Forsvarsudvalget 2009-10

FOU Alm.del Bilag 96

Offentligt

United Nations Assistance Mission to Afghanistan, Human Rights Unit

1

AFGHANISTANAnnual Report on Protection of Civiliansin Armed Conflict, 2008

January 2009UNAMA, HUMAN RIGHTS

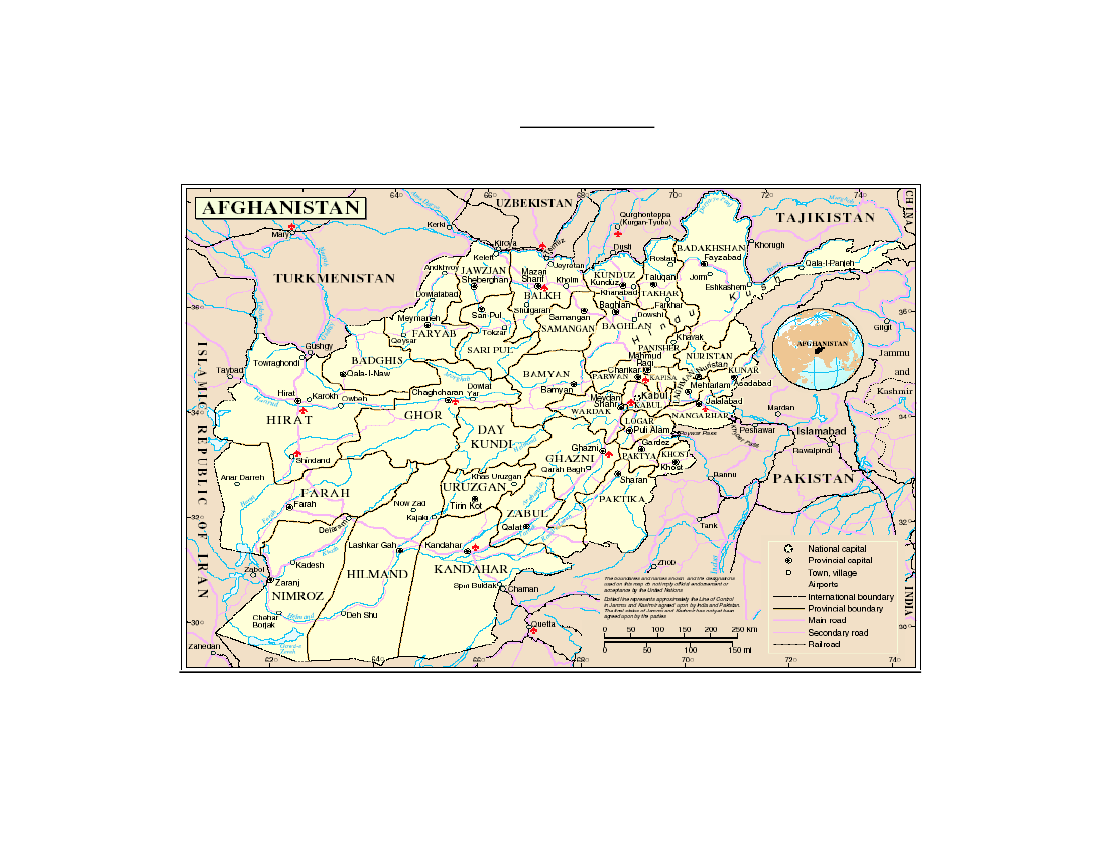

Map of Afghanistan

Source: UN Cartographic Centre, NY.

Table of ContentsExecutive Summary .............................................................................................................................iiGlossary ...............................................................................................................................................vProtection of Civilians in Armed Conflict: 2008UNAMA’s mandate in relation to protection of civilians................................................................1Introduction......................................................................................................................................1Legal responsibilities of the parties to the armed conflict...........................................................2UNAMA Human Rights’ strategy for Protection of Civilians......................................................4Methodology.................................................................................................................................4Protection of Civilians Database.................................................................................................6Impact of the Armed Conflict on CiviliansOverview for 2008 ...........................................................................................................................7Pro-Government ForcesPro Government Forces and Civilian Casualties ...........................................................................16Air-strikes...................................................................................................................................16Force Protection Incidents.........................................................................................................17Search and seizure operations/Home searches.........................................................................18Lack of accountability/redress...................................................................................................20Solatia/Compensation................................................................................................................21Casualties caused by actions of Afghan police and armed personnel.......................................22Conflict-related detention practices...........................................................................................22Location of military bases..........................................................................................................24AGEsAGEs and Civilian Casualties........................................................................................................26Suicide and IED attacks.............................................................................................................27Assassinations, Threats & Intimidation.....................................................................................28Attacks on educational facilities................................................................................................30Public perceptions of insurgent actions.....................................................................................32Humanitarian Space and Humanitarian Access .................................................................................34AppendixGraphs representing civilian casualties by Region/Month and Responsibility..............................35

i

Executive Summary1. This Report on the protection of civilians in armed conflict in Afghanistan in 2008 iscompiled in pursuance of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA)mandate under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1806 (2008). UNAMA conductsindependent and impartial monitoring of incidents involving loss of life or injury to civiliansas well as damage or destruction of civilian infrastructure and conducts activities geared tomitigating the impact of the armed conflict on civilians. UNAMA’s Human Rights Officers(national and international), deployed in all of UNAMA’s regional offices and someprovincial offices, utilize a broad range of techniques to gather information on specific casesirrespective of location or who may be responsible. Such information is cross-checked andanalysed, with a range of diverse sources, for credibility and reliability to the satisfaction ofthe Human Rights Officer conducting the investigation, before details are recorded in adedicated data base. However, due to limitations arising from the operating environment,such as the joint nature of some operations and the inability of primary sources in mostinstances to precisely identify or distinguish between diverse military actors/insurgents,UNAMA does not break down responsibility for particular incidents other than attributingthem to “pro-government forces” or “anti-government elements”. UNAMA does not claimthat the statistics presented in this report are complete; it may be the case that, given thelimitations in the operating environment, UNAMA is under-reporting civilian casualties. InJanuary 2009, UNAMA introduced a new electronic database which is designed to facilitatethe collection and analysis of information, including disaggregation by age and gender.2. In compliance with its mandate granted under UN Security Council Resolution 1806 (2008),paragraph (g), the Human Rights Unit of UNAMA (UNAMA Human Rights) undertakes arange of activities aimed at minimizing the impact of the conflict on civilians, includingreporting through the UN Secretary General to the Security Council, the SpecialRepresentative of the Secretary General (SRSG) UNAMA, the UN Emergency ReliefCoordinator, Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and other UNmechanisms as appropriate. UNAMA Human Rights advocates with a range of actorsincluding Afghan authorities, international military forces (IMF), and others with a view tostrengthening compliance with international humanitarian and human rights law. It alsoundertakes a range of activities on issues relating to the armed conflict and protection ofcivilians with the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), thehumanitarian community, and members of civil society.3. The armed conflict intensified significantly throughout Afghanistan in 2007 and 2008, witha corresponding rise in civilian casualties and a significant erosion of humanitarian space. Inaddition to fatalities as a direct result of armed hostilities, civilians have suffered frominjury, loss of livelihood, displacement, destruction of property, as well as disruption ofaccess to education, healthcare and other essential services.4. UNAMA Human Rights recorded a total of 2118 civilian casualties between 01 January and31 December 2008. This figure represents an increase of almost 40% on the 1523 civiliandeaths recorded in the year of 2007. The 2008 civilian death toll is thus the highest of anyyear since the end of major hostilities which resulted in the demise of the Taliban regime atthe end of 2001. Of the 2118 casualties reported in 2008, 1160 (55%) were attributed to anti-government elements (AGEs) and 828 (39%) to pro-government forces. The remaining 130(6%) could not be attributed to any of the conflicting parties since, for example, someii

civilians died as a result of cross-fire or were killed by unexploded ordinance. The majorityof civilian casualties, namely 41%, occurred in the south of Afghanistan, which saw heavyfighting in several provinces. High casualty figures have also been reported in the south-east(20%), east (13%), central (13%) and western (9%) regions.5. In 2007 Afghan security forces and IMF supporting the Government in Afghanistan wereresponsible for 629 (or 41%) of the total civilian casualties recorded. At around 39% of totalcivilian casualties, the relative proportion of deaths attributed to pro-government forcesremained relatively stable for 2008. However, at 828, the actual number of recorded non-combatant deaths caused by pro-government forces amounts to a 31% increase over thedeaths recorded in 2007. This increase occurred notwithstanding various measuresintroduced by the IMF to reduce the impact of the war on civilians.6. Air-strikes remain responsible for the largest percentage of civilian deaths attributed to pro-government forces. UNAMA recorded 552 civilian casualties of this nature in 2008. Thisconstitutes 64% of the 828 non-combatant deaths attributed to actions by pro-governmentforces in 2008, and 26% of all civilians killed, as a result of armed conflict in 2008. Night-time raids, and “force protection incidents” which sometimes result in death and injury tocivilians, are of continuing concern. Also of concern is the transparency and independenceof procedures of inquiry into civilian casualties by the Afghan Government and the IMF; theissuance ofsolatiapayments to victims (given that the different troop contributing countrieshave different conditions for such payments); and the placement of military bases in urbanand other areas with high concentrations of civilians which have subsequently becometargets of insurgent attacks.7. In the reporting period, international military forces did attempt to address a number ofsignificant concerns. This included streamlining and greater transparency of commandstructures between ISAF and Operation Enduring Freedom; the latter now, largely, operatesunder the Commander of ISAF who is simultaneously Commander of US ForcesAfghanistan. However, some operators still remain outside his command. It is alsonoteworthy that refined tactical directives on “force protection”, air-strikes and night-timeraids have been issued in the latter part of 2008. ISAF also introduced a centralised civiliancasualties tracking cell that is mirrored within US Forces Afghanistan by a similar trackingcell, aimed at investigating all claims of civilian casualties attributed to ISAF/US ForcesAfghanistan. International military forces showed themselves more willing than before toinstitute more regular and transparent inquiries into specific incidents (although theindependence of these inquiries is still questionable).8. AGEs remain responsible for the largest proportion of civilian casualties. Civilian deathsreportedly caused by AGEs rose from 700 in 2007 to 1,160 in 2008 – an increase of over65%. While seasonal trends remained broadly consistent, in practically every month of 2008the insurgent-caused death toll among civilians was higher than in the same month of 2007and outstripped that resulting from the actions of pro-government forces. The vast majorityof those killed by the armed opposition are victims of suicide and other IED attacks (725killed) and of targeted assassinations (271 killed). Together, these tactics accounted for over85% of the non-combatant deaths attributed to AGE actions. The remainder of AGE-inflicted fatalities resulted primarily from rocket attacks and from ground engagements inwhich civilians bystanders were directly affected.

iii

9. Accounting for 725 non-combatant deaths, or 34% of the total civilian casualties in 2008,suicide and IED attacks killed more Afghan civilians than any other tactic used by theparties to the conflict. UNDSS recorded 146 suicide attacks and 1,297 detonated IEDs in2008, with another 93 suicide attacks and 843 IEDs that were discovered before they couldbe detonated. Although the majority of such attacks have been directed primarily againstmilitary or government targets, attacks are frequently carried out in crowded civilian areaswith apparent disregard for the extensive damage they cause to civilians. Throughout 2008,insurgents have shown an increasing disregard for the harm they may inflict on civilians insuch attacks. There have been reports of insurgents using civilians as human shields duringoperations and of deliberately basing themselves in civilian areas heedless of the toll thatmay be inflicted on civilians. Insurgents have also increasingly targeted persons perceived tobe associated or supportive of the Government and its allies, including teachers, students,doctors and health workers, tribal elders, civilian government employees, former police andmilitary personnel, and labourers involved in public-interest construction work. UN andNGO staff members have also become victims of violence and have been killed, kidnappedor received death threats on numerous occasions. Schools, particularly those for girls, havecome under increasing attack thereby depriving thousands of students, especially girls, oftheir right of access to education. According to UNICEF, attacks on schools and educationalfacilities rose by 24%, from 236 incidents reported in 2007 to 293 in 2008.110. The deteriorating security situation and drastically reduced humanitarian access intensifiedthe challenge for the humanitarian agencies to address the growing needs of vulnerableAfghans. By the end of 2008, “humanitarian space” had shrunk considerably. Large parts ofthe south, south-west, south-east, east, and central regions of Afghanistan are now classifiedby the UN Department of Safety and Security as an “extreme risk, hostile environment” foroperations. In 2008, 38 aid workers (almost all from NGOs) were killed, double the numberin 2007, and a further 147 abducted. UNDSS recorded over 198 other direct attacks, threatsand intimidations targeting the aid community in 2008.11. As the conflict intensifies, Afghans are suffering; in addition to the growing number ofdeaths and injuries, vulnerable groups are also suffering in terms of destruction ofinfrastructure, loss of income or earning opportunities, and deterioration of access to basiclife-supporting services. UNAMA, concerned about the high cost to civilians, calls upon allparties to respect the relevant rules of international humanitarian law and human rights lawand to do everything in their power to ensure that the impact of their actions has the leastpossible negative impact upon the civilian population.

