Trafikudvalget 2009-10

TRU Alm.del

Offentligt

EVALUATION OF REGULATION261/2004Final reportMain reportFebruary 2010

Prepared for:

Prepared by:

European CommissionDirectorate-General Energy and TransportDM28 5/70BrusselsBelgium

Steer Davies Gleave28-32 Upper GroundLondonSE1 9PD+44 (0)20 7910 5000www.steerdaviesgleave.com

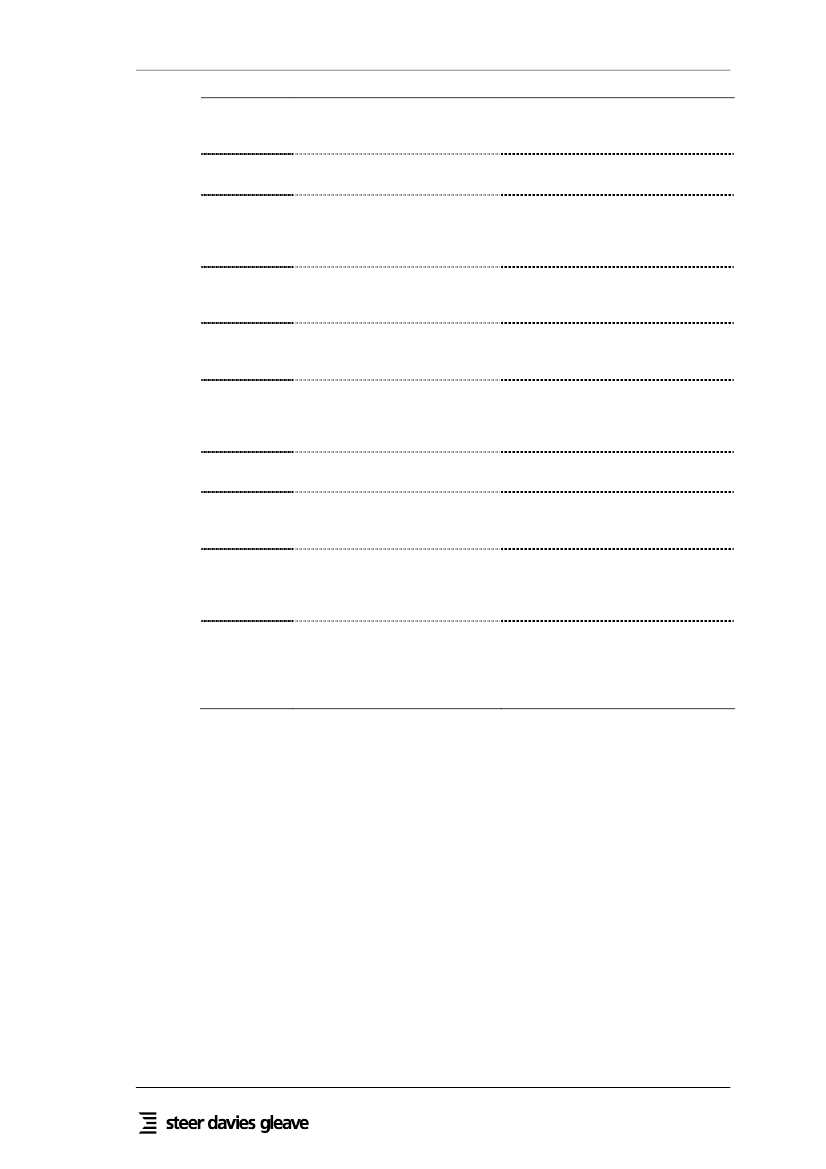

Final report

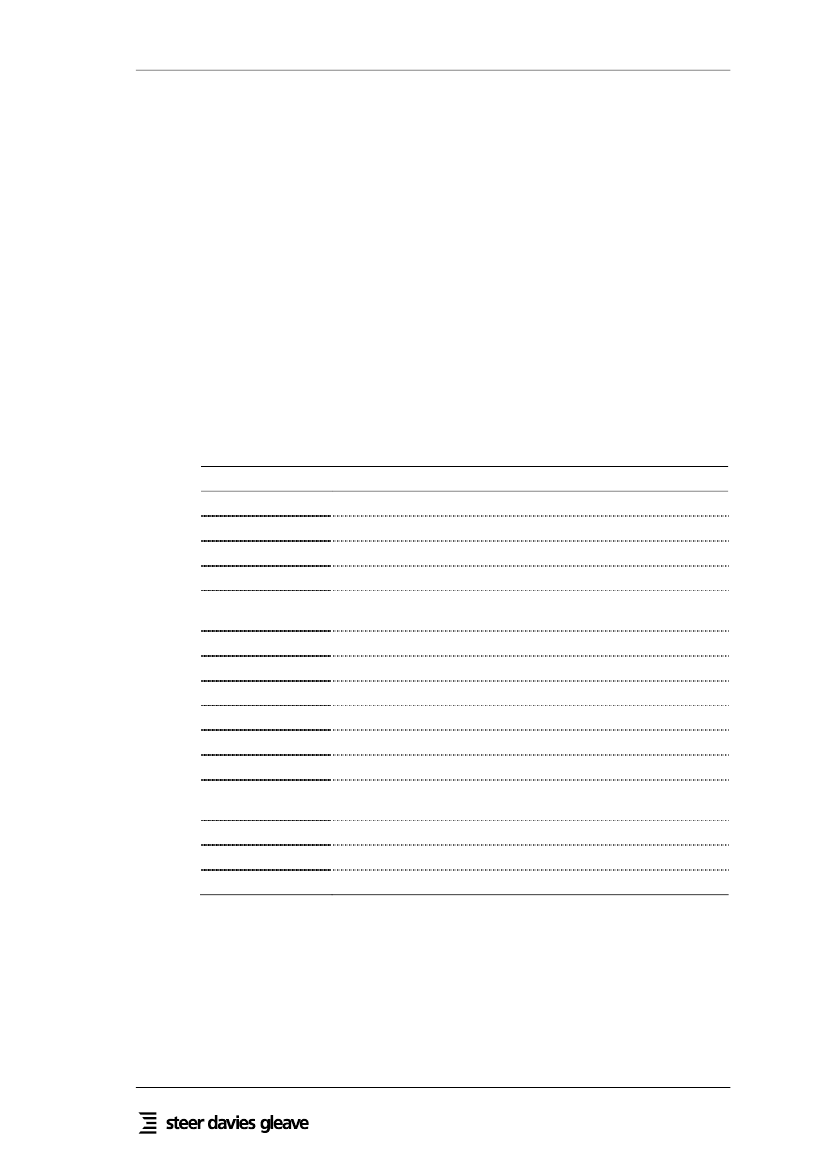

ContentsEXECUTIVE SUMMARYBackgroundFactual conclusionsRecommendations1.INTRODUCTIONBackgroundThe need for this studyThis reportStructure of this document2.RESEARCH METHODOLOGYIntroductionOverview of the approachSelection of case studiesDesk researchStakeholder inputs3.APPLICATION OF THE REGULATION BY AIRLINESIntroductionStatistical evidence for cancellations, delays and denied boardingComplaints to airlinesCost of complying with the RegulationEvidence for airline compliance with the RegulationStakeholder views on complianceConclusions4.ENFORCEMENT AND COMPLAINT HANDLING BY NEBSIntroductionOverview of the NEBsLegal basis for complaint handling and enforcementStatistics for complaint handling and enforcementThe complaint handling and enforcement processCo-operation between NEBs and with other organisationsOther activities undertaken by NEBsStakeholders views on complaint handling and enforcementConclusions

Page111377788101010101112171717252929343739393942465065676872

Contents

Final Report

5.

ALTERNATIVE PROCESSES FOR PASSENGERS TO CLAIMIntroductionAlternative dispute resolutionCivil court claimsCommercial claim servicesConclusions

777777788081838383849091919192949596989898102104

6.

STAKEHOLDER VIEWS ON POLICY ISSUESIntroductionWhether changes should be made to the RegulationThe content and drafting of the RegulationConclusions

7.

SUMMARY OF FACTUAL CONCLUSIONSIntroductionApplication of the Regulation by carriersComplaint handling and enforcement by NEBsAlternative means for passengers to obtain redressStakeholder views on the RegulationConclusions

8.

RECOMMENDATIONSOverviewMeasures to improve enforcementOther improvements which can be made without amending the RegulationChanges to the Regulation

FIGURESFigure 3.1Trends in delays and cancellations: AEA airlines (quarterly data;annual moving average)Trends in delays and cancellations: flights to / from UK airports(monthly data; annual moving average)Average minutes late vs traffic: flights to / from UK airports (monthlydata; annual moving average)Trends in delays and cancellations: ERA Airlines (monthly data;annual moving average, departures only)18

Figure 3.2

19

Figure 3.3

20

Figure 3.4

20

2

Final report

Figure 3.5

Causes of delay: AEA airlinesaverage)Causes of delay: ERA airlinesaverage)

(quarterly data; annual moving21(monthly data; annual moving2222

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.7Figure 3.8

Causes of Delay: Departures from French Airports (Annual Data)Delays and cancellations by airline, flights to / from UK airports, 2008(sorted by arrival / departure within 30 mins of schedule)Typical airline complaint handling process

2327323334344250707183

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.10 Compliance of Conditions of Carriage with Regulation 261/2004Figure 3.11 Punctuality survey results – Provision of compensationFigure 3.12 Punctuality survey results – satisfaction with handlingFigure 3.13 Stakeholder views of complianceFigure 4.1Figure 4.2Figure 4.3Figure 4.4Figure 6.1Number of complaints handled per year, per FTEComplaints received per sanction issued, 2008Stakeholders views on NEB-NEB/airline agreementsStakeholders views on Q&A documentStakeholders views: Whether the Regulation should be changed

TABLESTable 2.1Table 2.2Table 2.3Table 2.4Table 2.5Table 2.6Table 3.1Table 3.2Table 3.3Selection of case studiesStakeholder interviews: National Enforcement bodiesStakeholder interviews: AirlinesStakeholder interviews: Airline associationsStakeholder interviews: AirportsStakeholder interviews: Consumer associationsSummary of airline complaint proceduresAirline complaint response timescalesCompliance of airline ground handling manuals

Contents

Final Report

Table 4.1Table 4.2Table 4.3Table 4.4Table 4.5Table 4.6Table 4.7Table 4.8Table 4.9

Enforcement bodiesRelevant national legislationMaximum finesComplaints received in 2008 (except where stated)Outcome of complaints received in 2008, where availableSanctions imposed in 2008Languages in which complaints are handledTime taken to complete handle complaintsInvestigation of claims of extraordinary circumstances

Table 4.10 Responses issued to passengersTable 4.11 Policy on imposition of sanctionsTable 4.12 Issues with application of sanctions to carriers not based in the StateTable 4.13 Collection of sanctionsTable 4.14 Publication of informationTable 4.15 Inspections undertaken by NEBsTable 4.16 Conclusions: States’ compliance with Article 16Table 4.17 Conclusions: Nature and effectiveness of complaint handlingTable 5.1Table 8.1Small claims proceduresOther amendments for clarification and consistency

APPENDICESAACASE STUDIES (provided as separate document)

4

Final report

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYBackground

1.

Regulation 261/2004 introduced new rules on compensation and assistance for airpassengers in the event of denied boarding, cancellations, long delays and involuntarydowngrading. In 2006, the European Commission contracted Steer Davies Gleave toundertake an independent review of its operation and results. The study found thatthere had been a number of difficulties, arising in particular from ineffectiveenforcement in a number of Member States, and the fact that the wording of someparts of the Regulation left room for interpretation.In April 2007, the Commission issued a Communication to report on the Regulation,which concluded that a substantial improvement was required. It stated that therewould be a period of stability during which no legislative changes would be made, inorder to give Member States and air carriers the opportunity to improve theimplementation of the Regulation. In the meantime, it identified that further work wasrequired in a number of areas, including improved enforcement and clarification ofkey terms. The purpose of this study is to assess whether these measures have beensuccessful in ensuring that passengers’ rights are adequately protected, or whetherother measures now need to be taken.The research and interviews for this study were undertaken before the ruling of theEuropean Court of Justice in the caseSturgeon and Bock,relating to the distinctionbetween the treatment of cancellations and delays under the Regulation. Thisjudgement has significant implications for the issues evaluated in this study. It was notpossible to discuss this judgement with stakeholders within the timescale for thisstudy, but we have taken it into account in developing our recommendations.Factual conclusions

2.

3.

4.

This study has shown that the Commission and others have made significant efforts toaddress the problems with the operation of the Regulation identified at the time of our2006-7 study. Many National Enforcement Bodies (NEBs) also now undertakesignificantly more activity in relation to the Regulation than they did: all now handleindividual complaints1, and sanctions for non-compliance have been imposed in 14Member States.However, whilst these efforts have had some success, more has to be done to ensurethat passengers’ rights are properly protected. The following key problems remain:••the evidence available indicates that some carriers are still not consistentlycomplying with the requirements of the Regulation or are interpreting theRegulation in a way which minimises their obligations;as discussed in more detail below, in many Member States, enforcement is noteffective enough to provide carriers with an economic incentive to comply;

5.

1

Except Konsumentverket in Sweden, where complaints are handled by a non-NEB organisation.

1

Final Report

•••

in several Member States, there is no mechanism available by which individualpassengers can readily obtain redress from carriers;although rulings by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) have addressed some ofthe issues in the Regulation that were unclear, a number of issues have not beenaddressed andin some areas the rights granted by the Regulation can lead to differentunderstandings (for example relating to long delay and cancellation) or do notaddress all the problems that passengers may face (such as missed connectionsdue to delays).

6.

Ineffective enforcement continues to be a key problem and, in our view, most of theMember States reviewed for this study have not unambiguously complied with therequirement in Article 16 to introduce sanctions which are effective, proportionate anddissuasive. Although we have identified a number of improvements that have beenmade to the enforcement process, a number of significant issues remain, including:•••Two States have not unambiguously complied with the requirement in Article 16to introduce sanctions into national law.Even where sanctions have been introduced into national law, they are not alwaysapplied: in nearly half of the Member States, no sanction has ever been imposedon a carrier for non-compliance.In some States which have introduced sanctions into national law, thecircumstances in which sanctions can be imposed are extremely limited and meanthat sanctions cannot provide an economic incentive to comply with theRegulation in all cases.Some Member States have difficulties in either imposing sanctions on carriers notbased within the State, or cannot collect sanctions which are imposed. In someStates, this is because of an explicit limitation in national law, but more often thisis because of administrative requirements in national law which cannot be met ifthe carrier is not based within the State.In many Member States, the maximum sanctions which can be applied are toolow to provide carriers with an economic incentive to comply with theRegulation, taking into account that sanctions would only ever be imposed for asmall proportion of infringements. In some States the maximum level of sanctionis less than or equivalent to the costs that a carrier may avoid through non-compliance in some individual cases.In some States, there are other legal or administrative problems, which mean thatsanctions cannot be effective in providing an incentive to comply with theRegulation: for example, in Italy, whilst sanctions can be imposed the process tocollect them is slow.

•

•

•

7.

In addition, there are significant differences in the approach to enforcement indifferent Member States, which means that there is a risk that the single market for airtransport is being distorted.Several Member States are planning changes to national law and other improvementsto the enforcement process which should further improve the situation in the future.However, it is not clear that this will be sufficient to address the issues that we haveidentified.

8.

2

Final report

Recommendations

9.

We have made a number of recommendations, covering:•••improvements to the enforcement of the Regulation;other improvements to the operation of the Regulation which would not requireany legislative changes; andpossible changes to the requirements of the Regulation, if a decision is made torevise it.

Improvements to enforcement

10.

To date, virtually all enforcement activity has been in response to passengercomplaints to NEBs. In many Member States, significant resources are devoted tohandling complaints and in some cases mediating with carriers to achieve anacceptable resolution for the individual passenger. Whilst this is useful for thepassenger concerned, few passengers impacted by infringements complain to NEBs,and therefore in the vast majority of cases, infringement has no consequence for thecarrier other than that it avoids the costs associated with compliance.In our view the focus on complaints does not reflect the requirements of theRegulation, which gives passengers the right to complain to any NEB, but explicitlyplaces the onus on NEBs to take such measures that are necessary to ensure thatpassengers rights are respected. This could include effective handling of complaintsbut in itself this does not appear to be sufficient.In 2007, National Enforcement Bodies agreed an active approach to monitoringcompliance with the Regulation. However, little seemed to have been done in thissense. We suggest that the approach to enforcement should change, from a primarilyreactive approach focussed on responding to complaints, to a pro-active approachplacing the onus on carriers to demonstrate that they are complying, for example by:••••requiring carriers to provide evidence that they have complied with theRegulation;encourage Member States to verify, when monitoring carriers licensed in theirState, that they have set up user-friendly procedures for the prompt settlement ofdisputes under consumer protection Regulations;encourage Member States to require carriers to provide copies of the agreementswith airport managers or ground handlers which show the procedure to be appliedin the case of an incident;carrying out frequent unannounced inspections of carriers’ performance, in orderto track their responses to cases of delays, cancellations and denied boarding,including whether they issue the notices required by Article 14(2), as well as theircompliance with Article 14(1), the main scope of inspections at present;undertaking airport-based passenger surveys to monitor carriers’ performance;undertaking audits of carriers’ complaint handling processes to ensure that theresponses that carriers provide to passengers are accurate (for example, thatcompensation is paid when claimed by a passenger who has a right to it); andin addition to investigating whether carriers’ claims of extraordinarycircumstances are valid, require carriers to show that their decisions as to whether

11.

12.

•••

3

Final Report

compensation is payable for cancellations or long delays are consistent with theinterpretation set out by the ECJ in theWallentin-Hermanncase.13.Where inspections or investigation of complaints identify that carriers are notcomplying with the Regulation, fines need to be sufficient to provide the carrier withan economic incentive to comply with the Regulation in future and to deter othercarriers from not complying with it. If fines do not provide this incentive, it will be inthe commercial interest of carriers not to comply with the Regulation. Carriers that donot comply will have lower operating costs than carriers that do comply, and thereforethey will be able to offer lower fares, increase market share, and make greater profits.In many Member States, introducing fines that provide an incentive to comply withthe Regulation will require a change in national law, in order to:••increase the level of the maximum penalty that can be imposed so that it issufficient to provide an economic incentive in all cases; andremove restrictions on the imposition of sanctions which mean that they cannotfunction as an incentive, for example, difficulties in imposing sanctions onforeign carriers or in imposing sanctions where a carrier provides redress whenthe NEB intervenes.

14.

15.

We suggest that the Commission should ask every Member State to demonstrate thatthe level of fines defined in national law is sufficient to provide an economicincentive, in accordance with Article 16(3), taking into account the circumstancesunder which the State proposes to impose fines. This will vary between States inaccordance with variations in national law. For example, in certain States there aredifficulties in having civil penalties, which means enforcement must rely on criminalpenalties, which are inevitably harder to impose; in principle this is not a problem butthe level of the penalty when it is imposed must be correspondingly higher.A further option would be to amend Regulation 1008/2008, to make compliance withconsumer protection laws, including but not limited to this Regulation, a licensecondition. This would bring the EU into line with the US, where compliance witheconomic regulations, including those relating to passenger rights, is a licensecondition.Enforcement could be further improved through full implementation by all MemberStates of the NEB-NEB agreement, and by improving the data on delays andcancellations of individual flights available to NEBs, and ideally the public throughproduction of a Consumer Report similar to that produced by the US Department ofTransportation. We suggest that the European Commission should work with MemberStates, NEBs and Eurocontrol to achieve this.Other improvements to the operation of the Regulation

16.

