Udenrigsudvalget 2008-09

URU Alm.del Bilag 153

Offentligt

DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE AND CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA:LESSONS FROM THE EASTERN PROVINCEAsia Report N�165 – 16 April 2009

TABLE OF CONTENTSEXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. iI. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1II. EASTERN REAWAKENING.......................................................................................... 1A. DONORACTIVITIES......................................................................................................................2B. DETERIORATINGSECURITY, INCREASINGUNCERTAINTY.............................................................31. Increasing violence and impunity ................................................................................................32. Devolution still on hold ...............................................................................................................53. Muslim and Tamil alienation .......................................................................................................54. Policy shift needed.......................................................................................................................6C. RISKS TO AND FROMDEVELOPMENTWORK.................................................................................6

III. “CONFLICT SENSITIVITY” AND THE POLITICS OF AID ................................... 7A. THELIMITS OF“CONFLICTSENSITIVITY” ....................................................................................7B. DONORHESITATIONS...................................................................................................................9C. PRINCIPLES OFENGAGEMENT....................................................................................................10

IV. MANAGING THE RISKS BETTER ............................................................................ 12A.B.C.D.E.F.G.ENGAGING THEPROVINCIALCOUNCIL.......................................................................................12RESPONDING TOINSECURITY ANDIMPUNITY.............................................................................13EXTORTION, THEFT ANDFRAUD................................................................................................15DISARMAMENT, DEMOBILISATION ANDREINTEGRATION...........................................................17CHILDSOLDIERS........................................................................................................................18ECONOMIC ANDBUSINESSDEVELOPMENT.................................................................................19THEQUESTION OFLAND............................................................................................................211. Land regulations and policies ....................................................................................................212. Road building.............................................................................................................................223. Housing ......................................................................................................................................234. Irrigation ....................................................................................................................................235. High security zones and special economic zones ......................................................................23H. CONFLICT-RELATEDDISPLACEMENT.........................................................................................24

V. CONCLUSION: LESSONS FOR THE NORTH ......................................................... 28APPENDICESA.MAP OFSRILANKA.........................................................................................................................30B.MAP OF THEEASTERNPROVINCE.....................................................................................................31C.GLOSSARY.......................................................................................................................................32D.ABOUT THEINTERNATIONALCRISISGROUP....................................................................................34E.CRISISGROUPREPORTS ANDBRIEFINGS ONASIA SINCE2006 .........................................................35F.CRISISGROUPBOARD OFTRUSTEES................................................................................................37

Asia Report N�165

16 April 2009

DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE AND CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA:LESSONS FROM THE EASTERN PROVINCEEXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONSViolence, political instability and the government’sreluctance to devolve power or resources to the fledg-ling provincial council are undermining ambitious plansfor developing Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province. The eastcontinues to face obstacles to economic and politicalprogress and offers lessons for development agenciesand foreign donors considering expanding their workinto newly won areas in the Northern Province. Whilethere is still potential for progress in the east, it remainsfar from being the model of democratisation and post-conflict reconstruction that the government claims.Donors should adopt a more coordinated set of policiesfor the war-damaged areas of Sri Lanka, emphasisingcivilian protection, increased monitoring of the effectsof aid on conflict dynamics and collective advocacywith the government at the highest levels.International attention is currently and rightfully focusedon the need to protect upwards of 100,000 civilians atrisk from fighting in the northern Vanni region, but atthe same time, there are still important challenges inthe so-called “liberated” area of the Eastern Province.Even now, the Eastern Province is still not the “post-conflict” situation that development agencies had hopedit would be when they started work there in late 2007and early 2008. Despite the presence of tens of thou-sands of soldiers and police in the east, the LiberationTigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) have proven able tolaunch attacks on government forces and on their rivalsin the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Puligal (TMVP). Therehave also been violent conflicts between different fac-tions of the pro-government TMVP, and impunity forkillings and disappearances, many of them apparentlycommitted by government security forces and/or theirallies in the TMVP. Extortion and criminality linkedto the TMVP also remain problems. Insecurity and fearare undermining the ability of agencies and contrac-tors to implement projects.Violence between Tamils and Muslims has been keptto a minimum since June 2008, but tensions betweenthe communities over land and political power remainhigh, and there seems little prospect of reconciliationso long as current government policies remain in place.Tamils are largely alienated from the government, thanksto the heavy hand of government security forces andTMVP activities. Many Muslims feel threatened byTMVP control of the provincial council and what theysee as Tamil domination of the provincial administration.Both communities continue to suspect the governmenthas plans for large-scale “Sinhalisation” of the east.Sinhalese villagers, students, contractors and govern-ment employees have, in turn, been victims of violentattacks.The government still has not devolved power to theEastern Province, as required by the Thirteenth Amend-ment to the constitution, which established the provin-cial council system in 1987 in response to Tamil demandsfor regional autonomy in the north and east. The gov-ernor of the province, appointed by the president, isblocking the council’s initial piece of authorising leg-islation, and development planning and implementationcontinues to be run from Colombo and central govern-ment ministries. The government has yet to articulateany plans for a fair and lasting distribution of resourcesand political power that would satisfy all communities.In this environment, development of the east remainsaffected by the conflicts and threatens to exacerbatethem. Despite the need for development, there is a dan-ger of funds being wasted or misused. Donors shouldnot be treating the situation as a typical post-conflictenvironment. Instead, there is a need for additionalmonitoring and additional coordinated political advo-cacy. This is all the more important now that donorsare considering assistance for the reconstruction of theNorthern Province, once security conditions allow.Bilateral and multilateral donors need to work with thegovernment in a coordinated way and at the highestlevels to ensure that its policies provide for effectiveand sustainable development. This should include awritten agreement on basic principles, to be signedduring a high-level donor development forum and priorto the commencement of any new projects. The govern-ment should agree to provide the basic level of human

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page ii

security necessary to successful development work byending impunity for human rights violations and plac-ing its counter-insurgency campaign under strict legalaccountability.It should establish a political context conducive toaddressing the inevitable future conflicts over land anddevelopment in the north and the east by empoweringthe respective provincial councils to address develop-ment and security needs. In the north, this must beginwith free and fair elections that feature the full rangeof Tamil political parties and are conducted with inter-national monitoring. Independent representatives of allcommunities, including from opposition parties, shouldbe given a significant role in key development decisions.Finally, Tamils and Muslims need assurances that thereare no current plans for Sinhalisation – either of theeast or the north – and that demographic issues will bedealt with only through negotiation with independentrepresentatives of all three communities as part of asettlement of the larger conflict.At the same time, donors and development agencies needto establish stronger procedures to understand thepolitical dynamics in the east and in the north and tomonitor the effects and uses of their development pro-jects, so as to limit the risk that their assistance willaggravate existing conflicts or provoke new ones. Todo development right, it will have to be done slowly,carefully and with greater political investment. It willalso require additional staff and resources. Major donorsshould form a joint donor task force or monitoring unitto analyse current conflict dynamics in the east (andwhen possible, in the north) and develop the sharedprinciples for more “conflict-sensitive” work which thegovernment would be requested to adopt.For these efforts to work, development agencies needto defend the work of local and international non-governmental organisations more vigorously. Threatsand intimidation are crippling the necessary informationflows, and general insecurity undermines meaningfulproject monitoring and public consultation. Multilateraldonors in particular need to send strong messages tothe government that harassment and denial of visas tointernational humanitarian and development workersand intimidation of local NGOs and community activ-ists undermine their ability to do responsible develop-ment work and must stop.

