Udvalget for Fødevarer, Landbrug og Fiskeri 2008-09

FLF Alm.del Bilag 373

Offentligt

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

Proposal to include Northern Bluefin Tuna (Thunnusthynnus(Linnaeus, 1758)) onAppendix I of CITES in accordance with Article II 1 of the Convention

Summary

1. The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is found in the entire extent of the North Atlantic Oceanand its adjacent seas, particularly the Mediterranean Sea. It usually occupies thesurface and subsurface waters of coastal and open-sea areas, between 0m and 200min depth.2. The species is managed by the International Commission for the Conservation ofAtlantic Tunas (ICCAT) as two stocks (eastern and western), based on separatespawning grounds, genetic differentiation, differing ages for reaching sexualmaturity, and the apparent absence of breeding in the middle of the North Atlantic.However, the migratory ranges of both stocks overlap considerably.3. Maturity is reached at approximately 4 years of age in the East Atlantic andMediterranean, and at 8-12 years of age in the West Atlantic. Recent studies suggestthat individual spawning may only occur every two to three years. It commences inApril in the Gulf of Mexico. In the Mediterranean, it occurs during May-June in theeast, and in June-July in the centre and west.4. A virtual population analysis of the East Atlantic and the Mediterranean stockconducted in 2008 by ICCAT scientists based upon estimated catches, whichaddressed the period 1955-2007, yielded an estimate for spawning stock biomass in2007 of 78,724 tons. This contrasts with the biomass peak estimated for 1958 at305,136 tons, and with the 201,479 tons estimated for 1997. The absolute extent ofdecline over the 50-year historical period ranging from 1957 to 2007 is estimated at74.2%, the bulk of which (60.9%) has happened in the last 10 years.5. The corresponding analysis for the West Atlantic Stock yielded an estimate forspawning stock biomass in 2007 of 8,693 tons, which contrasts with the 49,482 tonsestimated for 1970, implying an absolute extent of decline of 82.4% over the 38-year historical period.6. Continued fishing at current fishing mortalities is expected to drive the spawningstock biomass in the East to very low levels; i.e. to about 18% of the 1970 level and6% of the unfished level. This combination of high fishery mortality, low spawningstock biomass and severe fishing overcapacity results in a high risk of fisheries andstock collapse. It has been postulated that, even if a near-complete ban on all BluefinTuna fishing in the Northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean were implemented andenforced from 2008 to 2022, the population would still probably fall to record lowsin the next few years (Mackenzie et al. 2009).

1

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

7. There is strong uncertainty about the potential recruitment for the West Atlanticstock. According to the last assessment by ICCAT scientists, under the mostpessimistic scenario a closure of the fishery would not achieve the rebuilding of thestock by 2019. However, recovery is projected to occur within this timeframe underdifferent assumptions of recruitment. Recently, there has been a decline of fishingmortality on large West Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. The TAC has not been takenprimarily due to U.S. underharvest which range from 40-80 percent of quota in20066-2008. According to the ICCAT scientist, there are two plausible explanationsfor the decline in U.S. harvest of large Wet Atlantic stock of Bluefin Tuna; the firstis that the availability of fish to the U.S. fishery has been abnormally low due to thechange in the spatial distribution of the stock; the second is that the overall size ofthe population in the West Atlantic has declined substantially from the level ofrecent years. The ICCAT scientist believe there is uncertainty about the issue andthat more research need to be done (Report of the Standing Committee on Researchand Statistics, October 2008) Based on the numbers and trends, some scientistssuggest that the western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is currently in danger of extinction,and suggest a moratorium on fishing the western stock should be immediatelyimplemented.8. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is traditionally consumed fresh in Mediterranean countries,and it is also one of the most appreciated species for the sashimi market in Japan.Capture-based farming activities in the Mediterranean have exacerbated fishingpressure over the East Atlantic stock. There is still substantial mortality on spawnersin the western stock along the coast of Canada as a result of a directed fishery. Inaddition, there is some mortality of the West Atlantic stock within the Gulf ofMexico due to bycatch in other fisheries.9. In the Mediterranean, Bluefin Tuna is mostly caught by purse seine vessels and thentugged live to tuna farms where the fish are fattened during a period of 6 to 8months. Fishing vessels are usually from different countries than those where thetuna are later farmed, so this transfer of live fish to farms generally implies aninternational trade. Estimated farming capacity is as much as twice the 2008 TotalAllowable Catch (TAC), while estimates of fleet size indicate there is sufficientactive fishing capacity to fully supply the farms to their indicated limits.10. After slaughter, the bulk of this production is exported to Japan as frozen productswhere it is consumed as sushi and sashimi. The total imports of 32,356 tons ofprocessed Bluefin Tuna reported by Japan to ICCAT for 2007 contrast with theTotal Allowable Catch for that year of 29,500 tons. This mismatch between ICCATimport records and the Total Allowable Catch is all the more evident when domesticconsumption in European Mediterranean countries, intra-European trade, andcatches by the national Japanese fleet operating in the Atlantic and theMediterranean Sea (provisionally reported at 2,238 tons in 2007) are taken intoaccount. All these elements taken together suggest catches significantly higher thelegal quotas, (up to 61,000 tons in 2007, according to ICCAT scientists).11. All Bluefin Tuna fishing and farming nations in the Mediterranean are contractingparties of ICCAT and thus obliged to comply with its legislation. However, ICCAThas consistently set catch quotas for the East Atlantic and Mediterranean stockabove levels recommended by its scientists and the failure of its managementmeasures is demonstrated by the continuously decreasing population. In 19922

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

ICCAT first adopted a recommendation requiring reporting of tuna imports; a morecomprehensive Catch Documentation Programme replaced this in 2007 and enteredinto force in June 2008. However, the efficiency of this programme is still doubtfulsince total catches reported to date are only 2,781 tons, less than 10% of the TotalAllowable Catch for that year.12. In July 2008, the new stock assessment made by ICCAT Scientists advised that themaximum Total Allowable Catch for the East Atlantic and Mediterranean stockshould be between 8,500 and 15,000 tons and that fishing during the spawningseason (May, June and July) should be banned. They went on to suggest theestablishment of a moratorium to increase the probability of rebuilding the stock.However, in November 2008, ICCAT failed to adopt any of the measures advised.The measure adopted by ICCAT in 2008 established Total Allowable Catches forThe East Atlantic and Mediterranean stock that decline annually, Specifically themeasure established Total Allowable Catch of 22,000 tons, and 18,500 tons for year2009, 2010 and 2011 respectively. The fishery was left open during the first half ofthe spawning season when the bulk of catches are made. The season is open from 15April to 15 June, with the possibility of extending the season to 20 June based uponweather conditions (ICCAT Rec. 08-05).13. It is submitted that the listing of Northern Bluefin Tuna on Appendix I of theConvention is consistent with Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP 14), Annex 1 C, i.e.:A marked decline in the population size in the wild, which has beeneither:observed as ongoing or as having occurred in the past (but with a potential to resume);orinferred or projected on the basis of any one of the following:– a decrease in area of habitat; or– a decrease in quality of habitat; or– levels or patterns of exploitation; or– a high vulnerability to either intrinsic or extrinsic factors; or– a decreasing recruitment.Even regarding the species as being of medium productivity, the projected declinefalls within the range specified in footnote (2) to the Resolution concerning theappropriate levels of decline to consider for commercially exploited aquatic species.14. It is further submitted that the current situation regarding the status of the species ispast the stage where Appendix II listing would be sufficient, even if Article XIV ofthe Convention and the existence of ICCAT prior to the entry into force of CITESwere not an issue.15. However, it is acknowledged that Parties may be apprehensive about the extremeconsequences of an Appendix I listing in the longer term and the difficulty in gettingsuch a listing reversed should the management regime improve. Accordingly, thelisting proposal is accompanied by a draft Resolution which would mandate theStanding Committee to advise on the sufficiency of management measures adoptedby ICCAT and, if appropriate , to request the depositary Government to submit aproposal to a subsequent meeting of the Conference of the Parties to downlist thespecies to Appendix II.

3

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

16. Although Northern Bluefin Tuna resembles some related species, genetic techniquesprovide very precise tools to identify it. Consequently, the listing of the species isnot anticipated to pose significant implementation difficulties with regard toconfusion with similar species, especially given the value of the species relative tothat of its closest relatives.-----

4

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

Proposal to include Northern Bluefin Tuna (Thunnusthynnus(Linnaeus, 1758)) on Appendix I of CITES in accordancewith Article II 1 of the ConventionSUPPORTING STATEMENT

