Udvalget for Fødevarer, Landbrug og Fiskeri 2009-10

FLF Alm.del Bilag 250

Offentligt

WWF Response to the2009 Green Paper :Reform of theCommon Fisheries Policy

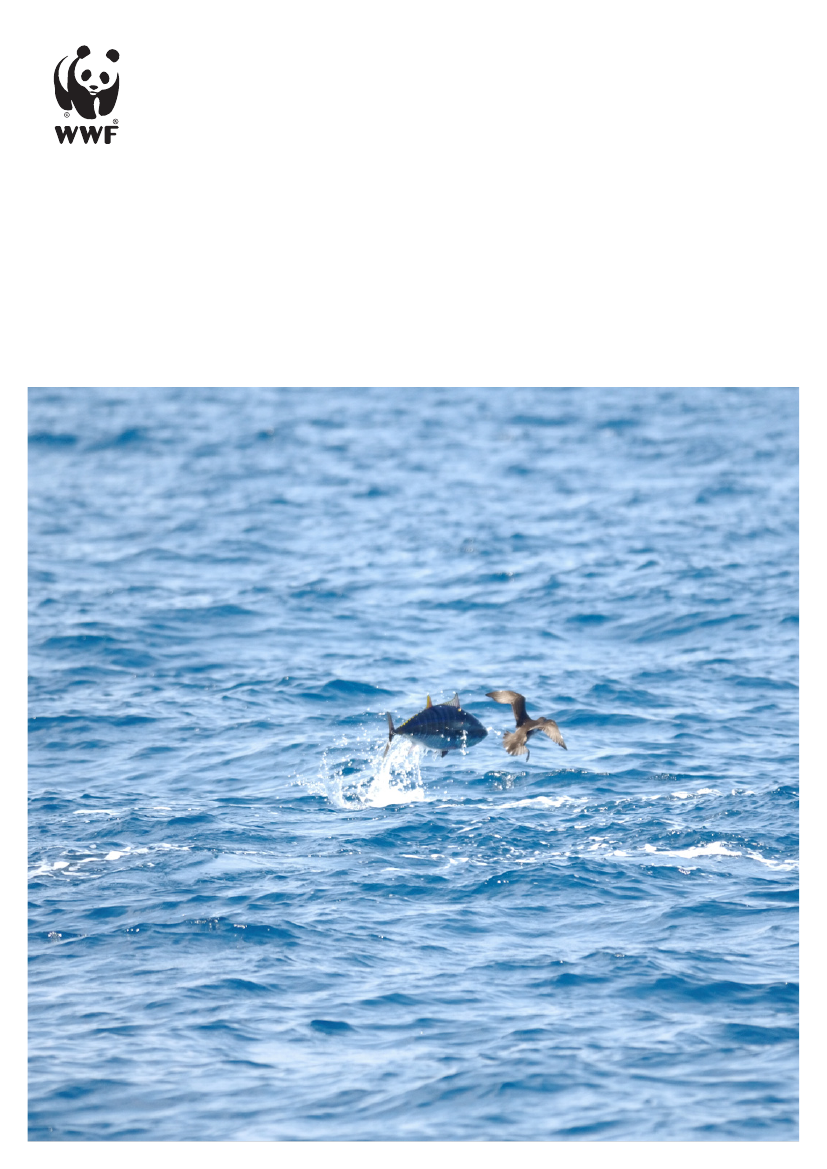

Published November 2009 by WWF, World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund), Brussels,Belgium. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner.� text 2009, WWF. All rights reserved.Editor: Helen McLachlan, WWF-ScotlandLayout: Florence Danthine and Stefania Campogianni, WWF European Policy OfficePrinted on recycled paper.Photo: � WWF/ F. Bassemayousse

WWF Response to the Reform of the CommonFisheries Policy Green Paper 2009

Table of ContentsExecutive summary ………………………………………………………………………………………………..2Fleet Overcapacity ...................................................................................................................................... 3Focussing the Policy Objectives ............................................................................................................... 6Focusing the decision-making framework on core long-term principles ............................................. 9Encouraging the industry to take responsibility in implementing the CFP........................................ 15Developing a culture of compliance ....................................................................................................... 18A differentiated fishing regime to protect small-scale coastal fleets.................................................. 23Making the most of our fisheries............................................................................................................. 25Relative stability and access to coastal fisheries ................................................................................. 28Trade and Markets .................................................................................................................................... 30Integrated Maritime Policy ....................................................................................................................... 33Scientific Advice (Further improving the management of EU fisheries & the knowledge base forthe policy) .................................................................................................................................................. 35Structural Policy and Financial Support................................................................................................. 37External Dimension................................................................................................................................... 39Aquaculture ............................................................................................................................................... 45

1

Executive SummaryWWF believes there is hope that sustainable fisheries management can be achieved inEuropean fisheries. Our vision is one of healthy marine ecosystems supporting abundant fishstocks which in turn provide sustainable livelihoods for fishing industries and fisheriesdependent communities around the world. We therefore welcome this opportunity to presentour views on the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) reform. In our response we propose that therevised CFP Regulation establishes a mandatory requirement for all European fisheries tooperate according to ecosystem based Long Term Management Plans (LTMPs) by 2015. TheRegulation should standardise these by setting out minimum criteria that all plans need to meet,including balanced stakeholder groups that will develop the plans for European Parliamentaryand Council approval, thus delegating more responsibility to the industry and otherstakeholders. Adopting this approach will allow the EU to address its environmentalcommitments under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) as well as institute asound model for the regionalisation of the CFP and the much needed devolution of decisionmaking.This approach addresses the five main structural failings identified in the greenpaper in the following way:A deep rooted problem of overcapacity.WWF agrees that without tackling overcapacity allother initiatives will be undermined. One of the criteria we recommend for the LTMPs is anassessment of capacity, and where overcapacity is identified within the fishery, a capacityreduction strategy must be agreed and implemented.Imprecise policy objectives resulting in insufficient guidance for decisions and implementations.LTMPs will provide clear management strategies for all fisheries, setting unambiguous,timebound targets and harvest control rules as well as strategies for addressing ecosystemimpacts.A decision making system that encourages a short term focus.LTMPs will establishmanagement in a long term framework and stakeholders should be incentivised by the benefitsthat such a management strategy should deliver, maximising returns over time.A framework that does not give sufficient responsibility to the industry.The balancedstakeholder groups that we propose to agree and implement the LTMPs have the industry askey players co-managing the fishery alongside government managers, scientists, controlagencies and environmental interests. Industry will have significantly increased responsibilitiesif they choose to engage in these fora effectively.Lack of political will to ensure compliance and poor compliance by the industry.Through theuse of more inclusive stakeholder groups to develop and deliver LTMPs, the provision of rightsbased management, and the use of appropriate incentives there should be greater complianceby industry as the rules will be largely of their own making. Sufficiently harsh penalties for noncompliance will also play a key role.Our approach of adopting effective ecosystem based LTMPs alongside improved control andcompliance, and standardisation of procedures such as penalties and data collection, across theEU should set us on a firmer footing towards the more economically desirable prospect ofsustainable European fisheries. We advocate that the same approach should govern EU fleetactivities wherever they fish and should guide EU external relations with third countries, inRegional Fisheries Management Organisations and in Fisheries Partnership Agreements.

2

Fleet OvercapacityIt is vital that a balance is achieved between fisheries resources and fleet capacity if theproductive potential of Europe’s marine waters is to be realised. As the Green Paper rightlystates, the future CFP must have in-built mechanisms to ensure that the size of the Europeanfleets is adapted and remains proportionate to available fish stocks, and that this is a pre-requisite for all other pillars to work. Overcapacity must be addressed as a priority.A fundamental change in how we manage Europe’s fishing fleets is needed and key to this willbe that all European fisheries are managed according to ecosystem based Long TermManagement Plans (LTMP) which adhere to strict criteria established in the reformedRegulation. Adopting such an approach will provide the framework not only for setting andachieving sustainability goals but also for the new regionalisation of the CFP.We set out our model for LTMPs later in this document (in answer to questions 8 & 9); one ofthe elements that WWF believes must be incorporated into each Plan is an assessment ofcapacity within the fishery and where overcapacity is identified, acapacity reduction strategyshould form part of the formal LTMP, with co-ordination at Regional level for implementation atMember State level. Balancing capacity to resources will in essence become one of the targetsof the LTMPs; targets will be time limited, and penalties will be incurred for failure to fulfil.There is a need to establish a common definition of capacity to avoid using crude physicalattributes that cannot and do not provide genuine measures of fleet capacity. For example,vessels of similar size may deploy very different levels of fishing power, depending on the gearused. Similarly, engine size may be highly relevant in some cases (e.g. trawl fisheries) and lessso in others.FAO defines fishing capacity as:The amount of fish (or fishing effort) that can be producedover a period of time (e.g. a year or a fishing season) by a vessel or a fleet if fully utilized and fora given resource condition. Full utilization in this context means normal but unrestricted use,rather than some physical or engineering maximum.The FAO definition combines two basicand complementary approaches to managing fishing capacity: ‘input based’ and ‘output based’.Input based measures consider production factors used to harvest fish, such as the number ofvessels active in a fishery or the level of effort they apply ( days at sea, number of trapsdeployed, etc).1. Should capacity be limited through legislation? If so, how?Limits on capacity should be contained in legally binding measures. As outlined above WWFbelieves that balancing capacity to available resources should form one of the mandatorytargets in a formal LTMP, as specified in the Regulation. Each LTMP will have the requirementto assess capacity as part of the overall descriptor of the fishery (Member States should berequired to provide the necessary fleet information in a consistent manner). Where overcapacityis identified a capacity reduction strategy must be developed as part of the LTMP.It will be necessary for the assessment to be carried out at fishery level which will be Regional inmost cases. Where there is only one Member State prosecuting a fishery it will be at MemberState level. A capacity reduction strategy will need to be agreed at this level, agreeing targetsand timelines for reduction. It is likely that the details for meeting targets will then beimplemented at Member State level.

