Udenrigsudvalget 2008-09

URU Alm.del Bilag 307

Offentligt

DIIS WORKING PAPERDIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

WORKING PAPER

The new ‘New Poverty Agenda’ in Ghana:what impact?Lindsay WhitfieldDIIS Working Paper 2009:15

1

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

LINDSAY WHITFIELDProject Senior Researcher[email protected]DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towardsproper publishing. They may include importantdocumentation which is not necessarily publishedelsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published underthe responsibility of the author alone. DIIS WorkingPapers should not be quoted without the expresspermission of the author.

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15� Copenhagen 2009Danish Institute for International Studies, DIISStrandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, DenmarkPh: +45 32 69 87 87Fax: +45 32 69 87 00E-mail: [email protected]Web: www.diis.dkCover Design: Carsten SchiølerLayout: Allan Lind JørgensenPrinted in Denmark by Vesterkopi ASISBN: 978-87-7605-339-0Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included)DIIS publications can be downloadedfree of charge from www.diis.dk

2

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

DIIS WORKING PAPER SUB-SERIESON ELITES, PRODUCTION AND POVERTYThis working paper sub-series includes papers generated in relation to the research pro-gramme ‘Elites, Production and Poverty’. This collaborative research programme, launched in2008, brings together research institutions and universities in Bangladesh, Denmark, Ghana,Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda and is funded by the Danish Consultative ResearchCommittee for Development Research. The Elites programme is coordinated by the DanishInstitute for International Studies, Copenhagen, and runs until the end of 2011. More infor-mation about the research and access to publications can be found on the website HYPER-LINK “http://www.diis.dk/EPP”www.diis.dk/EPP.Earlier papers in this subseries:Rweyemamu, Dennis: “Strategies for Growth and Poverty Reduction: Has Tanzania’s SecondPRSP Influenced implementation?” DIIS Working Paper 2009:13.Kjaer, Anne Mette, and Fred Muhumuza: “The New Poverty Agenda in Uganda” DIISWorking Paper 2009:14.

3

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

AbstractAcronymsIntroductionGrowth and Poverty Reduction since the 1980s.The PNDC and NDC period (1982-1992): achievements and failuresThe ‘New Poverty Agenda’ comes to Ghana, the New PatrioticParty comes to power (2001-2008)The Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy 2003-05 and its impactThe Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy 2006-09 and its impactThe NPP government and the economic transformation agendaFactors influencing government policy actions

5679141819222426

4

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

This paper describes and explains the impact of the international-driven ‘NewPoverty Agenda’ in Ghana, focusing on the impact of the Poverty ReductionStrategy Papers (PRSPs) adopted by the New Patriotic Party government inpower from 2001 until 2008. The paper argues that the New Poverty Agendahas had some impacts, but not they have been limited and not necessarily help-ful in achieving long term poverty reduction. The PRSP was seen by the gov-ernment in Ghana as necessary to secure debt relief and donor resources, andthe strategies produced by the government contained broad objectives ratherthan concrete strategies on how to achieve those objectives and thus had littleimpact on government actions. The paper discusses what was actually imple-mented under the NPP government and the factors influencing those actions.It highlights the constraints Ghanaian governments face in pursuing economictransformation within contemporary domestic and international contexts.

5

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

ERPGPRS IGPRS IIHIPCIMFMDBSMDGsMDRIMTEFNDCNPPPNDCPRSPPSIsUNCTAD

Economic Recovery ProgrammeGhana Poverty Reduction Strategy (2003-2005)Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy (2006-2009)Heavily Indebted Poor CountryInternational Monetary FundMulti-Donor Budget SupportMillennium Development GoalsMultilateral Debt Relief InitiativeMedium Term Expenditure FrameworkNational Democratic CongressNew Patriotic PartyProvisional National Defence CouncilPoverty Reduction Strategy PaperPresidential Special InitiativesUnited Nations Conference on Trade and Development

6

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

The most recent poverty reduction drive ofthe international aid community began in the1990s by the World Bank in response to criti-cisms of the negative impacts of structuraladjustment programs. It picked up steam atthe end of the 1990s as these criticisms con-tinued. The global anti-structural adjustmentmovement had turned the focus on ‘growth’into a heresy against the poor, although theirreal target was the particular brand of growthstrategy embodied in the Washington Con-sensus prescriptions of stabilize, liberalize,and privatize. Furthermore, the United Na-tions and bilateral aid agencies increasinglyfocused on ameliorating the immediate needsof ‘the poor’ in Least Developed Countries.With the turn of the millennium, consensuson a new ‘new poverty agenda’ emerged atthe international level.1The consensus wasbuilt on five pillars:(1) the Millennium Development Goals,which made commitments to reduce pov-erty and identified targets to be achieved;(2) a diluted and more pragmatic version ofthe Washington Consensus prescriptionsfor growth combined with emphasis onsocial and safety nets as well as good gov-ernance;(3) a mechanism for operationalizing thisstrategy at the country level, i.e. the Pov-erty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs);(4) emphasis on tools for delivering aid insupport of PRSPs and operationalizingthe new principles of aid effectiveness (i.e.ownership, alignment and harmonization),S Maxwell, ‘Heaven or Hubris: reflections on the New ‘NewPoverty Agenda’,Development Policy Review21(1), 2003, pp 5-25.1

such as general budget support and sectorwide approaches;(5) a commitment to results-based manage-ment, which led to more focus on settingindicators and monitoring and evaluationprocedures.This paper describes the impact of this ‘newpoverty agenda’ in Ghana. It focuses on theimpact of the PRSPs adopted by the NewPatriotic Party government in power from2001 until 2008, both in terms of process-es surrounding the PRSP including its at-tendant aid modalities and procedures, andin terms of their content and influence onthe government’s implemented policies andactions. The story of Ghana’s first PRSPis somewhat well rehearsed in the existingliterature.2This paper updates the story toinclude the second PRSP, but also goes be-yond the existing narrative about how theinternational PRSP process was translated inthe Ghanaian context to focus on its impact.The paper is based on extensive fieldwork inGhana over several years, particularly during2008.3It is argued here that the ‘new povertyagenda’ has had a limited impact in Ghana.It did increase the allocation of resources tosocial services. The idea of the PRSP was toassure donors and international NGOs thatmoney saved through debt relief would gotowards poverty reducing expenditures. Theexistence of the PRSP and implementationSee for example L.Whitfield, ‘Trustees of development fromconditionality to governance: poverty reduction strategy pa-pers in Ghana’,Journal of Modern African Studies43(4), 2005,pp 641-664; B Woll, ‘Donor harmonisation and governmentownership: multi-donor budget support in Ghana’,EuropeanJournal of Development Research20(1), 2008, pp 74-87.2

The author acknowledges financial support for this field-work from the British Academy SG 46722 and from the Elitesand Productive Sector Initiatives research programme at theDanish Institute for International Studies.3

7

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

of key policy actions agreed between theIMF and NPP government were conditionsfor granting of debt relief under the HeavilyIndebted Poor Country Initiative. The PRSPalso provided a rationalization for the pro-vision of general budget support, under inthat donors needed to know what the coun-try’s medium term development strategywas (and approve it) before they would pro-vide money directly to government’s budget.The introduction of general budget supportin Ghana, increased the level of resourcesavailable to the Ministry of Finance (whichwould have previously gone directly to lineministries through donor programmes orprojects), but it also introduced a whole newset of joint government-donor processesand committees and a new set and way offormulating conditionalities which the gov-ernment must meet in order to receive bud-get support.What the PRSP process did not do wasstrengthen the existing national planningsystem, which was in disarray. Nor did thePRSP documents themselves serve as plan-ning tools or significant guide the imple-mented actions of the NPP government.The PRSP had little impact on what wasformulated and implemented at the min-istry level because it contained a broad setof objectives with no specific strategies forhow to achieve those objectives and with noprioritization. Actions by government min-istries, agencies and departments during theperiod of the first PRSP were determined byongoing projects and programs negotiatedwith donors, or in rare cases new initiativessolely funded by the government. Duringthis period many ministries produced sectorstrategies, which in turn were used to writethe text of the second PRSP. Thus, while the‘new poverty agenda’ did have an impact, itseffects were largely limited to restructuring

the aid system and had little effect on mov-ing forward a long term poverty reductionagenda.The first two sections explain the contextin which the ‘new poverty agenda’ was intro-duced in Ghana. Growth and poverty trendssince the 1980s, a turning point in Ghana’seconomic history, show that the country hasachieved modest success on both accounts,but that this success has not been accom-panied by economic transformation andthat this accounts for the limited impact ofgrowth on poverty reduction. Section twohighlights the political and institutional con-straints Ghanaian governments faced in the1980s and 1990s in implementing an agendafor structural change. Section three looks athow the New Poverty Agenda affected theeconomic, political and institutional land-scape in Ghana, as well as the legacy of theNew Patriotic Party government. The fi-nal section pulls together the beginning ofa framework for understanding the factorsinfluencing the policy actions of Ghanaiangovernments since the return to democraticrule in 1993, as well as the factors imped-ing the formulation and implementation ofa long term poverty reduction agenda.

