Udvalget for Fødevarer, Landbrug og Fiskeri 2008-09

FLF Alm.del Bilag 353

Offentligt

European CommissionDirectorate General for Health and Consumers

Study on fees or charges collected by the Member States tocover the costs occasioned by official controlsFramework Contract for evaluationand evaluation related services - Lot 3: Food Chain(awarded through tender no2004/S 243-208899)

Final ReportPART ONE: MAIN STUDY AND CONCLUSIONS

Submitted by:Food Chain Evaluation Consortium (FCEC)Civic Consulting - Van Dijk MC -Arcadia International - Agra CEASProject Leader: Agra CEAS Consulting

European CommissionDG SANCORue de la Loi 2001049 Brussels28.01.2009

Contact for this assignment:Dr Maria ChristodoulouAgra CEAS Consulting20-22 rue du Commerce1000 Brussels, Belgiumtel:+32 2 736 00 88direct: +32 2 738 05 15fax:+32 2 732 13 61[email protected]www.ceasc.com

Study on fees or charges collected by the Member States to coverthe costs occasioned by official controls

Final ReportPART ONE: MAIN STUDY AND CONCLUSIONS

Prepared by the Food Chain Evaluation Consortium (FCEC)Civic Consulting – Van Dijk MCArcadia International – Agra CEASProject Leader: Agra CEAS Consulting

Food Chain Evaluation ConsortiumC/o Civic ConsultingPotsdamer Strasse 150D-10783 Berlin-GermanyTelephone: +49-30-2196-2297Fax: +49-30-2196-2298E-mail:[email protected]

Expert Team

Agra CEAS Consulting:Dr Maria ChristodoulouConrad CaspariDr Dylan BradleyDr Edward OliverDr Mauro GioeAnna Holl

fcecFood Chain Evaluation ConsortiumCivic Consulting – Van Dijk MCArcadia International – Agra CEAS

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

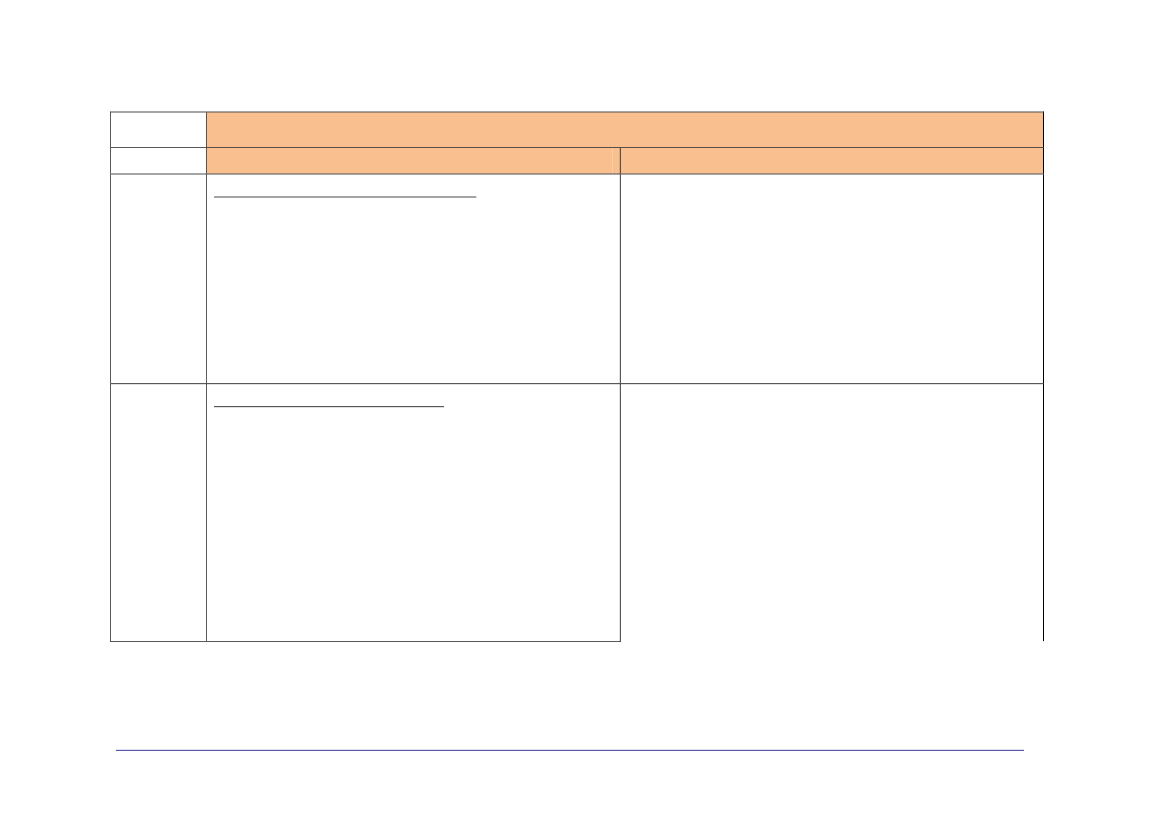

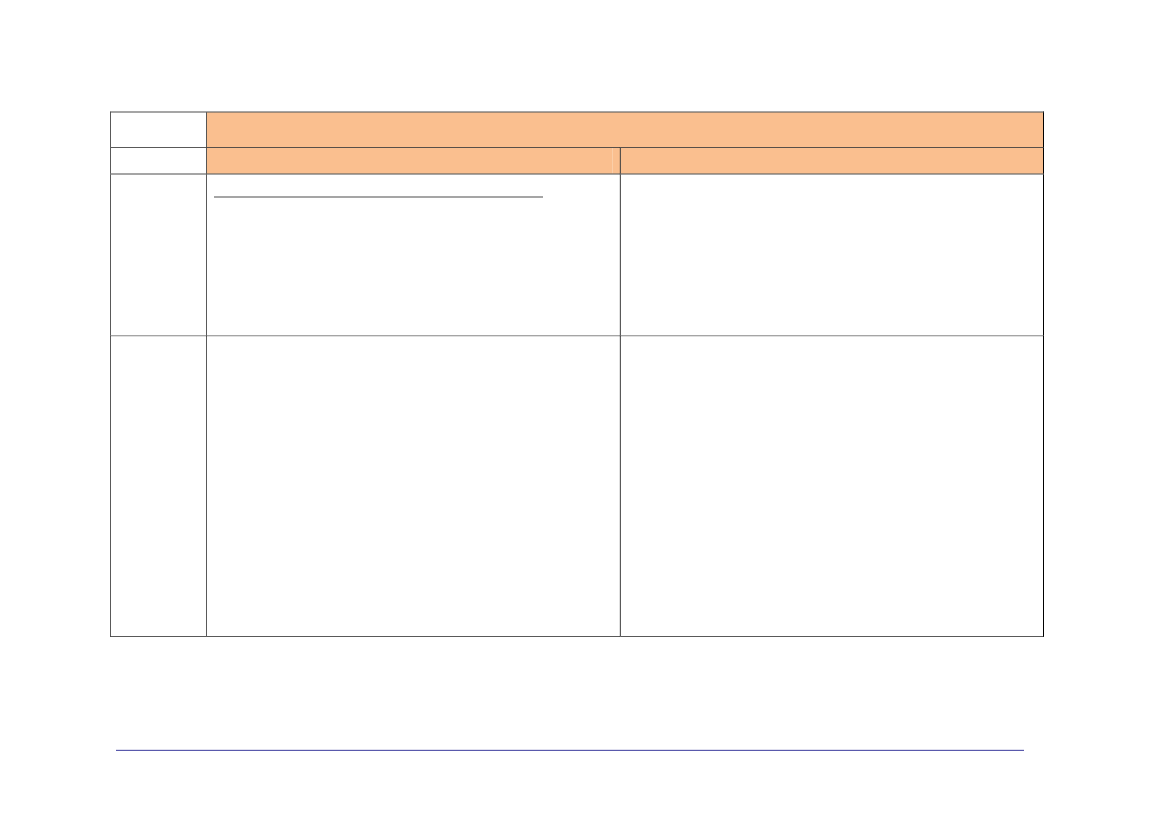

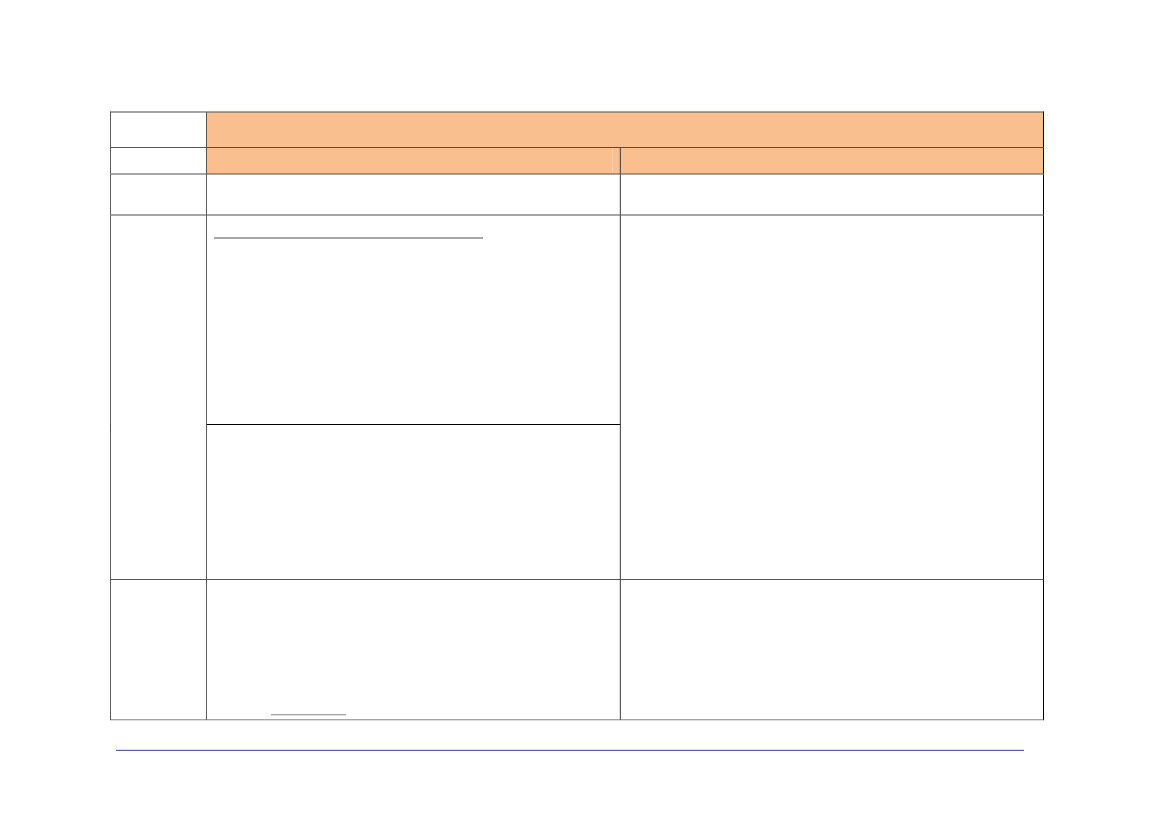

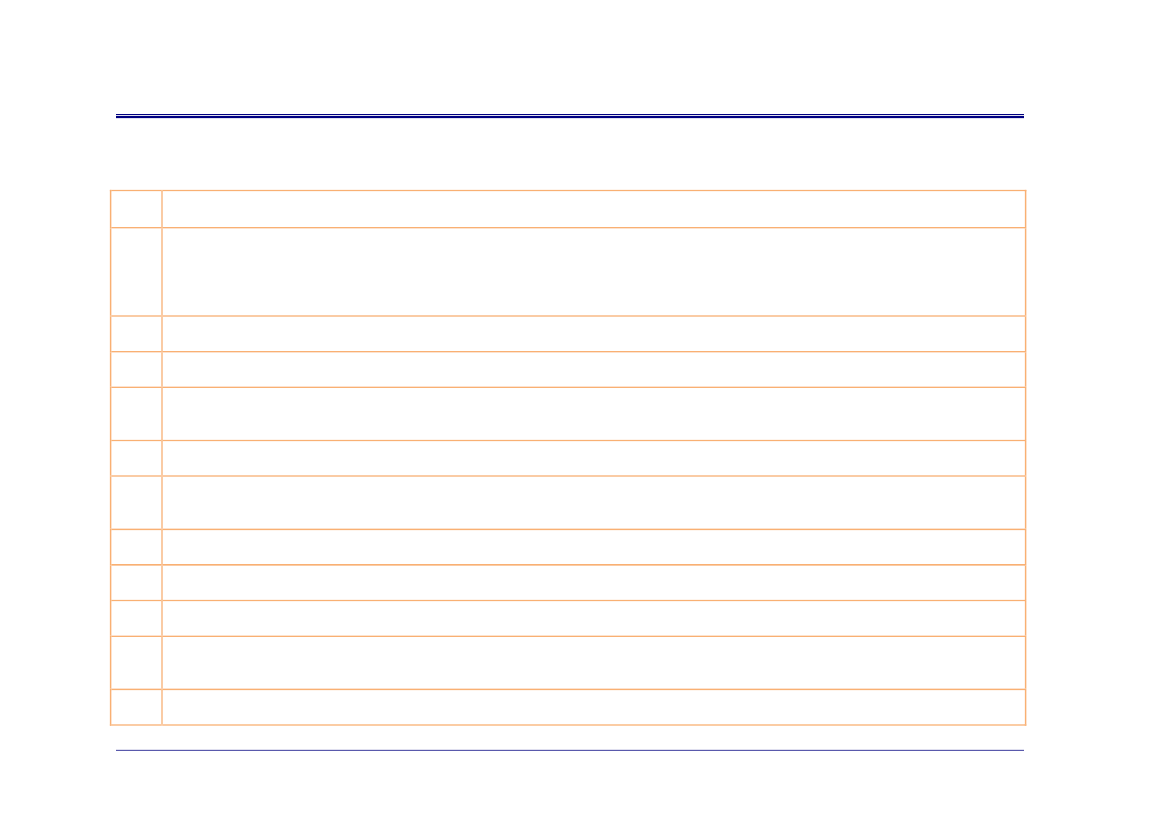

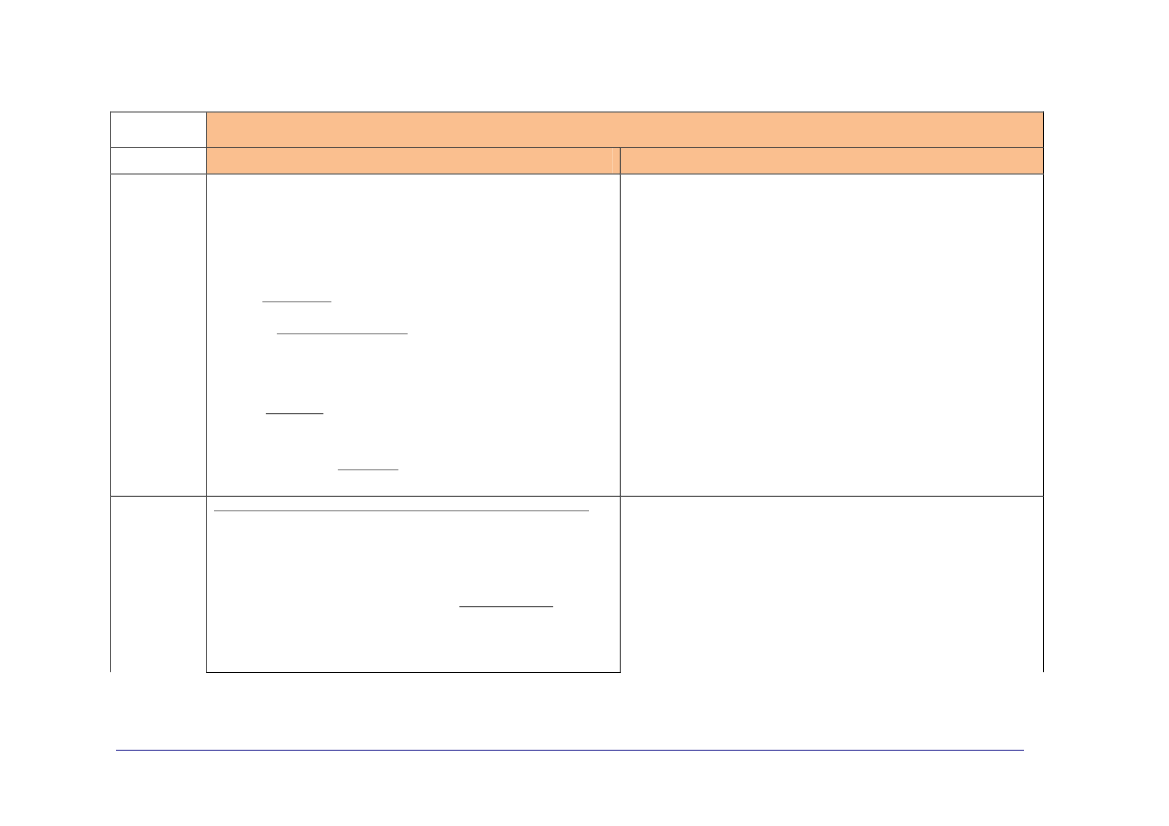

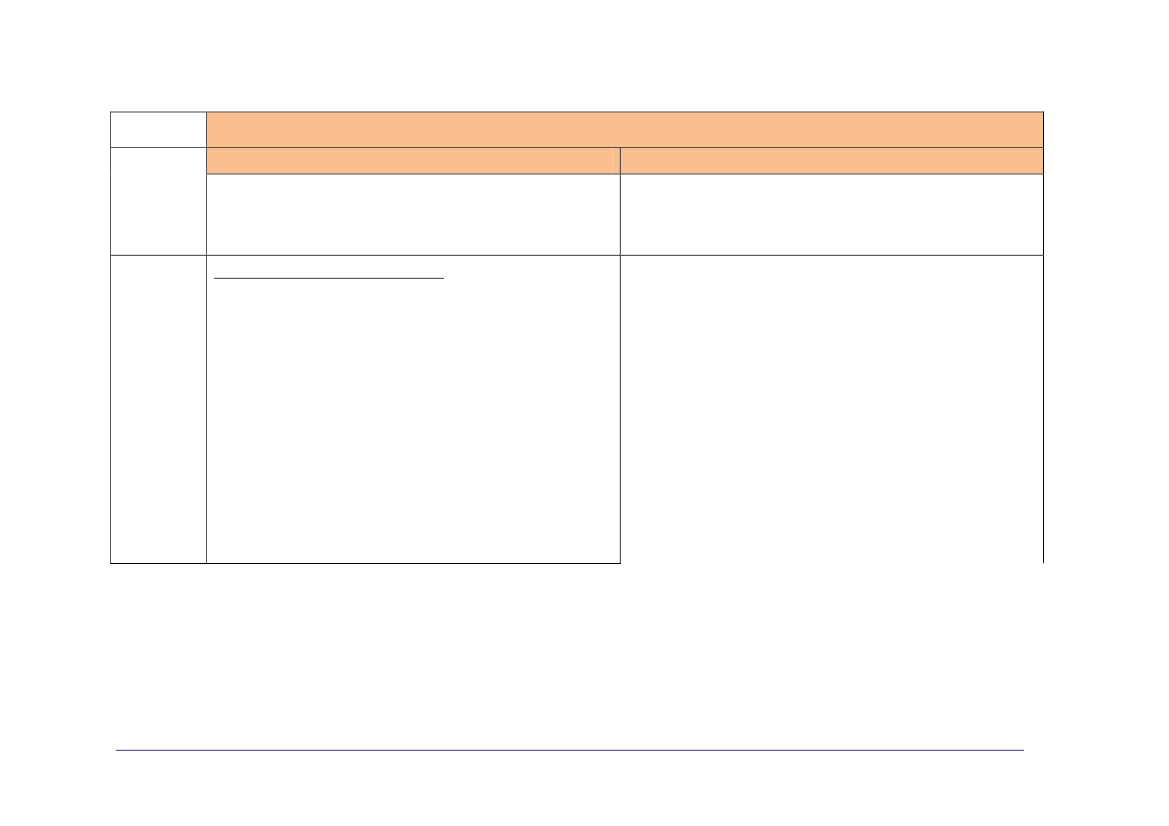

ContentsPART ONE: MAIN STUDY AND CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................1EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................11. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY .......................................................................................................................11.1. BACKGROUND.......................................................................................................................................................11.2. OBJECTIVES...........................................................................................................................................................21.3. SCOPE....................................................................................................................................................................21.4. METHODOLOGY.....................................................................................................................................................21.4.1. Overall methodological approach and objectives......................................................................................... 21.4.2. Desk research ................................................................................................................................................ 31.4.3. Survey of competent authorities (CAs) .......................................................................................................... 41.4.4. Case studies................................................................................................................................................... 51.4.5. Interviews with key partners and stakeholders.............................................................................................. 61.4.5.1. At EU level ...............................................................................................................................................................61.4.5.2. At MS level (case studies) ........................................................................................................................................7

2. DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT OF THE CURRENT SYSTEM OF FEES..............................................92.1. INTERVENTION LOGIC............................................................................................................................................92.1.1. Principles and objectives of EU policy.......................................................................................................... 92.1.2. The requirements for official controls ......................................................................................................... 102.1.3. The financing of official controls ................................................................................................................ 112.2. SYSTEM DESCRIPTION..........................................................................................................................................112.2.1. Competent Authorities................................................................................................................................. 122.2.2. Activities for which fees are collected ......................................................................................................... 142.2.3. Fee rates used.............................................................................................................................................. 162.2.4. Determination of the fee .............................................................................................................................. 182.2.5. Fee collection method and use of fee revenue ............................................................................................. 182.3. EVALUATION OF THE CURRENT SITUATION..........................................................................................................202.3.1. Enforcement of Article 27 of Regulation 882/2004 ..................................................................................... 21

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

iii

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

2.3.2. Contribution to the functioning of the internal market................................................................................ 222.3.2.1. Distortions between MS..........................................................................................................................................222.3.2.2. Distortions within MS (between regions) ...............................................................................................................252.3.2.3. Distortions between sectors ....................................................................................................................................262.3.2.4. Distortions according to scale .................................................................................................................................282.3.2.5. Distortions at the level of imports ...........................................................................................................................29

2.3.3. Contribution to maintaining the efficiency and effectiveness of OCs.......................................................... 302.3.3.1. Adequacy of the financial resources .......................................................................................................................302.3.3.2. Cost-efficiency issues .............................................................................................................................................32

3. OPTIONS FOR THE FUTURE .............................................................................................................................383.1. THE DEVELOPMENT AND ASSESSMENT OF THE VARIOUS OPTIONS.......................................................................383.1.1. Range of options and scenarios................................................................................................................... 383.1.2. Key components........................................................................................................................................... 423.1.3. Assessment criteria...................................................................................................................................... 443.2. TOWARDS MORE HARMONISATION......................................................................................................................453.2.1. Full harmonisation ...................................................................................................................................... 453.2.1. Intermediate scenarios ................................................................................................................................ 473.3. TOWARDS MORE SUBSIDIARITY...........................................................................................................................493.3.1. Full subsidiarity .......................................................................................................................................... 493.3.2. Intermediate scenarios ................................................................................................................................ 513.4. EXTENSION TO OTHER SECTORS...........................................................................................................................533.5. STATUS-QUO(MIXED SYSTEM) ............................................................................................................................573.5.1. Do nothing option........................................................................................................................................ 573.5.1. Status quo with improvements ..................................................................................................................... 584. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................................68ANNEX 1 ......................................................................................................................................................................741.1 LIST OF RELEVANT BACKGROUND LEGISLATION ................................................................................751.2 LIST OF REVIEWED FVO REPORTS AND MS NOTIFICATION LETTERS TO DG SANCO ..............78

