Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2006-07, Forsvarsudvalget 2006-07

Bilag 23, FOU Alm.del Bilag 48

Offentligt

The Iraq Study Group Report

The IraqStudy GroupReport

J a m e s A . B a k e r, I I I , a n dLee H. Hamilton, Co-ChairsLawrence S. Eagleburger,Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Edwin Meese III,Sandra Day O’Connor, Leon E. Panetta,William J. Perry, Charles S. Robb,Alan K. Simpson

v i n ta g e b o o k sA Division of Random House, Inc.New York

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION: DECEMBER 2006All rights reserved.The Authorized Edition ofThe Iraq Study Group Reportis published in theUnited States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York,and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.Maps � 2006 by Joyce PendolaVintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.ISBN: 0-307-38656-2ISBN-13: 978-0-307-38656-4

www.vintagebooks.comA portion of the proceeds from the purchase of this book will be donated to theNational Military Family Association, the only nonprofit organization that rep-resents the families of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard,and the Commissioned Corps of the Public Health Service and the NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration, prepares spouses, children, and par-ents to better deal with the unique challenges of military life. The Associationprotects benefits vital to all families, including those of the deployed, wounded,and fallen. For more than 35 years, its staff and volunteers, comprised mostly ofmilitary family members, have built a reputation as the leading experts on mili-tary family issues. For more information, visit www.nmfa.org.Printed in the United States of America10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1First Edition

Contents

Letter from the Co-ChairsExecutive Summary

ixxiii

I. AssessmentA. Assessment of the Current Situation in Iraq1. Security2. Politics3. Economics4. International Support5. ConclusionsB. Consequences of Continued Decline in IraqC. Some Alternative Courses in Iraq1. Precipitate Withdrawal2. Staying the Coursev

331222273233373738

Contents

3. More Troops for Iraq4. Devolution to Three RegionsD. Achieving Our Goals

383940

I I . T h e Wa y F o r w a r d — A N e w A p p r o a c hA. The External Approach: Building anInternational Consensus1. The New Diplomatic Offensive2. The Iraq International Support Group3. Dealing with Iran and Syria4. The Wider Regional ContextB. The Internal Approach: Helping Iraqis HelpThemselves1. Performance on Milestones2. National Reconciliation3. Security and Military Forces4. Police and Criminal Justice5. The Oil Sector6. U.S. Economic and ReconstructionAssistance7. Budget Preparation, Presentation,and Review8. U.S. Personnel9. Intelligence

4344465054

59596470788386909293

vi

Contents

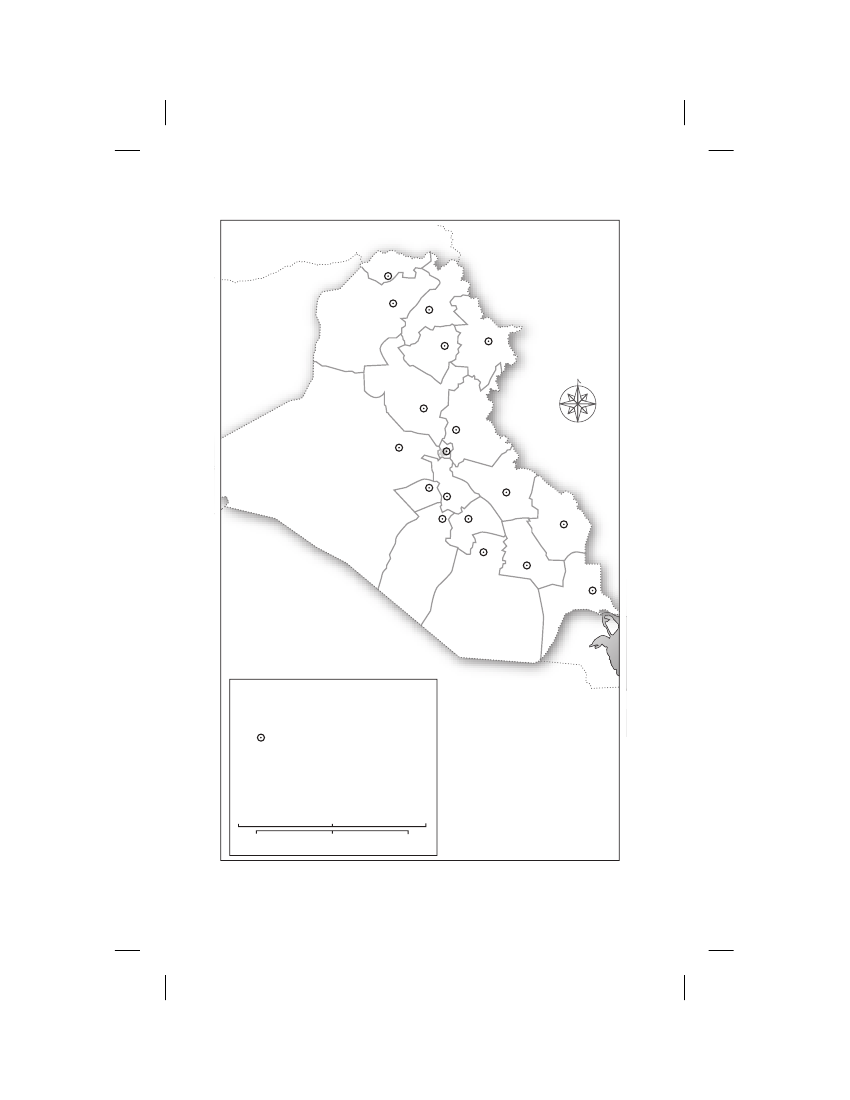

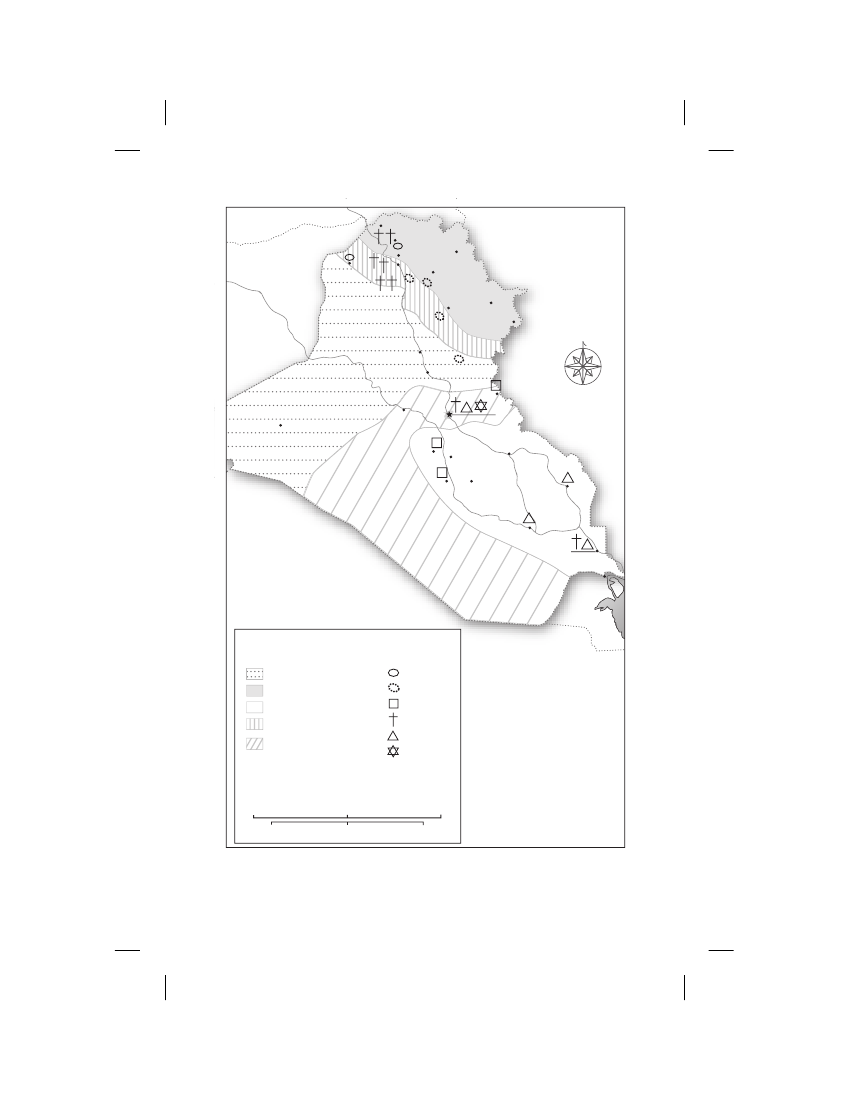

AppendicesOverview Map of the RegionOverview Map of IraqAdministrative DivisionsDistribution of Religious GroupsLetter from the Sponsoring OrganizationsIraq Study Group Plenary SessionsIraq Study Group ConsultationsExpert Working Groups and MilitarySenior Advisor PanelThe Iraq Study GroupIraq Study Group Support99100101102103106107

