Forsvarsudvalget 2007-08 (2. samling), Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2007-08 (2. samling), Udenrigsudvalget 2007-08 (2. samling)

FOU Alm.del Bilag 79, UPN Alm.del Bilag 50, URU Alm.del Bilag 79

Offentligt

House of CommonsInternational DevelopmentCommittee

ReconstructingAfghanistanFourth Report of Session 2007–08Volume IReport, together with formal minutesOrdered by The House of Commonsto be printed 5 February 2008

HC 65-I[Incorporating HC 1097-i, Session 2006-07Published on 14 February 2008by authority of the House of CommonsLondon: The Stationery Office Limited£0.00

International Development CommitteeThe International Development Committee is appointed by the House ofCommons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of theDepartment for International Development and its associated public bodies.Current membershipMalcolm Bruce MP (LiberalDemocrat, Gordon)(Chairman)John Battle MP (Labour,Leeds West)Hugh Bayley MP (Labour,City of York)John Bercow MP (Conservative,Buckingham)Richard Burden MP (Labour,Birmingham Northfield)Mr Stephen Crabb MP (Conservative,Preseli Pembrokeshire)James Duddridge MP(Conservative, Rochford and Southend East)Ann McKechin MP (Labour,Glasgow North)Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisleyand Renfrewshire North)Mr Marsha Singh MP (Labour,Bradford West)Sir Robert Smith MP(Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine)

PowersThe Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers ofwhich are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk.PublicationsThe Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The StationeryOffice by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including pressnotices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/indcomCommittee staffThe staff of the Committee are: Carol Oxborough (Clerk), Matthew Hedges(Second Clerk), Anna Dickson (Committee Specialist), Chlöe Challender(Committee Specialist), Ian Hook (Committee Assistant), Jennifer Steele(Secretary), Alex Paterson (Media Officer) and James Bowman (Senior OfficeClerk).ContactsAll correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the InternationalDevelopment Committee, House of Commons, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA.The telephone number for general enquiries is 020 7219 1223; the Committee’semail address is [email protected]FootnotesIn the footnotes for this Report, references to oral evidence are indicated by ‘Q’followed by the question number. References to written evidence are indicatedby the page number as in ‘Ev 12’.

Reconstructing Afghanistan

1

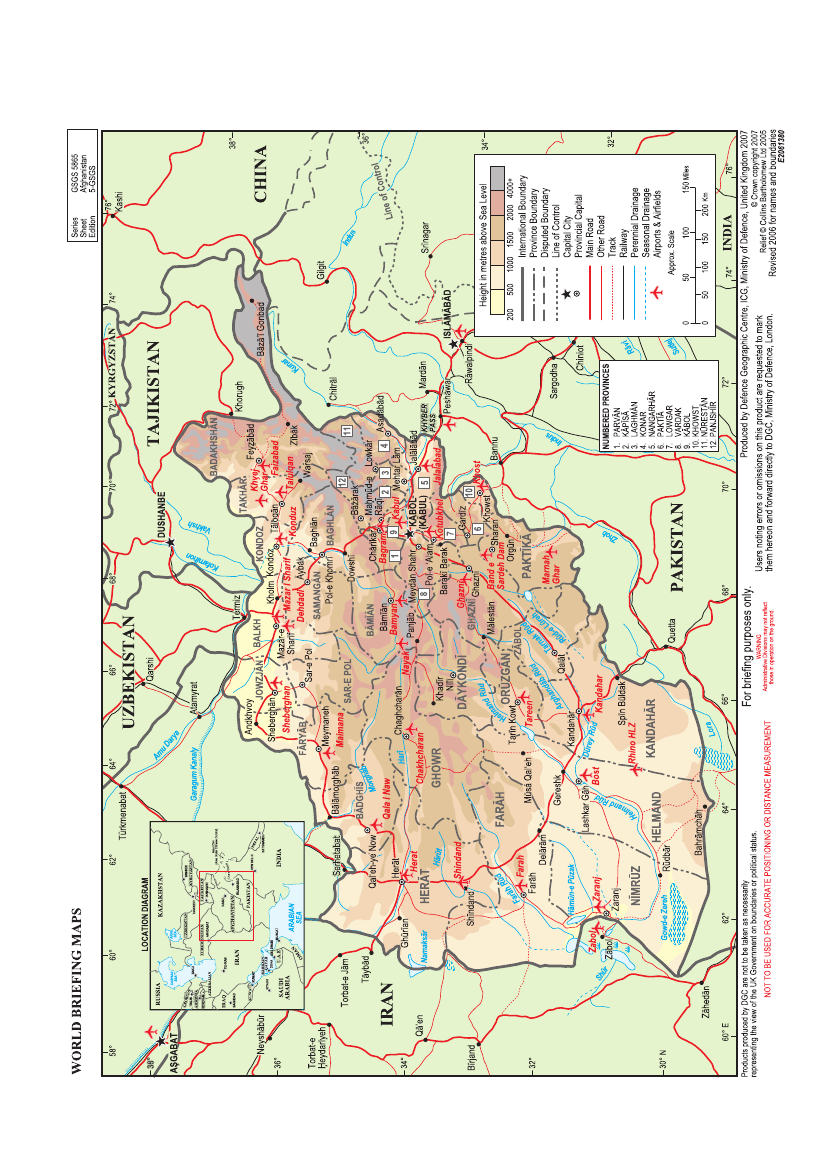

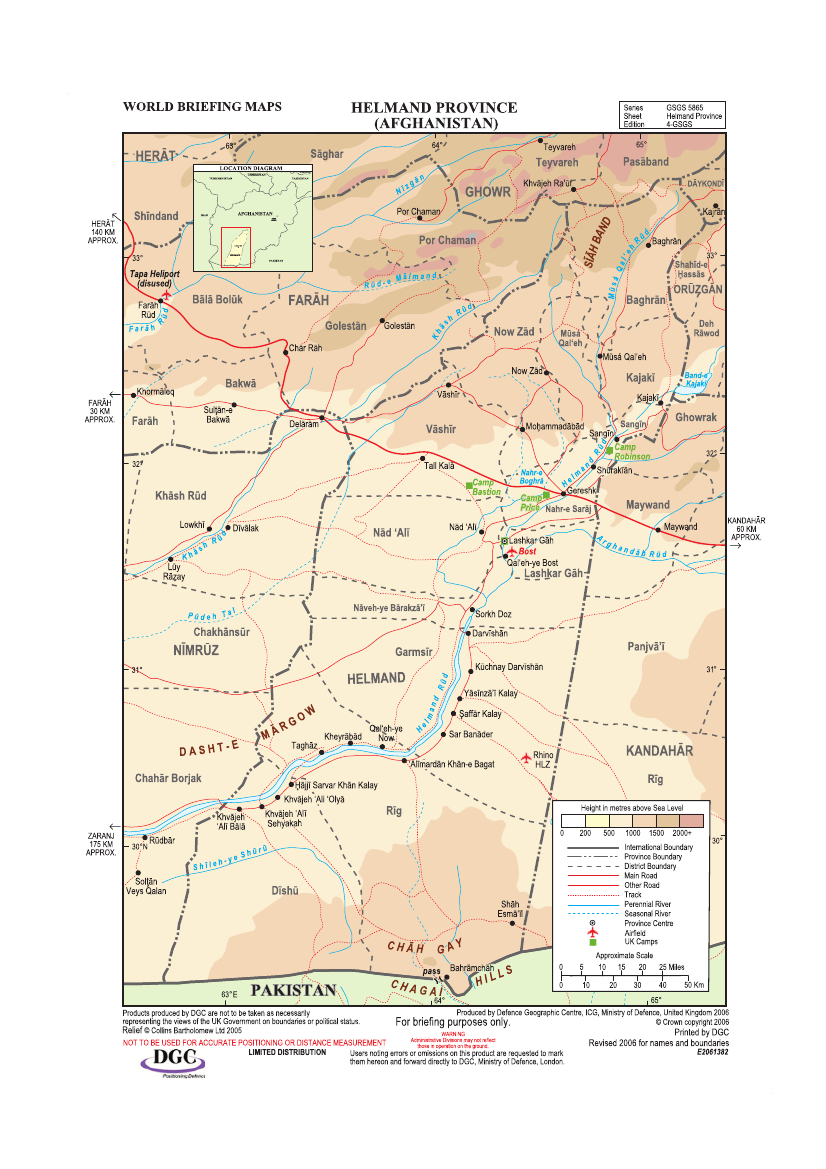

ContentsReportMap 1: AfghanistanMap 2: Helmand provincePage

34

Summary1IntroductionOur inquiryThe importance of being in AfghanistanDevelopment gains since 2001The gap between expectations and capabilityThe structure of the report

