Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2005-06

Bilag 61

Offentligt

THE NEXT IRAQI WAR?SECTARIANISM AND CIVIL CONFLICTMiddle East Report N�52 – 27 February 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. iI.II.INTRODUCTION: ESCALATING SECTARIAN VIOLENCE ................................ 1ROOTS OF SECTARIANISM ...................................................................................... 6A.B.C.BEFOREAPRIL2003 ..............................................................................................................6CPA POLICIES.......................................................................................................................8CONSTITUTION-MAKING.....................................................................................................12

III. THE NEW SECTARIANISM...................................................................................... 14A.B.C.ZARQAWI’SSECTARIANAGENDA........................................................................................14SCIRIANDBADRSEIZECONTROL......................................................................................17RELIGION AS THEPRINCIPALSOURCE OFPOLITICALMOBILISATION.....................................22

IV. ERODING RESTRAINTS ........................................................................................... 23A.B.C.D.WEAKENING OF THEU.S.-BACKEDCENTRALSTATE............................................................23AYATOLLAHSISTANI’SWANINGINFLUENCE.......................................................................24THEABSENCE OFVIABLENON-SECTARIANALTERNATIVES.................................................26CHANGINGPOSTURE OFNEIGHBOURINGSTATES?................................................................28

V.

THE DECEMBER 2005 ELECTIONS ....................................................................... 30

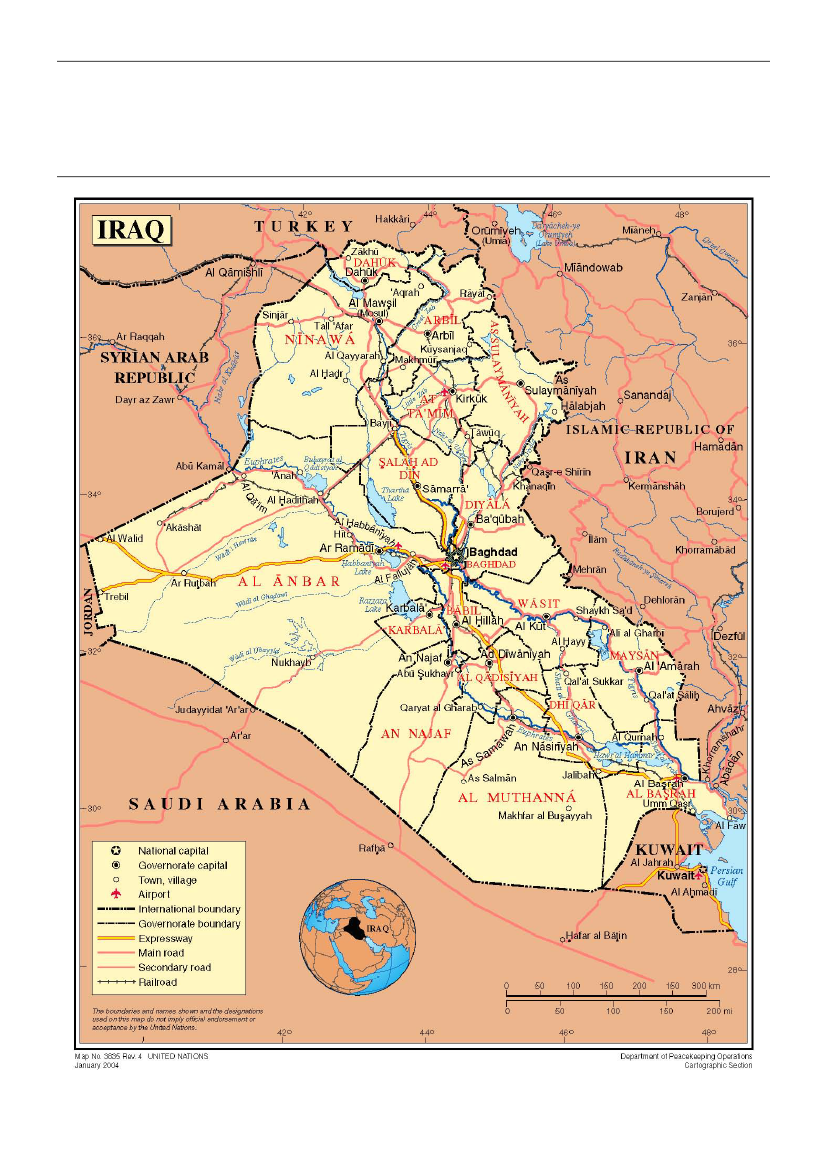

VI. CONCLUSION.............................................................................................................. 33APPENDICESA.B.C.D.E.F.MAP OFIRAQ......................................................................................................................36INDEX OFNAMES................................................................................................................37SEATALLOCATIONFOLLOWINGDECEMBER2005 ELECTIONS............................................39ABOUT THEINTERNATIONALCRISISGROUP.......................................................................40CRISISGROUPREPORTS ANDBRIEFINGS ON THEMIDDLEEAST ANDNORTHAFRICA.........41CRISISGROUPBOARD OFTRUSTEES...................................................................................43

Middle East Report N�52

27 February 2006

THE NEXT IRAQI WAR? SECTARIANISM AND CIVIL CONFLICTEXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONSThe bomb attack on a sacred Shiite shrine in Samarra on22 February 2006 and subsequent reprisals against Sunnimosques and killings of Sunni Arabs is only the latestand bloodiest indication that Iraq is teetering on thethreshold of wholesale disaster. Over the past year, socialand political tensions evident since the removal of theBaathist regime have turned into deep rifts. Iraq’s mosaicof communities has begun to fragment along ethnic,confessional and tribal lines, bringing instability andviolence to many areas, especially those with mixedpopulations. The most urgent of these incipient conflictsis a Sunni-Shiite schism that threatens to tear the countryapart. Its most visible manifestation is a dirty war beingfought between a small group of insurgents bent onfomenting sectarian strife by killing Shiites and certaingovernment commando units carrying out reprisals againstthe Sunni Arab community in whose midst the insurgencycontinues to thrive. Iraqi political actors and theinternational community must act urgently to prevent alow-intensity conflict from escalating into an all-out civilwar that could lead to Iraq’s disintegration and destabilisethe entire region.2005 will be remembered as the year Iraq’s latentsectarianism took wings, permeating the political discourseand precipitating incidents of appalling violence andsectarian “cleansing”. The elections that bracketed the year,in January and December, underscored the newly acquiredprominence of religion, perhaps the most significantdevelopment since the regime’s ouster. With mosquesturned into party headquarters and clerics outfittingthemselves as politicians, Iraqis searching for leadershipand stability in profoundly uncertain times essentiallyturned the elections into confessional exercises. Insurgentshave exploited the post-war free-for-all; regrettably, theirbrutal efforts to jumpstart civil war have been metimprudently with ill-tempered acts of revenge.In the face of growing sectarian violence and rhetoric,institutional restraints have begun to erode. The cautioning,conciliatory words of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, theShiites’ pre-eminent religious leader, increasinglyare falling on deaf ears. The secular centre has largelyvanished, sucked into the maelstrom of identity politics.U.S. influence, while still extremely significant, isdecreasing as hints of eventual troop withdrawal getlouder. And neighbouring states, anxious to protecttheir strategic interests, may forsake their longstandingcommitment to Iraq’s territorial integrity if they concludethat its disintegration is inevitable, intervening directly inwhatever rump states emerge from the smoking wreckage.If Iraq falls apart, historians may seek to identify yearsfrom now what was the decisive moment. The ratificationof the constitution in October 2005, a sectarian documentthat both marginalised and alienated the Sunni Arabcommunity? The flawed January 2005 elections thathanded victory to a Shiite-Kurdish alliance, which draftedthe constitution and established a government thatcountered outrages against Shiites with indiscriminateattacks against Sunnis? Establishment of the InterimGoverning Council in July 2003, a body that in itscomposition prized communal identities over national-political platforms? Or, even earlier, in the nature of theousted regime and its consistent and brutal suppression ofpolitical stirrings in the Shiite and Kurdish communitiesthat it saw as threatening its survival? Most likely it is acombination of all four, as this report argues.Today, however, the more significant and pressingquestion is what still can be done to halt Iraq’s downwardslide and avert civil war. Late in the day, the U.S.administration seems to have realised that a fully inclusiveprocess – not a rushed one – is the sine qua non forstabilisation. This conversion, while overdue, isnonetheless extremely welcome. Ambassador ZalmayKhalilzad’s intensive efforts since late September 2005 tobring the disaffected Sunni Arab community back into theprocess have paid off, but only in part. He is now alsoon record as stating that the U.S. is “not going to investthe resources of the American people to build forces runby people who are sectarian”. Much remains to be done,however, to recalibrate the political process furtherand move the country on to a path of reconciliationand compromise.First, the winners of the December 2005 elections,the main Shiite and Kurdish lists, must establish agovernment of genuine national unity in whichSunni Arab leaders are given far more than a token

