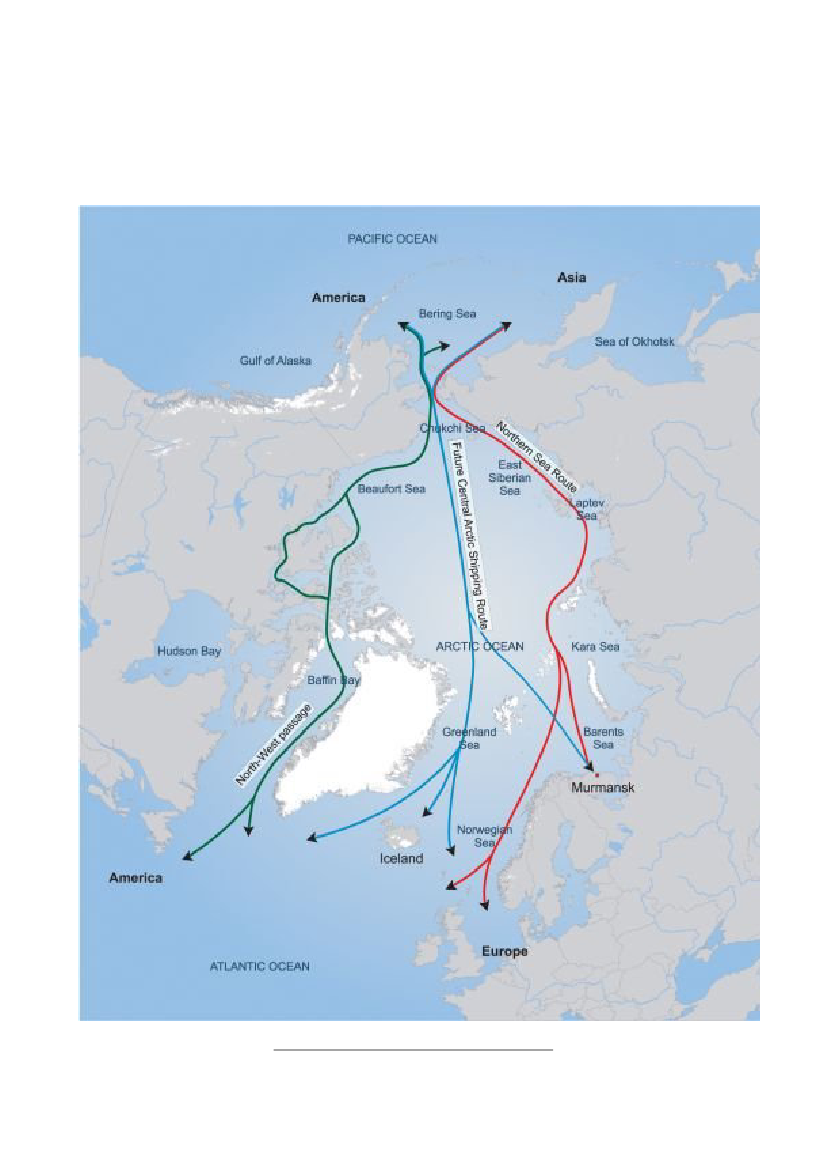

APPENDIX: MAP OF POSSIBLE SHIPPING ROUTES IN THE ARCTIC ..................................... 19

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

1

I.

INTRODUCTION

1.The Arctic is a region undergoing major change. A retreating ice shelf is progressivelyopening access to activities such as commercial transit and resource exploration for longer periodsof the year. This increased accessibility is presenting significant economic opportunities, whichmust be underpinned by a stable geopolitical framework that will ensure that any emergingtensions are addressed and that necessary co-operative arrangements on issues such as disasterconsequence management and search and rescue are in place.2.This report, prepared for the Sub-Committee on Transatlantic Defence and SecurityCo-operation, provides background information on the changes occurring in what some nationsrefer to as ‘the High North’ and others simply as the Arctic – what your Rapporteur has chosen torefer to in the title as ‘the top of the world.’ It explores potential flashpoints between regionalactors, as well as those States’ Arctic strategies, and describes the network of arrangementsalready in place to address various challenges in the region. Finally, the report explores whetherthere is a basis for increased attention and/or involvement in the region by NATO.3.The report draws not only on published reports and briefings received by Assembly membersin meetings from Canada to Norway to the United States between 2008 and 2010, but also oncomments received during our spring Session in Latvia in May 2010. This update also includesinformation gathered on this Sub-Committee’s visit to Denmark, Greenland and Iceland in latesummer of 2010.1*****4.From the outset, your Rapporteur seeks to emphasize her view that international effortsshould aim first and foremost at ensuring that the opportunities presented by changing conditionsin the Arctic be preserved in a spirit of responsible stewardship, rather than being lost throughself-defeating competition or exclusion.5.Geopolitical competition was the prominent feature of the Arctic region during the Cold War,when nuclear deterrence strategy elevated its strategic importance. Any intercontinental ballisticmissile exchange would have employed Arctic air space, while nuclear submarines typically pliedArctic and Nordic waters. The Arctic was seen as a vital sea lane, with the gap betweenGreenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom constituting a key strategic line of defence for theAlliance. Intelligence stations in Greenland, Norway and Canada closely monitored Soviet militaryactivity. When the Cold War ended, this region soon slipped off the political radar, and as itsstrategic function diminished, NATO largely pulled back its forces and bases. One notable examplewas the 2006 withdrawal of U.S. forces from the Icelandic base in Keflavik, which was home toMaritime Patrol Aircraft, rescue helicopters and fighter aircraft operating in the far North Atlantic.6.Today, global warming, demographic changes and resource scarcity are resuscitatingpolitical attention. The increasing strategic importance of this part of the world and its greateraccessibility because of climate change has concurrently raised the attention paid to it in policy andacademic circles. The region has seen increased military activity such as the development andfielding of new military assets and facilities; symbolic actions such as flag-planting on the oceanfloor; and the issuing of strategic documents calling for the defence of national interests. Actorssuch as China and the European Union have also demonstrated increasing interest in accessingArctic resources and participating in regional institutions.

1

A detailed report on the Sub-Committee’s 2010 mission to Denmark, Greenland, and Iceland is available on theNATO PA’s website, http://www.nato-pa.int/Default.asp?SHORTCUT=2209

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

2

7.For the moment, the Arctic has rightly been characterized by Norwegian Prime MinisterJens Stoltenberg as “High North, low tension”. However, whether it will continue to becharacterized primarily by a dynamic of co-operation or one of competition in the years to come isnot yet clear. The increasing stew of activities, including increased maritime traffic, fishing, militaryactivity, and resource exploration, exploitation and transport, calls for proactive engagement inorder to avoid potential geopolitical tensions and ensure that the capabilities, norms and networksare in place to address any possible contingencies.

II.