69910111213

2

Working in insecure environmentsConditions of service for UK staffLogistical supportDFID’s programme in AfghanistanThe Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF)Improving economic managementThe distribution of DFID funds

14141516171919

3

Donor CoordinationThe Paris DeclarationThe Afghanistan CompactImpact of aidA high level UN coordinator

2222222326

4

Improving securitySecurity conditionsRegional securityInternational Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the UK troop contributionSecurity Sector ReformThe Afghan National Army (ANA)The Afghan National Police (ANP)The justice sector

2828303132323235

5

Governance and sub-national governanceSub-national governanceThe Independent Directorate for Local GovernanceCommunity Development Councils

38383940

6

Narcotics and counter-narcoticsOpium poppy productionCounter-narcotics policyDrug traffickingCrop eradication

4343454646

2

Reconstructing Afghanistan

Alternative livelihoodsThe Counter-Narcotics Trust Fund

4748

7

Rural livelihoodsDFID’s livelihoods programmePriority areasMicrofinance

49495051

8

Provincial Reconstruction Teams and Helmand provinceProvincial Reconstruction TeamsThe UK effort in Helmand province

535354

9

Conclusion

58596871737475757677

RecommendationsAnnex A: The Committee’s visit programme in AfghanistanAnnex B: Letter to the Secretary of State for International DevelopmentList of AcronymsFormal MinutesWitnessesList of written evidenceList of unprinted evidenceList of Reports from the Committee during the current Parliament

Reconstructing Afghanistan

3

Map 1: Afghanistan

4

Reconstructing Afghanistan

Map 2: Helmand province

6

Reconstructing Afghanistan

SummaryAs a result of 30 years of conflict Afghanistan is one of the poorest countries in the worldand will not meet any of the Millennium Development Goal targets in 2015. The UK and theinternational community have a responsibility to assist Afghanistan to achieve lasting peace,stability, reconstruction and development. We support fully the UK Government’s effort inAfghanistan and the priority which it attaches to these goals.Despite the difficulties it faces, Afghanistan has made significant progress in governance,economic growth, health and education. Such achievements deserve to be recognised.However Afghanistan will need substantial development assistance for a long time. DFIDand the international community have a vital role to play in this regard.Increasing insecurity and the continuing insurgency are threatening the reconstructioneffort in many parts of Afghanistan. The role of NATO forces in building up a capableAfghan security sector is thus important. Cooperation with Pakistan in controlling theborders more effectively is also essential to stop the supply of Taliban recruits. There is noeasy solution to the security problems—a long-term commitment is required.Since our visit last October, a number of developments have highlighted to us that thepolitical situation in Afghanistan and the relationship between the Government ofAfghanistan (GoA) and the international community could become increasingly fragile. Thecivilian and military international effort is entirely dependent on the goodwill of theGovernment and people of Afghanistan. Whilst the Government of Afghanistan is fullyentitled to criticise the international effort, in relation to the UK contribution we areconcerned that the tone and timing of the GoA’s recent comments may risk underminingBritish public support for the UK’s long-term commitment to Afghanistan.It is clear to us that without tangible improvements in people’s lives the insurgency will notbe defeated. Such improvements need to be led by Afghan institutions. This meansincreasing the capacity of the Government of Afghanistan to deliver services throughout thecountry. Reforms of government structures at the sub-national level are crucial because therural areas are precisely where insurgents are recruited and poppy cultivation is greatest.The creation of an Independent Directorate of Local Governance is a step in the rightdirection and clarification of the role of Provincial Governors should be a priority.Community Development Councils have been an effective mechanism for ensuring localownership of development projectsThe opium trade is controlled by powerful criminal gangs who operate with impunity in alawless environment and therefore support the insurgency. Small farmers grow poppiesbecause the drug traders come to their farm to buy the crop. It is difficult to transport othercrops—even high-value, low-volume crops like saffron or mint—to market because theroads are not safe. It is not surprising that poor farmers consider poppy cultivation to be anattractive choice in a high-risk environment and in the absence of other meaningful optionsfor earning a living. Expectations that poppy cultivation will be reduced over a short periodare therefore misplaced. Crop eradication by aerial spraying risks increasing insecurity inalready insecure provinces. Instead there is a desperate need for an integrated counter-narcotics strategy which provides irrigation, credit, infrastructure and alternative

Reconstructing Afghanistan

7

employment opportunities. The strategy must also include criminal prosecution of bigtraders and extension of the rule of law to rural areas.The position of women in Afghan society has improved since the fall of the Taliban butthese gains could easily be lost. Insufficient attention has been paid to this by the donorcommunity. There is a dangerous tendency to accept in Afghanistan practices which wouldnot be countenanced elsewhere, because of what is described as the particular “culture” and“tradition” of the country. We believe the rights of women should be upheld equally in allcountries. The Government of Afghanistan has a vital role to play in this by ensuring thatthe international human rights commitments which it has made are fully honoured.The UK effort in Helmand is a joint civilian-military one. Under difficult circumstances theProvincial Reconstruction Team is working to improve its operational practice and to trynew methods of working. We commend this effort. However progress in Helmand willultimately depend on building local capacity and winning local consent. The Taliban are notan homogenous group and some have already come over to the Government side. Efforts atdisarmament and reintegration should continue.The UK Government’s commitment to working in Afghanistan must be reflected inappropriate training, support and working conditions for civilian staff.Progress in training the Afghan National Army has been good. Similar progress has notbeen made with the Afghan National Police and this threatens the establishment of the ruleof law.Commitments made by the international donor community to channel funding throughGovernment of Afghanistan structures have not been met. The use of parallel structures andforeign contractors dilutes significantly the beneficial impact of aid. Donor coordinationwould have been strengthened by the appointment of a high-level UN SpecialRepresentative and we are dismayed that plans for this have been so far been blocked by theGovernment of Afghanistan.We were frequently told that the people of Afghanistan are uncertain about the future, thelong-term commitment of the international community and the consequent resilience ofnational institutions. Greater donor co-ordination and support for the Government ofAfghanistan would help meet these concerns.

Reconstructing Afghanistan

9

1IntroductionOur inquiry1. The previous International Development Committee last reported on Afghanistan in2002–03.1In December 2005 we held a one-off evidence session to provide an update ondevelopments there.2In July 2007 we decided that the situation in Afghanistan merited afull inquiry, including a visit. As the International Development Select Committee wenaturally focus on development. We nevertheless recognise the interaction betweendevelopment and security, including key regional security issues.2. DFID has declared that it intends to undertake more work in fragile and insecureenvironments.3It acknowledges that “fragile states are the hardest countries in the world tohelp develop. Working with them is difficult and costly and carries significant risks.”4DFIDaims to develop appropriate ways of working in such states, to be more effective at doing soand to work more closely with other government departments. The purpose of this inquiryis to examine how DFID is meeting the challenge of delivering development assistance inthe insecure environment which is Afghanistan.3. We began our inquiry in October 2007. We received written evidence from 15organisations and individuals. We held three oral evidence sessions in the UK takingevidence from government officials, non-governmental organisations, an independentconsultant and the Secretary of State for International Development. During the course ofthe inquiry we also met with a group of visiting Afghan members of the NationalAssembly. We are grateful to all these organisations and individuals for their contributionto this inquiry.4. We visited Afghanistan at the end of October 2007. Full details of our visit programmecan be found as Annex A to this report. We spent three days in Kabul meeting DFID andFCO officials, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), non-governmentalorganisations, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative, female members of theNational Assembly, Government Ministers and officials, other donors and academiccommentators. We also visited some DFID-funded projects. We then split into two groupswith one group flying north to Mazar-e-Sharif in Balkh province and the other south toLashkar Gah in Helmand. In Mazar-e-Sharif we met the Provincial Governor, theProvincial Council, representatives of the Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) fromSweden and Finland and a USAID representative and visited a number of projects. InHelmand we stayed at the Provincial Reconstruction Team base in Lashkar Gah. We metthe UK Commander of Task Force Helmand, UK troops, the Provincial Governor,members of the Provincial Council and representatives of line ministries in the province.We also visited a number of projects. Our final day was spent in Kabul. We visitedCommunity Development Council projects and we met the President of Afghanistan, the1234International Development Committee, First Report of Session 2002-03,Afghanistan: the transition fromhumanitarian relief to reconstruction and development,HC 84.International Development Committee, Session 2005-06,Reconstructing Afghanistan,HC 772DFID,Why we need to work more effectively in fragile states,January 2005.DFID,ibid.p 5

10

Reconstructing Afghanistan

Pakistan Ambassador, Ashraf Ghani—a former Finance Minister, and the National YouthParliament.5. Our visit was extremely informative and we are grateful to all those who took the time tomeet us and share their views with us. We are also grateful to our hosts in DFID and theForeign Office for facilitating the visit and to our close protection team for their diligencein ensuring our safety.6. We had hoped to report our findings to the House at the end of 2007. However we notedthe Prime Minister’s comments in the debate on the Queen’s Speech on 6 November thathe intended to make a statement on Afghanistan, including on the Government’sproposals for development there.5We therefore decided to wait for the statement so as tobe able to take full account in this report of any change in Government policy. We resolvedinstead to write to the Secretary of State with some of our preliminary views in order thatthey might inform the Government’s discussions. The text of the letter is reprinted asAnnex B to this report.