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page ii

role. That government, in turn, should make everyeffort to restore a sense of national identity andaddress Iraqis’ top priorities: personal safety, jobsand reliable access to basic amenities such aselectricity and fuel. It should also start disbandingthe militias that have contributed to the country’sdestabilisation. The U.S. has a critical role to playin pressuring its Iraqi war-time allies to accept suchan outcome. States neighbouring Iraq as well as theEuropean Union should push toward the same goal.Secondly, substantive changes must be made tothe constitution once the constitutional processis reopened one month after the government entersoffice. These should include a total revision of keyarticles concerning the nature of federalism and thedistribution of proceeds from oil sales. As it stands,this constitution, rather than being the glue thatbinds the country together, has become both theprescription and blueprint for its dissolution. Again,the U.S. and its allies should exercise every effortto reach that goal.Thirdly, donors should promote non-sectarianinstitution building by allocating funds to ministriesand projects that embrace inclusiveness,transparency and technical competence andwithholding funds from those that base themselveson cronyism and graft.Fourthly, while the U.S. should explicitly state itsintention to withdraw all its troops from Iraq, anydrawdown should be gradual and take into accountprogress in standing up self-sustaining, non-sectarian Iraqi security forces as well as inpromoting an inclusive political process. AlthoughU.S. and allied troops are more part of the problemthan they can ever be part of its solution, for nowthey are preventing – by their very presence andmilitary muscle – ethnic and sectarian violencefrom spiralling out of control. Any assessment ofthe consequences, positive and negative, that canreasonably be anticipated from an early troopwithdrawal must take into account the risk of anall-out civil war.Finally – and regrettable though it is that this isnecessary – the international community, includingneighbouring states, should start planning forthe contingency that Iraq will fall apart, so as tocontain the inevitable fall-out on regional stabilityand security. Such an effort has been a taboo, butfailure to anticipate such a possibility may lead tofurther disasters in the future.

RECOMMENDATIONSTo the Winners of the December 2005 Elections:1.Strongly condemn sectarian-inspired attacks, suchas the bombing of the al-Askariya shrine in Samarrabut also reprisal attacks, and urge restraint.Establish a government of national unity thatenjoys popular credibility by:

2.

(a)(b)

including members of the five largestelectoral coalitions;dividing the key ministries of defence,interior, foreign affairs, finance, planningand oil fairly between these same lists, witheither defence or interior being given to arespected and non-sectarian Sunni Arableader, and the other to a similar leader ofthe United Iraqi Alliance;assigning senior government positions topersons with technical competence andpersonal integrity chosen from within theministry; andadopting an agenda that prioritises respect forthe rule of law, job creation and provisionof basic services.

(c)

(d)

3.

Revise the constitution’s most divisive elementsby:

(a)

establishing administrative federalism onthe basis of provincial boundaries, outsidethe Kurdish region; andcreating a formula for the fair, centrally-controlled, nationwide distribution of oilrevenues from both current and future fields,and creating an independent agency toensure fair distribution and preventcorruption.

(b)

4.

Halt sectarian-based attacks and human rightsabuses by security forces, by:

(a)

beginning the process of disbanding militias,integrating them into the new security forcesso as to ensure their even distributionthroughout these forces’ hierarchies, at boththe national and local levels;continuing to build the security forces(national army, police, border guards andspecial forces, as well as the intelligenceagencies) on the basis of ethnic andreligious inclusiveness, with members ofIraq’s various communities distributedacross the hierarchies of those forces aswell as within the governorates;

(b)

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page iii

(c)

ensuring that the ministers of defence andinterior, as well as commanders and seniorofficers at both the national and local levelare appointed on the basis of professionalcompetence, non-sectarian outlook andpersonal integrity; andestablishing an independent commission,accountable to the council of deputies, tooversee the militias’ dismantlement and thecreation of fully integrated security forces.

9.

(d)

Engage Iraq’s neighbours, including Iran, inhelping solve the crisis by taking the measuresdescribed in recommendation 11 below, andactively promote the reconciliation conferenceagreed to in Cairo in November 2005, encouragingrepresentatives of all Iraqi parties and communities,as well as of governments in the region, to attend.

To Donors:10.Allocate funding to ministries and governmentprojects, as well as civil society initiatives, strictlyaccording to their compliance with principles ofinclusiveness, transparency and competence.

5.

In implementing de-Baathification, judge formerBaath party members on the basis of crimescommitted, not political beliefs or religiousconvictions, and establish an independentcommission, accountable to the council of deputies,to oversee fair and non-partisan implementation.Both former Baathis and non-Baathis suspectedof human rights crimes or corruption should beheld accountable before independent courts.

To States Neighbouring Iraq:11.Help stabilise Iraq by:

(a)(b)

expressing or reiterating their strategicinterest in Iraq’s territorial integrity;encouraging the winners of the December2005 elections to form a government ofnational unity and accede to demands tomodify the constitution (as outlined inrecommendation 3 above);strengthening efforts to prevent funds andinsurgents from crossing their borders intoIraq; andpromoting, and sending representatives to,the planned reconciliation conference inBaghdad.

To the Government of the United States:6.Press its Iraqi allies to constitute a government ofnational unity and, in particular, seek to preventthe defence and interior ministries from beingawarded to the same party or to strongly sectarianor otherwise polarising individuals.Encourage meaningful amendments to theconstitution to produce an inclusive document thatprotects the fundamental interests of all principalcommunities, as in recommendation 3 above.Assist in building up security forces that are notonly adequately trained and equipped, but alsoinclusive and non-sectarian.

(c)

7.

(d)

8.

Amman/Baghdad/Brussels, 27 February 2006

Middle East Report N�52

27 February 2006

THE NEXT IRAQI WAR? SECTARIANISM AND CIVIL CONFLICTI.INTRODUCTION: ESCALATINGSECTARIAN VIOLENCEThe event marking the onset of their increasingly ruthlessfight was the car bombing of a crowd exiting the ImamAli Mosque in Najaf on 29 August 2003 that killed morethan 85 worshipers, including Ayatollah MuhammadBaqr al-Hakim, SCIRI’s powerful and charismatic leader,the attackers’ target.3Since then, an unremittingbattle between insurgents and government forces(backed by U.S. troops) has spawned a much morepernicious sectarian conflict – Sunni on Shiite, Shiite onSunni – in which the most radical elements on each sideare setting the agenda. Thus, attacks on Shiite crowdsby suicide bombers allegedly acting on orders ofcertain insurgent commanders are countered bysweeps through predominantly Sunni towns andneighbourhoods by men dressed in police uniformsaccused of belonging to commando units of theministry of interior (controlled, since April 2005, bySCIRI and its Badr Organisation).

Following the advent of its first elected government inApril 2005, Iraq has witnessed an alarming descent intosectarian discourse and violence. Centred on the principaldivide between Sunnis and Shiites, this developmenthas prompted increasingly inflammatory rhetoric,indiscriminate detention, torture and killings on the basisof religious belief, attacks on mosques and families’induced departures from towns and neighbourhoodsbased on their religious identity.While there has been tension, and some violence, betweenethnic groups (for example, Arabs and Kurds) or amongShiite militias (such as the Badr Organisation and theMahdi Army) that could similarly contribute to Iraq’sdisintegration, this report focuses on the most significantcentrifugal forces that are tearing the country apart.1Theseforces, while religious in inspiration and identification,are profoundly political in origin and character. Their mainrepresentatives are the Supreme Council for the IslamicRevolution in Iraq (SCIRI) – and its military arm the BadrOrganisation (formerly the Badr Corps,al-Faylaq al-Badr)– that formally came to power as part of a Shiite-Kurdishcoalition after the January 2005 elections, and insurgentgroups seeking to jumpstart civil war and foment chaosby targeting Shiite populations, especially but notexclusively the insurgent outfits known asTandhim al-Qa’ida fi Bilad al-Rafidayn(al-Qaeda’s Organisation inMesopotamia) andJaysh Ansar al-Sunna(Partisans of theSunna Army).21

Iraq’s national security adviser, Mowaffak al-Rubaie, put itthis way, summarising the conclusions of a study preparedunder his supervision by the National Joint IntelligenceAnalysis Centre: “The report says that a war between Arabs andKurds, or between Turkomans and Kurds, is unlikely. Shouldcivil conflict break out, it is more likely to be a war betweenSunnis and Shiites, mainly in the mixed areas: Tel Afar,Diyala governorate, Baghdad. There is also the possibilityof an intra-Shiite civil war”. Crisis Group interview, Baghdad,2 September 2005.2Tandhim al-Qa’ida fi Bilad al-Rafidayn(Al-Qaeda’sOrganisation in Mesopotamia, or Al-Qaeda in the Land ofthe Two Rivers, i.e., Iraq) is the group created by a Jordanian,Ahmad Fadhel Nazzal al-Khalaila, better known as Abu Musab

al-Zarqawi. It was known previously asTawhid wa Jihad(Monotheism and Holy War). As the suicide attacks on threehotels in Amman on 9 November 2005 show, the group, whilenon-Iraqi in origin, has gained Iraqi recruits over the past twoyears; both its spokesman and military commander claim to beIraqis. See Crisis Group Middle East Report N�47,Jordan’s9/11: Dealing with Jihadi Islamism,23 November 2005, andCrisis Group Middle East Report N�50,In Their Own Words:Reading the Iraqi Insurgency,15 February 2006.Jaysh Ansaral-Sunnaappears to be a reincarnation ofAnsar al-Islam,agroup comprising jihadi Kurds and Afghan Arabs (includingZarqawi) that was decimated by a combined force of U.S. troopsand Kurdish Regional Government fighters in north eastern Iraqin March 2003. For background, see Crisis Group Middle EastBriefing N�4,Radical Islam in Iraqi Kurdistan: The MouseThat Roared?,7 February 2003. All insurgent groups, includingZarqawi’s, deny intending to foment a sectarian civil war, evenif evidence on the ground suggests the opposite. See the sectionon Zarqawi further below. For an analysis of the insurgents’discourse in this respect, see Crisis Group Report,In Their OwnWords,op. cit.3The attack is generally attributed to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.His jihadi followers in Zarqa (Jordan) have claimed that theattacker was Yassin Jarad, the father of Zarqawi’s second wife,who had gone to Iraq to fight with his son-in-law. See Hazemal-Amin, “Jordan’s Zarqawists visit their sheikhs in prison andawait the opportunity to join Abu Musab in Iraq”,Al-Haya,14December 2004.