NEW OPPORTUNITIES FROM A CHANGING CLIMATE

8.What we refer to as the Arctic is the region around the North Pole and includes the ArcticOcean (which overlies the North Pole) and parts of Canada, Greenland (a part of the Kingdom ofDenmark), Russia, the United States (Alaska), Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Finland. Broadlyspeaking the Arctic region can be defined as the area north of the Arctic Circle (66�33´N).9.Climate change is having consequences on the Arctic Circle as average temperatures in theregion are rising. A report issued in July 2010 by the U.S. Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration said that average global temperatures from January to June 2010 have been thewarmest since records began in 1880.2As a result of rising temperatures, the Arctic ice is gettingthinner, melting and rupturing. Indeed, the polar ice cap as a whole is shrinking – by as much as30% in the last 30 years, according to the Danish Defence Command’s Rear AdmiralLars Kragelund.10. As research scientist William Chapman has pointed out, the polar pack ice has historicallybeen both a blessing and a curse to Arctic nations, providing protection along their northernborders from enemy naval threats, while at the same time inhibiting trade and commerce alongthose same sea routes. However, the changing climate is turning this situation on its head,presenting unique opportunities for navigation and commerce and unprecedented challenges tocommunities and nations bordering the pristine environment.311. At a local level, the melting of Arctic ice and the rising temperatures are changing vegetationpatterns and having an impact on animal and fish species, potentially influencing the huntingculture of natives of the region.12. Beyond these important local concerns, however, the changing climate has attractedattention due to extraordinary interest in the potential for new shipping lanes through the Arctic, aswell as the likelihood of major untapped reserves of oil and gas.

A.

SHIPPING LANES

13. A significant implication of the receding polar ice has been the appearance of waterwaysprogressively replacing the ice fields [seeAppendix for a map of these routes].In 2007, 2008 andagain in 2009, the Northwest Passage, broadly describing the route north of Canada between theNorth Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, was open for two weeks, and scientists are makingpredictions of ice-free Arctic summers as early as 2013.4The Northern Sea Route along Russia’scoast has seen similar ice changes.

23

4

“Press Release: June 2010 Global State of the Climate – Supplemental Figures and Information,” NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 15 July 2010.William L. Chapman, ‘Arctic Climate Change: Recent and Projected’,Bulletin of the Program and Arms control,Disarmament, and International Security,University of Illinois, Autumn 2009.Predictions range from 2010 to 2030. Ebinger and Zambetakis, ‘The geopolitics of Arctic melt,’InternationalAffairs85: 6, 2009 p. 1216.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

3

14. These increasingly navigable waterways may have a dramatic impact on global shipping byopening sea routes between Europe and Asia that are thousands of miles shorter than the existingones. Indeed, according to Danish defence officials, new shipping lanes could reduce the traveldistance between Rotterdam and Yokohama by 40%, and from Rotterdam to Seattle by 25%.15. Shipping lanes through the Arctic would also avoid the dangers of piracy (such at that in theGulf of Aden) and mean lower shipping costs. The shortened trips between Europe and the Pacificcould reduce emissions and energy consumption, increase trade and diminish pressure on themain transcontinental navigation channels.16. Demonstrating the feasibility of using the Arctic for global shipping, in September 2009 twoGerman commercial ships, accompanied by two Russian icebreakers, successfully sailed theNorthern Sea Route through the Northern Passage and delivered goods to Japan, South Koreaand Russia. This route reportedly shortened their journey by 4,000 km.5In September 2010, aRussian vessel became the first commercial super-tanker to survive the treacherous Northern Searoute.17. And yet, some analysts believe enthusiasm for new shipping opportunities may beexcessive. Many suggest that the need to reinforce ships using Arctic waters, coupled with thedifficulties and expense of obtaining insurance for such navigation, are likely to make the costs ofsuch activity exorbitant.6Other obstacles include restrictions on ship size due to shallowpassages; and the inexistence of suitable harbour facilities along the Northwest Passage, shouldships require repair. Some analysts therefore question whether the Arctic shipping lanes really are‘shorter’ in any meaningful way than existing transit routes.7

B.

ACCESS TO POSSIBLE ENERGY RESERVES

18. Shipping is only one of several economic interests at play in the Arctic. Estimates suggestthat the Arctic zone may contain up to 25% of the world’s oil and gas reserves.8In a 2009 report,the United States Geological Survey estimated that over 90 billion barrels of natural gas liquids arelocated in the Arctic (84% of which could potentially be found in offshore areas). Most of theprojected reserves are located in waters less than 500 meters deep and will likely fall within theuncontested jurisdiction of one Arctic Ocean coastal State or another.919. The impact of climate change in the Arctic, coupled with technological advancements inoffshore extraction and rising energy costs, could make extraction of these resources moreattractive. While most reserves appear to be contained in the littoral States’ undisputed ExclusiveEconomic Zones (EEZ), and extraction remains a costly and uncertain proposition, Arctic countries

5

67

8

9

Navigation depends not only on the amount of sea ice in the region, but also on how well equipped the vesselsare to deal with ice themselves; such ships are more expensive to build and procure and they burn much morefuel. Also, shippers must beware of temperature variations, which could create dangerous conditions andtemporarily close passages. See Daniel Fata, ‘Arctic Security: the New Great Game?’,Halifax InternationalSecurity Forum,Nov. 2009, p. 2 and p. 10.Jean-Francois Minster, “L’Arctiquesans la banquise?” (‘The Arctic without the Icefields?’),Politiqueinternationale,no. 125, Autumn 2009.See, for example, Svend Aage Christensen, ‘Are the northern sea routes really the shortest?’, Danish Institute forInternational Studies, March 2009.Apparently, the Arctic accounts for some 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil resources, some 30% of the world’sundiscovered natural gas reserves and some 20% of undiscovered natural gas liquids in the world. The Arcticalready produces almost 10% of the world’s known conventional petroleum resources today. Douglas Duncan,U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Department Of The Interior, Statement Before The Committee On NaturalResources, Subcommittee On Energy And Mineral Resources, June 4, 2009Michael Byers, “Conflict or Co-operation: What Future for the Arctic?”, in “Swords and Ploughshares – GlobalSecurity, Climate Change and the Arctic,” Autumn 2009, p.18.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

4

are likely to continue seeking to secure their potential long-term interests over strategic finds in thearea.20. The announcement in late summer 2010 that a Scottish company had found signs of gas offthe western coast of Greenland raised expectations that the area held great potential forexploration and extraction of natural resources. Environmental groups warned of the risks of suchactivity in the challenging and pristine Arctic region, suggesting that an oil spill could bedevastating and impossible to remedy in winter conditions.

C.

FISHING

21. Fishing stocks are also a highly valued resource that may become increasing available forexploitation through the newly navigable waterways. Large commercial fisheries exist in the Arctic,including in the Barents and Norwegian Seas north of Europe, the Central North Atlantic offGreenland and Iceland, and the Newfoundland and Labrador Seas, off north-eastern Canada. Thedecline of summertime sea ice is expected to expand areas suitable for fishing and to allow anorthward migration of species of fish not previously found in the region, potentially attracting bothsanctioned and ‘rogue’ fishermen.

D.