1

UNICEF, School incident reports 2008, 12 January 2009.

iv

GlossaryThe following terminology and abbreviations are utilized in this Report:ABP:Afghan Border Police.AGEs:Anti-Government Elements. These encompass all individuals and groups currently involvedin armed conflict against the Government of Afghanistan and/or IMF. They include those whoidentify as ‘Taliban” as well as individuals and groups motivated by a range of objectives andassuming a variety of labels.ANA:Afghan National Army.ANP:Afghan National Police.ANSF:Afghan National Security Forces. A blanket term including ABP, ANA, ANP and NDS.ASF:Afghan Special Forces. These are part of the ANA and are often called ANA Commandos; insome cases OGA (see below) paramilitaries have informally been referred to as ASF.BBIED:Body-Borne Improvised Explosive Device; see IED.Casualties:May be of two classifications:•Direct:casualties resulting directly from armed conflict – including those arising frommilitary operations conducted by pro-government forces (Afghan Government Forces and/orInternational Military Forces) such as force protection incidents; air raids, search and arrestevents, counter insurgency or “Global War on Terror” operations. It also includes casualtiesarising from the activities of AGEs, such as targeted killings, IEDs, VBIEDs, and BBIEDs,or direct engagement with pro-government forces, etc.•Other:casualties resulting indirectly from the conflict, including casualties caused byexplosive remnants of war (ERW), deaths in prison, deaths from probable underlyingmedical conditions that occurred during military operations, or where access to medical carewas denied or was not forthcoming. It also includes deaths arising from incidents whereresponsibility cannot be determined with any degree of certainty, such as deaths or injuriesarising from cross-fire. Finally, it includes casualties caused by inter/intra-tribal or ethnicconflict.Civilian/Non-Combatant:Any person who is not taking an active part in hostilities. It includes allcivilians as well as public servants who are not being utilised for a military purpose in terms offighting the conflict, and encompasses teachers, health clinic workers and others involved in publicservice delivery, as well as political figures or office holders. It also includes soldiers or any personwho arehors de combat,whether from injury or because they have surrendered or because theyhave ceased to take an active part in hostilities for any reason. It includes persons who may becivilian police personnel or members of the military who are not being utilized in counterinsurgency operations, including when they are off-duty.Children:According to theConvention on the Rights of the Child,a ‘child’ is defined as anyperson under the age of 18 (0-17 inclusive). Injury figures for children are likely to be under-

v

reported due to the fact that age information for injured individuals is often not readily available orreported.COM-ISAF:The Commander of ISAF; see ISAF.ERW:Explosive Remnants of War. This can include land mines, un-detonated or unexplodedordinances, shells, rockets, etc.Force protection incidents:situations where civilians fail to heed warnings from militarypersonnel when approaching or overtaking military convoys or failing to follow instructions atcheck points. Force protection incidents can also occur when individuals are perceived as too closeto military bases or installations and there is a failure to follow warnings from military personnel.GoA:Government (of the Islamic Republic) of AfghanistanHumanitarian space:The term ‘éspace humanitaire’ was coined by former Médecins SansFrontières (MSF) president Rony Brauman, who described it in the mid-1990s as “a space offreedom in which we are free to evaluate needs, free to monitor the distribution and use of reliefgoods, and free to have a dialogue with the people”. The UN Office for the Coordination ofHumanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’sGlossary of Humanitarian Termshas no specific entry forhumanitarian space, but it does mention the term as a synonym for the ‘humanitarian operatingenvironment’: “a key element for humanitarian agencies and organisations when they deploy,consists of establishing, and maintaining a conducive humanitarian operating environment”. TheGlossary goes on to state that: “…adherence to the key operating principles of neutrality andimpartiality in humanitarian operations represents the critical means, by which the prime objectiveof ensuring that suffering must be met wherever it is found, can be achieved. Consequently,maintaining a clear distinction between the role and function of humanitarian actors from that of themilitary is the determining factor in creating an operating environment in which humanitarianorganisations can discharge their responsibilities both effectively and safely.” The authors of theOCHA/Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) report on integrated missions, publishedin 2005, also address the need to “preserve” humanitarian space, and focus on the distinctionbetween civilian and military functions. Humanitarian space also encompasses the concept thatcivilians have a right to access life-saving or life-preserving assistance.IDPs:Internally Displaced PersonsIED:Improvised Explosive Device. A bomb constructed and deployed in ways other than inconventional military action. IEDs can also take the form of suicide bombs, such as BBIEDs orVehicle Borne (VBIEDs), etc.Incidents:Events where civilian casualties resulted from armed conflict. Reports of casualtiesarising from criminal activities etc., arenotincluded in UNAMA’s civilian casualty reports.IMF: “InternationalMilitary Forces” includes all foreign soldiers forming part of ISAF and USForces Afghanistan (including OEF) who are under the command of Commander of ISAF (COM-ISAF). The term also encompasses those forces not operating under the Commander of ISAF,including certain Special Forces..

vi

Injuries:Include physical injuries of differing severity. The degree of severity of injury is notrecorded in UNAMA Human Rights’ Database. Injuries do not include cases of shock orpsychological trauma.ISAF:International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan. ISAF has a peace-enforcementmandate under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. However, it is not a UN force but a “coalition of thewilling” deployed under the authority of the UN Security Council. In August 2003, upon the requestof the UN and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, NATO took command ofISAF. The NATO force currently comprises some 55,000 troops (including National SupportElements) from 41 countries as well as 26 Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs). SinceNovember 2008, the Commander of ISAF serves also as the Commander of US Forces Afghanistan,although the chains of command remain separate.NATO:North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. Members of NATO are the main troop contributingcountries to ISAF; see ISAF.NDS:National Directorate of Security. Afghanistan’s State intelligence service.OEF: “OperationEnduring Freedom” is the official name used by the US Government for itscontribution to the War in Afghanistan under the umbrella of its Global War on Terror (GWOT). Itshould be noted that Operation Enduring Freedom - Afghanistan, which is a joint US and Afghanoperation, is separate from ISAF, which is an operation of NATO nations including the USA andother troop contributing nations. Most US forces operating under OEF since October 2008 havebeen incorporated into “US Forces Afghanistan” (see below) under the command of GeneralMcKiernan, who is also ISAF Commander – although some special forces remain under separatecommand.OGAs:Other Government Agencies. This is used to refer to certain security operatives who do notoperate under regular military chains of command. Frequently who has command responsibility forsuch entities is unclear.Pro-government forces (PGF):•Afghan Government Forces.All forces who act in all military or paramilitary counter-insurgency operations and are directly or indirectly under the control of the Government ofAfghanistan. These forces include, but are not limited to, the Afghan National Army (ANA),the Afghan National Police (ANP), the Afghan Border Police (ABP), the NationalDirectorate of Security (NDS).•International Military Forces (IMF)and OGA.PRTs:Provincial Reconstruction Teams. These are small teams of civilian and military personneloperating within ISAF’s regional commands working in Afghanistan’s provinces to helpreconstruction work. Their role is to assist the local authorities in the reconstruction andmaintenance of security in the area.UNDSS:United Nations Department of Safety and Security.US Forces Afghanistan:or “USFOR-A” is the functioning command and control headquarters forUS forces operating in Afghanistan. USFOR-A is commanded by General McKiernan, who alsoserves as the NATO/ISAF commander. Under this new arrangement, activated in October 2008, theapproximately 20,000 US forces, operating as part of Operation Enduring Freedom, were placedvii

under the operational control of USFOR-A. The ISAF and OEF chains of command remain separateand distinct, and US Central Command continues to oversee US counterterrorism and detaineeoperations.VBIED:Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive device; See IED.

viii

Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict: 2008UNAMA’s mandate in relation to protection of civiliansUNAMA Human Rights conducts activities aimed at promoting and protecting human rights inaccordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1806 (2008), paragraph (g), which explicitlymandates UNAMA to monitor the situation of civilians, to coordinate efforts to ensure theirprotection and to assist in the full implementation of the fundamental freedoms and human rightsprovisions of the Afghan Constitution and international treaties to which Afghanistan is a Stateparty. This Report has been compiled pursuant to this mandate.IntroductionArmed conflict in Afghanistan, although sporadic after the ousting of the Taliban regime in 2001,never really abated in certain areas of the country. Since 2005 the security situation has deterioratedwith insurgent/AGE attacks and operations by pro-government forces encroaching into more areasof the country. As the conflict has widened and deepened throughout 2007 and 2008, almost a thirdof the country is now directly affected by armed conflict, while pockets of armed conflict havestarted to occur in areas which were formerly relatively tranquil. Armed conflict is particularlyprevalent in the south, south-east, east, central and western regions of the country, and is nowspreading into the north, north-east and central highlands regions.As the conflict has intensified, it is taking an increasingly heavy toll on civilians. AGE tactics haveshifted, from frontal or ambush attacks on pro-government forces, to insurgent or guerrilla typeactivities, including asymmetric attacks such as IEDs, VBIEDs and BBIEDs and targetedassassinations. Operations are frequently undertaken regardless of the impact on civilians in termsof deaths and injuries or destruction of civilian infrastructure. The GoA and its allies, in attemptingto quell the insurgency, are also undertaking more operations in areas where civilians reside; thishas resulted in a rising toll on civilians and destruction of civilian infrastructure.AGEs’ attacks on humanitarian workers and government employees (including medical andeducational staff) have increasingly impaired access by Afghans to humanitarian assistance, inparticular to life-saving medicine, food, and education. This has a particularly detrimental impact onwomen and children living in conflict affected areas. Large parts of the south, south-west, south-east, east, and central regions of Afghanistan are now classified as ‘extreme risk, hostileenvironment’ further inhibiting access by humanitarian agencies in direct service delivery.Operations carried out by pro-government forces also result in high numbers of civilian casualties,notwithstanding efforts to implement policies and procedures to minimize the impact of theiroperations on civilians. Air-strikes remain responsible for the largest percentage of civilian deathsattributed to pro-government forces. Practices regarding search and seizure operations (includingnight time raids) are also of concern, and there have been reports of a number of joint Afghan andIMF operations in which excessive use of force has allegedly resulted in civilian deaths. There havebeen a number of “force protection incidents” whereby civilians have been killed after they failed tofollow instructions when perceived as being too close to military convoys or military installations,or while approaching check points.The effects of the armed conflict on civilians has been documented in reports by the UN SecretaryGeneral to the Security Council, the Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs, and inmissions undertaken by the Representative of the UN Secretary General on the Human Rights ofInternally Displaced Persons (August 2007), the High Commissioner for Human Rights (November

1

2007), the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Arbitrary or Summary Executions (May 2008),and the Secretary General’s Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict (July 2008).The UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Philip Alston,concluding a 12 day visit to Afghanistan in May 2008, found that “Afghanistan continues to sufferfrom a large number of avoidable killings of civilians.”2He raised concerns regarding the highnumber of unlawful killings by the Afghan police and the impunity that exists in such cases; the“wanton and brutal killing of civilians” by insurgents, including targeted executions and civiliansbeing killed in suicide and IED attacks; and the existence of special national and internationalarmed units apparently not accountable to any conventional military command or civilianGovernment authority. The Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs at the SecurityCouncil Open Debate on the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 27 May 2008, in referenceto Afghanistan, stated that he remained concerned by civilian casualties resulting from air-strikesand search operations conducted by national and multi-national forces, as well as the number offorce protection incidents.UNAMA, often in collaboration with members of the humanitarian community, has undertakenactivities geared to the reduction of civilian casualties arising from the armed conflict. Initiativeshave included the investigation of alleged incidents involving civilian casualties or destruction ofcivilian infrastructure, advocacy aimed at securing compliance with international humanitarian lawand international human rights norms, collection and analysis of information regarding the impactof the armed conflict on civilians, design and implementation of an electronic database to compilestatistics and reports, and the compilation of reports within the UN system and publicly. UNAMAHuman Rights also participates in the Protection Cluster as co-chair, and has undertaken advocacyalong with other humanitarian and civil society actors with Government authorities, AfghanNational Army and international military forces concerning the impact of the armed conflict oncivilians and the necessity of compliance with applicable international humanitarian and humanrights law.UNAMA remains concerned at the high level of civilian casualties from the ongoing armed conflictin Afghanistan and believes more has to be done by all parties to the conflict to reduce the impacton civilians. While certain pro-government forces have been responsive to the issue of civiliancasualties arising from their operations, civilian deaths caused by air-strikes is still a seriousconcern. AGEs continue to undertake asymmetric attacks and conduct operations in civilian areas,particularly suicide bombings, heedless of the toll on civilians.Legal responsibilities of the parties to the armed conflictThe current situation in Afghanistan is quite complex, involving armed hostilitiesbetween theGovernment of Afghanistan and its supporters (including IMF) on the one side, and insurgentsencompassing individuals and groups of diverse backgrounds, motivations, and commandstructures, including those characterised as Taliban on the other.Common Article 3 to the four Geneva Conventions establishes the minimum standards that partiesto an armed conflict should observe concerning the treatment of civilians in non-international armedconflict.3Common Article 3 thusextends the reach of humanitarian law into situations occurringwithin the territory of a sovereign State and bind not only State actors but also non-State actorsinvolved in the conflict.Press Statement, Professor Philip Alston, Special Rapporteur of the United Nations Human Rights Council onextrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions (Kabul, 15 May 2008 ).3Uhler et al.,The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 - Commentary: IV Geneva Convention Relative to theProtection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, p.35.2

