Udenrigsudvalget 2009-10, Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2009-10

URU Alm.del Bilag 25, UPN Alm.del Bilag 5

Offentligt

TROUBLED WATERS –PALESTINIANSDENIED FAIR ACCESSTO WATERISRAEL-OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORIESWATER IS A HUMAN RIGHT

Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights.Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards.We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interestor religion – funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

Amnesty International PublicationsFirst published in 2009 byAmnesty International PublicationsInternational SecretariatPeter Benenson House1 Easton StreetLondon WC1X 0DWUnited Kingdomwww.amnesty.org� Amnesty International Publications 2009Index: MDE 15/027/2009Original language: EnglishPrinted by Amnesty International,International Secretariat, United KingdomAll rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.The copyright holders request that all such use beregistered with them for impact assessment purposes.For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use inother publications, or for translation or adaptation, priorwritten permission must be obtained from the publishers,and a fee may be payable.

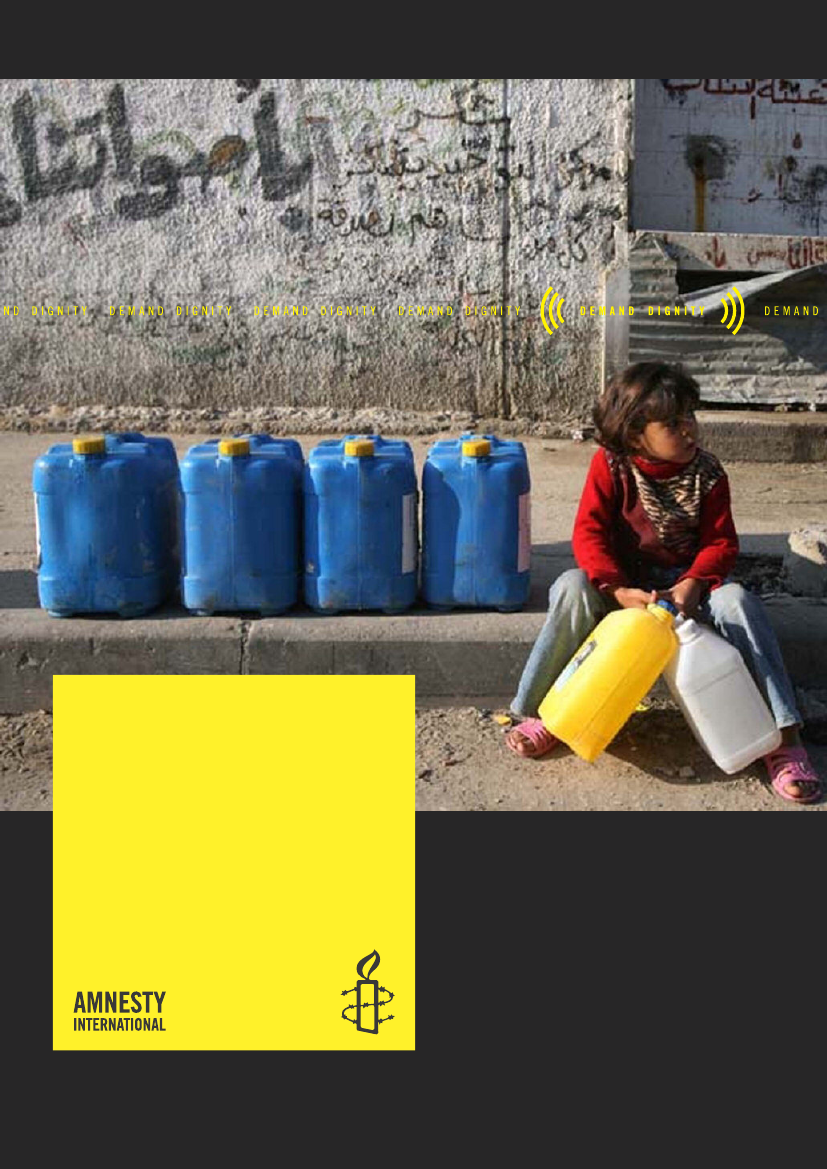

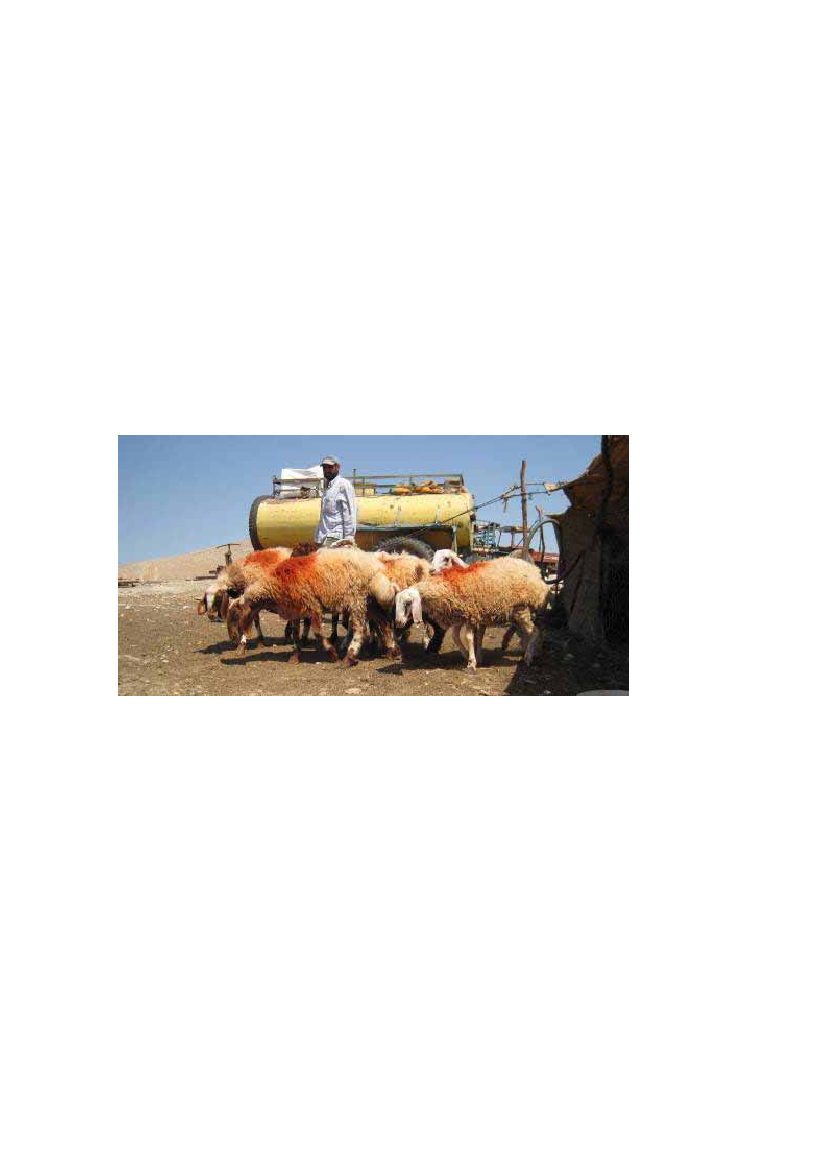

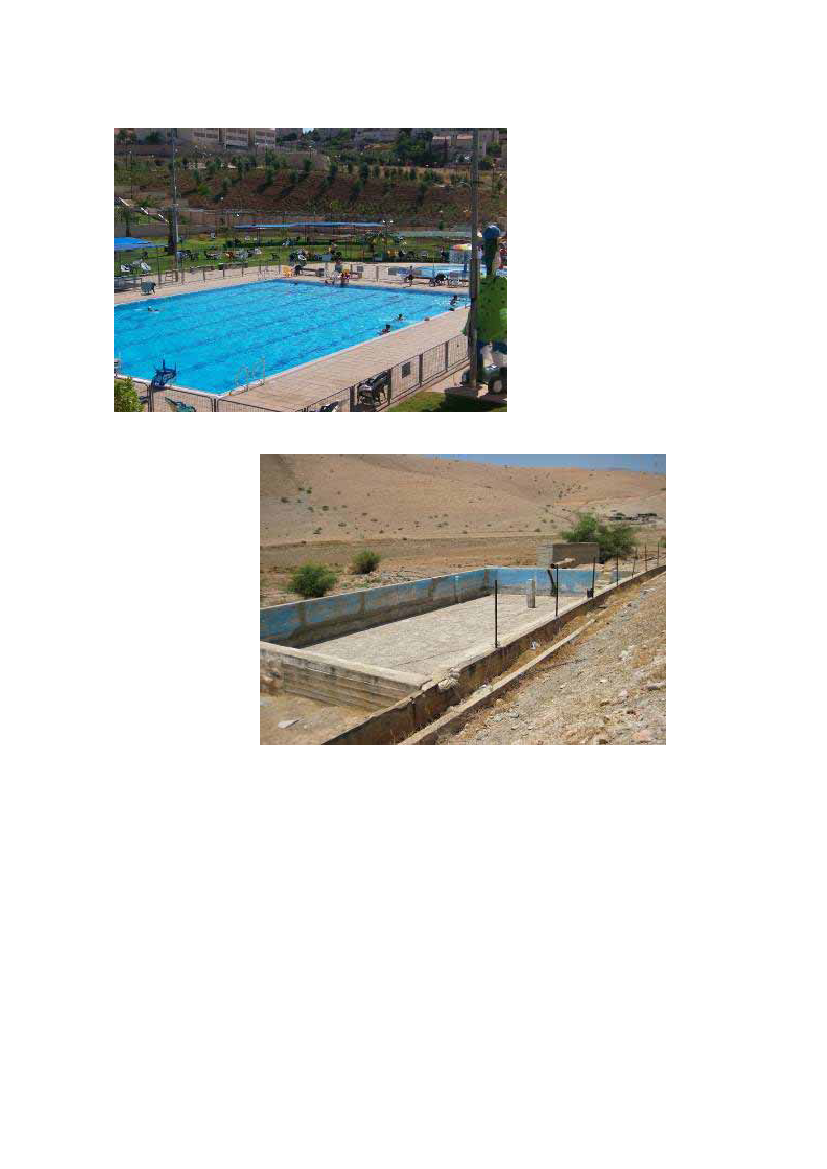

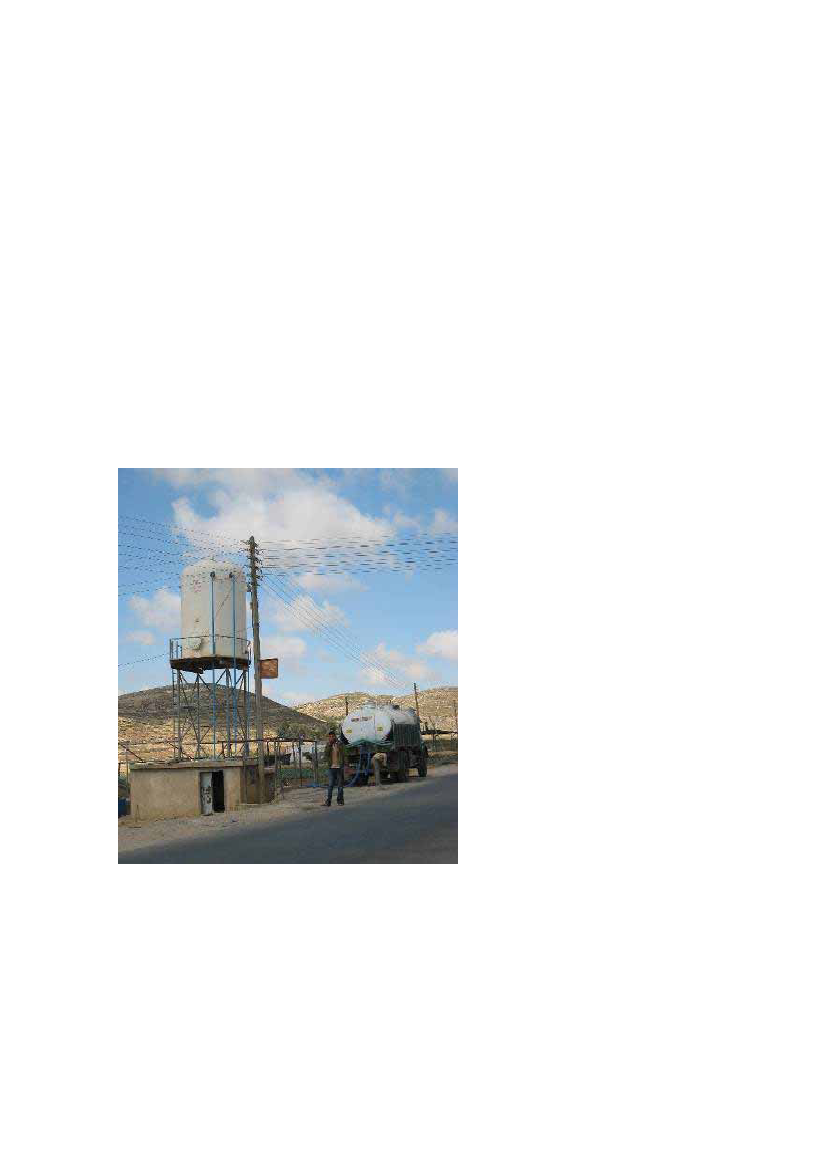

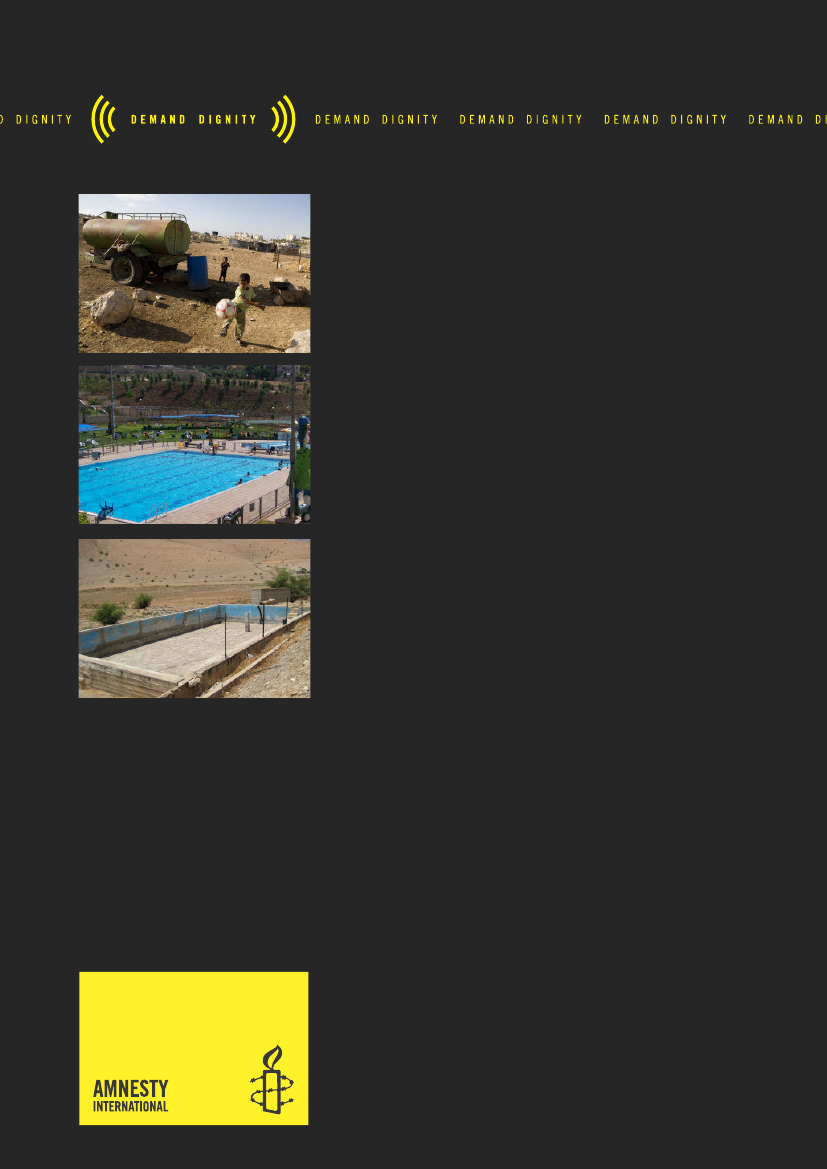

Cover photo:A Palestinian girl takes a rest while collecting drinkingwater in Gaza.� Iyad El Baba-UNICEF-oPtBack cover from top:A water tanker in the West Bank; Palestinians in the arearely on such tankers as their homes have no running water.� Keren Manor/Activestills.orgIsraeli settlers enjoy the swimming pool in the MaalehAdumim settlement, unlawfully established in the WestBank in violation of international law, while nearbyPalestinian communities struggle to access even minimalquantities of water for their basic needs.� Angela Godfrey-GoldsteinA water reservoir stands empty in Jiftlik, a Palestinianvillage in the West Bank.� Amnesty International

CONTENTSINTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................3HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .........................................................................................6WATER RESOURCES IN ISRAEL/OPT.............................................................................8Groundwater Resources ..............................................................................................8Surface Water Resources ............................................................................................8UNEQUAL ACCESS TO WATER ......................................................................................9The West Bank: Israeli over-exploitation of shared resources ..........................................9Gaza: unsafe water supplies......................................................................................10ISRAELI MILITARY ORDERS .......................................................................................11OSLO ACCORDS: INSTITUTIONALIZING ISRAELI CONTROL OF RESOURCES .................17Inequality in access to water resources codified ..........................................................20Israeli Claims: Maintaining the status quo ..................................................................21POLICIES OF DENIAL .................................................................................................23THE WATER CRISIS IN GAZA ......................................................................................25Dwindling resources .................................................................................................26THE JOINT WATER COMMITTEE (JWC) – A PRETENCE OF COOPERATION ..................28MILITARY PERMIT REGIME HINDERING WATER PROJECTS ......................................29RESTRICTING ACCESS TO WATER AS A MEANS OF EXPULSION ...................................36Destruction of water cisterns – Vulnerable communities targeted ..................................36The Southern Hebron Hills .......................................................................................38Confiscation of water tankers in the Jordan Valley .......................................................40Destruction of agricultural water facilities...................................................................43Unlawful Israeli settlements connected to the water network ........................................45THE FENCE/WALL - BARRING ACCESS TO WATER .......................................................46Water-rich land inaccessible .....................................................................................47Bearing the cost – solving the problems created by the fence/wall.................................51MOVEMENT RESTRICTIONS AFFECTING ACCESS TO WATER ........................................52WATER