Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2009-10

UUI Alm.del Bilag 189

Offentligt

5/2010

ENG

Security and Human Rights in South/Central IraqReport from Danish Immigration Service’s fact-finding mission to Amman, Jordan andBaghdad, Iraq25 February to 9 March and 6 to 16 April 2010

Copenhagen, September 2010Danish Immigration ServiceRyesgade 532100 Copenhagen ØPhone: 00 45 35 36 66 00Web: www.newtodenmark.dkE-mail: [email protected]

Overview of fact finding reports published in 2008, 2009 and 2010Protection of victims of trafficking inNigeria,Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact-findingmission to Lagos, Benin City and Abuja, Nigeria, 9 – 26 September 20072008: 1Protection of victims of trafficking inGhana,Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact-findingmission to Accra, Ghana. February 25 to March 6 20082008: 2Recruitment of IT specialists fromIndia,An investigation of the market, experiences of Danishcompanies, the attitude of the Indian authorities towards overseas recruitment along with the practices ofother countries in this field. Report from the fact finding mission to New Delhi and Bangalore, India4th to 14th May 20082008: 3Report of Joint British-Danish Fact-Finding Mission to Lagos and Abuja,Nigeria.9 - 27 September2007 and 5 - 12 January 20082008: 4Cooperation with the National Agency for the Prohibition of Traffic in Persons and other related matters(NAPTIP). Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact-finding mission to Abuja,Nigeria.14 to 24February 20092009: 1Security and Human Rights Issues in Kurdistan Region ofIraq (KRI),and South/Central Iraq (S/CIraq), Report from the Danish Immigration Service´s (DIS), the Danish Refugee Council´s (DRC) andLandinfo’s joint fact finding mission to Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, KRI; and Amman, Jordan, 6 to 23March 20092009: 2Honour Crimes against Men in Kurdistan Region ofIraq (KRI)and the Availability of Protection,Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact-finding mission to Erbil, Sulemaniyah and Dahuk, KRI,6 to 20 January 20102010: 1Entry Procedures and Residence in Kurdistan Region ofIraq (KRI)for Iraqi Nationals, Report fromDanish Immigration Service’s fact-finding mission to Erbil, Sulemaniyah, Dahuk, KRI and Amman,Jordan, 6 to 20 January and 25 February to 15 March 20102010: 2Human rights issues concerningKurds in Syria,Report of a joint fact finding mission by the DanishImmigration Service (DIS) and ACCORD/Austrian Red Cross to Damascus, Syria, Beirut, Lebanon,and Erbil and Dohuk, Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), 21 January to 8 February 20102010: 3Allegations against the National Agency for the Prohibition of Traffic in Persons (NAPTIP) andwarnings against return toNigeria,Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact-finding mission toAbuja, Nigeria, 9 to 17 June 20102010: 4Security and Human Rights inSouth/Central Iraq,Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact-finding mission to Amman, Jordan and Baghdad, Iraq, 25 February to 9 March and 6 to 16 April 20102010:5

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

ContentsIntroduction and Disclaimer................................................................................................................. 31.Security, human rights and indiscriminate violence in South/Central Iraq ................................. 51.1.1.2.Baghdad ............................................................................................................................... 10Disputed areas, Ninewa (Mosul), Diyala (Khanaqin) and Tameen (Kirkuk) ..................... 11

Disputed areas ............................................................................................................................ 11Ninewa (Mosul) ......................................................................................................................... 12Diyala (Khanaqin) ...................................................................................................................... 13Kirkuk ........................................................................................................................................ 131.3.1.4.1.5.2.Armed groups, insurgent groups and criminal gangs .......................................................... 14Security and humanitarian concerns.................................................................................... 15Security and returns ............................................................................................................. 17

Security and human rights for ethnic and religious communities .............................................. 212.1. Non-Arab ethnic communities: Kurds (incl. Feyli Kurds), Turkmen, Assyrians, Chaldeans,Shabaks .......................................................................................................................................... 232.2.2.3.Palestinians .......................................................................................................................... 23Religious communities: Christians, Sabean-Mandeans, Yazidis, Jews .............................. 24

3. Security and human rights for other groups ................................................................................... 253.1. Professional groups ................................................................................................................. 263.1.1. Judges and lawyers........................................................................................................... 263.1.2. Journalists......................................................................................................................... 283.1.3 Government officials......................................................................................................... 283.2. Persons cooperating with US forces, international organisations or foreign companies ........ 283.3. Former Baathists ..................................................................................................................... 293.4. Forced recruitment, including recruitment of children ........................................................... 304. Availability of protection from authorities against non-state actors .............................................. 334.1. Persons threatened by militias................................................................................................. 334.2. Persons involved in private disputes ....................................................................................... 334.3. Women at risk of honour crimes ............................................................................................. 34

1

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

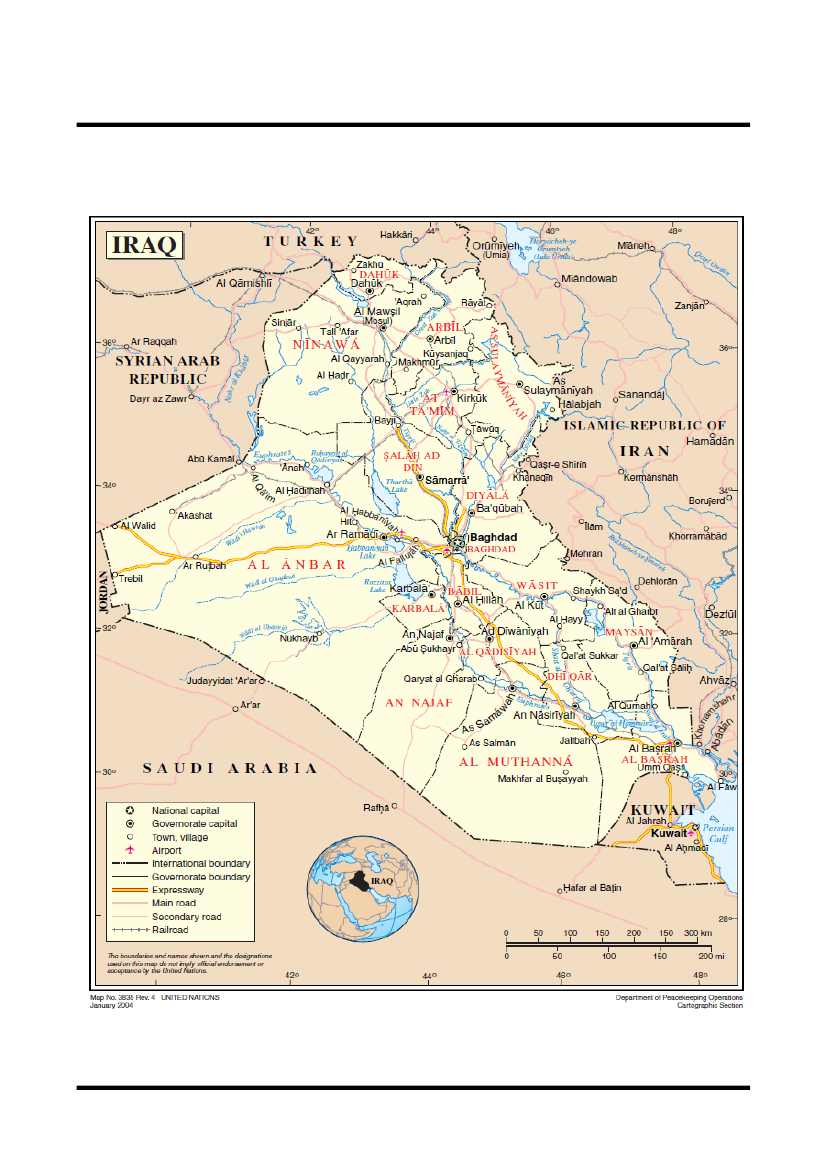

5. Protection and tribal network ......................................................................................................... 356. Civil society organisations and protection ..................................................................................... 377. The judiciary and law enforcement ................................................................................................ 387.1. The judiciary ........................................................................................................................... 397.2. Law enforcement..................................................................................................................... 427.3. Access to fair trial ................................................................................................................... 447.3.1. Persons suspected of terrorism or insurgent activities ......................................................... 467.3.2. False accusations .................................................................................................................. 468. Internal Flight Alternative in S/C Iraq ........................................................................................... 48Individuals and organisations consulted ............................................................................................ 49Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... 50Annex 1: Map of Iraq ......................................................................................................................... 52

