Udvalget for Fødevarer, Landbrug og Fiskeri 2010-11 (1. samling)

FLF Alm.del Bilag 281

Offentligt

House of CommonsEnvironment, Food and RuralAffairs Committee

The CommonAgricultural Policyafter 2013Fifth Report of Session 2010–11Volume I: Report, together with formalminutes

Ordered by the House of Commonsto be printed 5 April 2011

HC 671-IPublished on 15 April 2011by authority of the House of CommonsLondon: The Stationery Office Limited£0.00

Environment, Food and Rural Affairs CommitteeThe Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee is appointed by the Houseof Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of theDepartment for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and its associated bodies.Current membershipMiss Anne McIntosh (Conservative,Thirsk and Malton)(Chair)Tom Blenkinsop (Labour,Middlesborough South and East Cleveland)Thomas Docherty (Labour,Dunfermline and West Fife)Richard Drax, (Conservative,South Dorset)Bill Esterson (Labour,Sefton Central)George Eustice (Conservative,Camborne and Redruth)Barry Gardiner (Labour,Brent North)Mrs Mary Glindon (Labour,North Tyneside)Neil Parish (Conservative,Tiverton and Honiton)Dan Rogerson (LiberalDemocrat, North Cornwall)Amber Rudd (Conservative,Hastings and Rye)Nigel Adams (Conservative,Selby and Ainsty)and Mr David Anderson (Labour,Blaydon)were members of the Committee during this inquiry.PowersThe Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers ofwhich are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk.PublicationsThe reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The StationeryOffice by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including pressnotices) are on the Internet atwww.parliament.uk/efracomCommittee staffThe current staff of the Committee are Richard Cooke (Clerk), Lucy Johnson(Second Clerk), Sarah Coe (Committee Specialist—Environment), Rebecca Ross(Committee Specialist—Agriculture), Clare Genis (Senior Committee Assistant),Jim Lawford and Anna Browning (Committee Assistants), and Hannah Pearce(Media Officer).ContactsAll correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the Environment, Foodand Rural Affairs Committee, House of Commons, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA.The telephone number for general enquiries is 020 7219 5774; the Committee’se-mail address is: [email protected]. Media inquiries should be addressedto Hannah Pearce on 020 7219 8430.

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

1

ContentsReportSummary1IntroductionPurpose and Scope of the inquiryBackground to the Common Agricultural PolicyThe origin and evolution of the CAPThe current structure of the CAPPage

3568910131314151718192022242729313132323435363737373838394042

2

Objectives of the Common Agricultural PolicyThe need for a common policy on agricultureObjectives and priorities for the post-2013 CAPFood SecurityAgricultural CompetitivenessNatural resourcesFarmers’ incomesDiversity of farming systems

3

Drivers for reform of the CAPFuture agricultural policy and world trade

456

The budget of the CAP in the post-2013 financial frameworkThe Commission’s Communication: the CAP towards 2020The Single Payment Scheme post-2013Divergent perspectives on the future of direct paymentsArguments for the retention of direct paymentsPoor business conditions in agricultureEnsuring EU food securityDirect payments make EU farmers globally competitiveRewarding farmers for delivering public benefitsArguments against the retention of direct paymentsDirect payments do not make farming more competitiveThe Single Payment Scheme is not targetedMore money needs to be spent on the environmentCommercial prospects for agriculture are improvingConclusions on the future of the Single Payment SchemeDefra’s handling of the debate over the Single Payment Scheme

7

A more equitable distribution of funding

8 The balance of funding between direct payments and payments forenvironmental public goodsDoes the CAP need to be greener?The Commission’s proposals to ‘green’ Pillar 1

464648

2

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

9

Additional proposals for direct paymentsThe future of coupled paymentsTargeting of direct payments to active farmersCapping of paymentsSupport for small farmersSupport for Less Favoured Areas or Areas of Natural Constraint

5353545658596163646670717273

10 Increasing the competitiveness of EU agricultureResearch and Knowledge TransferImproving the functioning of the supply chainPrice volatility and market management measures

11 Simplification12 Defra’s handling of the response to the Communication13 Conclusion on the Commission’s Three OptionsConclusions and recommendations

Formal minutesWitnessesList of printed written evidenceList of additional written evidenceList of Reports from the Committee during the current Parliament

7980818183

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

3

SummaryThe Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is again at a crossroads: decisions made now willdetermine our future food prices and availability and shape Europe’s countryside and ruralcommunities. This round of CAP reform is being played out against a very differentbackground to past reforms: food security is rising up the political agenda, placing arenewed emphasis on agricultural policy.The Coalition Government has committed to supporting UK agriculture and encouragingincreased production. Funds provided from the CAP are the centre-piece of UKagricultural spending. Defra must engage proactively in Europe to ensure that thereformed policy will deliver a more competitive, productive and sustainable UKagriculture, in line with its commitments.The primary objective of the Common Agricultural Policy should be to deliver foodsecurity for the EU including a significant degree of self-sufficiency. At the same time, theCAP should help farming businesses become more competitive and profitable and shouldmanage our natural resources sustainably, including maintaining agricultural activity inareas where it enhances our physical and cultural landscapes. Recognising the combinedchallenges of a growing world population, climate change, and environmental degradation,the future CAP must help farmers to produce more while having fewer adverse impacts onour natural environment.The European Commission has set out a range of options for the CAP after 2013. We arenot convinced that any of the options as they currently stand represent a good deal for theUK. In this report, we have set out what changes Defra should seek to achieve on behalf ofthe UK as a whole. We have focussed on the key issues for UK agriculture: the future ofdirect payments and the balance between supporting farmers and protecting theenvironment.We believe that direct payments have a place within the CAP, for as long as businessconditions in agriculture fail to deliver a thriving and profitable industry. While we shareDefra’s ambition to reduce reliance on subsidies, we are not convinced that simplyreducing direct payments is the way to achieve this. If Defra is to retain credibility, it mustset out exactly how UK farmers will become self-supporting, against a backdrop of risinginput prices and greater competition from third countries. In this context, we encourageDefra to clarify its own food security strategy, taking into account the recommendations ofthe Foresight report and its own position on the CAP.Our witnesses rejected the European Commission’s proposals to ‘green’ Pillar 1 throughcompulsory additional agri-environmental measures as they risk creating additionalcomplexity of implementation while not delivering tangible benefits. We agree that thefuture CAP should place greater emphasis on sustainable farming, but believe that this willbe more successful if farmers are encouraged by incentives rather than stifled by regulation.Additional agri-environmental measures must be directed at ‘win-wins’ forcompetitiveness and sustainability if they are to gain traction in the long-term. In principlewe agree that strengthening and expanding the agri-environment component of Pillar 2

4

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

would be more appropriate than establishing a new raft of measures in Pillar 1. However, ifUK farmers are not to be disadvantaged, there must be a common approach and acommon target for implementation across Europe. For this reason, we suggest Defraconsider whether full EU-financing would be more appropriate for measures that areintended to be applied across Europe.The Commission’s proposals are lacking in both vision and detail as to how it intends toincrease the competitiveness of EU agriculture. Elements of their proposals, such aspayment ceilings and additional support for small farmers, risk making UK businesses lesscompetitive. Defra should negotiate changes to these elements and ensure that the finallegislative proposals represent a clear plan for growth in EU agriculture. In particular, thefinal proposals must give fuller consideration to rectifying imbalances in the food supplychain and strengthening farm extension services and knowledge transfer. Any newdefinition of eligible recipients of CAP payments must not disadvantage the UK’s tenantfarmers and commoners.Defra’s handling of the debate over the future CAP has not impressed us thus far. We areconcerned that their stance on direct payments lacks clarity and may reduce their ability tonegotiate constructively with other Member States, or with the devolved administrations. Itis incumbent on Defra to ensure that the devolved administrations’ views are fairlyrepresented. We encourage Defra and the devolved administrations to produce a jointposition statement on the CAP post-2013 swiftly.

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

5

1Introduction1. Agriculture is the main land use in the European Union, covering nearly half of its landarea. The agri-food sector represents 8.6% of EU employment and 4% of the EU’s GDP.1The EU is one of the largest global exporters and importers of agricultural products: itsexport of agricultural goods, mainly high value or processed products, accounts for about17% of total global trade.2Consequently, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is one ofmost important components of the European Union, both in terms of budget and itsimpact on the EU’s 500 million citizens. The CAP accounted for around 43% of the totalEU budget in 2010 (expected to fall to 39% by 2013), which is equivalent to about 0.45% ofthe EU’s GDP.3Through a combination of direct payments to farmers, measures toregulate agricultural commodity markets and grants for improving the environment, theCAP exerts significant influence over the European countryside and rural livelihoods, aswell as global food prices and availability. Moreover, as a key player in the World TradeOrganisation (WTO), the EU’s agricultural policy can shape global trade agreements.2. In 2006, the European Commission was invited by the Council of the European Unionto “undertake a full, wide-ranging review covering all aspects of EU spending, includingthe Common Agricultural Policy”.4Although there is no requirement to reform much ofthe underpinning legislation, the Commission has signalled its intention to carry out areview of the instruments within the CAP. Reform of the future CAP is proceeding intandem with negotiations over the next EU Financial Framework, which must be in placeby the end of 2013.53. The CAP has undergone periodic reform since its inception in 1957, with the overall aimof becoming more market-orientated and less trade-distorting, as well as maintainingdiscipline within the EU budget. This round of reform will be conducted against abackground of financial constraints in many Member States, including those that are majorrecipients of the CAP. The EU’s flexibility over its agricultural policy is further constrainedby existing WTO regulations and subsequent commitments that it has made during theDoha Development Round of trade talks.6In addition, concerns over food security aregiving a new gravity to agricultural policy.4. This is the first major CAP reform with 27 Member States, representing a greaterdiversity of farm structures and priorities. The accession of 12 Central and Eastern

12345

European Parliament resolution of 8 July 2010 on the future of the Common Agricultural Policy after 2013(TA(2010)0286), para F.Ibid,para P.Ibid,para U; Ev 170.Official Journal of the European Union,C 139, 14 June 2006, p 15.In October 2010, the Commission published its review of the EU Budget (Communication from the Commission tothe European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of theRegions,The EU Budget Review,COM(2010) 700 final, 19 October 2010). The Commission must present its proposalsfor the next Multiannual Financial Framework before 1 July 2011.The Doha Development Round is a round of world trade talks organised by the World Trade Organisation (WTO)with the aim of negotiating changes to the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs that was agreed in 1993 at theconclusion of the Uruguay Round. The Doha Round talks have been stalled since 2008, but the WTO is drafting newtexts with the hope of restarting talks this year (“Doha talks running at snail’s pace, agree negotiators”,AgraEurope,11 March 2011).

6

6

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

European Countries after 2003 brought an extra seven million farmers into the EU.7Anadditional and unpredictable factor is that, under the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, the EuropeanParliament will now have joint decision-making powers with the Council of the EuropeanUnion. This may make the negotiating process more transparent, but also more complex.Reconciling the varying objectives of 27 Member States and the European Parliament willunquestionably be a political challenge for the EU.5. The European Commission initiated the dialogue over the ‘CAP post-2013’ with a publicconsultation held over the summer 2010,8followed by a Communication onThe CAPtowards 2020published in November 2010.9The Agriculture and Fisheries Councilproduced initial conclusions on the Communication in March 2011; however, these failedto win unanimous support from Member States.10The European Parliament is expected topass a resolution in response to the Commission’s Communication in June 2011. Further,more detailed legislative proposals are expected in autumn after the proposals for the post-2013 EU Multiannual Financial Framework have been published. The Commission hopesto conclude negotiations on the CAP by the end of 2012 to allow one year forimplementation.6. This Committee has a long-standing interest in CAP reform. The previousEnvironment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee published reports on theUKGovernment’s Vision for the Common Agricultural Policyin 2006,Implementation of CAPReform in the UKin 2004, andThe Mid-Term Review of the Common Agricultural Policyin2003, as well as scrutinising the work of the Rural Payments Agency.11

Purpose and Scope of the inquiry7. In this inquiry we have scrutinised the Commission’s proposals in light of UK interestsin particular.12Defra is going into negotiations on the CAP that will determine our futurefood prices and availability and shape Europe’s countryside and rural communities until2020, or beyond. Our recommendations and analysis set out where we believe the limits toDefra’s negotiating position should be.7European Parliament resolution of 8 July 2010 on the future of the Common Agricultural Policy after 2013(TA(2010)0286), para G. Specifically, the EU was enlarged in 2004 to include: Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Latvia,Estonia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Slovenia. Bulgaria and Romania acceded in 2007.The public consultation was concluded with a public conference in July 2010. A summary of the responses to theconsultation together with a video recording of the conference can be viewed on the European Commission’sAgriculture and Rural Development website: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and SocialCommittee, and the Committee of the Regions,The CAP towards 2020: Meeting the food, natural resources andterritorial challenges of the future,COM(2010)672/5; hereafter “the Communication”.Council of the European Union,Presidency conclusions on the communication from the Commission: The CAPtowards 2020: meeting the food, natural resources and territorial challenges of the future,3077thAgriculture andFisheries Council meeting, 17 March 2011, www.consilium.europa.eu. Seven Member States voted against thedocument: Denmark, Sweden, the UK, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Malta. “Latest EU Farm Council Wrap”,AgraEurope,17 March 2011.The UK Government’s “Vision for the Common Agricultural Policy”,Fourth Report of Session 2006–07, HC 456;TheRural Payments Agency and the Implementation of the Single Payment Scheme,Third Report of Session 2006–07, HC107;The Implementation of CAP Reform in the UK,Seventh Report of Session 2003–04, HC 226;Rural PaymentsAgency,Sixth Report of Session 2002–03, HC 382;The Mid-Term Review of the Common Agricultural Policy,ThirdReport of Session 2002–03, HC 151.The terms of reference are available on the Committee’s website:http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/environment-food-and-rural-affairs-committee/inquiries/cap-reform/