2

Customary rules of international humanitarian law are also applicable to the parties in the armedconflict in Afghanistan. In this respect, international judicial bodies have indicated that a number ofnorms contained in the Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols are now part ofcustomary international law.4This has been further reaffirmed by the International Committee ofthe Red Cross (ICRC), which has concluded that a number of the rules of the four GenevaConventions and Additional Protocol I have now acquired the force of customary international law,and that many of these rules are equally applicable in international as well as non-internationalarmed conflict.5Among the most important of these are the principles of distinction andproportionality, as well as other rules limiting the means and methods of warfare.Concerning the question of accountability nothing precludes insurgents, once they arehors decombat,from being prosecuted under the criminal laws of the country concerned. In any case,international human rights standards to which the State is a party or which form part of customaryinternational law continue to apply in situations of armed conflict.6Members of the pro-governmentmilitary forces are also accountable for violations of international humanitarian law andinternational human rights norms.While the primary responsibility for the protection of the civilian population during armed conflictlies with the Afghan Government, all parties to the armed conflict, including the IMF, haveresponsibilities under international law to protect civilians/non-combatants and to minimize theimpact of their actions on the civilian population and civilian infrastructure.All non-State parties involved in the conflict also have obligations under international humanitarianlaw. They also are liable for violations of the criminal and other laws of Afghanistan.The Government of Afghanistan (GoA) has an obligation and a responsibility to ensure law andorder throughout the territory of Afghanistan. This means that it has the right and the duty toenforce the laws of the country subject to norms of international law which it has accepted or whichare binding on it. Given the prevailing security conditions and the nature of the conflict in manyparts of the country, UNAMA recognizes the difficulties faced by the Afghan Government andinternational military forces in their efforts to ensure law and order. Law enforcement personnel areunder attack by insurgency groups, which also carry out attacks through suicide/IED bombings,abductions and extrajudicial executions, and often fail to properly distinguish between civilian andmilitary objectives, and between civilians and military objects in the conduct of their operations.Data on patterns of AGE activities suggests that insurgents deliberately base their operations insidecivilian areas so as to use the local population as camouflage, or for the purpose of attracting amilitary response by pro-government military forces which might result in civilian casualties anddestruction of property. This in turn is utilized by AGEs to undermine support for the Governmentand military forces (national and international) operating in support of it. Similarly, military forces(whether Government or IMF) have a duty to ensure that their military bases and facilities arepositioned so as not to endanger civilians unnecessarily.In contested areas, civilians are particularly vulnerable as they struggle to safeguard lives andlivelihoods in an environment of decreasing access to essential services. The combination of fearand anger, associated with widespread intimidation and the high number of avoidable deaths, feedsa cycle of violence and lawlessness that further undermines respect for basic norms of humanity.There is now an urgent need for all key stakeholders to take stock of the growing civilian death tolland to pursue measures aimed at mitigating the impact of the conflict on civilians.456

See for example ICTY, Case No. IT-95-16-T, para. 524.ICRC,Customary International Humanitarian Law,ed. Jean-Marie Henckaerts and Louise Doswald-Beck(CUP/ICRC, Cambridge 2005)International Court of Justice,DRC v. Ugandacase, para. 216.

3

UNAMA Human Rights’ strategy for Protection of CiviliansUNAMA Human Rights is focussed on the implementation of strategies and initiatives geared tomitigating the effect of the armed conflict on civilians. In achieving this goal, UNAMA HumanRights staff collect, monitor and analyze information relating to specific incidents of allegedcivilian casualties, and develops advocacy strategies based on the information obtained. Suchstrategies include,inter alia,direct advocacy with pro-government military forces, AfghanGovernment officials, Afghan Parliamentarians and Ministers of State, Embassies and DiplomaticMissions, UN Agencies, and international and national NGOs. UNAMA Human Rights alsoundertakes a coordinating role, in conjunction with other units of UNAMA, UN agencies, andmembers of civil society through mechanisms such as the Afghanistan Protection Cluster.In March 2008 the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) agreed to scale-up humanitarian actionincluding the establishment of a Protection Cluster. The Protection Cluster - an inter-agencycommittee chaired by UNHCR and co-chaired by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and theOHCHR/UNAMA - coordinates the efforts of NGOs, the Afghan Independent Human RightsCommittee (AIHRC) and UN agencies for the protection of Afghans and,inter alia,to mitigate theeffects of the armed conflict on them.A workshop convened in Kabul in August 2007 by UN and various implementing partners on theprotection of civilians revealed that civil society in Afghanistan wants UNAMA and the OHCHR toplay a key role in providing public reports on civilian casualties in order to strengthenaccountability and promote transparency in the follow-up to incidents where civilians are killed orinjured.7As part of its ongoing activities, UNAMA has supported the establishment of a SpecialInvestigative Team within the AIHRC to monitor the impact of the conflict on civilians.Overall, the purpose of UNAMA Human Rights monitoring and reporting on the impact of armedconflict on civilians is to:••assist the Government of Afghanistan and all relevant stakeholders to provideprotection to civilians affected by armed conflict;engender respect amongst the parties to the conflict for international humanitarianlaw, international human rights law and the Constitution and laws of Afghanistan soas to minimize the numbers of civilians killed or wounded or otherwise detrimentallyaffected as a result of armed conflict;develop strategies, such as advocacy and coordination, aimed at mitigating the effectof the armed conflict on civilians; andinform the public, both in Afghanistan and abroad, of the effect of the conflict oncivilians.

••

MethodologyThe information used to compile UNAMA’s reports is obtained from a range of sources byUNAMA Human Rights with staff in regional and provincial offices throughout Afghanistan.In response to the deteriorating security situation and increasing insurgency and counterinsurgency operations thathave resulted in greatly amplified risks to civilians in Afghanistan, the Office for the Coordination of HumanitarianAffairs in collaboration with the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, the Afghanistan IndependentHuman Rights Commission, the United Nations Children’s Fund, the Office of the High Commissioner for HumanRights, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Norwegian Refugee Councilorganized a workshop on the protection of civilians in armed conflict in Afghanistan held on 13-15 August 2007.7

4

When reports of incidents are received, UNAMA Human Rights conducts independentinvestigations to substantiate or discount the initial report. The civilian casualty figures reported byUNAMA Human Rights are the result of investigations and reports prepared by the team’s staffmembers in accordance with the Security Council monitoring mandate. UNAMA Human Rightsinvestigates all reports it receives of civilian casualties arising from the armed conflict, no matterwhich group, entity, or authority is alleged to be responsible.UNAMA Human Rights investigates reports of civilian casualties by tapping as wide a range ofsources and types of information as possible. All sources, and the information they provide, areanalysed for their reliability and credibility. In undertaking investigation and analysis of specificincidents, UNAMA Human Rights endeavours to corroborate and cross-check all information fromas wide a range of sources as possible including, for example, testimony of victims, victim’srelatives, and witnesses, health personnel, community elders, religious leaders and tribal leaders,pro-government military forces, local, provincial, regional and central Government officials, UnitedNations Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS), mass media, published reports anddocuments, and other secondary sources.Wherever possible, investigations are based on the primary testimony of victims and/or witnesses ofthe event and on-site investigations. On some occasions, primarily due to security constraintsregarding access, this level of investigation is not possible. In such instances UNAMA HumanRights relies on a range of techniques to gain information through reliable networks, using a widerange of sources. As already noted, all reports are assessed for credibility and reliability.Every effort is made to ensure that data contained in UNAMA Human Rights’ reports on specificincidents is comprehensive; however, such data is not exhaustive. Where UNAMA Human Rightsis not satisfied with the evidence concerning a particular incident, it will not be reported. In someinstances, investigations may take several weeks before conclusions can be drawn. This may alsomean that conclusions as to civilian casualties arising from a particular incident may be adjusted asmore information comes to hand and is analysed. However, where information is equivocal, thenconclusions will not be drawn until more satisfactory evidence is obtained, or the case will beclosed without conclusion and will not be included in statistical reporting or trends analysis. Asinformation is updated, and conclusions and statistics are modified, this can result in slightdifferences between the statistics published from month to month.Due to limitations in the operating environment, UNAMA does not break responsibility for civiliancasualties into particular sub-groups, other than to attribute incidents (where possible) to pro-government forces or AGEs. In relation to pro-government forces, operations are often conductedjointly between Afghan military forces and contingents of IMF; frequently, sources of informationare not able to distinguish between the different elements of those forces and different chains ofcommand, such that specific responsibility can be attributed. ISAF will often deny directinvolvement in a specific incident, leaving it to be assumed who was directly responsible sinceother military forces operating in the country do not communicate to UNAMA whether they werepresent or not. UNAMA concludes that distinguishing direct responsibility, given such limitations,would be misleading, since it is, in most instances, not possible to properly distinguish betweenwhich components of Afghan Military Forces or IMF were actually involved. Similarly, the natureof the armed insurgents, being composed of diverse groups which do not necessarily identify asTaliban and do not act under a single line of authority, and are not apparently motivated by thesame goals and ideologies, makes it equally difficult to attribute actual responsibility for civiliancasualties to particular individuals or groups of AGEs. This is particularly so when the evidence,even of eye-witnesses, is not properly able to distinguish between them.In some incidents, the non-combatant status of the reported victims of an incident is disputed. Insuch cases UNAMA Human Rights is guided by all the information to hand, as well as the5

applicable standards of international humanitarian law. This means that UNAMA Human Rightsdoesnotpresume fighting-age males are automatically civilians. Rather, such claims are assessedon the particular facts that are available concerning the incident in question. Thus, if the non-combatant status of one or more victim(s) remains under significant doubt, such deaths are notincluded in the overall number of civilian casualties.In light of the above, UNAMA Human Rights does not claim that the statistics presented in thisreport are complete; it may be the case that, given the limitations in methodology noted above,UNAMA Human Rights is under-reporting civilian casualties.Protection of Civilians DatabaseBetween October and December 2008, UNAMA Human Rights introduced a new electronicdatabase for the management and recording of cases of civilian casualties in Afghanistan to all fieldoffices as an enhanced tool for measuring the impact of the armed conflict on civilians and to assistefforts for their protection. The database, which became operational on 01 January 2009 willfacilitate human rights staff to record and analyze information and manage cases in an effective anduniform manner, and will greatly assist UNAMA Human Rights’ advocacy aimed at enhancing theprotection of civilians through easier and faster reporting.The database obliges users into a structured recording process and requires an analysis of allsources of information before a report can be generated for public use. For reasons ofconfidentiality, and the safety of staff and sources, access to the database is restricted to UNAMAHuman Rights Officers who are registered users, both in the field and in the UNAMA HumanRights office in Kabul.It is planned that with the aid of the database and improved information gathering, analysis andreporting techniques, UNAMA Human Rights will be able to better, and more efficientlydisaggregate data, and consequently be able to more clearly understand the impact of armed conflicton women and children.

6

Impact of the Armed Conflict on CiviliansOverview for 2008The armed conflict intensified significantly throughout Afghanistan in 2007 and 2008, with acorresponding rise in civilian casualties and a significant erosion of humanitarian space. In additionto fatalities as a direct result of armed hostilities, civilians have suffered from injury, loss oflivelihood, displacement, destruction of property, and disruption of access to education, healthcareand other essential services.UNAMA Human Rights recorded a total of 2,118 civilian casualties between 01 January and 31December 2008. This figure represents an increase of just over 39% on the 1,523 civilian deathsrecorded in 2007(see Graph #1).The 2008 civilian death toll is thus the highest of any year sincethe end of major hostilities which resulted in the fall of the Taliban regime.Of the 2,118 casualties reported in 2008, 1,160 (55%) were allegedly caused by AGEs and 828(39%) by pro-government forces. The remaining 130 (6%) could not be attributed to any of theconflicting parties because, for example, some civilians died as a result of cross-fire or were killedby unexploded ordinance(see Graph #2).The majority of civilian casualties occurred in the southof Afghanistan, which saw heavy fighting in several provinces. High casualty figures have alsobeen reported in the south-east, east, central and western regions(see Graph #3).January 2008 saw the number of civilian casualties almost on a par with that experienced in January2007 – January has traditionally seen lower insurgent and PGF activity, largely due to the fact it ismid-winter. However, this pattern radically changed in February 2008 when 168 civilians died,more than tripling the number of such casualties recorded in February 2007 when 45 civilians werekilled. This indicated that the AGEs were commencing their activities earlier than in previous yearsdespite the winter. Contributing to this higher figure was one particular incident on 17 February2008, when a suicide bombing at a dog fight in Arghandab district, Kandahar, killed 67 civilianspectators. While the use of IEDs, VBIEDs and BBIEDs has been a constant tactic used by AGEs,the incident in Arghandab indicated the growing randomness of the effect of such attacks as well asan increasing disregard of the use of such tactics in civilian areas and the consequent loss of civilianlife – a trend that was to continue throughout the year. Such incidents included the 7 July bombingof the Indian Embassy in Kabul, which killed 55 civilians, and another attack in Kabul on 27November near Masood Square, killing 4 civilians and injuring a further 10.From February 2008 until the end of December 2008 civilian casualties were consistently higherthan those recorded for 2007, except in June 2008 when 172 civilian casualties were recordedcompared with the figure of 253 for June 2007. July 2008 was a particularly deadly month, with323 civilian casualties recorded. The figure, however, for August 2008 was even higher, with 340civilian deaths recorded, making it the highest number of civilian casualties recorded for any monthsince the end of 2001. A contributing factor was the high number of civilian casualties caused by anoperation conducted by the IMF in the village of Azizabad in Shindand District of Herat Provinceon 22 August.Despite the dramatically rising civilian casualty figures reported throughout 2008, the month ofSeptember 2008 saw a drop in the levels of reported civilian casualties to 162, a reduction of 52%from the figure recorded for August 2008. The September 2008 figure was only slightly higher thanthe figure in September 2007 during which 155 civilians died. This drop in casualties was largelyattributable to various factors, including the new tactical directives issued by Commander ISAF onuse of air-strikes, the fact that Ramadan and International Peace Day were both celebrated duringthe month, and there were increased security operations by the Pakistan Government against

