Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2005-06

Bilag 63

Offentligt

Command’sResponsibilityDetainee Deaths in U.S. Custody in Iraq and AfghanistanWritten by Hina Shamsi and Edited by Deborah PearlsteinFebruary 2006

Table of ContentsI. Introduction................................................................ 1II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force ......... 5Twelve Individual Cases Profiled.................... 6III. Death by Officially Unknown, “Natural”or Other Causes .................................................... 21Nine Individual Cases Profiled...................... 21IV. Failures in Investigation ........................................ 29V. Failure of Accountability......................................... 35VI. The Path Ahead .................................................... 41VII. Appendices .......................................................... 43VIII. Endnotes.......................................................... 103

A Human Rights First Report

About UsHuman Rights First is a leading human rights advocacy organiza-tion based in New York City and Washington, DC. Since 1978, wehave worked in the United States and abroad to create a secureand humane world – advancing justice, human dignity, andrespect for the rule of law. All of our activities are supported byprivate contributions. We accept no government funds.

AcknowledgementsThis report was written by Hina Shamsi and edited byDeborah Pearlstein.Others who contributed to the report are Maureen Byrnes,Avi Cover, Miriam Datskovsky, Ken Hurwitz, Allison Johnson,Priti Patel, Michael Posner, and Lauren Smith. Michael Russomade substantial contributions at all stages of research andreport-writing.Human Rights First would like to thank the many former militaryofficers and other experts who generously provided insights onaspects of the report.Human Rights First gratefully acknowledges the generous supportof the following: Anonymous (2); Arca Foundation; The AtlanticPhilanthropies; The David Berg Foundation; Joan K. Davidson(The J.M. Kaplan Fund); Charles Lawrence Keith and Clara MillerFoundation; The Elysium Foundation; FJC – A Foundation of DonorAdvised Funds; Florence Baker Martineau Foundation;Ford Foundation; The Arthur Helton Fellowship; Herb BlockFoundation; JEHT Foundation; John D. & Catherine T. MacArthurFoundation; John Merck Fund; The Kaplen Foundation; MerlinFoundation; Open Society Institute; The Overbrook Foundation;Puget Sound Fund of Tides Foundation; Rhodebeck CharitableTrust; The Paul D. Schurgot Foundation, Inc.; TAUPO CommunityFund of Tides Foundation; The Oak Foundation.Cover design: Sarah GrahamCover photo: Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Headquarters333 Seventh Avenue13thFloorNew York, NY 10001-5108Tel: 212.845.5200Fax: 212.845.5299www.humanrightsfirst.org

Washington D.C. Office100 Maryland Avenue, N.E.Suite 500Washington, DC 20002-5625Tel: 202.547.5692Fax: 202.543.5999

Command’s Responsibility documents a dozen brutal deaths as the resultof the most horrific treatment. One such incident would be an isolatedtransgression; two would be a serious problem; a dozen of them is policy.The law of military justice has long recognized that military leaders areheld responsible for the conduct of their troops. Yet this report alsodocuments that no civilian official or officer above the rank of majorresponsible for interrogation and detention practices has been charged inconnection with the torture or abuse-related death of a detainee in U.S.custody. And the highest punishment for anyone handed down in the caseof a torture-related death has been five months in jail. This is notaccountability as we know it in the United States.John D. HutsonRear Admiral (Ret.), JAGC, USN

The torture and death catalogued in excruciating detail by this importantHuman Rights First report did not happen spontaneously. They are theconsequence of a shocking breakdown of command discipline on the partof the Army’s Officer Corps. It is very clear that cruel treatment ofdetainees became a common Army practice because generals andcolonels and majors allowed it to occur, even encouraged it. What isunquestionably broken is the fundamental principle of commandaccountability, and that starts at the very top. The Army exists, not just towin America’s wars, but to defend America’s values. The policy andpractice of torture without accountability has jeopardized both.David R. IrvineBrig. Gen. (Ret.) USA

Command’s Responsibility — 1

I. IntroductionDo I believe that [abuse] may have hurt us in winning the hearts and minds of Muslims aroundthe world? Yes, and I do regret that. But one of the ways we address that is to show the worldthat we don’t just talk about Geneva, we enforce Geneva . . . . [T]hat’s why you have these mili-tary court-martials; that’s why you have these administrative penalties imposed upon thoseresponsible because we want to find out what happened so it doesn’t happen again. And ifsomeone has done something wrong, they’re going to be held accountable.U.S. Attorney General Alberto GonzalesConfirmation Hearings before the Senate Judiciary CommitteeJanuary 6, 2005

Basically [an August 30, 2003 memo] said that as far as they [senior commanders] knew therewere no ROE [Rules of Engagement] for interrogations. They were still struggling with the defi-nition for a detainee. It also said that commanders were tired of us taking casualties and they[told interrogators they] wanted the gloves to come off . . . . Other than a memo saying that theywere to be considered “unprivileged combatants” we received no guidance from them [on thestatus of detainees].Chief Warrant Officer Lewis WelshoferTestifying during his Court Martial for Death of Iraqi General Abed Hamed MowhoushJanuary 19, 2006

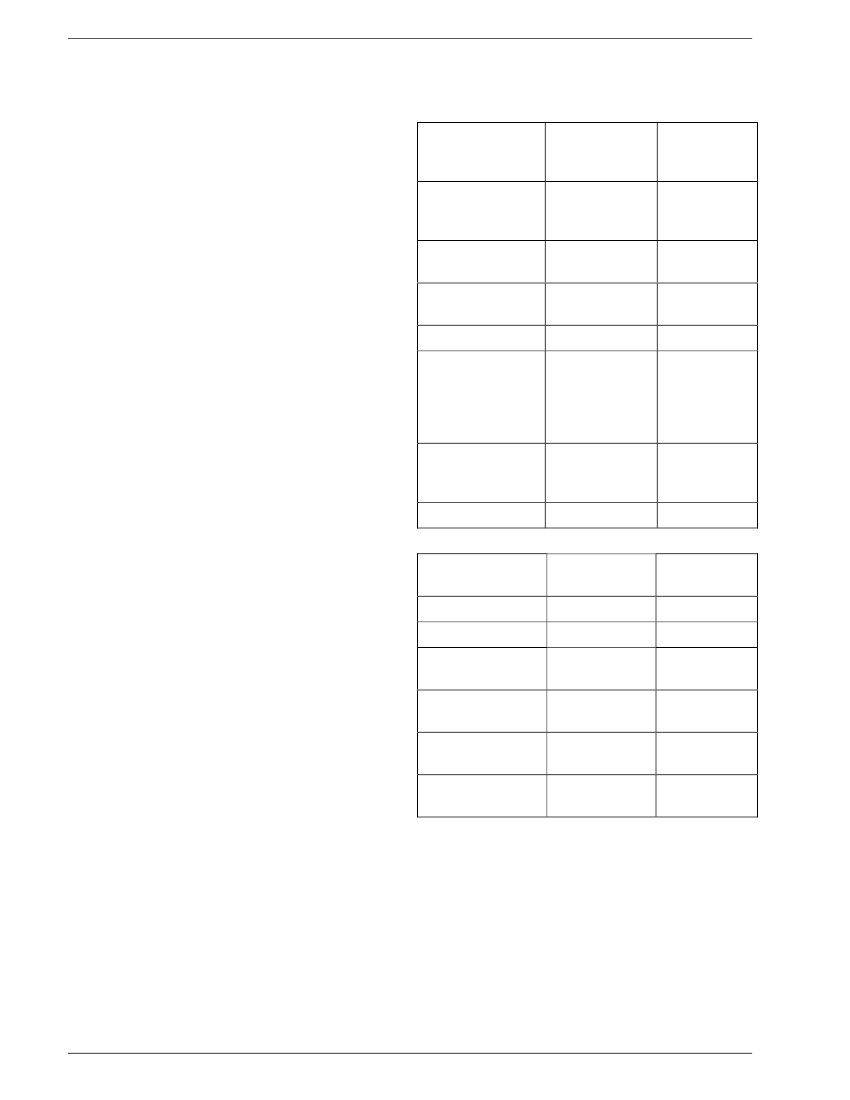

Since August 2002, nearly 100 detainees have diedwhile in the hands of U.S. officials in the global “war onterror.” According to the U.S. military’s own classifica-tions, 34 of these cases are suspected or confirmedhomicides; Human Rights First has identified another11 in which the facts suggest death as a result ofphysical abuse or harsh conditions of detention. Inclose to half the deaths Human Rights First surveyed,the cause of death remains officially undetermined orunannounced. Overall, eight people in U.S. custodywere tortured to death.Despite these numbers, four years since the first knowndeath in U.S. custody, only 12 detainee deaths haveresulted in punishment of any kind for any U.S. official.Of the 34 homicide cases so far identified by themilitary, investigators recommended criminal charges in

fewer than two thirds, and charges were actuallybrought (based on decisions made by command) inless than half. While the CIA has been implicated inseveral deaths, not one CIA agent has faced a criminalcharge. Crucially, among the worst cases in this list –those of detainees tortured to death – only half haveresulted in punishment; the steepest sentence foranyone involved in a torture-related death: five monthsin jail.It is difficult to assess the systemic adequacy ofpunishment when so few have been punished, andwhen the deliberations of juries and commanders arelargely unknown. Nonetheless, two patterns clearlyemerge: (1) because of investigative and evidentiaryfailures, accountability for wrongdoing has been limitedat best, and almost non-existent for command; and (2)

A Human Rights First Report

2 — I. Introduction

commanders have played a key role in underminingchances for full accountability. In dozens of casesdocumented here, grossly inadequate reporting,investigation, and follow-through have left no one at allresponsible for homicides and other unexplaineddeaths. Commanders have failed both to provide troopsclear guidance, and to take crimes seriously byinsisting on vigorous investigations. And commandresponsibility itself – the law that requires commandersto be held liable for the unlawful acts of their subordi-nates about which they knew or should have known –has been all but forgotten.The failure to deal adequately with these cases hasopened a serious accountability gap for the U.S.military and intelligence community, and has produceda credibility gap for the United States – betweenpolicies the leadership says it respects on paper, andbehavior it actually allows in practice. As long as theaccountability gap exists, there will be little incentive formilitary command to correct bad behavior, or for civilianleadership to adopt policies that follow the law. As longas that gap exists, the problem of torture and abuse willremain.This report examines how cases of deaths in custodyhave been handled. It is about how and why this“accountability gap” between U.S. policy and practicehas come to exist. And it is about why ensuring thatofficials up and down the chain of command bearresponsibility for detainee mistreatment should be a toppriority for the United States.