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 2

Sectarian passions are inflamed on both sides with eachgruesome suicide attack or discovery of mutilated bodies,an almost daily occurrence. Most frequent have been theegregious bombings of crowds of worshipers, mournersin funeral processions, shoppers or job-seekers queuingto join the police4in predominantly Shiite towns andneighbourhoods.5Most attacks take place in Baghdad andtowns ringing the capital, a majority of which have mixedpopulations, or on roads leading from Baghdad to theShiite holy cities of Najaf and Karbala, which traverse astring of Sunni-inhabited towns – Latifiya, Mahmoudiya,Iskanderiya, Yusefiya, Musayyeb – in the so-calledTriangle of Death.6In the Shiites’ litany of outrages,attacks targeting religious leaders (Baqr al-Hakim) orfestivals (Arba’in, 2004) stand out.Mass casualties occur even when no political target isinvolved but the attackers seek to spread fear, anger anddiscord (fitna), for example the suicide bombings in Hillaon 28 February 2005 (some 125 dead)7and in a busleaving a Baghdad station for the southern (Shiite) town

of Naseriya on 8 December 2005 (at least 32 dead).8Therealso have been brazen armed attacks in broad daylightagainst Shiites walking in the street, passing a checkpointwhile driving or simply being in their own homes orplaces of work. One particularly notorious incident, in lateSeptember 2005, involved the execution-style killingof five (Shiite) teachers and their driver in Muwelha,a (Sunni) suburb of Iskanderiya, by armed men dressed aspolice officers.9So pervasive has become the fear of attacks thatcrowds respond to the merest suspicion of one havingtaken place or about to occur. Thus the rumour that asuicide bomber was about to blow himself up in themidst of a procession on the occasion of a Shiitereligious festival on 31 August 2005, triggered a massstampede on a bridge in Baghdad’s (Shiite) Kadhemiyaneighbourhood in which hundreds of worshippers –men, women and children – were either trampledunderfoot or drowned in the Tigris. Coming on theheels of a mortar barrage in the vicinity of the crowdearlier that morning that reportedly killed as many asseven, the alarm was sufficient to cause mass death inthe absence of any physical attack.10For a year and a half, from August 2003 until February2005, such attacks met with barely a response from mostShiites, except deepening anger and calls for revenge. Theonly ones accused of meting out revenge from the outsetwere members of the Badr Organisation, allegedlyresponsible for the assassination of former regime officialsand suspected Baath party members, in addition tosuspected insurgents, but for a long time these actions didnot reach critical mass. The Shiite religious leadershiprepeatedly and insistently called on the masses to exerciserestraint and on survivors to refrain from avengingthemselves for the deaths of their close relatives. This, andthe expectation that they, the Shiites, were about to cometo power through the U.S.-engineered transition, mollifiedthe community and left the attacks both one-sided anddramatically unsuccessful: if the aim was to jumpstartsectarian war, the provocations failed to yield the intendedresponse.8

4

Some insurgent propagandists draw a distinction betweencivilians (illegitimate target) and candidates queuing up atpolice recruitment centres (legitimate). Under internationalhumanitarian law, both groups are considered civilian andtherefore cannot be attacked.5To be sure, car bombings have occurred in non-Shiite townsas well, such as Ba’quba, which has a mixed Sunni/Shiitepopulation. (Sunni) Kurds, too, have been a target, for examplein suicide bombings against Kurdish parties, police, politiciansand government installations in the territory of the KurdistanRegional Government (KRG). In Khanaqin, outside the KRG,attackers killed two birds with one stone on 18 November 2005when they hit two Shiite mosques in the predominantly (Shiite)Kurdish town. In Sunni towns, bombings appear mainly to havetargeted police stations.6“Even before Zarqawi became a star”, said an Iraqi who usedto visit Karbala and Najaf in 2003 and 2004, “there were attackson Shiite travellers on this road”. Crisis Group interview,Amman, 9 December 2005. Crisis Group interviewed an Iraqifrom Sadr City, the large Shiite slum area of Baghdad, who hadtravelled to Najaf to bury a relative in May 2005. The funeralparty was ambushed by seven armed men wearing militaryuniforms who were running a checkpoint on the road betweenMahmoudiya and Latifiya. “They screamed, ‘Get out, you dirtyShiites!’, and took six of my relatives”. The six (young) menturned up at the Mahmoudiya morgue two days later, reportedlyshowing signs of torture. As a further horrifying example of theattack’s sectarian nature, the killers cut off part of one of thevictims’ arms that sported a tattoo of the (Shiite) Imam Ali’ssword. Crisis Group interview, an elderly relative whosurvived the attack, Sadr City, 29 August 2005.7The incident caused an upset in Iraqi-Jordanian relations whenthe dead attacker’s Jordanian family reportedly celebrated theirson’s “martyrdom” in Iraq. For more on this incident, see CrisisGroup Report,Jordan’s 9/11,op. cit., p. 8, fn. 56.

The lethal December 2005 attack at the bus station, carried outby a suicide bomber who had boarded the bus, followed a triplecar bombing at the same station in August 2005 that killed atleast 43 people. Associated Press, December 2005.9The men reportedly burst into a primary school in Muwelha,rounded up five teachers and their driver, then shot themexecution-style in an empty classroom. A local police officerclaimed the men were disguised Sunni Arab insurgents. SabrinaTavernise, “Five teachers slain in an Iraq school”,The New YorkTimes,27 September 2005.10See Borzou Daragahi and Ashraf Khalil, “Hundreds Die inBaghdad Bridge Stampede”,The Los Angeles Times,31 August2005.

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 3

However, once the Shiite parties, brought together in theUnited Iraqi Alliance, won a simple majority of votes inthe January 2005 elections and, in alliance with theKurdish list, gained power three months later, the picturechanged dramatically, especially after SCIRI took overthe Interior Ministry, allowing the Badr Corps to infiltrateits police and commando units. Soon, Iraqis witnessed asteep rise in killings of Sunnis that could not be explainedby the fight against insurgents alone. Carried out duringcurfew hours in the dead of night and reportedly involvingarmed men dressed in police or military uniforms arrivingin cars bearing state emblems, raids in predominantlySunni towns or neighbourhoods appeared to cast a widenet. Those seized later turned up in detention centres11or,with a disturbing frequency, in the morgue after havingbeen found – hands tied behind their backs, blindfolded,teeth broken, shot – in a ditch or river. These raidsprompted suspicions that they were carried out by Badrmembers operating under government identity andtargeted the Sunni community rather than any particularinsurgent group or criminal gang.In a well-publicised incident, men dressed in greencamouflage uniforms identified by witnesses as membersof the Volcano Brigade detained some 30 (Sunni Arab)men in Baghdad’s (mostly Shiite) Hurriya neighbourhoodone night in August 2005 around 1 a.m. Several dayslater, their mutilated corpses were found in a dry riverbednear the Iranian border. Surviving relatives denied theyhad had any role in the insurgency and accusedgovernment forces of targeting Sunni tribes (in this casethe Dulaim and Mashahada) as revenge for their pastsupport of Saddam Hussein’s regime.12In late October, militia men of the Mahdi Army raided the(Sunni) village of Madayna in Diyala governorate in anapparent attempt to free hostages captured by localhighway robbers. Meeting resistance and sufferingcasualties, they reportedly returned with commando unitsof the interior ministry and took reprisals, burning downhomes and executing a number of villagers. “This is thebeginning of a sectarian war”, Diyala’s deputy governor,a member of the (Sunni) Iraqi Islamic Party (IIP), declaredafterwards.13Disturbing evidence has also emerged of amethodical effort to assassinate senior officers of theousted regime’s military, including air force pilots who

