Sundhedsudvalget 2009-10

SUU Alm.del Bilag 517

Offentligt

World Alzheimer Report 2010The GlobAl economic impAcT of DemenTiA

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

Alzheimer’s Disease InternationalWorld Alzheimer Report 2010The Global Economic Impact of Dementiaprof Anders Wimo, Karolinska institutet, Stockholm, Swedenprof martin prince, institute of psychiatry, King’s College london, UKpublished by Alzheimer’s disease international (Adi) 21 September 2010

Acknowledgementsprofessor Bengt Winblad (Karolinska institutet, Stockholm, Sweden) and dr linusJönsson (i3 innovus and Karolinska institutet, Stockholm, Sweden) have contributedsignificantly to the methodological development in the cost estimates.Swedish Brain power (SBp) provided unrestricted financial support for the work ofAnders Wimo for this study.Alzheimer’s Association (US) for support with reviewing and launching this report.photos: Cathy Greenblat – www.cathygreenblat.comdesign: Julian howell

ADI would like to thank those who contributed financially:Vradenburg FoundationGeoffrey Beene Foundation – www.geoffreybeene.com/alzheimers.htmlAlzheimer’s Association – www.alz.orgAlzheimer’s Australia – www.alzheimers.org.auAlzheimer’s Australia WA – www.alzheimers.asn.auAlzheimer Scotland – www.alzscot.orgAlzheimer’s Society – www.alzheimers.org.ukAssociation Alzheimer Suisse – www.alz.chAlzheimerföreningen i Sverige – www.alzheimerforeningen.sedeutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft – www.deutsche-alzheimer.deStichting Alzheimer Nederland – www.alzheimer-nederland.nl

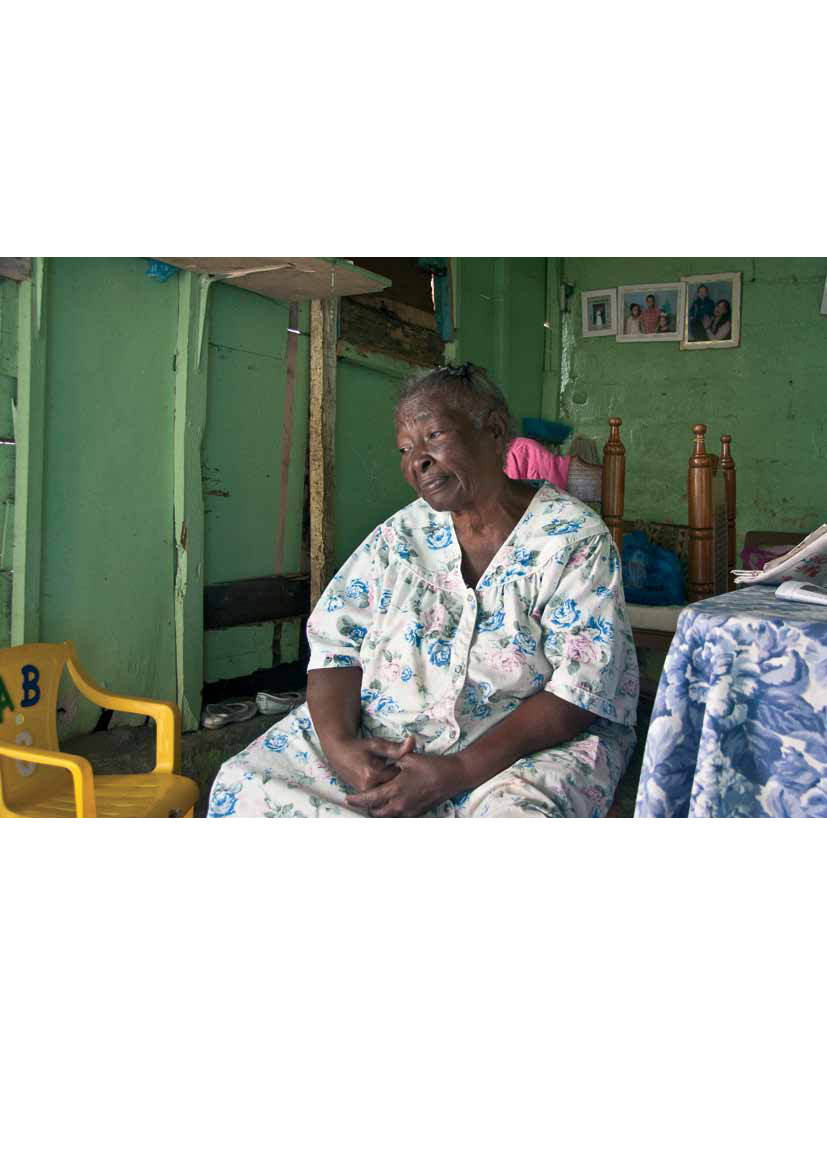

Cover imageAna de Jesus de Bido, a pastor and geriatrician, and her physicianhusband run a care facility in the Villa Francisca barrio in Santodomingo, dominican republic. here she was on a home visit with82-year-old Ana luisa Candelario, who cares for her 92-year-oldhusband. Ana luisa takes little care of herself, often not eating, andpastor Ana consoled her and explained the importance of caregiverstaking care of themselves.

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

1

Alzheimer’s diseAse internAtionAl

World Alzheimer report 2010the GlobAl economic impAct of dementiA

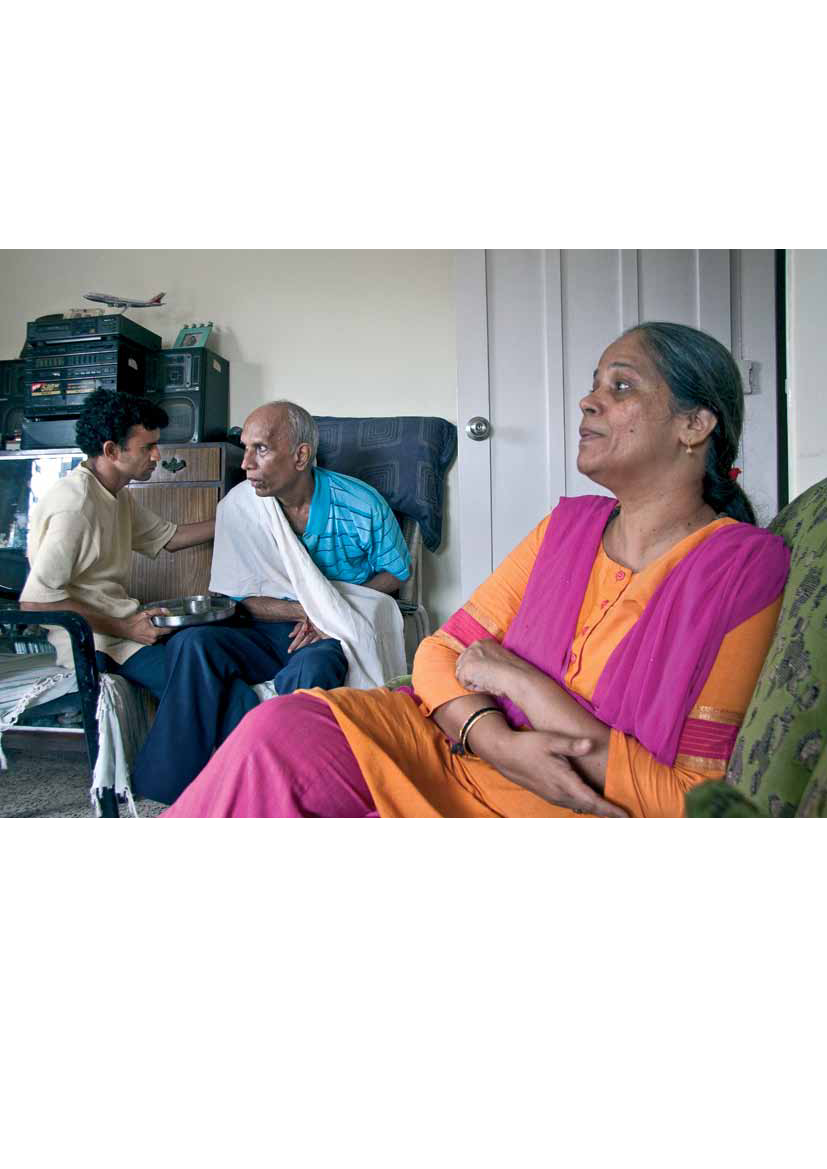

As mandakini became more confused, it was clear that she could no longer live alone. Two of her sons indicated thatthey could not take care of her because they had young children. her son Satish and his wife Neha, who also hadyoung children, brought her to their home, where they take care of her with the assistance of a professional caregiver.eight-year old Srushti has found ways to relate to her grandmother, and her two-year-old sister shows no fear. Thoughmandakini speaks very little, Srushti has found that her grandmother enjoys the religious chants that have beenimportant to her throughout her life. Now Srushti leads and they chant together.

2

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

forewordIn the World Alzheimer Report 2010, we build upon the findings detailed in the WorldAlzheimer Report 2009, to explore the cost of dementia to our societies. The Reportcontains an explanation of the methods used, detailed results for different economicand geographic regions, and we offer conclusions and recommendations in the finalsection.As you will see, the figures are cause for great concern and we hope that this Reportwill act as a call to action for governments and policy makers across the world. Itis vital that they recognize that the cost of dementia will continue to increase at analarming rate and we must work to improve care and support services, treatmentand research into dementia in all regions of the world. Lower income countries facea severe lack of recognition of dementia, placing a heavy burden on families andcarers who often have no understanding of what is happening to their loved one. Highincome countries are struggling to cope with the demand for services, leaving manypeople with dementia and caregivers with little or no support. Consequently, we urgekey decision makers to take notice of this very important document and to work withAlzheimer associations and with ADI to make dementia a national and global healthpriority.We would like to thank a number of people for their hard work on the developmentof this Report. We are grateful to the Report’s authors, Prof Anders Wimo and ProfMartin Prince, for their tireless efforts and dedication, and Niles Frantz and MaryKateWilson from the Alzheimer’s Association in the USA for their valuable input. Thankyou also to the sponsors who made the Report possible and to those who tookthe time to review the contents: the Organisation for Economic Co-operation andDevelopment (OECD) in Paris, the Alzheimer’s Association in the USA and GlennRees at Alzheimer’s Australia. Finally, we would like to thank Cathy Greenblat for herphotographs.Daisy AcostaChairmanAlzheimer’s disease international

Marc Wortmannexecutive directorAlzheimer’s disease international

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

3

contentsExecutive Summary 4Background4methods5results5Conclusions6recommendations7

Introduction 8previous evidence8references for introduction10

Methods 12Key design issues for cost of illness studies12prevalence versus incidence approaches12Top-down versus bottom-up approaches12Which costs are to be included, and how should they be computed?12The viewpoint13The representativeness of data sources on resource utilization13The ideal scenario for computing cost of illness … and the reality13Methods used in our cost of illness analyses14Summary14The evidence on the prevalence of dementia, and numbers affected worldwide14The evidence on the utilization of medical and social care, and informal care16

Results 24results of base option24Sensitivity analyses28how should we compare costs between countries, using a single cost metric?28Which informal care inputs should be included?29how should we cost the inputs of informal caregivers?30Comparison of this report with previous worldwide cost estimates of dementia32references for methods and results34

Conclusions and recommendations 38Strengths and weaknesses38The regional distribution of global costs39Comparisons with other estimates of the cost of dementia42Comparison with the cost of other chronic diseases44Alzheimer’s disease international’s recommendations45references for conclusions and recommendations48

Glossary 50Alzheimer’s Disease International 51

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

4

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

executive summaryThe total estimated worldwide costs of dementia are US$604 billion in 2010.About 70% of the costs occur in Western Europe and North America.Costs were attributed to informal care (unpaid care provided by family and others), directcosts of social care (provided by community care professionals, and in residential homesettings) and the direct costs of medical care (the costs of treating dementia and otherconditions in primary and secondary care).Costs of informal care and the direct costs of social care generally contribute similarproportions of total costs, while the direct medical costs are much lower. However, in lowand middle income countries informal care accounts for the majority of total costs anddirect social care costs are negligible.

Background• Dementia is a syndrome that can be caused by a number of progressive disorders that affectmemory, thinking, behaviour and the ability to perform everyday activities. Alzheimer’s diseaseis the most common type of dementia. Other types include vascular dementia, dementia withLewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia.• Dementia mainly affects older people, although there is a growing awareness of cases that startbefore the age of 65. After age 65, the likelihood of developing dementia roughly doubles everyfive years.• In last year’s World Alzheimer Report, Alzheimer’s Disease International estimated that there are35.6 million people living with dementia worldwide in 2010, increasing to 65.7 million by 2030and 115.4 million by 2050. Nearly two-thirds live in low and middle income countries, where thesharpest increases in numbers are set to occur.• People with dementia, their families and friends are affected on personal, emotional, financialand social levels. Lack of awareness is a global problem. A proper understanding of thesocietal costs of dementia, and how these impact upon families, health and social careservices and governments may help to address this problem.• The societal cost of dementia is already enormous. Dementia is already significantly affectingevery health and social care system in the world. The economic impact on families isinsufficiently appreciated.• In this World Alzheimer Report 2010, we merge the best available data and the most recentinsights regarding the worldwide economic cost of dementia. We highlight these economicimpacts by providing more detailed estimates than before, making use of recently availabledata that considerably strengthens the evidence base.– The World Alzheimer Report 2009 provides the most comprehensive, detailed and up-to-date data on the prevalence of dementia and the numbers of people affected in differentworld regions.– The 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s studies in Latin America, India and China haveprovided detailed information on informal care arrangements for people with dementia inthose regions.– For this Report, Alzheimer’s Disease International has conducted a global survey of keyinformants regarding the extent of use of care homes in different world regions.

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

5

Methods• Different methods can be used to estimate the cost of an illness. The base approach in thisReport is a societal, prevalence-based gross cost of illness study. Annual costs per person withdementia for each country have been applied to the estimated number affected in that country,and then aggregated up to the level of World Health Organization regions, and World Bankincome groupings.• The costs considered include informal (family) care as well as direct medical and social carecosts. Direct medical costs refer to the medical care system, such as costs of hospital care,medication and visits to clinics. Direct social care costs are for formal services provided outsideof the medical care system, including community services such as home care, food supply andtransport, and residential or nursing home care.• For informal care, we estimated how much time family caregivers spend caring, includingtime spent with basic activities of daily living (such as eating, dressing, bathing, toileting andgrooming) and with instrumental activities of daily living (such as shopping, preparing food,using transport and managing personal finances).• The costs in this Report, as well as the prevalence of dementia, reflect estimates for 2010and are expressed as US dollars. To permit aggregation across countries, and comparisonsbetween countries and regions, costs were converted to US dollars from local currenciesbased on current exchange rates.• Cost of illness studies depend on a set of sources and assumptions. We have conductedcomprehensive sensitivity analyses in which we use different source data or vary assumptionsto see how this would affect the results (“Sensitivity analyses” on page 28).

