Trafikudvalget 2010-11 (1. samling)

TRU Alm.del Bilag 59

Offentligt

Routes to Sustainable Transport

1

Routes to Sustainable Transport

2

Table of ContentsIntroductionAustriaDenmarkEuropean ParliamentFinlandFlandersGermanyGreeceItalyThe NetherlandsNorwayPolandSwedenSwitzerlandUnited KingdomEndnotes46142024304856606876848896104108

Routes to Sustainable Transport

3

Routes to Sustainable Transport

4

IntroductionTransportation is a large energy consumer in modern societies. In a future with considerably less fossilfuels and restrictive policies towards global warming it seems improbable that transportation can stillincrease its share of the available energy. The term Sustainable Transport is used as a signal of a newdevelopment in transportation, which involves strategy shifts with regards to for example energy-efficienttransport, the use of renewable energy sources, motor and vehicle technologies, taxation systems,private/public transportation, and physical planning. Countries and regions aim to reduce emissions ofCO2, to ensure security of energy supply, to maintain mobility and to protect their economy and growth –and Sustainable Transportation seems to be a key concept.No country or region can claim to have a sustainable transportation system in place yet. Many of theneeded technologies are not commercially available. The transitions needed involve enormousinvestments, from society, industry and for the citizens. And not least, we demand effective and cheaptransportation, which provides us with the mobility we need at any time – and therefore, the claim for alarge transition is often met with scepticism. Accordingly, new policy options are discussed, experimentedwith and evaluated.The purpose of this report is to help to exchange knowledge to policy-makers by providing an overview ofcurrent developments, major challenges, policies and strategies in the EPTA member countries andregions. The presentations from the various countries share a common structure, while at the same timeallowing for a focus on country-specific issues. Each country is reporting on issues concerning:

The State of PolicyEnergy Use for TransportRegulation and Technology Options for Sustainable TransportLand Use and Physical PlanningBorder-crossing Transport in EuropePresentations have been kept short to ensure readability, accessibility and oversight. We hope that thiswill be valuable to parliamentarians and other decision-makers.This report is the result of a joint project of some of the members of the European ParliamentaryTechnology Assessment network (EPTA):

Member Organisations:CAPCIT - The Advisory Board of the Parliament of Catalonia for Science and Technology. Catalonia,Spain.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

5

Committee for the Future, Parliament of Finland. Finland.DBT - The Danish Board of Technology. Denmark.GPTCA - Greek Permanent Committee of Technology Assessment. Greece.IST - Institute Society and Technology. Flandern, Belgium.The Norwegian Board of Technology. Norway.OPECST - Office Parlementaire d´Evaluation des Choix Scientifiques et Technologiques. France.PER - Parliamentary Evaluation and Research Unit. Sweden..POST - Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. UK.Rathenau Institute. Netherlands.STOA - European Parliament. European Union.TA-SWISS - Center for Technology Assessment. Switzerland.TAB - Office of Technology Assessment at the German Parliament. Germany.VAST - Comitato per la Valutazione delle Scelte Scientifiche e Tecnologiche. Italy.

Associate Members:BAS - Bureau of Research. Poland.The Committee on Culture, Science and Education of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council ofEurope.ITA - Institute of Technology Assessment. Austria.OSTC - Belgian Federal Office for Scientific, Technological and Cultural Affaires. Belgium.

The different institutions are responsible for the description of the country or region where they belong.The project has been coordinated and managed by the Danish Board of Technology (Teknologirådet),which holds the EPTA precidency for 2010. We would like to thank all participating institutions for theircontributions to this extremely important topic.

Lars Klüver, directorIda Leisner, project managerUlla Holm Vincentsen, project managerSune Bjarke Stefansson, project assistant

Copenhagen, October 26, 2010

Routes to Sustainable Transport

6

AustriaITA – Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Technology AssessmentProject Manager: Walter PeisslAuthor: Willy Raimund

State of PolicyCurrently, there is no “overall sustainable transport strategy” in Austria as such, but sustainable transportgoals are integral parts of theAustrian National Climate Strategy(“Österreichische Klimastrategie 2007”; including “soft measures”in transport such as mobility management, bundled in the national transport climate protectionprogramme “klima:aktivmobil”),which attempts to achieve the “Kyoto goals” (for AT: minus 13%green house gas (GHG) emissions 2008-2012 compared to 1990.Furthermore GHG emissions are to be reduced by 16% by 2020 compared to 2005 levels (excludingemission trading), according to the EU’s “20-20-20 targets”, and theAustrian National Energy Strategy(“Energiestrategie Österreich”), paving the way for the EU “20-20-20” targets at national level. For transport in AT this means that by 2020 10% of the whole energyinput will have to come from renewable energy sources, contributing to the target of a 19% reductionof final energy consumption in transport. As of 2008, the transport sector in AT was 95% dependenton fossil fuels1(almost entirely oil).These goals for transport are quite ambitious, since it is the sector with the fastest growing GHGemissions (+60.8% from 1990 to 2008) and the one which deviates most from the sectoral target of theclimate strategy.To help meet the ambitious targets, varying instruments have been implemented to boost a cut in GHGemissions, energy consumption and to encourage energy efficiency in transport:Climate and Energy Fund, a national fund endowed with €150 million per year for climate protectionand energy efficiency measures in all sectors“klima:aktivmobil”programme, Austria’s national climate protection programme in transport,offering consulting and financial support for CO2-prevention measures (€25 million per year)an e-mobility master plan “under construction” (bringing together the action plans of varyiousministries)For the “white hope”– e-mobility – alone, approximately €30 million per year is spent via “klima:aktivmobil”, “e- mobility model regions”, “beacons of light for e-mobilty” and the technology researchprogrammes “A3plus” and “energy systems of the future”.

1

Erneuerbare Energie in Zahlen, S.8, BMLFUW Dez. 2009

Routes to Sustainable Transport

7

Governance and Responsibilities for ImplementationThe latest version of the Austrian National Climate Strategy (2007) has only been endorsed by the federalgovernment but not by the regional governments of Austria’s nine provinces (“Bundeslaender”). Thatmeans that the federal level is responsible for reaching (or not) the targets set in the strategy.Nevertheless, a “climate protection law” is under construction, which is to determine the sharing of theburden regarding GHG emission reductions between the federal and regional levels for the “post-Kyoto”period (2013-2020).Accordingly to the targets and visions described above, 200,000 e-cars should be on Austrian roads by2020, which is a very ambitious plan, considering that 185 e-cars registered as of the end of 2009.

Energy Use for Transport34% of Austria’s final energy consumption (and 26.1% of GHG emissions, 2008) are within the transportsector (2009). Between 1990 and 2005, final energy consumption in transport rose by 80%2.In 2008 renewable energy sources contributed 5.3%3to the final energy consumption of the transportsector in Austria. Biofuels in particular helped to increase this share (and save GHG emissions: e.g. 1.375million tons between 2007 and 2008). In the future, e-mobility (with electricity from renewable energysources such as water, wind, biomass, solar energy) is expected to make a major contribution toincreasing the share of renewables in transport to 10% by 2020 and to reducing energy consumption,especially from fossil energy sources.

Plans, policies and discussions on increasing the use of renewable energy sources for transport.See point 1) and 2) above

Regulation and Technology Options for Sustainable TransportAs of today, a clear focus is laid on e-mobility/BEV (battery electric vehicles) but also on hybrids(combination of internal combustion engine plus electric motor):On the one hand e-mobility is an important part of all strategies regarding GHG emission reductions andenergy efficiency gains (see above). The Austrian Energy Strategy for instance is reckoning on some tenthousands of e-cars (powered with electricity from renewable energy sources) in 2020.

23

Klimaschutzbericht 2010, S. 43, Umweltbundesamt, Wien 2010Erneuerbare Energie in Zahlen, S.8, BMLFUW Dez. 2009

Routes to Sustainable Transport

8

On the other hand both federal and regional level have come up with several funding and supportopportunities for different purposes (“model regions” and “beacons of light” for e-mobility, RT&D fundsfor technological developments, financial support for companies and private persons for the purchase ofe-vehicles4and for electricity charging stations, exemption from vehicle purchasing tax, exemptions fromlocal driving prohibitions due to high air pollution figures …).Beyond alternative propulsion technologies such as BEV and hybrids, the blending of biofuels into fossilpetrol (bio ethanol) and diesel (biodiesel) contributed to a significant drop of GHG emissions fromtransport and the share of fossil energy sources in transport. Since 2005, 5.75% (in terms of energycontent) of regular fuels for road vehicles come from biogenic sources.There is an Austrian road-pricing scheme for both cars (including two-wheelers such as motorcycles etc)and lorries, but only on motorways (”Autobahnen und Schnellstrassen”). For cars, every vehicle using themotorways has to pay a “flat rate” in the form of a sticker independently of the mileage. For heavy-dutyvehicles the charge is dependent on the mileage and on the EURO class of the respective vehicle (thecleaner, the cheaper). In some places this road pricing scheme leads to “detouring traffic” on non-motorways, for which no charge is made.Freight transport on Austrian roads has seen a decrease in the last two years due to the general economiccrisis (e.g. minus 20% between January 2008 and January 20095). This of course leads to less energyconsumption and GHG emissions in/from transport, but is not “sustainable” as such, since the mileage willincrease again once the economy prospers and since freight transport on more sustainable modes (railand inland shipping) has also fallen to roughly the same extent.Congestion charging schemes are often discussed, especially for cities and urban agglomerations, but asyet there is no such scheme in place anywhere in Austria.The “purchase tax” on the purchase of a motorized vehicle (“Normverbrauchsabgabe - NoVA”) can beconsidered a green tax, since vehicles with lower standardized CO2emissions (in terms of theNEDC/MVEG6driving cycle) pay less.The NoVA has to be paid when a vehicle is registered for the first time in Austria (registration tax). As thetax burden is linked progressively to the vehicle's fuel consumption, NoVA is an incentive to buy moreefficient cars regardless of the expected mileage. On 1 July 2008 the NoVA system was improved by abonus-penalty system. This means that vehicles with CO2emissions of more than 180 g/km have to pay anadditional NoVA of 25 Euros per gram in excess. If the car emits less than 120 g/km, a bonus of 300 Euroswill be paid out. Furthermore, a bonus of 500 Euros is due if the vehicle has an alternative propulsionsystem (hybrid, gas, electric etc.). In 2010 the new system was tightened. Vehicles with an emission ofmore than 160 g CO2/km have to pay the additional NoVA of 25 Euros per gram excess. Electric vehiclesare exempt from this tax (so far).45

not at federal level, but most of the provinces provide funding for private persons when buying e-vehiclesKlimaschutzbericht 2010, S. 43, Umweltbundesamt, Wien 20106NEDC…New European Driving Cycle; MVEG…Motor Vehicles Emission Group)

Routes to Sustainable Transport

9

The “engine-related insurance tax” (“Motorbezogene Versicherungssteuer”) on motor vehicles is stillbound to the vehicle's power in kW and not yet “greened” by binding it to the vehicle's CO2emissions.

Methods for Monitoring Environmental Impacts from the Transport SectorYearly “Climate protection reports” of the Umweltbundesamt (Federal Environmental Agency):According to EU reporting requirements, these reports provide recent figures regarding GHGemissions from all sectors (compared to the year before and to 1990, the Kyoto baseline year).Transport is included and emission developments are split into sub-sectors like cars, heavy-dutyvehicles, biofuels etc. Since CO2emissions are calculated indirectly from the amounts of fuel sold,energy values (PJ) are also available in this way.All air pollutants are also monitored by the Umweltbundesamt.There is a yearly report specifically on road transport/passenger cars, again by Umweltbundesamt, on"CO2emissions of newly registered passenger cars”, describing the development in GHG emissionsfrom new cars.

Regulation on Specific Use of TechnologiesIn Austria the usual EU EURO classification (setting limits to emitted air pollutants pervehicle) is in place.Particle filters are not mandatory for diesel vehicles. Nevertheless a consumer pays € 300.-more when purchasing a diesel car without filter. In 2009 90% of all newly purchased dieselcars were equipped with a filter.

Available and/or Necessary Technologies Beyond 2020Beyond 2020 wide parts of the drive train of road vehicles will be electrified. At present BEV lead,followed by all types of hybrids and alternatives (plug-in hybrids, range extenders, hybrids etc.) However,technological solutions targeting vehicles only will never be able to solve the transport problem as awhole. It needs a balanced mix of awareness raising, intermodality, ICT, technology measures etc.

R & D Plan for Developing New Transport Technologies or InfrastructureThere is no plan specifically on this matter. However, transport technology is mainly tackled in R&Dprogrammes of the transport ministry (known as IV2S+) and at present a comprehensive “Master plan one-mobility” is being prepared by the government.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

10

Land Use and Physical PlanningGenerally speaking land use planning tools are quite weak at federal level in Austria (except perhapsinfrastructure measures “of general public interest”). Land use planning mainly takes place at local andprovincial level, which brings huge problems regarding climate change caused by more traffic resultingfrom scattered structures.

