Udvalget for Udlændinge- og Integrationspolitik 2009-10

UUI Alm.del Bilag 131

Offentligt

iraq

civiliansunder fire

cOnTenTs

1/inTrOducTiOn2/TargeTedfOr speaking OuTHuMan rIgHts DEfEnDErsWoMEn’s rIgHts caMpaIgnErsMEDIa WorkErspolItIcal actIvIsts

5777911

3/viOlenceagainsT religiOus and eThnic minOriTiesflIgHt anD DIsplacEMEnttErrItorIal DIsputEs

131416

4/viOlenceagainsT wOmen and girlslIcEnsED to kIll WoMEnInsuffIcIEnt protEctIon

192020

5/aTTacksOn gay menlIcEnsED to kIll gay MEnno protEctIon

212122

6/displacedpeOplerEturnIng DEspItE tHE DangErvIolEncE agaInst rEfugEEs

232325

recOmmendaTiOnsEnDnotEs

2627

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

4iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

Painting by Iraqi artist and human rights defenderHussein al-Ibrahemi, portraying his experiences asa refugee in Syria.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

� Amnesty International

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

5

1/inTrOducTiOn

of armed groups opposed to the Iraqi government andthe presence of US troops, and whose aims includeundermining public confidence in the government andits security forces by making Iraq appear ungovernable.Civilians in Iraq are also being targeted by politicalmilitias, most of them linked to Shi'a political partiesrepresented in the Iraqi parliament. Armed groups andmilitias with an extremist Islamist agenda – includingal-Qa'ida and affiliated Sunni Islamist groups as wellas the Mahdi Army, a Shi'a militia – have killed womenand men because of their political views, their religiousor other identity, and their perceived or allegedtransgression of traditional gender roles or moral codes.In this climate of fear many Iraqis adapt their livesin the hope of avoiding attack. Some try to disguiseaspects of their identity, including some who seek toconceal their religious affiliation for fear that they willbe targeted for sectarian reasons. Others adhere tostrict moral codes against their free will, includingwomen and girls who feel obliged to wear the hijab(Islamic headscarf) in order to avoid attack by religiousmilitants. Some – perhaps many – simply feel it saferto keep silent about their views.This report focuses on civilians who are particularlyat risk of attack because of their human rights orprofessional work; their political activities; their identity,gender or sexual orientation; or their plight asdisplaced people.1Not all are targeted by armed groups, militias orsecurity forces; people challenging traditional genderroles or moral codes are also at risk of attack byrelatives, including some who consider that they aredefending family “honour”. For example, at least25 men were murdered in Baghdad in the first quarterof 2009 because of their perceived sexual orientation;some were tortured before being killed and their bodieswere mutilated. In Basra, dozens of women have beenkilled in recent years; sometimes, their killers left notesby their bodies indicating that they had been killed fortheir allegedly “un-Islamic” behaviour. In both cases,those who committed the killings included relatives ofthe victims as well as members of Islamist armedgroups or militias.In general, community, political and religious leadershave failed to take effective steps to stop and preventattacks on vulnerable groups, and to bring those

Hundreds of civilians are still being killed or maimedevery month in Iraq, even if the past two years haveseen an overall reduction in the number of civiliandeaths. As a result, safety and security remain keyconcerns for Iraqis – especially for those who, becauseof their religious, ethnic or other identity or because oftheir profession or work, are particularly vulnerable tobe targeted for violent attack.Although civilians have been killed, injured orotherwise abused by Iraqi security forces and foreigntroops based in Iraq, and by members of privatemilitary and security companies, most killings ofcivilians are being carried out by armed groups.On 25 January 2010, for example, three co-ordinatedbomb attacks on hotels in Baghdad killed 36 peopleand left more than 70 injured, many of them civilians.The Islamic State of Iraq, an umbrella organization ofarmed groups linked to “al-Qa'ida in Iraq”, wasreported to have claimed responsibility for this andother attacks, including bombings that killed about400 people and injured more than 1,600 – theoverwhelming majority of them civilians – in centralBaghdad in August, October and December 2009.The Islamic State of Iraq and other armed groups,most of them Sunni Iraqi and not necessarily linked toal-Qa'ida, have claimed responsibility for many violentattacks on civilians. However, in many other incidentsno one has claimed responsibility and it is oftenimpossible to determine precisely who was responsible.Often, attacks are attributed to particular armed groupswithout clear evidence but on the basis that theyresemble their pattern of behaviour. Generally, themost devastating attacks involve suicide bombers andoften appear intended to cause large numbers ofcivilian casualties. These are believed to be the work

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

6iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

responsible to justice. Indeed, some have expressedviews apparently intended to incite violence againstfellow Iraqis because of their identity.In the northerly, semi-autonomous Kurdistan Region,comprising Dohuk, Erbil and Sulaimaniyagovernorates, which has been much less affected bythe violence prevailing in the rest of Iraq, theauthorities have taken some positive steps to combatviolence against women, although these still need to befurther developed and consolidated. Overall, however,the Iraqi authorities have failed to take effective actionto protect individuals and groups at risk.In particular, the authorities have failed to conductthorough and impartial investigations into many attackson and other violent crimes against civilians, and aclimate of impunity continues to prevail. In the case ofviolence against women and girls, and attacks on menperceived to be gay, the climate of impunity isunderpinned by Iraqi legislation and jurisprudence,which provides for lenient punishment for attackerswho are deemed to have acted in defence of “honour”.Impunity is further entrenched by the involvement ofthe authorities themselves in numerous incidents ofintimidation of and attacks against critics, includingjournalists reporting on alleged corruption andmisconduct by officials. In the Kurdistan Region, thetwo ruling parties are believed to be responsible for apattern of targeted violent attacks against journalistsand opposition political activists.This report is largely based on interviews and otherresearch carried out by Amnesty International innorthern Iraq in April and December 2009. Those whoprovided information to Amnesty International camefrom many different parts of the country and includedhuman rights defenders, women’s rights activists,journalists, members of religious and ethnic minoritiesand members of Iraq’s gay community. Otherinformation was provided by Iraqi refugees in countriessuch as Syria and Jordan, both of which host largenumbers of refugees from Iraq. Amnesty Internationalhas previously raised the concerns and many of thecases highlighted in this report in its numerouscommunications to the Iraqi authorities.Amnesty International is urging armed groups andmilitias in Iraq to immediately cease all human rightsabuses including attacks against civilians, abductions,

hostage-taking and the killing, torture and otherill-treatment of captives. Leaders of armed groupsand militias must issue clear orders that fighters refrainfrom such unlawful attacks. Many attacks carried outby them constitute war crimes or crimes againsthumanity, and the perpetrators must be broughtto justice.Amnesty International is also urging the Iraqi securityforces and the United States Forces-Iraq (USF-I), aswell as private security companies assisting them, torespect the human rights of civilians at all times, andis calling on the Iraqi authorities to improve protectionof groups that are particularly at risk of attack. Timely,impartial and thorough investigations must be held intoall attacks against civilians and alleged human rightsviolations, and the perpetrators of such attacks andviolations must be held to account in conformity withIraq’s obligations under international law. Withoutdetermined action to end the climate of impunity, thekilling, maiming and persecution of various groups ofcivilians in Iraq will continue.

IntErnatIonal HuManItarIan laWunder international humanitarian law, parties to anarmed conflict must at all times distinguish betweennon-combatants (including civilians, prisoners of war,the wounded and sick and others) and combatants, andbetween civilian objects and military objects. theprinciple of distinction, codified in the four genevaconvention and its two additional protocols, is also arule of customary international humanitarian law,binding all parties to a conflict, whether internationalor non-international.under customary international humanitarian law,responsibility for war crimes may arise for conductengaged in during international and non-internationalarmed conflicts. conduct amounting to war crimesincludes, but is not limited to, acts such as wilful killing;torture or inhuman treatment; taking hostages;intentionally directing attacks against the civilianpopulation; intentionally directing attacks against peopleinvolved in humanitarian assistance or peace keeping;and indiscriminate attacks, which violate fundamentalprinciples of international humanitarian law, includingthe principle of distinction between civilians and civilianobjects on the one hand, and members of armed forcesand military objects on the other.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

7

2/TargeTedfOrspeaking OuT

People who have expressed particular views or stoodup for human rights have been threatened, attacked,abducted and killed, and continue to be at grave risk.Among them are activists and journalists who reporton abuses by armed groups or militias or allegedcorruption by officials, lawyers representing victims oftorture, activists campaigning for minority rights, andwomen campaigning for women’s rights, legal reformsor shelters for abused women and girls. Many humanrights defenders and activists have described toAmnesty International the attacks, threats andharassment that they have faced.

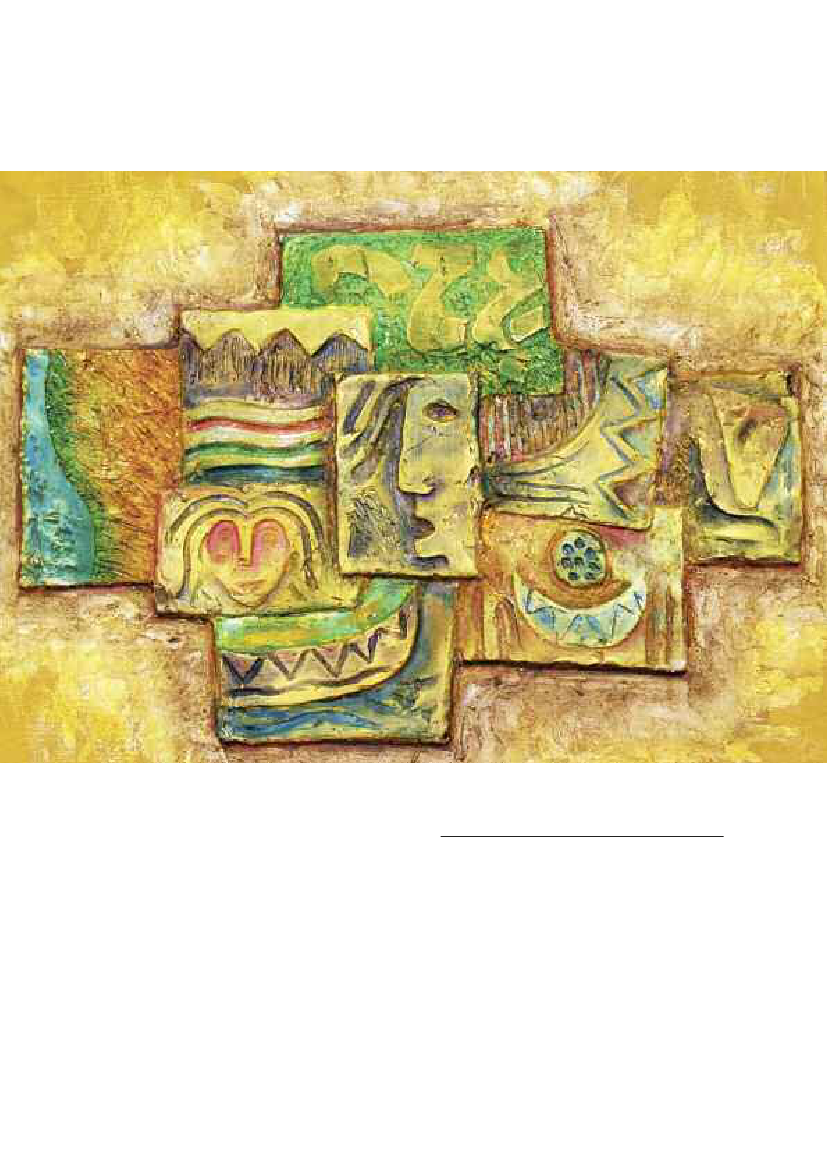

Sahar Hussain al-Haideri, journalist and human rightsdefender, shot dead on 7 June 2007 in Mosul (see page 8).No one has been brought to justice for her murder.