8

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

GROWTH AND POVERTY

REDUCTION SINCE THE 1980s

There has been little structural transfor-mation of the Ghanaian economy sincethe end of British colonial rule. The co-lonial economy was dependent on cocoaand gold exports, and this still holds truetoday. Agriculture remains untransformed,and the nascent but inefficient industrythat emerged in the 1960s was significantlyreduced since trade liberalization in the1980s. The story of how Ghana’s economywent wrong after independence in 1957is well documented.4In the early 1980s,Ghana began recovering from a devastat-ing economic crisis characterized by nega-tive growth (-0.3%) on average during the1970s. Since then the country has experi-enced modest economic growth and sig-nificant poverty reduction.JJ Rawlings led a military coup in Decem-ber 1981 which overthrew the Third Repub-lic. His Provisional National Defence Coun-cil (PNDC), a bureaucratic-authoritariangovernment, began an Economic RecoveryProgramme in 1983. The Programme, sup-ported by the World Bank and IMF, con-tained much of the standard structural ad-justment fare. Growth rates averaged 5.2%per year between 1984 and 1992, but thendeclined after the return to democratic rulein January 1993 to hover around 4% for therest of the 1990s. This growth was the pro-duce of the policy changes, a relatively sta-ble political environment, the rehabilitationFor an overview of the economic history of Ghana, see EAryeetey, J Harrigan & M Nissanke (eds),Economic Reformsin Ghana: the miracle and the mirage,Oxford, James Currey,2000; E Hutchful,Ghana’s Adjustment Experience:The Paradox ofReform,Oxford, James Currey, 2002; and T Killick,DevelopmentEconomics in Action,London, Heinemann, 1978.4

of the country’s traditional export indus-tries (gold and cocoa), investment in humancapital and infrastructure, and increased aidinflows. Production of cocoa and gold in-creased, but world market commodity pricesfluctuated and generally were not favorableduring the 1980s and 1990s.5The large pub-lic investments funded by aid since the 1980sdid not lead to significant improvements inproductivity or substantial private invest-ment. Growth rates increased under the NewPatriotic Party government reaching 5.2% in2004 at the end of the first Kufuor admin-istration and 6.5% in 2008 at the end of itssecond Kufuor administration. However,private sector investment remained minimal,little formal sector employment was created,and growth in agriculture outside of export-oriented sectors was slow.6Despite increased growth in all sectors ofthe economy since 1983, industry and agri-culture growth rates tailed off in the 1990s,while growth in the service sector remainedstrong. Much of the increase in services wasderived from wholesale and retail trade, andrestaurants and hotels7. The share of industryin GDP generally declined largely as a resultof poor performance from manufacturing. Inagriculture, there are significant differencesbetween growth rates in staple crops (which

Although export volumes more than doubled between1984 and 1988, the growth in export values was much lessdue to the decline in world cocoa and gold prices. World co-coa prices fell from 1984 until 1992, and by 1989 were lessthan half their 1984 values.5

E Aryeetey & A McKay, ‘Ghana: the challenge of translatingsustained growth into poverty reduction’, inDelivering on thepromise of pro-poor growth: Insights and Lessons from country ex-periences,T Besley & L Cord (eds), New York, Palgrave Macmil-lan, 2007, pp 147-168.6

E Aryeetey & A Fosu, Economic Growth in Ghana 1960-2000, inThe Political Economy of Economic Growth in Africa1960-2000,volume 2 country case studies, (eds) B Nduluet al., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008, pp 289-324.7

9

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

���������������������������������������������

���������������

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

����������������������������������������

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������� ���������� ��� ����������� ������ ��� ��� ������ �������� ����� ������ ������������� ���������� ����� ���� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

contribute more than 50% of total agricul-tural GDP growth) and export crops such ascocoa and timber which have been the driv-ers of agricultural growth. Outside of cocoa,the agriculture sector has performed poorly.8Low agricultural productivity is attributed tothe limited use of new technologies in pro-duction, limited access to inputs, credit andland, reliance on rainfall, and poor marketingand distribution networks. This explains whyWorld Bank, Ghana: Meeting the Challenges of Acceleratedand Shared Growth. Country Economic Memorandum. Vol-ume I: synthesis. Draft, 5 September 2007.8

food crop farming has the highest incidenceof poverty in terms of occupation.The country’s major exports remain co-coa, timber, and minerals (gold, diamondsand bauxite), with gold and cocoa as the leadexport earners. The higher growth rates inthe second half of the 2000s were driven byincreased international prices for gold andcocoa and increased production of thesecommodities. The share of non-traditionalexports increased since 2000, but cocoa andgold still account for about two-thirds ofGhana’s exports. These two lead exports areprimary commodities with little linkage to the

10

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

�������������������������������������������������������

���������

����������

�����������������������

�����������

����������������������������

��������������

������������

�

�����

���

��������������

���������������������������������������

domestic economy. The mining sector is aneconomic enclave which lacks effective link-ages with other sectors of the economy andresults in limited employment creation, andgovernments since the 1980s mining sectorreforms have lacked a cogent program forutilizing mining revenues.9Non-traditionalexports include mostly agricultural and pro-cessed agricultural produces.Poverty reduction has been significant inthe 1990s and 2000s, but uneven across thegeographical regions and across occupation

