Dansk Interparlamentarisk Gruppes bestyrelse 2009-10

IPU Alm.del Bilag 6

Offentligt

INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION122ndAssembly and related meetingsBangkok (Thailand), 27thMarch - 1stApril 2010

Second Standing Committee onSustainable Development,Finance and Trade

C-II/122/R-rev22 December 2009

THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS IN DEVELOPING SOUTH-SOUTH AND TRIANGULARCOOPERATION WITH A VIEW TO ACCELERATING ACHIEVEMENTOF THE MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALSReport submitted by the co-RapporteursMr. Fran§ois-Xavier de Donnea (Belgium) and Mr. Given Lubinda (Zambia)INTRODUCTIONThe Millennium Development Goals1.Poverty and hunger, which are on the agenda of all summit meetings and worldconferences, have many causes: political, economic, demographic, social, cultural,environmental, etc. To eliminate poverty and hunger, progress must therefore be made in alarge number of areas that are both interdependent and complementary. The range of effortsrequired is summed up in the United Nations development agenda and in the internationallyagreed development goals, in particular the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).2."We are now more than halfway towards the target date – 2015 – and the largely benigndevelopment environment that has prevailed since the early years of this decade, and that hascontributed to the successes to date, is now threatened. We face a global economic slowdownand a food security crisis, both of uncertain magnitude and duration. Global warming hasbecome more apparent. These developments will directly affect our efforts to reduce poverty:the economic slowdown will diminish the incomes of the poor; the food crisis will raise thenumber of hungry people in the world and push millions more into poverty; climate changewill have a disproportionate impact on the poor. (…)" (Ban Ki-moon, UN Secretary-General,Foreword to "the MDG-Report 2008").3.More generally, the situation in the world’s developing countries –which contributedleast to the crisis and are most severely affected – has led some economists to warn of "lostdecades for development", which could have catastrophic consequences for rich and poorcountries alike. After struggling with high food, fuel and fertilizer prices as well as the effects ofclimate change, these countries face rapidly shrinking trade and export-import credits. Privatecapital flows to emerging economies this year are projected to be down by 82 per cent fromthe boom year of 2007, the Institute of International Finance says. The World Bank, which hasdescribed the crisis as a "development emergency", projects a finance gap of up toUS$ 700 billion in these countries, and the possibility of a "lost generation", with added deathsof 1.5 to 2.8 million infants by 2015. Over 100 million people are expected to be tipped intoextreme poverty each year for the duration of the crisis. According to the Food and AgricultureOrganization (FAO) of the United Nations, the number of people worldwide that are sufferingfrom hunger will rise by 11 per cent in 2009, as a result of the current economic crisis.

-2-SOUTH-SOUTH COOPERATION

C-II/122/R-rev

4.In this context, South-South cooperation, as an important element of internationalcooperation for development, offers viable opportunities for developing countries andcountries with economies in transition in their individual and collective pursuit of sustainedeconomic growth and sustainable development. Developing countries have the primaryresponsibility for promoting and implementing South-South cooperation, not as a substitute forbut rather as a complement to North-South cooperation, and in this context the internationalcommunity should support the efforts of the developing countries to expand South-Southcooperation.5.Developing southern nations have increasingly turned to each other for economicdevelopment assistance. South-South cooperation has contributed to substantial economicgrowth in developing countries. South-South cooperation (SSC) refers to cooperative activitiesbetween newly industrialized southern countries and other, lesser-developed nations of thesouthern hemisphere. Such activities include developing mutually beneficial technologies,services and trading relationships. SSC aims to promote self-sufficiency among southern nationsand to strengthen ties among states whose market power is more equally matched than inasymmetric North-South relationships.6.TheMarrakechHigh-levelConferenceonSouth-SouthCooperation(16-19 December 2003) and the successive "South Summits" (Havana, Cuba, 10-14 April 2005and Doha 2005, etc.) reviewed the progress made in South-South cooperation.7.The Marrakech Declaration recognizes that South-South cooperation has experiencedsuccesses and failures which are linked, in a broad sense, to the external internationalenvironment which influenced development policies and strategies. In the 1950s and 1960s,South-South cooperation evolved and developed in the context of the common struggle ofdeveloping countries to reach development and growth. The institutions for South-Southcooperation were developed in this period, including the Group of 77 countries (G77) and theNon-Aligned Movement (NAM). These and other multilateral organizations, including theUnited Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the United NationsDevelopment Programme (UNDP) and other institutions in the UN system, helped formulateand articulate southern needs and concerns, and provided a framework for fruitful North-South dialogue and mutually beneficial relationships.8.The Marrakech Declaration expresses the conviction that South-South cooperation ismore needed today than ever. No single country, even the most advanced among developingcountries, has much hope of reaching individually expected growth and development andinfluencing outcomes of international agenda. Today, it is becoming increasingly clear that theachievement of the MDGs, food security, trade, private-sector development, peace andsecurity and other matters, are cross-border issues and have to be tackled through joint andcomplementary efforts, which is why regional cooperation between countries is an importantpriority.9.Of course, South-South cooperation can and has taken place in a number of verydifferent areas, including information and communication technology (ICT), trade, investment,finance, debt management, food, agriculture, water, energy, health and education, transport aswell as in exchange of resources, experiences and know-how in these areas to make South-South cooperation contribute to economic growth and sustainable development. According tothe Accra Agenda for Action (September 2008) South-South cooperation on development aims

