Udenrigsudvalget 2009-10

URU Alm.del Bilag 222

Offentligt

DIIS polIcy brIefGlobal economy, regulation and Development

Reforming Global Banking Rules− how the G20 Can Savethe Global EconomyAt the September 2009 Pittsburgh Summit the leaders ofthe G20 set out a series of far reaching regulatory reformsto “tackle the root causes of the crisis and transform thesystem for global financial regulation”. The centrepiece ofthe reform effort was Basel III, a new set of capital ade-quacy rules to be drawn up by the Basel Committee onBanking Supervision (BCBS), a group of internationalbanking regulators, by the end of 2010. As the G20 con-venes in Toronto almost one year later, Basel III is enteringa critical phase in the reform process – a phase which willdetermine whether we see fundamental reform of the international banking system or merely a return to ‘business asusual’. Drawing on the experience of the previous attemptto overhaul global capital standards, Basel II, this DIISpolicy brief proposes a set of institutional and structuralreforms to the BCBS to ensure that it succeeds in realizingthe G20’s vision for a sounder and more resilient financialsystem.Basel III: a New BegINNINgfor BaNkINg regulatIoN?In the wake of the financial crisis a consensus has emergedamongst international policymakers that a new approachto capital regulation is essential to the future stability ofthe global financial system. The G20 has been the leadingadvocate for capital adequacy reform at the internationallevel. Two months after the collapse of American invest-ment bank Lehman Brothers in September 2008, thegroup called on the BCBS to strengthen capital require-ments for banks’ structured credit and securitization ac-tivities, culminating in the publication of a new tradingbook framework in July 2009. At the Pittsburgh Summitthe G20 went even further. Setting a final draft deadline ofend-2010 and an implementation deadline of end-2012,the group ordered the BCBS to formulate an entirely newset of capital rules, Basel III, as the centrepiece of its finan-cial reform effort.In December 2009 the BCBS took the first steps towardsthe creation of a new capital regime, issuing a set of pre-polIcy recommeNdatIoNs

The G20 must intensify their efforts tosecure fundamental reform of internationalbanking rules at their Toronto summit, atask delegated to theBasel Committee onBanking Supervision(BCBS) in 2009. As partof these effort, the G20 must explicitlyaddress the problem of regulatory capture,thede factocontrol of regulatory agenciesby the regulated interests. Three kinds ofmeasures are necessary:•Restrictions on the ‘revolving door’between regulatory agencies and theprivate sector, including: mandatory pub-lic disclosure of officials’ past and presentindustry ties; moratoria on regulatorsaccepting jobs in the financial sector; andefforts to reduce regulatory dependenceon private technical expertise from well-resourced financial institutions.The BCBS should open itself up to publicscrutiny, disclosing records of the dates,agendas and participants of all committeeand subcommittee meetings. It shouldconduct regular consultations withconsumer groups and regional banks – aswell as large international banks – toensure that all stakeholders are heard.The BCBS should prioritize rules overdiscretionary measures. This will helpnational regulators resist pressure toengage in a regulatory ‘race-to-the-bottom’.�

•

•

DIIS polIcy brIefliminary proposals whose details would be filled in oversubsequent rounds of negotiations during 2010. There arefour key elements to the latest proposals:(i)International leverage ratio: a simple ratio ofequity to total assets introduced as a safeguardagainst the risks inherent in the use of internalmodels.Countercyclical capital buffers: buffers whichrise above regulatory minima in economicbooms and can be subsequently drawn uponas losses are incurred during downturns.More restrictive definitions of capital, aimed atimproving the loss absorption capacity of banks’capital bases.Minimum liquidity standard: a standard de-termining the minimum ratio of highly liquidassets to total assets that banks are required tohold to cover temporary funding shortfalls.Nevertheless, it is not yet clear whether the BCBS will beable to resist the industry’s lobbying campaign and ensurethat crucial provisions of Basel III emerge intact from theregulatory process. Are we going to see a new beginningfor banking regulation? Or are we going to see, thanks tothe pervasive influence of regulatory capture, a return to‘business as usual’?