defenders have been targeted because of theirreporting of abuses by armed groups or militias:“These groups and gangs have imposed a reign ofterror on human rights campaigners. [Their] threatsincluded warnings against the publication of anyinformation we had gathered about their activities andconsider to be gross human rights abuses, such astargeting of civilians, abductions and bombings.”2A human rights defender from southern Iraq, who fledthe country in 2006 after surviving an attack on his lifebut then returned to Iraq in 2007, told AmnestyInternational in April 2009 that the human rightsorganization in which he is involved has been forced tocut back its activities for security reasons and to ceaseactively monitoring and documenting abuses for fear ofreprisals. In his assessment, victims of human rightsabuses and their relatives have also becomeincreasingly reluctant to provide information about theabuses they have suffered out of fear for their own andtheir families’ future safety.

human righTs defendersIn the wake of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq,hundreds of non-governmental organizations (NGOs)emerged and thousands of people were able openlyto become involved in human rights-related activities.This initial enthusiasm for a new-found freedom ofexpression, association and assembly was graduallyreplaced, however, by deepening fear and trepidationamid the widespread lawlessness and violence thatsubsequently engulfed much of Iraq. Threats andattacks have forced many human rights defendersto scale down or stop their activities or flee thecountry.Adib Ibrahim al-Jalabi,a medical doctor and leadingfigure in the Islamic Organization for Human Rights(IOHR), was murdered on 12 May 2007 byunidentified armed men, believed to be connected toal-Qa'ida, shortly after he left his clinic in Mosul. OtherIOHR members received death threats by armedgroups, includingHareth Adeeb Ibrahim,head of theIOHR, who believes that he and other human rights

wOmen’s righTs campaignersWomen who have taken the lead in confrontingviolence against women and promoting women’s rightshave been directly targeted because of their activities,

� IWPR

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

8iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

notably by members of Islamist armed groups andmilitias. Some have been attacked and killed becauseof their efforts to promote gender equality.Sahar Hussain al-Haideri,a 44-year-old journalist andwoman human rights defender, was shot dead on7 June 2007 in Mosul. She had frequently reported ondiscrimination against women and criticized Islamistarmed groups for abusing women’s rights. She hadsurvived an earlier abduction attempt and had receiveddeath threats. Ansar al-Islam, an Islamist armed group,was reported to have claimed responsibility for hermurder.Male relatives of women victims of violence frequentlythreaten or attack women activists. A woman lawyer inthe Kurdistan Region told Amnesty International thatshe had received death threats on her mobile phonefrom relatives of a woman who had been abused byher husband and for whom she had filed divorcepapers. One message she received in 2008 read:“Where do you want to hide? If she gets a divorce wewill take our right. We know that you are her lawyer.We are able to get hold of you and kill you.”In Sulaimaniya, a shelter run by ASUDA, an NGOhelping women at risk of violence, was attacked on11 May 2008. Gunmen, believed to be relatives of awoman who was being given refuge at the shelter, firedseveral shots into it from a neighbouring building,seriously wounding the woman. The Kurdish authoritiessubsequently arrested several male relatives of thewoman who had been shot, but released them for lackof evidence. To date, no one has been charged or triedfor the attack.Because many women human rights defenderscampaign for gender equality, they are often viewedas defying social norms, structures and practices. Bychallenging the traditional role of women they run therisk of being socially ostracized, as well as attacked. Ata meeting in April 2009 in northern Iraq, Iraqi womenhuman rights defenders told Amnesty International thatthey had been accused of being “unbelievers” andthreatened for demanding that women be givenequality under the law, including the Personal StatusLaw that governs matters relating to marriage, divorceand inheritance. One woman observed:

Demonstrators in Baghdad demanding freedom of thepress, August 2009.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

�AP Photo/Khalid Mohammed

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

9

“Itis a challenge to work on gender issues and onviolence against women. We are frequently accused ofportraying a bad image of our society, but we have toexpose the reality.”Despite the risks and challenges they continue to face,women’s rights activists have achieved some progress.For example, a quarter of seats of the Iraqi parliamentare now reserved for women and, in the KurdistanRegion, changes to the Penal Code and PersonalStatus Law have enhanced women’s rights.

media wOrkersMedia professionals in Iraq continue to be at high riskof attack or injury because of their work. TheCommittee to Protect Journalists documented thecases of 89 journalists and 44 media support workers,most of them Iraqis, who were killed in targeted attacksbetween March 2003 and October 2009.3Scores ofother journalists have been killed in crossfire and otherviolent incidents. Outspoken journalists have beenthreatened and attacked for their reporting on officialcorruption and violent crimes committed by armedgroups and militias.Sarwa Abdel Wahab,a 36-year-old journalist, waspulled out of her car on 4 May 2008 and shot dead byunidentified gunmen in the al-Bakr district of Mosul. Inthe weeks before her killing she had published articlescritical of Islamist armed groups on the Muraslon newssite and received at least one threatening phone callfrom a person reportedly linked to the Islamic State ofIraq armed group.Ahmed 'Abd al-Hussein,a journalist withal-Sabahnewspaper, received death threats in August 2009because of an article in which he blamed the IslamicSupreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), a Shi'a political party,of involvement in a bank robbery which resulted indeaths. Those charged in connection with the robberyincluded at least one security guard of 'Adel 'AbdulMahdi, one of Iraq’s Vice-Presidents and a seniormember of the ISCI, who denied any involvementof his party in the incident.'Emad 'Abadi,a 36-year-old journalist with Al Diyar TVstation, was attacked by unidentified gunmen in central� Amnesty International� Alhurra

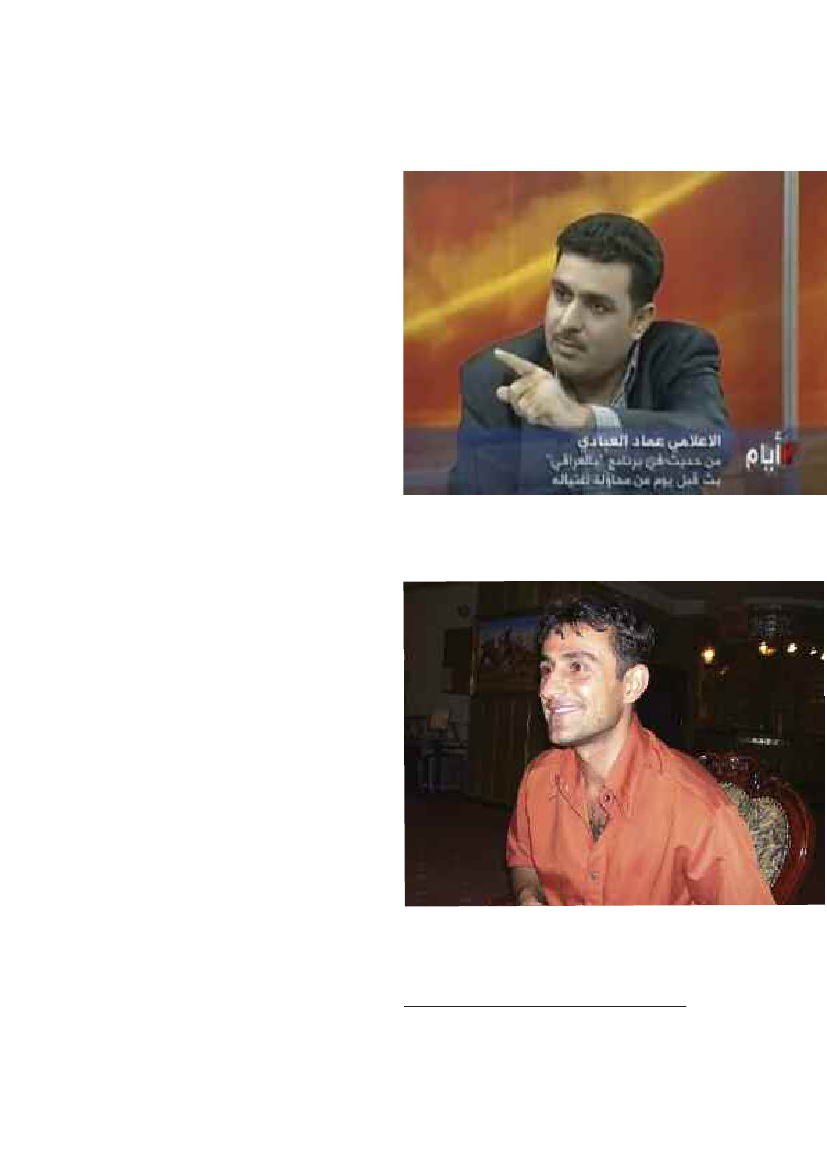

'Emad 'Abadi during a TV discussion the day before he wasshot and wounded by unidentified gunmen in November2009 in Baghdad.

Nabaz Goran, a freelance journalist, was abducted andbeaten unconscious on 4 April 2007 by five armed menwearing uniforms in Erbil, northern Iraq. On 29 October2009 he was again attacked and beaten by threeunidentified men near his office.

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

10iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

Baghdad on 23 November 2009. He was shot in thehead and neck, but survived. 'Emad 'Abadi presenteda programme calledThoughts without Fences(Afkarbila aswar)in which he frequently criticized theauthorities for mismanagement and corruption. Heis also an outspoken defender of media freedom.Representatives of the Iraqi Journalists’ Associationhave also been targeted. On 23 February 2008,74-year-oldShihab al-Tamimi,head of the association,was shot by unidentified gunmen while he was in hiscar after leaving the association’s Baghdad office. Hedied of his injuries three days later. No one is known tohave been charged or tried for the killing. He hadreceived several death threats in connection with hiswork as head of the association. On 20 September2008, his successor,Mu'aid al-Lami,survived a bombattack near the organization’s office.� Amnesty International

Iraqi security forces have frequently ill-treatedjournalists. On 13 February 2009, for example,members of the Iraqi army beat journalistAhmedal-Azariand other staff of al-Itijah TV after they hadidentified themselves as journalists and questioned asoldier’s refusal to let them enter the city of Kerbela.Reporters Without Borders reported numerous violentattacks against journalists in the Kurdistan Region inthe context of the parliamentary elections in March2010. For example,Akar FarsandRzgar Muhsin,bothjournalists with Yekgirtu TV, which is affiliated to theopposition Kurdistan Islamic Union, were beaten byarmed men and prevented from filming at a pollingstation in Erbil on 7 March, election day.Kurdish journalists who have published articles criticalof officials of the two ruling parties in the KurdistanRegion – the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) andthe Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) – continue tobe at risk of threats and violent attacks.Sabah 'Ali Qaraman,a 28-year-old journalist whopublished articles critical of Kurdish officials, wasreported to have escaped an abduction attempt on19 January 2010. Three men in a jeep stopped himoutside his home in the Kifri district of Sulaimaniyagovernorate; he quickly realized that they intended toabduct him and managed to escape. He said that herecognized one of the attackers as a “retired official” ofthe PUK and later filed a complaint against him. As yet,the authorities are not known to have arrested thealleged assailant.

