Sundhedsudvalget 2008-09

SUU Alm.del

Offentligt

UnclassifiedOrganisation de Coopération et de Développement ÉconomiquesOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

ECO/WKP(2008)20

15-May-2008___________________________________________________________________________________________English - Or. EnglishECONOMICS DEPARTMENT

ECO/WKP(2008)20UnclassifiedMOVING TOWARDS MORE SUSTAINABLE HEALTHCARE FINANCING IN GERMANYECONOMICS DEPARTMENT WORKING PAPER No. 612byNicola Brandt

All Economics Department Working Papers are available through OECD's Internet web site atwww.oecd.org/Working_PapersEnglish - Or. English

JT03245679Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origineComplete document available on OLIS in its original format

ECO/WKP(2008)20

ABSTRACT/RÉSUMÉMoving towards more sustainable healthcare financing in GermanyThe aim of the recent healthcare reform was to increase the sustainability of healthcare finances, byreducing its negative impact on employment and increasing cost-effectiveness via enhanced competition.Higher budget contributions will help decouple healthcare finances from labour income a bit, if and oncethey materialise. An improved risk adjustment between insurers could reduce incentives for risk selection,raising chances for competition to lead to more cost-effectiveness instead. However, the segmentation ofthe healthcare system in a private and a social insurance market will continue to pose equity and efficiencyproblems. Owing to its design, the price signal in the new financing system for social health insurance willbe both weak and distorted and this will need to be corrected for competition to produce desired results.More freedom for contractual relations between insurers, healthcare providers and pharmaceuticalcompanies could help to better reap the benefits of competition, but the government will need to watch theresults closely and adjust framework conditions if needed.JEL classification:I11, H51, H73Keywords:Healthcare; public sector efficiencyThis Working Paper relates to(www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/Germany).the2008OECDEconomicSurveyofGermany

*****Pérenniser le financement des dépenses de santé en AllemagneLa réforme récente du secteur de la santé vise à assurer un financement plus viable des dépenses desanté en réduisant leurs effets négatifs sur l’emploi et en améliorant leur efficacité économique grâce à uneconcurrence accrue. Si l’augmentation prévue des contributions budgétaires se matérialise, elle permettraun certain découplage entre le financement du secteur de la santé et les revenus du travail. Une meilleurerépartition des risques entre les assureurs pourrait réduire la tendance à une sélection des risques, si bienque la concurrence pourrait en fait conduire à une plus grande efficacité économique. Cela étant, lasegmentation du système de santé dans un marché où cohabitent assurance privée et assurance publiquecontinuera de poser des problèmes d’équité et d’efficacité. Par sa conception même, le nouveau système definancement de l’assurance maladie publique limite et fausse les signaux transmis par les prix ; il faudradonc remédier à ce problème pour permettre à la concurrence de produire les résultats souhaités. Une plusgrande liberté des relations contractuelles entre assureurs, prestataires de soins et laboratoirespharmaceutiques permettrait sans doute de tirer un meilleur parti de la concurrence, mais les autoritésdevront faire preuve de vigilance et adapter les conditions cadres le cas échéant.Classification JEL :I11, H51, H73Mots clefs :Santé ; gestion publiqueCe Document de travail se rapport àl’Étude économique de l’OCDE de Germany 2008(www.oecd.org/eco/etudes/Germany).Copyright OECD, 2008Application for permission to reproduce or translate all, or part of, this material should be made to:Head of Publications Service, OECD, 2 rue André Pascal, 7775 Paris Cedex 16, France.

2

ECO/WKP(2008)20

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Moving towards more sustainable healthcare financing in Germany ............................................................. 5The efficiency of the German healthcare system ........................................................................................ 5Public spending on healthcare in Germany is higher than in most OECD countries … ......................... 5… yet available indicators suggest that outcomes are only average ........................................................ 6Germany faces important challenges to improve spending efficiency .................................................... 7The recent reforms aim at improving cost-effectiveness and equity ....................................................... 9Healthcare financing reform ...................................................................................................................... 10The reform improves the framework conditions for competition between insurers… .......................... 10… but the price signal will be both weak and distorted......................................................................... 10The surcharge should be flat and redistribution should be tax-financed ............................................... 11Private health insurance reform ................................................................................................................. 14Making health insurance mandatory and more affordable will improve universal access tohealthcare… ........................................................................................................................................... 14… but including private insurers in the social insurance financing reform would be better ................. 14The reform provides only limited room to enhance competition among private insurers ..................... 15Competition based on healthcare provision .............................................................................................. 15The system will be further opened to direct and selective contracting… .............................................. 15… but the co-existence of collective and selective contracts involves challenges ................................ 18There is a risk that selective contracts could be financed as add-ons to collective contracts ................ 19The government needs to evaluate whether competition produces desired results ............................... 19New health plans expand consumer choice but may be misused for risk selection............................... 20The pharmaceutical market ....................................................................................................................... 21Administrative measures have helped curb spending for pharmaceuticals ........................................... 21But the government has also been successful with setting marked-based incentives recently .............. 23Enhanced possibilities for rebate agreements could reshape the market ............................................... 23If successful, the instrument could be developed further ...................................................................... 24Following other countries, Germany is introducing cost-benefit analysis for patented medicines ....... 24More competition in pharmaceutical distribution would be helpful ...................................................... 24Bibliography ............................................................................................................................................ 26Tables1. Health quality indicators, German rankings ............................................................................................... 72. General budget contributions to social health insurance........................................................................... 12Figures1. Healthcare spending and outcomes ............................................................................................................. 6Boxes1. The German healthcare system ................................................................................................................... 82. Collective contracting in the German healthcare system .......................................................................... 163. Novel forms of care .................................................................................................................................. 174. Cost-containment instruments in the German pharmaceutical market ..................................................... 225. Recommendations how to make healthcare financing more sustainable .................................................. 25

3

ECO/WKP(2008)20

4

ECO/WKP(2008)20

Moving towards more sustainable healthcare financing in GermanyBy Nicola Brandt1

The efficiency of the German healthcare systemPublic spending on healthcare in Germany is higher than in most OECD countries …The development of healthcare expenditure is a concern in all OECD countries, as its increase hasoutpaced GDP growth over the last 30 years, putting considerable strain on public budgets. In Germanyhealth spending per capita increased, in real terms, only by 1.3% per year on average between 2000 and2005. This also reflects the success of recent cost-containment measures (Figure 1). Even so, the Germanhealthcare system remains expensive. Only France allocates a larger share of its GDP to public spendingon healthcare. The share of public and private healthcare spending in German GDP is the fourth highestamong OECD countries.Notwithstanding Germany’s success in containing rising healthcare costs in recent years, thecombined effects of ageing and technological progress in the healthcare sector are likely to exertconsiderable upward pressure on healthcare spending over the years to come. OECD projections suggestthat public expenditures on health could rise by more than 1½ percentage points of GDP, even in a cost-containment scenario, while extrapolating spending trends from the 1980-2000 period would give a muchhigher increase, reaching up to 3½ percentage points of GDP (Oliveira Martins and de la Maisonneuve,2006).Rising healthcare costs have also put a strain on employment in Germany, as healthcare is mainlyfinanced via social charges levied on labour income (Box 1). This has increased labour costs and reducedwork incentives, especially for low income earners. Average contributions to finance social healthinsurance have increased from 8.2% in 1970 to 13.9% in 2007. Since July 2005 an additional contributionof 0.9% is levied on members of social health insurance funds (SHIFs).

1.

This paper is largely based on material from theOECD Economic Survey of Germanypublished in April 2008 underthe authority of the Economic and Development Review Committee (EDRC). The author would like to thankFrancesca Colombo, Valérie Paris, Martin Albrecht, Val Koromzay, Andrew Dean, Andreas Wörgötter, David Carey,and Felix Hüfner for valuable comments on earlier drafts. The paper has also benefited from discussion with theGerman authorities. Special thanks go to Margaret Morgan for technical assistance and to Susan Gascard for technicalpreparation.