The importance of being in Afghanistan7. Afghanistan is an insecure country in a politically unstable region. In particular itsimmediate neighbours Pakistan and Iran are the focus of international attention. Increasedinsecurity in the region would have significant international implications and would makethe task of bringing security and stability to Afghanistan an even more difficult one.8. Afghanistan is also one of the poorest countries in the world and is off-track in progresstowards all the Millennium Development Goals.6Over half the population live on less thanUS$1 a day.7The British and Irish Afghan Agencies Group (BAAG) reports thatAfghanistan is ranked 173 out of 178 countries listed in the 2004 United NationsDevelopment Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index; life expectancy is 47years; 600 children under five die every day and 25% of all children before their fifthbirthday; and the maternal mortality rate is the second highest in the world.8Turningaround such stark statistics would normally take many years; in an insecure environmentthe challenge is even greater.9. Amidst the ongoing insurgency and with poppy cultivation increasing in 2007, thenewly-appointed British Ambassador to Afghanistan, Sir Sherard Cowper-Coles, expressedhis belief that the UK’s commitment to Afghanistan would last for decades.9The UKcommitment in terms of development was cemented at the London Conference in January2006 when the Government signed a ten-year Partnership Agreement with theGovernment of Afghanistan including a pledge to give £330 million in developmentassistance over the three year period 2006–09.10This is part of a total package of £500million, which includes funding for counter-narcotics. It makes DFID’s programme in5678910HC Deb, 6 November 2007, col 23-34Ev 50 [DFID]Q 2 [Mr Drummond]Ev 82 [BAAG]BBC News 24, “UKin Afghanistan for decades,”20 June 2007, bbc.co.ukEv 52 [DFID]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

11

Afghanistan its sixth largest in the world and the UK Afghanistan’s second largest bilateraldonor.10. In his 2007 Mansion House speech the Prime Minister said, “In Afghanistan we willwork with the international community to match our military and security effort with newsupport for political reform and for economic and social development.”11We fully supportthe continuing commitment of the UK Government, in partnership with theGovernment and people of Afghanistan, to help to bring peace and security toAfghanistan and to promote political reform and reconstruction and development. Weaccept that the commitment, in terms of development assistance, is likely to last at leasta generation. As one of the poorest countries in the world, with continuinghumanitarian needs, Afghanistan should remain a major focus for DFID.11. Since our visit, a number of developments have highlighted to us that the politicalsituation in Afghanistan and the relationship between the Government of Afghanistan(GoA) and the international community could become increasingly fragile. The civilianand military international effort is entirely dependent on the goodwill of the Governmentand people of Afghanistan. Whilst the Government of Afghanistan is fully entitled tocriticise the international effort, in relation to the UK contribution we are concerned thatthe tone and timing of the GoA’s recent comments may risk undermining British publicsupport for the UK’s long-term commitment to Afghanistan.

Development gains since 200112. Afghanistan has suffered from years of foreign occupation and conflict. What isstriking is that, since the fall of the Taliban in 2001, and despite continued conflict in partsof the country, Afghanistan has begun to make progress in some key areas includinghealth, education, governance and the economy. For example, in health it is now estimatedthat access to basic health care has increased from 9% to 82%.12We visited a hospital inLashkar Gah with little modern equipment but we were told that the nationalimmunisation programme carried on in government and insurgent controlled areasregardless of the security situation. DFID told us that immunisation against measles wassaving 35,000 lives annually.13The under-five mortality rate has improved from one in fourto one in five since 2004. The proportion of women receiving ante-natal care has increasedfrom 5% to 30%.14Gains in the health sector have been achieved by an innovative fundingprocess which sees the Ministry of Health sub-contracting service delivery to NGOs andother actors.13. There are now over five million children enrolled in schools, one-third of them girls.15Written evidence from DFID confirms that this represents 37% of children between sixand thirteen. Of the primary school-age population 29% of girls and 43% of boys areenrolled. In urban areas this rises to 51% of girls and 55% of boys.16Under the Taliban it111213141516Speech by the Prime Minister, the Rt Hon Gordon Brown MP, The Lord Mayor’s Banquet, 12 November 2007Q 7 [DFID]Q 2 [DFID]Ev 50 [DFID]Ev 50 [DFID]Ev 61 [DFID]

12

Reconstructing Afghanistan

was forbidden for girls to attend school making this is a significant milestone. It waspointed out to us that the insurgents often target girls on their way to and from school inorder to force the closure of girls’ schools. In areas of high insecurity such as Helmandmany schools remain closed. Since 2001 nearly 2,000 schools have been built althoughthere is still a desperate shortage of trained teachers.1714. Afghanistan held Presidential elections in 2004 and parliamentary elections in 2005. Inthe latter there was a requirement for 25% of the seats to be female. In the event 28% of theseats were won by women.18There are also community and provincial forums in whichwomen are represented.19The non-opium economy has grown fairly steadily with growthrates averaging 10% over the last three years.20While such growth rates are partly areflection of the low economic base from which Afghanistan has emerged as well as highlevels of aid dependence, they also reflect a significant increase in economic activity and amore open business environment.2115. Although there is a long way to go, such progress is significant. Typically post-conflictcountries slip back into conflict within five years and the gains made in the immediateaftermath of the conflict are lost in what Paul Collier has called “the conflict trap”.22Thishas not happened in Afghanistan. Yet these development gains do not appear in manynewspaper articles about the country which tend instead to focus on the insurgency inHelmand Province where the majority of British troops are stationed.It is important thatthe job of helping to bring security to Afghanistan, in which over 7,000 British troopsare engaged, is given full support by the British public. We recognise the strong UKmedia interest in this involvement given that British troops are putting their lives onthe line. While acknowledging that continuing insecurity threatens to set backprogress, we are also conscious that the media focus on this has meant thatachievements in political reform, economic growth and in the provision of basicservices are not getting the attention they deserve. We recommend that DFID’s mediastrategy for Afghanistan is strengthened to ensure that development achievements inAfghanistan are given the press coverage in the UK which they merit.

The gap between expectations and capability16. We found that there is a large gap between the Afghan people’s expectations about howlong reconstruction will take and the capacity of the international community and theGovernment of Afghanistan to deliver this. In a recent survey by the Asia Foundation only42% of respondents thought that the country was moving in the right direction and only49% considered themselves better-off than under Taliban rule. Evidence from AfghanAidstates that, “unmet reconstruction and development expectations on the part of Afghanrural populations are further destabilising the country.”23Yet building a successful state,17181920212223Q 31 [DFID]Ev 51 [DFID]Ev 67 [Afghanaid]Ev 51 [DFID]Centre for Strategic and International Studies,Breaking Point: measuring progress in Afghanistan,23 February 2007.Paul Collier,The Bottom Billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it,OxfordUniversity Press, 2007.Ev 81 [AfghanAid]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

13

which can deliver a wide array of services, is a long process, often not without setbacks.24Increasingly, even amongst donors, there is an expectation that state capacity to deliverservices can be achieved within a few years. This is unrealistic, especially where suchcapacity has never existed historically.17. On our visit we were repeatedly asked what the UK was doing in Afghanistan in termsof reconstruction and development. In Helmand and Balkh some Provincial Councilmembers were not aware of the fact that DFID channels 80% of its funding throughGovernment of Afghanistan mechanisms. Similarly in Kabul we found amongstCommunity Development Council members a lack of awareness of how the UK isindirectly helping to fund the schools which these Councils were building. Most Afghansresponding to the Asia Foundation survey were not aware of projects funded by the UK.They cited the USA, Japan and Germany as having provided most aid for projects in theirdistrict.25The reality is that the UK is the second largest bilateral donor.26Expectationsneed to be managed so that they accord more realistically with the capacity—both ofthe Government of Afghanistan and of the donor community—to deliver. Greaterpublicity of successes and of the nature and scope of DFID’s work in Afghanistanwould help in this regard. We recommend that DFID develop a new communicationsstrategy in Afghanistan to ensure accurate information about the scale of its work iswidely circulated.

