Udenrigsudvalget 2008-09

URU Alm.del

Offentligt

Closingt h egaps

Commission on Climate Change and Development

Copyright � 2009by the Commission on Climate Change and DevelopmentAll rights reserved.ISBN: 978-91-633-4720-7For electronic copies of this report, please visit www.ccdcommission.orgFor hard copies of this report, please contact the secretariat of theCommission on Climate Change and Development,Ministry for Foreign Affairs, SE-103 39 Stockholm, Sweden([email protected]).Printing: Edita Sverige AB, Stockholm, SwedenDesign and layout: Johan Resele/Global Reporting, Stockholm, SwedenCover photo: David Isaksson/Global Reporting and Dorling KindersleyEditing: Linda Starke, Washington, D.C., United States

Closing the Gaps:Disaster risk reduction and adaptationto climate change in developing countries

Report of theCommission on Climate Change and Development

Members of the CommissionGunilla CarlssonChairperson of the Commission,Swedish Minister for International Development CooperationAngela CropperDeputy Executive Director of the United NationsEnvironment ProgrammeMohamed El-AshrySenior Fellow, UN FoundationSun HonglieProfessor, Director of the China Climate Change Expert Committee,Chinese Academy of SciencesNanna HvidtDirector of the Danish Institute for International StudiesIan JohnsonChairman of IDEAcarbonJonathan LashPresident of the World Resources InstituteWangari MaathaiProfessor, Founder of the Green Belt MovementIvo MenzingerManaging Director at Swiss ReSunita NarainDirector of the Centre for Science and EnvironmentBernard PetitFormer Deputy Director-General of the Directorate General forDevelopment, European CommissionYouba SokonaExecutive Secretary of the Sahara and Sahel ObservatoryMargareta WahlströmUN Assistant Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction

Chairperson of the Expert GroupAnders WijkmanMember of the European Parliament

II

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

SecretariatJohan SchaarDirectorKatell Le GoulvenSenior Programme OfficerLloyd TimberlakeLead AuthorTurid TersmedenDesk OfficerLina PastorekDesk OfficerKerstin ÅbergAdministrative OfficerTuula Yli-Tainio MinduAdministrative Officer

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

III

Climate for ChangeThe Declaration of the Commission onClimate Change and DevelopmentSustainable development is possible but at risk. The planet’s crises – rapidclimate change, degraded ecosystems, scarcities of food, water, and energy –will outlast the serious economic downturn that now absorbs the attention ofglobal leaders and affects people worldwide. Some crises can be reversed, butthe damage to climate and ecosystems that contain and support all life may bebeyond repair and contribute negatively to economic prosperity. It is impera-tive that all countries adapt to this reality. We are all in this together.The way that nations respond to the global recession can provide the basis for anew path of development that begins to ease the planet’s interlocked emergencies.The international community seems less concerned about the failing climatesystem than about failing financial institutions. It hesitates to speak of millionsfor adaptation to climate change, but mobilizes billions for the financial crisis.Faced with a global crisis, nations risk turning inward, focusing on narrow con-cerns, which would be a historic mistake.Yet the climate upon which human civilization is based is changing faster thanimagined 20 years ago – or even 2 years ago. The change is accelerating andwill affect future economic growth and deepen the economic gaps.We must respond by mitigation – decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, creat-ing low-carbon paths of development for every nation, paths of developmentthat are both a right and a necessity.But past emissions are already causing rapid change; so we must adapt to climatechange – for present and future generations. Adaptation actions can spur devel-opment and the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. The crisesaffect all, but they hit the poorest and most vulnerable hardest. The climatecrisis is already claiming its victims.Climate change also presents humankind with a historic opportunity to makedevelopment more sustainable, encompassing a low-carbon economy and ad-dressing the risks posed by climate change. It offers an opportunity to createtrust and cooperation to better manage all crises, to fashion a market built on

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

V

ecological truths as well as economic data, to redefine the way we measuregrowth and prosperity. It provides an opportunity for developing renewable en-ergy for growth, providing the vulnerable with resources for adaptive capacity,and reducing the risk of disaster. The responses to climate change provide anopportunity to address the inherent inequity in the climate process and to cre-ate equity within nations, among nations, and between generations.This Commission has focused primarily on adaptation as an important elementof human development. We recognized the capacity of many peoples and fami-lies to use their knowledge and deep experience to adapt effectively, given ap-propriate signals and support. Our focus is on empowering the poorest peopleand countries to improve their ability to cope with an uncertain future – toreduce the negative effects and exploit the positive ones. Adaptation is also cru-cial because millions of lives and livelihoods are at stake and because countriesand regions that fail to adapt will contribute to global insecurity through, forexample, the spread of disease, conflicts over resources, and a degradation ofthe economic system.Seventeen years ago the world agreed on the necessity for the rich to aid thepoor in adapting and made it a treaty obligation in the UN Framework Conven-tion on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The evidence today is stronger, the moralcase unequivocal, and the political importance compelling. There can be noglobal agreement without adaptation assistance, and because of the nature ofclimate impacts, there will be much less global security without it. The worldwill be a worse place for all if we do not meet this treaty obligation.Adaptation is about forms of development in which the capacity to managerisk determines progress. Thus adaptation is much more than climate-proof-ing development efforts and official development assistance (ODA). It requiresaction, additional funding, and deep cooperation between rich and poor nationsand between rich and poor people within nations. It requires sustainable devel-opment: meeting the needs of the present in ways that do not compromise theability of future generations to meet their needs.RESPoNSIBILITIES, CoMMITMENTS, AND LEADERSHIP

A trust gap has opened between industrial and developing countries, stallingessential common action. It is rooted in a failure to fully acknowledge the pol-luter pays principle in climate negotiations and political dialogue. It results both

VI

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

from decades of unfulfilled commitments in development and trade and fromfears that developing countries with rapidly increasing emissions are not do-ing enough to curb them. The trust gap can be bridged when commitments byindustrial countries are met. Developing nations, for their part, need to ensuretransparent management of funds and the empowerment of their communities.The causes and effects of climate change lie thousands of miles and centuriesapart. Science has spoken: we now need the political will to act. In particular,strong and capable leadership is needed to overcome the current trust impasseand help us all live up to our responsibilities to current and future generations.This leadership will require an acknowledgement of urgency, a willingness toaccept scientific truth, a long-term perspective, and collective actions.SuSTAINABLE DEvELoPMENT

Ultimately, we need sustainable development, including a rapid move towarda low-carbon global economy. New green growth investment opportunities arenecessary to respond to the urgent and growing needs for climate change ad-aptation.Development that can be sustained in a world changed by climate must be enabledby building the adaptive capacity of people and defining appropriate technicaladaptive measures. Adaptive capacity results from reduced poverty and humandevelopment. Adaptive measures require the institutional infrastructure thatdevelopment brings. Action must be fast, scaled, focused, and integrated acrosssectoral divides:▶Speed:Wasting no time – climate change is happening faster than sciencepredicted.▶Scale:With growing numbers of people in danger, responses must match thescale of change.▶Focus:Managing risks, building the resilience of the poorest, and enhancingthe ecosystem functions upon which they depend.▶Integration:Uniting environment, development, and climate change, andmanaging synergies between mitigation and adaptation.

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

VII

GovERNANCE

The creation of adaptive capacity requires that international funds move effi-ciently to address impacts that are local. Participatory democracy, functioninginstitutions, and transparency are needed at all levels for effective adaptation.People at risk need democratic and political space so that they can inform them-selves and articulate their views and concerns. They need markets that work forthem so that they can trade and build their assets. This means that accountableand responsible government is more important than ever.Adaptation is best managed through policy coherence and through coordina-tion and cooperation among governments, civil society, and the private sector.The principle of subsidiarity should apply when dealing with adaptation.Impacts are local and contextual. The bulk of responsibility will fall on localand national governments, supported by international actions for appropriatecapacities and resources.Social protection – particularly the direct and predictable transfers of resourcesto the poor – must become a standard feature when building the adaptivecapacity of the most vulnerable households and individuals. It will include ef-fective disaster risk reduction for the most vulnerable.Women and men have traditionally played different roles in economic activityand natural resources management. Women and men should have equal rights,making full use of their different capacities; where they are affected differ-ently, attention must be given to the needs of the most vulnerable.INSTITuTIoNS

The adaptive capacity of people and communities is mediated through institu-tions. Disseminating information, building knowledge, articulating needs, ensur-ing accountability, exchanging goods and services, and transferring resources:all these are needed for adaptation and all are guided by and happen throughinstitutions. In an uncertain world, adaptation cannot be effective without ef-fective and accountable organizations and institutions.Families, neighborhoods, and communities and their local institutions musthave effective links with national, regional, and international institutions, whichhelp set the frameworks and provide many of the means in which and by whichthey adapt.

VIII

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

Twenty-first century challenges require twenty-first century institutions. Today’sorganizations must be able to manage public goods, bringing in the privatesector. They must be stakeholder-driven, efficiently moving resources fromglobal to local levels. They must be problem solvers, valuing ecosystems indealing with climate change.In the short term, we can use existing institutions for the deployment of finan-cial resources and modify these institutions to better manage knowledge andservices. In the longer term, as funding increases and agendas expand, new in-stitutions might be needed. Application of the subsidiarity principle, mentionedabove, will help distinguish among local, national, regional, and internationalresponsibilities.Local level

Local institutions know their communities and should have the main responsi-bility for identifying the poor and vulnerable and supporting them in buildingsafe rural and urban settlements. These institutions should ensure that dissemi-nation of climate information reaches the poorest and most vulnerable throughappropriate extension services.National level

Adaptation requires mechanisms cutting across governments’ sectoral formsof organization. National policy coordination for adaptation, disaster risk re-duction, poverty alleviation, and human development should be led from thehighest political and organizational level. Climate change is far too big a chal-lenge for any single ministry because it requires coordination among multiplesectors. Our report offers encouraging examples. All national sectors must beinvolved in climate actions.All governments have a responsibility to protect their poorest and most vulner-able citizens. Climate consequences will affect growing numbers of vulnerablepeople. Therefore governments need to be ready with the appropriate social safe-ty nets. In developing countries, external technical support is needed to strength-en institutions responsible for such systems, and national and international or-ganizations should cooperate in this effort.Communities in fragile states present challenges. International organizationsand bilateral donors have a special responsibility to support and channel re-sources to them via traditional and informal organizations.Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

IX

In terms of climate change, national governments have to deal with multipleassistance agencies, all of which are trying to prove to their constituencies thatthey are taking effective action. Responding to climate change makes the prin-ciples embedded in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the AccraAgenda for Action – ownership, alignment, use of country systems, division oflabor – therefore even more relevant.Governments should provide an enabling policy framework covering manage-ment, planning, and service delivery functions for adaptation that facilitate andsupport local governments and other actors’ efforts. They should ensure thatdevolved administrative responsibilities are matched by resources and technicalcapacity.Governments need to invest more in climate and meteorological information,biophysical monitoring, and early warning, integrating such data in their planning.Regional level