5

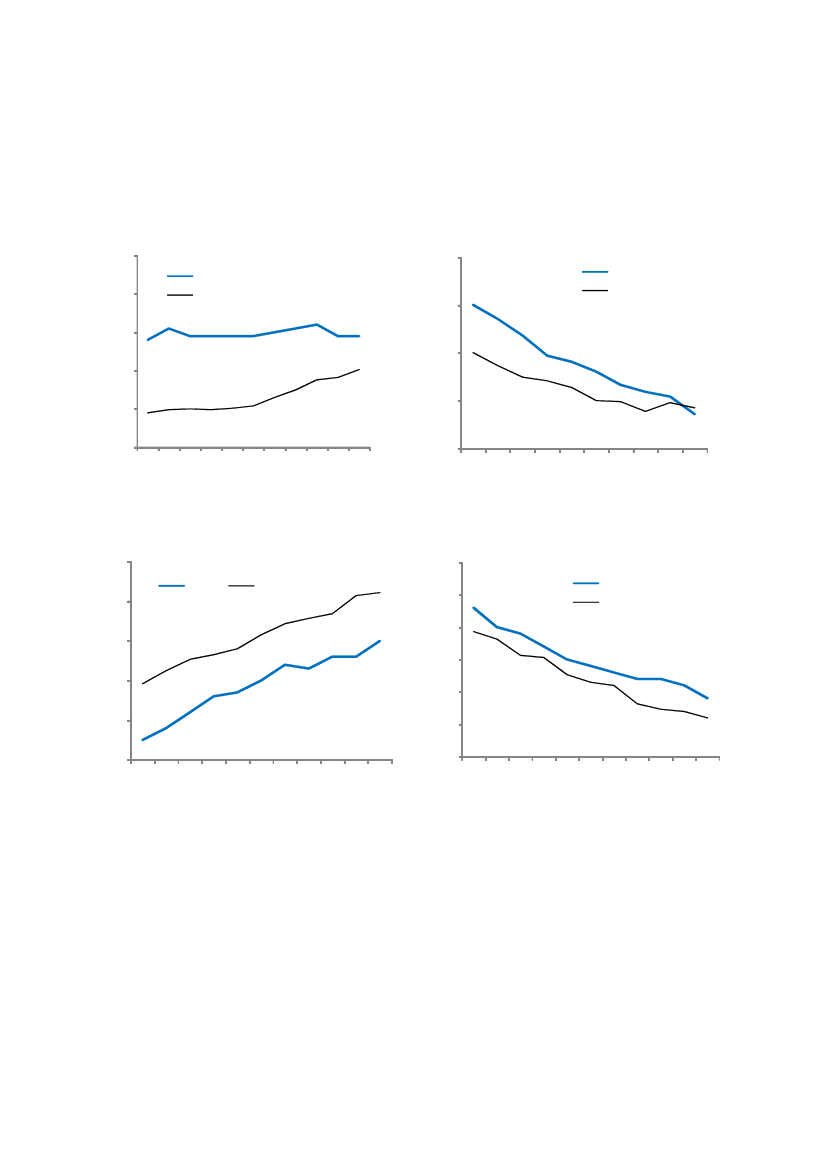

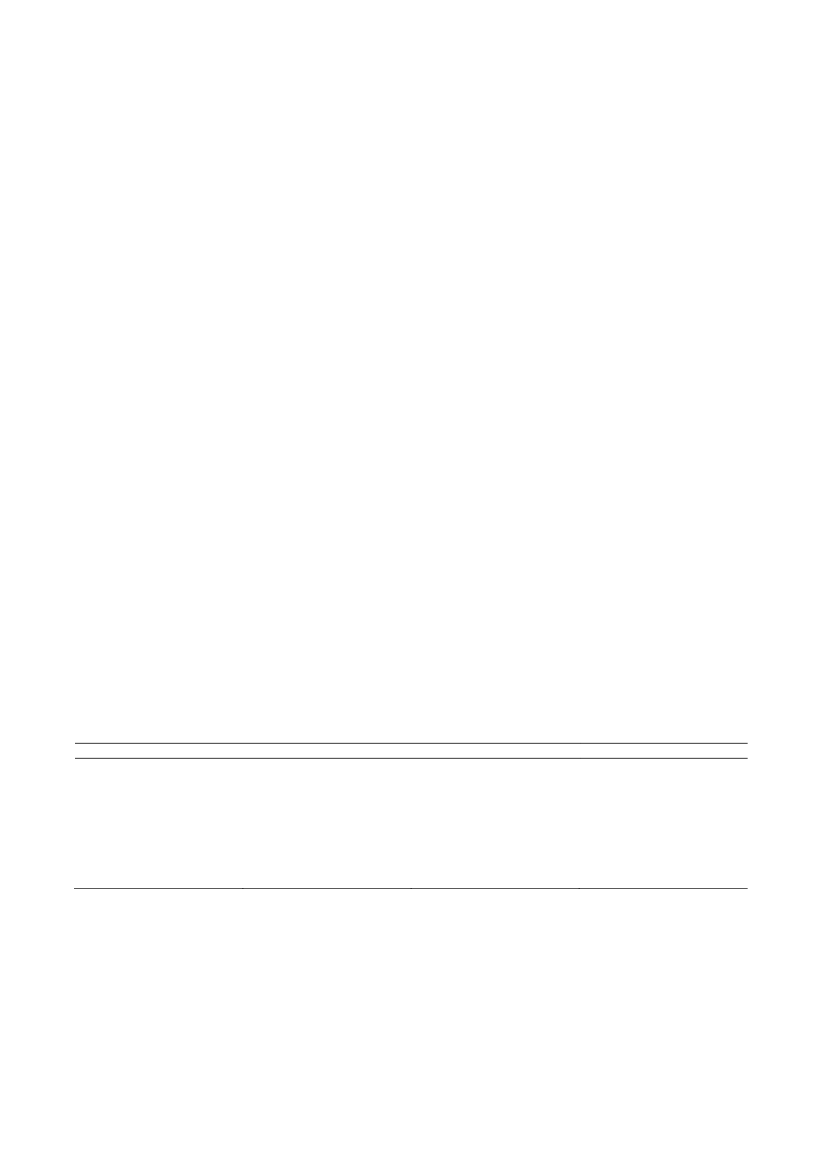

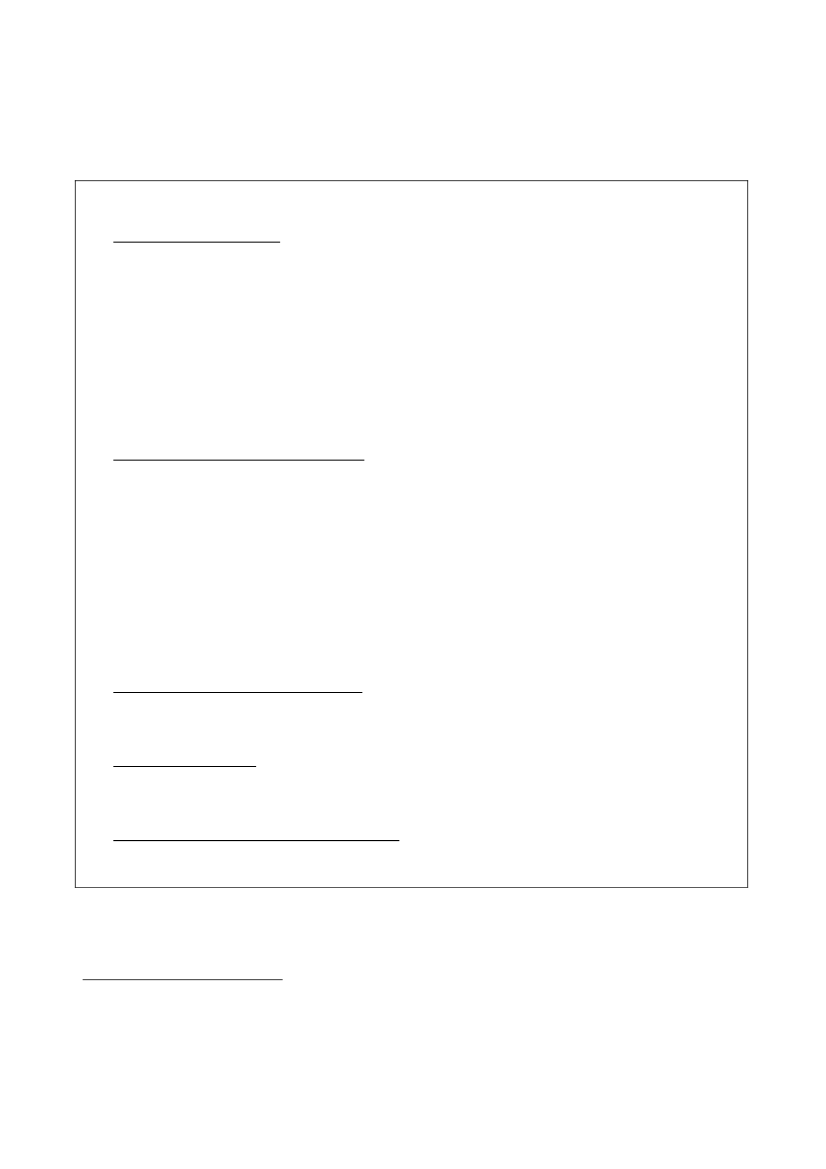

ECO/WKP(2008)20… yet available indicators suggest that outcomes are only averageFigure 1. Healthcare spending and outcomesPublic current expenditure on health% of GDP10Germany

Potential years of life lostThousand years per 100 000 population5.0GermanyPeer average

9

Peer average

4.5

84.073.5

6

5

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

3.0

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

20032003

Life expectancy at birthYears81GermanyPeer average

Infant mortalityDeaths per 1 000 live births6.0Germany

80

5.55.0

Peer average

794.5784.03.53.0

77

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2004

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Note: Peers are 6 countries with similar average GDP per capita (purchasing power parity basis) to Germany –Finland, France, Italy, Japan, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Potential years of life lost records years of life lost dueto death before age 70 that could potentially have been prevented. Infant mortality refers to deaths of children agedunder one year.Source:OECD (2007),Health at a Glance,OECD, Paris.