7

insurgents in the Tribal Areas. There was a reduction in civilian casualties reported from all regions,the most significant being from the western and southern regions.With 194 recorded civilian deaths, October 2008 did not see the extremely high number of civilianfatalities recorded in July and August, but considerably more than the 162 recorded for September2008. This suggests that the dip in casualty rates in September was temporary and did not reflect asignificant improvement in the overall situation. Indeed, the October death-toll was of particularconcern as it was more than double the 80 civilian deaths recorded for October 2007. The figure forOctober was not due to any particularly deadly event. Significantly, it appeared that the decline incivilian casualties evident in previous years as winter approached would likely be much lesspronounced than in past years. Of the 194 reported civilian casualties for October 2008, 115 (59%)died from attacks by AGEs, 74 (38%) as a result of operations conducted by pro-government forces,and 5 (3%) from crossfire and other conflict related incidents, roughly consistent with overall trendsthis year.With 176 recorded civilian deaths, November 2008 saw a further drop from the extremely highnumber of civilian fatalities recorded between July and August 2008 and represented a furtherdecline on the 194 civilian deaths reported in October 2008. However, the figure was still higherthan the 157 casualties recorded in September 2008, and the 160 civilian deaths recorded forNovember 2007. While the rise in figures for October 2008 initially indicated that the decline inmilitary and insurgent activities witnessed in previous years with the approach of winter was goingto be delayed, the figure for November seemed to indicate that winter was at last starting to have aneffect on military activities with a resulting drop in civilian casualties. Of the 176 reported civiliancasualties for November 2008, 90 (51%) died from attacks by AGEs, 72 (41%) as a result ofoperations conducted by pro-government forces, and 14 (8%) from crossfire and other conflictrelated incidents, roughly consistent with overall trends this year.With 104 reported civilian casualties in December 2008, civilian deaths declined significantly from176 recorded in November 2008. This decline was consistent with seasonal trends and parallels asimilar fall in reported security incidents as cold weather began to envelop the country. Comparedto December 2007, in which 88 civilian deaths were reported (a similarly significant decline indeath rates notable from the preceding month), the casualty figures recorded for December 2008represented an 18% increase in civilian deaths. Broadly consistent with overall trends, of the 104reported civilian casualties for December 2008, 54 (52%) died from attacks by AGEs, 33 (32%) as aresult of operations conducted by pro-government forces, and 17 (16%) from crossfire and otherconflict related incidents.From the beginning of winter there was also a shift in the location of attacks. Incidents tended toconcentrate in provinces less affected by the weather, such as Khost or those in southernAfghanistan. Indicating the spread of conflict into hitherto more stable regions, the northern regionreported a notably relatively higher number of civilian deaths from October 2008 when 1 civiliancasualty was recorded, to 7 in November 2008, to 10 civilian casualties in December 2008.Air-strikes by IMF took a heavy toll throughout the year. By the end of July 2008, some 224civilians had been reportedly killed by air-strikes, which constituted more than half of the 384 non-combatant deaths attributed to actions by pro-government forces for that period. In July there were anumber of high profile incidents, including an air strike on 6 July 2008 in Deh Bala district,Nangarhar, in which 47 civilians were killed, including some 30 children and 13 women travellingon foot to a wedding party. In several incidents, compounds with an alleged AGE presence weretargeted in air-strikes but civilians were also killed in such attacks. One incident occurred on 4 July2008 in Nuristan, in which UNAMA Human Rights documented the death of 17 civilians; thisincluded two women and some medical staff who were killed while trying to leave the area. This

8

was followed by a military operation that took place in Azizabad village of Shindand district, HeratProvince, on 21-22 August 2008 which resulted in 92 civilian casualties, including 62 children.Following the issuance of a new tactical directive by Commander of ISAF on the use of air-strikes,there was a marked reduction in civilian casualties attributed to pro-government forces in October2008. However this did not continue into November 2008; a particularly deadly event on 3November in Wach Bakhto village in Shawali Kot district, Kandahar province, resulted in a toll of37 civilians dead and a further 31 injured in an air-strike which information suggests may haveerroneously targeted a wedding celebration. In December 2008 the number of civilian deathsattributed to air- strikes once again declined, indicating that the spike in November had resultedfrom the one incident in Shawali Kot, in line with the declining trend seen in September andOctober.Hostility to search and seizure operations (including night time raids) became more pronouncedthroughout the year, despite amendment of standard operating procedures regarding such practices.In particular there were a number of joint Afghan and international operations in which excessiveuse of force allegedly resulted in civilian deaths.UNAMA data also suggests that 41 civilians were killed in “force protection incidents” becausethey were perceived, for example, as being too close to military convoys or failing to followinstructions at check points. This constitutes a relatively small part of the overall casualty figuresand suggests that amendments by IMF to “escalation of force procedures” and greater awarenessamong Afghan civilians have had a positive impact.Throughout 2008, AGEs continued to target individuals perceived to be associated with theGovernment or the international community for assassination. The victims of intimidation tacticsinclude doctors, teachers, students, tribal elders, civilian government employees, former police andmilitary personnel, and labourers involved in construction work. Incidents recorded by UNAMAthroughout the year further confirm already substantial evidence indicating that insurgents areundertaking a systematic campaign of intimidation and violence in order to undermine confidencein the GoA and its international backers.Threats against education facilities led to the closure of several schools and destruction of others ininsurgent-dominated areas of the country, such as a number of districts in Farah, Badghis, Helmandand Kandahar provinces. Attacks against education institutions, including girls’ schools, were alsonoted in other areas of the country, such as in the western, northern, eastern and south-easternregions. In 2008, 293 school-related security incidents and 92 deaths were reported, compared to232 school-based security incidents in the same period for 2007 and 213 incidents in all of 2006. Inearly September 2007, AGEs burned more than 100,000 textbooksen routefrom Kabul forKandahar and Nooristan provinces. It was also confirmed that more than 640 schools had ceased toprovide education services to students because of AGE threats. As a result of these factors alone, itis estimated that more than 230,000 children have been denied access to education.“Humanitarian space” has shrunk considerably. Large parts of the south, south-west, south-east,east, and central regions of Afghanistan are now classified by UNDSS as ‘extreme risk, hostileenvironment’. Aid organizations and their staff have been subjected to a growing number of directattacks, threats, and intimidation. Some highly publicized incidents included an ambush on anInternational Rescue Committee vehicle on 13 August 2008 in Logar province, in which threefemale international aid workers and their Afghan driver died and for which the Taliban claimedresponsibility. On 26 August 2008 an aid worker was abducted and subsequently killed inNangarhar province. In September 2008, there was a suicide attack on a UN convoy in Spin Boldakin which three UN staff died: two doctors involved in a polio eradication campaign and oneUNAMA driver. Attacks on NGOs also continued in September 2008, especially in Logar Province

9

in the central region where four NGO staff were reportedly abducted by AGEs, while another fourNGO staff were reportedly abducted in the eastern region. In October 2008 Kabul saw a notable risein the number of direct attacks on international and humanitarian targets, with a number of killingsand abductions.In 2008, a total of 38 aid workers were killed, 147 were abducted, 70 aid convoys and 63 aidfacilities were attacked. Insurgents also frequently targeted private transport companies andconstruction workers who are not categorized as aid workers but in many cases were involved in thedelivery of humanitarian aid and the implementation of development projects. According to theAgency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief (ACBAR), an umbrella group of NGOs, the situationhad “forced many aid agencies to restrict the scale and scope of their development and humanitarianoperations.” This effectively means that vulnerable people in need of assistance are unable toexercise their right to receive life-saving humanitarian support. Subsequent to the killing of its staff,the IRC after 20 years of operating in Afghanistan suspended all its programs for several weeks,which is illustrative of the continuing erosion of humanitarian space and the ramifications of this forvulnerable Afghans in violent and volatile areas.Women and children have, to a significant extent, been the unseen victims of the armed conflict inAfghanistan. The UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary Executions in May 2008observed: “Women are also threatened or targeted for assassination by the Taliban and other AGEsfor a range of reasons”. Women and children, even if they not the intended targets, were oftensubjected to violence, particularly through insurgent attacks carried out heedless of the implicationsfor civilians. Air-strikes, night raids on civilian dwellings, and force protection incidents conductedby Afghan Government soldiers and IMF in several cases resulted in the death or injury of womenand children.Violence inflicted directly or indirectly on women and children often results in seriouspsychological trauma. Ongoing violence and lack of security also significantly impedes or preventsaccess by civilians, in particular women and children, to essential services, including health careand education. Armed conflict causes social and economic harm, such as depriving families ofbreadwinners, or imposing extra financial burdens in relation to medical care for injured familymembers. As the UN Special Rapporteur Extrajudicial, Summary Executions observed: “Womenwho have lost men-folk in the current conflict very often end up in disastrous situations. Somereceive monetary assistance for their losses, but many are unaware of such a possibility.”Understanding adequately the ways in which women are affected by the conflict is difficult,inhibiting coordinated interventions at the policy, advocacy or programme levels to mitigate theimpact of the conflict on them. The new electronic database, introduced in January 2009, will helpUNAMA to improve the collection and analysis of information, including disaggregation of data oncivilian casualties by age and gender where possible. This will enable a fuller picture of the impactof the conflict on men, women, girls and boys. Also important to examine are the effects of conflictand insecurity on incidents of domestic violence; the impact of limitations of freedom of movementfor women’s access to basic and maternal health care; the differential impact of insecurity on girl’saccess to education; the effects of conflict-related displacement; and the poverty suffered by womenwhose male relatives have been killed or injured.The last months of 2008 saw a number of particularly high-profile incidents that illustrate theimpact of the armed conflict on children. In a widely condemned attack in Kandahar on 12November 2008, two attackers on a motorbike used toy water-pistols to spray a group of schoolgirls with acid. Sixteen individuals, including 12 students and 4 teachers were injured, 6 of themcritically. The acid-attack was widely blamed on insurgents, though the Taliban later denied anyinvolvement. Other incidents demonstrate the way in which children frequently fall victim tosuicide and IED attacks or air-strikes simply because they happen to be close to the intended target10

at the time of an attack. On 28 December 2008, for instance, a suicide bomb targeting the DistrictAdministrative Centre of Mandozaiy district, Khost, was detonated as a group of school childrenwas walking by. The attack killed 5 children and wounded 14. Finally, in December in an exampleof the use of children by insurgents to carry out acts of violence, a teenage boy in Sangin district,Helmand, was pushing a wheelbarrow filled with explosives that detonated near a passing patrol ofinternational soldiers. It is not clear if this was a suicide attack or whether the device was remotelydetonated.Overall, there is only limited information on the specific ways in which children are affected by thearmed conflict, including through internal displacement, detention by ANSF and IMF, andimpairment of access to education facilities due to insecurity and targeting of schools and teachersby AGEs. The Security Council in Resolution 1806 (para 14) expressed its strong concern about thekilling and maiming of children as a result of the conflict. The Security Council stressed theimportance of implementing Security Council Resolution 1612 in Afghanistan and requested thatthe child protection capacity of UNAMA be strengthened. During 2008, coinciding with a visit ofthe Special Representative of the Secretary General on Children and Armed Conflict, a special TaskForce aimed at monitoring the effects of armed conflict on children was established pursuant toSecurity Council Resolution 1612. UNAMA is part of this task force, which monitors the effects ofthe conflict on children and contributes to the Secretary General’s periodic reports to UN SecurityCouncil.Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War (ERW)ERW are of major concern in Afghanistan. According to the Mine Action Coordination Centre forAfghanistan (MACCA) on average, over 60 people are killed or injured every month in mine-relatedincidents and half of the victims are children. According to the MACCA, supported by the UnitedNations and the Government of Afghanistan through its Department of Mine Clearance, 179 people werekilled and 574 were injured as a result of mines and ERW in 2008, a slight rise on 2007.In Afghanistan, there are currently 5,560 known hazards, covering an estimated total area of 690 km� andimpacting over 2,090 communities. In 2008 alone, more then 84,000 anti-personnel mines, 900 anti-tankmines and 2.5 million ERW were destroyed by the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA).This resulted in the clearance of over 50km2of minefields and almost 113km2of former battle area. Over1.4 million Afghans received Mine Risk Education (MRE), of which over 40% were female and 70%were children. 15,000 teachers have now been trained to teach MRE.The MAPA has achieved over 70% progress towards achieving the goal set by the Afghanistan Compactand is over half way towards the Ottawa/ Mine Ban Treaty of completely clearing all mined areas.However, as highlighted above, the level of contamination throughout the country remains high and has aserious impact on the lives and livelihoods of millions of Afghan civilians.# Figures for those killed by ERW are not included in Protection of Civilian casualty figures presented in this report.

