Miljø- og Planlægningsudvalget 2008-09

MPU Alm.del Bilag 676

Offentligt

TOWARDS AEUROPEAN POLICY ON SUSTAINABLE MATERIALS MANAGEMENTDiscussion note for the interparliamentary conference on 3 and 4 October 2010

1. SITUATION: THE CHALLENGEThe European economy and society depend heavily on natural resources. The demand for organicand mineral resources has risen significantly as a result of global economic growth, which, in turn,results in considerable pressure in terms of availability, price and access. The extraction andprocessing of these raw materials often have an impact on biodiversity, violate the rights ofindigenous peoples and result in the discharge of pollutants. After raw materials and materials havebeen incorporated in products or appliances they are discarded at the end of the lifecycle and enterthe waste phase. At best they are re-used, recycled or recovered, but all too often they simply endup in a landfill resulting in a waste of material and energy content.Europe also has a lot of natural resources (lime, sand, clay, gravel, biomass, and so on). These,however, are largely inadequate to supply the European economy with the necessary materials1.Often they are also difficult to access or their extraction is not economically feasible. Consequentlythe European economy remains highly dependent on the import of raw materials from otherregions. But elsewhere in the world natural resources are also declining or are concentrated inregions that are often geopolitically unstable.The EU is a global producer of certainindustrial mineralsalthough it continues to be a net importerfor most of these. The EU, however, is highly dependent on the import ofmetallic mineralsbecauseits domestic production does not amount to more than c. 3% of global production. The EU is highlydependent on the import of“high technological”materials such as cobalt, platinum, rare earthmetals and titanium. Although only very small quantities of these metals are often needed theyhave become increasingly important for the development of high-technological products in view ofthe growing number of applications.2In the last decades there was a relative decoupling between global economic growth and the globaluse of resources3. Between 1980 and 2005 the global economy’s raw material intensity dropped by

1

Antonio Tajani, European Commissioner for Industry, recently published a report (MEMO/10/263) on the

prospect of scarcity of 14 critical raw materials for the EU.2

MEMO/10/263 (see footnote 1)Calculations based on Giljum, S., Lutz, C., Jungnitz, A., Bruckner, M., Hinterberger, F. 2008. Global

3

dimensions of European natural resource use. First results from the Global Resource Accounting Model (GRAM).SERI Working Paper 7, Sustainable Europe, Research Institute, Vienna.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

2

25%. But the improvement in terms of eco-efficiency was insufficient to reduce the consumption ofresources in absolute terms. In that same period Gross World Product doubled and raw materialconsumption rose by nearly 50%.The European economy became very vulnerable due to its strong dependence on a number ofcritical raw materials. It is clear that our economy is heading towards a hard and shockingconfrontation with sudden problems in terms of supply in a business-as-usual scenario. This doesnot only apply to different mineral resources but also to biomass. Renewable raw materials arescarcely used in the European industry, e.g., in the wood and chemical processing sectors, as aresult of the limited available surface area for cultivation and in some cases due to potentiallycompeting applications.National and EU policy on renewable raw materials has a strong impact on industrial users. To thisend the Commission will check the impact of the rise in demand for biomass on sectors that usebiomass.4A UNECE-FAO study predicts a timber shortage of 448 million m� by 2020 in theEuropean Union. This means that if policy remains unchanged the EU will have to import more thanhalf of its own timber production by then.5The question thus rises how we can prevent a rapid depletion of our finite raw material supplies ina world with a growing world population and an economy that continuously grows. How we can usethe available raw materials in the most judicious way possible in order to be able to respondmaximally to the population's legitimate needs. How we can limit the environment impact to suchan extent as we extract, process, produce, use and discard raw materials/materials/products inorder not to exceed the capacity of ecosystems.The answer to these challenges lies in a sustainable management of raw materials and materialsand in a sustainable product policy. The design, production, use and processing phases of ourproducts all have to focus on a more economical use of primary raw materials and energy and onthe replacement of non-renewable raw materials with sustainably produced renewable rawmaterials. In addition the further development of a service-based society can ensure that moresocial needs are alleviated with the use of fewer products. This entails (repair) and re-use systems,the leasing or renting of products, the sale of services and so on.

