Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2007-08 (2. samling)

Bilag 1

Offentligt

AFGHANISTANDetainees transferred to torture:ISAF complicity?

Amnesty International (AI) is an independentworldwide movement of people who campaignfor internationally recognized human rightsto be respected and protected. It has more than2.2 million members and supporters in over 150countries and territories.

� Amnesty International Publications 2007

All rights reserved. This publication is copyright,but may be reproduced by any method withoutfee for advocacy, campaigning and teachingpurposes, but not for resale. The copyrightholders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. Forcopying in any other circumstances, or for re-usein other publications, or for translation oradaptation, prior written permission must beobtained from the publishers, and a fee may bepayable.

The text of this report is availableto download at:www.amnesty.orgAI Index: ASA 11/011/2007Original language: English

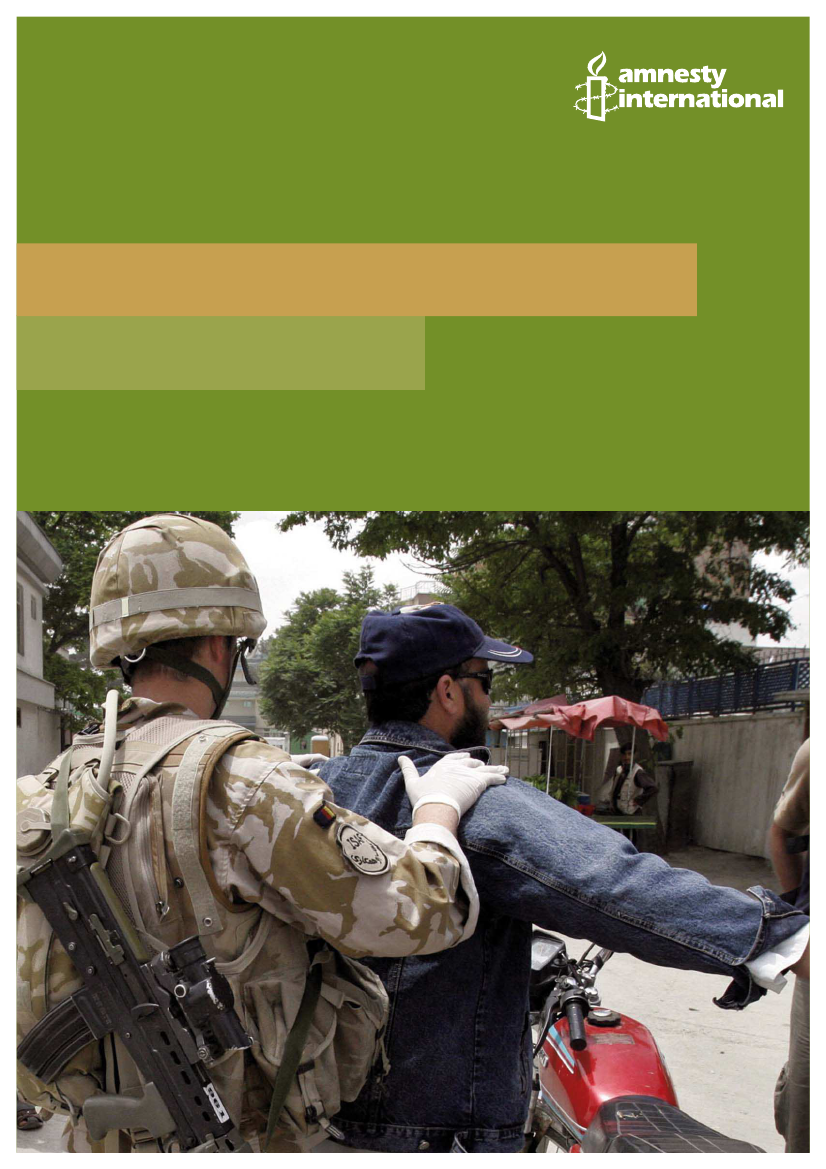

Cover image:A British soldier, part of theInternational Security Assistance Force (ISAF),searches an Afghan motorcyclist at a temporarycheckpoint after a suicide attacker on amotorbike blew himself up, killing onepoliceman and a civilian in Afghanistan's capital,Kabul, on 23 May 2007.� Musadeq Sadeq/AP/PA Photos

amnesty internationalAfghanistanDetainees transferred to torture:ISAF complicity?PublicAI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

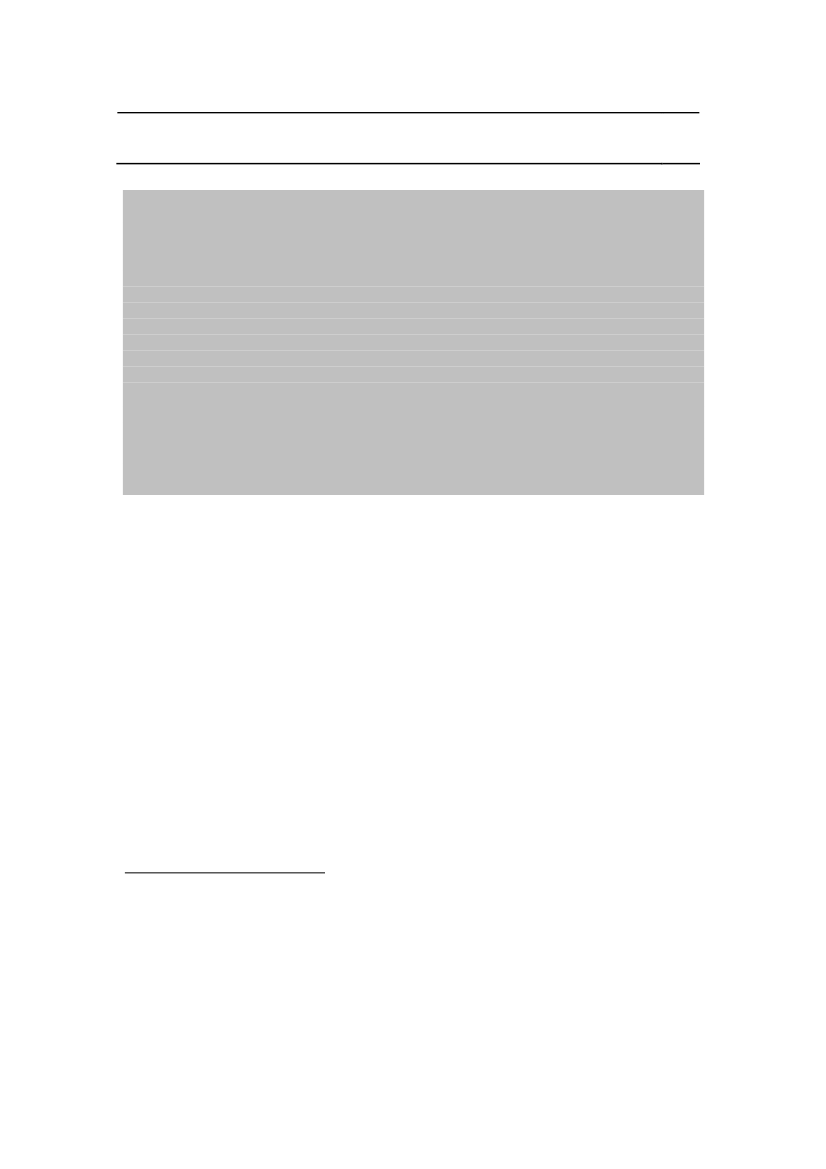

SummaryAmnesty International has received reports of torture, other ill-treatment, andarbitrary detention by Afghanistan’s intelligence service, the National Directorate ofSecurity (NDS). Detainees are transferred from international forces operating inAfghanistan as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to Afghanauthorities. By transferring individuals to a situation where there is a grave risk oftorture and other-ill treatment, ISAF states may be complicit in this treatment, and arebreaching their international legal obligations.This report builds on research by Amnesty International into Afghanistan’s justicesystem and focuses on ISAF detention and transfer policies. It does not cover theUS-led Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) detention system. Amnesty Internationalhas already highlighted its concerns regarding US detention policy in Afghanistanand will continue to do so. It has also raised concerns about failures by all parties tothe conflict to meet their international obligations – including international militaryforces, the Afghan Government and armed groups such as the Taleban.Concerns about the NDS first emerged in 2002, shortly after it was reformed from theprevious Afghan intelligence institution, with a UN call for robust reform. The UNreiterated its concerns about the NDS as recently as September 2007 when it calledfor investigations into allegations of torture and other ill-treatment by the NDS. Thefull mandate of the NDS is not made public but appears to include powers to arrest,charge, prosecute and judge individuals for a variety of security-related offences. Italso operates its own detention facilities.Since early 2007 Amnesty International has assessed a range of legal, technical andpractical issues relating to the transfer of detainees from ISAF custody to Afghanauthorities. This report examines Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) and otheragreements signed by a core group of countries (Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands,Norway and the UK) with the Afghan government to regulate such transfers. Anothergroup of countries (including Belgium, France, Germany and Sweden) are alsoseeking to sign similar types of agreements.But the issue of detainee transfer is not limited to these countries and it is incumbenton all 37 ISAF states, as a whole and led by NATO, to ensure they fulfil theirinternational obligations and take preventive and remedial action to address patternsof abuse within the Afghan detention system.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