Transport and Mobility: Rural Areas Versus Densely Populated AreasMotorization rates (cars per household) especially in rural areas are growing rapidly in Austria (overallfrom 460 cars per 1000 inhabitants in 1995 to 510 in 20087), as in the rest of Europe, whereas the rate isdecreasing in the Viennese urban area (the modal split of cars decreased from 40% to 32% during recentyears).In most land use plans, intermodality and “soft transport modes” such as walking and cycling are not dealtwith in the same intensity as motorized transport.

Influence of Physical or Urban Planning to Reduce of Transport GrowthThe car ownership rate in Vienna (403 cars/1000 inhabitants, 2005) and other urban agglomerations issignificantly lower than in rural areas such as Lower Austria (570 cars/1000 inhabitants, 2005) orBurgenland (575 cars/1000 inhabitants, 20058). The need to own a car in urban environments is not asgreat as in rural areas with insufficient or even no public transport. In urban agglomerations distances areshorter, roads more congested, public transport infrastructure is much better, and cycling and walkingfacilities are mostly also available.E-mobility offers a chance for a paradigm change away from “you have to own a car” to “use cars inintermodal context”, e.g. for the “last mile”, especially in rural areas.

Strategies for Sustainable Urban Mobility and the Shift from Private to Public TransportStrategies have been determined e.g. in the “Master Plan Transport Vienna 2003”, where targets likereducing the modal split of motorized individual transport are set. Many initiatives such as testing electricvehicles, “model regions for e-mobility” (“VLOTTE” in Vorarlberg and “ElectroDrive” in Salzburg) pluscycling and walking incentives try to help to achieve the general modal shift towards more sustainablemodes of transport.

78

Statistik Austria; http://www.statistik.at/web_de/services/wirtschaftsatlas_oesterreich/verkehr/024196.htmlVerkehr in Zahlen, S. 80; Herry Consult für bmvit; Wien November 2007

Routes to Sustainable Transport

11

Border-crossing Transport in EuropeRegulation/Policies of Transit TrafficTransit (border-crossing heavy-duty goods vehicles) is a serious problem for Austria. Nevertheless, aformer transit scheme for Austria ("eco points") was dropped by the EU and replaced with the possibilityfor “extra road-pricing“ in sensitive areas like the “Brenner” in Tyrol. Furthermore, the “road on rails“(heavy-duty road vehicles on trains) is hugely subsidised in Austria in order to avoid excessive heavy-dutyvehicle traffic on transit routes.The “alpine convention“ would also offer appropriate tools but is not legally binding yet.A desirable development would be to increase the EU share of goods transported via rail to Austrianlevels (about 31% compared to 18% on EU25 level (20049).Hauliers from abroad in particular (mainly from the EU member countries in the east) use older ratherthan the newest EURO generations of lorries. These pay more for road pricing than newer ones (EURO IV,EURO V), and cause greater air pollution.A specific issue here is also the VAT on fossil fuels. Since this tax is lower in Austria than in neighbouringcountries the overall price for diesel and petrol is lower in Austria with the effect that fuel (causing about5.6 million tons of GHG emissions) is purchased in Austria but used in other countries (“price induced fuelexport”). These 5.6 million tons count towards the Austrian climate balance, causing a major part of the6.9 million tons GHG emissions that Austria is in excess of its Kyoto targets10.

Emission Standards and Speed LimitsEmission standards are determined by EU regulations. Speed limits have been unchanged since years.Lowering the latter would help to save GHG emissions, but generally is not to be expected. Rigorouscontrols of existing limits would, while regionally implemented lower speed limits due to NEC (NationalEmission Ceiling) Directive do help to lower GHG and pollutant emissions.

Environmental Impact Assessment of Large Infrastructure Investments and GreenTransport CorridorsThe EIA of large infrastructure investments up to now has not helped too much to reduce the negativeenvironmental consequences of transport.“Green transport corridors” at present is not much more than a nice catchword. Nevertheless, memberstates are working on plans to introduce such corridors.

9

10

Verkehr in Zahlen, S. 114; Herry Consult für bmvit; Wien November 2007Klimaschutzbericht 2010, S. 43, Umweltbundesamt, Wien 2010

Routes to Sustainable Transport

12

HarmonisationRegarding the harmonisation of border-crossing railways, problems with e.g. signalling etc. are stillevident. The biggest problem, at least for Austria and e.g. Italy, seems to be the different frequencies ofthe electricity used to power the trains. Only “dual-frequency locomotives” can handle these differences.In addition, different gauges (especially between Austria and the “Russian system”) starting with theUkraine, but also – for instance – between France and Spain have not been solved yet.

European Strategies for Long Distance Transport – Concerns and Experiences in GeneralFrom an environmental point of view road TENs (Trans European Networks) are a reason of concern.“TENs” for a more sustainable transport system, for local and regional transport, for public transport andfor cycling would be desirable.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

13

Routes to Sustainable Transport

14

DenmarkDBT – The Danish Board of TechnologyAuthors: Ida Leisner and Naja Olesen

Pkm rose from 69.879 in 2000 to 75.326 in 2008. 83% pkm were driven in cars, 13% in publictransport – the rest other modes, with inland aviation having increased.I Denmark the road network is approximately 71.600 km and the cycle path network is more than12.000 km.

State of PolicySustainable transport entered the Danish government’s agenda with the transport initiative “Sustainabletransport – better infrastructure” from December 2008. In January 2009 the government and oppositionalparties agreed a Green Transport Policy. Until 2014 8,1 billion kr. (1,2 billion euros –figures to be checked)will be spent to improve the conditions for the environment, the security and the mobility in the transportsystem. Investments include the Fehmarn Belt connection - highway and electrified high speed rail. Otherinvestments are directed at improving the railway network, in particular updating signal systems to EUstandard (ERTMS).

Transport Policy AimsReducing of the transport’s CO2 emissions.Public transport should lift most of future growth in traffic. The railroad should be reliable, safe andmodern.Road capacity must be developed, in places with congestion problems, but also where future trafficgrowth resulting from economic and social development will require an expansion of infrastructure.Transport by bike must be encouraged - the choice of the bicycle is preferable, where it is a realisticoption.Denmark shall be a laboratory for green transport.Bridges, roads and railways must not destroy irreplaceable natureNoise and air pollution have to be reduced in cities.

Climate Targets and TransportGHG – reduction 2050 (1990 level)GHG – reduction 2020 Transport should contributeRenewables share of energy consumption 2020Renewables share of transports energi consumption 2020Share of biofuels (surface transport) 202080-95%> 20%30%10%

10%

Routes to Sustainable Transport

15

R&DA strategic research programme aimed at transport has set aside 8 billion euros in 2010 for research insustainable transport and infrastructure.A fund (approx 40 billion euros) has been set aside for projects that will develop technical solutions togreen traffic.

The Climate CommissionThe government’s Climate Commission has worked out suggestions for a coherent energy system, whichcan ensure improved energy efficiency, increased share of renewable energy and promote thecompetition on the energy market. The vision is to make Denmark independent of fossil fuels before2050. The energy system includes the transport sectors energy consumption as well.The Danish Board of Technology’s project on sustainable transport has taken up the idea and willinvestigate what it takes to switch over the transport system to 100% renewable energy before 2050.

Governance and Responsibility for Sustainable Development in the Transport SectorDue to globalisation and rising competition (liberalisation) in the transport sector, the organisation of thesector has changed. Big international operators in both rail and bus service has entered the market,causing a fragmentation of public transport. Increase in transit freight transport and a shift from rail toroad has created a pressure on road network capacity. Accordingly, needs for coordination, planning andregulation have increased. The national Danish Transport Authority together with regional transportauthorities and local governments carries out these tasks. The Ministry of Transport has the overallresponsibility for implementing strategies for a sustainable transport sector. Regulation and procurementis delegated to several authorities.

Energy Use for TransportEnergy Consumption in the Transport Sector and Renewable Energy SourcesThe energy consumption in the transport sector was in 2007 225 PJ. This corresponds to approximatelyone third of the whole energy consumption of 685 PJ. The energy consumption in the transport sector ishigher than the energy consumption in the households.Today the share of renewable energy in the transport sector accounts for 1 % of the total share. Windpower and bio fuels are the two primary sources of renewable energy in the transport sector.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

16

Plans, Policies and Discussions on Increasing the use of Renewable Energy Sources forTransportWind power and biofuels are the most important renewable energy sources in Denmark.Ongoing discussions are about the balance (we allready import biofuels which can be not sustainable) andorder of introducing biofuels and wind power electricity for transport. This is connected to technologies:biofuels can be used directly without shifting the carpark to BEV’s. Much research and development isaimed at second-generation biofuels. On the other hand, BEV’s are clean tech regarding CO2 and otherpolluters, and they can be integrated into the energy system as both capacity and consumer. Expectationsare that even with the current policy BEV’s will not reach sufficient numbers in 2020 (original target was ½million, now the figure is reduced to 80.000). Some argue that in the short term biofuels might be thebetter option for transport, to achieve CO2 reduction targets before 2020.

Regulation and Technology Options for Sustainable TransportBEVsBEVs were boosted when Better Place (an american BEV company) agreed with the Danish energyconsortium, DONG Energy, to invest 770 mio.dkr. in building a network for BEVs in Denmark.DONG Energy sees BEVs as having the potential to increase flexibility in the energy system and turnsurplus wind energy into business.BEVs are exempted from the otherwise high taxes on cars in Denmark until 2012. Currently it is discussedwhether the exemption should be prolonged.

Green TaxesThe green tax has long been an important tool to reducing the use and covering the expenses related tothe environment. Depending on how far the vehicle can run on the litre the owner has to pay a green tax.If the car runs at least 20 km it costs approximately 35 Euros every 6 months and if the car runs les than4,5 km on the litre it costs 1.240 Euros every 6 months.A reduced tax on cars with low fuel consumption has increased the share of small, energy efficient cars.The green taxes and better information about the car’s energy efficiency have increased the average GHGemissions from the new and more efficient cars more than 20 % since 2000.

Road PricingIt was a governmental decision to introduce roadpricing by 2012, using the same model and technology asthe Netherlands. However, as the Netherlands stopped their plans, the Danish Government took theconsequence to postpone the Danish plans.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

17

Methods for Monitoring Environmental Impact from the Transport SectorThe Environmental Protection Agency keeps an eye on the quality of air through measurements. Toprotect the citizens from adverse health effects of air pollution there has been set limits on how muchpollution in the air we can accept and for each of the substances there are threshold limits. Denmarkcomplies with the threshold limits for most of the substances but for particulates and NO2, we still needto do an extra effort. The Environment Protection Agency also measures the levels of noise from trafficand railways in Denmark.In general, large infrastructure projects should undergo an environmental impact assessment beforecarried out.

Particle FiltersSince 1st. of April 2010 diesel cars should use a particle filter or otherwise pay a fee/tax of 1000 kr a year.To install a particle filter on old cars will however cost 5.000 – 10.000 kr, which from a cost-benefitanalysis can be more expensive than paying the fee/ tax. A recent evaluation showed that by 1.September 2010 only 1000 out of 354.000 diesel cars had installed the particle filter. Further, critique saysthat the standard for the particle filter is not good enough to remove dangerous particles.

LandUse and Physical PlanningPhysical planning and transport infrastructure building is in Denmark focused on three main transportcorridors connecting Denmark to Scandinavia and the rest of Europe. Around Copenhagen the so-called”finger plan” has prevailed for more than half a century, building space are the fingers and green zonesare in between. This strategy is about to be developed for all of Zealand, so that urban development willtake place in cities with railway connections. This is meant to avoid continued urban sprawl.

Transport and Mobility in Rural Areas Versus Densely Populated AreasAs part of a plan to avoiding further marginalisation of rural areas, the Government has initiated a plan tobuild new infrastructure (roads and highways) to connect rural areas with the more densely populatedareas with dynamic economies. It also includes particular rules of physical planning, making it moreattractive for production and retail companies to settle in these areas.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

18

Urban Planning Aiming at Reducing Transport GrowthIt is a general aim in Denmark to encourage bicycling, but some cities have chosen to take it further andhave become cities of cyclists. Copenhagen and Odense are cities of cyclists and they have both made amassive effort in developing a comprehensive cycle infrastructure.Cyclists in Copenhagen travel a total of 1.2 million km by bike every day. This is the equivalent of cyclingto the moon and back – twice! There is a total of 350 km of cycle tracks and 40 km of green cycle routes inCopenhagen, equivalent to the length of Jutland. 37% of those working or studying in Copenhagen bikeevery day. A big city with so many cyclists offers many benefits. In terms of the environment alone,cyclists help keep the city’s CO2 traffic emissions at a low level compared to other big cities. When wereach the stage that over 50% of commuters choose to cycle to their place of work or education, thenCopenhagen traffic will be able to save an additional 80,000 tons of CO2 per year.