3

Where overcapacity is not identified, the assessment can be used to meet the legal requirementfor a strategy – ie. it can be demonstrated that there is no need for a capacity reduction strategyin that instance. Member States failing to provide information should face meaningful penalties,such as financial sanctions and/or a quota decrease or zero quota.The appropriate level of capacity is closely linked with the status of stocks; as stocks improve ordecrease the capacity limit can therefore vary. Legislative tools to limit capacity will need to becarefully structured so that they are not too rigid to react to resource fluctuations.2. Is the solution a one-off scrapping fund?A one-off scrapping fund would not solve the problem of overcapacity. In the first instance thereare indications that Member States would be unwilling or unable to meet match funding requiredfor such a scheme even if it were available, and secondly it is unclear whether the right vesselswould be removed from the system.In July 2008, the EU adopted an emergency package of measures to tackle the fuel crisis in thefisheries sector - the Fleet Adaptation Scheme (FAS) - which was primarily anad hocspecial,temporary regime derogating from some provisions of the European Fisheries Fund (EFF)regulation for a limited period (up to the end of 2010). The FAS constituted an experiment in thefeasibility of a one-off scrapping fund and the results suggest that the scheme was notsuccessful as Member States failed to use the FAS to restructure their fleets due to the highinitial costs.However at Member State level capacity reduction measures such as transferable fishing rightshave been implemented in Scotland and Denmark at minimal governmental cost. This has freedresources for subsequent sectoral research and innovation investment1. France and Italy arealso starting to reduce their fleets significantly. Italy is dismantling purse seine vessels: 19 in2009 giving a 28 % capacity reduction, and 12 more in 2010 representing a 24% capacityreduction.WWF believes that the approach of a capacity reduction scheme within an LTMP will provide amore flexible, realistic and effective way forward for Member States to reduce overcapacity,more in line with the Danish and Scottish examples. It may be helpful for Community money tobe made available to support individual capacity reduction strategy objectiveswhere these aredemonstrably in line with sustainability targets.3. Could transferable rights (individual or collective) be used more to support capacityreduction for large-scale fleets and, if so, how could this transition be brought about?Which safeguard clauses should be introduced if such a system is to beimplemented? Could other measures be put in place to the same effectThe use of rights based management tools is already a fact of life throughout the EuropeanUnion, taking many different forms. A recent evaluation found that all coastal Member Stateshave already implemented some type or types of RBM.2MRAG, IFM, CEFAS, AZTI Tecnatio & PolEM (2009). An analysis of existing rights based management(RBM) instruments in Member States and on setting up best practices in the EU, Final Report. London:MRAG2MRAG, IFM, CEFAS, AZTI Tecnatio & PolEM (2009). An analysis of existing rights based management(RBM) instruments in Member States and on setting up best practices in the EU, Final Report. London:MRAG1

4

If properly designed, RBM schemes can be successful at providing long-lasting cost-effectivesolutions to the overcapacity problem, while enhancing economic efficiency, assisting wealthcreation, and enhancing the overall environmental performance of a fishery. Such an approachcan also provide for a solution to phase out dependency on subsidies and in return achieve abalanced fleet.WWF believes that transferable rights could form one of the tools within a Long TermManagement Plan (LTMPs), and that where any rights based system is developed, it should bedone within the context of the LTMP.A complicating factor, potentially limiting the application of a consistent rights-based approach iswithin a LTMP comprising several Member States with different RBM systems. In this situation,we would envisage that the fundamentals of the rights based system (basic mechanism,legality, security) are agreed as a priority in the drafting of the plan by the authorities inagreement with stakeholders, but over time the rights-based approaches of the various MemberStates will evolve to complement one another and the LTMP itself. The advantages of such asystem are that any disagreements or conflicts between systems can be dealt with at theconception stage of the LTMP, and through negotiation between the stakeholder constituents.In accordance with our views of how the inshore zone should be managed, WWF supportstailoring RBM schemes that grant fair and equitable user rights to local and sustainable coastalfleets, and that encourage the allocation of such shares for minimally destructive vessels. Suchpreferential treatment must not however be to the detriment of the target stocks, the widermarine environment or the overall objectives of the LTMP.One example of tailoring a scheme in such a way is the Cape Cod Hook Fishermen whoadopted a community ownership model. To prevent large industry take over of their tradeablequota shares they established a Trust which runs a non-profit permit leasing business that buysquota, aggregating it and associated permits into a pool, and leases quota at affordable rates toqualifying Cape Cod fishers, prioritising local and sustainable fishers who comply withmonitoring and regulations.WWF supports the idea of promoting rights based management systems on the level of acommunity, cooperative, or nominated representatives of a group, which then allocates andmonitors use of the resource.A second example is the Spencer Gulf Prawn Fishery in South Australia which uses IndividualTransferable Quotas (ITQs). Both have explicitly defined user rights and in both cases, securityof access to the resource and responsibilities of use are clearly defined and legally binding,which has been shown to further long-term sustainable use.The effectiveness of any rights-based management systems will depend on the model used, theinstitutional approach (market versus community-based), how rights are specified, theconditions under which they can be transferred, the duration of the use-rights, and the basis forallocating of the rights. Key to any RBM scheme will be legal basis of the scheme and thesecurity of the right/access.WWF supports the requirement to review RBM programs after an appropriate time and refine

5

them, if necessary, to meet the goals for the fishery or region. The review period will be specificto the fishery or fisheries under the management regime and should enable MS governments inconjunction with the Regional body to alter/adjust their fisheries management priorities.4. Should this choice be left entirely to Member States or is there a need for commonstandards at the level of marine regions or at EU level?Decisions about the allocation of fishing rights is a matter of decision for national governments ratherthan the EU. Since this is the case, the Common Fisheries Policy, which addresses EU fisherieslaw, does not directly control — either to limit or to promote — Member States' use of RBM tools.There has been concern that the benefits of a rights based system would be undermined if somefleets in a region had it and others did not. However as noted in answer to question 3we believethere is scope for a means of harmonisation through the LTMP process.Under a system whereby all fisheries are subject to ecosystem based LTMPs we envisage that arights based management scheme could be co-ordinated at a Regional level in order to standardisethe approach taken by different Member States targetting the same stock.

