Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2006-07

Bilag 18

Offentligt

Failure to ProtectA Call for the UN Security Council to Act in North Korea

Failure to ProtectA Call for the UN Security Councilto Act in North KoreaThe Honorable Václav Havel,Former President of the Czech RepublicThe Honorable Kjell Magne Bondevik,Former Prime Minister of NorwayProfessor Elie Wiesel, Boston University,Nobel Peace Prize Laureate (1986)

U.S. Committee forHuman Rights in North Korea

Cover PhotoCaption:An unidentified 71-year-old woman carries last year’s driedcabbage leaves in Anju, North Korea, April 5, 1997Photo:Associated Press. Licensed for use.

Failure to Protect:A Call for the UN Security Council toAct in North KoreaReport Commissioned By:The Honorable Václav Havel, Former President of the Czech RepublicThe Honorable Kjell Magne Bondevik, Former Prime Minister of NorwayProfessor Elie Wiesel, Boston UniversityNobel Peace Prize Laureate (1986)

Prepared By:

U.S. Committee forHuman Rights in North Korea

October 30, 2006Copyright � 2006 DLA Piper US LLP and U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea.All rights reserved.

ForewordAlthough in recent weeks the international focus has been on North Korea’snuclear weapons test, the situation in that country is also one of the mostegregious human rights and humanitarian disasters in the world today. Yetsadly, because North Korea is also one of the most closed societies on Earth,information about the situation there has only trickled out over time.With the unanimous adoption by the UN Security Council of the doctrinethat each state has a “responsibility to protect” its own citizens from the mostegregious of human rights abuses, a new instrument for international diplomacyhas emerged. While states retain sovereignty to control their own territory, ifthey fail to protect their own citizens from severe human rights abuses, theinternational community now has an obligation to intervene through regionalbodies and the United Nations, up to and including the Security Council.In this context, we commissioned the global law firm DLA Piper LLP towork with the U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea in preparingan objective and definitive report on the failure of the North Koreangovernment to exercise its responsibility to protect its own people.The evidence and analysis contained in this report is deeply disturbing.Indeed, it is clear that Kim Jong Il and the North Korean government areactively committing crimes against humanity. North Korea allowed as manyas one million, and possibly many more, of its own people to die during thefamine in the 1990s. Hunger and starvation remain a persistent problem,with over 37 percent of children in North Korea chronically malnourished.Furthermore, North Korea imprisons upwards of 200,000 people in itsmodern-day gulag, and it is estimated more than 400,000 have died in thatsystem over 30 years.It is on this basis that we strongly urge the UN Security Council to takeup the situation of North Korea. Protecting the people of North Korearequires nothing less.

Václav HavelFormer President of the Czech Republic

Kjell Magne BondevikFormer Prime Minister of Norway

Professor Elie Wiesel, Boston UniversityNobel Peace Prize Laureate (1986)

Table of ContentsApproachMap of North KoreaTable of AcronymsExecutive Summary ........................................................................................iI. Background on the Situation in North Korea ..............................................1A. Historical Context of International Concern over theKorean Peninsula ......................................................................................1B. Economic Development............................................................................6C. Economic and Social Indicators ................................................................9II. The Crisis ................................................................................................10A. Major Human Rights Concerns ..............................................................101. Food Policy and Famine ........................................................................122. Treatment of Political Prisoners ..............................................................303. Abduction of Foreigners ........................................................................42B. Transnational Effects of the Crisis in North Korea ..................................481. Weapons of Mass Destruction................................................................482. Refugee Outflows ..................................................................................583. Drug Trafficking ....................................................................................624. Money Counterfeiting and Laundering..................................................65C. The International Response ....................................................................681. The Six-Party Talks ................................................................................682. The United Nations ..............................................................................703. South Korea: Development of the Sunshine Policy ................................764. United States of America........................................................................80III. North Korea and the UN Security Council ............................................83A. Violation of the Responsibility to Protect................................................83B. “Non-Traditional” Threat to the Peace ....................................................94Recommendations ......................................................................................100Appendix I: Background, Duties, and Operations of UNSecurity Council......................................................................101Appendix II: The New “Responsibility to Protect” Doctrine underInternational Law ..................................................................109Appendix III: Crimes Against Humanity ....................................................119Appendix IV: Lessons from Past Security Council Interventions ................134

ApproachThe intent of this report is to apply a new doctrine of international law –the responsibility of all states to protect their own citizens from the mostegregious of human rights abuses – to the situation in North Korea. Based ona comprehensive review of published information and first-hand interviews, thisreport concludes that North Korea has violated its responsibility to protect itsown citizens from crimes against humanity being committed in the country,that North Korea has refused to accept prior recommendations from UNbodies to remedy the situation, and, therefore, UN Security Council action iswarranted.In addition, the report explains that North Korea also qualifies as a non-traditional threat to the peace. This designation could provide a completelyindependent justification for Security Council action because of the transnationalimpact of the internal problems in the country.This report also describes North Korea’s involvement in the production ofnuclear, chemical, and biological weapons and related delivery systems.Nevertheless, this information is provided only to present a complete pictureof the situation and to explain how North Korea allocates its resources, not asa justification for further Security Council action. Between the Six-PartyTalks and prior Security Council action on North Korea’s missile launches andnuclear weapon test, substantial work is already being done to address thesecurity threat.President Havel, Prime Minister Bondevik, and Professor Wieselcommissioned this report because they believe that, for far too long, thesecurity threat posed by North Korea has relegated the human rights concernsin the country to a second-class status. North Korea’s nuclear weapons test,conducted on October 9, 2006, demonstrated the fallacy of the argument thatnot antagonizing its government on human rights concerns would promotesuccessful engagement on security issues. Our clients believe, in the wake ofthat test, the human rights and humanitarian crisis in North Korea deserves tobe treated on a parallel track with the security threat and should no longer besuppressed from international discussions.It is worth noting that North Korean authorities regularly deny thehuman rights and humanitarian violations described in this report. Suchgovernmental denials cannot be taken at face value. The only real way forNorth Korea to contradict or invalidate the claims and stories described inthis report and in the cited documents is by inviting United Nationsofficials, Human Rights Council representatives, or reputable NGOs toverify or invalidate on site the information that has been presented.Lastly, North Korea’s isolation from the outside world makes it difficultto gather verifiable information about the country. Therefore, all statisticscited in this report are best estimates, subject to that important caveat.DLA Piper LLPU.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

Map of Nor th Korea

Source:Adapted from Princeton University GIS open source map.

Table of AcronymsBWBTWCCCL 10CEDAWCRCCWDMZDPRKEUFAOGDIGDPHEUIAEAICCICCPRICESCRICISSICTRICTYKEDOKPAMNDMTNGONPTPDSPOWUNHCRUNDPUNICEFUSSRWFPWMDBiological WeaponsBiological and Toxic Weapons ConventionAllied Council Control Law No. 10Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of DiscriminationAgainst WomenConvention on the Rights of the ChildChemical WeaponsDemilitarized ZoneDemocratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea)European UnionFood and Agriculture OrganizationGross Domestic IncomeGross Domestic ProductHighly Enriched UraniumInternational Atomic Energy AgencyInternational Criminal CourtInternational Covenant on Civil and Political RightsInternational Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural RightsInternational Commission on Intervention and State SovereigntyInternational Criminal Tribunal for RwandaInternational Criminal Tribunal for the Former YugoslaviaKorean Peninsula Energy Development OrganizationKorean People’s Army (North Korea)Ministry of National Defense (South Korea)Metric TonsNongovernmental OrganizationTreaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear WeaponsPublic Distribution SystemPrisoner of WarUN High Commissioner for RefugeesUN Development ProgramUN Children’s FundUnion of Soviet Socialist Republics (or Soviet Union)World Food ProgrammeWeapons of Mass Destruction

Executive SummaryThe Situation in North Korea•The human rights and humanitarian situation in the Democratic People’sRepublic of Korea (North Korea) continues to deteriorate, with no degreeof measurable improvement. Members of the international community,including governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), andmany United Nations (UN) bodies have reported grave violations ofhuman rights and humanitarian law. Because the North Korean governmentrefuses to implement recommendations made by the UN – includingthose made by the General Assembly, the former Commission on HumanRights, and the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in North Korea –the people of North Korea continue to suffer. Therefore, UN SecurityCouncil action is both warranted and necessary.