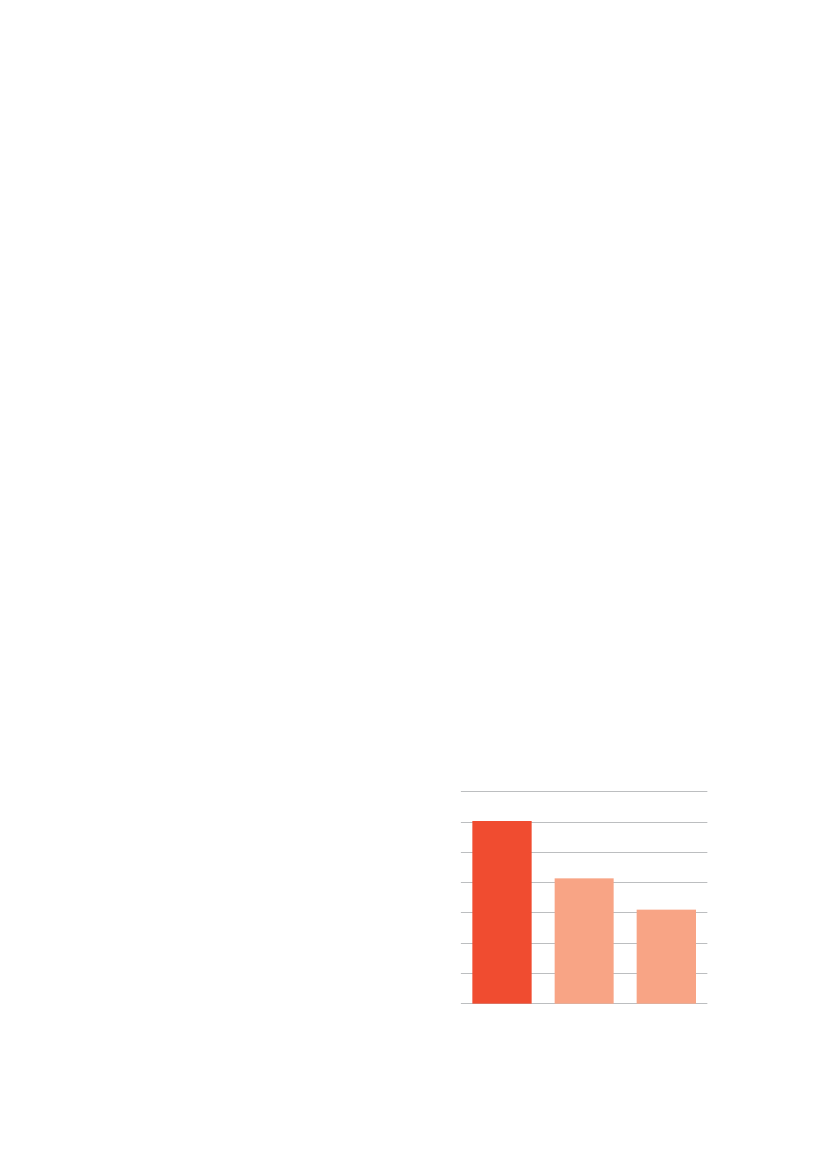

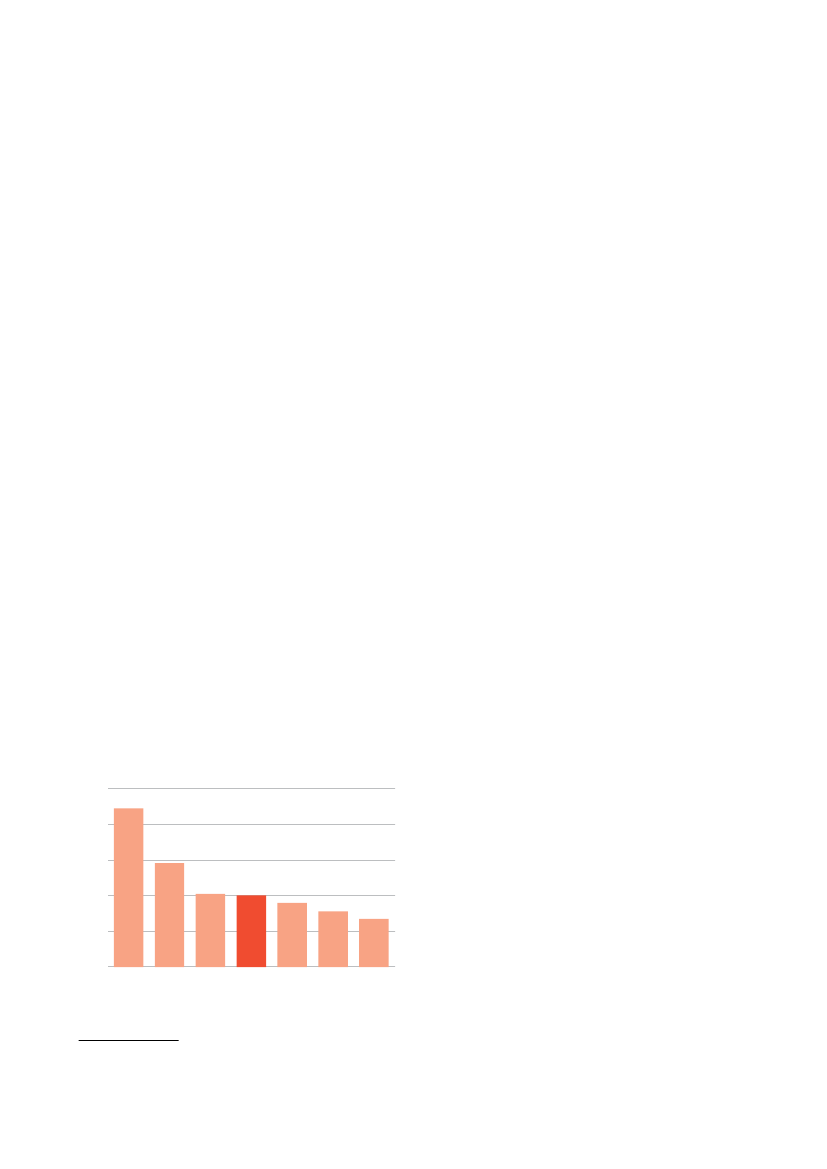

Results• The total estimated worldwide costs of dementia are US$604 billion in 2010.• These costs account for around 1% of the world’s gross domestic product, varying from0.24% in low income countries, to 0.35% in low middle income countries, 0.50% in high middleincome countries, and 1.24% in high income countries.• If dementia care were a country, it would bethe world’s 18th largest economy, rankingbetween Turkey and Indonesia. If it were acompany, it would be the world’s largest byannual revenue exceeding Wal-Mart (US$414billion) and Exxon Mobil (US$311 billion)(figure 1).• Costs of informal care (unpaid care providedby families and others) and the direct costsof social care (provided by community careprofessionals and in residential home settings)contribute similar proportions (42%) of totalcosts worldwide, while direct medical carecosts are much lower (16%).Figure 1Cost of dementia compared to companyrevenueUS$ billions700600500400300200100

• Low income countries accounted for just0DementiaWal-MartExxon Mobilunder 1% of total worldwide costs (but 14% ofthe prevalence), middle income countries forCost of dementia compared to company revenue10% of the costs (but 40% of the prevalence)and high income countries for 89% of the costs (but 46% of the prevalence). About 70% of theglobal costs occurred in just two regions: Western Europe and North America.

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

6

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

• These discrepancies are accounted for by the much lower costs per person in lower incomecountries – US$868 in low income countries, US$3,109 in lower middle income, US$6,827 inupper middle income and US$32,865 in high income countries.• In lower income countries, informal care costs predominate, accounting for 58% of all costsin low income and 65% of all costs in lower middle income countries, compared with 40% inhigh income countries. Conversely, in high income countries, the direct costs of social care(professional care in the community, and the costs of residential and nursing home care)account for the largest element of costs – nearly one half, compared with only one tenth inlower income countries.

Conclusions• The scale of the global cost of dementia is explainable when one considers that around 0.5% ofthe world’s total population live with dementia.– A high proportion of people with dementia need some care, ranging from support withinstrumental activities of daily living (such as cooking or shopping), to full personal care andround the clock supervision.– In some high income countries, between one third and one half of all people with dementialive in resource- and cost-intensive residential or nursing home care facilities.– Medical care costs also tend to be relatively high for people with dementia, particularly inhigh income countries with reasonable provision of specialist care services.• Costs are lower in developing countries, both per person and societally (as a proportion ofGDP). In these regions, there is a much greater reliance on the unpaid informal care provided byfamily and others.– While wage levels are low, these are increasing rapidly, and hence the opportunity cost orreplacement cost of these informal inputs is set to rise.– In our key informant survey, we estimated that in low and middle income countries only6% of people with dementia live in care homes. However, this sector is expanding rapidly,particularly in urban settings in middle income countries, boosted by demographic andsocial changes that reduce the availability of family members to provide care.– Medical help-seeking is relatively unusual in low and middle income countries, wheredementia is often viewed as a normal part of ageing. Demand for medical care is likelyto increase in the future, with improved awareness, better coverage of evidence-basedinterventions, and, possibly, more effective treatments.• Worldwide, the costs of dementia are set to soar. We have tentatively estimated an 85%increase in costs to 2030, based only on predicted increases in the numbers of people withdementia. Costs in low and middle income countries are likely to rise faster than in high incomecountries, because, with economic development, per person costs will tend to increasetowards levels seen in high income countries, and because increases in numbers of peoplewith dementia will be much sharper in those regions.• There is an urgent need to develop cost-effective packages of medical and social care thatmeet the needs of people with dementia and their caregivers across the course of the illness,and evidence-based prevention strategies. Only by investing now in research and cost-effectiveapproaches to care can future societal costs be anticipated and managed. Governments andhealth and social care systems need to be adequately prepared for the future, and must seekways now to improve the lives of people with dementia and their caregivers.

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

7

Recommendations

123

Alzheimer’s Disease International calls on governments to make dementia a healthpriority and develop national plans to deal with the disease.Alzheimer’s Disease International reminds governments of their obligations underthe UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, and the MadridInternational Plan for Action on Ageing to ensure access to healthcare. It callson governments to fund and expand the implementation of the World HealthOrganization (WHO) Mental Health Gap Action Plan, including the packages of carefor dementia, as one of the seven core disorders identified in the plan.Alzheimer’s Disease International requests that new investment in chronic diseasecare should always include attention to dementia. For example, the WHO GlobalReport on ‘Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions’ alerts policymakers, particularlythose in low and middle income countries, to the implications of the decreases incommunicable diseases and the rapid ageing of populations. Healthcare is currentlyorganized around an acute, episodic model of care that no longer meets the needsof patients with chronic conditions. The WHO Innovative Care for Chronic Conditionsframework provides a basis on which to redesign health systems that are fit for theirpurpose.Alzheimer’s Disease International calls on governments and other major researchfunders to act now to increase dementia research funding, including research intoprevention, to a level more proportionate to the economic burden of the condition.Recently published data from the UK suggests that a 15-fold increase is required toreach parity with research into heart disease, and a 30-fold increase to achieve paritywith cancer research. International coordination of research is needed to make thebest use of resources.Alzheimer’s Disease International calls on governments worldwide to developpolicies and plans for long-term care that anticipate and address social anddemographic trends and have an explicit focus on supporting family caregivers andensuring social protection of vulnerable people with dementia.Alzheimer’s Disease International supports HelpAge International’s call forgovernments to introduce universal non-contributory social pension schemesi.Alzheimer’s Disease International calls on governments to ensure that people withdementia are eligible to receive and do receive disability benefits, where suchschemes are in operation.

4

567

i http://www.helpage.org/Researchandpolicy/Socialprotection

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

8

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

introductionAlzheimer’s Disease International’s first WorldAlzheimer Report, released on 21 September 2009,provided up-to-date information on the prevalenceand impact of dementia from a global perspective(1).We estimated 35.6 million people living withAlzheimer’s disease and other dementias worldwidein 2010, increasing to 65.7 million by 2030 and 115.4million by 2050. We highlighted that nearly two-thirdsof all people with dementia lived in low and middleincome countries, this proportion being set to growbecause the sharpest increases in the numbers ofpeople with dementia will be in rapidly developingregions including Latin America, China and India.People with dementia, their families and friends areaffected on personal, emotional, financial and sociallevels. In the 2009 Report, we advocated for greaterawareness, more services, more funding for researchand, ideally, national dementia strategies in everycountry worldwide(1).In this World Alzheimer Report 2010, we focus onthe economic impact of dementia, again providingthe latest and most reliable estimates possible fromthe available evidence. Lack of awareness is a globalproblem, leading to common misunderstandingsabout Alzheimer’s disease and other forms ofdementia:• It is not a very common problem.• It is a normal part of ageing.• Nothing can be done.• Families will provide care – it is not an issue forhealth care systems or for governments.A proper understanding of the societal costs ofdementia, and how these impact upon families,health and social care services and governmentsmay help to correct these misapprehensions.Dementia is already significantly affecting everyhealth system in the world, and large amounts ofmoney are spent in caring for people with dementia.The aim of this Report is to highlight these economicimpacts so that governments, health and social caresystems are adequately prepared for the future, andcan seek ways to improve the lives of people withdementia and their caregivers now.Cost of illness (CoI) studies are descriptive. Theycan be used to quantify the total societal economicburden of a health condition, and can highlight therelative impact on different health and social caresectors. The distribution of costs between differentcountries and regions can also be estimated and

What is dementia?dementia is a syndrome that can be caused bya number of progressive illnesses that affectmemory, thinking, behaviour and the ability toperform everyday activities. alzheimer’s diseaseis the most common type of dementia. Othertypes include vascular dementia, dementia withLewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia. theboundaries between the types are not clear, anda mixture of more than one type is common.dementia mainly affects older people, althoughthere is a growing awareness of cases that startbefore the age of 65. after age 65, the likelihoodof developing dementia roughly doubles everyfive years. a detailed overview of dementia canbe found in the World alzheimer Report 2009,available from www.alz.co.uk/worldreport.

compared. CoI studies can also be used to describeor (with less certainty) predict changes in the extentor distribution of costs over time. While CoI studiesconducted on different health conditions can beused to compare burden, some caution is needed inusing these estimates to set priorities. The methodsused, particularly the types of costs included orexcluded, and the data used to estimate them maynot be strictly comparable across different healthconditions. Also, it has been argued that prioritizationfor investment in healthcare should be determinedby the relative incremental cost-effectiveness ofavailable interventions, rather than the burden of thedisease(2). Transparency is crucial with regard to theassumptions underlying any cost calculations andcomparisons.

Previous evidenceCost of illness studies for dementia have alreadybeen carried out for some regions and countries,mainly from high income parts of the world: forexample, Europe(3), United Kingdom(4), Sweden(5),Australia(6), the USA(7)and Canada(8). All thesereports have shown that Alzheimer’s and otherdementias are imposing huge societal economicburdens, both through direct (medical and socialcare) and indirect (unpaid caregiving by families andfriends) costs. Evidence is just beginning to emergeof the extent of the economic burden in middleincome countries(9-12).

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

9

Previously, three papers that highlight the globaleconomic burden have been published(13-15). Thesereports were, at the time of their publication, basedon the best available data for Alzheimer’s anddementia. Cost estimates were generated fromthe Dementia Worldwide Cost Database (DWCD) acontinuously updated resource maintained at theKarolinska Institutet Alzheimer’s Research Center,Stockholm, Sweden. The most recent of thesethree reports updated previous estimates of globalcosts from US$315 billion in 2005 to US$422 billionin 2009, an increase of 34% (18% in fixed prices)in just four years(15). US$312 billion per year (74%of the worldwide total) is contributed by countriesdesignated by the UN as more developed regionsand 110 billion (26% of the total) by less developedregions.One major limitation of these papers was that theDWCD contained very few data from low and middleincome countries and Eastern Europe. Therefore,the cost models relied largely on extrapolation ofeconomic conditions from higher to lower incomecountries, adjusted for Gross Domestic Product(GDP) per person. Also, it was not possible todistinguish between direct medical costs (withinthe health care sector) and direct social care costs(within the community and care home sector). Whilewe still have incomplete data, the evidence-base hasbeen strengthened in three respects:

1 The World Alzheimer Report 2009 provides themost comprehensive, detailed and up-to-datedata on the prevalence of dementia and thenumbers of people affected in different worldregions(1).2 The 10/66 Dementia Research Group’sstudies in Latin America, India and China haveprovided detailed information on informal carearrangements for people with dementia in thoseregions(1,16).3 Alzheimer’s Disease International has conducteda global survey of key informant opinionsregarding the extent of use of care homes indifferent world regions.In this Report, we are merging the best available dataand the most recent insights regarding the worldwidecost of Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Clearly,the societal cost of dementia is already enormous.With the forecast growth in disease prevalence(1),costs will rise further, particularly in low and middleincome countries. There is an urgent need to developcost-effective packages of medical and social carethat meet the needs of people with dementia andtheir caregivers across the course of the illness,and evidence-based prevention strategies. Onlyby investing now in research and cost-effectiveapproaches to care can future societal costs beanticipated and managed.

When a caregiver in a Kyoto grouphome embraced this residenteveryone around smiled. Althoughit is widely held that touching is notappropriate in Japanese culture,dr Yoshio miyake explained that‘in Japan, training courses forprofessional caregivers of peoplewith dementia take place in manyand different settings, where non-verbal communication with them,including touch or physical contact, isemphasised very often.’