Border-crossing Transport in EuropeThe biggest Danish border crossing infrastructure project, the Fehmarn Belt connection, prolongedtowards Sweden via a new Helsingør-Helsingborg connection. The case shows the focus on connectingScandinavia to Europe, paving the way for transit freight transport and high-speed rail connectionsbetween larger cities. Unfortunately the environmental aspects are not that much in focus. High-speedrail is discussed as an option, mainly to connect the large Danish cities with large cities outside Denmark.The plan for the Fehmarn Belt connection is to have electrified rail. However, in the short term there areno plans for electrification.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

19

Routes to Sustainable Transport

20

European ParliamentSTOA – Science and Technology Options AssessmentAuthor: Dr. Jarka Chloupková

State of PolicyGlobally, transport contributes with 13-14% to Green House Gases (GHC).iFor Europe, this figure mountsto 21%ii; a half of this amount is attributed to long distance transportiii- a sector totally dependent on oil.Not only is this a pressure on natural resources and environment, in addition, the increase in congestionsand bottlenecks in the European transport network restricts the free flow of goods and people, especiallyin the centrally located and densely populated regions of the European Union. Such trends run counterthe Lisbon strategy, which aims at making Europe the most competitive and the most dynamicknowledge-based economy in the world. The increased traffic led to a reduction of the quality of life -emissions of air pollutants, noise and reduced spaces for living.The future European transport has to overcome a range of challenges and will be on the agenda of theEuropean Parliament's in the years to come. STOA projects were undertaken with the aim of reducing oildependency by 80% and CO2 emission by 60% in the year 2047.This report is primarily based on a number of completed STOA projects, carried out by Ida Leisner, JensSchippl, Christian Dieckhoff, Torsten Fleischer, and Anders Kofoed-Wiuff et al. Given the importance oftransport related issues, STOA is currently running a project "Technology Options for Urban Transport"and will soon start a new one around the theme of "User perceptions on eco-efficient transport futuresfor Europe".

Energy Use for TransportTrucks (freight) consume the largest amount of energy used for transport, followed by aviation(passengers), mainly oil, emitting most of transport related CO2 emissions. The breakdown for well-to-wheel energy consumption is: Trucks (54%), Aviation (27%), Private cars and motorcycles (14%) - statusquo of 2005.

Regulation and Technology Options for Sustainable TransportThe European Commission has established a proposal that requires a reduction of the average emissionsof CO" from new passenger cars in the EU from around 160 g/km to 130 g/km in 2012 - the average sold

Routes to Sustainable Transport

21

car produced between 160-190 g/km during 1995 - 2006 period. In scenarios, a reduction down to 100g/km is assumed to be obtained by 2030.With an aim to improve energy efficiency and reducing emissions, a wide range of technological pathwaysare being discussed. Hydrogen production from renewable sources (wind, photovoltaic, solarthermal,water) via electrolyses enables close to zero emissions of GHG. A 'clean' production of hydrogen fromnuclear power is also feasible. Hybrid technology offers a possibility to save energy and emissions by usingestablished technologies and infrastructures. The commercialization of electric cars (Battery ElectricVehicles) depends on the development of sustainable batteries. Electric vehicles and plug-in hybridelectric vehicles offer multiple benefits by improving fuel efficiency as well as the utilisation of windenergy by using electricity in a more flexible way - e.g. by charging at certain times or serving as"batteries" for the electricity systems.Biofuels can be derived from a wide range of biomass and might serve as a relatively clean 'bridging' and'additional' technology. First generation of biofuels, mainly biodiesel and bioethanol, are the onlyrenewable transport fuel option that is commercially deployed. Second generation biofuels are producedby synthesis, in most cases from synthesis gas which is then treated in a so-called 'biomass-to-liquid'process (BTL) - offering an option to define specific fuel properties. It is estimated that 20-30% of EU 27road transport fuels in 2030 could be covered by biofuels. Natural gas technology (CNG) is feasible in thetransport sector and has the potential to bring at least mid-term GHG emissions improvements. Autogas(LPG), an uncomplicated technology, is becoming popular in several European countries. It is likely thatinnovative technological developments will be implemented and established faster in the road sector.For air transport, there are less options and kerosene fuelled gas turbines will probably remain therelevant technology for the near future.

Land Use and Physical PlanningThe task is to influence spatial planning with the aim to prevent transport growth that would jeopardizecitizens' mobility. Sustainable (urban) infrastructure ought to serve mobility needs of the population -examples walking, cycling or public transport. Transport technologies and transport flows need to beorchestrated efficiently without wasting resources. ICT applications allow 'load matching' - improvingcapacity use and reducing empty running of trucks. An optimized distribution of warehouses shouldreduce transport volume. Industrial areas and railway station could be located closer together. IntelligentTransport Systems could improve traffic flow and thus accessibility. Route guidance has a potential toimprove efficiency by avoiding detours or by circumnavigating congested areas. Rail transport would bethe best way to introduce electricity in freight transport.Land use planning is a relevant measure for the long run and will be more effective if coordinated atEuropean level. Distribution of airports in a country, such as development of a few huge airports could

Routes to Sustainable Transport

22

strengthen high-speed railways, given there is a corresponding infrastructure. Transport volumes in theair sector could be tackled by the implementation of high-speed railway lines.

Border-crossing Transport in EuropeThe Trans-European transport network is a European Union current strategy, among others aiming ataiding with free movement of goods, people and services. It is also an element for economic growth andthe creation of employment. It includes upgrading and building new airports, new high-speed railwaylines, motorways of the sea, etc. Examples include the railway corridor Lyon-Trieste-Divaca/Koper-Divaca-Ljubljana-Budapest-the Ukrainian border and the Fehrman Belt railway corridor between Denmark andGermany.

ConclusionIt was concluded that no single policy can solve these problems. In conclusion, options for reducing oildependency, including lowering CO2 emissions include: Investment in rail infrastructure to encouragemodal shift, including cross-border high-speed rail; Reorganisation of airports distribution with the aim oftravel reduction – only few mega airports and integration of rail and air; Introduction of hybrid trucks,especially if combined with renewable energies, including hydrogen and biomass. Further measureswould utilise the ICT potential within the transport sector, and a link-up of transport modes –intermodality. Reassessing of pricing measures – fuel prices, carbon based taxation, road pricing – couldbe wise.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

23

Routes to Sustainable Transport

24

FinlandCommittee for the Future

State of PolicyMinistry of transport and Communications published A Climate Policy Programme 2009-2020 fortransport sector on March 17th2009.The aim the Programme is to substantially reduce emissions from business, industry, administration andpeople’s everyday lives by means of transport and communications policies.Besides the use of biofuels, emissions from transport will be cut by 2.8 million tonnes compared to theestimated emissions level of 2020.The administrative sector of the Ministry of Transport and Communications will adapt to the climatechange in construction, maintenance and management of the transport and communicationsinfrastructure so as to maintain the level of transport and communications services. Advantage will betaken of the possible benefits of the climate.The following measures will be taken to achieve the climate policy aims of the administrative sector:1. The vehicle fleet will be renewed. 2. Energy efficiency in transport will be improved. 3. The growth ofpassenger traffic volumes in urban areas will be directed to more environmentally friendly transportmodes. 4. The attainment of Finland’s climate policy objectives will be supported by information societyand communications policy. 5. A decision will be made in 2012 on the financial steering methods used inthe transport sector. 6. Action will be taken to adapt to the climate change.

Climate Programme in Transport Sector Aims1. That in 2020 specific emissions of new cars sold in Finland would be near the EU objective (95 g/km; thecurrent level is at around 163.5 g/km) and the rate of vehicle fleet renewal would be around 7 per cent ayear. The goal with regard to the entire vehicle fleet is that by 2020 the average carbon dioxide emissionswould be 137.9 g/km at the most (currently around 180.1 g/km).2. That goods transport and public transport operators party to energy efficiency agreements will savenine per cent in energy consumption and that the overall energy efficiency in the transport sector willimprove. The emissions reduction potential from improved energy efficiency is 0.3 million tonnes.3. That by 2020 a total of 100 million more public transport journeys and 300 million more walking andcycling journeys will be made, which means an around 20 per cent increase to the current figures.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

25

4. That the administrative sector will systematically promote the use of information society services,which decrease emissions in business, industry, administration and people’s everyday lives.5. That the climate change will not lower the current service level in transport and communications. Inorder to attain the goal the Ministry’s administrative sector will update its instructions about transportinfrastructure construction, maintenance and management, outline an action plan for exceptionalcircumstances and invest in research.

Climate Targets and TransportThe emissions reduction potential:from the vehicle fleet renewal (1) amounts to 2.1–2.4 million tonnes,from improved energy efficiency (2) is 0.3 million tonnes andfrom the change in the modal split (3) amounts to 0.3 million tonnes.

161412Milj. t CO210ekv.864201990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006Total CO2 emissions in domestic transport

Waterborne transportAviationRailway transportRoad transport

Routes to Sustainable Transport

26

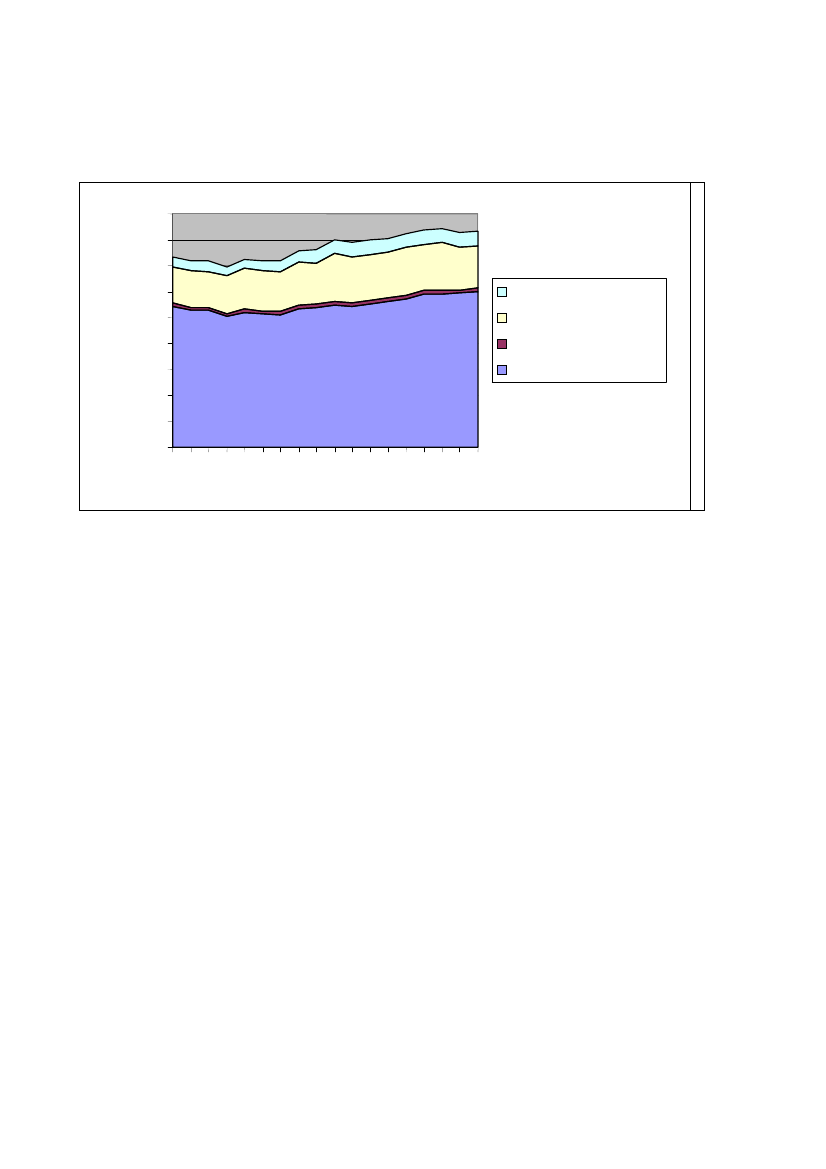

18,016,014,012,0Milj. t.10,08,06,04,02,00,0199019921994199619982000200220042006AviationMaritime transportRailway transportRoad transport