In many cases, regional coordination will provide the best opportunities fordealing with these issues. Regional organizations should identify added value,analyze lessons learned, and ensure the provision of information on experi-ences and ongoing activities.There is a need to address climate change at the level of river basins and agro-ecological zones, making regional agencies more important. These should be-come more innovative in helping countries produce regional climate infor-mation and knowledge, design common early warning systems for extremeweather conditions, manage shared water resources, control regional infectiousdiseases, and develop and create various agricultural and ecosystem manage-ment systems.International level

The international arena provides great opportunities for major actions suchas carbon markets and technology transfer. Yet given that adaptation is basedmainly on local actions, international organizations must become more adeptat reaching the local level directly and through national governments and re-gional organizations.Adaptation and mitigation both require an improved knowledge network, withmuch greater investment in generating, disseminating, and exchanging know-

X

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

ledge. It is particularly important to build scientific knowledge and capacityfor climate change research in low-income countries. The IntergovernmentalPanel on Climate Change (IPCC) should continue its four-yearly reports butshould focus also on the rapid turnaround and dissemination of peer-reviewedresearch findings, especially to low-income countries. The World MeteorologicalOrganization should be equipped to service these new requests of the IPCC.The IPCC should engage more actively with other existing institutions (such asthe UN Environment Programme, the World Bank, UN specialized agencies,academia, civil society, and think tanks) to ensure that climate change knowl-edge and information reach users in a timely way, particularly in low-incomecountries.The UNFCCC secretariat should focus on intergovernmental debate and policysetting, not on regulatory, financial, or operational functions. Regulatory serv-ices, the scaling up of carbon trading, and the provision of global corporateguidance (as distinct from political guidance) could be entrusted to a new regu-latory institution that would also effectively provide the least developed coun-tries with access to the carbon markets.The knowledge gap for adaptation is vast, but a growing knowledge network isbeing developed. The UN should provide a focal point for UN-related climatechange knowledge, “delivering as one” within developing countries, providingadvice on issues from water and crop management to insurance and disasterrisk reduction.The United Nations, international organizations (including civil society), andgovernments should work together to quickly and drastically scale up national,regional, and international systems for disaster response and preparedness.The new system should have a standby financial mechanism that would be trig-gered automatically by a major event, assuring rapid response. It should facili-tate recovery through a focus on vulnerability reduction; promote risk transfer,including social transfers and insurance products; and invest in staff with thecreativity and capacity to handle surprises. It should strengthen national andregional capacities.UN agencies are not effectively coordinating their responses to climate change.Governments should support the efforts of the UN Secretary-General (SG) tostrengthen coordination among UN agencies, funds, and programs. We urge

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

XI

the SG to continue to keep climate change issues at the top of governmentand governance agendas, encouraging and maintaining political will. The SGshould bring in stakeholders and set priorities throughout the UN system.The Commission recognizes the leadership of the SG and urges the SG to con-vene, in cooperation with international financial institutions, an independenthigh-level task force to articulate a vision for development that achieves themultiple goals of mitigation, adaptation, and meeting human needs. High on itsagenda should be the connections between the different global crises and theadequacy of global public policy and global governance in dealing with themsimultaneously.FINANCE

Resources are essential, but getting adaptation right is not only about money.Adopting a new approach to development and fixing our institutions will pro-vide the kind of incentives needed for more adaptive actions. The transition toa low-carbon green economy can support the global recovery by creating newjobs across a wide range of industries, but it will also secure ecosystem servic-es on which the world depends, especially the adaptive capacity of the poorest.In this context, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradationoffers a promising mechanism for simultaneously delivering mitigation, adap-tation, and economic benefits while sustaining vital ecosystem services.Money is needed now, and more will be needed in the future to help developingcountries adapt. The estimated price tag for this is probably higher than whatis currently spent on ODA, but that is still uncertain. Hence we need a step-by-step approach that will allow us to invest as our knowledge and understandingof climate change impacts and adaptation needs improve.Three main issues must be managed to get adaptation financing right: mobili-zation of resources, management of resources, and allocation of resources.First, mobilization of resources. The Commission urges donors to honor theirODA commitments. This would improve the adaptive capacity of countries.ODA should be used now for urgent needs and to kick-start other forms offinance. In the long run, resources for adaptation will be a blend of ODA andnon-ODA resources. The latter should meet the following criteria: additionality,adequacy, predictability, and political feasibility.

XII

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

By additional, we mean additional to the commitment of paying 0.7% ofgross national income as ODA. The concept of additionality applies to the rais-ing of funds but does not prescribe how the extra funds must be spent. TheCommission emphasizes the importance of transparency in funding and there-fore urges the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation forEco-nomic Co-operation and Development to suggest an appropriate markerfor adaptation finance that donors will use when reporting their financial con-tributions. This will allow the tracking of additional resources for adaptation.Second, management of resources. The Commission finds the proliferation offunds for adaptation problematic; it creates a coherence problem and puts pres-sure on the management capacity of developing countries. No further verticalfunds should be created for adaptation.Existing funding mechanisms should be effective, efficient, well coordinated,and accessible for actors at different levels. They should meet the followingcriteria: transparent and balanced governance; accountability of industrial anddeveloping countries; demand-driven, with involvement of recipients duringidentification, definition, and implementation of programs; managementdevolved to the lowest level of effective governance; and independent evalua-tion and oversight.Third, allocation of resources. This should take into account climate changevulnerability and in the early stage should make use of existing channels toimplement high-priority items in National Adaptation Programs of Action, asidentified by countries. The aim should be to integrate adaptation activities intothe normal planning and budgeting processes of countries.A TWo-STEP APPRoACH

Because the creation of new mechanisms might delay essential action, we rec-ommend a two-step approach to mobilizing “new and additional” funds foradaptation in developing countries. This stepwise approach aims to narrow thetrust gap between industrial and developing countries. It provides immediatehelp to the poorest people as progress is made toward a long-term approach toadaptation funding within the context of a new agreement on climate change.As a first step, we urge donor countries to mobilize $1–2 billion (although not atthe expense of current ODA-financed programs) to assist the vulnerable, low-income countries (especially in Africa) and selected small island states (belowCommission on Climate Change and Development

|

XIII

a certain gross domestic product), which are already suffering from climateimpacts. The second step is an effective mechanism for funding adaptation thatwould be created through climate negotiations.ODA and other public funds are unlikely to provide the full resources requiredto finance adaptation efforts of all developing countries in the long term. Thereis a wide range of estimates of the needs.The main messages of our report are that adaptation will be possible and cost-effective, that costs will rise for decades or centuries, and that costs will accel-erate with continuing failure to mitigate.Although more work is required to better estimate these needs, there are prom-ising options proposed to raise funds. Some could bring between $5 billion and$15 billion additional funds a year – which is in the lower range of estimatedneeds.We urge governments to adopt the mechanisms that provide additional and pre-dictable resources and are politically feasible, equitable in terms of all donorsand recipients, and respectful of the principle of common but differentiatedresponsibility.A BETTER CHANCE

During the course of its work, the Commission on Climate Change and De-velopment has met governments and citizens struggling with the effects of cli-mate change in Bolivia, Cambodia, and Mali. We offer this declaration and itsrecommendations as a contribution to the sustainable development path thatclimate change requires. We offer it for the consideration of political leaders atthe Copenhagen climate meeting and beyond.All governments have responsibilities toward their most vulnerable citizens.All resources mobilized to mitigate and adapt to climate change must ensuretheir rights, their voice, their security.In 20 years the next generation will not judge us by the precise arrangements wemake to reduce the emissions that cause global warming and help the victimsof climate change, but rather by whether these arrangements proved effective.If we fail, their lives will be worse and will be more limited. If we succeed, wewill have provided them at least a better chance.

XIV

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

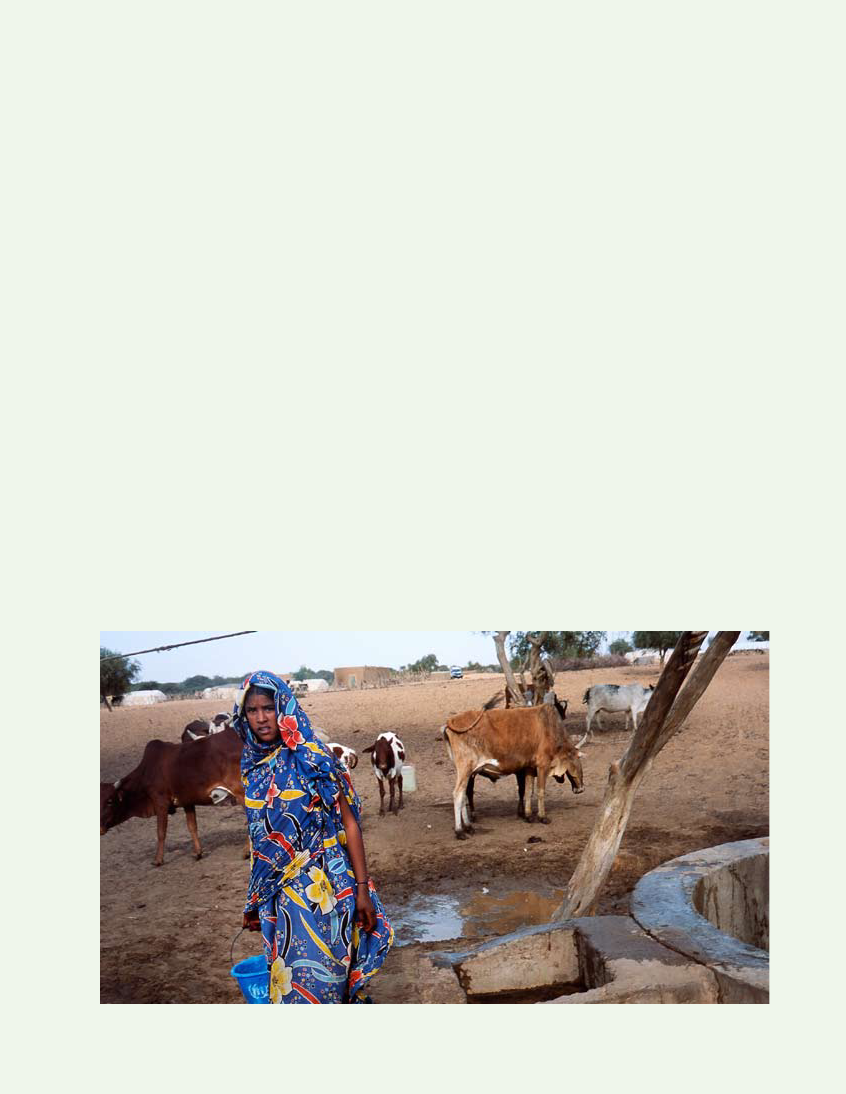

PrefaceFor many years negotiations and debates on climate change have focused onthe need to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. We assumed that successfulmitigation would help us avoid the harmful effects of increasing temperatures.But mitigation has yet to begin at the required scale and space. People aroundthe globe observe changes to their environment with profound consequences.The rainy season cannot be trusted to last long enough to recharge dry wellsand restore soil moisture. Returning migratory birds no longer signal the righttime for putting seeds in the ground. And violent storms and rains occur whenand where they are least expected. Those with little margin to maintain a de-cent life for themselves and their children, relying directly on what ecosystemsprovide, are most affected.In September 2007, Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt therefore in-formed the Secretary-General of the United Nations of his government’s initia-tive to launch an international commission on climate change and development.Its focus would be threefold: how to design and support adaptation to climatechange, how to reduce the increasing risk of weather-related disasters, and howto strengthen the resilience of the poorest and most vulnerable communitiesand countries.Much has changed since that day in New York. In December 2007 climate nego-tiators agreed on a Bali Action Plan, where adaptation is one of the pillars ofthe continued negotiation process. Scientists report that climate change is hap-pening more rapidly than had been predicted. And the climate crisis is not alone.Food, energy and water scarcities, ecosystem degradation, and a global eco-nomic downturn are taking their simultaneous toll, especially on the poorest.The Commission on Climate Change and Development decided to build itscase from the ground up. Through our meetings with citizens and governmentsin Bolivia, Cambodia, and Mali, we sought to gain an understanding of thethreats poor people face, how they can build their adaptive capacity, and whatis needed in the form of institutions and resources to provide the most effectivesupport and the best outcomes.