While it is notoriously difficult to evaluate spending efficiency in the healthcare sector overall theevidence seems to suggest that there is room for further improvement in Germany. Most health statusindicators, such as life expectancy, are more favourable in peer countries with similar GDP per capita whospend less on healthcare on average (Figure 1). On face value this would suggest that healthcare spendingis more efficient in these countries. Concerning recent developments in efficiency, however, approximatedby these indicators, the picture is a bit different. The number of years of life lost due to death before age 70(potential years of life lost), that could have been prevented a priori, has come down much faster in6

2005

2005

76

2004

ECO/WKP(2008)20Germany than in peer countries, while other outcome indicators have developed broadly on par. Togetherwith the observation that Germany has been relatively successful in containing the growth of healthcarespending in recent years, these indicators would suggest that it has improved the spending efficiency of itshealthcare system to a greater extent than its peers. However, these results should be treated with caution.Health status indicators cannot be directly linked to healthcare spending, as other factors such as lifestyle,income and the environment also play an important role.Nevertheless, more detailed indicators with a closer link to the quality of treatments also suggest thatthere is room for better outcomes. Germany in general achieves only average or worse for the availableranking indicators (Table 1, see also OECD, 2007). Keeping in mind that international comparability ofthese indicators is limited, it still seems striking that Germany does not achieve better outcomes given thatit invests so much more resources in its healthcare system than other countries.One reason for Germany’s above average spending consists in the high capacity it maintains in thehealthcare sector. Germany ranks on top of most other OECD countries in terms of doctors, nurses andhospital beds per inhabitant according to OECD health data.2While maintaining high capacity isexpensive, it has advantages for patients. Unlike many other countries Germany does not report problemswith waiting times for elective surgery (Hurst and Siciliani, 2003). Access to new medicines, to the familydoctor and to specialists also compare well in international comparison.3At the same time, the substantialcapacity of the German healthcare system suggests that there is enough supply to allow for morecompetition in a number of areas.Table 1. Health quality indicators, German rankingsIndicatorCervical cancer 5-year survival ratesBreast cancer 5-year survival ratesColorectal cancer 5-year survival rates (males)In-hospital mortality rate, strokeHemorrhagic strokeIschemic strokeIn-hospital mortality rate, myorcardical infarctionMortality rate asthmaSource:OECD (2007),Health at a Glance.

Rank18 out of 1918 out of 199 out of 117 out of 2312 out of 2320 out of 2414 out of 25

German data66%78%55%21%11%12%0.16 per 100 000

Germany faces important challenges to improve spending efficiencyCurrently, healthcare coverage is provided through a mix of social health insurance for about 90% ofthe population and primary private health insurance for eligible individuals that opted out of the system.Labour-income dependent social health contributions are set by insurers. The government has usedrationalisation rather than rationing to improve efficiency in recent years and competition between insurershas been one tool, as insurers in the social health system have competed on the basis of their contributionrates since 1996 and most members have been free to switch insurers since then (Box 1). Despite efforts todevelop this system further over recent years, a number of problems remain, that prevent competition fromyielding desired results.

2.

These measures are not fully comparable in the OECD health data collection and the German measure maywell be biased upward in comparison to other countries, but this would probably not change the qualitativeresult.See theEuro Health Consumer Index 2007of the Swedish thinktankHealth Consumer Powerhouse.

3.

7

ECO/WKP(2008)20In the current system there are incentives for insurers to direct their efforts at attracting high incomemembers with low morbidity risk (risk selection) rather than to improve the cost-effectiveness of theirservices. The reason is that while adjustments for differences in the income and risk structure of insurers’members exist, they remain incomplete. Currently, only 92% of income differences between insurers’members are adjusted for, as administrative expenditures are not included in the income adjustmentmechanism. There is indirect risk adjustment mainly for differences in income, age and gender. Thesecharacteristics have some predictive power for morbidity risk, but remain imperfect. While the introductionof partial outlier risk sharing for cases with large expenditures in 2002 had extended the risk structureadjustment, it currently remains incomplete. The distribution of risks was very uneven when free choice ofinsurers was introduced in 1996 and switching has led to further risk separation since then. Switching hasbeen largely limited to young and healthy members with relatively high income, many of whom havechosen company-based funds (Betriebskrankenskassen) that can set lower contributions, largely thanks tothe historically more favourable risk- and income-structure of their membership. The sick and the poor, inturn, have tended to stay with their local health insurance funds (AllgemeineOrtskrankenkassen).Whilethis need not be a result of conscious risk selection, but could be because of the well-off and people withlower morbidity risks having better information and lower switching costs than the sick (Nuscheler andKnaus, 2005), risk separation is still undesirable. Indeed, risk separation can drive insurers with anunfavourable risk structure out of the market even if they are more cost-effective than competitors with aneconomically more favourable membership. It has been a policy goal for some time to reduce theremaining incentives for risk selection, which has also prevented better treatment of the chronically ill(SachverständigenratGesundheit2000/2001).A second problem for effective competition consists in the system of healthcare provision based oncollective contracts between insurers and associations of providers (Box 1 and 2), which along with abenefit basket and fee schedules for physicians and hospitals defined at the national level leaves little roomfor insurers to distinguish themselves on the basis of their products and compete on quality. Therefore,insurers had little incentive to offer new and improved products and this has hampered innovation. Inaddition, separate negotiations and quasi-budgets for hospitals and physicians in the outpatient sector havehampered care coordination and thus both healthcare quality and efficiency.Box 1. The German healthcare systemSocial health insurance:Around 90% of the German population are covered by social health insurance, whichis financed via proportional social charges levied on labour-income up to a threshold (€3 600 per month in 2008) andshared evenly between employers and employees except for a surcharge of 0.9 percentage points which is exclusivelyfinanced by the members of SHIFs . There is free co-insurance for spouses without or with limited income and forchildren.There are more than 200 SHIFs (Krankenkassen) who act as quasi-public non-profit corporations. Most socialhealth insurance members have been free to choose their insurer since 1996. Insurers compete on the basis of theircontribution rate, which they set themselves at a level which allows covering costs.Contractual relations with providers:Nongovernmental corporatist bodies are the main actors in the socialhealth insurance system; in particular insurers or their associations contract services collectively with physicians’ anddentists’ associations. Services are rewarded by lump sums paid to doctors’ associations which they distribute amongtheir members in line with the quantity of services provided. Hospitals are represented by organisations based onprivate law.Private health insurance:The self-employed and individuals with gross monthly earnings exceeding a thresholdfor three years in a row (currently €4 012.50) can opt out of the social health insurance and take out private healthinsurance instead. Civil servants get 50% of their health care costs reimbursed by their employers if they take outprivate insurance to cover the rest. Premia are flat and rated by individual risk. People who qualify for privateinsurance can stay in the social health insurance system and many do, as risk-rated premia that increase with age andthe need to pay insurance for all family members can make private insurance financially unattractive. After a switch toprivate insurance it is difficult to go back to the social insurance system.

8

ECO/WKP(2008)20A further problem is the segmentation of the health insurance market hampering equity andefficiency, as around 10% of the population opt out of the social insurance system to take out privateinsurance instead. Private health insurance members are in general wealthier than social health insurancemembers, because they have to surpass an income threshold to qualify (Box 1). Equity problems arise,because the social health system involves many re-distributional elements that are deemed sociallydesirable, for instance the transfer from higher to lower incomes through the income-dependence ofcontributions and from childless singles to families through the free co-insurance of spouses and childrenwithout own income. Exempting people with higher incomes from contributing to this seems questionable.The segmentation also impacts on risk pooling in unfavourable ways and therefore on efficiency, as ittends to remove good risks from the social health insurance system (Colombo and Tapay, 2004). Peoplewith private health insurance tend to be not only wealthier, but also healthier than the population insuredvia social insurance, as income and health are in general highly correlated and people with high-morbidityrisk qualifying for private insurance often stay in the social insurance system on account of the high premiathey would have to pay as a result of individual risk-rating by private insurers (Box 1).The recent reforms aim at improving cost-effectiveness and equityThe original aim of the healthcare reform enacted in April 2007, the competition reinforcement act forsocial health insurance (Gesetzzur Stärkung des Wettbewerbs in der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung),was to put healthcare financing on a more sustainable footing and limit its effect on employment. As thename of the reform law suggests, the government saw enhanced competition as the main tool to achievehigher cost-effectiveness. Reform elements include:•A financing reform of the social health insurance system to partially decouple healthcare costsfrom labour income. A central health fund will collect uniform – rather than insurer-specific –labour-income dependent contributions and general tax money, which will then be distributed toinsurers as income- and risk-adjusted capitations. Insurers that cannot cover their costs with themoney received from the central health fund have to levy surcharges on their members, whileinsurers with surpluses can grant refunds.Greater freedom for insurers in their contractual relations with providers to allow them tocompete based on the quality of their products and their efficiency (cost-effectiveness). Inparticular insurers possibilities to contract a limited set of – at least for the German system –rather novel forms of care directly and selectively with providers will be broadened.Greater contractual freedom for insurers to enhance price competition in the pharmaceuticalmarket, in particular through improved possibilities to engage in rebate agreements withpharmaceutical companies.In addition, the recent reform addressed the problem that an increasing number of citizens has nohealth insurance, by making health insurance mandatory and improving affordability of privatehealth insurance.