A. PROPOSALInclusion ofThunnus thynnus(Linnaeus, 1758) in Appendix I in accordance witharticle II 1.Qualifying criteria(Conf 9.24 (rev. CoP 13) annex 2a)C . A marked decline in the population size in the wild, which has beeneither:I)observed as ongoing.... (but with a potential to resume)In the case of commercially exploited marine species, a range of 5-20% of the baselineis deemed to constitute a marked decline in most cases, with a range of 5-10% beingapplicable for species with high productivity, 10-15% for species with mediumproductivity and 15-20% for species with low productivity. However, it is accepted thatsome species may fall outside this range. Low productivity is correlated with lownatural mortality rate and high productivity with high natural mortality. One possibleguideline for indexing productivity is the natural mortality rate, with the range 0.2-0.5per year indicating medium productivity.A general guideline for a marked recent rate of decline is the rate of decline that woulddrive a population down within approximately a 10-year period from the currentpopulation level to the historical extent of decline guideline (i.e. 5-20% of baseline forexploited fish species).Stock assessments made by the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS)of ICCAT consider a range of natural mortality (M) for East Atlantic and MediterraneanBluefin Tuna of 0.49, 0.24, 0.24, 0.24, 0.24, 0.20, 0.175, 0.15, 0.125, 0.10 for the years1 to 10, respectively. This means an average annual M for adults in the Eastern stock(ages 3 to 10) of 0.18, and even lower for West stock adults, which have a higher age atfirst maturity. For the West Atlantic stock, the ICCAT scientists assume a constantnatural mortality of 0.14 for all ages of the stock. These data make both the EastAtlantic and Mediterranean stock and the western stock of Atlantic Bluefin Tunaqualifying as a low productivity species (to be subject to the criteria of 20% of thebaseline regarding marked decline).Absolute extent of decline for the East Atlantic and Mediterranean stock over the 50-year historical period from 1957-2007 was assessed by SCRS ICCAT at 74.2% in termsof biomass of the spawning population (meaning on 25.8% of the populations remainedthen). Additionally, SCRS ICCAT forecasted that current fishing mortalities were“expected to drive the spawning stock biomass to very low levels; i.e. to about 18% ofthe SSB (spawning stock biomass) in 1970 and 6% of the unfished SSB”. The bulk of

5

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

the historical decline has happened in the last 10 years, with a linear trend from 2003 to2007 suggesting a rapid decline of biomass well below the 20% baseline within muchless than 10 years (see SCRS, 2008a: Appendix 9, Table 4 corresponding to run 14,pages 154-155). Based on independent analysis, Mackenzie et al. (2009) concludedthere is moderate probability that the expected decline in biomass between 1999 and2010 will reach 90%. In summary, the above studies point to a high probability thatspawning stock biomass for the Eastern stock of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is currentlyalready below 20% of its historical baseline. Besides, the best scientific informationavailable points to the almost certitude that SSB will be below the 20% historicalbaseline within the next 10 years, given the very high rate of decline estimated for thelast years.Concerning the West stock of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, the stock assessment conducted bySCRS ICCAT in 2008 shows an absolute extent of decline of the spawning populationof 82.4% over the 38-year historical period (meaning only 17.6% of the spawningbiomass in 1970 would remain). The shark decline of the Western spawning stockbiomass occurred between 1970 and 1985 (SSB in 1985 is now approximately 18.9 %of SSB in 1970). Since then, the stock has remained at relatively constant, but lowlevels.Affected by tradeA species "isor may be affected by trade"if :I) It is know to be in trade and trade has or may have a detrimental impact on the statusof the speciesThe Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is subject to a massive international trade, including a highincidence of illegal trade of the East Atlantic and Mediterranean stock.. For 2007 Japanreported to ICCAT the import of 32,356 tons of processed Atlantic Bluefin Tuna(ICCAT Circulars 1951/07 and 500/08). ICCAT SCRS estimated real catches ofAtlantic Bluefin Tuna in 2007 at 61,000 tons, which highly contrast with the legal quotaestablished at 29,500 tons for that year, and the maximum annual catch recommendedby ICCAT SCRS to prevent collapse and initiate rebuilding for that stock, estimated atbetween 8,500 tons and 15,000 tons.AnnotationAppendix I listing would be accompanied by a Conference resolution that wouldmandate the Standing Committee of the Convention to rule that the conditions forsustainable fishing had been met and, in that event, to ask the Depositary Government(Switzerland) to submit a proposal to a subsequent CoP to downlist the species toAppendix II. A ruling to this effect by the Standing Committee only requires a simplemajority of the Committee members and CoPs have a high rate of acceptance ofproposals that are submitted by the depositary Government at the request of a relevantCITES Committee.B. PROPONENTWill be completed(this proposal has been prepared by the Principality of Monaco)

6

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT1. TAXONOMY1.1 Class:Osteichthyes1.2 Order:Perciformes1.3 Family:Scombridae1.4 Species:Thunnus thynnus(Linnaeus, 1758)1.5 Scientific synonyms:none1.6 Common names:Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, Northern Bluefin Tuna (English), Thonrouge de l´Atlantique (French), Atún rojo del Atlántico (Spanish)1.7 Code numbers:none

Figure 1 .Thunnus thynnusFromfish2056, NOAA's FisheriesCollection

2. OVERVIEW

3. SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS3.1 Distribution:The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is found in the entire extent of the North Atlantic Ocean andits adjacent seas, particularly the Mediterranean Sea, ranging from the southernboundary of the equator to the northern boundary of the north of Norway, and from thewestern boundary of the Gulf of Mexico to the eastern boundary of the Black Sea.(Fromentin, 2008).3.2 Habitat:Bluefin tuna mostly occupy the surface and subsurface waters of the coastal and open-sea areas, between 0m and 200m depths. However, both juvenile and adult BluefinTuna can dive to depths of 500m to 1000m. Juvenile and adult Bluefin Tuna also tend toaggregate along ocean fronts, such as upwelling areas and meso-scale oceanographicstructures associated with the general circulation of the North Atlantic and adjacent seas(Rookeret al.,2007; Fromentin, 2006).3.3 Biological characteristics:Population Structure and Migration PatternsThe Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is currently managed by the International Commission forthe Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) as two separate stocks – the eastern andthe western - separated in the North Atlantic Ocean by the 450W meridian. This

7

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

separation between eastern and western populations was established from studies andobservations that showed that: (1) Atlantic Bluefin Tuna have two separate spawninggrounds on either side of the Atlantic Ocean - in the Mediterranean Sea on the easternside, and the Gulf of Mexico on the western side, (2) there are distinct differences in theage at sexual maturity between western and eastern populations, (3) juveniles and adultsare present on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, and (4) there is a lack of indication ofbreeding in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean (Fromentin, 2008).However, this idea of two separate stocks on either side of the North Atlantic Ocean hasbeen challenged by the transatlantic migrations of these tuna. Recent electronic taggingand chemical signature studies have revealed a greater mixing between eastern andwestern Atlantic stocks than previously believed. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna of mixedorigins (both eastern and western) can be found all along the East coast of NorthAmerica, as well as throughout the North Atlantic Ocean (Blocket al.,2005). The onlyregions that appear to be exclusively composed of tuna of either purely western, orpurely eastern origins, are the spawning grounds in the Gulf of Mexico and theMediterranean Sea respectively (Rookeret al.,2008; Blocket al.,2005).Nevertheless, despite this apparently high rate of mixing, the most recent study onmitochondrial DNA has revealed a significant population subdivision among the Gulf ofMexico, the western Mediterranean, and surprisingly, the eastern Mediterranean Sea(Boustanyet al.,2008). These latest results indicate that although the distributions oftuna from different origins do overlap within the North Atlantic Ocean and adjacentseas, individuals show strong natal homing to their spawning grounds either in the Gulfof Mexico, or the Western or Eastern Mediterranean Sea.ReproductionBluefin tuna is oviparous and iteroparous, as are all tuna species. It has asynchronousoocyte development and is a multiple batch spawner. Egg production is age (or size)-dependent. It had been generally assumed that Bluefin Tuna spawns every year, butelectronic tagging experiments, as well as experiments in captivity, have raisedquestions about this assumption and have suggested that individual spawning mightoccur only once every two or three years. Spawning fertilization occurs directly in thewater column and hatching takes place without parental care after an incubation periodof 2 days (Fromentin, 2006). It is generally agreed that BFT spawning takes place inwarm waters (> 24�C) of specific and restricted locations (around the Balearic Islands,Sicily, Malta, Cyprus and some areas of the Gulf of Mexico) and occurs only once ayear (Fromentin, 2006). Spawning begins earlier in the Gulf of Mexico, in April. In theMediterranean Sea, spawning occurs during May-June in the East, and June-July in thecentre and the West (Rookeret al.,2007).RecruitmentFish larvae (around 3-4 mm) are typically pelagic with a yolk sac and relativelyundeveloped body form. The yolk sac is re-absorbed within a few days. Little is knownabout the effects of the age-structure of the spawning stock, as well as the condition ofthe spawners, on the viability of the offsprings. It was suggested that the North AtlanticOscillation (NAO) might affect Bluefin Tuna recruitment success in the East Atlantic,but further statistical analyses did not confirm such hypothesis. The identification of themajor abiotic and biotic forces controlling Bluefin Tuna recruitment thus remainsobscure (Fromentin, 2006).

