Skatteudvalget 2009-10

SAU Alm.del

Offentligt

Tax Expenditures in the Nordic CountriesA report from a Nordic working group, presented at theNordic Tax Economist meeting in Oslo, June 2009

January 2010

1

Disclaimer:At the Nordic Tax Economist meeting, held annually, civil servants from the Ministries ofFinance and Taxation of the Nordic countries meet to exchange experiences, discuss taxationtrends and issues, and to build and maintain networks. To each meeting a report is preparedon a topic decided upon at the previous meeting. The report is written by a group of civilservants from all the countries and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Governmentsor the Ministries of Finance and Taxation.

Michael Riis JacobsenAndrea GebauerKirsti MellbyeFransiska PukanderSeppo KariSøren OlsenLars Lindvall2

Table of contentsIntroduction ...................................................................................................................... 5Benchmark ........................................................................................................................ 62.1 Theory .......................................................................................................................... 62.1.1 The concept........................................................................................................... 62.1.2 Normative tax system........................................................................................... 72.1.3 Measurement........................................................................................................ 72.2 Criticism of tax expenditure analysis ........................................................................ 93 Analysing tax expenditures............................................................................................ 103.1 Practical issues of tax expenditure analyses .......................................................... 103.2 Reporting and evaluation of tax expenditures ........................................................ 113.2.1 Classification...................................................................................................... 123.2.2 Important elements of reporting........................................................................ 143.2.3 Challenges in evaluating tax expenditures: Effectiveness and efficiency......... 153.3 Reporting and evaluation in other countries .......................................................... 173.3.1 In general............................................................................................................173.3.2 The German evaluation of tax expenditures..................................................... 174 Country overviews .......................................................................................................... 204.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 204.2 Main features ............................................................................................................. 204.2.1 Definition of tax expenditures and the benchmark system............................... 204.2.2 The volume of tax expenditure........................................................................... 214.2.3 Reporting, classification and evaluation of tax expenditures...........................234.2.4 Critique from National Audit Offices................................................................244.2.5 Tax expenditure and fiscal policy...................................................................... 254.3 Tax expenditures in Denmark ................................................................................. 264.3.1 Introduction........................................................................................................ 264.3.2 Definition of tax expenditures............................................................................ 274.3.3 Methods of calculation....................................................................................... 284.3.4 Reporting and evaluation.................................................................................. 284.3.5 Overview of the most important tax expenditures.............................................304.3.6 Challenges and future development...................................................................334.4 Tax expenditures in Finland..................................................................................... 354.4.1 Introduction........................................................................................................ 354.4.2 Definition of tax expenditures............................................................................ 354.4.3 Methods of calculation....................................................................................... 374.4.4 Reporting and evaluation.................................................................................. 374.4.5 Overview of the most important tax expenditures.............................................374.4.6 Challenges and future development...................................................................394.5 Tax expenditures in Norway .................................................................................... 404.5.1 Introduction........................................................................................................ 404.5.2 Definition of tax expenditures............................................................................ 403

12

4.5.3 Methods of calculation....................................................................................... 424.5.4 Reporting and evaluation.................................................................................. 424.5.5 Overview of the most important tax expenditures.............................................444.5.6 Challenges and future development...................................................................464.6 Tax expenditures in Sweden .................................................................................... 464.6.1 Introduction........................................................................................................ 464.6.2 Definition of tax expenditures............................................................................ 474.6.3 Methods of calculation....................................................................................... 484.6.4 Reporting and evaluation.................................................................................. 484.6.5 Overview of the most important tax expenditures.............................................494.6.6 Challenges and future development...................................................................495 Conclusions and suggestions for future work .............................................................. 516 Literature ........................................................................................................................ 537 Appendix - What do other countries report?............................................................... 55

4

1 IntroductionThe background for this work is partly the increased interest in tax expenditures from partiesoutside the ministries, for instance the National Audit Offices, but also a realisation that thereis a need to produce more reliable, transparent and maybe also comparable tax expenditureanalyses in the Nordic Countries. It is our ambition that this report can shed some light onsome issues related to tax expenditures and maybe also serve as an “easy entry” to the taxexpenditure concept. We also present a comprehensive overview of how tax expenditures aretreated in the Nordic countries.The main objective of tax expenditure analysis is increased expenditure control byidentifying tax provisions that escape the scrutiny applied to regular subsidies and transferson the expenditure side of the budget. Originally tax expenditure analyses ambitiously wereregarded as tools for revealing the inferior nature of tax expenditures as a way to appropriatepublic resources. It was believed that a thorough tax expenditure analysis would unveil that alot of tax expenditures violated the objectives of efficiency, fairness and simplicity in the taxsystem. Since the first tax expenditure analysis was presented in the US more than forty yearsago, the concept of tax expenditures has spread worldwide and today virtually all OECD-countries make tax expenditure analysis in one form or another.Using tax expenditure analysis in the tax policy work to pursue such idealistic principles ofthe tax system as mentioned above is highly ambitious and demands a definition of anormative tax system which reflects the principles of efficiency, fairness and simplicity. Thishas proven to be a difficult task, and have brought about extensive discussions and alsosubstantial criticism of the definitions and methodologies used in tax expenditure analyses,not the least in the US.The examination of tax expenditure analyses of the Nordic countries in this report shows thatthe levels of ambitions are fairly moderate compared to those mentioned above, and themethodologies are to a larger extent based on pragmatic choices and prevailing tax rules.These analyses are therefore less vulnerable to the general criticism regarding the normativeassessments of the benchmark, but have on the other hand to some extent been criticised forthe lack of transparency.The working group does not work out detailed recommendations for a reform of taxexpenditure analyses in the Nordic countries. However, we make some suggestions forpossible future improvements. One suggestion is that the Nordic countries endeavour toclarify the tax expenditure analysis. Another is that more emphasis could be placed onevaluatingtax expenditures. We believe that this could help to increase both transparencyand the accuracy of tax expenditure analysis.The report is structured in a theory part (chapter 2 and 3) and a practical part (chapter 4).Chapter 2 presents the theoretical background of defining a benchmark. In chapter 3 wediscuss some important elements of tax expenditure analyses, with a specific emphasis onreporting and evaluation. In chapter 4 the treatment of tax expenditures in Denmark, Finland,Norway and Sweden is described and discussed. Each country has been responsible for itsown description. The chapter starts with a summary of common features and points towardssome differences. The challenges concerning the treatment of tax expenditures, which are

5

common in these countries, are also discussed. In chapter 5 the group concludes and pointsat some possible areas for future work and improvements.

2 Benchmark2.1TheoryThe concept

2.1.1

The termtax expenditurerefers to provisions in the tax code that give favourable taxtreatment for an activity or a group of taxpayers. Tax expenditures may take a number offorms like exemptions, allowances, credits, preferential rates, deferral rules etc. They are, ineffect, policy instruments of government to promote specific social or economic policies andthus are closely related to direct spending programs. Negative tax expenditures are taxsanctions. A tax sanction is the result of levying tax at a higher rate than the norm.The identification of tax expenditures is a difficult task for many reasons. The tax code mayinclude a number of provisions that lead to revenue losses but nonetheless promote thestandard goals of a good tax system. They are integral parts of the tax system and are notjudged as tax expenditures. Neither can the tax expenditure analysis rely entirely onlegislative documents, since the objectives of tax provisions are not always expressed clearlyand openly there. So, there is a need for a systematic method for identifying tax expenditures.Such an approach was developed in the US in the late 1960s, well captured in the following(Surrey & McDaniel (1985)):“The tax expenditure concept posits that an income tax is composed of twodistinct elements. The first element consists of structural provisions necessaryto implement a normal income tax, such as the definition of net income, thespecification of accounting rules, the determination of the entities subject to tax,the determination of the rate schedule and exemption levels, and the applicationof the tax to international transactions. The second element consists of thespecial preferences found in every income tax. These provisions, often calledtax incentives or tax subsidies, are departures from the normal tax structure andare designed to favour a particular industry, activity, or class or persons. …Whatever their form, these departures from the normative tax structurerepresent government spending for favoured activities or groups, effectedthrough the tax system rather than through direct grants, loans, or other forms ofgovernment assistance.”Under this approach tax expenditures are defined as deviations from a normal tax structure,also called a benchmark or a reference tax system. With this concept we may understand a‘pure’ tax system as a system that focuses on raising revenue, while also fulfilling theprinciples of a good tax system, neutrality, equality and the requirement to be implementable.According to the quotation, other criteria for tax rules to be judged as tax expenditure are thatthey favour some narrow activities or tax payer groups and that they serve some specific

6

policy goals.1The overall idea that tax expenditures can be identified by comparing the actualtax system against a normative one has been very influential in practice. Most developedcountries have adopted it as the basis of their tax expenditure analysis.2.1.2Normative tax system