-3-

C-II/122/R-rev

to observe the principle of non-interference in internal affairs, equality among developingpartners and respect for their independence, national sovereignty, cultural diversity andidentity and local content. It plays an important role in international development cooperationand is a valuable complement to North-South cooperation. The so-called Heiligendammprocess or the dialogue between the G8 countries and the important emerging economies(Brazil, China, India, Mexico and South Africa) recognizes that neither the G8 countries nor theimportant emerging economies can meet the challenges of the global economy alone; it is inpart dedicated to determining joint responsibilities for development, focusing specifically onAfrica.10.(a)(b)(c)(d)I.

This report will mainly focus on the following aspects of SSC:SS Development Cooperation (official development assistance - ODA)SS TradeSS foreign direct investment (FDI)SS Regional Cooperation/IntegrationOFFICIAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE(ODA)1

11. South-South development cooperation has a long history, with some southerninstitutions and developing countries and economies contributing development assistance foralmost half a century. The Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development (KFAED), forexample, the first fund of its kind to be established by a developing country, was set-up in1961, with the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) and Arab Bank for Economic Development inAfrica (BADEA) in operation since the mid-1970s. China has also been providing assistance toAfrican countries for almost 50 years, including constructing the Tazara railway betweenTanzania and Zambia in the late 1960s. The number of southern development assistancecontributors has since grown further with several developing countries taking steps to establishfull-fledged development cooperation agencies while broadening the focus from mainlytechnical cooperation to more comprehensive development programmes.12. Triangular development cooperation has been interpreted as Organisation for EconomicCo-operation and Development-Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) donors ormultilateral institutions providing development assistance to southern governments to executeprojects/programmes with the aim of assisting other developing countries. At present, triangularflows do not appear to be a significant part of the global development cooperationarchitecture, although lack of data makes this difficult to ascertain.Defining ODA13. The lack of international agreement on how concessionality is measured has resulted insouthern contributors not necessarily knowing whether development assistance flows shouldbe defined as ODA, or whetherloan terms are breaching the concessionality limit of IMFcountry programmes. While DAC donors report data on the basis of the OECD definition ofODA, this is not necessarily the case for southern contributors. As a result, the current ODAdefinition does not adequately measure the genuine transfer of resources that takes place todeveloping countries.

1

Most of the information in this chapter has been taken from the following source: ECOSOC-DCF,Background study for the Development Cooperation Forum: trends in South-South and triangulardevelopment cooperation, April 2008.

-4-Data issues

C-II/122/R-rev

14. A second main problem hindering in-depth analysis of South-South concessionalfinancing flows is lack of accessible and comprehensive information and data. This ishighlighted in the 2008 OECD-DAC Development Cooperation Report, which states "it ishighly desirable that consistent and transparent accounting of flows from these countries is putin place as soon as possible, perhaps through the new ECOSOC Development CooperationForum".15. A particular problem is the lack of reliable data on triangular development cooperation.It is important to note that most triangular flows are not “additional” development assistanceprovided by southern contributors, but rather included as part of northern donor flows toprogramme countries. OECD-DAC indicates that there is no "tagging" in its system of howmuch development assistance from developed countries is executed by agencies in developingcountries, and DAC donors do not supply such data.Scale of South-South Development Cooperation16. In the 1990s, development assistance from the 22 DAC member countries accounted forabout 95 per cent of all international flows using the OECD-DAC definition. While DACdonors still provide the bulk of development cooperation flows, disbursements by non-DACcontributors have been increasing.17. On the basis of more detailed analysis, the southern contributors covered in a2008 background study for the Development Cooperation Forum (DCF)2are estimated tohave disbursed between US$ 9.5 billion and US$ 12.1 billion in 2006-2007, representing 7.8to 9.8 per cent of total flows. This estimate is between US$ 2.4 billion and US$ 5 billion higherthan earlier figures. The range reflects considerable variation in the quality and availability ofdata from four major contributors, i.e. China, India, Republic of Korea and Venezuela. Itshould be noted that these figures most likely underestimate total Southern developmentcooperation as the flows of several smaller bilateral and multilateral contributions have notbeen included due to lack of data and differences in definitions of what constitutesdevelopment cooperation (as discussed above).18. The largest southern contributors, in terms of resource flows, are China, India, SaudiArabia and Venezuela (providing each at least US$ 1 billion per year), followed by theRepublic of Korea and Turkey (providing more than US$ 500 million per year). Thecontribution of southern contributors to all multilateral institutions accounts for an average ofabout 18 per cent of ODA, compared with a DAC-donor average of 29 per cent. However theaverage masks a wide variation.