2

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

Introduction and DisclaimerThe Danish Immigration Service (DIS), Documentation and Research Division has undertaken twofact-finding missions concerning South/Central (S/C) Iraq and Iraq‟s disputed areas.1The missionstook place in Amman, Jordan from February 25 to March 9, 2010 and in Kurdistan Region of Iraq(KRI) and Baghdad, Iraq from April 6 to April 16, 2010. All information for the report at hand wasgathered in Amman and Baghdad while a stay in KRI was chiefly for logistical and planningpurposes concerning the trip to Bagdad. The first part of the mission which took place in Ammanwas carried out with participation of Country of Origin Information Service (COIS), UnitedKingdom (UK) Border Agency for the purpose of training on how to conduct fact-finding missions.The aim of the mission was to gather updated information on the general security and the humanrights situation in S/C Iraq as well as in disputed areas, including the situation concerning ethnicand religious minorities, as well as information concerning availability of protection fromauthorities and tribes. In addition, the delegation also gathered information on the judiciary and lawenforcement as well as Internal Flight Alternative (IFA) in Iraq.In Jordan and Iraq, the delegation consulted representatives of international organisations includingUnited Nations (UN) agencies and International Organization for Migration (IOM), InternationalNon-Governmental Organisations (INGOs) and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs).Additionally, the delegation consulted two sources that requested to be cited as „a source inBaghdad‟ and „a reliable source [in] Iraq‟. A list of all interlocutors is included at the end of thisreport. All interlocutors have been referred to as requested by them.All interlocutors consulted were informed that the delegation‟s mission-report would be a publicdocument. All interlocutors were also informed that they would have their statements forwarded tothem for corrections, comments and approval. The interlocutors accepted to have their finalstatements included into the report at hand.It should be noted that in a few cases the delegation (i.e. the authors of this report) found itnecessary to carefully adjust or clarify phrases in some of the approved notes by adding minorsupplementary explanations. These small adjustments have been marked with a closed bracket […].The delegation received extensive support from the Danish Embassy in Baghdad during itspreparations and the visit in the city. The Danish Embassy provided the delegation with logisticaland practical support and organized the delegation‟s meetings in Baghdad.The delegation to Amman and Baghdad comprised Jens Weise Olesen, Chief Adviser (Head ofDelegation) and Vanessa Worsøe Ostenfeld, Regional Adviser, both Documentation and ResearchDivision, DIS. Stewart Wheatley, COIS, UK Border Agency, UK Home Office participated in themission to Amman as a trainee and the report at hand is the sole responsibility of the DIS.Finally, publication of the report at hand was delayed as the delegation awaited approval ofstatements from an individual source – „a reliable source [in] Iraq‟- with central contributions to thereport.1

Iraq‟s disputed areas comprise parts of the Governorates of Tameem, Ninewa, Salah Al-Din and Diyala.

3

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

Lastly, it should be noted that the report does not contain information other than that which wasgathered up until mid-April 2010.The report is available on DIS‟s website:www.newtodenmark.dk

4

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

1. Security, human rights and indiscriminate violence in South/CentralIraqFrancine Pickup, Head, Inter-Agency Information and Analysis Unit (IAU), Strategic PlanningAdvisor, Office of the Deputy Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Resident andHumanitarian Coordinator (ODSRSG RC/HC), Amman stated that despite a downward trend in theoverall number of security incidents in Iraq from August 2007 to December 2009, the proportion ofcivilian casualties is shown to have increased steadily, with figures for December 2009 showingover 70% of all casualties classified as civilian.A new information tool developed by IAU, providing a detailed breakdown of attacks andcasualties throughout Iraq, both by Governorate and category of attack, will be available shortly viatheir website: www.iauiraq.org.The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) priorities have refocusedmore on the development context and capacity building in light of the improved overall securitysituation of the last twelve months. Concerning the latest security-related trends, potential tribalaspects of violence have not been explored as yet. Any kind of analysis of tribal or ethnic violenceis difficult to assess when it comes to determining which groups are specifically at risk.Reporting limitations make it difficult to determine if violence could be considered indiscriminateor not. It was added that compiling analyses with reference to ethnic or religious indicators iscomplex as government and some organisations and agencies are against it. Violence is also linkedto economic circumstances rather than political which is often overlooked as the primary focus ispolitical violence and not the violence caused by criminals and gangs.With regard to current security trends, Fyras Mawazani, Executive Director, NGO CoordinationCommittee for Iraq (NCCI), Amman, stated that although there has been a decrease in the numberof incidents since the beginning of 2007, the proportion of civilian casualties is on the increase withboth targeted and indiscriminate attacks occurring. NCCI confirmed the statistics on causalitiesprovided to the delegation by Francine Pickup, IAU, ODSRSG RC/HC, Amman. Fyras Mawazani,NCCI, Amman, added that earlier lots of attacks were military and involving insurgent groups, andthese incidents have dropped considerably during the last couple of years.As foreign troops are leaving Iraq, the number of attacks on these decreases and thus the number ofcausalities among these troops drops. However, even though insurgents target foreign and Iraqitroops and government institutions, including ministries it is very often civilians who becomevictims of such attacks.A source in Baghdad stated that in the last six months the situation Iraq is finding itself in clearlyone of internal conflict where protection of the civilian population does not exist.The source agreed with Francine Pickup, IAU, ODSRSG RC/HC, Amman that the securitysituation in Iraq for ordinary citizens has not improved and that there is still a lack of protection.A reliable source [in] Iraq stated that even though the political side of the source would like to seean improvement in the overall situation in Iraq an improvement in the security and human rightssituation in Iraq is very limited. It was added that the current security environment is fragile andunpredictable and one in which security deteriorates rapidly. There is no real improvement in

5

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

security in Iraq. While the number of attacks and security incidents may have dropped, this is noindication of a safer environment.The current security environment impacts on how the source can operate, adding that escorts whichare mandatory for movement are not always available. A movement of two kilometres in the city ofBaghdad could take a week to organize and access to grass roots is not easy. According toinformation from sources in Baghdad, Basra, Kirkuk, Mosul and Erbil, direct access to what ishappening on the ground is limited and one is always faced with lengthy procedures in order tocarry out activities. For example, a visit to a prison would take months to prepare. It is right toconclude that only “the tip of the iceberg” is probably known to the reliable source when it comes toobtaining information on human rights violations in Iraq.It was stated that generally, it is difficult to come to a firm conclusion as to who is most at risk inS/C Iraq. It was further explained that generally, information is supplied by NGOs, civil societylawyers and academics and that to a certain degree, the source follows up on allegations regardinghuman rights violations with the Government of Iraq (GoI) Ministry of Interior. It was explainedthat it [the source] has no mandate to investigate allegations that are made, however that it gathersand compares information regarding human rights and draws attention to human rights violations. Itwas added that within the context of planning and predicting of the next 5-10 years in Iraq, humanrights unfortunately tend to be of a lesser priority.The building of a National Human Rights Commission represents an important component in thenation-building of Iraq and underlined that giving the Iraqis ownership of this process is crucial.However, political divisions along ethnic, sectarian are religious lines are making it very difficult toestablish a fully independent human rights commission. The process of building a human rightscommission is only just beginning and already there are major issues due to these divisions. Theseproblems are already evident within existing Iraqi national commissions.Concerning human rights, there are no real improvements in Iraq. Detention and prison conditions,deprivation of the rights of women, inequality and protection of civilians is as bad as ever. It wasconsidered that recommendations and conclusions in United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq(UNAMI) latest human rights report covering the 1sthalf of 2009 probably will be reiterated inUNAMI‟s forthcoming human rights report.2Individuals can be targeted for their professional background, due to their ethnicity or religion orother reasons. The environment of chaos and a lack of effective state authorities are behind thiscurrent situation. However, to speak of or define systematic targeting of a certain group is difficult.It would be easy to interpret incidents that occur, including targeted killings, in this light, howeverthey must be understood in the context in which they happen and the lack of state authority. Havingsaid this, there are incidents that definitely are tainted by the appearance of systematic targetedkillings.

