Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2006-07

Bilag 47

Offentligt

UN Assistance Mission for Iraq(UNAMI)

1.

ةﺪﺤﺘﻤﻟا ﻢﻣﻷا ﺔﺜﻌﺑقاﺮﻌﻠﻟ ةﺪﻋﺎﺴﻤﻟا ﻢﻳﺪﻘﺘﻟ

Human Rights Report1 January – 31 March 2007

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................. 1INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 2SUMMARY................................................................................................................................................... 3PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS...................................................................................................... 5EXTRA-JUDICIAL EXECUTIONS AND TARGETED AND INDISCRIMINATE KILLINGS........................................ 5FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION..........................................................................................................................11MINORITIES...............................................................................................................................................14PALESTINIAN REFUGEES............................................................................................................................15WOMEN.....................................................................................................................................................17DISPLACEMENT OF THE CIVILIAN POPULATION..........................................................................................19HUMANITARIAN SITUATION.......................................................................................................................20RULE OF LAW...........................................................................................................................................22DETENTIONS..............................................................................................................................................22DETENTIONS IN THEREGION OFKURDISTAN.............................................................................................25TRIAL PROCEDURES BEFORE THE CRIMINAL COURTS AND THE DEATH PENALTY........................................25IRAQIHIGHTRIBUNAL..............................................................................................................................27PROMOTION .............................................................................................................................................28HUMANRIGHTSPROJECT FORIRAQ2006-2007 ........................................................................................28RULE OFLAWINITIATIVE..........................................................................................................................28NON-GOVERNMENTAL SECTOR..................................................................................................................29REGION OFKURDISTAN.............................................................................................................................29

1

IntroductionThe Human Rights Office (HRO) of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq(UNAMI) engages in the promotion and protection of human rights and the rule of law inclose collaboration with Iraqi governmental and non-governmental sectors, in accordancewith UN Security Council Resolution 1546 (2004), paragraph 7 (b) (iii), which mandatesUNAMI “to promote the protection of human rights, national reconciliation, and judicial andlegal reform in order to strengthen the rule of law in Iraq.” In order to fulfill this mandate,UNAMI HRO monitors the human rights situation in Iraq and assists, especially throughcapacity-building activities, in the rehabilitation and reconstruction of state and civil societyinstitutions. It collaborates closely with national human rights activists and seeks to maintaindirect contact with victims and witnesses of human rights violations.1UNAMI HRO’s Human Rights Report, previously published on a bimonthly basis, willhenceforth be issued on a quarterly basis. The report, which details serious and widespreadhuman rights violations, is intended to assist the Government of Iraq in ensuring protectionof basic human rights and respect for the rule of law. Given prevailing security conditionsand the nature of the violence engulfing many parts of the country, UNAMI recognizes theenormous difficulties facing the Iraqi Government in its efforts to restore law and order. Itslaw enforcement personnel are under relentless attack by insurgency groups, and both Sunniand Shi’a armed groups carry out direct attacks on civilians through suicide bombings,abductions and extrajudicial executions while making no distinction between civilians andcombatants. Such systematic or widespread attacks against a civilian population aretantamount to crimes against humanity and violate the laws of war, and their perpetrators aresubject to prosecution.Nonetheless, Iraq remains bound by both its international treaty obligations and its domesticlegislation in taking measures to curb the violence. The International Covenant on Civil andPolitical Rights (ICCPR), in particular, is clear on the basic protections that must be affordedto persons and from which no derogation is permissible even in times of emergency.2UNAMI’s mandate includes assisting the Government of Iraq in fulfilling its human rightsobligations, and remains willing to engage the authorities in a constructive dialogue in orderto achieve these objectives. The ultimate aim – ensuring lasting stability and security – canonly be realized through the protection of fundamental rights and respect for basic humandignity. UNAMI stands ready to support the Iraqi Government in that effort.

UNAMI HRO has a physical presence in Amman, Baghdad and Erbil, with over 30 staff members employedin total. UNAMI HRO in Basra closed when the human rights staff was withdrawn for security reasons inOctober 2006. Security conditions on the ground continue to severely restrict freedom of movement of UN staffin all regions except three governorates under the authority of the Kurdistan Regional Government, impairingboth protection and promotion activity by UNAMI HRO.2Iraq ratified the ICCPR in 1971, and all successive governments are bound by this treaty obligation.

1

2

Summary1. The Government of Iraq continued to face immense security challenges in the face ofgrowing violence and armed opposition to its authority and the rapidly worseninghumanitarian crisis. A number of large-scale insurgency attacks had devastating effects onboth the civilian population and Iraqi law enforcement personnel, and continued to claimlives among Multinational Force (MNF) personnel. Civilian casualties of the daily violencebetween January and March remained high, concentrated in and around Baghdad. Violentdeaths were also a regular feature of several other cities in the governorates of Nineveh,Salahuddin, Diyala and Babel. The implementation of the Iraqi-led Baghdad Security Plan(KhittatFardh al-Qanun)on 14 February saw an increase in Iraqi and MNF troop levels andcheckpoints on the streets of Baghdad, expanded curfew hours and intensified securityoperations and raids. The challenge facing the Government of Iraq is not limited toaddressing the level of violence in the country, but the longer term maintenance of stabilityand security in an environment characterized by impunity and a breakdown in law and order.In this context, the intimidation of a large segment of the Iraqi population, among themprofessional groups and law enforcement personnel, and political interference in the affairsof the judiciary, were rife and in need of urgent attention.2. In its previous reports on the human rights situation in Iraq, UNAMI regularly cited theIraqi Government’s official data, including the Ministry of Higher Education’s statistics onkillings among academics and the Ministry of Interior’s statistics on killings among policeofficers. It is therefore a matter of regret that the Iraqi Government did not provide UNAMIaccess to the Ministry of Health’s overall mortality figures for this reporting period. UNAMIemphasizes again the utmost need for the Iraqi Government to operate in a transparentmanner, and does not accept the government’s suggestion that UNAMI used the mortalityfigures in an inappropriate fashion.3. Evidence which cannot be numerically substantiated in this report nonetheless show thatthe high level of violence continued throughout the reporting period, attributable to large-scale indiscriminate killings and targeted assassinations perpetrated by insurgency groups,militias and other armed groups. In February and March, sectarian violence claimed the livesof large numbers of civilians, including women and children, in both Shi’a and Sunnineighborhoods. One of the most devastating attacks occurred on 3 February when a truckpacked with a ton of explosives detonated, killing an estimated 135 people and injuring 339others in a busy market in the predominantly Shi’a district of al-Sadriyya of Baghdad. Whilegovernment officials claimed an initial drop in the number of killings in the latter half ofFebruary following the launch of the Baghdad Security Plan, the number of reportedcasualties rose again in March.4. In its previous reports, UNAMI expressed its concern that many Baghdad neighborhoodshad become divided along Sunni and Shi’a lines and were increasingly controlled by armedgroups purporting to act as protectors and defenders of these areas. Efforts to find a long-term and durable solution to mass displacement will necessitate a reversal of this trend,

3

enabling civilians to return to their homes safely and voluntarily. According to figures fromthe United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), an estimated 736,422persons were forced to flee their homes due to sectarian violence and military operationssince the bombing of the al-Askari shrine in Samarra’ on 22 February 2006. Of these, morethan 200,000 were displaced since December 2006. Together with 1.2 million IDPs displacedprior to 22 February 2006, they are in need of continuous assistance, including shelter andimproved access to the Public Distribution System (PDS). Additionally, Palestinian refugeesresiding in several neighborhoods in Baghdad continued to be victims of the deterioratingsecurity situation. According to a Palestinian human rights organization and other Palestiniansources, 198 Palestinians were killed in targeted assassinations or attacks on their residentialcompounds since 4 April 2003. Many Palestinians responded to continuing threats andattacks by leaving their homes and seeking refuge in camps along the Iraq-Syria border.5. UNAMI notes again the serious trend of growing intolerance towards minorities, whoserepresentatives continued to lodge complaints about discrimination, intimidation andindividual targeting on religious and political grounds. The 2005 Iraqi Constitution protectsthe “religious freedoms” of all of its citizens. Of equal concern are ongoing attempts tosuppress freedom of expression through tighter control of the broadcast media and printedpress. UNAMI noted several incidents of harassment, legal action and intimidation againstjournalists addressing issues of corruption and mismanagement of public services in theRegion of Kurdistan. Across the country, attacks against journalists and media outletscontinued, resulting in a high number of casualties among media workers.6. UNAMI remained concerned at the apparent lack of judicial guarantees in the handling ofsuspects arrested in the context of the Baghdad Security Plan. While in his public statementsPrime Minister Nouri al-Maliki pledged that the government would respect human rights andensure due process within a reasonable time for those under arrest, there were no references toany mechanisms for monitoring the conduct of arresting and detaining officials. The newemergency procedures announced on 13 February contained no explicit measures guaranteeingminimum due process rights. Rather, they authorized arrests without warrants and theinterrogation of suspects without placing a time limit on how long they could be held in pre-trialdetention.The use of torture and other inhumane treatment in detention centers under theauthority of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defense continues to be of utmostconcern. UNAMI re-emphasizes the urgent need to establish an effective trackingmechanism to account for the location and treatment of all detainees from the point of arrest.