2

The study focuses on 18 developing countries providing development assistance as well as three ofthe larger southern regional multilateral institutions:• Ten major bilateral contributors (Brazil, China, India, Kuwait, Republic of Korea, Saudi Arabia,South Africa, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Venezuela) each with development assistanceprogrammes of more than US$ 100 million per year and eight smaller bilateral Middle Eastern,Asian and Latin American contributors (Argentina, Chile, Egypt, Israel, Malaysia, Singapore,Thailand and Tunisia);• Three southern multilateral institutions which cover a large number of programme countries,namely the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA), the Islamic DevelopmentBank (IsDB) and the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID). Sub-regional institutionshave been excluded as information has been more difficult to access.

-5-

C-II/122/R-rev

Triangular Development Cooperation19. The rationale underlying triangulation is that southern contributors, which are stillthemselves developing, are felt to be better placed and have the relevant experience torespond to the needs and problems of programme countries. In particular, many Southerncontributors have come up with successful models or practices, which can be moreappropriately transferred to other developing countries, than those of northern donors.20. In addition to having more appropriate technical expertise, such programmes can bemore cost-effective as experts from developing countries are often paid less than nationals indonor countries and training costs (fees, use of facilities, travel, accommodation, etc.) aregenerally lower than in developed countries. Furthermore the expertise or training can beconducted in the language appropriate to the programme country such as Brazilian technicalassistance to Portuguese-speaking African and Asian countries.21. Chile’s triangular cooperation is centered on the provision of technical assistance to LatinAmerican and Caribbean countries in partnership with Japan (JICA), Germany (GTZ), Sweden,Finland, the European Union (EU), FAO, the Organization of American States (OAS) and theInter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA). For example, Finland hasfinanced Chilean long-term technical assistance to develop small and medium-sized furnitureproduction in Nicaragua. In 2006, Chilean technical assistance accounted for 7 per cent of thetotal cost of triangular projects, with northern donors and programme countries contributing49 and 44 per cent, respectively.Destination – Allocation22. To date, geography has been a major factor in determining the direction of southernbilateral development cooperation, albeit with few exceptions such as China. Focusing flowson the neighboring region or subregion makes sense for a contributor as there is likely to be abetter understanding of countries’ needs, language and cultural similarities, opportunities toimprove trade, and it is probably less costly than administering a programme halfway aroundthe world. It also allows southern contributors to focus strongly on regional projects, whichprogram countries have often complained are under-funded by northern donors.23. Some southern contributors have been criticized for not taking sufficient account ofhuman rights when providing assistance to programme countries. However, as with somenorthern donors, political and strategic considerations, as well as trade and investmentopportunities, have been stronger motives for delivery of assistance than human rights. Mostsouthern assistance, in fact, does not go to countries with a poor human rights record. With theexception of Myanmar, many of the countries listed as the largest beneficiaries of southernassistance also feature among top ten recipients of aid from OECD-DAC countries.24. Promoting bilateral trade and investment has also been a powerful motive fordevelopment assistance flows (as indeed for many northern donors). Focusing developmentassistance and investment on resource-rich African countries, such as Angola, Nigeria, Sudan,Tanzania and Zambia, for instance, has been an aspect of China’s policy in recent years, withobvious benefits for trade.

-6-

C-II/122/R-rev

Quality (in the light of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and DAC Good Practices)Policy conditionalities25. Southern assistance has little, if any, policy conditionalities compared with aid providedby northern donors and the major international institutions. Many northern donors also aligncountry policies, especially for programme-based support, with those of the IMF and WorldBank, which in turn often contain governance as well as macroeconomic conditionalities.Procurement procedures and tying of assistance26. While the majority of southern development assistance is seen as being tied, theshortcomings listed above do not apply to all of it. For example, tied southern developmentassistance does not necessarily equate with overpriced poor quality or substandard goods andservices. In fact, a number of programme countries have indicated that the goods and servicesprovided are of appropriate quality, in addition to being better priced and therefore yieldingbetter value for money. Ghana, for example, indicates that project assistance from southerncontributors, such as China and India, is more cost-effective than that of northern donors inpart because the project costs are lower, the process is less bureaucratic and the projects arecompleted faster.27. Technical cooperation by southern contributors may not only be at a lower cost, but alsoprovide more appropriate technical skills and technologies compared to northern donors.Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness28. To improve the effectiveness of aid, DAC donors, along with some of the southerncontributors, have signed up to the Paris Declaration. However, some southern contributorshave concerns that the Paris Declaration will constrain their development cooperation and soare cautious about too close an association. Furthermore, moving towards the Paris Declarationtargets may mean that some of the benefits of southern development assistance to programmecountries decline. For example, a move towards more performance-based approach (PBA)assistance (if it were to imply a focus on health and education sector programmes) may meanthere is less direct project funding available for infrastructure projects, and it will be up toprogramme country governments to allocate PBA assistance on the basis of the nationaldevelopment strategy. Another target is to untie development assistance, but this couldpotentially lead to slower project implementation if the competitive bidding process takes time.29. Until now, southern contributors have not been involved in the work of OECD-DAC instrengthening aid effectiveness. The Accra Agenda for Action (point 19a) encourages alldevelopment actors, including those engaged in South-South-cooperation, to use the ParisDeclaration principles as a point of reference in providing development cooperation.30. More widely, OECD-DAC is liaising with bilateral southern contributors with the aim ofreaching agreement/endorsement of good development practices as developed by the DAC,while recognizing that this requires stronger participation of those contributors in the policyformulation process as well as in co-shaping the outcomes. In the first instance, DAC isengaging with non-DAC members of the OECD, OECD "enhanced engagement" countries(Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and South Africa), and accession candidates (Chile, Estonia,Israel, Russian Federation and Slovenia).

