Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2004-05 (1. samling)

Bilag 28

Offentligt

B’TselemThe Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories

- Draft -

Forbidden Roads:The Discriminatory West Bank Road RegimeAugust 2004

8 Hata’asiya St. (4thFloor), Talpiot, Jerusalem 93420Tel. (02) 6735599Fax (02) 6749111[email protected]http://www.btselem.org

Forbidden Roads:The Discriminatory West Bank Road RegimeAugust 2004

Researched and written by Yehezkel LeinEdited by Shirly Eran and Eyal RazData coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Antigona Ashkar, Yael Handelsman, SohadSakala, Shlomi SwisaFieldwork by ‘Atef Abu a-Rob, Salma Dab’i, Iyad Haddad, Musa Abu Hashhash, NidalKan’ana, Eliezer Moav, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi, Suha ZeidTranslated by Zvi Shulman

IntroductionOn 23 March 2004, the day after the assassination of Hamas leader Ahmad Yassin, theIsraeli media reported that the IDF had imposed a total closure on the OccupiedTerritories and a siege on cities in the West Bank. Such reports, which regularly appearin the Israeli media, paint a misleading picture of the reality in the West Bank. Accordingto the reports, the severe restrictions on the movement of Palestinians are a response toa particular event or threat. The reality is altogether different. The sweeping restrictionsare largely permanent, and have been for some time. They are only marginally affectedby the defense establishment’s assessment of the level of security threats at any giventime.This report deals with one of the primary, albeit lesser known, components of Israel’spolicy of restricting Palestinian movement in the Occupied Territories: restrictions and2

prohibitions on Palestinian travel along certain roads in the West Bank. Thisphenomenon is referred to in the report as the “Forbidden Roads Regime.” The regime,based on the principle of separation through discrimination, bears clear similarities to theracist apartheid regime that existed in South Africa until 1994. In the regime operated byIsrael, the right of every person to travel in the West Bank is based on his or her nationalorigin.The Roads Regime that Israel operates in the West Bank differs from the South Africanapartheid in at least one important way. While every last detail of the apartheid systemwas formulated in legislation, the Roads Regime in the West Bank has never been puton paper, neither in military legislation nor in any official decision. Implementation of theregime by IDF soldiers and Border Police officers is based solely on verbal orders givento the security forces. Therefore, enforcement of the Roads Regime entails a greaterdegree of arbitrariness than was the case with the regime that existed in South Africa.In an attempt to justify its policy, Israel contends that the restrictions on Palestinian travelalong these roads result from imperative security considerations and not from racistmotives. Indeed, since the outbreak of the intifada in September 2000, there has beenan alarming increase in the number of attacks by Palestinian organizations againstIsraeli civilians inside Israel and in the Occupied Territories. More than 600 Israelicivilians, including over 100 minors, have been killed. Attacks aimed at civilians violateall standards of law and morality, and constitute war crimes in international humanitarianlaw. The attacks are unjustifiable, regardless of the circumstances. Not only is Israelentitled to take action to defend its citizens against such attacks, it is required to do so.However, its actions must comply with Israeli and international law.The Forbidden Roads Regime is based on the premise that all Palestinians are securityrisks and therefore it is justifiable to restrict their movement. This is a racist premise, andcannot justify a policy that indiscriminately harms the entire Palestinian population, inviolation of their human rights and of international law.The Forbidden Roads Regime was designed in accord with the geopolitical divisionestablished in the Oslo Agreements. The agreements provided that Palestinians maygenerally travel in Areas A and B. In these areas, certain governmental powers weretransferred to the Palestinian Authority. In Area C, which remained under sole Israeliauthority, Israel restricts Palestinian travel, and on some of the roads Palestinian travel iscompletely prohibited. Israeli civilians are allowed to travel without restriction in Area C.

3

In Area B, restrictions are occasionally placed on travel by Israeli civilians, and Israelicivilians are completely forbidden to enter Area A (except for unusual cases). It shouldbe noted that the prohibition on entry of Israelis to Area A and parts of Area B isincorporated in military orders. As mentioned, the prohibitions on Palestinian movementare not set forth in military orders.1Israeli officials contend that this arrangement is a reasonable solution, “that is intendedto prevent excessive friction between Palestinians and Israelis.”2However, a careful lookat the “Oslo map” exposes the discriminatory and harmful basis on which the policy isbased. Areas A and B constitute dozens of islands separated by a sea defined as AreaC. The redeployment of IDF forces in 2000, pursuant to the Wye Agreement, createdeleven separate blocks defined as Area A (comprising eighteen percent of the WestBank), some 120 separate blocks defined as Area B (comprising twenty-two percent ofthe West Bank), and one contiguous block, which is defined as Area C and covers aboutsixty percent of the West Bank. Palestinians who want to go from one Palestinian blockto another must cross Area C, which is subject to the Roads Regime. Israelis, on theother hand, can move freely between the settlements and into Israel, without having toenter Areas A or B.The first chapter of this report briefly describes the integral relationship between thepaving of roads in the West Bank and the establishment of the settlements. The chapteralso discusses the legal means Israel used to gain control over the land on which it builtthese roads.The second chapter, presents the findings of B’Tselem’s research regarding theelements comprising the Roads Regime. This chapter details the means used to enforcethe regime; classification of the roads into three categories based on the severity ofrestrictions; the consequences of the regime on the Palestinian population, with fiveillustrative examples; and the IDF’s refusal to incorporate the regime in militarylegislation.

Order Regarding Defense Regulations (Judea and Samaria) (No. 378), 5730 – 1970,Declaration Regarding Closing of Area (Prohibition on Entry and Stay) (Area A). Similar orderswere issued regarding parts of Area B.2Letter from the IDF Spokesperson’s office to B’Tselem, 21 June 2004. The statement quotedrelates in general to the restrictions on movement imposed on Israelis and Palestinians on certainroads, and not specifically to Areas A, B, and C.

1

4

The third chapter of the report briefly describes the bureaucracy that Israel operates toissue movement permits that enable Palestinians to travel on some of the restrictedroads.The fourth chapter analyzes the Roads Regime from the perspective of international law.

5

Chapter One: Roads, Land Expropriation, and the Establishment ofSettlementsSince the occupation began in 1967, Israel has established an extensive system ofroads covering hundreds of kilometers in the Occupied Territories.3According to oneestimate, the cost of these roads amounts to about ten billion shekels.4In some cases,the roads were improvements and expansions of existing roads, while others were builtalong new routes. The roads are intended almost completely to serve the settlements.Israeli officials have denied this when justifying taking control of land to build these roadsto the High Court of Justice and to international officials and organizations. Rather, thestate pointed to military needs and the desire to improve the infrastructure to benefit thePalestinian population. Yet it is hard to find one road that Israel built in the West Bankthat was intended for any purpose other than to serve and perpetuate the settlements.Israel’s road construction policy in the West Bank differs drastically from the policyinstituted by the British and the Jordanians during their rule of the West Bank. Thegeographer Elisha Efrat points out that the roads in the West Bank, “always reflected thesurrounding topography.”5The location of Palestinian population centers alongside thecentral ridge enabled only two roads running north-south, one along the Jenin-Jerusalem-Hebron route (Route 60) and one along the Jordan Valley (Route 90). A fewroads branched out from Route 60, most of them in the northern West Bank.In the early 1970s, the situation quickly changed as a result of the settlements. Theestablishment of new settlements almost immediately brought with it the construction ofaccess roads to link them to the existing main roads. In many instances, the location ofthe settlements required new routes over difficult topographic terrain.6Frequently, theseroads served a small number of settlers, no more than a few dozen. The Israeli policyled, among other things, to extensive damage to the landscape of the West Bank. Theconstruction far exceeded the changes needed to meet the transportation needsresulting from the increase in population and economy of the area.

34

The entire West Bank is some 5,600 square kilometers.Anat Georgy and Motti Bassok, “Roads for Ten Billion Shekels,”Ha’aretz,Rosh Hashanahspecial supplement, 26 September 2003.5Elisha Efrat,Geography of Occupation,(Jerusalem: Carmel Publications, 2002), 148 (inHebrew).6Ibid., p. 150.

6

The idea of a bypass roads system, which enables access to settlements and travelbetween settlements without having to pass through Palestinian villages, was first raisedduring the settlement push in the late 1970s. In the “Settlement Master Plan for 1983-1986,” the chapter discussing roads states that, “The road is the factor that motivatessettlement in areas where settlement is important, and its [road] advancement will leadto development and demand.”7According to the plan, one of the primary objectivesdetermining the routes of the roads was to “bypass the Arab population centers.”8It wasaccording to this conception that Israel built dozens of new roads in the West Bankduring the 1980s.Beginning in 1993, with the signing of the Declaration of Principles between Israel andthe Palestine Liberation Organization (Oslo I), and in the framework of the redeploymentof IDF forces in the West Bank, the bypass road system gained momentum.In 1995, new road construction reached a peak. Israel began the construction of morethan one hundred kilometers of roads in the West Bank, which constituted more thantwenty percent of all the road starts that Israel made that year.9In following years, Israelcontinued to build bypass roads, though at a slower rate. In July 2004, four bypass roadswere under construction.10Contrary to the customary purpose of roads, which are a means to connect people withplaces, the routes of the roads that Israel builds in the West Bank are at times intendedto achieve the opposite purpose. Some of the new roads in the West Bank were plannedto place a physical barrier to stifle Palestinian urban development.11These roads preventthe natural joining of communities and creation of a contiguous Palestinian built-up areain areas in which Israel wants to maintain control, either for military reasons or forsettlement purposes.Ministry of Agriculture and Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization,Master PlanFor Settlement of Samaria and Judea, Plan for Development of the Area for 1983-1986(Jerusalem: Spring, 1983), p. 27. The plan also mentions the Drobless Plan, named after thechair of the WZO’s settlement division, who was among the officials who conceived the plan..8Ibid9Adva Center,Government Funding of Israeli Settlement in Judea, Samaria, and Gaza and inthe Golan in the 1990s: Local Authorities, Residential Construction, and Road Construction,May2002.10Za’tara bypass road, which links the Noqdim-Teqo’a block and Har Homa (fifteen kilometers);the Ya’bad bypass road, which links Harmesh and Mevo Dotan (eight kilometers); the bypassroad linking Qedar and Ma’aleh Adumim (seven kilometers); and the bypass road linking NILI andBeit Ariyeh (four kilometers).11For an illustration, see B’Tselem,Land Grab: Israel’s Settlement Policy in the West Bank,May2002, Chapter 8.7