RECOMMENDATIONSTo Japan, the World Bank, AsianDevelopment Bank, United Nations, U.S.,EU and Other Bilateral Donors:1. Meet to review all development assistance to SriLanka and agree on principles for equitable andsustainable development in the east and north, toform the basis of a formal memorandum of under-standing with the government, to be supported byan adequately funded monitoring process. The gov-ernment should be requested to:a) empower the Eastern – and once elected, theNorthern – Provincial Council to play a key rolein development decisions through maximisingthe devolutionary potential of the ThirteenthAmendment and allowing the councils to passenabling provincial-level legislation withoutobstruction from the president, governors orparliament;b) consult actively with independent community andpolitical leaders from the three ethnic commu-nities, including opposition parties, on all signifi-cant development initiatives in the north andthe east;c) offer assurances to Tamils and Muslims that thereare no government plans for Sinhalisation of theeast or the north and that demographic issueswill be dealt with only through negotiation withindependent representatives of all three communi-ties as part of a settlement of the larger conflict;d) provide basic security guarantees to the citizensof the north and east and adequate security fordevelopment work, beginning with a crackdownon the criminal activities of pro-governmentarmed groups, including the TMVP and theKaruna faction, and an end to disappearancesand killings associated with the government’scounter-insurgency campaign;e) guarantee free and fair provincial elections inthe north, with the full range of political partiesallowed to campaign safely and no party allowedto campaign while armed, with internationalobservers in place, and to be held only after themajority of displaced have returned home fromgovernment camps;f) provide a timetable for the prompt return homeof all those displaced from the north, and allowfreedom of movement for the displaced prior toreturn and full access for humanitarian organisa-tions to any displaced while they remain in camps;

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page iii

g) respect the right of donors to work with localand international NGOs of their choosing whowill be free from harassment and visa restric-tions; andh) reestablish the rule of law throughout the coun-try, beginning with the president’s activation ofthe Constitutional Council and the subsequentappointment of independent police, humanrights and judicial services commissions.2. Recognise that the Sri Lankan context is not a typi-cal post-conflict situation and pay special attentionto conflict dynamics that may arise through devel-opment work by:a) establishing a joint donor task force to reviewthe past two years of donor projects in the East-ern Province and study the political forces cur-rently affecting conditions for development workin the east and, when security permits and civil-ians have begun to be resettled, in the north.b) devoting increased resources for the ongoingand collective monitoring of the effects ofdevelopment projects on conflict dynamics,either through a joint donor task force or throughproviding additional staff to the existing DonorPeace Support Group;c) hiring additional conflict advisers, increasing thenumber of project reviews, and establishingregular provincial-level monitoring meetingson land-related policies, especially with regardto fears of Sinhalisation;d) engaging in high-level and coordinated lobby-ing in defence of the work of local and interna-tional NGOs, insisting as a condition of aid thatthey be allowed to play an active role in moni-toring and responding to conflicts over land anddevelopment in the north and the east; ande) undertaking a collective study to determine thenature and extent of extortion, theft and “taxa-tion” by armed groups and government securityforces in the north and east, increasing moni-toring of the issue, and sending strong messagesto the central government, the TMVP and pro-vincial politicians that every effort must be madeto end such practices and hold those involvedaccountable.3. Support the empowerment and effectiveness of theEastern – and eventually the Northern – ProvincialCouncil by:a) requesting the government grant them the nec-essary authority to negotiate projects directly withdonors, at least in those areas listed as provin-

cial and concurrent powers under the ThirteenthAmendment; andb) working to achieve maximum political consensusfor development projects by obtaining agreementfrom both the ruling coalition on the council andthe political opposition, and by encouraging theprovincial councils to give a meaningful roleto opposition parties and community leaders indevelopment and land-related decisions.4. Work together to monitor current land use patternsand policies in the east and north by:a) underwriting a study of the effects that planneddevelopment projects in the east and northmight have on land use and ethnic relations andhow to prevent land-related projects from exac-erbating conflict dynamics;b) linking further funding for housing, irrigation orrelated development projects to the government’sdrafting new and equitable land titling, distributionand dispute resolution policies through a trans-parent and inclusive process of consultation;c) working closely with the government and imple-menting agencies who build donor-funded housesto ensure that the proper land titles or permitsare issued; andd) monitoring for any encroachment or arrival ofsettlers in and around emerging commercial hubsand newly built or expanded roads.5. Support conflict-sensitive business development by:a) giving preference to local residents in both thecontracting and sub-contracting work done withdonor money and encouraging government andprivate investors to do the same; andb) actively seeking out Tamil and Muslim businessesthat might be interested in expanding into theeast, to offset the existing advantages of Colomboand Sinhala businesses.6. Insist on a collective basis that international stan-dards are respected at all stages of displacement byestablishing as a condition for development assis-tance the following minimum principles, to becommunicated to the government and to donors’implementing partners, with mechanisms for moni-toring compliance:a) unrestricted access to the displaced for all rele-vant humanitarian agencies and representativesof donor countries;b) guarantees of protection for internally displacedpersons (IDPs) and humanitarian workers, includ-ing the presence of the International Committee

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page iv

of the Red Cross at all sites where the militaryand police conduct security screenings;c) freedom of movement for IDPs once they havecompleted security screenings, with the displacedallowed to stay with relatives or host families;d) civilian authorities in charge of security atcamps and hospitals that house the displaced;e) immediate preparation for a safe and timelyreturn of IDPs to original homes or whereverthey wish to go, preceded by a rapid and inde-pendent study of the number and location ofmines in the north; andf) no support given to camps with a semi-permanent or permanent character.

of the Thirteenth Amendment, including all nec-essary authority to negotiate projects with donors,at a minimum in those areas listed as provincial andconcurrent powers under the Thirteenth Amendment,and the authority to prevent emergency powers, highsecurity zones (HSZs) or special economic zones(SEZs) from being used to seize land without localconsultation, accountability or compensation.11. Give Tamils and Muslims in the east and north con-crete assurances that land policies will be devisedthrough inclusive and transparent means and willnot be used as a tool to politically weaken theircommunities.12. Include the views of independent Tamil and Mus-lim political representatives and community lead-ers in development decisions in the east and northand make genuine efforts to ensure that all threecommunities in the east benefit fairly from govern-ment economic development, including the Kap-palthurai Industrial Development Zone, and theOluvil and Valachchenai fisheries ports.13. Cease using HSZs and/or SEZs to displace residentswithout being granted monetary compensation orthe right to effective legal challenge.14. Grant compensation to businesses in the east andnorth that have suffered damage from war and eth-nic violence and to those in the Eastern Provincewhose properties were looted during and after thefighting in 2006 and 2007.15. Enact preferential hiring and contracting policiesfor local residents for all development projects inthe east and north.16. Ensure that security restrictions which limit live-lihood options – eg, on fishing, cattle-grazing orwood-collecting – are kept to a minimum and thatwhen enforced they are applied in clear, consis-tent and non-arbitrary ways.

To UNHCR, UNICEF and the ProtectionUnits of Humanitarian Organisations:7. In the absence of a full-scale field presence for theUN Office of the High Commissioner for HumanRights, develop a plan for an extensive and coor-dinated network of protection offices in the northand east which can report on compliance with inter-national standards for the protection of the dis-placed and those resettled in their home villages.

To UNICEF:8. Strengthen monitoring mechanisms and report onany evidence of underage recruitment by all armedgroups, including pro-government groups otherthan the Pillayan and Karuna factions, and insistthat under any future “action plan”, UNICEF hasthe power of unlimited, independent inspection ofall camps and offices of both Pillayan and Karunafactions and has adequate staff to monitor compli-ance with all terms of the agreement.

To the Government of Sri Lanka:9. Negotiate an agreement with international devel-opment partners to provide the conditions neces-sary for sustainable and equitable development inthe Eastern and Northern Provinces, as outlined inrecommendations above.10. Grant provincial councils a strong degree of con-trol over land, in line with, or beyond, the terms

To the Eastern Provincial Council:17. Extend the deadline for registering land clams un-til the regulations have been rewritten to remove anyserious causes for concern expressed by represen-tatives of any of the three ethnic communities.

