Sundhedsudvalget 2009-10

SUU Alm.del Bilag 176

Offentligt

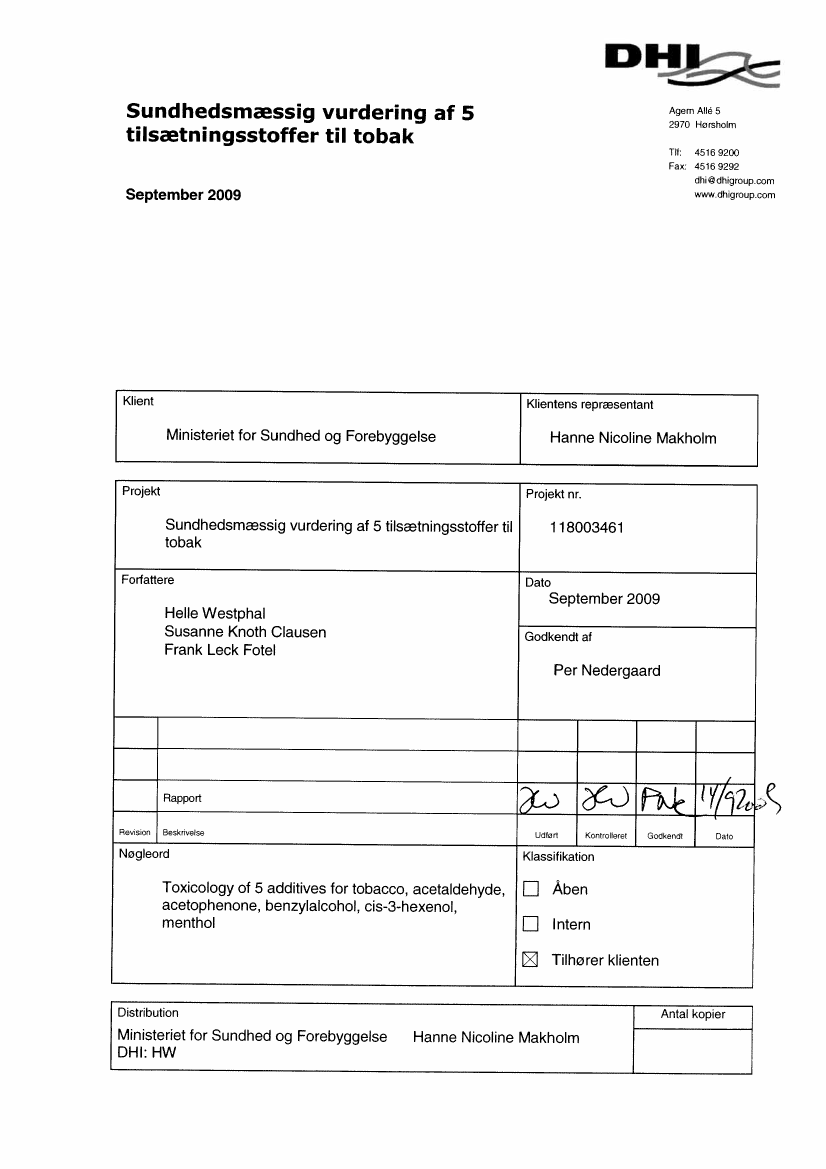

Sundhedsmæssig vurdering af 5tilsætningsstoffer til tobak

Ministeriet for Sundhed ogForebyggelseSeptember 2009

INDHOLDSFORTEGNELSE

12344.14.24.34.44.5

BAGGRUND ................................................................................................................... 1RESUMÈ ........................................................................................................................ 2SAMLET DATA OVERSIGT ........................................................................................... 4STOFPROFILER ............................................................................................................ 7Acetophenon................................................................................................................... 7Acetaldehyd .................................................................................................................... 8Benzylalkohol.................................................................................................................. 9Cis-3-hexenol ................................................................................................................ 10Menthol ......................................................................................................................... 11

BILAGABCDEToxicological profile of AcetophenoneToxicological profile of AcetaldehydeToxicological profile of Benzyl alcoholToxicological profile of Cis-3-hexenolToxicological profile of Menthol

Kvalitetssikringsskema

DHI

1

BAGGRUNDMinisteriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse har bedt DHI om en nærmere vurdering af 5tilsætningsstoffer til tobak.Kræftens Bekæmpelse har udarbejdet en rapport vedr. tilsætningsstoffer i tobak, der be-lyser toksikologiske data for en række tilsætningsstoffer. DHI har i 2008 vurderet tilsæt-ningsstoffer på det grundlag, som er anført i Kræftens Bekæmpelses rapport, og herud-fra samt på baggrund af umiddelbart tilgængelige øvrige data kategoriseret de anvendtetilsætningsstoffer. Resultatet af DHI’s kategorisering og umiddelbare vurdering forelig-ger i form af rapporten ”Tilsætningsstoffer til tobak. Eksponering, risikovurdering ogkategorisering” fra december 2008Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse har bedt DHI om en nærmere vurdering af 5stoffer, hvor det skønnes relevant at søge og indhente data fra litteraturen.Formålet er at kvalificere den sundhedsmæssige vurdering af 5 stoffer, der på baggrundaf den foreløbige vurdering potentielt kan have særlige sundhedseffekter ved rygning,idet 4 af stofferne er anvendt som tilsætningsstoffer i tobaksvarer og ét stof dannes vedforbrænding af dels en række tilsætningsstoffer i tobak og dels fra selve tobakken.DHI har indhentet eksisterende data i form af publicerede originalartikler og rapporterfor på denne baggrund at kvalificere vurderingen. Der er søgt efter og indhentet publice-rede data fra videnskabelige kilder, primært engelsksprogede. Ved datasøgning og vur-dering af data til de toksikologiske profiler for enkeltstoffer er der søgt efter stoffernesforventede effekt ved rygning, herunder med særlig vægt på tilgængelig viden om evt.afhængighedsskabende effekt.Der er udarbejdet toksikologiske profiler for følgende 5 stoffer:•••••MentholAcetaldehydAcetophenonCis-3-hexenolBenzylalkohol

De toksikologiske profiler er udarbejdet på engelsk og foreligger som bilag i denne rap-port. For at lette tilgangen for ikke-fagfolk er der endvidere udarbejdet en tabel mednøgledata og hovedkonklusioner for de 5 stoffer. For hvert af de fem stoffer er der tilli-ge udarbejdet mindre profiler på dansk, hvor data er trukket frem fra de toksikologiskeprofiler. Ved evt. tvivlsspørgsmål, er det i de egentlige toksikologiske profiler, der skalsøges efter supplerende viden.

1

2

RESUMÈI forbindelse med kvalificering af den sundhedsmæssige vurdering af 5 tilsætningsstof-fer til tobak, har DHI indhentet og vurderet data for 5 stoffer: Menthol, acetophenon,cis-3-hexenol, benzylalkohol og acetaldehyd. De første 4 stoffer anvendes alle somsmagstilsætning (”flavour”) og sidstnævnte stof, acetaldehyd, er et af de stoffer, derdannes i højst mængde ved forbrænding af tobakken. Acetaldehyd dannes ud fra selvetobakken og fra andre stivelsesholdige og sukkerholdige kilder som f.eks. sukkerarter,kakao, lakrids, andre blade, frugt etc.I forbindelse med redegørelsen for eksisterende data på sundhedspåvirkninger ved ryg-ning, er der særligt set efter evt. data vedr. påvirkning af afhængighed. Det er – somnævnt i det tidligere arbejde - en diskussion i sig selv at afklare, hvornår et stof, der bi-drager til en bestemt smag, kan siges at påvirke afhængigheden. Vi har i vort arbejdesøgt at fokusere på, om der er fundet data, der kan underbygge en formodning om, atstoffet har yderligere effekt på afhængigheden. Dvs. om stoffet kan siges at have en sær-lig virkning på effekten/afhængigheden af nikotin, som er det stof, der medfører afhæn-gighed af tobaksrygning.Kun 1 – måske 2 - af de undersøgte 5 stoffer kan relateres til mulig påvirkning af ryge-mønstret:Cis-3-hexenol er fundet beroligende/stressreducerede i test af dyr og øger tilsyneladendebehagevirkningen ved rygning. Det kan derfor muligvis have en effekt på afhængighe-den af tobaksrygning.Menthol er ikke fundet at påvirke afhængigheden af nikotin, men ét studie viser, atmenthol-cigaret-rygere i højere grad end andre rygere er ”wake-up-smokers”. Dvs. atmenthol-cigaretrygere i højere grad end andre rygere ryger hurtigere efter de er vågnetom morgenen. Derfor kan menthol muligvis påvirke afhængigheden af tobak, om enddet i så fald er mere indirekte end via nikotin-afhængigheden.Ingen af disse to stoffer er i øvrigt fundet at bidrage til sundhedseffekter ved indtagel-se/rygning.For de 2 øvrige smagstilsætningsstoffer, acetophenon og benzylalkohol, er der tale omstoffer, der lugter og smager af bær/frugter. Begge stoffer indtages også via såvel kostensom via udeluft. Stofferne besidder lav sundhedsfare og der er ikke fundet studier, derunderbygger en mistanke om påvirkning af afhængigheden af tobaksrygning.Det sidste stof, acetaldehyd, er et stof, der bl.a. relateres til kræftrisikoen fra tobaksryg-ning. Stoffet kan endvidere virke toksisk i kroppen og give forgiftningssymptomer. Tilyderligere oplysning er acetaldehyd også det stof, der kan give forgiftning i kroppen,hvis ikke man kan nedbryde alkohol (f.eks. ved overdosis, særlige asiatiske befolk-ningsgrupper eller antabusbehandling).Acetaldehyd dannes ved pyrolyse (forbrænding) af glycerol, celluloseholdige stof-fer/plantedele og nogle sukkerarter samt ikke mindst selve tobakken, der udgør langtden største kilde. Det er ved en rotteundersøgelse af acetaldehyd og nikotin fundet, atrotter med adgang til enten nikotin, acetaldehyd eller en blanding af disse foretrækker –og selvadministrerer oftere - blandingen med nikotin og acetaldehyd. Så det er muligt,

2

at acetaldehyd har en effekt på afhængigheden af nikotin. Da langt den største kilde tildannelsen af acetaldehyd som nævnt stammer fra selve tobakken, vil en fjernelse af deacetaldehyd-dannende tilsætningsstoffer fra tobakken dog blot medføre at rygetobakville bestå af ”mere” tobak i stedet og dermed vil en eliminering af tilsætningsstofferikke ændre væsentligt ved acetaldehydindtaget ved rygning.Det samlede billede af problemstillingen omkring tilsætningsstoffer og tobak er særde-les komplekst og ingen stoffer vil formodentlig være undersøgt tilstrækkeligt til at mankan konkludere klart på rygeadfærd og dermed rygerrelaterede sygdomme. Det er mu-ligt, at man ved undersøgelse af nogle af de øvrige tilsætningsstoffer vil kunne findestoffer, der muligvis påvirker afhængigheden, således at man ville kunne samle en listeover flere uønskede tilsætningsstoffer til tobak.