Sex ratio and age at first maturity8

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

The proportion of males appears to be higher in catch samples of large individuals,which could be due to a higher natural mortality or lower growth for females (SCRS,1997). In contrast, higher or equal (depending on the year) proportions of females havebeen found for all size classes in the catches of purse seiners operating in the centralMediterranean (Hattour, 2003).Various past studies showed that Atlantic Bluefin Tuna mature at 110-120cm (25-30kg)in the East Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea, so at approximately 4 years old (accordingto the East Atlantic and Mediterranean growth curve). The size of the fish spawning inthe Gulf of Mexico has always been greater than 190cm, which would correspond toabout 8 to 12 years of age (Fromentin, 2005). This disparity in age-at-maturity betweenWest Atlantic and Mediterranean Bluefin Tuna has been used as a major argument forseparation into two stocks (Fromentin, 2006).3.4 Morphological characteristics:Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is the largest tuna species. It has an elongated fusiform body,being more robust at the front. Its maximum length can exceed 4 m long. Its officialmaximum weight is 726 kg, but weights of up to 900 kg have been reported in variousfisheries of the West Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea. The body of the Atlantic BluefinTuna is deepest near the middle of the first dorsal fin base. The back is dark blue, whilelower sides and belly are silvery white, with colourless transverse lines alternated withrows of colorless dots. Bluefin tuna have 39 vertebrae, with 12 to 14 dorsal spines and13 to 15 dorsal soft rays. The first dorsal fin is yellow or bluish; the second dorsal fin,which is higher than the first, is reddish-brown. The anal fin and finlets are duskyyellow and edged with black; the median caudal keel is black in adults. Swim bladdersare present and the pectoral fins are very short, less than 80% of head length(Fromentin, 2006).3.5 Role of the species in the ecosystem:The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is often regarded as a quintessential predator of pelagicecosystems (Rookeret al.,2007). Juveniles and adults are opportunistic; their dietconsists mainly of crustaceans, fish and cephalopods during their early years, butcentres primarily on fish such as herring, anchovy, sand lance, sardine, sprat, bluefishand mackerel as adults. Their diet can also include jellyfish and salps, as well asdemersal and sessile species such as, octopus, crabs and sponges (Fromentin, 2005).The ecological extinction of this species would thus have unpredictable cascadingeffects in the Mediterranean ecosystem and entail serious consequences to many otherspecies in the food web.

4. STATUS AND TRENDS4.1. Habitat trendsNot applicable.4.2. Population sizeAtlantic Bluefin Tuna - EastA virtual population analysis (VPA; Murphy, 1965; Gulland, 1965; Jones, 1964)conducted in 2008 by the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS) ofICCAT, based upon estimated catches (including IUU), which addressed the period of1955-2007 and included estimates of real catches, yielded an estimate for spawning9

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

stock biomass (SSB) for the East Atlantic and Mediterranean stock in 2007 of 78,724tons (SCRS, 2008a: Appendix 9, Table 4 corresponding to run 14, pages 154-155). Thiscontrasts with the biomass peak estimated for 1958 at 305,136 tons, and with the201,479 tons estimated for 1997. The absolute extent of decline over the 50-yearhistorical period ranging from 1957 to 2007 is, therefore, estimated at 74.2% of thespawning population level at the start of the series, indicating that the size of the currentspawning stock is only 1/4 of that in 1957. The bulk of the spawning stock biomassloss has happened in the last 10 years. Indeed, the rate of decline in the last 10 years(1997-2007) is estimated at 60.9%, with a total loss of spawning biomass of 122,750tons from the 1997 estimate. Current fishing mortality (F) is at least 3 times the levelthat would result in Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY), and spawning stock biomass ismost likely to be less than 20% of the level needed to support MSY; for 2007, it isestimated at only 14% of the level corresponding to maximum fishing mortality (FMAX),even assuming the high recruitment levels typical of the 1990s (SCRS, 2008b).A second virtual population analysis conducted in 2008 by ICCAT scientists, which wasbased upon reported catches for the period of 1955 to 2007, indicated a long-term rateof decline of 64% from the baseline spawning stock biomass (Based upon reportedcatches, spawning stock biomass in 2007 was 100,047 tons, and the spawning stockbiomass in 1955 was 281,954 tons). This last analysis didn't account for the illegal over-quota catches, which were estimated by SCRS to roughly equal the reported catches in2007 (real catches were estimated at 61,100 t for that year and at around 50,000 tons peryear in recent times).Atlantic Bluefin Tuna - WestThe virtual population analysis (VPA) conducted by SCRS ICCAT in 2008 yielded anestimate for spawning stock biomass in 2007 of 8,693 tons which contrasts sharply withthe 49,482 tons estimated for 1970, meaning an absolute extent of decline over the 38-year historical period estimated at 82.4% of the spawning population level at the start ofthe series (SCRS, 2008a: Appendix 9, Table 4, pages 167-168). Overfishing during the1970s and 1980s lead to decline of the West Atlantic stock. Since then, the spawningstock biomass has remained relatively stable at approximately 15-18 % of its pre-exploitation level biomass.Assuming that average recruitment cannot reach the high levels recorded in the early1970s, recent fishery mortality (2004-2006) is about 30% to 50% higher than the levelrequired to achieve maximum sustainable yield (MSY) and the spawning stock biomassis about half of the biomass level required to support MSY (SCRS, 2008b).4.3. Population structureAtlantic Bluefin Tuna - East.See also sections 4.2. and 4.4.The main pattern recorded by SCRS consists of the rapid decline in abundance of olderspawners (8+) due to the dramatic increase of fishery mortality since 2000 in thissegment of the population, driven by the booming demand from tuna farms in theMediterranean. This fact has led to the strong overall decrease in spawning stockbiomass (SCRS, 2008 a,b). According to Mackenzieet al.(2009), who used an age-structured stochastic modeling approach similar to that used in working groups of theInternational Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), the mean age of matureBluefin Tuna has declined since the mid-1980s, and the proportion of large spawners(age 8+) has declined especially since the late 1970s. The share of repeat spawners in10

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

the population has also declined and has remained generally low since the mid- to late1980s. Based on these considerations, the authors conclude that “age structure andreproductive demographics for the population have shifted to configurations whichlikely reduce reproductive potential and increase vulnerability of the remainingpopulation to additional stressors”.4.4. Population trendsAtlantic Bluefin Tuna - East.The last population assessment conducted by the ICCAT SCRS in 2008 was based onvirtual population analysis (VPA) and shows that spawning stock biomass (SSB) hasbeen declining rapidly in the last several years while fishing mortality (F) has beenincreasing rapidly, especially for large individuals (ages 8+; a 3 to 4-fold increase in Fsince 2000). Analyses show that recent (2003-2007) spawning stock biomass is lessthan 40% of the highest estimated levels (at the start of the times series 1970-1974 or1955-1959, depending on the analysis). The decline in spawning stock biomass appearsto be more pronounced after the year 2000. All the analyses indicate a general recentincrease in fishing mortality for large fish and, consequently, a decline in spawningstock biomass (SCRS, 2008b). Continued fishing at the current fishing mortalities isexpected to drive the spawning stock biomass to very low levels; i.e. to about 18% ofthe SSB in 1970 and 6% of the unfished SSB. This combination of high fishingmortality, low spawning stock biomass and severe fishing overcapacity results in a highrisk of fisheries and stock collapse. (SCRS, 2008a,b).According to Mackenzieet al.(2009), even if a near-complete ban on all Bluefin Tunafishing in the NE Atlantic and Mediterranean were implemented and enforced from2008 to 2022, the population would probably fall to record lows in the next few years,unless environmental conditions promote exceptionally high recruitment. The sameauthors estimate that there is moderate probability (25%) that the expected decline inbiomass between 1999 and 2010 will reach 90%.In October 2008 the SCRS advised ICCAT to adopt one of the following managementapproaches in its meeting of November 2008 in order to rebuild the East AtlanticBluefin Tuna stock according to the objectives of the ICCAT Convention:(i)(ii)F0.1or FMAXstrategies (implying short-term real catches at between 8,500 tand 15,000 t, or less),(ii) a closure of the entire Mediterranean in May-June-July, or (iii) amoratorium over the East Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea during 1, 3 or 5years followed by an F0.1strategy (SCRS, 2008b).

Instead, total allowable catches were adopted by ICCAT for 2009 and 2010 at 22,000and 19,950 tons respectively; in other words, between 2.34 and 2.58 times theprecautionary F0.1quota advised by SCRS ICCAT.Atlantic Bluefin Tuna - West.The total catch for the West Atlantic BFT stock peaked at nearly 20,000 tons in 1964.Catches dropped sharply thereafter and after reaching a small peak in 2002, at 3,319tons, they steadily declined to only 1,624 tons in 2007. The United States was unable tocatch its quota in 2004-2007 due to the scarcity of fish available to the fleet. The SCRSassessment made in 2008 showed that spawning stock biomass declined steadilybetween the early 1970s and 1992; since then, it has fluctuated between 18% and 27%

11

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

of the 1975 level. Even though fishing mortality on spawners (age 8+) declined since2002, the stock does not show any signs of population recovery (SCRS,2008b).In spite of the overall negative status of the population, catch per unit effort (CPUE)values in the Gulf of Lawrence have increased from 1997 to 2004, and have remainedhigh since then. However, SCRS Atlantic Bluefin Tuna experts have hypothesized thatthis might reflect the passage of a single year class (SCRS, 2008a: pg. 14). There isstrong uncertainty about the potential recruitment for this stock. According to the lastassessment by the SCRS (SCRS. 2008a,b) under the most pessimistic recruitmentscenario, closing the fishery would not achieve the rebuilding of the stock by 2019.However, recovery is projected to occur within this timeframe under differentassumptions of recruitment.4.5. Geographic trendsHistorical analysis of Atlantic bluefin fisheries showed that it dates back to ancienttimes. The species has been exploited for centuries in the Mediterranean Sea and at theentrance of the Gibraltar Straits. Since the 1920s, it has been increasingly exploited inthe northeast Atlantic. Large changes have been observed since then and there wereseveral extinctions/discoveries of important fishing grounds in the Mediterranean aswell as in the East Atlantic during the 20th century. Bluefin tuna are now absent or rarefrom formerly occupied habitats, such as the North Sea, Norwegian Sea, Black Sea, Seaof Marmara, off the coast of Brazil and Bermuda, and certain locations off thenortheastern American coasts, while high catches have been recently made in new areas,such as the eastern Mediterranean, the Gulf of Sirte and the central North Atlantic. Thereasons for these changes in spatial and temporal patterns remain unclear and are likelyto result from interactions between biological, environmental, trophic and fishingprocesses (SCRS, 2008a).In the Mediterranean, while traditional Atlantic Bluefin Tuna fisheries mostly operatedalong specific areas of the coasts until the mid-1980s (e.g., the Gulf of Lions, theLigurian, Ionian and Adriatic Seas), the fisheries rapidly expanded over the wholeWestern basin during the late 1980s and early 1990s, and, more recently, over theCentral and Eastern basins, so that Bluefin Tuna is now exploited over the wholeMediterranean Sea for the first time in the millennia of its fisheries history (Fromentin,2006). The SCRS expresses concern because this situation means that no refuge appearsto exist any more for Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the Mediterranean during the spawningseason (SCRS, 2008a).