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

10

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

references for introduction(1) Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report2009. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2009.(2) Williams A. Calculating the global burden of disease:time for a strategic reappraisal? Health Econ 1999February;8(1):1-8.(3) Wimo A, Jönsson L, Gustavsson A, McDaid D, Ersek K,Georges J. The economic impact of dementia in Europein 2008 – cost estimates from the Eurocode project.International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. In press 2010.(4) Knapp, M. and Prince M. Dementia UK – A report into theprevalence and cost of dementia prepared by the PersonalSocial Services Research Unit (PSSRU) at the LondonSchool of Economics and the Institute of Psychiatry atKing’s College London, for the Alzheimer’s Society. THEFULL REPORT. London: The Alzheimer’s Society; 2007.(5) Wimo, A., Johansson, L., and Jönsson, L.Demenssjukdomarnas samhällskostnader och antaletdementa i Sverige 2005 (The societal costs of dementiaand the number of demented in Sweden 2005) (inSwedish). Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2007. Report No.:2007-123-32.(6) Access Economics PTY Limited. The Dementia Epidemic:Economic Impact and positive solutions for Australia.Canberra: Access Economics PTY Limited; 2003.(7) US Alzheimer’s Association. 2010 Alzheimer’sdisease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2010March;6(2):158-94.(8) Alzheimer Society of Canada. Rising Tide: The Impact ofDementia on Canadian Society. A study commissioned bythe Alzheimer Society. Toronto, Ontario: Alzheimer Societyof Canada; 2010.(9) Wang H, Gao T, Wimo A, Yu X. Caregiver time and costof home care for Alzheimer’s disease: a clinic-basedobservational study in Beijing, China. Ageing Int. In press2010.(10) Wang G, Cheng Q, Zhang S, Bai L, Zeng J, Cui PJ et al.Economic impact of dementia in developing countries: anevaluation of Alzheimer-type dementia in Shanghai, China.J Alzheimers Dis 2008 September;15(1):109-15.(11) Allegri RF, Butman J, Arizaga RL, Machnicki G, SerranoC, Taragano FE et al. Economic impact of dementia indeveloping countries: an evaluation of costs of Alzheimer-type dementia in Argentina. Int Psychogeriatr 2007August;19(4):705-18.(12) Zencir M, Kuzu N, Beser NG, Ergin A, Catak B, SahinerT. Cost of Alzheimer’s disease in a developing countrysetting. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005 July;20(7):616-22.(13) Wimo A, Jönsson L, Winblad B. An estimate of theworldwide prevalence and direct costs of dementia in2003. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006;21(3):175-81.(14) Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. An estimate of the totalworldwide societal costs of dementia in 2005. Alzheimer’sand Dementia 2007;(3):81-91.(15) Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. The worldwide societalcosts of dementia: Estimates for 2009. Alzheimers Dement2010 March;6(2):98-103.(16) Prince M, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Albanese E, Arizaga R,Dewey M et al. The protocols for the 10/66 DementiaResearch Group population-based research programme.BMC Public Health 2007 July;7(1):165.

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

11

methods

World Alzheimer report 2010

Ten years ago, when Vijay was 52, he and Anu were told thathis increasing problems were due to early onset Alzheimer’s.They were not prepared for this news, but Anu managed thefamily life and become the sole earner. She pursued manyavenues to find what Vijay needed. Anu also sought out andbenefited from advice and assistance from others and shejoined a support group. She loves Vijay very much and benefitsfrom the assistance of mr deepak, a caregiver seen herefeeding Vijay. Anu now offers support and advice to othercaregivers through ArdSi and she willingly shares her storythrough the mass media to create better understanding andfight stigma.

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

12

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

methodsKey design issues for cost of illness studiesPrevalence versus incidenceapproachesCoI studies can either be prevalence or incidencebased. With the prevalence approach, the averagecosts are computed from all people in a populationfound to be affected at a specified time, with datacollected in a cross-sectional survey; peoplewith dementia will include some recently incidentcases, and others at varying stages in the diseasecourse(1,2). The rate at which the costs are observedto occur are then applied to a given period, typicallyone year, to compute the annual cost of illness,either as an average for each person with dementiaor, by multiplying by the total numbers affected, fora whole country or region. An alternative approachis to use longitudinal data (in which people withassumed newly diagnosed dementia (incident cases)have been followed up over time) to estimate thetypical costs of illness over the disease course,as annual costs and the future (discounted) costsduring the expected or calculated survival period.This approach can also be applied, although lessaccurately, to cross-sectional data. The choice ofapproach depends on the purpose of the study; ifthe idea is to estimate the aggregated economicsocietal burden of a condition for a country or region,the prevalence approach is suitable. If the aim is toillustrate the economic consequences of evolvingand cumulative care needs within individuals overtime, then the longitudinal approach is preferable.in Latin America, India and China demonstrate thatfor older people, at the population level, dementiais overwhelmingly the leading contributor amongchronic diseases to disability(3)and needs forcare(4). It was also demonstrated that for peoplewith dementia, it was the severity of dementia (asopposed to comorbid stroke, number of physicalimpairments or depression) that was the majorcontributor to hours of ADL care(5). However, the‘net’ costs of healthcare (costs that only depend ondementia as opposed to other comorbid conditions)are often difficult to estimate.

Which costs are to be included, andhow should they be computed?Care resources are generally scarce, so the use ofa resource in one way will result in a loss of benefitssomewhere else(6). Opportunity cost is the value ofa resource in its best alternative use(7), and this isthe approach recommended by most economists.Ideally, opportunity costs are based on marketprices. However, with respect to care, market pricesare not easy to identify and collect.Costs of illness are often sub-classified as directmedical costs, direct social care costs and indirectcosts. Direct cost calculations are typically based onthe value of resources used while indirect costs arebased on resources lost.Direct medical costsrefer to the medical caresystem, such as costs of hospital care, drugs andvisits to clinics.Direct social care costsarise from formal servicesprovided outside of the medical care system; forexample, community services such as home care,food supply (‘meals on wheels’) and transport, andresidential or nursing home care. Depending onhow care is organized, it may be difficult to make aclear distinction between social and medical care,and some ‘social care’ costs may still relate in partto medical care services, for example home nursingor nursing and medical care provided to care homeresidents.Indirect costsusually refer to production losseslinked to the person with the illness (arising fromimpaired productivity while working, sick leave, earlyretirement, or death). This type of indirect cost isgenerally less relevant in the context of dementia,

Top-down versus bottom-upapproachesIn a ‘top-down’ analysis, the total costs for a specificresource (for example, health care costs or socialsector costs) are distributed appropriately to differentconditions. Such studies are often based on datafrom local or national registers of service users. Withthe ‘bottom-up’ method, detailed cost data froma defined sub-population (often from a local area)are extrapolated to the ‘total’ dementia populationin a given country or region. One limitation of thisapproach is that not all costs linked to peoplewith dementia may be directly attributable to thatcondition. Comorbidity with other chronic diseases(such as stroke, heart disease or arthritis) is relativelycommon. However, recently published analysesfrom the 10/66 Dementia Research Group studies

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

13

where most of those affected are older peoplewho would in most cases be retired. The costs ofinformal care, arising from the unpaid inputs offamily caregivers, friends and others (see below) aremore often considered as indirect costs, but this is acomplicated issue(8,9).

costs, the corresponding figures are 11 out of 31studies.

The ideal scenario for computing costof illness … and the realityAn ideal worldwide CoI study has a societalviewpoint including comprehensive accountingof informal care, direct medical and social carecosts. Precise data on the prevalence of dementiaand resource utilization should be derived fromrepresentative population-based studies. Thesedata and the unit costs applied to the resourcesused should refer to the same index year. The samemethods should be used to collect these data acrossall countries.The reality is different:• Estimates of the size of the older population are ofvariable quality for different countries.• Data on dementia prevalence (the proportion ofthe older population affected) applied to the totalpopulation size to estimate the numbers of peoplewith dementia is not available for all countries(5).• Most studies of care arrangements andresource utilization for people with dementiause convenience rather than representativepopulation-based samples. Many of the estimatescome from small studies and, hence, may beimprecise. Many studies are not recent, andcare arrangements and patterns of healthcareutilization may change over time. For manycountries, there are few or no studies available,but informal care arrangements are likely to behighly dependent on culture and place.• Many basic indicators, for example demographicand macroeconomic data, are not yet providedfor 2010. However, projections can be found inonline databases.For all of the above reasons, it is necessary to relyon some degree of imputation (making an educatedand informed estimate when precise data are notavailable) and a range of assumptions. The CoIfigures that are presented here must be regarded asestimates rather that exact calculations.

The viewpointAny analysis of health economics has a viewpoint,even if this is not always made explicit. With asocietal viewpoint, which is recommended in mostcases, all relevant costs and outcomes should beincluded(10). However, the focus can be upon thecontributions of different payers; for example, localor national government, an insurance company,caregivers or patients (the latter referred to as ‘out ofpocket costs’). Above all, it is essential that there istransparency regarding the viewpoint adopted.

The representativeness of data sourceson resource utilizationStudies on resource utilization and costs associatedwith dementia typically use one of two mainapproaches for sampling: representative samplesfrom population-based studies or ‘convenience’samples of those receiving help from dementia careservices or Alzheimer associations. Studies aresometimes labelled as ‘population-based’ even ifthe recruitment process for the study is more or lessbased on clinical service contact. Naturally, peopleidentified through convenience sampling tend tohave more advanced and severe dementia, theircaregivers typically report higher levels of strain, andthe families are more likely to have accessed andto have used more health and community supportservices. If the aim is to characterise people affectedby the disease to the extent that they need and havesought formal care (‘users’ of care), then clinical-based study populations are sufficient. However,if the aim is to describe all people with the illness,then population-based studies including both thosewho use formal care and those that do not areneeded, otherwise average and total costs may beoverestimated. Since many reports, particularly thosewith a top-down design, include many sources, it isnot easy to judge whether the underlying sourcesin this Report are population based or clinical/userbased. Of the 42 studies that are used in this Reportfor estimating the costs of informal care, we regard11 studies as having population based designs(cohort studies, case control studies) or includingcontrols (people without dementia). For the direct

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

14

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

Methods used in our cost of illness analysesSummaryOur base case approach is a societal, prevalence-based gross CoI study in which country-specificannual per capita costs (direct medical and socialcare costs, and informal care) have been applied toestimated numbers of people with dementia in eachcountry (derived from the World Alzheimer Report2009(5)), and aggregated up to the level of WHOregions (see box), and World Bank country income-level groupings.• Most of the source papers (see below) providingevidence on direct medical and social care, andinformal care, have a bottom-up design. Mostused convenience sampling, although somedata were derived from more representativepopulation-based surveys.• The costs in the current Report (as well as theprevalence of dementia) reflect estimates for2010 and are expressed as US dollars. Costsestimates based on previous years are inflatedto 2010 using relevant country-specific data fromthe International Monetary Fund (IMF) or WorldEconomic Outlook (WEO)i, or if lacking fromthose sources, from the World Bankiior WorldFact Bookiii. Data on per capita Gross DomesticProduct (GDP) was obtained in a similar way.• To permit aggregation across countries, andcomparisons between countries and regions,costs are expressed as US dollars converted fromlocal currencies based on current exchange rates.An alternative approach based on purchasingpower parity (PPP) was used in the sensitivityanalysis (see page 28 for further details).To facilitate comparisons with previous studies, wealso present data according to current World Bankclassifications. Based on its Gross National Income(GNI) per capita, every economy is classified as lowincome, middle income (subdivided into lower middleand upper middle), or high income. Economies aredivided according to 2009 GNI per capita calculatedi World Economic Outlook Database [database on the Internet].IMF. 2010 [cited 2010-02-07]. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/01/weodata/weoselgr.aspxii Data Research [database on the Internet]. World Bank. 2010 [cited2010-06-07]. Available from: http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTDEC/0,,menuPK:476823~pagePK:64165236~piPK:64165141~theSitePK:469372,00.htmliii World Fact Book [database on the Internet]. 2010 [cited 2010-05-30]. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

CLassifiCatiOn Of COuntRiesin this Report, countries are classified accordingto the system that will be used in future GlobalBurden of disease reports from the World healthOrganization (WhO). a similar approach wasused in the World alzheimer Report 2009. theclassification is principally geographic, withseven sub-regions in asia (australasia, asiaPacific high income, asia Central, asia east, asiasouth, asia southeast and Oceania), three ineurope (europe Western, europe Central, europeeastern), six in the americas (north america,Caribbean, Latin america andean, Latin americaCentral, Latin america southern, Latin americatropical), and five in africa (north africa / middleeast, sub-saharan africa Central, sub-saharanafrica east, sub-saharan africa southern andsub-saharan africa West).

using the World Bank Atlas methodiv. The groupsare: low income, $995 or less; lower middle income,$996 – $3,945; upper middle income, $3,946 –$12,195; and high income, $12,196 or more.

The evidence on the prevalence ofdementia, and numbers affectedworldwideFor the World Alzheimer Report 2009(5), weconducted a systematic review of the globalprevalence of dementia, identifying 147 studies in21 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) world regions.Previous estimates of numbers of people withdementia worldwide, published inThe Lancetin2005(11), were based on expert consensus. A largenumber of new studies unearthed in the systematicreview, particularly from low and middle incomecountries, enabled us to conduct quantitative meta-analyses in 11 of the 21 GBD world regions. The newestimates showed that age standardised prevalence(for those aged 60 years and over) did not vary muchbetween world regions, with between 5% and 7%affected in most regions. The exceptions were thefour sub-Saharan African regions where between2% and 4% were affected. When compared with ourearlier ADI/Lancet consensus estimates, those foriv http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/world-bank-atlas-method

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

15

three regions were higher – western Europe (7.3% vs.5.9%), south Asia (5.7% vs. 3.4%) and Latin America(8.5% vs. 7.3%). Those for east Asia were lower(5.0% vs. 6.5%).Having applied these prevalence proportions tothe United Nations estimates of the total olderpopulation, we estimate 35.6 million people withdementia in 2010, with the numbers nearly doublingevery 20 years, to 65.7 million in 2030 and 115.4million in 2050. These figures represented a 10%increase on the figures published inThe Lancetin2005. 58% of all people with dementia worldwide livein low and middle income countries, rising to 71% by2050. Proportionate increases over the next twentyyears in the number of people with dementia willbe much steeper in low and middle compared with

high income countries. We forecast a 40% increasein numbers in Europe, 63% in North America, 77%in the southern Latin American cone and 89% inthe developed Asia Pacific countries. These figuresare to be compared with 117% growth in east Asia,107% in south Asia, 134-146% in the rest of LatinAmerica, and 125% in north Africa and the middleEast. Given that the new figures published in lastyear’s World Alzheimer Report are based on themost up to date and comprehensive review of theevidence base, we believe these to be the mostrobust and valid figures currently available.