The Cases to DateThe cases behind these numbers have names andfaces. This report describes more than 20 cases indetail, to illustrate both the failures in investigation andin accountability. Among the cases is that of Manadelal-Jamadi, whose death became public during the AbuGhraib prisoner-abuse scandal when photographsdepicting prison guards giving the thumbs-up over hisbody were released; to date, no U.S. military orintelligence official has been punished criminally inconnection with Jamadi’s death.The cases also include that of Abed Hamed Mow-housh, a former Iraqi general beaten over days by U.S.Army, CIA and other non-military forces, stuffed into asleeping bag, wrapped with electrical cord, andsuffocated to death. In the recently concluded trial of alow-level military officer charged in Mowhoush’s death,the officer received a written reprimand, a fine, and 60days with his movements limited to his work, home,and church.And they include cases like that of Nagem SadoonHatab, in which investigative failures have madeaccountability impossible. Hatab, a 52-year-old Iraqi,was killed while in U.S. custody at a holding campclose to Nasiriyah. Although a U.S. Army medicalexaminer found that Hatab had died of strangulation,the evidence that would have been required to secureaccountability for his death – Hatab’s body – wasrendered unusable in court. Hatab’s internal organswere left exposed on an airport tarmac for hours; in theblistering Baghdad heat, the organs were destroyed;the throat bone that would have supported the Armymedical examiner’s findings of strangulation was neverfound.Although policing crimes in wartime is always challeng-ing, government investigations into deaths in custodysince 2002 have been unacceptable. The casesdiscussed in this report include incidents where deathswent unreported, witnesses were never interviewed,evidence was lost or mishandled, and record-keepingwas scattershot. They also include investigations thatwere cut short as a result of decisions by commanders– who are given the authority to decide whether and towhat extent to pursue an investigation – to rely onincomplete inquiries, or to discharge a suspect beforean investigation can be completed. Given the extent ofthe non-reporting, under-reporting, and lax recordkeeping to date, it is likely that the statistics reportedhere, if anything, under-count the number of deaths.

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 3

Among our key findings:•Commanders have failed to report deaths ofdetainees in the custody of their command, re-ported the deaths only after a period of days andsometimes weeks, or actively interfered in efforts topursue investigations;Investigators have failed to interview key wit-nesses, collect useable evidence, or maintainevidence that could be used for any subsequentprosecution;Record keeping has been inadequate, furtherundermining chances for effective investigation orappropriate prosecution;Overlapping criminal and administrative investiga-tions have compromised chances foraccountability;Overbroad classification of information and otherinvestigation restrictions have left CIA and SpecialForces essentially immune from accountability;Agencies have failed to disclose critical informa-tion, including the cause or circumstance of death,in close to half the cases examined;Effective punishment has been too little andtoo late.

Closing the Accountability GapThe military has taken some steps toward correctingthe failings identified here. Under public pressurefollowing the release of the Abu Ghraib photographs in2004, the Army reopened over a dozen investigationsinto deaths in custody and conducted multiple investi-gation reviews; many of these identified serious flaws.The Defense Department also “clarified” some existingrules, reminding commanders that they were requiredto report “immediately” the death of a detainee toservice criminal investigators, and barring release of abody without written authorization from the relevantinvestigation agency or the Armed Forces MedicalExaminer. It also made the performance of an autopsythe norm, with exceptions made only by the ArmedForces Medical Examiner. And the Defense Depart-ment says that it is now providing pre-deploymenttraining on the Geneva Conventions and rules ofengagement to all new units to be stationed in Iraq andresponsible for guarding and processing detainees.But these reforms are only first steps. They have notaddressed systemic flaws in the investigation ofdetainee deaths, or in the prosecution and punishmentof those responsible for wrongdoing. Most important,they have not addressed the role of those leaders whohave emerged as a pivotal part of the problem –military and civilian command. Commanders are theonly line between troops in the field who need clear,usable rules, and policy-makers who have providedbroad instructions since 2002 that have been at worstunlawful and at best unclear. Under today’s militaryjustice system, commanders also have broad discretionto insist that investigations into wrongdoing be pursued,and that charges, when appropriate, be brought. Andcommanders have a historic, legal, and ethical duty totake responsibility for the acts of their subordinates. Asthe U.S. Supreme Court has recognized since WorldWar II, commanders are responsible for the acts oftheir subordinates if they knew or should have knownunlawful activity was underway, and yet did nothing tocorrect or stop it. That doctrine of command responsi-bility has yet to be invoked in a single prosecutionarising out of the “war on terror.”Closing this accountability gap will require, at aminimum, a zero-tolerance approach to commanderswho fail to take steps to provide clear guidance, andwho allow unlawful conduct to persist on their watch.Zero tolerance includes at least this:

•

•

•

•

•

•

A Human Rights First Report

4 — I. Introduction

First, the President, as Commander-in-Chief,should move immediately to fully implement theban on cruel, inhuman and degrading treatmentpassed overwhelmingly by the U.S. Congressand signed into law on December 30, 2005.Fullimplementation requires that the President clarify hiscommitment to abide by the ban (which was called intoquestion by the President’s statement signing the billinto law). It also requires the President to instruct allrelevant military and intelligence agencies involved indetention and interrogation operations to review andrevise internal rules and legal guidance to make surethey are in line with the statutory mandate.

Finally, Congress should at long last establishan independent, bipartisan commission toreview the scope of U.S. detention and interroga-tion operations worldwide in the “war on terror.”Such a commission could investigate and identify thesystemic causes of failures that lead to torture, abuse,and wrongful death, and chart a detailed and specificpath going forward to make sure those mistakes neverhappen again. The proposal for a commission hasbeen endorsed by a wide range of distinguishedAmericans from Republican and Democratic membersof Congress to former presidents to leaders in the U.S.military. We urge Congress to act without further delay.

Second, the President, the U.S. military, andrelevant intelligence agencies should takeimmediate steps to make clear that all acts oftorture and abuse are taken seriously – not fromthe moment a crime becomes public, but fromthe moment the United States sends troops andagents into the field.The President should issueregular reminders to command that abuse will not betolerated, and commanders should regularly givetroops the same, serious message. Relevant agenciesshould welcome independent oversight – by Congressand the American people – by establishing a central-ized, up-to-date, and publicly available collection ofinformation about the status of investigations andprosecutions in torture and abuse cases (including trialtranscripts, documents, and evidence presented), andall incidents of abuse. And the Defense and JusticeDepartments should move forward promptly with long-pending actions against those involved in cases ofwrongful detainee death or abuse.

This reportunderscores what a growing number ofAmericans have come to understand. As a distinguishedgroup of retired generals and admirals put it in aSeptember 2004 letter to the President: “Understanding whathas gone wrong and what can be done to avoid systemicfailure in the future is essential not only to ensure that thosewho may be responsible are held accountable for any wrong-doing, but also to ensure that the effectiveness of the U.S.military and intelligence operations isnot compromised by an atmosphere of permissiveness,ambiguity, or confusion. This is fundamentally acommand responsibility.” It is the responsibility ofAmerican leadership.

Third, the U.S. military should make good on theobligation of command responsibility by devel-oping, in consultation with congressional,military justice, human rights, and other advi-sors, a public plan for holding all those whoengage in wrongdoing accountable.Such a planmight include the implementation of a single, high-levelconvening authority across the service branches forallegations of detainee torture and abuse. Such aconvening authority would review and make decisionsabout whom to hold responsible; bring uniformity,certainty, and more independent oversight to theprocess of discipline and punishment; and makepunishing commanders themselves more likely.

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 5

II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or ForceAn American soldier told us of our father’s death. He said: “Your father died during the interro-gation.” So we thought maybe it was high blood pressure under personal stress. This wouldhappen in American detention centers. People would die of high blood pressure. But afterwardsthe people who were imprisoned, detained with him said: “No. They would torture him and theyassigned American soldiers to him especially for the torture. He died during the torture.” . . .Honestly, my mother, after the case, after they brought my father dead, she entered a state wecan say a coma or like a coma. She withdrew from life.Hossam Mowoush (in translation)Son of Iraqi Maj. Gen. Abed Hamed Mowhoush,1Killed in U.S. Custody November 26, 2003

Of the close to 100 deaths in U.S. custody in the global“war on terror,”2at least a third were victims of homi-cide at the hands of one or more of their captors.3Atleast eight men, and as many as 12, were tortured todeath.4The homicides also include deaths that themilitary initially classified as due to “natural causes,”and deaths that the military continues to classify as“justified.” This chapter briefly reviews the facts of someof these worst cases, and the consequences – or not –for those involved.