TOURISM

22. The potential for increased Arctic tourism has also drawn attention and concern from someofficials. The receding waterways have opened the area to greater numbers of visitors keen toexperience the region’s unique natural and cultural offerings. For example, 42 cruise ships touredthe waters off the coast of Greenland in 2010 (some several times); the largest of these carried asmany as 4,200 passengers.23. Danish defence officials are concerned, however, about the dangers of Arctic travel for cruiseships that are often unprepared for local conditions and travelling in uncharted waters. Any rescueoperation would rely on the extremely limited means deployed in the area, and would bedramatically complicated by the vast Arctic geography and harsh climate. Several incidents inwaters off Antarctica prompted the International Maritime Organization to ban the use andtransport of heavy fuel oil on ships operating in the Antarctic.10The ban is scheduled to come intoeffect in 2011, and could significantly reduce Antarctic tourism because large cruise ships aredependent on heavy oil.11

III.

NATIONAL ARCTIC POLICIES IN AN EVOLVING GEOPOLITICAL SITUATION

24. The opportunities described above have brought renewed attention to the actions of littoralstates in the Arctic, as well as to long-running territorial disputes which could take on greatersignificance in the context of emerging economic interests.25. The region has undeniably seen increased military activity by the littoral states, againdemonstrating its growing strategic importance. This has included nations acquiring new navalassets; an increased frequency of patrols; and calls for demonstration of more visible and capable‘presence’ in the Arctic. Specific examples include Canadian plans for a military training base anddeep sea docking facility in the Arctic, Norwegian plans to purchase five Aegis-equipped frigates,and Russian plans to build 13 submarines.12

101112

Gene Sloan, “Heavy-fuel ban forces large cruise ships out of Antarctic,” USA Today, 2 April 2010.Libby Zay, “Large Cruise Ships Banned in Antarctica,” Aol Travel, 2 April 2010.“Arctic Security: Neither a Great Game nor a Scramble,” Matthew Willis,RUSI Newsbrief,January 2010, p. 22.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

5

26. This section of the report will therefore detail the increasing activities of states in the Arctic,as well as the strategies they have laid out for their intents in the region.

A.

RUSSIA

27. No State’s actions in the Arctic in recent years have received more attention than those ofRussia. This was especially true in August 2007, when a Russian deep-water submersiblereportedly planted a titanium flag on the North Pole seabed 4,300 meters below the ice-coveredsurface of the Arctic Ocean. “The Arctic is ours,” lead explorer and Russian parliamentarianArtur Chilingarov proclaimed at the time.13In a similar, yet less symbolic, move to claim territory,Russia has affirmed that the 1,240-mile underwater Lomonosov Ridge in the Arctic is connected toits East Siberian region.1428. A general increase in Russian military activity, including Russian naval exercises anddeployments such as patrolling of Arctic waters by the Russian Northern Fleet, was confirmed byNorwegian Foreign Minister Jonas Gahr Store, who told Assembly members that "Norway hasbeen observing an expansion of Russian activities in its northern territories that involve warships,planes and its submarine fleet operations for some time.”29. This assertiveness has also manifested itself in Icelandic airspace. In August 2007, Russiarenewed training sorties of strategic bombers over the Arctic (across the Barents Sea into theNorwegian and North Seas) that had been suspended after the end of the Cold War. Since thedeparture of the US military from Iceland in September 2006, Russian military planes have flownthrough NATO’s air surveillance space around Iceland as many as 64 times without following therules of international airspace such as prior notifications of flight plans.30. Russia has a unique stature in the High North: in terms of geography, Russia representsalmost half of the latitudinal circle. Russian Minister of Regional Development Viktor Basarginrecently underlined the importance of the Arctic for Russia: the region accounts for 14 % ofRussia’s GDP and 25 % of the country’s exports. It holds 80 % of Russia’s natural gas reserves,90 % of its nickel and cobalt reserves and 60 % of its copper, as well as potential undiscoveredreserves under the sea bottom. Russia is in the process of producing a new concept for strategicdevelopment of the Arctic, moving from an approach which focused upon preserving resources forfuture generations to one of exploiting these resources.1531. The country has also declared its intent to defend those interests: a major policy paperreleased in March 2009 revealed plans to develop Arctic military formations to defend Russianinterests on a continental shelf it projected to become the nation's "leading resource base" by2020.16The strategy emphasizes the region’s importance to Russia’s economy as a major sourceof revenue, mainly from energy production and profitable maritime transport.32. Federation Council member Vyacheslav Popov, former Chief Commander of the NorthernFleet, described the new Arctic forces as largely made up of capabilities existing in the Northernand Pacific Fleets as well as in military districts that border the Arctic Ocean, in addition to newborder guard facilities and modernized airfields nearby. Russian authorities underscore that thesecapabilities are primarily intended to combat terrorism at sea, smuggling, and illegal migration, andto protect aquatic biological resources. The Federal Security Service is to play a central role inprotecting national interests in the region.13

141516

“Cold Calling: Competition heats up for Arctic Resources,” Mark Galeotti,Jane’s Intelligence Review,October 2008.“Climate Change and National Security,” Pierre Claude Nolin, Special Rapporteur, NATO PA, 17 April 2009.Barents Observer, 6 October 2010."The Foundations of State Policy of Russian Federation in Arctic Area for the Period Up to 2020 and Beyond", 27march 2009; released by the Security Council of the Russian Federation

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

6

33. Russia has also announced plans to upgrade its ice-breaking fleet (already the largest in theArctic), to step up its over-flight patrolling and to increase investment in mapping and surveillanceof the Russian Arctic.17In July 2010, Russia launched a 90-day scientific expedition to clarify theouter border of the continental shelf.18It also planned to establish ten Arctic rescue centresintended to monitor and prevent emergency incidents along the Northern Sea Route.1934. Even as Russia's foreign minister expressed concern about NATO's Arctic intentions andNorway's effort to strengthen its High North defences in March 2009 after a major NATO exercisein northern Norway, Russia held its own Arctic exercise in the northern Barents Sea, in whichsupersonic Tu-160s and older Tu-95 bombers dropped precision bombs and missiles.2035. Some observers linked such activities to the challenging rhetoric emanating from someMoscow voices. For example, Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev argued in agovernment publication that "the United States of America, Norway, Denmark and Canada areconducting a united and coordinated policy of barring Russia from the riches of the shelf… It isquite obvious that much of this does not coincide with economic, geopolitical and defence interestsof Russia, and constitutes a systemic threat to its national security."2136. Most western officials express little concern regarding Russian actions, firstly because, asNorwegian Foreign Minister Jonas Gahr Store put it, “we do not see this build-up as a threat toNorway. It is Russia's right." NATO’s former Secretary General, Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, alsoplayed down Russian activities in the region, stating in January 2009 that Russian actions in theArctic did not constitute a threat or even a nuisance.22Similarly, Canadian defence officials toldthe Sub-Committee in September 2009 that, while recent Russian activities in the region had beenextensively covered by the media, Canada saw Russian behaviour as non-threatening, andcontinued to believe it was in the Russian interest to keep tensions low in the Arctic.37. Furthermore, Russian authorities tend to underscore their strategy’s co-operative characterby emphasizing the need to preserve the Arctic as a zone of peace and co-operation, andunderlining the role of regional bilateral and multilateral co-operation. Official documentsemphasize the primary role of international law and multilateralism in international relations andmore especially in the High North.38. A recent illustration of Russia’s co-operative approach was the April 2010 resolution of aforty-year dispute between Arctic neighbours, Norway and Russia. The preliminary delimitationagreement for the Barents Sea splits the previously disputed 175,000 square kilometre Grey Zoneequally between the two countries. It is described by officials on both sides as fair and in line withthe United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS -discussed in more detailbelow).23Many observers see the Barents Sea compromise, and surrender of a significant portionof the Russian claim, as concrete evidence of Russia’s increasingly co-operative attitude regardingthe region.24