7

The Settlement master plan for 1983-1986, mentioned above, expressly states that oneof the primary considerations in choosing the site to establish settlements is to limitconstruction in Palestinian villages. For example, in its discussion of the mountain ridgearea, the plan states that it “holds most of the Arab population in the urban and ruralcommunities… Jewish settlement along this route (Route 60) will create a psychologicalwedge regarding the mountain ridge, and also will likely reduce the uncontrolled spreadof Arab settlement.”12This demonstrates that the desire to demarcate Palestinianconstruction was a guiding principle in determining the routes of the new roads.The routes set for most of the new roads ran across privately-owned Palestinian land. Toenable this, Israel used two legal means: “requisition for military needs” and“expropriation for public use.”International humanitarian law allows the occupying state to seize temporary control ofprivate property of residents in Occupied Territory (i.e. land, structures, personalproperty) provided that the seizure is necessary for military needs. To take advantage ofthis, Israel defined some of the roads it planned to build as a response to meet “militaryneeds.” Until the end of the 1970s, Israel contended that the settlements played animportant military role, so it was allowed to seize private land to establish them and buildroads to serve them. In the High Court’s judgment in a petition against establishment ofthe Beit El settlement on privately-owned Palestinian land, Justice Vitkin approved theaction, stating:Regarding the pure security consideration, there is no question that thepresence of communities in occupied territory – even “civilian”communities – makes a significant contribution to security in that area,and facilitates the army’s role.13The “military needs” contention was given new meaning in the 1990s, in the wave ofroad construction that followed the redeployment in the West Bank. Previously thepresence of settlers for whom the roads were intended, was considered an aid to thearmy, now, military necessity was defined as supplying safe roads for the civilianpopulation.14

Ministry of Agriculture and the Settlement Division of the WZO,Master Plan,footnote 7.HCJ 258/79,Ayub et al. v. Minister of Defense et al., Piskei Din33 (2) 113, 119.14For a summary of Israel’s understanding of the role of the bypass roads in the framework ofthe IDF’s redeployment in the West Bank following the Oslo Agreements, see State Comptroller,13

12

8

The second legal means that Israel employs, as stated, is “expropriation for a publicpurpose.” As a rule, requisition of property in occupied territory, unlike the temporaryrequisition for military needs, is forbidden under international law.15The only exception isexpropriation in accordance with the local law that is intended to benefit the localpopulation.16Thus, Israel relied on the Jordanian expropriation law applying in the WestBank.17When defending the expropriations before the High Court, the State Attorney’sOffice repeatedly argued that the planned roads would also serve the Palestinianpopulation, and that its needs were taken into account during the planning. In ajudgment given relating to a petition against the expropriation of private land to build aroad linking the Karnei Shomron settlement to Israel while bypassing Palestiniancommunities, Justice Shilo accepted the state’s position and held:Bypassing population centers prevents necessary delay in movementwithin the settlements, and thus time and energy, while the populationin those centers welcome being free of the troubles due to the noise,air pollution, and blockage of roads also in residential areas… Ifsettlement of this kind is established [the new neighborhood of KarneiShomron, Y.L.], it will benefit from the road, but the residents of theexisting villages, Habla and others will benefit no less.18As time passed, Justice Shilo’s vision came true, at least in part. The bypass road, likeother bypass roads, also served Palestinians in the area.Israel used both means – requisition and expropriation – in order to take land on whichto build roads. Apparently, the decision on which means to use was made arbitrarily.From Israel’s perspective, it was advantageous to claim requisition for military needs,which reduced the legal obstacles that Palestinians could use. This was especially trueafter the High Court ruled in principle that building bypass roads to serve the settlementswas indeed a military need. However, expropriation of land on the pretext of improvingthe road infrastructure on behalf of the local residents, Palestinians and Jews alike,would likely be more acceptable to certain groups in Israel and abroad. This may have“Construction of Bypass Roads in Judea and Samaria in the Framework of Operation Rainbow,”Annual Report 48(1998).15Article 46 of the Regulations Attached to the Hague Convention Respecting the Laws andCustoms of War on Land of 1907.16See the decision of Justice Barak in HCJ 393/82,Jama’it Askan Alm’almun CooperativeSociety v. Commander of IDF Forces, Piskei Din37 (4) 785.17Land Law: Acquisition for Public Purpose, Law No. 2 of 1953.18HCJ 202/81,Tabib et al. v. Minister of Defense, Piskei Din36 (2) 622.

9

been the reason for the recommendation made by the Attorney General regardingbypass roads that were planned following the Oslo Agreements: “A civil expropriationorder is preferable over a military requisition order, whenever possible.”19Not only did Israel almost always decide to build roads in the West Bank to meet theneeds of settlers and not Palestinians (even if the latter benefited from the roads), incertain cases, settlers built new roads through the means of the local authorities, withoutstate approval. According to the State Comptroller:In 1994-1996, a number of roads were built in Judea and Samariawithout the approval of the competent authorities in the region. Theroutes of these roads passed in large part over private land belongingto the Palestinians living in the region. During execution of the project,the defense establishment retroactively approved the construction ofsome of these roads.20According to the State Comptroller, in most cases in which the competent IDF officialsrealized that the roadwork was being done without approval, the army rushed to obtainrequisition orders to retroactively legalize the injury to private property. In one case (the“Wallerstein Road” linking the Beit El and Dolev settlements), part of the road built by thesettlers ran through Area B, area in which according to the Oslo Agreements, Israel wasnot entitled to seize private property for that purpose.21Therefore, regarding this sectionof the road, the necessary requisition orders were not issued and no order was given totake control of the land. However, the IDF did not stop construction work on the road.22Building new roads on the initiative of settlers, without approval of the relevantauthorities, became a common element of the many illegal outposts that have beenerected in the West Bank since the end of the 1990s.23It should be mentioned that theconstruction of these roads is only one expression of the state’s forgiving attitude towardsettler lawbreakers, a policy that has been in effect for many years.241920

State Comptroller,Annual Report 48,1036.Ibid., p. 1038.21Since the beginning of the al-Aqsa intifada, Israel has not referred the Oslo Agreements ingeneral, and this provision in particular. The requisition of private property for military needs iscarried out now, in Israel’s view, pursuant to humanitarian law.22State Comptroller,Annual Report 48,p. 1039.23To illustrate this point, see Sarah Leibowitz-Dar, “Zambish Outposts,”Ha’aretzWeekendSupplement, 18 July 2002.24On this point, see B’Tselem,Law Enforcement vis-a-vis Israeli Civilians in the OccupiedTerritories,March 1994; B’Tselem,Tacit Consent: Israeli Law Enforcement on Settlers in the

10

In sum, we see that the reason for the vast majority of the roads that Israel has built inthe West Bank is to strengthen its control over the land. In some instances, the roadsmet the settlers’ transportation needs, and in other cases, served to limit Palestinianconstruction. These reasons had nothing to do with the legal arguments that Israel usedto justify its taking control of private Palestinian land.

Occupied Territories,March 2001; B’Tselem,Hebron Area H-2: Settlements Cause MassDeparture of Palestinians,August 2003..

11

Chapter Two: The Forbidden Roads Regime – Research FindingsThis chapter presents the findings of B’Tselem’s investigative research conducted inMay and June 2004. The research entailed testimonies given by Palestinian drivers andpassengers throughout the West Bank, conversations with Israeli security forces, andinformation gathered from observation points staffed by B’Tselem personnel along majorroads and intersections in the West Bank. In addition, the picture presented in thischapter is based on testimonies, correspondence, and general information that B’Tselemhas gathered since the beginning of the al-Aqsa intifada.The failure to incorporate the Roads Regime in the military legislation or in officialdocuments makes it difficult to precisely characterize the regime. As a result, thecategories presented below, which relate to the methods of police enforcement and thenature of the restrictions and prohibitions on each group of roads, are based onB’Tselem’s analysis, and do not reflect any official legal status.The lack of written documentation also makes it difficult to determine when the regimebegan, or important milestones in its development. A cross-check of the information thatB’Tselem obtained during the two-month research period with the vast information thatthe organization has accumulated in recent years indicates that the Forbidden RoadsRegime developed gradually since the beginning of the current intifada. As of May 2002,at the end of Operation Defensive Shield, most of the principal components of theregime were in place, as described in this chapter.A few points about the research:The research relates only to the travel of Palestinians in vehicles with licenseplates that are issued by the Palestinian Authority (hereafter: Palestinian vehicles).It does not relate to the rules applying to travel by Palestinians in vehicles bearingyellow [Israeli] license plates (hereafter: Israeli vehicles), or in vehicles bearinginternational plates.The research deals only with those roads in the West Bank that servedPalestinians and Israelis until the outbreak of the intifada, , and since then,Palestinian travel on the roads has been restricted or prohibited. Therefore, theresearch does not include roads that Israelis do not use which are located in AreasA or B, even if the IDF prohibits or restricts Palestinian use on these roads; roadsthat Palestinians do not use that generally serve as access roads to settlements,12

even if the IDF prohibits Palestinians from using them; roads that both Israelis andPalestinians are not allowed to use.Roads inside East Jerusalem are not included, even though East Jerusalem isan integral part of the West Bank. We do not include these roads because of thedifferent regime that Israel applies in this area, even though the Israeli authoritiesgenerally prohibit Palestinians from traveling on these roads.

A.

Means of enforcement

The IDF uses three primary means to enforce the Roads Regime: staffed checkpoints,physical roadblocks, and patrols. These means complement each other and are used, aswill be shown below, in one combination or another, on almost all the forbidden roads.Enforcement of the regime is also achieved by measures that deter Palestinian driversfrom traveling on these roads, such as extensive delays, confiscation of vehicles, andimposition of fines.The roads in the West Bank currently contain forty-seven permanent staffed checkpointsand eleven other checkpoints that are occasionally staffed.25Nineteen of the checkpointsare located at entry points into Israel. Most of these entry-point checkpoints are located afew kilometers from the Green Line and serve also to enforce the Roads Regime. Someof the checkpoints at entry points into Israel are the responsibility of the Border Police,and others are under IDF responsibility. At eight of the forty-seven checkpoints, Israelhas erected a control tower. The soldiers at these checkpoints observe the traffic fromabove, and sometimes along the road itself where they check the passersby. In additionto the staffed checkpoints, security forces set up dozens of surprise checkpoints, usuallylasting a few hours, throughout the West Bank on a daily basis.Following the outbreak of the al-Aqsa intifada, the IDF has blocked access to theforbidden roads from nearby Palestinian villages by means of hundreds of physicalroadblocks. There are four types of physical obstacles: dirt piles, concrete blocks,trenches, and iron gates. These obstacles make passage by vehicle impossible, and

25

This figure does not include the thirteen checkpoints in Hebron.