Tax expenditure analysis is based on the concept of a normative tax system. This concept isthe measuring rod to identify and to measure the amount of tax expenditures. The normativetax system captures the generally accepted elements of the tax system that are necessary toachieve the fiscal goals and to fulfil the objectives of equity, efficiency and simplicity.Tax expenditure analysis requires good understanding of the objectives and functions of theelements of a particular tax. Based on such understanding the normative structure can bedefined and the tax expenditures identified as deviations from the norm. This understandingcan be drawn from some idealized tax structures developed in tax research. Income tax andVAT are good cases in point. The so called Schanz-Haig-Simons economic income concept(SHS income) has been an influential tool when specifying the norm for the income tax basein the US and elsewhere. It defines one period’s income as consumption plus the change innet wealth during the period. The concept is of course abstract and leaves several importantaspects of a normative tax system open. Therefore the benchmark tax system usually is acombination of elements from the theoretical abstract and the actual tax system. Similarly, ageneral non-cascading sales tax could be a useful abstract concept behind the benchmark taxsystem of VAT or, even more broadly, behind all taxes on private consumption.Examples of elements of the actual tax system usually accepted in the benchmark are the taxrate schedule, the unit of taxation, the time frame of taxation, accounting principles,realization principle2as the basis of taxation and the potential non-elimination of inflationgains. Some allowances motivated by redistribution of income may be part of the benchmark.Similarly deductions or relieves that are grounded on simplification of tax administration orthe tax code may be defined as parts of the benchmark.That the benchmark tax is a compromise between the theoretical ideal and the actual taxsystem has rendered tax expenditure analysis subject to much criticism in recent years,especially in the US. The concern is that under this approach the norm cannot be definedrigorously enough to ensure that the identification of tax expenditures leads to an objectiveand reliable outcome. This criticism has led to at least two new ideas in tax expenditureanalysis. One is that the connections to the theoretical ideals (SHS income) are not usefulsince the choice of the norm is mainly a pragmatic exercise. The other is that classifyingrelevant provisions into subgroups could relieve the problems from branding all items asprovisions.2.1.3Measurement

Tax expenditure literature usually list three different approaches to estimate the cost of taxexpenditures: revenue forgone, revenue gain and outlay equivalence method. There are two1 OECD (1996) gives also other supplementing criteria for a provision to be considered as a tax expenditure. They include that the objectiveof the tax expenditure could be achieved by a direct subsidy, that the tax in question is sufficiently broad in range such that a norm can beestablished and also that there is no offsetting provision elsewhere in the tax system. However it is not clear whether those requirementshave been applied systematically.2 Usually only realized income is subject to individual income tax.

7

distinguishing features in this classification: whether the method takes behavioural responsesinto account or not and whether the measure describes the size of the subsidy net or gross oftaxes.•Revenue foregone: a static estimate of the loss of tax revenue. Hence the method doesnot take account of behavioural responses. The cost of a tax allowance is then theproduct of tax rate and the observed amount of the allowance.Revenue gain: the amount by which tax revenue is reduced as a consequence of theintroduction of a tax expenditure, taking into account behavioural changes and theeffects on revenues from other taxes as a consequence of the introduction.Outlay equivalence: the direct expenditure that would be required in pre-tax terms, togrant the same after-tax gain for the taxpayers as the tax expenditure.

•

•

The revenue foregone method is based on the assumption that the introduction of taxexpenditures does not affect the behaviour of taxpayers or the revenues from other taxes. It istherefore the easiest estimation method. In general, there are good reasons to believe thattaxpayers change their behaviour in response to the tax expenditure (increase their demandfor the tax-subsidised good or increase/decrease their demand for income). Therefore therevenue forgone method gives a narrow picture of the revenue effects of a tax provision.However, if the tax expenditure is re-estimated the behavioural effects will indirectly beaccounted for if the tax base changes due to the tax expenditure.The method of revenue gain takes the behavioural change and the change in tax interactioninto account. Of course this makes the method much more complicated to apply in practice.Although the method is superior in principle, many governments seem to assume that theaccuracy that may be gained is not worth the efforts required to apply the method.Outlay equivalence is a measure that leaves the net budget impact (on the surplus or deficit)and the after-tax incomes of taxpayers the same in the situation with tax expenditure and inthe situation with equivalent outlay but without tax expenditure. Outlay equivalence takesinto account the fact that regular transfers are sometimes estimated gross of the tax paid bythe recipient, whereas tax transfers are by definition net of tax. In order to estimate these taxexpenditures on the same basis as regular expenditures, it is necessary to add the tax that istypically levied upon the regular transfer. Otherwise, it appears as if the tax expenditure is acheaper way to get the same amount of cash into the hands of the recipient than the regularexpenditure.Methods of measurements are a much broader matter, however.. There are at least thefollowing additional aspects:••Which methods are used? E.g. present value calculations or implementation of microsimulation models.Is the calculation one periodic or does it take into account counterbalancing effects inlater years. One example here is the so called EET model of voluntary pensionsavings which deviates from a SHS income based norm in several respects. Theessential feature is that those deviations spread over years. Another example but withsome different features are the depreciation rules. Even if the main approach would be

8

•

one periodic, the tax expenditure reporting could also give multi-periodic presentvalue estimates.Usually tax expenditures are estimated provision by provision, one at a time. Sincethe tax provisions may interact, for example through the progressive tax schedule, thetotal amount of tax expenditure cannot simply be calculated by summing up all theparts.Criticism of tax expenditure analysis

2.2

The aim of tax expenditure analysis is widely shared, i.e. to improve the control of the use ofgovernment resources on the revenue side of the budget. The usefulness of the concept of taxexpenditure has, however, been questioned for years, almost since its introduction in the late1960s (JCT 2008).The most important part of the criticism is focused on the concept of a benchmark tax system.The main objection is that the concept does not have a sufficiently rigorous formal basis andis more or less a result of a series of subjective, pragmatic choices. As an example, it iscommon that the tax expenditure analysis officially refers to SHS income as a starting pointwhen the normal structure for income tax is defined. Here it follows the approach introducedby Surrey. In principle comprehensive income can be defined quite precisely. However, SHSincome is not an operational concept that could be measured exactly and easily enough to beused either as a basis for taxation or as a tool in tax expenditure analysis. Therefore thebenchmark applied is usually a compromise between SHS income and the actual tax systemor, put differently, an extension of the actual tax system towards the theoretical concept.Due to the vagueness of the benchmark, the classification of at least some tax expenditureshas weak grounds and their status will easily become subject to discussions. If there is nohard theory behind the benchmark it is very hard to defend the identification decisions. Thereis much experience from such a debate from the US.One line of criticism targets the transparency of the benchmark. It can be traced back toBittker (1969) who questioned Surrey’s way of officially connecting the normal tax system tothe SHS-concept but at the same time include several other elements into it withoutimplicating the theoretical grounds. Bittker considered these additions as subjective choices.According to Burman (2003) the US tax expenditure debate has had an ideological stance.Those who have favoured an income tax have supported the current way to identify andmeasure tax expenditures. On the other hand, those who have preferred consumption taxfeatures in the tax system have proposed changes towards savings relieves in the benchmarksystem.The criticism also includes the hidden reform agenda on the background of tax expenditurereporting and also that tax expenditure analysis implies an idea of a clean and apolitical taxpolicy that does not fit well with social decision making. It seems that this kind of debate andthe resulting credibility problem are, to some extent, a result of unclear theoretical grounds ofthe identification process.Another main subject of criticism has been the measurement methods (Burman 2003). Thetax expenditure estimates usually give a static first year revenue loss due to a particular taxprovision. They do not include any behavioural responses which may be incorporated in

9

more serious revenue estimates. Neither do they reveal the long term costs of taxexpenditures. Here tax expenditure estimates may deviate a great deal from estimates made inother instances in tax policy analysis.The tax expenditure analysis is currently facing a challenge to improve its theoretical groundsand measurement processes. One obvious response to the criticism is to improve transparencyof the reporting by communicating the definitions and foundation of the analysis more openlyand clearly. The US Joint Committee on Taxation aims to solve the credibility problem byintroducing a new pragmatic framework to identify and report tax expenditures.3The coreidea of the approach is to refuse theoretical ideals in the light of the benchmark tax andinstead to build the reference base on the general principles of the current system. Paralleldiscussions on alternative ways to improve the methods are going on in several countries andin the OECD.4

3 Analysing tax expendituresBeyond the broad conceptual description of tax expenditures in section 2, there are numerousspecific issues that analysts have to deal with when making tax expenditure analyses. Due topractical reasons most tax expenditure analyses necessarily have to be based on acompromise between the theoretical concepts described above and pragmatic and feasiblesolutions. Finding a reasonable balance between theoretical orthodoxy and pragmaticadjustments seems to be the key to make an appropriate and useful tax expenditure analysis.Below we describe some practical matters related to tax expenditure analysis, and we try toshed some light on how tax expenditures are reported (including different ways of classifyingtax expenditures) and the need for evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of taxexpenditures.3.1Practical issues of tax expenditure analyses

Making tax expenditure analyses raises a lot of practical issues on how to define andoperationalise the appropriate benchmark, and there is no universal recipe on how to solvethem. The crucial task is to define a suitable tax code and a feasible and adequate tax basethat serves as a reference. Calculating tax expenditures requires a distinction of the normativecomponents of a particular tax from its tax expenditure component, and deciding what shouldbe part of the benchmark structure and income and what should constitute a tax expenditure.Such considerations have to be made for each individual tax, which hampers the directapplication of a general theory or methodology.Tax expenditure analyses around the world differ widely both when it comes to definitionsand applied methodology. This can make tax expenditure analyses from different countriesvirtually incomparable, and a comparison of the number and amount of tax expenditures canbe rather misleading. A general definition tends to generate a lot of tax expenditures, while amore narrow definition can lead to less or almost no tax expenditures at all. In between thereare systems based on various concepts that differ along several dimensions. Some are looselybased on a “norm” where the norm can change over time (as in France) and others are veryrestrictive and detailed but not necessarily strictly based on principles (as in Canada and to3 See Joint Committee on Taxation (2008).4 See e.g. OECD (2008/1) and OECD (2008/2).