Powers of the UN Security Council•Charged with the critical mission of maintaining peace and security betweennations, the UN Security Council possesses unparalleled authority to makebinding decisions that uphold the United Nations’ commitment to preventwar, preserve human rights, and promote international political stability.According to Chapter VI, Article 34, of the UN Charter, the SecurityCouncil may “investigate . . . any situation which might lead to internationalfriction . . . to determine whether the continuance of the . . . situation islikely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security.”Under Chapter VII, Article 39, the Security Council “shall determine theexistence of any threat to the peace . . . and shall make recommendations,or decide what measures shall be taken . . . .”Security Council action can include the adoption of resolutions requiringaction on the part of the offending government to curtail its offendingacts. Under Article 25 of the UN Charter, all members of the UN “agreeto accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council.”Here, two independent justifications enable the Security Council to actwith regard to the situation in the country: (1) the North Korean governmenthas failed in its responsibility to protect its own people from crimesagainst humanity; and (2) the situation in North Korea constitutes a non-traditional threat to the peace.

•

•

•

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

i

Failure of the Responsibility to Protect•The North Korean government is manifestly failing to protect its owncitizens from crimes against humanity, with the government activelycommitting those crimes against its own people and others. Since priorUN actions have failed to motivate North Korea to address these seriousconcerns, it is time for the UN Security Council to take up the situationof North Korea.

Background•On September 20, 2005, during the World Summit, the assembled leadersin the UN General Assembly adopted a statement in which they said: “weare prepared to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner,through the Security Council . . . [if ] national authorities are manifestlyfailing to protect their populations from . . . crimes against humanity.”Subsequently, this statement was unanimously endorsed in Resolution1674 by the Security Council on April 28, 2006.For acts that would ordinarily constitute domestic criminal offenses to beelevated to the level of international “crimes against humanity,” a state andthe perpetrators acting on its behalf must be knowingly involved in aseries of widespread and systematic attacks directed against a civilianpopulation, such as murder, extermination, torture, imprisonment, or otheracts intentionally causing great suffering or serious bodily or mental harm.

••

Application•The North Korean government is actively involved in committing crimesagainst humanity with respect to both: (1) its food policy leading tofamine and (2) its treatment of political prisoners.Food Policy and Famine:North Korea allowed as many as one million,and possibly many more, of its own people to die during its famine inthe 1990s. Hunger and starvation remain a persistent problem in thecountry. Over 37 percent of children in North Korea are chronicallymalnourished. Even today, North Korea denies the World FoodProgramme access to 42 of 203 counties in the country.Treatment of Political Prisoners:North Korea imprisons upwards of200,000 people in its modern-day gulag without due process of lawand in near-starvation conditions. More than 400,000 are estimatedto have died in that system over 30 years.iiFAILURE TO PROTECT

Non-Traditional Threat to the Peace•In addition to North Korea’s violation of the responsibility to protect itsown citizens, North Korea is also a non-traditional threat to the peace.“Traditional” threats to the peace are typically caused by military action;so-called “non-traditional” threats to the peace occur when a country’sactions or failure to act result in serious cross-border impacts. Examplesof non-traditional threats can include drug trafficking, failing to preventthe spread of communicable diseases, serious human rights abuses leadingto mass refugee outflows, and environmental degradation.

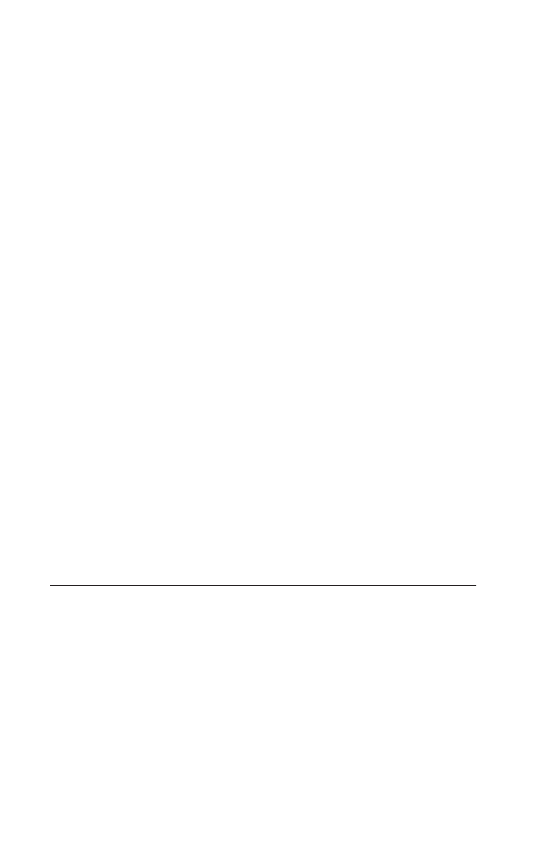

Background•Although there is no precise definition of what represents a non-traditional“threat to the peace,” the Security Council – through its past actions inevaluating other cases – has elucidated a list of factors that collectively canconstitute such a threat to the peace. Because the Security Council takes acase-by-case approach, no one factor or set of factors is dispositive. Eachpast case embodied a unique set of circumstances; in each case, theSecurity Council considered the totality of circumstances in determiningthat a threat to the peace was taking place.To guide our work, we first reviewed the initial Security Council resolutionsadopted in response to internal country situations that the Security Councildeemed a threat to the peace previously. This review enabled us to identifythe criteria that helped the Council make its decisions. These criteria areused in this report as the determining factors relevant to North Korea.These factors include: (1) widespread internal humanitarian/human rightsviolations; (2) the substantial outflow of refugees; (3) other cross-borderproblems (for instance, drug trafficking); (4) conflict among governmentalbodies and insurgent armies or armed ethnic groups; and (5) the overthrowof a democratically elected government.

•

ApplicationHuman./Human RightsViolationsNorth KoreaRefugeeOutflowsOther (DrugTrafficking,Counterfeiting)ConflictamongFactionsOverthrow ofDemocraticGovernment

�

�

�

-

-

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

iii

•

In the case of North Korea, three of these five determining factors havebeen met. Satisfying three of five factors was sufficient to justify SecurityCouncil involvement in five of the seven case studies we examined,including the situations in Haiti, Yemen, Rwanda, Liberia, and Cambodia.The factors specifically present in North Korea are as follows:WidespreadInternal Humanitarian/Human Rights Violations:Asdescribed above, there are two sets of activities in which the NorthKorean government is engaging that constitute crimes against humanityand meet this factor: its food policy leading to famine, and its treatmentof political prisoners.Outflow of Refugees:It is estimated that some 100,000 to 400,000North Koreans have fled the country in recent years.Other Cross-Border Problems:–Drug Production and Trafficking:It is believed that the NorthKorean government earns $500 million to $1 billion per year fromillicit drug production and trafficking. It is estimated that NorthKorea harvests 30 to 44 tons of opium and manufactures 10 to 15tons of methamphetamines per year.–Money Counterfeiting and Laundering:The North Koreangovernment produces and launders high-quality counterfeit US$100 bills or “supernotes.” It is estimated that North Korea producesbetween $3 million and $25 million in supernotes per year.

Conclusion•As a result of the severity of the overall situation in North Korea and inconsideration of all of the information analyzed in detail in this report, theSecurity Council has independent justification for intervening in NorthKorea either because of the government’s failure in its responsibility toprotect or because North Korea is a non-traditional threat to the peace.Security Council intervention is a necessary international and multilateralvehicle to alleviate the suffering of the North Korean people.

iv

FAILURE TO PROTECT

RecommendationsInitially, the UN Security Council should adopt a non-punitive resolution onthe situation in North Korea in accordance with its authority under ChapterVI of the UN Charter and past Security Council precedents.The resolution should:•Outline the major reasons for the Security Council intervention, focusingon the North Korean government’s failure to protect its own people andthe threat to international peace and security caused by the major issuesdescribed in this report;Urge the North Korean government to ensure the immediate, safe, andunhindered access to all parts of the country for the United Nations andinternational organizations to provide humanitarian assistance to the mostvulnerable groups of the population;Call on the North Korean government to release all political prisonersdetained in violation of their rights under the International Covenant onCivil and Political Rights, to which North Korea is a state party;Insist the North Korean government allow the UN Special Rapporteur onHuman Rights in North Korea to visit the country; andRequest the Secretary-General to remain vigorously engaged in thesituation in North Korea and that he report back to the Security Councilon a regular basis.

•

•

••

Should North Korea fail to comply with a Chapter VI resolution, the SecurityCouncil should consider adopting a binding resolution under Chapter VII.