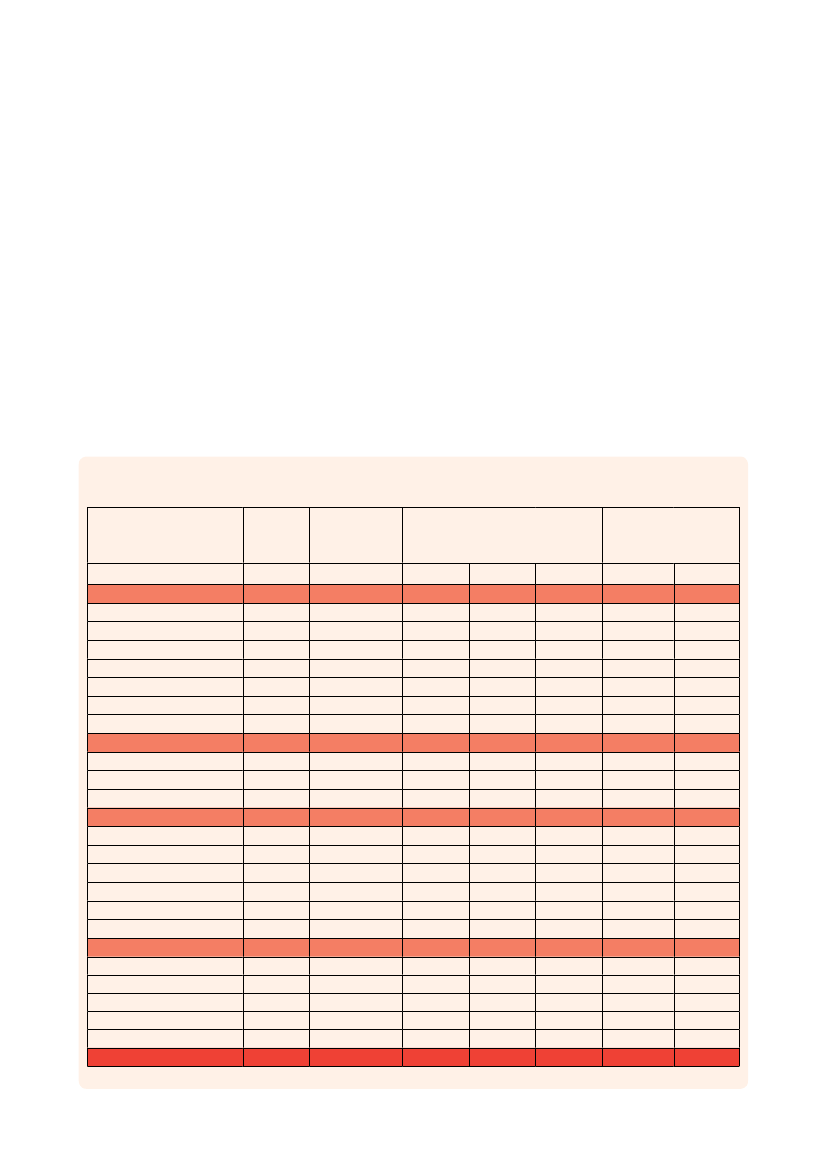

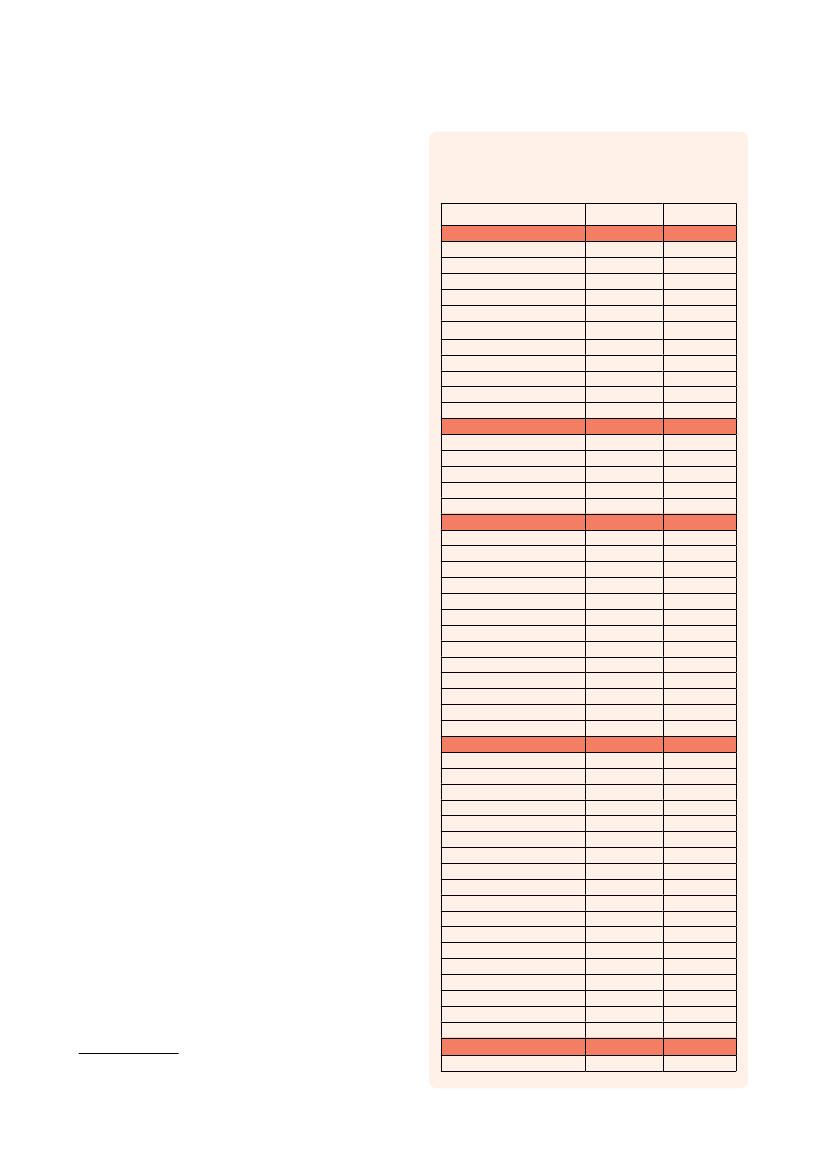

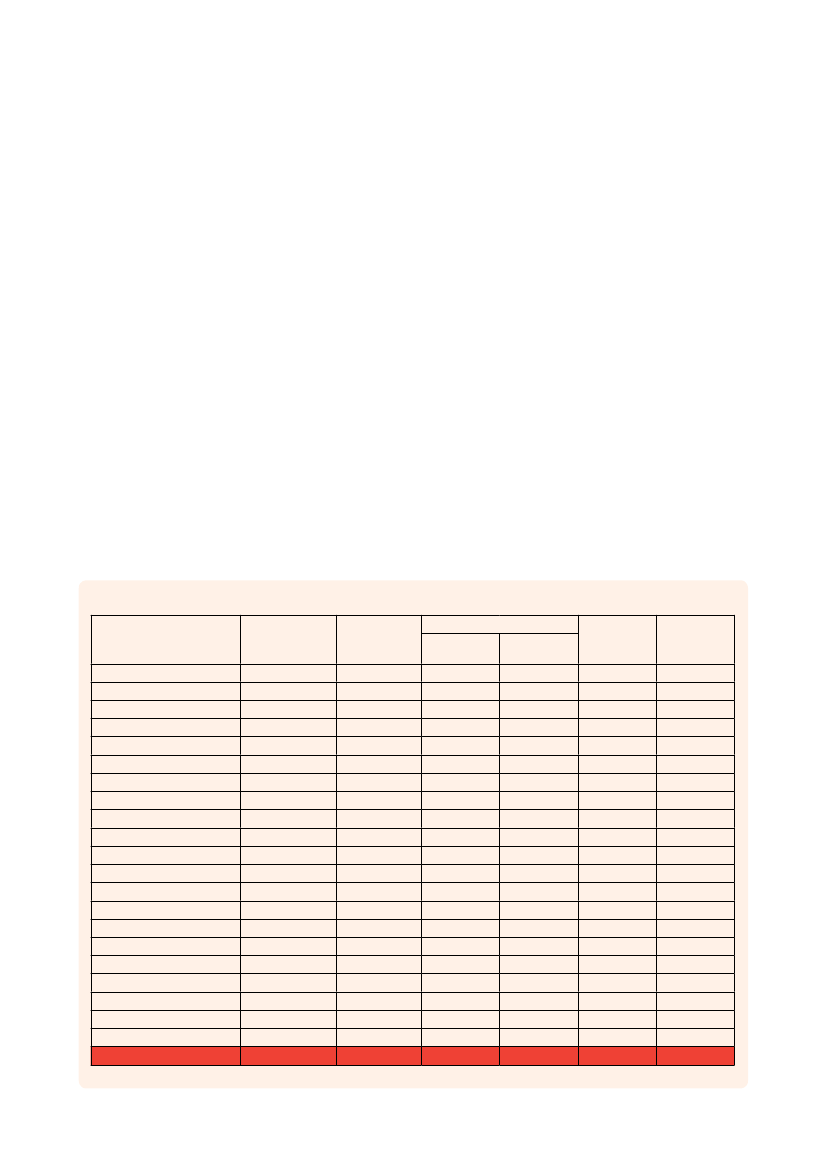

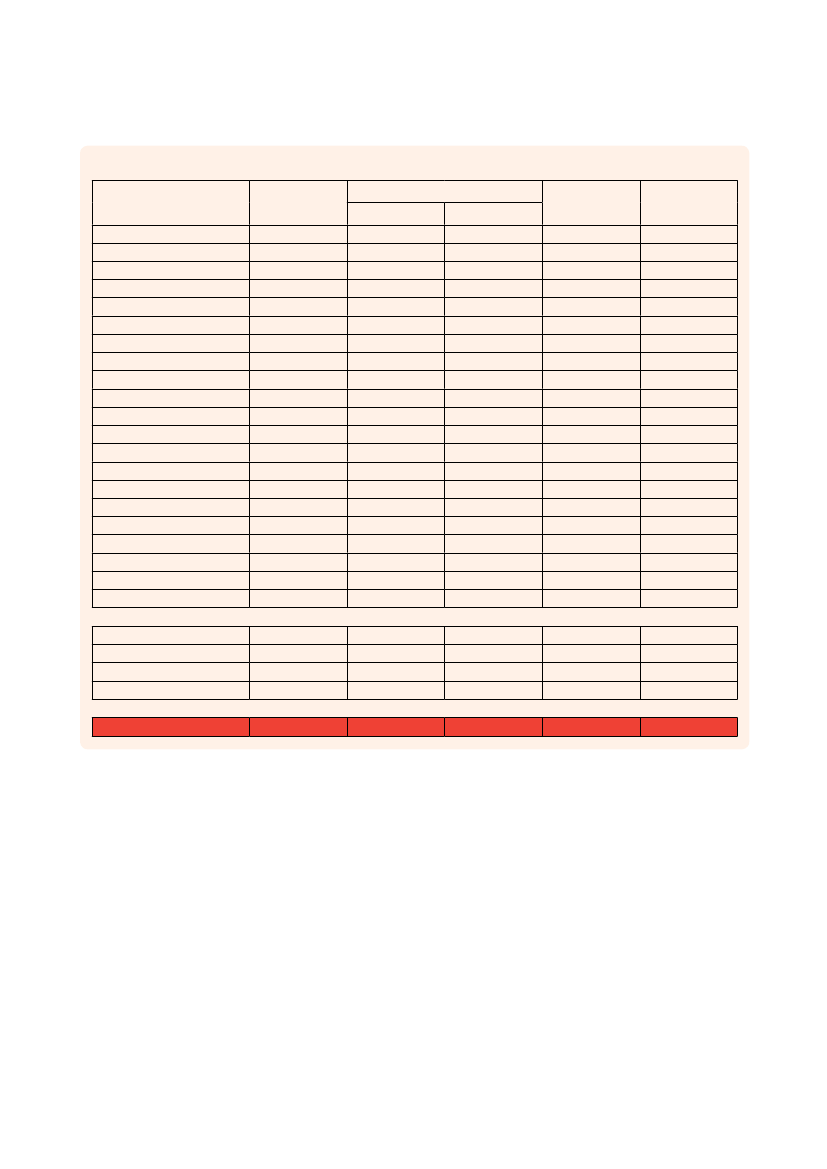

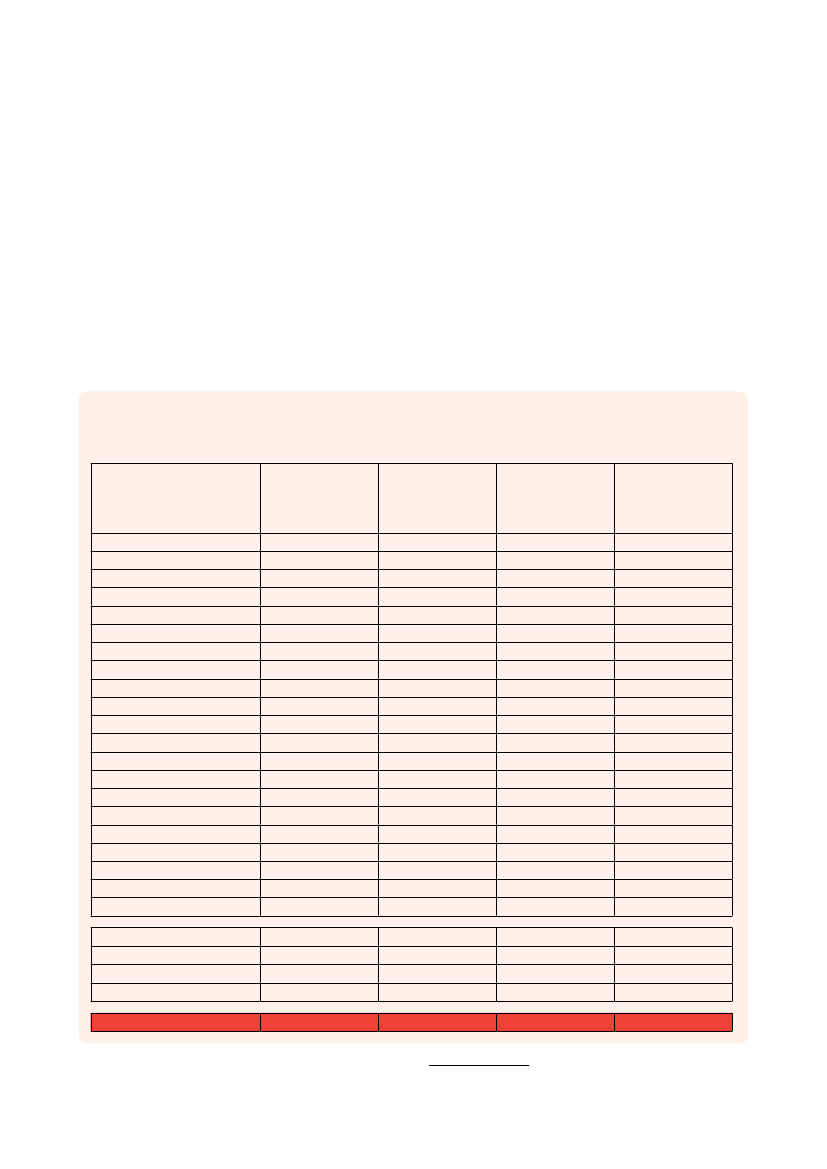

Table 1Total population over 60, crude estimated prevalence of dementia (2010), estimated number of people withdementia (2010, 2030 and 2050) and proportionate increases (2010-2030 and 2010-2050) by GBD world regionOver 60Crudepopulationestimated(millions) prevalence (%)2010ASIAAustralasiaAsia PacificOceaniaAsia, CentralAsia, EastAsia, SouthAsia, SoutheastEUROPEEurope, WesternEurope, CentralEurope, EastTHE AMERICASNorth AmericaCaribbeanLatin America, AndeanLatin America, CentralLatin America, SouthernLatin America, TropicalAFRICANorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa, CentralSub-Saharan Africa, EastSub-Saharan Africa, SouthernSub-Saharan Africa, WestWORLD406.554.8246.630.497.16171.61124.6151.22160.1897.2723.6139.30120.7463.675.064.5119.548.7419.2371.0731.113.9316.034.6615.33758.5420103.96.46.14.04.63.23.64.86.27.24.74.86.56.96.55.66.17.05.52.63.71.82.32.11.24.7Number of people with dementia(millions)201015.940.312.830.020.335.494.482.489.956.981.101.877.824.380.330.251.190.611.051.861.150.070.360.100.1835.56203033.040.535.360.040.5611.939.315.3013.9510.031.572.3614.787.130.620.592.791.082.583.922.590.120.690.170.3565.69205060.920.797.030.101.1922.5418.1211.1318.6513.442.103.1027.0811.011.041.296.371.835.548.746.190.241.380.200.72115.38Proportionateincreases (%)2010-2030 2010-20501077189100701171081144044432689638813613477146111125719270948528215714840026131130434987939166246151215416435200428370438243283100300225