17.

18.

Some other minor initiatives could be taken which would improve the operation of theRegulation. We suggest that the Commission should:•encourage Member States to procure a harmonised online common complaintsinterface to handle and direct complaints automatically, in place of the standardcomplaint form, and provide information on how to complain to carriers;

4

Final report

••

update the Question and Answer document to reflect recent case law; andcontinue with regular interaction and encouragement with NEBs, airlineassociations, and also the key airlines.

Changes to the Regulation

19.

The Commission may be able to further clarify the Regulation through issuing furtherguidance, supplementing or possibly replacing the Q&A document, and the ECJ islikely to consider further cases which may lead to further clarification of the rights andobligations that the Regulation creates. In addition, the Commission and MemberStates may be able to further improve the operation of the Regulation. Nonetheless, inthe interviews we undertook for this study, most stakeholders told us that theRegulation should be revised. These interviews were all conducted before the ruling ofthe Court of Justice in the caseSturgeon and Bock.As identified by the Court, theRegulation appears to provide different rights to passengers facing equivalentinconvenience due to delays and cancellations. The Court ruled, on the basis of theprinciple of equal treatment, that there is a right to compensation for delays longerthan three hours, except where the delays are caused by circumstances which aresufficient to offer an exemption from payment of compensation under Article 5(3)(“extraordinary circumstances which could not have been avoided even if allreasonable measures had been taken”).Whilst the ruling addresses one of the most important open questions in theRegulation, there are several others to which the same principle of equal treatmentcould be applied to justify revising the text. In our opinion, these issues can only beaddressed properly by revising the text of the Regulation so that the rights andobligations it creates are explicit and consistent with the principle of equal treatment.We also recommend that the Regulation should be revised to address the other areas ofthe text which are unclear.The most significant changes that we propose are:•Further to the Sturgeon judgement, passengers facing delays and cancellationsshould receive similar treatment. In particular, passengers should have equivalentright to benefits such as compensation, assistance and rerouting after the sameperiods, and should have equivalent rights if the delay or cancellation causesthem to miss connecting flights.Advance schedule changes, which are in effect delays notified in advance, shouldbe explicitly treated in the same way as cancellations notified in advance.The Commission should reflect on whether the circumstances under whichairlines should be required to pay compensation for cancellations and delaysshould be limited to cases not due to force majeure.The Article relating to downgrading should be revised to be consistent with theArticle on denied boarding, as both generally arise from overbooking.

20.

21.

•••22.

We also suggest a number of more minor changes, including that the total derogationfor helicopter services should be replaced with an option for Member States to givetotal or partial derogations to certain limited types of service (including helicopters butalso, for example, services with fixed wing aircraft taking off and landing on grass

5

Final Report

runways or the sea), and various other adjustments to address elements of theRegulation which are unclear.

6

Final report

1.

INTRODUCTIONBackground

1.1

Regulation 261/2004 introduced new rules on compensation and assistance for airpassengers in the event of denied boarding, cancellations, long delays and involuntarydowngrading. Depending on the circumstances, the Regulation requires air carriers to:••••provide passengers with assistance, such as hotel accommodation, refreshmentsand telephone calls;offer re-routing and refunds;pay compensation of up to €600 per passenger; andproactively inform passengers about their rights under the Regulation.

1.2

The Regulation also required Member States to set up National Enforcement Bodies(NEBs) with the ability to impose dissuasive sanctions, and specifies that passengershave the right to complain to any NEB.In 2006, the European Commission contracted Steer Davies Gleave to undertake anindependent review of the operation and results of the Regulation. The study, whichreported in 2007, found that there had been a number of difficulties, arising inparticular from ineffective enforcement in a number of Member States, and the factthat the drafting of some parts of the Regulation was unclear.In April 2007, the Commission issued a Communication2to report on the operationand results of the Regulation, as required by Article 17. This concluded that asubstantial improvement in the operation of the Regulation was required. It stated thatthere would be a period of stability during which no legislative changes would bemade, in order give Member States and air carriers the opportunity to improve theimplementation of the Regulation. In the meantime, it identified that further work wasrequired in a number of areas, including improved enforcement and clarification ofkey terms.The need for this study

1.3

1.4

1.5

The Communication issued in 2007 stated that if the efforts the Commission wasplanning to make to improve the operation of the Regulation did not produce asatisfactory result, it would have to consider amending the Regulation to ensure thatpassengers rights were fully respected.Since 2007, there have been a number of developments which should have helped toimprove the operation of the Regulation. These include:••measures taken by the Commission, for example to facilitate voluntaryagreements between NEBs and also between NEBs and airlines;rulings issued by the European Court of Justice, clarifying the interpretation of

1.6

2

COM final 168 (2007)

7

Final Report

•1.7

key Articles of the Regulation; andother legal developments, such as the entry into force of the Regulation onconsumer protection cooperation (Regulation 2006/2004).

The Commission intends to release a further Communication on the operation of theRegulation, and the extent to which this has been improved by the measures taken. Inorder to inform this Communication, it is necessary to undertake a new evaluation ofthe effectiveness of the enforcement of the Regulation and of the extent of compliancewith it. This will identify whether the measures taken since 2007 have succeeded inimproving the operation of the Regulation so that it now provides a high level ofprotection for passengers.This study has been undertaken by Steer Davies Gleave. We have been supported onresearch in Poland, Slovak Republic and Hungary by Helios Technology Limited. Theconclusions represent the views of Steer Davies Gleave alone.This report

1.8

1.9

This report is the Final Report for the study. It reflects comments received from theCommission on the First Findings Report, which set out the factual conclusions fromthe study.On the date that First Findings Report for this study was issued, the European Court ofJustice issued its ruling in the caseSturgeon and Bock3, relating to the distinctionbetween the treatment of cancellations and delays under the Regulation. Thisjudgement has significant implications for the issues evaluated in this study. It was notpossible to discuss this judgement with stakeholders within the timescale for thisstudy, but we have taken it into account in developing our recommendations.A limited amount of information has been redacted from the published version of thisreport.Structure of this document

1.10

1.11

1.12

The rest of this report is structured as follows:•••••••Section 2 summarises the methodology used for this study;Section 3 sets out how the Regulation is being applied by carriers;Section 4 describes enforcement and complaint handling by NEBs;Section 5 discusses alternative dispute resolution processes;Section 6 sets out stakeholder views on possible policy measures;Section 7 summarises the conclusions; andSection 8 sets out our recommendations.

1.13

Case studies have been undertaken of complaint handling, enforcement and alternativedispute resolution processes in 15 Member States. These are provided in appendix A,

3

Joined Cases C 402/07 and C 432/07

8

Final report

which, due to its size, is provided as a separate document.

9

Final Report

2.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGYIntroduction

2.1

This section provides a summary of the research methodology used. It describes:••••the overall approach used;the selection of case studies;the scope of the desk research that has been undertaken; andthe stakeholders that have participated in the study, and how they have providedinputs.

Overview of the approach

2.2

The Commission requested us to collect evidence to address a number of questions,most of which can be categorised as either relating to:••enforcement and complaint handling undertaken by National Enforcement Bodies(NEBs); andapplication of the Regulation by air carriers.

2.3

In order to address these questions, we developed a research methodology divided intotwo parts:••case study research; andcross-EU interviews and analysis.

2.4

The rationale for this division is that enforcement and complaint procedures arespecific to Member States and are therefore best evaluated through a case studyapproach. It was agreed to undertake case studies of complaint handling andenforcement in 15 Member States as part of this study. However, key airlines coverthe whole of the EU (for example, the Irish-registered carrier Ryanair operatesdomestic flights in the UK, France, Spain and Italy) and therefore questions relating tothe application of the Regulation by airline have been addressed through a cross-EUapproach. Information from both elements of the research has been used for theconclusions, and will be used as the basis for the development of recommendations.Both the case study and the cross-EU research use a mixture of stakeholder interviewsand desk research. However, as there is limited published information available whichaddresses the issues that were raised by the Commission, we have been primarilyreliant on stakeholder interviews.Selection of case studies

2.5

2.6

As noted above, it was agreed to undertake detailed case studies of complaint handlingand enforcement in 15 Member States as part of this study. This section summariseshow the case studies were selected. We have also collected some, more limited, dataon complaint handling and enforcement in the other 12 Member States in order to beable to present the position on complaint handling and enforcement across the EU.

10

Final report

2.7

We undertook case studies in the eight Member States with the largest aviationmarkets, measured in terms of air passenger numbers (UK, Spain, Germany, Italy,France, Greece, Netherlands and Ireland). The other seven case studies were selectedin order to ensure that the study covered:•••••Member States where the Commission was aware of particular difficulties withenforcement, or where particular difficulties were identified in the study weundertook for the Commission in 2006-7;at least one State in which enforcement was previously identified as ‘bestpractice’;Member States in which the nature of the NEB is unusual, for example, to includeStates where complaint handling and/or enforcement is undertaken by a consumerprotection authority rather than a civil aviation authority;a selection of new Member States; andStates covering a wide geographical scope and variation in sizes.

2.8

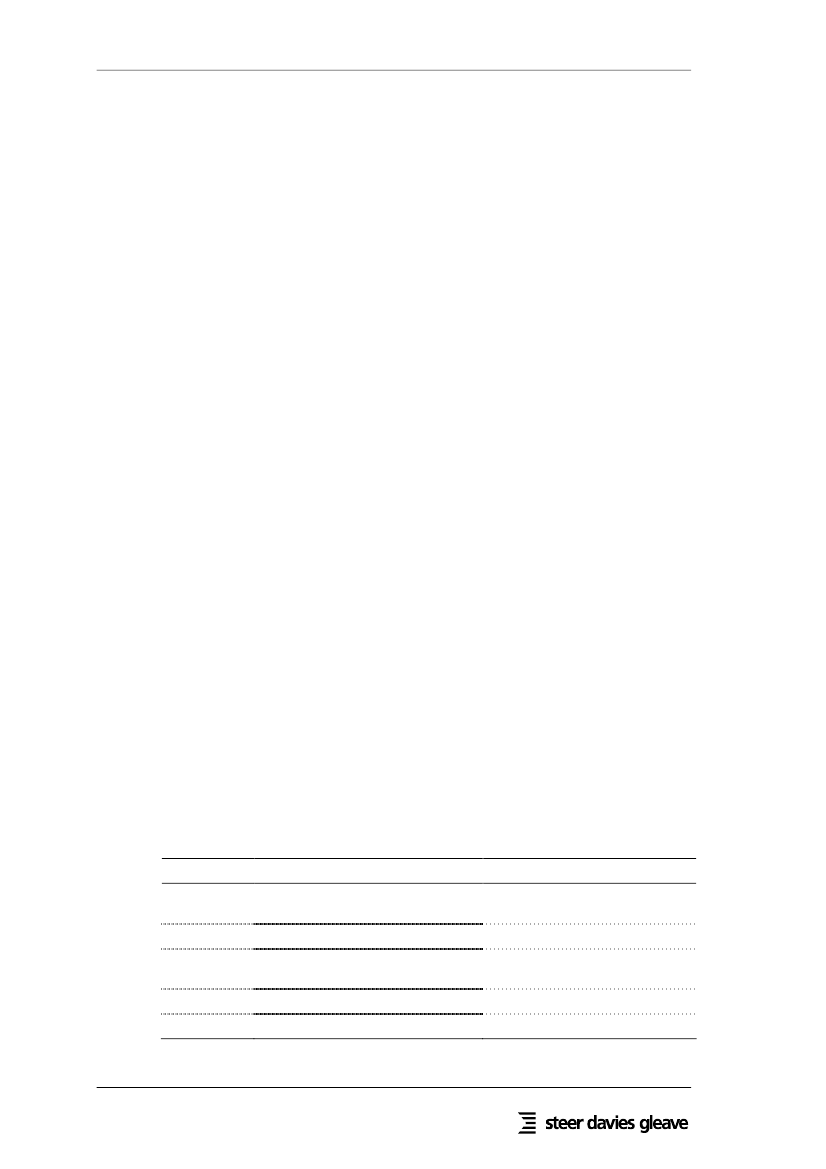

The selection of States is summarised below.TABLE 2.1StateDenmarkFranceGermanyGreeceHungaryIrelandItalyLatviaNetherlandsPolandPortugalSlovak RepublicSpainSwedenUKSELECTION OF CASE STUDIESRationale for selectionWide geographical spread; identified as example of best practiceLargest 8 States measured by passenger numbersLargest 8 States measured by passenger numbersLargest 8 States measured by passenger numbersNew Member State with large air transport market, and unusual structure for NEB(consumer authority)Largest 8 States measured by passenger numbersLargest 8 States measured by passenger numbersIssues previously identified with enforcement (low maximum fines)Largest 8 States measured by passenger numbersNew Member State with large air transport marketWide geographical spread; issues identified with enforcementNew Member State with large air transport market; particular issues due to airlineinsolvencyLargest 8 States measured by passenger numbersWide geographical spread; unusual structure for NEB (consumer authority/ADR)Largest 8 States measured by passenger numbers

Desk research

2.9

The following information has been collected and analysed through desk research:••information from airline websites on airline complaint procedures;data for delays and cancellations, from national authorities and from airlineassociations; and

11

Final Report

•2.10

data for NEB complaint procedures, from NEB websites.

We have also obtained and analysed a significant amount of supporting informationprovided by stakeholders:••NEBs have provided data on passenger complaints, sanctions imposed and thelegal basis for enforcement; andairlines have provided information on their policies and procedures relating to theRegulation, the number of complaints received, and on the cost of compliancewith the Regulation.

Stakeholder inputs

2.11

Relatively little information is publicly available relating to the issues that we havebeen asked to address, and therefore we have relied extensively on information andopinions provided by stakeholders. This section summarises the stakeholders whichhave contributed to the study, and how they have contributed. This is divided asfollows:•••••National Enforcement Bodies;airlines and airline representative associations;airport operators and their representative association;passenger/consumer representatives; andother relevant stakeholders, such as tour operators.

2.12

We would like to thank all of the stakeholders that contributed to the study.National Enforcement Bodies

2.13

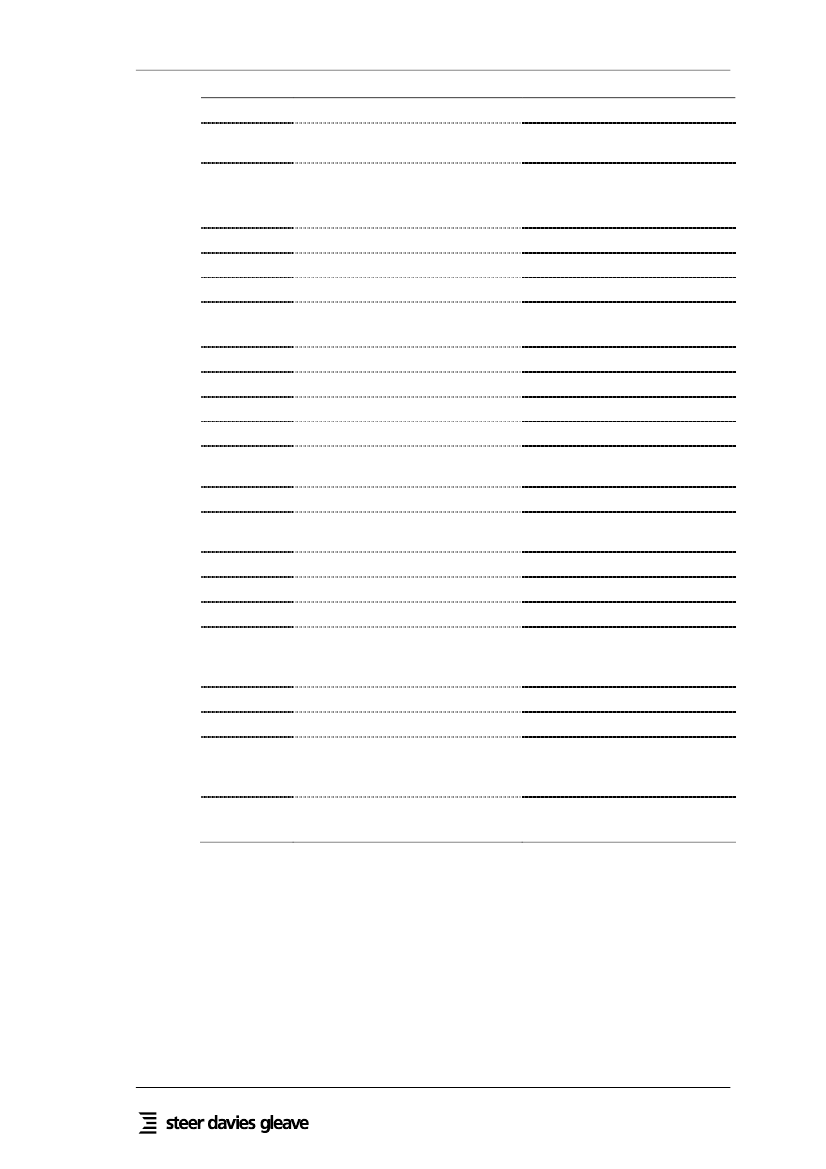

We contacted the NEBs in all 27 Member States to obtain information on thecomplaint handling and enforcement processes in each Member State, and tounderstand their views on how airlines were complying with the Regulation andpossible changes to it. In the 15 Member States selected as case studies, we undertookdetailed face-to-face interviews with the NEBs, and reviewed the legislation,procedures and other relevant documents that applied. Several of these NEBs alsoprovided us with written submissions which we have used. In the other 12 MemberStates, we provided the NEB with a questionnaire which was followed up with atelephone interview where necessary. The NEBs are listed in Table 2.2.TABLE 2.2Member StateAustriaBelgiumBulgariaCyprusCzech RepublicSTAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWS: NATIONAL ENFORCEMENT BODIESOrganisationBundesministerium für Verkehr, Innovation undTechnologieSPF Mobilité et TransportsGeneral Directorate Civil AviationAdministration, Ministry of TransportDepartment of Civil AviationCivil Aviation AuthorityForm of input to studyWritten responseWritten responseWritten response and telephone interviewWritten response and telephone interviewWritten response and telephone interview

12

Final report

DenmarkEstonia

Statens Luftfartsvæsen (CAA Denmark)Tarbijakaitseamet (Consumer ProtectionBoard)Civil Aviation Authority

Face-to-face interviewWritten response and telephone interviewWritten response and telephone interviewPartial written responseWritten responseWritten response and face-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewWritten response and face-to-face interviewInput to HACP written responseWritten response and face-to-face interviewWritten response and face-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewWritten response and telephone interviewWritten response and telephone interviewWritten response and telephone interviewWritten response and face-to-face interviewWritten response and face-to-face interviewWritten response and face-to-face interviewWritten response and telephone interviewFace-to-face interviewWritten response and telephone interviewWritten response and face-to-face interviewWritten submission and face-to-faceinterview (with both organisations)Written response and face-to-face interviewWritten response and face-to-face interview

Finland

Consumer Complaint BoardConsumer Ombudsman & Agency

FranceGermanyGreeceHungaryIrelandItalyLatviaLithuaniaLuxembourgMaltaNetherlandsPolandPortugalRomaniaSlovakiaSloveniaSpainSweden