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

iv

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

ANNEX 2 ......................................................................................................................................................................812.1: SURVEY OF EU-27 CAS: RESULTS ................................................................................................................822.2: SURVEY OF EU-27 CAS: QUESTIONNAIRE...............................................................................................103ANNEX 3 ....................................................................................................................................................................119COMPETENT AUTHORITIES RESPONSIBLE FOR THE VARIOUS OFFICIAL CONTROLS (OCS)COVERED BY THE SCOPE OF THIS STUDY ....................................................................................................119

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

v

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

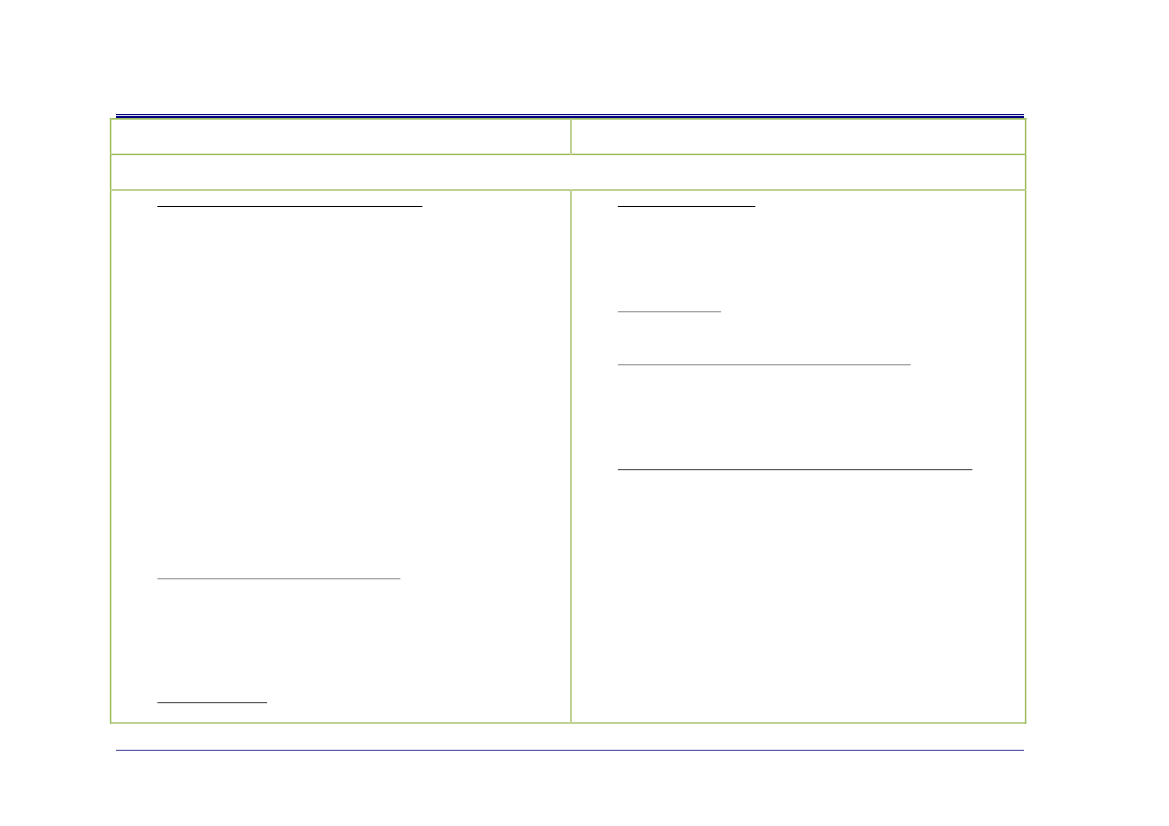

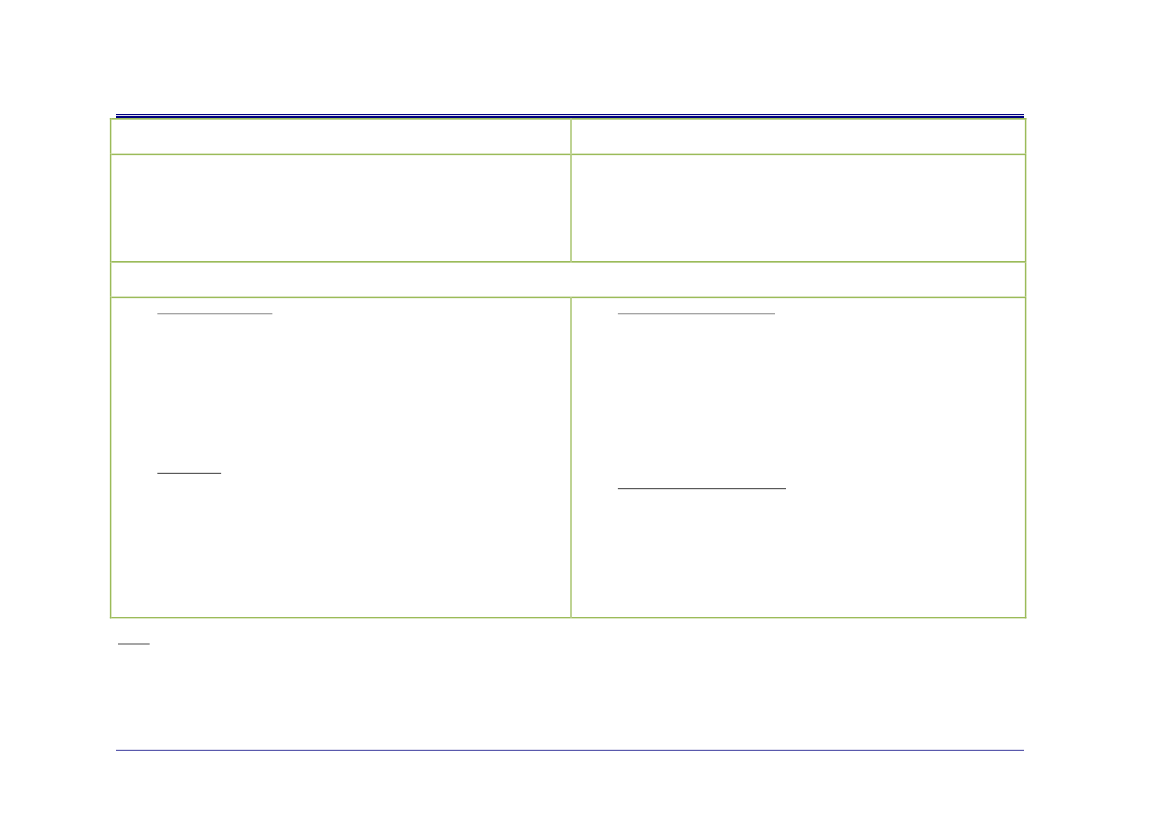

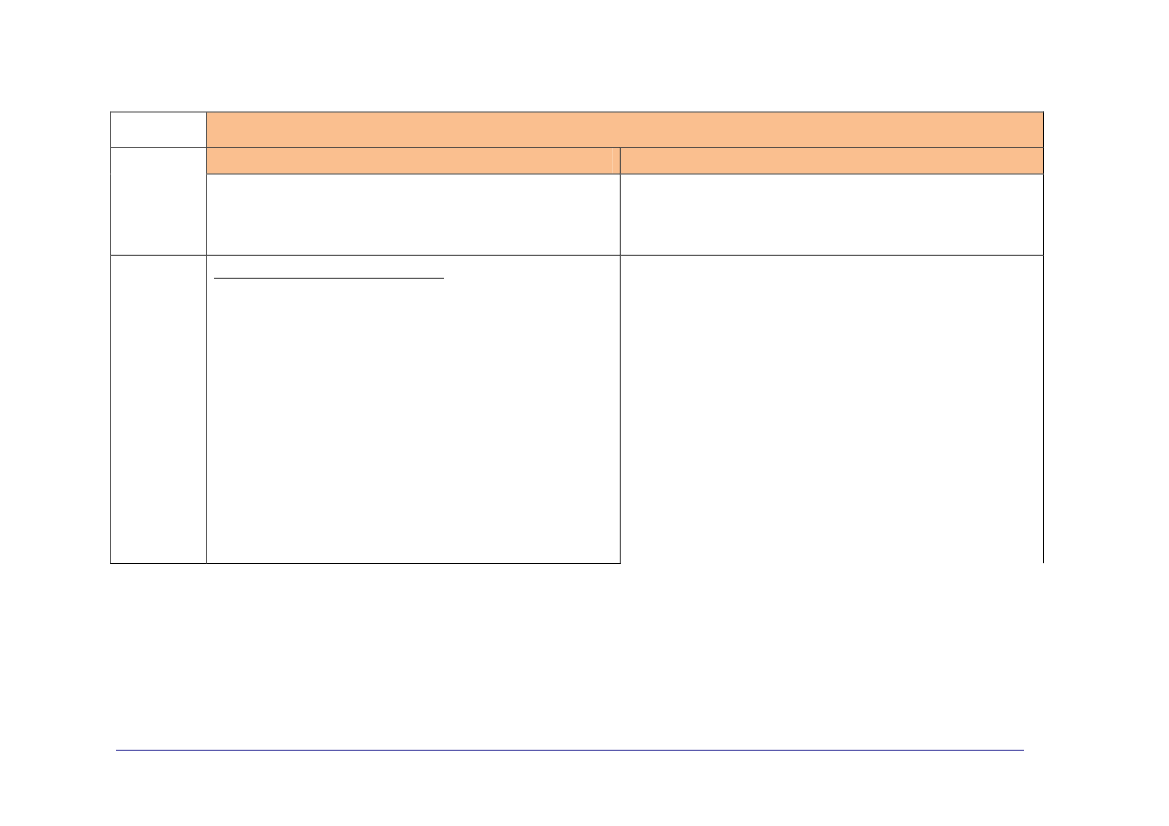

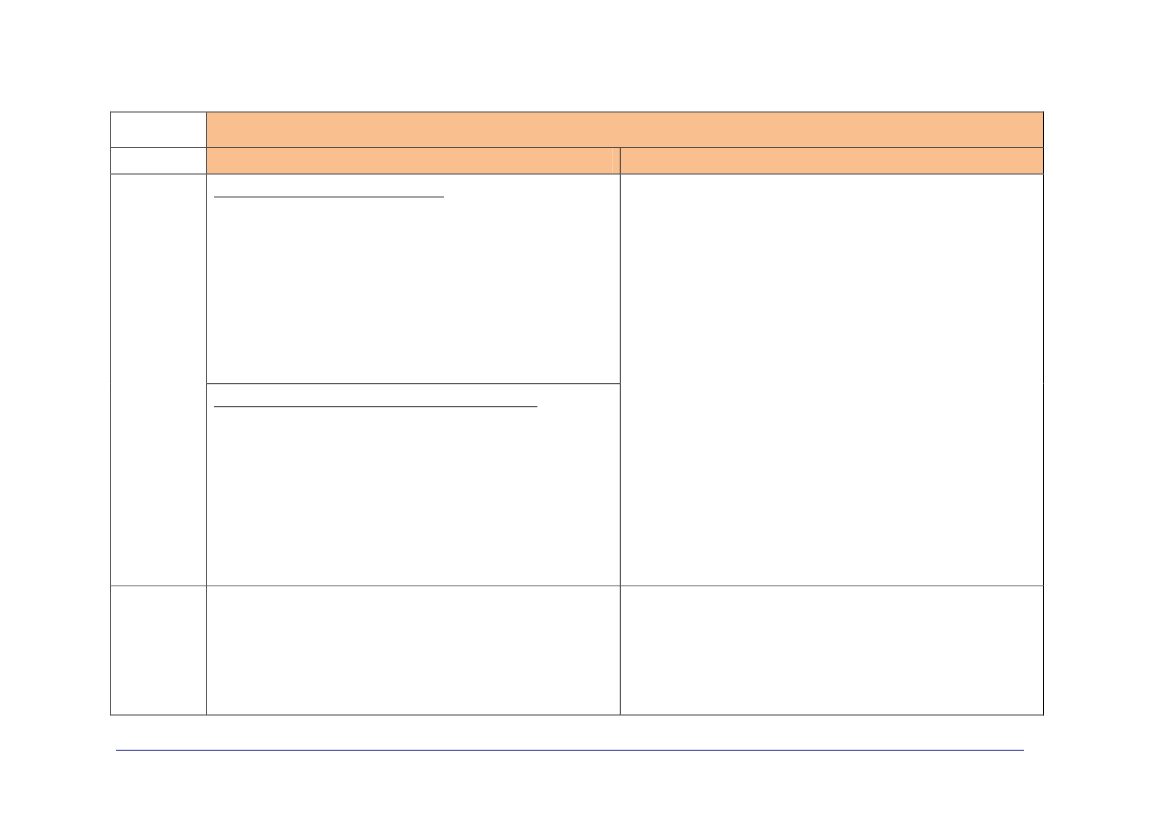

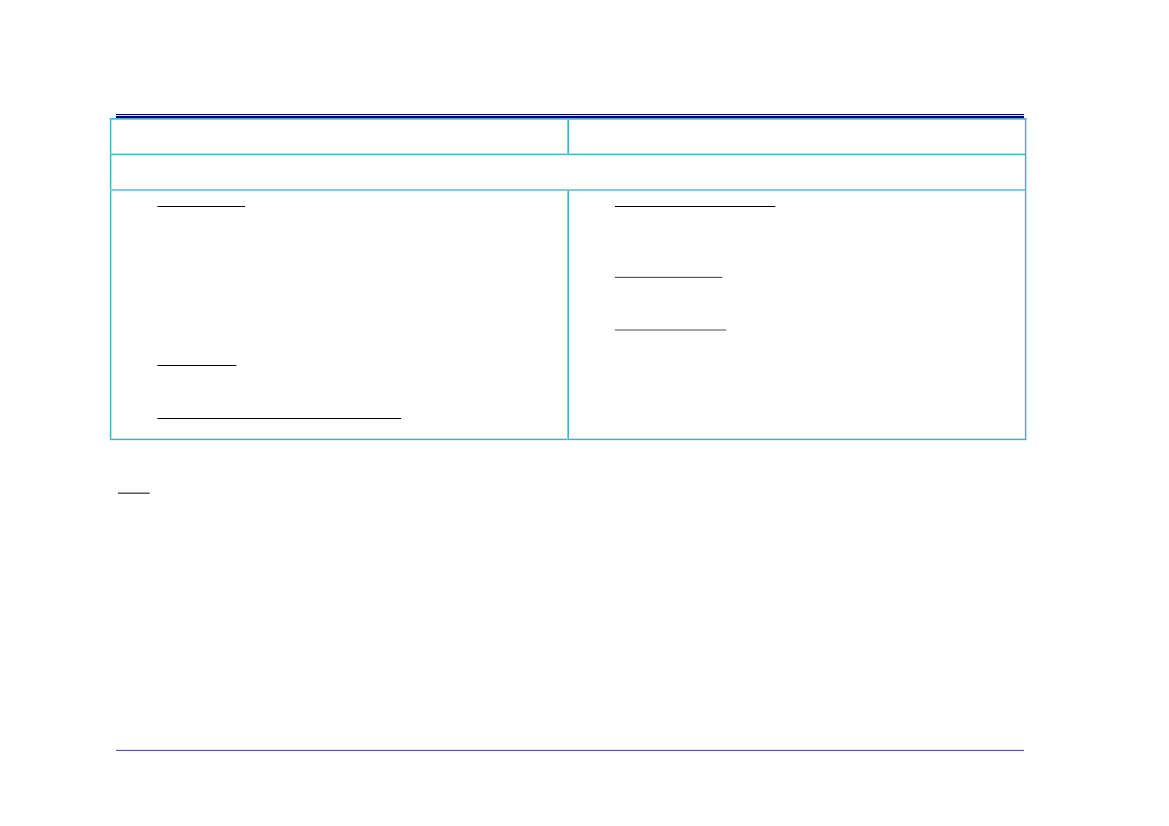

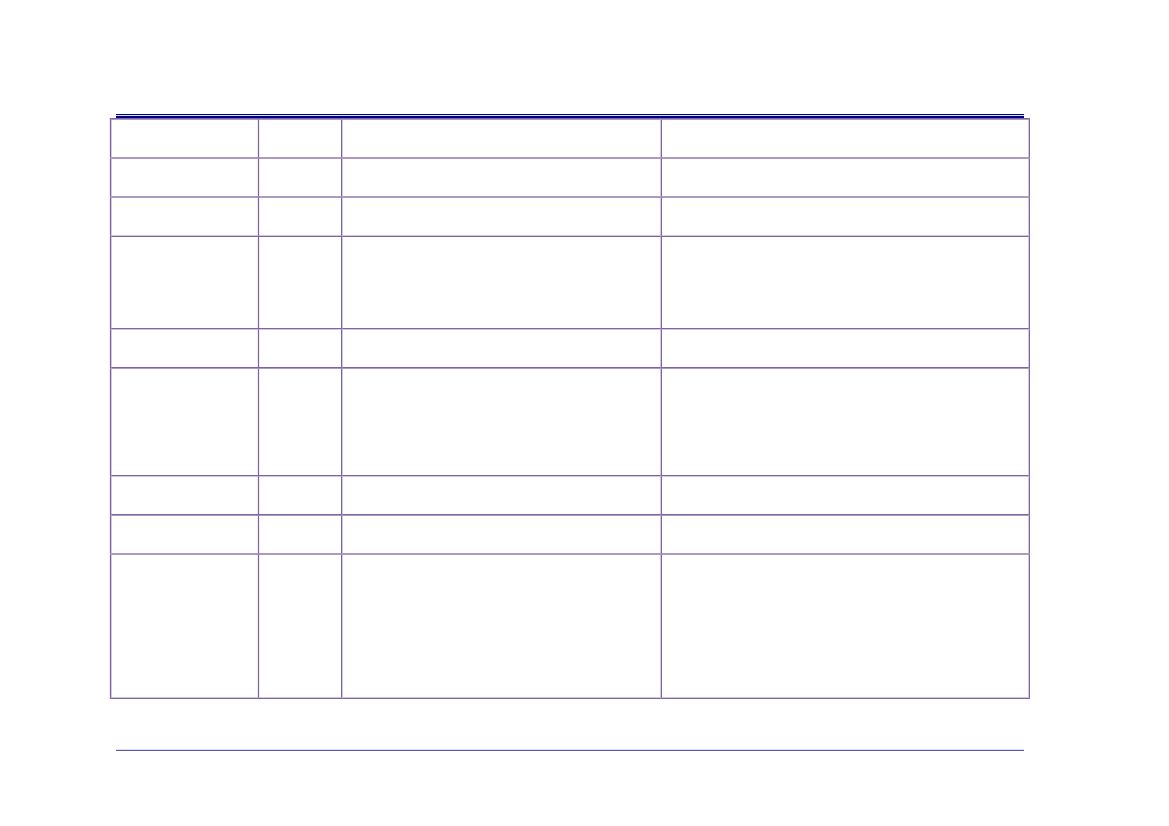

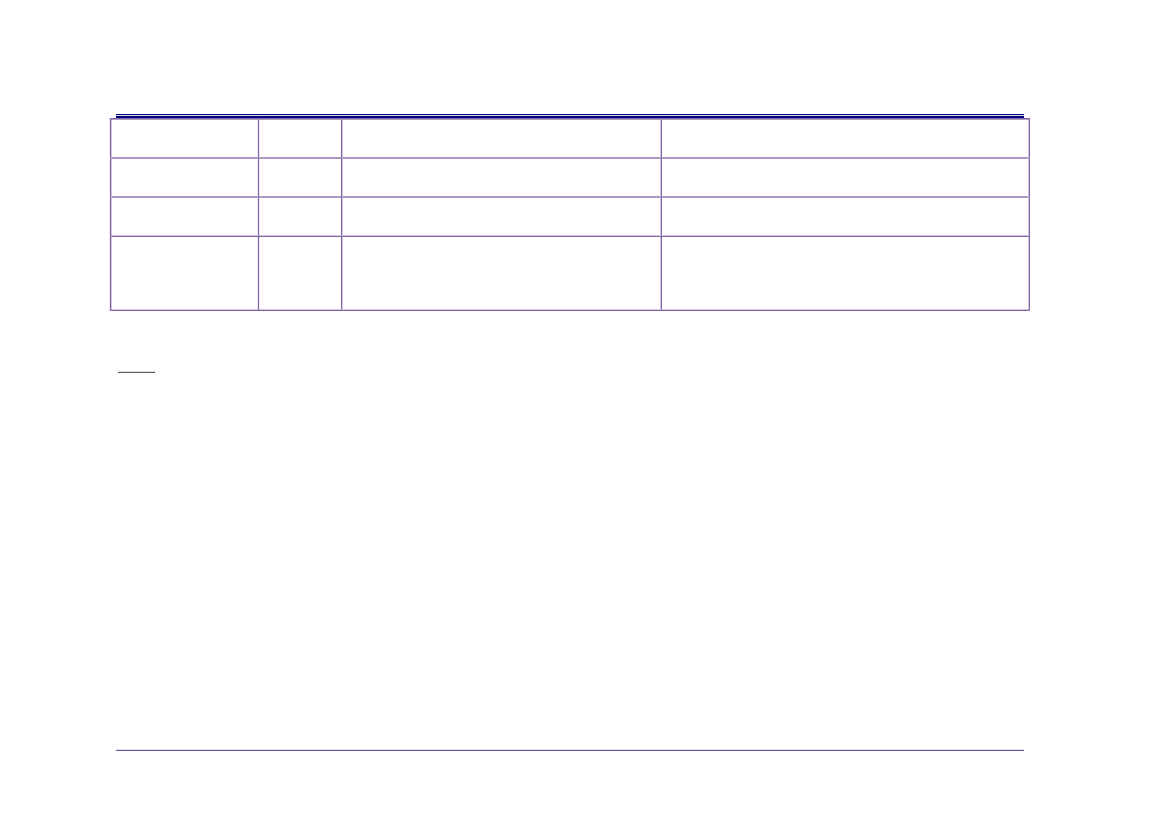

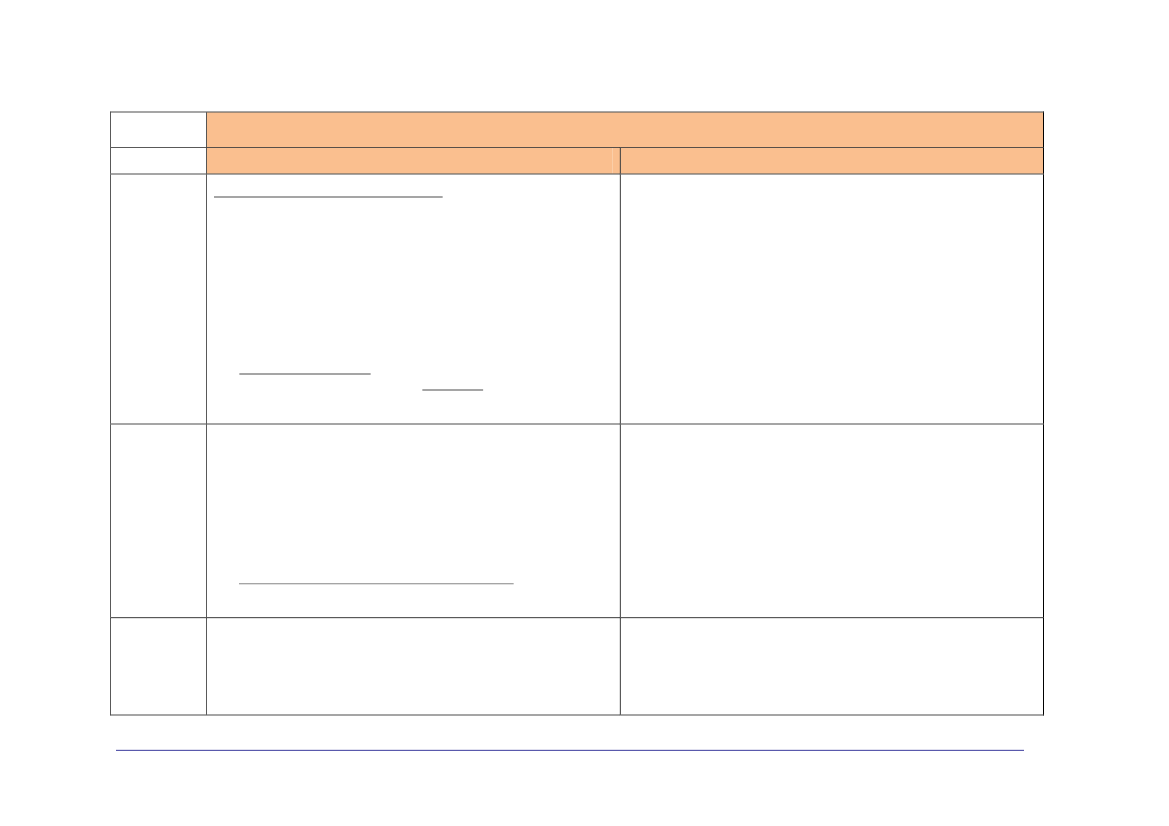

List of TablesTable 1-1Table 2-1Table 3-1Table 3-2Table 3-3Table 3-4European professional organisations interviewed ....................................................................... 7Share of the costs of official controls covered by fee revenue .................................................. 19Range of options, scenarios and components............................................................................ 39Moving towards more harmonisation: overall assessment........................................................ 48Moving towards more subsidiarity: overall assessment ............................................................ 52Extension to other sectors: overall assessment.......................................................................... 56

