Det Udenrigspolitiske Nævn 2004-05 (1. samling)

Bilag 15

Offentligt

AFRICA IN THE 21stCENTURY- An analytical overview

6 December 2004

Executive SummaryThe overview analyses challenges and options facing Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) at the start ofthe 21stcentury. It provides an analytical basis for the formulation of a coherent Danish Africapolicy, which includes foreign, development, trade and security policy towards Africa. Recentyears have witnessed new opportunities and encouraging developments in Africa, led byAfrican countries’ own initiatives. A new Danish policy is meant to support these positivedevelopments. Despite the encouraging signs, the challenges for peace, security, growth andpoverty reduction remain huge. Africa is the continent furthest from reaching the MillenniumDevelopment Goals.The African Economy – the challenge of generating growthEconomic growth is crucial to poverty reduction. In SSA the average per capita income hasdeclined in the 1980s and 1990s. For the majority of the countries, even the most recent growthrates are still too low to reduce the number of extremely poor men, women and children.Private sector-led growth is fundamental for Africa. A few African countries have so farmanaged to transform the good political intentions into sustainable changes that create anenabling environment for the private sector. The informal sector of Africa’s economies is stillsubstantial (often equal to 50% of GDP), and encompasses both a large share of theagricultural activities, micro-enterprises and self-employment in urban centres.The agricultural sector constitutes the economic backbone of most African countries, and thissector will remain the mainstay of economic growth benefiting Africa’s poor for years to come.Increased agricultural production is necessary to fight starvation and malnutrition, and rapidgrowth in agricultural production and productivity is a precondition for economic take-off andsustained poverty reduction. The agricultural sectors constitute the largest part of the privatesector, with agriculture accounting for more than 50% of GDP, over 50% of export earnings,and employing over 70% of the workforce.Poverty and environmental degradation mutually reinforce each other. The environmentalaspects of growth have to be addressed in order to implement sustainable solutions.The HIV/AIDS pandemic represents a major threat to economic development in Africa. Outof the 38 million people in the world suffering from HIV/AIDS approximately 25 million livein Africa. Recent estimates of the macroeconomic costs of HIV/AIDS suggest that theHIV/AIDS related drops in GDP range between 0,3 and 1,5%. Although this appears modestit will translate into larger effects over time.Globalisation offers an opportunity to integrate Africa in the world economy. Some barriersremain for increased international trade of African products. Industrialised countries’requirements to meet sanitary and phytosanitary standards and related food safety regulationsare probably the most difficult hurdles among the many non-tariff barriers confronting African

2

exporters. African countries and African exporters need to develop capabilities that ensureconformity with these standards.Closer coherence between trade policies and development and security policies is still needed atglobal, regional as well as country levels. While the liberalisation of world trade is expected togenerate a large global welfare-improvement, it is less likely to reduce poverty in Africa. Freeaccess to industrialised markets is not sufficient to reduce poverty. Preferential arrangementsfor the next 10-15 years could provide Africa with the window of opportunity to improve theproductivity and competitiveness of African businesses. Job creation for unemployed anddiscontent youth is another area to focus on.Peace and stabilityViolent conflicts in Africa affect the lives of millions, and civilians account for more than 90%of casualties in conflict. Conflicts seriously affect neighbouring states and cause instability aswell as hamper economic development in the affected country and in the sub-region. Theyfurthermore often last for more than a decade. Most of Africa’s conflicts occur in weak stateswith poor political and economic governance and poor development records. The root causesof most conflicts can be traced decades back, and they are often result of continued lack ofdevelopment – politically and economically.Development of democracy, good governance and respect for human rights are key aspects ofnation building to prevent conflicts. Long-term political and economic commitment frominternational partners to assist a country in addressing social, economic and political needs addsubstantially to conflict prevention.Responses to conflicts in Africa have been reinforced in recent years by Africa itself. The roleof AU and the regional organisations has been strengthened and is expected to result in anoperational African Security Architecture. This promising new activism has led to a significantdecrease in the number of new, armed conflicts and to new, if still fragile, peace solutions intwo major conflict areas.It will be important to increase focus on the prevention of conflicts, on building a regionalframework for effective crisis management in imminent or on-going conflicts in Africa, and onconsolidating peace through post-conflict measures.There are currently 4-5 million refugees and an estimated 12-13 million internally displacedpeople in SSA. Influxes of refugees and migrants have large social consequences for thoseaffected and for the countries receiving them, and it lead to instability with the risk of furtherconflict. Special attention to this problem has to be part of the effort of resolving conflict andpreventing new conflicts. Living conditions for both internally displaced, refugees and the localpopulation are often insufficient, and the capacity to provide protection for refugees is ofteninadequate. This places a large humanitarian burden on many African countries, and there is noreason to believe that migration figures will decline dramatically over the next decade.

3

Denmark will become member of the UN Security Council in 2005-2006. One of the Danishpriorities is security, growth and development in Africa. Experiences from the new DanishAfrica Programme for Peace, decades of experience in development cooperation and recentDanish involvement in peacekeeping missions provide strategic guidance to this work. As partof the Danish membership it could be considered to address some of the factors that fuel orare relevant to conflicts in Africa, including natural resources, regional approaches, unemployedand discontent youth, human rights violations, and illegal trade of small arms.Good governance, human rights and democracyGood governance and democracy is a fundamental prerequisite for effective use of resourcesfor poverty reduction and a corner stone for nation building, peace and stability. There areencouraging signs that several countries in Africa, both individually and collectively, showcommitment hereto. However, economic, cultural, and structural factors tend to prevent thefull implementation of good intentions. Corruption is a major problem, and long-termsolutions will depend not least on the successful implementation of public service reform andprocurement regulations.The means to enforce human rights are often not present. Institutions such as the courts,police and prison services, human rights commissions, national administrations and parliamentdo not have the capacity to deal with human rights issues. A strong civil society voice on thismatter has in many countries been instrumental in pressing through some of the necessaryimprovements.Denmark is generally considered a consistent and qualified partner in supporting goodgovernance; human rights and democratisation efforts and can contribute through developmentsupport as well as the bilateral and multilateral political dialogue with African partners.Development of Human ResourcesAfrica needs a more well-educated and healthy workforce to be able to increase economicgrowth for the benefits of the poor. Health and education indicators are generally lower forAfrica than for any other continent and the indicators have shown only marginal improvementsover the last three decades. But even when a country succeeds in creating a well-educated andhealthy workforce, this development is often undermined by a number of factors, one beingHIV/AIDS.The education systems suffer a number of problems and shortcomings due to understaffing,under-funding, poor teacher training etc. The low quality of primary schools leads to lowenrolments, poor attendance and high dropout rates, especially for girls. The education sectoris, moreover, heavily affected by the impact of HIV/AIDS, since teachers is a high-risk group.The health sector of most African countries faces numerous problems caused mainly by thecombination of declining resources in real terms and an escalating disease burden. HIV/AIDS,drug resistant malaria and other mainly preventable diseases have aggravated this burden.Furthermore, countries are now facing a double disease burden due to the arrival of “modern”

4

mainly life-style related diseases. At the same time the health situation for the poor is gravelyaffected by lack of access to clean water and sanitation.Africa is by far the most severely affected region in terms of HIV/AIDS. In many countries,life expectancy is now 40 years or less. African women are at greater risk of becoming infectedat an earlier age than men. This development, affecting all parts of society, poses a seriousthreat to the development process.Gender inequalities impose large costs on the well being of women, men and children,profoundly affecting their ability to improve their lives. Gender inequalities reduce productivityin farms and enterprises, thus impeding prospects for reducing poverty and achieving economicprogress.Denmark has extensive experience in the field of development of human resources based onlong-term sector programmes with eight partner countries in SSA and with South Africa.A coherent approachA coherent and strategic approach to the challenges in SSA would contribute to a morepeaceful and prosperous Africa. The broad range of challenges for Africa in the 21stcenturydemands a multifaceted and coherent approach, based on Africa’s own will. The newopportunities can be grasped with new initiatives to bring about security, growth anddevelopment. The Danish membership of the UN Security Council provides an opportunity toincrease the attention towards Africa in the years to come.