13

force drivers who want to get onto the forbidden roads to go to staffed checkpoints, thuscontributing to the effectiveness of the checkpoints.26Completed sections of the separation barrier in the northwest part of the West Bank andaround Jerusalem also channel traffic to checkpoints. Patrols by security forces alongthe forbidden roads serve as a supplemental means of enforcing the regime onPalestinians who dare to enter the roads by bypassing a staffed checkpoint or a physicalroadblock. The patrols are conducted daily by soldiers, Border Police, and police officersfrom the Police Department’s Samaria and Judea (SHAI) District .The most common measure used to deter Palestinians from using these roads is delayat the checkpoints. Generally, the pretext for the delay is to check the documents of thevehicle and the individuals. The soldiers or police officers collect the identity cards of thetravelers, and sometimes also take the keys to the vehicle, and pass on the informationto army or General Security Service [Shabak] personnel, who check if the travelers arelisted as “wanted” or “needed for interrogation.” The wait can last many hours, duringwhich the soldiers keep the ID cards and keys.The patrols operated by the SHAI District of the Police Department strictly enforce thetraffic laws against Palestinian vehicles traveling on the forbidden roads. The policeofficers impose high fines for a variety of traffic offenses, such as failing to havecompulsory insurance, not wearing a seat belt, and dropping a passenger off in a placethat cars are not allowed to stop. During the period of the B’Tselem’s research, thetestimonies given by Palestinian taxi drivers indicated that all of them had been fined inrecent months for such traffic offenses. Most of them also displayed the dozens of ticketsthey had received. B’Tselem’s daily observations over the past year clearly show that thepolice focus their law enforcement efforts on Palestinian drivers, and rarely stop Israelivehicles.The delays and fines are not ostensibly intended to prevent Palestinian travel on theroads, but to enforce the law and safeguard security. In practice, they are only aimedagainst Palestinians, and are employed in a tendentious and offensive manner. As such,they serve as a strong deterrent and significant consideration for Palestinians in

26

In June 2004, the IDF removed about thirty dirt piles and has since opened some iron gates forpart of the day.

14

selecting which road to use. As a result, Palestinians reduce their travel along roads onwhich they are ostensibly allowed to use.The most severe punitive and deterrent means used by the IDF to enforce the regime isconfiscation of Palestinian vehicles caught without a “special permit” on one of theforbidden roads.27Although the IDF has seized vehicles for quite some time, Israeliofficials continue to deny that the seizure of Palestinian vehicles constitutes an officialpolicy. For example, at a meeting with B’Tselem on 20 June 2004, the head of the CivilAdministration, Brig. Gen. Ilan Paz, and the IDF legal advisor for Judea and Samaria,Col. Yair Latstein, said that, “We are unaware of such a phenomenon, but the matter willbe investigated.28

Fuad ‘Azat Fuad al-Jiyusi, a resident of Tulkarm, drives a taxi for a living. On 15 June2004, he picked up three residents of Tulkarm who wanted to go to the Allenby Bridge.When the taxi reached the IDF checkpoint at Jit, the soldiers refused to let him cross,contending that he did not have the proper permit. The soldiers also delayed four otherPalestinian taxi drivers. Al-Jiyusi related to B’Tselem what happened then: “At about10:00 A.M., a Hummer jeep, license number 703823, pulled up at the checkpoint. Thesoldier at the checkpoint who was holding the ID cards, gave them to the soldier sitting inthe jeep and ordered all of us to follow him in their cars. We followed him from thecheckpoint to the army checkpoint at the entrance to the Shevi Shomron settlement.There is a lot next to the checkpoint, where confiscated vehicles are kept. We parked ourtaxis in the lot and remained at the checkpoint for another hour, until the soldiers broughtour documents and recorded details about us and our taxis… The confiscation of vehicleform states that my vehicle was confiscated from the 15thto the 19thof June 2004.”29

Confiscation is a harsh means, in particular because of the serious financial loss to theowners of the confiscated vehicles, most of whom are taxi drivers. Also, the procedure isextremely arbitrary and subject to the sole discretion of the soldiers in the field, both inmaking the decision to confiscate and in setting the period of confiscation.See the discussion on the special permits, in Section 2 of this chapter, and in Chapter 3.The statement was made during a meeting that B’Tselem held with Civil Administration officialson 20 June 2004.29The testimony was given to Najib Abu Rokaya by telephone on 16 June 2004.2827

15

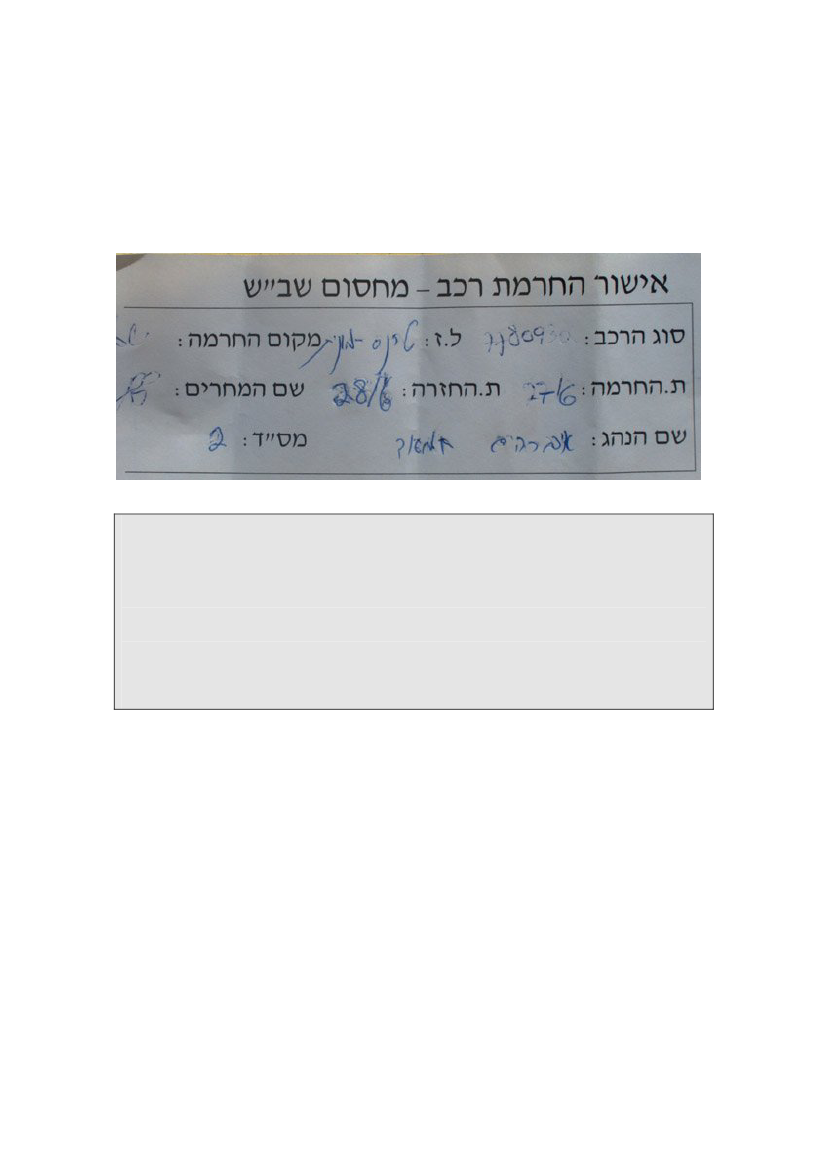

Although the IDF has been seizing vehicles systematically, particularly in the Nablusarea, the IDF has not issued official, standard confiscation forms that state the details ofthe driver and vehicle, the soldier or unit that carried out the confiscation, the offense forwhich the vehicle was confiscated, and the length of time of confiscation. In some cases,the owners of the vehicles are given improvised forms, not printed on official IDFstationery, and the details that the soldiers have to fill in vary from checkpoint tocheckpoint. In some cases, no written confirmation of confiscation is provided, and theowner is told orally when he can take his vehicle.30The IDF seizes Palestinian vehicles throughout the West Bank. However, the practice ismost common in the Nablus area, where the IDF has set up special parking lots to holdthe confiscated vehicles. These lots are located near the four staffed checkpoints: SheviShomron, Tapuah junction, Tell, and Beit Furik. The Shevi Shomron lot is the busiest ofthe four. This lot contained an average of fifteen cars each day B’Tselem researchersobserved the lot during the course of the research.The soldiers inform the owners how long the period of confiscation will last, whichusually ranges from two to fourteen days. In many cases, however, Palestiniansinformed B’Tselem that soldiers granted their requests to release their vehicles earlierthan scheduled.

Nabil ‘Abd a-Rahim Taha drives a taxi along the route between ‘Azzun ’Atma, which liessouth of Qalqiliya, and the Beit Iba checkpoint, west of Nablus. In March 2004, he wasgiven a movement permit allowing him to drive in the West Bank. The permit was validfor three months, until 11 June 2004. Abu Taha related to B’Tselem that, “On 6 April,while I was transporting passengers, an army jeep stopped me near the Jit intersection,which leads to the Beit Iba checkpoint. One of the soldiers took my ID card and twocellular phones that I had with me, and told the passengers to get out. Then he orderedme to go to the Shevi Shomron checkpoint, where he confiscated the taxi for four days.He claimed that it was forbidden for Palestinian taxis to drive along the road I was on.”31

3031

See the sample “Confiscation Form,” Appendix 4, below.The testimony was given to ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi on 4 June 2004.

16

B.

