Forsvarsudvalget 2009-10

FOU Alm.del Bilag 96

Offentligt

United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan

AFGHANISTANANNUAL REPORT ON PROTECTION OF CIVILIANSIN ARMED CONFLICT, 2009

UNAMA, Human RightsKabulJanuary 2010

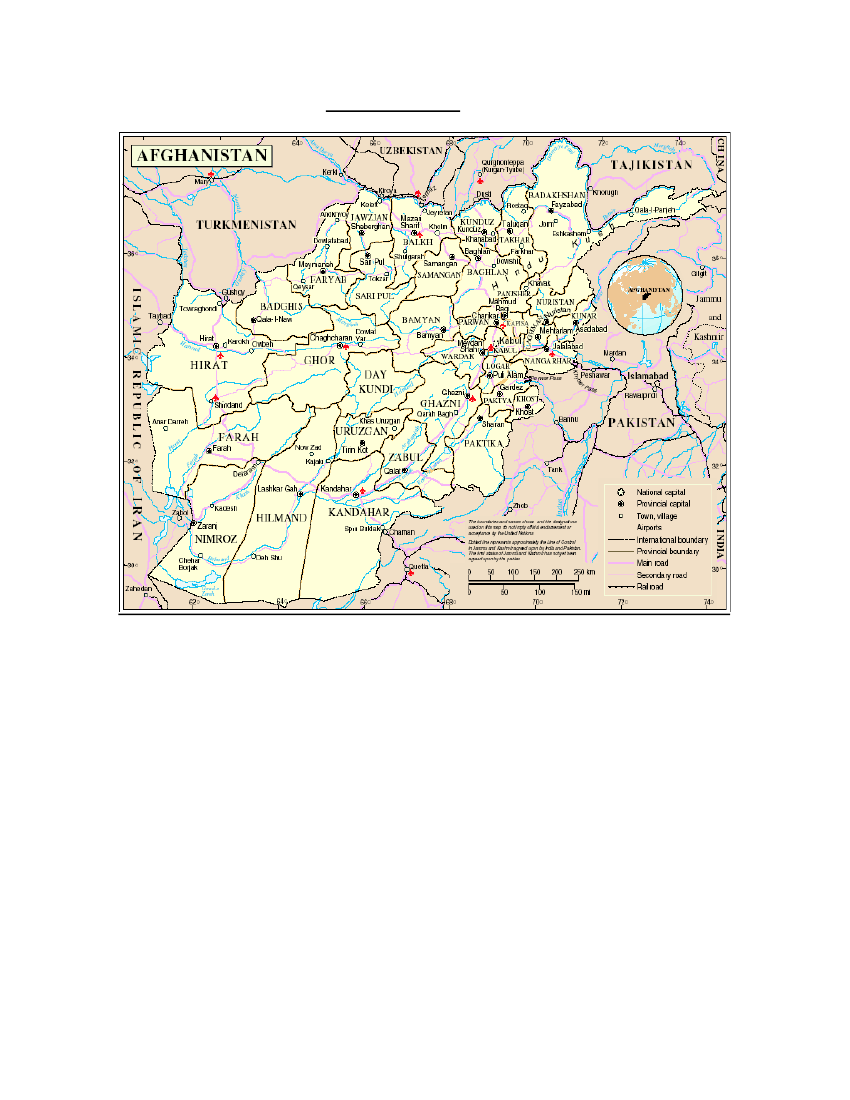

Map of Afghanistan

Source: UN Cartographic Centre, NY

AFGHANISTANAnnual Report on Protection of Civiliansin Armed Conflict, 2009

UNAMAUNAMA, Human Rights United NationsKabulJanuary 2010

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

TABLE OF CONTENTSExecutive SummaryI. Impact of the Armed Conflict on Civilians: 2009 ................................................1II. Anti-Government Elements.................................................................................8AGE and Civilian Casualties .......................................................................8Suicide and IED attacks ...................................................................9Assassinations, Threats and Intimidation ......................................12III. Pro-Government Forces ...................................................................................16PGF and Civilian Casualties ......................................................................16Aerial attack ...................................................................................17Location of Military Bases.............................................................19Search and seizure operations........................................................20Searches and attacks against medical facilities..............................21Accountability/Redress ..............................................................................22IV. Conclusion .......................................................................................................24Appendices.............................................................................................................25

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Executive SummaryThe intensification and spread of the armed conflict in Afghanistan continued to takea heavy toll on civilians throughout 2009. At least 5,978 civilians were killed andinjured in 2009, the highest number of civilian casualties recorded since the fall of theTaliban regime in 2001. Afghans in the southern part of the country, where theconflict is the most intense, were the most severely affected. Nearly half of all civiliancasualties, namely 45%, occurred in the southern region. High casualty figures havealso been reported in the southeastern (15%), eastern (10%), central (12%) andwestern (8%) regions. Previously stable areas, such as the northeast, have alsowitnessed increasing insecurity, such as in Kunduz Province. In addition to a growingnumber of civilian casualties, conflict-affected populations have also experienced lossof livelihood, displacement, and destruction of property and personal assets.UNAMA Human Rights (HR) recorded a total of 2,412 civilian deaths between 01January and 31 December 2009. This figure represents an increase of 14% on the2118 civilian deaths recorded in 2008. Of the 2,412 deaths reported in 2009, 1,630(67%) were attributed to anti-Government elements (AGEs) and 596 (25%) to pro-Government forces (PGF). The remaining 186 deaths (8%) could not be attributed toany of the conflicting parties given as some civilians died as a result of cross-fire orwere killed by unexploded ordinance.AGEs remain responsible for the largest proportion of civilian deaths. Civilian deathsreportedly caused by the armed opposition increased by 41% between 2008 and 2009,from 1,160 to 1,630. Deaths resulting from insurgent-related activities in 2009 werea ratio of approximately three to one as compared to casualties caused by PGF. 1,054civilians were victims of suicide and other improvised explosive device (IED) attacksby AGEs and 225 were victims of targeted assassinations and executions. These makeup the majority of casualties caused by AGE activities and is 53% of the total numberof civilian deaths in 2009. Together, these tactics accounted for 78% of the non-combatant deaths attributed to the actions of the armed opposition. The remainder ofcasualties caused by AGE actions resulted primarily from rocket attacks and groundengagements in which civilian bystanders were directly affected.Suicide and IED attacks caused more civilian casualties than any other tactic, killing1,054 civilians, or 44% of the total civilian casualties in 2009. Although such attackshave primarily targeted government or international military forces, they are oftencarried out in areas frequented by civilians. Civilians are also deliberately targetedwith assassinations, abductions, and executions if they are perceived to be supportiveof, or associated with, the Government or the international community. A broad rangeof civilians — including community elders, former military personnel, doctors,teachers and construction workers — have been targeted. Other actors, such as theUN and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have also been targeted, oftenreceiving threats, and in some cases becoming victims of violence. Through theseactions, the armed opposition has demonstrated a significant disregard for thesuffering inflicted on civilians. Intermingling with the civilian population and thefrequent use of residential homes as bases puts civilians at risk of attack by theAfghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and international military (IM) forces.

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Pro-Government forces - Afghan National Security Forces and International Military(IM) forces - were responsible for 596 recorded deaths; this is 25% of the totalcivilian casualties recorded in 2009. This is a reduction of 28% from the total numberof deaths attributed to pro-Government forces in 2008. This decrease reflectsmeasures taken by international military forces to conduct operations in a manner thatreduces the risk posed to civilians.Notwithstanding some positive trends, actions by PGF continued to take an adversetoll on civilians. UNAMA HR recorded 359 civilians killed due to aerial attacks,which constitutes 61% of the number of civilian deaths attributed to pro-Governmentforces. This is 15% of the total number of civilians killed in the armed conflict during2009. IM forces and ANSF also conducted a number of ground operations that causedcivilian casualties, including a large number of search and seizure operations. Theseoften involved excessive use of force, destruction to property and culturalinsensitivity, particularly towards women.UNAMA HR remains concerned at the location of military bases, especially thosethat are situated within, or close to, areas where civilians are concentrated. Thelocation and proximity of such bases to civilians runs the risk of increasing thedangers faced by civilians, as such military installations are often targeted by thearmed opposition. Civilians have been killed and injured as a result of their proximityto military bases, homes and property have been damaged or destroyed; this can leadto loss of livelihood and income. The location of military facilities in or nearresidential neighborhoods has also had the effect of generating fear and mistrustwithin communities and antipathy towards IM forces given their experience of beingcaught in the crossfire or being the victims of AGE attacks on Government or pro-Government military installationsInternational military forces did take strategic and specific steps to minimize civiliancasualties in 2009. The change in ISAF command, clearer command structures, and anew tactical directive have all contributed to the efforts by ISAF to reduce the impactof the armed conflict on civilians. However, a Civilian Casualty Tracking Cell, thatwas established in 2008 in ISAF (with a similar tracking mechanism in USFOR-A)has not proved very effective in addressing UNAMA concerns in a timely manner.Measures need to be taken to improve the Tracking Cell so that it can be moreresponsive and helpful in relation to civilian casualty incidents.This report on the protection of civilians in armed conflict in Afghanistan in 2009 iscompiled in pursuance of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan(UNAMA) mandate under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1868 (2009).UNAMA Human Rights undertakes a range of activities aimed at minimizing theimpact of the conflict on civilians; this includes independent and impartial monitoringof incidents involving loss of life or injury to civilians and analysis of trends toidentify the circumstances in which loss of life occurs. UNAMA Human Rightsofficers (national and international), deployed around Afghanistan, utilize a broadrange of techniques to gather information on specific cases irrespective of location orwho may be responsible. Such information is cross-checked and analyzed, with arange of diverse sources, for credibility and reliability to the satisfaction of the HumanRights officer conducting the investigation, before details are recorded in a dedicateddatabase. An electronic database was established in January 2009. The database is

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

designed to facilitate the collection and analysis of information, includingdisaggregation by age and gender. However, due to limitations arising from theoperating environment, such as the joint nature of some operations and the inability ofprimary sources in most instances to precisely identify or distinguish between diversemilitary actors/insurgents, UNAMA HR does not break down responsibility forparticular incidents other than attributing them to “pro-Government forces” or “anti-Government elements.” UNAMA HR does not claim that the statistics presented inthis report are complete; it may be the case that, given the limitations in the operatingenvironment, UNAMA HR is under-reporting civilian casualties.UNAMA HR information on civilian casualties is, routinely, made available,internally and externally, to the Security Council through the UN Secretary General,the Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG) UNAMA, the UNEmergency Relief Coordinator, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for HumanRights (OHCHR), and other UN mechanisms as appropriate. UNAMA Human Rightsadvocates with a range of actors, including Afghan authorities, international militaryforces, and others with a view to strengthening compliance with internationalhumanitarian law and international human rights law. It also undertakes a range ofactivities on issues relating to the armed conflict, and protection of civilians with theAfghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), the humanitariancommunity, and members of civil society.2009 was the worst year in recent times for civilians affected by the armed conflict.UNAMA HR recorded the highest number of civilian casualties since the fall of theTaliban regime in 2001. The conflict has intensified and spread into areas thatpreviously were considered relatively secure. This has resulted in increasing numbersof civilian dead and injured and with corresponding devastation and destruction ofproperty and civilian infrastructure, often leading to loss of income and livelihoods.The use of asymmetric tactics by the armed opposition is a significant factor in thegrowing number of civilians who are killed and injured. The use of air strikes and theplacement of military facilities in civilian areas greatly increase the risk of civiliansbeing killed and injured. The United Nations calls upon all parties to the conflict torespect and uphold their obligations under international humanitarian law andinternational human rights law in order to minimize the impact of the conflict uponcivilians.

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

I.

IMPACT OF THE ARMED CONFLICT ON CIVILIANS: 2009

This has been the worst year for civilian casualties since UNAMA HR begansystematically documenting these incidents in 2007. The conflict has intensified: ithas spread, affecting previously tranquil areas, such as in the northeast, and deepenedas it has moved from rural to urban areas. The continued volatile security situation asa result of increased armed attacks, persistent fighting throughout the year, includingthe winter months, cross-border infiltration of armed groups and the increase in thenumber of pro-Government forces have all contributed towards an intensification ofthe conflict. In addition to conducting hostilities, the Taliban has established shadowgovernments in some areas, directly confronting or undermining the authority of theGovernment of Afghanistan (GoA). Conflict has grown intense, particularly in thesouthern regions, and impacted on some major urban areas, sharply increasing itsaffects on civilians. The usual winter lull in hostilities has also largely failed tomaterialize depriving civilians of any respite. The manner in which the conflict isconducted continues to evolve including in ways that increase the risk posed tocivilians.Moreover, access to vulnerable populations continues to be challenging as growinginsecurity shrinks humanitarian space. In addition to those who are directly victimizedby incidents of warfare, resulting in death and injury, a large swathe of the populationcontinues to suffer the indirect and accumulated costs of armed conflict. This includestheir ability to move freely without fear or harassment and to access services essentialfor their health, well-being, and education. The conflict has also taken a heavy toll oncivilians by destroying infrastructure, undermining livelihood opportunities,displacing communities, and eroding the quality and availability of basic services.This has often disproportionately affected vulnerable individuals, such as women,children and the internally displaced. Armed conflict, of course, has significantrepercussions for socio-economic development efforts and exacerbates thedevelopment deficit.UNAMA HR recorded a total of 2,412 civilians killed over the 12 month period underreview. This figure represents an increase of 14% on the 2,118 civilian deathsrecorded in 2008. The 2009 civilian death toll is the highest of any year since the fallof the Taliban regime in 2001. UN preliminary figures show that there is a 29.6% yearon year increase in security-related incidents, with an average of 960.3 incidents permonth as compared to 741.1 incidents per month for 2008. The elections period sawthe most pervasive violence of 2009. AGEs discouraged Afghans from voting andwere responsible for threats and assassinations against electoral candidates and staff.Violence surrounding the 20 August Presidential and Provincial Council elections waswidespread and significant; it included, for example, two suicide attacks in Kabul on15 and 18 August respectively and a suicide attack in Kandahar city on 25 August.Overall, September proved to be the deadliest month, with 336 civilians killed.Of the 2,412 civilian deaths reported in 2009, 1,630 (67%) were caused by AGEs and596 (25%) were caused by PGF. The remaining 186 (8%) could not be attributed toeither of the conflicting parties. As in previous years, the majority of civiliancasualties occurred in the southern region of Afghanistan. However, the south-east,east, west and central regions also reported high numbers of civilian casualties. The