8

9

10

11

12

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

7

8. The CAP is a convoluted policy, having been moulded to fit the multifarious wishes ofgovernments and Agriculture Commissioners over the years. Since the Treaty of Rome in1957, the requirements of EU agricultural policy have shifted, notably with a muchstronger focus on preserving natural resources, while our future policy will have to meetthe challenges of food security and climate change. For this reason, we start with a freshanalysis of the CAP’s objectives towards 2020 (Chapter 2) and the internal and externalfactors to take account of when shaping the new CAP (Chapter 3).9. The overall size of the CAP budget and the way that it is distributed between MemberStates will be one of the most important issues for the UK. We give consideration to high-level issues surrounding the CAP budget in Chapter 4. However this report precedes EU-level discussions on the Multiannual Financial Framework post-2013, precluding detailedanalysis.10. The UK tends to take a reformist stance on the CAP, having argued for over ten yearsthat direct payments and market support should be phased out in favour of increasedspending on targeted measures to protect the environment.13This places us in a minoritywithin Europe, particularly compared to influential old Member States such as France andGermany. It is already clear that the future of direct payments will be the central issue inthe debate over the post-2013 CAP. We address the nature and distribution of directpayments from a UK perspective in Chapters 6 and 7. In Chapter 8, we scrutinise theCommission’s ideas for legitimising the CAP by bringing agri-environment measures intoits core policy.11. Turning to the substance of the Commission’s Communication, the proposals torestrict payments to active farmers, to give more support to small farmers and to cappayments to large farmers were highlighted by many of our witnesses as issues ofimportance to the UK. We discuss these and other specific elements of the proposals inChapter 9. Reflecting Defra’s aim to deliver a thriving farming sector, we then discuss waysin which the CAP can enhance the competitiveness of UK agriculture (Chapter 10) andreduce red-tape for farmers and administrations (Chapter 11).12. We announced this inquiry on 4 November 2010. We held seven oral evidence sessionsand heard from 14 organisations or individuals including farming groups, environmentalNGOs, the European Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development and Rt HonJames Paice, the Minister of State for Agriculture and Food (a full list is given at the end ofthe report).We received written evidence from 34 individuals or organisations. We alsotook part in a visit to Brussels to discuss aspects of CAP reform. We are very grateful to allthose who helped us with our inquiry. This report is necessarily limited to the details givenin the Commission’s Communication. This is a rapidly moving area and additional detailsof the proposals have emerged between evidence-taking and publication of this report.

13

Cunha and Swinbank,An inside view of the CAP reform process,2011, p 121; Defra and HM Treasury,A Vision forthe Common Agricultural Policy,December 2005; Defra,UK Response to the Commission Communication andConsultation: “The CAP towards 2020: Meeting the food, natural resources and territorial challenges of the future”,January 2011.

