Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2005-06

Bilag 78

Offentligt

COLOMBIA: TOWARDS PEACE AND JUSTICE?Latin America Report N�16 – 14 March 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. iINTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1I.II. THE POLITICAL CONTEXT...................................................................................... 3III. JUSTICE AND REPARATION PROBLEMS ............................................................ 8A.B.ADMINISTRATION OFJUSTICE...............................................................................................8REPARATIONS FORVICTIMS................................................................................................11

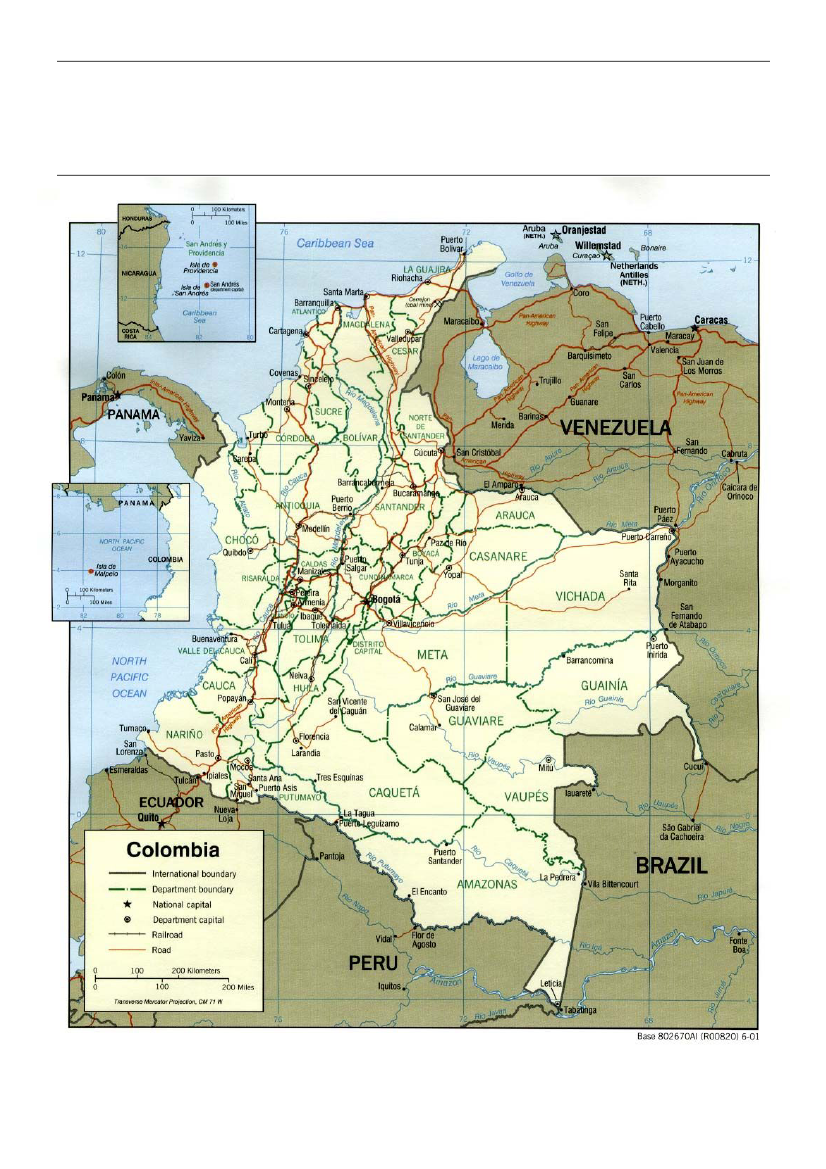

IV. REINSERTING THE PARAMILITARIES .............................................................. 14V. INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT AND PROSPECTS FOR INSURGENTDEMOBILISATION .................................................................................................... 17VI. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 19APPENDICESA.MAP OFCOLOMBIA.............................................................................................................21B.CHRONOLOGY OFPARAMILITARYDEMOBILISATIONS ANDLIST OFREMNANTGROUPS......22C.ABOUT THEINTERNATIONALCRISISGROUP.......................................................................25D.CRISISGROUPREPORTS ANDBRIEFINGS ONLATINAMERICA/CARIBBEAN.........................26E.CRISISGROUPBOARD OFTRUSTEES...................................................................................27

Latin America Report N�16

14 March 2006

COLOMBIA: TOWARDS PEACE AND JUSTICE?EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONSHow Colombia implements its controversial new legalframework for demobilising the far-right paramilitariesand returning them to society is critically important. It caneither take a decisive step towards ending its 40-yeararmed conflict or see prolongation of violence and therise of an ever more serious threat to its democracy. Mostparamilitaries have turned themselves in but the Justiceand Peace Law (JPL) – criticised by human rights groupswhen enacted in July 2005 – has still not been applied.There is concern the Uribe administration prioritisesquick fix removal of the paramilitaries from the conflictat the cost of justice for victims and the risk of leavingparamilitary economic and political power structures largelyuntouched. International support for JPL implementationshould be conditioned on a serious government strategyto apply the new framework, as well as steps by PresidentUribe to contest paramilitary efforts to keep their crime(including drug) fiefdoms and build their political power.By early March 2006, President Alvaro Uribe hadachieved demobilisation of some 24,000 of an estimated27,000 to 29,000 paramilitaries, including its mostnotorious commanders, using a 2002 law which authorisespardons for rebellion and sedition. Focusing on dismantlingthe overt military structures of the paramilitaries, butnot their powerful mafia-like criminal networks thatcontinue to exist in many parts of Colombia, however,his government has not sent a clear signal that it isdetermined to apply the JPL rigorously and take intoaccount the arguments of its many critics. Indeed, thenew law is still not being implemented – because of aconstitutional court review but also tactical calculations.The government appears to believe it may endangerdemobilisation of the remaining 4,000 or 5,000paramilitaries if they witnessed an early demonstrationthat the JPL was being applied stringently. However, theoverlap of the congressional elections (12 March) andpresidential elections (28 May) with the final phase ofparamilitary demobilisation has raised suspicion in somecircles that the reluctance to send a clear message abouthow the JPL will ultimately be implemented is alsoaffected by electoral considerations. Uribe is running forre-election and while it would only damage him inthe long run to have any taint of support from theparamilitaries, there is evidence that former commandersand circles supporting them have attempted to useintimidation and money to get some of their owncandidates into the new Congress, elected on 12 March,and weaken the anti-Uribe opposition.Whether, if re-elected, Uribe could achieve sustainablepeace depends in large measure on how his administrationhandles the implementation of the JPL and the reinsertionof former paramilitaries. The law has a history of stronghuman rights criticism because it does not guaranteevictims’ rights to reparations and truth and opens the doorto impunity – or at best relative judicial slaps on thewrist – for former paramilitaries who committed heinouscrimes. These concerns need to be addressed now througha transparent government strategy that prioritises fulldismantling of the paramilitary military and criminalstructures, the rigorous prosecution of past atrocitiesand partnership of the victims and civil society inimplementing the JPL. The government also needsto remedy the flaws of its programs for reinsertingdemobilised paramilitaries.The law was designed to apply as well to demobilisationof the country’s left-wing insurgencies, the RevolutionaryArmed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the NationalLiberation Army (ELN). It is highly unlikely that it couldbe used in the foreseeable future with the larger and morepowerful FARC, which has staked out a position ofunremitting hostility toward Uribe and is unwillingto negotiate. But the commitment the government showsnow to a transparent and rigorous application of theJPL to the paramilitaries could help advance therapprochement with the smaller ELN, which talks inHavana in late 2005 and February 2006 seem to have setin motion (though a number of other obstacles exist, suchas fragmentation of the insurgent organisation).

RECOMMENDATIONSTo the Government of Colombia:1.Design and implement now a strategy for therigorous and transparent implementation of theJPL that embraces the following:

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page ii

(a)

prompt and rigorous law enforcementaction against demobilised or still activeparamilitaries as well as their sponsorsand supporters, including members ofthe security forces collaborating withparamilitaries, who are interfering withthe democratic electoral process; andmonitoring and screening mechanisms toensure that prosecution of demobilisedparamilitaries under the terms of the JPLfully comply with all stipulations of thelaw, including:

To the Attorney General:5.Increase efforts to consolidate a comprehensiveand standardised database on human rightsviolations and serious crimes, including gender-based crimes, committed by the paramilitaries,the FARC and the ELN and link this databaseto information gathered by other state agenciesas well as civil society and human rightsorganisations.