2

UNAMI‟s human rights report covering the 2ndhalf of 2009, the period 1 July - 31 December 2009, is now available athttp://www.uniraq.org/documents/UNAMI_Human_Rights_Report16_EN.pdf . The report was released on 8 July 2010.

6

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

Mass violence causes people to move. Reference was made to the Christians from Mosul that havemoved in masses from Mosul and where many return as the situation calms. This sort of movementis still occurring. Additionally, people are still deciding to leave Iraq and few would return becauseof the security situation. Those Iraqis who do return to Iraq are those who are desperate and have noother solutions after having tried to make it outside Iraq.Concerning the security situation, a reliable source [in] Iraq stated that since 7 March till mid April2010, the number of incidents has been rising steadily as well as the number of victims affected.Prior to this, there were a couple of months of relative calm. The development illustrates that goingthrough a period of calm cannot be an indicator of a bettering of the security situation in Iraq.Reference was made to a national staff to the UN who received a threat on her car window twoweeks ago stating allegations of her being a traitor, causing her redeployment to Erbil. Even UNstaff are still terrorized and the psychological terror against individuals is one many live with daily.Due to the fact that UN in order to carry out its activities is dependent on the support of UnitedStates (US) forces, UN staff are considered part of the coalition and thereby occupiers of Iraq.Being employed by the UN involves a security risk to the employee that is to be taken seriously.Relatively speaking, the security situation is much better than it was in 2005 and 2006. One couldspeak of an Iraq moving from a very bad situation to a bad situation security-wise.An UN source [in Baghdad] informed that Iraq has made significant progress in dealing with theinsurgency and improving its security since the peak of violence in 2006 and 2007. The violencewitnessed in Iraq has been in essence political and further improvement of security will dependlargely on internal and to some extent, external political factors.Assuming that major ethnic/religious groups and political parties would constructively approach thenext stages after the March 2010 parliamentary elections, Iraq is expected to continue to experiencegradual stabilization. It will be important to closely monitor Iraq‟s overall political progress inconjunction with actions by Armed Opposition Groups (AOGs). While some of the groups willcontinue their efforts to influence political developments through violence it is possible that manyAOGs will incrementally move towards a less ideological, more opportunistic and/or criminalenterprise approach.The UN in general will remain a high-value target for some of the AOGs. However, with thedrawdown and withdrawal of the US forces and increased reliance by the UN on Iraqi SecurityForces and diversification of UN activities and presences, it is possible that security and safety forUN staff would generally improve. This in turn could increase the UN‟s ability to deliver itsmandates. Geographical differences will continue to be observed as most of the Sunni AOGs areconcentrated in Northern, North Central, Western, Baghdad and the upper South Central areas.The security situation in the Iraq Kurdistan Region (KRI) will likely remain permissive for UNoperations but may be periodically influenced by political dynamics in the region and tensions overthe Disputed Internal Boundaries (DIBs).A reliable source [in] Iraq stated that generally, law enforcement and military forces in Iraq areunable to control the situation and protect the people from security incidents that may occur. Thereare areas that even law enforcement authorities and military forces are unable to go, for exampleareas of Mosul city as well as along disputed areas. Baghdad also has areas that authorities will not

7

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

go into. In such areas there may be a presence of Al Qaeda Iraq (AQI) or insurgent groups that infact have control and are harassing and targeting the local population. The authorities remaincompletely incapable of addressing such issues. It was added that UNAMI Security Section Iraq(SSI) would be able to provide more information on this.An international NGO in Amman stated that the organisation has a reading of the securitychallenges, as well as the challenges facing minorities in S/C Iraq. It was added that it is present in12 governorates in Iraq, including the governorates of KRI, but due to limited access, does not havea full picture.Concerning security related issues, an international NGO in Amman explained that it relies ondifferent sources with regard to the situation in S/C Iraq. Information is provided throughmonitoring media as well as through UNDSS (United Nations Department for Safety and Security)and UNAMI SSI monitoring reports, information from deployed staff, local NGOs, local staff,INGOs and authorities, including local government agencies.It is difficult to provide a detailed analysis of the security situation but provided an overview of thetrends of the past year or so. As mentioned, the international NGO relies on a variety of sources,adding that different sources do have different indicators and frameworks in compiling theirinformation and thus have varying information on security.The number of security incidents has decreased since the surge in 2007. An international NGO inAmman described this surge as a turning point, and for the international NGO, freedom ofmovement for internationals/foreigners has improved in certain locations, although many actorsconsider it still necessary to move with armed protection. However, insurgents and/or armed groupsare still present in S/C Iraq, despite the fact that the number of incidents involving these groups hasdecreased.In 2008, there were high hopes for improvement in security and opinions have been split amonginternational NGOs about the security situation in S/C Iraq. South Iraq was considered more securethan the rest of Iraq, largely due to the increased homogeneity of the area. However, in the secondhalf of 2009, this part of Iraq has experienced deterioration with regard to security. A sharp increasein crimes during second half of 2009 contributes to this trend and there has also been a sharpincrease in robberies and kidnappings for pure financial gain. This development is largely linked tohigh unemployment, lack of income and the general very poor level of services available to Iraqis.Tribal issues also contribute to violence in parts of Iraq. However, while „tribal issues‟ is asomewhat unchanging aspect in Iraqi society, the number of crimes due to economic hardship hasincreased. This increase is not prompted by tribal conflicts, but rather due to economic hardship.Crimes committed for financial gain are more widespread now, an example being kidnappings ofchildren of wealthy persons. It also occurs that criminals pose as security forces or police inuniform. This leads to further mistrust towards the authorities as basically people are not able todistinguish between real police and criminals.It was considered that while UN claims to be back in Iraq, this is no indicator of an improvedsecurity situation in general. UN presence is heavily guarded and movement by UN is done alwayswith the escort of multinational forces and anyway subject to restrictions, leaving few areas whereUN actually can move around.