117124142

vii

Letter from the Co-Chairs

There is no magic formula to solve the problems of Iraq. How-ever, there are actions that can be taken to improve the situa-tion and protect American interests.Many Americans are dissatisfied, not just with the situa-tion in Iraq but with the state of our political debate regardingIraq. Our political leaders must build a bipartisan approach tobring a responsible conclusion to what is now a lengthy andcostly war. Our country deserves a debate that prizes substanceover rhetoric, and a policy that is adequately funded and sus-tainable. The President and Congress must work together. Ourleaders must be candid and forthright with the American peo-ple in order to win their support.No one can guarantee that any course of action in Iraq atthis point will stop sectarian warfare, growing violence, or aslide toward chaos. If current trends continue, the potentialconsequences are severe. Because of the role and responsibil-ity of the United States in Iraq, and the commitments our gov-ernment has made, the United States has special obligations.Our country must address as best it can Iraq’s many problems.ix

Letter from the Co-Chairs

The United States has long-term relationships and interests atstake in the Middle East, and needs to stay engaged.In this consensus report, the ten members of the IraqStudy Group present a new approach because we believe thereis a better way forward. All options have not been exhausted.We believe it is still possible to pursue different policies thatcan give Iraq an opportunity for a better future, combat terror-ism, stabilize a critical region of the world, and protect Amer-ica’s credibility, interests, and values. Our report makes it clearthat the Iraqi government and the Iraqi people also must act toachieve a stable and hopeful future.What we recommend in this report demands a tre-mendous amount of political will and cooperation by the execu-tive and legislative branches of the U.S. government. Itdemands skillful implementation. It demands unity of effort bygovernment agencies. And its success depends on the unity ofthe American people in a time of political polarization. Ameri-cans can and must enjoy the right of robust debate within ademocracy. Yet U.S. foreign policy is doomed to failure—as isany course of action in Iraq—if it is not supported by a broad,sustained consensus. The aim of our report is to move ourcountry toward such a consensus.We want to thank all those we have interviewed and those whohave contributed information and assisted the Study Group,both inside and outside the U.S. government, in Iraq, andaround the world. We thank the members of the expert workinggroups, and staff from the sponsoring organizations. We espe-cially thank our colleagues on the Study Group, who haveworked with us on these difficult issues in a spirit of generosityand bipartisanship.x

Letter from the Co-Chairs

In presenting our report to the President, Congress, andthe American people, we dedicate it to the men and women—military and civilian—who have served and are serving in Iraq,and to their families back home. They have demonstrated ex-traordinary courage and made difficult sacrifices. Every Ameri-can is indebted to them.We also honor the many Iraqis who have sacrificed on be-half of their country, and the members of the Coalition Forceswho have stood with us and with the people of Iraq.James A. Baker, IIILee H. Hamilton

xi

Executive Summary

The situation in Iraq is grave and deteriorating. There is nopath that can guarantee success, but the prospects can be im-proved.In this report, we make a number of recommendationsfor actions to be taken in Iraq, the United States, and the re-gion. Our most important recommendations call for new andenhanced diplomatic and political efforts in Iraq and the re-gion, and a change in the primary mission of U.S. forces in Iraqthat will enable the United States to begin to move its combatforces out of Iraq responsibly. We believe that these two rec-ommendations are equally important and reinforce one another.If they are effectively implemented, and if the Iraqi governmentmoves forward with national reconciliation, Iraqis will have anopportunity for a better future, terrorism will be dealt a blow,stability will be enhanced in an important part of the world, andAmerica’s credibility, interests, and values will be protected.The challenges in Iraq are complex. Violence is increasingin scope and lethality. It is fed by a Sunni Arab insurgency, Shi-ite militias and death squads, al Qaeda, and widespread crimi-nality. Sectarian conflict is the principal challenge to stability.xiii

Executive Summary

The Iraqi people have a democratically elected government, yetit is not adequately advancing national reconciliation, providingbasic security, or delivering essential services. Pessimism is per-vasive.If the situation continues to deteriorate, the consequencescould be severe. A slide toward chaos could trigger the collapseof Iraq’s government and a humanitarian catastrophe. Neigh-boring countries could intervene. Sunni-Shia clashes couldspread. Al Qaeda could win a propaganda victory and expandits base of operations. The global standing of the United Statescould be diminished. Americans could become more polarized.During the past nine months we have considered a fullrange of approaches for moving forward. All have flaws. Ourrecommended course has shortcomings, but we firmly believethat it includes the best strategies and tactics to positively influ-ence the outcome in Iraq and the region.External ApproachThe policies and actions of Iraq’s neighbors greatly affect itsstability and prosperity. No country in the region will benefit inthe long term from a chaotic Iraq. Yet Iraq’s neighbors are notdoing enough to help Iraq achieve stability. Some are under-cutting stability.The United States should immediately launch a newdiplomatic offensive to build an international consensus for sta-bility in Iraq and the region. This diplomatic effort should in-clude every country that has an interest in avoiding a chaoticIraq, including all of Iraq’s neighbors. Iraq’s neighbors and keystates in and outside the region should form a support group toreinforce security and national reconciliation within Iraq, nei-ther of which Iraq can achieve on its own.xiv

Executive Summary

Given the ability of Iran and Syria to influence eventswithin Iraq and their interest in avoiding chaos in Iraq, theUnited States should try to engage them constructively. Inseeking to influence the behavior of both countries, the UnitedStates has disincentives and incentives available. Iran shouldstem the flow of arms and training to Iraq, respect Iraq’s sover-eignty and territorial integrity, and use its influence over IraqiShia groups to encourage national reconciliation. The issue ofIran’s nuclear programs should continue to be dealt with by thefive permanent members of the United Nations SecurityCouncil plus Germany. Syria should control its border withIraq to stem the flow of funding, insurgents, and terrorists inand out of Iraq.The United States cannot achieve its goals in the MiddleEast unless it deals directly with the Arab-Israeli conflict andregional instability. There must be a renewed and sustainedcommitment by the United States to a comprehensive Arab-Israeli peace on all fronts: Lebanon, Syria, and President Bush’sJune 2002 commitment to a two-state solution for Israel andPalestine. This commitment must include direct talks with, by,and between Israel, Lebanon, Palestinians (those who acceptIsrael’s right to exist), and Syria.As the United States develops its approach toward Iraqand the Middle East, the United States should provide addi-tional political, economic, and military support for Afghanistan,including resources that might become available as combatforces are moved out of Iraq.Internal ApproachThe most important questions about Iraq’s future are now theresponsibility of Iraqis. The United States must adjust its rolexv

Executive Summary

in Iraq to encourage the Iraqi people to take control of theirown destiny.The Iraqi government should accelerate assuming re-sponsibility for Iraqi security by increasing the number andquality of Iraqi Army brigades. While this process is under way,and to facilitate it, the United States should significantly in-crease the number of U.S. military personnel, including com-bat troops, imbedded in and supporting Iraqi Army units. Asthese actions proceed, U.S. combat forces could begin to moveout of Iraq.The primary mission of U.S. forces in Iraq should evolveto one of supporting the Iraqi army, which would take over pri-mary responsibility for combat operations. By the first quarterof 2008, subject to unexpected developments in the securitysituation on the ground, all combat brigades not necessary forforce protection could be out of Iraq. At that time, U.S. combatforces in Iraq could be deployed only in units embedded withIraqi forces, in rapid-reaction and special operations teams,and in training, equipping, advising, force protection, andsearch and rescue. Intelligence and support efforts would con-tinue. A vital mission of those rapid reaction and special opera-tions forces would be to undertake strikes against al Qaeda inIraq.It is clear that the Iraqi government will need assistancefrom the United States for some time to come, especially incarrying out security responsibilities. Yet the United Statesmust make it clear to the Iraqi government that the UnitedStates could carry out its plans, including planned redeploy-ments, even if the Iraqi government did not implement theirplanned changes. The United States must not make an open-ended commitment to keep large numbers of American troopsdeployed in Iraq.xvi

Executive Summary

As redeployment proceeds, military leaders should em-phasize training and education of forces that have returned tothe United States in order to restore the force to full combatcapability. As equipment returns to the United States, Con-gress should appropriate sufficient funds to restore the equip-ment over the next five years.The United States should work closely with Iraq’s leadersto support the achievement of specific objectives—or mile-stones—on national reconciliation, security, and governance.Miracles cannot be expected, but the people of Iraq have theright to expect action and progress. The Iraqi governmentneeds to show its own citizens—and the citizens of the UnitedStates and other countries—that it deserves continued support.Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, in consultation with theUnited States, has put forward a set of milestones critical forIraq. His list is a good start, but it must be expanded to includemilestones that can strengthen the government and benefit theIraqi people. President Bush and his national security teamshould remain in close and frequent contact with the Iraqileadership to convey a clear message: there must be prompt ac-tion by the Iraqi government to make substantial progress to-ward the achievement of these milestones.If the Iraqi government demonstrates political will andmakes substantial progress toward the achievement of mile-stones on national reconciliation, security, and governance, theUnited States should make clear its willingness to continuetraining, assistance, and support for Iraq’s security forces and tocontinue political, military, and economic support. If the Iraqigovernment does not make substantial progress toward theachievement of milestones on national reconciliation, security,and governance, the United States should reduce its political,military, or economic support for the Iraqi government.xvii