7. During this reporting period, UNAMI further expanded its monitoring and reportingactivities in the three northern governorates under the authority of the Kurdistan RegionalGovernment (KRG), where the security situation remained stable. Infringements to freedomof expression, including press and media freedoms, were of serious concern. Equally seriouswas the lack of due process with regard to detainees held by Kurdish security forces(Asayish), the majority on suspicion of involvement in acts of terrorism and other seriouscrimes. Hundreds have been held for prolonged periods without referral to an investigativejudge or charges brought against them. UNAMI also noted the absence of serious measuresby the KRG authorities to address the growing level of violence against women, includingprompt investigations and criminal prosecution of perpetrators.

4

Protection of Human RightsExtra-judicial executions and targeted and indiscriminate killings

8. The civilian population continued to be disproportionably affected by the growing levelof violence in the country. Sectarian violence was most pronounced in areas with diverseethnic and religious groups or where such groups were located in close proximity to eachother, such as Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk and Mosul. In Basra and Kirkuk, competing factionsoften and openly clashed with each other. Relatively quieter areas of Missan, Wasset, al-Muthanna and Dhi-Qar governorates were also affected by the overall climate of instabilityand corruption, as well as by tensions resulting in part from the rapid influx of displacedpopulations.9. The distinction between acts of violence motivated by sectarian, political or economicconsiderations was frequently blurred as a multitude of armed and criminal groups claimedresponsibility for numerous acts of terror. The prosecutorial and investigative capacity of theIraqi state was and is likely to remain inadequate in the face of relentless attacks by armedgroups operating with impunity under the umbrella of both Sunni insurgent groups and Shi’amilitia.10. During this reporting period UNAMI made repeated efforts to obtain overall mortalityfigures which in the past it had received from the Ministry of Health’s Operations Center andthe Medico-Legal Institute in Baghdad.3However, the Iraqi Government told UNAMI that ithad decided against providing the data, although no substantive explanation or justificationwas provided. It is noteworthy that this directive does not apparently apply to any otherministry from which UNAMI obtains official data. Following the publication of its lastHuman Rights Report on 16 January 2007, the Prime Minister’s Office told UNAMI that themortality figures contained in the report were exaggerated, although they were in fact officialfigures compiled and provided by a government ministry. UNAMI urges the IraqiGovernment to make available this crucial data and would welcome an opportunity to discussits publication through an alternative appropriate forum. On 1 March, the Ministry of Interiorannounced that 1,646 civilians were killed in February, the majority of them in Baghdad. Itwas unclear on what basis these figures were compiled.11. UNAMI continues to monitor and record violations of human rights by all sides throughindividual reporting, witness statements, interviews with victims and other sources. Patternsof violence witnessed in this reporting period were largely consistent with those highlightedin previous UNAMI Human Rights Reports. Armed groups from all sides continued to targetthe civilian population. In doing so, these groups frequently violated the sanctity of places ofreligious worship, such as mosques to store weapons and ammunition, occupied civilianbuildings such as schools, and disregarded the protected status of health facilities and healthThe Operations Center gathers statistics on a weekly basis from all hospitals across Iraq except the Region ofKurdistan. The Medico-Legal Institute (MLI) in Baghdad collects and analyses data from all six medico-legalinstitutes across the country. Both the Operations Center and the MLI collate data on deaths resulting fromunnatural causes, including ordinary criminality and killings resulting from acts of violence in the context ofsectarian or other conflict.3

5

professionals in violation of international humanitarian and human rights laws. Kidnappingsand hostage-taking remained a daily occurrence in certain areas of Iraq.12. Suicide and car bombs continued to claim a large number of civilian casualties. Anincreasing number of Iraqis sought various means to flee the country, seeking asylum orrefugee status abroad. Large-scale attacks were perpetrated between January and March, withseveral incidents claiming the lives of more than 50 people each. On 16 January, in a singlecar bomb attack on al-Mustansiriya University in Baghdad, some 70 people, mostly students,were reportedly killed and 140 wounded. The attack apparently came in the wake of repeatedthreats and calls for the suspension of classes in academic institutions by insurgent groups,most notably Ansar al-Sunna. On 22 January, two bombs exploded in the Bab al-Sharqimarket in central Baghdad, killing an estimated 88 people and wounding 160 others. Thispredominantly Shi’a market had previously been attacked in December 2006. On 1 Februarytwo suicide bombers at a crowded market in al-Hilla reportedly killed between 45 and 70people and injured 125 others. On 3 February, one of the largest targeting of civiliansoccurred in Baghdad in a busy market in the district of al-Sadriya, when a truck packed withapproximately a ton of explosives detonated, killing some 135 people and injuring 339others. On 12 February two car bombs exploded in Baghdad’s Shorja market, killing anestimated 76 people and injuring over 155 others and setting numerous stalls, shops and anearby high-rise building on fire. Four days later, on 18 February, two car bombs targetingthe main shopping centre of Baghdad al-Jadida, a mainly Shi’a district in eastern Baghdad,reportedly killed 62 people and wounded 129 others. On 24 February, 56 people werereported killed in an explosion outside a mosque in al-Habbaniya, apparently timed to inflictmaximum casualties as worshippers began leaving the mosque. Among the dead were fivechildren. In some cases, entire families were reported killed. On 6 March, an estimated 120pilgrims died in a targeted attack while en route to Karbala.13. Sectarian violence was most pronounced in areas with diverse ethnic and religious groupssuch as Baghdad and in the governorates of Babil, Diyala, Salahuddin and Nineveh. On 25March, a series of attacks and counter attacks between Sunni and Shi’a armed groups in al-Iskandariya and al-Haswa in northern Babil led to the burning of a number of mosques onboth sides, and the killing of at least four people. Two other incidents took place in Tala’fartowards the end of March. On 27 March, two truck bombs targeted a market in apredominately Shi’a neighborhood in the town. According to reports received, one of thetruck drivers alleged he was distributing flour on behalf of a humanitarian organizationbefore detonating the explosives and killing scores of people gathered around the vehicle. Anestimated 75 people were killed and up to 185 were wounded. The following day, thedirector of Tala’far Hospital announced that the bodies of 60 people bearing gunshot injurieshad been brought to the hospital. The killings, carried out in apparent retaliation for theearlier suicide attacks, were reportedly carried out in the Sunni neighborhood of al-Wahda inTala’far. The victims were said to have been shot in the back of the head, while 40 otherswere abducted by armed militia, allegedly in collusion with local police. Reports of the arrestof 18 police officers in connection with these incidents have yet to be confirmed. In one ofthe more devastating attacks in Kirkuk since January, a series of explosions on 19 Marchtargeted Tis’een Quarter, a Turkoman district. The blasts killed an estimated 20 civilians,