8

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

During the latest months, South Iraq has witnessed an increase in attacks against US forces andIraqi security forces, occurring in connection with operations aimed at targeting insurgent elements.Operations consequently led to retaliation attacks from insurgent groups which have been muchstronger than before.However, information concerning these incidents is hard to obtain as the primary source would bethe armed forces. The international NGO in Amman is obtaining information via secondary sourcesprovided by local sources, while only the major incidents are reported in UN security reports.In order to have a stable and positive development in Iraq, there has to be a stable and capacitatedgovernment. However, the South is still fragile and in need of strong capacitated authorities. This isthe case for most of Iraq. There are strong differences concerning whether or not Iraq should becentralized or decentralized, and the discrepancies that exist affect the local political dynamicsmaking these unstable. Therefore it will take some time before one will witness a stable politicalenvironment. The local elections of January 2009 were hailed as being very positive, however infact it took until April 2009 to get local governing bodies in place. The 2009 elections illustratedthat it is difficult to establish a clear political consensus.Many are quite quick to claim that Iraq is a rich country with lots of resources (mainly oil) at hand.However, few point to the fact that Iraq does not have the necessary capacity to spend its riches. Inits way of spending, Iraq is very far from delivering basic services to the population, and this ismainly due to lack of capacity and due to rampant corruption.Another issue is that areas in S/C Iraq which suffered massive displacement are currently lackinghuman capital. Mostly throughout central Iraq, especially Baghdad skilled persons fled, while in theSouth this was less the case as there was much less fighting in the South. Reference was made to themedical profession which is in crisis, as there is a serious lack of qualified staff. In general, stateinstitutions are still suffering in Baghdad due to lack of human resources as many professionalshave fled the country.Central Iraq experienced the first massive brain drain after the fall of the regime in 2003, while thesecond big wave of skilled persons fleeing came about in 2006. Due to the lack of skilled persons,many students for instance have become teachers even before they graduated.Security in Iraq in general, is also dependent on the regional dynamics. For example a situationwhere Iran is clashing with Gulf countries has an impact of Iraq. Alternately, if Iran is negotiatingwith countries in the region, the situation in Iraq might improve.Kent Paulusson, Senior Mine Action Advisor, United Nations Development Programme - Iraq(UNDP - Iraq), Amman explained that it is the UNDSS that determines the UN security level inIraq. This level is presently at Phase 4 all over Iraq, including KRI. Currently the central parts ofIraq are more unstable than southern Iraq, however it was added that areas north of Basra could alsobe quite stable, e.g. in Nassiriya.There appears to be an increasing separation between religion and politics in Iraq, and this means adiminishing of sectarian violence. However, it is impossible to say which way the situation evolvesfor Iraq. Some improvement in the security situation appeared in 2008. In the spring of 2009, therewas a steady increase in the number of incidents however the situation is nowhere near the volatilesecurity situation of 2006-2007.

9

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

Nicola Graviano, Programme Manager and Liana Paris, IDP3Monitoring Project Officer, IOM -Iraq, Amman informed that internal displacement due to conflicts in Iraq does not occur to the sameextent as before, although it is still taking place in some cases.Hakan Salo, Regional Security Advisor, IOM - Iraq, Amman commented that the current situationwas “a little bit better” than it had been in the last two or three years. It was added that the statisticaldownward trend in attacks and casualties “does not prove anything” and that it is the civilianpopulation that is suffering most. A significant factor is the volatile nature of attacks, which meanthat the security situation could intensify very quickly from a period of relative calm. However, itwas added, security incidents often come in waves.Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Amman stated that IOM is unable to provide anyanalytical assessment on the links between the security situation and displacements levels withinIraq, although commented that most internal displacement occurred during the period 2006 and2007, and that displacement has since subsided.The fact that some areas are more receptive for return does not necessarily mean that they arecompletely secure for everybody: individual circumstances are different for every migrant orinternally displaced person (IDP) even in the same area.Hakan Salo, IOM - Iraq, Amman stated that to some degree people have stopped receiving “bulletson their doorsteps” or threats from sectarian violence. The number of security incidents has comedown from a height of around 200 incidents per month, to less than 100 currently. The UN agencyIAU would be able to provide further statistical information on this subject.However, it was added that the types of risks have perhaps taken on a different shape and thesecurity incidents that occur currently include indirect fire, vehicle bombs and suicide attacks.The situation is still volatile, and indiscriminate violence does still occur and that the main aim ofthese attacks is to kill as many people as possible. Attacks can take place a mosques and marketplaces, targeting as many as possible. Tensions are still high and fear widespread.Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM – Iraq, Amman informed that IOM does not have anyinformation on who had orchestrated these attacks.1.1. BaghdadKent Paulusson, UNDP - Iraq, Amman explained that in Baghdad, the Iraqi military and securityforces are currently taking over some responsibilities from US forces and the professionalism ofthese forces is of concern. For example, there have been recent incidents of bombings where it islikely that forces at checkpoints have been bribed by terrorists wishing to pass. It appears as ifinsurgents are able to influence forces.Concerning the security situation in Baghdad, an international NGO in Amman stated that it hasjust a small representation in Baghdad.

3

Internally Displaced Person

10

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

The second half of 2008 saw some improvement in Baghdad which however, has been short-termand the situation has since deteriorated. As of today, impunity is prevalent in Baghdad and otherparts of Iraq. Returns to Baghdad were encouraged during the short period of improvement andreturns do still take place. Returns that are taking place are however happening along sectarianlines. Persons returning are doing so to mostly homogenous areas and therefore not actuallyreturning to their place of origin.Crime is also a big issue in Baghdad as well as the rest of Iraq, and the feeling of impunity thatexists in Iraq is adding to the problem. Law enforcement is “close to zero”, and there is a generalatmosphere of impunity, according to an international NGO in Amman, and this is confirmed by itsbeneficiaries.Hakan Salo, IOM - Iraq, Amman informed that the hotspots for indiscriminate violence in Iraqincluded Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk and Mosul. Additionally, finding valid information on thesituation is problematic due to travel restrictions for security reasons imposed on independentobservers. Diyala is one of the most difficult areas to get around, even if there are no incidents,there are lots of tensions and fear of insecurity.1.2. Disputed areas, Ninewa (Mosul), Diyala (Khanaqin) and Tameen (Kirkuk)Disputed areasConcerning the situation of minorities, Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Ammanexplained that Christians were fleeing to the North “as we speak”. The Kurd-Arab fault line alongthe disputed boundaries leads to a tense environment and minorities find themselves caught up inthe situation. Among those fleeing are Christians but also Turkmen as well as Yazidi families. Inmany areas minority groups are being utilised at the time of elections in attempts to change thepower and voting dynamics of an area. In Kirkuk people finding themselves in a minority positionare fleeing to more homogenous areas.Along disputed boundary areas where there are minority groups, there continue to be small flows ofpersons being displaced and who feel they are unable to return to their area of origin. The majorityof displacement however, has happened from Baghdad and Diyala. Returns are occurring, but theyare localized and it is very hard to make generalizations regarding any trends concerning themovement of return. However, “we can say that the bulk of IOM-assessed return has occurred toBaghdad, Diyala, Anbar, and Kirkuk governorates.”A reliable source [in] Iraq informed that in disputed areas, Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG)forces are de-facto the controlling authorities and not the GoI forces. Officially, this should not bethe case, however on the ground this is the reality largely due to KRG forces superiority with regardto organisation and effectiveness.Concerning disputed areas, an international NGO in Amman stated that most of the areas, includingthose in Ninewa, are being controlled by the KRG forces, while Kirkuk is an exceptional case.While Iraqi security forces are in place in disputed areas, the control is de-facto in the hands of the

11

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

KRG forces. Recently joint checkpoints of both ISF and KRG forces have been established in someareas, overseen by the Multi-National Forces Iraq forces (MNF-I).4In fact security in the disputed areas in actuality is better compared to other areas of Iraq. Theunresolved status of the disputed areas is a great source of tension, however until a solution isfound, a fragile security will probably remain.A reliable source [in] Iraq stated that slowly areas are being more homogenous. Many minoritiesfrom S/C Iraq go to Bashekhan, Ninewa in the North.Ninewa (Mosul)A reliable source [in] Iraq stated that the current situation in Iraq is volatile and persons are stillbeing displaced. There are reports of incidents involving kidnappings, murders and harassmentagainst groups and persons. There is movement e.g. from Mosul city to enclaves within the disputedareas where KRG are able to provide security. Many persons are under such circumstancescompelled to take on a Kurdish identity or express loyalty to the local authorities in order to firstly,obtain protection, and secondly, obtain access to services that may be available in the area.In Ninewa, there are efforts towards stabilizing the area in which the US is playing a supportiverole. KRG involvement in the areas that are disputed result in those areas being more secure. Itshould be considered however, that the KRG involvement is based on its determination to get thoseareas under official KRG control and therefore leads to tension in the areas.Mosul is probably the worst place when considering security conditions, but also minorities withindisputed areas may be in a tough situation. However, disputed areas themselves are relatively safecompared to many other areas in the vicinity of the disputed areas.In Mosul, GoI forces officially control security and that KRG Peshmerga does not interfere in thecity. Generally, KRG Peshmerga are far better organized and reliable and as a result more effectivethan GoI forces in addressing security.As for Mosul city, the Head of Police is replaced quite frequently, and each time a new head takesoffice, all files are removed thereby allowing an atmosphere of complete impunity. The situation isparticularly acute in Mosul with regards to security. The disputed areas are in actuality much saferfor minorities due to KRG control. Comparing to the situation in Mosul in 2008 where severalattacks on Christians took place, there has in effect been no change since. There may be periods ofcalm for a short while during which security restrictions have been set in place. However, once suchrestrictions are lifted, the situation turns volatile once again. There is no foreseeable change to thissituation in the near future.An example of the violence that still occurs, involving civilian victims, Fyras Mawazani, NCCI,Amman referred to the recent violence against Christians in Mosul. OCHA reported on 28 February2010 that “between 20 and 27 February 2010, some 683 Christian families (4,098 people) becamedisplaced from Mosul city to Ninewa governorate; most of the displacement occurred between 24