8

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

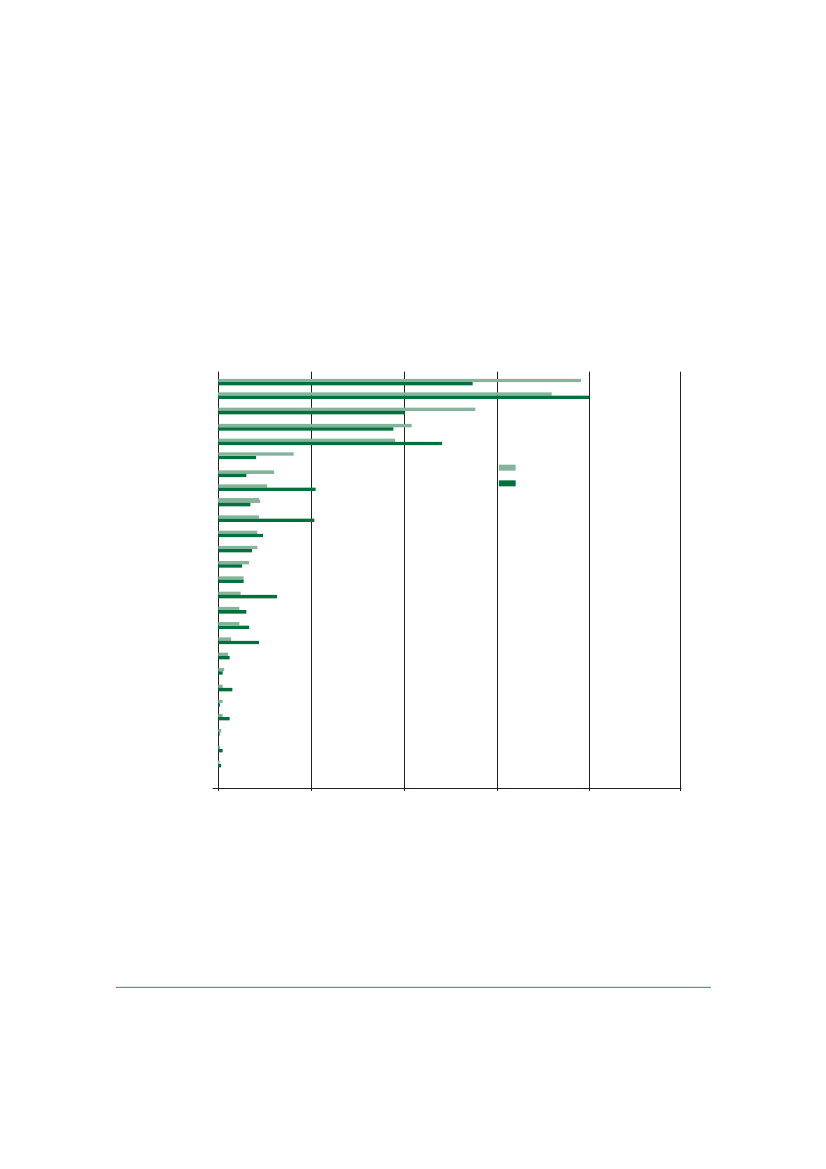

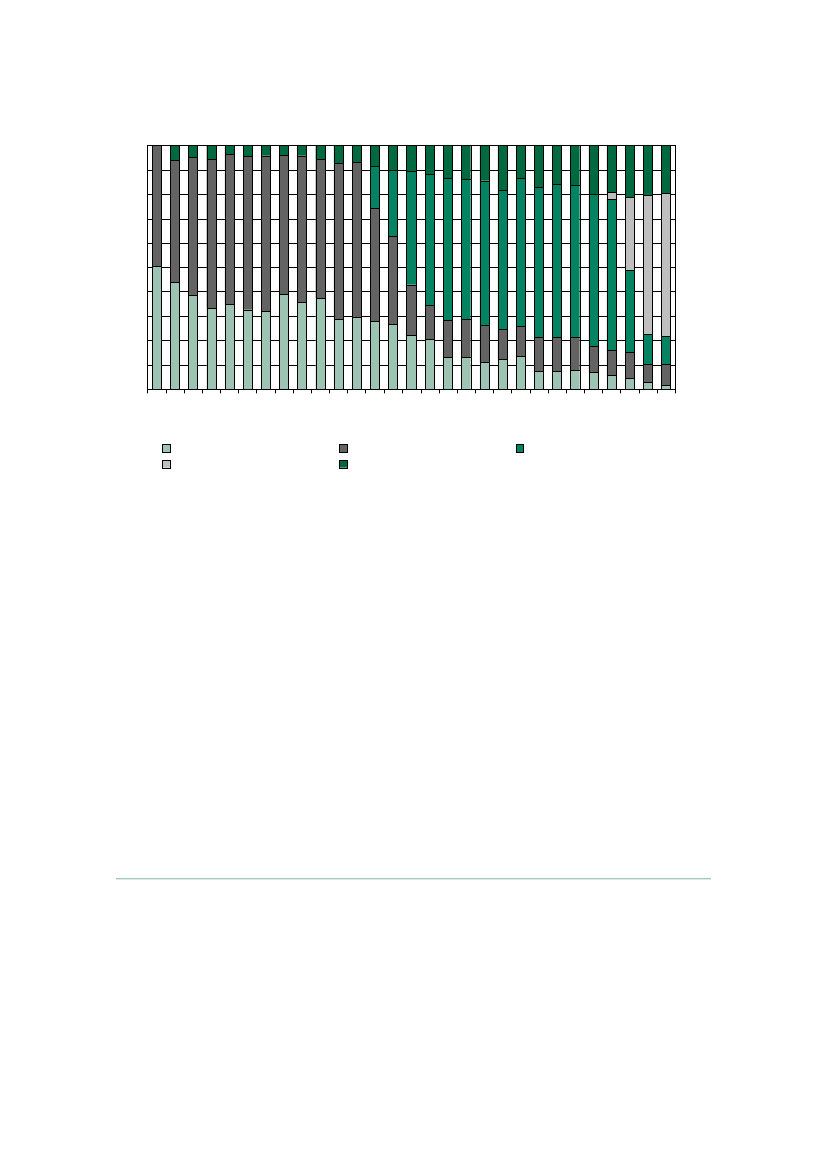

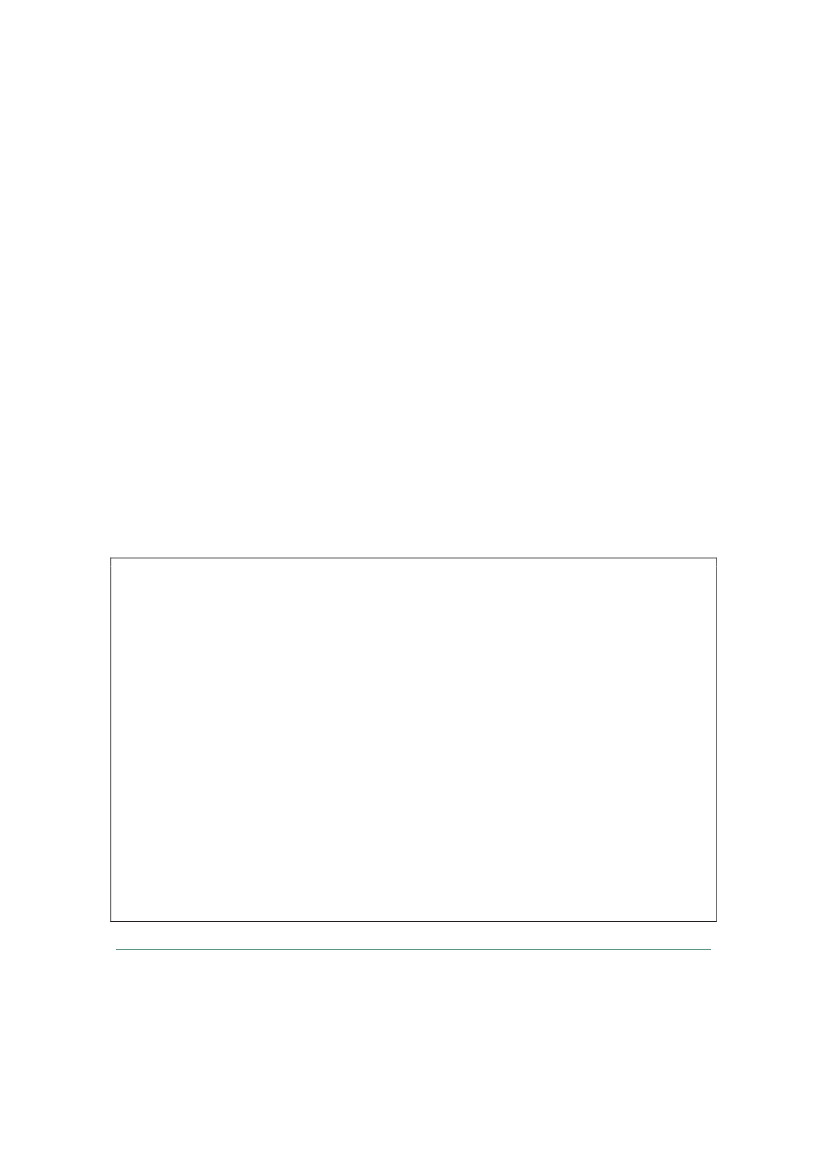

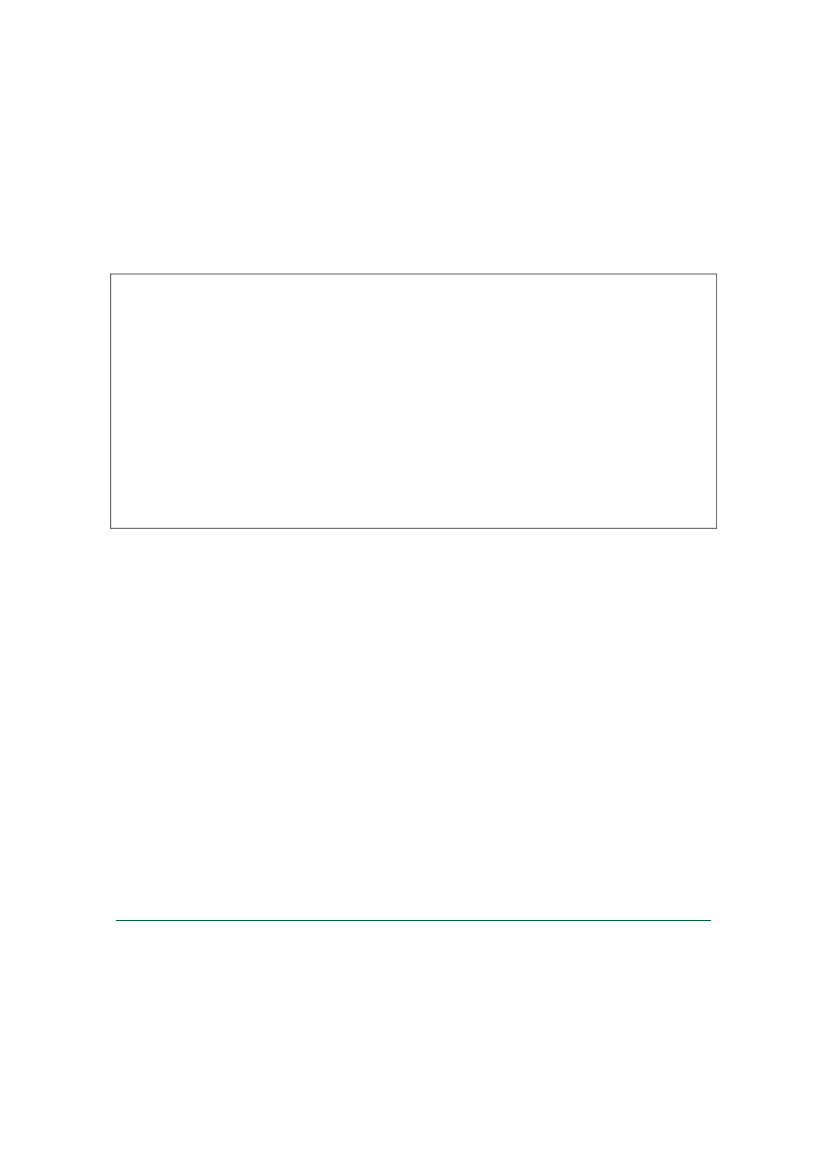

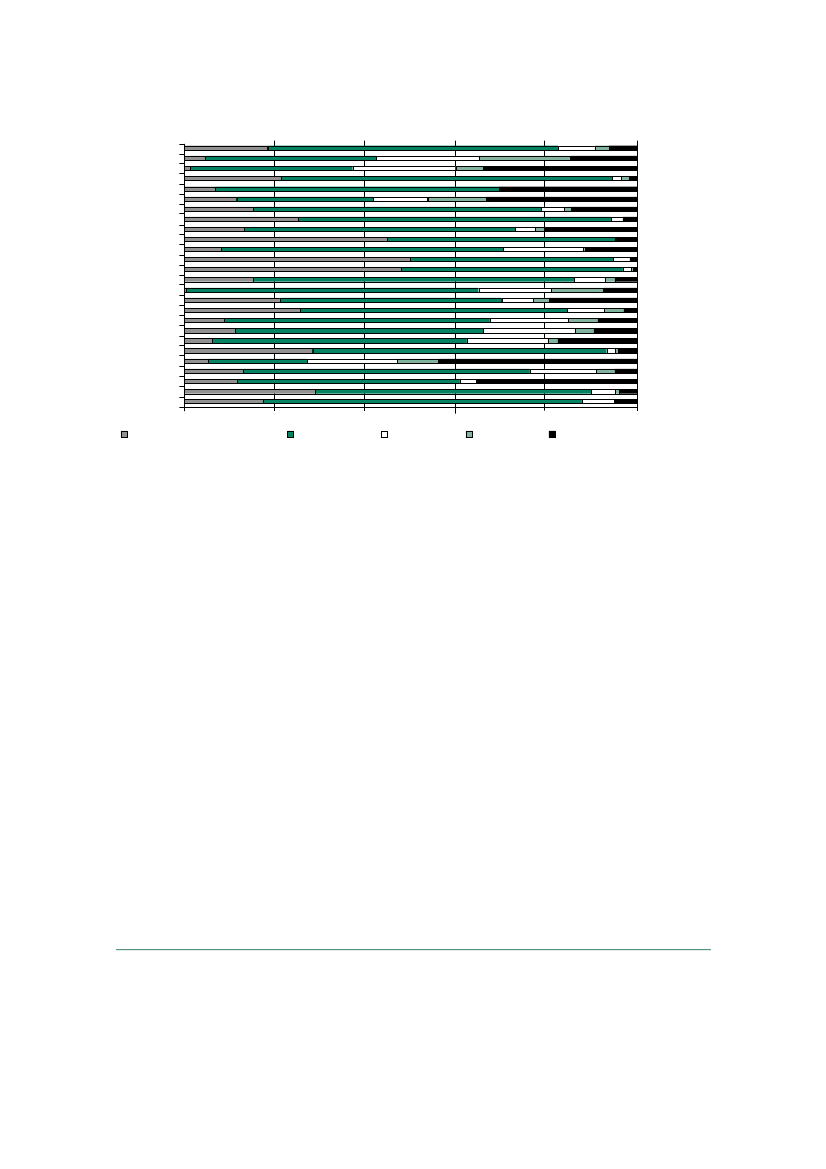

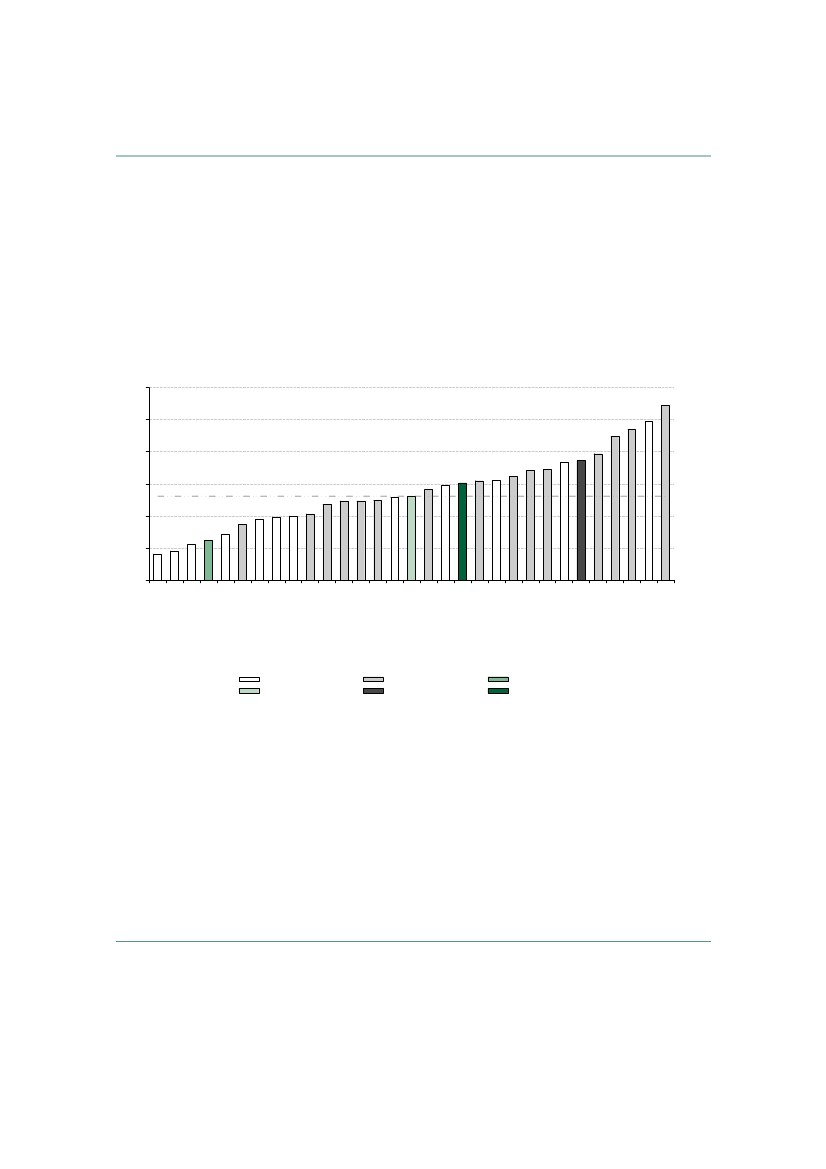

Background to the Common Agricultural Policy13. The Common Agricultural Policy sets out the EU’s common approach to agricultureand its system of payments. It is structured around three groups of instruments: directpayments, market measures and rural development.14The CAP receives 98% of the EU’sPreservation and Management of Natural Resources budget, which was allocated €416bnfor the 2007–2013 Financial Perspective.15In 2010, the UK’s contribution to the EUaccounted for 10.4% of the CAP budget and the UK’s share of the allocation for directpayments was 9.5%. France contributed about 18.0% of the CAP budget and receivedabout 20.1% of the direct payments allocation. Greece contributed 2.2% and received 5.2%(Figure 1).16Figure 1: Member States relative contributions and receipts from the CAPGermanyFranceItalyUnited KingdomSpainNetherlandsBelgiumPolandAustriaGreeceDenmarkSwedenFinlandPortugalIrelandCzech RepublicRomaniaHungarySlovakiaSlovenaBulgariaLuxembourgLithuaniaCyprusLatviaEstoniaMalta

ContributionsReceipts

0.63%0.67%0.34%0.25%0.32%0.80%0.27%0.09%0.25%0.65%0.16%0.09%0.16%0.25%0.12%0.17%0.05%0.01%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Source: European Parliament (2010/117/EU), Definitive adoption of the European Union’s general budget for thefinancial year 2010, p 20; Council Regulation (EC) No 73/2009, Annex VIII. The graph shows Member States’receipts from Pillar 1 of the CAP in 2010 as a percentage of the total budget for Pillar 1 and Member States’contributions based on the relative share of each country’s payments to the EU Budget. Pillar 2 is not included.

141516

There are some additional programmes directed by the Commission such as plant and animal health inspections andpromoting fruit in schools.European Commission,European Union Public Finance (Fourth Edition),2008.European Parliament (2010/117/EU),Definitive adoption of the European Union’s general budget for the financialyear 2010,p 20; Council Regulation (EC) No 73/2009, Annex VIII.

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

9

The origin and evolution of the CAP14. The Common Agricultural Policy was established in the aftermath of the SecondWorld War, following a long period of rationing and food shortages. As a result, a keydriver of the original CAP was enhancing self-sufficiency through boosting domesticproduction; to facilitate this, European prices for agricultural commodities weremaintained at levels in excess of the world market. Market price support required acombination of high import tariffs, intervention buying and export subsidies.15. As yields and production rose, the requirement for public storage (the ‘wine lakes’ and‘butter mountains’) and for subsidies for exporting excess goods also increased. This hadnegative implications for the perception of the CAP among EU citizens and ininternational trade negotiations—disagreements over agricultural support were one of thefactors leading to the collapse of the WTO Uruguay Round trade negotiations in December1990. Moreover, the cost of the CAP almost trebled between 1980 and 1992.1716. The 1992 MacSharry reforms aimed to reduce expenditure on the CAP and removesome of the incentives for farmers to over-produce. Payments were decoupled fromproduction for cereals and beef and the intervention prices for cereals, dairy and beef werereduced. Direct payments for cereals and beef, known as the Single Farm Payment, werebrought in to compensate producers for the resulting loss of income. For the first time,measures to support rural economic diversification and environmental protection wereincluded in the CAP.17. The Agenda 2000 reforms, agreed in 1999, were inspired by preparations for the policyand budgetary consequences of the Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs)joining the EU. These reforms included further reduction of the intervention prices,extension of the dairy quota and the establishment of the rural development regulation.Modulation, which is a transfer from the single farm payment to fund rural development,was introduced on a voluntary basis.18. The 2003 Mid-term Review of the Agenda 2000 package, also known as the FischlerReforms, is generally considered to be the most radical of the CAP reforms in that itdecoupled farm income support from production in most sectors (Figure 2).18The FischlerReforms also made it compulsory for recipients of the Single Farm Payment to meetenvironmental and animal welfare standards. In 2002, the Council agreed to limit CAPspending on Pillar 1 at its 2006 levels for the financial perspective to 2013. The 2008 HealthCheck consolidated the Fischler reforms through decoupling the remaining sectors (exceptthe suckler cow, goat and sheep premia) and confirming the abolition of milk quotas in2015. The requirement for farmers to keep 10% of their land in set-aside was abolished.19. The percentage of the EU budget spent on the CAP has fallen from a high point ofabout 75% in the mid 1980s to under 40% by 2013, even though the agricultural land areahas increased by 40% following the 2004 and 2007 enlargements of the EU.19

171819

Cunha and Swinbank,An inside view of the CAP reform process,2011, p 69.Member States were given the option to retain some coupled payments for both cereals and livestock.European Parliament resolution of 8 July 2010 on the future of the Common Agricultural Policy after 2013(TA(2010)0286), para U.