INFRASTRUCTURE DESTROYED IN MILITARY ATTACKS ...................................56Damage to water facilities in Gaza during Operation “Cast Lead” ..................................58Damage to water facilities during Israeli military campaigns .........................................59Impact on Health.....................................................................................................60ISRAELI SETTLERS’ ATTACKS ON WATER FACILITIES .................................................62PA/PWA FAILURES AND MISMANAGEMENT ................................................................65SEWAGE DISPOSAL MALPRACTICE – ENDANGERING WATER RESOURCES ...................67Failure to protect the water supply in the OPT: Israel...................................................68Failure to protect the water supply in the OPT: PA/PWA...............................................71THE ROLE OF INTERNATIONAL DONORS ....................................................................73INTERNATIONAL LAW: THE RIGHT TO ACCESS TO WATER...........................................75International Human Rights Law ...............................................................................76International Humanitarian Law ................................................................................80Applicability of international law in the OPT ...............................................................81International law and the use of transboundary groundwater resources ..........................82CONCLUSION and RECOMMENDATIONS .....................................................................85GLOSSARY.................................................................................................................89ENDNOTES ................................................................................................................90

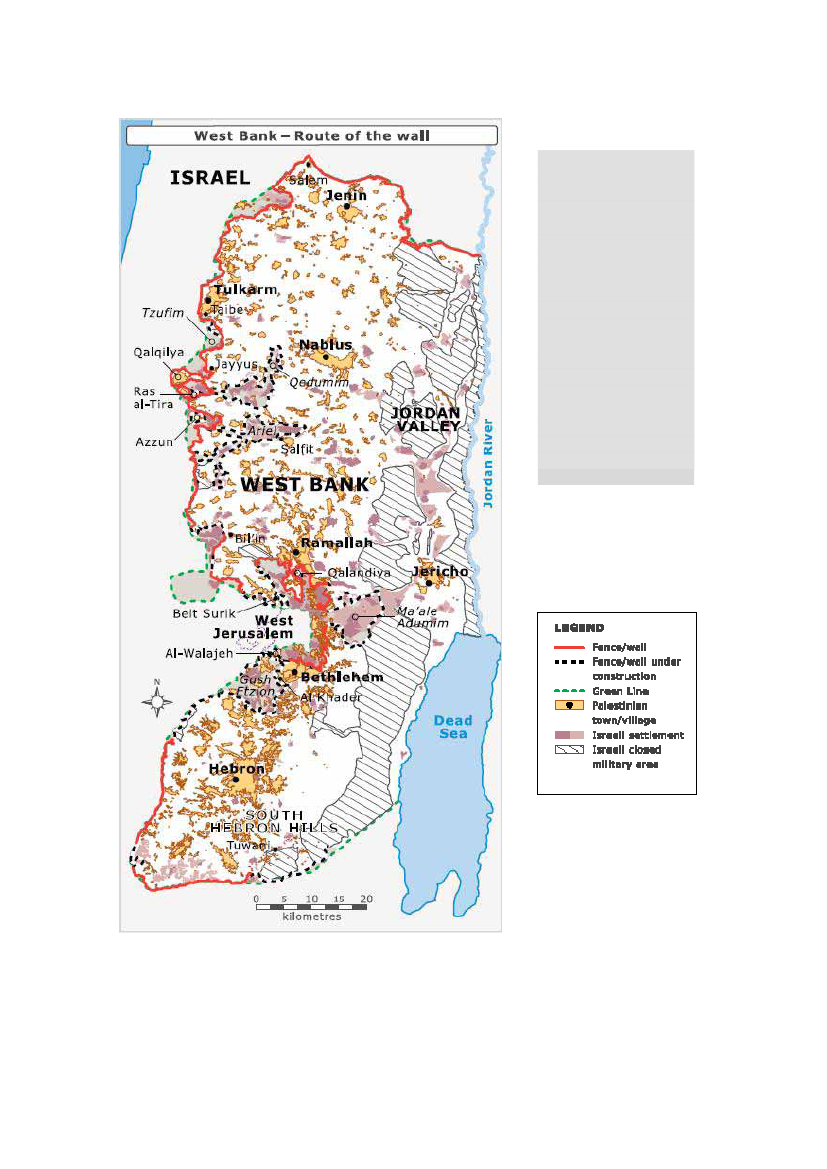

West Bank, includingEast Jerusalem, occupiedby Israel since June19675,600km� total area: about130km north-south and65km east-west200+ unlawful Israelsettlements and “outposts”550+ Israeli militarycheckpoints, blockades andobstacles709km-fence/wall, 80 percent of it on Palestinianland inside the West Bank

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

1

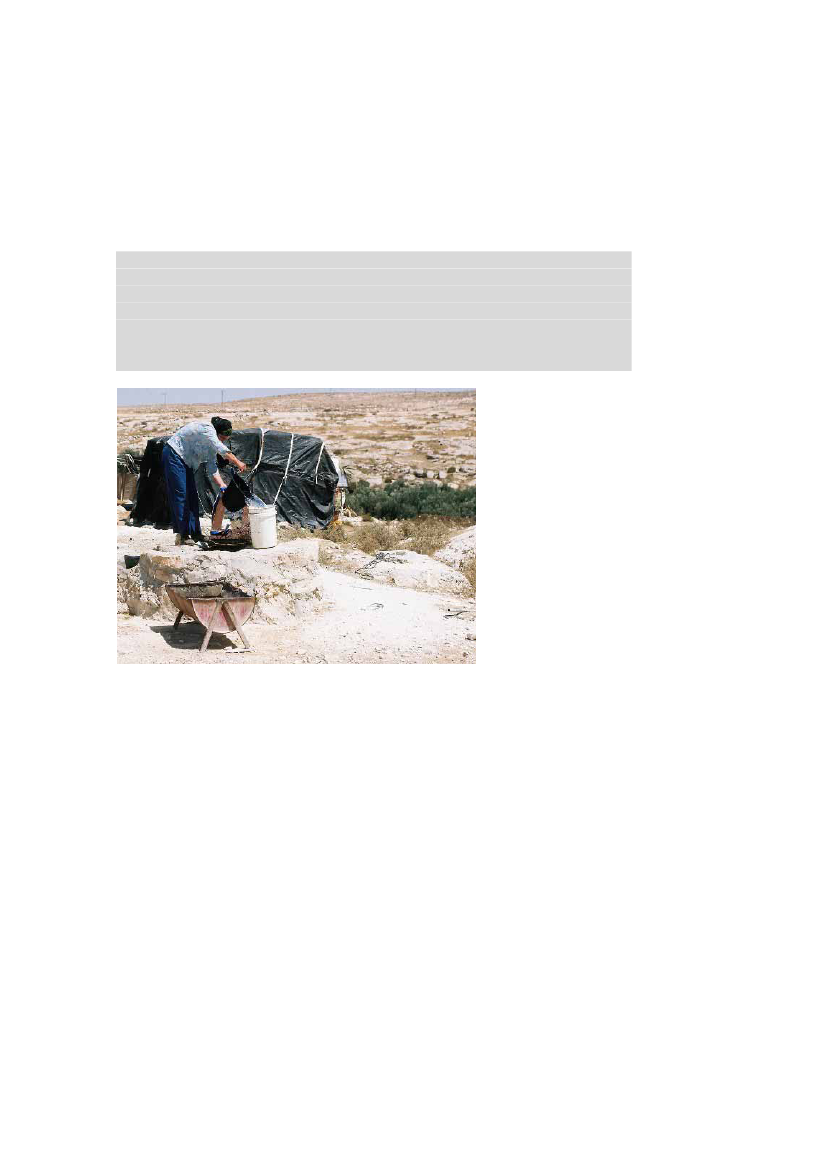

“Water is life; without water we can’t live; not us,not the animals, or the plants.”“Water is life; without water we can’t live; not us, not the animals, or the plants. Before we had somewater, but after the army destroyed everything we have to bring water from far away; it’s verydifficult and expensive. They make our life very difficult, to make us leave. The soldiers firstdestroyed our homes and the shelters with our flocks, uprooted all our trees, and then they wreckedour water cisterns. These were old water cisterns, from the time of our ancestors. Isn’t this a crime?Water is precious. We struggle every day because we don’t have water.”Fatima al-Nawajah, a resident of Susya, a Palestinian village in the South Hebron Hills, to Amnesty International, April 2008.A Palestinian woman draws waterfrom a cistern in Susya. � ShabtaiGold (IRIN)

In Susya, most of therain-harvesting watercisterns which thevillagers used to collectand store water for useduring the dry seasonwere demolished by theIsraeli army in 1999 and2001, along with theancient caves and othershelters that were thevillagers’ homes. InNovember 1999, theIsraeli army sealed the caves to prevent their continued use, destroyed other homes and thewater cisterns, and forcibly expelled the villagers from the area. In March 2000, however, thecave dwellers obtained a temporary injunction from the Israeli Supreme Court allowing themto return and preventing their further expulsion by the Israeli army pending the court’s finaldecision in the matter, which has yet to be reached. Since then, the villagers have been ableto remain in the area but under threat of future expulsion and with hardly any water supply.The increasing restrictions imposed by the Israeli army on the Palestinian villagers’ access towater and the constant threat of demolition of their homes and destruction of their propertyhave led more than half of the villagers to leave the area.On 3 July 2001, the Israeli army destroyed dozens of homes and water facilities in Susya andseveral other Palestinian villages nearby.1The army smashed the villagers’ rainwaterharvesting cisterns, some of them centuries old, with bulldozers and filled them with graveland cement to prevent their repair. The soldiers also smashed water heating solar panels that

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

2

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

had been provided to the villagers by a non-governmental organization. Some water cisternswere left undestroyed but they, together with the tents and shacks that now serve as thevillagers’ homes, and even the one toilet which they have built, all have demolition orderspending.