GBD Region

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

16

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

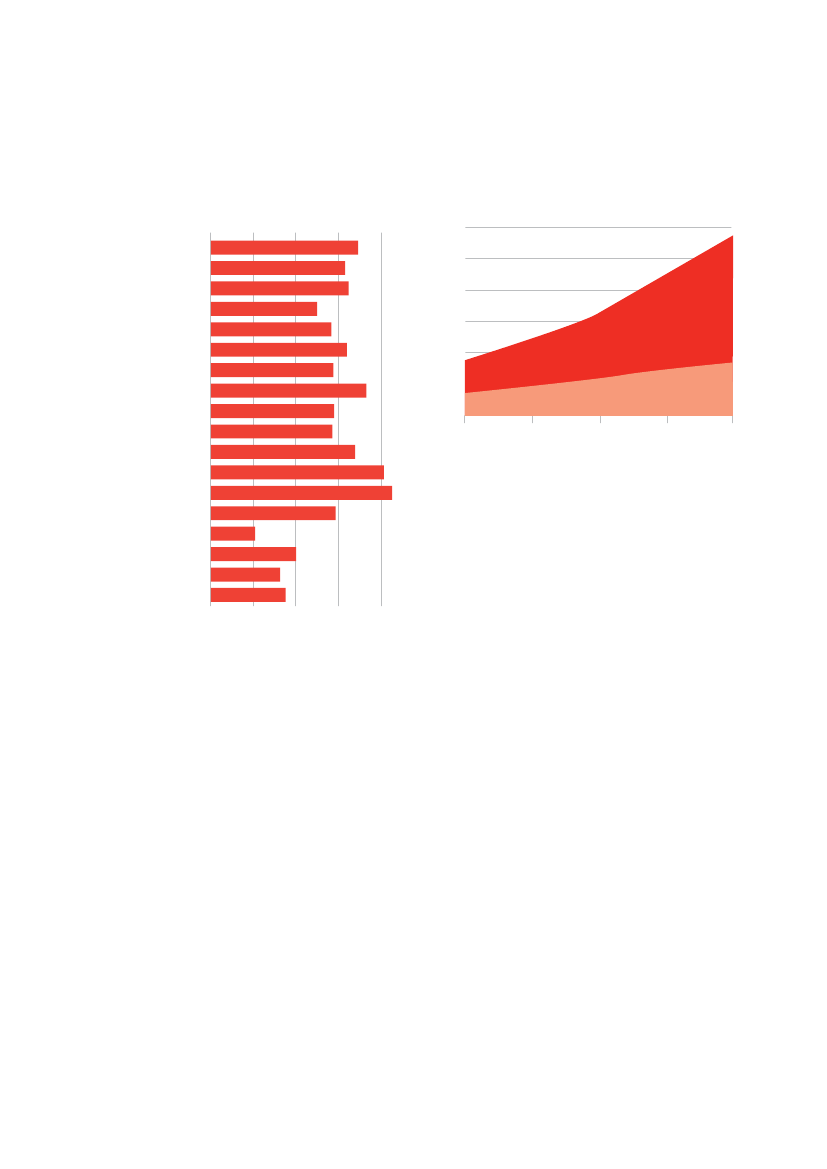

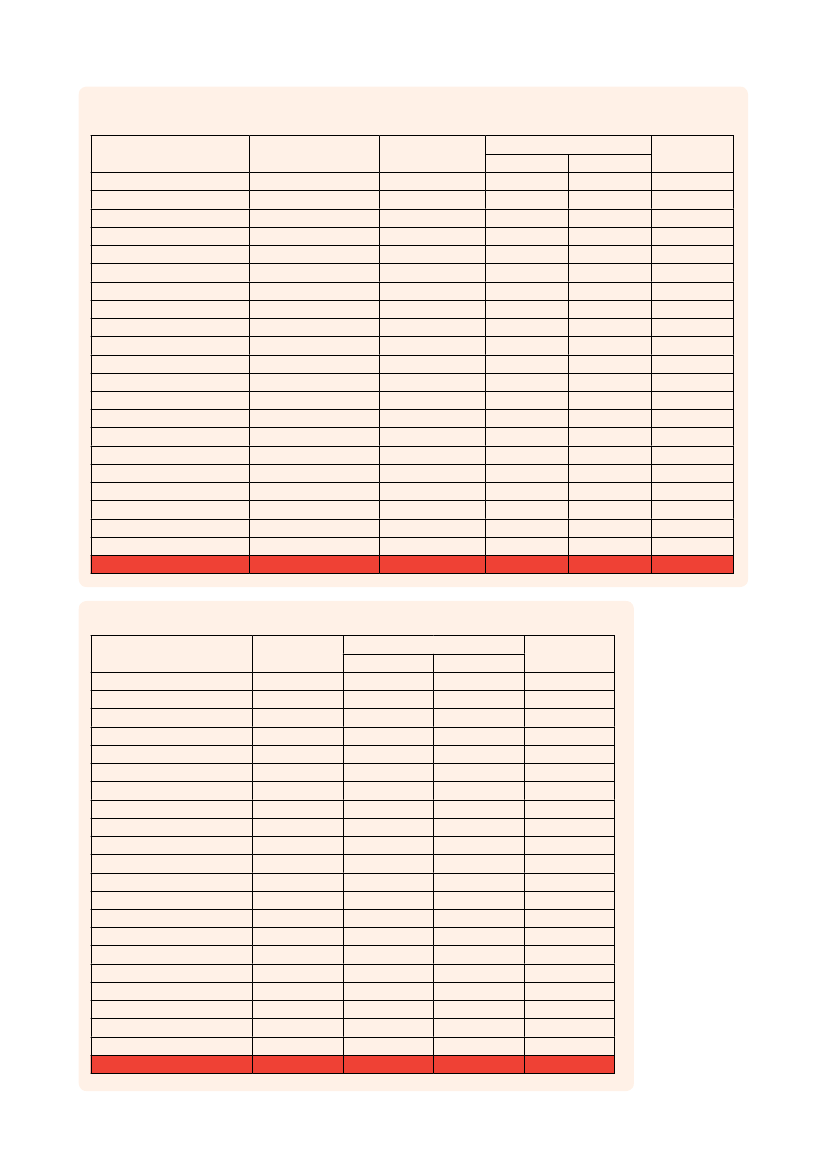

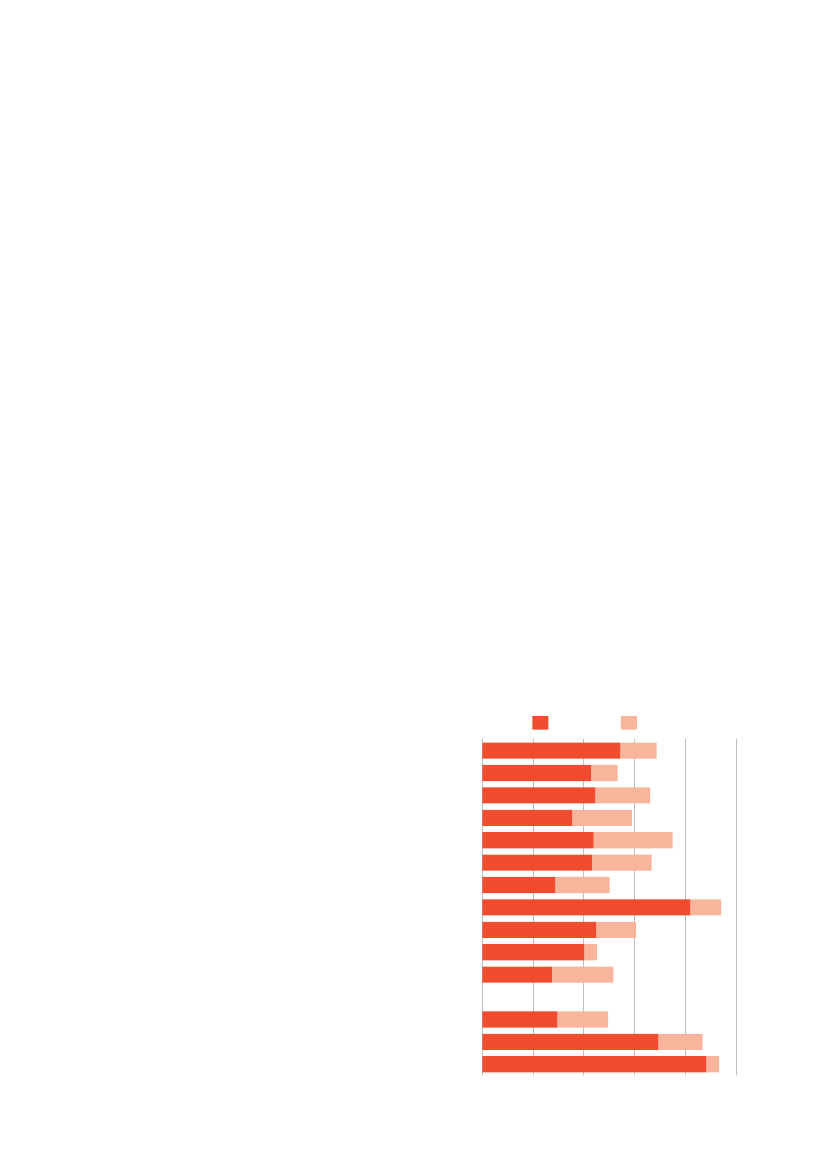

Figure 2Estimated prevalence of dementia for those aged60 and over, standardised to Western Europe population, byGBD region (%)Standardised prevalence %0AustralasiaAsia PacificOceaniaAsia EAsia SAsia SEAsia CentEurope WEurope CentEurope EAmerica NCaribbeanLatin AmericaN Africa/ Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa WSub-Saharan Africa ESub-Saharan Africa CentSub-Saharan Africa S2468

Figure 3The growth in numbers of people with dementia inhigh income countries and low and middle income countriesNumbers of people with dementia (millions)120100806040200201020202030Year20402050low and middleincome countries

high income countries

The evidence on the utilization ofmedical and social care, and informalcareseaRCh stRateGyFor the previous Cost of Illness (CoI) estimates for2005 and 2009(12,13), a comprehensive literaturesearch was done. The resulting database has beenupdated and refined for the present Report. Forthe cost data, we focused on papers and reportsno older than 2000, although older studies wereconsidered for countries where there was no newerdata. Older studies were also accepted regardingthe amount of informal care. The key criterion wasthat direct and indirect costs as well as amountsof informal care could be identified. The searchwas done in PubMed/Medline, Ingenta, CochraneLibrary, NHSEED/HTA, HEED, EMBASE, Currentcontents, PsycINFO, ERIC, Societal servicesabstracts and Sociological abstracts. The searchterms (MESH/Subheadings when appropriate) weredementia/Alzheimer’s disease/Alzheimer diseasecombined with cost and/or economic and informalcare. Two recent systematic reviews comprising

published papers between 1969 and 2008 with atleast an abstract in English were also included(14,15).Secondary papers from reference lists wereconsidered for inclusion. Another source was variousreports that were not found in scientific databases,such as reports from governmental authorities andAlzheimer associations.imPutatiOn aPPROaChesOur general aim was to generate evidence-basedestimates of resource utilization for each country.Where more than one estimate was available for agiven country we selected the one that we regardedto be the most appropriate study. Where no estimatewas available we first used estimates from othersimilar countries within the same region, or, failingthat, adjacent regions. For particular resources, forcertain regions, more complex procedures wereused and these are described in the relevant section.diReCt COstsData on direct costs were available from 21 countriesrepresenting 49% of the worldwide dementiapopulation (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Canada,

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

17

China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary,Ireland, Israel, Italy, Korea, New Zealand, Norway,Spain, Sweden, Turkey, UK and USA). For manycountries, there were no available data on directcosts. For each country, we sought to estimateboth total direct costs and the distribution betweendirect medical and social care costs. Regionalimputation from local similar countries was possiblefor a further 74 countries representing 27% of theworldwide dementia population, mainly in Europebut also in Latin America. For the remaining 24%of the dementia population, in 97 countries mainlyin Africa and Asia, no data was available even fromneighbouring countries. From macro-economicresearch it is known that there is a strong correlationat country-level between per capita expenditure onhealth care and per capita Gross Domestic Product(GDP). This relationship can be used to impute directcare costs by assuming that these costs per personwith dementia as a proportion of GDP per capitafor the countries and regions where imputationis necessary are similar to the proportions in thecountries for which cost data are available(12). Ina simple linear regression model, the relationshipbetween the costs per person with dementia andyear and the GDP per person and year was tested.Based on this model (derived from 31 papers(16-46)),for each US$1 increase in annual per capita GDP theannual cost per person with dementia increased byUS$0.37 (p<0.001, r2=0.43, 95% confidence interval0.22-0.51). The regression approach did not workwell for the estimation of the distribution betweendirect medical and direct non medical costs, and sothe percentage distribution observed in one country(China) was used to specify the likely distribution forall countries within the Asian and African regions forwhich these data were not directly available.infORmaL CaReFamily members, friends and others who take oncaring roles are likely to experience role strain,negative impacts on their physical and mentalhealth, and their quality of life, and consequentchanges to their social network(47-51). Their inputshave an important influence on the societal costs ofdementia, since they are producers of an extensiveamount of unpaid informal care(52-57). However,translating this contribution into economic costs isnot straightforward.

• Assistance with basic activities of daily living(ADL), such as eating, dressing, bathing, toileting,grooming, and getting around – sometimesreferred to as personal care.• Assistance with instrumental activities of dailyliving (IADL), such as shopping, preparing food,using transport, and managing personal finances.• Supervision to manage behavioural symptoms orto prevent dangerous events(53).Personal care is relatively easy to assess andinterpret across countries and cultures, but thenature and relative importance of IADLs are likelyto be much more culture-specific. Furthermore, theperson with dementia and the caregiver may eachcontribute to the performance of these activities, forexample shopping (referred to as ‘joint production’).Second, costing informal care is also complicatedand controversial(8,58-64). Two methods are frequentlyused, the ‘opportunity cost’ and the ‘replacementcost’ approaches. Informal care is unpaid. Insome high income countries there are systems tocompensate or remunerate family caregivers, but theamounts concerned are relatively small. However,whether a caregiver is paid or unpaid does not affectthe economic valuation of their inputs. Payments andother transfers have an impact on the distribution ofthe economic burden but not on the total societalcost. To calculate the opportunity cost it is firstnecessary to identify the possible alternative use ofthe caregiver’s time. If the alternative is working onthe labour market – as may be the case, especiallyfor younger caregivers who often give up or cut backon work to provide care – then the cost for informalcare should be valued according to the productionloss due to absence from work. More challengingis the costing of caregiver time for retired people(as is often the case with spouses of people withdementia). There is no obvious answer to how thisshould be calculated, since there are no obviousmarket prices(62). ‘Willingness to pay’ approachesmay be an option(65, 66). The replacement costapproach assumes that the informal caregiver’sinputs should be calculated according to the cost ofreplacing them with a professional caregiver.Third, some people with dementia live in carehomes, where professional staff provide mostcare, and informal care is less relevant. These maybe residential care homes (providing low intensitycare, with few trained staff), or nursing homes(providing high intensity care with more trained

First, quantifying caregiver time is problematic. Theinputs most commonly assessed are:

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

18

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

nursing and medical staff), or specialist facilitiesfor dementia care. There are few reliable estimatesof the proportion of people with dementia living inthese facilities, as opposed to their own homes inthe community. Estimates for the United Kingdomvary between 35 and 50%(36,67,68), while for Canadathe estimate was 45-50%(16,69). In settings in highincome countries, people with dementia residingin care homes contribute a substantially higheramount to the total cost of illness than in low andmiddle income countries. In low and middle incomecountries, anecdotal information suggests thatfew such facilities exist, and that the large majorityof people with dementia are cared for, informally,in the community. In order to estimate total costsaccurately and to apportion costs appropriatelywithin sectors, it is crucial to estimate the relativeproportions of people with dementia living at homeor in a long-term residential or nursing home carefacility. In most countries, there is no publisheddata on this. So, for the purpose of this Report, ADIcommissioned a worldwide questionnaire surveyof key informants (including Alzheimer associationstaff, ADI’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Panelmembers and 10/66 Dementia Research Groupprincipal investigators) to provide more informationon this issue. Informants were asked, in their opinion,what proportion of people with dementia residedin care homes, in both city areas and rural areas.The questions had fixed 10% point range responseintervals (and one 100% option). The range ofestimates is wide from some countries, since severalrespondents had answered. Extreme outliers (8respondents out of 86) were excluded. Two trendsare obvious: the proportion of people with dementiaresiding at home is higher in low income countriesand higher in rural areas (table 2). In high incomecountries, the mean proportion living at home is66% (95% confidence interval 64%-68%), while inlow and middle income countries 94% of peoplewith dementia live at home (95% confidence interval92%-96%).For the estimates in the cost model, we used thecentral values (after excluding outliers). Imputationwas used for nearby countries with similar carestructures. From a UN demographic database wegathered information on the rural-urban populationdistributions for all relevant countriesi, whichcombined with the results from the ADI questionnairei World Urbanization Prospects The 2009 Revision [database onthe Internet]. UN. 2009 [cited 2010-05-25]. Available from: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/index.htm