The structure of the report18. The structure of the report is as follows: Chapter 2 provides an outline of DFID’sprogramme in Afghanistan and a discussion of the tools available to work in such insecureenvironments. Chapters 3 to 7 each focus on one of five areas we consider to be the mainchallenges and priorities for DFID and other donors. These are: donor coordination,security, governance and sub-national governance, counter-narcotics and rural livelihoods.Because of the UK’s focus on Helmand, Chapter 8 looks specifically at the UK effort hereand especially at the work of the Provincial Reconstruction Team which is a joint civil andmilitary effort.19. Throughout the report we have sought to identify the impact of development on therole and position of women in Afghan society. Whilst there have been many gains forwomen in Afghanistan since 2001 in terms of the constitution and public commitments tosafeguarding women’s legal and civil rights, there remain a number of serious challenges towomen's human rights and position in society. The realisation of their politicallyacknowledged civil and political rights and social and economic status is not currentlyguaranteed.27We believe it is fundamental to the rebuilding of Afghanistan thatinternational commitments made by the Government of Afghanistan and by donors onthe rights of women are honoured and given greater priority.

24252627

See, Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development,Transforming Fragile States: examples ofpractical experience,Nomos: Germany, April 2007.The Asia Foundation,Afghanistan in 2007,Asia Foundation, 2007, p43.DFID, Afghanistan Development Facts. Figures are for 2005 according to the OECD DAC. The USA is the largestbilateral donor (US$1.34 billion)Ev 83, 103 [BAAG; GAPS]

14

Reconstructing Afghanistan

2Working in insecure environmentsConditions of service for UK staff20. The British Mission in Afghanistan, which includes all FCO, DFID and other civilservants is one of the largest in the world. There are 143 UK civil servants based in Kabulalone. DFID Afghanistan has 43 staff and the Foreign Office has a political team of 10which is the largest anywhere in the world. In addition there are counter-narcotics, HMRevenue & Customs, rule of law, Serious Organised Crime Agency and Intelligence staff.The large number of civil servants reflects the priority which the UK Government attachesto Afghanistan.21. In our report on DFID’s Departmental Report 2006 we questioned whether DFID hada comparative advantage in fragile states or if it was simply acting as the donor of lastresort, seeking to fill those gaps which other donors had failed to.28The Departmentreports that “between 2001 and 2006 DFID increased bilateral expenditure in fragile statesfrom £243.5 million in 2000–01 to £745.6 million in 2005–06. This represents an increasefrom 17% to 30% of DFID's overall bilateral spend. In 2006–07 this increased further to£800.1 million or 31% of our bilateral spend.”29According to DFID, internationalcommitments on poverty reduction and peace and stability will not be met withoutengaging with fragile states.3022. Questions about where DFID has a comparative advantage apply not only to the choiceof country in which it works but also to the terms and conditions for DFID staff. Becauseof its continuing insecurity, Afghanistan is considered to be a difficult environment inwhich to work for long periods at a time. DFID staff work in-country for six-week periodsfollowed by a two-week break or ‘breather’ during which they must leave the country. Moststaff sign-on for a 12-month posting although we were told that some intend to stay longer.All posts are unaccompanied which means that staff with families have to cope with longperiods of separation from spouses and children. Consequently staff attracted to theposting tend to be young and without dependants. Housing is generally shared andmovement is restricted and dependent on the availability of close protection and armouredvehicles. We requested information from other donors about the conditions of work fortheir staff. From the responses we received, UK conditions are broadly comparable withother donors although the UK package is considered by others to be among the best.23. Nevertheless for some people there is no adequate compensation for the loss of familyor social life. This means there is a limited pool of people who will agree to work in fragilestates and an even more restricted number will stay for longer than one year. Institutionalknowledge and capacity is easily lost when there is a high staff turnover. Such factors needto be taken into account if DFID is intending to continue and indeed to expand its work ininsecure environments and fragile states. It may be appropriate for DFID to consider

282930

International Development Committee, First Report of Session 2006-07,Department for International DevelopmentDepartmental Report 2006,HC 71, paras 20-24.Ev 53 [DFID]DFID,Why we need to work more effectively in fragile states,January 2005.

Reconstructing Afghanistan

15

increased use of contracted staff with relevant experience to increase the pool of expertiseavailable.24. Another concern is that DFID staff are given less time to prepare for deploymentsabroad than their colleagues in the FCO.The work DFID staff undertake inenvironments such as Afghanistan is demanding and context-specific. We believe thatthey should be given a level of support which is commensurate with the responsibilitiesthey are asked to bear, including an appropriate level of language, cultural and securitytraining.25. It also strikes us that the practice of having a two-week breather every six weeks hasimplications for the efficiency of Embassy staff work. It is necessary to have someone elsetake over your work when you are away which means that much time is lost in the handingover process before and after breathers. In the absence of the person with leadresponsibility a decision may be made which that person might not have made. We learnedof a specific example of where this had happened in Helmand. Increasing the numbers ofcivilian staff is one way around this problem. Another might be to extend the continuouswork period to two months.26.We agree that Afghanistan should be a priority for DFID. We understand thatconsideration is being given to how best to encourage staff to work in insecureenvironments and to increasing the length of postings. We believe that this is animportant issue if DFID intends to remain in countries such as Afghanistan since thereis a limited pool of staff who will undertake such postings. Current working conditionsare comparable with those of other donors but consideration should be given to theimpact of six-week periods of work on overall efficiency. We would urge DFID toencourage those staff who gain experience of working in Afghanistan to return tosimilar posts after a sufficient break so as to build up a cadre of DFID staff withexperience of working in insecure environments.

Logistical support27. Afghanistan is a fairly large country, divided into 34 administrative provinces, with amountainous terrain which makes travel and communications difficult. Although UKtroops have special responsibilities in Helmand Province, the DFID programme is acountry-wide one. This means that DFID and other civil servants periodically need to beable to travel outside Kabul to other parts of the country including Helmand to monitorprojects and to build up relationships with provincial leaders. Security considerations andthe lack of passable roads mean that travel by air is usually the most appropriate method.However they are currently dependent on military air transport, itself in high demand.31The Prime Minister has recently announced that more helicopters will be made available toassist the military effort.32The Secretary of State for International Development, Rt HonDouglas Alexander MP, told us that such helicopters could also assist the civilian effort.33

313233

Defence Committee, Thirteenth Report of Session 2006-07,UK Operations in Afghanistan,HC 408, paras 112-116.HC Deb, Col 303-307, 12 December 2007Q 179 [DFID]

16

Reconstructing Afghanistan

28. We were able to travel north to Balkh province in a fixed-wing Beechcraft aeroplanewhich belonged to HM Customs & Revenue but access to this is dependent on their needfor it. Those of us who travelled to Helmand did so in military aircraft. We wereaccompanied on these visits by a number of DFID and FCO staff who used the opportunityto travel to Helmand and Balkh. In Afghanistan we learned that there had been a requestfor a non-military aircraft to assist the civilian effort but that a bid for a suitable aircraft hadto be cancelled, and the deposit forgone, because HM Treasury had not approved thefunds. The Secretary of State said that consideration was being given to purchasing a fixed-wing aircraft from the Stabilisation Aid Fund.34We welcome the approval of an increasednumber of helicopters in Afghanistan for the military effort announced by the PrimeMinister on 12 December 2007. We would also welcome an update on the deploymentof those helicopters and confirmation of how much increased effective capacity will beavailable. In addition we noted the use we made of US operated helicopters in Helmandand would like to know if they will still be available after the increase in the UKcontribution.29.We also note that DFID and Embassy employees are hindered in carrying out theirjobs in a timely fashion when they are subject to lengthy waits for secure transport.Given the priority which the UK Government has placed on Afghanistan, we considerthat appropriate logistical support for the civilian effort is essential. We recommendthe early provision of a dedicated aeroplane for the use of DFID and other Embassystaff to carry out their work in Afghanistan.30. In Kabul and elsewhere international staff frequently undertake short journeys inarmoured vehicles with close protection teams. This is unavoidable at present. UK closeprotection teams adopt a low-key approach and ensure their weapons are not visible. Weregard this less confrontational and less visible approach as preferable.