2. EUROPE IS WELL PLACED TO TAKE THE LEADThe European Union is well placed to play a pioneering role and show global leadership in theframe of sustainable materials management and in sustainable product policy.

4

The Raw Materials Initiative – meeting our critical needs for growth and employment in Europe

COM(2008)699 (Nov 2008)5

ENECE-FAO, Forest Products Annual Market Review, Geneva Timber and Forest Study Paper 22, 2007.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

3

Firstly because Europe only has a limited amount of own raw materials and thus is (too) heavilydependent on supplies that are becoming increasingly scarce and which often have to be importedfrom geopolitically instable regions. A continuing big dependence of such supplies will weaken theEuropean economy’s position considerably and will result in a competitive disadvantage comparedwith continents or regions that do have their own supplies.Secondly because the European economy still is the biggest economic market in the worldeconomy. This means that Europe can set the tone for the rest of the world. European productsnorms also force foreign manufacturers to adapt their product design should they wish to export toEurope. As a result European policy has a broad impact.Thirdly as one of the most prosperous regions worldwide the European Union has the moralobligation to develop those products and processes that can be generalised at global level andwhich can create and regenerate prosperity now and in the future, here and elsewhere. Ourecological footprint which we leave elsewhere in the world has also decreased as a result of thedevelopment of sustainable products and processes. Sustainable products in closed material cyclesreduce our share in the environmental degradation and social disruption which is often associatedwith the extraction of raw materials and the export of waste flows in/to the rest of the world.Fourthly, a sustainable materials policy is a necessary complement to European waste, energy andclimate policy. Without a sustainable materials policy waste policy and energy and climate policywill generate suboptimal solutions. The European promotion of renewable energy thus results inthe withdrawal of biomass flows from the recycling process (e.g., particle board industry, paperrecycling, compost production), while these can, in effect, make a greater contribution to reducingCO2 emissions in the production phase or to increased carbon storage. Conversely the replacementof primary raw materials with secondary raw materials can save a lot of energy and CO2 in theproduction of new materials and thus result in an important contribution to European ambitions asregards the reduction of CO2 emissions6. Without a complementary materials and products policyEuropean waste policy may possibly be deficient in terms of separating waste flows into high-quality secondary raw materials and in supplying these to the European recycling industry. Toomany products or materials flows tend to escape the European market or are so polluted or mixedthat they can only be recycled in sub-standard applications (downcycling) or that an energeticvalorisation is necessary. Injudiciously introduced material recycling objectives in waste policy, onthe other hand, can slow down the development of lighter and more fuel-efficient cars, which inturn can have an impact on sustainable product policy. This shows that only an integrated policy interms of raw materials, materials, products, waste, energy and climate can prevent internal

6

The extraction of metals from ores, for example, requires the use of a lot of primary energy, which

contributes to greenhouse gas emissions whereas the re-melting of recovered metals requires considerably lessenergy. The Report on the Environmental Benefits of Recycling (Bureau of International Recycling (BIR),October 2008) shows that the recycling of certain metals in comparison with their primary extraction is muchmore CO2-friendly with a reduction of CO2 emissions which varies between 58% and 99%.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

4

contradictions and ensure that the various policy areas can reinforce instead of oppose oneanother.A well-considered raw materials, materials, and product policy is the missing complement in thisframe. The subject is highly topical; in the frame of the Belgian EU Presidency (2010) the subjectof sustainable materials management is one of the four priorities in terms of the environment. Mid-July 2010 the subject will be on the agenda of the informal meeting of Environment Ministers (inGhent) and it is also the subject of this interparliamentary environment conference.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