17

181920

2122

2324

Klaus Dodds, “From Frozen Desert to Maritime Domain: New Security Challenges in an Ice-free Arctic,”Bulletin ofthe Program and Arms control, Disarmament, and International Security,University of Illinois, Autumn 2009.Elena Kovachich, “Russia clarifies its border on the Arctic shelf,”The Voice of Russia,20 July 2010.“Russia to launch Arctic rescue centre,” Barents Observer, 8 June 2010.David Pugliese and Gerard O'Dwyer, “Canada, Russia Build Arctic Forces; As Ice Recedes, Nations Manoeuvrefor Control,”Defense News,6 April 2009.Ibid.James G. Neuger, “NATO Sees Little risk of Arctic Confrontation as Ice Caps Melt,”Bloomberg,29 January 2009.Bjørn S. Jahnsen, “Agreement reached between Norway and the Russian Federation in the negotiations onmaritime delimitation,” Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 27 April 10.Randy Boswell, “Norway, Russia strike deal on Arctic boundary,” CanWest News Service, 28 April 2010.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

7

B.

CANADA

39. The Canadian High North is a vast region of approximately 10 million km2(40% of Canada’slandmass), characterized by extremely harsh weather conditions. Canada has the second-largestArctic coastline. While confirming that climate change was having an impact in the area, principallybecause of the lengthening of the period during which the melting of ice allows an increase inshipping through previously inaccessible regions, a Canadian national defence official told ourSub-committee in September 2009 that he rejected the idea that a “mad rush for territory" wasunderway in the Arctic.40. Canada sees improved accessibility of the region leading to increased activity in severalsectors, including maritime and air traffic, mining, tourism, and re-supply of remote outposts.Given the increased amount and diversity of traffic, the likelihood of an incident requiringsearch-and-rescue or environmental consequence management has increased, Canadian defenceofficials told the Sub-Committee. Canada is also concerned about the risk of increasedinvolvement of organized crime, particularly in the trafficking of valuable gems (of which Canada isthe fourth global producer).41. In security terms, Canada sees no conventional military threat in the Arctic. Even so,Canada is investing in additional capabilities and presence in the Arctic to meet new challenges,although defence officials insist this does not constitute any kind of “militarization”.42. Indeed, Canada’s government has clearly put the High North at the top of its policy agenda inrecent years. In July 2007, Canada’s Prime Minister Stephen Harper suggested that, "Canada hasa choice when it comes to defending our sovereignty over the Arctic - we either use it or lose it.And make no mistake - this government intends to use it."2543. Harper announced plans to launch a new fleet of up to eight Arctic off-shore patrol ships, aswell as to establish an Arctic training base in Resolute Bay and a deep-water berthing andrefuelling facility at Nanisivik (plans reportedly delayed by the global economic crisis). Canadaalso announced its intent to create a 500-strong army unit – four companies of 120 troops apiece –for Far North operations, and held its largest-ever military exercise in the region. Defence officialsalso told the Sub-Committee that the exploitation of space systems by Canada would be critical toensuring a comprehensive picture of activities unfolding in the Arctic, especially in northern waters.44. In July 2010, the Canadian Coast Guard began implementing the Northern Canada VesselTraffic Services Zone, which requires large vessels moving through the Northwest Passage andthe Canadian Arctic to register with the Coast Guard.26The program is intended to prevent Arcticpollution and improve search-and-rescue capabilities; however, it has been sharply criticised by theshipping industry.2745. Native populations feature prominently in Canada’s northern thinking, perhaps becauseCanada has the largest indigenous population of all the Arctic nations. Canada has pursuedregional agreements to protect these populations, such as an agreement to examine co-operativeprojects with Indigenous Peoples, co-signed by the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs andNorthern Development and the Russian Ministry of Regional Development.

25

2627

David Pugliese and Gerard O'Dwyer, “Canada, Russia Build Arctic Forces; As Ice Recedes, Nations Manoeuvrefor Control,”Defense News,6 April 2009.Randy Boswell, “Canada will track ships sailing Arctic waters,” CanWest News Service, 23 June 2010.Leo Ryan, “Canada to get tough with Arctic rules offenders,” Lloyd’s List, 8 July 2010.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

8

C.

THE UNITED STATES

46. The United States Arctic Region Policy, published in January 2009, emphasizes that the U.S.considers itself an Arctic nation with broad and fundamental national security interests there. Thispolicy represents a turnaround from what some observers saw as the disinterest of the BushAdministration in Arctic security issues demonstrated by the unilateral withdrawal of U.S. forcesfrom the Keflavik air base in Iceland in 2006.47. The U.S. Arctic Region Policy focuses primarily on security, while also mentioning boundaryissues, scientific research, transportation, energy and environmental protection. It calls forincreased infrastructure and security assets in the region. The U.S. prioritizes freedom of the seas,navigation and overflight, as well as other security concerns, such as missile defence and earlywarning and regional deployments of sea and air systems for strategic sealift, strategic deterrenceand maritime security operations.28Indeed, the strategic importance of the Arctic for the U.S. hasbeen recently underlined by its missile defence plans, which have led to an upgrading of theearly-warning radar at Thule in Greenland and the deployment of missile interceptors atFort Greely in Alaska.2948. While safeguarding its prerogative to operate independently in the Arctic, the currentadministration emphasizes the need for international co-operation in the region, in particular withinthe context of the Arctic Council. U.S. Deputy Secretary of State James Steinberg said inSeptember 2010 that “it should surprise no one today that we lack the forums, bodies, rules andnorms to deal with a cross-cutting challenge such as this. So we need to reinforce and build on themechanisms already in place, like the Arctic Council, the UN process and our bilateralrelationships, to build a more effective strategy going forward.”3049. The Obama Administration also supports ratification of the UN Convention on the Law of theSea (UNCLOS); indeed, in the wake of the Gulf of Mexico oil spill, President Obama issued anexecutive order regarding “Stewardship of the Ocean, Our Coasts, and the Great Lakes,” whichestablishes a National Ocean Council and sets the goal of the Treaty’s ratification.31DeputySecretary of State Steinberg emphasized the administration’s intent to urge the Senate to ratify theUNCLOS, because “becoming a signatory not only lets us lead by example but supports our ownefforts there as well.”32The Treaty’s priority on the Senate’s crowded legislative agenda, however,remains unclear.

D.