The Afghan detention system has fallen between the cracks of reform initiativessupported by the international community, specifically between army and policerecruitment and training on the one hand, and the Afghan legal system on the other.Yet detention is an integral part of any justice system and the internationalcommunity must address its shortcomings together with those of other sectors.The need for increased efforts to reform the detention system in Afghanistan wasrecently highlighted by the UN Security Council when it extended ISAF’s mandate on19 September 2007. Along with the obligation to assist the Afghan government, theSecurity Council added a new aspect to ISAF’s role, stating the need for:“…further progress in the reconstruction and reform ofthe Afghan prison sector, in order to improve therespect for the rule of law and human rights…”(UNSecurity Council Resolution 1776)The cases highlighted in this report include allegations of torture by Afghanauthorities of transferred detainees; incidents where ISAF states have lost track oftransferred detainees; the difficulties in independently monitoring detainees in Afghancustody; and the practice of on the spot transfers without documentation.Based on this research, Amnesty International concludes that if ISAF states are tocomply with their international legal obligations, they must temporarily suspend alltransfer of detainees to the Afghan authorities. During this immediate moratorium,ISAF states should ensure that detainees captured by their forces remain in theircustody and are treated according to international human rights and humanitarianlaw. In order that such a moratorium period is as short as possible, ISAF shouldengage more proactively in the Afghan detention system, and ensure that the Afghanauthorities take urgent measures to eliminate torture and other ill-treatment.In view of the consistent reports of torture and other ill-treatment of detainees by theNDS, and the concerns of the UN and other institutions, the obligation of ISAF statesto protect individuals from such treatment cannot be discharged by relying uponMoUs and similar bilateral agreements signed between the Afghan government andISAF states. They cannot rely on such undertakings by the Afghan government thatill-treatment will not occur.International legal obligations to protect individuals from torture and other forms of ill-treatment must not be circumvented for the sake of expediency. While the Afghanjustice and security sectors remain weak and unable to uphold Afghanistan’sinternational obligations regarding the treatment of detainees, the obligation toprotect must be met by ISAF states that capture detainees.Amnesty International is not advocating for ISAF states to reduce their engagementin Afghanistan, nor for ISAF to introduce forms of long-term internment or take overthe judicial functions of the Afghan state. Instead, they should find policy andoperational solutions that address the evidence in this report and the issues of torture,ill-treatment and arbitrary arrest practised by the NDS. This is the only way to ensurethat ISAF states do not become complicit in torture.During the proposed moratorium, ISAF states, led by NATO, must work collectively tocreate a national engagement plan to reform the Afghan prison system so that itoperates in full compliance with international law and standards.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

ISAF states should explore the feasibility of placing staff and trainers within Afghandetention facilities in order to monitor and train new Afghan detention officials.Training of the police and judiciary could be expanded to include the detentionsystem, either through the European Policing Mission in Afghanistan, or through aconsortium of governments, or even individual states. This would complement themilitary aspects of ISAF’s role, with the civilian elements of state building.Furthermore, the Afghan government must work to end all practices of torture, otherill-treatment and arbitrary detentions; reform the NDS; publish the secret Presidentialdecree governing its operations; and train its personnel to ensure full compliance withinternational law and standards.Independent monitors, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)and the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), must begiven unrestricted access to all NDS facilities. The Afghan government should alsoinvite the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture to visit Afghanistan to follow up onreports of torture and other ill-treatment, and to provide his advice for safeguardingindividuals’ rights.Finally the Afghan government must investigate any complaints of torture and otherill-treatment promptly and independently. All detainees must be protected fromfurther abuse. Victims must be provided with access to redress in accordance withinternational standards.Amnesty International believes now is the time for the key actors - ISAF states led byNATO, the Afghan Government, the UN, the EU, the AIHRC and the ICRC– to worktogether to urgently address these issues.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

AfghanistanDetainees transferred to torture:ISAF complicity?Table of Contents

1.2.3.

Introduction........................................................................................................ 4Context .............................................................................................................. 4The international legal framework...................................................................... 73.1.3.2.International Humanitarian Law.................................................................. 7International human rights law ................................................................... 8The failure of MoUs to protect.................................................................. 13Monitoring detention: An insufficient safeguard........................................ 15The need for redress................................................................................ 18Detainees handed over by foreign forces................................................. 20Concerns about the NDS ......................................................................... 28Institutional framework ............................................................................. 31The NDS.................................................................................................. 32

4.

Memorandums of Understanding between ISAF and the Afghan authorities ... 114.1.4.2.4.3.

5.

Transfers and torture ....................................................................................... 205.1.5.2.

6.

Afghan detention structures: the need for reform ............................................. 316.1.6.2.

7.8.

Conclusion....................................................................................................... 35Recommendations........................................................................................... 36

Appendix ................................................................................................................. 39

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

GlossaryAIAIHRCANAANPBCCLAEUPOLFCOICCPRICRCIHLISAFKhADMoUNATONGONDSOEFSRSGUNUNAMAUNCATAmnesty InternationalAfghanistan Independent Human Rights CommissionAfghan National ArmyAfghan National PoliceBritish Columbia Civil Liberties AssociationEuropean Union Police Mission in AfghanistanForeign and Commonwealth OfficeInternational Convention on Civil and Political RightsInternational Committee of the Red CrossInternational Humanitarian LawInternational Security Assistance ForceKhadamat-e Etela'at-e Dawlati (or State Information Service)Memorandum of UnderstandingNorth Atlantic Treaty OrganisationNon-Governmental OrganizationNational Directorate of Security*Operation Enduring FreedomSpecial Representative of the Secretary-GeneralUnited NationsUnited Nations Assistance Mission in AfghanistanUnited Nations Convention against Torture

*

Please note the NDS is sometimes referred to as the National Security Directorate (NSD). In this report it is referredto as the NDS throughout.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

AfghanistanDetainees transferred to torture:ISAF complicity?1. IntroductionDetainees held in Afghanistan continue to face torture and other ill-treatment in thecontext of ongoing conflict involving the Afghan government, international militaryforces and armed groups such as the Taleban. Amnesty International (AI) isincreasingly concerned about the fate of many detainees who face the risk of tortureand other ill-treatment when they are transferred to Afghan authorities by theInternational Security Assistance Force (ISAF).AI is particularly concerned about the policy of ISAF states to hand overpeople to the National Directorate of Security (NDS), Afghanistan’s intelligenceservice. AI’s research and the work of others reveal a pattern of human rightsviolations, perpetrated with impunity by NDS personnel.1Scores of NDS detainees,some arrested arbitrarily and detained incommunicado, that is without access todefence lawyers, families, courts or other outside bodies, have been subjected totorture and other ill-treatment, including being whipped, exposed to extreme cold anddeprived of food.AI has been particularly concerned about detention practices in Afghanistansince 2002, including detention by US forces operating under Operation EnduringFreedom (OEF),2and the Afghan prison system in general.3While this report focuseson the detention policy of ISAF states and specific Afghan authorities, AI has alsoraised concerns about failures by all parties to the conflict to meet their international

See sections 5 and 6.See Amnesty InternationalUSA: Memorandum to the US Government on the rights of people in US custody inAfghanistan and Guantánamo Bay(AI Index: AMR 51/053/2002), April 2002; Amnesty International,USA: USdetentions in Afghanistan: an aide-mémoire for continued action(AI Index: AMR 51/093/2005), June 2005, andUSA:Human Dignity Denied: Torture and Accountability in the “War on Terror”(AI Index: AMR 51/145/2004), October 2004.3See Amnesty International,Afghanistan: Justice and rule of law key to Afghanistan’s future prosperity,AmnestyInternational, ASA 11/007/2007, 22 June 07;Afghanistan: Police reconstruction essential for the protection of humanrights,Amnesty International, ASA 11/003/2003;Afghanistan: Crumbling prison system desperately in need of repair,Amnesty International, ASA 11/017/2003, July 2003;Afghanistan: Re-establishing the rule of law,AmnestyInternational, ASA 11/021/2003, August 2003.2