3

3

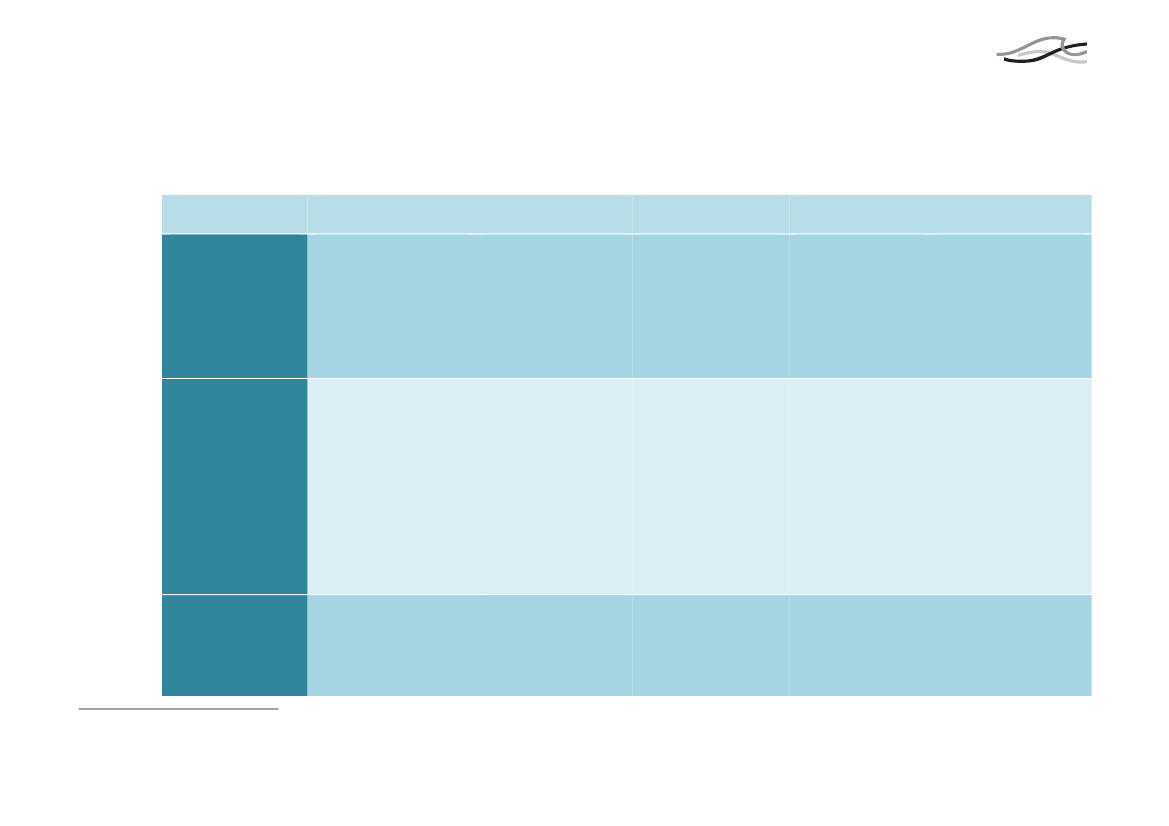

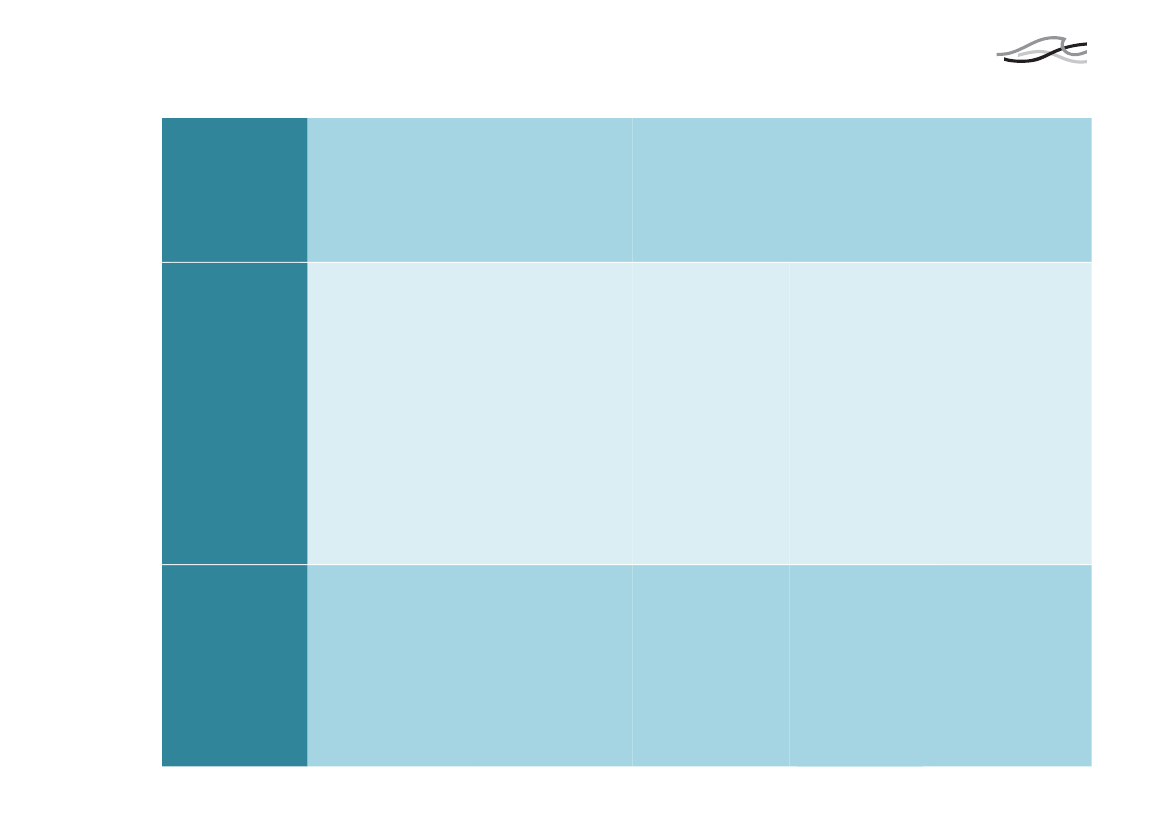

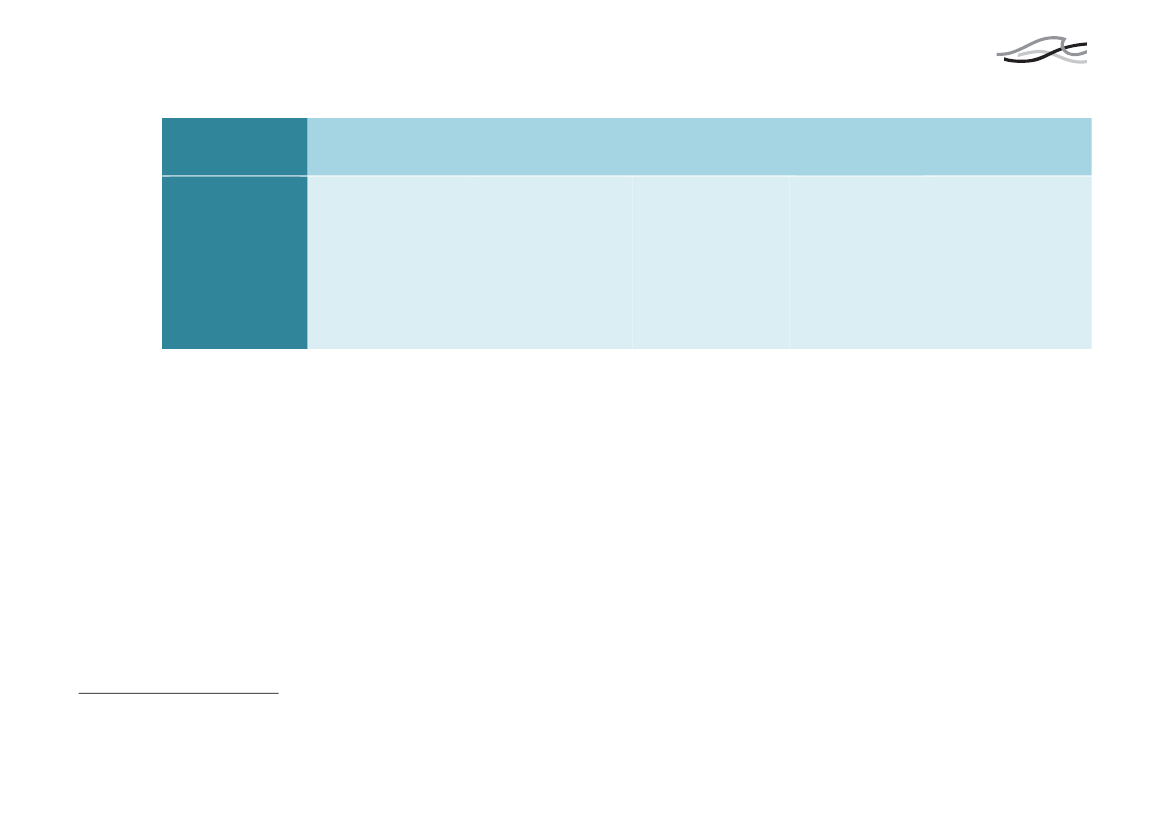

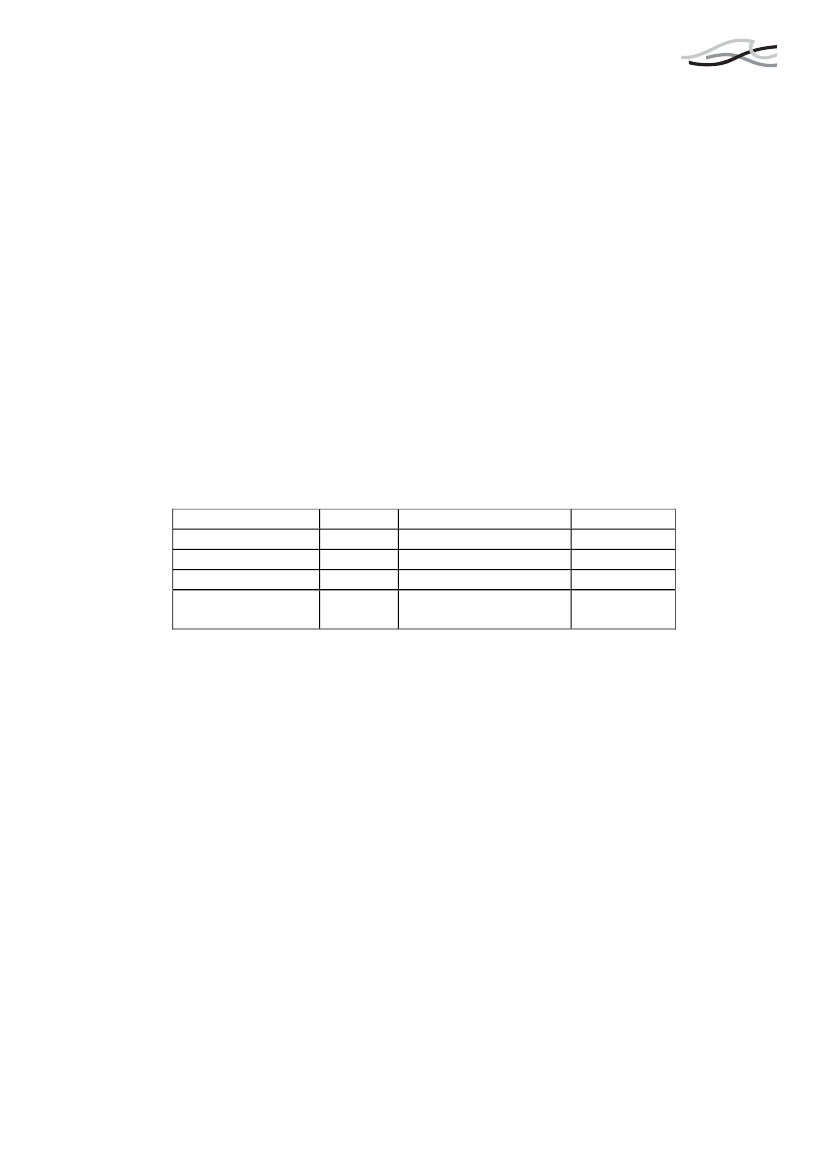

SAMLET DATA OVERSIGTAcetaldehydIndtaget dagligmængde via rygning1Ca. 18-32 mg i dosis perdag fra tobak, heraf max.2-4 mg fra tilsætningsstof-fer.Max. andel fra tilsætnings-stoffer er 12% af estimeretindtag via rygning, sand-synligvis mindre.StofkarakteristikStoffet er et forbrændings-produkt af sukkerarter,cellulose (plantestivelse)og glycerol.Findes i planteekstrakter,tobaksrøg, inde- og udeluft,udstødningsgas og i vand.Årlig eksponering via ude-luft er 1,0 �g/m3 (Sverige).Der er målt fra 600- 1600�g i røg fra én cigaret.

AcetophenonCa. 99 �g per kg bw perdag svarende til ca. 7mg/dag fra rygning.

Benzylalkohol0,05mg/kg bw dagligsvarende til ca. 3,5mg/dag for en ryger.

Cis-3-hexenolCa. 48 �g/dag

MentholCa. 1,66 mg

QNE 0,0006%

QNE 0,015%

QNE: 0,00003%

QNE: 1,043%

Aromatisk stof – dufter afbær/frugter (blomster/mandelagtig)

Findes naturligt i frugter,æteriske olier og tobak.Bruges i kosmetik.

”Grøn” smag.Findes naturligt i plan-ter og planteprodukter.Dagligt indtag i Euro-pa via kosten er esti-meret til 4300 �g/dagper person.

Menthol anvendes i vidudstrækning i en langrække produkter bl.a. ifødevarer og kosmetik.

Eksponering via alm.udeluft, fødevarer, drik-kevand, samt hudkontaktmed forbrugerproduktermed indhold af stoffet.Ca. 99% går videre uom-dannet i røgen ved pyro-lyse.Er ikke undersøgt somenkeltstof i tobak.Anvendes i fødevarer oger vurderet sikkert viaindtagelse af WHO +JECFA2.Lav toksicitet.Ingen undersøgelservedr. afhængighed.Ref. Dosis beregnet afEPA til 0,3mg/kg/dag.

Data

Det diskuteres i litteraturen,om tilsætningsstoffernekan bidrage til den kræft-fremkaldende effekt vedrygning set i forhold til, atde acetaldehyddannendetilsætningsstoffer udgør en

Lav toksicitetMetaboliseres til car-boxylsyrer i kroppen.Bliver til kuldioxid ogvand i kroppen.

Menthol er ved indtagelseikke fundet kræftfremkal-dende.Undersøgt af mange for-skellige institutioner mht.effekter fra rygning.

1

Indtaget daglig mængde ved rygning af 20 cigaretter beregnet ud fra Quantum Not Exceeded (QNE), dvs. max. anvendt andel i tobakken af det pågældendetilsætningsstof i tobak. BW står for body weight, det vil sige at dosis måles i dosis per kg. legemsvægt.2JECFA: Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA)

4

forsvindende lille mængdeaf tobakkens bidrag.