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

XV

For this to happen, a number of gaps must be bridged. There is a trust gap be-tween rich and poor countries, gaps between institutions, and a resource gap.These are addressed in individual chapters of our report.Taking adaptation actions today is a requirement for sustainable developmenttomorrow. Early action is needed to reduce future costs and irreversible eco-logical damage. We, the Commission, are convinced that the different crisescan only be resolved in unison. Assigning the right value to the climate andecosystems, ensuring that no system is used beyond its capacity, and creatingpolitical space for dialogue and action – these are steps needed to deal with ourmultiple threats. The Commission is united in its belief that the climate crisisgives us both obligations and opportunities. It is in this spirit we offer our report.Gunilla CarlssonSwedish Minister for International Development CooperationChairperson, Commission on Climate Change and Development

XVI

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

AcknowledgmentsThe Commission and the secretariat have received advice and support frommany individuals, institutions, and organizations from around the world. Thisreport would not have been possible without their generous contributions.The Commission and the secretariat sincerely thank the group of experts whoprovided substantive inputs to the work of the Commission since its creation:Simon Anderson, Margaret Arnold, Tariq Banuri, Salvano Briceno, Ian Christo-plos, Victor Galaz, Luis Gomez-Echeverri, Richard Klein, Merylyn McKenzieHedger, Johan Rockström, Camilla Toulmin, and Anders Wijkman.Other experts who have shared their knowledge with us throughout the processinclude: Arun Agrawal, Shardul Agrawala, Jonathan Allotey, Jon Barnett, ReidBasher, Boni Biagini, Yvan Biot, Emily Boyd, Ramzi Elias, Siri Eriksen,Alex Evans, Marianne Fay, Tigue Geoghegan, Pär Granstedt, Natasha Grist,Holger Hoff, Saleemul Huq, Francis Johnson, Shefali Juneja, Saroj Khumar Jah,Bo Kjellen, Fiona Lambe, Elisabeth Lindgren, Silvia Llosa, MJ Mace, StewartMaginnis, Julia Marton-Lefèvre, Andrew Maskrey, Heather McGray, GregoryMock, Helena Molin-Valdez, Georgia Moyka, Benito Müller, Fredrik Möberg,Vikas Nath, Lina Nerlander, Fredrick Njau, Marcus Oxley, Nicolas Perrin, DavidReed, Espen Ronneberg, Fiona Rotberg, David Satterthwaite, Lisa Schipper,Melanie Speight, David Steven, Annika Söder, Susanna Söderström, YashTandon, Antonio Tujan, Koko Warner, Richard Weaver, Michael Webber, andVicente Yu.We would like to express our gratitude to the people who welcomed and guidedus during our field visits: Aghatan Ag Alhassane, Juan Carlos Alurralde, IvarArana, Victor Cortez, Yem Dararath, Halima Diakite-Diallo, Mamadou Gakou,Liliana Gonzalez, Jenny Gruenberger, José Luis Gutierrez, Erik Illes, SokontheaKith, Mama Konate, Mok Mareth, Sara Martinez Bergström, Sidi al Moctar,Oscar Paz, Tin Ponlok, Sara Ramirez, Juan Pablo Ramos, Arne Rodin, MakSithirith, Chan Sophal, Roland Stenlund, Johanna Teague, Leslie Thompson,Ibrahim Togola, Johanna Togola, and Chhieng Yanara. This gratitude is extend-ed to the staff of the SIDA offices in Bolivia, Cambodia, and Mali, to the staffof the Bolivia National Programme for Climate Change, the Cambodia Fisher-

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

XVII

ies Action Coalition Team, and the Mali Folke Center, as well as to the popula-tions of Batallas, Kampong Chhnang, and Bougoula.We also benefited from thoughtful comments and suggestions from colleaguesat the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, the Swedish International Develop-ment Agency, and the Commission’s reference group. We are particularly grate-ful to: Anders Berntell, Jan Bjerninger, Per Björkman, Johan Borgstam, OlofDrakenberg, Lars Ekecrantz, Lars-Göran Engfeldt, Harald Fries, Nina Frödin,Elisabeth Groll Lindell, Stina Götbrink, Niclas Hellström, Peter Holmgren,Torgny Holmgren, Emilia Högquist, Susanne Jacobsson, Dag Jonzon, PernillaJosefsson Lazo, Carly Jönsson, Angela Kallhauge, Jan Knutsson, Patrick Kratt,Peter Larsson, Karin Lexén, Lars-Erik Liljelund, Lars Lundberg, Klas Marken-sten, Ann-Sofie Nilsson, Anders Nordström, Mirjam Palm, Johan Röstberg,Joakim Sonnegård, Jakob Ström, Staffan Tillander, Eva Tobisson, Lena Tran-berg, Anders Turesson, Anna Yazgan, Petra Åhman, and Ulrika Åkesson.Our sincere thanks also go to the Stockholm Environment Institute and the De-partment for Development Policy of the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairsfor hosting the secretariat and supporting our work on a daily basis.And finally we are indebted to the people who have helped us with the pro-duction of this report: Susanna Ahlfors, David Isaksson, and Johan Resele ofGlobal Reporting; Ing-Marie Sjunnebo and John Sundberg of Edita; Fauvettevan der Schoot of Multi-Language Services, Inc; and Linda Starke.

XVIII

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

Table of ContentsAdapting to Change...................................................................................VPreface.....................................................................................................XVAcknowledgments.................................................................................XVIIExecutive Summary.................................................................................XX1. Adaptation: The Context for Change......................................................12. The Trust Gap..........................................................................................83. The Focus Gap: The Human Dimension...............................................134. Governance Gaps..................................................................................245. Financing Gaps.....................................................................................34Acronyms..................................................................................................44Appendixes1. Food Security......................................................................................452. Water...................................................................................................493. Natural Resources, Forests, and Trees...............................................524. Health..................................................................................................555. Energy Access.....................................................................................606. Risk and Insurance..............................................................................657. Migration..............................................................................................688. Cities....................................................................................................729. Disaster Risk Reduction......................................................................7510. Commission’s Terms of Reference......................................................7811. Commissioner Biographies.................................................................79

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

XIX

Executive SummaryThe international Commission on Climate Change and Development waslaunched in late 2007 by the Swedish government. Chaired by Swedish Minis-ter for International Development Cooperation Gunilla Carlsson, the Commis-sion has 13 members from countries in all regions. They represent internationaland regional organizations as well as science, civil society, and the private sector.The Commission examined adaptation to climate change and its links withdevelopment and disaster risk reduction and was asked to issue policy recom-mendations on how the resilience of vulnerable communities and countries canbe strengthened through official development assistance (ODA), on appropriateinstitutional and financial architecture, and on the mobilization of new finan-cial resources.In Chapter 1 we argue that the only solution to climate change is a rapid movetoward a low-carbon global economy. This must be done urgently, efficiently,and with great determination, so that adaptation remains possible.The poor are overwhelmingly the present and future victims of climate change.Its impacts are mixed with and overlap the impacts of other syndromes such asrising food prices, the financial crisis, energy shortages, ecosystem degrada-tion due to other human causes, and demographic changes. These must bemanaged in a highly coordinated manner.The poor need adaptive capacity, which consists mainly of assets, health,education, and governance. Thus in poor countries adaptation is inseparablefrom development, where the capacity to manage risk determines progress.Adaptation is much more than climate-proofing development efforts and ODA.It requires action, additional funding, and deep cooperation between rich andpoor nations and between rich and poor people within nations. It requires sus-tainable development: meeting the needs of the present in ways that do not com-promise the ability of future generations to meet their needs.Development must quickly reach rapidly growing numbers of people, focus onreducing vulnerability, and integrate adaptation, mitigation, and human devel-opment goals.

XX

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

Chapter 2 examines the ethics of climate change, mitigation, and adapta-tion, including the trust gap between industrial and developing nations. In theUN Framework Convention on Climate Change of 1992, wealthy nations pledgedto help poorer nations adapt to climate hardships created for them by others.Unless this pledge is honored, the poorer countries will not agree to a post-2012global framework on climate change. Yet climate ethics are complex, as causesand effects are separated by thousands of miles and by generations. The issue ofbasic fairness developed in this chapter informs much of the rest of this report.Chapter 3 focuses on the human dimension of climate change. While the ef-fects of climate change may be vast, their brunt will be borne locally by indi-viduals, families, villages, and neighborhoods. Discussions of climate changemust be turned upside down, switching from a global to a local focus. Nationalgovernments must set frameworks to ensure that adaptation measures and dis-aster risk reduction reach all, including the most vulnerable. Historically, badgovernance and a failure to respond to local needs have hindered developmentefforts. Those problems will frustrate adaptation if not managed. Moving to-ward participatory democracy is essential.Adaptation discussions tend to focus on big weather-related catastrophes. Yetadaptation to smaller, unreported events is at least as important. First, the in-crease in smaller floods, landslides, and so on is increasing poverty through theaccumulated effects. Second, households and societies that are more resilient tosmall shocks are less vulnerable to big ones.Adaptation strategies must increase the adaptive capacities of people, businesses,and ecosystems. Some development agencies and national governments are suc-cessfully using social transfers – regular and predictable grants to poor house-holds – as a way to improve access to services and address the underlying causesof inequalities in well-being. They need to be expanded and scaled up as vul-nerability increases.Adaptation is shaped by institutions at the local, national, and internationallevels; adaptive capacity at the local scale depends on developing capacity foradaptation at wider scales. The private sector is a key resource in adaptation.Three main institutional ingredients are necessary to improve people’s adaptivecapacity: targeted capacity development, inclusive governance, and ownership.