-7-II.TRADE

C-II/122/R-rev

31. Today, the world economy is more than ever interlinked via trade and investment flows.Since 1995, world merchandise trade has been growing at an average annual rate of7.5 per cent. Overall, the developing countries’ share of global merchandise trade increasedfrom 29 per cent in 1996 to 37 per cent in 2006.32. The dynamic South – including China (especially as a manufacturing hub), Brazil (notablyas an agricultural and agro-processing hub) and India (principally as a services hub), in additionto the first and second tiers of newly industrialized countries (NICs), as well as some othercountries in Africa, Asia and Latin America – has been the locomotive of export expansionfrom developing countries in general, and of trade among themselves (South–South trade) inparticular. South–South merchandise trade has more than tripled in just over a decade, fromUS$ 577 billion in 1995 to over US$ 2 trillion in 2006. In 2006, South–South trade accountedfor 17 per cent of world trade and 46 per cent of developing countries’ total merchandisetrade. The manufacturing sector represented almost half of South–South trade, but thecommodity sector including fuels, has been driving up interregional trade flows amongcountries of the South. Major energy producers and new and considerable demand for energyare also coming from the South.33. Growing faster than both the world gross domestic product (GDP) and worldmerchandise trade, between 1980 and 2006 the total world exports of international trade inservices increased from around US$ 400 billion to US$ 2.8 trillion. World services tradecontinues to accelerate, particularly in recent years, with an average annual growth rate of12 per cent between 2000 and 2006. Recent analyses and estimates also suggest thatSouth-South services exports, predominantly intraregional in nature, now account for over10 per cent of world services exports.34. The dynamic South has become an essential trade partner of both developed economiesand economies in transition. Exports from developed countries to the South increased by70 per cent in the decade ending in 2005, largely at the same pace as their exports to the restof the world. Their imports from the South in the same period, on the other hand, increasedby a massive 161 per cent, while imports from the rest of the world stood at 97 per cent. AsRecent years (2000–2006) have witnessed a genuine explosion of merchandise trade betweendeveloping countries and countries with economies in transition. Thus, exports fromdeveloping countries to the latter increased by more than 382 per cent from 2000 to 2006.The growth of their imports from economies in transition during the same period was recordedat 123 per cent.35. At this pivotal point in the world economy, particularly with regard to trade andinvestment, it is imperative to assess how the international community can best take thisdynamic transformation of trade and investment patterns as an opportunity to makeglobalization more inclusive than it has been, and to place world economic growth on a moresolid and balanced foundation. Indeed, the dynamic South has become, as Mr. ManmohanSingh, the Prime Minister of India, put it, "an international public good", as it offers newopportunities to sustain global growth at a time when there are concerns about a globaleconomic slowdown.36. Experts argue that the current global economic slowdown and credit crunch are having aserious negative impact upon the real economy of many developing countries, particularly thepoorest and most vulnerable ones. The export earnings of many developing countries have

-8-

C-II/122/R-rev

deteriorated due to a fall in manufactured exports to developed country markets, a fall incommodity prices, or both. The global liquidity crunch made it increasingly more costly fordeveloping country exporters to borrow from international financial markets or to apply forexport credits and/or export insurance. It also reduced private and official capital inflows(e.g. FDI and ODA) to developing countries, which constrained governments’ ability tomitigate the negative impact upon domestic market or industries.37. Within South–South trade, developing Asia acts as the centre of gravity of the majority oftrade flows. In 2006, Asia’s exports accounted for 86 per cent of total South–South exports, ofwhich intra-Asian trade claimed 78 per cent. Furthermore, as a market, Asia receives morethan half the South–South exports from Africa, and around a third from developing SouthAmerica. In recent years, there has been a surge in developing Asia’s imports from otherregions, particularly from Africa, driven largely by massively increasing demand for energy andindustrial raw materials. As for trade between Africa and America, it has been relatively limited,but with a clear sign of rising further.South–South trade – destination breakdown, 2006(as a percentage of total South–South trade*AfricaAmericasAsiaAfrica1.40.62.6Americas0.65.83.3Asia4.33.977.6* Source: UNCTAD, 12thSession, Accra, Ghana – "Emergence of a new South andSouth-South trade as a vehicle for regional and interregional integration fordevelopment.