10

some extent the US and UK). However, since most countries are claiming more or less thesame methodology and definitions at the overall level (e.g. revenue foregone method, incometax benchmark etc.), these variations are probably more due to how the methodology and thedefinitions are applied in practice, and maybe due to the lack of practical guidelines foundedon undisputed theory.The most difficult task seems to be related to choosing the right tax base. Many countries usethe Schanz-Haig-Simmons (SHS) income definition for tax expenditure purposes. The mainreason for this is probably that the SHS definition constitutes a tax base that neutralise the taxtreatment of consumptions and savings (while a conventional comprehensive incomedefinition gives a preferential treatment of consumption). However, it is by no meansstraightforward to apply this income definition in practice. A lot of income and expenditurecomponents have to be treated separately. How do you treat governmental transfers andgrants, consumption of public goods or what kind of expenses constitutes a cost of earnedincome and so forth? There are also difficult issues related to the appropriate taxable periodto be used. How do you treat unrealised gains or other tax credits or the missing opportunityto get negative deferred taxes? Which unit of taxation do you choose, families, couples orindividual taxpayers, and should you use equivalent scales to adjust for family size? How doyou measure imputed income when there is no “physical” profit or payout? The SHSdefinition of income is too rigid and demanding to be applied comprehensively in a nationalincome tax and a range of pragmatic choices has to be made.Choosing the right rate structure can also lead to practical challenges. The lack of a clearlydefined set of tax laws implies a vast amount of subjective judgement in the analyses, whichincrease the level of arbitrariness. This is especially true when it comes to choosing the taxrates that applies to deductible expenses and losses.3.2Reporting and evaluation of tax expenditures

Although tax expenditures, like direct expenditures, affect the government’s budget byreducing the resources available, tax expenditures typically are not included in the budget(especially after the year of enactment), are normally not limited to a maximum cost set, andoften continue permanently without regular evaluation or reauthorization. Furthermore, thelevel of tax expenditures can increase when new taxes are introduced or existing taxes arealtered. Direct expenditures do not necessarily have maximum cost set, but the level ofexpenditures appear more transparent in the budget. While direct expenditure programs aremore or less routinely reviewed and funded through the normal course of the annual statebudget process, such a process is often lacking for tax expenditures. As a result, taxexpenditures can become expensive subsidies that lead to considerable amounts of forgonerevenues without legislative action or even awareness.Apart from the fiscal deficit dimension, tax expenditures can also increase tax systemscomplexity and distort both its neutrality and the allocation of resources. Furthermore, taxexpenditures themselves are often non-transparent (e.g. concerning financial volume, targetattainment, and beneficiaries). For all these reasons, it is important that tax expenditures – aswell as the tax system itself and spending programs – receive (periodic) review to ensure thatthey are effective and are justified continued support from the public.In addition, a more comprehensive assessment of government activity leads to a betterunderstanding of the effects of providing tax expenditures, and helps to make tax policy moretransparent. Tax expenditure reporting is thus a contribution to the design of the whole tax11

system because it improves transparency by promoting and informing public debate on allelements of the tax system.All in all, the key functions of reporting and evaluating tax expenditures can be summarisedas follows:----Increasing cost control and transparency,Aid for efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability,A more comprehensive assessment of government activity, andContribution to the design of the tax system.5

When reporting tax expenditures it might be helpful to distinguish between existing and newtax expenditures. In general, when new tax expenditures are introduced, or existing onesexpanded, it receives special attention. The legislative process will often be the naturalstarting place to determine whether the initiative can be defined as a tax expenditure or not.Depending on the institutional framework it might be difficult to classify changes as taxexpenditures later on. This focus on tax expenditures in the legislation process will make therevenue effects, distribution etc. more transparent as is the case with other changes in the taxsystem.In general, there is little discussion about the need of tax expenditure reporting andevaluation, but in reality this is often lacking.3.2.1Classification

Tax expenditures differ in many ways (e.g. target, tax base, volume, recipients and type oftax measure). For the purpose of analysing and reporting, tax expenditures can be structuredin an appropriate manner. Tax expenditures can be classified and structured according todifferent methods and purposes. Theoretically, there is not one correct way to classify taxexpenditures, and the choice of classification method is subjective. The most commonmethods are to classify them according to their taxable base, their purpose and/or objective orthe type of measure (see table 3.1).It should be noticed that tax expenditures can be classified on the basis of more than onemethod. When reported, however, tax expenditures ought to be structured according to onemain classification method, as the reporting would otherwise be difficult to follow. Stickingto the same classification will also make it possible to follow any trends in the taxexpenditures.

5 See Australian Treasury (2009), p. 2.

12

Table 3.1: Types of classificationClassificationaccording toTaxable baseExampleDeviations from the benchmark tax onlabour is divided into one category,deviations from the benchmark tax oncapital into another category etc.Used in: Norway and Sweden.- Budget function- Recipients- Related type of direct spendingPros and consSimple, but does not give anyextra information.Important for tax revenueforecasts.

Purpose and/orobjective

Type of taxmeasure

Additional information, butapproach does not alwaysallow objective (comparable)judgments.Used in: Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.Allowances, exemptions, deductions,A direct and simple approachrate relieves, and tax deferralswith few categories which iswidely used for researchpurposes.Used in: Finland.

As table 3.1 shows, one method of classifying tax expenditures is to categorise themaccording to their taxable base. For example, deviations from the benchmark tax on labourare defined as one category, deviations from the benchmark tax on capital as anothercategory, and so on. This simple classification system gives an overview of the taxexpenditures within each tax category and to some extent it gives an idea of who the directrecipients of the tax expenditures are, but gives limited additional information. In general,this method is used to demonstrate how different kinds of tax revenues are affected by taxexpenditures. It is particularly important in the context of tax revenue forecasts.Classifying tax expenditures according to their purpose and/or objective (that is budgetfunction, recipients, and related type of direct spending) is another widely used method. TheGerman Government, for instance, differentiates between tax expenditures which are directlyaimed at companies (business sector level) and others which are aimed at private households(but nevertheless indirectly to companies). Besides, for further categorisation the objectivetargets preservation, economic adjustment, and productivity are used.6However, the Joint Committee on Taxation in USA classifies according to tax transfers (e.g.refundable portion of the earned income credit and child tax credit), social spending (e.g.IRAs, fringe benefits, mortgage interest deduction) and business synthetic spending (e.g.energy subsidies and R&E credit).7Another approach to classify according to technicalreasons can be found by the OECD’s classification: “technical” tax expenditures, otherincome exemptions, tax expenditures which could not be repealed without being replaced bya spending program, and other tax expenditures.8Classifying tax expenditures in this manner gives additional information. For example, it canbe shown, which tax expenditures belong in a special context (e.g. make work pay,6 See German Government (2007), p. 8 f. and 112.7 See Joint Committee (2008), p. 17.8 See OECD (2008/2), p. 6.

13

retirement, employees benefits or education9) or who are the recipients of tax expenditures.However, one should bear in mind that the different kinds of classification not necessarilygive the full picture of incidence, i.e. the persons who benefit from the tax expenditure in theend. Furthermore, the fact that it is often unclear to which category a tax expenditure belongsand why the categories are chosen as they are, represents an important disadvantage of thiscategorising method. Besides, the volume of additional information generally increases withthe number of categories, while the clarity of the categorization decreases. All in all,objective judgements and comparisons are often difficult.Furthermore, tax expenditures can be classified according to what type of tax measure theyrepresent. That means, how the tax expenditure is designed from a regulatory point of view:allowances, exemptions, deductions, rate relieves, and tax deferrals.10This relatively directand simple approach which is widely used for research purposes contains only few categoriesand allows objective (comparable) judgements.All in all, the Nordic countries classify, as many other countries, first of all according topurpose and/or objective on the one hand and tax base on the other. For example, Norwayuses tax base and budget function. Denmark divides the tax expenditures into categoriesbetween purposes (e.g. education, health, business development etc.). In Sweden, taxexpenditures are divided into two broad categories: expenditures which would affect thebudget balance if they where abolished and expenditures which do not. In addition to thisdivision, the tax expenditures that affect budget balance are classified according to their taxbase and presented in subgroups. Moreover, the expenditures are also classified with respectto their general purpose. However, Finland is the only Nordic country which classifies inaddition to the budget function also to the type of tax measure.3.2.2Important elements of reporting

Reporting tax expenditures in one form or the other, helps keeping focus on this part of thetax system. When reporting, the following should be considered: what to report; how oftenand where to report.In the ideal world tax expenditure reports should be as comprehensive as possible. Dependingon benchmark, reporting should include tax incentives, tax credits, tax breaks, exemptionsand other measures. Therefore the report should include a complete list of all explicit andimplicit exemptions in all taxes (including personal income, corporate income and salestaxes), regardless of the fiscal impact. When present, tax expenditures in local governmenttaxation should also be included. In practice, there is often used a minimum level for a taxexpenditure to be reported/calculated.The ambitious report include detailed information about all tax expenditures (see for instanceGerman “Datenblätter” – tabular summary of each tax expenditure containing original andactual objectives, legal citation, possible time limitation and/or digressional design, fiscalvolume, and – if available – results from former evaluations).11The following information is valuable when reporting tax expenditures:9 See for example OECD (2008/1), p. 36 with target to compare tax expenditures and spending programs.10 See for example OECD (1996), p. 9, OECD (2003), p. 2, Kran (2004), p. 130, Thöne (2005), p. 55 f., Boss and Rosenschon (2008), p. 5.11 German Government (2007), p. 186 ff.