Focusing the Policy ObjectivesWWF strongly advocates that the EU move as rapidly as possible to an Ecosystem-BasedFisheries Management (EBFM) system, given the failure of the current single-speciesmanagement model to deliver on conservation goals and the need to address wider ecosystemimpacts of fishing activities.There are many interpretations of ecosystem-based management approaches and differentterms in different socio-political and cultural contexts worldwide. However, OSPAR, HELCOMand the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD), based on a recommendation byICES, consistently define EBM as “thecomprehensive integrated management of humanactivities based on the best available scientific knowledge about the ecosystem and itsdynamics, in order to identify and take action on influences which are critical to the health ofmarine ecosystems, thereby achieving sustainable use of ecosystem goods and services andmaintenance of ecosystem integrity”.3With respect to achieving EBM, the best approach is often to start with societal objectives (e.g.,as reflected in relevant policies - in an EU context these will be the CFP and MSFDcommitments), and then to assess the greatest threats to achieving those objectives. Withcurrent management practices, fisheries will often emerge as being a source of importantobjectives and also the source of a number of different threats (over-exploitation of targetspecies, impacts on conservation species, impacts on critical habitats, etc.). As long as thosethreats are not swamped by impacts from other sectors, they will be mitigated at least by takingaction in the fisheries sector, with or without collaboration with other sectors4. So it is importantthat the CFP adopt as strong an Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management (EBFM) approach aspossible as the delivery on EBM by the CFP alone can be considerable, regardless of action byother sectors.

http://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/msp/020709/verreet_en.pdf&http://www.ospar.org/content/content.asp?menu=00180302000066_000000_0000004Rice et al (2009) Managing ecosystems, managing fisheries: how do ebm and ebfm relate? MEAM Vol2, No 2 (dec08-feb 09)

3

6

For the purposes of the CFP reform EBFM would represent a significant step in the rightdirection; as it presents a more holistic approach to secure healthy and sustainable fisheriesthat restore and conserve fish populations.5. How can the objectives regarding ecological, economic and social sustainability bedefined in a clear, prioritised manner which gives guidance in the short term andensures the long-term sustainability and viability of fisheries?As the Green Paper notes, today ecological, economic and social considerations are all givenequal weight in the CFP. The Council of Ministers, reaching decisions under the framework ofthe current Policy, considers itself free to set TACs and quotas that place short term socio-economic concerns ahead of ecological considerations – in effect spending long term capitalassets rather than living off the interest that would be accrued by sustainably managing theresource. Analysis shows that the Council of Ministers routinely over-ride the ecological adviceprovided by the Commission in setting catch limits5(and the European Commission’s proposalsare frequently watered down versions of the scientific advice they received from ICES) resultingin quotas constantly being set on average 40% over scientific advice.The CFP should reflect the fact that without a healthy marine ecosystem, a thriving fishingindustry cannot exist; fisheries are dependent on fish, fish are dependent on functioningecosystems. There is ample evidence that, in fisheries that have been subject to a morerigorous prioritisation of ecological sustainability, recovery has been attainable. For example, inthe US, their fisheries legislation6requires regional fisheries management councils to set annualcatch limits no higher than the levels of allowable biological catch established by their scientificand statistical committees, to ensure overfishing does not occur, by no later than 2010 forfisheries subject to overfishing and by 2011 for all other fisheries. In 2008, the US reported asignificant increase in stocks rebuilt. Overall, US results are far better than the EU’s with 16% ofstocks subject to overfishing in 2008 and 23% in an overfished state, compared to 88% in theEU.7WWF calls for a prioritization of the pillars to enable a recovery of marine ecosystems andrelated priority fish stocks. In policy terms this would mean that Ministers are only able to setharvest targets within harvest strategies that include biological limits based on the precautionaryprinciple outlined by the scientific advice.The current objective states“the Common Fisheries Policy should therefore be to provide forsustainable exploitation of living aquatic resources and of aquaculture in the context ofsustainable development, taking account of the environmental, economic and social aspects ina balanced manner,”(EC 2371/2002). Apart from giving precedence to ecologicalconsiderations, a clarification of economic aspects could also improve the CFP. Evidenceshows that, over the medium to long term, allowing European and global fisheries to recoverwould result in a far more profitable industry. One study identified that allowing European fishstocks to recover to MSY levels could generate 400,000 tonnes of additional catch.8The WorldBank & FAO report, “Sunken billions” concluded that globally economic losses in marine5

WWF, 2007. Mid-Term Review of the EU Common Fisheries Policyhttp://assets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_cfp_midterm_review_10_2007.pdf6Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management, amended 200772008 Status of US Fisheries, Report to Congress, NMFS, May 2009,www.nmfs.noaa.gov/sfa/status offisheries/sosmain.htm8MRAG, 2009. Studies supporting reform of the Common Fisheries Policy, A vision for Europeanfisheries post 2012. A report for WWF by MRAG

7

fisheries resulting from poor management, inefficiencies, and overfishing add up to a staggeringUS$50 billion per year9In addition, current economic analyses usually fail to account for the other ecosystem servicesprovided by a healthy marine ecosystem, such as climate regulation, tourism values, etc.10Bybroadening the definition of economic benefits associated with sustainable fisheries and healthyoceans, the CFP would be able to more adequately consider and ‘trade-off’ both the net benefitsand losses of different levels of marine ecosystem functioning.As the Green Paper notes, economic and social viability over the long run can only result fromrestoring productivity. To give guidance in the short term, priority must be given to ecologicalsustainability. Clear and transparent standards for fish stock abundance and timetables forrestoration of that abundance must be specified in the CFP and made binding on the EuropeanParliament and Council of Fisheries Ministers in their decision making practices.6. Should the future CFP aim to sustain jobs in the fishing industry or should the aim beto create alternative jobs in coastal communities through the IMP and other EUpolicies?It is clear that current fisheries resources will not support present levels of employment in thecatching sector and that addressing overcapacity will mean losing jobs. This is a fact and onethat needs to be managed in order to minimise hardship on fisheries dependent communities.Alternative forms of employment could be achieved through Regional Development Strategieswhere they can identify more readily the infrastructure development needed to manageemployment or unemployment in communities dependent on fishing. In support of this webelieve that EFF funds should remain available for the sector and concentrated on Axis 4investments addressing the development needs of economically depressed fishing communitiesthrough promotion of such alternatives as ecotourism and integrated coastal livelihood andmanagement programmes.7. How can indicators and targets for implementation be defined to provide properguidance for decision making and accountability? How should timeframes beidentified for achieving targets?Clear targets for fisheries management are essential and at the highest level there are someobvious commitments that Member States need to be guided by and build into the newRegulation. For example there are requirements under the Marine Strategy FrameworkDirective (2008/56/EC) to:••Achieve and/or maintain good environmental status (GES) following the qualitativedescriptors (listed in Annex 1) in the marine environment by the year 2020 at the latest,and;To achieve Maximum Sustainable Yield Targets and other management objectivestowards ecosystem level sustainability by 201511(as an intermediate goal towards

9

WB-FAO, The Sunken Billions - The Economic Justification for Fisheries Reform,http://www.globefish.org/files/Sunken%20Billions%20Report%20Advance%20Edition_659.pdf10Millenium ecosystem assessment. Current state and trend assessments, chapter 18 marine systemshttp://www.maweb.org/en/Condition.aspx#download11Under the EU Sustainable Development StrategyObjective 3: Improving management and avoidingoverexploitation of renewable natural resources such as fisheries, biodiversity, water, air, soil and

8

higher precautionary biomass levels compatible with GES in 2020) as practical targetsfor decision making and accountability.These should form the high level objectives that will guide the development of ecosystem basedLTMPs and that within each LTMP there will be a series of indicators and interim targetsestablished that will track progress and assist in delivering these. LTMPs should establish thetimelines within which the targets should be met.The balanced stakeholder groups that we recommend formulate plans should include scientistsas well as managers, industry and environmental interests which should help in arriving attargets based on best scientific advice and that make all stakeholders accountable for trackingand achieving them.It is likely that a raft of targets will be established in order to meet high level objectives. Forexample, identifying critical or sensitive habitat impact and how this can be avoided by thefishery, capacity reduction where it is identified as a problem, and discard and bycatchminimisation.The GES process will start to roll out during the period of the reform. Detailed indicators must berolled out by 2010 and an initial assessment of the state of the seas to be completed by 2012.The results of this work will inform the LTMPs and the move towards good environmental status.

Focusing theprinciples

decision-making

framework

on

core

long-term

8. How can we clarify the current division of responsibilities between decision-makingand implementation to encourage a long-term focus and a more effectiveachievement of objectives? What should be delegated to the Commission (inconsultation with Member States), to Member States and to the industry?9. Do you think decentralised decisions on technical matters would be a good idea?What would be the best option to decentralise the adoption of technical orimplementing decisions? Would it be possible to devolve implementing decisions tonational or regional authorities within Community legislation on principles? What arethe risks implied for the control and enforcement of the policy and how could they beremedied?Reform of the governance structure for the CFP will be vital. In line with an ecosystems basedapproach there needs to be a shift towards a fisheries management policy where outcome-based macro level objectives are set centrally and are then delivered at a regional and MemberState level and where clear accountability mechanisms are built into the system. This approachwould reduce dependency on the Council for annual fishery management decision making andprovide stakeholders with a greater sense of ownership for the management of fisheries.Of the options considered in the Green Paper we therefore favour the one whereby actualmanagement takes place at a Regional and Member State level but is based on standardised

atmosphere, restoring degraded marine ecosystems by 2015 in line with the Johannesburg Plan (2002)including achievement of the Maximum Yield in Fisheries by 2015.