Colombo/Brussels, 16 April 2009

Asia Report N�165

16 April 2009

DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE AND CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA:LESSONS FROM THE EASTERN PROVINCEI. INTRODUCTIONSri Lanka has been in violent conflict for more thanthree decades. An estimated 85,000 people have died,most in fighting between the government and the Lib-eration Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The LTTEwas largely defeated in the east of the country in 2007and is now trapped in a small area in the north, shield-ing itself behind more than 100,000 civilians. Thereis an urgent need to ensure that these civilians areallowed by the LTTE and the Sri Lankan governmentto leave this area through an extended humanitarianpause. But even as attention is focusing on that crisis,violence continues in the east, despite efforts at politi-cal and economic development.These efforts have been supported by the internationalcommunity, which has also pledged assistance to thenorth of the country after the LTTE is defeated. But ifthis assistance is handled in the wrong way, it risksexacerbating a complex conflict that is by no meansover. This report examines the way redevelopment hasbeen managed in the east and suggests lessons for thenorth, an area particularly devastated by war.This report is based on interviews across the east of thecountry throughout 2008 and the first three months of2009. These included meetings with Sinhalese,1Tamiland Muslim community leaders, local governmentofficials, local NGOs and activists. Crisis Group alsomet with a range of officials, diplomats and aid offi-cials in Colombo. The east remains a sensitive issuein Sri Lanka and given the environment of intimida-tion and violence and the almost complete impunityfor political killings, few people were willing to talkon the record.

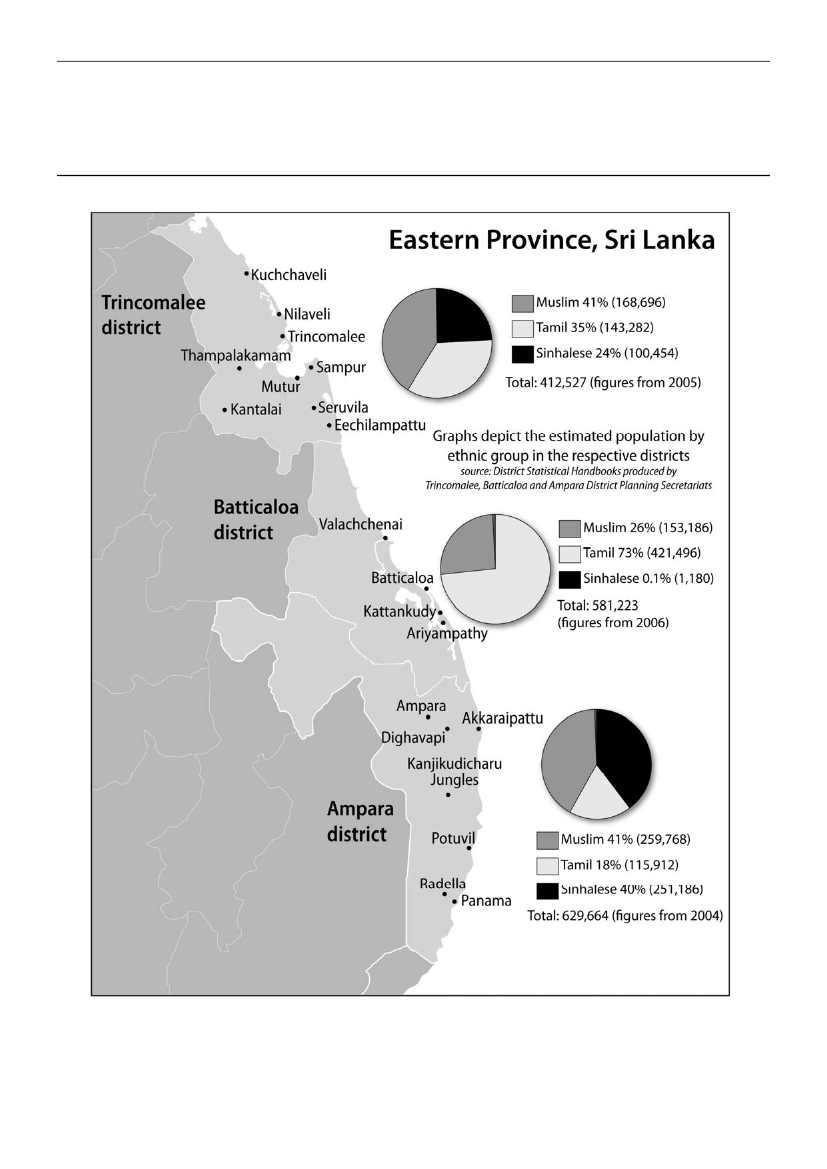

II. EASTERN REAWAKENINGWithin days of the capture of the LTTE’s last easternmilitary camp in July 2007, the president and seniorofficials announced government plans for a “massive”development program for the east.2Known asNagen-ahira Navodaya,or “Eastern Reawakening”,3the pro-gram calls for industrial development and infrastruc-ture projects, ranging from power plants, roads, bridges,and water and sanitation improvements, to touristdevelopment and other private business initiatives.There are also projects to provide economic opportu-nities, build housing, and resettle and rehabilitate thosedisplaced by fighting in areas formerly held by theLTTE.The government is already claiming success in the east.Maintaining that “the key to peace is prosperity”,4itpoints to new roads and bridges throughout the prov-ince, the ongoing construction of an industrial parkand a coal power plant near Trincomalee harbour, fish-eries ports in Valachchenai and Oluvil, and expandedmineral extraction along the north coast of Trinco-malee district. New irrigation projects are planned, andthe government has announced a bumper rice cropdue to an additional 130,000 acres of land now undercultivation.5All but a small number of people dis-placed by fighting in 2006-2007 have now been reset-tled, housing is being built, and electricity, drinking

1

In everyday usage, Sinhala and Sinhalese are often interchange-able. In this paper, Sinhala will be used in all cases exceptwhen referring to the ethnic group as a collective noun, asin “the Sinhalese”.

For an analysis of the role of land and development in ethnicconflict dynamics in the east, see Crisis Group Asia ReportN�159,Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province: Land, Development,Conflict,15 October 2008. See also Crisis Group Asia Re-port N�134,Sri Lanka’s Muslims: Caught in the Crossfire,29 May 2007.3Nagenahira Navodayacan also be translated as “EasternRevival” or “Eastern Rejuvenation”. The government’s web-site detailing their development plans for the east is www.neweast.lk.4“Development work moves ahead in the East”, Secretariatfor Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP), 28 November,2008, at www.peaceinsrilanka.org.5“Bumper paddy harvest in the east”, Secretariat for Coor-dinating the Peace Process (SCOPP), 5 March 2009.

2

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 2

water and social services are being provided to manyareas formerly under the control of the LTTE.6

A. DONORACTIVITIESThe government has estimated the cost of its easterndevelopment plans at $1.8 billion over four years. Withlittle money of its own to spend, the government hasbeen courting international investors and canvassingsupport from multilateral and bilateral donors.7Donorsand development agencies were initially cautious, con-tent to continue with programming already underwayin the east.8By mid-2008, however, especially in thewake of the Eastern Provincial Council elections inMay, donors have approved significant new levels ofaid. It is difficult to calculate the exact amounts offoreign humanitarian and development assistance tothe east, but more than $500 million has been com-mitted in loans and grants from 2007 onwards, notincluding large amounts of post-tsunami assistance.9In June 2008 the World Bank announced its new $900million Country Assistance Strategy for Sri Lanka for2009-2012. An estimated $300 million of this is sched-uled to be spent on projects in the north and east.10

Development work in the east will range from housingand livelihood support to village-level infrastructure,road building and support for irrigation and agricul-ture. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is also activein the east, implementing new programs worth some$50 million, as well as ongoing projects. Under itsCountry Partnership Strategy launched in October 2008,the ADB is funding the rehabilitation of roads, thestrengthening of the power system, improvements towater and sanitation networks and a range of smaller-scale community infrastructure projects.11A variety ofUN agencies have projects in the east; the UN is nowshifting from the humanitarian relief it offered in 2006-2007 to “early recovery”, largely in line with the focusof other donors.12The Japanese government, traditionally Sri Lanka’s larg-est bilateral donor, has committed roughly $100 millionin grants and loans for ongoing projects in the east,including rural road development, rebuilding irrigationsystems, micro-finance, livelihood support to farmersand community-level businesses, demining and otherhumanitarian support.13Other bilateral donors, includ-ing France and the European Union (EU), are offeringsignificant support, including the final portion of money