6

wounded 42 others and damaged a Sunni mosque and a husseiniyya belonging to theTurkoman Shi’a community.14. Relatively quieter areas of Missan, Wasset, al-Muthanna and Dhi-Qar governorates werealso affected by the overall climate of instability, as well as by tensions resulting in part fromthe rapid influx of displaced populations. Particularly prevalent were targeted assassinations,among the victims being former Ba’ath Party members, professional groups, students,members of minority groups and security officials. In the latter half of March ten people,including three women, were reportedly killed in al-‘Amara. In Basra in late March, fiveengineers working at the Electricity Directory in the city were kidnapped, allegedly by MahdiArmy militiamen. Their fate and whereabouts remained unknown.15. In January and up to mid-February, areas most affected by the violence in Baghdad werethose where armed groups competed for territorial domination, such as al-A’dhamiya, al-Dora, al-Khadhimiya and al-Ghazaliya, as well as Sadr City. In one incident, severaleyewitnesses reported to UNAMI on the killing of 24 persons in al-Fehama area, close toHaifa Street, on 6 January. The killings wre said to have been carried out by an insurgentgroup seeking control of the Haifa Street area. The bodies of those killed, all allegedmembers of the Mahdi Army, were reportedly hung on lampposts and an announcement tothat effect was made by the perpetrators through loudspeakers. On 12 January, three armedmen reportedly fired indiscriminately in the southern part of Haifa Street wounding oneperson before driving away. Residents in the area also reported sniper fire from variousbuildings in the vicinity of Haifa Street.16. UNAMI continued to receive reports of possible collusion between armed militia andIraqi Special Forces in raids and security operations, as well as reports of the failure of theseforces to intervene to prevent kidnapping and murder and other crimes. In one incident on 11January, 11 employees of Ministry of Oil were abducted by an armed group en route to workfrom their residential compound in al-Nahrawan. Eyewitnesses stated that their vehiclepassed through several police checkpoints without being stopped, checked or apparentlyraising suspicion. In another case on 27 January, 8 employees working for al-QimmahComputer Company in the district of al-Karrada near the Technology University wereabducted from the company’s headquarters, allegedly by gunmen wearing police uniforms.On 19 February armed men, reportedly wearing Iraqi Special Forces’ uniforms abducted aPalestinian man, Mahmoud Sa’id Salih, in al-Yusufiyya. His fate and whereabouts remainedunknown.17. Despite reports from Iraqis in late February that security had somewhat improved, therewere a series of indiscriminate attacks targeting civilians, and the rate of kidnappingsremained high. While some of those abducted were released after the payment of ransoms,many others remained missing and may have been among the unidentified victims whosebodies reached Medico-Legal institutes in various cities across the country. There were alsonumerous targeted attacks and assassination attempts on former Ba’th Party members,prominent political figures, and professionals such as journalists and educators. Two seniorgovernment officials were targeted in failed assassination attempts during this reportingperiod. On 26 February, an explosion at the Ministry of Municipalities was timed to coincide

7

with a visit by Vice-President Adel Abdul-Mahdi to attend a staff award ceremony, At least10 people were killed and 18 injured in the blast. On 23 March, Deputy Prime MinisterSalam al-Zoba’i escaped an assassination attempt at his home. One of his guards wasallegedly involved in the suicide attack. Nine other people were reported killed in theincident, including the deputy prime minister’s brother, Abdul-Rahman al-Zoba’i, his cousinRashid al- Zoba’i, his secretary Ahmad Hatem al-Kubaisi, and his advisor Mufid AbedZahra.18. At the beginning of January, up to 50 or more unidentified bodies were being found on adaily basis in Baghdad alone, with scores more in areas such as Mosul and Suwayra. Iraqipolice reported finding 168 dead bodies in various parts of Iraq during the first week ofJanuary. In early February, media sources reported a surge in the incidence of killings.According to the Baghdad police, 50 mutilated bodies were found in Baghdad on 5 February,and a further 140 in several other cities in the ensuing days. By late February, governmentofficials announced that the number of such killings had decreased, which they attributed tothe success of the Baghdad Security Plan. Despite this announced decrease, the number ofvictims was nevertheless high, with up to 25 bodies still being found on some days duringthis period in Baghdad. March again witnessed a rise in the number of casualties, withreports of large number of bodies found in Baghdad, al-Ramadi, al-Hilla, Kirkuk, Mosul,Khalis, Tikrit and Himreen, On 19 March, for example, 55 bodies were reportedly founddumped on the streets of Baghdad and al-Ramadi, and 44 others in six Iraqi cities thefollowing day.19. During the reporting period, UNAMI continued to investigate several incidents involvingthe alleged killing of civilians in the context of military operations conducted by MNFforces, in some cases jointly with Iraqi armed forces or security personnel. Theseinvestigations were ongoing at this writing. In one incident in al-Ramadi on 21 February,MNF forces reportedly clashed with armed insurgents said to be sheltering in a complex ofseveral buildings. Following clashes between the two sides which involved aerialbombardment by the MNF, medical sources at al-Ramadi Hospital reported that 26 peoplehad been killed, among them four women and children. UNAMI was also investigating anincident in the village of al-Zarka in the governorate of Najaf on 28 January, in which over260 people were reportedly killed. Armed clashes broke out between Iraqi security forces andfollowers of a Shi’a group calling itself the Soldiers of Heaven (Jundal-Sama’),followed byaerial bombardment by MNF forces which were called in to provide air support. Severalhundred people said to be followers of the Soldiers of Heaven were also rounded up anddetained. Their fate and current whereabouts remained unknown.Education sector and the targeting of academic professionals

20. Conditions in the education sector continued to deteriorate due to threats to lecturers andstudents, deadly attacks on educational institutions, and the individual targeting of teachingprofessionals. UNAMI has consistently reported on and repeatedly condemned acts ofviolence that caused the death and injury of hundreds of innocent civilians and tore apart thesense of community essential for maintaining stability and security. Officials of the Ministry

8

of Higher Education told UNAMI that 200 academics have been killed between 2003 andlate March 2007, although the circumstances surrounding many of these deaths remainedunclear. The Ministry also said that some 150 others were in detention at the end of March,having been arrested at various times since April 2003. UNAMI is seeking furtherinformation on their cases; some of them were believed to be held in the custody of the Iraqiauthorities, and others in MNF custody. The apparently sectarian-motivated assassinations,kidnappings and threats to academics and teachers continued at an alarming level throughoutthe three months. UNAMI recorded at least seven assassinations of academic professionals,and a number of attacks on or in the vicinity of academic institutions, causing substantialcasualties among the student population.21. Attacks on educational institutions also led many schools and universities to periodicallysuspend classes for weeks at a time, replace absent lecturers with recent graduates and findalternative locations and times to enable students to attend lectures and sit for examinationsin relative safety. Violence continued to severely undermine the right of Iraqi children andyouths to adequate education and intellectual development.22. In one incident on 14 November 2006, Ministry of Higher Education personnel andvisitors to its Scholarship Department were targets of a mass abduction. Some 150 staff andvisitors, including post-graduate students, at the Ministry’s Scholarship Department in the al-Andalus district of Baghdad were seized en masse by unknown gunmen and taken to anundisclosed location. While the majority was released in the ensuing days, the fate of anestimated fifty-six Ministry of Higher Education employees, all allegedly Sunni Muslims,remained unknown. According to Ministry of Higher Education records, the fate andwhereabouts of some 70 people remain unknown. No armed group is known to have claimedresponsibility for these abductions to date, although some of those abducted andsubsequently released alleged that the operation was carried out with the knowledge ofpersonnel manning at least one Ministry of Interior check point.23. Two attacks on al-Mustansiriya University in January and February further underminedthe laudable efforts of the Ministry and its staff to maintain the functioning of institutions ofhigher education. The first attack on 16 January involved two coordinated car bombsdetonated in the vicinity of the main building of the University. Over 70 people, mostlystudents, were reportedly killed and some 140 others wounded in the attack. The second, alarge-scale suicide attack targeting the University’s College of Economics andAdministration on 25 February, killed 41 students. Two other educational institutions werealso attacked: Maysaloon High School in the Hay al-Yarmuk district of Mosul where threemortar rounds landed on 10 January, wounding four female students as well two women andthree children who resided in nearby homes; and the al-Khulud School for Girls in Baghdad’sHay al-‘Adl district where mortars reportedly killed five students and wounded 21 others on28 January.24. In addition to direct attacks, there were also at least two indirect acts of violence in thevicinity of educational institutions in January: on 7 January, a roadside bomb detonated nearthe University of Technology in al-Sina’a Street in Baghdad, killing one civilian and