Total CO2 emissions transport sector of Finland, domestic plus international

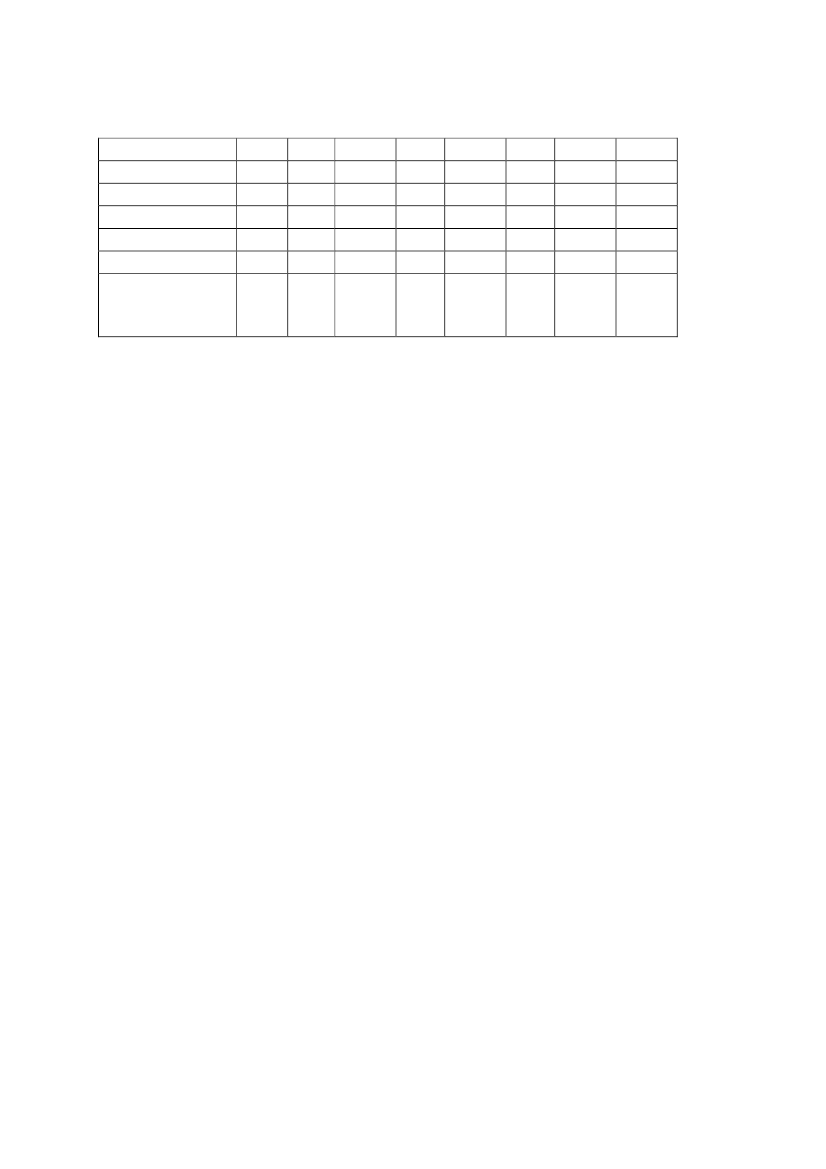

Emissions of Transport and the Energy Use for TransportEmission sand energy use of transport of Finland [t]Energyuse [PJ]146147149152155161169178185195200195194189197

YEARI198019811982198319841985198619871988198919901991199219931994

CO501 781506 689509 193514 718516 608511 579506 334507 670509 628511 639497 372474 699461 090442 769428 560

HC70 44571 09171 83972 67673 66873 89974 28675 56577 45979 19977 70074 09572 04269 53267 223

NOx192 735191 297189 852188 786189 072191 398192 304196 475199 811203 102201 392190 585185 666185 518186 596

Particles8 9349 1339 3119 4939 7059 93510 13710 15110 1439 9809 8819 3159 0229 0078 871

CH44 2864 2864 3244 3554 4054 4284 4474 5404 6664 7754 6524 3954 2564 0943 953

N2O442442453466483506521549579607632627626631639

SO231 64030 01228 43628 00627 58327 72326 28926 91226 17225 81925 39924 49623 94423 92424 250

CO2[milj. t]111111111112121314141514141414

Routes to Sustainable Transport

27

1995420 64665 703 181 0588 548 3 832 648 22 737141951996408 69763 188 174 8268 167 3 672 650 21 399141941997400 84061 391 174 3287 889 3 540 666 22 148152051998391 85559 282 164 5497 316 3 393 673 20 720152061999382 27157 429 169 0047 108 3 292 695 20 667162152000365 53954 171 160 0886 587 3 098 686 19 962162132001352 98651 778 155 0736 254 2 956 698 19 586162152002337 58149 244 148 2785 980 2 823 696 19 846162162003319 68546 595 144 5535 813 2 688 702 20 160162202004299 33643 424 134 5125 391 2 467 689 18 790162252005277 01340 450 133 8455 286 2 302 692 19 741172272006252 92337 371 121 3734 855 2 064 675 18 159162232007243 25235 502 118 3564 802 1 935 675 18 318172302008221 12529 062 112 1574 494 1 706 647 18 177162272009187 92224 81595 1423 872 1 396 605 14 071152122010181 93924 02794 3813 863 1 323 619 13 795152182011179 72123 90993 5273 827 1 304 632 13 598162242012177 95623 76293 0233 810 1 287 647 13 456162292013174 30723 49692 0273 742 1 261 661 13 216162342014170 15323 10589 6053 667 1 227 674 12 502172382015165 90322 68387 4053 603 1 193 687 11 838172412016160 76022 11284 9303 482 1 160 698 11 218172432017155 79021 74082 6603 386 1 127 709 10 637172442018150 74421 49180 6363 310 1 098 721 10 091172462019145 84420 92978 7933 236 1 069 733 9 578172472020141 86020 63477 1323 155 1 047 750 9 092172482021138 05820 21175 6313 097 1 027 764 8 633172482022134 39919 99774 3513 046 1 008 778 8 196172482023130 97619 65273 2463 005 989 793 7 782172482024127 96919 33372 2642 969 973 807 7 389172482025126 08619 07271 3742 928 962 820 7 014172482026124 34618 90770 7722 904 952 833 6 660172482027122 95118 75170 2162 870 943 844 6 322172482028122 01418 66169 7482 837 937 853 5 99817248The figures covers the domestic and international transport from and to Finladn but not the internationaloverlights. In case of electric railways and trams the emissions are based on the total power supply in Finlandand is calculated from share of the electricity use of trains and trams.Lähde: LIPASTO 2008 laskentajärjestelmäLast Updated22.10.2009By Kari Mäkelä, VTTEmail:[email protected]

Routes to Sustainable Transport

28

The Current Share of Energy Consumption Used for TransportThe energy consumption in the transport sector was in 2007 227 PJ. This corresponds to one fifth of thewhole energy consumption of1 132 PJ.The energy consumption in the transport sector is higher than theenergy consumption in the households.The share of gross energy production coming from renewable energy sources such as bio fuels, hydrogen,electricity and other alternative fuelsThe use of renewable energy sources at present in transport (excluding railways) is insignificant.

Plans, Policies and Discussions on Increasing the Use of Renewable Energy Sources forTransportGovernment has introduced an Energy Package to enhance the use of renewable energy sources. Thepackage includes different instruments (subsidies, R & D funding, and regulations) to develop andincrease the use bio fuels and other renewable sources of energy. The Package does not have anydedicated means for transport. At the same time the Government has introduced a proposal for a reformof energy taxation, based on CO2 emissions – including some exceptions. New taxation is aimed to comeinto force at the beginning of year 2011.

Land Use and Physical PlanningTransport and Mobility in Rural Areas Versus Densely Populated AreasThe main challenge in reducing the use of energy in transport in Finland is that the country is sparselypopulated and distances are long. The population is rapidly concentrating to urban areas but at the sametime there is some signs of disintegration of urban areas in the regions of our biggest cities.

Strategies for Sustainable Urban Mobility and the Shift from Private to Public Transport orCycling/Walking and Regulative Measures Like Road PricingReference to the Climate Policy Programme 2009-2020.

Border-crossing Transport in EuropeIn terms of vehicle volumes and total value of cargo Finland is the biggest import border-crossing countryof Russia in road transport. Finland applies same rules for transit transport as to domestic. The only

Routes to Sustainable Transport

29

exception is the maximum total weights and dimensions the vehicles. The maximum size of Russianvehicles is the same as in most of EU countries.There are no user charges or road tolls in use and also all technical regulations are equal to EUregulations.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

30

FlandersIST – Institute Society & TechnologyAuthors: Donaat Cosaert and Marian Deblonde

State of Policy : PACT 2020Flanders hardly has space to spare for new transport infrastructures. For that reason, more intelligent usemust be made of what already exists. This is possible by dividing transport among the varioustransportation modes – both for the conveyance of passengers and goods. The relentless volume of roadtraffic has additional disadvantages: the number of traffic victims is unacceptable; there is the problem oftoo much traffic noise, plus the excess of greenhouse gas emissions and concentrated fine dust particlesinto the atmosphere. Flanders needs to promote environmentally responsible transport modes, especiallywithin the urban centres.Pact 2020 consists of twenty ambitious objectives with a clear delineation of the target figures. With thisFuture Pact, the signatories want to book progress within five principal domains:

A Competitive and Sustainable EconomyFlanders iseasily accessibleby road and rail, via the waterways and by air, using both private and publictransit and transport modes. The region manages to attract a sufficient number of logistics players thatare in a position to contributeadded valueand benefits andgenerate more employment.Flanders will have stabilized its access toenergy sources.This guarantees increased certainty of energysupply and results in sharper pricing. TheCO2emissionshave beenlowered,in keeping with theEuropean commitments already concluded.Flanders makesmore efficient use of energy andmaterials. Energy consumption inside buildings hasbeen lowered considerably and new housing development meetsoptimal performance norms.In its water and air quality standards, soil protection and purification, and the elimination of nuisancenoise, Flanders scores on a par with the top European economic regions. The emission ofgreenhousegasseshas been lowered conform to the European objectives. The average annual concentration offinedust particleshas beenloweredby 25% vis-à-vis 2007.Flanders will have developed atraffic and transportation systemto rank among thefinest and mostefficient in Europe.The year 2020 will register a substantially lowered count of traffic fatalities andseriously injured victims. Flanders has managed to combine the various transportation modes in anintelligent manner.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

31

Logistics and InfrastructureThe economic gateways are readily accessible via the various transportation modes (road, rail, water, orair) and via the array of available carriers (both private and public). As a result, we will register less than5% in hours lost (calculated on the total number of hours travelled by vehicle) on the trunk roads while, atthe same time, we will limit the environmental impact of goods and passenger transport.To this effect, missing links within the transportation network (on the road, on water, and by rail) in theSpatial Structural Plan Flanders will be eliminated. The transportation flows will be dynamically managedin order to be able to make optimal use of the available infrastructure. In order to derive maximum valuefrom logistic operations, we will be attracting logistics players with the ability to generate full added valueand employment.

High Quality of Life: MobilityIn 2020, Flanders will have developed a traffic and transportation system to rank among the mostefficient in Europe. To this end, co-modality, supported by a purposeful location policy and by the STOPprinciple (first pedestrians, then cyclists, then public transport, and finally private vehicles), will figure asthe cornerstone of the Flemish mobility policy, to the extent that from an economic, social, ecological,andlogistic point of view the optimal mode is being implemented. We will ensure that we satisfy theenvironmental objectives that are, likewise, being imposed on other European countries by 2020.Investmentsin traffic and transportation systems will be supported within the policy by means of a socio-economicevaluation and a Flemish accessibility monitor.By 2020, Flanders will figure as one of the best European regions in terms of traffic safety, expressed bothin terms of the number of killed or seriously injured road casualties per million kilometres travelled andper million inhabitants. Vis-à-vis the objectives outlined in the Flemish traffic safety plan, to be in place by2015, a drop of 20% in fatalities and of 25% in seriously injured road casualties will be realized in 2020.

Transport Policy AimsFlanders is looking forward to 2020. In that year, it wants to assume a leading position among the bestperforming European regions, an ambitious goal, indeed, yet one that has every chance of succeeding ifthe Flemish community can fully bring to bear all of its considerable assets on the endeavour. For thatreason, Flanders in Action anno 2008 is focussed on break-through actions.Break-throughs demand drastic interventions that really will make the difference so as to strengthen andbreathe new life into the Flemish economy and its society in a number of crucial aspects. Authorities,industry, the civil society, and the citizens, all must roll up their sleeves and get to work in order to enablecrucial break-through.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

32

Environmentally Friendly and Responsible TransportThe quality of life within urban centres is being raised through the construction of park and nature zonesand by the realisation of improved traffic flows. Flanders maximizes passenger traffic that is conscious ofenvironmental health. It stimulates research into alternative and less polluting fuels and energy-responsible vehicles. It offers financial incentives for the purchase of vehicles with reduced exhaustemission and encourages new forms of pooled and collective transport. Likewise, it devotes greatattention to the strengthening of the Flemish automotive industry and its supply network. All parties mustbe in a position to satisfy the demand for lighter and renewable materials and for hybrid power trains forvehicles.