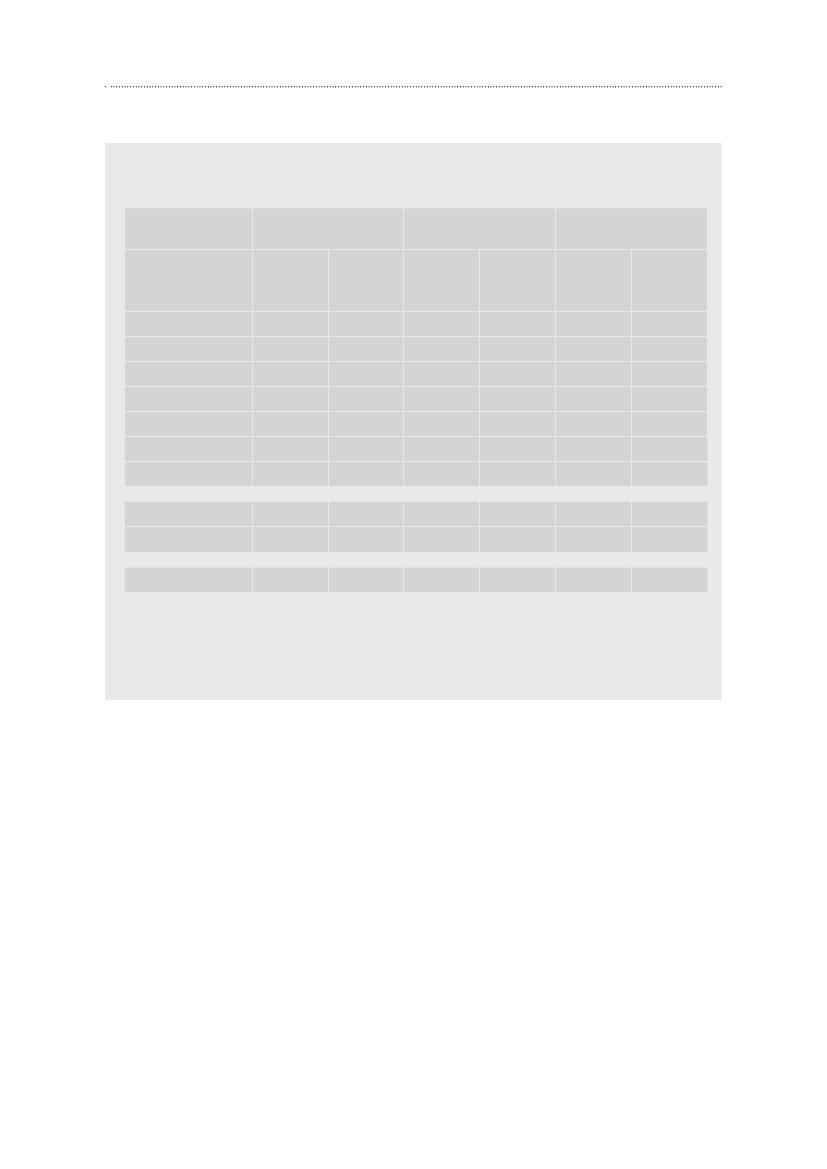

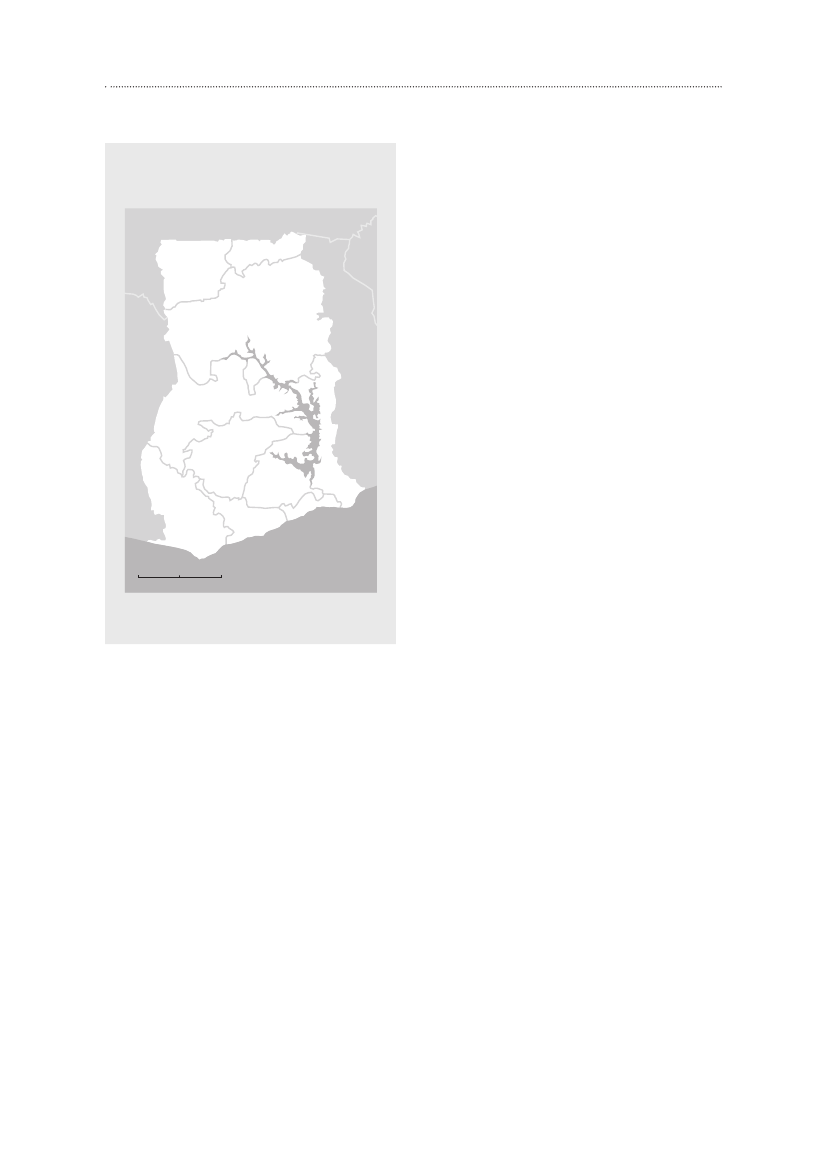

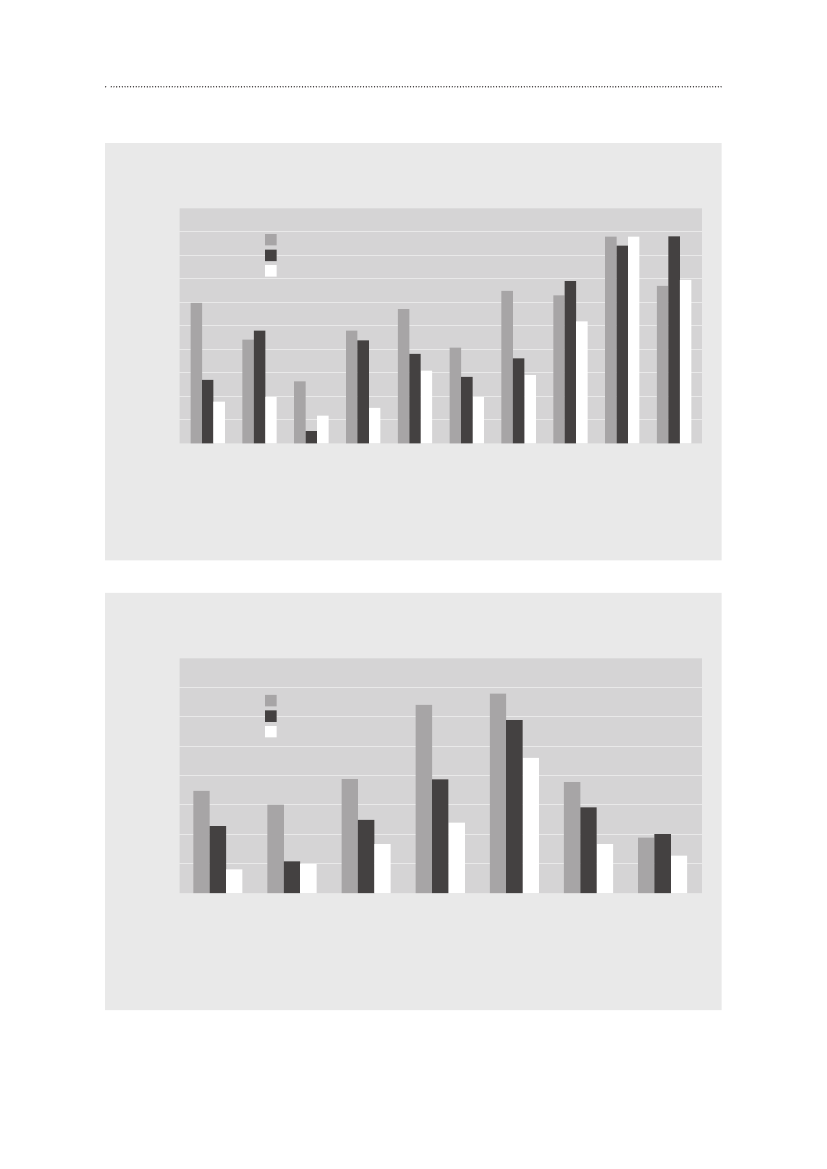

as a result of the sources and nature of eco-nomic growth. Ghana Living Standards Sur-veys were carried out in 1987/88, 1988/89,1991/92, 1998/99, and most recently in2005/06. Poverty was and still is predomi-nantly a rural phenomenon, but with strongregional patterns. There was a north-southdivide, with substantially higher levels of de-privation in the three northern regions com-pared to the southern part of the country.10Figure 1 indicates the administrative regionsof Ghana. Table 1 and Graphs 1 and 2 sum-marize poverty trends by rural/urban, re-gions, and occupation.The 1998/99 Survey showed a fall inheadcount income poverty from 51.7% ofthe population in 1992 to 39.5% in 1998,but this decline was concentrated in thecapital city Accra and the rural forest zonewhere cocoa, gold, and timber are produced.The rest of the country seems to have beenleft behind in this phase of poverty reduc-tion. The 2005/06 Survey showed a furtherdecline in headcount income poverty to28.5% of the population, but also a moreeven geographic distribution of poverty re-duction. Poverty reduction was greatest inregions generally left out in 1990s, but pov-erty increased in one of the most northernregions. Government policies to promotecocoa production alongside increases inthe international price of cocoa led to in-creased cocoa production which in turnhad a large impact on poverty reduction assmall farmers play a significant role in itsproduction. Farmers in general, non-farmself-employed and public sector employ-ees enjoyed the greatest gains in standardof living. Despites these gains, by localitythe rural savannah in the northern regions10

9

T Akabzaa, ‘Mining in Ghana: implications for national eco-nomic development and poverty reduction’, inMining in Africa:regulation and development,B Campbell (ed.), London, PlutoPress, 2009, pp 25-65.

The substantial economic inequality between the north andsouth dates back to the colonial period.