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

XXI

Chapter 4 addresses the governance gap. It shows that despite the strong inter-dependence between economy, environment, and development, governmentscontinue to try to manage issues in silos as if they were separate one fromanother. Climate change, one of the greatest threats to human civilization, hasbeen placed in what is often the weakest governance silo: environment.Local institutions know their communities and should have the main responsi-bility for identifying the poor and vulnerable and supporting them in buildingsafe rural and urban settlements. These institutions should ensure that dissemi-nation of climate information reaches the poorest and most vulnerable throughappropriate extension services.National policy coordination for adaptation, disaster risk reduction, povertyalleviation, and human development should be led from the highest politicaland organizational level. Climate consequences will affect growing numbersof vulnerable people. Therefore governments need to be ready with the appro-priate social safety nets.The need to address climate change at the level of river basins and agro-eco-logical zones makes regional agencies more important. These should becomemore innovative in helping countries produce regional climate information andknowledge, design common early warning systems for extreme weather condi-tions, manage shared water resources, control regional infectious diseases, anddevelop and create various agricultural and ecosystem management systems.The international arena provides great opportunities for major actions suchas carbon markets and technology transfer. Yet given that adaptation is basedmainly on local actions, international organizations must become more adept atreaching the local level directly and through national governments and region-al organizations. The commission offers a number of ways that they can do so.Chapter 5 deals with the mechanisms for financing adaptation. Acknowledg-ing the difficulties of counting the costs of adaptation at any given time, it ar-gues that costs will only increase as society continues to delay serious effortson mitigation. The report calls for new and additional resources for financingadaptation. It calls for greater coordination of financing mechanisms and moni-toring of resources at the global and national levels.Mobilization of resources is key. Honoring ODA commitments improves theadaptive capacity of countries and would provide funds to help kick-start urgent

XXII

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

adaptation measures. In the long run, resources for adaptation will be a blendof ODA and non-ODA resources. The latter should meet the following criteria:additionality, adequacy, predictability, and political feasibility.The proliferation of funds for adaptation is problematic; it creates a coherenceproblem and puts pressure on the management capacity of developing coun-tries. No further vertical funds should be created for adaptation. Existing fund-ing mechanisms should be effective, efficient, well coordinated, and accessiblefor actors at different levels. A step-wise approach for mobilizing financial re-sources is envisaged.Allocation should take into account climate change vulnerability and in theearly stage should make use of existing channels to implement high-priorityitems in National Adaptation Programs of Action, as identified by countries.The aim should be to integrate adaptation activities into the normal planningand budgeting processes of countries.Nine appendixes cover the issues of food security; water; natural resources,forests, and trees; health; energy access, climate, and development; risk andinsurance; migration; cities and: disaster risk reduction;▶Food security depends on more than how much food is grown; it dependson people’s access to markets (including for labor), the stability of supply,and quality. All are affected by climate change and must be managed.▶Water is mainly an issue of political power, especially for the poor. Efficientmanagement is also crucial, particularly for the use of rainwater.▶Natural resources management depends on land tenure and user rights. Goodmanagement, especially of forests, can have both mitigation and adaptationresults.▶Energy is necessary for development, and energy access issues must be partof mitigation and adaptation strategies.▶Health will be affected by changing disease patterns, requiring more empha-sis on prevention and improved sanitation.▶Insurance approaches must evolve toward new forms of transferring andsharing risks more effectively targeting the poor and based on climate changemodels.

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

XXIII

▶Cities, especially the mega-cities of poor nations, require problem-solvingpartnerships between local governments and residents of informal commu-nities for innovative urban land use.▶Migration should be recognized as an adaptive strategy, to be managed andfacilitated rather than restricted.▶Disaster risk reduction strategies should focus on underlying risk rather thanresponse and on the safety of human settlements.

XXIV

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

1. Adaptation: The Context for ChangeDevelopment and climate change are the central problems of the 21st Century.If the world fails on either, it will fail on both. Climate change undermines development.No deal on climate change which stalls development will succeed.”Lord NichoL as sterN

The international Commission on Climate Change andDevelopment was launched in late 2007 by the Swedishgovernment. Chaired by Swedish Minister for InternationalDevelopment Cooperation Gunilla Carlsson, the Commis-sion has 13 members from countries in all regions. Theyrepresent international and regional organizations as wellas science, civil society, and the private sector.The Commission examined adaptation to climate changeand its links with development and disaster risk reductionand was asked to issue policy recommendations on howthe resilience of vulnerable communities and countries canbe strengthened through official development assistance(ODA), on appropriate institutional and financial architec-ture, and on the mobilization of new financial resources.1The Commission’s first message is that the only responseto climate change is a rapid move toward a low-carbon glo-bal economy. This must be done urgently, efficiently, andwith great determination.Yet mitigation – efforts to decrease the amounts ofgreenhouse gases (GHGs) released into the atmosphere –has yet to begin at the required scale and pace. In fact, GHGemissions have increased steadily since the UN FrameworkConvention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted in1992. Thus anthropogenic emissions are already changingthe climate and, due to their long residence in the upperatmosphere, will continue to do so for many decades if notcenturies to come. Civilization will have to adapt to thesechanges.Policy makers and scientists have all been slow to focuson adaptation, largely because mitigation got much of their

attention. In fact, many environmentalists feared that anyfocus on adaptation would take attention away from the ur-gent need to mitigate. That has changed.The Fourth Assessment Report of the IntergovernmentalPanel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted that even if globalsociety does succeed in reducing emissions, some climatechange impacts are now unavoidable (see Box, p. 2.) andsolutions must be found to adjust to them.As a result, the 2007 Bali Action Plan called for strong andextremely ambitious steps on adaptation, giving priority tourgent and immediate needs of vulnerable developing coun-tries, including the full range of risk reduction measures.

A stronger sense of urgencySince the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report, a number ofscientists and scientific organizations have published paperssuggesting that climate change is happening much fasterthan the panel suggested. The 2009 meeting of the Ameri-can Association for the Advancement of Science heard howcarbon emissions have been growing at 3.5% per year since2000, up sharply from 0.9% per year in the 1990s.The European Union has set a goal of not allowing thetemperature increase to exceed 2� Celsius. Staying underthat target would imply emission cuts of at least 80% by2050. Many scientists argue that an increase of 2� is toohigh and call for more drastic cuts in emissions. Positivefeedback mechanisms such as a reduced albedo and thethawing of the permafrost are likely to accelerate climatechange, and the planet appears to be moving toward dan-gerous tipping points.Evidence is also growing that the absorptive capacity ofcarbon sinks such as oceans and terrestrial ecosystems isdiminishing. Deforestation, soil erosion, overfishing, andbad management of freshwater resources have further re-

1

See Appendix 10 for the Commission’s full terms of reference.

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

1

of the trends will accelerate, leading to an increasingrisk of abrupt or irreversible climatic shifts.3

Different impacts for different regionsin africa, the situation is quickly becoming more serious: analystsproject that by 2020, between 75 million and 250 million people willbe exposed to increased water stress due to climate change, and insome countries yields from rainfed agriculture could be reduced by upto 50%.in asia, by the 2050s freshwater availability in central, south, east,and southeast asia, particularly in large river basins, is projected todecrease, and diarrheal diseases associated with floods and droughtsare expected to increase in east, south, and southeast asia.in Latin america, productivity of some important crops is projectedto decrease and livestock productivity to decline, with adverse conse-quences for food security. changes in precipitation patterns and thedisappearance of glaciers in the andes are projected to significantlyaffect water availability for human consumption, agriculture, and en-ergy generation.in small island states, sea-level rise is expected to threaten vital in-frastructure, settlements, and facilities that support the livelihood ofisland communities. By mid-century, climate change is expected toreduce water resources in many small islands in the caribbean andPacific to the point where they become insufficient to meet demandduring low-rainfall periods.source: intergovernmental Panel on climate change,Climate Change2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III tothe Fourth Assessment(Geneva: 2007).

Interconnected crisesThe impacts of climate change are mixed with and overlapthe impacts of other syndromes such as rising food prices,the financial crisis, energy shortages, ecosystem degrada-tion due to other human causes, and demographic changes.The lack of atmospheric space to safely dispose of GHGemissions is one of several linked scarcities now affectingsociety. Others include scarcities of affordable petroleum-based products, affordable food, and fresh water.4Climatechange is accelerated by the use of carbon-based energy andthe alteration of forests to farmland; it changes the avail-ability of fresh water. Agriculture needs a predictable cli-mate, water, energy sources, and fertilizer, much of whichis petroleum-based. It is not clear how long these scarcitieswill persist or how they will continue to affect one another.These strong connections mean that the scarcities mustbe managed in a highly coordinated manner. The next-gen-eration technologies, protective investments, and shifts inpolicies needed to correct economic and financial imbal-ances can also serve the collective purpose of protectingour common environment from overexploitation. Failureon one will be failure on both.

Focus on the poorduced the capacity of Earth’s systems to respond to futureshocks.2In March 2009 in Copenhagen, 2,500 researchers fromsome 80 countries presented their most recent findings.Their main message, according to conference organizers,was that:Recent observations confirm that, given high ratesof observed emissions, the worst-case IPCC scenariotrajectories (or even worse) are being realized. Formany key parameters, the climate system is alreadymoving beyond the patterns of natural variabilitywithin which our society and economy have devel-oped and thrived. These parameters include globalmean surface temperature, sea-level rise, ocean andice sheet dynamics, ocean acidification, and extremeclimatic events. There is a significant risk that manyAll nations and all people must adapt to climate change.This truth is demonstrated by the heat waves of 2003 in Eu-rope and North America and by Hurricane Katrina in 2005and other hurricanes affecting US cities. Although singleevents can rarely be attributed to climate change, they doshow that it is the poor, even in wealthy countries, who aremost affected by extreme weather events.

2

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment,Ecosystems and Human Well-being:Synthesis(Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005).“Key Messages from the Congress,” International Scientific Congress –Climate Change: Global Risks, Challenges & Decisions, University of Co-penhagen, 10–12 March 2009.See, e.g., A. Evans, “Multilateralism for an Age of Scarcity. Building Inter-national Capacity for Energy, Food and Climate Security,” Working Paper(New York: Center for International Cooperation, New York University,July 2008).