5

3. THEFIRSTEUROPEAN ANSWERS ARE INSUFFICIENT3.1.

Policy answers: a first attempt

The European Union chose not to rest on its laurels. With the EU Raw Materials Initiative7 the EU(1) attempted to develop a strategy in order to arrive at fair, non-discriminatory access tointernational supplies, (2) to create a frame for the sustainable extraction of its own supplies and(3) to arrive at a more efficient use of materials and extensive recycling in the EU.European waste policy – which is enshrined in the European Waste Framework Directive8and inseveral individual waste directives9- is largely based on the waste management hierarchy and theprinciple of extended producer responsibility. The waste management hierarchy prefers to preventwaste, then focuses on its re-use, above recycling and recovery. Waste disposal (landfill orincineration without or with limited energy yield) is only the last option. Through the introduction of(extended) producer responsibility and acceptance obligations the manufacturers of e.g., electricand electronic equipment, of vehicles, packaging or car tires are responsible for the environment-friendly management of their products once they are discarded and end up in the waste stage.Certain objectives in terms of re-use, recycling and recovery need to be achieved, possibly dividedby materials group. The Waste Framework Directive also stipulates when priority waste flows(granulates, paper, glass, metal, tires and textile) can be qualified as “end waste” or “by-product’,which in turn should facilitate their reinsertion in a production process.Next to this the European Union also developed a Thematic Strategy on the Prevention andRecycling of Waste10and a Thematic Strategy on the Sustainable Use of Natural Resources11whichare important for sustainable materials management policy.The European Union is also trying to work towards an Integrated Product Policy12which attempts tominimise the environmental impact of products throughout their entire lifecycle. The Europeanpolicy in this regard is based on five basic principles: (1) reflection on the lifecycle, (2) cooperation

7

EU Raw Materials Initiative — meeting our critical needs for growth and jobs in Europe. COM (2008) 699.Waste Framework Directive, 2008/98/EC.Like the ELV Directive (2000/53/EC), the Directive on Waste Electrical and Electronical Equipment (WEEE)

8

9

(2002/96/EC) and the Packaging Directive (94/62/EC).10

EU Thematic Strategy on the Prevention and Recycling of Waste, COM (2005) 666.EU Thematic Strategy on the sustainable use of natural resources, COM (2005) 670.Integrated product policy, Building on environmental lifecycle thinking, Commission of the European

11

12

Commission to the Council and the European Parliament, COM (2003) 302.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

6

with the market, (3) the involvement of all stakeholders, (4) permanent improvement and (5) adiverse range of policy tools.The European Commission has created a framework for setting out community regulations asregards the ecological design of energy-related products with the European Ecodesign Directive13.Energy-related products which fall under the implementation measures of this Directive will have tocomply with certain regulations in order to be launched to market and/or be used. In order toassess when implementation measures need to be drawn up for certain products significantenvironment aspects and the improvement potential throughout the various stages of the lifecycleare, among others, taken into account. For each of these stages, among others, the predicted useof materials, energy and other resources is assessed as well as the expected production of wasteand the potential for reuse, recycling and recovery of materials and/or energy. The specificrequirements in terms of ecological design may take the form of requirements in term of a lowerconsumption of a given resource, such as limits for the use of this resource in the various stages ofthe product's lifecycle, where applicable (e.g., limits for the quantities of a given material which areincorporated in the product or minimum required quantities of recycled material).Finally the European Union also wishes to arrive at a sustainable procurement policy forgovernments.3.2.

Policy answers: shortcomings

Up until now the outlined policy initiatives have contributed to increasing the European economy’seco-efficiency. They were not able to prevent the increase in absolute terms of raw materialconsumption. The effectiveness of this policy still leaves something to be desired. It is also obviousthat “solutions-as-usual” are not sufficient.The policy is lacking for several reasons:

•

•

•

The Eco‐Design Directive and Integrated Product Policy are hampered far too much by avoluntary and permissive approach. The elaboration of concrete standards is trapped in aComitology, whereby representatives of the Member States and of the industry often drifttowards the lowest common denominator of what is deemed feasible‐also by the stragglers‐in their ambition to arrive at a consensus. This does not result in a forerunner policy, whichcould serve as an incentive for the entire industry; nor does it stimulate innovation.The producer’s responsibilities and acceptance obligations which are introduced in numerouswaste directives are being undermined by the "pooling" of products in collective collectionand processing systems, which are being set up by collective waste managementorganisations. The potential of “design for reuse” or of “design for recycling” of products ofpioneers is thus not fully exploited.In spite of the acceptance obligation for several products it is impossible to close materialscycles because many discarded products are exported to countries outside of the EU,

13

Directive 2009/125/EG of the European Parliament and the Council establishing a framework for the setting

of ecodesign requirements for energy-related products.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

7

•

•

•

sometimes as second‐hand products. Often the Basel Convention on the Control ofTransboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal is violated with theexport of electric and electronic equipment or discarded vehicles. In the frame of the IMPEL‐TSF Project (EU Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law‐cluster on Transfrontier Shipments of Waste) random checks were carried out on 10,481road and port transports between October 2008 and May 2009 in 22 European MemberStates and four non‐EU European countries. Nineteen percent of these transports violatedthe European Directives for transfrontier shipments of waste. 37% of these were illegaltransports and 46% administrative offenses. Moreover Western waste is often processed indeveloping countries with little or no personal protective equipment or measures forcontrolling environmental pollution.Too many mixed waste flows, which are difficult to separate, or the presence of too manyimpurities means that opportunities are missed to recycle these materials again in fullyclosed cycles. In practice recycling often means downcycling in sub‐standard applications. Asa result the recycling objectives of the waste directives are achieved in a suboptimal manner.Next to this sorted recyclates are often exported abroad to be recycled in an inferior manner.European waste policy provides for a range of recyclates but these are often not suited oravailable to European manufacturers and processors of raw materials.Under European waste policy many recyclable materials are lost because of the lack of(ambitious) specific material recycling goals in the “recovery” objectives. As a result, e.g., inthe case of plastics, manufacturers and processors often quickly opt for energeticvalorisation meaning the material content of the materials is lost. This in spite of the fact thatyou can save more energy by recycling (process energy in the production of “virginmaterials”) than you can reprocess in the frame of energy recovery. The choice for energeticvalorisation in favour of material recovery is underscored by the fact that the EuropeanWaste Framework Directive opens the borders for the recovery of industrial waste. In view ofthe fact that incineration in conventional incinerators will probably be considered as“recovery” and of the current overcapacity of incinerators in the Netherlands and Germanyincinerators may impose dumping tariffs thus hiving off recyclable flows from recycling(plastics, paper, cardboard and so on).Finally the European Energy and Climate Package – and more specifically the Directive onRenewable Energy (2009/28/EG)‐results in a magnet effect on biomass flows in favour ofenergetic valorisation and to the disadvantage of material recovery (particle boards, paperand cardboard, compost, and so on).