•

•

•

While the governing coalition partners shared the reform goal to decouple healthcare costs more fromlabour income, the final result of the reform effort has been a difficult political compromise between theirdifferent concepts how to reach this goal. The Christian Democrats preferred a Swiss-style social healthsystem based on community rated4flat-rate premia with tax subsidies for low-income earners, while4.That means unlike in the German private health insurance system premia would not be subject toindividual risk rating; they would not depend on the individual age and risk of the insured, but on theaverage age and morbidity risk in the insured community.

9

ECO/WKP(2008)20preserving a separate private market segment. Decoupling from labour income would have been achievedby making contributions independent of income. Social Democrats, instead, wanted to preserve income-dependent contributions, while achieving some decoupling through an enlargement of the base. Theirproposal was to extend it to income sources other than labour and include private health insurancemembers in the social system.Healthcare financing reformThe reform improves the framework conditions for competition between insurers…The new financing model based on the central health fund will be introduced for the social healthinsurance system in 2009. While social health insurers currently decide on their labour-income dependentcontribution rate independently, the government will then set a uniform rate for all insurers. To makeinsurers’ revenues completely independent from their members’ income, the central health fund willdistribute flat premia to insurers for each of their members. Moreover, it is planned to introduce morbidity-oriented risk adjustment in 2009, which would provide insurers with financial adjustments for memberswith costly catastrophic chronic diseases. A scientific advisory board has recommended 80 diseases to beincluded in the calculation of these adjustments.The new adjustment for differences in income and risk structure will be an important improvement, asincentives for insurers to compete for high-income members with low morbidity risk are strong as long asthe adjustment remains as incomplete as it is now. The introduction of a more complete income and riskstructure adjustment will allow insurers to concentrate on providing their members with cost-effective,high quality treatment. Incentives to avoid offering good treatment, as it could attract costly customers withhigh morbidity risk, should become less important. This will improve chances for competition to lead tocost-effectiveness rather than risk selection.… but the price signal will be both weak and distortedThe price signal for competition in the new system will come from a surcharge that those insurers willhave to levy that cannot cover the costs with the payments they receive from the central health fund.Insurers with lower costs in turn can grant refunds to attract new members. Patients can switch their insureranytime, including when they announce surcharges and insurers have to inform their members about thispossibility with their surcharge announcement. Insurers can choose whether they want to levy income-dependent or flat surcharges, but to avoid financial hardship, even the flat surcharge cannot exceed 1% ofmembers’ income subject to contribution charges. A check as to whether the 1% ceiling applies will beperformed once the surcharge is higher than € 8 per month. Thus, for low-income members the surchargecannot exceed € 8, while for higher income members it cannot exceed € 36 per month, given the currentthreshold for income that serves as a contribution base. The government will initially set contribution ratesso that the central health fund covers 100% of the social health system’s expenditures. If the proportion ofthe system’s costs financed by the central health fund falls below 95%, the government will have toincrease contribution rates. By implication, the current goal seems to be that surcharges cover not morethan 5% of the system’s costs.The price signal will be weak, as only a low share of the system’s total cost will be financed bysurcharges. In addition, the 1% hardship rule limits surcharges beyond the differences in contribution ratesthat exist between different insurers today, which can reach up to 4 percentage points. On the other handcontribution rates are shared between employers and employees in the current system, whereas in the newsystem employees will pay the surcharges alone, which by itself would increase the impact on them. Yet,this effect is very likely to be too weak to outweigh the limitation of the surcharge built in through itsrelatively low percentage of members’ income and of the system’s total costs.

10

ECO/WKP(2008)20The hardship clause will lead to the size of the surcharge partly reflecting members’ income ratherthan only the cost-efficiency of the surcharging fund, which is a distortion. As the surcharge is intended tobe a price signal and thus the vehicle to enhance competition for cost effectiveness, it should ideally reflectinsurers’ efficiency only.Moreover, redistribution associated with the 1% ceiling or with an insurers’ family structure willoccur within the membership of surcharging insurers, leading to additional distortions(Sachverständigenrat, 2006). As a result of the hardship clause, insurers can only raise limited revenuesthrough surcharges on low-income members and they will have to obtain the rest by increasing surchargeson those who earn more. This will put insurers with many low income members at a competitivedisadvantage. In the extreme, the hardship-clause can lead to subsequent waves of members hitting the 1%ceiling, which will oblige insurers to increase the surcharge levied on members above the ceiling evenmore. As a result of this effect, a simulation study shows that 61% of the members of some insurers with ahigh percentage of low income members would hit the 1%-ceiling with a relatively low surcharge of € 10per months (Schawo and Schneider, 2006). If local insurance funds needed a flat surcharge of € 20 permonth to fill their financing gap none of them would be able to raise the full amount they need as a resultof the 1% rule. Likewise, surcharging insurers with many contribution-free family members have to levyhigher surcharges on those of their members who do pay than insurers with the same costs but with fewercontribution-free family members.The surcharge should be flat and redistribution should be tax-financedThe implicit choice to limit the price signal to finance only 5% of the system’s overall costs and to 1%of members’ income seems to be an opportunity lost, especially in terms of encouraging more low-incomeearners to react to it. With a directly collected flat surcharge combined with the possibility to switchinsurers any time, including before they levy announced surcharges, the incentive for low income earnersto switch might have been enhanced to a considerable degree. The envisaged large share of labour incomedependent contributions to the system’s overall finances and the possibility to leave insurers announcingsurcharges immediately should be sufficient to protect low income earners from financial hardship.Therefore, the government should make the surcharge flat without any limitation in terms of its share inmembers’ income.To the extent that additional redistribution is needed, it should not be organised within themembership of surcharging insurers, but through tax subsidies to avoid distorting competition and ensurethat redistribution is financed by all taxpayers.5Otherwise, insurers with an unfavourable income or familystructure will be put at a competitive disadvantage and undesirable incentives to attract high-incomemembers without co-insured family members will remain. As reducing incentives for risk selection is oneimportant reform goal, this should be avoided. It should be noted, however, that tax subsidies would notonly distort incentives for lower income earners to search for an efficient insurer, but it would also involvesubsidising relatively inefficient insurers with public funds.Higher flat surcharges would help decouple healthcare finances more from labour costsIncreasing the flat surcharge would help decouple healthcare financing from labour costs, which hadbeen an important reform goal, but it also raises the need for higher subsidies for low-income earners,which can create problems of their own. Decoupling would occur even if tax subsidies were needed to5.Tax subsidies could be administered through the central health fund or they could be paid directly torecipients (seeSachverständigenrat,2006). As long as labour income contributions finance 100% of thesystem’s costs, the central health fund can finance subsidies for surcharges of individuals with low incomewithout requiring further tax contributions.