38. Tariff barriers in general were substantially reduced in the past three decades, as a resultof unilateral liberalization and various tariff negotiations either at the multilateral, regional orbilateral levels. The trade-weighted average of effectively applied tariff in the world was around2.1 per cent in 2006. However, tariff barriers among developing countries remain on averagehigher than in world trade, despite numerous South–South preferential regional tradeagreements (RTAs). In 2006, the weighted average of applied tariffs in South–South trade(i.e. tariffs effectively imposed by a developing country on exports from another developingcountry) was 4.3 per cent, compared to the weighted average of 2.3 per cent imposed bydeveloped countries on exports from the South. In aggregate terms, approximately 71 per centof tariffs imposed on exports from developing countries were by other developing countries.39. Beyond tariffs, in South–South trade, the types of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) that havebeen identified as major trade impediments include customs and administrative entryprocedures, para-tariff measures (e.g. additional import charges and duties), and otherregulatory measures affecting infrastructure and institutions, but there is no comprehensiveinformation that is required for an in-depth analysis of the actual impacts of various NTBs ontrade and development.40. Although a substantial part of trade from certain southern donors is allocated under theform of barter trade ( for instance raw materials in exchange for the construction of schools androads, especially in Africa) there are no separate statistics available on barter trade. This lack ofdata makes it also difficult to ascertain whether the terms of trade in these transactions arefavourable or unfavourable for the poorer party.

-9-

C-II/122/R-rev

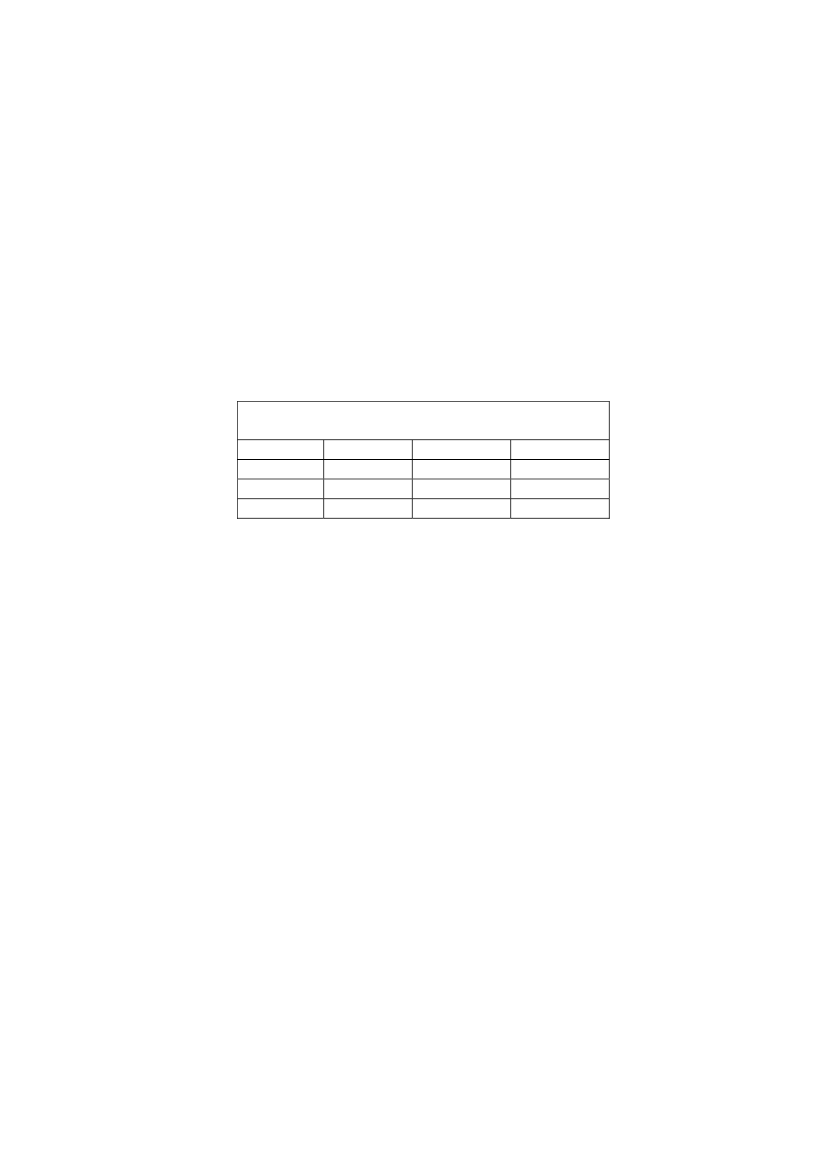

41. Trade agreements among developing countries comprise key instruments for effectiveSouth–South cooperation, and should thus be further encouraged. A successful conclusion ofthe São Paulo Round of negotiations on the global system of trade preferences amongdeveloping countries (GSTP) is important in this regard. The provision of tariff-free and quota-free access to exports of least developed countries (LDCs) is an important vehicle forstrengthening the participation of LDCs in South–South trade. A number of developingcountries have started to provide such preferences. Free trade agreements (FTAs) and regionaltrade agreements (RTAs) could encompass measures to enhance a wide range of economiccooperation among developing countries although complementarity and the sometimesrelatively dissimilar nature of the economies concerned can be serious challenges.42. The greatest challenge for South–South–North triangular cooperation is to ensure thatdevelopment gains from the new and dynamic opportunities of global trade are equitablydistributed among all stakeholders. Within the South, a worrying degree of divergence amongdeveloping countries is noted with regard to the benefits they are deriving from globalization.Most of the progress that has been achieved is due to significant advances made by severaldynamic developing countries. Low-income countries, particularly LDCs, are still left waitingfor the fruits of increasing interdependence in the global economy.43. At the same time, impressive trade performance by the dynamic part of the South doesnot imply that these developing countries have overcome their inherent and persistent tradeand development constraints, challenges and vulnerability. UNCTAD’s Trade andDevelopment Index, for example, reveals that even countries of the dynamic South still sufferconsiderably from widespread poverty and serious infrastructure deficits, as well as financial,structural and institutional shortcomings. They also face the daunting challenge of bridging theinequality gap within their societies, and of ensuring more widely distributed trade anddevelopment gains for women and the urban and rural poor.III.FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