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

v

I. Background on the Situation in North KoreaA. Historical Context of International Concern over the KoreanPeninsulaThe Korean peninsula has long been a focus of other nations’ concern. Atthe crossroads between China, Japan, and Russia, Korea has been the subject ofrepeated invasions and occupations, and lingering tensions. Today, it continuesto require international attention. The following history is presented here toexplain some of the historical cross-currents that have troubled the Koreanpeninsula, and as a summary of how the international community has oftenbeen called upon to intervene to restore peace and stability there.For centuries, Korea was China’s most important tributary state1benefitingfrom Chinese protection but struggling to maintain its independent identity.Japan and China signed the Li-Ito Convention in 18852after China assistedKorea’s king in suppressing a pro-Japanese coup. This tenuous peace brokedown when the Korean government invited Chinese forces into the country toassist in a peasant uprising. Japan viewed China’s intervention as a breach ofthe Convention and sent its own troops to Korea, and war broke out betweenthe two powers in August 1894.3Japan emerged victorious. As a result,China was forced to formally acknowledge Korea’s independence and renounceall claims to its territory in the Treaty of Shimonoseki signed by Japan andChina on April 17, 1895.4In the early 1900s, Russia moved forces into Korea and Manchuria, leadingto war between Russia and Japan.5Japan was again victorious.6The UnitedStates was eager to see peace restored and mediated the Treaty of Portsmouth,

SeeLEEKI-BAIK, A NEWHISTORY OFKOREA20, 73, and 189 (Translated by Edward W. Wagnerwith Edward J. Shultz, Harvard University Press, 1976);see also Sino-Japanese War,ENCYCLOPEDIABRITANNICA(2006)available athttp://search.eb.com/eb/article-9067946 [hereinafterSino-Japanese War].2This treaty was also known as the Convention of Tientsin.SeeLEE,supranote 1, at 279;see alsoSino-Japanese War, supranote 1 (explaining that under the Li-Ito Convention both Japan andChina agreed to troop withdrawals from Korea).3See Sino-Japanese War, supranote 1; LEE,supranote 1, at 287.4See id.at 289;see also History of Korea,ENCYCLOPEDIABRITANNICA(2006),available athttp://search.eb.com/eb/article-9108454 [hereinafterHistory of Korea].5SeeLEE,supranote 1, at 306; DONOBERDORFER, TWOKOREAS4-5 (Basic Books 2001); LEE,supranote 1, at 306;Russo-Japanese War,ENCYCLOPEDIABRITANNICA(2006),available athttp://search.eb.com/eb/article-9064492 [hereinafterRusso-Japanese War].6SeeOBERDORFER,supranote 5, at 5;History of Korea, supranote 4.1

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

1

signed in 1905, recognizing Japan’s exclusive role in defense of the peninsula.7The Korean king was subsequently forced to sign a treaty establishing Korea asa Japanese protectorate.8Five years later, in 1910, Japan formally annexed Korea as part of itsexpanding empire.9With international acquiescence, Japan ruled Korea undera governor-generalship administered by military officials.10Despite someorganized Korean resistance, Japan’s dominance of Korea remained unchallengedby foreign powers until the end of World War II.11By the time Japan surrendered to the Allies, the Allies had considered waysto promote a gradual path to Korean independence. In 1943, the UnitedKingdom, China, and the United States issued the Cairo Declaration thatpromised independence for Korea “in due course”12; they expected Korea to bea trusteeship under United Nations supervision. These Allied expectationsgained further expression in the Potsdam Declaration of 1945.13Japan offered to surrender Korea on August 10, 1945. By that date,120,000 Soviet troops had already occupied North Korea14, including some30,000 Russian-trained troops of Korean ethnic extraction. The Russian-trained forces included an individual who called himself Kim Il Sung, whowas eventually to become the dictator of the Communist regime in theNorth.15The terms of the Japanese surrender provided that Japan would yieldthe Korean territory north of the 38th parallel to the Soviet Union andeverything south of the 38th parallel to the United States.16

SeeLEE,supranote 1, at 309; OBERDORFER,supranote 5, at 5;History of Korea, supranote 4.SeeLEE,supranote 1, at 309;History of Korea, supranote 4.9SeeLEE,supranote 1, at 313;Background Note: North Korea(U.S. Department of State, Nov.2005,available athttp://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2792.htm [hereinafterBackground Note].10SeeLEE,supranote 1, at 314;History of Korea, supranote 4.11See Background Note, supranote 9.12Id.; see alsoCHUCKDOWNS, OVER THELINE: NORTHKOREA’SNEGOTIATING STRATEGY15 (AEIPress, 1999).13See id.; see alsoBRADLEYK. MARTIN, UNDER THELOVINGCARE OF THEFATHERLYLEADER:NORTHKOREA AND THEKIMDYNASTY259 (Thomas Dunne Books, 2006) (explaining thecircumstances leading to division of the peninsula at the 38th parallel); OBERDORFER,supranote5, at 6 (same).14T.R. FEHRENBACH, THEFIGHT FORKOREA: FROM THEWAR OF1950TO THEPUEBLOINCIDENT38 (Grosset & Dunlap, 1969).15KIMJOUNGWON, DIVIDEDKOREA: THEPOLITICS OFDEVELOPMENT, 1945-1972 86 (HarvardUniversity Press, 1975);see alsoWILLIAMH. VATCHER, PANMUNJOM: THE STORY OF THEKOREANMILITARYARMISTICENEGOTIATIONS146 n. 16 (Frederick A. Praeger, 1958) (asserting that Kim IlSung was among those sent by the Russians).16SeeMARTIN,supranote 13, at 50.8

7

2

FAILURE TO PROTECT

Early attempts at unification failed. The US-USSR Commission, establishedby the Moscow Conference in 1945, ended in disagreement over how toaccommodate Korean views in the process.17At the request of the UnitedStates, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution providing for peninsula-wide elections in Korea overseen by a UN Temporary Commission on Korea.18The goal was to elect a National Assembly that would establish a nationalgovernment and arrange for both US and Soviet troops to leave the peninsula.19Elections were held in the South under UN supervision, but the USSRblocked the UN Commission from entering the North.20As a result, aconstitution was adopted and a president elected by popular vote, but only inthe South.21General Assembly Resolution 293 of October 21, 1949, declaredthat the “Government of the Republic of Korea is a lawfully establishedgovernment . . . the only such Government in Korea” and that the elections ofMay 10, 1948, were “a valid expression of the free will of the electorate.”22In the North, the Communist Party adopted a constitution and elected a“Supreme People’s Assembly.”23The Assembly ratified the constitution inSeptember 1948 and named Kim Il Sung premier.24He officially establishedthe Democratic People’s Republic of Korea on September 9, 1948, and it wasrecognized by the USSR as the only lawful government in Korea.25In an effort to unify the peninsula under Communist control, Kim Il Sunglaunched an invasion of the South on June 25, 1950, with the approval of theSoviet Union and the People’s Republic of China.26When word of theCommunist invasion reached the United Nations, the Security Council swiftlypassed a resolution condemning the invasion, calling for the immediate end offighting and demanding that “the authorities in North Korea” withdraw northof the 38th parallel “forthwith.” Passed when the Soviet Union was boycottingUN participation, this resolution called upon all UN members to refrain fromassisting North Korea.27A second Security Council resolution on June 27, 1950,

See id.;ROBERTA. SCALAPINO& CHONG-SIKLEE, COMMUNISM INKOREA365-367 (Universityof California Press, 1972) (describing the inability of the Soviets and Americans to reach anagreement on how to proceed with Korean unification).18See id.19See id.20See id.21See id..22UN SECURITYCOUNCIL, RESOLUTIONS ANDDECISIONS OF THESECURITYCOUNCIL1950 4(United Nations, 1965) (referring to UN General Assembly action);see also A White Paper onSouth-North Dialogue in Korea(National Unification Board of the Republic of Korea, 1988),at 16-17.23See id.24Id.25See id.26SeeMARTIN,supranote 13, at 63-64, 66-67.27S.C. RES. 82, UN Doc. S/RES/82 (Jun. 25, 1950),supranote 22, at 4-5.17

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

3

called for UN members “to provide such assistance to the Republic of Korea asmay be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peaceand security in the area.”28Backed by these two UN resolutions, US PresidentHarry Truman committed American forces to turn back the North’s aggression.By mid-September 1950, 16 nations contributed ground forces to the UNCommand.29UN troops recaptured Seoul on September 2830and, by October 1,had pushed northern troops back to the 38th parallel and beyond, reachingPyongyang on October 20 and the Chinese border on October 26.31Fightingcontinued as the People’s Republic of China entered the war, but, on June 1,1951, UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie announced that the objectives of theJune 25 and June 27, 1950, United Nations resolutions had been carried out.32While armistice negotiations began in July 1951, fighting continued formore than two years.33At long last, an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953,establishing a military boundary, roughly at the 38th parallel, that wouldbecome thede factoborder between North and South Korea.34In the end, thewar that lasted a little over three years had resulted in approximately fourmillion casualties.35After the Korean War, Kim Il Sung eliminated domestic opposition and allthose believed to pose a threat to his power in the North.36He became theabsolute ruler of North Korea “and set about transforming North Korea intoan austere, militaristic, and highly regimented society.”37Dissent from orcriticism of Kim Il Sung became a punishable crime.38Reports noted that“citizens were arrested, and some even sent off to one of the country’s extensivegulags, for inadvertently defacing or sitting on a newspaper photograph of theGreat Leader or his son and chosen successor.”39