Definition of a DetaineeIn this report, we include any death of a detainee under effectiveU.S. control as a “death in custody.” We adopt the definition of“detainee” used by the U.S. Army Criminal Investigative Command(CID) – the Army’s agency for investigating crimes committed bysoldiers – “any person captured or otherwise detained by an armedforce.”5For the purposes of this report, we do not include peoplekilled in the course of combat or as a result of injuries sustainedduring combat, or persons shot at checkpoints when it is allegedthat they disobeyed orders to stop their vehicle. We do includeprisoners in U.S. military detention centers, as well as those whohave been killed while being interrogated in their homes, or shot atthe point of their capture, after surrendering to U.S. troops. Once aperson has been captured, the U.S. military or intelligence agencyassumes control over him, and can restrain him against his will. It isunder these circumstances that American law and values are mostacutely tested.

A Human Rights First Report

6 — II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force

PROFILE: HOMICIDESo then the interrogator came that used to interrogate [me] in the Baghdadi jail. . . . He told me:“We are going to let you see your father.” Of course this was a point of relief. [Mohammed wastaken by U.S. forces to the facility where his father was held, the “Blacksmith Hotel.”]. . . . Theytook me to my father’s room. He was under very tight security. I looked in and I saw him. Helooked completely drained and distraught and the impacts or signs of the torture were clear onhim. His clothes were old and torn. He was really upset. When I first saw him I was over-whelmed and had a breakdown. I started crying and I embraced him and I told him: “Don’tworry. I am brave. I am going to be able to handle these circumstances like you taught me.” Atthis instant the interrogator stormed in. He grabbed me and I tried to remain seated . . . . So hethreatened my father that if he didn’t speak he would turn me over to the men who interrogatedmy father and do to me what they did to him or he would have me killed in an execution opera-tion . . . . So they took me to him and they said: “This is your son, we are going to execute him ifyou don’t confess.” My father didn’t confess. One of them pulled me to a place where my fathercouldn’t see. He pulled his gun, he took it out of the place where it was kept and he shot a fireinto the sky. And he hit me a hit so that I would cry out. So, this moment there was at the placewhere I was, blood, I mean drops of blood. They [then] took [me] to the side and they broughtmy father and said: “This is your son’s blood. We killed him. So, it is better for you to confesslest this happen to the rest of your sons.” My father, when he saw the blood, he must havethought that I had been killed. At this moment, he fell to the ground.Mohammed Mowoush (in translation), describing hislast sight of his father, Iraqi Maj. Gen. Abed Hamed6Mowhoush. Killed in U.S. Custody November 26, 2003

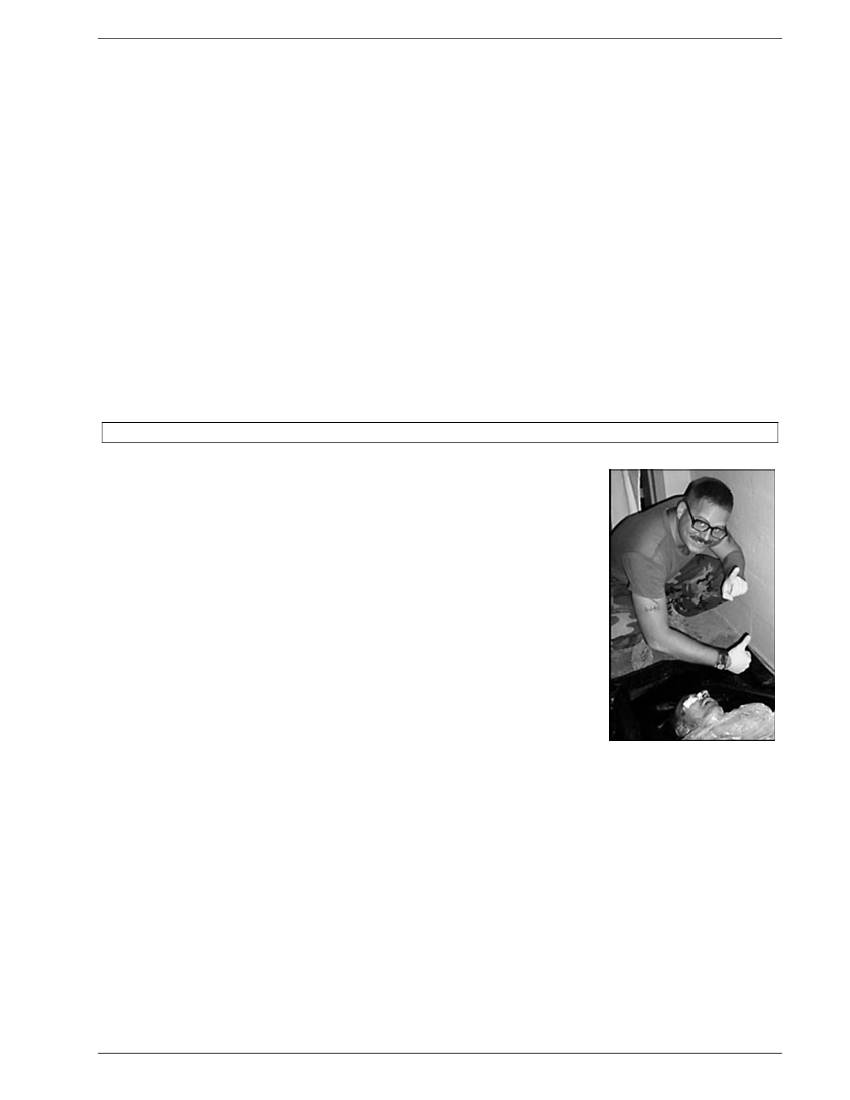

Abed Hamed MowhoushAbed Hamed Mowhoush turned himself over to U.S.forces in Iraq on November 10, 2003,7about a monthbefore U.S. forces captured ousted Iraqi leaderSaddam Hussein, and at a time when pressure onArmy intelligence to produce information was at itsheight. At Forward Operating Base (“FOB”) Tiger,where Mowhoush appeared, the U.S. Army had set upa base camp and prison operations earlier in the year;the facility was near the town of Al Qaim at the westernedge of Anbar province, about a mile from the Syrianborder.8By mid-October 2003, FOB Tiger was staffedwith about 1,000 soldiers from the 1st Squadron of the3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment (“ACR”), based in FortCarson, Colorado Springs, Colorado.9Their missionincluded the detention and interrogation of capturedprisoners, a mission that took on added importance thatNovember, as U.S. forces picked up Iraqi menand boys in the region in an effort to quell a risinginsurgency.According to ChiefWarrant OfficerLewis Welshofer,who was deployedto Iraq in March2003 as part of themilitary intelligencecompany of the 3rdMajor General Abed Hamed10ACR, guidelinesMowhoush with a grandsonon how to conductprisoner interrogations at FOB Tiger were sparse.11Welshofer described a captain’s memo he had receivedin late August 2003, which stated that there were nospecific rules of engagement for interrogations in Iraq,and that U.S. Army Central Command officials were stillstruggling with the basic definition of a “detainee.”12Although specific rules were hard to come by, com-mand was clear that intelligence to date wasinadequate and, as Welshofer put it: “[t]hey werelooking for ideas outside the box.”13In the meantime,captured detainees were to be considered “unprivileged

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 7

combatants”14– a status that the Bush Administrationhad separately suggested meant detainees were not tobe afforded the protections of the Geneva Conven-tions.15Welshofer understood this guidance to includedetainees like Mowhoush,16a former uniformed MajorGeneral in the Iraqi Army,17and a soldier whom in pastconflicts the United States would have consideredpresumptively under Geneva protections.18Soon after, a September 10, 2003 memo from Lt. Gen.Ricardo S. Sanchez, then U.S. Army Commander ofthe Coalition Joint Task Force in Iraq, underscored withnew specificity the confusion over the applicability ofGeneva protections in Iraq.19Even as he recognizedthat other countries might view certain practices asinconsistent with the Geneva Conventions, GeneralSanchez authorized such harsh interrogation tech-niques as sleep and environmental manipulation, theuse of aggressive dogs, and the use of stress posi-tions.20Welshofer testified later that the meaning of“stress positions” had never been explained in his Armytraining back in the States;21Welshofer was left largelyto his own devices to fill in the meaning of the term.According to Welshofer, the Sanchez memo (disclosedpublicly for the first time in January 2006) was the onlyguidance on permissible interrogation techniques inIraq he ever received.22

Still unsatisfied with Mowhoush’s answers in interroga-tion, Welshofer’s unit brought Mowhoush with themwhen they moved a few days later from FOB Tiger to aconverted railroad station called the Blacksmith Hotel.28The “Hotel” was a makeshift facility, set up to handle aninflux of Iraqi prisoners anticipated from sweepsintended to stop the growing insurgency.29There, onNovember 24, Welshofer called in interrogationreinforcements.30According to military documents andtrial testimony, Welshofer engaged CIA and possiblyArmy Special Forces personnel – together with a“Scorpion” team of Iraqi paramilitary forces on the CIApayroll – to ratchet up the pressure.31Three separatesoldiers eventually recounted what they saw andheard.32The new team beat Mowhoush with sledge-hammer handles;33as one soldier testified, eight to tenof the non-military forces “interrogate[d] Mowhoush and‘beat the crap’ out of him.”34Specialist Jerry Loper, aguard at the Blacksmith Hotel, was standing outside theinterrogation room the night of November 24 whensome of the beatings were going on, and describedhearing the thudding sound of Mowhoush being hit. “Itwasn’t like they were hitting a wall,” said Loper, “[t]herewere loud screams.”35After Mowhoush’s death, anArmy autopsy revealed the effects of the beatings:Mowhoush had “massive” bruising and five brokenribs.36The next day, Welshofer interrogated Mowhoush again,this time on the roof of the interrogation building. Here,in the absence of any more specific instructions forinterrogation techniques, Welshofer reached backbeyond his basic training in the Army, to his ownservice as a trainer at a military school in Hawaii whereU.S. service members are coached on what they mightface if there were to fall into enemy hands.37Themilitary’s “SERE” courses (standing for Survival,Evasion, Resistance, Escape) were based on studiesof North Korean and Vietnamese efforts to breakAmerican prisoners; the courses aimed to subjecttrainees to the brutal detention conditions they wouldhave faced at the hands of the United States’ formerenemies.38Among other things, the courses put troopsthrough prolonged isolation, sleep deprivation, andpainful body positions; studies of the effects on troopssubjected to these techniques showed most sufferingfrom overwhelming stress, despair, and intenseanxiety, and some from hallucinations and delusions aswell.39Internal FBI memos and press reports havepointed to SERE training as the basis for some of theharshest techniques authorized for use on detainees bythe Pentagon in 2002 and 2003.40When Welshofer wasasked during his court martial whether anyone told him