“Development work moves ahead in the East”, Secretariatfor Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP), 28 November2008, at www.peaceinsrilanka.org. The large majority of theprojects listed by the Peace Secretariat as success stories areforeign funded and implemented.7The government’s 2009 budget contains no allocation forprojects associated withNagenahira Navodaya,and the gov-ernment’s finances are now under extreme pressure. It isnegotiating with the International Monetary Fund for a $1.9billion emergency loan. Crisis Group interviews, diplomatsand aid officials, Colombo, April 2009.8Significant amounts of money remained for rebuilding hous-ing, schools, hospitals and infrastructure destroyed in theDecember 2004 tsunami, and internationally funded recon-struction work continued during 2006 and 2007. Most butnot all post-tsunami funds have now been spent in the east.9The exact total of international aid dedicated for humanitar-ian and development work in the east is impossible to calculate,since figures made public by donors cover different periodsof time and often do not specify amounts being spent in specificdistricts or provinces. It is generally unclear what percentageof funds in a multiyear project remains to be spent. Informa-tion on funding for projects beyond 2009 is not available fromall donors. Nonetheless, based on figures provided by themajor multilateral and bilateral donors, between $500 mil-lion and $1 billion has been made available for work in theeast from 2007-2011.10“Country Assistance Strategy for the Democratic SocialistRepublic of Sri Lanka for the Period FY2009-FY2012”, TheWorld Bank, at www.worldbank.lk. See also “World Bank

6

says North-East projects progressing well”,Sunday Times,16 November 2008.11In addition, “In the north and east, ADB will implementongoing projects and small livelihood projects (providingrural finance, upgrading fishery harbors, providing chillingfacilities for milk, repairing minor irrigation tanks, support-ing the dairy industry, etc.), and will rehabilitate small-scaleinfrastructure (hospitals, schools, markets). ADB will alsocontinue to support training and skills development in thenorth and east”, p. 27. The ADB has some remaining fundsfor rebuilding houses damaged by the war and the tsunami.Crisis Group interview, ABD officials, March 2009.12Crisis Group interview, UN officials, Colombo, November2008. The UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS) and UNHabitat are completing post-tsunami housing and infrastruc-ture projects; UN Development Programme (UNDP) has atransition and recovery project that focuses on housing, roads,livelihoods and community-level peacebuilding; and the Of-fice of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) con-tinues the humanitarian relief and protection work begunwith renewed war and displacement in 2006; the work of theOffice for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)is being phased out in the east.13This total does not include the cost of projects completedin 2007 and 2008, nor for projects planned for 2009 and on-wards that are not yet underway. So the actual figure for pro-jects in the east from 2007 to 2011 is likely to be two orthree times higher than this. Crisis Group interview, Japa-nese embassy official, Colombo, March 2009. The bulk ofJapanese support goes directly to the Sri Lankan govern-ment, though small grants are also made to NGOs.

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 3

for post-tsunami reconstruction.14Support from the EUhas focused on road repair, housing, and income gen-eration and livelihoods support.15The U.S. Agency forInternational Development (USAID) has been particu-larly active in the east with a wide range of smaller butsymbolically important initiatives, working entirelythrough non-governmental and private-sector organi-sations rather than the government. Their “Economicand Social Transition” (EAST) strategy aims to support“the positive transformation in the Eastern Province”by “developing the regional economy, strengtheninglocal governance, and increasing citizen participation”.16For some development agencies, the east has seemed tooffer real opportunities for peacebuilding. In the wordsof one senior aid official in May 2008, “There’s nowa unique opportunity to stabilise the east. If we helpthem do it right in the east, it becomes a model fordealing with the north….We’re treating the east like apost-conflict situation, doing what we’d be doing in apeace process….While we might not have agreed 100per cent with the way the election was run or with notdisarming paramilitaries, we’re acting now to makethe most of the situation. The opportunity is now. Youcan’t afford to wait for the whole conflict to be settled”.17

While this was a minority opinion prior to the Mayprovincial council elections, it became the dominantposition among donors by mid-2008.18

B. DETERIORATINGSECURITY, INCREASINGUNCERTAINTYThe Eastern Province and its people need help rebuild-ing their lives and economic infrastructure, but devel-opment agencies need to be careful about how theyengage in the area. The peace and development “divi-dend” expected by many donors after the May 2008provincial council elections has so far not materialised.Instead, the risks facing such work have increased,especially in the final months of 2008 and early 2009.

1.Increasing violence and impunityThere has been a marked deterioration in the securitysituation since mid-2008, particularly in Batticaloa dis-trict. Political killings, enforced disappearances, attackson police and army outposts, robberies, extortion andother criminal violence have become daily occurrences.In a single 24-hour period in November 2008 eighteenpeople were murdered in Batticaloa district by differentgroups.19Fear among civilians, business people and thoseinvolved in development work is extremely high.20While it is difficult to determine responsibility forindividual attacks, a general picture of the sources ofviolence can be drawn. Much of the violence is aproduct of increasingly bitter conflict between mem-bers of the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Puligal (TMVP),now led by Eastern Province Chief Minister S. Chan-drakanthan, better known as Pillayan, and supportersof TMVP founder and now government minister V.Muralitheran, alias Karuna.21The 18 October 2008 mur-

14

The French government has allocated $56 million for roadbuilding in the east. Most European donors, including theBritish, Germans, Swedes and Dutch, have significantlyreduced their bilateral aid, in part because Sri Lanka is nowconsidered a “middle-income” country and in part becauseof concerns about security and impunity for human rightsviolations. The German government has allocated over 65million euros for reconstruction and development of thenorth and east. Crisis Group interviews, diplomats and aidofficials, March 2009.15The European Commission spent roughly 80 million eurosin the east on post-tsunami projects and has some 70 millioneuros in funds still to disburse. This makes it one of the largestbilateral donors, after China and Japan. Its aid is implementedby the ADB, World Bank, UN agencies and international andlocal NGOs. Crisis Group interview, EC officials, Colombo,April 2009.16USAID, at http://srilanka.usaid.gov/country_strategy.php.USAID development assistance to the east since 2007 totalsnearly $45 million. The two main components of USAID’sprogramming are Supporting Regional Governance (SuRG)and Connecting Regional Economies (CORE). These willinclude training and financial support for business develop-ment and small-scale economic development and livelihoodsprojects, human rights and Tamil language training for po-lice, participatory governance training for newly elected localgovernment officials, and support for demobilised child sol-diers. A range of post-tsunami reconstruction projects werecompleted during 2008. Crisis Group interviews, USAIDofficials, Colombo, March 2009.17Crisis Group interview, senior development agency official,Colombo, May 2008.

Provincial council elections saw the victory of a coalitionof the TMVP, led by Pillayan, and various pro-governmentMuslim parties. After political wrangling between the presi-dent and Muslim politicians, who received the largest numberof seats on the council, Pillayan was named chief minister.See Crisis Group Report,Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province,op.cit., pp. 9-11.19“Sri Lanka: Human Rights Situation Deteriorating in theEast”, Human Rights Watch, 24 November 2008.20Crisis Group interviews, businessmen, NGO workers andcommunity activists, Batticaloa, March 2009.21The government’s peace secretariat has admitted that “kill-ings and abductions within [the TMVP] and between themand the LTTE take place....It is an unhappy situation, but onethat has not been engineered by anybody other than the par-ticipants themselves”. “The Human Rights Watch Syndrome”,Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP), 26November 2008. For more on the activities of the Pillayan

18

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 4

der of Pillayan’s most important adviser, Kumaras-wamy Nandagopan, was a major blow; while the gov-ernment blamed the attack on the LTTE, Pillayanhimself hinted at other sources.22Karuna’s decision inMarch 2009 to leave the TMVP and join PresidentMahinda Rajapaksa’s Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP)has transformed but not ended the conflict.23TMVPcadres from both the Pillayan and Karuna factions arealso widely accused of criminal activities, includingextortion, abductions and killings.24The second halfof 2008 and early 2009 have also seen a growingnumber of LTTE attacks in the east, both against theTMVP, including some apparently successful attemptsto infiltrate TMVP offices, and against the police, armyand civil defence personnel.25Finally, there is credi-ble evidence to suggest that many of those killed aretargeted by the TMVP and government security forcesas LTTE members or supporters, either as part of thegovernment’s general counter-insurgency strategy orin response to specific LTTE attacks on, or infiltrationof, the TMVP.26