1

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

2

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

obligations – including international military forces, the Afghan Government andarmed groups such as the Taleban.4ISAF’s mandate to operate in Afghanistan stems from UN Security Councilresolution 1386 of 20 December 2001. The resolution emphasises that ISAF should“assist the Afghan Interim Authority in the maintenance of security in Kabul and insurrounding areas.”5As ISAF has expanded to cover the whole country, theimportance of ISAF as a detainee transferring organization has increased and AI hasbeen increasingly troubled by reports of detainees being subjected to torture andother ill-treatment by Afghan authorities.Since early 2007 AI has been investigating the policies of NATO and ISAFstates governing detainee transfers (primarily the use of agreements orMemorandums of Understanding6) and has been documenting cases of torture andother ill-treatment. This report outlines the complexity of detainee transfers inAfghanistan and demonstrates areas of significant concern where AI believes thatthe international community has failed to meet its international obligations,particularly the principle ofnon-refoulementwhich is absolute and allows for noexceptions.AI is not seeking for ISAF to take over the Afghan judicial process, nor doesthe organization believe that the human rights and other challenges in the Afghanjudicial system will be best resolved by a reduction or drawing back fromengagement in the sector. There is a need for the international community, includingISAF states, the UN, the EU with the Afghan government, AIHRC and ICRC to find away to address detainee transfers and the issue of torture and other ill-treatment.The detention system has fallen into the cracks between reforms in thesecurity justice sectors, between army and police recruitment and training, and thereform of the Afghan legal system. Detention is an integral part of any justice systemand the failure to improve conditions and the provision of human rights in it is asymptom of a failure of the international community’s own commitments to promoteand uphold human rights in Afghanistan.Amnesty International is independent of any government, political persuasion orreligious creed. It neither supported nor opposed the war in Afghanistan in OctoberAfghanistan: Amnesty International demands immediate release of all hostages,(AI Index: ASA 11/010/2007), 2August 2007;Afghanistan: Mounting civilian death toll – all sides must do more to protect civilians,AI Index: ASA11/006/2007, 22 June 2007;Afghanistan: All who are not friends, are enemies: Taleban abuses against civilians,(AIIndex: ASA 11/001/2007), 19 April 2007;Afghanistan: NATO must ensure justice for victims of civilian deaths andtorture(AI Index: ASA 11/021/2006), 27 November 2006.5UN Security Council resolution 1386, 20 December 2001.6MoUs and other agreements have been signed between the British, Canadian, Danish, Dutch and Norwegiangovernments and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Several other countries, including Belgium,France, Germany and Sweden are in the process of signing MoUs.4

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

3

2001, and takes no position on the legitimacy of armed struggle against foreign orAfghan armed forces. As in other international or non-international armed conflicts,AI’s focus has been to report on and campaign against abuses of human rights andviolations of international humanitarian law by all those involved in the hostilities.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

4

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

2. ContextOn 7 October 2001, the US-led OEF was launched as a response to the attacks onthe US on 11 September 2001. Security Council Resolution 1368 adopted on 12September 2001 granted international legal authority for OEF, condemning the 11September attacks and affirming the right of states to individual and collective self-defence. OEF aimed at ousting the Taleban government which had provided a safehaven for Osama bin Laden and al-Qa’ida. US forces were supplemented by ISAFforces in 2001.ISAF’s establishment, and its powers of detention, flow from UN SecurityCouncil resolution 1386 of 20 December 2001. In accordance with the BonnAgreement and UN Security Council Resolution 1386, ISAF was established to“assist the Afghan Interim Authority in the maintenance of security in Kabul and insurrounding areas” under Chapter VII of the UN Charter.7ISAF was also allowed to“take all necessary measures to fulfil its mandate”.8This authority was expanded tocover the whole of Afghanistan by UNSC resolution 1510 on 13 October 2003.Just prior to the expansion of ISAF’s mandate NATO, in its first missionoutside of Europe, assumed control over ISAF on 11 August 2003.9The ISAFmission has, in four stages, taken over from the US-led OEF as its geographicalscope has grown from Kabul in 2001 to the entire country by October 2007. ISAFforces initially moved to the north of Afghanistan (October 2004), then to the west(September 2005), then the south (July 2006) and finally took over from OEF forcesin the east in October 2006. At present ISAF is made up of more than 35,000personnel drawing resources from 37 states, including the 26 NATO MemberStates.10ISAF and the remaining OEF forces are co-operating and conducting jointoperations with Afghan security forces, including with the Afghan National Army(ANA), the Afghan National Police (ANP) and the NDS. Due to the lack of ANA forces,ANP and NDS are sometimes deployed to take part in military operations.

See UN Security Council Resolution 1386 of 20 December 2001, referring to annex 1 of the Bonn Agreement. Themission has been subsequently extended and expanded to all Afghanistan. UN Security Council Resolution 1510 on13 October 2003 authorized the expansion of ISAF beyond Kabul. See UN Doc S/Res/1746 (2007). See also UN DocS/Res/1386 (2001), 1413 (2002), 1444 (2002), 1510 (2003), 1563 (2004), 1623 (2005) and 1659 (2006).8Security Council resolution 1386 (2001), paras 1 and 3.9See the analysis in “NATO in Afghanistan: A test of the transatlantic alliance” US Congressional Research Service(CRS), updated 16 July 2007. Introduction available on http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33627.pdf, accessed 26July 2007.10NATO describes itself as leading ISAF. In practice this means that NATO provides administrative and institutionalresources for activities undertaken under ISAF. Taken from the ISAF website at http://www.nato.int/ISAF accessed19 September 2007.

7

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

5

Between 2002 and 2005 ISAF forces normally handed over detainees to OEFforces. As ISAF expanded and eventually became larger than OEF, ISAF forces,from 2005, began to transfer detainees directly to the Afghan authorities. At the timeNATO received advice that the NDS was the most appropriate institution for it totransfer detainees to.AI’s primary concern is that by trying to fulfil its detention mandate, andsupporting Afghan sovereignty by transferring detainees to Afghan authorities, ISAFstates are in breach of their international obligations not to send a person in to asituation where they are at substantial risk of torture or other ill-treatment.The centrality of human rights is included in ISAF’s UN mandate and in otherinternational agreements about international engagement in Afghanistan. The UNSecurity Council resolution establishing ISAF stressed that “all Afghan forces mustadhere strictly to their obligations under human rights law…and under internationalhumanitarian law.”11ISAF’s mandate is to “to assist the Afghan Interim Authority inthe maintenance of security”12It is therefore clear that ISAF forces must themselves,at the very least, adhere strictly to the same international legal obligations.The two international agreements on the future of Afghanistan - the BonnAgreement and the Afghanistan Compact - include clear international human rightsobligations. Thus the Bonn Agreement provides for the establishment of theAfghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission,13as well as providing, inArticle V(2):“TheInterim Authority and the Emergency Loya Jirga shall act in accordancewith basic principles and provisions contained in international instruments onhuman rights and international humanitarian law to which Afghanistan is aparty.”14The Afghanistan Compact lists “Governance, Rule of Law and Human Rights”among the “three critical and interdependent areas or pillars of activity for the fiveyears from the adoption of this Compact”.15The Compact provides, among otherthings, that by 2010:“Governmentsecurity and law enforcement agencies will adopt correctivemeasures including codes of conduct and procedures aimed at preventing

1112

UN Security Council Resolution 1386 (2001), 20 December 2001, Preamble.Ibid.,para. 1.13Agreement on Provisional Arrangements in Afghanistan Pending the Re-establishment of Permanent GovernmentInstitutions, signed 5 December 2001, http://www.undp.org.af/bonnagreement.htm, para. III(6).14Ibid.,para. V(2)15Afghanistan Compact between the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and the international community, London,February 2006, p. 2.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

6

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

arbitrary arrest and detention, torture, extortion and illegal expropriation ofproperty with a view to the elimination of these practices;”16The Bonn agreement is mentioned in Security Council Resolution 1386,further underlying the undertaking of the international community to place protectionof respect for human rights at the centre of international efforts to help rebuildAfghanistan and maintain its security.

16

Ibid.,p. 8.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

7

3. The international legal frameworkAI is concerned that ISAF states are breaching their international obligations byhanding over detainees to the NDS where detainees are at grave risk of torture andother ill-treatment. In order to address the legal aspects of this issue it is necessaryto understand the legal framework in which international forces operate inAfghanistan.According to the ICRC, the international armed conflict in Afghanistan endedwith the establishment of the transitional government in June 2002. Until that time,according to the ICRC “Persons detained in relation to an international armed conflictinvolving two or more states as part of the fight against terrorism – the case withAfghanistan until the establishment of the new government in June 2002 - areprotected by International Humanitarian Law (IHL) applicable to international armedconflicts […]”.17With the establishment of the transitional government, the armed conflictbecame one “not of an international character.”18All parties to a non-internationalarmed conflict are obliged, as a minimum, to apply Article 3 common to the fourGeneva Conventions. In addition, many of the provisions of internationalhumanitarian law treaties have become rules of customary international law, that is,rules derived from consistent state practice and consistent consideration by statesthat they are bound by these rules. Such rules apply to all states regardless of treatyobligations. Certain rules originally formulated for international armed conflict are nowunderstood to bind parties to non-international armed conflict as well. In the contextof the conflict in Afghanistan, Common Article 3 of the four Geneva Conventions andthe relevant rules of customary international humanitarian law continue to apply, asdo the rules of international human rights and domestic law.