The InterrogationsBy the time Mowhoush, 57, arrived at FOB Tiger inmid-November, his four sons had been in U.S. custodyfor approximately 11 days, held in a prison outsideBaghdad.23According to one of them, Hossam, U.S.forces made clear to the sons in the course of interro-gations that they had been arrested for the purpose ofmaking sure General Mowhoush turned himself in.24According to the son, Mowhoush arrived at the baseexpecting that he would be able to set his sons free.25But Mowhoush’s sons remained in detention; one ofthem would later play a part in U.S. efforts to extractfrom their father what information they could.Chief Welshofer was among the first interrogatorsMowhoush would see. According to Welshofer, hisinterrogation of Mowhoush on the day of Mowhoush’sarrival on November 10 was limited to direct questions– a two-hour affair that passed with little of conse-quence.26By the end of that week, though, Welshoferhad begun to take a different approach. Welshofer tookMowhoush, his hands bound, before an audience offellow detainees and slapped him – an attempt,according to Welshofer, to show Mowhoush who was incharge.27

A Human Rights First Report

8 — II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force

that SERE techniques were not to be used in Iraq,Welshofer was unequivocal: “No sir.”41With these techniques in his interrogator’s mind,Mowhoush’s next session included having his handsbound, being struck repeatedly on the back of his arms,in the painful spot near the humerus, and being dousedwith water42– all these, according to Welshofer andothers who later testified, drawn from the lessons oftechniques learned in SERE.43Later that evening, ChiefWelshofer arranged for a short meeting betweenMowhoush and his youngest son, Mohammed, then 15years old; Welshofer hoped the meeting would compelMowhoush to convey more useful information.44Helater described Mowhoush as being moved to tearsupon seeing his son.45According to Mohammedthough, the meeting was more than a conversation; ininterviews with Human Rights First, Mohammedexplained that U.S. personnel made Mowhoush believehis son would be executed if he did not speak to theirsatisfaction, and soldiers fired a bullet into the groundnear Mohammed’s head within earshot but just beyondthe eyesight of Mowhoush.46Mohammed reports thiswas the last time he saw his father alive.47By November 26, Welshofer was ready to try yetanother technique – stuffing his subject into a sleepingbag until Mowhoush was prepared to respond.48Welshofer had already proposed the sleeping bagtechnique to his Company Commander, Major JessicaVoss, who authorized its use.49Much later, trialtestimony would make clear that the technique hadbeen used on at least 12 detainees.50It provedcatastrophically ineffective in Mowhoush’s case. Duringhis final interrogation, Mowhoush was shoved head-firstinto the sleeping bag, wrapped with electrical cord, androlled from his stomach to his back. Welshofer sat onMowhoush’s chest and blocked his nose and mouth.51At one point, according to Loper, Mowhoush started toclinch and kick his legs, “almost like he was beingelectrocuted.”52It was at this point Mowhoush gave out,dying (according to the autopsy report) of asphyxia dueto smothering and chest compression.53The day after his death, the U.S. military issued a pressrelease stating that Mowhoush had died of naturalcauses.54

Taking AccountDespite the brutality of Mowhoush’s death, and thelikely involvement of officials from the CIA, only oneindividual, Chief Welshofer, has faced court martial forhis actions. Over the course of a 6-day trial in Colo-rado, more than two years after Mowhoush’s finalinterrogation, a 6-member Army jury heard testimonythat civilian leaders in the Administration had instructedthat Geneva Convention protections against cruel andinhuman treatment would not apply in this conflict; thatthe U.S. commanding general in Iraq, General San-chez, had authorized “stress positions” ininterrogation55; and that, according to Welshofer and hisown commanding officer, Major Voss, stuffing adetainee in a sleeping bag was widely understood tofall within that general authorization.56Jurors also heardtestimony, some closed to the public, of the involve-ment of the CIA and Special Forces, as well as of theIraqi paramilitary group, the “Scorpions.”57Secret Armydocuments had long noted this involvement: “[T]hecircumstances surrounding the death are furthercomplicated due to Mowhoush being interrogated andreportedly beaten by members of a Special Forcesteam and other government agency (OGA) employeestwo days earlier.”58And jurors heard Welshofer’s owntearful testimony – that he was trying to be a loyalsoldier, and trying to do his job.59Although he was originally charged with murder,Welshofer was convicted of lesser charges: negligenthomicide and negligent dereliction of duty.60Thatconviction carried a possible sentence of more thanthree years in prison, but Welshofer received a farmore lenient sentence from the Army jury: a writtenreprimand, a $6,000 fine, and 60 days with movementrestricted to his home, base, and church.61The others implicated in Mowhoush’s death have facedless. Chief Warrant Officer Jefferson Williams andSpecialist Jerry Loper, who were present duringMowhoush’s interrogation, were originally charged withmurder, but the charges were later dropped. Inexchange for testimony against Welshofer, Williams willreceive administrative (not criminal) punishment, andLoper will be tried in a summary proceeding rather thana full court martial.62Another soldier, Sgt. 1st ClassWilliam Sommer, had his murder charge dropped aswell and may receive nonjudicial punishment.63Nocharges have been brought (nor are charges expectedto be brought according to law enforcement andintelligence officials) against CIA personnel, andSpecial Forces Command determined (without publicexplanation) that none of their personnel were guilty ofwrongdoing.64Major Voss, the officer who commanded

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 9

the Military Intelligence unit responsible for interrogat-ing Mowhoush, was reprimanded for her failure toprovide adequate supervision, but she was not chargedin the death.65The commander of the 3rd ACR from2002-2004 (including the period of Mowhoush’s death)was Colonel David A. Teeples.66At a preliminaryhearing in Welshofer’s case, Teeples testified to his

belief that the sleeping bag technique was approvedand effective;67Teeples was reportedly “reluctant” topress charges against Welshofer, despite the view ofmilitary lawyers that Welshofer should be prosecuted.68Teeples does not appear to have been disciplined inconnection with Mowhoush’s death.

Special Forces & the CIAThe involvement of special military forces and members of other governmental agencies in the interrogation and detention of detaineeshas raised serious concerns regarding proper investigative procedures and accountability. The Army’s CID has jurisdiction over crimescommitted by all U.S. Army personnel; CID’s Field Investigative Units are trained to conduct investigations that implicate classified activi-ties,69and individual detachments have investigated deaths in which Special Forces personnel played a part.70Yet it appears thatalternative investigative procedures have sometimes been used where Special Forces were involved. For example, in one case involvingthe 2ndBattalion of the 5thSpecial Forces Group, commanders conducted their own investigation and failed to inform CID of the death.71When CID did learn of the incident, it simply reviewed and approved the pre-existing inquiry – an inquiry that itself remains classified.72Brigadier General Richard Formica completed an investigation into allegations of detainee abuse in Iraq by Special Forces personnel, butthe Army has also classified the resulting report, refusing to release even a summary of its findings.73Deaths in which the CIA has been implicated (alone or jointly with Army Special Forces or Navy SEALS) have presented additionalproblems.74Such deaths are required to be investigated by the CIA Inspector General and, if cause exists, referred to the Department ofJustice for prosecution.75Yet while five of the deaths in custody analyzed by Human Rights First appear to involve the CIA,76only acontract worker associated with the CIA has to date faced criminal charges for his role in the death of detainees. Further, the CIA hassought to keep closed the courts-martial of Army personnel where CIA officers may be implicated,77and has in military autopsies classifiedthe circumstances of the death.78These efforts have encumbered the investigation and prosecution of both CIA officials and militarypersonnel.79Thus, for example, in the military trial of Navy SEAL Lt. Andrew Ledford, charged in connection with the death of detaineeManadel al-Jamadi, CIA representatives protested questions regarding the position of al-Jamadi’s body when he died, and the role ofwater in al-Jamadi’s interrogation; questions by defense lawyers were often prohibited as a result.80Finally, press reports suggest, theDepartment of Justice is unlikely to bring criminal charges against CIA employees for cases involving the death, torture, or other abuse ofdetainees, including the deaths of al-Jamadi and General Abed Hamed Mowhoush and a detainee whose name has not been made publicand who died of hypothermia at a CIA-run detention center in Afghanistan.81The Department of Justice has not made the reasons for itsdecisions known.Reports of internal efforts at the CIA to address detainee abuse by agents are less than encouraging. After completing a review in spring2004 of CIA detention and interrogation procedures in Afghanistan and Iraq, the CIA Inspector General made 10 recommendations forchanges, including more safeguards against abuse, to CIA Director Porter Goss.82Eight of the 10 have been “accepted,”83but thechanges did not apparently prevent consideration of a proposal for handling deaths of detainees in CIA custody. According to theWash-ington Post:“One proposal circulating among mid-level officers calls for rushing in a CIA pathologist to perform an autopsy and thenquickly burning the body.”84