Coming from multiple and often uncertain sources, thecurrent violence is terrifying. “Previously, when theLTTE was stronger, we knew what the survival strate-gies were”, says one businessman in Batticaloa. “TheLTTE was predictable and disciplined. With the army,you were okay if you were not directly involved withthe LTTE. But now, it’s hard to predict. I’m havingtrouble knowing what to do to survive”.27While the large majority of the civilian victims havebeen Tamils, Sinhalese and Muslims have also beentargeted. On 21 February 2009, the Sinhala village ofKarametiya was attacked by an armed group pre-sumed to be LTTE; sixteen were killed and anotherten injured.28Three Sinhala construction workers wereshot to death in Kokadicholai, in Batticaloa, on 20October 2008.29Attacks on Sinhala farmers in theSeruvila area in Trincomalee district attributed to theLTTE have led to reprisal killings of Tamils in neigh-bouring villages.30There have also been a number ofviolent attacks on Muslims and altercations betweenMuslims and police and security forces.31

and Karuna factions in the Eastern Province, see Crisis GroupReport,Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province,op. cit., pp. 14-17, 19-20.22Chris Kamalendran, “Pillayan says LTTE not involved”,Sunday Times,16 November 2008.23After months of being the clear favourite of the centralgovernment, Karuna formally left the TMVP and joined theruling Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) in a public ceremonyin Colombo with the president on 9 March, where Karunawas named minister for national integration and reconcilia-tion. “Ex-rebel made Sri Lankan minister”, BBC News, 9March 2009. The Ampara area TMVP leader and the presi-dent’s district coordinator, Inyabarathy, also joined theSLFP. So, too, did 1,500 other people, many of them bussedto Colombo on orders of Karuna without being told theywould be joining the SLFP. TMVP offices under the controlof Karuna’s faction are now being converted to SLFP offices.His cadres remain armed. Crisis Group interviews, commu-nity leaders, Batticaloa, March 2009.24The March 2009 abduction and murder of a six-year-oldgirl in Trincomalee was attributed to TMVP members loyalto Pillayan. Karuna’s faction has been using the public out-rage over the murder to weaken public support for Pillayan.Jamila Najmuddin, “TMVP denies involvement in Varsha’smurder”,Daily Mirror,18 March 2009.25Karuna himself has admitted that the LTTE poses a seriousthreat in interior sections of the east. See Jamila Najmuddin,“Life in the East, a far cry from normal”,Daily Mirror,10December 2008. Others argue that fighting within the TMVPwas due in part to disgruntled members of the TMVP carry-ing out assassinations for the LTTE as a pre-condition to re-joining the rebels. “Ticking time-bomb in the east”,TheIsland,16 November 2008.26One particularly disturbing case that received some public-ity was the discovery of the mutilated bodies of two Tamilmen who had a few days earlier been seen in police custodyin Batticaloa. The police claim the men had been released

in good condition prior to their murder by unknown parties.“Sri Lanka: Human Rights Situation Deteriorating in theEast”, Human Rights Watch, op. cit. Arguments in civil suitagainst the police are due to be heard before the SupremeCourt in June 2009.27Crisis Group interview, businessman, Batticaloa, Novem-ber 2008. “Current power dynamics in the east are very fluid.People barely know who is in charge today; they could getkilled tomorrow for what is OK to do today”. Crisis Groupinterview, donor official, Colombo, December 2008.28Jeevani Pereira, “Hunger and fear reign in Karametiya”,Daily Mirror,25 February 2009. Karametiya is located onthe outskirts of the Gal Oya National Park, in Ampara dis-trict. With the 3 April killing of thirteen suspected Tigers inAmpara, the government claims to have successfully trackeddown and eliminated the small band of LTTE fightersblamed for this and other attacks in the east. Norman Pali-hawadena, “STF ambush kills 13 Tiger killers on the prowl”,Island,4 April 2009.29Senaka de Silva, “Three killed in Kokkadicholai”,DailyMirror,22 October 2008. The 21 August 2008 murder ofone of a small number of Sinhala students at Batticaloa’sEastern University led to the transfer of all Sinhala and Mus-lim students from the eastern campus. The 16 November2008 killing of a Sinhala doctor working at the Navatkudahospital in Batticaloa district forced the temporary with-drawal of all Sinhala government doctors from the east.Jamila Najmuddin, “Life in the East, a far cry from normal”,Daily Mirror,10 December 2008.30Senaka de Silva, “Farmers killed by suspected Tigers”,Daily Mirror,26 March 2009.31In one incident in August 2008, 28 Muslims collectingfirewood in the forests near Potuvil, in Ampara district, werearrested on charges of supplying provisions to LTTE fighters.One of the firewood collectors died in custody, allegedly due

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 5

The near-complete impunity for killings and disappear-ances adds to the widespread fear. Many survivorschoose not to report cases of disappearances, robbery,extortion, sexual violence and other criminal attacksgiven the unwillingness of the police to seriouslyinvestigate; in many cases, police even refuse to acceptcomplaints. “Everyone is too scared to complainabout anything”, explains a human rights lawyer. “Noone wants to file legal actions or police complaintsabout any issue at all because the person they areangry with may be linked to an armed group and seekretribution”.32There is still no evidence of any seriousinvestigations into political killings and disappearancesover the past few years.

to be made by the central government, operatingthrough the governor and the nation building minis-try, which is effectively controlled by presidential ad-viser Basil Rajapaksa.36Both the Eastern ProvincialCouncil and development agencies complain of politi-cal interference with their work.37A bright spot is that the lack of central governmentsupport for the Eastern Provincial Council has pro-duced a certain degree of common ground betweenthe council’s ruling TMVP-Muslim coalition and theopposition coalition of the United National Party(UNP) and the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC).All parties would like to see the provincial councilassume the full range of powers granted, in principle,by the Thirteenth Amendment.

2.Devolution still on holdDespite the government’s public commitment to imple-menting the Thirteenth Amendment, which establishedprovincial councils with limited devolved powers,there has yet to be any real devolution to the EasternProvincial Council.33Nor have any powers over landor taxation been transferred to the council. Indeed, thegovernor of the province, a retired general appointedby and working closely with the president, has pre-vented implementation of the provincial council’s firstlegal statute, which would formally establish its pow-ers of limited taxation.34Otherwise the council remainsentirely dependent on the central government for itsfunding; in early 2009 the council was reportedlybankrupt.35Policy decisions about development work and impor-tant political matters in the Eastern Province continue

3.Muslim and Tamil alienationMany Muslims continue to feel vulnerable to attacksand extortion from the TMVP and, to a lesser extent,from government security forces. Tensions betweenTamils and Muslims, aggravated by the actions of thePillayan and Karuna factions, remain high.38Manyremain bitter over the nomination of Pillayan, ratherthan the Muslim candidate Hisbullah, as provincialchief minister and complain that Tamils continue tocontrol the provincial administration and council.39Few Tamils, on the other hand, express satisfactionwith the limited benefits they receive from having aprovincial council controlled by the TMVP. Most con-tinue to see the TMVP as a dangerous and parasiticforce on the community. Many also believe Muslimscontinue to have more political influence and betteraccess to resources. And virtually all Tamils complainof repressive government security policies and fearexpanded government-sponsored Sinhalisation. The con-tinued displacement of more than 5,000 Tamils fromtheir homes in the government’s Sampur High Secu-rity Zone in Trincomalee is a major source of alien-ation40and has fed fears that more such high-security

to police abuse. 26 of the suspects were convicted and sen-tenced to a year in prison in February 2009. “26 PottuvilMuslims sentenced to imprisonment”, Peace Secretariat forMuslims, 10 February 2009, at www.peacemuslims.org.32Crisis Group interview, human rights lawyer, Batticaloa,November 2008.33The government announced in November 2008 that a “highlevel three-member committee” would be formed to devolvepower to the east in terms of the Thirteenth Amendment to theconstitution. There has been no further news about its activi-ties. P. Krishnaswamy, “Three-member committee to devolvepower to the East”,Sunday Observer,30 November 2008.34M.M. Abdul Kalam, “Governor is obstructing devolutionof power to Eastern Provincial Council”,Federal Idea,6January 2009, available at http://federalidea.com/fi/2009/01/post_90.html.35Crisis Group interviews, donors and diplomats, Colombo,March 2009. See “EPC languishing without funds”,DailyMirror,17 January 2009. According to the article, the coun-cil is “facing a severe financial crisis as only Rs.200 millionout of a total allocation of Rs.836 million had been receivedby the council which even had no funds to pay staff salaries”.