Standing Out in Traffic ManagementFlanders can boast of outstanding achievements in intelligent mobility technology. The authorities,industry, and research institutions are collaborating in that respect to devise ICT applications to trafficmanagement. ICT is the key to such novel technological mobility applications. The new systems inform theroad traveler about the fastest, least expensive, and environmentally friendly traffic solutions. Thisinformation can be received via different media: via the Internet, electronic information panels, andinformation kiosks at railway stations and along the highways; it is likewise accessible via the traveller’sGPS, GSM, or PDA. Businesses will be collaborating on logistical themes via electronic communicationplatforms. For instance, the transport of goods will be conducted as much as possible by using multi-modalities, outside of peak times, and by using improved grouping.Flanders has the ambition to become a genuine intelligent pivot for transport and logistics in Europe. Forthat purpose, it is integrating traffic management for citizens and businesses into a wide-ranging actionplan that has a variety of approach angles:concern for infrastructure;multimodal transferia;broad policy plan as compass;intelligent kilometrage levy;multimodal brokering;logistics with added value.

Concern for InfrastructureFlanders needs to invest in accordance with an appropriately conceived plan, not only to make maximumuse of existing traffic infrastructures but also to improve and expand them where necessary. Freighttransport combines a variety of transportation modes (ship, train, truck). Individuals also purposefullyselect the most efficient transport mechanism for every travel route: on foot, by bicycle, train,

Routes to Sustainable Transport

33

automobile, or plane. That kind of multimodal system demands a radical change in one’s mentality andway of thinking.

Multimodal TransferiaTransferia render the traffic and transportation systems more effective. A transferium is a transit pointwhere travellers can make a transfer from one conveyance to another (for instance, from automobile tostreetcar), or a transit point for the transfer of containers (for instance, from an inland transport barge toa truck). More transferia enable a better distribution of passenger and freight movement across thevarious transport modes.

Broad Policy Plan as CompassTransportation activities exert their impact on a number of different domains, for instance, in the areas ofspatial development, industrial terrains, logistics, and mobility. This calls for a well-considered planningpolicy in the process of which the various administrations, partners, and initiatives join in a concertedeffort to harmonize and attune their individual plans to one another. That kind of approach likewiseneeds to offer investors and businesses adequate reliability and legal certainty about its composition, thusto increase Flanders’ attractiveness asa desirable place to establish a business.

Intelligent Kilometrage LevyThe introduction of an intelligent kilometrage levy pursues traffic-technical, economic, and ecologicalgoals. From a traffic-technical point of view, such a levy improves the accessibility, and optimizes the use,of the traffic infrastructure. From an economic standpoint, it asks the road user to pay his or her share ofthe infrastructure investment and maintenance costs. The levy furthermore serves an ecological purpose:the polluter pays for the pollution caused to the environment. As a result, road users will give greaterthought to the impact of their road conduct and modify their behaviour accordingly.

Multimodal BrokeringThe authorities and business organisations safeguard the presence of sufficient independent multimodaltransport brokers. The latter’s tasks are to stimulate businesses, assist them with counsel and advice, andsupport them in the realisation of a proper and appropriate transport mix.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

34

Logistics with Added ValueInvestments in novel ICT solutions and innovative mobility applications are highly necessary. By betterattuning the logistics and the education sectors to one another, one also improves the influx of talent intothe region. Flanders maintains its position as a logistics top player and is the most readily accessibleregion.

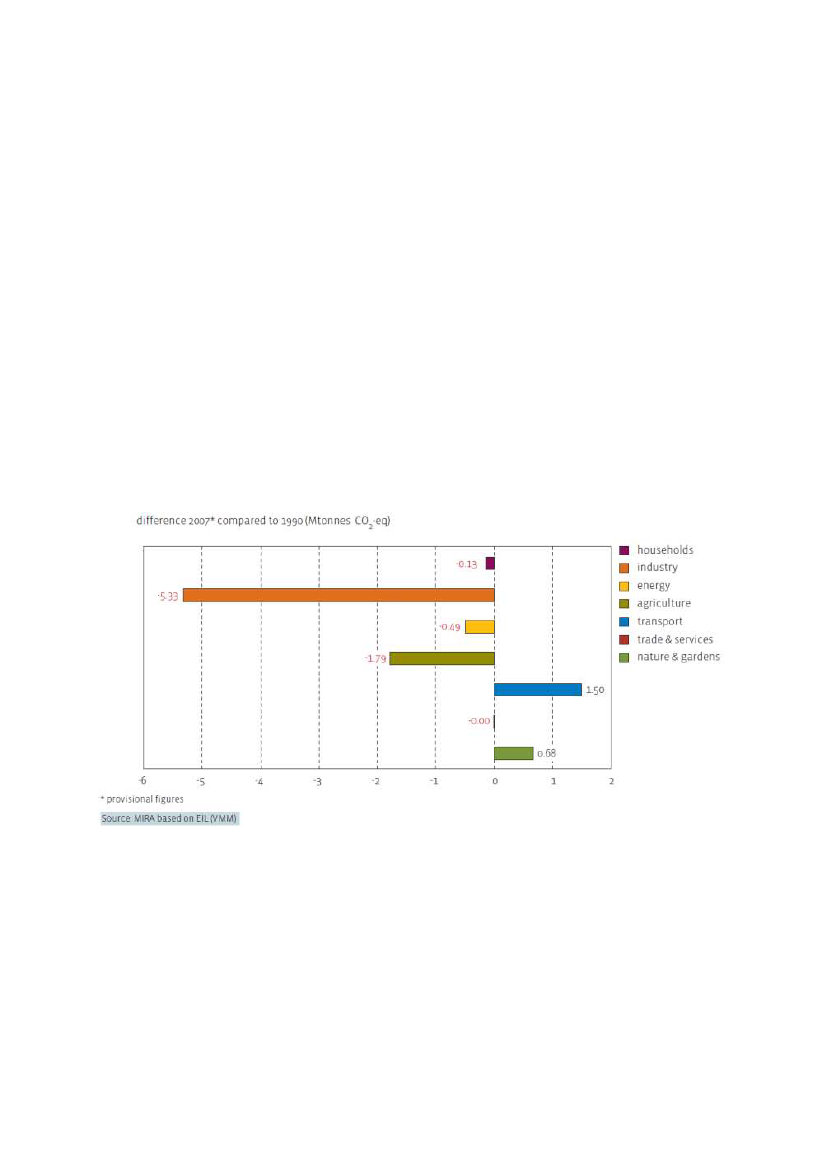

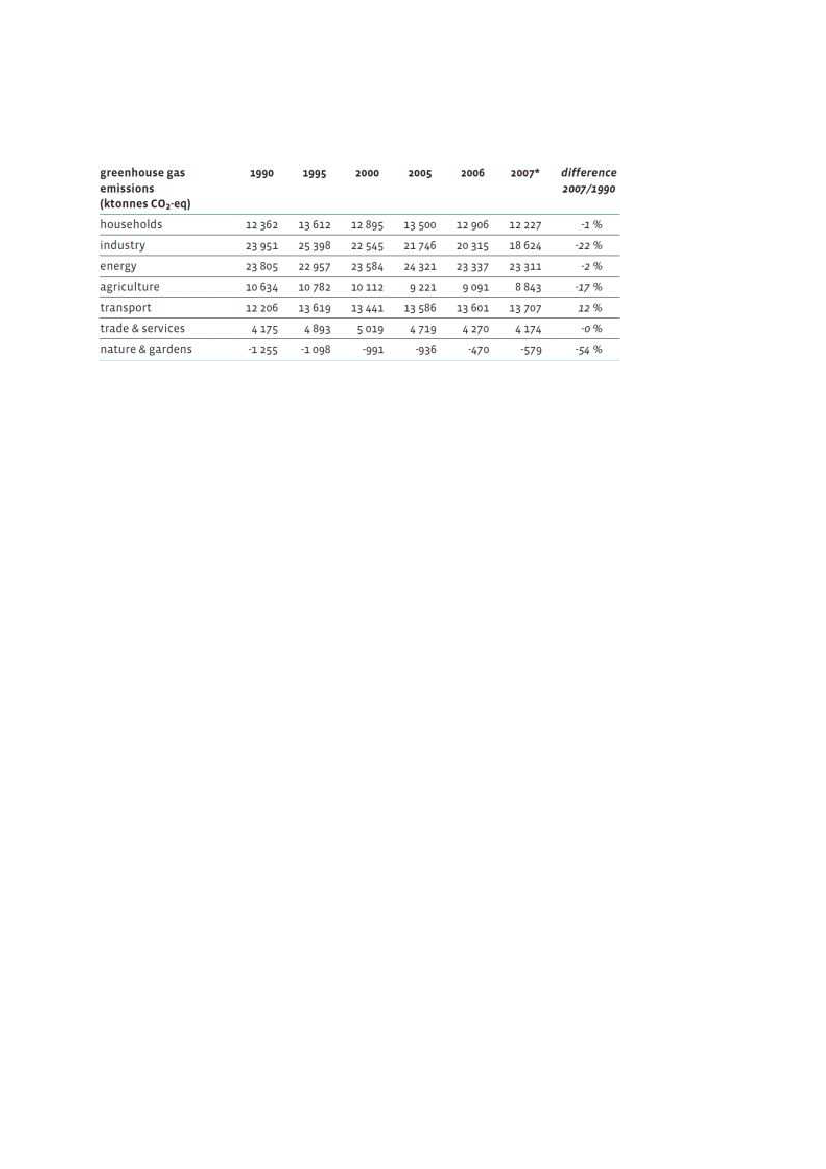

Emission of Greenhouse Gases: Transport Is the Only Sector in WhichEmissions Continue to IncreaseTransport (including private transport; 17 %) and households (15 %) are important sources. The emissionsof greenhouse gases by transport continue to increase further after a strong increase at the start of the1990s. In contrast to passenger transport, the increased energy efficiency of most modes of transport wasnot enough for freight transport to compensate for the growth of the transport flows.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

35

The CO2 emissions followed this trend up to 2006. In 2007 there was a slight deviation due to the use ofbiodiesel by road traffic. Biofuels are considered to be CO2 neutral. The changes in the energyconsumption and the CO2 emissions were largely determined by road traffic, which represents the bulk oftransport flows. The gradual increase of diesel cars in the vehicle fleet and an increased availability andpurchase of more energy efficient vehicles explain the slight fall for passenger transport. The strongergrowth in freight transport, on the other hand, resulted in rising greenhouse gas emissions.

R&DFlanders’ DRIVE was set up in 1996 as anindustry initiativeby: Agoria Flanders, LMS International,Bekaert, Bosal, Tenneco and Sirris. Activities started in 2001 with the support of the Flemish Government.In 2004, the building and infrastructure of Flanders' DRIVE in Lommel came into operation.At first, Flanders' DRIVE focused solely on product innovation. Since 2005, we expanded our focus toinclude process innovation for production and assembly companies as well. The Flemish government gaveFlanders' DRIVE new impetus for the 2007-11 period so that Flanders’ Drive could develop into aninternational competency pool.C aim at:a coordinated approach to innovation, driven by the industrya targeted build up of competencies and research with the aim of international recognitionthe development of a wide network in Flanders and the ELAT triangle (Eindhoven, Leuven, Aachen)with the objective of exchanging experience, cross-pollination and cooperationa cross-border and international profile.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

36

Energy Storage: Battery and Battery Management in Electric VehiclesThe availability of sustainable, reliable and cost-effective energy storage, in batteries for example, iscrucial to the development and acceptance of vehicle electrification. This project is studying the latestgeneration of lithium-ion batteries for electric and hybrid vehicles. There is a special focus on the batterymanagementsystem.The first step in this project is to define the demands a vehicle places on the battery system. Marketresearch into the available technology is already in its final stage. Based on the data gathered, the first setof battery cells have already been bought. Tests with these cells will begin shortly. The basic structure ofthe battery pack has already been defined as well. Details will be provided in the coming months.GOALSThis project will develop a modular battery pack, which can be used for hybrid as well as fully electric carsand buses. The pack consists of lithium cells connected in parallel or series that are controlled by anintelligent battery management system. Knowledge about lithium batteries is being built up and used todevelop an intelligent management system that controls batteries safely and efficiently.

Research Vehicle for Active Safety: Active SuspensionActive safety systems for avoiding accidents are extremely complex electro-mechanical systems. Theproduct developer has a strong interest in managing this complexity in a short development time. Thisproject uses a specific methodology called V-methodology. In this project it is used specifically in thedevelopment of a new active suspension system. If this system is coupled to a vision system, the vehiclecan see potholes in the road and anticipate them. The active suspension is fitted to and tested on a realvehicle, which can later be used to test other active safety applications. The basic functions of the systemhave already been fitted and tested. Safety functions and energy management have been integrated andan initial parameter optimisation was carried out on the vehicle.GOALSThe goal of this project is to make V-development methodology proprietary, specifically through thedevelopment of active suspension. The approach of judging the forces acting on the wheels and theintelligent management of the suspension lead to improvements in comfort and vehicle dynamics. Avehicle equipped with active suspension will display stable ride characteristics under all conditions. Theresearch has been backed by an innovative rapid prototype, a powerful computer which can calculatecomplex algorithms. The project includes research into future vehicles' architecture and the use ofsensors.