Ét studie fra 1966 vedr.mulig påvirkning af elek-triske impul-ser/hjerneaktiviteten.Grænseværdi herfor var0.007 mg/m3.Ingen sene-re publikationer vedr.reaktioner på nervesy-stemet.Irriterende ved kontakt.Lav akut toksicitet.Lav toksicitetIngen fundne toksiko-logiske effekter vedinhalation.Mentholcigaretrygere erofte “voksne” rygere. IUSA ryger flere sorte endhvide mentholcigaretterog selv om de ryger min-dre, bliver de alligevelmere syge.Diskussion af, ommenthol kan øge denkræftfremkaldende effektaf cigaretter. Konklusioneri litteraturen fra mangeforskellige kilder viser atdette ikke er tilfældet,ligesom menthol næppehar effekt på rygerelate-rede sygdomme. Den evt.kræftfremkaldende effekter derfor velundersøgt.Næppe.Ingen fundne data.Giver en frisk smag tilprduktet. Kan tilsyne-ladende virke beroli-gende/reducererstress i dyr.Er patenteret i USA i1970 pga. af dets be-hagelige effekt pårygeoplevelsen. Så-fremt øgning af beha-gevirkning ved rygninganføres som effekt påafhængigheden afÈt studie viser at menthol-cigaretrygegre i højeregrad er ”Wake-up-smokers”, det er derformuligt at stoffet kan påvir-ke afhængigheden. Data,tyder ikke på, at mentholpåvirker afhængighedenaf nikotin.

Sygdomsfremkal-dende effekter

Stoffet er fundet kræftfrem-kaldende i dyr. Internatio-nalt anerkendt, at stoffethar kræftfremkaldendeeffekt.Det er ved forbrænding oginhalation af tobak, derprimært inhaleres acetal-dehyd, der anses som ho-vedansvarlig for den kræft-fremkaldende effekt vedrygning.Acetaldehyd er i øvrigt detstof, der dannes ved ned-brydning af alkohol i krop-pen – og kan give forgift-ningssymptomer

Afhængighedsska-bende?

I et rotteforsøg er der fun-det mulig sammenhængmellem indholdet af acetal-dehyd og lysten til at indta-ge nikotin (i drikkevand).Der kan derfor være taleom, at acetaldehyd kanhave en synergistisk effektmed nikotin ved tobaksryg-ning og dermed muligviskunne øge den afhæn-gighedsskabende effekt.

5

tobak, er dette mulig-vis tilfældet for cis-3-hexenol.Regulering3B-værdi: 0,02 mg/m3B-værdi: 0,01 mg/m3B-værdi: 0,1 mg/m3JECFA ADI: 0-5 mg/kg afbenzylforbindelser.Grænseværdier:Loftværdi i DK + USA: 25ppmGrænseværdier: I Dan-mark, Finland, USA, Bel-gien m.fl.: 5-10 ppmGrænseværdi i arbejds-miljøet: ingen i DK ellerandre normalt sammen-lignelige lande. I Polen:240 mg/m3USA: 10 ppm (44mg/m3?)Ingen grænseværdi.Ingen grænseværdiIngen B-værdiIngen B-værdi

B-værdi er ”Bidragsværdi”, dvs. den værdi, som danske virksomheders udledning af et stof til udeluften maksimalt må være. Af hensyn til luftkvaliteten erder i Danmark fastsat B-værdier for en række stoffers maksimale bidrag ved udledning til udeluft.JECFA ADI er den internationalt fastsatte acceptable daglige indtag af et stof via kosten.Grænseværdier er arbejdsmiljøgrænseværdier. Det vil sige maksimale tilladte koncentrationer af et stof i arbejdsmiljøet.

3

6

4

STOFPROFILERFor alle 5 stoffer er der udarbejdet toksikologiske profiler med reference til originallitte-raturen og med en mere indgående præsentation af fundne data. Profilerne er udarbejdetpå engelsk. I det følgende præsenteres stofferne også i en kortfattet og lettere tilgænge-lig profil på dansk. Profilerne skal læses i sammenhæng med data fra tabellen ovenfor.

4.1

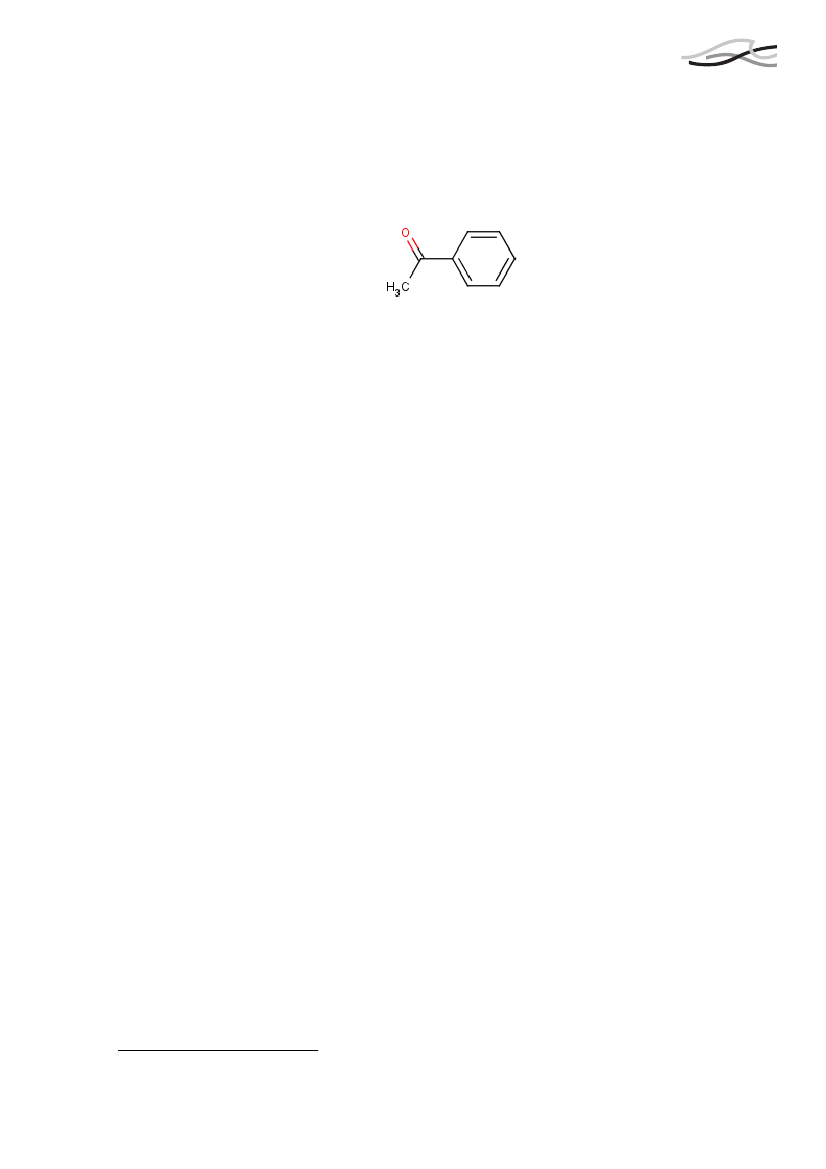

AcetophenonForekomst og anvendelseAcetophenon forekommer naturligt i bær, skaldyr, oksekød og nødder. Stoffet anvendessom smagsgiver i tobak.Den almindelige befolkning kan blive eksponeret for acetophenon via indånding af denomgivende luft, ved indtagelse af fødevarer og drikkevand, og ved hudkontakt medforbrugerprodukter, der indeholder acetophenon. Det daglige indtag herfra er ca. 176�g/dag/person. Rygeres eksponering fra cigaretter er for acetophenon ca. 99 �g/kgkropsvægt ved rygning af 20 cigaretter om dagen, svarende til ca. 7 mg per dag.Grænseværdier og fareklassificeringDer er ifølge vores datasøgninger ikke publiceret andre artikler omkring skadelige ef-fekter på centralnervesystemet end ét russisk studie fra 1966. I dette blev det anbefaletat den gennemsnitlige, maksimale tilladte dosis blev sat til 0.003 mg/m3atmosfæriskluft for at undgå eventuelle effekter på centralnervesystemet.Acetophenon er fareklassificeret som “Skadelig ved indtagelse” (Xn;R22) og”Irriterende for øjne” (Xi;R36).Acetophenon vurderes ikke til at være kræftfremkaldende for mennesker.I arbejdsmiljøet er der et fastsat et 8 timers vægtet gennemsnit, der højst må være 10ppm (svarende til 10 milligram per kubikmeter luft).Acetophenon er ikke på Miljøministeriets Effektliste fra 2000 over stoffer, der udgør enalvorlig økotoksikologisk effekt på miljøet.SundhedseffekterFra dyrestudier ved man at acetophenon bliver optaget, omsat og udskilt indenfor 24 ti-mer. Stoffet udskilles primært i urinen og i noget mindre grad i afføringen.Acetophenon er blevet testet af tobaksfirmaet Phillip Morris’ testlaboratorier i et studiehvor 333 ingredienser blev testet. Acetophenon blev ikke testet som enkeltstof, men i engruppe af stoffer, og data tydede ikke på at nogen af de 333 testede ingredienser øgededen overordnede giftighed af tobak i nævneværdig grad.

7

DHI

WHO ved JECFA har vurderet acetophenon som smagsgivende ingrediens i fødevarerog undersøgelsen gav ikke anledning til bekymring omkring sikkerhed. Et amerikanskekspertpanel fra aromastof- og ekstraktproducenters forening (FEMA) har vurderet ace-tophenon som værende ”generally recognised as safe” (GRAS). Dette er dels baseret på,at stoffet hurtigt optages, omsættes og udskilles både i mennesker og dyr og dels på, atstoffet har en bred sikkerhedsmargin og et ringe genotoksisk og mutagent potentiale4.Ved bred sikkerhedsmargin forstås her, at forholdet mellem et konservativt estimat afindtaget og det no-observed-adverse-effekt5-niveau, der er bestemt på baggrund af sub-kroniske og kroniske studier er højt.KonklusionDer findes begrænset litteratur omkring effekterne af at tilsætte acetophenon til tobak,og acetophenon som enkeltstof er ikke blevet undersøgt i studier af tobaksrygning.Fra anvendelsen af acetophenon som smagsgivende ingrediens i fødevarer er der ikkerapporteret skadelige effekter og stoffet betragtes som sikkert at bruge. For acetophenontilsat tobak tyder eksisterende data ikke på, at stoffet øger sundhedsrisikoen vedrygning, acetophenon er ikke undersøgt som enkeltstof i studier omkring rygning.

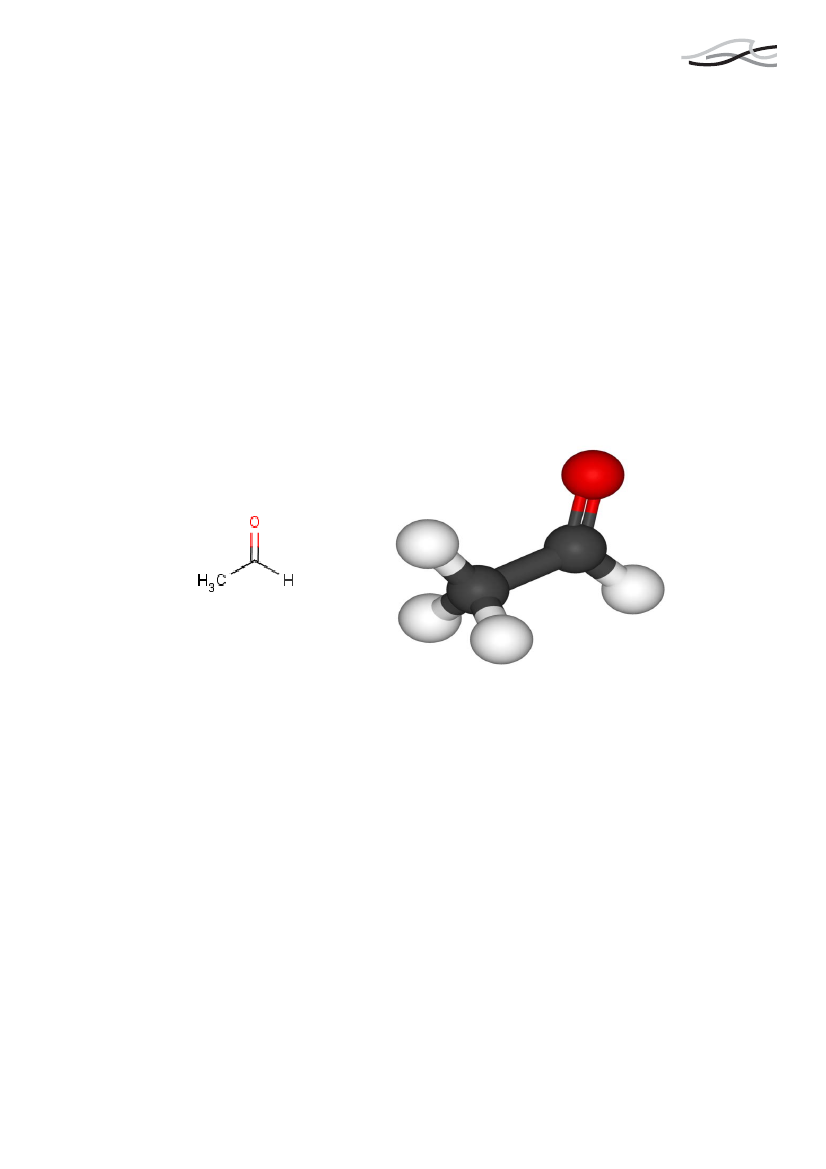

4.2

AcetaldehydForekomst og anvendelseAcetaldehyd forekommer som nedbrydningsprodukt af sukkerstoffer og alkohol imennesker. Acetaldehyd er ikke et tilsætningsstof til tobak, men et pyrolyseprodukt(forbrændingsprodukt) af tilsatte og naturligt forekommende sukkerstoffer, cellulose ogalkoholer. Acetaldehyd er således en af hovedkomponenterne i tobaksrøg.Cellulose er den vigtigste bestanddel i cellevæggen i plaster, og den primære kilde tilacetaldehyd er selve tobakken.I et svensk studie er den gennemsnitlige koncentration af acetaldehyd i almindeligudluft angivet til ca. 1.0 �g/m3. Mængden af acetaldehyd i tobaksrøg er rapporteret tilvære i størrelsesordenen 600-1500 �g per cigaret.