Susya toilet under demolition order by the Israeli army � AI

The official reason given by the Israeli authorities for the destruction was that the structureslacked building permits – permits which the Israeli army systematically refuses to grant toPalestinians in the area. The aim, clearly, was to expel the Palestinian villagers from the areain order to make way for the expansion of the nearby Israeli settlement of Sussia (establishedin 1983). The expansion of the settlement in the 1990s was accompanied by increasedharassment of Palestinian villagers by Israeli settlers and efforts by the army to expel thePalestinian cave dwellers and other inhabitants of the villages in the South Hebron Hills, whoare among the most disempowered of Palestinian communities.In September 2008 the Israeli army informed the remaining villagers that a military orderhad been issued to declare 150 dunums (15 hectares) of land near the village a “closedmilitary area”, thereby denying the villagers access to the 13 rainwater harvesting cisternslocated there and making their water shortage worse still.Meanwhile, in the nearby Israeli settlement of Sussia, whose very existence is unlawful underinternational law, the Israeli settlers have ample water supplies. They have a swimming pooland their lush irrigated vineyards, herb farms and lawns – verdant even at the height of thedry season – stand in stark contrast to the parched and arid Palestinian villages on theirdoorstep.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

3

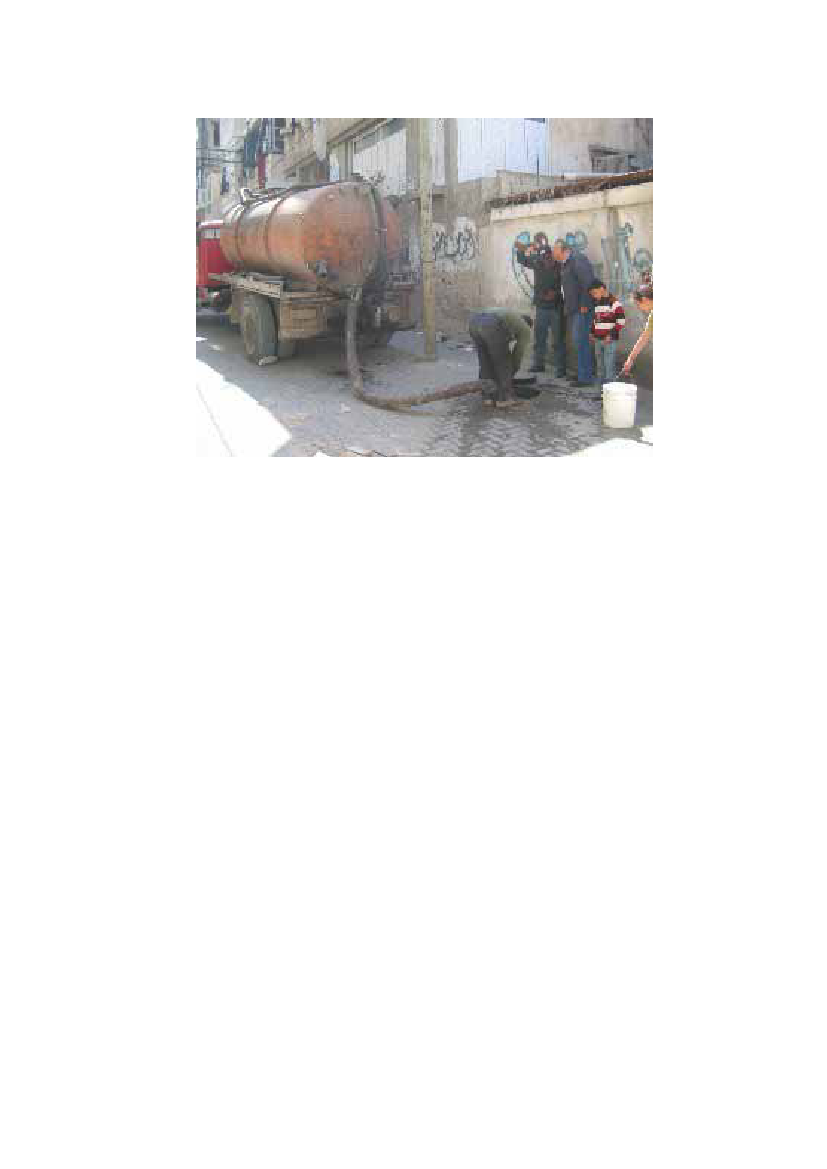

INTRODUCTIONLack of access to adequate, safe, and clean water has been a longstanding problem for thePalestinian population of the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT).2Though exacerbated inrecent years by the impact of drought-induced water scarcity, the problem arises principallybecause of Israeli water policies and practices which discriminate against the Palestinianpopulation of the OPT. This discrimination has resulted in widespread violations of the rightto an adequate standard of living, which includes the human rights to water, to adequatefood and housing, and the right to work and to health of the Palestinian population.The inequality in access to water between Israelis and Palestinians is striking. Palestinianconsumption in the OPT is about 70 litres a day per person – well below the 100 litres percapita daily recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) – whereas Israeli dailyper capita consumption, at about 300 litres, is about four times as much. In some ruralcommunities Palestinians survive on far less than even the average 70 litres, in some casesbarely 20 litres per day, the minimum amount recommended by the WHO for emergencysituations response.3Access to water resources by Palestinians in the OPT is controlled by Israel and the amountof water available to Palestinians is restricted to a level which does not meet their needs anddoes not constitute a fair and equitable share of the shared water resources. Israel uses morethan 80 per cent of the water from the Mountain Aquifer, the only source of undergroundwater in the OPT, as well as all of the surface water available from the Jordan River of whichPalestinians are denied any share.The stark reality of this inequitable system is that, today, more than 40 years after Israeloccupied the West Bank, some 180,000 – 200,000 Palestinians living in rural communitiesthere have no access to running water and even in towns and villages which are connected tothe water network, the taps often run dry. Water rationing is common, especially but not onlyin the summer months, with residents of different neighbourhoods and villages receivingpiped water only one day every week or every few weeks. Consequently, many Palestinianshave no choice but to purchase additional supplies from mobile water tankers which deliverwater at a much higher price and of often dubious quality. As unemployment and povertyhave increased in recent years and disposable income has fallen, Palestinian families in theOPT must spend an increasingly high percentage of their income – as much as a quarter ormore in some cases – on water.In the Gaza Strip, the only water resource, the southern end of the Coastal Aquifer, isinsufficient for the needs of the population but Israel does not allow the transfer of waterfrom the West Bank to Gaza. The aquifer has been depleted and contaminated by over-extraction and by sewage and seawater infiltration, and 90-95 per cent of its water iscontaminated and unfit for human consumption. Waterborne diseases are common.Stringent restrictions imposed in recent years by Israel on the entry into Gaza of material andequipment necessary for the development and repair of infrastructure have caused furtherdeterioration of the water and sanitation situation in Gaza, which has reached crisis point.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

4

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

Water shortages and poor sanitation services in the OPT affect all sectors of the Palestinianpopulation and especially the poorest and most vulnerable communities, those living inisolated rural areas and in overcrowded refugee camps.While Palestinians throughout the OPT are being denied access to an equitable share of theshared water resources and are increasingly affected by the lack of adequate water supplies,Israeli settlers face no such challenges - as indicated by their intensive-irrigation farms, lushgardens and swimming pools.4The 450,000 Israeli settlers, who live in the West Bank inviolation of international law, use as much or more water than the Palestinian population ofsome 2.3 million.5The restrictions imposed by Israel on Palestinians’ access to water supplies in the OPT aremanifested in multiple ways: control of water resources and land, and restrictions on themovement of people and goods make it excessively difficult for Palestinians to access theirwater resources and to develop and maintain the water and sanitation infrastructure.Furthermore, a complex system of permits which the Palestinians must obtain from theIsraeli army and other authorities in order to carry out water-related projects in the OPT hasdelayed and rendered more costly, and in many cases prevented, the implementation ofmuch needed water and sanitation projects.During more than four decades of occupation of the Palestinian territories Israel has over-exploited Palestinian water resources, neglected the water and sanitation infrastructure in theOPT, and used the OPT as a dumping ground for its waste – causing damage to thegroundwater resources and the environment. Urgent measures are now needed to ensure thatadequate water supplies are made available today and in the future, and to prevent furtherdamage to the water resources and the environment.Israeli policies and practices in the OPT, notably the unlawful destruction and appropriationof property, and the imposition of restrictions and other measures which deny thePalestinians the right to water in the OPT, violate Israel’s obligations under both humanrights and humanitarian law.Due to Israel’s failure to fulfil its obligations, as the occupying power, the burden of dealingwith these challenges has fallen to international donors and, since its establishment in themid 1990s, to the Palestinian Authority (PA), the Palestinian Water Authority (PWA),6andother local service providers, all of whom depend on international donors for funds. Yet, theIsraeli authorities continue to obstruct Palestinian and international efforts to improve accessto water in the OPT.In the face of water shortages and amid deepening poverty in recent years some Palestinianshave resorted to drilling unlicensed wells, while others have connected to the water networkillegally, and many have stopped paying their water bills. These practices have furthercompounded the problem by undermining the economic viability and the authority of thePWA, which has proved to be unable or unwilling to stop such practices.The restrictions imposed by Israel on access to and development of water resources forPalestinians have been accompanied by other factors that have hindered the efficient deliveryof many urgently needed water and sanitation projects in the OPT. These include the PWA’s

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

5

near-total dependence on international donors for funds, donors’ choices and priorities, andpoor coordination among donors.7Adding to this, the PA and PWA have been beset byinternal divisions compounded by weak and fragmented management structures, lack ofexpertise and of political will, and allegations of mismanagement and corruption.This report examines the main patterns and trends affecting access to water for Palestiniansin the OPT, and analyses how these are impacting severely on the population’s rights, asprotected under international human rights and humanitarian law, and which are necessaryfor the Palestinians to live in dignity.

NOT EVEN A DROPOn 10 March 2008, Fa’iq Ahmad Sbeih received a visit from an Israeli army patrol at his farm in al-Farisya, afew km north of Jiftlik, in the Jordan Valley area of the West Bank. The soldiers confiscated 1,500 metres ofrubber hose which brought water to his farm from a spring on a hill above his land, and crushed the smallmetal pipe which was connected to the hose. The confiscation order delivered by the army stated that thehose was confiscated “due to lack of permit”. The army considers the spring water as “state property”In the past, local farmers had tried to build a water cistern to collect water from the spring and to harvest therain water but the army prevented them, because they did not possess, and could not obtain from the army, apermit to do so. When an Amnesty International delegate visited the farm on 11 March 2008 Fa’iq Sbeih wasbeside himself with worry: “Thisis my family’s livelihood. We work day and night and we need water; and theweather is getting hotter every day. Already the situation is difficult this year because we have had so littlerain; you can see how little water there is in the stream and we only took a bit of it. I can’t buy another pipe;and if I do the army may come and take it again.”The army subsequently returned the rubber hose to Fa’iq Sbeih, though it was damaged and no longer usable,and reiterated the ban on him using the water from the spring. With the onset of the hot season he tried tokeep some of his crops alive by buying water from other areas, delivered by tanker, but he still lost most of thecrop.8Without access to water from the spring Palestinian farmers like Fa’iq Sbeih have no option but to travelseveral km to buy small quantities of water that they then transport to their orchards by tanker. This is themost expensive way to obtain water, the more so because the restrictions imposed by the Israeli army requirethe water tankers to take long detours and circuitous routes to make their deliveries. The unlawful Israelisettlements which surround al-Farisiya face no such problems. Their residents have free access to the waterfrom the spring which Fa’iq Sbeih and his family are not permitted to use, and which forms a small streamthat flows down towards the Israeli settlements. As well, they have ready access to an abundant supply ofwater from nearby wells to which Fa’iq Sbeith and other Palestinian farmers have no access.The nearby Israeli settlement of Shamdot Mechola advertises on its website: “Breathtakingtours to Amaryllisbulbs hot houses which are harvested, packed and shipped to Europe and USA and potted in time to bloomduring the winter holiday season. Short tours of our “Hi-tec” dairy farm, vineyards and orchards. Tours offarms in the Jordan Valley who specialize in crops of vegetables, fruits, flowers and spices for export in hot dryclimate.”9

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

6

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

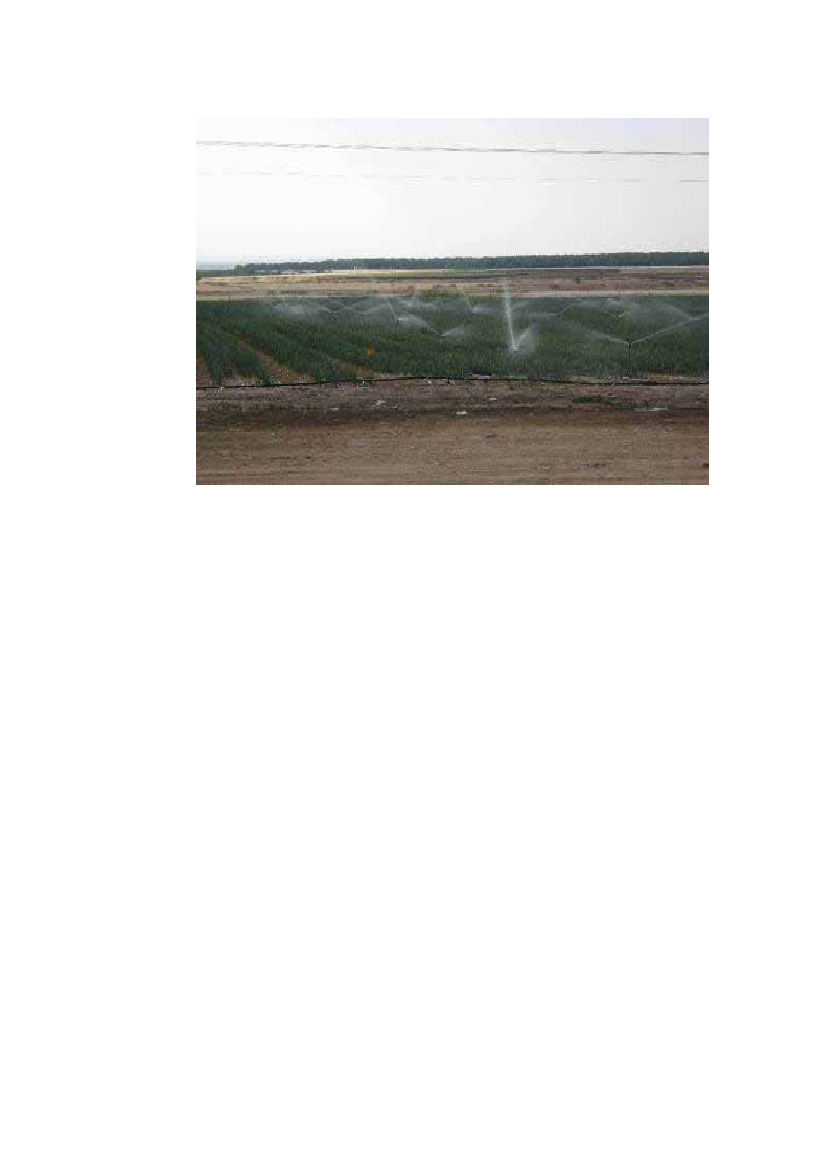

Sprinklers in Israeli settlement farms in the Jordan Valley, West Bank � AI

According to one international water expert, commenting on the discriminatory use of waterby Israeli settlers in the OPT: “Itis easy to make the desert bloom by using someone else’swater and by denying them access to their fair share of water.”

HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDBetween the two world wars Britain ruled Palestine under a League of Nations mandate,which ended with a UN decision in November 1947 to partition the territory of MandatePalestine into two states, Israel and Palestine – 53 and 47 percent of the territory,respectively. The State of Israel was established in May 1948 amid Arab protests and a warbroke out between Arab and Israeli forces from which Israel emerged victorious. More than800,000 Palestinians were either expelled or fled from Israel and became refugees in theGaza Strip, the West Bank and neighbouring countries. The war ended in 1949, with Israelhaving conquered additional territory and the State of Israel having been enlarged tocomprise 78 percent of Mandate Palestine. The remaining 22 percent, the West Bank andthe Gaza Strip, remained under the control of Jordan and Egypt, respectively. Hostilitiesbetween Israel and Egypt, Syria and Jordan in June 1967 ended in Israel’s occupation of theWest Bank (including East Jerusalem, which Israel later annexed in violation of international

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

7

law) and the Gaza Strip.10These areas became known as the Occupied Palestinian Territories(OPT).Some 4,000,000 Palestinians, more than 1,500,000 of them refugees, currently live in theOPT under Israeli military occupation - some 1.5 million in Gaza and some 2.5 million in theWest Bank - including more than 200,000 who live in East Jerusalem.11Negotiations between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in the early1990s led to the Oslo Accords and to the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) in1994, with jurisdiction in parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Negotiations on apermanent status agreement on Jerusalem, settlements (the Israeli colonies unlawfullyestablished in the OPT), the delineation of borders, allocation of water resources, andPalestinian refugees were deferred, but were to be concluded by 1999. However, by 2000no progress had been achieved on any of these issues and Israel was continuing to buildunlawful settlements and so-called “bypass” roads in the OPT at an unprecedented pace.12A Palestinian uprising (intifada) against the continued Israeli occupation broke out inSeptember 2000. Since then, more than 6,000 Palestinians and more than 1,100 Israelis,most of them unarmed civilians, have been killed in violent attacks and confrontations. Tensof thousands of Palestinians have been arrested by the Israeli army; currently, some 6,500are detained or serving sentences in Israeli prisons and the Israeli army has destroyed morethan 6,000 Palestinian homes as well as large areas of agricultural land and otherPalestinian property throughout the OPT.In September 2005 Israel withdrew its settlers and troops from Gaza, but retained control ofGaza’s land borders, air space and territorial waters, and since then has kept Gaza under anincreasingly stringent blockade, punctuated by periodic outbreaks of armed confrontations.Stringent restrictions imposed by Israel on the movement of Palestinians within the OPT havestifled the Palestinian economy and caused high unemployment and poverty. MostPalestinians in the OPT now depend on international aid.Israel has continued to seize large areas of Palestinian land and to build unlawful settlementsand “by-pass” roads and other infrastructure to support them. Currently more than 450,000Israeli settlers live in the OPT, about half of them in East JerusalemSince 2000 most of the provisions of the Oslo Accords have become irrelevant and the PA’sability to function has been sharply curtailed by Israeli restrictions. Inter-factional tensionsbetween the two main Palestinian political parties, Fatah and Hamas, increased after Hamaswon the Palestinian parliamentary election in 2006 and led to severe armed clashes in whichhundreds of people were killed in 2007 in the Gaza Strip. Since then Hamas has maintaineda de-facto administration in the Gaza Strip and a PA caretaker government administers partsof the West Bank, while Israel retains overall control over both areas.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

8

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

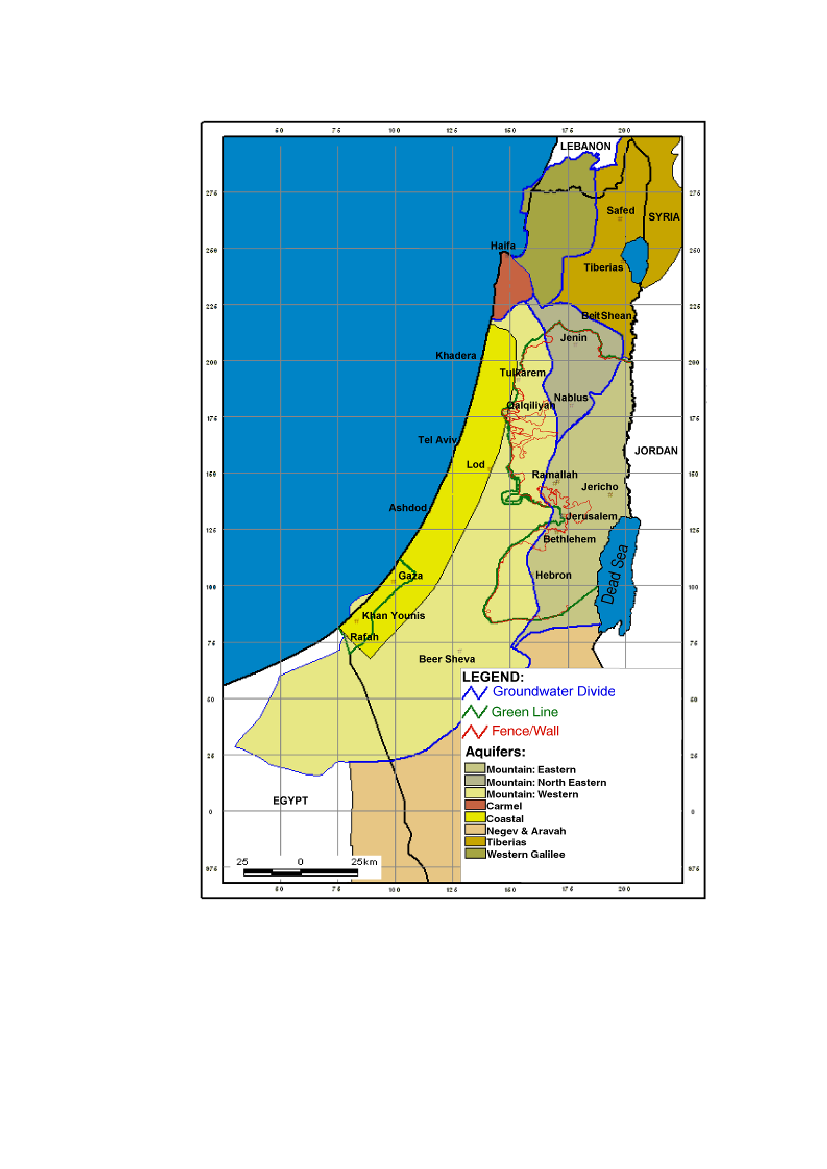

WATER RESOURCES IN ISRAEL/OPTGROUNDWATER RESOURCESGroundwater is water that is located beneath the ground surface in soil pore spaces and in the fractures oflithologic formations. The groundwater bearing strata, a unit of rock layer or an unconsolidated deposit iscalled an aquifer when it can yield a usable quantity of water. The depth at which soil and rock pore spaces orfractures and voids in rock become completely saturated with water is called the water table. Groundwater isusually recharged from rain and eventually flows to the surface naturally; natural discharge often occurs atsprings and seeps. An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing permeable rock (limestone, dolomite)or unconsolidated materials (gravel, sand, silt, or clay) from which groundwater can be usefully extractedusing a water well.13The Mountain Aquiferis a shared Israeli-Palestinian groundwater resource, lying under bothIsrael and West Bank. It is the sole remaining water resource for the Palestinians and one ofthe most important groundwater resources for Israel. It is replenished mostly in the WestBank by the infiltration of rainfall and snowfall and flows northwards and westward towardsthe territory of Israel and towards the Jordan River in the east. It is actually composed ofthree aquifers (or basins) – the Western, North-Eastern and Eastern aquifers – with a totalaverage yield of 679 to 734 MCM/Y (as detailed below). The figure of 734 MCM/Y isaccording to the Hydrological Service of Israel (HSI), the most authoritative source on thematter, whereas the estimate of 679 MCM/Y is that used by the Israeli authorities to decidethe yearly quantity of water allocated to the Palestinians under the Oslo Accords.14- Western Aquifer:- North Eastern Aquifer:427 MCM/Y (HSI)142 MCM/Y (HSI)362 MCM/Y (Oslo Accords)145 MCM/Y (Oslo Accords)

- Eastern Aquifer:165 MCM/Y (HSI)172 MCM/Y (Oslo Accords)(Much of the water from the Eastern Aquifer is brackish/saline)15The Coastal Aquiferis located under the coastal plain of Israel and the Gaza Strip. Its yearlysustainable yield is estimated at up to 450 MCM in Israel16and a mere 55 MCM/Y in Gaza.In Gazathe aquifer polluted due to over-extraction and sewage infiltration, and 90-95 percent of the water it supplies is unfit for drinking.Additional groundwater resources in Israelinclude the Western Galilee and Carmel Aquifersin the north and the Negev-Aravah Aquifer in the south. There is no reliable figure for theyield of these aquifers.

SURFACE WATER RESOURCESTheJordan Riveris the most important shared surface water resource for Israel and the WestBank. It supplies up to 650 MCM/Y of water to Israel17and none to the Palestinians (seebelow).

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

9

UNEQUAL ACCESS TO WATERTHE WEST BANK: ISRAELI OVER-EXPLOITATION OF SHARED RESOURCESIsrael’s water consumption stands at some 2,000 to 2,200 MCM/Y for a population of 7million (some 1,500 MCM is fresh water, with the remainder composed of desalinatedseawater and treated wastewater).18Most of Israel’s fresh water supplies are drawn from theshared groundwater and common surface water resources – more than 400 MCM/Y from theMountain Aquifer and up to 650 MCM/Y from the diverted Jordan River.19Jordan RiverSince Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967, it has denied its Palestinian inhabitantsaccess to the water resources of Jordan River, preventing them from physically accessing theriver banks and diverting the river flow upstream into Lake Kinneret/Tiberias/Sea of Galilee,which supplies up to 700 MCM/Y of water to Israel. Jordan also diverts the flow of theJordan River’s tributaries within its territory, as do Syria and Lebanon further upstream. As aconsequence, compared to 1953, when a UN report estimated the yearly flow of the JordanRiver through the West Bank as 1,250 MCM, this flow has now been reduced to a trickle, ofhighly saline water heavily contaminated by untreated sewage.20As well as depriving thePalestinians of a crucial source of water, the drying up of the Jordan River has had adisastrous impact on the Dead Sea, which has seen the fastest drop in its water level to anunprecedented low.21Mountain AquiferAs Palestinians in the West Bank have no access to the Jordan River, the Mountain Aquifer istheir only remaining source of water. Israel, on the other hand, has two other main waterresources (Lake Kinneret/Tiberias/Sea of Galilee and the Coastal Aquifer).Even so, Israel limits the amount of water annually available to Palestinians from theMountain Aquifer to no more than 20 per cent, while it has continued to consistently over-extract water for its own usage far in excess of the aquifer’s yearly sustainable yield.Moreover, much of Israel’s over-extraction is from the Western Aquifer, which provides boththe largest quantity and the best quality of all the shared groundwater resources in Israel-OPT.According to the Israeli Ministry of Environmental Protection: “Thisaquifer supplies about417 MCM per year, a quarter of the total national production, although the average multi-annual natural replenishment rate is estimated at about 360 MCM.”22The World Bank put Israel’s extraction from the Western Aquifer in 1999 at 591.6 MCM -that is, 174.6 MCM (or 229.6 MCM according to the Oslo Accords figures) in excess of theaquifer’s yearly sustainable yield.23Such sustained over-extraction has reduced the aquifer’s current yield and future reservesand has caused potentially serious damage to the quality of the water supply for both Israelisand Palestinians. As the Israeli Ministry of Environmental Protection noted, “Overexploitationmay lead to a rapid rate of saline water infiltration from surrounding saline water sources.”24