11

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������

���������������������

���������������

�������������

�����������

��������

�������

�������

�����

���������������������

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������

���������������������

�����������������������������������

�������������������������������������� ����������

�������������

����������������

�������� ��������������������������

�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

12

����������

����������

�������

�������

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

and food crop farmers still have the highestpoverty incidence.While many donor agencies, particularly theWorld Bank, describe Ghana’s growth overthe past fifteen years as pro-poor in the sensethat it has reduced poverty and done so moreequitably in the last five years, Ghanaians arenot quite as optimistic. The government pov-erty report shows that although the incidenceof poverty has been falling since 1991/92,the depth of poverty for those still classifiedas poor has not changed. The emerging mid-dle class registered large gains, and the richestquintile became even richer. While all regionsbenefited from recent growth, the reductionin poverty was lower for the poorer areas ofthe country, and thus the gaps between thevarious regions and localities have widened.11While Ghana has achieved significant lev-els of poverty reduction, the sources of thatreduction call into question the sustainabil-ity of present achievements and the ability toachieve further poverty reduction from thepresent sources of economic growth. Threemajor factors account for the poor’s inabilityto participate in the growth witnessed sincethe 1980s: (1) agricultural performance, (2)the limits to employment creation, and (3) thecomposition, effectiveness and distributionalpattern of public spending.12With the excep-tion of cocoa, agricultural production process-es have not become more intensive and yieldshave largely stagnated below achievable levels.Underdevelopment of the financial sector,itself partly caused by continued weaknessesin macroeconomic policy, remains the mainfactor discouraging private sector investment.Neither the urban informal sector nor the ruraleconomy has created substantial opportunitiesfor employing hired labor. Restructuring in1112

the industrial sector following the initial eco-nomic reforms in the 1980s was hampered bydevaluation, high interest rates, lack of accessto long-term credit, and increased competitionfrom imported consumer goods. Lastly, pub-lic spending has been dominated by interestpayments on external and domestic debt, pay-ing public sector personnel, and spending onhealth and education. Aryeetey and McKay ar-gue that public expenditure patterns appear tobe driven largely by revenue flows and politicalexpediency and reflect no particular commit-ments to policies and expected growth out-comes.13The ‘new poverty agenda’ as it playedout in Ghana had little impact on any of thesethree factors.Several explanations have been put for-ward as to why there has been growth withoutstructural transformation in Ghana. One viewis that the impediments to structural transfor-mation require hard political choices. Some ofthe reforms required, such as in land tenurereform and public service reform, will entailhigh political costs from the negatively affect-ed groups. The political elite (of both majorpolitical parties) have not shown the will totake the hard decisions.14However, there isnothing particularly patrimonial about fearingthe wrath of civil servants or chiefs at electiontime, but rather a rational political calculation.Another view is that the political elite (againof both parties) lack a coherent developmentvision, with the similar outcome that publicspending is politically expedient in the sensethat it corresponds to the electoral cycle rath-er than any long term development strategy.151314

Ibid.

World Bank, ‘Ghana’.Aryeetey & McKay, ‘Ghana’.

For this argument, see T Killick, ‘What drives change inGhana?’ inThe Economy of Ghana: analytical perspectives on sta-bility, growth and poverty,E Aryeetey & R Kanbur (eds), Suffolk,James Currey, 2008, pp 20-35; and D Booth et al., Drivers ofChange in Ghana: Overview Report. Final draft. 2004.15

See Aryeetey & McKay, ’Ghana’.

13

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

A third view does not negate the first two, butrather argues that they are incomplete with-out taking into consideration aid dependencyand the ideas and incentives that it generates.16Foreign aid and the aid system play a role inshaping the incentives of political leaders andthe public service as well as the parameterswithin which a coherent development visionand articulated strategy must be produced andpursued.These explanations will be elaborated, re-vised or refuted through subsequent workon the politics of pro-poor growth in Gha-na which aims to move through the macro,meso and micro levels of analysis. This pa-per represents a first step in this direction.The next section looks at the political periodwhen Rawlings was head of the PNDC andthen NDC governments. It draws out somekey aspects of that period important for un-derstanding both the performance of thatgroup of political elite, as well as the contextin which the NPP took power and the NewPoverty Agenda was introduced.

THE PNDC AND NDC PERIOD

(1982-1992): ACHIEVEMENTS AND

FAILURES

The PNDC government pursued importantpolicy reforms, and its political leaders andtechnocrats negotiated strongly with theWorld Bank and IMF to achieve what theythought were the best policies.17The PNDCalso brought unprecedented infrastructuraldevelopment to rural and poor parts of thecountry, particularly through the construc-tion of feeder roads and electrification. Un-der the Economic Recovery Programme,the three northern regions were finally con-nected to the national electricity grid anda rural electrification program extended tomost district capitals. These initiatives partlyexplain why Rawlings and the NDC (formedout of the PNDC) were able to win the elec-tions in 1992 and 1996, and why the NDCpolled well in rural areas and in the threenorthern regions.18The costs of adjustmentwere felt most strongly in the urban areas,and the main opposition New Patriotic Partychanneled this discontent into political sup-port.There was a desire by the technocrats be-hind the Economic Recovery Programmeto address structural constraints. In 1989,Ghanaian officials publicly criticised theWorld Bank and IMF for having too muchfaith in the ability of domestic productionto respond to short-term prices changes andrequested that structural bottlenecks be ad-

See L Whitfield & E Jones, Ghana: Breaking out of Aid De-pendence? Economic and Political Barriers to Ownership, inThe Politics of Aid: African Strategies for Dealing with Donors,Ox-ford, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp 185-216.16

See Y Tsikata, Ghana, inAid and Reform in Africa,S Devarajan,D Dollar, & T Holmgren (eds), Washington DC, World Bank,2001, pp 45-100.17

R Jeffries, ‘The Ghanaian elections of 1996: towards theconsolidation of democracy?’,African Affairs97, 1998, pp 189-208.18

14

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

dressed.19The key technocrats and top po-litical leaders with technical knowledge sawmacroeconomic stability and liberalizationas just the first stage. They had planned torevive a version of import-substitution in-dustrialization, but this time with the rightincentives.20However, their ability to do sowas hindered by two main factors: the returnto multiparty rule and the onset of aid de-pendence.Ghana’s initial success with economic re-form attracted much donor support. In the1980s, the Bretton Woods institutions sawGhana as its showpiece for economic reformin Africa, resulting in an expanded range ofpolicy interventions tied to increased con-cessional credit.21The economic team lostcontrol over the pace of the reforms asdonors wanted to support the reform pro-cess and the number of donors increased.Central coordination of the reform processdissolved as donors negotiated straight withline ministries who did not know what thecentral economic team was doing.The return to democratic rule also hadsome negative effects on the economic re-forms. With the return to multiparty politicsahead of the 1992 elections, priorities of thegovernment moved away from economicreform towards the political imperative ofremaining in power.22Political power withinthe NDC government shifted away from thetechnocrats of the PNDC era to politicalbrokers and party financiers, and economic

1920

Hutchful,Ghana’s Structural Adjustment Experience,p 155.

Interview with Kwesi Botchwey, 12 April 2008, Oxford,UK.J Harrigan & S Younger, ‘Aid, Debt and Growth’, inEconomicReforms in Ghana: the miracle and the mirage,E Aryeetey, J Har-rigan & M Nissanke (eds), Oxford, James Currey, 2000, pp185-207.2122

Hutchful,Ghana’s Structural Adjustment Experience,p 221-3.

rationales were overtaken by political ones.The chief architect of the ERP resigned inlate 1995, and crucial players in the macro-economic team left their key governmentalpositions. After the key architects of the re-forms left the NDC government by the mid-1990s, the reform effort stalled at the liber-alization stage. There was not a reversal inthe reform process, but pursuit of reformswas characterized by less rigor, a little lesscommitment and more politicization of thereform process.The return to democratic rule probablyincreased the legitimacy of policies pushedby the NDC government during its secondterm (1997-2000), but not necessarily dur-ing the first term since the opposition partiesboycotted the 1992 parliamentary electionsand thus were left without a voice in the firstParliament. One of the main motives withinthe PNDC for pursuing democratization wasto gain greater legitimacy for the reform pro-cess, recognizing that many reforms couldnot be pushed through but required broadersocietal support. However, it is hard to saywhether the positive effect of greater legiti-macy outweighed the negative effect of thenew politics.There were additional factors, partly relat-ed to or reinforcing the first two, which alsoshaped the implemented policy actions ofthe NDC government and its ability to thinkabout and implement a long term growth andpoverty reduction strategy. First, the 1990swere characterised by a vicious cycle of in-creasing government spending, whilst aimingto break even on the budget. The 1992 elec-tions resulted in a significant increase in gov-ernment spending. Fiscal shocks in the secondhalf of the 1990s resulted in further inflationand currency depreciation. These shocks hadmultiple sources: delay in introducing a ValueAdded Tax for political reasons, an increase

15

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

in civil servant salaries, expenditure on ruralinfrastructure, and lastly corruption and partypatronage. In an attempt to balance the bud-get without sacrificing public spending, thegovernment became increasingly reliant onone-off receipts from state divestures and in-creased domestic and foreign borrowing. In1999, the country suffered two major exter-nal shocks: rising oil prices and a decline inworld prices for its major exports cocoa, goldand timber. These shocks were compoundedby the loss of fiscal discipline and looseningof monetary policy in the run up to the 2000elections, and the subsequent suspension ofaid and loan disbursements by the IMF andother donors due to non-compliance with IMFconditions.23Rapid inflation and currency de-preciation followed. These macroeconomicproblems meant that the NDC governmentdepended on donors to shore up fiscal deficitsand achieve macroeconomic stability.Second, the economic reform process ofthe 1980s had been very centralized withinthe Ministry of Finance, rather secretive, andalmost ‘institutionless’.24Thus, there had beenno attempt to build a public administrationthat could devise strategies and implementthem. The legacies of this historical trajecto-ry created problems in the democratic periodwhen the public administration was expectedto function and to negotiate with a myriad ofdonors but the civil service lacked the orga-nization, personnel, skills and motivation todo so.25Third, there was an attempt to create thecapacity for long term planning, but it died