4

Det genotoksiske og mutagene potentiale er bl.a. et udtryk for, om stoffet ændrer cel-lers arvelige egenskaber. Dette kan bl.a. give et praj om evt. forventede kræftfremkal-dende effekter.No-observed-adverse-effect-level er det højeste niveau for dosis, hvor man ikke harfundet sundhedseffekter. Ved division af den beregnede mængde for indtag med dennedosis fås sikkerhedsmarginen. Bred – eller høj - sikkerhedsmargin udtrykker, at der erstor forskel mellem indtaget dosis og ned til den dosis, hvor vi ved der ikke er fundetsundhedseffekter.

5

8

DHI

Grænseværdier og fareklassificeringI Danmark er bidragsværdien for acetaldehyd sat til 20 �g/m3. Bidragsværdien er engrænseværdi for en industrivirksomheds maksimalt tilladelige bidrag til tilstedeværelsenaf et stof i luften.I EU er acetaldehyd klassificeret som skadelig, og irriterende for øjne og respirationsor-ganer, med begrænset dokumentation for kræftfremkaldende egenskaber. Den Californi-ske miljøstyrelse har anført acetaldehyd som et stof kendt som kræftfremkaldende.Grænseværdien for arbejdsmiljøet er i USA 45 mg/m3.SundhedseffekterDet tilgængelige data for acetaldehyds toksikologiske egenskaber tyder på at acetalde-hyd er et af de vigtige toksiske stoffer i tobaksrøg, og at acetaldehyd muligvis er kræft-fremkaldende.Studier af tilsatte sukkerstoffer til tobak og tobaksrøgs sammensætning tyder på at derer sammenhæng mellem visse typer af sukkerstoffer og mængden af acetaldehyd i rø-gen. Tilsætningen af sukkerstoffer til tobak kan derfor forøge mængden af acetaldehyd itobaksrøg, og dermed også påvirke tobaksrøgens toksicitet.Den primære kilde er dog selve tobakken og en mindre mængde tilsætningsstof vil øgeandelen af den rene tobak.Det er i studier med rotter påvist at acetaldehyd kan medføre forøget selvadministrerin-gen af nikotin, det er derfor muligt at acetaldehyd spiller en rolle i udviklingen af niko-tinafhængighed.KonklusionAcetaldehyd er muligvis et af de vigtigste toksiske stoffer i tobaksrøg og formentligkræftfremkaldende. Eksperimentielle data viser, at der er sammenhæng mellem typen afsukker der tilsættes tobak og mængden af acetaldehyd i røgen, således at nogen sukke-rarter tilsat tobakken giver forøget mængde acetaldehyd, mens andre sukkerstoffer ikkeindvirker på mængden af acetaldehyd. Der foreligger eksperimentielle data, som indike-rer at acetaldehyd kan spille en rolle i tobaksafhængighed.

4.3

BenzylalkoholForekomst og anvendelseBenzylalkohol forekommer naturligt i frugter, samt æteriske olier fra eksempelvisjasmin, og i tobak. Benzylalkohol har en behagelig sød og frugtagtig duft.Benzylalkohol anvendes i kosmetik, og som smagsstof og konserveringsmiddel.Benzylalkohol bliver endvidere anvendt som hjælpestof i den farmaceutiske industri.Eksponeringen for benzylalkohol er ca 50 �g/kg kropsvægt svarende til ca. 3,5 mg foren person, der ryger 20 cigaretter om dagen.

9

DHI

Grænseværdier og fareklassificeringBenzylalkohol er klassificeret som sundhedsskadelig (Xn; R20/22) i EU.Det maksimale industrielle bidrag (B-værdi) for benzylalkohol er 0,1 mg m-3i Danmarkog der findes flere anviste grænseværdier for benzylalkohol i industrier.Den amerikanske grænse for arbejdsmiljøet er sat til 10 ppm, hvilket svarer til 44 mgm-3. Der er ingen grænseværdier for arbejdsmiljøet i Danmark. I Polen er arbejdsmiljø-grænseværdien 240 mg m-3.SundhedseffekterAntallet af studier omkring inhalation af benzylalkohol er meget begrænset. Effektkon-centrationerne i de få relevante studier er relativt høje. Hvis man forholder den megetlille mængde af benzylalkohol, der tilsættes til tobak, med den meget lave toksicitet, erdet derfor vurderet at benzylalkohol ikke vil forøge toksiciteten af tobak af betydning.Der er ikke fundet studier, der tyder på at benzylalkohol kan have effekt på tobakkensafhængighedsskabende egenskaber.KonklusionDet er ikke sandsynligt at tilsætningen af benzylakohol til tobak forøger tobakkens tok-sicitet, og der er ingen indikationer på at benzylalkohol spiller en rolle i tobakkens af-hængighedsskabende egenskaber.

4.4

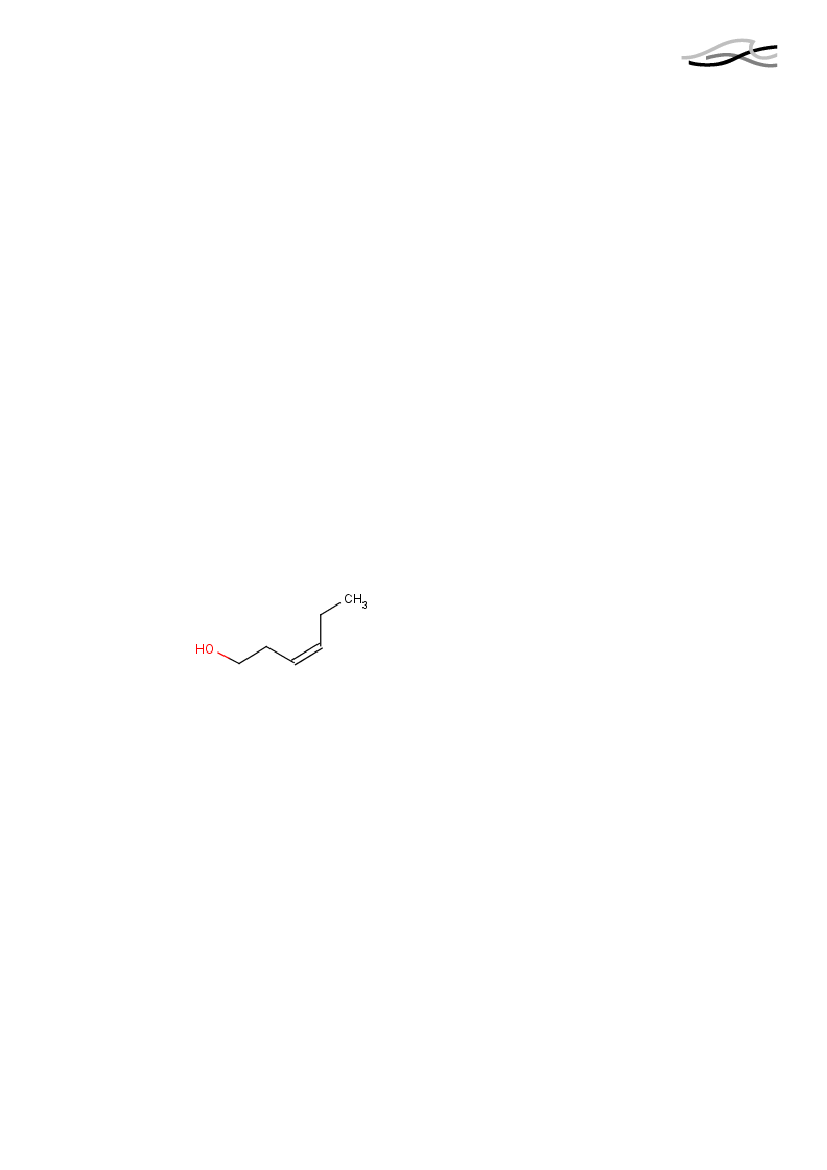

Cis-3-hexenolForekomst og anvendelseCis-3-hexenol forekommer naturligt i mange planter og planteprodukter. Det dagligeindtag i Europa af cis-3-hexenol er af WHO estimeret til 4300 �g/person/dag. Cis-3-hexenol har været brugt som additiv i cigaretter siden 1970.Rygeres eksponering for Cis-3-hexenol er ca. 0,1 �g/kg kropsvægt om dagen vedrygning af 20 cigaretter.Grænseværdier og fareklassificeringDer er ikke identificeret nogen grænseværdier for cis-3-hexenol. I EU er cis-3-hexenoludelukkende klassificeret for dets brandfarlige egenskaber.SundhedseffekterStudier i dyr indikerer at den akutte toksicitet af Cis-3-hexenol er ganske lav, det er der-for usandsynligt at tilsætningen af stoffet til tobak, øger giftigheden af tobak.Det skal dog bemærkes at Cis-3-hexenol er dokumenteret for at forøge behagelighedenved rygning, og det er vist eksperimentielt at cis-3-hexenol har angstdæmpende og bero-ligende egenskaber hos dyr, samt at stoffet kan reducere stress i mennesker. Det er såle-des muligt at tilsætningen af cis-3-hexenol til tobak kan forøge tobakkens afhængig-hedsskabende egenskaber.

10

DHI

KonklusionGrundet den lave toksicitet af cis-3-hexenol er det usandsynligt at tilsætningen af stoffettil tobak vil kunne påvirke den samlede toksicitet af tobaksproduktet. Cis-3-hexenol erallerede i 1970èrne blevet påvist at kunne forøge den behagelige oplevelse ved at rygetobak, og stoffet er eksperimentielt blevet påvist at kunne reducere stress hos menne-sker. Det er derfor muligt at tilsætningen af cis-3-hexenol til tobak kan forøge de af-hængighedskabende egenskaber af tobak.