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

vi

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

AcronymsAVEC: Association of Poultry Processors and Poultry Trade in the EU countriesBIP/s: Border Inspection Post/sCA/s: Competent Authority/iesCCA/s: Central Competent Authority/iesCIBC / IMV / IBC: International Butchers’ ConfederationCLITRAVI: Liaison Centre for the EU Meat Processing IndustryDG: Directorate GeneralDG SANCO: DG Health and ConsumersEASVO - European Association of State Veterinary Officers (member of FVE)ECB: European Central BankEDA: European Dairy AssociationEU: European UnionEUCOLAIT: European Association of Dairy TradeEUROPECHE: Association of the National Organisations of Fishery Enterprises in the EUFBO/s: Feed/Food Business Operator/sFCEC: Food Chain Evaluation ConsortiumFCI: Food Chain InformationFEFAC: European Feed Manufacturers’ FederationFVE: The Federation of Veterinarians of EuropeGHP: Good Hygiene PracticesHACCP: Hazard Analysis Critical Control PointsMNCP: Multiannual National Control PlanMS: Member State/sNMS: New Member State/sOCs: Official ControlsPOAO: Products of Animal Origin

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

vii

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

SCFCAH: Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal HealthSG: Steering Group (for this study)ToR: Terms of ReferenceUECVB: European Livestock and Meat Trading Union

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

viii

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

PART ONE: MAIN STUDY AND CONCLUSIONSExecutive SummaryRegulation 882/20041(hereafter referred to as ‘The Regulation’) sets out requirements for theauthorities in EU Member States that have responsibility for monitoring and verifying compliancewith, and enforcement of, feed and food law, animal health and animal welfare rules, i.e. the'Competent Authorities' (CAs) responsible for organising and undertaking 'official controls' (OCs).According to Article 65 of the Regulation, three years after its entry into force, the Commission shouldreview the experience gained from its application, in particular in terms of scope and the fee-settingmechanism, and whether/how the current fees regime can be improved. The data collected and resultsof this study, which focused on the implementation of the financing provisions of the Regulation(Articles 26-29), will feed into a Commission Report to the European Parliament and Council for apossible modification of the current legislation.The objectives of the study are two-fold:a) to establish a detailed picture and evaluate the present situation as regards the application of thecurrent fees regime, in particular the way in which the system operates in practice; and,b) to assess the advantages and disadvantages of a range of policy options (regarding the scope ofcurrent rules and the fee-setting mechanism).As such, the final aim is to provide input to the Commission’s development of proposals to improvethe fees system in future.The assessment of the current system and future policy options take into account the wider objectivesand principles of EU policy in this sector. As such, the study considers the overall objective of theRegulation to ensure a harmonised approach with regard to official controls, the objectives of EU foodand feed law2to ensure a high level of protection of human life and health and achieve the freemovement in the Community of compliant feed and food, and the objectives of the Lisbon Strategy topromote better regulation and support industry competitiveness. Furthermore, the principles ofproportionality, subsidiarity (Article 5 of the Treaty) and FBO responsibility (in accordance withcurrent food and feed law) frame the approach of this study.The study was carried out in the period April-November 2008 through a survey of EU27 CAs, in depthanalysis (case studies) in six MS representing a variety of fee regimes (Germany, the UK, Italy,Poland, France and Slovakia), interviews with key experts and stakeholders at EU level3, andextensive literature and data review (including relevant FVO reports and national legislation).The study has found that significant progress has been made in the application of the Regulation byMS, and in particular the financing provisions of Articles 26-29, since their entry into force on 1January 2007. However, the enforcement of these provisions has been slow and gradual, withsignificant delays in most MS. In some cases, full implementation is still pending subject to theapproval of draft national legislation enacting Article 27, despite the fact that the deadline for its

Regulation (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on official controlsperformed to ensure the verification of compliance with feed and food law, animal health and animal welfare rules.Regulation (EC) 178/2002 (General Food law) and the Hygiene Package (Regulations (EC) 852/2004, 853/2004 and854/2004).Including consultations with the following EU professional organisations: AVEC, CIBC/IMV/IBC, CLITRAVI, EDA,FEFAC, FVE, and the UECBV.32