3.1. International Humanitarian LawThe standards of humane treatment set out by international humanitarian law(IHL) are binding on all parties in any armed conflict, whether international or non-international. It is a fundamental rule of IHL that all those taking no active part in theconflict (including civilians not participating in hostilities and captured, surrenderedand wounded combatants) must be treated humanely. Torture, cruel or inhumantreatment and outrages upon a persons dignity, in particular humiliating anddegrading treatment, are prohibited. This basic rule is explicitly reflected in a numberof IHL treaties.17

See ICRC, “International humanitarian law and terrorism: questions and answers,” (Accessed 16 May 2007)available at http://www.icrc.org/Web/eng/siteeng0.nsf/iwpList488/0F32B7E3BB38DD26C1256E8A0055F83E18Article 3(1) common to the four Geneva Conventions.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

8

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

Torture is a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions, which obliges highcontracting parties to “search for” persons suspected of committing such crimesregardless of their nationality and prosecute them in their own national courts orextradite them to where they would face prosecution.19Torture in all contexts,including non-international armed conflict, is also a crime of universal jurisdiction -any state must, under customary international law, do one of the following forsuspected perpetrators of torture, even where the suspects are neither nationals norresidents of the state concerned, and the crime did not take place in its territory: (1)bring such persons before its own courts, (2) extradite such persons to any stateparty willing to do so or (3) surrender such persons to an international criminal courtwith jurisdiction to try persons for these crimes. Torture may also constitute a crimeagainst humanity or a war crime under the jurisdiction of the International CriminalCourt.20

3.2. International human rights lawInternational human rights law applies at all times, in war time or peace.21Human rights law is contained in treaties including the International Convention onCivil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the UN Convention against Torture (UNCAT),to which Afghanistan and all ISAF states are states parties. While some rightsguaranteed by international human rights treaties can be subject to derogation duringtimes of public emergency, the right to freedom from torture and other ill-treatment isnon-derogable.Article 4 of the ICCPR provides that even “[I]n time of public emergency whichthreatens the life of the nation” states may not derogate from the prohibition ontorture and other ill-treatment in Article 7 of that Covenant.In a General Comment on this article, the UN Human Rights Committeereaffirmed that certain rights prescribed in the ICCPR could never be curtailed in anemergency, including the prohibition on torture or cruel, inhuman or degradingtreatment or punishment (Article 7), the right to be treated with humanity and dignitywhen deprived of liberty (Article 10); the prohibitions on hostage-taking, abductionsand unacknowledged detention; and deportation or forcible transfer of populationswithout a valid international legal basis (Article 12).22Other provisions mentionedinclude the right to an effective remedy (Article 2(3)) and the right to proceduralSee, Fourth Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Times of War, 12 August 1949,arts. 146, 147.20Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, 1998 UN Doc. 2187 UNTS 90, entered into force 1 July 2002,arts. 7(1)(f), 8(2)(ii), 8(2)(i-ii). See also the International Law Commission’s Draft Code of Crimes Against the Peaceand Security of Mankind, arts. 8, 9.21See for instance Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, AdvisoryOpinion of 9 July 2004, ICJ Reports 2004, para. 106. See also Human Rights Committee, General Comment 31 onArticle 2 of the Covenant: The Nature of the General Legal Obligation Imposed on States Parties to the Covenant(2004), para. 11.22UN Human Rights Committee, General comment no. 29: States of emergency (article 4), para. 13.19

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

9

guarantees with regard to non-derogable rights (i.e. to a fair trial when facing thedeath penalty).23

•

The principle ofnon-refoulement

Under international law, and as part of the absolute prohibition on torture andother ill-treatment, states must never expel, return or extradite a person to a countrywhere they risk torture or other ill-treatment – the principle ofnon-refoulement.This isa rule of customary international law applicable to all states.Article 3(1) of the UNCAT provides;“No state shall expel, return (“refouler”) or extradite a person to another Statewhere there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in dangerof being subjected to torture.”Moreover, Article 3(2) requires a sending government to take intoconsideration the existence of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rightswhen assessing the risk of torture.Under Article 1 of the UNCAT, the obligations of states parties also extend toofficial complicity in, consent or acquiescence to acts of torture. Article 4 of UNCATrequires all State Parties to prohibit participation and complicity in torture.24Additional obligations can be found in the rules of state responsibility, whereby astate may be in breach of its international obligations where it knowingly assists inthe unlawful act of another state.25The absolute prohibition on transferring detainees to where they risk torture orother ill-treatment is more than a narrow, technical, procedural requirement involvingthe transfer of detainees across borders, or between states. Rather, it is part andparcel of the prohibition on torture and other ill-treatment itself. As the Human RightsCommittee (HRC) has emphasised:“No person, without any exception, even those suspected of presenting adanger to national security or the safety of any person, and even during astate of emergency, may be deported to a country where he/she runs the riskof being subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”26Ibid,paras. 14 and 15.Convention Against Torture Art 4(1): “Each State Party shall ensure that all acts of torture are offences under itscriminal law. The same shall apply to an attempt to commit torture and to an act by any person which constitutescomplicity or participation in torture.”25See Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, adopted by the International LawCommission in its 53rd session (2001), UN Doc. A/56/10 (supplement 10), ch..IV.E.1, 12 December 2001, arts. 16-17.26Concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee: Canada, UN Doc. CCPR/C/CAN/CO/5, 2 November2005, para. 15.2423

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

10

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

The fact that the HRC made this statement while commenting on Article 7 ofthe ICCPR, which has no explicit provision fornon-refoulement,further underlinesthe absolute nature of the prohibition on transferring detainees to where they risktorture or other ill-treatment. The same rule applies to the prohibition on torture andother ill-treatment, or the corollary obligation that detainees (and others) “shall in allcircumstances be treated humanely” as provided in international humanitarian law ingeneral, and Common Article 3 in particular.States’ obligation not to torture or ill-treat detainees extends to the conditionsin which, or to which, detainees are released or transferred. A state cannot claim tobe treating detainees humanely while knowingly handing them over to torturers – bethey within one state outside it, citizens of the same state or officials of another -anymore than it can knowingly ‘release’ detainees in a minefield and claim that theirsafety is no longer its responsibility. In both cases international law obliges states totransfer or release detainees to a safe environment.In a legal opinion prepared for the UNHCR in 2001, Elihu Lauterpacht andDaniel Bethlehem expressed this principle clearly, describing “the essential contentof the principle ofnon-refoulementat customary law” as follows:“No person shall be rejected, returned or expelled in any manner whateverwhere this would compel them to remain in or return to a territory wheresubstantial grounds can be shown for believing that they would face a realrisk of being subjected to torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment orpunishment. This principle allows of no limitation or exception.”27The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture similarly called on governments to respecttheir obligation to prevent acts of torture and other ill-treatment “by not bringingpersons under the control of other States if there are substantial grounds forbelieving that they would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”28

Sir Elihu Lauterpacht and Daniel Bethlehem,The Scope and Content of the Principle of Non-refoulement,Opinionfor UNHCR’s Global Consultations, UNHCR, June 2001, para. 253. See also, for instance, Guy S. Goodwin-Gill,TheRefugee in International Law(Oxford: OUP, 1996), pp. 167-170; Jean Allain, “TheJus cogensNature of Non-refoulement,” 13IJRL538 (2001).28Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture Theo van Boven to the General Assembly, UN Doc. A/59/324, 1September 2004, para. 27. In 2005, the Rapporteur explicitly criticized attempts by states to circumvent the absolutenature of the prohibition on torture and other ill-treatment in the name of countering terrorism, including “returningsuspected terrorists to countries which are well-known for their systematic torture practices.” See Statement of theSpecial Rapporteur on Torture, Manfred Nowak, to the 61st Session of the U.N. Commission on Human Rights,Geneva, 4 April 2005.

27

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

11

4. Memorandums of Understanding betweenISAF and the Afghan authoritiesIn order to put the ISAF’s UN Security Council mandate into operation, NATOestablished an Operational Plan. The Operational Plan agreed between NATO andthe Afghan government, among other issues, provides that ISAF forces hand overdetainees to Afghan authorities within 96 hours. Officials at NATO Headquartershave informed AI that exceptions to the 96 hour rule are primarily in cases where adetainee is receiving medical treatment.29ISAF states, as the legal state entity, are able to set their own conditions foroperating within the framework of NATO’s Operational Plan. A number of ISAF statestook the view that the Operational Plan provisions for detainee transfer were toogeneral, and subsequently concluded MoUs and other agreements specificallyaddressing the issue of detainee transfers.The UK MoU states, for example, that the UK can only detain persons “forforce protection, self-defence, and the accomplishment of mission in so far as isauthorized by relevant UN Security Council resolutions”. It goes on to say that “[t]hepurpose of the Memorandum is to…ensure that Participants will observe the basicprinciples of international human rights law”.30However issues remain with such MoUs and similar agreements, not leastbecause they do not specify to which Afghan institution detainees will be transferredto nor address how the Afghan system will separate the functions of interrogation anddetention. AI has been able to establish that most detainees are passed on to theNDS, either directly or through another agency such as the ANA or ANP.NATO officials have asserted that at the moment of the handover to theAfghan authorities, ISAF’s responsibility for the detainee ends and responsibilityshifts to the state that has chosen to hand over the detainees..At a national level theCanadian government has confirmed that it has a “residual responsibility” after thedetainees are handed over but has declined to say what that residual obligation is.31

It was also emphasized that NATO forces are encouraged to hand over detainees as soon as possible and that inmost cases detainees are handed over before the 96 hour limit. Interview with NATO Officials, NATO HQ (Brussels),27 April 2007.30Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and NorthernIreland and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan concerning transfer by the United Kingdom ArmedForces to Afghan Authorities of persons detained in Afghanistan, para. 1c and 2.1.31Statement by Canadian Forces’ Colonel Neil Anderson during an interview on CBC Radio One, The Current, 10April 2006.