4.5

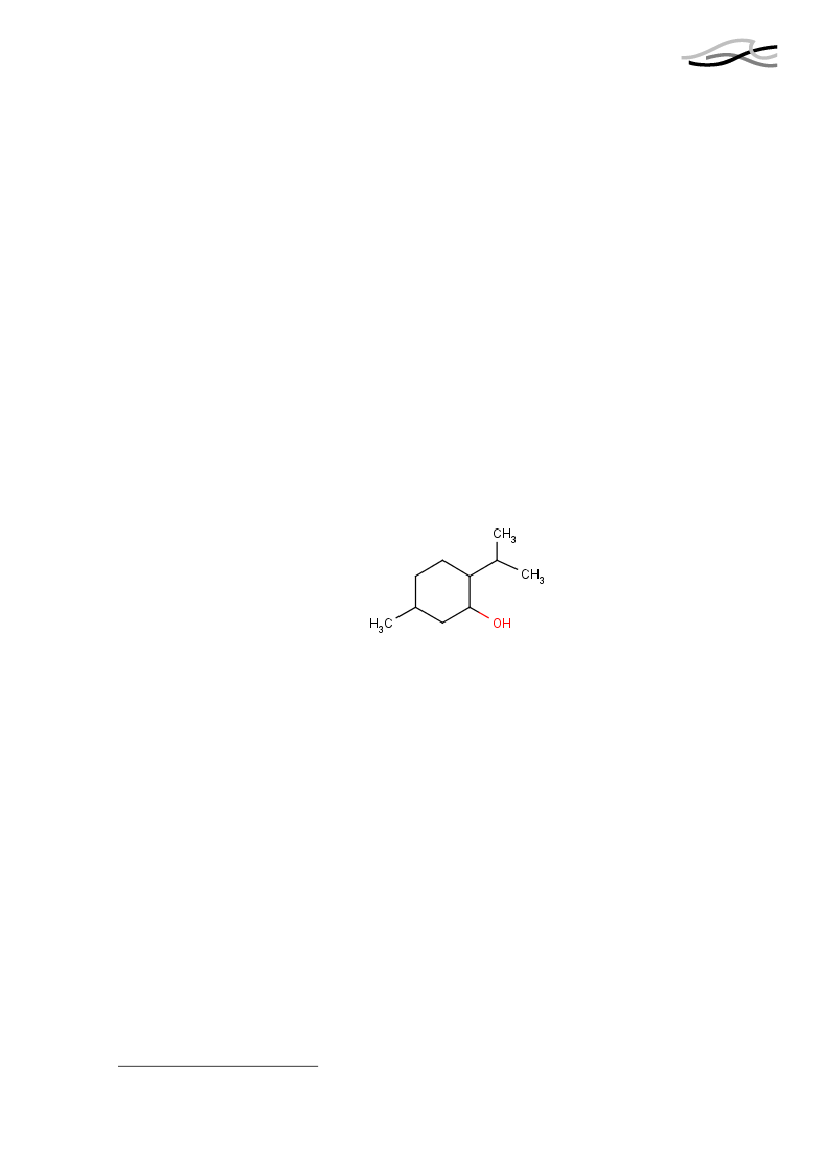

MentholForekomst og anvendelseMenthol er en naturligt forekommende alkohol, der er ekstraheret fra planterne Menthapiperata og Mentha arvensis. Menthol kan også fremstilles syntetisk og det er detsyntetiske produkt, der anvendes i mange kommercielle produkter.Menthol anvendes mod kløe, som antiseptisk middel og som et kølende stof ikosmetiske produkter til huden, ligesom det anvendes som smagsgivende ingrediens itandpasta og i andre produkter til mundhygiejne.Grænseværdier og fareklassificeringDen fælles ekspertkomité for tilsætningsstoffer til fødevarer, JECFA under AO/WHO,har fastsatte i 1968 et acceptabelt dagligt indtag (ADI) til 0-0,2 mg/kg kropsvægt. EUangiver ADI til at være 2 mg/kg kropsvægt. Forskellen i værdierne ligger sandsynligvisi brug af forskellige omregnings- og sikkerhedsfaktorer. I 1998 blev ADI ændret til 4mg/kg kropsvægt af JECFA.Menthol er ikke registreret på Miljøministeriet Effektliste fra 2000, der lister stoffermed særligt alvorlige økotoksikologiske effekter. Der er ikke fastsat nogen grænser formenthol i arbejdsmiljøet.SundhedseffekterDer findes enorme mængder af data omkring menthols sundhedseffekter i forbindelsemed rygning. Mange studier af menthols indflydelse på udvikling af kræft og afhængig-hed af nikotin er amerikanske. Det skyldes det forhold at der er store afgrænsede grup-per i den amerikanske befolkning, der henholdsvis ryger menthol og almindelige ciga-retter, og at der findes ret forskellige sygdomsmønstre i disse to befolkningsgrupper.Èt studie viser, at der ikke er forskel i blod- og urinprøver med hensyn til indhold afNNK (et kræftfremkaldende stof), nikotin og kulstofmonooxid efter rygning af hen-holdsvis almindelige og mentholcigaretter, mens et andet studie sætter spørgsmålstegnved den prædiktive værdi af disse markører.Med hensyn til om menthol har indflydelse på vejrtrækningen, inhalationsdybde, samtmængde af inhaleret tjære, tyder data ikke på, at det er tilfældet. Menthol har måske ind-flydelse på, hvordan man oplever det at ryge, men det giver sig ikke udslag i nogen ob-jektivt målbare parametre.

11

DHI

Der er in vitro6data der tyder på at menthol kan forsinke omsætningen af nikotin ikroppen og nedsætte nyrenes evne til at udskille nikotin, men disse antagelser har ikkekunnet påvises i forsøg med mennesker.Risikoen for udvikling af lungekræft og andre kræfttyper i luftvejene ser ud til at væreforøget, især hos sorte mænd, der ryger mentholcigaretter, men en række undersøgelsertyder på, at det er noget andet end menthol, der er ansvarlig for denne forskel.Der er enkelte studier, der tyder på, at sorte er mere afhængige af nikotin end hvide i ogmed at de har vanskeligere ved at holde op med at ryge, og de der ryger, ryger tidligerepå dagen, end hvide rygere. Men det kan ikke konkluderes, at det er menthol, der er an-svarlig for denne forskel.Der er en række antagelser omkring menthols mulige effekter på udvikling af luftvejs-kræft og afhængighed af nikotin, men der er ingen entydige resultater, der kan slå fast atdet er menthol, der er den direkte årsag til at sorte rygere har højere forekomst af lunge-kræft og en øget afhængighed af nikotin.

”In vitro”, dvs. forsøg udført udenfor kroppen, typisk laboratorieeksperimenter udført på f.eks.celler i reagensglas.12DHI

6

BILAG

13

DHI

Toxicological profile ofAcetophenone

SEPTEMBER 2009

Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse

CONTENTS

1234566.16.1.16.1.26.1.36.26.2.16.36.46.577.17.28910

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1IDENTIFICATION ........................................................................................................... 1USE AND OCCURRENCE ............................................................................................. 2PHYSICAL/CHEMICAL PROPERTIES .......................................................................... 2BIOTRANSFORMATON AND TOXICOKINETICS ......................................................... 3HEALTH EFFECTS ........................................................................................................ 3Single exposure toxicity .................................................................................................. 4Acute toxicity ................................................................................................................... 4Irritation/Corrosion .......................................................................................................... 4Allergy ............................................................................................................................. 4Repeated exposure toxicity ............................................................................................ 5General ........................................................................................................................... 5Genotoxicity .................................................................................................................... 5Carcinogenicity ............................................................................................................... 5Reproduction toxicity ...................................................................................................... 5REGULATORY INFORMATION ..................................................................................... 6Environment .................................................................................................................... 6Classification and Health ................................................................................................ 6EVALUATION ................................................................................................................. 6CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................ 7REFERENCES ............................................................................................................... 8

DHI

1

INTRODUCTIONThe purpose of the present report is to evaluate the impact of adding acetophenone tocigarette tobacco with regard to potentially increased health risk, with the primary focuson increased risk of cancer and increased dependence of nicotine. The evaluation isbased on a literature search described below.The search terms used were acetophenone, CAS 98-86-2, acetylbenzene, phenyl methylketone, CNS, neurotox, immunotox, smoke, smoking, inhalation, addiction or addictive.The cited literature was collected from two different searches. The first search wasmade in the Toxnet cluster database, where data for the different toxicological endpoints were collected from HSDB, ChemIdPlus, Gene-tox, IRIS and CCRIS. Thesecond search in the STN database (Toxcenter, Embase and Scisearch databases) didnot give any relevant hits. Additional literature was provided by The Tobacco Manufac-turers association of Denmark.The literature on the effects of adding acetophenone to tobacco is very limited. Theidentified data either concern the classical toxicological aspects of acetophenone, not re-lated to smoking, or concern the testing of a mixture of many additives, including ace-tophenone, that has been testedin vitroandin vivofor adding toxicological effects totobacco.The primary source of toxicological data is a safety evaluation from 2007 performed bythe American Expert Panel of the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association(FEMA) of a number of substances “Generally Regarded As Safe (GRAS)” (1) and aWHO/JECFA safety evaluation of certain food additives, including ketones, from 2001(2).

2

IDENTIFICATIONChemical NameSynonyms

CAS no.

Acetophenone1-Phenyl-1-ethanone1-PhenylethanoneAcetofenonAcetophenoneAcetylbenzeneAcetylbenzolBenzene, acetyl-Benzoyl methideBenzoylmethideEthanone, 1-phenyl-HypnoneKetone, methyl phenylMethyl phenyl ketonePhenyl methyl ketone98-86-2

A-1

DHI

EINECS No.Molecular formulaStructure

202-708-7C8-H8-O

3

USE AND OCCURRENCEAcetophenone is the simplest aromatic ketone and is a natural component of berries,seafood, beef, and nuts (1). The substance is used as a flavorant in tobacco (3).Acetophenone is used for production of resins, as a precursor for styrene, as rawmaterial for the synthesis of some pharmaceuticals and as excipient for some drugs(4,5,6).Monitoring data from NIOSH1indicate that the general population may be exposed toacetophenone via inhalation of ambient air, ingestion of food and drinking water anddermal contact with this compound and other consumer products containingacetophenone (3). The daily per capita intake of acetophenone is approximately 176�g/day (1).It can be calculated that smokers are exposed to 0.09856 mg acetophenone per kg bwper day when smoking 20 cigarettes per day.

4

PHYSICAL/CHEMICAL PROPERTIESThe substance is identified as given in the below table:

1

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health is the United States federal agency responsible for conducting research and making

recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness.

A-2

DHI

PropertyPhysical stateMolecular weightMelting pointBoiling pointVapour pressureDensityWater solubilityLog P octanol/waterOther dataHenry’s law constantAtmospheric OH RateConstant

ValueClear liquid or crystals(7)120.15 (3)20�C (8)202�C(8)0.397 mm Hg (25�C) (8)1.033 (15�C) (3)6130 mg/l (25�C) (8)1.58 (8)1.04 x 10-5atm-m3/mole (25�C) (8)2.74 x 10-12cm3/molecule-sec (25�C)(8)

5

BIOTRANSFORMATON AND TOXICOKINETICSIn rabbits and dogs acetophenone is absorbed, metabolized and excreted as polar me-tabolites within 24 h (1). Acetophenone undergoes alpha-oxidation and subsequent oxi-dative decarboxylation to yield benzoic acid that is excreted mainly in the urine as hip-puric acid (benzoylglycine) (1).Acetophenone and structurally related aromatic ketones and alcohols have been shownto be absorbed rapidly from the gut, metabolized efficiently by the liver, and excretedprimarily in the urine and to a very small extent in the faeces (2).

6

HEALTH EFFECTSThe effect of adding additives to tobacco has been evaluated in a test series by PhillipMorris test laboratories (9,10,11,12). A number of 333 ingredients added to typicalcommercial blended test cigarettes were evaluated in a bacterial mutagenicity screening(Ames test), a mammalian cell cytotoxicity assay (neutral red uptake) and a 90 daysnose-only inhalation study in rats (9). The 333 ingredients were divided into threegroups, and tested at a normal (low) level and a high level. No ingredients were evalu-ated on a single substance level. Acetophenone was included in the test series and wasadded to two of the three test groups. The conclusion from the studies was that additionof the ingredients to tobacco did not significantly add to the overall toxicity of cigarettes(9).Acetophenone has also been evaluated as a flavour by WHO, JECFA2, and it did notgive rise to any safety concern (2). A group of 38 flavouring agents that included aceto-phenone and 36 structurally related aromatic secondary alcohols, ketones, and relatedesters by the Procedure for the Safety Evaluation of Flavouring Agents, that included

2

The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives is an international scientific expert committee that is administered jointly by theFood and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO and the World Health Organization WHO.

A-3

DHI

evaluation of estimated intake, metabolism and safety margin based on animal studies(2).The group of aromatic substituted secondary alcohols, ketones, and related esters, in-cluding acetophenone, has been reaffirmed as GRAS (GRASr) by FEMA based, in part,on their rapid absorption, metabolic detoxication, and excretion in humans and otheranimals; their low level of flavor use; the wide margins of safety between the conserva-tive estimates of intake and the no-observed-adverse effect levels determined from sub-chronic and chronic studies and the lack of significant genotoxic and mutagenic poten-tial (1).

6.16.1.1

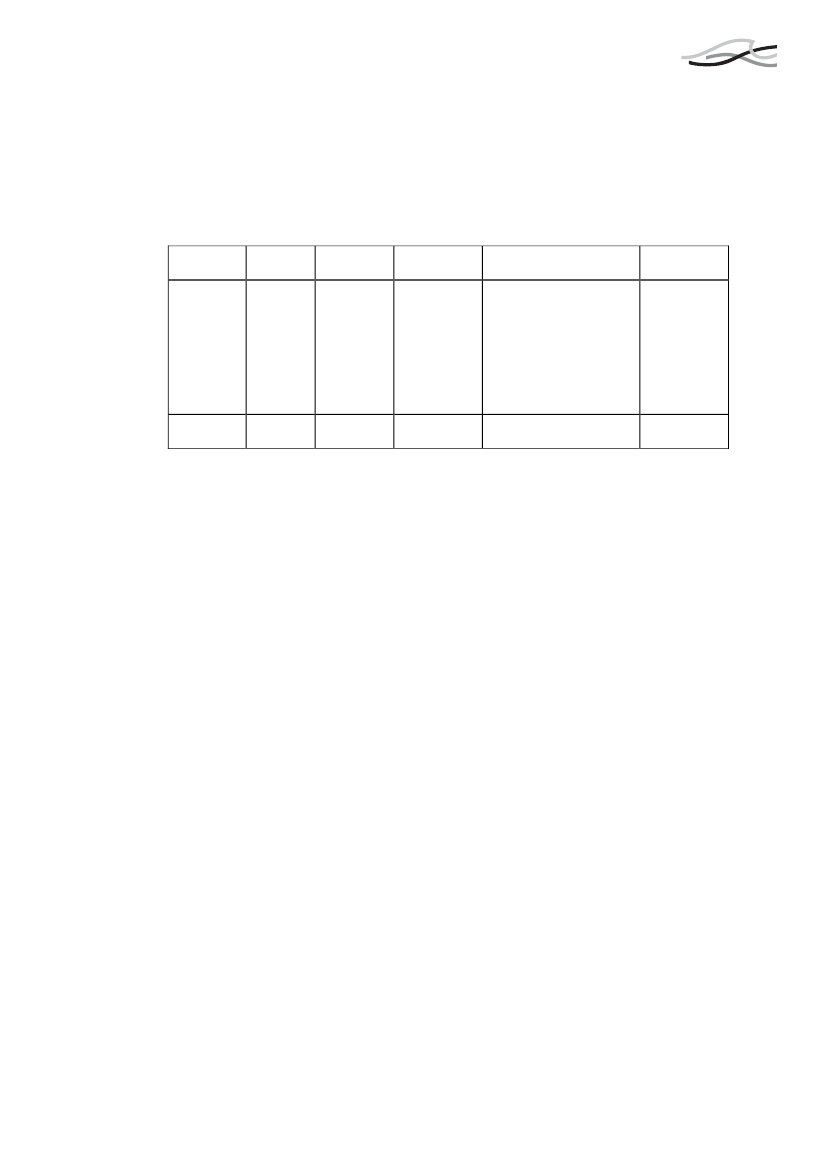

Single exposure toxicityAcute toxicityThe oral acute toxicity of aromatic substituted secondary alcohols, ketones, as aceto-phenone is low (1).The listed values in the table apply to acetophenone.Route of exposureOralOralOralDermal1)

SpeciesRatsRatsMouseGuineapigs

LD501)900-3200 mg/kg bw900 mg/kg bw1780 mg/kg bw>20 mL/kg

Reference(1)(13)(1)(14)

LD50 (mg/kg bw): Lethal dose to half of the animals.