Executive Summary

Our report makes recommendations in several other areas.They include improvements to the Iraqi criminal justice sys-tem, the Iraqi oil sector, the U.S. reconstruction efforts in Iraq,the U.S. budget process, the training of U.S. government per-sonnel, and U.S. intelligence capabilities.ConclusionIt is the unanimous view of the Iraq Study Group that theserecommendations offer a new way forward for the UnitedStates in Iraq and the region. They are comprehensive andneed to be implemented in a coordinated fashion. They shouldnot be separated or carried out in isolation. The dynamics ofthe region are as important to Iraq as events within Iraq.The challenges are daunting. There will be difficult daysahead. But by pursuing this new way forward, Iraq, the region,and the United States of America can emerge stronger.

xviii

I

Assessment

There is no guarantee for success in Iraq. The situation inBaghdad and several provinces is dire. Saddam Hussein hasbeen removed from power and the Iraqi people have a demo-cratically elected government that is broadly representative ofIraq’s population, yet the government is not adequately ad-vancing national reconciliation, providing basic security, or de-livering essential services. The level of violence is high andgrowing. There is great suffering, and the daily lives of manyIraqis show little or no improvement. Pessimism is pervasive.U.S. military and civilian personnel, and our coalitionpartners, are making exceptional and dedicated efforts—andsacrifices—to help Iraq. Many Iraqis have also made extraordi-nary efforts and sacrifices for a better future. However, theability of the United States to influence events within Iraq is di-minishing. Many Iraqis are embracing sectarian identities. Thelack of security impedes economic development. Most coun-tries in the region are not playing a constructive role in supportof Iraq, and some are undercutting stability.Iraq is vital to regional and even global stability, and iscritical to U.S. interests. It runs along the sectarian fault lines of

the iraq study group report

Shia and Sunni Islam, and of Kurdish and Arab populations. Ithas the world’s second-largest known oil reserves. It is now abase of operations for international terrorism, including alQaeda.Iraq is a centerpiece of American foreign policy, influenc-ing how the United States is viewed in the region and aroundthe world. Because of the gravity of Iraq’s condition and thecountry’s vital importance, the United States is facing one of itsmost difficult and significant international challenges indecades. Because events in Iraq have been set in motion byAmerican decisions and actions, the United States has both anational and a moral interest in doing what it can to give Iraqisan opportunity to avert anarchy.An assessment of the security, political, economic, and re-gional situation follows (all figures current as of publication),along with an assessment of the consequences if Iraq continuesto deteriorate, and an analysis of some possible courses ofaction.

2

A. Assessment of the CurrentSituation in Iraq

1. SecurityAttacks against U.S., Coalition, and Iraqi security forces are per-sistent and growing. October 2006 was the deadliest month forU.S. forces since January 2005, with 102 Americans killed. Totalattacks in October 2006 averaged 180 per day, up from 70 perday in January 2006. Daily attacks against Iraqi security forces inOctober were more than double the level in January. Attacksagainst civilians in October were four times higher than in Janu-ary. Some 3,000 Iraqi civilians are killed every month.Sources of ViolenceViolence is increasing in scope, complexity, and lethality. Thereare multiple sources of violence in Iraq: the Sunni Arab insur-gency, al Qaeda and affiliated jihadist groups, Shiite militiasand death squads, and organized criminality. Sectarian vio-lence—particularly in and around Baghdad—has become theprincipal challenge to stability.Most attacks on Americans still come from the SunniArab insurgency. The insurgency comprises former elementsof the Saddam Hussein regime, disaffected Sunni Arab Iraqis,3

the iraq study group report

and common criminals. It has significant support within theSunni Arab community. The insurgency has no single leader-ship but is a network of networks. It benefits from participants’detailed knowledge of Iraq’s infrastructure, and arms and fi-nancing are supplied primarily from within Iraq. The insur-gents have different goals, although nearly all oppose thepresence of U.S. forces in Iraq. Most wish to restore SunniArab rule in the country. Some aim at winning local power andcontrol.Al Qaeda is responsible for a small portion of the violencein Iraq, but that includes some of the more spectacular acts:suicide attacks, large truck bombs, and attacks on significantreligious or political targets. Al Qaeda in Iraq is now largelyIraqi-run and composed of Sunni Arabs. Foreign fighters—numbering an estimated 1,300—play a supporting role or carryout suicide operations. Al Qaeda’s goals include instigating awider sectarian war between Iraq’s Sunni and Shia, and drivingthe United States out of Iraq.Sectarian violence causes the largest number of Iraqicivilian casualties. Iraq is in the grip of a deadly cycle: Sunni in-surgent attacks spark large-scale Shia reprisals, and vice versa.Groups of Iraqis are often found bound and executed, theirbodies dumped in rivers or fields. The perception of un-checked violence emboldens militias, shakes confidence in thegovernment, and leads Iraqis to flee to places where their sectis the majority and where they feel they are in less danger. Insome parts of Iraq—notably in Baghdad—sectarian cleansingis taking place. The United Nations estimates that 1.6 millionare displaced within Iraq, and up to 1.8 million Iraqis have fledthe country.Shiite militias engaging in sectarian violence pose a sub-stantial threat to immediate and long-term stability. These mili-4

Assessment

tias are diverse. Some are affiliated with the government, someare highly localized, and some are wholly outside the law. Theyare fragmenting, with an increasing breakdown in commandstructure. The militias target Sunni Arab civilians, and somestruggle for power in clashes with one another. Some even tar-get government ministries. They undermine the authority ofthe Iraqi government and security forces, as well as the abilityof Sunnis to join a peaceful political process. The prevalence ofmilitias sends a powerful message: political leaders can pre-serve and expand their power only if backed by armed force.The Mahdi Army, led by Moqtada al-Sadr, may numberas many as 60,000 fighters. It has directly challenged U.S. andIraqi government forces, and it is widely believed to engage inregular violence against Sunni Arab civilians. Mahdi fighterspatrol certain Shia enclaves, notably northeast Baghdad’s teem-ing neighborhood of 2.5 million known as “Sadr City.” As theMahdi Army has grown in size and influence, some elementshave moved beyond Sadr’s control.The Badr Brigade is affiliated with the Supreme Councilfor the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), which is led byAbdul Aziz al-Hakim. The Badr Brigade has long-standing tieswith the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps. Many Badr mem-bers have become integrated into the Iraqi police, and othersplay policing roles in southern Iraqi cities. While wearing theuniform of the security services, Badr fighters have targetedSunni Arab civilians. Badr fighters have also clashed with theMahdi Army, particularly in southern Iraq.Criminality also makes daily life unbearable for manyIraqis. Robberies, kidnappings, and murder are commonplacein much of the country. Organized criminal rackets thrive, par-ticularly in unstable areas like Anbar province. Some criminalgangs cooperate with, finance, or purport to be part of the5

the iraq study group report

Sunni insurgency or a Shiite militia in order to gain legitimacy.As one knowledgeable American official put it, “If there wereforeign forces in New Jersey, Tony Soprano would be an insur-gent leader.”Four of Iraq’s eighteen provinces are highly insecure—Baghdad, Anbar, Diyala, and Salah ad Din. These provinces ac-count for about 40 percent of Iraq’s population of 26 million. InBaghdad, the violence is largely between Sunni and Shia. InAnbar, the violence is attributable to the Sunni insurgency andto al Qaeda, and the situation is deteriorating.In Kirkuk, the struggle is between Kurds, Arabs, andTurkmen. In Basra and the south, the violence is largely anintra-Shia power struggle. The most stable parts of the countryare the three provinces of the Kurdish north and parts of theShia south. However, most of Iraq’s cities have a sectarian mixand are plagued by persistent violence.U.S., Coalition, and Iraqi ForcesConfronting this violence are the Multi-National Forces–Iraqunder U.S. command, working in concert with Iraq’s securityforces. The Multi-National Forces–Iraq were authorized byUN Security Council Resolution 1546 in 2004, and the man-date was extended in November 2006 for another year.Approximately 141,000 U.S. military personnel are serv-ing in Iraq, together with approximately 16,500 military person-nel from twenty-seven coalition partners, the largest contingentbeing 7,200 from the United Kingdom. The U.S. Army hasprincipal responsibility for Baghdad and the north. The U.S.Marine Corps takes the lead in Anbar province. The UnitedKingdom has responsibility in the southeast, chiefly in Basra.Along with this military presence, the United States is6