A Human Rights First Report

10 — II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Abdul JameelLieutenant Colonel Abdul Jameel, a former officer inthe Iraqi army, was detained at a Forward OperatingBase near Al Asad, Iraq, and died there on January 9,2004.85He was 47 years old.86According to Pentagon documents obtained by theDenver Post,Jameel had been kept in isolation with hisarms chained to a pipe in the ceiling.87During aninterrogation by Army Special Forces soldiers, heallegedly lunged and grabbed the shirt of one soldierand was then beaten.88Three days later, Jameelescaped from his cell, but was recaptured.89During asubsequent interrogation session, Jameel refused hisinterrogators’ orders to stay quiet, and was put in a“stress position”: he was tied by his hands to the top ofhis cell door, then gagged.90Within five minutes, hewas dead.91A “senior Army legal official” admitted thatJameel had been “lifted to his feet by a baton held tohis throat,” causing a throat injury that “contributed” tohis death.92According to an autopsy conducted by the U.S. ArmedForces Medical Examiner’s Office and reviewed byHuman Rights First, Jameel’s death was a homicidecaused by “Blunt Force Injuries and Asphyxia”93– alack of oxygen.94The autopsy found “[t]he severe bluntforce injuries, the hanging position, and the obstructionof the oral cavity with a gag contributed to [his] death.”95The autopsy detailed evidence of additional abuseJameel suffered: a fractured and bleeding throat, morethan a dozen fractured ribs, internal bleeding, andnumerous lacerations and contusions all over hisbody.96Among the findings of the Army’s criminal investigatorswas that Jameel “was shackled to the top of a door-frame with a gag in his mouth at the time he lostconsciousness and became pulseless.”97Criminalinvestigators found probable cause to recommendprosecution of 11 soldiers – including members of the3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment (the same Regimentinvolved in the death of Iraqi Major General Mow-housh), as well as the Special Forces personnel – forcharges including negligent homicide, assault, andlying to investigators.98The investigation into Jameel’sdeath also examined CIA involvement.99The ArmySpecial Forces Command declined to follow therecommendations, and investigation findings of anyCIA involvement have not been publicly released.100Upon reviewing the case, Army commanders decidedthat the soldiers’ actions were at all points a lawfulresponse to Jameel’s “misconduct.”101The reasons forthe commanders’ decisions are unclear. The sameperson, Colonel David A. Teeples, was commander ofthe 3rd Armored Cavalry at the time of Jameel’s deathand also that of Iraqi Major General Abed Mowoush.102Because the killing was found to be justified, nodisciplinary action was taken.103

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Fashad MohammedThe Armed Forces Medical Examiner’s report onautopsy number ME 04-309 reads: “This approximately27 year-old male civilian, presumed Iraqi national, diedin US custody approximately 72 hours after beingapprehended. By report, physical force was requiredduring his initial apprehension during a raid. During hisconfinement, he was hooded, sleep deprived, andsubjected to hot and cold environmental conditions,including the use of cold water on his body andhood.”104Although the autopsy described “multipleminor injuries, abrasions and contusions” and “bluntforce trauma and positional asphyxia,”105it found boththe cause of death and manner of death “undeter-mined.”106The autopsy, which was not conducted until threeweeks after Mohammed’s death,107is a drier version ofaccounts pieced together in subsequent inquiries.

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 11

Mohammed was apparently apprehended by membersof Navy SEAL Team 7, which was operating with theCIA, in northern Iraq on or about April 2, 2004.108TheSEALS then brought Mohammed to an Army baseoutside Mosul.109The Navy SEALS who interrogatedMohammed subjected him to hooding, sleep depriva-tion, and exposure to extreme temperatures—allmethods that deviate from the techniques described inthe Army Field Manual on Intelligence Interrogation FM34-52, but that were approved by the Secretary ofDefense for use at Guantanamo,110and later authorizedin part by Lt. Gen. Ricardo S. Sanchez for use in Iraq.111A Pentagon official relates that after an interrogation,the SEALS let Mohammed sleep. He never woke up.112

We know very little about Mohammed’s last hours andthe military has released even less information about itsinvestigation into his death and charges broughtagainst those responsible. The most recent pressreports indicate that as many as three Navy SEALSwere charged with abusing Mohammed; chargesincluded assault with intent to cause death and seriousbodily harm, assault with a dangerous weapon,maltreatment of detainees, obstruction of justice, anddereliction of duty. Murder or manslaughter chargeswere not brought, reportedly because of lack ofevidence.113Human Rights First asked the Departmentof Defense on January 26, 2006 for an update on thestatus and outcome of any prosecutions in Moham-med’s case; as of February 10, 2006 we had receivedno response.

PROFILE: HOMICIDEAsphyxia is what he died from – as in a crucifixion.Dr. Michael Baden, Chief Forensic Pathologist, New YorkState Police, giving his opinion of the cause of Manadel114al-Jamadi’s death

Manadel al-JamadiAccording to press accounts, Manadel al-Jamadi, anIraqi citizen of unknown age, was captured and torturedto death in Abu Ghraib by Navy SEALS and CIApersonnel working closely together; he died onNovember 4, 2003.115The SEAL and CIA team thatcaptured al-Jamadi took turns punching, kicking andstriking him with their rifles after he was detained in asmall area in the Navy camp at Baghdad InternationalAirport known as the “Romper Room.”116A CIA securityguard later told CIA investigators that after al-Jamadiwas stripped and doused with water a CIA interrogatorthreatened him, saying: “I’m going to barbecue you ifyou don’t tell me the information.”117A Navy SEALreported that the CIA interrogator leaned into al-Jamadi’s chest with his forearm, and found a pressurepoint, causing al-Jamadi to moan in pain.118A govern-ment report states that another CIA security guard“recalled al-Jamadi saying, ‘I’m dying. I’m dying,’translated by the interpreter, to which the interrogatorreplied, ‘I don’t care,’ and, ‘You’ll be wishing you weredying.’”119When al-Jamadi was taken to Abu Ghraib, he was notentered on the prison rolls – he was a “ghost” de-tainee.120The intelligence agents took him to theshower room where,military policetestified, a non-covertCIA interrogator(identified as MarkSwanner byThe NewYorker)ordered themto shackle al-Jamadito a window about fivefeet from the floor, inCharles Graner next tothe corpse ofa posture known asManadel al-Jamadithe “Palestinianhanging,” making itimpossible for him to kneel or sit without hanging fromhis arms in pain.121Less than one hour later, Swannersummoned guards to re-position al-Jamadi, claimingthe detainee was not cooperating.122When the guardsarrived they found al-Jamadi’s corpse, hooded with asandbag and with his arms handcuffed behind his backand still shackled to the window – which was nowabove his head.123According to one of the guards,blood gushed from al-Jamadi’s mouth as the guardsreleased him and his arms were almost coming out oftheir sockets.124A CIA supervisor requested that al-

A Human Rights First Report

12 — II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force

Jamadi’s body be held overnight and stated that hewould call Washington about the incident.125The nextmorning the “body was removed from Abu Ghraib on alitter, to make it appear as if he were only ill, so as notto draw the attention of the Iraqi guards and detain-ees.”126Al-Jamadi’s death became public during theAbu Ghraib prisoner-abuse scandal, after photographsof prison guards giving the thumbs-up over his bodywere released.127U.S. forces did not release al-Jamadi’s body to theInternational Committee of the Red Cross (“ICRC”) untilFebruary 11, 2004, more than three months after hisdeath.128The ICRC delivered the body to Baghdad’smortuary the same day, but one expert from Baghdad’smain forensic medico-legal institute said that therefrigeration of al-Jamadi’s body for that period made itdifficult for the Iraqis to establish the real cause ofdeath by autopsy.129An autopsy conducted by the U.S.military five days after al-Jamadi’s death had found thatthe cause of death was “Blunt Force Injuries Compli-cated by Compromised Respiration.”130The autopsyreport noted al-Jamadi had six broken ribs and agunshot wound to the spleen.131A medical examinerwho later examined the autopsy report at the request ofa lawyer for one of the SEALS and was informed of al-Jamadi’s shackling position gave the opinion that thelikely cause of his death was the hanging position,rather than beatings inflicted prior to his arrival at AbuGhraib.132According to Dr. Michael Baden, New YorkState police chief forensic pathologist, “asphyxia iswhat he died from – as in a crucifixion.”133Dr. EdmundDonahue, the president of the American Academy ofForensic Scientists, who reviewed the autopsy at therequest of National Public Radio, gave a similaropinion, saying: “When you combine [the hanging

position] with having a hood over your head and havingthe broken ribs, it’s fairly clear that this death wascaused by asphyxia because he couldn’t breatheproperly.”134During a later court martial proceeding, one Navy SEALtestified that he and his fellow SEALS were not trainedto deal with Iraqi prisoners.135Although Navy lawyerstestified they trained the SEALS to treat detaineeshumanely, one SEAL stated: “The briefing I rememberis that these [prisoners] did not fall under the GenevaConvention because they were not enemy combat-ants.”136Of the 10 Navy personnel – 9 SEALS and one sailor –accused by Navy prosecutors of being involved in al-Jamadi’s death,137nine were given nonjudicial punish-ment.138In contrast to a general court martial, which is acriminal felony conviction, nonjudicial or administrativepunishment is usually imposed by an accused’scommanding officer for minor disciplinary offenses, anddoes not include significant jail time.139The only personformally prosecuted in the case was Navy SEALLieutenant Andrew K. Ledford, the commander of theSEAL platoon, who was charged with dereliction ofduty, assault, making a false statement to investigators,and conduct unbecoming an officer.140At court-martial,Ledford was acquitted of all charges.141The decisionwhether to prosecute CIA personnel for possiblewrongdoing is pending,142but government officials haveindicated that charges are unlikely to be brought.143Theinterrogator, Mark Swanner, continues to work for theCIA.144To date, no U.S. official has been punishedcriminally in connection with al-Jamadi’s death. HumanRights First asked the Department of Defense onJanuary 26, 2006 the status of the al-Jamadi case; asof February 10, we had received no response.