Classification of the roads

The following classification of the roads is based on the degree to which Palestiniandrivers are able to travel on them in practice. As mentioned above, no official prohibitionin writing exists from which we can learn the nature of the restrictions on Palestinianmovement along each of the roads. B’Tselem has divided the roads into threecategories: completely prohibited, partially prohibited, and restricted use.1.Completely prohibited roads

This category includes roads on which Israel completely forbids Palestinian vehicles.On some of the roads, the prohibition is explicit and obvious: Israel places a staffedcheckpoint through which only Israeli vehicles are allowed to pass. An example is Route557, which leads to the Itamar and Elon Moreh settlements. Soldiers at the Beit Furikcheckpoint told B’Tselem on several occasions that the section of Route 557 betweenthe Huwwara intersection and the villages near the checkpoint is defined as a “sterileroute” on which Palestinian travel is forbidden, without exception. The prohibition existseven though the road had previously served residents of the Palestinian villages BeitFurik, Beit Dajan, Sallem, and Deir al-Hatab.On other roads where Palestinian travel is totally forbidden, the IDF enforces theprohibition by blocking the access roads to the villages. Although no official prohibitionhas been announced, Palestinian drivers have no access to the road. Drivers whomanage to get onto the road cannot get to the villages, to which access is also blocked.This is the case, for example, with the seven villages along Route 443, which runs fromJerusalem to Modi’in.32Ostensibly, a Palestinian driver can go onto the road at itssouthern end, near the Givat Ze’ev settlement, and drop passengers off near thephysical obstacles placed along the roadway. In practice, Palestinians completely refrainfrom using this road.A B’Tselem staff member encountered a patrol from the SHAI District Police Departmenton Route 443 and asked the police officer what happens if a Palestinian is found drivingon the road. The officer replied: “You won’t see Palestinian vehicles on this road,” andadded that if he encountered a Palestinian vehicle, he would “stop it, check thedocuments relating to the vehicle and the driver, and transmit the details by radio toThe villages are a-Tira, Beit ‘Or al-Fuqa, Khirbet a-Masbah, Beit Or a-Tahta, Beit Liqya, BeitSira, and Safa.32

17

check if the driver was wanted for questioning by the Shabak or Police. If everything isall right, I let him go. They [the person at the other end of the radio transmission] mightask me to bring the Palestinians in for further check.”33In some instances, not only is travel forbidden, but crossing the road by car is also notallowed. This prohibition restricts Palestinians from reaching roads that are notprohibited.34In these cases, Palestinians can travel along the road until they reach aforbidden road, where they have to get out of the car, cross the forbidden road by foot,and get into another vehicle. In the area between Jenin and the villages situated to itseast runs a “forbidden” road that links the settlements Ganim and Kadim to Israel. As aresult, residents of Jalbun, Faqqu’a, Deir Abu Da’if cannot make the journey to or fromJenin in one vehicle. Another example is the road linking the Negohot settlement toIsrael, which is defined as a “sterile road;” which prevents movement between the Ithnaand Beit ’Awwa, which lie west of Hebron, and the villages to their south. In theselocations, Palestinians cross the forbidden roads by foot and get into vehicles on theother side to reach their destination.B’Tselem’s research indicates that the West Bank contains seventeen roads andsections of roads in which Palestinian vehicles are completely prohibited. The totallength of these roads and sections is about 124 kilometers.

The details of the officer are on file at B’Tselem.As stated at the beginning of this chapter, this research does not address roads that do notserve Israeli civilians, so we shall suffice by mentioning that they exist.34

33

18

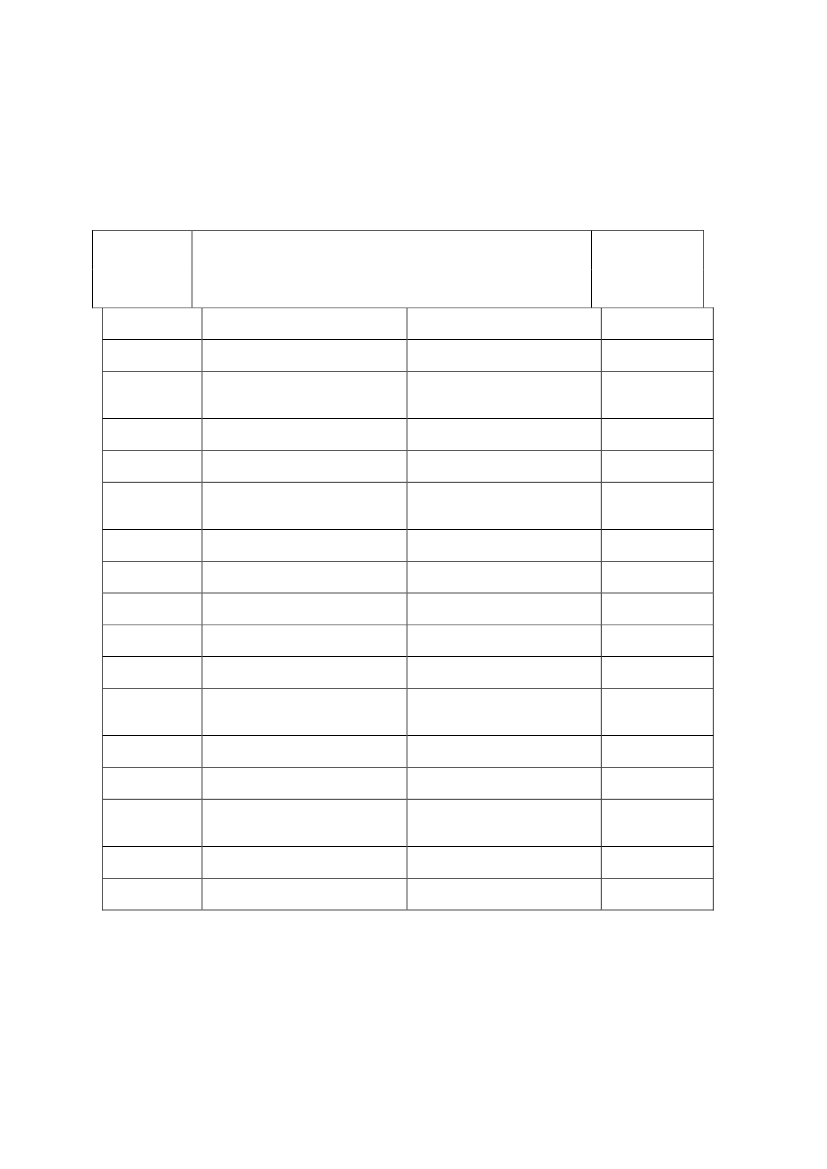

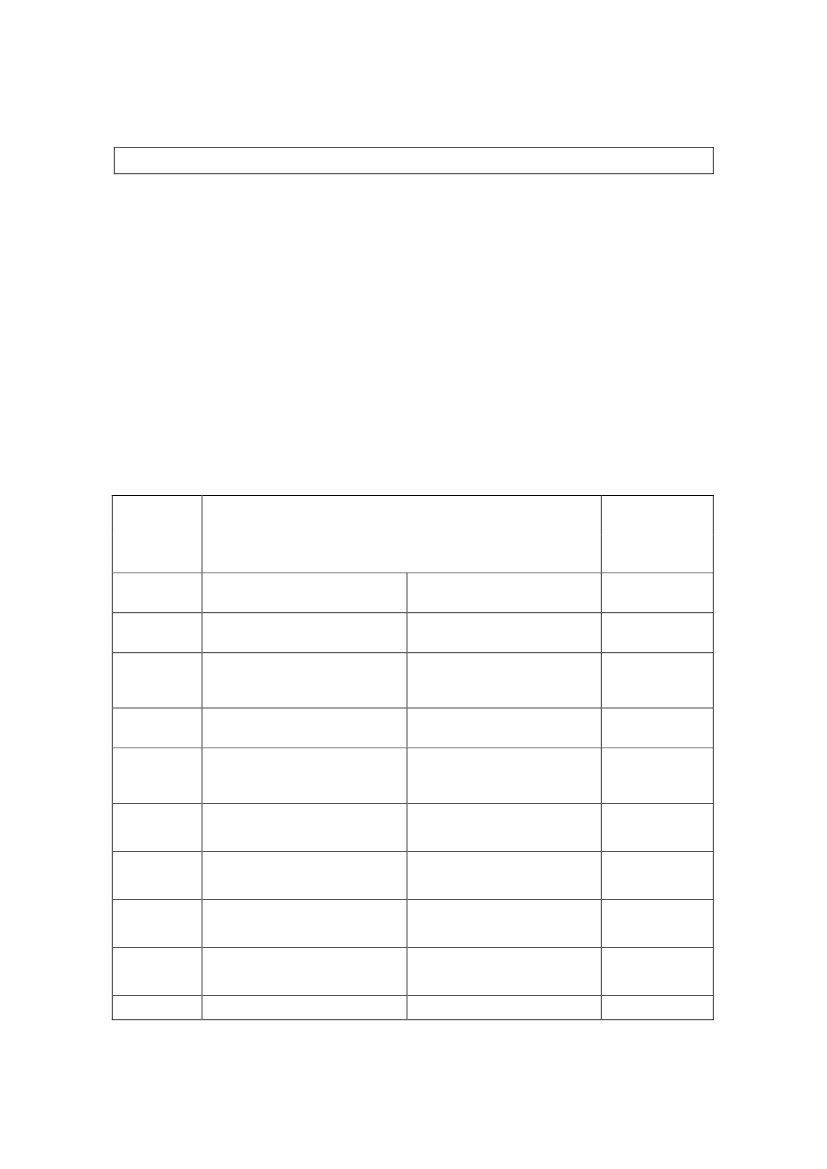

Table No. 1: Completely prohibited roadsPalestinian travel without a permit is forbidden on this roadNumber /Name6060Jalameh –Jenin55755755Ariel – Salfit446505466463TalmunimRoad404 (BeginNorth)443Qedar –Ma’alehAdumimNegohotRoadTana RoadLength (Km)FromGilo intersection (JerusalemMunicipality border)Sham’a checkpointJalameh, on the Green Line,south of AfulaAccess road to Elon Morehsettlement, east of NablusKafriyat checkpoint, south ofTulkarmCheckpoint at entrance toIsrael in the separation barrier,south of Qalqiliya“Trans-Samaria Highway,”access to Ariel settlementTrans-Samaria HighwayMashah, east of QassemvillageBeit El, north of RamallahRas Karkar intersectionAccess road to Beitillu, north ofTalmunHar Hotzvim, JerusalemGivat Ze’ev intersectionMa’aleh AdumimBorder of Area B, east ofNegohotOne kilometer north of TanaToTunnels checkpointGreen Line, north of MeytarGanim settlement, east ofJeninHuwwara checkpoint, southof NablusGreen LineGreen LineNorthern entrance to SalfitDeir Balut checkpointRoute 5 (Green Line)Route 60 (Ramallah bypassroad)Dolev settlement, northwestof RamallahDolev-Talmun intersection’AtarotcheckpointBeit Horon Intersection, eastof Modi’in“The Container” checkpoint,East Jerusalem, south of al-‘IzariyyaGreen LineGreen Line, north of Meytar381214343866612614658

2.