Center for Economic Policy Analysis, Ghana: The PovertyReduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) Arrangement, May1999-November 2002.Selected Economic Issues,No. 4. Accra,Ghana.232425

in its infancy, and that legacy lives on today.In late 1987 the decision was announced toestablish a National Development PlanningCommission to deal with issues of long termdevelopment. Up until then, economic poli-cy had focused on reversing the decline andenacting major policy changes of liberaliza-tion and privatization, but it was realized thatlonger term economic thinking was needed.With a combined Ministry of Finance andEconomic Planning, the planning was relegat-ed to the background, particularly given theneed to manage short term economic crises.The Commission was established in 1990, andlater enshrined in the 1992 Constitution andgiven legal basis by an Act of Parliament in1994. A new division of labor was supposedto be created between a Ministry of Financeand the Planning Commission, with econom-ic planning going to the latter and the formerresponsible for investment programming andbudgeting. However, this never happened.Eboe Hutchful states that the Ministry of Fi-nance and Economic Planning, supported bythe World Bank, did not consider the Plan-ning Commission an appropriate initiativeat the time.26The Finance Minister, KwesiBotchwey, regarded the move as motivated inpart by political considerations and intendedto reduce the power of the Finance Minister.For the World Bank, a planning institution re-minded them of the inefficient state planningof the 1960s and state controls.Thus, the Planning Commission wascrippled at birth and has never overcome itsdownsized position. It was never properlystaffed or equipped and became stigmatizedas ‘political Siberia’, and the envisioned de-centralized national development planningsystem never really took off. Nevertheless,

Hutchful,Ghana’s Structural Adjustment Experience,pp 146-8.See Whitfield & Jones, ‘Ghana’.26

Hutchful,Ghana’s Structural Adjustment Experience,pp 111-2.

16

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

the constitution requires that the Presidentpresents a Coordinated Programme of Eco-nomic and Social Development Policies toParliament. The Planning Commission pro-duced a long term policy framework calledGhana Vision 2020in 1994 and then the firstmedium term development plan, which Pres-ident Rawlings presented in 1995. It was anattempt by those writing it to reassert con-trol over the direction of their developmentstrategy and policies and use it as a basis fromwhich to negotiate donor-funded projects.27The goals of Vision 2020 included structuraltransformation of the economy, correctionof socio-economic imbalances, enhancementof the role of the private sector, strengthen-ing infrastructure, and provision of greatersocial and economic amenities. It was writtenby civil servants in the Planning Commissionand Ghanaian experts outside government,but it had the support of some important po-litical leaders.However, this medium term developmentplan had little influence on government poli-cy actions, and it did not become a platformfor negotiating with donors. As could be ex-pected from the Planning Commission’s mar-ginal position politically and institutionally, itdid not have the authority to ensure that min-istries and agencies formulated policies andprogrammes to implement its objectives. Italso had to compete with the three year Medi-um-Term Expenditure Framework controlledby the Ministry of Finance which outlinedactivities and expenditures for all ministriesand agencies. The MTEF was adopted as partof the public financial management reformlaunched in 1996 and funded primarily by theWorld Bank. Furthermore, none of the do-27

nors supported the Vision 2020 document.Donors criticized it for lacking a clear strat-egy to deliver on the aspirations embodied init, which was true. However, it is argued thatthe Planning Commission pitched the docu-ment somewhere between what it thoughtwas required for economic development andwhat it thought would be supported by do-nors, but in leaving the government spaceto be flexible, the document lacked detailand prioritization. By the second half of the1990s, the government was dependent on do-nor resources for the investment portion ofgovernment expenditure. The plan had littleinfluence since donor-funded projects largelydetermined what ministries implemented.Lastly, the antagonistic stance of thePNDC and NDC governments towards theprivate sector hampered their ability to movebeyond the liberalization phase. PresidentRawlings gave the impression of being an-tagonistic to the private sector, which wasborn from his rhetoric and actions during therevolutionary period of the PNDC. AlthoughRawlings’ PNDC pushed through major eco-nomic reforms, this was done through col-laboration between the economic team inthe PNDC and the World Bank and IMFteams. Rawlings supported the liberalizationand privatization reform agenda, but he waspredominantly a political entrepreneur withlimited economic vision and appreciation ofprivate business.28The PNDC and its succes-sor NDC governments were not perceived byGhanaian business as being a strong support-er of the domestic private sector.29Further-more, the political elite in these governmentsdid not develop collaborative relationships28

Hutchful,Ghana’s Structural Adjustment Experience,p 245.

Interview with Ernest Aryeetey, Director of the Institutefor Statistical, Social and Economic Research, University ofGhana, 13 April 2007.

R Tangri, ‘The Politics of Government-Business Relations inGhana’,Journal of Modern African Studies30(1), 1992, pp 97-111.29

17

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

with economic elite in productive sectors.The collaboration that existed between thestate and business largely took place aroundstate-awarded contracts in construction, pro-curement and timber concessions. As a result,the contemporary Ghanaian business class islargely politically divided. Businessmen arealigned with the two major parties and thosebusinesses not supporting the ruling party aremarginalized.30

THE ‘NEW POVERTY AGENDA’

COMES TO GHANA, THE NEW

PATRIOTIC PARTY COMES TO

POWER (2001-2008)

Ghana became eligible for debt relief underthe Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initia-tive (HIPC) in 1999, but the NDC govern-ment decided not to apply for it. Neverthe-less, the government was required to preparea PRSP in order to continue accessing WorldBank and IMF balance of payment support,which it desperately needed at the time. ThePlanning Commission was charged with theresponsibility of formulating the PRSP. With-in the rest of the state bureaucracy, the PRSPwas seen as a donor-driven process and minis-tries showed little interest in it.31The Decem-ber 2000 national elections led to a changein ruling party before the PRSP formulationprocess was completed.The New Patriotic Party (NPP) came topower under President Kufuor and with aslim majority in Parliament. It remained inpower after the 2004 elections, with Kufuortaking a second term. In order to understandthe impact of the New Poverty Agenda inGhana, and particularly the PRSP process, itis necessary to analyze the impact from theperspective of how the NPP government sawthe purpose of the PRSP. The first PRSP wasa necessity for accessing debt relief and a toolfor mobilizing funds from donors. Ministersand chief directors saw the chief importanceof the GPRS to be in its use for acquiringfuture donor funding and resource allocationfrom the Ministry of Finance.32Having ac-31

T Killick & C Abugre,‘PRSP Institutionalisation Study FinalReport, Institutionalising the PRSP approach in Ghana’, Over-seas Development Institute, London, 2001.Woll, ‘Donor harmonisation and government ownership’.

30

See D Booth et al., Drivers of Change in Ghana.

32

18

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

cessed debt relief, the second PRSP remaineda tool for mobilizing resources from donors,but also now had a life of its own as jointdonor-government funding mechanisms hadbeen created around it, such as general budgetsupport. The content of PRSP documentswas not really important, as the PRSP was notmeant to be a national development strategythat set priorities, determined resource alloca-tion and guided the formulation of programsat the ministry level.The NPP’s development vision spelled outin its 2000 election manifesto stemmed fromits critique of the economic policies of thePNDC regime and NDC governments. TheNPP political leadership criticised the passiverole of the government, particularly on in-dustrial policy since much of Ghana’s nascentindustrial capacity crumbled under importliberalisation. Therefore, the NPP’s develop-ment vision focused on a positive partnershipwith the private sector, but also an active staterole to remove impediments and foster devel-opment of the domestic private sector. TheNPP government also articulated a strongcommitment to restoring macroeconomicstability. However, the NPP government didnot implement this development vision. Itsproclaimed Golden Age of Business nevermaterialized, as the NPP government failedto address key constraints that producers facewhich result in high production costs. Whilethe NPP government did achieve macroeco-nomic stability, it squandered this achieve-ment at the end of its second term.The Ghana Poverty Reduction

Strategy 2003-05 and its impact

Upon assuming power in January 2001, theNPP government’s immediate task was tosolve the macroeconomic problems it hadinherited: rising inflation, currency deprecia-

tion, a huge domestic debt, shortfalls in aidflows and massive external debt servicing.The NPP government therefore reconsid-ered applying for debt relief under HIPC.Despite cutting development expenditureand freezing expenditure on goods and ser-vices, the 2001 budget had a huge deficit.Thus, the NPP government had to either cutpublic spending massively or to ask the in-ternational community for more aid money(and Ghana’s biggest donors were pushing itto apply for HIPC). Finally, after direct dis-cussions with IMF, British and French gov-ernment officials, President Kufuor decided‘to go HIPC’.33Under new political leadership, the Plan-ning Commission quickly wrapped up thePRSP process in order to access debt reliefas quickly as possible. Most Ministers tooklittle interest in the process, again seeing itas a donor demand and activity of the Plan-ning Commission with little implication fortheir work.34The situation changed when theWorld Bank country director stated that thisdocument would be the reference documentfor donor aid. The President put his supportbehind it, and the Cabinet put its stamp on it.The final text of the Ghana Poverty Reduc-tion Strategy 2002-2004 (GPRS) was largelywritten under the NDC government, so theNPP political leadership inserted its MediumTerm Priorities as the focus in implementa-tion of the GPRS. The NPP governmentgave the document an emphasis on povertyreduction through wealth creation and assist-ing poor groups to engage in income generat-ing activities.33

DK Osei, ‘Ambassador D.K. Osei’ inAn Economic History ofGhana: reflections on a half-century of challenges and progress,IAgyeman-Duah (ed.), Banbury, Abyeia Clarke, 2008, p.125Evaluation of the Comprehensive Development Framework:Ghana Case Study. Comprehensive Development FrameworkEvaluation Secretariat, 15 October 2002. Draft report.