DFID’s programme in Afghanistan31. DFID is committed to providing £330 million in development assistance toAfghanistan in the three year period 2006–09. In the 2007–08 financial year DFIDprovided £107 million, excluding administrative costs. Of this, DFID committed £20million to Helmand Province, an increase from £16 million in 2006–07, of which £4million went through the cross-departmental Global Conflict Prevention Pool (GCPP) forQuick Impact Projects35(see chapter 8). On 12 December the Prime Minister announceddevelopment and stabilisation assistance of £450 million for the period 2009–12.36TheSecretary of State informed us that £345 million of this was for development assistance and£105 million was for the newly created Stabilisation Aid Fund which replaces the GlobalConflict Prevention Pool.37DFID told us this represented a very significant scaling-up ofeffort in terms of stabilisation and reconstruction activity. However, how the additionalfunds would be spent had not yet been decided, except that there would be an increase in

34353637

Q 179 [DFID]Ev 53 [DFID]HC Deb, Col 303-307, 12 December 2007Q 130 [DFID]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

17

staff levels in Helmand.38We welcome the allocation of additional funds fordevelopment and stabilisation assistance across Afghanistan. We wish to be given moredetails on the allocation of the funding in response to this report.32. DFID’s programme in Afghanistan has three main objectives. These are:•••

Building effective state institutions;Improving economic management, and the effectiveness of aid to Afghanistan; andImproving the livelihoods of rural people.

These priorities have been decided upon in consultation with the Government ofAfghanistan which requested that donors identify only three priority sectors each.39Inaddition DFID’s wider goals are: improving donor coordination, supporting thedevelopment of the Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS), andcontributing to the wider UK government effort in Helmand.33. Because DFID attaches significant importance to building up effective state institutions,over 80% of its funding is channelled through the Government of Afghanistan. DFID toldus:“we direct over 80% of our assistance through Government channels because thishelps the Government to develop the capacity to deliver basic services; to managepublic finances effectively; and to build credibility and legitimacy with the Afghanpeople.”40The funds are mainly channelled through the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund(ARTF) administered by the World Bank.The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF)34. The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund was established as a means of providingsupport to an inexperienced government in an insecure environment. In order to ensurefull accountability the World Bank reimburses the Government of Afghanistan forapproved expenditure and all the accounts are audited by an external agency,Pricewaterhouse Coopers. Currently 27 donors contribute to the Fund and DFID is thelargest single contributor. The ARTF has two strands: a “recurrent window” to support theoperating costs of the Afghan Government (predominantly public sector wages) and an“investment window” to fund development programmes.35. A number of NGOs have expressed concerns about the large percentage of DFID fundswhich go through the ARTF and the consequent implications of this for NGO funds. Forexample Oxfam writes:

383940

Q 140 [DFID]Q 5 [DFID]Ev 53 [DFID]

18

Reconstructing Afghanistan

“A number of donors, including the UK's Department for InternationalDevelopment (DFID), provide significant funds through the Afghan ReconstructionTrust Fund (ARTF), which provides a predictable and accountable source of fundsfor recurrent government expenditure. However, it is regrettable that DFID has verysubstantially reduced its funding for Afghan and international NGOs, who play animportant role in grassroots capacity building, rural development and support fordelivery of essential services.”4136. The allocation of DFID funds is based on the assumption that the state must be built-up and enabled so that it can carry out the normal functions of the state includingdevelopment and reconstruction. In his statement to Parliament the Prime Ministercommented that the UK Government believed that channelling aid through the Afghangovernment was “the best route to achieving sustainable progress and the best value formoney.”42DFID told us that:“We are very conscious of NGO concerns about this. We made a conscious decisionto try to shift the way we did business to give the Government authority over it, butwhen we look at the way government does business a lot of the money put through itis then delivered by NGO programmes. The health sector is a good example. TheMinistry of Health subcontracts NGOs to deliver programmes. So they still have abig role to play. Obviously, there are things that NGOs do which are beyond servicedelivery, and we need to ensure the capacity of advocacy NGOs is still being built upto hold government to account.”43Building a robust civil society capable of holding the government to account is crucial innewly-formed democracies and NGOs are often best placed to facilitate this importanttask. In Afghanistan it is particularly important that NGOs promoting women’s rights arealso funded.4437. DFID went on to clarify that if NGOs could deliver services in more insecure areas itwould be appropriate to use them in these areas:“As the security situation improves in some places but not others there is a constantquestion in our mind as to how to deliver services in the less secure areas. One mustalso take account of where the NGOs are able to deliver. If NGOs are to help todeliver services in the more difficult places where the Government’s nationalprogrammes find it hard to operate we should think hard about helping them. If theNGO proposals for delivering services are in places where the Government’sprogrammes can start to reach, then there is much more of a case for the delivery ofthose services to be provided or subcontracted by government.”45However we were told that many NGOs have stopped programmes in insecure provincesbecause of security concerns. ActionAid reported that “field activities have been severely4142434445Ev 116 [Oxfam]HC Deb, Col 303-307, 12 December 2007Q 14 [DFID]Ev 133 [Womankind Worldwide]Q 14 [DFID]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

19

hampered due to increased acts of violence and threats to staff; as a result of this volatileenvironment programme costs have significantly increased.”46Moreover NGOs may bereluctant to receive government funding directly because it affects their perceivedneutrality.47We were told that only four NGOs are operational in Helmand Province. Wewill examine in chapter 8 the difficulties for non-military actors attempting to deliverdevelopment in provinces where security is poor.38.We agree that DFID’s objectives should be to help build and support a viablesovereign state in Afghanistan and that the majority of DFID funds should thereforecontinue to be directed through the Government of Afghanistan. The priority fordonors should be the “Afghanisation of development”—building up Afghan capacity atall levels for successful development and reconstruction. However DFID must alsocontinue to ensure that funding is available for NGOs in their key advocacy tasksincluding helping to establish a robust civil society capable of holding the governmentto account. DFID should also ensure that NGOs promoting women’s rights areadequately funded.Improving economic management39. Another key element of DFID’s assistance to the Government of Afghanistan is inimproving economic management. While economic growth has been steady, theGovernment is heavily dependent on foreign aid to meet its recurrent costs. TheGovernment of Afghanistan currently raises only 6% of its revenue through taxation.48DFID is working with the Ministry of Finance to increase tax revenue and manage it moreeffectively.40. On our visit we saw the beneficial impact of economic growth, especially in Kabul andMazar-e-Sharif. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has forecast 12% economicgrowth this year.49The IMF has also established a set of targets for the Government tosupport economic reform, including increasing revenue mobilisation. We were told thatthe Government of Afghanistan was working towards these targets.We encourage theGovernment of Afghanistan to continue to work towards International Monetary Fundrevenue mobilisation targets as a means to ensuring that its future funding base issecure. We believe that DFID’s assistance in this respect is vital to progress.The distribution of DFID funds41. Approximately 20% of DFID funds is allocated directly to Helmand Province tosupport the wider UK effort there. DFID told us:“We support development in Helmand both through our rural livelihoods programmeand through HMG's Quick Impact Projects, designed to deliver immediate benefits to

46474849

Ev 62 [ActionAid]Ev 62 [ActionAid]Q 132 [DFID]Ev 51 [DFID]

20

Reconstructing Afghanistan

local communities. DFID spent around £16 million in Helmand in 2006–07, and wehave committed to spend up to £20 million this year. “50The Helmand Agricultural and Rural Development Programme supported theconstruction of four roads, 554 wells, and 482 community projects.51The programme alsoprovides access to micro-credit to promote non-opium livelihoods.5242. Concerns have been expressed that the geographical focus of UK aid is based onmilitary imperatives. For example BAAG suggests that:“DFID should consolidate gains already made in areas that are stable, for exampleBalkh and Jowsjan. The British focus on Helmand may lead to a situation wheregains made in stable provinces cannot be consolidated. BAAG members have beenencouraged to suggest projects in Helmand and Kabul areas but find it difficult toidentify and maintain funding for projects in equally poverty-stricken areas.”53Similarly the Institute for State Effectiveness writes that:“Countries which have greater troop presence are being placed under increasedpressure to allocate development funding in line with political and military-protection strategies using the civilian arms of PRTs as “development” agencies. Anexaggeration of this funding strategy will have long term consequences for bothdonor harmonisation as well as equity of funding across different provinces.Numerous examples already exist from north eastern provinces where claims arebeing made that insecure provinces in the south are benefiting through increasingaid, as compared to the relatively stable north where the perception is of reductionsin aid funding.”5443. In fact most DFID funding for Helmand is channelled through Government ofAfghanistan programmes and not the Provincial Reconstruction Team. The recentincrease in stabilisation assistance for Helmand is evidence that the Government considersHelmand to be a UK priority. These funds will be channelled through the Stabilisation AidFund (see paragraph 31).44.We do not consider that the UK Government’s development programme is undulyslanted towards Helmand at present. 80% of DFID’s funding is channelled through theGovernment of Afghanistan. The UK effort in Afghanistan is thus a “whole ofAfghanistan” one. Misunderstandings about this need to be countered in Afghanistan,and in the UK, by improved media strategies.45.Given the UK leadership of the Provincial Reconstruction Team in Helmand it isimportant that sufficient resources are available to ensure that stabilisation anddevelopment follow military action speedily. This need not be solely the responsibility

5051525354

Ev 53 [DFID]Ev 50 [DFID]Ev 58 [DFID]Ev 81 [BAAG]Ev 114 [Institute for State Effectiveness]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

21

of the UK since other donors are present there. DFID should also try to ensure thatgains made in more secure provinces are not lost for lack of funds and shouldcoordinate with other donors more effectively in this regard.46. During our visit we were told that in Afghanistan ‘everything is a priority’ because‘everything is broken’. As a country emerging from conflict the establishment of securityand the rule of law is important for the survival of the state. At the same time people’sunmet needs in terms of employment and access to basic services threatens to underminetheir faith in the newly created state. Simultaneously tackling security and development isa large part of the challenge of working in environments such as Afghanistan. YetAfghanistan is a large country with many regional variations which means that prioritiesand needs vary across the country. In the following chapters we examine the major issueswhich we think need to be addressed by the international effort in Afghanistan.