Direction Générale de l'Aviation CivileLuftfahrt-Bundesamt (LBA)Hellenic Civil Aviation AuthorityHungarian Authority for Consumer ProtectionHungarian Civil Aviation AuthorityCommission for Aviation RegulationENACConsumer Rights Protection CentreCivil Aviation AdministrationDirection de la Consommation du Ministère del’Economie et du Commerce extérieurDepartment of Civil AviationCivil Aviation Authority Netherlands - FlightOperations InspectorateCivil Aviation OfficeINAC, Legal Regulations DepartmentNational Authority for Consumer ProtectionSlovenská obchodná inšpekcia (Slovak TradeInspectorate)ústredný inšpektorát (Central Inspectorate)Directorate of Civil AviationAgencia Estatal de Seguridad AéreaEnforcement: Swedish Consumer AgencyComplaints: National Board for ConsumerComplaintsEnforcement: UK CAAComplaints: UK Air Transport Users Council

UK

Airlines and airline associations

2.14

We consulted with airlines in order to obtain information on their application of theRegulation, and on the complaint handling and enforcement processes undertaken byNEBs. We sought to include in the study:•••One key airline with major operations in each case study State;At a minimum, the top 5 European airlines by passenger numbers (Air France-KLM, Lufthansa, British Airways, easyJet and Ryanair); andA mix of different airline types (legacy, low cost and charter), States of

13

Final Report

registration, and sizes.2.15Table 2.3 lists the airlines we approached; it also lists the type of carrier and where inthe case study States each carrier has a base. Some of the carriers we approacheddecided not to respond directly to us, but we did undertake interviews with twocarriers who approached us directly requesting to participate. Several legacy carriersresponded through their representative organisation, AEA, but were not able toprovide individual responses to us.TABLE 2.3AirlineAegean AirlinesAir France-KLMAir BalticAir BerlinAlitaliaBMIBritish AirwaysBrussels AirwayseasyJetIsle of ScillySkybusLufthansaNorwegianOlympic AirlinesRyanairSASTAP Air PortugalTUI groupWizz AirSTAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWS: AIRLINESType of carrierRegional carrierLarge legacy carrierRegional carrierLarge low cost carrierMedium sized legacy carrierMedium sized legacy carrierLarge legacy carrierSmaller legacy carrierLarge low cost carrierSmall regional carrierLarge legacy carrierSmaller low cost carrierLegacy carrierLarge low cost carrierMedium sized legacy carrierMedium sized legacy carrierVarious charter carriersSmaller low cost carrierBases in case study StatesGreeceFrance, NetherlandsLatviaGermanyItalyUKUK-France, Germany, Spain, Italy,UKUKGermany-GreeceGermany, Ireland, Italy,Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UKDenmark, SwedenPortugalUK, Germany, FranceHungaryType of participationFace-to-face interviewTelephone interview andinput through AEAFace-to-face interviewWritten responseInput through AEA onlyWritten responseInput through AEA onlyWritten responseFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewInput through AEA onlyFace-to-face interviewDid not respondFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interview

2.16

We also consulted with the five main associations representing airlines operatingwithin the EU, listed in Table 2.4 below.TABLE 2.4OrganisationIATAELFAAIACAAEASTAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWS: AIRLINE ASSOCIATIONSFull nameInternational Air Transport Association*European Low Fares Airline AssociationInternational Air Carrier AssociationAssociation of European Airlines*RepresentsAll ‘legacy’ airlinesEuropean low cost airlinesLeisure (charter) airlinesEuropean legacy airlines

14

Final report

ERA

European Regional Airlines Association

European regional airlines

* A joint meeting was held with IATA and AEA

Airport operators and associations

2.17

We also approached one airport in each of the case study States, usually the mainairport. The rationale for approaching the airport operator was that at certain airports,airport employees, particularly terminal managers, are in a good position to make anindependent assessment of whether and how airlines operating to the airport arecomplying with the Regulation.However, many of the airports we approached were not willing to respond orconsidered that they did not have any contribution to make; the airports that didcontribute are listed in Table 2.5.TABLE 2.5StateDenmarkFranceGermanyGreeceHungaryIrelandItalyLatviaNetherlandsPolandPortugalSlovakiaSpainSwedenUKSTAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWS: AIRPORTSAirportKøbenhavns LufthavneAéroports de ParisBerlin AirportsAthens International AirportBudapest Ferihegy InternationalDublin Airport AuthorityAeroporti di RomaRiga International AirportSchiphol GroupPolish Airports State EnterpriseANA Aeroportos de PortugalAirport BratislavaAENALFV (Stockholm)BAA (London Heathrow)Type of participationWritten responseNot able to obtain a responseNot willing to provide responseWritten responseNot able to obtain a responseWritten responseNot able to obtain a responseNot able to obtain a responseNot able to obtain a responseWritten responseWritten responseFace-to-face interviewWritten responseNot able to obtain a responseFace-to-face interview

2.18

Passenger and consumer representatives

2.19

We also sought to involve one passenger or consumer association in each of the casestudy States plus Belgium, and we also had a written response from the EuropeanPassenger Federation (EPF). Not all of the consumer organisations that we contactedwere able to respond.TABLE 2.6StateEUDenmarkSTAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWS: CONSUMER ASSOCIATIONSAssociation nameEuropean Passenger FederationForbrugerrådet – FR (Danish Consumer Council)Type of participationWritten responseWritten response

15

Final Report

FranceGermany

UFC - Que ChoisirVZBV - Verbraucherzentrale BundesverbandSchlichtungsstelle Mobilitat

Telephone interviewWritten response and telephoneinterviewWritten response and telephoneinterviewTelephone interviewWritten responseDid not respondTelephone interviewWritten responseWritten responseDid not respondWritten responseFace-to-face interviewWritten responseFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interviewFace-to-face interview

GreeceHungaryIrelandItalyLatviaNetherlandsPolandPortugalSlovakiaSpainSwedenUKBelgium

Centre for the Protection of ConsumersOFE (consumer protection association)Consumers Association of IrelandAssoutenti4ECC LatviaAssociation of TravellersPolish National Consumer AssociationAssocia§ão Portuguesa para a Defesa doConsumidorAssociation of Slovak ConsumersFACUASwedish Consumers AssociationWhich?Test Achats

Other organisations

2.20

The following other organisations have provided input to the study:•••EUClaim, a commercial organisation which handles passenger claims againstairlines under the Regulation;ECTAA, the European Travel Agents and Tour Operators Association; andTUI Group Plc, one of the two largest holiday operators in the EU, which repliedboth on its own behalf and on behalf of the airlines it owns.

4

In addition the report draws on published statements by other consumer organisations, but they have not directlyparticipated in the study.

16

Final report

3.

APPLICATION OF THE REGULATION BY AIRLINESIntroduction

3.1

This chapter examines the evidence we have collected on how airlines have appliedthe Regulation. It discusses:•••••the frequency with which incidents covered by the Regulation occur;procedures put into place for handling complaints;the cost of complying with the Regulation;evidence regarding the extent to which airlines are complying with theRegulation, provided by airlines and other organisations; andstakeholder views on how and whether airlines are complying.

Statistical evidence for cancellations, delays and denied boarding

3.2

In principle, the introduction of the Regulation might have been expected to reduce thelevel of airline-caused delay and cancellations, by providing carriers with additionalincentive to ensure reliable operations. In addition, there was a risk that it might haveincentivised airlines to reclassify cancellations as long delays, because carriers’obligations in the event of long delays are less onerous. Our 2006-7 study for theCommission found no evidence of any such impact, but noted that it was relativelyearly to make this assessment. Therefore, we have updated the analysis of the leveland causes of delays and cancellations.Our analysis draws on data published by the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), theFrench Civil Aviation Authority (DGAC), the Association of European Airlines(AEA) and the European Regional Airlines Association (ERA). We have alsoreviewed a number of other data sources including Eurocontrol eCODA data, but thiswas not useful for the analysis that we needed to undertake. The scope of the analysisthat can be undertaken is, in any case, restricted by the fact that, in many parts ofEurope, there is no published source of data on flight delays and cancellations.Level of delays and cancellations

3.3

3.4

The sources evaluated for this study indicate that the Regulation has had no impact onthe frequency and severity of delays, or on the number of cancellations. In addition,there is no evidence for carriers’ reclassifying cancellations as long delays. However,it is possible that carriers may use a different approach to categorisation for statisticalpurposes to that used when determining their obligations under the Regulation, andtherefore it is not possible to derive a definitive conclusion from this analysis.Figure 3.1 shows trends in delays and cancellations from data provided by AEA. Thisis based on data from AEA members, which are network airlines operating a mix oflong-haul and short distance services. The data suggests that the Regulation has nothad a significant impact on the percentage of flights delayed or cancelled, or theaverage delay minutes recorded for arrivals or departures. Unfortunately the AEA datadoes not provide any information on the number of long delays, so it cannot be used toestimate in how many cases carriers have an obligation to provide assistance to