3

4

2

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

1.adaptation: the context for change

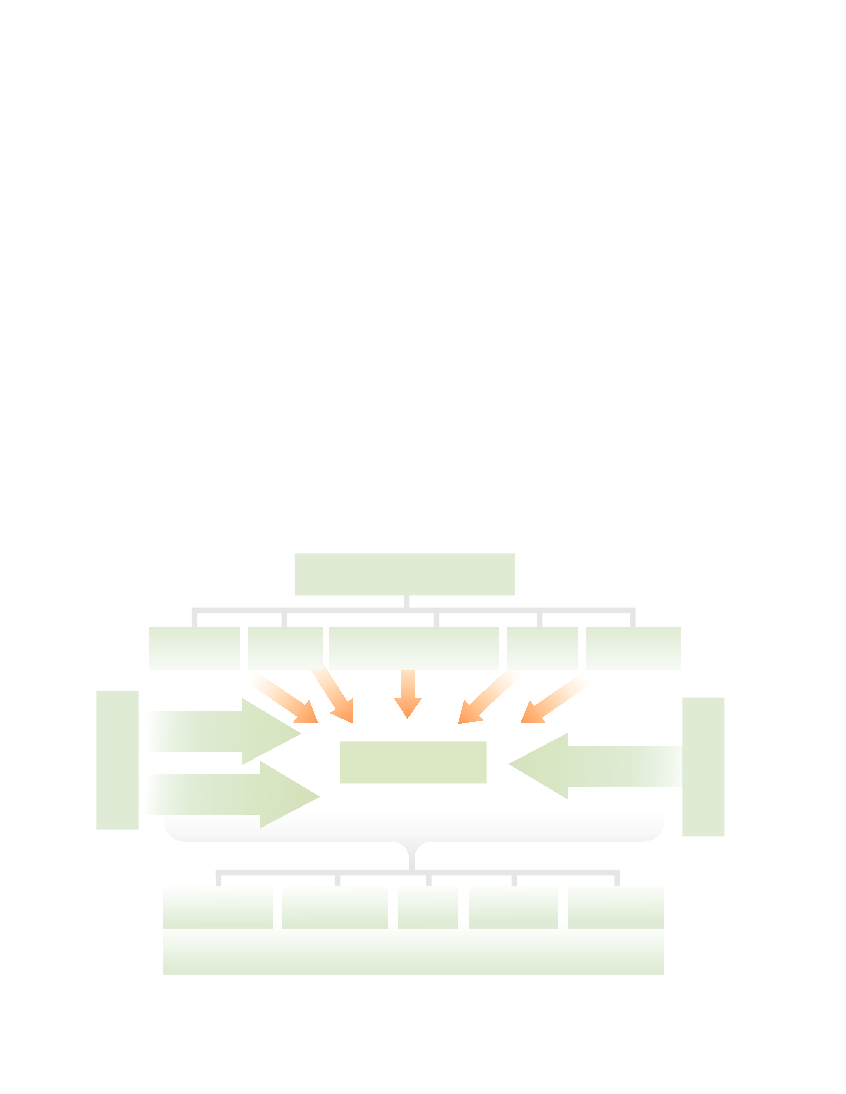

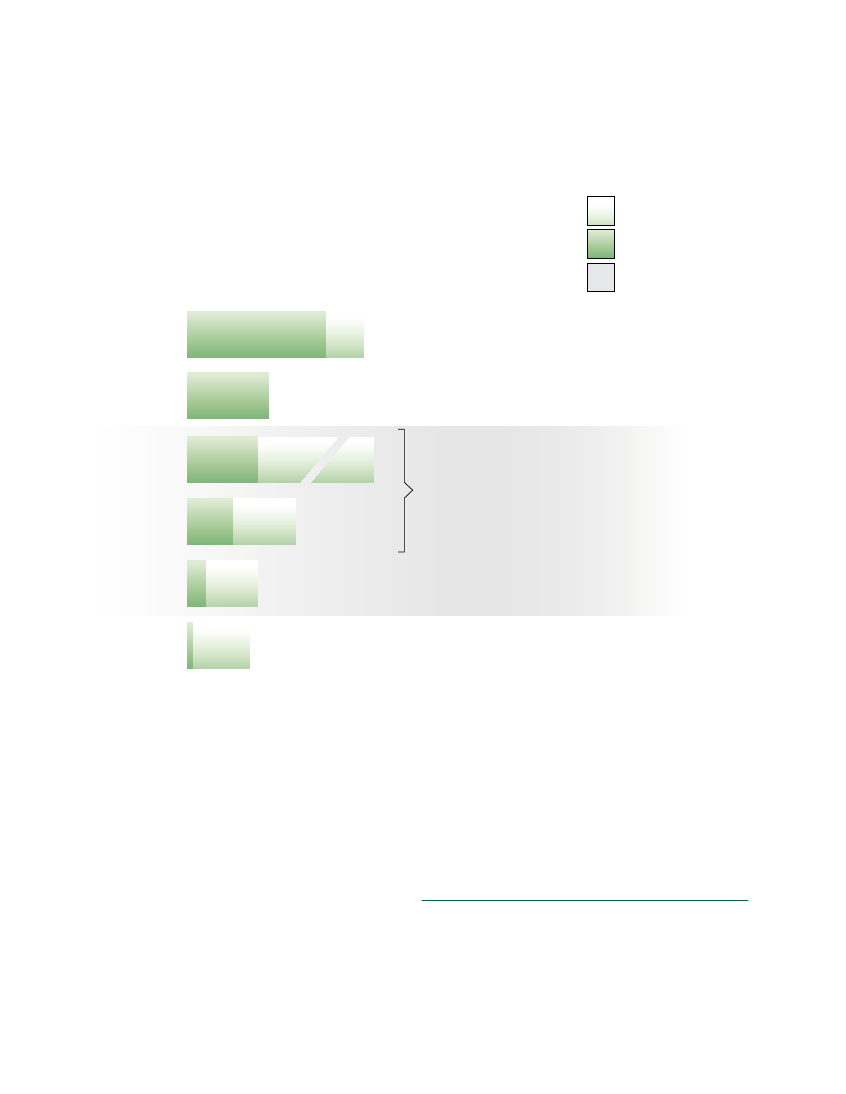

Continuum of adaptation activitiesFigure 1.

Vulnerability focus

Impacts focus

Addressing the driversof vulnerability

Building responsecapacity

Managing climate risks

Activities seek toreduce poverty andother non-climaticstressors that makepeople vulnerable

Activities seek to buildrobust systems forproblem solving

Activities seek toincorporate climateinformation intodecision-making

Confronting climatechange

Activities seek toaddress impactsassociated exclusivelywith climate change

source: r. J. t. Klein and Å. Persson, “Financing adaptation to climate change: issues and Priorities”(Brussels: centre for european Policy studies, 2008).

This report focuses on adaptation to climate change bypoor countries and by poor people in those countries:▶Because climate change threatens poverty reductionand the achievement of the Millennium DevelopmentGoals,▶Because poor people in poor countries depend directlyon endangered ecosystems and their services for theirwell-being,▶Because poor people in poor countries lack the resourc-es to adequately defend themselves or to adapt rapidly tochanging circumstances, and▶Because their voices are not sufficiently heard in inter-national discussions, particularly in climate change ne-gotiations.

drought-tolerant crop varieties, agricultural diversification,vaccines, upgraded drainage systems, enhanced wateruse efficiency, enlarged reservoirs, or revised buildingcodes. Building adaptive capacity aims to address the mul-tiple drivers of vulnerability, including poverty. Betweenbuilding adaptive capacity and instituting adaptive meas-ures, there exists a continuum of adaptation activities. (SeeFigure 1.)6Adaptive capacity increases with human development. Itcan be summarized under four simple headings – wealth,health, education, and governance:▶Wealth, or access to assets, provides the buffers andbackup that take people through crises and enable themto recover. Assets may be financial or material, directlyaccessible or through insurance, and come from the so-cial networks of family and kin or through government

Adaptation and developmentWhat is adaptation? The UNFCCC provides a clear answer:“Adaptation is a process through which societies makethemselves betterable to copewith an uncertain future.Adapting to climate change entails taking the rightmeas-uresto reduce the negative effects of climate change (orexploit the positive ones) by making the appropriate adjust-ments and changes” [emphasis added].5Adaptation is about building adaptive capacity and carry-ing out appropriate adaptive measures. Adaptive measuresseek to address climate change impacts by, for example, anew seawall, crop insurance schemes, research on heat- and

5

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),ClimateChange: Impacts, Vulnerabilities and Adaptation in DevelopingCountries(Bonn: 2007), p. 12.R. J. T. Klein and Å. Persson, “Financing Adaptation to ClimateChange: Issues and Priorities” (Brussels: Centre for European PolicyStudies, 2008), adapted from H. McGray, A. Hammill, and R. Bradley,with E. L. Schipper and J. Parry,Weathering the Storm: Options forFraming Adaptation and Development(Washington, DC: World Re-sources Institute, 2007).

6

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

3

▶

▶▶

social protection schemes for those with few means oftheir own.Health safeguards the productive capacity of the indi-vidual and the integrity of families. This comes throughclean water and effective sanitation, safe childbirth, andfood of the right kind and amount so that children growto their full potential.Education gives people access to information, knowl-edge of their options, and the ability to make informedchoices.Governance, or rather the fullness of the institutionalenvironment, provides the means through which people,working with others, have access to resources, articulateneeds, and exercise their rights.

A new development pathThe development path under climate change will involverethinking and reformulation on four levels: speed, scale,focus, and integration.▶Speed:Wasting no time – climate change is happeningfaster than science predicted. The IPCC prediction thatin Africa between 75 million and 250 million peoplewill be exposed to increased water stress by 2020 allowsfor little more than a decade of development.▶Scale:Development must decrease the vulnerability ofall of the planet’s poorest, and especially the “bottombillion.” Growing numbers of people are in danger;responses must match the scale of this change.▶Focus:Development should be centered on managingrisks, building the resilience of the poorest, and enhancingthe ecosystem functions upon which they depend. Thisrequires new focus and emphases in all sectors, includ-ing food security, with special attention to poor people’saccess to markets; water, with special attention to equityof access and the efficient use of rainwater; natural re-sources management, with special attention to land tenureand user rights of the poor; energy, with special atten-tion to a decentralized mix of renewable and low-carbonoptions for the poor; migration, with special attention topolicies that benefit the most vulnerable regions and min-imize transaction costs on remittances; and disaster riskreduction, with special attention to the most vulnerablegroups and settlements and to rehabilitated infrastruc-ture that contributes to reduced risk. (See appendixes forfurther discussion of these issues.)▶Integration:Adaptation, mitigation, and human devel-opment goals are closely interrelated. (See Box, p. 5)Mitigation measures such as afforestation, reforestation,and avoided deforestation are also effective adaptation,as they improve economic and ecosystem resilience. Thecurrent approach, which tries to deal with them sepa-rately, will not only be ineffective, it will be counterpro-ductive. The conceptof sustainable development unitedthe two concerns of environment and development; ournew development path unites environment, development,and climate change (adaptation and mitigation).

Understanding adaptation in this way tells us that adaptiveaction must be highly context-specific. In countries andcommunities where human development indicators are low,priority must be given to strengthening the adaptive capac-ity of people and institutions. If capacity is already there,through assets, insurance, a healthy and well-educatedpopulation, and formal and informal institutions that medi-ate support and through which needs can be analyzed andarticulated, then action will naturally emphasize climate-specific measures – that is, measures that would not havebeen necessary if climate change were not happening.This report looks at the adaptive capacity of people,firms, and ecosystems and discusses their interactions,complementarities, and competition. It also looks at adap-tive capacity across scales – local, national, international– and how interfaces among these scales facilitate or standin the way of adaptation.Adaptation to climate change is about forms of develop-ment in which the capacity to manage risk determines pro-gress. Thus adaptation is much more than climate-proofingdevelopment efforts and official development assistance.The Commission finds that it requires action, additionalfunding, and deep cooperation between rich and poor na-tions and between rich and poor people within nations. Itrequires sustainable development: meeting the needs of thepresent in ways that do not compromise the ability of futuregenerations to meet their needs.