4

U.S. Forces-Iraq (USF-I) formally replaced Multi-National Force-Iraq (MNF-I) on January 1, 2010.

12

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

and 27 February. This follows increased attacks by unidentified armed groups, which have left atleast 12 individuals dead.”5Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Amman stated that IOM is not aware of who could bebehind the recent targeting of Christians in Mosul. Essentially, nobody has taken responsibility andnobody knows who was behind it. Displacement incidents from Mosul continue, and political issuesplay a role in this being the situation.Diyala (Khanaqin)Regarding security in Diyala, an international NGO in Amman stated that the governorate iscomparable to Baghdad as it also is a somewhat mixed governorate of Shia and Sunni Arabs andKurds. Additionally in Diyala, there are some of the same militias and armed groups operating as inBaghdad. The second half of 2008 also witnessed an improvement in security and thereby resultingin some return to the governorate. However, this development was not sustained and the recentpolitical process has not improved security in Diyala. The economic factors contribute toheightening insecurity, including decreasing oil prices that led to a drop in economic support fromGoI.Regarding the recent deterioration of the security situation in Diyala, the international NGO inAmman informed that this is also due to an increase in the presence of armed groups in thegovernorate. Furthermore, the level of sectarian discourse has increased in Diyala. An example ofthis trend is that Sunnis increasingly are feeling marginalized and fear being subject to arbitraryarrest, all the while Shia are claiming that they simply are applying the law. Security challengespresent in Diyala are comparable to those in Baghdad.KirkukA reliable source [in] Iraq stated that Kirkuk, with its unique status, is a completely different matter.The situation is fragile and Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and US forces have a strong presence in thearea. AQIs and insurgent groups‟ presence contribute to making the situation particularly volatile,and there are reports that AQI is using children as suicide bombers or combatants in Kirkuk.Concerning disputed areas, an international NGO in Amman stated there is no decision on when thestatus of Kirkuk will be determined.Due to the fact that Kirkuk is so contested, it is very difficult for persons originating from there totransfer their Public Distribution System (PDS) card6as it entails changing official demographics ofthe areas. This is not contained to Kirkuk, but is in actuality happening all along the disputedboundary areas.

5

OCHA,Iraq, Displacement in Mosul, Situation Report No. 1,28 February 2010.

6

Iraq‟s state food rationing system is known as the Public Distribution System (PDS). Monthly PDS parcels aresupposed to contain rice (3kg per person); sugar (2kg per person); cooking oil (1.25kg or one litre per person); flour(9kg per person); milk for adults (250g per person); tea (200g per person); beans (250g per person); children's milk(1.8kg per child); soap (250g per person); detergents (500g per person); and tomato paste (500g per person). (IRIN,IRAQ: Iraqis welcome WFP role in state food aid system,January 6, 2010.)

13

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

1.3. Armed groups, insurgent groups and criminal gangsConcerning different armed groups that operate in Iraq, United Nations High Commissioner forRefugees - Iraq (UNHCR - Iraq), Baghdad stated that the situation is fluid, and while there are some„official‟ militias that are known, and each political party has its own militia, underneath this thereare a number of “invisible” militias that one does not know about. Many would say that one worriesabout the militias one does not know about.There are reports of armed groups dressing in government military uniforms. This has led torestrictions on the making and selling of uniforms.A reliable source [in] Iraq explained that it is not possible to generalize with regards to the intent ofattacks and motives that lay behind armed groups‟ activities. The result of attacks and incidents isindiscriminate loss of life however it is difficult to state that overall attacks are terrorists aiming atkilling as many as possible. The use of the term terrorism has been used and misused to a greatextent in Iraq and continuation of this often leads to overlooking the complexity of the situation,including the intent of perpetrators. Additionally, the law is deficient in its use and handling ofterrorism in e.g. criminal proceedings.The anti-terrorist law in the hands of the government is subject to abuse, and when the governmentwishes to target an individual it serves as a convenient tool. For example, political persons may bearrested under the auspices of the anti-terrorist law and as it is carried out by the Ministry ofInterior, i.e. without a warrant, access to basic rights and fair trial is not likely.There are Sunni and Shia groups as well as Baathist groups, all claiming to be resistance groupscarrying out their insurgent activities. These groups also target professionals who according to themare disruptive from an ideological point of view. These professionals could be judges, lawyers andin some cases journalists or even persons that do not go in line with these groups‟ policies. It wasadded that journalists are mostly targeted by the authorities with the aim of shutting them up.David Helmey, Operations Officer and Rania Guindy, International Caseworker, OverseasProcessing Entity, IOM - Baghdad, Baghdad stated that the biggest threat to security in Iraq iscurrently emanating from AQI, and there are different opinions as to how many there are.AQI is working with the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), except when it comes to Diyala governoratewhere the two groups are rivals as ISI have sided with the Sahwas.Additionally, armed opposition groups (AOGs) remain very active and there are a range of differentgroups, including offshoots of the Mehdi Army. The Mehdi Army itself is an undisciplined, looselyorganized group that is also involved in demonstrations. The group was described as not asideologically-based as AQI. The Mehdi Army is known for carrying out shootings and forabductions for financial gain. The Mehdi Army controls Sadr City and it has official offices in thisdistrict of Baghdad. There are over 1 million inhabitants in Sadr City.There is a fine line between criminal gangs and the newly-established ideologically-based groups.There is an area in North-western Baghdad characterized by slum-like conditions which couldlikely be an AQI base. AQI also has a presence in Mosul and Abu Ghraib – one of the mostdangerous areas in Iraq, and the group is likely to be present in Kirkuk and Ramadi as well. It wasadded that there are signs that AQI is back in Diyala as well.