6.1.2

Irritation/CorrosionSkin and EyesAcetophenone is classified as irritating to skin or eyes in EINECS (15).

6.1.3

AllergyNo skin sensitisation was noted when 2% acetophenone in petrolatum was tested onhumans (3).

A-4

DHI

6.26.2.1

Repeated exposure toxicityGeneralRoute ofexposureOralSpeciesRatTime ofexposure28 daysNOAEL1)75 mg/kgbw (sys-temic toxici-ty225 mg/kgbw (neuro-logical ef-fects)1)>1000mg/kg bwCriticalEffectsReduced forelimb gripstrength and motoractivity. Increased sa-livation. Reduced bodyweight gain.Reference(1)

Oral1.

Rats

17 weeks

No reported effects

(1)

NOAEL (mg/kg bw/day): No Observable Adverse Effect Level.

6.3

GenotoxicityAcetophenone was tested for mutagenicity in Ames test, with and without metabolicactivation, and the results were negative (1,16).Likewise when tested for effects on bacterial DNA repair inE. colipolA the resultswere negative (17).Acetophenone was tested for potential to induce chromosomal aberrations at doses of800-1299 �g/ml in chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cells, with a negative result withoutmetabolic activation and with a positive result at 600-1000 �g/ml with metabolicactivation (1).

6.4

CarcinogenicityAcetophenone has been evaluated not to be a human carcinogen based on lack of humandata and animal data (18).

6.5

Reproduction toxicityIn a developmental toxicology study where female rats were dosed via gavage for aminimum of 14 days until day three of lactation a NOAEL for reproductive effects werefound to be 225 mg/kg bw. Above this dose level, at 750 mg/kg bw per day, the livebirth index, pup survival during lactation and pup body weights were decreased (1).

A-5

DHI

77.1

REGULATORY INFORMATIONEnvironmentA hygienic evaluation of acetophenone as an atmospheric air pollutant is reported in aRussian paper from 1966 (19). The threshold of the reflex effect on the electrocorticalbrain activity of the most sensitive persons was 0.007 milligram per cubic meter. Underchronic inhalation conditions (24 hours/day for a total of 70 days) a 0.07 milligram percubic meter concentration elicited in rats functional shifts, such as depressed cholineste-rase activity, which were not elicited by 0.007 milligram per cubic meter of acetophe-none. It was recommended that 0.003 milligram per cubic meter of acetophenone be of-ficially adopted as the 24-hour average maximum allowable concentration foratmospheric air (19).To our knowledge no other reports have been publiced since this publication from 1966about adverse reactions to acetophenone in the central nervous system.

7.2

Classification and HealthEU: Acetophenone is classified as “Harmful if swallowed” (Xn;R22) and “Irritating toeyes” (Xi;R36) (20).Acetophenone has been evaluated not to be a human carcinogen based on lack of humandata and animal data (18).Workplace Environmental Exposure Level (WEEL): The 8 hours Time-weighted Aver-age is 10 ppm (3).Acetophenone is not registered on the Effect List 2000 of the Danish EnvironmentalProtection Agency as a substance causing particularly serious ecotoxicological effects(21).

8

EVALUATIONIn 1993, the American Expert Panel of the Flavor and Extract ManufacturersAssociation (FEMA) evaluated the group of secondary alcohols, ketones and relatedesters, including acetophenone as Generally Regarded As Safe (GRAS) as additives tofood. This was based, in part, on their rapid absorption, metabolic detoxication, andexcretion in humans and other animals; their low level of flavour use; the wide marginsof safety between the conservative estimates of intake and the no-observed-adverseeffect levels determined from subchronic and chronic studies and the lack of significantgenotoxic and mutagenic potential (1).Evaluated as a flavouring agent by WHO/JECFA, acetophenone did not give rise to anysafety concern (2).

A-6

DHI

9

CONCLUSIONThe literature on the effects of adding acetophenone to tobacco is limited. The identifiedliterature either concerns the classical toxicological aspects of acetophenone, which arenot related to smoking, or it concerns the evaluation of a mixture of additives, includingacetophenone. Acetophenone has not been evaluated as a single chemical compound forpotential adverse effects in tobacco smoke.However, it can be argued that it is the most realistic set-up to evaluate the mixture ofadditives actually used for the cigarette brands on the market, and not do an evaluationof single compounds. On the other hand it is difficult to evaluate the potential effect ofat single compound if it has not been tested in an experimental set-up dedicated toinvestigate the effects of that single compound.When acetophenone is used as a flavoring agent in foods no adverse effects have beenreported and is regarded as safe. When added to tobacco data indicate that acetophenonedoes not add to the risk of smoking, but it must be noted that acetophenone has not beenevaluated as a single compound.

A-7

DHI

10

REFERENCES

1.

Adams TB, McGowen MM, Williams MC, Cohen SM, Feron VJ, Goodman JI, et al. TheFEMA GRAS assessment of aromatic substituted secondary alcohols, ketones, and relatedesters used as flavor ingredients. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2007;45:171-201.

2. Gry J, Renwick AG, Sipes IG. Safety evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants.Aromatic substituted secondary alcohols, ketones and related esters. JECFA evaluation.2001. 48.WHO Food Additives Series)3. Anonymous. Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB) - Comprehensive, peer-reviewedtoxicology data for about 5,000 chemicals.http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?HSDB2009.4. Siegel H, Eggersdorfer M. Ketones in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. In:Wienheim: Wiley-VCH; 2002.(.5. Sittig M. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. In:1988. p. 39. (.6. Kumar G, Braish T. Anonymous. Process Chemistry in the Pharmaceutical Industry.2007;2:142-5.7. Nielsen PK, Bech AG, Hansen CP, Løcke H, Nielsen IM, Bengtsen M et al. Tilsætningsstof-fer i cigaretter. Et litteraturstudie. København: Kræftens Bekæmpelse; 2007.8. Anonymous. ChemIDplus - Dictionary of over 370,000 chemicals (names, synonyms, andstructures).http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?CHEM2009.9. Carmines EL. Evaluation of the potential effects of ingredients added to cigarettes. Part 1:cigarette design, testing approach, and review of results. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002;40(1):77-91.10. Rustemeier K, Stabbert R, Haussmann HJ, Roemer E, Carmines EL. Evaluation of the po-tential effects of ingredients added to cigarettes. Part 2: chemical composition of mainstreamsmoke. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002;40(1):93-104.11. Roemer E, Tewes FJ, Meisgen TJ, Veltel DJ, Carmines EL. Evaluation of the potential ef-fects of ingredients added to cigarettes. Part 3: in vitro genotoxicity and cytotoxicity. FoodChem Toxicol. 2002;40(1):105-11.12. Vanscheeuwijck PM, Teredesai A, Terpstra PM, Verbeeck J, Kuhl P, Gerstenberg B, et al.Evaluation of the potential effects of ingredients added to cigarettes. Part 4: subchronic inha-lation toxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002;40(1):113-31.13. Smyth HF, Carpenter CP. Further experience with the range finding tests in the industrialtoxicology laboratory. Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 1948;30:63-8.

A-8

DHI

14. Anonymous. LD50 value from skin exposure of guinea pigs. Journal of Industrial Hygieneand Toxicology. 1944;26:269.15. Anonymous.European INventoryofExisting CommercialchemicalSubstances(EINECS).http://ecb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/esis/index.php?PGM=ein2002.16. Anonymous. Chemical Carcinogenesis Research Information System (CCRIS).http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?CCRIS1985.17. Anonymous. Genetic Toxicology Data Bank (GENE-TOX) - Peer-reviewed genetic toxicol-ogy test data for over 3,000 chemicals.http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?GENETOX2009.18. Anonymous. US Environmental Protection Agency, Integrated Risk Information System,Acetophenone (CAS 98-86-2).http://www.epa.gov/NCEA/iris/subst/0321.htm2009.19. Imasheva NB. Threshold Acetophenone Concentrations Determined by Acute and ChronicExperimental Inhalation. USSR Literature on Air Pollution and Related Occupational Dis-eases. 1966;16:58-69.20. Anonymous. European chemical Substances Information System (ESIS).http://ecb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/esis/2009.21. Miljøstyrelsen. Effektliste 2000.http://www2.mst.dk/common/Udgivramme/Frame.asp?http://www2.mst.dk/Udgiv/publikationer/2000/87-7944-099-1/html/default.htm2000.

A-9

DHI

Toxicological profile ofAcetaldehyde

SEPTEMBER 2009

Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse

DHI

CONTENTS

1234566.16.1.16.1.26.1.36.26.2.16.36.46.56.66.777.17.28910

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1IDENTIFICATION ........................................................................................................... 1USE AND OCCURRENCE ............................................................................................. 1PHYSICAL/CHEMICAL PROPERTIES .......................................................................... 2BIOTRANSFORMATON AND TOXICOKINETICS ......................................................... 2HEALTH EFFECTS ........................................................................................................ 3Single exposure toxicity .................................................................................................. 3Acute toxicity ................................................................................................................... 3Irritation/Corrosion .......................................................................................................... 3Allergy ............................................................................................................................. 4Repeated exposure toxicity ............................................................................................ 4General ........................................................................................................................... 4Cytotoxicity ..................................................................................................................... 5Genotoxicity .................................................................................................................... 5Carcinogenicity ............................................................................................................... 5Reproduction toxicity ...................................................................................................... 5Addiction ......................................................................................................................... 5REGULATORY INFORMATION ..................................................................................... 6Environment .................................................................................................................... 6Classification and Health ................................................................................................ 6EVALUATION ................................................................................................................. 6CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................ 7REFERENCE S .............................................................................................................. 7

DHI

1

INTRODUCTIONThe purpose of the present toxicological profile for acetaldehyde is to reveal the possi-ble health effects on smokers by acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke, and to investigate ifadditives in tobacco lead to significant increase in acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke. Alsopossible effect of acetaldehyde in tobacco addiction was investigated. The search profileused was: acetaldehyde, CAS no 75-07-0, oncogen, tumor, neoplasm, carcinogen, ad-diction, and dependence.The profile has been compiled on searches in the following da-tabases: ESIS, AtsDR, IRIS, IARC, InChem, DOSE, ChemID plus, HSDB, STN, andToxline.

2

IDENTIFICATIONChemical NameSynonymsCAS no.EINECS/ELINCS No.Molecular formulaStructure

AcetaldehydeAcetic ethanol, Ethylaldehyde75-07-0200-836-8C2H4O

3

USE AND OCCURRENCEExposure to acetaldehyde may occur in its production and in the production of aceticacid and various other chemical agents. It is a metabolite of sugars and ethanol inhumans and has been detected in plant extracts, tobacco smoke, engine exhaust, ambientand indoor air, and in water (15). The substance is a pyrolysis product of sugars,cellulose, and glycerol (16). In Sweden from December 1986 to August 1987, the meanyearly exposure to acetaldehyde from air pollution was 1.0 �g/m3(5). Acetaldehyde is amajor component of tobacco smoke, being primarily produced by the combustion of(poly) saccharides (21). Stavanja et al. found that the acetaldehyde yield in tobaccosmoke (800-880 �g/cigarette) was not significantly affected by the type of sugar used inthe tobacco (24). Moir et al. measured the acetaldehyde yield in mainstream smokebetween 872�101 and 1555�222 �g/cigarette, depending on the smoking condition used(20). Baker et al. found that addition of malic acid to tobacco gave rise to a significantincrease in acetaldehyde yield from 626 �g per cigarette in control to 695 �g percigarette from tobacco where 1700 ppm of malic acid was added (3). In another studyBaker et al. found that the yield of acetaldehyde was strongly dependent on the

B-1

DHI

saccharide type added to tobacco (2). Carmines et al. reported significant yield ofacetaldehyde from pyrolysis of licorice extract (7). Hecht reported 770-864 �gacetaldehyde per cigarette (13).

4

PHYSICAL/CHEMICAL PROPERTIESThe substance is identified as given in the below table:Physical stateMolecular weightMelting pointBoiling pointVapour pressureDensityWater solubilityLog P octanol/waterOther data

Colourless liquid or gas (15) occur asvapour in tobacco smoke (23)44.05 (15)-123oC(9) (15)20.1oC(9) 21oC(15)902 mm Hg (45oC) (9)0.788 (16oC) (15)1.00E+06 mg/l (25oC) (9)Log Pow = -0.34 (9)Pungent, fruity odor (15) Leafy greentaste (15)

5

BIOTRANSFORMATON AND TOXICOKINETICSAvailable studies on toxicity indicate that acetaldehyde is absorbed through the lungsand gastrointestinal tract; however, no adequate quantitative studies have been identi-fied (27). Absorption through the skin is probable (27). Following inhalation by rats,acetaldehyde is distributed to the blood, liver, kidney, spleen, heart, and other muscletissues. Low levels were detected in embryos after maternal intraperitoneal injection ofacetaldehyde (mouse) and following maternal exposure to ethanol (mouse and rat) (27).Acetaldehyde is a metabolic intermediate in humans. By far, the main source of expo-sure to acetaldehyde in the general population is through metabolism of ethanol. Severalisoenzymic forms of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) have been identified in thehuman liver and other tissues. There is polymorphism for mitochondrial ALDH. Sub-jects that are homozygous or heterozygous for a point mutation in the mitochondrialALDH corresponding gene have low activity of this enzyme, can only metabolize acet-aldehyde slowly and are intolerant of ethanol. The liver is the most important metabolicsite (15).Acetaldehyde is apparently metabolized to N-nitroso-2-methylthiazolidine 4-carboxylicacid. This chemical was detected in the urine of human subjects during both oral andnasal breathing. A fraction of this may be formed as a two-step synthesisin vivofromacetaldehyde and L-cysteine to yield 2-methylthiazolidine 4-carboxylic acid, which iseasily nitrosated (15).