11

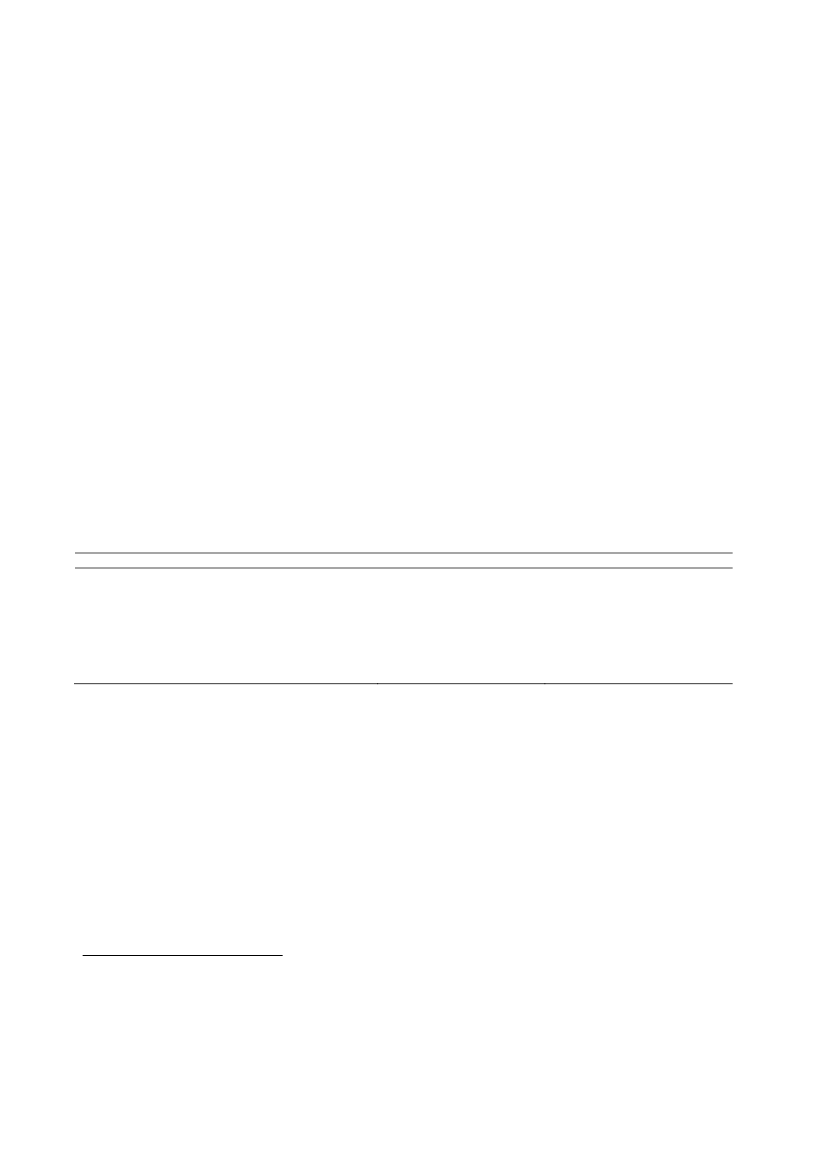

ECO/WKP(2008)20avoid financial hardship, because general taxes draw on a larger base than social contributions. In theNetherlands, which had introduced a similar system in 2006, flat-rate contributions make up a much largerpart of total contributions. The intention was for it to cover 50% of the costs (Greßet al.,2007). This canmake for a more significant price signal with a potential to increase price competition. On the other hand,higher flat-rate premia also raise the need to protect lower income earners from financial hardship, which isdone through tax subsidies in the Netherlands. As pointed out above, this reduces the price signal forsubsidised insurance members, while at the same time providing tax subsidies to inefficient insurersassuming that competition is undistorted by differing income and risk-structures. Switzerland experiencesthese problems with its system of flat premia combined with subsidies for low income earners. The Swisscase also shows that it can be difficult to contain increases in tax subsidies, if continued health costinflation pushes up the premia, raising a need for further financial help for low income earners (OECD,2006). There seems to be no way around an equity-efficiency trade-off when competition is used as a toolto attain more cost-efficiency in healthcare and there is currently no example of a country that hasaddressed both problems at the same time in an entirely satisfactory way.When developing the reform further, Germany should aim at striking a careful balance between theneed for the surcharge to be high enough to act as a functioning price signal and the need to avoid thatnecessary tax subsidies for lower income earners create efficiency problems of their own. A moderatesurcharge that requires little or no tax subsidies for low income earners may well be the right solution, butthere is probably scope to raise the financing contribution of the surcharge to a higher share than thecurrently envisaged 5% of the system’ s total costs.Higher budget contributions will limit the impact of healthcare financing on labour costs …To reduce the effect of rising healthcare expenditure on labour costs, contributions from the federalbudget to the central health fund will be gradually increased until they reach € 14 billion after 2015.Conceptually, the government intends budget contributions to compensate insurers for benefits for whichthey receive no or only partial member contributions, such as the free co-insurance for spouses andchildren without earnings subject to social contributions. Budget contributions extend the financing ofthese redistributive elements to all taxpayers, thus partly addressing the equity problem that arises as aresult of the segmentation of the healthcare system in social and private insurance.Table 2. General budget contributions to social health insuranceIn billion eurosYear200420052006200720082009201020152016Source: Ministry of Health.

2004 healthcare reform12.54.24.24.24.24.24.2-

2006 budget law12.54.21.50000-

2007 healthcare reform---2.52.54.05.51314

However, there may be some doubt as to whether the reform will actually materialise in view of thesee-saw policy changes with respect to general budget contributions to the social healthcare system in therecent past. Table 2 shows how envisaged budget contribution paths have been changed by subsequent law.As a result budget contributions have been reduced substantially in 2007 compared to 2006 and,notwithstanding the planned increasing path of budget contributions, they will not exceed their 2006 levelbefore 2010. The government has found no agreement yet on how to finance increasing budget12

ECO/WKP(2008)20contributions to the central health fund. The government should solve this issue soon to avoid putting thisimportant reform at risk.If it materialises, however, the increasing path of budget contributions will eventually help relieve theburden of healthcare financing on non-wage labour costs with potentially favourable employment effects,especially for low-wage earners. This would be the case even if increasing federal budget contributionswere to be financed mainly through an increase in income taxes. This is so because income tax is leviednot only on labour income, but also on other bases, more people pay income taxes than insurancecontributions, including 10% of the population currently covered by private health insurance; and, unlikethat for contributions the base for income labour taxes is not capped. A shift from insurance contributionsto income taxes would thus spread the financing burden more widely. The pressures of healthcarefinancing on non-wage labour costs could decrease even more if higher budget contributions were to befinanced by increases in other taxes,e.g.consumption taxes, or by expenditure reductions in other areas. Arecent study suggests, that the positive effects on efficiency, economic growth and fiscal sustainability ofshifting the tax burden from labour income to other sources can be substantial (Botman and Danninger,2007).… but for now the burden of healthcare financing on non-wage labour costs has increasedFor the time being, political decisions have decreased revenues, while increasing costs of insurers.This has led to contribution increases in 2007, thus running counter to the government’s goal of reducingnon-wage labour costs. In anticipation of lower contributions from the federal budget and higher costs formedicines as a result of the VAT increase by 3 percentage points in early 2007, a majority of insurersincreased their contribution rates at the beginning of 2007. As a result, average contribution rates were0.6 percentage points higher in 2007 than in 2006. This combined with favourable labour marketdevelopments helped insurers to achieve an unexpected combined surplus of € 1.78 billion in 2007, whichmay put some of them in the position to lower contribution rates. Yet, these revenues are probably at leastto some extent of a cyclical nature.Higher budget contributions and the abolition of free co-insurance for spouses would be helpfulThe VAT increase in 2007 has contributed to an unfavourable, if unintended, impact on healthcareexpenditures and thus on non-wage labour costs, running counter to one of the stated goals of the taxreform, namely the partial shifting of social contributions from labour income to other tax bases. The VATincrease in 2007, together with favourable cyclical effects, has allowed the government to lowerunemployment benefit contributions quite significantly from 6.5% to 3.3% in 2008. On the other hand, ithas fully impacted on the prices of medicines, as they are subject to full VAT rates in Germany unlike inmost other OECD countries. For policy consistency, the government might want to consider whether itshould not increase budget contributions to alleviate the effect of the increase in VAT on insurers’finances.6In addition and as an alternative to a part of the budget contributions to the central health fund, thegovernment should also reconsider free co-insurance for spouses as it increases non-wage labour costs forthose who do pay, while also contributing to an unintended unemployment or low-employment-trap forsecond earners. This puts a strain on the contribution base and on economic growth. Engaging all taxpayers in the financing of free co-insurance for spouses through budget contributions would be moreequitable than the current financing via social charges and it would also reduce the negative effect on non-wage labour costs to some extent. However, the negative incentives for second earners to take up full-time6.Reducing the VAT rate on pharmaceuticals, instead, is not a good option, as it decreases the transparencyof the tax system further and runs counter to efforts of increasing tax collection efficiency (OECD, 2008).