29

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

12

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

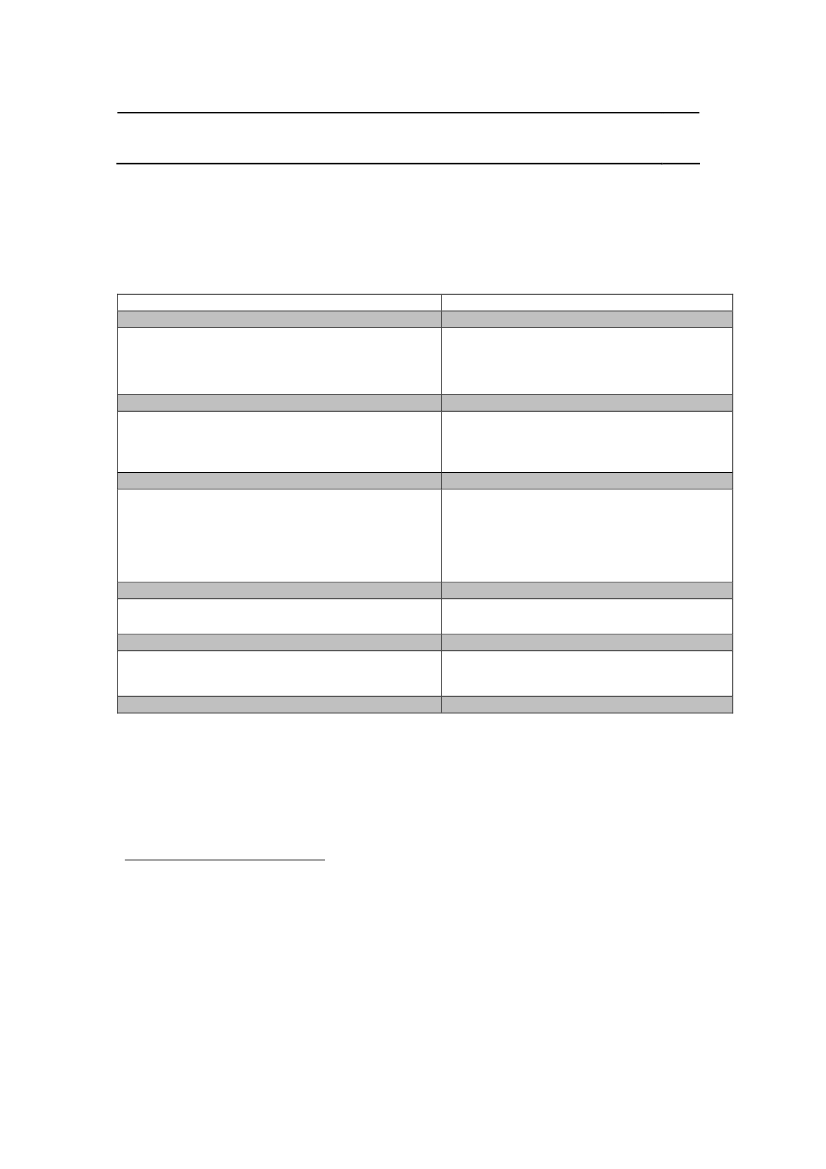

Memorandums of Understanding and other agreements between the AfghanGovernment and ISAF states: some common elements*••••focus on the hand over of detainees by respective NATO/ISAF states to unspecified“Afghan authorities”;provide that Afghan authorities will accept the transfer of detainees from detaining countryforces, and Afghan authorities will keep records of transferred detainees;provide that the signatories treat detainees in accordance with international law includinghuman rights and humanitarian law (the UK only specifies human rights law);provide that representatives of the respective ISAF state, the International Committee forthe Red Cross (ICRC), the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC)have access to the detainees after they have been handed over (the Dutch add relevantUN bodies to this list, and the Norwegian MoU limits it only to the AIHRC);provide that the ISAF state will be notified prior to the initiation of legal proceedingsagainst, release or transfer to a third country of the detainee (with the exception ofCanada);provide that no person transferred will be subject to the death penalty.

••

* AI has examined the MoUs and other agreements signed between the British, Canadian, Danish, Dutch andNorwegian governments and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.

In the course of legal action against the Canadian government by AmnestyInternational-Canada and the British Colombia Civil Liberties Association (see boxbelow), the arrangement between the Canadian government and the Afghangovernment has been closely scrutinized. As a result of the legal proceedings, theCanadian government negotiated a second arrangement, strengthening referencesto monitoring the conditions of detention and treatment of detainees after transferand emphasizing Canada’s commitment to supporting rule of law and justice inAfghanistan. While these changes are an improvement, AI believes that Canada’scontinued reliance on MoUs concerning the treatment of detainees, with occasionalmonitoring of the MoU’s implementation, is not sufficient to meet international legalrequirements.Central to this conclusion is that monitoring is a technique to detect tortureonly after it happens, and cannot substitute for prior precautions that prevent torturefrom happening in the first place. In other words, monitoring detects thetransgressions, but does not forestall them. As such, monitoring cannot meetCanada’s absolute legal obligation to prevent torture, although it can be helpful toinform Canada should Afghanistan breach its obligations to prevent torture and otherill-treatment. Canada’s Foreign Minister has confirmed that in a period of a fewmonths, Canadian monitors detected instances where detainees alleged torture—further evidence that Afghan custody and a substantial risk of torture are inseparabledespite Canadian efforts at monitoring.3232

Murray Brewster, “Canadians hear six claims of torture from Afghans”,Globe and Mail (Toronto),8 June 2007;Bruce Campion-Smith, “MacKay admits 6 Afghan abuse allegations exist”,Toronto Star,9 June 2007.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

13

Legal action in CanadaAmnesty International Canada (AI-Canada), in conjunction with the British Columbia CivilLiberties Association (BCCLA) has challenged the Canadian government’s policy of handingover detainees to the Afghan authorities in the Canadian courts. Over the past five years AI-Canada has repeatedly called on the Canadian government to substantially revise its policyon the handling of detainees apprehended in the course of military operations in Afghanistanand has outlined serious human rights concerns, including torture and other ill-treatment, bothwith respect to the practice that was in place between 2002 and 2005 of transferringdetainees into the custody of US forces in Afghanistan, and the more recent practice, in place33since December 2005, of also transferring detainees into the custody of the Afghanauthorities.In February 2007, AI-Canada and the BCCLA filed an application in the Federal Court ofCanada seeking an order that the practice of transferring detainees cease and that Canada34locate and account for detainees it has already transferred.AI considers that the outcome of the case will be of international significance as the approachchosen by the Canadian government is in conformity with current NATO policy and similar tothe approach chosen by other ISAF states.

4.1. The failure of MoUs to protectAt the time the first MoUs were signed in 2005, ISAF states may haveentertained high expectations regarding the Afghanistan government’s treatment ofits detainees, and the MoUs arose from a clearly legitimate need to regulate a newbilateral – and multilateral – situation created by the involvement of armed forces ofthese states in the non-international armed conflict within Afghanistan.35NATO andISAF states were advised that the NDS presented the best long term option forreceiving transferred detainees.36Had Afghanistan complied with its international obligations regarding thetreatment of detainees, each MoU would have been no more than an essentiallytechnical arrangement between states abiding by their international legal obligations,in which was included a general reiteration of these obligations. Arrangements forextra precautions, such as monitoring by diplomatic and military staff from ISAFstates, would have been a welcome addition.However, AI remains gravely concerned that detainees handed over by ISAFto the Afghan authorities are currently at substantial risk of torture and other ill-treatment. AI reiterates that, in these circumstances, the undertaking by the Afghan33

Arrangement for the transfer of detainees between the Canadian forces and the Ministry of Defence of the IslamicRepublic of Afghanistan adopted 18 December 2005. Arrangement for the transfer of detainees between theCanadian forces and the Ministry of Defence of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, adopted 3 May 2007.34Amnesty International Canada and British Columbia Civil Liberties Association v. Chief of the Defence Staff for theCanadian Forces, Minister of National Defence and Attorney General of Canada,Federal Court file number T-324-07.35For further discussion on the non-international status of the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan please see section 3.36Meeting between NATO officials and Amnesty International representatives, Brussels, 8 October 2007