(b)

To the National Commission for Reparation andReconciliation:6.Make victim and civil society participation,including by indigenous, Afro-Colombian andwomen's groups, a priority, both in the work ofthe national and regional commissions and inimplementation of the JPL.Engage victim associations and civil societyorganisations broadly in a dialogue aimed atbuilding consensus on the commission’s strategiesand work plans and emphasise its independencefrom the executive.Identify lands obtained by members of illegalarmed groups through violence and intimidationand seek to return those properties to internallydisplaced persons.Request support for identifying victims fromexperienced human rights-related forensicsorganisations such as the Argentine ForensicAnthropology Team and the InternationalCommission on Missing Persons.

(i)

hand-over of all ill-gotten assets,including land, to the NationalReparation Fund;disclosure of involvement in crimesand knowledge of paramilitarystructures and financing sources;dismantlement of the paramilitaryunit and criminal networks to whichthe prosecuted individual belonged;liberation of all kidnap victims andidentification of the burial sites ofdisappeared persons;hand-over of all under-age fightersto the Colombian Institute for FamilyWelfare; andassurance that there are no drugtraffickers among the JPL-prosecutedindividuals.

(ii)

7.

(iii)

(iv)

8.

(v)

9.

(vi)

2.

Establish positions of vice-minister in the ministryof the interior and justice and high commissionerin the presidency, charged with implementingprograms for reinsertion of ex-combatants intosociety and coordinating the efforts of governmentand state agencies, as well as the private sector andNGOs, in particular on the local and departmentallevels.Incorporate a more effective monitoring systeminto the reinsertion programs to address the dangerthat ex-combatants will re-enter criminal anddrug trafficking networks or otherwise becomesecurity threats again.Provide additional financial and institutionalassistance for the Reference and OpportunityCentres to develop psychological support foreasing the reinsertion process for victims,particularly women.

To the Government of the United States:10.Maintain its requests for extradition of formerparamilitaries to the U.S. to face drug traffickingcharges.Condition material support for JPL implementationand reinsertion programs for ex-combatants uponthe above-listed reforms but provide immediateaid to prosecution efforts of the Attorney General.Emphasise assistance to vulnerable populations,and in the case of the internally displaced helpthe Colombian authorities identify land illegallyobtained through violence and return it to theoriginal owners.Help the UN High Commissioner for HumanRights field offices, Colombian human rightsorganisations and the Organisation of AmericanStates (OAS) verification mission to improvetheir monitoring of the JPL, demobilised ex-paramilitaries and human rights violations.

11.

3.

12.

4.

13.

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page iii

To the European Union and its member states andthe Government of Canada:14.Condition material support for JPLimplementation and reinsertion programs forex-combatants upon the above-listed reforms.Provide financial support throughout the conflictto the National Reparation fund to ensure thatvictims, particularly women, and indigenousand Afro-Colombian groups are adequatelycompensated for their losses.

To the OAS Verification Mission:16.Focus on complete paramilitary demobilisationand introduce a system establishing whether thenumber of demobilised fighters matches that ofweapons turned in.Design a strategy for verifying the reinsertionprocess that serves as an early warning mechanismfor violations by ex-combatants and reportperiodically on government response to suchviolations.

15.

17.

Bogotá/Brussels, 14 March 2006

Latin America Report N�16

14 March 2006

COLOMBIA: TOWARDS PEACE AND JUSTICE?I.INTRODUCTIONThe government strongly defends the new law, which,according to President Uribe, reflects a balance betweenthe requirements of justice and peace.6Others, suchas the late Senator Roberto Camacho, have called it“pioneering” legislation that will serve as a “frameworkof reference in other [demobilisation] processes aroundthe world”.7The many critics in and outside Colombiacomplain that it does not guarantee victims’ rights toreparations and truth and opens the door for demobilisedparamilitaries who committed grave crimes to enjoyimpunity, while throwing up obstacles to the destructionof their powerful criminal networks.8Whatever its serious shortcomings, the law and thelegislative process that produced it at the least placed thedifficult transitional justice issue at the heart of nationaldebate. The JPL is the first transitional justice law inColombia’s history. In contrast to the amnesty-baseddemobilisations of insurgent groups that the countryexperienced in the early 1990s, it provides a means fordealing with the grave crimes committed by armed groups.This was recognised by European Union (EU) foreignministers, who in October 2005 described it as “asignificant development, since it provides an overall legalframework for [disarmament, demobilisation andreintegration]”, while also criticising it for “not tak[ing]into sufficient account the principles of truth, justice andreparation in accordance with internationally agreedstandards”.9However, by the first week of March 2006 nearly 24,000of the estimated 27,000 to 29,000 paramilitaries10have

Creation of a legal framework for demobilisation andreinsertion of members of irregular armed groups hasbeen an issue of great concern and controversy during thelast three years in Colombia. The entrance into force ofLaw 975, better known as the Justice and Peace Law(JPL), on 25 July 2005 was preceded by a drawn-outand turbulent legislative process. In August 2003,the government of Alvaro Uribe submitted a draft tocongress,1which was not passed, in large part due tostrong domestic and international human rights criticism.2No headway was made the next year but early in 2005the executive presented a second proposal,3whose weakprovisions prompted an alternative draft from a group oflegislators headed by Senator Rafael Pardo.4Months ofvigorous debate ended with passage of the JPL, thoughcriticism continued, including from the Office of the UNHigh Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) inColombia.5

Proyecto de ley estatutaria No. 85 Senado “Por el cual se dictandisposiciones en procura de la reincorporación de miembrosde grupos armados que contribuyan de manera efectiva ala consecución de la paz nacional”, 21 August 2003, atwww.presidencia.gov.co.2“Observaciones al Proyecto de Ley Estatutaria que trata sobrela reincorporación de miembros de grupos armadas”, UN HighCommissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR), Bogotá, 28August 2003, according to which the Alternative SentencingBill opened the door to impunity by allowing such sentences forhuman rights violations without requiring reparation fortruth to be established. The law failed to clarify governmentresponsibility for victims and meet international humanitarianstandards.3The Justice, Peace and Reparation bill was presented by theMinistry of the Interior, Proyecto de Ley 211/05 Senado, 293/05Cámara, Bogotá, 9 February 2005.4The Truth Justice and Reparation bill was presented byCongresspersons Rafael Pardo, Gina Parody, Luis FernandoVelasco and Wilson Borja, Proyecto de Ley 208/05 Senado,290/05 Cámara, Bogotá, 3 February 2005.5“Consideraciónes Sobre la Ley de Justicia y Paz”, UNHCHR,Bogotá, 27 June 2005; “Sin Paz y Sin Justicia”, ComisionColombiana de Juristas, 29 June 2005; “La CIDH de PronunciaFrente a la Aprovación de la Ley de Justicia y Paz en Colombia”,

1

Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, WashingtonDC, 15 July 2005.6See “Presidente Uribe explica la Ley de Justicia y Paz”,SNE,5 June 2005, at http://www.presidencia.gov.co.7Roberto Camacho, “Quéva a pasar con la AUC”?, ForoParamilitarismo, Desmovilización y Politica,Bogotá, 21September 2005.8“Smokeand Mirrors: Colombia’s Demobilisation ofParamilitary Groups”,Human Rights Watch, August 2005;Consideraciones sobre la ley de “justicia y paz”, UNHCHR,Bogotá, 27 June 2005.9Council of the European Union, General Affairs, 2678thmeeting, Luxembourg, 3 October 2005.10The number of paramilitaries has been growing since thenegotiations with the Uribe administration began in 2003. In thebeginning, the government said that 15,000 fighters would be

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 2

been demobilised on a different legal basis. At least 3,500paramilitaries in the north-western Urabá region and thecentral Casanare department are yet to demobilise, despitethe fact that the first and second deadlines for fulldemobilisation (31 December 2005 and 28 February2006) have passed.11Law 782, which has been used,authorises pardons for rebellion and sedition and inpractice will preclude criminal investigation of those whootherwise have no pending charges against them, which ismost of the demobilised.12The JPL, whose implementingregulations were only enacted in December 2005, hasnot yet been applied and is not likely to be until aftercompletion of congressional and presidential electionsand the next government has taken office in August 2006.Moreover, a constitutional court ruling on the law is stillpending. It is to be expected that only a small number offormer paramilitaries who demobilised under Law 782,in particular the most notorious commanders such asSalvatore Mancuso, Iván Duque and Diego Murillo, willbe prosecuted under the JPL because they fear losing itsbenefits and face ordinary criminal investigation orInternational Criminal Court (ICC) investigation forserious crimes in the future.13This will undoubtedly limitthe effectiveness of the JPL for punishing all offenders,establishing the truth and making victim reparation happen.