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

8

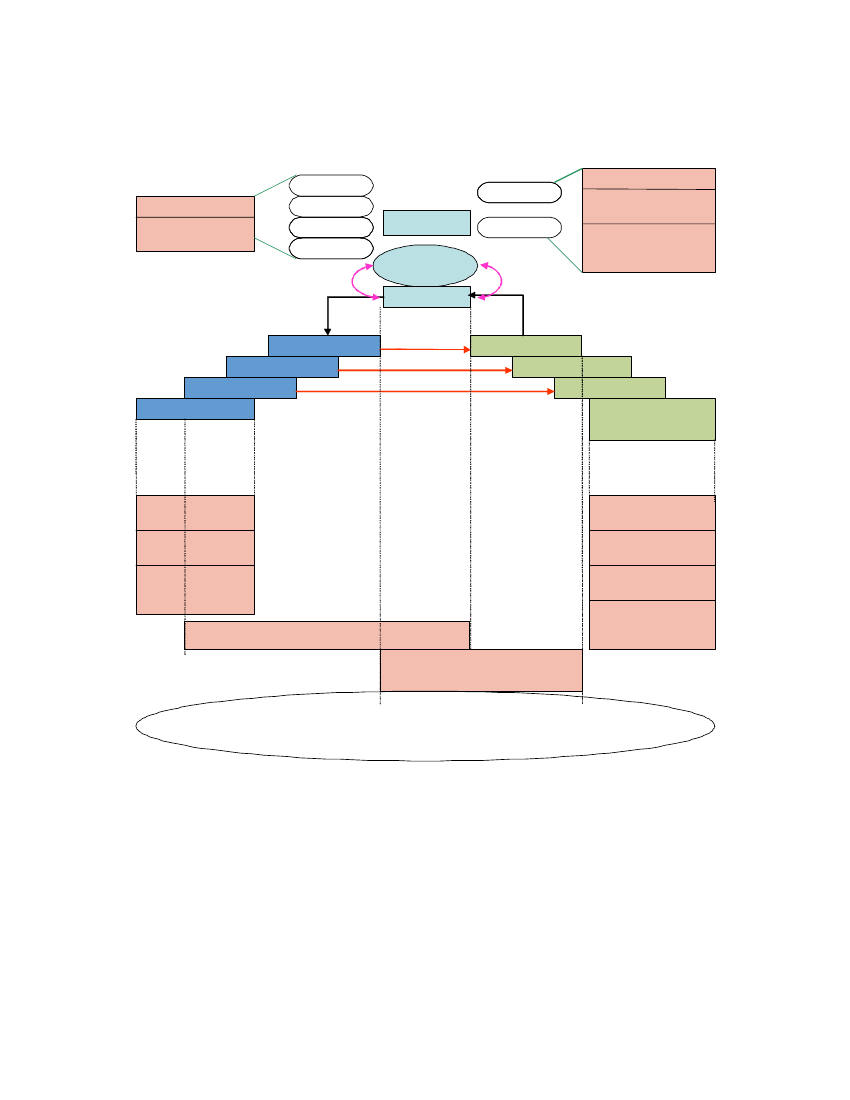

4. RECOMMENDATIONSIn spite of the various efforts made European policy so far has not succeeded in directing materialuse within the Union in such a way that natural resources within and outside of the Union aresaved and that the negative impact on air, water, climate and soil quality is reduced in such a waythat public health is safeguarded and the capacity of ecosystems respected.So far the emphasis in European policy was too much on the waste phase, whereby policyexamined reactively - using an end-of-the-pipe approach – how waste problems could be managed.Attention only gradually shifted towards more process-integrated measures and finally to productdesign.In order to limit the negative environment impact of material use in the frame of sustainablematerials management and to maintain the natural material content throughout the lifecycles ofproducts or services as much as possible, it will be necessary to focus more on sustainablematerials extraction, ecological product design, eco-efficient production, sustainable consumptionand waste management based on a lifecycle approach.A more prudent and responsible use of the available raw materials, a better closure of materialcycles and a replacement of finite raw materials with renewable raw materials requires thedevelopment of complimentary policy. The familiar instruments of European waste policy will haveto be implemented better and broader and be completed with measures in the raw materialextraction, design and production phases. The emphasis has to shift from waste policy to materialspolicy. The waste management hierarchy (prevention > reuse > material recycling > energyrecovery > landfill) has to be completed with a material management hierarchy which indicateshow materials have to be incorporated in design and production (prevention > reuse >recyclate/secondary raw materials > renewable primary raw materials > non-renewable primaryraw materials) (see figure annex 1).Based on this approach we have the following recommendations for European policy-makers:4.1.