5. THREATSThe main threat for the Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean stock species is overfishingincluding both legal overfishing – meaning unsustainable catch limits set well abovelevels recommended by scientists; and illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU)fishing activities. This threat may also be impacting the West Atlantic Stock. AtlanticBluefin Tuna is traditionally consumed fresh in Mediterranean countries, and it is alsoone of the most sought after species for the sashimi market in Japan. The boomingcapture-based farming activities that started in the Mediterranean (the main spawningand fishing ground for the species) in 1996 have exacerbated fishing pressure over theEast Atlantic stock, to the point that 61% of the spawning biomass has disappeared inthe last 10 years (see section 4.2.). In 2009 fishing continues in excess of scientific12

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

recommendations for East Atlantic and Mediterranean Bluefin Tuna, since the 2008ICCAT meeting failed to adopt the measures advised by scientists to recover the stock.The Western stock is not recovering, in spite of the low catch quotas. There is stillsubstantial mortality on spawners, due to by-catch within the Gulf of Mexico breedingground and as a result of a directed fishery along the coast of Canada. In addition, thereis some mortality of the West Atlantic stock within the gulf of Mexico due to bycatch inother fisheries.

6. UTILIZATION AND TRENDS6.1 National utilizationBluefin tuna in the Mediterranean is mostly caught by purse seine vessels (nearly 70 %of the catch – SCRS, 2008b). Fish caught by purse seine vessels are then tugged live totuna farms where they are then fattened during a period of 6 to 8 months. Fishingvessels are usually from different countries than those where the tuna are later farmed,so this transfer of live fish to farms constitutes international trade. After slaughter, thebulk of this production is exported to Japan as frozen products where it is consumed assushi and sashimi. The main types of products exported are belly meat, dressed fish(headless, whole), fillets, loins, and gilled and gutted fish. Tuna farming in theMediterranean started in 1997. Farming capacity abruptly increased from a few hundredtons in 1997 to 30,000 tons in 2003 (WWF, 2006) and around 64,000 tons in 2008,representing approximately 51,000-57,000 tons round weight of (large) fish at time ofcapture (SCRS, 2008a). This estimated farming capacity represents a capacity excess ofmore than 32,000 tons - as much as twice the 2008 Total Allowable Catch (TAC). Inaddition, the estimates of fleet size indicate there is sufficient active fishing capacity tofully supply the farms to their indicated limits (SCRS, 2008a). In recent years an arrayof Japanese restaurants in Europe have also contributed to the demand of this farmedBluefin Tuna. Catches by longliners and tuna traps are also partly exported to Japan aswild fish products. The rest of their catch, together with tuna caught by handlines andother gear, is consumed domestically in the main producer countries (Spain, France andItaly) as a fresh product, usually from small size fish.Stockpiles of frozen Bluefin Tuna are known to exist in Japan and some other Asiancountries. The amount of the Japanese cold store of Bluefin Tuna reported by NOAA inNovember of 2008 was 21,783 tons1. Additional stores of frozen Bluefin Tuna areknown to exist in other Southeast Asian nations and in reefer vessels2.6.2. Legal tradeThe most comprehensive sources of information on international trade of AtlanticBluefin Tuna are the Eurostat database (Statistical Office of the EuropeanCommunities) and the ICCAT database of the Bluefin Tuna Statistical Document(BFTSD) Program. While Eurostat provides information on all trade flows legallyrecorded on Bluefin Tuna involving the 27 member states of the European Union (themain quota holder of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna and the entity concentrating the bulk ofcapture-based farming production of this species), the ICCAT BFTSD (which lasteduntil 2008, when it was replaced by the new Bluefin Tuna Catch Document scheme)National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Regional Office, NOAAhttp://swr.nmfs.noaa.gov/fmd/sunee/coldstor/jcsnov08.htm2El triunfo de la barbarie, published in Ruta Pesquera (Spain), January 20091

13

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

records all imports of processed Bluefin Tuna into ICCAT contracting parties, whichinclude all major producers and consumers of the species.Tables 1 and 2 summarize the information available on the Eurostat database onexternal trade for 2007 (Eurostat Traditional external trade database access, ComExt;Eurostat id. Code of extraction: k2832469.xls 1), referring to the following CN8 TARICcodes identifying Atlantic Bluefin Tuna products:0301940003023510030235900302391103023991030345110303451303034519LIVE BLUEFIN TUNAS ''THUNNUS THYNNUS''FRESH OR CHILLED BLUEFIN TUNAS ''THUNNUS THYNNUS'', FORINDUSTRIAL PROCESSING OR PRESERVATIONFRESH OR CHILLED BLUEFIN TUNAS ''THUNNUS THYNNUS'' (EXCL.TUNAS FOR INDUSTRIAL PROCESSING OR PRESERVATION)BLUEFIN TUNAS ''THUNNUS THYNNUS'', FRESH OR CHILLED, FORINDUSTRIAL PROCESSING OR PRESERVATIONBLUEFIN TUNAS ''THUNNUS THYNNUS'', FRESH OR CHILLED (EXCL.TUNAS FOR INDUSTRIAL PROCESSING OR PRESERVATION)FROZEN BLUEFIN TUNAS "THUNNUS THYNNUS" FOR INDUSTRIALPROCESSING OR PRESERVATION, WHOLEFROZEN BLUEFIN TUNAS "THUNNUS THYNNUS" FOR INDUSTRIALPROCESSING OR PRESERVATION, GILLED AND GUTTEDFROZEN BLUEFIN TUNAS "THUNNUS THYNNUS" FOR INDUSTRIALPROCESSING OR PRESERVATION, WITHOUT HEAD AND GILLS, BUTSTILL TO BE GUTTEDFROZEN BLUEFIN TUNAS "THUNNUS THYNNUS" (EXCL. FORINDUSTRIAL PROCESSING OR PRESERVATION)BLUEFIN TUNAS "THUNNUS THYNNUS", FROZEN, FOR INDUSTRIALPROCESSING OR PRESERVATION, WHOLEBLUEFIN TUNAS "THUNNUS THYNNUS", FROZEN, FOR INDUSTRIALPROCESSING OR PRESERVATION, GILLED AND GUTTEDBLUEFIN TUNAS "THUNNUS THYNNUS", FROZEN, FOR INDUSTRIALPROCESSING OR PRESERVATION (EXCL. WHOLE AND GILLED ANDGUTTED)

03034590030349210303492303034929

Data on live Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in Tables 1 and 2 refer to trade on live specimenscaught by industrial purse seine fleets for farming purposes. Information on EUcountries is segregated between those member states involved in the catch and farmingof Bluefin Tuna (Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Greece and Malta), and the rest, whichare net consumers. Eurostat information mainly refers to external trade involving EUmember states and third countries, which means that data on intra-EU trade might beincomplete.It should be pointed out, however, that the main domestic markets for Bluefin Tuna atEU level are found in the main harvesting nations - notably Spain, France and Italy. Noinformation is available on the size of this domestic market for Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,although it is thought to be very important, given the long tradition of Bluefin Tunaconsumption in those countries. The lack of information on the magnitude of domesticmarkets in the Mediterranean means that the picture provided by the available officialdata on international trade presented here only provides a partial overview of theEuropean market (and this without considering the huge estimates of Illegal, Unreportedand unregulated, or IUU, fishing described in section 6.4).

14

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

Table 3 shows the information on imports of processed Atlantic Bluefin Tuna during2007 by ICCAT Contracting Parties (East Atlantic stock), as available on the ICCATregister of the Bluefin Tuna Statistical Document (BFTSD) Program. Total imports of32,356 tons of processed Bluefin Tuna reported by Japan to ICCAT for 2007, (totalJapanese imports in Table 3 from East Atlantic and Mediterranean; see ICCATCirculars 1951/07 and 500/08), contrast sharply with the legal Total Allowable Catchfor that year (29,500 tons). This mismatch between ICCAT import records (BFTSD)and the TAC is all the more evident when the unquantified levels of domesticconsumption in European Mediterranean countries are taken into account, together withthe real magnitude of the intra-European trade and the catches by the national Japanesefleet operating in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea (provisionally reported at 2238 tons in 2007). All these elements taken together suggest significant catches over thelegal quotas (IUU), in line with ICCAT SCRS estimates of real catches (61 000 in2007). These comparisons, however, should be made with caution since trade data for2007 includes some farmed fish caught in 2006, and trade information refers toprocessed presentations (to which adequate conversion factors need to be applied -including appropriate growth rates during the farming period - in order to yieldestimates of round weight at the moment of catch). Indeed, Bluefin Tuna import recordsavailable at the ICCAT BFTSD database include the following: dressed, gilled andgutted, filletted, round and others (such as belly meat) - all of which usuallyunderestimate the original round weight of the fish at the moment of harvesting.