The process of creating the entities required to implementthe JPL, such as the Justice and Peace Unit (JPU) in theattorney general’s office and the National Commission forReparation and Reconciliation (NCRR), has gone slowly.While the pending constitutional court ruling has playeda role in postponing the application of the JPL, thegovernment has also been reluctant to send a clear signalthat the law will be rigorously and transparently appliedas soon as possible. Facing former commanders withimminent prosecution and jail sentences, it is believed,could prompt still active paramilitaries to pull out of thedemobilisation process or even take up arms again. TheUribe administration’s caution may also be due in part toa desire not to confront the paramilitary commanders withthe prospect of a stringent application of the JPL beforethe end of the electoral cycle, since they wield considerableinfluence over important parts of the electorate.Consequently, the JPL is for the moment, as a seniorColombian official said, in “limbo”.14This situation isexacerbated by the difficulties of the government’sprogram for reinserting paramilitaries, which increasesthe risk of seeing the rearming of some groups.The overlap of elections, reinsertion of many thousandsof former combatants into civilian life, and entrance intoforce of the JPL has already created political problemsfor the Uribe administration. Much will depend onthe constitutional court’s ruling. Notwithstandingthis uncertainty, however, transparent and efficientimplementation of the JPL is needed to move Colombiatowards peace. The administration needs to define astrategy for this that gives priority to ensuring thatparamilitary military and criminal structures are fullydismantled, past atrocities can be prosecuted, and allillegally acquired assets, drug trafficking activity andother crimes are accounted for.15It is important to analyse the application of the JPL andthe reinsertion of ex-combatants in the broader contextof government policy and the electoral campaign. Thereis strong evidence that demobilised paramilitaries haveused intimidation to promote their own congressionalcandidacies and those of others whom they favour inmuch of the country.16This is a serious threat toColombia’s democratic institutions and its chances to1415

demobilised. This was increased to first 20,000 and then 25,000.The end total will likely be above 27,000 and possibly couldreach 30,000. The government’s and the paramilitaries’explanation for this dramatic increase is that not only fightersare demobilising but also support cadres, such as drivers andcooks. The same reason is cited for the low ratio of weaponshanded in to fighters, roughly 1:3. However, the emergenceof rearmed, demobilised groups of paramilitaries in severalColombian departments, which was recently denounced bythe OAS verification mission, indicates that weapons have alsobeen hidden. See section II below; “Sexto informe trimestral delSecretario General al Consejo Permanente sobre la Misión deApoyo al Proceso de Paz en Colombia”, Washington DC, 1March 2006.11See Appendix B.12SeeEl Tiempo,2 March 2006.13One important incentive for demobilised paramilitaries whohave committed serious crimes to opt for prosecution under theJPL is that they believe it will shield them from ICC prosecutionin the future. ICC sources told Crisis Group that the Uribeadministration has been acutely aware of this possibility and hasattempted to draft the JPL in such a way that it could precludeICC prosecution of crimes against humanity because theperpetrators were sentenced sufficiently by Colombia’sjudicial system. The maximum jail sentence contemplated bythe JPL is eight years; if prosecuted under other Colombiancriminal statutes law, the paramilitaries could receive lifesentences for the kind of crimes they are accused of. UnderJPL the paramilitaries can also anticipate being able to retainmore of their illegally acquired wealth. For all these reasons,paramilitary leaders have real interest in a quick implementationof the JPL.

Crisis Group interviews, Bogotá, 5 and 6 December 2005.“As long as current regulations are not modified, only aproactive attitude on the part of the judicial apparatus, a strongpolitical will and exceptionally wide-ranging resources will beable to limit the persistence of impunity”, “Report of the HighCommissioner for Human Rights on the Situation of HumanRights in Colombia”, UNHCHR, January 2006, p. 32.16For example, Alfonso Palacio, candidate for mayor in the LaJagua municipality (Cesar), recently received death threats from“Tolemaida”, an active paramilitary leader under the orders ofCommander Rodrigo Tovar (Jorge 40).

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 3

achieve a sustainable peace that needs to be addressed.Uribe, who polls indicate holds a large lead in thepresidential race, has a strong interest in ensuring thathis political future is not tainted by a debt to formerparamilitaries. His government should also be receptiveto proposals to address JPL flaws by giving civil society,particularly victims, a larger role in its implementation.International support for the demobilisation processshould be made dependent on this.What is done in the next months with regard to theparamilitaries will also affect the government’s strugglewith the country’s two left-wing insurgencies.Commitment to the transparent and rigorousimplementation of the law could help advance therapprochement that is being attempted with the ELNthrough discussions conducted in Cuba and contributeto the establishment of a negotiation agenda with thatmovement. Eventual application of the JPL to the FARCis at present a very much more remote possibility due tothat larger movement’s adamant refusal to negotiate withthe Uribe administration.

II.

THE POLITICAL CONTEXT

The need to apply the JPL rigorously and transparently,in itself a daunting task, comes at a sensitive politicalmoment. The government’s failure to build consensusby incorporating amendments proposed by legislatorsand civil society organisations during the drawn-outcongressional process reduced the law’s acceptance.In order to gain much needed credibility and financialsupport, in particular outside Colombia, the Uribeadministration must now show it is committed to rigorousapplication.17There are no signs, however, thatimplementation will start soon, certainly not beforecompletion of the congressional and presidential electioncycle.18The constitutional court ruling, which couldmodify some core provisions of the law or suspend itin totality, is expected in May or June.19A pragmatic approach to paramilitary demobilisation andJPL implementation appears to be taking root both insideand outside Colombia.20Two diplomats in Bogotá toldCrisis Group the international community would havepreferred a “tougher” law that contemplated more severepunishment for those responsible for grave crimes and putmore emphasis on reparations for victims and findingtruth. But since the JPL was passed by a democratically-elected legislature and departs from the practice ofsweeping amnesties,21it is important to “reconcile justice

1718

Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 4 November 2005.The congressional election was on 12 March 2006; thepresidential election, conducted in two rounds unless a candidatereceives more than 50 per cent of the vote in the initial round, is28 May and 18 June.19In a non-binding opinion on 15 February 2006, StateProsecutor Edgardo Maya found the JPL unconstitutional inpart. He cited problems, among others, with omission ofinformation on crimes committed by individuals prosecutedunder the law, and provisions on the state’s responsibility forinvestigating crimes, the definition of victims, exclusion ofarmed forces members in its coverage, and the transfer ofillegally acquired assets to the National Reparation Fund.“Concepto no. 4030 del Procurador General de la Nación antela Corte Constitucional frente a la llamada Ley de Justicia yPaz”, Bogotá, 15 February 2006.20Crisis Group interviews, Brussels, 11 January 2006 andBogotá, 17-19 January 2006.21The first legal framework for the demobilisation and reinsertionof insurgent groups, Law 35 of 1982, granted amnesties to rebelgroups who demobilised without requiring them to hand theirweapons over to the state. Law 77 of 1989 provided the basisfor pardons granted to members of the Movimiento 19 deAbril (M-19), Ejercito Popular de Liberación (EPL), PartidoRevolucionario de los Trabajadores (PRT) and y MovimientoArmado Quintín Lame (MAQL) in 1990-1991. Once pardoned,some 4,000 ex-combatants were able to benefit from reformswhich facilitated their participation in politics. See Gabriel

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 4

and realpolitik” and cooperate with the Colombianauthorities in order to avoid more victims in the future.22This stance largely conforms with Uribe administrationpolicy. After paramilitary demobilisation ground to a haltfrom December 2003 until November 2004,23the HighCommissioner for Peace proudly announced demobilisationof one bloc after another throughout 2005. Despite atemporary halt by the main paramilitary organisation, theUnited Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC), dueto a U.S. extradition request for the arrested leaderDiego Murillo (alias Don Berna or Adolfo Paz) on drugcharges,2423,685 men, women, and children paramilitaries

had presented themselves for demobilisation as of 4March 2006. This is a significant number that reflectsprogress toward a major Uribe goal: “the extrication ofone armed actor from the conflict”.25Data on human rights and international humanitarian lawviolations from a variety of sources indicates an overallreduction in violations committed by paramilitary groupsbetween 2003 and 2005. According to the Centre forResearch and Popular Education (CINEP) in Bogotá,assassinations committed by paramilitaries have decreasedfrom 1,240 in 2003, to 686 in 2004 and 329 in 2005.Torture cases have fallen from 128 in 2003 to 77 in 2004and 59 in 2005. Disappearances have gone from 130 in2003 to 102 in 2004 and 65 in 2005. The number of deaththreats, however, increased from 271 in 2003 to 307 in2004 before falling to 243 in 2005. CINEP also recordedtwo sexual violations by paramilitaries in 2003, fourin 2004 and three in 2005.26Figures released by thegovernment’s National Fund for the Defence of PersonalFreedom show a drop in extortion-related kidnappingsinvolving paramilitary groups from 75 in 2004 to twentyin 2005.27The Vice President’s Office recorded a drop inhuman rights violations committed by paramilitaries,including abductions from 176 in 2003 to 110 in 2004and 29 in 2005, and massacres from fourteen in 2003to thirteen in 2004 and two in 2005.28A critical question, however, is whether the paramilitarycommand and control structure, communications andcapacity for regeneration are being dismantled. A seniorU.S. military official acknowledged that despite the manyparamilitary fighters who have given up some weapons(roughly one weapon for every three demobilising), aconsiderable number of groups have maintained theirstructures and their control over drug trafficking andillicitly acquired assets.29However, it is becoming ever clearer that the demobilisationand reinsertion of the paramilitaries, as it has been handledsince November 2003, involves a potentially high price