9

decisions and principles agreed at Community level. Critical to this approach will be to achieveprinciples which have environmental sustainability as a priority and are based on sound science.The key to delivering decentralization of decision making and providing the way forward on longterm sustainability is amandatoryrequirement for all European fisheries to be managedaccording to Long Term Management Plans (LTMPs). The new Regulation should make this amandatory requirement by 2015. By committing to this the next step will be establish what themanagement unit of the plans will be and this in turn will guide the regionalisation process.The swift and systematic adoption of well designed LTMPs will allow Member States to manageEU fisheries on a multi annual basis, in line with the precautionary principle and an ecosystemsbased approach. In turn, this will contribute to achieving good environmental status (GES), asrequired under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD).Instead of LTMPs being developed largely on a single stock basis these plans need to addresseither a fishery or a particular area. This will ensure that stakeholders who have an interest inthe fisheries within that area or fishery can contribute to their management. Recent researchhas confirmed that the most effective way to achieve sustainable fisheries is with science-basedLTMPs arrived at via open and transparent stakeholder processes.12. As discussed above, weare supportive of the transition to a system whereby the European Council, Parliament andCommission set overall objectives for ecosystem health and stock abundance based on thelatest science, and those objectives are translated by Regional and Member State stakeholderbodies into LTMPs that can deliver on the overall objectives. Objectives should be revised andprioritised to be clear, straightforward and consistent. Well-defined and prioritised objectivescontribute to long-term management by producing clear guidelines, which make the processand outcome of implementation more consistent.The revised CFP Regulation needs to establish:----Amandatory requirementfor all European fisheries to be managed by LTMPs by acertain date (we suggest 2015).The high levelsustainability objectivesof the plans such as achievement of MSY by2015 (and MEY by 2020) and a commitment to fulfilling the relevant MSFD goals.Establishclear criteriafor what elements need to be included in the development andimplementation of plans.Clearaccountabilityfor failure to develop plans within the required time and penaltiesfor failure to comply with plans once agreed.

Key to the success of the plans will be the criteria and their implementation. These wouldinclude:1. Plans are fisheries based or region based instead of stock specific. This is a major changefrom what is happening at present, and will be one of the main issues to address but isessential if we are to take an ecosystems approach.2. Balanced stakeholder group(s) need to be established, as well as a means of co-ordination at a Regional level. Plans need to be agreed, implemented and reviewed by12

Camilo Mora, R. Myers, M. Coll, S. Libralato, T. Pitcher, R. Sumaila, D. Zeller, R. Watson, K. Gaston,B. Worm, «Management Effectiveness of the World's Marine Fisheries,» PloSBiol 7(6):e1000131.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000131 .

10

these balanced stakeholder groups, which should include government managers,scientists, industry (processors as well as catching sector), control agencies and NGOs.3. Description of the fishery(ies) – this should include vessels, gear, species, economics(revenue, management costs), employment as well as any recreational interests.4. Plans are ecosystem based – they need to introduce impact assessments (takingaccount of a wider range of impacts on target and non target species (including non fishspecies) and habitat, as well as the impact of other fisheries/activities on the targetspecies within a fishery).5. Management is based on total removal rather than landings.6. Analysis and risk assessment are used to address data poor fisheries and allowprecautionary quotas to be set.7. Clear targets and timelines are set, and unambiguous harvest control rules, to determinecatch level or effort, are established.8. The plans will need to establish targets other than simply stock and will be informed bythe impact assessment process. These could include, discard and bycatch minimisationplans, habitat protection strategies.9. The fishery should also be assessed for overcapacity which if identified should require astrategy to bring it into line with resources. Detailed capacity reduction would likely bedelivered at Member State level. A marketing strategy (which would help maximiseeconomic return) would also be useful at Member State level.10. Effective monitoring and control requirements.11. Formal penalties for failure to comply. These need to be standardised across MemberStates, consistent with the EU’s new Control Regulation where applicable.12. Triggers for fisheries, which would warn when management has to shift from rebuildingto recovery mode, are established in the plan.13. Formal periodic review and ability to adapt or be flexible in face of new data.There would need to be a regional body that had an overview of the region to ensure that theplans within any one region were compatible and together would not result in an area becomingover exploited. Once agreed at a Regional level LTMPs would be submitted to the Commissionwho would likely seek initial scrutiny jointly by STECF, a DG Environment equivalent andpossibly an evolved form of the RACs.The Commission will need to feel confident that agreed plans meet the Regulation criteria andstand a good chance of meeting the targets. They will also have the right to take action wherethere is failure to meet the criteria, or where plans are not forthcoming in line with requireddeadlines. The final approval of an LTMP will of necessity remain with the Parliament andCouncil under the Treaty although this approval would be expected to be routine under theproposed schemeIf approved it is then incumbent on the Member States to implement the plan with stakeholdersat the fishery level. At this level there will be the need to create Member State Co-managementCommittees (CCs) for each LTMP. Composition of the CC needs to include relevant industryrepresentatives (incl catch sector and processors), national decision-makers, national/regionalscientists, control authorities & environmental interests including NGOs. It will be this body thatis responsible for the day to day implementation of the plan.The whole system will be transparent – this will be enabled by the full description of the fisheryrequired to guide the development of the plan – and based on sound science. Periodicperformance reviews of LTMPs against common standards would be carried out by STECF &