44. FDI from developing countries has grown rapidly over the previous two decades, with itsshare of world outward FDI stock rising from 8 per cent in 1990 to 14.7 per cent in 2007. Thenumber of investing countries from the South has also increased: in the 1990s the newlyindustrialized economies of Asia and Latin America were the main ones investing substantiallyabroad, but over the last decade, a more diverse set of outward investing developing countries– such as China, India, South Africa and others from West Asia and Latin America – havebecome significant players.45. A significant proportion of FDI from developing countries was to other developingcountries, particularly neighbouring countries, giving it a South–South and regionalcharacteristic. South–South FDI has increased sharply during the previous two decades, fromUS$ 3.7 billion in 1990 to US$ 73.8 billion in 2007. These figures probably understated thereality of South–South FDI because of the lack of precise data.46. South–South FDI was a substantial source of FDI for some LDCs, such as Cambodia, theDemocratic Republic of the Congo, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Lesotho and Malawi.47. The impact of regional integration on FDI varies across regions, depending on the depthof integration and economic complementarities. On the whole, regional integration can have apositive influence on FDI, primarily through increasing the market size, and the positiveperceptions associated with the integration process among the business community. Regionalintegration also often facilitates cooperation in infrastructure development, which in turn has a

- 10 -

C-II/122/R-rev

positive impact on inward FDI. The main driver behind South–South FDI within a regionalcontext is geographical proximity, because of regional firms’ familiarity with neighbouringmarkets, and their ability to take advantage of existing regional agreements.48. Intraregional FDI as a share of total South–South FDI varies from region to region, withLatin America and South-East Asia demonstrating the highest share of intraregional South–South FDI. This reflects the depth and extent of current regional integration, particularly withinMERCOSUR and members of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Regionalintegration in those two regions could enhance intraregional trade and investment flowsbecause of complementarities of production and products among the constituent countries.49. The current economic crisis is likely to affect South-South FDI flow, with a variation inthe level and types of impacts to be expected between and within regions. In 2007, FDI indeveloping countries reached US$ 1 trillion or 8 per cent of world GDP. In 2008, total FDI washalved to US$ 500 billion. The aforementioned impacts depend upon the current integrationof a region in global networks, and the existing level of interdependence with developedcountries. Experts agree that South-South FDI could help developing countries insulatethemselves to some extent against the vagaries of the global economic system. Developingcountries play an active role in the new dynamic of international trade and investment flows.50. On the other hand, a secure environment as part of a stable investment climate, poses aserious challenge for a number of African States. Failing or weak States are not in the interest ofthe global community. In this respect DAC-donors and southern actors share a common longterm interest: only functional States can be reliable sources of raw materials or targets forforeign investment.51. Africa, especially sub-Saharan Africa, is not a key part of global production networks andmay not therefore be as severely or directly impacted by the crisis through the transmissionmechanism. However, the region is likely to suffer from falling commodity prices and decliningODA, as well as the higher cost of borrowing in the international financial markets. FDI flowsto Africa are likely to decline, but the decreases will not be equally distributed across theregion. The impact of FDI flows on poverty reduction, especially in Africa, need to be assessedbut there is some concern that while FDI flows might increase in the region, poverty might alsoincrease.IV.REGIONAL AND CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION/INTEGRATION FOR DEVELOPMENT

52. The following broad definition of regional integration, which reflects the CotonouPartnership Agreement (CPA), is proposed in a communication from the EuropeanCommission: "regional integration is the process of overcoming, by common accord, political,physical, economic and social barriers that divide countries from their neighbours, and ofcollaborating in the management of shared resources and regional commons".53. The European experience is a point of reference for many ACP regions. The politicalgoals and the specific objectives of regional integration are broadly similar.54.-Three main objectives of regional integration can be distinguished.Political stabilityis a pre-requisite for economic development. Regional organizationsplay an increasing role in defusing conflicts within and between countries and inpromoting human rights. Regional integration also helps build trust, enhanceunderstanding between groups and deepen interdependence.

- 11 --

C-II/122/R-rev

Economic development:In larger and more harmonized markets, the free movement ofgoods, services, capital and people enables economies of scale and stimulatesinvestment, thus spurring economic growth and increasing South-South trade. The rightmix of gradually increased regional and extraregional competition and a measuredprotection allows smooth integration into the global trading system and makes regionalintegration a vehicle for growth and accelerated poverty reduction.Regional public goods:Only cooperation between neighbouring countries can addresschallenges of a transnational dimension such as food security, natural resources,biodiversity, climate change, and disease and pest control.