5

CONTENTS1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................82.DEVELOPMENT TRENDS AND GOALS IN AFRICA............ 102.1 RICH IN RESOURCES BUT AT THE MARGIN OF WORLD ECONOMY...................................... 102.2 THE CHALLENGE OF ADDRESSING POVERTY......................................................................... 112.3 THEMILLENNIUMDEVELOPMENTGOALS............................................................................ 122.4 ARE THEMDGS ACHIEVABLE INAFRICA?............................................................................. 132.5 POVERTYREDUCTIONSTRATEGIES AS A WAY FORWARD? .................................................. 152.6 THEDANISH CONTRIBUTION TO POVERTY REDUCTION..................................................... 17

3. THE AFRICAN ECONOMY – THE CHALLENGE OFGENERATING GROWTH.................................................................................. 193.1 ECONOMICGROWTH................................................................................................................. 203.1.1 Agriculture as basis for growth ................................................................................................. 203.1.2 Private sector development......................................................................................................... 223.1.3 HIV/AIDS as barriers to economic development in Africa...................................................... 233.2 TRADE.......................................................................................................................................... 233.2.1 The EU: Africa’s largest trading partner.................................................................................. 243.2.2 Africa’s trade with the United States........................................................................................ 253.2.3 Intra-African Trade................................................................................................................. 253.2.4 Africa, the WTO and the Doha Agenda ................................................................................. 263.3 INVESTMENT AND CAPITAL FLOWS INAFRICA...................................................................... 273.3.1 Domestic savings and investments ............................................................................................. 283.3.2 Tax revenue............................................................................................................................. 283.3.3 Remittances ............................................................................................................................. 293.3.4 Foreign Direct Investment......................................................................................................... 293.3.5 Official Development Assistance ............................................................................................... 303.4 DEBT............................................................................................................................................. 313.5 THE ENVIRONMENTAL DIMENSION........................................................................................ 323.5.1 Urban Environment ................................................................................................................ 333.5.2 Natural Resource Management ................................................................................................ 333.5.3 Renewable Energy.................................................................................................................... 343.5.4 Climate change......................................................................................................................... 343.6 THEDANISH CONTRIBUTION TO THE STRENGTHENING OFAFRICAN ECONOMIES....... 35

4. PEACE AND STABILITY............................................................................ 364.1 THE CONFLICT SCENARIO......................................................................................................... 374.2 CAUSES OF CONFLICTS INAFRICA............................................................................................ 38

6

4.3 RESPONSES TO CONFLICTS INAFRICA..................................................................................... 414.4 SECURITY SECTOR REFORMS ANDAFRICANSECURITYARCHITECTURE........................... 424.5 THELICUSINITIATIVE............................................................................................................. 444.6 CONFLICT PREVENTION............................................................................................................ 444.7 DANISH CONTRIBUTIONS TO PEACE AND STABILITY INAFRICA........................................ 45

5. GOOD GOVERNANCE, HUMAN RIGHTS ANDDEMOCRACY........................................................................................................... 475.1 BRIEF HISTORY AND POLITICAL CULTURE.............................................................................. 475.2 AN APPROACH TO ANALYSING GOVERNANCE INAFRICA................................................... 505.3 PUBLIC SECTOR REFORM............................................................................................................ 515.4 ANTI-CORRUPTION..................................................................................................................... 535.5 DECENTRALISATION.................................................................................................................. 545.6 DEMOCRATISATION................................................................................................................... 545.6.1 Constitutional reform ............................................................................................................... 545.6.2 Elections.................................................................................................................................. 555.6.3 Political parties ........................................................................................................................ 555.6.4 Parliament............................................................................................................................... 565.6.5 Security Sector.......................................................................................................................... 565.6.6 Independent institutions............................................................................................................ 575.6.7 Civil society.............................................................................................................................. 575.7 ACCESS TO JUSTICE AND THE RULE OF LAW........................................................................... 585.8 PROMOTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS.............................................................................................. 595.9 SUPPORT FOR INDEPENDENT MEDIA...................................................................................... 605.10 REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS................................................................ 615.11 DANISH EXPERIENCES:MAINTAINING A DIALOGUE ON GOVERNANCE......................... 61

6. DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN RESOURCES.................................. 646.1 EDUCATION................................................................................................................................. 646.2 HEALTH........................................................................................................................................ 676.3 FACTORS EFFECTING HUMAN RESOURCES............................................................................. 696.3.1 HIV/AIDS .......................................................................................................................... 706.3.2 Migration ................................................................................................................................ 716.3.3 Gender dimension .................................................................................................................... 736.3.4 Vulnerable groups.................................................................................................................... 736.4 DANISH CONTRIBUTIONS TO DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN RESOURCES.............................. 74

7. A COHERENT APPROACH...................................................................... 75ABBREVIATIONS................................................................................................... 77

7

1.

Introduction

Recent years have seen new opportunities and encouraging developments in Africa. A numberof African countries have initiated ambitious reform programmes that clearly provide anopportunity for the private sector to thrive and which offer a durable starting point for stronggrowth. African leaders and institutions have shown a new, collective will to address thecontinent’s conflicts and to significantly reduce their number and severity. In a growing numberof African states, basic democratic principles are being entrenched. Significant progress hasbeen achieved, and the experience has generated new strategies and models to be appliedAfrica is a continent in the process of change. Led by African countries’ own initiatives, thepossibility now exists in a majority of African countries to reverse the downward spiral ofearlier decades.Nevertheless, the challenges remain enormous. Poverty remains profound and inequality iswidespread. Peace and stability are often fragile, as tensions persist, and political corruption,violence and oppression are still common. Each year, millions of Africans die from diseasesthat are curable by simple, well-known treatments. Africa is the continent furthest fromreaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDG’s), and the challenges here are greater thanfor any other continent.Internationally, there has been increased focus on the African challenges. Within the overallpriorities for Danish development assistance 2005-20091, the Danish Government has decidedto launch a forward-looking Danish Africa policy that addresses these opportunities andchallenges. With more than 40 years of development experience in sub-Saharan Africa – and acurrent focus on eight programme countries - Denmark has an obligation and natural part inassisting Africa in its pursuit of the MDGs. There are several instruments available for thispurpose, since Africa receives approximately 60% of Danish bilateral assistance. Danishmembership of the UN Security Council in 2005-2006 provides another relevant framework forpursuing an agenda for Africa.In accordance with Government priorities, a broad coherent policy is necessary in order forDenmark to effectively contribute to poverty reduction by supporting the many newpossibilities for renewed economic growth and development in Africa and to tackle the difficultchallenges that the continent still faces.The purpose of this analytical overview is to provide a solid basisfor the formulation of such a coherent policy, which must include instruments of foreign policy, development policy,trade policy and a security policy towards Africa.The geographical area covered by this analysis will be Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and statisticaldata will relate to this group of 48 countries. This demarcation does not ignore the importanceof relations between Sub-Saharan countries and North Africa or the role that North Africancountries play in the regional organisations, and these countries will be drawn into the analysis’Security, Growth – Development, Priorities of the Danish Government for Danish Development Assistance 2005-2009’,August 20041

8

where relevant. However, the situation in the countries of North Africa is affected by a numberof distinct economic, cultural and political factors that set them apart from the rest of Africa.At the same time, selecting SSA as the area of focus does not imply that SSA is a uniformgroup of countries for which a single social concept can be assumed or a standard solutionapplied. It should be noted that the term ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ covers 48 highly differentcountries with a total population of approximately 700 million. Each of these countries facestheir own challenges. Each African country has its own unique historical background, socialconditions, political structure, etc. Lessons and conclusions drawn from the analysis shouldtherefore be applied in the specific regional and national context.According to Danish Government priorities, Danish Africa policy takes its point of departurein the development plans of the African countries themselves. Within the overall objective ofpoverty reduction the aim is to create sustainable economic growth, support regionalcooperation, assist the African countries in resolving conflicts, promote human rights,democratisation and good governance, and improve social conditions – children’s schooling,combating HIV/AIDS and other diseases – and enhance the possibilities of African exportersto sell their goods competitively on the world market.2At the same time it is necessary toenhance the environmental sustainability so as to secure the desired global stability anddevelopment.The chapters deal with key aspects of these development objectives.Chapter 2 of this analytical overview presents the overall economic trends for Africa withspecial emphasis on the poverty issue and on the goals and strategies formulated to address thischallenge.Chapter 3 provides an analysis of key issues relating to Africa’s economic potential, includinggrowth, trade, investments, development assistance and the environmental dimension.Chapter 4 analyses the dynamics of conflict in Africa and the challenges posed by conflicts todevelopment.Chapter 5 examines the state of governance in Africa and its importance for pursuing povertyreduction in African countries.Finally, chapter 6 focuses on education and health as central factors in developing humanresources.