1

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

conflict has spread into what were previously relatively tranquil areas, including thenortheast, which had previously seen limited AGE activity.The tactics responsible for the largest number of civilian casualties during the yearwere IEDs, suicide attacks, and aerial attacks (air strikes and close air support). Theseattacks frequently resulted in civilian fatalities and the destruction of civilian propertyand infrastructure. Often used in an indiscriminate manner, many civilians bore thebrunt of IED and suicide attacks and were killed and injured as a result. AlthoughAGEs continued to principally target ANSF and IM forces the placement of IEDs andthe location of suicide attacks often resulted in large numbers of civilians being killed.Many IEDs (both remote controlled and trigger detonated) are placed along roadsheavily used by civilian vehicles and pedestrians. UNAMA HR has recorded,moreover, a number of instances in which IEDs have been placed in crowdedresidential and commercial areas, such as market places and shops. Suicide attackshave targeted government buildings, such as Ministries and provincial ANSFbuildings that are often located in busy civilian areas.2009 year saw a marked increase in the number of civilians who were targeted by theAGEs as they were, apparently, perceived to support, or be associated with, the GoA,ANSF, or IM forces. As a result, traditional tribal structures, especially in thesouthern regions of Afghanistan, have been severely affected, and often undermined,as community and tribal leaders are targeted by elements of the armed opposition.Other civilian actors, such as humanitarian and construction workers, have alsobecome victims of AGE activities, including through threats, abductions, and killings.The Taliban frequently took advantage ofPashtunwali(the traditional code ofhonour), particularly in the southern regions of Afghanistan, where the traditions ofhospitality oblige the host to provide shelter and food to guests. In some cases,insurgents have intentionally used civilians’ homes and civilians themselves as shieldsfrom military attack in violation of international humanitarian law.1As a result,civilians are put at further risk as they are detained by pro-Government forces. Theirhouses are searched and property destroyed because of their perceived support of theinsurgency.Mullah Omar issued a new “code of conduct,” called “The Islamic Emirate ofAfghanistan Rules for Mujahideen,” in July for Afghan Taliban in the form of a bookwith 13 chapters and 67 articles for distribution to Taliban forces. It called on Talibanfighters to win over the civilian population and avoid civilian casualties, including bylimiting the use of suicide attacks to important targets and setting forth guidelines forabductions. It is unclear whether any measures are in place to give effect to, ormonitor compliance with, this “code of conduct”.The year saw a marked improvement, from the perspective of civilians, in the waythat pro-Government forces conducted military operations. The new commandstructure is more transparent and streamlined, with COMISAF now heading bothISAF and USFOR-A commands. The unclassified sections of the COMISAF GeneralMcChrystal’s Initial Assessment to the US Secretary of Defence and in numerousstatements thereafter by COMISAF, noted that a future strategy should be based on apopulation-centric approach, involve closer collaboration with the Afghangovernment and community leaders, protect civilians and work to minimize civiliancasualties. However, with the expected surge of more than 30,000 troops, anticipated

2

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

to be completed by mid-2010, UNAMA HR remains concerned that the increase infighting could result in an increase in civilian casualties. Adherence to the TacticalDirectives and the counter-insurgency guidelines could, however, limit civiliancasualties even as fighting increases.Throughout the year, President Karzai took a strong stance in favour of measures toreduce civilian casualties. He made this issue a defining feature of his relations withthe international community and the international military forces. In comments andspeeches, President Karzai repeatedly condemned civilian casualties and nightsearches. In February, Karzai commented that he had “tocampaign for an end tocivilian casualties and for an end to the arrest of Afghans….The Afghan people expecttheir government to protect them and to stand for them.”2Several PresidentialCommissions were established to investigate the killings and injury of civilians as aresult of IM forces’ operations. These Commissions need to ensure that their findingsare made public and that their recommendations are implemented by the GoA in atimely manner.Although, the overall proportion of civilian deaths attributed to pro-Governmentforces has declined in recent times, air strikes remain a concern; they are responsiblefor 61% of civilian deaths attributed to pro-Government forces in 2009.UNAMA HR remains extremely concerned with the location of military bases inpopulated areas, such as bazaars and district centres. This has the effect of increasingthe risk that civilians will be harmed when AGEs target international military baseswith IEDs, rockets, and suicide attacks. In line with international humanitarian law,military bases should be placed outside residential and commercial areas in order tominimize the effects of the conflict on civilians.Despite considerable improvements in the procedures that regulate search and seizureraids, there continues to be a high level of hostility towards these practices. Excessiveuse of force, damage to property, and insensitivity towards cultural norms stillcharacterizes many of these raids. UNAMA HR continued to record a decline in‘force protection incidents,’ whereby civilians were killed and injured because theywere too close to a military convoy or failed to follow instructions. This decline indeath and injury of civilians is a result of constructive amendments through directivesas well as an increased awareness amongst Afghan civilians.There is a wide range of armed actors operating in Afghanistan. Many illegal armedgroups (IAGs) are still active, notwithstanding the Disarmament of Illegal ArmedGroups (DIAG) process. These IAGs have been implicated in a number of humanrights abuses within the context of the armed conflict. The Government has also madeefforts to recruit local forces, sometimes referred to as militia, to provide security inparticular communities. International military forces continue to support locally-organized, anti-insurgent militias. In both cases, accountability mechanisms torespond to abuses by IAGs and local militias are extremely weak. There is no clearcommand structure, transparency, nor apparent government responsibility to regulatetheir activities. In April 2009, the UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenariesconducted an official visit to Afghanistan and looked at, among other issues,“questions of accountability of non-State actors, the rights of victims to an effectiveremedy and the regulatory structure for private security companies.” The Working

3

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Group was in the process of preparing a report, for submission to the UN HumanRights Council, at year- end.Access to basic services continues to be severely disrupted in conflict-affectedregions. This includes the closure of schools, the intimidation of students, especiallygirls, as well as staff. Clinics and patients were targeted for attack by AGEs andsearched by pro-Government forces, thus undermining their status as neutral civilianobjects. According to UNICEF, between January and November 2009, there were613 recorded school-related incidents, as compared to 348 incidents recorded in 2008.UNICEF notes that the southern regions have been particularly hard hit, as more than70% of schools were closed in Helmand Province and more than 80% were closed inZabul Province.Aid workers from NGOs and UN agencies have experienced harassment, threats,intimidation and death during the year as a result of AGE activities. The environmentthey were able to operate in became increasingly restricted as the conflict spread.Truck convoys, often carrying food or aid supplies, were stopped. Drivers were oftenbeaten by AGEs; in a few cases they were abducted, and the goods burnt or looted.Some international organisations have tragically been caught up in insurgent attacks,such as the 25 August suicide attack in Kandahar that killed an ICRC staff member.Women and children, and those who are vulnerable, face particular disadvantages inthe context of the problems associated with the armed conflict. Violence and relatedinsecurity greatly affects their ability to access essential services, such as educationand health care. Women and children are also victims of air strikes, house-raids,suicide and IED attacks. These attacks often lead to deep psychological scars andtrauma; the prevailing situation inhibits access to, or creation of, productive andhelpful coping mechanisms.One of the consequences of the deteriorating security situation is that many femaleshave been further confined to their homes. In a very conservative society, attacks onwomen who, traditionally, have a limited public role, further inhibit their participationin public life. The conflict further impacts on women’s freedom of movement andgreatly restricts access to essential, life-saving services as well as education. In somecases, UNAMA HR has noted that the risks inherent in the deteriorating securitysituation influence whether women decide to participate in public life, particularly forthose who work in high-profile positions.At least 345 children were killed due to conflict-related violence. UNAMA HR hasrecorded numerous incidents were children have been affected as a result of attacks,including air strikes, rocket attacks, IED and suicide attacks. UNAMA HR noted thatthere have been reports of recruitment of children into armed groups. There wereseveral cases throughout the year of children being used to carry out suicide attacks orto plant explosives, often resulting in their deaths as well as that of numerouscivilians.The detention and ill-treatment of minors allegedly associated with armed groups byboth the ANSF and the international military forces remained a concern. There havebeen detailed reports of children detained for up to a year in government detentionfacilities as well as reports that children have been held at the Bagram Theatre

4

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Internment Facility (BTIF) without due process; in some cases they allegedly sufferedill-treatment. Mohammed Jawad, aged 12 in 2002 at the time of his arrest forallegedly throwing a hand-grenade at a US military vehicle was eventually released inJuly 2009 from Guantanamo. Jawad, during his time in detention in Afghanistan andGuantanamo, was subjected to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment amounting totorture according to his legal defense team. Since his release, the authorities havefailed to provide proper support for his reintegration.Different UN and other entities continued to monitor the effects of armed conflict onchildren pursuant to Security Council Resolution (SCR) 1612. A subsequent SCR,1882, involves naming parties which are responsible for killing and maiming ofchildren, including those who perpetrate grave sexual violence against children in wartime. On 18 October, the GoA appointed a high level focal point to help address thisissue. In December, the Government committed to launch an inter-ministerialGovernment Steering Committee on Children and Armed Conflict, with the objectiveof developing an Action Plan for the protection of children affected by armed conflict.UNAMA HR remains concerned about the situation of conflict-related detainees,particularly those held by US forces and the National Directorate of Security (NDS).There continues to be little or no information on the conditions and treatment of thosein detention, especially those held by NDS at the provincial level. NDS continues tooperate without a known legal framework that clearly defines its powers ofinvestigations, arrest, and detention and rules applicable to its detention facilities.UNAMA HR continues to receive allegations that former detainees were subject toill-treatment, including torture, by NDS.Many of the cases and incidents documented by UNAMA HR have not beenadequately investigated by the Government, so that only a few of the allegedperpetrators have been brought to justice. Some of the law enforcement duties of thepolice in Afghanistan have been adversely affected by other duties related to theconflict. As ANP personnel routinely take on counter-insurgency duties — such asestablishing checkpoints to look for insurgents — their capacity to carry outtraditional duties of criminal investigation has been undermined. Therefore, thoroughinvestigations of conflict-related incidents often do not occur.New procedures introduced for detainees held at BTIF, which was replaced with anew detention facility established in Parwan Province at the Bagram Air Base inDecember, could constitute the basis for a fairer process for detainees as well asimproved treatment and conditions. However, it is extremely important that alldetainees enjoy due process guarantees to which they are entitled under Afghandomestic law and international human rights and international humanitarian law.This year marked the tenth anniversary of the UN Security Council working on theprotection of civilians in armed conflict and the 60thanniversary of the GenevaConventions of 1949. According to the report of the UN Secretary-General on theprotection of civilians in armed conflict (May 2009), there is suffering “owing to thefundamental failure of parties to conflict to fully respect and ensure respect for theirobligations to protect civilians.” On 11 November, the Security Council had an OpenDebate on the protection of civilians in armed conflict culminating in the adoption ofSCR 1894 (2009). The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Ms Navi Pillay, in