13

ECO/WKP(2008)20work that result from free co-insurance can only be abolished by requiring every couple to pay for theinsurance of both spouses (OECD, 2008). In addition, this would lower contributions with a potential tounleash further positive employment effects. The government sees free co-insurance of spouses as oneelement of compliance with the constitutional requirement to protect marriage, but given the negative side-effects, it should consider whether there are other instruments to achieve the same goal. Correspondingsocial concerns about the availability of health care for non working spouses are on one hand already takencare by the current health insurance reform, which introduces mandatory health care insurance.Affordability issues on the other hand would have to be dealt with by contributions from the budget andcould be financed with savings on payments to compensate SHIFs for non-contributing members.Private health insurance reformMaking health insurance mandatory and more affordable will improve universal access to healthcare…To address the issue of an increasing number of uninsured citizens – around 200 000 people in early2007 – the reform makes health insurance mandatory and takes measures to improve affordability. Whilepeople covered by private health insurance are wealthier on average than those in social health insurance,transferral to the private insurance system can lead to a loss of insurance coverage due to an inability topay the premia as a result of income or job loss later on or strong increases in premia associated with risk-rating, including premia increasing with age.To make it easier for people with high morbidity risk and for those who have experienced incomelosses after qualifying for private health insurance to pay their insurance premia, private health insurerswill have to offer a standard insurance policy dubbed “basic tariff” from 2009. There will be no riskadjustments, except once for age and gender when entering the contract, and coverage will be similar to thesocial health insurance. Private health insurance companies have to offer this tariff to anybody qualifyingfor their system who asks for it, although strict time limits apply for switching for those who are alreadycovered by a different private insurance policy.7The premium cannot exceed the maximum contribution tosocial health insurance and additional subsidies apply for people who cannot afford the premium.8… but including private insurers in the social insurance financing reform would be betterHowever, including private health insurers and their clients in the new financing system based on thecentral health fund would be preferable as it would address the equity and efficiency problems resultingfrom the segmentation of the healthcare system in social and private insurance. While the equity problemwill be addressed somewhat by channelling more federal budget contributions into the central health fund,this will not compensate for the full amount of redistributive elements in the social health insurance andpast experience has shown that budget contributions are vulnerable to change. Including private healthinsurers in the financing system based on the central health fund would be a better targeted and morereliable measure to improve financing equity.

7.

People who are already in the private health insurance can switch to the basic tariff of a company of theirchoice, but only during the first 6 months of 2009. Those who are older than 55, pensioners and peoplewho can prove that they are unable to pay the premia can switch beyond that time limit. Those who moveinto the private health insurance system after 2008 have the choice to switch to the basic tariff of anyinsurance company without any time limits.Private insurers will be obliged to halve the premia for the basic tariff for people belonging to the privatehealth insurance system who are eligible for means-tested unemployment benefit or would become eligibleas a result of the premia. These individuals can receive additional subsidies from the municipalities or theFederal Labour Agency if they are still unable to pay their contributions to private health insurance.

8.

14

ECO/WKP(2008)20A unified system to finance the social health insurance coverage for all citizens would also improverisk pooling and increase efficiency, as explained above, helping to lower contributions with a potential toboost economic growth and employment. Recent studies suggest that the social health insurance systemloses around € 750 million each year, as a result of switching between the private and the social healthinsurance systems (Albrechtet al.,2007a). Allowing high-income earners with low morbidity risk towithdraw from the system makes risk sharing among the remaining social health insurance memberscostlier, thus leading to higher contributions. Since contributions are levied on labour income this also actsas a brake on employment, thus undermining both economic growth and the basis for social contributions,thereby leading to a vicious circle that negatively affects society as a whole. Including private insurance inthe financing system based on the central health fund as practiced in the Netherlands would provide formore efficient risk pooling and improved financing equity. Private health insurers would still be free tooffer additional coverage that goes beyond social health insurance.The reform provides only limited room to enhance competition among private insurersTo stimulate competition between private health insurers, the government has made it easier totransfer accumulated reserves to a new insurer, but this is very limited. Reserves serve to smoothcontributions over the life cycle. Without them premia would rise even more sharply with age, asmorbidity increases. That means that if reserves are not portable, switching insurance company becomesmore and more unattractive over time. However, strict time limits will apply for people already insured inthe private insurance system and transferring reserves will be limited to the amount of assets that wouldhave been accumulated on a basic tariff. People on an insurance contract with a broader coverage risklosing a considerable part of their assets and switching will remain unattractive for them. Thus,competition between private insurers will be limited to the basic tariff which will probably be attractivemainly for those confronted with high risk-surcharges on regular private health insurance contracts. Thus,the basic tariff may be subject to negative risk selection. To prevent that insurers will face competitivedisadvantages through different morbidity risks within the basic tariff a risk-structure-adjustment will beimplemented.Competition based on healthcare provisionThe system will be further opened to direct and selective contracting…Freedom for insurers to contract selectively and directly is enhanced further with the new reform,which will enable insurers to influence the quality and cost-effectiveness of services that they provide anddistinguish themselves on the basis of their offer. If instead they were to remain bound to buy healthcaresolely on the basis of collective contracts (Box 2), the only parameter that they could influence would betheir own administrative costs.

15

ECO/WKP(2008)20

Box 2. Collective contracting in the German healthcare systemInambulatory care,regional physicians’ and dentists’ associations negotiate collective contracts with insurers ortheir associations. The insurers make total payments to the physicians’ associations for the remuneration of all of theirmembers, in lieu of paying the physicians directly. The collective payment to the physicians’ association is intended toreimburse it for its obligation to ensure access to healthcare for everyone within reasonable distances and time limits.The total payment is usually negotiated as a capitation per member or per insured person. The physicians’associations distribute these payments among their members as fees for services based on a floating point system. Allapproved medical procedures are listed in the Uniform Value Scale which assigns points to each service. Themonetary value of these points depends on the total budget negotiated with the insurer divided by the total number ofdelivered reimbursable points for all services within the regional physicians’ association, At the end of each quarter,every office-based physician invoices the physicians’ association for the total number of service points delivered. Withthe reform the floating point-system will be changed to a fee for service system with fixed euro values for each servicewhich will be developed jointly by insurer and physicians’ associations. The morbidity risk is thus transferred to insurersin the sense that they have to pay more, if doctors have to treat more cases because morbidity increased.Hospitalsare financed on a dual basis: investments are planned by the governments of the 16Länder,andsubsequently co-financed by theLänderas well as the federal government, while insurers finance recurrentexpenditures and maintenance costs. Since January 2004, the German adaptation of the Australian diagnosis-relatedgroup (DRG) system has been the sole payment system for recurrent hospital expenditures, except for psychiatric carewhere per diem charges still apply. There are quasi-budgets, in the sense that regional associations of insurers andhospitals agree on a level of DRG activity in advance for one year based on historical data. If this agreed level isexceeded, only 35% of the full additional DRG income is payable within the first year. Conversely, if the agreed DRGactivity level is not reached, the hospital is required to pay back 60% of the underachievement. In other words,payments for under or over-shoots are adjusted marginally rather than at full cost. This level of performance is thentaken into account in negotiating the agreed level of activity for the following year. In addition to smoothing the financialimpact of activity changes on hospitals, such an arrangement also protects insurers from sudden increases in activity.

The government uses selective contracts also to develop a number of – at least for Germany –relatively novel forms of care (see Box 3), as it turned out to be difficult to do this within the traditionalframework of collective negotiations between corporatist associations of insurers and providers. Separatecontracts for the in- and outpatient sectors and limited possibilities to transfer resources across them hadprovided few incentives for providers to cooperate across sectors and improve care coordination. Selectivecontracts involving providers from different sectors can address this problem. Moreover, collectivecontracts in the outpatient sector are essentially based on lump-sum payments from insurers to physicianassociations, which they then distribute to their members in line with the quantity of services provided.There were no incentives for providers to develop innovative forms of care in this system. Again, thisproblem can be addressed by allowing insurers to contract directly and selectively with providers and thegovernment has increasingly opened up possibilities to do this over the past few years. However, it shouldbe noted that selective contracting will be limited to the care models described in Box 3, while collectivecontracts will continue to be legally binding for all other healthcare services.