22

Reconstructing Afghanistan

3Donor CoordinationThe Paris Declaration47. The success of the development and reconstruction effort in Afghanistan is heavilydependent on the extent to which all donors are working towards the same objectives. TheParis Declaration of 2 March 2005 is an agreement which commits signatories to increaseefforts in harmonisation, alignment and managing aid for results accompanied by a set ofactions and indicators which can be used to monitor donor coordination.48. In the Declaration there are 12 indicators of progress. The objective of aligning donorprogrammes with those of recipient countries is measured by the percentage of aid flows tothe government sector that is reported on partners’ national budgets (indicator 3). TheDeclaration also commits donors to seek to harmonise their approaches and wherepossible use programme-based approaches and to undertake shared analysis and reviews(indicators 9 and 10).55

The Afghanistan Compact49. The principles of good partnership enshrined in the Paris Declaration were cementedin the Afghanistan Compact signed in London in January 2006.56The Compact is aframework for cooperation for the five-year period up to the end of 2010. It followedimplementation of the Bonn Agreement which re-established permanent governmentinstitutions in Afghanistan after the military action of 2001. At the London conference$10.7 billion in development assistance was pledged for the five-year period.5750. The Compact is monitored by the Joint Coordination and Monitoring Board (JCMB)which meets about four times a year. It is co-chaired by the Afghan Government and theUN Special Representative of the Secretary-General. The Compact is designed to supportthe implementation of the interim-Afghanistan National Development Strategy (i-ANDS)and focuses on security, governance and development goals.51. Afghanistan received approximately $1.5 billion in development assistance betweenMarch 2005 and March 2006.58We were told while we were in Afghanistan that well over90% of the budget came from external revenue. By far the largest contributor to totalOfficial Development Assistance (ODA) is the USA which provided $1.34 billion in 2005.The European Commission was the second largest donor providing $256 million and theUK provided $220 million.59Total ODA for 2007–08 is expected to be much higher at $4.3billion of which $1.9 billion will be channelled through the Government of Afghanistan.

5556575859

OECD Development Cooperation Directorate,The Paris Declaration on aid effectiveness,www.oecd.orgEv 52 [DFID]Ev 52 [DFID]Peace Dividend Trust,Afghanistan Compact Procurement Monitoring Project,April 2007,p vi.DFID,Afghanistan Development Facts.

Reconstructing Afghanistan

23

Impact of aid52. The impact of development assistance is greatly reduced without effectivecoordination.60The Institute for State Effectiveness writes that:“One of the challenges regarding aid and development in Afghanistan is proliferationof projects, funding channels, and mal-coordinated bilateral initiatives. This itselfgenerates a coordination problem. In 2002, the UN agencies and NGOs prepared alarge appeal based on hundreds of atomised projects, which failed to deliver a realdividend to the population. Rather, the Afghan population resent enormously theperceived lack of effectiveness, appropriateness and accountability in theseprojects.”61Similarly ActionAid told us that:“There is insufficient direction and support provided by the UN and JCMB, both ofwhich are substantially under-resourced, and too little coordination between donorsand the government of Afghanistan. Of all technical assistance to Afghanistan, whichaccounts for a quarter of all aid to the country, only one-tenth is coordinated amongdonors or with the government. Nor is there sufficient collaboration on projectwork, which inevitably leads to duplication or incoherence of activities by differentdonors.”6253. Coalition member states have also been criticised for failing to ensure that military,humanitarian, stabilisation and reconstruction efforts are sufficiently coordinated.63Theimportance of this aspect of coordination—joining up different sectors—was made evidentto us in Helmand. We visited a newly built maternity teaching unit at a local hospital. Theunit had been built with UK funds in July 2007. Unfortunately the building was not beingused as there had been delays in organising the delivery and funding of the training. DFIDreports that these problems have now been dealt with and they expect the trainingprogramme, funded by the World Bank, to start in the next few months.64We lookforward to receiving confirmation of the start of the maternity training programme inthe unit built with UK funds in Lashkar Gah.54. The deficit in harmonisation between donor approaches is problematic andincompatible with commitments made in the Paris Declaration. It means that theGovernment of Afghanistan has to respond to the different priorities and objectives ofdifferent donors.55. In addition to problems with harmonisation there is insufficient focus on ensuring thatdonor programmes are aligned with those of the Government of Afghanistan. Indicator 3of the Paris Declaration seeks to increase the percentage of donor assistance which is

6061626364

James Manor (ed)“A framework for assessing programme and project aid in low-income countries under stress” inAid that works: successful development in fragile states,World Bank, 2007,p 43.Ev 108 [Institute for State Effectiveness]Ev 116 [Oxfam]T. Noetzel and S. Scheipers,Coalition Warfare in Afghanistan: burden sharing or disunity?Chatham House, October2007.Ev 61 [DFID]

24

Reconstructing Afghanistan

reported on the national budget. The Afghanistan Compact commits donors tochannelling an increased percentage of their aid through Government channels, eitherdirectly to the budget or through trust fund mechanisms. Where this is not possible theCompact asks that donors use national rather than international partners to implementprojects, increase their procurement within Afghanistan and use Afghan goods andservices.6556. The Institute for State Effectiveness (ISE) points out that DFID together with Norway,Canada, the Netherlands, the EC and the World Bank have been exemplary in supportingGovernment of Afghanistan initiatives including the interim-Afghanistan NationalDevelopment Strategy. According to the ISE other donors led by the UN have pushed foran alternative approach and as a result projects rather than national programmes haveproliferated.6657. Of a total of $4.3 billion in donor expenditure for 2007 $1.9 billion was channelledthrough the core budget, of which $500 million went to the Afghanistan ReconstructionTrust Fund, and $2.4 billion was provided off-budget.67As discussed in the previouschapter the UK Government puts 80% of its funding through government channels ofwhich a significant portion, £70 million in 2007, goes to the ARTF.68The USA, the largestdonor, will put only 3% of its aid budget into the ARTF in 2007–08.69This means thatalthough such assistance may be aligned with objectives set out in the Afghanistan NationalDevelopment Strategy, it has a much lower impact on the local economy. The Secretary ofState assured us that the US did seek to align its programmes with Government ofAfghanistan priorities but DFID was continuing to press the US to put more funds throughGovernment of Afghanistan channels and was hopeful of change in this regard.7058. The funding of disparate projects also means that the Government of Afghanistan doesnot actually know what funds are coming into the country. DFID told us that there wasquite a serious issue about how much control the Government of Afghanistan has overdonor funding.71ActionAid writes that, “a lot of aid money coming to the country is goingthrough external budget. Not all donors are reporting their contributions to the Ministry ofFinance thus making it difficult to know the exact amount of money coming into thecountry.”7259. A recent report by the Peace Dividend Trust Fund points out that funds have a muchgreater impact when resources are provided directly to the government compared withfunds provided to NGOs or international companies to carry out projects because in thelatter case donors often use foreign contractors and supplies rather than Afghan ones.Wenote that, according to the Peace Dividend Trust, out of a total of US$1.36 billion spent

6566676869707172

The Afghanistan Compact, Annex II, www.unama-afg.orgEv 108 [Institute for State Effectiveness]Ev 61 [DFID]Ev 54 [DFID]USAID,US Assistance Briefing2007-08.Q 137 [DFID]Q 8 [DFID]Ev 63 [ActionAid]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