5

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

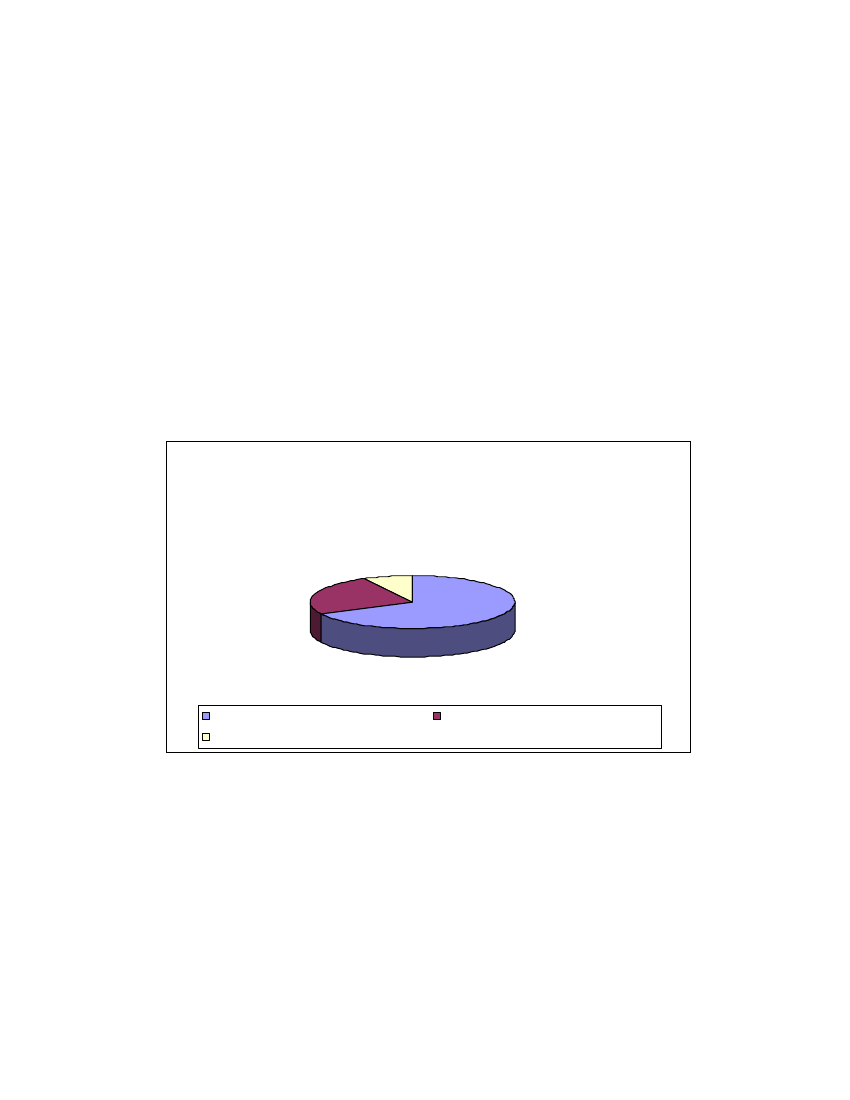

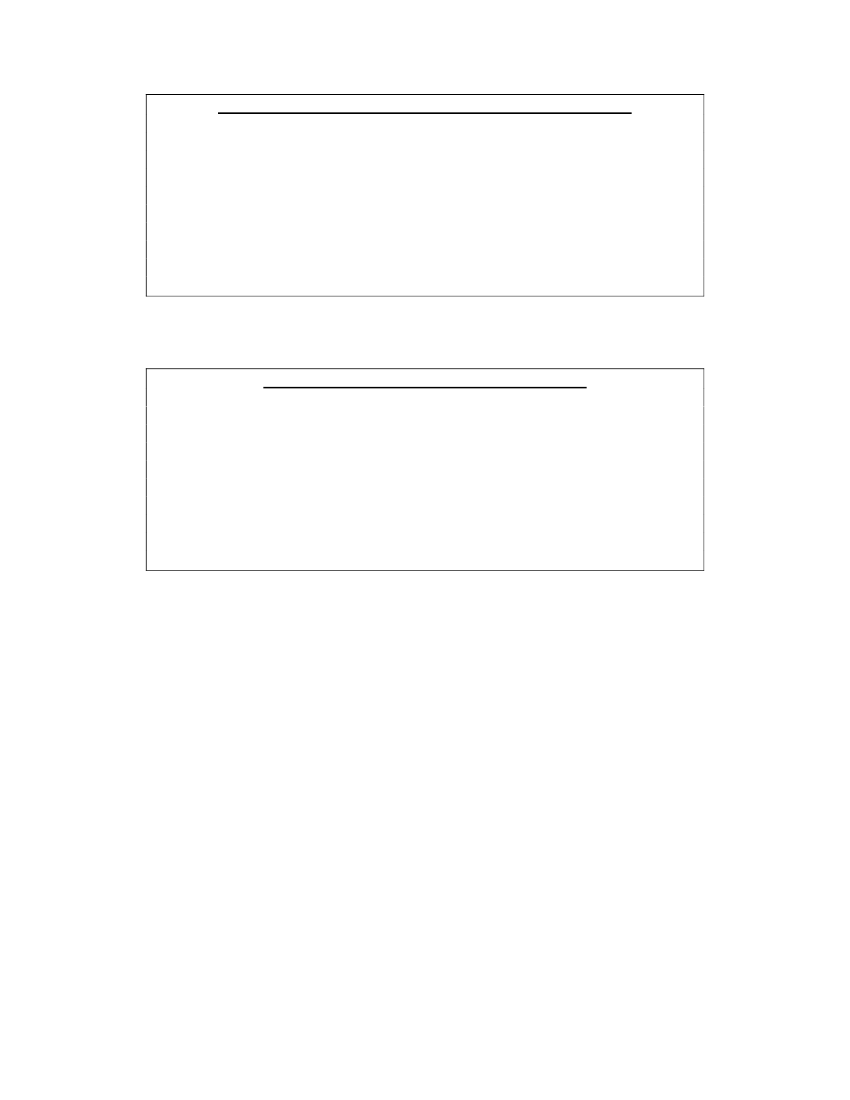

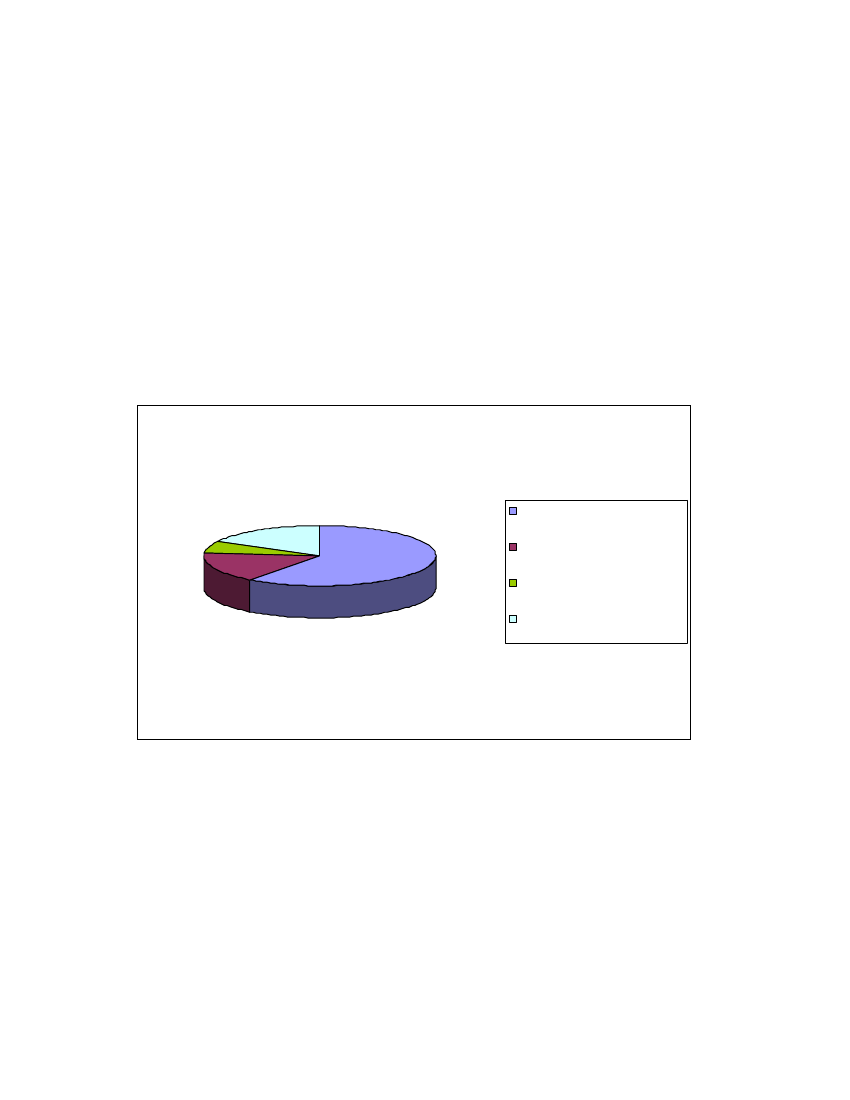

her address to the Open Debate, stressed the vital importance of redressinggrievances, ending impunity and protecting the human rights of civilians: “[T]herecontinues to be an urgent need to improve overall accountability procedures,including through criminal prosecution when warranted as redress for victims, whilebringing the legal framework governing conflict-related detention – by all who takeand hold detainees- into line with human rights law.”The United Nations remains concerned about the high cost of the conflict on civilians.It has repeatedly underlined, through public statements by the UNAMA SRSG, MrKai Eide, that all parties should respect their obligations under internationalhumanitarian law and international human rights law. Actions by all parties to thearmed conflict must be transparent and accountable to ensure the least possibleadverse impact upon the civilian population. Equally, all those who perpetrate abusesagainst the civilian population, in transgression of their obligations under the rules ofwar and national legislation, should be held to account in a timely and transparentmanner.Chart 1: Reported civilian casualties Jan – Dec 2009

8%25%

67%

Anti-Government Elements (1630)Responsible party undetermined (186)

Pro-Government Forces (596)