Internal Logistics Improvements Through RFID Technology: Monitoring GoodsFlows with Radio Frequency IdentificationRadio Frequency Identification (RFID) is a technology used in many domains, such as in clothing tags toprevent shoplifting for example. In this project, this technology is being used for the first time to chart and

Routes to Sustainable Transport

37

follow the flow of goods actively. RFID can contribute to a more efficient and streamlined delivery ofcomponents to production lines, and thus also to a reduction of logistics costs. This project is researchingthe possibilities of using RFID technology to analyse and redesign internal goods flows.The participants in this project have defined their scope and explored the technology. Currently, researchcase studies are under preparation.The aim of this project is cost savings through the improvement of internal logistics flows with the help ofRFID technology.ETHODOLOGYBy applying RFID technology, goods flows can be examined and analysed. Using dynamic models, goodsflows can then be visualised and improved.

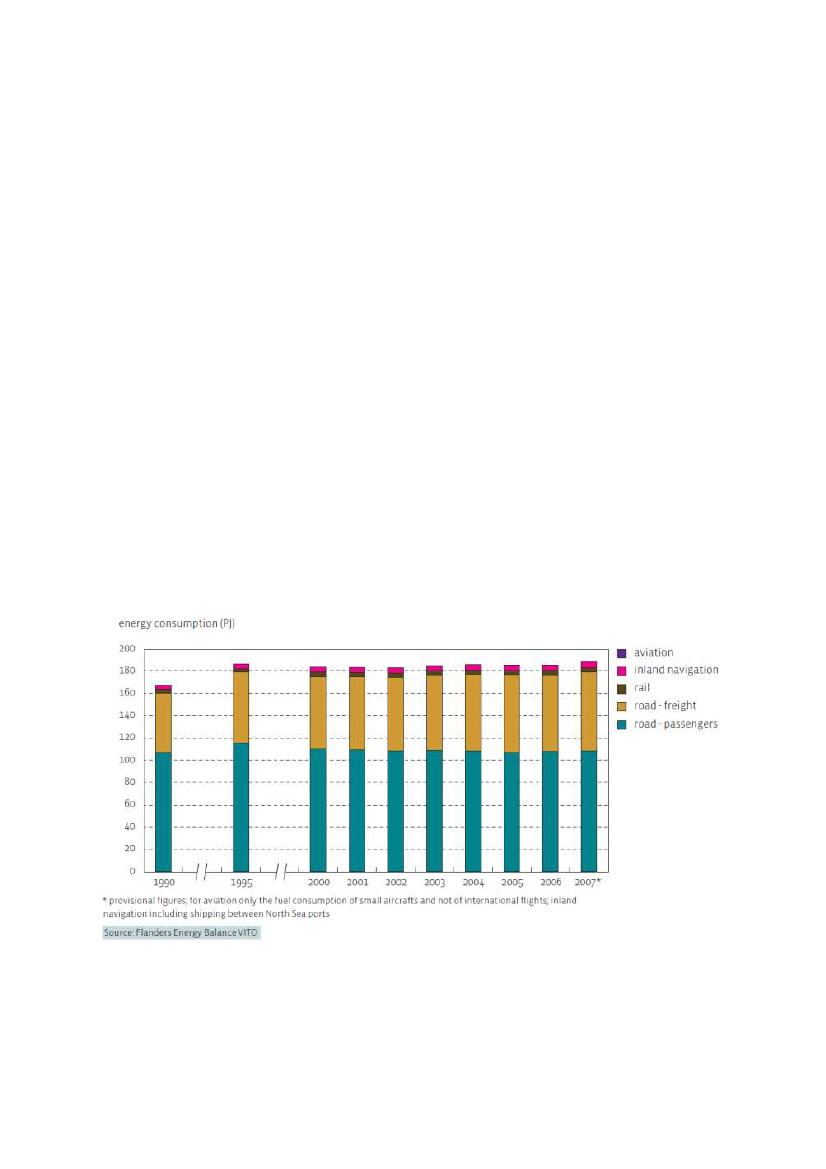

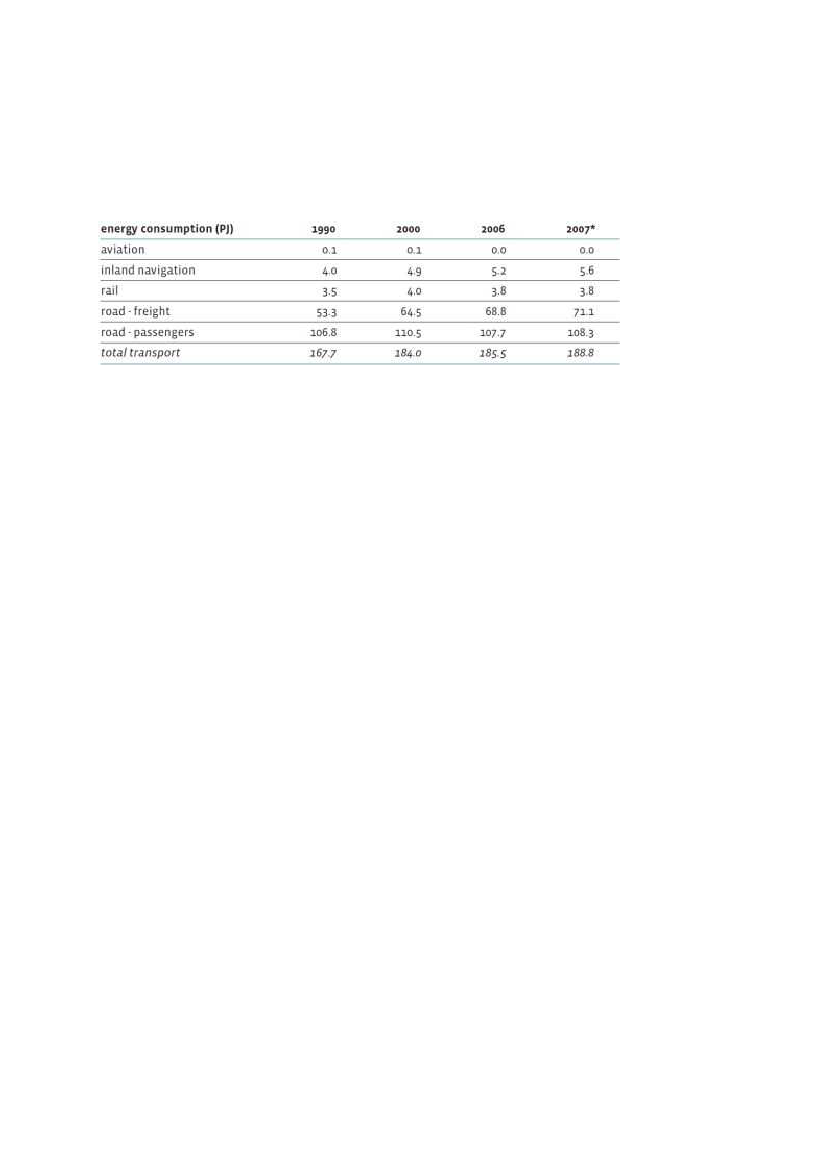

Energy Consumption for TransportEnergy consumption of transport is not decreasing in spite of efficiency improvement.In 2007, the transport sector was responsible for 11.7 % (188.8 PJ) of the gross domestic energyconsumption in Flanders. Road transport accounted for 95 % of the transport sector. Compared to 1990,the total energy consumption of the sector increased by 12.6 %. The energy consumption of passengertransport by road experienced a certain stabilisation from 2000 onwards. This is the result of a smallerincrease in activity combined with an increase in the energy efficiency of vehicles. For freight transport byroad, which also uses more energy efficient technologies, there was a general increase in the energyconsumption (+33.4 % compared to 1990) due to the still strongly increasing activity.

The energy consumption by rail has increased by 6.4 % compared to 1990, this is less than the increase inactivity. The further electrification of the railway is responsible for that as electric motors are much moreefficient than diesel engines.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

38

In 2007, 74 % of the energy consumption for rail was provided by electricity, in 1990 that was still only 53%. Inland navigation saw an increase in energy consumption of 40.3 % in the period 1990-2007. Economicconcerns ensured that the energy efficiency of the ships was also forced upwards.

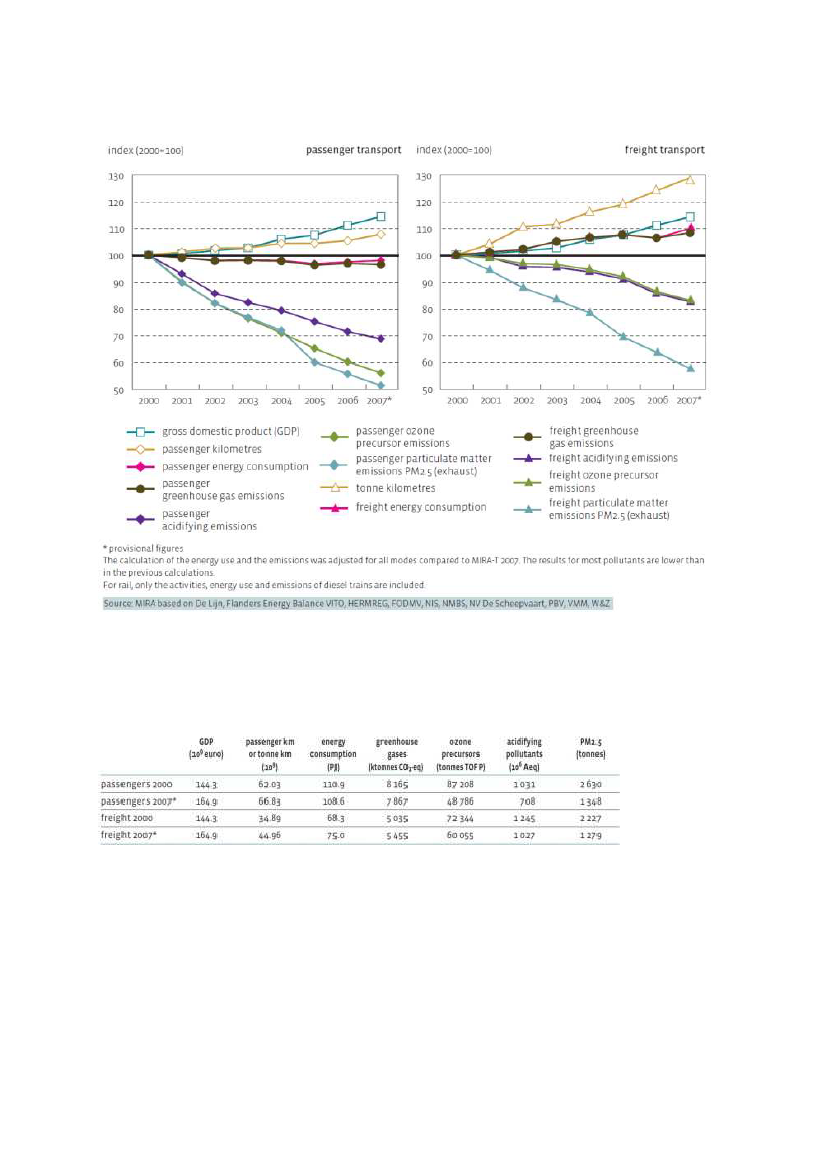

The Climate Commission: Eco-efficiency of Passenger Transport Better thanthat of Freight TransportThis indicator compares the environmental pressure caused by the transport sector (emissions, resourceuse) with a relevant activity indicator. For that reason the sector was divided into passenger traffic (firstfigure) and freight traffic (second figure). Decoupling occurs when the growth rate of a pressure indicatoris lower than the growth rate of the activity indicator. Decoupling is absolute if the growth of the pressureindicator is zero or negative and is relative if the growth of the pressure indicator is positive but not aslarge as that of the activity indicator.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

39

The energy consumption of passenger transport (road and rail traffic) decreased by 2.1 % in the period2000-2007. There was an absolute decoupling with the passenger kilometres. The energy consumption ofgoods transport (road and rail traffic and inland navigation) increased by 9.9 % in this period; although arelative decoupling occurred with the tonne kilometres.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

40

Plans, Policies and Discussions on Increasing the Use of Renewable EnergySources for Transport.BiofuelsPotential for local production of biodiesel (1st generation)In Flanders: 1.3 ktoe/yrIn Belgium: 13 ktoe/yrPotential for local production of bio-ethanol (1st generation)In Flanders: 440 ktoe/yrIn Belgium: 930 ktoe/yrSeven producers of biofuels received a quotum from Belgian authorities4 biodiesel producers; 300 ktoe/yr3 bio-ethanol producers; 127 ktoe/yrThese quota are valid till september 2013. Still no obligation to partly mix biofuels in the regular fuelcircuit.