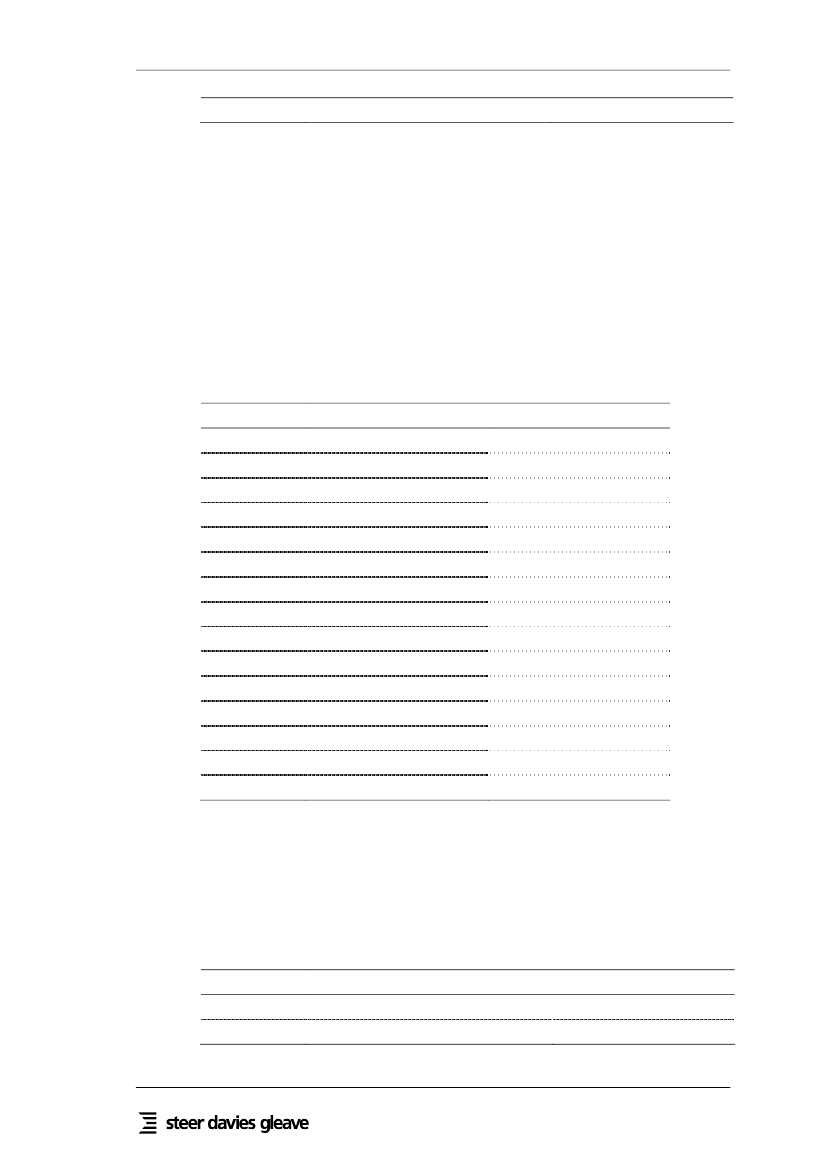

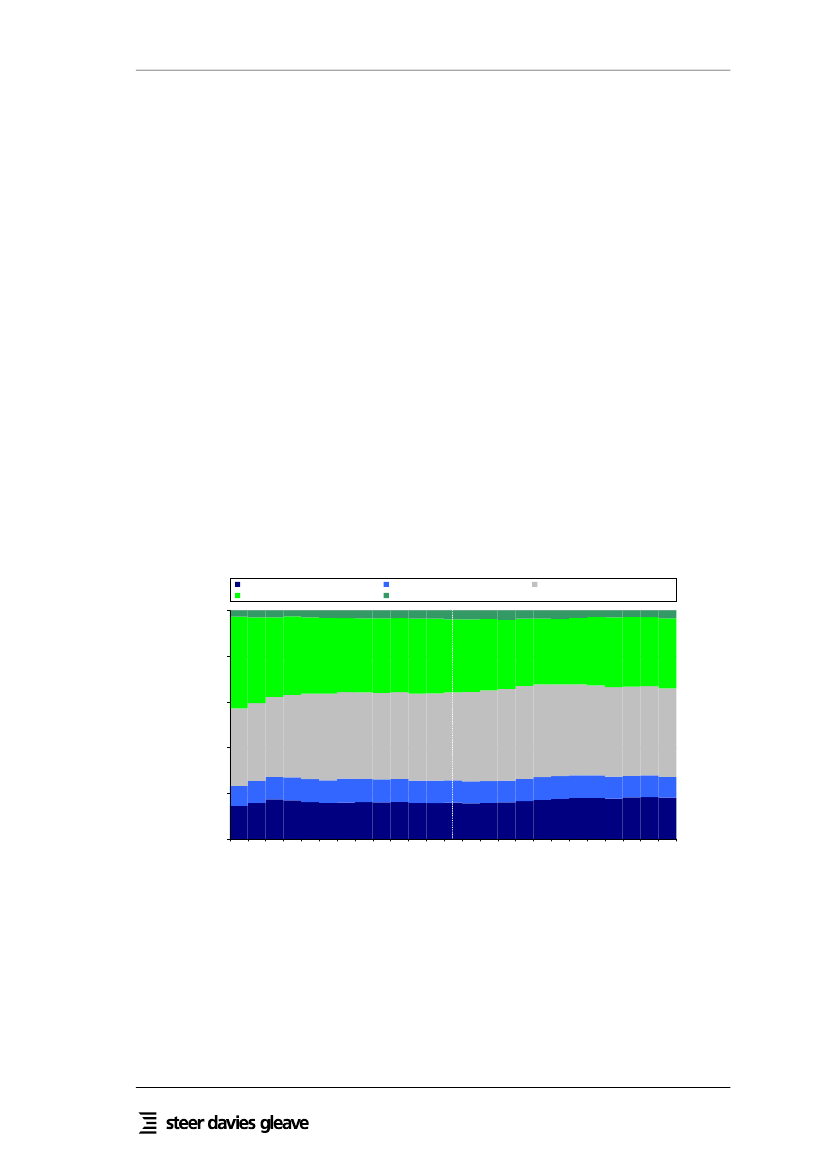

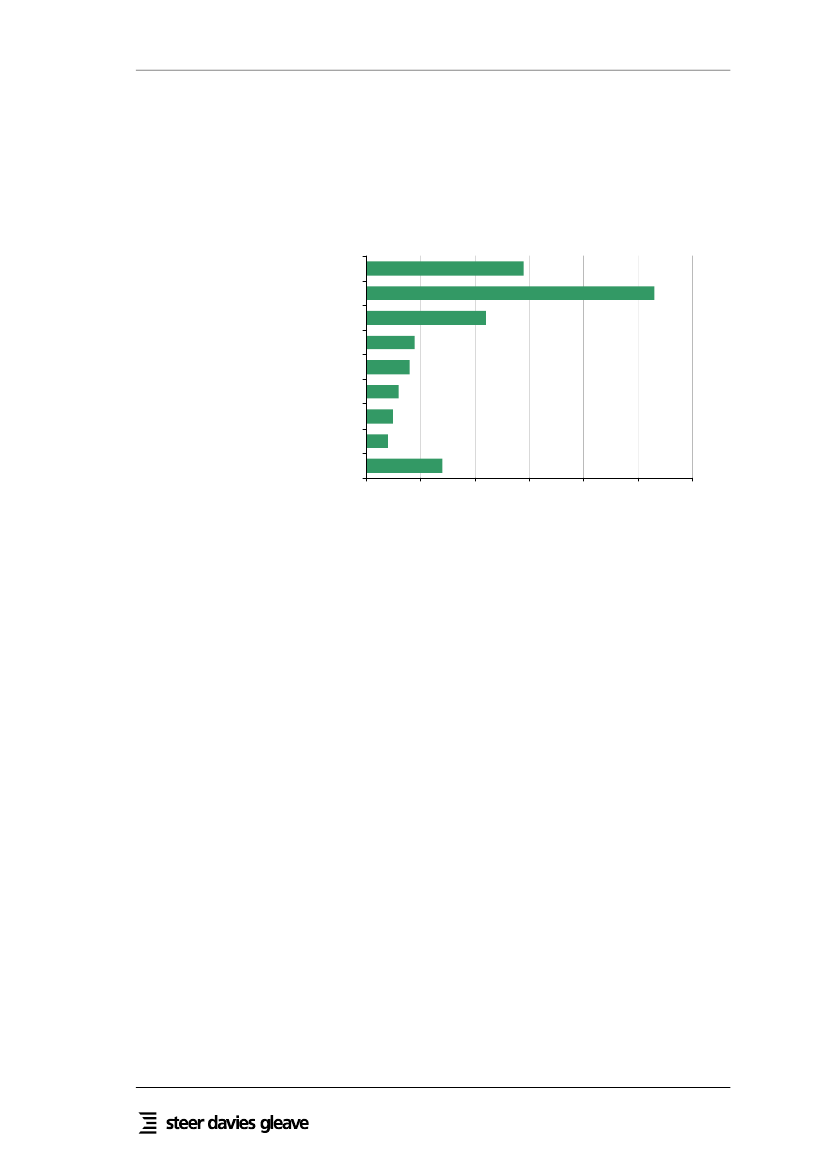

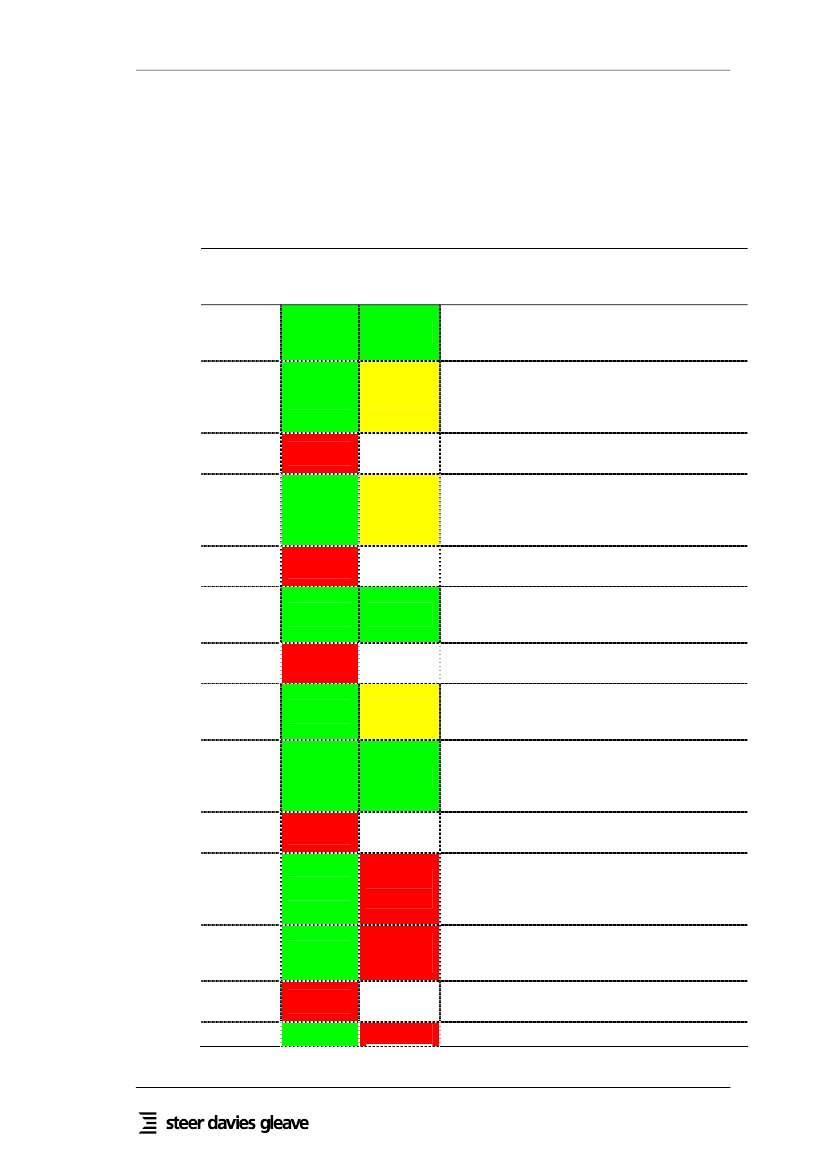

3.5

17

Final Report

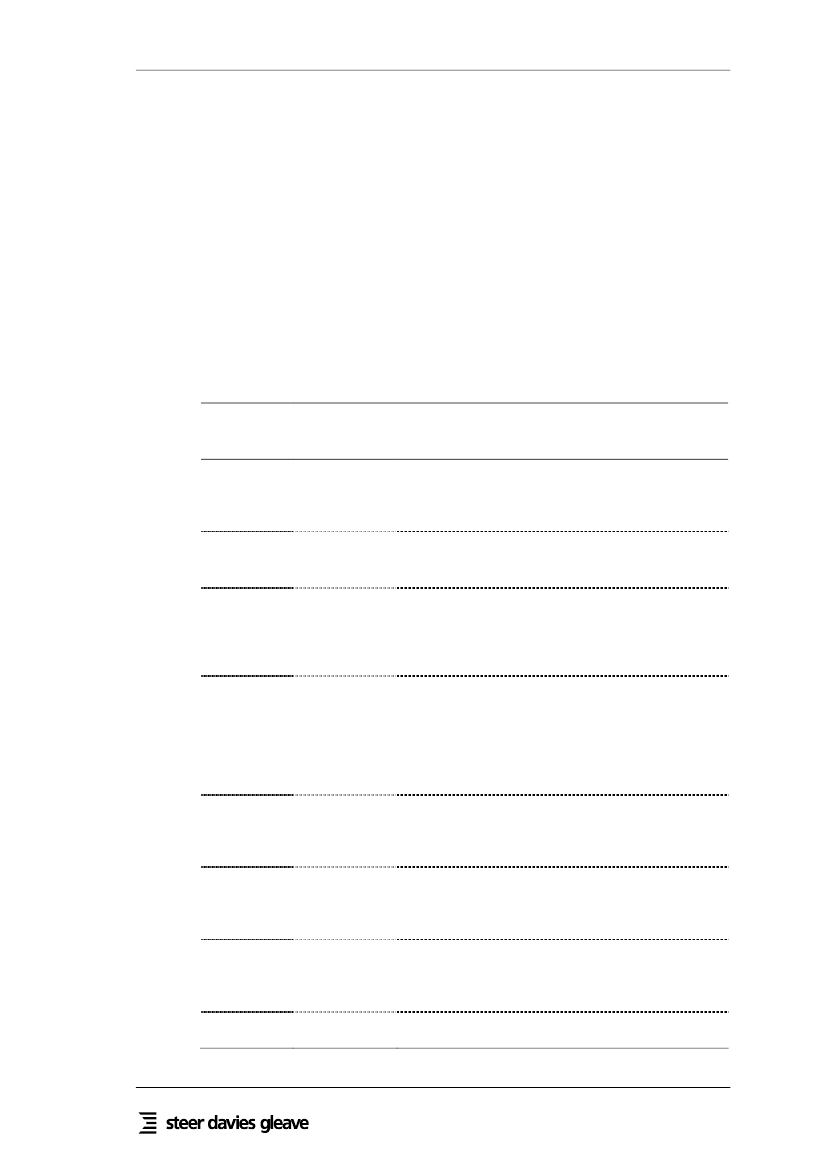

passengers. The data shows around 1.4% of AEA airline flights are cancelled.FIGURE 3.1TRENDS IN DELAYS AND CANCELLATIONS: AEA AIRLINES(QUARTERLY DATA; ANNUAL MOVING AVERAGE)45Regulation 261/200435%44

40%

30%

43Average delay minutes

25%% of Flights

42

20%

41

15%

40

10%% Departures over 15 mins% Departures cancelled% Arrivals over 15 minsAverage delay mins (departures)Average delay mins (arrivals)2000 Q12001 Q12002 Q12003 Q12004 Q12005 Q12006 Q12007 Q12008 Q1

39

5%

38

0%

37

Source: SDG analysis of AEA data

3.6

The data suggests that, in the year following the implementation of the Regulation,delays increased, peaking in the third quarter of 2006. There has been no significantchange in the proportion of flights cancelled and there is no evidence to suggest thatairlines have re-classified cancellations as long delays.Figure 3.2 (below) shows UK CAA data for delays and cancellations at 10 major UKairports. This shows similar trends to the AEA data but has the advantage ofseparately identifying long delays, and also being more up-to-date. The data shows asignificant decline in long delays since mid 2008, when traffic volumes started to fall.This result is consistent with the opinion of stakeholders that the decline in air trafficcaused by the economic situation has reduced the incidence of long delays andcancellations. In particular, there is no evidence of a re-classification of cancellationsas long delays since the introduction of the Regulation.

3.7

18

Final report

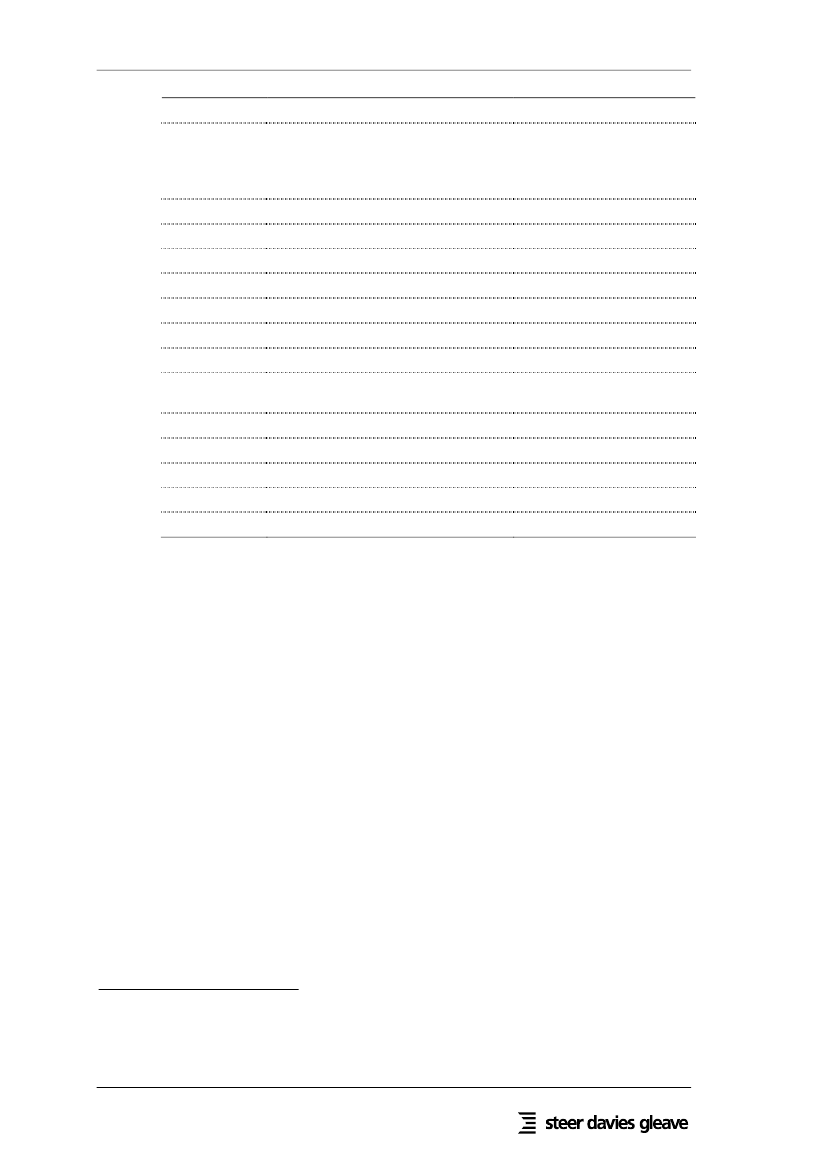

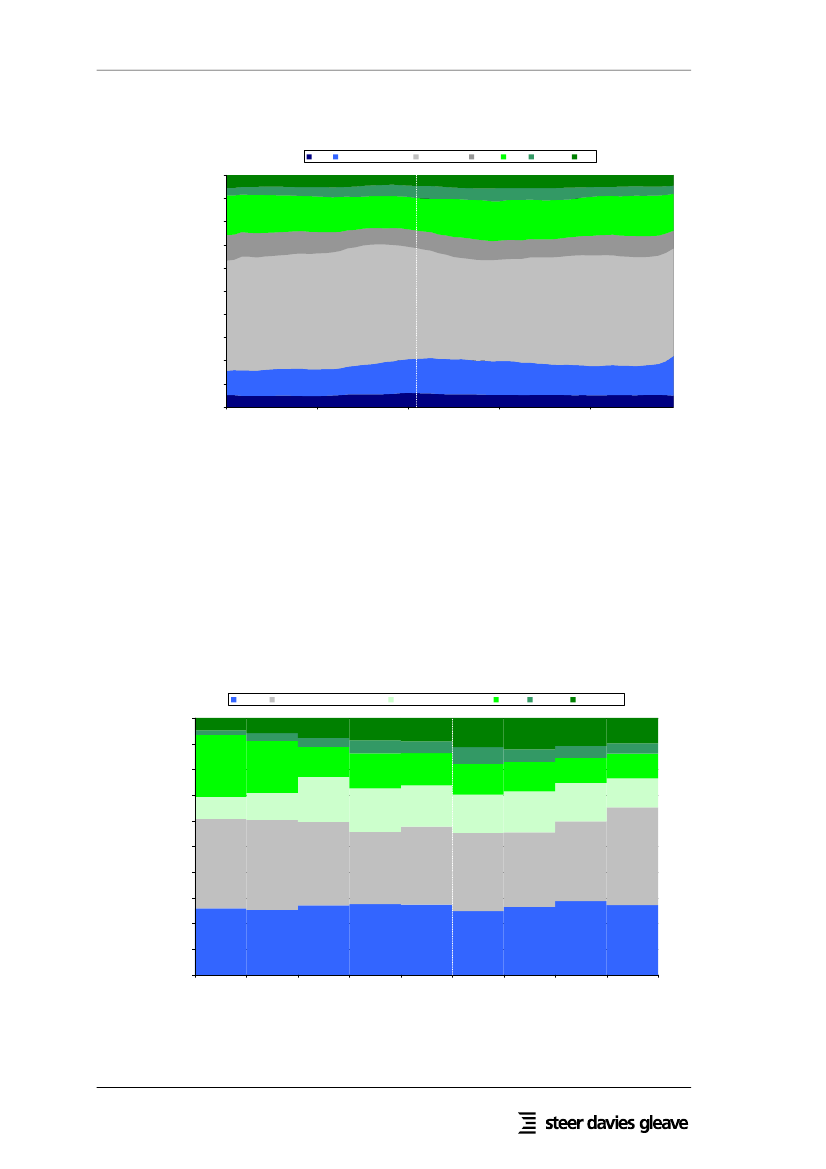

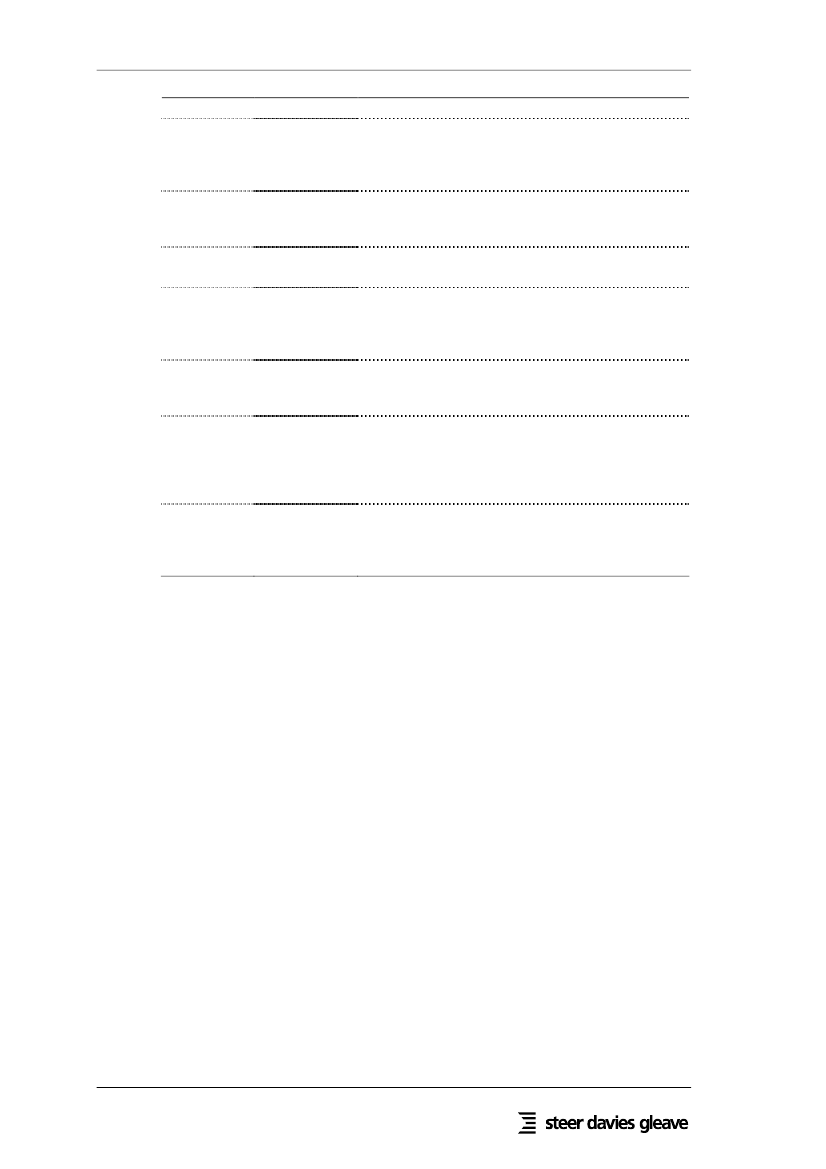

FIGURE 3.2

TRENDS IN DELAYS AND CANCELLATIONS: FLIGHTS TO / FROM UKAIRPORTS (MONTHLY DATA; ANNUAL MOVING AVERAGE)21

7%1-3 hour delays3-6 hour delaysOver 6 hour delaysPossible cancellationsAverage minutes late

Regulation 261/2004

6%

18

5%

15Average minutes late

% of Flights

4%

12

3%

9

2%

6

1%

3

0%Jan 2000Jan 2001Jan 2002Jan 2003Jan 2004Jan 2005Jan 2006Jan 2007Jan 2008Jan 2009

0

Source: SDG analysis of UK CAA data

3.8

CAA separately identifies delays of different lengths, although unfortunately it doesnot identify delays over 2 hours, which would be valuable in assessing for whatproportion of flights obligations are created by the Regulation; it indicates 4.3% offlights are delayed by 1-3 hours and around 0.7% are delayed over 3 hours. The dataincludes a ‘planned flights unmatched’ category, which represents planned flights forwhich an air transport movement has not been found. This unmatched category is usedhere as a proxy for possible cancellations, but the actual level of cancellations is likelyto be lower, as flights can fail to be matched for a number of reasons other than thecancellation of the flight.5For consistency with the AEA data, delayed flights aremeasured as a proportion of actual rather than scheduled flights.Figure 3.3 compares flight delays to the number of flights operated at the airports inthe sample, and clearly shows the link between recent declines in traffic volume andlower delays.

3.9

5

The possible reasons given by CAA for a flight not matching are: diversion to another airport, cancellation, theflight was a short-haul flight which operated more than an hour earlier than scheduled, the actual flight tookplace in the following month, or an incorrectly reported item of data caused the flight not to match.