15

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

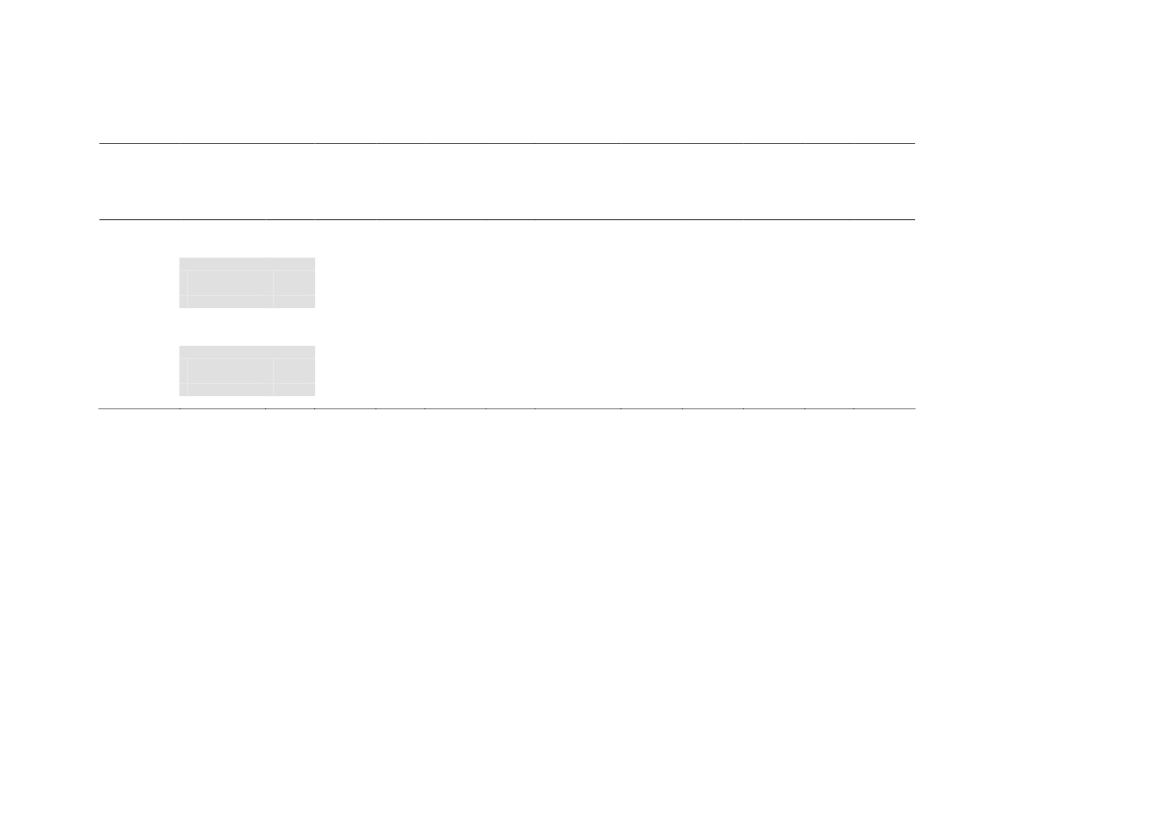

Table 1.Exports of processed and live Atlantic bluefin tuna from EU27 countries in 2007 based on Eurostat database. Shaded cells indicate intra-EU trade. EU27 BFT producers include Spain,France, Italy, Cyprus, Greece and Malta. Volume of trade is given in tonnes.IMPORTING ENTITIESEU27 BFTproducersEU27othersCroatiaIsraelJapanKoreaSwitzerlandThailandTunisiaTurkeyUSAOthers*

processedEU27 BFTproducersEU27 othersliveEU27 BFTproducersEU27 others

3937.553.4

300.346.10.05

31.3

13837.10.1

203.9

34.3

49.81

492.1

11.20.1

1571.2553.5

10.651.3

557.8

900

229

10.8

* includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Russia, UAE, Canada and Norway

16

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

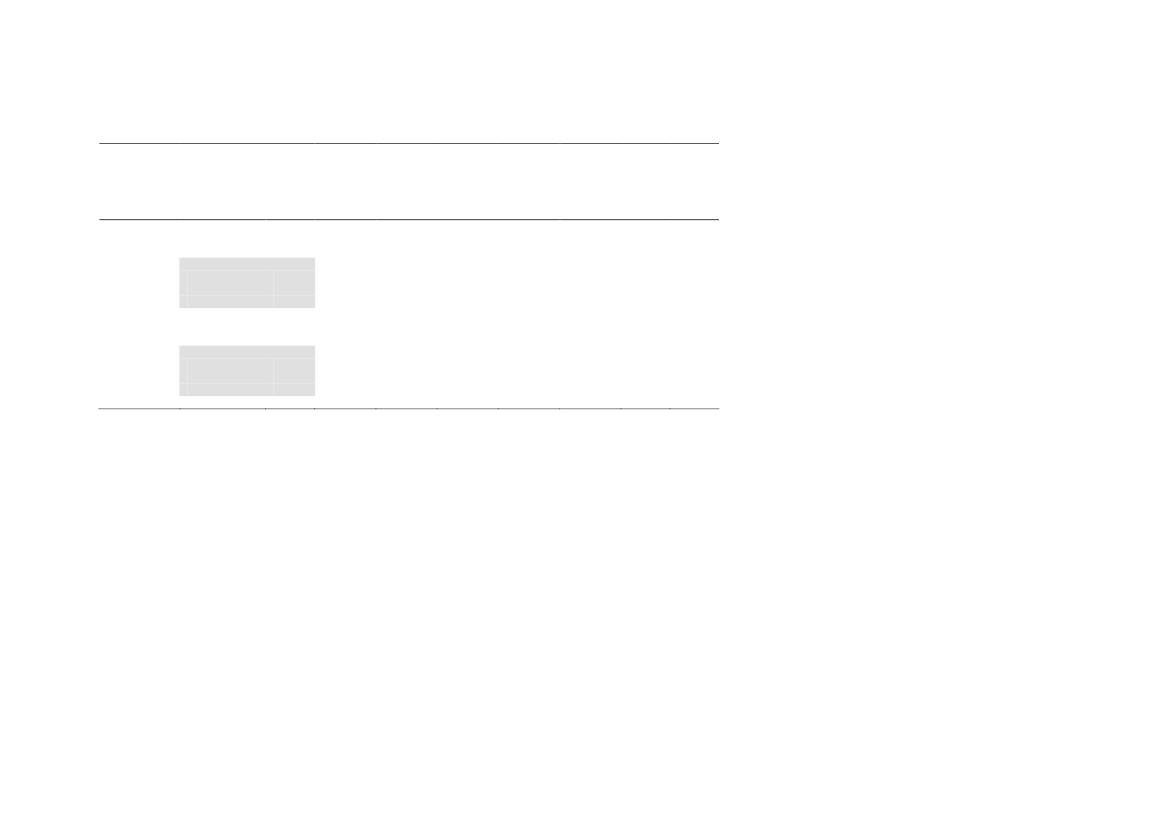

Table 2.Imports of processed and live Atlantic bluefin tuna into EU27 countries in 2007 based on Eurostat database. Shaded cells indicate intra-EU trade. EU27 BFT producers include Spain,France, Italy, Cyprus, Greece and Malta. Volume of trade is given in tonnes.EXPORTING ENTITIESEU27 BFTproducersEU27othersCroatiaLibyaMoroccoTunisiaTurkeyUSAOman

processedEU27 BFTproducersEU27 othersliveEU27 BFTproducersEU27 others

5784.788.4

32986.05

19.8

413

70.11.7

18.6

1.9

0.5

10345.93.3

156.25

340

2101.41.9

17

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

Table 3.Imports of processed Atlantic bluefin tuna (East Atlantic stock) in 2007 based on ICCAT database (records of the Bluefin Tuna Statistical Document –BFTSD- Program). EU27 BFTproducers include Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Greece and Malta. Volume of trade is given in tonnes.Fishing and primary exporting countryEU27 BFTproducersAlgeriaChinaCroatiaGuineaKoreaLibyaMoroccoTaiwanTunisiaTurkey

EU27 BFTproducersChinaJapanUSA39.3621711.7099.23

14.92

16.07

345

771.19

416.9

10.29

37.189.04

88

2853.16

12

724.81

1010.95

2025.6738.75

14.38

2702.762.08

1203.17

18

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

6.3. Parts and derivatives in tradeSee section 6.2 above.6.4 Illegal tradeA catch assessment produced by Advanced Tuna Ranching Technologies (ATRT)WF,based on trade statistics of Bluefin Tuna products was presented by WWF scientists inthe last SCRS meeting (SCRS, 2008a). For 2006, the study relied on complete officialstatistics on international trade for the year, including ICCAT Bluefin Tuna statisticaldocuments (BFTSD) supplemented with Eurostat trade data. Trade figures were cross-checked against databases from national trade and custom agencies in Spain, France,Malta, Italy, United States, Japan, Korea and Tunisia, and fine-tuned with reliable catchand caging data when appropriate. Total estimated catches of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna(wild round weight) in the east Atlantic and the Mediterranean amounted to 58,681 tons.For 2007, this study was based on direct field assessments of Mediterranean tuna farmsin 2006 and 2007, supplemented with Eurostat trade data (from January to July 2007)and official reports of catches and industry estimates collected until August 30, 2007.Total estimated catches of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (wild round weight) in the EastAtlantic and Mediterranean amounted to 56,149 tons for the year 2007. Spreadsheetssupporting these calculations are held at the ICCAT Secretariat as part of the record ofthe 2008 Bluefin Tuna stock assessment. The results of this study were endorsed by theSCRS and coincided in general with that made by the Group on the basis of activecapacity (SCRS, 2008a) – i.e. 61,000 tons (SCRS, 2008b). Consequently, the differencebetween the estimated catch of 61,000 tons and the legal quota of 29,500 tons for 2007can be attributed to illegal trade, most of which is happening at the international level.6.5 Actual or potential trade impactsThe current exploitation of Bluefin Tuna in the Mediterranean is mainly driven by theJapanese market of sushi and sashimi. This Japanese market is responsible for thegrowth of Bluefin Tuna farming activities and the associated purse seine catches inrecent years in the Mediterranean. This use of Bluefin Tuna production has become themain threat for its sustainable exploitation, since it is responsible for the bulk of thecatch. The inclusion of Bluefin Tuna in Appendix I of CITES would allow onlydomestic consumption or consumption within the European Union, which could, in alllikelihood, result in harvest levels that are consistent with the Total Allowable Catchadvised by SCRS scientists for the East Atlantic and Mediterranean stock - i.e. between8,500 to 15,000 tons.