10

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

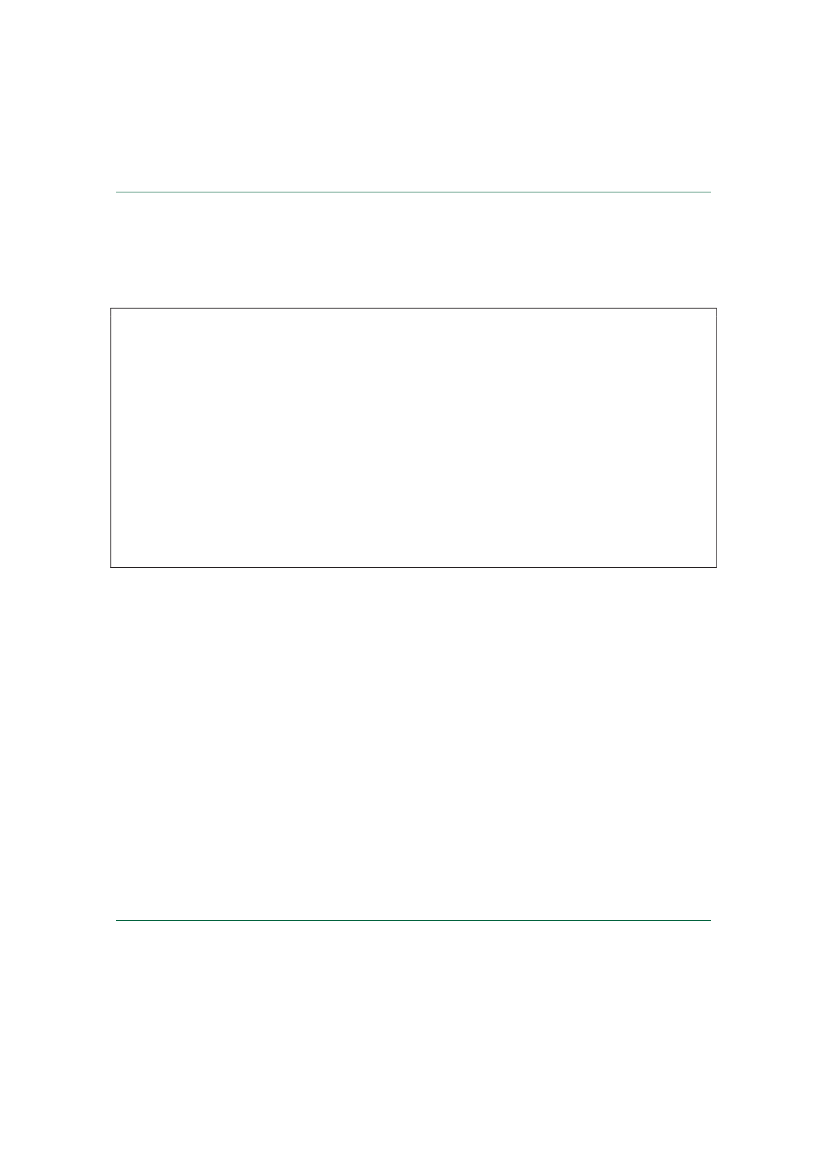

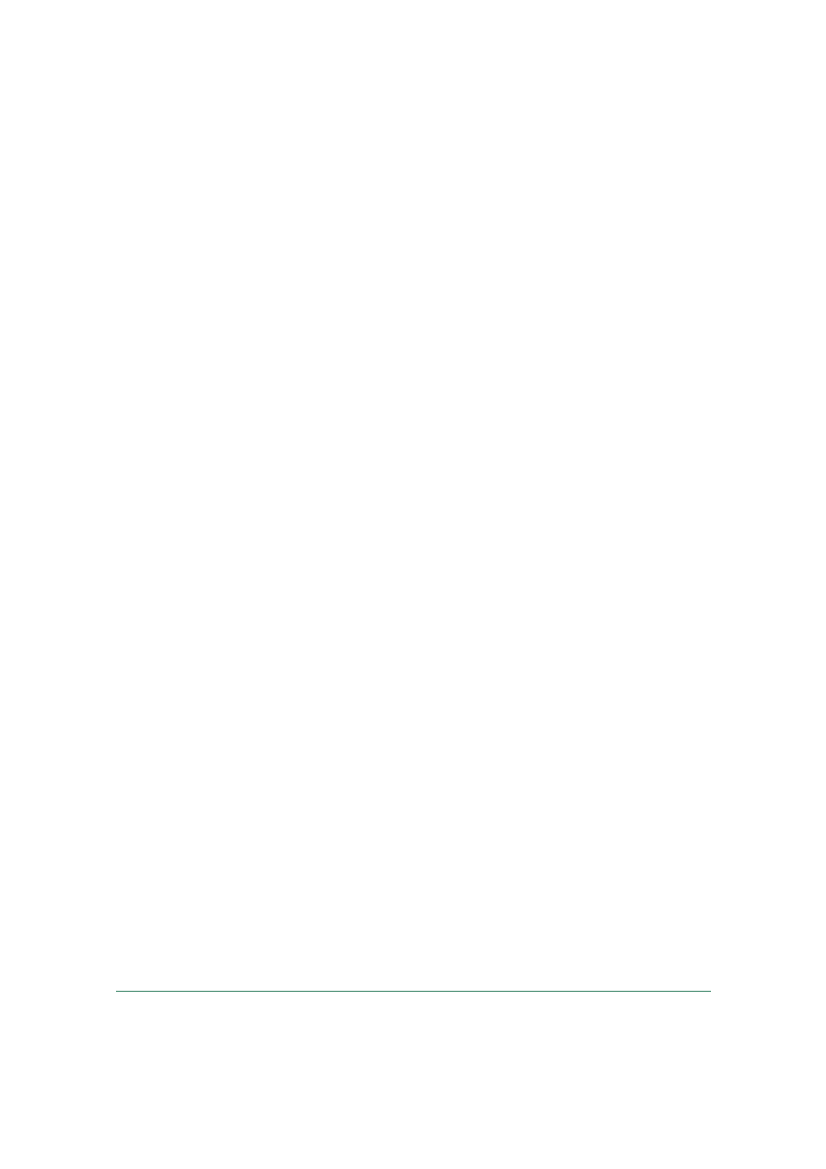

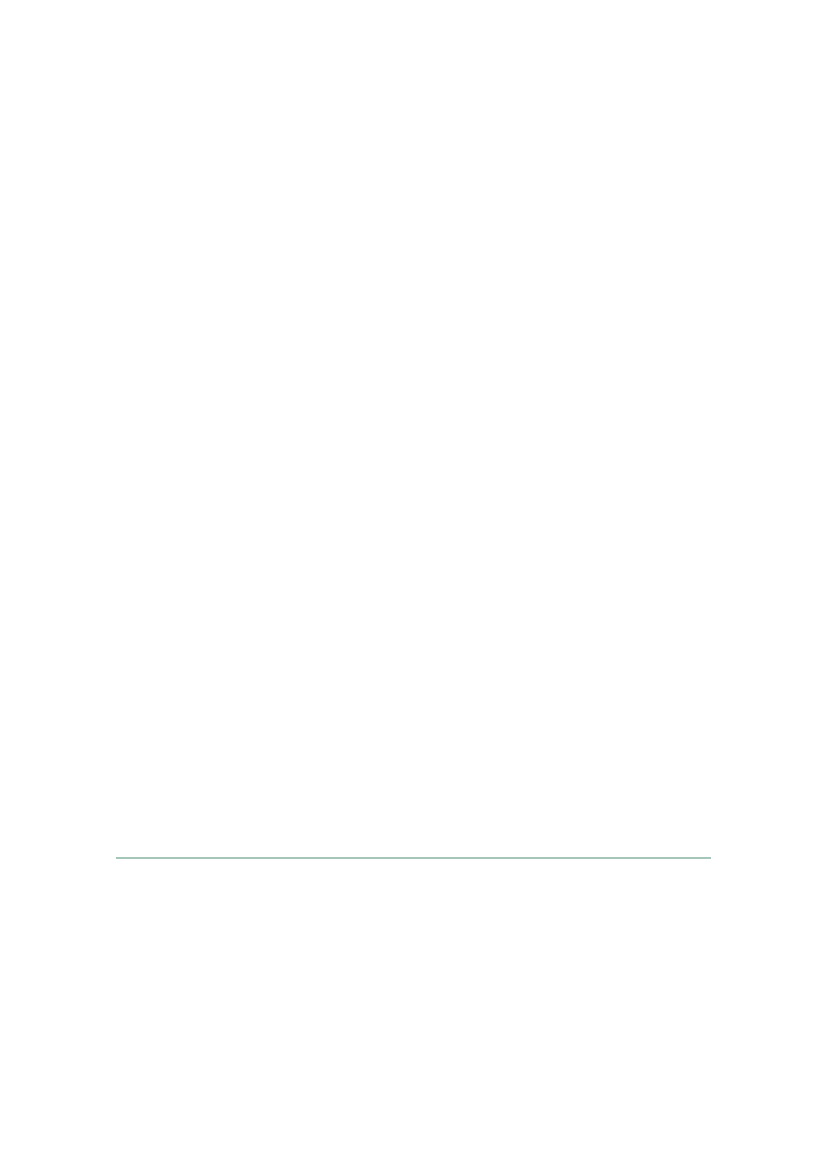

Figure 2: The evolution of CAP expenditure100%90%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%19801981198219831984198519861987198819891990199119921993199419951996199719981999200020012002200320042005200620072008

0%

Export subsidiesDecoupled direct payments

Other market supportRural development

Coupled direct payments

Data source: European Parliament Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development, Report on the future of theCommon Agricultural Policy after 2013, 21 July 2010, A7-0204/2010, p25

20. Awareness of the CAP’s history is an important part of understanding its current logic.Direct payments, the main element of the CAP, were brought in initially as compensationfor policy changes that disadvantaged producers. Over time they have acquired newfunctions, and, through being extended to the new Member States, have arguably becomemore entrenched within the CAP than was originally envisaged.The current structure of the CAP21. Direct payments and market measures make up Pillar 1 of the CAP and are fullyfinanced from the European Agriculture Guarantee Fund (EAGF).20Pillar 1 accounts forabout 80% of CAP spending.21Rural development programmes make up Pillar 2 of theCAP and are co-financed by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development(EAFRD) and national governments.22The UK is the fifth largest recipient of directpayments but has one of the smallest shares of the rural development fund.23

20

Regulation (EC) No 1290/2005 on the financing of the common agricultural policy established a common legalframework for CAP spending. Regulation (EC) No. 1234/2007 describes the organisation of the common market inagricultural products. Regulation (EC) No 73/2009 established common rules for direct support schemes and certainsupport schemes for farmers under the common agricultural policy.Pillar 1 was allocated about €313bn for the Financial Perspective 2007–2013 and Pillar 2 €96bn (after modulation).There are other smaller funds in Heading 2, such as the European Fisheries Fund and LIFE+. Source: EuropeanCommission,Investing in our future: the European Union’s Financial Framework 2007–2013,June 2010, p 5.Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for RuralDevelopment (EAFRD).During 2007–2013 the UK is projected to receive €23.6bn in direct payments, accounting for approximately 8.5% ofthe EU total post-modulation (the exact figures will vary). Over the same period, the UK will receive €2bn, or about2% of the Pillar 2 budget. Sources: Commission Decision of June 2007 (2007/383/EC); Defra,Rural DevelopmentProgramme for England 2007–2013 Programme Document,2007, informal briefing from Defra.