Evaluation and adjustment of existing acceptance obligations and extension to

other product categories

Existing acceptance obligations have to be evaluated and adjusted with a view to the introductionof ambitious material-specific recycling objectives, which include quantitative and qualitativerequirements for the produced recyclates. In addition it is also necessary to investigate to whichextent the levelling that takes place in the “pool” of collectively gathered products can beprevented. This is possible, among others, through the introduction of forms of “individual”acceptance obligations or by differentiating the disposal contribution to the collective wastemanagement organisations in function of demountability and recyclability.Specifically it is necessary to examine how the instrument of the acceptance obligation can signifya specific trigger for ecodesign (whereby material-efficient design is rewarded).In order to prevent the collection of large appliances/products from taking precedence over that ofsmaller appliances collection goals can be introduced per sub group. In the case of discarded

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

9

products with valuable materials, which escape the European market beforeprocessing guarantee systems may be considered to guarantee their return.

dismantling or

It should also be investigated for which other product categories - such as carpets, mattresses,furniture, textiles or building materials - it might be interesting to enforce the acceptanceobligation and to impose specific collection objectives and norms in terms of prevention, reuse,recycling and useful applications.4.2.

Introduction of product norms that promote recycling

An important bottleneck continues to be the use of too many different types of materials that aredifficult to separate or additives that complicate recycling. In the frame of the Eco-Design Directiveor the Waste Directives for specific product categories product norms need to be created whichresult in products with a (more) limited number of components, of which the materials are easierto separate and whereby impurities are avoided, which are an obstacle for qualitative recycling(“upcycling”) in the same or other high-quality applications.In the case of new components in new products it is also possible to impose that these have to bemanufactured using (a minimum share of) recyclates or renewable raw materials. In this way amarket for qualitative recyclates is created, which prevents waste or recyclates from being appliedoutside of Europe. In non-OECD countries often only a limited share is recycled, meaning valuableresidual fractions are lost. Moreover these recycling processes often offer much lower protection interms of the environment and health than in Europe.4.3.

Introduction of certificates or guarantees of origin for recyclates and

renewable raw materials

It is also recommended to investigate to which extent a market can be created within the EuropeanUnionforsecondaryandrenewablerawmaterialsbyimposingthatmaterialmanufacturers/suppliers have to source a given percentage of the materials that they market fromrecyclates and/or renewable raw materials. It would be possible, by analogy with the guarantees oforigin in terms of renewable electricity, to impose, for example, that the producers of recyclatesand renewable raw materials issue “recycling certificates” or “guarantees of origin”, which can bebought by material manufacturers to meet their objectives. The often suboptimal preferentialapplication of biomass flows in the energy industry can be countered with minimal objectives interms of renewable raw materials (and the associated guarantees of origin).4.4.

Prevent illegal leakage currents of waste to the Third World

Today many waste products do not end up in the regular recycling channels, meaning valuablesecondary raw materials are often irrevocably lost. There are indications that a significantpercentage of all EU waste shipments does not comply with regulations although the situationvaries considerably in the Member States. A targeted examination of these shipments in 2006revealed that more than 50% of all EU waste shipments does not comply with regulations and thatthere are irregularities for 43% of all shipments. This mainly applies to the export of discardedvehicles and electronic equipment, which leave Europe as reusable products but end up being

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

10

dismantled abroad. Moreover the Member States interpret the classification of waste for shipmentin different ways which results in obstacles for the internal scrap market and thus in tradedistortions. This is all the more regrettable because the physical transport of exported wasteproducts and imported raw materials (from recycling outside of the EU according to less stringentconditions) result in considerable environmental leakage.14Europe needs to thoroughly tackle the illegal export of waste by setting up a more effective control.To this end the Member States and the relevant departments need to work together more closely.A uniform definition is also necessary of which products are classified as waste and which productsneed to be considered as second-hand products. Europe needs to encourage R&D into standardisedtesting for verifying the residual operation of discarded electric and electronic appliances (e.g.,Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) chips).At international level Europe needs to advocate global standards in terms of waste collection andrecycling aimed at reaching a high level of environment and public health protection and aminimum quality of secondary raw materials.4.5.