4

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

1.adaptation: the context for change

Structure of the reportOur report is structured around four main parts follow-ing this chapter. Chapter 2 examines the ethics of climatechange, mitigation, and adaptation, including the trust gapbetween industrial and developing nations. Wealthy nationspledged in the UN Framework on Climate Change of 1992to help poorer nations adapt to climate hardships created forthem by others. Unless this pledge is honored, those countrieswill not agree to a global framework on climate change.Yet climate ethics are complex, as causes and effects areseparated by thousands of miles and by generations. Theissue of basic fairness developed in this chapter informsmuch of the rest of this report.Chapter 3 focuses on the human dimension of climatechange. While the effects of climate change may be vast,their brunt will be borne locally by individuals, families,villages, and neighborhoods. Discussions of climate changemust be turned upside down, switching from a global to alocal focus. National governments must set frameworks toensure that adaptation measures and disaster risk reductionreach all, including the most vulnerable. Historically, badgovernance and a failure to respond to local needs havehindered development efforts. Those problems will frus-trate adaptation if not managed. Moving toward participa-tory democracy is essential.Chapter 4 addresses the governance gap. It shows thatdespite the strong interdependence between economy, en-vironment, and development, governments continue to tryto manage issues in silos as if they were separate one fromanother. Recognizing the limitations of individual actions,the report calls for an enlightened, prudent, yet proactiveglobal public policy.Chapter 5 deals with the mechanisms for financingadaptation. Acknowledging the difficulties of counting thecosts of adaptation at any given time, it argues that theywill only rise as society continues to delay serious effortson mitigation. The report calls for new and additional re-sources for financing adaptation but also recognizes theimportance of official development assistance to kick-starturgent adaptation efforts. A step-wise approach for mobi-lizing financial resources is envisaged. It calls for greatercoordination of financing mechanisms and monitoring ofresources at global and national levels.The appendixes cover the issues of food security; water;

Synergies between mitigation and adaptationMitigation and adaptation can be mutually reinforcing. increasing thestorage of carbon and avoiding its release from forests and soils canhave multiple benefits. the reducing emissions from deforestation andForest degradation program offers a promising mechanism for simulta-neously delivering mitigation, adaptation, and economic benefits whilesustaining vital ecosystem services. the basic principle is that coun-tries and those that own and manage forests would be paid to protectand increase the public goods they provide. similar ideas with regardto carbon sinks in soils are under discussion.such measures could be combined with adaptation efforts and pro-duce synergies. Maintaining or increasing forest coverage, avoiding till-age of highly organic soils, or integrating bio-char may lead to improve-ments in water retention and soil productivity, ultimately promoting theresilience of ecosystems and of the communities that depend on them.Mitigation would go hand in hand with adaptation. a high value wouldbe assigned to the sustainable management of natural resources andpotentially also promote the implementation of the conventions on bio-diversity and desertification.But there are also conflicts. ample experience tells us that withoutsecure rights and proper governance arrangements, the poor and land-less risk being forced out when the value of forests and land increases.New opportunities will enrich some while others lose out. if safeguardsagainst such risks are not put in place, new climate policy may furthermarginalize the poor and vulnerable.

natural resources, forests, and trees; health; energy access,climate, and development; risk and insurance; migration;cities; disaster risk reduction; and the Commission’s termsof reference and biographies of the Commissioners.

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

5

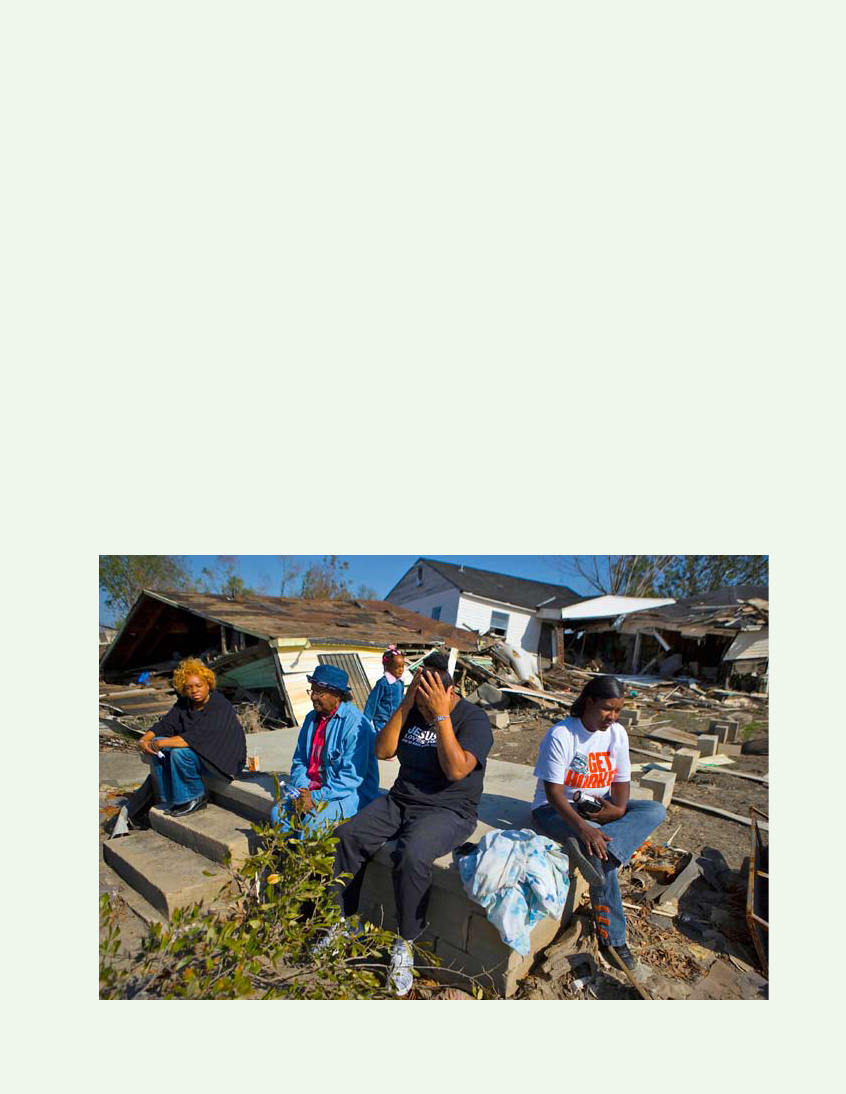

United StatesFor nearly eight years, Mike Miller, director of supportivehousing for UNITY of Greater New Orleans, has workedwith the city’s homeless population. The burly, beardedMiller reckons that demand for his services has increased60% since floods caused by Hurricane Katrina brokethrough badly built dikes in 2005.According to a US government survey, slightly more thanone-third of all New Orleans buildings – houses, churches,medical centers, and so on – are considered officially vacant.In early 2009, Miller is visiting James Kelly, 61, andDeborah Williams, 54, who have set up barebones house-keeping on the second floor of an abandoned house in a neigh-borhood of abandoned buildings, like many neighborhoodsin the city. In a back room are a battered bureau, a flimsy din-ing table, and a neatly made bed. The owner of the buildingis letting the pair live there in hopes of discouraging arson.It took Kelly and Williams three weeks to clear their livingspace of post-Katrina debris and lay plywood over rottingwood floors. There is still a large hole in the ceiling andthe walls are stained with water and mildew, but Williamssweeps the floor daily. A nearby church provides them withwater, and Kelly receives a monthly $600 disability checkthat pays for food.“It’s actually insanity to live in a place like this,” he says.“But it’s better than the street, where you can get raped orkilled.”UNITY’s Miller also knows that abandoned buildingscan be havens for drug dealers, drug users, and prostitutes.P h oto : Vincent L aforet

6

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

So he restricts his searches of vacant buildings to daylighthours, looking for signs of habitation, like bedrolls, clothes,or prescription vials. He says that 9 out of every 10 build-ings he searches show signs of people living in them.Kelly and Williams are just two of what Miller estimatesmay be as many as 10,000 people living in these abandonedstructures, a large portion of them, like Kelly and Williams,senior citizens.In New Orleans, lax construction codes had allowedhouses to be built below likely flood levels, and slow-mov-ing bureaucracy and begrudging federal aid have restrictedmany homeowners from either reclaiming or selling theirproperties.For renters, the situation is even worse. The LouisianaRecovery Authority has reported that more than 82,000rental units were badly damaged or destroyed by Hurri-cane Katrina, more than 44,000 of those in the greater NewOrleans region. It reports that rental rates in metropolitanNew Orleans have risen 52% since the hurricane, althoughcoming down from a post-disaster spike caused by land-lords looking to cash in on strong demand and very limitedsupply.City officials decided just before Christmas 2007 to teardown nearly 5,000 public housing units to make way forprivately built housing that promised to supply a small per-centage of below-market-rate housing at some time in thefuture. This decision was formally criticized in a UN reportthat decried “the disparate impact that this natural disastercontinues to have on low-income African-American resi-dents, many of whom continue to be displaced more thantwo years after the hurricane.”The lack of affordable housing hurts the most vulner-able, but it also contributes to maintaining a shortage ofinexpensive labor and creates a drain on social servicesprovided by both governmental and non-governmental or-ganizations.UNITY has obtained more than 3,000 federally spon-sored vouchers that low-income residents can use to helppay rent. But demand exceeds supply, and attention to theproblem is generally lacking, except in extreme circum-

stances, like the formation of two homeless encampmentsclose to public thoroughfares that UNITY helped to clearin the summer of 2007. Says Miller, “We play clean-up forthe whole broken system.”A short time after his visit to James Kelly and DeborahWillams, Miller was able to obtain for Williams an apart-ment specifically designed for her particular medical con-dition. Meanwhile, Kelly lives alone in the vacant buildingthe two had shared, waiting for his own chance to moveinto a real home for the first time in 10 years.“This is just surviving,” Kelly says. “This isn’t living.All I know is things are supposed to be better than this.We’re all trying to make the best out of a bad situation, butthis just ain’t no way for people to live.”

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

7

2. The Trust GapClimate change is a perfect moral storm. One consequence of this is that,even if the difficult ethical questions could be answered, we might still find it difficult to act.For the storm makes us extremely vulnerable to moral corruption.ProFessor stePheN G a rdiNer7

While climate change raises many scientific, technical, andeconomic issues, it is often described as primarily an issueof political will. Yet this shortcuts the fact that most na-tions are democracies, and thus political will must dependon the value citizens place on defending the vulnerable andthose who have had little to do with causing the problem,including future generations.The IPCC wrote in its 2007 report that determining whatconstitutes dangerous anthropogenic interference with theclimate system “involves value judgments. Science can sup-port informed decisions on this issue.”8Thus coping withclimate change, both mitigation and adaptation, becomesprimarily an ethical issue.The simplest ethical argument runs along the followinglines: the stronger and richer peoples and nations have beenputting GHGs into the atmosphere; this approach to devel-opment helped them get stronger and richer; their actionsare harming – and will cause greater and greater harm to– the weaker and the poorer, who have had very little todo with causing the problem; the rich should take a leadin cleaning up what they have done and should take stepsto protect the weak as well as future generations, who areblameless.Many argue the ethical stance quite vehemently, notingthat all of the world’s major religions and ethical systemsposit a duty of the stronger to help the weaker, especiallywhen it is the actions of the stronger that are inadvertentlyharming the weaker.Other commentators maintain that such “finger point-ing” arguments simply do not work in political negotiationsand are in fact an impediment to those discussions. A focuson the vulnerable without apportioning responsibilitymight be more helpful.Though the ethical argument appears at first glance

fairly straightforward, the quest for fairness in allocatingrights to emit GHGs has achieved little success. Sugges-tions range from all people being entitled to an equal shareof the atmospheric commons, to a “polluter pays” approachthat has countries paying for pollution they have generated,to a position accepting a state’s current rates of pollution –a sort of “squatter’s rights” approach. Some approaches fo-cus on the productivity of the carbon generated and otherson guaranteeing each nation at least a “subsistence level” ofGHG emissions.