Turriago and José María Bustamante,Estudio de los procesosde reinserción en Colombia. 1991 – 1998(Bogotá, 2003); MarcoPalacios, “La Solución Politica al Conflicto Armado”, in RafaelPardo (ed.),El Siglo Pasado(Bogotá, 2001), pp. 501-508.22Crisis Group interviews, Bogotá, June 2005 and 16 January2006.23After the dismantling of the paramilitary Cacique Nutibarabloc in Medellín in November 2003, there were no othercollective demobilisations until November 2004, mostly due toan extensive, often deadly reshuffling of power within the UnitedSelf-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC) and uncertainty overthe legal framework for demobilisation and reinsertion ofirregular armed groups. In April 2004, the former leader of theAUC, Carlos Castaño, disappeared, probably killed by otherparamilitaries. In July, the government inaugurated the Zona deUbicación in Santa Fe de Ralito (Córdoba), where ten membersof the newly-created “AUC negotiation general staff” and 400bodyguards gathered after the government lifted their arrestwarrants. Three – Salvatore Mancuso, Ramón Isaza and IvánDuque – were permitted to appear before Congress where theyvociferously reiterated opposition to “spending a single day injail” and demanded a “political” negotiation. In September, arecorded explanation to the paramilitary commanders by HighCommissioner for Peace Restrepo that Uribe, not the U.S., hadthe last word on extradition was leaked to the Colombian press,allegedly by Mancuso and produced a crisis in the negotiations.Demobilisation of the Bananero and Catatumbo blocs inNovember and December 2004, respectively, along with that ofseveral smaller paramilitary units, restored some credibility tothe process, at least in government eyes, and came at the sametime as constitutional amendment allowing Uribe to run for re-election.24Murillo was arrested on 27 May 2005, charged withmurdering a congressman from Córdoba department. He wasput under house arrest on a farm near Santa Fe de Ralito, the siteof the government-AUC negotiations. In October, a New Yorkcourt demand for his extradition on drug trafficking charges wasrejected by the government. After U.S. Ambassador WilliamWood expressed his “disillusion” about the Colombian refusal,Murillo was transferred to the high security prison in Cómbita(Boyacá). Threatening to halt demobilisation and hinting thegovernment had agreed with them to foreclose extradition to theU.S., the AUC commanders achieved the transfer of Murillo toItagui prison in Medellín. Medellín is a stronghold of paramilitarygroups commanded by Murillo and has been for years the site ofintermittent talks between imprisoned ELN spokesman Francisco

Galán and civil society organisations, the Catholic Church andforeign and Colombian officials. SeeEl Tiempo,5 October 2005.25Crisis Group interview, High Commissioner for Peace,Bogotá, February 2003.26CINEP, Bogotá, 2005. Figures for the last semester of2005 are based on estimates taken from human rights andinternational humanitarian law violation reports and may besubject to change.27Fondelibertad. Bogotá, 2005. No consolidated data wasavailable for 2003.28Vice President’s Office, Human Rights Observatory, Bogotá,2005. Kidnapping figures were measured from January toOctober / November. Data on massacres was only availableup to October 2005.29Crisis Group interview, Miami, February 2006.

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 5

for Colombia and the Uribe government. The lack oftransparency that has characterised negotiations withthe AUC and the legitimacy deficit resulting from theway the JPL was enacted30could make it more difficultto apply the law and even affect the president’s re-election aspirations, while the reinsertion program’sshortcomings will become harder to address as timegoes by.31There is mounting evidence that the demobilisedparamilitaries – who were not defeated militarily bygovernment forces and in part continue to act aseconomically and politically powerful mafia-like groups32– are not willing to play by the JPL rules and honour theiragreements with the Uribe administration.33“Theinfluence of paramilitarism continues to be felt in diverseregions of the country, through pressures, threats andclandestine agreements to control local political, economicand social aspects”, UNHCHR says.34In effect, the government, with electioneering in full swingand the deadline for complete paramilitary demobilisationpast,35appears to be under increased pressure from bothdemobilised and still active paramilitaries, who aredetermined to make good the pledges they made in 2004and 2005 to expand their representation in congress andmaintain a firm grip on many regions.36A study releasedby the Colombian NGO Fundación Arco Iris in December2005 documented strong paramilitary interference in the2002 congressional elections and the races for governorand mayor in 2003. Two congressmen who reportedly

attended a meeting with AUC commander Rodrigo Tovar(alias Jorge 40) in January 200637were elected to thelower house and the senate by implausibly high marginsin 2002.38The spectre of paramilitary interference in the electoralprocess emerged forcefully again in January 2006 withgood evidence of attempts to place candidates on partylists for the congressional elections and to promotefavoured candidates by force, intimidation and bribery,particularly in the Atlantic coast departments. It wasreported that Tovar, who commanded the powerfulNorthern bloc of the AUC, which is currently completingits demobilisation, met with five candidates, fourcongressmen and a number of mayors of municipalitieson the Atlantic coast in Curumaní (Norte de Santander),before his recent demobilisation.39Reportedly, theaim was to “design the electoral strategy for the SierraNevada”.40After witnessing on 3 January a verbal fightbetween two senators from Córdoba department whoaccused each other of running with paramilitary support,President Uribe was compelled to ask the attorneygeneral’s office to investigate.41In Medellín and the coffeebelt, the political influence of paramilitary leaders DiegoMurillo, Iván Báez and Carlos Jiménez (alias Macaco) isnotorious.42Jairo Angarita, the former leader of the AUC’s Sinú andSan Jorge blocs, is another case in point. After demobilisingin January 2005, he announced his intention to stand forcongress in 2006 on the list of Congresswoman ZulemaJattin of Córdoba department, a paramilitary stronghold.43In November, he grudgingly withdrew after a presidentialcommuniqué was issued that stated members ofparamilitary groups could not participate in politics untilthey were fully demobilised and the JPL was applied,44and President Uribe ordered the arrest of any demobilisedparamilitary attempting to interfere with the electoralprocess. Only weeks later, however, as he and some 2,000fighters of the Central Bolivar bloc (BCB) were beingdemobilised, paramilitary commander Iván Duque defiedthe president’s order by calling for two congressionalseats to be reserved for demobilised members of his

See Crisis Group Latin America Report N�14,Colombia:Presidential Politics and Peace Prospects,16 June 2005;Crisis Group Latin America Report N�8,Demobilising theParamilitaries in Colombia: An Achievable Goal?,5 August2004.31See section IV below.32Fundación Ideaz Para la Paz has warned about the upsurge of“third generation” paramilitary groups with self-aggrandisinginterests and highly volatile command structures. See FundaciónIdeaz para la Paz,Siguiendo el conflicto,no. 25, Bogotá, 12August 2005.33An increasing number of independent observers in and outsideColombia believe the JPL is the result not only of the legislativeprocess in Congress but also of AUC negotiations in Santa Fede Ralito, Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 17 January 2006.34“Report of the High Commissioner”, op. cit., p. 32.35The government was forced to postpone the originaldeadline for full paramilitary demobilisation, 31 December2005, to 28 February 2006 owing to the temporary suspensionof demobilisations by the AUC in late 2005. Some 4,000paramilitaries of the Elmer Cardenas bloc and the CasanarePeseant Self-Defence Forces were still active and no timetablefor their demobilisation existed. See annex.36SeeRevista Semana,6-12 June 2005 and Rodrigo Tovar (Jorge40), “Desmovilización responsable y reinserción productiva”,2 March 2005, available at www.consejerosdepaz.org.