21

2223

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

11

22. Direct payments are principally decoupled from production and take the form of theSingle Payment Scheme (SPS). SPS entitlements must be matched to eligible land. Thepayment is called the Single Farm Payment (SFP) in the EU-15 Member States.24Themethod by which the SFP is calculated varies among the EU-15, either historic or area-based. In historic systems, the payment depends on the individual farmer’s receipts in thereference period 2000–02. In area-based systems, a flat rate is paid per hectare and the rateis based on the subsidies received by farmers in the region during the reference period.England opted for a ‘dynamic hybrid’ system, shifting individual recipients from a historicto a regional per hectare basis over a number of years. Scotland and Wales retained thehistoric system and Northern Ireland uses a static hybrid system. In most of the new EU-12Member States, payment is calculated on a flat rate per hectare system, which is called theSingle Area Payment Scheme (SAPS).2523. In return for receipt of the direct payment, the farmer must keep his land in GoodAgricultural and Environmental Condition (GAEC) and meet the Statutory ManagementRequirements (SMRs). This is known as cross-compliance. SMRs are determined byexisting EU legislation, while GAEC is defined by the Member States.26Under EUregulations, at least 1% of farmers receiving direct payments must be inspected annually toensure they are compliant, and fines are imposed for infractions.2724. Pillar 2 funds three types of activity (called Axes):••

Axis 1: Improving the competitiveness of agriculture and forestry, for example grantsfor new machinery.Axis 2: Improving the environment and countryside, mainly through agri-environmentschemes. The CAP provides the majority of funding for environmental protection inEurope.28

•

Axis 3: Improving the quality of life in rural areas and diversification of the ruraleconomy, such as grants to help farmers to diversify or to establish information centresto encourage tourism.25. Each Member State can choose how to allocate its Pillar 2 budget as long as at least 10%is spent on Axes 1 and 3 and 25% on Axis 2. The Commission has stipulated over 40

24

The ‘old Member States’, also known as the EU-15, comprise Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium,Luxembourg, Denmark, Ireland, United Kingdom, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Austria, Finland and Sweden. The ‘newMember States’, or the EU-12, are those states that joined after 2003, which are: Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia,Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Romania. Different mechanisms are usedin the old and new Member States because the EU-12 acceded after the 2003 Fischler reforms established the SingleFarm Payment.In this report, the term ‘Single Payment Scheme’ will refer to the system of deciding the level of direct payments andthe Single Farm Payment (SFP) will mean the actual payment received by farmers.Examples of Statutory Management Requirements include regulations on water pollution in Nitrate VulnerableZones, protection of the habitats of wild birds and other vulnerable species, regulations on livestock identificationand movement. GAEC standards include crop-rotation, maintaining terraces, minimum livestock densities, bufferstrips next to watercourses, and hedgerow management. A guide to cross compliance in England is available fromwww.crosscompliance.org.ukIn England, separate inspections are performed by the Rural Payments Agency, Environment Agency and the AnimalHealth and Veterinary Laboratories Agency (AHVLA) to check different aspects of cross-compliance. The RuralPayments Agency (RPA) imposes a fine of 3% of the SFP for the first breach.The main other EU financial instrument for the environment is LIFE+, which was allocated about€2.2bnbetween2007–2013. Source: European Commission,Investing in our future: the European Union’s Financial Framework 2007–2013,June 2010, p 5.