1

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

E.1

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

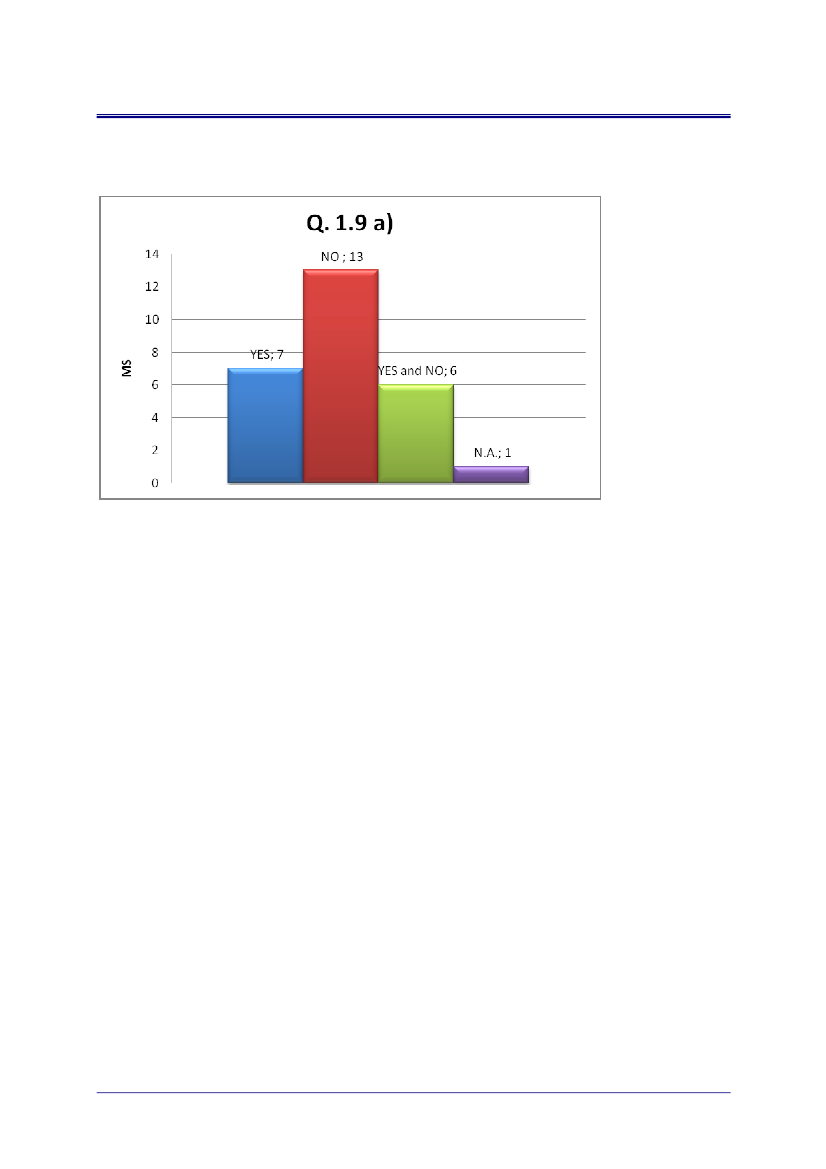

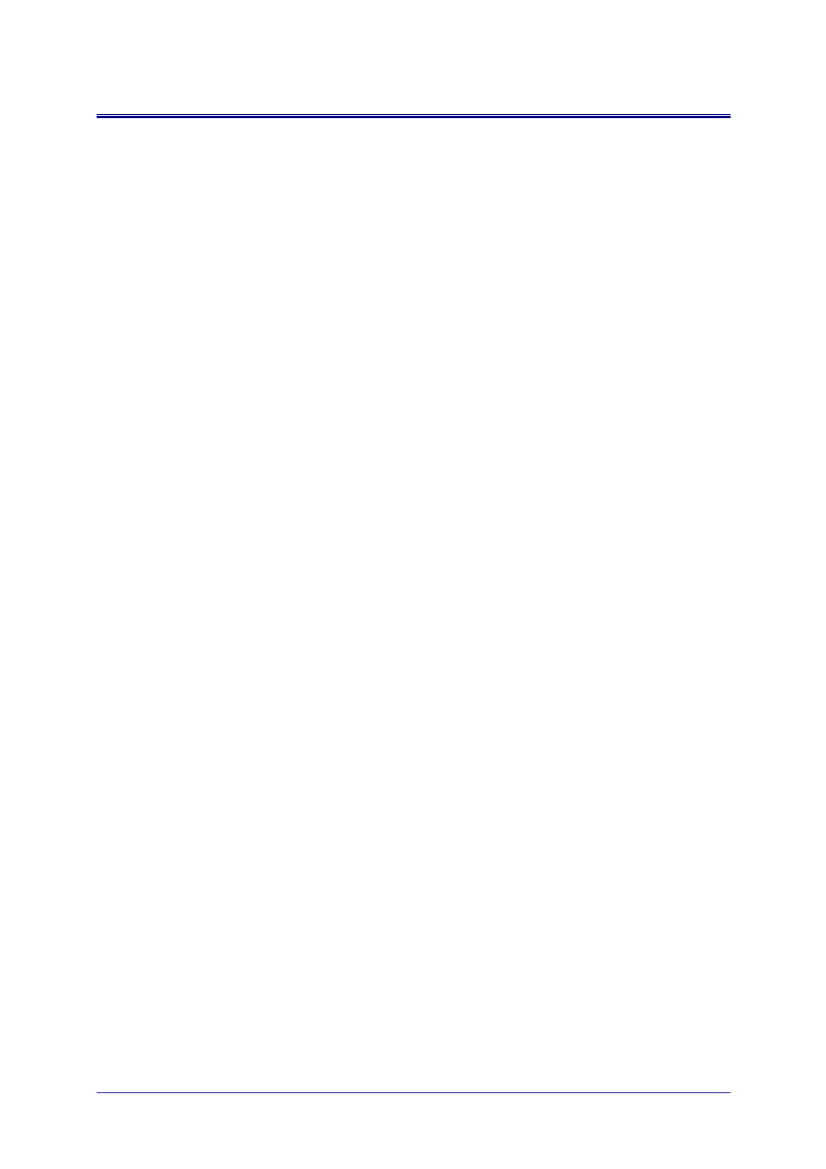

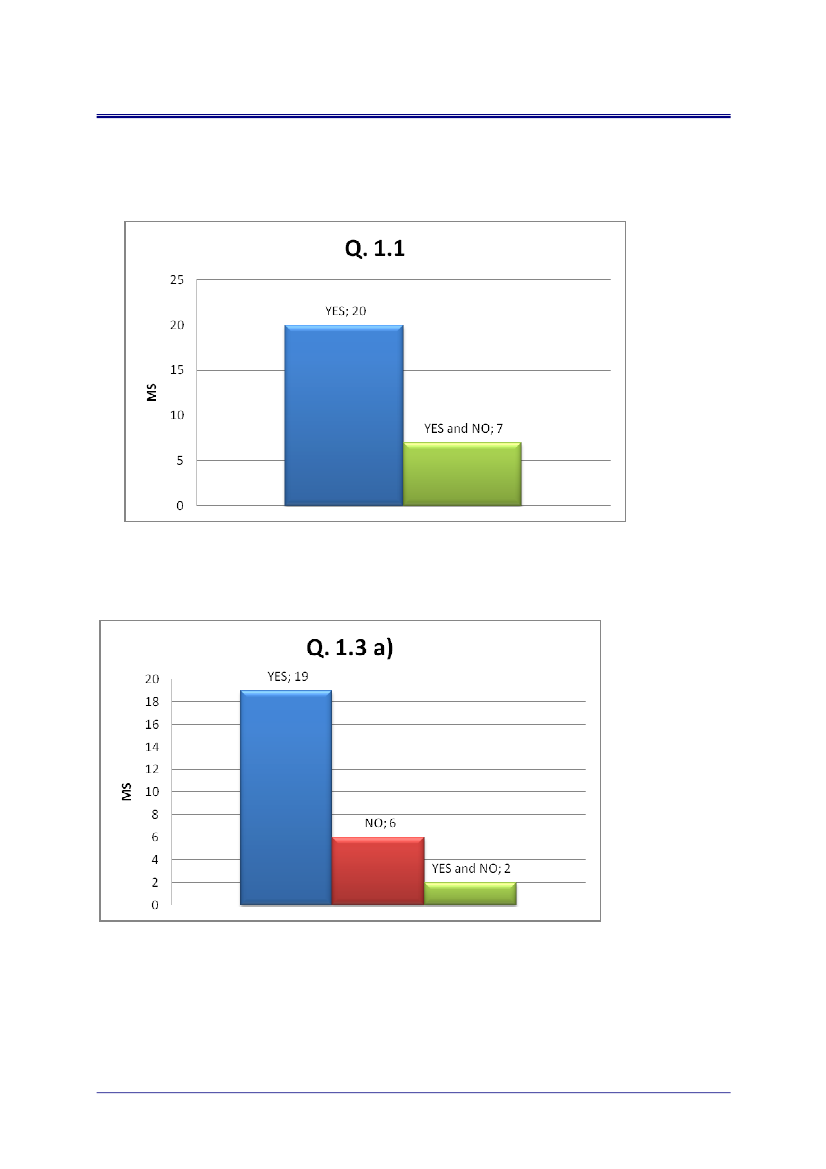

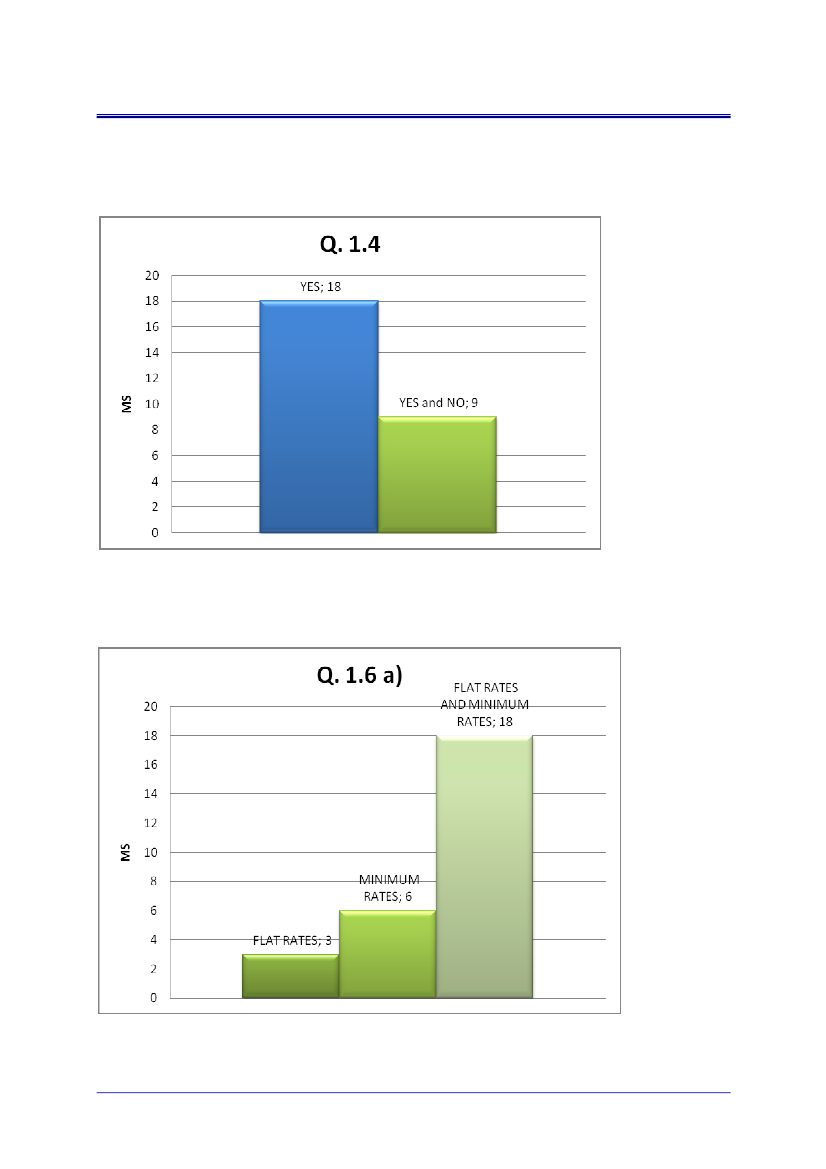

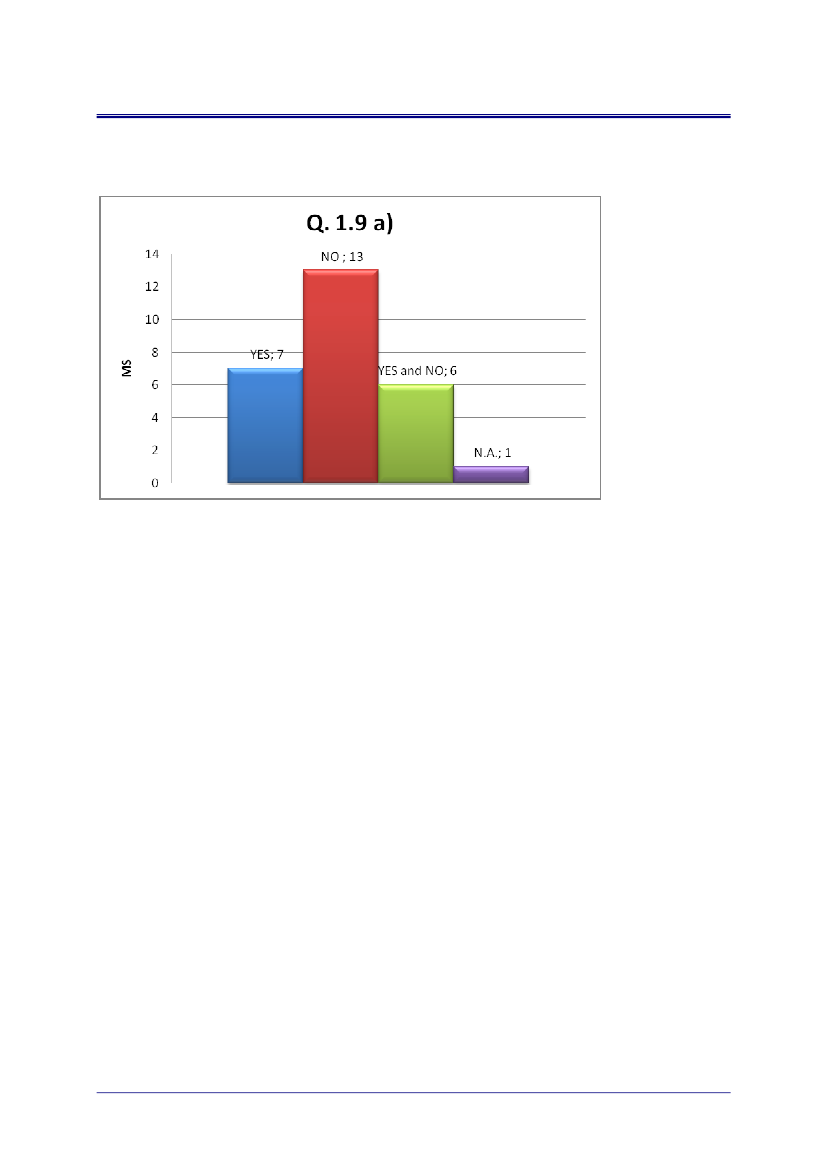

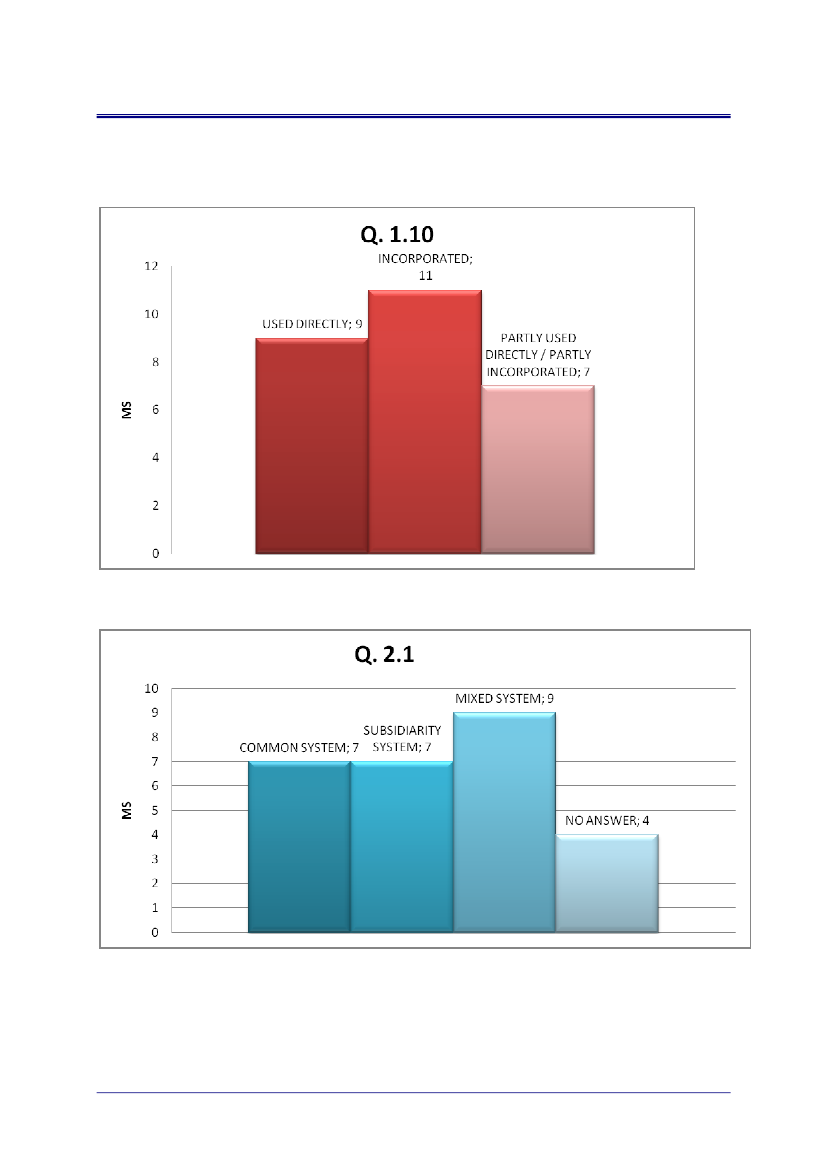

definitive entry into force was 1 January 2008. In these cases the fee system in place is largely basedon that laid down in previous, repealed legislation (Directive 85/73).Despite progress a number of important shortcomings have been identified in the current state ofimplementation of Articles 26-29, as follows:Competent Authorities (CAs):There are significant differences in the organisation, structure andstaffing (number and profiles of staff) between MS, which have financial implications for the cost ofofficial controls (OCs). Contrary to the Commission’s expectations, more than one CA is involved inmost cases, which may create lack of transparency and of central/overall responsibility. In MS withdecentralised management, the central CA is not always in control and efficient/effective coordinationis not always ensured. The study findings confirm issues which are already highlighted in relevantFVO reports. In several MS initiatives are under way to rationalize veterinary services, such as the useof appropriately trained contractual staff for the OCs rather than civil servants.Activities for which fees are collected:A distinction is made throughout the study between OCactivities for which fee collection is ‘compulsory’ (Article 27.2, activities of Annexes IV and V), andthose for which fee collection is optional or ‘non-compulsory’ (Article 27.1). The study has found that,in the case of‘compulsory’fees: 9 MS collect such fees only partly; fees for milk production and forresidue controls were found to be ‘controversial’ and often not collected at all; on the other hand, insome MS fees are collected for the same OCs more than once along the production chain (e.g. atslaughter and cutting plant even within the same establishment, contrary to Article 27.7). In the case of‘non-compulsory’ fees: 19 MS collect fees for activities beyond those of Article 27.2, while 6 do notcollect any such fees; fees are collected in some MS for OCs on products of non-animal origin.Fee rates used:Regulation 882/2004 leaves it up to MS to define fee system: either minimum fees asdefined in Annex IV (domestic controls) and V (import controls) or fee rates calculated on the basis ofthe actual costs of OCs (‘flat rates’). In practice, a multitude of fee rates apply for the variousactivities: 18 MS use a mix of the two systems (flat rates and minimum rates); the current situation isquite complex, not transparent and confusing for FBOs; the CAs appear to have interpreted relevantprovisions of Article 27 rather ‘openly’. Furthermore, 12 MS apply fees below minimum rates,however it is not clear or sufficiently justified whether the conditions of Article 27.6 (controls ofreduced frequency and criteria of para 5) are respected in these cases.Fee calculation:Article 27.4 stipulates that where flat rates are used, fee levels need to be set withinthe limits of the minimum fees set out in Annexes IV and V, and a maximum set by the actual controlscosts; the fee calculation in this case must respect the criteria of Annex VI. In practice: the calculationmethod used is not always available, or has not always been communicated to the Commission(contrary to requirements of Article 27.12); even when the method is available, it is not alwaystransparent what type of costs are included under the various cost categories and what reference timeperiod is used; in most cases it is not clear whether the actual costs included in the calculation respectthe criteria of Annex VI (staff salaries; staff costs including overheads; lab analysis and sampling).Fee collection & use of revenue:The rationale of the system is to ensure adequate financial resourcesto provide the necessary staff and other resources (Article 26). In practice: in the majority of MS thecollected revenue is incorporated into the General State Budget, either entirely (11 MS) on in part (7MS); only 9 MS claim to be ‘ring fencing’ revenues specifically for the CAs performing the controls;14 MS indicated they do not cover the OC costs through the fees, while a further 6 MS claim this isoccurring in some cases (regions, activities). This partial cost coverage may be due to inappropriatefee setting (insufficient fee levels) as well as inappropriate fee collection / use of revenue. The positionappears to be better in the case of imports controls, partly because Article 27.8 stipulates that such feesshould be paid to the CA in charge.Enforcement of Article 27:Although the Regulation should be directly enforceable, Article 27allows some discretion to MS on the actual fee system to use and the activities for which OCs should

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

E.2

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

be charged beyond those of Article 27.2. The study has found that, in practice, there is significantvariation between MS in the enforcement of Articles 26-29. Underlying this, there is a strongperception - in some cases documented by FVO reports - of significant variation in the organisationand effectiveness of OCs, and that – as documented by the study findings - CAs have rather liberallyinterpreted provisions of Articles 26-29 (this is particularly a problem in some MS with decentralisedmanagement and lack of sufficient central control by the CCA).The study has therefore concluded that, as it currently stands, the system of fees for OCs does not fullyfulfil its key objective: to provide sufficient resources for the effective and efficient operation of theOCs. Furthermore, the actual implementation of the system raises issues with regard to its contributionto the functioning of the internal market and the cost-efficiency of the system of OCs.Contribution to the functioning of the internal market:MS broadly agree with the rationale ofArticles 26-29. However, could the heterogeneity in their application in practice cause distortions incompetition? The study has investigated various potential distortions that may arise in this context. Ithas found that in practice:•Distortions at EU level:There is a general concern amongst stakeholders in the various MS thatimplementation of rules by national authorities put them at disadvantage vis-a-vis other MS.However, it is difficult to substantiate these claims due to lack of clarity and uniformity in MSapproaches which makes the comparison of actual fees difficult. Although evidence of unjustifiedvariations in fee levels were found between MS, there is no evidence of significant distortion incompetitiveness between MS caused by differing fee levels. Other key factors affectingcompetitiveness appear to be more significant.•Regional distortionsare a concern particularly in some MS with decentralised management e.g.amongst the case study countries (Germany, also Italy and Spain);•Discrimination against themeat sector,which is seen as unfairly bearing the cost of the OCs, fromwhich other sectors along the chain also benefit;•Discrimination againstsmaller or disadvantaged FBOs,which compound the difficulties theyface in the general economic climate; this is particularly evident for those MS that have not adoptedspecial provisions for these businesses in line with Article 27.5.Cost efficiency issueshave been raised with regard to:•Staff costs:Stakeholders argue that Regulation 882/2004 could go further than the generalrequirement to have “a sufficient number of suitably qualified and experienced staff”. In practice,there are wide variations in the number and profile of staff involved in controls, and this hasrepercussions on salary costs;•Administrative costs:There is lack of transparency on what type of costs are taken into account,the formulation of Annex VI is considered too broad (in particular criterion 2: ‘associated costs’),resulting in wide variation between MS and unjustifiably high costs in some cases;•Proportionate and risk based controls:important cost savings could be made in the costs of OCsif the guiding principles of OCs (risk basis, FBO responsibility and ‘self-control’ systems) weresufficiently taken into account by MS in implementing the provisions of Articles 26-29.To address the various shortcomings in the current application of the Regulation4, the study hasexamined the following key options: moving from the current system towards more harmonisation;

It is noted that addressing some of the current shortcomings identified by this study requires action that extendsbeyond the financing provisions of Regulation 882/2004, to the wider legislation in the area of food and feed

4

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

E.3

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

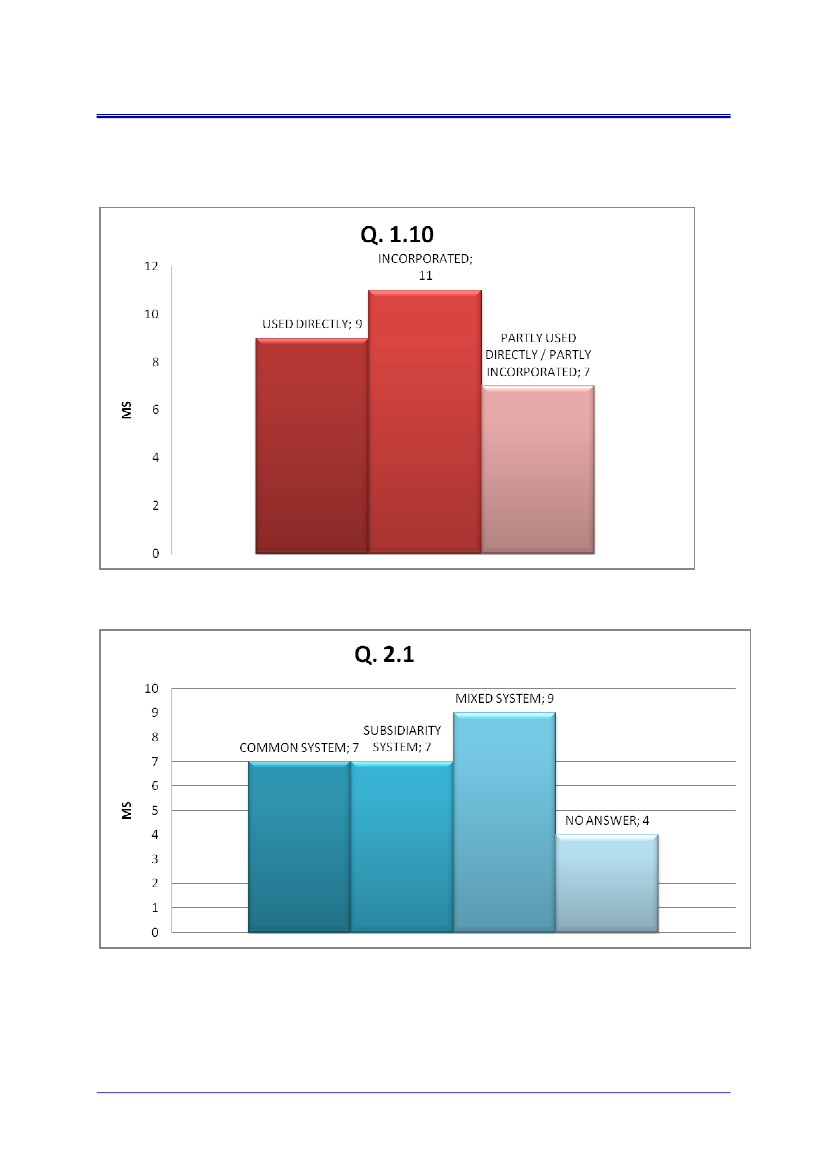

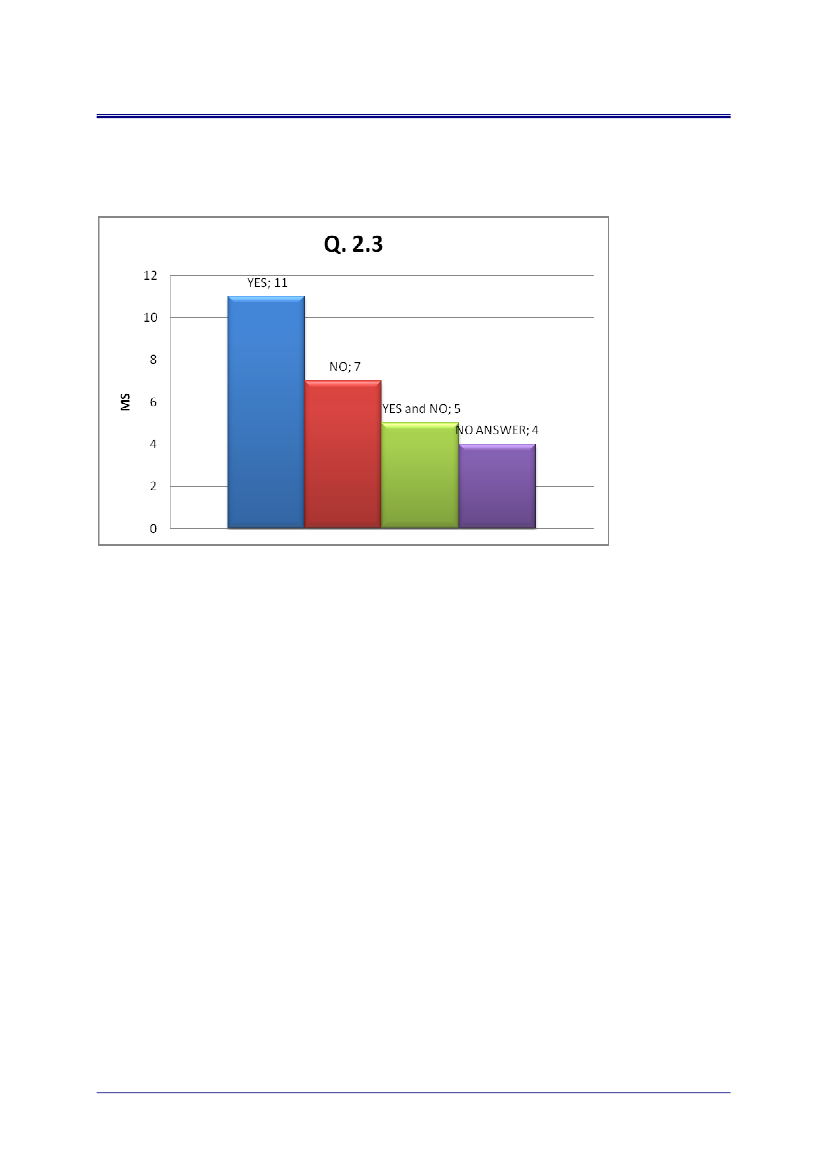

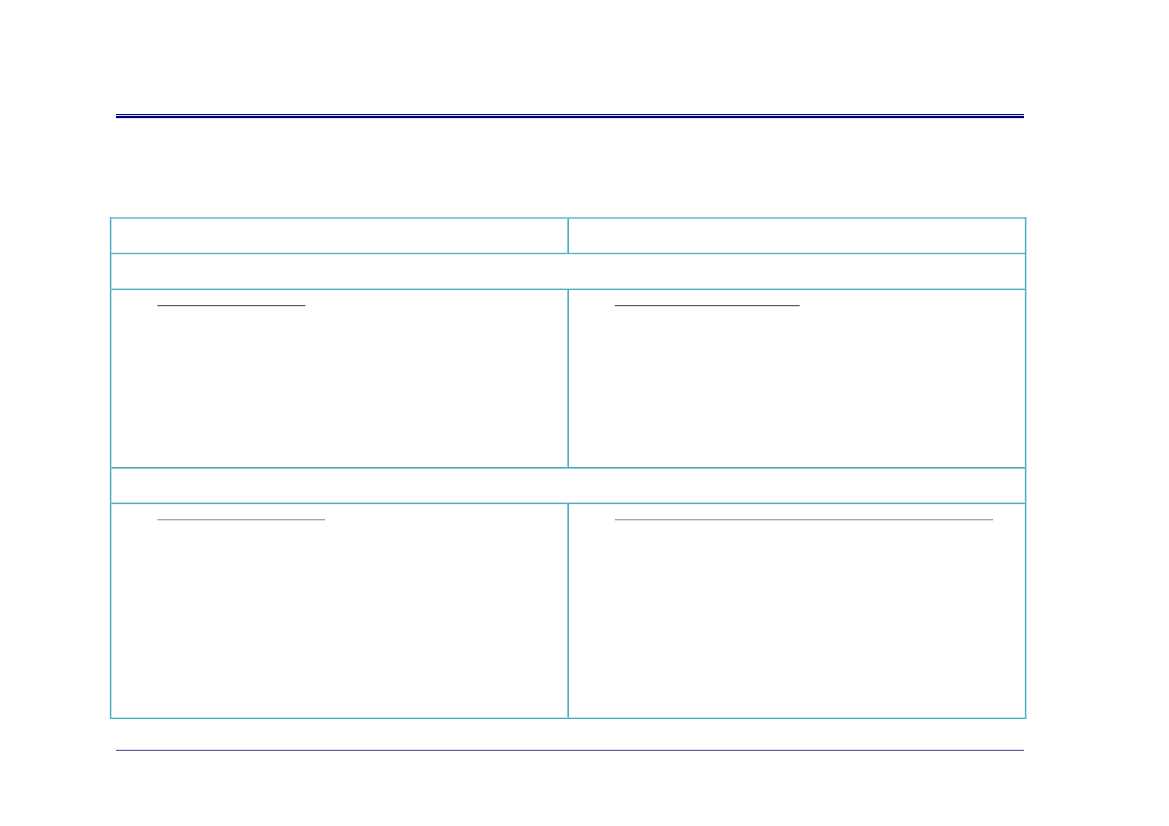

moving towards more subsidiarity; and, the continuation of thestatus quo.A complementary option,which transcends the above three alternative options, is the extension of the financing obligation tosectors beyond those currently covered by the Regulation.The key components of the financing system (basis of fee charging; level of fee rates; fee calculationmethod; fee reductions and penalties; and, list of activities covered by fees), as identified on the basisof the intervention logic of the current legislation (Articles 26-29), were combined to develop a rangeof scenarios within the above options (Table3-1).The basis of fee charging is compulsory for all MSunder the harmonisation option, optional under the subsidiarity option, and a mixed approach underthe continuation of current rules.The scenarios were assessed in terms of advantages and disadvantages, feasibility (whether and underwhich conditions they would work in practice), and the acceptance that they might have from thevarious groups of stakeholders. Key criteria for the assessment were the main goals and principles ofthe Regulation, as well as the wider objectives of Community food and feed law and the Lisbonstrategy, in particular: improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the official controls;simplification of the current system; and providing the right incentives for FBOs to encouragecompliance and discourage non-compliance. As these criteria may not necessarily point in the samedirection, the initial assessment of the scenarios provided here aims to provide a balance between thevarious objectives and needs of stakeholders.The assessment has shown that neither harmonisation nor subsidiarity would work in their mostextreme expression. Although both scenarios would simplify the current system at the level of centralmanagement (particularly if full subsidiarity is pursued), they ultimately carry the risk that they maynot lead to sufficient cost-recovery in some MS, and that the level of cost-recovery may varysignificantly between MS. This could undermine the overall effectiveness of the official controlsystem at EU level, and/or act as a disincentive to improving its efficiency.An intermediate solution would clearly provide the most pragmatic way forward. Intermediatescenarios provide different degrees of balance between the flexibility that the majority of MS require,as an incentiveinter aliato rationalise the system, with the simplification needed at the level ofcentral management (Commission, MS CCAs). The study has found that the rationale for a flexibleapproach, which underlies the current Regulation, continues to apply today. The majority of MS CAsand stakeholders have indicated that a system that allows MS flexibility to set the fee rates, within acommonly agreed set of rules, continues to be the most favoured option. This approach is consideredthe most appropriate for the system to be able to adapt to national conditions.On balance, amongst the various scenarios that can be envisaged at an intermediate level, thoseleading to more subsidiarity appear to be more attractive than those that lead to more harmonisation.This is because the degree of flexibility given to MS increases, while the degree of complexity of thelegislation diminishes.Moving towards more subsidiarity, if the primary aim of the legislation is to ensure that MS have thefunds necessary to cover the costs of official controls whatever the means, scenario 4 (maintain onlythe general obligation for MS to provide adequate funding, in the line of a modified Article 26) couldpresent an attractive alternative to pursue for the purposes of simplification.

safety. The discussion of solutions to such shortcomings was therefore limited to its relevance to the costs andthe financing of the official controls.

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

E.4

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

The disadvantage of this scenario would be that it could result in wider variations between MS thanthose created by the current system. To reduce these variations, conditions could be attached in theform of common principles at EU level for a more harmonised calculation of the fees and/or feereductions/penalties across the EU (scenario 3).Although the continuation of thestatus quowould be an alternative intermediate solution, the analysisof current shortcomings under section 2.2 has shown that todo nothingis clearly not an acceptable ora pragmatic option. However, if the current mixed approach of the Regulation (which represents thepolitical reality of the evolution of the system since Directive 85/73) was to be maintained, certainimprovements could be introduced as follows: at a general level improve the understanding of theRegulation; provide a rationale for setting minimum fee levels and review Annexes IV and V in thelight of this rationale; reinforce transparency and accountability criteria; refine and define certainprovisions more precisely at technical level; update Articles 26-29 with the progress made since theadoption of the General Food Law and the Hygiene Package.Whatever the scenario to be pursued at an intermediate level, the study has identified the need for thedefinition of common principles that can apply for a more harmonised calculation of the fees and/orfee reductions/penalties across the EU. These could be general principles only or they could be moredetailed criteria defined at a technical level. General principles would include: transparency in thecalculation method of fee setting and for calculating fee reductions/penalties, on the basis of actualcosts; and, the obligation for MS to communicate these to the Commission and the public. Detailedtechnical criteria would include for instance the calculation method to be followed for fee setting andfor fee reductions/penalties, cost-recovery targets that should be sought, precise cost categories thatshould be taken into account, and even maxima/ceilings for each cost element.The level at which common principles should be set needs to be further explored, as it is crucial incontrolling MS flexibility and mitigating the potential disadvantages of subsidiarity. The greater thedegree to which EU legislation moves from defining common principles and general guidelines (as iscurrently the case with Articles 27-29) to more technical criteria, the more difficult it will be for MSto deviate from a common denominator. On the other hand, this increases the complexity of theprovisions and the extent of follow up needed at central level (Commission, MS CCAs).In terms of the calculation of fee reductions and penalties, in particular, the principles could build onthe advantages and benefits of self-control systems, as introduced at EU level by the HygienePackage. Both MS and stakeholders are in principle in favour of providing incentives to FBOs toassume greater responsibility. The study has examined the possibility to follow an integratedapproach more consistently linking compliance and non-compliance, and therefore fee reductions andpenalties, to the uptake of self-control systems by industry (through abonus-malussystem). Suchsystems have already been developed in few MS (e.g. Belgium), highlighting the advantages of anintegrated approach. The study has concluded that, although the development of such systems needsto be encouraged at EU level, their actual design can at present only be pursued at MS level.Furthermore, the cross-cutting theme of the extension in scope of the Regulation was favourablyassessed, in relation in particular to the inclusion of all stages along the food chain. The case of theextension of the system to stages upstream and downstream of the slaughtering and meat cuttingoperations along the meat production chain was a case in point. The study has concluded that anextension in this form would spread the costs of controls currently pursued only at a particular pointin the chain but for the benefit of stages upstream/downstream more equitably along the food chain.Again, this approach is currently being adopted/explored in several MS.This forward looking element of the project aimed to provide an initial assessment of certain keyscenarios. The purpose was not to provide a full feasibility analysis (whether at political or technical

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

E.5

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

level). Nonetheless, specific recommendations were made to develop these scenarios, or indeed otherpotential combinations of their components, including through future impact assessments.

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

E.6

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

1. Introduction to the study1.1. BackgroundRegulation 882/20045(hereafter referred to as ‘The Regulation’) sets out requirements for theauthorities in EU Member States that have responsibility for monitoring and verifyingcompliance with, and enforcement of, feed and food law, and animal health and animalwelfare rules, i.e. the 'competent authorities' (CAs) responsible for organising and undertaking'official controls' (OCs).According to Article 65 of the Regulation, three years after its entry into force, theCommission should review the experience gained from its application, in particular in termsof scope and the fee-setting mechanism, and whether/how the current regime can beimproved. This study, which was launched in April 2008, aims to respond to this requirement.The data collected and results of the study will feed into a Commission Report to theEuropean Parliament and Council (which will also be discussed at the SCFCAH) for apossible modification of the current legislation.Part One of this Final Report outlines the methodology and overall results, includingconclusions and recommendations, of the work carried out by the study team (FCEC - FoodChain Evaluation Consortium, led by Agra CEAS Consulting for this evaluation).Part Two (provided in a separate volume) describes in detail the system and conclusions ofthe work in the six case study countries.The Final Report (Parts One and Two) forms the basis of the Final meeting with the SteeringGroup for this study, scheduled before end 2008.