Assessment

building its largest embassy in Baghdad. The current U.S. em-bassy in Baghdad totals about 1,000 U.S. government employ-ees. There are roughly 5,000 civilian contractors in the country.Currently, the U.S. military rarely engages in large-scalecombat operations. Instead, counterinsurgency efforts focuson a strategy of “clear, hold, and build”—“clearing” areas ofinsurgents and death squads, “holding” those areas with Iraqisecurity forces, and “building” areas with quick-impact recon-struction projects.Nearly every U.S. Army and Marine combat unit, andseveral National Guard and Reserve units, have been to Iraq atleast once. Many are on their second or even third rotations;rotations are typically one year for Army units, seven monthsfor Marine units. Regular rotations, in and out of Iraq or withinthe country, complicate brigade and battalion efforts to get toknow the local scene, earn the trust of the population, andbuild a sense of cooperation.Many military units are under significant strain. Becausethe harsh conditions in Iraq are wearing out equipment morequickly than anticipated, many units do not have fully func-tional equipment for training when they redeploy to the UnitedStates. An extraordinary amount of sacrifice has been asked ofour men and women in uniform, and of their families. TheAmerican military has little reserve force to call on if it needsground forces to respond to other crises around the world.A primary mission of U.S. military strategy in Iraq is thetraining of competent Iraqi security forces. By the end of 2006,the Multi-National Security Transition Command–Iraq underAmerican leadership is expected to have trained and equippeda target number of approximately 326,000 Iraqi security ser-vices. That figure includes 138,000 members of the Iraqi Armyand 188,000 Iraqi police. Iraqis have operational control over7

the iraq study group report

roughly one-third of Iraqi security forces; the U.S. has opera-tional control over most of the rest. No U.S. forces are underIraqi command.The Iraqi ArmyThe Iraqi Army is making fitful progress toward becoming a re-liable and disciplined fighting force loyal to the national gov-ernment. By the end of 2006, the Iraqi Army is expected tocomprise 118 battalions formed into 36 brigades under thecommand of 10 divisions. Although the Army is one of themore professional Iraqi institutions, its performance has beenuneven. The training numbers are impressive, but they repre-sent only part of the story.Significant questions remain about the ethnic composi-tion and loyalties of some Iraqi units—specifically, whetherthey will carry out missions on behalf of national goals insteadof a sectarian agenda. Of Iraq’s 10 planned divisions, those thatare even-numbered are made up of Iraqis who signed up toserve in a specific area, and they have been reluctant to rede-ploy to other areas of the country. As a result, elements of theArmy have refused to carry out missions.The Iraqi Army is also confronted by several other signifi-cant challenges:• Units lack leadership. They lack the ability to work togetherand perform at higher levels of organization—the brigade anddivision level. Leadership training and the experience of lead-ership are the essential elements to improve performance.• Units lack equipment. They cannot carry out their missionswithout adequate equipment. Congress has been generous8

Assessment

in funding requests for U.S. troops, but it has resisted fullyfunding Iraqi forces. The entire appropriation for Iraqi de-fense forces for FY 2006 ($3 billion) is less than the UnitedStates currently spends in Iraq every two weeks.• Units lack personnel. Soldiers are on leave one week amonth so that they can visit their families and take themtheir pay. Soldiers are paid in cash because there is no bank-ing system. Soldiers are given leave liberally and face nopenalties for absence without leave. Unit readiness rates arelow, often at 50 percent or less.• Units lack logistics and support. They lack the ability to sus-tain their operations, the capability to transport supplies andtroops, and the capacity to provide their own indirect firesupport, close-air support, technical intelligence, and med-ical evacuation. They will depend on the United States forlogistics and support through at least 2007.The Iraqi PoliceThe state of the Iraqi police is substantially worse than thatof the Iraqi Army. The Iraqi Police Service currently numbersroughly 135,000 and is responsible for local policing. It hasneither the training nor legal authority to conduct criminalinvestigations, nor the firepower to take on organized crime,insurgents, or militias. The Iraqi National Police numbersroughly 25,000 and its officers have been trained in counterin-surgency operations, not police work. The Border Enforce-ment Department numbers roughly 28,000.Iraqi police cannot control crime, and they routinely en-gage in sectarian violence, including the unnecessary detention,9

the iraq study group report

torture, and targeted execution of Sunni Arab civilians. The po-lice are organized under the Ministry of the Interior, which isconfronted by corruption and militia infiltration and lacks con-trol over police in the provinces.The United States and the Iraqi government recognizethe importance of reform. The current Minister of the Interiorhas called for purging militia members and criminals from thepolice. But he has little police experience or base of support.There is no clear Iraqi or U.S. agreement on the character andmission of the police. U.S. authorities do not know with preci-sion the composition and membership of the various policeforces, nor the disposition of their funds and equipment. Thereare ample reports of Iraqi police officers participating in train-ing in order to obtain a weapon, uniform, and ammunition foruse in sectarian violence. Some are on the payroll but don’tshow up for work. In the words of a senior American general,“2006 was supposed to be ‘the year of the police’ but it hasn’tmaterialized that way.”Facilities Protection ServicesThe Facilities Protection Service poses additional problems.Each Iraqi ministry has an armed unit, ostensibly to guard theministry’s infrastructure. All together, these units total roughly145,000 uniformed Iraqis under arms. However, these unitshave questionable loyalties and capabilities. In the ministries ofHealth, Agriculture, and Transportation—controlled by Moq-tada al-Sadr—the Facilities Protection Service is a source offunding and jobs for the Mahdi Army. One senior U.S. officialdescribed the Facilities Protection Service as “incompetent,dysfunctional, or subversive.” Several Iraqis simply referred tothem as militias.10

Assessment

The Iraqi government has begun to bring the FacilitiesProtection Service under the control of the Interior Ministry.The intention is to identify and register Facilities Protectionpersonnel, standardize their treatment, and provide sometraining. Though the approach is reasonable, this effort may ex-ceed the current capability of the Interior Ministry.

Operation Together Forward IIIn a major effort to quell the violence in Iraq, U.S. mili-tary forces joined with Iraqi forces to establish security inBaghdad with an operation called “Operation TogetherForward II,” which began in August 2006. Under Opera-tion Together Forward II, U.S. forces are working withmembers of the Iraqi Army and police to “clear, hold, andbuild” in Baghdad, moving neighborhood by neighbor-hood. There are roughly 15,000 U.S. troops in Baghdad.This operation—and the security of Baghdad—iscrucial to security in Iraq more generally. A capital city ofmore than 6 million, Baghdad contains some 25 percentof the country’s population. It is the largest Sunni andShia city in Iraq. It has high concentrations of both Sunniinsurgents and Shiite militias. Both Iraqi and Americanleaders told us that as Baghdad goes, so goes Iraq.The results of Operation Together Forward II aredisheartening. Violence in Baghdad—already at high lev-els—jumped more than 43 percent between the summerand October 2006. U.S. forces continue to suffer high ca-sualties. Perpetrators of violence leave neighborhoods inadvance of security sweeps, only to filter back later. Iraqi11

the iraq study group report

police have been unable or unwilling to stop such infiltra-tion and continuing violence. The Iraqi Army has pro-vided only two out of the six battalions that it promised inAugust would join American forces in Baghdad. The Iraqigovernment has rejected sustained security operations inSadr City.Security efforts will fail unless the Iraqis have boththe capability to hold areas that have been cleared andthe will to clear neighborhoods that are home to Shiitemilitias. U.S. forces can “clear” any neighborhood, butthere are neither enough U.S. troops present nor enoughsupport from Iraqi security forces to “hold” neighbor-hoods so cleared. The same holds true for the rest of Iraq.Because none of the operations conducted by U.S. andIraqi military forces are fundamentally changing the con-ditions encouraging the sectarian violence, U.S. forcesseem to be caught in a mission that has no foreseeable end.

2. PoliticsIraq is a sovereign state with a democratically elected Councilof Representatives. A government of national unity was formedin May 2006 that is broadly representative of the Iraqi people.Iraq has ratified a constitution, and—per agreement withSunni Arab leaders—has initiated a process of review to deter-mine if the constitution needs amendment.The composition of the Iraqi government is basically sec-tarian, and key players within the government too often act intheir sectarian interest. Iraq’s Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish leadersfrequently fail to demonstrate the political will to act in Iraq’s12

Assessment

national interest, and too many Iraqi ministries lack the capac-ity to govern effectively. The result is an even weaker centralgovernment than the constitution provides.There is widespread Iraqi, American, and internationalagreement on the key issues confronting the Iraqi government:national reconciliation, including the negotiation of a “politicaldeal” among Iraq’s sectarian groups on Constitution review, de-Baathification, oil revenue sharing, provincial elections, the fu-ture of Kirkuk, and amnesty; security, particularly curbingmilitias and reducing the violence in Baghdad; and governance,including the provision of basic services and the rollback ofpervasive corruption. Because Iraqi leaders view issues througha sectarian prism, we will summarize the differing perspectivesof Iraq’s main sectarian groups.Sectarian ViewpointsThe Shia,the majority of Iraq’s population, have gained powerfor the first time in more than 1,300 years. Above all, many Shiaare interested in preserving that power. However, fissures haveemerged within the broad Shia coalition, known as the UnitedIraqi Alliance. Shia factions are struggling for power—over re-gions, ministries, and Iraq as a whole. The difficulties in hold-ing together a broad and fractious coalition have led severalobservers in Baghdad to comment that Shia leaders are held“hostage to extremes.” Within the coalition as a whole, there isa reluctance to reach a political accommodation with the Sun-nis or to disarm Shiite militias.Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has demonstrated an un-derstanding of the key issues facing Iraq, notably the need fornational reconciliation and security in Baghdad. Yet strainshave emerged between Maliki’s government and the United13

the iraq study group report

States. Maliki has publicly rejected a U.S. timetable to achievecertain benchmarks, ordered the removal of blockades aroundSadr City, sought more control over Iraqi security forces, andresisted U.S. requests to move forward on reconciliation or ondisbanding Shiite militias.