2526

27

28

12

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

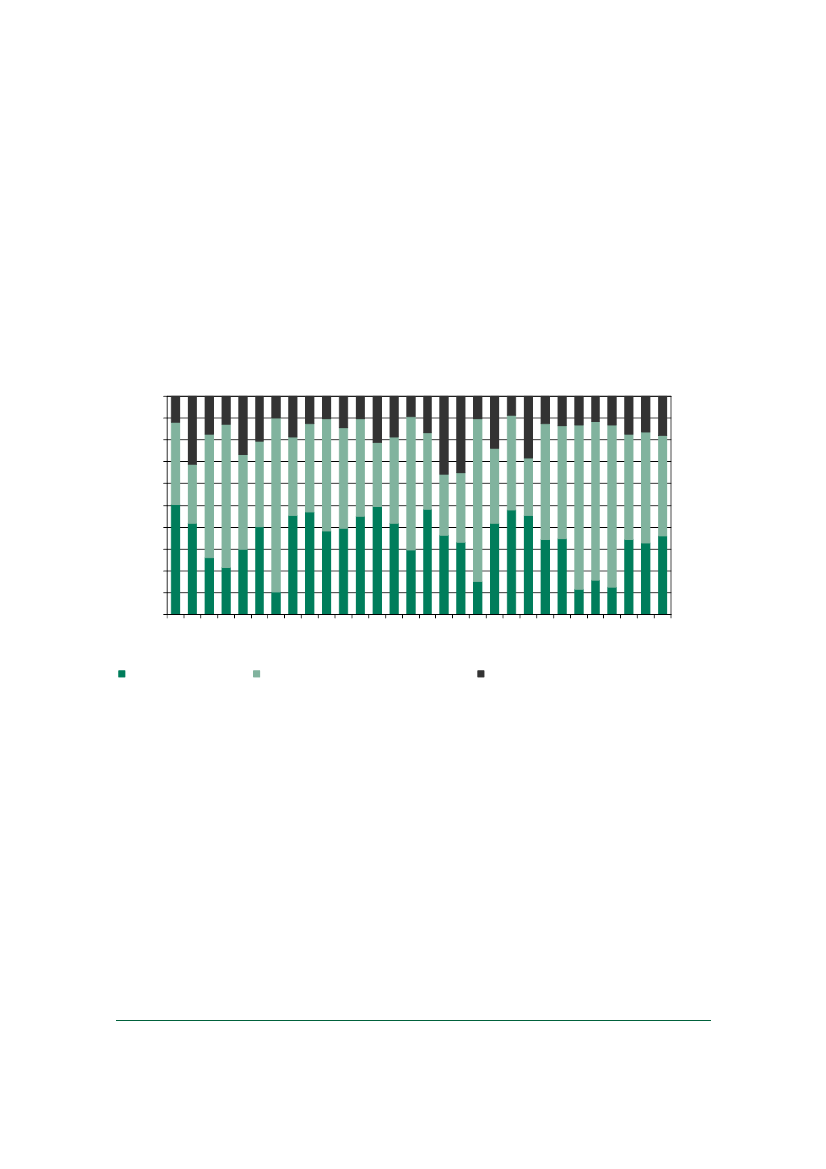

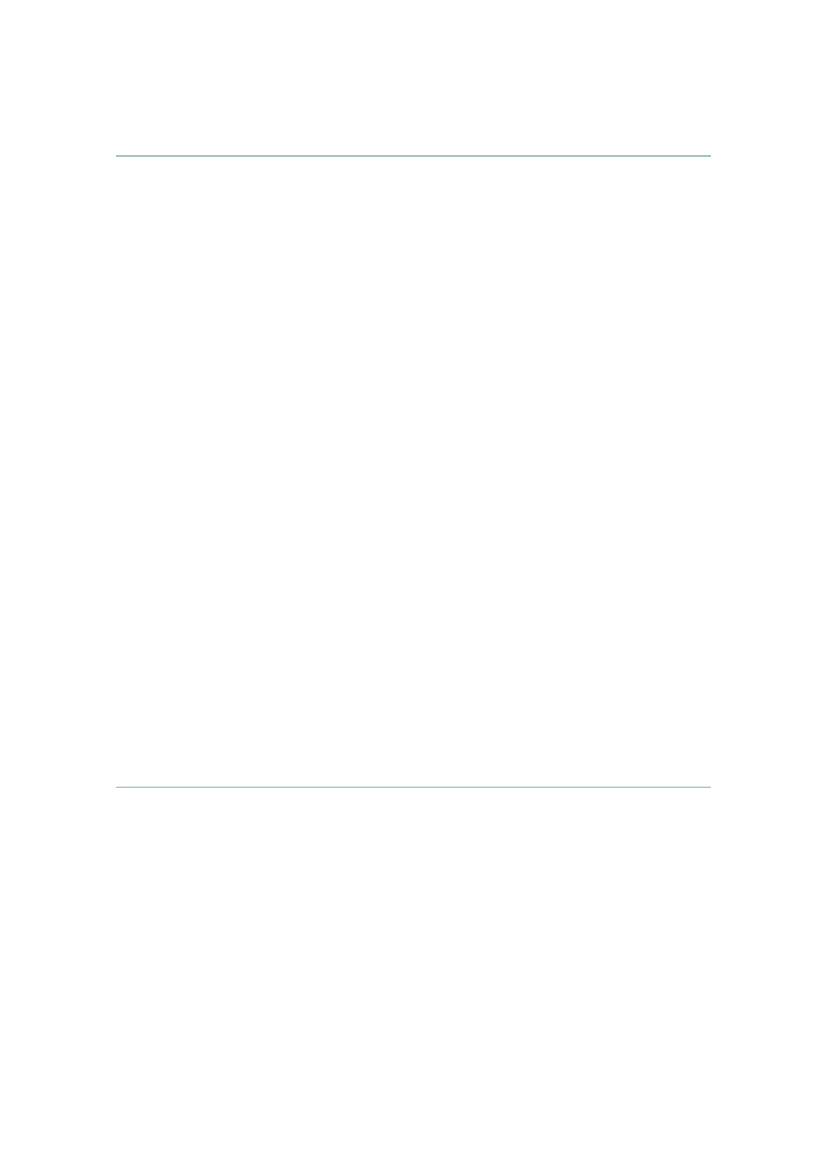

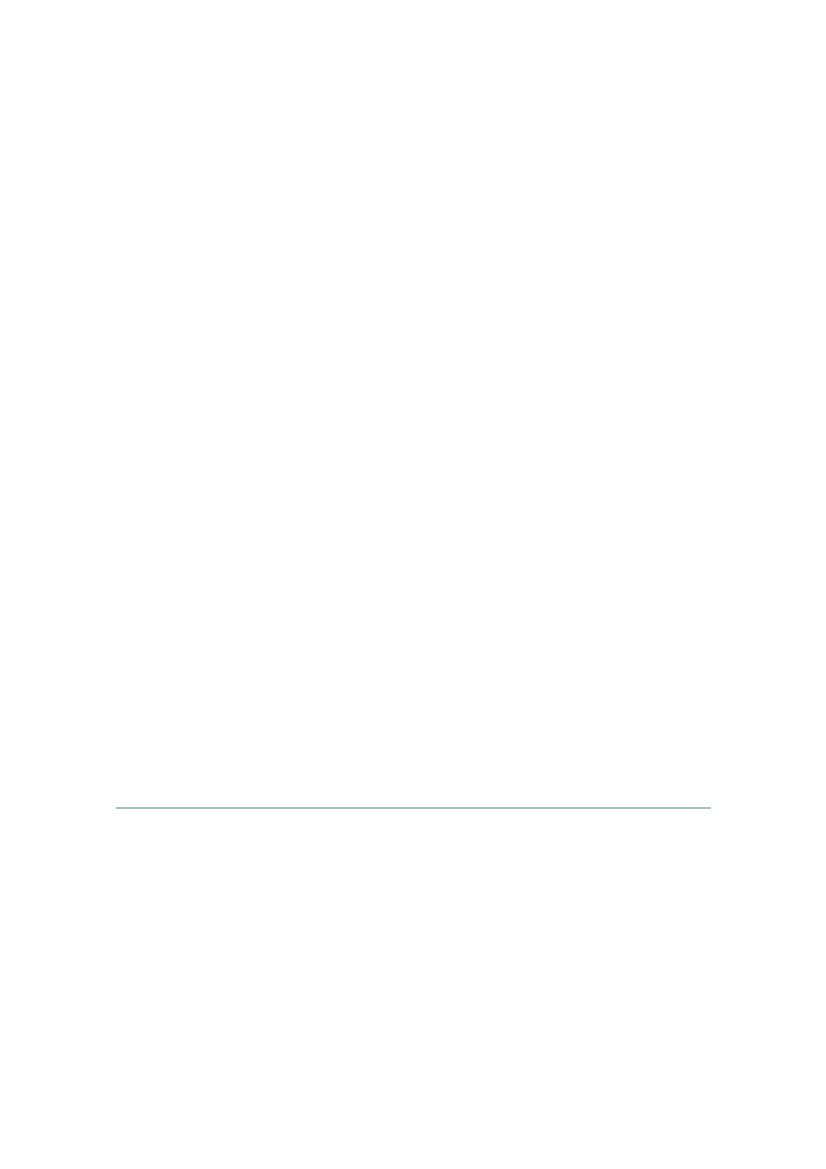

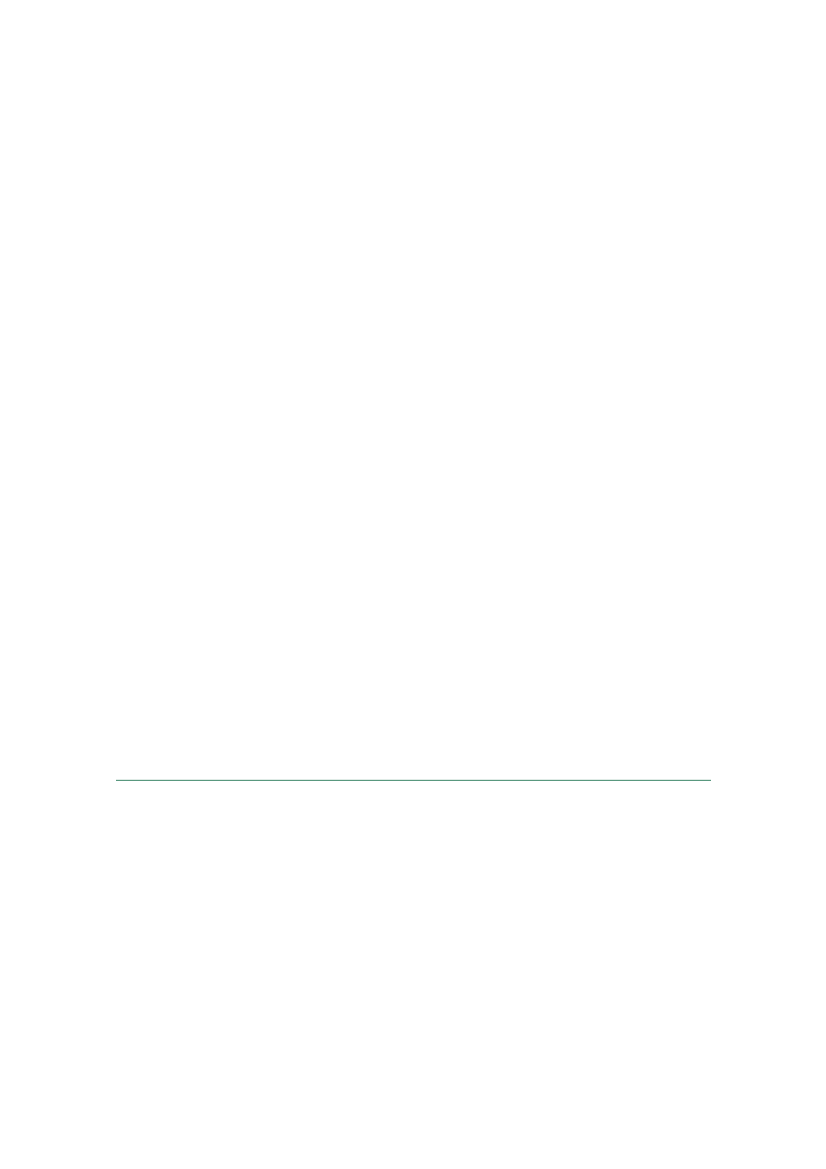

measures that can be applied, from which Member States can choose which to fund.29Inthe UK, the choice of measures funded by the rural development programme is a devolvedissue.26. There is considerable disparity between Member States in terms of their allocation todifferent objectives within Pillar 2. England, under the previous Government, opted tospend about 80% of its total rural development programme budget (the RuralDevelopment Programme for England—RDPE) on Axis 2 agri-environment schemes (theEnvironmental Stewardship schemes), and about 10% each on improving the vitality ofrural areas and competitiveness.30In comparison, the EU-wide average is about 50% onAxis 2 (environment) and 33% on Axis 1 (competitiveness) (Figure 3).Figure 3: Relative importance of the three thematic RD axes by Member State for the programmingperiod 2007–2013100%90%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%

HL

AT

PL

PT

RO

SI

SK

FI

SE

EU-27

EU-15

Axis 1: Competitiveness

Axis 2: Environment and land management

Axis 3: Quality of life and diversification

Data source: European Commission, Agricultural Policy Perspectives Briefs, No. 1, January 2011, p5

2930

Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005 of 20 September 2005 on support for rural development by the EuropeanAgricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD).EFRA Committee,Farming in the Uplands,Third Report of Session 2010–11, HC 556, Ev 45.

EU-12

MT

BG

DK

DE

CY

HU

UK

EL

BE

EE

ES

FR

CZ

IE

IT

LV

LT

LU

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

13

2Objectives of the Common AgriculturalPolicy27. The original objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy were set out in the Treatyestablishing the European Economic Community (also known as the Treaty of Rome) in1957. They were retained in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)(Box 1).Box 1: Article 39 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)The objectives of the common agricultural policy311. The objectives of the common agricultural policy shall be:(a) to increase agricultural productivity by promoting technical progress and by ensuring therational development of agricultural production and the optimum utilisation of the factors ofproduction, in particular labour;(b) thus to ensure a fair standard of living for the agricultural community, in particular byincreasing the individual earnings of persons engaged in agriculture;(c) to stabilise markets;(d) to assure the availability of supplies;(e) to ensure that supplies reach consumers at reasonable prices.

The need for a common policy on agriculture28. When the Treaty of Rome established the Common Market, there was strong stateintervention in agriculture in the six founding Member States. If agricultural produce wasto be included in the free movement of goods while maintaining state intervention,national intervention mechanisms had to be made compatible across the Community. Thisis the basic purpose on which the common agricultural policy was founded and remainsvalid today.32Dr Moss, Principal Agricultural Economist at the Agri-Food and BiosciencesInstitute (AFBI) and Senior Lecturer at Queen’s University, Belfast, stated “measures whichimpact on the functioning of the markets for agricultural commodities should remaincommon”.33The Commission’s Communication states that the “overwhelming majority ofviews expressed [in response to their public consultation] concurred that the future CAPshould remain a strong common policy.34A Eurobarometer survey conducted in early2010 concluded there was “an overall preference for the European level to manageagricultural issues”.35

31

Official Journal of the European Union,C115, 9 May 2008, p 62. The Treaty of Lisbon, which entered into force on 1December 2009, amended the Treaty establishing the European Community, which was renamed the Treaty on theFunctioning of the European Union.European Parliament Fact Sheet 4.1.1The Treaty of Europe and Green Europe.Ev 126The CAP towards 2020,p 2.TNS Opinion and Social on behalf of the European Commission,Europeans, Agriculture and the CommonAgricultural Policy—Summary Report,Special Eurobarometer 336, March 2010. It should be noted that only 57% ofthose surveyed had heard of the Common Agricultural Policy.

32333435

14

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

29. It is asserted, through the subsidiarity principle, that EU-level action is justified onissues that cross national borders.36Agricultural policy influences several supra-nationalissues, such as food security (as agricultural products move freely within the EU), thepreservation of natural resources and biodiversity (although specific habitats might bedeemed a local issue), and tackling climate change. For the same reason, a common EUagricultural policy is desirable for the purpose of international trade negotiations, givingMember States greater influence than they would have as lone entities.30. Member States are likely to differ in the priority that they place on agriculture and ruraldevelopment. The potential for distortion of competition because some producers aresupported more than others increases the more CAP expenditure or policy is determinednationally or is co-financed. The Andersons Centre claimed that UK farmers would beplaced at a disadvantage if more funding was decided nationally as “the UK Treasurywould strongly resist providing funds”.37Several other witnesses agreed that a‘renationalisation’ of the budget could harm UK farmers’ competitiveness.3831.Given the strategic importance of food and the openness of markets within the EU,it is essential that the EU retains a common policy on agriculture. First, this helps tomaintain fair competition for agricultural products within the EU. Second, agriculturalpolicy affects cross-border issues such as food security and climate change where actionat a supra-national level is appropriate. Third, through acting collectively, the EU isable to be a major player in global agricultural trade.

Objectives and priorities for the post-2013 CAP32. The Commission’s Communication gives three overall objectives for the future CAP,and several sub-objectives within each main objective (Box 2).Box 2: The Commission’s objectives for the future CAP39Objective 1: Viable food production•to contribute to farm incomes and limit farm income variability•to improve the competitiveness of the agricultural sector and to enhance its value share in thefood chain•to compensate for production difficulties in areas with specific natural constraints because suchregions are at increased risk of land abandonmentObjective 2: Sustainable management of natural resources and climate action•to guarantee sustainable production practices and secure the enhanced provision ofenvironmental public goods•to foster green growth through innovation•to pursue climate change mitigation and adaptation actions

363738

European Parliament Fact Sheet 1.2.2Subsidiarity.Ev w28For example, the Tenant Farmers Association (TFA) (Ev 110), the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) (Ev107), Dr Moss, Principal Agricultural Economist, Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) and Senior Lecturer,Queen’s University, Belfast (Ev 124), the National Assembly for Wales Rural Development Sub-Committee (Ev w23),the Welsh Assembly Government (Ev w31), the Scottish Agricultural College (Ev w35).The CAP towards 2020,p 7.

39

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

15

Objective 3: Balanced territorial development•to support rural employment and maintaining the social fabric of rural areas•to improve the rural economy and promote diversification•to allow for structural diversity in the farming systems, improve the conditions for smallfarmers and develop local markets

33. Although witnesses agreed the need for a common policy, we received mixed viewsabout the objectives of the policy in future, ranging from maintaining farmers’ incomesthrough providing food security to protection of the environment and rural landscapes. Inthe following section, we present the views of UK interested parties on the purpose of theCAP and recommend a set of objectives and priorities for our agricultural policy.Food Security34. Our predecessor Committee in their inquirySecuring food supplies to 2050: thechallenge for the UKnoted the difficulty with defining ‘food security’.40For some, foodsecurity is simply about access to enough food, for others it is synonymous with self-sufficiency or even food sovereignty.41In this report, we concur with our predecessors thatfood security is ‘to have access at all times to sufficient, safe, sustainable and nutritiousfood, at fair prices, so as to help ensure an active and healthy life’.4235. The urgent need to address the food security question has been impressed on theCommittee by the recent Foresight report,the Future of Food and Farming.43This reportconfirmed the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO)’s predictions that foodsupplies will need to double to meet the predicted demands of 8–10 billion people by 2050,without bringing more land into production. Moreover, this “growing demand for foodmust be met against a backdrop of rising global temperatures and changing patterns ofprecipitation”.44We also note the conclusions of theSecuring food supplies to 2050inquirythat: “Doing nothing to contribute to the world's food supplies would be morallyunacceptable: at a time when a fundamental shift in thinking is required, the UK should setan example, not bury its head in the sand”.4536. This does not mean that we should use the CAP as a tool to increase EU productionnow beyond the level suggested by market conditions, which would be a return to post-warlogic. The National Farmers’ Union (NFU) claim that UK self-sufficiency in all food-groups (including for example tropical fruits that cannot be grown here) will fall from 59%

4041

EFRA Committee, Fourth Report of Session 2008–09,Securing food supplies up to 2050: the challenges faced by theUK,HC 213.Food sovereignty as a term was coined by the Via Campesina in 1996. It encompasses the idea that people shouldhave a right to locally produced and culturally appropriate food and to define their own food production systems(www.foodsovereignty.org)EFRA Committee,Securing food supplies up to 2050: the challenges faced by the UK,para 6.Foresight and Government Office for Science,The Future of Food and Farming: Challenges and choices for globalsustainability—Final Project Report,January 2011, p 15. Further information on the ForesightGlobal Food andFarming Futuresproject is available from their website, www.bis.gov.uk/foresightThe Future of Food and Farming,p 15.Securing food supplies up to 2050: the challenges faced by the UK,para 47.

4243

4445

16

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

to under 50% by 2030 if current trends continue.46However, we should not strive for totalself-sufficiency as this would be impossible with our current diets. The UK is currently 72%self-sufficient in domestically-produced foods, which are more relevant to our basic foodsecurity in terms of calorific intake than self-sufficiency over all food groups.47TheFutureof Food and Farmingreport rejected food self-sufficiency but emphasised that food systemgovernance needed to be improved as well, for example to avoid the introduction of exportbans at times of food stress.4837. There was a broad consensus among witnesses that the strategic importance of foodjustified Government intervention through agricultural policy to ensure food security; formany this includes retaining a significant degree of self-sufficiency, at least until globalgovernance of the food system has been improved.49For example, Dr Moss said:I think it is important that Europe retains a significant degree of self-sufficiency infood for strategic reasons. Very simply [...] we can opt not to buy a motor car, we canopt not to have fancy clothes or live in fancy houses, but food is of absoluteimportance; imperative importance.5038. Food security involves a balance between production and sustainability. Our futurefood security depends on sustainable management of the land and preservation ofagricultural social capital.51The Minister of State for Agriculture and Rural Developmenttold us that it was in the EU’s strategic interest to increase food production capacity,pointing out that climate change projections suggest that “northern Europe will beincreasingly the bread basket of the world”.5239.We believe that the EU will need to play a greater role in meeting food supplychallenges in the future, particularly as future climate change may result in currentlyproductive areas becoming less so. Until failures in the global governance system offood supply are addressed, there remains a strategic interest for the EU to retain asignificant degree of food self-sufficiency. The first objective of the CommonAgricultural Policy should be to maintain or enhance the EU’s capacity to produce safeand high-quality food.