34

19

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

The Medium Term Priorities included mea-sures for• macroeconomic stability;• economic transformation, such as mod-ernizing agriculture and promoting agro-processing;• strengthening the private sector, such asaccess to long term credit;• infrastructure, such as roads and energy;• education and skills training, such as build-ing model senior secondary school in eachdistrict;• health, such as a model health centre ineach district and reforming the health pay-ment system• and a few measures on the environment,gender, water and sanitationThese priorities diverged from the prefer-ences of some major donors who did notconsider them pro-poor at all or who didnot see them as linked to a diagnosis ofthe country’s poverty problem.35The term‘wealth creation’ used in the GPRS appearsto have been created after the NPP govern-ment was elected, as it does not appear inits election manifesto, in contrast to the newdiscourse of the international aid commu-nity which focused on poverty reduction. Asthe second PRSP would indicate, the NPPgovernment saw the new poverty agenda astoo narrow and not ambitious enough.The NPP government produced a Coordi-nated Programme for the Economic and So-cial Development of Ghana 2003-2012 andsubmitted it to Parliament as required by theconstitution. The document states that thegovernment’s aim is to transform the natureof the economy by harnessing agricultural

resource potential through value additions.It refers to the Medium Term Priorities indi-cated in the GPRS as laying the foundation,but its two strategies for accelerating growthfocus on agro-based industrial developmentand information technology. The Coordi-nated Programme is quite different from theGPRS text. However, this Programme is nev-er mentioned in public statements or donordocuments, and one would be excused fornot knowing that it even existed. The GPRS,on the other hand, is referred to consistentlyin donor documents and much official gov-ernment discourse. This schism was solvedduring the second term of the NPP govern-ment when GPRS II contained more of thegovernment’s agenda, and when the GPRS IIwas presented to Parliament as the govern-ment’s Coordinated Programme.For the NPP government, the GPRSserved mainly to access debt relief, and assuch it was a declaration of intentions to usedebt relief for poverty reduction actions. Inorder to access debt relief, the governmenthad to meet the conditions specified in theHIPC agreement, implement its World Bankand IMF agreements, and implement its PRSPfor a year.36The government completed theHIPC process in late 2004. It also acquiredrelief on debt to the Bretton Woods institu-tions in 2006 under the Multilateral Debt Re-lief Initiative. Twenty percent of the HIPCfunds (revenue calculated to be saved annu-ally as a result of debt relief) went to servic-ing domestic debt, and the rest was allocatedto ministries, departments, agencies and lo-cal government bodies for poverty reductionexpenditures. Starting in 2007, the budgetallocated all debt relief funds to specific ac-tivities, as opposed to just stating the amount36

35

Ibid.

For more detail on the conditions see Whitfield and Jones(2009) and Whitfield (2005).

20

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

going to each ministry. However, the fundswere quite small, especially when distributedacross a wide range of activities, and thus didnot amount to a large new source of discre-tionary expenditure.Multi-donor Budget Support was intro-duced in 2003 as a mechanism for how do-nors would give budget support and what thegovernment must do in order to receive thisdirect financing. It created a common struc-ture for ‘dialogue’ between donors and thegovernment, which included key discussionstwice a year and a formal annual assessment.Disbursements were linked to a set of bench-marks established for judging progress whichare contained in a performance assessmentmatrix. These targets and conditions are cho-sen annually through negotiations betweenthe budget support donors and the gov-ernment. Nine donors signed up to budgetsupport in 2003, which expanded to elevendonors in 2007, although these donors onlygive a portion of their aid portfolio throughbudget support. The budget support ar-rangement is backed by an extensive systemof sector working groups. There are regularmeetings of the budget support group andparallel regular meetings of the budget sup-port sector working groups. Donors triedto use the MDBS to increase their leverageover implemented policies.37Initially, budgetsupport conditionalities focused on publicfinancial management, and the governmenthad little input. Only in 2005 did the govern-ment begin to have input into the proposalfor targets and conditions. By the time of

37

T Lawson et al., ‘Evaluation of outputs, outcomes and im-pacts and recommendations on future design and manage-ment of Ghana MDBS’, Joint Evaluation of Multi-Donor Bud-get Support to Ghana, Final Report to the Government ofGhana and to the MDBS partners. Overseas DevelopmentInstitute, London and Ghana Centre for Democratic Devel-opment, Accra.

GPRS II, budget support targets came fromthe joint donor-government sector workinggroups, which largely took them from sectorstrategies. Thus, the introduction of generalbudget support structures increased donors’access to discussions over the budget andsector level policy.In sum, what got implemented during thefirst Kufuor administration were actions toachieve macroeconomic stabilization (thefocus of 2001 and 2002) and actions whichwere tied to the release of significant mon-ies, including the conditions negotiated in theHIPC agreement, conditions in the WorldBank’s Poverty Reduction Support Credit andthe IMF’s Poverty Reduction and GrowthFacility, and (from 2003) conditions in theMulti-Donor Budget Support Mechanism.Also implemented were on-going donor-gov-ernment projects and programs, and from2004, activities funded from HIPC savings.Although dependence on donor resourcesto support the budget declined during thefirst term of the NPP government, donorresources still accounted for most of theinvestment expenditure. Investment expen-diture increased over 2003 and 2005 due toincreased aid flows while domestic fundingfor investment remained constant. The larg-est component of government spending wasthe public sector wage bill. Resources allocat-ed to social services increased, but the 2004Annual Progress Report on the GRPS notesthat ‘increased allocation to social servicesto provide relief and safety nets to the poorand vulnerable has crowded out resources tothe economic services sector which supportswealth creation an sustained poverty reduc-tion’.38Budget allocations to the agriculture38

National Development Planning Commission, 2005 AnnualProgress Report. Implementation of the Ghana Poverty Reduc-tion Strategy 2003-2005, Accra, Government of Ghana, p 21.

21

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

sector declined from 7.1% in 2001 to 3.03%in 2004.The Growth and Poverty Reduction

Strategy 2006-09 and its impact

Multilateral and bilateral donors pressuredthe government (through the government’sdependence on IMF and World Bank bal-ance of payments support arrangements)to continue with the GPRS as its primarydevelopment plan, even when the govern-ment’s lack of interest with its indicatorswas apparent. However, donors’ main in-terest was to uphold the credibility of theprocess because donor funding arrange-ments were nominally based on the GPRSand there was no ready alternative on whichto formalize the donor-recipient relation-ship.39In terms of content, however, do-nors played a less prominent role than dur-ing the first PRSP.The context in which the second PRSP wasproduced was different from the first. Hav-ing achieved macroeconomic stability anddebt relief by 2005, the emphasis shifted togrowth-inducing policies and programs thathave the potential to support ‘wealth creationand sustainable poverty reduction’. As the ti-tle suggests, the Growth and Poverty Reduc-tion Strategy (GPRS II) declared a need tofocus more on the productive sector, so thatthe costs of social sector spending could besustained. This argument was there in the firstPRSP, but it was made more forcefully in thesecond. GPRS II was an agriculture-led strat-egy which seeks to diversify the economy’sstructure away from dependence on cocoa tocereals and other cash crops for export mar-kets and increase agro-processing and light39

industry based on textiles and garments andvalue-added minerals.The GPRS II was also produced by thePlanning Commission using the same sys-tem of expert working groups as during thefirst PRSP. The Preface which aggressivelysets out an alternative to the New PovertyAgenda was written by the Chairman ofthe Commission at that time, J.H. Mensah.Mensah is a veteran politician and develop-ment economist. He served under PresidentNkrumah in the country’s first government,and as Finance Minister under K.A. Busia,Ghana’s second President. He was the Se-nior Minister in Kufuor’s first administra-tion, but became marginalized in the secondadministration and was posted to the Plan-ning Commission. Given that Mensah is anoctogenarian and part of a very old gen-eration, it seems the younger generation ofNPP politicians may have pushed him out.Thus, the extent to which the GPRS II reso-nates with the rest of the NPP political elitecan be questioned.On the other hand, the content of theGPRS II was just an aggregate of existing sec-tor strategies and international commitments.As stated by the Director General of thePlanning Commission: ‘GPRS II essentiallyintegrates the otherwise disparate develop-ment agendas and sectoral commitments thatcompete for inclusion in the annual nationalbudget into one comprehensive developmentpolicy framework’.40Thus, the Preface mayreflect the desire of Mensah and the PlanningCommission, and probably many politicalleaders in the NPP, but it did not affect thecontent of GPRS per se.