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

10

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

According to the World Bank, “Palestinianshave access to one fifth of the resources of theMountain Aquifer. Palestinians abstract about 20% of the “estimated potential” of theaquifers that underlie both the West Bank and Israel. Israel abstracts the balance, and inaddition overdraws without JWC [Joint Water Committee] approval on the “estimatedpotential” by more than 50%, up to 1.8 times its share under Oslo. Over-extraction by deepwells combined with reduced recharge has created risks for the aquifers and a decline inwater available to Palestinians through shallower wells.”25In 2007, according to the World Bank, overall Palestinian water extraction26from theMountain Aquifer in the West Bank was 113.5 MCM (down from 138.2 MCM in 1999) andaccording to PWA figures total Palestinian extraction in 2008 was 84 MCM, with thereduction due to operational problems for some wells and a drop in the level of the watertable, caused by Israeli over-extraction and low annual rainfall.27According to the Israeliauthorities, Palestinians also extract some 10 MCM/Y from unlicensed wells and obtain some3.5 MCM/Y from illegal connections to Israeli water lines in the West Bank.28To boost insufficient supplies the Palestinians must buy water from Israel – water that Israelextracts from the Mountain Aquifer and which the Palestinians should be able to extract forthemselves if Israel were to allow them a more equitable share of the aquifer. In recent yearsthe quantity of water bought by Palestinians from Israel has increased, to some 50 MCM/Y,but this is not enough to match the increase in population in the West Bank and supplies areoften reduced by Israel to the Palestinians (but not to the Israeli settlers in the OPT) duringthe hot season, when needs are greater.The total amount of water available to Palestinians from these various supplies in recentyears has been a maximum of some 170-180 MCM/Y, which reportedly fell to a mere 135MCM in 2008, for a population of 2.3 million. However, as much as a third (some 34 percent) is lost in leakages due to old and inefficient networks,29and these cannot be readilyreplaced and modernized due to the restrictions on Palestinians’ movements and otherobstacles imposed by Israel, including the requirement that permits be obtained from theIsraeli army for even small development projects. In practice, therefore, Palestinians haveaccess to an average of no more than 60-70 litres per capita per day, and some survive onmuch less even than this, as little as 10-20 litres per person per day.Even at an average of 60-70 litres per person per day, the amount of water available toPalestinians is the lowest in the region. While there has been a meagre increase in the totalamount of water available to Palestinians in the OPT during the more than 40 years of Israelioccupation, the amount available per capita is now less than in 1967 as the Palestinianpopulation has more than doubled since then.30

GAZA: UNSAFE WATER SUPPLIESThe southern end of the Coastal Aquifer is the sole source of water for the 1.5 millionPalestinian inhabitants of the Gaza Strip, but it is only one of several sources of water forIsrael. Due to the aquifer’s east to west flow, the quantity of water extracted in Gaza does notdiminish the available yield in Israel; consequently, Israel has not imposed restrictions onPalestinian extraction from the part of this aquifer which underlies Gaza. However, extractionby Israel from this aquifer in the area to the east of Gaza affects the supply available to be

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

11

extracted in Gaza.31As well, most of the water from Wadi Gaza, a stream and surface watersource which originates in the Hebron mountains in the West Bank and then flows south-eastthrough Israel and into Gaza, is diverted into a dam in Israel, just before it reaches Gaza.32There are no available reliable figures for the annual flow of Wadi Gaza or for the amountcollected on the Israeliside.33The yearly sustainable yieldof the Coastal Aquifer inGaza, some 55 MCM, fallsfar short of the population’sneeds. Israel does not allowthe transfer of water fromthe Mountain Aquifer in theWest Bank to Gaza. (In anycase, such transfers wouldbe feasible only if Israelallowed the Palestinianpopulation of the West Bankaccess to a more equitableshare of the MountainAquifer, as the currentallocation is not sufficient tomeet even their own needs.)Residents filling containers of drinkingwater at a water purification plant inKhan Yunis, Gaza Strip � AI

With no other source of water available to them, Palestinians in Gaza have long resorted toover-extraction from the Coastal Aquifer, by as much as 80-100 MCM/Y – a rate equivalent totwice the aquifer’s yearly sustainable yield.34The result has been a marked, progressivedeterioration in the quality of the water supply, already contaminated by decades of sewageinfiltration into the aquifer. Today some 90-95 per cent of Gaza’s water is polluted and unfitfor human consumption.

ISRAELI MILITARY ORDERSWhen Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip in June 1967, a multilayer legal systemexisted in the OPT, MADE UP of Ottoman, British, Jordanian (in the West Bank) andEgyptian (in Gaza) laws – the legacy of the powers that had previously controlled the area.The Israeli army issued a series of Military Orders seizing control of water and land resourcesin the OPT.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

12

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

Military Order 92,issued on 15 August 1967, granted complete authority over all water-related issues in the OPT to the Israeli army.Military Order 158of 19 November 1967 stipulated that Palestinians could not constructany new water installation without first obtaining a permit from the Israeli army and that anywater installation or resource built without a permit would be confiscated.Military Order 291of 19 December 1968 annulled all land and water-related arrangementswhich existed prior to Israel’s occupation of the West Bank.35These and other Israeli Military Orders remain in force today in the OPT and apply only toPalestinians. They do NOT apply to Israeli settlers in the OPT, who are subject to Israelicivilian law.The Israeli army also took control of the West Bank Water Department (WBWD),36which hadbeen established by Jordan in 1966 to develop and maintain the West Bank water supplysystem. The WBWD operates some 13 wells that are located in the West Bank and aremostly controlled by Israel. The water from these wells is sold to Palestinian communitiesand to Israeli settlements.In 1982 the West Bank water infrastructure controlled by the Israeli army was handed over toMekorot, the Israeli national water company. Mekorot operates some 42 wells in the WestBank, mainly in the Jordan Valley region, which mostly supply the Israeli settlements.Mekorot sells some water to the Palestinian water utilities, but the amount that it sells isdetermined by the Israeli authorities, not by Mekorot.Under the new Israeli military regime imposed in the OPT, Palestinians could no longer drillnew wells or rehabilitate or even just repair existing ones, or carry out other any water-relatedprojects (from pipes, networks, and reservoirs to wells and springs and even rainwatercisterns), without first obtaining a permit from the Israeli army. In theory, such permits fordrilling or rehabilitating wells could be obtained after a lengthy and complicated bureaucraticprocess; in practice, most applications for such permits were rejected. Only 13 permits weregranted in the 29 years from 1967 to 1996 (when the PWA was established), but all of thesewere for projects for domestic use only and they were not sufficient to make up even for thereplacement of wells that had dried up or fallen into disrepair since 1967.37Meanwhile, Israel continued to develop its own water infrastructure, both within Israel itselfand in the OPT, reducing the yield of existing Palestinians wells and springs in the OPT, andcutting off Palestinian access to the Jordan river and the springs along the river’s bank.Israel devoted considerable resources to developing water networks and infrastructure toserve the illegal settlements which it established in the OPT, but consistently neglected thedevelopment and maintenance of the water infrastructure for the Palestinians, who wererequired to pay their taxes to the Israeli military administration but received few services inreturn. For the most part any benefits accrued to the Palestinian population were incidental.For example, some Palestinian communities were connected to water networks which servednearby Israeli settlements or military bases.The regime put in place by the Israeli army not only prevented the development of new

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

13

Palestinian wells and infrastructure, but also limited the use and upkeep of existing ones. Itprevented the rehabilitation of old wells and imposed quotas on the quantity of water whichPalestinians could extract from their wells, capping the amount at the level being extracted atthe point when the well was first metered. Meters were installed in the early 1970s tomonitor pumping and to ensure Palestinian compliance with the capped allowance. Themeasures were simply imposed; there was no process of consultation with local Palestiniancommunities about their needs and how these would be met.The quotas were set at a time when the levels of extraction from many wells had temporarilydiminished due to the 1967 war and the changes it caused, including the displacement ofmany Palestinians who had fled from the West Bank at the time of the fighting and in itsaftermath. Following the war, Palestinian water use dropped drastically due to the reductionin irrigated areas from 100,000 to 57,000 dunums.38In addition, large areas of Palestinianland had been appropriated by Israel for military use and for Israeli settlements, and hadbeen made inaccessible to Palestinians; and many Palestinians who had previously beenfarmers in the West Bank were by then working in Israel. As well, many wells had fallen intodisrepair or had dried up, including as a result of the drilling of Israeli deep wells.In addition to those mentioned above, a plethora of military orders issued by the Israeli armywere also aimed at, or had the effect of, preventing or restricting Palestinian access to waterand land in the OPT. For example,Military Order No. 1039of 5 January 1983 (ConcerningPlanting Fruits and Vegetables - broadening the scope of Military Order No 1015 of 27August 1982 to include vegetable as well as fruits),stipulates that:“Inaccordance with the authority vested in me, and in my capacity as commander of theIsrael Defense Forces in the region and because I believe that this Order is necessary for thewelfare of the residents, and with the intention of preserving the water resources[AmnestyInternational’s emphasis] and the agricultural product of this region for the generalbenefit…It is prohibited to develop any vegetables in the Jericho district except afterobtaining a written license from the relevant authority according to the conditions the latterdemands (Article 2 A).”Article 10 of the original order, Military Order No 1015, stipulates: “Anyperson contraveningthese provisions is punishable by one year’s imprisonment, or a fine of up to 15,000 NIS[about US$5,000] or both, and an additional fine of 500 NIS[about US$160] for each daythe contravention continues. If the person has been ordered by a court to uproot the cropsplanted without a permit, the relevant authority may uproot the crops and impose on theaccused all the cost of the uprooting of the crops.”For four decades, Israeli military orders issued ostensibly to “protect” nature resources andreserves, including water resources, have had a crippling impact on Palestinian agriculturalactivities throughout the West Bank, while Israeli settlers, during the same period, have beengiven virtually unlimited access to water supplies to develop and irrigate the large farmswhich help to support unlawful Israeli settlements.39