11

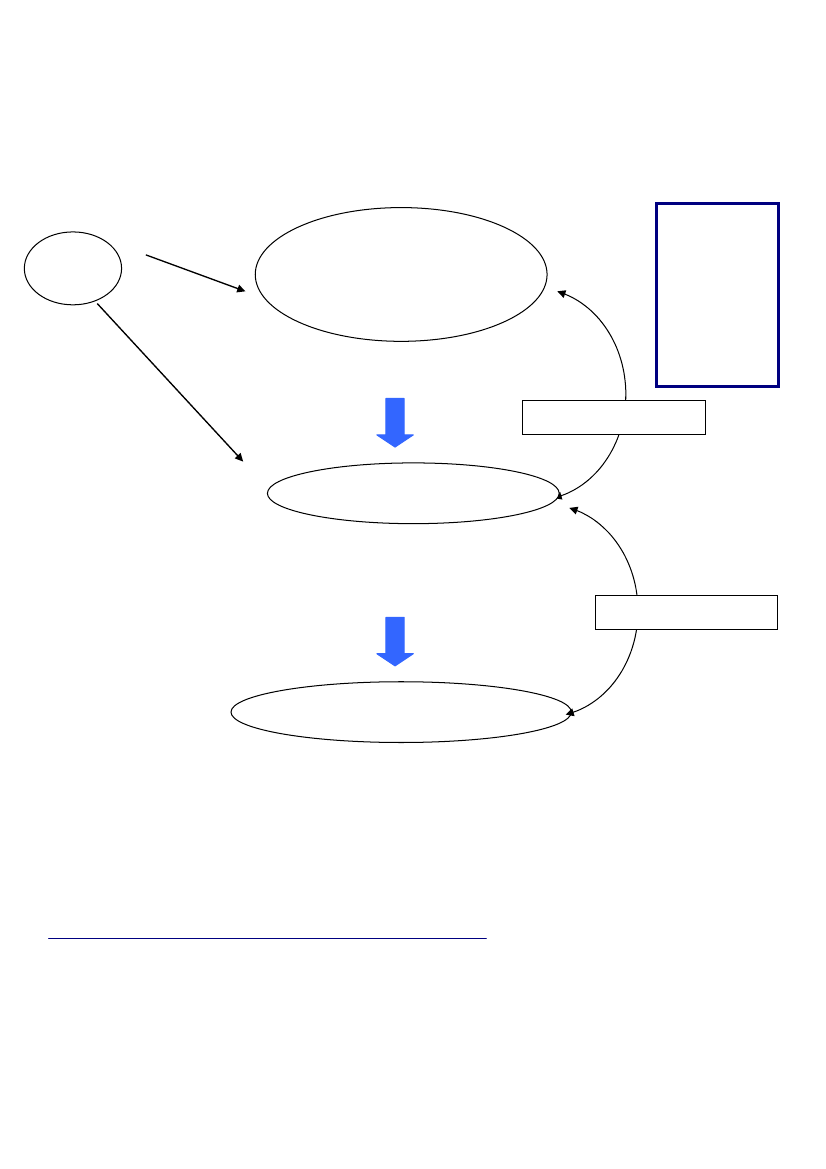

DG Environment, with participation of scientists involved in CCs, and, as a result, mandatoryadjustments could be requested of CCs.It should be noted that there may be instances where a fishery is only prosecuted by oneMember State in which case the Member State in question would fulfil the role of bothdeveloping and implementing the plan. The plan would still need to demonstrate its compatibilityat a Regional level and be signed off by the Commission, Parliament and Council.Diagram 1provides a visual map of this new regionally based governance structure.WWF believes that an effective marketing strategy should form a key component of sustainablefisheries management. This should maximise economic return and factor in continuity of supplyresulting in the much desired end point of removing less from the sea but achieving moremoney for what is removed. A marketing strategy may be most appropriate at a Member Statelevel as markets will vary between Member States and there may be competition betweenMember States. As such we would not envisage that this is a mandatory requirement but wouldlike to see such an approach being adopted at implementation level.In future LTMPs it would be useful to look at the concept of biomass removal to allow amore comprehensive ecosystem approach but given current data and resources this may bebeyond the capabilities of this reform process timeframe. It should however be something thatis planned for in future management.Adopting an effective framework such as this alongside strong criteria to guide the developmentand delivery of LTMPs maximises the chances of meeting MSFD commitments. The criteria areessential if this is to work and without them there is a very real chance of failure.It is also key that strong and clear accountability measures are built into the Regulation.Member States failing to agree effective LTMPs for their fisheries must face meaningfulpenalties, such as financial sanctions and/or a quota decrease or in extreme cases, zero quota.As in the US system failure of the regional body to put forward a plan meeting statutoryrequirements results in the Federal fisheries director stepping in to develop a plan, failure byMember States to meet the deadline could result in the Commission imposing an LTMP for thatparticular fishery as an emergency measure.For more detail on our Long Term Management Plans proposal we append our paper on thistopic. It can also be found at the following link:http://www.panda.org/what_we_do/how_we_work/policy/wwf_europe_environment/initiatives/fisheries/publications/?179101/2012-Common-Fisheries-Policy-Reform-Long-Term-Management-Plans-and-Regionalisation-of-EU-Fisheries

12

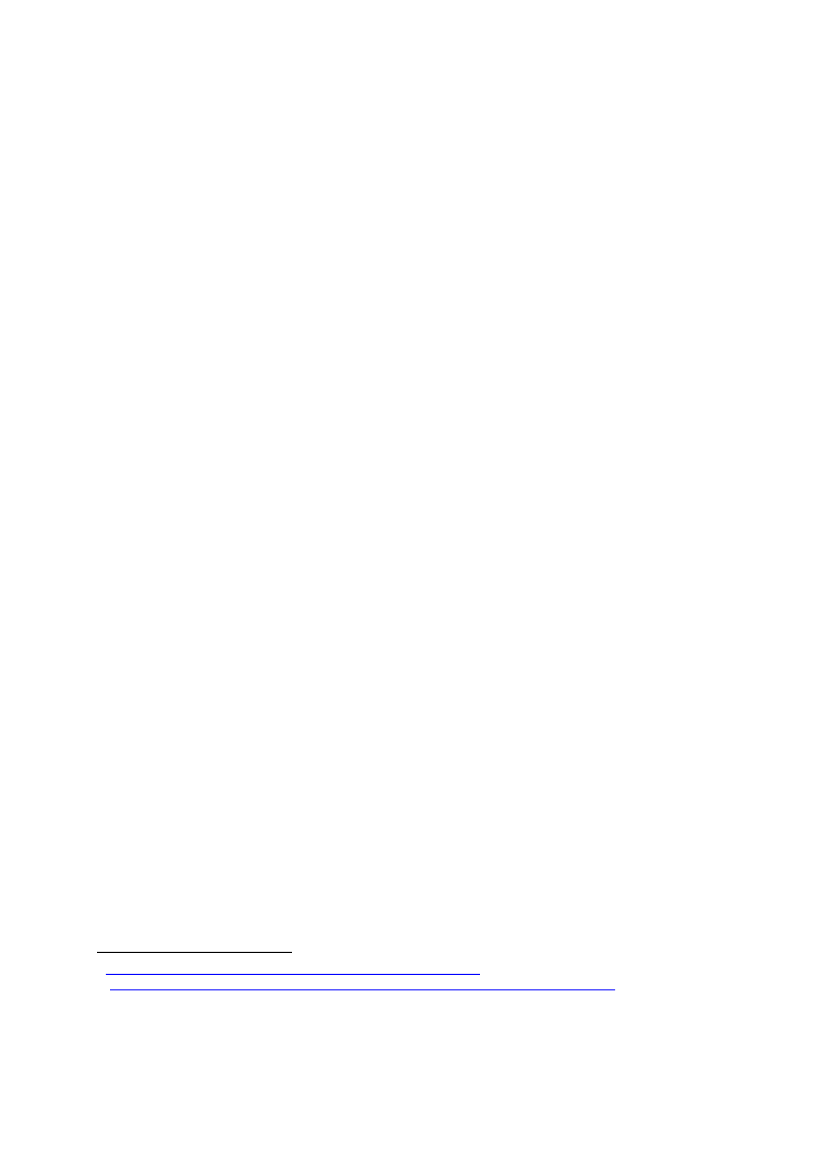

DIAGRAM 1: FRAMEWORK FORIMPLEMENTING LTMPS AND DELIVERING REGIONALISATION

ICES

EUROPEANCOMMISSION/PARLIAMENT/COUNCILLEVELAgree management plan unit (fisheries/region)and establish Regional LTMP stakeholder group(s)1

AdvisorySTECF21. RAC2. ACFA

Feedback/Review

REGIONAL LEVEL

Multi Member States Stakeholder Group(s)1develop andagree plan(s) for submission to Commission/Council forapproval3

Feedback/Review

MEMBER STATE LEVEL

Establish co-management committee1to implement plan onday to day basis and report back to regional body

123

Mixed stakeholder group (government, scientists, fisheries, processors, control, NGOs)

Currently there is no ICES advice for the Mediterranean. Main guidance on Mediterranean forCommission comes from STECFIt is likely that this will be multi Member State but in some instances where only one Member Stateprosecutes the fishery then it will develop the plan to implementation level, ensure compatability atRegional level and submit directly to Commission.

13

10. How could the advisory role of stakeholders be enhanced in relation to decision-making? How would ACFA and the RACs adapt to a regionalised approach?History has demonstrated that key to effective fisheries management is the inclusion of fisheriesstakeholders. WWF views effective andbalancedstakeholder participation to be critical to thesuccess of the development and implementation of LTMPs for all fisheries.It is likely to work best when no one interest group is overly dominant, which is the case with thecurrent RACs where a two thirds industry to one third other interests balance exists. WWF seeLTMPs being developed by stakeholder groups more mixed than the RACs. At Regional levelthis needs to include Member State representatives, control agency representatives, scientistswith appropriate knowledge of the fishery (possibly 2-3 for the plan regardless of number ofMS), a limited number of key catching sector representatives (3-4 max for each MS),environmental interests (1-2 for each MS, in reality likely to be less given available capacity). Atthis level the fundamental components of the plan(s) for shared stocks will be developed andagreed.This does not mean that there is no role for RACs but simply that in their current form we do notbelieve they should be considered the appropriate stakeholder group for development of plans.Instead it is likely that RACs will continue to play an advisory role to both LTMP Regionalstakeholder groups and/or the Commission on aspects of management through the process ofplan review.These LTMP stakeholder fora will facilitate a much more effective form of engagement for allconcerned because they will be fishery focussed and all members will therefore have the longterm interest in the same fishery as their central concern. A more mixed group should bepossible to achieve at different scales, regardless of how big or small, which is a vitalconsideration given the aspiration that all European fisheries are covered by LTMPs. Some keyelements will be essential to enhance the role of stakeholders in any fora and these include.•Fair representation•Transparency•Good access to science•Training in fisheries management•Provision of incentives to stakeholders•Holding stakeholders accountable for meeting their management responsibilities.•Access to environmental justice•With respect to RACs and their ongoing advisory role, WWF have identified a number of actionsto improve the way they function and arrive at decisions and recommendations13. Werecommend that these improvements be undertaken without delay as the RACs will play animportant continuing role during the 2010-2012 period.With respect to ACFA it may be that its role will become redundant over time given the keyrequirement to have scientists and managers actively participating in the new stakeholderbodies. It is hard to say but if the new system arose as we describe it we would not envisagefighting to retain ACFA as yet another advisory body in the process as we feel the new structurewould have good checks and balances built in.

13

WWF, 2009, How to improve the Regional Advisory Councils.http://www.panda.org/eu/fisheries

14

From the perspective of environmental justice there is a need for explicit recognition that therole played by stakeholder groups in decision-making processes gives them, and theirconstituent members, the right to challenge the legality of the acts and omissions of the ECinstitutions in the European Courts of Justice.