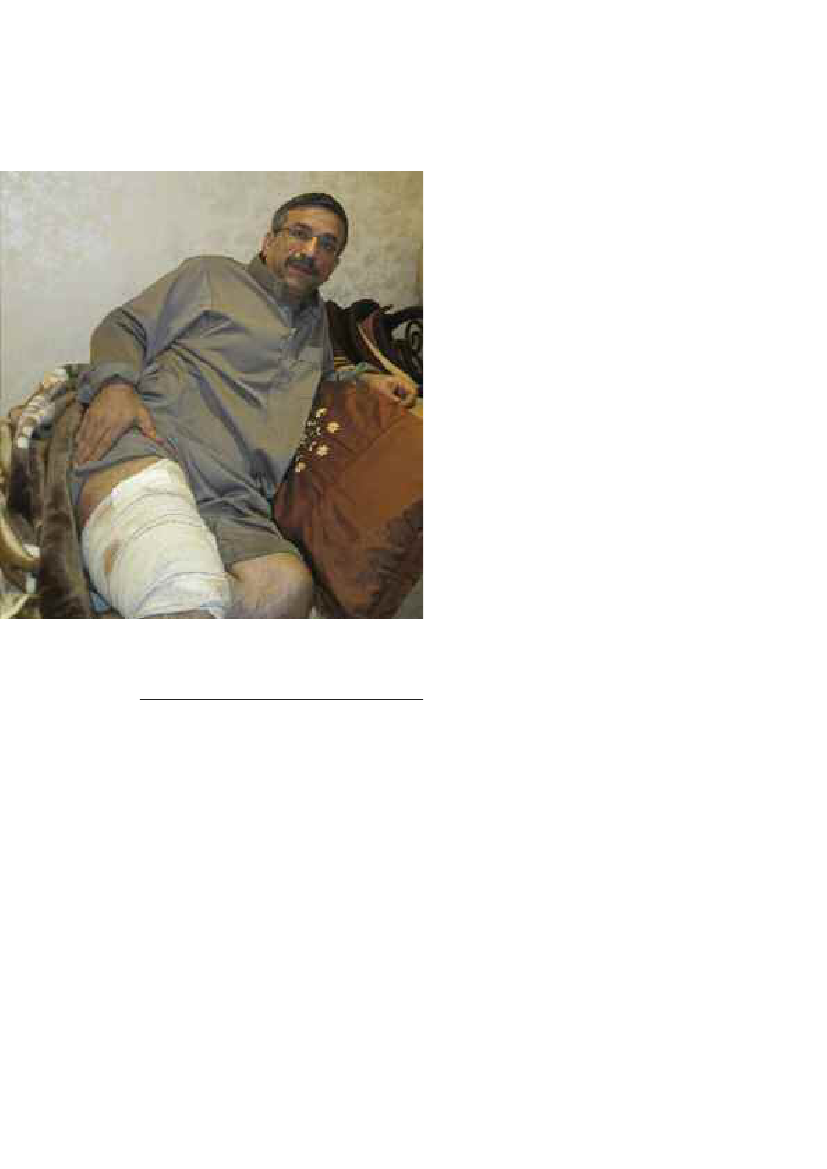

Sardar Qadir, a Kurdish opposition candidate, recoveringafter being shot in the leg by an unidentified attacker,December 2009.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

11

Nabaz Goran,a 32-year-old journalist withJihanmagazine who published numerous articles critical ofthe Kurdish leadership, was attacked on 29 October2009 by three men near his office in the Iskan districtof Erbil. The attackers – whom he believes were linkedto the KDP – asked him for his name and then beathim on the head with a metal object. No one is knownto have been arrested for the assault.In another incident, a Kurdish journalist was killed insuspicious circumstances.Souran Mama Hama,a23-year-old journalist withLevinmagazine, was shotdead outside his parents’ house in Kirkuk on 21 July2008. His attackers were in a car and wore civilianclothes. Souran Mama Hama had published articlescritical of alleged corruption and nepotism within theKDP and PUK, and was believed to have receivedanonymous death threats a few days before hismurder. No one has been arrested for the killing.

Several activists of the newly established Kurdishopposition party, the Goran (Change) Movement, havealso been attacked. In December 2009, at least fiveGoran activists were shot at in the Kurdistan Region.One of them,Raouf Qadir Zaryani,a former PUKsupporter who had switched his political allegiance,was shot dead in front of his house on 25 December inHalabja Taze, Sulaimaniya governorate, by unidentifiedmen in a vehicle.Sardar Qadir,a businessman and Goran candidate inIraq’s parliamentary elections, was wounded in the legon 4 December 2009 when he was shot at through awindow at a relative’s home in the Iskan district ofSulaimaniya. He told Amnesty International that he hadnot received threats but that he thought he had beenfollowed in the preceding weeks and that the attackwas politically motivated:“I cannot put the blame on any particular party.However, I am a victim of the lack of democracy we aresuffering from.”Dara Tawfiq, a military officer and former PUKsupporter who switched to the Goran Movement, wasattacked outside his house in the Bakhtiari district ofSulaimaniya on 7 October 2009. He told AmnestyInternational:“I returned to my home at about 3pm and was aboutto open the gate when I was beaten with an iron rod. Iturned around and protected my head with my arm.Blood was running from my head. I could see the twoattackers, one of them tall the other short and with amoustache, who both spoke in the local dialect.”The two attackers escaped in a car driven by a thirdman who fired twice at a passer-by who had witnessedthe attack. Dara Tawfiq had received no threats butbelieves that he was attacked because of his supportfor the Goran Movement.The attacks continue. On 16 February 2010 armedmen reportedly linked to the PUK violently disrupted ameeting of Goran Movement members in Sulaimaniya,following which 11 Goran activists were arrested. Theoffice of the Kurdistan Islamic Union, anotheropposition party, was attacked by unidentified gunmenin Sulaimaniya on 14 February 2010; four days laterseveral of its members were detained by the authoritiesin Dohuk.

pOliTical acTivisTsViolence against political activists in Iraq regularlyincreases in the run-up to elections. For example, at leastnine candidates of different political parties standing inthe provincial elections in January 2009 were killed.Several more recent attacks were apparently linked tothe 2010 parliamentary elections. For example, on7 March, election day, dozens of people were killed inseparate incidents, including bomb explosions at tworesidential buildings in Baghdad that alone killed atleast 25 people.On 7 February 2010,Soha 'Abdul Jarallah,aparliamentary candidate for the Iraqi NationalMovement, was killed in front of her relatives’ home inthe Ras al-Jadda district of Mosul. She was shot deadby unidentified gunmen who escaped in a car.On 23 December 2009,Sa'ud al-'Issawi,a candidatefor Iraq’s Unity Alliance, and his two bodyguards werekilled in Falluja when a magnetic bomb attached totheir vehicle exploded.Safa 'Abd al-Amir al-Khafaji,the head teacher of agirls’ school in Baghdad’s al-Ghadi district, was shotand seriously wounded by unidentified gunmen on12 November 2009 soon after she announced that shewould contest the elections as a candidate for the IraqiCommunist Party.

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

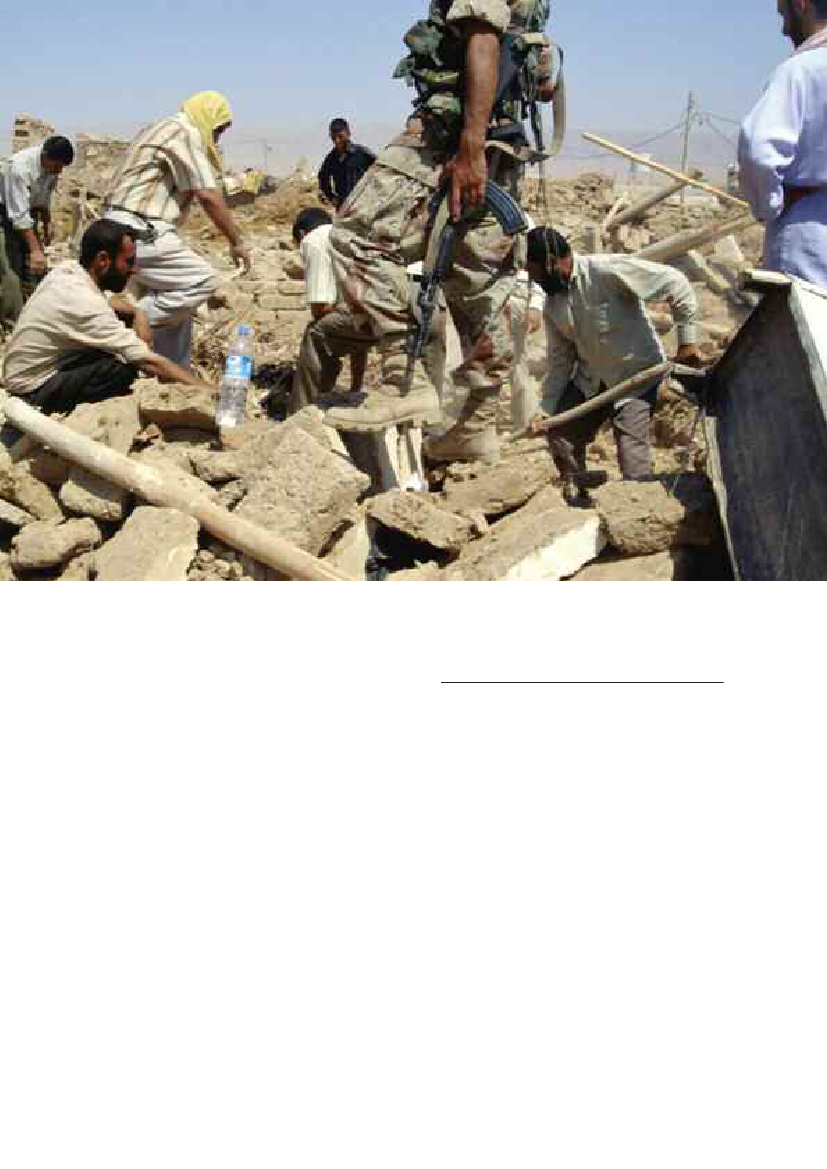

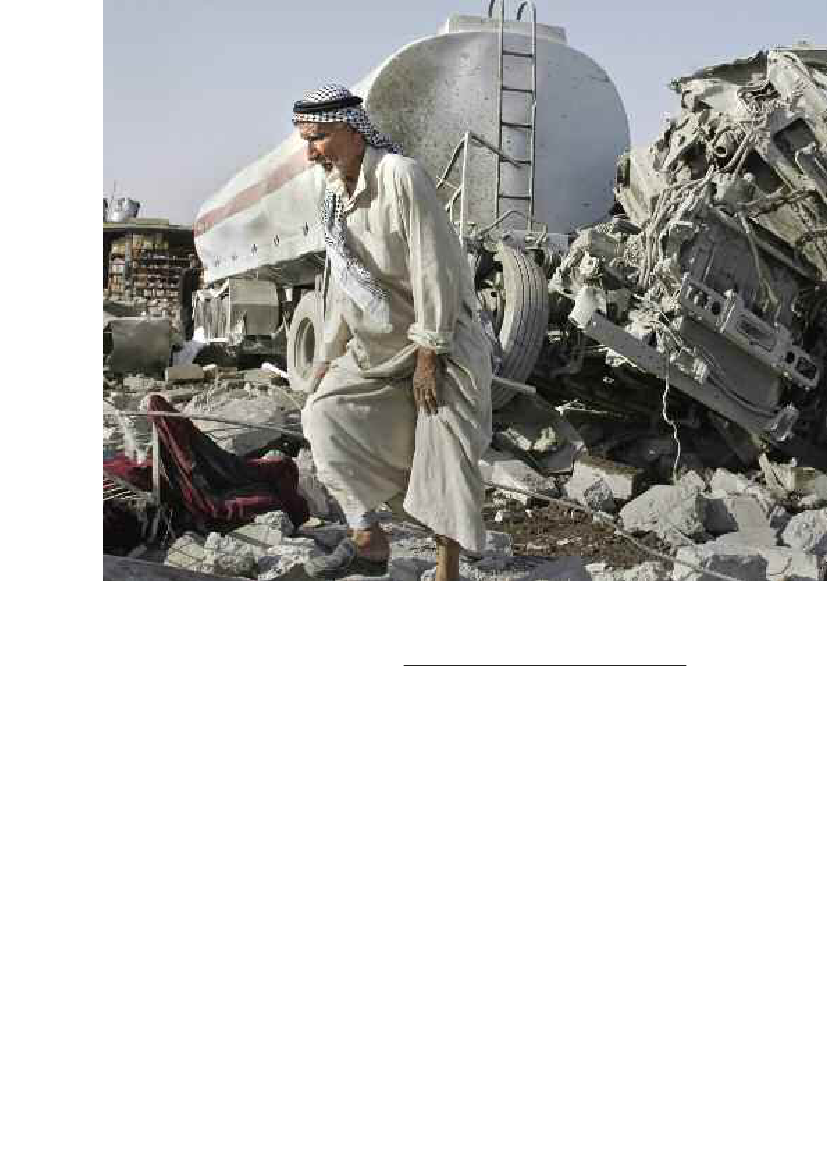

Rescuers digging through the remains of homes destroyedby a suicide truck bombing targeting predominantly Yezidisettlements in Sinjar district, north-west Iraq. The attack,on 14 August 2007, killed more than 400 people.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