The nation building ministry is represented in the east byMinister Susantha Punchinilame, who has established an of-fice in Trincomalee and is said to be closely monitoring, andinterfering with, the work of the provincial council. CrisisGroup interviews, government officials, Trincomalee, No-vember 2008.37Crisis Group interviews, diplomats and development offi-cials, Colombo, November 2008 and February 2009.38Crisis Group interviews, NGO workers and communityleaders, Batticaloa, March 2009.39Crisis Group interviews, politicians and community lead-ers, Kattankudy, November 2008.40This is a government figure, as reported by UNHCR. CrisisGroup interview, Colombo, March 2009. A longer discussion

36

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 6

zones linked to economic development could be in thepipeline.41There is some evidence that the LTTE isable to operate more effectively in the east due in partto the growing alienation of Tamils from the govern-ment and their designated government-sanctioned rep-resentatives, the TMVP.42

C. RISKS TO AND FROMDEVELOPMENTWORKWithout such a significant shift in policy, developmentwork in the east will continue to face, and to pose,serious risks.Increased violence has already taken the lives of devel-opment workers and threatens the successful completionof projects. Complaints about extortion from variousfactions of the TMVP and unidentified criminal groupsare also common, in Batticaloa especially. Extortionscares away potential entrepreneurs and provides sup-port to violent and unaccountable armed groups.There are also longer-term political and social risksfrom the pursuit of development in a violent and mili-tarised context, where political decisions are madewithout meaningful public consultation. In the absenceof fair and inclusive decision-making processes, dis-putes over the distribution of land, economic oppor-tunities, and government benefits and resources aremore likely to take on an ethnic colour and turn violent.The political stability of the east has long sufferedfrom precisely these sorts of conflicts. Violent dis-putes between Tamils and Muslims have been kept toa minimum since the provincial council elections, butdeep tensions remain.44The central government has donelittle to foster dialogue and reconciliation between thetwo communities.The most widely discussed risk from development pro-jects is state-sponsored Sinhalisation. As donors anddevelopment agencies recognise, fears of Sinhalisationare widespread among Tamils and Muslims in the eastand undermine the trust necessary for sustainabledevelopment. Understood as a process whereby economicdevelopment either directly or indirectly brings inenough new Sinhalese to alter the demographic balanceof particular districts or of the province as a whole, nomajor Sinhalisation has yet taken place. Nonetheless,the powerful influence of the almost entirely Sinhalamilitary over civilian affairs in the province, the lackof transparency with which development decisions aremade, the role of the government ally and Sinhalachauvinist Jathika Hela Urumaya in supporting the

4.Policy shift neededDespite the large number of internationally-financedprojects underway in the east, the government’s prom-ises of “demilitarisation, democratisation, developmentand devolution”43have yet to be realised. Projectshave been undertaken with little transparency or pub-lic consultation and in an insecure and militarised con-text. This undermines much of their positive potential.The east today has all the ingredients for continuedinsurgency and counter-insurgency: a virtually power-less provincial council, a divided TMVP, insecureMuslims, alienated and restless Tamils, growing divi-sions within ethnic communities and political parties,and continued violent repression of dissent.Opportunities for political stability and sustainabledevelopment in the Eastern Province have little chanceof being realised without a major change in how theeast is governed. This should begin with the govern-ment enforcing the law and providing basic securityguarantees to its citizens. This will require crackingdown on the TMVP and Karuna’s faction and curbingthe excesses of the government’s counter-insurgencycampaign. The government must assure Tamils andMuslims that there are no plans for the Sinhalisationof the east. The Eastern Provincial Council must beempowered to play a key role in development deci-sions. The government should begin to share power inother ways and include the views of independent Tamiland Muslim political representatives and communityleaders in its development decisions in the east. Solong as it refuses to do so, the “development” of theeast – and soon of the north – will continue to feelthreatening to many Tamils and Muslims and its posi-tive potential for fostering trust and ultimately recon-ciliation between communities will be lost. It will bemerely “victor’s development”, possibly paving theway for future violent conflict.

of displacement in the east and north can be found below inSection V.H.41Crisis Group interviews, government officials and commu-nity leaders, Trincomalee, November 2008; Colombo, March2009.42Crisis Group interviews, government officials and com-munity leaders, Batticaloa and Colombo, March 2009.43N. Ram, “We are firmly committed to a political solution:President Rajapaksa”,The Hindu,27 October 2008.

Violent clashes in May and June 2008 between Tamilsthought to be members of the TMVP and Muslims in Kattan-kudy and Batticaloa left more than a dozen dead. See D.B.SJeyaraj, “The killing of T.M.V.P. leader Shantan in Kaathaan-kudi”,Tamilweek,31 May 2008. An explosion opposite theHusainiya mosque in Kattankudy left five wounded on 25October 2008. “Hand grenade explosion at a mosque inKattankudy, five injured”,Muslim Guardian,26 October2008, available at www.muslimguardian.com.

44

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 7

redevelopment of Buddhist sites in the east – theseand other factors lend some credence to fears of Sin-halisation.45To date, the government has made noserious attempt to reassure Tamils and Muslims in theeast that their fears are unfounded.Less noticed by donors is the risk that “development”will involve the economic takeover or de facto coloni-sation of the east by Sinhala business interests fromColombo and other parts of the country, in some casesworking in partnership with foreign investors. This isa realistic danger given the disproportionate degree ofpolitical control that Sinhala politicians and adminis-trators have over the east.In addition, continuing large-scale military presence andsecurity restrictions almost guarantee that economicopportunities will be distributed unequally, with Sin-halese granted more freedom than Tamils and Muslims.This can already be seen in existing fishing restric-tions and in the many stories of restrictions placed onrock-cutting, cattle grazing, firewood gathering andother livelihood opportunities traditionally available toTamils and Muslims in the east. Members of any ethnicmajority which largely controls the state are almostcertain to benefit disproportionately from economicdevelopment unless there are countervailing forces atwork: a strong political force representing minorities,a strong system of legal protections, or outside moni-toring and protection. None of these exist today.

III. “CONFLICT SENSITIVITY” ANDTHE POLITICS OF AIDA. THELIMITS OF“CONFLICTSENSITIVITY”The deteriorating security situation and lack of politi-cal reform in the east has begun to worry many donorsand development agencies. There is no talk yet ofsuspending work or withdrawing, but there is growingconcern that political instability in the Eastern Prov-ince is putting the government’s development plans atrisk and posing challenges to donor-funded projects.In the words of one donor active in the east, “We arefairly unhappy with how things have turned out in theeast and the commitments not honoured by the gov-ernment”.46Nonetheless, even as development agencieshave grown more willing to acknowledge the risksfrom and to their work, many argue their “conflictsensitivity” policies ensure they can be managed to atolerable degree.47“Conflict-sensitive development”, as understood bymost development agencies working in Sri Lankanow, involves five basic components:

targeting assistance to conflict-affected populationsand their conflict-related needs. In this vision, eco-nomic development can reduce sources of conflictin the east by improving people’s lives and reducingthe gap between the prosperous Sinhala-majorityWestern Province and the Tamil- and Muslim-majority east;48ensuring that benefits and resources are “spreadfairly across districts and across different ethnicgroups” so that aid to one community does not fuela sense of grievance among another;49

For an analysis of fears of Sinhalisation in the east, seeCrisis Group Report,Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province,op. cit.,pp. 21-27. For further claims of Sinhalisation, see “The Hu-man Rights and Humanitarian Fallout from the Sri LankanGovernment’s Eastern Agenda and the LTTE’s Obduracy”,University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna), briefing no.6, 22 January 2007, at www.uthr.org.