25

between March 2005 and March 2006 from major donors the local impact was around31% or the equivalent of $424 million.73Data provided by the Peace Dividend Trust for2005 also suggests that, although US Official Development Assistance was six times aslarge as UK ODA, its local impact was only twice as much.7460. The military have the benefit of military doctrines which have been developed on aninternational basis over many years within NATO. There is no parallel body of agreedprinciples—or “doctrine”—for civilian post-war reconstruction and development. PRTswork in different ways in different parts of Afghanistan. Some have budgets of tens ofmillions of dollars—others hardly any resources of their own. Some donors, like the UK,put the majority of their assistance through the Afghan government, while others, like theUSA, do not. The need for development assistance in post-conflict and insecureenvironments, which require a military presence to impose security, is not going to goaway.Development agencies need to come to international agreements amongthemselves about what constitutes good practice for post-war reconstruction anddevelopment in fragile states, especially when they are working in partnership with themilitary. The development community needs a body of agreed principles every bit asmuch as the military.61. During our visit we discussed with the World Bank its procedures for monitoringexpenditure under the ARTF. In addition we were given the results of an independentreview of the Fund carried out in 2005. The review found that the ARTF structure andprocedures were functional and in line with best practice in post-conflict settings. TheFund is also in accordance with the Paris Declaration’s “good partnership principles” onownership, alignment, harmonisation and mutual accountability for donor funding.Moreover it has allowed the Government of Afghanistan to provide key public servicesacross the country.7562. DFID told us that it is helping to improve donor coordination by encouraging donorsto help the Government develop a comprehensive Afghanistan National DevelopmentStrategy (ANDS) and by working towards the development of a joint donor strategyprocess which aligns donor support to the ANDS.76As lead donor for coordination this isan important role but we were told that some donors continue to pursue pet projects.63.The international community committed themselves to the Afghanistan Compactunder which they have agreed to provide an increased proportion of their assistancethrough the core government budget. While DFID is exemplary in this respect, otherdonors are not. This means that the Government of Afghanistan does not “own” thedevelopment and reconstruction process and that the local impact of donor assistanceis greatly reduced. DFID’s efforts at improving donor coordination in this regard arecommendable but the results are currently unsatisfactory. The AfghanistanReconstruction Trust Fund has been shown to be effective. The use of parallelstructures to deliver assistance by the US does nothing to build up Afghan capacity, and

73747576

Peace Dividend Trust,Afghanistan Compact Procurement Monitoring Project,April 2007, p vi.Excluding contributions to the UN for which there are no calculations of local impact.Scanteam,Assessment: ARTF: final report,Oslo 2005.Ev 51 [DFID]

26

Reconstructing Afghanistan

will therefore lengthen the time-period for which aid is necessary. Such policies are alsocontrary to Paris Declaration principles and commitments made under theAfghanistan Compact. We believe DFID should make renewed efforts to encourage theUS and other donors to channel a greater proportion of their funding through theAfghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund.64. When we visited the government hospital in Lashkar Gah we learnt that it provided achild immunisation service in both government and insurgent controlled areas. It treatedpatients from the insurgent controlled countryside as well as government controlled towns.When it trained staff, community midwives for example, some went to work in insurgentcontrolled areas. There are good humanitarian reasons to provide health services to all,and it doubtless helps the battle for hearts and minds in insurgent controlled areas forhealth services to be seen to be available from the Afghan government. It is difficult toimagine health services provided by a western government being tolerated in an insurgentcontrolled area. This underlines the value, wherever possible, of channelling developmentaid through the Afghan government. Health was the only government provided service inHelmand which we saw reaching out to insurgent held areas.We urge the UK to use itsleadership role in the Provincial Reconstruction Team to encourage donors to providemore resources to Afghan government health services in Helmand.

A high level UN coordinator65. In its recent report on Afghanistan the Defence Committee called on the Governmentto press the UN to appoint a high-profile individual responsible for coordinating theinternational effort.77The idea of a joint UN, EU and NATO coordinator has beendiscussed. In his statement to Parliament the Prime Minister confirmed that such an envoywould be in place by February 2008.7866. Recent press reports state that plans to create the role of UN super-envoy to coordinatethe international effort in Afghanistan have been abandoned. Instead there will be areplacement for the existing role of UN Special Representative.79The Secretary of Stateconfirmed to us that discussions were ongoing but he was optimistic that the EU, UN andNATO would better align their work in the future.80There was strong speculation thatLord Ashdown would be appointed as the next UN Special Representative. However he haswithdrawn from the process because he felt that he did not have the full support of thePresident of Afghanistan. The Secretary of State told us that the UK had been unyielding inits support for increased donor coordination which an effective UN representative couldbring and that the identification of a suitable candidate was therefore urgent.81

7778798081

Defence Committee, Thirteenth Report of Session 2006-07,UK Operations in Afghanistan,HC 408 para 30.HC Deb, Col 303-307, 12 December 2007Daily Telegraph, 7 January 2008Q 126 [DFID]Oral Evidence from the Secretary of State for International Development, 31 January 2008 (on Iraq), Qs 52-53

Reconstructing Afghanistan

27

67.We are disappointed that sufficient international momentum could not be gainedfor the appointment of a high level joint UN, NATO, EU coordinator for Afghanistan.Criticisms by the Afghan Government of the UK and the international community’sefforts seem to be becoming more frequent. Problems of donor coordination areleading to a proliferation of disparate projects, low local impact of funding and creatinga poor impression in Afghanistan about donors’ lack of agreement. We believe suchoutcomes are harmful to the international effort in Afghanistan and may set backprogress in reconstruction. If the international community will not agree theappointment of a super-envoy, ways must be found to ensure that the role of UNSpecial Representative is properly resourced and that the incumbent has sufficientweight in dealing with partner countries. We hope that the Government of Afghanistancan recognise the long-term benefits for them of the UN appointing a strongrepresentative to improve coordination.

28

Reconstructing Afghanistan

4Improving securitySecurity conditions68. Increasing insecurity and the continuing insurgency are threatening the reconstructioneffort in parts of Afghanistan. ActionAid writes that, “at no time since 2001 has the securitysituation in the country looked so dire. Over the last year, the Taliban have regrouped,reorganised and refunded their insurgency, launching bitter battles across the southernthird of Afghanistan.”82Oxfam also report increasing death rates resulting from the conflictin 2007.83In June 2007 the BBC reported that:“The Taliban have new confidence and new tactics, and their campaign against thegovernment and its NATO backers has been increasingly successful since thebeginning of this year. In the east of the country, around Jalalabad, suicide bombingshave become such frequent occurrences that the road from there to Kabul is nowknown as the Baghdad road.”8469. During our visit in late October 2007 the security situation was relatively calm(although our visit programme in Helmand was altered slightly following a suicide bomboutside the Lashkar Gah bus station which killed one person). However soon after ourdeparture Afghanistan suffered one of its worst suicide bombings to date in the northerntown of Baghlan when around 70 people were killed, including five MPs and many school-children.85In January there was an attack on the Serena Hotel in Kabul where we stayedduring our visit.86This is being considered as the start of a new campaign to targetforeigners. The Secretary of State assured us that the incident had not affected DFID’scommitment to working in Afghanistan although it had restricted the movements of DFIDand Embassy staff and may affect its ability to recruit staff for longer terms.8770. Some analysts have commented on the increasing reach of the insurgency,88and someeven question whether the “war” is winnable.89The Prime Minister’s statement of 12December 2007 sought directly to contradict such conclusions—“let me make it clear at theoutset that as part of a coalition we are winning the battle against the Taliban insurgency.”90Lord Malloch-Brown, Minister of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, stated

828384858687888990

Ev 63 [ActionAid]Ev 124 [Oxfam]“Can the war in Afghanistan be won?” bbc.co.uk/news, 17 June 2007.“At least 50 dead as bomber hits MPs’ school visit,” The Independent, 7 November 2007; Survivors recall Baghlanbomb horror”,www.bbc.co.uk/news“Taliban attack luxury Kabul Hotel” bbc.co.uk/news, 15 January 2008Q 124 [DFID]“Warning shots turn into lethal new development as violence drifts north,” The Guardian, 7 November 2007.“The Taliban can lose every battle—yet still win the war”, The Daily Telegraph, 12 December 2007; “Britain’s Afghanmission is a fruitless and failing pursuit,” The Guardian, 12 December 2007.HC Deb, Col 303-307, 12 December 2007.