19

Final Report

FIGURE 3.3

AVERAGE MINUTES LATE VS TRAFFIC: FLIGHTS TO / FROM UKAIRPORTS (MONTHLY DATA; ANNUAL MOVING AVERAGE)20

145,000

140,000

19

Flights matched per month

135,000

18Average minutes late

130,000

17

125,000

16

120,000

15

115,000Flights matchedAverage minutes late110,000Jan 2000

14

13Jan 2001Jan 2002Jan 2003Jan 2004Jan 2005Jan 2006Jan 2007Jan 2008Jan 2009

Source: SDG analysis of UK CAA data

3.10

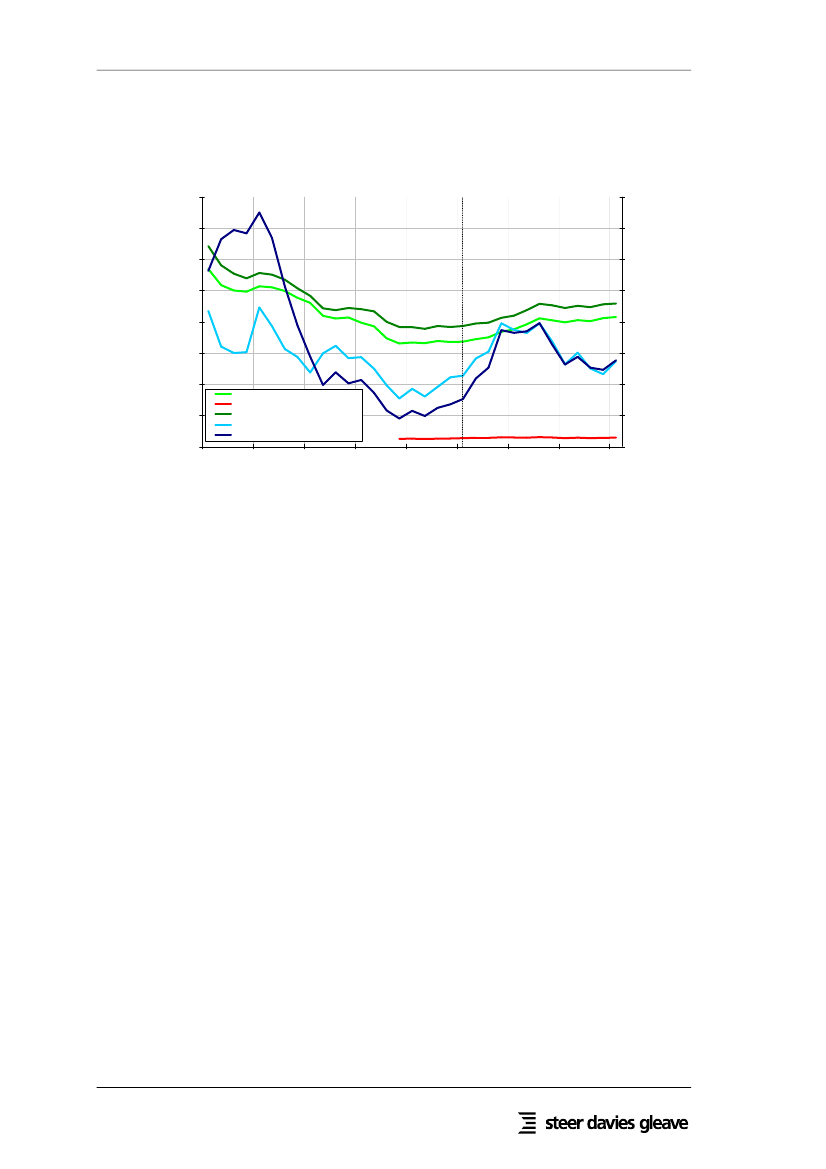

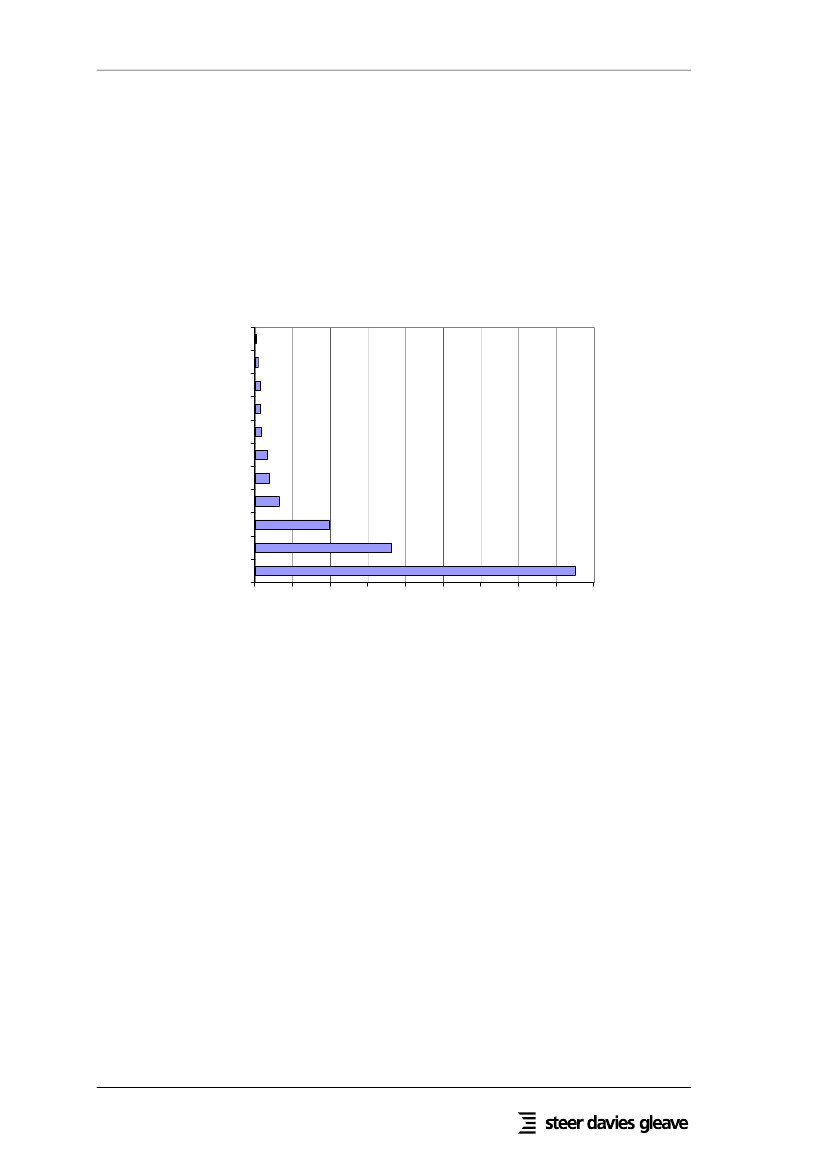

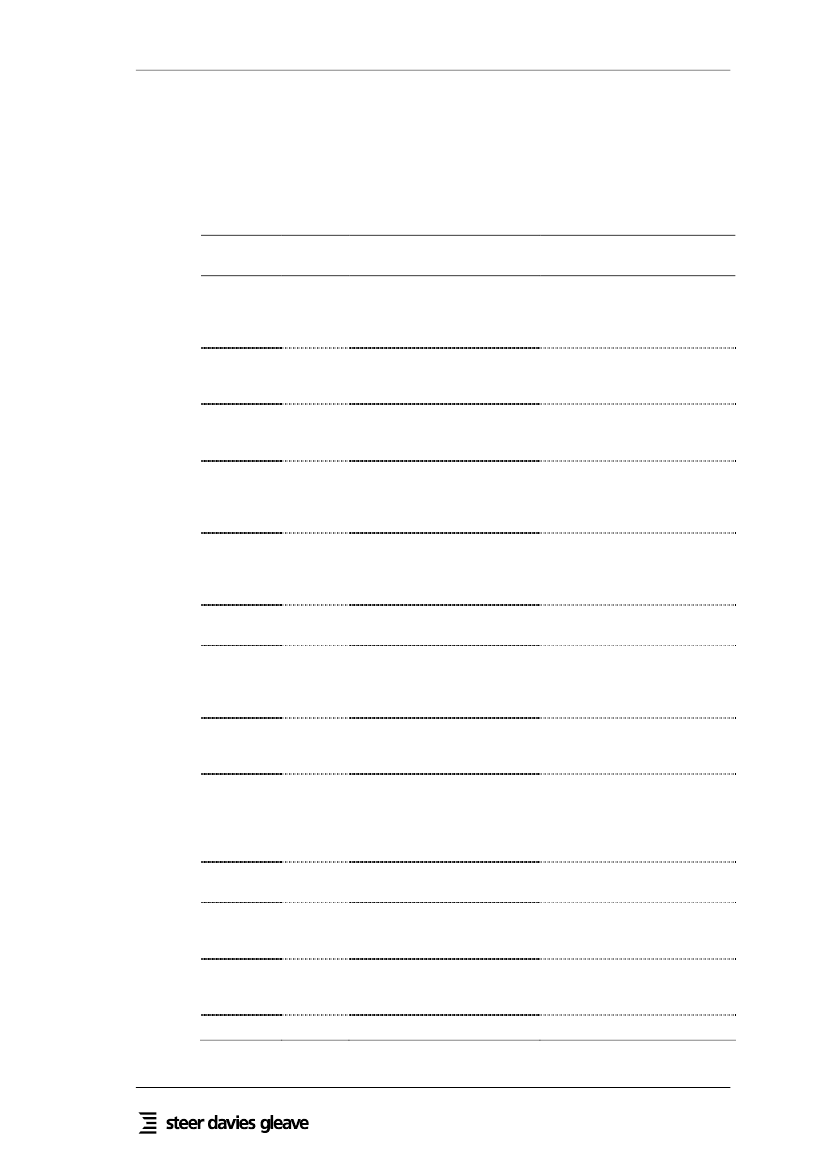

Figure 3.4 shows data provided by the European Regions Airline Association (ERA)for its members, which are generally smaller short-haul operators. The ERA datashows that, for these carriers, there has actually been some increase in the proportionof long delays since the Regulation took effect. The data shows that approximately2.0% of ERA airline flights are cancelled and around 3.4% delayed over 1 hour.FIGURE 3.4TRENDS IN DELAYS AND CANCELLATIONS: ERA AIRLINES (MONTHLYDATA; ANNUAL MOVING AVERAGE, DEPARTURES ONLY)

4.0%% over 60 mins late% cancelledRegulation 261/2004

3.5%

3.0%

% of Departures

2.5%

2.0%

1.5%

1.0%

0.5%

0.0%Jan 2002Jan 2003Jan 2004Jan 2005Jan 2006Jan 2007Jan 2008Jan 2009

Source: SDG analysis of ERA data

20

Final report

Causes of delays and cancellations

3.11

We have also analysed data for the causes of delays and cancellations, in order to:••identify whether the overall trends in delays and cancellations are impactedby factors which airlines cannot directly control, such as air trafficmanagement constraints; andassess the proportion of cases in which airlines could be exempt frompaying compensation for cancellations under Article 5(3) of the Regulation.

3.12

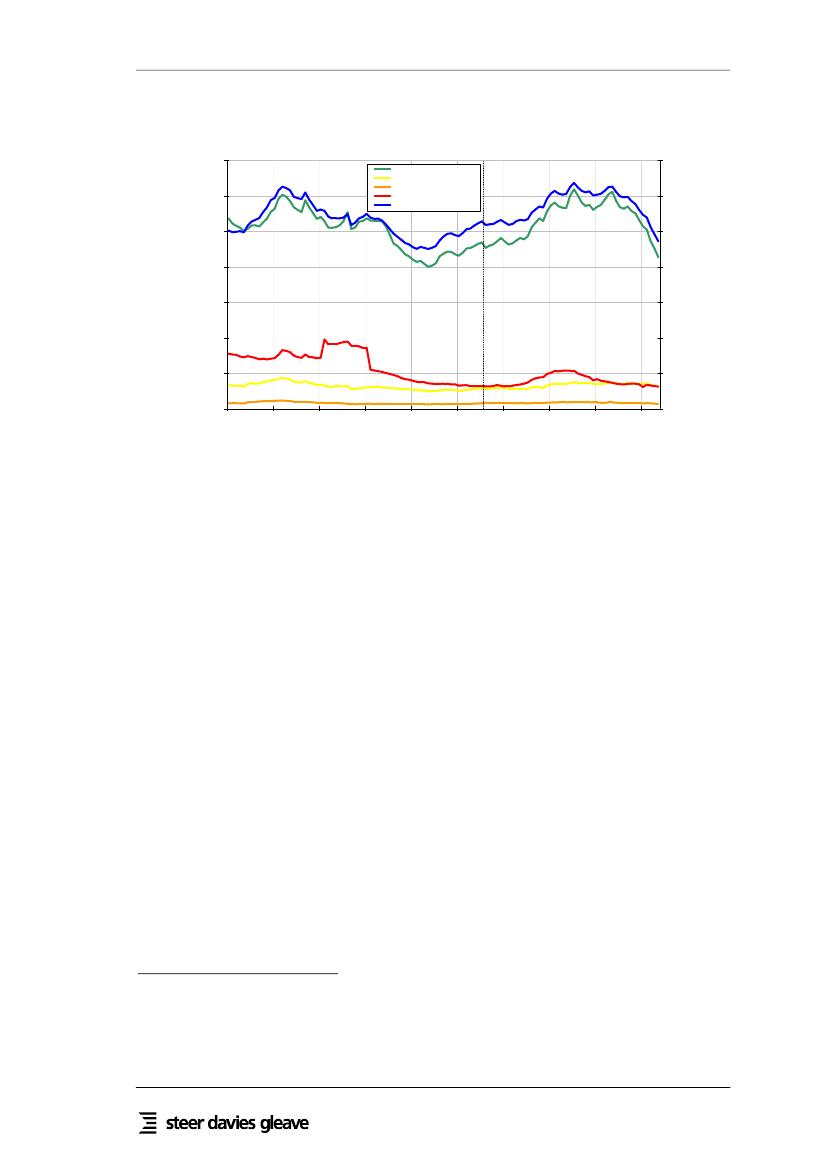

DGAC, AEA and ERA provide data on the causes of delays, although none provideany data on the causes of cancellations. It would be reasonable to assume that flightswould be cancelled for similar reasons although this would not always be the case.Overall, the data indicates that airlines are responsible for around 40% of delays, andthere has been no consistent change in this since the introduction of the Regulation.Figure 3.5 shows causes of delay for AEA departures delayed by more than 15minutes. Again, this data has been smoothed to eliminate seasonality, specifically ahigher rate of weather-related causes in the first and fourth quarters of every year. Thedata shows that airlines may be considered responsible for an average of 43% ofprimary delays (and presumably the same proportion of reactionary delays), and therehas been not been a significant change in this since the Regulation took effect.FIGURE 3.5CAUSES OF DELAY: AEA AIRLINES(QUARTERLY DATA; ANNUAL MOVING AVERAGE)Maintenance / Equipment FailureWeatherReactionary (late arrival)

3.13

Load & Aircraft Handling; Flight OpsAirport & Air Traffic Control100%

80%

% delays by cause

60%

40%

20%

Regulation 261/20040%2002 Q12003 Q12004 Q12005 Q12006 Q12007 Q12008 Q1

Source: SDG analysis of AEA data

3.14

However, ERA data (for delays of 60 minutes or more), shown in Figure 3.6, doessuggest a slight decrease in airline-related delays following the implementation of theRegulation. The ERA data indicates that, at the implementation of the Regulation inFebruary 2005, airlines were responsible for around 46% of primary delays (thisexcludes the reactionary and ‘other’ categories). The moving average reduces toaround 40% by late 2006, and increases again from August 2007 onwards.

21

Final Report

FIGURE 3.6

CAUSES OF DELAY: ERA AIRLINES(MONTHLY DATA; ANNUAL MOVING AVERAGE)OpsAircraft / TechnicalReactionaryOtherATCWeatherPax

100%Regulation 261/200490%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%Jan 2003Jan 2004Jan 2005Jan 2006Jan 2007WeatherPassengers20062007

Source: SDG analysis of ERA data

3.15

DGAC, the French civil aviation authority, publishes data on the causes of delay fordepartures from 15 French airports. The data is published on an annual basis, and isshown in Figure 3.7. The data indicates that airlines are responsible for 36-44% ofprimary delays, with a slight increase in this proportion since the introduction of theRegulation. The main change visible is that there has been a gradual reduction in theproportion of delay attributed to air traffic management in France since 2000.FIGURE 3.7CAUSES OF DELAY: DEPARTURES FROM FRENCH AIRPORTS(ANNUAL DATA)Airlines100%Regulation 261/200490%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%2000200120022003200420052008Reactionary & MiscellaneousAirports & safety servicesATFM

Source: SDG analysis of DGAC data

22

Final report

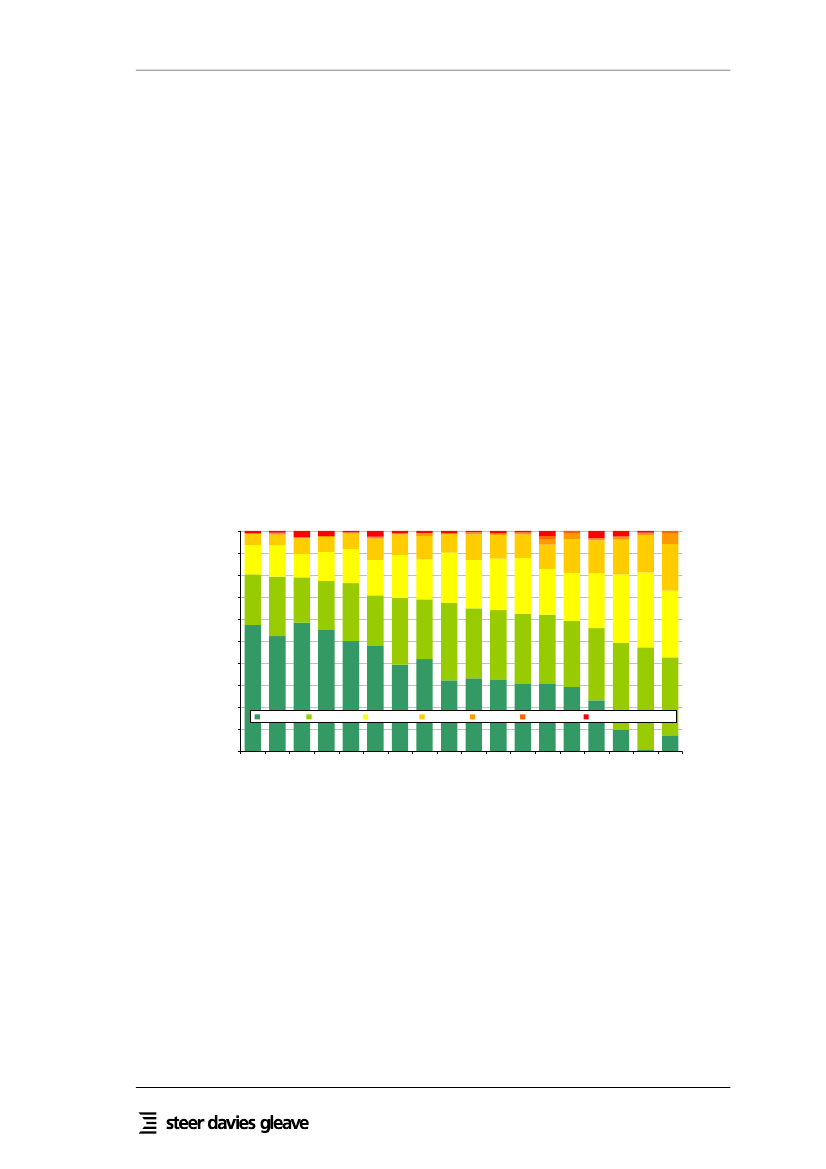

Delays and cancellations by airline

3.16

We have also undertaken analysis of the proportion of flights delayed by airline, inorder to identify whether there are significant differences between different types ofcarrier (low cost, charter etc) which may lead to some having greater obligations thanothers under the Regulation. The analysis is limited to the airlines selected forinclusion in the study sample.Although many of the sources reviewed for the study present airline-specific data,CAA data has been the most useful, being available for all of 2008, and coveringalmost all of the case study airlines. A limitation is that it is only based on flights toand from UK airports, which for some airlines may only form a small proportion oftheir overall operations; however this also means that the flights in the sample are allwithin a relatively similar operating environment.Figure 3.8 shows CAA data for arrivals and departures at UK airports. As statedpreviously, ‘planned flights unmatched’ is used as a proxy for cancellations, but actualcancellations are likely to be somewhat lower.FIGURE 3.8DELAYS AND CANCELLATIONS BY AIRLINE, FLIGHTS TO / FROM UKAIRPORTS, 2008(SORTED BY ARRIVAL / DEPARTURE WITHIN 30 MINS OF SCHEDULE)