EU legal acts quoted in this Report refer, as applicable, to the last amended version. Full references to the actsquoted in this Report are given inAnnex 1.1.

5

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

1

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

1.2. ObjectivesThe objectives of the study are two-fold:c) to establish a detailed picture and evaluate the present situation as regards theapplication of the current fees regime in the EU, in particular the way in which thesystem operates in practice; and,d) to assess the advantages and disadvantages of a range of policy options (regardingthe scope of current rules and the fee-setting mechanism).As such, the final aim is to provide input to the Commission’s development of proposals toimprove the system in future.1.3. ScopeThe study covers activities related to the official controls in relation to establishments basedin the EU and in relation to goods introduced into the EU, with regards to the product sectorswhere the current rules apply, in particular the livestock and livestock product sectors.Although the study focuses on the financing provisions of Regulation 882/2004, as containedin Articles 26-29 of Regulation 882/2004 (and in particular Article 27), a range of otherCommunity legislation is relevant to the study. This legislation is summarised inAnnex 1.1.It is noted that reference to ‘mandatory’ and ‘non-mandatory’ fees throughout this Report ismade with respect to MS obligations and possibilities underRegulation 882/2004, Article 27para 2 and para 1respectively, not with respect to whether the fee is charged on acompulsory or other basis.1.4. Methodology1.4.1. Overall methodological approach and objectivesThe activities undertaken during the study have been based on the following mainmethodological tools:••••Desk research, including data and documentation analysis;Survey of competent authorities at MS level (for the EU27);Interviews with European stakeholders/partners (including the Commission);Case studies, basedinter aliaon detailed interviews with MS stakeholders/authoritiesin 6 MS (Germany, UK, Italy, France, Poland, and Slovak Republic);

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

2

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

The study team has undertaken the design and implementation of the survey and interviewprocess, with the following two key criteria in mind:1. To have an open and transparent dialogue, involving all potentially interested partners andstakeholders at European and MS level. Our commitment to this objective is demonstratedby the fact that the survey has been addressed to all competent authorities in the EU-27,with the process closely monitored by our team. We have also contacted allrepresentatives of the various relevant stakeholders at both EU and MS level.2. To provide a synthetic and concrete analysis of the results, so as to be able to deliveractionable recommendations to the Commission services, in particular in the context ofthe Commission’s review of Regulation 882/2004.To this end, the study team has tried to ensure maximum flexibility throughout the survey andinterview process. Flexibility was sought both in terms of adjusting the sample of relevantpartners/stakeholders, but also in terms of updating the detailed list of questions used duringthe interviews with new findings and comments. New insights have thus been built into theprocess as the interviews were progressing.At the same time, the team has sought to ensure that the Commission’s reporting deadlines areadhered to and that a sound and robust basis for the synthesis at EU level is provided. Thishas involved the establishment of a clearly set out analytical framework and of a tightreporting and synthesis system for the inputs provided by the various phases of the project.The study was carried out during the period March to October 2008.

1.4.2. Desk researchFor the purposes of this study, key relevant literature and material reviewed includes thefollowing:1. Background legislation and other official documents of relevance. A non-exhaustive listof the main background legislation at EU level is provided inAnnex 1.1.The purpose ofthe review has been to understand in detail the subject matter of this study and the way inwhich the various legal instruments interrelate.2. The notification letters submitted by the MS to DG SANCO, in complying with Article 12of Regulation 882/2004. To date, 18 MS have notified the Commission of the measurestaken to enforce the financing provisions of the Regulation (Annex1.2).3. FVO reports carried out in the EU-27, in particular those relating to hygiene controls andimport controls. A list of the reviewed FVO reports, indicating where available referenceto the issue of fees, is provided inAnnex 1.2.The purpose of our review has been toobtain a first view of the situation, and – where possible/applicable - to cross-check withthe information provided by MS in their answers to the survey questionnaire. Thesereports, together with the FVO country profiles on the system of official inspections in the

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

3

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

areas covered by Regulation 882/20046and the National Controls Plans7where available,also provide useful background material on the structure of the CAs in the MS. This hasbeen useful in the context of identifying the relevant stakeholders both for the EU-27survey and the case studies, and key issues of relevance to the financing of officialcontrols.4. Background material available at national level, including national legislationimplementing Article 27 of Regulation 882/2004.5. Material and data provided by industry stakeholders. Such material has included data onfees collected independently by some of the EU professional organisations (includingnotably the UECBV and CLITRAVI).Desk research continued throughout the project course as new material and data, in all of theabove categories, became available.1.4.3. Survey of competent authorities (CAs)The survey of CAs was addressed to all MS of the EU-27, including the case study countries.It was based on a questionnaire, developed in consultation with the Commission services,which covered the various issues of the fees system under Regulation 882/2004, including allsectors of Annexes IV and V of the Regulation (in the meaning of Article 27.2) but also othersectors to which non-compulsory fees may be currently applied by MS (in the meaning ofArticle 27.1). The questionnaire is attached inAnnex 2.The aim has been to collect facts/hard data on the current operation of the system (Section 1of the questionnaire), and views/suggestions for the future (Section 2 of the questionnaire).The process of questionnaire completion has been monitored closely by the Consultants viatargeted meetings and communication, both with the desk officers responsible for hygiene andofficial controls in the MS Permanent Representations and directly with the CAs in the EU-27MS. Requests for further clarification, following questionnaire submission, were also made toa number of MS.A challenge from the outset has been to identify the relevant CAs in the MS, given the scopeand complexity of the sectors to which fees for official controls apply, and the fact thatseveral CAs and/or delegated bodies are often involved in the organisation of official controls(this issue is further discussed in section 2.2.1). As a result, questionnaire completion hasnecessitated extensive internal consultations within the MS, involving not only the CAs(notably, in most MS, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Health), but also thenational/local authorities, in some cases even the laboratories and veterinary institutes.

6

FVO country profiles on food and feed safety, animal health, animal welfare and plant health.NCPs are to be drawn by MS pursuant to Article 41 of Regulation 882/2004.

7

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

4

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

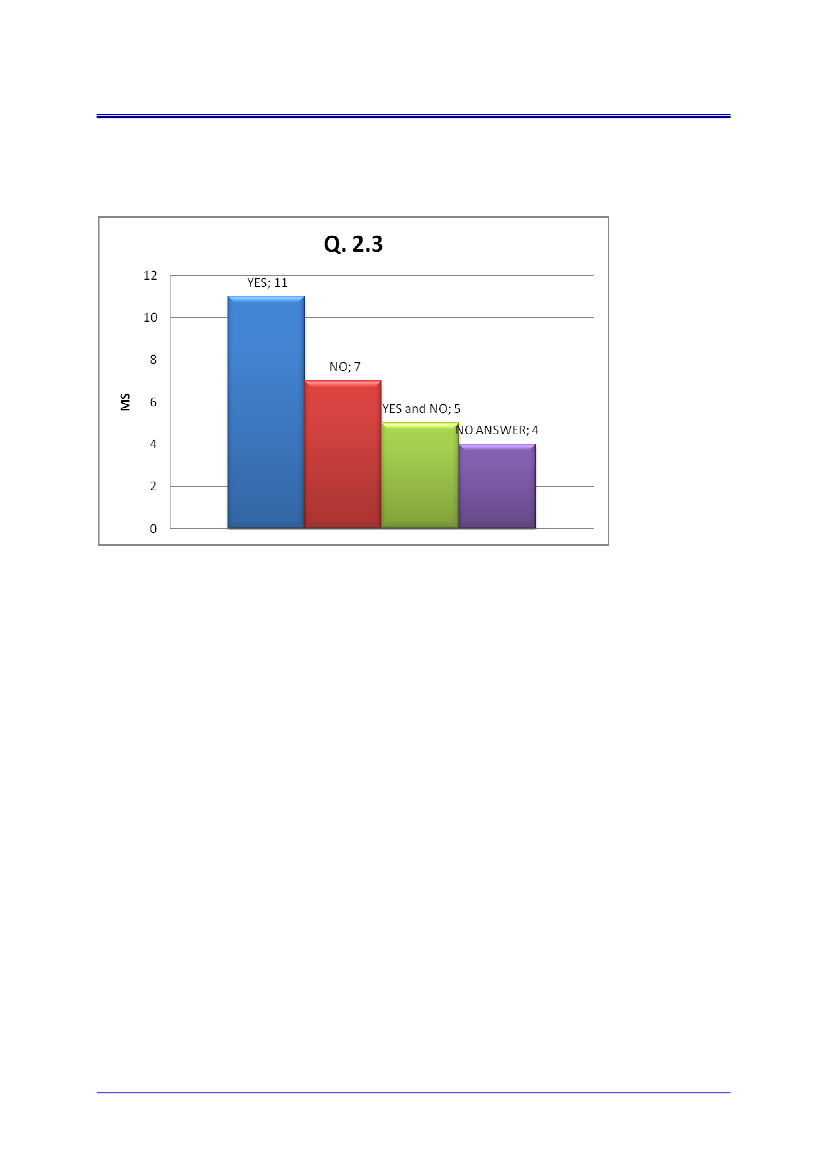

The outcome has been a full response to the survey by all EU-27 MS8. It is also noted that thishas largely been within the anticipated timelines (nearly two thirds of MS responded by thedeadline of 27 June). For the case study countries, the survey results were incorporated andfollowed up in the discussions with MS authorities and stakeholders at national level.The full analysis of the survey results (both quantitative and qualitative) is submitted as aseparate spreadsheet file9, while some of the results are used in this Report.1.4.4. Case studiesThe study covered the EU as an entity with treatment of all MS of the EU-27. Given thepotentially wide scope of this coverage, further in-depth analysis was undertaken in six MS,as follows:1. Germany2. Italy,3. UK,4. France,5. Poland6. Slovakia

The selection of these countries represents a mix of different situations as identified duringthe Inception Phase of the study, in terms in particular of centralised/decentralisedorganisation and management of the system for the collection of the fees, and the nature of thesystem applied (whether minimum rates or flat rates). Two NMS have also been included inthis selection.The case studies were carried out and drafted using a common framework. In practice, anydifferences in the final presentation are due to the specific character of the administration ofthe official controls system and the administrative structures in each country. For the samereason, the partner and stakeholders contacted/interviewed in each country may be slightlydifferent, with interviews focussed on the key relevant partners and stakeholders in each case.The case studies are presented in full in a separate volume (Part Two) of the Final Report.Results and information from this work are incorporated in the analysis that follows in thismain part of the Report.

8

In some cases (4 MS) more than one response were received by the various CAs involved.A package of the completed questionnaires has been submitted separately to the DG SANCO services.

9

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

5

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

1.4.5. Interviews with key partners and stakeholdersThe partners and stakeholders selected for interview at EU and MS level (for the case studycountries) cover the range of sectors of relevance to this study.1.4.5.1. At EU levelAt European level, the interview programme has included, as partners, the Commissionservices (DG SANCO, other relevant DGs in particular DG Agriculture and DG MARE). Interms of the stakeholders, it has included both EU and national professional organisations.All of the interviews were carried out face-to-face. In view of the large number ofexperts/representatives involved in some cases, where applicable, interviews were conductedby grouping together some of the partners/stakeholders. The latter has been particularly thecase in terms of the interviews with the European professional associations.The final list of interviewed professional organisations is presented inTable 1-1.Several ofthese interviews have been conducted with a group of relevant experts or representatives. Theaim has been to enlarge the debate process to a larger number of people from the various MS,so as to provide different perspectives for the discussion and our analysis. This approach wasalso dictated by the fact that several of the professional associations are umbrellaorganisations representing a wide and often divergent range of views from their nationalmembers.For the same reason, these interviews were conducted using a step by step approach with mostof the EU professional associations. This has involved:1. A preparatory phase with the lead organisation prior to the full interview with itsmembers. The objective has been to focus the discussion during the main interviewon identifying key issues for the organisation as a whole, including common pointsand points where an internal debate may be in evidence;2. Main interview with the organisation and its members (where appropriate, e.g.UECBV, CLITRAVI, EDA, AVEC).3. A second interview which took place towards the end of the study period, to confirmthe points expressed during the first interview and also to focus the discussion onthe options for the future (second ‘group’ interviews were conducted with theUECBV, CLITRAVI and AVEC).