fought in the war against Iran. These killings have beenattributed to Iranian-sponsored Shiite parties that, with thetables turned, are bent on settling scores.14As such attacks accumulate, Iraqis’ perceptions areincreasingly shaped along sectarian lines, with Sunnis andShiites seen not only as victims but as the intended targets.Public and political discourse has followed apace,frequently taking on an unabashedly sectarian colouration,even as sectarianism is denounced.15Amidst the manypolitical slogans painted on Baghdad buildings, forexample, one can find sectarian specimens, such as: “Longlive the Sunni area!”16Political leaders often resort toAccording to Tareq al-Hashemi, secretary general of the(Sunni) Iraqi Islamic Party, some 55 pilots were killed in the sixmonths before September 2005: “There is a sense of revenge.They have a list of former pilots in Saddam’s regime, and theyare looking for them. It is part of a strategic Iranian plan to pushthe Sunnis out”. Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 5 September2005. The assassinations are attributed specifically to SCIRI, agroup that was established in and financed and armed by Iran,and that fought on the Iranian side during the Iran-Iraq war in aneffort to put an end to the Baathist regime. Some reports suggestthat the victims also include Shiite pilots not sympathetic toIran. If true, the killings may be part of an Iranian effort to createa pro-Iranian Iraqi air force, one unlikely to attack Iran, ashappened in September 1980.15For example, Adnan Dulaimi, leader of the Iraqi ConsensusFront, declared in July 2005: “If we are attending this conferencein the name of the Sunnis, it does not mean that we embracesectarianism….We are only talking about realities on the ground.We find that the Sunnis, since the start of the occupation, havesuffered from detentions, marginalisation, killings….It hasbecome worse in the last few days….This week we arranged thefunerals of more than twenty youths who used to frequentthe mosques… and the imams are detained without any arrestwarrant from a judge, taken from their homes during curfew”.Speech given during a “public emergency conference” forSunnis held at the al-Nida’ Mosque, Baghdad, 14 July 2005.16To be fair, one can also find unabashedly anti-sectarianslogans, such as: “No to Shiites, no to Sunnis, yes to Iraqi unity”(on al-Wahda primary school in the Dura neighbourhood inAugust 2005). More commonly, rival slogans cohabit acontested space and refer to the conflict’s principal protagonists,including: undefined “mujahidin” (literally holy warriors, i.e.,resistance fighters), Prime Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari (ofthe Islamic Daawa party), “Falluja” (the town in al-Anbargovernorate that some see as the heart of the insurgency andothers as a symbol of resistance and suffering), Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Saddam Hussein, Muqtada Sadr and the Mahdi Army,and SCIRI and the Badr Corps. For example, in Dura one canfind “Long live Falluja! Long live the mujahidin!”, “Victory forSaddam Hussein and Iraq!”, “Long live Muqtada Sadr!”, and“Long live the mujahidin! Down with the USA!” (on a Sadristmosque); in Ghazaliya neighbourhood, “Down with Jaafari andthe Badr Corps!”, “Long live al-Anbar governorate, theAmericans’ grave!”, “Long live Zarqawi!”, and “Long liveSaddam!”; in Ameriya neighbourhood, “Long live Falluja,symbol of the resistance!”; in Sadr City, “Yes, yes, Muqtada!14

The exposure by U.S. forces of an underground makeshiftdetention facility in Baghdad in November 2005 that held173 undernourished detainees – some of whom may havebeen tortured – and was run by the Interior Ministry evokedmemories of the Baathist regime’s methods.12Crisis Group interviews with surviving relatives, Baghdad,4 September 2005.13Quoted in Mariam Fam, “Militias growing in power inIraq”, Associated Press, 7 November 2005.

11

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 4

code, understood by all, to injure members of the oppositecommunity.17Moreover, in their speeches and sermonssome politicians and religious leaders have highlightedthe fate and good deeds of members of their owncommunity while excoriating the opposite community’spolitical leadership for having either perpetrated or donetoo little to prevent perceived sectarian outrages. Thus,some Shiite leaders immediately cast the above-mentionedKadhemiya bridge disaster in sectarian terms, accusingSunnis of having precipitated, if not caused, the deaths ofhundreds of Shiite worshipers.Sheikh Jalal-al-Din al-Saghir, for example, a Shiite clericwho belongs to SCIRI, bewailed the “beloved” victims’fate in a sermon on the first Friday following the event;berated the kind of “jihad” that would rocket men, womenand children congregating for religious purposes;18contended that the ministry of defence (headed by Saadounal-Dulame, a Sunni) rather than the ministry of interior(under Bayan Jaber, a SCIRI colleague) had beenresponsible for security in the neighbourhood and queriedwhy Dulame had permitted his ministry to be “penetratedby Wahhabi19and criminal elements”;20demandedto know why the ministry of health (whose minister,Abd-al-Mutaleb Ali, is a follower of Muqtada Sadr andthus a rival to SCIRI) had been unprepared to handle thedisaster with only three ambulances on the scene;thanked the (Shiite) members of the Iraqi National

Guard on duty in Kadhemiya on the day of thedisaster; and expressed “surprise” at the fact thatsome officials and clergy, “especially the clerics witholive-green turbans”, failed to condemn “this criminalact”.21By contrast, at a Sunni mosque, Sheikh Ahmad Abd-al-Ghafour al-Samarraie, a member of the (Sunni) MuslimScholars Association (MSA), dwelled only briefly on theKadhemiya incident in his Friday sermon, to observe that(Sunni) residents of neighbouring Adhemiya had riskedtheir lives to save some of the (Shiite) victims fromdrowning. He then launched into a tirade against thosewho sought to pin responsibility for the incident on“members of a certain sect” (the Sunnis), placing the onuson (Shiite) security forces instead:Why does the world talk of masked terrorism andnot of organised terrorism? Why does the worldtalk of terrorists and ignores state terrorism? Thereare gangs that exploit state instruments and kill andexecute people with government-issued weaponsdriving government cars, with the governmenteither unaware or choosing to overlook this.Sheikh Abd-al-Salam al-Qubaysi, speaking next, thenhomed in on what he saw as the real problem: “Whowould have believed that SCIRI and Daawa would dosuch things – take people from their homes, kill them andset fire to them? There are entities now in Iraq pushingtoward sectarian war because they realise that theirinfluence is shrinking in the Iraqi and Shiite street and nowthey want to win the Shiite street’s compassion by theseactions”.22The Iraqi media magnify the problem by their dailyportrayal of violence, with especially politically-affiliatedstations and papers ladling out a partisan broth thatpolarises the Sunni and Shiite communities. Theabovementioned Hurriya killings, for example, receivedprime billing (with a gruesome picture of one victim andinflammatory headlines) on the front page ofAl-Basa’er,a newspaper associated with the Muslim ScholarsAssociation – its effect, if not its intent, to further inflame

No, no, Abd-al-Aziz [al-Hakim, the SCIRI leader]!”, “Downwith SCIRI!”, and “Down with the Ghadr Corps!” (The latter isa play on the word “Badr” in Arabic. Badr is the name of thefirst battle fought in the name of Islam, led by Imam Ali in 624,whereas “ghadr” – substituting the Arabic letter “gh” for “b” –is the word for perfidy.)17In a typical use of code words, some Sunni Arab politiciansdismiss their Shiite opponents as Iranians. For examples, seeCrisis Group Middle East Report N�38,Iran in Iraq: How MuchInfluence?,21 March 2005, pp. 4-6. To some Shiite politicians,the epithet “terrorist” easily fits all Sunnis, not only insurgentscommitting outrages against civilians.18“What kind of jihad is this that happened in Kadhemiya”?, heasked. “Is this a jihad for the sake of Islam, Arabism, nationalunity or Iraq?” The words “Arabism” and “national unity” areoften seen as code words for positions held by Sunni Arabs(although Muqtada al-Sadr has also larded his speeches withArab nationalist rhetoric, one reason why he is viewed withconsiderably sympathy by many Sunni Arabs). Sunni Arabpolitical leaders raised these slogans in their campaign against adraft constitution they saw as imposed by Kurds and Shiites tobreak up the country.19Wahhabism is the variant of Salafism championed by theAl-Saud dynasty in Saudi Arabia.20Saadoun Dulame, a former exile in the UK, has come underintense criticism from Sunni Arabs for his decision to join theShiite-Kurdish government. Among other accusations flung athim, he has been called an Iranian agent (tawwab, see below).Crisis Group interviews, Baghdad, December 2005.

Sermon at Bratha Mosque, Baghdad, 2 September 2005.“Clergy with olive-green turbans” refers to clerics sympatheticto Saddam Hussein, whose Baathi loyalists routinely wore olive-green military fatigues. Again to be fair, al-Saghir also praisedresidents of neighbouring Adhamiya, which has a majoritySunni population, for having shown “their full support andsympathy for the victims and the injured, to the extent even thatone resident faced martyrdom after he saved several injuredpeople and then drowned when he tried to save another victim”.22Sermons at Um al-Qoura Mosque, Baghdad, 2 September2005.