3.17

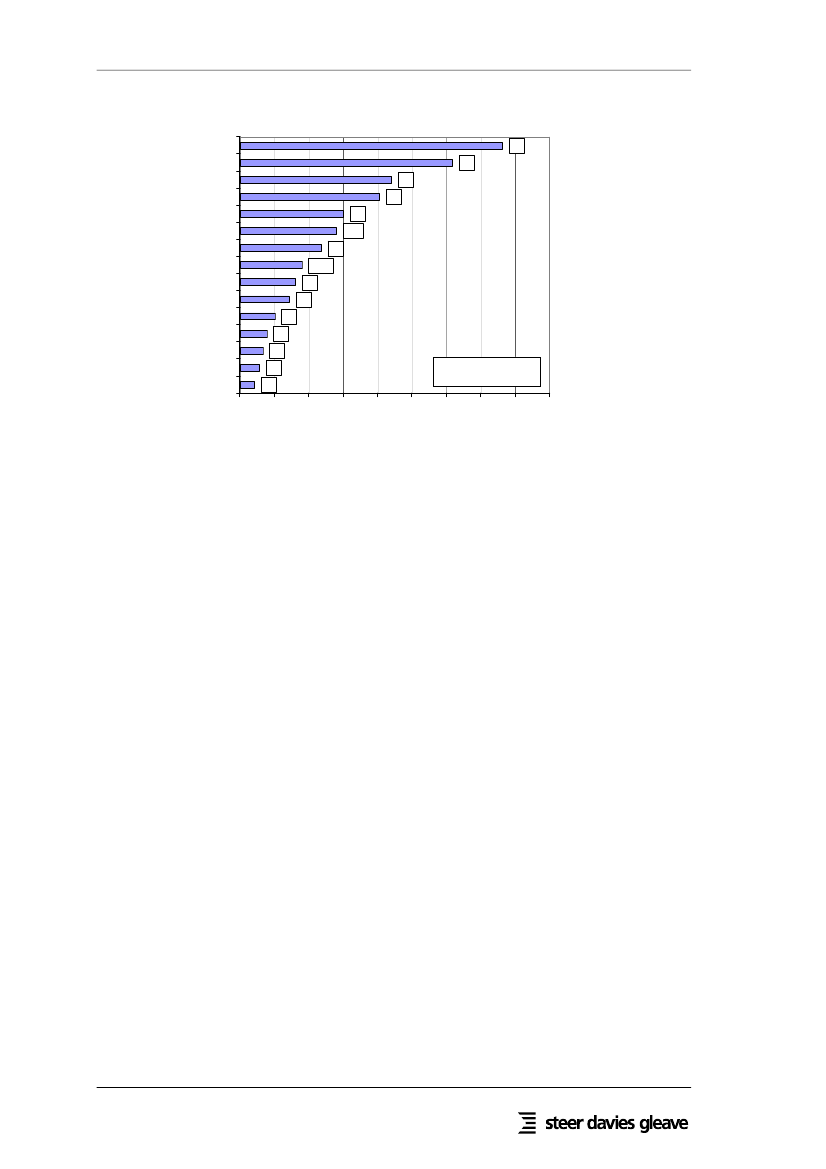

3.18

100%95%90%85%% of Flights80%75%70%65%60%0-15 mins55%50%aysinesrsAitCrBhoalticiceAirwaysFiairaltItAirAirwaysinesceliaKLMhwesSASansyJeBMyanrantugitaWizzAirwAirlIbOlymeriapicaEasAirl

16-30 mins

31-60 mins

1-3 hours

3-6 hours

Over 6 hours

Possible cancellations

Al

Lufth

els

out

Ai

ish

Por

rF

R

uss

Brit

Ai

Br

Source: SDG analysis of UK CAA data

3.19

The analysis shows significant variation in the proportion of different carriers’ flightswhich are delayed. However, there is no consistent evidence of a trend for one type ofoperator to be more punctual than another. The two charter airlines in the sample hadlevels of punctuality that, overall, were not significantly worse than other carriers, butthey did have a higher proportion of very long delays (over 3 hours), and almost noflights which may have been cancelled. This is consistent with information providedby the carriers, which is that they do not generally cancel flights.

Th

om

son

rS

Air

23

Final Report

Analysis of information provided by airlines

3.20

In addition to the publicly available data discussed above, from each airline wecontacted we requested airline-specific data on punctuality and reliability. All airlinescontacted either were not able to extract such data, or regarded it as too sensitive torelease. As a result we were unable to compare public data against airline sources.Two airlines were willing to provide us with figures for the proportion of passengerssubject to denied boarding:••one low cost airline provided these figures, but the numbers were negligible, asthe airline does not usually overbook; andone legacy carrier provided these figures, which were very low compared to thenumbers impacted by delays and cancellations.

3.21

Conclusions

3.22

The data sources do not allow unambiguous conclusions to be drawn about theproportion of flights for which there are obligations created by the Regulation.However, the data available indicates that 1-2% of flights are cancelled and 2-3% aredelayed by over 2 hours, implying that in total there are obligations created by theRegulation for around 4% of flights. It is possible that cancelled flights might have abelow-average number of passengers, particularly where flights are cancelled forcommercial reasons, and therefore this does not necessarily imply that there areobligations created for 4% of passenger journeys.The sources evaluated for this study indicate that the Regulation has had no impact onthe occurrence of long delays and cancellations:•••There is no evidence of any impact on the frequency and severity of delays, or onthe number of cancellations.There is no evidence (on the basis of the data we have seen) for carriers’reclassifying cancellations as long delays.There is no evidence that the proportion of delays for which airlines areresponsible has changed from the historical average of 40%.

3.23

3.24

In addition, analysis of punctuality data by airline shows no clear relationship betweenbusiness model and on-time performance.However, it should be noted that the scope of the analysis that can be undertaken isrestricted by the fact that, in many parts of Europe, there is no published source of dataon flight delays and cancellations. Some cross-European data is available fromEurocontrol, but this only provides delays over 1 hour, and is very limited compared(for example) to what is publicly available in the USA. If equivalently detailed wasmade publicly available in Europe, we would be able to analyse the issue in greaterdepth. This additional level of detail would also be useful to NEBs. AlthoughEurocontrol has data on individual flights this does not appear to be available toNEBs. If the data were published at the level of detail available in the US, NEBswould be able to make a number of checks on airlines’ claims, for example checkingwhether delays and cancellations occurred as stated, and investigating the load factors

3.25

24

Final report

of cancelled flights to check for likely commercial cancellations.Complaints to airlines

3.26

Through interviews with airlines and analysis of airline websites, we have sought tounderstand the approaches airlines take to receiving and responding to passengercomplaints. This section discusses the differences observed between the airlinesstudied.Information published by airlines on their complaints procedures

3.27

To understand what barriers, if any, prevent passengers from making a complaintunder the Regulation, we reviewed the websites of the airlines in the study’s samplelist. This review identified:••••whether it was readily possible to obtain information on how to complain;through which channels the airline could be contacted regarding complaints(email, post, telephone etc);any restrictions the carrier placed on complaints (for example, relating to thelanguage in which complaints can be submitted); andany information provided on how quickly the airline would respond.

3.28

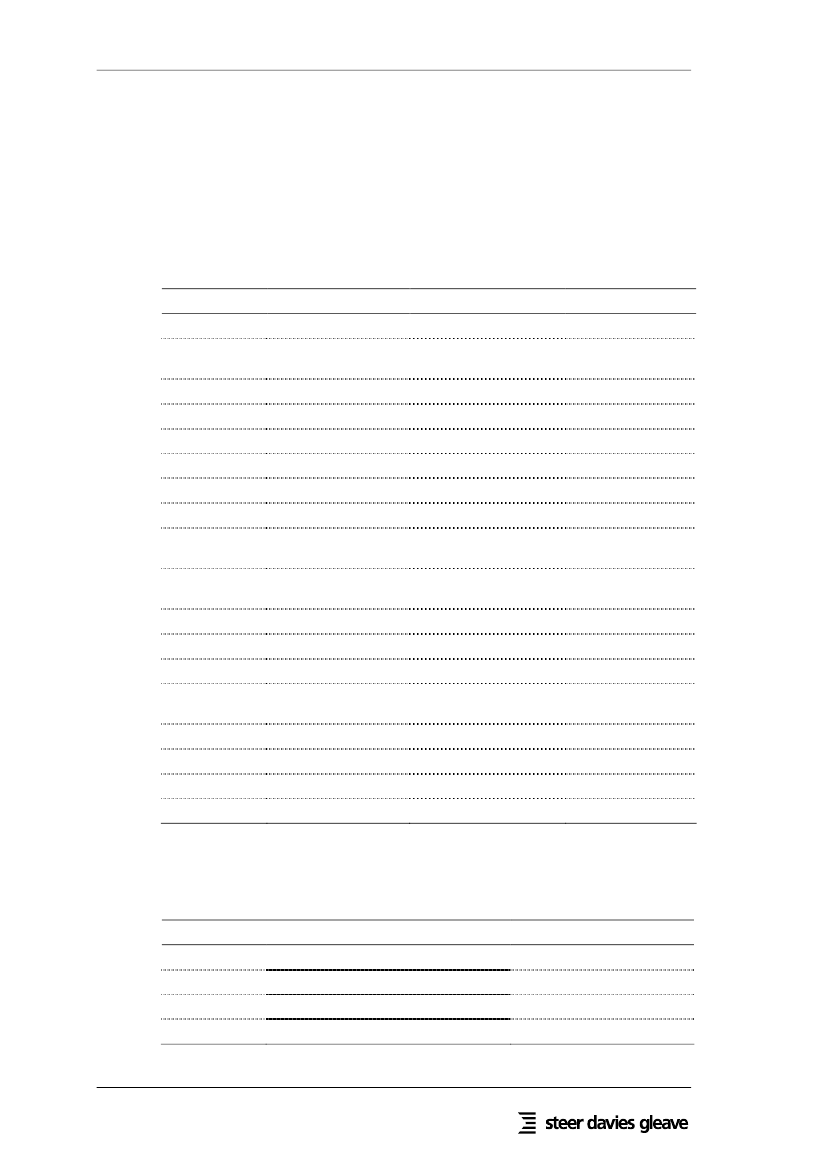

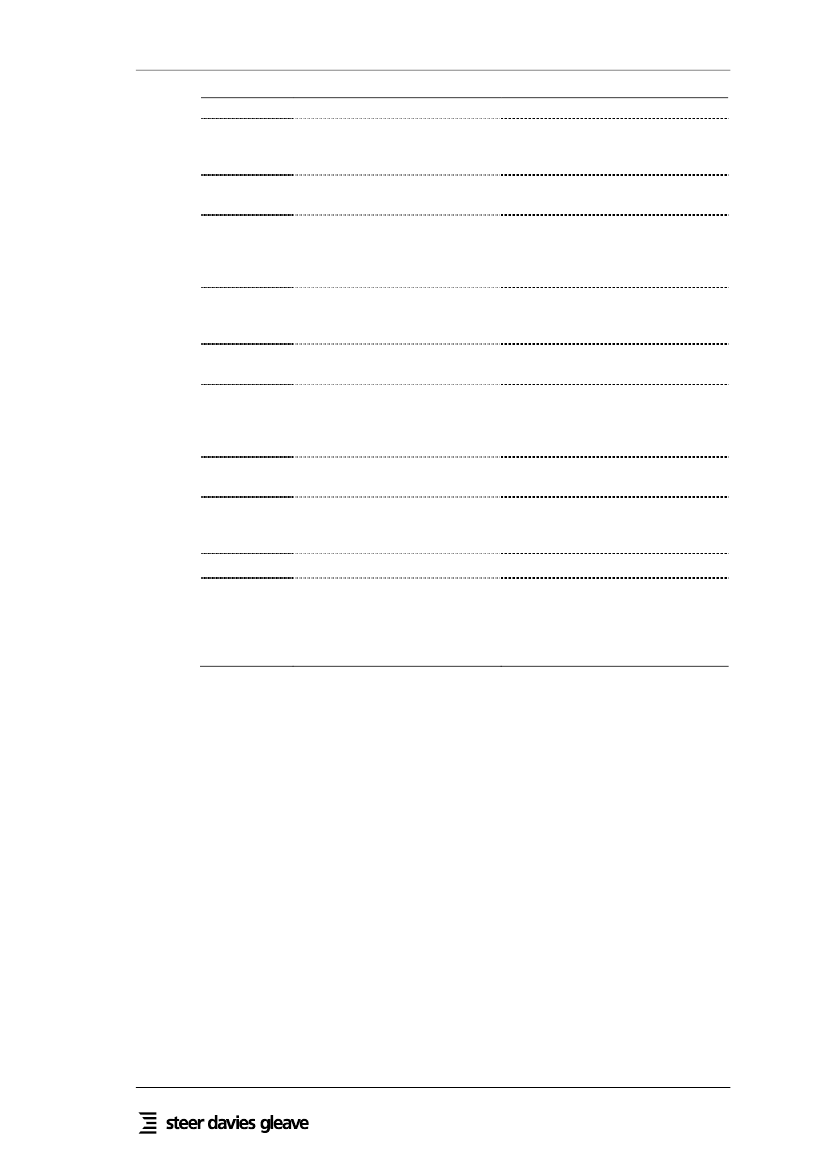

A summary of our findings for each airline is presented in Table 3.1. Note that theairlines selected for inclusion in this section are based on our initial list of airlines, anddiffer from those we were ultimately able to contact.TABLE 3.1ComplaintsprocedureDelay-specificcomplaint contactdetailsComplaintcontact detailsComplaintcontact detailsComplaintcontact details

SUMMARY OF AIRLINE COMPLAINT PROCEDURESPhonenumberYes -generalYes -generalYes -generalNoSpeed ofresponseEmail on day ofcomplaint, claimup to 4 weeksNone statedNone statedNone stated

AirlineSNBrusselsAirlinesAir FranceCondorFlugdienstLufthansa

Online contactOnline form -complaint-specificOnline form -complaint-specificEmail address -complaint-specificEmail address -complaint-specific

Postal addressYes - general

Any restrictions?None stated

Yes - complaint-specificNoYes - complaint-specific

None statedGerman and EnglishonlyComplaints allowedin any language,responses from achoice of 14None statedEmails restricted tochoice of 9languagesMail/fax only, inEnglish onlyNone stated

OlympicAirwaysWizz Air

General contactdetailsGeneral contactdetails

Yes -generalYes -general,PremiumrateNoYes -complaint-specificNo

Email address -generalOnline form -complaint-specific

Yes - generalYes - general

None statedUp to 30 days forresponse

RyanairAlitalia

Complaintcontact detailsComplaintcontact detailsGeneral contact

NoNo

Yes - complaint-specificYes - complaint-specificYes - complaint-

Up to 7 days forresponseNone stated

AirBaltic

No

None stated

None stated

25

Final Report

Airline

Complaintsproceduredetails

Phonenumber

Online contact

Postal addressspecific

Any restrictions?

Speed ofresponse

KLM

Complaintcontact detailsGeneral contactdetailsComplaintcontact detailsComplaintcontact detailsGeneral contactdetailsComplaintcontact detailsComplaintcontact detailsComplaintcontact details -difficult to findComplaintcontact details -difficult to find

Yes -complaint-specificYes -generalNo

Online form -complaint-specificNoOnline form -complaint-specificOnline form -complaint-specificEmail address -complaint-specificOnline form -complaint-specificOnline form -complaint-specificOnline form -complaint-specific

Yes - complaint-specificYes - generalYes - general

None stated

None stated

TAPPortugalIberia

None statedAccept complaints inalmost alllanguages*English, Danish,Swedish orNorwegian onlyNone statedNone stated

None statedAverage responsetime is 7 days*Up to 14 days forresponseNone statedNone stated

SAS

No

Yes - complaint-specificYes - generalYes - complaint-specificYes - complaint-specificNo

AirSouthwestBritishAirwaysBMI

Yes -generalYes -complaint-specificYes -complaint-specificYes -general

None stated

None stated

easyJet

Restricted toEnglish, French,Italian, Spanish,German and PolishNone stated

None stated

Thomsonfly

Yes -general

No

Yes - complaint-specific

None stated

*This information was provided by the airline at interview, and was not available on the website.

3.29

Of the 18 airlines in the sample list, 12 provided contact details which werespecifically for complaints (often labelled as customer relations). Only one carrierprovided contact details specifically for complaints regarding delays and cancellations.The reminder provided general contact details.Most (13) of the carriers reviewed provided a phone number, however it is difficult toinfer from this how easy it would be for a passenger to make a complaint as only fourof these numbers were specifically for complaints. Most of the phone numbers werecharged at national rates (€0.06-€0.14/minute). This level of charge is common amongcustomer service telephone lines across different sectors, however it could be off-putting to a complaining passenger if they have to make multiple lengthy calls. WizzAir charges a premium rate (£0.65/€0.76 per minute) to call customer services inEnglish, and offers fifteen local numbers all but one of which is premium rate.12 out of the 18 airlines provided an online contact direct to customer relations. Threequarters of these contacts were in the form of an online form rather than an emailaddress, however, which would be slightly less convenient. Five of the airlines in thesample list did not provide any form of online contact. All but two of the airlinesprovided a postal address, and ten provided an address specifically for handlingcomplaints. Ryanair only accepts complaints via mail or fax.Although a lack of contact details is an immediate barrier to a passenger obtaining

3.30

3.31

3.32

26

Final report

redress, additional restrictions can also be made by the airlines requirements on theform of the complaint. A number of airlines only accept complaints in a small numberof languages: English only in the case of Ryanair, German or English only for CondorFlugdienst, and a choice of English or three Scandinavian languages for SAS. Most(12 out of 18) airlines in the sample do not state any restrictions on languages in whichcomplaints may be received.3.33Most of the airlines in the sample do not give expected timescales for handlingcomplaints. Of the four that do, the length of time varies considerably: Ryanair statesit will provide a substantive written response within 7 days, while Wizz Air allows upto 30 days to respond. Any timescales given can only reflect the length of time for theairline’s first response, as from the evidence given by NEBs we understand thatreaching resolution of complaint may involve multiple responses from an airline, andtherefore take much longer.Airline processes for handling complaints