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Nagem Sadoon HatabNagem Sadoon Hatab, a 52-year-old Iraqi, was killed inU.S. custody at a Marine-run temporary holding campclose to Nasiriyah.145Soon after his arrival at the campin June 2003, a number of Marines beat Hatab,146including allegedly “karate-kicking” him while he stoodhandcuffed and hooded.147A day later, Hatab report-edly developed severe diarrhea, and was covered infeces.148Once U.S. forces discovered his condition,Hatab was stripped and examined by a medic, whothought that Hatab might be faking sickness.149At thebase commander’s order, a clerk with no training inhandling prisoners dragged Hatab by his neck to anoutdoor holding area, to make room for a new pris-oner.150The clerk later testified to the ease with which he wasable to drag the prisoner: Hatab’s body, covered bysweat and his own feces, slid over the sand.151Hatabwas then left on the ground, uncovered and exposed inthe heat of the sun. He was found dead sometime after

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 13

midnight.152A U.S. Army medical examiner’s autopsy ofHatab found that he had died of strangulation – a victimof homicide.153The autopsy also found that six ofHatab’s ribs were broken and his back, buttocks, legsand knees covered with bruises.154The guards at the detention center to which Hatab hadbeen brought were ill-prepared for their duty at best.The previous commander of the facility, Major WilliamVickers, would later testify that none of the approxi-mately 30 Marines at the camp had been trained to runa jail before their assignment: “Not then or evenafter.”155Most were reservists and according to MajorVickers’ testimony, the Marines, members of the 2ndBattalion, 25thMarine Regiment, were assigned to theguard role after Army and other Marine units refusedit.156The base commander at the time, Major ClarkePaulus, had been in that position for a week beforeHatab’s death, and had spent only a day observing theprison operations before taking command.157Hispredecessor, Major Vickers, added that the camp hadoriginally been designated a temporary holding facility,where Marines would interrogate prisoners for a day ortwo before their release or transfer.158Instead, prison-ers were kept for longer, resulting in overcrowding anda strain on guards.159The treatment of Hatab’s body did not improve after hisdeath. A Navy surgeon, Dr. Ray Santos, testified thatwhen Hatab’s body arrived at the morgue: “It keptslipping from my hands so I did drop it several times.”160The U.S. Army Medical Examiner, Colonel KathleenIngwersen, who performed the autopsy, reportedlyacknowledged that Hatab’s body had undergonedecomposition because it was stored in an unrefriger-ated drawer before the autopsy.161In fact, testimony ata later court martial indicated that a container ofHatab’s internal organs was left exposed on an airporttarmac for hours; in the blistering Iraqi heat, the organswere destroyed.162Hatab’s ribcage and part of hislarynx were later found in medical labs in Washington,D.C. and Germany, due to what the Medical Examiner,Colonel Ingwersen, described as a “miscommunication”with her assistant.163Hatab’s hyoid bone – a U-shapedthroat bone located at the base of the tongue164– wasnever found,165and Colonel Ingwersen testified that shecouldn’t recall whether she removed the bone from thebody during the autopsy or not.166The bone was a keypiece of evidence, because it supported the ArmyMedical Examiner’s finding that Hatab died of strangu-lation.167

Although eight Marines were initially charged in thecase, only two were actually court-martialed.168MajorPaulus, who ordered Hatab dragged by his neck andpermitted him to lie untreated in the sun, was originallycharged with a number of offenses, including negligenthomicide, while Sergeant Gary P. Pittman was chargedwith five counts of assault for beating prisoners(including Hatab) and two counts of dereliction ofduty.169Neither was sentenced to any prison time,however, in part because of the lax handling of themedical evidence.170The judge in the court martialproceedings, Colonel Robert Chester, ruled that theautopsy findings and other medical evidence –evidence which was also Hatab’s remains – could notbe considered, because it had been lost or destroyedand thus could not be examined by the defense.171Thejudge’s decision eliminated the possibility that prosecu-tors could win conviction on the most serious chargesthey had brought. In addition, at Sergeant Pittman’scourt martial, prosecutors acknowledged that themilitary had either lost or destroyed photos of Hatabbeing interrogated in the days before his death.172As a result, prosecutors were unable to win convictionon any charges relating to culpability for Hatab’s death:Paulus was convicted of dereliction of duty andmaltreatment for ordering a subordinate to drag Hatabby the neck, and for allowing Hatab to remain unmoni-tored in the sun.173Sergeant Pittman was acquitted ofabusing Hatab, though he was sentenced for assaultingother detainees.174Charges against Lance CorporalChristian Hernandez (who dragged Hatab by the neck),including negligent homicide, were dropped, and thecases against the other Marines similarly did notproceed to trial.175One Marine, William Roy, accepted areduction in rank from a lance corporal to a private firstclass in exchange for his testimony. But because thedemotion was a non-judicial punishment, and the basisfor it is not public, the precise contours of his culpabilityremain unclear.176

A Human Rights First Report

14 — II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Abdul WaliOn June 18, 2003, Abdul Wali turned himself in tosoldiers at an Army firebase in Asadabad, Afghanistan,after he learned they were looking for him.177The son ofthe governor of the province where the base is locatedaccompanied Wali and initially acted as his interpreterduring interrogation.178According to this interpreter, theU.S. interrogator was so aggressive in questioning Walithat the interpreter left in disgust.179Three days later, onJune 21, Wali was dead.180The man who interrogated Abdul Wali was not asoldier; David Passaro was a former Army Ranger whohad been hired as a civilian contractor by the CIA.181Reportedly convinced that Wali had information aboutweapons that would be used to attack U.S. personnel,Passaro questioned Wali on June 19 and 20.182At eachof these sessions, the U.S. government alleges,Passaro beat Wali, both with his hands and with aflashlight.183According to prosecutors, Passaro kickedWali in the groin “on at least one occasion.”184Wali,who apparently suffered from poor health, did notsurvive to see a third such interrogation.185Army criminal investigators looked into Wali’s death,found that no Army personnel were implicated andreferred the case to the Department of Justice forpossible prosecution of Passaro.186In June 2004, afederal grand jury in the Eastern District of NorthCarolina indicted Passaro on four counts of assault.187As of February 2006, the case against Passaro wasmoving toward trial, with the government and defenseengaged in arguments about the defenses that wouldbe allowed, and which witnesses would testify in theproceedings.188According to his lawyer, Passaro’sposition at trial will be that abusive questioningtechniques were not criminal because they wereconsistent with authorized interrogation policies, andthat his actions were legally justified under a series ofExecutive Branch memos that appear to permitaggressive interrogation techniques.189No one has been charged with murder or manslaughterin connection with Wali’s death. Human Rights Firstasked the Department of Defense on January 26, 2006for any update on the status of Wali’s case; as ofFebruary 10, 2006 we had received no response.

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

HabibullahHabibullah died on the night of December 3, 2002,because of abuses inflicted upon him by U.S. soldiersat the Bagram detention facility in Afghanistan.190Habibullah was captured by an Afghan warlord and,according to detailed reporting by theNew York Times,was brought to the Bagram detention facility on the lastday of November, 2002.191Members of the 377thMilitary Police Company at that facility reportedlysubjected detainees held at the base to peronealstrikes –a knee strike aimed at a cluster of nerves onthe side of the thigh, meant to quickly disable anescaping or resistant prisoner.192One soldier stated thathe gave Habibullah five peroneal strikes for being“noncompliant and combative.”193Immediately upon his arrival, Habibullah was placed inan isolation cell and shackled to the ceiling by hiswrists.194During one interrogation, an interrogatorallowed him to sit on the floor because his knees wouldnot bend enough for him to sit on a chair; as Habibullahcoughed up phlegm, soldiers laughed at his distress.195One day later, Habibullah was found hanging from theceiling and unresponsive.196One soldier thought that hefelt the almost-incapacitated prisoner spit on him; thesoldier yelled and began beating Habibullah while hewas still chained to the ceiling.197The next time anyonechecked on Habibullah, he was dead.198The U.S.-conducted autopsy found that Habibullah haddied of an embolism – a blood clot, almost certainly theproduct of the repeated beatings, had traveled through