Sistani, Sadr, HakimThe U.S. deals primarily with the Iraqi government, butthe most powerful Shia figures in Iraq do not hold na-tional office. Of the following three vital power brokers inthe Shia community, the United States is unable to talkdirectly with one (Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani) anddoes not talk to another (Moqtada al-Sadr).grand ayatollah ali al-sistani:Sistani is the lead-ing Shiite cleric in Iraq. Despite staying out of day-to-daypolitics, he has been the most influential leader in thecountry: all major Shia leaders have sought his approvalor guidance. Sistani has encouraged a unified Shia blocwith moderated aims within a unified Iraq. Sistani’s influ-ence may be waning, as his words have not succeeded inpreventing intra-Shia violence or retaliation against Sunnis.abdul aziz al-hakim:Hakim is a cleric and the leaderof the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution inIraq (SCIRI), the largest and most organized Shia politi-cal party. It seeks the creation of an autonomous Shiaregion comprising nine provinces in the south. Hakim hasconsistently protected and advanced his party’s position.SCIRI has close ties with Iran.14

Assessment

moqtada al-sadr:Sadr has a large following amongimpoverished Shia, particularly in Baghdad. He has joinedMaliki’s governing coalition, but his Mahdi Army hasclashed with the Badr Brigades, as well as with Iraqi, U.S.,and U.K. forces. Sadr claims to be an Iraqi nationalist.Several observers remarked to us that Sadr was followingthe model of Hezbollah in Lebanon: building a politicalparty that controls basic services within the governmentand an armed militia outside of the government.

Sunni Arabsfeel displaced because of the loss of their tradi-tional position of power in Iraq. They are torn, unsure whetherto seek their aims through political participation or through vi-olent insurgency. They remain angry about U.S. decisions todissolve Iraqi security forces and to pursue the “de-Baathifica-tion” of Iraq’s government and society. Sunnis are confrontedby paradoxes: they have opposed the presence of U.S. forces inIraq but need those forces to protect them against Shia militias;they chafe at being governed by a majority Shia administrationbut reject a federal, decentralized Iraq and do not see a Sunniautonomous region as feasible for themselves.

Hashimi and DhariThe influence of Sunni Arab politicians in the govern-ment is questionable. The leadership of the Sunni Arabinsurgency is murky, but the following two key SunniArab figures have broad support.15

the iraq study group report

tariq al-hashimi:Hashimi is one of two vice presi-dents of Iraq and the head of the Iraqi Islamic Party, thelargest Sunni Muslim bloc in parliament. Hashimi op-poses the formation of autonomous regions and has advo-cated the distribution of oil revenues based on population,a reversal of de-Baathification, and the removal of Shiitemilitia fighters from the Iraqi security forces. Shiite deathsquads have recently killed three of his siblings.sheik harith al-dhari:Dhari is the head of theMuslim Scholars Association, the most influential Sunniorganization in Iraq. Dhari has condemned the Americanoccupation and spoken out against the Iraqi government.His organization has ties both to the Sunni Arab insur-gency and to Sunnis within the Iraqi government. A war-rant was recently issued for his arrest for inciting violenceand terrorism, an act that sparked bitter Sunni protestsacross Iraq.Iraqi Kurdshave succeeded in presenting a united front of twomain political blocs—the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP)and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The Kurds havesecured a largely autonomous Kurdish region in the north, andhave achieved a prominent role for Kurds within the nationalgovernment. Barzani leads the Kurdish regional government,and Talabani is president of Iraq.Leading Kurdish politicians told us they preferred to bewithin a democratic, federal Iraqi state because an independ-ent Kurdistan would be surrounded by hostile neighbors. How-ever, a majority of Kurds favor independence. The Kurds havetheir own security forces—thepeshmerga—whichnumber16

Assessment

roughly 100,000. They believe they could accommodate them-selves to either a unified or a fractured Iraq.

Barzani and TalabaniKurdish politics has been dominated for years by two fig-ures who have long-standing ties in movements for Kur-dish independence and self-government.massoud barzani:Barzani is the leader of the Kurdis-tan Democratic Party and the President of the Kurdishregional government. Barzani has cooperated with hislongtime rival, Jalal Talabani, in securing an empowered,autonomous Kurdish region in northern Iraq. Barzani hasordered the lowering of Iraqi flags and raising of Kurdishflags in Kurdish-controlled areas.jalal talabani:Talabani is the leader of the PatrioticUnion of Kurdistan and the President of Iraq. WhereasBarzani has focused his efforts in Kurdistan, Talabani hassecured power in Baghdad, and several important PUKgovernment ministers are loyal to him. Talabani stronglysupports autonomy for Kurdistan. He has also sought tobring real power to the office of the presidency.

Key Issuesnational reconciliation.Prime Minister Maliki outlineda commendable program of national reconciliation soon afterhe entered office. However, the Iraqi government has not takenaction on the key elements of national reconciliation: revising17

the iraq study group report

de-Baathification, which prevents many Sunni Arabs from par-ticipating in governance and society; providing amnesty for thosewho have fought against the government; sharing the country’soil revenues; demobilizing militias; amending the constitution;and settling the future of Kirkuk.One core issue is federalism. The Iraqi Constitution,which created a largely autonomous Kurdistan region, allowsother such regions to be established later, perhaps including a“Shi’astan” comprising nine southern provinces. This highlydecentralized structure is favored by the Kurds and many Shia(particularly supporters of Abdul Aziz al-Hakim), but it isanathema to Sunnis. First, Sunni Arabs are generally Iraqi na-tionalists, albeit within the context of an Iraq they believe theyshould govern. Second, because Iraq’s energy resources are inthe Kurdish and Shia regions, there is no economically feasible“Sunni region.” Particularly contentious is a provision in theconstitution that shares revenues nationally from current oil re-serves, while allowing revenues from reserves discovered in thefuture to go to the regions.The Sunnis did not actively participate in the constitu-tion-drafting process, and acceded to entering the governmentonly on the condition that the constitution be amended. InSeptember, the parliament agreed to initiate a constitutionalreview commission slated to complete its work within one year;it delayed considering the question of forming a federalized re-gion in southern Iraq for eighteen months.Another key unresolved issue is the future of Kirkuk, anoil-rich city in northern Iraq that is home to substantial num-bers of Kurds, Arabs, and Turkmen. The Kurds insisted thatthe constitution require a popular referendum by December2007 to determine whether Kirkuk can formally join the Kur-dish administered region, an outcome that Arabs and Turkmen18

Assessment

in Kirkuk staunchly oppose. The risks of further violencesparked by a Kirkuk referendum are great.Iraq’s leaders often claim that they do not want a divisionof the country, but we found that key Shia and Kurdish leadershave little commitment to national reconciliation. One promi-nent Shia leader told us pointedly that the current governmenthas the support of 80 percent of the population, notably ex-cluding Sunni Arabs. Kurds have fought for independence fordecades, and when our Study Group visited Iraq, the leader ofthe Kurdish region ordered the lowering of Iraqi flags and theraising of Kurdish flags. One senior American general com-mented that the Iraqis “still do not know what kind of countrythey want to have.” Yet many of Iraq’s most powerful and well-positioned leaders are not working toward a united Iraq.security.The security situation cannot improve unless lead-ers act in support of national reconciliation. Shiite leaders mustmake the decision to demobilize militias. Sunni Arabs mustmake the decision to seek their aims through a peaceful politi-cal process, not through violent revolt. The Iraqi governmentand Sunni Arab tribes must aggressively pursue al Qaeda.Militias are currently seen as legitimate vehicles of politi-cal action. Shia political leaders make distinctions between theSunni insurgency (which seeks to overthrow the government)and Shia militias (which are used to fight Sunnis, secure neigh-borhoods, and maximize power within the government). ThoughPrime Minister Maliki has said he will address the problem ofmilitias, he has taken little meaningful action to curb their in-fluence. He owes his office in large part to Sadr and has shownlittle willingness to take on him or his Mahdi Army.Sunni Arabs have not made the strategic decision to aban-don violent insurgency in favor of the political process. Sunni19

the iraq study group report

politicians within the government have a limited level of supportand influence among their own population, and questionableinfluence over the insurgency. Insurgents wage a campaign of in-timidation against Sunni leaders—assassinating the family mem-bers of those who do participate in the government. Too often,insurgents tolerate and cooperate with al Qaeda, as they share amutual interest in attacking U.S. and Shia forces. However, SunniArab tribal leaders in Anbar province recently took the positivestep of agreeing to pursue al Qaeda and foreign fighters in theirmidst, and have started to take action on those commitments.Sunni politicians told us that the U.S. military has to takeon the militias; Shia politicians told us that the U.S. military hasto help them take out the Sunni insurgents and al Qaeda. Eachside watches the other. Sunni insurgents will not lay down armsunless the Shia militias are disarmed. Shia militias will not dis-arm until the Sunni insurgency is destroyed. To put it simply:there are many armed groups within Iraq, and very little will tolay down arms.governance.The Iraqi government is not effectively pro-viding its people with basic services: electricity, drinking water,sewage, health care, and education. In many sectors, produc-tion is below or hovers around prewar levels. In Baghdad andother unstable areas, the situation is much worse. There arefive major reasons for this problem.First, the government sometimes provides services on asectarian basis. For example, in one Sunni neighborhood ofShia-governed Baghdad, there is less than two hours of elec-tricity each day and trash piles are waist-high. One Americanofficial told us that Baghdad is run like a “Shia dictatorship” be-cause Sunnis boycotted provincial elections in 2005, and there-fore are not represented in local government.20