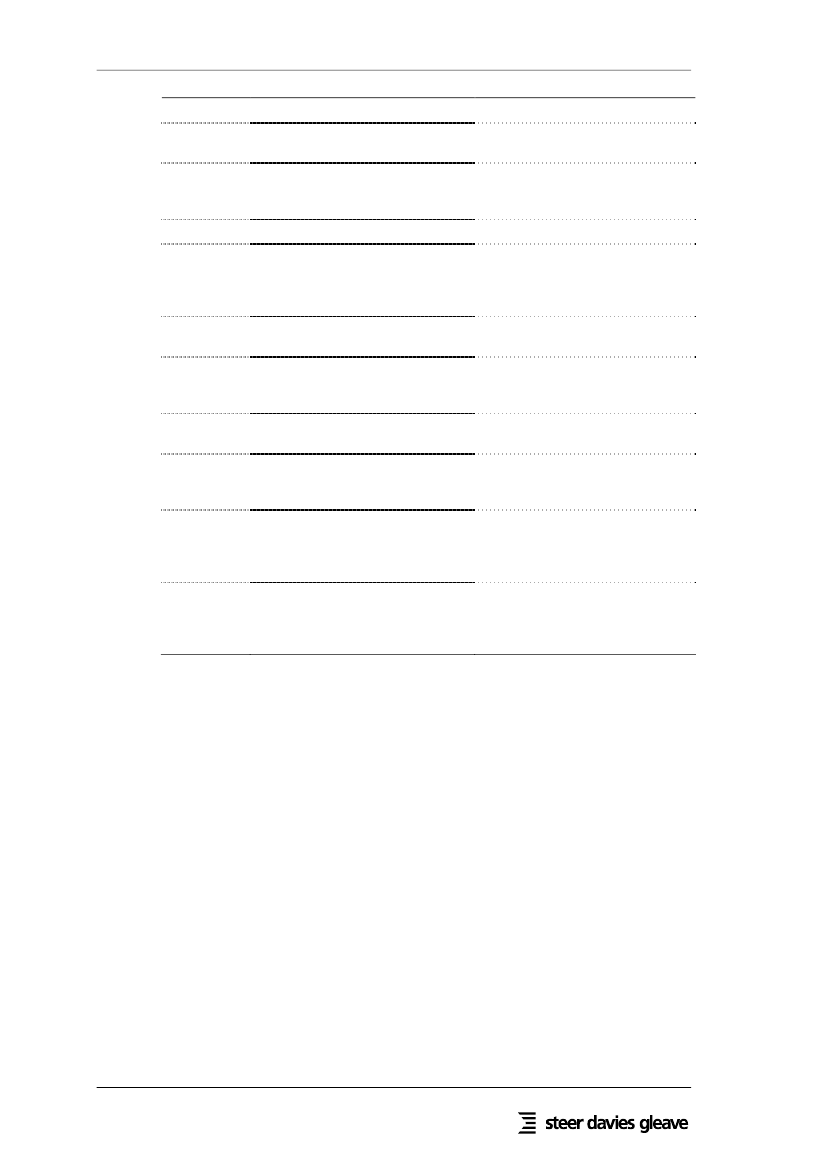

3.34

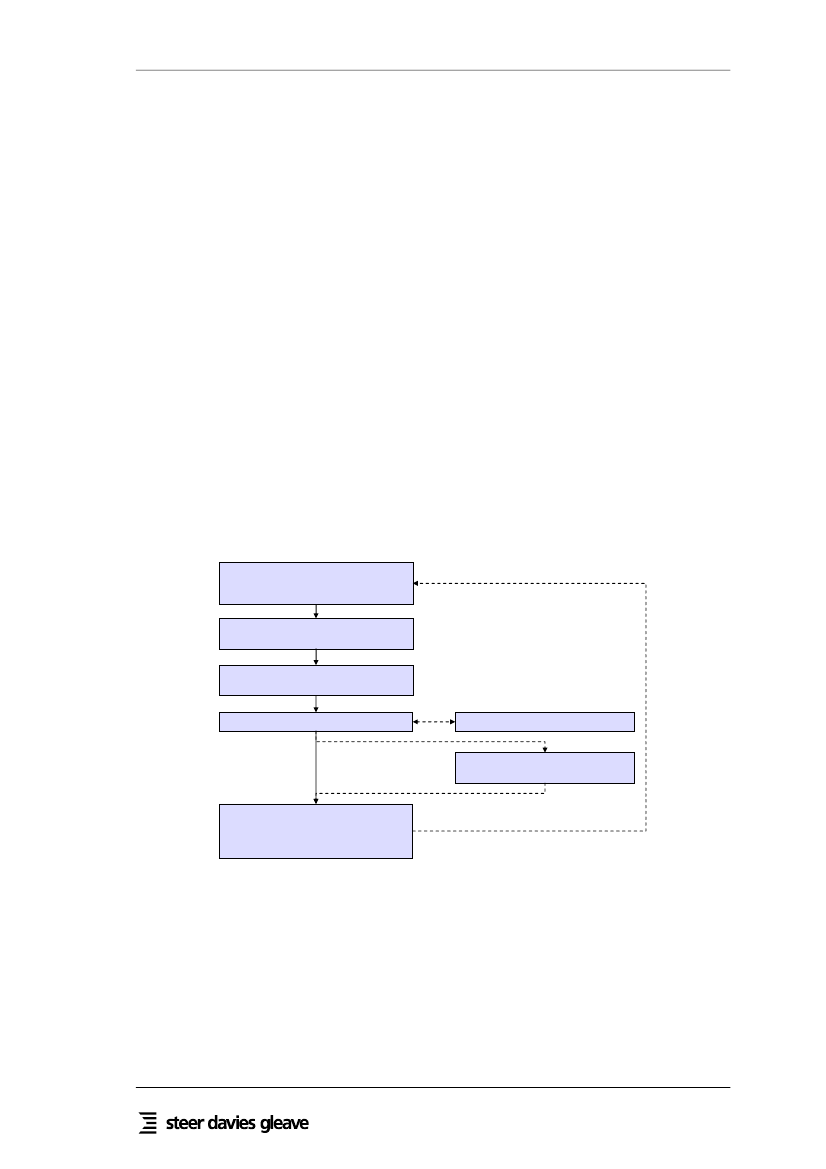

From each airline we contacted, we requested details of the procedures they used tohandle complaints from passengers. This enabled us to identify good practice, andprovides the counterpart to the NEB investigation procedures described below.Although the procedures varied by airline, we identified some areas of commonality.Figure 3.9 shows a typical complaint handling procedure.FIGURE 3.9TYPICAL AIRLINE COMPLAINT HANDLING PROCESS

Receive complaint (via letter, email, fax,written form, phone call, internet form,during flight)Register complaint in complaintsdatabase

When compliant gets to front of queue,assign complaint to handler

Assess complaint

Retrieve technical data if necessary

If complex case, consider escalationto supervisor or legal team

Send summary response to passenger:this may include compensation, orexplanation of reason not to givecompensation

If passenger not satisfied,process may repeat

3.35

Three of the carriers we interviewed stated that they contract out at least part of thecompliant handling process. This outsourcing was implemented through severaldifferent approaches:•One carrier informed us that the first stage of complaint handling is contractedout, and that if more detailed or complex information is required then thecomplaint is handled by the airline’s own customer relations team. The legaldepartment is called on where the complaint raises legal issues.A second carrier contracts out more of the process, and stated that complaints are

•

27

Final Report

•3.36

only rarely escalated to the carrier’s head office or legal team. The carrierinformed us that this had no effect on the way in which the complaints werehandled, as the contractor is given precise instructions and there is a team withinhead office managing the contract.The third carrier contracted out customer relations to third party call centres, butwhich work under the direction of a supervisor from the airline.

One carrier informed us that it uses artificial intelligence software to speed up theprocess and reduce staff time required: simple customer contacts (such as queriesabout the luggage allowance) are filtered out and responded to automatically, whilethose that require individual attention are marked for agents to handle.Airline stated response times to passengers were in general much shorter than thosereported by NEBs and consumer organisations. Table 3.2 shows the timescales forresponses to passengers stated by airlines.TABLE 3.2AIRLINE COMPLAINT RESPONSE TIMESCALESNumber of airlines4131

3.37

Upper limit of stated timescale for responseWithin a weekWithin two weeksWithin one monthWithin two months

3.38

Due to the wide geographical coverage of some airlines, many stated that they couldhandle complaints in multiple languages:••Some legacy carriers were often able to handle complaints in many languages,stating that they were able to handle complaints in the language of every countryin which they had a sales office.Other carriers take the opposite approach, and will receive complaints only in onelanguage. However, one informed us that although this was its public policy, itwould in fact respond to complaints in other languages when it has the capability.

3.39

The response to the passenger may also be informed by commercial considerations: anairline informed us that, for frequent business travellers, it may provide servicesbeyond that required by the Regulation, whereas a single-trip economy passengerwould receive the minimum possible. This is consistent with views provided byanother airline, which stated that it did not believe that it had a commercial incentiveto provide a higher standard of customer service than the minimum required by law.Number of complaints received

3.40

Although airlines were unwilling to provide information on their on-timeperformances, some were willing to share data on the number of complaints receivedthat related to the Regulation. On the basis of the very limited information provided tous, and assuming that the carriers providing information were representative of other

28

Final report

carriers, there were around 1.0 million complaints to EU carriers in 2008, of whicharound 30% related to the issues covered by the Regulation; this compares toapproximately 550 million journeys on flights from or within the EU6andapproximately 22 million on flights which are either delayed over 2 hours orcancelled, on the basis of the estimates described in paragraph 3.24 above. Thecombined NEBs received approximately 28,000 complaints in total over a similarperiod; it is clear that NEBs only receive a small fraction of potential complaints.3.41Of the airlines that were unable to provide this information, some stated commercialsensitivity, but others informed us that did not have the figures. One major low costcarrier told us that they treat complaints as ‘customer contacts’, and do not distinguishthem from other queries (such as queries regarding baggage allowance).Cost of complying with the Regulation

3.42

We also requested information from carriers on the cost of compliance with theRegulation. Not all of the costs attributed to handling delays and cancellations can bedirectly attributed to the Regulation, as many carriers already provided someassistance to passengers under these circumstances. Not all airlines were prepared toprovide costs, but those that did gave a reasonably consistent picture: five airlinesreported that costs were in the range of 0.1%-0.5% of turnover. However, a smallregional airline operating services which are particularly likely to be impacted by poorweather estimated 10%. The airlines did not provide consistent information and sothese figures are not directly comparable, but they are a guide to the likely level ofcost incurred.Most airlines had a common approach to handling the provision of assistance, makingarrangements through either their staff or ground handling agents. However, onemajor airline had entirely contracted out provision of assistance to a third party. Thereasons given by the airline were to reduce costs (the contractor is able to get bulkdiscounts on hotel rates) and reduce reliance on ground handlers, who may not havesufficient staff, contacts or capability to arrange accommodation in the event of amajor incident. In the event of an incident occurring, the carrier’s operational controlcentre contacts the contractor who is then responsible for arranging assistance on thecarrier’s behalf.Evidence for airline compliance with the RegulationGround handling manuals

3.43

3.44

At each meeting with airlines, we emphasised that part of the aim of the study was togather concrete evidence regarding the implementation of the Regulation, and that anymaterials which they could provide in support of statements they made would bevaluable. A number of airlines responded with confidential documents which we havebeen able to assess against the requirements in the Regulation. It should be noted thatwe would expect some self-selection bias and therefore the conclusions drawn here

6

Source: Energy and Transport in Figures (2007)

29

Final Report

may not be reflected in other carriers.3.45We asked each airline for a copy of the section of its ground-handling manual whichreferred to responses to delays, cancellations and denied boarding. These set out theactions that airlines require their agents to take in response to delay incidents,describing the measures that are put into place for passengers. While the manualsprovide evidence of an airline’s intention to comply (or not to comply) with theRegulation, the experiences of NEBs and consumer organisations suggest that theymay not always be adhered to in practice. We were also advised by an airlineassociation that we should not rely fully on instructions given to ground handlers, asdifferent airlines would handle incidents in different ways: for example, theoperational control centre might make individual arrangements or give individualinstructions in each case.Only one third of the airlines that participated in the study were willing to provide thisinformation. Where a document was provided, we checked it for compliance with theRegulation (Table 3.3). Of the six excerpts from ground handling manuals wereceived, we found that two were broadly compliant, although in one case this isdependent on interpretation of the Regulation (it stated that passengers should only bererouted via other carriers’ flights under exceptional circumstances).Three had serious or multiple non-compliances:•••One carrier did not offer compensation for cancellations.A second stated that compensation was not payable for denied boarding whichhad been caused by extraordinary circumstances, and failed to offer passengersthe option of reimbursing their ticket instead of re-routingOne instructed its handlers to give passengers a list of local hotels and refundtheir costs, rather than organising the accommodation for them (‘self-reliance’). Italso specified very low values for the vouchers to be given for care.

3.46

3.47

3.48

In addition, one had minor non-compliances in its ground handling manual, including:stating that passengers travelling using frequent flyer miles were not to be paid deniedboarding compensation; and only referring to denied boarding due to over sale (whichcould exclude denied boarding due to technical problems causing a reduction inaircraft capacity).TABLE 3.3COMPLIANCE OF AIRLINE GROUND HANDLING MANUALSNumber of airlinesParticipated in studyProvided ground handling manualManual is broadly compliantManual has minor non-compliancesManual has serious / multiple non-compliances166213

Notices required under Article 14(2)

3.49

A number of airlines provided us with a copy of the information notices that they are

30

Final report

required under Article 14(2). With one exception, the notices we were provided withwere compliant, although in some cases this depends on the interpretation of theRegulation. To the extent that there is a lack of clarity in the Regulation, airlines mayattempt to use disputed terms to their advantage. For example:•Some of the airlines state in their information notices that it will paycompensation for all cancellations “within the airline’s control” or use similarterms, rather than not pay compensation for cancellations due to “extraordinarycircumstances which could not have been avoided even if all reasonable measureshad been taken”. While superficially similar, this is likely to exclude a higherproportion of cases than the criteria defined in the ECJ ruling inWallentin-Hermann.Several stated that they would only provide re-routing via their own flights.Again, whether this is compliant depends on interpretation of the Regulation.

•3.50

The one information notice which was not compliant stated that the carrier would notprovide assistance in the case of delays which were not its responsibility.Most of the information notices we were provided with did not provide contact detailsfor the carriers’ customer services departments, and therefore if the carrier did notcomply with the obligations stated in the notice it would not be immediately clear tothe passenger how to pursue any claim, short of complaining to the NEB (and mostNEBs would not accept a complaint if the passenger had not sought to complain to thecarrier first). In addition, one of the notices did not specify what the amounts ofcompensation payable were, even though it did specify the distance bands.In addition, one airline provided training materials they used with their staff. Thisdocument was fully compliant with the Regulation.Airline terms and conditions