7. LEGAL INSTRUMENTS7.1 NationalIt has already been noted that management of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is under thecompetence of ICCAT (see 7.2), the international Regional Fisheries ManagementOrganization in charge of the conservation of tuna and tuna-like fishes in the AtlanticOcean (ICCAT, 2007). ICCAT, in its annual meeting, adopts legislation withmanagement measures that are binding for its 48 contracting parties. All Bluefin Tunafishing and farming nations in the Mediterranean are contracting parties of ICCAT andthus obliged to comply with its legislation. The legislation is, therefore, then adopted bythe GFCM (General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean), the RegionalFisheries Management Organization managing the fisheries in the Mediterranean, where

19

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

the East Atlantic Bluefin Tuna stock is heavily exploited. The European Union (EU), acontracting party of ICCAT, makes a transposition annually of the ICCAT managementmeasures into the EU legislation, which then become binding for its member States. Themain tuna producing countries in the Mediterranean are members of the EU, which holdsnearly 60 % of the annual TAC for Bluefin Tuna established by ICCAT.In 2009, Monaco has totally banned trade and use of Bluefin Tuna on its territory.7.2 InternationalICCAT was established at a Conference of Plenipotentiaries, which prepared andadopted the International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas signed inRio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1966. After a ratification process, the Convention enteredformally into force in 1969.As already stated, ICCAT currently manages Atlantic Bluefin Tuna as two stocks, thewestern and the eastern stocks, with the boundary between the two spatial units beingthe 45�W meridian. This delimitation was established for management convenience(SCRS, 2002). Starting in 1974 ICCAT adopted a series of recommendations onmanagement measures concerning both stocks. Initially, the main measures were relatedto a minimum landing size and fixing of a catch quota. More recently, recovery planswere adopted for the species. However, ICCAT has consistently set catch quotas for theEast Atlantic and Mediterranean stock above levels recommended by its scientists(SCRS). The continuously decreasing population trends of the East Atlantic andMediterranean stock are evidence of the failure of ICCAT’s management measures todate. ICCAT´s own scientific committee (SCRS) estimated that the eastern Bluefin Tunacatch in 2007 was twice the current total allowable catch (TAC), and four times thesustainable level, and highlighted the ineffectiveness of the adopted TAC in controllingthe catch (SCRS, 2008). SCRS’ scientists continually advise that the currentmanagement measures will lead to a further reduction in spawning stock biomass of theeastern stock, with a high risk of stock collapse.In 2007 ICCAT, in common with many other regional fisheries bodies, agreed toconduct an independent review of its own performance against its objectives (Hurryetal.,2008). For this purpose, it appointed an independent panel consisting of GlennHurry, Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Fisheries Management Authority(AFMA) and the current Chairman of the Western and Central Pacific FisheriesCommission, Moritaka Hayashi, Professor (nowemeritus)of International Law, WasedaUniversity in Japan, and Jean-Jacques Maguire, a well known and respectedinternational fisheries scientist from Canada. The review, delivered in September 2008,stated that:“ICCAT contracting parties’ performance in managing fisheries on Bluefin Tunaparticularly in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea is widely regarded as aninternational disgrace …”.“The Panel found the management of fisheries on Bluefin Tuna in the eastern Atlanticand Mediterranean and the regulation of bluefin farming to be unacceptable and notconsistent with the objectives of ICCAT. This finding coupled with the publishedstatements from the European Community (EC) has prompted the Panel to recommendto ICCAT thesuspension of fishing on Bluefin Tunain the eastern Atlantic andMediterranean until the CPCs fully comply with ICCAT recommendations on bluefin.”

20

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

“The Panel further recommends that ICCAT consider animmediate closure of allknown Bluefin Tuna spawning groundsat least during known spawning periods.Referring to illegal fishing pushing annual catches to twice the quota levels and fourtimes scientific recommendations.”The report concluded that “It is difficult to describe this as responsible fisheriesmanagement.”

The introduction of Bluefin Tuna farming activities in the Mediterranean in 1997exacerbated the problems with management of the fisheries. The first recommendationrelated to farming activities was adopted in 2002 and subsequent recommendations wereadopted in the following years. However, the resulting reported information isunreliable, due to non-compliance, misreporting, and doubtful growth rates for the fish.As previously noted, the current farming capacity in the Mediterranean is estimated bythe SCRS to be around 64,000 tons (SCRS, 2008a), more than double the TotalAllowable Catch adopted for past years.In 1992 ICCAT first adopted a recommendation requiring trade information. Followingthis recommendation, all Bluefin Tuna imported into the territory of a Contracting Partyor at the first entry into a regional economic organization, had to be accompanied by anICCAT Bluefin Tuna Statistical Document. The information required in the documentincluded the name of the exporter country, the area of harvest, the type of product andweight, and the point of export. As proven by the high estimates of illegally caughtBluefin Tuna, this recommendation failed to quantify the real amount of traded BluefinTuna.In 2007, ICCAT adopted a more complete programme, the Bluefin Tuna CatchDocumentation Programme, which entered into force in June 2008. This included notonly trade information but also catch, transfer, transhipment, and farming information.Although the program just entered into force, its efficiency is open to discussion, sincetotal reported catches for 2008, as shown on the ICCAT webpage, are to date 2,781 tons,less than 10% of the Total Allowable Catch for that year.38. SPECIES MANAGEMENT8.1 Management measuresIn October 2006 the SCRS stock assessment revealed that the fishing mortality for theeastern stock of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna was more than three times the level that the stockcould sustain, and that this trend was expected to drive the spawning biomass to verylow levels, giving rise to a high risk of fishery and stock collapse (SCRS, 2006).Scientists advised that the only scenarios which have the potential to address the declineand initiate recovery are those which include, among other measures, the closure of theMediterranean to fishing during the spawning months (May, June, and July) and a TotalAllowable Catch of 15,000 tons or less. The SCRS estimated that catches were 56% overthe legal TAC. However, in November of the same year, ICCAT, in its plenary session,adopted the first “Recovery plan for Bluefin Tuna in the Eastern Atlantic andMediterranean” which did not take into account any of the mentioned essentialrequirements for rebuilding the stock. The TAC was fixed at 29,500 tons for 2007,

3

http://www.iccat.int/en/BCD.htm

21

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

decreasing gradually to 25,500 tons by 2010; and the seasonal closure included only onemonth of the three month spawning season advised.In July 2008, the new stock assessment for the East Atlantic and Mediterranean stockmade by the SCRS (SCRS, 2008a) indicated that the spawning stock biomass iscontinuing to decline (calculated as 30-40% of the levels in the 1970’s), while fishingmortality was increasing rapidly, especially for large fish. Again scientists warned thatcontinuing fishing at this level is expected to drive the spawning stock biomass to 18 %of that in 1970, which, combined with the current high fishing mortality and severeovercapacity, results in a high risk of fisheries and stock collapse (SCRS, 2008a). At thistime the SCRS advised that the maximum Total Allowable Catch should be between8,500 and 15,000 tons, and that fishing should be banned during the spawning season(May, June and July). They went on to suggest the benefits of establishing a moratoriumto increase the probability to rebuild the stock - an option that was reinforced during themeeting by the estimate of catches for 2007 of 61,000 tons (more than double of theTAC - see 8.3).In September of the same year, the ICCAT performance review (see 7.2) (Hurryet al.,2008) stated:“…the Panel (to) recommend to ICCAT thesuspension of fishing on Bluefin Tunainthe eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean until the CPCs fully comply with ICCATrecommendations on bluefin.” “The Panel further recommends that ICCAT consider animmediate closure of all known Bluefin Tuna spawning groundsat least duringknown spawning periods.”

In October 2008 the IUCN World Conservation Congress adopted, by majority, arecommendation on the species. Those voting in favour included Spain, a key fishingnation, and Japan, the most important market country. Only some members votedagainst. In the recommendation, which IUCN asked ICCAT, at its next meeting ofNovember 2008, to establish a science based recovery plan according to SCRS advice,including the closure of the fishery during the crucial months of May and June and aTotal Allowable Catch of less than 15,000 tons. It also asked ICCAT to establishimmediately a suspension of the fishery until it can be brought under control, and toestablish protected areas in main spawning grounds4.Two weeks before the ICCAT plenary session in November 2008, ICCAT’s chairmansent a letter5to the head delegates of ICCAT contracting parties urging to take scienceseriously into account, stating that:“…there will be no future for ICCAT if we do not fully respect and abide by the scientificadvice. If we do not follow the instructions science is giving us, our credibility will beirreversibly jeopardized and the mandate to manage tuna stocks will be surely taken out ofour hands”.