-

55. "Integration is no doubt a vital tool for accelerating the economic, social, cultural andpolitical development of African countries; because affirmation of a common will to cometogether and for integration is likely to alleviate and indeed eliminate the sources of violentconflicts. Furthermore, enlargement of national markets and harmonization of regulatoryframeworks will help create an environment conducive to profitability of investments in theContinent. Clearly, other measures will be necessary to wipe away the poverty phenomenonand place Africa on the fast track of home-grown development. However, integration is anobligatory and unavoidable approach for weak countries, given the difficulties associated withglobalization. African micro-nation-states in the making are for the most part anachronistic,lacking in visibility and credibility; States without a hold on history; States without clout vis-à-vis contemporary forces dominated by more powerful leader states and multinational entities.Africa must form vast and viable internal markets to overcome this difficult situation. Suchmarkets will pave the way for inter-African division of labour according to relative domesticand external advantages, and confer on these huge collective entities a genuine power ofnegotiation with the markets already constituted on other continents."56. This extract from the strategic Plan of the African Union Commission analyses with greatlucidity one of the big paradoxes of the globalization process. Today, developed countriesaccelerate the construction of regional blocks to confront the challenges of globalization. Thepoor countries however seem to have to confront in a disparate order the double challenge ofboth development and international competition.57. A number of developing countries are already applying strong programmes in support ofSouth-South cooperation. The use of the existing expertise and the experiences available in themore advanced developing countries is a major factor in this equation. As regional and sub-regional integration proceeds, more opportunities for cooperation will be emerging in crucialsectors such as infrastructural development, coordination mechanisms for transnationalenvironmental issues, political dialogue and consensus building: the experience of the NewPartnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), with its African Peer Review Mechanism, isshowing the feasibility and the effectiveness of this new encompassing concept of regionalcooperation, for instance. The EU is committed to supporting the regional leadership ofNEPAD, in the framework of the overall policies for sub-Saharan Africa as illustrated in theEuropean Commission’s Communication "Focus on Africa". The EU is also supporting regionalcooperation mechanisms in Africa, for example, through the ACP-EU Water Facility, whichfavours coordinated management at regional level of water resources, in the framework of theJohannesburg Plan of Implementation.

- 12 -

C-II/122/R-rev

58. Yet, in some regions, especially in Africa, it should not be overlooked that the positiveeffects of integration can only be realized when the overall policy framework and thegovernance and security situation are conducive to such integration. Therefore, given thelimitations in these areas, many past initiatives have not yet lived up to expectations.59. South-South cooperation could play an increasing role in the areas of crisis prevention,early warning, emergency response and post-crisis reconstruction, building on recent,successful initiatives.60. In the light of MDG 1 (halving poverty by 2015) and the current food crisis, specificattention and reflection is needed about the role of regional integration in ensuring foodsecurity and in agriculture. The Sahel and West Africa Club (SWAC) for instance proposes thedrafting of food security country profiles, negotiating a revised “Food aid charter”, stimulatingstrategic thinking and analysis and developing prevention, early-warning and responsemechanisms to combat pests affecting food security in the region. The growing commercialpressures on land or the rising competition for land in rural areas by investors, threatens thefuture of agricultural production in the poorest areas. In this field too, a subregional or regionalapproach could be more successful.61. Today, it is becoming increasingly clear that the achievement of the MDGs, foodsecurity, trade, private-sector development, peace and security and other matters, are cross-border issues and have to be tackled through joint and complementary efforts, which is whyregional cooperation between countries is an important priority. This has also been taken intoaccount by the African Union Commission.PARLIAMENTARY INVOLVEMENT IN SSC AND TDC FOR ACHIEVING THE MDGs62. Parliamentary involvement in achieving the MDGs is particularly pressing now with onlysix years before the deadline of 2015, until when the international community has to attain theambitious albeit important range of goals: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, achieveuniversal primary education, promote gender equality and empower women, reduce childmortality, improve maternal health, combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases, ensureenvironmental sustainability, and develop a global partnership for development, with targetsfor aid, trade and debt relief.63. The parliamentary dimension to international cooperation must be provided byparliaments themselves first of all at the national level in four distinct but interconnected ways:(a)(b)(c)(d)(e)(f)(g)(h)Influencing their respective countries’ policies on matters dealt with in the UnitedNations and other international negotiating forums;Keeping themselves informed of the progress and outcome of international and regionalnegotiations, including issues related to regional and international cooperation withparticular emphasis on South-South cooperation;Timely scrutiny and ratification, where the Constitution allows, of international/regionaltexts and treaties signed by governments;Reviewing national legislation to promote regional integration and South-Southcooperation as well as the achievement of the MDGs;Voting for sufficient budget allocations to programmes and sectors that address MDGs;Scrutinizing reports on MDG programmes and sectors and recommending timely actionsto enhance the achievementof the MDGs;Contributing actively to the implementation process; andEngaging the general public in discussions aboutthe MDGs and in the implementation ofprogrammes aimed at addressing and achieving them.