The polluter pays principleA number of these approaches, and the negotiating stancesof the wealthier countries, tend to ignore a widely agreedprinciple that has been the basis of much international andnational environmental law for at least the last quarter-century. The polluter pays principle (PPP) requires that thecosts of pollution be borne by those who cause it.The principle first appeared internationally in the 1972Recommendation by the OECD [Organisation for Econom-ic Co-operation and Development] Council on GuidingPrinciples Concerning International Economic Aspects ofEnvironmental Policies,which said: “The principle to beused for allocating costs of pollution prevention and controlmeasures to encourage rational use of scarce environmen-tal resources and to avoid distortions in international tradeand investment is the so-called Polluter-Pays Principle.”

7

S. Gardiner, “A Perfect Moral Storm: Climate Change, Intergenera-tional Ethics and the Problem of Corruption,”Environmental Values15 (2006), pp. 397–413.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,Climate Change 2007:Synthesis Report. Summary for Policmakers(Geneva: 2007), p. 18.

8

8

|

Commission on Climate Change and Development

2.the trust Gap

It added that the principle “means that the polluter shouldbear the expenses of carrying out the above-mentionedmeasures decided by public authorities to ensure that theenvironment is in an acceptable state.”The PPP helps to internalize environmental externali-ties of economic activities so that the prices of goods andservices fully reflect the costs of production. Four differentaspects of the principle have been described: economically,it promotes efficiency; legally, it promotes justice; it pro-motes harmonization of international environmental poli-cies; it defines how to allocate costs within a state.9The principle has evolved into something called the ex-tended or strong PPP, as the OECD in the late 1980s includ-ed in the PPP costs related to accidental pollution, whichwould presumably cover GHG emissions.The PPP was reaffirmed in the 1992 Rio Declaration andis mentioned inAgenda 21and the World Summit on Sus-tainable Development’s Johannesburg Plan of Implemen-tation. It has become one of the fundamental principles ofinternational environmental law, and it is explicitly men-tioned or implicitly referred to in a number of multilateralenvironmental agreements.

The trust gapThe apparent willingness of wealthier countries to dismissduring the climate change negotiations a principle that theyand their organizations have insisted on for years is one ofseveral reasons that there is a “trust gap” between rich andpoor countries that makes climate and many other negotia-tions so difficult.One reason for this gap is that industrial nations have of-ten committed to increasing their official development as-sistance, but few have done as promised. Since 1970, leadersof most industrial countries have agreed many times thataid-giving nations should provide resources equal to 0.7%of their gross national income (GNI).Promises of more aid were made in Monterrey, Mexico,in 2002, when leaders pledged to increase aid to help coun-tries meet the Millennium Development Goals. The 0.7%commitment has been repeated more than 50 times, butmost industrial countries are still far from honoring theirpromises.In fact, the 22 main aid-giving countries gave $119.8 bil-lion in aid in 2008, the highest figure ever. But this only

represents 0.3% of OECD members’ combined GNI – wellbelow the percentage target.10Another breach of trust has occurred in the area of trade.In November 2001, World Trade Organization member na-tions agreed in Doha to a new round of trade negotiationsthat would benefit poor countries, allowing them a betterchance to trade their way out of poverty. In early 2009, thesetalks remained stalled, largely due to disagreements be-tween some industrial nations and rapidly developing ones.Mistrust does not flow in only one direction. Northernnations tend to worry that the South wants a free ride onmitigation, while getting considerable help with adapta-tion. They see rapidly developing economies such as Chinaand India as able and needing to do more. They denouncethe view, common in developing countries, that the Northcaused climate change, so the North should sharply cut itsown GHG emissions, leaving the South to develop along acarbon-intensive path until it is much richer.Recent work has shown that the notion that developingnations can remain carbon-intensive cannot withstand em-pirical scrutiny and is, in fact, dangerous for the South it-self. The South’s cumulative carbon emissions are alreadylarge enough to jeopardize climatic stability and its ownfuture growth, regardless of Northern emissions. By impli-cation, a fossil-fueled South will undermine its own devel-opment long before it reaches Northern income levels. (SeeFigure 2, p. 10.) Sustainable development will thereforerequire a shift toward clean energy in the South, beginningimmediately, as well as rapid reduction of Northern emis-sions.11Those who do not trust one another to keep to com-mitments can rarely negotiate successfully, especially onsomething as complex as a post-Kyoto climate framework.

9

H. C. Bugge, “The Principles of Polluter Pays in Economics and Law,”in E. Eide and R. van der Bergh, eds.,Law and Economics of the Envi-ronment(Oslo: Juridisk Forlag, 1996).Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),“Development Aid at Its Highest Level Ever in 2008,” press release(Paris: 30 March 2009).D. Wheeler and K. Ummel, “Another Inconvenient Truth: A Carbon-Intensive South Faces Environmental Disaster, No Matter What theNorth Does,” Working Paper 134 (Washington, DC: Center for GlobalDevelopment, December 2007).