r

6

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

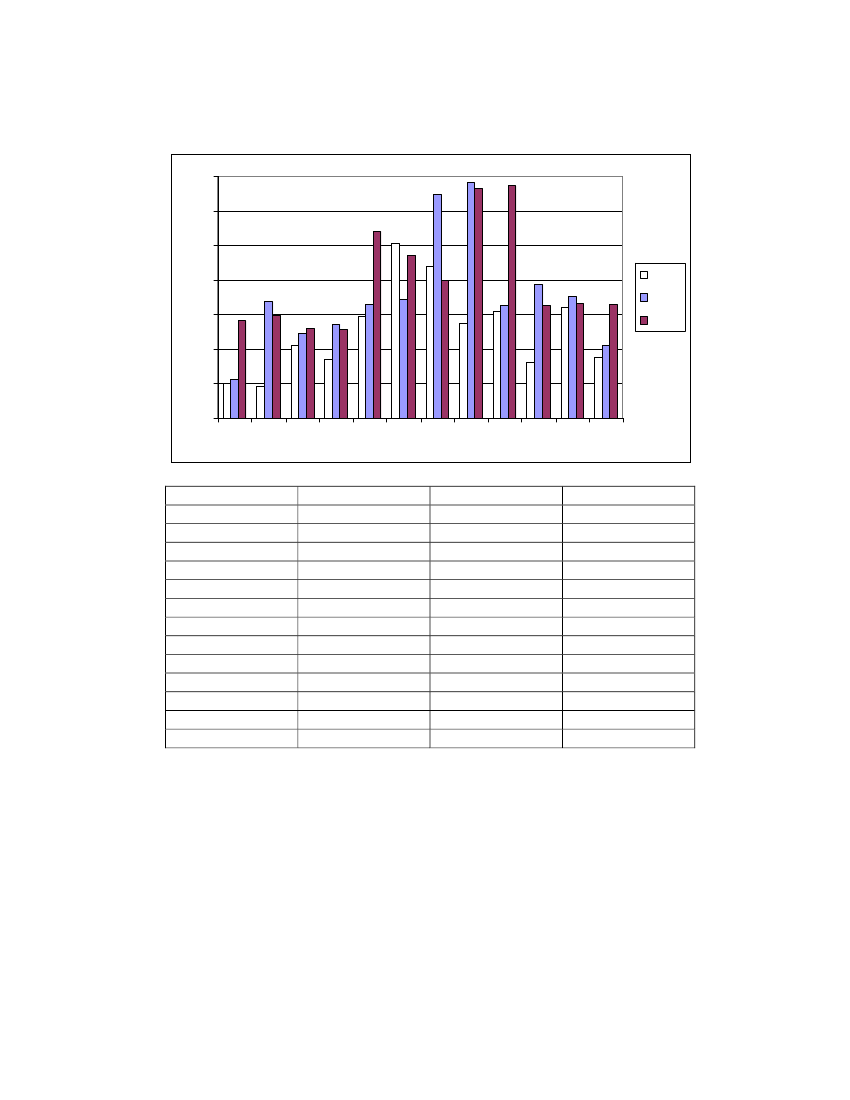

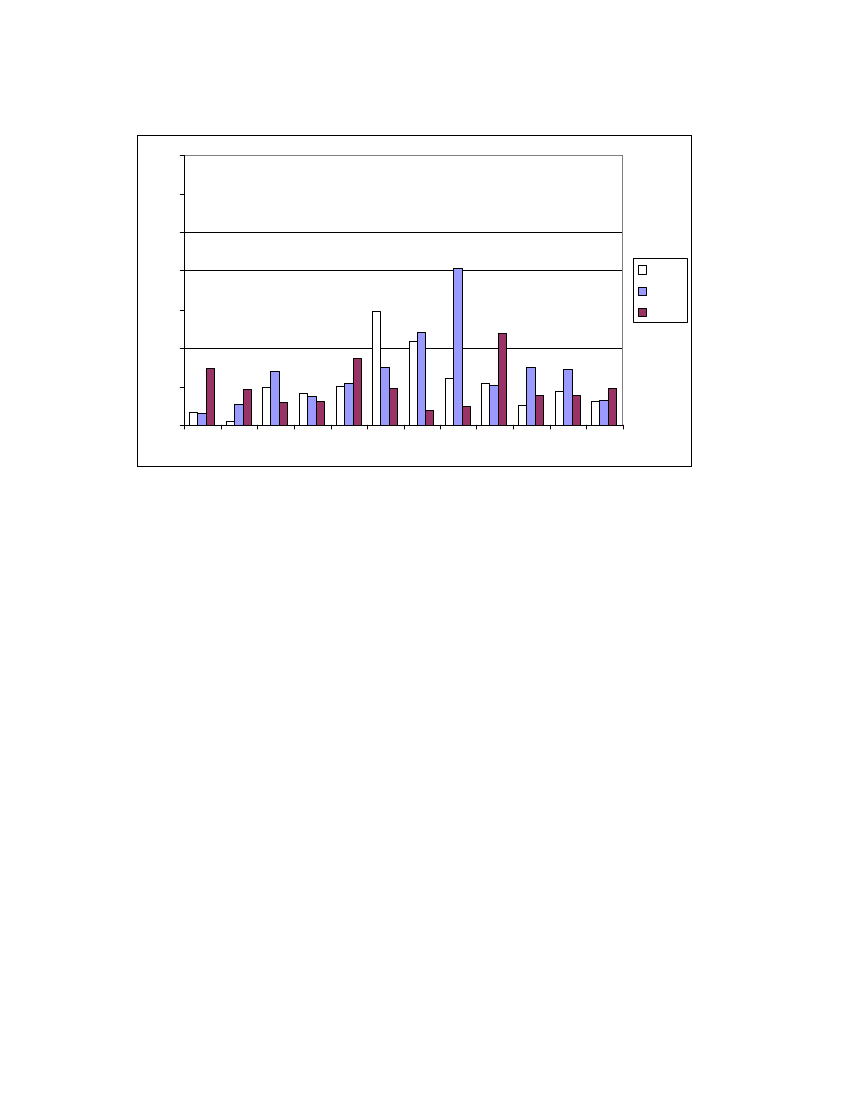

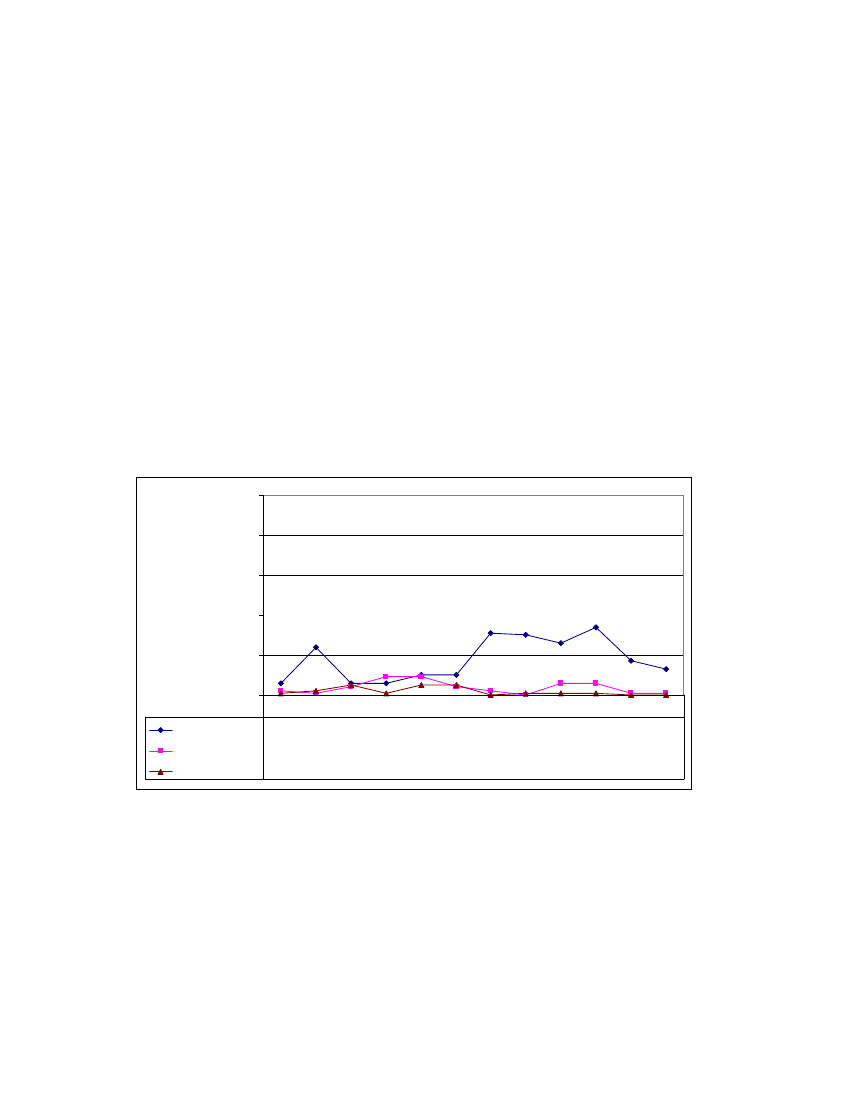

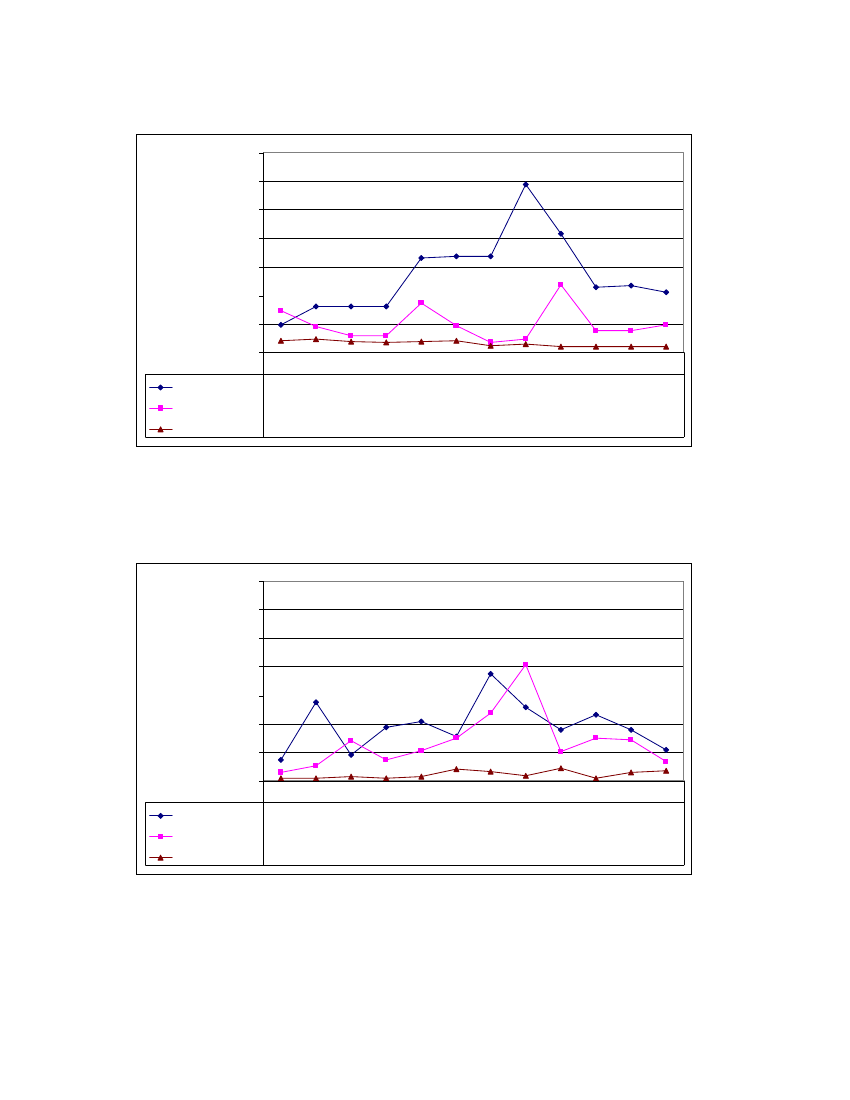

Chart/Table 2: Total number of civilians reported killed as a result of armedconflict in Afghanistan, 2007, 2008, and 2009350300250200150100500Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec200720082009

MonthJanuaryFebruaryMarchAprilMayJuneJulyAugustSeptemberOctoberNovemberDecemberTOTAL

200750451048514725321813815580160881523

2008561681221361641723233411621941761042118

20091411491291282712361983333361621651642412

7

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

II.

ANTI-GOVERNMENT ELEMENTS

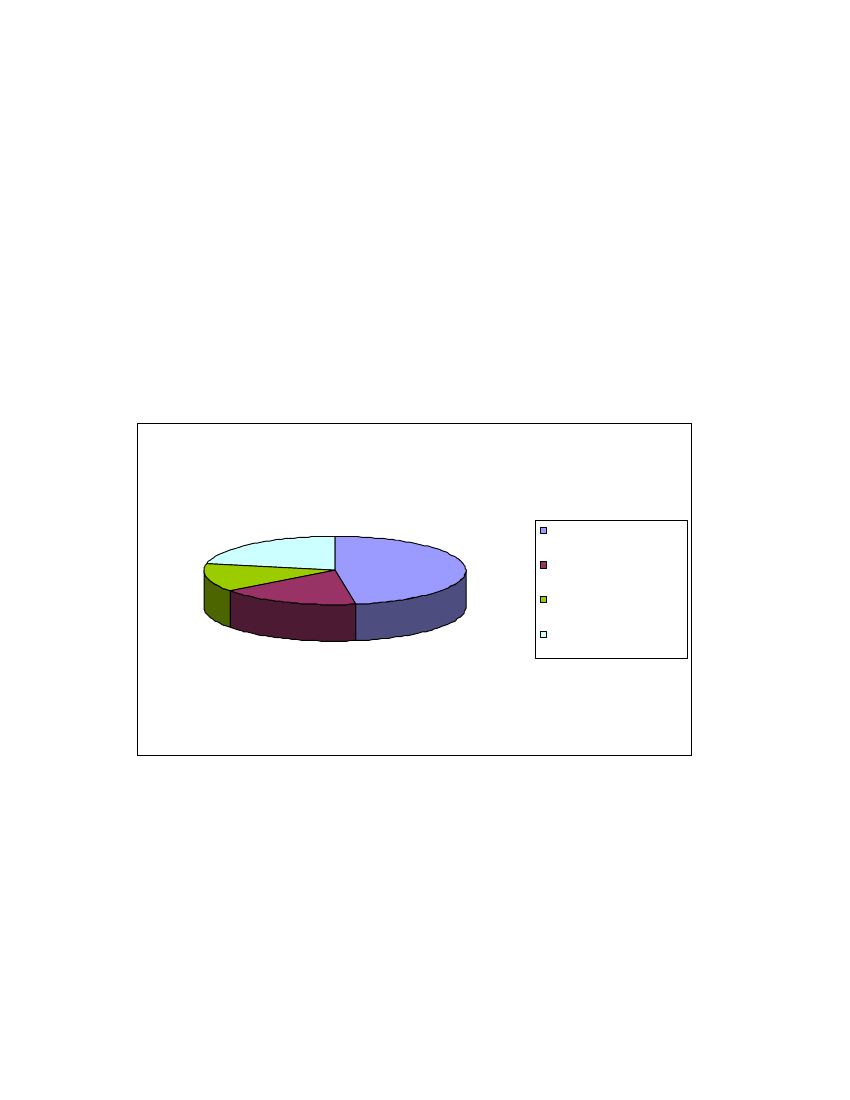

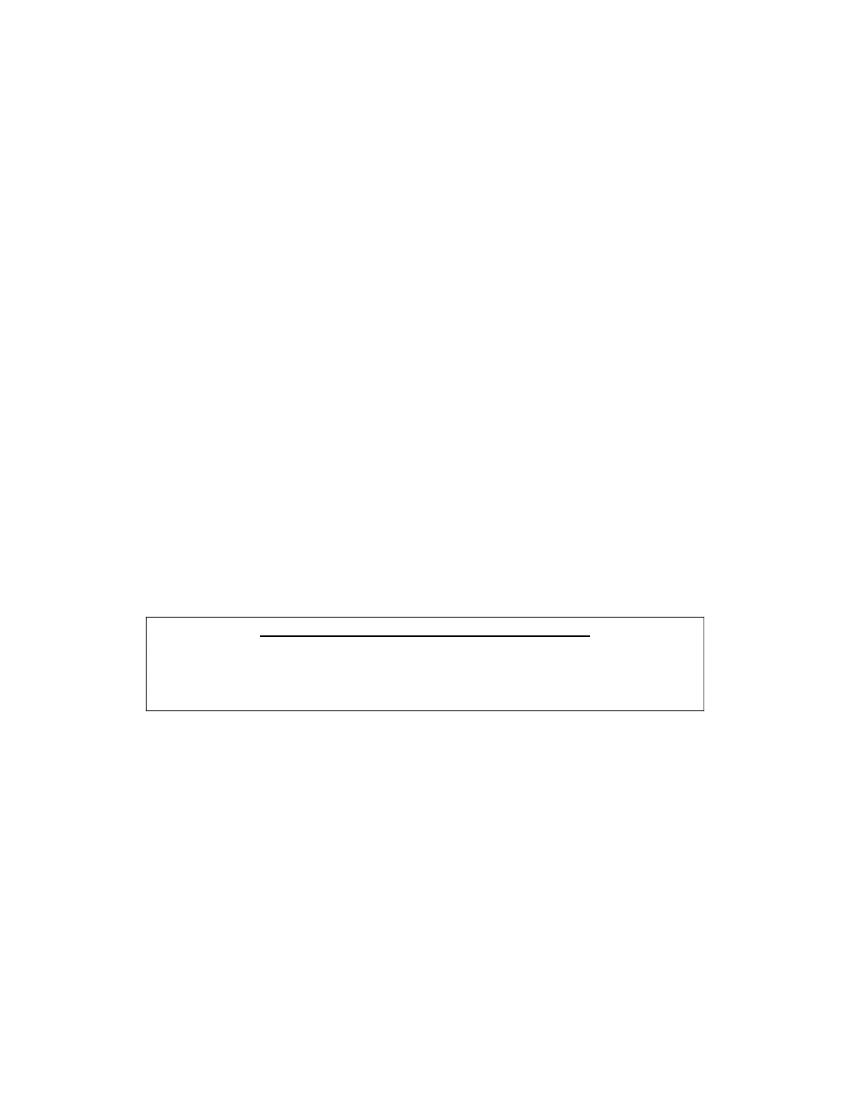

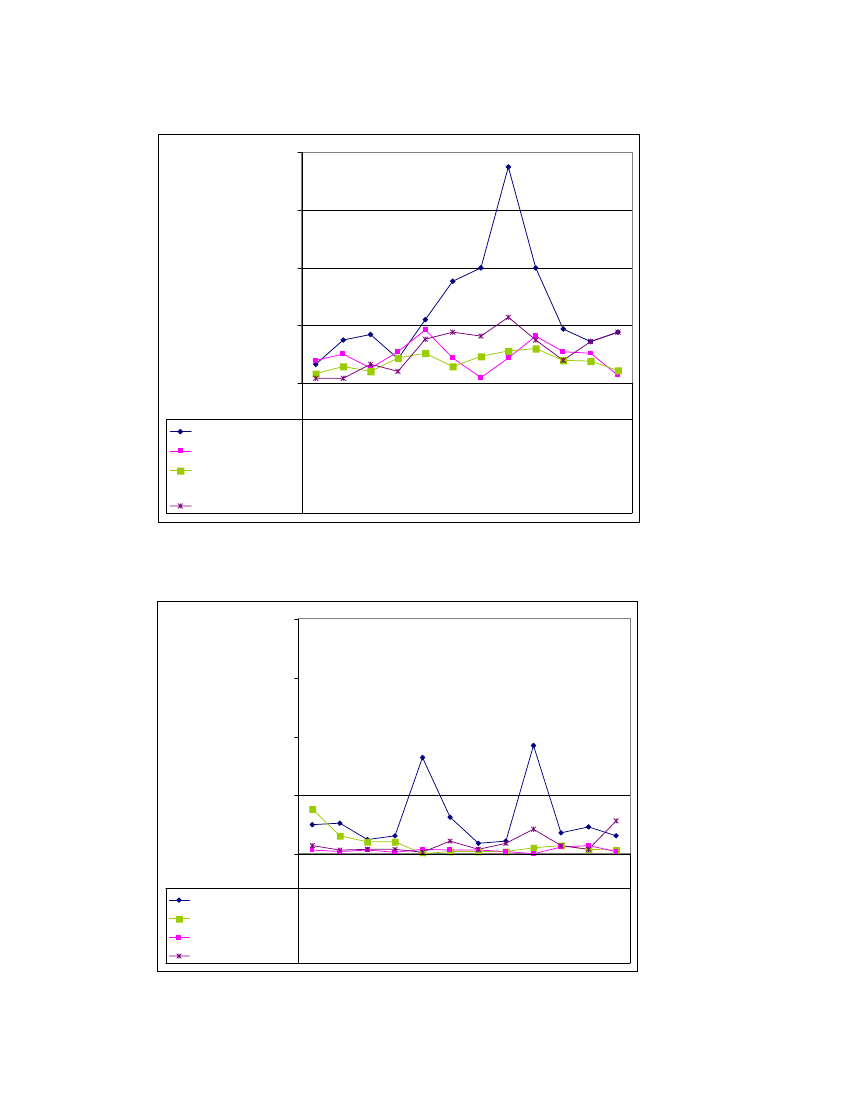

AGEs and Civilian CasualtiesAGE activities have taken the heaviest toll on civilians. Civilian deaths reportedlycaused by anti-Government elements totaled 1,630 in 2009; this represents an increaseof 41% from 2008 and accounts for 67% of the total number of civilian deaths in2009.Suicide and other attacks involving IEDs continued to claim the most civilian lives in2009 with an overall toll of 1,054 killed. 225 civilians were killed as a result oftargeted assassinations and executions. Together, these tactics accounted for over 78%of the civilian deaths attributed to AGE actions. The remainder of AGE-inflictedcasualties resulted primarily from rocket attacks and from ground engagements inwhich civilian bystanders were directly affected.Chart 3: Civilian Deaths Attributed to AGEs disaggregated by incident type