45

Crisis Group interview, Colombo, February 2009.The strongest doubts are expressed by bilateral donors.Multilateral donors, especially the ADB and World Bank,remain more confident in their ability to manage the risks.48The vision of “conflict sensitivity” endorsed by the JapanBank for International Cooperation (JBIC) emphasises theimportance of addressing regional disparities in economicdevelopment. See Keiju Mitsuhashi, “The Conflict-SensitiveApproach of JBIC’s Development Assistance in Sri Lanka”,JBICI working paper no. 31, August 2008, pp. 22-7. The ADBmakes a similar argument. See “Country Partnership Strat-egy, Sri Lanka 2009-2011”, Asian Development Bank, p. 30.49Crisis Group interview, senior development official, Colombo,May 2008. What constitutes “fair” distribution of supportand opportunities can be difficult to determine, particularlyin the east. If “fair” distribution means proportional distri-bution, is proportionality determined by district, province or47

46

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 8

ensuring that programs do not alter the demographicbalance in the east, with a specific focus on a pos-sible increase in the number of Sinhalese. In thewords of one donor, “if there is massive Sinhalisa-tion, it will undermine development, affect secu-rity and our ability to work”;50consulting with those who live in the areas wheredevelopment activities are due to take place;51andmonitoring the actual course of development pro-jects and their effects on conflict dynamics, throughsharing information among agencies.

To date, however, these policies have proven unableto respond to the full range of risks involved in devel-opment work in the east.Most consultations by donors are unable to give thepublic a meaningful role in shaping who controls andbenefits from development projects. They are mostoften focused on gathering people’s general preferencesor discussing particular donor initiatives. The keyquestion, however, is not what is done buthowandbyand for whom.Few would dispute the value of mostdevelopment programs under way: houses, roads, power,water, schools, businesses, industry, tourism. Whatmatters is political control. With fear running so highin the east, few are willing to express in public anopinion that runs counter to those in power.52As aresult of fear, government secrecy and the politics ofdivide and rule, there also remains little knowledge,even among educated and politically connected peo-ple, about what “developing” the east will mean tolocal communities and the overall political and socialeffects.

Nor are adequate procedures or personnel in place formonitoring the political situation and the effects ofdevelopment work. Many areas where donor-supportedprojects are under way are difficult to access and/orheavily militarised. Information currently gathered bydonors and their international and domestic NGOpartners is not widely or evenly enough disseminated,and there exist neither established procedures nor thepolitical will to act on troubling information in a co-ordinated and effective manner. Donors have rejectedproposals to conduct a joint field assessment of thepolitical and social dynamics in the east.53Rather thanexpanding the number of staff available for monitor-ing projects and overall conflict dynamics, a signifi-cant number of embassies and donors have withdrawnor not replaced conflict advisers brought in during the2002-6 peace process.54It is thus far from clear thatdevelopment agencies are equipped to spot problemsbefore they get out of hand or to react effectively tothem.55

national population figures? This has been one of the centralpolitical questions for development work in the EasternProvince for more than 50 years.50Crisis Group interview, senior development official, Co-lombo, May 2008.51The ADB, for instance, conducts extensive public consul-tations with all important stakeholders as part of the ProjectPreparation Technical Assessment it does before approvingany loan to the government. Crisis Group interview, ADBofficials, Colombo, March 2009.52Whatever meaningful consultation is currently possible,then, must be done quietly and through established networksof trust. Should security conditions improve, however, and thegovernment express its willingness, donor-sponsored consul-tations could play a useful role in larger regional peace proc-esses for the north and east involving the government, theTMVP, opposition parties and other Tamil parties, includingthe Tamil National Alliance, if appropriate security guaran-tees were in place.

Crisis Group interview, development official, Colombo,November 2008. “No one is paying attention to these issuesbecause they are seen as the business of the government, andyou’ll get into trouble with the government if you try to ad-dress them....Anything defined by the government as politi-cal becomes a particular challenge for the UN, given that ithas a development not a political mandate in Sri Lanka”. Cri-sis Group interview, UN official, Colombo, May 2008. TheUN was the target of sustained government harassment andcritical propaganda in 2007 and 2008 and has grown particu-larly cautious as a result.54Visa restrictions as part of the government clampdown onINGOs and the UN have further shrunk the pool of staff withexperience and detailed knowledge of Sri Lanka’s politicallandscape. The ADB hired a conflict adviser in late 2008,after a number of years without one. The World Bank is cur-rently in the process of hiring one.55The “conflict filter” announced by the World Bank in itslatest Country Assistance Strategy has the potential to assistin achieving the bank’s overall goal of ensuring that “bene-fits from projects are transparently distributed and potentialtensions are mitigated through broad consultations and re-dressal mechanisms”. As “the basis for assessing a project’sconflict-sensitivity during the concept, design and imple-mentation/supervision stages”, the “conflict filter” aims toensure that “conflict-generated needs are adequately identi-fied and addressed in projects, and opportunities to strengthenreconciliation and inter-ethnic awareness have been adequatelyidentified”. “Sri Lanka: Country Assistance Strategy 2009 –2012”, World Bank, 24 July 2008, p. 69. The effectivenessof the conflict filter will largely depend on the amount andquality of the resources that the bank devotes to it. Bank of-ficials offer assurances that the conflict filter is being incor-porated into all its projects and that principles of conflictsensitivity are being mainstreamed throughout all the bank’sactivities in Sri Lanka. They insist that staff will not be penal-ised for failing to meet project completion deadlines in order

53

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 9

More important, no matter how good the monitoring,many of the most important effects of developmentprojects are indirect and will be visible only after a sig-nificant delay. Roads, power plants and other infra-structure projects might seem good in themselves butthey pave the way for other development activities withunknown and possibly negative political and socialeffects.For similar reasons, while a given package of interna-tional aid might itself be fully “conflict sensitive”, theassistance frees up resources which the governmentcan use in other, perhaps less careful or equitable ways.In the words of one Western diplomat, “What does itmean to be conflict sensitive at the micro level whenyou are supporting non-conflict sensitive governmentpolicies by freeing up new government money?”56Todate, the government’s vision of the future east remainsvague, especially with regard to the political effects ofeconomic development. While donors repeat their de-termination not to fund programs that alter the ethnicbalance, the government itself has made no such pub-lic promises.57Ensuring that the ultimate effects ofaid are non-discriminatory and do not aggravate theconflict is particularly difficult when the government’sintentions for the province are not made unclear.As a result, donor definitions of “conflict sensitivity”do not address the biggest risk: lending support togovernment polices – political as well as economic –that are neither transparent nor based on meaningfulpublic consultations or political negotiations. Despite

its rhetoric of democracy and pluralism, the centralgovernment has chosen to impose its policies on theeast. It has neither made clear its ultimate goal nornegotiated with independent political representativesable to bargain effectively on behalf of the differentconstituencies in the east. Supporting development workin such a context risks endorsing policies that willlikely have profound effects on the possibility of ajust and sustainable settlement of the overall conflictbefore it has become clear what those policies are.Unless development agencies insist on clear and prin-cipled guidelines for managing the cumulative politicaland social effects of the entire development process,their support will help enforce a new political andeconomic balance of power on a population that hasnot been adequately consulted, much less given itsclear consent.

B. DONORHESITATIONSAfraid of angering the government with an approachseen as too political, external development agenciesand bilateral donors have remained relatively quiet, evenas the conditions for their work have deteriorated.58The government’s concerted efforts to limit the activi-ties of international humanitarian organisations, restrictvisas for international workers, and label numeroushumanitarian organisations as pro-terrorist have con-tributed to donors’ caution.59Few donors have acknowl-edged publicly the extent to which government attacks58

to respect principles of conflict sensitivity, that the bank isprepared to slow down implementation of projects and haltdisbursement of funds in order to prevent political interfer-ence or negative effects on conflict dynamics. Crisis Groupinterviews, World Bank officials, Colombo, March 2009. TheADB’s conflict-sensitivity policies emphasise “transparency”,“the involvement of all stakeholders and beneficiaries” andfrequent conflict assessments, but the bank has not intro-duced any new conflict-sensitivity instruments for Sri Lanka.“Country Partnership Strategy, Sri Lanka 2009-2011”, AsianDevelopment Bank, pp. 28-30.56Crisis Group interview, Colombo, April 2009. A numberof northern European donors have scaled back or ended theirdevelopment assistance to Sri Lanka in part because of con-cerns about the “fungibility” of aid to a government commit-ted to a military victory at the expense of human rights andhumanitarian norms. Sri Lanka’s status as a “middle-income”country was also a factor in the reduction of aid by the UK,Sweden, the Netherlands and other countries.57When asked if the Sri Lankan government had an officialpolicy on the effects of development on the demographicbalance in the east, or a more general policy for conflict-sensitive development, government officials refused to answer.Crisis Group correspondence, senior Sri Lankan governmentofficials, July 2008.