11

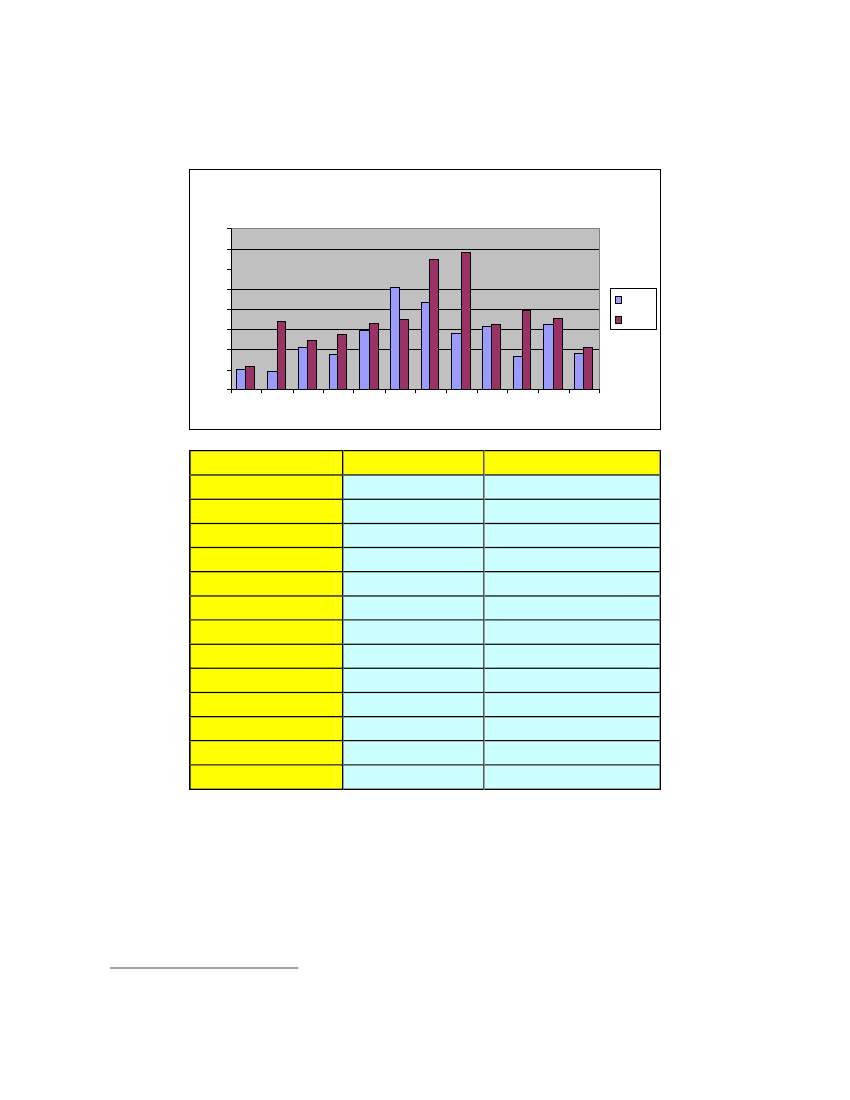

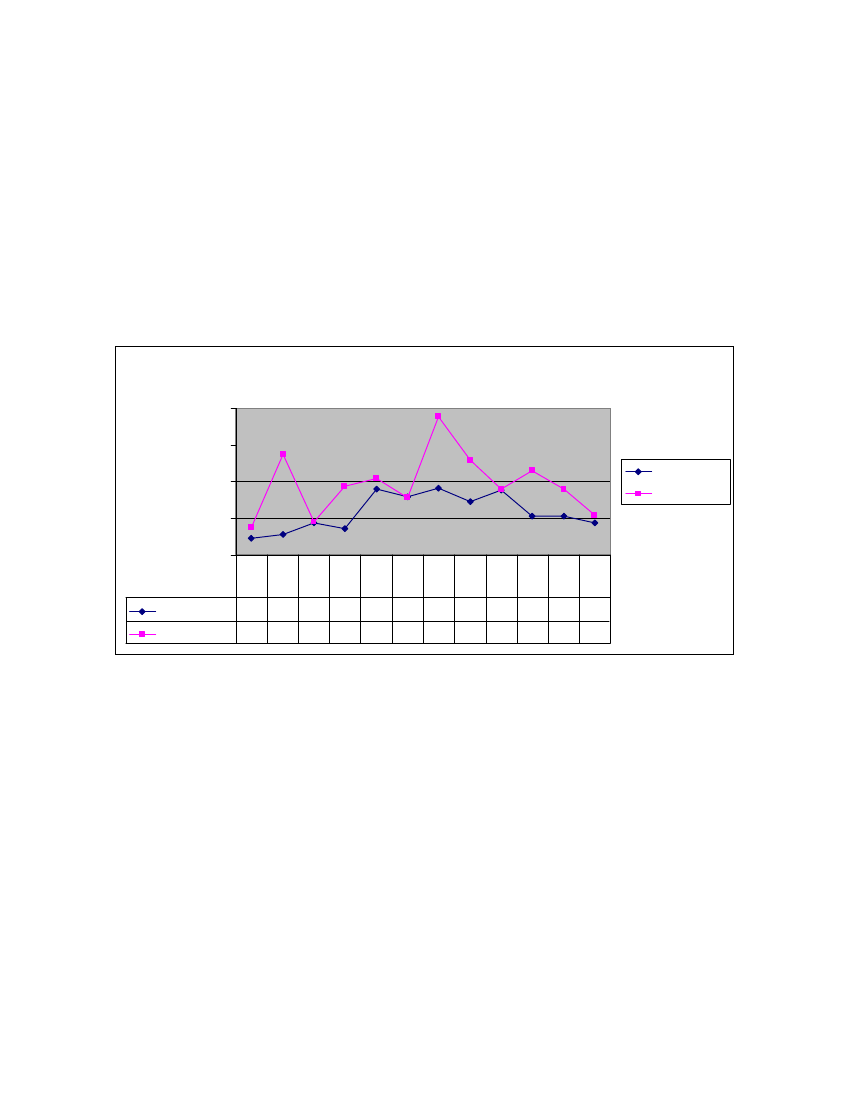

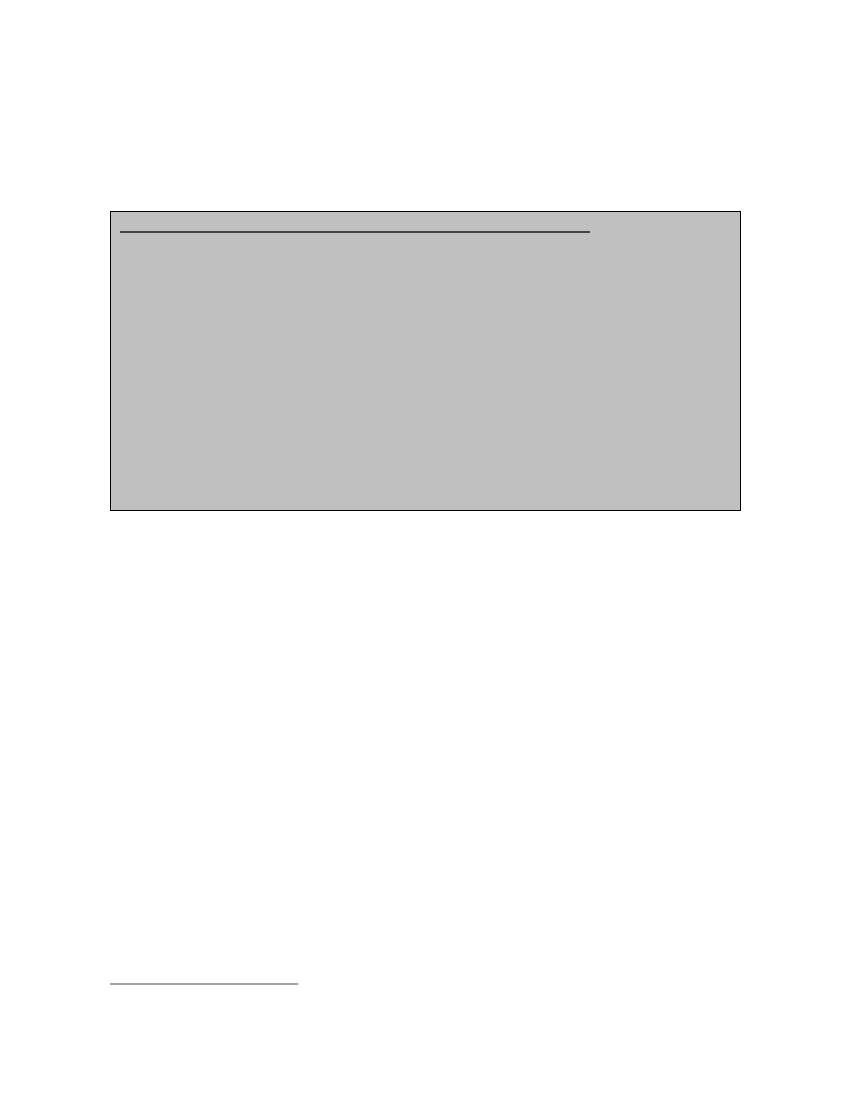

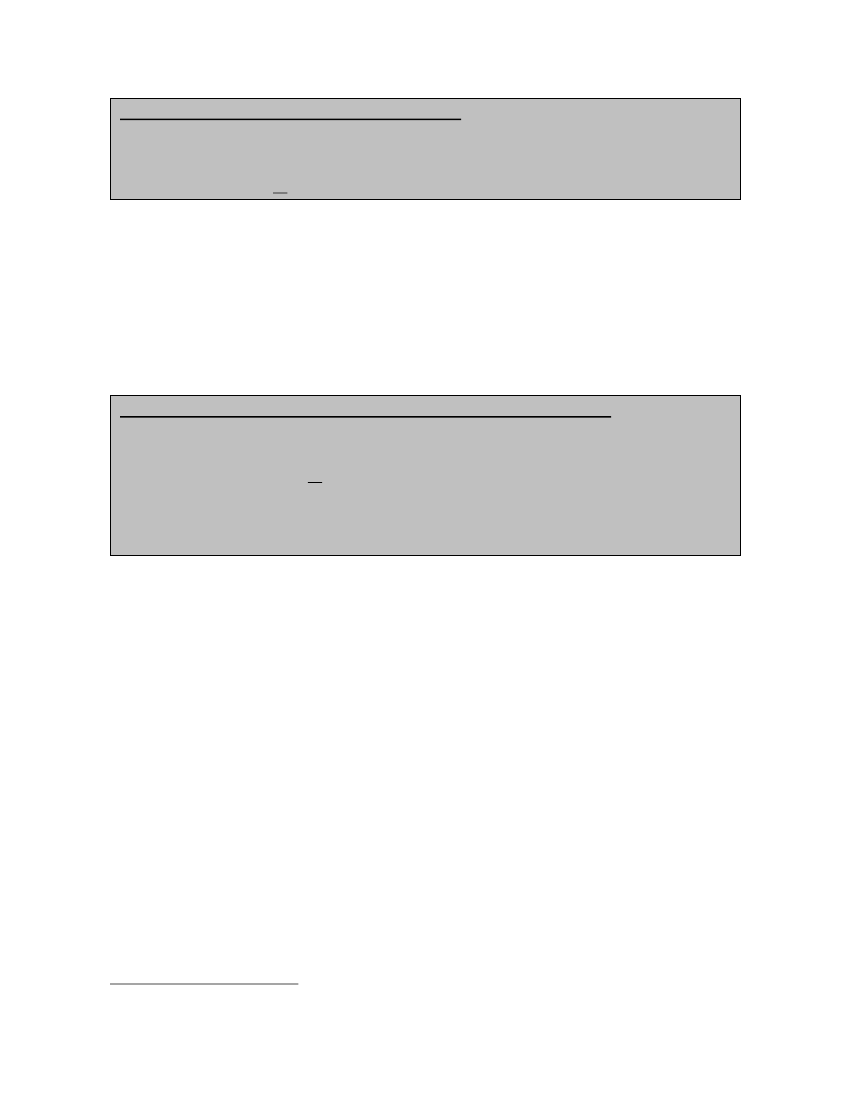

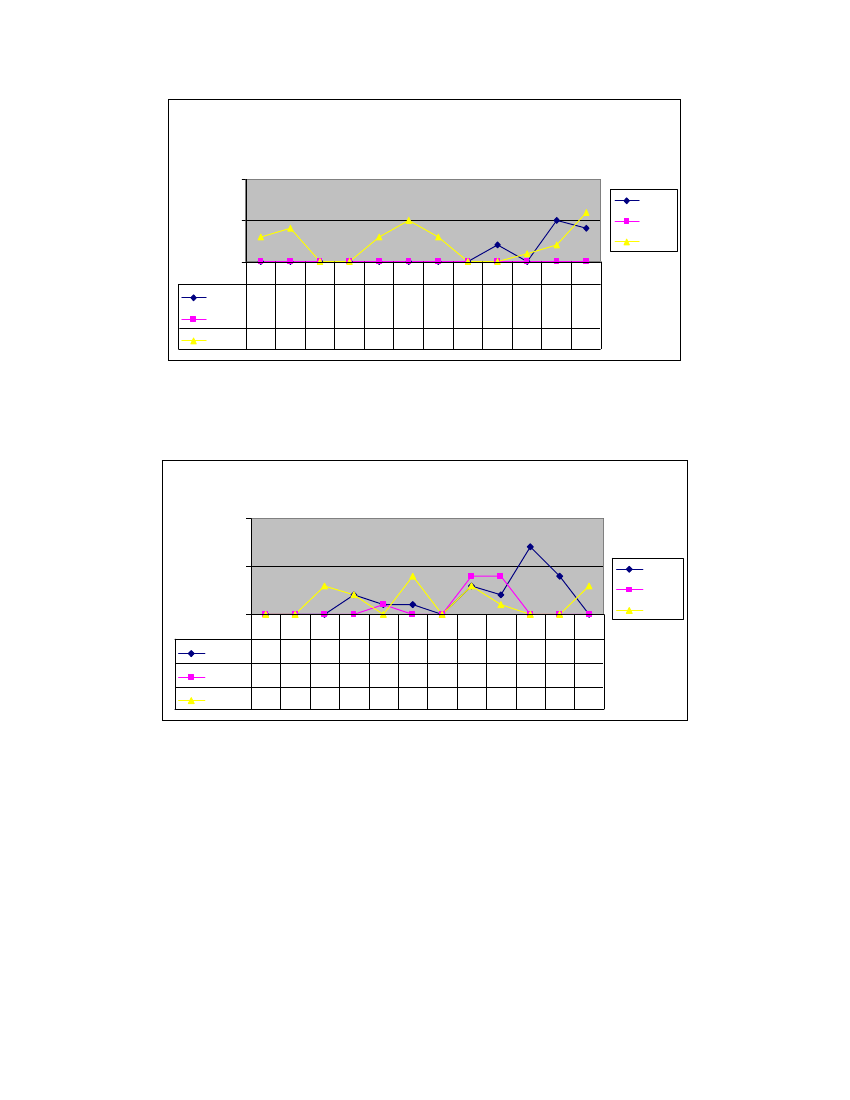

#1 Graph/Table showing the number of reported civilian casualties as a result of armedconflict in Afghanistan in 2007 and 2008♦

Reported Civilian Casualties in Armed Conflict400350300250200150100500Jan Feb Mar Apr May JunJul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec20072008

MonthJanuaryFebruaryMarchAprilMayJuneJulyAugustSeptemberOctoberNovemberDecemberTOTAL

200750451048514725321813815580160881523

2008561681221361641723233411621941761042118

Information contained in these graphs is sourced from reports of civilian casualties investigated by UNAMARights and is updated regularly.