14

First of all it is important to describe the applied benchmark used to identify tax expenditures.If the definition is not transparent, it is not clear what kind of information you get from thereporting.As the main focus probably will be on the estimates of the annual revenue loss, in the senseof costs which the expenditures create, it should be clear which method is used whencalculating the tax expenditures (revenue foregone, revenue gain or outlay equivalence).Including cost in recent years and cost estimates for the future will give an indication of anytrends in the single tax expenditure. It might not be necessary to re-calculate all taxexpenditures every year. Instead, different parts/categories of the tax expenditures could bere-calculated e.g. every 2-4 year, or when the (groups of) tax expenditures are evaluated inconnection with other parts of the tax- or spending system.When reporting existing tax expenditures and re-estimating tax expenditures, one has to beaware that behavioural responses have an impact, even though the revenue foregone methodis applied. In the longer term the level of tax expenditures will reflect behavioural responsesdue to the tax expenditure itself. Change in economic fluctuations, market conditions etc. willalso effect the level of the existing tax expenditures. Changes in the general tax rates can alsohave an impact on tax expenditures, even though the specific legislation regarding the taxexpenditure has not changed.Besides listing all tax expenditures one by one, they can be listed according to tax base,purpose, who benefits from the tax expenditures etc. (see 3.2.1). Furthermore the reportingcould include legal citation, reasons for enactment (intended objectives), and year ofenactment for each tax expenditure. If there is a time limitation and/or degression this will beuseful information as well. In addition, information from (former) evaluations could besummarized in the report.Last but not least, tax expenditure reports should be timely and accessible. One target of taxexpenditure reporting is to give policymakers and voters the information which they need toevaluate spending through the tax code. This allows them to weigh tax preferences againstother spending and decide what really deserves funding. Tax expenditure reporting could, forinstance, be incorporated into budget process or in a permanent list on the internet. Wherevertax expenditures are reported, the reports should be up-to-date and easily (online) available.3.2.3Challenges in evaluating tax expenditures: Effectiveness and efficiency

Evaluating tax expenditures is a key component of providing data on the effectiveness of themeasures and the achievement of intended objectives (if explicitly specified). Furthermore,evaluation improves legislation since it provides evidence of what is working and what is not.However, evaluating tax expenditures is not at all an easy task. Especially, the extent towhich resources could be rationalized or better allocated to strengthen government financesand to support progress towards broader economic and social objectives is not obvious. Butalso many other challenges arise and have to be tackled (e.g. benchmark system, evaluationcriteria, data problems, interactions, and behavioural effects).12Not only to identify and measure tax expenditures but also to evaluate them there is a needfor reliable benchmark system. Merely changing this system at frequent intervals can render12 See for example LAO (2003), p. 5.

15

analysis of tax expenditures less useful and therefore discredit and weaken them. In addition,evaluation criteria are needed. Designing principles as generally as possible can be seen asapplications of the substantive goals of equity, efficiency, and ease of administration. Due tocompletely different types of tax expenditures with nearly incomparable targets and effects,evaluating tax expenditures systematically is problematic. Nevertheless comparable resultsare necessary to give fruitful advice to the public and politicians. If methods necessarilydiffer, one possibility to ensure comparable results is to use a common evaluation framework.Apart from these evaluation scheme problems, there are a lot of practical difficulties inevaluating tax expenditures (e.g. data problems, interactions and behavioural effects) whichcan strongly affect the value of evaluations. One major challenge is that significant empiricaldata is required to evaluate the theoretical background of tax expenditures. Whereas data forcollected taxes typically are registered, data for tax expenditures which are taxes not collectedare not always recorded. The introduction of tax expenditures can even directly lead to a lackof information. All in all, widely data collecting and providing of data (by taxpayersbenefiting from tax expenditures) is necessary in order to evaluate the effectiveness of taxexpenditures. For purpose of comparison, tax expenditure data has to have the same standingand be of the same level of quality as spending data in the budget. An increased use ofmandatory reports from businesses and households can establish an improved dataset forevaluating tax expenditures. This extra information must be weighted against the cost, bothmonetary and in terms of integrity, of obtaining this information and possible politicalobjectives of administrative burdens.Further challenges result from interactions between different tax expenditures and/or betweendifferent political subdivisions when tax expenditures exist at both federal and state level. Inthese cases changing one tax expenditure can affect costs and effectiveness of another andthereby make it difficult to isolate the effects of individual tax expenditures. When analyzingthe distributional effect of a certain tax expenditure it is therefore important to analyze the taxsystem as a whole. Analyzing one tax expenditure in isolation might give a false impressionof the real distributional effect of all elements of the tax and expenditure system. This couldbe true in the case where the same group of persons or firms receive a tax deduction in onearea but have to pay an extra tax or fee in another area.In addition, there is often limited information regarding how taxpayers’ behaviour areaffected by the existence of tax expenditures. Therefore, the overall effect often differssignificantly from the first stage effect. Furthermore, looking at tax expenditures next todirect spending is not always an apples-and-apples comparison. Direct spending does e.g. notnecessarily take account of taxes, whereas tax expenditures mostly are stated after taxes.All in all, evaluating costs, efficiency, and equity impact of tax expenditures requires a highlevel of ambition. Comprehensive assessments will potentially require a lot of resources,which are not allocated today. Therefore, depending on the amount of resources allocated forassessments a more targeted approach, which focuses on individual tax expenditures ofspecial interest, could be considered. Evaluations of tax expenditures along with otherevaluations of the tax system in general or when specific areas are evaluated will could alsobe considered. Such an approach should include studies both by the administration itself aswell as by other institutions. A sunset provision is another possibility to ensure that (newly)created tax expenditures do not continue indefinitely unless merited.

16

3.3

Reporting and evaluation in other countriesIn general

3.3.1

In general, international comparisons of tax expenditures are difficult.13Definitions of taxexpenditures share a common core across countries. Every country defines tax expendituresas exceptions from some baseline standard for the entire tax. Although the benchmark isalmost identical, the countries differ in the purpose of the exercise of the identification of taxexpenditures and this cause differences in what is considered as tax expenditures in thespecific country. Japan, for instance, defines its benchmark in terms of its basic principles oftaxation: equity, neutrality and simplicity. This benchmark is expected to give a large numberof tax expenditures. In the other end of the spectre, the Netherlands considers its benchmarkto be the “primary structure” of the actual tax system in place, which is expected to inducerelatively few tax expenditures. Thus, with the choice of definition the number of identifiedtax expenditures can vary considerable. Few countries identify tax sanctions.Some countries have made it a legal requirement to report tax expenditures, and others havenot. Some report outside the budget and some in annexes to the budget. Reporting of taxexpenditures alongside similar outlay programs is seldom done. In general most countriesreport annually, but some countries report every two years or less frequent. Most countriesgenerally cover only a few years when reporting, but some countries like Canada, theNetherlands, and USA covers a period for 7-8 years.Most countries acknowledge the importance of evaluation, but no countries have systematicprograms to evaluate tax expenditure. Even in the few countries where evaluating programsare required by law, the evaluations only comprise of an estimation of the cost of taxexpenditure.143.3.2The German evaluation of tax expenditures

In 2007, the German Federal Ministry of Finance commissioned – based on the FederalGovernment’s report on subsidies – a systematic evaluation of the Federal Government’smost important tax expenditures.15The current research project, undertaken by the CologneCentre of Public Economies (FiFo), the Mannheim-based Centre for European EconomicResearch and Copenhagen Economics, determines if there are rational goals for these taxexpenditures, as well as effectiveness and efficiency in achieving objective targets.The tax expenditures in question reach from VAT reductions to income tax measures andinstruments with environmental objectives. These tax expenditures belong to completelydifferent categories with both incomparable targets and effects, and this makes it impossibleto evaluate them according to one method. Nevertheless a systematic evaluation is ensured byasking the same questions in a common evaluation framework for each of the taxexpenditures. The following structure is used:

13 This section draws on OECD (2008).14 For detailed information see Annex 7.1. Further overviews on this topic are especially provided by Bratić (2006), p. 117, AustralianTreasury (2009), p. 3, OECD (2008/1), p. 79 ff., and OECD (2008/2), p. 2 f.15 See for example German Government (2007), p. 5 and GSI (2007), 1 f. To clarify the importance of this research project, it has to beconsidered that the 20 most important German tax expenditures nearly amount to 90 % of the fiscal resources that are spent in the context oftax expenditures by the Federal Government (see German Government (2007), p. 18).