14

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

The latest security incidents that have taken place in early April [2010] have been a bit surprisingtaking into consideration the recent patterns and therefore have been hard to read. However,generally Iraq is still in a state of chaos and this is reflected in the security situation. Everyone inIraq is a target of the AOGs who want to weaken the government. Indiscriminate violence is stillvery high. Tensions are high and the AOGs are trying to show their strength. It was added that thereare AOGs that are aligned with different politicians.According to an international NGO in Amman, it is hard to speculate on who make up the insurgentgroups in S/C Iraq, although it is commonly known that some are believed to have links toneighbouring countries.Small and medium-sized groups are organizing themselves in criminal gangs. Concerning theincidents that are reported of children, judges, scholars, doctors, journalists and others beingtargeted for kidnappings, the perpetrators of such acts may well be linked to these sorts of criminalgangs rather than political groups. Some of these criminal gangs or persons within the gangs enjoysome sort of protection that may be tribally linked (see section on Protection by tribal network).Concerning Sahwas, i.e. Sons of Iraq or Awakening Councils, Sylvia A. Fletcher, GovernanceTeam Leader and Mohamed El Ghannam, Senior Programme Advisor, Rule of Law & JudicialReform, UNDP - Iraq, Amman stated that they are not widespread and only exist in Sunni areas inthe two governorates of Anbar and Diyala. The Sahwas are protecting people from terrorist groupsand Sahwas have also been targeted by insurgent and armed groups. It was added that the Sahwasdo not provide protection against ordinary criminal activities.A UN source [in Baghdad] stated that although there have been several mass casualty attacks in thelead-up to the parliamentary elections [March 2010], AQI and other Sunni AOGs have lost much oftheir capacity to carry out frequent and high-impact operations. The threat posed by the Shia AOGshas been sharply reduced, mainly due to a unilateral ceasefire and early participation in the politicalprocess. However, they still retain significant capabilities and, in some cases, outside support. ShiaAOGs mainly operate in Baghdad, South Central and Southern Iraq.1.4. Security and humanitarian concernsFrancine Pickup, IAU, ODSRSG RC/HC, Amman explained that from a humanitarian perspective,there are still needs and OCHAs Humanitarian Action Plan identifies the main humanitarianconcerns to OCHA. Food insecurity is low, largely due to the Iraqi PDS system. There are,however, major gaps in social services, and these are almost completely broken down in manyplaces. IDPs and refugees remain vulnerable, however many in this category are quite affluent incomparison to local populations.Francine Pickup, IAU, ODSRSG RC/HC, Amman, noted that analysis of IDPs and refugees againstlocal host populations does not draw out any strong indicators that they are necessarily more in needof humanitarian assistance, however this varies from place to place and IDPs living in camps are themost vulnerable. It is necessary to target assistance according to need and not status.It was further added that there is no correlation between the security situation and returns which sheconsidered as strange. The rate of returns is not expected to rise significantly while the securitysituation remains unstable, particularly due to the socioeconomic situation which is characterized bylack of services and job opportunities.

15

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

Other humanitarian factors facing Iraq are a lack of investment and capacity within the stateinfrastructure to improve service provision. People often think of Iraq as a rich country, however inactuality this is not the case. A significant majority of Iraq‟s budget goes to operationalexpenditures, such as payment of government salaries and the PDS. Very little is channelled intoinvestment of services. A primary expenditure is the PDS system, costing between five and sixbillion USD yearly. Reforming the PDS system is a UN as well as a GoI priority. As an oil-dependent economy Iraq is vulnerable to falling oil prices. Additionally, the oil industry in Iraq isnot creating many jobs and the private sector in general is very weak. It is expected that governmentsocial services will deteriorate in the coming years unless oil prices increase.On the issue of unemployment, Francine Pickup, IAU, ODSRSG RC/HC, Amman, stated that theunemployment rate for Iraq is approximately 15% which is not particularly high. IAU added thatIOM would have its own data regarding unemployment rates among IDPs. However it is importantto consider that many are not adequately employed and much employment is informal and part-timeand underemployment is an issue. The government is the largest employer and employees have jobsecurity for life.However, finding employment in the public sector is difficult for young people as older personsoccupy a large proportion of jobs in the public sector. Private sector employment is limited and thatemployment in the private sector is often more insecure and lower paid. Job seekers often lack theskills required. It was added that often the only public job opportunities for women would beteachers, medical doctors.Economic activity among women up to secondary school education is restricted due to the lack ofsectors which are considered socially acceptable to women, and low education status. Anecdotalevidence suggests that women‟s freedom of movement, education and participation in public life ismore difficult than it once was, but there is a lack data for comparison on this issue.Concerning return of asylum seekers Fyras Mawazani, NCCI, Amman, stated that the NGO isagainst the return of rejected asylum seekers to Iraq because security and livelihood is fragilethroughout the country. The unemployment rate in Iraq is 18 % according to UN figures however,NCCI, Amman considered the unemployment figures provided by the UN to be too low and onlyreflecting the official unemployment rates. NCCI, Amman added that employment in Iraq is notsecure unless you are employed by the Government authorities.Regarding access to schooling, education facilities are in a desperate state as there is a lack ofteachers. Many teachers have been targeted by insurgents and most have fled the country. Almostall of the new teachers have only recently graduated and they are not well qualified. At the sametime it has been very difficult to establish a new curriculum for Iraq.Concerning housing Fyras Mawazani, NCCI, Amman, explained that many returnees find itdifficult to return home as their houses have been left in bad conditions. The government hasestablished a Housing Commission in order to return houses to returnees. However, the commissionis marred by corruption. It was added that many refugees sold their houses before leaving Iraq andthey may not have a house to return to.

16

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

1.5. Security and returnsLooking at the level of violence, a source in Baghdad considered it to be problematic that personswere forced to return to Iraq. Relatively speaking, the number of civilian casualties has increasedsteadily and one cannot speak any longer of an improvement in security for Iraqis.Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Amman explained that IOM has field monitoringteams in Iraq which provide information on displacement and returns; this includes ethnic andreligious data. Data collected by IOM is separate and independent from that gathered by UNHCR.Iraqis returning from European countries through the IOM Assisted Voluntary Return andReintegration (AVRR) programme are asked why they left and why they return, and responsesdiffer from area to area. Patterns indicate that security situation is a factor[ and] lack of economicopportunities is another major reason to leave Iraq. IOM does not promote returns from abroad toIraq but gives the possibility to return to those migrants who wish to do so voluntarily. IOM doesnot influence the decision to return, which is eventually taken by migrants themselves, taking intoaccount personal situation and family priorities.Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Amman, informed that their main focus is the needsof returnees and IDPs and not on human rights and security. Many Iraqis that are displaced, feelthey are unable to return, and are finding themselves living under difficult circumstances as all IDPsdo everywhere in the world.The majority of returning IDPs return to their place of origin, so Kurds go to KRI, however in somecases, they may choose to return to other areas to take care of family matters. It was added thatthere are major disparities in return patterns and some return to areas perceived to be safe whileothers may not be able to do so due to lack of economic means.In considering IDP movements from KRI to the rest of the country, this is occurring on an ongoingbasis with assistance provided through the [Bureau of Displacement and Migration] (BDM) and the[Ministry of Displacement and Migration] (MoDM). „Pull factors‟ for return to Central andSouthern Iraq include improved security and the MoDM returnee grant. „Push factors‟ include therelatively high living costs in the KRI which had adversely affected IDPs. Some IDPs arecompletely dependent on the food rations they receive through the PDS system.According to IOM monitoring, 76% of persons displaced to Basra and assessed by IOM say thatthey want to stay in the area and integrate. This is often because they feel safe there and may havehistorical, family, or economic ties to the area.Roughly 80% of the returns from Europe are to KRI. Approximately 15-17% of migrants arereturning to Baghdad while 3-5% are returning to Basra. It was added that most cases of refugees'resettlement come from Baghdad area.It is IOM‟s experience that Iraqis returning from Europe do so to their place of origin. Return ofIDPs in KRG to the rest of Iraq is also an ongoing process, and the BDM and UNCHR as well asIOM is involved in assisting Iraqis wishing to return to areas of origin. When asked why IDPs areleaving KRG, Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Amman explained that a high cost ofliving and high unemployment could also be push factors. It was added that there are no reports ofIDPs being pushed out of KRI by the KRG authorities.