9

wounding two others; and on 27 January, a bomb planted on a bus detonated near al-Mustansiriya University, killing four civilians and wounding six others.25. Academic professionals continued to be targeted in apparently sectarian-motivatedattacks or because of their largely secular views and teachings. In the case of a BasraUniversity professor whose name was withheld for security reasons, UNAMI was able tofollow the pattern of intimidation and threats of death by the group that called itself theDoctrine Battalion (SarayaNusrat al-Mathhab).After a series of credible threats, theprofessor went first into hiding and then left the country. On 27 January, the professorreported to UNAMI that the Doctrine Battalion sent him a letter referring to him as a“criminal atheist,” accusing him of cooperating with the occupation forces, and ordering himto leave Basra on pain of death. According to his account, an AK47 bullet was enclosed withthe letter, and the front door of his apartment was marked with an “X” sign and the word“Wanted”.26. Other academics and teachers did not escape their assassins. Kamel Abdul-Hussein, anIraqi professor at Mosul University’s Faculty of Law, was shot dead by unknown gunmen onhis way home at the al-Kafa’at quarter on 11 January by unknown gunmen. Sheikh YunisHamid al-Sheikh Wahib, deputy head of the Association of Salahuddin Scholars and imam ofthe Awlad al-Hasan mosque, was gunned down at his home in Samarra’ on 13 January.Majid Nasser Hussein, a professor at Baghdad University, was shot dead in Baghdad’s al-Amiriyya district on 17 January; and Dhiya al-Mugoter a professor at al-MustansiriyaUniversity’s Faculty of Economy and Administration, was gunned down in the al-A’dhamiyadistrict of Baghdad on 23 January. The Minister of Higher Education’s convoy was itselftargeted by unknown gunmen in the al-Dora district of Baghdad on 24 January. TheMinister, Thiab al-Ujaili, escaped unharmed but two of his bodyguards were killed in theattack. On 28 March, Sami Sitrik, acting dean of al-Nahrain University’s Law Collegesurvived an assassination attempt.27. UNAMI received information that three professors from al-Nahrain University inBaghdad – Adnan Abed, Amer al-Qaisy and Abdul-Muttalib al-Hashimi - were abducted onthe afternoon of 28 January in Aden Square in al-Kadhimiya district of the city. A lawstudent and son of Abdul-Muttalib al-Hashimi, Ali Abdul-Muttalib, was also abducted in thesame incident, which reportedly took place at an unofficial checkpoint manned by unknowngunmen. The four victims were Sunnis abducted in a predominantly Shi’a neighborhood ofthe city. Several hours later, their bodies were brought to the Medico-Legal Institute inBaghdad by police from al-Shu’la police station. The Ministry of Higher Education issuedstatements on 28 January and again on 1 February condemning the incident, urging thesecurity forces to protect university professors. Several days later, the dean of al-NahrainUniversity’s Law Faculty resigned in protest at the Iraqi authorities’ failure to provideadequate protection to university professors.

10

Freedom of expression

28. In Baghdad and elsewhere, journalists remained one of the most vulnerable professionalgroups, with an increasing number among them killed, abducted or otherwise threatened.Whereas some journalists were specifically targeted, others died on the job, were caught incross-fire or fell victim to aerial bombings or other attacks. In March, Reporters WithoutBorders recorded 153 journalists and media workers as having been killed in Iraq sinceMarch 2003, while two remained missing. They included both Iraqi and foreign nationals.However, according to the Iraqi Society for the Defence of Journalists’ Rights, 170journalists and media workers were killed between 2003 and 15 January 2007.29. On 30 December, Ahmed Hadi Naji disappeared on the way to the Associated Pressoffice in Baghdad, where he worked as an occasional cameraman. His body was found on 5January at the Medico-Legal Institute, bearing a single bullet wound to his head. Al-Da’wareporter Karim Sabri Sharar al-Ruba’i was kidnapped from his home in Baghdad on 11January by unknown gunmen, and by the end of March his fate and whereabouts remainedunknown. On 4 February, journalist Suhad Shakir al-Kinani was killed when her car wascaught in crossfire between an MNF patrol and an armed group. Al-Kinani worked for theCouncil of Representatives’ press office in Baghdad. Hussein al-Zubaidi, a journalist with theweekly al-Ahali newspaper, was killed by gunmen in Baghdad on 19 February, while thebullet-riddled body of Abdul-Razzaq Hashim al-Khakani, a journalist with Jumhuriyat al-Iraq radio, was found at the Medico-Legal Institute on 20 February. He had been kidnapped aweek earlier in the predominantly Sunni district of al-Jihad in Baghdad. Two employees ofas-Safir daily newspaper in Baghdad were targeted in February. On 11 February, thenewspaper’s chief editor Hussein Jasim al-Jibouri was injured in an assassination attempt,and died on 16 March. The body of journalist Jamal al-Zubaidi was found on 3 March inBaghdad’s al-‘Amel district. He was reportedly last seen leaving his office on 23 February. Aday later, Mohan Hussein al-Dhahr, editor of the daily al-Mashreq, was killed outside hishome in the al-Jami’a district. His would-be abductors shot him dead as he tried to escape.He reportedly received six bullets to the head. Al-Mashreq, for which he worked for fouryears, is a privately-owned, widely read Baghdad newspaper whose management was said tohave received numerous death threats to cease publication. Yusuf Sabri, a cameraman withthe privately-owned Biladi TV, was killed on 6 March in a car bomb blast in Baghdad as hewas filming Shi’a pilgrims leaving the capital for the holy city of Karbala. The body ofHamid al-Dulaimi, a producer for the TV channel al-Nahrain, was found on 19 March at theMedico-Legal Institute in Baghdad. The circumstances surrounding his death remainedunclear.30. The as-Sabah daily newspaper, run by the official Iraqi Media Network, was targeted onseveral occasions and a number of its staff were abducted or killed. The newspaper’saccountant, ‘Aqil Adnan Majid, was abducted outside the newspaper’s premises in Baghdadon 9 January. A driver and another staff member were also abducted, and their bodies werefound on 14 January in the al-Adhamiya district. Both men had been beheaded. On 13January, the newspaper’s correspondent in al-Anbar was killed in a roadside bomb, and on 16January, a guard employed by the newspaper was found dead on the roof of its officebuilding.11

31. On 25 February, the office of Wasan Media in Baghdad's al-Karkh sector was raided byMinistry of Interior forces after they blocked off the street where the premises were located,arresting 11 of its employees. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) andInternational Freedom of Expression (IFEX), the police also seized the company's car, theemployees' personal cars, broadcast equipment, computers, cell phones, and documents. CPJcited Brigadier General Qassim Atta al-Musawi, spokesman for the Baghdad Security Plan,as saying that Ministry of Interior forces "received information that [the employees] work ina media company that sells films to the Al-Jazeera channel." According to informationreceived by UNAMI, all 11 employees remained in the custody of the Ministry of Interior bythe end of March. The legal basis for their arrest and continued detention were unclear.32. While most deaths of journalists and media workers were recorded in Baghdad,journalists in other towns and cities were also affected by lack of security, sectarian violenceand suppression of freedom of expression. One source told UNAMI that the situation inBa’quba was so critical that media reporting was no longer possible unless carried out in totalsecrecy, and that satellite television channels broadcasting from Diyala Governorate hadclosed down their operations there. In Mosul, freelance journalist Khadr Younis al-’Ubaidiwas shot dead on 12 January. He worked for al-Diwan, the local tribes press body. JournalistFalah Khalaf al-Diyali of al- Saha daily newspaper was shot dead by unidentified gunmen on15 January in the city of al-Ramadi. Freelance photographer Munjid al-Tumaimi was gunneddown in Najaf on 28 January, reportedly while taking pictures at al-Najaf hospital of bothdead and wounded persons from an earlier raid. The unidentified perpetrators confiscated hiscamera and mobile phone. In Kirkuk, gunmen reportedly wearing Iraqi military uniformabducted Turkoman journalist Talal Hashim Biraqdar on 3 March. He was a reporter for theal-Diyar weekly newspaper. At the time of the writing, his fate and whereabouts remainedunknown.33. UNAMI remained concerned about infringements to freedom of expression in the Regionof Kurdistan, in particular press and media freedoms. The KRG authorities continued tosubject journalists to harassment, arrest and legal actions for their reporting on governmentcorruption, poor public services or other issues of public interest. In February, the KRGMinister of Culture, Falakuddin Kaka’i, openly criticized the stifling of intellectuals andartists, but other government officials complained to UNAMI about poor reporting standardsand ethics among journalists, accusing them of publishing incorrect or unverified informationand sought to justify legal action against them on these grounds. In a positive development,however, UNAMI welcomed a recent review by the Kurdistan National Assembly of currentlegislation governing freedom of expression in the Kurdistan region and the initiation ofinvestigations into several cases involving the suppression of media freedoms.34. In a meeting held in Sulaimaniya on 24 February and organized by Leveen Magazineand the Iraq Civil Society Program, journalists criticized the draft Journalists Law preparedby the Kurdistan Journalists Syndicate, an association accused by some journalists as lackingindependence and competence to represent journalists’ interests in the Kurdistan region.Other than the Journalists’ Syndicate’s draft, two other drafts have been submitted separatelyto the Kurdistan National Assembly, one of them prepared by a group of academics at