Partially prohibited roads

19

The second category includes roads on which Palestinians are allowed to travel only ifthey have special movement permits. The permit is called a “Special Movement Permitat Internal Checkpoints in Judea and Samaria.” The Civil Administration, through theDistrict Civil Liaison office, issues the permit.35The DCLs also issue permits for specialbus lines running between the checkpoints that block off the major cities. During periodsof “calm,” the IDF allows permit holders to travel along these roads. When the situation is“tense,” the IDF opens some of these roads for bus travel only.The fact that the policy is not set forth in written orders makes it easy for soldiers tocontend that the rules applying elsewhere in the West Bank do not apply where they areoperating. For example, in the Nablus area, soldiers occasionally prevent drivers holdingthe special permits, which are ostensibly valid throughout the West Bank, to travel onthese roads. The soldiers contend that, in this area, only permits issued by the IsraeliDCL for the Nablus area, referred to as the Huwwara DCL, are valid. The head of theCivil Administration, Brig. Gen. Ilan Paz, said that, “I have received complaints of thiskind,” but he referred to the matter as a “malfunction.”36

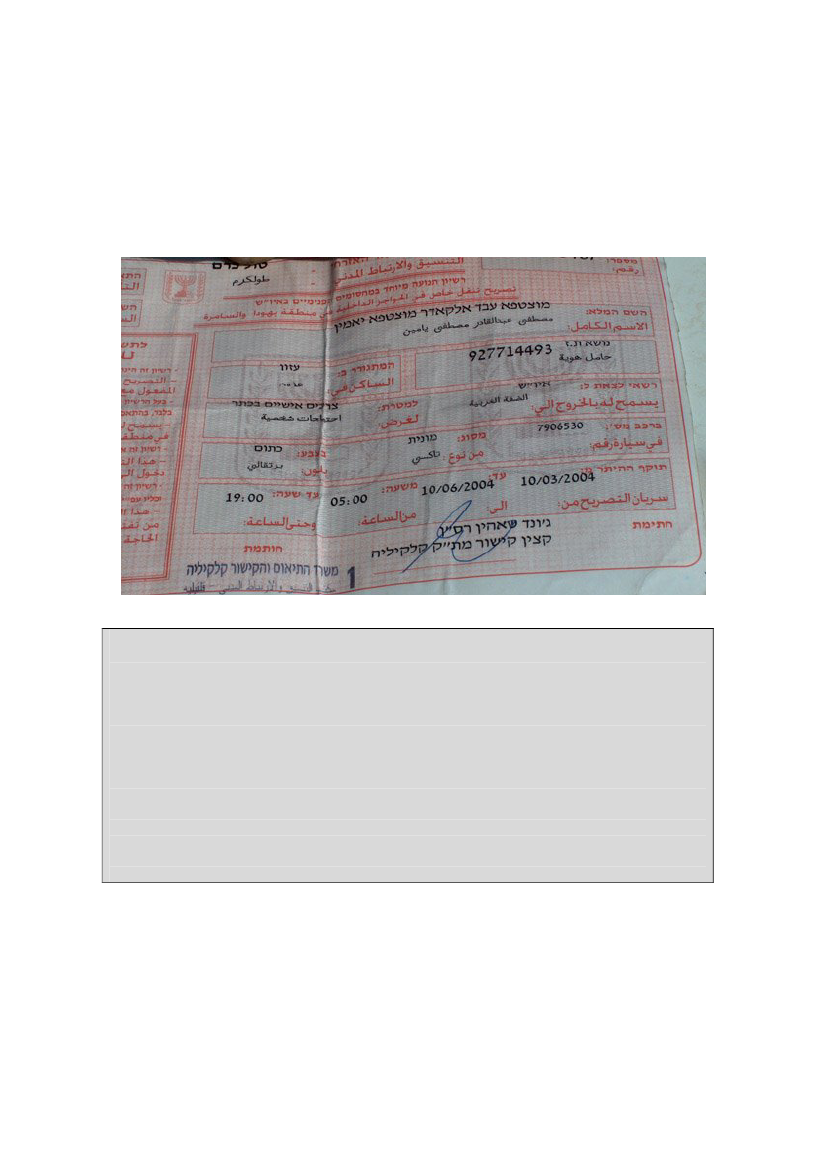

Mustafa ‘Abd Alqader Mustafa Yamin, a resident of ‘Azzun, is married with two children.He drives a taxi between his village and the checkpoints at the entrance to Nablus. Toenable him to work, he obtained a movement permit issued by the Israeli DCL officenear the Qedumim settlement. He was issued a permit for three months – from 10 Marchto 10 June 2004. In his testimony to B’Tselem, he stated: “The route I take from ‘Azzunto Nablus passes through the villages al-Funduq and Jit. There is an army checkpointnorth of Jit at which the soldiers check the Palestinian vehicles trying to get onto the roadleading to the Huwwara checkpoint via the Yizhar settlement. Several times, I tried to getto Huwwara by this road, but the soldiers at the checkpoint did not let me. They checkedmy papers and told me that my permit was issued by the Qedumim DCL, which is in theQalqiliya District, so it is not valid in Nablus District. To travel on that road, they said, Ihad to get a permit from the Huwwara DCL. So, I have to go around the checkpoints,drive to the Tapuah junction via the Trans-Samaria Highway, and then continue on toHuwwara. They act as if the Qedumim DCL and the Huwwara DCL do not belong to theFor a discussion on the hardships entailed in obtaining the movement permits, see Chapter 3below.36The comments were made at a meeting that B’Tselem held with Civil Administration officialson 20 June 2004.35

20

same army.

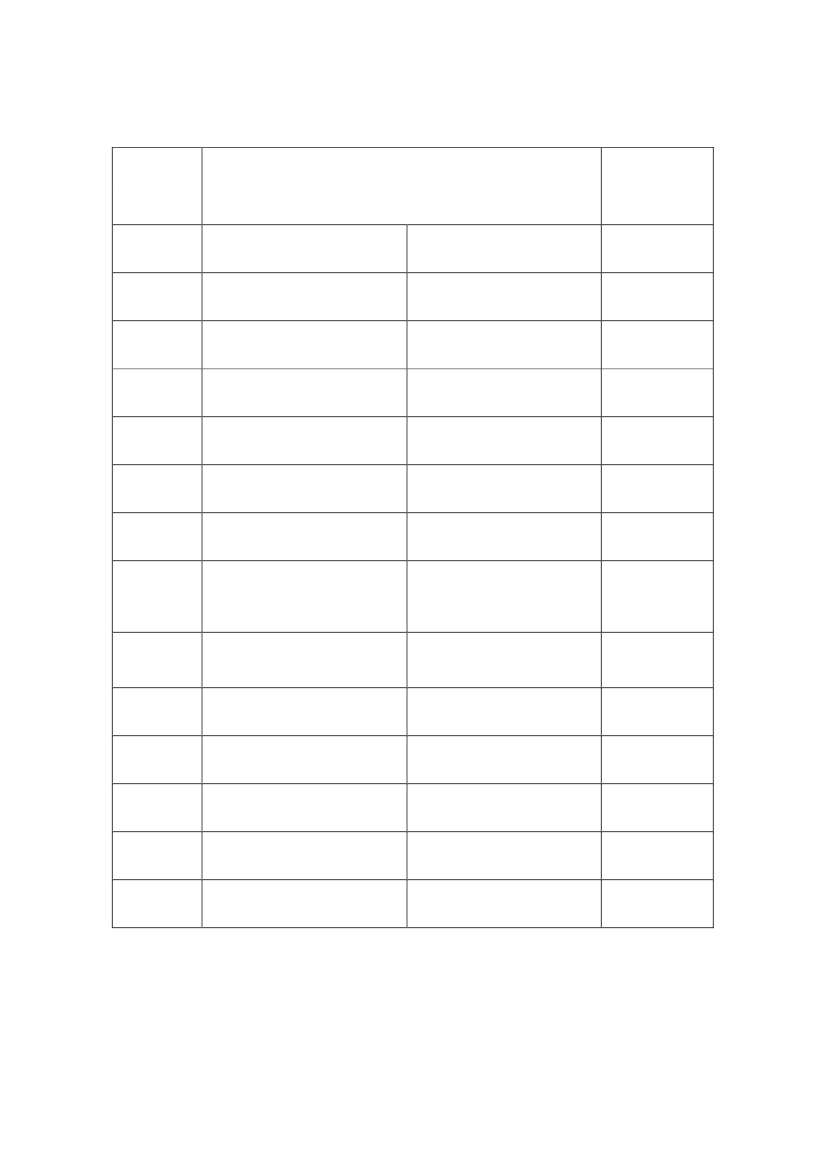

This category also includes roads on which in addition to holders of the special permitsthe army allows Palestinians whose identity cards indicate that they live in villages thatcan be accessed only by the forbidden roads. For example, travel is allowed along theAlon Road in the sections north of the Ma’aleh Ephraim intersection (Routes 578 and508), and the entire Valley Road (Route 90), only by Palestinians who are registered asliving in Jericho or one of the Palestinian villages in the Jordan Valley.B’Tselem found that the West Bank contains ten roads and sections of roads that fallwithin this category, totaling 244 kilometers.