NORWAY

50. The situation in the High North is at the top of the Norwegian government’s policy agenda,Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg told Assembly members in May 2009, and Norway hassought to ensure that NATO also increased its focus on this issue.51. Indeed, Norway’s Arctic Strategy, published in March 2009, aims for a strategy of sustainablegrowth and development in the High North. Norway sees regional challenges and opportunitiesthrough a very broad lens: education and research, environmental and resource management,safety and emergency response systems, energy, fisheries, tourism and other economic activities,health, culture and gender equality. In order to avoid tensions, Norway places strong emphasis onco-operation with regional partners, including and especially with Russia.Norway sees28

293031

32

Ingrid Lundestad, “US Security Policy and Regional Relations in a Warming Arctic,” University of Illinois,Autumn 2009, p. 16.Margareth Blunden, “The New Problem of Arctic Stability,”Survival,51:5, Oct-Nov 2009, pp. 121-142.Speech delivered at the the 8th IISS Global Strategic Review, 11 September 2010.“Executive Order: Stewardship of the Ocean, Our Coasts, and the Great Lakes,” The White House: Office of thePress Secretary, 19 July 2010.Speech delivered at the the 8th IISS Global Strategic Review, 11 September 2010.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

9

co-operation across several institutions as useful in order to maintain dialogue, even when anygiven forum finds itself deadlocked on a particular issue.52. The Norwegian strategy prioritizes exercising Oslo’s authority in the High North in a credible,consistent and predictable way; leading international efforts to develop knowledge in and about theregion; further developing regional people-to-people co-operation; ensuring stewardship of theregion’s environment and natural resources; and safeguarding the livelihoods, traditions andcultures of indigenous peoples. Oslo also seeks to provide a suitable framework for furtherdevelopment of petroleum activities in the Barents Sea, and will seek to ensure that these activitiesboost competence in Norway in general and in northern Norway in particular, and foster local andregional business development.53. Finally, Oslo’s strategy emphasizes strengthened co-operation with Russia.Onemanifestation of this policy is the significant Norwegian investment in the development of theShtokman natural gas field, located in the Russian sector of the Barents Sea. Moreover, followingthe April 2010 Barents Sea delimitation compromise(described in paragraph 38 above),it is likelythat the co-operation between the two countries will continue to grow.3354. In a concrete demonstration of its priorities, in August 2009 Norway moved its OperationalCommand Headquarters north to become the first country to site its military command leadershipin the Arctic. The purchase of five new Arctic-capable frigates is said to be the most expensivearmaments project in the country’s history.34

E.

DENMARK

55. The Arctic has become one of Denmark’s main foreign policy areas, the delegation learnedduring its visit to Copenhagen and Greenland in late summer 2010. Denmark has good reasons tofocus on the High North, according to the Danish Defence Command’s Rear Admiral Kragelund.The first is the fact that Greenland remains a part of the Kingdom of Denmark and Denmarktherefore has to ensure its defence, and enforce sovereignty on its territory.56. Denmark’s seafaring tradition is another factor driving its High North policy: given that 90% ofworld trade is moved by ship, and that 10% of this total is conducted by Danish-owned or operatedships, Denmark is directly concerned by developments affecting shipping in and through the Arctic.Finally, Denmark, of course, has a strong national interest in monitoring the development of naturalresource deposits and the heightened international interest that they have generated.57. In response to these interests, Denmark maintains six permanent installations in Greenland,and has committed a limited number of inspection vessels and air assets in order to perform arange of tasks from military defence and maintenance of sovereignty and surveillance, tohydrographic surveying and support to science missions. Danish defence forces are also taskedwith missions more commonly associated with Coast Guards, including search and rescue as wellas environmental disaster consequence management.58. The recently-agreed Danish Defence Agreement 2010-2014, a consensus document amongall major parties governing five years of defence budgeting and planning, contains a number ofArctic-related stipulations. It mandates a reorganization creating a unified Arctic Command bycombining the current Greenland Command and Faroe Command. Other measures the Agreementstipulates include the development of an Arctic Response Force (to be designated from existingcapabilities, not built from scratch), and a detailed risk analysis of the Greenlandic area as well asthe potential future tasks of the Danish Armed Forces there (including assessment of the Danish3334

“Norway and Russia agree on maritime delimitation,” Barents Observer, 27 April 2010.Margareth Blunden, “The New Problem of Arctic Stability,” p. 126.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

10

use of Thule Air Base) as the situation evolves. How these plans would be affected by budgetaryshortfalls was not yet clear at the time of writing.3559. Regional co-operation is a central focus of Danish policy in the Arctic, Defence MinisterGitte Lillelund Bech told this Sub-Committee; she pointed to the ”shared interest” in maintainingtensions low through international co-operation. Under Danish initiative the so called “Arctic five”(Denmark, Russia, U.S., Canada, Norway) was created in 2008 in order to provide a forum for thefive Arctic coastal states to discuss Arctic issues. Rear Admiral Kragelund explained that under theIlulissat Declaration, the ‘Arctic five’ had committed to address any disputes through existinginternational legal structures. Denmark also recently signed an agreement on deepened co-operation with Canada in the Arctic, including joint training. Kragelund suggested co-operationwith the United States was also quite close, in particular as regards the Thule Air Base.60. Danish defence officials expressed concern about the growing risk of an accident resultingfrom the increasing ship traffic along the coasts of Greenland, which are roughly the same size asthose of the United States. A total of up to five, relatively small Danish military vessels areavailable to respond to contingencies in these areas, and even these limited assets were notdesigned specifically for search and rescue but had been adapted to that purpose.

F.

ICELAND

61. This Sub-Committee visited Iceland in late summer 2010 to gather information on theIcelandic government’s views on the Arctic. Iceland is the only nation state whose territory isentirely in the Arctic, as commonly defined by the international community and the Arctic Council.In 2009, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Iceland published a comprehensive report of Iceland’sArctic co-operation and regional interests. The High North is one of the key priority areas ofIceland’s foreign policy. The Icelandic Coast Guard is responsible for Iceland’s coastal defenseand maritime search and rescue. Iceland's territorial waters are defended by recently modernizedships, planes and helicopters.62. Trends in the High North present clear economic opportunities for Iceland, which couldbecome a major transhipment hub for shipping and resource movement, for example. Iceland´sArctic policy places emphasis on security founded on close co-operation of all the states in theregion based on international law such as the UNCLOS, for solving all outstanding and futuredisputes in the Arctic. Environmentally sustainable resource development as well as preparednessagainst environmental threats and accidents in Arctic waters and search and rescue are of utmostimportance in Icelandic policy. Transportation of oil and gas must be closely monitored and thegrowing number of inadequately equipped ships in ice-infested areas is of great concern.63. There are also increasing signs of ‘hard’ security concerns in the High North, according toindependent security expert Tinna Vidisdottir.36While avoiding militarization was a worthwhilegoal, policymakers should not ignore the developing military-strategic situation in the region, whichis characterized by clear evidence of increased military interest, according to Mrs Vidisdottir.Iceland is especially concerned by the increased activity by Russian military aircraft in NATOairspace it monitors.64. Iceland believes these incursions underline the importance to the defence of Allied territoryand airspace of Iceland’s radar installations, of the logistical and personnel support it offers, and itswell-established direct links into NATO’s defence systems.