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

14

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

government in the various MoUs to treat detainees handed over by ISAF states inaccordance with international law cannot and does not absolve these nations of theirlegal obligation not to transfer a persons to a situation “where there are substantialgrounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”37Onlyonce it can safely be assessed that no such risk actually exists may ISAF stateshand over detainees without violating this obligation. AI is gravely concerned that thisis currently not the case.AI has reviewed the Canadian, Danish, Dutch, Norwegian and UK MoUs andother agreements concluded with the Afghan Ministry of Defence. These agreementsaim to give the Afghan government control over detainees in its territory. They alsoensure a clear distinction between the ISAF mission and the detention of Afghansand others in the US detention centre at Bagram airbase outside Kabul.38They alsoestablish that detainees are supposed to be treated in accordance with internationalstandards. For example, the arrangement between the Canadian and Afghangovernments provides the assurance that “the participants will treat detainees inaccordance with the standards set out in the Third Geneva Convention.”39In the current situation, there is little to distinguish these agreements from thepractice of seeking ”diplomatic assurances”, used in other contexts as a disclaimeraimed at absolving the responsibility of the state transferring detainees to stateswhere torture and other ill-treatment occur. This practice has been widelycondemned by international human rights bodies40as well as human rights NGOs.41While in both cases the agreements may seek to ensure that detainees arenot tortured or otherwise ill-treated, they have failed to do so. They also constitute arecognition that the state from which assurances are sought has failed in the past tolive up to existing international legal obligations, and that this flouting of internationalobligations will continue, at least as far as those detainees not covered by the“assurances” are concerned.UN Convention against Torture, Article 3.The distinction from detainees held by the US, under Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), is important because theISAF and OEF operations operate under different mandates. As such the Afghan Government engages with the twointernational military operations separately, and through different legal instruments. Amnesty has separately raisedconcerns about practices by US forces at Bagram such asGuantánamo and beyond: The continuing pursuit ofunchecked executive power,(AI Index: AMR 51/063/2005).39Arrangement for the transfer of detainees between the Canadian Forces and the Ministry of Defence of the IslamicRepublic of Afghanistan, para. 3, 18 December 2005. This quote refers to the first MoU signed between Canada andAfghanistan. It remains in force and the MoU signed on 3 May 2007 is considered as additional.40See for instanceCommittee Against Torture, Communication No. 233/2003, Agiza v. Sweden,20 May 2005. Seealso Human Rights Committee, Communication No 1416/2005.Alzery v. Sweden,10 November 2006. UN Doc.CCPR/C/88/D/1416/2005; Council of Europe, Group of Specialists on Human Rights and the fight against Terrorism,29 -31 March 2006, Statement by the High Commissioner,http://www.unhchr.ch/huricane/huricane.nsf/view01/C19C689539C57EABC1257146002CE1B9?opendocument.41See for instance Amnesty International,‘Diplomatic assurances’ – No protection against torture or ill-treatment,(AIIndex: ACT 40/021/2005), December 2005; and Human Rights Watch, “Empty promises: Diplomatic assurances nosafeguard against torture”, April 2004.3837

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

15

4.2. Monitoring detention: An insufficient safeguardAI is concerned that some ISAF states appear to regard the inclusion, withinMoUs and other bilateral agreements with the Afghan Government of arrangementsto monitor transferred detainees as sufficient to fulfil their international obligations toensure that they do not transfer detainees to a situation where they are at risk oftorture or other ill-treatment. AI is aware of a number of challenges to effectivemonitoring that, in practice, undermine this assumption.In a number of cases, while transferring countries have negotiated access tothe detainees for their representatives, they have not committed to a systematicmonitoring of all detainees that they transfer.For example the Arrangement between the Canadian and Afghangovernments provides that:“the Afghan authorities will accept (as Accepting Power) detainees who havebeen detained by the Canadian Forces (the Transferring Power) and will beresponsible for maintaining and safeguarding detainees, and for ensuring theprotections provided in Paragraph 3, above [referring to the Third GenevaConvention], to all such detainees whose custody has been transferred tothem.”42A supplementary agreement between the Canadian and Afghan governmentsestablishes that Canadian officials will notify the Afghan Independent Human RightsCommission of any such transfers.43Another agreement, between the UK government and the Afghan government,provides that “representatives of the Afghanistan Independent Human RightsCommission [AIHRC], and UK personnel… and others as accepted between theParticipants, will have full access to any persons transferred by the UK A[rmed]F[orces] to Afghan authorities whilst such persons are in custody.” The agreementalso states that the ICRC and other relevant institutions” will be allowed to visit suchpersons” and that the UK will notify the ICRC and the AIHRC within 24 hours of thetransfer.44Arrangement for the Transfer of Detainees between the Canadian Forces and the Ministry of the Islamic Republicof Afghanistan, para 5 18 December, 2005. The Arrangement signed on 3 May 2007 also adds, “the Afghanauthorities will be responsible for treating such individuals in accordance with Afghanistan’s international humanrights obligations including prohibiting torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment…” Arrangement for theTransfer of Detainees between the Canadian Forces and the Ministry of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, para 4,3 May 2007.43Letter from Brig General TJ Grant to the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, Kandahar Office, 20February 2007.44Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and NorthernIreland and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan concerning transfer by the United Kingdom ArmedForces to Afghan Authorities of persons detained in Afghanistan, para. 4.1 and para 5.142

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

16

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

In addition, Article 38 of Afghanistan’s Prison law (2005) allows a number ofinstitutions, including the AIHRC, access to some detention centres without priornotice to the Ministry of Justice. However, the law is not applicable to NDS detentioncentres. In response, the ICRC and the AIHRC have concluded bilateral agreementswith the NDS allowing for monitoring of NDS detention centres.45In practice, however, even the monitoring safeguards contained in suchagreements are not met. The AIHRC has indicated that it has often been deniedaccess to detention centres run by the NDS, and lacks the resources and capacity tocarry out extensive monitoring. An AIHRC Commissioner stated that “the AIHRC hasmonitored NDS detention centres, but we had to contact them in advance. It is notfree access, although recently we received a letter signed by the head of NDS toprovide access to AIHRC’s monitors, but this is not happening at the moment…inKandahar, we have not [been] provided [with] full access and still we don’t feelconfident about their full cooperation.”46While access by AIHRC monitors to NDS detention centres has improved, theissue of whether or not they are able to visit without prior notice differs depending onthe prisons and the detainees they are trying to visit. There are reportedlyconsiderable differences between AIHRC’s access in Kabul compared with NDSdetention centres in the provinces. Furthermore, insecurity in some areas of thecountry, particularly the south, restrict the commission’s access to Helmand, Uruzganand Zabul provinces.AIHRC staff members have reportedly expressed concern that they do nothave the capacity to respond the volume of detention cases they seek to monitor.47In response the Canadian government has recently made a special financialcontribution to the AIHRC to build the capacity of the commission’s nationalmonitoring section.The role of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) inmonitoring is also significant given its UN mandate “to continue to work towards theestablishment of a fair and transparent justice system, including the reconstructionand reform of the correctional system” and more specifically “to continue to contributeto human rights protection and promotion, including monitoring of the situation ofcivilians in armed conflict.”48UNAMA is one of the organisations who have raised serious concerns aboutthe treatment of detainees by the NDS. UNAMA has initiated at least one programme4546

Articles 13 and 30, Law on Prisons and Detention Centers, Ministry of Justice, 31 May 2005.Email exchange between Amnesty International and AIHRC, 14 March 2007 and 25 March 2007.47Information and quote from Graeme Smith, ‘We Can’t Monitor these People’,The Globe and Mail,24 April 2007.48Security Council resolution 1746 (2007) paras. 4 and 13.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

17

with the NDS, alongside the AIHRC to provide human rights training to NDSofficers.49Given the mandate of UNAMA and its resources it is appropriate forUNAMA to expand its support for the AIHRC in gaining access to NDS detentioncentres.The ICRC also monitors Afghan detention centres, including those run by theNDS and, when relevant, informs the Afghan government about its findings. Howeveras noted above it has not been possible for the ICRC to monitor all NDS prisons, orall prisons managed by the Ministry of Justice because of unstable securityconditions.50AI is concerned that provisions in the MoUs governing monitoring are onlyimplemented in part. More fundamentally, the organisation emphasises that - evenwhere carried out by a professional, independent and dedicated organization - visitsto places of detention, while constituting a crucial element in the prevention of tortureand other ill-treatment, are far from being sufficient on their own. These concerns arereinforced by the experiences of the ICRC in Iraq and Guantánamo Bay – and indeedin relation to Bagram in Afghanistan, where torture and other ill-treatment wereinflicted extensively despite ICRC’s regular visits, monitoring of reported abuse andrelaying of concerns.51In this regard, AI recognizes that the ICRC does not claim that visits by itsstaff to places of detention are all that are needed to safeguard against torture andother ill-treatment, and have refused to take part in monitoring “diplomaticassurances” because of their discriminatory nature, as seen above.52“The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security” Report of the UN Secretary-General, S/2007/152, para. 41, 15 March 2007. "A joint AIHRC and UNAMA arbitrary detention monitoring campaignbegan in October 2006 throughout Afghanistan with the cooperation of the Ministries of Justice and the Interior andthe Office of the Attorney General. Initial findings indicated that in a significant proportion of cases pre-trial detentiontimelines had been breached, suspects had not been provided with defence counsel, and ill-treatment and torturehad been used to force confessions. Access to the National Directorate of Security and Ministry of the Interiordetention facilities remained problematic for the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission and UNAMA.”50The ICRC has not for instance been able to monitor 11 of the 33 provincial prisons administered through theministry of Justice because of insecurity. The Provincial Prisons of Afghanistan: Technical assessment andrecommendations regarding the state of the premises and of the water and sanitation infrastructure, follow-up report,ICRC March 200751“On 29 March 2005, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the only international organization withaccess to detainees held by the USA in Guantánamo and Afghanistan revealed that, more than three years into the"war on terror", it remained concerned that its "observations regarding certain aspects of the conditions of detentionand treatment of detainees in Bagram and Guantánamo have not yet been adequately addressed".(300) It hascharacterized these issues as "significant problems".(301) For its part, Amnesty International is concerned that in the"war on terror" the USA has systematically violated the rights of those it has taken into custody, including the right ofall detainees to be treated with respect for their human dignity and to be free from cruel, inhuman or degradingtreatment. In some cases, the treatment alleged has amounted to torture.”Guantánamo and beyond: The continuingpursuit of unchecked executive powerp.83 section 12, AMR 51/063/200552The ICRC has developed a set of pre-conditions without which it would refuse to visit detainees. One of these is “tosee all prisoners who come within its mandate and to have access to all places at which they are held.” See ICRCwebsite, http://www.icrc.org/Web/Eng/siteeng0.nsf/iwpList265/929018E28243CCB0C1256B6600600D8C, accessed28 October 2005.49

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

18

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

AI remains concerned that provisions for monitoring within the MoUs, as withother forms of diplomatic assurance regarding torture and other ill-treatment, oftenappear to be overstated, mistaken or misunderstood. The organization believes thatwhere torture and other ill-treatment is occurring, as in the Afghan detention system,occasional or periodic visits from monitors will not be able to provide sufficientprotection on their own.AI has long advocated for a 12 point plan in order to prevent torture and otherill-treatment (included in appendix) and believes that monitoring can play aconstructive role, but the limitations of monitoring as a protective measure should berecognised.