17

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

Returnees who took part in AVRR, have returned mainly to their place of origin, however NicolaGraviano and Liana Paris, IOM – Iraq, Amman stated that IOM is not always able to provide anyfurther analysis on whether such returnee groups have been become displaced again. Although IOMaims to contact returnees after between three to six months of their return to assess their situation,sometimes returnees do not want to be monitored by IOM or returnees have changed their contactdetails.With regard to return of IDPs, according to Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Ammanwhen they return to their place of origin, they will stay in one place, but need the support of thelocal community to reintegrate.IOM had received “limited and anecdotal reports” of returnees being targeted, often this would beindividuals or families. IOM did not have any information on why such targeting had occurred orwho the perpetrators were.Nicola Graviano and Liana Paris, IOM - Iraq, Amman said that they have no specific accounts ofIDP returnees experiencing problems when travelling back to their home area and that movementfor IDPs was no different than for ordinary civilians. However, it was added that security in Iraqremains unpredictable and fragile and varies from place to place.When asked if returnees are particularly targeted, an international NGO in Amman stated thatreturnees are affected by the general situation in S/C Iraq. It is hard to verify if these persons are atrisk of being especially targeted, however the international NGO has heard of returnees fromEurope and Canada being considered well-off and therefore perhaps prone to attacks from criminalgangs. However, there are no confirmed reports of this being the case. It is hard to obtain qualifiedreports concerning this matter. Furthermore, every governorate, even district, has its own localdynamics that affect how persons fare upon returning to S/C Iraq.Additionally, in the case of S/C Iraq, many returnees are coming back from Syria and Iran and theyare often without many funds. Another factor of a more psychological nature is that these returneesinitially fled during Saddam Hussein‟s regime for political reasons, and upon return, they areperceived as martyrs in some sense, and criminals may be more apprehensive with regard totargeting these persons. Finally, the number of returnees in the South is not that high, so it is hard tosay whether not these persons are targeted by criminals or not. It is difficult to conclude [whether]returnees are targeted or not on the basis of such a small number.Some refugees are returning to Iraq because they don‟t have the resources to stay abroad, e.g. fromJordan or Syria. Some think that they can return to the places that are now largely homogenous,while others return to obtain compensation that has been provided by GoI to returnees. In somecases, returnees leaving their families abroad merely register and collect their compensation uponwhich they leave Iraq for their families once more.There are no clear trends with regard to returns. A major impediment that discourages return is thelack of employment available to Iraqis returning to the country.An international NGO in Amman stated that a figure of 15-18% unemployment in Iraq given byother sources is underestimated to portray the situation in Iraq. These figures are derived throughInternational Labour Organisation (ILO) methodology which cannot be applied in the Iraqi context.

18

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

There is a lot of underemployment in Iraq and many merely are employed with causal labour. Amodest estimate is that unemployment is at least 40%. Of the Iraqi population, 60 % is under 25years of age, and thereby each year about a million persons are entering the labour market. It wasadded that ordinary people who are not employed within the government sector would state thatthey are unemployed.The perception of employment is also very different in Iraq and the means of sampling needs to bemodified to the Iraqi context. At least 40% of Iraqis do not have an income. The government of Iraqis by far the largest employer, as is the case in many Middle Eastern countries. Working in theprivate sector is regarded for “losers” while persons working in the state sector have some sort ofsecurity in their job and livelihood as well as access to services. Additionally as a civil servant, onehas an acquired right to transfer one‟s government employment should he or she relocate withinIraq.According to Fyras Mawazani, NCCI, Amman, the very poor segments of Iraqi society were unableto flee Iraq while members of the lower middle class fled to Syria whilst the upper middle classmembers fled to Jordan. Returnees have come back to Iraq predominantly for economic reasons,although unemployment and housing needs continues to be a problem for such groups once theyreturned.Refugees returning to Iraq also continue to face problems in light of the security situation. Despitethe fact that the security situation in Iraq has improved during the last years with regard to thenumber of civilian deaths since 20077, Fyras Mawazani, NCCI, Amman, felt it was too early toconclude that the security situation has stabilised, particularly in Baghdad and Mosul. Figures mayindicate that security is better however, it would be misleading to conclude that security isguaranteed. There are daily explosions and attacks in Baghdad. In Southern Iraq, Fyras Mawazani,NCCI, Amman, considered it to be safer today than it used to be, but there are still problems overpoverty and drought as well as lack of educational services. On the other hand, daily violencecontinues to be a problem particularly in central governorates, including Baghdad as well as Anbar.Many Sunni refugees do not necessarily want to return home, as they may feel particularlythreatened in their place of origin. Returnees from neighbouring countries and KRI mostly originatefrom predominantly Shia-dominated areas and are returning to the South. Some, both Shia andSunni, will also not wish to return to their place of origin if they are perpetrators of human rightsviolations or other crimes and thus fear revenge.Conditions today are not met so that Iraqis can be returned against their will, and NCCI hasparticipated in international forums to lobby on the issue of return. In meeting its objective incapacity building and empowerment of civil society in Iraq, NCCI is currently working with 247

Iraqi Body Count, The annual civilian death toll from violence in 2009 was the lowest since the 2003 invasion, at4,644 by Dec 31 (2008: 9,217), and had the lowest recorded monthly toll (205 in November). However, for the firsttime since 2006 there has been no significant within-year decline, and the second half of 2009 saw about as manycivilian deaths as the first. This may indicate that the situation is no longer improving.http://www.iraqbodycount.org/analysis/numbers/2009/

19

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

local partners points inside Iraq. NCCI has a memorandum of understanding with the 24 NGOpartners who are all members of the NCCI platform to provide information on humanitarian issues,security, human rights and political issues. The 24 NGOs provide NCCI with bi-weekly reports onsecurity and human rights violations in all of the 18 Iraqi governorates for the members of theNCCI platform. On specific requests, NCCI Amman is able to share some of its information.

20

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

2. Security and human rights for ethnic and religious communitiesConcerning minorities UNHCR - Iraq, Baghdad stated that it appears that the government is readyto look into the issue of minorities. However, the economy is not stable in Iraq and the minorities(lacking armed protection) may be at greater risk of being targeted.A reliable source [in] Iraq stated that generally, targets against persons for whatever reason may notbe as rampant as in 2006-2007. Looking at calmer areas, it may be less likely that persons aretargeted and the changing demographics also play a determining role. Persons finding themselves asa minority in a certain areas may be more vulnerable to attacks and threats.Reporting what happens on the ground with regards to human rights violations is difficult. It wasstated that reporting on human rights violations on the ground in Iraq only shows “the tip of theiceberg”. Capacity for independent monitoring is limited and underreporting is to be expected.Official reporting may be rushed and inaccurate, referring to the Ministry of Health‟s hesitation torelease genuine numbers regarding casualties in very critical periods.Concerning the establishment of a National Human Rights Commission in Iraq, the source washesitant in labelling its future establishment as “a milestone of historical dimension”.Irrespective of where minorities find themselves in S/C Iraq, they may suddenly be at risk due to thecycles of violence that characterize S/C Iraq. There is no effective control and groups or individualsmay find themselves at the wrong place at the wrong time. There may be periods of calm whensuddenly violence breaks out. In such a situation, minorities will be particularly vulnerable.Generally in KRI, there seems to be a higher tolerance for minorities, and KRG is more able toprovide safety. In S/C Iraq (GoI area) as a minority, “your destiny is uncertain.” There is no lawenforcement protecting minorities in S/C Iraq and no „minority-friendly‟ body anywhere to provideassistance. In 2007, when Christians were being expelled from Baghdad, there were efforts to tryand address issues related to selling of property to ensure that persons were not forcefully sellingtheir houses.Concerning the security and human rights situation, it is still unpredictable with regard tominorities. Today there may not be much to report, while next week there is plenty. There may becircumstances in which one‟s background is relevant in relation to one‟s security, be it ethnic orreligious, or even one‟s gender and age. However in other instances, it may be irrelevant.Essentially, place and time, as well as a range of other factors, may be determining.Ethnic and religious minorities are in a violent environment often targeted as well as pressured intoleaving certain locations. It was added that pressure to relocate can stem from a wish to influencedemographics of certain areas. A person could be forced to sell his or her land and/or house andmove away, or be deprived of services in a certain area. It was stated that pressure on minorities canderive from both authorities and local communities, however added that the situation is highlycomplex. There are centres of power locally, and the divides in society are also reflected ingovernment.Further it was explained that it is important to be cautious in using the term „ethnic cleansing‟ andtargeting on the basis of ethnicity in the Iraqi context. Reference was made to an incident in Mosulwhere a tax collector was assassinated. The tax collector was a Christian and it was the general