22%47%

IED Attacks (773)Suicide Attacks (281)Executions andAssassinations (225)Other AGE Tactics (351)17%

14%

8

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

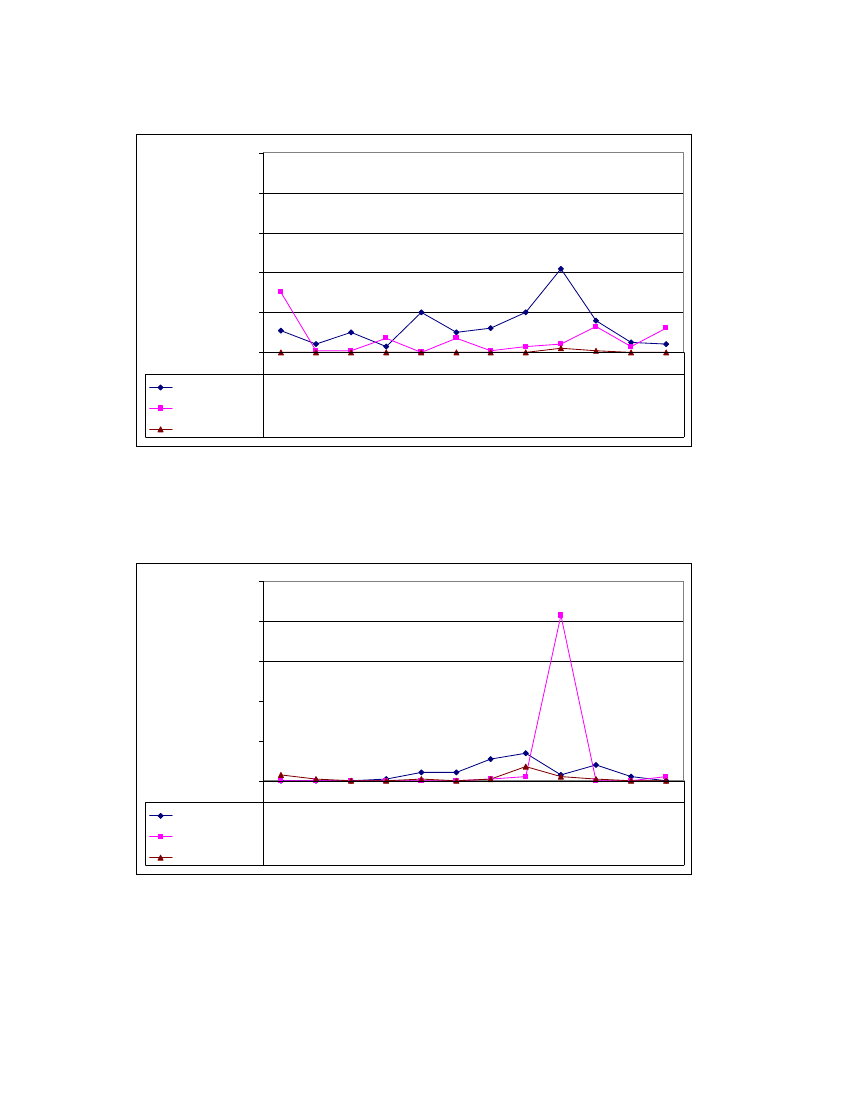

Chart 4: Civilian Deaths Attributed to AGEs – 2007, 2008, 2009350300250200150100500Jan Feb Mar Apr May JunJulAug Sep Oct Nov Dec200720082009

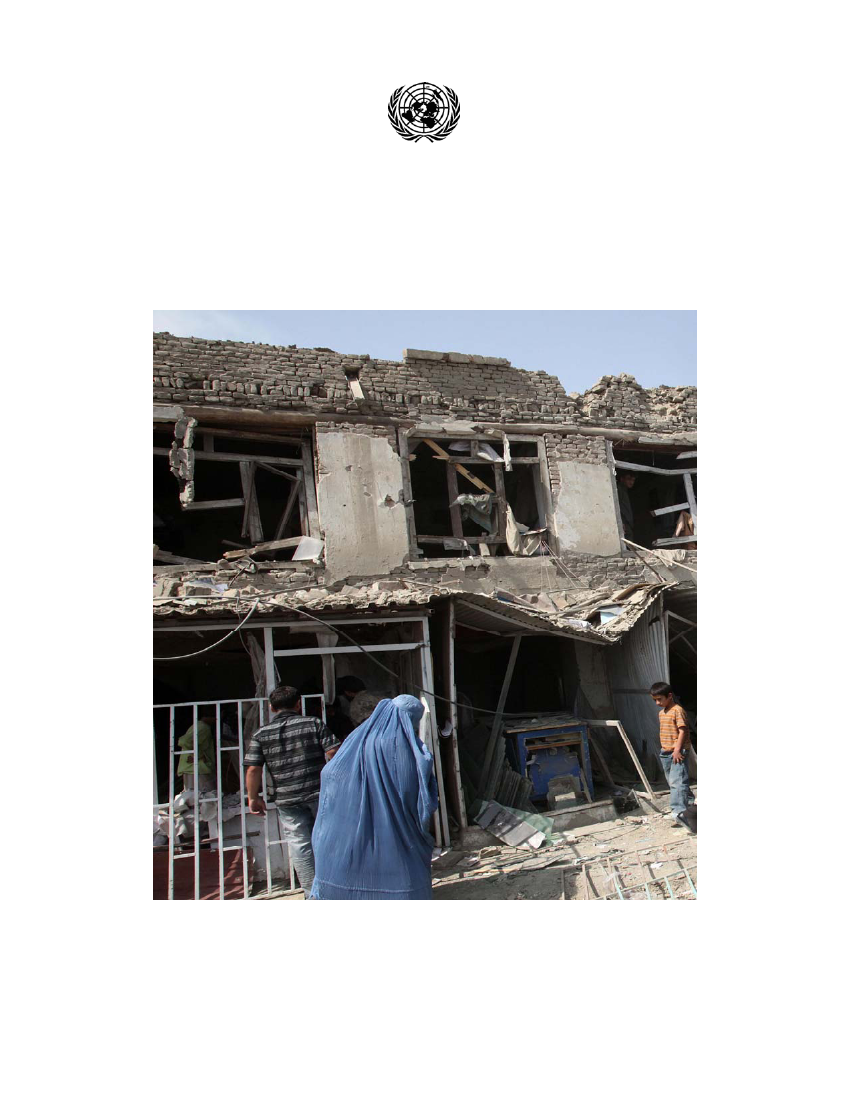

Suicide and IED attacksIEDs and suicide attacks accounted for more civilian casualties than any other tactic,and the number of civilians killed increased dramatically since 2008 by 45%. IEDsplanted by AGEs accounted for 773 civilian deaths (47% of all civilians killed byAGEs) and suicide attacks accounted for 281 civilian deaths (17% of all civilianskilled by AGEs) in 2009.Since the intensification of the insurgency in 2006, there has been a gradual butcontinual shift by AGEs towards the use of asymmetric attacks, such as IEDs andsuicide attacks. Too often, these attacks are carried out in a manner that fails todiscriminate between civilians and military targets or to take adequate precautions toprevent civilian casualties. Thus, they have an impact far beyond their initial target.August and September proved to be the year’s most deadly periods of insurgentactivity, with the detonation of multiple SVBIEDs (car and truck bombs).•••On 15 August, seven civilians were reportedly killed and at least 90 injured in asuicide bomb blast outside ISAF HQ in Kabul;On 18 August, seven people were reportedly killed and at least 50 injured in anSVBIED attack near Camp Phoenix on the Jalalabad Road in Kabul. In thisexplosion, two UN staff members were killed and one injured; andOn 25 August, at least 46 civilians were allegedly killed and more than 60 injuredwhen a truck bomb exploded in a commercial and residential area of Kandaharcity. The explosion destroyed several commercial buildings and left a largenumber of families homeless. It is understood that the SVBIED explodedprematurely before reaching its intended target, apparently the NationalDirectorate of Security. While the Taliban issued a statement denyinginvolvement in the incident, no other local actor is known to use car bombs of thisnature.9

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

In September, a number of SVBIED attacks resulted in 24 civilians killed and 52injured: on 17 September, an attack on an ISAF convoy on the road to the KabulInternational Airport, allegedly killed 20 civilians and injured 45 others. The Talibanacknowledged responsibility. On 8 and 9 September respectively attacks against thefront gates of the ISAF military airport at Kabul International Airport and an attack infront of Camp Bastion in Helmand reportedly resulted in the death of four civiliansand seven injured.Although the vast majority of suicide attacks target ANSF or IM forces, their use inresidential areas means that, frequently, civilians are the victims of such attacks.Moreover it is of great concern that AGEs frequently feign civilian status whileconducting suicide and other attacks, making it difficult for pro-Government forces todistinguish between civilians and fighters.3Twin explosions leading to civilian casualties in KhostOn 22 June, at least 10 civilians died and 41 were injured as a result of twoexplosions in Khost city. Reportedly, among the casualties, at least two children,between 9 and 17 years, were killed and at least 11 children were injured. Theincident occurred around one o’clock between a GoA department and a Mosque,close to the market area. The first blast, near to the GoA department, resulted from ahand grenade, attracting a crowd of people, and was followed shortly afterward by asecond explosion. The authorities believe that the attack was conducted by theHaqqani network.AGEs have also undertaken a number of “complex attacks” involving multiple, wellcoordinated teams, including individuals equipped as suicide bombers and othersarmed with a range of weapons, including grenades. These frequently targetgovernment buildings where civilians are often present. Three complex attacks carriedout in Gardez and Jalalabad on 21 July, and in Khost on 25 July on government andsecurity forces’ installations, reveal well-planned and sophisticated operations. On 28October, a complex attack was launched against a guest house in Kabul, resulting inthe deaths of eight civilians, including five UN personnel and injury to at least nineothers. The attack was well organized and executed, and included the use of multiplesuicide bombers, hand grenades, and small-arms fire. Although, the Taliban claimedresponsibility for the attack, it appears to have been carried out by members of theHaqqani network.

10

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Complex attack against multiple government buildings in KabulThe coordinated attack against the Ministry of Justice Central Prison DirectorateHQ, the Ministry of Education and NDS in Kabul on 11 February resulted in at least21 civilians killed, including 13 staff from the Ministry of Justice. At least 14 stafffrom the MoJ was injured. In this incident, UNAMA HR received reports that severalof the civilians were deliberately singled out for attack and shot, despite clearly beingnon-combatants. In a statement, the Taliban claimed the attack was in retaliation forthe mistreatment of detainees in Afghan detention facilities, the execution of severalTaliban members in November 2008, and the shooting of a number of Taliban duringan operation in the Pul-i-Charkhi Prison in December 2008.Attacks against NDS officials and facilities by AGEs were often disproportionate tothe intended target, resulting in the deaths and injury of numerous civilians.The Deputy Head of NDS targeted by an SVBIEDOn 2 September, an SVBIED attack in Laghman Province targeted and killed theDeputy Head of NDS, and four other NDS staff, as they were exiting a meeting at theCentral City Mosque, in Mehterlam City in Laghman Province. The Mosque issituated near a busy bazaar. As a result, the explosion reportedly killed 18 civiliansand injured 61 others, including women and children. The Taliban claimedresponsibility for the attack. Following an investigation, four people weresubsequently arrested by the provincial authorities. On 31 December, around 1000-1200 people demonstrated in the city calling for the government impose the harshestsentence against the accused.IEDs were used more often than any other AGE tactic. Their use was often systematicand indiscriminate resulting in high casualty rates, particularly in the south and southeast regions. In Khost Province, a trend of using magnetic IEDs that adhere to theoutside of a vehicle was detected, particularly in a string of attacks in June thatresulted in three civilians killed and injury to numerous others. In a press statement,the Deputy Special Representative of Secretary General (DSRSG), UNAMA,condemned the indiscriminate use of IEDs in Maywand district of Kandahar duringthe month of September and appealed to those responsible to desist from such actions.Civilian vehicles using an alternative route to the main highway, because damage tothe main road had made it unusable, were struck by IEDs, killing a total of some 37civilians and injuring at least 18 others, including women and children. This includeda 29 September incident when at least 30 civilians were reportedly killed and 19injured when their bus struck an IED.AGEs have also perpetrated IED and suicide attacks in residential areas. As noted in arecent report by a consortium of NGOs,4the indiscriminate use of IEDs, particularlyin residential areas, caused civilians to experience feelings of trauma. The same studyfound that “there was a clear link between fear and anxiety, and insecurity associatedwith the current conflict.” These effects can be long lasting, creating a climate of fearand often result in reduced mobility and restricted access to basic services by thepopulation.