Table No. 2: Partially Prohibited RoadsPalestinian travel without a permit is forbidden on this roadNumber /NameFrom9060508, 578(“AlonRoad”)557505Green Line, northwest of theJordan RiverJit intersection, west of NablusMehola intersection, fromRoute 90, south of the GreenLineAccess road to EinavsettlementPatzal intersection north ofJericho’AtarotcheckpointGivat Ze’ev intersectionRoute 1Gush Etzion intersection, Route60Carmel settlement, southeastToGreen Line, north of Ein GediHuwwara intersection, southof NablusMa’aleh Ephraim intersection1161250Length (Km)

Kafriyat checkpoint, south ofTulkarmMa’aleh Ephraim intersection,north of Jericho, on “AlonRoad”Givat Ze’ev intersectionRamot, East JerusalemMa’aleh AdumimGreen Line, Emek Ha’elaSham’a intersection, south of

711

45436417367317

3731025

21

of Hebron

Lita on Route 60

3.

Restricted use roads

This category includes roads that can be reached only via an intersection at which theIDF maintains a checkpoint, because the other access roads from Palestinian villagesadjoining these roads are blocked by the IDF. In general, Palestinians do not have todisplay a movement permit to cross these checkpoints. However, the IDF checks thepeople and vehicles wanting to pass through the checkpoint. At some checkpoints,where few soldiers are stationed as compared to the amount of traffic which passes thecheckpoint, the checks take a long time. Thus, many Palestinian drivers refrain fromusing these roads. There is greater presence of Israeli police patrolling these roads, andthe police strictly enforce the traffic laws against Palestinians, and readily issue tickets toPalestinian offenders. At times, the IDF places further restrictions on movement on theseroads, such as permitting only public transportation and commercial vehicles to use theroads.Some of the main arteries in the West Bank fall into this category. These include Route60, which runs through the West Bank from north to south, the “Trans-Samaria Highway”(Routes 5 and 505), which runs between the Green Line and the Jordan River, and the“Trans-Judea Highway” (Route 35), which runs from north of Hebron to the Green Line.Some sections of these roads are not subject to the restrictions.At some of the checkpoints at the entry points to these roads, the IDF also preventsPalestinians holding movement permits from crossing by car. Exceptions are made inhumanitarian cases and for individuals holding VIP cards. At these checkpoints, thePalestinians have to get out of the vehicle, cross the checkpoint by foot and get intoanother vehicle on the other side.B’Tselem found that there are fourteen roads or sections of roads in the West Bankwithin this category, totaling some 364 kilometers.

Table No. 3: Restricted Use Roads

22

Palestinian travel without a permit is forbidden on this roadNumber /NameFrom606060458 (“AlonRoad”)585557505505 – 5“Trans-SamariaHighway”465 (“Trans- BinyaminHighway”)449137535356Dotan intersection, west ofQabatyaHuwwara intersectionTunnels checkpointMa’aleh Ephraim intersectionNazlat ‘Issa, near Baqa al-GharbiyaDeir a-Sharf, west of NablusMa’aleh Ephraim intersectionTapuah intersection, end of“Trans-Samaria Highway”ToJit intersection, west ofNablusQalandiya checkpoint, northof JerusalemSham’a checkpointRoute 1Route 60Access road to EinavsettlementTapuah intersectionGreen Line335649381871631Length (Km)

Route 60, north of OfrasettlementBorder of Area A north ofJerichoBeit Ha’arava intersection,south of JerichoRoute 60, al-Khadr intersectionRoute 60, north of HebronRoute 60, north of Hebron

Green Line, north of RantisvillageRimonim intersection, east ofRamallaha-Za’im intersection, East ofJerusalemGreen Line, east of ZurHadassahTarqumiya checkpoint, GreenLine, northwest of HebronCarmel settlement, southeastof Hebron

31

133581811

It is important to note that the category of completely prohibited roads is relatively fixedas is the level of enforcement of the prohibition on travel. On the other hand, during

23

periods of “calm,” the IDF is less stringent in enforcing the prohibitions on roads in thesecond and third categories. Thus, Palestinian travel on these roads increases and thedifference between these two categories decreases.

C.

The effect on Palestinian travel habits

The Forbidden Roads Regime has created a fundamental change in the travel habits ofPalestinians in the West Bank. Rather than use the main roads between the cities, mostof the population is forced to use alternate long and winding routes. The regime hasforced most Palestinians to leave their cars at home and travel by public transportation,in part because private cars are not allowed to cross some of the checkpoints. Driversare also worried about the many fines that Israel imposes on Palestinians traveling onthese roads.The Roads Regime alters the normal routine of Palestinians in the West Bank in suchareas as economics, education, and health. Since the beginning of the al-Aqsa intifada,B’Tselem has documented thirty-nine cases in which Palestinian civilians died followingdelays at checkpoints or soldiers’ refusal to let them cross, which kept the individual fromreceiving medical treatment. Fifteen minors were among those who died in suchcircumstances. These cases are extreme and uncommon. However, many otherPalestinians have been delayed at checkpoints on their way to receiving medicaltreatment, as have medical crews on their way to giving treatment. All this is in additionto the critical harm to family and social life, and the regular insults and humiliation thatPalestinians suffer on a daily basis.The effects of the regime on daily life of Palestinians are felt in several ways:�wasted time resulting from the additional time needed to reach their

destinations, and from the hardship entailed in using their cars;�arriving late, or not at all, at destinations as a result of the uncertainty of

travel along alternate routes, crossing forbidden roads, and at checkpoints;�exhaustion resulting from travel along run down alternate roads and from

having to change from one car to another after crossing checkpoints, physicalroadblocks, or a forbidden road;

24

�

increased cost of travel resulting from the longer routes drivers are forced

to use;�wear-and-tear on vehicles resulting from travel on run-down, dirt roads.

Following are several examples of the forbidden roads and the alternate routes thatPalestinians use.1. The Qedar – Ma’aleh Adumim Road: Completely prohibitedThe main road running from the north to the south of the West Bank passes throughEast Jerusalem, an integral part of the West Bank. In the early 1990s, Israel placed atotal closure on the Occupied Territories. Palestinians were prohibited from entering EastJerusalem unless they had a special permit. Palestinian drivers have had to usealternate routes that run east of Jerusalem’s municipal border. The route runs from BeitSahur, which is situated near Bethlehem, passes by the entrances to the settlementsQedar and Ma’aleh Adumim, and continues to the Qalandiya checkpoint, north ofJerusalem.Halfway between Beit Sahur and Ma’aleh Adumim lies a checkpoint staffed by BorderPolice officers. At this checkpoint, the Border Police officers demand that Palestiniansdriving in private cars display special passage permits. Drivers of taxis and commercialvehicles generally do not face this requirement.A six-kilometer road joins the settlements Qedar and Ma’aleh Adumim. The IDF forbidsPalestinian vehicles from traveling on this road. To ensure that the road is used solely byresidents of Qedar (about 550 persons), the Border Police officers at the checkpointdirect all Palestinian vehicles to the narrow, run-down road through Sawahra a-Sharqiya,Abu Dis, and al-‘Izariyya. This is the only road available to the 2.3 million Palestinians inthe West Bank, making it very congested. Travel along this road, which used to take sixor seven minutes, now takes fifteen to twenty minutes, and sometimes more, notincluding the surprise checkpoints that are sometimes set up along the route.It should be noted that while the southern entrance to this road has concrete blocks andstaffed checkpoints, the entrance from the north (near the Ma’aleh Adumim settlement)does not have a sign or any other indication that Palestinian travel on the road isprohibited. However, Palestinians have learned the hard way to refrain from using theroad.

25

2. Route 60 – the Nablus bypass section: Partially prohibitedRoute 60 is the main north-south artery in the West Bank, which links the six majorPalestinian cities. Its importance is comparable to the Coastal Road or the Jerusalem –Tel-Aviv Highway. Since the outbreak of the intifada, Israel has restricted Palestiniantravel on this road, primarily by use of physical obstacles on the roads linking the roadwith villages situated on both sides. On the few roads that are not blocked, Israel hasplaced staffed checkpoints, and police patrols on the road are especially diligent inenforcing the traffic code.In addition, the security forces impose especially severe restrictions on the section of theroad that bypasses Nablus on the west, for a distance of twelve kilometers. This sectionruns from the Jit intersection, near the Qedumim settlement, and the Palestinian villageHuwwara. The Yizhar settlement lies near this road. Part of this section of the roadcrosses through Area B, but is also used by residents of nearby settlements (Homesh,Einav, Avnei Hefetz, Shevi Shomron, and Qedumim) on their way to Jerusalem orsettlements along the road to Jerusalem. Only Palestinian vehicles with permits areallowed on this section of the road. As a result, many Palestinians from the Jenin, Tubas,and Tulkarm districts, some half a million people, have to drive to the Ramallah area orthe southern part of the West Bank along alternate roads. To do this, the drivers havetwo options. The first route runs via Route 55 (the Nablus-Qalqiliya Road) to the Trans-Samaria Highway, from which they can get back onto Route 60. Israeli security forcespatrol and set up surprise checkpoints on Route 55, so many Palestinians refrain fromusing this option. The other route runs along roads that pass through the local villages toget to the “Trans-Samaria Highway,” and return to Route 60 from there. A trip that oncetook no more than ten minutes, now takes between twenty and forty minutes.3. The Ariel-Salfit RoadSalfit is the governmental and commercial center of surrounding Palestinian villages. Itplays an especially important role for the villages situated to its north: Haris, Kifl Haris,Qira, Marda, Jam’in, Zita-Jam’in, and Deir Istiya. Prior to the institution of the RoadsRegime, residents of these villages used Route 5, which branches off the “Trans-Samaria Highway” and continues south to the northern entrance of Salfit. This road isthree kilometers long and also serves as the main access road to the Ariel settlement.