HydrogenHydrogen technology at most a complement to, not a competitor of, other energy sources for transportuse.Flanders has the largest underground pipeline grid for hydrogen (900 km) worldwide.Consortium of 35 Flemish organisations active in the domain of hydrogen and fuel cell technology.Lacking infrastructure of filling stations

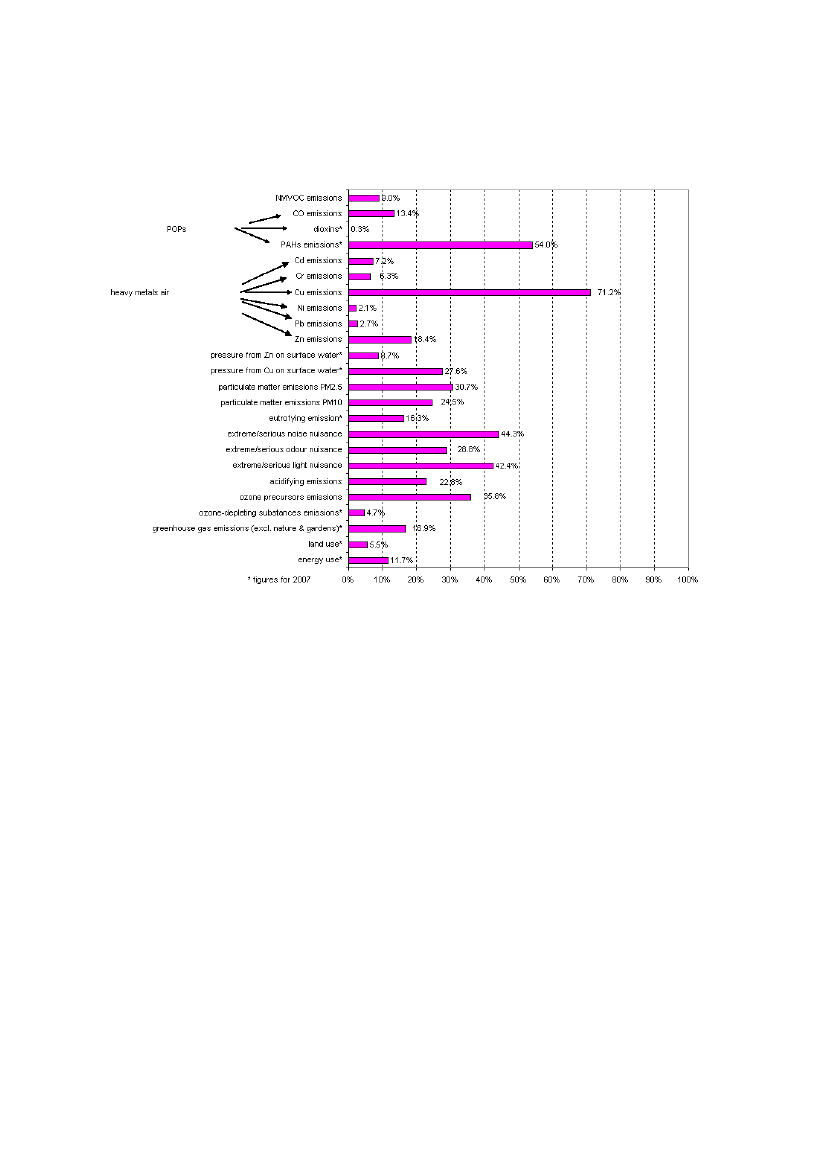

Methods for Monitoring Environmental Impact from the Transport SectorThe transport sector causes air pollution that is harmful to humans and nature. The traffic makes amajor contribution to the emissions of CO, NOx, NMVOC and CO2. These emissions make a significantcontribution to climate change, photochemical air pollution and acidification. Particles and heavy metalsare also emitted by the traffic and are harmful to health.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

41

Figure: Share of transport in the environmental pressure of various themes (Flanders, 2008)(

The sector also causes major pressure on other environmental themes. Rail, air and road traffic causenoise nuisance. Rail, water and road infrastructure result in fragmentation and barrier function resultingin a decrease in biodiversity. The lighting of the roads also causes nuisance. The increasing amount ofmeans of transport also causes an increase in the waste problem once the vehicles are taken out of use.The marginal environmental damage costs caused by the transport sector are important but the marginalexternal costs for transport are mainly controlled by the costs caused by congestion.

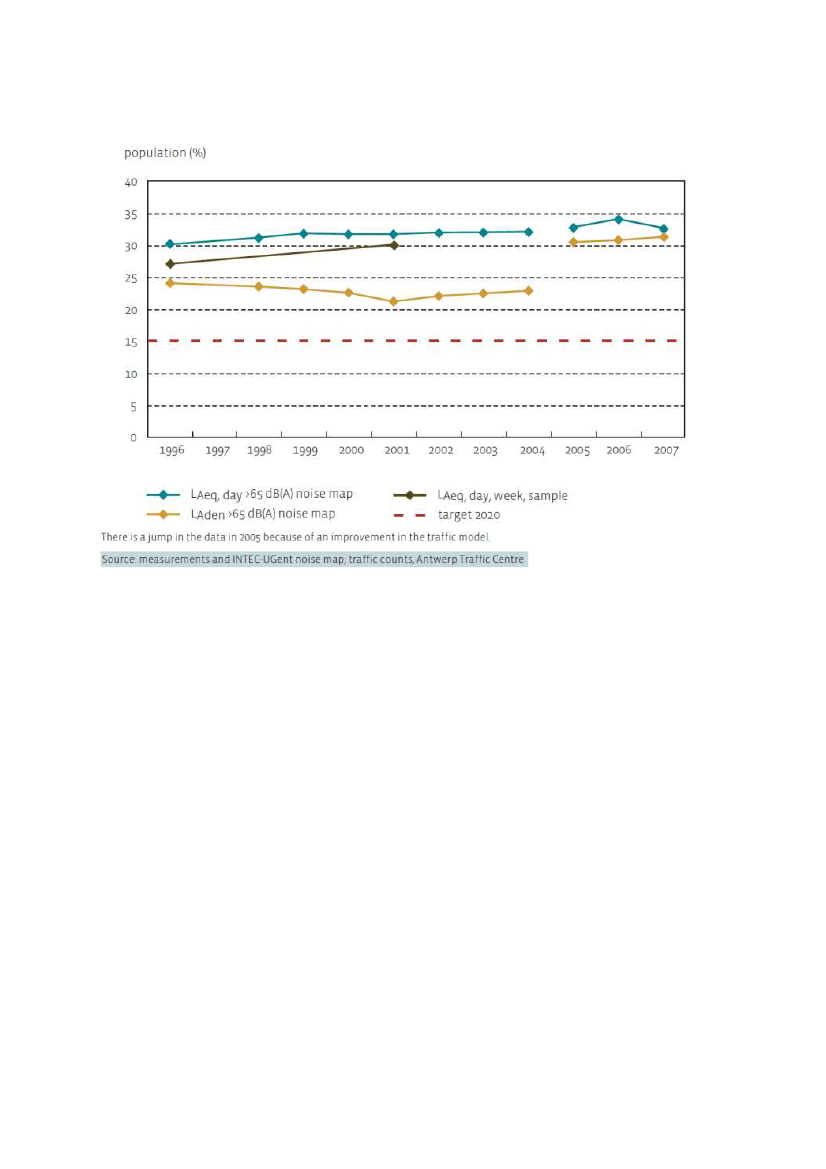

Road Traffic is a Major Source of Noise Nuisance.The exposure of the population to sound pressure levels above 65 dB is described by means of threeindicators which show the sound pressure level at the building facade, i.e. a measured indicator (LAeq,day, week, sample), a calculated indicator that shows the exposure during the day (LAeq, day >65 dB(A)noise map) and a calculated indicator that includes the need for quiet at night (LAden >65 dB(A) noisemap).

Routes to Sustainable Transport

42

Sound Pressure Levels in Flanders Keep IncreasingThe long-term target in the MINA plan 3+ (2008-2010) stipulates that in 2020 only 15 % of the populationwill be exposed to outside traffic noise during the day in front of the house (LAeq >65 dB(A)). At presentthis is still twice as much.Between 1996 and 2001 the sound pressure level at the measured indicator has increased significantly.We see the same change in the indicator that shows the sound pressure level during the day. The soundpressure level for a good night’s rest has also increased since 2001. In 2007, the exposure to high soundpressure levels during the day has decreased while the indicator that includes the need for a night’s restincreased slightly. This seems to indicate that traffic is shifting to the night hours and/or that the averagedriving speed during the day is increasing. A detailed analysis of the data is needed to confirm this.

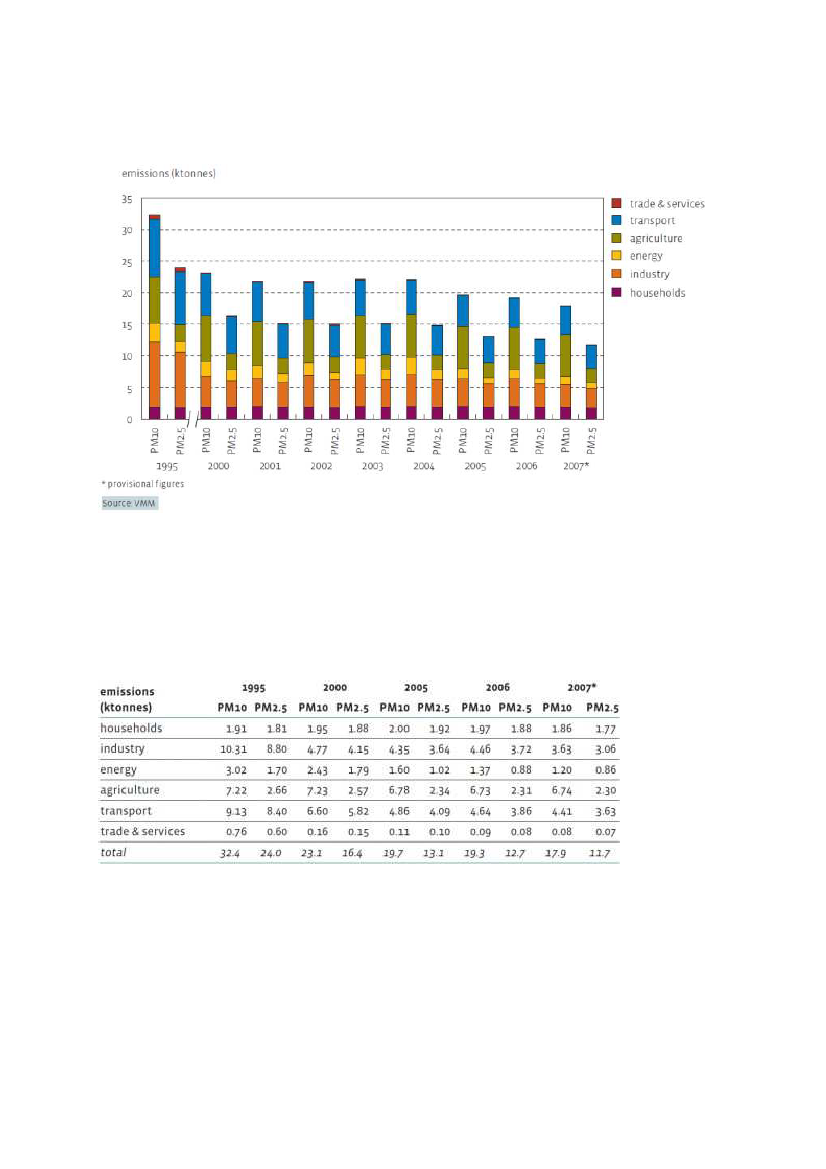

Emission of PM10 and PM2.5Attention is increasingly shifting to finer fractions of particulate matter such as the PM2.5-fraction. Thesefiner fractions could be even more harmful to health than the larger PM10-fraction. PM2.5 may enter theatmosphere via direct emission (primary particles). This indicator shows the emissions of primary PM2.5divided according to the different sectors.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

43

Transport remains a major source of PM10 and PM2.5 emissions. The method of calculation for transportwas changed, as a result of which these figures can differ strongly from figures reported earlier. Afteragriculture, transport (25 %) and industry (20 %) the most important emission sources of PM10. ForPM2.5, transport, with a share of 31 % is the most important emission source. Industry comes second (26%). The introduction of Euro 4 engines in 2005 caused a stronger decrease in the emissions of fineparticles (PM2.5) in both passenger and freight transport.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

44

Technologies Beyond 2020BiofuelsEstimated demand (by 2020) for biodiesel in BelgiumScenario 1: 800 ktoe/yrScenario 2: 708 ktoe/yrEstimated demand (by 2020) for bio-ethanol in BelgiumScenario 1: 90 ktoe/yrScenario 2: 107 ktoe/yrR&D of a diversity of energy sources—both different generations of biofuels and alternatives forbiofuels—should be supported. Where the step is made from experiment to societal introduction, theprecautionary principle should be appliedFlemish authorities should stimulate research with respect to a diversity of energy sources and thesustainability impacts of various circumstances of mobilisation, production and use of various generationsof biofuels and of alternatives to biofuels.