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

The BCBS’s proposals have caused alarm in the financeindustry and in the eyes of some commentators haveheralded a new era in the history of banking regulation –an era of ‘more capital, more liquidity and less risk’. Suchconclusions are premature.With the drafting process entering its final stages theBCBS has come under increasing pressure from thebanking industry to water down its latest proposals.In April 2010, the deadline for comments on the pro-posals, the BCBS was flooded with protests from largefinancial institutions warning that Basel III coulddestroy the economic recovery, potentially trigger-ing a ‘double-dip’ recession. One prominent Frenchbank claimed that the proposals would produce “twoyears of recession guaranteed, or four years of zero growth”in Europe. More recently the Institute of InternationalFinance (IIF), the major lobby group for large interna-tional banks, released a study estimating that the propo-sals would cause a cumulative reduction in GDP of $920billion (4.3% of GDP) in the euro zone and $951 billion(2.7% of GDP) in the United States by 2015 – represent-ing an overall loss of more than nine million jobs across theglobal economy. These assessments have not been confirm-ed by independent analysis. The chief economic advisor tothe Bank of International Settlements, for instance, sug-gested in May that “the net impact of the Basel committeereforms on growth will be negligible” and “our preliminaryassessment is that improvements to the resilience of thefinancial system will not permanently affect growth – ex-cept for possibly making it higher”.2