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

14

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

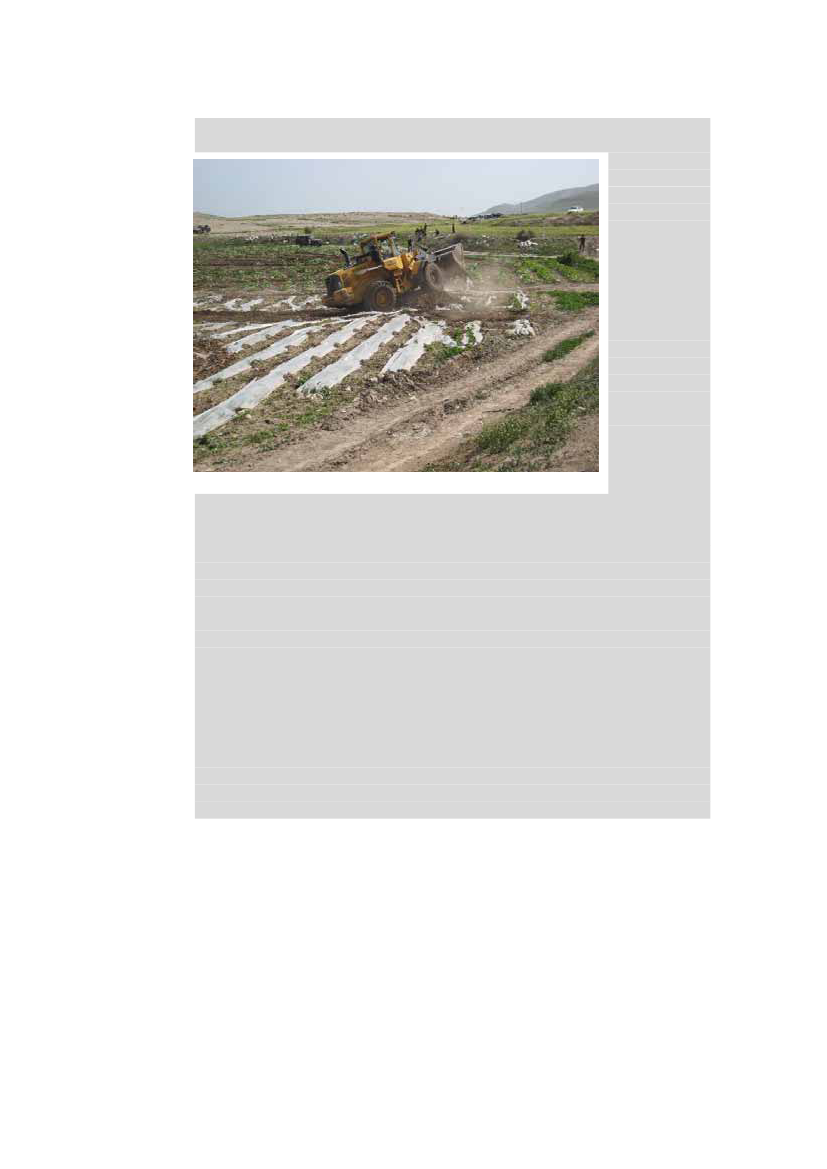

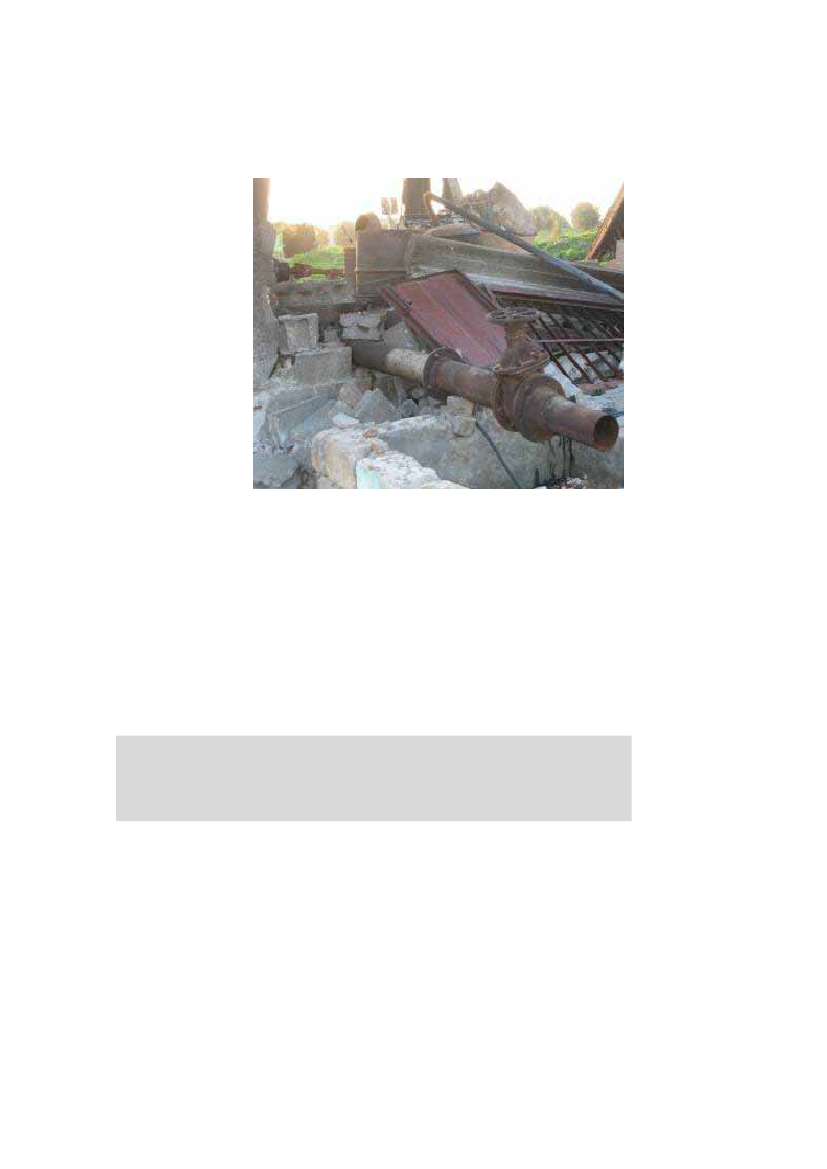

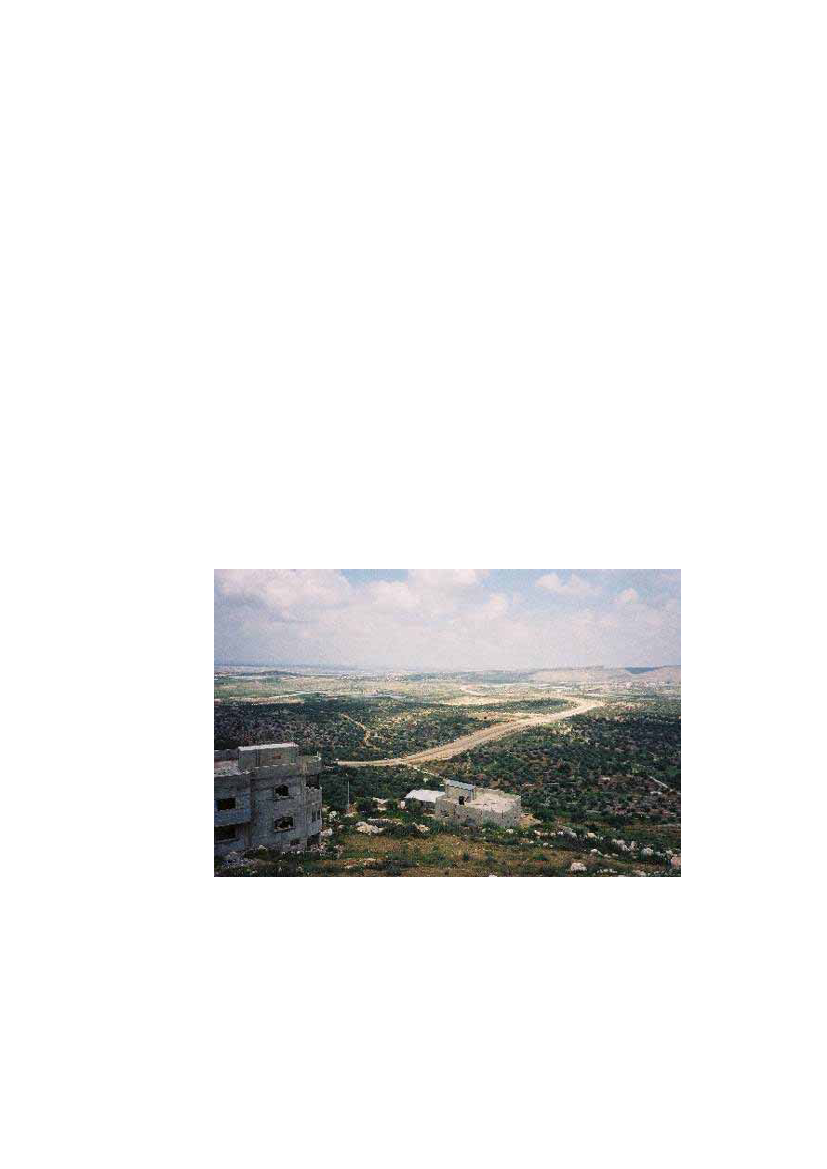

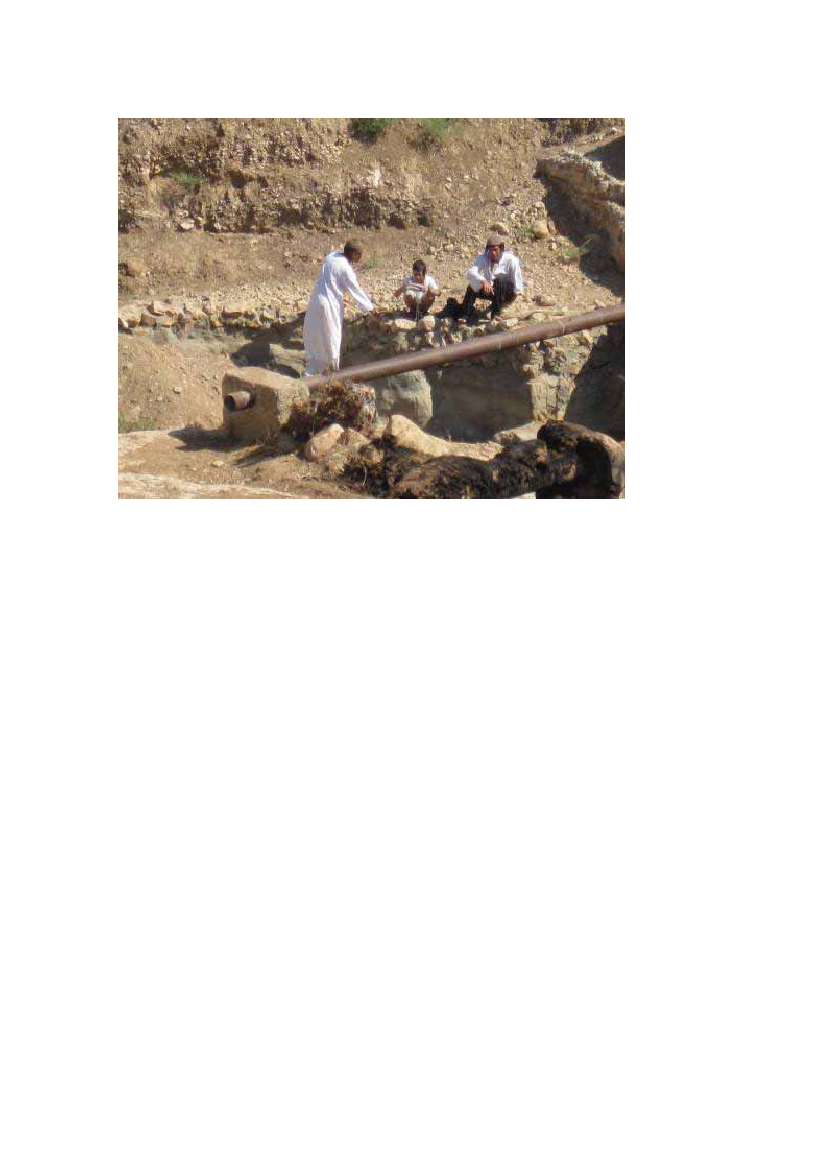

HOPES AND LIVELIHOOD DESTROYEDOn 11 March 2008,an AmnestyInternationaldelegate witnessedIsraeli soldiersdestroy a Palestinianfarm in the outskirtsof Jiftlik, in theJordan Valley area ofthe West Bank.Nearby, Israelisettlers have largefarms cultivatedwith verdantirrigated crops.

Mahmud Mat'ab Da'ish’s vegetable crops and irrigation network, bring uprooted by an Israeli army bulldozer while soldierssurround the field in Jiftlik, Jordan Valley, West Bank; 11 March 2008 � AI

Mahmud Mat'ab Da'ish, his wife Samar and their seven children and other relatives looked on in dismay as anIsraeli army bulldozer uprooted their crops – and their livelihood. Having quickly crushed the young vegetableplants, the army bulldozer continued to drive up and down the field, methodically scooping up and tearing toshreds the drip irrigation system which the family had installed at great cost.Tens of Israeli soldiers in uniforms, accompanied by men in plain clothes, surrounded the area, preventing thefarmers from approaching the field. The farmers pleaded with the soldiers to allow them at least to salvagetheir costly drip irrigation network, but the soldiers refused. The army had uprooted the same field two monthsearlier but the family had then replanted vegetables in the hope that these would be allowed to survive. Amonth later the army returned once again, this time to destroy the family’s home – a simple dwelling built ofthin corrugated iron sheets, wood and stones. After this, the family was left to live in a tent provided by theInternational Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).Samar Da’ish told Amnesty International: “Whymust they destroy the little we have? What harm have we doneby cultivating this small bit of land, so that we can feed our children? Look, they did not spare a single plant.Why so much cruelty to human beings, to the land, to nature?”Many other military orders have been issued by the Israeli army which do not specificallyrefer to water resources but which restrict activities in the water sector. These include ordersseizing land or declaring particular areas “closed” on undefined “security grounds”, makingthem inaccessible to Palestinians. Other military orders have designated Palestinian lands as“firing ranges” for use by the Israeli army or as “state land”, including the areas where Israeli

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

15

settlements are located. More than a third of all land in the West Bank falls into one or otherof these categories, and the restrictions imposed apply only to Palestinians. Israeli settlers,by contrast, have access to these areas, where they have unlawfully appropriated large areasof water-rich Palestinian land.Israel’s policy has been, and remains, to limit the overall amount of water (and land)available to the Palestinian population, while preserving for itself privileged access to most ofthe water and land in the OPT. To this end, Israel has not sought to change either thelocalized system of management of water resources by local councils, notables, and familieswho own wells located on their lands or the patterns of use of the water allocated to thePalestinians in the OPT. Rather, Israel has imposed restrictions on the overall quantity ofwater accessible to the Palestinians in the OPT to an extent where it has severely impairedrealization of the Palestinians’ right to adequate food, health, work and to achieve a decentstandard of living. Israeli policies and restrictions have served to restrict agricultural andindustrial development, and have thereby seriously hindered and obstructed social andeconomic development. According to the World Bank, “Thecost to the economy of foregoneopportunity in irrigated agriculture is significant, with upper bound preliminary estimates thatcould be as high as 10% of GDP and 110,000 jobs.”40As noted by the UN Secretary-General in 1992: “Thegeneral settlement policy ofconfiscating land and imposing restrictions on water resources has meant that a largeproportion of the population that would normally have earned a living by traditionalagriculture have gradually begun to seek employment in Israel as unskilled workers becauseof the lack of jobs in the territories. This appears to be partially responsible for the economicdependence of the occupied Palestinian and other Arab territories on Israel, particularly asregards agricultural produce.”41

THE IMPACT OF WATER SHORTAGES – COPING STRATEGIESPalestinian families who do not have enough water to meet their basic needs often have no choice but toresort to coping strategies which carry risks for their own health, negatively affect their food security, anddamage the groundwater resources. These include:- Buying water from unsafe sources (agricultural wells, which are not monitored for quality or adequatelychlorinated) and boiling before consumption by young children, as most families cannot afford to buysufficient fuel to boil all their drinking water.- Reusing the same water for several tasks: water used to boiled vegetables is reused to wash dishes, thenreused again to wash floors and then finally reused to flush toilets.- Flushing toilets less frequently.- Washing less regularly and fully, using a bucket or jug to limit the water used instead of showering.- Washing clothes and floors as infrequently as possible and using a small quantity of water to hand-washclothes in a bucket rather than using a washing machine.- Only growing rain-fed crops in their home gardens or not keeping a home garden at all in dryer areas.- Keeping fewer animals or none at all.- Drilling unlicensed shallow wells.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

16

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

STRUGGLING TO COPE WITH WATER SHORTAGE“Iam a widow and have six small children, three boys and three girls, aged 6-12. My husband was killed in2003. His two daughters from his first wife, who died, live with us. We live in a small house in Yatta. The onlyincome we have is an allotment of 1,000 NIS a month that we receive from a charity in Yatta. This sum is notenough to pay for food for nine people.In addition to our income problems, we also suffer from water shortage, as do most residents of the town. Theshortage affects all aspects of our life. We are connected to the town’s water network, but since January 2008,we haven’t gotten water through the network because we live at a high altitude, and the water pressure isinsufficient to get the water to us. We buy all our water from tankers. The town sells the water at a rate of 120NIS for ten cubic meters. You have to wait your turn, and we get water only once every twenty or thirty days.This is not often enough, so I have to buy water from private tankers, who charge 170 or 180 NIS. It is hard onus financially, but we have no choice. I save lots of water. I always warn the children not to waste water, andtell them to pay attention to every drop of water they use. The children already know they have to conservewater. Every two children are given one bucket of water to shower with. We have rugs on the floor all yearround, so I don’t wash the floor. That saves water.For more than two years, I haven’t washed the carpets or blankets. I use a washing machine that uses lesswater than other machines, and I use the shortest washing cycle so as to save water, even though the clothesdon’t come out clean enough. My husband’s son lives next to us, and he sometimes asks if he can take someof our water. Sometimes, we don’t have enough to give him. We’ve gotten used to living like this because wedon’t have a choice. When my husband died, we owed 4,500 NIS to the town for water, and 5,000 NIS forelectricity. I don’t have the money to pay these debts, and I’m afraid they’ll disconnect us. We don’t get waterfrom the network, but I’m afraid they’ll cut off the electricity. The house, is surrounded by more than twodunams of land. If we had water, we could farm it and make some income that way.”Fatima Zein, a resident of Yatta, to the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem42

“Thehuman right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity.”[UN Committee onEconomic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 15, para 1]