Clear definitions for “end waste” and “by-product” in the Waste Framework

Directive

A correct and uniform interpretation of the notion of “end waste” and “by-product” in the frame ofthe European Waste Framework Directive in combination with adequate control should promote theenvironment-friendly recycling of secondary raw materials.Since the introduction of the REACH Regulation15some industries prefer to not label potential'secondary raw materials' as such but instead to label them as waste. In so doing these flows areno longer subject to the rules of the Regulation as waste is not covered under this Regulation.

A more judicious use of biomass in the energy sector

The increased demand for biomass for energy purposes leads to a degradation of biodiversity andfood safety and results in a reduced availability of biomass for the wood-processing industry andfor the recycling industry (particle board industry, paper and cardboard industry and so on).The question rises whether we can produce/mobilise sufficient biomass and keep it in a closed cyclefor food supply, energy supply and use as raw material in industry with the highest possiblecontribution to the preservation of biodiversity and to the limitation of climate change (carbon14

The Raw Materials Initiative – providing for our critical needs in terms of growth and employment in Europe

COM(2008)699 (Nov 2008)15

REACH (Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of CHemicals) is a system for registering, evaluating and

authorising chemicals that are produced or imported in the EU. The Regulation (Regulation no. 1907/2006)dates from 18 December 2006, and became applicable on 1 June 2007.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

11

sequestration) and the smallest possible impact on the environment (water use, soil erosion and soon). This requires the production/mobilisation of biomass within a clear sustainability framework.Under Directive 2009/28/EG a number of sustainability criteria have been listed for biofuels andbioliquids16. Biofuels are increasingly popular since the Directive for the promotion of the use ofenergy from renewable sources (2009/28/EG).The objectives that have been set amount to aminimum share of 10% renewable energy in transport.In the long term sustainability conditions will also have to become applicable to other (stationary)forms of bio energy and will not be limited to the one application of biomass into biofuels. Thisgives rise to indirect effects and shifts. Ultimately sustainability criteria should be applicable for allbiomass-based products. This should be addressed at European - and preferably at global - level.17In addition Europe has to work towards the development and use of second and third generation(delete fourth generation) biofuels and it should also impose high energy efficiencies for the use ofbiofuels in the energy sector in order to avoid the waste of biomass. The co-firing of biomass incoal plants with low energy efficiency also has to be excluded. Often the compensation for “greenpower” from co-firing helps maintain such climate-damaging plants from an economic point ofview. Finally the energetic valorisation from biomass flows, which are eligible for use as rawmaterial or for material recovery has to be excluded, especially if there is an effective demand forit.4.7.

Knowledge building, research and development

Europe has to focus on innovation in all the stages of the lifecycle in order to come closer tosustainable materials management and integrated product policy.

•

•

Europe can establish an expertise centre on closing material cycles, whereby primary andsecondary raw material flows in Europe are mapped, including the import and export flowsand the leakage currents, as well as sustainable techniques in terms of mining, processing,production, use, collection, dismantling and recycling. Europe has to work on establishingbest practices, manuals, knowledge exchange forums and support mechanisms.Europe has to stimulate R&D in terms of ecodesign, eco‐efficient production processes,separation and recycling technologies, new application areas for recyclates and concepts ofproduct services.

16

Directive 2009/28/EG was published on 5 June 2009 and became applicable on 25 June 2010. From this date

Member States have 1.5 years to transpose this directive into legislation. In practice the directive will thusbecome applicable from autumn 2010.17

On the occasion of the review of the Directive (2014) the remaining gaps in the sustainability frame need to

be addressed thoroughly and preferably in the short term (before 2014). It is important that the Commissionrealises this in an open and transparent process, in which the stakeholders are involved.