’Security, Growth – Development, Priorities of the Danish Government for Danish Development Assistance 2005-2009’,August 20042

9

2.

Development trends and goals in Africa

Africa is in many respects a rich continent – rich in raw materials, natural resources, andbiodiversity. It has a diversity of cultures and a large and young population pursuing a myriadof livelihood strategies. In income terms, however, Africa is not wealthy, and the number ofpoor people is substantial - and growing.When assessing the overall situation in Africa, it is important to consider historical and externalfactors as well as those factors internal to the countries themselves

2.1 Rich in resources but at the margin of world economyFavourable natural conditions for agriculture exist in large parts of the continent, and severalAfrican countries are rich in natural resources such as water, arable land, fish stock, forestproducts including timber, diamonds and other precious stones and metals as well as fossil fuelsas oil and coal. Some regions contain an abundance of flora, fauna and wild life found nowhereelse in the world. Although highly varying precipitation and soil degradation in some countriesthreaten the conditions for agriculture, and natural disasters in the form of drought and floodsoccur regularly, the overall picture is not that of a continent deprived of basic naturalconditions for feeding its population and extracting a development dividend from sustainablemanagement of natural resources.Nevertheless, it is a general feature of many African countries that a large share of the totalagricultural production is used for consumption, while export earnings depend on a few (oftenonly one or two) unprocessed agricultural commodities or minerals. One of the very few newgrowth sectors is tourism, often based on sustainable practices. In 2001, manufactured goodsaccounted for only 33% of total exports (27% if South Africa is excluded), while the remainingexports consisted of unprocessed commodities. Although the share of manufactured exportshas nearly doubled since 1990, it is still much lower than that of any other region of the world.The level of processing which takes place also remains very low. For some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, oil presents another window of opportunity, although the magnitude of oilreserves is less significant on a global scale3. Gas reserves could likewise become a greatersource of income.The world demand for those commodities traditionally exported from Africa is either growingvery slowly or declining. The supply has exceeded the demand and this trend has beenstrengthened as new producers have turned up e.g. in South East Asia. For some commodities,such as coffee, the supply has increased significantly. The stagnant demand and the increasingsupply have resulted in declining prices. World market prices for traditional Africancommodities have fallen between 40% and 60% over the three decades 1970-2000 (except fortobacco and petroleum). These historical trends – a structural decline in commodity prices overtime - are likely to continue and leave little room for export-led economic growth unlessSub-Saharan Africa oil reserves account for 35-50 billion barrels of the world’s 1000-1200 billion barrels. Reference:www.eia.doe.gov.Figures may be underestimated.3

10

African countries start to both diversify the production and add value. Even with falling termsof trade, countries outside Africa (like Vietnam) have been able to achieve high growth rates inexport revenue from traditional commodity exports through expanded production, increasedproductivity and processing. Falling commodity prices should therefore not be an excuse fornot increasing efficiency and better management in export production.Excluding Nigeria (a major oil exporter) and South Africa, SSA countries exportedaround $11 billion worth of commodities in 1999. If the real prices of commodities hadremained constant between 1970 and 1999, African export levels in 1999 would havebeen $30 billion. The $19 billion loss owing to the fall in commodity prices was abouttwice the amount received by Africa in foreign aid in 1999.Rich countries subsidise their farmers to the tune of $320 billion a year, a sum close toAfrica’s annual GDP.A key aspect of the international terms of trade for Africa is the existence of subsidies onproduction in industrialised countries on products where developing countries have acomparative advantage, such as sugar and cotton. The abolition of these production and exportsubsidies is likely to result in higher world market prices, providing African producers withhigher prices for their agricultural exports. The removal of subsidies given to American andEuropean cotton farmers for instance is estimated to result in an increase in the world cottonprice by 12 cents per pound. This, in turn, could increase revenues from cotton by $250 milliona year for West and Central African countries, equal to about 14% of the total developmentassistance received by these countries annually. In terms of people affected the figures are evenmore staggering. Subsidising 40–50,000 cotton producers in USA and Europe leaves 6-8million African cotton farmers on the brink of starvation.If un- and underemployed youth in Africa is a significant factor in armed conflicts and maybein terror network’s recruitment – as discussed in chapter 6 – such a trade policy is hardlyconducive to Europe’s or USA’s own security agenda.The marginal role of Africa in the global economy is demonstrated by comparing its 10% shareof the world’s population to its share of only 1.3% of the world’s exports, 0.6% of the world’stotal foreign direct investment, and 1% of the world’s Internet subscribers.

2.2 The challenge of addressing povertyThe economies of Sub-Saharan Africa have been in decline for more than a quarter of acentury, and an increasing proportion of the world’s poor people are found in Africa (29% in2002). The number of poor people in Africa (here defined as people living for under USD 1 per

11

day) has increased from 227 million in 1990 (which was 44.6% of the total SSA population) to314 million in 2001 (46.5%).4While other low-income countries have on average grown rapidly, Sub-Saharan Africa has notonly failed to keep up with other regions of the world; it has suffered an absolute decline.Unlike other developing regions, Africa’s average output per capita in constant prices was lowerat the end of the 1990s than 30 years before – falling by more than 50% in some countries. Inreal terms, fiscal resources per capita in many African countries were less than in the late 1960s.Excluding South Africa, the region’s income per capita averaged just $315 in 1997 whenconverted at market exchange rates. When expressed in terms of purchasing power parity(PPP) – which takes into account the higher costs and prices in Africa – real income averagedone-third less than in South Asia, making Africa the world’s poorest region. The total incomeof all Sub-Saharan African countries is not much more than that of Belgium. A typical Africancountry has a GDP between $2 and $3 billion, equivalent to that of a provincial European townof, say 100,000 inhabitants.Just as the extent and character of poverty vary among the African countries, so do the causes.Key factors include Africa’s position in the global economy and its vulnerability to externalshocks caused by economic trends, the international terms of trade and distorted developmentprocesses (initiated during colonialism and aggravated by geo-political interests during the ColdWar). Additional causes are related to domestic factors, such as poor governance and weakinstitutions, deficiencies and shortages in human and institutional capacity, and social andethnic tensions. Natural disasters, the AIDS pandemic, and violent conflicts within regions orbetween ethnic groups, are also very significant factors.While the complexity of the poverty problem calls for many different responses at the sametime (dealing with production, trade, human resources, conflict prevention, etc.), there is anemerging international consensus regarding the importance of defining shared objectives andformulating and implementing policies which can address core aspects of poverty and whichcan prioritise available resources so that benefits reach the poor.

2.3 The Millennium Development GoalsIn September 2000, 147 heads of State and Government endorsed the Millennium Declarationat the UN Millennium Summit. The declaration defines a limited number of achievable goals tobe reached by the year 2015, with the overall objective of halving the proportion of the world’spopulation who live in absolute poverty. Accordingly, the entire group of UN member states,international organisations, funds, programmes and specialised agencies have committedthemselves to fighting poverty and improving people’s lives.

4

Development Committee, joint WB and IMF:Global Monitoring Report 2004;policies and actions for achieving the MDGsand related outcomes.