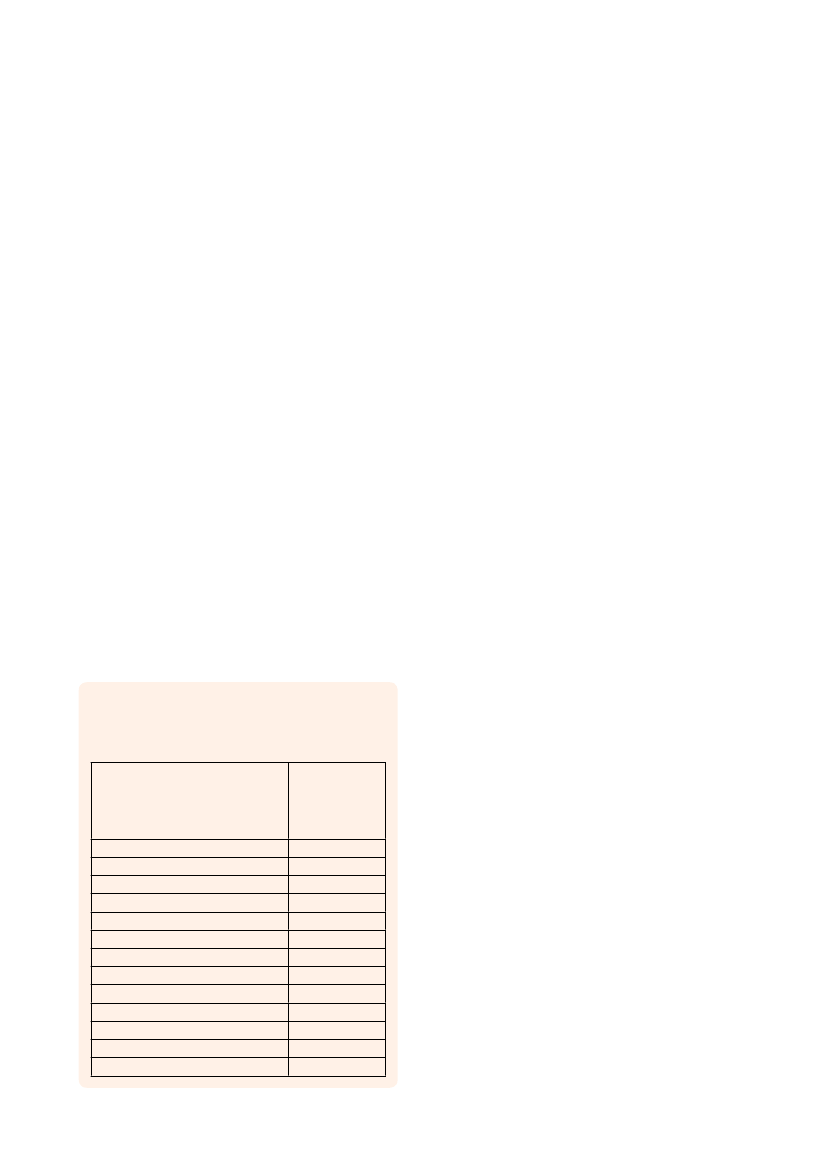

Table 2Estimated proportion of people with dementiathat are living at home (%).Source: ADI survey (unpublished)CountryASIAArmeniaChinaIndiaJapanJordanPakistanNepalSingaporeSri LankaThailandTurkeyAFRICAEgyptMauritiusNigeriaSouth AfricaZimbabweAMERICASArgentinaArubaBahamasBoliviaBrazilDominican RepublicHondurasJamaicaMexicoPeruPuerto RicoVenezuelaUnited StatesEUROPEBelgiumCroatiaCyprusGermanyGreeceIrelandIsraelItalyMacedoniaFormer Yugoslav Rep. ofNetherlandsPolandRomaniaSerbiaSlovakia (Slovak Republic)SloveniaSwedenSwitzerlandUnited KingdomAUSTRALASIAAustraliaUrban areas Rural areas50-59%70-99%90-94%60-79%95-99%100%100%90-99%70-99%80-89%70-79%100%80-89%80-89%90-94%70-79%50-89%80-89%95-99%70-94%70-94%90-94%95-99%70-79%80-99%90-94%70-79%90-94%70-79%50-59%80-89%70-79%50-59%80-89%60-69%80-89%50-59%50-59%60-69%80-89%80-89%95-99%80-89%40-49%50-59%60-69%50-94%50-69%50-59%80-94%95-99%70-79%95-99%100%100%100%95-100%95-99%90-94%100%80-89%90-94%100%95-99%70-94%80-89%95-99%90-99%90-99%95-99%100%70-79%95-100%95-99%70-89%95-99%80-89%70-79%95-99%95-99%60-69%95-99%60-69%80-89%50-59%90-94%70-79%95-99%100%100%90-94%60-69%50-59%50-59%50-94%50-69%

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

19

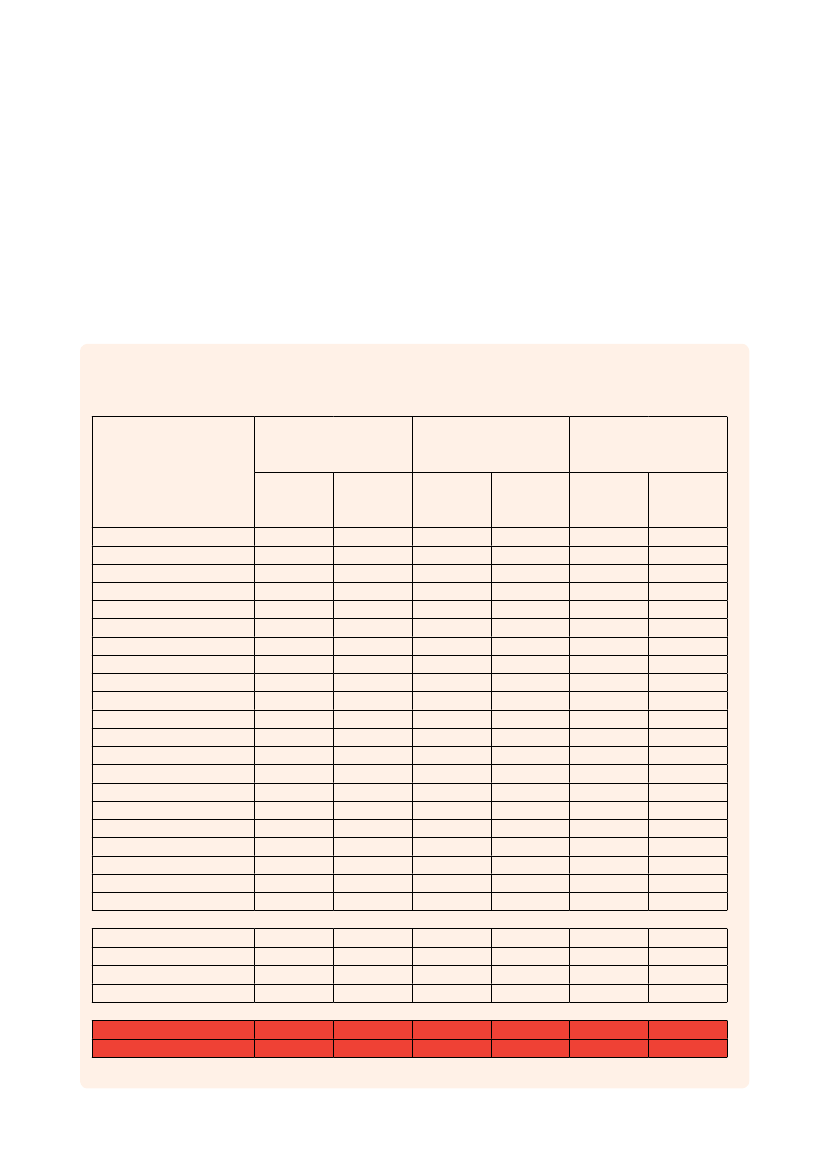

gave a weighted proportion of people with dementialiving at home in the community, and hence likely tobe in receipt of informal care.Based on our review of the international literature, weidentified:• 10 appropriate studies where time spent assistingwith basic ADLs was quantified, covering 25countries representing 63% of the worldwidedementia population(5,32,33,37,38,56,70-73).• 42 papers or reports with time spent assistingwith basic ADLs and IADLs combined, covering30 countries representing 73% of the worldwidedementia population(5,21,30-33,35-38,41,43,44,46,52,54-57,70-92).• 13 papers or reports with estimates of timespent in supervision, covering 25 countriesrepresenting 63% of the worldwide dementiapopulation(5,30,31,33,38,52,56,71-73,79,88,89).Regional imputation was carried out for theremaining countries according to the procedurespreviously described (page 16). However, for allTable 3WHO-region specific figures of informal careinputs (hours per day)WHO region(red=imputed)AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan Africa SouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestAll

African regions, global average figures were used.Although the degree of imputation required wasquite substantial, this still represents a considerableadvance on the evidence base available for previousreports, since to a large extent we were able touse region-specific figures. The detailed estimatesfrom six Latin American countries, India and China,where research is being done by the 10/66 group,provided important data from low and middle incomecountries for this review, which was not available forprevious worldwide cost estimates.The WHO-region specific estimates for informalcare inputs are summarised in table 3. Despite theproblems, noted above, in quantifying caregivingtime spent assisting with IADL, we used thecombined ADL figures (combining basic ADL andIADL care inputs) as the base option for calculatingthe costs of informal care. Our justification wasthat support for IADLs is an important part ofthe caregiver’s life with a person with dementia,and that there are many more papers describingcombined ADLs than those covering only basic ADLcare inputs. Cost estimates generated only fromassistance with basic ADLs (personal care), andfrom all categories of informal care (assistance withbasic ADLs, IADLs and supervision) are part of thesensitivity analysis.The base option for costing informal care for thisReport uses the opportunity cost approach, valuinginformal care by the average wage for each country .Since not all average wage figures were expressedas an hourly rate, a division factor of 8 was used fordaily wage figures, 40 for weekly and 172 for monthlywage figures. Average wage figures were availablefor 131 countries, covering 96% of people withdementia worldwide. This method may, arguably,overestimate costs arising from the contributions ofthose who would not normally form part of the labourforce, for example retired spouses. However, from aglobal viewpoint, it is necessary to use sources thatare globally available, in this case the InternationalLabour Organisation (ILO) / Laborsta database. Inthis database, income data is available for differentperiods (for example, International StandardIndustrial Classification of all Economic Activities(ISIC) rev 2, rev 3) and for different sectors (suchas agriculture, manufacturing) as well as a ‘Total’estimate representing all sectors economic activity.Not all of these data were available for all countries. Ifi

Basic Combined Super-ADLADLvision2.02.03.61.23.61.31.31.12.12.12.13.02.91.92.92.91.12.02.02.02.02.03.33.64.62.74.72.72.73.54.44.44.03.02.91.94.42.91.43.63.63.63.63.62.62.61.23.31.22.62.63.33.43.42.82.12.63.12.62.62.62.62.62.62.62.6

i Laborsta Internet [database on the Internet]. ILO. 2010 [cited2010-02-23]. Available from: http://laborsta.ilo.org/STP

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

20

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

Table 4

Comparisons between different average wage alternativesISIC categoriesISIC rev 2: 2-9ISIC rev 3: C-QManufacturing (ISIC rev 2 and 3)

1999-2008Total (ISIC rev 2 and 3)Total (ISIC rev 2 and 3)Total (ISIC rev 2 and 3)

Number ofcomparisons17250383

Meanratio1.081.031.00

95% CIfor ratio1.03-1.121.02-1.030.98-1.02

a ‘Total’ estimate was not provided, we used differentsummaries representing many, but not all sectors(including sectors 2-9 with ISIC rev 2 and sectorsC-Q for ISIC rev 3), and if those were lacking, weused data for the manufacturing sector (sector 3 withISIC rev 2 and sector D with ISIC rev 3). To assessthe possible effect of using different data sourcesto estimate average wage, we estimated the ratiobetween earnings per month calculated from ‘Total’(all sectors), most sectors (C-Q from ISIC rev 3 or2-9 from ISIC rev 2) or manufacturing only (both ISICrev 2 and 3), for countries where each of these data

sources was available (table 4). Our conclusion is thatadjustments are not necessary.For some countries, particularly in Africa, there wereno figures about hourly wage available at all. Forthese countries, imputation was done, based oncountries where hourly wage figures were availablefrom the same WHO region. The imputation wasadjusted according to the GDP per person fromcountries in the same WHO region with as similarGDP figures per person as possible. This imputationis examined in the sensitivity analysis.

Table 5

Sex of caregivers, by WHO regionProportion (%)of caregiversthat are female72%81%55%71%55%77%86%66%74%82%71%80%85%82%74%91%71%81%81%81%81%67%

Table 6Sex differences in average wage in differentWHO regionsWHO region(red=imputed)AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan AfricaSouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestAll

WHO region(red=imputed)AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan Africa SouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestAll

Menvs All1.081.111.081.241.201.041.081.081.071.171.031.031.101.101.101.081.021.041.041.111.041.06

Women Womenvs All vs Men0.890.670.840.710.800.840.840.890.930.850.890.970.820.820.820.880.900.990.990.830.990.850.830.600.780.580.670.810.780.830.870.720.870.940.740.740.740.820.880.960.960.750.960.80

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

21

Since, in many countries, average wages forwomen are lower than those for men, we neededto determine the cost of care by male and femalecaregivers separately. In our review of the literatureregarding care arrangements for people withdementia (25 studies representing countries with78% of the global dementia population) we foundthat a woman was identified as the main informalcaregiver for 55-91% of people with dementia(table 5)(5,21,26,37,38,42,45,72,84,92-107).We looked at the ILO databaseito assess themagnitude of average wage differences betweenmen and women (table 6), which, when applied to theproportion of caregivers of each sex allowed us tocalculate an appropriately weighted hourly cost foreach WHO region. For some regions, imputation wasused with data from the nearby WHO region.We have also included an option in the sensitivityanalysis, varying the opportunity costs of caregiverinputs where care is provided by spouses, since theymight be assumed often to be retired or otherwisenot usually economically active. For these sensitivityanalyses, on an ad hoc basis, we valued these inputsat 25% and 50% of the average wage, applied toother non-spouse caregivers. From the caregiverliterature(5,21,26,30,31,37,38,42,45,49,55,57,72,84,89,92,93,96-102,108-112)spouses are the main caregivers for around40% of people with dementia, but with importantregional differences as seen in table 7.

Table 7Relation of informal caregiver to person withdementia by WHO regionProportion (%) ofmain caregivers thatare spouses of theperson with dementia43%36%41%38%40%24%8%48%36%36%52%18%15%8%46%54%38%41%41%41%41%41%

WHO region(red=imputed)AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan Africa SouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestAll

Sensitivity analysisSince CoI studies depend on a set of sources andassumptions, there are always uncertainties in CoIestimates. To consider the impact of the significantuncertain background factors, we have conducteda comprehensive set of sensitivity analyses in whichwe use different source data or vary assumptionsto see how this would have affected the results.However, another component of the sensitivityanalysis is to highlight the fact that there aredifferent views of what should be included in a CoIestimate and how to do it, for example regardinginformal care. There are several presentations in thesensitivity analysis to facilitate comparisons withother studies and approaches.

i Laborsta Internet [database on the Internet]. ILO. 2010 [cited2010-02-23]. Available from: http://laborsta.ilo.org/STP

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

22

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

References for Methods are combined withreferences for Results, page 34

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

23

World Alzheimer report 2010

Results

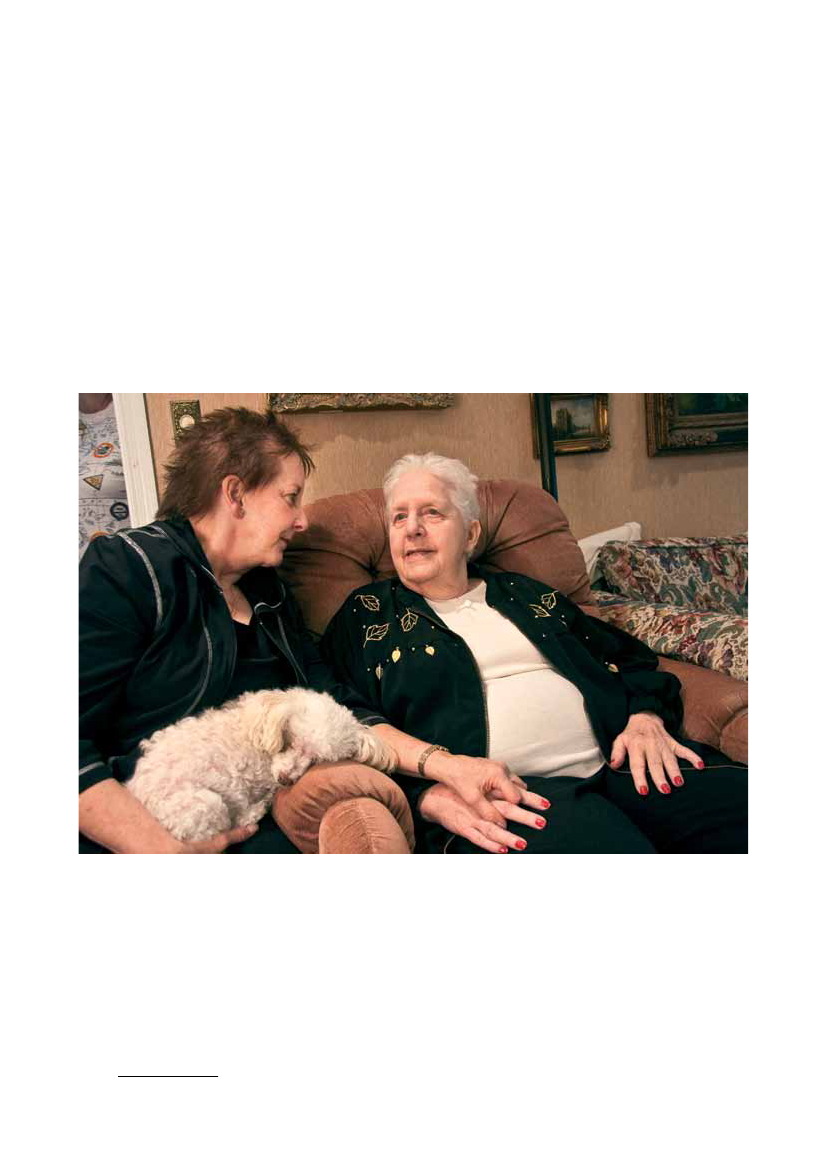

At the Alzheimer’s Cote d’Azur Christmas party, Amelia andher son pierre listened to the singers with interest. pierre is notmarried and lives next door to his mother, who he adores.