16

ECO/WKP(2008)20

Box 3. Novel forms of careIntegrated Care Programmes have been designed to better coordinate care between general practitioners (GPs)and specialists, across the inpatient and the outpatient sectors, rehabilitation and in some cases with pharmacies.Since 2 000 insurers have been allowed to negotiate integrated care models, in general involving actors from at leasttwo different sectors or different specialties The hope was to improve both quality and cost-effectiveness of healthcareprovision. Yet, take up was slow initially because the law prescribed that sectoral budgets would have to be cut by theamount spent on integrated care programmes to avoid increasing healthcare expenses. This turned out to beimpractical, as negotiators were reluctant to agree to cut their budget partly to sponsor healthcare providers in othersectors. To improve the legal framework and financial incentives for integrated care programmes, insurers have beenallowed to contract directly and selectively since 2004 with providers from different sectors and specialisations onintegrated care programmes. As a start-up, financing up to 1% of sectoral budgets has been earmarked for theseprojects, initially until 2006, but this has been extended with the 2007 reform. That means that insurers are allowed toretain up to 1% of all hospital bills and up to 1% of payments for ambulatory care physicians. If insurers do not investthe money in integrated care projects within 3 years, they have to pay it back to hospitals and ambulatory carephysicians.Disease Management Programmes (DMPs) are supposed to provide improved healthcare for some chronicdiseases, by establishing clinical pathways and up-to-date evidence-based guidelines for these programmes. Theycurrently exist for diabetes, breast cancer, coronary heart disease and asthma. They are intended to better involvepatients in treatment decisions and to improve care coordination across sectors as well as rehabilitation. The Institutefor Quality and Efficiency in the Health Care Sector (IQWiG), founded in 2004, is supposed to provide research andadvice. The number of registered DMPs for some chronic diseases has increased significantly since 2002. Since 2004,hospitals have also been allowed to offer inpatient care within DMPs. The main incentive for insurers to provide DMPshas been their financial promotion through the risk structure adjustment, as insurers receive additional funds for thestandardised costs of treatment for their members enrolled in DMPs. This will become redundant and will probably beabolished once the new risk structure adjustment mechanism is introduced in 2009: this will provide adjustments forthe standardised costs of treatment for 50-80 chronic diseases. DMPs can be offered and financed as integrated careprogrammes. While they have not been evaluated comprehensively, preliminary research in some regions suggeststhat at least some of them have helped improve quality (Altenhoffenet al.,2002). However, another study suggestsinstead that the link of DMPs to the risk structure adjustment has led to an excessive enrolment of patients in theseprogrammes without due regard to their therapeutic value (Häussler and Berger, 2007).General Practitioner (GP) centred models have been promoted since the healthcare reform of 2004 whichobliged insurers to offer such programmes to their patients. The idea is that the general physician will direct patientsthrough treatments, avoiding costly multiple treatment or diagnosis and improving the flow of information betweendifferent healthcare providers, thus improving cost efficiency.Special ambulatory care: The 2007 has made it easier for insurers to buy outpatient care for their clients outsidecollective contracts directly from healthcare providers or groups of them based on selective contracts. Insurers canthen offer healthcare plans to their members whereby they bind themselves to use only those ambulatory care servicesfor which the insurer has contracted selectively.Highly specialised outpatient care in hospitals: The possibility for hospitals to provide highly specialisedoutpatient care, for example for cancer or AIDS patients, has been introduced in 2004 as part of the integrated careprogrammes. However, it has hardly been used so far.

While the care models described in Box 3 have existed before, the 2007 reform aims at strengtheningthem further. It obliges social insurers to offer GP-centred models, as tariffs for those of their memberswho participate in DMPs, integrated care9and special ambulatory care. Members who wish to enrol in9.Integrated care plans will be expanded by the recent reform, as they can now involve non-medicalhealthcare providers (such as speech therapists) and long-term care providers. The 1% start-up financingprovision for integrated care (see Box 6.3), which was due to expire in 2006, is extended until 2008.

17

ECO/WKP(2008)20these programmes would bind themselves to limit their free choice of physicians for some time in line withthe model provided. Insurers can offer financial incentives for members who choose to enrol in one ofthese models, including lower co-payments and premia. They are obliged to offer incentives to enrol inGP-centred models. To boost the supply of highly specialised outpatient care in hospitals, which hadhardly been developed until now,Ländercan now accredit hospitals in their territory to provide theseservices. Insurers will have to reimburse highly specialised ambulatory care based on fees prevailing in theoutpatient sector.10… but the co-existence of collective and selective contracts involves challengesHowever, as collective contracts will continue to be the norm and all insurers will be legally bound bythem, their co-existence with selective contracts will involve challenges. To prevent selective contractsfrom being financed as add-ons, insurers have to be able to cut their payments for collective contracts bythe value of services they have contracted selectively (Casselet al.,2006; Greßet al.,2006). Indeed, thereform law requires such an adjustment. However, the details of the adjustment mechanism have beenlargely left to collective contracting partners to negotiate. This has not worked well in the past, given thatselective contracting benefits only some of the members of collective contracting parties, while hurtingothers (Jacobs, 2007). Physicians’ associations, as an example, would have to agree to a downwardadjustment of the payments they receive from insurers based on collective contracts, while only those oftheir members who engage in selective contracts can be expected to obtain re-compensation.11Against, thisbackdrop, there is a risk that collective contracting partners will not come up with a fair adjustmentmechanism that could help generate overall savings.Primarily as a result of these difficulties, take up of selective contracts has been strong so far only forthose models for which extra financial incentives were provided, namely DMPs and integrated careprogrammes.12For other programmes, such as special outpatient care and GP-centred models, take-up hasbeen limited and those that were developed were often financed as add-ons to the collective contracts. Inthe case of highly specialised ambulatory care in hospitals the incomplete risk structure adjustment hasproved to be an additional problem hampering take-up, as insurers offering this kind of care for patientswith catastrophic chronic diseases would have risked attracting new members requiring highly costlytreatments without receiving financial re-compensation.10.Highly specialised ambulatory care can now also be provided as an integrated care programme, evenwithout the involvement of actors from other sectors, which is generally required for a programme toqualify as integrated care. This gives insurers and hospitals, that develop such a highly specialisedoutpatient care programme, access to the start-up financing provided for integrated care.In addition, the 2007 reform would probably complicate negotiations on the insurers’ side, by stipulatingthat regional umbrella associations now have to negotiate uniform contracts for all insurers in the region,while they negotiated individually or by type of insurer before. Insurer roof associations would face thesame problem as physicians’ associations when negotiating an adjustment mechanism, as their memberswill probably engage in selective contracting to different degrees, and those who do so less may not wanttheir competitors to be able to reduce their collective payments to a large extent.For integrated care the 1% start up financing rule has ensured take-up, but this due to expire. There is astrong incentive for insurers to enrol chronically ill patients in DMPs, as this allows them to receive extramoney through the current risk structure adjustment. However, the more comprehensive risk structureadjustment to be introduced in 2009 will make this provision superfluous, as it should provide adjustmentsfor diseases covered by DMPs. The new risk structure adjustment should avoid disincentives to offer high-quality treatment to the chronically ill, while removing the extra payments that insurers can receive forpatients enrolled now in DMPs. In principle, this may even be beneficial, as it could make that sure thatinsurers develop only cost-effective services. However, the problem of how to adjust collective paymentsfor services provided and paid for through DMPs will become more pressing by then.

11.

12.

18

ECO/WKP(2008)20There is a risk that selective contracts could be financed as add-ons to collective contractsGoing forward, the government will have to watch very carefully whether insurers are able to engagein selective contracts without financing them as add-ons. If this is not the case, the government will need tofind ways to strengthen the position of insurers in negotiations. Otherwise, there is a risk of an inefficientexpansion of services and payments for those programmes that insurers are obliged to offer, underminingthe potential for new forms of care to help enhance the cost-effectiveness of healthcare provision.One option to strengthen insurers’ position in contract negotiations would consist in allowing them tocontract all of their services directly and selectively. They may well wish to continue contracting a part oftheir services collectively as this may involve lower transaction costs. In addition, collective contracts areassociated with a clear responsibility for physicians association to guarantee access to healthcare withinreasonable geographic and time limits, which has proved to work well. As insurers engage more inselective contracts, the responsibility to provide access will need to be shifted to them.13This will involvecosts for them and it may not work as well as the current system at least in the beginning. However,allowing insurers to walk away from collective contracts altogether might strengthen their negotiationpower sufficiently to enable them to enforce cuts in their collective contracting payments that wouldaccount for the services they contracted collectively.The government needs to evaluate whether competition produces desired resultsIt is hard to predict now whether competition based on selective contracts will actually succeed inenhancing cost-effectiveness and quality, not least since the novel healthcare programmes described inBox 3 have not been evaluated thoroughly and systematically, so far. The government should monitoroutcomes closely and augment quality assurance foreseen by law and implemented by contractual partnersthrough regular independent evaluations.Regular evaluation and publication of results will also be important, because patients and insurersneed sufficient information for competition to lead to better quality. Selective contracts involve bindingmembers to limit their choice of healthcare providers. The insured will only be willing to do this if they aresure that the healthcare plans they are being offered are of high quality. Likewise, they will only switchfrom insurers offering lower quality to those offering higher quality if they have the necessary informationto judge this.While the government has worked on improving information on healthcare quality, including byestablishing the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG), more remains to be done. TheIQWiG provides independent evidence-based information including for consumers through a webpage, butthe programmes described in Box 2 have not been evaluated systematically for patients, so far. It could bea task for the government to define a standard set of indicators and other high-quality information thatproviders will be required to publish regularly. Independent product testing and certification organisations,such asStiftung Warentest,may also have a role to play to test the quality and cost-effectiveness of offeredhealth plans. While this is a challenging task, it is necessary to strive for providing the required informationfor competition for quality to work. Working on improving the reliability of information about healthcarequality needs to be a continuous process in a system that relies on competition to provide better value formoney for consumers.Whether patients will actually demand the new services is not clear and insurers may have to offersubstantial financial incentives for them to agree to limit their choice of physicians, while they areenrolled. Experience in the Netherlands has shown that patients can be very reluctant to do this. In this13.This is also what the reform law stipulates.