12

The Millennium Development GoalsMDGs are a framework of 8 goals, 18 targets and 48 indicators to measure progress towardsthe goals:Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hungerGoal 2: Achieve universal primary educationGoal 3: Promote gender equality and empower womenGoal 4: Reduce child mortalityGoal 5: Improve maternal healthGoal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, TB and other diseasesGoal 7: Ensure environmental sustainabilityGoal 8: Develop a global partnership for developmentThe consensus behind the MDGs was further strengthened at the WTO Meeting in Doha inNovember 2001, where agreement was reached on a new round of talks with a focus on therequirements of the developing countries. At the Monterrey Conference in March 2002, ODAand good governance were targeted as preconditions for sustainable development. This positivetrend continued at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg inSeptember 2002, where the global support for the MDGs was underlined. WSSD furtheremphasised Goal 7 (Ensure environmental sustainability), adding further goals such as theprovision of basic sanitation, implementation of national strategies for sustainabledevelopment, maintenance or restoration of the stocks of fish to achieve sustainable fisheries,decoupling of economic growth and deterioration of the environment and of natural resourcesand increased use of sustainable energy. These crosscutting environmental issues are especiallyimportant in the African context, as the African economies are heavily dependent on accessand utilisation of natural resources.

2.4 Are the MDGs achievable in Africa?Despite various differences in assessments of the situation, most analysts agree that Africa’sprospects for reaching the MDGs by 2015 are far bleaker than the average trend for the worldas a whole, as this goal is predicated on reversing the economic decline. Whereas MDG no. 1,eradicating extreme poverty and hunger5, is likely to be met on a global scale, this is due mainlybecause of a foreseen reduction in absolute poverty in China and India.For Sub-Saharan Africa, projected dates for reaching three key targets – eliminating hunger,reducing poverty and improving sanitation - cannot be established, because the situation in theregion is not just stagnant but worsening.6Calculations show that in order to achieve the income MDG, GNI growth must increase to 7%or more in most African countries7On the basis of current trends, only a handful of countries56

Measured by halving, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day.Human Development Report, 2004,UNDP

13

in sub-Saharan African are likely to achieve their income poverty MDG, though with markeddifferences among the countries. Hence, Guinea-Bissau requires an annual growth rate percapita of 11.7%, while the figure for Benin is only 0.8% In addition to Benin, the required percapita growth rate is less than 2% for Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique and Uganda andbetween 2% and 2.5% for South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire and Namibia. Finally, among countriesrequiring growth rates of more than 8% are Liberia, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republicof Congo.The figures indicate that while all the African states may not reach the MDGs, some countriesmay reach some of them. With the current policies, institutions, and external resources, only 3-4 countries may reach some or all the targets under the poverty reduction goal. With improvedpolicies, institutions and additional external resources, however, a limited number of countries -- representing approx. 15 percent of Africa’s population - may reach not only the poverty goal,but also one or more of the targets within the education, health and environment goals.8Experts insist that much better results can be ensured with increased and improved assistance.On the question of MDG 8 – Establishing a Global Partnership - some scholars9argue that anadditional transfer of official development assistance (ODA), combined with placing theMDGs at the centre of all national and international poverty reduction strategies would make itpossible for Africa to reach the MDGs by 2015. The required level of ODA geared towards theMDGs and assuming a particular focus on Africa would thus be around USD 125-140 billion(equivalent to 0.5-0.6% of donor countries’ GNP), about twice that of the present USD 58billion (0.23%) This figure is well within the UN target of 0.7%, but still well above the EUcountries 2002 collective target of 0.39% in 2006.It is undoubtedly true that the prospects of achieving some of the MDGs in Africa willimprove with increased ODA. However, increased funds in itself is not sufficient. Equallyimportant are the quality of aid and a co-ordinated and harmonised approach to aid, improvedrelevance of short- and long-term national policies and enhanced effectiveness inimplementation. Violent conflicts are major constraints in the pursuit of MDGs. Conflictsinevitably lead to destruction of infrastructure, and decline in economic growth and in socialinfrastructure. Many of those countries that have the bleakest prospects have been affected byarmed conflict in recent years (e.g. Sudan10, Liberia, Somalia and Sierra Leone). The burdensdue to large numbers of refugees or internally displaced people also make it more difficult toreach the MDGs.

Based on UNIDO Industrial Development Report 2004, p. 40 (the calculation of the required growth rate is based onpoverty head count in 1999 assuming unchanged income distribution). Considering the high increase in population in mostcountries this will be equivalent to annualper capitagrowth rates of 4-5%.8Development Committee, joint WB and IMF;Global Monitoring Report 2004.9For example Jeffrey Sachs in Draft versions of “Millennium Project, Summary of a Global Plan to achieve the MDGs”,OECD-DAC, July 200410Sudan is understood to have untapped oil reserves of a magnitude that could provide the economic development neededto lift the country out of poverty (Bannon, Ian & Collier, Paul (2003): Natural Resources and Violent Conflict, The WorldBank).7

14

MDGs are but goals or targets to be met. They do not offer strategies to achieve the goals.Poverty Reductions Strategies and national sector policies represent attempts to formulatespecific strategies.

2.5 Poverty Reduction Strategies as a way forward?In most African countries, a comprehensive reform process took place during the 1980s andearly 1990s, strongly directed by the World Bank and IMF. The reform had a unilateral focuson liberalisation, privatisation and macro-economic stability. After an intense dialogue in themid-1990s with major donors, including the Nordic countries, the World Bank responded tocriticism of the structural adjustments policies by adopting a much stronger emphasis on socialaspects of development and governance, leading to a stronger focus on poverty reduction. Itwas also recognised that imposing the same global formula on countries with very differentconditions and possibilities did not lead to the expected results in terms of reduced poverty.This refocusing process led to the introduction of the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paperconcept, which emphasise national ownership and diversified strategies, as well as on means ofachieving measurable impact on poverty and social development.Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) has become central to the provision of developmentassistance. They were introduced by the World Bank and IMF as a condition for obtaining debtrelief under HIPC II11(1999) and were based on the idea of linking aid flows to thedevelopment of comprehensive poverty reduction strategies by the recipient countriesthemselves.Despite the fact that PRSPs were originally donor-driven, the intention has been to establishnationally-formulated strategies where ownership of the national planning and budget prioritiesand subsequent monitoring is vested in the national government, in close consultations withcivil society and the private sector. The PRSP concept evolved as a response to lessons learntwith previous (World Bank and IMF) experiences and mistakes. Evaluations had pointed to atendency to undermine national capacity by creating parallel systems and by imposing policyconditionalities; however, conditionalities did not succeed in generating more effective use ofresources. Furthermore, the PRSP approach was guided by the recognised need to refocusdevelopment assistance more firmly towards poverty reduction rather than focusing only onmacro-economic stability, privatisation and conditions for economic growth.

11

The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, launched by the World Bank and the IMF in 1996, is the mostcomprehensive international response to provide debt relief to the world’s poorest, most heavily indebted countries. It seeksto cut external debt to a sustainable level. HIPC II was an expanded initiative.

15

The core principles for the PRSP approach are:-results orientation,with monitoring targets for poverty reduction;-comprehensiveness,via integration of macroeconomic, sectoral, social and structuralelements;-country-drivenprocess;-participatory process,including all major stakeholders in planning as well as inmonitoring;-partnershipsbetween government and other actors/donors;-long termperspective, with focus on reforming institutions and building capacity.