B-2

DHI

66.1

HEALTH EFFECTSSingle exposure toxicitySingle dose LD50S in rats and mice and LC50S in rats and Syrian hamsters showed thatthe acute toxicity of acetaldehyde is low (27).

6.1.1

Acute toxicityRoute of exposureSpeciesLD501)/ LC502)Reference

InhalationInhalationInhalation

RatRatHamster

OralOralIntraperitoneal1)2)

MouseRatMouse

13,300 ppm /24000 mg m-3(LC50 4h)37000 (LC500,5h)17000 ppmppm / 31000mg m-3(LC504h)900 (LD50)661 (LD50)500 (LD50)

(1)(27)(9)

(10)(10)(10)

LD50 (mg/kg bw): Lethal dose to half of the animals.LC50 (mg/m3air): Concentration in air lethal to half of the animals after 4 hours exposure

6.1.2

Irritation/CorrosionSkinCutaneous erythema was observed in the patch testing of twelve human subjects of“oriental ancestry” (28).EyesAcetaldehyde vapor irritation of the human eye is detectable at 50 ppm in air and be-comes excessive for chronic industrial exposure above 200 ppm (27). Higher concentra-tions and extended exposure may injure the corneal epithelium, causing persistent lac-rimation, photophobia and foreign body sensation. A splash of liquid acetaldehyde canbe expected to cause painful but superficial injury of the cornea, with rapid healing; theliquid evaporates so rapidly at body temperature that contact is brief and self limited.(15) op cit (12).InhalationSome effects of exposure are irritation and lung oedema (15). Kruysse et al. (17)reported from an inhalation study on Syrian Golden Hamster. The animals wereexposed to 0-4560 ppm acetaldehyde over a 90 day period. The highest level inducedgrowth retardation, ocular and nasal irritation, increased number of erythrocytes,increased weights of heart and kidney, and severe histopathological changes in the

B-3

DHI

respiratory tract, mainly necrosis, inflammatory changes, and hyper and metaplasia ofthe epithelium. At 1340 ppm treatment-related changes were increased kidney weightsin males, and slight hyper and metaplastic changes of the tracheal epithelium. 390 ppmwas considered no effect level (17). Woutersen et al. exposed male and female Wistarrats to acetaldehyde vapour at nominal concentrations of 0, 750, 1500 and 3000/1000ppm during 6h/day, 5 days/week for up to 28 months. The highest concentration wasgradually decreased due to severe growth retardation. Major compound-related effectsincluded increased mortality, growth retardation, nasal tumours, and non-neoplasticnasal changes in all test groups. The nasal changes comprised of degeneration,hyperplasia, metaplasia and adenocarcinomas of the olfactory epithelium at all exposurelevels. It was concluded that acetaldehyde was both cytotoxic and carcinogenic to thenasal mucosa in rats (29).In humans, at low levels of exposure (concentrations up to 100 ppm (180 mg m-3) inair), acetaldehyde is rapidly absorbed and metabolized. Inhalation at higher concentra-tions (greater than 100-200 ppm) can cause irritation to the mucous membranes andciliastatic effects on the upper respiratory tract (15). Acetaldehyde may facilitate the up-take in the human body of other atmospheric contaminants by the bronchial epitheliumbecause of its ciliotoxic and mucus coagulating effect (15).Effects on nervous systemAcetaldehyde is reported to be less irritating but stronger central nervous depressantthan formaldehyde (11).Steinhagen and Barrows found a 50% decrease in respiratory rate in two strains of miceduring inhalation of 5000 mg m-3acetaldehyde for 10 minutes (25).6.1.3AllergyAlthough a possible mechanism has been identified, available data are inadequate toassess the potential of acetaldehyde to induce sensitization (27).

6.26.2.1

Repeated exposure toxicityGeneralRoute ofexposureSpeciesTime ofexposureLOAEL1)/LOAEC2)CriticaleffectsReference

Inhala-tionInhala-tion

WistarRatsWistarRats

13-52weeks

750 ppm(1350 mgm-3)52 weeks 750 ppm(1350 mgm-3)

Growth re-tardation

(29)

Degenerative (29)changes inthe olfactorynasal epithe-lium

B-4

DHI

Route ofexposure

Species

Time ofexposure

LOAEL1)/LOAEC2)

Criticaleffects

Reference

Inhala-tion1.2.

WistarRats

28months

750 ppm(1350 mgm-3)

Incidence ofnasal tumors

(29)

LOAEL (mg/kg bw/day): Lowest Observable Adverse Effect LevelLOAEC (mg/m3air/day): Lowest Observable Adverse Effect Concentration

6.3

CytotoxicityAcetaldehyde has been demonstrated to induce single- and double-stranded DNA breaksin human lymphocytes (22).

6.4

GenotoxicityAcetaldehyde induces chromosomal aberration and sister chromatid exchange in a va-riety of test systems. The mutagenic effect of acetaldehyde was studied at the hypoxan-thine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase locus in human lymphocytes in vitro by selec-tion of mutant cell clones in medium containing thioguanine. Cells treated with 1.2-2.4mM acetaldehyde for 24 hr or 0.2-0.6 mM acetaldehyde for 48 hr showed a dose-dependent decrease of cell survival and a 3- to 16-fold increase of the mutant frequency(15). In a study where provisional mutational spectra at the hypoxanthine phosphori-bosyl transferase (HPRT) locus in vitro have been worked out for acetaldehyde in hu-man (T)-lymphocytes, it was concluded that acetaldehyde predominantly caused largegenomic deletions (18).

6.5

CarcinogenicityThere is inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of acetaldehyde. Thereis sufficient evidence in experimental animals for the carcinogenicity of acetaldehyde.Overall evaluation from IARC is that acetaldehyde is possibly carcinogenic to humans(16). In a 28 months inhalation study on rats, exposed to 0, 750, 1500 and 3000/1000ppm during 6 h/day, 5 days/week, It was concluded that acetaldehyde is both cytotoxicand carcinogenic to the nasal mucosa of rats (29). Homann et al. studied the effects ofacetaldehyde on cell regeneration and differentiation of the upper gastrointestinal muco-sa in rats. Administered orally to rats, acetaldehyde can cause hyperplastic and hyper-proliferative changes in epithelia of the upper gastrointestinal tract (14).

6.6

Reproduction toxicityAvailable data are inadequate for assessment of reprotoxicological effects.

6.7

AddictionAt concentrations comparable to those found in tobacco smoke (maximum effect at 4μg/kgb.w. nicotine, 16μg/kgb.w. acetaldehyde, intravenous), rats self-administeredB-5DHI

around 5 times more acetaldehyde/nicotine mixture than nicotine or acetaldehyde alone(8). In another experiment on the self-administration of nicotine in adolescent rats, itwas found that acetaldehyde in the concentrations similar to concentrations in tobaccosmoke, interacted with nicotine to increase responding in a stringent self-administrationacquisition test where nicotine alone is only weakly reinforcing (4). Harman and salso-linol condensation products of acetaldehyde and biogenic amines may be responsiblefor the observed reinforcing effect of acetaldehyde (26) (19).

77.1

REGULATORY INFORMATIONEnvironmentAcetaldehyde enters the environment during industrial production, as a product of in-complete combustion, and as a product of alcohol fermentation. Due to the high vapourpressure and low tendency for sorption onto soil, acetaldehyde is most likely to be pre-sent in air. Acetaldehyde is readily biodegradable with approximate half-lives 10-60hours in air and 1.9 hour in water (27). No quantitative data on levels in ambient waterwere identified. Concentration in ambient air average about 5�g m-3(27).

7.2

Classification and HealthAcetaldehyde is classified harmful, irritation to eyes and respiratory system, limitedevidence of a carcinogenic effect (Carc. Cat. 3; R40 - Xi; R36/37) by the EuropeanCommission.The California Environmental Protection Agency has listed acetaldehyde as a substanceknown to cause cancer (6).Threshold Limit Value (working environment) for acetaldehyde is 25 ppm (45 mg m-3)in USA.Max. allowable industrial contribution value for air (B-værdi) for acetaldehyde is 0.02mg m-3in Denmark.

8

EVALUATIONThe toxicological information on acetaldehyde indicates that acetaldehyde is possiblyone of the important toxic compounds in tobacco smoke, and possibly also acarcinogen. Acetaldehyde is not added to tobacco, but appears as a pyrolysis productprimarily from the tobacco itself and from many common additives, such assaccharides. Studies on sugars and tobacco smoke composition reveal that there is astrong relationship between the type of sugar added to tobacco and the yield ofacetaldehyde. This means that addition of sugars to tobacco might have significanteffect on the toxicity of cigarette smoke. In self-administering studies in rats it wasshown that rats tend to administer more nicotine when acetaldehyde was present indrinking water than nicotine alone. It is possible that acetaldehyde plays a central role intobacco addiction.

B-6

DHI

9

CONCLUSIONAcetaldehyde is possibly one of the most important toxic compounds in tobacco smoke.Experimental data suggest that there is a relationship between the type of sugars addedand the acetaldehyde yield, meaning that some sugars added to tobacco leads toincreased acetaldehyde yield, and others do not. There is experimental data suggestingthat acetaldehyde might play a role in tobacco addiction.

10

REFERENCE S

1.Appelman, L. M., R. A. Woutersen, and V. J. Feron.1982. Inhalation toxicity of acetal-dehyde in rats. I. Acute and subacute studies. Toxicology23:293-307.2.Baker, R. R., S. Coburn, C. Liu, and J. Tetteh.2005. Pyrolysis of saccharide tobaccoingredients: a TGA-FTIR investigation. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis74:171-180.3.Baker, R. R., E. D. Massey, and G. Smith.2004. An overview of the effects of tobaccoingredients on smoke chemistry and toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol.42 Suppl:S53-S83.4.Belluzzi, J. D., R. Wang, and F. M. Leslie.2005. Acetaldehyde enhances acquisition ofnicotine self-administration in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology30:705-712.5.Bostrom, C. E., J. Almen, B. Steen, and R. Westerholm.1994. Human exposure to ur-ban air pollution. Environ. Health Perspect.102 Suppl 4:39-47.6. California Environmental Protection Agency. Chemicals known to the state to cause canceror reproductive toxicity december 19 2008.www.oehha.ca.gov. 19-12-2008. 20-4-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation7.Carmines, E. L., R. Lemus, and C. L. Gaworski.2005. Toxicologic evaluation of lico-rice extract as a cigarette ingredient. Food Chem. Toxicol.43:1303-1322.8. Charles, J. L., V. J. Denoble, and P. C. Mele. Behavioral Pharmacology Annual Report.1983. Ref Type: Report9. ChemID. acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde . 22-4-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation10. ChemIDplus Advanced. Acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde . 2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation11.Gosselin, R. E., R. P. Smith, and H. C. Hodge.1984. Clinical Toxicology of CommercialProducts. Baltimore.12.Grant, W. M. and J. S. Schuman.1993. Toxicology of the eye. Charles C Thomas,Springfield.

B-7

DHI

13.Hecht, S. S.2006. Cigarette smoking: cancer risks, carcinogens, and mechanisms. Langen-becks Arch. Surg.391:603-613.14.Homann, N., P. Karkkainen, T. Koivisto, T. Nosova, K. Jokelainen, and M. Salaspuro.1997. Effects of acetaldehyde on cell regeneration and differentiation of the upper gastroin-testinal tract mucosa. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.89:1692-1697.15. HSDB. acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde . 5-3-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation16. IARC. IARC Monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risk of chemicals to hu-mans. (71,2), 319-335. 1999.Ref Type: Serial (Book,Monograph)17.Kruysse, A., V. J. Feron, and H. P. Til.1975. Repeated exposure to acetaldehyde vapor.Studies in Syrian golden hamsters. Arch. Environ. Health30:449-452.18.Lambert, B., B. Andersson, T. Bastlova, S. M. Hou, D. Hellgren, and A. Kolman.1994. Mutations induced in the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase gene by three ur-ban air pollutants: acetaldehyde, benzo[a]pyrene diolepoxide, and ethylene oxide. Environ.Health Perspect.102 Suppl 4:135-138.19.Lewis, A., J. H. Miller, and R. A. Lea.2007. Monoamine oxidase and tobacco depend-ence. Neurotoxicology28:182-195.20.Moir, D., W. S. Rickert, G. Levasseur, Y. Larose, R. Maertens, P. White, and S. Des-jardins.2008. A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco ciga-rette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chem. Res. Toxicol.21:494-502.21.Seeman, J. I., M. Dixon, and H. J. Haussmann.2002. Acetaldehyde in mainstream to-bacco smoke: formation and occurrence in smoke and bioavailability in the smoker. Chem.Res. Toxicol.15:1331-1350.22.Singh, N. P. and A. Khan.1995. Acetaldehyde: genotoxicity and cytotoxicity in humanlymphocytes. Mutat. Res.337:9-17.23.Smith, C. J., T. A. Perfetti, R. Garg, and C. Hansch.2003. IARC carcinogens reportedin cigarette mainstream smoke and their calculated log P values. Food Chem. Toxicol.41:807-817.24.Stavanja, M. S., P. H. Ayres, D. R. Meckley, E. R. Bombick, M. F. Borgerding, M. J.Morton, C. D. Garner, D. H. Pence, and J. E. Swauger.2006. Safety assessment of highfructose corn syrup (HFCS) as an ingredient added to cigarette tobacco. Exp. Toxicol.Pathol.57:267-281.25.Steinhagen, W. H. and C. S. Barrow.1984. Sensory irritation structure-activity study ofinhaled aldehydes in B6C3F1 and Swiss-Webster mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.72:495-503.