30

3738

See below.Arcanos, “Colombia: el país después de la negociación”,December 2005, pp. 39-47.39El Tiempo,18 January 2006.40Semana,23-30 January 2006, p. 34.41El Tiempo,16 January 2006, p. 1/2.42Semana,23-30 January, p. 38.43Angarita was Salvatore Mancuso’s deputy. In September2005 he declared he was “proud” to work for “the reelectionof the best president that the country has ever had”,El Tiempo,7 September 2005.44Presidencia de la República, Communiqué, 31 October2005.

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 6

group and reiterating that he wanted the demobilisedAUC to participate in elections soon as a legalorganisation.45Duque, who was a member of the AUC’snegotiation committee, has not been arrested.On 16 December 2005, U.S. Ambassador William Woodpublicly stated that paramilitaries attempting to participatein, or interfere with the elections should be denied anyjudicial benefits under the JPL.46Uribe responded harshly,rejecting any U.S. attempt to use Plan Colombia47tojustify interference in internal affairs.48The U.S. embassyquickly denied such an intention and reaffirmed itsconfidence in the government’s intention to implementthe JPL effectively.49A few days later, however, formerAmbassador Miles Frechette reiterated Wood’s pointin a radio interview, saying that the political influence ofillegal armed groups (including guerrillas and organisedcriminals) was on the rise since the 2002 elections, andthis was not well received in the U.S.50The constitutionalcourt ruled on 11 November 2005, with respect to the lawon electoral guarantees (Leyde garantías electorales),thatany electoral activity by demobilised members of illegalarmed groups who had not completed the full reinsertionprocess was prohibited.51

Under mounting domestic and international pressure, theheads of the pro-Uribe U and Cambio Radical parties– Juan Santos and Germán Vargas Lleras, respectively– dropped five candidates from their lists on 18January 2006, who were accused of direct links withthe paramilitaries.52Gina Parody, a pro-Uribecongresswoman, agreed to run for the senate on the Uparty list only after these actions.53The president of theLiberal party (and former president of Colombia), CesarGaviria, who several times had warned about paramilitaryinfiltration of the campaign and accused the governmentof insufficient response,54dropped a senate candidate,Vicente Blel, from his party’s list.55The Conservative party has not penalised CongressmanAlfonso Campo, who attended the meeting with Tovar.Instead it had to accept the Uribe decision not to inauguratehis campaign on 28 January in an event in which theseverely weakened Conservatives were to participate.Uribe’s decision was probably a reaction to the crisiscreated by the government’s apparently unfoundedaccusation that Senator (and Liberal party candidate)Rafael Pardo had conspired with the FARC against his re-election.56However, many expelled candidates rapidlyreappeared on the lists of minor pro-Uribe parties, such asHabib Merheg and Dieb Maloof with Colombia Viva,Rocio Arias with Dejen Jugar al Moreno and ElenoraPineda with Convergencia Ciudadana.57First unofficialresults of the 12 March polls suggest mixed results forthese “recycled” candidates. While Merheg and Maloofobtained seats in Congress, Arias and Pineda did not.58The political scene is further complicated by Uribe’srecent efforts – fruitless thus far – to engage the FARCin negotiations on a hostages/prisoner swap and tomove forward the exploratory talks with the ELN inCuba. Observers express a little optimism about therapprochement with the ELN, which has includedthe temporary release of the movement’s spokesman,Francisco Galán, from Itaguí prison and the establishmentof a “group of guarantors”59and a “peace house” (casade

These seats would be decided by the government, notelections.El Tiempo,12 December 2005. For more, seeFundación Ideas para la Paz,Siguiendo el conflicto,no. 37,Bogotá, 4 November 2005.46Ambassador Wood’s words were: “Last summer in the debateon the Justice and Peace Law, the embassy asked if an attemptto pervert the democratic process through corruption orintimidation by the paramilitaries would be deemed afundamental violation and would remove all benefits. Thenegotiators on the law assured us that it would. We take them attheir word. But we also want to make clear that we will urge theelimination of all benefits to any beneficiary under the Justiceand Peace law who is involved directly or indirectly in corruptionor intimidation in the elections”. Excerpt from remarks beforethe attorney general’s course on human rights and internationalhumanitarian law, Bogotá, 16 December 2005.47Plan Colombia is a multi-billion dollar U.S. aid package forColombia launched in 2000. Its primary aim is to fight drugtrafficking and terrorism. See Crisis Group Latin AmericaReport N�1,Colombia’s Elusive Quest for Peace,26 March2002.48“Comunicado de la Presidencia de la Republica sobredeclaraciones del Embajador de los Estados Unidos”,SNE,16 December 2005, available at www.presidencia.gov.co.49“Aclaración”, U.S. Embassy, 16 December 2005, athttp://Bogotá.usembassy.gov; RevistaCambio,23-30 January2006, pp. 24-25.50El Tiempo,19 December 2005.51“Sentencia C-1153/05”, Corte Constitucional, Bogotá, 11November 2005; “Ley 996 de 2005 por medio de la cual sereglamenta la elección de Presidente de la República, deconformidad con el artículo 152 literal f) de la ConstituciónPolítica de Colombia, y de acuerdo con lo establecido en el

45

Acto Legislativo 02 de 2004, y se dictan otras disposiciones”,Bogotá, 24 November 2005.52Habib Merheg, Dieb Maloof and Luis Vives were expelledfrom the U party and Jorge Caballero and Jorge Castro fromthe Cambio Radical party.El Tiempo,17 January 2006.53El Tiempo,27 January 2006.54El Espectador,11 December 2005.55El Tiempo,18 January 2006.56El Tiempo,26 January 2006, p. 1/6.57Daniel Coronell, “Los traslados”,Semana,6-13 February2006, p. 11.58El Tiempo,13 March 2006.59The guarantors include prominent civil society representativesand academics: Morits Akerman, Daniel García-Penna, ÁlvaroJiménez, Gustavo Ruiz and Alejo Vargas.

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 7

paz),60as well as two direct encounters between the Uribeadministration and members of the ELN central command(COCE) in Havana, in December 2005 and February2006.61While the meetings have built some trust betweenthe two parties, and the government has officiallyacknowledged Galán and Antonio Garcia as ELNrepresentatives, agreement on a negotiation agenda is stillpending. In early March the ELN asked citizens to votein the year’s elections and said it would not attempt tosabotage them as in the past, but its condemnation ofthe JPL62makes it questionable whether the Uribeadministration will be able to persuade the movement tocooperate with that law and thus demonstrate that it isapplicable to all armed groups, rather than, in effect, speciallegislation for the paramilitaries.If chances of demobilising the ELN on the basis of theJPL in the medium term are slim, they are next to nilfor the FARC, whose continued diatribes against thenegotiations with the paramilitaries and rejection of theJPL leave little room for their demobilisation under thatlaw.63Lack of progress on a hostages/prisoner swap,despite recent international efforts at facilitation, points tocontinuation of the armed confrontation. On 16 December2005, only four weeks after Uribe authorised it to act, an

international commission composed of French, Spanishand Swiss representatives, delivered a proposal outlininga 180-square kilometre demilitarised area in Praderamunicipality (Valle del Cauca), where internationalobservers and members of the International Committeeof the Red Cross (ICRC) would ensure safe passage fornegotiators and give special attention to the hostages.64Uribe’s public and almost immediate support for theinitiative caused surprise, not least because of his previousopposition to demilitarised areas.65However, on 29December FARC ruled out any exchange with the Uribeadministration, which it accused of playing electoralpolitics.66Subsequent heavy fighting in the south seemsto have polarised the issue further, and diplomatic effortsto promote the proposal, including a visit of French ForeignMinister Philippe Douste-Blazy, have been unsuccessful.

60

Established in Quirama (Antioquia) on 12 October 2005, the“peace house” is a site where ELN spokesman Francisco Galáncan meet, under the auspices of the group of guarantors, withcivil society representatives to discuss negotiations betweenthe government and the ELN. In its first three months,representatives of international organisations and governmentsas well as the private sector and the Church, and academicsvisited the peace house, which still exists. Galan was originallygranted a three-month safe-conduct to leave prison for themeetings. On 12 December, this was extended for an additionalthree months.61The meeting in Cuba was attended by the ELN commanders,Antonio García and Ramiro Vargas, as well as Galán. See JaimeZuluaga, “El ELN y el gobierno nacional: por el camino de lasnegociaciones”,UN Periódico,15 January 2006, pp. 2-3.62In August 2005, the ELN said that the “badly called justiceand peace law is the most inadequate instrument to overcomethe obstacles in the quest for peace we have outlined”. Accordingto the ELN the obstacles are: 1) “denial of the social, economicand political causes that gave rise to the conflict,” 2) pretendingthat peace is only a government-insurgent issue, 3) denying thedeep humanitarian crisis affecting the underprivileged sectorsof society, for which urgent measures need to be taken whilecontinuing to work for a political solution to the conflict, 4) thegovernment’s unwillingness to recognize the existence of aninternal armed conflict, 5) the fa§ade that are the negotiationsbetween the government and the paramilitaries. There neverwas a war between them, they have always cooperated andcoordinated their actions (…)” Jaime Zuluaga,UN Periodico,15 January 2006, p. 3.63See Crisis Group Latin America Report N�14,Colombia:Presidential Politics and Peace Prospects,16 June 2005.