Even as their professed commitment to conflict sensitivityimplicitly recognises the political nature of their role, WorldBank and ADB officials argue that as development organisa-tions they must make decisions based on economic and devel-opment criteria, not political ones. Crisis Group interviews,Colombo, May and November 2008. The World Bank’sstatement condemning violent attacks on the media, whichasserts that “free and independent media is fundamental tothe sustainable economic development of Sri Lanka”, is ashift from this position. See World Bank, “Freedom of In-formation Necessary for Sri Lanka’s Development”, 8January 2009.59Crisis Group interviews, diplomats and development offi-cials, Colombo, March 2009. Government visa regulationsannounced in mid-2008 limit any international aid workersto a total of no more than three years in Sri Lanka. This hasled to an exodus of the most experienced expatriate staff.Restrictions placed on UN hiring policies were found by theUN general counsel to violate the UN’s diplomatic privileges.See Namini Wijedasa, “UN takes umbrage over Sri Lanka’streatment of staff”,Lakbima News,7 December 2008. InMarch 2009, the ministry of defence denounced as a terrorista Tamil staff member of CARE International killed in fight-ing in the northern province; CARE itself was accused ofsupporting the LTTE. See Jamila Najmuddin, “CARE says aidworker was not a terrorist”,Daily Mirror,26 March 2009.

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 10

on independent civil society organisations and impu-nity for human rights violations, together with LTTEand TMVP violence and intimidation, have made itmuch more difficult for their programs to have sus-tainable and equitable benefits.60Rather than pursuing a collective agreement with thegovernment, followed up by close monitoring andactive protection of the rights of those affected, donorshave engaged with the government individually andwithout serious policy coordination among them-selves. Many insist that public attempts to conditionaid on improved governance or human rights protec-tion will only limit room for manoeuvre in “an abso-lutely challenging and difficult environment. The morepublic we are, the less space we have”, says one sen-ior development official. “Formal conditionalities aren’teffective in this country, so we need to find other waysof being effective”.61The work of development agencies and their NGOpartners has been further handicapped by the beliefamong many that the east constitutes a “post-conflict”situation.62This has led some donors to downplay thesignificance of worsening violence in the east, rang-ing from new conflicts – the internal battles within theTMVP – to old forms of violence – LTTE attacks ongovernment forces and Tamil rivals – to frozen but

volatile conflicts – alienation and mistrust felt byTamils and Muslims.

C. PRINCIPLES OFENGAGEMENTThe east is far from being a typical development envi-ronment. For engagement in the east – and ultimatelyin the north – to be responsible and avoid aggravatingexisting conflicts or producing new ones, donors anddevelopment agencies must adopt careful, coordinatedand politically aware policies.Conflict-sensitive development work begins withserious efforts to understand the local, regional andnational-level conflict dynamics and political contextsin which projects are to be implemented. A joint donortask force to study the political forces currently shap-ing economic and social development in the east and toreview the past two years of donor projects is urgentlyneeded. When security permits and civilians have begunto be resettled, a task force to investigate conditions inthe north will also be needed.Agencies should devote increased resources for moni-toring the effects of projects and emerging govern-ment land policies. Ideally this would be a joint effortbetween all major donors, either growing out a jointdonor task force or through providing additional staffto the existing Donor Peace Support Group to form aproper secretariat.63This needs to be matched by acommitment to revise, delay or shut down projects ifthey are aggravating conflicts or undermining equita-ble development. Individual development agenciesneed to hire additional staff, increase the number ofproject reviews, and establish regular local monitor-ing meetings on land-related policies and the effectsof development, especially with regard to fears ofSinhalisation. Monitoring must be rigorous enougheither to disprove rumours and reassure Tamils andMuslims of the government’s good intentions, or toalert the international community that local fears arewell-founded and to defend those whose rights areviolated by development work. If local missions donot at present have adequate resources to conductsuch monitoring, they need to press their capitals toprovide them.

60

So far an effective response has been handicapped by lackof shared vision and serious policy level coordination. Withsome notable exceptions, there is widespread resignationamong donors in Colombo about the possibility of making apositive impact in the east and elsewhere, which has contrib-uted to a loss of interest in Sri Lanka in most major capitals.This is despite, or perhaps because of, the shared understand-ing that undemocratic governance is seriously endangeringthe prospects for equitable, sustainable and conflict-sensitivedevelopment in the east and throughout the country.61Crisis Group interview, Colombo, March 2009. Formalconditionalities have not, however, been tried. Some donors,including the U.S. and the World Bank, did draft an informalset of principles for their work in the east which was report-edly discussed with the government. The four principles werethe rapid return to civilian rule, protection of human rights,demobilisation of paramilitaries, and no support for demo-graphic changes. These “conditions” were not made public,however, nor was there any procedure for monitoring or en-forcing compliance. While there has been no large-scaleSinhalisation to date, there has been little success achievingthe other principles. Despite formal civilian governance, themilitary retains the final say over most policies in the east.Crisis Group interviews, diplomats and development agencyofficials, March 2009.62Crisis Group interviews, development agency officials, Co-lombo, May-June 2008. See, for example, Sonali Samarasinghe,“When the WB lunched with an armed child recruiter”,Sun-day Leader,19 October 2008.

63

For more coordinated analysis and information sharing tobe possible and effective, the Bilateral Donors Group and theDevelopment Partners Forum should meet more regularlyand be allocated more resources. These groupings also offeruseful and appropriate platforms for donors to speak up andact more effectively in defence of their beleaguered local andinternational NGOs.

Development Assistance and Conflict in Sri Lanka: Lessons from the Eastern ProvinceCrisis Group Asia Report N�165, 16 April 2009

Page 11

Donors should engage the government in a coordinatedway to encourage the establishment of policies thatsupport conditions for inclusive, equitable and sustain-able development. Before all else, donor agencies shouldinsist they are given a relatively clear picture of thegovernment’s overall development plans; only thencan they make reasonable judgments about the likelysocial and political effects of their particular projects.Donors failed to engage the government in a coordi-nated and principled way when the east was first openedfor development work. The government’s forthcom-ing appeals for international assistance to reconstructthe north will offer another chance for a negotiatedagreement that could apply to both the north and theeast. Sri Lanka’s traditional development partners –Japan, the ADB, the World Bank and the UN, togetherwith the U.S., EU and other bilaterals – should meetto review all development assistance to Sri Lanka andto devise shared principles for equitable and sustain-able development.64These should form the basis for aformal memorandum of understanding with the gov-ernment, to be supported by an adequately fundedmonitoring process.65The central terms of this agree-ment should be:

active inclusion of and consultation with independ-ent community and political leaders from all threeethnic communities, including opposition parties;real assurances to Tamils and Muslims that thereare no government plans for Sinhalisation of theeast and that demographic issues will be dealt withonly through negotiation with independent repre-sentatives of all three communities as part of a set-tlement of the larger conflict;the provision of basic security guarantees to thecitizens of the east, beginning with a crackdown onthe criminal activities of various pro-governmentarmed groups, including the TMVP and the Karunafaction, and an end to disappearances and killingsassociated with the government’s counter-insurgencycampaign;the right of donors to work with local and interna-tional NGOs of their choosing who will be free fromharassment and visa restrictions; andin the north, free and fair provincial elections withenough security to allow active campaigning forthe full range of political parties, with the presenceof international observers. No elections should takeplace while large numbers of people remain ingovernment camps, and donors should explicitlylink their development assistance to the promptreturn of all those displaced from the north and tofull access for humanitarian organisations to anydisplaced who remain in camps.

empowerment of the Eastern – and once elected, theNorthern – Provincial Council to play a key role indevelopment decisions through maximising the devo-lutionary potential of the Thirteenth Amendment;

64