S.C. RES. 83, UN Doc. S/RES/83 (Jun. 27, 1950),supranote 22, at 4-5.The sixteen allied nations to contribute troops to the UN Command were: Australia, Belgium,Canada, Colombia, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, Republic ofKorea, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, the United States, and the United Kingdom.30SeeMARTIN,supranote 13, at 79.31See History of Korea, supranote 4.32SeeVATCHER,supranote 15, at 18; FEHRENBACH,supranote 14, at 94.33See id.34See History of Korea, supranote 4; MARTIN,supranote 13, at 87;Background Note, supranote 9(noting that signatories to the armistice included the North Korean People’s Army, the ChinesePeople’s Volunteers, and the UN Command).35See History of Korea, supranote 4; LEE,supranote 1, at 379-81.36See History of Korea, supranote 4; MARTIN,supranote 13, at 94; OBERDORFER,supranote 5, at10-11; SCALAPINO& LEE,supranote 17, at 463.37History of Korea, supranote 4.38SeeOBERDORFER,supranote 5, at 21.39OBERDORFER,supranote 5, at 21;see infrasection II.A.2.2829

4

FAILURE TO PROTECT

Kim Il Sung relied on the Soviet Union and China for financial andmilitary support.40Especially when the schism developed between the SovietUnion and China in the 1960s, North Korea had to walk a fine line, keepingon good terms with both countries by avoiding complete dependence oneither one.41In order to do so, Kim Il Sung promulgated an ideology hecalledjuche,an independent form of Korean Socialist thought that emphasizeda supreme leader’s absolute control over his people.42In the late 1980s and early 1990s, North Korea experienced a precipitousdecline in aid as Communism fell in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Unionwas dissolved.43Relations with China were strained by China’s establishmentof diplomatic ties with South Korea in 199244and China’s efforts to put tradewith North Korea on a cash basis. Aside from economic and diplomaticimpacts, the fall of the socialist bloc and strained relations with Chinaprompted North Korea to abandon its campaign for a single Korean seat atthe UN and, in September 1991, North and South Korea were both admittedto the UN as separate nations.45North Korea’s original constitution, which was adopted in 1948, wasreplaced with a new constitution in 1972, establishing Kim Il Sung as president.Revised in 1992 and 1998, the current constitution asserts that the position ofpresident is permanently vested in the deceased Kim Il Sung. Although thehead of state is ostensibly the president of the Presidium of the SupremePeople’s Assembly, North Korea’s absolute dictator Kim Jong Il rules from thepost of chairman of the National Defense Commission.46Kim Jong Il, the oldest recognized son of Kim Il Sung, was born onFebruary 16, 1942, most likely in the Soviet Union, although the regimeclaims he was born on Mt. Paektu, a place revered by Koreans as the legendarysource of the Korean identity.47During the Korean War, Kim Jong Il lived inexile in China, although he did not interact with Chinese people or learn theirlanguage.48After returning to North Korea, where he received his formaleducation, including graduating from Kim Il Sung University, he was assigned

SeeOBERDORFER,supranote 5, at 153;Background Note, supranote 10.See id.; see alsoSCALAPINO& LEE,supranote 17, at 576-587 (describing the development oftensions within the communist world).42SeeDOWNS,supranote 12, at 13; NICHOLASEBERSTADT, KOREAAPPROACHESREUNIFICATION132 (Armonk, National Bureau of Asian Research, 1995); KONGDANOH& RALPHC. HASSIG,NORTHKOREATHROUGH THELOOKINGGLASS16-24 (Brookings Institution Press, 2000).43See Background Note, supranote 9;North Korea,ENCYCLOPEDIABRITANNICA(2006),available athttp://search.eb.com/eb/article-34951 [hereinafterNorth Korea].44See Background Note, supranote 9;North Korea, supranote 43.45See Background Note, supranote 9.46SeeSCALAPINO& LEE,supranote 17, at 790, MARTIN,supranote 13, at 155.47SeeMARTIN,supranote 13, at 187.48See id.at 216.4041

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

5

to work in the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party, “the regime’s nervecenter.”49Due to apparent clashes with his uncle, a contender for leadershipof the regime, it is believed that Kim was sent to work for the party chapter inNorth Hamgyong Province.50He is also believed to have kept informationregarding food shortages at that time from coming to his father’s attention.51His succession was largely assured, however, when he returned to work at theCentral Committee and, in 1973, was elected to the politburo and namedParty Secretary for Organization and Guidance.52In spite of Marxist ideals tothe contrary, Kim Il Sung chose his son as his successor.53In the mid-1980s,Kim Jong Il took “day-to-day charge of the party, the military, theadministration – even international affairs.”54In 1993, fearful that he mightexperience the fate of his family friend Nicolae Ceausescu, Kim Jong Il utilized,his newly granted position as chairman of the party’s military commission totransform North Korea from a party dictatorship to a military dictatorship.55International concerns raised by the decisions and policies of Kim Jong Ilare discussed in depth in other sections of this report.

B. Economic DevelopmentNorth Korea has sufficient resources to be a functioning, growing economythat can employ its people and generate significant trade with other nations.However, by 1990 economic mismanagement, political and economic isolation,and over-militarization had left the country in economic shambles.The northern half of the Korean peninsula is rich in mineral resources,including sizeable, valuable deposits of coal, copper, gold, iron ore, tungsten,and graphite.56Power can be produced both from the country’s coal reservesand from several major river systems that support hydropower. North Koreais said to have high rates of literacy but its readers are unable to obtain materialsnot produced by the regime itself; the people of North Korea are thereforeisolated from the outside world and likely ignorant of modern informationtechnologies.57

Id. at 236;OBERDORFER,supranote 5, at 347.SeeMARTIN,supranote 13, at 238-39.51See id.at 239.52See id.at 270.53See id.at 192.54Id.55See id.at 484-85;see alsoRYOHAGIWARA, KIMJONGIL’SHIDDENWAR: SOLVING THEMYSTERYOFKIMILSUNG’SDEATH AND THEMASSSTARVATIONS INNORTHKOREA7-20 (Saitama, Japan,2004).56SeeChin S. Kuo,The Mineral Industry of North Korea(U.S. Geological Survey-MineralsInformation, 1996).57SeeHELEN-LOUISEHUNTER, KIMIL-SONG’SNORTHKOREA207-220 (Praeger Publishers,1999); CIA WORLDFACTBOOK,North Korea(Central Intelligence Agency, 2006).4950

6

FAILURE TO PROTECT

Japanese colonial rule during the first half of the 20th century industrializedthe country. The Japanese concentrated industrial activity in the North, duein part to the proximity to mines, timber, and hydropower.58In addition tomining, industries included steel, chemical, fertilizer, and textile production.59Unfortunately, the Korean War destroyed many of the factories and infrastructureinherited from the Japanese colonial period. Following the war, North Korearebuilt its industries and infrastructure, largely with subsidies from the SovietUnion.60Today, economic development remains stunted by excess spendingon the military combined with the failure to invest in developing substantialdomestic industrial capacity.After the Korean War, the North Korean government imposed a Soviet-styled, centrally planned command economy.61Until recently, private tradehas been almost entirely prohibited. Following the Soviet model, economicdecisions have been implemented through a series of long-range multi-yearplans, in which planners decide what industries should be created, what thoseindustries produce and in what quantities.62Distribution of production,including agricultural production, was also centrally controlled. One historianhas said, “North Korea offers the best example in the post-colonial developingworld of conscious withdrawal from the capitalist world system in a seriousattempt to construct an independent, self-contained economy.”63The country became increasingly dependent on aid and subsidies from theSoviet Union and other socialist bloc countries, as well as illicit economicactivity, including drug production and trafficking and counterfeiting thatwere (and still are) used to generate hard currency.64In the late 1980s, facingits own currency difficulties, the Soviet Union began demanding payment forpast and current aid, which North Korea was unable to make. By 1987, aidfrom the Soviet Union had dropped significantly.65The 1990 collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc had a devastatingimpact on North Korea’s economy.66For example, it lost most of its importedcoal and refined petroleum.67Between 1990 and 1993, imports from Russiafell by 90 percent. North Korea was unable to respond – or in any event didSee id.See id.60See generallyBRUCECUMINGS, KOREA’SPLACE IN THESUN: A MODERNHISTORY430-35 (W.W.Norton & Co., 2005).61See id.at 430;see alsoJOSEPHSANGHOON, THENORTHKOREANECONOMY: STRUCTURE ANDDEVELOPMENT70 (Hoover Institution Press, 1974).62See id.63SeeCUMINGS,supranote 60, at 429.64See id.at 19.65See id.at 20.66MARCUSNOLAND, FAMINE ANDREFORM INNORTHKOREA4-5 (Institute for InternationalEconomics Working Paper, 2003).67See id.5859