12

Salahudddin University proposing, among other things, the creation of an independent mediacouncil. The Minister of Culture, Falakuddin Kaka’i, told UNAMI that he had proposed aprovision in the draft law that would allow the court to impose a fine instead of imprisonmentfor journalists convicted of defamation. According to a parliamentary official, the proposalwas likely to be adopted.35. Most arrests of journalists recorded by UNAMI were carried out by the KRG’sAsayish(Security) forces, which by law have jurisdiction over economic crimes, such as smuggling,and political crimes, including espionage and acts of sabotage and terrorism. On 26 January,theAsayishforces of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) arrested freelance journalistMuhammad Siyasi Ashkanayi, ostensibly for espionage on behalf ofParastin,theintelligence agency of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). In late February,Asayishofficials in Sulaimaniya told UNAMI that Ashkanayi was still undergoing interrogation intheir custody. He had not been charged with an offence nor referred to an investigative judge,and was still in detention at the end of March. In another case, Garmian Hamakhan, ajournalist with internet portal Kurdistan Online was arrested in Sulaimaniya by Ministry ofInterior police on 2 February while covering a demonstration of taxi drivers in Kalar district.Police detained him for a day and destroyed his photographs before releasing him. Twenty-five journalists from the Kalar district petitioned President Barzani and the Speaker of theKurdistan national Assembly, demanding an investigation into the Hamakhan case. On 19February, Munir Assad, a reporter for al-Hurra Television was detained for several hours bythe KDP’sAsayishafter taking photographs of an incident in which young men from aKurdish tribe attacked members of the minority Yezidi community in the district ofShaikhan. The Baghdad-based Iraqi Association to Defend Journalists’ Rights condemnedthe detention of Munir Assad, called on the KRG not to arrest journalists without judicialwarrant and requested the Council of Representatives in Baghdad to establish appropriatemechanisms to protect journalists from arbitrary arrest.36. On 17 February, Reuters correspondent-photographer Shwan Salahuddin “Kurd” wasfilming the aftermath of bomb explosions in the Rahimawa quarter in Kirkuk when,according to information received by UNAMI, he was arrested by Kirkuk police, beaten witha pistol butt and taken to a police station. He was released several hours later. The IraqiAssociation to Defend Journalists’ Rights called for an investigation into the incident. On 19February, Kirkuk police commander Major General Torhan announced that the police hadmade a mistake in arresting Shwan Salahuddin, apologized for the assault and instructed thepolice to respect the rights of journalists. In Sulaimaniya, freelance journalist Asso Jabbarpublished an article in the Kurdistan Daily News, condemning statements made during aseminar held in Erbil on 15 February by Saro Qadir, head of the KDP’s Information Office,in which he allegedly described the Kurdish community as “dogs.” The reported statementswere subsequently denied by Saro Qadir. Jabbar and several other journalists, includingAdnan Uthman from Hawlati newspaper, and Mam Burhan Qane’ from Chawder newspaper,initiated a petition in Sulaimaniya, collecting thousands of signatures to protest Saro Qadir’sstatements. Saro Qadir responded by filing a claim against them with the police in Erbil,reportedly warning that the journalists would be arrested if they entered Erbil. One of theorganizers of the petition, journalist Dilshad Salih, further alleged that he had received adeath threat in a note warning him to abandon the campaign.

13

37. In the town of ‘Aqra, DuhokAsayishforces closed down the Kurdistan Islamic Union’s(KIU) radio station on 12 December 2006, apparently on the basis that it was operatingwithout a license. The Head of the Media Information Bureau of the KIU said that accordingto the law on media licenses, political parties were not required to apply for licenses whenestablishing new media outlets. Another KIU official claimed that the closure may havebeen, at the same time, politically motivated. By the end of March, the KIU had applied andwas granted a license, but its radio station remained closed, apparently after failing to obtainadditional security clearance from the Asayish authorities.38. In its November-December 2006 Human Rights Report, UNAMI reported the arrest ofjournalists Shaho Khalid and Dilaman Salah by theAsayish Gishti(General Security) andhad raised this and other similar cases with KRG Minister of Region for the Interior, KarimSinjari. UNAMI welcomed the Minister’s assistance and has since learned that theAsayishofficials who arrested and allegedly mistreated the journalists have since been disciplined anddischarged from duty. On 7 February, in a speech celebrating the unification of the Ministryof Justice in Erbil and Sulaimaniya, the KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani said that acommittee should be created to review issues such as journalists’ rights, women’s andchildren’s rights and corruption. To UNAMI’s knowledge, no such committee had beenestablished by the end of March.Minorities

39. Attacks against religious and ethnic minorities continued unabated in most areas of Iraq,prompting sections of these communities to seek ways to leave the country. The continuinginability of the Iraqi government to restore law and order, together with the prevailingclimate of impunity, has rendered religious minorities extremely vulnerable to acts ofviolence by armed militia.40. Many of the reports of targeted attacks on minorities emanated from NinevehGovernorate. In the city of Mosul on 26 January, a suicide attack on the al-Rashidiya mosquefrequented by Turkoman Shi’a reportedly resulted in the killing of 7 civilians and thewounding of 17 others. On 15 February, dozens of Kurds from the Mizori tribe attacked theYezidi district of Shaikhan in Nineveh Governorate, damaging private property and Yezidicultural buildings. The attack was allegedly an act of vengeance against two Yezidi menfound in a car in the company of a married Kurdish woman. The following day, amidst theallegations made by a Yezidi representative that KDPAsayishforces facilitated the attack,President Barzani sent a high level delegation to meet the Emir of the Yezidi community,Tahsin Bek. According to reports received by UNAMI, tensions between the Yezidi andKurdish communities were high and calls for revenge were made in Yezidi villages andtowns, particularly in the district of Sinjar on the Syrian border. On 19 February, PresidentBarzani appealed for calm and assured the Yezidis that those responsible would be brought tojustice. In late February, the head of Duhok Provincial Council, Fadhil Omer, announced that80 people suspected of involvement in the events in Shaikhan had been summoned forquestioning by the authorities, and that 19 of them were detained pending further

14

investigation. Prior to the arrests, however, KRG officials informed UNAMI that the incidentwas triggered by a “misunderstanding”, that the KDPAsayishwas not involved in theviolence and that there were no casualties. On 25 March, UNAMI learned that dozens ofYezidis organized a demonstration in Bozan village, near Shaikhan, to protest the Februaryviolence. The demonstrators removed the Kurdistan flags from official buildings and raisedIraqi flags instead. The KDP’s DuhokAsayishforces responded by arresting and detainingthree participants, while others reportedly fled the area to evade arrest.41. In February, UNAMI received information regarding continuing difficulties faced byIraq’s Baha’i community, one of the smallest of the country’s religious minorities numberingan estimated 1,000 families. Today, most are settled in Baghdad, Diyala, Erbil, Basra andMosul, but with minimal contact with each other due to prolonged persecution and theprevailing security situation. Since the 1970s, successive Iraqi governments denied theBaha’is basic rights, including freedom of religious worship and the right to obtain officialidentification documents. Adherence to the Baha’i faith became a capital offence in 1979through a decree passed by the then Revolutionary Command Council (RCC). While allRCC decrees were declared null and void by the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) afterthe fall of the Saddam Hussein government in April 2003, the Baha’i community’s legalstatus has not been clarified. Their personal records remain ‘frozen’ and they continue toface difficulties in registering their children in schools, in obtaining documentation for travelpurposes or for the use of state services. By late March, UNAMI was seeking confirmation ofreports that the Iraqi authorities were preparing to regularize the legal status of the Baha’icommunity.42. In Kirkuk, socio-political rights of minorities remained under discussion. On 4 February,the High Committee for Implementing Article 140 of the Constitution issued two proposalsfor the KRG Prime Minister’s approval, outlining procedures for the return of the Arabs andothers to their places of origin with a compensation package. The proposal received mixedreactions among the various communities. In early February, Arabs in Kirkuk staged aprotest to convey their disapproval of the two proposals. They urged Prime Minister Nourial-Maliki to reject both proposals, stating that a divided Iraq would worsen the securitysituation in Kirkuk. Kirkuk Provincial Council members Muhammad Khalil and Muhammadal-Obaidi of the Arab Republic Gathering List also dismissed the two proposals. However,the Committee of National Understanding and Solution, formed by the PUK to register Arabfamilies willing to return to their places of origin, stated on 15 February that 5,400 Arabfamilies have opted to return. According to Muhammad Khalil, Prime Minister al-Maliki wasprepared to establish a committee to examine the distribution of administrative posts inKirkuk, apparently at the request of several Arab parties and the Turkmen Front.Palestinian refugees

43. The flight of Palestinian refugees towards the Syrian border continued, increasing inparticular after the arrest of 30 Palestinian men by Iraqi Special Forces on 23 January. Anumber of Palestinian families from the Hay al-Amin, al-Nidhal Street and al-Baladiyyat