�AP Photo/Mohammed Ibrahim

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

13

3/viOlenceagainsTreligiOus andeThnic minOriTies

exposed again the vulnerability of minority groups.More than a hundred people were killed between mid-July and mid-September 2009 in attacks targetingChristians, Sabean-Mandaeans, Yazidis, TurkomanShi'as, Shabaks and Kaka'is.The deadliest attack on civilians in recent yearshappened on 14 August 2007, when more than 400people were killed in four co-ordinated bombings inal-Qahtaniya and other villages in the Sinjar district,inhabited mainly by Yazidis.The occupations, customs and general lack of politicalpower of members of minority groups have contributedto their vulnerability. For example, many Sabean-Mandaeans have been targeted by criminal or otherarmed groups or militias because of their traditionaloccupations as goldsmiths and jewellers. Similarly,the sale of alcohol has largely been the domain ofChristians and Yazidis, making them a target for someIslamist armed groups and militias. However, survivorsand witnesses of such attacks, including abductions,have frequently reported that the perpetrators“justified” their crimes on the basis of the victims’ faith.Others targeted have been women of religious minoritygroups who failed to adhere to a strict Islamic dresscode. As well, members of minority groups perceivedas supporters of the US-led foreign military forces thathave been present in Iraq since 2003 have beenattacked by armed groups and militias who accusethem of “collaboration” with enemy forces.Religious or ethnic affiliation can often be discernedby knowing a person’s name, and official identity cardsstate the religion of the holder. Several members ofreligious minorities told Amnesty International that theyhave sometimes feared to show their identity cardsbelieving that if they did they would be attacked.Such fears were underlined by an incident thatfollowed the murder of a 16-year-old Yazidi girl,Du'a Khalil,by male relatives in early April 2007 inBashiqa, near Mosul, for having a relationship with aSunni Muslim man. Claims that Du'a Khalil hadconverted to Islam reportedly triggered the killing on22 April of 23 Yazidi men who were travelling on a busbetween Mosul and Bashiqa. The vehicle was stoppedby gunmen, who identified Yazidi passengers by theiridentity cards, then forced them to disembark andkilled them on the spot.

� Silvia Izquierdo AP/PA Photos

Within weeks of the US-led invasion in 2003, members ofreligious and ethnic minority communities were targetedfor violent attack, including abductions and killings.For example, 271 members of the Sabean-Mandaeanreligion were abducted and 163 killed between May2003 and October 2009, according to the MandaeanAssociations Union.4Some 65 attacks on Christianchurches were recorded between mid-2004 and theend of 2009, causing dozens of casualties.5Many other Christians have been killed in targetedattacks in the street or at their workplaces and homes.For example, on 22 February 2010 three members ofa Christian family, 59-year-oldAishwa Marokiand hissonsMokhlasandBassim,were killed in their housein the al-Saha district of Mosul by unidentifiedgunmen, apparently victims of a sectarian attack. Theywere among at least eight Christians killed in Mosulthat month.Four years before, the bombing in February 2006 ofthe al-Askari mosque in Samarra, one of Shi'a Islam’sholiest sites, sparked an upsurge in sectarian violencebetween Sunni and Shi'a Muslims. The violence leftevery Iraqi more at risk of attack simply on account oftheir religious identity and affiliation. In particular,places at which people gather to express their faithhave been targeted for attacks. On 1 February 2010,for example, at least 40 Shi’a pilgrims were killed in aBaghdad neighbourhood by a suicide bomber.A string of deadly attacks following the pull-out of UStroops from Iraqi cities and towns in June 2009

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

14iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

MInorItIEs In Iraqthe Iraqi constitution of 2005 states that Iraqcomprises “multiple nations, religions and sects”(article 3) and specifically lists some but not allminority groups. article 2(2) refers to the “Islamicidentity of the majority of the Iraqi people” andguarantees religious freedom to other religions,explicitly mentioning christians, sabean-Mandaeansand yazidis. the constitution also specifies arabicand kurdish as the official languages and guaranteesthe rights of linguistic minorities to be educated intheir mother tongue (article 4(1)), referringspecifically to armenian, syriac and turkoman.religious and ethnic minorities not mentioned in theconstitution include Baha'is, Jews, kaka'is, romaand shabaks.Iraqi election laws provide for parliamentary and localcouncil seats to be reserved for representatives ofminority groups. legislation passed in november2008 provides for a few seats to be reserved in thelocal councils of Baghdad, Basra and Mosul forminorities, including christians, sabean-Mandaeans,shabaks and yazidis. the kurdistan regionalgovernment has reserved 10 per cent ofparliamentary seats for three minority groups –assyro-chaldaeans, armenians and turkomans.among the religious minorities, christians andyazidis are the largest groups with several hundredthousand members each. other sizeable religious-ethnic minority groups include the shabaks and thekaka'is who live mainly in northern Iraq.the Baha’i religion was banned in Iraq by law in1970. a 1975 ban on issuing identity cards for Iraqisadhering to the Baha'i religion was lifted in april2007, but obstacles continue to be reported.only a small number of Jews remained in Iraqfollowing the establishment of the state of Israel in1948. the Iraqi nationality law (law no. 26 of 2006)effectively excludes Jews who left Iraq from regainingIraqi nationality.

On 17 February 2010, unidentified gunmen checkedthe identity cards of two Christian students –22-year-oldZia Tomaand 21-year-oldRamsin Shmael– at a bus stop in Mosul and subsequently shot them.6Zia Toma was killed and Ramsin Shmael was injuredbut survived.The UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion andbelief stated: “Indicating a person’s religious affiliationon official documents carries a serious risk of abuse orsubsequent discrimination based on religion or belief,which has to be weighed against the possible reasonsfor disclosing the holder’s religion.”7

flighT and displacemenTFear for their lives has driven a disproportionately highnumber of members of minority communities to fleeIraq in recent years. The UN Secretary-General,reporting on the situation in Iraq in July 2009, notedthat “the recent surge in violence, particularly againstminorities, has led to a continuation of Iraqis leavingthe country as well as some internal displacement.”8Amnesty International has interviewed many Iraqirefugees in recent years, including in neighbouringcountries where hundreds of thousands are still living.Some say they were targeted because of their religionor because they were unwilling to convert to Islam.A 25-year-old engineer and member of the Sabean-Mandaean religion who had fled to Jordan toldAmnesty International in March 2009 that he hadfeared to divulge his religion when studying at aBaghdad university before graduating in 2007. Later,after he tried to flee the country but was denied entryto Syria, he got a job in a restaurant where otherworkers told him he should convert to Islam and attendprayers when they found out his faith. He did not doso. Later, in August 2008, he was abducted, as hemade his way home from work, by masked men whoforced him into a car. They blindfolded him and droveto an unknown location where they held him prisoner.They then stripped, raped and beat him until he lostconsciousness while demanding that he convert toIslam. They later dumped him on a road.

� AP/PA Photo/Jerome Delay

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

After fleeing to Jordan in December 2008, he toldAmnesty International:“I was so scared the abductors would kill me. I believethey dumped me alive because they were nervous tobe discovered by security forces operating in the area.”A 58-year-old Christian, a retired nurse who is marriedwith three children, told Amnesty International that shefled Iraq the day after she and her husband wereattacked at their home in Mosul by four masked menin February 2007. Her husband was beaten andkicked, and she was threatened at gunpoint. Thecouple was given 24 hours to convert to Islam or leavetheir house. The nurse told Amnesty International:“We hired a taxi that took us the next day early in themorning to Syria. We left everything behind.”A human rights defender, a member of Iraq’s Christianminority, spoke to Amnesty International in Erbil inDecember 2009 soon after she had fled from Mosul.She had remained in Mosul in 2008 despite a waveof attacks on Christians that year which prompted anestimated 12,000 people to flee their homes. Shefinally decided to flee because of her fear that risingpolitical tension in the run-up to the March 2010

� Associated Press

The aftermath of a double truck bombing which killedat least 34 people on 10 August 2009 in Khazna, apredominantly Shabak village, near Mosul.

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

16iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

parliamentary elections would further expose membersof minority groups to attack. Since she fled, violenceagainst the Christian community in Mosul had indeedincreased, including fatal bomb attacks on churcheson 15 and 23 December 2009.

TerriTOrial dispuTesViolence between different ethnic communities in thenorth of Iraq, where control over territory is disputedmainly between Kurds, Arabs and Turkomans, brokeout shortly after the March 2003 invasion.The conflicts are rooted in the past expulsion by thecentral Iraqi authorities of local Kurds and otherminority communities and their replacement withArabs from central and southern Iraq. During theso-called Anfal campaign in the late 1980s, tens ofthousands of Kurdish civilians were victims of enforceddisappearance, and many were killed by Iraqi forces inmass executions, ground offensives andbombardments, including some using chemicalweapons. The violence resulted in the massdisplacement of Kurds as well as other minorities. Tensof thousands of other people – mainly Kurds – wereforcibly displaced in the 1990s from Kirkuk and othernow “disputed territories”. Many of the displaced havenot been able to return to their places of origin.The 2005 Constitution envisaged a process to addresspast injustices, allow displaced people to return orreceive compensation, and conduct a census followedby a referendum in the “disputed territories”, includingKirkuk, before the end of 2007 (Article 140). However,neither the census nor the referendum has been held.The lack of clarity about the future status of the“disputed territories” is fuelling violence and tensions.The Kurdish authorities have expanded their de factocontrol and influence over much of the “disputedterritories”. Meanwhile, the return of displaced Kurdsto the governorate of Kirkuk has prompted protests byother minority groups, particularly the Turkoman andArab communities.In the “disputed territories”, members of religious andethnic minority groups are increasingly becomingpawns in a power struggle between an Arab-dominatedcentral government and the Kurdistan RegionalGovernment. This has led or contributed to divisions

A Sabean-Mandaean goldsmith from Baghdad, whoescaped to Jordan with his four children in January 2009after his wife was abducted. He told Amnesty Internationalshortly afterwards: “I don’t let the children leave the home– because I still believe I am in Iraq and I am scared abouttheir safety.”