46474849

“Take action now to avoid food shortage—NFU”,Farmers Guardian,31 December 2010.HC Deb, 18 October 2010, c425WThe Future of Food and Farming–Final Project report,p 19–20.For example, the RSPB (Q 8), TFA (Ev 111, Q 40, Q 58), the Country Land and Business Association (CLA) (Q 78), theNational Farmers’ Union (Q 124–125, Q 157), George Lyon MEP (Q 297), Brian Pack OBE (Q 342), the Agriculture andHorticulture Board (AHDB) (Ev 161, Q 362), the Food and Drink Federation (Ev 168, Q 398), Mr James Paice, Ministerof State for Agriculture and Food (Q 480), the Scottish Agriculture College (Ev w35), Farmers’ Union of Wales (Evw45). See also the European Parliament resolution of 8 July 2010 on the future of the Common Agricultural Policyafter 2013 (TA(2010)0286), para 6, 10–11, 67. The previous EFRA Committee concluded in theirSecuring foodsupplies to 2050report that the UK should not take world food supplies “for granted” and that “A healthy domesticagriculture is an essential component of a secure food system in the UK” (para 47).Q 218See Dr Moss (Q 232), the RSPB (Ev 108), the CLA (Ev 117–118), the Society of Biology (Ev w 19).Q 480. The AHDB similarly said that “the UK is predicted to be less impacted on by climate change than many othercountries meaning that our contribution to total food and crop production may potentially need to be greater inthe future than at present”. (Ev 161).

505152

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

17

Agricultural Competitiveness40. The European Commission believes that improving the viability of EU agriculture in aglobal market is central to the first objective of maintaining production capacity:On the one hand, agriculture can potentially contribute substantially to many of thechallenges faced by Europeans with right incentives and in the right setting [...] Onthe other hand, its structure is diverse and economic situation fragile [...] In effect,short-term survival dominates the perception of many farmers over the long-term,broader perspective. If agricultural policy does not address the former, it will havelittle success in promoting the latter.5341. In the UK, agriculture accounts for a relatively small proportion of the workforce andGDP (about 0.5% of Gross Value Added.54) However, it contributes significantly to otherparts of the economy: for example food and drink processing is the UK’s largestmanufacturing sector and buys two-thirds of the production of British farmers.55TheGovernment wants to rebalance the economy away from services and the financial sectortowards manufacturing. UK agriculture could be important in achieving this through itsrole in supporting the UK agri-food industry.5642. The UK Government and devolved administrations consider improving the overallcompetitiveness and viability of UK agriculture to be key aims of the CAP. The WelshAssembly Government wanted a CAP that “strengthens the competiveness of our landbased industries”,57and the Scottish Executive also aims to “optimise the productive use ofnatural resources”.58Defra called for “transformational reforms which we believe arenecessary to deliver a thriving, sustainable and internationally competitive EU farmingsector” in order to reduce reliance on public subsidies.59Farming representatives andenvironmental NGOS also agreed with the need to tackle the issue of farm businesscompetitiveness.6043.Enhancing the competitiveness and viability of the EU agricultural sector should bethe second objective of the CAP. A competitive and viable EU agricultural sector is thekey to producing more while having less impact on the environment and to reducingfarmers’ reliance on income support from the tax-payer in the long-term.

535455

European Commission,The reform of the CAP towards 2020: Consultation Document for Impact Assessment,2010.Defra,Agriculture in the United Kingdom,2008. Gross Value Added (GVA) of farmers and primary producers was£5.8bn, while GVA of the agri-food sector (including catering and retail) was £85bn, which is 6.7% of national GVA.Ev 167. It has been estimated that, in Scotland, one job in agriculture supports 0.85 jobs elsewhere in the ruraleconomy.(Croasdale S., Hosie D., Hanrahan K. and Young, J.,Input-Output Modelling for the Scottish Government,2009, www.scotland.gov.uk).“Cameron urges economy ‘rebalance’ to restore growth”,BBC Newswebsite, 7 March 2011.Ev w33Ev w38Ev 171For example, the TFA (Ev 110), the RSPB (Ev 106), the NFU (Ev 119).

5657585960

18

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

Natural resources44. Farmers are responsible for managing over half of the EU’s land area.61Severalwitnesses, particularly Defra and environmental NGOs, emphasised the central role theCAP could play in sustainable land management. Defra argued that the future CAP shouldreward farmers for “delivering environmental benefits by managing the land effectively topromote long term resilience”.62Similarly, the Country Land and Business Association(CLA) told us that:We genuinely believe that farmers are primarily in business to produce food, butbecause they manage the bulk of the territory, they’re the only businesses out therewho can supply biodiversity, landscape management, water protection, climateprotection over a wide scale, and in principle they’re willing to do this, but they wantto see it as a business.6345. Markets tend not to reward farmers properly for their activities that deliverenvironmental or societal benefits, such as protecting farmland birds or ensuring a highstandard of animal welfare—this is a form of market failure (Box 3). The Royal Society forthe Protection of Birds (RSPB) said there is a “clear case for policy intervention, throughthe CAP, to secure environmental delivery due to the market failure to reward manyenvironmental public goods”;64similarly the Society for Biology said that “public subsidyshould be for public goods”.65Box 3: Public Goods and Market FailuresThe strict economic definition of apublic goodis a good whose consumption is non-excludableand non-rival. This means that the consumption of such a good by one individual does not reducethe amount of that good which can be consumed by any other individual (non-rival) and no-onecan be excluded from the consumption of the good (non-excludable). Examples of public goods arelaw enforcement, defence and street lighting. Because of the nature of such goods, there is nomarket incentive to produce them as consumers cannot be charged (via the market) for theirconsumption, resulting inmarket failure.Consequently, public goods have traditionally beenprovided by public authorities/government.Farmers often create public goods, including environmental protection, conservation ofbiodiversity, soil fertility and water quality, landscape preservation, food safety, animal and planthealth, and rural development. Agricultural production also creates negative externalities, forexample water pollution, which are not properly accounted for in the cost of the product and aretherefore paid for by society. Although some witnesses referred to food production as a publicgood, this is not strictly true as there are efficient markets for food and if one person consumes thefood, there is less available for others.66

616263646566

European Commission,The reform of the CAP towards 2020: Consultation Document for Impact Assessment,2010.Ev 172Q 95Ev 107Ev w19Ev 151

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

19

46.The third objective of the CAP should be to ensure the sustainable management ofthe EU’s natural resources, biodiversity and landscapes, recognising that farmers arethe managers of over half of the EU’s land area.Farmers’ incomes47. The European Commission gives “a fair standard of living for the agriculturalcommunity” as one of the ways to achieve its mission, which is to promote the sustainabledevelopment of Europe's agriculture and to ensure the well-being of its rural areas.67Commissioner Ciolo told us that “one of the most important objectives of the CommonAgricultural Policy is to ensure a good standard of living for farmers”, adding that directpayments should ensure a minimum level of income for farmers.6848. This emphasis on income support was not supported by all witnesses. ProfessorSwinbank, Emeritus Professor of Agricultural Economics, University of Reading, felt therewas “no need for income support across the generality of European agriculture”.69Dr Mossand the NFU argued that it would not be possible to deliver every single farmer in European acceptable standard of living via the CAP.70Many agricultural economists question theuse of the CAP as an income support policy as it is not means-tested and the available farmincome data is not sufficient to enable this. In addition, Member States have their ownmechanisms to deal with economic hardship—the Welfare State for example—whicharguably are more efficient and targeted than EU-level measures.71The Minister describedincome for farmers as being at the top of his list of objectives for the reformed CAP, butemphasised that he did not mean this to be achieved through subsidies.7249. Nonetheless there may be a convincing case for maintaining farmers’ incomes in someareas of low productivity, where this is necessary to ensure the delivery of important publicgoods (Box 3). In our report intoFarming in the Uplands,we concluded that farmingactivity was central to the future of the cherished landscapes and traditions of upland areasand should be supported through CAP instruments.73On the other hand, economists haveargued that socioeconomic objectives, such as avoiding depopulation, could be achievedmore efficiently through EU cohesion funding or national projects than through theCAP.7450. The Minister told us he supported the use of the CAP in economically vulnerable areas,saying “we agree that there should be measures within in it [the proposals from theCommission], preferably in Pillar 2, to support those farmers in the uplands and in the

6768697071

http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/agriculture/index_en.htmQ 172Q 257Q 126, Q 201Ev 154, Q 229. For further information, seeA Common Agricultural Policy for European Public Goods: Declaration bya Group of Leading Agricultural Economists,2009, http://www.reformthecap.eu/declaration-2009 and Tangermann,S.,Direct Payments in the CAP post 2013,Noteto DG IPOL, January 2011, PE 438.624.Q 448Farming in the Uplands,para 5, 38, 60.A Common Agricultural Policy for European Public Goods: Declaration by a Group of Leading AgriculturalEconomists,2009, http://www.reformthecap.eu/declaration-2009

727374

20

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

hills”.75However, Defra’s written evidence suggests this could be achieved throughinstruments other than the CAP.76Given the importance of maintaining a common systemof support for agriculture in the EU, we would argue that any support for farmers in lessproductive areas should be delivered through the CAP rather than through nationalinstruments—to do otherwise risks creating competitive distortions that could negativelyaffect UK producers.51. The impacts of climate change on European agriculture are unpredictable, but it ispossible that some currently productive regions will become unsuitable for agriculturalactivity with consequences for the delivery of public goods. For this reason, futureapproaches to maintaining agriculture across the EU must be flexible to reflect changingcircumstances.52.The fourth objective of the CAP should be to help to maintain agricultural activityin areas where it delivers significant public benefits, such as the maintenance ofbiodiversity and cultural landscapes. However, the CAP should not aim to deliver anacceptable standard of living to every farmer in the EU through income supportalone—farmers should be encouraged to look to the market for returns.Diversity of farming systems53. The Commission’s Communication gives ‘structural diversity’ in farming systems asone of the objectives of the CAP. The EU exhibits a wide range of different farmingsystems, ranging from semi-subsistence farming to large agri-businesses such as the Co-operative Group. Currently, EU agriculture has been unwilling to adopt some moreintensive methods of farming, found for example in South America, such as the use of GMcrops, cloning of livestock, or very large-scale dairy units (‘super-dairies’). There was ageneral view among our witnesses that the public valued the current model of EUagriculture. For example, the CLA said:This is the genuine question that we all have to ask ourselves: does the Europeanpublic want and expect that its agricultural land is farmed South American-style, inestates of tens of thousands of hectares with 50 combines in a field? [...] We eachhave our own personal view on that. Some will say, “If it’s cheap and efficient andhigh quality”—which it can be, and I’m not saying that those things are bad quality—“then bring it on.” But others will say, “No, that’s not the European way of doing it,”and we’re trying to find a balance in there. We will have some large farms, I hope,but I think Europe wants smaller farms, so that’s part of it.7754. The Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) felt that the preservation of thecultural landscapes generated by farming should be one of the key objectives of the CAP.They expressed concern that a focus on improving competitiveness would lead tointensification and consolidation of production, with negative consequences for Europeanagricultural landscapes and habitats.78During our inquiry into the English Uplands, we75767778Q 460Ev 172Q 93Ev 108

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

21

heard how the valued cultural heritage of the uplands, which had been preserved by itshistory of low-intensity land use, could be threatened by farm restructuring.7955. Structural diversity in farming allows for the continuation of ‘high nature value’ (HNV)farming systems. These tend to be low intensity, low income and small-scale but maintainenvironmentally-friendly practices such as extensive grazing and leaving land fallow.Conservation groups have stressed the importance of protecting these farming systems asmajor reservoirs of European biodiversity.8056. Small-scale farming, can also be important in maintaining connections between localcommunities and their food supply. George Lyon MEP, Rapporteur to the EuropeanParliament’s own-initiative report on the future of the Common Agricultural Policy after2013, said “Local communities want to see local food production and therefore that is apriority we must still address in the future”.81Commissioner Ciolo noted that his publicconsultation on the future of the CAP highlighted a desire for small farmers to have moreopportunities to play a role in the “the delivery of diversity of food and quality of food”.8257. We note that there are concerns that the untrammelled pursuit of agriculturalcompetitiveness might have unwelcome consequences for the diversity of EU farming andthe social and environmental benefits that flow from this, including cultural landscapesand local food sources. Equally, the Common Agricultural Policy should not seek todiscourage restructuring and consolidation where this enables farmers to achieve greatercompetitiveness and profitability.The fifth objective of the CAP should be to fosterdiversity in EU agriculture, where this is valued by EU citizens, but not enforce it.