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

6

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

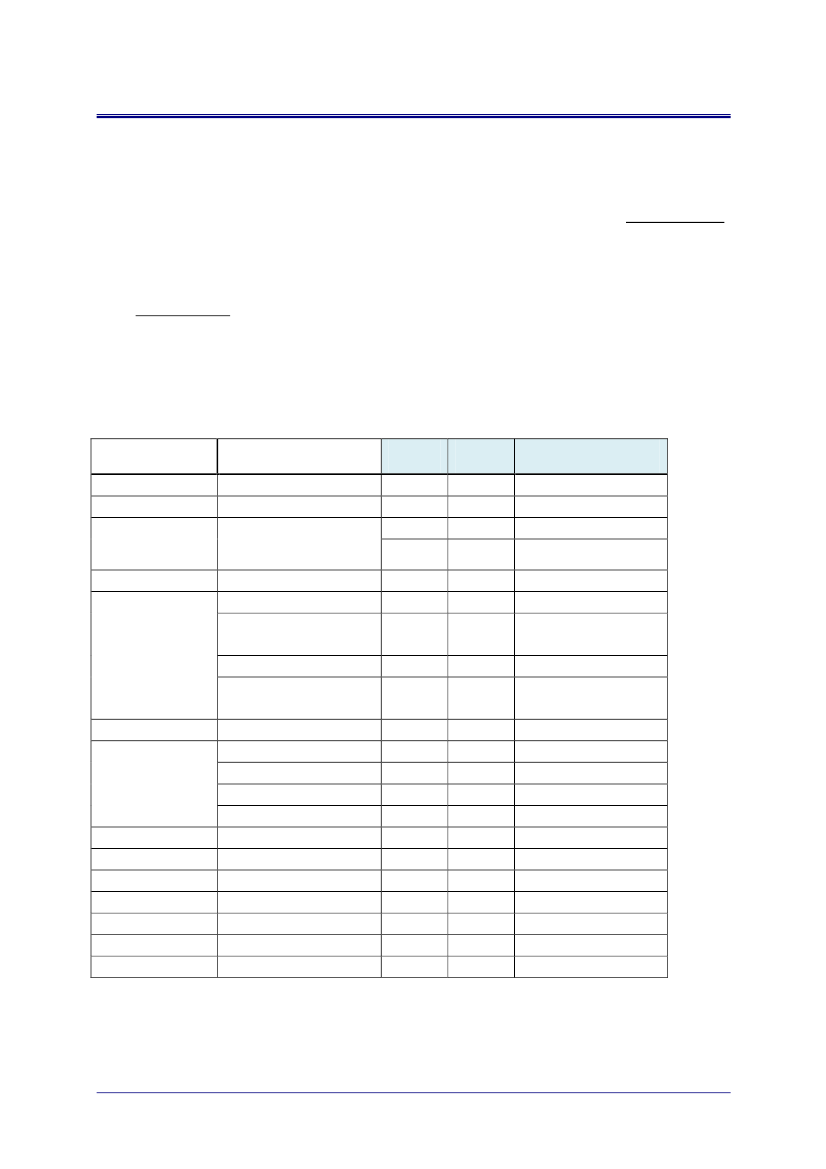

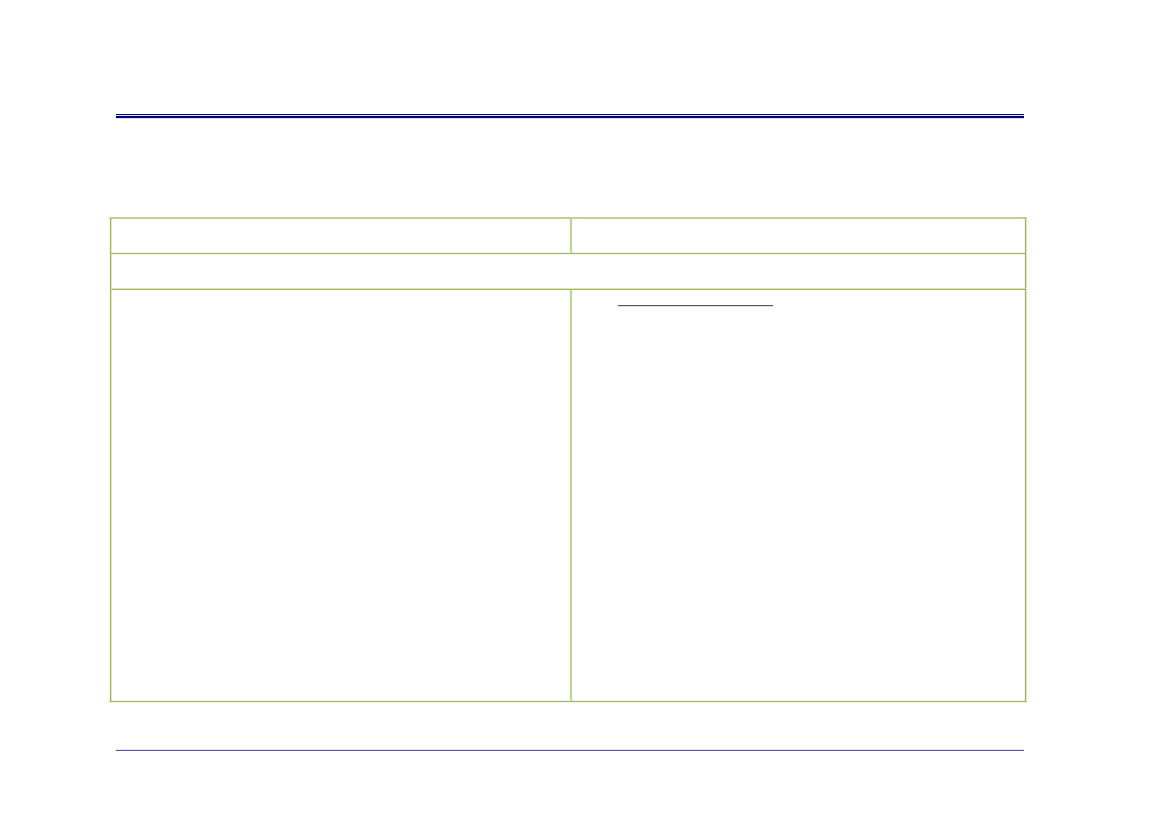

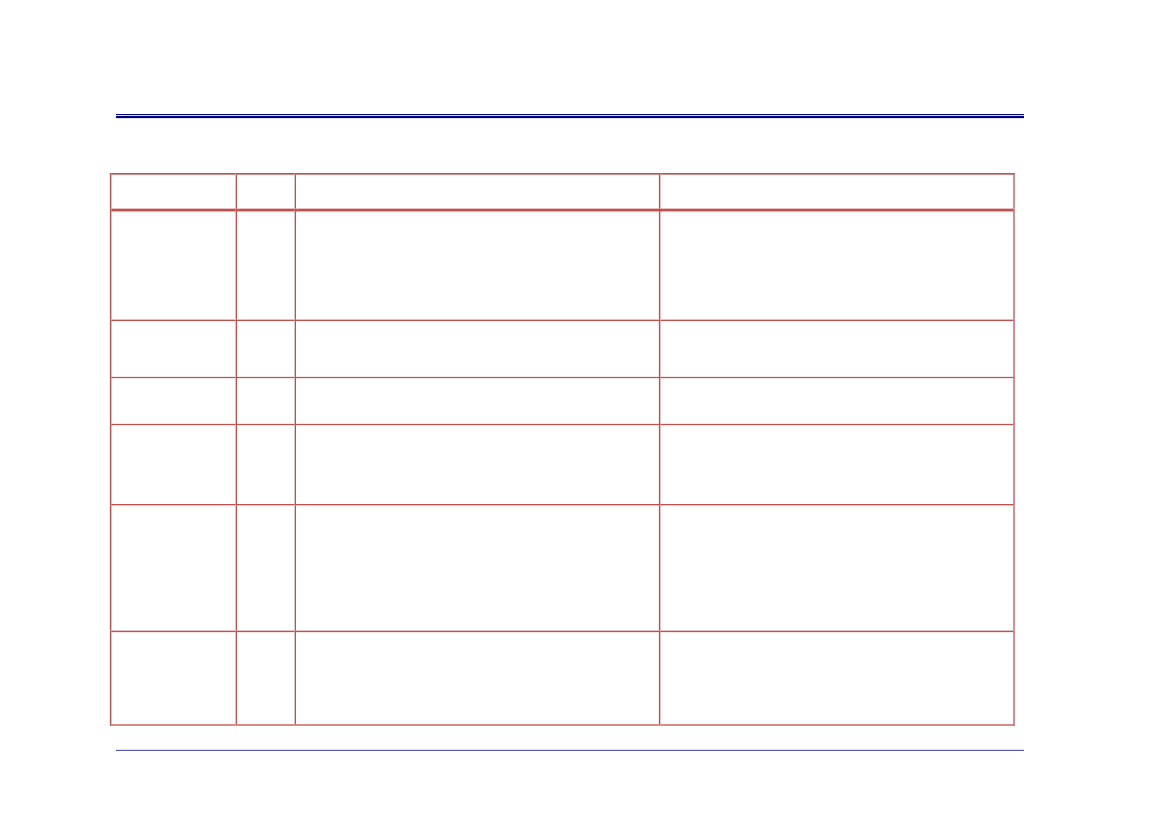

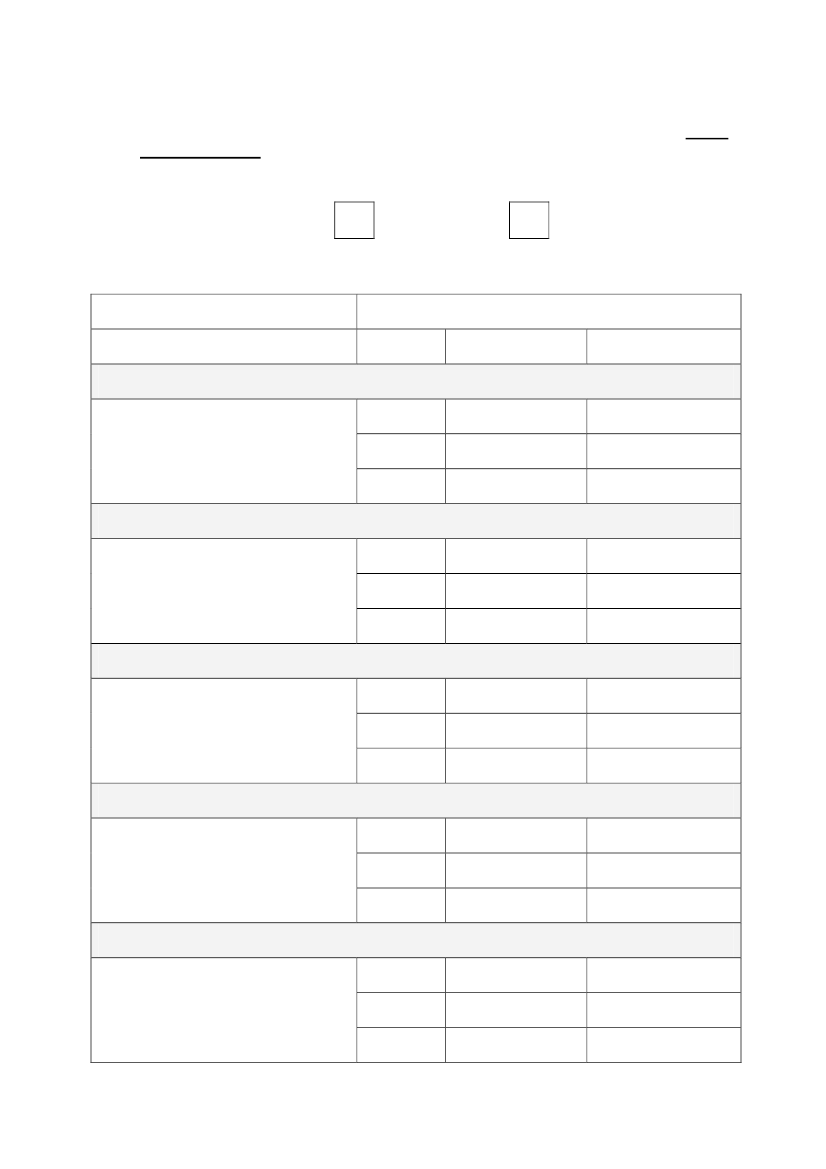

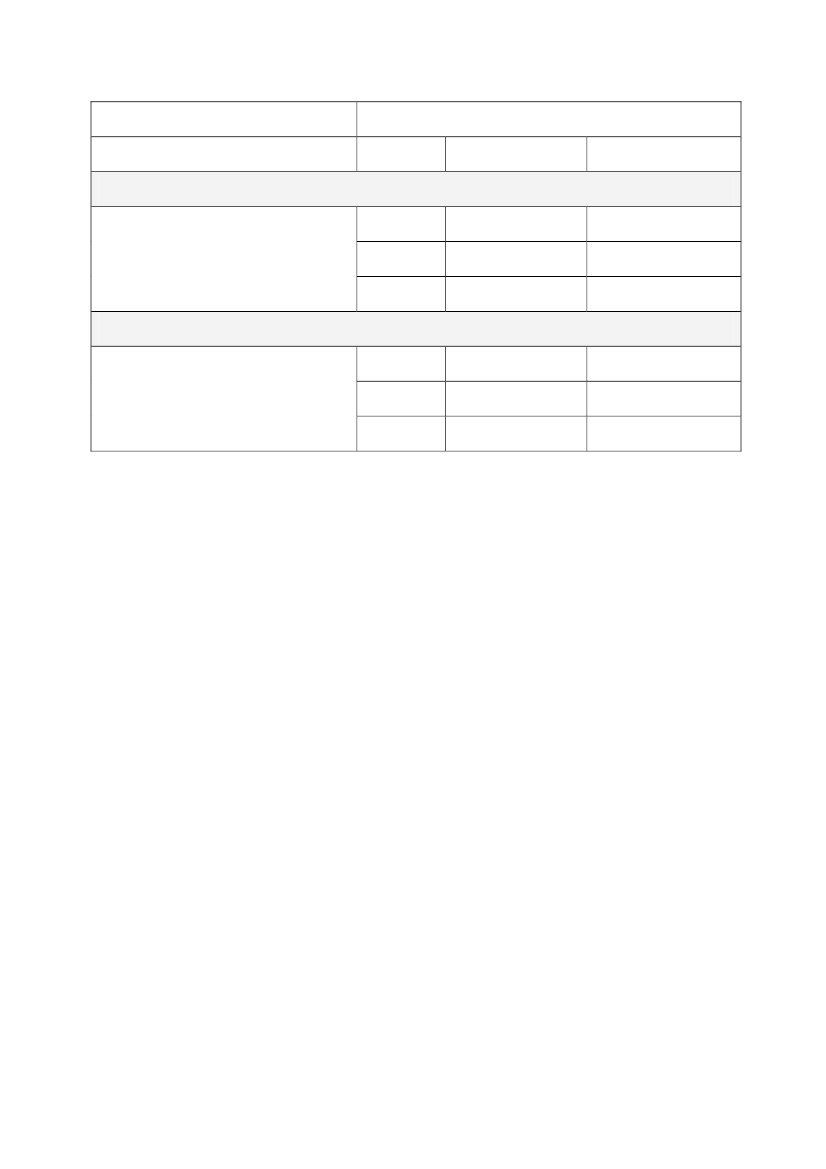

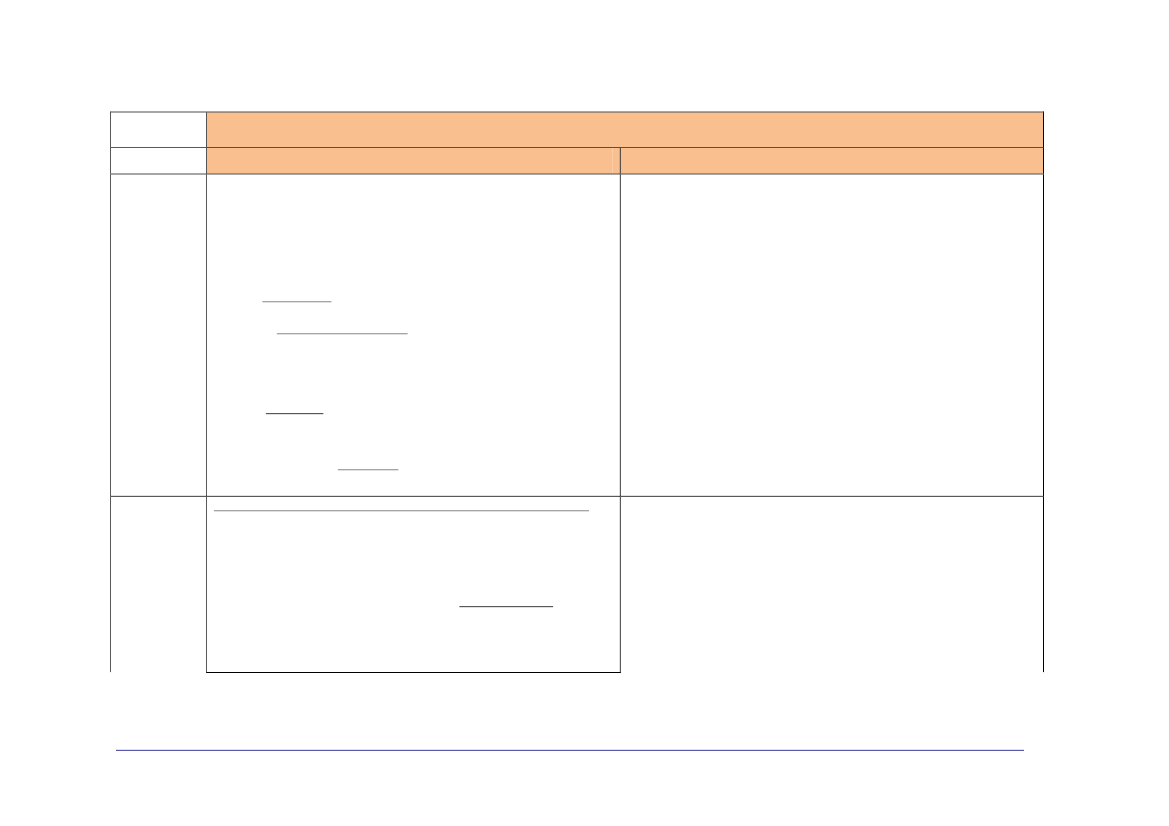

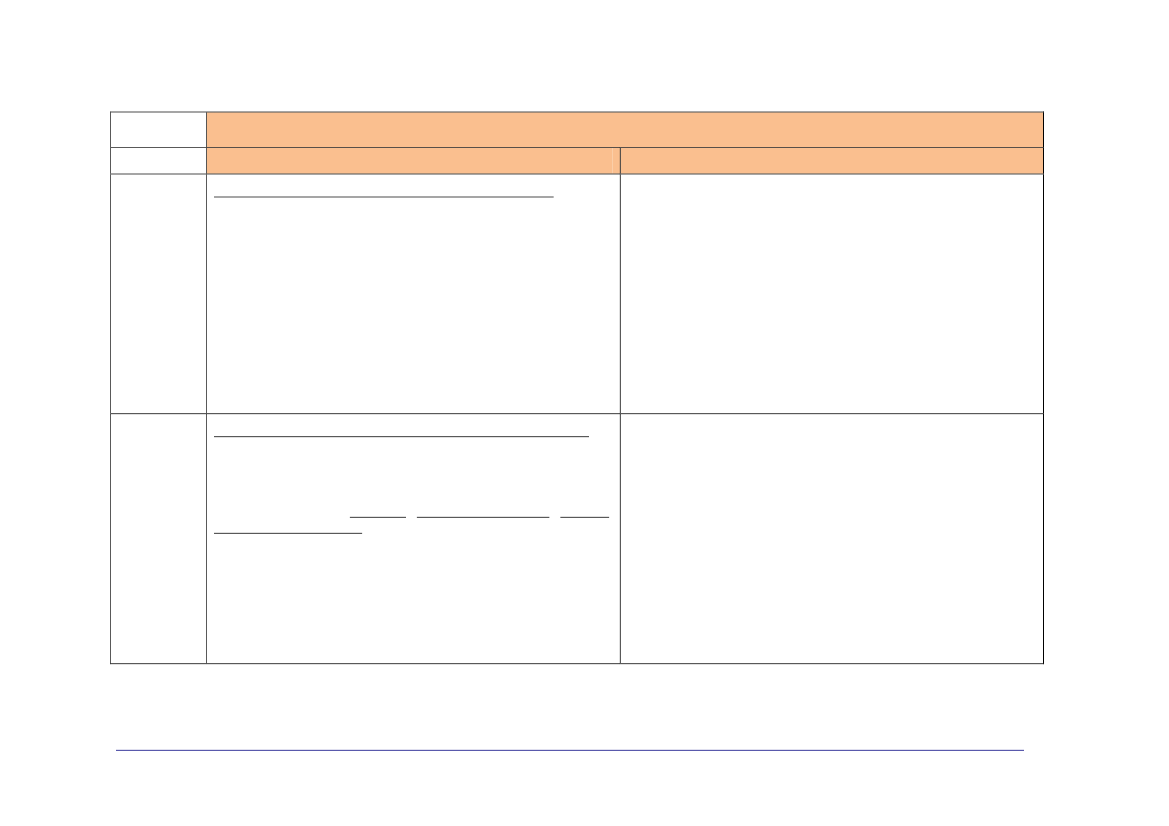

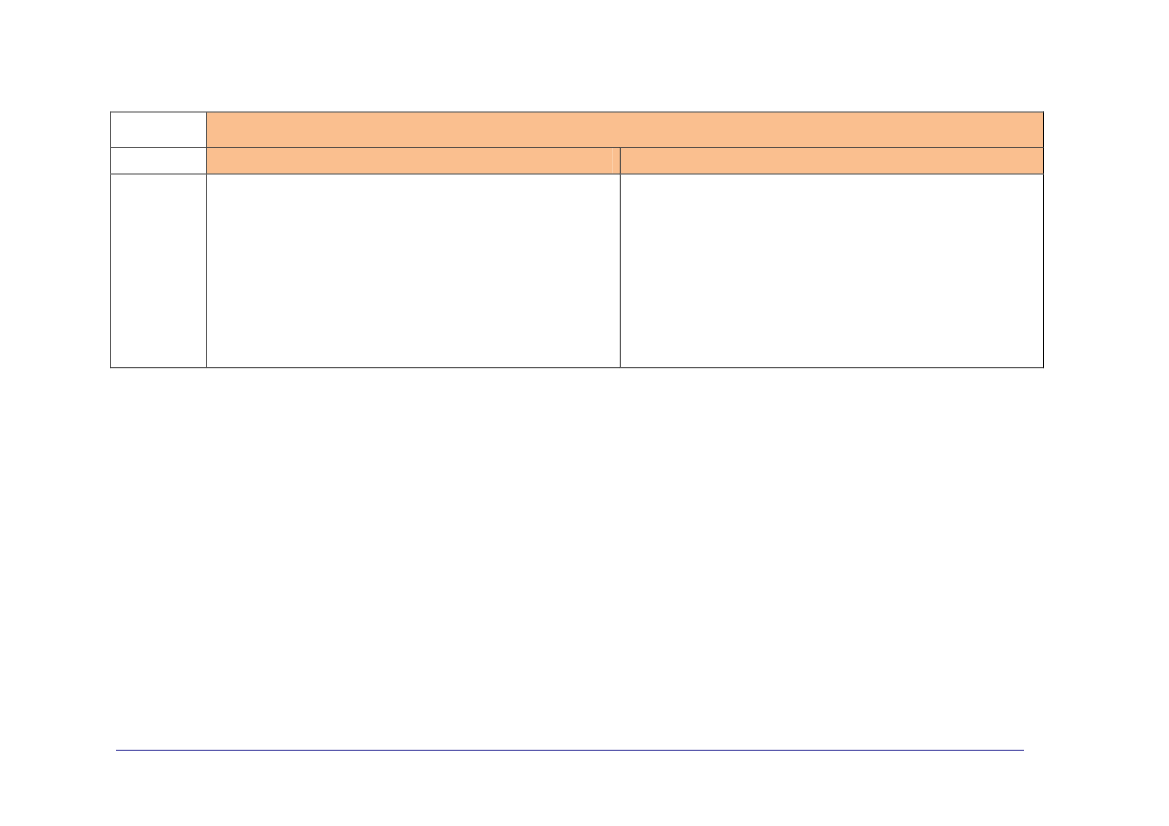

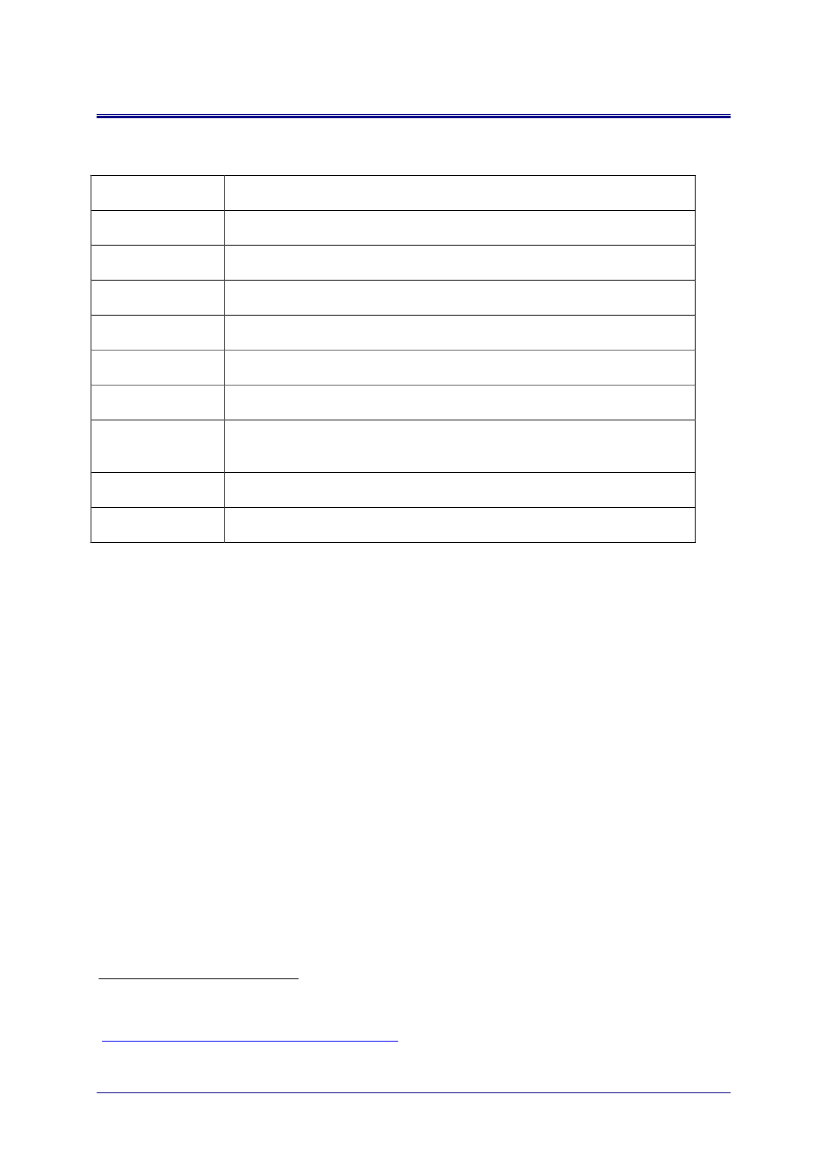

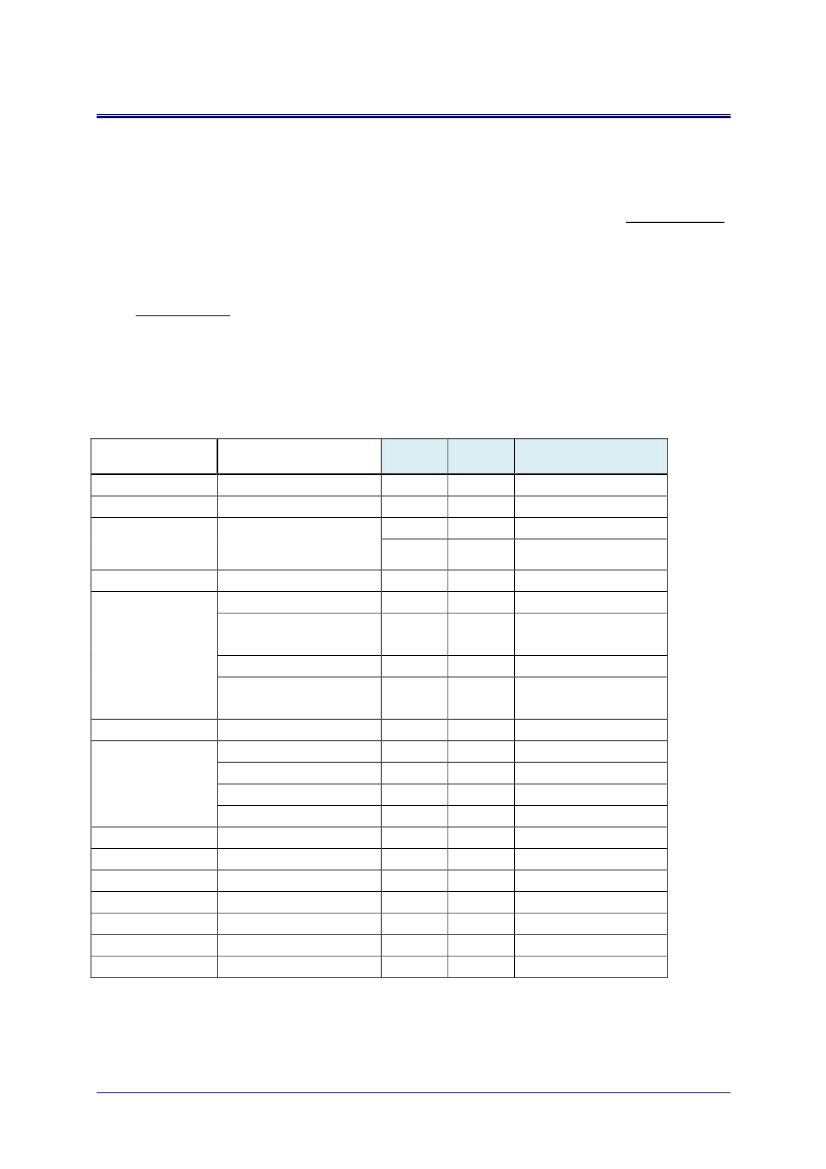

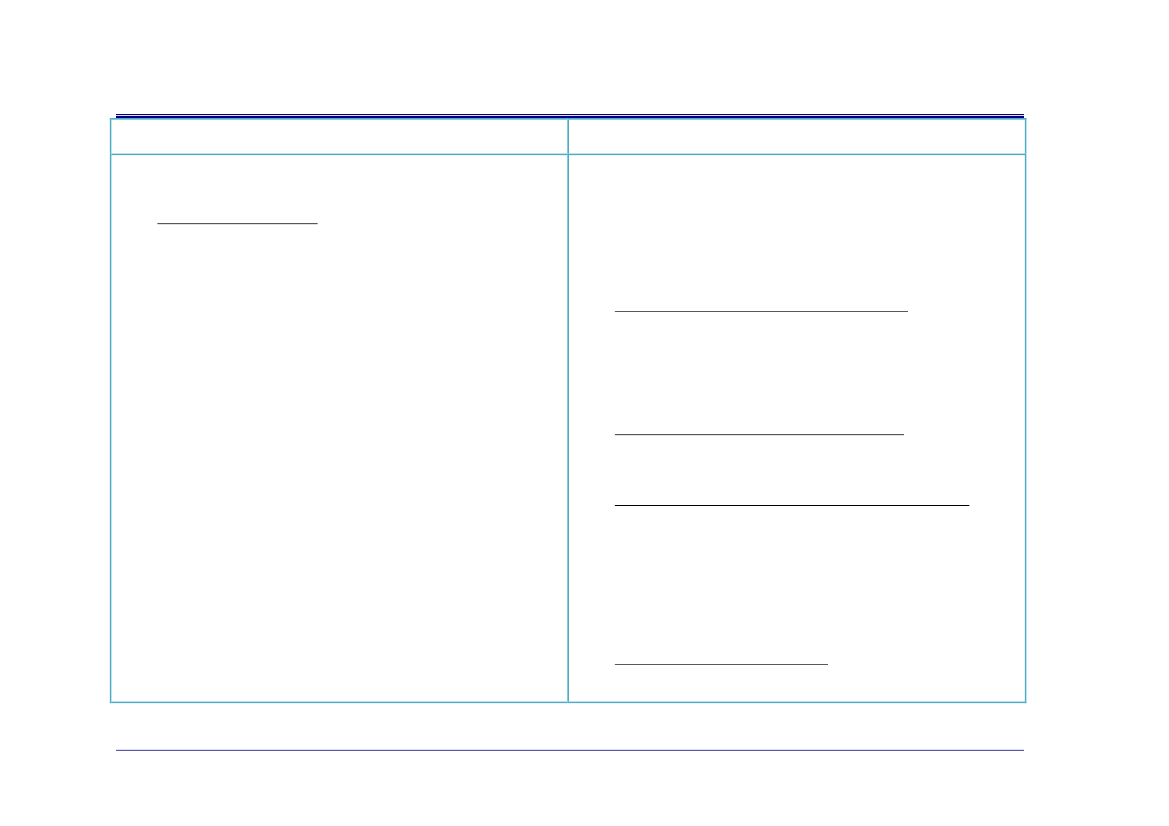

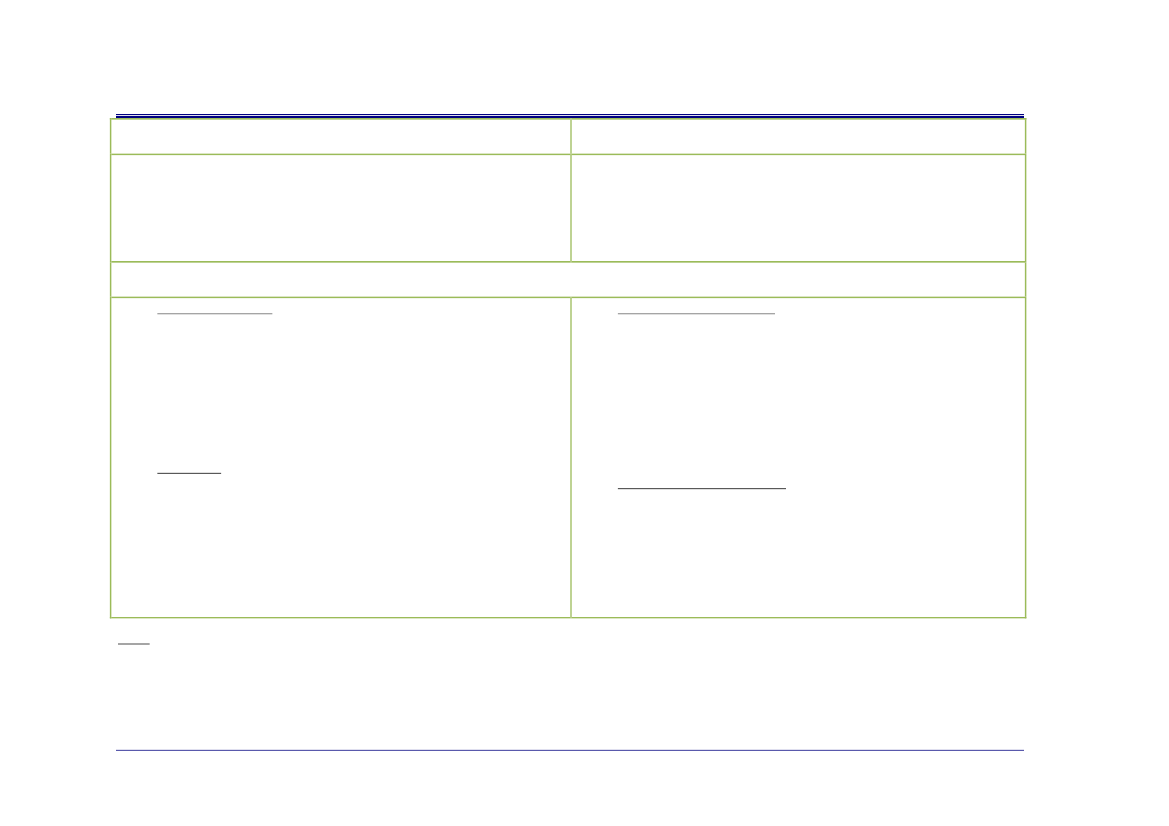

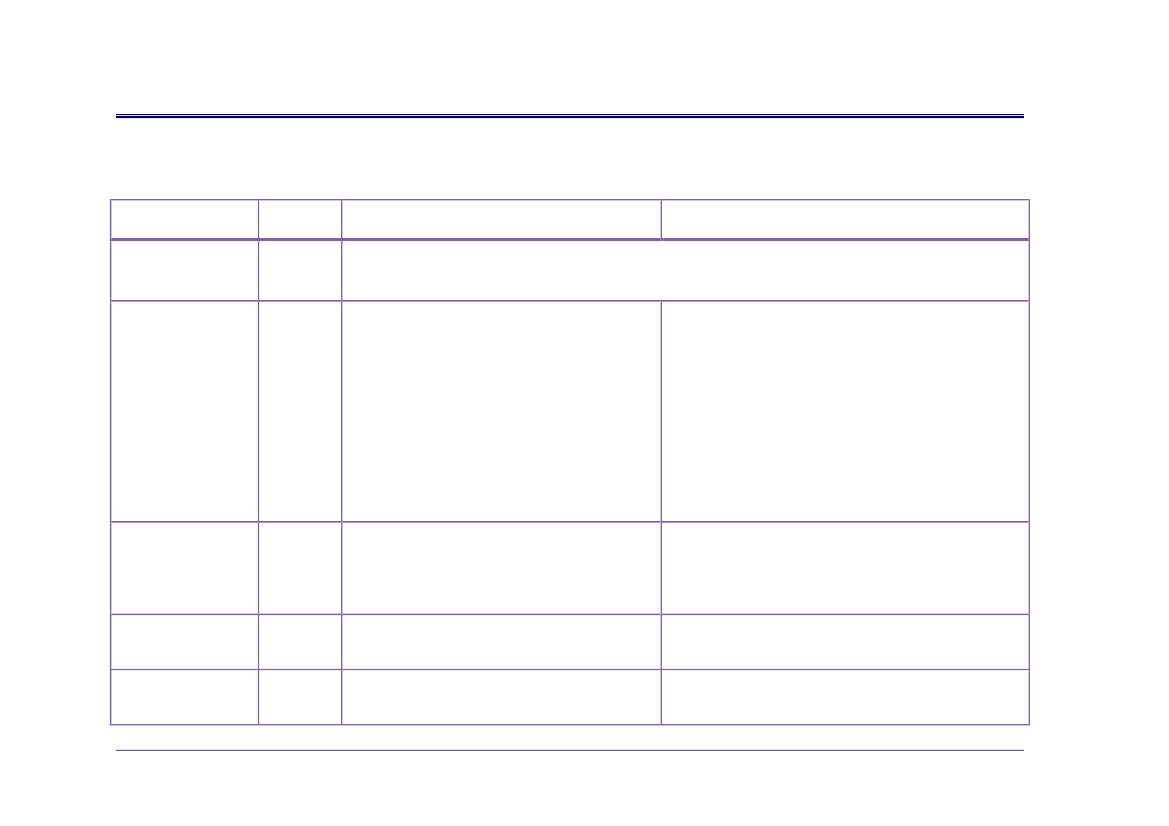

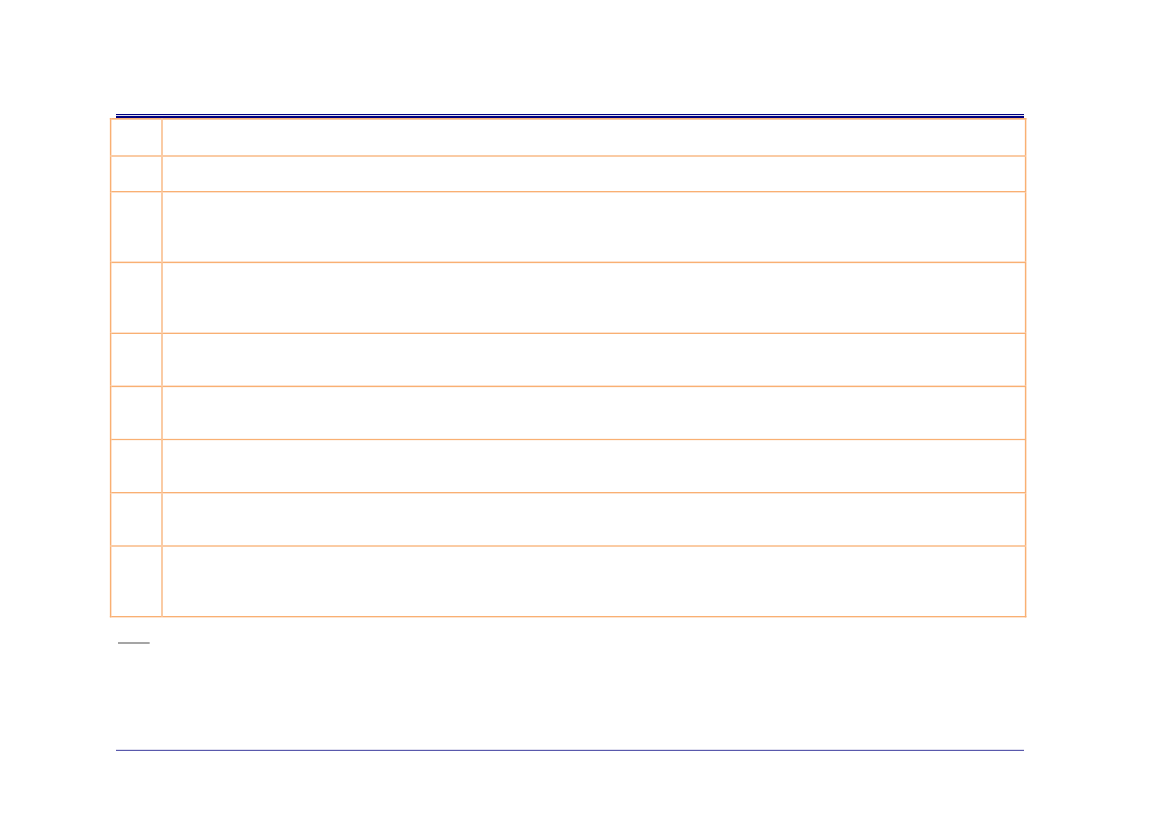

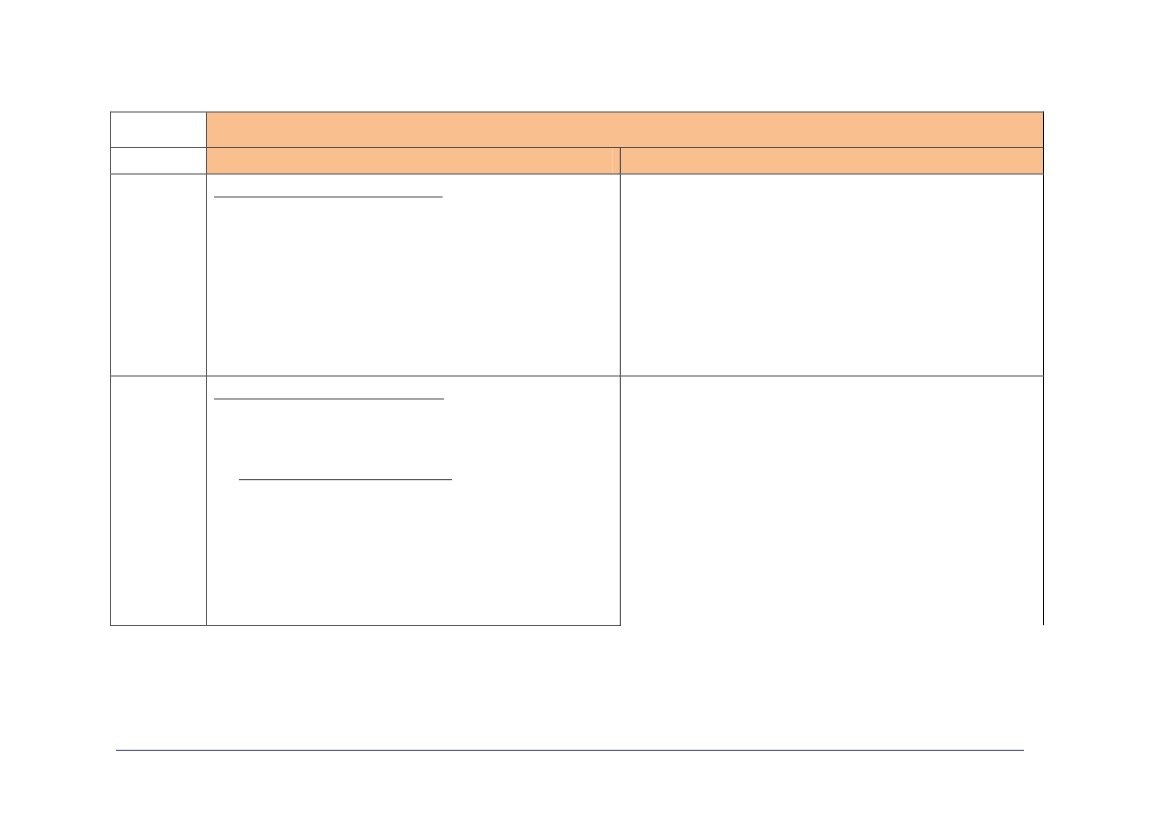

Table 1-1 European professional organisations interviewedOrganisationUECBVCLITRAVIAVECCIBC/IMV/IBCEDAEUCOLAIT (a)EUROPECHE (a)Full nameEuropean Livestock and Meat Trading UnionLiaison Centre for the EU Meat Processing IndustryAssociation of Poultry Processors and Poultry Import/Export TradeInternational Butchers’ ConfederationEuropean Dairy AssociationEuropean Association of Dairy TradeAssociation of the National Organisations of Fishery Enterprises in theEuropean UnionEuropean Feed Manufacturers’ FederationFederation of Veterinarians of Europe

FEFACFVE

(a) This organisation was contacted for an interview, but no interview was conducted due to limited memberinterest. Member organisations in the case study countries were approached/interviewed in some cases.

The study team has synthesised the information and views collected through this process, andthese are incorporated in the analysis of this Report.In addition, the Consultants were invited by the French Ministry of Agriculture to attend aconference co-organised with the French Presidency on the modernisation of sanitaryinspections in slaughterhouses, and in particular the section dealing with the costs of officialinspections and the fee system10. The conference was attended by relevant CAS and delegatedbodies from various MS of the EU-27 and gave the opportunity to liaise and get feedbackboth a wider base of MS than the case studies alone.1.4.5.2. At MS level (case studies)The case studies have involved a detailed investigation of the system applied, the issuesraised, and the implications of the different systems. To this end, a second round of detailedinterviews was conducted in the case study countries. This interview process, in terms of thestakeholders contacted and the issues addressed, was developed in all of the six case study

10

Lyon 7-11 July 2008. Conference details can be found at:

http://pfue-inspectionsanitaireenabattoir.lso-intl.com/

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

7

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

countries in close consultation with their permanent representations in Brussels, the centralnational CAs, and the European professional organisations.On average, the interview programme in each of the selected MS has covered at least 6-8interviews for the large case studies (Germany, Italy, the UK) and 4-5 for the small casestudies (France, Poland and Slovakia)11. Typically the interviews have included the relevantMinistries (Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Health), industry representatives (liveanimals, traders, meat processors, dairy processors, poultry sector, animal feed industry, fishindustry), and a national veterinary institute (where applicable and if active in this area). Thefull list of authorities/stakeholders selected for interview in the case study countries isprovided in Annex in Part Two of the Final Report.The bulk of the interviews were conducted face-to-face. As was the case with the Europeanstakeholders, several of the national interviews were carried out with a group of relevantofficials/representatives, and involved extensive preparatory work and meetings. Allinterviews were conducted in the national language, by appointing native language expertsfrom the Consultants’ team in charge of the case study in each country.The study team has processed the data and information from these interviews in two steps:•The first step involved the analysis and synthesis of the interview results in a MS report,summarising the key points of the MS position per question. This analysis wasincorporated in particular in Part Two of the Final Report.•The second step was the comparison and cross-referencing of the analysis carried outper MS, with the results of the analysis of the information, data and views collectedthrough the EU interviews and the survey. This analysis is incorporated in particular inthis main part of the Report.

11

Case study definition in accordance with the project contract (FCEC/Agra CEAS offer of January 2008).

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

8

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

2. Description and assessment of the current system of feesThis section presents the intervention logic of EU policy in this area, in particular of thefinancing provisions of Regulation 882/2204 (Articles 26-29) as set within the context of EUfood and feed law and wider EU policy principles and objectives. Based on this, the analysisdescribes the current enforcement of Articles 26-29 by the MS, assesses the extent to whichthe various principles and objectives have been achieved, and highlights shortcomings.The analysis is based on the synthesis of data and information resulting from the stakeholderinterviews, the survey and the case studies, as well as from the desk research and analysis ofsecondary data and sources of information.2.1. Intervention logic2.1.1. Principles and objectives of EU policyThe analysis aims to establish the extent to which the financing provisions of Regulation882/2004 serve the objectives and principles both of this Regulation and the wider objectiveswithin which this is set, in particular those of EU food and feed law and the Lisbon Strategy.In terms of objectives, the assessment of Articles 26-29 includes consideration of thefollowing:•Objectives ofRegulation 882/2004:⇒to ensure a harmonised approach with regard to official controls;•Objectives ofEU food and feed law(Regulation 178/2002 and the Hygiene Package):⇒to ensure a high level of protection of human life and health and the protection ofconsumers' interests, including fair practices in food trade, taking account of,where appropriate, the protection of animal health and welfare, plant health andthe environment;⇒to achieve the free movement in the Community of food and feed manufactured ormarketed according to the general principles and requirements of EU law;•Objectives of theLisbon Strategy(interalia):⇒to promote better regulation and maintain/support competitiveness.In terms of principles, the analysis takes into account the need for Articles 26-29 to ensurerespect of:

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

9

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