3536

“Danish defence sources expect military to postpone upgrades in Greenland,” BBC Worldwide Monitoring, 7 June2010.Until September 2010, Vidisdottir was the head of the recently-defunct Icelandic Defense Agency.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

11

65. Indeed, Iceland believes that the NATO Air Surveillance operations from its territory, in whichAllied air detachments patrol Icelandic (and thus NATO) airspace in several annual visits, havecontributed to NATO’s situational awareness of the Arctic. The Iceland-based radar systems(integrated into NATO’s Alliance-wide Integrated Air Defence System comprising sensors andcommand and control facilities) also help the Alliance maintain awareness of the region.

G.

OTHER NATIONS/ACTORS

66. Non-NATO members Sweden and Finland, of course, also play a significant role in theArctic. Former Norwegian Foreign Minister Thorvald Stoltenberg presented a report on Nordicforeign and security policy co-operation at an extraordinary meeting of the Nordic Foreign Ministersin February 2009. The report’s well-received proposals suggested that Nordic co-operation in thenorthern seas and the Arctic would be ‘highly relevant’. Specific measures proposed byStoltenberg include the establishment of a Nordic maritime monitoring system, contributing to acomplete overview of activity in the sea and on its surface; a Nordic Maritime Response Force,rescue co-ordination centre, and amphibious unit, with resources suitable for Arctic conditions; asatellite system for surveillance and communications by 2020; and other co-operation on Arcticissues, to include improvements in search and rescue capabilities and co-ordination.67. An additional ingredient in the ‘stew’ of activities in the Arctic is the interest of nations welloutside the region. Unsurprisingly, none have garnered more attention than China. Its interest inthe High North has been drawn by the potentially shorter shipping routes, the energy resources ofthe region, and heightened interest in climate change debates. China has sent officials to recentconferences in remote Arctic locations, and conducted four scientific expeditions to the regionsince 1999, the most recent of which occurred in July of 2010. China was also granted informalobserver status to Arctic Council meetings in 2007, and has sought the status of permanentobserver. Chinese investments in Iceland, including the construction of a new embassy, also testifyto its growing interest in the region.68. Another actor seeking permanent observer status with the Arctic Council is the EuropeanUnion, which most recently issued an Arctic policy document in December 2009. The main lines ofthe EU’s Arctic policy include: mitigating climate change; reinforcing multilateral governancethrough relevant international, regional and bilateral agreements, frameworks and arrangements,including the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea; ensuring EU policies respect the Arctic’sunique environmental characteristics and the needs of Arctic residents; and maintaining the Arcticas an area of peace and stability. The EU has welcomed Iceland’s possible accession as astrategic opportunity that would enable the EU to play a more active and constructive role and tocontribute to multilateral governance in the Arctic Region.69. In October 2008, the European Parliament (EP) considered the interests of the EU in theArctic and noted that three member States have substantial regional engagements (Denmark,Finland and Sweden) while another two (Iceland and Norway) are close partners through theEuropean Economic Agreement. Rather than promoting a ‘Law of the Sea’ approach, the EPsuggested that a new governance structure might be developed, which was more inclusive andless dependent on geographical proximity to the Arctic.37

37

Dodds, “From Frozen Desert to Maritime Domain: New Security Challenges in an Ice-free Arctic.” p. 14.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

12

IV.

TERRITORIAL DISPUTES AND LEGAL/INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS

70. Several longstanding territorial disputes exist in the Arctic; experts disagree on the likelihoodof any one of these disputes turning into a conflict, particularly in the context of newly accessiblenatural resource deposits.

A.

ARCTIC OCEAN DISPUTES

71. Canadian Defence officials briefed members of the Sub-Committee in September 2009 onCanada’s three discrete territorial disputes in the Arctic. These are with the United States,regarding a maritime boundary in the Beaufort Sea, with known oil and gas resources in thedisputed zone; again with the United States over whether the Northwest Passage is, as Canadaclaims, internal waters rather than a strait for international navigation, as claimed by Washington;and finally, with Denmark over ownership of Hans Island and the maritime boundary withGreenland in the Lincoln Sea.72. Russia and the United States also have an unresolved dispute regarding their maritimeboundary in the Arctic Ocean, Bering Sea, and northern Pacific Ocean. The U.S.-U.S.S.R.Maritime Boundary Agreement was signed in 1990 and was quickly ratified by the U.S. Senate in1991, following a decade of negotiations between the two nations. However, representatives in theRussian Duma maintain that the treaty is an unjustified, and perhaps a criminal, concession ofRussian territory and, thus, have not ratified the agreement.38While the agreement continues to beprovisionally enforced, prospects for an official diplomatic resolution remain dim because theUnited States maintains that it “has no intention of reopening negotiations.”39.73. Regional actors largely agree that, at this time, regional frameworks serve as an appropriatebasis to address these conflicts and that they are extremely unlikely to erupt into actual hostility.Further, some observers hope that the recent agreement between Norway and Russia regardingthe Barents Sea will be a catalyst for the resolution of other outstanding territorial disputes.40

74. The legal and institutional framework regarding Arctic issues is composed of two mainelements: the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and the Arctic Council. Otherorganizations, including the International Maritime Organization (IMO), and the BarentsEuro-Atlantic Council are also active, but in a secondary role.

B.

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA

75. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which entered into force in 1994, established atreaty regime to govern activities on, over and under the world’s oceans, and thus constitutes theoverarching legal framework for maritime matters in the Arctic region. The convention provides forimportant rights and obligations regarding the delimitation of the outer limits of the continental shelfand the protection of the maritime environment (which includes ice-covered areas, freedom ofnavigation, and maritime science research).

38

39

40

“Russian newspaper urges Bush, Putin to discuss US-Russian sea border,” BBC Summary of World Broadcasts:Vedomosti, Moscow, in Russian 26 September 2003, 27 September 2003.“Fact Sheet: Status of Wrangel and Other Arctic Islands; U.S. has ‘no intention of reopening discussion’ of the1990 Maritime Boundary Treaty,” U.S. Department of State: Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs,8 September 2009. .Maxime Bernier, “Canada’s Arctic Sovereignty,” Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence,18 June 2010.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

13

76. Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg, speaking to Assembly members in May 2009,neatly summarized the attitude of regional actors when he said that,“[A] legal framework for the Arctic is already in place. The Arctic is governed by theprinciples of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. We do not need a new,international legal regime for the Arctic. But need governments to come together to developpolicies and specific rules to manage the increasing human activity in the region.”77. Indeed, there is broad agreement on the centrality of the UNCLOS, as demonstrated by itsreaffirmation in the May 2008 Ilulissat Declaration, endorsed by representatives from Norway,Russia, Canada, the United States and Denmark. The declaration underlined the coastal States’agreement that the UNCLOS legal framework would establish extended continental shelf limits inthe Arctic, and that there was no need to develop a new comprehensive international legal schemeto govern the region.78. UNCLOS’ most relevant provisions in this sense are those giving the coastal Statessovereign jurisdiction over the resources, including oil and gas, of its continental shelf. CoastalStates are supposed to submit their claimed shelf limit to the UN Commission on the Limits of theContinental Shelf, which is tasked with reviewing such claims and recommending outer limits toeach coastal state’s continental shelf. This process was marked more by co-operation thantension or conflict, Canadian defence officials told our Sub-Committee.79. The Barents Sea compromise between Norway and Russia is likely to serve as the premiersuccess story of the UNCLOS framework.41The majority of the diplomatic heavy lifting wasaccomplished through bilateral negotiations, but in a joint statement released by the Russian andNorwegian Ministries of Foreign Affairs, both countries heralded the important role played byinternational law.4280. Full implementation of the Treaty by all interested parties in the Arctic will remain impossible,however, until the United States Senate ratifies UNCLOS, as described in paragraph 49 above.