Despite all these recommendations, ICCAT again failed in November 2008 to adopt anyof the measures advised, and, therefore, to bring about a change in the current rapiddeterioration of the stock, or forestall prevent its imminent collapse. The measureadopted by ICCAT established Total Allowable Catches for the East Atlantic andMediterranean stock that decline annually. Specifically, the measure establishes total45

See resolution 4.028 in http://www.iucn.org/congress_08/assembly/policy/index.cfmICCAT circular #2146/08

22

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

Allowable Catches of 22,000 tons, 19,950 tons, and 18,500 tons for years 2009, 2010,and 2011 respectively. The fishery was left open during the first half of the spawningseason, when the bulk of catches are made. The season is open from 15 April to 15 June,with the possibility of extending the season to 20 June based upon weather conditions.The first ever real estimate of the actual catch capability of the Mediterranean purseseine fleet targeting Bluefin Tuna revealed that this fleet alone has a yearly catchpotential of 54,783 tons, almost double than the annual total TAC set for 2008 and morethan three and a half times the maximum catch level advised by scientists to avoid stockcollapse (between 8,500 to 15,000 tons) (WWF, 2008). This figure does not take intoaccount the catch potential of the rest of the Bluefin Tuna fleet, such as longliners, traps,bait boats, pelagic trawlers, hand line boats, etc. This result was then publicly endorsedby the European Commission who welcomed the report and shared the analysishighlighting that “…the whole fishery is plagued by overfishing by a fleet that keepsgrowing in size and efficiency...”6. The SCRS, in its stock assessment meeting of 2008,found similar results: “In view of the assessment of stock status, this level ofactivecapacity, leading to estimates of 2007 catch level on the order of 60,000 t, is at least 3times the level needed to fish at a level consistent with the Convention objective.”(SCRS, 2008a). However, despite these figures, the 2008 ICCAT meeting could onlyagree to “freeze” the Bluefin Tuna fishing capacity at the 2007 level through 2008 withreductions in the ensuing years.8.2 Population monitoringICCAT requests statistical information from its contracting parties strictly for scientificpurposes. This information allows its scientific committee (SCRS) to perform theBluefin Tuna stock assessment when required by the Commission. This informationincludes detailed data on fleets, catches, temporal and spatial distribution of catches byfishing gear, and size frequencies of the catches. Although this requirement is bindingfor ICCAT contracting parties, scientists carrying out the stock assessment repeatedlycomplain of data limitations due to substantial under-reporting of catches and otherrelevant information. Moreover, in June 2008 during the session dedicated to theassessment of the stock, the chairman of the SCRS wrote a letter to the ICCATCommission explaining the difficulties of carrying out the stock assessment with thescarce data reported up to the start of the meeting for the East Atlantic andMediterranean stock; only 15% of the total TAC for that stock (SCRS, 2008a: Appendix6). The letter added that:“It is also disappointing that such a large group of scientists and international expertsmeets during two weeks at a considerable expense to their organizations and is unable tocomplete the work required because of a (chronic) lack of data being transmitted in time.This situation is even more incomprehensible given the high international concern aboutBluefin Tuna stock status” (SCRS, 2008a: Appendix 6).

8.3 Control measures8.3.1 InternationalThe only existing control of movement of Bluefin Tuna products across internationalborders is carried out by ICCAT through the new Bluefin tuna Catch DocumentationProgramme (Recommendation 07-107) which includes trade information and also catch,transfer, transhipment, and farming information. This recommendation was adopted inPress Released from the European Commission, March 2008:http://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/press_corner/press_releases/2008/com08_27_en.htm7http://www.iccat.int/en/RecsRegs.asp6

23

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

2007 and entered into force in June 2008. Its implementation is still flawed. It addressesthe tagging of the fish, but it is left optional to the contracting parties and “preferably atthe time of kill”. Since most of the harvested Bluefin Tuna is transferred live to tunafarms (usually located in a different country) for fattening and then, after slaughter, toreefer vessels, to be immediately processed and frozen, this measure, even if applied,would have very little effect on verification of Bluefin Tuna movement acrossinternational borders.8.3.2 DomesticDifferent control schemes are applied in ICCAT contracting parties with differentdegrees of success. Canada, for instance, has a comprehensive management, monitoring,control and surveillance program on its Atlantic Bluefin Tuna fishery on the westernstock, with high level of compliance. In this fishery tuna is caught through tended line orrod and reel and every fish is tagged on board. All tags are individually numbered andare entered into a computer tracking system, so at any given moment is possible to knowthe tags that have been issued, their numbers and owners. When the fish is landed it hasa tag affixed to it which allows tracking of the fish to the marketplace. Then, everysingle Bluefin Tuna landed in Canadian waters is verified by an independent docksidemonitor, who checks the number of fish, individual weight, tag number and other vitalstatistics. All this information is entered into a database that is accessible in real time tofisheries managers, scientists and enforcement officers. Verification is undertaken by anat-sea surveillance program, which patrols the waters 120 days per year, and from the airabout 300 missions per year. Strong penalties are also in place8The United States has atagging program that is similar to Canada’s.On the other hand, compliance of the rules in Mediterranean waters is considered poor.The EU, which holds nearly 60% of the TAC of the eastern stock of Bluefin Tuna,carried out an unprecedented verification scheme in 2008 through the newly establishedCommunity Fisheries Control Agency (CFCA), whose role is to organize operationalcoordination of fisheries control and inspection activities by the Member States. TheJoint Deployment Plan for the Bluefin Tuna fishery carried out by the CFCA revealedthat purse seiners and tug boats, that together are responsible for the bulk of the catches,were involved in a considerable level of infringements. Most infringements were relatedto catch documentation and the Vessel Monitoring System (VMS). The use of spotterplanes searching for Bluefin Tuna, forbidden by ICCAT, was found to be “quitewidespread” and infringements related to the Bluefin Tuna minimum landing size werealso discovered. Finally, the report of the CFCA states“It can be concluded that despite all meetings with the stakeholders convened by theCommission and Members States before the start of the season, it has not been a priorityof most operators in the fishery to comply with the ICCAT legal requirements. Asregards the recording and reporting of Bluefin Tuna catches and the use of tugs andspotter planes the ICCAT rules have not been generally respected.”9

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/tuna-thon-video-eng.htmSpecific Report regarding the implementation of the Joint Deployment Plan for bluefin tuna fishingactivities in 2008 in the Mediterranean Sea and Atlantic (preliminary version, November 2008) submittedby the CFCA to the Fisheries Commission of the European Parliament.9

8

24

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

Canada, in the Compliance Committee session of the ICCAT meeting in November2008, reported cases of alleged non-compliance in ICCAT fisheries. Of the 44 reportedcases of alleged non-compliance by ICCAT contracting parties, 40 were related to theBluefin Tuna fisheries in the Mediterranean10.In January 2009, NOAA (the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)reported to the congress on the “Implementation of Title IV of the Magnuson-StevensFishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act of 2006”11. In the reportNOAA identified 6 nations whose fishing vessels were engaged in illegal, unreported,and unregulated fishing in 2007 or 2008. Vessels from 4 of those nations werecommitting infringements in relation to the Bluefin Tuna fishery in the Mediterranean.These examples corroborate the poor control and compliance in relation to theMediterranean Bluefin Tuna fishery already mentioned by several independent reports.8.4. Captive breeding and artificial propagationMost tuna caught by the industrial purse seine fleets operating in the Mediterranean aretransferred live to farms for farming/fattening purposes (usually for a period of a fewmonths). This activity qualifies as capture-based aquaculture according to FAOstandards (Ottolenghiet al.,2004), but does not involve the breeding in captivity of theanimals. A similar species, Pacific Bluefin Tuna (Thunnusorientalis),is subject to truecaptive breeding in Japan, where a small production is entering the local market andknown askindai.The EU-funded project SELFDOTT is currently investigating thebreeding of Atlantic Bluefin tuna in captivity.8.5. Habitat conservationThere are no protected areas within the Mediterranean of relevance for the protection ofAtlantic Bluefin Tuna. The report of the independent review of ICCAT of September2008 (Hurryet al.,2008) recommended that ICCAT “consider an immediate closure ofall known Bluefin Tuna spawning grounds at least during known spawning period”.Furthermore, in October 2008, the World Conservation Congress (WCC), throughCGR4.MOT038 “Action for recovery of the East Atlantic and Mediterranean populationof Atlantic Bluefin Tuna” requested ICCAT “to set up protection zones for spawninggrounds in the Mediterranean including the waters within the Balearic Sea, CentralMediterranean, and Levant Sea, during the spawning season.” The ICCAT meeting ofNovember 2008 failed to implement the above requests and postponed for any decisionon this issue two more years, to the annual meeting of the ICCAT in 2010 (ICCATRecommendation 08-05).In October 2008, the Meeting of the Working Group on Marine Protected Areas, Speciesand Habitats (MASH) of the OSPAR Convention for the Protection of the MarineEnvironment of the North-East Atlantic formally identified Atlantic Bluefin Tuna as aspecies “requiring urgent action”. The species is listed in the OSPAR List of Threatenedand/or Declining Species and Habitats.