21

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 5

sectarian passions.23Moreover, satellite TV stations suchas al-Jazeera and al-Arabiya, both based outside Iraq, areseen as supporting the insurgents’ cause through partisanbroadcasts betraying a Sunni vantage point.24As for thenew crop of Iraqi channels, neutral ground has recededto give way to partisan reporting, if not in fact then inpredominant perception. A relatively independent channelsuch as al-Sharqiya is seen as Baathist by many Shiitesand watched mostly by Sunnis.25Al-Iraqiya, which theShiite-led government took over from U.S. control, isconsidered pro-Shiite and indeed threw its support behindthe Shiite list in the December 2005 elections.26On top of this, political parties have established “humanrights” departments that churn out a literature ofvictimisation concerning the groups, or broadercommunity, they profess to represent. The MuslimsScholars Association, for example, uses a standardquestionnaire to compile basic data on Sunnis claiming tohave suffered abuse at the hands of government agents ormilitias. It then publishes lists with no more than thevictim’s name, date and place of the incident and reported(often presumed) perpetrator, with titles such as: “Namesof Those Assassinated for Sectarian Reasons” and“Incidents of Sectarian Killings of Sunnis”. Organisationslike the MSA, the Sunni Waqf, the University TeachersUnion (Rabetet-al-Tadrisiyinal-Jamaiyin)and the IraqiLawyers Union (Naqabet-al-Muhaminal-Iraqiya)alsorelease abundant documents detailing atrocities.27

Anecdotal evidence suggests that, prompted by seeminglyarbitrary assassinations – understood as sectarian becauselacking any obvious alternative motive – hostile rhetoricand spreading fear, growing numbers of Iraqis living inmixed towns28or neighbourhoods in which they are aminority are moving to areas where their religious kinpredominate, often trading places with members ofthe other community, who find themselves in the samepredicament.29In doing so, reportedThe New York Timesin November 2005, these people “are creating increasinglypolarized enclaves and redrawing the sectarian map of Iraq,especially in Baghdad and the belt of cities around it”.30These pre-emptive but nonetheless involuntary departuresare all the more tragic in that they polarise and tear apartextended families, given the pervasive phenomenon ofSunni-Shiite inter-marriage.

The headlines screamed: “We Are Not Sheep To BeSlaughtered … Relatives of the Hurriya Victims Are CallingFor the Murderers To Be Punished”, and “Interior [Ministry]… Commits a New Nazi Crime in Its Series of Horrific Crimes”,Al-Bas’er,31 August 2005.24“These satellite channels look at the Iraqi crisis as harmful tothe Palestinian cause. They think in terms of conspiracy theory.They are convinced that they will soon see a turbaned man [i.e.,a Shiite cleric] shaking hands with a Jew”, Crisis Groupinterview, Sheikh Fateh Kashaf al-Ghitta, himself a“turbaned man”, Baghdad, 24 November 2005. In December2005, Iraqi demonstrators criticised al-Jazeera for hosting apolitician who denounced Shiite clerics for taking part inpolitics and accused Ayatollah Sistani of collaborating with theU.S. occupation. Associated Press, 15 December 2005.25The channel is owned by Saad al-Bazzaz, a former Baathistbased in London who also owns the dailyal-Zaman.SomeShiites believe that al-Sharqiya is a mere continuation of al-Shabbab, the channel run by Uday, Saddam Hussein’s elderson, until the fall of the regime. Crisis Group interviews,Baghdad, November-December 2005.26A Daawa-affiliated station placed the number 555 on thescreen as a logo, a reference to the UIA list in the December2005 elections.27Crisis Group received copies of the MSA questionnaire,lists and media releases in September 2005.

23

While the phenomenon of sectarian “cleansing” seems topredominate in Baghdad and towns around it, the city of Basrain the south has not remained unaffected. Anecdotal evidencesuggests that members of its minority Sunni community haveleft under pressure. One refugee was quoted as saying: “For aSunni family like mine that was swimming in a lagoon ofShiites, it was almost impossible to continue living in Basra”,Newsweek,4 October 2005.29Members of smaller minorities – Christians, Yazidis, Shabak,Sabean-Mandeans, Bahai and others – seek to remain beneaththe Sunni-Shiite sectarian (or Arab-Kurdish ethnic) radar, hopingto avert immediate harm due to their otherness or, if necessarywhen moving through contested terrain, by concealing theirdenominational or ethnic identity. For example, Baghdad-bornChristian professionals working in the relative safety of theKurdish region traverse the dangerous Mosul area on theirweekends home by replacing their license plates (to reflect Arabrather than Kurdish towns of registration) and their identity cards(to assume Muslim Arab names) once they leave the Kurdishregion. Crisis Group interview, one such professional, anAssyrian Christian, Dohuk, 26 September 2005.30Sabrina Tavernise, “Sectarian hatred pulls apart Iraq’s mixedtowns”,The New York Times,20 November 2005. For an earlierreport on sectarian tit-for-tat killings and minority families’involuntary departure from Baghdad’s Ghazaliya neighbourhood,see Alissa J. Rubin, “Revenge killings fuel fear of escalationin Iraq”,The Los Angeles Times,11 September 2005. See alsoGhaith Abdul-Ahad, “Iraq’s deepening sectarianism”,The Hindu,4 May 2005.

28

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 6

II.A.

ROOTS OF SECTARIANISMBEFOREAPRIL2003

Like all societies in which adherents to two or morereligions, or branches of the same religion, live together,Iraq has not been free of sectarianism (ta’efiya) during itsmodern history. “It was always there”, said a middle-agedIraqi, speaking of his youth. “Everybody knew whateverybody else was. After leaving a Sunni home, the Shiitevisitor would wash his mouth. If you, as a Shiite, had abad dream, you would say this was because you had eatenat a Jew’s or a Sunni’s house”.31Sunnis and Shiites readilymarried each other, usually maintaining their own religiousidentity (unless one partner was forced by the spouse’smore influential family to change it as part of the marriageagreement) but bequeathing the father’s to the children.32Sectarianism, in other words, was largely social andcultural, endemic but relatively benign.33It becamevirulent only when it was politicised by actors who soughtto exploit religious and ethnic identities for political gain,for example as a mobilisation tool with which to acquire alarger following – a phenomenon also observed in otherarmed conflicts, such as in the former Yugoslavia.34Sectarianism was employed as a political instrument atdifferent times during Iraq’s modern history but rarely tothe extent of triggering significant violence, much lesscivil war. In the 1920s, the British mandatory authoritiesdid not shrink from using sectarian categories in theirattempt to bring order to the countries they and the othervictorious powers had forged from the ruins of theOttoman Empire. Favouring one sectarian group overanother proved an effective divide and rule strategy,

including in Iraq.35Social factors facilitated this policy. Inthe 1920s and 1930s, Sunni Arabs dominated the country’spolitical and military institutions, reflecting in part theirpredominance as landed overlords, whereas the majorityof Shiites were landless labourers on the Sunnis’ domains,especially in historically Sunni areas.36By the end of themonarchy (1958), this situation had started to shift,however, with Shiites present, though still under-represented, in government, inter-marriage becomingacceptable and Shiites (in many cases replacing the Jewswho left in 1951) moving into a position of economicdominance, especially in commerce.37When the Baath party seized power in 1968, its ideologywas self-professedly secular.38In fact, whatever else can

Crisis Group interview, Amman, 30 November 2005.Sunni-Shiite inter-marriage is particularly extensive amongIraq’s urban elites. One Baghdadi reported that 50 per cent ofthe children in his middle-school class in the 1970s came frommixed marriages. Crisis Group interview, Amman, 16 February2006. As a percentage of the total population, mixed marriagesappear more limited. One family court in Baghdad reported thatmixed marriages it had recorded constituted at most 5 per centof all unions in 2002; by late 2005, there were virtually none.The New York Times,18 February 2006.33One Iraqi put it this way: “Sects exist in Iraq. This is afact. But there is a difference between sect and sectarianism.Sectarianism never existed in Iraq before, and now we shouldget rid of it”. Crisis Group interview, Wamidh Nadhmi,deputy secretary general of the Iraqi National Founding Congress(al-Muatammaral-Taasisi al-Watani al-Iraqi)and secretarygeneral of the Arab Nationalist Trend in Iraq, Baghdad, 6September 2005.34Laura Silber and Allan Little, “The Death ofYugoslavia”, BBC documentary (London, 1996), revisededition.32

31

The British Mandatory authorities saw the Shiite clergy(mujtahids) as a particularly backward element of Iraqi societyin the 1920s that retained a hold over the Shiite masses, therebykeeping them from integrating into the new Iraqi identity.According to Toby Dodge, this is one reason why Gertrude Bell,the powerful Oriental Secretary to the UK High Commissioner,kept (Sunni) Mosul inside Iraq and gave the role of governingIraq to Sunni politicians. Otherwise, she wrote, Iraq would existas “a mujtahid-run, theocratic state, which is the very devil”.Toby Dodge,Inventing Iraq: The Failure of Nation Buildingand a History Denied(New York, 2003), pp. 67-69. “We allknow that the British came to Iraq for its strategic location andits oil”, said Muzaffer Arslan, the adviser for Turkoman affairsto President Jalal Talabani. “They did not come to bringdemocracy. They installed a king from outside, put Sunnis ingovernment although Shiites were the majority and manipulatedthe Kurds to serve their own, not the Kurds’ interests”. CrisisGroup interview, Baghdad, 27 November 2005.36For a fascinating glimpse at the intersection of confessionaland class differences in Iraq during the first half of the twentiethcentury, see Hanna Batatu,The Old Social Classes and theRevolutionary Movements of Iraq(Princeton, 1978), pp. 44-50.According to Batatu (p. 45), “the Sunni-Shi’i dichotomycoincided to no little degree with a deep-seated social economiccleavage….Of course, Sunni social dominance had its immediateroots in the preceding historical situation” – Ottoman rule.37According to Batatu, ibid, p. 49, the Shiites’ economicadvance “was on the whole encouraged rather than hinderedpolitically, because it suited the balance-of-power interests notonly of the English but also – from the forties onward – ofthe [Hashemite] monarchy which, like the English, was anextraneous political factor, the kings being of non-Iraqi origin”.Moreover, “[a]ccess to state offices being more difficult for themthan for Sunnis – now not so much by reason of calculatingprejudice as on account of their lower educational qualifications,the result, really, of their fewer opportunities in earlier times –the Shi’is had turned their energies toward commerce, and thuscome to excel in this line of activity”.38Kanan Makiya takes issue with the notion that Baathistdoctrine was secular, arguing that its pan-Arabism was deeplyrooted in Islam, and in particular in Sunni Islam: “The partyfound its ultimate justification in a broadly defined Arab-Islamictradition of politics”, even if its “moral absolutism…is directed