19

ECO/WKP(2008)20context, there is some doubt whether insurers should have been required to offer their clients voluntary GPcentred models with financial incentives for take up. Over 90% of German patients report having a familydoctor and only just over a quarter say that they have no GP directing them through treatments (Schoenet al.,2007). Moreover, there is no clear evidence that GP centred models do help reduce overallhealthcare spending (Greßet al.,2004). A recent study suggests that the cost of diagnosis and treatmentduplication as a result of free and direct access to specialists in Germany is overestimated (Albrechtet al.,2007b). Thus GP centred health models may not generate the necessary savings for insurers to recover theassociated financial incentives they are required to offer to their members. Leaving it up to insurers todecide whether they think they can reap savings with GP centred models and how they want to designthem might have been a better option. Alternatively, Germany could have introduced a mandatorygatekeeper model, as this, at least, would not involve extra costs for insurers.New health plans expand consumer choice but may be misused for risk selectionThe reform obliges insurers to offer healthcare plans with deductibles or partial repayment of premiain return for limited use of healthcare services. Furthermore, they will have to offer a choice betweenbenefits-in-kind, which is the norm now, and reimbursement plans. Before this deductibles were availableonly for people who were voluntarily insured in the social healthcare system, but could have taken outprivate health insurance.While increasing the range of tariffs available to all social health insurance members will certainlyincrease consumer choice, it is not so clear whether deductibles or tariffs with repayments will generatesavings for the social insurance system as a whole, as desired. For this to happen, savings would have to behigher than the financial incentives that would have to be granted to those who choose this option. There isno direct link between the quantity of healthcare services used and insurers’ payments to physiciansassociations as these are based on capitations and past expenditure.14A reduction in doctors’ visits couldonly reduce insurers’ payments to physicians’ association in the longer run, if the decrease in healthcareservices use were to become noticeable so that it could become a basis for renegotiating capitationpayments to physician’s associations. Although the law states explicitly that if an SHIF provides such newtariffs the costs have to be financed by savings and efficiency gains within these new tariffsex ante,it willhave to be closely monitored if this is also the caseex post.It is therefore important that the regular reportsabout the effects of the new tariffs contain specific information about how the requested savings arerealised.At the same time, tariffs with deductibles or repayments can have undesirable side effects. First,patients should not reduce necessary physicians’ visits to enjoy cost savings through deductibles, not leastbecause this could increase treatment costs later. Yet, surveys suggest that lower income earners do skipdoctors’ visits when sick to avoid out-of-pocket payments. The proportion of people reporting that theyhave done so in the last year is actually relatively high in Germany compared to other countries(Schoenet al.,2007). There is also a risk that deductibles are used for risk selection. As they are mainly interestingfor higher income earners with low morbidity risk who would visit doctors infrequently in any case, theycould be used to attract this group of individuals. The improved risk structure adjustment to be introducedin 2009 will reduce this risk, depending on how complete it is. However, since the way the surcharge in thenew financing system is currently designed entails some incentives for insurers to try and attract higherincome members, as discussed before, the danger that deductibles might be used for risk selection is real. Itwill be necessary for the government to monitor very closely the effects of the new tariffs on insurers’finances and competition between them, including on whether it leads to risk selection.

14.

However, morbidity structures of insured in selective contracts are taken into account to adjust the amountsnegotiated in collective contracts.

20

ECO/WKP(2008)20The pharmaceutical marketAdministrative measures have helped curb spending for pharmaceuticalsIn some respects, price and market access regulation in the German pharmaceutical market isrelatively light compared to other OECD countries, but efforts to contain costs with a host of small-scale,overlapping and often temporary instruments has made the regulatory environment rather complex (Box 3,see also Häussleret al.,2006). There is no direct producer price regulation, unlike in most other OECDcountries (Docteur and Oxley, 2003), and accredited medicines are immediately re-imbursable unless theyare on a negative list. Thus, unlike in many other countries, there is no need for medicines to be admitted toa positive list to be re-imbursable, providing for fast access to new medication. However, there is indirectprice regulation for medicines for which substitutes are available in that they are grouped and assigned areference price, which is the maximum that insurers will reimburse.Not all of the instruments used to control costs have proved to be sustainable. They have includedincentives for pharmacists and physicians to join in cost containment measures, but also purely fiscal andoften temporary measures, such as price moratoria and an increase in global rebates that pharmaceuticalcompanies or pharmacists have to grant to insurers. New instruments have sometimes led to strategicreactions by market participants, in turn inducing the government to introduce new reforms to counteractthe unintended side effects (see Box 4. on theaut-idemrule as an example). In addition, temporary priceregulations have led at least once to significant spending increases after they have expired, as happenedwith the increase of the rebate that pharmaceutical companies had to grant to insurers from 6% to 16% in2004 only, which led to an expenditure increase of 16.8% for medications in 2005 (Schwabe and Pfaffrath,2006).While cost-containment measures have probably prevented even higher expenditure increases inrecent years, there are some indications that there is still room for savings without loss of quality throughmore effective price competition and more efficient prescription behaviour. Reference prices have beensuccessful as a ceiling for prices of medicines to which they apply, but there is also evidence that they actas a floor at the same time discouraging price competition below this (Danzon and Ketcham, 2003).Indeed, some reports claim that prices of generics are a lot cheaper in other countries, such as Sweden orthe UK (Schwabe and Paffrath, 2006; Häussleret al.,2006; Marty 2006). In any case, many policymeasures to contain costs in recent years affected the generics industry, based on the assumption that pricecompetition in that sector could work better than it does in Germany elsewhere in the pharmaceuticalmarket and that prescription behaviour could be made more cost-effective.15

15.

According to one report (Schwabe and Paffrath, 2007) the potential to save through more cost-effectiveprescription behaviour without loss of therapeutic value amounted to €3.2 billion in 2006: € 1.3 billioncould have been saved by substituting prescribed medicines through cheaper generics, that is medicationswith the same active ingredient, another €1.3 billion by substituting medicines with others that have adifferent active ingredient, but an equivalent therapeutic value,e.g.analogous compounds. Another€ 600 million could have been saved by avoiding the prescription of medicines of disputed effectiveness(Schwabe and Pfaffrath, 2006). However, the corresponding savings potential is measured to besignificantly lower with a different methodology in a similar publication evaluating the pharmaceuticalmarket in Germany (IGES, 2006).

21

ECO/WKP(2008)20

Box 4. Cost-containment instruments in the German pharmaceutical marketThe reference priceis the maximum price that insurers will reimburse for a medicine belonging to a group with thesame or pharmacologically similar active ingredients or with different active ingredients, but equivalent therapeutic value. Thisbeen quite successful in containing prices for medications to which they apply. However, their market share decreasedsubstantially in the late 1990s, especially after the possibility to assign new patented medicines with little or no therapeuticvalue added (analogous compounds or me-too innovations) to reference-priced groups was abolished in 1996. This had led tosharp increases in costs for pharmaceuticals. In 2004 the possibility to assign patented analogous compounds to reference-priced groups has been re-instituted, helping to counteract the trend of a declining market of pharmaceuticals to which a priceceiling applies.Regional target agreementsbetween insurers and physicians’ associations, which are mapped to the individualphysician throughpractice-specific indication-specific targetsset limits on expenditures on pharmaceutical prescriptions.The practice-specific targets are supposed to be enforced by control committees, a joint body formed by insurers andphysicians’ associations. They perform preliminary efficiency controls, when a physician overshoots the target by more than15%, to establish whether the overshoot can be justified by specific practice circumstances. If the overshoot is larger than25% and cannot be justified, the physician has to reimburse it to insurers. The insurers can also pay bonuses to doctors’associations if their members have prescribed less than foreseen in the target agreements. The recourse procedure usuallytook years, although it was limited through the 2007 reform to a maximum period of two years, and sanctions are applied onlyrarely. It cannot be excluded, though, that the threat alone helps induce physicians to aim for more efficiency, although it mayalso lead to a reduction of necessary prescriptions.Abonus-malus

ruleis intended to control prescription overshoots based on defined daily doses for groups ofmedicines which are significant for overall expenditures. If a physician prescribes more, he or she has to reimburse 20 to 50%depending on the extent of the overshoot. If expenses prescribed by physicians of a doctors' association are below the target,a bonus will be paid to their association which will be supposed to forward these payments to its most efficient members.Doctors' associations can replace the rules with other arrangements that can reach the same goal. Medications that aresubject to abonus-malusrule are not subject to practice-specific targets or efficiency controls. Thebonus-malusrule is notapplied to medicines for which there are rebate agreements and the recent spread of these agreements has made the ruleredundant.Theaut-idem