♦

Human

12

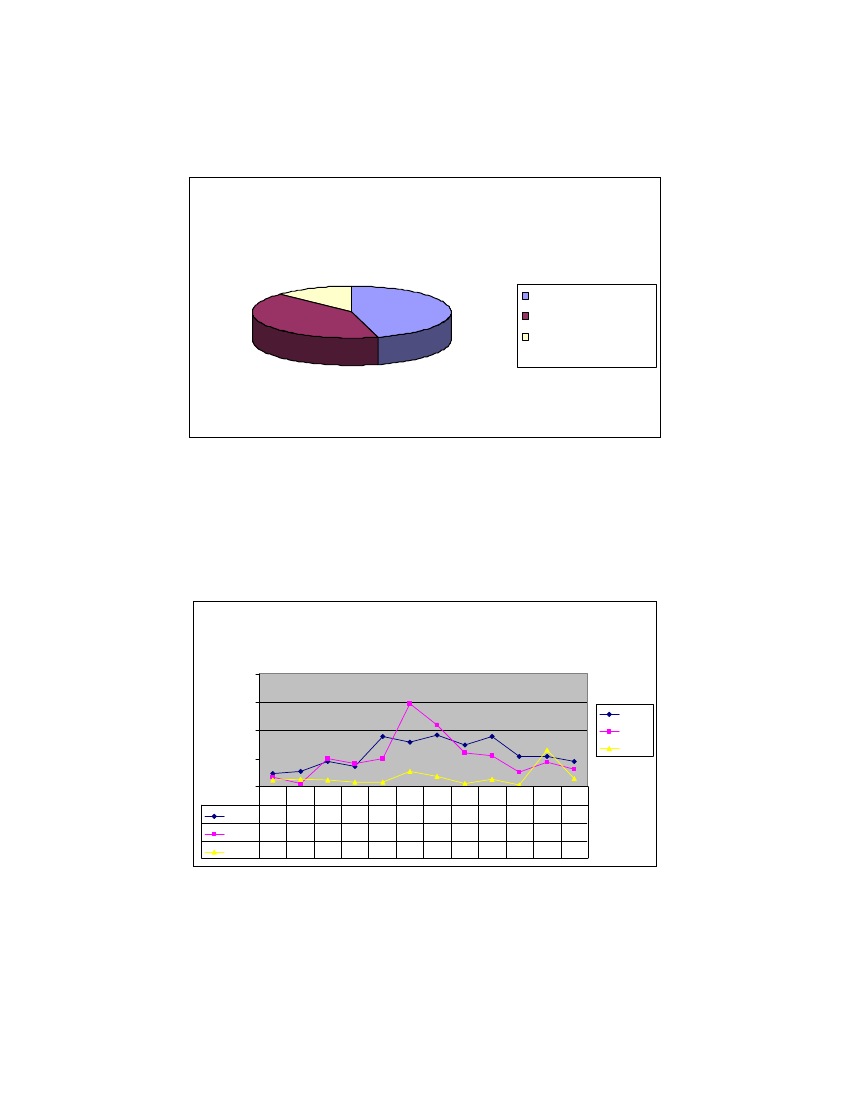

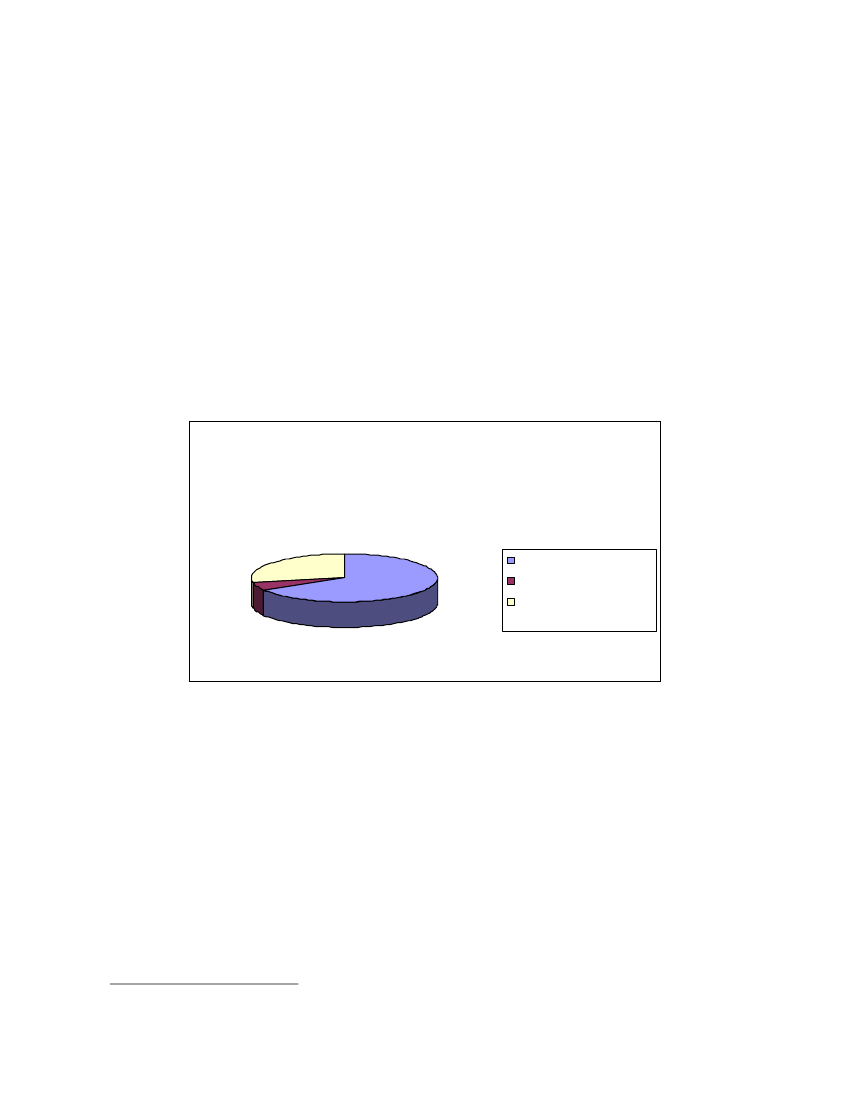

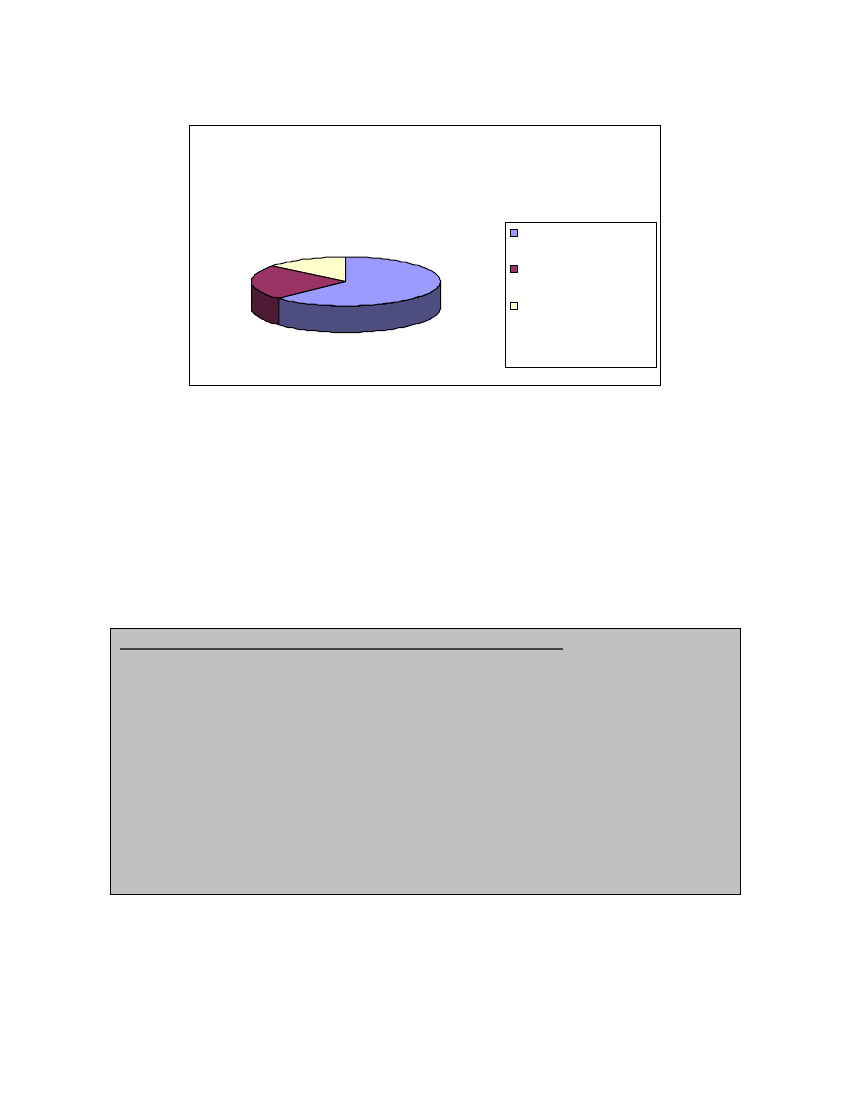

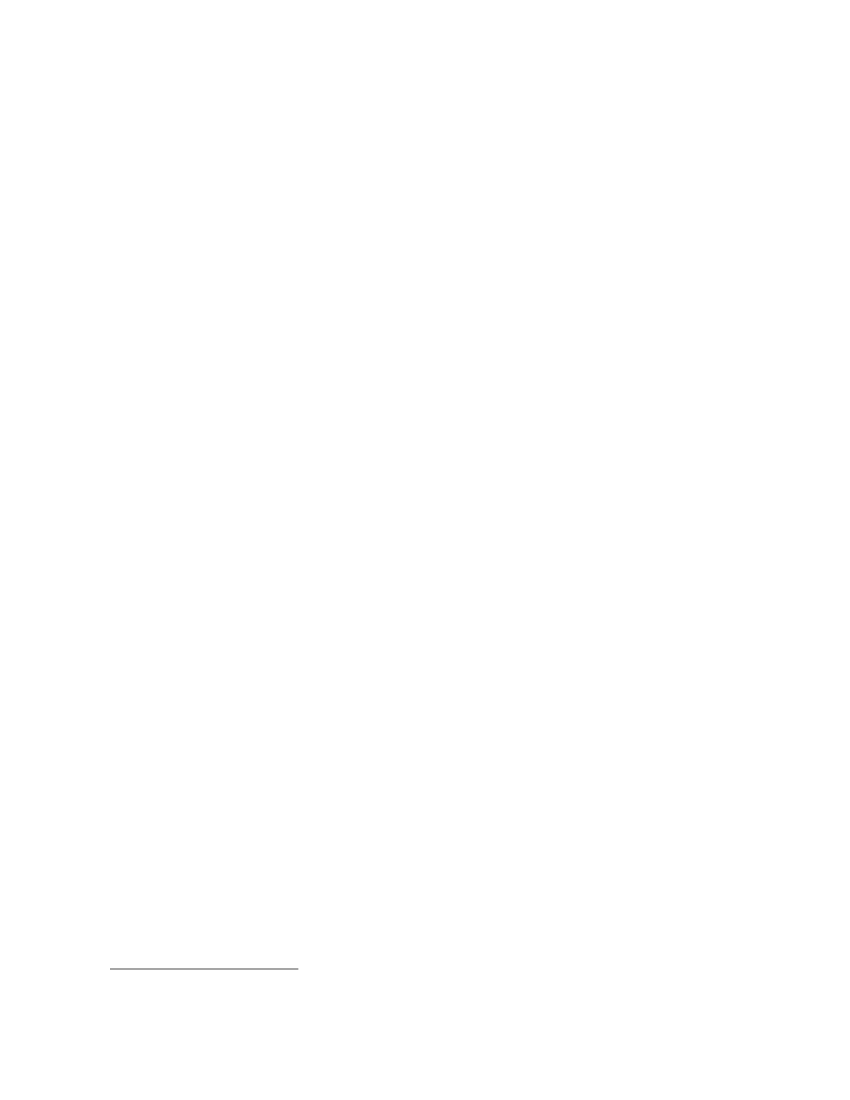

#2 - Graph representing the number of reported civilian casualties for 2007

Reported Civilian Casualties Jan-Dec 2007

13%46%AGEs: 700Pro-Govt Forces: 629Other: 19441%Total: 1523

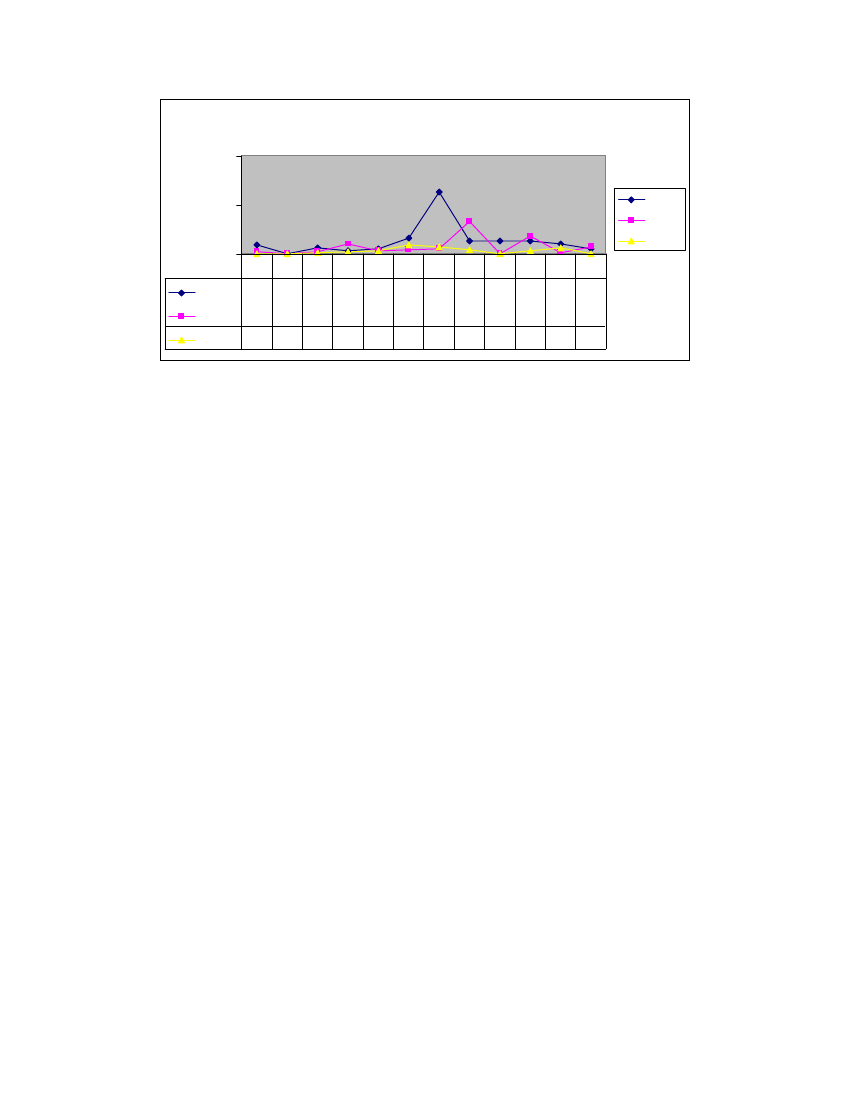

#3 - Graph representing the number of reported civilian casualties, January to the endDecember 2007, by month and responsibility