26

Beginning in early 2001, the IDF blocked the southern entry point to this road. Sincethen, all Palestinian travel on this road has been prohibited. . To reach Salfit, residents ofthe Palestinian villages north of Salfit must travel along the “Trans-Samaria Highway,”which is defined as a “restricted-use road,” to its intersection with Route 60 at theTapuah junction, and then turn south to the road leading to Yasuf. At the entrance toYasuf, the IDF placed a physical roadblock that forces the passengers to get out of thecar, cross the road by foot, and get into another car that will take them, via Yasuf andIskaka, to the eastern entrance of Salfit. This alternate route is twenty kilometers. Thetrip from Kifl Haris to Salfit, which previously took five minutes, now takes at least thirtyto forty minutes, assuming there is no delay at one of the checkpoints and that thevehicle is not stopped by a police patrol .4. Route 466 – the road to Beit ElRamallah is the district seat for dozens of nearby towns and villages, and serves forcertain purposes as the “capital” of the entire West Bank. The status of Ramallah hasincreased since the 1990s, when Israel prohibited Palestinians from entering EastJerusalem. Until the beginning of the intifada, all traffic to Ramallah came from the eastto Route 466, which leads from Route 60 to one of the main entrances to the city, knownas the City Inn Intersection.”37However, since Route 466 also leads to the Beit El settlement, the IDF has prohibitedPalestinian travel on this road. The IDF enforces the prohibition by means of a staffedcheckpoint near the City Inn Intersection. Palestinian vehicles, except for ambulancesand VIP vehicles, are forbidden to cross in either direction.The prohibition especially harms residents of two groups of villages situated east ofRamallah: Burqa, Beitin, and ‘Ein Yabrud, which lie west of Route 60, and Deir Jarir,Tayba, Rammun, and Deir Dibwan, which lie east of Route 60. Residents of thesevillages now have to travel to Ramallah on alternate paths that greatly extend theirjourney. Residents of Burqa, Beitin, and ‘Ein Yabrud must travel north to Bir Zeit andthen turn south to reach Ramallah. Residents of the second group have to drive east tothe “Alon Road” and then south to the Qalandiya checkpoint, north of Jerusalem, andthen continue north to Ramallah. Residents of Tayba told B’Tselem that the trip toRamallah, which prior to the intifada took fifteen minutes, now takes at least one hour.The name was taken from the hotel located nearby. The IDF refers to the intersection as theJudea and Samaria Intersection.37

27

5. Route 463 – the road to Talmun and Dolev: Completely ProhibitedAnother group of villages dependent on Ramallah for services is situated west andnorthwest of the city. Residents of these villages – Qibya, Shuqba, Shabtin, Deir AbuAsh’al, Beitillu, Deir ‘Ammar, and Ras Karkar – wanting to go to Ramallah start their tripon Route 463 and travel along a branch road that passes Deir Ibzi’. During the intifada,the IDF has prohibited Palestinian vehicles from traveling along the section of Route 463that also leads to the settlements Dolev, Talmun, and Nahliel. The army placed concreteblocks where the road branches in the direction of Deir Ibzi’.Residents of these villages now have to travel along a winding dirt road that runs toNi’ama, from which they take a paved road to Deir Ibzi’. Travel along the three-kilometerdirt road adds about fifteen minutes to the trip to Ramallah. The alternate path is run-down, and travel along it is exhausting, dusty, and difficult for the vehicles.

D. The regime and the military legislationOne of the unique features of the Forbidden Roads Regime is that Israel has failed toincorporate it in written orders. This failure distinguishes the regime from other Israelipolicies in the Occupied Territories.In May 2004, B’Tselem wrote to the offices of the Judge Advocate General and the IDFSpokesperson to inquire about the legal basis for the various restrictions on Palestiniantravel in the context of the Forbidden Roads Regime and for the actions taken againstPalestinians who violate the restrictions. They replied that the legal basis for therestrictions and the actions taken against Palestinians is found in the Order RegardingDefense Regulations (No. 378), 5730 – 1970 (hereafter: “the Order”).The Order, which was issued early in the occupation, includes ninety-seven sections thatgrant the IDF numerous powers, including the handling of criminal proceedings, carryingout arrests and administrative detention, conducting searches, confiscating property,closing institutions or areas, and restricting freedom of movement. The Order empowersthe IDF commanders in the West Bank to issue declarations and orders setting forth themeasures to be taken and the directives that will apply in each and every case.Examples of such orders are orders for the administrative detention of a particularindividual, a declaration closing a particular area for a fixed period of time, and an orderto seize a house for military needs. Section 1(d) of the Order empowers the

28

commanders to issue verbal orders, but the High Court of Justice ruled that “properadministration dictates that even where it is allowed to give an order verbally, where theurgency has passed, and where justified, an order should be given in writing.”38The most relevant section relating to the Forbidden Roads Regime is Section 88(a)(1),which grants the military commander the power “to prohibit, restrict, or regulate the useof certain roads or establish routes along which vehicles or animals or persons shallpass, in either a general or specific manner.”In response to B’Tselem’s letter inquiring into the legal basis, the IDF Spokesperson’soffice recognized the existence of roads in the West Bank that are closed to Palestiniantravel, contended that the Order establishes the power to issue such restrictions, andstated that the power is given “to anyone who is empowered as a military commander(i.e., the commanding officer, division commanders and their deputies, sector brigadecommanders, and other officials, who are so empowered by the commanding officer).”The letters also states: “Presently, no written orders have been issued that preventPalestinian travel on particular roads in Judea and Samaria.” The IDF Spokesperson’soffice explained the lack of written orders by referring to Section 1(d) of the Order,whereby “the military commander may also give any order verbally.”39Regarding confiscation of vehicles found on the forbidden roads without a permit, theIDF Spokesperson’s office’s response statedSection 80 of the Order Regarding Defense Regulations and thedirectives issued pursuant thereto by the IDF military commander in theregion regulate the procedure for temporarily seizing vehicles that wereused for the commission of an offense against the defenselegislation… The directives states that, if an offense is committed, theIsrael Police Force shall open an investigation. Following theinvestigation, a decision will be made whether to file an indictmentagainst the suspect. In such a case, the vehicle may be seized as anexhibit during the criminal proceeding against is owner.It should be noted that in other matters, the IDF incorporates orders and directives givenpursuant to the Order in writing. The army’s failure to state in writing the directives38

HCJ 469/83,Hebron National United Bus Company Ltd. et al. v. Minister of Defense et al.,Takdin Elyon92 (2) 1477.39Letter from the IDF Spokesperson’s office to B’Tselem, 21 June 2004.

29

regarding the forbidden roads is a deviation from normal practice and contrary to theHigh Court’s ruling.Regarding opening investigations against Palestinians who travel along the roads inviolation of the order, mentioned in the IDF Spokesperson’s office response, B’Tselem isunaware of any police investigation of a driver whose vehicle was seized that led to anindictment for committing the said violation. We see, therefore, that seizure is used as anarbitrary punitive measure, outside any formal judicial or administrative procedure, forthe purpose of deterring Palestinians from using the forbidden roads.

30

Chapter Three: District Civil Liaison Offices and Movement PermitsIn response to criticisms of the extensive restrictions on movement on Palestinian travelin the Occupied Territories, Israeli authorities cite the fact that Palestinian civilians areable to obtain permits to move around within the West Bank. However, the permitsystem is founded on the same basis that underlies the Forbidden Roads Regime:Palestinians are not entitled to freedom of movement unless they prove, to thesatisfaction of the security forces, that they do not constitute a security risk, and meet allthe requirements to obtain a permit. This way of thinking is wrong, and flagrantlydiscriminates on grounds of national origin.Even if we ignore for the time being the fundamental inequity of this approach, andexamine its consequences, we see that Palestinians holding the desired movementpermits still suffer hardships: they are forbidden to travel along some of the roads, theiraccess to many villages is blocked, and they are not allowed to pass by motor vehiclethrough some staffed checkpoints.Palestinians also face bureaucratic hardships. The Civil Administration is responsible forissuing the permits. The Civil Administration operates under the jurisdiction of theCoordinator of Government Operations in the Territories, who is part of the Ministry ofDefense. In practice, the Civil Administration is under the direct charge of thecommanding officer of Central Command, who regulates by means of the militarylegislation the administration’s powers and functions and establishes to a great extent itspolicy and order of priorities. The Civil Administration acts as a kind of staff headquartersthat operates a system of District Civil Liaison offices (hereafter: DCLs). Individualswanting a permit file their requests with the DCLs. Similarly, there are Palestinian DCLs,which are subject to the Palestinian Authority.The DCLs were established in 1995 in the framework of the Interim Agreement (OsloII)in order to foster coordination and cooperation between the Israel governmentalsystems in the West Bank and the Palestinian Authority. The need for these systemsarose from the many civil and security powers that remained in Israel’s hands.40One ofthe functions of the Israeli DCL is the handling of requests forwarded to it by PalestinianDCLs on behalf of Palestinians. Since the outbreak of the al-Aqsa intifada, the DCLs40

The Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, 28September 1995, Annex III, Protocol Concerning Civil Affairs.

31

have essentially ceased to enable coordination between the Israeli and Palestinianauthorities, and have concentrated on the handling of requests for permits. Unlike in thepast, many Palestinians now apply directly to the Israeli DCL, rather than go through thePalestinian DCL.41The obligation to obtain permits for all aspects of life is one of the oldest methods thatarea, the IDF has used to maintain control over the local population. However, untilJanuary 2002, Palestinians were not required to obtain permits to travel within the WestBank, except for East Jerusalem. In the words of the Civil Administration’sspokesperson, Talia Somech, “The idea was born out of the necessity of the complexsecurity situation, which requires prolonged sieges. Following the hardships placed onthe movement of Palestinians… it was decided to ease passage by means of theissuance of permits to cross sieges.”42According to the IDF Spokesperson, these permits are intended primarily forpedestrians, while permits for vehicles are exceptional.43As of July 2004, only 3,412Palestinians from among the 2.3 million Palestinians living in the West Bank hold thisspecial permit, known as a “Special Movement Permit at Internal Checkpoints in Judeaand Samaria.”44In addition, the Israeli DCLs issued permits for 135 buses which takepassengers from the checkpoint at the exit of one Palestinian city to the checkpoint atthe entrance to another city.A prerequisite to submitting a request for a movement permit is a valid magnetic card.Magnetic cards, a kind of second identity card which confirms that the holder is not a“security risk,” have been used in the West Bank for the past decade and are only issuedfollowing approval by the General Security Service. The Palestinian applicant files hisrequest on a tax-stamped form that is obtained at the Palestinian DCLs. The form mustbe completed in Hebrew, so most applicants have to retain the services of a “scribe,”who generally sits in the Palestinian DCL. The cost for submitting the request ranges

There are currently nine Israeli DCLs operating in the West Bank. These DCLs are located asfollows : near Sallem, in the northwest part of the West Bank; near Huwwara, south of Nablus;south of Tulkarm; at the Qedumim settlement; at the Civil Administration offices in the Beit Elsettlement, near the Ma’aleh Adumim settlement; near the Etzion intersection, south ofJerusalem; on Mt. Manoah, south of Hebron; near the Vered Yericho settlement, southwest ofJericho.42The comments were made in a letter to B’Tselem of 17 September 2003.43See the IDF Spokesperson’s letter of 8 February 2004.44See the IDF Spokesperson’s letter of 15 July 2004.