35

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 7

be said of the regime of Saddam Hussein (which graduallyshed much of its Baathist ideological baggage), it wasan equal-opportunity killer at most times, its principalcriterion being Iraqis’ loyalty to the regime, not their ethnicor religious background. Although Shiites and Kurds wereroutinely under-represented in the most senior executivepositions, and the very core of Saddam Hussein’s securityapparatus (for example, his bodyguards and the SpecialRepublican Guards) was drawn from (Sunni Arab)tribesmen, especially members of his own Albu Naserclan, the primary criterion for cooptation was blind loyaltyto the president. This, combined with professionalproficiency, could lead to impressive careers regardless ofethnic or confessional background.39In fact, the consolidation of Saddam Hussein’s personalpower and the realisation of his personal ambitions cameat the expense of segments of the population most readilyassociated today with the notion of Sunni Arab rule. Rightup to its downfall, the regime gave ample proof, byexecuting numerous Sunni Arab personalities and evenmembers of Saddam Hussein’s own tribe and family (forexample, his sons-in-law Hussein and Saddam Kamel in

199640), that no specific lineage offered any protectionwhatsoever to anyone perceived as a threat.41It was at times of intense national crisis that repressionassumed a more sectarian hue. Shiites became the regime’sprime target, first during the Iran-Iraq war42and thenespecially in the aftermath of its 1991 defeat in Kuwait,when an uprising spawned in the ranks of the retreatingarmy swiftly assumed Shiite overtones (encouraged bySCIRI/Badr elements pouring across the border from Iran).Even if the principal butcher in the bloody repression thatfollowed, Muhammad Hamza al-Zubeidi, was one of theirown, in the Shiites’ collective memory the perpetratorswere a Sunni Arab-based regime.43This goes a long waytoward explaining current animosities toward Sunni Arabsand the provisional government’s resistance to the notionof inclusiveness during the political transition in 2005.However, if the current outbreak of sectarianism does notflow directly from the sectarian policies of the previousregime, it arguably follows from that regime’s very nature.Its violently repressive authoritarianism eradicatedold (non-sectarian) social forces and their politicalrepresentatives – for example the Iraqi Communist Party40

at a nonreligious end: the demarcation of national identity in aworld that insists upon frontiers”. To Iraqi Shiites, Makiyacontends, pan-Arabism goes hand in hand with Sunnism and,because Sunnis constituted only about one-fifth of Iraq’spopulation in the twentieth century, “[m]uch of the violencein modern Iraqi politics is attributable to the structuralincompatibility between political goals [pan-Arabism] and theconfessional distribution of Iraqi society….Arabism was in theend bound to be perceived as the hegemony of a minority ofSunnis over Kurds, Shi’ites, and non-Muslims on terms set bythis minority and designed to secure for it a new eventualmajority”. Kanan Makiya,Republic of Fear: The Politics ofModern Iraq(Berkeley, 1998), pp. 211-215. Others disagree,pointing at the party’s historical roots in the anti-colonial strugglewhich brought together Sunnis and Shiites. The party’s traditionalleadership faded only after the 1963 coup and counter-coup,which marked the beginning of the Tikriti-led takeover of theparty. E-mail communication from a historian, 23 January 2006.As Saddam Hussein strengthened his hold over the countryin the 1970s and 1980s, the importance of Baathist ideologyreceded in the face of the ruthless, violent power politics thatcame to define his rule.39Thus, some of Saddam Hussein’s close collaborators andconfidants were not Sunni Arab (for example, Sabah Mirza, aShiite Kurd, and Kamel Hanna, a Christian); the upper echelonsof the Army had plenty of officers who were not Sunni Arabs;and several of the Republican Guards’ and Special Forces’ mostprominent officers were also not Sunni Arabs, including Abd-al-Wahid al-Ribat, Hussein Rashid, Yaljin Omar Adel andBareq al-Haj Hunta.

For a vivid description of this bloody episode, see AndrewCockburn and Patrick Cockburn,Out of the Ashes: TheResurrection of Saddam Hussein(New York, 1999), chapter 8.41The best sources on this dimension of Saddam Hussein’s ruleare David Baran,Vivre la Tyrannie et lui survivre: L’Iraken transition(Paris, 2004), and Amatzia Baram, “The RulingPolitical Elite in Ba’thi Iraq, 1968-1986: The Changing Featuresof a Collective Profile”,International Journal of Middle EastStudies,vol. 21, no. 4 (September 1989), pp. 447-493. TheMuslim Brotherhood counted among the Baath regime’s firstvictims. Well-entrenched in Ramadi, Falluja, Samarra andBaghdad’s Adhamiya neighbourhood, its members faced arrest,torture and execution from 1968 on. The first religious leaderkilled by the regime was the Brotherhood’s Sheikh Abd-al-Azizal-Badr, who died under torture in 1969. See essays in FalehAbdul-Jabar (ed.),Ayatollahs, Sufis and Ideologues: State,Religion and Social Movements in Iraq(London: 2003),especially pp. 98 and 173.42Said one Iraqi commentator, “after the Iranian revolution,Saddam Hussein became anxious about radical Shiism. Thisis one of the reasons why he attacked Iran [in September 1980]:to stop the spread of radical Shiism to Iraq”. Crisis Groupinterview, Amman, 30 November 2005. The Daawa party’santi-regime activities, especially after 1977, gave the Iranianrevolution a direct internal Iraqi dimension. While targetingIslamist Shiite parties, especially Daawa, the regime alsocarried out an aggressive policy of cooptation during the Iran-Iraq war, funding and arming Shiite tribes in the south.43In the predominantly Shiite town of Hilla, the Shiite tribe ofAlbu Alwan played a key role in suppressing the insurgency.Another feature of the regime was that in most Shiite townsthe secret police was staffed primarily by Shiites – from Hilla toBasra to al-Amara. Muhammad Hamza al-Zubeidi reportedlydied in U.S. captivity in Baghdad on 2 December 2005.

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 8

and the National Democratic Party – and generated newones, especially religious and tribal forces, as a way ofextending the regime’s control.44“The present sorry stateof Iraqi politics”, contends the noted Iraqi social scientistSami Zubaida, “dominated by religious authority andsectarian interests, is not the natural state of Iraqi societywithout authoritarian discipline. It is the product preciselyof that authoritarian regime and the social forces thatengendered it, greatly aided by the oil wealth that accrueddirectly to the regime”.45In sum, the Baath regime’s ethnic/sectarian legacy ismixed. The potential for the outbreak of ethnic andsectarian violence certainly existed in Iraq’s past, butnothing suggested it would be the inevitable result of theregime’s removal. Such a development required the abilityof political actors with express ethnic and sectarianagendas to operate in a permissive environment. This isprecisely what followed the arrival of U.S. and alliedforces. Exile parties, such as SCIRI and Daawa, whichthrived on a sectarian identity (as well as the Kurdishparties with their ethnically-based political agenda),eagerly jumped at the opportunity and, in the absence ofinternal rivals, pressed ahead and transformed Iraq’ssecular tradition beyond recognition. Iraq’s new foreignrulers, furthermore, arguably reinforced ethnic andsectarian identities through their misconceptions andresulting actions, especially by the way they went aboutestablishing the institutions of the new state.

Both measures were seen as essential to the country’sstabilisation: the continued presence of key elements ofthe former regime, so it was feared, could set the stage forthe emergence of a fifth column that would subvert andthen seize control of the new order.47Importantly, theold regime was perceived as based in the Sunni Arabcommunity, a view that meshed with the predominanceof opposition parties rooted in the other two principalcommunities, the Shiites and Kurds. The destruction ofthese key institutions therefore had a sectarian aura. In thewords of a former CPA official:Senior CPA advisors and the political leadership inboth Washington and Baghdad saw Iraq as anamalgam of three monolithic communities, and aslong as you kept the Shiites and Kurds happy,success was guaranteed, because they were notBaathists, formed the majority and essentially hadthe same ideas as liberal Americans. This simplisticmindset explains most of the mistakes of U.S.policy, including the disbandment of the army andBaath party, which they also saw in sectarian terms.Today we have the sectarian and ethnically-basedpolitics that the U.S. always claimed existed, aself-fulfilling prophecy.48Iraqi perceptions of the army, security forces and Baathparty are a good deal more complex, however. To mostIraqi Arabs, Sunni or Shiite, the army was a nationalinstitution, one (as Crisis Group wrote previously) “whoseorigins predated Saddam Hussein’s rule, whose identitywas distinct from that of his Baathist regime, and whichhas been intimately linked to the history of the Iraqi nation-state since the 1920s”.49They would readily agree,however, that the Republican Guard Corps and the SpecialRepublican Guard Corps consisted primarily of SunniArabs, especially in the upper ranks, and were, by design,sectarian institutions.