•The principle ofproportionality:as set out in Article 5 of the Treaty, EU Regulationshould not go beyond what is necessary in order to achieve the objectives pursued12;•The principle ofsubsidiarity:as set out in Article 5 of the Treaty, where objectivescannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States and would therefore, by reason oftheir complexity, trans-border character and, with regard to feed and food imports,international character, be better achieved at Community level, the Community mayadopt measures13;•The principle ofFBO responsibility:actual Community food and feed law is based onthe principle that FBOs at all stages within the business under their control areresponsible for ensuring product safety14.2.1.2. The requirements for official controlsRegulation 882/2004 sets out requirements for the authorities in EU MS that haveresponsibility for monitoring and verifying compliance with, and enforcement of, feed andfood law (and animal health and animal welfare rules), i.e. the 'competent authorities' (CAs)responsible for organising and undertaking 'official controls' (OCs)15.This regulation sets out the general approach that must be taken, and the principles that mustbe adopted, by the authorities in EU MS. It also provides the legal basis for the EuropeanCommission to assess the effectiveness of national official control arrangements.Most of the provisions applied from 1 January 2006, while others applied from 1 January2007. However, a 1-year derogation (to 1 January 2008) was given to MS for the entry intoforce of the financing provisions of Regulation 882/2004 (Articles 26 to 29), which are thesubject of this study.A novelty of the new Regulation has been that CAs can delegate specific tasks to relevantcontrol bodies provided these meet certain conditions (experience, accreditation, staffqualifications, impartiality etc.) and are audited by the CA. This is a very sensitive issue as itraises concern that MS use their right to delegate to avoid accountability (including vis-à-visthe Commission). From the Commission’s point of view there should be only onecentral/single competent authority (or at least only one per type of controls, e.g. veterinary,phytosanitary, aquatic).

12

Preamble (48) of Regulation 882/2004; preamble (66) of Regulation 178/2002.Preamble (48) of Regulation 882/2004.Preamble (4) of Regulation 882/2004; Article 17.1 of Regulation 178/2002.

13

14

15

According to Article 2(1) of Regulation 882/2004,“‘official control’ means any form of control that theCompetent Authority or the Community performs for the verification of compliance with feed and food law,animal health and animal welfare rules”.

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

10

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

2.1.3. The financing of official controlsThe provisions of Regulation 882/2004 relating to the financing of official controls arecontained in Articles 26-29.In summary, the main principles pursued in these provisions are the following:•Member States must ensure that adequate financial resources are made available forofficial controls (Article 26);•Inspection fees are imposed on feed and food business operators, common principlesmust be observed for setting the level of such fees and the methods and data used for thecalculation of the fees must be published or otherwise made available to the public(Article 27);•When official controls reveal non-compliance with feed and food law, the extra coststhat result from more intensive controls must be borne by the feed and food businessoperator concerned (Article 28).The requirements laid down in Regulation 882/2004 as regards charges for meat hygieneofficial controls were previously contained in Council Directive 85/73, as last amended byDirective 96/43 (Annex1.1).Regulation 882/2004, which supersedes the Directive, requiresthat, from 1 January 2007, MS must charge no more than the actual costs of controls and,other than in specified cases, no less than specified minimum charge rates. The Regulationeffectively allows MS to retain the charge rates set out in Directive 85/73 until 1 January2008, though as minima rather than as standard amounts. Some MS have altogether used thisopportunity to look at possible options to review their fee system.Within these boundaries, the Regulation leaves it to MS to determine the level of fees orcharges. For certain activities for which fee charging is ‘compulsory’ (Article 27.2), theminimum levels laid down in Annex IV (controls on domestic production) and Annex V(import controls) must be respected. Beyond this, the Regulation provides MS with someflexibility within which to determine the fee system, provided that specified factors are takeninto account. The key requirement is that fees should not be higher than the actual costs of theofficial controls.The minimum fee or charge rates in the Directive and in the Regulation (Annexes IV and V)are throughput rates for inspection costs relating to the slaughter per species/type of animal orbird. For controls and inspections connected with cutting operations, the fee is per tonne ofmeat entering the cutting plant for the purpose of being cut up or boned there.2.2. System descriptionThis section outlines and comments on the key elements of the operation of the currentsystem (Task1: system description)of the ToR.

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

11

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

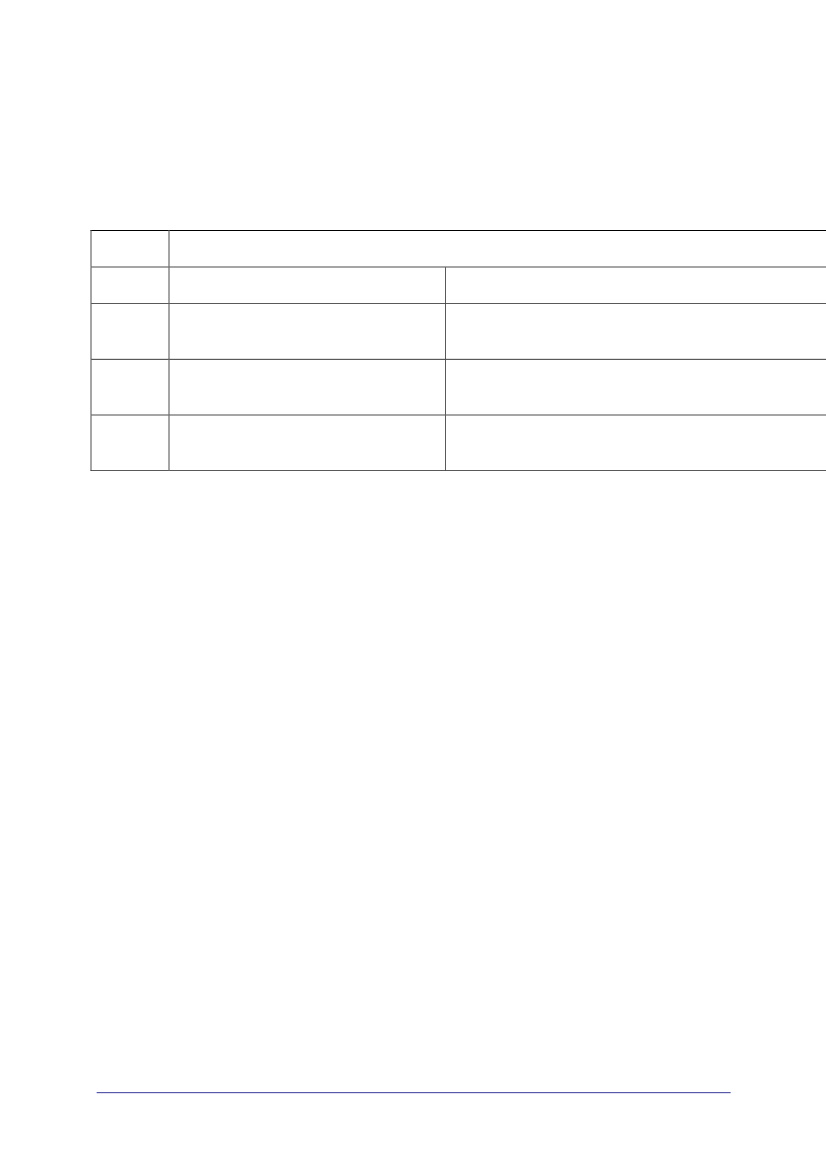

It is noted from the outset that in several MS the current system continues to be based on theprevious financing legislation (Directive 85/73); in these cases, draft proposals to enforceRegulation 822/2004 are currently undergoing the national legislative making process.2.2.1. Competent AuthoritiesAs already noted in the methodology section of this Report, a key observation – and challenge- of this study from the outset has been the very different level of structure and organisation ofthe CAs involved in the system of official controls in the MS. This includes both theadministrative structures in place for the collection of fees for the controls, and for theconduct of the controls. Two issues have in particular been identified:1. The organisational structure of the CAs responsible for the official controls. Dependingon the MS and often depending on the product sector, this may include central, regionaland district level administrations, as well as external delegated bodies (Agencies,Laboratories etc.). This issue is demonstrated simply by the list of CAs that respondedto the survey (Annex1).It is also confirmed by our review of the CAs performingofficial controls from relevant FVO reports and MNCPs (where available), which ispresented inAnnex 3.It is noted that current structures are dictated by the constitutional law and particularadministrative traditions of a MS, and are therefore not readily amenable to change.2. The staff composition (official veterinarians, hygienists and assistants) of the CAs andexecutive bodies responsible for performing the official controls also variessignificantly between MS. In contrast to the overall administrative structures referred toabove, the staff composition is subject to change.In particular, there is currently a trend in several EU MS to seek to rationalise publicservices, and as part of this trend, the veterinary services and their staff are beingreformed/restructured. In some MS (e.g. NL) the model of employment of the staffperforming the official controls is shifting away from the higher-cost direct payroll ofthe public service towards lower cost/freelance contractual arrangements; such optionsare currently also being examined in other MS (e.g. France, the UK).Both issues have financial implications in terms of the actual cost of official controls, andthese are of relevance to this study:•The addition of several layers of competent/executive bodies in the system of official

controls wouldà prioribe expected to have cost implications and needs to bejustified/supported on efficiency/effectiveness grounds.•Similarly, the use of appropriately trained (in the context of EU rules) staff employed on

a contractual basis over the alternative of highly qualified staff employed as officialcivil servants – without compromising the quality of the controls – could createsignificant cost savings. This appears to be the main motivation in the case of MS thathave adopted or are currently thinking of adopting this approach.