B-8

DHI

26.Talhout, R., A. Opperhuizen, and J. G. van Amsterdam.2007. Role of acetaldehyde intobacco smoke addiction. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.17:627-636.27. WHO. Environmental Health criteria 167: Acetaldehyde. 1995.Ref Type: Data File28.Wilkin, J. K. and G. Fortner.1985. Cutaneous vascular sensitivity to lower aliphatic al-cohols and aldehydes in Orientals. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res.9:522-525.29.Woutersen, R. A., L. M. Appelman, A. Van Garderen-Hoetmer, and V. J. Feron.1986. Inhalation toxicity of acetaldehyde in rats. III. Carcinogenicity study. Toxicology41:213-231.

B-9

DHI

Toxicological profile ofBenzyl alcohol

SEPTEMBER 200

Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse

CONTENTS

1234566.16.1.16.1.26.1.36.26.2.16.36.46.56.66.777.17.28910

INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1IDENTIFICATION.......................................................................................................... 1USE AND OCCURRENCE ............................................................................................ 1PHYSICAL/CHEMICAL PROPERTIES ......................................................................... 2BIOTRANSFORMATON AND TOXICOKINETICS ........................................................ 2HEALTH EFFECTS....................................................................................................... 2Single exposure toxicity................................................................................................. 2Acute toxicity ................................................................................................................. 2Irritation/Corrosion......................................................................................................... 3Allergy ........................................................................................................................... 3Repeated exposure toxicity ........................................................................................... 3General ......................................................................................................................... 3Cytotoxicity.................................................................................................................... 4Genotoxicity .................................................................................................................. 4Carcinogenicity ............................................................................................................. 4Reproduction toxicity ..................................................................................................... 4Addiction ....................................................................................................................... 4REGULATORY INFORMATION.................................................................................... 4Environment .................................................................................................................. 5Classification and Health ............................................................................................... 5EVALUATION ............................................................................................................... 5CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................. 5REFERENCE LIST ....................................................................................................... 6

DHI

1

INTRODUCTIONThe purpose of the present toxicological profile for benzyl alcohol is to reveal the poss-ible health effects on smokers by the presence of benzyl alcohol in tobacco smoke. Thesearch profile used was: benzyl alcohol, CAS no 100-51-6, oncogen, tumor, neoplasm,carcinogen, addiction, and dependence.The profile has been compiled on searches in thefollowing databases: ESIS, AtsDR, IRIS, IARC, InChem, DOSE, ChemID plus, HSDB,STN, and Toxline.

2

IDENTIFICATIONChemical NameSynonyms

Benzyl alcoholBenzenemethanol, Phenyl-methanol, Phenylcarbinol, Phenyl-methyl Alcohol100-51-6202-859-9C7-H8-O

CAS No.EINECS/ELINCS No.Molecular formula

Structure

3

USE AND OCCURRENCEBenzyl alcohol occurs naturally in fruits, essential oils, e.g. jasmine, and in tobacco (3).Benzyl alcohol has a pleasantly sweet and fruity odour (3). Benzyl alcohol is used incosmetics, as flavour and preservative (24). Also, it is used in the manufacture of otherbenzyl compounds, and as a pharmaceutical aid (9). Quantity not exceed (QNE) in to-bacco is reported to be 0,015% (21).

C-1

DHI

4

PHYSICAL/CHEMICAL PROPERTIESThe substance is identified as given in the following table:Physical stateMolecular weightMelting pointBoiling pointVapour pressureDensityWater solubilityLog P octanol/waterOther data

Liquid (8)108 g/mol (24)-15.3oC (7)205.3oC (6)0.094 mm Hg (25oC) (24)1.0419 (16oC) (24)4.29E+04 mg/l (25oC) (5)Log Pow = 1.1(10)Faint aromatic odour, sharp burningtaste(24)Benzyl alcohol will transfer 95% intactto smoke, during pyrolysis (2).

5

BIOTRANSFORMATON AND TOXICOKINETICSBenzyl alcohol is oxidised in the liver by the enzyme alcoholdehydrogenase (ADH) tobenzaldehyde, which is oxidized to benzoic acid. Benzoic acid conjugates with the ami-noacid glycine to form hippuric acid, which is excreted by the kidneys. Transformationand excretion is relatively fast. Within 6 hours from oral intake of benzyl alcohol, 75-100% is found in the urine as hippuric acid (24). It can be calculated that smokers areexposed to 0.05 mg benzyl alcohol per kg bw per day when smoking 20 cigarettes perday.

66.16.1.1

HEALTH EFFECTSSingle exposure toxicityAcute toxicityRoute of exposureInhalationInhalationSpeciesRatsRatsLD50 / LC50>4178 (4h)(LC50)4417 (1000ppm) (8h)(LCLo)1230- 3200(LD50)1580 (LD50)1360 (LD50)1)2)

OralOralOral

RatsMouseMouse

Notes(NOEC, No observedEffect Concentration)(LCLo, Lowest Con-centration were deathwere observed)(four studies referredin Nair, 2001)

Reference(25)(18)

(24)(24)(17)

C-2

DHI

Route of exposureOralDermalIntravenousintraperitonealIntraperitoneal1)2)

SpeciesRabbitCatMouseMouseRats

LD50 / LC501040 (LD50)10000 (LDLo)324 (LD50)650 (LD50)400 (LD50)

1)

2)

Notes

-

Reference(16)(15)(14)(13)(11)

LD50 (mg/kg bw): Lethal dose to half of the animals.LC50 (mg/m3air): Concentration in air lethal to half of the animals after 4 hours exposure

6.1.2

Irritation/CorrosionSkinUndiluted benzyl alcohol was moderately irritating when applied to the depilated skinof guinea pigs for 24 hours (1). Benzyl alcohol has demonstrated a maximum incidenceof sensitization of 1% of humans tested in patch testing (25).Eyes2% benzyl alcohol in saline water, 0.9% sodium chloride, applied to the eyes of rabbits,caused injury of endothelium, with severe bluish swelling of the cornea. Also, the irisesbecame hyperemic and had poorly reactive pupils(20).InhalationAccording to Lewis, Benzyl alcohol is moderately toxic by inhalation (23). In aninhalation study no mortality was seen at 4000 mg/m3/4h (25).Effects on nervous systemIn human pain studies, benzyl alcohol was an effective local anaesthetic (24). It is usedas a local anaesthetic and to reduce pain associated with lidocaine injection (4). In astudy were cat was exposed to benzyl alcohol via the dermal route tremor and muscleweakness was observed at 10000 mg/Kg body weight (12).

6.1.3

AllergyBenzyl alcohol gave both positive and negative results for sensitization in animals (25).

6.26.2.1

Repeated exposure toxicityGeneralBenzyl alcohol exhibits relatively low repeated dose toxicity (25).Route ofexposureSpeciesTime ofexposureNOAEL /2)NOAEC1)

Criticaleffects

Reference(25)

Oral

Rat

2 years

400NOAEL

Weigth gainHistopa-thologic le-sions

C-3

DHI

Route ofexposure

Species

Time ofexposure

NOAEL /2)NOAEC

1)

Criticaleffects

Reference(25)

Oral

Mouse

13 weeks 200NOAEL

Weigth gainHistopa-thologic le-sions

1.2.

NOAEL (mg/kg bw/day): No Observable Adverse Effect Level.NOAEC (mg/m3air/day): No Observable Adverse Effect Concentration.

6.3

CytotoxicityOhmiya and Nakai (26) studied the uptake of benzyl alcohol by human erythrocytes, thebinding of benzyl alcohol to celle membranes and hemolysisin vitro.The critical hemo-lytic level was estimated to 500 nmoles/mg protein.

6.4

GenotoxicityBenzyl alcohol has shown no mutagenic activity inin vitroAmes tests, and has shownno genotoxic activityin vivo(25).

6.5

CarcinogenicityNo signs of carcinogenicity has been documented in long term carcinogenicity studies(25).

6.6

Reproduction toxicityNo data found

6.7

AddictionNo data found

7

REGULATORY INFORMATIONJECFA has established an ADI at 0-5 mg/kg for benzyl compounds like benzyl alcohol,benzyl acetate, benzaldehyde and benzoic acid (22).Benzyl alcohol is included as a flavouring substance intended for use in or on foods-tuffs, by the European Community in Commission Decision 2002/113/EC (19).Reviewing a 2 year study, the EPA determined the human reference dose (RfD), forchronic oral exposure of 0.286 mg/kg/day, which was rounded to 0.3 mg/kg/day (24).

C-4

DHI

7.1

EnvironmentNo data found.

7.2

Classification and HealthBenzyl alcohol is classified as harmful (Xn; R20/22) by the European Commision.Max. allowable industrial contribution value (B-værdi) for benzyl alcohol is 0.1 mg m-3in Denmark,Companies have provisionally advised exposure limits for benzyl alcohol. USWorkplace Environmental Exposure Limit has set the limit value to 10 ppm, corres-ponding to 44 mg m-3(25).No threshold limit value in Denmark. Threshold limit value in Poland is 240 mg m-3.

8

EVALUATIONThe number of studies concerning inhalation of benzyl alcohol is very limited. The ef-fect concentrations in the few relevant studies are relatively high. The effect concentra-tion from Ohmiya and Nakai (26) is very difficult to relate to expected effects on hu-mans. Considering the small amount of benzyl alcohol added to tobacco, the relativelylow toxicity of benzyl alcohol and the general toxicity of tobacco, it is therefore eva-luated that benzyl alcohol will not increase the toxicity of tobacco significantly. Thereare no studies relating benzyl alcohol to tobacco addiction.

9

CONCLUSIONThe addition of benzyl alcohol to tobacco is not likely to affect the overall toxicity ofthe product. There is no indication that benzyl alcohol plays a role in tobacco addiction.

C-5

DHI

10

REFERENCE LIST

1. 1994. Patty´s Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. John Wiley and Sons Inc, New York.2.Baker, R. R. and L. J. Bishop.2004. The Pyrolysis of tobacco ingredients. Journal ofAnalytical and Applied Pyrolysis71:223-311.3. Brown & Williamson. Summary on data on benzyl alcohol. 1992.Ref Type: Report4. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation5. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation6. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation7. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation8. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation9. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation10. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation11. ChemID. Benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol . 1-5-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation12. ChemIDplus Advanced. Benzyl alcohol. ChemID . 10-6-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation13. ChemIDplus Advanced. Benzyl alcohol. ChemID . 10-6-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation14. ChemIDplus Advanced. Benzyl alcohol. ChemID . 10-6-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation15. ChemIDplus Advanced. Benzyl alcohol. ChemID . 10-6-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation

C-6

DHI

16. ChemIDplus Advanced. Benzyl alcohol. ChemID . 10-6-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation17. ChemIDplus Advanced. Benzyl alcohol. ChemID . 10-6-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation18. ChemIDplus Advanced. Benzyl alcohol. ChemID . 10-6-2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation19. European Commission. Commission Decision of 23 january 2002 ammending CommissionDecision 1999/217/EC as regards the register of flavouring substances used in or on food-stuffs. European Commision 2002/113/EC. 2009.Ref Type: Electronic Citation20.Grant, W. M. and J. S. Schuman.1993. Toxicology of the eye. Charles C Thomas,Springfield.21. House of Prince. Liste over indberettede tilsætningsstoffer. 2006.Ref Type: Report22. JECFA. Benzyl acetate, Benzyl alcohol, Benzaldehyde, and Benzoic acid and its salts.JECFA series 37. 1996.Ref Type: Report23.Lewis, R. J.1996. Sax´s Dangerous properties of Industrial Materials. Van Nostrand Rein-hold, New York.24.Nair, B.2001. Final report on the safety assessment of Benzyl Alcohol, Benzoic Acid, andSodium Benzoate. Int. J. Toxicol.20 Suppl 3:23-50.25. OECD. OECD Screening Information Data Set: Benzoates. 2001. UNEP Publications.Ref Type: Data File26.Ohmiya, Y. and K. Nakai.1978. Interaction of benzyl alcohol with human erythrocytes.Japanese Journal of Pharmacology28:367-373.

C-7

DHI

Toxicological profile ofCis-3-hexenol

SEPTEMBER 2009Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse

CONTENTS

1234566.16.1.16.1.26.1.36.26.2.16.36.46.56.677.17.28910