40

Woll, ‘Donor harmonisation and government ownership’,p 77.

‘Results and Resources Analysis 2007’, presentation byRegina Adutwum, Director-General, National DevelopmentPlanning Commission, to the Consultative Group meeting, 30June 2008.

22

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

Ministries prepared sector strategies in2003 and 2004 to guide their activities. Thesestrategies alluded to the GPRS text, but theGPRS was so general and all inclusive thatalmost anything could be justified as being‘inline’ with its priorities. In reality, the con-tent of sector strategies was determined innegotiations with donors active in that sec-tor, especially those willing to pool fundsfor the implementation of the sector strat-egy. These sector strategies in turn were thebasis for the content of the second PRSP.The emergence of sector strategies was par-tially driven by donors, who were seeking toimplement new aid modalities such as thesector-wide approach or pooled funds andthus needed a strategy around which theycould coordinate their projects and fund-ing. This drive gained momentum with thegrowing emphasis on donor harmonizationand alignment with government’s own poli-cies in order to increase recipient owner-ship of aid supported activities. Ministriestook up the opportunity to produce theirown strategies which donors would thensupport.The reality is much more complicated.Donors tried to get their ideas and priori-ties incorporated and ministry policymak-ers are fully aware after decades of workingwith donors about what particular donorswould and would not finance. Donors pro-vided resources to formulate the strategies,paying domestic or international consul-tants to help design the strategies and fornumerous rounds of public consultations.Sector policies are often comprehensive,but fail to set clear priorities and a sequencefor implementation. This lack of prioriti-zation is partly the result a large numberof donor agencies being involved in thepolicymaking process, in addition to themany different departments within minis-

tries, and policy makers tried to include allof their priorities so there is sufficient buyin and financial support. Sector policies arelargely done for the benefit of donors bylower middle level bureaucrats, and gener-ally civil servants were not going to get intoa fight over a policy document as long asit did not proscribe them from doing thethings they wanted.In short, GPRS II may have had an over-arching vision, but it did not produce a na-tional development strategy that was then toguide the develop programs to implement it.To find out what was implemented by the sec-ond NPP government, one has to look at theministry level and even at specific projects. Itis in specific projects where government of-ficials discuss and negotiate with donors ‘howto’ achieve their objectives. It is hear that poli-ticians and civil servants do (or do not) bringideas to the table, and it is here that they en-counter the rigidities of the aid system andthe weaknesses of the public administrationto formulate, negotiate and implement pro-grams.The MDBS is supposed to be aligned withthe government’s priorities in the GPRS.However, since donors do not see the GPRSas properly prioritized, negotiations overthe policy matrix of the Performance As-sessment Framework for disbursing generalbudget support are basically about pickingpriorities.41Policy actions and targets in theMDBS policy matrix seem to be closer to theGPRS II priorities than was the case underthe GPRS I.

41

T Lawson et al., Report from the MDBS Budget SupportJoint Evaluation Dissemination Workshop held 24 April 2007.

23

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

The NPP government and the

economic transformation agenda

For President Kufuor’s first term, and prob-ably the beginning of his second term, theNPP government had limited access tofunds outside donor aid flows for the pur-poses of investments and the provision ofservices. Domestic funding for investmentremained constant during GPRS I, with allincreased investment expenditure over theperiod from 2003 to 2005 coming from in-creased aid flows. After making paymentsregarding domestic and foreign debt, theremaining government revenue went topublic sector salaries, administration, statu-tory payments, and counterpart funding fordonor projects. The largest component ofgovernment spending was the public sec-tor wage bill, as it had been in the 1990s.This left little room for maneuver and madeit difficult to change investments or focusthem in a landscape dominated by multipledonor projects of various sizes. However,this is not to say that the NPP governmentwould have been able to agree on major in-vestment strategies even if it did not facethe constraints inherent in depending ondonors. As discussed below, there are otherfactors which affect the ability of the partyin power to formulate and implement poli-cies and initiatives.In a post-HIPC environment of mac-roeconomic stability, the second Kufuoradministration emphasized infrastructuraldevelopment in order to address critical infra-structural bottlenecks slowing down growth.The government was funding its infrastruc-ture projects primarily through the interna-tional capital market and loans from China,but also through loans from traditional donorsand public–private partnerships with foreigncompanies where possible. After completingits Poverty Reduction and Growth Facilitywith the IMF in October 2006, the govern-ment decided not to enter into another agree-ment with the IMF, but rather used its newcredit rating to issue a Eurobond in Septem-ber 2007 that raised $750 billion on the inter-national private capital market.However, in 2006 the government’s fis-cal deficit grew to 7.5% of GDP due to itsexpansionary policies.42The main driver ofgovernment spending was the wage bill as aresult of pay awards in the health sector thattriggered further requests for pay increaseswithin the public sector. The second driverof government spending was energy sec-tor subsidies. The supposedly autonomousregulatory body increased electricity tariffsin 2006, but these were not passed on to theconsumer at the government’s request and itsubsidized the electricity company, which hadtariffs 50% below the cost of power genera-tion. Although tariff adjustments were passedthrough to consumers in 2007, they did notreach cost recovery level.Electricity shortages in 2006 and 2007created a crisis, and the government priori-tized investments in the energy sector. Thegovernment responded to the need for fiscalspace for energy-related expenditures, as wellas payroll expenditures again, with across theboard 30% cuts in budget ceilings for servicesand non-energy related capital expenditures.43This had also been done in 2006 to accom-modate high payroll spending. Governmentincreased poverty reduction spending in 2006and 2007 at around 10.5% of GDP, with ba-sic education, health and rural electrificationaccounting for over 60% of domestically fi-nanced total poverty reduction spending.42

World Bank. Ghana 2007 External Review of Public Finan-cial Management, Volume 1: main report. Report no. 40676-GH, June 2008.Ibid.

43

24

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

However, government spending in 2007and 2008 also included prestige projectswhich had no or limited effect on productiv-ity. These included Ghana@50 to celebrate50 years of independence in July 2007; build-ing three new football stadia in order to hostthe African Cup of Nations in early 2008;hosting the Summit of Heads of State fromAfrica, Caribbean and the Pacific countries inOctober 2008; hosting the UNCTAD confer-ence in April 2008; and the construction ofJubilee House, the new presidential palace.These events required considerable outlaysfrom the government, but it is not officiallyknown yet how much.The trade deficit grew in 2007 and 2008due to rapid growth in non-oil imports andincrease in the oil bill, which overshadowedgood export performance and caused a de-cline in the currency value while the fiscaldeficit caused higher inflation.44By January2009, the country was back into the throwsof macroeconomic instability. The NPP gov-ernment had overshot its 2008 budget projec-tions by 697%.45The country’s fiscal deficitsurged in 2008 as a result of overspending,increased petrol prices, the effect of the en-ergy crisis on the economy, and a short fallin the expected returns on investment fromhosting the Africa Cup of Nations.46Fiscaldeficits of the past few years had been fi-nanced from the proceeds from the privatiza-tion of state assets and from leftovers of theEurobonds issued in 2007, while the currentaccount deficit was financed with foreign re-serves. By 2009, those sources were not lon-

44

International Monetary Fund. Staff Report for the 2008 Ar-ticle IV Consultation. 16 June 2008.’WB paints gloomy picture of Ghanaian economy’, DailyGraphic, 7 January 2009, www.ghanaweb.com.Government of Ghana is ‘Broke’, GNA, 16/01/09, accessedfrom www.ghanaweb.com.