17

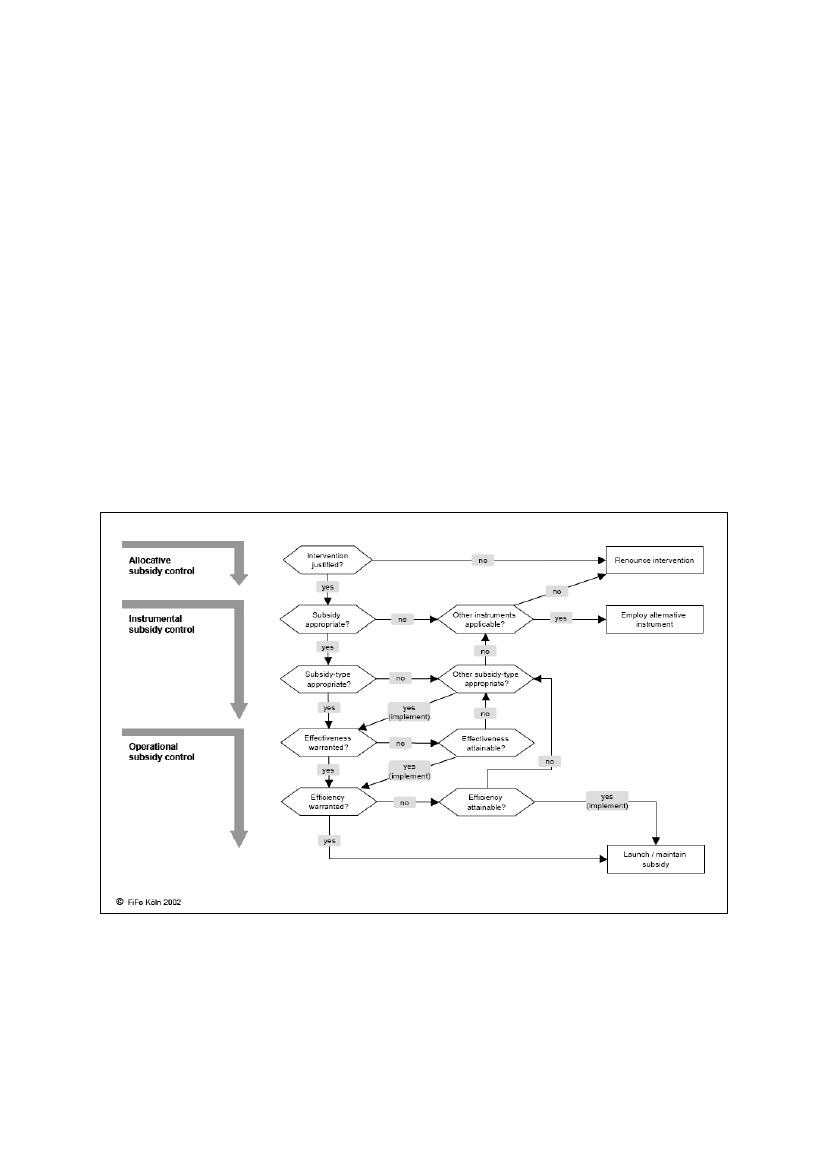

1. Short description of the tax subsidy and its history2. Measurement of the actual volume of the tax expenditures3. Record of past evaluations and their resultsa. Past evaluations of the tax measure in questionb. Past evaluations of comparable tax expenditures home and abroad4. Core evaluation:a. Rationale of the subsidyb. Relevance of the subsidy and instrumental subsidy-controlc. Testing for effectivenessd. Testing for efficiency5. Conclusions and proposals for actions to be takenWhile steps 1-3 compile the information necessary to build a well balanced evaluation on,step 4 is the core evaluation part. This structure is modelled after the scheme for an optimalsubsidy control developed by FiFo on the basis of international benchmarking endeavour andcommon best practise (see figure 3.1).Figure 3.1: Simplified scheme of optimal subsidy control

Source: Thöne (2003), p. 41.

This three-steps-approach (allocative subsidy control, instrumental subsidy control andoperational subsidy control) contains all the basic questions that have to be asked to justify orto renounce tax expenditures. That means: Is the subsidy justified? Is it relevant? Is it well-designed? Is it effective? And last but not least: Is it efficient? If one of these 5-level-questions has to be denied, the decision process of the respective subsidy is immediately18

terminated. In this case a renouncement or at least an employment of an alternative measureis recommended.For example, if a certain tax expenditure cannot (or no longer) be justified on principalreasons, the necessary and sufficient conditions for its abolishment are fulfilled.16In general,there is no more need to analyse the further questions. Nevertheless the forthcoming Germanevaluation report will contain full evaluations of all German tax expenditures in question.

16 See Thöne (2003), p. 38 f.

19

4 Country overviews4.1Introduction

In this chapter we discuss the treatment of tax expenditures in Denmark, Finland, Norwayand Sweden. Section 4.2 starts with a summary of common features and points towardsdifferences. The common challenges are also discussed. Then more detailed descriptions oftax expenditures in each country follow.4.2Main features

Tax expenditures are calculated in all of the Nordic countries. The general principles indefining and calculating tax expenditures are quite similar, but there are differences.Differences can be found for example in the reporting practices and the reasoning behind taxexpenditure calculations, and in the political objectives concerning the use of taxexpenditures.4.2.1Definition of tax expenditures and the benchmark system

Tax expenditures are generally defined as deviations from a benchmark tax system. In all ofthe countries discussed here, the underlying idea behind the definition of the benchmarksystem is the concept of comprehensive income taxation, a broad based system where allincome is largely taxable. For pragmatic reasons, the benchmark system is in all countriesmore or less based on the prevailing tax system. Sweden applies a more ambitious approachin defining the benchmark, as the benchmark is based on the idea of uniform taxation, i.e.each type of tax should be levied uniformly and without exemptions. The benchmarknevertheless allows for exemptions and can thus also be perceived as pragmatic. Besides taxexpenditures, all countries also calculate tax sanctions in cases of unfavourable tax treatmentof specific groups or activities. Denmark, however, only calculates tax sanctions when thereis a close link to the tax expenditures, like when a tax sanction reduces a tax expenditure. Thegeneral features of the benchmark systems are fairly stable, although as they are to a largeextent based on the prevailing tax systems, they do change when the general tax systemschange.17Defining the benchmark system can be complicated in practice, even though the benchmarkis based on the current tax system. Deciding which tax rules should be included in thebenchmark and which constitute tax expenditures is not always straightforward. Examples ofthese questions are the treatment of interest deductibility, earned income tax deductions,deductibility of pension income contributions, VAT exemptions and excise duties.All the Nordic countries use the dual income tax system where labour income and capitalincome are taxed separately, although with great individual variations. This system isgenerally included in the benchmark. Progressive taxation, including standard deductions, ispart of the benchmark in all countries. In Denmark and Sweden in-work tax deductions arealso considered part of the benchmark. Denmark includes deductions for many, but not allexpenses in the benchmark, whereas the other countries only allow for deductions of costs17 An example of these changes is the adoption of the shareholder model in taxation and in the benchmark in Norway in 2006.

20

directly linked to generation of income. Generally the deductions that are allowed for in thebenchmark are of general nature and do not favour specific groups or activities.All countries except Finland include interest rate deductions in their benchmarks. Imputedrent from owner occupied housing is considered as real income in all countries but the taxexpenditure is not calculated in Denmark due to difficulties in defining the benchmark. InNorway a wealth tax is included in the benchmark. Deviations from the standard rate orlower assessment values than real values are regarded as tax expenditures.All countries have a standard rate for corporate taxation and deviations are defined as taxexpenditures. In Norway real profit is taxed as ordinary income, with the same rate as otherincome sources.In value added taxation, the standard VAT rate (25 per cent in Denmark, Norway, andSweden, while 22 per cent in Finland) defines the benchmark in all of the countries, anddeviations from the standard rate create tax expenditures. In Finland all, and in Sweden some,VAT exemptions are also considered part of the benchmark, in Denmark and Norwayexemptions are considered to create tax expenditures.The countries define the benchmark with respect to excise duties in different ways and thescope of excise duties included varies as well. Finland has no special benchmark for exciseduties, but defines tax expenditures as deviations from the standard rate. The same applies forDenmark and Sweden, but included in the benchmark for energy is a split between where andto what the energy is being used. Denmark considers a new benchmark for environmentalexcise duties that reflect externalities. Norway on the other hand applies a benchmark that isbased on the theory of optimal taxation and thus a normative benchmark. The benchmark isdivided between fiscal and environmental excise duties. For fiscal excise duties theexemption of taxes on factors on production is part of benchmark and the environmentaltaxes are in line with external costs. Sweden and Finland only considers excise duties thatinvolve tax expenditures with a certain magnitude, whereas Norway and Denmark includeall, or most of the excise duties.