11

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Assassinations, Threats and IntimidationUNAMA HR recorded 225 reported assassinations and executions by AGEs. Armedopposition groups have continued to show a great willingness to systematically targetcivilians through threats, intimidatory tactics, abductions and executions; in somecases by beheadings and hanging.Persons were most often assassinated or executed due to AGE suspicions that thetargeted individuals had acted as informants or “spies” for the GoA or IM forces; forworking with the IM forces as interpreters, truck drivers or security guards at militarybases; for actively supporting the Government; or for belonging to the ANSF. Themajority of assassinations took place in the south, southeast and central regions ofAfghanistan.There are a number of ways in which AGEs identified their targets. It was notuncommon for road blocks and checkpoints to be established by armed groups inorder to search cars for civilians carrying identity papers which indicated whereindividuals work. Civilians were harassed as a consequence and, in a few cases, werekilled. These searches have taken place in the south, southeast, west, central and eastof the country. “Night letters” were used to warn entire communities against engagingin particular activities and to threaten specific individuals. Many such letters warnedpeople that failure to stop working with the government or the internationalcommunity would lead to “retribution”. Such threats create a climate of fear andintimidation. In cases documented by UNAMA HR, individuals who had beenabducted and killed were sometimes found with a letter attached to their body as awarning to others. These tactics point to a systematic campaign to intimidate andundermine support for the government and international forces in Afghanistan. Thesecampaigns of intimidation can oblige individuals and entire communities to alter orrestrict their usual activities, giving rise to untold hardship, including loss of income.Distribution of leaflets by AGEs in Farah ProvinceOn 17 June, a number of leaflets were found distributed around the mosques in Farahtown threatening people not to work either for the government or the internationalcommunity. These leaflets were also found in Pusht Rod and Khak Sefid Districts.In some cases, being perceived as “supportive” of the Government or its partners inthe international community can revolve around acts such as publicly greetinginternational forces. In February, such a greeting appears to have led to the executionof two children and the severe beating of another in Sayad Abad District of WardakProvince. This form of warning targets both men and women, and sometimeschildren. Frequently, the focus is on civilian government employees, constructionworkers, students and teachers, religious leaders and community/tribal elders anddoctors, as well as former police and military personnel.Reprisals can be swift and harsh. UNAMA HR has documented numerous caseswhere civilians were abducted and killed for their apparent support for, or associationwith, the Government and its allies or, most commonly, for allegedly being “spies”.Adults and children in the south, southeast, east and central regions of the countrywere more frequently subjected to such tactics. For example, on 12 July, an individualsuspected of spying for the government and IM forces was publicly hanged in Chak12

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

District in Wardak Province. On 9 November, a local daily wage labourer, workingfor IM forces, was allegedly abducted and killed by AGEs in Nari District, KunarProvince; he was said to have provided information to IM forces that resulted in someinsurgents being killed during a previous operation. On 15 November, five maleswere abducted by a group linked to a local Taliban commander in Khaki SafedDistrict of Farah Province. Two of them were beheaded for being affiliated with theGovernment. The remaining three were released.UNAMA HR has noted that key tribal elders, particularly in the south, southeast andcentral regions, have been targeted by the Taliban. The reasons appear to be twofold:to weaken support for the Government and to undermine those tribal structures thatare not supportive of the armed opposition. In the south, at least six prominent tribalelders and community leaders were killed by the Taliban in November. Many of theelders either showed their support for the government or had held key positions, suchas in the district shuras. On 1 November, AGEs assassinated a prominent communityelder from Dehrawood District, Uruzgan Province as well as an elder who chaired thedistrict shura of Nawa District, Helmand Province; on 6 November, the head of thefemale wing of Sarpoza Prison was killed in Kandahar city; on 10 November, thedeputy head and a member of the district shura in Nawa District were both killed; andon 30 November, a tribal elder and a member of a shura in Shinkey District in ZabulProvince was killed. In the majority of these cases, the Taliban claimed responsibilityor had previously threatened the victims.Langar villagers, accused of collaboration, threatened and killed by the TalibanFollowing an international military forces operation in Langar area of ChinartoDistrict [unofficial district within Chora district] of Uruzgan Province on 28 April,the Taliban accused the villagers of collaboration with the IM forces. The Talibanwere, apparently, angry at the significant losses incurred in the operation.Consequently, they issued a number of verbal threats and reportedly drew up a list of42 alleged collaborators, who were to be killed. Villagers were also warned that theywere not authorized to use cell phones without the permission of the Taliban.Allegedly, several villagers were taken to the mountains and killed. On 11 May, theTaliban reportedly abducted four people from the area and accused them of spying;two were executed and the other two were severely beaten. On 20 May, an individualtraveling from Tirin Kot to Chinarto was allegedly stopped by the Taliban and killedbecause he was carrying a cell phone. As a result of the violence and threats, a totalof 60 families fled to Tirin Kot, where most remain displaced.There were also a number of attempted assassinations against high profile individualsand government employees; this has had a negative impact on their ability to carry outtheir responsibilities effectively for the benefit of the civilian population. A number ofassassinations were conducted in the south during March. These targeted a member ofthe Wolesi Jirga in Helmand Province and a mullah in Uruzgan Province. The latterappears to be part of a trend of attacks against clerics deemed to be pro-Government.In November, for example, there were three separate IED assassination attempts.These included an attack on convoys of the Governor of Kandahar, a Member ofParliament in the Paghman District of Kabul, and a BBIED attack in the vicinity ofthe Governor’s Office in Farah City, in which 15 civilians were reportedly killed and40 injured. An SVBIED exploded near the house of former Vice President Ahmed Zia13

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Masood, brother of the slain Ahmad Shah Masood, on 15 December in Kabul. ZiaMasood survived, but eight civilians were killed and 40 were injured. Many of theperpetrators remained unidentified even though the fact that the authorities are oftennotified about these threats but fail to make provision for either adequate security forpeople who hold high profile positions or to initiate the type of investigation thatwould bring the perpetrators to justice.Attempted assassination of Ismail Khan, Water and Energy, Minister, in HeratOn 27 September, a VBIED attack against the convoy of the Minister for Water andEnergy, Ismail Khan, in Herat city failed as he was traveling in Injil District on theway to the airport. He survived, but at least 4 individuals died and 15 were injured,including two women and two children. The Taliban claimed responsibility for theattack.Threats against the head of DOWA in KhostBetween April and September the head of DoWA (Department of Women’s Affairs)and another member of her staff were subjected to intimidation and death threats byAGEs. As a result of these threats, the two women refrained from attending theirworkplace for fear of being targeted, impacting on DoWA’s capacity to undertaketheir regular activities. Local authorities failed to provide adequate and sufficientsupport and protection to the office and staff. On 19 May, the head of DoWA’s officialvehicle exploded in front of her house. This incident and the on-going phone callswere reported to ANP, NDS, the Governor and MoWA in Kabul. However, herprotection was not strengthened and for several months she stopped working. Shehas continued to receive threatening phone calls subsequent to her car being blownup, as well as a threat to kidnap her younger son. In September, although she stillreceives threatening phone calls, the head of DoWA resumed her official duties.Killing of Sitara Achekzai, Provincial Council member, in Kandahar cityOn 12 April, Provincial Council [PC] member and women’s rights activist, SitaraAchekzai, was killed by two men on a motorbike in Kandahar city. A Talibanspokesperson, Qari Mohammad Yusof Ahmadi, was reported in the media as statingthat the Taliban had killed her because of her position as a Provincial Councilmember, and that they would continue to kill PC members regardless of gender.Reporting on the conflict is often dangerous and complicated, because talking toeither side can invite suspicion and intimidation. Afghan journalists were targeted bythreats, abductions and killing thereby curtailing freedom of speech across many partsof the country. At least two journalists were killed in March. In May, AGE abducted 7civilians, including five journalists of the Al Jazeera network in Kunar Province; fourof them were later released except for one individual. However, it was less than amonth later that one of them was held by the NDS for several days. Journalists whodo talk to the Taliban are frequently detained by the NDS. On 17 June, two journalistsfrom Al-Jazeera were released after three days in NDS detention. Allegedly, the pairwere detained, and accused of being biased, in the production of a report on theTaliban in the north of the country. To minimize risks, journalists often practice self-

14

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

censorship. Numerous international journalists have also been abducted, along withtheir Afghan colleagues. Most were subsequently released.UN and NGO employees have also been singled out for intimidation, and on a fewoccasions, have been killed. Many staff members who travel between work and homehide the true nature of their work; many do not carry identity cards showing theirplace of work, and many do not tell their family relatives or communities the realnature of their job for fear of reprisals.

15

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

III.