While the PRSPs and the MDGs have much in common and are mutually reinforcing, they areconceptually different entities. The importance ofcountry ownershipin PRSPs is crucial. Theownership approach allows for strategic choices that fit the specific national situation, whereasthe MDGs have the character ofglobalisedand aggregated goals and targets, which have to bemet with whatever means or strategies are available.Typical elements in PRSPs include infrastructure development, improving governance, and anenabling environment for private sector development and diversification of production. Theseelements may not themselves impact directly on the MDGs in the short run, but they may setthe stage for long-term development, reaching further than 2015 and the MDGs.By May 2004, a total of 19 countries in Africa had produced first-generation PRSPs, and someare already refining them into second-generation PRSPs based on the experiences from the firstthree years.While it is still too early to draw definite conclusions about the PRSP experience, two recentevaluations12indicate that a considerable challenge remains for many countries to link PRSPs tothe rolling national Medium-Term Expenditure Frameworks (MTEF) and budgets. PRPSs arecriticised for not adequately addressing the need for macro-economic planning and for lackingfeasible policies to implement. Related to this is the need for greater prioritisation of genderequality in PRSPs, not least the need for increasing the allocation of resources to interventionspromoting gender equality in national budgets. Mainstreaming of gender equality has potentialfor improving the efficiency of poverty reduction. Screening of first generation PRSPs alsorevealed general weak information of environment13and environmental health issues14. Thestrong links between poverty, environment and health justify a stronger focus on the need forThe Poverty Reduction Strategy Initiative, An Independent Evaluation of the World Bank support through 2003; WorldBank 2004 and Report on the Evaluation of Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) and the Poverty Reduction andgrowth Facility (PRGF), IMF, 2004.13Bojö and Reddy 2001, 200314WHO 200412

16

better integration of environment and health concerns in pro-poor development planning.Consultation processes prior to the formalisation or revision of PRSPs reveal that there isscope for improvement, and that not all interested parties have ownership of the strategies. Onthe positive side, however, the evaluation points out that most donors have agreed that thePRSPs should be the focal point around which they will administer their developmentcooperation, based on the principles of partnership, ownership, harmonisation and alignment.While implementation of the strategies may take some time, they are expected to improve theeffectiveness and impact of government policies on long-term development, increase value formoney, and contribute to poverty reduction.

2.6 The Danish contribution to poverty reductionDanish development cooperation has always had a strong emphasis on poverty alleviation, butthe modalities and criteria for cooperation have changed with the lessons learned during thepast 40 years. In bilateral cooperation activities, focus on poverty reduction has been enhancedwithin the broader approaches to development, and isolated, short-term projects have nowgiven way to a more comprehensive, long-term commitment to sector support with focus onpolicy and institutional development. In its multilateral cooperation, Denmark has played anactive role in placing poverty reduction on the international agenda, including more recently inthe dialogue with the World Bank on PRSP. The donor-recipient relation has changed topartnership cooperation based on principles of national ownership of and responsibility fordevelopment plans. Focus has moved to supporting effective policies, good governance andcreating conducive environments for development. Efforts have been made to achieveimproved quality of development assistance through better coordination and harmonisationbetween donors and alignment of the cooperation with the national development plans,priorities and systems.Danish development cooperation now concentrates on a limited number of programmecountries instead of the previous approach of spreading project assistance to a large number ofcountries. In order to improve effectiveness and efficiency, the 60 ‘recipient countries’ forDanish bilateral assistance was reduced in the mid-1990s to 20 ‘main recipient countries’, 11 ofwhich were in Sub-Saharan Africa. Subsequently, the number of ‘programme countries’ hasbeen further reduced to 15. Presently, Denmark cooperates with eight programme countries inSub-Saharan Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda andZambia) and has some development activities with another two countries (South Africa andNiger). A main purpose of concentrating bilateral development assistance on a limited numberof partner countries is to achieve “critical mass” as a donor, allowing Denmark to play a majorrole in local donor coordination and harmonisation effects.A basic characteristic of the programme countries is that they (seen in the African context) arerelatively good performers in terms of sound sector policies, a more or less holistic povertyapproach and in their movement towards stable macro-economic and political frameworks.1515

The selection of programme countries was based on seven criteria adopted by the Danish Parliament in 1989 with broadpolitical backing. The criteria that still remain are: 1) Assessment of the level of economic and social development,

17

The 1990s saw the emergence of the concepts of Sector Programme Support (SPS) and SectorWide Approach (SWAp). Denmark was among the first donors to adopt this approach, whichremains the basis for Danish bilateral development cooperation. The cooperation builds onpartnerships focusing on three pillars: cooperation in social sectors/human capital; investmentin conditions for equitable, economic growth; and interventions to achieve good governance.During this period, the understanding of the gender dimension also developed, and theapproach changed from ‘remember to help the women’ to an appreciation that thedevelopment process would fail without proper understanding of gender relations andinvolvement of both men and women.The goals for Danish development assistance are set out in ’Partnership 2000’, a policydocument endorsed in October 2000 by a broad majority of the Danish Parliament.PARTNERSHIP 2000Poverty reduction is the overriding objective of Danish development policy. Denmark willcontribute to reducing poverty in the world through long-term and binding partnerships withdeveloping countries. The objective of these partnerships is to strengthen the ability of thedeveloping countries to create sustainable development processes that will benefit the poor.Denmark will base its development cooperation on partners whose policies and activities createthe necessary conditions for poverty reduction for the many rather than prosperity for a narrowelite.Partnership 2000 establishes the political foundation for Denmark’s development policy,emphasising that reduction of poverty through long-term and binding partnerships remains thefocus of Danish development cooperation.In recent years, the importance of harmonisation of donor procedures and alignment ofinterventions with national strategic frameworks and procedures has gained momentum.Several partner countries have developed first- or second-generation PRSPs, and alignment anddonor harmonisation now constitute core pillars of Danish bilateral and multilateraldevelopment cooperation. The experience with this approach has so far been very positive inseveral countries, including Tanzania, Uganda, Ghana, Mozambique and Zambia. In Zambia,for instance, a common framework with explicit commitments is changing the relationshipbetween the Zambia government and its development partners. One initiative – on the donordevelopment needs and the country’s own development plans; 2) Assessment of the total donor assistance and the capacityto absorb and make good use of the assistance; 3) Possibility of improving sustainable development through dialogue withthe country; 4) Possibility of cooperating with the country with a view to enhancing respect for human rights in accordancewith the international standards and conventions; 5) Possibility of cooperating with the country in ensuring that genderaspects are fully integrated and centrally placed in the development process; 6) Assessment of previous experience frombilateral development cooperation between Denmark and the country; and 7) Provided the six foregoing criteria arepositively met – the possibility for Danish private sector participation in the development cooperation.

18

side lead by Denmark - is the preparation of a joint assistance strategy, which will be completedin 2005. Under Zambia guidance, cooperation between partners is thus expected to make aidmore effective and cut transaction costs.While many so-called ‘like-minded’ donors (including the UK, the Netherlands, Sweden, andNorway) have moved very rapidly towards the provision of general budget support, Denmarkhas so far been more hesitant, particularly regarding general budget support (not earmarked to aparticular sector). Budget support implies the provision of funds channelled through andadministered as part of the national budget, in accordance with the national poverty reductionpolicy and usually based on well-defined conditions. Budget support facilitates economicmanagement and reduces partner transaction costs. Apart from increasing national ownership,budget support enhances the predictability of funds, being that clear benchmarks ‘trigger’ anagreed (and usually significant) amount of funds within specified time frames. Being thatexternal funding is very important when African countries plan and budget, predictability ismost vital, not least in terms of enhancing poverty-reducing efforts. Budget support, however,also entails a reduction of the control formerly possessed by donors and the ability to trackindividual donor’s funds, thus minimising the possibility of documenting the direct outcome ofindividual donors’ support. Danish assistance acknowledges the many benefits of budgetsupport, but in order to keep risks (especially ‘fiduciary risks’) at an acceptable level, the extentof Danish development assistance provided in the form of budget support does not usuallyexceed 20-25% of the country programme. The level of budget support is generally determinedbased on the country’s financial management, track record of implementing ‘good policies’,reliability in meeting targets and so forth.It remains a challenge for Danish development cooperation to improve alignment andharmonisation by ensuring that all assistance is reflected in the national budget, is managed bypartners and not by Danish-controlled parallel or semi-parallel structures, and is coordinatedwith other donors based on national strategic frameworks.Because of the multifaceted nature of the challenges in sub-Saharan Africa, a holistic andcoherent approach is required that combines foreign and development policies, multi- andbilateral assistance, trade policy and security policy, and also emphasis on the environmentaldimension.

3.

The African economy – the challenge of generating growth

Despite the variety of their situations, the economies of African countries share many structuralfeatures: they depend on the production and export of a limited number of primarycommodities while being compelled to import most manufactured goods. Their agriculturalsectors constitute the largest part of the private sector, with agriculture accounting for morethan 50% of GDP, over 50% of export earnings, and employing over 70% of the workforce.The informal sector of Africa’s economies is substantial (often about or more than 50% ofregistered GDP), and encompasses both a large share of the agricultural activities, micro-enterprises and self-employment in urban centres.