4.2.2

The volume of tax expenditure

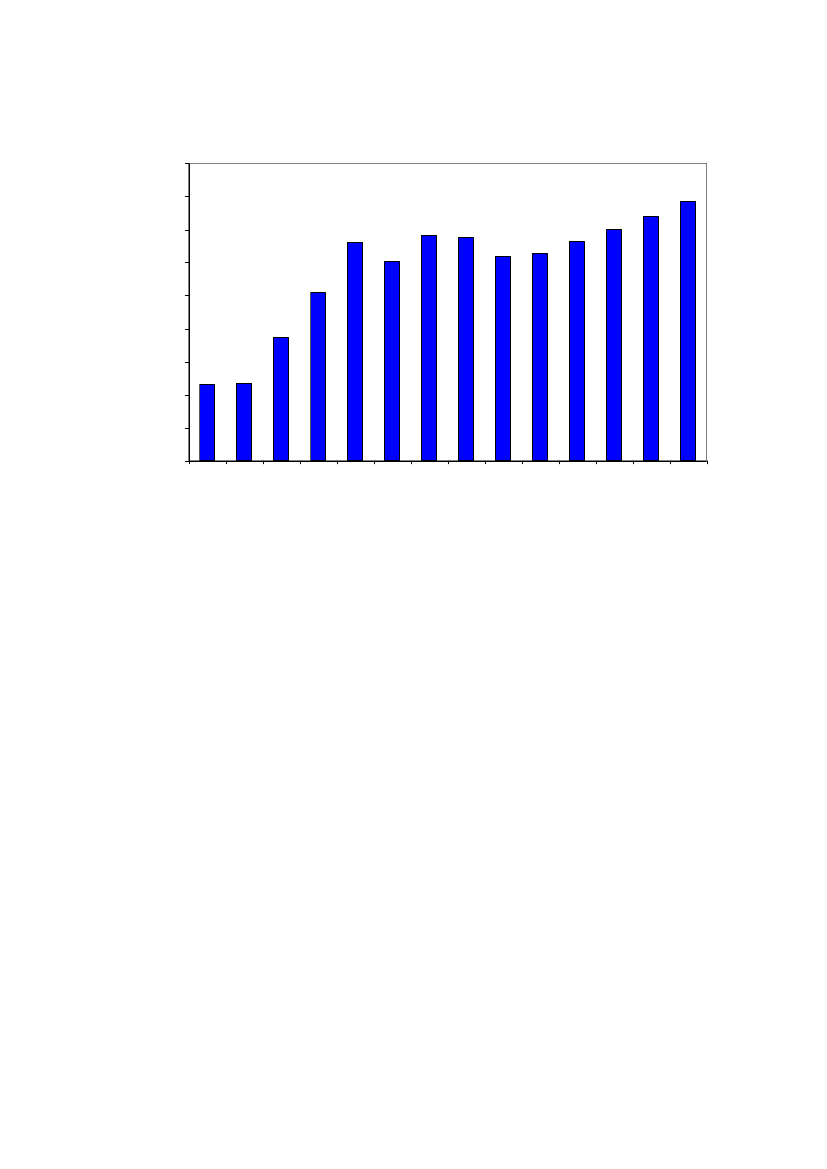

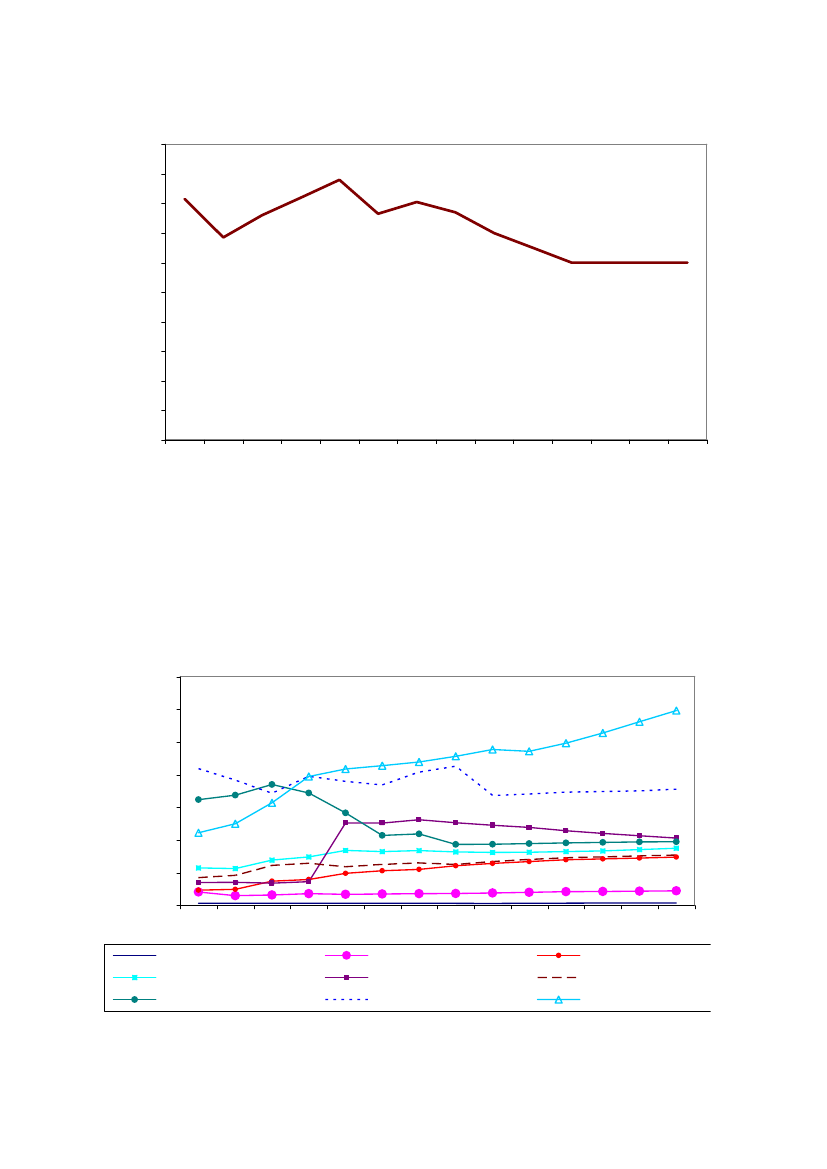

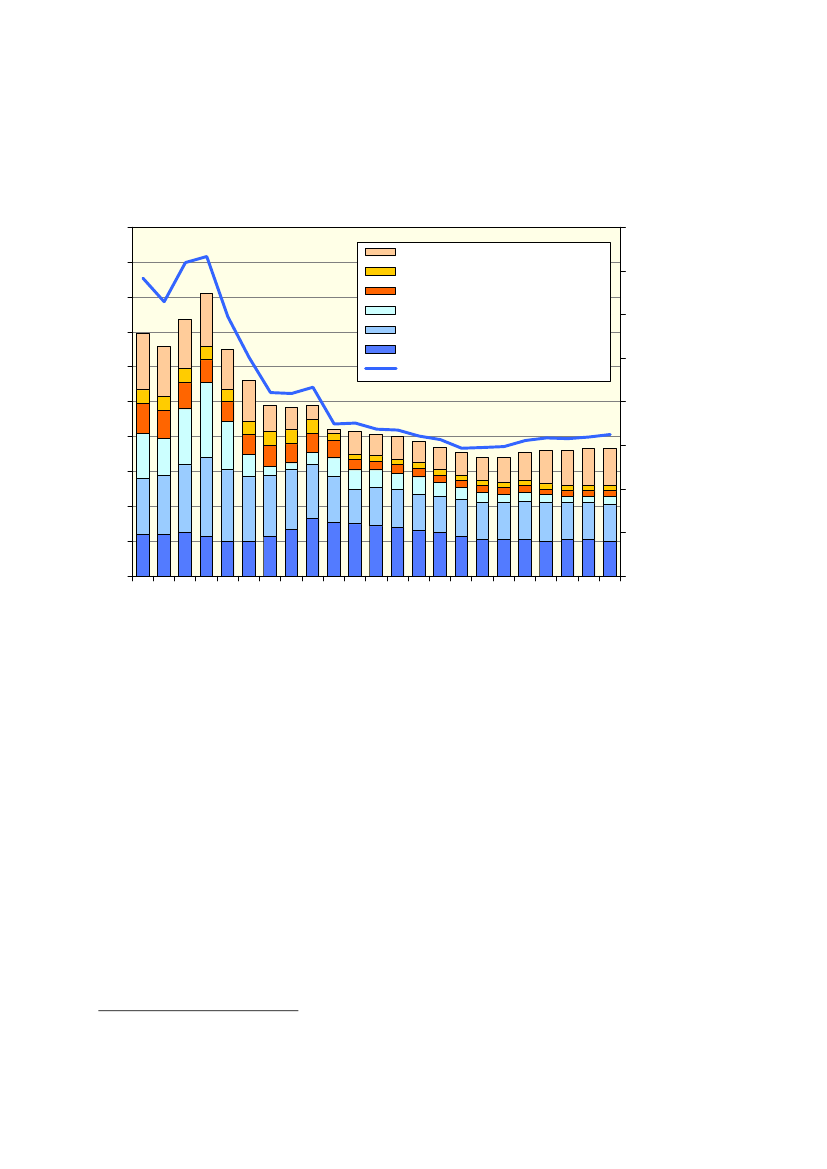

Comparing tax expenditures between countries and over time is not straightforward. Thecoverage of the tax expenditure calculations varies, as does the definition of tax expendituresin the first place. A more orthodox definition of the benchmark usually leads to a highernumber of tax expenditures. It should also be kept in mind that tax systems, and thus thebenchmarks, within each country change, and this will affect the evolvement of taxexpenditures over time.Moreover, the data used may be of varying quality. This, among other things, calls forcaution when interpreting tax expenditures. Nevertheless, the number of tax expendituresranges from 60 in Norway to 115 in Sweden. The total estimated volume of tax expendituresis by far the largest in Sweden, 25 billion euros, and smallest in Denmark, 5 billion euros. InFinland the estimated value of tax expenditures was 13 billion euros, and in Norway 16billion euros. The share of tax expenditures as per cent of GDP is largest in Sweden, 8 percent, and smallest in Denmark, 2.2 per cent. In Finland the share is slightly lower than inSweden, 7 per cent, and in Norway the share of tax expenditures is 5.4 per cent of GDP. As21