3.51

3.52

3.53

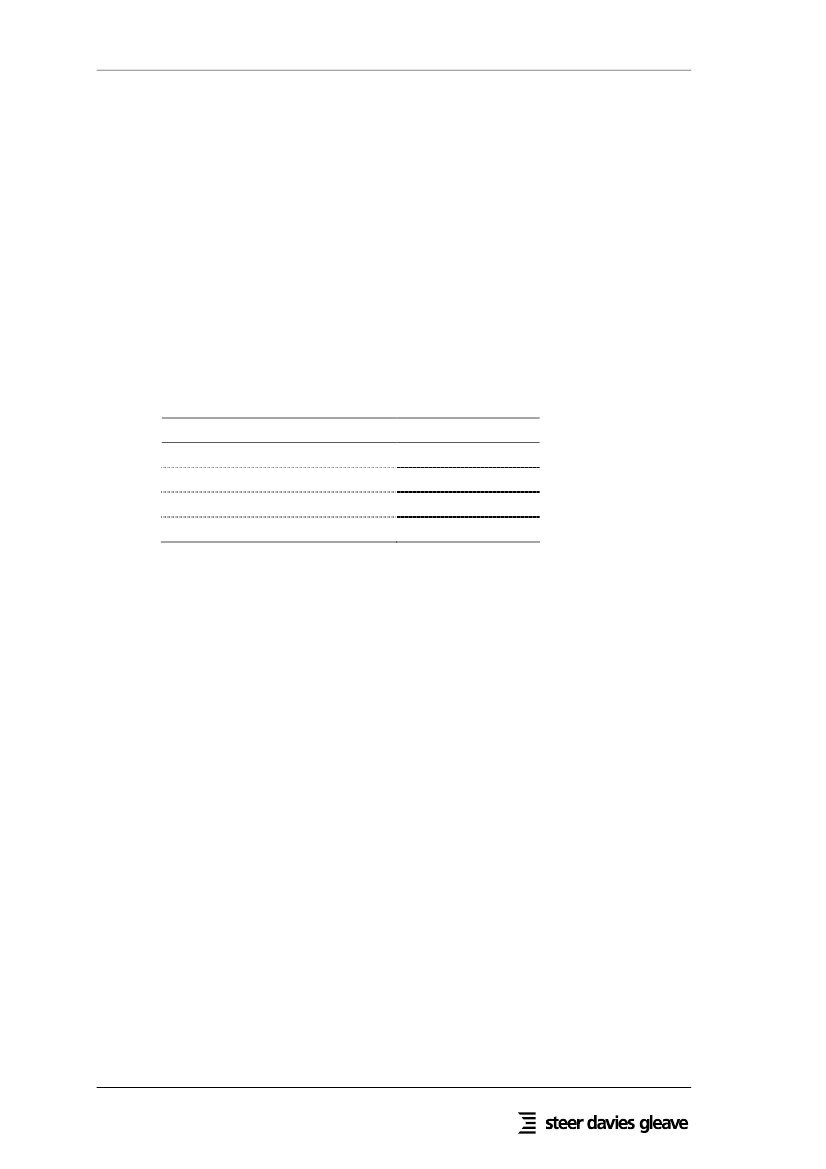

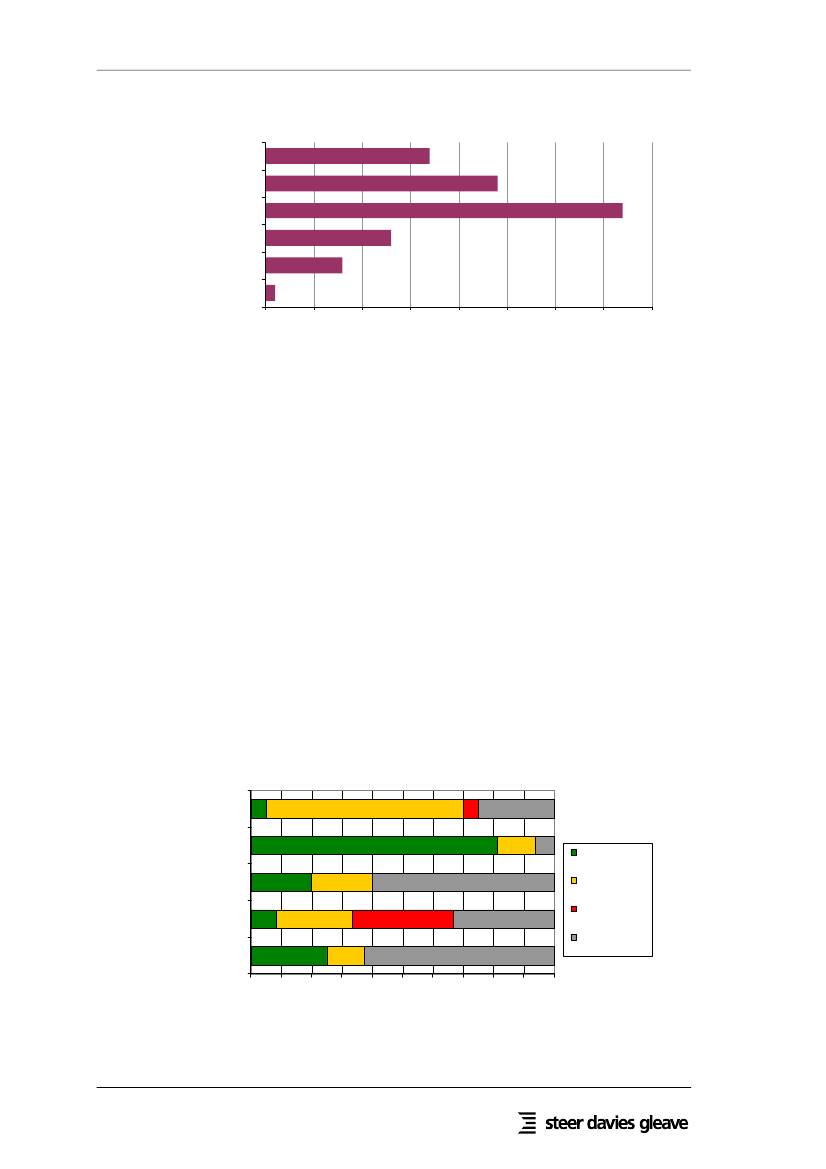

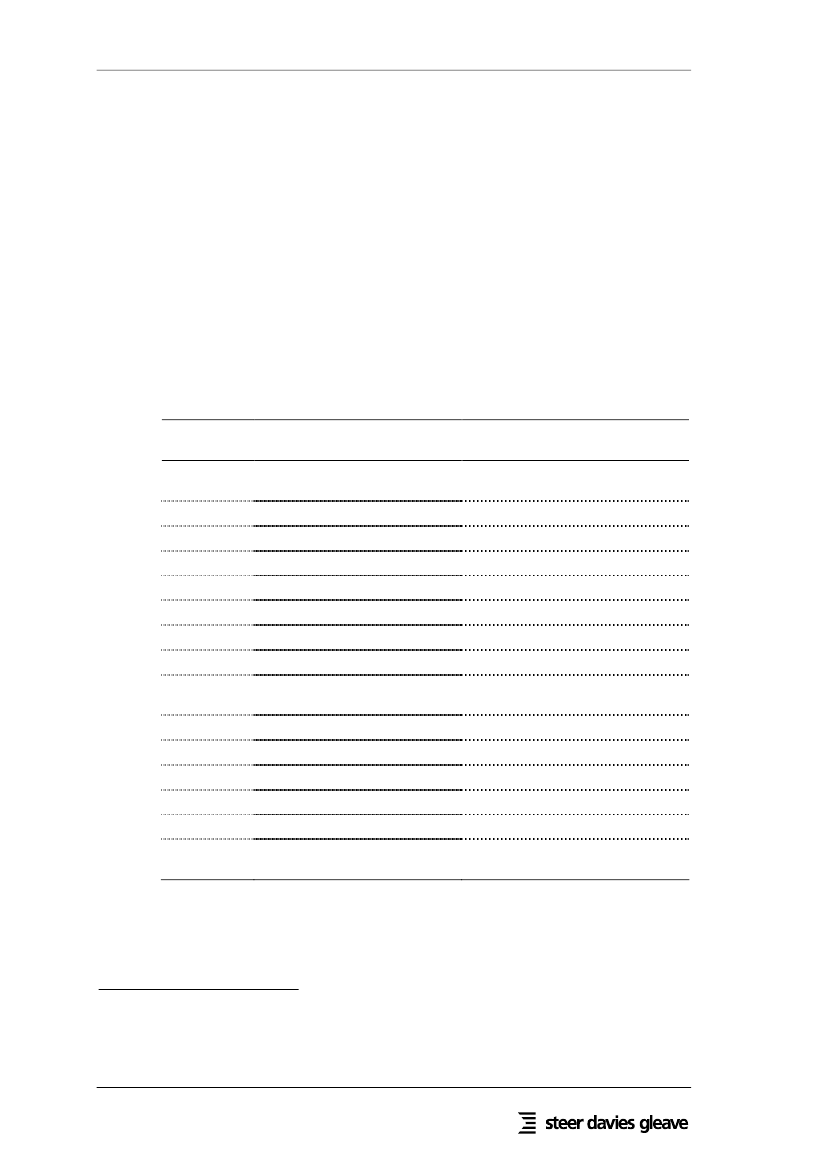

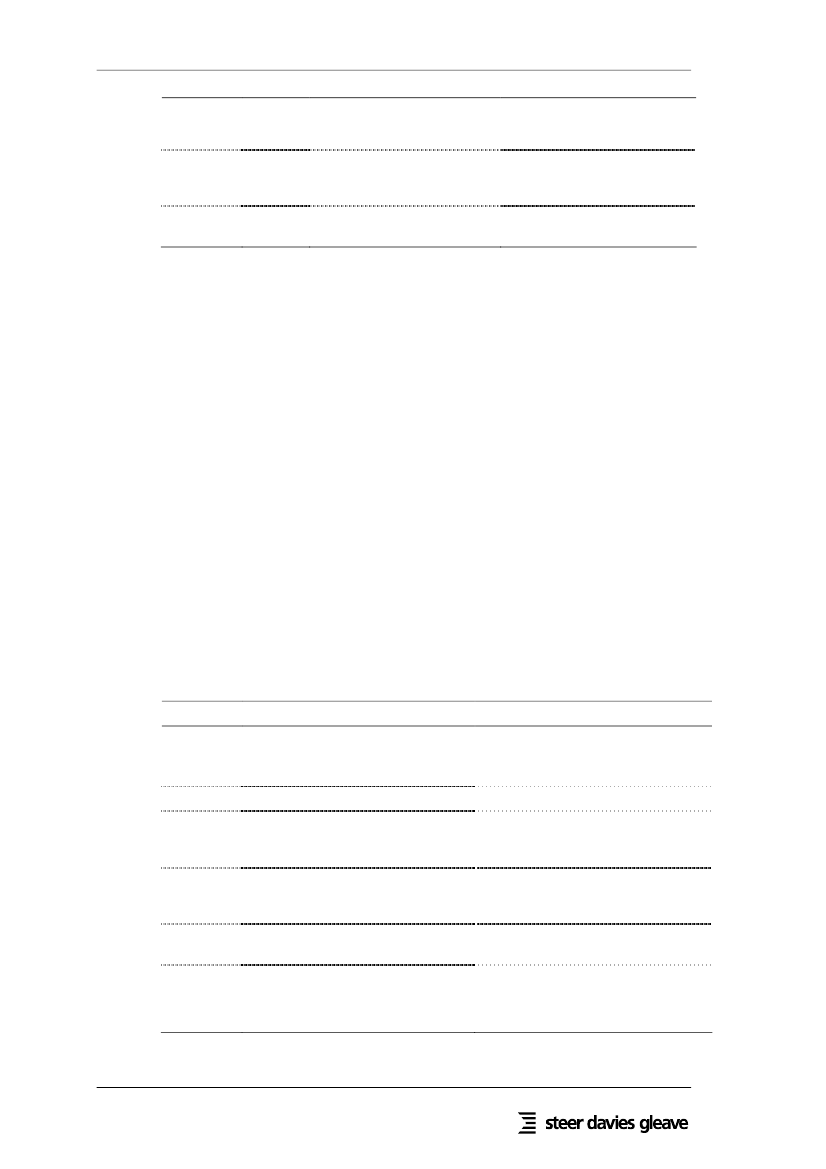

An area of evidence which could be looked at to establish the level of airlinecompliance is airlines’ terms and conditions. These would set out the airlines’theoretical commitments to the passenger, although NEBs and consumer organisationshave informed us that they are not always adhered to in practice.The compliance of airlines terms and conditions with this Regulation (amongst others)was the subject of a study we undertook for the Commission in 2008, which reviewedthe Conditions of Carriage of 85 carriers operating in the EU. Since this wasundertaken relatively recently, we have not sought to replicate this work, but wesummarise the relevant conclusions. It is however likely that some carriers will havechanged their Conditions of Carriage since this study was undertaken, and thereforethat the compliance of the Conditions with the Regulation could now have improved.The research found that 39% of carriers’ Conditions were significantly non-compliantwith the Regulation and a further 12% were misleading with regard to carriers’obligations, in that they implied that the carrier would have fewer legal obligationsthan it actually would. This arose largely from how the carriers had adapted IATA’srecommended practice on Conditions of Carriage (RP1724), which predates theRegulation and as a result is not consistent with it. 15% described the carriersobligations in detail and broadly accurately, 17% had a general statement that in the

3.54

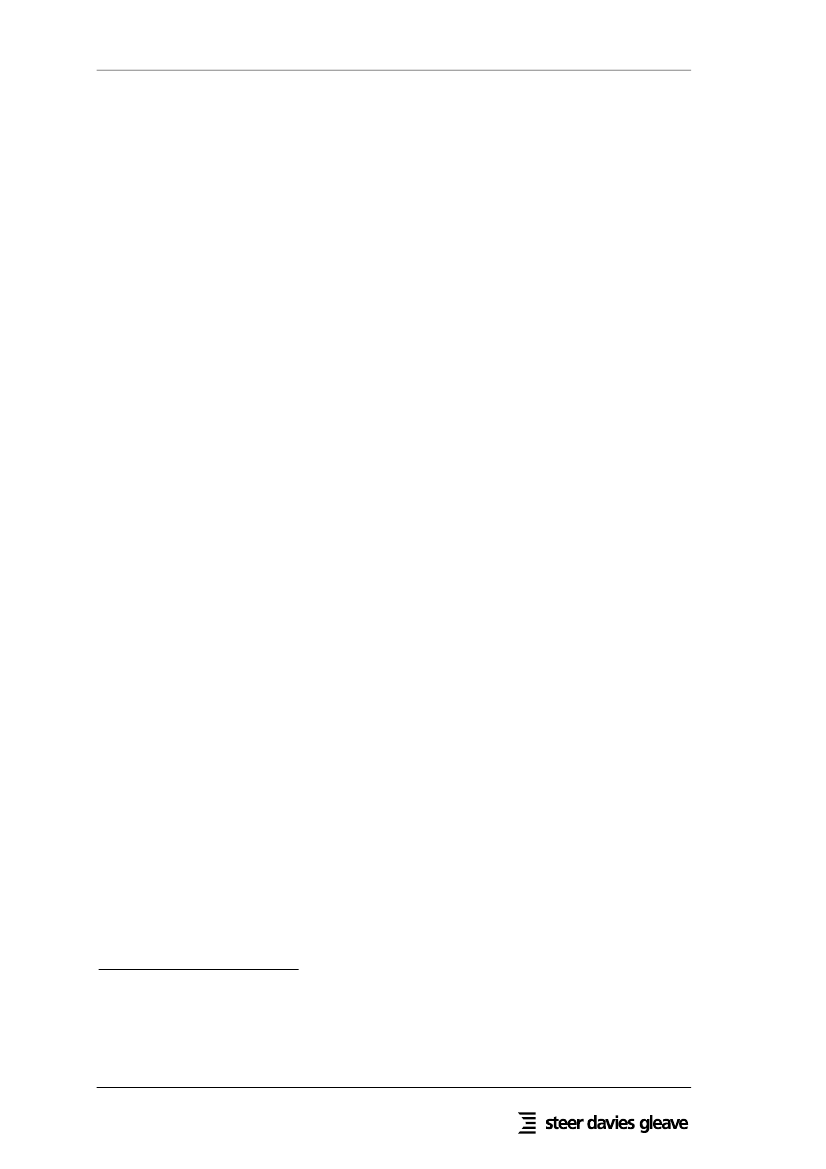

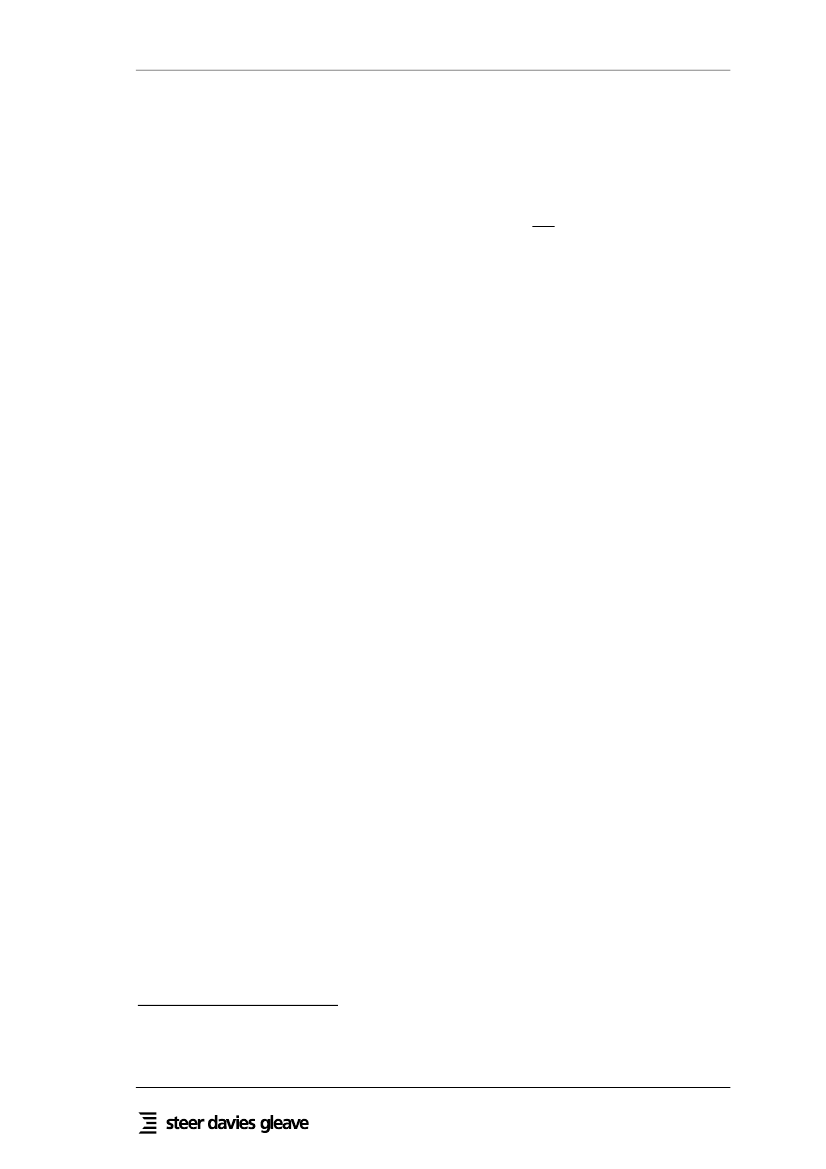

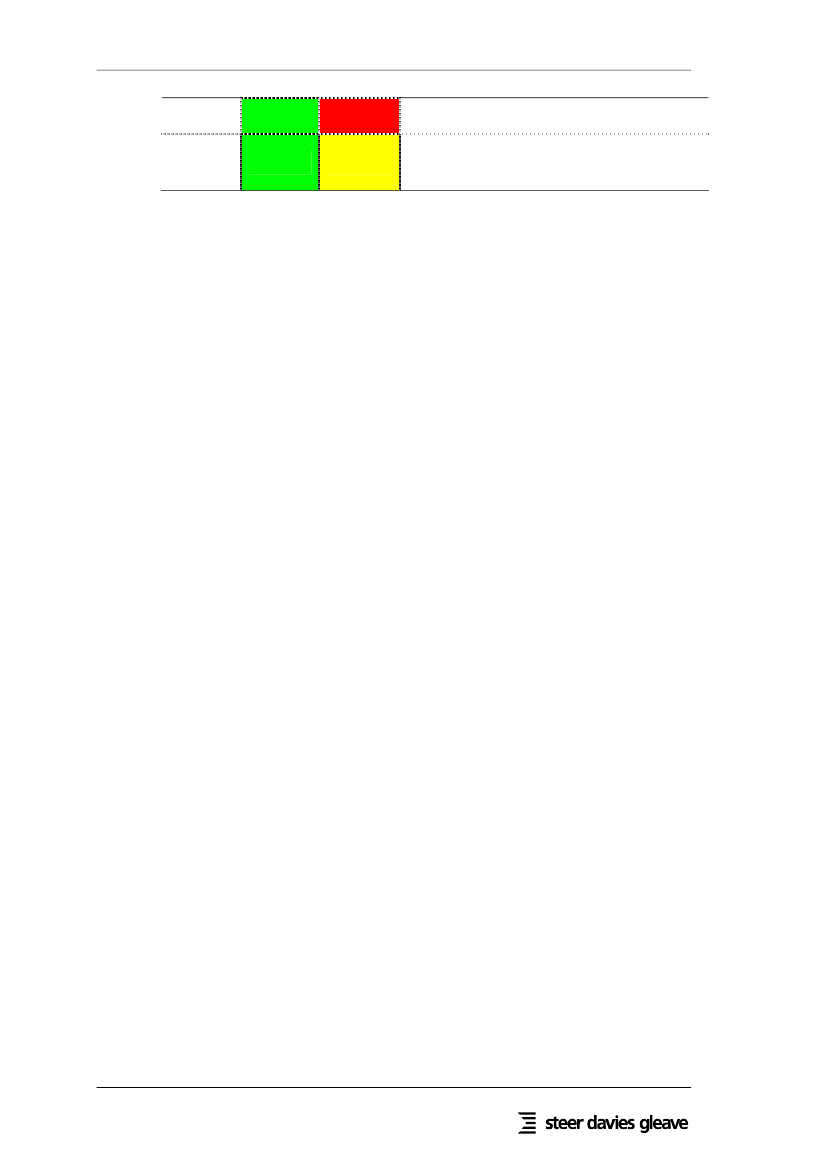

3.55

31

Final Report

event of denied boarding, delay or cancellation, the carrier would comply with theRegulation, and 2% had a general statement that the carrier would comply withapplicable law.FIGURE 3.10COMPLIANCE OF CONDITIONS OF CARRIAGE WITH REGULATION261/2004

No reference15%

Compliant -detailed15%Compliant -comply withRegulation17%Compliant -comply withapplicable law2%Compliant butmisleading12%

Extensive/severenon-compliance16%

Significant non-compliance23%

Source: Steer Davies Gleave study for European Commission on Conditions of Carriage and Preferential Tariff Schemes, 2008.

Other airline evidence

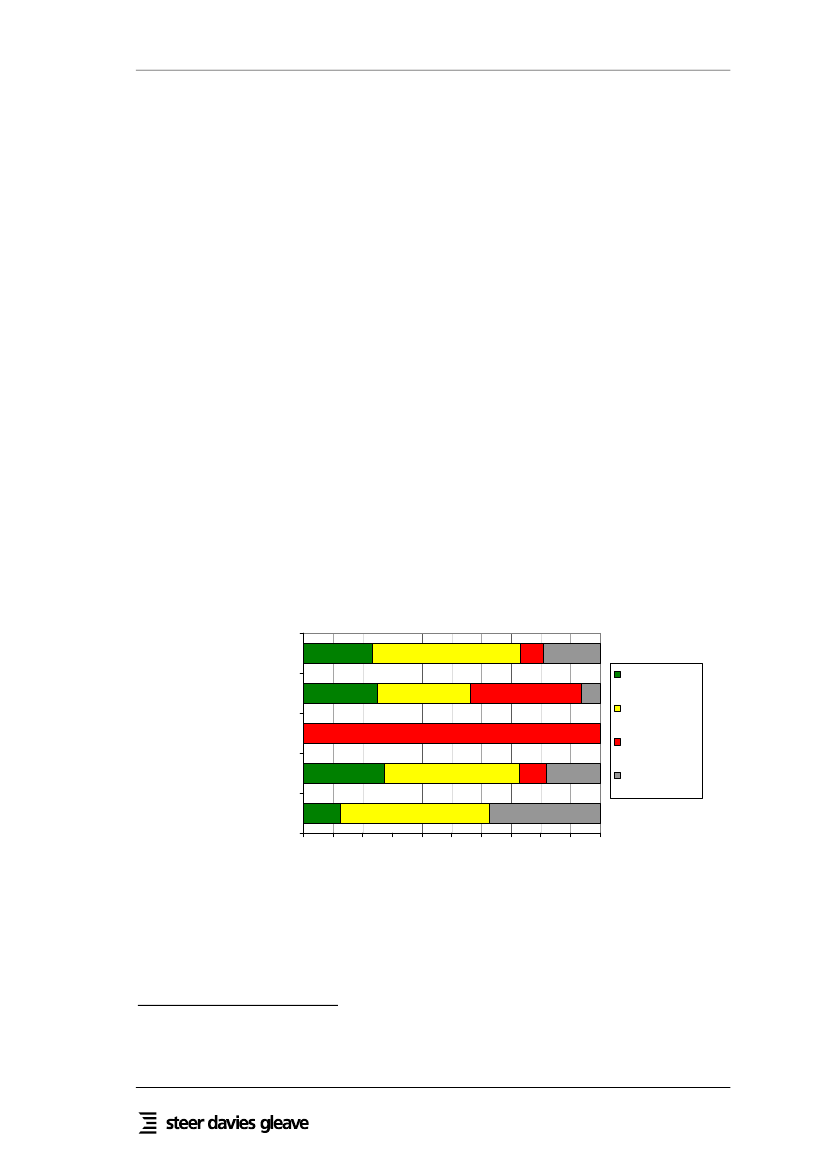

3.56