4.3. The need for redressWhile the MoUs ensure access to detainees, in differing degrees, byorganizations such as the AIHRC, ICRC and the UN, they include no means ofredress in cases where torture or other ill-treatment do take place. Under Article 12 ofthe UN Convention against Torture, every state party must “ensure that its competentauthorities proceed to a prompt and impartial investigation, wherever there isreasonable ground to believe that an act of torture has been committed in anyterritory under its jurisdiction.”53Of the five countries with agreements regarding detainee transfer, only thesecond Canadian agreement specifies provisions for investigation into allegations oftorture or other ill-treatment.54However AI fears that investigations by the Canadiangovernment into allegations may not have been “competent” and “impartial”.55Under both the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)and the UN Convention against Torture, victims of torture and other ill-treatment havethe right to “effective remedy” or “redress”, including “fair and adequate

In its conclusions and recommendations on the UK in 2004 the UN Committee against Torture addressed the issueof the extra-territorial application of the UN Convention against Torture. The Committee expressed concern over theUK’s “limited acceptance of the applicability of the Convention to the actions of its forces abroad, in particular itsexplanation that "those parts of the Convention which are applicable only in respect of territory under the jurisdictionof a State party cannot be applicable in relation to actions of the United Kingdom in Afghanistan and Iraq"”; TheCommittee rejected this approach, observing that “the Convention protections extend to all territories under thejurisdiction of a State party and considers that this principle includes all areas under thede factoeffective control ofthe State party's authorities”. See UN Committee Against Torture, Conclusions and Recommendations: UnitedKingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland - Dependent Territories, UN Doc. CAT/C/CR/33/3, 10 December 2004,para. 4(b).54Arrangement for the Transfer of Detainees between the Canadian Forces and the Ministry of the Islamic Republicof Afghanistan, para 10, 3 May 2007.55Under cross examination conducted 11 July, 2007 in Federal Court file number T-324-07, Scott Proudfoot from theCanadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, was only able to say that it was “their impression”that the investigations were “thorough and serious and independent”.

53

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

19

compensation.”56The right to redress, or reparations, for victims of human rightsviolations includes the following components:•••••Restitution,for instance release (of detainees and prisoners), restoration oflegal rights and return of property;Compensation,including for physical or mental harm, lost opportunities,harm to reputation or dignity and legal and medical costsRehabilitation,including medical and psychological care, legal and socialservices, and social reintegrationSatisfaction,including cessation of continued violations, disclosure of thetruth (without causing further harm), search for victims who have been forciblydisappeared or killed, and an apology for the wrong done.Guarantees of non-repetition,including steps to ensure effective civiliancontrol of military and security forces and that all civilian and militaryproceedings abide by international standards of due process, fairness andimpartiality, and strengthening the independence of the judiciary

None of these are specifically referred to in the MoUs.

56

See Articles 2(3)(a) of the ICCPR and 14(1) of the UN Convention against Torture, respectively.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

20

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

5. Transfers and torture"We cannot rule out that torture is going on"57The following section addresses a number of issues raised by ISAF’s detaineetransfer policies. Concerns relate to a range of situations including when transferreddetainees have allegedly been tortured by the Afghan authorities; when governmentsare concerned that transferred detainees may have been tortured; and whengovernments, having exposed transferred detainees to the risk of torture and other ill-treatment cannot track or trace them.In examining ISAF detention procedures, Amnesty International has focusedparticularly on the ISAF practice of handing over the majority of detainees to the NDS.While recognising that a minority of detainees are transferred to other Afghanagencies, AI has particular concerns about the frequency and scope of torture andother ill-treatment perpetrated by NDS personnel, as illustrated by the three casesbelow.Additionally, to demonstrate that torture, other ill-treatment, and arbitrarydetention of persons, does not relate only to detainees arrested and transferred byinternational forces, concerns relating to arrests carried out solely by the NDS arealso highlighted.

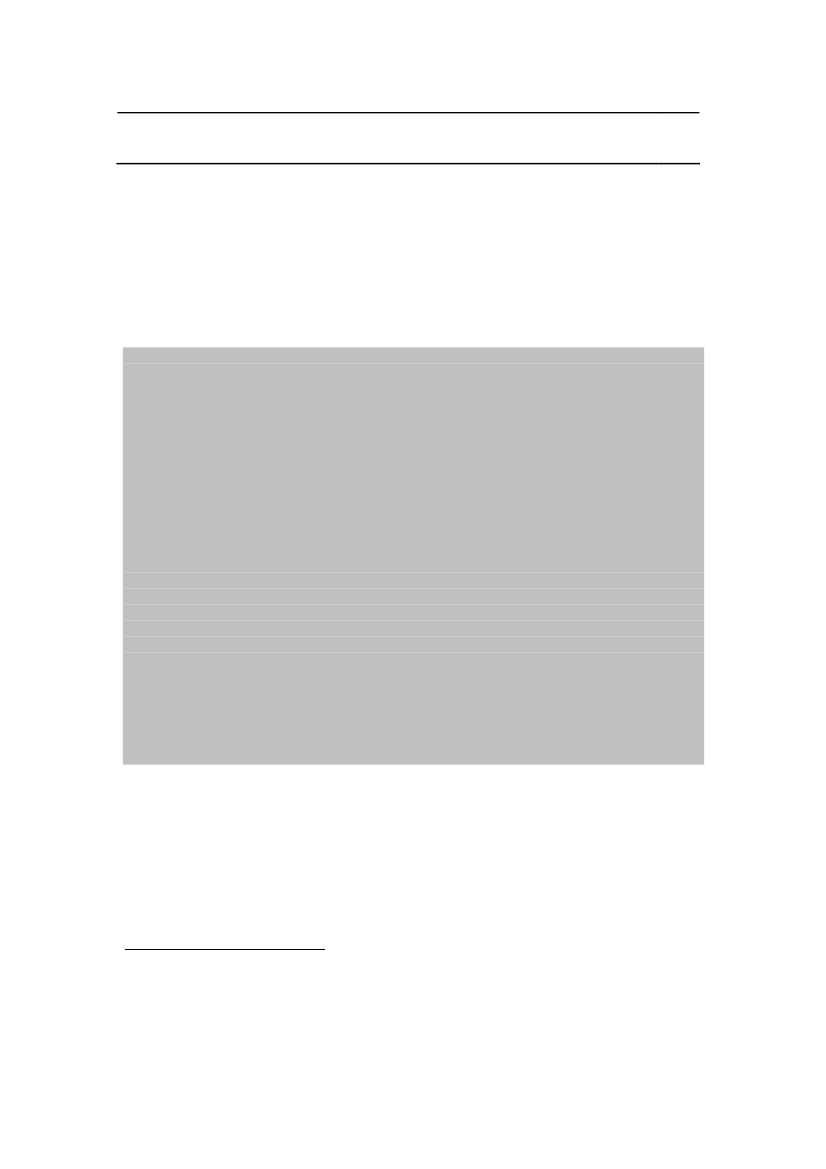

5.1. Detainees handed over by foreign forcesFive ISAF states have MoUs with the Afghan Government regarding detaineetransfers. A further four are actively seeking an MoU.58Of the remaining 14 ISAFstates with more than 100 personnel in Afghanistan, four have confirmed to AI thatthey do not have an MoU, while the remainder refused to comment or were unable toverify the existence of an MoU (see table below for a full list of countries).59Individual governments have responded in different ways to the issue ofdetainee transfers. These have included downplaying the number of transfers thatoccur, either by not revealing the true extent of their transfers (i.e. Canada), notkeeping an accurate record themselves (i.e. Belgium and Norway); by failing to takeaccount of the large number of people transferred in the field – who are neverLiv Monica Stubholt, Ministry of Foreign Affairs interviewed by the Norwegian News Agency NTB, 27 July 2007.Two countries, Estonia and Australia, have MoUs with a second ISAF state, the UK and Netherlands respectively.Individuals detained by Estonia and Australia are handed over to the respective ISAF force before being handed overto the Afghan Government.59Information regarding the transfer of detainees from US forces is also not considered here due to complicationswith the mandate and operating procedures of Operation Enduring Freedom.5857

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

21

recorded as having been in the custody of international forces (this mainly includesforces involved in heavy fighting such as the British, Canadian and Dutch forces)60and finally some governments have struggled with providing adequate independentmonitoring of the detainees they have transferred (particularly the British and theDutch).Table 1: ISAF states and detainee transfersStatus of MoU61

CountriesCanada,Denmark,Norway, UKtheNetherlands,

Governments with signed MoUs or agreementswith the Afghan government regarding thetransfer of detainees

Governments pursuing an MoU or agreement withthe Afghan government regarding the transfer ofdetaineesGovernments who have an agreement with asecond ISAF state regarding the transfer ofdetainees. Detainees are then transferred fromthe second ISAF state (the UK or Dutch) to theAfghan authorities as per their MoUs.