Reported Civilian Casualties Jan-Dec 2007 byMonth & Responsibility200150100500AGEPGFOtherJan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec2316112751344491136418895087927911873588541353252534364443014147 109 60AGEPGFOther

13

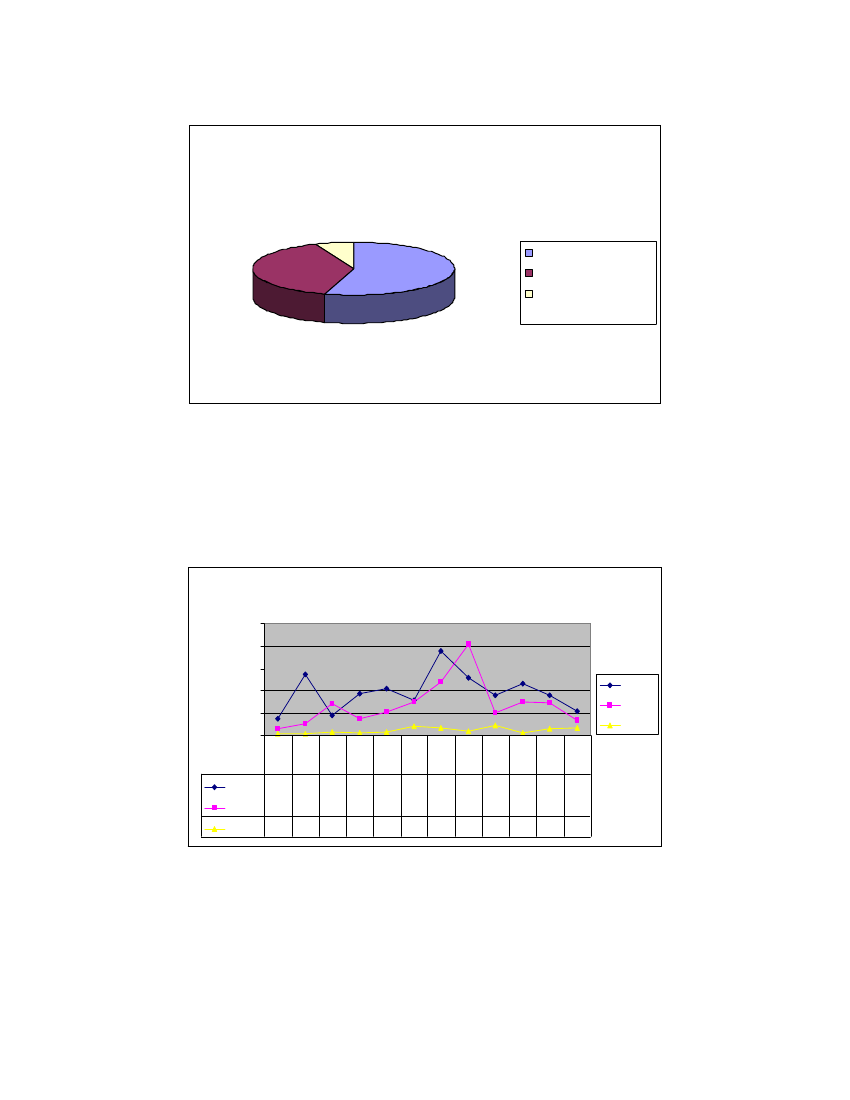

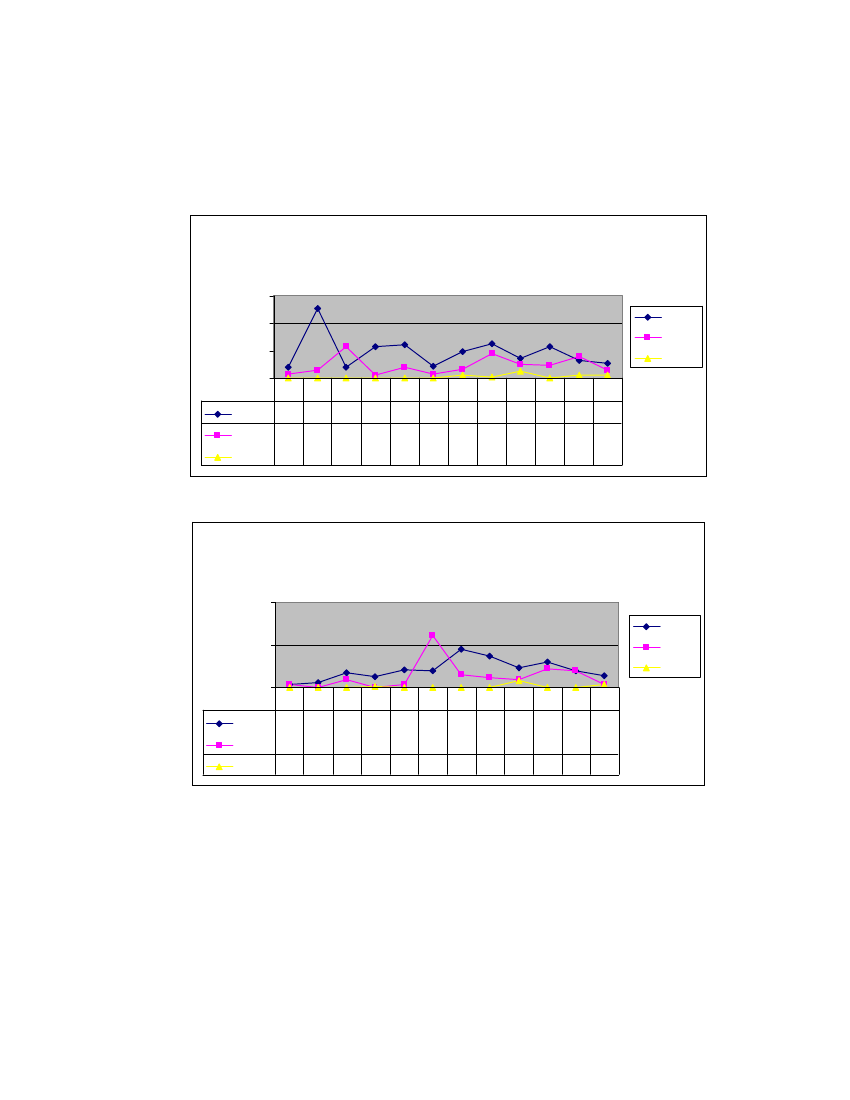

#4 - Graph representing the number of reported civilian casualties for 2008 (total: 2118)Reported Civilian Casualties Jan-Dec 2008

6%AGEs: 1160Pro Gov Forces: 82839%55%Other: 130Total: 2118

#5 - Graph representing the number of reported civilian casualties, January to the endDecember 2008, by month and responsibility