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

� Amnesty International

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

17

within the minority communities, including theircompeting political parties. The Kurdish authoritieshave supported the establishment of self-defencemilitias that are mainly deployed at the entrancesof Christian villages and churches, despite protestsexpressed within the Christian communities.Members of minority groups who have been critical ofKurdish attempts to expand influence in the “disputedterritories” have reported harassment and ill-treatmentby Kurdish security forces, particularly before recentelections. For example,Murad Kashti al-Asi,a Yazidipolitical activist in Sinjar, Nineva governorate, who isopposed to the Kurdish political parties, was reportedto have been detained several times and threatenedand ill-treated. His most recent period of detention, inNovember 2008, appeared to be linked to theprovincial elections.9There have also been incidents reported of Iraqiauthorities intimidating and harassing the Kurdishpopulation in “disputed territories”. In October 2008,for instance, Iraqi security forces were reported to have

� Amnesty International

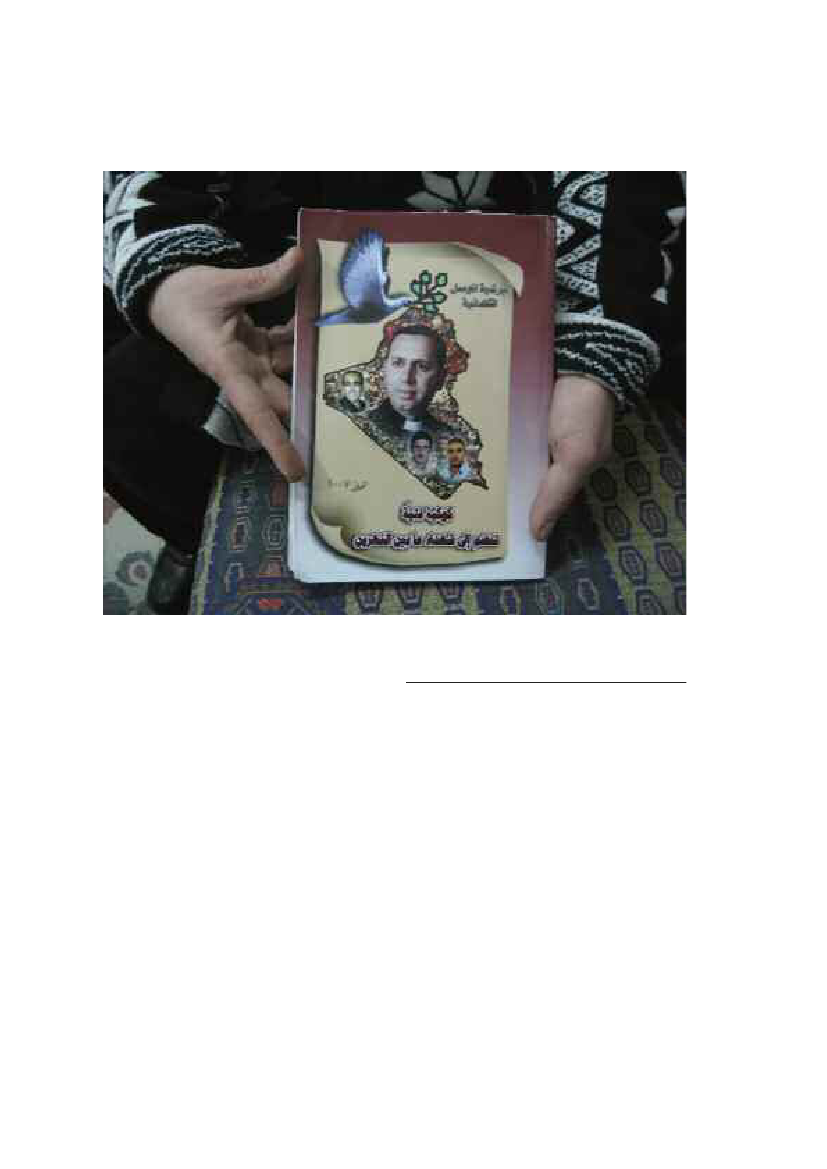

Cover of a book showing Ragheed Ghanni, a priest killedin June 2007 by unidentified gunmen in Mosul.

raided and harassed the Kurdish population ofQaratepe village.10A draft constitution of the Kurdistan Region passed inJuly 2009 listed areas that the Kurdish authoritiesenvisaged would be annexed to the Kurdistan Region.This led to protests from officials of the centralgovernment in Baghdad, further heightening politicaltension. Organizations representing ethnic andreligious minorities have also protested against theterritorial claims made in the draft constitution.

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

18iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

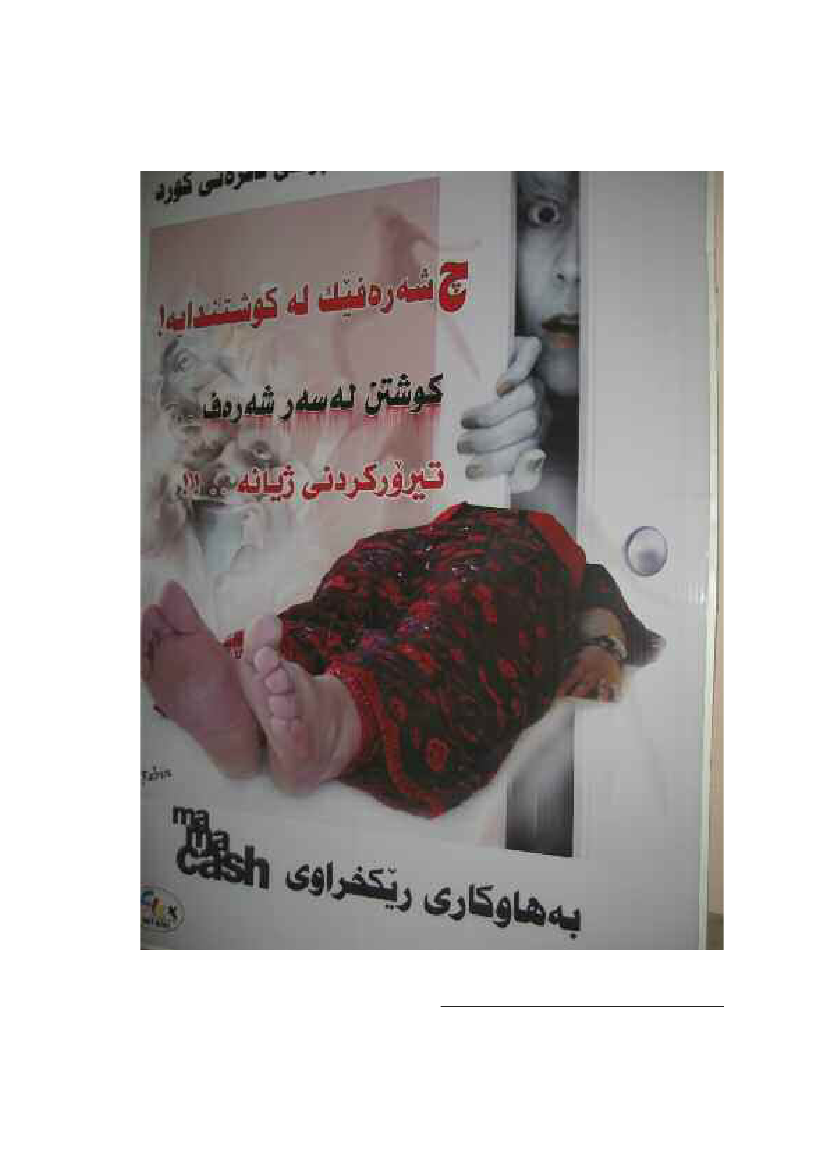

Poster by the Kurdish women’s organization Khatuzeen,campaigning against “honour killings”.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

� Amnesty International

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

19

4/viOlenceagainsT wOmenand girls

at the Women’s Prison of al-Kadhimiya in Baghdadwho said that they had been beaten, raped orotherwise sexually abused in police stations.11Subsequently, members of the Iraqi parliament’sHuman Rights Committee who visited the prison inMay 2009 told the media that at least three womendetainees had complained of being raped in detention– apparently prior to their transfer to the prison.Few men who have committed rape in Iraq are knownto have been convicted. However, in one rare butwidely publicized case, several US soldiers wereprosecuted in the USA in connection with the rape andmurder of 14-year-old'Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabiand the murders of her parents and sister in March2006 in Mahmoudiya, near Baghdad. Steven DaleGreen, held to be the principal perpetrator, wassentenced to life imprisonment on 21 May 2009.

Wars and conflicts, wherever they are fought, invariablyusher in sickeningly high levels of violence againstwomen and girls. All parties to the armed conflict inIraq have been involved in violent crimes specificallyaimed at women and girls, including rape. Perpetratorshave included members of armed groups, militias, Iraqigovernment forces and foreign military forces. Inaddition, women and girls continue to be attacked andsometimes killed by male relatives and Islamist armedgroups or militias for their perceived or allegedtransgression of traditional roles or moral codes. Mostof these crimes are committed with impunity.Crimes of sexual violence against women in Iraq aregrossly under-reported, not least because of thevictims’ fear of reprisal, and reported incidents are notsystematically recorded.Amnesty International has interviewed severaltraumatized women survivors of rape whosubsequently fled Iraq. One of them, who did not file acomplaint about her rape with the Iraqi authorities, toldAmnesty International in June 2007:“I feared that my brother-in-law would kill me if hefound out that I had been raped. When his familywanted to have me medically examined, I refused.Instead, I had to swear that I had not been raped.There was no one I could tell what had happened.”Women have been raped in Iraqi detention centres,according to various reports. In 2007 the UNAssistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) reported that itsstaff had interviewed several women and girls detained

Patterns of gender discrimination and violence that areevident beforehand frequently become more acuteduring periods of armed conflict. This has been thecase in Iraq, where the majority of women whoresponded to a survey conducted through networksof Iraqi women’s organizations and published in 2008said they considered that violence against women wasrising.12Many Iraqi women and girls are subjected to harmfultraditional practices, including forced and earlymarriage. Female genital mutilation is reported to bewidely practised in Kurdish areas. The Iraqi authoritiesare aware of such practices but do little to stop them.Iraqi women human rights defenders say that manyabused wives were forced to marry – often as ateenager without obtaining the judicial approvalformally required under Iraqi law for a marriage ofanyone aged between 15 and 18. Marriages of girlsyounger than 15 are illegal but they continue to beconducted in private or religious ceremonies withoutthose responsible being held to account.Women are also suffering violence at the hands of theirfathers, brothers and other relatives, particularly if theytry to go against the wishes of the family. Many faceterrible retribution if they refuse to be forcibly marriedor dare to associate with men not selected by theirfamilies. This is despite Iraqi legislation that specificallyprohibits forced marriage, and international law,applicable in all parts of Iraq, that guarantees the rightto choose a spouse.