C.

THE ARCTIC COUNCIL

81. The Arctic Council, founded in 1996, is a high-level intergovernmental forum to fosterco-operation and collaboration on issues such as sustainable development, environmentalprotection, and social well-being of indigenous communities. It touts its inclusion of the ArcticIndigenous communities in discussions focused on sustainable development and environmentalprotection. But in a geopolitical sense, it is most noteworthy for its inclusion of Russia (as well asother members Canada, Denmark [including Greenland and Faroe Islands], Finland, Iceland,Norway, Sweden and the United States) in a multilateral forum. The EU has sought to become apermanent observer of the Arctic Council, but was rejected in 2009 due to a dispute with Canadaover commerce in seal products.82. Examples of the Council’s work include a 2009 Arctic Marine Shipping Assessmentrecommending that the eight Arctic States harmonize search-and-rescue through pooled financialand technical resources. Other recommendations regard shipbuilding standards for Arcticnavigation (in co-operation with the IMO); improved navigation infrastructure such as charts andcommunications systems; development of a harmonized marine traffic awareness system;guidelines on oil and gas exploration; and recommendations on the sharing of technologiesnecessary in responding to environmental accidents under challenging Arctic conditions.4142

“Norway and Russia agree on maritime delimitation,” Barents Observer, 27 April 2010.Jonas Gahr Støre and Sergey Lavrov, “Joint Statement on maritime delimitation and co-operation in the BarentsSea and Arctic Ocean,” 27 April 2010.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

14

83. While participants agree that the Arctic Council is a useful and necessary institution, its criticssuggest that a major gap in its mandate is that it does not cover security issues. Anothershortcoming is that it is not being utilized consistently as the primary forum for Arctic debate. Forexample, the Ilulissat Declaration [discussed in paragraph 77] was made at the Arctic OceanConference in May 2008 by the five costal states. Some members of the Arctic Council, includingindigenous peoples, Finland, Iceland, and Sweden were not invited to the conference and are notparty to the Declaration.84. The five Arctic coastal nations met once more in Ottawa in March 2010. As some of theArctic states are not part of the Arctic five (such as Iceland, Finland and Sweden) this resulted insharp criticism from U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton who expressed her hope that “the Arcticwould always showcase our ability to work together, not create new divisions.”85. Finnish Foreign Minister Alexander Stubb, speaking at the Assembly’s June 2010 Rose-RothSeminar in Helsinki, advocated strengthening the Arctic Council by, among other things, creating apermanent secretariat, extending the Arctic Council’s remit, expanding the number of observers,and creating an Arctic information centre.4386. Other international fora also play a role in regional co-operation in the Arctic. Of particularinterest to members of the Assembly is the existence of the Conference of Parliamentarians of theArctic Region, a parliamentary body comprising delegations appointed by the national Parliamentsof Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the United States, and theEuropean Parliament. The Conference also includes Permanent Participants representingIndigenous peoples, as well as observers. The Conference meets every two years and adoptsrecommendations to the Arctic Council and to the governments of the eight Arctic states and theEuropean Commission.87. Other organizations active in the High North include the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, whichwas launched in 1993 through a declaration by the five Nordic Countries, the Russian Federationand the EU Commission. The International Maritime Organization (IMO), for its part, approvedguidelines in 2002 for ships operating in Arctic ice-covered waters. These recommendations,which include provisions on ship construction, operation and equipment, as well as crew training,are intended to improve safety and prevent accidents that could cause pollution. Danish officialstold the Sub-Committee that the IMO could usefully mandate additional requirements for vessels inthe Arctic, including a obligation that ships travel at least in pairs, such that one could quickly cometo the assistance of the other in case of emergency.

V.

MANAGING CHANGE IN THE ARCTIC: IS THERE A ROLE FOR NATO?

88. The Alliance, for the time being, does not have an official position on its role in the HighNorth. Indeed, the first and only mention of the region in a high-level statement by NATO memberStates came in the following statement in the Strasbourg/Kehl Summit Declaration of April 2009:“Developments in the High North have generated increased international attention. Wewelcome the initiative of Iceland in hosting a NATO seminar and raising the interest ofAllies in safety- and security-related developments in the High North, including climatechange.”

43

A detailed summary of the Seminar is available on the Assembly’s website,http://www.nato-pa.int/default.asp.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

15

89. Even so, the elaboration of a new Strategic Concept for NATO, to be finalized and adoptedat the Lisbon Summit in late 2010, has presented an opportunity for discussion and possibleproposals on what NATO’s role in the region may be.90. The report issued by the Group of Experts advising the NATO Secretary General inMay 2010 highlighted a need to enhance NATO’s maritime situational awareness in the High Northand around the globe. The group, however, cautioned that “NATO is by no means the sole answerto every problem affecting international security.”44

A.

A ROLE FOR NATO PROPER?

91. Several NATO member states have called for a greater Allied focus on the HighNorth. Norwegian officials, as recently as the Assembly’s Spring Session in Oslo in May 2009,have said there “absolutely” was a role for NATO in the High North, given the fact that the Allianceis at the core of the security and defence strategies of all but one Arctic Ocean State. NorwegianForeign Minister Jonas Gahr Store visited NATO headquarters in 2007 and 2008 to makepresentations on the High North to the North Atlantic Council. Norway’s initiative to bring this issueonto NATO’s agenda, as Store said at a 2009 conference, was “not about bringing NATO home –but to make it clear that NATO never left.”92. Norwegian officials suggest that NATO already has a certain presence and plays a role in theHigh North today, primarily through the Iceland-based Integrated Air Defence System. Someexercise activity under the NATO flag also takes place in Norway and Iceland but, to a large extent,such activities are bilateral or multilateral by invitation. NATO conducted one such exercise, called‘Cold Response’, in March 2009 in northern Norway. The exercise included more than 7,000troops from France, Germany and Spain and 250 from Sweden and Finland, in a scenario in whicha fictional country moves against offshore oilfields and other mineral assets of a regional State.93. Iceland has also played a role in ensuring that the Arctic is on NATO’s agenda. It hosted ahigh-level seminar for NATO officials on the High North in January 2009, bringing together civilianand military leaders from across the Alliance for the official introduction of the issue to NATO’sagenda.4594. The seminar allowed Iceland to underline its view that the High North is Allied territory, andtherefore of immediate interest to NATO. Icelandic officials have also asserted that NATO’s rolemust include heightened situational awareness through greater expertise and knowledge of theregion, as well as contributing to the development of capabilities that could be applied tocontingencies such as disaster relief operations or search and rescue at sea. Iceland has alsodescribed the High North as fertile ground for application of the Alliance’s ‘comprehensiveapproach’, combining civilian and military elements as well as co-operation with other actors andorganizations to best effect.95. Speaking at the Icelandic seminar, NATO’s former Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Schefferlaid out what he saw as a “clear” role for NATO to play in response to greater potential foraccidents requiring search and rescue missions in the Arctic, as well as the increased risk ofecological disasters requiring relief operations. De Hoop Scheffer was unequivocal: “Alliednations have the necessary capabilities and equipment to carry out such tasks, and ourEuro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre has the necessary extensive experience tocoordinate any relief effort, and support search and rescue operations.”