15

areas fled their homes, and by late March 997 of them were seeking protection at makeshiftcamps close to the border with Syria or in the no-man’s-land between Iraq and Syria.44. On the evening of 22 January, persons described as militiamen reportedly drove intoseveral of the Palestinian compounds in Baghdad and demanded that the residents sign awritten undertaking not to attack Iraqi forces. In the early hours of the following day, a groupof Iraqi Special Forces raided a building in al-Nidhal Street where some seventeenPalestinian families resided. According to reports received by UNAMI, the Iraqi SpecialForces used violence during the raid, arresting seventeen men who they blindfolded andhandcuffed. The men were taken to what they subsequently described as an abandoned Iraqisecurity forces building in the al-Sa’dun district of Baghdad, and released several hours later.On the same day, 13 other Palestinians from the Hay al-Amin district of Baghdad werebriefly arrested. The reasons for these arrests remained unclear.45. Another Palestinian compound in al-Baladiyyat was raided by Iraqi Special Forces on 13and 14 March, and some 42 Palestinians reportedly detained. All but 13 of them werereleased on 14 March, and UNAMI interviewed two of them. According to their accounts,the raid resulted in one person being killed as he headed towards the al-Quds mosque situatedin close proximity to the compound. One of the detainees stated that he was beaten whilebeing dragged for a distance of some 400 meters to the al-Rashid police station. He showedUNAMI staff traces of injuries he had sustained, which matched photographs of the injurieshe had earlier submitted and appeared consistent with the type of abuse described. He statedthat in detention, there were temporary improvements in the treatment of inmates when MNFpersonnel or senior Iraqi officials were present. Additionally, he described generalharassment and beatings by local Iraqi residents at the Palestinian residential compounds,allegedly in collusion with Iraqi forces. UNAMI remains concerned about the fate of the 13Palestinians who remained in detention at the end of March.46. The Palestinian community in Baghdad lodged numerous complaints with UNAMI andUNHCR regarding the systematic attacks on its compounds of al-Baladiyyat, al-Hurriyya, al-Amin and several other locations. The complaints cited systematic targeting of Palestinianrefugees by armed militia, in particular the Mahdi Army. In one case, Anwar Ahmad YousefSha'ban and his son were abducted, tortured and then killed on 1 March. Their bodies werefound the following day in the al-Dora district of Baghdad. On 11 March, Omar HusseinSadeq was killed by unknown gunmen in al-Janabi Street in the district of al-Ghazaliyya. Hisbrother Muhammad was also killed on 15 March in the district of al-Shu’la,47. Since 2003, intimidation and harassment by armed militia and raids on residential areasled to frequent displacement of Palestinians between their compounds and to an increasedmovement towards Iraq’s borders. In mid-December 2006, UNHCR reported that there were320 Palestinians at al-Tanf camp in the no-man’s-land between Syria and Iraq. In Februaryand March, UNHCR reported significant increases in the number of Palestinians fleeingBaghdad towards the Syrian border. On 31 March, there were 341 Palestinians at al-Tanfcamp and a further 656 at the al-Walid border crossing inside Iraq. UNHCR, whose mandateincludes the Palestinian refugees in Iraq, has advocated for the legalization of the refugeestatus of all Palestinians in Iraq who fled Palestine after the creation of the state of Israel in

16

1948, those who left the Occupied Territories in 1967, and those who had fled during theGulf War in 1991. UNHCR urged that they be granted all rights under international anddomestic laws, including the entitlement to travel and residency documents. UNHCR hasalso asked the Iraqi Government and MNF to ensure the safety of Palestinian refugees andhas called upon neighboring countries to open their borders to Palestinians fleeing Iraq andtreat them in accordance with applicable international standards.48. The Palestinian Human Rights Association recorded 189 Palestinians killed in Baghdadbetween 4 April 2003 and 19 January 2007. Since then, Palestinian sources reported that afurther nine persons were killed, bringing the total number of deaths to at least 198 by 31March 2007. The majority of the killings were reportedly carried out in drive-by shootings,killings following the abduction of the victims, or as a result of indiscriminate fire or mortarattacks on Palestinian compounds. Three of the victims were killed on 7 February in a singledrive-by shooting incident in Baghdad’s al-‘Adl district.Women

49. In the governorates of Erbil, Duhok and Sulaimainiya, women’s right to life and personalsecurity remained of serious concern to UNAMI, given the high incidence of “honor killings”and other abuses against women. According to the newspaper portal source, Awena, injuriesand deaths by immolation and suspected honor crimes were on the rise. In its 27 Januaryissue, Awena reported on data gathered by the Duhok criminal court and the Duhok AzadiHospital, revealing that in the governorate, there were 289 burns cases resulting in 46 deathsrecorded in 2005, and 366 burns cases resulting in 66 deaths recorded in 2006. In most cases,the extent of injuries and overall circumstances appeared to exclude routine claims ofaccidents or suicides. According to the Emergency Management Centre in Erbil, 576 burnscases resulting in 358 deaths have been recorded in Erbil Governorate since 2003. Over halfof these women had sustained between 70-100% degree burns which, according to doctors,suggested that they were self inflicted. However, the absence of thorough investigations bythe authorities has meant that the available evidence remained inconclusive.50. Between January and March, UNAMI received information on some forty cases ofalleged honor crimes in the governorates of Erbil, Duhok, Sulaimaniya and Salahuddin,where young women reportedly died from “accidental burns” at their homes or were killedby family members for suspected “immoral” conduct. In one instance on 24 January, awoman who sustained 40 per cent burns to her body claimed that this was caused by a bakingaccident in the kitchen, while on 28 January, a 21-year-old woman from Erbil sustained 60per cent burns from an alleged accident involving an exploding water boiler. In the sameweek, police found the charred remains of an unidentified woman on the outskirts of acollective town in Erbil. In Sulaimaniya, a woman and her married boyfriend were reportedlyshot and killed by her brother on 2 February 2007. On 15 February, a Kurdish woman waskilled by her husband for “dishonouring” her family when she was found in a car in Shaikhandistrict, Nineveh, in the company of two Yezidi men. In late February, a woman and her maleneighbor were allegedly murdered by her family members because of a video clip, allegedlyshowing them discussing sexual matters, circulated on mobile phones of people in the

17

community. On 6 March, the Sulaimaniya Directorate of Health issued a report stating that in2006, 88 women between the ages of 15 and 45 were the victims of shootings, 41 of whomhad died. According to a source at the Emergency Management Centre in Erbil, in casesinvolving suspected “honor crimes”, the victim is typically shot at her home and left to diebefore her body is moved elsewhere. Where family members report these deaths, theycommonly claim the cause of death as suicide or cite infidelity on the part of the victim asjustification for the crime.51. UNAMI continued to receive reports of domestic and communal violence that appearedto have received little regulatory attention by the KRG authorities, while the local mediacontinued to report such incidents on a regular basis. In Kirkuk, two teenage sisters werearrested on 12 January and charged with murder for allegedly killing their grandmotherwhom they said had failed to intervene when the girls were sexually abused by their uncleover a period of many years. On 14 February a female lawyer, Nazanin Muhammed, wasshot dead in Kirkuk by unknown gunmen. Both Kurdistan TV and Hawler Post reported thatthe victim’s husband may have murdered her because of a domestic dispute. According to anofficial at the Emergency Hospital in Erbil, the number of rape cases in Erbil Governoratehas increased markedly in recent years: 596 recorded cases in 2006 as compared to 150 in2003. In the KRG region, allegations of rape are routinely dealt with through mediation andreconciliation at the community level, and very few cases reach the courts. This includeshospital officials, who use informal conciliation channels to protect rape victims from beingkilled by relatives for having ‘dishonoured’ the family and to prevent retaliatory killings ofalleged rapists. Article 398 of the Iraqi Penal Code also provides for the resolution of sexualoffences through a marriage contract between the alleged offender and the victim.52. The Kurdistan National Assembly was slow to address violence against women and todebate legislative reform aimed at providing improved legal protection for women. Theheads of the Kurdistan National Assembly’s Legal Committee and Human RightsCommittee, as well as government officials such as the KRG Minister of Human Rights andMinister of Region for the Interior, cited social attitudes requiring longer-term solutions asreasons for the slow pace of progress in this regard. In this reporting period in Erbil, theKurdistan National Assembly’s Committee for Women’s Affairs and a number of non-governmental groups concerned with women’s rights discussed a draft law which is set toreplace the Personal Status Law (No 188 of 1959) currently in force.53. In Baghdad, according to reports received by UNAMI, a woman identifying herself asSabreen al-Janabi was admitted to Ibn Sina Hospital in the International Zone on the night of18 February, claiming that three Iraqi officers serving with the Seventh Brigade’s SecondRegiment of the Ministry of Interior’s Public Order Forces (QuwwatHifth al-Nitham)rapedher while she was in their custody. According to her account, the Public Order Forces raidedthe Hay al-‘Amel district of Baghdad earlier that day and arrested her together with elevenmen, apparently on suspicion of involvement in terrorist acts. After Sabreen al-Janabi’shusband contacted the MNF asking for their intervention, MNF forces reportedly visited theSecond Regiment’s headquarters, interviewed the detainees and released nine of those held,including al-Janabi. She was said to have suffered bruises and was taken to hospital whereshe was medically examined following the rape allegations. The case attracted significant