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

24

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

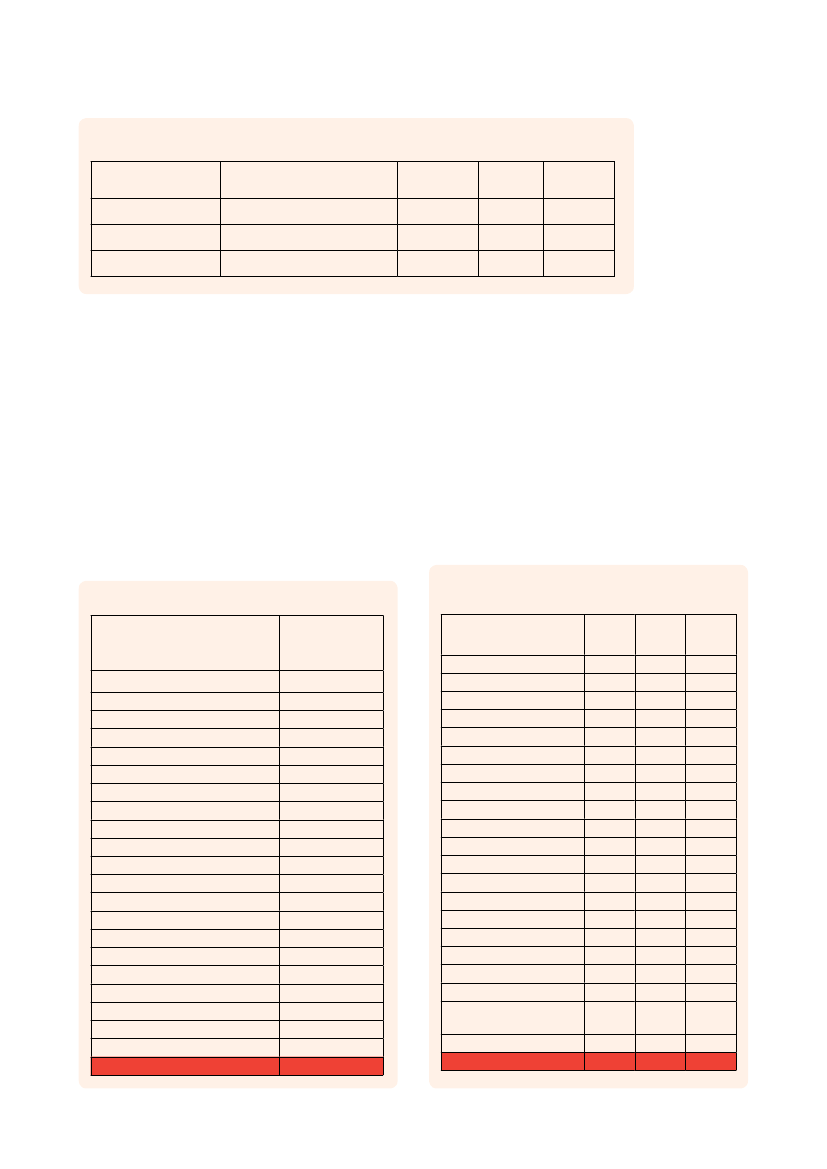

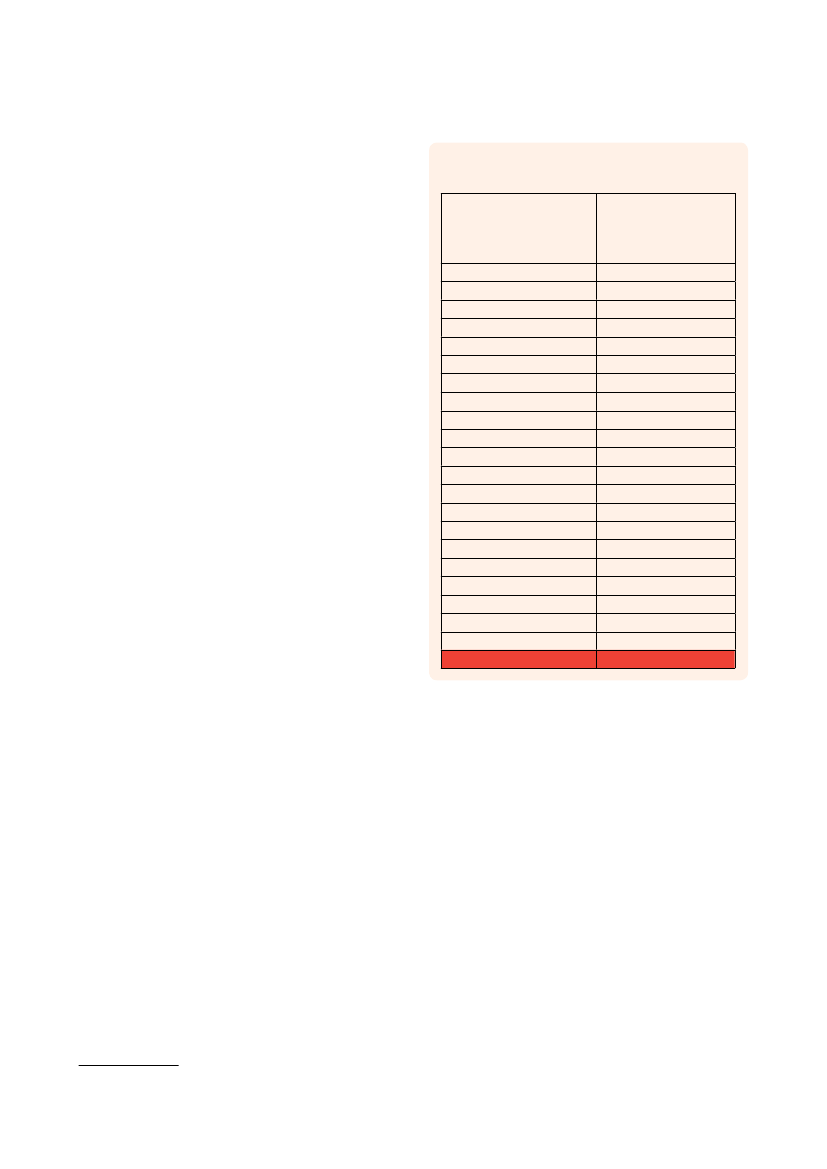

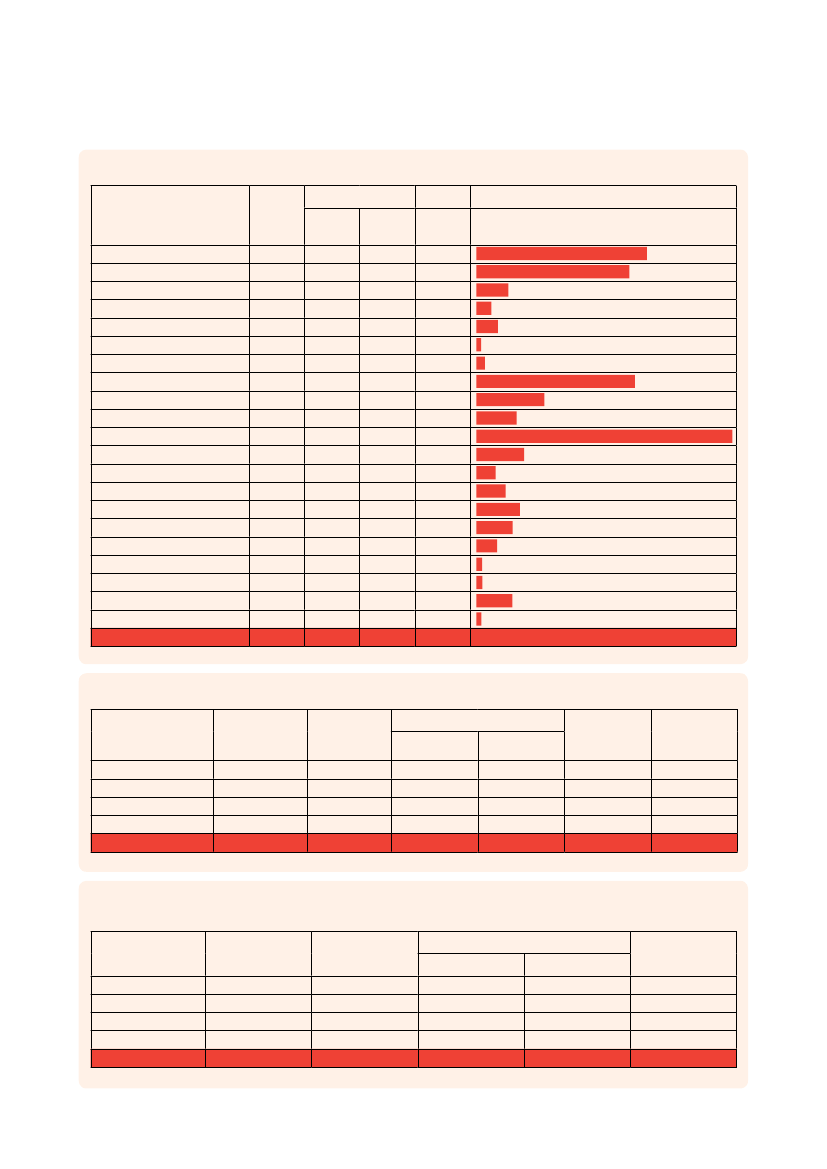

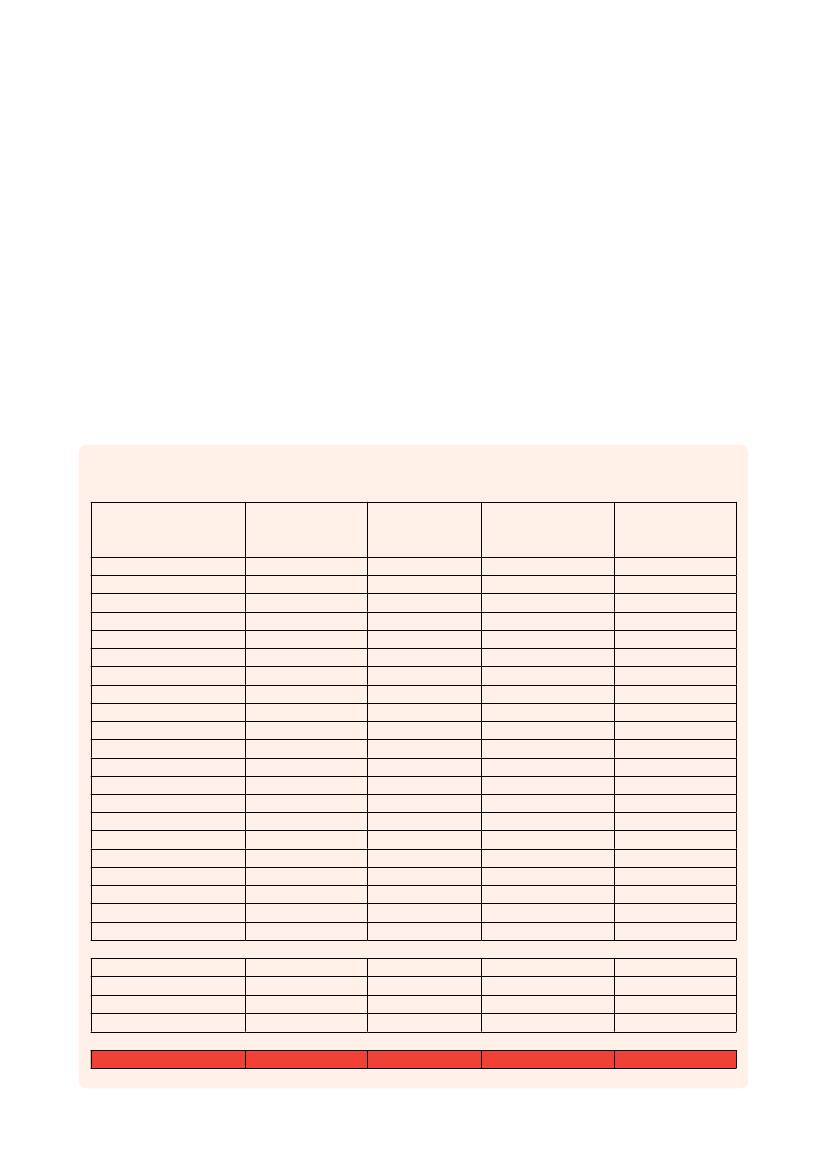

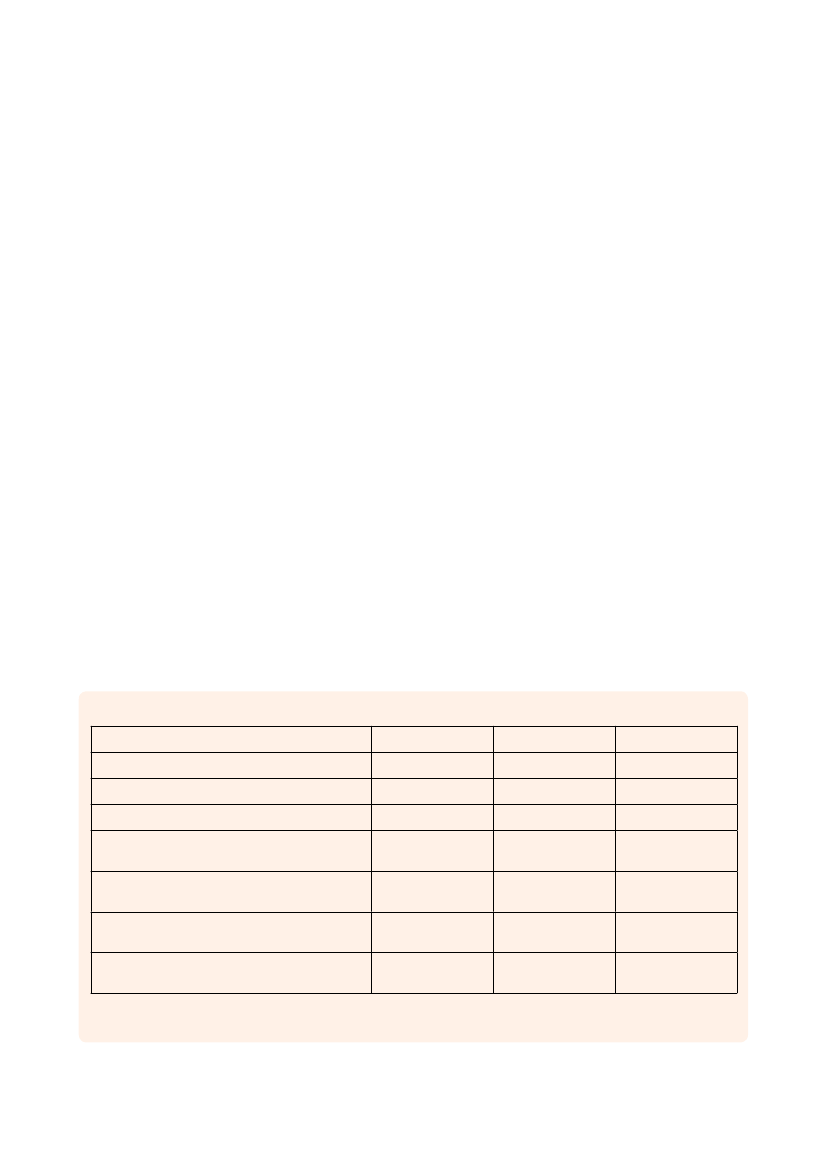

resultsResults of base optionThe total estimated worldwide costs of dementiaare US$604 billion in 2010 (table 8). About 70%of the costs occur in Western Europe and NorthAmerica (table 9). Costs of informal care and thedirect costs of social care generally contribute similarproportions of total costs, while the direct medicalcosts are much lower (table 10). However, in low andmiddle income countries direct social care costs arenegligible and informal care costs predominate. Theresults of the base option are seen in tables 8–15.The cost per person with dementia is highest inNorth America (US$48,605 – table 11) and lowestin the South Asia region (US$903 – comprisingcountries such as India and Bangladesh) andWestern Sub Saharan Africa (US$969). The costper person with dementia is therefore more than 50times higher in the richest world regions than in thepoorest.The differences between developed and developingcountries are even more obvious when the WorldBank classification is applied (tables 12-15). Lowincome countries, where 14% of people withdementia reside, contribute less than 1% of the totalcosts (table 13).The costs of informal care constitute the majority ofcosts in the low income and lower middle-incomecountries while the direct costs of social care have amuch larger role in the high income countries (table14), probably due to the costs of long term residentialand nursing home care in these countries.The total cost per person with dementia is 38 timeshigher in high income countries than in low incomecountries, and the direct costs of social care are 120times higher (table 15).