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

12

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

More generally, both these issues have been a challenge for this study, as it is not easy toseparate the review and evaluation of the fees system from the overall organisation, structureand therefore cost of the official controls. They also have significant implications whenexamining the options for the future.The involvement of several layers of administration (either vertically within the same CA, orhorizontally across CAs, or at regional/local level) raises questions of conformity withRegulation 882/2004. The Regulation envisages that one central CA (Article 2.416) wouldnormally be responsible for the overall supervision and operational control of the system ofOCs. Furthermore, when the competence to carry out official controls has been delegated toan authority or authorities other than the central CA, efficient and effective coordinationshould be ensured between the CAs involved including at regional/local level (Article 4.3)and at vertical level (Article 4.5). More stringent provisions, including audits by the CAs,apply when control tasks are delegated to control bodies (Article 5).Both the desk review (analysis of FVO reports) and the case studies have shown that, inpractice, these provisions are not always complied with, and that the CCA does not alwayshave full control or information on the actual operation of the system when a number of CAsor delegated bodies are involved.It is noted that Regulation 882/2004 requires MS to draw up multi-annual control plans(MNCP) which will provide information on the structure and organisation of the systems offood and feed control, includinginter aliathe designation of CAs at central, regional andlocal level and delegation of tasks to control bodies (Article 42.2(c) and (f)). However, todate, such plans are not available in all MS, and even where they exist they are not publiclyavailable but can only be provided at the request of the Commission17. Consequently, it isdifficult on the basis of objective sources to establish how exactly competence for the officialcontrols falling under Regulation 882/2004 is organised at MS level.From the survey of EU-27 CAs it is clear that in many cases more than one CA is involved18.This issue was also highlighted in the case studies (Part Two of the Final Report).

16

Article 2.4 reads:‘Competent authority’ means the central authority of a Member State competent for theorganisation of official controls or any other authority to which that competence has been conferred.

Despite efforts to consult the MNCPs on this, the Consultants have only seen the MNCP in two of the casestudy countries. It is not known how many MS have drawn MNCPs, or how many MS have submitted those tothe Commission.Indeed, as is highlighted in the methodology part of this Report, separate responses to the survey werereceived from more than one CA in the case of four MS. One of these was Germany, for which responses wereseparately received from 13 out of the 16 Lander. In most of the other MS, although one response was received,there was a significant consultation process between the various CAs and/or bodies involved for the completionof the survey questionnaire.18

17

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

13

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

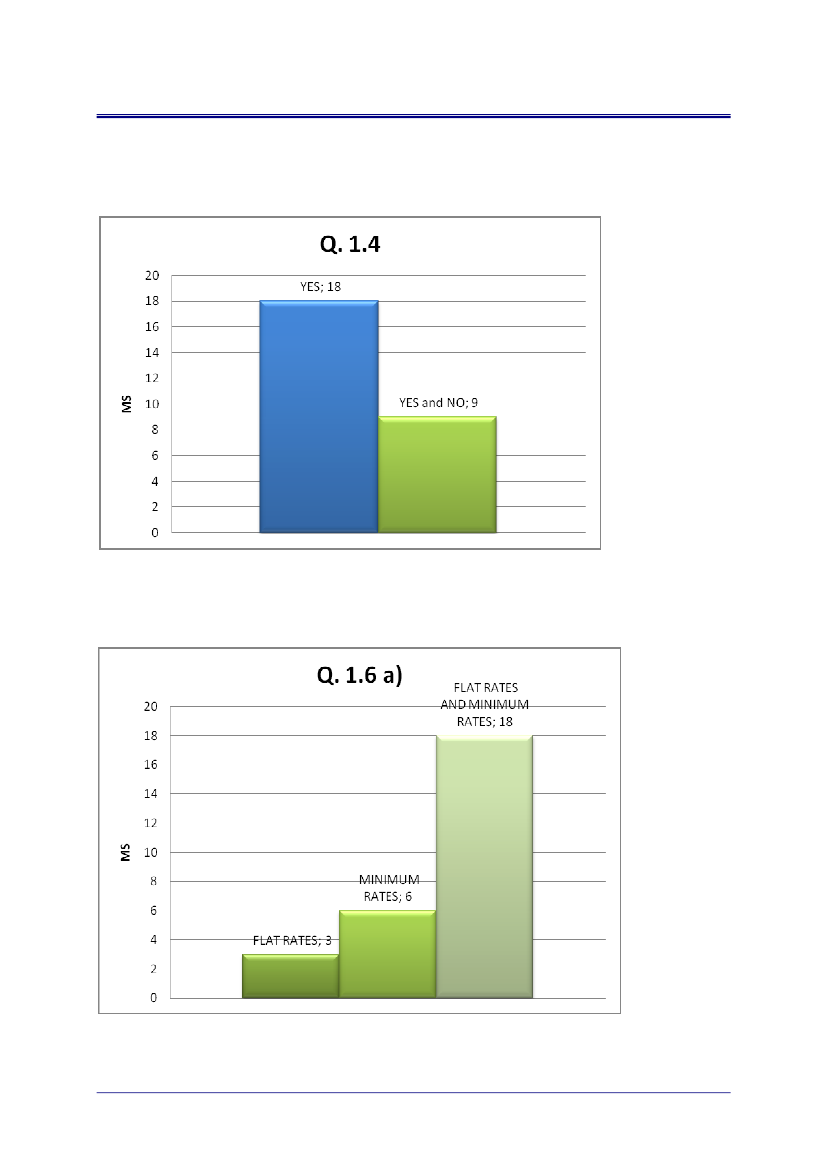

2.2.2. Activities for which fees are collectedThe study has found that in practice fees are currently collected for the official control of thefollowing types of goods, establishments and activities:a)Fees collected on a ‘compulsory’ basis (Article 27.2)

The types of goods, establishments and activities, for the official control of which fees are tobe collected, is established in section A of Annex IV (concerning domestic production) andAnnex V (imports) of Regulation 882/2004. Fee collection for these activities is ‘compulsory’within the meaning of Article 27.2.From the results of the survey, 18 MS (including France, Germany, Italy, Poland andSlovakia) collect fees for all the activities according to Article 27.2; however, the remaining 9MS (including the UK) collect such fees only partly (Question1.4,Annex 2).Fees for milkproduction controls and fees for residue controls are the two types of control activities forwhich several of these MS do not collect fees, and at least 3 MS do not collect fees for a widerrange of activities.In the case ofmilk productioncontrols, although Regulation 882/2004 states that charges forofficial controls in dairy plants are compulsory (under Annex IV, section B, Chapter IV). Infact, however, these charges are not made - at least - in the following MS: UK, Germany,Netherlands, Latvia. Two main reasons are given for this:•It appears that this reflects the fact that there was some debate during the negotiationson Regulation 882/2004 as to whether fees in the dairy sector should be charged on a‘compulsory’ basis (within the meaning of Article 27.2) or not (in this case falling underArticle 27.1). This point was made in the UK case study, but also by some other MS inthe survey. Some MS argued that they should be considered to be compulsory, as theywere also mandatory under the previous charging legislation, Directive 96/43/EC(which amends and consolidates Directive 85/73/EEC). Other MS were opposed to theintroduction of mandatory fees in this area under the new Regulation. In the event, itwas agreed that MS would be required to impose fees on a compulsory basis only whenthey had previously done so under Directive 96/43/EC, but with the compromise thatthe minimum rates for milk production controls remained and could be applied by thoseMS where fees are imposed.•According to the European Dairy Association (EDA), the minimum fees charged on acompulsory basis (Article 27.2) for controls on specified substances and residues inmilk production exceed as much as 20 times the previous fee on these controls19.

The EDA have already expressed their concerns on this in a letter sent to DG SANCO on 13 February 2007.According to the fee calculation provided by the EDA, for the EU-25 the fee revenue collected according toDirective 85/73 amounted to Euro 2.64 million, while under Regulation 882/2004 it would reach Euro 44.32million (if applied in full throughout the EU-25).

19

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

14

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

•The CAs of some MS complain of a lack of clarity on how minimum fees should becollected. This point was made in the Germany and Slovakia case studies, but also bysome other MS in the survey. In particular, the CAs in Germany claim that it is unclearwho is liable to pay fees for milk production inspections (dairies or farmers) and whichtime span the quantity of raw milk specified in Annex IV/B/IV refers to. Similarly, theCAs in Slovakia, although they are charging fees for milk production controls, theynonetheless commented that they were unclear whether dairy farmers or milkprocessing companies should pay these fees and the milk quantity to which this refers(whether total annual production or the volume subjected to controls).b)‘Non-compulsory’ fees (Article 27.1)

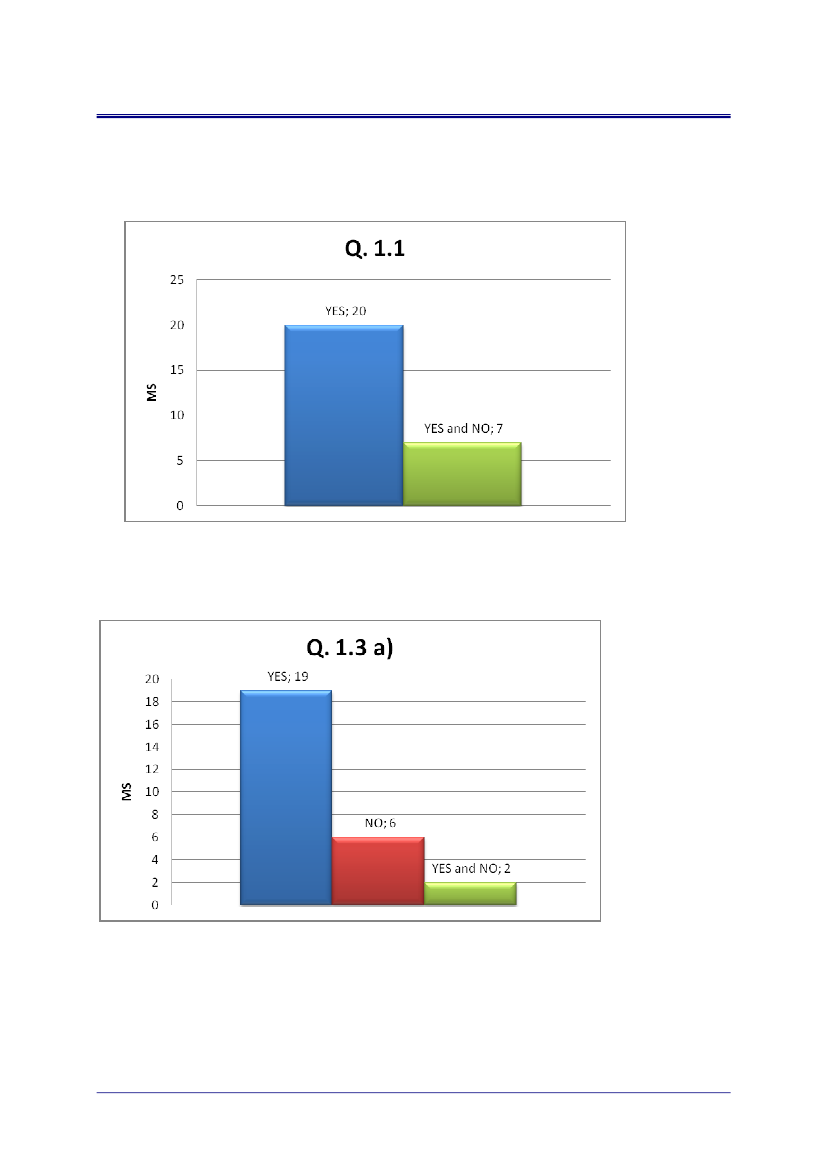

According to the survey, 19 MS (including the UK and Poland) collect fees for activitiesfalling under Article 27.1, i.e. for which fee collection is ‘not-compulsory’ within the meaningof Article 27.2 (Question1.3a,Annex 2).On the other hand, 6 MS (including France, Italyand Slovakia) do not collect fees for activities beyond those that they are obliged to collectunder Article 27.2, and 2 MS (Germany, Spain, i.e. with a decentralised management of thesystem) collect such fees in some regions but not in others.It would also appear that some MS use significant leeway in interpreting the term ‘routinecontrols’ of Article 28 of the Regulation (which provides for additional fees on expensesarising from additional official controls beyond the ‘routine controls’). The case of the feedsector is an example here. It would appear that Denmark is the only MS that charges fees for‘routine’ controls in the feed sector20. This situation is causing concern to the EU feedfederation (FEFAC).c)Fees collected at several points along the production chain (Article 27.7)

Another observation from the survey and the case studies is that, in practice, fee collectioncan occur more than once along the production chain for what would effectively constitute thesame controls. This is contrary to Article 27.7 which specifies that where several OCs arecarried out at the same establishment, these should be considered as a single activity and becharged a single fee. Evidence of double charging was found for instance in the meat sector inItaly, where industry stakeholders complained they paid double fees at both slaughter andmeat cutting points; and in Portugal and France where the fish industry appears to be payingfees at more than one of the three stages listed in Annex IV/B/V of Regulation 882/2004.Cross-charging or overcharging may also be occurring for the same controls performed morethan once when products are traded across MS. For example, dairy products from another EUMS brought to the NL to be further processed into other products for further export are re-examined on residues. The fact that these products are coming from an approved EU-factoryand from a MS applying a residue plan does not appear to be sufficient.

These are in addition to the ‘compulsory fee’ for the approval of feed establishments provided under section Aof Annex IV of the Regulation, which are indeed collected in most MS (and which according to FEFAC do notpose a problem to the EU feed industry).

20

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

15

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

d)

Fees collected for OCs on products of non-animal origin

It is noted that both the survey and the case studies identified cases where fees are collectedfor products of non-animal origin. For example, in Belgium the current fee system collects abase contribution from all FBOs along the food chain including catering and controls onproducts of plant origin. The proposed draft law for the full enforcement of Regulation882/2004 in Italy is also moving to this direction. Fees for some plant health controls alsoappear to be currently being collected in Bulgaria and Greece.Fees are collected in several MS (including the UK, Denmark, Hungary, NL, Poland, andSweden) on import controls on products of plant origin (these can include food and non-fooditems). This appears to be taking place within Directive 2002/89/EC21 (import controls forplant health). This Directive, which came into full effect on 1 January 2005, required that allconsignments of regulated material be subject to a documentary, identity and plant healthcheck prior to customs clearance. The directive also introduced phytosanitary fees to coverthe costs associated with performing these checks. Minimum fees are contained in Annex VIIIof the Directive and several of the above mentioned MS are following these fees.2.2.3. Fee rates usedRegulation 882/2004 leaves it up to MS to define the actual fee system they will use, providedthat the two main boundaries set by the Regulation (minimum fees of Annexes IV and V, anda maximum set by the actual controls costs) are respected.In practice, the study has found that a multitude of scenarios arise out of these possibilities.The resulting picture is quite complex and can be confusing, or at least lack transparency forFBOs, with a multitude of fee rates applied for the various activities. It appears that theoriginal intention of the legislator was that only one of the two systems would be used, or atthe most, a combination of the minimum rates for all activities listed in Annex IV and V andflat rates for the other activities. From our interviews in the case study countries and theresponses to the survey it can be concluded that CAs have interpreted the relevant provisionsof Article 27 in various ways and rather ‘openly’; this is often attributed, by both the CAs andstakeholders, to a perceived vagueness or confusion in the formulation of the provisions in theRegulation.In particular, the following possibilities currently exist:

Council Directive 2002/89/EC of 28 November 2002 amending Directive 2000/29/EC on protective measuresagainst the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against theirspread within the Community. Directive 2002/89 and Annexes amend Directive 2000/29/EC.

21

Food Chain Evaluation Consortium

16

Study on fees or charges collected by MS for official controls: Final ReportDG SANCO Evaluation Framework Contract Lot 3 (Food Chain)

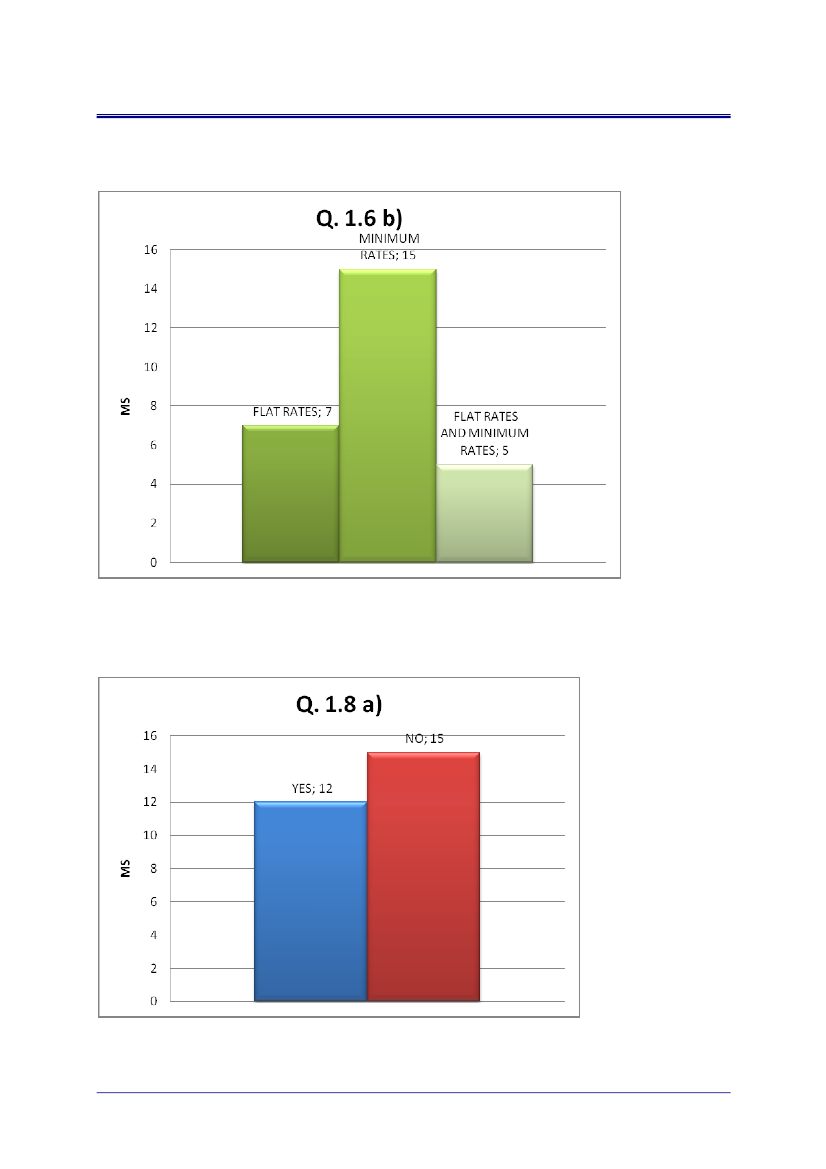

i.

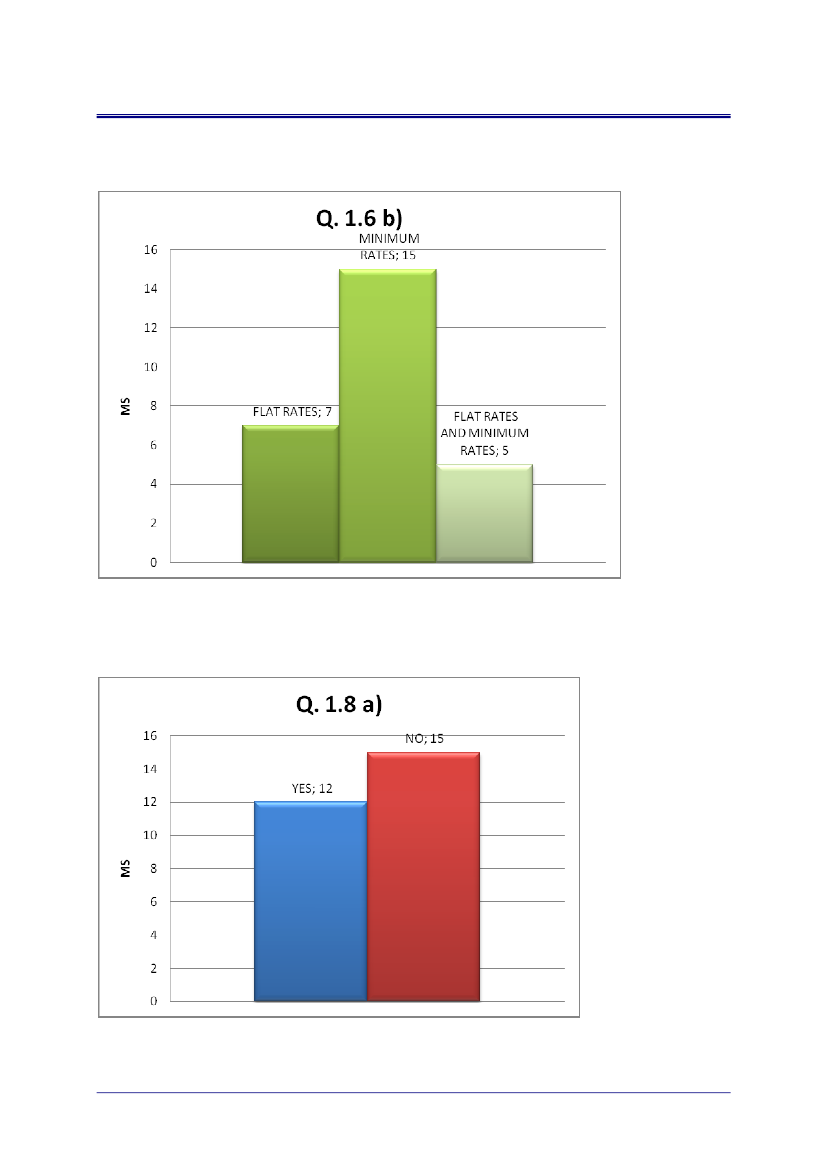

Flat rates or minimum ratesAccording to Article 27.4(b) fees collected for the purposes of official controls may be fixedat a‘flat-rate’or, where applicable, at the amounts fixed in section B of Annex IV and V(‘minimumrates’).The survey of EU-27 CAs has demonstrated that 18 out of the 27 MS (including Germany,Italy and the UK amongst the case study countries) in practice use a mix of flat rates andminimum rates (Question1.6a,Annex 2). A further 6 MS (including Poland and Slovakia) useminimum rates for the activities outlined in Annexes IV and V (and do not collect fees for anyother activities); on the other hand, only 3 MS (including France) use flat rates throughout allactivities for which fees are collected (within the meaning of either paragraph 1 or paragraph2 of Article 27).In the majority of cases where a mix of the two systems is used, the combination of flat ratesand minimum rates were for different activities but could also be for the same categories ofactivities within Annex IV and V.

ii.