PRO-GOVERNMENT FORCES

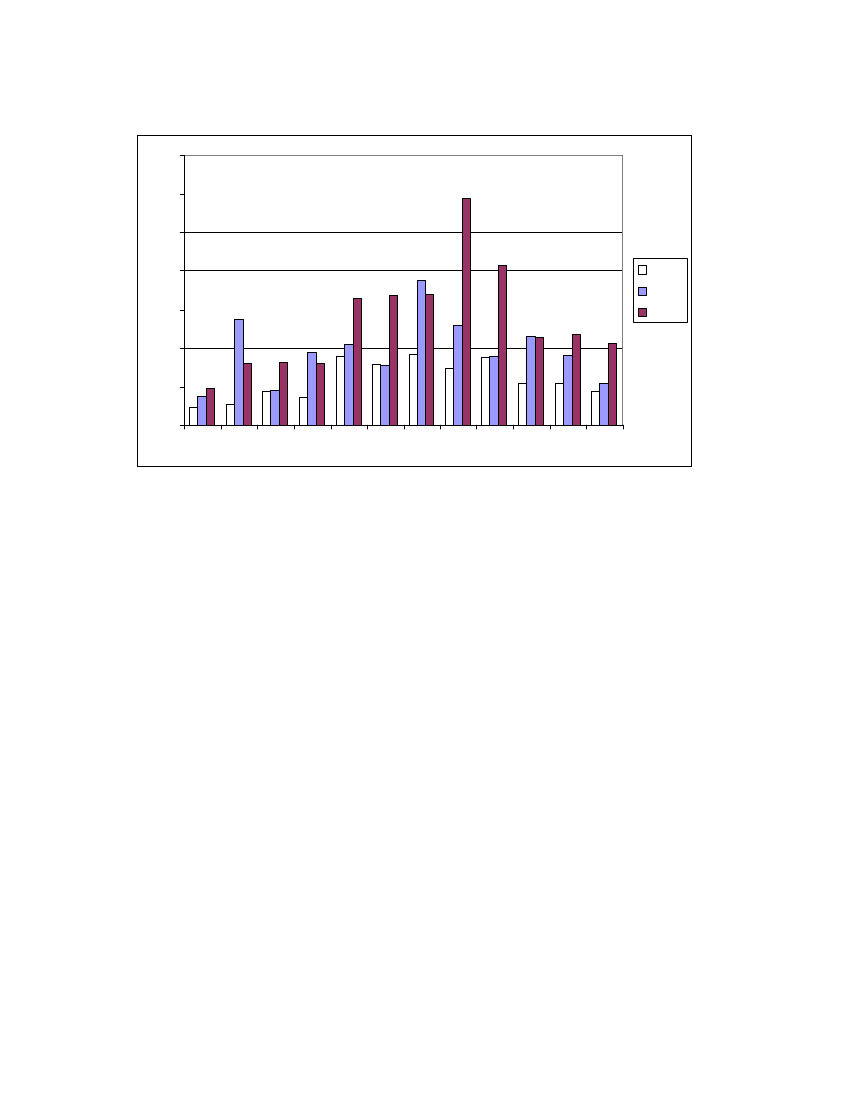

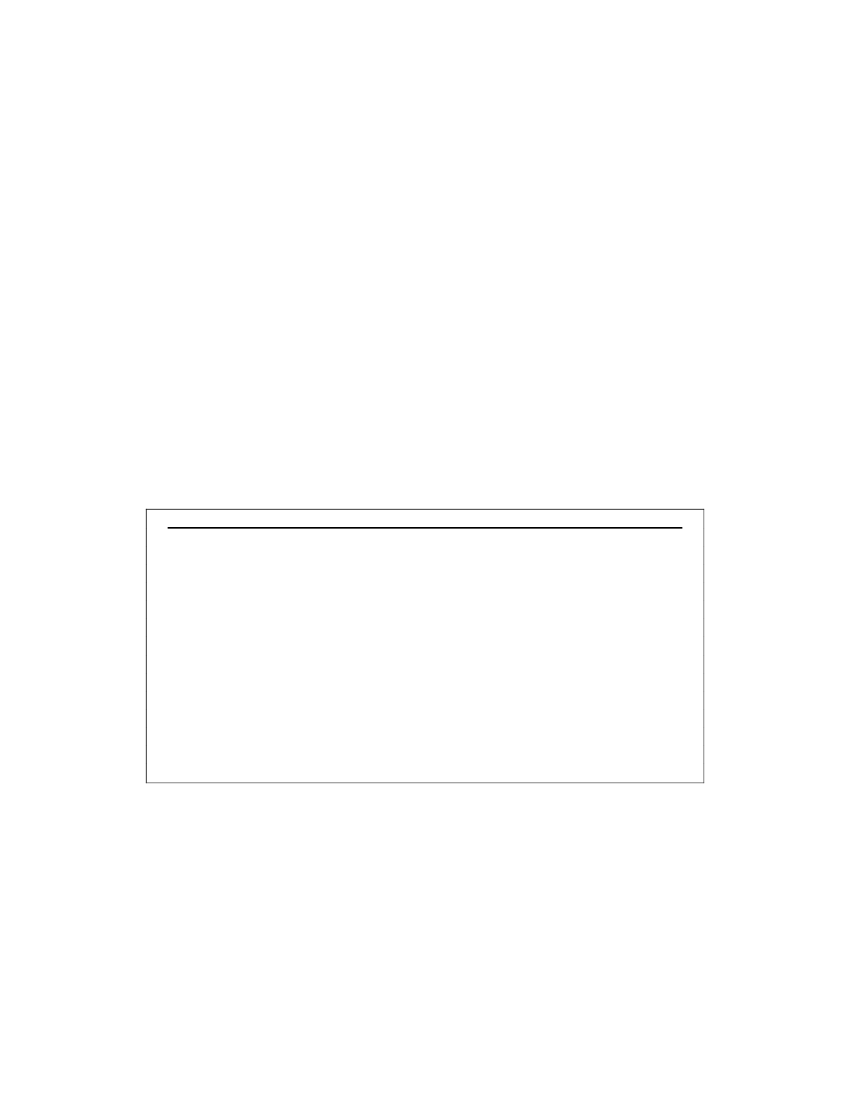

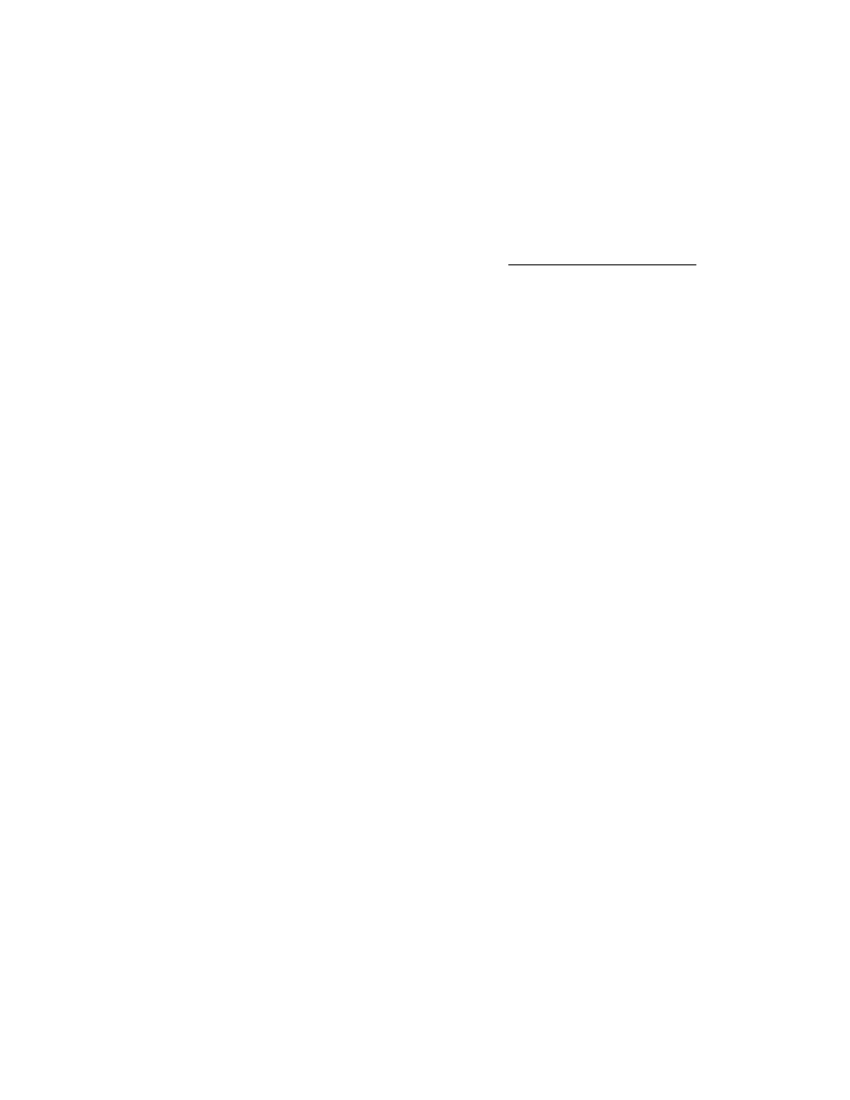

PGF and civilian casualtiesPro-Government forces (ANSF and IM forces) were responsible for 596 recordeddeaths; this represents 25% of the total civilian casualties recorded in 2009. Thisamounts to a decrease of 28% from 828 deaths in 2008. This decrease is a reflectionof the continued measures taken by international military forces to improve theconduct and manner in which forces undertake military operations and to reduce theimpact of the war on civilians.In the context of pro-Government military operations, air strikes claimed the mostcivilian lives, with 359 killed (61%). Search and seizure operations claimed thesecond largest number of civilian lives, with 98 killed (16%). Together, these tacticsaccounted for 77% of the civilian deaths attributed to PGF actions.Chart 5: Civilian Deaths Attributed to PGF, disaggregated by incident type

17%6%

Aerial Attacks - Air Strikes &Close Air Support (359)Search / Raid (98)Escalation of Force / ForceProtection (36)Other PGF Tactics (103)

16%

61%

16

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

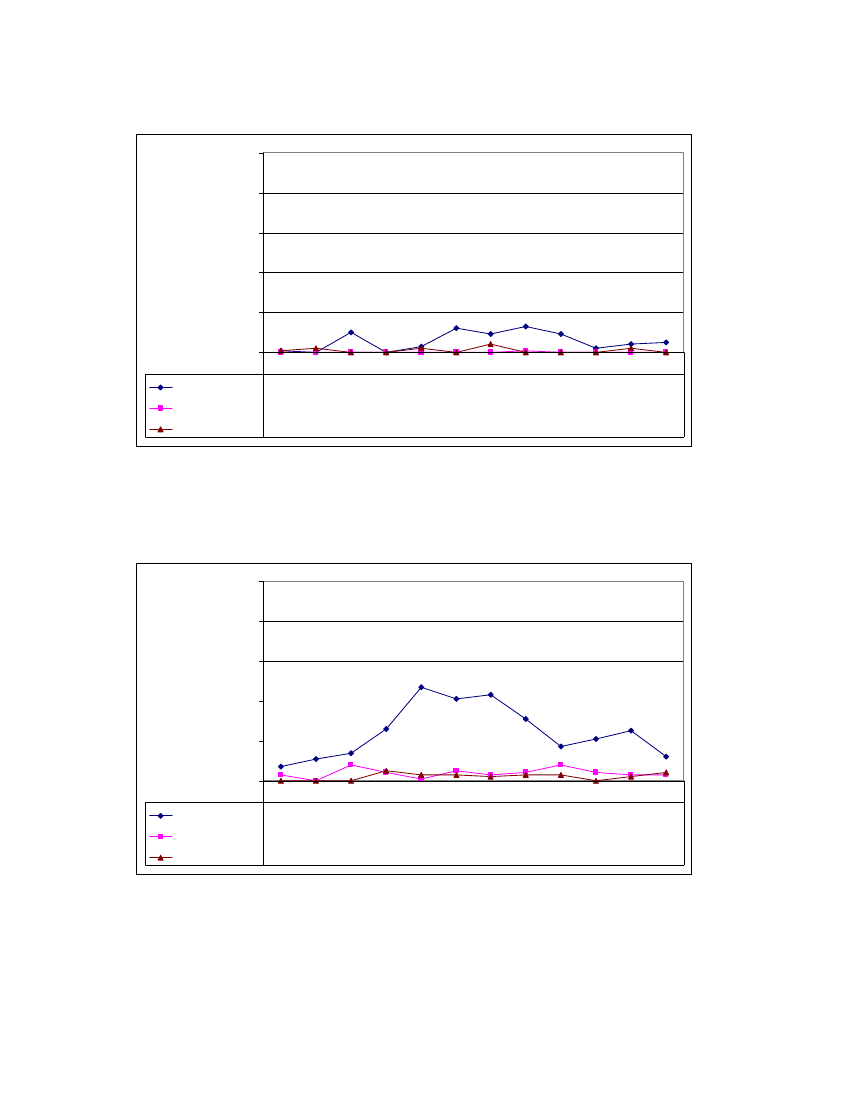

Chart 6: Civilian Deaths Attributed to PGF – 2007, 2008, 2009350300250200150100500Jan Feb Mar Apr May JunJulAug Sep Oct Nov Dec200720082009

High-level policy decisions on the conduct of international military forces havecontributed to an improved environment for civilians affected by the armed conflict.The 2 July Tactical Directive issued by COMISAF, applicable to all forces ofISAF/USFOR-A, was designed to reduce civilian casualties. It limited the use of force– such as close air support – in residential/populated areas. It also revised theguidelines for operations involving residential compounds, and searches of housesand religious establishments; which now should always be accompanied, orconducted, by the ANSF.However, despite this improved situation, UNAMA HR continued to receive accountsof civilian casualties and the detention of Afghans, who often remain in undisclosedlocations, subsequent to night searches.Aerial attacksAir strikes and close air support account for the largest percentage of civilian deathsattributed to pro-Government forces. UNAMA HR recorded 65 incidents in which airstrikes resulted in the deaths of civilians in 2009. In all, this resulted in 359 civiliandeaths in 2009 and 15% of those killed overall. These percentages are significantlylower than the figures recorded for 2008, when 552 civilians died. This appears to bea result of the 2 July Tactical Directive that authorized the use of aerial attacks undervery specific conditions.May and September were the deadliest months for civilian casualties in the context ofair strikes due to an incident in Bala Baluk District on 4 May that claimed 64 livesand an air strike near Omer Khel village in Aliabad District, Kunduz Province on 4September that claimed the lives of 74 civilians. This figure includes an Afghanjournalist, captured at the scene of the incident, who was also killed in a rescueattempt in which a foreign journalist was freed.

17

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

As noted in our Mid-Year Bulletin, (July 2009), while the number of deadly air strikeincidents remains relatively low compared to the overall number of air strikes, theystill result in a significant amount of lives lost. Civilians remain at risk from air strikesin night raids, when in the vicinity of an ambush on pro-Government forces’ convoysor when mistakenly identified as AGEs.Civilian casualties as a result of an air strike in Mizan District, Zabul ProvinceOn 28 July, an ISAF air strike reportedly killed six civilians, including two children,and injured six others in Takhon Village, Mizan Disrict of Zabul Province whilsttargeting Taliban. A helicopter launched a strike, after chasing Taliban riding amotorcycle into an orchard in which civilians were working. ISAF acknowledged thatsix civilians were killed and six others were injured.Air strikes also highlight the problem of AGEs sheltering in the homes of civiliansand sometimes deliberately using civilian as shields. In several cases investigated byUNAMA HR, information was received that important AGEs targeted in militaryoperations had deliberately taken shelter in houses inhabited by persons not connectedto the insurgency. Traditional codes of hospitality and power imbalances inhibit theability of villagers living in areas with a strong AGE presence to refuse shelter to anAGE commander. Information indicates that AGEs take advantage of these factors touse civilian houses as cover to deter PGF raids. While using human shields violatesobligations of international humanitarian law, there is also an obligation on ISAF totake all necessary measures to reduce harm to civilians. AGE violation ofinternational law does not authorize ISAF to violate its own obligation to internationalhumanitarian law.Air strike against hijacked oil tankers in Aliabad District, Kunduz ProvinceOn 3 September, a group of Taliban hijacked two fuel tankers along the mainKunduz-Baghlan road. They tried to cross the Kunduz river towards Chahar DaraDistrict, near to Omarkhel village in Aliabad District. The trucks got stuck in the riverbed and when the insurgents failed to release them, the Taliban invited nearbyvillagers to collect the fuel. As the villagers were siphoning off the fuel, several hourslater, in the early hours of the morning of 4 September, an air strike was conducted.Investigations were complicated as a result of the ensuring fireball, which incinerateda large number of people making identification extremely difficult. It is not disputedthat some Taliban were at the site but it should have been apparent that manycivilians were also in the vicinity of the trucks. According to UNAMA HR’sinvestigations, 74 civilians, including many children, were killed. Despite severalrequests, by UNAMA HR, to the Civilian Casualty Tracking Cell, ISAF did not releasethe unclassified version of its report nor shown video footage as requested. As a resultof the air strike, several high ranking German officials, resigned after it came to lightthat they had withheld information that civilians had been killed and injured.It is of concern to UNAMA HR that many victims of air strikes that have resulted inthe loss or injury of family members and destruction of property remain unaware as tothe reasons for the air strike. Neither are they always informed of who conducted theair strike. This lack of information and the failure to be transparent with the affected18

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

communities often results in allegations of impunity and that those responsible are notheld to account.Location of military basesUNAMA HR has highlighted concerns in numerous reports, briefings, and dialoguewith ISAF on the issue of the location of military facilities within or near areas wherecivilians are concentrated. The presence of IM bases in residential areas continues tobe a major concern. This runs counter to international humanitarian law principlesdesigned to protect the civilian population against the dangers arising from militaryoperations.When military bases are established in or near residential areas – in either urban orrural areas –this is an additional security threat given the high likelihood of attacks byarmed groups or from retaliatory activities by IM forces. The presence of IM basescan generate hostility amongst the civilian population, particularly if civiliancasualties arise as a result of their presence.UNAMA HR has recorded numerous incidents of rocket attacks launched by AGEstowards ISAF bases and missing their target. In some cases, these rockets landed inempty spaces. However, in many documented incidents, rockets fired by AGEs fellshort of their targets, hit civilian houses, and killed and injured people occupyingthem. In one such incident in May a school in Asmar district in Kunar Province washit by an AGE rocket that was targeting an IM base a kilometer away from the school.Eight school girls and a teacher were injured as a result. UNAMA HR has alsodocumented numerous cases in which ISAF launched rocket attacks in the direction ofareas where AGEs are presumed to have launched attacks, and have also hitresidential areas, causing civilian casualties as a result. UNAMA HR remainsconcerned that ISAF retaliatory fire towards suspected AGE locations that are close tovillages continues to kill and injure civilians. Any action by pro-Government forcesmust take into account the principles of proportionality and distinction, in particularwhen responding to rocket attacks launched from populated areas. Every feasibleprecaution must be taken to ensure that use of military force not impact on civilianareas causing death or injury to residents.VBIED at the main gate of ISAF HQ, KabulOn 15 August, a VBIED managed to bypass heavy security to explode his vest at theentrance to the main gate at ISAF HQ located in a busy and heavily fortified sectionof downtown Kabul, surrounded by international and national organizations.According to a spokesperson of the Taliban, which claimed responsibility for theattack, 500 kilos of explosives had been used. UNAMA HR's investigations concludedthat 7 civilians were killed and at least 90 others were injured.Although many ISAF bases and ANA army bases are located on the outer perimeterof urban areas, a recent trend is of smaller bases being co-located with the ANSF, andsometimes with provincial civilian authorities, in locations, such as bazaars that arenormally in the heart of built-up commercial and residential areas. The repercussionsas a result of the locations of such bases, including heightened security risks forcivilians, reduced or obstructed mobility for civilians and additional check-points,have given rise to a host of concerns among the affected population. Both pro-19