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

7

not respond – and its own economy collapsed. Data suggests that the economymay have shrunk by 30 percent between 1991 and 1996.68Today, North Korean industry is operating at a fraction of capacity.69Unemployment outside the agricultural sector may be as high as 30 percent.70The country remains heavily dependent on foreign assistance, including foodaid, from South Korea and China.North Korea has experimented with modest reforms over the years, includingsome nascent special economic zones.71In July 2002, Kim Jong Il enacted aseries of potentially significant measures that included some price reforms.However, given the current political and security climate, the effect of all ofthese initiatives remains hard to assess, and it is probably too early to do so.72It is also uncertain whether these reforms are transient or whether they willform the initial stages of a longterm overhaul of the North Korean economyalong a “Chinese model” or some other pattern.73Indeed, in October 2005,the government rolled back some of these measures, reinstituting the rationingsystem and banning the private trade of grain.Apart from these measures, the country’s largely self-imposed isolation frommuch of the world likely hinders economic progress.74Its recent missile tests,in the face of threats of sanctions, further imperil its fragile recovery. Thecountry continues to export narcotics and counterfeit goods, includingcigarettes, pharmaceuticals, and US, Chinese, and European Union currency.75No discussion of the North Korean economy can be complete withouthighlighting the country’s oversized military. Notwithstanding the collapse ofthe economy and two decades of chronic food crises, Kim Jong Il has institutedtheSongun Chongch’ipolicy, which provides the military with a disproportionateshare of the country’s resources.76Official estimates state that approximately

SeeMarcus Noland, TESTIMONY BEFOREU.S. SENATEFOREIGNRELATIONSSUBCOMMITTEE ONEASTASIAN ANDPACIFICAFFAIRS, Jul. 8, 1997.69See Background Note: North Korea, supranote 10.70SeeSTEPHANHAGGARD& MARCUSNOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS: THEPOLITICS OFFAMINE INNORTHKOREA(U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2005), at 21[Hereinafter HAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS].71See generallyMARCUSNOLAND, A NEWINTERNATIONALENGAGEMENTFRAMEWORK FORNORTHKOREA?Political Economy of North Korea: Historic Background and Present Situation,(InternationalInstitute for Economics, 2005), at 20 [hereinafter NOLAND,Political Economy of North Korea];Young-Sun Lee & Deok Ryong Yoon,The Structure of North Korea’s Political Economy: Changesand Effects(Korean Institute for International Economic Policy, 2004), at 33-35.72SeeNOLAND,Political Economy of North Korea, supranote 71, at 36;See, e.g., Economic ReformsAre Changing Hardline North Korea Some Say,AGENCEFRANCEPRESSE, Sept. 10, 2006.73SeeLee & Yoon,supranote 71, at 38.74SeeNOLAND,Political Economy of North Korea, supranote 71, at 36.75See Background Note, supranote 9.76SeeLee & Yoon,supranote 71, at 27-29.68

8

FAILURE TO PROTECT

15 percent of GDP is devoted to the military, but many analysts believe thatthe actual amount is between 15 and 25 percent, with some estimates statingit is as high as 30 percent.77If the number is greater than 17.7 percent, itwould mean North Korea has the highest military expenditures as a percent ofGDP of any country in the world.78The military is, in fact, an entire second economy in North Korea, and isrun separately from the rest of the economy. The military is given priority formaterials and resources – including food – and the rest of the economyreceives the remainder.79It also operates its own defense manufacturing facilities,farms, mines, and banks. The military is estimated to employ over one millionsoldiers and other support personnel. In addition, the country maintains amassive reserve of 4.7 million people.80North Korea appears willing to maintainthe current size of its military and military expenditures, notwithstanding itsadverse effects on the rest of the civilian economy.81The military economyalso plays a role in generating exports and hard currency through its sizeableexport sales of weapons.82Arms exports are estimated at approximately $100million to $600 million annually.83

C. Economic and Social IndicatorsThe population of North Korea is estimated to be approximately 22.7million.84Conservative estimates of mortality rates during the famine suggestas many as one million and possibly many more people died, or 3 to 5 percentof the pre-famine population.85Because of the insular and isolated stance of the North Korean government,it is difficult to make reliable estimates of the usual socio-economicindicators.86For 2004, the Bank of Korea estimated North Korea’s grossdomestic income (GDI) at $20.8 billion, 1/33rd of South Korea’s, and its percapita GDI at $914, approximately 1/15th that of South Korea.87See id.at 27-28 and 27, n. 5.SeeWORLDFACTBOOK,supranote 57 (noting military expenditures as percent of GDP,e.g.,Eritrea – 17.7 percent; Jordan – 11.4 percent; Saudi Arabia – 10 percent; China – 4.3 percent;US – 4.06 percent; Iran – 3.3 percent; South Korea – 2.6 percent).79SeeLee & Yoon,supranote 71, at 29.80See id.81See id.at 27.82See id.at 29.83See World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers(US Department of State, 2005),available athttp://www.state.gov/t/vci/rls/rpt/wmeat/1999_2000/; Jon Herskovitz,N. Korea’s Missiles FindFewer Buyers,GULFTIMES, Sept. 6, 2006 (stating a US government study in 2004 found $560million in missile sales in 2001 alone).84See Background Note, supranote 9.85SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70.86North Korea does not release its own economic statistics. Thus, all information is from esti-mates and analysis by secondary sources.87Gross Domestic Product of North Korea in 2004(Bank of Korea, May 31, 2005).7778

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

9

GDP is roughly divided as follows: 30 percent agriculture (including food,forestry, and fishing), 34 percent industry, and 36 percent services.88Themajority of the industrial production is from mining (18.5 percent of GDP).89Of the services sector, approximately 23 percent represents governmental services.90The Bank of Korea estimated North Korea’s trade volume in 2004 amountedto $2.9 billion, 1/167th of South Korea’s trade volume.91China is the North’slargest trading partner. Bilateral trade between North Korea and China wasestimated to be $1.5 billion in 2005.92Life expectancy at birth is 63.6 years, the infant mortality rate is 42 deathsper 1,000 live births, and the mortality rate for children under 5 is 55 per1,000.93The rate of malnutrition for children under 5 years old is 23.9percent.94Many other socio-economic indicators are unavailable or unknown,due to the government’s failure to release such information or allow outside,independent assessments.

II. The CrisisA. Major Human Rights ConcernsFor years, North Korea has denied that there are any human rights violationsin the country. In 1988, for example, the North Korean Ambassador to theUnited Nations wrote to the Minnesota Lawyers International Human RightsCommittee that violations of human rights do not take place and are“unthinkable” in North Korea.95In 1994, an official publication,The People’sKorea,proclaimed “there is no ‘human rights problem’ in our Republic eitherfrom the institutional or from the legal point of view.”96Despite these assertions, however, North Korea is often referred to byknowledgeable observers as one of the worst human rights situations in the

See id.See id.90See id.91See id.92“China Raises Its Stake in North Korea,” ASIATIMES, Dec. 17, 2005.93SeeWorld Bank Group, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Data Profile,available athttp://devdata.worldbank.org/external/CPProfile.asp?PTYPE=CP&CCODE=PRK (citing WorldDevelopment Indicators database, Apr. 2006).94See id.95Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea),Minnesota LawyersInternational Human Rights Committee and Human Rights Watch/Asia, Dec. 1988.96OH& HASSIG,supranote 42, at 134,citing The People’s Korea, No. 1661(August 13, 1994), at 8.8889

10

FAILURE TO PROTECT

world today.97The UN General Assembly recognized this when, onDecember 15, 2005, it adopted a resolution expressing its deep concern about“systemic, widespread and grave violations of human rights” in North Korea.98But because of the self-imposed isolation of the country, documenting the fullextent of the abuses of Kim Jong Il and his regime is an impossible challenge.Only in the last 10 years – with the exodus of North Koreans escaping to fleethe famine – has even a partial view of the terrible situation come to light.North Korea has been highlighted for attention by many human rightsorganizations and governments because of its human rights record. At thesame time, it has also signed – and essentially ignored – many of the keyhuman rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil andPolitical Rights (ICCPR)99, International Covenant on Economic, Social, andCultural Rights (ICESCR)100, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms ofDiscrimination Against Women (CEDAW)101, and Convention on the Rightsof the Child (CRC).102This report is not intended to provide a complete overview of the humanrights situation in North Korea.103Instead, by examining the body of existingevidence, this report presents two key groupings of human rights abuses –food policy and famine, and the treatment of political prisoners – that, intheir scale, scope, and severity fall clearly within the definition of “crimesagainst humanity.”104In addition, the abduction of foreigners is also examined.