6465

El Tiempo,13 December 2005.Crisis Group Report,Presidential Politics and PeaceProspects,op. cit.66FARC-EP communiqué, 29 December 2005.

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 8

III. JUSTICE AND REPARATIONPROBLEMSImplementation of the JPL, when it eventually begins,will put considerable pressure on state institutions. Thegovernment’s strategy to dismantle military structuresbefore applying the JPL faces serious challenges relatedto the administration of justice, victim reparations andparticipation of civil society, in particular victims, in theprocess. Serious doubts remain also about whether theJPL can be part of a broader pacification strategy thatincludes the FARC and ELN.

list’s requirements will be verified.68Even otherwiseoptimistic members of the attorney general’s office worryabout being overburdened with verifying extensive listsbefore the judicial process even begins.69According tothe JPL, those on the list must meet six conditions,including demobilisation and dismantling of the armedgroup of which they were members and the handing overof illegally obtained assets to the authorities.70But it isunclear how the executive plans to verify these conditionsand filter out those who do not meet the requirements.71In practice, it will be next to impossible for it to knowwhether weapons have been hidden or at the end of a trialwhether all illegal assets have been turned over.Another significant problem is the absence of a sufficientlycomprehensive database for serious crimes and humanrights violations and the difficulties the JPU will have toaccess and share information on demobilised individualswith other state agencies as well as the Church and civilsociety organisations. The judicial authorities are confidenttheir efforts to consolidate a database, which reportedlyincludes more than 15,000 cases of human rights violationsdocumented by both the human rights offices of the vicepresident and the attorney general, will produce enoughinformation for indictments.72Additionally, unlike withthe paramilitaries, there is no mention of reinsertion supportfor their newly released kidnapped victims, most of whomare women and children. The JPU will need to track downthese victims for the database to ensure they are offered

A.

ADMINISTRATION OFJUSTICE

The JPL presents the authorities with multiple difficulties.The new judicial infrastructure the law created lacks thecapacity to fulfil its tasks and will be highly dependent onwhat is at present insufficient cooperation between stateagencies with roles to play in implementation and onthe suspect good will and cooperation of demobilisedindividuals. There is also too little clarity regardingdetermination of eligibility for JPL-benefits, difficulty ineffectively monitoring the demobilisation and subsequentreinsertion of members of armed groups, and lack ofcertainty about the place and conditions of imprisonmentfor sentenced individuals.The Justice and Peace Unit (JPU) in the attorney general’soffice, the core of the new judicial infrastructure, is chargedwith investigating all individuals whose names aresubmitted by the executive as potential beneficiaries ofreduced sentences. Following this investigation, whichmay last a maximum of six months, JPU attorneys takethe demobilised individual’s voluntary confession and,depending on the case, may proceed with a criminalprosecution that must not take longer than 60 days. TheJPU is further in charge of determining the reparationssentenced individuals must make to victims through theNational Fund for Reparations.67On 7 February 2006, Attorney General Mario Iguaránannounced that the new unit was ready to start work butserious questions remain as to how it will operate andwhether it will contribute to establishing the truth aboutserious crimes. A first concern relates to the list of namesof the potential beneficiaries. Neither the JPL nor itsregulations make clear how this list will be drawn up,which government agency is responsible for which part ofthe process, and how an individual’s satisfaction of the

67

See section III.B. below.

According to the JPL regulations, the presidency submitsthe list of names to the ministries of interior and justice and ofdefence, which then send it to the attorney general’s office.69Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 5 December 2005.70To be eligible for benefits under the JPL, ex-combatants musthave fully demobilised and contributed to the dismantlement ofthe illegal armed group they belonged to, returned all ill-gottenassets, handed all underage fighters over to the ColombianFamily Welfare Institute (ICBF), ceased all actions aimed atinterfering with the free exercise of political and public rights,have returned all hostages and not have been organised forillegal drug trafficking. Drug trafficking is not subject toreduced sentences under JPL. It remains, though, unclear towhat degree aggressive prosecution of those demobilisedparamilitaries suspected of that crime will take place.71Its lack of clarity increases the chance most demobilisedparamilitaries will not apply for consideration under the JPL butwill be satisfied they were able to demobilise on the basis ofLaw 782. They have no incentive to apply for a place on the listas long as it is not certain whether the government will accepttheir request since an application would presumably meanscrutiny by the JPU. According to the law’s logic, only thosewho have committed grave crimes and believe they will not getaway after demobilising on the basis of Law 782 will have aninterest in being covered by the JPL. Thus, lack of clarity as tohow the executive will put together the list enhances the prospectof greater impunity.72Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 5 December 2005.

68

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 9

appropriate reparations. Nevertheless, questions remainabout how other information sources, including thethousands of cases local courts are processing, areincorporated into the database, and how informationcollection is coordinated with other agencies.73Both thestate prosecutor’s judicial justice and peace unit and theombudsman’s justice and peace unit, newly establishedby the JPL, will be important for ensuring that victims’testimony, particularly women's testimony and evidenceof human rights violations collected by civil society arebrought forward.74However, unless government agenciesefficiently share resources and provide gender-sensitiveelements in their programs, there is a risk informationwill be insufficient and even contradictory.75Crisis Groupsources indicate the Church has decided not to sharethe confidential database on human rights violationswhich its Pastoral Social has built.The success of the plea-bargaining process rests largelyupon the ability of the judicial system to verify confessionsand check them against other sources. But neither the JPLnor its regulations offer enough assurance in this respect.According to Article 5 of the regulatory degree,demobilised individuals must freely confess their crimesto become eligible for reduced sentences. If it laterappears they “forgot” a particular crime, their JPL-sentence would be increased only by 20 per cent. This ishigh on the list of provisions the state prosecutor has saidhe believes are unconstitutional. The relatively small costof being caught out in a lie will make it more difficult forauthorities to obtain the information they need forindictments and criminal prosecutions.76Much willdepend on the ability and dedication of the individual JPUattorney and the good will and cooperation of the JPL-prosecuted ex-combatant.Officials say that omissions will be minimal, becauseex-combatants will expect to be implicated when otherformer fighters confess77but this is a gamble. It is to beexpected that relatively few will be prosecuted under theJPL since by the time it begins to be implemented almosteveryone will have already demobilised under Law 782.Likely only the relative few will have opted to await thenew law, and prosecution under it, who fear they could7374

not get away without at least some punishment for theserious crimes they committed and possibly face theprospect of ICC prosecution. However, the lack of asufficiently comprehensive database on human rightsviolations and effective information sharing between stateagencies will make it almost impossible for the JPUto break the “rule of silence” among JPL-prosecutedsuspects. In addition, in spite of the officials’ confidencein their ability to recognise falsehoods,78prosecuted ex-combatants know they risk loss of benefits or a regularcriminal prosecution only if it is proven they haveintentionally omitted information.79Another difficulty is that imprisoned paramilitaries canapply through former commanders for inclusion on thebeneficiaries’ list.80This means that the majority ofparamilitaries already serving long sentences as well ascommon criminals and drug traffickers who can make thecase they were part of a paramilitary group could becomeeligible for sentence reductions.81High Commissioner forPeace Luis Restrepo, who is charged with evaluating allrequests for JPL benefits, has announced that he will

Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 7 December 2005.Civil Society organisations have widely documented humanrights violations. However, the lack of uniform methodologymakes consolidation of their data difficult. Fundación País Libre,for instance, relies mostly on press reports; CINEP´s databaseis a mix of documented cases and submitted complaints, whilethe Church relies on confidential testimony collected in parishes.75Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 6 December 2005.76The 60-day timeframe for verifying the confessions is itselfa serious obstacle to establishment of “judicial truth”. CrisisGroup interview, Bogotá, 5 December 2005.77Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 20 December 2005.