Encouraging the industry to take responsibility in implementing theCFP11. How can more responsibility be given to the industry so that it has greater flexibilitywhile still contributing to the objectives of the CFP?As outlined above we believe that the adoption of LTMPs and the stakeholder groups requiredto establish and implement them provide stakeholders with greater responsibilities for thefisheries they are involved with, and the management process.Using this model the central (Brussels) governmental role is to provide long-term policy andoutcome-based targets with the Regional and Member State levels responsible for thedevelopment of technical means to meet them. The decision-making process becomes moreflexible and responsive to local conditions, and enables active stakeholder engagement in localpolicy and technical implementation decision processes. This would allow different regions toutilize different tools, better suited to their circumstances.WWF believes that the development of this kind of framework approach and building strongpartnerships between industry, management and science are important to generate confidencein management, and to encourage a better culture of compliance. Once such a framework is inplace the role of the Council and Parliament in approving management plans should be one ofroutine oversight, rather than micromanagement.12. How could the catching sector be best structured to take responsibility for self-management? Should the POs be turned into bodies through which the industrytakes on management responsibilities? How could the representativeness of POs beensured?A system of participatory governance or co-management is an institutional context that, if welldesigned, can allow fishermen to participate in fisheries management decision making. It can bea successful dynamic partnership using the capacity and interest of user-groups and becomplemented by enabling legislation and other administrative requirements14. Fishermen canbe part of the decision making process and work with Member States and other stakeholders toensure that long-term management objectives are met. It can also improve fisher support, foroutcomes, confer legitimacy on the regulations and foster compliance, which may also reducemonitoring and surveillance costs15,16. Co-management is a means of building trust andempowering stakeholders to participate in the shared governance of fisheries. For moreinformation on the Co-management Committees please refer to Question 9 on Decentralization.

14

Nielsen J.R. and T. Vedsmand. 1997. Fishermen’s organizations in fisheries management:perspectives for fisheries co-management based on Danish fisheries. Marine Policy, 21: 277-28815Schumann, S. 2007. Co-management and consciousness: fishers assimilation of managementprinciples in Chile. Marine Policy, 31: 101-111.16Kuperan, K., N.M.R. Abdullah, R.S. Pomeroy, E.L. Genio and A.M. Salamanca. 2008. Measuringtransaction costs of fisheries co-management. Coastal Management, 36: 225-240.

15

It has been shown that stakeholder compliance with decisions in which they played little or norole has been mixed at best17and that key to sustainable fisheries management is the effectiveengagement of fisheries stakeholders. We believe this needs to be on a balanced basis andthat stakeholders should include government managers, environmentalists, scientists andindustry (both catch sector as well as market players to try and improve some of the economicreturns of fishing).Existing Producer Organisations (POs) are not homogenous in how they operate in relation totheir members. In some instances it may make sense for POs to act as management bodieswhilst in others it won’t and some may be able to transform themselves into becoming a suitableco-management partner.It is clear that there is a need for the appropriate level of representation at the local and regionalstakeholder level which can talk on behalf of the catching sector. Without achieving this there isa high risk that plans will flounder due to lack of support on agreed management.WWF welcomes industry’s role being extended beyond that of just quota allocation where this isdone within the structure of a co-management body. In Scotland the Conservation CreditsScheme (CCS) was launched in February 2008 with it’s overarching aim being to improvefisheries management in Scotland by adopting best practices in stock conservation, andsupporting (and ensuring) the future economic prospects of fishing communities. It is run by theScottish Government Marine Directorate (SGMD) and advised by a 25 member steering groupwith members from industry, science and an environmental NGO. The Steering Group, whichmeets monthly to assess the progress of the CCS, also provides a forum for government,science, industry and NGOs to discuss proposed measures, conferring a degree of ownershipover the process and outcomes and thus a level of buy-in from the fishing sector and others.The CCS is based on strong conservation orientated objectives. As the name implies, it creditsfishermen for adopting conservation measures with a currency of real value to them – additionaldays at sea, and the possibility to operate under the more flexible conditions of “hours-at-sea”.In Galicia, the EU’s largest fishing region, successful participatory co-management schemes arebeing adopted in the design, management and monitoring of fishing reserves or long-termmanagement plans with strong conservation and management objectives. This newparticipatory model, initially adopted in the small fishing community of Lira, is being followed bydozens of fishermen organisations in Galicia and the rest of Spain and supported by NGOs likeWWF.A planning process for any participatory or co-management scheme is essential to guaranteethe success of the scheme. Ensuring an appropriate suite of conditions and a robust processwill increase the likelihood of success, and lessons should be learnt from other similarschemes18.

MRAG, 2009. Studies supporting reform of the Common Fisheries Policy, A vision for Europeanfisheries post 2012. A report for WWF by MRAG18Chuenpagdee, R. and Jentoft, S. 2007. Step zero forfisheriesco-management: What precedesimplementation? Marine Policy, 31: 657–668.

17

16

13. What safeguards and supervisory mechanisms are needed to ensure self-management by the catching sector does not fail, and successfully implements theprinciples and objectives of the CFP?Self-management by the catching sector is not an aspiration shared by WWF for the newgovernance system. WWF believes a system of co-management is more appropriate and thatthis should be delivered by the new stakeholder groups of the LTMPs. These will include abalance of catching and processing industry representatives as well as government managers,scientists and environmental NGOs.With such a mix of stakeholders represented both at Regional and Member State level webelieve that a balanced set of objectives and targets can be agreed, as well as a means ofachieving them. All stakeholders should share the common goal to achieve a rebuilding of thefishery, minimise the environmental impact of the fishery, and ultimately witness animprovement in the economic return from the fishery, and overall health of stocks and theirsupporting ecosystem.Key to the functioning of the LTMPs will be a robust set of monitoring and control criteriaappropriate to the fishery. Incentives should be an option within LTMPs to assist withcompliance. However there will also be the need for clear penalties for failure to comply(reverting to centralised management with lower, more precautionary TACs) to be established atCommunity level and standardised across Member States.14. Should the catching sector take more financial responsibility by paying for rights orsharing management costs, e.g. control? Should this only apply to large-scalefishing?At present fisheries enforcement represents a substantial financial burden on Member States. Inseveral Member States it has been estimated that the cost of fishing to the public budgetexceeds the total value of the catches19. A considerable proportion of that cost is spent oncontrol and enforcement.Moreover, many European fleets operate at a loss, crippled by the costs of fuel and reducedfishing opportunities, and kept afloat by inappropriate subsidies. Adaptive measures such asreducing fleet size and a move towards less fuel-intensive practices are a first step towardsincreased resilience. However, actions must go further including: harmful subsidies to beeliminated and the resources redirected from fishing capacity to improved management,oversight and research. Any funds used for buyback or decommissioning must be linked tosubstantial, permanent reductions in overcapacity.There is also a clear argument for the industry themselves bearing some of the cost of theseadjustments. As an example, at present in the UK the Seafish Industry Authority, which worksacross all sectors of the seafood industry to promote quality, sustainable seafood, is fundedfrom a statutory levy on all fish, shellfish and seafood products landed, imported or cultivated inthe UK. Of an annual budget of around £11 million just under 80% is from levy. The rest comesfrom grant funding and consultancy work. The levy is due on all first-hand purchases of sea fish,shellfish, and sea fish products including fishmeal landed in the United Kingdom or from any UKregistered fishing vessel owner, fish and shellfish farmer, grower or cultivator who lands productin the United Kingdom for subsequent sale direct to a foreign customer, or who trans-ships19

Commission of the European Communities. 2009. Green paper: Reform of the Common FisheriesPolicy.

17

product within British fishery limits.A similar system could, and arguably should, be set up whereby fisheries pay a levy on fishingopportunities to support the costs of control and enforcement and other management.15. When giving more responsibility to the industry, how can we implement the principlesof better management and proportionality while at the same time contributing to thecompetitiveness of the sector?The assumption of responsibility for some of the management by the industry implies acommitment to better management principles. Such responsibility should not be given unlessthis commitment is clear. These principles lie at the core of an ecosystem-based fisheriesmanagement approach which itself rests on the principle of stakeholder involvement in objectivesetting and achievement. These principles are then operationalised through long-termmanagement plans with criteria relating to each principle. The MSC’s Principles and Criteria forSustainable Fishing, being based on the FAO’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries area useful starting point. It may also be necessary to ensure that any such industry givenresponsibility are themselves structured into formal industry associations with such principlesthemselves enshrined in the association statutes.16. Are there examples of good practice in particular fisheries that should be promotedmore widely? Should incentives be given for the application of good practices? If so,which?There are a number of examples across European fisheries, five of which have been highlightedin the WWF “Net Gains” film. These include initiatives in the UK, Greece, Spain and Denmark,adopting a range of measures including using onboard surveillance cameras to control discardsand the uptake of selective fishing.Another example is the Scottish Conservation Credits Scheme. In December 2007 MemberStates were given the flexibility to run their own days at sea scheme as a pilot ahead of futureEU-wide implementation of “effort pot” schemes, the Scottish Government took up thisopportunity and in February 2008 launched the Scottish Conservation Credits Scheme (CCS),which is explained in answer to Question 12.Effective monitoring and control will be key for the success of any plan. Stakeholderparticipation and agreement over targets is key to achieving compliance with any managementplan. That said it is well recognised that incentives can be an effective means of improvingcompliance and as such should be considered as options to be built into management plans.