19

Economic policies have changed markedly since the initiation of structural adjustment policiesin the mid-1980s. The attempts to ‘roll back the state’ through liberalisation of prices,abolishing many government parastatals and reduction of the public sector have had bothpositive and negative impact on conditions for production and trade: while the reduction ofbureaucratic obstacles to agricultural production and marketing has benefited the majority ofagricultural smallholders, the public sector in many countries has at the same time beenweakened to such an extent that it is unable to provide even the most basic services.Around three-fourths of Africans live in the countryside. The urban areas are home to theAfrican elite, the middle class, and the urban poor. The latter group is by far the largest andfastest growing due to significant and accelerated migration from the rural areas.

3.1 Economic GrowthEconomic growth is crucial to the reduction of poverty in Africa. The existing empiricalevidence confirms that economic growth generally leads to a decrease in the number of peopleliving on less than one dollar per day. In this sense “growth is good for the poor”. However,the pattern of growth also matters a great deal, and the actual impact on the poor variesconsiderably depending on circumstances and context. Well-designedpro-poor policiescan do alot to ensure that social and economic indicators for the most disadvantaged groups improvemore rapidly than for the rest of the population.16In Sub-Saharan Africa, the average per capita income declined by 1.9% in the 1980s and by0.2% in the 1990s. The early 2000s show a slight improvement, but as indicated in thediscussion of the MDGs in Chapter 2, for the majority of the countries, even the most recentgrowth rates are still too low to reduce the number of extremely poor.3.1.1 Agriculture as basis for growthThe agricultural sector constitutes the economic backbone of most African countries, and thissector will remain the mainstay of pro-poor economic growth benefiting Africa’s poor.17Smallholders with land sizes usually not exceeding 1 hectare dominate the sector, which alsoincludes livestock holders, small-scale agricultural processing enterprises and marketing actors.Increased agricultural production is necessary to fight starvation and malnutrition. Most poorpeople live in the countryside, and experience from high-performing economies shows thatrapid growth in agricultural production and productivity is a precondition for economic take-Hunberto Lopez, ’Pro-Growth, pro-poor: Is there a trade off?’, World Bank, draft manuscript. Lopez argues that in thelong run, pro-growth policies, regardless of their impact on inequality, are likely to be pro-poor.17Recent research and policy initiatives have identified pro-poor growth as the most important ingredient to achievesustainable poverty reduction. The MDGs emphasize the importance of pro-poor growth. However, it is often unclear whatpro-poor growth means and how it should be monitored. One definition is that the poor should benefit disproportionatelyfrom economic growth, such that social and economic indicators should improve faster for the poorer relative to the rest ofa country’s citizen. It should also have a focus on both agriculture and non-farm rural growth, since the majority of the poorlive in rural areas.16

20

off and sustained poverty reduction. Agricultural production is also critical since agriculturalprogress generates local demand for other goods and services. It is generally agreed that forevery dollar income goes up in the agriculture sector total income in society goes up by around2.5 US$, and agriculture will have to underpin the export performance of African countries foryears to come.Historically, agricultural policies in Africa have tended to encourage the production of cashcrops for export, while local food crop prices have been kept low to avoid protests from theurban population. At times, conditions for marketing agricultural products have been sodifficult that farmers have tended to produce mainly for their own consumption. Although thishas changed with the economic reforms in the 1980s, serious obstacles to increased agriculturalproduction remain. Free trade can give many advantages, but free trade in itself cannot solvethe many problems faced by poor farmers. These problems include insufficient access toagricultural inputs, poorly developed physical and marketing infrastructure, the virtualabolishment of agricultural extension services in many countries, poorly developed agriculturalresearch, limited access to agricultural credits, limited access to information on national andinternational commodity prices, and competition from subsidised products exported by richcountries. Low productivity levels are a further impediment to higher growth. In somecountries, land tenure issues, soil degradation, deficiency of water for irrigation, drought, andincreasing lack of fuel wood add to the problems. Increasing production is therefore not simplya matter of liberalisation and free trade. It is as well about overcoming a myriad of supply sideconstraints. Moreover, many African governments are challenged to consider agriculture part ofthe business sector and to see farmers as potential investors, who – like any other businesssector actor – have to balance their goal of increasing income with that of spreading the risks.A particular problem is faced by the livestock sector, which has a substantial developmentpotential in Africa. Agricultural development policies (both national policies and donorapproaches) tend to focus on crop production – even in arid and semi-arid areas, where cropproduction is difficult, expensive and unsustainable. The economic development potential oftraditional African pastoralism is even more neglected. While pastoralism suffers from negativestereotyping and is often perceived as primitive, non-productive and environmentallydestructive, research shows that pastoralism is in fact productive and contributes significantlyto national economies.In addition to increasing the volume of agricultural production, it is important thatopportunities exist for diversification of incomes for the rural population. Small-scalemanufacturing activities, in agro-processing for example, may contribute to raising ruralincomes, while the existence of various forms of wage labour (e.g. related to marketing andtransport activities) is important. Even small amounts of purchasing power among the poorwill, as already highlighted, create the markets necessary to attract investments and improve theservice sector. This could contribute to a reversal of the vicious circle of indebtedness in whichmany African farmers are presently trapped.Improved organisation of farmers is necessary in order to strengthen their influence on theconditions for their livelihood. Although the rural population make up about three-quarters of

21

the population in most African countries, only few examples exist of farmers (or pastoralists)able to mount an effective lobby. They have been too scattered, badly organised and too poorto place the important challenges to the agricultural sector on the national political agenda.Attempts to organise themselves into co-operatives have often been frustrated by excessivegovernment controls.3.1.2 Private sector developmentAlthough agriculture is part of the private sector, the concept is often used to refer to non-agricultural activities in urban areas only. This is unfortunate. It is encouraging that Africanleaders now agree that private sector-led growth is fundamental for improving the welfare ofthe people. These leaders are making serious efforts to create an enabling environment for theprivate sector. However, few African countries have so far managed to transform the goodpolitical intentions into sustainable changes on the ground. Authoritarian and centralisttraditions are difficult to break, and poor governance, lack of effective property rights;ineffective judicial systems; high interest rates; red tape and corruption all pose seriousobstacles to the development of a vibrant private sector in Africa.Lack of effective property rights and registration means that very few individuals can prove thatthey actually own their land and houses – they do not have a title deed. Without a reliablesystem for ascertaining who owns what, assets cannot be used as collateral. Ineffective judicialsystems make it both expensive and time consuming to enforce even simple commercialcontracts. Commercial laws are rudimentary and not geared to a modern market economy andeven less so to an international business environment.Employees are often subject to adverse working conditions such as low salaries, unhealthy ordangerous working environments, oppression of labour organisation and the like. Labourmarket organisations and branch and producer associations are still relatively weak, and thuslimited in raising political attention for these issues, although their influence is increasing. InSouth Africa, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe, e.g., they are active in raising issuespolitically.Poor physical infrastructure and transport logistics create high costs and uncertainties for bothdomestic and export oriented economic entities. Transport and insurance costs are in generalvery high in Africa compared to other areas of the world. Africa has lower labour productivityeven compared to other developing countries. Poor physical infrastructure and heavy burden ofdisease among the workforce lead to high real labour costs for companies, thereby eroding theircomparative advantage in cheap labour. Inadequate skills lead to a pervasive need forexpatriates in technical and administrative positions. Other areas such as vocational training andinternet access also pose a challenge.Africa’s private sector also faces a number of challenges from beyond Africa’s borders. Theinternational environment for business has become more volatile, more competitive, and morecomplex as globalisation proceeds. Success is more difficult to achieve, and failure harder toavoid for companies from all over the world, but most companies outside Africa have thebenefit of better conditions in their home markets. Africa’s private sector must confront the