79808182

Farming in the UplandsEv w 15; Commission for Rural Communities,High ground, high potential—a future forEngland’s upland communities,June 2010, p 8.Ev w18; European Forum for Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, Birdlife International, Butterfly ConservationEurope and the WWF,CAP Reform 2013: Last chance to stop the decline of Europe’s High Nature Value farming?Q 279Q174

22

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

3Drivers for reform of the CAP58. This is the fifth round of CAP reform in the last twenty years and is unlikely to be thelast; the Minister described it as “another stepping stone towards whatever will be”.83TheCommission has given no clear indications as to the long-term future of the CommonAgricultural Policy. However, it is likely that some form of common policy will still beneeded to avoid distortion of competition.8459. Defra were critical of the Commission for failing to set out a “clear vision for the futureof CAP expenditure”.85The RSPB also felt the lack of a direction for the future CAP leftfarmers “in limbo” and said it would be “excellent if there was a clear signal in 2014 aboutthose groups of farmers that were going to receive income support in the long term”, andthose that would not.86Changes to the single farm payment are seen by 65% of uplandsfarmers as their most important challenge for the future, highlighting the importance of aclear future trajectory for the CAP.8760. The drivers of past reforms of the CAP have been internal budgetary pressures andexternal political pressures, such as the need to reach an agreement on the WTO Uruguaytrade round. The Tenant Farmers Association (TFA) felt that these drivers were weakerthis time round as “there is not really the WTO impetus that there was in the last reform,or the reform before that. I know that the budget issues are still important, but they are notas important as they were when the CAP budget was more than half the total amount ofspending in the EU”.88Although agreement on the WTO Doha Development Round isbeing sought, this is not expected to require radical changes to the structure of EUagricultural support as direct payments are considered to be compatible with WTOconditions for non-trade distorting support (that is, ‘Green Box’).8961. A recent political analysis of past CAP reforms concluded that external pressures aremore likely to lead to ambitious reform.90The NFU agreed that lack of external factorsdriving reform made ambitious changes more difficult to achieve.91

8384

Q 450The Commissioner told us that the CAP would have to continue in some form if EU citizens continued to expect EUfarmers to produce at higher standards than competing producers in third countries (Q 173). The Minister arguedthat there would still need to be payments to reward farmers for providing public benefits and these would have tobe delivered through a common framework to avoid competitive distortions between Member States (Q 450). Seealso paras 28–31 of this report.Ev 171Q4Uplands Farm Practices Survey, cited inFarming in the Uplands,Ev 68.Q 48Ev 155–156, 158–159. ‘Green Box’ payments are deemed to be non trade-distorting, for example, decoupledpayments are seen as ‘Green Box’ because they do not influence farmers’ production decisions. Under the UruguayRound Agreement on Agriculture there is no limit on the amount of Green Box support that signatories can offer.On the other hand, signatories are expect to reduce their spending on measures that do affect production (‘Amber’Box), such as payments per head of livestock (coupled payments).Cunha and Swinbank,An inside view of the CAP reform process,2011, p 14.Q 131

8586878889

9091

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

23

62. We believe that the absence of external pressures from the WTO should not preventthe Commission striving for ambitious reform. The recent Foresight report into theFutureof Food and Farmingdescribes the confluence of a growing population, increasing wealthand changing diets, and the potential effects of climate change as a “major threat thatrequires a strategic reappraisal of how the world is fed”.92One of the key messages of theForesight report is that future food security can only be achieved through ‘sustainableintensification’ (Box 4).Box 4: Key recommendations of the ForesightGlobal Food and Farming Futuresproject93Action has to occur on all of the following four fronts simultaneously:

•

More food must be produced sustainably through the spread and implementation of existingknowledge, technology and best practice, and by investment in new science and innovation,and the social infrastructure that enables food producers to benefit from all of theseDemand for the most resource-intensive types of food must be containedWaste in all areas of the food system must be minimisedThe political and economic governance of the food system must be improved to increase foodsystem productivity and sustainability, including reducing agricultural subsidies andencouraging free trade

•••

63. The Royal Society has described sustainable intensification as where “yields areincreased without adverse environmental impact and without the cultivation of moreland”.94The UK Government has committed itself to “work in partnership with our wholefood chain including consumers to ensure the UK leads the way on sustainableintensification of agriculture”.95A reformed Common Agricultural Policy could surely playa key part in achieving this policy objective.64.We believe that the absence of external pressures from the WTO should not preventthe Commission striving for ambitious reform. The aim for this round of CAP reformshould be to enable EU farmers to achieve the ‘sustainable intensification’ that isrequired to meet the global challenges of feeding a predicted world population of 9billion by 2050 without irrevocably damaging our natural resources.65. Our predecessor Committee’s report on UK food security concluded that “clearleadership from Defra is crucial to the security of the UK's food supplies” and encouragedDefra to report its actions to promote UK food security as part of the DepartmentalAnnual Report.96Subsequently, the previous Government publishedFood 2030,its “vision

92

The Future of Food and Farming—Final Project Report,p 40. Forecasts suggest the world population will grow toover 9 billion by 2050; economic growth will allow people in less-developed countries to demand a more varied andhigh-quality diet; and there will be greater competition for land at the same time as the effects of climate changemay reduce area of land suitable for agriculture.The Future of Food and Farming—Final Project Report,p 12.The Royal Society,Reaping the benefits: Science and the sustainable intensification of agriculture,October 2009, p1.Foresight,The Future of Food and Farming Action Plan,January 2011; see also Defra press release 24 January 2011.Securing food supplies up to 2050: the challenges faced by the UK,paras 94, 138.

93949596

24

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

for a sustainable and secure food system for 2030”.97The NFU recently called on theGovernment to produce a new ‘food plan’ to reflect the challenges identified in theForesight report.98In response, the Secretary of State referred toFood 2030but said: “It hasnot been at the top of my agenda”.99So far, the Government has not signalled any intentionto produce a new food strategy.10066.The Government’s position on the Common Agricultural Policy must be coherentwith its strategy for ensuring food security. Defra should decide whether, and if so how,it intends to implement the previous Government’sFood 2030strategy, taking intoaccount the recommendations of the ForesightFuture of Food and Farmingreport andthe UK’s position on the future Common Agricultural Policy.

Future agricultural policy and world trade67. The EU is one of the major players in agricultural trade, importing mainlycommodities and exporting high quality and processed products. The evolution of theCAP has been closely linked to the opening up of EU agriculture to world markets,presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for UK producers.68. Although the EU has granted extensive market access to many of the least-developedcountries under the ‘Anything but Arms’ initiative, prohibitive tariff barriers exist toprevent over-quota imports of sensitive products, such as meat and dairy, from moredeveloped countries.101Resolution of the Doha Development Round could lead to cuts intariffs of around 50% overall for developed countries, although ‘sensitive’ products, forexample beef, would probably be protected.102The EU also committed itself to phasing outexport subsidies during previous Doha Round trade talks. The WTO is expected toproduce a new draft text for the Doha Development Round shortly.103Separately, theEuropean Commission is negotiating a bilateral trade agreement with Mercosur; this couldopen up European markets to highly competitive agri-food exports from countries such asBrazil and Argentina.10469. Econometric analyses conducted by the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI)indicate that trade liberalisation would have a significant effect on food production and

979899

HM Government,Food 2030,January 2010.“NFU calls for new government food plan”,Farmers Guardian,15 February 2011.“UK farmers' leader attacks government for lack of national food plan”,The Guardian,15 February 2011.

100 Defra have said: Food 2030 usefully set the scene and described the key issues facing the food chain. TheGovernment are now taking action to meet their objectives of supporting British farming, encouraging sustainablefood production, and helping to enhance the competitiveness and resilience of the whole food chain with the aimof ensuring a secure, environmentally sustainable and healthy supply of food with improved standards of animalwelfare. (HC Deb, 7 March 2011, col 767W). At the Westminster Food & Nutrition Forum,Food and drink industry2011: challenges and opportunities,8 March 2011, the Defra representative said that Ministers had no desire torevisit the themes identified inFood 2030(transcript available from www.westminsterforumprojects.co.uk).101 Ev 159; http://ec.europa.eu/trade102 Ev 128; “New WTO modalities paper—a detailed summary”,Agra Europe,12December 2008.103 “WTO officials pledge new Doha draft by end-March”,Agra Europe,31 December 2010.104 Mercosur is a South American trading bloc comprising Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. According to theEuropean Commission, negotiations were re-opened in May 2010 and talks were last held in Brussels in March 2011.http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/december/tradoc_118238.pdf

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

25

prices in the UK, particularly in the livestock sector.105Dr Moss, a lead author on the study,concluded:... your average farmer is not as aware of the protection that is there with the exportsubsidies and the import restrictions, but that is really what is maintaining the pricesin many cases for Europe [...] It is only when that existing protection is removed thatyou start to see a big knock-on effect on the beef and sheep meat sectorsparticularly.10670. Farming and land-owning organisations were concerned about the impacts of full tradeliberalisation on British producers. They argued that imported products often did not meetthe same welfare and environmental protection standards as British products and weretherefore cheaper.107Under the WTO Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures,governments can regulate trade in agri-food products only on food safety, plant and animalhealth grounds and as long as these do not act as ‘disguised trade barriers’.71. The British Retail Consortium (BRC) claimed that retailers sourcing products fromoutside the UK apply similar standards as would apply if they sourced them from withinthe UK.108This implies that price differences arising from variation in productionstandards would not reduce the attractiveness of UK products to UK retailers. However,according to the British Pig Executive, in 2005 an estimated 70% of pork imports wouldhave been illegal to produce in the UK on the grounds of pig welfare.10972. Farming groups felt that achieving recognition of production standards, such as animalwelfare, carbon footprint or water usage, was a key part of moving towards fairer trade anda more sustainable food chain. The AHDB said:Where there are externalities (or public goods) which are not currently priced/valuedby the market or through regulation/taxation on a standard basis across the world,UK farmers need to be supported to compete on an equal footing if we are not tomerely export food production to countries where welfare or environmentalstandards are lower.110The Foresight report also recommends that “future reform of institutions such as theWorld Trade Organisation cannot ignore the issues of sustainability and climatechange”.111While the CLA and NFU shared this aspiration, they felt that progress within

105 AFBI modelled the impact of (1) implementing the Doha trade round reforms and (2) further reducing import tariffsfor agricultural products to bring them in line with the rest of the economy. Implementing the Doha round reformshad little effect on cereals and only a moderate effect (3-6% reduction) on beef, sheep and dairy productioncompared to a baseline scenario. Further trade liberalisation had considerably greater effects on the livestock sector,with sheep and cow numbers falling by 10% and 20% respectively (Ev 125–150).106 Q 207107 For example the AHDB (Ev 161), the TFA (Q 50), the CLA (Q 118, Q 120), the NFU (Q 141) and the Royal Society forthe Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) (Ev w5).108 Q 402109 British Pig Executive,An Analysis of Pork and Pork Products Imported into the United Kingdom,April 2006.110 Ev 161.111The Future of Food and Farming—Final Project Report,p 20.

26

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

the WTO framework would be slow.112Defra and the RSPB warned that consideration ofstandards of production should not become “protectionism by another name”.11373. Rather than adding trade barriers, there is a market-based alternative through betterlabelling of products to enable consumers to make informed choices. However, ProfessorSwinbank noted that society could not always be relied on to make the ‘right’ choices,arguing that “if in the longer run, with the information, consumers say they do not want topay higher prices for animal welfare products, it raises a question about that animal welfarelegislation itself”.114The TFA were more blunt, claiming that, “I am afraid the vast majorityof people, despite what we hear and see in the press, still buy on price”.11574.In the interests of fairer trade in the long-term, the EU should argue more stronglyfor recognition of standards of production (for example animal welfare, use of water,greenhouse gas emissions) within trade agreements. We believe this is essential inachieving the global shift towards sustainable intensification recommended by theForesightFuture of Food and Farmingreport.

112 Q 120, Q 142113 Q 15, 476114 Q 245115 Q 71

The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013

27

4The budget of the CAP in the post-2013financial framework75. Negotiations on the future CAP are proceeding concurrently with negotiations on thenext Multiannual Financial Framework. Given the current economic situation in the EU,there is of course considerable interest in achieving greater value for money from EUspending.76. The Commission has not yet given any figures for the future CAP budget; it is expectedto produce a Communication on the next Multiannual Financial Framework before July2011 including a breakdown of the budget for the CAP. The 2010 EU Budget Review notedthat the CAP budget had fallen in recent years, but still represented a major publicinvestment.116Somewhat surprisingly, the Review did not recommend any direction for thefuture CAP budget. Commissioner Ciolo has been clear that a significant reduction to thebudget would require a substantial re-thinking of the policy.11777. The European Parliament’s resolution on the CAP post-2013 said “it is essential thatthe budget the EU allocates to the CAP is at least maintained at current levels”.118HoweverGeorge Lyon MEP, who drafted the resolution, suggested this was rather optimistic; he toldus:I don’t think that we are likely to see any increase whatsoever in the CommonAgricultural Policy budget. Indeed I think it’s more than likely that it will start todecrease over time. The question is not if; it is a question of when.11978. Defra argued unequivocally for a reduction in the budget, stating:Spending on the CAP will need to reduce very materially during the next FinancialPerspective: the future CAP must be affordable, and EU spending on agriculturemust deliver real value for money for EU citizens.12079. Our witnesses were cautious about the potential effects of a substantial cut to thebudget. The CLA said “Our fear is that the UK will set extremely high ambitions andexpect them to be delivered from an unreasonably low budget”.121The RSPB also felt thatthe current budget would need to be retained to meet its ambitions, saying “I would wagerthat to meet those environmental outcomes the CAP budget would not be less than what it