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

20iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

Kurdistan Azizfrom the Kolkarash village near Heran,Erbil governorate, was 16 years old when shedisappeared in May 2008. She has not been seen sinceand is believed to have been murdered. In February2008 she had run away with a young man she loved toErbil, where both were detained in a form of protectivecustody by the Kurdistan Region authorities. However,at the end of February she returned to her parents’home after they signed an agreement guaranteeing hersafety. On 21 May 2008 her father informed the localpolice that his nephew had called him and hadconfessed to her murder. At the beginning of 2010 thesuspected perpetrator of the crime remained at large.

women (Law 14 of 2002). This has been reflected insome recent court rulings.

insufficienT prOTecTiOnSome women do escape violence and seek refuge inspecial shelters, but there are far too few of these.In the Kurdistan Region, several shelters have beenestablished by the authorities and NGOs. In the rest ofIraq, however, the authorities do not provide sheltersand those that do exist are run by NGOs and oftenhave to function more or less clandestinely.Even women and girls who have obtained emergencyprotection remain at risk as refuge locations, includingprivate houses, have been attacked by their malerelatives. All shelters in Iraq can be seen as no morethan short- or medium-term “solutions” and cannotprovide a durable resolution for women at risk.In the Kurdistan Region, shelter staff, police officersand community leaders are involved in negotiationsabout the return of a woman at risk to her family. Thefamily is usually required to sign a commitment not toharm her. However, in a number of cases women havebeen attacked and even killed by relatives who hadpledged to do the women no harm.

licensed TO kill wOmenWomen continue to be killed with impunity by theirrelatives because their behaviour is perceived to haveinfringed traditional codes. In 2008 the Iraqi authoritiesrecorded 56 so-called honour killings of women in thenine southern governorates.Most men get away with these murders because theauthorities are unwilling to carry out proper investigationsand punish the perpetrators. Iraqi legislators havefailed to amend laws that effectively condone, evenfacilitate, such violence against women and girls.The Penal Code, for example, provides that a convictedmurderer who pleads in mitigation that he killed with“honourable motives” (Article 128) may face just sixmonths in prison. The Code also effectively allows ahusband to use violence against his wife. The “exerciseof a legal right” to exemption from criminal liability ispermitted for: “Disciplining a wife by her husband, thedisciplining by parents and teachers of children undertheir authority within certain limits prescribed byIslamic law (Shari’a), by law or by custom” (Article 41).As a result, police frequently fail to arrest men accusedof violence against their female relatives. In the rarecases when they do and prosecutions are mounted,judges often hand down disproportionately lenientsentences, even when a woman has been murdered.This sends out a terrifying message to all women in Iraq– that they may be killed and beaten with impunity.The Kurdistan Regional Government, however, hasamended the Penal Code to remove the “honourablemotive” clause in cases involving crimes against

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

21

5/aTTacksOngay men

Moqtada al-Sadr, a Shi'a cleric and political leader.Many of the victims were tortured and their bodiesmutilated and dumped in the streets. Many other menand boys fled Iraq after receiving death threats.In April 2009 Amnesty International interviewed severalIraqis who had recently fled due to the violence theywere facing because they were gay men.Hakim,a 34-year-old man from Najaf, reported that his partner hadbeen kidnapped and abused by members of the MahdiArmy in October 2008, apparently after they found outabout their secret relationship. Following his release,both men received death threats from the Mahdi Army,including on one occasion a note that was deliveredwith three bullets.

Members of the gay community in Iraq live underconstant threat. They are confronted by widespreadintolerance towards their sexual identity and scores ofmen who were, or were perceived to be, gay have beenkilled in recent years, some after torture. Violent actsagainst gay men have occurred against a backgroundof frequent public statements by some Muslim clericsand others condemning homosexuality.13Attacks against gay men, including killings, havefrequently been reported since the 2003 invasion.Qassim,a 40-year-old hairdresser from Baghdad andrefugee in Jordan, told Amnesty International in June2006 about several incidents targeting gay men thatoccurred in August and September 2004 in Baghdad:“I was at a gym with my boyfriend. When he returnedto my car to get me a bottle of water he was shot deadoutside the gym. I was terrified and went into hiding.”About two weeks later two of his friends were killed inBaghdad. A few days later an explosive device wasthrown at his car and he decided to leave Iraq.The UN reported that at least 12 people were killedbecause of their sexual orientation between October2005 and May 2006, during which afatwaappearedon the website of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani callingfor the killing of homosexuals “in the most severeway”.14During the first few months of 2009 at least 25 menand boys were killed in Baghdad because of theirsexual orientation or gender expression. This was mostcommon in the predominantly Shi’a district of al-SadrCity. According to reports, the perpetrators were theirrelatives and members of the Mahdi Army, followers of

A 41-year-old gay man from the Hayy Ur district ofBaghdad told Human Rights Watch that a friend of his,a gay man, was attacked and killed in February 2009by members of the Mahdi Army while he was walkingin the neighbourhood with friends. The man himselflater survived an abduction by members of the MahdiArmy, who forced him at gunpoint out of his store on6 March 2009. During his abduction, the militiaabused him, including by beating him unconsciousand raping him with a broomstick. He was releasedafter his family paid a ransom, but the abductorsthreatened to kill him if he left the house after hisreturn. For one month he did not leave the house untilhe fled Baghdad.15The wave of attacks on gay men in early 2009coincided with statements by Muslim clerics,particularly in al-Sadr City, urging their followers to takeaction to eradicate homosexuality from Iraqi society.They used language that effectively constitutedincitement to violence against men known or alleged tobe gay.

licensed TO kill gay menGay men face similar discrimination as women underthe legislation that provides for lenient sentences forthose committing crimes with an “honourable motive”.Iraqi courts continue to interpret provisions of Article128 of the Penal Code as justification for givingdrastically reduced sentences to defendants who haveattacked or even killed gay men they are related to ifthey say that they acted to “wash off the shame”. In itsrulings, the Iraqi Court of Cassation has confirmed thatthe killing of a male relative who is suspected of

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

22iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

same-sex sexual conduct is considered a crime with an“honourable motive”, thus qualifying for a reducedsentence under Article 128.16Although provisions under Articles 128 have beenamended in the Kurdistan Region by Law 14 of 2002and, therefore, may no longer be applied in connectionwith crimes committed against women there, theycontinue to be applicable throughout the whole of Iraqin connection with crimes against gay men.For example, on 24 October 2005 the Court ofCassation of the Kurdistan Region confirmed theconviction for murder and one-year prison sentenceimposed on a man from Koysinjak who had confessedto killing his gay brother earlier in 2005. The courtfound that he had killed his brother with “honourablemotives” because he “wanted to end the shame whichthe victim [of the crime] had brought over his family bypracticing depravity and by being engaged inhomosexuality and prostitution.” The court alsoaccepted that a one-year prison sentence was in thiscase appropriate for premeditated murder, a crimewhich carries the death penalty.Impunity or, at most, a disproportionately lenient prisonsentence for the murder of gay men by their relatives,appears to be the rule rather than the exception in Iraq.

Graffiti in Kufa, Najaf governorate, photographed bymobile phone, April 2009. It reads: “Death to gays anddirty people”.

� Private

nO prOTecTiOnA group of gay men reportedly provide emergencyshelter at secret locations in Baghdad for individualswho are at risk. However, members of the gaycommunity under threat of attack or murder cannotexpect any assistance from the authorities, even whenurgent protection is needed.On the contrary, members of the security forces andpossibly other authorities appear in some cases to haveencouraged the targeting of people suspected of same-sex relationships, in blatant violation of the law andinternational human rights standards. For example, asenior police officer in the Karada district of Baghdadwas reported to have told the media that“homosexuality is against the law” and that the policewere involved in a “campaign to clean up the streetsand get the beggars and homosexuals off them.”17

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

23

6/displacedpeOple

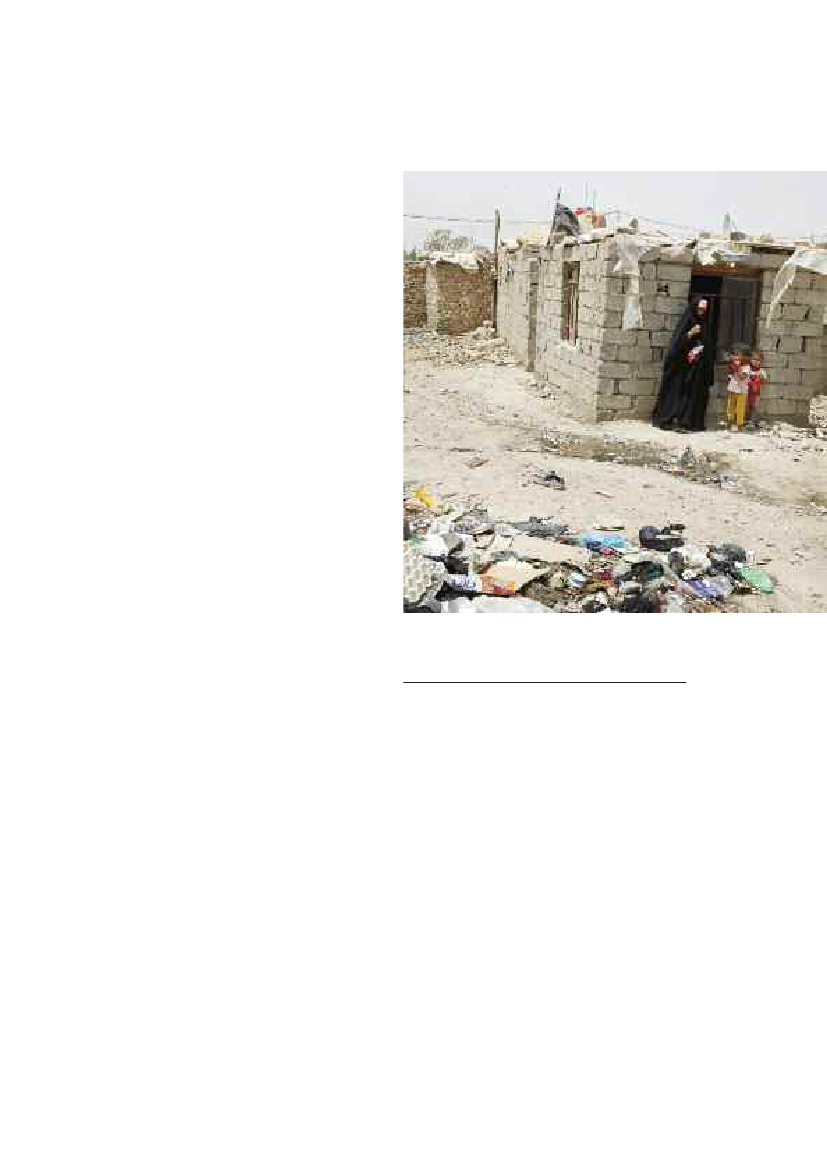

About 2.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs)are living in Iraq, including about 1 million who havebeen displaced since before 2003. In addition, thereare an estimated 1.5 million Iraqi refugees, mainly inneighbouring countries. Mass displacement, bothinternally and abroad, was particularly triggered by theFebruary 2006 bombing of the al-Askari mosque inSamarra and the ensuing sectarian violence.Many displaced people in Iraq face economic hardshipand lack of basic services, including access to cleanwater and health services. According to theInternational Organization for Migration (IOM), in two-thirds of surveyed families who were displaced afterFebruary 2006 all family members of working age wereunemployed.Because of lack of choice, many IDPs have settled inunsafe locations. Among them are about 400 familiesliving in the Shu'ala district of Baghdad in a compoundthat is frequently targeted in rocket attacks.18IDPs are also frequently threatened with eviction wherethey have settled on property claimed by others.Evictions are facilitated by Prime Minister Order 101,which also provides for subsidies for those evicted.However, not all evicted IDPs have received suchfinancial assistance.In April 2009, the IOM reported on about 250 IDPfamilies who were facing eviction in five differentlocations, including 40 families in Najaf who couldnot afford to pay for their housing. In October 2009,it reported that about 70 families in the Qassim sub-district of the governorate of Babil who built houseson land they do not own were at risk of eviction.