44

45

"NATO 2020: Assured Security; Dynamic Engagement", Analysis and Recommendations of the Group of Expertson a new Strategic Concept for NATO at 41, 17 May 2010, p. 9.Norway has expressed willingness to follow up on the seminar in 2011.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

16

96. The former Secretary General further suggested that NATO should not only provide a forumfor its member States to discuss any concerns they might have in the Arctic with each other andother member States, but also to consider “conducting practice search and rescue operations, oreven disaster relief exercises … to acquaint the relevant staffs and personnel with the uniquechallenges presented by the Arctic conditions.”4697. However, not all Allies share the view that NATO should take on a direct, formal role in theregion. For example, at the 2010 Rose-Roth Seminar, Canadian Ambassador to Finland,Christopher Shapardanov argued against a direct NATO engagement, stating that its involvementcould complicate inter-state relations and that the Alliance had other pressing priorities. Localpopulations have also expressed reservations. For example, at the 2010 seminar, a representativeof the Sami people suggested that they equate increased NATO activity with militarization,something they strongly oppose.

B.

CO-OPERATION WITH RUSSIA?

98. Many officials and analysts have suggested to this Sub-Committee that engaging Russia inco-operation in the High North is among the most important measures to ensure continued stabilityand access to opportunities in the region. Challenges related to the new Arctic sea lines ofcommunication, for instance, are amongst the many areas where co-operation could be of mutualbenefit, for example with regards to surveillance and patrolling. In this context, the Arctic Council,of which Russia is a full member, plays an important role.99. However, given that security issues are not part of the Arctic Council’s mandate, someanalysts have suggested that it would be logical to address this “gap” through a regular dialogueon High North security issues in the context of the NATO-Russia Council (NRC). According to thisproposal, this could be an area in which NATO could engage Russia in information-sharing andperhaps even joint exercises and operations, to ensure interoperable capabilities and co-operationin search and rescue or consequence management operations. Indeed, in January 2009 Jaap deHoop Scheffer pointed out that NATO and Russia have a history of shared experiences in searchand rescue and disaster management, which could be usefully built upon, and expanded, toaddress common challenges in the Arctic region.100. However, there are significant drawbacks to such an approach. As Finnish parliamentarianJohannes Koskinnen pointed out to the Defence and Security Committee at its May 2010 meetingin Riga, pursing arctic security in the NRC format leaves both Finland and Sweden out of theconversation.101. The extent to which Russia would be willing to engage in such discussions in a NATO formatis also far from clear. Russia has largely discounted a role for NATO in the Arctic; Foreign MinisterSergei Lavrov told the press in September 2010 that “we do not see what benefit NATO can bringto the Arctic… I do not think NATO would be acting properly if it took upon itself the right to decidewho should solve problems in the Arctic.” Russian parliamentarian Victor Zavarzin also toldAssembly members that a NATO presence in the Arctic could weaken existing bilateral andmultilateral relationships which functioned well.

46

NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, speech on security prospects in the High North, Reykjavik,29 January 2009.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

17

VI.

CONCLUSIONS

102. The most effective way to preserve the opportunities inherent in changing conditions in theArctic is to ensure that a regional institutional and legal framework is in place and able to cope withthe real risks of potential oil spills, disasters at sea, smuggling, and inter-state competition.103. Asking whether NATO should be present in the High North is, in your Rapporteur’s opinion,the wrong question. To quote the former Chairman of NATO’s Military Committee GeneralKlaus Naumann, “the Nordic area …was, is and will remain of crucial importance for NATO … asan integral part of NATO’s efforts to provide undivided security for all its member nations andthroughout” the Atlantic area.47Certainly, NATO members Norway, Denmark, and Iceland allmake the case that their territories and commitments in the region imply NATO’s presence there.The use of radar installations in Greenland or Iceland to monitor Allied airspace is only the mostconcrete example. It is clear, then, that NATO is already fundamentally ‘in’ the High North.104. However, the more difficult question is whether there is a need for NATO to further developits collective, institutional commitment to the region, especially with many other priorities on theAlliance’s agenda. This is especially true given that, as the Canadian Ambassador to NATOrecently pointed out to Assembly members, littoral States are broadly content with the current leveland extent of bilateral relations among Arctic States, and with what has been achieved via theArctic Council and the UN Law of the Sea.105. Your Rapporteur believes that even in this context, NATO can offer added value in the Arctic.The Alliance can play a positive role as a forum for dialogue and information-sharing on High Northissues. NATO should also be looking at what capabilities it can provide to assist nations in theregion in the event of a significant contingency, such as a tanker spill or cruise ship accident.NATO’s Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre (EADRCC) serves as a focal pointfor co-ordinating disaster relief efforts among NATO member and partner countries, notablyRussia. Its officials could usefully gain knowledge of and experience in the region in preparationfor a possible disaster, possibly through exercises that would foster interoperability between NATOand Partner countries in dealing with complex emergency situations in harsh Arctic conditions.106. Your Rapporteur also agrees with those calling for NATO to take a comprehensive approachto challenges in this area. We especially need to ensure that NATO develops a good workingrelationship with organizations such as the Arctic Council, the UN Convention of the Law of theSea, the International Maritime Organization and the European Union.107. Finally, your Rapporteur believes that NATO has a collective interest in maintaining itsawareness of developments in the region. We are, after all, an “Atlantic” Alliance. The undeniableincrease in military activity and interest in the Arctic requires the Alliance to make sure that it hasthe means to see and understand developments there, and to ensure that preparations are inplace for unintended contingencies that could require Allied assistance. In all cases, stability isbest served by ensuring transparency, through information sharing among NATO member States(as well as Partners -- especially Russia) in relation to military activities.*****108. Despite the challenges inherent to the increased geopolitical significance of the Arctic region,your Rapporteur remains optimistic about the perspective of keeping the High North an area of lowtension, where emerging opportunities can be properly supported by a stable, inclusive regionaldynamic. Nobody will gain from militarising the Arctic.47

Klaus Naumann, “The Future Role of NATO Seen With a Glance at the Nordic Security Landscape,” Presentationat the Icelandic North Atlantic Association, Reykjavik, 13 September 2010.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

18

109. In order to contribute to this goal, NATO should pursue two distinct objectives: first, it shouldendeavour to maintain its collective awareness of this rapidly changing and strategically importantregion. Second, as a supporting part of a web of institutional and legal arrangements in the region,the Alliance can play a role in ensuring continued co-operation in the Arctic. NATO can, andshould, fill gaps in the existing regional security architecture by providing a forum for dialogue andinformation-sharing amongst Allies, co-operation with Russia, and co-ordination of assistance tolittoral States in consequence management.

213 DSCTC 10 E rev.1

19

APPENDIX: Map of Possible Shipping Routes in the Arctic