Developing a culture of compliance17. How can data collection systems be improved in the short and medium term toensure coherent information for enforcement purposes?In order to improve data collection and ensure coherence for enforcement, WWF proposes thefollowing measures and issues are addressed:1. Increase Transparency

18

There is a lack of transparency and common approach in Member State reporting to theCommission on national fleet and fisheries20. A harmonised system from which consistent datacan be used by both Eurostat and DG MARE but also between Member States isrecommended21. An appropriate regional and global network to manage data should bedesigned and constructed to improve the exchange of information.2. Harmonize measuresWWF stresses the need for setting up concrete and efficient standardized actions andprocedures at sea and on land between Member States to improve the culture of complianceand data collection. This standardization should be coordinated by the Common FisheriesControl Agency (CFCA) and collected and managed appropriately. A general short-coming isthat some controlling obligations e.g. prior notification at arrival to port is not the same in allfisheries area. This is costly for both authorities and industry to handle parallel systems andshould be addressed to make the obligations standard across all Member States and fisheriesareas.According to the Commission’s analysis of the EU fisheries, 80% of the fleet are represented byvessels under 15 m22. It is crucial that such a large proportion also be included in modernisedsurveillance standards to eliminate any loopholes in the system.3. Catch and landings dataTo be effective, the EU’s overarching data management system needs to be able to collect,compare and verify input-output data. Currently this is a lengthy process involving multipleMember States’ controlling authorities. The electronic logbook should have a batch numbertracker device to enable real-time data review and crosschecking with Vessel MonitoringSystems (VMS), to detect and minimise tampering of VMS at sea. All reported information fromvessels must be electronically transmitted to a common database and accessed by MemberStates abiding by these CFP regulations. Buyer registration and submission of electronic salesnote should also be an integral component to reporting and cross checking systems.The data collection on the measure of fish catches is based, in most cases, on Total AllowableLandings in which no account is taken of discards. In 2006, ICES estimated that total removalsamounted to around three times the reported landings suggesting either under-reporting oflandings or a substantial problem with continuing discards23The accurate and timely reporting of both catch and landings data (which should be linked witheffort data) is feasible for all boats >15m. The introduction of electronic recording and reportingsystem (ERS) that has been agreed and implemented by the European Commission throughoutthe EU fleets will greatly increase the speed and accuracy of data reporting, and enable moreefficient monitoring of catches by fisheries officers. The time interval leading up to theimplementation of the system (>24m by Jan 2010 and >15m by July 2011) should ensure thatthis recommendation is implemented under the current plans of the Commission.20

COM (2008) 670 - Reports from Member States on behaviours which seriously infringed the rules of theCommon Fisheries Policy in 200621WWF (2008). Position paper; Control and Enforcement proposal,http://www.fishsec.org/downloads/1192830458_12534.pdf22European Commission (2008), Facts and Figures on the CFP23ICES (2006). Report of the Working Group on the Assessment of Northern shelf Demersal stocks, 9-18May (CM 2006/ACFM:30)

19

4. Observer coverageFor a change in the management system to be successful, sufficient enforcement and observercoverage is needed. WWF believes that there is a clear need for the use of on-board observersand video surveillance technologies (such as Closed Circuit Television - CCTV systems) tobecome a standard component of European fisheries management. This could be seen as away of increasing surveillance and baseline data, particularly if integrated with VesselMonitoring Systems (VMS). In addition, the use of e-logbooks would complement an observerprogramme. The Danish example of trialling an Electronic Monitoring System on fishing vesselsappeared to deliver sufficient reliability of the catch documentation and collection of pertinent at-sea commercial fishery data24.WWF recommends that CCTV become a mandatory requirement across fleets alongside anagreed level of spot checking by onboard observers across the fleets.5. Policing capabilities and forensic accounting worthy of the EUIntelligence, allied to online access for sales notes, can be complemented by a team offorensics accountants, with the capacity to identify any unusual behaviour. Forensicaccountants have been used in the UK and Ireland asad hocmeasures, but increasinglyinspectorates are developing their own in house forensic capacity comprising accountants, dataanalysis and investigative skills. The EU through the CFCA should systematically develop andemploy these policing techniques.18. Which enforcement mechanisms would in your view best ensure a high level ofcompliance: centralised ones (e.g. direct Commission action, national or cross-national controls) or decentralised ones?European Commission’s roleWWF supports the Commission’s suggestion to take a more pro-active role to ensure MemberStates abide by the CFP rules as proposed in the Commission’s proposal on the reform of thecommunity control system25.Member States’ roleMember States must take more responsibility for their industries behaviour and ensure legalmeasures are adequate as deterrents. WWF has strongly supported the Control Regulation’sprovision requiring harmonization of penalties across member states.Coordinated action across Member States and the ECBy allowing direct intervention and penal actions through the option as a last resort therestriction of fishing opportunities Member States are obliged to improve their own compliancesystems. However this may limit the Member States’ willingness to ensure transparency orsharing electronic data. Therefore, spot check audits by Commission inspectors should becarried out at timely intervals. The Commission Inspectors initiatives carried out in 2005-2006 inthe Baltic region comparing control and enforcement systems for the Baltic cod fishery26obliged the nations to reassess their surveillance and enforcement strategies. Fisheries control24

Jørgen Dalskov & Lotte Kindt‐Larsen National (2009). Institute for Aquatic Resources TechnicalUniversity of Denmark, Fully Documented Fishery, Mid-term status report.25COM (2008) 721 establishing a Community control system for ensuring compliance with the rules ofthe Common Fisheries Policy26European Commission, DG MARE (2007). Evaluation report of Catch Registration in Baltic SeaMember States 2005-2006.

20

information builds mainly on how the management regulations are stipulated. It is vital thatthese are outlined in a way that makes it possible to control and for the industry to comply aswell as Member States to control and cross-check.Cross-national CoordinationThe centralised planning and harmonisation of monitoring control and surveillance betweencountries in Joint Deployment Plans (JDPs) have demonstrated that increases in Monitoring,Control and Surveillance (MCS) activity are useful for many reasons, including cost savingsthrough increased efficiency, training and transfer of skills and experience. Cross-nationalinspection agreements can improve the level of compliance by Member States in regionalwaters. Given that inspection at sea in many Member States is ineffectual, expensive and notorganized, it remains crucial to coordinate available MCS resources to maximize their utility.Regional cooperation will decrease national costs and improve resource efficiency systems atsea, as well as build trust among enforcement agencies. Some effective cross-national tacticsinclude:•••Regional information sharing in real-time – information such as VMS/VDS, e-logbook,landing information could be held centrally for a regionMulti-lateral agreements on patrolling and inspection throughout a regionRegional observer and inspector training and deployment programmes

The Community Fisheries Control Agency’s (CFCA) adoption and implementation of JDPs haveproven successful in pooling resources from neighbouring Member States in regional fisheriescross border inspections27. These campaigns have improved dialogue between Member Stateson management level as well as increase the presence of inspection and in detectinginfringements that were otherwise difficult to detect. For instance the CFCA’s JDP in the NorthSea detected the use of illegal gear attachments (i.e. small mesh blinders in the cod end) onmany of their deployments 2007-200828. Increases in number and intensity of inspections canincrease compliance greatly within a number of fisheries29The Future Role of the CFCAThe CFCA can be more effective once harmonized data collection and reporting are in place.CFCA or a body of the Commission must also achieve third party control to audit and thusensure Member States adequately plans its national control resources and activities accordingto CFP rules and regulations.19. Would you support creating a link between effective compliance with controlresponsibilities and access to Community funding?Control, enforcement and an effective penalties system are central elements of all fisheriesmanagement. Currently the European Community dedicates 46 million Euros to control andenforcement, while 837 million Euros are spent on structural assistance for fisheries30. Themajority of the Community fishing fleet is dependent on funding through the European FisheriesFund as well as additional funds and subsidies. The EC should not tolerate the use of thesefunds for the purpose of sustaining non-compliant activity. By and large, with some exceptions,the measures taken by Member States since the last reform in 2002 have not been effective in2728

https://www.fiskeriverket.se/download/18.efdc1411fa22aacf0800046/arsredovisning_2008.pdfhttp://www.cfca.europa.eu/northsea/index_en.htm).29MRAG (Marine Resources Assessment Group) Ltd. (2008). Analysis of Policy to Combat IUU, A reportfor WWF Sweden.30European Court of Auditors. Special report No 7/2007.