The poor Baghdad suburb of Chikook, where thousandsof displaced people live without adequate drinking water,a sewage system or other basic services.

reTurning despiTe The dangerThere have been frequent reports of attacks on IDPsattempting to return to their homes. In some incidents,returning IDPs have been killed. For example, in March2009, two IDP families failed in their attempt to returnfrom the Kirkuk governorate to their homes in Diyalagovernorate when two members of the families werekilled in a militia attack.According to estimates by the UN refugee agencyUNHCR, about 200,000 displaced people returned totheir homes in 2009, including about 37,000 refugeesfrom outside Iraq.19However, according to an IOMsurvey of about 4,000 returnee families, 38 per centsaid they felt safe “only some of the time”.Furthermore, 34 per cent reported that their homeshad been completely or partially destroyed. Othermajor concerns for returnees included food insecurity,lack of water and energy supplies, and unemployment.

� UNHCR/B.Heger

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

24iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

Several Iraqi refugees who had returned to Iraq orintended to do so imminently, told AmnestyInternational that their decision was driven by their lackof resources or that they could not legally reside in ahost country.Majid,a 62-year-old retired army officer and widowerfrom Baghdad, said that he had fled to Syria after twoof his nephews were beheaded by members of anarmed group or militia in December 2007. However,after he discovered that his family could not join himand having exhausted his meagre savings, he decidedto return, even though he was extremely scared to do so.Muhsin,a former interpreter for the Multinational Forcefrom Mosul, decided to return in February 2009 to seehis family in Baghdad after he had spent two years inseveral European countries without his asylum claimhaving been accepted – although Iraqis who workedwith the Multinational Force are considered to be atparticular risk. On his arrival at Baghdad airport,security officers questioned him about his stay inEurope and why he had travelled to Baghdad insteadof Mosul. He was beaten, threatened with detentionand forced to hand over about US$1,300 before hewas released the next day. About a month later he wasvisited by police at his rented apartment in Baghdadand taken into custody. He was held at a detentioncentre in Baghdad for about a week where he wasthreatened with indefinite detention, beaten andsubjected to other abuses. He was released after a USofficer intervened on his behalf. In June 2009, he andhis family fled Iraq.Despite the ongoing violence in Iraq, several Europeangovernments continue to forcibly return rejected Iraqiasylum-seekers to Iraq. In 2009, the authorities inDenmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and theUK forcibly returned scores of Iraqis to unsafe parts ofIraq, such as central Iraq, in breach of UNHCRguidelines. For example, on 15 October 2009 UKauthorities forcibly deported 44 rejected Iraqi asylum-seekers to Baghdad; the Iraqi authorities allowed only10 of them to enter. The Norwegian authorities forciblyreturned 30 Iraqis to Baghdad in December 2009 and13 in January 2010. In February 2010 Iraqi Vice-President Tariq al-Hashemi urged Europeangovernments not to deport Iraqi asylum-seekers to Iraquntil security and economic conditions had improved.

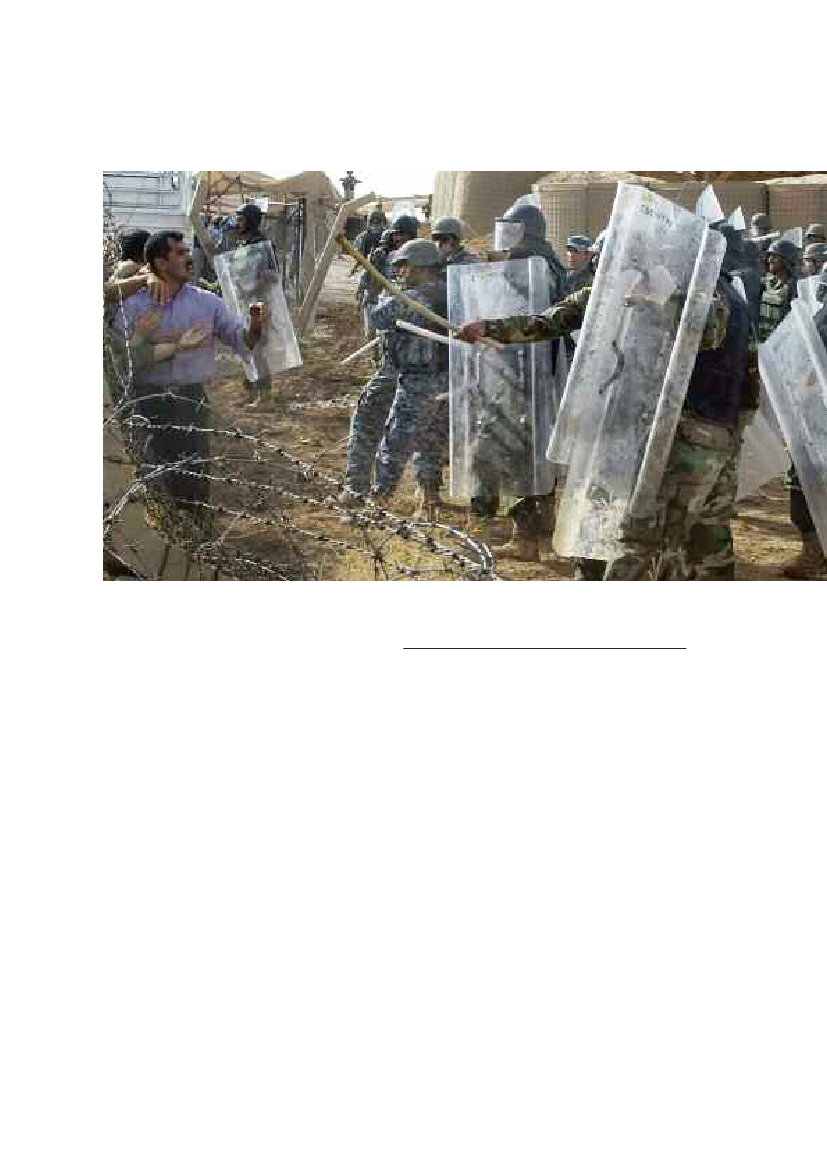

Iraqi police and security forces confront residents in CampAshraf, July 2009.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

� Private

� Private

� Private

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

25

viOlence againsT refugeesIn addition to internally displaced Iraqis, there areabout 35,000 refugees from other countries registeredby the UNHCR in Iraq. The largest groups arePalestinians as well as Turkish and Iranian nationals.Gross human rights violations against Palestinians,including killings, since the US-led invasion in 2003have led to a reduction in the number of Palestinianrefugees in Iraq from 34,000 to 12,000. Palestinianshave been threatened, abducted, tortured and killed,mainly by Shi'a militias. They have been targetedbecause of their ethnic identity and because they arereputed to have received preferential treatment underthe former Ba'ath government in Iraq.Many of the thousands of Palestinians who havesought to flee Iraq have been denied entry intoneighbouring countries and have ended up inmakeshift camps near the border where conditionsare harsh. Some residents of these camps have beenresettled, but al-Waleed camp on the Iraqi-Syrianborder continues to host mainly Palestinian refugees.Other vulnerable refugees are some 3,400 members orsupporters of the People’s Mojahedeen Organization of

� Private

Iraqi police and security forces confront residents in CampAshraf, July 2009.

Iran (PMOI), an Iranian opposition group, who areliving in Camp Ashraf in Diyala governorate. Followingmonths of rising tension, Iraqi security forces forciblyentered and took control of the camp, which had beenunder US military control until June 2009, on 28 and29 July 2009. Video footage taken as Iraqi securityforces entered the camp showed them deliberatelydriving military vehicles into crowds of protestingresidents. They used live ammunition, apparentlykilling at least nine refugees, and detained 36 otherswho they subsequently tortured. The 36 were taken toal-Khalis police station in Diyala, where they mounteda hunger strike, and were then moved to Baghdaddespite repeated judicial orders for their release. Theywere freed and allowed to return to Camp Ashraf inOctober after an international campaign for theirrelease. However, in early 2010 the authorities werereported to be insisting that the camp residents moveto another location in southern Iraq.

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

26iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

recOmmendaTiOnsAmnesty International makes the followingrecommendations which are essential if Iraqisare to live in safety and to fully to exercize theirhuman rights.

“honourable motives” for crimes against women andmembers of the gay community perceived to betransgressing traditional gender roles or moral codes.Ban or enforce existing bans on harmfultraditional practices for girls, namely female genitalmutilation and forced and early marriages.Provide assistance to all displaced people,including shelter, health care and other essentialneeds.Do not forcibly return any refugees or asylum-seekers to countries where they are at risk of humanrights violations.

TO The armed grOups and miliTiasEnd all attacks on civilians and other humanrights abuses, including abductions, hostage-taking,and the killing, torture and other ill-treatment ofcaptives.

TO The iraqi auThOriTiesExercise due diligence and protect the humanrights of all civilians in Iraq.Review and improve protection measures forhuman rights defenders, other critical voices andvulnerable groups, including by consultation withrepresentatives of groups at risk.End discrimination, including with regard toprotection measures, on the basis of gender, race,ethnicity, nationality, origin, colour, religion, sect,belief or opinion, or economic or social status – asrequired by Iraqi and international law.Ensure prompt, impartial and thoroughinvestigations into all attacks on and other violentcrimes against civilians, and bring those responsibleto justice in conformity with international law andwithout recourse to the death penalty.Immediately disarm all militias.Train and instruct law enforcement personnelto identify at risk individuals or groups and ensureeffective protection measures.End the indication of the holder’s religion onidentity cards in light of the risk of grave humanrights abuses entailed in the inclusion of religiousaffiliation on identity cards, in consultation withreligious minority communities.Abolish legislation that provides disproportionatelylenient sentences for perpetrators claiming

TO iraq’s religiOus, cOmmuniTy andpOliTical leadersSpeak out against intolerance and violent attacksagainst anyone, including those perceived to betransgressing moral codes or traditional gender roles.

TO The uniTed sTaTes fOrces-iraqExercise due diligence and protect the humanrights of all civilians in Iraq.Ensure prompt, impartial and thoroughinvestigations into all attacks on and other violentcrimes against civilians by US forces, and bringthose responsible to justice in conformity withinternational law and without recourse to the deathpenalty.