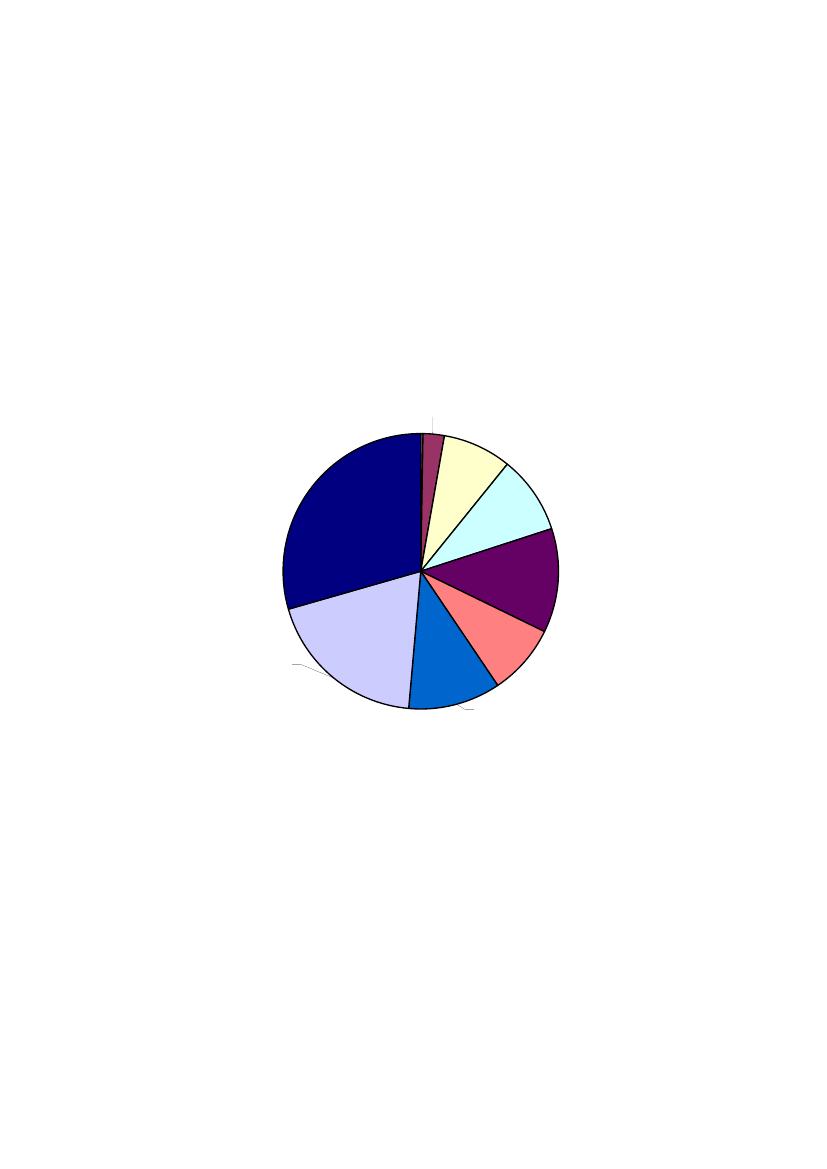

per cent of total tax revenue, the tax expenditures amount to 4.4 in Denmark, 17 in Sweden,16 in Finland and 13 in Norway.18As method of calculation, all countries apply the revenue-foregone method. Tax expendituresare calculated as the direct revenue effect of abolishing a specific tax rule that is not part ofthe benchmark system. Denmark and Sweden also use the outlay equivalent method. Thismethod calculates the corresponding amount needed on the expenditure side of thegovernment budget to reach the same effect. Norway calculates some tax expenditures aspresent value. This method is used when there is a time horizon, by estimating today’s valueof a future gain. The tax expenditures related to depreciation rates higher than actualdepreciation and tax expenditures related to employee premiums and contributions tooccupational pension schemes are calculated using this method. A common feature amongthe countries is that behavioural responses are not taken into account when calculating taxexpenditures. Moreover, interactions between different taxes are not taken into account. Thetax expenditure calculations rely on tax administration data and other statistical data. Inaddition, Finland and Norway utilise microsimulation models in calculating tax expendituresin personal income taxation. In Denmark and Sweden the Ministry of Taxation and Ministryof Finance, respectively, performs the calculations, and in Norway the work is dividedbetween the Ministry of Finance and Statistics Norway. In Finland the Government Institutefor Economic Research makes the calculations.Since the late 1990’s, the share of tax expenditures to GDP has declined in Denmark. This ismainly due to abolition of tax expenditures related to taxation on energyconsumption. Therehave also been some changes in the composition of the tax expenditures. The Danish Taxreform (Forårspakke 2.0) will reduce the tax expenditures with app. 0.2 billion euros. InFinland the share of tax expenditures to GDP has remained relatively stable during thisperiod, but it has come down remarkably since the mid-eighties, which is the start of thereporting period. Lately there has been an increasing tendency towards introducing new taxexpenditures in Finland, so generally the volume of tax expenditures can be expected toincrease rather than decrease in the years to come. Since the late nineties in Norway, anincreasing number of deductions and allowances have been defined as tax expenditures. Thishas contributed to an increasing volume of tax expenditures. One of the objectives of the2006 tax reform in Norway was to abolish several exemptions and allowances that werepoorly justified, but the reform was only partly successful in this matter. The general trend inNorway is that the reported tax expenditures are growing. A substantial part of this growthcan be attributed to growing tax bases, but some tax policy changes have also contributed tothis development. In Sweden the level of tax expenditures has been fairly constant over thelast few years. Although there has been some year-to-year variation it is hard to point in anydirection.In all of the countries, the composition of tax expenditures evolves over time when new taxexpenditures are introduced and old ones abolished. The distribution of tax expenditures todifferent policy areas is different in the Nordic countries, but currently tax expenditure onhousing seems to be among the most important tax expenditures in all of these countries. Themost important tax expenditures in Denmark are in the area of business development,corresponding to 30 per cent of total tax expenditures. Besides from business development,traffic and communication, housing and energy supply represent areas with a relatively highlevel of tax expenditures. Tax expenditures directed to business development and housing has18 The figures in this paragraph refer to 2008 or 2009.

22

increased substantially since the late 1990’s in Denmark, and at the same time taxexpenditures for energy supply has decreased. In Finland, the most important taxexpenditures are in the area of social security, housing and labour income taxation. The shareof tax expenditures directed to manufacturing has decreased since the late 1980’s, and sincelate nineties, the share of tax expenditures on labour income has increased. In Norway, themost important tax expenditures relate to lack of taxation of imputed income from, and lowassessment values on, housing. The regionally differentiated employers’ social securitycontribution and employee premiums and contributions to occupational pension schemes alsogive rise to major tax expenditures. In Sweden, the largest tax expenditure in 2009 isassociated with returns to housing as it is not taxed as other capital income. Three other largetax expenditures involve VAT, indirect taxation of labour income and energy taxes.4.2.3Reporting, classification and evaluation of tax expenditures

Tax expenditures reflect political priorities, and by reporting tax expenditures, these prioritiesare made visible. Tax expenditures have been reported since late 1990’s in all of the countriesexcept for Finland, where they have been reported since 1988. All countries except Denmarkreport tax expenditures yearly to the Parliament. In Denmark tax expenditures were reportedin an appendix to the Budget Proposal until 2006, when the Danish Government decided toexclude them. The Danish Ministry of Taxation publishes a list of changes to taxexpenditures due to legislation on its homepage. In Sweden tax expenditures are reported in aGovernment Communication in conjunction with the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill, and they arere-reported in the autumn as supplement to the Budget Bill. In addition to the actual numbers,Sweden also publishes the methodology of the calculations. In Norway tax expenditures arereported in the National Budget, and in Finland the main categories of tax expenditures arepresented in Report on the Central Government Final Accounts. Although there is nosystematic tax expenditure reporting in Denmark, new tax expenditures are explicitlymentioned when a bill includes tax expenditure. Revenue and distributional effects and thepurpose of the new tax expenditure are then presented. In Sweden, when a new taxexpenditure measure is introduced, this is explicitly pointed out in the tax expenditure report.In Finland, the status of the tax expenditure reporting is relatively low at the moment, and nospecial attention is given to new tax expenditures in tax expenditure reporting. Norway hasno systematic approach to new tax expenditures in the tax expenditure report, but in the latestreport (2008) new tax expenditures were pointed out.There are differences between the countries not only in how the tax expenditures arereported, but also in what is left out of the tax expenditure reports or not calculated. The mainreason for leaving something out is methodological difficulties. In Finland, real estatetaxation, inheritance tax or social security contributions are not covered in the taxexpenditure reports. Also most of the excise duties are not covered, as is also the case inSweden. In Norway all existing tax expenditures are included in the report, but not all arecalculated. This for example applies to the inheritance tax and several tax expendituresrelated to payments in kind. In Denmark tax expenditures are not calculated where abenchmark is difficult to establish, as for example in private pensions systems, where thetime horizon and correlation to public transfers complicates the matter.There are different ways of classifying tax expenditures (see chapter 3.2), and the informationgiven by the tax expenditure reports also depends on the classification. In Denmark andFinland, tax expenditures are classified according to operational categories. In Finland thisclassification was originally based on budgetary categories, but in that sense the classificationis no longer valid, since the budget categories have changed. Tax expenditures are also23