Assessment

Second, security is lacking. Insurgents target key infra-structure. For instance, electricity transmission towers aredowned by explosives, and then sniper attacks prevent repairsfrom being made.Third, corruption is rampant. One senior Iraqi official es-timated that official corruption costs Iraq $5–7 billion per year.Notable steps have been taken: Iraq has a functioning auditboard and inspectors general in the ministries, and senior lead-ers including the Prime Minister have identified rooting outcorruption as a national priority. But too many political leadersstill pursue their personal, sectarian, or party interests. Thereare still no examples of senior officials who have been broughtbefore a court of law and convicted on corruption charges.Fourth, capacity is inadequate. Most of Iraq’s technocraticclass was pushed out of the government as part of de-Baathifica-tion. Other skilled Iraqis have fled the country as violence hasrisen. Too often, Iraq’s elected representatives treat the ministriesas political spoils. Many ministries can do little more than paysalaries, spending as little as 10–15 percent of their capitalbudget. They lack technical expertise and suffer from corruption,inefficiency, a banking system that does not permit the transfer ofmoneys, extensive red tape put in place in part to deter corrup-tion, and a Ministry of Finance reluctant to disburse funds.Fifth, the judiciary is weak. Much has been done to estab-lish an Iraqi judiciary, including a supreme court, and Iraq hassome dedicated judges. But criminal investigations are con-ducted by magistrates, and they are too few and inadequatelytrained to perform this function. Intimidation of the Iraqi judi-ciary has been ruthless. As one senior U.S. official said to us,“We can protect judges, but not their families, their extendedfamilies, their friends.” Many Iraqis feel that crime not only isunpunished, it is rewarded.21

the iraq study group report

3. EconomicsThere has been some economic progress in Iraq, and Iraq hastremendous potential for growth. But economic developmentis hobbled by insecurity, corruption, lack of investment, dilapi-dated infrastructure, and uncertainty. As one U.S. official ob-served to us, Iraq’s economy has been badly shocked and isdysfunctional after suffering decades of problems: Iraq had apolice state economy in the 1970s, a war economy in the 1980s,and a sanctions economy in the 1990s. Immediate and long-term growth depends predominantly on the oil sector.Economic PerformanceThere are some encouraging signs. Currency reserves arestable and growing at $12 billion. Consumer imports of com-puters, cell phones, and other appliances have increased dra-matically. New businesses are opening, and construction ismoving forward in secure areas. Because of Iraq’s ample oil re-serves, water resources, and fertile lands, significant growth ispossible if violence is reduced and the capacity of governmentimproves. For example, wheat yields increased more than 40percent in Kurdistan during this past year.The Iraqi government has also made progress in meetingbenchmarks set by the International Monetary Fund. Mostprominently, subsidies have been reduced—for instance, theprice per liter of gas has increased from roughly 1.7 cents to 23cents (a figure far closer to regional prices). However, energyand food subsidies generally remain a burden, costing Iraq $11billion per year.Despite the positive signs, many leading economic in-22

Assessment

dicators are negative. Instead of meeting a target of 10percent, growth in Iraq is at roughly 4 percent this year. Inflationis above 50 percent. Unemployment estimates range widely from20 to 60 percent. The investment climate is bleak, with foreign di-rect investment under 1 percent of GDP. Too many Iraqis do notsee tangible improvements in their daily economic situation.Oil SectorOil production and sales account for nearly 70 percent of Iraq’sGDP, and more than 95 percent of government revenues. Iraqproduces around 2.2 million barrels per day, and exports about1.5 million barrels per day. This is below both prewar produc-tion levels and the Iraqi government’s target of 2.5 million bar-rels per day, and far short of the vast potential of the Iraqi oilsector. Fortunately for the government, global energy priceshave been higher than projected, making it possible for Iraq tomeet its budget revenue targets.Problems with oil production are caused by lack of secu-rity, lack of investment, and lack of technical capacity. Insur-gents with a detailed knowledge of Iraq’s infrastructure targetpipelines and oil facilities. There is no metering system for theoil. There is poor maintenance at pumping stations, pipelines,and port facilities, as well as inadequate investment in moderntechnology. Iraq had a cadre of experts in the oil sector, but in-timidation and an extended migration of experts to other coun-tries have eroded technical capacity. Foreign companies havebeen reluctant to invest, and Iraq’s Ministry of Oil has been un-able to spend more than 15 percent of its capital budget.Corruption is also debilitating. Experts estimate that150,000 to 200,000—and perhaps as many as 500,000—barrelsof oil per day are being stolen. Controlled prices for refined23

the iraq study group report

products result in shortages within Iraq, which drive con-sumers to the thriving black market. One senior U.S. officialtold us that corruption is more responsible than insurgents forbreakdowns in the oil sector.The Politics of OilThe politics of oil has the potential to further damage the coun-try’s already fragile efforts to create a unified central govern-ment. The Iraqi Constitution leaves the door open for regionsto take the lead in developing new oil resources. Article 108states that “oil and gas are the ownership of all the peoples ofIraq in all the regions and governorates,” while Article 109tasks the federal government with “the management of oil andgas extracted from current fields.” This language has led tocontention over what constitutes a “new” or an “existing” re-source, a question that has profound ramifications for the ulti-mate control of future oil revenue.Senior members of Iraq’s oil industry argue that a nationaloil company could reduce political tensions by centralizing rev-enues and reducing regional or local claims to a percentage ofthe revenue derived from production. However, regional lead-ers are suspicious and resist this proposal, affirming the rights oflocal communities to have direct access to the inflow of oil rev-enue. Kurdish leaders have been particularly aggressive in as-serting independent control of their oil assets, signing andimplementing investment deals with foreign oil companies innorthern Iraq. Shia politicians are also reported to be negotiat-ing oil investment contracts with foreign companies.There are proposals to redistribute a portion of oil rev-enues directly to the population on a per capita basis. Theseproposals have the potential to give all Iraqi citizens a stake in24

Assessment

the nation’s chief natural resource, but it would take time to de-velop a fair distribution system. Oil revenues have been incor-porated into state budget projections for the next several years.There is no institution in Iraq at present that could properlyimplement such a distribution system. It would take substantialtime to establish, and would have to be based on a well-developedstate census and income tax system, which Iraq currently lacks.U.S.-Led Reconstruction EffortsThe United States has appropriated a total of about $34 billionto support the reconstruction of Iraq, of which about $21 bil-lion has been appropriated for the “Iraq Relief and Recon-struction Fund.” Nearly $16 billion has been spent, and almostall the funds have been committed. The administration re-quested $1.6 billion for reconstruction in FY 2006, and re-ceived $1.485 billion. The administration requested $750million for FY 2007. The trend line for economic assistance inFY 2008 also appears downward.Congress has little appetite for appropriating more fundsfor reconstruction. There is a substantial need for continuedreconstruction in Iraq, but serious questions remain about thecapacity of the U.S. and Iraqi governments.The coordination of assistance programs by the DefenseDepartment, State Department, United States Agency for In-ternational Development, and other agencies has been ineffec-tive. There are no clear lines establishing who is in charge ofreconstruction.As resources decline, the U.S. reconstruction effort ischanging its focus, shifting from infrastructure, education, andhealth to smaller-scale ventures that are chosen and to somedegree managed by local communities. A major attempt is also25

the iraq study group report

being made to improve the capacity of government bureaucra-cies at the national, regional, and provincial levels to provideservices to the population as well as to select and manage infra-structure projects.The United States has people embedded in several Iraqiministries, but it confronts problems with access and sustain-ability. Moqtada al-Sadr objects to the U.S. presence in Iraq,and therefore the ministries he controls—Health, Agriculture,and Transportation—will not work with Americans. It is notclear that Iraqis can or will maintain and operate reconstruc-tion projects launched by the United States.Several senior military officers commented to us that theCommander’s Emergency Response Program, which fundsquick-impact projects such as the clearing of sewage and therestoration of basic services, is vital. The U.S. Agency for Inter-national Development, in contrast, is focused on long-termeconomic development and capacity building, but funds havenot been committed to support these efforts into the future.The State Department leads seven Provincial ReconstructionTeams operating around the country. These teams can have apositive effect in secure areas, but not in areas where theirwork is hampered by significant security constraints.Substantial reconstruction funds have also been providedto contractors, and the Special Inspector General for Iraq Re-construction has documented numerous instances of waste andabuse. They have not all been put right. Contracting has gradu-ally improved, as more oversight has been exercised and fewercost-plus contracts have been granted; in addition, the use ofIraqi contractors has enabled the employment of more Iraqisin reconstruction projects.