TO The inTernaTiOnal cOmmuniTyEnd all forcible returns to any part of Iraq; anyreturn of rejected asylum-seekers should only takeplace when the security situation in the wholecountry has stabilized.Provide financial, technical and in-kind assistanceto refugee-hosting states in the region, UNHCR andother organizations providing assistance to refugeesfrom Iraq.Share the responsibility by resettling refugeesfrom Iraq currently in the region, giving priority tothe most vulnerable cases.

amnesty international april 2010

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

iraqcIvIlIans unDEr fIrE

27

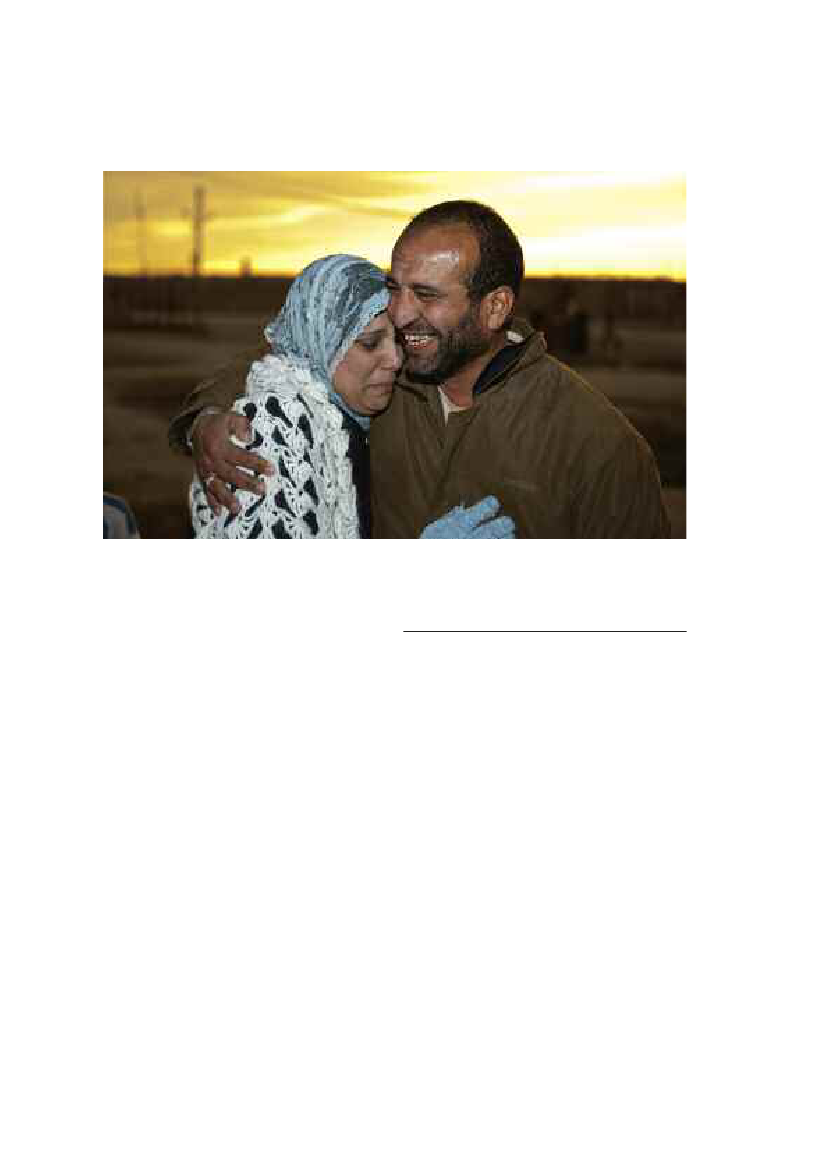

� UNHCR/B. Diab

A former resident of al-Tanf refugee camp, which wasclosed in February 2010, is reunited with her brother inal-Hol camp, northern Syria. The pair had not seen eachother since 2006.

endnOTes1For a more detailed assessment of at risk categories, see:UNHCR: Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the InternationalProtection Needs of Iraqi Asylum-Seekers,April 2009.2Front Line,Iraq, Testimonies of Iraqi Human RightsDefenders,July 2008, p10.3Committee to Protect Journalists,http://cpj.org/reports/2008/07/journalists-killed-in-iraq.php4Mandaean Associations Union, Mandaean Human RightsAnnual Report, November 2009.5Assyrian International News Agency, “Church bombings inIraq since 2004”, 25 December 2009.6Human Rights Watch,Iraq: Protect Christians fromviolence,23 February 2010.7UN document A/63/161, 22 July 2008.8UN Security Council, Report of the Secretary-Generalpursuant to paragraph 6 of the resolution 1830 (2008), 30July 2009, S/2009/393, para 25.9Laila Fadhel, “Kurdish expansion squeezes northern Iraq’sminorities”,McClatchynewspaper, 12 November 2008.10UNHCR,UNHCR: Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing theInternational Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylum-Seekers,April 2009, para 301.11UNAMI,Human Rights Report,1 April-30 June 2007.12Women for Women International,Stronger WomenStronger Nations,2008 Iraq report, p20.13For safety reasons, the names of individuals in this andthe following chapter have been changed.14UNHCR, Situation of Lesbians, Gay, Bisexual andTransgender Iraqis, June 2006, p3.15Human Rights Watch,“They want us exterminated”:Murder, torture, sexual orientation and gender in Iraq,August 2009, pp17-18.16Dr Himdad Majeed Ali Marzani,Murder for Honor (al-qatlbi-dafi' al-sharaf),Sulaimaniya, 2007, pp392-397.17Timothy Williams and Tareq Maher, “Iraq’s Newly OpenGays Face Scorn and Murder”,New York Times,7 April2009.18IOM data in this section from the IOM’s Emergencyneeds assessments in 2009.19UNHCR Iraq, Factsheet, December 2009.

Index: MDE 14/002/2010

amnesty international april 2010

� Pamela Juhl/Amnesty International

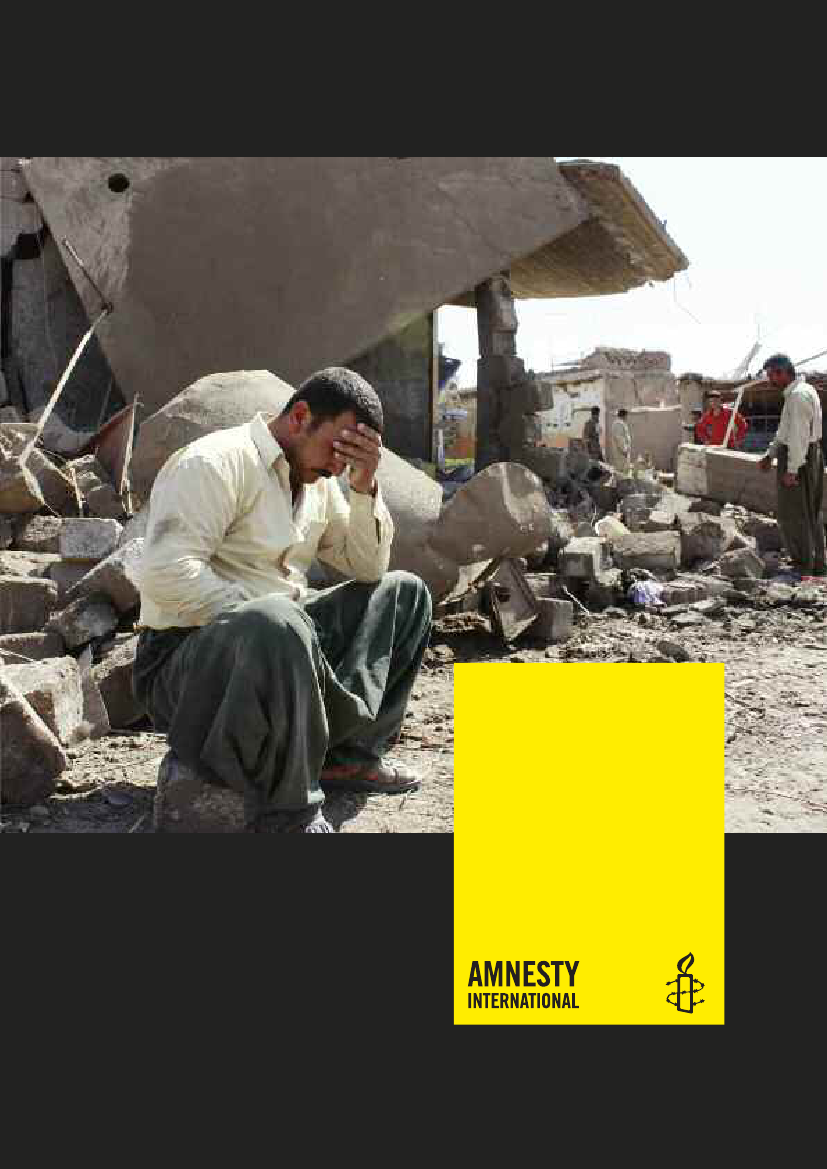

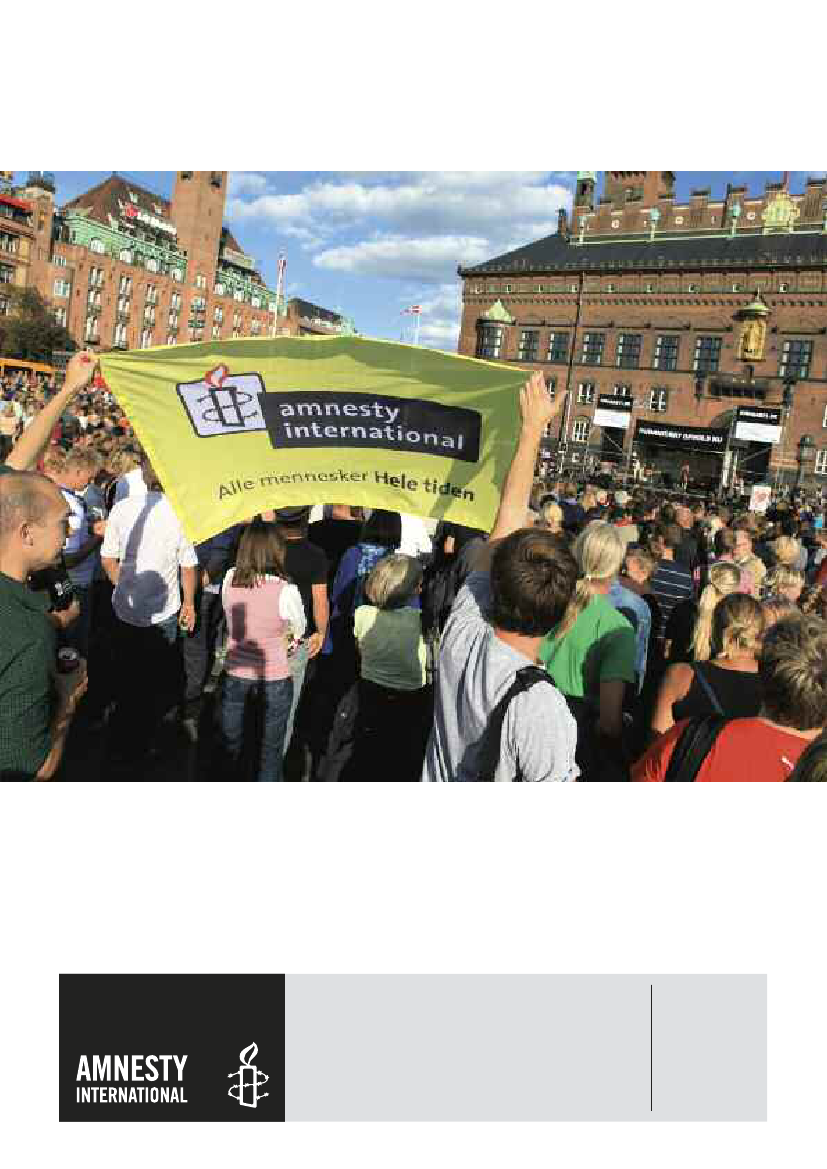

Above:Thousands of people gather in Copenhagen on18 August 2009 to protest against the forcible return toBaghdad of Iraqis who had sought asylum in Denmark.Cover:A man sits among the ruins of Wardak, a villagenear Mosul whose inhabitants mostly belong to the Kaka'iminority, after a pre-dawn suicide truck bombing on10 September 2009 which killed at least 16 people.� Associated Press

amnesty internationalis a global movement of 2.8 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories whocampaign to end grave abuses of human rights.our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in theuniversal Declaration of Human rights and other international humanrights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

april 2010Index: MDE 14/002/2010amnesty InternationalInternational secretariatpeter Benenson House1 Easton streetlondon Wc1X 0DWunited kingdomwww.amnesty.org