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

17

OSLO ACCORDS:INSTITUTIONALIZING ISRAELICONTROL OF RESOURCESContrary to Palestinian expectations, the Oslo Accords did not result in greater access forPalestinians to the water resources of the OPT. Even after the establishment of the PWA, upto the present day, Israel’s control of the water resources and of most of the land in the OPThas allowed the Palestinians little possibility to develop their water and sanitation sector andto put in place more efficient extraction systems and distribution networks in the OPT.The Israeli authorities contend that: “Watermatters, like other civil powers, have been forsome time under the full responsibility of the P.A.…Jurisdiction over water was transferred[to the PA] completely and on time…”43In truth, however, the PA did not acquire control of water resources in the OPT under theOslo Accords.44It acquired only the responsibility for managing the supply of the insufficientquantity of water allocated for use by the Palestinian population and for maintaining andrepairing a long-neglected water infrastructure that was already in dire need of major repairs.As well, the PA was made responsible for paying the Israeli authorities for half of the waterused for domestic purposes by Palestinians in the West Bank, which water Israel extractsfrom the shared aquifer and sells to the Palestinians.45Under the Oslo Accords, the PA was given no authority to make decisions relating to drillingof new wells, or upgrading existing wells, or implementing other water-related projects, andIsrael continues to control decision-making regarding the amount of water that may beextracted from existing wells and springs in the OPT virtually to the same extent as it didbefore the Oslo Accords.Thus, the Israeli authorities continue to monitor and control the amount of water extractedfrom Palestinian wells and springs in the West Bank, and Palestinians are not allowed to drillnew wells or rehabilitate existing wells without first obtaining authorization from the Israeliauthorities. Such authorization is rarely granted; even when it is, the process is an undulylengthy and complicated one and the potential for delays and consequent cost increases ishigh.As well, the multitude of other restrictions that the Israeli authorities have imposed andmaintain on the movement and activities of Palestinians in the OPT have further hindered orprevented the development of the water supply infrastructure and related facilities.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

18

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

TERRITORIAL JURISDICTION UNDER THE OSLO ACCORDSUnder the Oslo Accords Israel divided the West Bank intoAreas A, BandC.- Areas AandBinclude most major Palestinian towns, refugee camps and villages,accounting for some 95 per cent of the population but only 40 per cent of land of the WestBank. In these areas the PA is responsible for civil affairs and Israel for external security.-Area C,where Israel is responsible for both civil affairs and internal as well as externalsecurity, comprises some 60 per cent of the land area of the West Bank and includes all theland reserves and all the main roads, but is mostly inaccessible to Palestinians.Areas A and B are fragmented into scores of separate enclaves surrounded by Israelisettlements, settlers’ roads and closed military areas. Most Palestinians live in Areas A andB, but the infrastructure which serves these populations is located in or passes through AreaC, where Palestinian access is restricted or denied and construction and developmentactivities are rarely permitted by the Israeli army.The most productive locations for drilling wells are located on the lower flanks of the WestBank mountains, in Area C, but restrictions imposed by the Israeli army have delayed orprevented the drilling of even those wells which has been approved by the Joint WaterCommittee (JWC). Similarly, Israel has consistently refused to allow Palestinians to locatesewage treatment facilities and solid waste dumps in Area C, the only areas where there island available for such facilities.These arrangements have curtailed or prevented Palestinian development, including thedevelopment of much-needed water and sanitation infrastructure.

ISRAELI WATER LAW AND WATER AUTHORITIESThe Israeli Water Law (1959)46does not recognize the existence of shared surface orgroundwater resources. It is defined as: “…aframework for the control and protection ofIsrael’s water resources”.It stipulates that:- All sources of water in Israel are public property. A person’s land rights do not confer rightsto any water sources running through or under their land.- Every person is entitled to use water, as long as that use does not cause the salination ordepletion of the water resource.- Water use is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Agriculture (via the WaterCommission), which is authorized to:- Prescribe norms for the quantity, quality, price, conditions of supply and use of water...andrules for the efficient and economic utilization of water...- Ration water when necessary.The Minister of Environmental Protection is authorized to:-Promulgate regulations to prevent the pollution of water resources.The Water Commissioner, appointed by the government, is responsible for enforcement of theWater Law and Regulations, and for the maintenance of water quality, and is authorized to:- Approve or reject or prepare plans for the disposal of sewage.The Water Board is chaired by the Minister of Agriculture. The Water Commissioner serves asdeputy chairperson.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

19

The Tribunal for Water Affairs may impose fines, or, in extreme cases of non-compliance,prison sentences, to those who contravene the provisions of the Water Law or the Drainageand Flood Control Law.At the national level, Israel does not have a constitution and its Basic Laws do not containprovisions relating to the right to water. However, the Supreme Court ruled in 1989 that,“Theright to water is a substantive right… [It] does not have to be created by statutenecessarily, but can be grounded on other foundations, such as agreement, custom, or anyother manner.”47The Israeli national water company Mekorot (founded in 1937, prior to the establishment ofthe State of Israel) manages most of the water supplies in Israel and the OPT.

PALESTINIAN WATER LAW AND WATER AUTHORITIESThe Palestinian Water Law(Law No. 3/2002) was enacted in 2002.48Its provisions include:-“ThisLaw aims to develop and manage water resources, increasing their capacity, improvingtheir quality, and preserving and protecting them from pollution and depletion(Article 2);”- “All water resources available in Palestine are considered public property(Article 3.1);”- “Every person shall have the right to obtain his needs of water of a suitable quality(Article3.3);”- “It is prohibited to drill or explore or extract or collect or desalinate or treat water forcommercial purposes or to set up or operate a facility for water or wastewater withoutobtaining a licence(Article 4);”- “The Authority may … halt the production or supply of water if it appears that its source orsystem is polluted and it may close the source or system if pollution continues…(Article30);”- “The Authority…may declare any area that contains groundwater a protected area if thequality or quantity of water is in danger of pollution…on condition that it provides alternativewater resources(Article 31)”;- Articles 35 to 37 provide for punishment of up to two years’ imprisonment and/or fines ofup to 5,000 Jordanian Dinars (about US$ 6500), or double the punishment for repeatoffenders for breaches of this law, including for polluting water resources, drilling wellswithout licence, and supplying water without a licence;The PWA49sets the policy and plays a regulatory role, while services for domestic andindustrial supplies are mostly delivered by regional water utilities (such as the JerusalemWater Undertaking, JWU, for the Ramallah region, and the Coastal Municipality Water Utility,CMWU, in Gaza), municipalities (in urban centres), and Village Councils or Joint ServiceCouncils (in rural areas). Private wells have a low capacity and mostly supply water foragriculture, and increasingly to communities who have limited or no access to domestic watersupplies. In the West Bank the West Bank Water Department (WBWD) monitors theextraction levels of Palestinian wells on behalf of Israel and manages the sale of most of thewater supplied to Palestinians from some 13 wells which it operates together with thatsupplied by Mekorot, the Israeli water company.50In Gaza, the PWA assumed control of water resources and facilities in the mid-1990s exceptfor those located within the Israeli settlements in Gaza, which were eventually dismantled inSeptember 2005.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

20

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

INEQUALITY IN ACCESS TO WATER RESOURCES CODIFIEDUnder the Oslo Accords “Israelrecognizes the Palestinian water rights in the West Bank.These will be negotiated in the permanent status negotiations and settled in the PermanentStatus Agreement relating to the various water resources.”51Crucially, these rights were not defined and the inequitable division of the sharedgroundwater resources – the Mountain Aquifer - was maintained, with some 80 per centallocated to Israel and just 20 per cent to the Palestinians.This unequal allocation is all the more striking in view of the fact that their 20 percentallocation from the Mountain Aquifer is the sole source of water for the Palestinianinhabitants of the West Bank, while the 80 per cent allocated to Israel is only one of severalwater resources available to Israel, which can also draw fresh water from the Coastal Aquiferand Lake Kinneret/Tiberias/Sea of Galilee, including the Jordan River and tributaries, bothsignificant sources.Far from providing for an equitable re-distribution of the available shared groundwaterresources, the Oslo Accords specifically stipulated that there would be no reduction in thequantity of water that Israel extracts from the Mountain Aquifer, both for use within Israeland in the unlawful Israeli settlements located in the West Bank: “theexisting water systemssupplying water to the Settlements and the Military Installation Area, and the water systemsand resources inside them continue to be operated and managed by Mekoroth Water Co.”And “Allpumping from water resources in the Settlements and the Military Installation Area,shall be in accordance with existing quantities of drinking water and agricultural water… thePalestinian Authority shall not adversely affect these quantities.”52As well, the Oslo Accords did not provide for any re-distribution of the water from the JordanRiver, to which the Palestinians have been denied access since 1967.

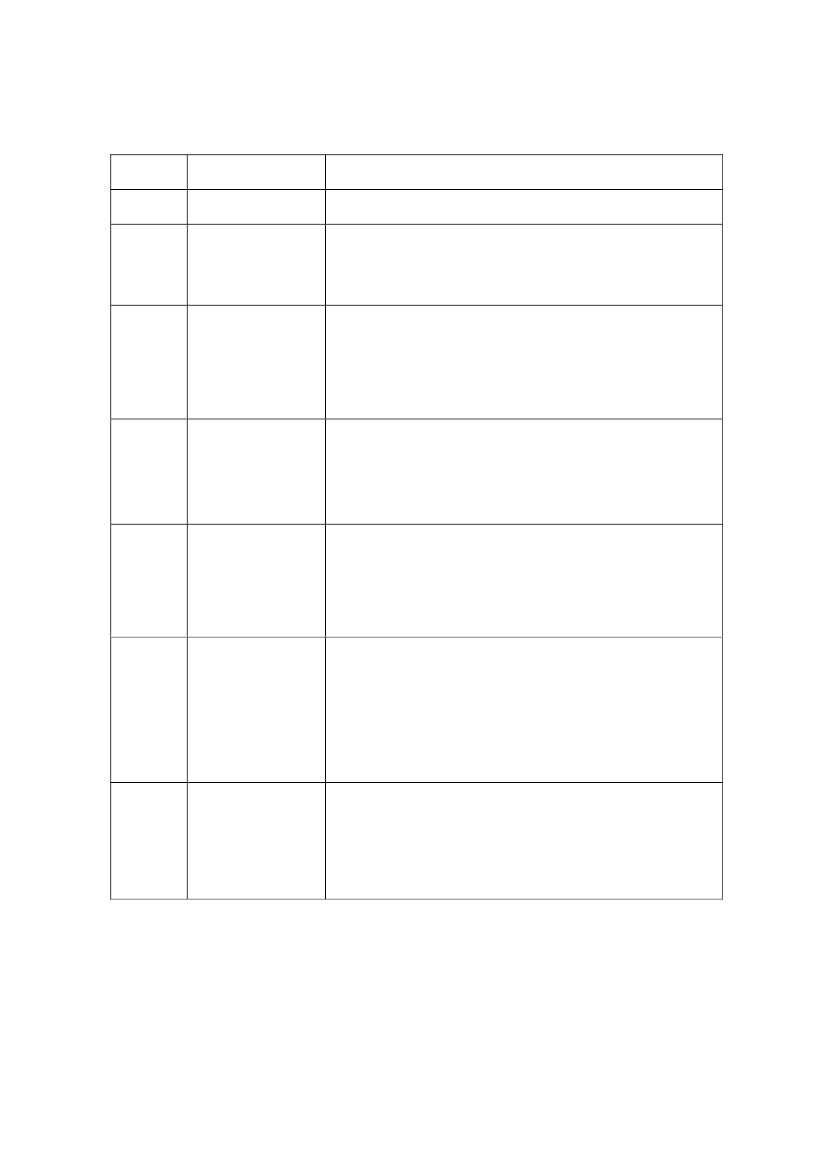

SHARED WATER RESOURCES Allocation as codified in the Oslo Accords53MOUNTAIN AQUIFEREstimated potential54679MCM/YDistributed as follows:WESTERN Aquifer:NORTH-EAST Aquifer:EASTERN Aquifer:362MCM/Y145MCM/Y172MCM/Y340 MCM/Y103 MCM/Y40 MCM/Y22 MCM/Y42 MCM/Y54 MCM/Y + 78 (forfuture needs, as above)ISRAEL483 MCM/YPALESTINIANS118 MCM/Y (+78 for futureneeds)

JORDAN RIVER

The Oslo Accords contain no provisions allowing access byPalestinians to any of the Jordan River water resources

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

21

ALLOCATION OF WATER SUPPLIES FOR “FUTURE NEEDS”The limited share of the Mountain Aquifer allocated to the Palestinians under the OsloAccords includes 78 MCM per year designated for “futureneeds”, and to be developed inthe future from the Eastern Aquifer and other unspecified “agreedsources in the WestBank”.55Crucially, the provision does not set any timeframe for realizing the development of thisprojected additional water supply although the Oslo Accords were only intended to cover thefive-year-period prescribed for achieving the final status agreement.A decade and a half later and in the continuing absence of any final status agreement, thisprojection has neither been realized, nor does it now appear achievable, so long as Israelcontinues to prevent the Palestinians from accessing the most productive areas of theEastern Aquifer.Moreover, in the period since the Oslo Accords, Israel has extracted far in excess of theagreed quantity of water from the Eastern Aquifer, up to more than three times as much.56At the same time Palestinian extraction from the Eastern Aquifer has declined in the pastdecade, down from 138 MCM per year in 1999 to 113 MCM in 2007,57and to 84 MCM in2008 according to the PWA. This appears to be due partly to a lowering of the water table(the aquifer level), possibly as a result of Israeli over-extraction, as well as to operationalproblems which have caused some Palestinian wells to become only partially operational or tocease operating for long periods. These operational problems have been exacerbated by therequirement that Palestinians must obtain Israeli permits before digging new wells orrehabilitating existing ones, and the delay or obstruction this entails, and by the extent towhich the Palestinians have to rely on international donors for the funding needed toundertake such infrastructural maintenance and improvement.In 2002 the then Israeli Water Commissioner Shimon Tal told the Israeli Knesset(parliament) that “theEastern Mountain Aquifer was allocated to them. They have not yetstarted developing it sufficiently, and the development is extremely expensive”.58

ISRAELI CLAIMS: MAINTAINING THE STATUS QUOThe Israeli authorities have consistently rejected calls to allow the Palestinians access to anequitable allocation of the shared water resources, insisting that Israel’s “prior establisheduse” of most of the water from the shared Mountain Aquifer justifies its continuingappropriation, in perpetuity, of most of the aquifer’s water for its own purposes, regardless ofthe consequences that this disproportionate and unfair division has for the Palestinianpopulation in the OPT and its impact on Palestinians’ human rights.In its response to the April 2009 World Bank report the Israeli Water Authority argued that:“Thiswater has been developed and used continuously in the past by Israel within the“Green Line” (well before 1967), whether by diversion of spring water or by drilling of wells.It is clear that Israel has a natural right over this water, which complies with internationalnorms (maintaining existing utilization).”59