26

Assessment

4. International SupportInternational support for Iraqi reconstruction has been tepid.International donors pledged $13.5 billion to support recon-struction, but less than $4 billion has been delivered.An important agreement with the Paris Club relieved asignificant amount of Iraq’s government debt and put the coun-try on firmer financial footing. But the Gulf States, includingSaudi Arabia and Kuwait, hold large amounts of Iraqi debt thatthey have not forgiven.The United States is currently working with the United Na-tions and other partners to fashion the “International Compact”on Iraq. The goal is to provide Iraqis with greater debt relief andcredits from the Gulf States, as well as to deliver on pledged aidfrom international donors. In return, the Iraqi government willagree to achieve certain economic reform milestones, such asbuilding anticorruption measures into Iraqi institutions, adoptinga fair legal framework for foreign investors, and reaching eco-nomic self-sufficiency by 2012. Several U.S. and international of-ficials told us that the compact could be an opportunity to seekgreater international engagement in the country.The RegionThe policies and actions of Iraq’s neighbors greatly influence itsstability and prosperity. No country in the region wants achaotic Iraq. Yet Iraq’s neighbors are doing little to help it, andsome are undercutting its stability. Iraqis complain that neigh-bors are meddling in their affairs. When asked which of Iraq’sneighbors are intervening in Iraq, one senior Iraqi officialreplied, “All of them.”27

the iraq study group report

The situation in Iraq is linked with events in the region.U.S. efforts in Afghanistan have been complicated by the over-riding focus of U.S. attention and resources on Iraq. SeveralIraqi, U.S., and international officials commented to us thatIraqi opposition to the United States—and support for Sadr—spiked in the aftermath of Israel’s bombing campaign inLebanon. The actions of Syria and Iran in Iraq are often tied totheir broader concerns with the United States. Many SunniArab states are concerned about rising Iranian influence in Iraqand the region. Most of the region’s countries are wary of U.S.efforts to promote democracy in Iraq and the Middle East.Neighboring Statesiran.Of all the neighbors, Iran has the most leverage in Iraq.Iran has long-standing ties to many Iraqi Shia politicians, manyof whom were exiled to Iran during the Saddam Husseinregime. Iran has provided arms, financial support, and trainingfor Shiite militias within Iraq, as well as political support forShia parties. There are also reports that Iran has supplied im-provised explosive devices to groups—including Sunni Arab in-surgents—that attack U.S. forces. The Iranian border with Iraqis porous, and millions of Iranians travel to Iraq each year tovisit Shia holy sites. Many Iraqis spoke of Iranian meddling,and Sunnis took a particularly alarmist view. One leading Sunnipolitician told us, “If you turn over any stone in Iraq today, youwill find Iran underneath.”U.S., Iraqi, and international officials also commented onthe range of tensions between the United States and Iran, in-cluding Iran’s nuclear program, Iran’s support for terrorism,Iran’s influence in Lebanon and the region, and Iran’s influencein Iraq. Iran appears content for the U.S. military to be tied28

Assessment

down in Iraq, a position that limits U.S. options in addressingIran’s nuclear program and allows Iran leverage over stability inIraq. Proposed talks between Iran and the United States aboutthe situation in Iraq have not taken place. One Iraqi officialtold us: “Iran is negotiating with the United States in the streetsof Baghdad.”syria.Syria is also playing a counterproductive role. Iraqisare upset about what they perceive as Syrian support for effortsto undermine the Iraqi government. The Syrian role is not somuch to take active measures as to countenance malign neg-lect: the Syrians look the other way as arms and foreign fightersflow across their border into Iraq, and former Baathist leadersfind a safe haven within Syria. Like Iran, Syria is content to seethe United States tied down in Iraq. That said, the Syrians haveindicated that they want a dialogue with the United States, andin November 2006 agreed to restore diplomatic relations withIraq after a 24-year break.saudi arabia and the gulf states.These countries forthe most part have been passive and disengaged. They have de-clined to provide debt relief or substantial economic assistanceto the Iraqi government. Several Iraqi Sunni Arab politicianscomplained that Saudi Arabia has not provided political sup-port for their fellow Sunnis within Iraq. One observed thatSaudi Arabia did not even send a letter when the Iraqi govern-ment was formed, whereas Iran has an ambassador in Iraq.Funding for the Sunni insurgency comes from private individ-uals within Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, even as those gov-ernments help facilitate U.S. military operations in Iraq byproviding basing and overflight rights and by cooperating on in-telligence issues.29

the iraq study group report

As worries about Iraq increase, the Gulf States are becom-ing more active. The United Arab Emirates and Kuwait havehosted meetings in support of the International Compact. SaudiArabia recently took the positive step of hosting a conference ofIraqi religious leaders in Mecca. Several Gulf States have helpedfoster dialogue with Iraq’s Sunni Arab population. While the GulfStates are not proponents of democracy in Iraq, they worry aboutthe direction of events: battle-hardened insurgents from Iraqcould pose a threat to their own internal stability, and the growthof Iranian influence in the region is deeply troubling to them.turkey.Turkish policy toward Iraq is focused on discourag-ing Kurdish nationalism, which is seen as an existential threatto Turkey’s own internal stability. The Turks have supported theTurkmen minority within Iraq and have used their influence totry to block the incorporation of Kirkuk into Iraqi Kurdistan. Atthe same time, Turkish companies have invested in Kurdishareas in northern Iraq, and Turkish and Kurdish leaders havesought constructive engagement on political, security, and eco-nomic issues.The Turks are deeply concerned about the operations of theKurdish Workers Party (PKK)—a terrorist group based in north-ern Iraq that has killed thousands of Turks. They are upset thatthe United States and Iraq have not targeted the PKK more ag-gressively. The Turks have threatened to go after the PKK them-selves, and have made several forays across the border into Iraq.jordan and egypt.Both Jordan and Egypt have providedsome assistance for the Iraqi government. Jordan has trainedthousands of Iraqi police, has an ambassador in Baghdad, andKing Abdullah recently hosted a meeting in Amman betweenPresident Bush and Prime Minister Maliki. Egypt has provided30

Assessment

some limited Iraqi army training. Both Jordan and Egypt havefacilitated U.S. military operations—Jordan by allowing over-flight and search-and-rescue operations, Egypt by allowingoverflight and Suez Canal transits; both provide important co-operation on intelligence. Jordan is currently home to 700,000Iraqi refugees (equal to 10 percent of its population) and fearsa flood of many more. Both Jordan and Egypt are concernedabout the position of Iraq’s Sunni Arabs and want constitutionalreforms in Iraq to bolster the Sunni community. They also fearthe return of insurgents to their countries.The International CommunityThe international community beyond the United Kingdom andour other coalition partners has played a limited role in Iraq.The United Nations—acting under Security Council Resolution1546—has a small presence in Iraq; it has assisted in holdingelections, drafting the constitution, organizing the government,and building institutions. The World Bank, which has commit-ted a limited number of resources, has one and sometimes twostaff in Iraq. The European Union has a representative there.Several U.S.-based and international nongovernmentalorganizations have done excellent work within Iraq, operatingunder great hardship. Both Iraqi and international nongovern-mental organizations play an important role in reaching acrosssectarian lines to enhance dialogue and understanding, andseveral U.S.-based organizations have employed substantial re-sources to help Iraqis develop their democracy. However, theparticipation of international nongovernmental organizations isconstrained by the lack of security, and their Iraqi counterpartsface a cumbersome and often politicized process of registrationwith the government.31

the iraq study group report

The United Kingdom has dedicated an extraordinaryamount of resources to Iraq and has made great sacrifices. Inaddition to 7,200 troops, the United Kingdom has a substantialdiplomatic presence, particularly in Basra and the Iraqi south-east. The United Kingdom has been an active and key player atevery stage of Iraq’s political development. U.K. officials toldus that they remain committed to working for stability in Iraq,and will reduce their commitment of troops and resources inresponse to the situation on the ground.5. ConclusionsThe United States has made a massive commitment to the fu-ture of Iraq in both blood and treasure. As of December 2006,nearly 2,900 Americans have lost their lives serving in Iraq. An-other 21,000 Americans have been wounded, many severely.To date, the United States has spent roughly $400 billionon the Iraq War, and costs are running about $8 billion permonth. In addition, the United States must expect significant“tail costs” to come. Caring for veterans and replacing lostequipment will run into the hundreds of billions of dollars. Es-timates run as high as $2 trillion for the final cost of the U.S. in-volvement in Iraq.Despite a massive effort, stability in Iraq remains elusiveand the situation is deteriorating. The Iraqi government cannotnow govern, sustain, and defend itself without the support ofthe United States. Iraqis have not been convinced that theymust take responsibility for their own future. Iraq’s neighborsand much of the international community have not been per-suaded to play an active and constructive role in supportingIraq. The ability of the United States to shape outcomes is di-minishing. Time is running out.32