HydrogenFlemish authorities shoulddevelop a clearlong term visionon energy policy and strategy, constituted by avariety of energyresources and technologiesand prioritising renewable energy resourcessupportR&Dto keep pace with international developments w.r.t.hydrogen and fuel cell technologyattune regional and federal initiatives w.r.t.(safety) regulations, permits, trainingin order to simplifyintroductions of new technologies or infrastructure

Electric vehicle (EV)Volvo: EV-production ( planned 2012/13, market development plan: leasing companies, localauthorities, ..)Unicore: metal production for LI – batteriesVito: energy management

Routes to Sustainable Transport

45

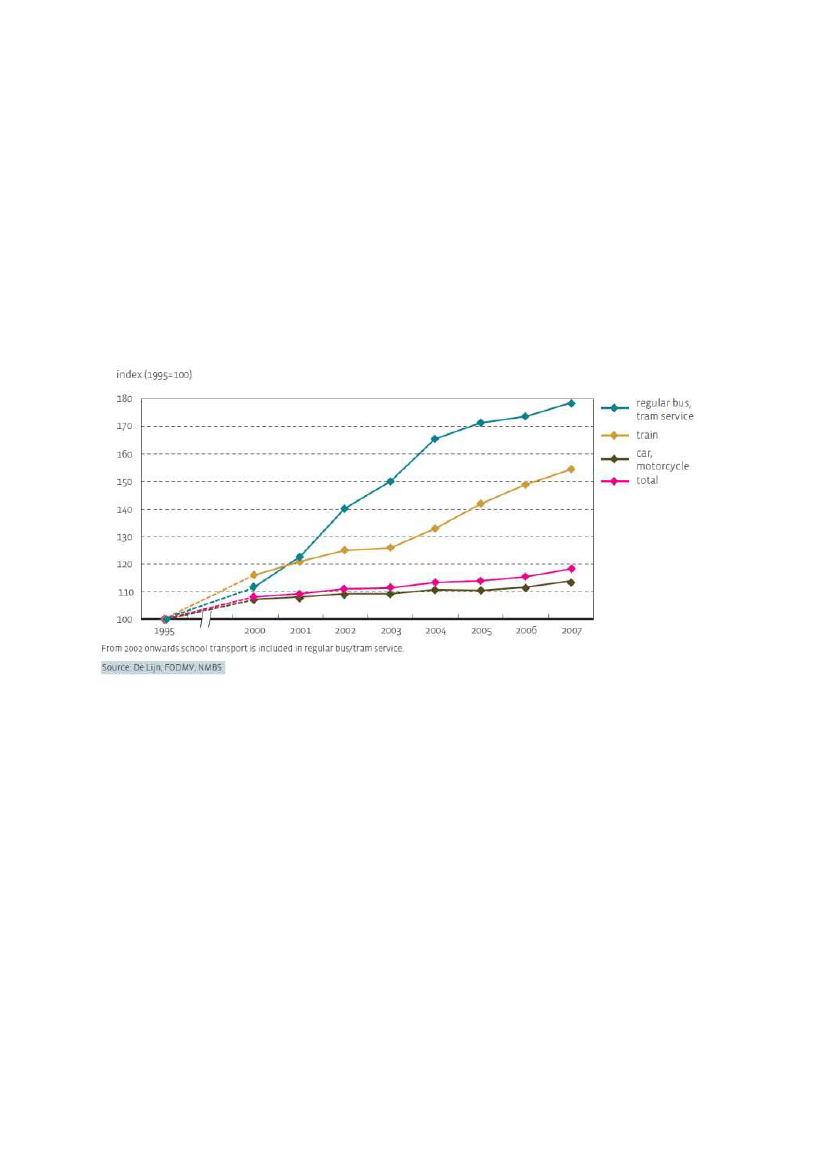

Strategies for Sustainable Urban Mobility and the Shift from Private to PublicTransport or Cycling/Walking and Regulative Measures like Road PricingPassenger Transport : Limited Modal Shift in Passenger TransportIn 2007 the total number of passenger kilometres amounted to 72.47 billion, 2.4 % higher than in 2006and 18.2 % higher than in 1995. In 2007 private motorised transport still accounted for 88 % of transportflows, regular bus/tram services represented 4 % and rail transport 8 %. In 1995 the shares were 91 %(car, motorcycle), 3 % (regular service bus/tram) and 6 % (rail). Despite the significant growth in publictransport, only a limited modal shift has been observed.

The number of passenger kilometres travelled with public transport has increased strongly since 1995.Between 1995 and 2000 there was a larger growth for train transport than for the regular bus/tramservices. In the period 2000-2004 mainly passenger transport with bus/tram services grew explosively(+48%). Passenger transport by train has experienced again a larger growth in the last four years (+23 %). Afocused pricing strategy and an expanded service stimulated the use of bus/tram services. For rail travelthere are also reduced prices for certain groups. The capacity was also increased further by a 5 % increasein the number of train kilometres and the introduction of more double deck carriages. Last year the traincontinued its growth by 3.8 %, regular bus/tram services reinforced their growth in return and increasedby 2.9 %.Passenger transport by car and motorcycle continued to increase. In 2007 the increase was 2.3 %, thelargest growth since 1999.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

46

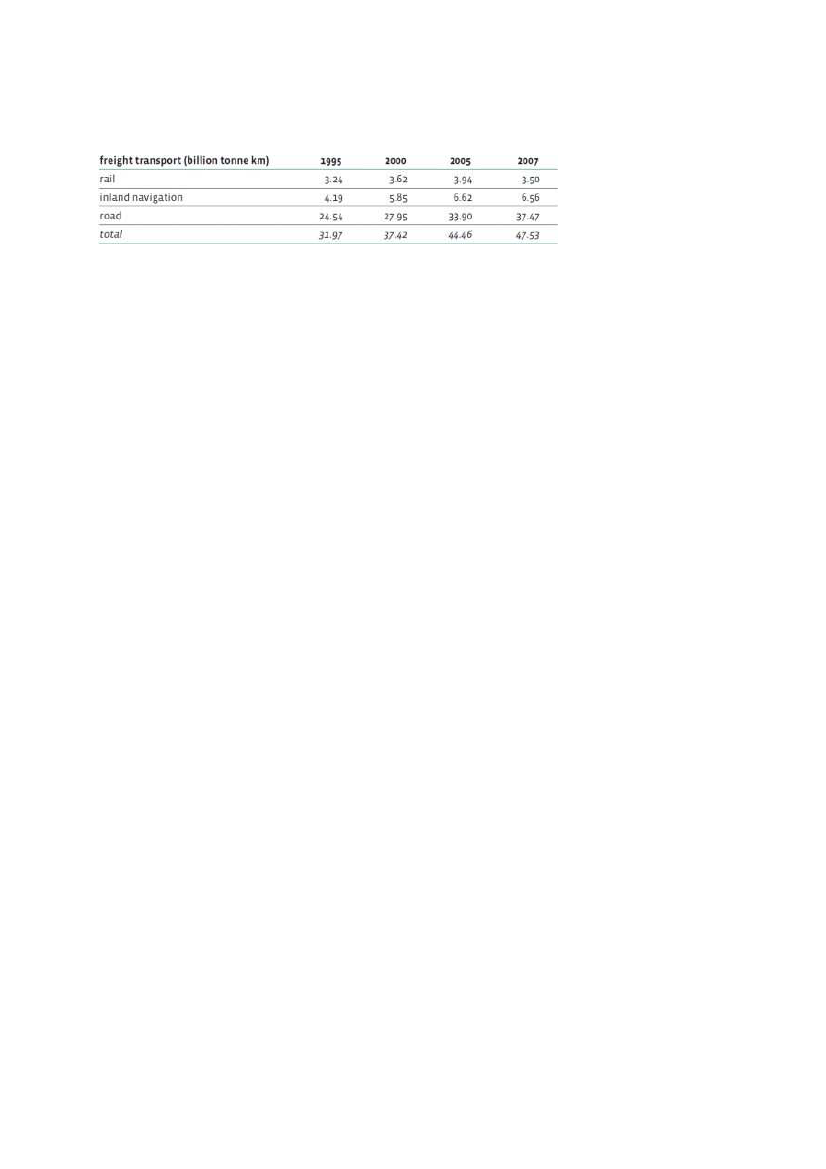

Freight Transport FlowsThe transport flows are a measure of the activity of the transport sector. The freight transport flows areevaluated on the basis of the tonne-kilometres covered by truck, train and inland shipping. The tonne-kilometres show the number of kilometres covered per tonne transported by a specific category of modesof transport, multiplied by the number of tonnes of freight transported.

Since 1995, the transport of freight by road has continued to grow. In 2007 it amounted to 37.47 billiontonne kilometres, a growth of 53 % compared to 1995. Freight transport by rail decreased in 2007 to 3.50billion tonne kilometres, a decrease of 14 % compared to 2006. This can be partially attributed to adecrease in the transportation of iron ore, coke and coal. In 2007, the number of tonne kilometres byinland navigation amounted to 6.56 billion. Compared to 1995, freight transport by water increased by 57%. Since 1998, inland navigation has been stimulated by the Flemish government’s embankmentprogramme, a financial incentive for the construction of loading and unloading facilities. That has resultedin a continuous increase in activity. In the last three years there has however been a stabilization.No modal shift in freight transport. In 2007 the total number of tonne kilometres was 47.53 billion, whichmeans a 49 % increase compared to 1995. Road transport made up 79 % of the total, railway transport 7% and inland navigation 14 %. In 1995, this was 77 %, 10 % and 13 %. The target values for 2010 (FlandersMobility Plan Policy Resolutions, sustainable scenario) are 69 %, 14 % and 17 % respectively. To reachthose objectives and to realise a modal shift must be stimulated further.

Routes to Sustainable Transport

47

Routes to Sustainable Transport

48

GermanyTAB – Office of Technology Assessment at the German BundestagAuthors: Reinhard Grünwald, Juliane Jörissen, Maike Puhe and Jens Schippl

State of PolicyGermany is a rather densely populated country and is located at the heart of the European Union. As formany other EU countries, the transport infrastructure is a basic pillar for economic growth and a highquality of life. On the other hand, induced by heavy growth rates in particular in road transport, Germanysuffers from congestions and bottlenecks which restrict the free flow of goods and people especially inthe densely populated regions. European enlargement and the heavy increase in east-west freightvolumes strongly contributed to this development.At the same time, the increased traffic volume has led to serious environmental consequences includingemissions of greenhouse gases, air pollutants and noise as well as reduced spaces for living and thesegregation effects caused by the expanding transport infrastructure. So, paradoxically one of the basicpillars of today’s quality of life at the same time threatens and reduces that quality.This introductory statement is underpinned by the following figures, which illustrate that especially in thefreight sector strong growth rates are expected for the next decades. Currently the German transportperformance totals 1.100 Mrd passenger-kilometers. Individual motor car traffic accounts for 80 % of thisnumber. In the area of freight traffic the gross number is ca. 650 Mrd tonne-kilometers of which roadtransport has a share of ca. 70 %, rail transport about 18 % and inland waterway transportation ca. 10 %.In a scenario11with ambitious CO2-reduction goals (1990-levels minus 40 % until 2020, minus 85 % in2050) this transport performance is projected to decrease only modestly (by less than 10 %) in thepassenger domain but to rise by more than 60 % in the freight sector till 2050. The modal split will changeonly slightly except a moderate increase of the share of freight transport by rail (from 18 % to 27 %)(Prognos, EWI, GWS (2010)).This means that the assumed greenhouse gas reduction in the transport sector derives mainly from anincreased efficiency of propulsion systems and transport carriers and from a switch to biofuels. Theirshare is expected to rise from 6 % today (2008) to 33 % in 2030 and 85 % in 2050.Against this background, it is of utmost importance to find ways for tackling the expected growth in thefreight sector. An important document is the so-called “Masterplan on Freight Transport and Logistics”(Masterplan Güterverlehr und Logisitk), that was published by the Federal Ministry of Transport in theyear 2008. The plan encompasses the following aims:Improving efficiency of the system and optimizing the capacity utilization of existing infrastructureThe quoted scenario exercise was commissioned by the German government and forms the analytical basisfor the recently adopted “energy strategy“ (Bundesregierung (2010)).11

Routes to Sustainable Transport

49