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Government forces and AGEs have a responsibility to minimize the impact of thearmed conflict on civilians. The relocation of military bases away from civilian areaswould mitigate the impact on civilians and reduce the number of lives lost and injuredas a result of these attacks.US marines based in the bazaar in Delaram District, Nimroz ProvinceA contingent of US marines is co-located with the District Administrator in a smallbase in the bazaar area of Delaram town in Nimroz Province. Their presence has ledto substantial opposition by the community. Local elders and the authorities havecomplained about the presence of the marines as they feel that it endangers the localpopulation. Their presence has led to more intrusive searches community membersvisiting the District Governor, a greater risk of a suicide attack being directed againstthe base and increased the likelihood of the community being targeted by AGE as‘spies’ for the IM forces. UNAMA HR raised these concerns both at the provincialand national level. In a meeting with senior ISAF personnel in Kabul in October,UNAMA HR was informed that the situation had been resolved and the base would beclosed down. However, upon further investigation, UNAMA HR found that the base,as of end of December, was still operating.According to international humanitarian law the parties to the conflict, shall, to themaximum extent feasible avoid locating military objectives within or near denselypopulated civilian areas.5This obligation applies to both IM forces and AGEs, whoalso, frequently, base themselves in residential areas.Search and seizure operationsThe conduct of pro-Government forces during night raids and searches continues tobe of concern, particularly regarding excessive use of force resulting in death andinjury to civilians. UNAMA HR recorded 98 civilian deaths as a result of theseoperations (16%). Concerns have ranged from allegations of ill-treatment, aggressivebehaviour and cultural insensitivity, particularly towards women. As a result, anumber of demonstrations have been held across the country to protest against thesepractices as well as prompting debate in both houses of the Afghan parliament oncivilian casualties and the presence of international forces in Afghanistan. The KhostProvincial Council went on strike as a result of a night search in April, during whichfour civilians were allegedly killed. In Laghman and Nangahar Provinces, severaldemonstrations were held between 8-9 December to protest against a night searchconducted by IM forces in Mehterlam District in Laghman Province. AGEs have alsocapitalized and exploited public anger towards searches. As a result of anunsubstantiated allegation of the desecration of the Holy Quran following a search inWarkdak Province in October, AGEs were able to exploit public sentiment country-wide, resulting in 15 demonstrations across five regions of the country; six of thesewere in Kabul. UNAMA HR has recorded numerous demonstrations around thecountry in protest against night searches and killings of civilians by IM forces.Improvements have been noted in the conduct of behaviour by ISAF forces duringsearch and seizure operations, as those operations have to be partnered with ANSF.However, this progress continues to be undermined by raids that are undertaken byinternational and Afghan Special Forces or other such government entities. The raidsoften result in excessive force, ill-treatment and deaths and injury. These forces often20

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

operate with little or no accountability and exacerbate the anger and resentment feltby communities towards the presence of international military forces.Night search operations in Ghazni Centre: killing and assault of civiliansOn 16 October, in the Mangur area of Ghazni centre, international military forces,conducted a night search operation that resulted in the death of four civilians,including a 10-year-old girl. IM forces and ANSF entered the village late at night,and reportedly searched five houses, opening fire when entering one of them. As aresult, a 70-year- old man, his 35-year-old son, his 60-year-old wife and their 10-year-old granddaughter were killed. Concurrently, in another house, allegedly an IMsoldier tied a man’s hands behind his back. Together, with his brother and his 17-year-old and 14-year-old sons, he was taken to a nearby school, where allegedly theywere assaulted whilst being questioned about the location of a Taliban commander.The man and his brother sustained serious head injuries as a result of the assault.Later, four more males, including a 13-year-old boy, who also had their hands tied,were taken to the school, and reportedly assaulted whilst being asked the samequestions. Both groups were left at the school, tied and were later released by thevillagers after the IM and ANSF forces had left. On 18 October, during a meetingbetween the village representatives and the provincial authorities and the IM forces,IM forces reportedly acknowledged that they had received false information.It is of concern to UNAMA HR that, often, individuals are arrested and detainedwithout their families being notified of their location, particularly when they are heldin places where there is no access to an ICRC office for detainee-familycommunication. UNAMA HR has documented a number of cases where familyrelatives have approached ISAF to enquire about the location of detainees. On theseoccasions they were often unable to access the Forward Operating Bases closest totheir villages, were unaware who to approach in ISAF to enquire about their relativesand were often turned away at the gate. UNAMA HR urges ISAF to ensure theprompt notification of detainee’s whereabouts to their family. Many communities seethe lack of accountability for the actions of the IM forces fostering a culture ofimpunity. When incidents are not investigated and perpetrators are not brought tojustice communities and others query whether IM forces are held accountable foractions that are contrary to international humanitarian and human rights law.Searches and attacks against medical facilitiesReports have also been received of incidents of medical facilities being affected bythe conflict. Health centres during an armed conflict are essentially immune fromattack given their presumption of status as civilian objects, with the exception ofwhere parties to the conflict use them as a base for military activities. Even if used formilitary purposes, the principles of proportionality and distinction remain. A civilianhospital does not lose its protection under international humanitarian law simplybecause it admits sick or injured combatants. In an incident on 26 August, in SarHawza District of eastern Paktika Province, a clinic in which an injured TalibanCommander and at least two other AGEs were receiving medical treatment was thescene of an air strike by PG Forces. As a result, the clinic was partially damaged andcivilian casualties were recorded. In another incident, IM forces entered an INGO-runmedical facility in Sayadabad District in Wardak Province. According to reports, thetroops searched all the rooms, often using force to enter and damaging property, while21

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

looking for insurgents. No arrests were made and, reportedly, upon leaving, medicalstaff was told to inform Coalition Forces if they received any insurgents in order todecide whether they should be treated. This incident resulted in the closure of themedical facility for three days. ISAF acknowledged that the hospital was searched butclaimed that they had sought permission beforehand, an assertion that UNAMA HRcould not verify.Tirin Kot Provincial Hospital searched by ISAF in Uruzgan ProvinceOn 12 April, ISAF forces conducted a search operation in the Tirin Kot Hospital afterreceiving information that injured Taliban fighters were receiving treatment. Incontrast with ISAF statements that only 4-5 people were involved in the search,UNAMA HR recorded that some 40 heavily armed soldiers, who arrived in at leastfive armoured vehicles, searched all the rooms and wards of the hospital. AlthoughISAF had stated that they had been invited to enter the hospital, UNAMA HR couldnot confirm this statement. UNAMA HR recorded complaints that the women’s wardwas entered by male soldiers. Concern was also raised that the medical staff were notallowed to help even those patients who required emergency care and some patientswere reportedly not allowed to enter the hospital during the search. As a result of thesearch, medical professionals working in the hospital felt that this made the hospital amuch less safe place to work and would make it even harder to attract well-qualifiedmedical staff.Accountability/RedressIn its 2008 Annual Report on civilian casualties, UNAMA HR noted growing angerby Afghans at the perceived impunity, of both sets of parties to the conflict, forcivilian casualties and damage to property, especially those civilian casualtiesattributed to the actions of international military forces.With changes in command and structure, so that both ISAF and US Forces-Afghanistan are now under the command of COMISAF, there have been somepositive steps in improving the conduct of IM forces as well as responsiveness toincidents involving civilian casualties. For example, in the aftermath of the Kunduzair strike on 4 September, two investigative teams were initiated: a Joint InitialAssessment Team and an Operational Investigation Team. General McChrystalvisited the site on 5 September to view the location of the attack and to meet victimsof the air strike.However, there still needs to be better coordination between the different securityforces, particularly those that are operating outside the control of ISAF. Without thiscoordination, the lack of accountability of pro-Government forces and othergovernment entities is likely to remain a significant concern. Many families who havebeen victims of an ISAF/ANSF operation complain that they have not gained accessto commanders in the field. Often, they do not even know who to approach with theirquestions and complaints when seeking redress. This was further emphasized by theUN High Commissioner for Human Rights in a press release on the launch of theMid-Year Bulletin in July, in which she said that “all parties involved in this conflictshould take all measures to protect civilians, and to ensure the independentinvestigation of all civilian casualties, as well as justice and remedies for the victims.”

22

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

UNAMA HR welcomed attempts by ISAF to address various issues of concern,including the establishment of Civilian Casualty Tracking Cells in 2008 within ISAFand OEF. However, after a good start, the tracking cell in recent times has not provedvery effective in terms of responding in a timely manner to UNAMA HR’s requestsand engaging on substantive issues with any authority. There must be genuine effortsin improving the Tracking Cell so that it can be more responsive to incidents ofcivilian casualties.The issue of condolence orsolatiapayments has been raised by UNAMA HR and theinter-agency Protection Cluster throughout the year. There continues to be no uniformstandard, procedure or even timeline between the different countries who mechanismsfor payment, creating confusion, anxiety and anger amongst affected Afghans. Aletter dated 9 August, from the inter-agency Protection Cluster, brought variousconcerns to the attention of General McChrystal, including the need for “a morecoherent, coordinated and fair approach for the provision of recognition and redress,”the greater transparency of existing condolence mechanisms, and the establishment ofa unified and comprehensive mechanism for providing redress.IV. CONCLUSIONAfghans have, repeatedly, identified security as their most pressing priority. As thearmed conflict has spread and intensified, the issue of security, or rather lack thereof,is of most acute concern for a growing number of Afghans. Whether the harminherent in violent conflict is experienced as the unintended outcome of militaryoperations, or is the result of indiscriminate or targeted actions, the civilians whosuffer the consequences must, to a significant extent, attempt to repair lives andlivelihoods without hope of redress or assurances that the harm they endured will notbe repeated.2009 was the most violent and deadly year since the fall of the Taliban regime in2001. It witnessed the highest number of civilian deaths and injuries since UNAMAstarted systematically recording civilian casualties in 2007. More people than everbefore are being affected by the conflict. As outlined in a survey conducted in 2009under the auspices of ICRC, “[V]ery few people in Afghanistan have been unaffectedby the armed conflict there. Those with direct personal experience make up 60% ofthe population….. In total, almost everyone (96%) has been affected in some way,either personally or due to the wider consequence of armed conflict.”6ISAF's declared strategy of prioritizing the safety and security of civilians is awelcome development and, as the latter months of 2009 indicate, such policies greatlyenhance the protection of all civilians. However, the inability or unwillingness of thearmed opposition to take measures that pre-empt and reduce the harm that their tacticsentail for civilians translates into a growing death toll and an ever larger proportion ofthe total number of civilian dead. In addition to the pain and suffering associatedwith the loss of loved ones, frequently the death of male family members, particularlyin poor and vulnerable households, means an end to an assured or sporadic incomethat is critical to the survival of the family unit.Given an anticipated increase in the incidence of armed conflict in 2010, it isincumbent on all stakeholders to effectively protect all civilians.

23

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009

Appendix IGlossaryThe following terminology and abbreviations are utilized in this Report:AGEs:Anti-Government elements. These encompass all individuals and groupscurrently involved in armed conflict against the Government of Afghanistan and/orIMF. They include those who identify as ‘Taliban” as well as individuals and groupsmotivated by a range of objectives and assuming a variety of labels.ANA:Afghan National Army.ANP:Afghan National Police.ANSF:Afghan National Security Forces; a blanket term that includes ABP, ANA,ANP and NDS.BBIED:Body-Borne Improvised Explosive Device; see IED.BTIF:Bagram Theatre Internment FacilityCasualties:May be of two classifications:•Direct:casualties resulting directly from armed conflict – including thosearising from military operations conducted by pro-Government forces (AfghanGovernment Forces and/or International Military Forces) such as forceprotection incidents; air raids, search and arrest events, counter insurgency or“Global War on Terror” operations. It also includes casualties arising from theactivities of AGEs, such as targeted killings, IEDs, VBIEDs, and BBIEDs, ordirect engagement with pro-Government forces, etc.•Other:casualties resulting indirectly from the conflict, including casualtiescaused by explosive remnants of war (ERW), deaths in prison, deaths fromprobable underlying medical conditions that occurred during militaryoperations, or where access to medical care was denied or was notforthcoming. It also includes deaths arising from incidents whereresponsibility cannot be determined with any degree of certainty, such asdeaths or injuries arising from cross-fire. Finally, it includes casualties causedby inter/intra-tribal or ethnic conflict.Civilian/Non-Combatant:Any person who is not taking an active part in hostilities.It includes all civilians as well as public servants who are not being utilised for amilitary purpose in terms of fighting the conflict, and encompasses teachers, healthclinic workers and others involved in public service delivery, as well as politicalfigures or office holders. It also includes soldiers or any person who arehors decombat,whether from injury or because they have surrendered or because they haveceased to take an active part in hostilities for any reason. It includes persons who maybe civilian police personnel or members of the military who are not being utilized incounter insurgency operations, including when they are off-duty.Children:According to theConvention on the Rights of the Child,a ‘child’ isdefined as any person under the age of 18 (0-17 inclusive). Injury figures for children24

Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, 2009