B. Consequences of ContinuedDecline in Iraq

If the situation in Iraq continues to deteriorate, the conse-quences could be severe for Iraq, the United States, the region,and the world.Continuing violence could lead toward greater chaos, andinflict greater suffering upon the Iraqi people. A collapse ofIraq’s government and economy would further cripple a coun-try already unable to meet its people’s needs. Iraq’s securityforces could split along sectarian lines. A humanitarian catas-trophe could follow as more refugees are forced to relocateacross the country and the region. Ethnic cleansing could esca-late. The Iraqi people could be subjected to another strongmanwho flexes the political and military muscle required to imposeorder amid anarchy. Freedoms could be lost.Other countries in the region fear significant violencecrossing their borders. Chaos in Iraq could lead those countriesto intervene to protect their own interests, thereby perhapssparking a broader regional war. Turkey could send troops intonorthern Iraq to prevent Kurdistan from declaring independ-ence. Iran could send in troops to restore stability in south-ern Iraq and perhaps gain control of oil fields. The regional33

the iraq study group report

influence of Iran could rise at a time when that country is on apath to producing nuclear weapons.Ambassadors from neighboring countries told us thatthey fear the distinct possibility of Sunni-Shia clashes acrossthe Islamic world. Many expressed a fear of Shia insurrec-tions—perhaps fomented by Iran—in Sunni-ruled states. Sucha broader sectarian conflict could open a Pandora’s box of prob-lems—including the radicalization of populations, mass move-ments of populations, and regime changes—that might takedecades to play out. If the instability in Iraq spreads to theother Gulf States, a drop in oil production and exports couldlead to a sharp increase in the price of oil and thus could harmthe global economy.Terrorism could grow. As one Iraqi official told us, “AlQaeda is now a franchise in Iraq, like McDonald’s.” Leftunchecked, al Qaeda in Iraq could continue to incite violencebetween Sunnis and Shia. A chaotic Iraq could provide a stillstronger base of operations for terrorists who seek to act re-gionally or even globally. Al Qaeda will portray any failure bythe United States in Iraq as a significant victory that will be fea-tured prominently as they recruit for their cause in the regionand around the world. Ayman al-Zawahiri, deputy to Osamabin Laden, has declared Iraq a focus for al Qaeda: they willseek to expel the Americans and then spread “the jihad wave tothe secular countries neighboring Iraq.” A senior European of-ficial told us that failure in Iraq could incite terrorist attackswithin his country.The global standing of the United States could suffer ifIraq descends further into chaos. Iraq is a major test of, andstrain on, U.S. military, diplomatic, and financial capacities.Perceived failure there could diminish America’s credibilityand influence in a region that is the center of the Islamic world34

Assessment

and vital to the world’s energy supply. This loss would reduceAmerica’s global influence at a time when pressing issues inNorth Korea, Iran, and elsewhere demand our full attentionand strong U.S. leadership of international alliances. And thelonger that U.S. political and military resources are tied downin Iraq, the more the chances for American failure inAfghanistan increase.Continued problems in Iraq could lead to greater polar-ization within the United States. Sixty-six percent of Americansdisapprove of the government’s handling of the war, and morethan 60 percent feel that there is no clear plan for moving for-ward. The November elections were largely viewed as a refer-endum on the progress in Iraq. Arguments about continuing toprovide security and assistance to Iraq will fall on deaf ears ifAmericans become disillusioned with the government that theUnited States invested so much to create. U.S. foreign policycannot be successfully sustained without the broad support ofthe American people.Continued problems in Iraq could also lead to greaterIraqi opposition to the United States. Recent polling indicatesthat only 36 percent of Iraqis feel their country is heading inthe right direction, and 79 percent of Iraqis have a “mostly neg-ative” view of the influence that the United States has in theircountry. Sixty-one percent of Iraqis approve of attacks on U.S.-led forces. If Iraqis continue to perceive Americans as repre-senting an occupying force, the United States could become itsown worst enemy in a land it liberated from tyranny.These and other predictions of dire consequences in Iraqand the region are by no means a certainty. Iraq has taken sev-eral positive steps since Saddam Hussein was overthrown:Iraqis restored full sovereignty, conducted open national elec-tions, drafted a permanent constitution, ratified that constitu-35

the iraq study group report

tion, and elected a new government pursuant to that constitu-tion. Iraqis may become so sobered by the prospect of an un-folding civil war and intervention by their regional neighborsthat they take the steps necessary to avert catastrophe. But atthe moment, such a scenario seems implausible because theIraqi people and their leaders have been slow to demonstratethe capacity or will to act.

36

C. Some Alternative Courses in Iraq

Because of the gravity of the situation in Iraq and of its conse-quences for Iraq, the United States, the region, and the world,the Iraq Study Group has carefully considered the full range ofalternative approaches for moving forward. We recognize thatthere is no perfect solution and that all that have been sug-gested have flaws. The following are some of the more notablepossibilities that we have considered.1. Precipitate WithdrawalBecause of the importance of Iraq, the potential for catastro-phe, and the role and commitments of the United States in ini-tiating events that have led to the current situation, we believeit would be wrong for the United States to abandon the countrythrough a precipitate withdrawal of troops and support. A pre-mature American departure from Iraq would almost certainlyproduce greater sectarian violence and further deterioration ofconditions, leading to a number of the adverse consequencesoutlined above. The near-term results would be a significantpower vacuum, greater human suffering, regional destabilization,37

the iraq study group report

and a threat to the global economy. Al Qaeda would depict ourwithdrawal as a historic victory. If we leave and Iraq descendsinto chaos, the long-range consequences could eventually re-quire the United States to return.2. Staying the CourseCurrent U.S. policy is not working, as the level of violence inIraq is rising and the government is not advancing national rec-onciliation. Making no changes in policy would simply delaythe day of reckoning at a high cost. Nearly 100 Americans aredying every month. The United States is spending $2 billion aweek. Our ability to respond to other international crises isconstrained. A majority of the American people are soured onthe war. This level of expense is not sustainable over an ex-tended period, especially when progress is not being made.The longer the United States remains in Iraq without progress,the more resentment will grow among Iraqis who believe theyare subjects of a repressive American occupation. As one U.S.official said to us, “Our leaving would make it worse. . . . Thecurrent approach without modification will not make it better.”3. More Troops for IraqSustained increases in U.S. troop levels would not solve thefundamental cause of violence in Iraq, which is the absence ofnational reconciliation. A senior American general told us thatadding U.S. troops might temporarily help limit violence in ahighly localized area. However, past experience indicates thatthe violence would simply rekindle as soon as U.S. forces aremoved to another area. As another American general told us, ifthe Iraqi government does not make political progress, “all the38

Assessment

troops in the world will not provide security.” Meanwhile,America’s military capacity is stretched thin: we do not have thetroops or equipment to make a substantial, sustained increasein our troop presence. Increased deployments to Iraq would alsonecessarily hamper our ability to provide adequate resourcesfor our efforts in Afghanistan or respond to crises around theworld.4. Devolution to Three RegionsThe costs associated with devolving Iraq into three semiau-tonomous regions with loose central control would be too high.Because Iraq’s population is not neatly separated, regionalboundaries cannot be easily drawn. All eighteen Iraqi provinceshave mixed populations, as do Baghdad and most other majorcities in Iraq. A rapid devolution could result in mass populationmovements, collapse of the Iraqi security forces, strengtheningof militias, ethnic cleansing, destabilization of neighboringstates, or attempts by neighboring states to dominate Iraqi re-gions. Iraqis, particularly Sunni Arabs, told us that such a divi-sion would confirm wider fears across the Arab world that theUnited States invaded Iraq to weaken a strong Arab state.While such devolution is a possible consequence of con-tinued instability in Iraq, we do not believe the United Statesshould support this course as a policy goal or impose this out-come on the Iraqi state. If events were to move irreversibly inthis direction, the United States should manage the situation toameliorate humanitarian consequences, contain the spread ofviolence, and minimize regional instability. The United Statesshould support as much as possible central control by govern-mental authorities in Baghdad, particularly on the question ofoil revenues.39

D. Achieving Our Goals

We agree with the goal of U.S. policy in Iraq, as stated by thePresident: an Iraq that can “govern itself, sustain itself, and de-fend itself.” In our view, this definition entails an Iraq with abroadly representative government that maintains its territorialintegrity, is at peace with its neighbors, denies terrorism a sanc-tuary, and doesn’t brutalize its own people. Given the currentsituation in Iraq, achieving this goal will require much time andwill depend primarily on the actions of the Iraqi people.In our judgment, there is a new way forward for theUnited States to support this objective, and it will offer peopleof Iraq a reasonable opportunity to lead a better life than theydid under Saddam Hussein. Our recommended course hasshortcomings, as does each of the policy alternatives we havereviewed. We firmly believe, however, that it includes the beststrategies and tactics available to us to positively influence theoutcome in Iraq and the region. We believe that it could enablea responsible transition that will give the Iraqi people a chanceto pursue a better future, as well as serving America’s interestsand values in the years ahead.40

II