Crisis Group interview, 5 December 2005.Benefits will only be completely revoked, however, if it isproved that the sentenced ex-combatant “intentionally” omittedinformation on crimes when confessing. It will be very difficultto establish whether the omission was intentional or unintentional.In the latter case, the JPL-sentenced individual will only face a20 per cent increase of his/her reduced sentence.80It has been reported that since the JPL was passed and thedecree issued, the government and the attorney general havereceived an avalanche of written requests. Up to early January2006, some 1,200 requests had been received, approximatelyhalf pertaining to paramilitaries but with a significant percentageto the insurgents and common delinquents who claim to haveparticipated in paramilitary structures as logistical supporters orinformants. SeeEl Tiempo,8 January 2006, 1-3. In a Februarypress conference, the attorney general spoke of 1,400 requests,of which approximately 800 pertained to members ofparamilitary groups. See Fiscalía General de la Nación, op. cit.81Two cases exemplify this. A group of 70 paramilitaries whobelonged to the Calima Bloc are serving a 40-year sentence forkilling at least 30 people in the Naya region (Cauca) in 2001.Their chiefs (Don Berna, Hernando Hernandez and Gordolindo)have already demobilised. The second case is that of MarioJaimes (alias El Panadero), who was captured in 1999 andcharged with killing eight people. After serving only sevenyears of a much longer sentence, he would be just one year fromfreedom, according to the maximum sentence contemplated bythe JPL.El Tiempo,8 January 2006, 1-3. The exact number ofimprisoned paramilitaries is not known. In early January 2006,it was reported that there are approximately 3,200 paramilitaryprisoners,El Tiempo,8 Januray 2006. Press reports of Februarytalk of 4,331. SeeEl Colombiano,11 February 2006.79

78

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 10

address this.82However, it is unclear what filteringstandards will be used to protect the process.The need for an effective filtering mechanism has becomeall the more urgent as a result of attempts by drugtraffickers to purchase paramilitary “franchises” in orderto infiltrate the demobilisation process.83In October 2004,“Los machos” and “Los Rastrojos,” two gangs of assassinsat the service of Diego Montoya (alias Don Diego) andWilber Varela (alias Jabón), notorious heads of the “Nortedel Valle” drug trafficking cartel, changed theirnames to Rural Self-Defence Forces of Norte del Valle(AutodefensasCampesinas del Norte del Valle)84and theValle Peasant Units (RondasCampesinas del Valle),respectively, in an effort to pose as genuine paramilitaries.According to reports, both Montoya and Varela showedinterest in demobilising their armed structures if given thesame treatment as AUC leaders, including legal benefitsunder the JPL and the suspension of extradition ordersagainst them.85Congresswoman Rocío Arías – recentlyexpelled from the Colombia Democrática party due tolinks to paramilitary groups in Antioquia department – issympathetic. She says the JPL is flawed in not providingplausible alternatives for drug traffickers who want toreintegrate into society.86Perhaps even more troubling are the possible implicationsthe JPL and its regulatory decree will have in relation toordinary criminals. Under Article 70, prisoners whosecrimes are not related to sexual offences, drug-traffickingor human rights violations are entitled to a 10 per centsentence reduction if they have shown good conduct andhave undertaken to compensate their victims.87Article 71modifies the penal code to place sedition on an equalfooting with rebellion. The considerable release ofprisoners which may occur as a result of these two articlescould further complicate the implementation process and

further strain the overburdened attorney general’s office.Doubts remain in particular, about the logic underlyingthe 10 per cent reduction clause. While the law’s defendersargue that sentence reductions promote faster reintegrationinto civilian life for demobilised ex-combatants,88itappears that they will benefit perpetrators of heinouscrimes.Operational issues could also prove obstacles to JPLimplementation. Pending application of the new law,paramilitaries are being demobilised on the basis of Law782, which effectively sets ex-combatants free and,according to human rights organisations, in practiceprecludes any judicial follow-up because there are fewoutstanding charges against most paramilitary combatantsother than those for rebellion and sedition, which Law782 will free them of.89The government will also needto ensure security in areas where large numbers of ex-combatants are concentrated. The assassination of flowergrower Hernando Cadavid90by five ex-members of theHéroes de Granada bloc (commanded by Diego Murilloalias Don Berna) and the recent killing of six civilians bysuspected demobilised fighters near Medellín91suggestthat some former fighters maintain links to their oldcriminal structures or are developing new ones.The question of where JPL-sentenced ex-combatants willserve their sentences also needs to be resolved. AlthoughArticle 30 gives the government this responsibility,options are still being discussed. The favourite of formerparamilitary leaders such as Ernesto Baez and HernánGiraldo92would allow those covered by the JPL to servetheir sentences in specially established agriculturalcolonies, presumably in areas where paramilitary groupsused to operate. The lack of specific guidelines in both thelaw and its regulations make a government decision allthe more necessary. If indeed agricultural colonies are tobe used, the government must give assurances that theywill meet tight security standards and ex-combatants willnot be able to conduct illicit activities from confinement.93The extradition issue is also related to the sentencing ofex-combatants. According to Article 30, sentences do nothave to be served in Colombia.94This worried paramilitaryleaders, who broke off demobilisation in November 2005

82

On 8 September 2005, the government presented a list of35 presumed-to-be FARC guerrillas as the first potentialcandidates to benefit from the JPL. After media pressure, sixwere shown to have committed ordinary crimes and wereremoved from the list. SeeEl Tiempo,29 October 2005, 1/6.83Ex–President and former OAS General Secretary CesarGaviria denounced this trend at a Liberal party event inBarranquilla and referred to the current process as “paramilitarylegitimation”, not reconciliation. SeeEl Tiempo,25 October2005, 1-4.84El Tiempo,29 October 2005, 1-6.85See below in this section.86See,El Tiempo,9 November 2005, 1-4.87In October 2005, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of a civilservant charged with misuse of public funds who wanted hissentence reduced under the terms of Article 70 of the JPL. Thisis an important precedent suggesting the court interprets the lawas applicable to all persons serving sentences, with the exceptionsalready mentioned. SeeEl Colombiano,3 November 2005.

Such arguments were made during the congressional debateon the JPL. SeeGaceta del Congreso289, Bogotá, 25 May 2005.89Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 7 December 2005.90On that occasion, Murillo called for public oversight ofdemobilisations. SeeEl Tiempo,25 October 2005, 1-4.91El Tiempo,13 February 2006.92El Tiempo,16 September 2005 andSemana,29 January2006, respectively.93The concern is to avoid a repetition of the prison conditionsthat the late drug lord Pablo Escobar once enjoyed.94SeeLey 975,25 July 2005, 10.

88

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 11

and demanded a government clarification.95However,this ambiguity has given the government some leverage.During the visit of John Walters, director of the WhiteHouse Office of National Drug Control Policy, inNovember 2005, Vice President Francisco Santos assertedthat the government would not negotiate extradition withillegal armed groups and would consider temporarilysuspending extradition orders for demobilised paramilitaryleaders only if assured of full cooperation in thedismantling of military and drug-trafficking structures,victim restitution and fulfilment of all other JPLrequirements.96Walters, who welcomed Santos’sassurance on the negotiation point, indicated that the U.S.would maintain its extradition demands.97Althoughparamilitary leaders such as the recently demobilisedHernán Giraldo claim that the “the peace process standsabove extradition”,98the lack of guarantees continues togenerate uneasiness among ex-combatants, and it isunclear how Uribe will handle this sensitive topic duringthe implementation process.

implementing the JPL because – to be blunt – the lawputs perpetrators first and victims second – despite theprovision that “the process of national reconciliation thatwill flow from the present law must in all cases promotethe right of victims to truth, justice and reparation”.99The JPL provides for creation of the National Reparationand Reconciliation Commission (NCRR) and the NationalReparation Fund (NRF). The former is chaired by the vicepresident and includes the public prosecutor, the ministersof interior and justice and of finance, the ombudsman,two victims’ representatives, five distinguished privatepersons and the director of Acción Social, the presidency’shumanitarian and international cooperation agency.100The NCRR will operate five regional commissionscharged with overseeing restitution of assets (Comisionesregionales de restitución de bienes).101Representativesof indigenous and Afro-Colombian citizens as well aswomen's organisations, three groups disproportionatelyaffected as victims of the conflict, both as displacedpersons and among the missing and killed, have madestrong pleas to participate at all levels in the reparationprocess.102The NRF is managed by the director ofAcción Social.Reparation is defined as the restitution of assets andpayment of compensation to victims, as well as theirrehabilitation and guarantees that the crimes will not berepeated. Only demobilised members of the armed groupswho are prosecuted and sentenced under the JPL – inall probability a small minority of the total of ex-combatants103– will be obliged to hand over to the NRFthe illegally-obtained assets they have in their possession.Following criteria developed by the NCRR, the judicialauthorities will then determine what kind of reparationsare to be made (collective or individual and material orsymbolic) and to whom. Except for collective governmentreparation programs, which are to be designed on the basisof NCRR recommendations to rebuild state institutionsin areas particularly affected by violence and generalhumanitarian measures (such as IDP assistance), whichare a government responsibility distinct from the issueof reparations, the authorities’ role is restricted to the

B.