18

media coverage and comment by Sunni and Shi’a political parties alike, overshadowing callsby the Iraqi Islamic Party and the Vice-President Tariq al-Hashimi for a prompt and thoroughinvestigation into the case. UNAMI was not in a position to verify media reports regardingthe findings of medical examinations carried out in the case. On 20 March, two days afterthe alleged rape, Prime Minister al-Maliki publicly rejected the allegations made by al-Janabiand instructed that the three police officers be honored. UNAMI received information that anarrest warrant was issued against al-Janabi but the legal basis for this remained unclear.UNAMI urges the Iraqi authorities to conduct a thorough and impartial investigation into theallegations and to take appropriate steps to guarantee the protection of both victims andwitnesses in all such cases.54. Other allegations of the rape of women by Iraqi military personnel emerged during thisreporting period. On 21 February, for example, a 40-year-old Turkoman woman and aresident of Tala’far district accused five security personnel of raping her during a house raidfour days earlier. The complainant, Majida Mohamed Amin claimed that the officer-in-charge video-taped the assault and threatened to abuse her children if she resisted. MosulDeputy Governor Khasrow Goran ordered an investigation into the incident. Three soldierswith the Iraqi armed forces and two officers with the Tala’far police reportedly arrested andreferred to the Mosul Criminal Court on rape charges.Displacement of the civilian population

55. The severe deterioration in the security situation in Iraq continued to hamper theimplementation of vital humanitarian assistance projects across the country and the safe anddignified return of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). According to UNHCRand International Organization for Migration (IOM) data, some 117,901 families or estimated707,000 persons (calculated based on the assumption that an average size family has sixfamily members) have been forced to flee their homes due to sectarian violence since thebombing of the al-Askari shrine in Samarra’ on 22 February 2006. These are in addition to1.2 million persons displaced prior to 22 February 2006.56. Despite its extremely volatile situation, Baghdad has most of the displaced population,some 120,000 IDPs who fled their homes since 22 February 2006. Many of these weredisplaced from within Baghdad, moving to more ethnically homogenous and thus safer,areas, while their houses were either given to or were occupied by other displaced families.With the exception of the three governorates in the Region of Kurdistan, where there is noongoing displacement, most other governorates produce and receive displaced persons.4According to the data gathered by IOM and UNHCR, some 87 per cent of the newlydisplaced seek refuge in the Center and South of the country.57. IDPs fled primarily due to direct threats to their lives because of their sect or religion,generalized violence or forced displacement. Most IDPs were moving to seek refuge inhomogeneous areas. Some IDPs have been displaced more than once. Women and childrenmake up three quarters of the newly displaced (in some cases, men remain in the place of4

Cluster F: Internally Displaced Persons in Iraq – Update 5 March 2007

19

origin while the women and children flee to other areas). Rape, threats of rape, domesticviolence, disappearances and detentions after displacement remained a major concern. ManyIDPs had irregular or no access to basic services, especially electricity, water, education andhealth, particularly in rural areas or in areas where the number of IDPs was high.Furthermore, once displaced, families often complained that schools refuse to enroll theirchildren due to the overcrowding, or that they themselves could not afford to send theirchildren to school, needing money for bus fees, school books and other materials. One of theemerging issues reported by non-governmental organizations was alleged use of drugs bychildren as well as their recruitment into the ranks of various militias and gangs.58. In the past few months, local authorities in ten Iraqi governorates imposed restrictions onthe entry of IDPs or stricter residency requirements. These measures were reportedlydesigned to mitigate the factors of added security risk and alleged saturation, but in somecases aread such as Kirkuk, the arrival of displaced Arabs was seen as affecting the currentethnic composition, and hence the outcome of future elections. In Najaf Governorate, thelocal authorities justified their decision to allow access to the cities only to those originatingfrom Najaf itself as a measure of protection against the overcrowding of public buildings, thedepletion of basic services and security concerns. IDPs in such locations are at risk ofexpulsion. These developments raise additional concerns in the context of on-goingdiscussions to hold new Governorate elections. Any election will require an updated voterregistration exercise with public participation. If IDPs have greater restrictions in theirmovement and the Public Distribution System (which would have to be used as a basis forany voter registry in 2007) continues to falter throughout the country, concern mounts that allIDPs could be disenfranchised from participating in an election.59. The Iraqi Ministry of Displacement and Migration bears primary responsibility for thecoordination of protection and assistance to IDPs. Urgent attention is required to ensureprotection and assistance to IDPs in emergency situations. Most surveyed IDPs identifiedfood, shelter and medical support as their priority needs while in displacement. Physicalprotection ranked high among the requested interventions. Efforts by the Iraqi authorities tocontain the violence in the country and bring the security situation under control have meantlower priority being given to addressing the protection and assistance requirements of theinternally displaced populations.Humanitarian situation

60. The humanitarian situation in Iraq has deteriorated since 2005 and needs immediaterecognition and support. Up to 8 million people are classified as vulnerable5, and thereforein need of immediate assistance: 2 million are estimated to be refugees/asylum seekersoutside Iraq; 1.9 million are estimated to be IDPs and 4 million are estimated to be acutelyvulnerable due to food insecurity. Lack of protection and human rights violations, escalatingviolence, lack of access to basic services, rising unemployment and rampant inflation allcontinued to contribute to a declining standard of living, thereby increasing the number ofvulnerable Iraqis, in particular among displaced, women and children. The violence has had a5

This estimate is based on information gathered by the UN Country Team.

20

particular impact on women and children, as the loss of the family breadwinner generallyreflected by casualty figures fail to enumerate the women and children affected. It can beestimated that for every man killed, 5 or more family members become vulnerable as a resultof losing the breadwinner. Female headed households face a particular challenge as thewomen cannot earn income within certain cultural environments. The situation of orphanedchildren is also precarious; without an adult caretaker they increasingly find little support,including assistance from the extended family.61. Obtaining verifiable and timely information on the humanitarian needs of the Iraqipeople has been challenging due to the security situation. However, it is widelyacknowledged that the situation is not consistent across the country: the worst affectedgovernorates are those in the central and southern parts of Iraq. The UN HumanitarianCoordinator for Iraq is guiding the humanitarian community in the creation of a singlestrategic framework for humanitarian action. This overarching framework will embrace thechallenges, issues and capacity to respond by different actors and stakeholders, and will serveas a guide for resource mobilization as well as coordination of planning, response,information collection and monitoring.62. The international community provided billions of dollars for recovery and developmentprograms for Iraq, but many of these were not implemented because of the deterioratingsecurity situation. The following figures indicate that daily living conditions were worseningdespite all the efforts made in the field of reconstruction: an estimated 54% of the Iraqipopulation is living on less than US$ 1 per day, among whom 15% is living in extremepoverty (less than US$ 0.5 per day); acute malnutrition rapidly rose from 4.4 to 9% from2003 to 2005, as per the latest available data. Some 432,000 children were reported to be inimmediate need of assistance,6while the annual inflation rate in Iraq jumped to an estimated70% in July 20067. The unemployment rate has risen to around 60%; only 32% of Iraqis haveaccess to drinking water8and health facilities lack critical drugs and equipment. Accordingto the Brookings Institution, 12,000 out of 34,000 doctors have left Iraq, 250 have beenkidnapped, and 2,000 physicians have been killed since 2003.963. Simultaneously with the deepening of the humanitarian crisis, the violence continued tohamper the ability of the Iraqi government to provide basic services to the most needysegments of the Iraqi population, and the Public Distribution System (PDS) food rationceased in certain areas such as al-Anbar, or was only partially functioning in areas wherecriminality and pilfering thrived. The gravity of the situation affecting many families may notfully emerge until humanitarian organizations and the Iraqi Government are able tosystematically gather data and reach to the growing number of inaccessible areas. Staffsecurity will continue to remain a priority for the UN and the NGO community in Iraq.64. Threats of kidnapping, assassination, and generalized violence continued to hamper thework of both international and national humanitarian non-governmental organizations,67

UNDPIraq Living Conditions Survey 2004 (volume ii).Iraq’s Central Office for Statistics (COSIT) – August 2006.8Government of Iraq/UNICEF 2007-2010Country Programme Action Plan.9Campbell, J.H., O’hanlon, M.E. (2007, February 22). Brooking Institution Iraq Index, 22.