45

46

ger available. Thus, the early achievements ofthe NPP government in terms of macroeco-nomic stability evaporated.In terms of social services, resource allo-cations increased, but it is not clear whetherthe quality of education has improved signifi-cantly. A major policy change was made inthe health sector which involved the estab-lishment of the National Health InsuranceScheme in 2005 to replace the cash and carrysystem established under structural adjust-ment. This was a major issue in the NPP’s2000 election manifesto, and with the bill tocreate it passed by Parliament before 2004elections, the NPP could point to a majorpolicy victory.In the productive sector, there were a fewkey initiatives. Kufuor launched the Presiden-tial Special Initiatives (PSIs) to create newpillars of growth in agro-processing and ingarments and textiles in order to take advan-tage of the US African Growth and Oppor-tunity Act. However, by the end of its tenurein office, the PSIs had not achieved much andremained in the initial phases of implementa-tion. Regarding the cocoa industry, the gov-ernment increased the producer price paid tococoa farmers, began a free mass spraying ofcocoa farms to control pest and diseases, im-proved feeder roads in cocoa growing areas,and encouraged domestic processing of co-coa. However, the government did not makemuch progress on its priorities under mod-ernizing agriculture. Concerning its priorityof farm mechanization, it imported tractorsfor selling individually and establishing farmmechanization centers in 2005 with HIPCfunds and an Indian Exim Bank facility. Thegovernment also began procurement anddistribution of processing equipment to sup-port agro-processing industries largely usingHIPC funds. The government also signed theMillennium Challenge Account compact with

25

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

the US in 2005, which focuses on modern-izing agriculture in 2005, but it did not startimplementation until early 2007. By the endof the NPP reign, that initiative was yet tomake any impact on the ground. But the gov-ernment did not make any progress on otherstated priorities such as providing irrigationfacilities, improving access to inputs for cropand livestock production, undertaking landadministration reforms, and improving ac-cess and increasing volume of credit availableat affordable rates.The NPP government did not take anytough decisions or push through reformson the key constraints. For example, it cre-ated a Ministry of Public Sector Reform, butthis ministry did not make much progress inpursuing civil service reform, and it created aMinistry for Private Sector Development, butone could say that the party’s Golden Age ofBusiness failed to materialize. It is also truethat Kufuor and the top political leadershipseemed to lack a strong vision for the coun-try. Not many NPP politicians brought newideas to the table. The Presidential SpecialInitiatives was one of the only ones, and thatidea was very state centric and did not in-volve ‘building partnerships with the privatesector’. The NPP government talked the talk,but produced few strategies to turn its dis-course into reality.

FACTORS INFLUENCING

GOVERNMENT POLICY ACTIONS

Why did the NPP government implementsome of its stated priorities and not others?Why did it particularly fail to implement itsagenda on modernizing agriculture? The fol-lowing discussion is a first attempt to answerthese questions in a way that highlights thekey explanatory factors and gives an overallpicture. This initial explanation serves to laythe foundation for future research which willlook at several of these factors in more de-tail.The factors influencing government policyactions were shaped by what the political andbureaucratic elite find desirable and perceiveto be feasible, and their authority and abilityto get those actions implemented. These fac-tors include:1. Macroeconomic constraints2. Donor pressure leveraged through financ-ing3. Pressure to win elections4. Internal dynamics of the ruling party5. Bureaucratic constraintsThese five factors are not specific to theNPP government, but apply to the 1993-2000 NDC government as well, but the dis-cussion here refers only to the two Kufuoradministrations. The external environmentalso shapes what is feasible, but is taken as anunchangeable given, whereas the five factorslisted above can be changed even though theyare difficult to change. The interplay of thesefactors determines government’s actions orinactions.The government is constrained by macro-economic parameters, as has been true sinceNkrumah’s independence government, due

26

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

to the structure of the economy which de-pends on a few key exports to fund importsand which has limited revenues to fund do-mestic expenditures. However, as can be seenfrom the narrative above, the NPP govern-ment’s expenditures where also influenced byother, political factors. The prestige projectswere clearly the result of pressure within theparty to both portray its party and its countryin a prestigious way, which were seen as moreimportant than some public investments thatwent unfunded due to ‘lack of funds’ in min-istries. Another example is that the govern-ment repeatedly delayed passing on increasesin oil prices to utility consumers, which re-sulted in huge subsidy bills. The action ofthe government was most likely predicatedon fears of a public backlash at election time,since utility prices are extremely politicized inGhana. Thus, pressure to win elections alsoleads to fiscal expansion and in turn createsor exacerbates macro-economic constraints.Political leaders strive to appease the elec-torate in order to get (re)elected. As a result,they focus on projects and actions that candeliver immediate results, or at least beforethe next election (which is every four years).They also focus on delivering visible benefits.Visible symbols of investment produce morepolitical points for incumbent politicians thanreforms or investments that take a long timeto bear fruit. Building roads, schools andhealth clinics which the ruling governmentcan take credit for makes good political sense.Investing in infrastructure is not always donewith the economy in mind but with short-term political considerations: rather than tar-geted investments, they are widely disbursed.Furthermore, donors also like visible things,because they can also plant their flag on it,creating double perverse incentives. The needto claim credit for bringing benefits to peo-ple’s lives can also result in the government

wanting to be the lead implementer in pro-ductive sector initiatives or start somethingnew instead of building on what the privatesector was already doing. Thus, needing toclaim credit can affect precisely how thingsare implemented.Dynamics of the internal workings of theNew Patriotic Party are important to under-standing the lack of cohesive vision of theNPP government and to its inability to ef-fectively implement its own priorities andinitiatives. There is little research to date ondebates and tensions within the party politi-cal elite and how this may undermine its ef-fectiveness in power. How the battles withinthe party play out, and how the top leadershiphandles them are very important in determin-ing the effectiveness of the party in powerto produce and implement a development vi-sion and initiatives.Organized interest groups do lobby forinfluence on government policies and initia-tives. Some are more influential than others.However, there are not many organized pro-ductive interests in Ghana, because there arefew strong industries. In an economy wheremuch of the economic elite are in construc-tion, real estate, services, and import and dis-tribution, there are few large and organizedsector groups pushing for policies to addressthe constraints of agro-processing and man-ufacturing and offering solutions. Food cropfarmers are also not organized well-enoughto advocate for policies to promote agricul-ture and to use electoral pressure in that way.There has not been a big pull within societyto deliver on an agricultural developmentstrategy. Agribusiness only really took offin the 1990s, but Ghanaian agribusinessmenhave not been very pro-active to date. Gen-eral voter concerns stress the provision ofsocial services and infrastructure much morethan agricultural policies, except for requests

27

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

for fertilizer subsidies. NGOs are also mostlyconcerned with social service provision suchas health, education, water.The last factor affecting what gets imple-mented is bureaucratic constraints on opera-tionalizing and implementing policies. Thepublic administration structures since inde-pendence have developed in an ineffectualway.47Since independence, the public admin-istration has been characterized by fragmen-tation due to the multiplication of publicsector organizations, which makes their man-agement difficult. Since Nkrumah’s time, pol-iticians had been suspicious of civil servants’loyalty, and top civil servants were encouragedto join the ruling party. Economic decline inthe 1970s led to an exodus of professionals,and acquiring or retaining good staff contin-ues to be a problem. Parallel administrativeunits have been set up under several govern-ments, such as during the late Nkrumah pe-riod and during the economic reforms of the1980s under the PNDC regime. On top ofthe chaotic structures that had arisen by the1990s, aid dependence brought with it parallelimplementation units, a slew of consultants,use of donor procedures, and a second set ofdonor supervisors.48Little has changed sincethen, despite recent attempts to reform theaid system.The result today is a public administra-tion system that does not work and whichseverely reduces the ability of the govern-ment to implement reforms and programs.Incentive structures within the civil serviceactively discourage initiative and pro-activity.47

AG Quartey, The Ghana Civil Service: engine for develop-ment or impediment?. IDEG Ghana speaks lecture/seminarseries, Accra, Woeli publishers, 2007.E Aryeetey & A Cox, ‘Aid Effectiveness in Ghana’, in ForeignAid in Africa: learning from country experiences, J Carlsson,G Somolekae & N van de Walle (eds), Uppsala, Nordiska Afri-kainstitutet, 1997, pp 65-111.

48

Furthermore, civil servants feel underpaidnext to domestic or donor funded consul-tants who receive much higher salaries, andthey feel frustrated by being bypassed whenMinisters appoint political advisers to getthings done. As a result, it takes a long timeto implement anything, and initiatives canget killed under the weight of this bureau-cracy. Public sector reform has been on theagenda for decades, but not moved very far.An affordable civil service reform will haveto include substantial retrenchments. But thisis politically difficult in a situation where thepublic sector accounts for about half of totalrecorded employment, and the economy hasbeen unable to generate productive formalsector jobs to keep pace with growth of thelabor force.The leadership, institutions, policies andpolitical coalitions needed to push forwardan agenda of structural transformation ofthe economy, and thus long term poverty re-duction, do not come easily – as the globalhistorical record shows. In Ghana, the con-straints posed by chronic macroeconomicinstability, donor agendas leveraged throughfinancing, pressure to win elections, the in-ternal dynamics of the ruling party, and theweaknesses of the public administrationappear formidable. However, this is not adeterminist or path dependency argument.Although the political elite face great incen-tives to maintain the status quo and disincen-tives to change, there is cause for optimism.Most of these constraints are internally gen-erated and thus the possibility of changefrom within. For example, macroeconomicinstability is the cause of both the narroweconomic structure but also of governmentpolicy actions. Furthermore, governmentleaders could choose to take less foreignaid or negotiate about what kind of aid totake. However, it has also has become abun-

28

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

dantly clear that foreign aid does not holdthe promise of economic development. Asthis paper has shown, it is hard for aid toalter the constraints and can even exacerbatethem.

29

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2009:15

30