1011

ICCAT document Doc. COC-318/2008http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/msa2007/intlprovisions.html

25

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

In the Western Atlantic, ICCAT adopted a prohibition on the direct catch of BluefinTuna in the main spawning area of the Gulf of Mexico in 1982 (ICCAT Rec. 1982-01),which has been implemented by the United States and Mexico. In addition, fishermenreported a harvest of approximately 48 tons of bycatch in 2007 from the western stock inthe Gulf of Mexico due to bycatch in other fisheries.9. Information on similar speciesDifferent tuna species are widely traded at the international level, including AtlanticBluefin TunaThunnus thynnus,Pacific Bluefin Tuna,Thunnus orientalis,SouthernBluefin Tuna,Thunnus maccoyii,bigeye tuna,Thunnus obesus,yellowfin tuna,Thunnusalbacares,albacore,Thunnus alalunga,and skipjack,Katsuwonus pelamis.Trade inthese species involve different kinds of presentation:, typically dressed, gilled andgutted, or transformed into loins or belly meat. All of these might be fresh/chilled orfrozen. Morphologically, all 3 Bluefin Tuna species look very similar, particularlyAtlantic and Pacific Bluefin Tuna. As whole adult fish, bigeye, yellowfin, albacore andskipjack are easily identifiable from bluefins based on external attributes (body shapeand other morphometrics, characteristics of the fins, etc.), but, depending on the type ofpresentation (i.e. dressed, or deep frozen), this might not always be so easy. Oncetransformed into loins or belly meat, the 3 bluefin species, bigeye and yellowfin are verydifficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from each other visually.However, Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is usually marketed as such in order to obtain a higherprice so the identification difficulties associated with a CITES listing should not beoverstated.Furthermore, in cases of doubt, genetic techniques provide very precise tools to identifyAtlantic Bluefin Tuna from any other tuna species, including the other two Bluefin Tunaspecies, that are morphologically very similar. In addition, one of the advantages ofusing genetic markers is that the species identification can be undertaken with almostany kind of samples, including tissue from fresh or frozen whole individuals, fin clipsand even dried tissue and larvae. Several approaches have been used to identify speciesof processed tissue but in uncertain cases the final verification should be alwaysvalidated afterwards by DNA sequencing (Chowet al.,2003, Lin and Hwang, 2007,Infanteet al.,2006). Genetic identification of tuna species can be undertaken usingseveral genetic markers that have been used in species relationships studies (AlvaradoBremeret al.,1997, Block and Finnerty, 1994, Chow and Kishino, 1995, Chowet al.,2006, Wardet al.,2005). However, misidentification can result if the genetic marker isnot appropriate. For instance, species identification based on nuclear gene markerscannot distinguish between Atlantic and Pacific Bluefin Tuna (Chowet al.,2006).Another problem associated with nuclear markers is the low genetic distance among thespecies belonging to the Neothunnus tribe (T.albacares, T. atlanticus, T. tonggol)and,in consequence, these markers provide very low resolution to distinguish any of thesespecies. In contrast, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) based methodology results in a betterspecificity and resolution since this kind of markers can fully distinguish any species ofthe eight species of the genusThunnus (AlvaradoBremeret al.,1997, Wardet al.,2005). Recently, sequencing part of the highly polymorphic mtDNA control region hasbeen proven as an excellent methodology to assess the presence of Atlantic Bluefin Tunain processed tissue from the Japanese market (Viñaset al.,2009). However, it should bementioned that about 3-4% of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna mtDNA is undistinguishable fromalbacore (Alvarado Bremeret al.,2005). Nevertheless, sequencing a fragment of the

26

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

mtDNA genome (particularly combining the analysis of the control region and thecytochrome-oxidase – COX I; see Viñaset al.,2009) emerges as the best technologyavailable to identify tuna species.10. CONSULTATIONS

11. ADDITIONAL REMARKS

27

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

12. REFERENCES

Alvarado Bremer, J. R., Naseri, I. and Ely, B. (1997) Orthodox and unorthodoxphylogenetic relationships among tunas revealed by the nucleotide sequence analysis ofthe mitochondrial control region.Journal of Fish Biology, 50: 540-554Alvarado Bremer, J. R., Viñas, J., Mejuto, J., Ely, B. and Pla, C. (2005) Comparativephylogeography of Atlantic bluefin tuna and swordfish: the combined effects ofvicariance, secondary contact, introgression, and population expansion on the regionalphylogenies of two highly migratory pelagic fishes.Molecular Phylogenetics andEvolution, 36: 169-187Block, B.A., Teo, S.L.H., Wall, A., Boustany, A., Stokesbury, M.J.W., Farwell, C.J.,Weng, K.C., Dewar, H., Williams, T:D. (2005)Nature 434: 1121-1127Block, B. A. and Finnerty, J. R. (1994) Endothermy in Fishes - a Phylogenetic Analysisof Constraints, Predispositions, and Selection Pressures.Environmental Biology ofFishes, 40: 283-302Boustany, A.M., Reeb, C.A., Block, B.A. (2008) Mitochondrial DNA and electronictraching reveal population structure of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnusthynnus). MarineBiology.DOI 10.1007/s00227-008-1058-0http://tagagiant.org/media/Boustany%20et%20al_Marine%20Biol_genetics.pdfChow, S. and Kishino, H. (1995) Phylogenetic relationships between tuna species of thegenusThunnus(Scombridae: Teleostei): inconsistent implications from morphology,nuclear and mitochondrial genomes.Journal of Molecular Evolution, 41: 741-748Chow, S., Nakagawa, T., Suzuki, N., Takeyama, H. and Matsunaga, T. (2006)Phylogenetic relationships amongThunnusspecies inferred from rDNA ITS1 sequence.Journal of Fish Biology, 68: 24-35Chow, S., Nohara, K., Tanabe, T., Itoh, T., Tsuji, S., Nishikawa, Y., Uyeyanagi, S.(2003) Genetic and morphological identification of larval and small juvenile tunas(Pisces: Scombridae) caught by a mid-water trawl in the western Pacific.Bulletin ofFisheries Research Agency, 8: 1-14Fromentin, J.M. (2008) Le thon rouge, une espèce surexploitée. Ifremer, Parishttp://wwz.ifremer.fr/institut/content/download/35340/290161/file/08_10_20_DP%20thon%20rouge.pdfFromentin, J.M. (2006) Chapter 2.1.5 : Atlantic Bluefin. In: ICCAT Field Manualhttp://www.iccat.int/Documents/SCRS/Manual/CH2/2_1_5_BFT_ENG.pdfFromentin, J.M. and Powers, J. E. (2005) Atlantic bluefin tuna: population dynamics,ecology, fisheries and management.Fish and Fisheries 6(4): 281-306

28

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009

Gulland, J.A. (1965) Estimation of mortality rates. Annex to Report of Artic FisheriesWorking Group, International Council of the Exploration of the Sea. C. M. 1965(3): 9pp. (mimeo)Hattour, A. (2003) Analyse du sex ratio per classe de taille du thon rouge (Thunnusthynnus)capturé par les senneurs tunisiens.Collective Volume of Scientific Papers,ICCAT, 55: 232-237http://www.iccat.int/Documents/CVSP/CV055_2003/no_1/CV055010232.pdfHurry, G.D., Hayashi, M. and Maguire, J.J. (2008) Report of the independent review,Internation Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).http://www.iccat.int/com2008/ENG/PLE-106.pdfICCAT (2007) Basic Text.http://www.iccat.int/Documents/Commission/BasicTexts.pdfInfante, C., Crespo, A., Zuasti, E., Ponce, M., Perez, L., Funes, V., Catanase, G. (2006)PCR-based methodology for the authentication of the Atlantic mackerel Scomberscombrus in commercial canned products.Food Research International, 39: 1023-1028Jones, R. (1964) Estimating population size from commercial statistics when fishingmortality varies wiht age.Rapp. P.-V. Reun. CIEM, 155: 210-214Lin, W. F. and Hwang, D. F. (2007) Application of PCR-RFLP analysis on speciesidentification of canned tuna.Food Control, 18: 1050-1057MacKenzie, B.R., Mosegaard, H. and Rosenberg, A.A. (2009) Impending collapse ofbluefin tuna in the northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean.Conservation Letters (in press)DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2008.00039.xMurphy, G.I. (1965) A solution to the catch equation.J. Fish. Res. Board. Can. 22(1):191-202Ottolenghi, F., Silvestri, C., Giordano, P., Lovatelli, A., New, M.B. (2004) Capture-based aquaculture. The fattening of eels, groupers, tunas and yellowtails. Rome, FAORooker, J.R., Secor, D.H., De Metrio, G., Schloesser, R., Block, B.A., Neilson, J.D.(2008) Natal homing and connectivity in Atlantic blufin tuna populations.Science 322:742-744Rooker, J.R., Alvarado Bremer, J.R., Block, B.A., Dewar, H., De Metrio, G., Corriero,A., Kraus, R.T., Prince, E.D., Rodriguez-Marin, E., Secor, D.H. (2007) Life History andStock Structure of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnusthynnus). Reviews in Fisheries Science15: 265-310Safina, C. and Klinger, D.H. (2008). Collapse of Bluefin Tuna in the Western Atlantic.Conservation Biology 22: 243-246

29

Draft :Thunnus thynnusAppendix I listing proposal, July 2009