21

making it extremely difficult for them to reach some of the most vulnerable populations. Asa consequence, international organizations maintained a reduced presence on the ground,with their operational headquarters located in neighboring countries. Since 2003, at least 82Iraqi and international aid workers have been killed, 80 kidnapped and 245 wounded10. Twoincidents in January highlighted the ongoing risks faced by humanitarian workers on theground. On 9 January, a UNICEF national staff member was killed in his car in Baghdad.The Iraqi Red Crescent Society resumed its work in Baghdad after the kidnapping of some35 visitors and staff members on 17 December 2006, although eleven of its staff remainedmissing.65. On 20 March 2007, the International Reconstruction Fund Facility for Iraq (IRFFI) held ameeting of the Core Donors to review the progress of the two trust funds managed by theUnited Nations and the World Bank. Presentations were made to the donors andrepresentatives of the Government of Iraq, indicating activities, challenges and future plans.Among the results was the agreement in principle that it would be useful to determine howIRFFI can better reflect the current situation in Iraq, including to assist the Government tomake use of its own resources and to ensure that funds achieve real improvement in servicedelivery. This echoes sentiments raised by the UN and donors in other fora, in regards toaddressing the humanitarian situation with Iraqi resources and international support.

Rule of LawDetentions

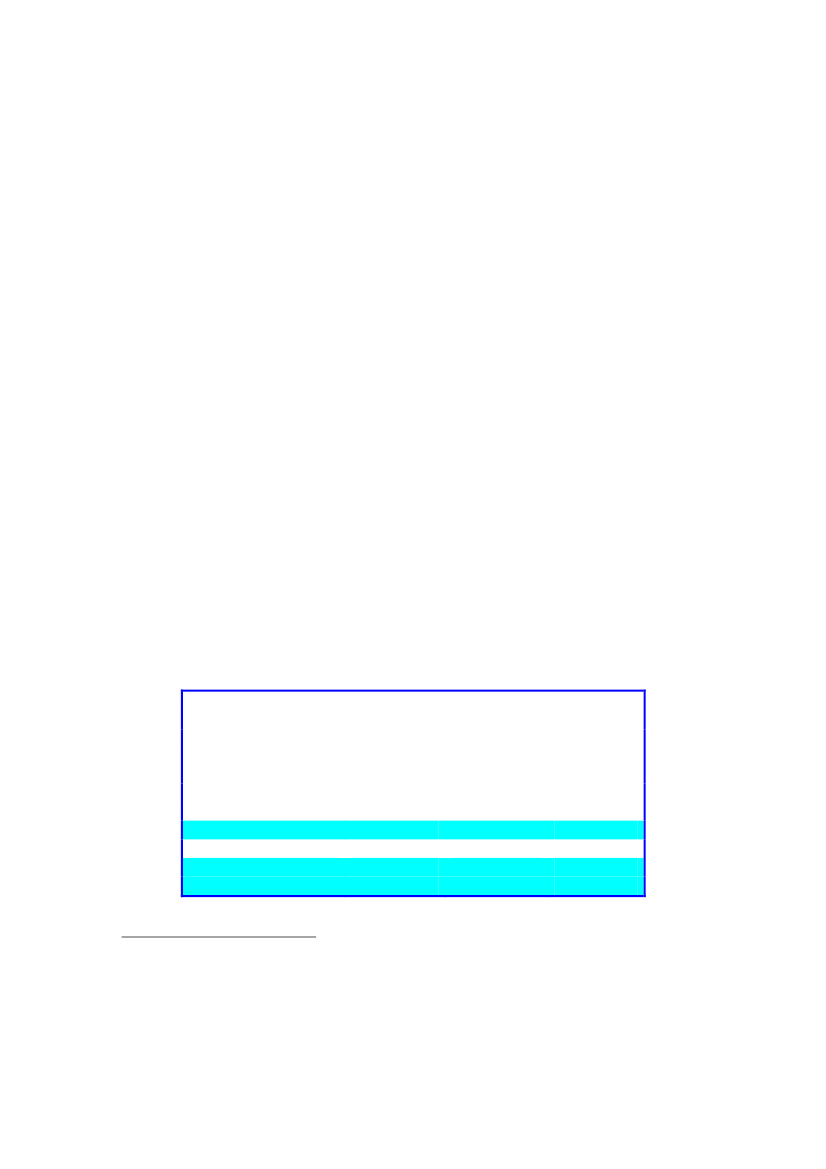

66. At the end of March, according to the Ministry of Human Rights, the total number ofdetainees, security internees and sentenced prisoners for the entire country stood at 37,641.11Detaining AuthorityMNFMOJMOIMODMOLSATotal excluding KRGTotal in KRG regionTotal across IraqJanuary14,5349,2632,9081,36245628,5232,09930,622February16,9319,1164,6921,60650332,8482,14434,992March17,8989,9655,5731,52550235,4632,17837,641

1011

According to the NGO Coordination Committee Report (NCCI), 1 February 2007, page.4.At the end of December 2006, the total number of detainees held across Iraq stood at 30,842, according toMinistry of Human Rights figures. The breakdown per detaining authority was as follows: MNF (14,534);Ministry of Justice (8,500); Ministry of Interior (4,034); Ministry of Defense (1,220), Ministry of Labour andSocial Affairs (456); and the Kurdistan Regional Government (2,098).

22

67. With the announcement by the Iraqi government of the implementation of the BaghdadSecurity Plan in mid-February, the overall number of detainees was expected to increasesubstantially. In anticipation of this surge, both the Iraqi authorities and the MNF weretaking measures to expand detention facilities to make room for several thousand newinmates, particularly in and around Baghdad. These measures included the transfer of some1,300 convicted prisoners from facilities in Baghdad to Fort Suse near Sulaimaniya in theKurdistan region. The prison is currently under the authority of the Iraqi Ministry of Justice.Steps were also taken to renovate new sites and to convert them into facilities capable ofholding detainees.68. UNAMI remained concerned at the apparent lack of judicial guarantees in the handling ofsuspects arrested in the context of the Baghdad Security Plan. While in his public statementsPrime Minister Nouri al-Maliki pledged that the government would respect human rights andensure due process within a reasonable time for those under arrest, he did not spell out whatmechanisms were in place to monitor the conduct of arresting and detaining officials. Theabsence of clear references to judicial safeguards was all the more worrying given the Iraqigovernment’s poor record in the handling of suspects and their treatment in detention. Thenew emergency regulations announced on 13 February contained no explicit measuresguaranteeing minimum due process rights. Rather, they authorized arrests without warrantsand the interrogation of suspects without placing a time limit on how long they could be heldin pre-trial detention. The emergency regulations made only a cursory reference to theobservance of “human rights” by personnel of the Ministries of Interior and Defense duringmilitary operations. UNAMI has learned that government officials have given privatecommitments that suspects would be referred to investigative judges in accordance withIraq’s Criminal Procedure Code; that judicial orders for the release or continued detention ofsuspects would be respected; and that detainees would be held only in officially recognizedfacilities. In the past, such commitments have not been respected, and the absence ofeffective monitoring and accountability mechanisms governing the conduct of lawenforcement personnel only serves to exacerbate the problem. Officials of the Ministries ofInterior and Defense already enjoy extensive powers under the 2004 emergency law. Thenew emergency regulations also provide that suspects accused of offences including murder,rape, theft, abduction, the destruction of private and public property and other crimes wouldbe punished in accordance with the 2005 anti-terror law, which provides the death penalty forall crimes listed.69. By late February, the Iraqi government announced that hundreds of people had beenarrested since the launch of the Baghdad Security Plan, and by the end of March over 3,000were in detention. Five Ministry of Defense brigade headquarters in and around Baghdadwere being used as initial holding centers prior to the transfer of the detainees to Ministry ofJustice facilities. No detailed information was available at this writing regarding the extent ofjudicial oversight over their cases, although UNAMI has learned that teams of investigativejudges visited these facilities, and that over 700 of the suspects were subsequently transferredto detention facilities in al-Rusafa under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Justice.

23