21

encouraging the development of higher levels of compliance31,32,33The CFP should include clear legal guidelines that subsidies are to be used to achievesustainable fisheries practices. WWF’s view is that private enterprises and individual vesselsfound to have committed infringements should be barred from benefiting from public assistanceor subsidies for at least the period of the operational programme of the fisheries fund. Removalfrom the list of eligible beneficiaries should also be made mandatory so that taxpayers do notsubsidise vessels and operators convicted of non-compliant activities. Moreover, those vesselsshould not receive taxpayers’ support and vessels that have received taxpayers’ money duringthe operational programme period should be required to repay that money. Any such fundsshould be re-invested in MCS.20. Could increasing self-management by the industry contribute to this objective? Canmanagement at the level of geographical regions contribute to the same end? Whatmechanisms could ensure a high level of compliance?It is clear that there is a strong need to develop a culture of compliance among all stakeholders.This is not a simple task but WWF believes that it will be made easier by the adoption ofi)ii)iii)standardised control and enforcement systems across the EU,appropriate incentives for compliance built into effective long term managementplans, and where this fails,clear and stringent penalties for lack of compliance

Member States and the European Commission need to create, fund and implement an effectivelegal framework for the fishing industry to secure full traceability and help ensure their long termfuture. As discussed in the previous section, harmonized data collection and management areessential to an effective EU-wide system. A regime of exchanging trustworthy documentationconnected to the actual flow – and trade – of fish and fish products should be established,including mandatory compliance checks on legal documentation all along the value chain. Withthis focus, products derived from IUU fishing can be isolated from the regular market. A newmandatory system for traceability and a provision for buyers of fish and fish products to ensurethat their fish and fish products come from legitimate sources should be established.WWF considers that the fishing and processing sectors can do more to reduce IUU fishing andcomply with the CFP rules. Examples exist where the catching and processing sectors haveinvested in and introduced systems that confirm where their fish comes from and that it hasbeen caught from the permitted area, in the right way and within the quota levels.Scotland is an example where an industry led buyers and sellers registration scheme aimed ateliminating “black fish” (fish from unreported landings) from the supply chain along withincreased land-based inspection has achieved spectacular reductions in unreported landings34.

31

MRAG (2009) Studies supporting reform of the Common Fisheries Policy; A vision for Europeanfisheries post 2012. A report for WWF by MRAG32WWF (2008). Lifting the lid on Italy’s Bluefin tuna Fishery,http://www.panda.org/about_our_earth/blue_planet/publications/?uNewsID=14710333

http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/06/13&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en

22

In the South Georgia Patagonian Toothfish fishery, the use of a range of at sea and onshoretechnological solutions has resulted in a significant reduction in IUU fishing. These include realtime catch recording, vessel monitoring systems, bar coding, fish box identifiers and readers,combined with tougher administrative procedures. Similar measures in a ScottishNephropsfishery have resulted in, among other things, improved quality, higher value landings and lessincentive to illegally fish35.Both Denmark and Ireland are examples where Member States combine traceability withfisheries control policy as an effective measure of both eliminating IUU but also improved datacollection from the supply chain. Sales and producer organisations have proven to be effectivedirect control of fisheries. Industry can coordinate with control authority through forensicinvestigation, processing observers or other coordinated action within the marketplace.In Norway, sales organisations are used as a third body of direct control with fisheries areincluded as a required measure in their legal framework. They carry out registration and controlof catches and landings (quantity and species). All catches must be sold through theseorganisations and all landings must be weighed and recorded on the sales notes36.Along with their suppliers, seafood companies have developed and implemented voluntary,market-based schemes to remove IUU fish from the supply chain. Important best marketpractices include eco-labelling certifiable products, catch and trade documentation schemes,maintaining a fish transaction data base, publishing lists of good and bad entities, settingcorporate standards and audit procedures and partnering with the Marine Stewardship Council(MSC) or other independent organizations to maintain credibility.All of these voluntary schemes contribute to improved performance, but cannot substitute forinstitutional reform to ensure that laggards comply with the law. Effective compliance will beattained only when fisheries crimes receive the level of attention and resources that they merit.Levels of penalties against participants in IUU fishing activities and criminal networks should besubstantial enough to act as deterrents. Effectiveness of any system depends on the ability toshare the information. Regional networks with specific legal framework outlining theresponsibilities of the regional Member States obligations can ensure compliance specifically forhigh-risk IUU fisheries.

A differentiated fishing regime to protect small-scale coastal fleets21. How can overall fleet capacity be adapted while addressing the social concerns facedby coastal communities taking into account the particular situation of small- andmedium-sized enterprises in the sector?WWF understands the reason for the Commissions thinking on this point but are not convincedof the approach. Particularly in northern European waters the distinction of communities being34

Scottish Fisheries Protection Agency (2007). Annual Report and Accounts 2006-2007, Edinburgh: TheStationary Office.35Ocean Resource Conservation Associates (2006) A report to WWF Sweden on traceability and BalticSea cod fisheries.36WWF Norway (2008) Management and Technical Measures in the Norwegian Cod and GroundfishFisheries.http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/norwegian_cod_fishery_report.pdf

23

dependent on small scale coastal vessels may not always be appropriate. For example somecoastal communities may be very dependent on some large vessels operating far from theirhome port but which are reliant on processing facilities etc in the local region while smallervessels may not be so vital for the overall survival of the community.A better approach is that of operating according to Long Term Management Plans (LTMPs). Asstated earlier we believe that all fisheries in Europe’s waters should be managed throughecosystem based LTMPs, which should rely on two related pillars: 1) the right ecosystem-basedfisheries management (EBFM) tools, to enable co-management and ecosystem sustainability,and 2) adequate rights-based management (RBM) tools, to ensure fishing capacity remainswithin limits compatible with sustainable exploitation of the stocks and economic profitability.This general scheme could be applied to any fishery, irrespective of its scale. This is particularlytrue for biological and ecological standards applicable to LTMPs, which should be the same EU-wide and for all fisheries (large and small scale).As stated earlier fishing access rights can be subject to trading restrictions to ensure that some‘community vital’ vessels participate in the fishery as long as such conditions are not to thedetriment of the target stocks, the wider marine environment or the overall objectives of theLTMP. In addition, harmful subsidies could be redirected to programs that transitionunsustainable employment out of the fish harvesting or processing sectors thus mitigating someof the social hardship of a transition to sustainability.22. How could a differentiated regime work in practice?23. How would small-scale fisheries be defined in terms of their links to coastalcommunities?24. What level of guidance and level playing field would be required at EU level?WWF disagrees with the principle that one should differentiate management regimes betweenlarge-scale and small-scale fleets by focusing on capacity adjustment and economic efficiencyfor the former and social objectives for the latter. On the contrary, WWF believes that balancedcapacity, economic efficiency, social aspects and ecological sustainability, should all underpinthe management of any fishery in Europe’s waters, irrespective of the scale. However key tomanagement must be the sustainability of the stock otherwise the other aspects will be unableto be met. WWF supports EFF investments in making small scale fisheries more ecologicallyand economically stable but does not believe that Europe can afford to sacrifice sustainabilityprinciples for short term economic gains in small scale fisheries any more than in larger scaleones.Small-scale fisheries, which can be less energy-intensive than larger-scale ones and canproduce a very high-quality product, highly prized by the market, can, and should, beeconomically profitable - particularly in the current environment of rising fuel prices. To achievethis, the new CFP should reward them by dropping any fuel subsidies (such as the currentdeminimisregulations), which result in coastal fisheries being out competed by frequently moreunsustainable and energy-intensive fisheries like those employing trawls. Instead, public aidshould be focussed on improving the effective marketing and selling of the product in order toachieve maximum return for the product, provide higher profit margins for fishermen, based onquality over quantity and sustainability. By doing this the current dependence on overfishing tokeep breaking even should be minimised and the position should be reached wherebyfishermen are removing less from the sea but earning more.

24

To achieve this objective it will be important to enhance the value of fishing products throughtraceability and labelling improvements, and to minimise the number of steps in the supply chainbetween net and plate. WWF France launched a project along with the Prud’homie of Saint-Raphaël which illustrates how such improvements can work in practice. This project, co-financed by Axis 4 of EFF, aims to protect the marine environment of the VAR by getting bettervalue for the fishermen refocusing attention on artisanal fishery as the centre of coastalactivities.Similar strategies are also being developed in Galicia, where fishermen-owned direct sellingenterprises improve fishermens incomes in order to reduce fishing pressure and encouragebetter practice. Commercialisation improvement strategies are often linked to sustainability andsocial-oriented programmes run by the own fishing sector37While no different ecological or management standards should be adopted for small or largerfleets, it will be necessary to apply flexible approaches to meet these objectives as in manyMember States management necessities are clearly different between small and larger fleets.