41

32

from NIS 60 – 80, which includes the stamp tax, photocopying, photo of the applicant,and, when necessary, the scribe’s fee.Tens of thousands of Palestinian residents of the West Bank are classified as “securityrisks” by Israeli security forces. Individuals in this category who submit requests for amagnetic card or movement permit (in those cases in which the applicant is classified as“prevented for security reasons” after being granted a magnetic card), the request isautomatically rejected. The Israeli official transmits the rejection verbally and withoutexplanation. According to Brig, Gen. Ilan Paz, head of the Civil Administration, theinformation regarding the reason for rejection is not made available to the DCLs, andthey are not allowed to overrule the decision. “The only way to remove a prevented-for-security-reasons classification is by meeting with a GSS official.”45The GSS has always used the dependence of Palestinians on permits as a means torecruit collaborators.46The phrase, “You help me, and I’ll help you” has long sincebecome an integral part `of meetings between GSS agents and Palestinian residentswho seek a magnetic card or movement permit. Testimonies given to B’Tselem over theyears indicate that a substantial number of Palestinians classified as “prevented” are notsuspected of committing any offense, or are themselves considered security risks. Inmany instances, Palestinians are given this classification because a relative or neighboris listed as a target to obtain intelligence data. A Palestinian classified as “prevented forsecurity reasons” who refuses to collaborate with the GSS has absolutely no chance ofobtaining a permit. However, the intervention of a third party is liable to help, and therehave been some cases in which a security-risk classification has been altered followingintervention by an attorney or human rights organization.Another condition that must be met is that the applicant is not “prevented for police-related reasons.” The Police consider conviction of a criminal offense, or intelligenceassessments that the person will commit a criminal offense in the future, as grounds forrejection.47According to Brig. Gen. Paz, head of the Civil Administration, most of thepersons rejected on such grounds were previously charged with staying in Israel illegally.The Police has in the authority to removing these grounds as a basis for rejection.4546

Ibid.See, for example, B’Tselem,Builders of Zion: Human Rights Violations of Palestinians fromthe Occupied Territories Working in Israel and the Settlements,September 1999, Chapter 4.47Machsom Watch and Physicians for Human Rights,Bureaucracy in the Service of Occupation:The District Civil Liaison Offices,May 2004.

33

Rejection based on police-related reasons can also be based on a traffic fine that hasnot been paid. In such instances, this reason for rejection is removed when the fine ispaid. But payment of a fine is not a simple matter for a resident of the West Bank. Thefine must be paid at Israeli post offices, which are located inside Israel or in thesettlements. To reach a post office, a Palestinian needs special permits.48These permitsare difficult to obtain if the applicant is listed as “prevented for Police-related reasons.”Most Palestinians in this situation rely on relatives or friends who have permits to entersettlements or into Israel. Palestinians who do not have such permits have reported toB’Tselem that they were allowed to enter the post office in the Barkan industrial zonenear the Ariel settlement after they displayed the ticket.The permit application form asks the purpose for which the applicant uses the vehicle.The applicant has to attach relevant documents, such as an employer’s letter,registration at the Trade Ministry, and medical documents, as well as a photocopy of theapplicant’s identity card, driver’s license, registration, and certificate of insurance.Liaison officers at the DCL review the request, and in some cases transfer the request tothe head of the DCL for review. According to Brig. Gen. Paz, “There are no definitivecriteria for examining requests for a permit.” When the applicant is not classified asprevented for “security” or “police-related” reasons, the DCL officer makes thedetermination. Brig. Gen. Paz also mentioned that, if a request is denied, the applicant isallowed to reapply at a later date, but there is no formal appeals procedure at which theindividual may state his case.49As mentioned, the decision is delivered to the applicantverbally at the reception counter, usually without explanation.The lack of transparency characterizing the approval or rejection of applications forpermits is certain to lead to arbitrary action and reliance on improper considerations. Thepermit system is an integral part of a roads regime that grossly infringes Palestinianfreedom of movement. Yet, Israel seeks to use the permit system to give the misleadingimpression that Israel is actually showing concern for the needs of the local population.

Order Regarding Defense Regulations (Judea and Samaria) (No. 378), 5730 – 1970;Declaration Regarding Closure of Area (Israeli Settlements), of 6 June 2002.49These comments were made at the meeting B’Tselem held on 20 June 2004 with CivilAdministration officials.

48

34

Chapter Four: The Regime in light of International LawThe Roads Regime that Israel has implemented in the West Bank severely infringes twoprincipal human rights: the right to equality and the right to freedom of movement . Inviolating these rights, the regime flagrantly breaches international human rights law andinternational humanitarian law.

A.

The right to freedom of movement and its exceptions

Everyone has the right to freedom of movement within his or her country. This right isrecognized in Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which wasadopted by the UN in 1948. Although the UN General Assembly called on all themember states to adopt the Declaration, it is not a binding international document. In1966, the General Assembly incorporated the right to freedom of movement in Article 12of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This covenant is legallybinding on all parties to it. Israel ratified the Covenant in 1991. However, Israel contendsthat the Covenant does not apply to its activities in the Occupied Territories, which aresubject to international humanitarian law.50This position is baseless. Article 2 of the Covenant explicitly states that a state that isparty to the Covenant must implement it in regards to all persons “subject to itsjurisdiction.” The UN Human Rights Committee, which is in charge of interpreting theCovenant and monitoring its implementation, has declared on various occasions indifferent contexts that the test for determining application of the Covenant in a givenarea is the degree of actual control by the relevant state, and not the official status of theterritory.51Furthermore, the Committee stated clearly that the Covenant does not ceaseto apply, regardless of the situation in the state, even in time of war. The Committeestated that international humanitarian law, which was created especially for situations ofwar and occupation, is not inconsistent with the Covenant, in that both spheres of laware complementary.52Consistent therewith, the Committee explicitly held that Israel must

See, for example, Israel’sSecond Periodic Report,CCPR/C/ISR/2001/2, 4 December 2001.See, for example, the Committee’s comments in 1991 regarding the obligation of Iraq to applythe Covenant in the territory of Kuwait so long as its occupation continued. CCPR A/46/40/1991,Par. 652.52General Comment 3, “On the Nature of State Obligations,” Par. 11.51

50

35

strictly conform to the provisions of the Covenant in its actions in the OccupiedTerritories.53Israel contends that the restriction on freedom of movement of the Palestinian populationarises from the need to protect Israeli citizens against attacks. Therefore, it argues, itsactions are lawful and do not breach its obligations under international law. Israel’s rightto protect its citizens is clear and recognized by all spheres of international law. From theperspective of Israeli citizens, the obligation to protect them is the state’s primary duty.Despite the importance of this purpose, Israel is not allowed to take measures that donot comport with international law.Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states that, “In time ofpublic emergency which threatens the life of the nation,” parties to the Covenant maytake measures derogating from their obligations under the Covenant. Had Israelrecognized the application of the Covenant, it might argue that the situation since theoutbreak of the intifada constitutes a “public emergency which threatens the life of thenation.” However, the Covenant states that, in such situation, a state party may violaterights incorporated in the Covenant only if the harm is proportional, the measure isconsistent with the state’s other obligations under international law, and the violationdoes not involve discrimination based solely on the ground of race, color, sex, language,religion, or social origin.

B. Indiscriminate harm and collective punishmentThe most conspicuous features of the Forbidden Roads Regime is its sweeping,indiscriminate nature. The regime denies Palestinians freedom of movement, and grantsspecial movement permits as a privileged right to Palestinians who meet Israel’s criteria.On certain roads, travel is even forbidden by persons holding this privileged right. Thefundamental right to freedom of movement may be denied only if the individualendangers public safety. In its implementation of the Roads Regime, Israel transferredthe burden of proof to the Palestinian population, making them responsible for provingthat they do not constitute a risk if they wish to exercise their right. The period of the

53

See, for example,Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Israel,CCPR/C/78/ISR, of 2003.

36

sweeping denial of the right to freedom of movement is open ended, and has continuednow for more than three years.Therefore, the Roads Regime violates the conditions set forth in Article 4 of theInternational Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which allows derogation “to theextent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation.”In this spirit, the High Court of Justice recently held that the route of the separationbarrier Israel is building northwest of Jerusalem disproportionately violates thefundamental rights of the local Palestinians, and the Court prohibited construction of thebarrier along that route. In making this decision, the Court recognized that the route thathad been planned was likely to contribute to the security of Israel’s citizens. In thedecision, President Barak stated:According to the principle of proportionality, the decision of anadministrative body is legal only if the means used to realize itsgovernmental objective is of proper proportion. The principle ofproportionality focuses, therefore, on the relationship between theobjective whose achievement is attempted, and the means used toachieve it….The route of the Separation Fence severely violates their right ofproperty and their freedom of movement. Their livelihood is severelyimpaired. The difficult reality of life from which they have suffered (due,for example, to high unemployment in that area) will only become moresevere.These injuries are not proportionate. They can be substantiallydecreased by an alternate route, either the route presented by theexperts of the Council for Peace and Security, or another route set outby the military commander.54The combination of the sweeping nature of the Roads Regime and the systematic andindiscriminate harm to all aspects of life of the Palestinians in the West Bank, makes theRoads Regime a case of collective punishment. Collective punishment is completelyforbidden in international humanitarian law. Article 50 of the Regulations Attached to theHague Convention of 1907 states that, “No general penalty, pecuniary or otherwise,54

HCJ 2056/03,Beit Sourik Village Council v. The Government of Israel,Paragraphs 40, 60-61.

37

shall be inflicted upon the population on account of the acts of individuals for which theycan not be regarded as jointly and severally responsible.” A similar prohibition is found inArticle 33 of the fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, which states:No protected person may be punished for an offense he or she has notpersonally committed. Collective penalties and likewise all measures ofintimidation or of terrorism are prohibited.