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

22

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

Israel’s position is open to challenge in several important respects. It is fundamentallydiscriminatory, both in essence and in its selective interpretation of the status quo ante andit implications.Firstly, the appropriation of a disproportionate percentage of shared resources by one partyfor a given period does not confer on that party a perennial right to exploit those resourcesdisproportionately to the exclusion of all other considerations.Secondly, Israel dates its “prior established use” of the Mountain Aquifer to the particulartime in the past most convenient to its claim.Thirdly, Israel fails to take into account that a large part of the Palestinian population of theOPT - two thirds of Gaza’s residents and almost a third of West Bank residents – were (or aredescended from those who were) formerly part of the population of what is today Israel butwere displaced by conflict.Fourthly, after its occupation of the OPT in 1967, Israel forcibly took control of waterresources and imposed significant changes in the area’s water sector. This includedextracting large quantities of groundwater and diverting surface water for its own benefit,while preventing access by the local Palestinian population to these same resources.Lastly, Israel has also forcibly imposed other changes in the OPT whose impact has directlyreduced access to water for the Palestinian population, notably the appropriation of largeareas of land, the establishment of unlawful Israeli settlements, and the prohibition onPalestinians taking measures to develop their own infrastructure and economy. The Israeliauthorities claim that Palestinian water shortages are caused by the Palestinians irrigatingfields that should not be irrigated because they have never been irrigated in the past – whilethey continue to supply large quantities of water to Israeli settlers to irrigate ever-expandingfarms in settlements unlawfully established after Israel occupied the West Bank.60The argument put forward by Israel is also legally untenable. The Israeli authorities haverecognized that the principles of “equitableand reasonable use”and of prevention ofappreciable or significant harm are two basic rules that can be “viewedas customary inrelation to the use and division of shared international water resources.”61Consequently,even if prior established use had been, or were to be, determined in a fair manner, theprinciple of equitable and reasonable use would still apply and could not justify thedisproportionate and inequitable allocation of water that currently exists.

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

23

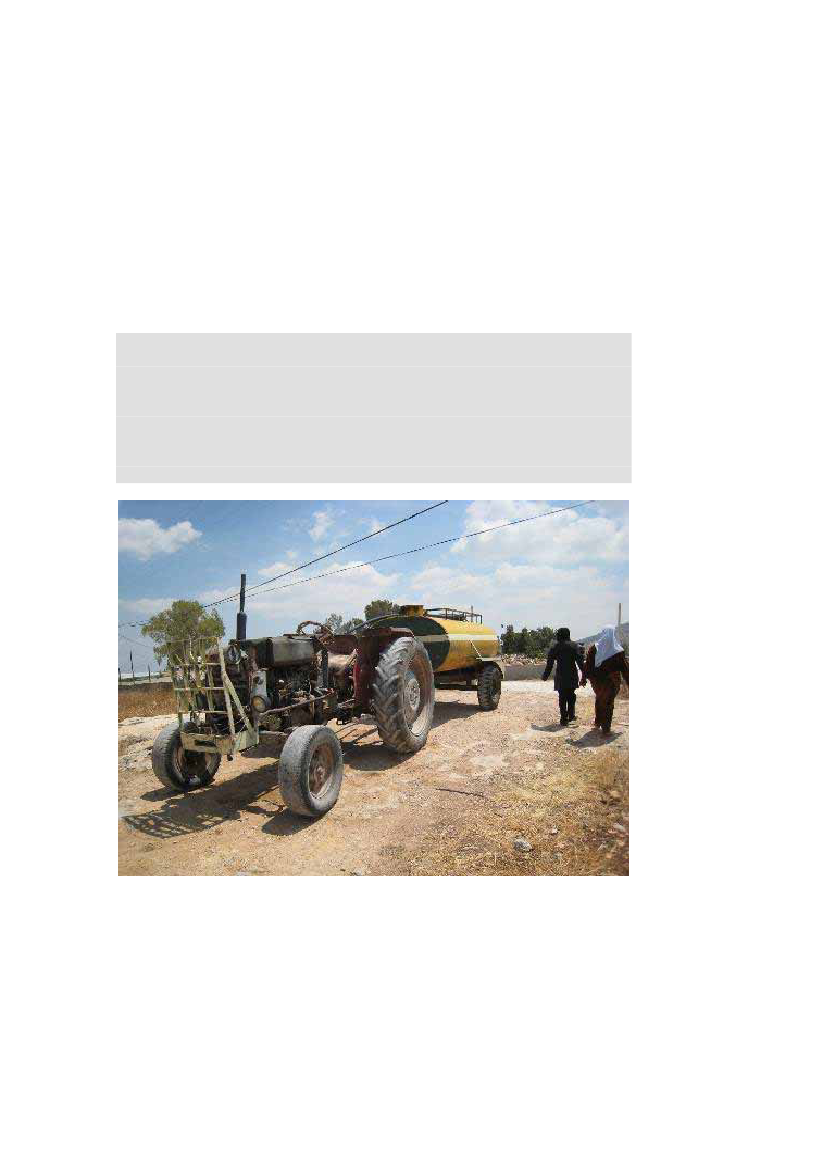

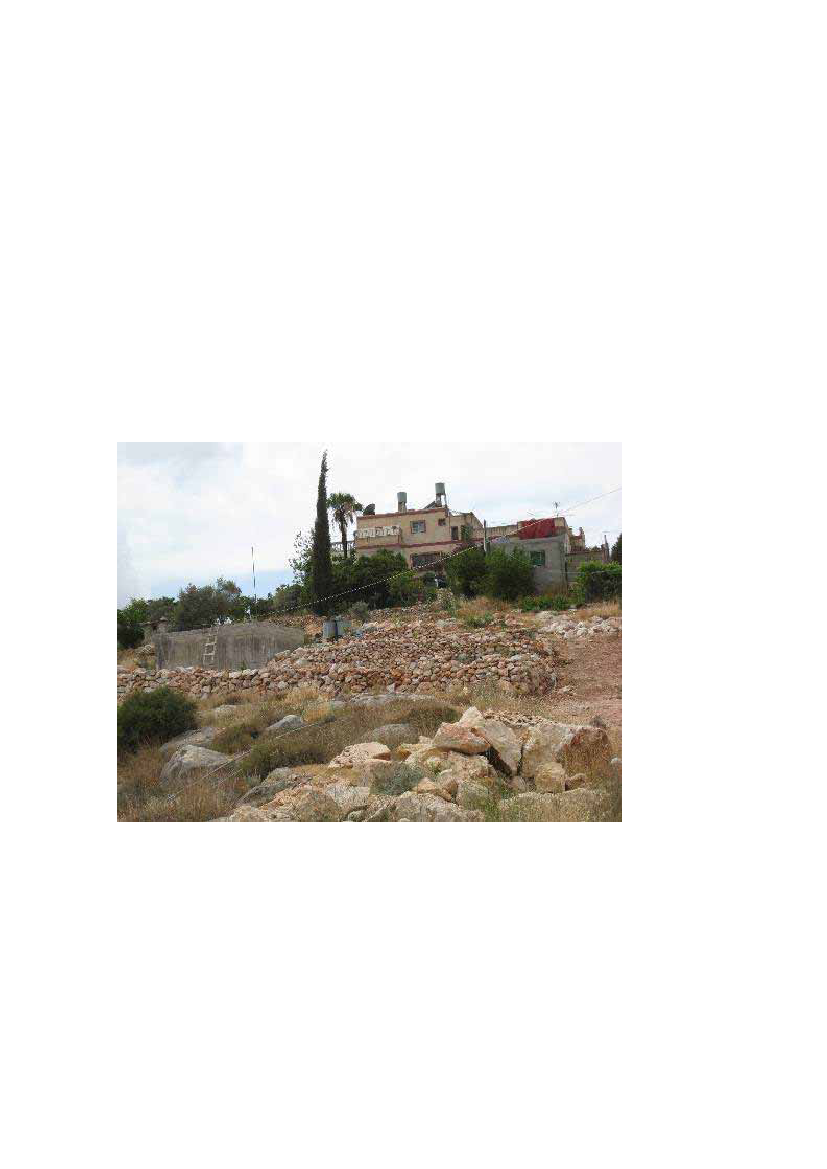

POLICIES OF DENIAL“There is no water in the village, so we have tobring it from far away and it’s expensive. I can’twash and clean as often as needed. We can’tafford it. It’s a daily struggle.”.Iman Jabar, a resident of al-‘Aqaba village, whose home has a demolition order pendingagainst it, told Amnesty International, “Thereis no water in the village, so we have to bring itfrom far away and it’s expensive. I have nine children (five girls and four boys aged from fiveto 19 years). We spend a lot of money on water and we have to make do with very little, justfor drinking and cooking and don’t have enough for the other needs. We need more water forwashing, washing the clothes and cleaning the house. I can’t wash and clean as often asneeded. We can’t afford it. It’s a daily struggle. The goats also need to drink. We can’t keepmore goats because we can’t afford the water, and we can’t grow food for us and fodder forthe animals, so we have to buy it and this too is expensive.”

A tractor used to pull a water tanker in al-'Aqaba village in the West Bank � AI

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

24

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

Al-’AQABA isa small Palestinian village in the north-east of the West Bank where almost allthe houses, as well as the nursery school, a clinic and other buildings, are under demolitionorders issued by the Israeli army. For years, the villagers have been resisting efforts by theIsraeli army to force them to abandon the village. Most have left but some 35 familiesremain, and the difficulties they face are exacerbated by the lack of water.The village is one of some 200 communities that have not been connected to the waternetwork. Nearby towns and villages, such as Tayasir and Tubas, are connected but they toosuffer from water shortages and their inhabitants often have to buy additional supplies fromwater tankers.Another villager, Akram Muhammad Salah Talib, told Amnesty international: “Ihave sixchildren and with my wife and my elderly parents we are 10 people. We also have sheep. Weneed two tanks of 10m3 per month and each tank costs 120 to 150 NIS [US$65 to 80 permonth]. It is an enormous expense and this amount only covers the most basic needs. Itdoes not allow us to live in good and hygienic conditions. In addition, the Israeli armydemolished my house five years ago and they also destroyed the water cistern where wecollected the rainwater. My cousin built a water cistern two years ago and the army gave hima demolition order for it.”In August 2009 the head of al-‘Aqaba’s village council, Haj Sami, issued an appeal for helpto relieve the water problem in the village. He told Amnesty International: “Wehave to travelquite far to buy water and bring it to the village by tanker. With the cost of transport thewater costs 15 NIS per m�, which is three or four times what it would cost if we had aconnection to the water network or a well in the village. It is unaffordable. People here livesimple lives; they work the land and herd goats and sheep; but without water they can doneither. There are more than 100 children in the school and nursery school in the village;there should be water for them to drink and wash their hands; this is a necessity not a luxury.People shower once a week because they haven’t enough water. Such hardship isunacceptable and inhuman. Would our Israeli neighbours accept to live in such conditions?No, so why do they deny us our basic rights? The Israeli army uses our village land formilitary training, a safety hazard for us, and controls this area, but provides no services anddoes not allow us to put in place services.”

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water

25

THE WATER CRISIS IN GAZA“The deterioration and breakdown of water and sanitation facilities in Gaza is compounding analready severe and protracted denial of human dignity in the Gaza Strip. At the heart of this crisis isa steep decline in standards of living for the people of Gaza, characterized by erosion of livelihoods,destruction and degradation of basic infrastructure, and a marked downturn in the delivery andquality of vital services in health, water and sanitation.”Maxwell Gaylard, UN Humanitarian Coordinator for the Occupied Palestinian Territory, 3 September 2009.62

The water situation in Gaza is dire. The Coastal Aquifer, Gaza’s sole fresh water resource, ispolluted by the infiltration of raw sewage from cesspits and sewage collection ponds and bythe infiltration of seawater (itself also contaminated by raw sewage discharged daily into thesea near the coast) and has been degraded by over-extraction.The average amount of water available to each inhabitant of Gaza slightly exceeds theaverage amount available in the West Bank, at about 80-100 litres per capita a day.63However, more than 90 per cent of the water extracted from the aquifer in Gaza iscontaminated and unfit for human consumption.64Waterborne diseases are common. TheDepartment of Health of the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) reported in its February2009 Epidemiological Bulletin for Gaza Strip that: “Waterydiarrhoea as well as acute bloodydiarrhoea remain the major causes of morbidity among reportable infectious diseases in therefugee population of the Gaza Strip.”65According to a report of the United Nations Environment Programme, UNEP, theEnvironmental Assessment of the Gaza Strip following the escalation of hostilities inDecember 2008 – January 2009,published in September 2009: “Thepollution ofgroundwater is contributing to two main types of water contamination in the Gaza Strip.First, and most importantly, it is causing the nitrate levels in the groundwater to increase. Inmost parts of the Gaza Strip, especially around areas of intensive sewage infiltration, thenitrate level in groundwater is far above the WHO accepted guideline of 50 mg/litre….Second, because the water abstracted now is high in salt, the sewage is also very saline andhence infiltrating sewage only adds to the salinity of the aquifer. It has been well known andwell documented for decades that higher levels of nitrates in drinking water can inducemethemoglobinaemia in young children.”66

BLUE BABIES IN THE GAZA STRIP“Methemoglobinaemiais a blood disorder characterized by higher than normal levels ofmethemoglobin, a form of haemoglobin that does not bind oxygen. When haemoglobin isoxidized it becomes methemoglobin, its structure changes and it is no longer able to bindoxygen or deliver it to the tissues, and anaemia can result. This state is referred to asmethemoglobinaemia. Infants suffering from methemoglobinaemia may appear otherwisehealthy but exhibit intermittent signs of blueness around the mouth, hands and feet. Theymay have episodes of breathing trouble, diarrhoea and vomiting. In some cases, infants withmethemoglobinaemia have a peculiar lavender colour but show little distress. Blood samples

Index: MDE 15/027/2009

Amnesty International October 2009

26

Israel/OPT – Troubled WatersPalestinians denied fair access to water