10

11

Commission on Climate Change and Development

|

9

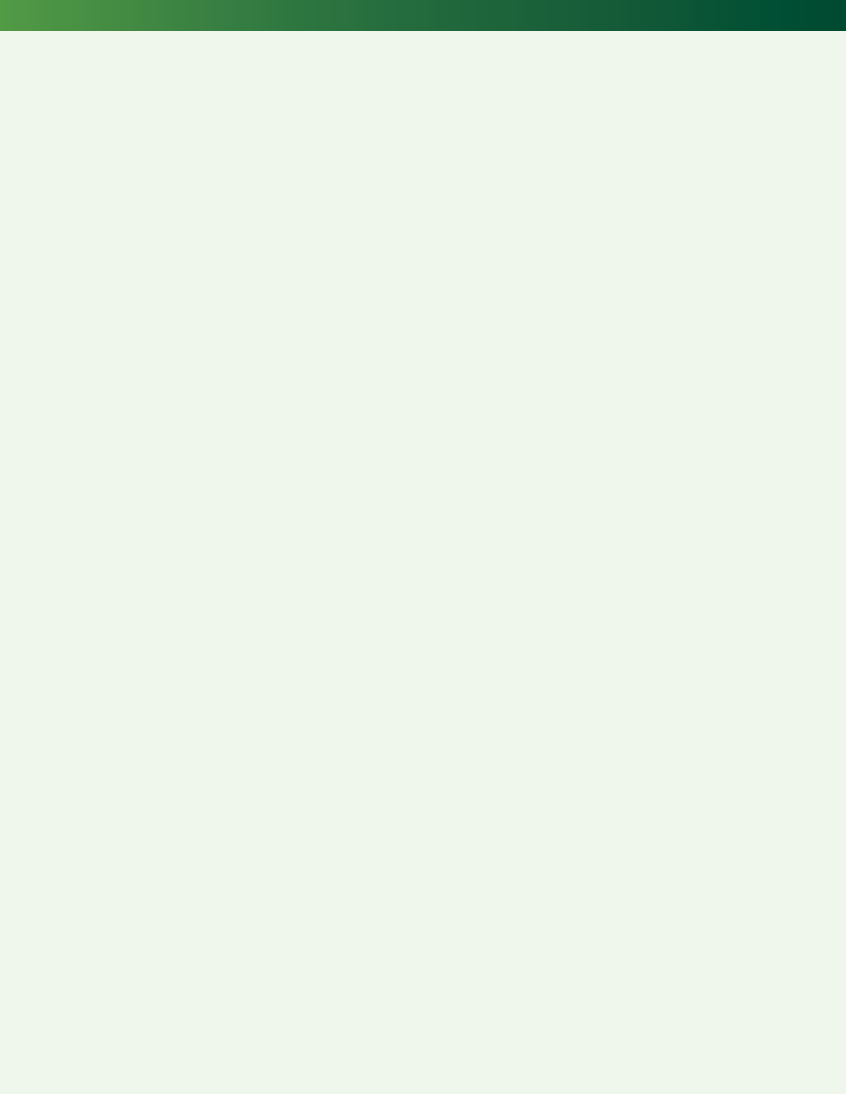

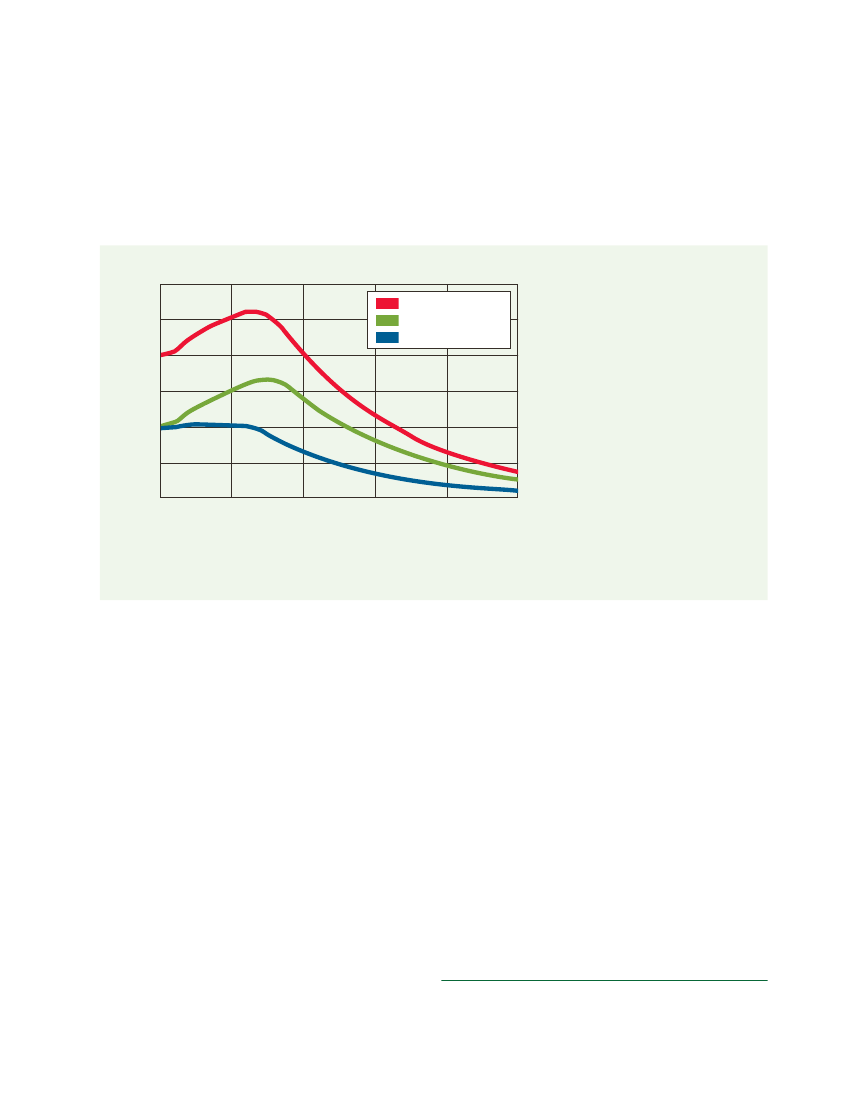

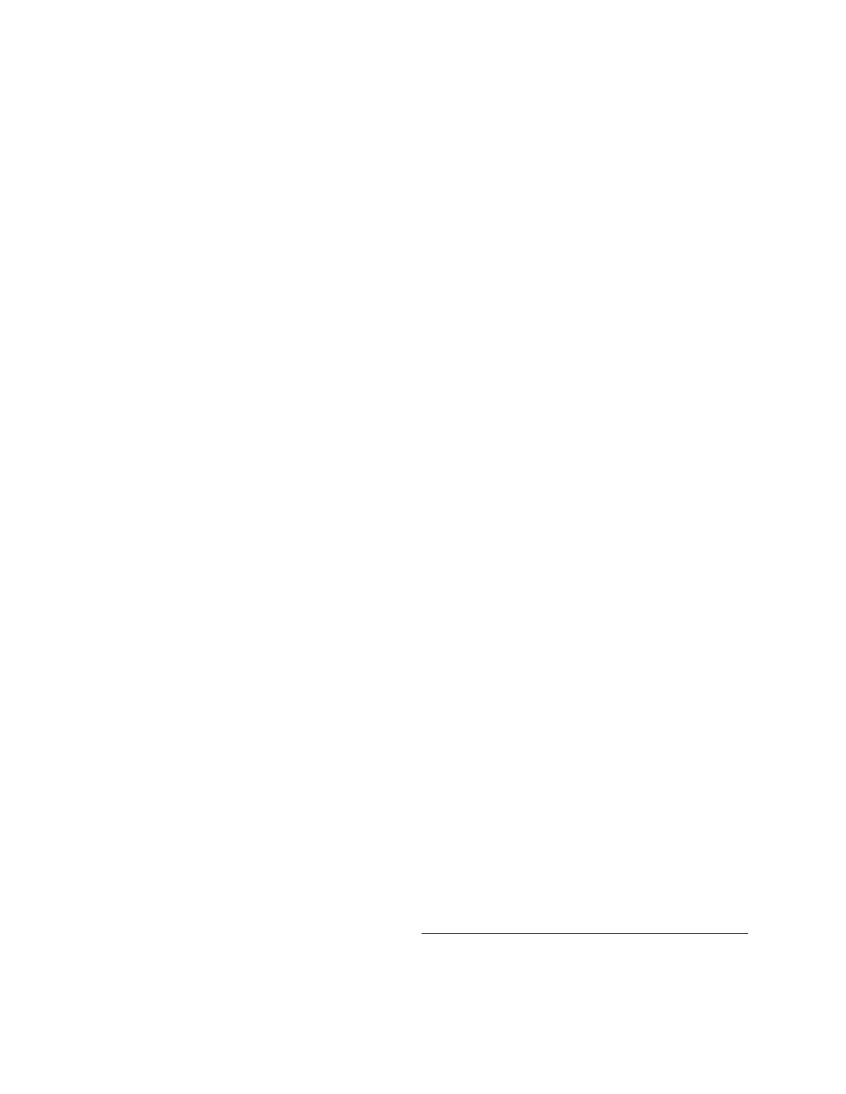

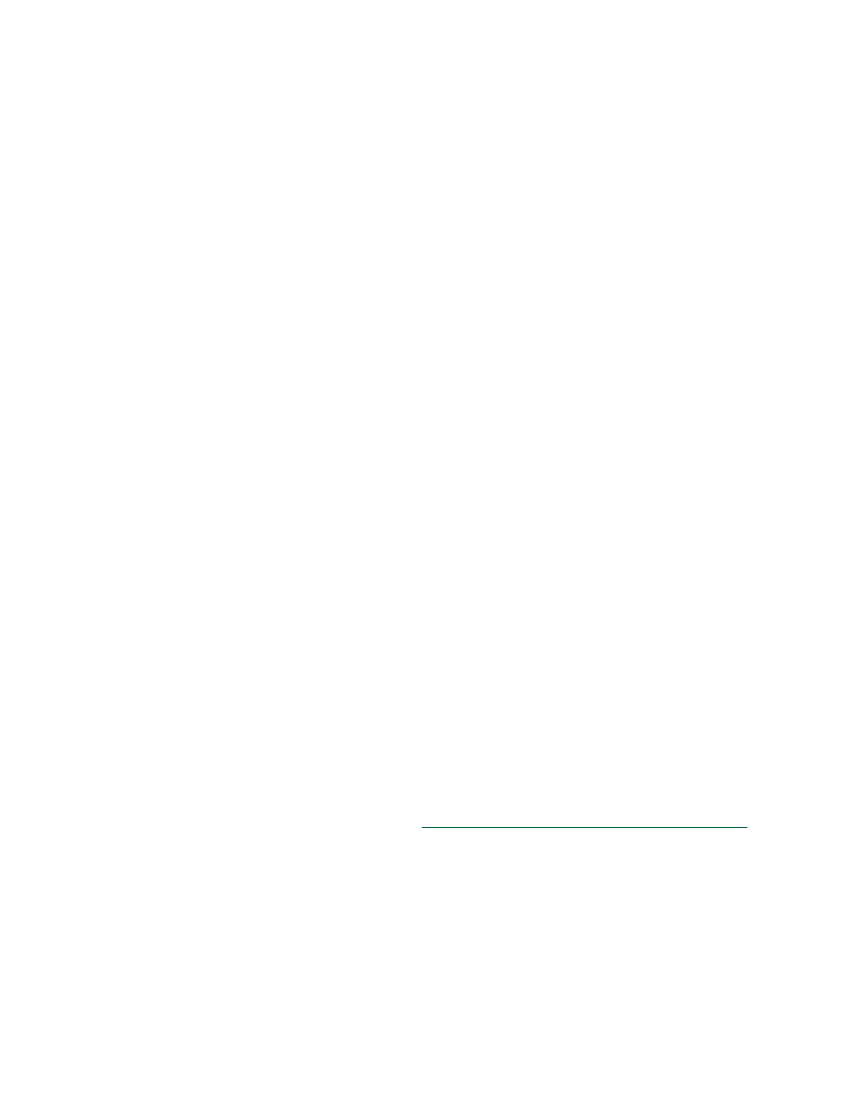

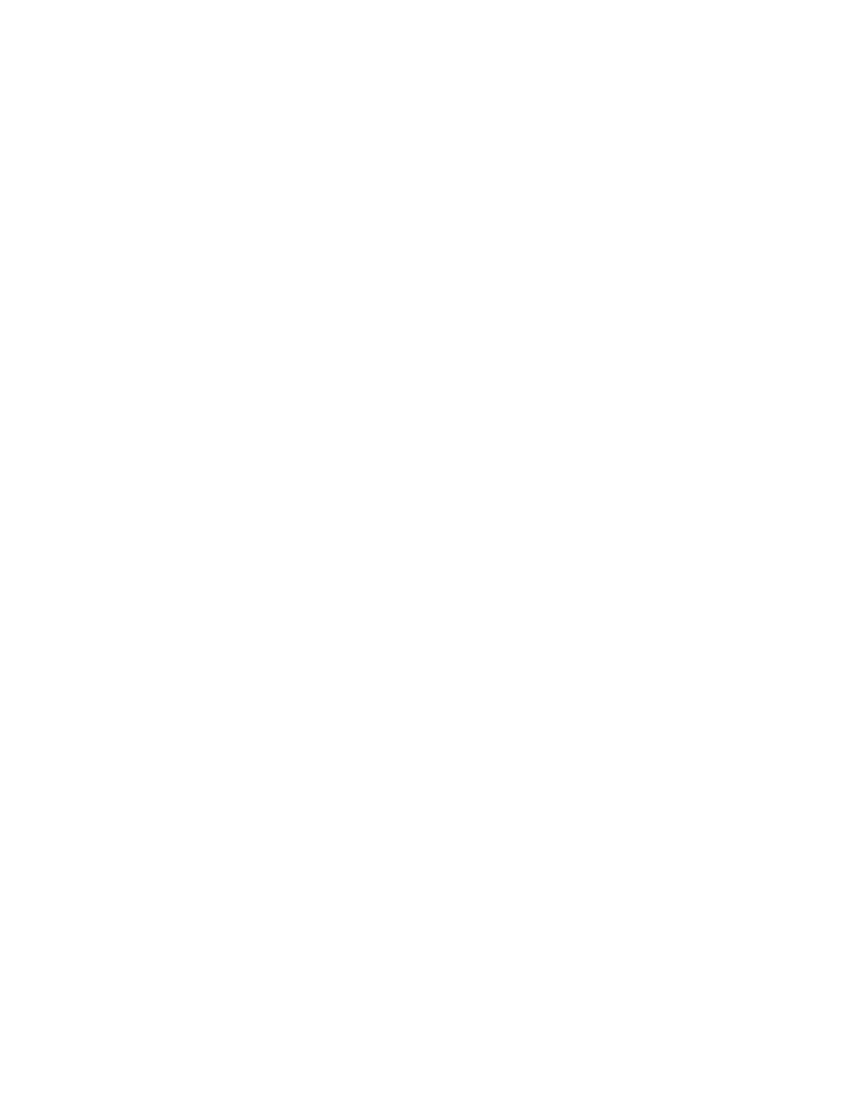

The South’s dilemmaFigure 2.

122�C Emergency pathway

Annual CO2 emissions (GtC)

10

Non Annex I emissionsAnnex I emissions

8

the red line shows the 2�c emergencyPathway, in which global co2emissionspeak in 2013 and fall to 80% below 1990levels in 2050.the blue line shows industralized countries’emissions declining to 90% below 1990levels in 2050.the green line shows, by subtraction,the emissions space that would remain forthe developing countries.

6

4

20200020102020203020402050

source: P. Bauer, t. athanasiou, and s. Kartha, “the right to development in a climate constrained World: the Greenhousedevelopment rights Framework,” heinrich Böll stiftung Publication series on ecology, Volume 1 (2008).

Industrial and developing nations must work quickly andeffectively to close the trust gap. Such an effort amongthe richer nations would include keeping past promises onincreased ODA, providing efficient aid for developing coun-tries’ adaptation to climate change, and identifying and in-vesting in synergies between mitigation and adaptation indeveloping countries – especially in land use, natural re-sources, and forestry management. Developing nations ontheir side need to ensure transparent management of fundsand a willingness to commit to goals and targets, based ontheir current capacity.