Table 8

Aggregated costs in each WHO region (billions US$)Number ofpeople withdementia311,3272,826,38816,553330,1255,494,3874,475,3242,482,0766,975,5401,100,7591,869,2424,383,057327,825254,9251,185,559614,5231,054,5601,145,63367,775360,602100,733181,80335,558,717Informal care(all ADLs)4.3034.600.070.4315.242.311.7787.058.597.9678.761.500.351.582.362.171.900.040.280.520.11251.89

Direct costsMedical0.705.230.020.284.331.161.4830.192.673.4236.830.780.312.611.422.672.050.020.080.110.0496.41

Social5.0742.290.010.242.840.570.7392.882.942.9497.450.710.282.371.292.420.540.010.040.060.02255.69

Total costs10.0882.130.100.9422.414.043.97210.1214.1914.33213.042.980.936.565.077.264.500.070.400.690.18603.99

Percentof GDP0.97%1.31%0.46%0.36%0.40%0.25%0.28%1.29%1.10%0.90%1.30%1.06%0.43%0.37%1.02%0.42%0.16%0.06%0.17%0.24%0.06%1.01%

AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan Africa SouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestTotal

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

25

Table 9The contribution of each WHO region to the global prevalence of dementia, and to global costs (informal care,direct medical and social care costs, and total costs)Proportion of peoplewith dementia0.9%7.9%0.0%0.9%15.5%12.6%7.0%19.6%3.1%5.3%12.3%0.9%0.7%3.3%1.7%3.0%3.2%0.2%1.0%0.3%0.5%100%Informal care(all ADL)1.7%13.7%0.0%0.2%6.1%0.9%0.7%34.6%3.4%3.2%31.3%0.6%0.1%0.6%0.9%0.9%0.8%0.0%0.1%0.2%0.0%100%Direct costsMedicalSocial0.7%2.0%5.4%16.5%0.0%0.0%0.3%0.1%4.5%1.1%1.2%0.2%1.5%0.3%31.3%36.3%2.8%1.1%3.6%1.2%38.2%38.1%0.8%0.3%0.3%0.1%2.7%0.9%1.5%0.5%2.8%0.9%2.1%0.2%0.0%0.0%0.1%0.0%0.1%0.0%0.0%0.0%100%100%Total costs1.7%13.6%0.0%0.2%3.7%0.7%0.7%34.8%2.3%2.4%35.3%0.5%0.2%1.1%0.8%1.2%0.7%0.0%0.1%0.1%0.0%100%

AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan Africa SouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestAll

Table 10

Aggregated cost types as percentages of total costs in the different WHO regionsInformal care(all ADL)42.7%42.1%74.7%45.2%68.0%57.1%44.4%41.4%60.5%55.6%37.0%50.3%37.5%24.1%46.6%29.9%42.3%60.0%70.1%75.3%62.8%41.7%Direct costsMedicalSocial7.0%50.3%6.4%51.5%16.9%8.4%29.5%25.2%19.3%12.7%28.7%14.2%37.2%18.4%14.4%44.2%18.8%20.7%23.9%20.5%17.3%45.7%26.1%23.7%32.7%29.7%39.8%36.1%28.0%25.4%36.8%33.4%45.7%12.0%26.8%13.2%20.0%9.9%16.5%8.2%24.9%12.3%16.0%42.3%Total costs100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%100%

AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan Africa SouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestAll

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

26

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

Table 11

Cost per person with dementia in each WHO region (US$)Direct costsInformalcareNon-(all ADL) Medical medicalTotalcosts32370290576059286240789031601301221289176674860590923663553682436881392610811122683496916986

Total costs

AustralasiaAsia Pacific High IncomeOceaniaAsia CentralAsia EastAsia SouthAsia SoutheastEurope WesternEurope CentralEurope EasternNorth America High IncomeCaribbeanLatin America AndeanLatin America CentralLatin America SouthernLatin America TropicalNorth Africa / Middle EastSub-Saharan Africa CentralSub-Saharan Africa EastSub-Saharan Africa SouthernSub-Saharan Africa WestAll

138121224345261295277451571112479780142611796845701375133538382057166064878751496097084

226218521026845788259595432824231832840323711200220223092529179428922411272412711

1629614963508723517128295133152667157322233215110891999209522954721431115581197191

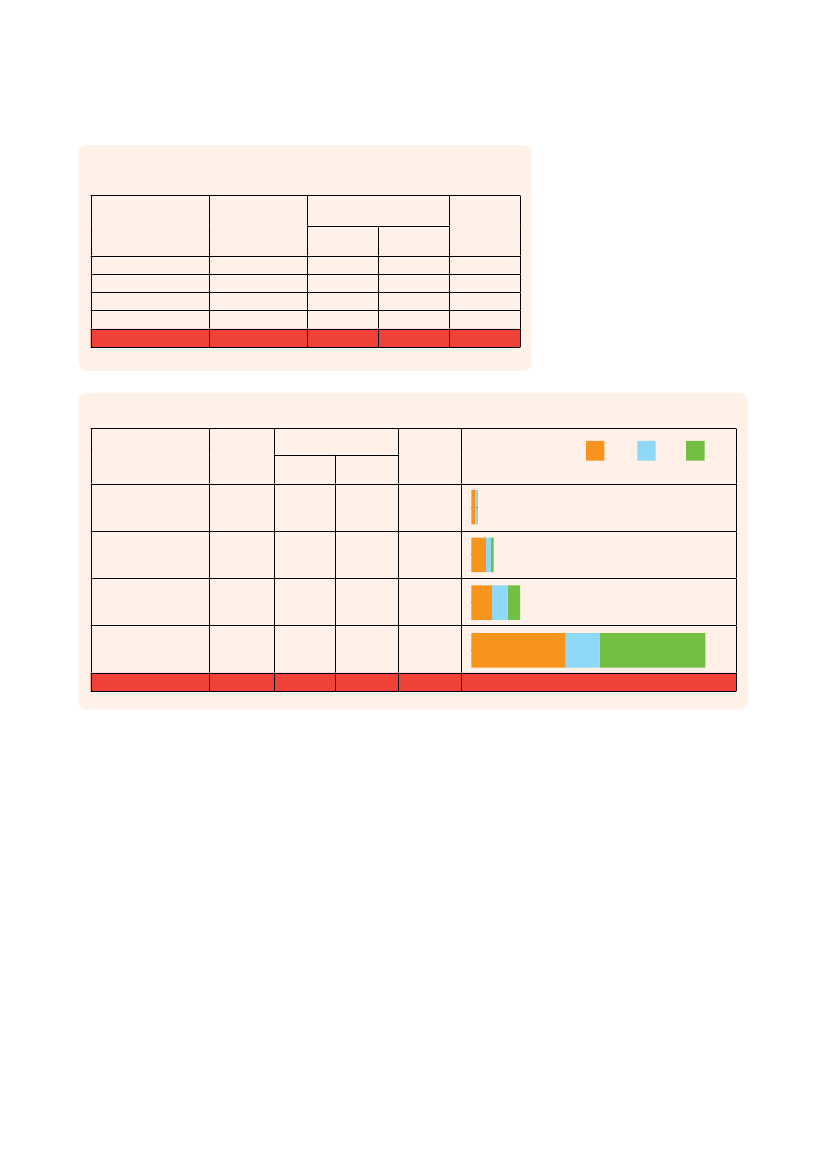

Table 12

Aggregated costs in different World Bank income groups (billions US$)Number ofpeople withdementiaInformalcare(all ADL)2.5218.9013.70216.77251.89

Direct costsMedical1.236.7410.4478.0096.41

Non-medical0.623.578.35243.14255.69

Total costs4.3729.2132.49537.91603.99

Percent ofGDP0.24%0.35%0.50%1.24%1.01%

Low incomeLower middle incomeUpper middle incomeHigh incomeAll

5036979939520447590251636750835558717

Table 13Aggregated costs in different World Bank income groups,as percentages of total global costsPrevalenceLow incomeLower middle incomeUpper middle incomeHigh incomeAll14.2%26.4%13.4%46.0%100%

Informal care(all ADL)1.0%7.5%5.4%86.1%100%

Direct costsMedical1.3%7.0%10.8%80.9%100%

Social0.2%1.4%3.3%95.1%100%

Totalcosts0.7%4.8%5.4%89.1%100%

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

27

Table 14Aggregated cost types as percentages of total costs in different WorldBank income groupsDirect costsMedical28.2%23.1%32.1%14.5%16.0%

Informal care(all ADL)Low incomeLower middle incomeUpper middle incomeHigh incomeAll57.6%64.7%42.2%40.3%41.7%

Social14.3%12.2%25.7%45.2%42.3%

Totalcosts100%100%100%100%100%

Table 15

Costs per person with dementia in different World Bank income groups (US$)Informalcare(all ADL)Direct costsMedical2447172,1944,766

Social1243801,75514,855

Totalcosts8683,1096,82732,865

Care costs

Informal

Medical

Social

Low incomeLower middle incomeUpper middle incomeHigh income

5002,0122,87913,244

All

7,084

2,711

7,191

16,986

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

28

World Alzheimer reporT 2010

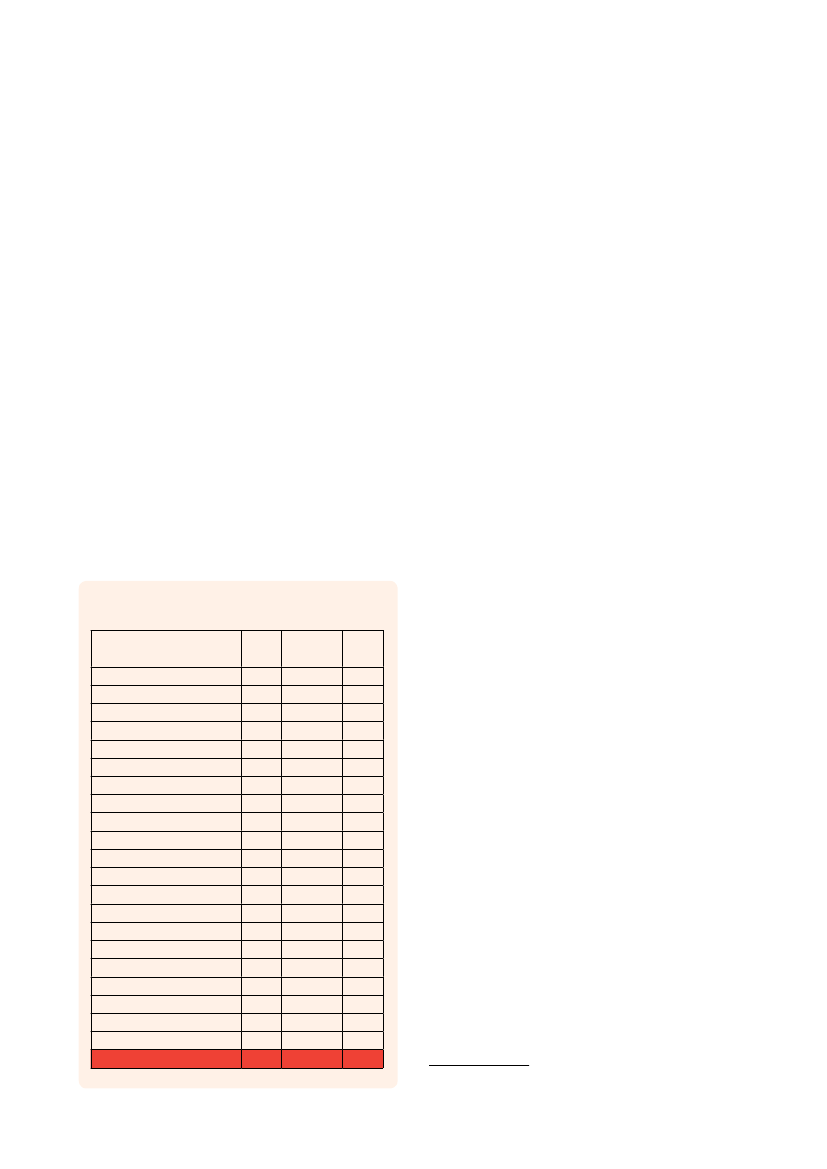

Sensitivity analysesFor the estimation of costs in the base case, wemade several assumptions, regarding, for example,the appropriate method for comparing costsbetween countries, the types of informal care thatshould be included in cost estimations, the hourlycosts to be attached to informal caregiver inputs,Table 16Summary of sensitivity analysis optionsBase case option

and the relative cost of inputs from different typesof caregiver. In order to understand the effect ofthese assumptions on the cost estimations, wecarried out sensitivity analyses in which we variedthese assumptions. The base case options andthe sensitivity analysis options are summarized intable 16.

ConsiderationHow should we compare costs between countries, using a single cost metric?Which informal care inputs should be included?

Sensitivity analysis option(s)According to purchasing power parity (PPP)1 Assistance with basic ADL only2 Assistance with combined ADL and time spentsupervising1 A regression model of average wage as afunction of GDP per person2 At replacement cost (the average wage for asocial care professional)1 Spouse caregiver inputs should be costed at25% of the average wage2 Spouse caregiver inputs should be costed at50% of the average wage

According to the exchangerate with US dollarAssistance with both basicand instrumental ADL (referredto as combined ADL), but nottime spent supervisingAt the average wage for thatcountry based on manualimputationEqually for spouses and non-spouses

How should we cost the inputs of informal caregivers?

How should we compare costs betweencountries, using a single cost metric?There are essentially two approaches: throughexchange rates (as used in the base option) orthrough purchasing power parity (PPP). One USdollar exchanged into Indian rupees and spent inIndia would have more purchasing power in Indiathan it would in the USA. The PPP approach uses aninternational dollar as the standard metric, equalizingthe purchasing power of different currencies for agiven basket of goods.Using a PPP basis is arguably more useful thanexchange rates when comparing generalizeddifferences in living standards between nationsbecause PPP takes into account the relative costof living and the inflation rates of the countries,while exchange rates may distort real differences inincome. For our purposes, the PPP estimates takeinto account the local value of the costs incurred, asopposed to their value on the international moneymarkets. If PPPs are used for the estimates instead

of exchange rates, the total worldwide costs are 7.4%higher. However, PPP is most useful when comparingcosts between countries and regions, particularlythose with widely differing levels of economicdevelopment. In relative terms, the contribution fromlower income countries is more substantial (table 17).Under the base case option, low income countriesaccounted for just 0.7% of total worldwide costs,middle income countries for 10.2% and high incomecountries for 89.1%. Using PPP, these proportionsare 2.1% for low, 20.0% for middle income and 77.9%for high income countries.The costs of dementia as a proportion of GDP arescarcely affected by the choice of exchange rates orPPP-based approaches, since both the numeratorand the denominator are increased in lower incomecountries. Using PPP, this proportion varied from0.25% in low income countries to 0.37% in lowermiddle to 0.54% in upper middle to 1.25% in highincome countries.

Alzheimer’S diSeASe iNTerNATioNAl

The GloBAl eCoNomiC impACT oF demeNTiA

29

Table 17Regions