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 15

his bloodstream and clogged the arteries leading to hislungs;199the autopsy determined the manner of death tobe homicide.200The Army Criminal InvestigationCommand looked into the death, and initially recom-mended closing the case.201According to criminalinvestigators’ findings it was impossible to determinewho was responsible for Habibullah’s injuries becauseso many were involved.202Investigators also failed tomaintain critical evidence in the case. A sample ofHabibullah’s blood was kept in the butter dish ofinvestigators’ office refrigerator until the office wasclosed.203Press interest in Habibullah’s death—and that ofDilawar, another detainee who died a week later at thesame facility—sparked renewed progress in thecriminal investigation, resulting in charges against thesoldiers allegedly responsible.204In October 2004,almost two years after Habibullah’s death, criminalinvestigators recommended that charges be broughtagainst 27 soldiers for their roles in the death ofDilawar and against 15 of the same soldiers for thedeath of Habibullah, including “two captains, themilitary intelligence officer in charge of the interrogationgroup, and the reservist commander of the militarypolice guards.”205The recommended charges rangedfrom dereliction of duty to involuntary manslaughter.206The soldiers included members of the 377thMilitaryPolice Company and interrogators from the 519thMilitary Intelligence Battalion.207To date, less than half of the soldiers against whomcharges were recommended –12 out of 27– have

actually been prosecuted for their roles in the deaths ofHabibullah and Dilawar.208Eleven cases have beenconcluded.209Apart from demotions and some dis-charges, only four of these individuals were givensentences that included confinement, and the sen-tences ranged from 60 days to five months.210InJanuary 2006, after a pre-trial inquiry, the Armydropped its criminal case against the only officercharged (with lying to investigators and dereliction ofduties) in connection with the deaths, Military PoliceCaptain Christopher M. Beiring.211Lieutenant Colonel Thomas J. Berg, the Army judgewho oversaw the pretrial inquiry, criticized the prosecu-tion for not presenting sufficient evidence to supporttheir charges against him.212Berg added that themilitary policy company had not been adequatelytrained before deployment for its mission at the Bagramdetention facility:213“Little of the training focused on theactual mission that the 377th [Military Police Company]anticipated that it would assume upon arrival in theater. . . . Much of the 377th’s training was described as‘notional’ in that soldiers were asked to imagine orpretend that they had the proper equipment for trainingexercises.”214As of January 2006, the trial of SergeantAlan J. Driver is pending.215Notably, no soldier has yetbeen charged with murder or voluntary manslaughterfor either of the deaths of Habibullah or Dilawar.216

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

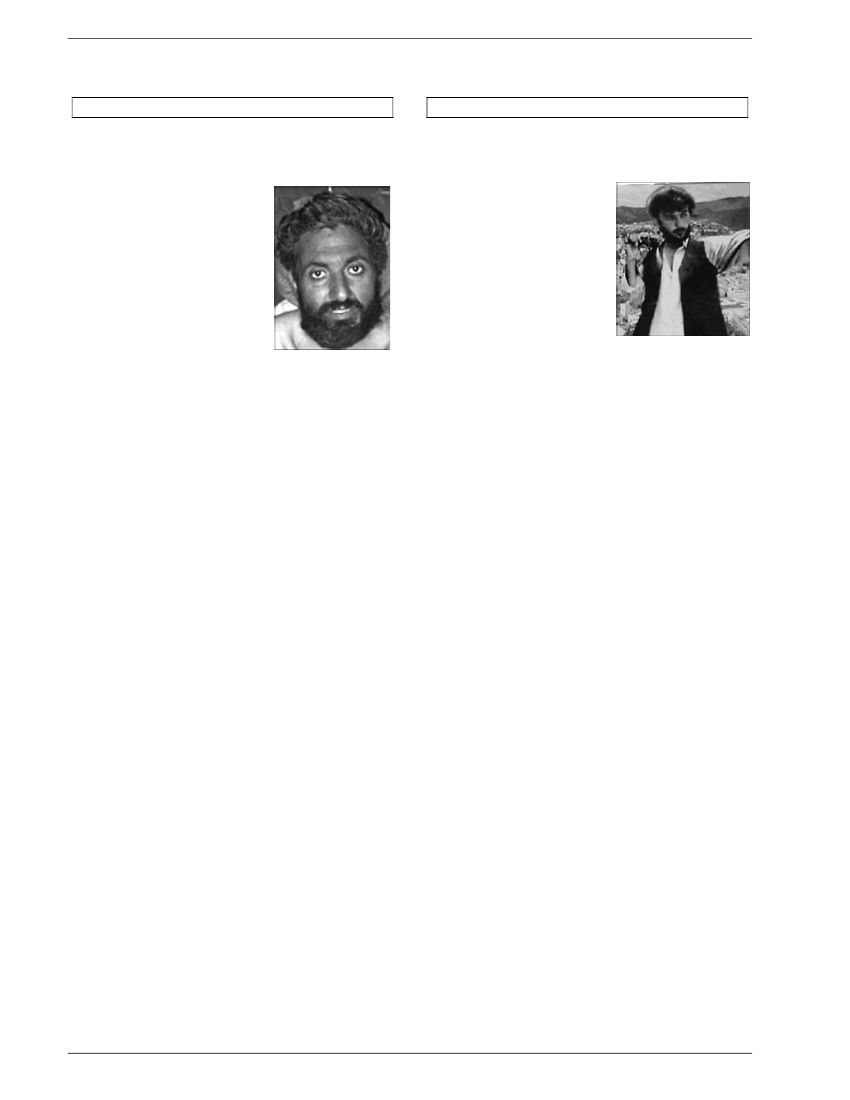

DilawarDilawar was the second detainee killed in a week at theBagram detention facility in Afghanistan.217A 22-year-old Afghan citizen whose case similarly became thefocus ofNew York Timesinvestigative reports, Dilawarwas driving his taxi past U.S. Camp Salerno when hewas stopped and his car searched by a local Afghancommander working with the Americans.218Dilawar wasthen taken into custody as a suspect in a rocketattack.219The commander of the Afghan soldiers waslater suspected of having launched the attackhimself.220Dilawar was brought to the Bagram detention facility onDecember 5, 2002.221The 122-pound taxi driver waslabeled a “noncompliant” detainee by U.S. soldiers, andwas subjected to the samekind of peroneal strikes thateventually contributed to thedeath of Habibullah.222During one of the beatingsby soldiers, Dilawar cried“Allah” when he was hit.223According to a U.S. soldier,U.S. military personnel foundthese cries funny and hitDilawar repeatedly to hearhim cry out.224Over a 24-hour period, one soldierestimated that Dilawar was

Dilawar

A Human Rights First Report

16 — II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force

struck over 100 times by soldiers.225According to an interpreter, during his fourth interroga-tion session on December 8, Dilawar was unable tocomply with commands to keep his hands above hishead, leading one soldier to push his hands back up.226During the same interrogation, two interrogatorsshoved Dilawar against a wall when he was unable tosit in a “chair” position against the walls because of theinjuries to his legs.227At the end of the interrogation,one of the soldiers ordered Dilawar to be chained to theceiling.228During his final interrogation session onDecember 10, Dilawar could not obey the orders theinterrogators gave him to stand in stress positions andkneel.229Dilawar died that day.230The official autopsy, conducted three days after hisdeath, showed that Dilawar’s legs had suffered“extensive muscle breakdown and grossly visiblenecrosis with focal crumbling of the tissue.”231Thedamage was “nearly circumferential,” from below theskin down to the bone. The manner of death was foundto be homicide.232Despite this conclusion, the militaryinitially said that Dilawar had died of natural causes.233Criminal investigation into his death, and that ofHabibullah had been at a “virtual standstill,”234and only

accelerated after theNew York Timesreported in newdetail how both men died in U.S. custody.235Therenewed investigation also cast into stark relief theflaws in the original investigative efforts: agents had notinterviewed the commanders of the soldiers responsi-ble for the deaths, failed to interview an interrogatorwho had witnessed most of Dilawar’s questioningduring his detention, and mishandled critical evi-dence.236It was only during the subsequentinvestigation – and at the individual initiative of at leastone soldier – that investigators finally took state-ments.237The statements revealed that witnesses whohad previously been overlooked had crucial informa-tion, including an eyewitness account of an interrogatorapparently choking Dilawar by pulling on his hood, andthat “most [soldiers at the base] were convinced that[Dilawar] was innocent.”238The status of prosecutions of the soldiers responsiblefor Dilawar’s death is described above.

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Sajid Kadhim Bori al-BawiSajid Kadhim Bori al-Bawi, an Iraqi actor, was shot andkilled in his home in Baghdad early in the morning ofMay 17, 2004.239According to his family, U.S. and Iraqisoldiers raided the house by crashing through the gatein a Humvee.240Al-Bawi’s brother, uncle, and nephewwere bound and held on their knees and the womenand children were kept in the living room while he wasinterrogated in a bedroom.241While they were waiting,the family heard shots ring out.242The troops left anhour after they arrived.243According to the family, thetroops took with them a robed and hooded man, andtold the family that they were arresting al-Bawi.244Butwhen the family went into the room where he had beenquestioned, they found al-Bawi’s corpse, stuffed behinda refrigerator and hidden under a mattress.245He hadbeen shot five times: in the leg, throat, armpit, andchest.246An administrative investigation247into al-Bawi’s deathfound the shooting to be justified.248The militaryreported in its initial public statements about theshooting that al-Bawi hadgrabbed a U.S. soldier’spistol, switched the safetyoff, and the soldier thenfired five shots in self-defense.249But themilitary’s statementsbecame the subject ofdispute. An Iraqi medicalexaminer who examinedthe body found that theshots had been fired fromtwo different directions; al-Bawi’s family reported thatSajid Kadhim Bori al-Bawi’sthey found two kinds ofson holds a portraitof his fathercasings in the room where250he died. Army criminalinvestigators only began their investigation a monthafter al-Bawi’s death, when an investigation wasrequested by the military’s Detainee Assessment TaskForce, based on aWashington Postarticle detailing al-

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 17

Bawi’s family’s allegations.251Despite the contradictionsbetween the findings of the administrative investigationand allegations by al-Bawi’s family and the medicalexaminer,252the criminal investigating agent spent ascant four hours reviewing the findings of the adminis-trative investigation, did not attempt any independentverification, and then forwarded the case for closure.253News reports detailing the family’s allegations wereincluded in the file, but the only change the criminalinvestigator made to the initial probe was to correct thespelling of al-Bawi’s name.254The criminal proberestated the conclusion that the killing was justified andrecommended no charges be brought.255The lack of any independent investigation into al-Bawi’sfamily’s allegations – or any investigation beyond a

review of the administrative findings – is troubling. At aminimum, there is a disconnect between the adminis-trative finding that one soldier fired all the shots withone weapon,256and the family’s allegations that al-Bawiwas shot from two directions with two different calibersof bullet.257Al-Bawi’s family reportedly was offered $1,500 incompensation by military officials, conditioned on theiragreeing that the United States has no responsibility foral-Bawi’s death.258The family has refused the money.259