REPARATIONS FORVICTIMS

Although large parts of the JPL and the regulatory decreeare dedicated to the subject, the legal framework fordemobilisation and reinsertion of armed groups isinadequate with respect to reparations for victims andlimits the state’s responsibility. The primary focus is onhow, and under what conditions, alternative sentenceswill be applied and the incentives for demobilised andprosecuted members of armed groups to cooperate withthe authorities. The reparations issue, therefore, is likelyto be the hardest for the government to handle while

9596

See section II above.El Tiempo,10 November 2005, 1-6. Nine paramilitary chiefsare sought for extradition: Ramiro “Cuco” Vanoy Murillo(demobilised on 20 January 2006 with the “Mineros” Bloc, he issought for drug-trafficking by a South Florida district courtsince 1999; at various times he worked for Pablo Escobarand was part of the Pepes, a criminal gang that fought againstEscobar,El Tiempo,11 January 2006, 1-12 andEl Tiempo,20January 2006, 1-16); Carlos Jimenez “Macaco” (allegedlycontrols drug trafficking in lower Cauca in Antioquia, south ofBolivar, Putumayo and Catatumbo; has been involved in armsfor drugs swaps and worked in the 1980s for the Valle Cartel,ElTiempo,6 November 2005, 1-4); Rodrigo Tovar Pupo “Jorge40” (extradition requested by the U.S. for drug-trafficking,aggravated murder and membership in a terrorist organisation;El Tiempo,29 January 2006, 1-6); Diego Murillo “Don Berna”;Francisco Zuluaga “Gordolindo”; Victor Mejía “El mellizo”;Vicente Castaño; Hernán Giraldo (ElEspectador,5 – 11February 2006, 2A andEl Tiempo,4 February 2006, 1-4); andSalvatore Mancuso. SeeEl Tiempo,9 Novermber 2005, 1-4.97Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 17 January 2006.98SeeEl Espectador,5 – 11 February 2006, 2A.

Justice and Peace Law, Article 4.The vice president, the ministers, the ombudsman and thedirector of Acción Social (charged with the technical secretariat)may delegate their responsibilities.101Each regional commission is composed of one member ofthe NCRR (who presides over it), a representative of the publicprosecutor’s justice and peace unit, a delegate of the municipalor district ombudsman, a delegate of the national ombudsmanand a delegate of the ministry of the interior and justice.102Crisis Group interview, Washington, February 2006. Theyhave also urged the U.S. to support their requests with theColombian government.103See section III A above.100

99

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 12

establishment of the NCRR and the NRF.104However, theColombian state is also partly responsible for the sufferingof the victims because it tolerated the paramilitary violencefor years. It would be appropriate for it to acknowledgethis partial responsibility and find ways of contributingmore assertively to victim reparations rather than leavingthe matter to the NRF.In principle, all reparations have to be “integral” inthe language of the JPL, that is to involve a series ofinterlocking steps,105and will be paid for by the NRF,including in those cases in which only the responsibilityof the armed group as a whole, not of an individualperpetrator of a crime or abuse could be established.The victims, individually or in groups, are entitled togovernment protection and may submit evidence andrequest a hearing during a trial. They have the furtherright to obtain information from the authorities regardingcases, and they can go before the ordinary courts anddemand the return of assets taken from them whichconvicted ex-combatants have not turned over to the NRF.The NCRR’s role in making reparations happen andpromoting reconciliation is vital but the body faces greatdifficulties. It is charged with guaranteeing that victimscan participate in the trials, obtain reparations and learnthe truth about crimes committed against them and theirfamilies. However, it lacks the necessary powers106and,in addition, will be overburdened with tasks as varied asproducing a study on the origins and evolution of thearmed conflict and reviewing the reparation measures and

reinsertion programs every two years.107Its members aresaid to have little administrative experience.108Perhaps most troubling, however, is that the burden ofproof is on the victims, who must defend their interestsand rights against perpetrators who in effect are notcompelled to reveal the full truth and give up all theirillegal assets.109In practice, reparation will depend on acombination of a victim’s perseverance, the degree ofsupport the NCRR offers, the effectiveness of the judicialauthorities, including in making information on the rightsof victims readily available, and the cooperation and goodwill of the perpetrators.110It will be even more difficultto satisfy the need of families of disappeared or missingpersons to learn what happened to their relatives. Even theinformation from perpetrators will need to be investigated,and help should be sought from organisations such as theInternational Commission on Missing Persons, which hasan impressive record in the Balkans, and the ArgentineForensic Anthropology Team, whose work in identifyingthe bodies of missing persons has now been supported bythe Buenos Aires government.111The diverse nature of the large universe of victims posesadditional problems. In many cases it will be difficult,if not impossible, to establish who is a victim.112Somerepresentatives of victim associations, such as theMovement of Victims of Crimes of the State and theParamilitaries (Movimientode Victimas de Crimenes delEstado y de los Paramilitares),question the NCRR’sindependence, because it is nominally chaired by the

On 9 February 2006, the director of Acción Social, LuisHoyos, met with the president of the NCRR, Eduardo Pizarro,to inform him of the successes of the government’s humanitarianassistance and social programs. Pizarro acknowledged theimportance of Acción Social’s work but made it clear that suchprograms could only be considered complementary to theNCRR’s victim reparation work. “Apoyo a victimas de AcciónSocial, un complemento a política de reparación”, AgenciaPresidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Social,Bogotá, 9 February 2006; Crisis Group interviews, Bogotá,7 December 2005 and 20 January 2006.105These steps are: 1) handing over to the authorities the illegally-obtained assets for victim reparation (not specified that all assetsmust be handed over); 2) public declaration by the prosecutedindividual of the crime committed in order to contribute to re-establishing the dignity of the victim; 3) public acknowledgmentof having caused harm to the victims and plea to be pardoned bythe victims as well as promise that the offences will not berepeated; 4) effective collaboration with the authorities infinding abducted and missing persons and the identification ofburial sites. JPL, Articles 45.1-45.4.106Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 7 December 2005.

104

According to the terms of the Justice and Peace Law, theNCRR is in change of: 1) guaranteeing victim participation injudicial truth-finding (esclareicimiento judicial) operations; 2)issuing a public report explaining the upsurge and evolution ofillegal armed groups; 3) following and verifying the reinsertionprocess and efforts by local authorities to demobilise illegalarmed groups fully (to this end, the NCRR can requestcooperation from international organisations and specialists); 4)following and evaluating the evolution of victim reparation asoutlined by the JPL and making recommendations to ensureadequate execution; 5) two years after promulgation of thelaw, reporting on the victim reparation process to the PeaceCommissions of the Senate and the lower house and the nationalgovernment; 6) recommending the criteria for victim reparationand management of the NRF; 7) coordinating the operation ofthe regional restitution commissions; 8) proposing nationalpolicies and programs that promote reconciliation and preventthe resurgence of violence; and 9) determining its ownoperational criteria and regulations.108Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 7 December 2005.109Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 6 December 2005.110Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 7 December 2005.111http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/0/d9bde57fbd4969f3c126f62003ec02d?; also see, http://www.ic-mp.org/home.php?acticmp on the International Commission on Missing Persons.112Crisis Group interview, Bogotá, 19 January 2006.

107

Colombia: Towards Peace and Justice?Crisis Group Latin America Report N�16, 14 March 2006

Page 13

vice president, and say they will not work with it inorder not to give it undeserved legitimacy.113Thetwo commissioners – out of thirteen – charged withrepresenting the victims are perceived as unable to dotheir job properly since they will be in a minority positionand not independent from the government.114Also, theJPL does not foresee any victim participation in the workof the regional restitution commissions, a seriousdeficiency given the scale of illegal land appropriationby the paramilitaries and the widespread absence of landtitles.As discussed above, establishing the truth about crimesand abuses committed by members of armed groupswill depend to a large degree on cooperation from theperpetrators during JPL-prosecutions. What emerges fromthe trials will likely be a limited “judicial truth” based onvoluntary confessions, not aggressive interrogations orparallel investigations carried out by an independent truthcommission.115The JPL’s weakness at establishing withhigh certainty who was responsible for which crimes andthe difficulties the government will face in dismantlingthe entrenched paramilitary structures will complicate theNCRR’s work considerably.116The commission will haveto elaborate the criteria for making reparations throughthe NRF only to the victims of convicted perpetratorsor to those who have otherwise proven their cases.Moreover, everything indicates the NRF will not havesufficient funds, mainly because few members of armedgroups will be sentenced under the JPL, and straw menhold many of their illegal assets.117The judicial authorities,