See, e.g., Tobacco Firm Has Secret North Korean Plant,THEGUARDIAN(UK), Oct. 17, 2005(stating North Korea “is regarded by some as having the worst human rights record in theworld”); Nicholas Kristof,The Hermit Nuclear Kingdom,NEWYORKTIMESBOOKREVIEW, Feb.10, 2005 (North Korea is “the worst human rights violator in the world”); Roberta Cohen,Talking Human Rights With North Korea,WASHINGTONPOST, Aug. 29, 2004 (North Korea “is theworld’s worst human rights violator”); Robert Windrem,Death, Terror in N. Korea Gulag,NBCNEWS, Jan. 15, 2003 (quoting U.S. Senator Sam Brownback: “It’s one of the worst, if not theworst situation — human rights abuse situation — in the world today.”)98G.A. RES. 60/173, UN Doc. A/RES/60/173 (Dec. 16, 2005).99North Korea acceded to the ICCPR on September 14, 1981.See Status of Ratifications of thePrincipal International Human Rights Treaties,Office of the UN High Commissioner for HumanRights, Jun. 4, 2004.100North Korea acceded to the ICESCR on September 14, 1981.See id.It is important to notethat this predated North Korea’s major problems with food policy and famine.101North Korea acceded to CEDAW on February 27, 2001.See id.102North Korea ratified CRC on September 21, 1990.See id.103See, e.g., White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea(Korean Institute for National Unification,2006) (providing a highly detailed overview of the human rights situation in North Korea).104See infraAppendix III.97

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

11

1. Food Policy and Famine105Between 1995 and 1998, North Koreans suffered through a catastrophicfamine that resulted in at least one million deaths, and possibly many more,from starvation and hunger-related diseases.106This represented between threeand five percent of the population.107While the acute famine has passed, thefood emergency continues to this day. Some human rights organizationsrecently warned that North Korea is once again on the brink of famine.108Asof 2004, out of the population of 22 million, 57 percent of the people do nothave sufficient food to stay healthy, 36 percent of the people are under-nourished, and 37 percent of children under 6 years old suffer from chronicmalnutrition.109Perhaps the most striking example of the malnutrition’simpact is that in 2003 the Korean People’s Army (KPA) was forced to reduceits height requirement for draftees from five feet, eleven inches (150 cm) tallto five feet, two inches (125 cm) tall.110Even though these statistics are ampleevidence to demonstrate that malnutrition is a problem, North Korea continuesto inhibit aid distribution and denies access to UN agencies and NGOs to 42of the 203 North Korean counties. The World Food Programme (WFP) isunwilling to provide food assistance to those counties without appropriatemonitoring being in place.111To discuss why UN Security Council action is necessary, the followingsection first presents the legal context for North Korea’s obligations to feed itspeople. Second, the antecedents of North Korea’s food crisis are reviewed.

For comprehensive treatments of the North Korean famine,seeHAGGARD& NOLAND,HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70; STEPHANHAGGARD& MARCUSNOLAND, FAMINEINNORTHKOREA: MARKETS, AID,ANDREFORM(Columbia University Press, forthcoming 2007)[hereinafter, HAGGARD& NOLAND, FAMINE], and MARCUSNOLAND, FAMINE ANDREFORM INNORTHKOREA(Institute for International Economics Working Paper, 2003). This section reliesheavily on these works.106This is a conservative estimate based on studies accepted by Haggard, Noland, and others.See,e.g.,HAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 18. AndrewNatsios, former head of the U.S. Agency for International Development, endorsed the view thatas many as 2.5 million people died during the famine.SeeANDREWNATSIOS, THEPOLITICS OFFAMINE(United States Institute of Peace, 1999), at 6,quotingHWANGJONGYUP, NORTHKOREA:TRUTH ORLIES(1998).107SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 18.108SeeKay Seok,North Korea is Headed Toward Another Famine,INTERNATIONALHERALDTRIBUNE, Apr. 5, 2006; A MATTER OFSURVIVAL: THENORTHKOREAN GOVERNMENT’SCONTROLOFFOOD AND THERISK OFHUNGER(Human Rights Watch, 2006), at 25 [hereinafter, A MATTEROFSURVIVAL]. Recent flooding has increased the likelihood that North Korea is on the brink offamine once again.SeeJon Herskovitz,UN Food Agency Says North Korea Accepts Aid Offer,REUTERS, Aug. 17, 2006.109See North Korea Famine In Detail,Reuters Foundation Alert Net,available athttp://www.alert-net.org/db/crisisprofiles/KP_FAM.htm?v=in_detail.110SeeNOLAND, FAMINE ANDREFORM INNORTHKOREA,supranote 105, at 10, n. 16.111SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 25; JeffreyRobertson,North Korea Plays Politics with Food Aid,ASIATIMES, Oct. 1, 2005.105

12

FAILURE TO PROTECT

Third, background on the “slow motion” famine is provided. Fourth, thefamine itself will be described, followed by a short discussion about thefamine’s impact. Next, North Korea’s use and misuse of international assistanceis reviewed. Finally, the nature of the continuing crisis will be followed by asummary of key findings.This section concludes, as have many other assessments, that the NorthKorean famine was not caused by a natural disaster, but rather by the NorthKorean government’s own failures. Furthermore, the government has failed toaddress or remedy the fundamental circumstances that led to the prior famine.Instead, Pyongyang continues emphasizing other priorities, such as supportingan oversized military, pursuing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs,exerting control over the citizenry, and maintaining its isolation from theoutside world.112North Korea remains heavily dependent on outside foodassistance, yet it has demonstrated repeatedly its willingness to jeopardize,sacrifice, or reject that assistance – along with jeopardizing the health and livesof its citizens – in pursuing other priorities.a. Legal Context: The Fundamental Right to FoodThe right to adequate food is central to the ability to enjoy and exercise allother human rights.113If a person is chronically hungry and malnourished, heor she cannot meaningfully enjoy the other inalienable rights of life.114Since its inception, the United Nations and its members have recognizedthe fundamental nature of the right to food. Initially this right was hortatory,as presented in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that“everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health andwell-being of himself and his family, including food.”115Subsequently, thisright was codified in the ICESCR, which reaffirms “the right of everyone to . . .adequate food” and “the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger.”116

SeeMARCUSNOLAND, SHERMANROBINSON& TAOWANG, FAMINE INNORTHKOREA: CAUSESANDCURES(Institute for International Economics, 2002), at 1-2.113SeeUNITEDNATIONSCOMMITTEE ONECONOMIC, SOCIAL,ANDCULTURALRIGHTS,SubstantiveIssues Arising From The Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, andCultural Rights,General Comment No. 12, at�57 (“The human right to adequate food is ofcrucial importance for the enjoyment of all rights.”)114See id.115UNIVERSALDECLARATION OFHUMANRIGHTS, G.A Res. 217A (III), UN Doc. A/810,adoptedDec. 10, 1948, at art. 25.116INTERNATIONALCOVENANT ONECONOMIC, SOCIAL,ANDCULTURALRIGHTS, G.A. Res. 2200A(XXI),adoptedDec. 16, 1966,entered into forceJan. 3, 1976, at art. 11. North Korea acceded tothe ICESCR on Dec. 14, 1981.112

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

13

The ICESCR and subsequent instruments recognize that nations have theresponsibility not only to recognize the right to food, but also to protect,respect, and fulfill that fundamental right. The ICESCR, for example, statesthat “[t]he States Parties will take appropriate steps to ensure the realization ofthis right, recognizing to this effect the essential importance of internationalcooperation based on free consent.”117Similarly, the CRC states that “Partiesshall . . . take appropriate measures . . . to combat disease and malnutrition . . .through,inter alia,the application of readily available technology and throughthe provision of adequate nutritious foods.”118It goes on to say that “StatesParties, in accordance with national conditions and within their means . . .shall in case of need provide material assistance and support programs,particularly with regard to nutrition.”119These international norms recognize that government has the primaryresponsibility for ensuring the right to adequate food. This is because thenation-state exercises enormous power over all aspects of its people’s lives –even in democratic, market-oriented societies. This does not always mean thatnations have an obligation literally to feed their people, except in times ofemergency. It does mean, however, that the state is responsible for theconditions that exist in its country – including conditions that may cause orresult in hunger – and the state is obligated to adopt policies that respect andsatisfy the fundamental right to food.ICESCR General Comment No. 12 defines the obligations that the state mustfulfill in order to implement the right to adequate food at the national level:• The obligation torespectexisting access to adequate food requires statesparties not to take any measures that result in preventing such access.• The obligation toprotectrequires measures by the state to ensure thatenterprises or individuals do not deprive other individuals of their accessto adequate food.• The obligation tofulfill(facilitate) means the state must proactivelyengage in activities intended to strengthen people’s access to and use ofresources and means to ensure their livelihood, including food security.120