classified according to types of tax (income tax, indirect taxation etc.) in Finland. In Norwaytax expenditures in direct taxation are classified according to taxable base. In indirecttaxation, tax expenditures are classified according to both the type of tax (VAT, excises) andobjectives (fiscal, environmental, health). In Sweden, tax expenditures are divided into twobroad categories: expenditures which would affect the budget balance if they where abolishedand expenditures which do not. For the former category, which includes most taxexpenditures, both the revenue forgone and the outlay equivalent are calculated. For taxexpenditures not affecting the budget balance, i.e. tax exempted transfers, only the outlayequivalent is calculated. The revenue foregone is readily available on the expenditure side ofthe government budget. In addition to this division the budget balance affecting expendituresare classified according to their tax base and presented in subgroups. Moreover, theexpenditures are also classified with respect to their general purpose. In this respect, adistinction is made between technically or administratively motivated tax expenditures andpolitically motivated tax expenditures.Despite of the reporting, tax expenditures are not an integrated part of the budget process inany of the countries. In most cases tax expenditures are not reported in connection with directexpenditure targeted to the same activities or recipient groups, so it seems that whendiscussing the distribution of public finance to different policy areas, tax expenditures are notsystematically included. One exception is found in Norway, where direct and tax transfers todifferent industries are reported under the heading “Industrial support” in the NationalBudget.Some have pointed to the lack of yearly evaluation and assessment of whether the publicsupport given trough tax expenditures is increasing or decreasing, and how well the targets ofthe tax expenditures are achieved.There is no systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of taxexpenditures in any of the countries discussed here. But there are good examples ofevaluation though. For example in Norway, tax allowance for R&D expenses has beenthoroughly evaluated by Statistic Norway. Prior to the Norwegian tax reform in 2006, agovernment appointed Tax Committee also evaluated several tax expenditures. In Denmarktaxation and other regulation of emissions of CO2have been evaluated in 2007. The doubleregulation of CO2can be regarded as a form for tax sanction. In Finland, the tax credit forhousehold services introduced in 2001, has been evaluated for employment effects. Morecomprehensive evaluations of tax expenditures are often done in connection with tax reforms.This has been the case in Finland when a comprehensive tax reform was introduced in thelate 1980’s. A distinction can be seen between the treatment of new tax expenditures andexisting ones – new tax expenditures tend to be better evaluated, (in terms of for example ofemployment effects), than existing ones. There is often an ex ante evaluation of the effects ofnew tax expenditures when they are introduced. It should be noted that not all directexpenditures are evaluated on a yearly basis.4.2.4Critique from National Audit Offices

Denmark, Finland and Sweden have all received critique from the National Audit Offices(NAO) concerning tax expenditures. The common main point stressed in all of the countriesis lack of transparency in the treatment of tax expenditures. The Swedish NAO hasemphasised, that the principles behind reporting and calculating tax expenditures are notsuited for continuous evaluation of different tax expenditures, and that the reporting of taxexpenditures is not well suited to fulfil its purpose. The Swedish NAO has advised theSwedish Government to consider how tax expenditures should be treated in the fiscalprocess. The Danish NAO has recommended annual publishing of the tax expenditures in24

connection with the budget process. It also recommended that each tax expenditure should berevised and evaluated every year. In Finland the central question raised by the NAO iswhether the legislation process and evaluation of tax expenditures is on an adequate level.The Finnish NAO also stressed that the rationale behind the tax expenditures should be clear,especially if there are other reasons besides the suitability of the tax expenditures, such as thebudgetary spending limits, that might encourage the policy makers to use tax expendituresinstead of direct budgetary expenditures.4.2.5Tax expenditure and fiscal policy

It is not easy to draw conclusions about the general atmosphere and discussion concerningtax expenditures in the Nordic countries. There clearly are different tendencies in the primaryobjectives behind tax expenditure reporting, the political interest in using tax expendituresand in the political and general discussion about the reporting of tax expenditures, and thetreatment of them in the budget process.Tax expenditures can be justified for various reasons, but there can also be less satisfactoryreasons behind the use of tax expenditures instead of direct expenditures. For the latter, theprinciple policy instrument, there are routines and systems designed for efficiency, controland fiscal discipline. In general such systems are missing for tax expenditures. For example,while a cap can be applied to direct expenditures, there is no direct limitation on taxexpenditures. Finland and Sweden apply budget caps to direct expenditures and it may beargued that such caps give incentives to give support through the budget income side, i.e.through tax expenditures. Denmark does not have a budget cap, but there is a long runbalanced budget goal. Due to the tax freeze since 2001, tax expenditures cannot be reduced.New tax expenditures can be introduced, which will reduce the room for direct expenditures.This is also the case in Norway, where the government operates with a balanced budget rule,i.e. a structural non-oil central government budget deficit corresponding to the expected realreturn (estimated at 4 per cent) on the Government Pension Fund – Global (the formerPetroleum Fund). Even though this implies that the government has a choice between taxexpenditures and direct transfers, it often seems like tax expenditures are regarded as easier toimplement than direct expenditures and also appears to be less costly. This probably stemsfrom a fact that applies to all the countries in question, namely that tax expenditures are notsubject the same scrutiny as direct expenditures. Although in Denmark changes in taxexpenditures are subject to the same scrutiny as other changes in the tax code. A fullintegration of tax expenditures into the budget process is hardly feasible. Lack of data,computational methods, benchmark choice and other methodological issues complicates thismatter.The Danish Government has decided to end tax expenditure reporting in the Budget Proposal.This does not mean that the tax expenditures are totally neglected though. The exclusion oftax expenditures is justified by that the fundamental objective with the Budget Proposal is toestablish the basis for next year’s direct expenditures and revenue. Distortions due to the taxsystem and direct regulation are not listed in the Budget Proposal, even though these costsexceed the costs due to tax expenditures. Even though collecting more information about taxexpenditures would improve transparency, it would also involve increasing costs andadministrative burden. The Danish Government has committed to decreasing administrativeburden, and so these costs should be carefully weighted against the gains from moreinformation. Yet the Danish Government agrees that the use of tax expenditures should notlead to open ended public spending.

25

In Finland the interest in using tax expenditures has been increasing recently, after beingrelatively limited for almost 20 years. There has been an increasing amount of requests fornew tax expenditures, and as a consequence, new tax expenditures have been introduced. Itcan be argued that this is due to budgetary spending limits on direct expenditures. At thesame time, the distance between tax expenditure reporting and the budget process has grown.The rationale behind each tax expenditure is discussed in a working group report published in1988, but they are not presented along the yearly reporting of tax expenditures. Following thecritique from the National Audit Office and the Parliamentary Audit Committee, the FinnishMinistry of Finance has appointed a working group with a mandate to evaluate, and suggestimprovements to, the treatment of tax expenditures.In Norway the stated purpose of reporting the tax expenditures is to obtain a greater degree oftransparency regarding political priorities and financial support to different groups oractivities. However, the pragmatic approach to the reference system used to identify taxexpenditures, limits the informational value of reporting tax expenditures. On the other hand,this approach implies that the issue of tax expenditures attracts only moderate attention inNorway, and the estimates are more or less undisputed.Despite of the differences, in can still be argued that the importance of discussing taxexpenditures in the Nordic countries is increasing rather than decreasing. In all of thecountries, the problems in defining the benchmark tax systems, and also in documentation ofthe calculation methodologies applied, limit the informational value of the tax expenditurereports. The lack of evaluation of tax expenditures also makes the matter more important.4.3Tax expenditures in DenmarkIntroduction

4.3.1

The first comprehensive survey of tax expenditures in the Danish tax system dates back to1996. After 1997, tax expenditures were included in an appendix to the Budget Proposal(Finansloven). The tax expenditures were not reported in connection with direct transfers orsubsidies. The tax expenditures were published in the Budget Proposal until 2006 andcovered the period up to 2009. The tax expenditures have not been updated with revisions inthe benchmark system the last couple of years, but were more or less a mere mechanicalprojection with the annual change in the GDP or consumption growth when relevant andtaking into account changes in the legislation with respect to tax expenditures. In 2006 theGovernment decided to stop publishing tax expenditures in the Budget Proposal. Instead,when a Bill implies tax expenditures, this must be accounted for explicitly. The revenueeffects, distribution, purpose etc. will thereby be transparent as is the case with other changesin the tax system.A list of changes in tax expenditures due to legislation is published on the Ministry ofTaxation homepage.19This reporting started in the financial year 2007/2008. The list will notupdate all tax expenditures every year, but will include new tax expenditures and changes inexisting tax expenditures.The benchmark for tax expenditures in Denmark is, in general, based on a pragmaticapproach. The tax expenditure is calculated as direct revenue when abolishing a special rule19 See www.skm.dk.

26

that is not considered part of the benchmark. Both the revenue foregone method and theoutlay equivalent method have been used, although the revenue foregone method is the mostwidely used method when reporting tax expenditures.4.3.2Definition of tax expenditures