Belgium, France, Germany, Sweden

Estonia (with the UK), Australia (with theNetherlands)

Governments with no agreement or MoU

Lithuania, Poland, Italy, Portugal, CzechRepublic

Governments unable to verify the presence of anMoU

Bulgaria, Macedonia

AI is concerned that the number of detainees transferred, and thereby placedat grave at risk of torture and other ill-treatment, may be significantly higher thanformerly reported by ISAF states. The organization believes that incomplete recordsof arrest and transfers are reflective of broader weaknesses in comprehensivemonitoring of detainees following their transfer.

In-field transfers occur when International Forces are on joint operations with Afghan institutions. The Afghaninstitution could be the ANA, ANP or NDS. In the course of joint ISAF and Afghan security forces operations, if peopleare arrested they can be automatically handed over the Afghan forces even if the international forces are directlyinvolved in the arrest. A transfer of this type was shown in a television documentary entitled “Fighting the Taleban” adocumentary by Sean Langan forDispatches,broadcast in the UK on Channel 4 on 8 January 2007.61Please note that the information in this table excludes the US as well as countries that have less than 100 troops inAfghanistan. See www.nato.int/isaf/ for information on troop strength. The countries excluded are; Albania, Austria,Azerbaijan, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Iceland, Slovakia, Slovenia and Switzerland.

60

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

22

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

•

Torture of detainees transferred by Canadian forces

In April 2007, the Canadian newspaperGlobe and Mailpublished allegationsof torture and other ill-treatment of Afghan detainees by Afghan security personnelincluding the NDS, after they had been detained by the Canadian military andhanded over to the Afghan authorities. Some interviewees who had been capturedover the previous 15 months described how:“…they were whipped with electrical cables, usually a bundle of wires aboutthe length of an arm. Some said the whipping was so painful that they fellunconscious. Interrogators also jammed cloth between the teeth of somedetainees, who described hearing the sound of a hand-crank generator andfeeling the hot flush of electricity coursing through their muscles, seizing themwith spasms. Another man said the police hung him by his ankles for eightdays of beating. Still another said he panicked as interrogators put a plasticbag over his head and squeezed his windpipe. Torturers also used cold as aweapon, according to detainees who complained of being stripped half-nakedand forced to stand through winter nights when temperatures in Kandahardrop below freezing.”62The Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) is reported tohave confirmed key elements of three of the cases published in theGlobe and Mailreport:•“Gul Mohammed, 25, a farmer, said he was captured by Canadians whileworking the fields west of Kandahar city. The Canadian troops handed himover to Afghan soldiers, starting what he described as a bloody six-monthodyssey at the hands of Afghan interrogators from the military, police andintelligence services. He said they beat him with rifle butts, deprived him ofsleep, shocked him with electrical probes, and thrashed him with bundles ofcables.”“Sherin, 25, a driver, said he was detained at a checkpoint operated byCanadian and Afghan troops in a district north of Kandahar city. A small manwith a quiet voice, he gripped his elbows with both hands and rocked backand forth while describing how he was interrogated by a man who identifiedhimself as a Canadian, before he was thrown in the back of a pickup truckand taken to NDS headquarters. He spent one and a half months in NDScustody, he said, where interrogators punched his face, pulled his beard, andbeat him with bundles of electrical cables for 60 strokes at a time.”

•

62

Graeme Smith, “From Canadian custody into cruel hands”,Globe and Mail,23 April, 2007. For a further account oftorture see: Graeme Smith, “Personal Account: A story of torture”,Globe and Mail,24 April 2007.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

23

•

“Abdul Wali, 23, a tailor, said he was arrested by the Canadians and wastreated politely until they handed him over to the Afghan soldiers, who beathim. He said the beatings were constant, except for pauses when Canadiansoldiers visited the outpost. Worse thrashings came later, he said, at thehands of the police and NDS.”63

Analysis of interviews with 15 individuals held in Afghan custody, but whowere originally captured by Canadian forces, reveals that 10 were transferred to theNDS, either directly or through the Afghan National Army (ANA) or Afghan NationalPolice (ANP). Of the 10 detainees held in NDS custody, six described torture andother forms of ill-treatment.64Canadian officials themselves have stated they havereceived at least six first-hand reports of torture.65The Canadian government has continued to state that more than 40individuals have been transferred.66However, AI believes that the number oftransfers may be as high as 200, and that this figure does not include many of theimmediate transfers which happen in the course of military operations in-field.

•

Losing track of transferred detainees

AI is also concerned that other ISAF states have been unable or unwilling tomaintain an accurate record of the number of detainees transferred to Afghanauthorities or their subsequent whereabouts.The Norwegian government, for example, appeared unable over the course ofa year to establish and disclose how many detainees its forces had transferred.Subsequently, in October 2007, the Norwegian government clarified that fivedetainees had been handed over since the signing of an MoU with the AfghanGovernment in October 2006. However it is still to establish how many people weretransferred prior to the MoU, or to account for their whereabouts and conditions.67Uncertainty over the current whereabouts and well-being of the five detaineesidentified as have been transferred after MoUs agreement has continued. TheNorwegian Defence Minister Anne-Grete Strøm-Erichsen said that three of the fivepeople handed over were since released, not due to proving their innocence, but bybuying their freedom from their captors.686364

Graeme Smith, “From Canadian custody into cruel hands”,Globe and Mail,23 April, 2007.Information regarding interviews from a confidential source in Afghanistan, July 2007.65“Six claims of torture from detainees: Minister”, Canada Press 8 June 2007 Canadian Press?http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20070608/detainee_allegations_070608/20070608/66Paragraph 52 of the Affidavit of Colonel Steven Noonan, Canadian Forces, sworn May 1, 2007, in relation toFederal Court of Canada file number T-324-07, and transcripts of cross examination conducted May 2, 2007.67Norske spesialsoldater overleverte fem fanger (“Norwegian special force soldiers handed over five prisoners”),Dagsavisen,13 October 2007.68Norske spesialsoldater overleverte fem fanger (“Norwegian special force soldiers handed over five prisoners”),Dagsavisen,13 October 2007.

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

24

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

In a further admission of the failure of MoUs, the Defence Minister said: “Ihave no guarantee that the detainees have not been tortured, other than havingsigned the Memorandum of Understanding.”69As described above, both before and after signing an MoU, the Norwegiangovernment appeared unable to confirm the whereabouts and condition of detainees.This has reinforced AI’s concern that such MoUs have failed to provide anytransparency in the transfer process, or any protection for the individuals’ concerned.In April 2007, the Norwegian embassy in Kabul sent an email to theNorwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that raised concerns about “the intelligenceservice (NDS) who allegedly have ill-treated and tortured several prisonerstransferred by international military forces in Afghanistan”. As well as highlightingtheir own concerns, they noted the difficulty in applying remedial pressure on theNDS.70The Ministry announced that Norway would establish what happened to theprisoners handed over by Norwegian soldiers, and whether the MoU had beenbreached.71If detainees had been tortured, the Ministry told another newspaper, theultimate consequence might be to "stop transfers" of prisoners.72Similarly, the Belgian government appears to have lost track of the singledetainee known to have been transferred to the Afghan authorities by Belgian forces.Reports received by Belgian Ministry of Defence state that an individual was arrestedby Belgian forces at Kabul international airport on suspicion of driving a fuel tankerintended as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device or car bomb on 18 April2007.The Belgian military has confirmed that paperwork for the transfer of thedetainee to the NDS was completed and that they were transferred, but they do notknow where the individual is being held.73AI has requested clarification from theBelgian authorities regarding this issue. At present Belgium is reported to be seekingto agree an MoU with the Afghan authorities, but AI fears that such an agreementwould appear to offer little difference to the capacity of the Belgian government to

Norske spesialsoldater overleverte fem fanger (“Norwegian special force soldiers handed over five prisoners”),Dagsavisen,13 October 2007.70Email from Andreas Lovold, Norwegian Embassy, Kabul to Norwegian Foreign Ministry, Oslo, written 2 May 2007.71Liv Monica Stubholt, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, interviewed by the Norwegian News Agency NTB, 27July 2007.72UD vil sjekke torturpåstander (“Ministry of Foreign Affairs will investigate allegations of torture”),Klassekampen,28July 200773Email exchange between AI Belgium (Francophone) and the Belgian Ministry of Defence, 31 August and 26September 2007.

69

Amnesty International November 2007

AI Index: ASA 11/011/2007

Detainees transferred to torture: ISAF complicity?

25

make clear, open records of incidents and to follow them up with the Afghangovernment.

•