21

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

perception that the tax collector was killed due to his religion, however it became evident that hewas targeted due to his profession and not because of his religious or ethnic background.Additionally, a Yazidi leader in Ninewa was arrested last November without a warrant. In the pressthe incident was blown up as a big issue and interpreted along religious/ethnic lines. However inactuality, his arrest was due to suspicion in connection with a bombing in Baghdad.Essentially the situation of Iraq is chaotic and this is as much at the root of the issues facing Iraqand the violations that go on in Iraq. Indeed, there are also incidents where persons are targeted asmuch for their religious background or as a minority. However, it is not only religious or ethnicaffiliation that determines whether or not a person would be targeted as this person‟s profession, hisor her family‟s status and personal relations could also be crucial.Regarding the flight of IDPs to Northern Iraq, an international NGO in Amman stated that some ofthe Christians from Mosul recently displaced in connection with the attacks in Mosul wouldprobably go to the KRI or stay within the disputed areas. Generally, it is the impression that peopleare considering other options, i.e. going abroad, as they do not foresee any increase in security andstability in the near future. However, the number of IDPs will most likely not be significant as mosthave already moved. Most who do return to areas of origin, do so to homogenous areas.None of the groups of minorities in areas of Iraq are able to protect themselves and demographicscan be a determining factor, i.e. the local ethnic composition. Providing minorities with weapons isno solution as is evident in the case of Christians in Mosul.A reliable source [in] Iraq explained that irrespective of what kind of minority one may belong to,one may be subject to risk in S/C Iraq and in disputed territories. Generally, it doesn‟t really matterwhat background you have. It really all comes down to the specific circumstances as well as place,time, etc. It is impossible to distinguish between minorities as to which group may be at greater riskas all potentially can risk attacks and persecution. For example, one does not generally hear of FeyliKurds being attacked, however a Feyli Kurd or group of Feyli Kurds may find themselves in a placewhere intolerance or other factors put him or them at risk.Some minorities had been arming themselves in order to feel safer, as was the case with Christiansin Mosul city. Minority-based militias that did come about have largely all been incorporated intothe law enforcement. Reference was made to KRG authorities having incorporating minorities inMosul into their police forces and that there were plans to getting Christians into the police forcesof Mosul city. However, Mosul remains a real mess.Minorities are likely to be safer in the disputed areas compared to Baghdad, in terms of basic safetyand risk of indiscriminate attacks. However with regards to access to livelihood, this may not be thecase. Officially the disputed areas remain under the control of the GoI authorities and thereby GoI isresponsible for providing security and services. However in actuality, minorities can be compelledto rely on the KRG forces in the disputed areas to obtain access to protection and services.It is hard to say if persons displaced to disputed areas are likely to enter KRI to seek jobs etc.,according to a reliable source [in] Iraq. It was added that currently in Erbil, there is more begging,indicating an increase in poverty among some IDPs. Christians it seems are able to make alivelihood in KRI because of strong networks in the area. KRG is perhaps not as supportive towardsTurkmens due to the fact that the Turkmen stand on Kirkuk is that it should not come under KRGcontrol. However, there are no reports of harassment of Turkmen in KRI.

22

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

2.1. Non-Arab ethnic communities: Kurds (incl. Feyli Kurds), Turkmen, Assyrians,Chaldeans, ShabaksAccording to UNHCR - Iraq, Baghdad, Feyli Kurds are among some of the 130,000 statelesspersons in Iraq. Others include Bidouns8and individuals who have become stateless due to mixedmarriages, e.g. children of mixed marriages or individuals acquiring another citizenship aftermarrying a person of another nationality. The number of Feyli Kurds who are stateless is howeverdecreasing as they now in accordance with the Nationality Law of 2006 are now able to get theircitizenship restored.9UNHCR - Iraq, Baghdad stated that the situation of Feyli Kurds is one that ischanging as they are eligible for restoration of nationality. Therefore the number of stateless FeyliKurds is decreasing as is their vulnerability. However, there are a number of bureaucratic delaysthat affect this process. Additionally, UNHCR heard of a case where a Feyli Kurd from Khanaqinwith no papers was told by the authorities to go to Baghdad in order to process papers.Minorities such as Assyrians and Chaldeans as well as Shabaks, do not have armed protection andmay be targeted by groups because of their religion.According to a reliable source [in] Iraq, minorities in the disputed areas find themselves caughtbetween the GoI and the KRG forces in the current political turmoil that characterizes the areas. Anexample is the case of Shabaks in Mosul. They are asserting that they are Kurds even thoughShabaks are speaking Arabic and wearing Arabic customary attire. For minorities such as theShabaks, it may be a better option to take the side of KRG, particularly as KRG forces are betterorganized and have greater abilities to provide a secure environment protecting persons at risk.2.2. PalestiniansConcerning Palestinians, , UNHCR - Iraq, Baghdad explained many of the Palestinian population,estimated at some 30,000, fled from Iraq in the years following 2003, because they were targeted.However, UNHCR continues to monitor the situation of Palestinians in Iraq, and added that whilemany are effectively locally integrated, particularly in Mosul, Baghdad and other locations, someindividuals continue to be targeted, or face serious protection concerns. UNHCR carries outsystematic counselling of this group and their situation is closely monitored. Individual cases facingserious protection concerns may be considered for resettlement. UNHCR - Iraq, Baghdad informedthat about 13,000 Palestinians remain in Iraq. The height of the reprisal attacks against Palestinianswas in 2006-2007. Currently, there are still incidents of discrimination at checkpoints. Palestiniansin some cases can face arbitrary detention.Concerning Palestinians, a reliable source [in] Iraq stated that there still are Palestinians in Baghdadand that they live in two compounds in Al-Baladiyya. The source did not have any information onthe number of Palestinians living in Baghdad, but explained that “there are some”. Previously, in2007, it monitored the group closely, and there were reports that police and others stormed theircompounds. Palestinians were a targeted group after the fall of the former regime, however the

8

Bidoun,the Arabic word for “without” refers to persons without documentation to prove their nationalityFeyli Kurds were under Saddam Hussein‟s regime stripped of their Iraqi citizenship.

9

23

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq

storming of their compounds has since stopped, and the source stated that it is not following thesituation of the Palestinians anymore.2.3. Religious communities: Christians, Sabean-Mandeans, Yazidis, JewsA reliable source [in] Iraq informed that there are still some incidents directed at Christians in S/CIraq, however the source had not heard of any widespread targeting of particularly Christians. It wasadded that in Iraq, no matter what you are, you may be targeted. By complete fluke according towhere you may be, you are never really safe in the highly volatile environment that stillcharacterizes S/C Iraq. It may be the case that Christians today are getting by and have found a wayof managing, however perhaps tomorrow this may not be the situation.It was added that to the best of the source‟s knowledge, there are no Jews in Iraq anymore. MostJews would have left for Israel some time back, while the very few that still lived in Iraq untilrecently are most likely to have left by now. However, the source could not exclude that one or twoJews were still living in Baghdad.With regard to the Sabean-Mandeans, generally the situation in Iraq has gone backward and a farmore conservative trend is winning ground. As a result, Muslims may be far more religious and lesstolerant to other religious groups. Non-Muslims are easily perceived as infidels. Yazidis inparticular are labelled as infidels due to their religious beliefs. However also so-called “people ofthe book”, i.e. Christians, may not be tolerated and can risk being harassed and targeted.Harassment and threats may easily be directed at Christians who e.g. have alcohol shops.

24

Security and Human Rights in South/Central Iraq