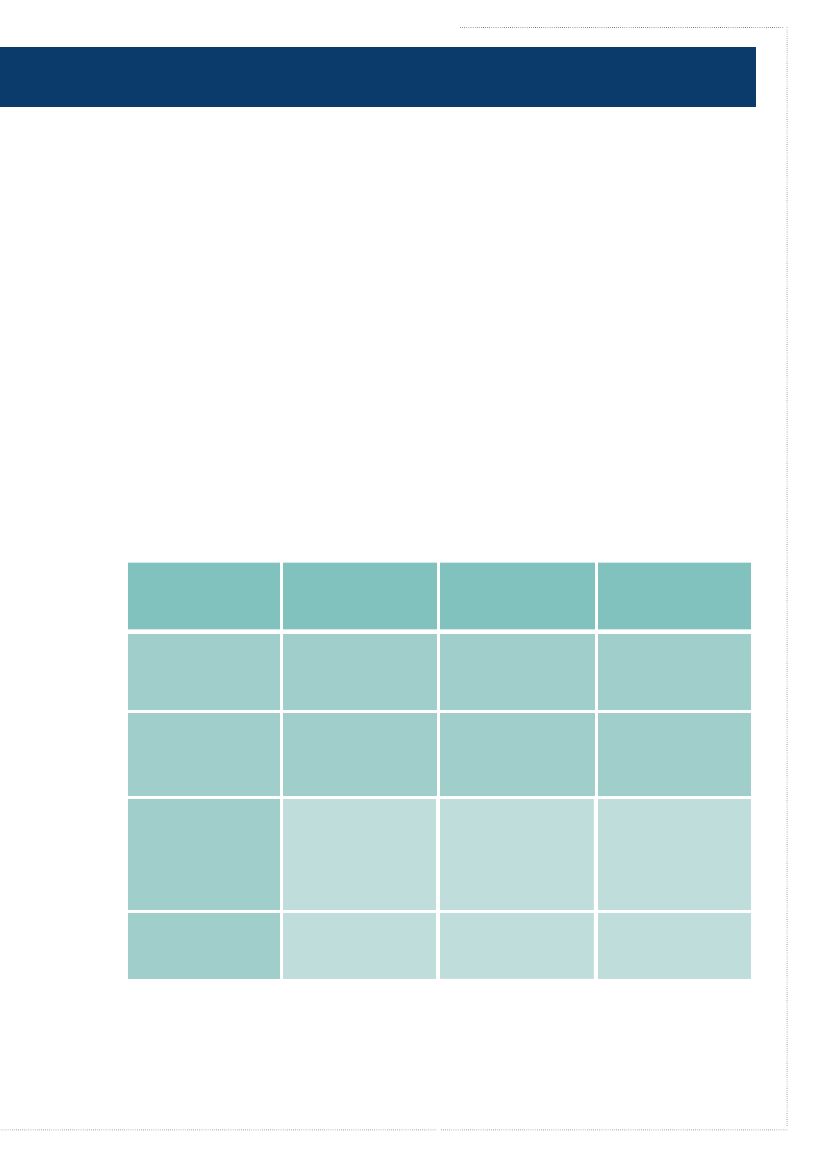

Lessons from the Past:the faiLure of BaseL iiWe are in familiar territory. Eleven years ago, partly inresponse to the Asian financial crisis, the BCBS set out tointroduce more stringent international capital standards.The existing regime, the 1988 Accord on Capital Ade-quacy (Basel I), had failed to keep up with the pace offinancial innovation, providing banks with easy opportu-nities to engage in regulatory arbitrage – reducing capitalwithout reducing risk – through activities such as securiti-zation. By closing loopholes in the 1988 Accord the Com-mittee hoped to maintain the current levels of capital inthe banking system while creating a more “comprehensiveapproach to addressing risk”. As the reform process finallydrew to a close in 2004, however, it became clear that theBCBS had failed to achieve these objectives (see table).Basel II, as the agreement came to be known, gave the larg-est banks the option to use internal risk models in theircapital calculations, allowing these banks to effectively settheir own capital requirements. Instead of increasing risksensitivity, the use of internal estimates provided bankswith an incentive to minimize capital and engage in evenriskier practices. The result was an dramatic decline inoverall capital levels in the banking system – in explicitcontradiction to the BCBS’s original aim. The BCBS alsofailed to achieve its aim of creating a more comprehensiveapproach to risk assessment. As well as allowing negligiblelevels of capital to be held against securitization exposures,Basel II largely ignored the risks associated with the tradingbook – the portfolio of assets traded in capital marketsrather than held until maturity. Needless to say, it was the-se assets that expirienced the heaviest losses in the financialcrisis.What went wrong? The answer lies in the institutional con-text within which Basel II was drafted. The BCBS operatedas an exclusive ‘club’, disclosing no information about its ac-tivities and restricting membership to G10 countries. Evenmore worryingly the BCBS consulted only a handful of largeinternational banks, with which it had close personal links.The longest-serving chairman of the BCBS was in fact a co-founder of the IIF, the most influential lobby group in nego-tiations for Basel II. The man who presided over most of theBCBS’s work on Basel II, meanwhile, was a close friend of theIIF’s managing director through his twenty-two year stint ata major American bank. These conditions allowed large

international banks to exert a disproportionate influenceover the content of Basel II, skewing regulatory outcomes intheir favour at the expense of their smaller rivals and, ultim-ately, the stability of the global financial system.

that the G20, as it meets in Toronto this week, heeds thelessons of Basel II’s failure. By adopting the kinds of insti-tutional reform proposed in this brief can we put oursel-ves in a position to create rules that serve the interests ofsociety as a whole, and not just those being regulated.

ConCLusionOminously for Basel III many of the conditions that under-mined the previous attempt to regulate banking systemsare still in place today. Indeed, there are already signs thathistory may be repeating itself. At a meeting in South Koreaearlier this month G20 finance ministers indicated that, onthe advice of the BCBS, they would delay implementationof Basel III from the original 2012 deadline to between2014 and 2016. Meanwhile, members of the BCBS haveprivately admitted that many of the key elements of BaselIII – such as the leverage ratio and countercyclical capitalbuffers – may be shifted to ‘Pillar 2’ of the accord, renderingthem non-binding and leaving their implementation to thediscretion of national supervisors. It is therefore essential

initiaL ProPosaLs anD finaL outComes in BaseL iiareainitiaL ProPosaLinDustryreCommenDationfinaL aCCorD(BaseL ii)

CreDit risk

incorporate creditratings from externalcredit rating agenciesinto the frameworkstandardizedmethodology basedon fixed riskparametersintroduce capitalcharge for derivativesrisk; capture counter-party credit risk in thetrading book

recognize internalcredit risk modelsof large banks

recognition ofinternal credit riskmodels for largebanksrecognition of Varmodels in 1996

market risk

substitute standard-ized methodology forinternal market risk(Var) modelsDrop capital chargefor derivatives risk;do not apply counter-party credit riskcapital requirementsto trading bookLower risk weights forrated tranches

traDing Book

Capital charge forderivatives riskabolished in 2001;minimal regulationof trading book

seCuritization

Link risk weights toexternal credit ratings

reduced risk weightsfor rated tranches

Source: Lall, 2010

�

DIIS polIcy brIefsuggesteD reaDings

Lall, Ranjit (2010). Reforming Global Banking Rules: Back to the Future? DIIS Working Paper 2010:16Højland, Martin & Vestergaard, Jakob (2010). Governing through Standards: The Elusive Case of Banking. Paperpresented at the ‘Governing through Standards’ conference at the Danish Institute for International Studies,24–26 February 2010.Tsingou, Eleni (2009). Revolving Doors and Linked Ecologies in the World Economy: Policy Locations and the Prac-tice of International Financial Reform. CSGR Working Paper 260/09. Centre for the Study of Globalisation andRegionalisation, Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick.Baker, Andrew (2010). Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Changein Global Financial Governance. International Affairs, Volume 86, Issue 3, Blackwell Publishing and ChathamHouse.The Warwick Commission (2009). The Warwick Commission on International Financial Reform: In Praise of Unle-vel Playing Fields. University of Warwick, Coventry, UK.Giles, Chris (2010). Bankers’ ‘doomsday scenarios’ under fire from Basel study chief. Financial Times, May 31st 2010,website: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/df82600a-6c4a-11df-86c5-00144feab49a.html

Diis ¶ Danish institute for internationaL stuDiesStrandgade 56, ��0� Copenhagen, Denmark ¶ Tel +�5 �2 69 87 87 ¶ Fax + �5 �2 69 87 00 ¶ e-mail: [email protected] ¶ www.diis.dk