22

same hurdles, often without the benefit of a stable and supportive business environment athome. A successful outcome of the Doha development round of trade negotiations and aglobal reduction in trade barriers will mean an erosion of the trade preferences of many Africancountries, thus actually increasing their competition on the world market (cf. 3.2.4).The informal sector, accounting for about than 50% of registered GDP in African economies,constitutes a particular challenge to private sector development. Characterised by an abundanceof micro-enterprises and extensive self-employment in the cities, the informal sector has beenrobust because of the high costs of formalisation associated with taxes and regulatorycompliance and because of the relative ease of operating informally. Although the informalsector has served as a safety valve for African countries in terms of employment and incomegeneration, these countries need the efficiencies and institutional capacity of formal sectorcompanies to bring their private sector into the global economy.3.1.3 HIV/AIDS as barriers to economic development in AfricaThe HIV/AIDS pandemic (ref. Section 5.3) represents a major threat to economicdevelopment in Africa. Early estimates of the macroeconomic effect of HIV/AIDS18assertedthat African economies would sustain the initial loss from HIV/AIDS due to the perceivedready supply of surplus labour and an assumption that AIDS mortality was concentratedamong the low-productive poorer segments of the populations. Although no agreed method ofmodelling the macroeconomic costs of HIV/AIDS exists, recent attempts to calculate the costshave estimated the HIV/AIDS related reduction in the growth rate of GDP to range between0,3 and 1,5 percent. Although this appears modest it will translate into larger effects over time.One analysis (Arndt19) finds that the GDP of Mozambique in the absence of policyinterventions will be 23% smaller in 2010 due to HIV/AIDS, while another (Cuddington andHancock20) estimate that the AIDS related cumulative loss of GDP in Malawi would be around10% in 2010. This type of analysis does not, however, take into account the above-mentionedlong-term cumulative effects, leading Bell et al.21to predict that the long-run effects ofHIV/AIDS will be much larger – possibly ending in economic collapse.

3.2 TradeAs discussed in relation to the MDGs (Chapter 2), the position of most African countries vis-à-vis non-African countries, measured by the size of their economy, share of world trade,investment, power and influence, continues to decline – at least in the formal sector.

Bloom, D.E and Mahal, A.S (1997) Does the AIDS Epidemic Threaten Economic Growth? Journal of Econometrics, 77:105-12419Arndt, C. (2002) HIV/AIDS and Macroeconomic Prospects for Mozambique, An Initial Assessment, TMD DiscussionPaper no. 88 Trade and Macroeconomic Division, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D.C.20Cudddington, J.T and Hancock, J.D (1994) Assessing the Impact of AIDS on the growth pat of the Malawian economy,Journal of Development Economics vol. 43, no. 2, pp 363-368.21Bell, C., Devarakan, S. and Gersbach. H (2003) The long-run economic costs of AIDS: theory and an application to SouthAfrica, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series no. 3152, World Bank, Washington D.C.18