Id.CONVENTION ON THERIGHTS OF THECHILD, G.A. Res.44/25,adoptedNov. 20, 1989,enteredinto forceSept. 2, 1990, at art. 24. North Korea signed the CRC on Oct. 21, 1990.119Id.at art. 27.120ICESCR,supranote 116.117118

14

FAILURE TO PROTECT

Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen has argued that there is nolonger an excuse for famine anywhere.121Others have adopted this view aswell.122According to this argument, famines or acute food shortages do notresult from poor growing conditions, drought, floods, or other naturaldisasters. Instead, food crises are caused by government policies that fail torespond to a country’s agricultural circumstances, fail to respond to naturalconditions or events, deny citizens the political rights to influence thegovernment and its policies, and/or hinder the ability of citizens to feed andhelp themselves.123Even if this is not universally true, the argument applies to North Korea.Logically, a government that can mobilize and sustain a modern army withover one million soldiers, pursue nuclear weapons, and launch long-rangemissiles can also successfully adopt and implement policies that protect itscitizens from food scarcity and insecurity. But the North Korean governmenthas failed to provide these protections for decades.Pyongyang has demonstrated repeatedly that keeping its population properlyfed is a low priority for the government. For example, an estimated 15 to 30percent of North Korea’s GDP is used to support the army, even during timesof famine and food insecurity.124Further, the government has repeatedly putinternational food aid at risk, both by the restrictions it places on that aid andby actions that threaten to end that aid, such as the launch of missiles and therefusal to participate in the Six-Party Talks. Finally, the government hasrefused to undertake the fundamental changes necessary to remove the threatof famine, food insecurity, and dependence on foreign food aid – aid whichcould evaporate at any time.

See, e.g.,AMARTYASEN, FAMINES ANDOTHERCRISES, in DEVELOPMENTASFREEDOM160, 175(Anchor, 1999).122See, e.g.,MEREDITHWOO-CUMMINGS, THEPOLITICALECOLOGY OFFAMINE: THENORTHKOREANCATASTROPHE ANDITSLESSONS(Asian Development Bank Institute 2002), at 1 (“Senhas effectively demonstrated that famine is rarely if ever about insufficient stocks of food; it isabout the politics of food distribution”); ALEXDEWAAL, FAMINECRIMES: POLITICS ANDTHEDISASTERRELIEFINDUSTRY INAFRICA117 (Indiana University Press, 1997), at 7. JOACHIM VONBRAUN, TESFAYETEKLU, & PATRICKWEBB, FAMINE AS THEOUTCOME OFPOLITICALPRODUCTIONANDMARKETFAILURES, IDS BULLETIN(No. 4, 1993), at 73.123See, e.g.,JEANDREZE& AMARTYASEN, HUNGER ANDPUBLICACTION46 (Oxford UniversityPress, 1989).124North Korea officially acknowledges that 15 percent of GDP is consumed by the military.Many observers believe that the actual figure is much higher.SeeLEEYOUNG-SUN& YOONDEOK-RYONG,The Structure of North Korea’s Economy: Changes and Effects,A NEWINTERNATIONALFRAMEWORK FORNORTHKOREA? (American Enterprise Institute, 2005), at 52; Yoel Sano,Military Holds the Key,ASIATIMES, Feb. 18, 2005.121

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

15

b. Antecedents of the Food CrisesThe North Korean government blames the famine of the 1990s on catastrophicflooding that occurred in 1995 and 1996. These natural disasters, however,were not the primary causes of the famine, nor even secondary ones. In reality,the famine was well under way by 1995, rooted in five decades of failedgovernmental policies that left the population highly vulnerable to food shortages.So long as Korea is divided, North Korea will face a permanent challengeto feed itself. Korea’s historical economic development tended to concentrateagriculture in the South, with its more favorable climate and the majority ofthe arable land. Because the North is colder, less fertile, and more mountainous,it has been the locus of mostly industrial activity.125Thus, splitting the Koreanpeninsula deprived North Korea of its historical breadbasket.126As a result, North Korea has had to compensate for this loss. Onlybetween 19 and 22 percent of North Korea, however, is considered arable.127Thus, North Korea would need to develop an economy able to purchase largequantities of imported food – which it has not done. The catastrophic famineof the 1990s and acute food shortages that continue to threaten NorthKoreans today have their direct roots in the government’s failure for fivedecades to adopt policies addressing the basic fact that North Korea cannotproduce sufficient food on its own to feed its population.128Like most Communist countries, North Korea established a centrallyplanned economy implemented through a series of multi-year industrialplans.129In agriculture, farmers and farmland were organized into collectivesand state farms.130All planning and production was centralized.131Privateproduction was prohibited, as were private markets and trade.132While drawing on the Communist planning framework, North Koreanfounder Kim Il Sung organized North Korean life around the ideological tenetofjuche,or a “spirit of self reliance.”133As with other sectors, North Koreanagriculture and food policies also came under the same philosophy, withPyongyang imposing self-reliance not only at the national level, but in a lessconsistent way at the provincial and county levels as well.134SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, FAMINE,supranote 105, at 1.SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 12-13.127SeeWORLDFACTBOOK,supranote 57.128SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 12-13; NOLAND,supranote 105, at 2-4.129See supraSection I.C.130SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 2-3; HAGGARD& NOLAND, FAMINE,supranote 105, at 2.131SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, FAMINE,supranote 105, at 2.132SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 3.133See supraSection I.A.134SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 3; HAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 12.125126

16

FAILURE TO PROTECT

Claiming thatjuchecould be applied to agriculture was both misleadingand destructive. The description was misleading because North Korea reliedheavily on the Soviet Union – not only for food imports and food subsidies,but also for other necessities of modern agriculture including fertilizer,insecticides, petroleum, and other fuel.135The philosophy was destructivebecause it resulted in sacrifices by the population wheneverjuchefell short ofreality, which the food supply constantly did.136The agricultural form ofjucheoften drove the government to adoptshortsighted, ill-advised policies in futile attempts to reach self-reliance. Forexample, over the years North Korea attempted to create more arable land, butthese attempts instead led to a self-defeating cycle: deforestation led to soilerosion and run-off, which in turn caused silting in rivers and eventuallyflooding, which then destroyed harvests and further reduced available farmland.Also, failure to rotate crops, intensive re-cropping of land, and too heavy areliance on fertilizers depleted the soil, leading to even more reductions inavailable fertile land and a steadily declining agricultural output.137Another factor that exposed much of the population to the threat ofhunger was the degree to which the government strictly controlled thedistribution of food. Food was distributed through two state-controlledchannels. While farm workers were allowed to retain an annual smallallowance from the harvest, the rest of the population – approximately 13.5million people and 62 percent of the population – depended entirely onmonthly or biweekly rations from the Public Distribution System (PDS).138In particular, city dwellers lived at the mercy of the rationing system.139The PDS allowed the government to exert further control over its citizensand to discriminate against less-favored and disfavored persons. The food aperson received depended on that person’s government-determined politicalstatus – members of the military, party officials, those in favored occupations,and those perceived as loyal to the government received more food, whilethose deemed less important or less supportive of the regime received lessfood.140Thus, privileged industrial workers received 900 grams of food a day,while ordinary workers received 700 grams, retired citizens 300 grams, andchildren between the ages of 2 and 4 and prisoners just received 200 grams.141

135136

SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 12-13.See id.at 13.137SeeMARCUSNOLAND, SHERMANROBINSON& TAOWANG,Famine in North Korea: Causes andCures,ECONOMICDEVELOPMENT ANDCULTURALCHANGE(University of Chicago Press, Vol.49(4), 2001), at 741-57.138SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 14.139See id.at 22.140See id.141SeeA MATTER OFSURVIVAL,supranote 108.A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