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Obeed Hethere RadadObeed Hethere Radad was shot to death on Septem-ber 11, 2003, in his detention cell in an Americanforward operating base in Tikrit, Iraq.260Both criminaland administrative investigations were conducted intohis death.261The soldier accused of the shooting,Specialist Juba Martino-Poole, stated during theadministrative investigation that he had shot Radadwithout giving any verbal warning because Radad was“fiddling” with his hand restraints and standing close tothe wire at the entrance to his cell.262The administrative investigation found “sufficient causeto believe” Martino-Poole violated the Army’s use offorce policy and the base’s particular directives on theuse of deadly force with which Radad could becharged; the administrative investigation recommendeda criminal investigation be initiated to determineoffenses.263But the investigation also determined thatthere was inadequate clarity on the use of weaponsand force with regard to detainee operations at thebase, and noted in particular the lack of any writtenstandard operating procedures.264The investigationalso criticized the location of weapons within thedetention facilities, and the insufficient numbers ofguards assigned to guard detainees.265A military lawyerwho later reviewed the administrative investigationfound it legally insufficient, apparently because it failedto determine what, if any, briefing on the use of forceguards received.266Army criminal investigators were only notified of thedeath after the administrative investigation con-cluded.267And before the criminal investigation wasover, Martino-Poole had sought a military discharge inlieu of a court martial for manslaughter.268Martino-Poole’s commander, Major General Raymond T.Odierno, approved the request for discharge withoutwaiting for criminal investigative agents to concludetheir investigation and forward their findings.269A littlemore than a week later, criminal investigators foundprobable cause to charge Martino-Poole with murder.270The Radad case was reviewed along with all detaineedeaths in custody after the revelations at Abu Ghraib,and the reviewer noted flaws in both the criminal andthe administrative investigations, but decided againstreopening the criminal investigation because “furtherinvestigation would not change the outcome.”271Martino-Poole later accused his commanders ofwanting to avoid disclosure of the lax security practicesat the base – practices that would likely have come tolight in a court martial proceeding.272

A Human Rights First Report

18 — II. Homicides: Death by Torture, Abuse or Force

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Mohammed SayariMohammed Sayari was in the custody of members ofthe U.S. Army Special Forces when he was killed nearan Army firebase on August 28, 2002 in Lwara,Afghanistan.273According to Army investigative recordsreviewed by Human Rights First, an Army staffsergeant from the 519thMilitary Intelligence Battalionwho was supporting the Special Forces team wasdispatched to the site of the shooting of a “suspectedaggressor” on a road just outside the firebase, to takephotographs documenting the scene.274When hearrived, the members of the Special Forces unit told thesergeant they had stopped Sayari’s truck because hehad been following them.275The soldiers ordered thepassengers traveling in Sayari’s truck to leave the areaand then, they said, they disarmed Sayari.276Accordingto their later testimony, the soldiers neglected torestrain Sayari’s hands, and left his AK-47 weapon tenfeet from him.277When a soldier turned away for amoment, they said, Sayari lunged for the rifle andmanaged to point it at the Special Forces soldiersbefore they shot him in self-defense.278Sayari’s body was fingerprinted and turned over to hisfamily.279The Military Intelligence sergeant (whosename is redacted in the records Human Rights Firstreviewed) then instructed other military personnel totransfer DNA evidence taken at the scene and otherphotographs to the Bagram Collection Point.280OnSeptember 24, 2002 the captain of the Special Forcesgroup that shot Sayari told the sergeant that a memberof the Staff Judge Advocate General’s Corps would becoming as part of the administrative investigation totake statements from Special Forces soldiers involvedin the shooting.281The captain then asked the sergeantfor the photographs he had taken.282After reviewing thephotographs, the Special Forces captain told thesergeant to include only certain of the photographs inthe investigation and ordered him to delete all the othercrime-scene photographs.283The administrativeinvestigation would eventually find Sayari’s shooting tobe justified.284The following day, the sergeant contacted criminalinvestigators to report “a possible war crime.”285According to one criminal investigation agent’s report,the sergeant had not reported his concerns to criminalauthorities earlier because he had waited to see theresults of the administrative investigation and he hadfeared for his safety while working with the SpecialForces team.286The sergeant told the agents thatseveral details at the scene made him question theveracity of the Special Forces soldiers’ story. He saidthat Sayari had been shot five or more times – in thetorso and head – but all the entry wounds appeared tobe in the back of the body, which made it unlikely thathe had been facing the soldiers and pointing his rifle atthem when he was shot.287One of Sayari’s sleeves hadbrain matter on it, suggesting that his hands were on orover his head when he was shot.288When the sergeantfirst arrived, he had noticed that Sayari’s corpse stillclutched a set of prayer beads in the right hand, whichwas inconsistent with the Special Forces soldiers’report that he had picked up and pointed an assaultrifle at them.289Among the photos that the SpecialForces captain instructed the sergeant to delete wasone showing Sayari’s right hand clenched around theprayer beads and another depicting bullet holes inSayari’s back.290The AK-47 could not be found.291Criminal investigators eventually found probable causeto recommend charges of conspiracy and murderagainst the four members of the Special Forces unit;they also recommended dereliction of duty chargesagainst three of them, and a charge of obstruction ofjustice against the captain.292Finally, they recom-mended that a fifth person, a chief warrant officer, becharged as an accessory after the fact.293After consultation with their legal advisors, however,commanders decided not to pursue any of the recom-mended charges in a court martial.294To date, the onlyaction commanders have taken in response to thecriminal investigators’ recommendations is to repri-mand the captain for destroying evidence.295Thecaptain was disciplined – he had inarguably destroyedevidence – but received only a letter of reprimand.296Nofurther action was taken against the soldiers.297Thecommanders who declined to report Sayari’s death –and who later declined to prosecute the soldiersinvolved – received similar leniency; they have receivedno disciplinary action for their conduct. Human RightsFirst asked the Department of Defense on January 20and 26, 2006 for an update on the status of Sayari’scase; as of February 10, 2006, we had received noresponse.

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 19

PROFILE: HOMICIDE

Zaidoun HassounZaidoun Hassoun, (also known as Zaydoon Fadhil), a19-year-old Iraqi civilian, and his cousin Marwan werearrested by members of the 1st Battalion, 8th InfantryRegiment, 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division in January2004 on the streets of Samarra, in Iraq, at or around an11 p.m. curfew time.298Army Lieutenant Jack Savillethen ordered his platoon to take the two Iraqis to a 10-foot-high bridge over the Tigris River and force the twoto jump.299Three soldiers, Sergeant (“Sgt.”) AlexisRincon, Specialist Terry Bowman and Sgt. ReggieMartinez, complied with the order.300Saville and StaffSgt. Tracy Perkins had earlier that night stated that“someone was going to get wet tonight” and “someoneis going for a swim.”301Marwan surfaced and swam tothe shore.302Zaidoun, who had proposed to his fiancéethree weeks previously and planned on starting a familyonce he graduated from high school, did not.303According to his cousin, he was sucked into the currentnear an open dam gate and was unable to escape.304Criminal charges initially filed against Saville allegedthat he had also pushed another Iraqi into the Tigris inBalad the previous month.305The platoon’s three immediate commanders, Lt. Col.Nathan Sassaman, the battalion commander, CaptainMatthew Cunningham, a company commander, andMajor Robert Gwinner, the deputy battalion com-mander, did not report the incident to criminalinvestigators, based on the assumption that there wasno proof Hassoun had drowned.306Sgt. Irene Cintron, a criminal investigative agentassigned to the case, suspected, however, “that thewhole chain of command was lying to [her].”307Duringthe criminal investigation into Hassoun’s death, agentsadministered a polygraph test to a member of thesquad that allegedly pushed him into the river.308Thesoldier told agents that his chain of command hadordered him to deny soldiers had forced Hassoun intothe river, and not to cooperate with criminal investiga-tors.309After the criminal investigation was underway,Lt. Col. Sassaman, the battalion commander, informedMajor General Raymond Odierno, the commander ofthe Fourth Infantry Division, of the truth; soldiers had infact forced Hassoun to jump into the Tigris.310Accordingto the official investigative report, which Human RightsFirst reviewed, the officer who conducted a subsequentArticle 32 hearing—analogous to a grand jury proceed-ing311– also found the commanders had “coach[ed]”their soldiers on what to sayto the investigating agents.312The three commanders – Lt.Col. Sassaman, CaptainCunningham, and MajorGwinner – obtained grantsof immunity from prose-cution, and admitted at thesoldiers’ trial that theallegations were true.313Zaidoun HassounThe commanders testifiedthat they thought theinvestigation into Hassoun’s death was the result of “apersonal vendetta” between Sassaman and the brigadecommander, motivated by personal antipathy andjealousy.314They also maintained their belief thatHassoun had not actually drowned as a justification fortheir refusal to cooperate with investigators; Cunning-ham protested that “[they] were not covering upanything that injured anybody.”315Saville plead guilty toa reduced charge of assault and received 45 days inprison and Perkins was convicted of the same chargeand sentenced to six months.316Two other soldiers,Sergeant Reggie Martinez (originally charged withinvoluntary manslaughter) and Sergeant Terry Bowman(originally charged with assault), received non-judicialpunishment.317The three commanders receivedreprimands for obstruction of justice but were notrelieved of their command.318

A Human Rights First Report

Command’s Responsibility — 21