250200150100

Reported Civilian Casualties Jan-Dec 2008 by Month& Responsibility

AGEsPGFOtherJan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

500

AGEs 37 137 45PGFOther154274707

94 104 78 188 129 89 115 9037553774 119 203 5120169227457214

543317

14

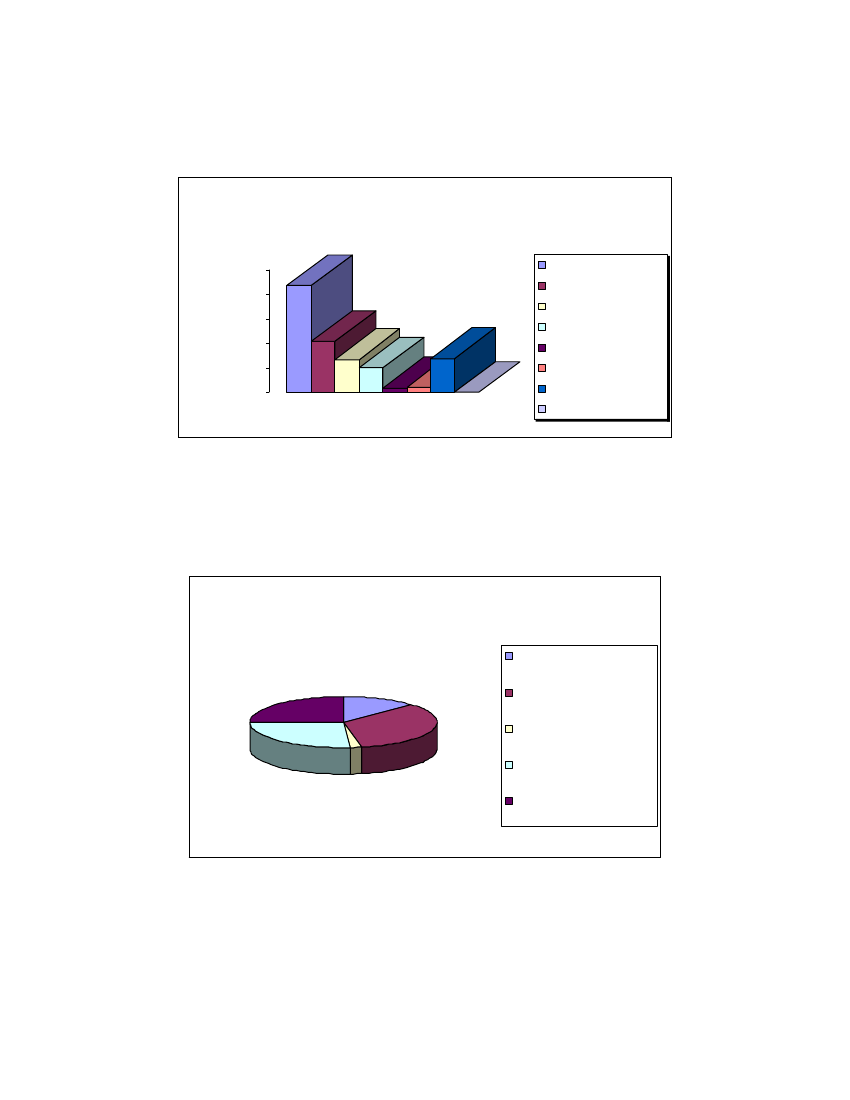

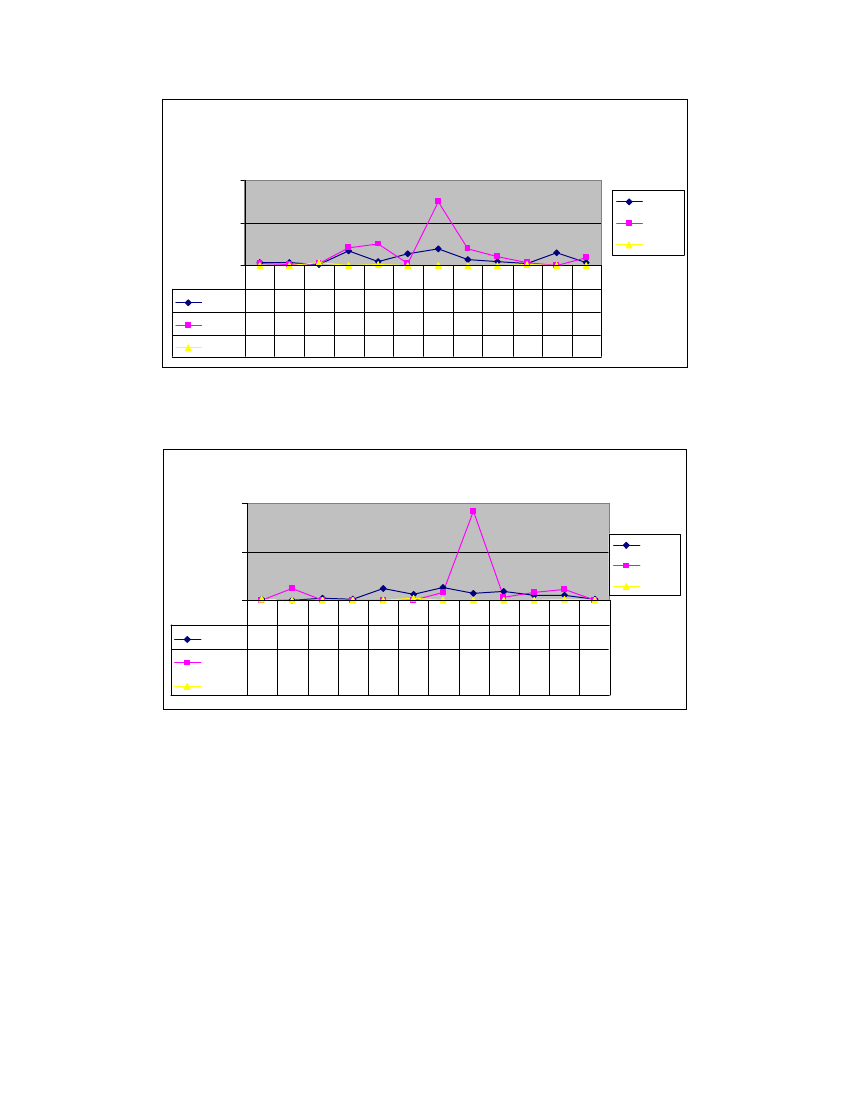

#6 - Graph representing the number of reported civilian casualties by Region for 2008

Reported Civilian Casualties Jan-Dec 2008 byRegion100080060040020001South: 872SouthEast :417East: 270West: 200North: 38North East: 45Central: 276Central Highlands: 0

#7 - Graph representing the number of reported civilian casualties, January to the endDecember 2008, by incident type

Civilian Casualties Jan-Dec 2008 by Incident Type

Executions by AGEs:27125%13%Suicide & IED attacks byAGEs: 725Escalation of Force byPro-Govt Forces: 4134%26%2%Air-Strikes by Pro-GovtForces: 552Other Tactics: 529

15

Pro-Government ForcesPro Government Forces and Civilian CasualtiesAfghan security forces and IMF supporting the Government in Afghanistan were responsible for 41% of the total civilian casualties recorded in 2007. At around 39 % of total civilian casualtiesrecorded in 2008, the proportion of deaths attributed to pro-government forces remained relativelystable. However, at 828, the actual number of recorded non-combatant deaths caused by pro-government forces amounts to a 31 % increase over the 629 such deaths recorded in 2007. Thisincrease occurred notwithstanding various measures introduced by IMF to reduce the impact of thewar on civilians, including internal as well as independent external investigations, after-actionreviews, the creation of mechanisms geared to reviewing trends and reducing the impact of the waron civilians, and the issuance of new tactical directives regarding the use of air-strikes.

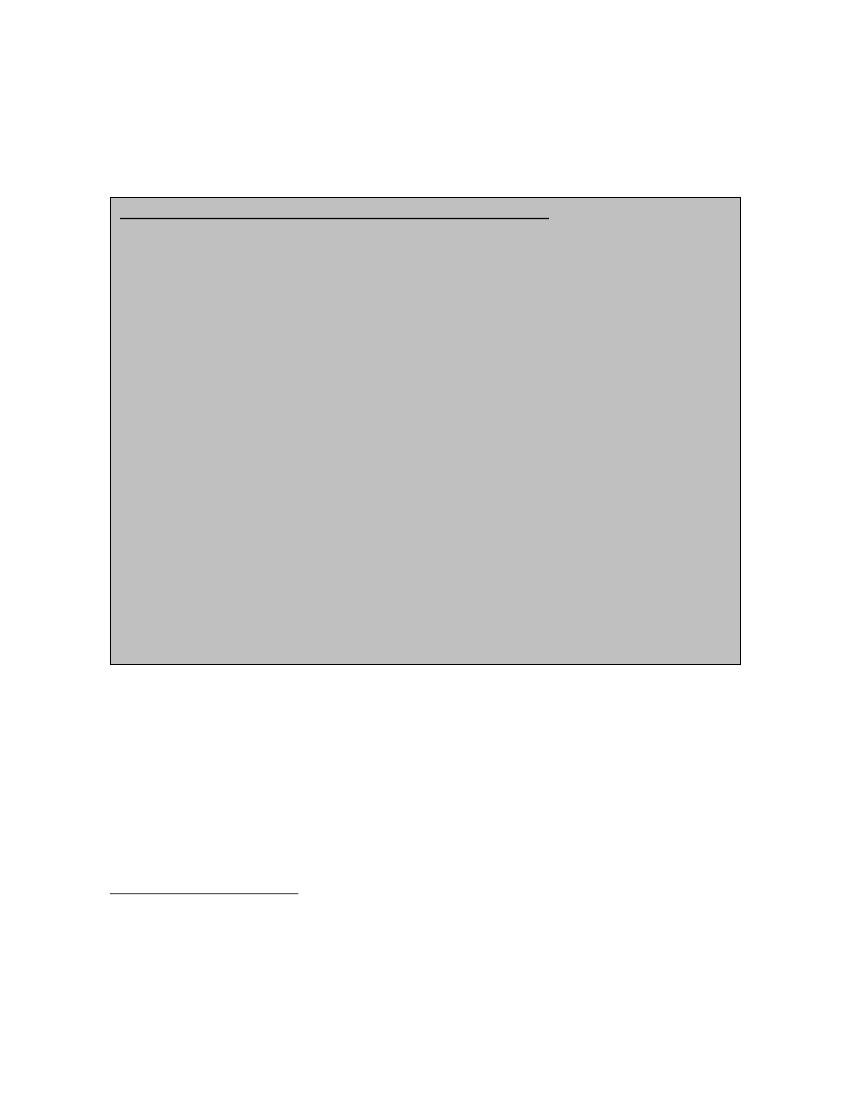

#8 –Graph representing PGF caused civilian casualties Jan-Dec 2008.8Percentage of PGF-Attributed Civilian CasualtiesResulting from Air-Strikes and Force ProtectionIncidents during 2008

28%

Air-Strikes: 552Force Protection: 41Other PGF Tactics: 235

5%

67%

Total: 828

Air-strikesAir-strikes account for the largest percentage of civilian deaths attributed to pro-government forces.UNAMA recorded 552 civilian casualties of this nature in 2008. This constitutes 64 % of the 828non-combatant deaths attributed to actions by pro-government forces in 2008 and 26 % of thosekilled overall. There have been several high-profile incidents, such as the widely reported 22August 2008 air-strike on Azizabad village in Shindand district, Herat in which 92 civilians werekilled.

8

Other tactics includes persons killed as a result of ground engagements, artillery fire, etc.

16

Case Study: Air raid on a wedding party, Deh Bala, NangarharOn 6 July 2008, at around 6:30 am, international military air assets carried out an attack on a remotemountainous area of Kamala village in Deh Bala district of Nangarhar province – an area widelyrumoured to be an AGE hideout. However, at the time of the strike, a wedding entourage was resting atKamala area, on their journey from the bride’s village to the groom’s village. 47 non-combatants, whowere part of a bridal entourage, were killed and 11 others wounded in the attack. Amongst the dead were35 children, 9 women and 3 men.District and provincial authorities informed UNAMA that two days prior to the operation, AGEs hadattacked a nearby Afghan National Boarder Police (ANBP) post and that intelligence reports received byIMF and ANSF indicated that AGEs had infiltrated the area and established camps there. An IMF pressrelease, which was issued immediately after the incident, made no mention of civilian casualties andstated that several militants had been killed using precision-guided munitions. Following severalindependent investigations and a strong community reaction, however, IMF later acknowledged thecivilian death toll and madesolatiapayments.

In the aftermath of the incident in Shindand district on 22 August 2008, COM-ISAF issued a newtactical directive in relation to air-strikes to ISAF contingents, which was mirrored in a similardirective to US Forces Afghanistan. While these appeared to have had an initial positive effect, witha drop in the number of civilian casualties resulting from air-strikes reported in October 2008, thenumber rose again at the beginning of November 2008 with two major incidents in Kandahar andBadghis provinces. In December 2008 the number of civilian casualties as a result of air attacksdropped again, though it is unclear whether this is due to the effect of the new tactical directive orsimply the fact that the winter is reducing the number of insurgent or IMF operations.Air-strikes called in by ground forces engaging insurgent fighters represent a particular threat tocivilians, as often compounds with an enemy presence also house civilians unable to leave whenfighting breaks out. In several incidents, compounds with an alleged insurgent presence weretargeted in air-strikes but civilians were also killed in such attacks.Case Study: Air attack on a wedding party, Shah Wali Kot, KandaharIn the afternoon of 3 November 2008, OEF and ANSF forces were on a joint patrol in the Bakhto Tangiarea of Shah Wali Kot district in Kandahar, when insurgents ambushed them. A firefight ensued and wasapparently ended by the withdrawal of the insurgents from the area. The patrol then moved on to WachBakhto village, where some sources reported that they opened fire on 3 houses. Close air support wascalled in and air-strikes hit Bakhto Tangi, causing damage to property but no casualties. However, air-strikes on Wach Bakhto village resulted in a large number of civilian casualties. An official Government-OEF joint investigation put the number of civilian dead at 37 and the number of injured at 35.According to eyewitness reports given to UNAMA, all those civilians killed and injured in Wach Bakhtowere attending a wedding-party in one residential compound. OEF and Government sources claimed thatinsurgents used villagers’ houses to attack the patrol and had infiltrated the wedding-party compound thatwas bombed. Eyewitnesses and victims interviewed by UNAMA, however, strongly denied the presenceof any insurgents at the wedding party.

Force Protection IncidentsUNAMA figures suggest that, in 2008, 41 civilians were killed in force protection incidents becausethey were perceived as being too close to military convoys or because they failed to followinstructions at check points. This constitutes a relatively small part of the overall casualty figures(see Graph #8)and suggests that amendments to escalation of force procedures have had a positive17

impact. The fact that the last quarter of 2008 saw as few as 6 deaths resulting from militaryescalation of force procedures appears to further support this. With a projected increase in thevolume of military traffic as substantial numbers of new troops deploy to Afghanistan, this issue isliable to grow in importance, and UNAMA will continue to monitor the effectiveness of steps takento minimize escalation of force incidents.

Case Study: Escalation of force measures by an ISAF convoy, Panjwai, KandaharOn 28 July 2008, a husband and wife and their two young children were returning home in a taxi inPanjwai district, Kandahar province. A passing ISAF convoy fired at the vehicle, wounding the father andkilling both of the young children. The Canadian contingent of ISAF forces had issued warnings to thelocal population to pull off the road and remain stationary while convoys are passing.Whilst there are conflicting reports as to whether the vehicle was moving at the time of the incident,according to the children’s father in an interview with UNAMA, the vehicle had parked on the side of theroad when they saw the convoy, but after the first two vehicles had passed, the third vehicle opened fire.A statement by ISAF notes that, “The vehicle was directed to keep its distance but it did not comply.ISAF soldiers gave hand, arm and audio signals as well as flashing light signals to stop. When the vehiclewas 10 meters away and still approaching rapidly, the ISAF soldiers, fearing an attack, fired on it.” Asubsequent investigation by the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service concluded that thesoldiers had “followed proper escalation of force procedures and acted within their rules of engagement”.However, anex gratiapayment is believed to have been made in this case.

Search and seizure operations/Home searchesThe Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions in May 2008 noted thatthe killings by pro-government forces that most frequently raise issues under international humanrights and humanitarian law are those that occur during surprise night time raids. Based onprotection of civilians regional consultations in mid 2007 and on the recently published AIHRCreport “From Hope to Fear: An Afghan Perspective on Operations of Pro-Government Forces inAfghanistan,”9it is clear that the current practice of house searches is deeply resented by Afghancommunities.Conduct towards women household members during searches often contravenes local customs andangers local communities. Exacerbating factors include aggressive behaviour, offensive language,pointing of weapons at family members, damage to property, use of dogs, and alleged theft ofpossessions. Inappropriate home searches by IMF and others can result in increased support forAGEs. This has implications for building an environment conducive to respect for IHL and humanrights law.

AIHRC,Hope to Fear: An Afghan Perspective on Operations of Pro-Government Forces in Afghanistan,p. 25-27,December 2008. Available at <www.aihrc.org.af> (last accessed on 28 January 2009).

9

18