23

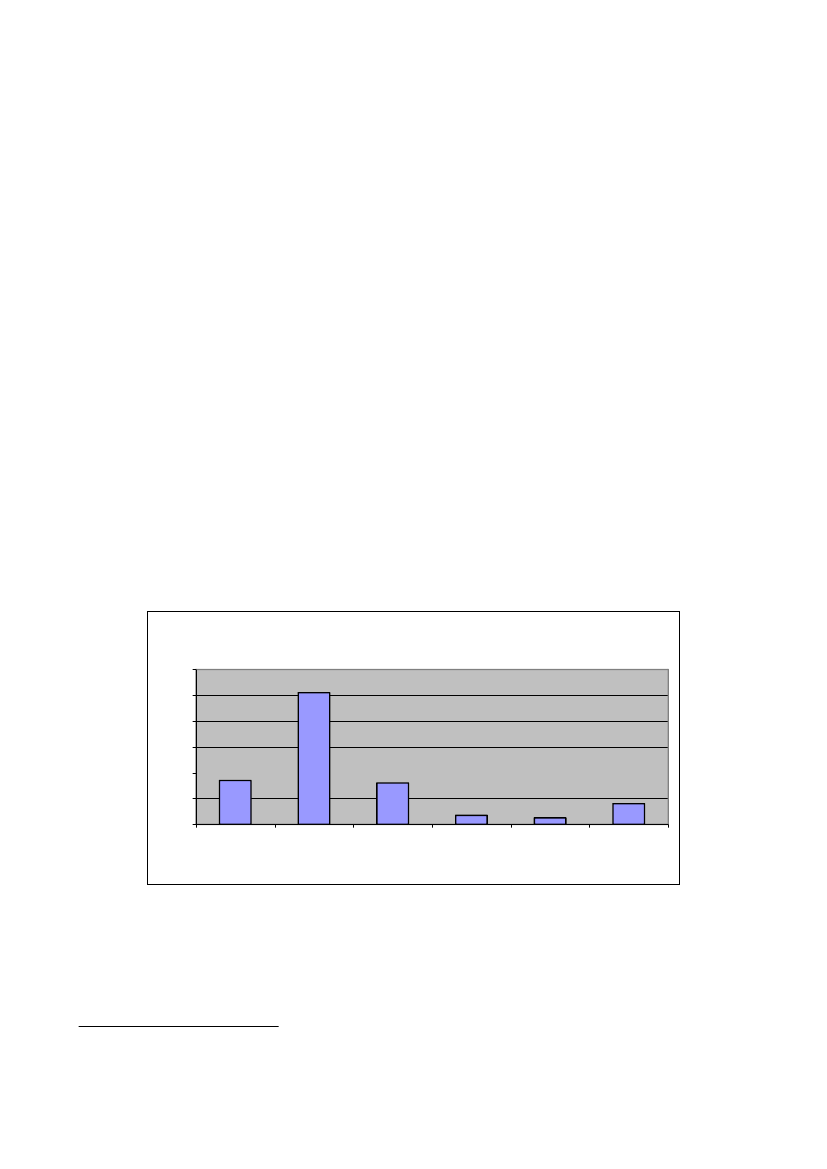

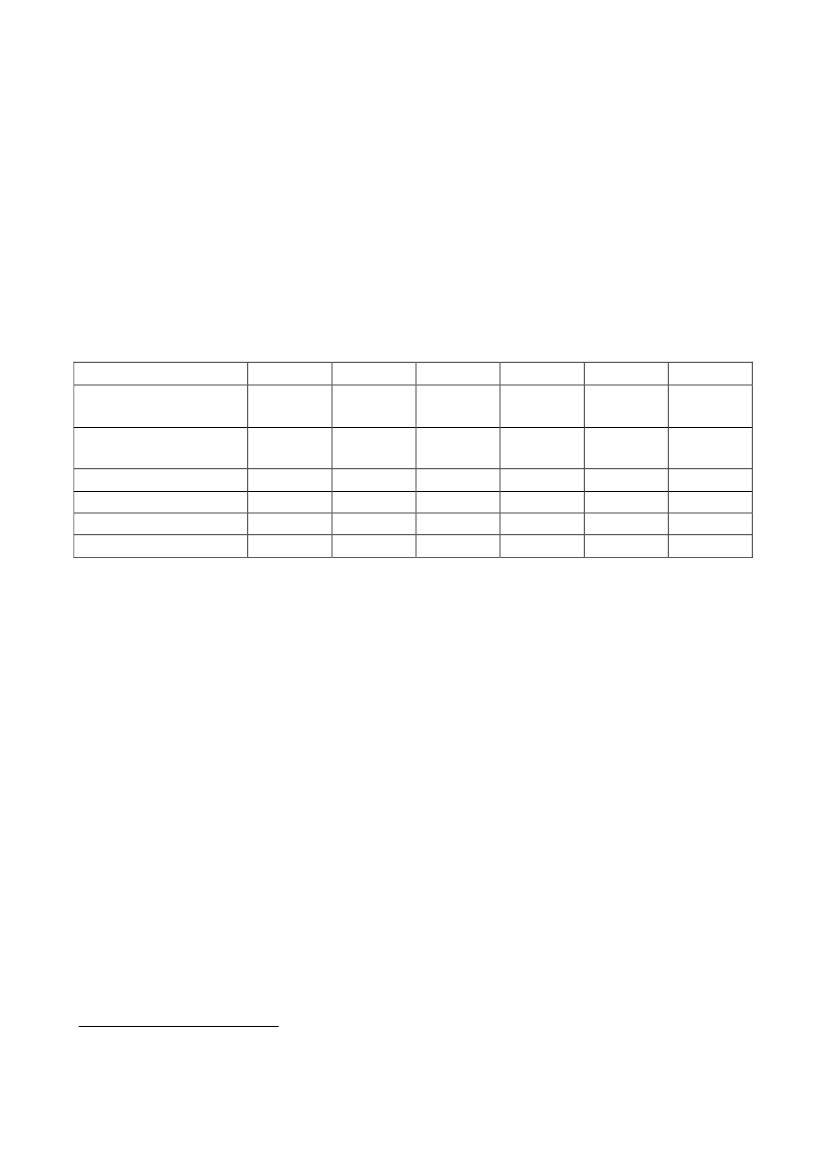

Many observers believe, however, that globalisation offers African states and their citizens animportant opportunity to undertake the economic and political reforms necessary for economicgrowth, democratic development and improvement in overall living and working conditions ofthe people. To seize this opportunity requires effective leadership, additional input of resourcesand management by both the private and public sector working together at all levels of society;international assistance to develop capacity; and improved access for African products to themarkets of the developed countries.International experience suggests that outward-looking countries tend to grow faster thancountries with more closed economies. Although it is difficult to compare conditions forexport-oriented countries in Asia to those of African countries trying to increase theirintegration into the global economy, it is notable that the Asian countries in question haveachieved higher growth rates, longer life expectancy and better schooling. They have alsoexperienced rising wages and declining numbers of people in poverty, thereby improving theirposition to achieve the MDGs. Countries unable to integrate into the world economy face aserious risk of being left behind. However, it is equally true that free trade is not sufficient toturn present trends around, and in some cases can even make things worse. Outward orientedpolicies require good and well-designed supplementary actions on the supply side, andimproved coherence in the trade and aid policies of the international donor community.3.2.1 The EU: Africa’s largest trading partnerEurope counts for about half of Africa’s exports (see figure 1). Exports to North America arebelow 20%, roughly the same as to Asia.Fig. 1: Destination of Africa's Exports (2002)605040

%3020100N/AmericaW/EuropeAsiaLA&Carib.M/EastAfrica

Region

The Cotonou Agreement, signed in Cotonou in 2000, regulates trade between the EU andAfrica22. The main objective of the Agreement is to promote the progressive integration of theAfrican countries into the global economy by enhancing production and capacity to attractinvestment and by ensuring conformity with WTO rules. In March 2001, the trade regulations22

The Cotonou Agreement replaced the Lomé Conventions (I-IV, 1975-1999).

24

of the EU’s General System of Preferences were supplemented by the so-called Everything ButArms (EBA) arrangement, which allows all least developed countries (LDCs of which 34 are inAfrica23) to export duty- and quota free to the EU all products other than arms. However, theremoval of restrictions for bananas has been deferred to 2006 and for sugar and rice to 2009.During the intervening period, progressive tariff cuts will be carried out for all three products,and access to tariff-free quotas for sugar and rice will be increased. The impact of the EBA forthe African LDCs has so far been limited, mainly because these countries already enjoyedpreferential access to the EU, but also because of the serious supply-side constraints within theLDCs to increase the volume of their production of exportable goods. The African LDCs,thus, have generally been unable to make use of the free market access provided by the EBA.According to the Cotonou Agreement, the future trade relations between the EU and Africawill be regulated by a series of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) under which the EUand regional groupings of African countries (including non-LDCs) offer reciprocal tradepreferences to each other. South Africa already has an EPA. The detailed negotiations withother African countries are likely to begin next year, as EPAs are expected to come into effectaround 2007. From the EU perspective, the EPAs should also aim to increase intra-regionaltrade in Africa (cf. 3.2.3)3.2.2 Africa’s trade with the United StatesIn 2000, the US Congress passed the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), whichprovide duty free access to US markets for those products originating from African countries.The eligibility to AGOA’s duty free access, however, is not without conditions. To qualify, theAfrican countries must demonstrate that they are making progress towards the establishment of(i) market-based economies, (ii) the rule of law and political pluralism, (iii) elimination ofbarriers to US trade and investment, (iv) protection of intellectual property, (v) efforts tocombat corruption, (vi) policies to reduce poverty, (vii) increasing availability of health care andeducational opportunities, (viii) protection of human rights and workers’ rights and, (ix)elimination of certain child labour practises. In January 2003, the US announced that 38 Africancountries have qualified for preferential treatment under AGOA.3.2.3 Intra-African TradeOne of the key characteristics of trade links within Africa is the low level of intra-regional trade.In 2001, only 5.4% of exports and 3.8% of imports within the 20 countries that are members ofCOMESA24came from COMESA. Trade with the rest of Africa is also remarkably low.

23Least Developed Countries (LDCs) are countries that fulfil a) low-income criterion (3-yr. average estimate of GDP per

capita; under $750 for inclusion, above $900 for graduation); b) a human resource weakness criterion based on indicators ofnutrition, health, education and adult literacy; and 3) economic vulnerability criterion based on indicators relating to amongothers agricultural production, exports, economic importance of non-traditional and economic smallness. All but two of theeight Danish partner countries in Africa (Ghana and Kenya) are classified as LDCs.

24

COMESA (Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa) is made up of Kenya, Uganda, Egypt, Sudan, Swaziland,Namibia, Angola, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Mauritius, Seychelles and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

25

The low trade flows between African countries reflect the structure of production characterisedby concentration of exports in a few unprocessed commodities exported to internationalmarkets. In many instances African companies and farmers are competing for the same marketswith identical commodities. Low levels of intra-African trade are also due to poor quality ofinfrastructure and financial linkages in Africa, as well as restrictions on trade and exchangeregimes adopted by most of the countries in previous decades. Moreover, high tariffprotections, restrictive import licensing requirements, notoriously slow and costly customsprocedures and other restrictive non-tariff barriers have limited the scope of intra-African tradein the past.The level of intra-African trade has been increasing, albeit very slowly. There has been asubstantial reduction in tariffs for African goods traded within Africa. Yet, unless themultitudes of non-tariff barriers that the countries currently impose on each other are seriouslytackled, significant increases in regional trade flows are unlikely to emerge. There is an urgentneed to remove border barriers, which implies streamlining customs procedures, harmonisingcustoms documentation and certificates of origin and establishing a well-functioning singletransit-transport regime. These reforms are costly and will therefore require a strong politicalcommitment on the part of the African leaders – a commitment that has been lacking in thepast. Indeed, most of the regional trading agreements in Africa have not been really effective inadvancing regional integration and promoting trade because ultimately, despite the rhetoric,countries were not always fully committed to the regional agendas. Implementation of treatieshas been sluggish at best and simply non-existent in some cases. Lack of commitment alsoexplains why most countries belong to more than one regional trading agreement. In thiscontext, there definitely seems to be too many – and too inefficient – regional integrationinstitutions in Africa.3.2.4 Africa, the WTO and the Doha AgendaThe WTO’s key mandate is to manage the liberalisation of world trade. One of the mainprinciples of the WTO is to serve as a forum for negotiation of a development-oriented globaltrade regime that can better serve the interests of the poorest nations. These negotiations arecurrently conducted within the framework of the Doha Development Round. The impasse atthe ministerial conference in Cancun, in November 2003, was a setback for the WTO. Eventhough the WTO succeeded in reaching the major goal set for Cancun by establishing anegotiating framework in July 2004, substantial negotiations in the Doha Round are not likelyto recommence in practice before the beginning of 2005.The main focus of the negotiations is on significantly reducing (and in some cases eventuallyremoving) tariffs and non-tariff barriers. However, liberalisation of markets erodes thepreferences given to a favoured country or group of countries. The poorest countries in Africahave favourable trade agreements with the EU and the US, two of Africa’s biggest tradingpartners. An erosion of these preferences is likely to result in loss of African market shares tomiddle income and developing countries in South Asia and Latin America. For example, theclothing industry is regularly seen as a starting point for accelerated industrialisation in Africa.The poorest African countries have enjoyed a quota-free entry for their textile products to theUS and EU through special agreements, while other major textile exporters such as China,

26