- 13 -

C-II/122/R-rev

64. It is an establishedfact that the achievement of the MDGs depends heavily on global andnational parameters in developing (southern countries) and industrialized (northern) countries.They represent a global partnership based on shared responsibility committing rich and poorcountries, the UN system and key institutions that determine the economic fate of thedeveloping countries: the World Bank, the IMF and the World Trade Organization. Therefore,the role of parliaments from both the South and North cannot be overemphasized. As alreadymentioned, the emerging trend in SSC is being seen in southern countries cooperating throughsharing of development experiences, cooperation projects, capacity-building, technicalassistance, but also increasingly in subsidized lines of credit and grants, and preferential marketaccess on a unilateral and reciprocal basis, while TDC through the provision of financialresources for the promotion of the potentials of SSC as developing countries isnormally short ofresources.65. Therefore, parliaments from both the South and the North can do the following inpractice:••Become involved in the development of the country’s policy through specialparliamentary committees and participation of sectoral working groups; andMonitor implementation on the ground not merely for its financial soundness butespecially for its effectiveness in delivering poverty reduction.Specific roles of parliamentarians are as follows:

66.

Role of Parliamentarians from Northern Countries67. The MDGs require governments in the developed world to honour their commitmentson aid and to make sure that the value of the aid given is not offset many times over by thenegative effects of unfair trade regimes and the requirements of debt repayment, which iscurrently the case. This places the onus on parliaments in developed countries to bringpressure to bear on their governments to honour their aid commitments, and to ensure that itis being used effectively, and, in addition, not to separate oversight of aid policy from a widerconsideration of trade policy and international finance.68. Northern parliaments can play a significant role in allocating, on an incremental basis,resources that promote South-South and Triangular Cooperation.69. Northern parliaments can encourage their governments to urge multilateralorganizations, such as the Bretton Woods institutions, to develop and foster theimplementation of programmes that promote trade between countries of the South.Role of Parliamentarians from Developing (Southern) Countries70. The MDGs provide parliaments with a perfectly tailored internationally agreedframework to hold their governments to account. Parliaments can play a role in the followingareas:The budget process71. Accountable and effective management of public financial resources constitutes one ofthe most fundamental responsibilities of governments. Scrutinizing these is the most importantmandate for Parliaments. Still, according to recent World Bank estimates, approximately5 per cent of global GDP disappears through corruption and mismanagement. This figure is

- 14 -

C-II/122/R-rev

much higher in developing countries that are lagging behind in achieving the goals. If theMDGs are to be achieved, scarce resources must be spent on the needs of the people, hencethe need for full transparency in the budget processes. Parliamentarians should ensure thatpublic expenditure management is accountable and transparent and that public spendingaccrues to the poor, instead of the rich, as is currently the case in too many developingcountries.Sectoral policies72. Parliamentary committees, in their debates with sectoral ministries, should ensure thatthe MDGs feature prominently in sectoral policies. More importantly, sectoral policies need tobe translated into effective service delivery (in health, education, sanitation, water, etc.) for allcitizens throughout the country. Countries must adopt policies that promote South-South andTriangular Cooperation.Legislation73. Parliamentarians also need to ensure that legislation becomes a relevant and effectivetool in reducing poverty and meeting the goals. In many countries inheritance, property andtax laws urgently need to be reviewed to ensure that women can fully participate andcontribute to development. Also, in order for poor people to lift themselves out of poverty byunleashing their entrepreneurial spirit, legal reform is needed to improve the business climate,particularly for domestic investors. In many developing countries the volume of capital flight isactually larger than that of aid received. Legislation should also be put in place in order tosupport SSC efforts that are conducive to achieving the MDGs.Governance74. Last but not least, the cross-cutting issue of the need to improve governance, to create acapable State that is needed to achieve the MDGs by improving quality and efficiency of thepublic sector, modernizing and reforming bureaucracy, decentralizing through empowermentof local authorities, and ensuring that political processes are inclusive, not just politicallyrepresentative through elected parliaments.South-South and Triangular Cooperation75. Parliaments must urge their governments to participate actively in efforts aimed atdeveloping SSC and TDC. This includes, among others, at the global level, the G77 and Chinaand the NAM countries, which has continued to serve as the broadest mechanisms forconsultation and policy coordination among developing countries. The positions adopted overthe years by the G77 and the NAM constitute a comprehensive philosophy and framework foraction for developing countries, and United Nations conferences, particularly the2000 Millennium Summit, have guided recent North-South and South-South initiatives at theglobal and regional levels.76. Countries must support Technical Cooperation among Developing Countries (TCDC) setup under the G77 and China, without prejudice to the necessary support to other regional andglobal organizations promoting and fostering SSC. Since its adoption in 1978, several decisionsand resolutions reaffirming the validity and importance of TCDC have been adopted by theUnited Nations General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the UNDPExecutive Board. In its resolution 1992/41, ECOSOC called upon all parties in thedevelopment effort to give the TCDC option first consideration in their technical cooperationactivities. It also invited all countries to improve the environment for TCDC and facilitate itswidespread use.