Reconstructing Afghanistan

29

that, “the Taliban do not control a single province or have the ability to hold territory,showing they are far from being a resurgent force.”9171. Yet, despite initial coalition military success, a Taliban-led insurgency has continued tothreaten security and stability in Afghanistan. Christian Aid told us that:“the current insecurity caused by a mix of the Taliban-led insurgency, the ongoingactivities of illegal militias tied to provincial warlords or factional commanders, andgeneral criminality is having a debilitating effect on the environment fordevelopment.”92This point was echoed in our conversation with the former Finance Minister, AshrafGhani.72. The security situation does, however, vary across the country. In the north and the westit is relatively peaceful and more development is possible. In the south it varies from placeto place. DFID told us that “in the area round Lashkar Gah it is relatively easy to get outand see what is going on; in other parts of Helmand the security situation has been moredifficult.”93However the areas of the country which are becoming more insecure have beensteadily increasing according to successive UN accessibility maps.9473. The UK Commander of Task Force Helmand, Brigadier Andrew MacKay, told us thatNATO forces were facing a classic insurgency in Afghanistan. He said the Taliban’s failureto win conventional battles had led them to start using ‘asymmetrical’ tactics such assuicide bombs and improvised explosive devices designed to spread fear, even in areaswhich are relatively secure.We note the UK Commander of Taskforce Helmand’sexplanation that the key objective of the military was to gain the consent of the localpopulation and to marginalise the insurgents and starve them of their support base. Wealso note that most people in Afghanistan do not support the insurgency so thatinfluence-winning activities are more important than overt military force. Cooperationand understanding between NATO forces and the Afghan Government and armedforces are crucial to success.74.We would also like to pay tribute to the commitment and sacrifice being made byUK forces in this difficult environment. We were disappointed by the tone and timingof the recent criticisms made by President Karzai of UK military operations inHelmand, particularly as these concerns were not raised with us by the Government ofAfghanistan during our visit. We are concerned that such comments risk underminingthe support of the British people for the UK’s long-term commitment to Afghanistan.75. Brigadier MacKay explained that in Afghanistan “tier 1 Taliban” are regarded as thehardliners, frequently linked to Al-Qaeda, who cannot be reconciled. Many of those whoare referred to as “tier 2 Taliban”, on the other hand, are often unemployed youth who will

91929394

Lord Malloch-Brown “Taliban no longer a credible threat,” Letter toThe Independent,29 November 2007.Ev 96 [Christian Aid]Q 20 [DFID]UN Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan Accessibility Maps; UNDSS,Half-year Review of the SecuritySituation in Afghanistan,13 August 2007.

30

Reconstructing Afghanistan

work for whoever is willing to pay them. This group, sometimes also referred to as the “$10Taliban”, was more likely to renounce violence and back the new Government.76. The Secretary of State told us that around 5,000 former fighters had already movedback into the mainstream.95However without providing such individuals and their familieswith jobs and incomes they are likely to return to the Taliban. This highlights the need for ajoined-up military, political and reconstruction effort.9677.Increasing insecurity and the continuing insurgency are threatening thereconstruction effort in many parts of Afghanistan. The relationship between securityand development is a key determinant of success in post-conflict environments. Whileit is important that the NATO forces remain in Afghanistan to help provide thesecurity which is a necessary precondition for reconstruction, it is clear to us thatwithout tangible improvements in people’s lives the insurgency will not be defeated.Regional security78. UN Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS) maps of Afghanistan reveal thatsecurity has deteriorated, particularly in the south eastern areas which border Pakistan.97Arecent Chatham House paper states that:“The conflict has increasingly become a regional one. Taliban bases in Pakistancannot be targeted by coalition forces; however, logistical and armament supplies outof Pakistan are significant, and Pakistan is used as a recruitment base. As long asparts of Pakistan serve as a safe haven for the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, coalition forceswill not be able to control Afghanistan.”9879. In discussions we had in Afghanistan Dr Barnett Rubin from the Centre onInternational Cooperation, New York University, also highlighted the key part thatPakistan played in Afghanistan’s future. The Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)in the borderlands are controlled by neither government and are the breeding ground forTaliban recruits and a major drug trafficking route.99Efforts on the part of theinternational community to encourage more meaningful dialogue between the twocountries have seen some positive outcomes, including the return of about four millionAfghan refugees. Nevertheless current instability in Pakistan, exacerbated by theassassination of Benazir Bhutto, creates the risk of further insecurity. The Secretary of Statefully acknowledged that the security of Pakistan and Afghanistan were inter-related andthat the UK would continue to monitor the border closely.100

9596979899

Q 126 [DFID]David Kilcullen, “Three pillars of counterinsurgency,” remarks delivered at the US Government CounterinsurgencyConference, 28 September 2006.“Aid map reveals expansion of no-go zones”, The Times, 5 December 2007.Noetzel and Scheipers,Coalition warfare in Afghanistan,p 1.Ev 126 [Oxfam]

100 Q 180 [DFID]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

31

80.We believe that greater international pressure should be placed on Pakistan tocontrol more effectively the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Unless this happensthe Taliban will have a steady supply of recruits and the international effort to bringstability and security to Afghanistan will be futile.81. There are also close ties and regular cross-border traffic between Iran and westernAfghanistan which would certainly become a focus for instability in the event of militaryaction against Iran.

International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the UK troopcontribution82. In December 2007 the Prime Minister announced that UK troop numbers inAfghanistan would remain at about 7,800. Afghanistan is the UK’s largest singledeployment and the UK troop contribution is the next largest after that of the USA. Thisreflects the Government’s commitment to bringing security and stability to Afghanistan.We support the Government’s commitment to bringing security and stability toAfghanistan and commend the work of our armed forces there.83. There are approximately 41,700 NATO troops (including support elements) from 37countries in Afghanistan under International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)command.101In addition there is a US-led counter-insurgency operation, OperationEnduring Freedom (OEF) with a separate command structure. A Chatham House paperon Afghanistan argues that this dual command structure violates the principle of unity ofcommand in military operations and increases the chance of operational confusion.102TheCommander of ISAF, US General Dan McNeill told us that he was not overly concernedabout the two command structures since he did not believe it was currently causingproblems.84. General McNeill did however express strong concerns about the extensive use ofnational caveats by contributing nations which, he said, severely hampered ISAF’s progressand meant that in practice troops would be needed in Afghanistan for a longer period.National caveats might for example prevent some troops from being sent to the southwhere insecurity is greatest. The Defence Committee commented on this in its report:“While we note the progress that has been made in reducing national caveats, we remainconcerned that national caveats risk impairing the effectiveness of the ISAF mission.”103We support the conclusion of the Defence Committee that the excessive use of nationalcaveats increases the risk of impairing the effectiveness of the International SecurityAssistance Force and will increase the length of time which NATO troops are requiredto be in Afghanistan. The UK Government should continue to press contributingnations to reduce these to facilitate more effective ISAF operations.

101 www.nato.int102 Noetzel and Scheipers,Coalition warfare in Afghanistan,p 3.103 Defence Committee, Thirteenth Report of Session 2006-07,UK operations in Afghanistan,HC 408, para 45.

32

Reconstructing Afghanistan

85. We saw good co-operation between civilians and the military in the Helmand PRT.The team was led by a UK diplomat who had previously worked on post-warreconstruction in the Balkans. Its members include the Deputy Commander of TaskforceHelmand and a DFID representative (see paragraph 165).We are concerned, however,that civilian-military co-operation is weakened because UK military commanders serveonly a six-month tour of duty while the civilians are in post for longer periods. We askthe Secretary of State to discuss with the Ministry of Defence the feasibility of extendingUK military commanders’ tours of duty in Helmand to, say, one year.

Security Sector Reform86. One of the key objectives of the NATO coalition in Afghanistan has been to create aneffective and legitimate Afghan security sector. Unfortunately progress with this objectivehas not been as rapid as had been hoped. Security Sector Reform was initially undertakenby dividing responsibilities between the different coalition partners. Germany was incharge of creating an Afghan National Police Force (ANP) and the US for building up theAfghan National Army (ANA). The UK assumed the lead role in counter-narcotics, Italyfor reforming the legal system and Japan for disarmament, demilitarization andreintegration. Some commentators argue that this approach, while theoretically sound, didnot work in practice, not least because the pillars are all interlinked and lack of progress inone area would impact on the others.104The Afghan National Army (ANA)87. In Afghanistan we were told that the Afghan National Army was making good progressbut that it was still three to four years from being capable of independent militaryoperations at brigade level and even then it would need the international community toretain an ‘overwatch’ responsibility (providing logistical and medical support andoperational back-up). The Army is currently being trained and mentored by NATO forces.The aim was to create a force of about 70,000–80,000 and they are about halfway there.Afghan troops were reported as having played a significant role in the retaking of the townof Musa Qala from the Taliban in December 2007 alongside NATO forces105There hasbeen significant progress in the building up of an effective Afghan National Army.There is still some way to go before it is a fully capable force and we commend the roleplayed by the UK to date in training and mentoring.The Afghan National Police (ANP)88. The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) told us that the Afghan NationalPolice were still five to six years away from being an effective force which has the trust ofthe Afghan people. The intention is to have a force of about 82,000 and currently there are50,000.106Many people told us that the police were corrupt and that top positions could be

104 Ev 97 [ActionAid]105 “Brigadier strides into battle against Taliban”, The Times, 17 December 2007.106 Q 24 [DFID]

Reconstructing Afghanistan

33