17

In sum, long before the food crises began in the late 80s and early 90s,North Korea faced significant challenges feeding its own people because it hadadopted policies that made the country vulnerable to food insecurity andfamine and too inflexible to respond to political, economic, or climaticchanges.c. The “Slow Motion” FamineThe North Korean famine is often described as happening in slow motion.142The description emphasizes that the famine could and should have beenanticipated by the government. It is equally apt to note that the descriptionimplies the government ignored or consciously refused to take steps to preventthe catastrophe, or to end it once it was under way, for instance by rapidlyseeking external food supplies. This famine did not result from a suddennatural disaster; it was inflicted by the state on its own people.As discussed above, the country’s geographic limitations and the government’sfutile stress onjucheself-reliance created an agricultural system highlydependent on importing fuel and other inputs. In the late 1980s, when theSoviet Union was faced with its own economic and monetary problems, itbegan demanding payment from North Korea for past and current aid –amounts North Korea could not repay.143When the Cold War ended and theSoviet Union collapsed in 1991, trade between the two countries ceasedaltogether and the North Korean economy collapsed.144Without Soviet aid,the flow of inputs to the North Korea agricultural sector ended, and thegovernment proved too inflexible to respond.145As a result, food productiondecreased precipitously.For a time, China filled the gap left by the Soviet Union’s collapse andpropped up North Korea’s food supply with significant aid.146By 1993, Chinawas supplying North Korea with a staggering 77 percent of its fuel importsand 68 percent of its food imports.147Thus, North Korea replaced dependenceon the Soviet Union with dependence on China – with predictably direconsequences. In 1993, China faced its own grain shortfalls and need forhard currency, and it sharply cut aid to North Korea.148

See id.at 3.SeeNOLAND, ROBINSON& WANG,supranote 137, at 3; HAGGARD& NOLAND, FAMINE,supranote 105, at 4.144See id.145SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 3;see alsoHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 14;SeeNOLAND, ROBINSON& WANG,supranote 137, at 5.146SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 14.147SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, FAMINE,supranote 105, at 4.148SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 13-14.142143

18

FAILURE TO PROTECT

While the cutoff in Chinese aid was the immediate trigger for the faminethat followed149, it did notcausethe famine. Before Chinese aid ended, NorthKorean food production was in a steady decline; the disaster that followed waslargely the result of the government’s failure to respond to this decline.150Eventhe catastrophic flooding that occurred in the second half of 1995 and againin 1996151did not cause the famine. According to WFP estimates, the countrywas already facing a food deficit at the time the floods hit.152The famine in the mid-1990s was preceded by several years of foodshortages. Available data suggests that death rates began to increase in 1993and 1994, thus marking the famine’s beginning.153In 1994, official NorthKorean broadcasts admitted that widespread hunger existed, though thegovernment was not forthcoming about the scope of the disaster.154In May1995, the government finally acknowledged food shortages and requestedassistance from Japan.155As Haggard and Noland conclude, the faminecannot be blamed on the floods or on the loss of aid from the Soviet Unionand China. Rather, it must be blamed on government actions and inactions:There is no question that bad weather made a difficultdecision worse, but it is not obvious that the floods werethe primary or even proximate cause of the North Koreanfamine . . . . It is essential to place the effect of the weatherin the context of two other crucial factors: the seculardecline in the North Korean economy, and in theagriculture sector in particular; and the failure of thegovernment to respond to this crisis by maintainingadequate commercial imports or by making clear andtimely appeals to the international community. Thedecline in the economy resulted in part from externalshocks, but even more from the misguided effort to pursuea strategy of self-sufficiency, including in food.156

See id.at 14;see also The Worst of Friends,TIMEMAGAZINE, Jul. 17, 2006 (noting “China’sreduction of rice supplies to the North—part of a previous effort to force Pyongyang to negotiateover its nuclear-weapons program—contributed to a devastating famine.”)150SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 13.151The North Korean government estimated that the flooding caused 5.4 million people to bedisplaced and 330,000 hectares of land lost with their harvests destroyed, as well as nearly 2million tons of grain. A second disastrous flood occurred in 1996. In a cruel irony, the floodswere followed by some of the worst droughts in the country’s history as well as tidal waves thatdestroyed additional farm land.SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 3; OBERDORFER,supranote 5, at 370.152See id.at 8.153SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 5154SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 5.155SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 14; NOLAND,supranote 105, at 3.156HAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 14.149

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

19

To summarize, the primary causes of the famine included (1) amisguided and futile attempt to force self-reliance in agriculture on a countrythat is incapable of reliably producing enough food to feed 22 million people;(2) the creation of an agricultural system highly dependent on fuel, fertilizer,and other inputs, subsidized by outside aid; (3) a long-term decline in theeconomy in general; (4) the loss of trade and subsidies from the Soviet Unionand later China; and, most importantly, (5) the government’s failure torespond to these circumstances.d. The FamineDue to North Korea’s insularity and self-imposed isolation, the conditionsthat existed as the famine unfolded are still difficult to assess. The onlysources are refugees and those few scholars and aid workers that were allowedlimited access to the country during and after the famine’s height. Even thoselimited sources provide a shocking story. In December 1995, the Food andAgriculture Organization (FAO) and WFP warned that 2.1 million childrenand 500,000 pregnant women faced immediate starvation, and millions morecould face the same the following summer.157In January 1996, theInternational Committee of the Red Cross issued a statement that 130,000people were on the brink of starvation, and 500,000 more would be in thesame position come the fall harvest.158The government had created a system in which 62 percent of the population –13.5 million people – depended on government rations for basic subsistence.159In response to problems with procuring food, however, the governmentproceeded to continually reduce rations. With the shut-off of Soviet aid in1987, daily grain rations were reduced for the average recipient by 10 percent.160In 1992, rations from the PDS were cut an additional 10 percent, and theserations were not distributed to everyone.161Then, in 1994, the PDS system began to collapse altogether, ultimatelybecoming meaningless. Rations were cut once again, this time from 450 to400 grams a day, although there were accounts from some refugees that manypeople actually were receiving less than 150 grams from the PDS. Otherrefugees reported that in many provinces there were no PDS rations beingdistributed at all.162Furthermore, the government completely eliminated PDS shipments to fourmountainous northeast provinces (North and South Hamgyong, Yanggang,SeeNOLAND, ROBINSON& WANG,supranote 137, at 4.See id.159SeeNOLAND, ROBINSON& WANG,supranote 137, at 6.160SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 9.161See id.at 9-10.162See id.at 10; HAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 14.157158

20

FAILURE TO PROTECT

and Kangwon), and prohibited shipments from other provinces to theseareas.163Residents in these mountainous areas were highly dependent on thePDS, and with the collapse of the industries that had previously employedthem, they had little or no ability to barter or purchase food. It is likely thatthe famine started in these mountainous Eastern provinces at that time, a yearbefore it spread to the rest of the country.164By 1997, the government had cutPDS rations to a paltry 128 grams a day, and the PDS system may have beenfeeding less than 10 percent of the population.165Farmers themselves, though capable to a limited extent of coping with thecrises, were not immune from the government’s measures to tighten andcontrol food supplies. The government reduced the annual allotment thatfarmers could legally hold back, from 167 to 107 kilograms per person. Inaddition, the government began seizing grain stores. Predictably, farmersresponded by hiding and hoarding grain and cultivating hidden plots, therebyfurther diverting production from the PDS.166Apart from the reduction in PDS rations, the government’s other responseswere often crude, cruel, and ineffective. For example, the North Koreangovernment encouraged the use of “alternative foods,” such as small brickswhose only ingredients were bark, leaves, and grass. This product had nonutritional value, and it caused dysentery, diarrhea, and internal bleeding – allpotentially fatal conditions.167Furthermore, for a period of time, the North Korean government “continuedto criminalize many of the very coping strategies for the famine it had forcedon its own population.”168For example, the right to free movement was heavilycurtailed and regulated. This inhibited and at times prevented people fromsearching for food alone and from relocating to areas experiencing less acutefood shortages.169Additionally, the private production and trading of foodremained illegal. The government subsequently relaxed some of these policiesto a minor extent – or at least tolerated their breach – but not soon enough toprevent the tragedy that Pyongyang’s policies had now inflicted on its own people.e. The Famine’s ImpactAssessing the impact of the famine and food shortages is made difficult bythe lack of information from the reclusive North Korean government and bythe lack of independent and first-hand information available to researchers,scholars, and other independent observers.SeeNATSIOS,supranote 106, at 5.See id.165SeeNOLAND,supranote 105, at 10.166SeeHAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGER ANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 18.167See North Korean Famine In Detail, supranote 109.168HAGGARD& NOLAND, HUNGERANDHUMANRIGHTS,supranote 70, at 20.169See id.163164

A CALL FOR THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO ACT IN NORTH KOREA

21