B.

CPA POLICIES

Among the first steps taken by Paul Bremer, the freshlyappointed chief of the Coalition Provisional Authority(CPA), were the orders banning the Baath party andabolishing the security apparatus, including the army.46

In the 1990s the regime reinforced the power of the tribes(offering them money in exchange for loyalty) and, despite itsavowed secularism, began to encourage Sunni clerics, thusfacilitating a drift toward Salafism.45Sami Zubaida, “Democracy, Iraq and the Middle East”,openDemocracy, 18 November 2005, p. 5, available athttp://www.openDemocracy.net. Zubaida explains (pp. 4-5):“The years of wars and sanctions in the 1980s and up to thedemise of the regime in 2003 witnessed the increased localisationand communalisation of Iraqi society….Local society andcommunal organisation tends to be ‘traditional’, religious andtribal. These forces were actually encouraged and fostered bythe Saddam regime as means of social control when the reach ofthe Ba’ath Party contracted”.46CPA Order Number 1, “De-Baathification of Iraqi Society”,16 May 2003, available at http://www.cpa-iraq.org/regulations/20030516_CPAORD_1_De-Ba_athification_of_Iraqi_Society_.pdf; and CPA Order Number 2, “Dissolution of Entities”(revised), 23 August 2003, available at http://www.cpa-iraq.org/

44

regulations/20030823_CPAORD_2_Dissolution_of_Entities_with_Annex_A.pdf.47The de-Baathification order offers the following rationale:“By this means, the Coalition Provisional Authority will ensurethat representative government in Iraq is not threatened byBa’athist elements returning to power and that those in positionsof authority in the future are acceptable to the people of Iraq”.48E-mail communication, 23 January 2006. In the words of aconstitutional scholar, the CPA engaged in a “reductionism thathas dominated ‘analyses’ and reinforced (and even reified)[sectarian] divisions. The subsequent real experience has onlydeepened them, with virtually no countervailing force to bind ina cross-cutting fashion”. E-mail communication, 29 December2005.49Crisis Group Middle East Report N�20,Iraq: Building a NewSecurity Structure,23 December 2003, p. i.

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 9

Kurds and Islamist Shiites view the army quite differently,namely as a selectively repressive institution that, alongwith the rest of the regime’s security apparatus, thwartedtheir political aspirations. Nationalist Kurds, for example,who suffered greatly from an army-led counter-insurgencycampaign in the 1980s (and even earlier eras), hold littlesympathy for this “national” institution. Likewise, manyIslamist Shiite militants have expressed hostility towardan institution that they, as Crisis Group wrote in2003, “associate with fierce domestic repression anddiscrimination in favour of Sunnis”.50The dissolution of the regime’s entire security apparatus –army, special forces, intelligence agencies, and ministryof defence, among others51– arguably hurt the Sunni Arabcommunity hardest. Even if the army was non-sectarian,its dismissal meant to Sunni Arabs the loss of its principalprotector, as well as its guarantee for the future. It is SunniArabs who have most explicitly – especially during theconstitutional negotiations in 2005 – embraced the notionof Iraqi unity,52a quality that, in their view, the armyembodied.53By encouraging the insurgency, the CPA’s decisionindirectly contributed to the sectarian rift in another way.The army’s humiliating summary disbandment put up to350,000 men in the street without pay, the promise of apension or, for senior officers, the prospect of recruitment

into the new security organisations.54Given thepredominance of Shiites in the army’s rank and file,the decision led to mass protests throughout Iraq (minusKurdistan), in Shiite areas no less than in Sunni ones. Inthe absence of comprehensive research, anecdotal evidencecollected over the past two-and-a-half years suggests thatmany former soldiers and officers joined (and perhaps evengave rise to) the incipient insurgency during the hotsummer months of 2003 or, in even greater numbers,resorted to crime as a way of making ends meet.In the resulting chaos and disaffection, the emerginginsurgency could blossom and sprout. But, although theinsurgency comprised both Sunnis and Shiites at thebeginning, over time it assumed a predominantlySunni (Arab) character because it fed especially on thedisaffection of Sunni Arabs who felt disfranchised andmarginalised. This community’s fears intensified whenthe regime’s removal brought to power parties that basedthemselves on ethnic and confessional identities and beganto pursue similarly based policies, such as the building ofnew security forces dominated by Shiites and Kurds.The de-Baathification order had a similar impact. TheBaath party was one of the regime’s principal instrumentsof control in which, over time, as the regime’s compositionand character changed, Sunni Arabs came to dominate –though not monopolise – the most senior echelons,while Shiites gravitated toward the rank and file. Its“disestablishment”, in CPA terminology, and the removalof “senior party members”55from “positions of authorityand responsibility in Iraqi society” and those of lower rankfrom the top three layers of management, in one swoopdeprived Iraq of its managerial class, regardless of thosemanagers’ character or past conduct.56The CPA then setup a de-Baathification Council to supervise this process.57It was controlled by Ahmed Chalabi, a former exile whoused it to eliminate potential rivals and, in the run-up to

Ibid., p.4.The list of “dissolved entities” included the following securityagencies, ministries and other regime pillars: the ministries ofdefence and information, the ministry of state for military affairs,the intelligence service (Mukhabarat), the national securitybureau, the directorate of national security (al-Amnal-Aam),thespecial security organisation (Murafiqin), the special protectionforce, the army, air force, navy, air defence force and otherregular military services, the Republican Guard, the SpecialRepublican Guard, the directorate of military intelligence(Istikhbarat), the Al-Quds Force, the emergency forces, FidayinSaddam, the Baath party militia, Friends of Saddam, AshbalSaddam, the presidential diwan, the presidential secretariat, andthe revolution command council.52For example, a prominent Sunni Arab leader, Adnan Dulaimi,said: “We do not believe in sectarianism but in Iraqi unity, evenif we insist on speaking in the name of the Sunnis, because theyform an important part of society….We want Iraq to remainundivided, one country….We are the heart of Iraq, the centre ofIraq….We are the builders of Iraqi civilisation….We will keepcarrying the banners of Islam and Arabism”. Speech givenduring a “public emergency conference” for Sunni Arabs, heldat the al-Nida’ Mosque, Baghdad, 14 July 2005.53“The army was not sectarian but a national army for all groupsthat defended the country”, said Nabil Younis, a lecturer atBaghdad University. Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 30August 2005.51

50

For an analysis of the early consequences of these decisions,see Crisis Group Middle East Briefing N�6,Baghdad: A RaceAgainst the Clock,11 June 2003, pp. 7-11.55Defined as those holding the ranks of regional commandmember (Udhual-Qiyada al-Qutriya),branch member (UdhuFar’a),section member (UdhuShu’ba)and team member(UdhuFirqa).56The order provides that persons “holding positions in the topthree layers of management in every national governmentministry, affiliated corporations and other government institutions(e.g., universities and hospitals) shall be interviewed for possibleaffiliation with the Ba’ath Party….Any such persons determinedto be full members … shall be removed from their employment.This includes those holding the more junior ranks of Udhu(Member) and Udhu ‘Amil (Active Member), as well as thosedetermined to be Senior Party Members”.57CPA Order Number 5, “Establishment of the Iraqi De-Baathification Council”, CPA/ORD/25 May 2003/05.

54

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 10

the January 2005 elections, to rally (sectarian) support ashe gambled on the Shiite card to gain power. Moreover,the Shiite parties that rose to prominence helped“sectarianise” the de-Baathification process by givingShiite Baath party members within their own communitythe opportunity to repent. The standard approach towardSunni Arab members, however, was to exclude themfrom senior posts in government and the security forces.In the eyes of many Sunni Arabs, de-Baathification hasbecome a blunt weapon wielded by the new Shiite-ledgovernment to exorcise its demons – these being not theformer regime alone, but Sunnis as such. The Shiite parties“claim that the Sunnis are responsible for all of Saddam’smistakes”, said Tareq al-Hashemi, secretary generalof the Iraqi Islamic Party. “But we are not. We are alsohis victims. And now they are talking about terrorism,about Baathism, about Wahhabism, but at the end of theday, they mean Sunnis”.58“De-Baathification is turningout to be de-Sunnification”, agreed Nabil Younis, alecturer at Baghdad University. “This is why Sunnis areafraid”.59Sunni Arabs further fear that, by enshrining de-Baathification in the new constitution,60future Shiite-dominated governments could use it to selectively keepSunnis out of public sector jobs, offering these to Shiites,who, ironically, were a majority in the Baath and, justas ironically, in many cases had joined simply to securepublic sector jobs that otherwise would have beenunavailable.Before the long-term sectarian impact of these decisionscould become clear, the CPA, with the help of the UnitedNations, established the Interim Governing Council inJuly 2003, a ruling body whose composition has been atthe heart of an ongoing controversy. On the face of it, thecouncil appeared inclusive, comprising representatives ofall of Iraq’s principal communities – Arabs, Kurds andTurkomans, as well as Muslims (both Sunnis and Shiites)and Christians.61In reality, it was neither inclusivein a true political sense, nor representative. As manycritics have pointed out, it was heavily weighted toward

the only existing political parties – those of the formerexiles – but in most cases62they had little indigenoussupport; it especially represented Sunni Arabsinadequately, since its Sunni members were formerexiles such as Adnan Pachachi and Ghazi al-Yawar,who lacked significant constituencies.63Worse, theparties that were favoured – the only parties thatexisted, as a result of having been raised in exileduring a regime that tolerated no domestic politicsoutside the Baath party – almost invariably had overtlyethnic (the Kurds) or sectarian (the Shiite religiousparties) agendas.64More pointedly, it was, in fact, in the council’s purportedinclusiveness that the problem lay, since selection wasbased on supposed representation of Iraq’s amalgam ofcommunities.65For the first time in the country’s history,sectarianism and ethnicity became the formal organisingprinciple of politics.66In the rush to give an Iraqi faceto the U.S. occupation, the CPA fell to default mode,empowering ethnic and sectarian groups whose presencein any event accorded with – and may have reinforced –62

Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 5 September 2005.Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 30 August 2005. As CrisisGroup advocated in June 2003, de-Baathification shouldhave been “de-Saddamisation”, i.e., a careful targeting of theinstitutions and personalities of the ousted regime, those whohad committed crimes and had blood on their hands or werecorrupt. Crisis Group Briefing,Baghdad,op. cit., p. 10.60Art. 134 (1) of the constitution reads: “The High Commissionfor de-Baathification shall continue its functions as anindependent commission, acting in coordination with thejudiciary and executive branches within the framework of thelaws regulating its functions. The Commission shall be attachedto the Council of Representatives”.61The term “Christians” is used here as a shorthand for ethnicAssyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs.59

58

The Kurdish parties, which since May 1992 governed theKurdish region and can therefore not be considered exile parties,excluded.63It also left out representatives of the populist movementof Muqtada Sadr, who promptly denounced the Council asan illegitimate, foreign-imposed body.64One of the exceptions was the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP),whose leader, Hamid Majid Mousa, was a council member.However, his appointment was reportedly due not to the factthat he was the ICP leader but his prominence as a (secular)Shiite, so filling out the Shiite quota on the council. CrisisGroup interview, Amman, November 2005.65As the Council itself declared, “The council is representativeof the makeup of the Iraqi people”. “Text of statement byIraqi Interim Governing Council”, 13 July 2003, available athttp://www.cpa-iraq.org. CPA administrator Bremer laudedthe Council for bringing together, “for the first time in Iraq’shistory, a balanced representative group of political leaders fromacross this country. It will represent the diversity of Iraq: whetheryou are Shi’a or Sunni, Arab or Kurd, Baghdadi or Basrawi,man or woman, you will see yourself represented in this council”.CPA, “Text of Ambassador Bremer’s Weekly TV Address”, 12July 2003, available at http://usinfo.state.gov.66As Crisis Group observed in August 2003, “The principlebehind the Interim Governing Council’s composition … sets atroubling precedent. Its members were chosen so as to mirrorIraq’s sectarian and ethnic makeup; for the first time inthe country’s history, the guiding assumption is that politicalrepresentation must be apportioned according to such quotas.This decision reflects how the Council’s creators, not the Iraqipeople, view Iraqi society and politics, but it will not be withoutconsequence. Ethnic and religious conflict, for the most partabsent from Iraq’s modern history, is likely to be exacerbated asits people increasingly organise along these divisive lines”. CrisisGroup Middle East Report N�17,Governing Iraq,25 August2003, p. ii.

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 11

its simplistic view of a society consisting, broadly, of Arabsand Kurds, Shiites and Sunnis. “The Americans played abig role in this new sectarianism”, said Ismael Zayer, theeditor of the dailyal-Sabah al-Jedid.“They characterisethe Iraqi people by their sect. They will ask you: ‘Are youa Sunni or a Shiite?’ Why are they asking this question?Now it has become a trend”.67Thus, just over half of theInterim Governing Council’s members were Shiites andabout 40 per cent were Sunnis (and one Christian); 68 percent were Arabs and 24 per cent were Kurds, the remaining8 per cent reflecting one Assyrian and one Turkoman.In Sunni Arab discourse today, the onset of all their illslies with the appointment of the Interim GoverningCouncil. In the words of Tareq al-Hashemi, the IIP’ssecretary-general, “All these problems started withBremer imposing a quota when he set up the InterimGoverning Council. He created a segregation betweenthe communities, favouring some religious groups overothers”.68The key winners were Shiite religious partieslike SCIRI and Daawa, whose ideology many Sunnisin Iraq associate with the regime in neighbouring Iran.“Bremer’s quota”, charged Nabil Younis, allowed theseparties to grab the power that had long eluded them andto which they felt entitled. “If you ask these people, theywill say: ‘It was our time to regain power’. They are eitherPersians or persons who lived in Persia. By contrast, ifyou speak to [true] Arab Shiites, such as Muqtada Sadr,you will find that they do not see differences betweenSunnis and Shiites”.69As if to confirm this, a politicianclose to Sadr, Sheikh Fateh Kashaf al-Ghitta, said:

The Americans brought with them the exiles. Mostof these were Shiite Arabs and Sunni Kurds.Because of this, and because of the regime’s rapidcollapse, most of the Sunni Arabs felt threatened.The Kurds said: “We were persecuted by the formerregime”. The Shiites say the same. And when theInterim Governing Council was established on asectarian basis, the others – the Sunni Arabs – said:“Where are we”?70During the following months, a growing insurgency withemerging Sunni Arab overtones increasingly destabilisedthe country, even as the political process, with fits andstarts, proceeded. This only reinforced the U.S. notionthat the Sunni Arabs were a problem that ought to beisolated and fought rather than included throughnegotiation and persuasion. “The Americans”, contendedWamidh Nadhmi, “found resistance in the Sunni [Arab]areas and said that the Sunnis are the problem. But allIraqis are against the occupation, except perhaps for theKurds; the first spark of resistance occurred in [Shiite]Kufa and Najaf”.71There were no Sunni Arab political leaders who couldmediate, only an insurgency that increasingly fed on SunniArab disaffection. A heavy-handed counter-insurgencyeffort created a self-fulfilling prophecy: raids on townsand villages alienated a Sunni Arab community that thenstarted to express growing sympathy with the insurgents.In this environment, the CPA invested its political hopesin the former exiles on the Interim Governing Council,thereby giving the political transition a distinctly Kurdishand religious Shiite colouration. Yet there was nothinginevitable about the Sunni Arabs’ political alienation.U.S. forces arguably found less resistance in their areasthan elsewhere during the invasion. Senior army officerscould have been brought into the new army early on andpolitical and tribal leaders without blood on their handscould have been actively courted. This was not done.The Interim Governing Council proved to be a weak anddysfunctional institution that lacked popular legitimacyand support. Yet it was responsible for drafting the interimconstitution (the Transitional Administrative Law), whichcontained the transition timetable. In June 2004 it wasreplaced by an interim government, also handpicked bythe CPA, to which nominal sovereignty was transferred atthe end of that month. During this entire period from July2003-January 2005, the Kurdish and Shiite religiousparties were able to use their institutional advantage toentrench themselves and, through ad hoc alliances (the

Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 25 August 2005.Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 5 September 2005. OtherSunnis agreed. Wamidh Nadhmi (a Baghdadi Sunni of Kurdishorigin) said: “One of the first mistakes the Americans made wasto form a governing council based on sectarian quotas without areferendum or consensus. It was just imposed. I don’t deny thatShiites are the majority but by how much? We don’t know;there has been no census. The Americans say that the Sunnisare under 20 per cent. I don’t think that’s right”. Crisis Groupinterview, Baghdad, 6 September 2005. Huda Hidaya al-Nu’aimi, an academic, agreed that sectarianism started with theCouncil’s appointment by sectarian quota and the empowermentof religious parties, which she termed “a divisive approach” togovernance. Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 4 September2005. Baher Butti, a psychiatrist and member of the country’sSyriac minority, concurred with the Sunni viewpoint: “Youknow, Bremer made a big mistake by using that quota system.It was not balanced”. Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 7September 2005.69Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 30 August 2005. Likewise,Sheikh Hassan Zeidan, leader of the National Front for IraqiTribes, blamed growing sectarianism on “parties that came fromoutside Iraq with the cooperation of foreign intelligence toexecute the project of dividing the country … especially Iranian68

67

intelligence and Israeli intelligence”. Crisis Group interview,Baghdad, 27 August 2005.70Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 24 November 2005.71Crisis Group interview, Baghdad, 23 November 2005.

The Next Iraqi War? Sectarianism and Civil ConflictCrisis Group Middle East Report N�52, 27 February 2006

Page 12

Kurdistan Coalition List and the United Iraqi Alliance)and close adherence to the self-designed timetable, toproject themselves as the only significant political actorsin the January 2005 elections.

C.

CONSTITUTION-MAKING