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

12

•

•

Europe has to encourage research into the consequences of the processing of nanoparticlesand micro‐electronics on the recyclability of materials and the health of employees in therecycling industry.Europe has to encourage R&D into the development of biomass for energy use, which doesnot compete with applications in the food industry or for the production of other rawmaterials.Stimulation of product services systems

Product services systems ensure that products can be used several times by multiple users withoutthem having to own the product in question. The development of a service economy will ensurethat consumers no longer have to buy expensive equipment which they only need to use for ashort period of time to meet their needs (e.g., copying services, car sharing, gardening, laundryand ironing services and so on). Thanks to lease and rental services manufacturers also remainthe owners of their products so that they can be encouraged to develop economic products that areeasy to repair, dismantle and recycle with a long lifecycle. This also results in a more efficient useof materials, products and energy to deal with these same needs. The European Union canencourage this by reducing VAT on services for the repair, lease or rental of products or by raisingthe guarantees that manufacturers have to give for the products that they market.In a B2B environment leasing formulas (e.g., chemical leasing, floor covering and so on) can alsogive rise to win-win situations. On the one hand it can mean that the manufacturer candifferentiate himself from the competition by offering a higher service level to the customer andthus can generate higher margins than from the mere sale of the product. On the other hand it isno longer in the manufacturer’s interest to sell as many products as possible. Instead the aimshould be to supply the best possible service with the fewest possible products or with a productthat easy to reuse or recycle, in view of the fact that the manufacturer is the owner and will haveto bear any potential costs for the product’s final processing.4.9.

Encouraging a sustainable purchasing policy

The European Union can encourage all the governments to implement a sustainable procurementpolicy, in which priority is given in specifications for public procurement to products and servicesthat tie in with sustainable materials management (products with a cradle to cradle certificate,secondary raw materials and so on).Examples from the Netherlands indicate that the government can not only take into accountecological but also social criteria for the procurement policy for goods and services. Thegovernment can influence the supply side as well as citizens as users with a well-considered policy.

Stimulation of landfill mining (Enhanced Landfill Mining, ELFM)

Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM) is the integrated valorisation of materials and energy from landfillsthrough the maximum recycling of materials and the conversion of the energy potential of the

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

13

recycling residue into renewable electricity and heat. EFLM can be seen as part of Enhanced WasteManagement. EFLM can be applied for the mining of historic landfills – especially when these posea threat to the environment – and as a strategy for the temporary storage of waste in anticipationof better material and energy recovery in the future. A valorisation as Waste-to-Product (WtP) oras Waste-to-Energy (WtE) will depend on the composition of waste flows and the availabletechnologies in terms of energy production and material recovery. EFLM technology is continuouslyevolving18and requires attention for technological thresholds as well as for non-technical barriers(legislation that has not been adjusted, social acceptance of secondary raw materials).Technological breakthroughs among others are required in the field of new separation technologies(for complex, outdated, reacted, heterogeneous material flows) and gas plasma techniques (togenerate electricity and heat from the resides that does not have to be converted into secondaryraw material).

18

EFRO project: 475 Knowledge valorisation – Clean Tech, Closing the Circle, a demonstration of Enhanced

Landfill Mining (EFLM) in a 15 Mton landfill in Houthalen-Helchteren (by the consortium REMO Milieubeheer andGroep Machiels, VITO, KULeuven, UHasselt, LRM, OVAM)

Discussion note on sustainable materials management

14

Annex. The materials management hierarchy: mirrors the waste management hierarchy

Share/ leasingtaxeson labourRe-use center2ndhandrepairVAT on repair/leasingservices

VAT on ecolabel productsecodesign

PRODUCTRE-USEPRODUCT

Public procurementEcolabelBest practice programs forDesign for re-useDesign for recyclingGuarantee regulation

durability

Material recyclingfeedstockEnergy-recoveryWaste disposal

Secondary materialSecondary raw materialWaste recovered fuelVirgin raw materialPrimery energy

WASTE---Disposal tax---Incineration taxTradable disposal/incineration rightsBan on disposal/incinartion of recyclableor compostable waste

USE

PRODUCTION---Virgin material tax---Carbon/energy taxTradable resource usecreditsMinimal share ofrenewable energyMinimal share ofcogneration inelectricity production

Re-use, recycling, recovery targetsSecondary material targets for certainparts in new products

Extended producer responsability